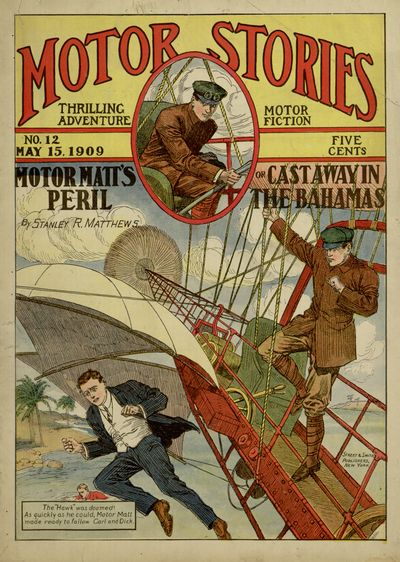

Title: Motor Matt's Peril; or, Cast Away in the Bahamas

Author: Stanley R. Matthews

Release date: March 3, 2015 [eBook #48402]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by David Edwards, Demian Katz, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Villanova University Digital Library (http://digital.library.villanova.edu/)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Motor Matt's Peril, or, Cast Away in the Bahamas, by Stanley R. Matthews

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Villanova University Digital Library. See http://digital.library.villanova.edu/Record/vudl:308331 |

|

THRILLING ADVENTURE |

MOTOR FICTION |

|

NO. 12 MAY 15, 1909. |

FIVE CENTS |

|

MOTOR MATT'S PERIL |

or CASTAWAY IN THE BAHAMAS |

|

By Stanley R. Matthews |

Street & Smith, Publishers, New York. |

| MOTOR STORIES | |

| THRILLING ADVENTURE | MOTOR FICTION |

Issued Weekly. By subscription $2.50 per year. Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1909, in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, Washington, D. C., by Street & Smith, 79-89 Seventh Avenue, New York, N. Y.

| No. 12. | NEW YORK, May 15, 1909. | Price Five Cents. |

MOTOR MATT'S PERIL

OR,

Cast Away in the Bahamas.

By the author of "MOTOR MATT."

CHAPTER I. CARL AS BUTTINSKY.

CHAPTER II. THE MOVING-PICTURE MAN MAKES A QUEER MOVE.

CHAPTER III. WARM WORK AT THE "INLET."

CHAPTER IV. PRISONERS ON A SUBMARINE.

CHAPTER V. THROUGH THE TORPEDO TUBE.

CHAPTER VI. THE CAPE TOWN MYSTERY.

CHAPTER VII. OFF FOR THE BAHAMAS.

CHAPTER VIII. AN ACCIDENT.

CHAPTER IX. MATT AND HIS CHUMS GO IT ALONE.

CHAPTER X. THE AIR SHIP SPRINGS A LEAK.

CHAPTER XI. WRECKED!

CHAPTER XII. LUCK—OR ILL-LUCK?

CHAPTER XIII. A MOVE AND A COUNTERMOVE.

CHAPTER XIV. MOTOR MATT'S SUCCESS.

CHAPTER XV. A FEW SURPRISES.

CHAPTER XVI. MATT TAKES TOWNSEND'S ADVICE.

NIGHT WATCHES FOR BIG GAME.

SPECIALISTS IN THE WOODS.

MISSOURI WILLOW FARM.

ANIMALS THAT DREAD RAIN.

Matt King, concerning whom there has always been a mystery—a lad of splendid athletic abilities, and never-failing nerve, who has won for himself, among the boys of the Western town, the popular name of "Mile-a-minute Matt."

Carl Pretzel, a cheerful and rollicking German lad, who is led by a fortunate accident to hook up with Motor Matt in double harness.

Dick Ferral, a Canadian boy who has served his time in the King's navy, and bobs up in the States where he falls into plots and counterplots, and comes near losing his life.

Archibald Townsend, otherwise "Captain Nemo, Jr.," of the submarine boat Grampus, who proves himself a firm friend of Motor Matt.

Lattimer Jurgens, an unscrupulous person who, for some time, has been at daggers drawn with Archibald Townsend.

Whistler, an able lieutenant of Lat Jurgens.

Cassidy, Burke and Harris, comprising the crew of the Grampus.

"The Man from Cape Town," who does not appear in the story but whose influence is nevertheless made manifest.

McMillan and Holcomb, police officers.

CARL AS BUTTINSKY.

"Py shinks, aber dot's funny! Dose fellers look like dey vas birates, or some odder scalawags. Vat vas dey doing, anyvays, in a blace like dis?"

It was on the beach at Atlantic City, New Jersey. Carl Pretzel was there, in a bathing suit.

Those who know the Dutch boy will remember that he was fat, and there is always something humorous about a fat person in a bathing suit.

Carl had been in the water. After swimming out as far as the end of the steel pier, he had returned and climbed up on the beach. An Italian happened to be passing with a pushcart loaded with "red-hots" and buns. Carl had a dime pinned in the breast of his abbreviated costume. He unpinned the dime, bought two "red-hots" and a bun, and fell down in the sand to rest and enjoy himself. The Italian lingered near him, staring with bulging eyes to a place on the beach a little way beyond Carl. The Dutch boy, observing the trend of the Italian's curiosity, looked in the same direction.

A girl was kneeling on the beach, tossing her arms despairingly. She was a pretty girl, her clothes were torn and wet, and her long, dark hair was streaming about her shoulders.

Certainly it was a curious sight, there in that densely populated summer resort, to see a young woman acting in that manner. Up on the board walk above the beach a gaping throng had gathered. A little way from the board walk a man seemed to be doing something with a photograph instrument.

Carl, intensely wrought up, floundered to his bare feet, a "red-hot" in one hand and half a bun in the other. Any one in distress always appealed to Carl—particularly a woman.

From the woman, Carl's eyes drifted toward the water. A boat was pulling in, and was close to the shore. There were three men in the boat, two at the oars and one standing in the bow. They were a fierce-looking lot, those men. All were of swarthy hue, had fierce black mustaches, gold rings in their ears, heads covered with knotted handkerchiefs over which were drawn stocking caps,[Pg 2] and all wore sashes through which were thrust long, ancient-looking knives and pistols.

The man in the bow, whom Carl could see almost entirely, had on a pair of "galligaskins," or short, wide trousers, and immense jack boots.

The ruffians in the boat, no less than the girl on the beach, seemed to be deaf and dumb. Not a word was said by any of them, but their faces twitched in response to their varying emotions, and they used their hands in ceaseless gestures.

Carl was right in thinking that the men in the boat had the appearance of pirates; and the scene was "funny," inasmuch as it showed the sea rovers of a past age against a twentieth century background.

"Py shinks," muttered Carl, his temper slowly rising, "I don'd like dot! Der poor girl iss at der mercy oof dem birate fellers, und der bolice, und nopody else, seems villing to lendt her a handt. Vell, I dell you somet'ing, oof dose birate fellers in der poat douch a hair oof dot girl's headt, den dey vill hear from me! I vish Modor Matt und Tick vas here. Mit dem to helup, ve could clean out der whole gang. Anyhow, I do vat I can py meinseluf."

When the boat was in the surf, the two who were rowing dropped their oars and sprang overboard. Laying hold of the boat, they dragged it up on the strand. The man in the bow jumped out, and all three made a rush for the girl.

"Leaf dot laty alone!" bellowed Carl, starting for the girl about the same time the three men did. "You t'ink dis vas some tesert islants dot you can act like dot! Bolice! bolice!"

The sight of Carl, in his little red bathing suit, streaking along the sand, brought roars of laughter from those on the board walk. The merriment puzzled Carl; and angered him still further, too, to think that such a raft of people would give way to mirth when a young woman was in such terrible danger.

"Get away from there!" shouted a man near the photographic instrument.

"Meppy you see me gedding avay," roared Carl as he ran, "aber I don'd t'ink. You vas a goward, und eferypody else vas a goward! I safe der girl meinseluf!"

"You'll spoil the picture!" howled one of the pirates; "get out of the picture!"

"I vill shpoil your face!" retorted Carl, failing to comprehend. "Ged oudt oof der picture yourseluf! Der laty iss nod to be hurted."

Carl reached the lady first. She seemed astounded and angry.

"Nefer fear, leedle vone," carolled the Dutch boy, planting himself between the girl and her supposed enemies, "dose vicked mens vill haf to valk ofer me pefore dey ged ad you! Yah, so helup me! Run for der poard valk vile I mix it mit dem und gif you der shance."

"Go 'way!" screamed the girl; "mind your own business, if you've got any!"

