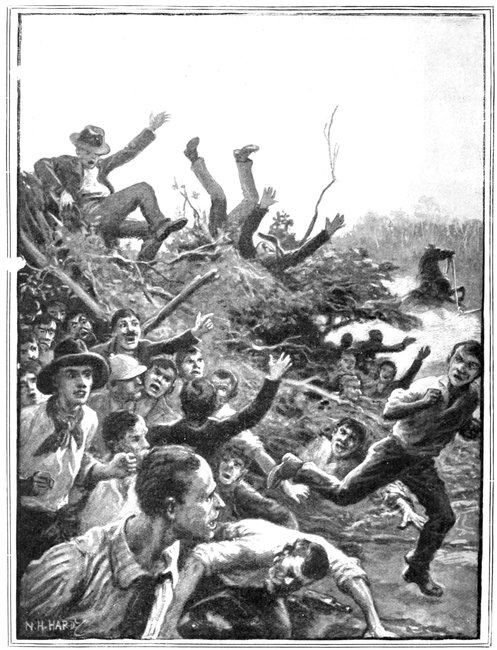

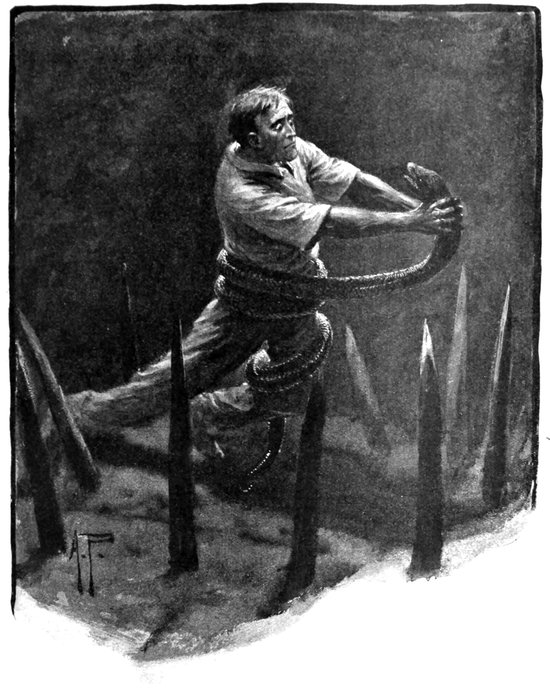

"BENEATH THE BOUGHS AND RAFTERS OF THE FALLEN HUMPY—KICKING, CURSING, AND SHOUTING—STRUGGLED FORTY OR FIFTY MEN."

SEE PAGE 110.

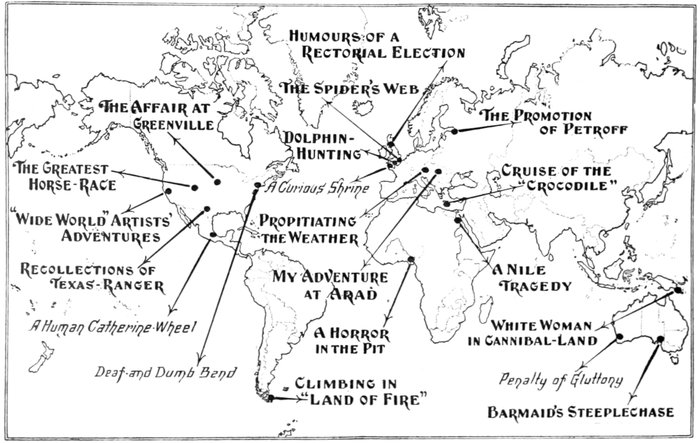

Title: The Wide World Magazine, Vol. 22, No. 128, November, 1908

Author: Various

Release date: July 17, 2015 [eBook #49469]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing, Victorian/Edwardian Pictorial

Magazines, Jonathan Ingram and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

"BENEATH THE BOUGHS AND RAFTERS OF THE FALLEN HUMPY—KICKING, CURSING, AND SHOUTING—STRUGGLED FORTY OR FIFTY MEN."

SEE PAGE 110.

Barmaid's Steeplechase.

The Greatest Horse-Race on Record.

The Promotion of Petroff.

The Humours of a Rectorial Election.

The Adventures of "Wide World" Artists.

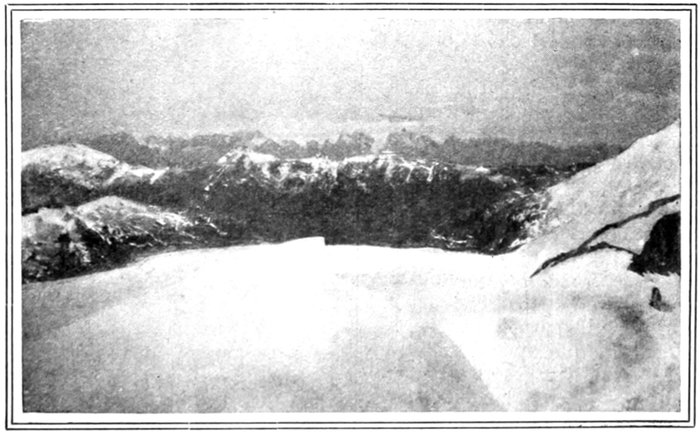

Climbing in the "Land of Fire."

The Spider's Web.

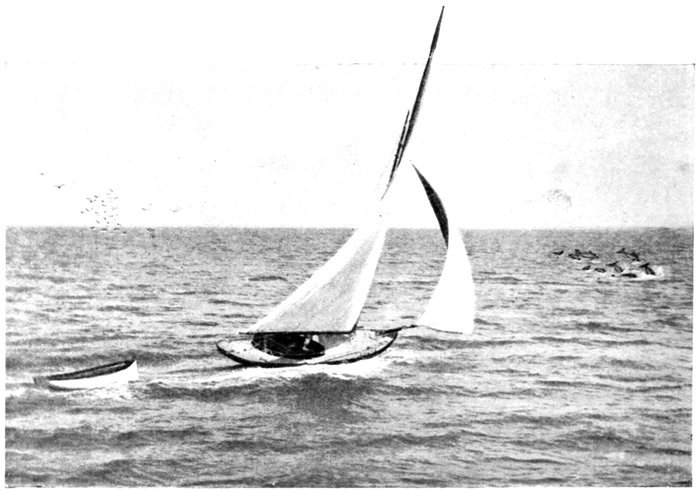

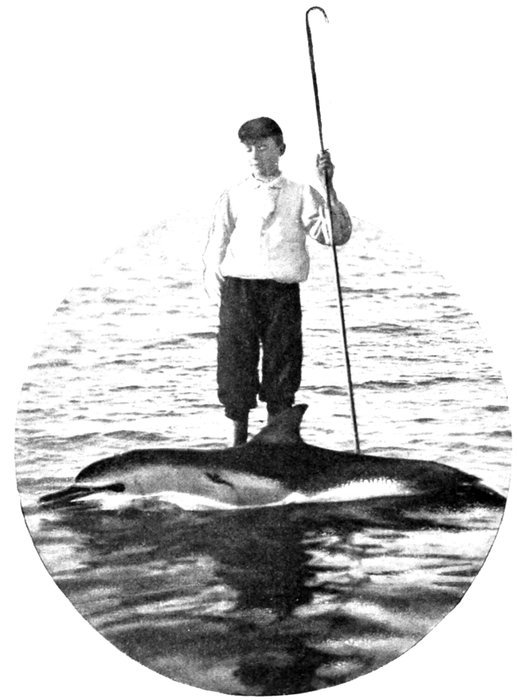

Dolphin=Hunting.

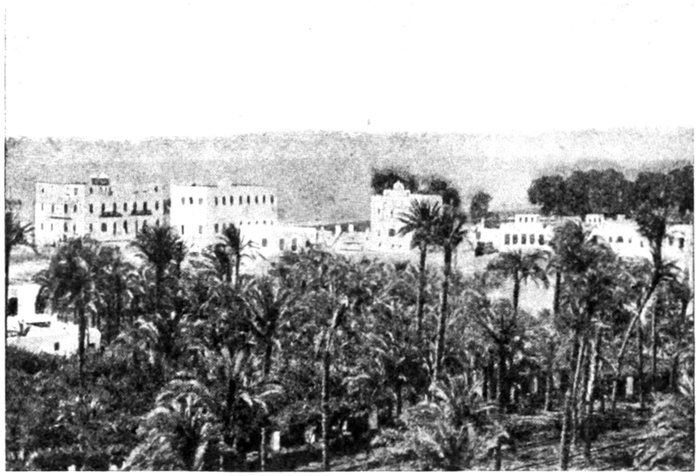

A Tragedy of the Nile.

