Route of

M de Lesseps

Consul of France,

in the PENINSULA of

KAMTSCHATKA,

and along the GULF of PENGINA, from the Port of St. Peter & St.

Paul as far as Yamsk.

Title: Travels in Kamtschatka, During the Years 1787 and 1788, Volume 1

Author: baron de Jean-Baptiste-Barthélemy Lesseps

Release date: March 13, 2015 [eBook #48479]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Moti Ben-Ari and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Route of

M de Lesseps

Consul of France,

in the PENINSULA of

KAMTSCHATKA,

and along the GULF of PENGINA, from the Port of St. Peter & St.

Paul as far as Yamsk.

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH OF

M. DE LESSEPS, CONSUL OF FRANCE,

AND

INTERPRETER TO THE COUNT DE LA PEROUSE, NOW

ENGAGED IN A VOYAGE ROUND THE WORLD, BY

COMMAND OF HIS MOST CHRISTIAN MAJESTY.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOLUME I.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR J. JOHNSON, ST. PAUL'S CHURCH-YARD.

1790.

My work is merely a journal of my travels. Why should I take any steps to prepossess the judgment of my reader? Shall I not have more claim to his indulgence when I have assured him, that it was not originally my intention to write a book? Will not my account be the more interesting, when it is known, that my sole inducement to employ my pen was the necessity I found of filling up my leisure moments, and that my vanity extended no farther than to give my friends a faithful journal of the difficulties I had to encounter, and the observations I made on my road? It is evident I wrote by intervals,[iv] negligently or with care, as circumstances permitted, or as the impressions made by the objects around me were more or less forcible.

Conscious of my own inexperience, I thought it a duty I owed myself to let slip no opportunity of acquiring information, as if I had foreseen, that I should be called to account for the time I had spent, and the knowledge which I had it in my power to obtain: but perhaps the scrupulous exactness to which I confined myself, entailed on my narration a want of elegance and variety.

The events which relate personally to myself are so connected with the subject of my remarks, that I have taken no care to suppress them. I may therefore, not undeservedly, be reproached with having[v] spoken too much of myself: but this is the prevailing sin of travellers of my age.

Besides this, I am ready to accuse myself of frequent repetitions, which would have been avoided by a more experienced pen. On certain subjects, particularly in respect of travels, it is scarcely possible to avoid an uniformity of style. To paint the same objects, we must employ the same colours; hence similar expressions are continually recurring.

With respect to the pronunciation of the Russian, Kamtschadale, and other foreign words, I shall observe, that all the letters are to be articulated distinctly. I have thought it adviseable, even in the vocabulary, to reject those consonants, the confused assemblage of which discourages the reader, and is not always necessary, The kh is to be pronounced as the ch of the[vi] Germans, or the j of the Spaniards, and the ch as in the French. The finals oi and in, are to be pronounced, the former as an improper diphthong (oï) and the latter in the English, not in the French manner.

The delay of publishing this journal renders some excuse necessary. Unquestionably I might have given it to the world sooner, and it was my duty to have done it; but my gratitude bad me wait the return of the count de la Perouse. What is my journey, said I to myself? To the public, it is only an appendage to the important expedition of that gentleman; to myself, it is an honourable proof of his confidence: I had a double motive to submit my account to his inspection. My own interest also prescribed this to me. How happy should I have been, if, permitting me to publish my travels as a supplement to his, he had deigned to render me an associate of[vii] his fame! This, I confess, was the sole end of my ambition; the sole cause of my delay.

How cruel for me, after a year of impatient expectation, to see the wished for period still more distant! Not a day has passed since my arrival, on which my wishes have not recalled the Astrolabe and Boussole. How often, traversing in imagination the seas they had to cross, have I sought to trace their progress, to follow then from port to port, to calculate their delays, and to measure all the windings of their course!

When at the moment of our separation in Kamtschatka, the officers of our vessels sorrowfully embraced me as lost, who would have said, that I should first revisit my native country; that many of them would never see it more; and that in a little time I should shed tears over their fate!

Scarcely, in effect, had I time to congratulate myself on the success of my mission, and the embraces of my family, when the report of our misfortunes in the Archipelago of navigators arrived, to fill my heart with sorrow and affection. The viscount de Langle, that brave and loyal seaman, the friend, the companion of our commander; a man whom I loved and respected as my father, is no more! My pen refuses to trace his unfortunate end, but my gratitude indulges itself in repeating, that the remembrance of his virtues and his kindness to me, will live eternally in my bosom.

Reader, who ever thou art, pardon this involuntary effusion of my grief. Hadst thou known him whom I lament, thou wouldst mingle thy tears with mine: like me thou wouldst pray to Heaven, that, for our consolation, and for the glory of France, the commander of the expedition, and those[ix] of our brave Argonauts, whom it has preserved, may soon return. Ah! if whilst I write, a favourable gale should fill their sails, and impel them towards our shores!—May this prayer of my heart be heard! May the day on which these volumes are published, be that of their arrival! In the excess of my joy, my self-love would find the highest gratification.