"Oh, you Dutch idiot!" raved one of the buccaneers, striking at Carl with a cutlass. "You've spoiled our work!"

The other two pirates were jumping up and down and saying things about Carl that were far from complimentary.

The Dutch boy tried to dodge the cutlass, but failed. It struck him squarely across the throat, and, had it been a thing of steel, would have separated his head from the rest of his body. But the cutlass was made of lath, covered with tinfoil, and broke as it fell.

"He's ruined the films!" howled the man at the photograph instrument.

"Sic him, Tige!" cried another, who was standing beside him.

A brindle bulldog, which Carl had not seen until that moment, gave a yip and started for the scene of the trouble.

"Vat's der madder, anyvays?" demanded Carl, convinced by the young lady's manner that she did not want to be rescued.

"Moving pictures, you Dutch idiot!" yelped the leader of the pirates. "If you'd had any sense you'd have known that without being told. Now we've got to do it all over again! Take him, Tige!"

The bulldog was hurling himself across the sand like a thunderbolt, and he was making straight for Carl. Neither the girl nor the pirates showed any inclination to stop the dog; on the contrary, they appeared to derive considerable satisfaction from the prospect of his getting close enough to use his teeth on the Dutch boy.

Carl was perfectly willing to face any number of pirates in order to rescue a beautiful maiden in distress, but he drew the line at coming company front with a vicious bulldog. When a person wears nothing but a bathing suit his means of offense and defense are naturally limited.

Since Carl could not help the girl, he made up his mind to do what he could to help himself. Whirling about, he laid himself out in the direction of the steel pier, the bulldog in hot pursuit and gaining on him at every jump.

Everybody, except the moving-picture people, was laughing. And excepting Carl. There was nothing especially amusing in the situation for him.

The Italian with the pushcart was haw-hawing and holding his sides. A boy, using his legs to get away from a dog, was something he could understand, and it pleased him.

Carl did not have time to go around the cart, so he ducked under it. The dog ducked after him. Carl had seen how the Italian was enjoying himself, and he resented it. By rising up under the cart Carl could overturn it, thus dropping a lot of buns and "red-hots" on the dog and possibly stopping the pursuit. Carl did not stop to debate the matter—he hadn't time—but rose up, thus sending the cart over upon the dog.

The Italian had been cooking the "red-hots" on a steel plate. The plate, of course, was hot, and it struck the dog. There came a yelp of pain, and the dog tore out from under the cart and hustled back toward the photograph instrument.

The Italian had changed his tune. He was not laughing, now, but was prancing around and howling frantically for the police.

"Sacre diabolo estrito crystal!" he shrieked. "You wreck-a da wag'—you spoil-a da bun, da red-a-hot! Polees! Me, I like-a keel-a you! Polees! polees!"

While he yelled, he started angrily toward Carl. The Dutch boy, whirling the overturned cart around, caused the Italian to stumble over it. Leaving him to writhe and sputter among the scattered buns and "wienes," Carl raced on toward the steel pier.

He was flattering himself that he would be able to regain the bathhouse without further molestation, but in this he was mistaken. An officer jumped down from[Pg 3] the side of the pier, as he came close to it, and grabbed him by the arm.

"Not so fast, there!" cried the policeman.

"Vat's der madder mit you?" wheezed Carl. "I don'd vas doing anyt'ing."

"Oh, no," was the sarcastic response, "you wasn't doing a thing! What did you kick over that dago's cart for?"

"Dose fellers hat set a dog on me!" cried Carl. "Ditn't you see der dog?"

Just then the Italian, two of the pirates and one of the men with the photographic apparatus, hurried up, all in a crowd.

"Pinch-a heem!" fumed the Italian; "he make-a plenty da troub'!"

"He's the original Buttinsky," scowled the picture man. "He pushed into that moving picture, spoiled a lot of film and made it necessary for us to do our work all over."

"He's the prize idiot, all right!" clamored one of the pirates.

"What's the matter, here?" demanded a voice, as a youth pushed into the crowd and ranged himself at the Dutch boy's side. "What's the matter, Carl?"

"Modor Matt!" exclaimed Carl, gripping the newcomer's arm. "You haf arrifed py der nick oof time, like alvays! Now, den," and here Carl faced the others belligerently, "my bard has come, und you vill haf to make some oxblanadions. Vat haf you got to say for yourselufs?"

THE MOVING-PICTURE MAN MAKES A QUEER MOVE.

A little farther along the beach, and well out of the way of high tide, four heavy posts had been planted in the sand. This was the mooring-place for the "Hawk," the famous air ship belonging to Matt and Dick Ferral, and which the three chums had brought from South Chicago.

The boys had had the Hawk in Atlantic City for two weeks, making four flights every day except on Sunday, or on days when high winds or stormy weather prevailed. There had been only one stormy day when it had been found necessary to house the Hawk under the roof of one of the piers, and only one other day when the wind had been so strong as to make an ascent too risky.

Four passengers were carried aloft in each flight. Six persons were all Matt thought advisable to take up in the air ship, and of course he had to go along to take charge of the motor, and with him went either Dick or Carl to act as lookout and "crew." A charge of $25 was made for each passenger, and the flights had so captured the fancy of wealthy resorters that the boys had advance "bookings" that promised to keep them in Atlantic City all the summer. With $400 a day coming in, and a very small outgo for expenses, the chums were making money hand over fist.

On the afternoon when Carl was taking his dip in the ocean, and incidentally spoiling films for the moving-picture people, Matt and Dick, with their usual four passengers, had been making their last flight of the day over Absecon Island and the eastern coast of New Jersey.

One of the passengers on that trip was a Mr. Archibald Townsend, of Philadelphia. Passengers always showed a great interest in the air ship, but Mr. Townsend had shown more curiosity and had asked more questions than any of the others.

As Matt and Dick were bringing the Hawk down to the beach, they had witnessed the overturning of the Italian's "red-hot" outfit, and had seen Carl get clear of the wreck and race on toward the steel pier. Leaving Dick to make the air ship secure in her berth, Matt had tumbled out of the car and hurried after Carl. As we have already seen, the young motorist reached his Dutch chum just as the officer had laid hold of him.

The officer's name was McMillan, and he was arrogant and officious to a degree. He had been on duty along that part of the board walk ever since the chums had reached Atlantic City, and he had interfered with their operations to such an extent that Matt had found it necessary, on one occasion, to report him. On this account, McMillan was not very amiably disposed toward the young motorist and his friends.

"I don't care who this fellow is," growled the officer, nodding his head toward Carl, "no one can come here an' raise hob on the beach without bein' jugged for it. I saw what happened. The Dutchman knocked over the dago's cart."

"Dot feller," and here Carl pointed to the moving-picture man, "set der dog on me. Oof I hatn't knocked ofer der cart, der dog vould haf got me sure. Vat pitzness he got setting der dog on me, hey? He iss to plame, yah, dot's righdt."

"What did you want to butt into our picture for?" demanded the photographer.

"How I know you vas daking some mooting bictures?" demanded Carl. "I see dot young laty on der peach, und she vas in some greadt drouples; den I see dem birate fellers in der poat, going afder her, und nopody vould run mit demselufs to der resgue. Den I go. You bed my life, no laty vat iss in tisdress can be dot vay ven I vas aroundt."

"We'll have to do our work all over again to-morrow afternoon," went on the moving-picture man, "and I have to pay these actors more money for another afternoon's work."

"How much will that be?" asked Matt, who saw very clearly that Carl had made a mistake and was in the wrong.

"There are six of 'em," replied the photographer, "and I pay them ten dollars apiece."

"That makes sixty dollars," said Matt, "and I'll——"

"Just a minute, King." It was Mr. Townsend who spoke. He had hurried toward the scene of the dispute and had arrived in time to hear the moving-picture man's explanation and Matt's offer to foot the bill. "This fellow's name is Jurgens," continued Mr. Townsend. "He comes from Philadelphia, and I happen to know that he gives these actors five dollars apiece for their work. If you give him just half of what he asks, King, you will be treating him fairly."

Jurgens glared at Townsend.

"What business have you got interfering here?" he asked, angrily.

"I am merely interfering in the interests of justice, that's all," replied Townsend, coolly, "and because I think you an all-around scoundrel, Jurgens. You and I have had some dealings already, you remember."

A black scowl crossed Jurgens' face.

"And our dealings are not finished yet, by a long shot," returned Jurgens.

Townsend tossed his hands contemptuously and turned his back on the photographer.

"I'll have my sixty dollars," cried Jurgens, to Matt, "or there'll be trouble."

"You'll take thirty," said Matt, taking some money from his pocket and offering it, "and not a cent more."