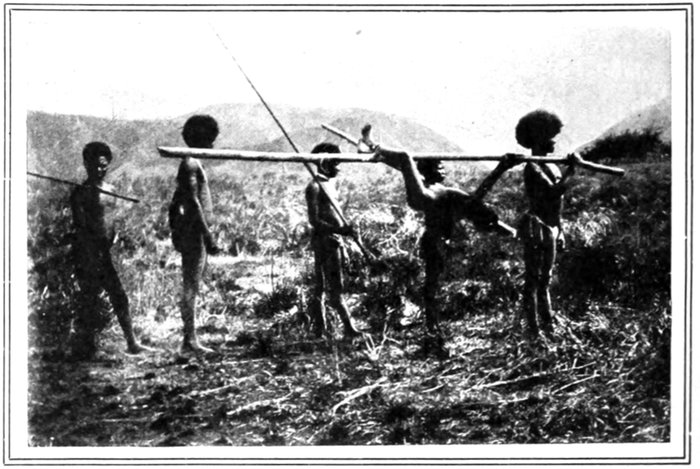

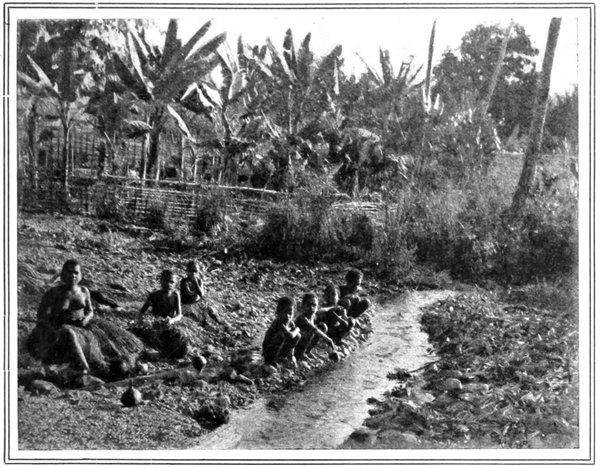

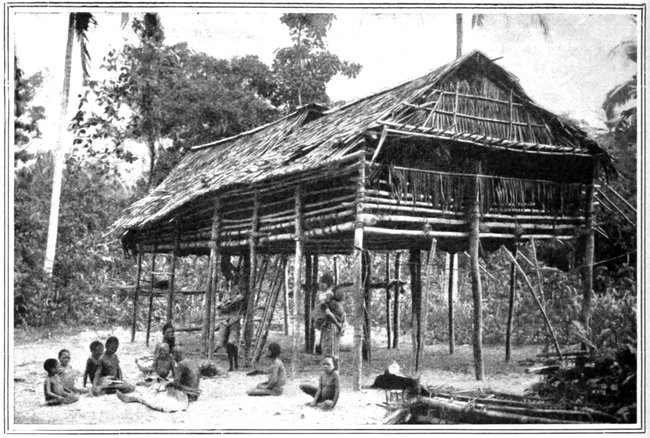

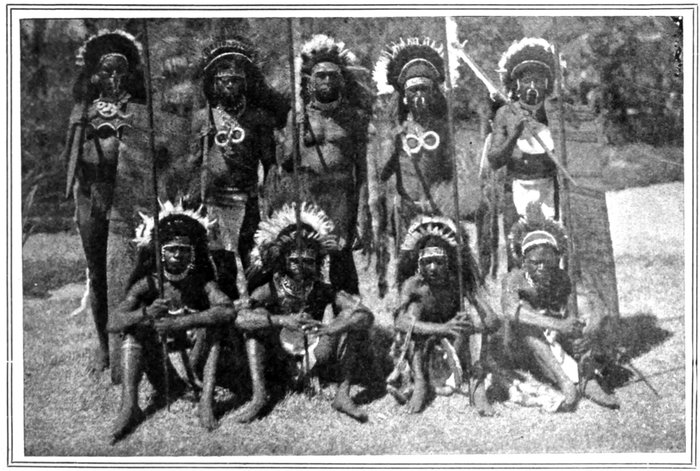

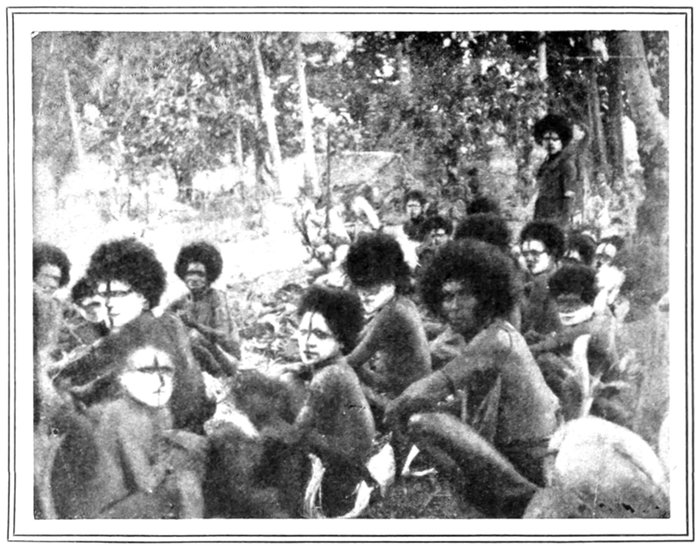

A White Woman in Cannibal-Land.

Recollections of a Texas Ranger.

Short Stories.

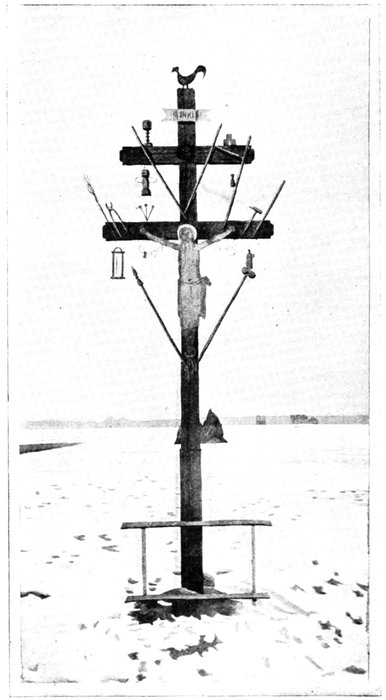

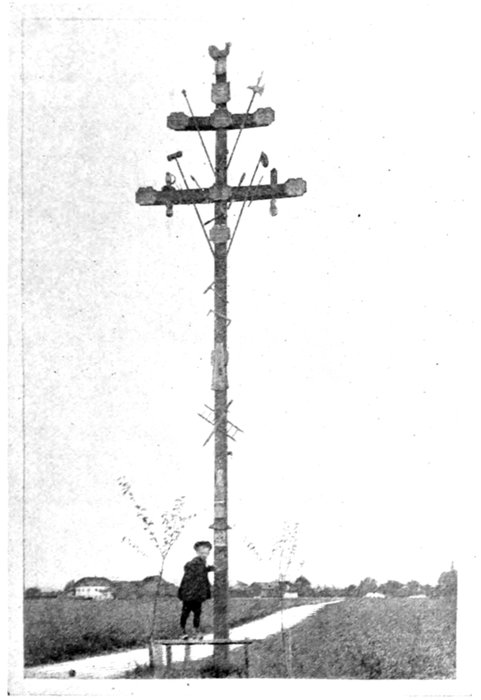

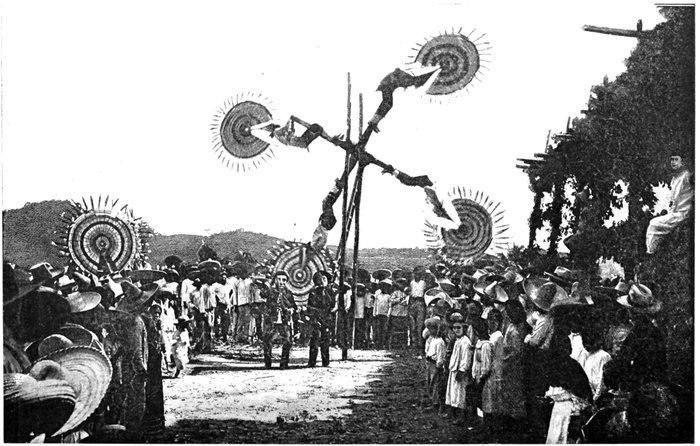

Propitiating the Weather.