| Page | |

| I quit the French frigates, and receive my dispatches | 3 |

| Departure of the frigates | 6 |

| Impossibility of going to Okotsk before sledges can | |

| be used | 7 |

| Details respecting the port of St. Peter and St. Paul | 9 |

| Nature of the soil | 15 |

| Climate | 16 |

| Rivers that have their mouth in the bay of Avatscha | 18 |

| Departure from St. Peter and St. Paul's with M. | |

| Kasloff and M. Schmaleff | 19 |

| Arrival at Paratounka | 22 |

| Description of this ostrog | 23 |

| Kamtschadale habitations | 24 |

| Balagans | 25 |

| Isbas | 28 |

| Chief or judge of an ostrog | 31 |

| Arrival at Koriaki | 37 |

| Arrival at the baths of Natchikin | 38 |

| Description of the baths | 41 |

| Mode of analizing the hot waters | 46 |

| Result of our experiments | 50 |

| [xii] | |

| Mode of hunting a sable | 55 |

| Departure from Natchikin, and details of our journey | 59 |

| Arrival at Apatchin | 65 |

| At Bolcheretsk, &c. | 66 |

| Shipwreck of an Okotsk galiot | 68 |

| Hamlet of Tchekafki | 70 |

| Mouth of the Bolchaïa-reka | 71 |

| Terrible hurricane | 74 |

| Description of Bolcheretsk, where I stayed till 27 | |

| January 1788 | 76 |

| Population | 80 |

| Fraudulent commerce of the Cossacs and others | 81 |

| Commerce in general | 84 |

| Mode of living of the inhabitants and the Kamtschades | |

| in general | 87 |

| Dress | ib. |

| Food | 88 |

| Drink | 93 |

| Indigenes | 94 |

| Reflections on the manners of the inhabitants | 97 |

| Balls | 101 |

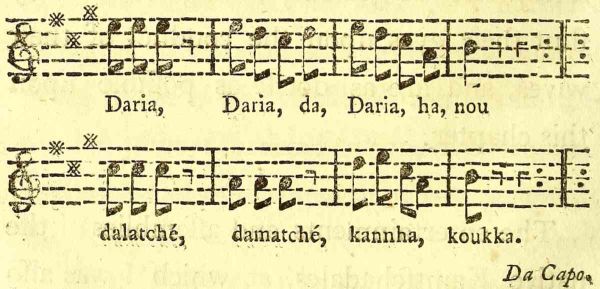

| Kamtschadale feasts and dances | 103 |

| Bear hunting | 106 |

| Hunting | 110 |

| Fishing | 114 |

| Scarcity of horses | 115 |

| Dogs | ib. |

| Sledges | 118 |

| Diseases | 127 |

| Medical sorcerers | 130 |

| Strong constitution of the women | 133 |

| [xiii] | |

| Remedy learned from the bear | 134 |

| Religion | 135 |

| Churches | 137 |

| Tributes | 138 |

| Coins | 139 |

| Pay of the soldiers | 140 |

| Government | ib. |

| Tribunals | 143 |

| Successions | 144 |

| Divorces | ib. |

| Punishments | 145 |

| Idiom | 146 |

| Climate | 147 |

| My long stay at Bolcheretsk accounted for | 150 |

| Departure from Bolcheretsk | 152 |

| Arrival at Apatchin | 155 |

| Origin of the ill opinion the inhabitants of Kamtschatka | |

| have of the French | 156 |

| Beniouski | 157 |

| M. Schmaleff quits us | 158 |

| Arrival at Malkin | 159 |

| At Ganal | 162 |

| At Pouschiné | 164 |

| Isbas without chimneys | ib. |

| Kamtschadale lamp | 165 |

| Filthiness of the inhabitants | 166 |

| The roads obstructed with snow | 167 |

| Ostrog of Charom | 168 |

| Arrival at Vereknei Kamtschatka | ib. |

| Ivaschin, an unfortunate exile | 170 |

| Colony of peasants | 172 |

| [xiv] | |

| Ostrog of Kirgann | 175 |

| Description of my dress | 177 |

| Visit the baron Stenheil at Machoure | 180 |

| New details respecting the chamans or sorcerers | 181 |

| Alarmed at a report of the Koriacs having revolted | 188 |

| Nikoulka rivers | 191 |

| Volcanos of Tolbatchina | 192 |

| Early marriages | 194 |

| I quit M. Kasloff to go to Nijenei Kamtschatka | 195 |

| Ostrog of Ouchkoff | 196 |

| Of Krestoff | 197 |

| Volcano of Klutchefskaïa | 198 |

| Klutchefskaïa inhabited by Siberian peasants | ib. |

| Ostrog of Kamini | 201 |

| Arrival at Nijenei | ib. |

| Entertainment given by the governor | 204 |

| Tribunals of Nijenei | 207 |

| Account of nine Japanese whom I found there | 208 |

| Departure from Nijenei Kamtschatka | 217 |

| I rejoin M. Kasloff | 219 |

| Overtaken by a tempest, which obliges us to halt | ib. |

| Manner in which the Kamtschades made their bed on | |

| the snow | 221 |

| Ostrog of Ozernoi | 223 |

| Of Onké | ib. |

| Of Khalali | 225 |

| Of Ivaschin | 227 |

| Of Drannki | 228 |

| Of Karagui | 229 |

| Yourts described | 230 |

| Singular dress of the children of Karagui | 234 |

| [xv] | |

| Koriacs supply us with rein deer | 236 |

| Account of the two sorts of Koriacs | 237 |

| A celebrated female dancer | 240 |

| Fondness of the Kamtschadales for tobacco | 243 |

| Departure from Karagui | 246 |

| Manner of our halting in the open country | 247 |

| Our dogs begin to suffer from famine | 248 |

| Soldier sent to Kaminoi for succour | 249 |

| Arrival at Gavenki | 250 |

| Dispute between a sergeant of our company and two | |

| peasants of the village | 251 |

| The inhabitants refuse us fish | 254 |

| Departure from Gavenki | 256 |

| Misled by our guide | 257 |

| Our dogs die of hunger and fatigue | 258 |

| We are apprehhensive of being starved to death in a | |

| desert | ib. |

| Obliged to leave our equipage | 259 |

| New distresses | ib. |

| Arrival at Poustaretsk | 262 |

| Fruitless attempts to find provisions | 263 |

| Melancholy spectacle exhibited by our dogs | ib. |

| Soldier sent to Kaminoi, stopt in his way by tempests | 265 |

| Sergeant Kabechoff sets out for Kaminoi | 266 |

| Description of Poustaretsk and its environs | 267 |

| Food upon which the inhabitants lived during our stay | 268 |

| Their mode of catching rein deer | 269 |

| Occupations of the women | 270 |

| Method of smoking | 271 |

| Dress | 272 |

| M. Schmaleff joins us | 273 |

| [xvi] | |

| Distressing answer from sergeant Kabechoff | 274 |

| M. Kasloff receives news of his promotion | 275 |

| I resolve to leave him | 276 |

| Calm established among the Koriacs | 278 |

| M. Kasloff gives me his dispatches, and the passports | |

| necessary for my safety | 280 |

| My regret at leaving him | 281 |

TRAVELS

IN

KAMTSCHATKA, &c.

I have scarcely completed my twenty-fifth year, and am arrived at the most memorable æra of my life. However long, or however happy may be my future career, I doubt whether it will ever be my fate to be employed in so glorious an expedition as that in which two French frigates, the Boussole, and the Astrolabe, are at this moment engaged; the first commanded by count de la Perouse, chief of the expedition, and the second by viscount de Langle[1].

The report of this voyage round the world, created too general and lively an interest, for direct news of these illustrious navigators, reclaimed by their country and by all Europe from the seas they traverse, not to be expected with as much impatience as curiosity.

How flattering is it to my heart, after having obtained from count de la Perouse the advantage of accompanying him for more than two years, to be farther indebted to him for the honour of conveying his dispatches over land into France! The more I reflect upon this additional proof of his confidence, the more I feel what such an embassy requires, and how far I am deficient; and I can only attribute his preference, to the necessity of choosing for this journey, a person who had resided in Russia, and could speak its language.

On the 6 September 1787, the king's frigates entered the port of Avatscha, or Saint Peter and Saint Paul[2], at the southern extremity of the peninsula of Kamtschatka. The 29, I was ordered to quit the Astrolabe; and the same day count de la Perouse gave me his dispatches and instructions. His regard for me would not permit him to confine his cares to the most satisfactory arrangements for the safety and convenience of my journey; he went farther, and gave me the affectionate counsels of a father, which will never be obliterated from my heart. Viscount de Langle had the goodness to join his also, which proved equally beneficial to me.

Let me be permitted in this place to pay my just tribute of gratitude to the faithful companion of the dangers and the glory of count de la Perouse, and his rival in every other court, as well as that of France, for having acted towards me, upon all occasions, as a counsellor, a friend, and a father.

In the evening I was to take my leave of the commander and his worthy colleague. Judge what I suffered, when I conducted them back to the boats that waited for them. I was incapable of speaking, or of quitting them; they embraced me in turns, and my tears too plainly told them the situation of my mind. The officers who were on shore, received also my adieux: they were affected, offered prayers to heaven for my safety, and gave me every consolation and succour that their friendship could dictate. My regret at leaving them cannot be described; I was torn from their arms, and found myself in those of[5] colonel Kasloff-Ougrenin, governor general of Okotsk and Kamtschatka, to whom count de la Perouse had recommended me, more as his son, than an officer charged with his dispatches.

At this moment commenced my obligations to the Russian governor. I knew not then all the sweetness of his character, incessantly disposed to acts of kindness, and which I have since had so many reasons to admire[3]. He treated my feelings with the utmost address. I saw the tear of sympathy in his eye upon the departure of the boats, which we followed as far as our sight would permit; and in conducting me to his house, he spared no pains to divert me from my melancholy reflections.[6] To conceive the frightful void which my mind experienced at this moment, it is necessary to be in my situation, and left alone in these scarcely discovered regions, four thousand leagues from my native land: without calculating this enormous distance, the dreary aspect of the country sufficiently prognosticated what I should have to suffer during my long and perilous route; but the reception which I met with from the inhabitants, and the civilities of M. Kasloff and the other Russian officers, made me by degrees less sensible to the departure of my countrymen.

It took place on the morning of 30 September. They set sail with a wind that carried them out of sight in a few hours, and continued favourable for several days. It will readily be believed, that I did not see them depart without offering the most[7] sincere wishes for all my friends on board; the last sad homage of my gratitude and attachment.

Count de la Perouse had recommended diligence to me, but enjoined me, at the same time, upon no pretext to quit M. Kasloff; an injunction that was perfectly agreeable to my inclinations. The governor had promised to conduct me as far as Okotsk, which was the place of his residence, and to which it was necessary that he should repair immediately. I had already felt the happiness of being placed in such good hands, and I made no scruple of surrendering myself implicitly to his direction.

