The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

[Pg i]

ILLUSTRATED MICHELIN GUIDES

TO THE BATTLEFIELDS (1914-1918)

THE

SOMME

VOLUME 1.

THE FIRST BATTLE OF THE SOMME

(1916-1917)

(ALBERT, BAPAUME, PÉRONNE)

MICHELIN & CIE—CLERMONT-FERRAND.

MICHELIN TYRE CO LTD—81, Fulham Road, LONDON, S.W.

MICHELIN TIRE CO—MILLTOWN, N.J., U.S.A.

[Pg ii]

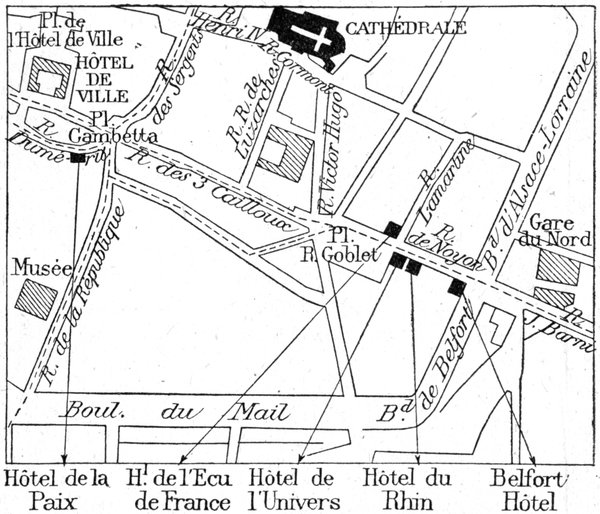

HOTELS in AMIENS

| HOTEL DU RHIN |

1, |

Rue de Noyon. |

Tel. |

44 |

| BELFORT HOTEL |

42, |

Rue de Noyon. |

Tel. |

649 |

| HOTEL DE L'UNIVERS |

2, |

Rue de Noyon. |

Tel. |

251 |

| HOTEL DE LA PAIX |

15, |

Rue Duméril. |

Tel. |

921 |

| HOTEL DE L'ECU DE FRANCE |

51, |

Place René-Goblet. |

Tel. |

337 |

The above information dates from March 1, 1920, and may no

longer be correct when it meets the reader's eye. Consult the

latest edition of the "Michelin Guide to France," or write to:—

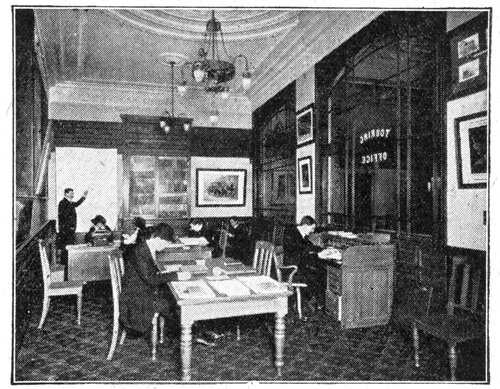

THE MICHELIN TOURING OFFICES

To visit Amiens, consult the Illustrated

Guide, "Amiens before and during the War."

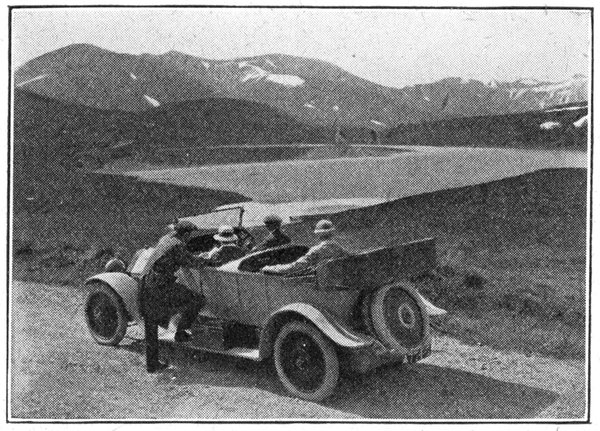

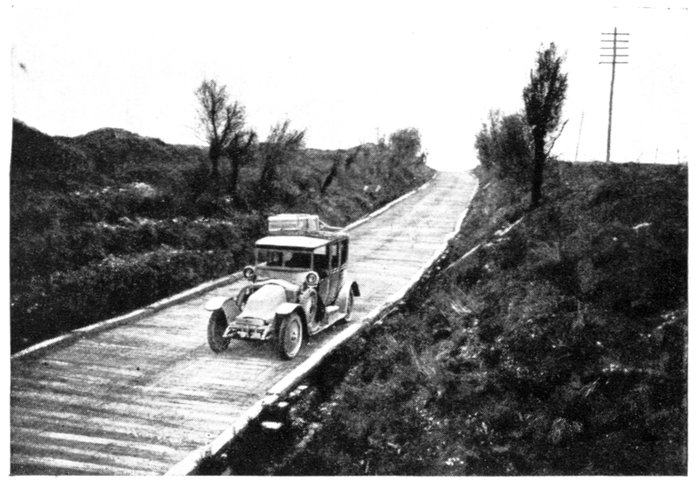

When following Itineraries described in this Guide, it is advisable

not to rely on being able to obtain supplies, but take a luncheon

basket and petrol with you from Amiens.

[Pg iii]

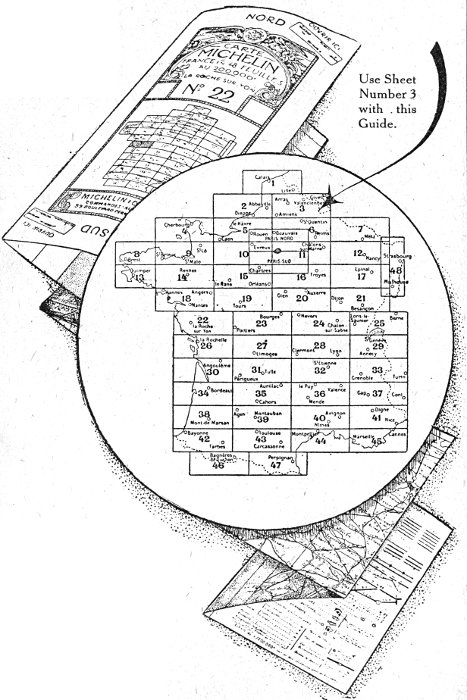

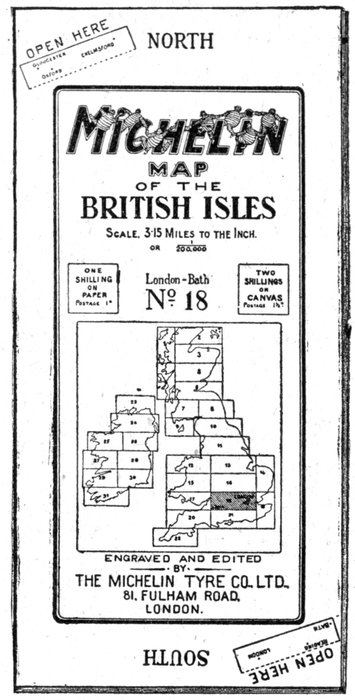

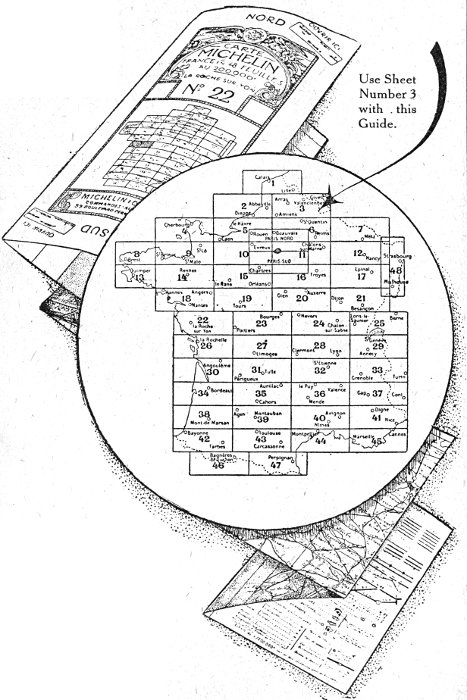

THE INDISPENSABLE

MICHELIN MAP

On Sale at all

Booksellers

and Michelin

Stockists.

Use Sheet

Number 3

with this

Guide.

This MAP

has been

specially

compiled

for

MOTORISTS.

2

[Pg iv]

The Best and Cheapest

Detachable Wheel

is

The Michelin Wheel

The Ideal of the Tourist.

The Michelin Wheel is

- ELEGANT

- STRONG

- SIMPLE

- PRACTICAL

May we send you our Illustrated Descriptive Brochure?

MICHELIN TYRE Co., Ltd.

81, FULHAM ROAD, LONDON, S.W.

[Pg 1]

IN MEMORY

OF THE MICHELIN WORKMEN

AND EMPLOYEES WHO DIED GLORIOUSLY

FOR THEIR COUNTRY

THE

SOMME

VOLUME I

THE FIRST BATTLE OF THE SOMME

(1916-1917)

(ALBERT—BAPAUME—PÉRONNE)

Published by

MICHELIN & Cie.

Clermont-Ferrand, France.

Copyright 1919 by Michelin & Cie.

All rights of translation, adaptation, or reproduction (in part or whole), reserved

in all countries.

[Pg 2]

THE OBJECTIVES OF THE OFFENSIVE.

In June, 1916, the enemy were the attacking party; the Germans were

pressing Verdun hard, and the Austrians had begun a vigorous offensive

against the Italians. It therefore became necessary for the Allies to make a

powerful effort to regain the initiative of the military operations.

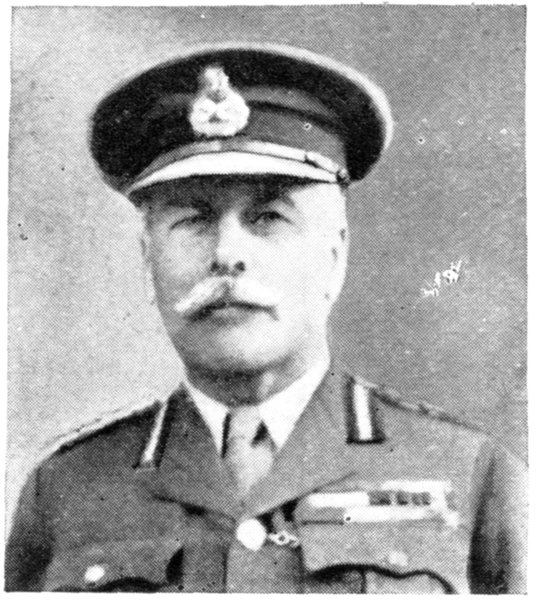

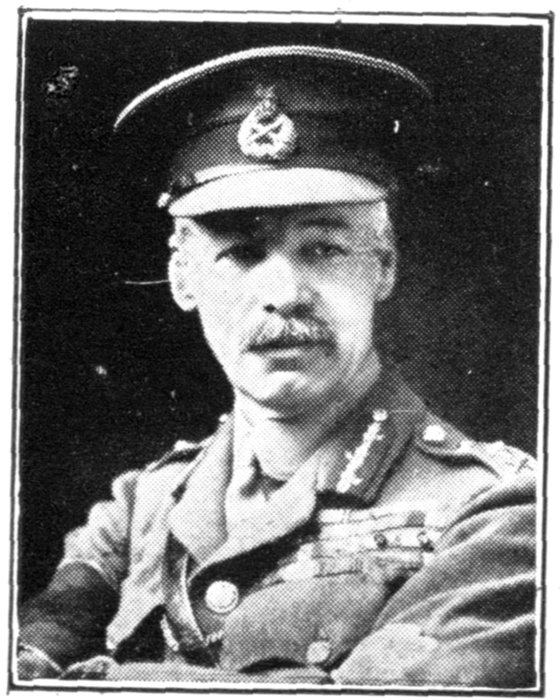

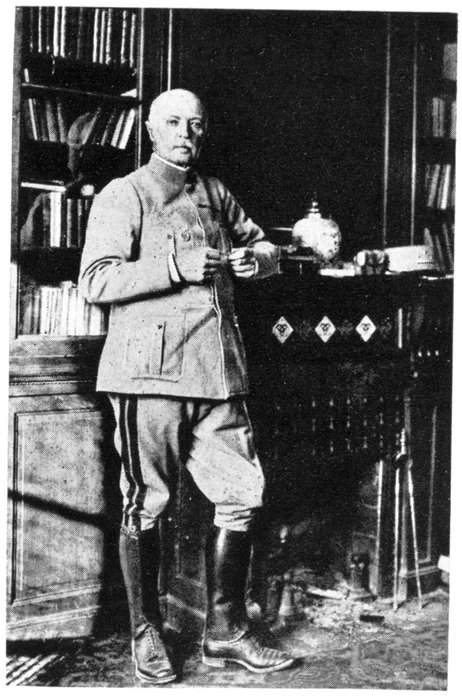

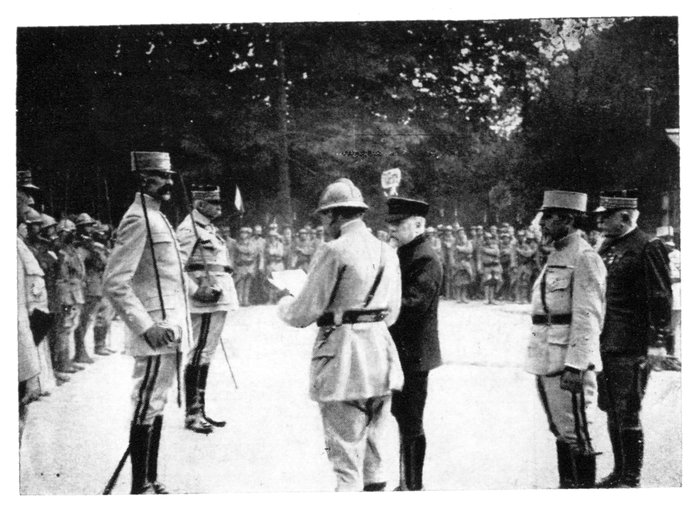

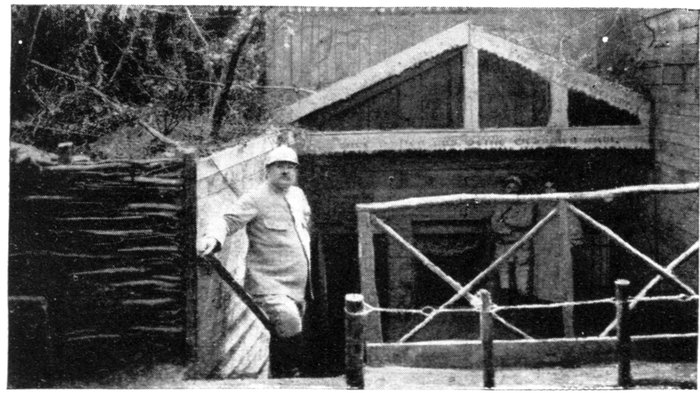

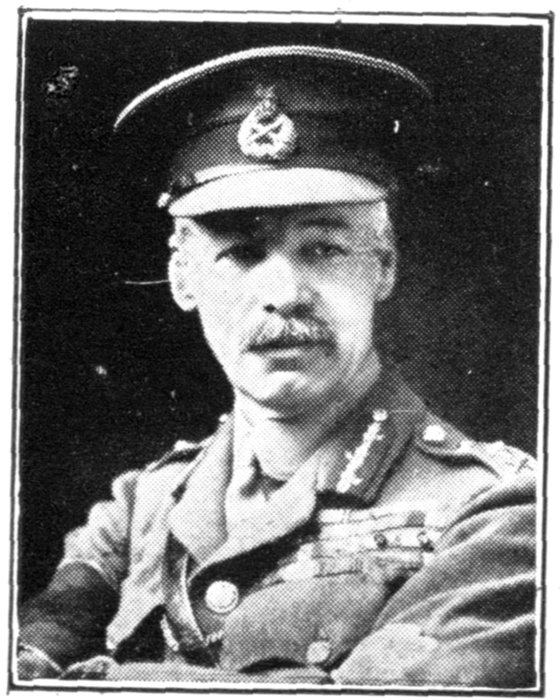

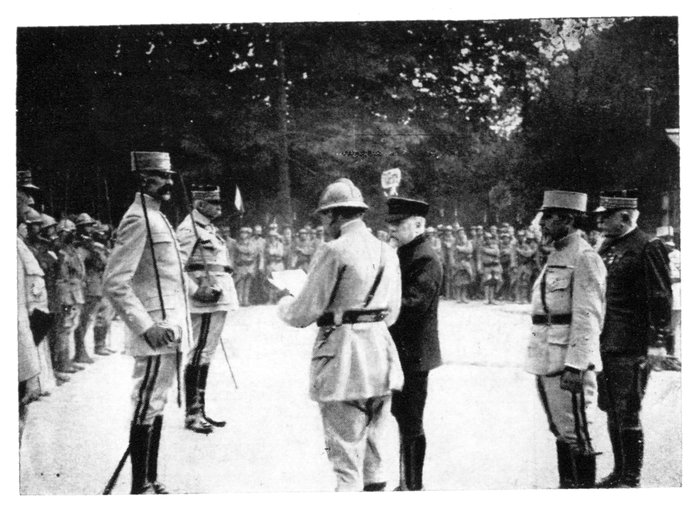

GENERAL FOCH, IN COMMAND OF THE

FAYOLLE-MICHELER ARMY GROUP,

DURING THE SOMME OFFENSIVE OF

1916.

The objectives of the Franco-British offensive were, to regain the initiative

of the military operations; to relieve

Verdun; to immobilise the largest

possible number of German divisions

on the western front, and prevent their

transfer to other sectors; to wear down

the fighting strength of the numerous

enemy divisions which would be

brought up to the front of attack.

Thanks to the immense effort made

by the entire British Empire, their

army had considerably increased in

men and material, and was now in a

position to undertake a powerful

offensive.

Under the command of Field-Marshal

Haig, two armies, the 4th

(General Rawlinson) and the 2nd

(General Gough) were to take part in

the offensive.

In spite of the terrible strain

France was undergoing at Verdun, the

number of troops left before that fortress,

under the command of General

Pétain, who had thoroughly consolidated

the defences, was reduced to the

strictest minimum, and the 6th and

10th Armies, under the command of

General Fayolle and General Micheler, respectively, were thus able to

collaborate with the British in the Somme offensive.

Within a few days of the enemy's formidable onslaught of June 23 against

the Thiaumont—Vaux front, in which seventeen German regiments took

part (see the Michelin Guide: "Verdun, and the Battles for its

Possession"), the Allied offensive was launched (July 1).

[Pg 3]

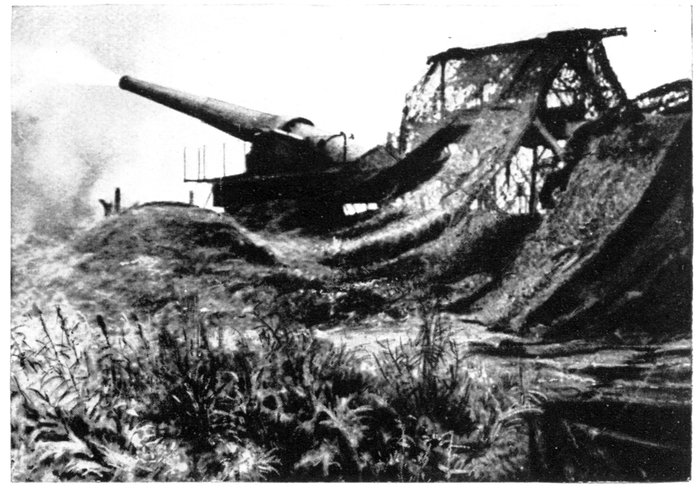

FRENCH

HEAVY

GUN ON

RAILS.

The Theory, Methods and Tactics adopted

With both sides entrenched along a continuous front, the predominating

problem was: How to break through the enemy's defences to the open ground

beyond the last trenches, and then force the final decision.

In 1915, the Allies had endeavoured unsuccessfully to solve it; in 1916,

the Germans, in turn, had suffered their severest check before Verdun.

Putting experience to profit, the Allies now sought to apply the methods

of piercing on broader lines.

The defences having increased in strength and depth, the blow would

require to be more powerful, precise, and concentrated as to space and time.

After the attacks of September, 1915, the French Staff set down as an

axiom that "material cannot be combatted with men." Consequently, no

more attacks without thorough preparation; nothing was to be left to chance.

The orders issued to the different arms, divisions, battalions, batteries,

air-squadrons, etc., were recorded in voluminous plans of attack, the least

of which numbered a hundred pages.

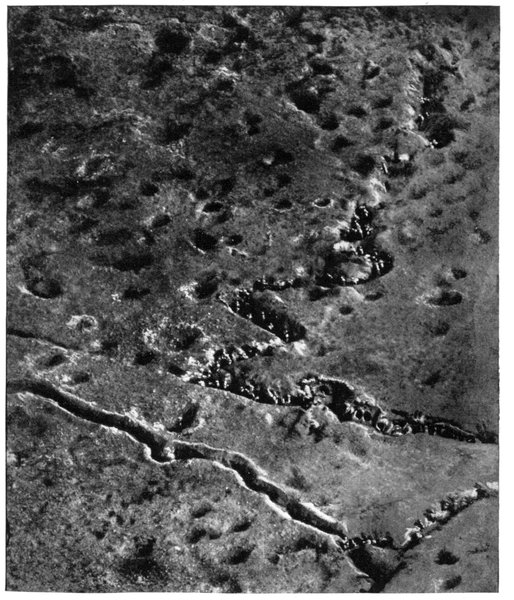

Thousands of aerial photographs were taken and assembled; countless

maps, plans and sketches made. Everything connected with the coming

drama was methodically arranged: the staging, distribution of the parts, the

various acts.

Such was the intellectual preparation which, lasting several months, was

carried out simultaneously with the equipping of the front line.

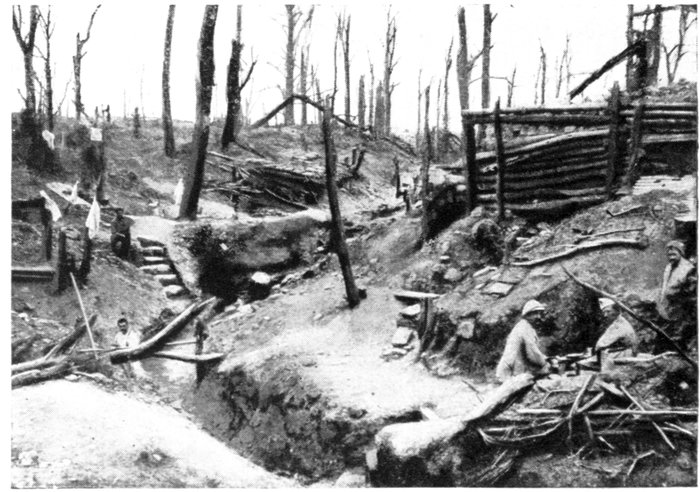

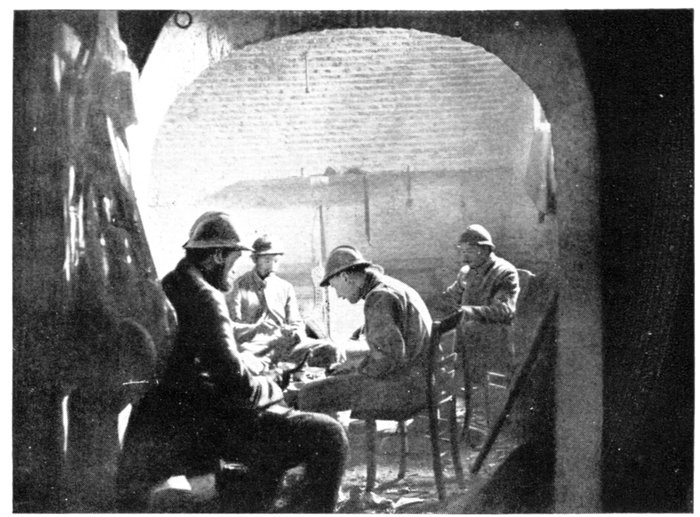

Equipping the Front Line

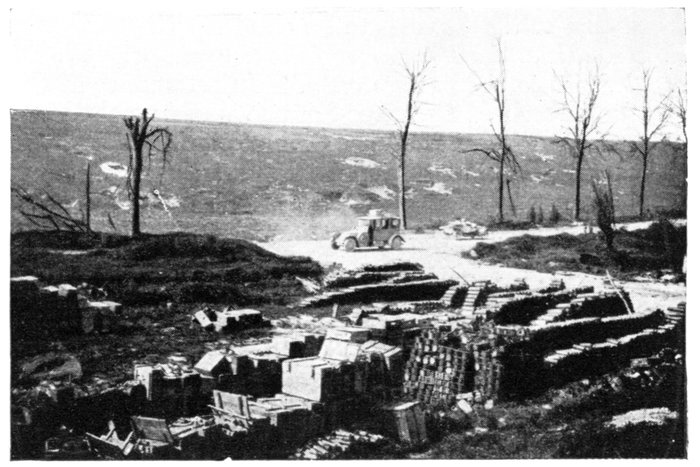

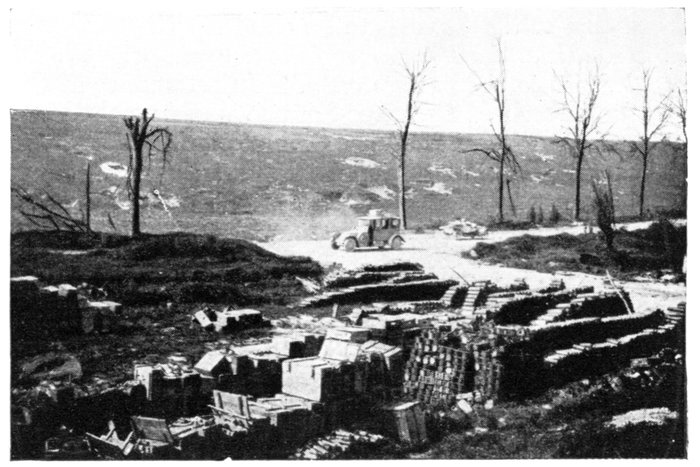

Preparing for a modern battle is a Herculean task. At a sufficient distance

behind the front line immense ammunition and revictualling depôts are

established. Miles of railway, both narrow and normal gauge, have to be

put down, to bring up supplies to the trenches. Existing roads have to be

improved, and new ones made. In the Somme, long embankments had to

be built across the marshy valleys, as well as innumerable shelters for the

combatants, dressing-stations, and sheds for storing the ammunition, food,

water, engineering supplies, etc. Miles of deep communicating trenches,

trenches for the telephone wires, assembly trenches, parallels and observation-posts

had to be made. The local quarries were worked, and wells bored.

[Pg 4]

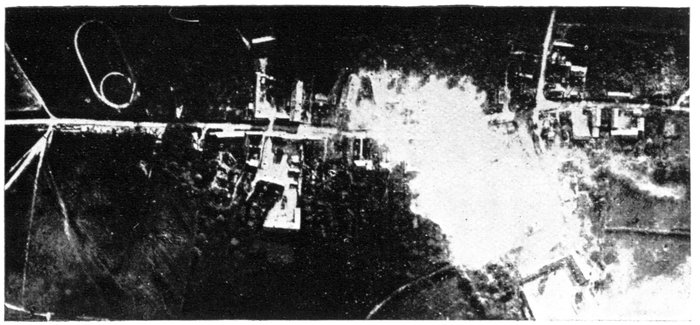

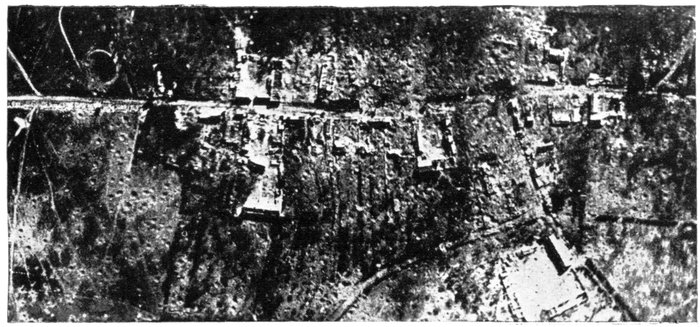

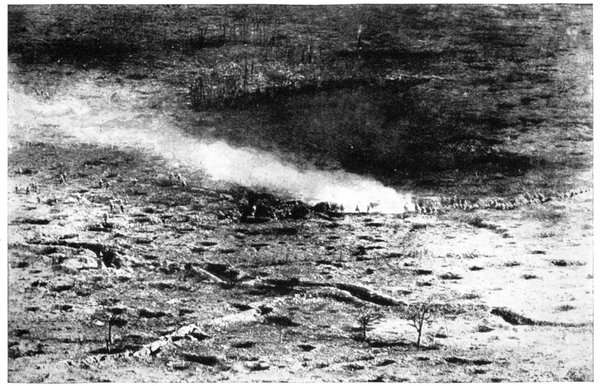

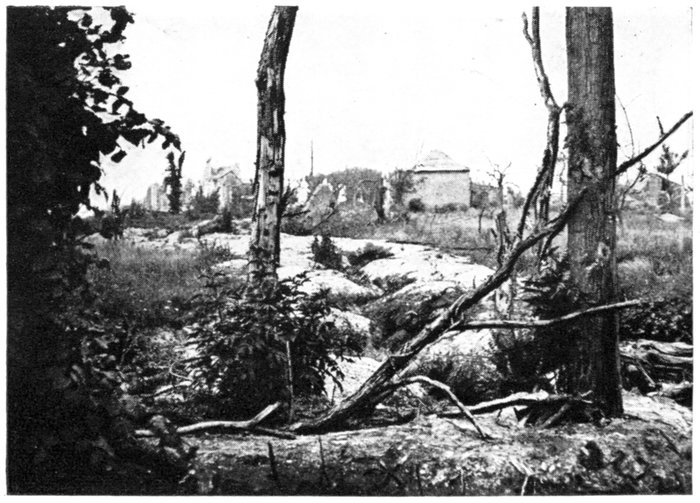

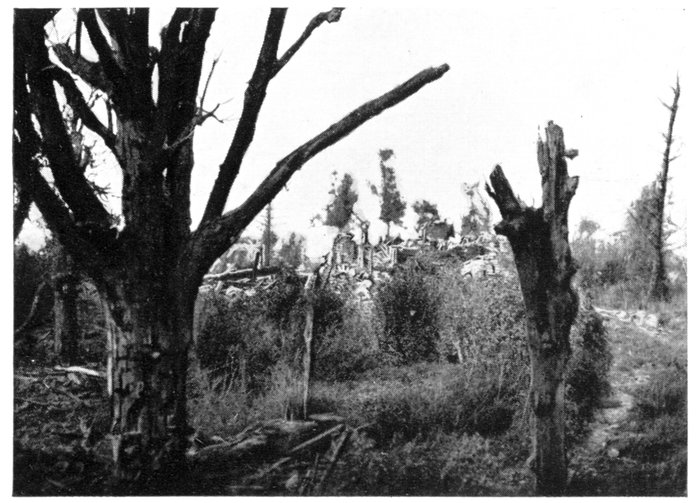

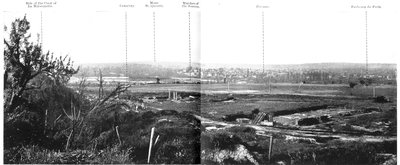

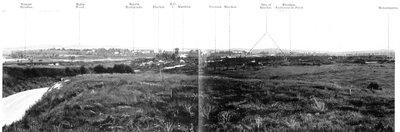

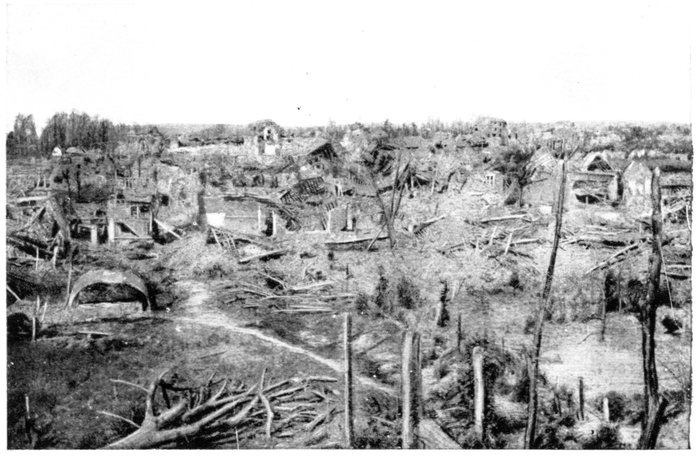

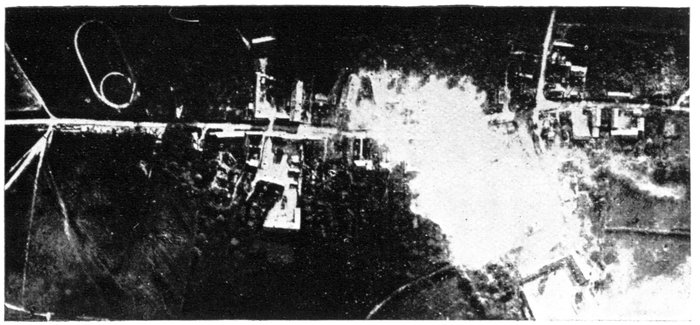

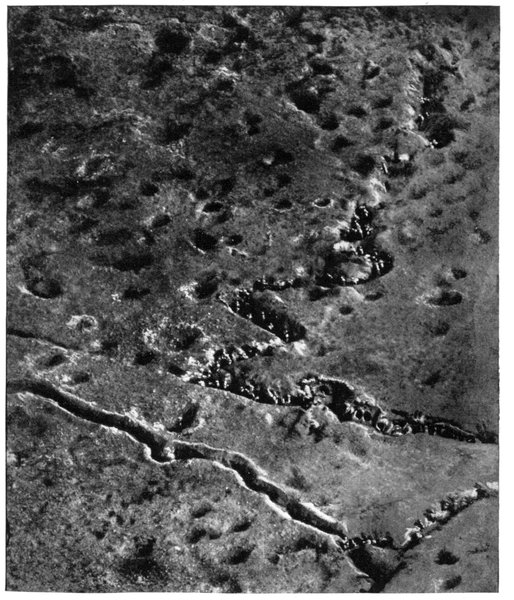

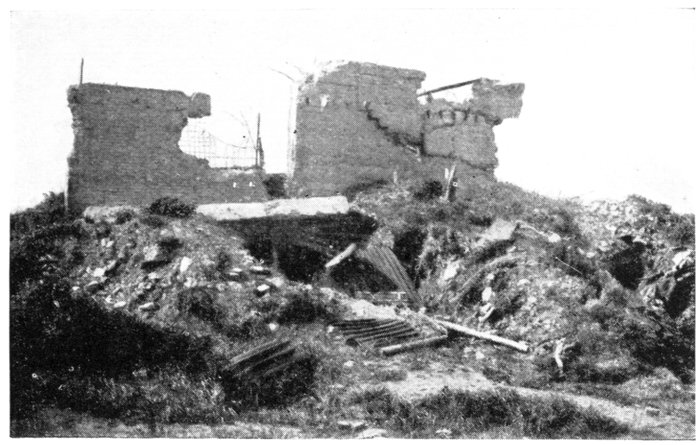

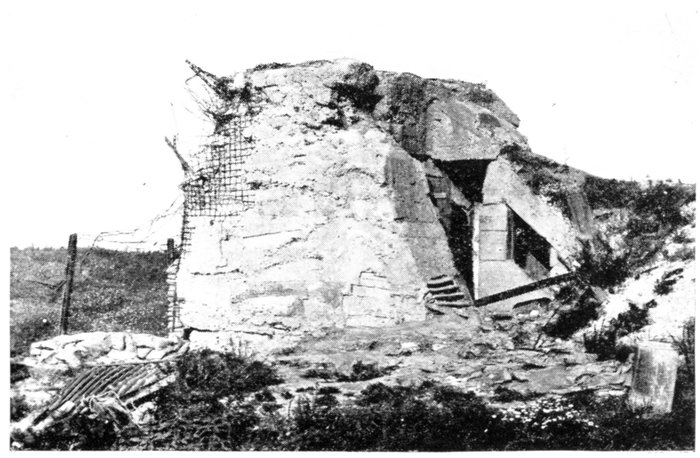

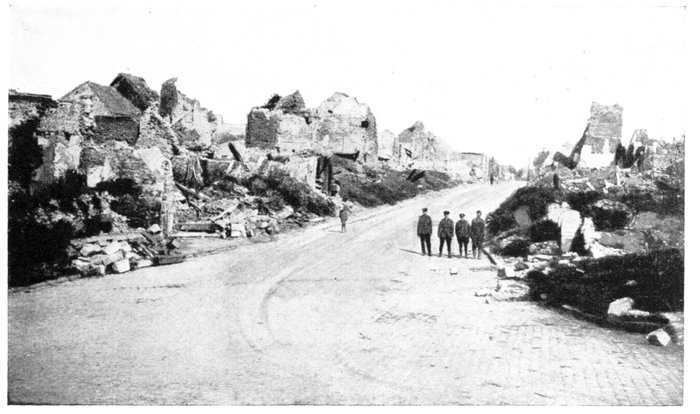

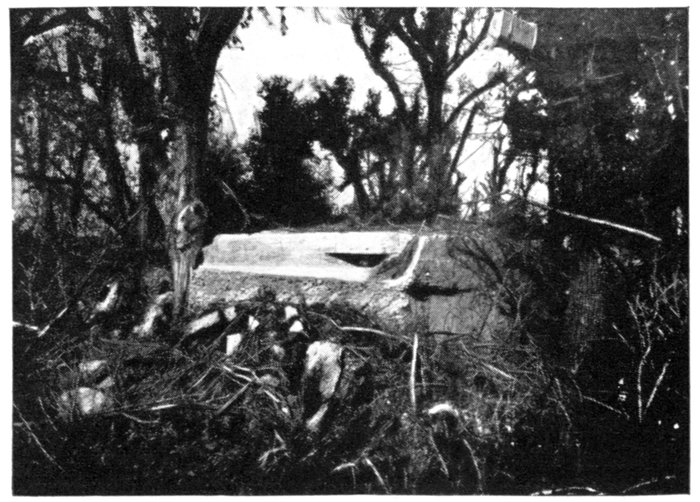

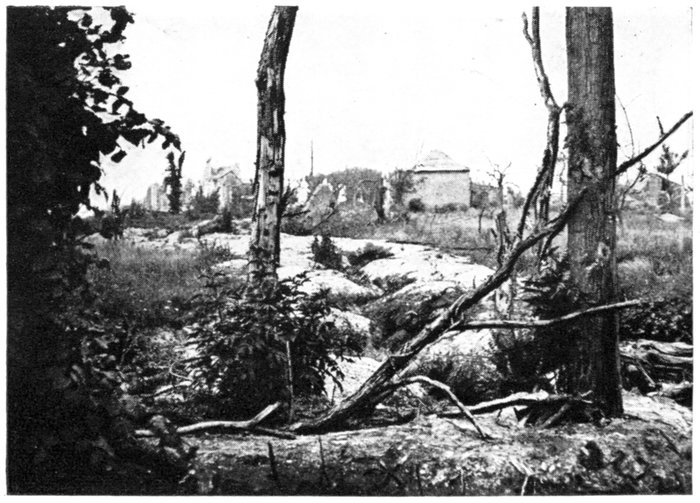

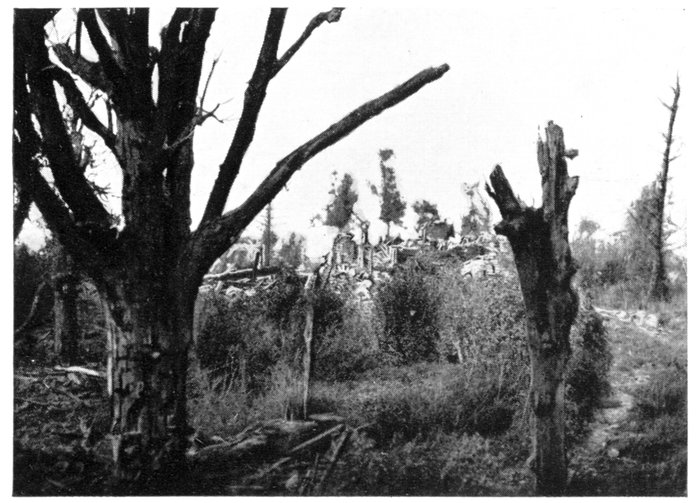

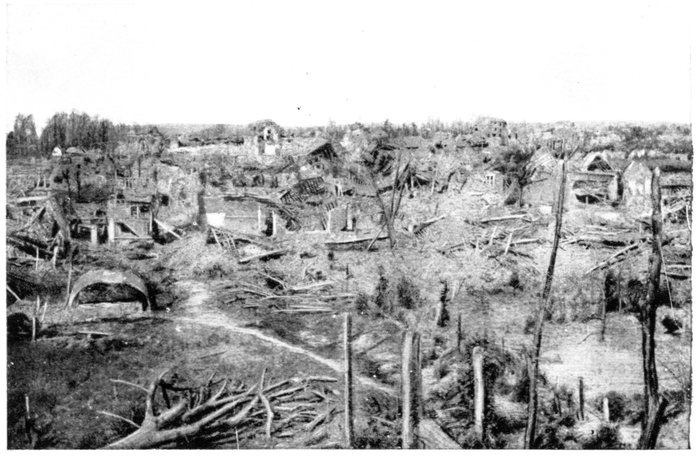

Ginchy, bombarded by the British on July 11, 1916.