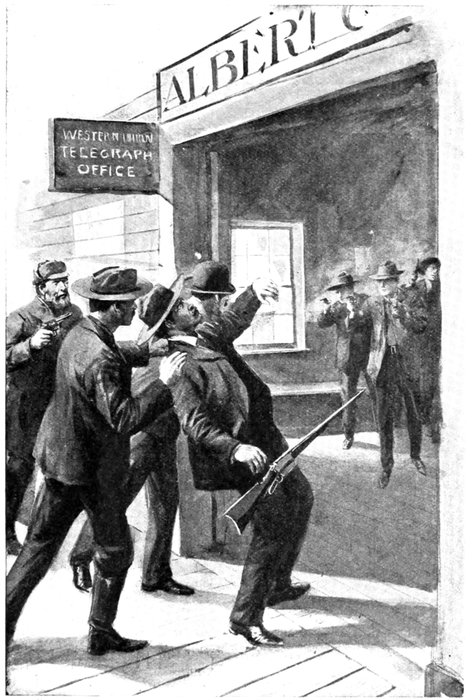

The Affair at Greenville.

The Wide World: In Other Magazines.

Odds and Ends.

Transcriber's Notes.

By C.C. Paltridge.

The story of an exciting race, incidentally giving one a vivid glimpse of the humours of an Australian bush meeting in the 'seventies.

I have never been a jockey, but I have ridden races under divers circumstances, having—as is the case with most of us Australians—put in a considerable time in the saddle one way and another.

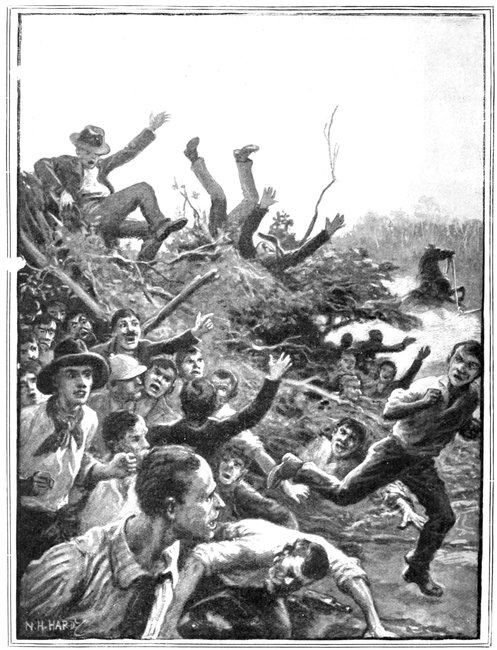

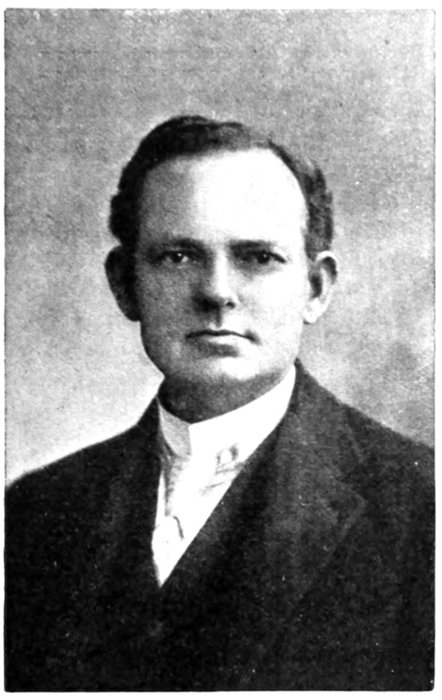

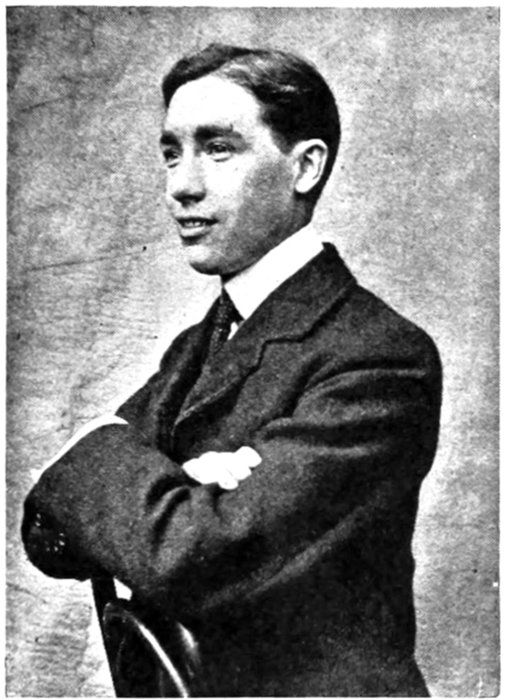

THE AUTHOR, MR. C.C. PALTRIDGE. From a Photograph.

My people have been mixed up more or less with racing ever since it started in our State—two uncles and a cousin have been crack amateurs over the "big sticks," and my brother and myself have each done his little bit in the same direction, though never attaining to notice in the cities. My own riding has been confined principally to obscure bush meetings, and undertaken on the spur of the moment, generally as a substitute for an absent or "hocussed" jockey.

This was the case at Orroroo, then a newly-surveyed and only partially-settled district in the north of South Australia, and the episode took place at the very first meeting held in that now prosperous and comparatively populous community.

Let me describe the scene, for probably few readers of this magazine outside Australia have ever beheld anything like it, though many of the middle-aged and old men "down under" will slap their thighs and say, "Jove! I've seen it hundreds of times."

Picture to yourself first of all a wide, undulating plain, dotted here and there with clumps of needle-bush growing in loose reddish sand, with lignum and ti-tree not altogether absent, while in the distance could be seen the mingled greens and blues of the salt-bush and blue-bush. Beyond that, miles away, was a long semi-circular line of black—the untouched acacia scrub.

In such a scene as this were gathered, one day in 1877, a small crowd of two or three hundred men, a sprinkling of women and children, and a multitude of dogs, while horses of every size, shape, and colour, from the great draught stallion, brought there to advertise his points to the new settlers, to the slim, clean-limbed thoroughbred, whose business was to make the sport, were tied to trees or being led up and down, awaiting their turn to run. Rogues and vagabonds of every description were among that small crowd—three-card men, purse-trick men, and all the lower strata of the criminal class, for in those days the bush race-meeting was a small goldmine to men for whom the cities and larger towns had become temporarily too warm.

The course was a circle of about a mile and a quarter in circumference, marked out by flags on either side, the jumps for the steeplechase—four sets of three stiff panels of post and rail—being erected just inside the inner flags. The race consisted of three heats of one mile each, run at intervals during the day, the riders, of course, weighing out every time.

I will not detail the events on the flat, from the maidens to the hurry-scurry; they passed off uneventfully amid the usual good-natured enthusiasm of a crowd of rough men out for a day's fun.

Just as the saddling-bell—a kerosene tin beaten with a stick—rang for the first heat of the steeplechase, Brady, the owner of a horse called Barmaid, came up to my uncle, whom I had accompanied to the meeting, and hurriedly whispered in his ear.

"Never!" cried my uncle, in amazement. "You don't mean it!"

"It is a fact," said Brady; "he's lying out there in the ti-tree, absolutely helpless. We nearly shook his teeth out, but he didn't move."

"Hocussed, eh?"

"Yes; and if Lean didn't do it I'm a nigger," snapped Brady. "I told him not to even speak[Pg 108] to him, and yet he goes and actually drinks with him! Confound him!" he added, viciously, as he thought of his lost chance, for though the horse Lean owned and was to ride, a big, raking brown gelding called Pawnbroker, was favourite, Brady's little bay mare was a clever fencer, and had pace enough to lose his rival on the flat. The stake, too, was twenty-five pounds, quite a respectable sum for so small a meeting, and Brady had his mare well backed.

Brady was the local publican, and, I believe, an honest man, while Lean made his living by going from meeting to meeting with his two horses, generally winning or losing as best suited his book, stopping at nothing that would make the game pay. At least, that was his reputation.

"What are you going to do?" asked my uncle, presently.

"I don't know," replied Brady; "unless you——"

"Goodness gracious, man!" interrupted my uncle. "With my leg?" He had recently broken it, and still needed a short stick to assist him in walking. "Besides," he added, "I am twelve stone, and you only want nine six." Suddenly he turned abruptly to me. "Do you want a ride, Charlie?"

"Ain't he too little?" objected Brady. "And can he ride?"

"He can ride if he's game."

I felt a hot flush spread over my face and alternate thrills of heat and cold run up and down my body as something like fear gave place to pleasure. At last, in a voice which, I am afraid, was none too steady, I said, "I am game."