Jurgens struck aside the hand fiercely.

"This dago is the boy that interests me," said the officer. "He's a poor man an' can't afford to have his stock in trade ruined by that Dutch lobster."

At this, Carl fired up.

"Who you vas galling a Dutch lopsder?" he demanded, moving truculently in the direction of McMillan.

"You!" snorted the officer, dropping a hand on his club.

Carl let fly with his fist. Matt grabbed the arm just in time to counter the blow.

"That's your game is it?" growled McMillan, jerking the club from his belt. "I'll take care of you, my buck! Come along to the station with me!"

"Wait a minute, officer," said Matt. "Stop making a fool of yourself, Carl," he added to his Dutch chum. "You made a mistake at the start-off, but that was no reason Jurgens should have set the dog on you. As for the Italian," and here Matt faced the officer again, "I'll pay him for the damage he has suffered."

"Fifty cents will probably settle that," laughed Townsend, "so if you throw him a five, King, he will be glad the accident happened."

One of the bank notes Jurgens had refused Matt now gave the Italian. His grieved look at once faded into an expansive grin, and he grabbed the money, thanked Matt in explosive Italian and ran back toward his overturned cart.

"That lets the dago out," said the officer, grimly, "but it don't let the Dutchman out, not by a jugful. He'll get a fine, and if Jurgens here wants to prefer charges——"

"I do," snapped Jurgens. "If I don't get that sixty dollars I'll make it hot for all these balloonists. That's the kind of a duck I am."

"I know what kind of a duck you are, Jurgens," said Townsend, sternly, "and if you know when you're well off, you'll leave Motor Matt and his friends alone."

"Sixty dollars," cried Jurgens, hotly, "and this gang can take it or leave it."

"You go with me," declared McMillan, twisting his left hand in the collar of Carl's bathing suit.

"Nonsense, officer!" said Townsend. "You're making a mountain out of a molehill. Let the boy alone."

"I know my business," snarled the officer, "an' I don't have to have strangers blow in here an' tell me what to do."

He took a step toward the board walk, jerking Carl along after him.

"I'm not a stranger in Atlantic City, officer," went on Townsend. "In fact, I'm very well acquainted with the chief of police here. Just a second until I show you my card."

The potent name of the chief brought McMillan to a halt. He had been reported once, and if a man who had influence reported him again, there might be a vacancy in the force.

"All I want is to do what's right," he mumbled.

Townsend had reached into his pocket and drawn out a handful of papers. While he was going over them, looking for his professional card, Jurgens made a lightning-like move. It was a most peculiar move and, for a moment, took everybody by surprise.

Throwing himself forward, Jurgens snatched a long, folded paper from among those Townsend held in his hands. Quick as a wink Jurgens whirled, dashed for the steps leading up to the board walk and was away like a deer.

"Stop him, officer!" shouted Townsend. "That's the kind of a man he is! Stop him!"

McMillan now saw that a real emergency confronted him. Releasing Carl, he rushed away on the trail of the thieving Jurgens.

Motor Matt, however, had kept his wits, and he was halfway to the steps before the officer had started.

When the young motorist bounded to the board walk, Jurgens was tearing through the crowd.

"Stop, thief! Stop, thief!" yelled Matt.

There were so many people thronging that part of the board walk that it seemed an easy enough matter to halt the rascally photographer. Yet, strange as it may seem, this was not the case. Men, who were escorting ladies and children, made haste to get them out of the way; others, who had no one depending on them, seemed bewildered, and pushed out of the way to watch. Fortunately, another officer appeared on the other side of the entrance to the pier and headed Jurgens off in that direction.

Turning to the left, Jurgens struck the ticket taker out of his path and raced onto the pier.

Matt followed, not more than a dozen feet behind.

The concert was over and, at that moment, there were not many people on the pier, and Matt had a straight-away chase through the little pavilions.

He felt sure that he would capture Jurgens, for when the thief reached the end of the pier, the Atlantic Ocean would cut short his flight and he would have to turn back.

But in this Matt was mistaken. Jurgens did not run to the end of the pier but climbed over the rail at the side and dropped from sight. When Matt reached the rail, he saw that Jurgens had dropped into a rowboat, that had been tied to the piles, and was bending to the oars. He shouted a taunting defiance at Matt as he continued to put a widening stretch of water between them.

At once Matt thought of the Hawk. In less than five minutes he and Ferral could be in the air, following the rowboat wherever it went. With the officers to watch the shore and perhaps pursue Jurgens in other boats, Matt felt positive that he and Dick would be able to overhaul Jurgens if other means failed.

Without loss of a moment, he started back toward the board walk.

WARM WORK AT THE "INLET."

Some one of the three boys was always on watch near the air ship whenever she was moored. This duty, during the excitement Carl had kicked up on the beach, had fallen to Dick Ferral.

Dick had made the ropes fast and was sitting in the sand near the car, wondering what all the commotion was about. There was usually a crowd of curious people around the Hawk, or staring down at her from the board walk, but now the counter-attraction at the pier had drawn them away, and that part of the beach was deserted.

Dick had seen Matt rush up the steps to the board walk, but the crowd was so thick he had not been able to observe his rush out on the pier. The rowboat, however, had not escaped his attention, and he had watched it pull away from the steel pier and move off toward the Heinz pier. Thereupon officers began running along the beach. McMillan kept abreast of the rowboat on the shore, and another man ran toward the Heinz pier, with the evident intention of catching the man in the boat if he tried to land there.

Presently Matt came dashing up, and Dick sprang to his feet. He could tell by his chum's manner that he was some way involved in the excitement.

"What's going on, mate?" asked Dick.

"Cast off the ropes, Dick!" called Matt, leaping to the cable nearest him. "We've got to overhaul that man in the boat, and capture him—if we can."

"What's he been doing?"

As he put the question Dick was working at one of the other cables.

"I'll tell you when we're in the air, Dick," rejoined Matt. "Carl butted into a moving picture, and a whole lot of trouble has come from it."

While Dick was casting off the last rope and heaving it aboard, Matt jumped into the car and got the motor going. By the time Dick was in the car with him, Matt switched the power into the propeller, tilted the steering rudder so as to carry the Hawk upward and seaward, and they were off.

"Keep your eye on the boat, Dick," called Matt, "and let me know just where she is all the time."

"Just now, matey," Dick answered, from the lookout station forward, "the boat's doubling the end of the Heinz pier."

"The rascal will not land there. He knows the police will be waiting for him. I don't see how it's possible for him to get away, with the whole shore line patrolled."

"What's he done? Keelhaul me if I haven't been trying to guess that for the last ten minutes."

"As I told you, Carl got into a moving picture. Some men were taking a picture on the beach, and Carl, seeing a young woman—as he thought—in distress, tried to save her from pirates. The gang set a dog on him, and in getting away from the dog, our pard upset a dago's pushcart. An officer had Carl, when I got over close to the pier, and the picture people and the dago were making it hot for him. I guess they'd have jailed Carl if it hadn't been for Mr. Townsend——"

"The Townsend we had with us on the last trip?"

"Yes. Townsend knew the picture man, and from the way he talked I guess he don't know much good of him. Anyhow, while Townsend was looking through some documents he had taken from his pocket, the picture man—Jurgens by name—grabbed a paper and made off with it. Great spark plugs! I never saw a more brazen piece of work. I chased Jurgens out on the steel pier, but he got away from me by taking to a rowboat that was moored there."

Ferral laughed. The idea of Carl mistaking what was going on and trying to save a girl from pirates, there in that fashionable resort, was too much for him. Temporarily he lost sight of the graver aspects of the affair. Even Matt grinned at the spectacle the Dutch boy, in his bathing suit, must have made, battling with pirates to save a girl who did not want to be saved.

"This thing has got a mighty serious side to it, Dick," said Matt, suddenly sobering. "I haven't the least notion what that paper was that Jurgens grabbed, but it must have been an important document. And Townsend lost it while trying to help Carl and me. That puts it up to us, Dick, to help him get it back."

"Right-o!" returned Ferral. "There's a boat putting off from the Heinz pier. McMillan's in it and two men are breaking their backs at the oars. They'll get this Jurgens swab, if I'm any prophet. They're going about two fathoms to Jurgens' one."

"How's Jurgens heading?"

"For the open sea. He's struck rough water just over the bar from the Inlet, and his boat's on end about half the time. If one of those combers hits him broadside on, he'll go to the sharks, paper and all."

"What's his notion for heading out into the ocean, I wonder?"

"Strike me lucky!" exclaimed Ferral. "Why, he's making for a sailboat, and the craft is laying to to take him aboard."