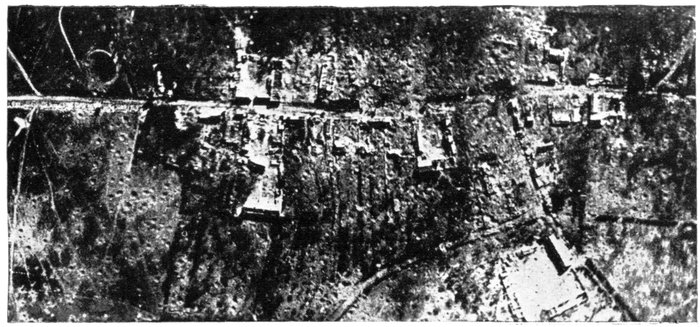

Ginchy, ten days later (July 21, 1916).

Ginchy, two days before capture by the British (Sept. 7, 1916). See p. 86.

ILLUSTRATING THE PROGRESSIVE DESTRUCTION AND LEVELLING OF A VILLAGE

BY ARTILLERY.

[Pg 5]

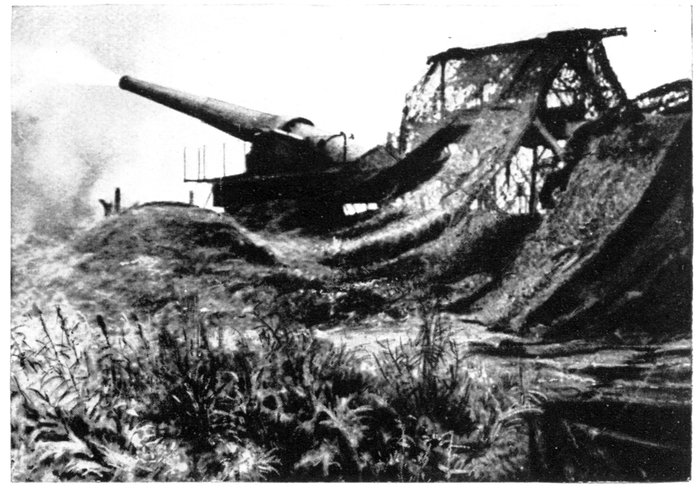

FIRING A 12-INCH LONG-RANGE GUN.

The Part Played by each Arm in the Different Phases of the Attack

In modern, well-ordered battle, it is the material strength which counts

most. The cannon must crush the enemy's machine-guns. Superiority of

artillery is an essential element of success.

According to the latest formula, "the artillery conquers, the infantry

occupies."

At each stage of the battle, each arm has a definite role to play.

The Artillery

Before the battle, the artillery must destroy the enemy's wire entanglements,

trenches, shelters, blockhouses, observation-posts, etc.; locate and engage

his guns; hamper and disperse his working parties.

During the battle, it must crush enemy resistance, provide the attacking

infantry with a protecting screen of fire, by means of creeping barrages, and

cut off the defenders from supplies and reinforcements by isolating barrages.

After the battle, it must protect the attacking troops who have reached their

objectives, from enemy counter-attacks, by barrage fire.

CAMOUFLAGED

HEAVY GUN

ABOUT TO

FIRE.

[Pg 6]

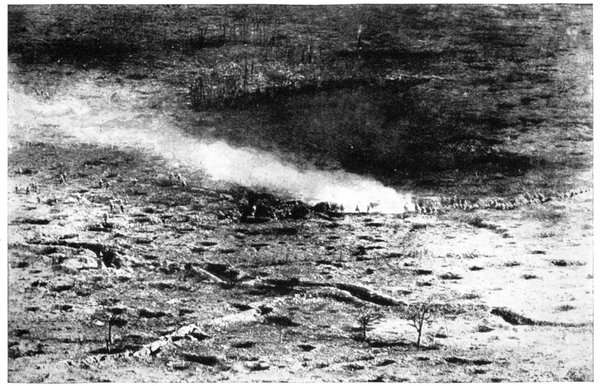

THE CAPTURE OF VERMANDOVILLERS.

The arrival of French reinforcements. Photographed from accompanying aeroplane

at 600 feet (p. 128).

The Infantry

Before the battle, the attacking troops assemble first in the shelters, then in

the assembling places and parallels made during the previous night. The

battalion, company and section commanders survey the ground of attack

with field-glasses.

During the battle, at a given signal, the assaulting battalions dash forward

from the departure trenches, the first wave deployed in skirmishing order;

the second and third, consisting of trench-cleaners, machine-gunners and

supports, follow thirty or forty yards behind, in short columns (single file or

two abreast). Reinforcements echeloned, and likewise in small columns,

bring up the rear, 150 to 200 yards behind.

As a matter of fact, in actual fighting, each regiment attacks separately.

The Commandant, realising the difficulties on the spot, must have in hand all

the necessary means of success, the most powerful being the artillery, which

accompanies and prepares each phase and development of the attack.[Pg 7]

Generally, the creeping barrage, timed beforehand, is loosed at the same

moment of time as the assaulting wave. The infantry follows as closely as

possible.

INFANTRY ADVANCE.

The attacking waves mark their advance with Bengal lights.

Constant and perfect liaison is necessary between the infantry and artillery.

This is ensured by means of runners, pennons, panels, telephones, optical

telegraphy, signals, rockets, Bengal lights, etc. A similar liaison is ensured

between the various attacking units, on the right, left and behind. Action

must be co-ordinated, an essential point on which the G.H.Q. always strongly

insist.

As soon as the enemy perceives the assaulting waves, every effort is made

to scatter them by means of artillery barrage and machine-gun fire, asphyxiating

gas, grenades and liquid fire, so that generally the storming troops cross

"no man's land" through a veritable screen of fire. The enemy's fire likewise

extends to the first-line trenches, to cut off the first waves from their supports.

Without stopping at the enemy's first-line organisations, the first attacking

wave overwhelms the position, annihilates all defenders encountered, and

only comes to a halt at the assigned objective. The following waves support

the first one, and deal with points of resistance. The trench-cleaners or

moppers-up "clean out" the position of enemy survivors with bayonet,

knife and grenade, in indescribable death grapples. Progress is slow along

the communicating trenches, and in the underground shelters, tunnels, cellars

and ruins, where the defenders have taken refuge. From time to time hidden

machine-guns are unmasked and have to be captured.

GERMAN PRISONERS HURRYING TO

THE ALLIES' LINES.

After the attack.—As soon as the "cleaning out" is finished, any prisoners[Pg 8]

are sent to the rear, being often

forced to cross their own barrage-fire.

Meanwhile the other defenders

will have withdrawn to their positions

of support.

Having reached their objective,

the assaulting troops must hold

their ground. Sentries are posted,

while the rest of the men consolidate

the position in view of the

inevitable counter-attack, which is

generally not long in coming.

Under bombardment, the

levelled trenches have to be remade,

the shell-holes organised

and flanked with machine-guns,

and communications with the rear

ensured for the bringing up of stores and, if necessary, reinforcements.

The assaulting troops may thus reach their objectives without excessive

losses or nervous strain, and may be kept in line for a second and third

similar effort, after a few days' rest, during which the artillery will have

destroyed the next enemy positions.

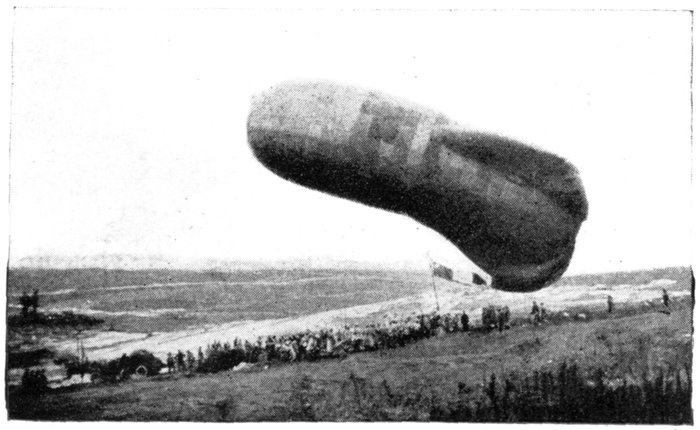

The Flying Corps

Before the battle.—Metaphorically speaking, the Flying Corps (aeroplanes

and observation balloons) is the "eye" of the High Command, which largely

depends on it for precise information regarding the enemy's movements and

positions. It likewise regulates the artillery fire, and furnishes that arm

with photographs, showing exactly the progress made by the destruction

bombardments. Another equally important duty is to "blind the enemy"

by destroying their aeroplanes and observation balloons.

During the battle.—Flying low, sometimes within a few hundred

feet of the ground, the airmen furnish invaluable information, and often

photographs, showing the progress of the attack, the terrain being marked

out with panels and Bengal lights. They also often attack the enemy with

their machine-guns.

[Pg 9]

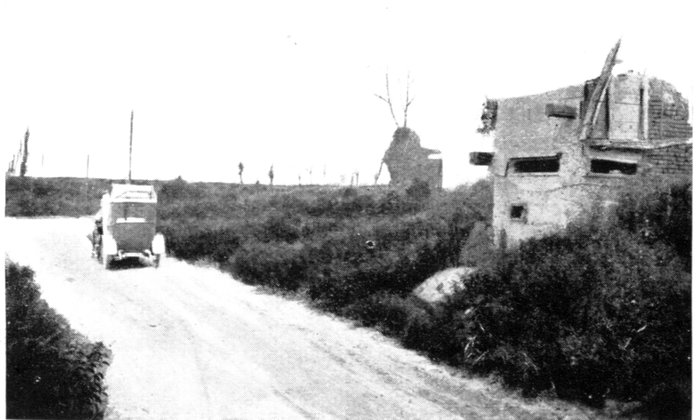

BRITISH TANKS

MAKE THEIR

DÉBUT.

After the battle.—The massing of enemy troops for counter-attacks is

signalled to the artillery, which regulates its barrages accordingly, then,

working in liaison, the two services "prepare" the ground for the next

attack.

These tactics were, gradually perfected on the Somme battlefields, where

the Germans learned by costly experience to improve their defences.

The offensive methods acquired also greater suppleness, and the new

arm—the tank—came to the relief of the infantry.

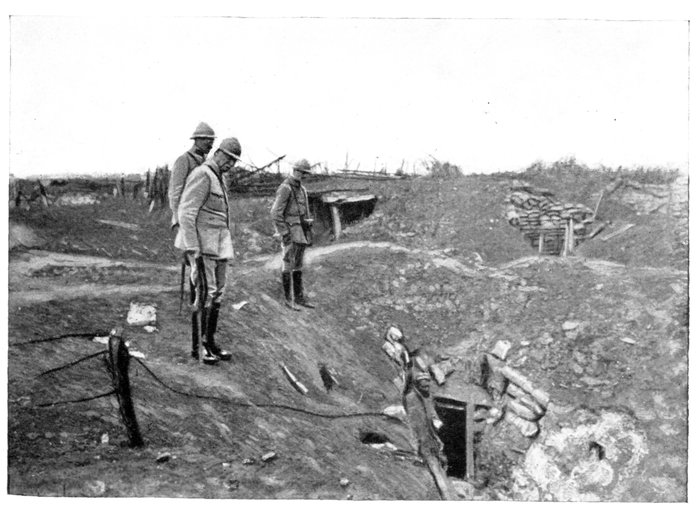

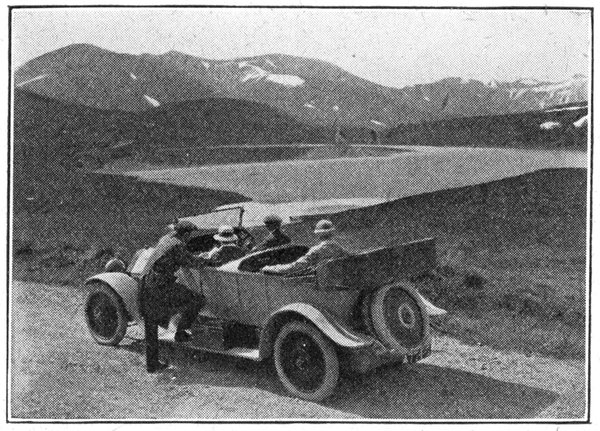

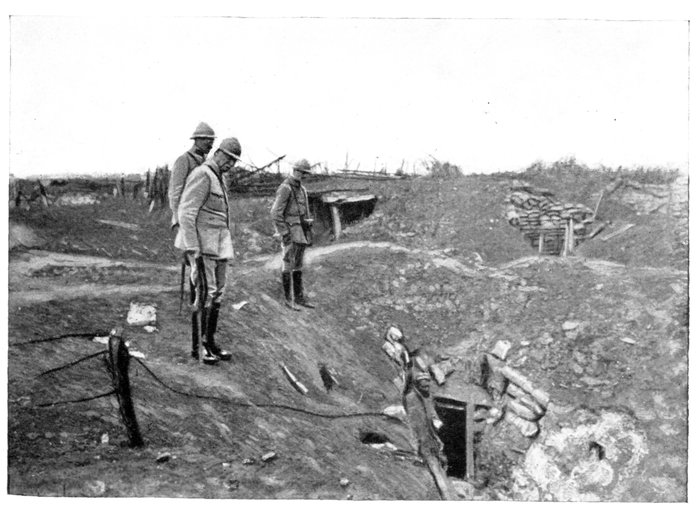

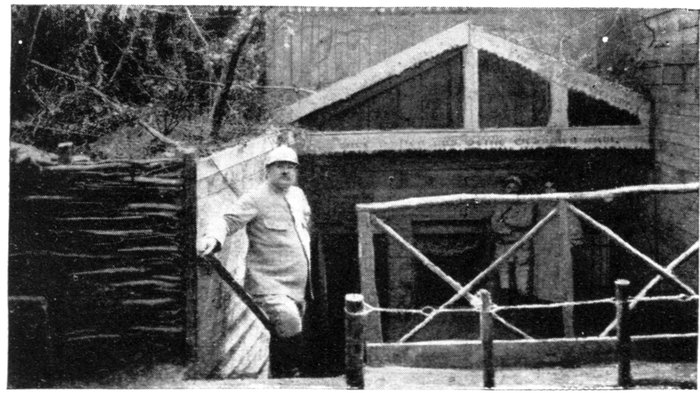

GENERAL FAYOLLE INSPECTING THE CONQUERED LINES.

[Pg 10]

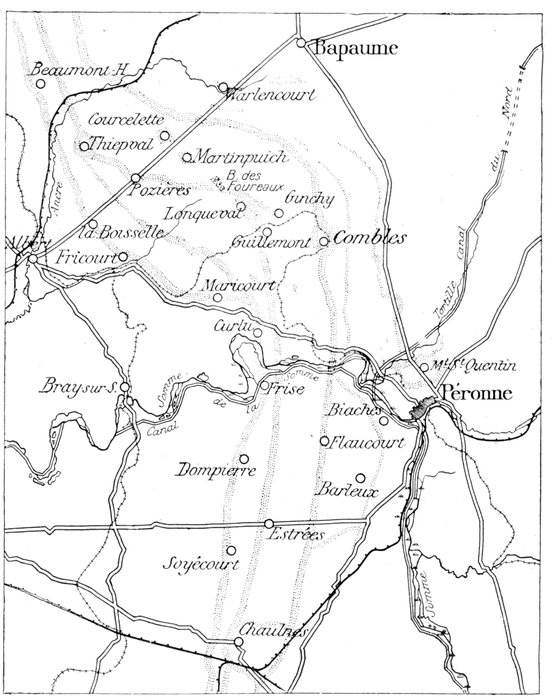

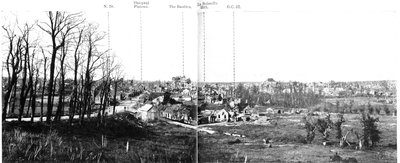

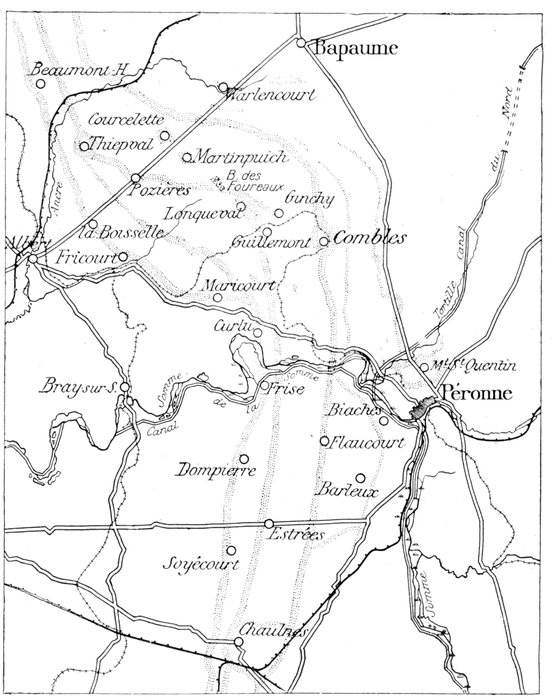

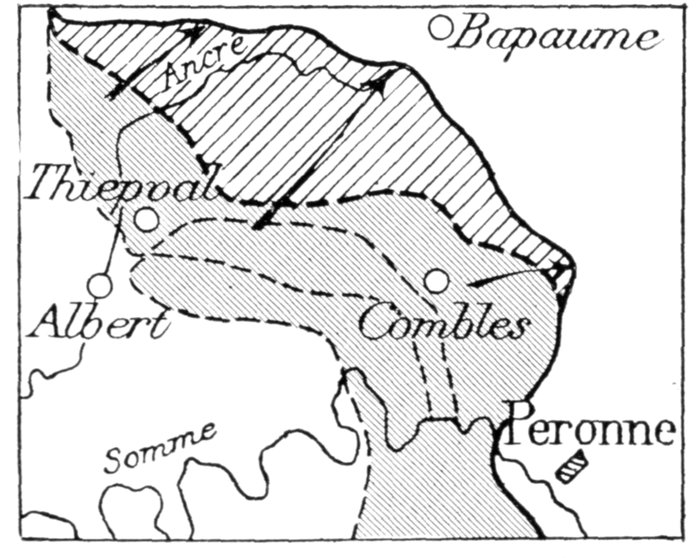

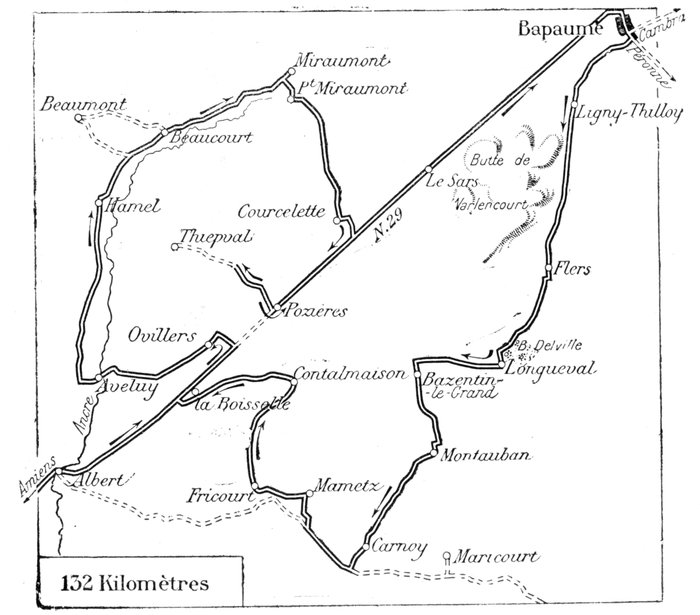

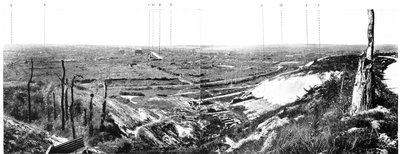

THE DOTTED ZONES REPRESENT THE GERMAN LINES OF RESISTANCE.

THE SOMME BATTLEFIELD.

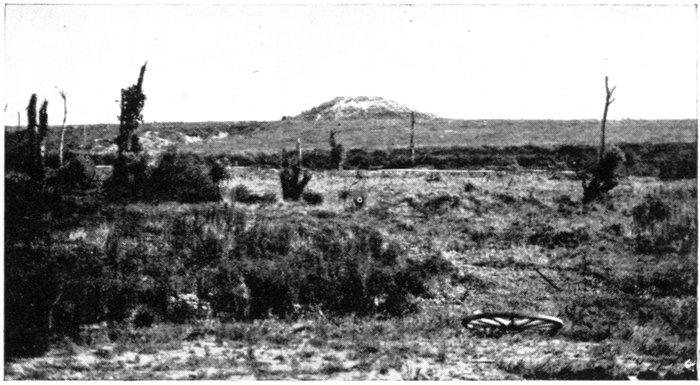

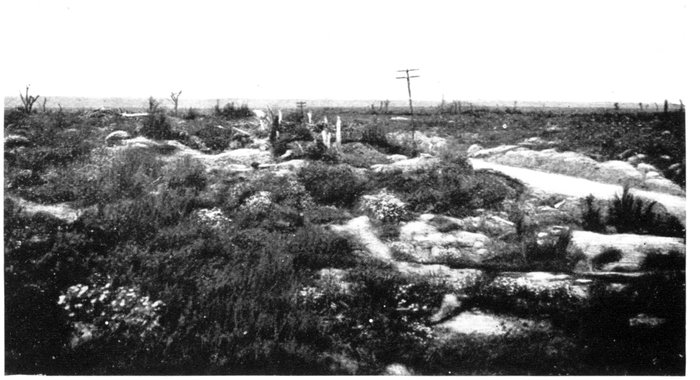

The battle extended over the Picardy plateau, south and north of the

Somme. Before the war, the region was rich and fertile, the chalky ground

having a covering of alluvial soil of variable thickness.

The slopes of the undulating hills and the broad table-lands were covered

with immense fields of corn, poppies and sugar beet. Here and there were

small woods—vestiges of the Arrouaise Forest, which covered the whole[Pg 11]

country in the Middle-Ages. There were scarcely any isolated houses, but

occasionally a windmill, farm or sugar-refinery would break the monotony of

the landscape.

The villages were surrounded with orchards, and their low, red-tiled houses

were generally grouped around the church. The plateau was crossed by

wide, straight roads bordered with fine elms.

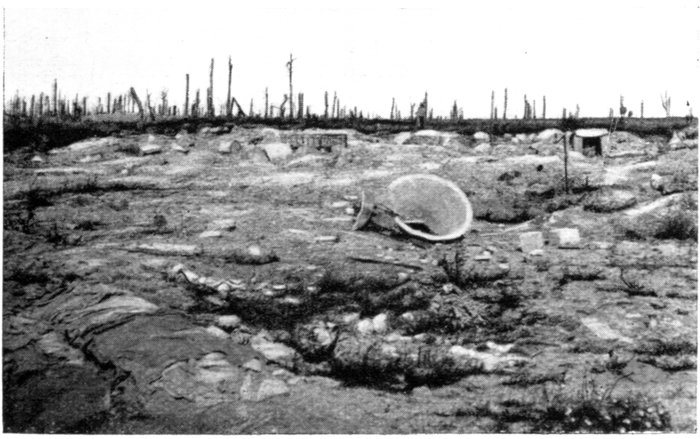

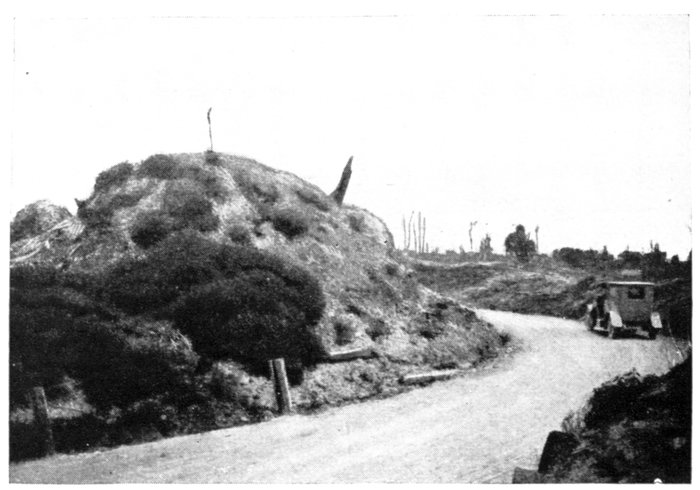

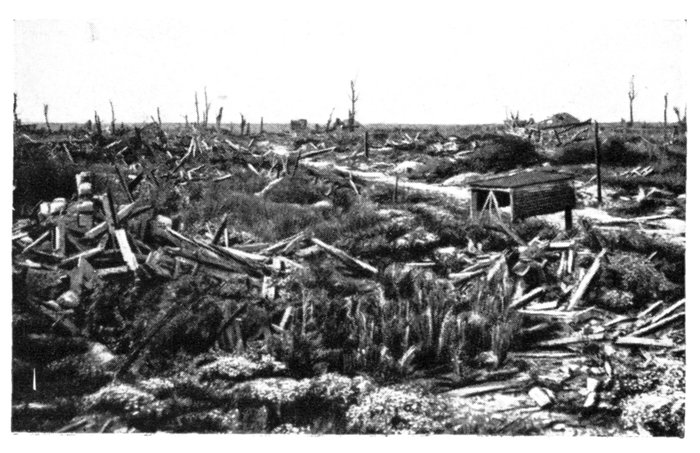

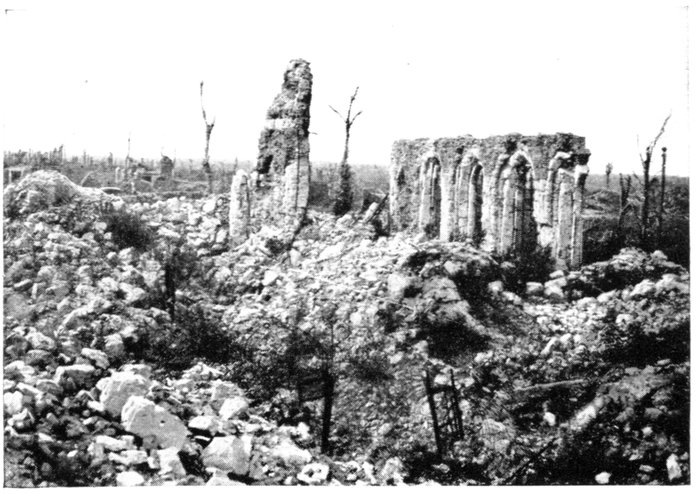

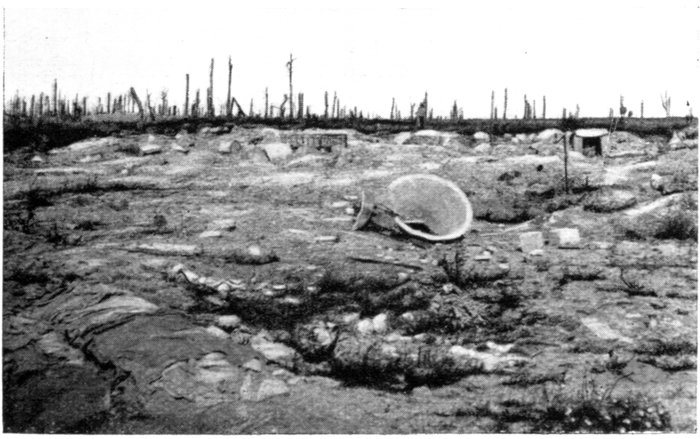

The war has robbed the district of its former aspect. The ground, in a

state of complete upheaval, is almost levelled in places, while the huge

mine-craters give it the appearance of a lunar landscape. The ground was

churned up so deeply that the upper covering of soil has almost entirely

disappeared and the limestone substratum now laid bare is overrun with

rank vegetation. From Thiepval to Albert, Combles and Péronne, and from

Chaulnes to Roye, the ground was so completely upturned as to render

it useless for agriculture for many years to come, and a scheme to plant this

area with pine trees is now being considered.

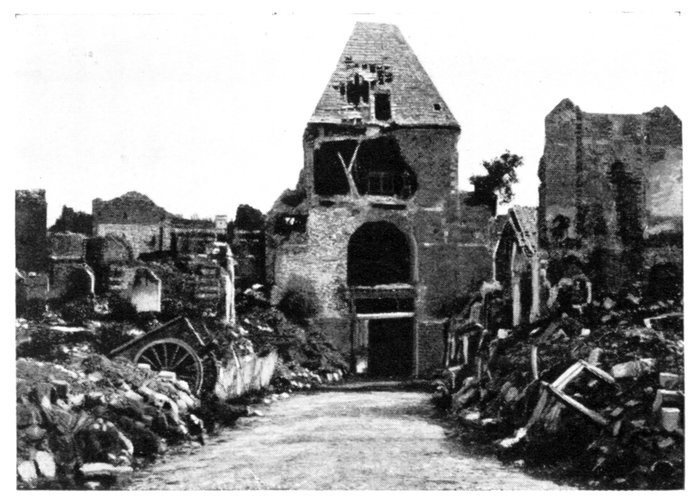

Nearly all the villages were razed, and now form so many vast heaps of

débris. This battlefield is a striking example of the total destructions wrought

by the late war.

The Topography of the Ground and the Enemy Defence-works

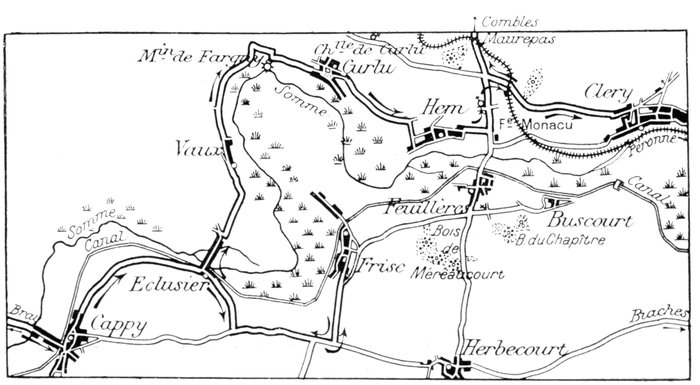

North of the Somme.—The battle zone, bounded by the rivers Ancre,

Somme and Tortille—the latter doubled by the Northern Canal—forms a

strongly undulating plateau (altitude 400-520 feet), which descends in a series

of hillocks, separated by deep depressions, to the valleys of the rivers (altitude

160 feet). The Albert—Combles-Péronne railway runs along the bottom of

one of these depressions.

The higher parts of the plateau form a ridge, one of whose tapering

extremities rests on the Thiepval Heights, on the bank of the Ancre. Running

west to east, the ridge crosses the Albert-Bapaume road at Pozières, passes

Foureaux Wood, then north of Ginchy. It is the watershed which divides

the rivers flowing northwards to the Escaut and southwards to the Somme.

The second line of German positions was established on this ridge, while

the first line extended along the undulating slopes which descended towards

the Allies' positions. There were other enemy positions on the counter-slopes

behind the ridge.

These positions took in the villages and small woods of the region, all of

which, fortified during the previous two years, bristled with defence-works and

machine-guns.

Some of these villages (Courcelette, Martinpuich, Longueval, Guillemont

and Combles), hidden away in hollows, were particularly deadly for the Allies;

the defenders, unseen, were able to snipe the assailants as they appeared on

the hill tops. The Allies had to encircle these centres of resistance before

they were able to enter them.

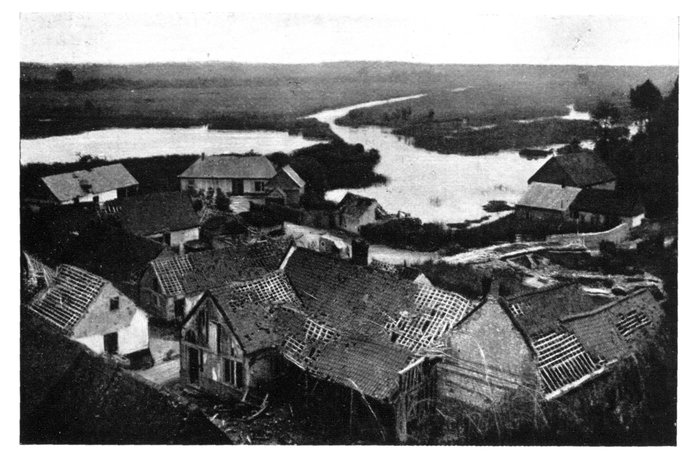

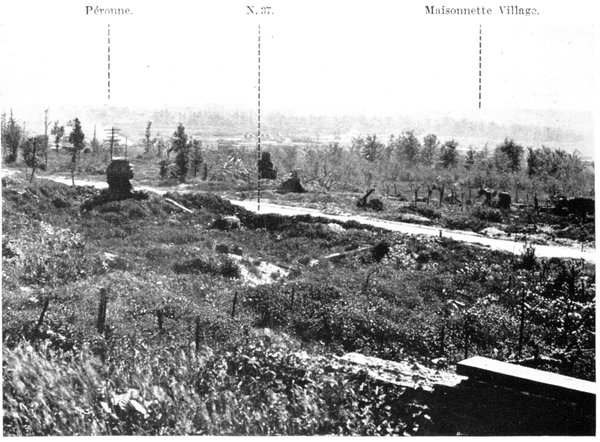

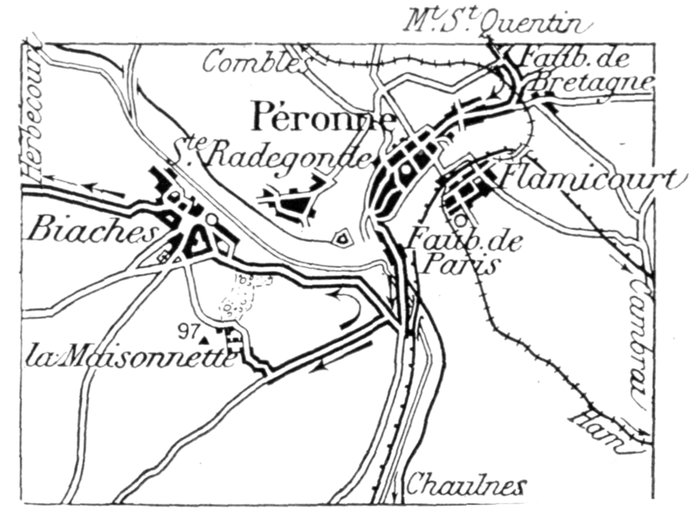

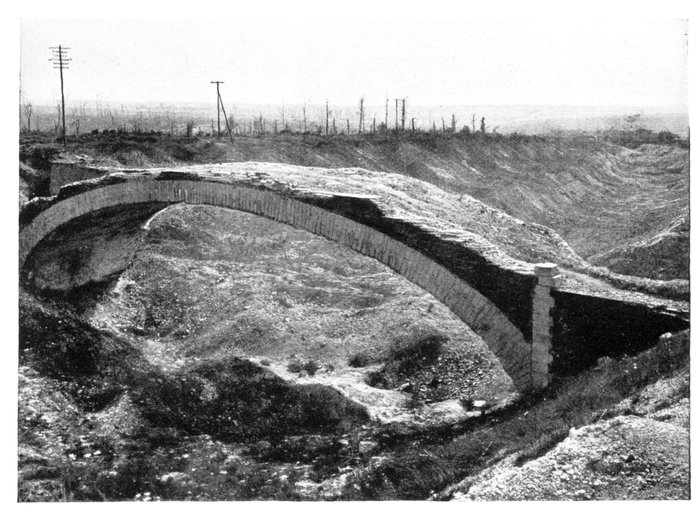

South of the Somme.—The battle zone, bounded by the large circular bend

of the Somme at Péronne, formed a kind of arena. The vast, flat table-lands

of the Santerre district, separated by small valleys, descend gently

towards the large marshy valley of the Somme, in which the canal runs parallel

with the river.