I was promptly hurried away to a bough "humpy," the only edifice of any kind on the course, constructed of forked uprights supporting a dozen short cross-pieces, or rafters, surmounted by green gum-boughs and ti-tree; this served as a drinking-booth (its chief purpose), weighing-room, stewards' room, clerk's room, and all the other offices required on a racecourse. An ordinary steelyard, such as butchers use, dangled from one of the rafters, to which was fixed a stirrup. I placed my foot in this, having previously donned a blue and yellow jacket and cap, and clung on until the clerk of the scales said, "Eight stone two." With a saddle and bridle weighing twelve pounds I had to carry six pounds of dead weight, made up partly of lead, in the usual way, and partly by rolling up a big rug and tying it on to the saddle, swag-fashion.

"It will help to keep you on, my boy," said my uncle as he fixed it.

The crowd jeered good-temperedly at me as I was led out. "Why don't you tie him on?" said one.

"Going on the wallaby?" (tramping), inquired another.

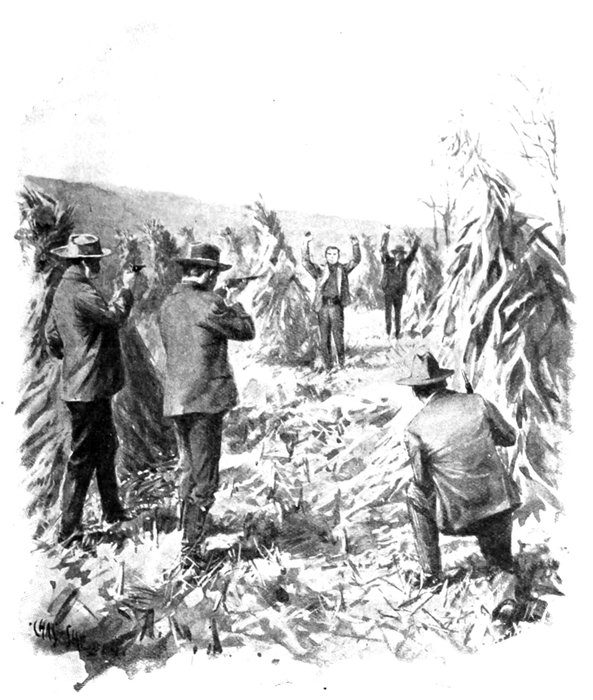

As we proceeded to the post, Brady addressed me in low tones. "I don't want to frighten you, sonny," he said; "but that Lean is a bad lot, so don't let him be too close to you as you go through the needle-bush. You'll be out of sight there and he might pull you off; run just ahead of him if you can, but don't have him alongside. When you are going at the jumps let her pick her own panel. Give her her head and sit tight; she won't stop and she won't fall. And win this heat if you can; it's two out of three, you know." A moment later I was among the half-dozen starters.

In a few minutes we were off, and I felt my heart come up into my throat as, leading the field, Barmaid took off at the first jump. Being practically a child—I was only twelve years old—I had not the hands of an expert, but I managed to steady her a bit between the fences, and, giving her her head at each obstacle, I won that heat without being caught, Pawnbroker being a not very close second. Two of the others fell, and a third was still declining the first fence when we finished.

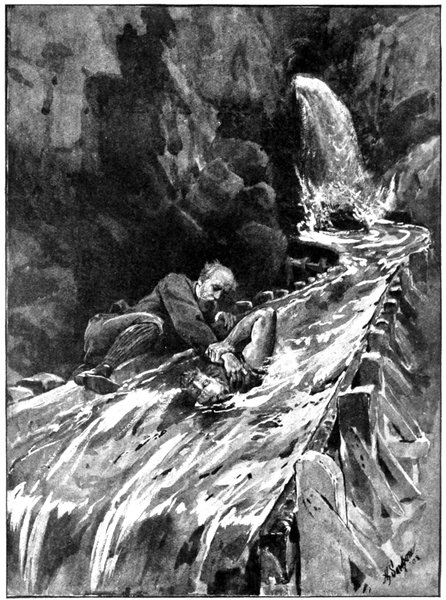

In the second heat I was not permitted to have things so much my own way. Lean caught me at the first fence, and we rose and landed together. I tried to get in front of him, but he kept Pawnbroker's head at the mare's shoulder and came on ever faster as I increased the pace, and we took the next fence at top speed. Lean had evidently thought I should funk it and pull off; the rest of the field were hopelessly behind.

Approaching the next fence, I foolishly steadied the mare and dropped back to his flank. This just suited him. We were racing at the moment through a small belt of low ti-tree, only our shoulders being visible to the crowd. The next jump was in the clear, a few yards from the bushes, and as we approached it—and while we were still almost concealed—Lean suddenly crossed right under the mare's nose, almost turning her off the course and throwing her completely out of her stride. Before she could recover we were upon the fence. She rose at it, there was a great crash, and I was thrown forward to her neck, while she floundered with her nose on the ground. I heard the sound of a great shout as the crowd cried, with one voice, "She's down!" The next moment, however, the plucky little mare had recovered herself, and we were sailing after the big brown as fast as bone and muscle could carry us. Just over the last jump I caught him[Pg 109] again, and, sending the mare for all she was worth, just failed by a neck to beat him; that made us heat and heat.

"SHE FLOUNDERED WITH HER NOSE TO THE GROUND."

I, of course, got a great lecture from my uncle for trying to catch him after the accident.

"There's another heat, you young duffer," he said; "why didn't you keep the mare for that?"

"I never thought of it," I told him, truthfully enough. In my excitement, and being so inexperienced, my only thought had been to get in first.

The crowd, however, were loud in their praises, patting me on the back, shaking my hand, and loading me with gifts of fruit and sweets.

When we came out for the third and last heat the sun was near setting, long shadows stretched over the dry grass, and a cool south-westerly breeze fanned our faces and blew the scraps of paper in which luncheons had been wrapped hither and thither among the crowd.

Barmaid had been well rubbed down and a couple of buckets of water poured over her, so that, barring an ugly mark on her stifle where she had struck, she looked almost as fresh as paint. She was led up to the humpy and I weighed out for the last time. Lean was not yet ready, and while we waited for him a man, more than half-tipsy, staggered up to the booth, leading his horse with a rein hung over his arm. The animal, evidently unused to a crowd, hung back, and only by dint of much persuasion was he at last brought close; then his liquor-soaked owner hooked the rein over the steelyard on which I had just weighed in and staggered to the counter for a drink.

The horse, already nervous and fidgety, was almost frightened to death by the noise of popping corks, breaking glass, and the mingled voices of the now noisy crowd. Suddenly, without warning, he started back, gave one,[Pg 110] two, three desperate tugs at the rein—and down came the whole humpy, bringing with it, of course, those who had been sitting on the roof to enjoy the last heat of the steeplechase!

The bridle of stout plaited greenhide held, and after a few wild plunges the horse went careering madly away over the plain towards the acacia scrub, the steelyard still dangling from the rein.

The scene that ensued is entirely beyond me to describe. Beneath the boughs and rafters of the fallen humpy—kicking, cursing, and shouting—struggled forty or fifty men, fighting wildly to release themselves.

"Who the dickens done that?" "Get orf my 'ed, whoever you are!" "Here, pull us out o' this, somebody!"—all sorts of weird cries and exclamations floated out from the mix-up, until at last, with many oaths, they emerged one by one from their captivity.

Meanwhile the crowd, whooping excitedly, were trailing over the plain in the wake of the flying horse. Talk about "two souls with but a single thought," here were two hundred in similar case. Their thought, of course, was the scales, without which the steeplechase could not be decided.

There were men riding, men running, men in carts, men in buggies, men with coats and men without, all laughing, cursing, and calling, while off in front went the runaway. Away they all sailed helter-skelter, some spreading out to the right and left to head the horse off before he reached the scrub.

Fortunately for all of us the fugitive's progress was hampered by the dangling scales, and so he was ultimately turned back, caught, and led triumphantly to the scene of the wrecked humpy, where the scales were hung to the bough of a tree, Lean weighed, and all was once more ready for the final.

There was more than a suspicion among the crowd that Lean had purposely arranged this little diversion in order that he might go out without weighing—an obvious advantage to him, I having already weighed.

One thing he had succeeded in doing—delaying the race until the sun had set and dusk began to fall, making it almost impossible to see across the course in the open, much less in the needle-bush.