His intention was to go as far as Bolcheretsk, and there wait till we could avail ourselves of sledges, which would greatly facilitate our journey to Okotsk. The season was too far advanced for us to risk an[8] attempt by land, and the passage by sea was not less dangerous; besides there was no vessel either in the port of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, or of Bolcheretsk[4].

M. Kasloff had his affairs to settle, which, with the preparations for our departure, detained us six days longer, and afforded me time to satisfy myself that the frigates were not likely to return. I embraced this opportunity of commencing my observations, and making minutes of every thing about me. I attended particularly to the bay of Avatcha, and the port of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, in order to give a just idea of them.

This bay has been minutely described by captain Cook, and we found his account to be accurate. It has since undergone some alterations; which, it is said, are to be followed by many others; particularly as to the port of Saint Peter and Saint Paul. It is possible indeed, that the very next ship which shall arrive, expecting to find only five or six houses, may be surprised with the sight of an entire town, built of wood, but tolerably fortified.

Such at least is the projected plan, which, as I learned indirectly, is to be ascribed to M. Kasloff, whose views are equally great, and conducive to the service of his mistress. The execution of this plan will contribute not a little to increase the celebrity of the port, already made famous by the foreign vessels which have touched there, as well as by its favourable situation for commerce[5].

To understand the nature, and estimate the utility of this project, nothing more is necessary than to have an idea of the extent and form of the bay of Avatscha, and the port in question. We have already many[11] accurate descriptions, which are in the hands of every one. I shall therefore confine myself to what may tend to illustrate the views of M. Kasloff.

The port of St. Peter and St. Paul, is known to be situated at the north of the entrance of the bay, and closed in at the south by a very narrow neck of land, upon which the ostrog[6], or village of Kamtschatka is built. Upon an eminence to the east, at the most[12] interior point of the bay, is the house of the governor[7], with whom M. Kasloff resided during his stay. Near this house, almost in the same line, is that of a corporal of the garrison, and a little higher inclining to the north, that of the serjeant, who, next to the governor, are the only persons at all distinguished in this settlement, if indeed it deserves the name of settlement. Opposite to the entrance of the port, on the declivity of the eminence, from which a lake of considerable extent is seen, are the ruins of the hospital mentioned in captain Cooke's voyage[8]. Below these, and nearer the shore, is[13] a building which serves as a magazine to the garrison, and which is constantly guarded by a centinel. Such was the state in which we found the port of St. Peter and St. Paul.

By the proposed augmentation, it will evidently become an interesting place. The entrance was to be closed, or at least flanked by fortifications, which were to serve at the same time as a defence, on this side, to the projected town, which was chiefly to[14] be built upon the site of the old hospital; that is, between the port and the lake. A battery also was to be erected upon the neck of land which separates the bay from the lake, in order to protect the other part of the town. In short, by this plan, the entrance of the bay would be defended by a sufficiently strong battery upon the least elevated point of the left coast; and vessels entering the bay could not escape the cannon, because of the breakers on the right. There is at present upon the point of a rock, a battery of six or eight cannon, lately erected to salute our frigates.

I need not add, that the augmentation of the garrison forms a part of the plan, which consists only at present of forty soldiers, or Cossacs. Their mode of living and their dress are similar to the Kamtschadales, except that in time of service they have a sabre, firelock, and cartouch box; in other[15] respects they are not distinguishable from the indigenes, but by their features and idiom.

With respect to the Kamtschadale village, which forms a considerable part of the place, and is situated, as I have already said, upon the narrow projection of land which closes in the entrance of the port, it is at present composed of from thirty to forty habitations, including winter and summer ones, called isbas and balagans; and the number of inhabitants, taking in the garrison, does not exceed a hundred, men, women and children. The intention is to increase them to upwards of four hundred.

To these details respecting the port of St. Peter and St. Paul, and its destined improvements, I shall add a few remarks upon the nature of the soil, the climate, and the[16] rivers. The banks of the bay of Avatscha are rendered difficult of access by high mountains, of which some are covered with wood, and others have volcanos[9]. The valleys present a vegetation that astonished me. The grass was nearly of the height of a man; and the rural flowers, such as the wild roses and others that are interspersed with them, diffuse far and wide a most grateful smell.

The rains are in general heavy during spring and autumn, and blasts of wind are frequent in autumn and winter. The latter is sometimes rainy; but notwithstanding its length, they assured me that its severity is not very extreme, at least in this southern part of Kamtschatka[10]. The snow begins to appear on the ground in October, and the thaw does not take place till April or May; but even in July it is seen to fall upon the summit of high mountains, and particularly volcanos. The summer is tolerably fine; the strongest heats scarcely last beyond the solstice. Thunder is seldom heard, and is never productive of injury. Such is the temperature of almost all this part of the peninsula.

Two rivers pour their waters into the bay of Avatscha; that from which the bay is named, and the Paratounka. They both abound with fish, and every species of water fowl, but these are so wild, that it is not possible to approach within fifty yards of them. The navigation of these rivers is impracticable after the 26 November, because they are always frozen at this time; and in the depth of winter the bay itself is covered with sheets of ice, which are kept there by the wind blowing from the sea; but they are completely dispelled as soon as it blows from the land. The port of St. Peter and St. Paul is commonly shut up by the ice in the month of January.

I should doubtless say something in this place of the manners and customs of the[19] Kamtschadales, of their houses, or rather huts, which they call isbas or balagans; but I must defer this till my arrival at Bolcheretsk, where I expect to have more leisure, and a better opportunity of describing them minutely.

We departed from the port of Saint Peter and Saint Paul the 7 October. Our company consisted of Messrs. Kasloff, Schmaleff[11], Vorokhoff[12], Ivaschkin[13], myself, and the suite of the governor, amounting to four[20] serjeants, and an equal number of soldiers. The commanding officer of the port, probably out of respect to M.[21] Kasloff, his superior, joined our little troop, and we embarked upon baidars[14] in order to cross the bay and reach Paratounka, where we[22] were to be supplied with horses to proceed on our route.

In five or six hours we arrived at this ostrog, where the priest[15], or rector of the district resides, and whose church also is in this place[16]. His house served us for a lodging, and we were treated with[23] the utmost hospitality; but we had scarcely entered when the rain fell in such abundance, that we were obliged to stay longer than we wished.

I eagerly embraced this short interval to describe some of the objects which I had deferred till my arrival at Bolcheretsk, where, perhaps, I may find others that will not be less interesting.

The ostrog of Paratounka is situated by the side of a river of that name, about two leagues from its mouth[17]. This village is scarcely[24] more populous than that of St. Peter and St. Paul. The small pox has, in this place particularly, made dreadful ravages. The number of balagans and isbas seemed to be very nearly the same as at Petropavlofska[18].

The Kamtschadales lodge in the first during summer, and retreat to the last in winter. As it is thought desirable that[25] they should be brought gradually to resemble the Russian peasants, they are prohibited, in this southern part of Kamtschatka, from constructing any more yourts, or subterraneous habitations; these are all destroyed at present[19], a few vestiges only remain of them, filled up within, and appearing externally like the roofs of our ice-houses.

The balagans are elevated above the ground upon a number of posts, placed at equal distances, and about twelve or thirteen feet high. This rough sort of colonnade supports in the air a platform made of rafters, joined to one another, and overspread with clay: this platform serves as a floor to the whole building, which consists of a roof in the shape of a cone, covered with a kind of thatch, or dried grass, placed upon long poles fastened together at the top, and bearing upon the rafters. This is at once the first and last story; it forms the whole apartment, or rather chamber: an opening in the roof serves instead of a chimney to let out the smoke, when a fire is lighted to dress their victuals; this cookery is performed in the middle of the room, where they eat and sleep pell-mell together without the least disgust or scruple. In these apartments, windows are out of the question; there is merely a door, so low and narrow, that it will scarcely suffice to admit the light. The staircase is worthy of the rest of the building; it consists of a beam, or rather a tree jagged in a slovenly manner, one end of which rests on the ground, and the other is raised to the height of the floor. It is placed at the angle of the door, upon a level, with a kind of open gallery that is erected before it. This tree[27] retains its roundness, and presents on one side something like steps, but they are so incommodious that I was more than once in danger of breaking my neck. In reality, whenever this vile ladder turns under the feet of those who are not accustomed to it, it is impossible to preserve an equilibrium; a fall must be the consequence, more or less dangerous, in proportion to the height. When they wish persons to be informed that there is nobody at home, they merely turn the staircase, with the steps inward.