Owing to the narrowness of this zone, the Germans were forced to establish

their positions close behind one another, and the latter were therefore in

danger of being carried in a single rush. On the other hand, the assailants'

rapid advance was first hampered, then held by the marshy valley, which

prevented them from following up their brilliant initial success.

During the battle, the Germans, driven from their first positions, hastily

prepared new ones, and clung desperately to the counter-slopes of the hills

which descend to the valleys.

[Pg 12]

The Different Stages of the Offensive

The offensive of the Somme, the general direction of which was towards

Cambrai, aimed at reaching the main northern line of communications, by

opening a gap between Bapaume and Péronne.

The main sector of attack—between the Ancre and the Somme—was

flanked on either side by diversion sectors north of the Ancre and south of

the Somme.

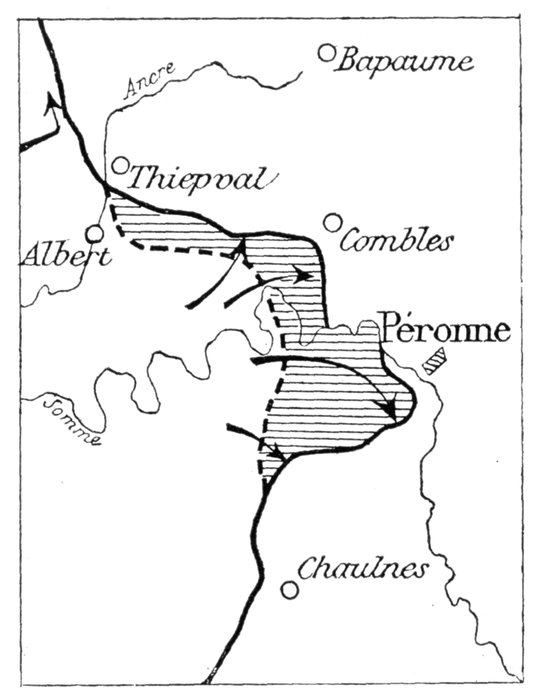

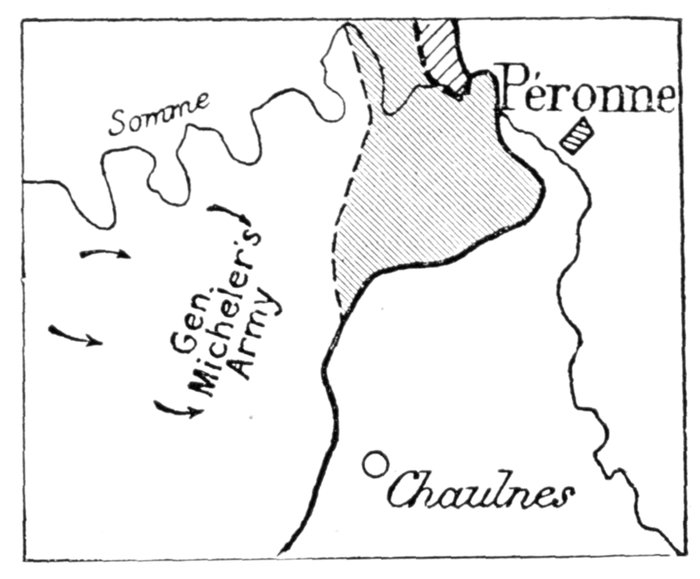

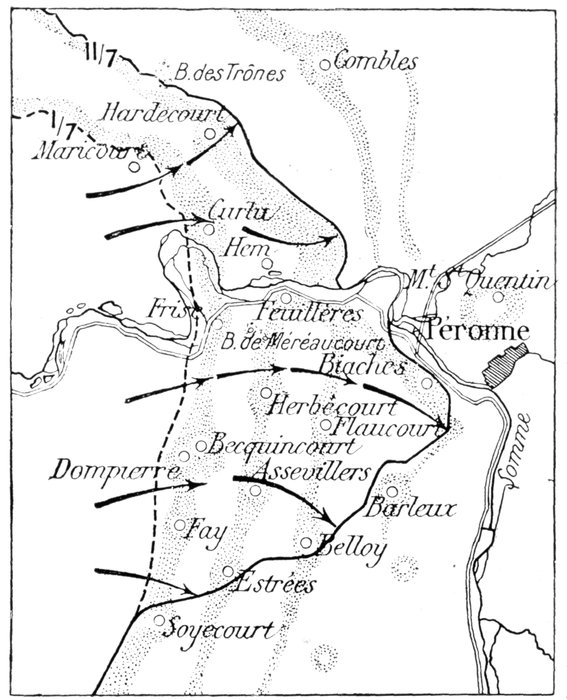

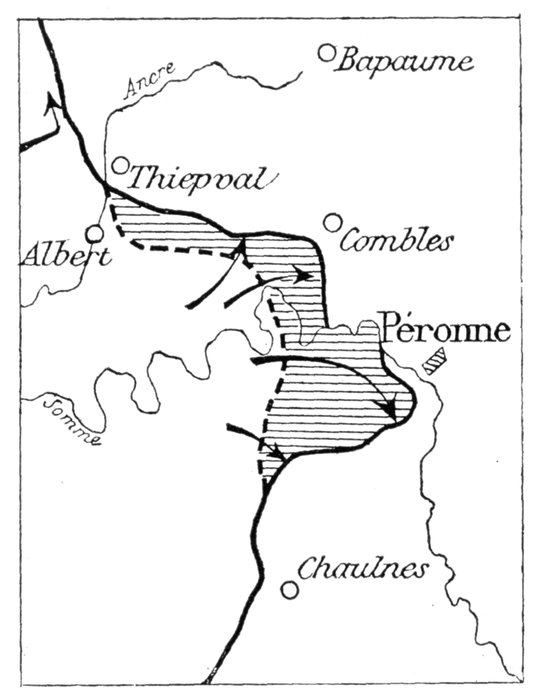

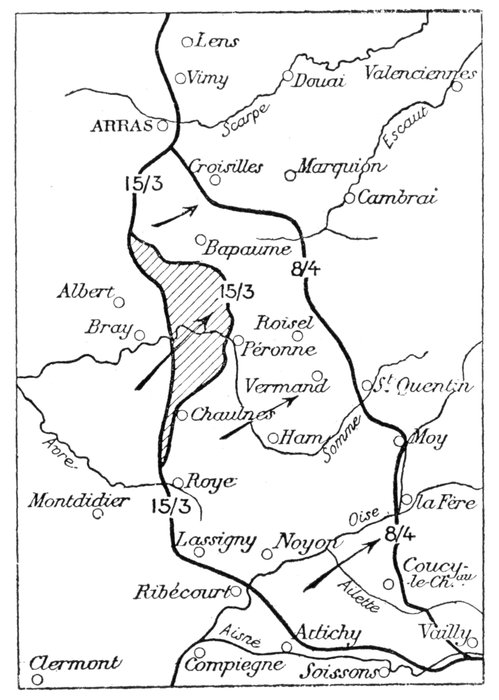

ATTEMPTED BREAK-THROUGH.

A breach was made south of the Somme, but the

marshes prevented development, while to the

north, the offensive was held on the Ancre lines.

Putting to profit the German failure at Verdun, where the enemy masses,

after appalling sacrifice of human

life, gradually became blocked in a

narrow sector (7½ miles in width),

the Allies widened their front of

attack.

After an effective "pounding"

by the guns which annihilated all

obstacles to a considerable depth,

the assaulting waves went forward

simultaneously along a 24-mile

front, feeling for a weak sector

where a breach could be made.

The attack was a complete success

in the diversion sector, south of

the Somme, thanks to the nature

of the ground, but, as previously

stated, it was not possible to follow

it up immediately.

North of the Somme the British

offensive was held.

Warned by the immense preparations,

the Germans were not

taken unawares. Their reserves

flowed in and resisted on new

defensive positions. The advance of the French 6th Army was slowed

down to correspond with that of the British.

The Battle of Attrition

(See the sketch-maps on pages 13, 18, 27.)

This attempted break-through (July 1-12) soon changed into a battle of

attrition (July 14, 1916, to March, 1917).

The Allies' plan now was gradually to shatter the German resistance by

a continuous push along the whole line, and by vigorous action at the

various strong-points.

The gains of ground diminished, but the German reserves were gradually

used up. In spite of their hastily constructed system of new defences, the

Germans realised the precarious nature of their new lines, and were forced,

in March, 1917, to fall back and shorten their front.

[Pg 13]

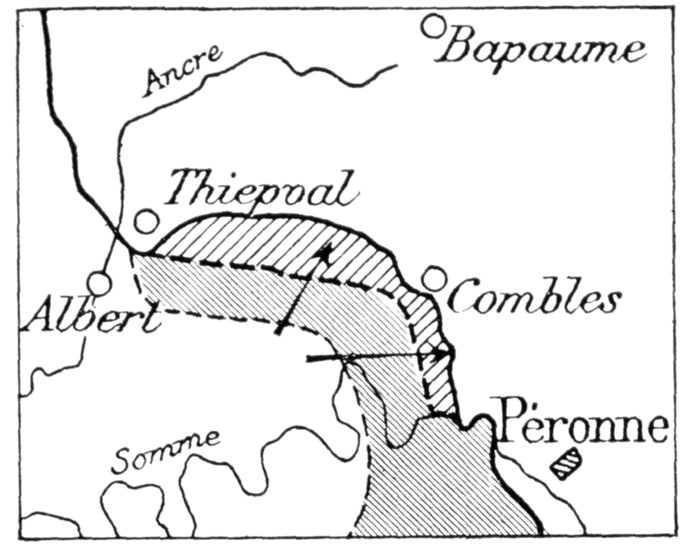

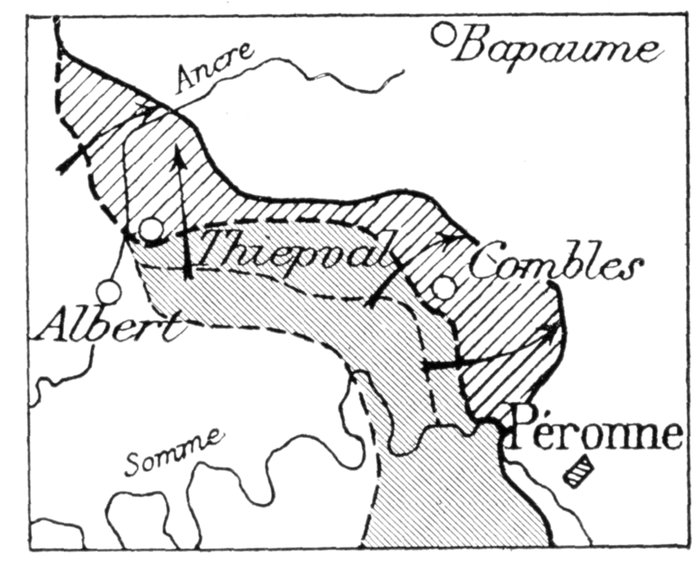

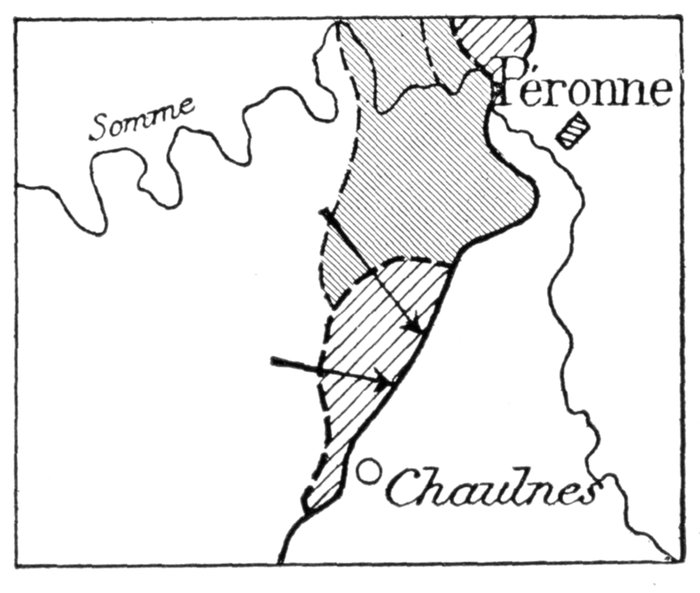

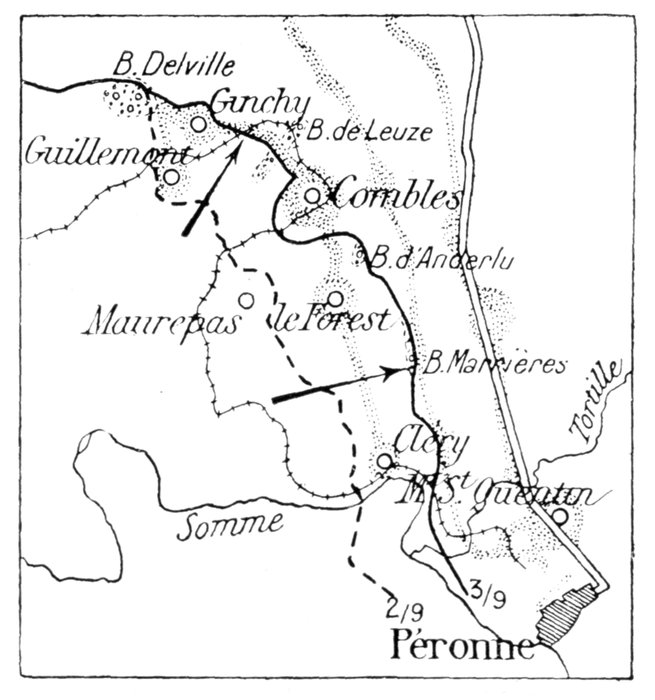

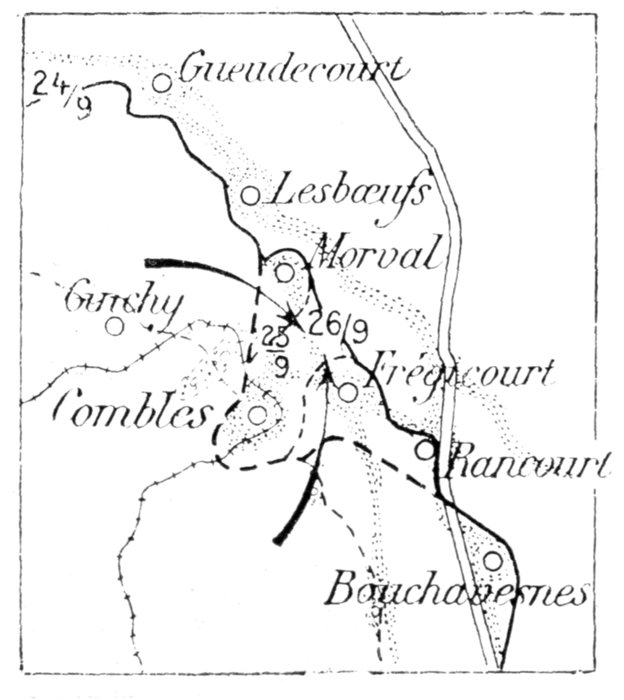

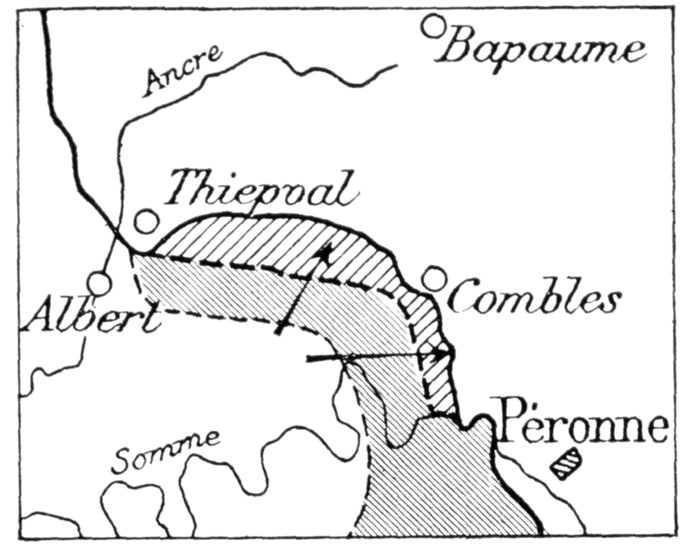

THE PHASES OF THE BATTLE OF ATTRITION.

The Franco-British troops enlarge the conquered

positions and attack the centres of resistance:

Combles and Thiepval (July 14—September 1).

Combles and Thiepval turned and conquered,

after being surrounded (September—November).

The Allies advance toward their main objectives:

Bapaume and Péronne (November—March).

The 6th Army (French) held by the Somme

Marshes, took up its new position. The 10th

Army (French) assembled on its right (August—September).

The 10th Army attacked, but was held in

front of Chaulnes (September—October).

The 10th Army (French) failed to encircle

Chaulnes, and consolidated its new positions

(October—November).

[Pg 14]

THE ATTEMPTED BREAK-THROUGH.

The British Attack

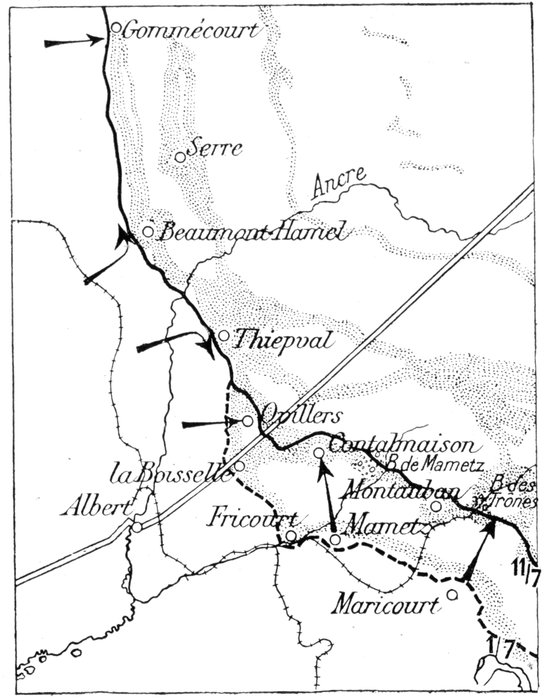

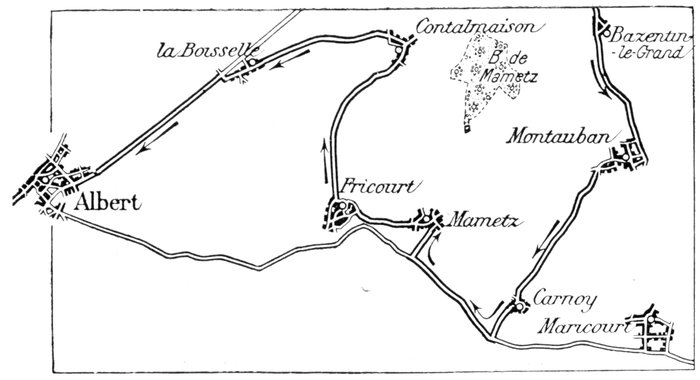

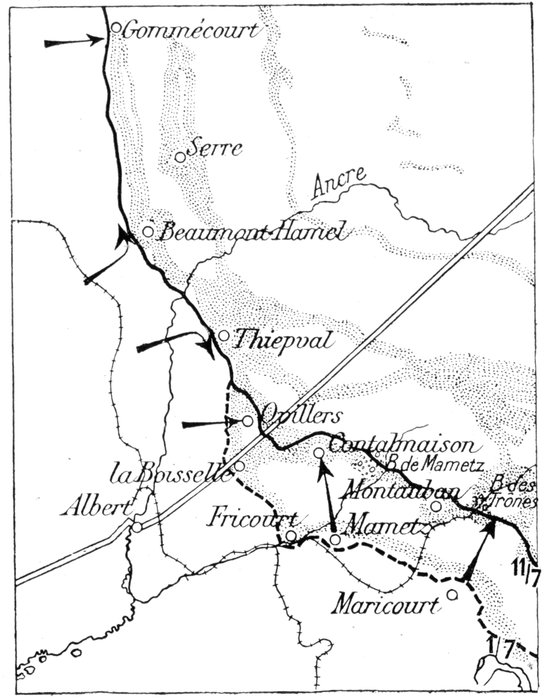

On July 1, the front of attack, about 21 miles long, extended from

Gommécourt to Maricourt.

The attack was made by the 4th Army (Gen. Rawlinson), comprising

five army corps, and by three divisions of the right wing of the 3rd Army

(Gen. Allenby).

The main sector of attack, lying between the Ancre and Maricourt, forms

a 90° salient; the summit of which encircled Fricourt.

The first German positions included Ovillers, La Boisselle, Fricourt,

Mametz and Montauban, and formed the objective of the attack.

The latter, directed generally towards Bapaume, was delivered against

both flanks of the salient.

From the start, the attack was held before the western side of the salient,

in spite of the great heroism of the British.

The right wing, on the southern side, succeeded in carrying the first

German position.

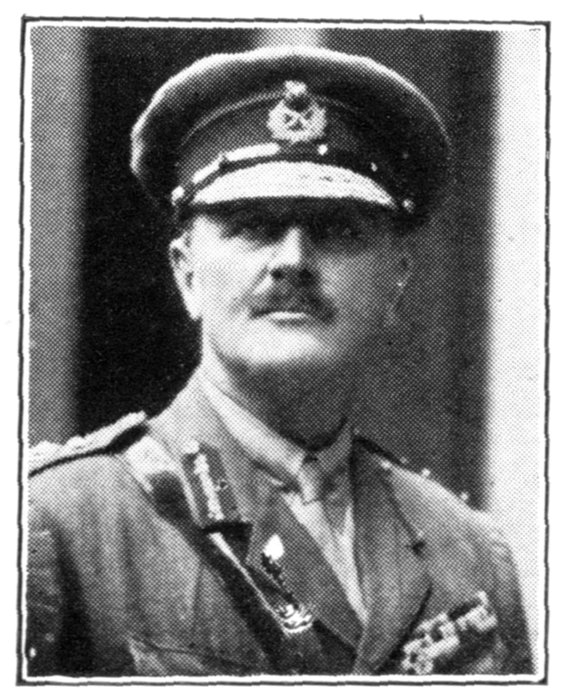

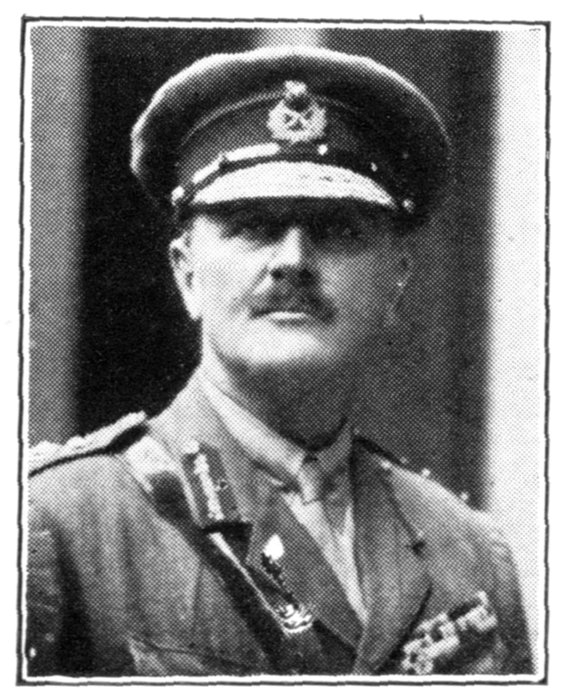

Photo, Russell, London.

GENERAL RAWLINSON.

Photo, F. A. Swaine, London.

GENERAL ALLENBY.

In face of this result, Field-Marshal Haig decided to push home the attack[Pg 15]

on his right (three corps under Gen. Rawlinson), while his left (two corps

under Gen. Gough) would continue to press the enemy, and thus form the

pivot of the manœuvre.

THE DOTTED

ZONES ON THIS

AND THE

FOLLOWING

SKETCH-MAPS

REPRESENT THE

GERMAN LINES

OF RESISTANCE.

The first assaults on July 1 gave the British Montauban and Mametz,

while Fricourt and La Boisselle wore encircled and carried on July 3.

Progress continued on the right, Contalmaison and Mametz Wood, reached

on the 5th, were carried on the 11th.

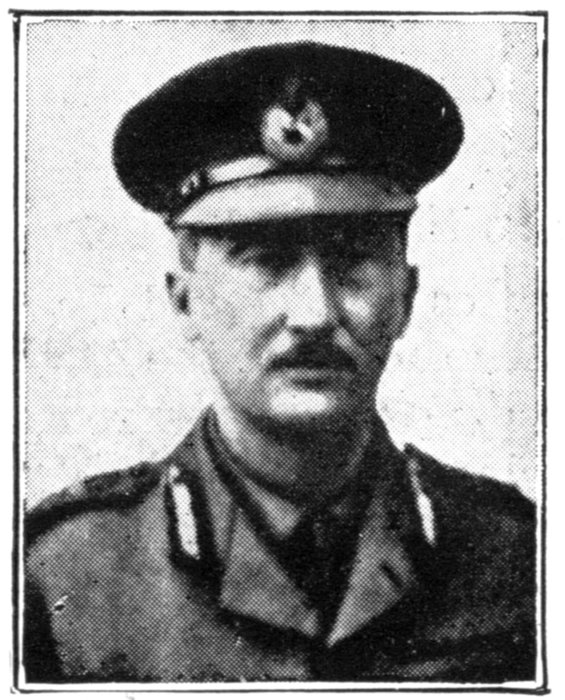

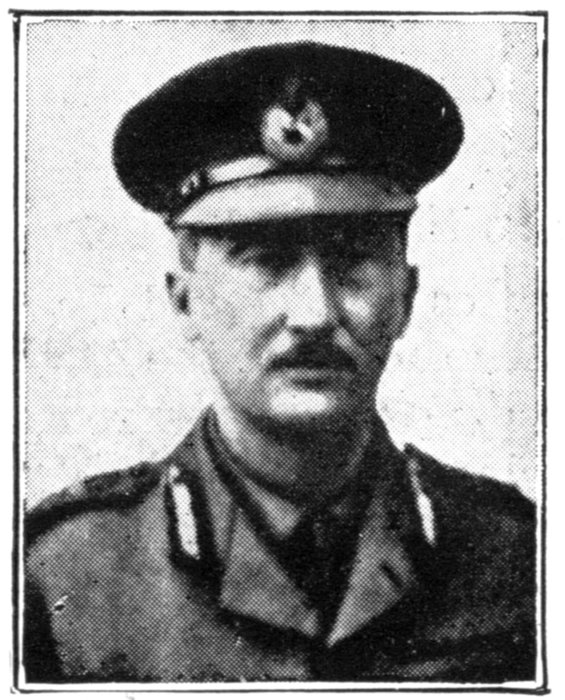

Photo, "Daily Mirror" Studios.

GENERAL GOUGH.

On the extreme right, the British, in

liaison with the French, reached the

southern edges of Trônes Wood, and

came into contact with the second

German positions. Over 6,000 prisoners

were taken. The Germane launched incessant

counter-attacks without result.

In the diversion sector, north of the

Ancre, the initial successes at Gommécourt,

Serre and on the Ancre could not

be followed up.

The Germans continued to hold Beaumont-Hamel

and Thiepval in force.

[Pg 16]

The French Attack

The French 6th Army (Gen. Fayolle) attacked along a ten-mile front,

astride of the Somme, from Maricourt to Soyécourt, in the general direction

of Péronne.

North of the Somme.—The 20th Corps had to conquer the German first

position, consisting of three or four lines of trenches connected by numerous

boyaux to the fortified woods and village of Curlu.

This position was carried in a single rush on July 1, and consolidated on

the three following days.

The second and third German positions were as strong as the first, and

included the villages of Hardecourt and Hem. On the 5th, Hem and the

plateau which dominates the village to the north were taken. On the 8th,

the French, in liaison with the British, first carried, then progressed beyond,

Hardecourt.

From July 1 to 8, the 20th Corps captured the first and second German

positions and consolidated their conquest on the following days.

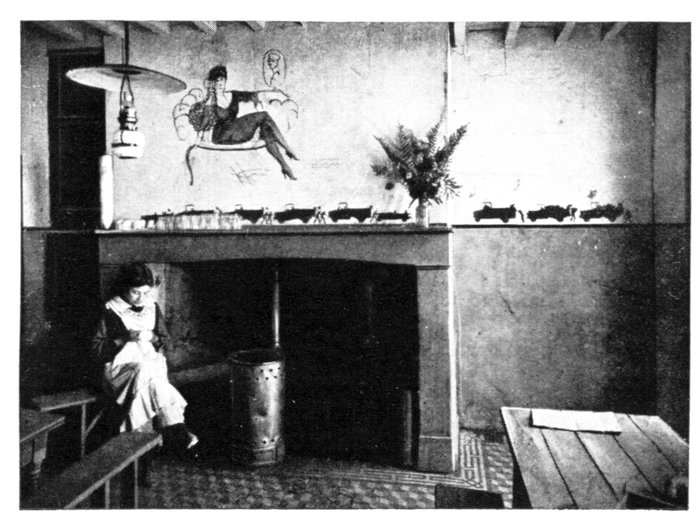

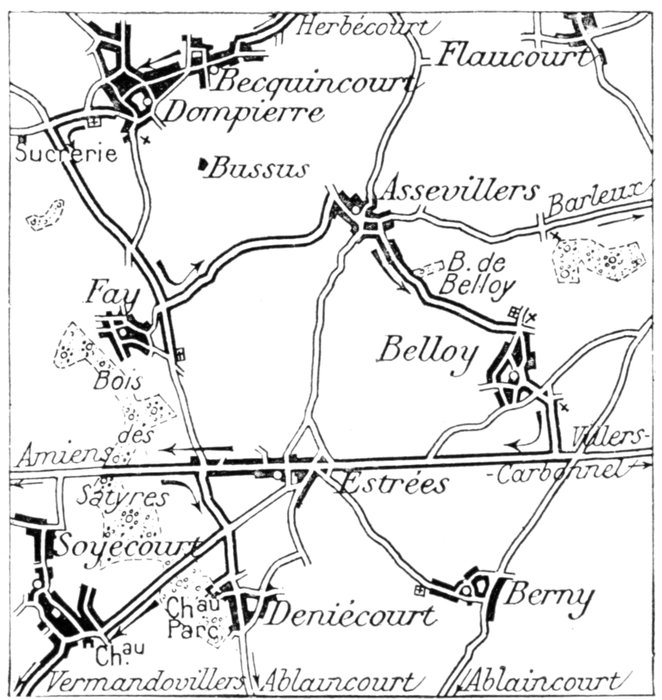

South of the Somme.—The attack

was launched on July 1, two hours

later than that on the northern

bank. With fine dash, the 1st

Colonial Corps and a division of

Brittany reserves carried the first

German position, including the

villages of Dompierre, Becquincourt

and Fay.

On the 2nd, the movement was

continued on the left. Frise, outflanked

from the south, was captured,

Méréaucourt Wood encircled,

and Herbécourt carried by a frontal

attack, after being turned from the

north. The approaches to Assevillers

and Estrées were reached.

The northern part of the second

position was captured.

On the 3rd, the advance continued

on the left. Flaucourt, in

the third position, was carried in

the course of an extraordinarily

daring coup-de-main. Assevillers likewise

fell.

Belloy was captured on the 4th;

the divisional cavalry patrolled freely

as far as the Somme, between Biaches and Barleux.

Biaches village and La Maisonnette observation-post fell on the 9th and

10th. The horses of the African Mounted Chasseurs were watered in the Somme,

and the Zouaves gathered cherries in the suburban gardens of Péronne.

During these ten days the French troops, by carrying out a vast turning

movement on the left, towards the south-east, had pierced all the German

positions. A breach had been made, but the marshy valley of the Somme

in this diversion sector made it very difficult to follow up the success;

moreover, the objectives assigned to these troops did not provide for such

exploitation.

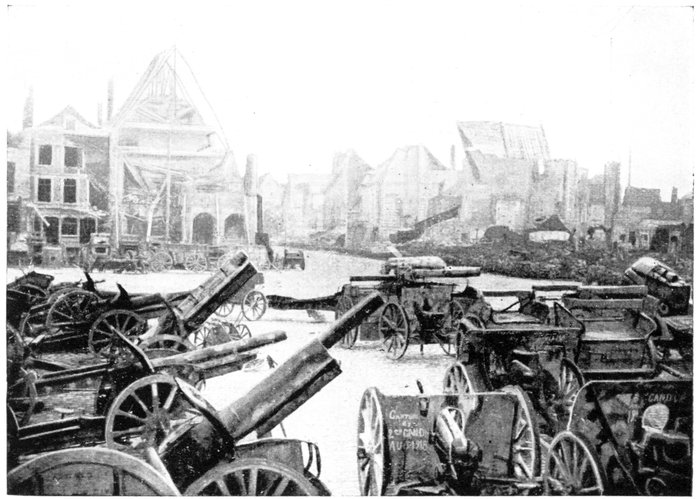

The French attack had been carried out with great dash. In addition to[Pg 17]

the many lines of defences, villages and fortified woods conquered, 85 guns,

100 machine-guns, and 26 minenwerfer were captured, and over 12,000

prisoners, including 235 officers, taken.

The gallant troops, which had thus inflicted a stinging defeat on the enemy,

included the famous 20th Corps, which, a few months before, in a veritable

inferno, had barred the road to Verdun.