There were, of course, only Barmaid and Pawnbroker to run, and I felt none too comfortable as Lean pulled his great brown beast up to my side and looked the mare over. When the flag fell he went away in the lead, evidently intending to repeat his crossing trick, but I lay back a good two lengths behind. After the second fence he slackened pace to let me creep up, but I touched the mare smartly with the whip and shot away in front. I did this so suddenly that he, holding his horse as he was at the moment, was some seconds before he could get going again. Then we both steadied and took the third jump carefully. Between the third and last fences was the clump of needle-bush, extending for about three hundred yards. These trees, as I said, grow in a loose reddish sand, and the going there was very heavy, while the needle-like foliage was so dense that I knew nothing could be seen of the race from the point where the people were. As I approached this point I remembered Brady's words, "Don't let him be too close to you in the needle-bush."

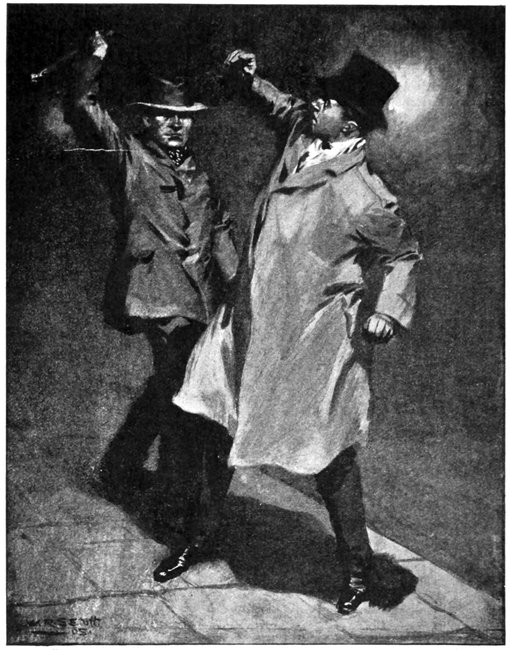

I felt that I had had enough of it all; a three-mile steeplechase is no joke for a youngster, and it was my first race. Lean, I knew, was a very bad man, and would not hesitate to settle me. So, determined to get my ordeal over, I plied my whip, and we literally flew. Pawnbroker, however, being the stronger horse, gained on me every stride in the sand, and it was with a gasp of terror that I presently saw his tan muzzle at my stirrup. "Barmaid! Barmaid!" I cried, as with tiring arm I coiled the whalebone round her flanks, but still that brown head and red, expanded nostril crept along her side. Then I felt a hand snatch at my shoulder. Grasping the rolled blanket on my saddle with one hand, I turned and lashed fiercely at my opponent's face.

With a curse of fury he swayed in the saddle and his horse dropped a little back. Next, grasping his whip, he aimed a blow at me with the handle which would have answered his purpose had it got home, but it fell just too short, and striking the mare just behind the saddle simply served to quicken her pace.

He caught me no more. The last fence I took alone, he coming along steadily some four or five lengths behind. Fearful and excited, however, I finished, using the whip as though running a dead-heat with the Evil One himself.

I told my uncle and Brady what had happened, of course, but, as they said, it was no use complaining; it would only be my word against his. And so the matter ended, Brady rewarding me for winning the race with a silver watch and chain.

Lean, under his proper name, afterwards became a notorious racing swindler, and was warned off most of the principal courses in Australia. He ended his days, appropriately enough, as lessee of one of the lowest "pubs" in Broken Hill.

By Alan Gordon, of Denver, Colorado, U.S.A.

A graphic description of a wonderful six-hundred-miles "endurance race" which took place recently in Wyoming and Colorado, arousing extraordinary public excitement. The photographs accompanying the article were furnished by the "Denver Post," under the auspices of which enterprising newspaper the contest was held and the prizes awarded.

Some time ago, while in Denver, Colorado, Mr. Homer Davenport, the famous American cartoonist, made a statement to the effect that the Arabian steed could travel farther and quicker than any other breed of horse extant. To this the owners of the Denver Post, as patriotic Westerners, promptly took exception. For hard, steady going, day after day, they said, the native Western "broncho" could wear the legs off anything that goes on four feet. This was what the proprietors of the Post believed, and so strongly did they feel it that they have since expended nine thousand dollars in instituting an "endurance race," which should demonstrate once and for ever the magnificent "staying" qualities of the broncho.

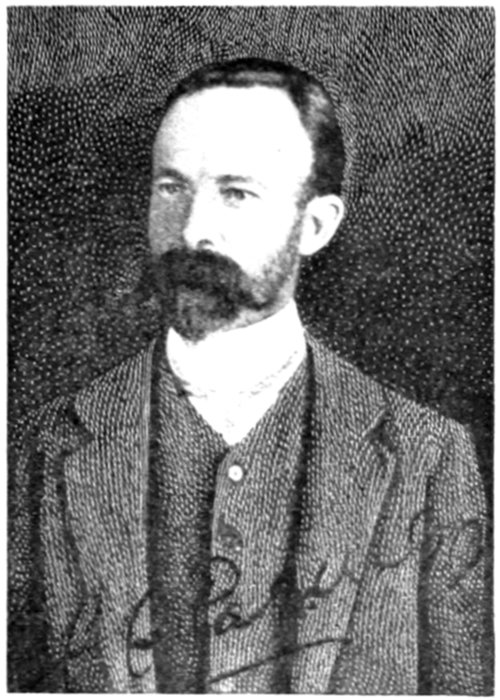

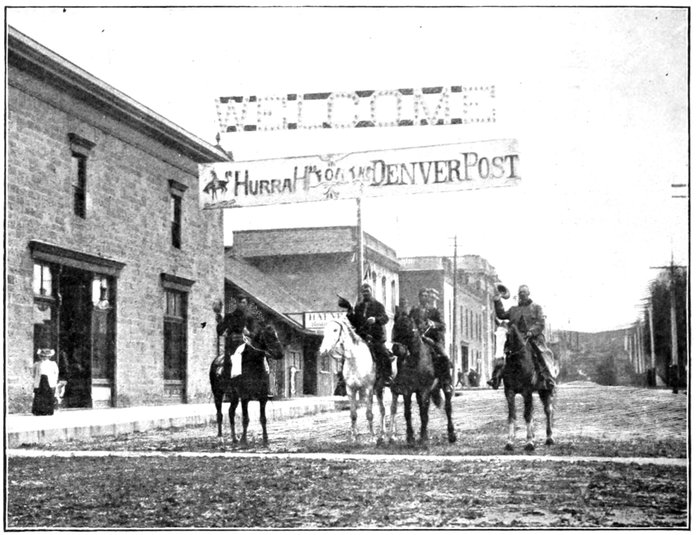

THE "DENVER POST" SPECIAL ABOUT TO LEAVE FOR THE STARTING-POINT WITH PRESS REPRESENTATIVES AND COMPETITORS.

From a Photograph.

Prizes were offered ranging in value from a thousand to fifty dollars, and extraordinary public interest was at once manifested in the contest. The whole West woke up, and entries simply poured in from Colorado, Wyoming, South Dakota, Utah, and other neighbouring States. The race was to be over a course five hundred and ninety-five miles long—from Evanston, Wyoming, to Denver, Colorado,[Pg 112] along the famous old "Overland Trail." The rules governing the contest were few and simple. Each competitor was to ride from start to finish on one horse. He was at liberty to go as he pleased and keep on as long as he pleased, but at regular intervals there were to be "checking stations," where veterinary surgeons would examine the horses and rule out any animal which was not in a fit state to proceed. In this way cruel overtaxing of the horses' strength—an unpleasant feature of some of the military long-distance races on the Continent—would be prevented. For the rest the rider could use his own discretion as to the best way of covering the six hundred miles of mountain, desert, and rolling plain that lay between the start and the winning-post.

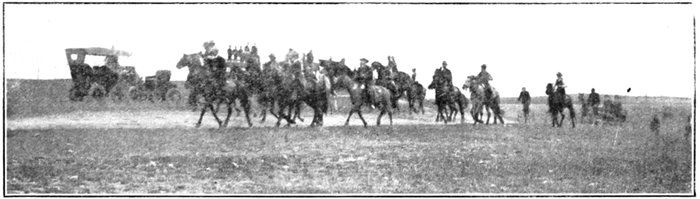

THE STARTING-POINT OF THE GREAT RACE AT EVANSTON, WYOMING.

From a Photograph.

Evanston is situated in the extreme southwestern part of Wyoming. The course followed the Union Pacific Railroad across the entire State to Cheyenne, in the south-east corner, taking roughly the form of a crescent, and thence dipped southward to Denver. It was a long, difficult stretch, for it crossed the "Continental Divide" of the Rocky Mountains and many a dry, sandy desert forsaken of man and beast. On this occasion, however, few of the riders found it lonesome, for automobiles followed them in many places, and casual friendly cow punchers dropped in and rode a few miles here and there for company with the boys who were entered to prove the supremacy of the broncho.