Motives of convenience may have suggested to these people the idea of building such strange dwellings, which their mode of living renders necessary and commodious. Their principal food being dried fish, which is also the nourishment of their dogs, it is necessary, in order to dry their fish, and other provisions, that they should[28] have a place sheltered from the heat of the sun, and at the same time perfectly exposed to the air. Under the collonnades or rustic porticos, which form the lower part of their balagans, they find this convenience; and there they hang their fish, either to the ceiling or to the sides, that it may be out of the reach of the voraciousness of their dogs. The Kamtschadales make use of dogs[20] to draw their sledges; the best, that is the most vicious, have no other kennel than what the portico of the balagans affords them, to the posts of which they are tied. Such are the advantages resulting from the singular mode of constructing the balagans, or summer habitations of the Kamtschadales.

Those of winter are less singular; and if equally large, would exactly resemble the habitations of the Russian peasants. These have been so often described, that it is universally known how they are constructed and arranged. The isbas are built of wood; that is to say, the walls are formed by placing long trees horizontally upon one another, and filling up the interstices with clay. The roof slants like our thatched houses, and is covered with coarse grass, or rushes, and frequently with planks. The interior part is divided into two rooms, with a stove placed so as to warm them both, and which serves at the same time as a fire-place for their cookery. On two sides of the largest room, wide benches are fixed, and sometimes a sorry couch made of planks, and covered with bears skin. This is the bed of the chief of the family: and the women, who in this country are the slaves of their husbands, and perform all[30] the most laborious offices, think themselves happy to be allowed to sleep in it.

Besides these benches and the bed, there is also a table, and a great number of images of different saints, with which the Kamtschadales are as emulous of furnishing their chambers, as the majority of our celebrated connoisseurs are of displaying their magnificent paintings.

The windows, as may be supposed, are neither large or high. The panes are made of the skins of salmon, or the bladders of various animals, or the gullets of sea wolves prepared, and sometimes of leaves of talc; but this is rare, and implies a sort of opulence. The fish skins are so scraped and dressed that they become transparent, and admit a feeble light to the room[21]; but objects cannot be seen through them. The leaves of talc are more clear, and approach nearer to glass; in the mean time they are not sufficiently transparent for persons without to see what is going on within: this is manifestly no inconvenience to such low houses.

Every ostrog is presided by a chief, called toyon. This kind of magistrate is chosen from among the natives of the country, by a plurality of voices. The Russians have preserved to them this privilege, but the election must be approved by the jurisdiction of the province. This toyon is merely a peasant, like those whom he judges and governs; he has no mark of distinction, and performs the same labours as his subordinates. His office is chiefly to watch over the police, and inspect the execution of the orders of government. Under him is another Kamtschadale, chosen[32] by the toyon himself, to assist him in the exercise of his functions, or supply his place. This vice-toyon is called yesaoul, a Cossac title adopted by the Kamtschadales since the arrival of the Cossacs in their peninsula, and which signifies second chief of their band or clan. It is necessary to add, that when the conduct of these chiefs is considered as corrupt, or excites the complaints of their inferiors, the Russian officers presiding over them, or the other tribunals established by government, dismiss them immediately from their functions, and nominate others more agreeable to the Kamtschadales, with whom the right of election still remains.

The rain continuing, we were unable to proceed on our journey; but my curiosity led me to embrace a short interval that offered in the course of the day, to[33] walk out into the ostrog, and visit its environs.

I went first to the church, which I found to be built of wood, and ornamented in the taste of those of the Russian villages. I observed the arms of captain Clerke, painted by Mr. Webber, and the English inscription upon the death of this worthy successor of captain Cook; it pointed out the place of his burial at Saint Peter and Saint Paul's.

During the stay of the French frigates in this port, I had been at Paratounka, in a hunting excursion, with viscount de Langle. As we returned, he spoke of many interesting objects he had observed in the church, and which had entirely escaped my attention. They were, as far as I can remember, various offerings deposited there, he said, by some ancient[34] navigators, who had been shipwrecked. It was my full intention to examine them upon my second visit to this ostrog; but whether it escaped my recollection, or that my research was too precipitate, from the short time that I had to make it, certain it is that I did not discover them.

The village is surrounded with a wood; I traversed it by proceeding along the river, and perceived at length a vast plain which extends to the north and the east as far as the mountains of Petropavlofska. This chain is terminated at the south and west by another, of which the mountain of Paratounka forms a part, and which is about five or six wersts[22] from the ostrog of that name. Upon the banks of the rivers that wind in this plain, there are frequent traces of bears, who are attracted by the fish with which these rivers abound. The inhabitants assured me, that fifteen or eighteen were frequently seen together upon these banks, and that whenever they hunted them, they were sure to bring back one or two, at least, in the space of twenty-four hours. I shall soon have occasion to speak of their chace, and their weapons.

We quitted Paratounka and resumed our journey; twenty horses sufficed for ourselves and our baggage, which was not considerable, M. Kasloff having taken the precaution of sending a great part of it by water, as far as the ostrog of Koriaki. The river Avatscha has no tide, and is not navigable farther than this ostrog; and not at all indeed, except by small boats, called batts. The baidirs only serve to cross the bay of Avatscha, and can proceed no farther than the mouth of the river, where[36] their lading is put into these batts, which, from the shallowness and rapidity of the water, are pushed forward with poles. It was in this manner our effects arrived at Koriaki.

As to ourselves, having crossed the river Paratounka at a shallow, and winded along several of its branches, we left it for a way that was woody and less level, but which afforded us better travelling; it was almost entirely in valleys, and we had only two mountains to climb. Our horses, notwithstanding their burthens, advanced very briskly. We had no reason to complain of the weather for a single moment; it was so fair, that I began to think the rigour of the climate had been exaggerated; but shortly after, experience too well convinced me of its truth, and in the sequel of my journey, I had every reason to accustom myself to the most piercing frosts, too happy[37] when in the midst of ice and snow, that I had not to contend with the violence of whirlwinds and tempests.

We were about six or seven hours in going from Paratounka to Koriaki, which, as far as I could judge, is from thirty-eight to forty wersts. Scarcely arrived, we were obliged to take refuge in the house of the toyon, to shelter ourselves from the rain; he ceded his isba to M. Kasloff, and we spent the night there.

The ostrog of Koriaki is situated in the midst of a coppice wood, and upon the border of the river Avatscha, which becomes very narrow in this part. Five or six isbas, and twice, or at most three times the number of balagans, make up this village, which is similar to that of Paratounka, except that it is less, and has no parish church. I observed in general that ostrogs of so little[38] consideration were not provided with a church.

The next day we mounted our horses and took the way to Natchikin, another ostrog in the Bolcheretsk route. We were to stop a few days in the neighbourhood for the sake of the baths, which M. Kasloff had constructed at his own expence, for the benefit and pleasure of the inhabitants, upon the hots springs that are found there, and which I shall presently describe. The way from Koriaki to Natchikin is tolerably commodious, and we crossed without difficulty all the little streams that fall from the mountains, at the foot of which we passed. About three-fourths of the way we met the Bolchaïa-reka[23]; from the site of its greatest breadth, which in this place is about ten or twelve yards, it appears to wind to a considerable extent to the north east; we journeyed on its bank for some time, till we came to a[39] little mountain, which we were obliged to pass over in order to reach the village. A heavy rain which came on as we left Koriaki, ceased a few minutes after; but the wind having changed to the north-west, the heavens became obscured, and we had abundance of snow; we were about two-thirds of our way, and it continued till our arrival. I remarked that the snow already covered the mountains, even such as were lowest, upon which it described an equal line at a certain elevation, but that below them no traces of it were yet perceptible. We forded the Bolchaïa-reka, and found on the other side the ostrog of Natchikin, where I counted six or seven isbas and twenty balagans, similar to what I had seen before. We made no stay there, M. Kasloff thinking it proper to hasten immediately to the baths, to which I was inclined as much[40] from curiosity as from necessity.