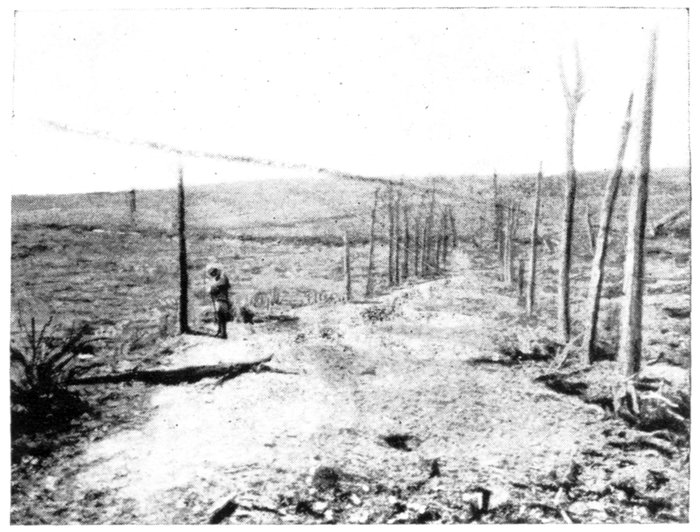

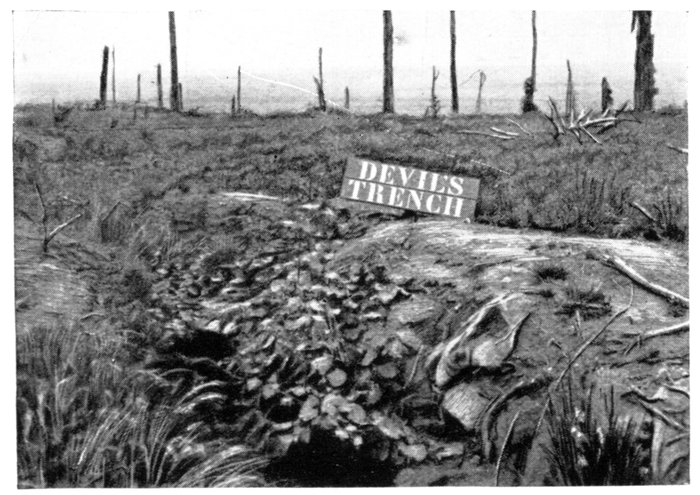

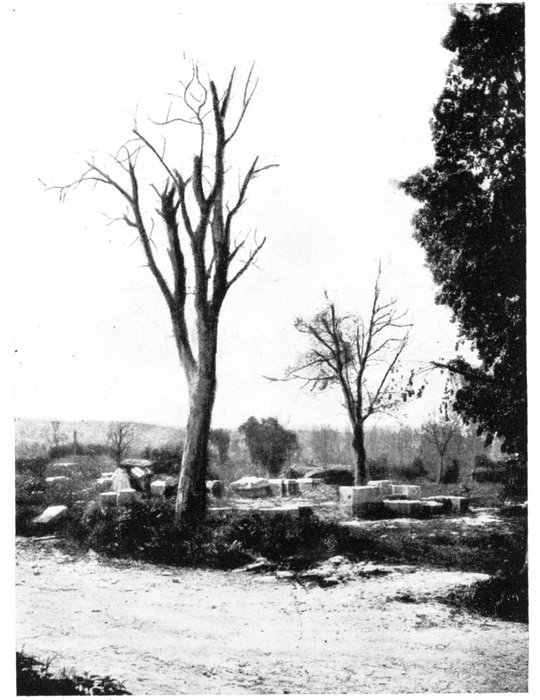

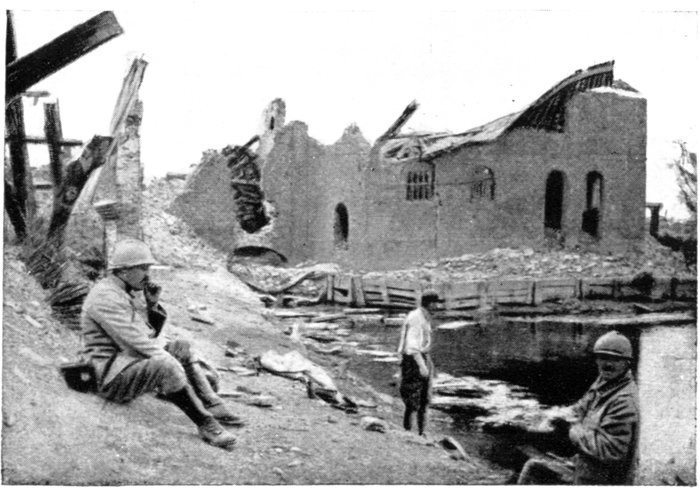

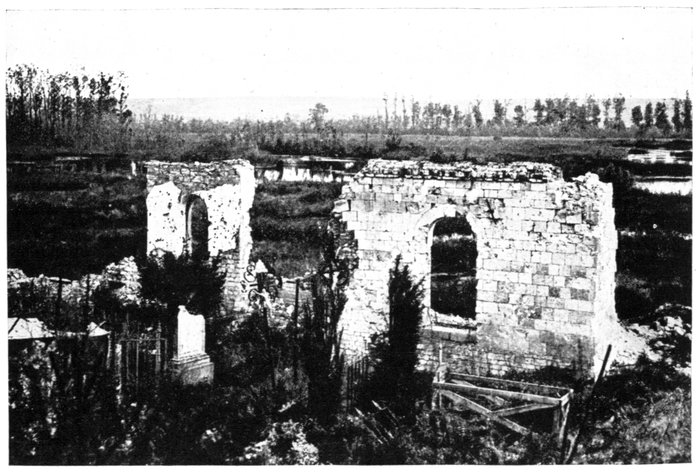

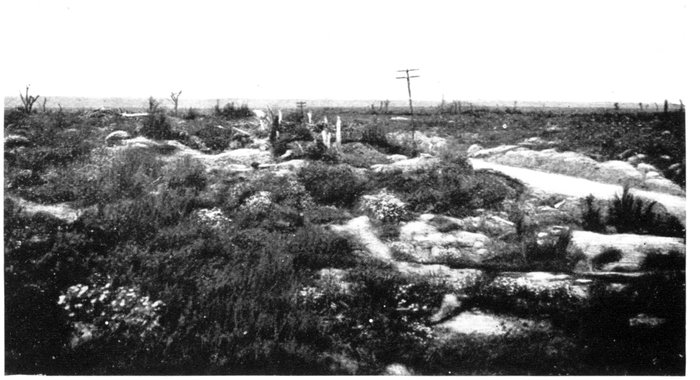

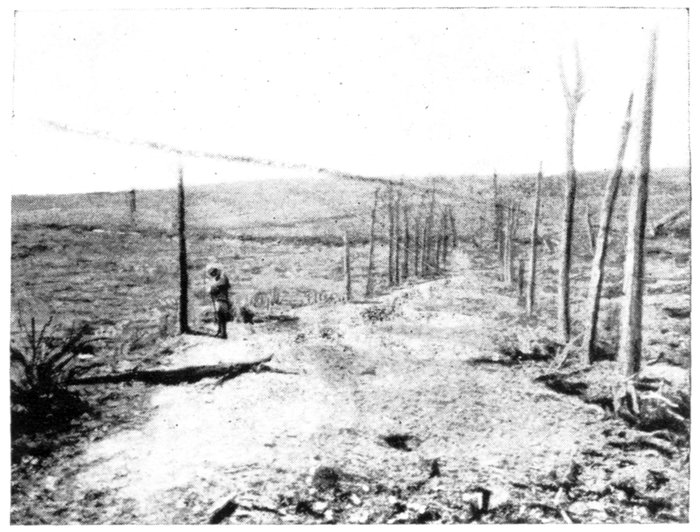

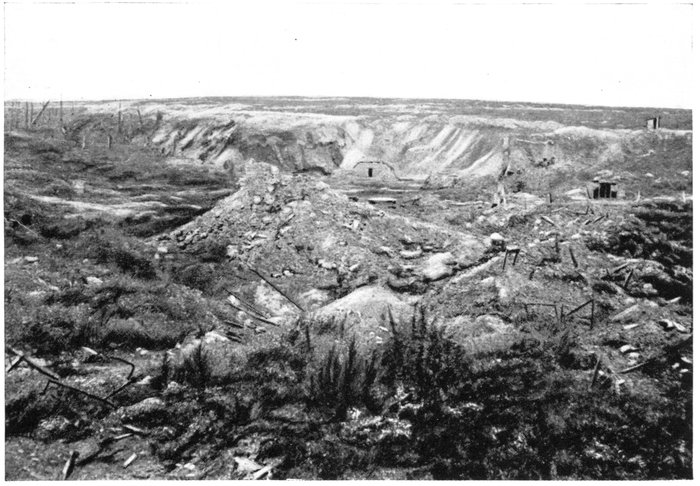

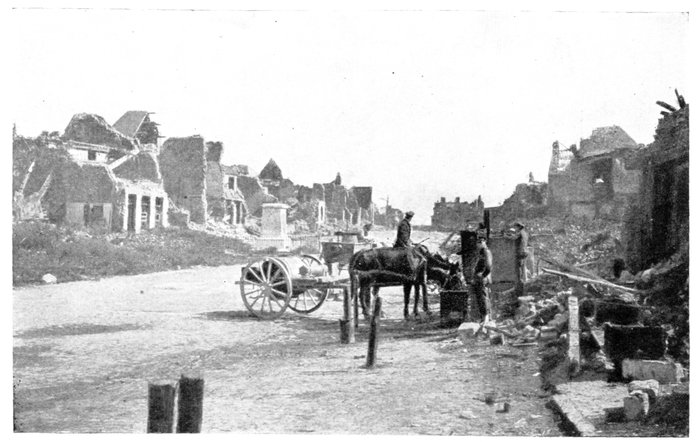

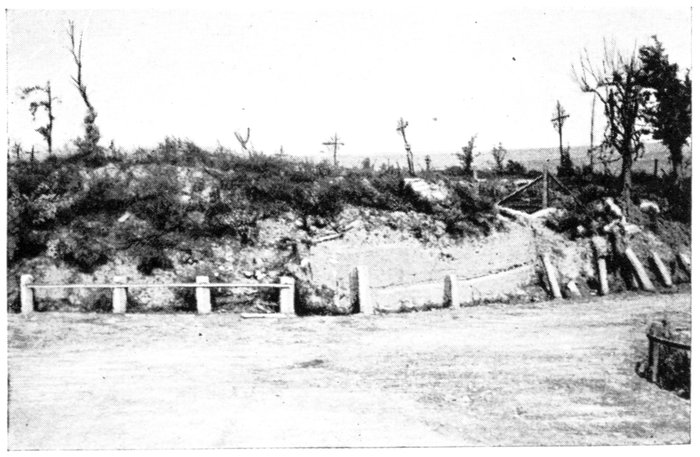

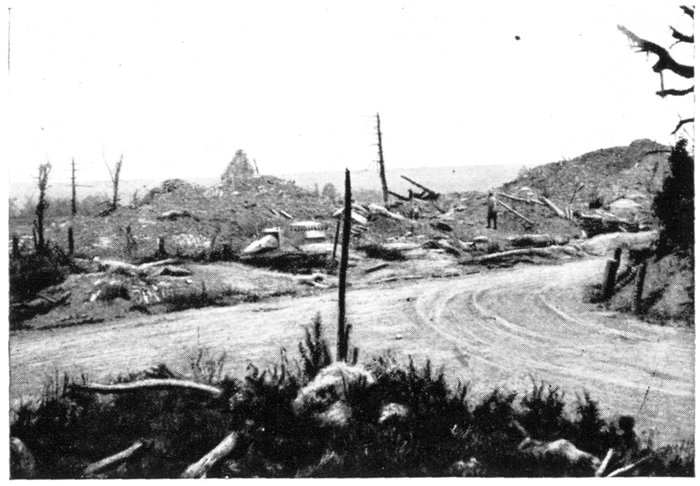

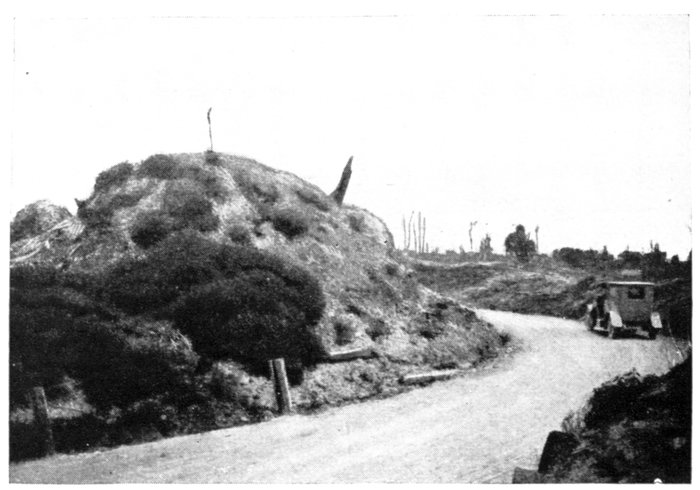

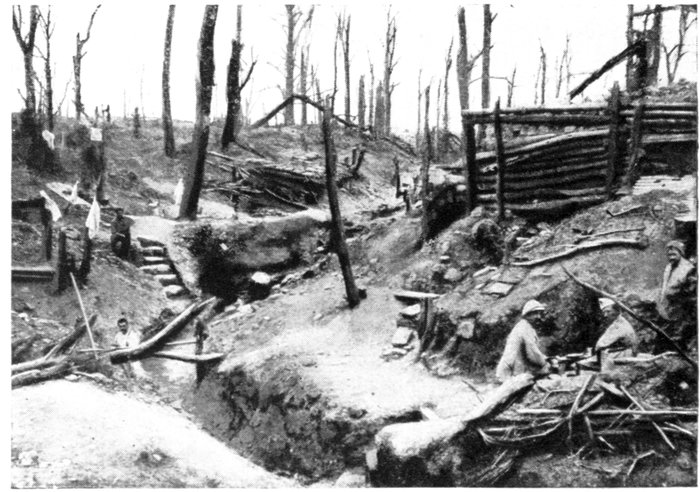

THE SITE OF MONACU FARM ON THE MAUREPAS

ROAD NEAR HEM WOOD.

[Pg 18]

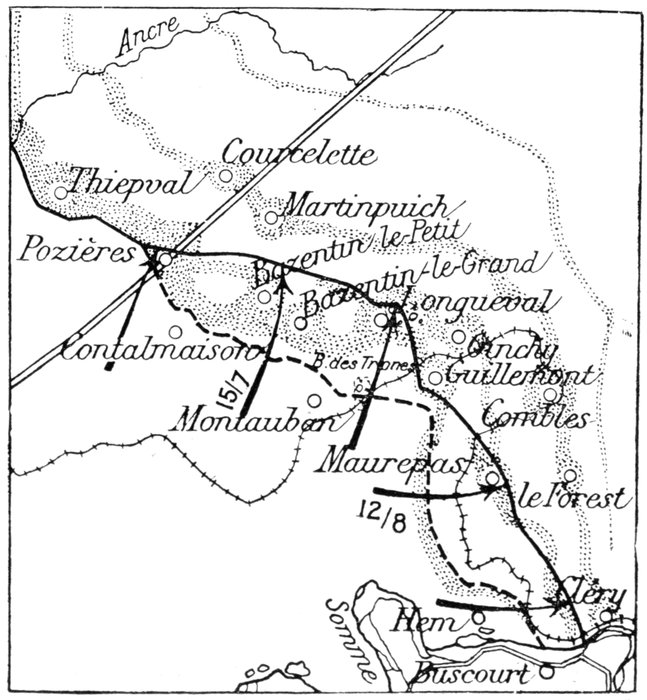

THE BATTLE OF ATTRITION (North of the Somme).

In the main sector of attack the German line had not been completely

broken. This attempt to break through was succeeded by a battle of

attrition, in the course of which the Allies, working in close collaboration,

dealt the enemy repeated blows.

North of the Somme.—After July 11, the Allied front between the Ancre

and the Somme, held by the strong German positions of the Thiepval Plateau,

passed in front of Contalmaison and Montauban. On the southern edges of

Trônes Wood it turned southwards towards Hem.

This line formed a salient to the east of Trônes Wood—a narrow space

bristling with guns. From the high ground of their second position in the

north, and that of Longueval, Ginchy and Guillemont, the German firing

line formed a semi-circle round this salient, which was threatened by incessant

counter-attacks. While maintaining the pressure on the west, it became

necessary for the Allies to widen the angle and enlarge the front, or, in other

words, to obtain greater freedom of movement.

This was the aim of the various Franco-British thrusts during the second

fortnight of July and in August.

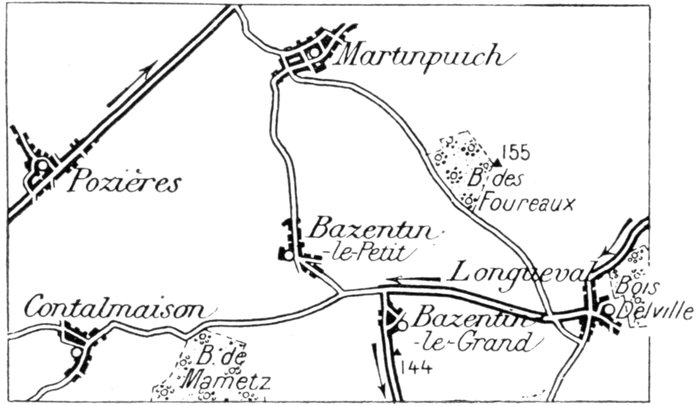

1.—Widening the Front

(July 14—September 1.)

In order to support the forthcoming French thrust towards the east, a

British attack to the north-east was deemed necessary.

The German second positions from Contalmaison to Trônes Wood, and

the crests of the ridge of the plateau formed the objective.

On July 14, the 4th British Army, by a clever manœuvre, took up positions

in the dark at attacking distance. Trônes Wood was carried on the first

day. Longueval, stormed from east and west, was partly captured. In

the centre, Bazentin-le-Grand with its wood and Bazentin-le-Petit were

taken. To the left, the southern outskirts of Pozières were reached.

[Pg 19]

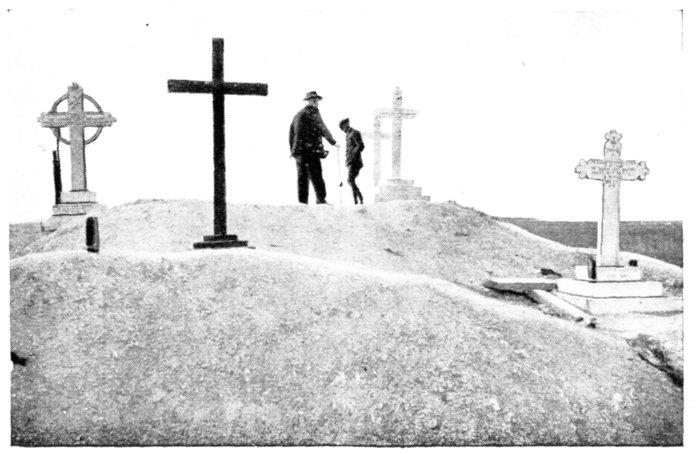

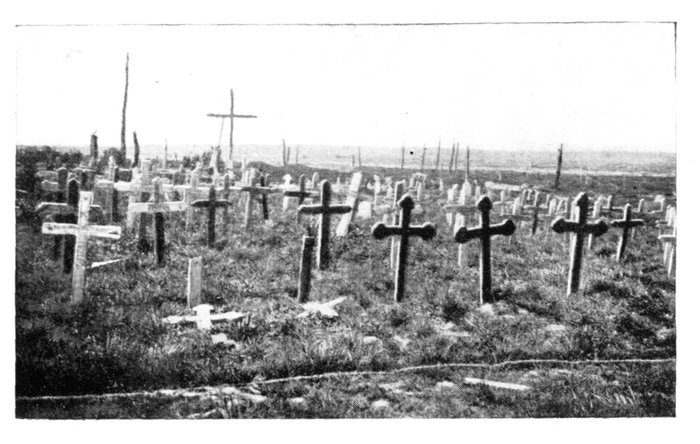

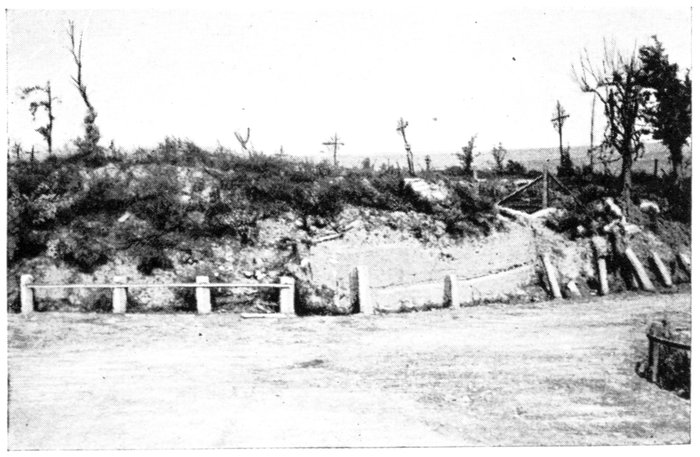

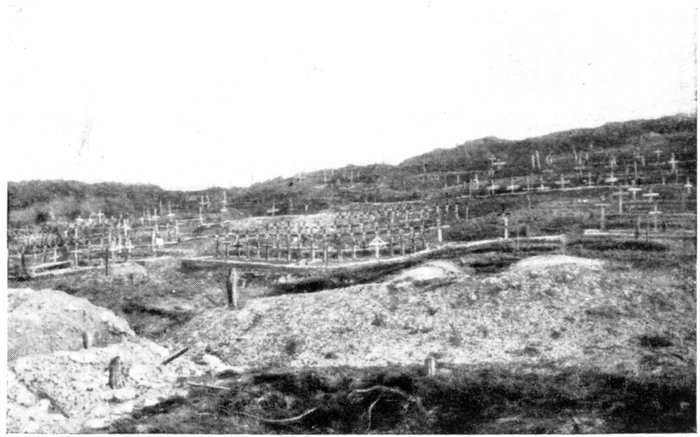

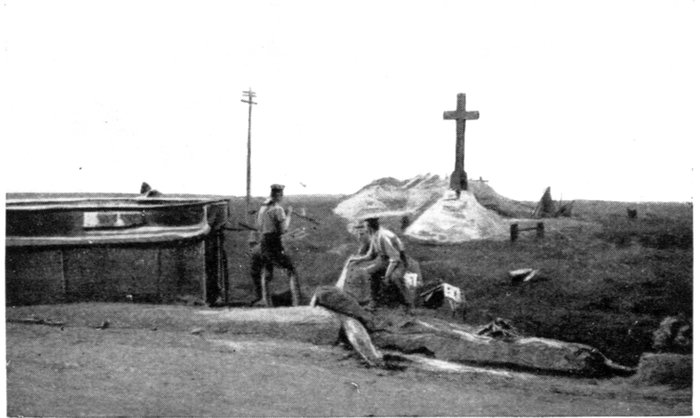

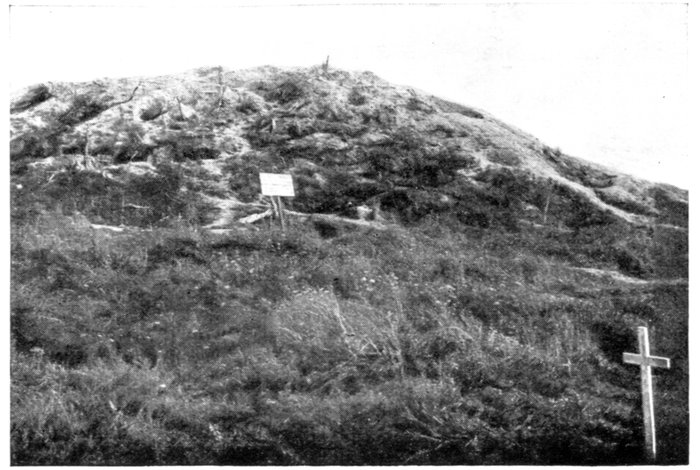

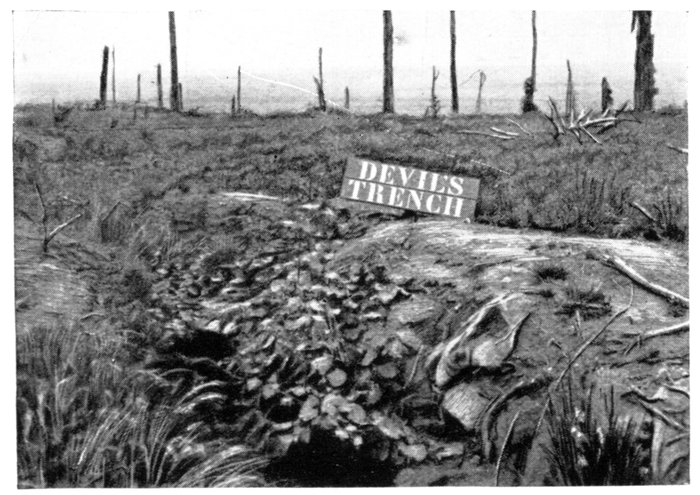

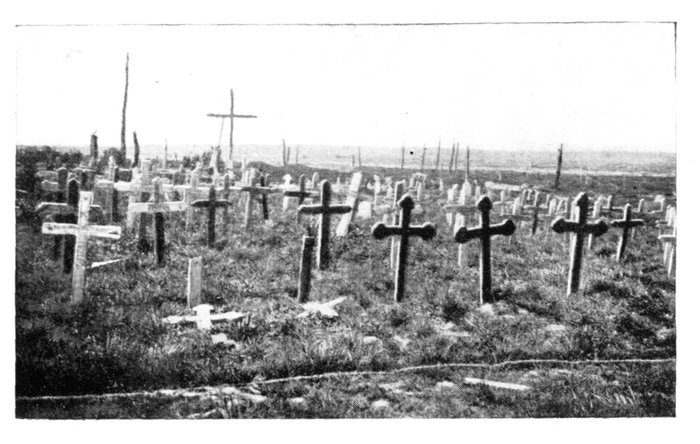

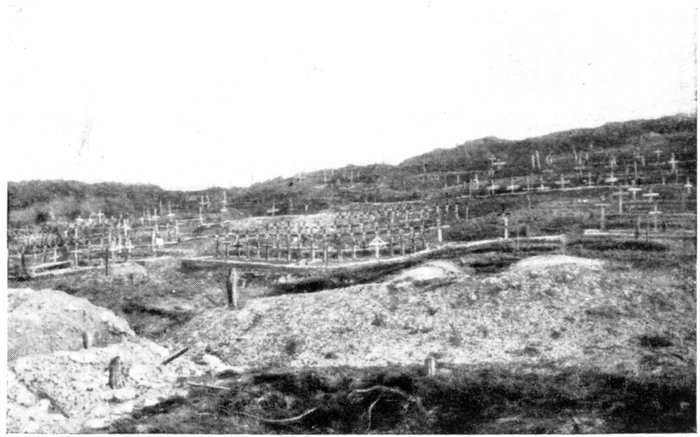

BRITISH GRAVES

IN TRÔNES

WOOD (p. 85).

On July 15-16, the British progressed beyond the German second position—carried

along a three-mile front—and established their advance-posts in the

vicinity of the German third position.

By this time the Germans had recovered from their set-back of the 14th

and offered an aggressive defence. Counter-attacking at the point of the

salient in the Allied lines at Delville Wood, they succeeded in slipping through,

but they were held in front of Longueval.

On the 20th and 23rd, the Allies delivered a general attack. The British

4th Army was now confronted by the enemy in force all along the line.

However, the village of Pozières, one of the strong-points of Thiepval Plateau,

to the west, was carried by the Australians on July 25. The French

advanced their lines as far as the ravine, in which runs the light railway

from Combles to Cléry.

Hidden in a hollow of the ground, Guillemont resisted the British assaults

of July 30 and August 7.

On August 12, the French 1st Corps continued its thrust eastwards,

turning Guillemont from the south. The Zouaves and 1st Cambrai Infantry

Regiment entered Maurepas.

More to the south, the 170th Infantry captured the fortified crest lying

1 km. 500 m. west of Cléry.

The British hung on to the western outskirts of Guillemont.

DELVILLE WOOD

NORTH OF

LONGUEVAL

(p. 60).

[Pg 20]

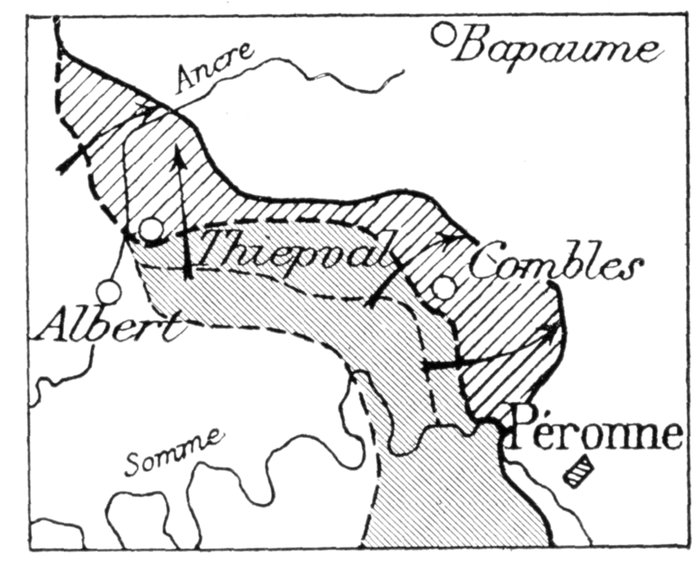

2.—The Surrounding and Capture of the Main Centres of Resistance

On September 1, the British lines, still hanging on to the southern slopes

of the Thiepval Plateau, followed the crest of the ridge north of the villages

of Thiepval, Bazentin-le-Petit and Longueval, in front of the outskirts of

Delville Wood, were then deflected south-east and joined with the French

lines in the ravine of the Combles railway. The French lines surrounded

Maurepas, then followed the road from Maurepas to Cléry. Thiepval and

Combles seemed impregnable.

Instead of making a frontal attack against these positions, the Allies first

turned and then surrounded them by a succession of thrusts.

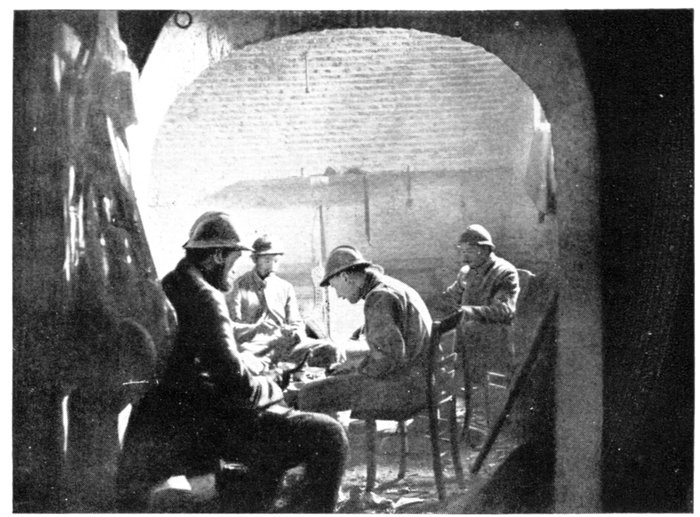

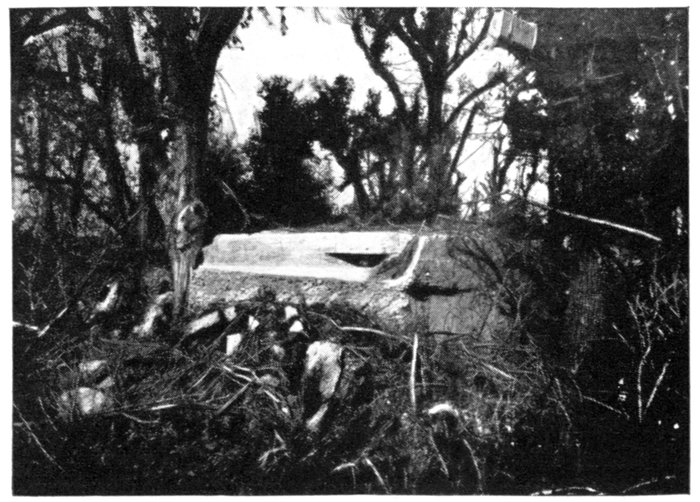

In addition to their successive lines of defence-works, which included a

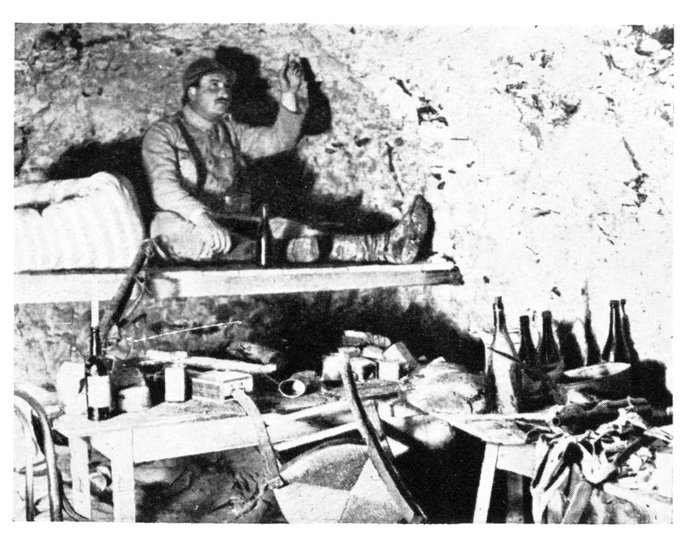

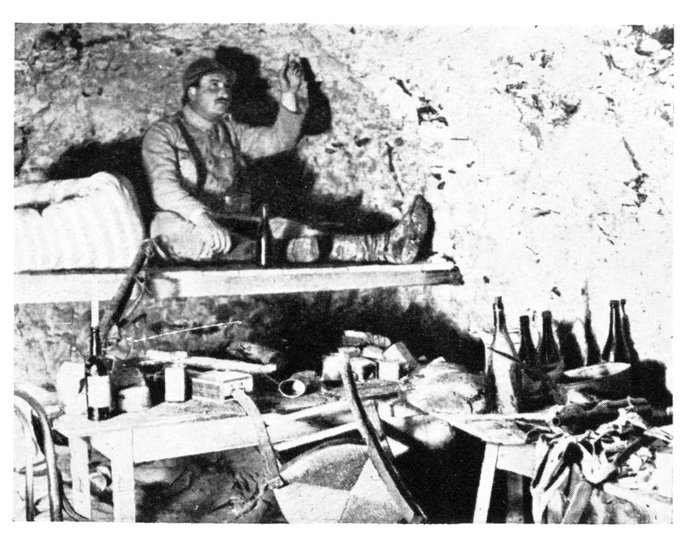

number of villages, the Germans had transformed the little town of Combles,

lying entirely hidden from view at the bottom of an immense depression—into

a redoubtable fortress. A large garrison was safely sheltered in vast

quarries connected by tunnels with the concrete defence-works.

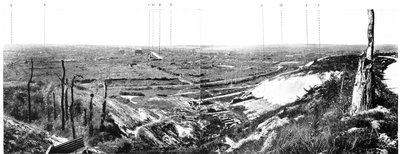

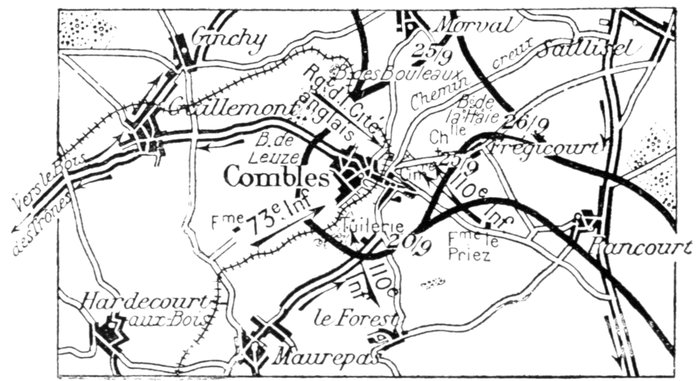

The Surrounding and Capture of Combles

In September, four Allied thrusts were necessary to encircle and capture

Combles (see p. 80).

The Attack of September 3

Ginchy and Guillemont formed the British objective. On the 3rd, in

spite of machine-gun fire from Ginchy, the Irish carried Guillemont, which

had resisted for seven weeks. Progressing beyond the village they reached

and captured Leuze Wood, 1 km. 500 m. west of Combles. On the 9th, they

enlarged their gains by the conquest of Ginchy (see p. 4).

The German positions connecting Combles with Le Forest and Cléry

formed the French objective.

This position—defended by four German divisions—was carried with

magnificent dash on the 3rd, from near Combles to the Somme.

On the 5th, the French progressed beyond the position and reached the

following line: Anderlu Wood, north-east of Le Forest, Marrières Wood,

and the crest north-east of Cléry; 2,500 prisoners were taken.

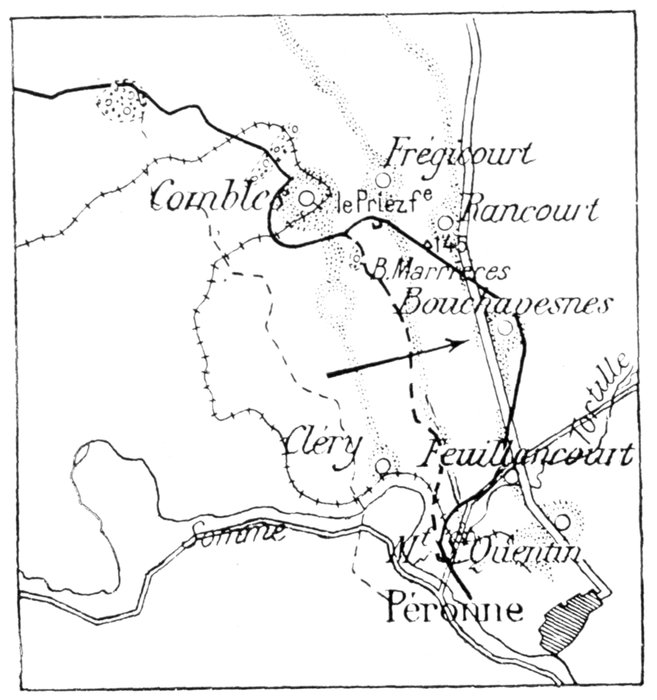

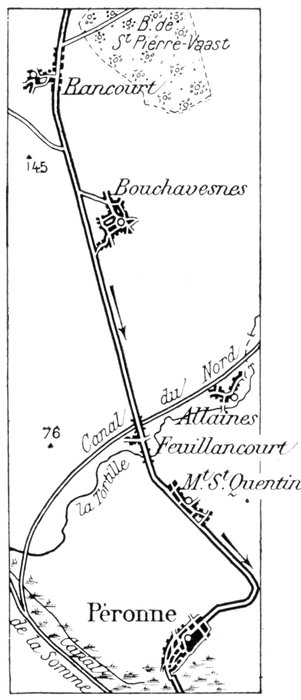

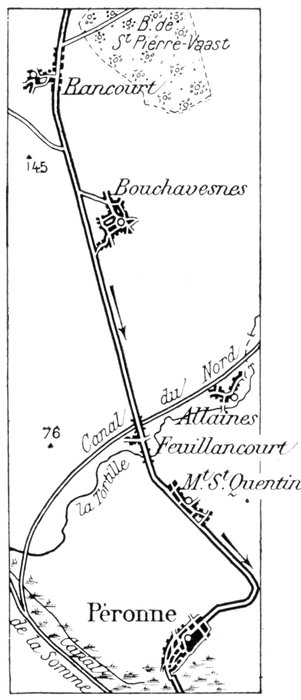

[Pg 21]

The French Attack of the 12th

Attacking again, the French were now confronted by two parallel lines

of defences. The first position (known as the Berlingots' trenches) ran

through Frégicourt, Le Priez Farm and Marrières Woods. The second

position, along the National road, 2 km. behind the first, rested on Rancourt,

Feuillancourt and the Canal du Nord, taking in Bouchavesnes.

Following close behind the creeping barrage, the attacking troops carried

the Berlingots' trenches in half an hour. From there, the left wing attacked

and captured Hill 145, and advanced as far as the National road, between

Rancourt and Bouchavesnes. The right wing reached the Valley of the

Tortille, opposite Feuillancourt.

Bouchavesnes, although not included in the objectives assigned to the

storming troops, was next attacked, and at 8 p.m. Bengal lights, announcing

its capture, were burning in the ruins of the village.

On the 13th, the French crossed the National road. The enemy showed

great nervousness, and brought up three new divisions.

[Pg 22]

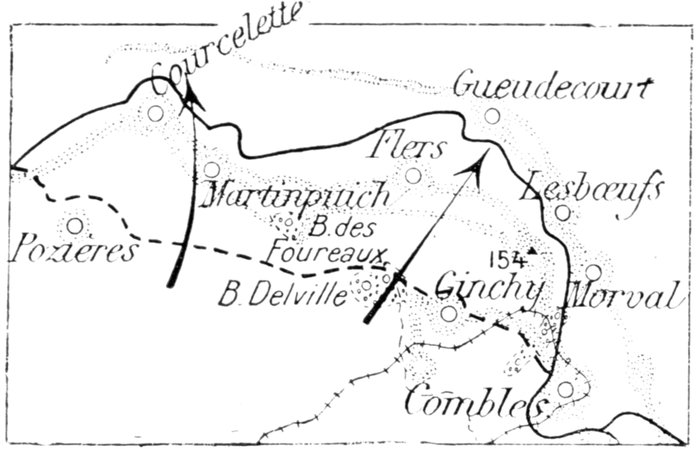

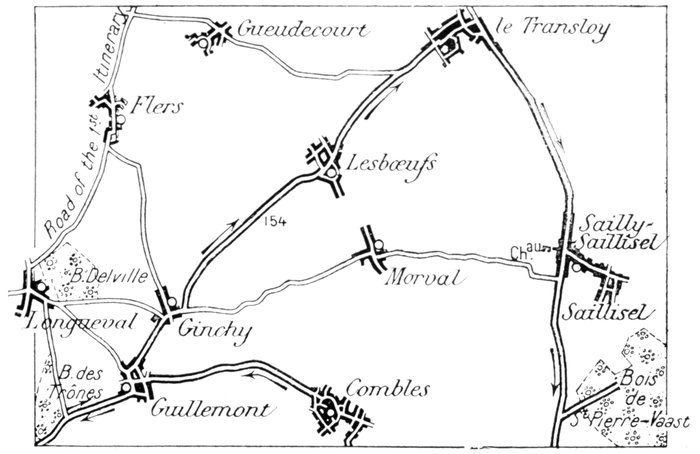

The British Attack of

September 15

The German positions of

Foureaux Wood, Hill 154

and Morval were the objectives

of the attack.

For the first time tanks

accompanied the storming

waves, giving the enemy an

unpleasant surprise, which

contributed largely to the

victory.

In the centre, the tanks

entered Flers before noon;

the troops advanced beyond the village and established themselves. On the

left, Foureaux Wood, bristling with strong-points and redoubts, and on the

right, Hill 154 were carried, and the Morval—Lesbœufs—Gueudecourt line

reached.

In consequence of this brilliant success of the British right, the attack

was extended on the left; the tanks entered Martinpuich and Courcelette.

In a single day the British advanced 2 km. along a 10 km. front, and captured

4,000 prisoners.