From Denver a special train was run to Evanston, taking with it the horses and riders of the section, and picking up others en route at little stations in Wyoming and Colorado. Some few of the competitors rode into Evanston on their cow-ponies. Two of these, Workman and Holman, actually came a distance of four hundred and fifty miles, at the rate of sixty-five miles a day, riding the same horses that were entered for the race! Holman, at least, regretted this afterward, as he admitted that his steed was not so fresh for the start as it should have been.

The little town of Evanston was hugely excited, and made a carnival out of the event. There was a big "barbecue" the day before the start, with races, bull-riding, a parade, and sundry other attractions, and the town was noisy with the whoops of the gay young fellows who expected to start out next day on their long, hard trip "down to Denver."

It was early in the morning when the start was made. The twenty-five contestants were lined up and ready for the pistol-shot before six o'clock. One of the judges made a short speech[Pg 113] to the riders, cautioning them to ride fair, remember the rules, and do their level best. Then he stepped back, the pistol cracked, and one of the most interesting and important races ever run in the West was "on."

THE PARADE BEFORE THE START.

From a Photograph.

The only recent long-distance ride worthy of comparison with this contest was that between Berlin and Vienna, run between officers of the Austrian and German armies. The distance between these two cities is about three hundred and sixty miles, and it was covered—over perfectly level roads—in seventy-two hours by Count Stahremburg, an Austrian. Second place was secured by Lieutenant Reitzenstein, a German officer, who took about two hours longer. These horses carried very light weights, and both of them were put out of commission for life, one of them falling exhausted at the post and the other dying next day. It remained to be seen whether the American broncho could outlast the thoroughbred steeds of the crack European cavalry regiments.

The race was run with several objects in view. One of them was to determine the value of the native broncho as a cavalry horse for the United States army; another was to discover how the bronchos compared with the standard-bred horses entered in the race. In order to make the data for comparison as complete as possible each horse was thoroughly examined and its markings and measurements noted. The weight of the entrants was about nine hundred pounds on the average, though this varied as much as one hundred and seventy-five pounds each way. The load they carried was about a hundred and eighty pounds, including the rider, saddle, and full equipment.

Charles Workman on Teddy took the lead, followed closely by Smith. An automobile which paced the riders for a few miles came back presently to report that these two were already opening quite a gap between them and the rest of the riders. As the day continued the news indicated that Teddy's long stride was carrying him farther and farther to the front, Smith galloping a mile or two behind, with Charlie Trew on Archie hanging to his flanks. Far behind these three came the rest of the field, scattered over many miles of dusty road.

At Carter, the first checking station, Workman registered at ten-thirty, no other racer being in sight. He was still alone when he passed through Church Buttes, though two other riders were looming up on the distant skyline. At Granger he was still first in and out, Teddy clipping the miles off one by one like a machine. But Smith was coming fast from the rear, and at Smith's heels still hung the game little thoroughbred stallion Archie. It was dark when Workman rode through Bryan, and by this time Smith had dropped back beaten, but side by side with Teddy ran Charlie Trew's Archie. By a great spurt the thoroughbred passed the broncho Teddy and came in to Green River first. Here Trew registered, having ridden one hundred and twelve miles the first day, and as he turned away Workman slipped down from the saddle.

"Halloa, Charlie! Beat me in, eh?" he grinned.

"You bet," came the cheerful answer.

"Your Archie hoss is a great little goer, but Teddy will wear him down to-morrow," commented the other man.

"Mebbe he will, and mebbe he won't," returned Trew, amiably, as he led his pony to the stable.

Both riders fed, watered, and rubbed down their horses before taking any refreshment themselves; then they lay down in the stalls and slept beside their animals till they were awakened before daylight and set off again. Although he[Pg 114] did not know it, Trew had already won the prize for the longest single day's travel covered in the least time.

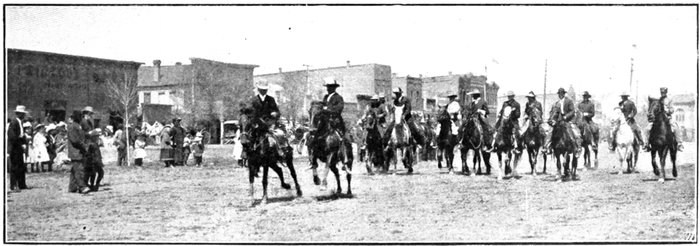

WYKERT AND CANTO ENTERING WAMSUTTER, WYOMING.

From a Photograph.

The rest of the twenty-five starters were scattered along forty miles of road to the rear. Most of them slept at Granger the first night, and one or two dropped out of the race at that point, it being already plain that their horses were overmatched. Most of the riders, however, accepted philosophically the fact that Teddy and Archie had so long a lead.

"It's a long trip to Denver, and I reckon we'll see them boys again before we drop in there," they told each other cheerfully.

The leaders reached Rock Springs about breakfast time. Teddy was still jogging along easily with long strides, but Archie was already labouring a little to hold his own. All along the route were veterinary surgeons to examine the condition of the horses and put them out of the race if necessary. Those looking over the couple now were of opinion that they were setting too hot a pace to last.

"If I were a betting man I would put my money on one of those horses back with the bunch," said one of the examiners confidently.

The next stretch led to Point of Rocks, over a road which had a good deal of sand. Teddy's steady trot ploughed right through it, and Archie had to break into occasional lopes to stay with the big broncho. After Point of Rocks came more sand, and still more. The Red Desert tried the horses, for at every step they sank down into the loose, thick sand, and Archie began to fall back, unable to stand the punishment of the gruelling pace. At Bitter Creek Workman was riding alone, and he was still alone when he rode into Wamsutter close on eleven o'clock, having covered a hundred and ninety-two miles in two days. Considering the heavy roads, his mount had done wonders. All over Wyoming people threw up their hats for the local horse when the news was flashed over the wires that Teddy led by a good many miles. But the veterinaries were still shaking their heads.

"Too fast! Too fast! Teddy will blow up like the Archie horse," they predicted, sagely.

It was an hour past noon when Charlie Workman rode into Rawlins next day, fifty miles nearer the end of his journey. He was followed a few hours later by "Old Man" Kern, on Dex. Kern was a man over fifty and the oldest in the race, but as hardy a pioneer as one would meet in a long day's journey. He was an ex-cow-puncher, ex-sheriff, ex-ranchman, and what he didn't know about horses was not worth knowing. After Kern came "Wild Jim" Edwards, a miner, from Diamondville, Wyoming, followed by Means and McClelland, both of Colorado. Trew was sixth, and after Trew came Casto, though some of these did not get in till next morning. Meanwhile Workman and his horse were eighteen miles farther on the road, in spite of the fact that they had been caught in a driving sleet storm and had lost the way. He put up for the night at Fort Steele, having made an average of ninety miles a day, and crossed the "Continental Divide" of the Rockies into the bargain. It was agreed on every hand that the wiry little man from Cody had a remarkable animal. The horse, however, was irritable, ate badly, and appeared to be nervous.

On the other hand, the steeds of some of the riders in the rear were still fresh. Jay Bird, Sam, Dex, Sorrel Clipper, Cannonball, and Buck, ridden respectively by Rolla Means, "Dode" Wykert, Kern, Edwards, Lee, and Wilcox, all showed up well. A good many[Pg 115] were looking for Means's thoroughbred, Jay Bird, to romp home a winner. Others noticed that Wykert and Lee, though they were fifty miles behind the pacemaker, came in each night as fresh as if they had merely been out for an exercise canter.

WORKMAN, ON HIS POWERFUL HORSE TEDDY, ARRIVING AT MEDICINE BOW.

From a Photograph.

Teddy got as far as Medicine Bow that night, and he was followed two hours later by "Old Man" Kern on his big bay, Dex. Means and Edwards also registered at that station for the night. By constant hard riding three of his competitors had caught the leader after four days' travel, Teddy having let down very considerably during the day. The rest of the riders were scattered between that town and Rawlins, a full day's journey behind. Lee, Wilcox, and Doling were among those close to Rawlins; Wykert was not far ahead of them; and Casto, on Blue Bell, was near the front.