The snow had penetrated through my clothes, and in crossing the river, which was deep, I had made my legs and feet wet. I longed therefore to be able to change my dress, but when we came to the baths our baggage was not arrived. We proposed drying ourselves by walking about the environs, and observing the interesting objects which I expected to find there. I was charmed with every thing I saw, but the dampness of the place, added to that of our clothes, gave us such a chilliness that we quickly put an end to our walk. Upon our return we had a new source of regret and impatience. Unable either to dry ourselves or change our dress, our equipage not being arrived, to complete our misfortune, the place to which we had retired was the dampest we could have chosen, and though[41] it seemed sufficiently sheltered, the wind penetrated on every side. M. Kasloff had recourse to the bath, which quickly restored him; but not daring to follow his example, I was obliged to wait the arrival of our baggage. The damp had penetrated to such a degree that I shivered during the whole night.

The next day I made a trial of these baths, and can say that none ever afforded me so much pleasure or so much benefit. But before I proceed, I must describe the source of these hot waters, and the building constructed for bathing.

They are two wersts to the north of the ostrog, and about a hundred yards from the bank of the Bolchaïa-reka, which it is necessary to cross a second time in order to arrive at the baths, on account of the elbow which the river describes below the village. A thick[42] and continual vapour ascends from these waters, which fall in a rapid cascade from a rather steep declivity, three hundred yards from the place where the baths are erected. In their fall, which is in a direction east and west, they form a small stream of a foot and half deep, and six or seven feet wide. At a little distance from the Bolchaïa-reka, this stream is met by another, with which it pours itself into this river. At their conflux, which is about eight or nine hundred yards from the source, the water is so hot that it is not possible to keep the hand in it for half a minute.

M. Kasloff has been careful to erect his building on the most convenient spot, and where the temperature of the water is most moderate. It is constructed of wood, in the middle of a stream, and is in the proportion of sixteen feet long by eight wide. It is divided into two apartments, each of six[43] or seven feet square, and as many high: the one which is nearest to the side of the spring, and under which the water is consequently warmer, is appropriated for bathing; the other serves for a dressing-room; and for this purpose there are wide benches above the level of the water; in the middle also a certain space is left to wash if we be disposed. There is one circumstance that renders these baths very agreeable, the warmth of the water communicates itself sufficiently to the dressing-room to prevent us from catching cold; and it penetrates the body to such a degree, as to be felt even for the space of an hour or two after we have left the bath.

We lodged near these baths in a kind of barns, covered with thatch, and whose timber work consisted of the trunks and branches of trees. We occupied two, which had been built on purpose for us,[44] and in so short a time, that I knew not how to credit the report; but I had soon the conviction of my own eyes. That which was to the south of the stream, having been found too small and too damp, M. Kasloff ordered another of six or eight yards extent, to be built on the opposite side, where the soil was less swampy. It was the business of a day; in the evening it was finished, though an additional staircase had been cut out to form a communication between the barn and the bathing house, whose door was to the north.

Our habitations being insupportable during the night, on account of the cold, M. Kasloff resolved to quit them, four days after our arrival. We returned to the village to shelter ourselves with the toyon; but the attraction of the baths led us back every day, oftener twice than once, and we scarcely ever came away without bathing.

The various constructions which M. Kasloff ordered for the greater convenience of his establishment, detained us two days longer. Animated by a love of virtue and humanity, he enjoyed the pleasure of having procured these salutary and pleasant baths for his poor Kamtschadales. The uninformed state of their minds, or perhaps their indolence, would, without his succour, have deprived them of this benefit, notwithstanding their extreme confidence in these hot springs for the cure of a variety of diseases[24]. This made M. Kasloff desirous of ascertaining the properties of these waters; we agreed to analyse them, by means of a process which had been given him for this purpose. But before I speak of the result of our experiments, it is necessary to transcribe the process, in order the better to trace the mode we adopted.

"Water in general may contain,

"1. Fixed air; in that case it has a sharp and sourish taste, like lemonade, without sugar.

"2. Iron or copper; and then it has an astringent and disagreeable taste, like ink.

"3. Sulphur, or sulphurous vapours; and then it has a very nauseous taste, like a stale and rotten egg.

"4. Vitriolic, or marine, or alkaline salt.

"5. Earth,"

Fixed Air.

"To ascertain the fixed air, the taste is partly sufficient; but pour into the water some tincture of turnsol, and the water[47] will become more or less red, in proportion to the quantity of fixed air it contains."

Iron.

"The iron may be known by means of the galnut and phlogisticated alkali; the galnut put into feruginous water, will change its colour to purple, or violet, or black; and the phlogisticated alkali will produce immediately Prussian blue."

Copper.

"Copper may be ascertained by means of the phlogisticated alkali or volatile alkali; the first turns the water to a brown red, and the second to a blue. The last mode is the surest, because the volatile alkali precipitates copper only, and not iron."

Sulphur.

"Sulphur and sulphurous vapours may be known by pouring, 1. nitrous acid into the water; if a yellowish or whitish sediment be formed by it, there is sulphur, and at the same time a sulphurous odour will be exhaled and evaporate. 2. By pouring some drops of a solution of corrosive sublimate; if it occasion a white sediment, the water contains only vapours of liver of sulphur; and if the sediment be black, the water contains sulphur only."

Vitriolic Salt.

"Water may contain vitriolic salts; that is salts resulting from the combination of the vitriolic acid with calcareous earth, iron, copper, or with an alkali. The vitriolic acid may be ascertained by pouring some drops of a solution of heavy earth; for then a sandy sediment will be formed, which will settle slowly at the bottom of the vessel."

Marine Salt.

"Water may contain marine salt, which may be ascertained by pouring into it some drops of a solution of silver; a white sediment will immediately be formed of the consistency of curdled milk, which will at last turn to a dark violet colour."

Fixed Alkali.

"Water may contain fixed alkali, which may be ascertained by pouring into it some drops of a solution of corrosive sublimate; when a reddish sediment will be formed."

Calcareous Earth.

"Water may contain calcareous earth and magnesia. Some drops of acid of sugar poured into the water, will precipitate the calcareous earth in whitish clouds, which will at length subside and[50] afford a white sediment. A few drops of a solution of corrosive sublimate, will produce a reddish sediment, but very gradually, if the water contain magnesia.

"Note. To make these experiments with readiness and certainty, the water to be analysed should be reduced one half by boiling it, except in the case of the fixed air, which would evaporate in the boiling."

Having thoroughly studied the process, we began our experiments. The three first producing no effect, we concluded that the water contained neither fixed air, iron, nor copper; but upon the mixture of the nitrous acid, mentioned for the fourth experiment, we perceived a light substance settle upon the surface, of a whitish colour, and extending but a little way, which led us to believe that the quantity of sulphur, or[51] of sulphurous vapours, must be infinitely small.

The fifth experiment proved that the water contained vitriolic salts, or at least vitriolic acid mixed with calcareous earth. We ascertained the existence of this acid, by pouring some drops of a solution of heavy earth into the water, which became white and nebulous, and the sediment that slowly settled at the bottom of the vessel appeared whitish and in very fine grains.

We had no solution of silver for the sixth experiment, in order to ascertain whether the water contained marine salt.

The seventh proved that it had no fixed alkali.

By the eighth experiment, we found that the water contained a great quantity of[52] calcareous earth, but no magnesia. Having poured some drops of acid of sugar, we observed the calcareous earth precipitate to the bottom of the vessel in clouds and a powder of a whitish colour; we mixed afterwards some solution of corrosive sublimate to find the magnesia; but the sediment, instead of becoming red, preserved the same colour as before; a proof that the water contained no magnesia.