The enemy threw two more divisions into the battle, and fiercely counter-attacked

the salient formed by the French lines at the Bapaume-Péronne

road. After getting a footing in Bouchavesnes on September 20, they were

driven out at the point of the bayonet.

The General Attack of September 25, and Capture of Combles

The Allied front line moved forward again, to complete the investment

of Combles.

Rancourt and Frégicourt fell on the 25th, in the French attack; Morval

was captured by the British.

The encirclement of Combles was complete, and the enemy had already

partially evacuated the place. On the 26th, the British entered the fortress

from the north, the French from the south, and captured a company of laggards.

[Pg 23]

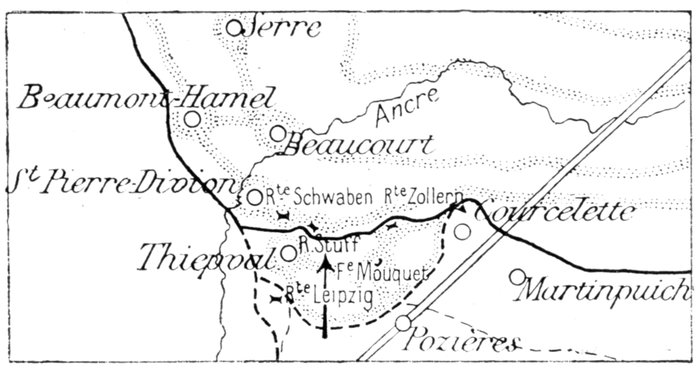

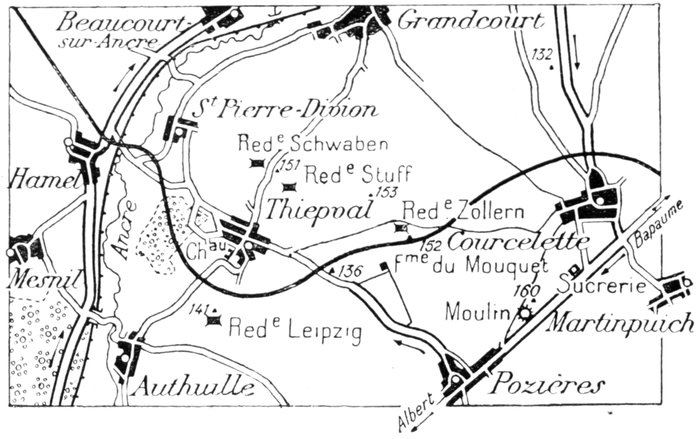

The Turning and Capture of Thiepval Plateau

West of the lines of the 4th British Array, and dominating the valley of

the Ancre, the powerfully fortified Thiepval Plateau still remained un-captured.

This very strong system of defences comprised the village, Mouquet Farm,

and the Zollern, Schwaben and Stuff Redoubts.

In July, the British had gained a footing in the Leipzig Redoubt, which

formed the first enemy positions south of the Plateau. In August, Pozières

had been carried by the Australians. On September 15, the British captured

Martinpuich and Courcelette, and progressed beyond the plateau to the east.

The Attack of September 26

On September 26, the day Combles was taken, an attack was made

against this formidable plateau. Mouquet Farm and Zollern Redoubt fell,

and on the 27th, Thiepval was captured (see p. 48).

The British carried the trenches connecting the Schwaben and Stuff

Redoubts, but the enemy still clung to the northern slopes of the plateau

which descends towards the Ancre.

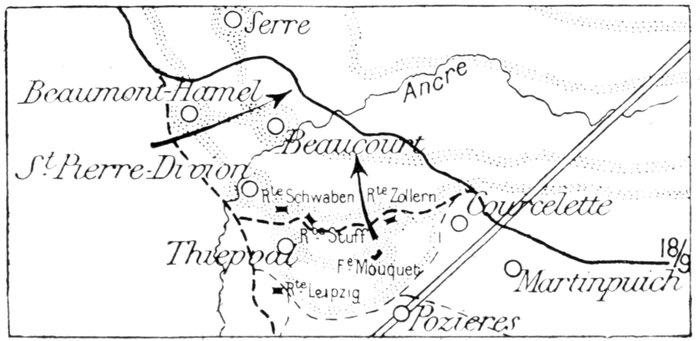

The Attack of November 13

The German lines now formed a sharp salient on the Ancre.

To reduce this salient and complete the capture of Thiepval Plateau,

the British attacked on both sides of the river.

The attack was delivered in a thick fog, on the 13th, when St. Pierre-Divion

and Beaumont-Hamel fell; the same evening Beaucourt village

was encircled, to be captured on the morrow. On the following days, the

assailants successfully resisted numerous counter-attacks. From the 13th

to the 19th, 7,000 prisoners were taken, and the whole of Thiepval Plateau

was captured.

[Pg 24]

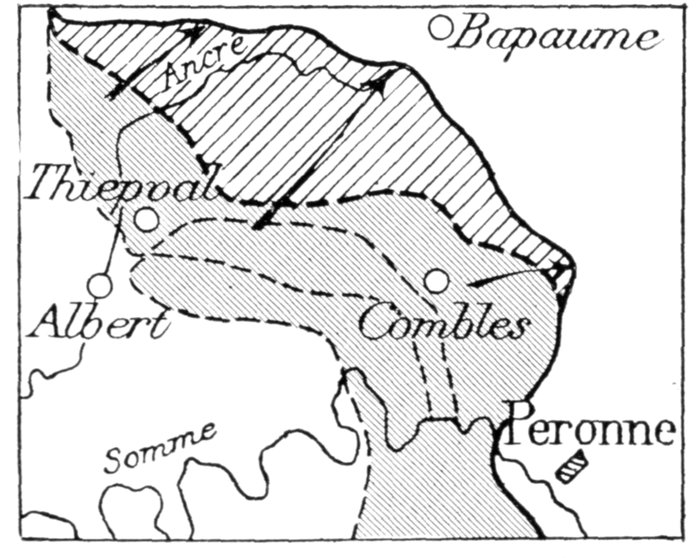

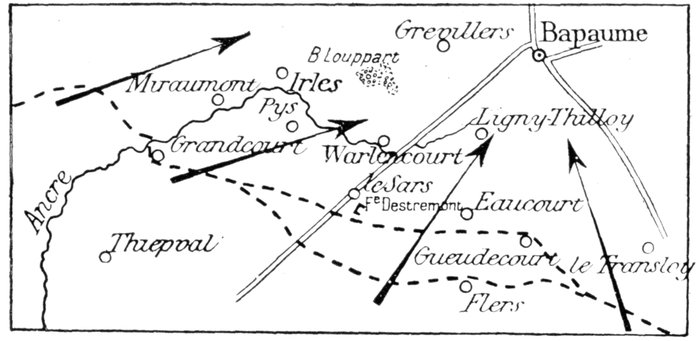

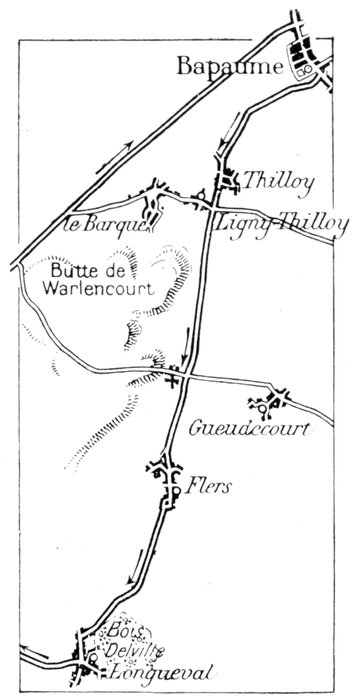

The Advance towards the Main Objectives (Bapaume—Péronne)

Towards Bapaume.—The British advance on the two wings—Thiepval

to the west and Gueudecourt to the east—forced the German centre

back on the Le Sars-Eaucourt line. Continuing to press the enemy, the

British carried Destremont Farm, in front of Le Sars, on September 29,

while on October 3, the village of Eaucourt-l'Abbaye was taken. On the

7th, a further advance was made along the spur which forms a salient in

front of Le Transloy village, and Le Sars village was carried the same day.

A single line of heights only now separated the British Army from

Bapaume, 6 km. distant from Le Sars. This line consisted chiefly of Warlencourt

Ridge, which dominates the country all round, and which had been

turned by the Germans into an apparently impregnable fortress.

Although the bad weather and the mud now forced the Allies to suspend

their offensive, sharp fighting continued. From December to the end of

January the British raided the enemy's trenches unceasingly.

After that, operations were resumed to reduce the Ancre salient completely.

The improvement, realised since the previous summer, in their offensive

strength, at once became apparent. Their artillery, reinforced, thoroughly

"pounded" the whole terrain, making it possible for the infantry to force a

way through all obstacles, and to advance continuously.

Advancing over the tops of the hills, which border the Upper Ancre, the

British directed their efforts alternately against both banks of the river,

and soon rendered untenable those positions still held by the Germans at

the bottom of the valleys. On February 7, 1917, Grandcourt was captured,

while the week following, Miraumont, Pys, Warlencourt with its famous Ridge,

and Ligny-Thilloy (within 3 km. of Bapaume) were surrounded.

The Germans now fell back on a new line of defences close to the town,

and by strong counter-attacks sought to stay the British advance. Their

efforts were in vain, however, and the British hemmed them in more closely

each day. Irles was occupied on March 10; Louppart Wood and Grévillers

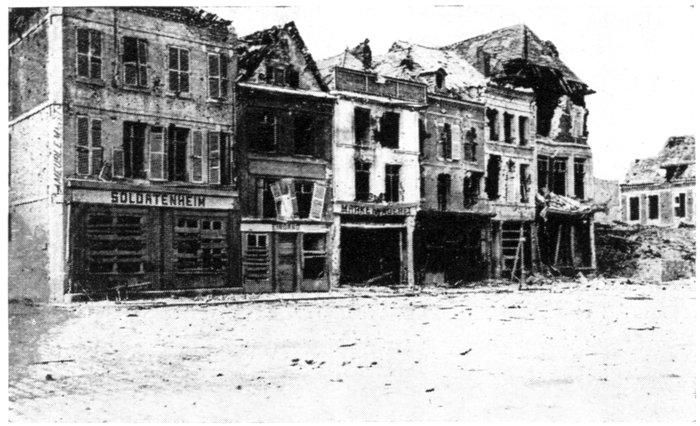

on the 13th. On the 14th, the British were at the gates of Bapaume, which

they entered three days later (the 17th), only to find that the town had been

burnt and methodically destroyed by the Germans.

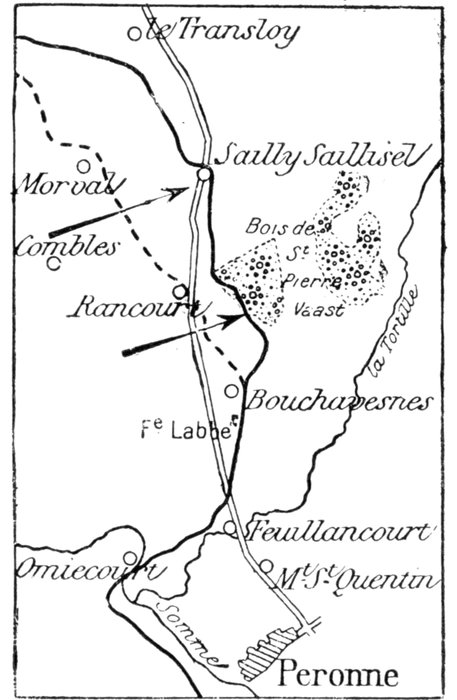

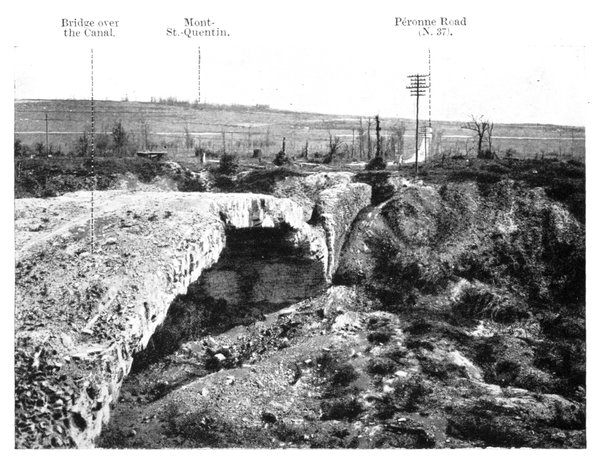

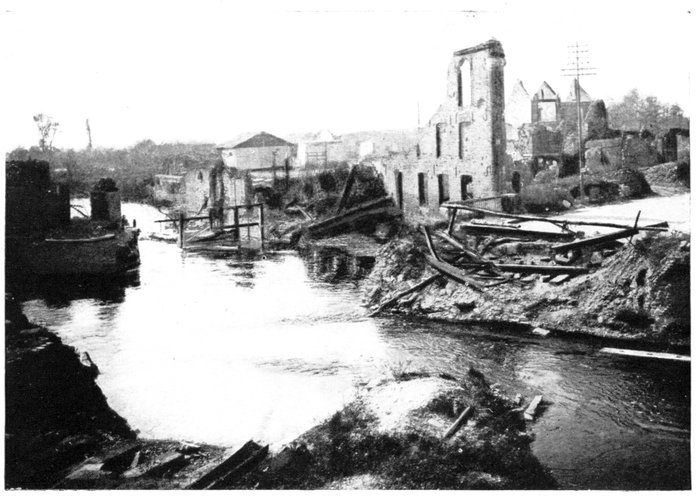

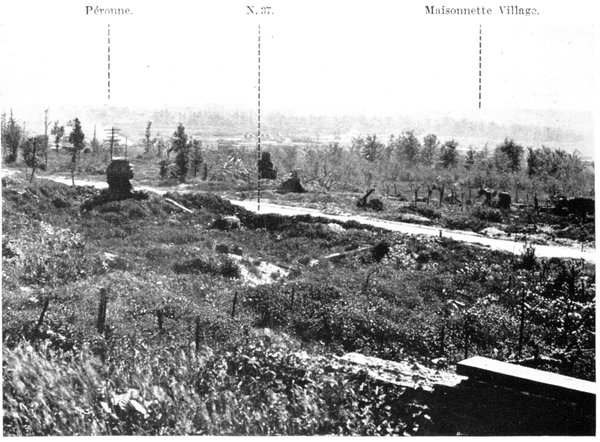

Towards Péronne.—On October 1, the French lines, in liaison with those

of the British south of Morval, took in Rancourt, Bouchavesnes and Labbé

Farm, passed in front of Feuillancourt and reached the Somme at Omiécourt.

[Pg 25]

After a halt, devoted to the consolidation of the ground, the French

resumed their advance, in spite of the bad weather. The objective was

now to widen the positions beyond the Bapaume-Péronne road, in order

to turn the town from the north, as the marshes of the Somme and the defences

of Mont-Saint-Quentin did not permit a frontal attack.

On October 7, the road was occupied from Rancourt to within about

200 yards of the first houses of Sailly-Saillisel, and the western and south-western

outskirts of Saint-Pierre-Vaast Wood were reached. During the

following weeks the fighting, which was furious, concentrated around Sailly-Saillisel.

On October 18, Sailly was carried, but Saillisel held out until the

beginning of November. Meanwhile, the French made several unsuccessful

attempts to carry the defence-works of Saint-Pierre-Vaast Wood, and finally

remained hanging on to the western outskirts, in close contact with the enemy.

At the end of 1916, the front line in this sector extended from the northern

outskirts of Sailly-Saillisel, along the western edges of Saint-Pierre-Vaast

Wood, then took in Bouchavesnes and crossed the Somme near Omiécourt.

The winter passed quietly, except in the region of Sailly-Saillisel and Saint-Pierre-Vaast

Wood, where skirmishing and grenade fighting were incessant.

The British took possession of the sector and fortified it strongly, raiding from

time to time the enemy trenches.

In March, 1917, the artillery duel increased in intensity, and the Germans

prepared to evacuate their positions.

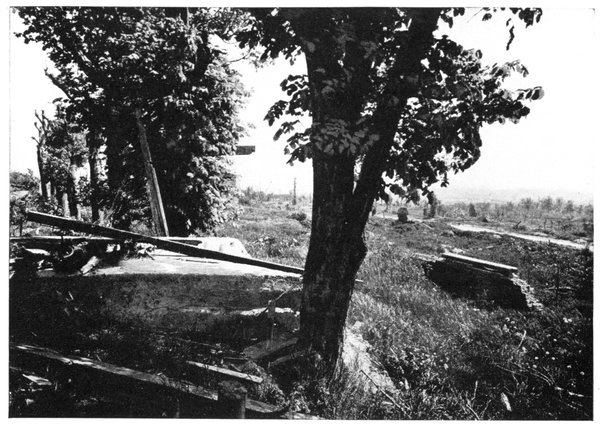

Their retreat began on March 15, after the country had been methodically

devastated. The British occupied the whole wood of Saint-Pierre-Vaast

on the 15th and 16th, almost without striking a blow. On the 17th, they held

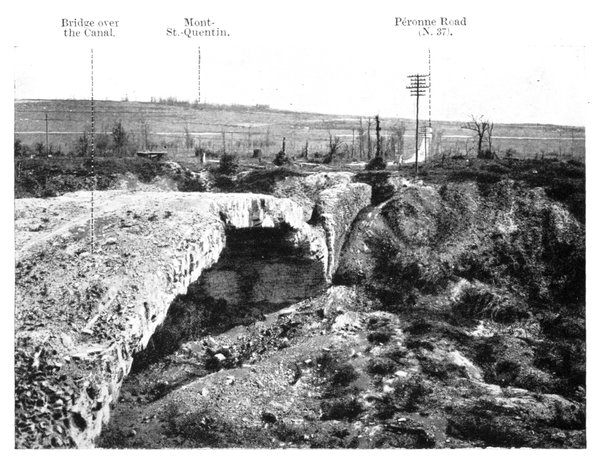

the Mont-Saint-Quentin—powerful advance fortress of Péronne. On the

18th, they finally entered the town from the north, while other detachments

reached it from the south-east, across the marshes of the Somme.

[Pg 26]

PRESIDENT POINCARÉ HANDING THE "COMMANDEUR DE LA LÉGION

D'HONNEUR" INSIGNIA TO GENERAL MICHELER.

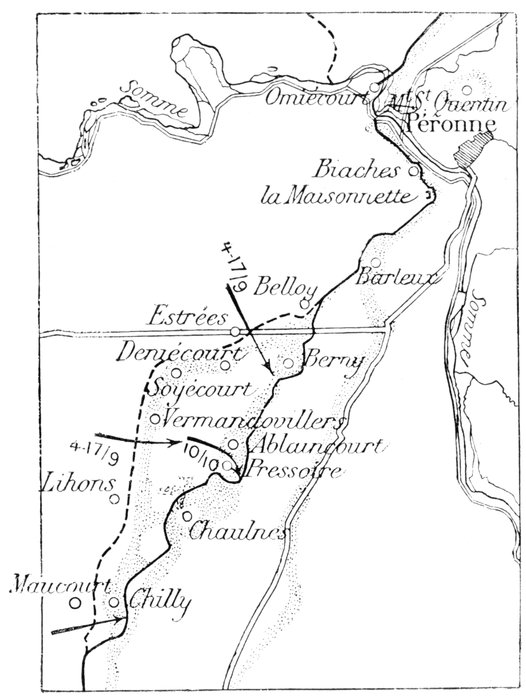

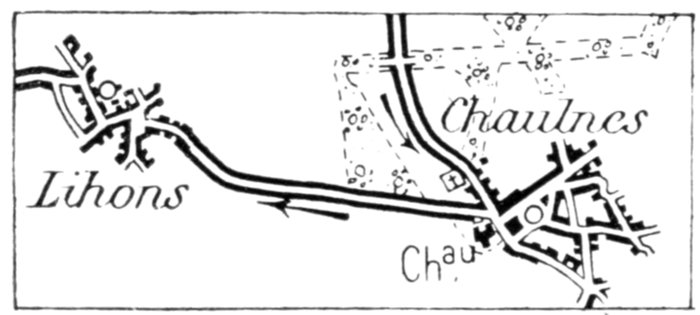

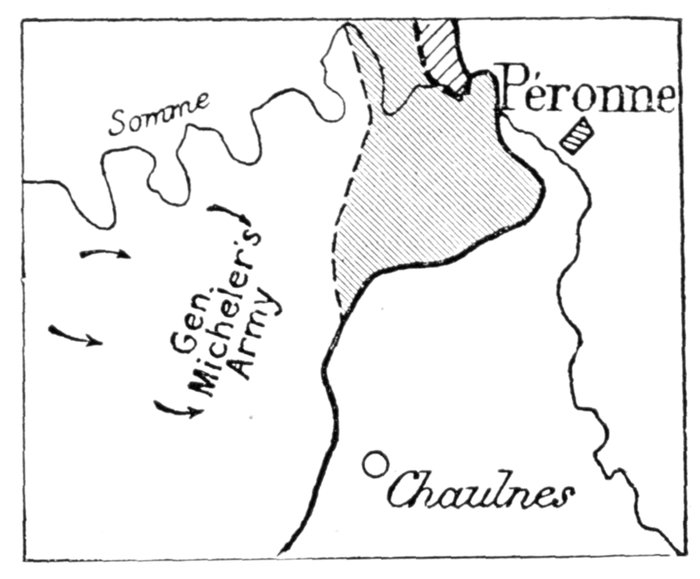

The Battle of Attrition, South of the Somme

In the early days of July, in the diversion section south of the Somme,

the French 1st Colonial Corps, having carried the three German positions,

faced south-east.

The French lines, resting on the western outskirts of Omiécourt, followed

the Somme Canal, encircled Biaches and La Maisonnette, turned south-west,

and passed in front of Barleux village, which, hidden in a depression of the

ground, had till then successfully resisted all assaults. The lines ran towards

Soyécourt (still held by the enemy), then southwards via Lihons and Maucourt.

From La Maisonnette to Maucourt, they formed the sides of an enormous

obtuse angle, the apex of which was Soyécourt.

The objective of the French 10th Army (General Micheler), disposed along

the sides of this angle, was to widen the latter by means of continued thrusts

in the direction of the southern end of the bend in the Somme. Its advance

being then stayed by the important stronghold of Chaulnes, the latter was to

be half-encircled, thereby seriously threatening the rear of the German

positions south of the town.

The French offensive was launched on September 4. The outskirts of

Deniécourt and Berny were reached in the first rush; in the centre, Soyécourt

was carried; on the left, Vermandovillers was partly captured and Chilly

passed by about half a mile.

On the 5th, the Germans counter-attacked unsuccessfully, and failed to

stay the French advance. On the 6th, half the village of Berny was taken.

In three days, 6,650 prisoners and 36 guns, including 28 heavies, were captured.

A fresh offensive was combined, with the attack of the 12th by the Franco-British

troops north of the Somme, and that of the 15th by the British troops

operating beyond Combles.

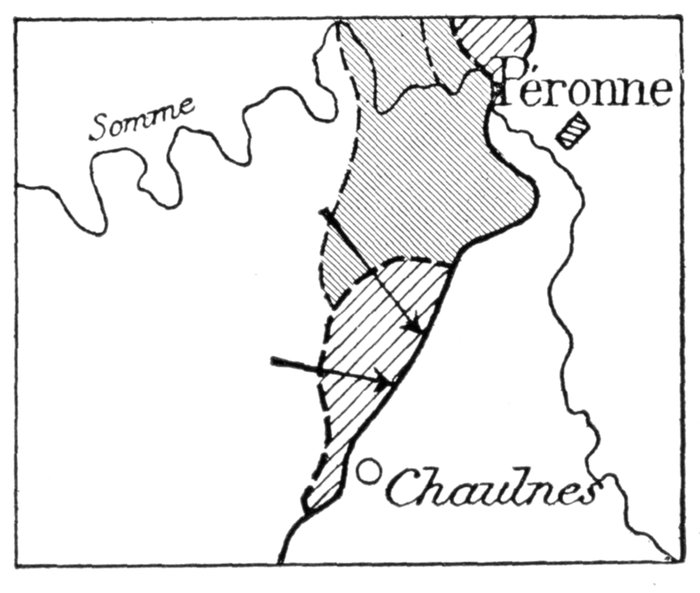

[Pg 27]

On the 17th, the conquest of Vermandovillers and Berny was completed,

and on the 18th, the village of Deniécourt was encircled and captured.

On October 10th, the offensive was resumed after a heavy bombardment

between Berny and Chaulnes. The hamlet of Bovent, north of Ablaincourt,

was conquered, together with the western edge of Chaulnes Wood. Parts of

these woods were captured in October, and at the beginning of November.

The villages of Ablaincourt and Pressoire were also occupied.

Thanks to this slow but continuous advance, and to the capture of these

various villages, the fortress of Chaulnes was outflanked and half-encircled.

However, the Germans managed to maintain themselves there, and the

French progress was held in this sector, as it had been further north, by the

stronghold of Barleux and the marshes of the Somme.

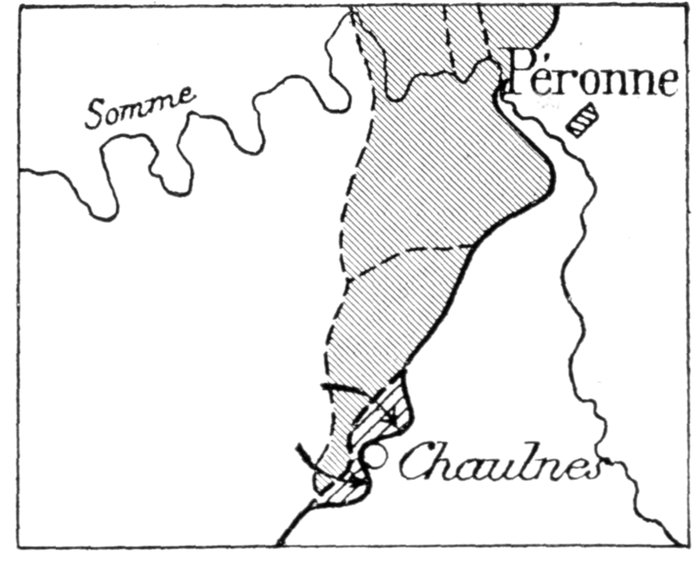

At the end of 1916, the front line of the sector south of the Somme started

from Omiécourt, left Barleux in German hands, and crossed the Maisonnette

Plateau. From there, it described a large circle via Berny (French) and

Chaulnes (German), skirting Roye and Lassigny (see sketch map, p. 29).

[Pg 28]

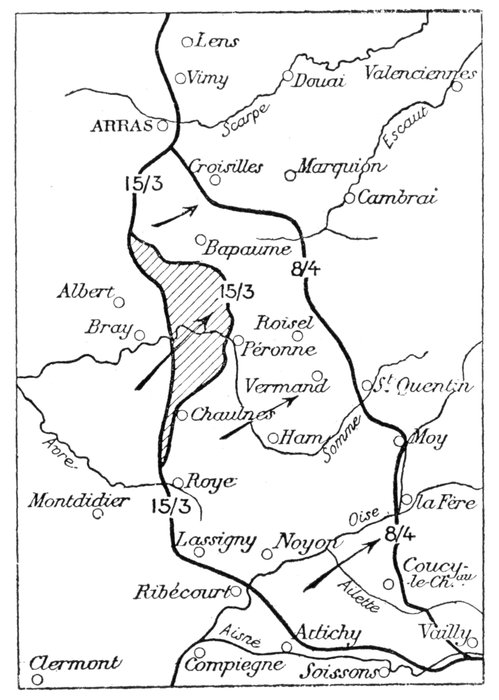

The German Retreat of March, 1917

Although the Somme offensive did not give immediate strategical results,

it nevertheless procured the Allies tactical advantages which were one of

the causes of the German retreat of March, 1917.

The capture of important points of support made the position of the

Germans a very precarious one, at all the points where they had so far succeeded

in maintaining themselves. They feared that if in 1917 the Allies

resumed their offensive—which the experience acquired in 1916 would render

still more formidable—further retreat, resulting in the piercing of their front

line, might become necessary. They consequently decided voluntarily to

shorten their lines by falling back on new positions in the rear, known as

the "Hindenburg Line" (see the Michelin Guide: "The Hindenburg

Line").

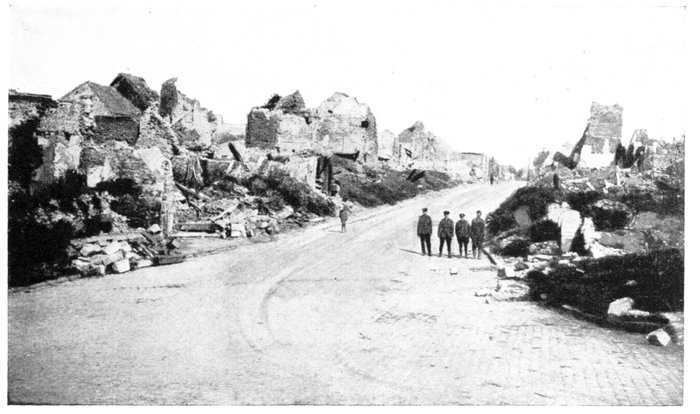

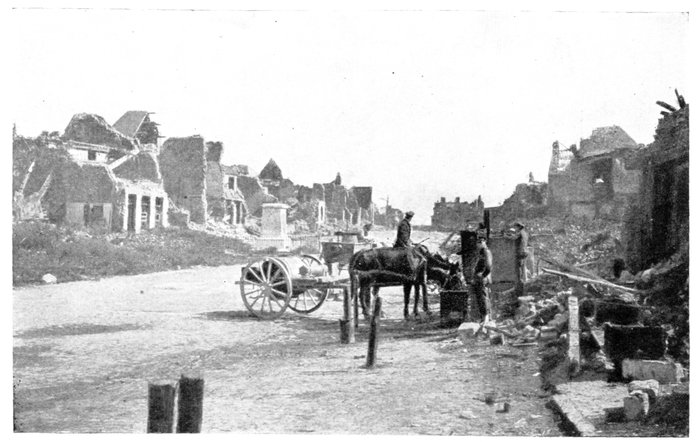

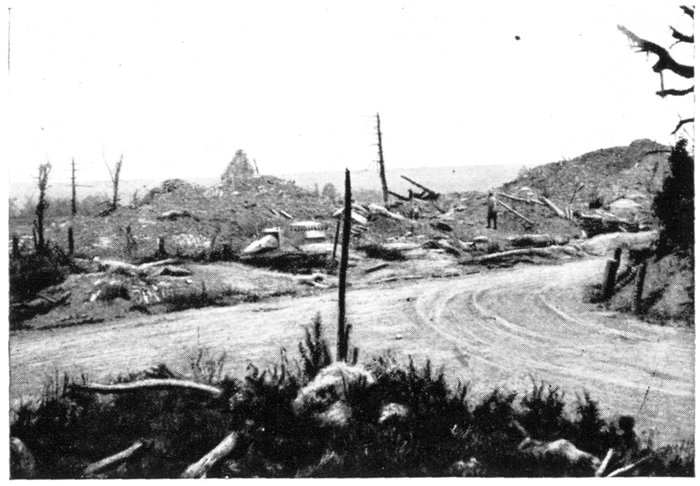

THE BAND OF THE AUSTRALIAN 5TH BRIGADE PASSING THROUGH

THE SMOKING RUINS OF BAPAUME ON MARCH 19, 1917, WHILE

THE BATTLE STILL RAGED NEAR BY, ON THE LINE BECQUINCOURT—NOVAINS.

The formation of a new defensive front was only possible by evacuating

a large area, and the German retreat extended to the whole of the region

comprised between Arras and Soissons. It was very skilfully carried out,

unhampered by the Allies, who contented themselves with following close

behind the retreating enemy.

On March 15 and 16, 1917, the French, informed by their Air Service of

the enemy's imminent retirement, made numerous raids into the German

trenches between the Oise and the Avre, advancing in places as much as

4 km. On the 17th, the cavalry, followed by the infantry, entered Lassigny

and Roye. Noyon was occupied early on the 18th.

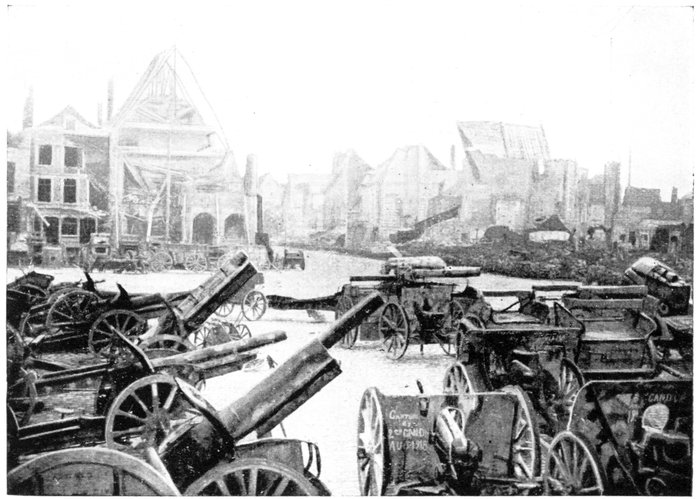

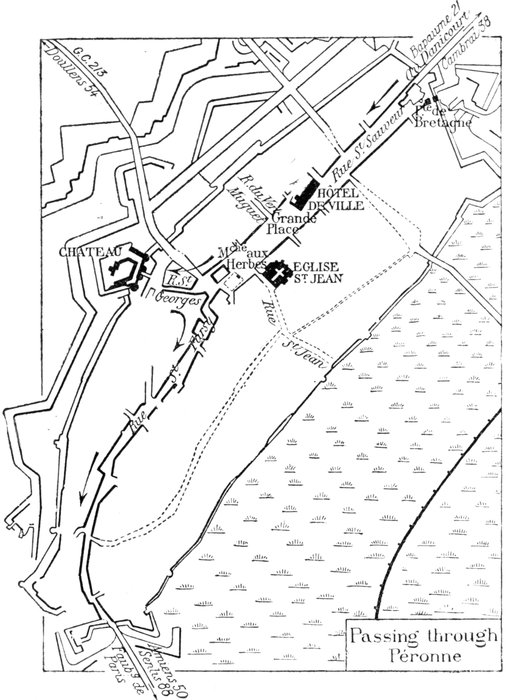

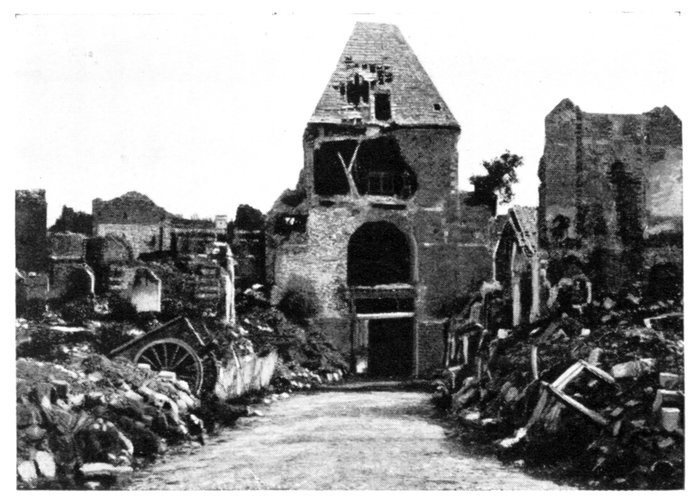

On the same day (March 17) the British, having relieved the French as

far as south of Chaulnes during the winter, captured La Maisonnette, Barleux,

Villers-Carbonnel and all the villages still occupied by the enemy within

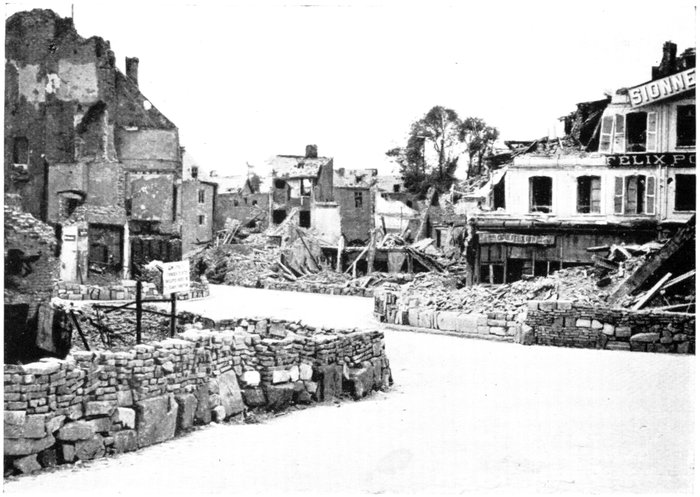

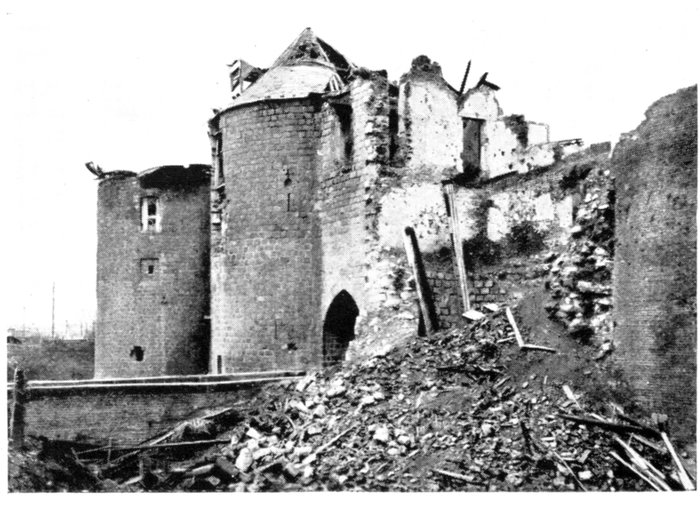

the loop of the Somme. On the 18th, they entered Péronne and Chaulnes.