From this point the best of the rear-guard began to close in on the leaders. Steadily the four horses of the vanguard—Teddy, Jay Bird, Sorrel Clipper, and Dex—pushed forward over the rolling hills towards the little city of Laramie, and just as steadily those behind jogged forward in their effort to overhaul them. By nightfall the four were in Laramie. Soon the horses were groomed, fed, and examined by the judges. The riders ate their beefsteaks and lay down beside the ponies. Some time in the small hours after midnight a solitary, dusty traveller rode into the town and dismounted stiffly from his tired horse. The man was Wykert and the horse Sam. By long night rides and continual going they had wiped out the distance between them and the vanguard, and were now ready to be in at the finish.

WYKERT LEADING INTO CHEYENNE.

From a Photograph.

When the riders moved out of Laramie toward Cheyenne the next morning, there were five of them instead of four. Wykert, with a grin, nodded greeting to his fellows.

"Mornin', boys."

"Mornin'. Where did you drop from?" asked Kern, nonchalantly.

"Me? Oh, I just happened along to be in at the finish."

"I'll tell them you're coming," laughed Means.

Wykert eyed the horse, Jay Bird, carefully.

"Well, I reckon you'll have to 'phone the news to Denver, then," he returned, casually.

For Jay Bird, game thoroughbred though he was, showed the effects of travel very plainly, and though Means might still jest about the[Pg 116] result he was already beginning to suspect that the native bronchos against which he was pitted would wear him down before the remaining one hundred and seventy-five miles of the race were covered.

At Granite Canyon "Old Man" Kern and his Dex were in the lead, with Teddy second, but the five horses kept well bunched, and it was Wykert who rode first into Cheyenne, the capital of Wyoming, that afternoon. Eight minutes later Edwards and Workman rode in together. Means and the thoroughbred were fourth, and the "Old Man" last.

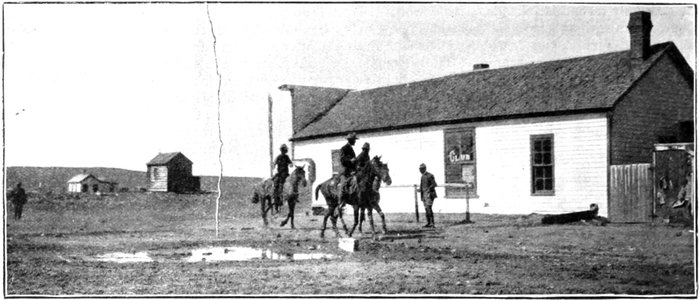

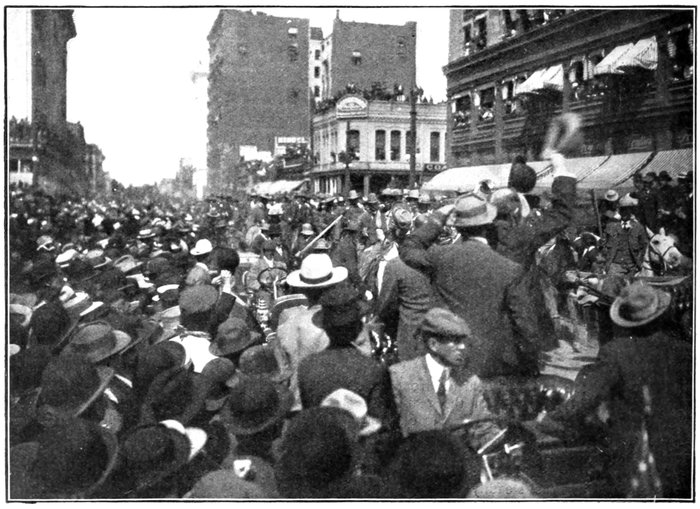

THE SCENE AT THE WINNING-POST, OUTSIDE THE OFFICES OF THE "DENVER POST." WHEN, AFTER THE SIX-HUNDRED-MILES RACE, WYKERT AND WORKMAN FINISHED IN A DEAD-HEAT, THE EXCITEMENT OF THE CROWD WAS INDESCRIBABLE.

From a Photograph.

Cheyenne gave the riders a great reception. The Governor of the State, a former governor, and a retired army general were among those who went out in automobiles to escort the boys into the city. Everybody cheered for one or another of the horses, and though the Wyoming ones were naturally the favourites the Colorado horses got a good round of applause as well.

It had been the intention of the riders to get a few hours' much-needed sleep at Cheyenne, but they had scarcely lain down in their stalls beside the ponies before word came to the others that Workman had slipped out and was on the road to Denver.

Tired as they were, the others were on their feet in an instant, slapping on their saddles and making ready to follow. It came cruelly hard on both mounts and riders, for all of them certainly deserved a good rest. Instead, they faced a long ride through the night, plodding on hour after hour in the darkness, persevering doggedly in spite of fatigue and the craving for sleep. They could not "quit" so long as it was in their horses to keep on going.

They were now on the final lap, the last hundred miles. The pace was hot, for each was hoping to wear out the others. Mile after mile they galloped through the night, the Denver Post automobile at their heels. At Carr the rest of the five caught up with Workman and Teddy. After half an hour's rest here two new pacemakers swung out to show the tired riders the road to Greeley. It was a "Texas jog" at first, then it quickened to a trot and grew faster, until Dex could no longer keep the pace. "Old Man" Kern drew to one side.

"It's too fast for me," he said, and let the motor-car pass him.

Jim Edwards was the next to fall back, and after him Rolla Means. Workman on Teddy and Wykert on Sam were left to fight it out alone.

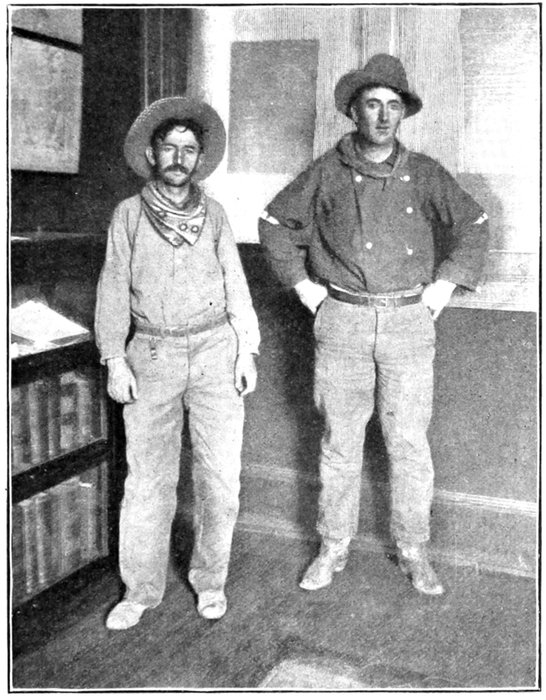

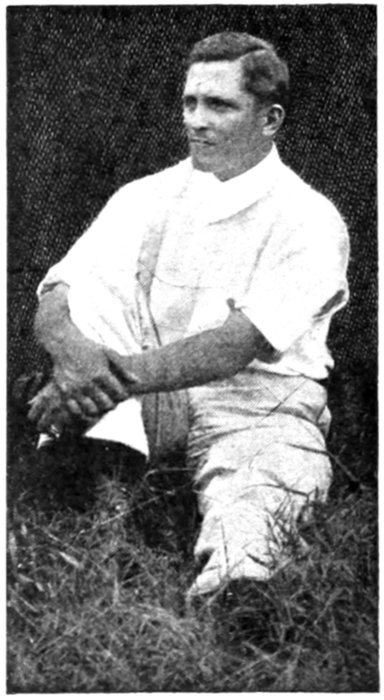

WORKMAN AND WYKERT, WHO DIVIDED THE FIRST AND SECOND PRIZES IN THE GREAT "ENDURANCE RACE."

From a Photograph.

Three times the big Wyoming horse pulled out in front, but "Dode" Wykert's roan hung steadily to his heels. Greeley was left behind, and then Fort Lupton, first one horse and then the other being ahead. At Brighton they were even, Sam being plainly in the better condition of the two, but unable to get ahead of Teddy. At last the outskirts of Denver showed in the distance. Automobiles and horsemen by hundreds had come out to escort them in. Still the two horses were neck and neck, and down in the heart of the city, where they passed between two living walls of excited humanity, they were still abreast. And so, under the finishing wire, in front of the offices of the Denver Post, the two plucky ponies made their last spurt in the great six-hundred-mile race with not an inch to choose between them. It had been a dead heat!

The first and second prizes were divided between the two men, but the "condition prize" of three hundred dollars was awarded to Wykert's Sam by a unanimous decision of the judges, for there was not the least doubt that Sam was comparatively fresh, while Teddy was very, very tired indeed.