We made use of this water for tea and for our common drink. It was not till after three or four days that we found it contained some saline particles.

M. Kasloff boiled also some of the water taken at the spring, till it became totally evaporated; the whitish and very salt earth or powder which remained at the bottom of the vessel, as well as the effect it produced[53] on us, proved that this water contained nitrous salts.

We remarked also that the stones taken out of this stream were covered with a calcareous substance tolerably thick, and of an undulated appearance, which, when mixed with the vitriolic and nitrous acid, produced symptoms of effervescence. We examined others taken from what appeared to be the fountain head of the waters, and where they have the greater degree of heat; we found them covered with a stratum of a kind of metal, if I may so call a hard and compact envelopement of the colour of refined copper, but the quality of which we could not ascertain; we found also some of this metal, which appeared like the heads of pins; but no acid could dissolve it. Upon breaking these stones, we discovered the inside to be very soft and mixed with gravel,[54] with which I had observed these streams to abound.

I ought to add here, that we discovered upon the border of the stream, and in a little moving swamp that was near it, a gum, or singular fucus[25], that was glutinous, but did not adhere to the ground.

Such are the observations which I made upon these hot waters, by assisting M. Kasloff in his experiments and enquiries. I dare not flatter myself with having given the result of our operations in a satisfactory manner; forgetfulness, or want of information upon the subject, may have led me into errors; I can only say that I have exerted all my attention and care to be accurate; but acknowledge at the same time, that, if there be defects, they are ascribable to me.

During our stay at these baths and at the ostrog of Natchikin, our horses had brought, at different times, the effects which we had left at Koriaki, and we began to make preparations for our departure. In this interval I had an opportunity of seeing a sable taken alive; the method was very singular, and may give some idea of the manner of hunting these animals.

At some distance from the baths, M. Kasloff remarked a numerous flight of ravens, who all hovered over the same spot, skimming continually along the ground. The regular direction of their flight led us to suspect that some prey attracted them. These birds were in reality pursuing a sable. We perceived it upon a birch-tree, surrounded by another flight of ravens, and[56] we had immediately a similar desire of taking it. The quickest and surest way would doubtless have been to have shot it; but our guns were at the village, and it was impossible to borrow one of the persons who accompanied us, or indeed in the whole neighbourhood. A Kamtschadale happily drew us from our embarassment, by undertaking to catch the sable. He adopted the following method. He asked us for a cord; we had none to give him but that which fastened our horses. While he was making a running knot, some dogs, trained to this chace, had surrounded the tree: the animal, intent upon watching them, either from fear, or natural stupidity, did not stir; and contented himself with stretching out his neck, when the cord was presented to him. His head was twice in the noose, but the knot slipped. At length, the sable having thrown himself upon the ground, the dogs flew to seize him; but he presently freed[57] himself, and with his claws and teeth laid hold of the nose of one of the dogs, who had no reason to be pleased with his reception. As we were desirous of taking the animal alive, we kept back the dogs; the sable quitted immediately his hold, and ran up a tree, where, for the third time, the noose, which had been tied anew, was presented to him; it was not till the fourth attempt that the Kamtschadale succeeded[26]. I could not have imagined that an animal, who has so much the appearance of cunning would have permitted himself to be caught in so stupid a manner, and would himself have placed his head in the snare that was held up to him. This easy mode of catching sables, is a considerable resource to the Kamtschadales, who are obliged to pay their tribute in skins of these animals, as I shall explain hereafter[27].

Two phenomena in the heavens were observed at the north-west, during the nights of the 13 and 14. From the description that was given of them, we judged that they were auroræ boreales, and we lamented that we were not informed time enough to see them. The weather had been tolerably fair during our stay at the baths; but the western part of the sky had been almost constantly charged with very thick clouds. The wind varied from west to north-west, and gave us now and then a shower of snow, which did not yet acquire consistency, notwithstanding the frosts which we experienced every night.

Our departure was fixed for the 17 October, and the 16 was spent in the hurry and bustle which the last preparations generally occasion. The rest of our route, as far as Bolcheretsk, was to be upon the Bolchaïa-reka. Ten small boats, which properly speaking, appeared to be merely trees scooped out in the shape of canoes, two and two lashed together, served as five floats for the conveyance of ourselves and part of our effects. We were obliged to leave the greater part at Natchikin, on account of the impossibility of loading these floats with the whole, and there were no means of increasing them. We had already collected all the canoes that were in the village, and even some of our ten had been brought from the ostrog of Apatchin, to which we were going.

The 17, at break of day, we embarked upon these floats. Four Kamtschadales, by means of long poles, conducted our rafts.[60] But they were frequently obliged to place themselves in the water, in order to haul them along; the depth of the river in some places being no more than one or two feet, and in others less than six inches. Presently one of our floats received an injury; it was precisely that which was freighted with our baggage, and we were obliged to unlade every thing upon the bank, in order to refit it. We waited not, but preferred leaving it behind, in order to proceed on our route. At noon another accident, much more deplorable for men whose appetites began to be clamorous, occasioned us a further delay. The float in which our cookery was embarked, sunk all at once before our eyes. It will be supposed we did not see the loss which threatened us, with indifference; we were eager to save the wreck of our provisions; and for fear of a greater misfortune, we wisely resolved to dine before we proceeded any farther. Our dinner[61] tended gradually to dispel our fears, and gave us courage to discharge the water which over-loaded our boats, and to resume our voyage. We had not advanced a werst, before we met two boats coming to our assistance from Apatchin. We sent them to the succour of the damaged float, and to supply the place of the boats which were unfit for service. As we continued to advance at the head of our embarkations, we at last entirely lost sight of them; but we met with nothing disastrous till the evening.

I observed that the Bolchaïa-reka, in the windings which it continually made, ran nearly in the direction of east-north-east and west-south-west. Its current is very rapid; it appeared to me to flow at the rate of five knots an hour; in the meantime the stones and the shoals which we met with every instant, obstructed our passage[62] to such a degree, as to render the last hour of our conductors truly painful. They avoided them with astonishing address, but as we approached nearer the mouth of the river, I observed with pleasure that it became wider and more navigable. I was equally surprised to see it divide into I know not how many branches, which united again, after having watered a variety of little islands, of which some are covered with wood. The trees are every where very small and very bushy; we met with a considerable number growing here and there in the very river itself, which increase still farther the difficulty of the navigation, and prove the carelessness, I may say the sloth, of these people. It never occurs to them to root out these trees, and thus open a more easy passage.

Different species of water-fowl, such as ducks, plovers, goëlands, divers, and others,[63] divert themselves in this river, the surface of which is sometimes covered by them; but it is difficult to approach near enough to shoot them. Game does not appear to be so common. But for the tracks of the bears, and the half-devoured fish, which continually presented themselves to our view, I should have believed that they had imposed upon me, or at least that they had exaggerated, in telling me of the multitude of these animals with which the country abounds; we could perceive none; but we saw a great number of black eagles, and others that had white wings; magpies, ravens, some partridges, and an ermine walking by the side of the river.

Upon the approach of night, M. Kasloff rightly judged that it would be more prudent to stop, than to continue our route, with the apprehension of encountering obstacles similar to what had already impeded[64] our navigation. How were we to surmount them? we were unacquainted with the river; and in the obscurity of the night, the least accident might prove fatal to us. These considerations determined us to leave our boats, and to pass the night on the right-hand bank of the river, at the entrance of a wood, and near the place where captain King and his party halted[28]. A good fire warmed and dried our whole company. M. Kasloff had taken the precaution to place in his float the accoutrements of a tent; and while we were pitching it, which was done in a moment, we had the satisfaction to see two of our floats arrive, which had not been able to keep up with us. The pleasure which this reunion afforded us, the fatigue of the day, the convenience of the tent, and our beds, which we had fortunately brought with us, all contributed to make us pass a most comfortable night.