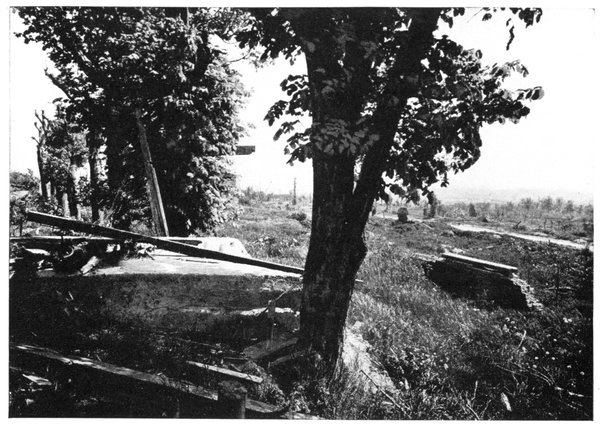

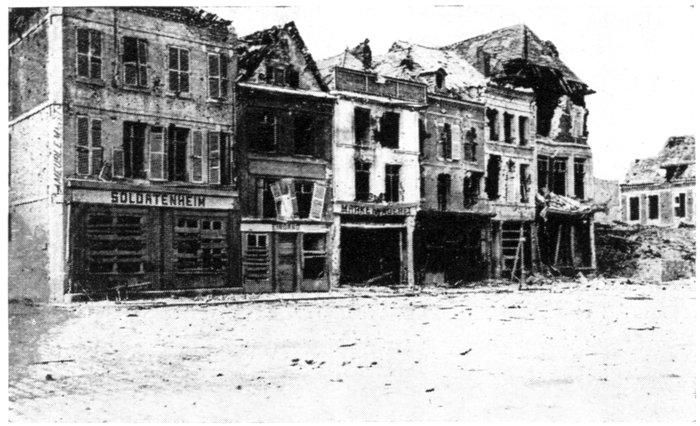

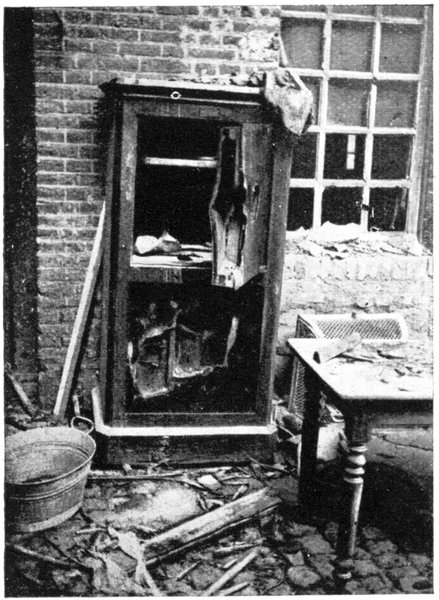

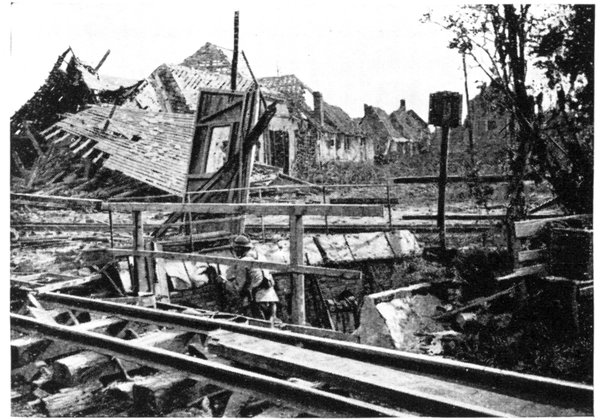

The whole region between the Somme and the Oise was liberated at that

time, after thirty months of German occupation, but only after it had been

systematically and totally devastated, according to elaborate plans drawn

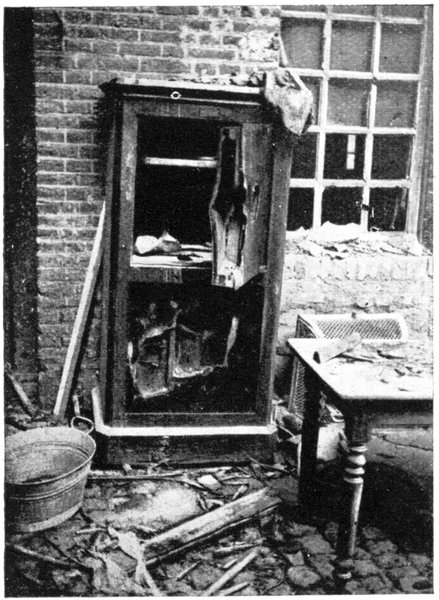

up beforehand. These destructions were absolutely unjustifiable from a[Pg 29]

military point of view. Towns and villages were wiped out, houses plundered,

industries ruined, factories destroyed, land devastated, agricultural

implements broken, farms burnt, trees cut down—in a word, everything

done to turn the place into "a desert incapable for a long time of producing

the things necessary to life" (Berliner Tagblatt).

It was from these new lines that in the spring of the following year the

Germans launched their great offensive, designed to separate the Allied

armies and resume their march "nach Paris."

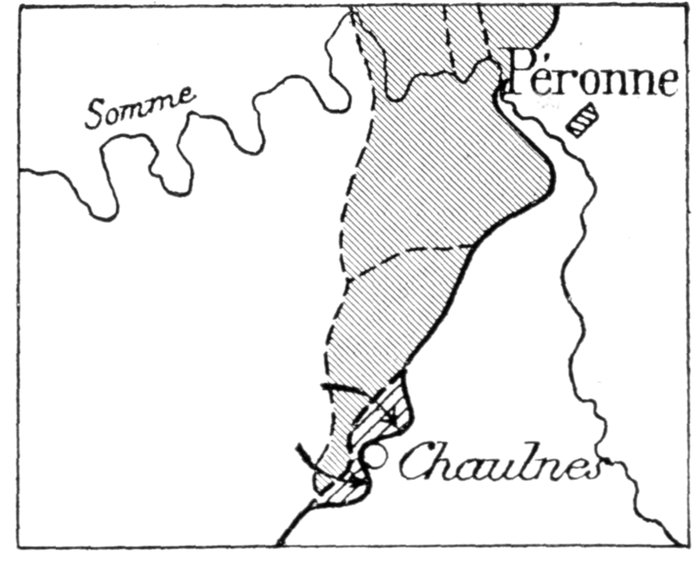

THE SHADED PORTION REPRESENTS THE GROUND

CONQUERED DURING THE 1916-1917

OFFENSIVE.

The German offensive

and the Allied counter-offensive

of 1918 are

dealt with in the Michelin

Guide: "The Second

Battle of the Somme

(1918)."

In addition to the

pushing back of the

enemy front, the Allies'

three immediate objectives

had been attained.

Verdun was soon relieved

of the German

pressure, as the enemy

"were exhausted and

compelled to use their

reserves for the Russian

front, and especially in

the Somme. Their

activities on the Verdun

front were limited to

making good their losses.

However, they were finally

obliged to weaken this

front to a point that they

were unable to reply to the

French attacks." (See the

Michelin Guide: "Verdun,

and the Battles for

its Possession.")

The Allies' further aim to keep the maximum of the German forces on

the western front was likewise attained. According to Field-Marshal Haig's

report, the transfer of enemy troops from west to east, begun after the

Russian offensive of June, lasted a very little time after the beginning of

the Somme offensive. Afterwards, with one exception, the enemy only

sent exhausted battle-worn divisions to the eastern front, which were always

replaced by fresh divisions. In November, the number of enemy divisions

present on the western front was greater than in July, in spite of the abandonment

of the offensive against Verdun.

[Pg 30]

As regards the wearing down of the enemy's fighting strength, their losses

in men and material were much heavier than those of the Allies.

Half the German forces in France came out of the battle physically and

morally worn.

From July 1 to December 1, the enemy had more than 700,000 men put

out of action (killed, wounded or prisoners). More than 300 guns were

captured and many others destroyed.

The German nation, badly shaken by the violence and duration of the

battle, alarmed at the events on the eastern front, and cruelty disappointed

by their failure before Verdun, were on the point of suing for peace at the

end of the Battles of the Somme.

On the other hand, the British had gained full consciousness of their

strength, and had fought in closer union with their French comrades.

The Allies of all ranks had learned to know and appreciate one another

better, and future operations were destined to become more closely

co-ordinated. "To fight under such conditions unity of command is

generally essential, but in this case, the cordial good feeling of the Allied

Armies, and their sincere desire to help one another, served the same purpose

and removed all difficulties" (Field-Marshal Haig).

Among the French, the veterans and young classes vied with one another

in heroism. Many "bleuets" (twenty-year old youths) were under fire for

the first time. In contact with their seasoned Verdun comrades, they fought

with splendid dash. After scaling the craggy slopes east of Curlu village,

many of them waved their handkerchiefs to cries of "Vive la France!"

Up to the middle in the foul Somme mud, which at times forced the men

out of the trenches into the open, in spite of the shells and bullets, the Allied

troops acquired the morale of Victory, while the High Command gained and

kept the initiative.

GERMAN TANK CAPTURED BY THE NEW ZEALANDERS

DURING THE ALLIED OFFENSIVE OF 1918.

Extracted from the Michelin Guide "The Second Battle of the Somme (1918)"

[Pg 31]

A VISIT TO THE SOMME BATTLEFIELDS.

FIRST DAY.

AMIENS-ALBERT-THIEPVAL-BAPAUME.

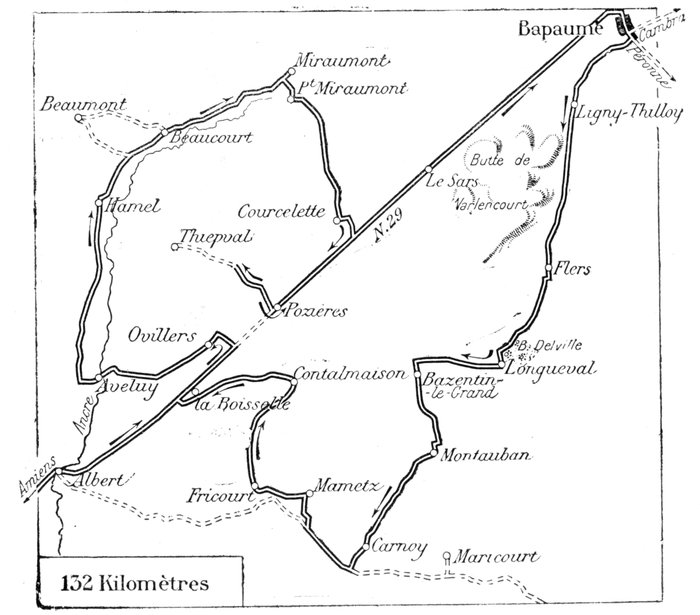

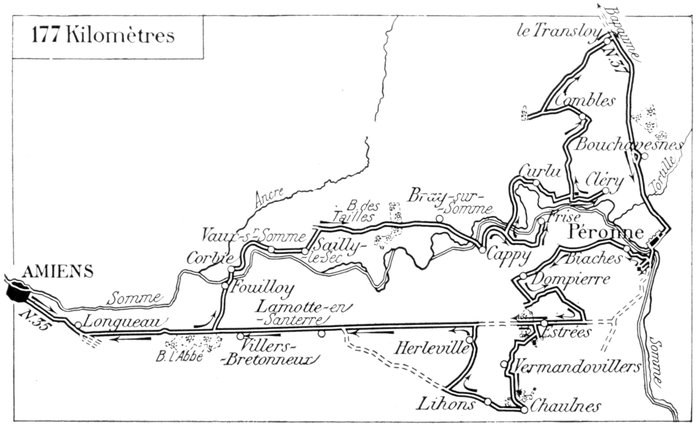

ITINERARY FOR THE FIRST DAY.

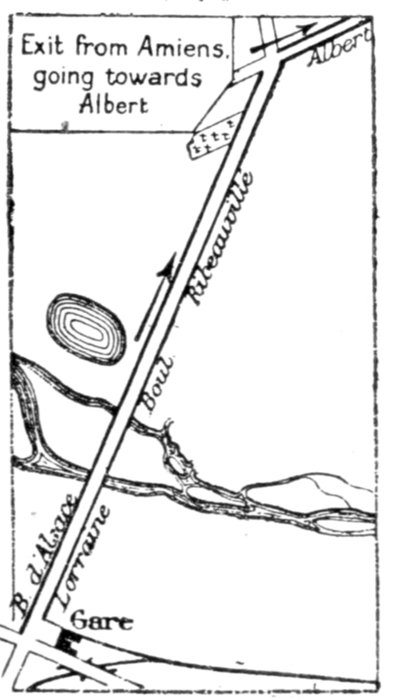

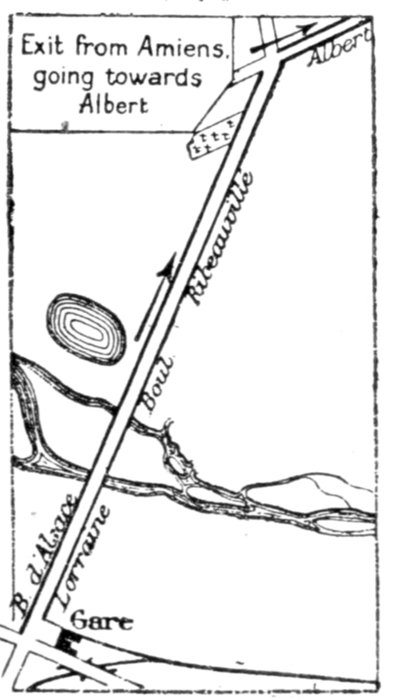

Exit from Amiens

going towards

Albert

Leave Amiens by the Boulevard d'Alsace-Lorraine, in

front of the station, on the left. Beyond the cemetery, take

N. 29 to Albert, on the right.

Eleven kilometres beyond Amiens, Pont-Noyelles is

passed through. This village was made famous by the sanguinary,

indecisive battle fought there on December 23,

1870, between the French and Germans. To the left of

the road, just outside the village, a monument commemorates

the battle.

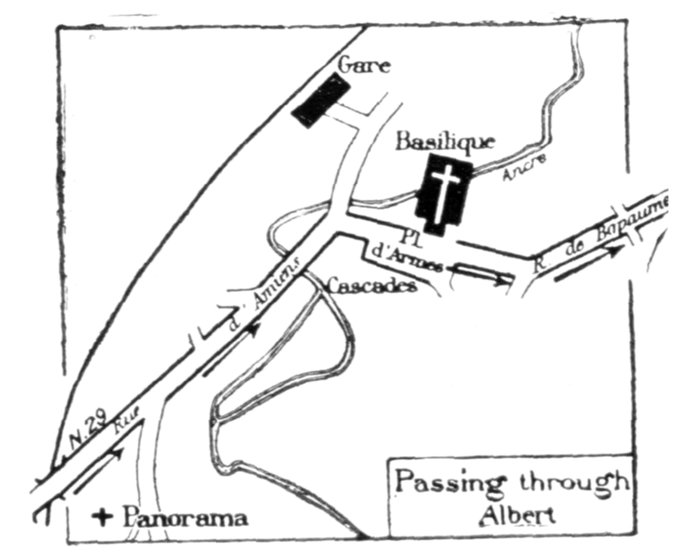

Twenty-eight kilometres beyond Amiens, N. 29 enters

Albert.[Pg 32]

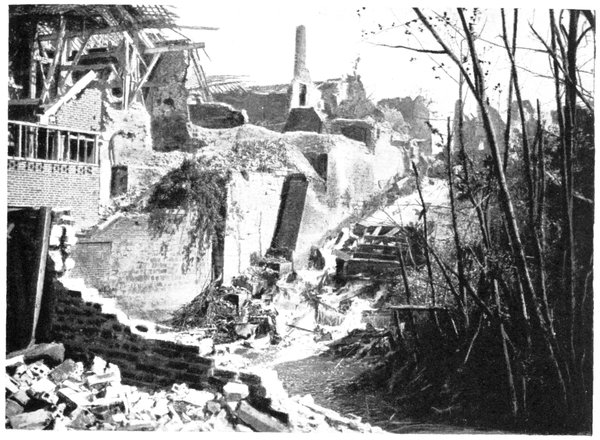

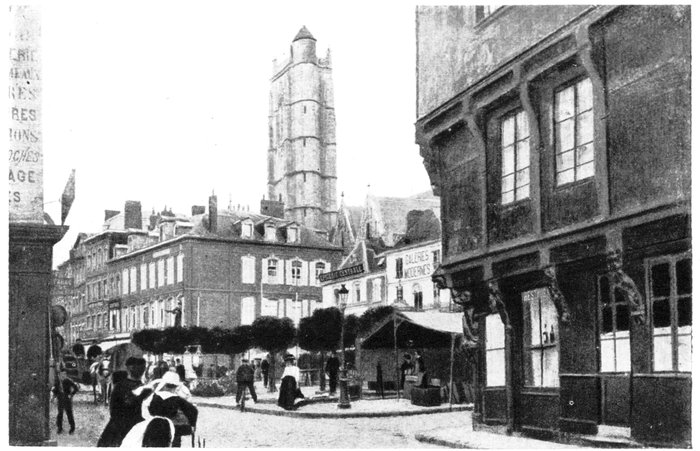

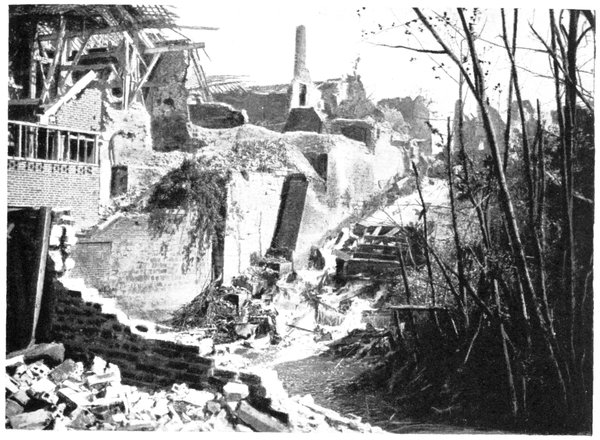

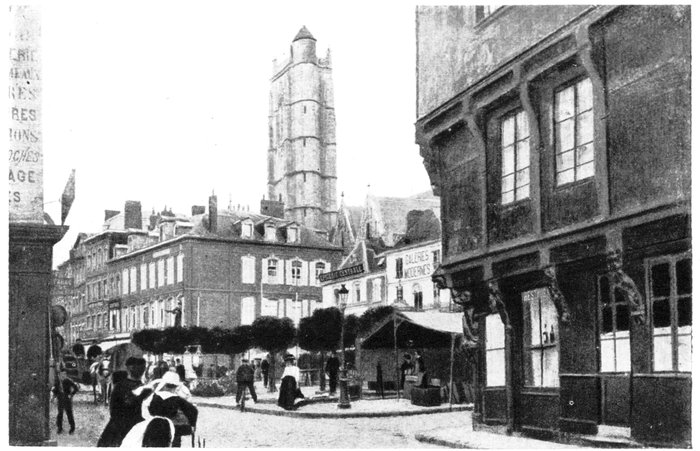

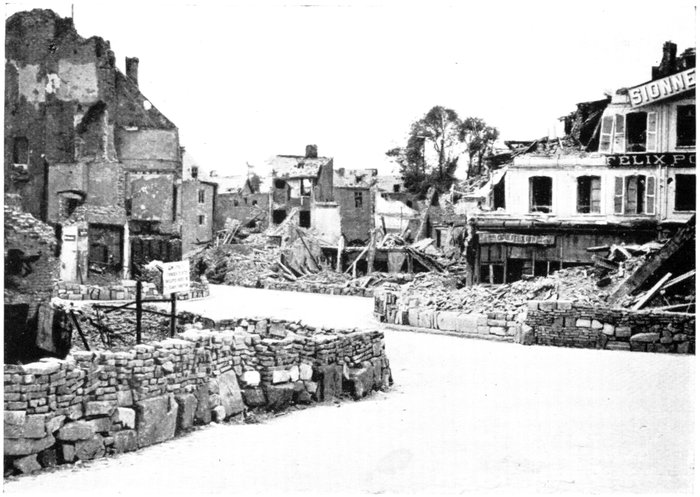

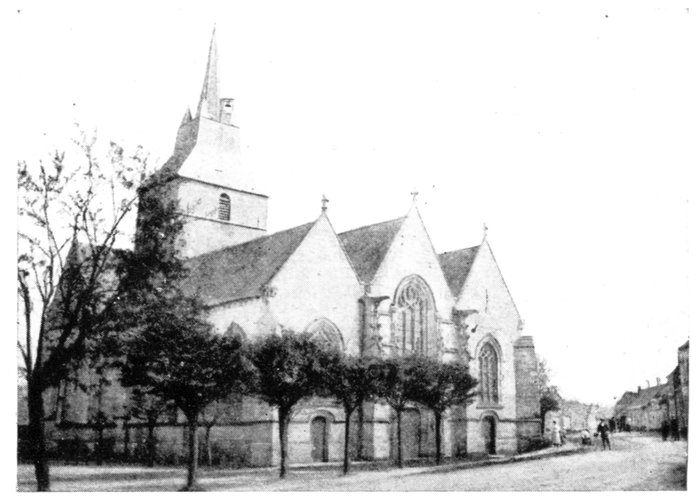

ALBERT.

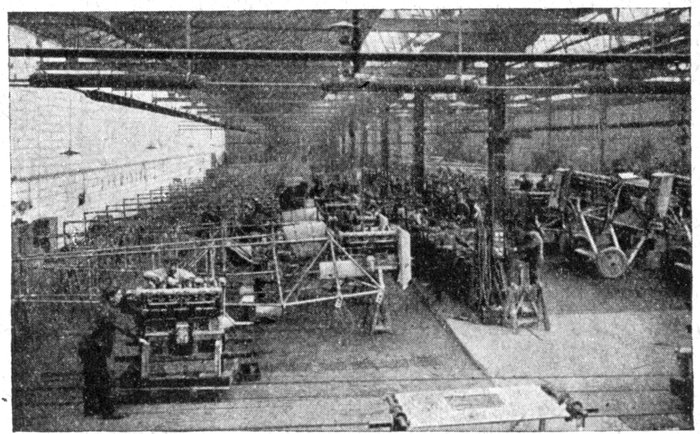

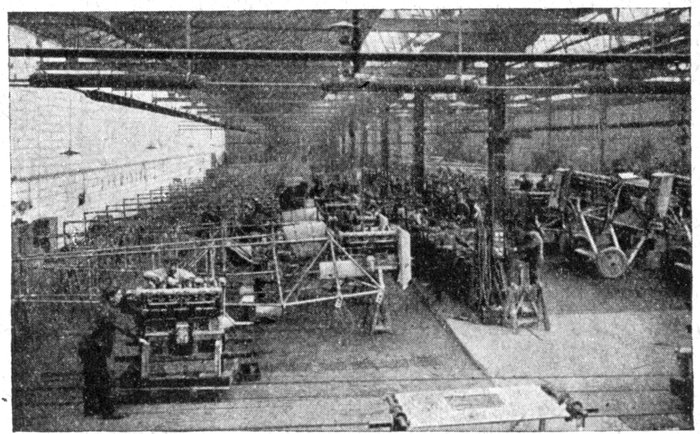

The prosperous, industrial town of Albert, whose population before the

war numbered more than 7,000 inhabitants, is to-day entirely in ruins.

Lying at the foot of a hill, on both sides of the River Ancre, Albert

formerly went by the name of Ancre.

At the beginning of the seventeenth century Albert belonged to Concini,

the favourite minister of Marie de Medicis, but after his downfall in 1619

it became the property of Charles d'Albert, Duke of Luynes, who gave it

his name.

Albert during the War

When, after the first Battle of the Marne,

the front advanced northwards, the Germans

tried on several occasions to break through

the French lines before Albert.

[Pg 33]

Fierce fighting took place in the immediate

vicinity of the town at the end of September,

1914, especially on the 29th, and in October and

November. The Germans were repulsed with heavy losses, but succeeded

in entrenching themselves strongly quite close to the city, and barred the

Albert-Bapaume road (N. 29) to the north-east, in front of La Boisselle

and the Albert-Péronne road, in front of Fricourt.

The shelling of the town began on September 29, 1914, and continued

unceasingly until it had been annihilated. The numerous iron and steel

works, mechanical workshops, sugar factories and brick-kilns, which had

contributed to the prosperity of the town, were specially singled out by the

enemy artillery. No public building, not excepting the civilian hospital,

was spared. In spite of the Red Cross flag which floated over the hospital,

the Germans, with the help of an aeroplane, directed a violent artillery fire

upon it on March 21, 1915, killing five aged inmates and wounding several

others, as well as the Superior.

In October, 1916, Albert was at last out of range of the German guns.

But in 1918 the British were unable to withstand the overwhelming

German thrust, except on the west of the town, and the latter fell into the

hands of the enemy on March 26, after desperate fighting. Albert remained

in the first enemy lines until August 22, when the British counter-offensive,

which was destined to clear the whole district—this time definitely—was

launched. The British entered the town in the early morning of August 22.

[Pg 34]

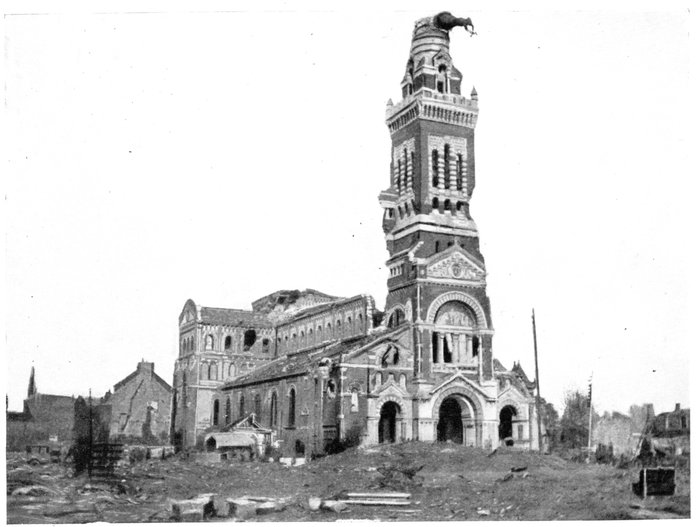

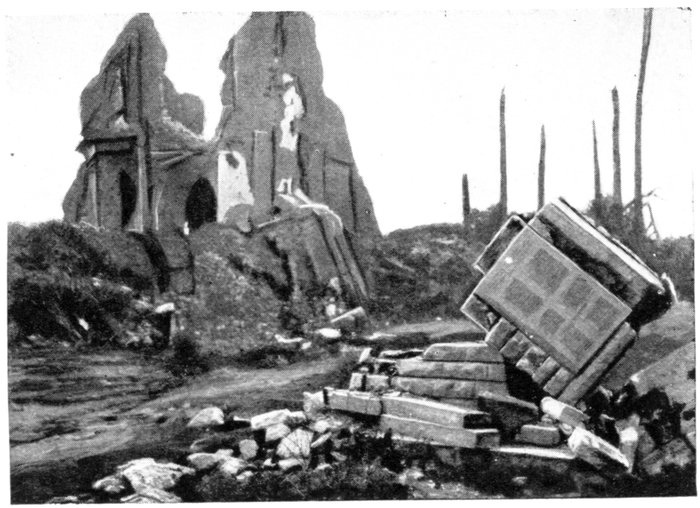

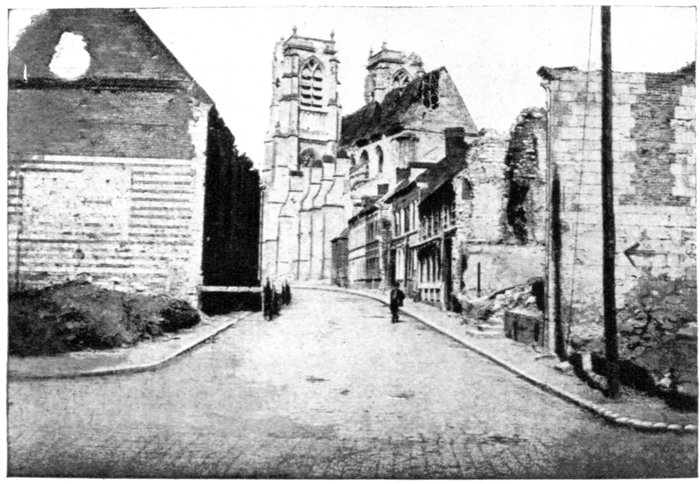

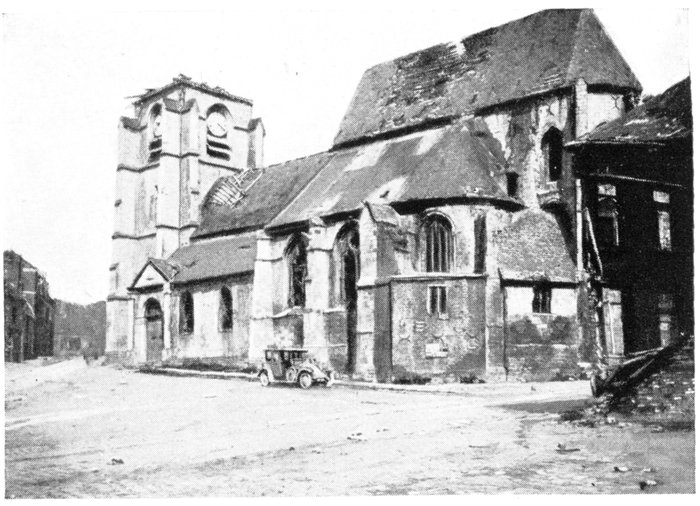

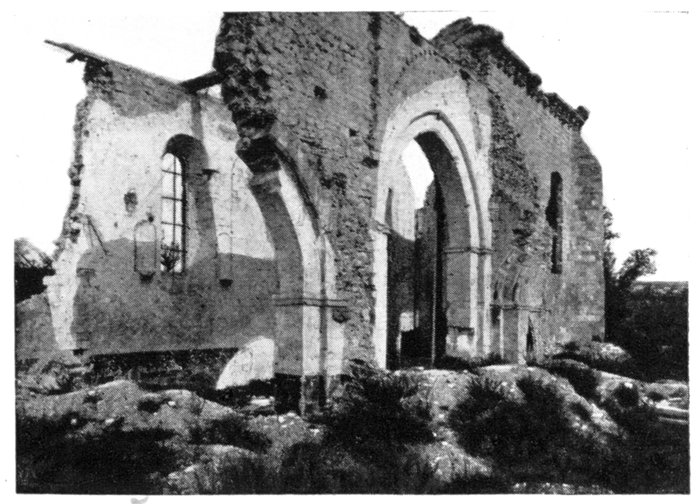

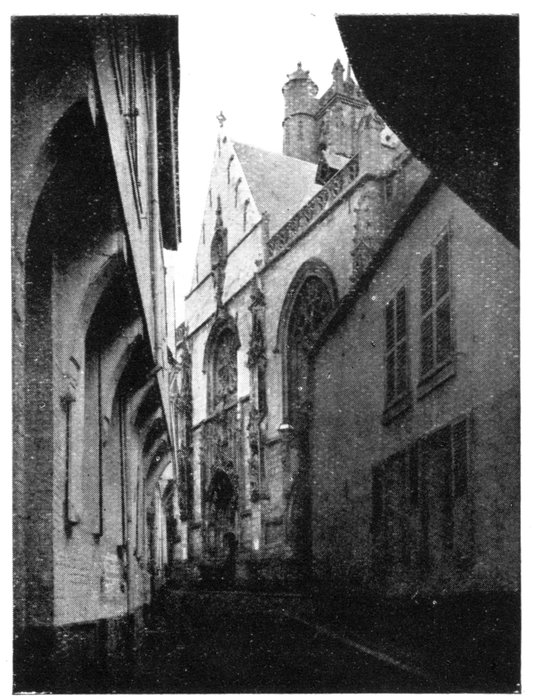

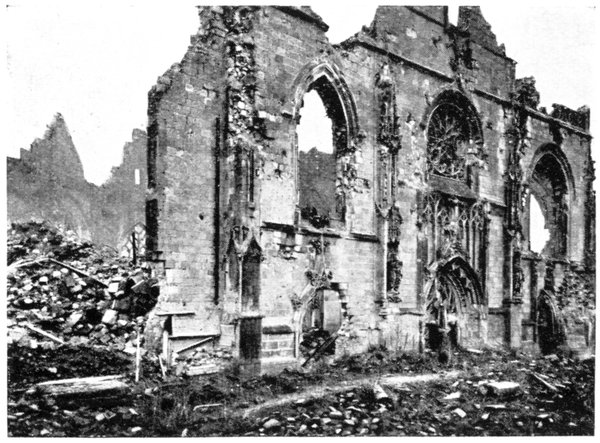

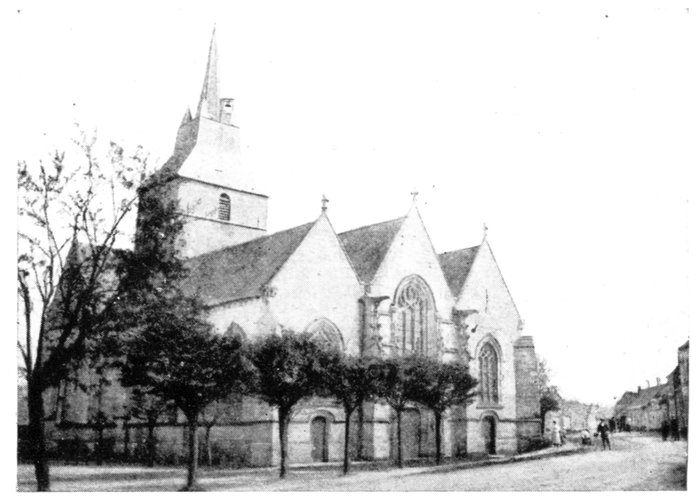

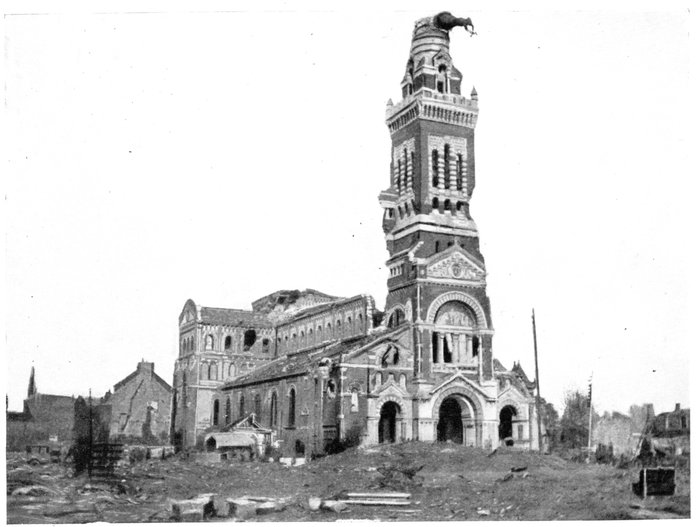

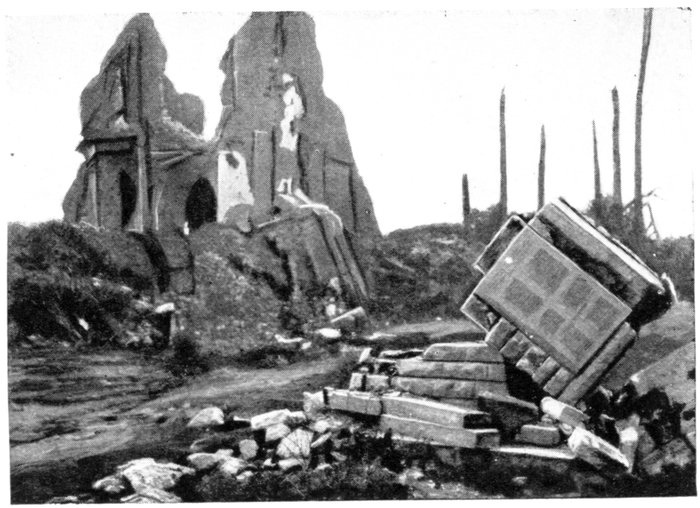

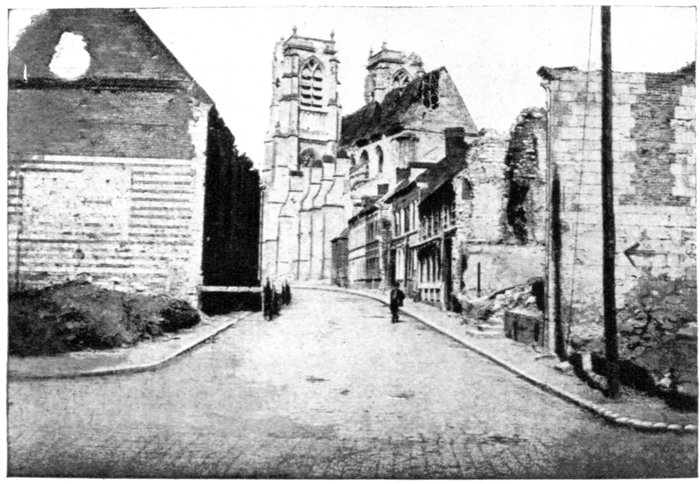

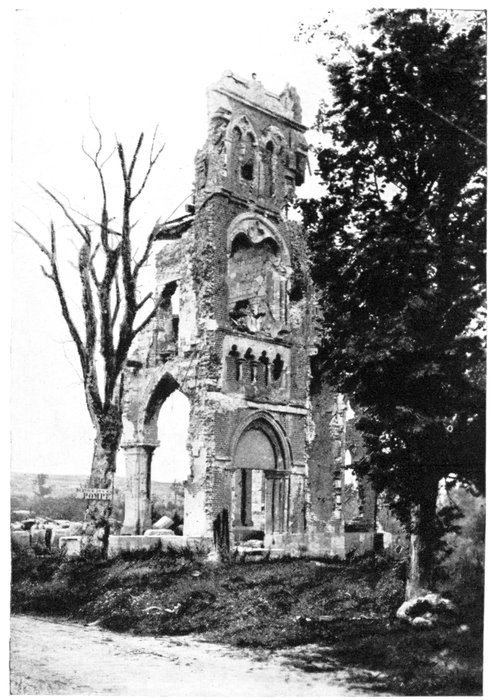

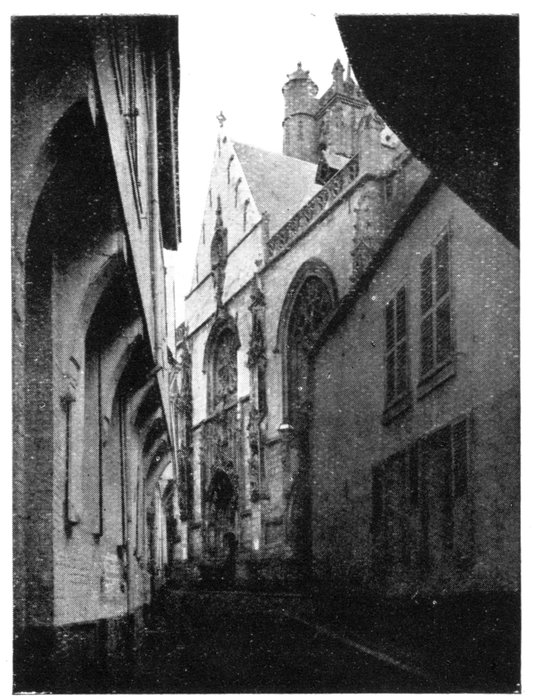

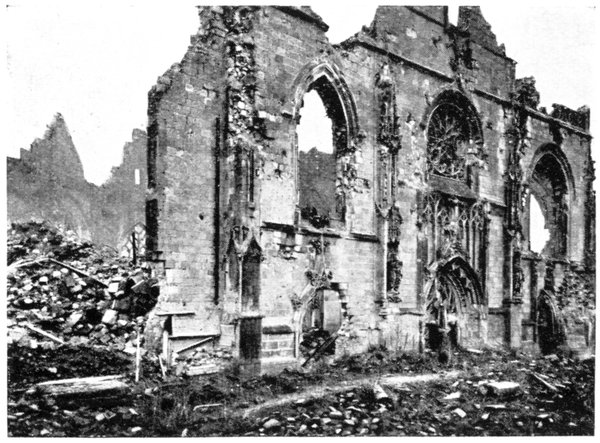

ALBERT CHURCH IN APRIL, 1917.