"What's the name of the boat? Can you make it out?"

The sun was down and shadows were settling over the water. Enough light remained, though, for the sharp eyes of Ferral to read the name on the sailboat's stern.

"She's the Crescent," he announced, "and one of the boats that berth in the Inlet. There! Listen to that!"

The crack of a revolver echoed up to Matt and Carl above the surge of the breakers.

"Who's doing the shooting, Dick?" asked Matt.

"McMillan. He sent a bullet across the Crescent's bows. That's an order for her to keep lying to until McMillan can come aboard. They're just taking Jurgens out of the boat and making the boat's painter fast. Ah!" There was excitement in Ferral's voice as he went on. "The skipper of the Crescent isn't obeying orders, but is going on out to sea. I'll bet McMillan is as mad as a cannibal. There he goes, blazing away at the Crescent—but he might as well throw his bullets into the air."

"The Crescent will be called to account for that!" exclaimed Matt.

"McMillan is pulling back to the pier," proceeded Dick, watching below. "What are we to do now, matey? We'd have had considerable trouble taking Jurgens off the rowboat, and it's a cinch we can't get him off that other craft."

"We'll follow the Crescent for a while," said the young motorist, "and see where she goes. Possibly she'll try to land Jurgens at some point on the mainland. If she does, we'll drop down there and do what we can to capture him."

For more than an hour the Crescent steered straight out into the ocean, the Hawk hovering above her. The sailboat was not putting out any lights, and the growing darkness rendered it impossible for Matt or Dick to see any one aboard her. They could hear voices, however, for sounds on the earth's surface are always wonderfully distinct to people in balloons or other air craft.

At the end of an hour and a half the Crescent put about. The Hawk followed the sailboat as far as the[Pg 6] channel leading through the bar at the entrance to the Inlet. Having made sure that the sailboat would return to her usual berth, the boys headed their air ship for the beach.

"I guess McMillan will be on the lookout for the Crescent, Dick," said Matt, "but we ought to make sure that Jurgens don't get away. I believe I'll get out of the Hawk, close to the Inlet, and leave you to take the air ship back to her moorings."

"I can do that all right, messmate," answered Dick.

There was plenty of room for landing, and when the Hawk had been brought within a couple of feet of the ground Matt dropped over the rail and Ferral took his seat among the levers.

As Matt hurried to the board walk, and on to the wharf at the Inlet, he looked around him for some officer whom he could pick up and take along with him. There was no officer in sight, however.

It was the dinner hour at the big hotels, and promenaders had nearly all deserted the ocean front. A dozen or more sailboats were heaving to the swell and knocking against the wharf at the Inlet, but only a few of the men belonging with them were on the wharf itself.

"Can you tell me where the Crescent is?" Matt asked of a man leaning against an electric-light pole.

"Jest seen 'er standin' in," was the reply. "She ought to be at the end of the wharf by this time."

"Is that where she lies when she's tied up?"

"Yes."

Thinking that surely he would find McMillan, or some other officer, at the end of the wharf, ready to deal with Jurgens the moment he tried to come ashore, Matt hurried on.

The Crescent had just warped into her berth. A man on the wharf was making her cable fast. Under the electric light Matt could see a group of three or four men in the cockpit of the little sailing craft. At about the same moment, a figure lurched forward from behind a barrel that stood on the wharf. The gleam of a star on the coat informed Matt that the man was an officer.

"Hello, there!" the young motorist called to the group in the cockpit. "Where's that man you picked up off the Heinz pier?"

Two of the men climbed to the side of the Crescent and jumped to the wharf planks. Neither of them was Jurgens.

"You've got us guessin', friend," said one of the men.

"Not much I haven't," answered Matt, stoutly. "I was one of those in the air ship and I saw you pick up Jurgens."

"You've got him, all right," put in the officer. "He's a thief, and I'm here to arrest him. The Crescent is liable to get herself into hot water by this afternoon's work."

The officer was not McMillan. While he spoke, he started for the edge of the wharf with the apparent intention of getting into the sailboat and making a search.

"Hold up a minute, officer," called the man from the Crescent, pulling off his coat.

The officer halted, and turned. At that instant, Matt saw the fellow who had been making the boat's cables fast to the posts, creeping toward the officer from behind.

"Look out, there!" he yelled. "One of those men is after you from the rear! They're trying to——"

Matt's words were cut short. While he was speaking, the man from the Crescent had whirled suddenly and thrown the coat over his head.

Matt had a fleeting glimpse of the officer, crumpling to the wharf under a vicious blow from behind, and then his own head was encompassed in the smothering folds of the coat and he was thrown struggling to the planks.

PRISONERS ON A SUBMARINE.

Motor Matt fought in vain to free himself. At least two men had laid hold of him, and the coat was kept drawn tightly over his face and head to prevent outcry. In this condition he was picked up, carried some distance along the wharf and finally laid down on his face while his hands were lashed at his back and his feet tied. Then, perfectly helpless and unable to see where he was being taken, he felt himself lifted and lowered. After a moment he was lifted and lowered again, this time, as he surmised, through a narrow hatch, for he felt the sides of the aperture striking his arms and shoulders as he went down.

Presently he landed on a hard deck, and was again carried a short distance. Here, when he was finally laid down, the coat was whisked from his face and he found himself in the blinding glare of an electric light.

Retreating footsteps came to him, followed by the slamming of a door.

As soon as his eyes had become used to the glow of the light, he discovered that he was in a small room with a curved iron deck overhead. An incandescent lamp was screwed into one of the walls, and there was a door in each bulkhead at the ends of the room.

Matt was bewildered by what had recently happened to him.

Had the crew of the Crescent resorted to violence in order to save Jurgens from capture? The law would take hold of the men good and hard for resisting an officer.

As Matt figured it, he had been brought aboard the sailboat. But what would his captors have to gain by a move of that kind? McMillan knew what the men on the Crescent had done for Jurgens, and it was a fair inference that the officer would soon pay the craft a visit, himself.

What put Matt in a quandary, however, was the fact that he could not reconcile his present surroundings with the Crescent. He was in an armor-plated room, and the sailboat was a small wooden vessel, and was hardly fitted with such a cabin as that to which the prisoner had been taken.

While Matt was wondering about this, a door in one of the bulkheads opened and another prisoner was carried in by two men and laid down beside him. This second captive likewise had his head smothered in a coat, but the blue uniform told Matt plainly he was the policeman. The officer was bound, just as Matt was, and as soon as he was laid down the coat was jerked away and the two who had brought him into the room started out.

"Wait!" called Matt, his voice ringing strangely between the steel walls. "What do you mean by making prisoners of us, like this?"

One of the men looked around and laughed grimly, but he made no other reply. The next moment the door had closed, and Matt and the officer were alone together.

"Here's a pretty how-de-do," fumed the officer. "These villains are goin' a good ways in their attempt to help that thief, Jurgens! Somebody'll smart for all this."

"Those men on the Crescent are foolish," said Matt. "It won't be long before McMillan gets us out of here."

"I don't know about that," was the answer. "Mebby it won't be so easy as you think for McMillan to get us away from these scoundrels."

"Where is McMillan? Do you know?"

"He was on the wharf with me, just before the Crescent got in. He thought him and me wasn't enough to get Jurgens off the boat, and so he went after another officer. You're Motor Matt, who's been making ascensions in that air ship—— I've seen you a good many times on the beach. My name's Holcomb."

"Where do you think we are, Holcomb?" Matt asked. "It can't be we're on the Crescent."

"Sure not. Looks to me as though we had been brought aboard Captain Nemo, Jr.'s boat, the Grampus. She bobbed up at the Inlet wharf yesterday. I'm on night duty at the Inlet, and I seen her last night."

"The Grampus?" echoed Matt. "She must be an ironclad."

"She's more'n that, Motor Matt. She's a submarine."

"A submarine! I haven't heard of such a boat being in Atlantic City."

"It ain't gen'rally known, I guess. Captain Nemo, Jr., is a queer sort of a fish, and he's invented a boat that he claims is a little better than any other under-water boat that was ever built. I talked with him on the wharf, last night. Who the cap'n is, nobody knows, and he hides himself under the name of Nemo, Jr. He talked straight enough, and fair enough, and allowed he was keeping quiet so as not to let reporters and other curious people bother him while he was in Atlantic City. It was your air ship that caused him to come here."

"The air ship?" queried Matt, more and more mystified.

"That's what he told me. Everything in the line of inventions, he says, interests him, especially if the inventions have anything to do with gasoline motors. This boat is run by a motor of that kind. Nemo, Jr., said he was goin' to take a fly with you to-day."