The next day we fitted ourselves out early and without difficulty. We arrived in four hours at Apatchin, but our floats could not come up as far as the village, on account of the shallowness of the water. We landed about four hundred yards from the ostrog, and atchieved this short distance on foot.

This village did not appear to me so considerable as the preceding ones, that is, it contained perhaps three or four habitations less. It is situated in a small plain, watered by a branch of the Bolchaïa-reka; and on the side opposite to the ostrog is an extent of wood, which I conceived might be an island formed by the different branches of this river.

I learned by the way, that the ostrog of Apatchin, as well as that of Natchikin, had not been always where they are at present. It is within a few years only that the inhabitants, attracted without doubt by the situation, or the hope of better and more commodious fishing, removed their houses to this place. The distance of the new ostrog from the former one is, as I was told, about four or five wersts.

Apatchin afforded nothing interesting. I left it to join our floats, which had passed the shallows, and were waiting for us three wersts from the ostrog, at the spot where the branch of Bolchaïa-reka, after having made a circuit round the village, returns again to its channel. The farther we advanced, the deeper and more rapid we found it; so that nothing impeded our course the whole way to Bolcheretsk, where we arrived at seven o'clock in the evening,[67] accompanied by one only of our floats, the rest not having kept pace with us.

We were no sooner landed, than the governor conducted me to his house, where he had the civility to give me a lodging, which I occupied during the whole time of my stay at Bolcheretsk. He not only procured me all the conveniences and pleasures that were in his power, but furnished me with all the information which might contribute to my advantage, and which his office permitted him to give. His politeness often anticipated my desires and my questions; and he contrived to stimulate my curiosity, by presenting to it every thing which he thought was calculated to interest me. It was with this view he proposed, almost immediately upon our arrival, my going with him to view the galliot from Okotsk, that had been unfortunately just[68] shipwrecked at a little distance from Bolcheretsk.

We had learned something of this melancholy news in our journey. It was said that the bad weather, which the galliot had encountered at its arrival, obliged it to come to anchor at the distance of a league from the coast; but finding that it still drove, the pilot saw no other means of saving the cargo than by running the vessel aground upon the coast; accordingly he cut the cables, and the ship was dashed to pieces.

Upon the first intelligence of this event, the inhabitants of Bolcheretsk flocked together to hasten to the succour of the vessel, and to save at least the provisions with which it was freighted. Immediately upon our arrival, M. Kasloff had given all the orders[69] which appeared to him to be necessary; but not satisfied with this, he would go himself to see them carried into execution. He invited me to accompany him, which I accepted with cheerfulness, promising myself much pleasure from having an opportunity of viewing the mouth of the Bolchaïa-reka, and the harbour which is formed by it.

We set off at eleven o'clock in the morning, upon two floats, of which one, that which carried us, was formed of three canoes. Our conductors made use of oars and sometimes of their poles, which frequently in difficult and shallow passages, enabled them to resist the impetuosity of the current, by keeping back the float, which would otherwise have been carried along with rapidity and infallibly overturned.

The Bistraïa, another very rapid river,[70] and larger than the Bolchaïa-reka, joins it to the west, about the distance of half a werst from Bolcheretsk. It loses its name at the conflux, and takes that of the Bolchaïa-reka, which is rendered very considerable by this addition, and empties itself into the sea at the distance of thirty wersts.

We landed at seven o'clock in the evening at a little hamlet called Tchekafki. Two isbas, two balagans, and a yourt almost in ruins, were all the habitations I could perceive. There was also a wretched warehouse, made of wood, to which they give the name of magazine, because it belongs to the crown, and first receives the supplies with which the galliots from Okotsk[29] are freighted. The hamlet was built as a guard to this magazine. We passed the night in one of the isbas, resolving to repair early in the morning to the wreck.

At break of day we embarked upon our floats. It was low water; we coasted along a dry and very extensive sand bank, at the left of the Bolchaïa-reka, as we advanced towards the sea, and which leaves to the north a passage of only eight or ten fathoms wide, and two and a half deep. The wind, which blew fresh from the north-west, suddenly agitated the river, and we dared not risk ourselves in the channel. Our boats also were so small, that a single wave half filled them; two men were constantly employed in throwing out the water, and were scarcely able to effect it. We advanced therefore as far as we could along this bank.

At length we perceived the mast of the galliot above a neck of low land that extended[72] to the south. It appeared to be about two wersts from us, south of the entrance of the Bolchaïa-reka. At the point of land just mentioned, we discovered the light house, and the cot of the persons appointed to guard the wreck: unfortunately we could only see all this at a distance. The direction of the river, from the place where it empties itself into the sea, appeared to me to be north-west, and its opening to be half a werst wide. The light-house is on the left coast, and on the right is the continuation of the low land, which the sea overflows in tempestuous weather, and which extends almost as far as the hamlet of Tchekafki. The distance of the hamlet from the mouth of the river is from six to eight wersts. The nearer we approach the entrance, the more rapid is the current.

It was not possible to pursue our voyage; the wind became stronger, and the waves[73] increased every moment. It would have been the height of imprudence to quit the sand bank, and cross, in such foul weather and such feeble boats, two wersts of deep water, which is the width of the bay formed by the mouth of the river. The governor, who had already met with some proofs of my little knowledge of navigation, was very anxious however to consult me upon this occasion. My advice was to tack about, and return to the hamlet where we had slept; which was executed immediately. We had great reason to be pleased with our prudence; scarcely were we arrived at Tchekafki when the weather became terrible.

I consoled myself with the idea, that I had at least obtained my end, which was to see the entrance of the Bolchaïa-reka. I can assert with confidence, that the access to it is very dangerous, and impracticable[74] to ships of a hundred and fifty tons burthen. The Russian vessels are too frequently shipwrecked, not to open the eyes both of navigators who may be tempted to visit this coast, and of the nations who may think of sending them.

The port, besides, affords no shelter. The low lands with which it is surrounded, are no protection against the winds which blow from every quarter. The banks also which the current of the river forms, are very variable, and of course it is almost impossible to know with certainty the channel, which must necessarily, from time to time, change it direction as well as its depth.

We passed the rest of the day at Tchekafki, being unable to proceed to the shipwrecked vessel, or to return to Bolcheretsk. The sky, instead of clearing up, became covered on all sides with still blacker and[75] thicker clouds. Soon after our arrival, a dreadful tempest arose, and the Bolchaïa-reka became agitated to an extreme violence, even so high up as our hamlet. Its billows surprised me, because of the little extent and depth of the river in this place. The point north-east of its mouth, and the low land, which this gale of wind extended, formed but one breaker, over which the waves rolled with a horrible noise. The gale was not likely to abate, but I was on shore, and thought myself able to brave it. I took it into my head therefore, to go a hunting in the environs of the hamlet. I had scarcely advanced a few steps, when the wind seized me, and I felt myself stagger; my courage however did not fail me, and I persevered; but coming to a stream, which it was necessary to cross in a boat, I ran the most imminent risk, and returned immediately, well punished for my petty presumption. These dreadful hurricanes being[76] very common at this season, it is not be wondered at that shipwrecks are so frequent on these coasts: the vessels are so small as to have but one mast; and, what is still worse, the sailors who manage them, if report may be credited, have too little skill to be confided in.

The next day we resumed our journey, and arrived at Bolcheretsk in the dusk of the evening.

As I forsee that my stay here will probably be long, from the necessity of waiting till sledges can be used, I shall proceed with my descriptions, and the recital of what I have seen myself, or learned from my conversations with the Russians and Kamtschadales. I shall begin with the town, or fort of Bolcheretsk, for so it is called, in Russia (ostrog, or krepost).