A Visit to the Ruins—The Basilica

Arriving by the Rue d'Amiens, tourists will see the cascade, on the right

behind a ruined factory.

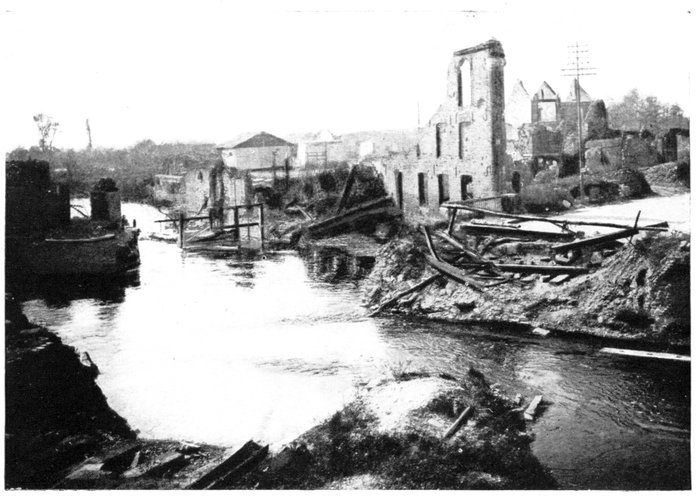

[Pg 35]

RUINED WORKS ON RIVER ANCRE, AND CASCADE.

Follow the Rue d'Amiens to the Place d'Armes, in which stand the ruins of

the Church of Nôtre-Dame-de-Brebière. Before the war as many as

80,000 people made pilgrimages to this basilica yearly, to see the ancient

statue of the Virgin, discovered in the neighbourhood by a shepherd, in the

Middle-Ages.

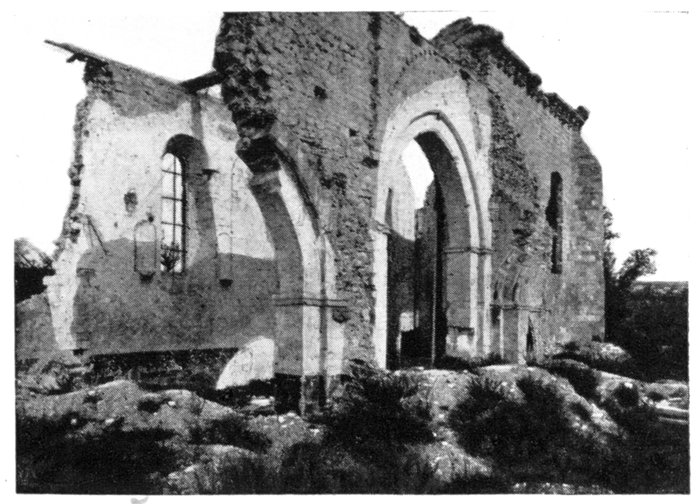

The church—a brick-and-stone construction in the Roman-Byzantine

style—was built at the end of the nineteenth century. The brick belfry,

over 200 feet high, was surmounted by a copper dome, on which stood a

gilt statue of the Virgin, sixteen feet high, with the infant Jesus in her outstretched

arms. The body of the church measured 276 feet in length and

68 feet in height, and was very richly decorated.

The church was spared by the first bombardments, on account of two

spies who, hidden in the top of the tower, made signals to the Germans, but

as soon as they had been discovered and shot, the church became a target

for the enemy artillery. The walls of the façade soon showed large gaps

in many places. The roof fell in and the belfry was badly damaged, especially

on the south side. A shell struck the top of the dome and burst against

the socle of the statue of the Virgin. The base gave way, but did not

entirely collapse, and the statue overturning remained suspended in mid-air

(photo, p. 34).

For several years the statue remained in this precarious position, and

there was a saying that "the war would end when the Virgin Statue of Albert

would fall."

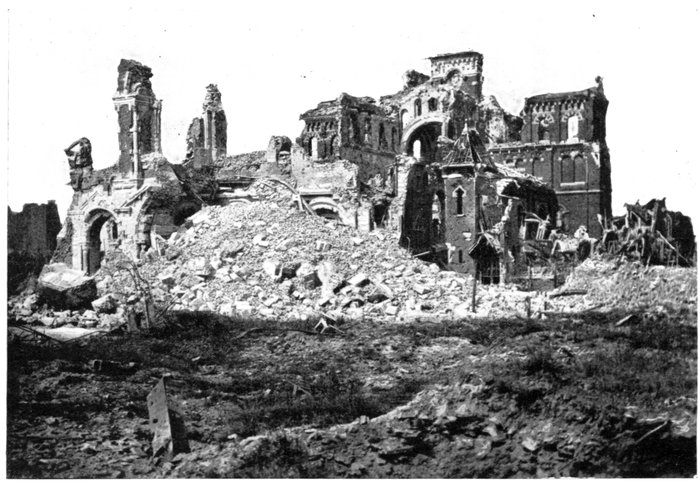

The bombardments in the spring of 1918 completed the ruin of the church.

Not only did the belfry collapse, carrying in its fall the statue of the Virgin,

but all the upper structure which had until then resisted, fell down, so that

to-day the immense building is a shapeless heap of stones, bricks and débris

of all kinds (photo, p. 34).

[Pg 36]

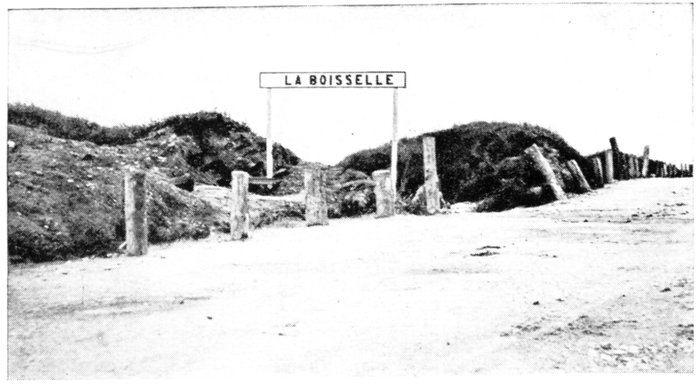

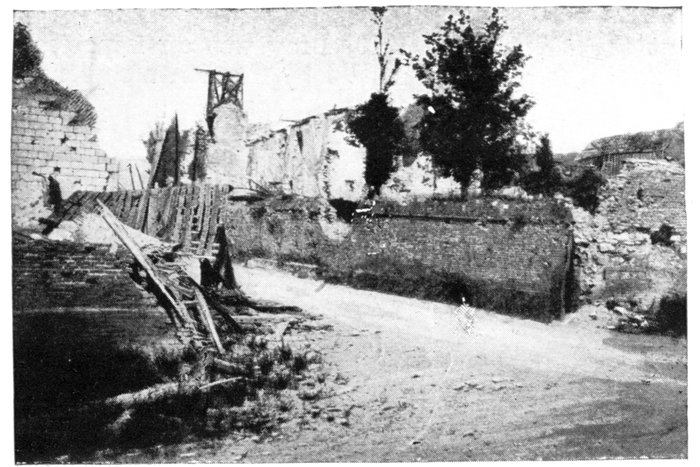

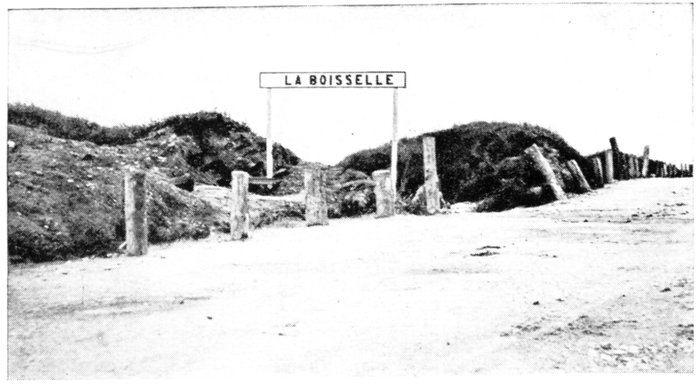

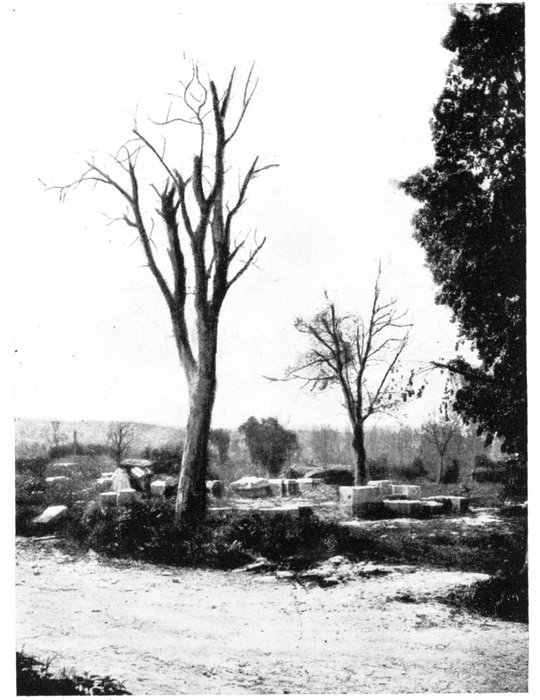

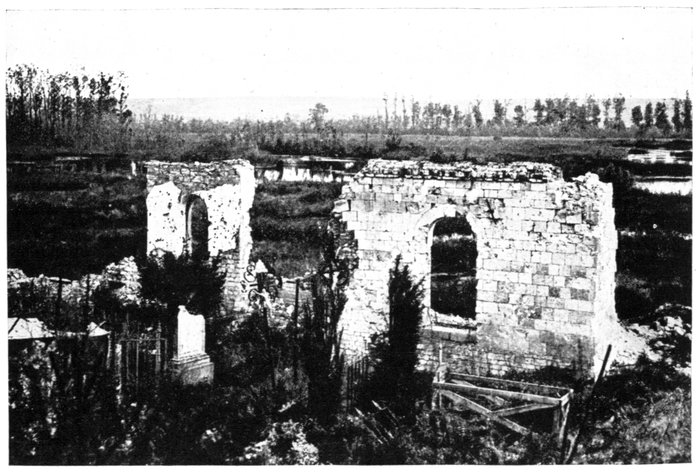

LA BOISSELLE. THE SIGN IS ALL THAT REMAINS OF

THE VILLAGE.

Leave Albert by the Rue de Bapaume, then take N. 29 which climbs La Boisselle

Hill. 2 km. beyond Albert there is a large cemetery on the right. The

site of Boisselle village (completely destroyed) is reached 2 km. further on.

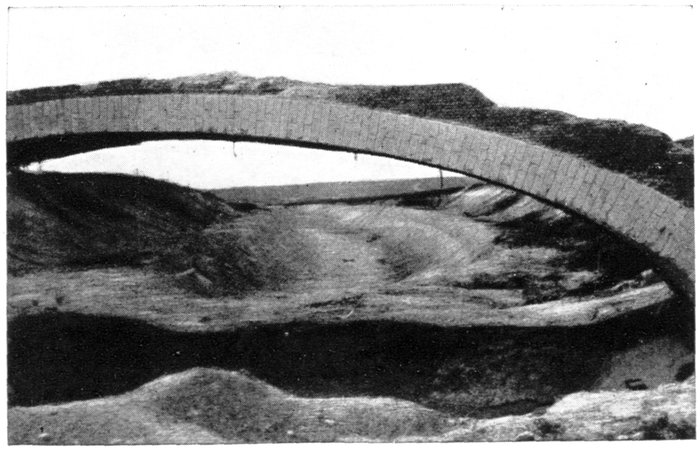

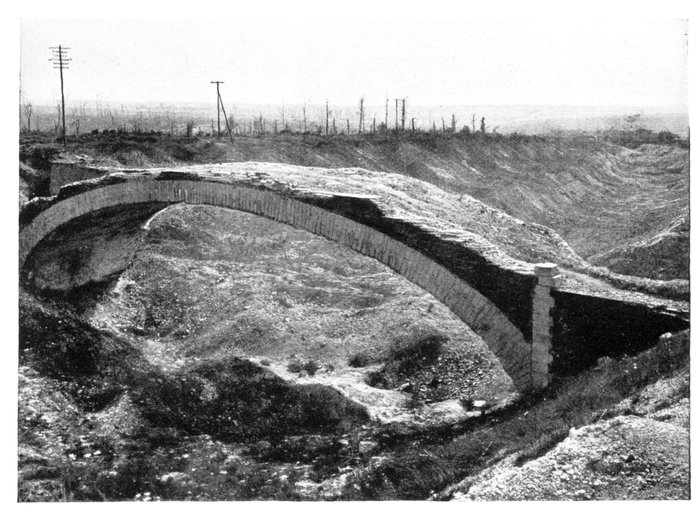

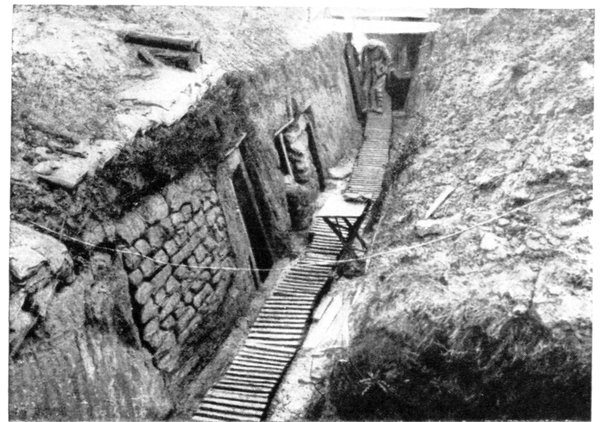

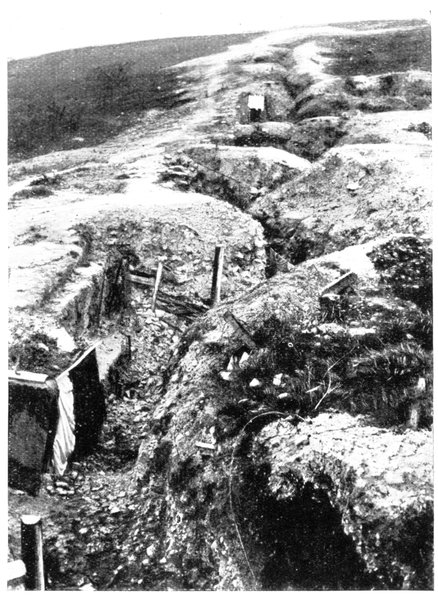

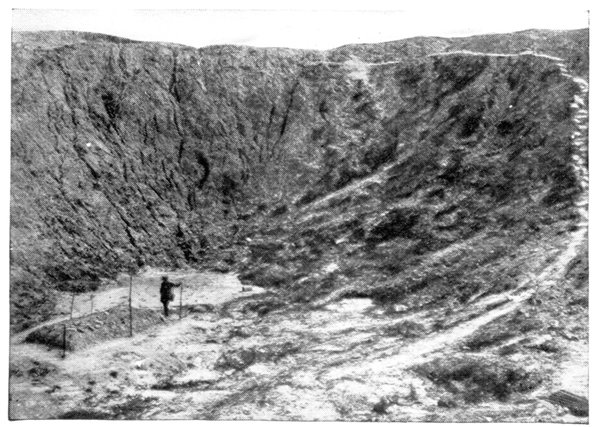

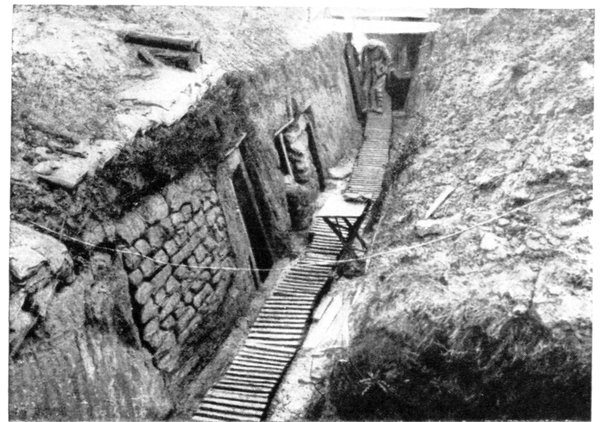

The Mine Warfare at La Boisselle

In October, 1914, the front line became fixed, west of this village. A

fierce trench-to-trench struggle continued throughout 1915, when it developed

into ceaseless, desperate mine warfare.

At the end of December, 1914, the French captured that part of La

Boisselle which lies south of the church. German counter-attacks, launched

almost daily, failed to drive them out. On January 17, 1915, after a violent

bombardment, the French were compelled to withdraw from that corner

of the hamlet, but the next day they succeeded in re-occupying the still

smoking ruins.

These attacks and counter-attacks had brought the German and French

trenches so close together that it became impossible to fight in the open.

The struggle was therefore continued underground. On both sides subterranean

galleries were bored under the opposing trenches, generally to a

depth of 20 to 26 feet. Mine-chambers, filled with cheddite, at the end of

the galleries, were fired electrically. In the ensuing upheaval the trenches

entirely disappeared, giving place to huge craters, for the possession of the

edges of which bitter hand-to-hand fighting followed.

BRITISH CEMETERY, BETWEEN ALBERT AND LA BOISSELLE,

ON THE RIGHT.

[Pg 37]

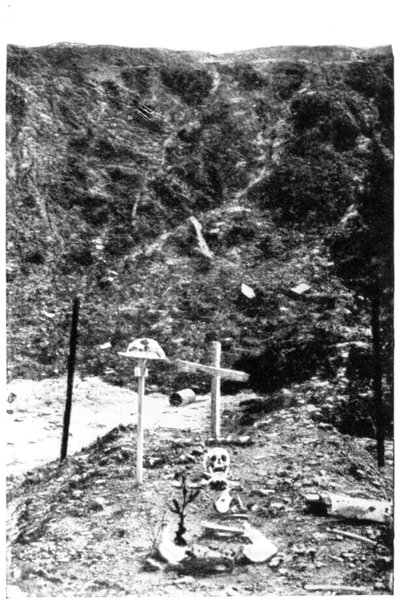

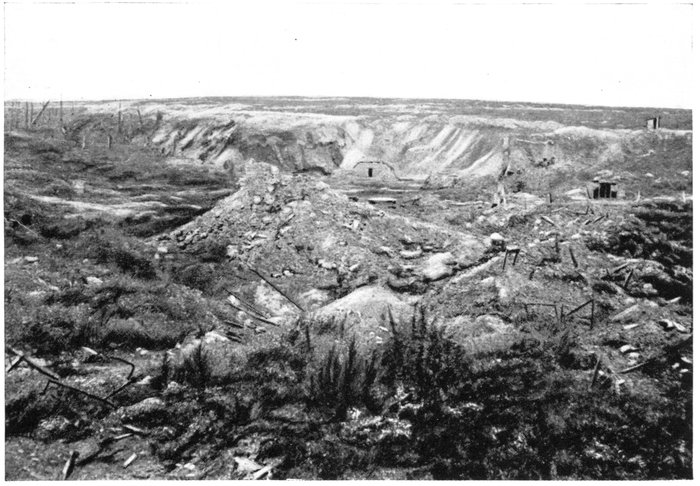

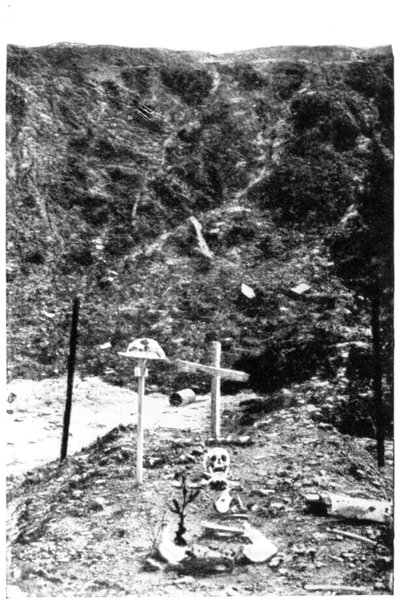

BRITISH GRAVES IN THE GREAT MINE

CRATER AT LA BOISSELLE.

During the night of February 6,

1915, the Germans fired three mines

in the southern part of La Boisselle

occupied by the French, and captured

the craters, but were unable

to debouch from them. The next

day a spirited French counter-attack

drove them back.

The communiqués of 1915 mention

many feats of this kind, and

to-day the traces which still remain

of this ferocious struggle attest its

extreme violence.

On each side of the Albert-Bapaume

road, opposite La Boisselle

village, huge craters form an

almost continuous line.

The largest crater lies on the

right. It has a diameter of about

200 feet and a depth of 81 feet.

British graves lie at the bottom

(photo opposite).

This mine warfare procured no

appreciable advantage to either

side.

Fresh defences were immediately made on the edge of or near the new

craters, in place of those which had been wiped out, and the front line

remained practically unchanged until the offensive of the Somme.

On July 1, 1916, the British rushed the German trenches in front of

La Boisselle and Ovillers, giving rise to a fierce engagement. After two days

of incessant fighting the whole of La Boisselle village was captured. A

battalion of the Prussian Guard made a desperate resistance at Ovillers, the

survivors—124 men and 2 officers—surrendering only on July 17.

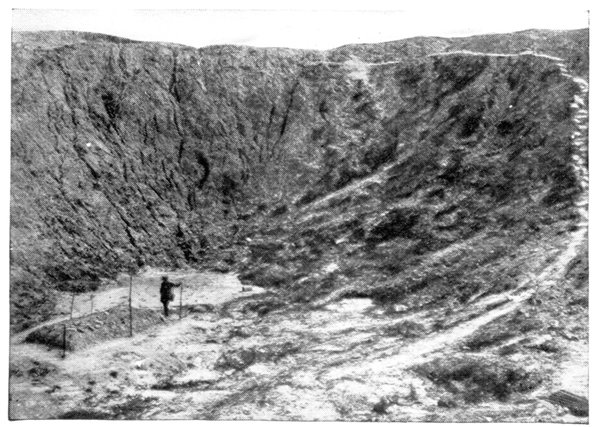

MINE

CRATER

AT LA

BOISSELLE.

[Pg 38]

Leave La Boisselle on the right,

and take N. 29.

Ten yards from milestone "Albert

5 km. 4," take the left-hand road to

Ovillers (600 yards distant). Of

this village not a wall remains

standing.

The road turns to the left and

crosses the village, in which numerous

shelters and military works can

still be seen.

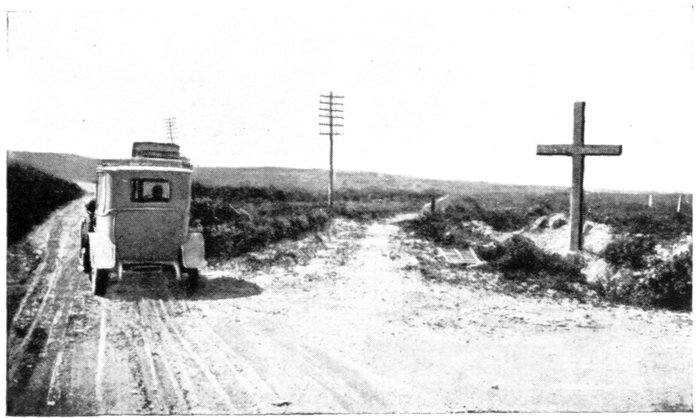

Outside Ovillers, on the right,

there is a large cross, erected by the

British in memory of their fallen

comrades of the 12th Division. A

little further on, there is a British

cemetery on the same side of the

road.

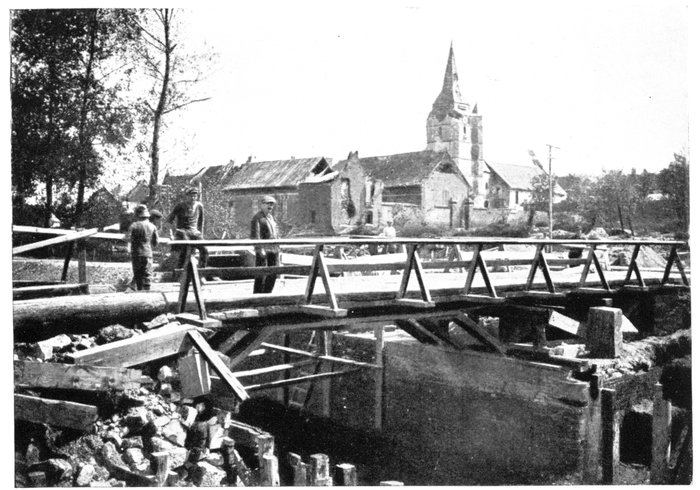

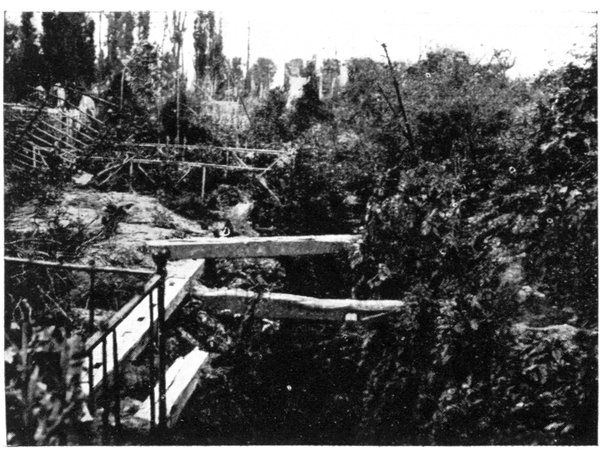

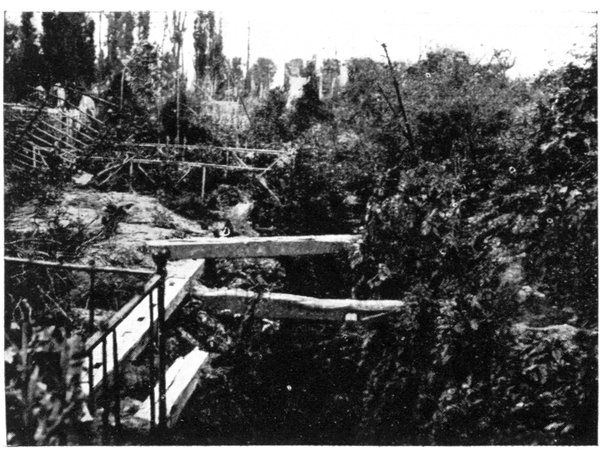

The road turns to the right, then descends steeply to the Ancre marshes.

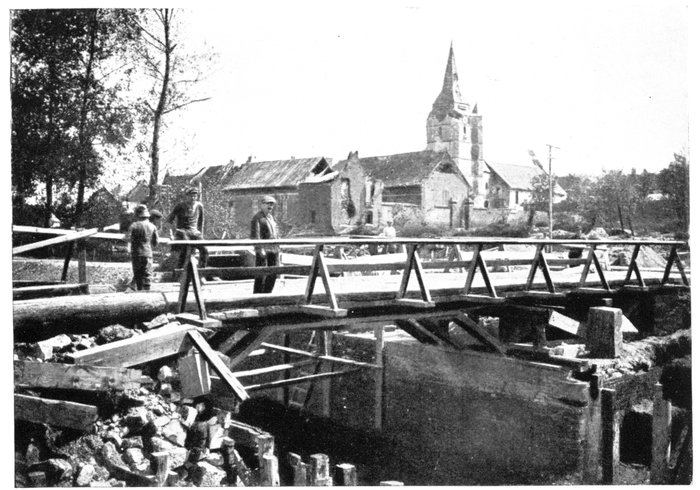

Cross these by the footbridge built by the Army Engineers, to Aveluy village on

the opposite side.

Of this village, only a few walls remain standing, among which are

numerous military works.

On leaving Aveluy, the road crosses the railway. Take the road on the right

immediately after.

Follow the marshy valley of the Ancre upstream.

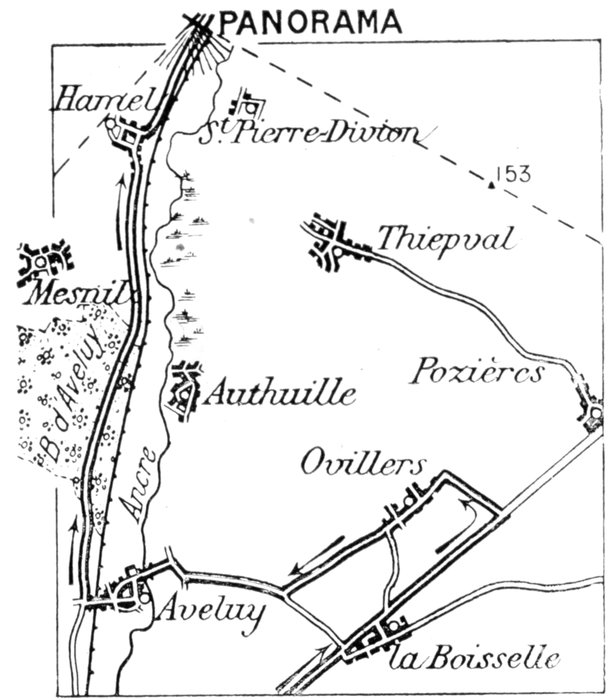

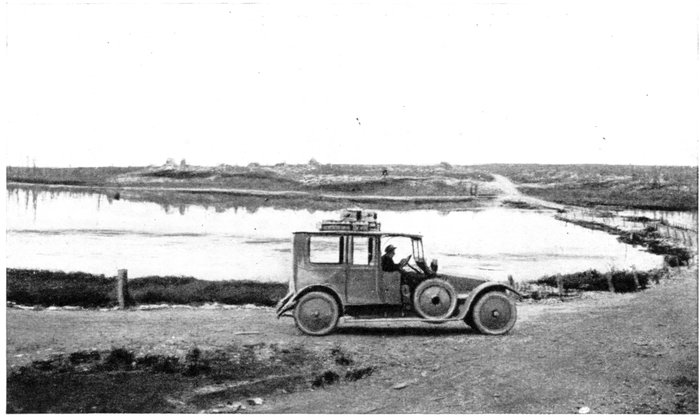

[Pg 39]

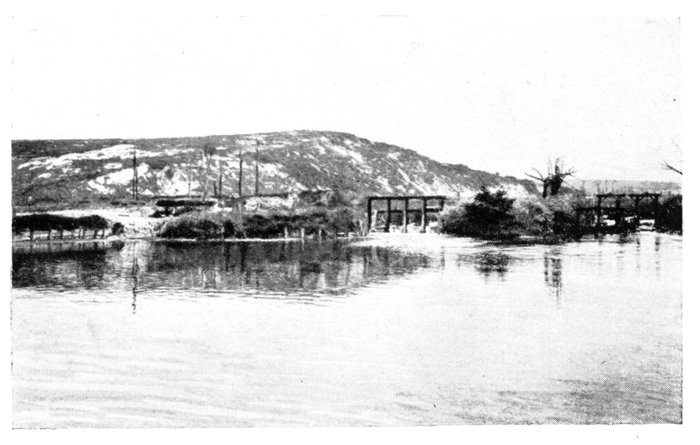

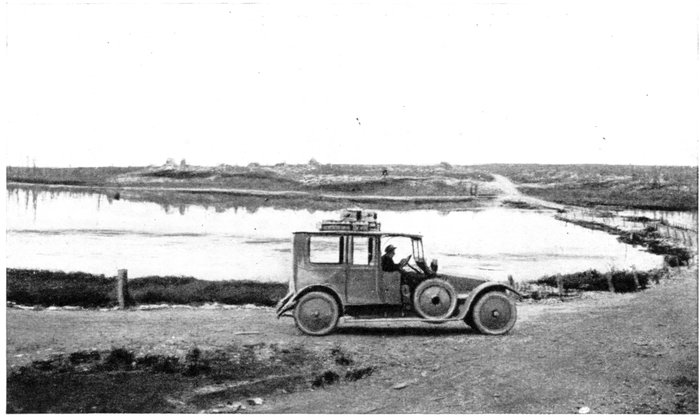

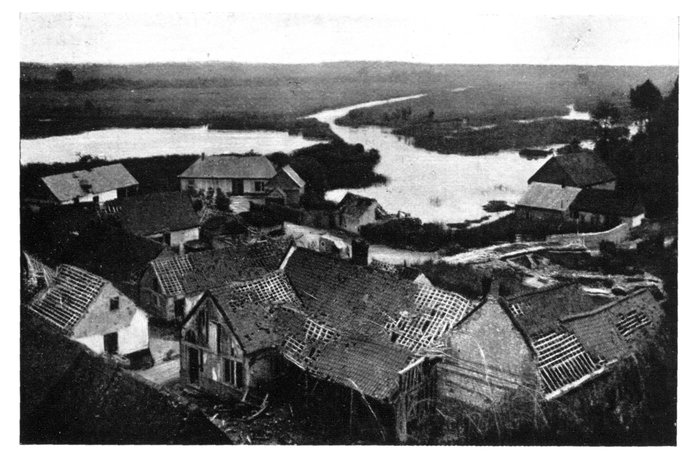

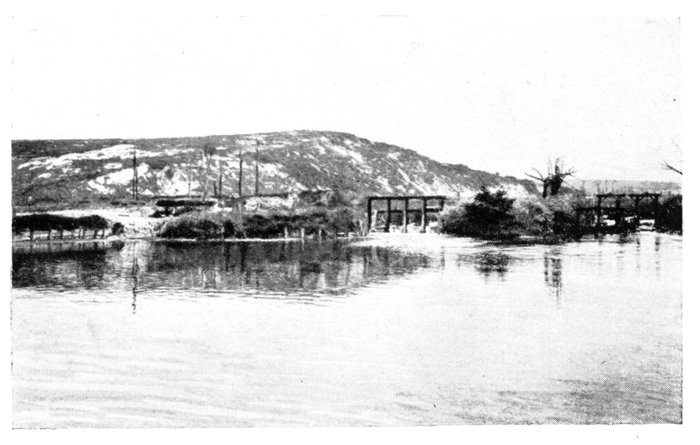

THE ANCRE MARSHES, IN FRONT OF THE RUINS OF AVELUY.

The road crosses Aveluy Wood, the trees of which are cut to pieces.

2 km. 500 beyond Aveluy, before the fork with the road to Mesnil, there is a

British cemetery on the right.

On leaving the wood, follow the railway to the ruins of Hamel village. Before

entering, note the British cemetery on the left.

Opposite, on the crest of the hill, on the left bank of the Ancre, is Thiepval

Wood, cut to pieces by the shells. The view of the Ancre Valley from here is

most impressive (photo below).

[Pg 40]

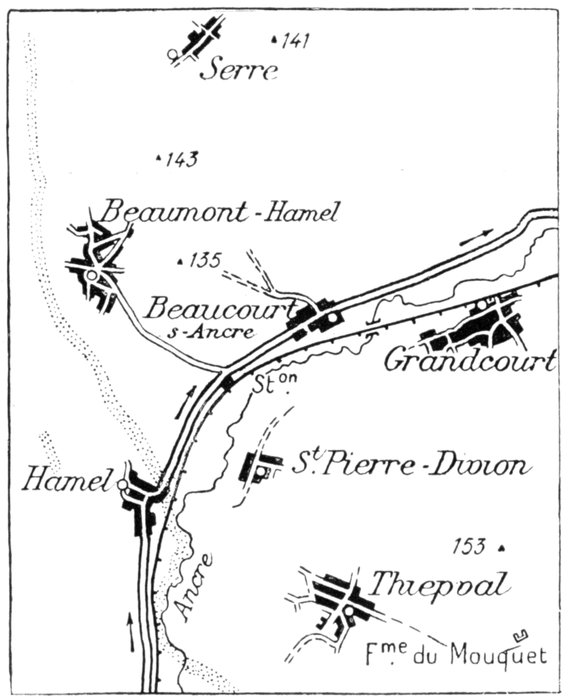

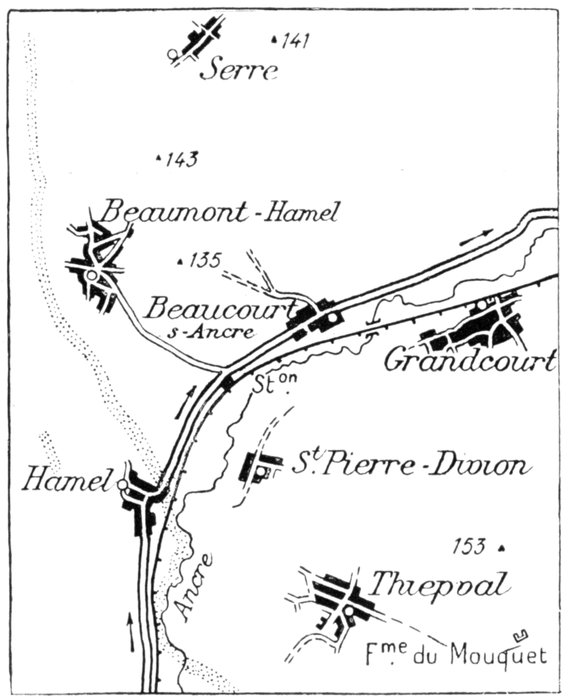

The British Operations in the Ancre Sector

During the first months of the offensive of 1916, the Germans, installed

on the top of the slopes which dominate both banks of the river, resisted

successfully in the Ancre sector. On the east, they occupied the whole of

the Thiepval Plateau (maximum altitude, 540 feet), which they transformed

into a veritable fortress. To the west, after crossing the Ancre below the

hamlet of St.-Pierre-Divion, their trenches ran in front of the high ground of

Beaumont-Hamel (Hill 135) and Serre (Hills 143 and 141). From these

elevated points they dominated the British positions, which is why the

British, before attacking, were forced to take the Thiepval Ridge (end of

September, 1916). This enabled them to take the German intrenchments in

the rear.