"I guess he didn't, then. No man by that name went up with us. But the point that's bothering me is, Holcomb, why were we brought here?"

"To save Jurgens, the movin'-picture man."

"How'll that save him?"

At that point the explosions of an engine getting to work echoed sharply through the steel hull of the Grampus. The whole fabric began to quiver, and muffled, indistinct voices could be heard. Immediately there was a perceptible downward movement.

"We're sinking!" exclaimed Matt.

"Looks like the scoundrels was takin' us to the bottom," said Holcomb grimly. "More'n likely McMillan has shown up with some more men and is makin' things lively for those on the wharf. The fellows that grabbed us are takin' us below the surface so the officers can't get at us, or Jurgens! Gadhook it all! Captain Nemo, Jr., didn't seem like a man who'd help out any underhand game like this. I reckon we're in for it, Matt. I ain't got any fears but that we'll come out all right in the end, but the outlook is a long ways from bein' pleasant. If Nemo, Jr., is trying'—— There! I reckon we've hit bottom."

Holcomb broke off his remarks abruptly. The downward motion of the Grampus had ceased with a slight jar. Before the two prisoners could talk further, one of the doors opened and Jurgens came into the room. He was followed by the man who had climbed out of the Crescent and had faced Matt on the wharf.

Closing the door behind them, the two men stood looking grimly down on Matt and the officer.

"I don't understand what your game is," cried Holcomb, angrily, "but if you know when you're well off, you'll set us at liberty, and be quick about it."

"You'll get your liberty, all right," said Jurgens. "Now that I've got hold of what I wanted, I'll not be long pulling out of Atlantic City. The moving-picture business can go hang for all of me! I've got a fortune in prospect, and I'll nail it here and now if it's the last thing I ever do."

"What do you mean by treating me like this?" demanded Matt; "what have I got to do with your plans?"

"You and the officer could have upset 'em mighty easy if we hadn't bowled you over and got you out of the way before the rest of those policemen got here."

"Is Captain Nemo, Jr., helping you in this game you're playing?" queried Holcomb.

"Helping me?" Jurgens turned to his companion from the Crescent with a husky, ill-omened laugh. "That's pretty good, eh, Whistler?"

"The best ever," answered Whistler, echoing the laugh.

"Townsend has helped me to the extent of furnishin' something I'd about given up laying my hands on," went on Jurgens, again turning his eyes on Matt and the officer. "I want you two to tell him that I'm off for the Bahamas, and that he'll have to get up in the morning if he beats Lat Jurgens."

"Townsend?" queried Matt.

"Yes," scowled the other, "Townsend. That's the name he uses when he's ashore. When he's afloat, he's Captain Nemo, Jr."

Matt was astounded.

"Have you stolen this submarine, Jurgens," he asked, "as well as that paper that——"

"You know all you're goin' to," interrupted Jurgens. Turning to Whistler he added: "Cut the boy loose and make him strip. It's time we got rid of him and the policeman and cleared out of here. We're a fathom under water, but Townsend may think of some way to get at us if we stay here too long."

Whistler bent over Matt and removed the ropes.

"You're going to put us ashore?" asked Matt, getting to his feet and stretching his benumbed limbs.

"We're goin' to send you to the surface, and you'll have to attend to gettin' ashore yourselves. Can you swim?"

Matt nodded.

"I can't," said Holcomb.

"Well," went on Jurgens, "I don't want to drown you, but the Grampus can't go to the surface just to let you off. You say you can swim," and he turned to Matt. "You'll come up not far from the wharf, and ten to one you'll find quite a lot of people on the wharf. As soon as they pull you in, you tell them to get out a small boat and lay to in her half a fathom off the end of the pier. That's where the officer will come up, and you can fish him in out of the wet. Now, strip."

"Why am I to do that?" demanded Matt.

"Because you'll be able to swim easier with your clothes off."

"I'll not take them off. If we're still alongside the wharf, I can make it without removing my clothes. How are you going to send me to the surface?"

"Come on and I'll show you. Drop in behind him, Whistler, and hold a gun ready in case he tries any foolishness."

Jurgens turned and opened the door through which he and his companion had just come. Matt followed him through the door, Whistler bringing up the rear with a drawn weapon.

Matt was bewildered by the trend of recent events. The quickest way for getting at the nub of the difficulty was by finding Townsend, otherwise Captain Nemo, Jr., and hearing what he had to say.

But how was Matt to be sent to the surface?

That was the point which, just then, was causing him the most wonder.

THROUGH THE TORPEDO TUBE.

Motor Matt was conducted along a narrow steel corridor. Two or three ruffianly looking men were passed. They were all in greasy overclothes and paid the prisoners little attention. A door finally admitted Matt and the two with him into a chamber in the very bow of the boat. Here there were a couple of torpedo tubes, although, so far as Matt could see, there were no torpedoes.

"We'll put him out of the starboard tube," said Jurgens. "Close the bow port, Whistler, and blow the water out of the tube. I'll take the gun while you're busy."

Whistler handed over the revolver and pulled a lever at the side of the chamber. Matt could hear a muffled sound as the port closed. Thereupon Whistler, by means of another lever, turned compressed air into the tube, and there came a stifled swishing sound as the water was ejected. Finally the sound ceased, and Whistler opened the breech door and stepped back.

The cavernous tube yawned blackly under Matt's eyes. He was a lad of grit and determination, but such an experience as he was about to pass through would have shaken even stronger nerves than his.

"Take me to the surface," said Matt, "and let me out of the submarine by way of the deck!"

"And mebby get spotted and captured ourselves, eh?" answered Jurgens. "Not much! Here's the way you're going to get out if you get out at all."

"What did you bring Holcomb and me into the submarine for? Why didn't you leave us on the wharf?"

"It would have been too easy for you to tip us off to the other officers. We needed a little time to get the Grampus submerged. I don't care how much you tip us off now. We'll not come to the surface again until we're well off Cape May." Jurgens snapped his fingers. "That for Townsend!" he added, defiantly; "let him catch me if he can."

"You seem to know as much about submarines as you do about moving pictures," remarked Matt, caustically.

"I know a good deal about a lot of things, and I've found the knowledge mighty handy a lot of times. If you're ready, squeeze into the tube. We haven't much time to spare."

"But——"

"Get in, I tell you!" and Jurgens waved the revolver threateningly. "There's not much danger, but you'd better put your fingers over your ears in order to save your ear drums. The pressure of the air that shoots you out of the tube is rather heavy. But I'd advise you to take off your clothes."

Matt saw that it was useless to argue with Jurgens or Whistler. The two men had some desperate scheme at the back of their heads and they were not resorting to any halfway measures in carrying it out.

Pulling his cap well down on his head, Matt squeezed into the dark tube.

"Ready?" called Jurgens.

"Yes," answered Matt, almost stifled, pushing his hands against his ears.

"Take a long breath—we're going to close the breech door."

The young motorist breathed deeply, and the next moment there was a clang as the breech was closed.

Instantly there followed a grinding sound as the outer port was opened. The chilling water rushed in. For the space of a heart beat Matt felt the water submerging his cramped body and filling the full length of the tube. Two or three ticks of a watch would have told the duration of the experience, but to Matt it seemed like an eternity.

Then there came a shock that nearly made him unconscious. He thought he was being torn limb from limb by the rushing air. In a twinkling—so swiftly that he scarcely realized it—he was shot from the end of the tube and into the water.

He was a fraction of a second in getting control of his limbs; after that, he began kicking and using his hands to propel himself upward.

Half stunned he came to the surface, and the lights of the wharf swam in his watery eyes. He gasped for breath and then sent up a thrilling cry for help.

The difficulty of keeping himself afloat, with all his water-soaked clothing to hold him down, was a good deal greater than he had thought it would be.

To his great relief, above the roaring in his ears he heard sounds of running feet on the wharf, and excited voices shouting something he could not understand. There was a splash beside him. Instinctively he threw out his hands and grasped a rope.

"All right?" cried a voice from the wharf.

"Yes," he answered.

Then those on the wharf began pulling him in and soon had him, dripping and spent, on the planks.

"Where's Holcomb?"

Matt made out McMillan's face bending over him. The question caused the young motorist suddenly to remember that there was something yet to be done for Holcomb.

"Get out a boat," said Matt, "and lay to about a fathom off the end of the pier. Holcomb is coming up—and he can't swim."

"Coming up?" repeated McMillan, blankly.

"Yes; they're going to shoot him out of the torpedo tube, just as they did me."