It is situated on the border of the Bolchaïa-reka,[77] in a small island formed by different branches of this river, which divide the town into three parts more or less inhabited. The most distant division, and which is farthest to the east, is a kind of suburb called Paranchine; it contains ten or twelve isbas. South-east of Paranchine, is the middle division, where there is also a number isbas, and among others, a row of wooden huts that serve for shops. Opposite to these is the guard-house, which is also the chancery, or court of justice[30]; this house is larger than the rest, and is always guarded by a centinel. A second branch of the Bolchaïa-reka again separates, by a very narrow stream, this group of habitations, built without order, and scattered here and there, from another at the north-west, nearer the river. The river in this part flows in the direction of south-east and north-west,[78] and passes within fifty yards of the governor's house. This house is easily distinguished from the rest; it is higher, larger, and is built like the wooden houses of St. Petersburg. Two hundred yards north-east of this house, is the church; the construction of which is simple, and like that of the village churches in Russia. By the side of it is an erection of timber work, twenty feet high, covered only with a roof, under which three bells are suspended. North-west of the governor's house, and separated from it by a meadow or marsh about three hundred yards wide, is another group of dwellings, consisting of twenty-five or thirty isbas, and some balagans. There are in general very few of these latter habitations at Bolcheretsk; the whole do not exceed ten; the isbas and wooden houses, without including the eight shops, the chancery, and the governor's house, amount to fifty or sixty.

From this minute description of the fort of Bolcheretsk, it must appear strange that it retains so inapplicable a name; for I can affirm, that no traces are to be found of fortifications, nor does it appear that there has ever been an intention of erecting any. The state and situation, both of the town and its port, induce me to believe, that government have felt the innumerable dangers and obstacles they would have to surmount, if they were to attempt to render it more flourishing, and make it the general depôt of commerce to the peninsula. Their views, as I have already observed, seem rather turned to the port of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, which for its proximity, safety, and easy access, merits the preference.

There is a degree of civilization at Bolcheretsk, which I did not perceive at Petropavlofska. This sensible approach to European manners, occasions a striking differrence[80] between the two places. I shall endeavour to point out and account for this as I proceed in my observations upon the inhabitants of these ostrogs; for my principal object should be, to give details of their employments, their customs, their tastes, their diversions, their food, their understandings, their character, their constitutions, and lastly, the principles of government to which they are subjected.

The population of Bolcheretsk, including men, women and children, amounts to between two and three hundred. Among these inhabitants, reckoning the petty officers, there are sixty or seventy Cossacs, or soldiers, who are employed in all labours that relate to the service of government[31]. Each in his turn mounts guard; they clear the ways; repair the bridges; unlade the provisions sent from Okotsk, and convey them from the mouth of the Bolchaïa-reka to Bolcheretsk. The rest of the inhabitants are composed of merchants and sailors.

These people, Russians and Cossacs, together with a mixed breed found among them, carry on a clandestine commerce, sometimes in one article, and sometimes in another; it varies as often as they see any reason for changing it; but it is never with a view of enriching themselves by honest means. Their industry is a continual knavishness; it is solely employed in cheating the poor Kamtschadales, whose credulity and insuperable propensity to drunkenness, leave them entirely at the mercy of these dangerous plunderers. Like our mountebanks, and other knaves of this kind, they go from village to village to inveigle the too silly natives: they propose to sell them brandy, which they artfully present to them[82] to taste. It is almost impossible for a Kamtschadale, male or female, to refuse this offer. The first essay is followed by many others; presently their heads become affected, they are intoxicated, and the craft of the tempters succeed. No sooner are they arrived to a slate of inebriety, than these pilferers know how to obtain from them the barter of their most valuable effects, that is, their whole stock of furs, frequently the fruit of the labour of a whole season, which was to enable them to pay their tribute to the crown, and procure perhaps subsistance for a whole family. But no consideration can stop a Kamtschadale drunkard; every thing is forgotten, every thing is sacrificed to the gratification of his appetite, and the momentary pleasure of swallowing a few glasses of brandy[32], reduces him to the utmost wretchedness. Nor is it possible for the most painful experience to put them on their guard against their own weakness, or the cunning perfidy of these traders, who in their turn drink, in like manner, all the profits of their knavery.

I shall terminate the article of commerce by adding, that the persons who deal most in wholesale, are merely agents of the merchants of Totma, Vologda, Grand Ustiug, and different towns of Siberia, or the factors of other opulent traders, who extend even to this distant country their commercial speculations.

All the wares and provisions, which necessity obliges them to purchase from the magazines, are sold excessively dear, and at about ten times the current price at Moscow. A vedro[33] of French brandy costs eighty roubles[34]. The merchants are allowed to traffic in this[85] article; but the brandy, distilled from corn, which is brought from Okotsk, and that produced by the country, which is distilled from the slatkaïa-trava, or sweet herb, are sold, upon government account, at forty one roubles ninety-six kopecks[35] the vedro. They can be sold only in the kabacs, or public houses, opened for that purpose. At Okotsk, the price of brandy distilled from corn is no more than eighteen roubles the vedro; so that the expence of freight is charged at twenty-three roubles ninety-six kopecks, which appears exorbitant, and enables us to form some judgment of the accruing profit.

The rest of the merchandize consists of nankins and other China stuffs, together with various commodities of Russian and foreign manufacture, as ribands, handkerchiefs,[86] stockings, caps, shoes, boots, and other articles of European dress, which may be regarded as luxuries, compared with the extreme simplicity of apparel of the Kamtschadales. Among the provision imported, there are sugar, tea, a small quantity of coffee, some wine, but very little, biscuits, confections, or dried fruits, as prunes, raisins, &c. and lastly, candles, both wax and tallow, powder, shot, &c.

The scarcity of all these articles in so distant a country, and the need, whether natural or artificial, which there is for them, enable the merchants to sell them at whatever exorbitant price their voracity may affix. In common, they are disposed of almost immediately upon their arrival. The merchants keep shops, each of them occupying one of the huts opposite the guard-house; these shops are open every day, except feast days.

The inhabitants of Bolcheretsk differ not from the Kamtschadales in their mode of living; they are less satisfied, however, with balagans, and their houses are a little cleaner.

Their clothing is the same. The outer garment, which is called parque, is like a waggoner's frock, and is made of the skins of deer, or other animals, tanned on one side. They wear under this long breeches of similar leather, and next the skin a very short and tight shirt, either of nankin or cotton stuff; the women's are of silk, which is a luxury among them. Both sexes wear boots; in summer, of goats or dogs skins tanned; and in winter, of the skins of sea wolves, or the legs of rein deer[36]. The men constantly wear fur caps; in the mild season they put on longer shirts of nankin, or of skin without hair; they are made like the parque, and answer the same purpose, that is, to be worn over their other garments. Their gala dress, is a parque trimmed with otter skins and velvet, or other stuffs and furs equally dear. The women are clothed like the Russian women, whose mode of dress is too well known to need a description; I shall therefore only observe, that the excessive scarcity of every species of stuff at Kamtschatka, renders the toilet of the women an object of very considerable expence: they sometimes adopt the dress of the men.

The principal food of these people consists, as I have already observed, in dried fish. The fish are procured by the men, while the women are employed in domestic occupations, or in gathering fruits and other vegetables, which, next to the dried fish, are the favourite provisions of the Kamtschadales[89] and Russians of this country. When the women go out to make these harvests for winter consumption, it is high holy-day with them, and the anniversary is celebrated by a riotous and intemperate joy, that frequently gives rise to the most extravagant and indecent scenes. They disperse in crowds through the country, singing and giving themselves up to all the absurdities which their imagination suggests; no consideration of fear or modesty restrains them. I cannot better describe their licentious frenzy than by comparing it with the bacchanals of the Pagans. Ill betide the man whom chance conducts and delivers into their hands! however resolute or however active he may be, it is impossible to evade the fate that awaits him; and it is seldom that he escapes, without receiving a severe flagellation.

Their provisions are prepared nearly in[90] the following manner; it will appear, from the recital, that they cannot be accused of much delicacy. They are particularly careful to waste no part of the fish. As soon as it is caught they tear out the gills, which they immediately suck with extreme gratification. By another refinement of sensuality or gluttony, they cut off also at the same time some slices of the fish, which they devour with equal avidity, covered as they are with clots of blood. The fish is then gutted, and the entrails reserved for their dogs. The rest is prepared and dried; when they eat it either boiled, roasted, or broiled, but most commonly raw.