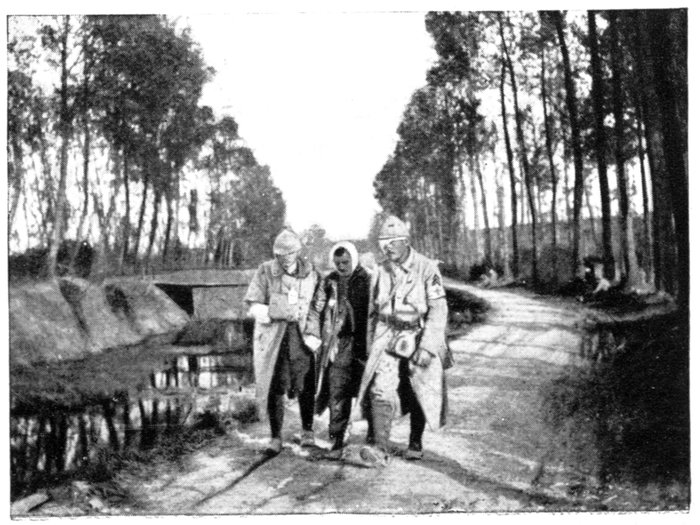

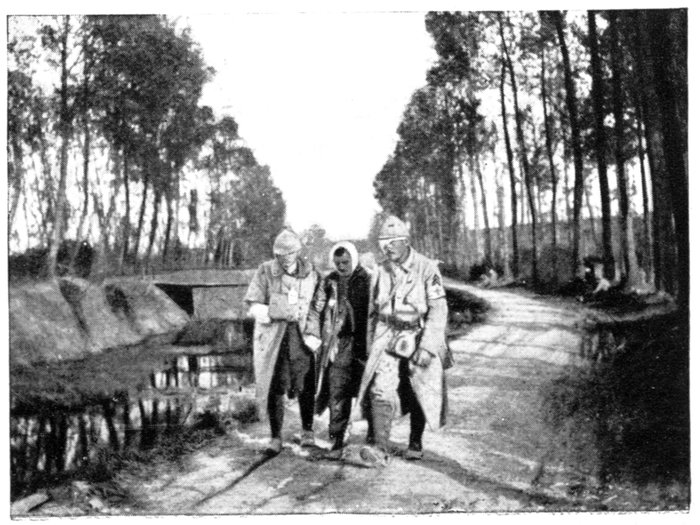

On November 13, 1916, the attack was launched under very unfavourable

weather conditions. The ground was sodden, and a thick fog hid everything

from view. In spite, however, of the five successive lines of trenches which

protected the enemy positions, the British first captured the hamlet

of St.-Pierre-Divion, then, three

hours afterwards, the fortress of

Beaumont.

In 1918, the German thrust

broke down, as in 1914, on the

banks of the Ancre. Caught in the

swampy ground, they were unable

to establish themselves strongly on

the heights of the western bank.

Leaving advanced posts only in the

valley, with strong patrols, they

reoccupied their old entrenched

positions; but with the ground in

such a state of upheaval, a prolonged

resistance there was impossible.

The Germans were unable to

prevent the British, on August 22,

1918, from crossing the Ancre near

Aveluy and carrying, within forty-eight

hours, the Thiepval and Beaumont

Heights, against which their

efforts had so long been unsuccessful.

The road passes the railway station of Beaumont-Hamel. The important

market town of this name (1 km. 500 beyond the station) is now a mere heap

of chaotic ruins.

The report of the Enquiry Commission appointed by the French Government,

contains the following:—

"On October 12, 1914, an aeroplane flew over Beaumont-Hamel. The

Germans pretended that two women (Mme. Roussel and Mme. Flament)

signalled to the aeroplane, the first-named by leading a red horse and a white

horse into her yard, the second woman by displaying a large piece of cloth-stuff.

The facts are: Mme. Flament had simply used her handkerchief, and

Mme. Roussel, in the absence of her mobilised husband, having to attend to

their large farm, had led two horses into the yard, to facilitate the cleaning

of the stable.

"Together with other inhabitants of the village who were under arrest for

similar futile motives, Mme. Roussel and Mme. Flament were questioned by[Pg 41]

the officer attached to the Colonel commanding the 110th Infantry Regiment.

After having ordered them to confess their guilt, this officer was particularly

infuriated against Mme. Flament, and promised the others that their lives

should be spared if they would denounce her. He had a personal grievance

against the woman. A few days before he had asked her for champagne

wine, and she had replied that she had not any, but, on leaving the house, he

noticed that some of his men had wine and, believing that she had mocked

him, he had indulged in violent reproaches.

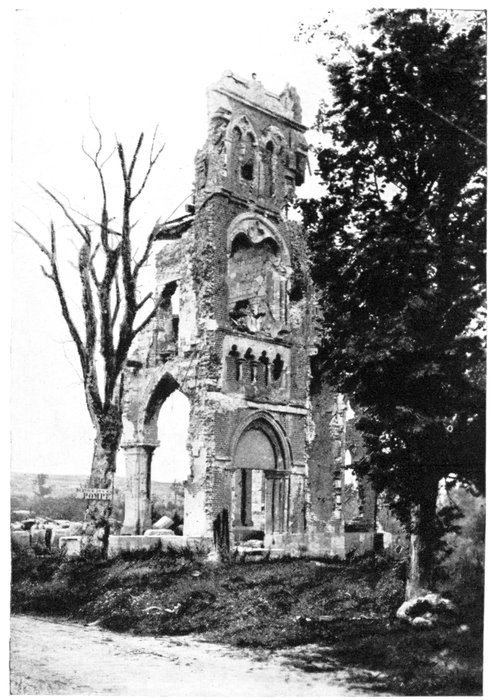

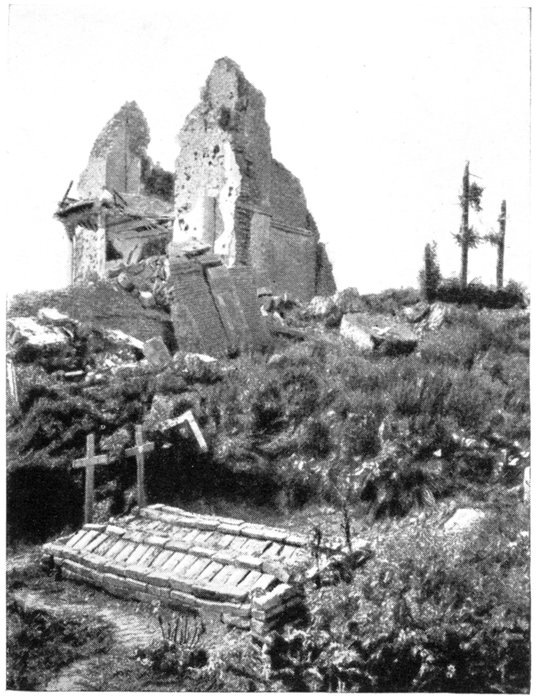

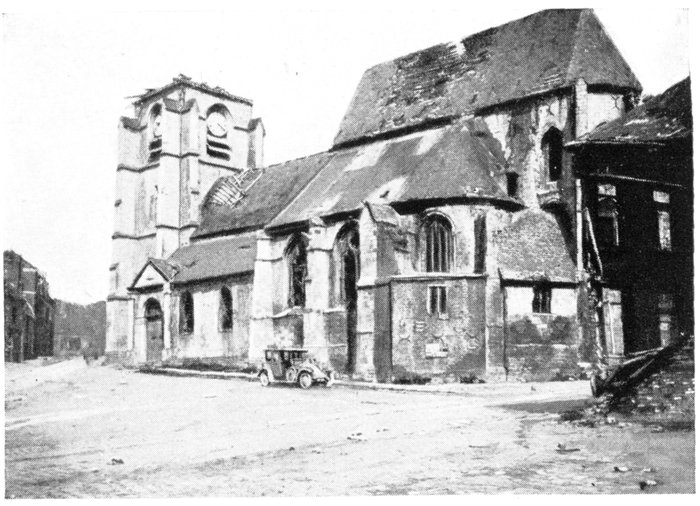

BEAUMONT-HAMEL, WHERE THE CHURCH USED TO STAND.

"In spite of the danger, the brave women replied that they preferred to

die rather than accuse an innocent person. Exasperated by their resistance,

the German allowed them three minutes for reflection, and then had them

placed against the wall of the church. While his soldiers covered the women

with their rifles, he counted, 'one, two ——,' then, in the belief that this sham

execution had terrorized the defenceless women, he allowed them half an

hour's respite and sent them back to the Town Hall. At the expiration of

this delay he again pressed them with questions, seized two sums of money

(one of 776 francs, the other of 1,345 francs, which Mme. Roussel and

Mme. Flament, believing that their last hour had come, had requested a

friend to hand over to their families), threatened in a fit of rage to have

Mme. Flament buried alive, and ordered all the persons under arrest to

swear that they were innocent. At the last moment, the courage to carry out

this abomination failed him, and he sent the unfortunate women back to

Mme. Roussel's house. Here they were watched until October 28, and were

then sent to Cambrai with the other inhabitants who had been held as

hostages, because they were unable to pay the whole of the war contribution of

8,000 francs which had been set upon the district."—Report of December 8,

1915, page 22, Vol. V.

One kilometre beyond the station of Beaucourt-Hamel the road crosses

the village of Beaucourt, where not a single wall remains standing

(see sketch-map, p. 40).

[Pg 42]

It was on November 13, 1910, that the British, after capturing Beaumont-Hamel,

carried Hill No. 135, between Beaumont and Beaucourt, and reached

the outskirts of Beaucourt. The entire village was occupied the next day.

But the approaching winter and continuous bad weather did not allow

them to exploit their success. In the operations of the previous two days,

they had been greatly hampered by the deep sticky mud through which, in

places, the men had had to advance up to their waists. It was therefore

decided to make the new positions their winter quarters.

The cessation of the offensive did not, however, mean inaction. From

November, 1916, to the end of January, 1917, raids were incessantly carried

out in the enemy trenches.

Early in February, 1917, a violent and incessant bombardment was the

forerunner of fresh attacks. From February 8 onwards, the British made

considerable progress along the Beaucourt-Miraumont road.

After leaving Beaucourt, keep along this road. A great heap of red bricks,

on the right, by the side of the river Ancre, is all that remains of Baillescourt

Farm, the defence-works of which were captured on February 8, 1917.

A few days later, the British reached the outskirts of the important

position of Miraumont.

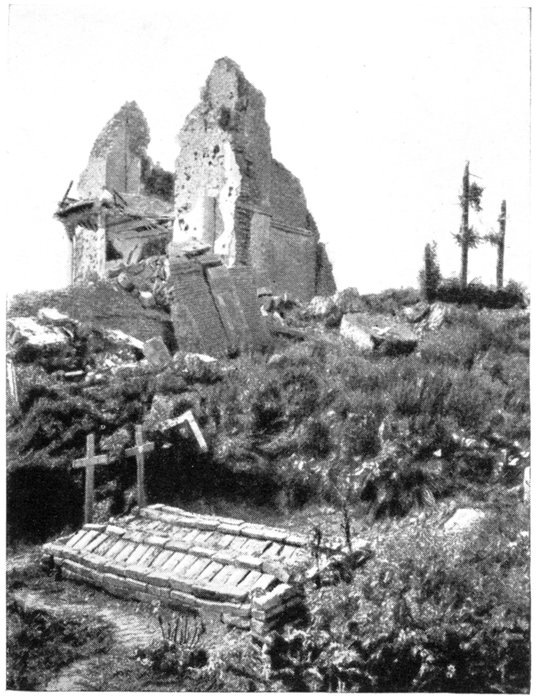

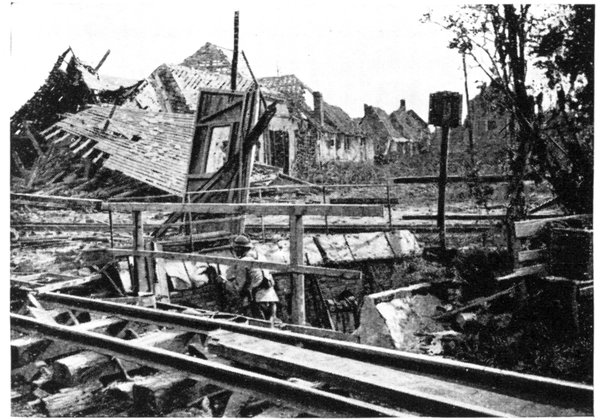

MIRAUMONT.

RUINED CHURCH

ON THE LEFT.

This large village was divided by the Ancre and the Albert-Arras railway,

the village proper being situated on the north bank. The smaller agglomeration

of houses lying on the south bank, known as Petit-Miraumont, was the

first to fall into the hands of the British, after desperate fighting. The

approaches to Petit-Miraumont had been covered with successive lines of

trenches, bristling with barbed wire entanglements, redoubts and concrete

blockhouses for machine-guns. All these positions had to be carried one by

one. The village itself was only captured on February 24, 1917.

Two days later, Miraumont-le-Grand, defended only by a rearguard

company and a section of machine-gunners, was easily carried by the British.

This marked the beginning of the "strategical withdrawal" which, the

following month, ended with the capture of Bapaume, Miraumont (7 km. to

the west) being one of its advance fortresses.

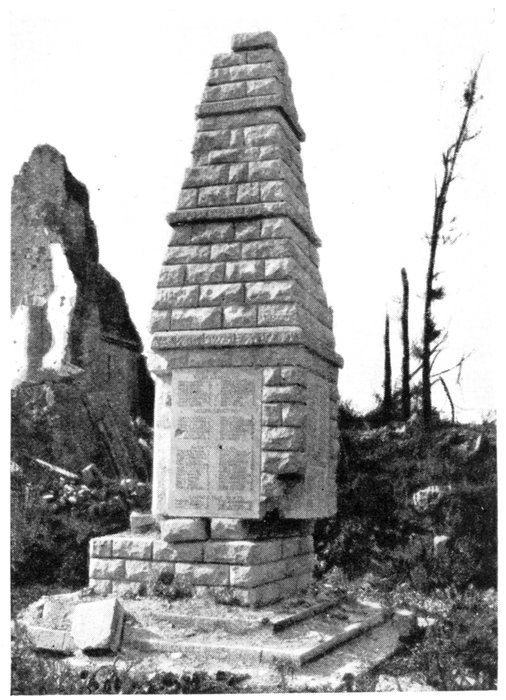

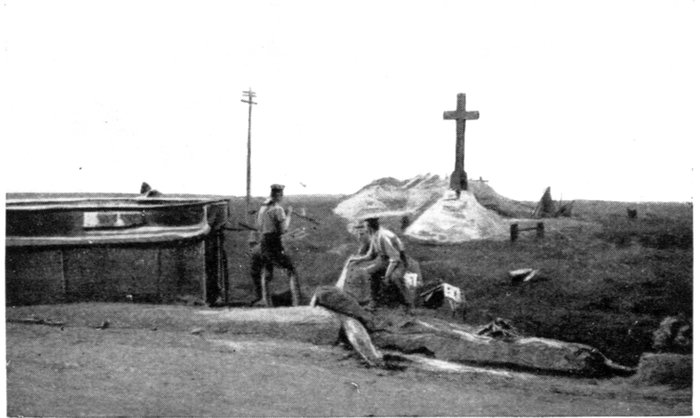

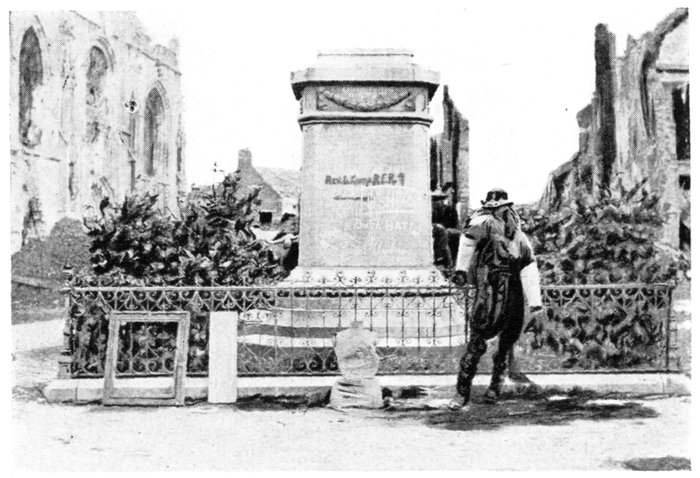

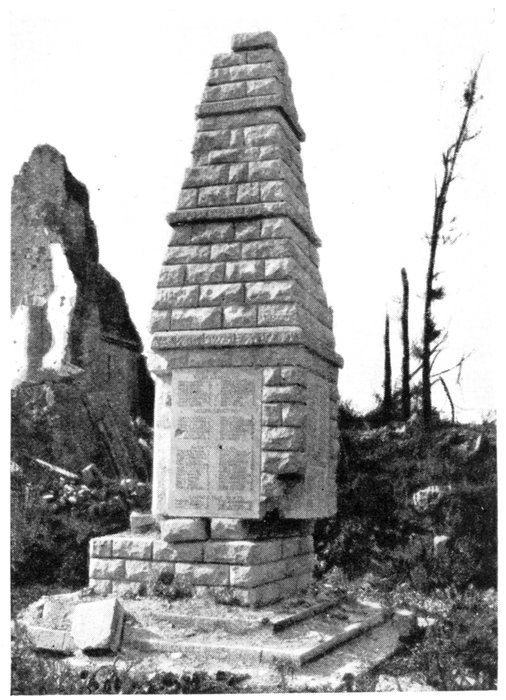

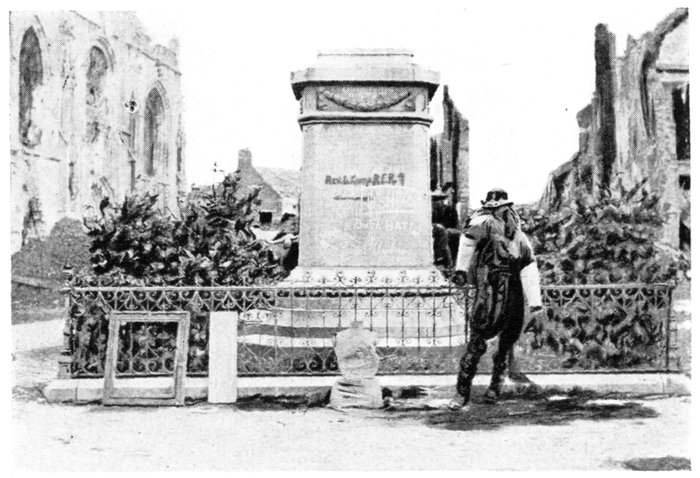

GERMAN MONUMENT IN FRONT OF

MIRAUMONT CHURCH (1917).

Lost again in the following year, Miraumont was one of the few positions

which the Germans fiercely defended at the time of the British counter-offensive

of August, 1918. They tried all they knew to stop the British

advance on Bapaume at this point. The fight lasted all day on August 24,

and the German retirement began only after the capture of Grandcourt and

Thiepval (on the south) and of Irles and Loupart Wood (on the north-east)[Pg 43]

threatened them with complete

encirclement. That night, a strong

detachment of British troops

slipped into the fortified ruins of

the village, held by picked machine-gunners.

A fierce struggle followed

in the dark. At daybreak the

German garrison attempted a

sortie, and succeeded in encircling

the British detachments. However,

a British aeroplane, which was

hovering over the scene of the

struggle, signalled that reinforcements

were coming, and finally the

Germans were encircled, and

several hundreds of them taken

prisoners.

After the fights of 1916, Miraumont

was one of the least damaged

of the reconquered villages. Many

of the houses retained parts of

their walls, and some their frame-work,

though in a dislocated condition.

To-day nothing remains.

Of the modern church which used

to stand on the highest point of

the village, only a fragment of wall

remains (photo, p. 42). On the right, in the devastated cemetery which

surrounds the church, stands a massive stone monument, erected by the

Germans before their retreat of 1917 (photos, above and below).

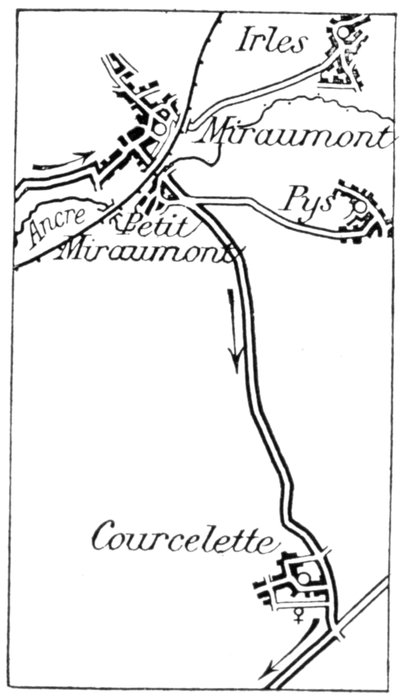

At the entrance to Miraumont, take the Courcelette road on the right, which

crosses the marshes, then passes under the railway bridge and afterwards

traverses the site of Petit-Miraumont (now razed). It next climbs the hill

on the left bank of the Ancre. Leave the road to Pys on the left, and keep

straight on to Courcelette. Numerous shelters, trenches and British and

German graves may be seen along the road.

The village of Courcelette was taken by the British during the offensive

of September 15, 1916.

MIRAUMONT.

RUINS OF

CHURCH AND

GERMAN

MONUMENT

(1918—see above).

[Pg 44]

THE BRITISH OFFENSIVE OF

SEPTEMBER 15, 1916.

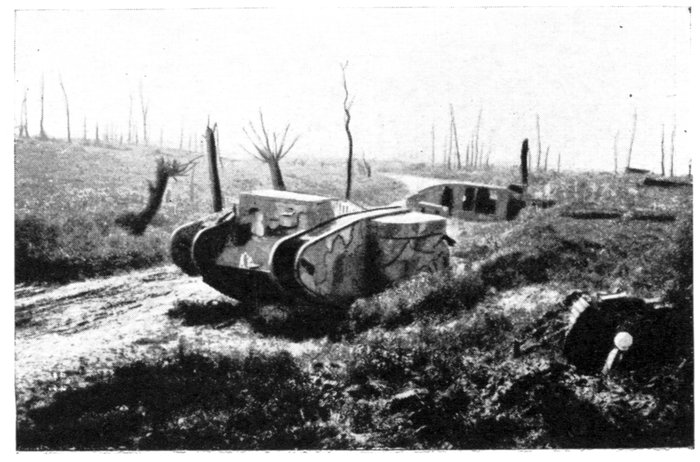

The First Tanks

MIRAUMONT. BRITISH GRAVES IN FRONT

OF CHURCH.

The British objective was Courcelette,

Martinpuich and the neighbouring

heights which protected

the Bapaume Plateau (see p. 22).

The offensive began on September

15, along a front of about

six miles, from the neighbourhood

of Combles to the trenches before

Pozières.

In a few hours, the infantry,

preceded in its advance by impassable

artillery barrages, carried

Martinpuich and the small hills

which dominate it. Other detachments

captured Courcelette on the

left.

The fighting was particularly

desperate before Courcelette. The first two assaulting

waves broke against the double line of enemy

trenches, flanked by redoubts and salients armed

with mortars and machine-guns. Further artillery

preparation was necessary, and it was only at

nightfall that the Canadians were able to enter

the village. A tank immediately set about clearing

the streets.

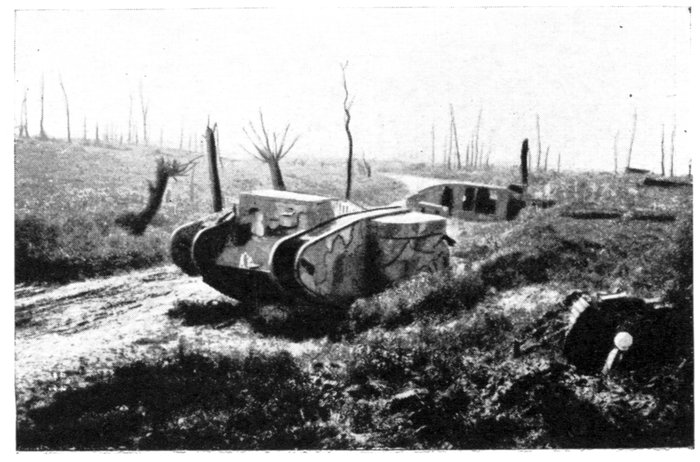

It was in this offensive that tanks were used for

the first time, to the great disturbance of the

enemy's morale.

At Martinpuich they crushed down the walls

which were still standing, and behind which

machine-guns were hidden.

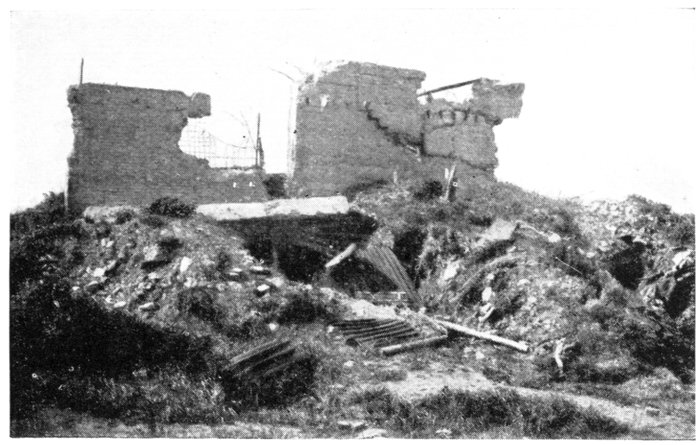

COURCELETTE. ALL THAT IS LEFT OF THE CHURCH.

[Pg 45]

MARTINPUICH. THE CHURCH USED TO STAND HERE.

One tank went for the fortified sugar factory in front of Courcelette

village, knocked down the walls, crushed the numerous machine-guns hidden

behind them, destroyed all the defence-works and quickly overcame the

enemy's resistance.

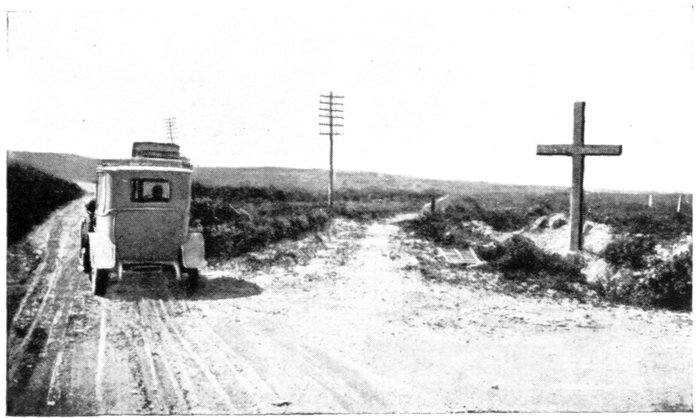

On leaving Courcelette, take N. 29 on the right towards Pozières and Thiepval

(see sketch-map, p. 44).

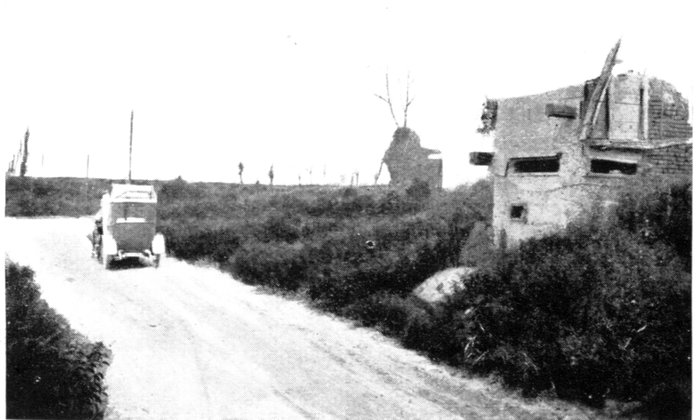

BRITISH TANK BETWEEN COURCELETTE AND N. 29.

[Pg 46]

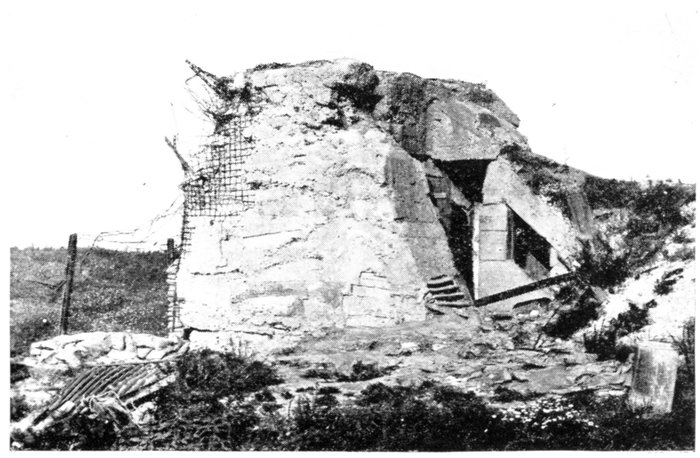

On the right of the road stand the ruins of a large sugar factory with a

concrete observation-post. Further on, also to the right, there is a cross

erected by the British.

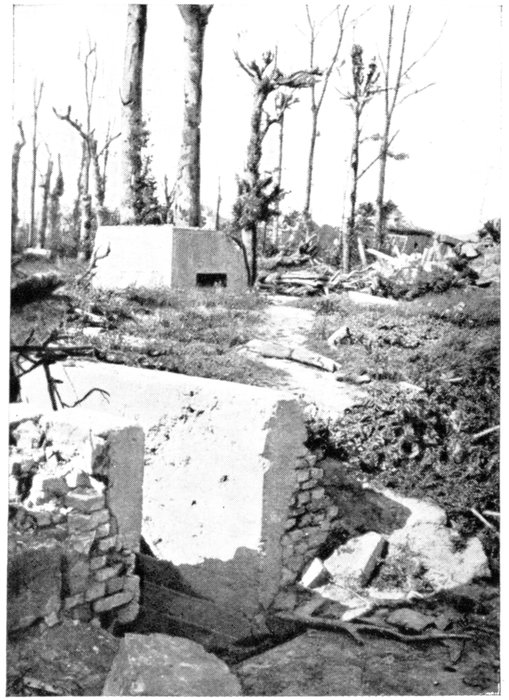

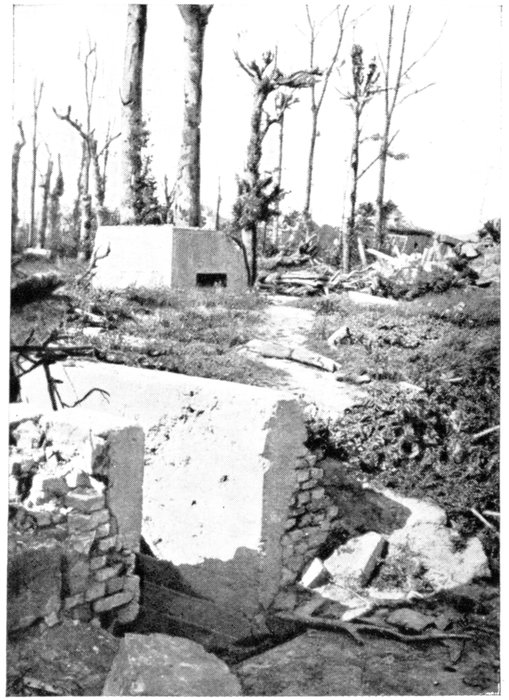

THE SUGAR

REFINERY

BETWEEN

COURCELETTE

AND

POZIÈRES.

GERMAN OBSERVATION-POST OF CONCRETE,

IN THE ENGINE-ROOM.

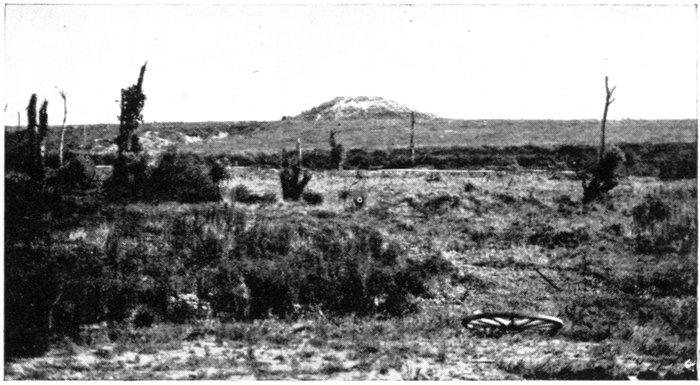

Before reaching Pozières, N. 29 passes over Hill 160. The windmill which

formerly stood there has disappeared.

From the top of Hill 160, which dominates the whole district, there is an

extensive view in the direction of Bapaume. To keep this observation-post,

the Germans transformed Pozières into a fortress defended by more than

200 machine-guns.

After capturing Ovillers-la-Boisselle and advancing little by little along

the National road as far as the outskirts of Pozières, the British attacked

on July 23, 1916, but only at midnight were they able to get a footing in the

village. Throughout the night and the two following days, the fighting went

on with unabated fury. It was only on July 26 that the Germans were

definitively driven from the northern part of the village, and the fortified

cemetery, and a few days later from the windmill on Hill 160.

BRITISH CROSS. In front: OVERTURNED TANK.

[Pg 47]

POZIÈRES. GERMAN OBSERVATION-POST.

Violent counter-attacks were made in August, liquid fire being used in

some cases. These attacks were particularly fierce to the north-west of the

village and in the vicinity of the windmill, on the night of August 16, when

six assaulting waves were broken by the British artillery barrage-fire.

When this furious struggle died down, nothing was left of the village.

Its site, completely levelled and upturned, is now indistinguishable from the

surrounding country—formerly fruitful fields of corn and beet, to-day a

chaotic waste of shell-holes.

A German observation-post of concrete is seen on the right, and another,

less damaged, with very deep shelters (photo below), also on the right. On

leaving the village, 300 yards further on, to the right, there is a large British

cemetery.

In the village of Pozières, the road, to Thiepval, which branches off to

the right, is only passable for about 1 km. 500. From this point the tourist

should go on foot to Thiepval.

POZIÈRES. GERMAN OBSERVATION-POST.

[Pg 48]

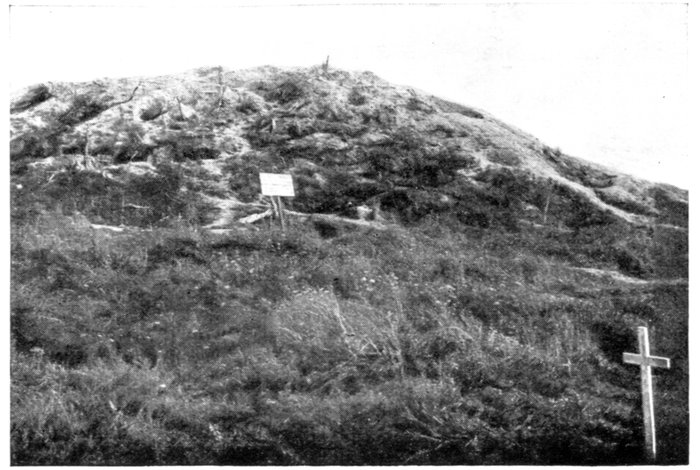

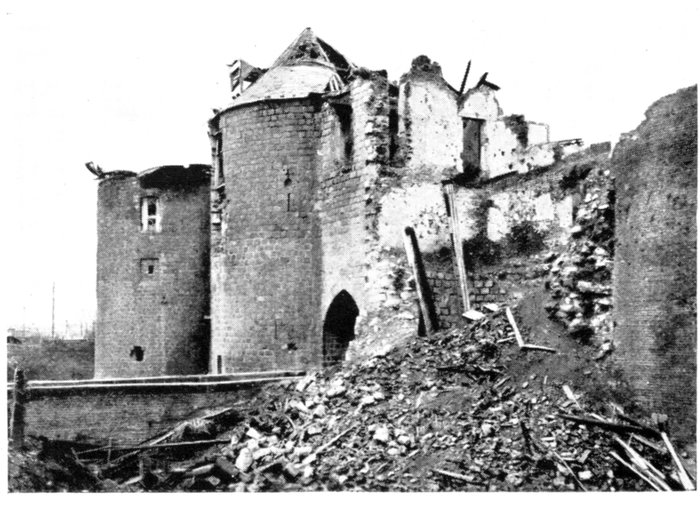

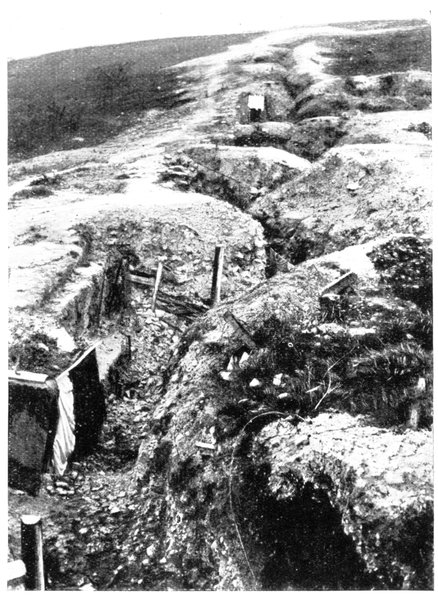

The Capture of Thiepval by the British

Situated on a plateau surrounded by hills, Thiepval had been transformed

into a veritable fortress. Since September, 1914, the Wurtemburger 180th

Regiment had been garrisoned there, and made it a point of honour to hold

the place at all cost. For twenty months, formidable defence-works had

been made; redoubts, blockhouses and concrete vaulted shelters, built on

the surrounding high ground, formed a continuous, fortified line around the

village. Inside, a labyrinth of trenches, connected by subterranean passages,

linked up with strong points and to bombardment-proof shelters.

The British were forced to lay siege to the place. The operations, begun

on July 3, 1916, lasted till October.

On July 7, the British carried the greater part of the Leipzig Redoubt

(Hill 141), a powerful stronghold which protected Thiepval from the south,

and consisting of a system of small blockhouses connected up by a network

of trenches. A wide breach opened by the artillery, enabled the troops to

gain a footing in the position and conquer it trench by trench.

Throughout the months of July and August the struggle went on, with

unabated fury, around the fortress. Fighting with grenades, the British

advanced inch by inch, so to speak, and eventually gained a footing in the

village, to the east and south. Each advance was immediately followed by