"Great guns! Can they do that? It ain't possible that——"

"Don't stand there talking, McMillan," put in another[Pg 9] voice. "Matt has told you what to do, so go ahead and do it. The scoundrels can use the torpedo tube to get rid of Holcomb, and if Holcomb can't swim he'll be in plenty of danger. Find your boat and get her off the end of the pier. Lively, now!"

The speaker, as McMillan dashed away, came closer to Matt. It was Archibald Townsend.

"You've had a rough experience, my lad," said Townsend. "How do you feel?"

"A little dizzy," replied Matt.

He peered around him. They were alone under the electric light, all the others on the wharf having gone with McMillan to help in the rescue of Holcomb.

"I don't wonder," rejoined Townsend. "Being slammed through a torpedo tube isn't a very pleasant experience."

"Do you call yourself Captain Nemo, Jr., when you're afloat in the submarine, Mr. Townsend?" asked Matt.

"Jurgens has been talking with you, I see," went on Townsend. "Well, he's given it to you pretty straight, scoundrel though he is and with small regard for the truth. Yes, I'm Captain Nemo, Jr., of the submarine Grampus. And Jurgens has stolen my boat and captured two of my men! Losing the boat and that paper makes this a hard-luck story for me."

"Can't you get back the boat in some way?" queried Matt, his excitement growing as his brain cleared and strength returned to him.

"If Jurgens would bring the Grampus to the surface I might have some chance, but it's impossible if he keeps her below."

"She's lying right off the pier, just below the spot where she was moored."

"She might as well be a thousand miles away so far as my ability to recover her is concerned. My only hope just now is that the men working for me, who were captured when Jurgens stole the boat, may be able to turn on their captors and get the Grampus back in their hands."

"Jurgens told me to tell you that he was off for the Bahamas, and that you'll have to get up in the morning if you beat him."

A frown crossed Townsend's face.

"I knew very well that was where he was going," said the owner of the Grampus.

"Had the paper he took from you," queried Matt, "anything to do with his trip to the Bahamas?"

"Everything. I can hardly understand how the theft of that chart, and of the boat, happened to come in so pat for Jurgens. But I'm going to tell you more about the chart later, Matt. Just now you're as wet as a drowned rat and must want to get back to your hotel and put on some dry clothes."

"I want to make sure, before I leave the Inlet," returned Matt, "that McMillan and the others succeed in rescuing Holcomb."

"This way, then," said Townsend, starting along the wharf; "I'll go with you. After we see Holcomb landed, I'll go with you to the hotel and broach a subject that just popped into my mind."

On reaching the end of the pier it was evident to Matt and Townsend that Holcomb had just come to the surface. A sharp cry of command came from some one in the rowboat and the craft could be seen moving swiftly away toward the right.

Matt's keen eyes detected a black spot on the water, but before the boat could reach it the spot had disappeared.

"He's gone down!" gasped Matt. "If Jurgens' scheme has caused Holcomb to lose his life, the prospect will look pretty dark for him."

"Jurgens is bound to come to some bad end," declared Townsend. "I've known him for two or three years, and he has always been crafty and unscrupulous. But I don't think he'll ever hang for the drowning of Holcomb. If my eyes show the situation clearly, Holcomb has just come to the surface again—and those in the boat have got hold of him."

This was the way it appeared to Matt, and that both he and Townsend were correct was presently proved by the rowboat turning back in the direction of the wharf.

"Did you get him, McMillan?" called Townsend, as the boat came close.

"Yes," was the officer's response. "He's full of water, and unconscious, but there's plenty of life in him. We'll have him all right in a brace of shakes."

Holcomb, in nothing but his underclothes, was lifted to the pier. The men in the boat climbed after him, and he was rolled and prodded until he was able to open his eyes and speak.

"That's enough for us, Matt," said Townsend. "Let's go to your hotel. The idea that darted into my mind a little while ago is growing on me, and I'd like to put it up to you and hear what you think about it."

Matt, wet and uncomfortable, was also anxious to get to his hotel. Not only that, but he was curious to learn what it was that Townsend, otherwise Captain Nemo, Jr., had on his mind.

THE CAPE TOWN MYSTERY.

On their way to the hotel, Matt and Townsend met Dick Ferral. Carl, after exchanging his bathing suit for every-day clothes, had wandered about looking for Matt, and had only just come to the air ship to relieve Ferral. In a few words Matt told his chum what had happened, and Ferral accompanied Matt and Townsend to the hotel.

"You and Matt own the Hawk together, don't you, Ferral?" Townsend had asked.

"That's the way of it," Ferral had answered.

"Then I want to talk with the two of you."

These remarks merely served to whet the curiosity of the two boys.

On reaching the hotel, the three repaired at once to the boys' room, and after Matt had got into some dry clothing and all were seated comfortably, Townsend plunged at once into the subject that lay nearest his mind.

"It is clear to me," said he, "that Jurgens mixed up in this moving-picture business just for a 'blind.' He must have heard that I was coming to Atlantic City for a look at your air ship, King, and have laid his plans for the capture of the submarine. The Grampus, as near as I can figure out, was captured by confederates of Jurgens' while I was in the air with you. Jurgens had no idea that he would be able to secure that paper from me[Pg 10] direct, but probably hoped to find it in the Grampus, or to take it from me when I returned to the submarine after that flight in the Hawk."

"If Jurgens' men captured the Grampus while you were in the air with us, Mr. Townsend," said Matt, "the capture must have been effected in broad daylight, while the Inlet was alive with sailing craft. Would that have been possible?"

"Easily possible. The Grampus is a steel shell, you know, and what takes place aboard of her cannot be seen by any one on the outside. The skipper of the Crescent happened to be a friend of Jurgens', and the Crescent happened to be handily by to pick Jurgens out of the rowboat. We'll know more about that part of it as soon as McMillan investigates and reports. Just now, the point for us to remember is that luck has been with Jurgens. His men captured the submarine, Jurgens captured the paper, and the Crescent, with her skipper and crew, helped Jurgens and his clique to foil the ends of right and justice."

Townsend paused. He was a man of fifty-five or sixty, with gray mustache and gray hair, but with alert and piercing black eyes. His looks and manner were such as to inspire confidence, and both Matt and Dick felt that he was to be trusted implicitly.

"But why has Jurgens gone to all this trouble?" inquired Matt. "He has made himself a thief and a fugitive, and what does he hope to gain by it?"

"Ah," returned Townsend, "now you are touching upon the mystery of the Man from Cape Town. I shall have to tell you about that before you can get any clear understanding of what Jurgens has done.

"Nearly a year ago a ragged specimen of a man stopped me at the corner of Broad and Chestnut Streets, Philadelphia, and asked if I wasn't the man named Townsend who had invented and was then building a new submarine which was to have a cruising radius of several thousand miles. I told him that I was. Thereupon the stranger informed me that he was the Man from Cape Town, and that he wanted to borrow a dollar.

"The Man from Cape Town was very different from your ordinary beggar, and I handed him the dollar. Thereupon he took a folded paper from his coat, gave it to me, and asked me to keep it for him. He declared, gravely enough, that the paper was worth a fortune, and that when my submarine was completed, we would go in her to the place where the fortune had been tucked away, find it and divide it between us.

"That sort of talk led me to look upon the Man from Cape Town as a harmless lunatic. I discovered that the paper was a chart of the Bahama Islands, and that it gave the latitude and longitude of a particular island, together with other information necessary for the finding of what purported to be an iron chest.

"This chart I looked upon as rank moonshine, and tucked it away in a pigeonhole of my desk. Months passed, and I had almost forgotten the Man from Cape Town, his chart and his iron chest, when something occurred to bring the entire matter prominently to my mind.

"A night watchman at the yard where I was building the Grampus found a man going through my desk at midnight. When the fellow was captured, he was just getting away with a paper which he had abstracted from one of the pigeonholes. That paper was the chart, and the would-be thief was—Jurgens, Lattimer Jurgens.

"Jurgens had been a workman in the shipyard, but had been discharged for incompetency. While at the yard I presume he learned, in some manner known only to himself, that I had possession of the chart, that it was in my desk, and that it purported to locate a fortune.

"While Jurgens' attempted theft recalled the chart to my mind, it did not add anything to its importance in my estimation, for Jurgens was just the sort of man to take stock in such wild yarns about hidden treasure; however, in order to keep the chart from being stolen, I put it away in the office safe. As for Jurgens, I let him go with a warning.

"About three weeks after that I was called hurriedly to one of the city hospitals. There I found the Man from Cape Town, a total wreck and lying at the point of death. He had strength enough left to insist that the iron chest contained a fortune, and he made me promise to start for the Bahamas as soon as the Grampus was finished, find the chest, and then take it to his daughter, who lived in New Orleans, open it in her presence, and divide the contents equally.

"I still considered the Unknown as the subject of delusions; but, as I should want to try out the Grampus on a long cruise as soon as she was completed, I agreed to carry out the man's request. He died blessing me so fervently that I was a little ashamed of myself for not having more faith in his story.

"A few days, perhaps a week, later, Jurgens came to see me. He declared that the Man from Cape Town had been his brother, and that the chest, now that his brother was dead, belonged to him. I asked Jurgens where the chest came from, what it contained, and how it had happened to be cached in the Bahamas. These questions he could not answer. I had been fairly sure, all along, that Jurgens was not telling the truth, and his lack of information made me positive of it. I declined to give him the chart, or to treat with him in any way regarding it. Thereupon Jurgens left me, vowing vengeance, and asserting that, by hook or crook, he would obtain what he was pleased to call, his 'rights.'

"Some time later, when the Grampus was ready for sea, I shipped my crew and tried the boat out, up and down the Delaware. The trials resulted in a few changes to the machinery, and when the submarine was finally in shape, I made her ready for the trip to the Bahamas. The day we were to start, I read a column or more about the Hawk, and what you lads were doing here in Atlantic City. I have always been interested in air ships quite as much as in submarines, so I decided to come to Atlantic City and have a look at the Hawk before going to the Bahamas.

"At that time, I know positively that Jurgens was in this resort, making moving pictures for a firm in Chicago. Some one in his service must have telegraphed him of my change of plan, thus enabling him to lay his schemes to capture the Grampus. I tried to keep my movements as secret as possible, but it is certain that they leaked out.

"On leaving the Grampus to visit the beach, this afternoon, three trusty men were in charge of the submarine. The officer on duty at the Inlet wharf says that three men came there and claimed to have a letter from me to the man in charge of the Grampus; that the letter was opened by Cassidy, the machinist in charge of the boat, and that the men were admitted below decks. That, undoubtedly, is when the capture took place.

"As I said before, it is my belief that Jurgens either hoped to find the chart concealed in the Grampus, or else to capture me on my return from the beach and take the chart by force. Events worked the scheme out differently, and the chart was snatched from my hands while I was going over the papers I had taken from my pocket. Now, the chart is gone, and the Grampus is gone."

Townsend relapsed into silence, his keen eyes leveled on Motor Matt's face.

The faces of Matt and Ferral, at that moment, were a study. It was a strange story they had heard, but that it was a true story they did not for a moment doubt.

"How much are you making, here in Atlantic City?" Townsend asked abruptly.

Matt told him, wondering what that had to do with the matter.

"You understand," Townsend went on, "that my interest is wholly in the Grampus. I must recover the boat. It is a fair surmise that Jurgens, and those with him, will lay a course for that particular island in the Bahamas. I have that chart, and all the other information contained in it, as clearly in my mind as though the paper itself was before my eyes. Furthermore, I questioned you so thoroughly about the Hawk, while we were in the air this afternoon, that I know the air ship's capabilities. In less than two weeks, Motor Matt, we could make a round trip to the Bahamas in your air ship. What I want is to charter the Hawk for two weeks, and to pay you five thousand dollars for the use of the craft. I am rich enough to do this, and my hope is that we will be able to recover the Grampus. If you boys will agree, I will pay over twenty-five hundred dollars before we start from Atlantic City and give you the remainder of the five thousand upon our return."

The two chums were thunderstruck. They had not had the least idea of the way Townsend's talk was trending.

"Sink me!" mumbled Ferral, "but that sounds like a large order."

"Not so large, perhaps," returned Townsend, "as it seems at first sight."

"How long a trip is it?" asked Matt, a bit dazed.

"Perhaps a thousand miles, as the crow flies, or fifteen hundred as we'll have to go. We could follow down the coast line, and then jump across the Florida Straits to the Bahamas. You tell me you can make thirty miles an hour in the Hawk, and that you can do even better with favoring winds. Say, at a rough estimate, that we make seven hundred miles a day. Why, inside of three days we should be where we want to go in the Bahamas. If we spend three or four days there, and as much time getting back, ten days ought to see the trip completed."

"But if we strike rough weather?" asked Matt.

"This is the time of year when the weather ought to be at its best. Nevertheless, if a stormy day comes, we could alight and wait for the weather to clear. Even at that, we ought to be back in Atlantic City in two weeks."

"It's a good deal of a guess, Mr. Townsend, as to whether, even if we do find the Grampus in the Bahamas, you will be able to get her back."

"I am staking five thousand on the guess," said Townsend, quietly. "You're the right sort of a fellow to make such a venture a success, Motor Matt, and the proposition I have made you I wouldn't make to every one. What do you say?"

Matt and Dick withdrew for a little talk. They would lose their "advance bookings" for flights in the Hawk, but they stood to make a greater profit by this air cruise to the Bahamas than they could possibly hope for in Atlantic City.

"When do you want to start?" Matt asked.

"We should start in the morning," replied Townsend, "as early as possible."

"We'll go," said Matt.

"Good!" cried Townsend, a gleam of satisfaction darting through his eyes.

Taking a checkbook and a fountain pen from his pocket, he drew a chair up to the table and wrote for a few moments.

"There's your twenty-five hundred," said he, handing the check to Matt. "I've made out the check to King & Ferral. I'll leave you boys to do the outfitting, and will meet you on the beach, ready for the start, at seven in the morning. Good night."

With that, Townsend shook hands with Matt and Dick and went away. Dick, highly delighted, started in to do a sailor's hornpipe.

"Twenty-five hundred," he gloried, "and twenty-five hundred more to come. Strike me lucky, mate, but we're going to be millionaires if this keeps up."

"We've got to earn the money yet, Dick," returned Matt, "and that cruise to the Bahamas will be anything but a picnic."

OFF FOR THE BAHAMAS.

Next morning Matt and Dick were astir at three o'clock. The gasoline tank was filled and a reserve supply of fuel taken aboard. The oil supply was also looked after, and rations of food and water were stowed in the car. This accomplished, there was a short flight to the gas works where the bag of the airship was filled to its utmost capacity.

The twenty-five hundred dollar check was left with a friend to be deposited, and by six-thirty the Hawk and her crew were again on the beach with everything in readiness for a record flight.

Carl's delight, as soon as he learned what was in prospect, reached a point that made it almost morbid. He was of little use in the outfitting, and ran circles around the Hawk trying to do something which either Matt or Dick was already doing. Finally, about six o'clock, Matt sent Carl to the hotel to get their small amount of personal luggage and to bring a hot breakfast for all hands.

At a quarter to seven, when Townsend came along the beach, the hurried meal had been finished. The owner of the Grampus gave the boys a cheery good morning, and began placing in the car a bundle of maps and charts, and a sextant.

"I presume," said he, "that we can figure our course all right by dead reckoning, but in case we find any difficulty about that, the sextant will enable us to determine our exact location. The maps are all of the coast line, and are so complete that I think we shall be able to tell, just from the look of the country over which we are passing, where we are. I have also a barometer, and, as luck will have it, fair weather is indicated. There's a compass, too, wrapped up with the maps, and if you[Pg 12] lads have looked after the victualling, I think we are fully equipped for a dash to the Bahamas."

For Townsend's benefit, Matt enumerated the stores that had been placed aboard.

"You have missed nothing, Matt," observed Townsend, approvingly, "and I am pleased to see it. If there is nothing else to keep us, we had better cast off and make the start."

Matt gave Townsend his position aboard. Dick and Carl knew the stations they were to occupy, and after they had released the cables and thrown them into the car, they took up their customary places.

Matt turned over the engine, which, after a volley of "pops," settled down into steady running order.

"South by west, Matt," called Townsend. "That will start us across Delaware Bay in the vicinity of Cape May."

"South by west it is, sir," said Matt, adjusting the ascensional and steering rudder to carry the Hawk upward and in the direction indicated.

At a height of five hundred feet the Hawk was brought to an even keel, the racing propeller carrying her through the air at a speed which was slightly better than thirty miles an hour.

"Fine!" exclaimed Townsend, taking a look over the rail and watching Absecon Island slip away behind them. "We'll eat up the miles, at this pace, and with no stops to make."

"But the Grampus is also eating up the miles," said Matt, "and will probably make no more stops than we do. How fast can she run, Mr. Townsend?"

"She can do fifteen miles submerged, and twenty to twenty-five on the surface."

"Her course to the Bahamas will be more direct than ours."

"True enough, but our speed is so much faster that, in spite of the roundabout course we're taking, we'll be able to reach Turtle Key and be there to receive the Grampus when she arrives."

"Durtle Key," put in Carl. "Dot's vere ve vas going, eh?"

"That's where the iron chest is supposed to be, and, of course, that's where the Grampus will make for. The Bahamas are all of coral formation and are underlaid with many caverns. For the most part, the islands are hollow; and it is in a hollow under Turtle Key that the Man from Cape Town claimed to have hidden the chest."

"Iss dere pread fruit und odder dropical t'ings on der island?" asked Carl, who was looking forward to a brief period of romance in an island paradise.

"As described on the chart," replied Townsend, "Turtle Key is no more than a hummock of coral, bare as the palm of your hand, and with a surface measuring less than an acre in extent. There is no water, no trees, and no inhabitants if we except the turtles."

Carl was visibly disappointed.

"I vas hoping I could climb some trees und shake down a gouple oof loafs oof pread fruit," he mourned, "und I vas t'inking, meppy, dot I could catch a monkey und pring him pack, und a barrot vat couldt say t'ings. Py shiminy, I don'd like dot kind oof a tesert islandt."

"Where is it, Mr. Townsend," asked Dick, "on the eastern or western side of the group?"

"On the western side, just off Great Bahama Island and well in the Florida Straits."

"I sailed all through that group on the old Billy Ruffian," went on Dick, "wherever the channels were deep enough to float us. There's a good deal of shoal water, and a lot of places where you can go off soundings at a jump. That submarine, if she takes a straight course, will have to keep on the surface a good share of the time."

"Jurgens will take to the Florida Straits and then turn in when he gets opposite Turtle Key. That will give him deep water all the way. After I left you boys last night," added Townsend, shifting the subject, "I had a call from McMillan. He told me that the skipper of the Crescent claimed to have had nothing to do with the picking up of Jurgens off the Heinz pier. Whistler, one of the men on the sailboat, got the three men comprising the crew on his side, and they overpowered the skipper, tied him hand and foot and laid him on the floor of the cuddy. Anyhow, McMillan says that when he boarded the Crescent, the skipper was helpless in the cabin and all the others who had been on the boat had disappeared. It looks a little 'fishy' but that must have been the way of it. The skipper of the Crescent couldn't afford to harbor a fugitive like Jurgens."

"It was all a brazen piece of work from start to finish," observed Matt. "The capture of the Grampus was second only to the desperate play Jurgens made when he stole the chart. Jurgens, from what I saw and heard while Holcomb and I were aboard the Grampus, knows a good deal about the submarine, but——"

"He learned all that while he was working in the shipyard," put in Townsend.

"But does he know enough to run the craft?" queried Matt.

"I think not. He and his gang are probably forcing Cassidy, my machinist, to run the submarine for him. If Cassidy, Burke and Harris, my men in the Grampus, succeeded in turning on their captors and recapturing the boat, we'll be having all our work for nothing—that is, so far as the Grampus is concerned. In that event, we'll look for the iron chest."

"Dot's der talk!" cried Carl. "Ve vill findt der dreasure. It vas some birate dreasure, I bed you! I vouldt like to findt a chest full mit bieces oof eight und dot odder druck vat birates used to take from peobles pefore dey made dem valk der blank."

"Bosh, Carl!" exclaimed Dick, disgustedly. "You're a lubber to take stock in any such yarn. Anyhow, I should think you'd had enough to do with pirates."

This reference to the way Carl had butted into the moving pictures brought grins to the faces of Townsend and Matt. It was a sore spot with Carl, and he tried at once to get his companions to thinking of something else.

He picked up the sextant and turned it over and over in his hands.

"How you findt out vere ve vas mit dis?" he queried.

"Hand it over, Carl," replied Townsend, "and I'll show you."

Carl was standing by the rail. Just as he started to hand the sextant to Townsend, a gust of air struck the Hawk and she made a sidewise lurch that jerked the car uncomfortably. Carl let go the sextant and grabbed with both hands at the rail; and the sextant, flung a little outward by the motion of Carl's hand, slipped clear of the rail and dropped downward into space.

A cry of dismay escaped Townsend and Dick.

"Himmelblitzen!" growled Carl, very much put out[Pg 13] with himself, "I vas aboudt as graceful as a hibbobotamus. Vat a luck! Vell, Misder Downsend, I puy you anodder."

"It isn't so easy to buy another, Carl," said Matt, circling the Hawk about and dropping earthward. "We've got to get that sextant, if we can. Watch close all of you, and try and see where it fell."

At that moment the Hawk had been approaching Stone Harbor, and was above the beach. The sextant may have been ruined by the fall, but Matt was hoping against hope that it would be found in usable condition, and that they would not have to delay their voyage to land at some seaport and buy another.

AN ACCIDENT.

"I think I see it, mate!" called Dick, as the Hawk came closer to the clear stretch of sand. "To the right a little—about two points—and keep her dropping as she is."

"I see it, too!" declared Townsend, leaning out over the rail.

When ascending or descending, the car of the air ship, as might naturally be supposed, was always tilted. In the present instance it was inclined at a dangerous angle, for Matt was trying to bring the craft to an even keel as nearly over the spot where the sextant was lying as he could.

The inclination of the car made it exceedingly difficult for those who were standing to keep their feet, and it was only by clinging to the rail that they could do so. Matt had a chair, and there were supports against which he could brace his feet, thus leaving his hands free at all times to manage the motor.

When about twelve feet above the beach, another gust of air struck the air ship, buffeting her roughly sideways, Townsend was leaning so far over the rail that the jerk of the car caused him to lose his balance. His hands were torn from the rail and he pitched headlong out of the car.

At this mishap, which threatened tragic consequences, consternation seized the boys.

"Donnervetter!" whooped Carl, "he vill be killed."

Quickly as he could, Matt brought the Hawk to the beach. There was no way of mooring the craft, and she swung back and forth in the wind, making it necessary for Matt to stay aboard.

"Tumble out, Dick, you and Carl," Matt called. "See if Townsend has been hurt."

Dick and Carl found Townsend trying to get up. His face was set as with pain, and it was clearly evident that he had not come through the mishap uninjured.

"What's the matter?" asked Dick.

"It's my foot," answered Townsend, stifling a groan. "I turned in the air and struck almost on my feet. I'm lucky, I suppose, not to have landed on my head and broken my neck. It's a sprain, I guess, but it hurts like Sam Hill. Help me up."

Dick and Carl got on each side of Townsend and lifted him erect. The injury to his right foot was so great that he could not step on it, and was almost carried back to the car by the two boys.

"We'd better put in at Stone Harbor, Mr. Townsend," said Matt, a troubled look crossing his face, "and let a doctor have a look at you."

"I'm sure it's only a sprain," returned Townsend, pluckily, "and we won't delay the voyage by stopping at Stone Harbor. Just make me comfortable on the floor of the car and have Carl take off my shoe and wrap a bandage around the foot. I'll get along. It was my own fault," he added, "for I had no business to be leaning so far over the rail. Pick up the sextant, Ferral."

Dick went for the sextant. It had fallen in soft sand and, although damaged to some extent, had not lost its usefulness.

While Dick was recovering the sextant, Carl was making Townsend as comfortable as possible on the floor of the car. A folded canvas shelter, which Matt had devised as a covering for the Hawk, was brought into requisition and spread out for Townsend to lie on. Townsend's shoe was then removed. The foot and ankle as yet showed no signs of the injury, but every touch caused so much pain that Townsend had to clinch his teeth to keep from crying out.

Matt, for such an emergency as had just presented itself, always carried a bottle of arnica in the toolbox. Carl got out the arnica, soaked a rag with it and bound the rag around Townsend's foot. Over this another bandage was placed, and Townsend lay back on his makeshift couch and rested.

"It would only delay us a few hours," said Matt, "to stop at Stone Harbor and have a doctor give your foot proper attention."

"I don't think that's necessary, Matt," answered Townsend. "Get under way again. We've lost half an hour already."

The accident, although it had resulted in an injury which might have been infinitely more serious, dropped a pall over the spirits of the three boys. If omens counted for anything, the cruise was to end in disaster.

Matt started the machinery and got the air ship aloft and once more headed on her course. How he and his chums were ever going to reach Turtle Key, hampered by an injured passenger, was more than he knew. The outlook was dubious, to say the least.

Noon found them over the State of Delaware and reaching along toward Chesapeake Bay. The wind grew steady and shifted until it was almost directly behind them, and the Hawk went spinning through the air at the rate of forty miles an hour.