Sorrel Clipper, with Edwards up, finished third some five hours later, and received the two hundred dollars prize. Kern came in shortly after, and six hours after him Casto, on Blue Bell, crossed the line. It was nearly twelve hours after this that Lee, on Cannonball, ambled leisurely down Champa Street and claimed the sixth and last prize.

It was a great race, pluckily run, and every horse that came in for prize-money was of the broncho breed. Rolla Means's Jay Bird, which had made so strong a bid for the first place, had given out entirely about Greeley, some sixty miles from the finish. This was the last of the standard-bred horses to stay with the leaders. For speed, wind, and "bottom" the bronchos had come through the test splendidly.

It was a great triumph for the game little broncho. Not pretty to look at, he is the best in the world for the conditions which prevail on the plains and in the Rockies. For other surroundings, perhaps, other types of horse are best, but for rough-and-ready going in all kinds of weather, with no feed except what it can pick up, the broncho asks odds of none.

By Maxime Schottland, Doctor Juris.

The amazing experience which befell a drunken old Russian bootmaker. "The events described occurred within my own cognizance while living in St. Petersburg," writes the author. "The episode could only have happened in Russia, unless there is any other country where the military caste is held in such veneration among civilians."

It was the birthday of Petroff, the bootmaker, and he had been celebrating it in the customary manner. That is to say, he had consumed so much of his favourite beverage, vodka, that he had now become hopelessly and helplessly intoxicated. In fact, so drunk was Petroff that the proprietor of the St. Petersburg inn where he had been soaking steadily all the afternoon had just turned him out into the street on the sufficient grounds that he could neither drink nor purchase any more liquor.

As poor Petroff staggered from the inhospitable doors of the inn, accompanied by the jeers of the remaining patrons, he fell into the arms of a couple of stalwart policemen.

"Lemme go," he protested, as the detaining hands tightened on his wrists. "I tell you I'm not—hic—drunk! I'm all ri'—shober as a judge, in fact. I want to go home."

The policemen laughed callously.

"You're going to the station with us," remarked the senior, with a grin at his comrade. "A night in the cells will cool your head, old man. Now, then, come along. Go quietly, or it will be the worse for you."

Petroff's legs swayed, and he would have fallen had not his escort, who were accustomed to dealing with such cases, held him tightly in their grasp.

The spectacle of the tipsy old man being led through the streets in custody promptly attracted a crowd, who followed the little procession at a respectful distance. Petroff turned his bleary eyes upon them, in the vain hope that they might light upon someone who would soften the hearts of his captors. Then another thought struck him with a chill feeling of dismay. If—as seemed certain to be his fate—he were locked up all night his wife would demand an explanation the next time he saw her. Mme. Petroff was a bit of a virago, and the drunken old reprobate had a wholesome terror of what might be in store for him if she got wind of his misbehaviour.

"Lemme go home," he whimpered. "I've a mosh important engagement—hic! My wife is waiting for me. It's all ri', I tell you."

The crowd laughed uproariously, as though they had just heard an excellent joke, while the policemen gave their prisoner a push forward.

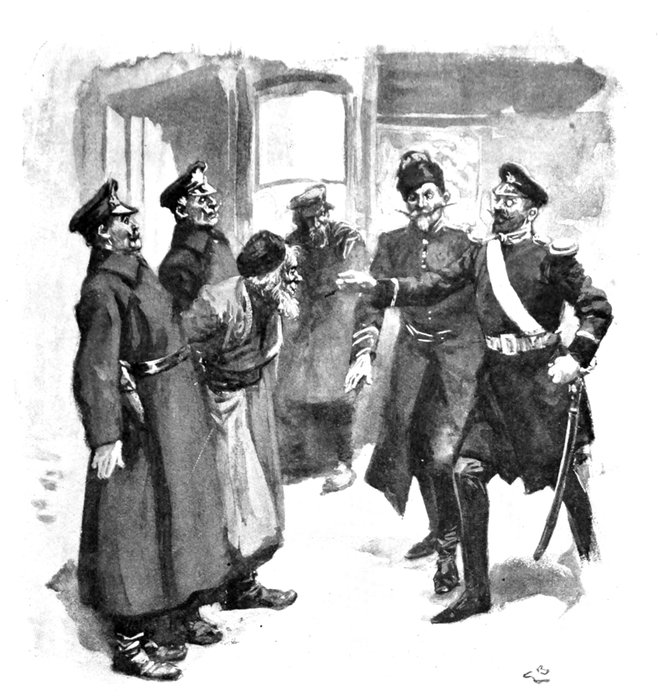

Petroff wept bitterly. He was just going to burst into an angry denunciation upon their conduct, when his attention was attracted by a couple of officers in military uniform, who strode up to him with outstretched hands.

"My dear fellow," exclaimed the younger of the two, looking at him in a puzzled fashion, "what on earth is the meaning of all this? It won't do, you know. We must take care of you."

Petroff's eyes began to blink, and he pinched himself to make certain he was not dreaming. But no; everything was quite real. Here were two of the Czar's officers, whom he had no recollection of ever having seen before, actually claiming his acquaintance! Wonders would never cease! It was no time, however, for argument. Evidently the strangers meant him well, and if they were making a mistake he meant to profit by it. Shaking the speaker's hand, accordingly, he poured out his wrongs in an eager torrent.

The brilliant uniforms of the two new-comers had a magic effect upon Petroff's custodians.

"I beg your Excellency's pardon," said one of them, with a deferential salute, "but we found this—er—gentleman drunk in the streets, and we thought it best to take him to the station. May I inquire if you know him?"

The officer nodded.

"Certainly," he returned. "We know him very well indeed. In fact, he's a neighbour of ours. I'm afraid he's had too much to drink. We'll take charge of him, though, and see him safely home. Here's something for your trouble," he added, slipping a couple of roubles into the other's hand.

"Please call a cab, and we'll take the professor to his rooms," observed the second officer, who had not yet spoken.

Petroff smiled affably. It was much pleasanter to be called a professor than a drunken old man.

"It's all ri'," he exclaimed, delightedly. "These gentlemen are—hic—old friends of mine. We'll all go home together—see?"

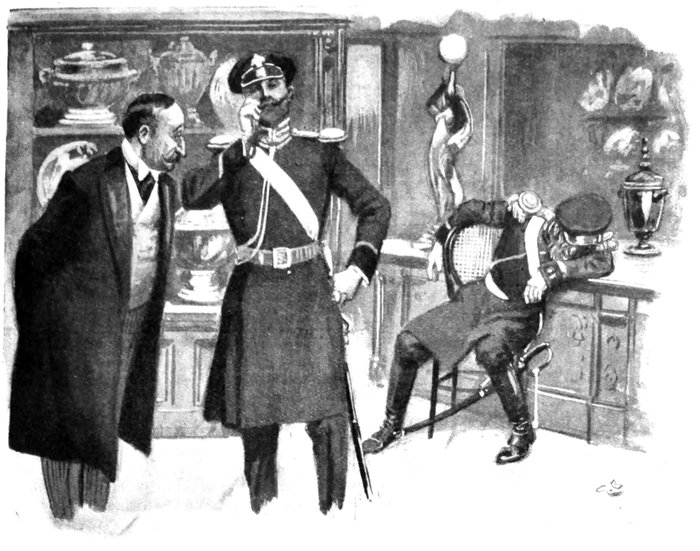

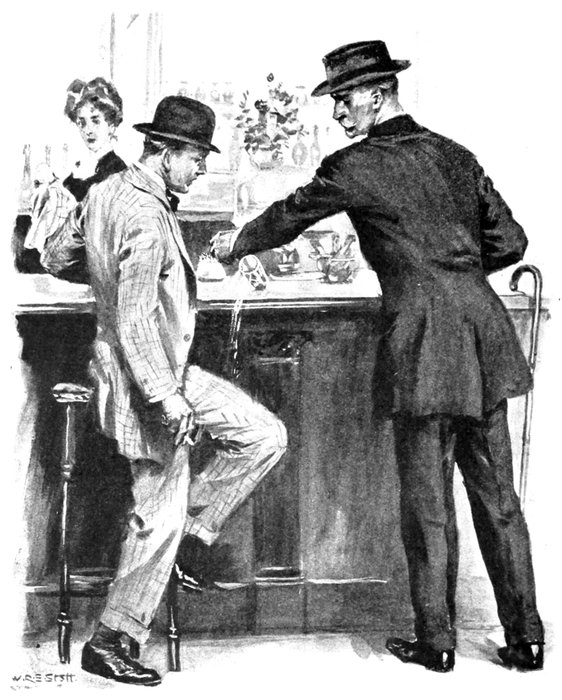

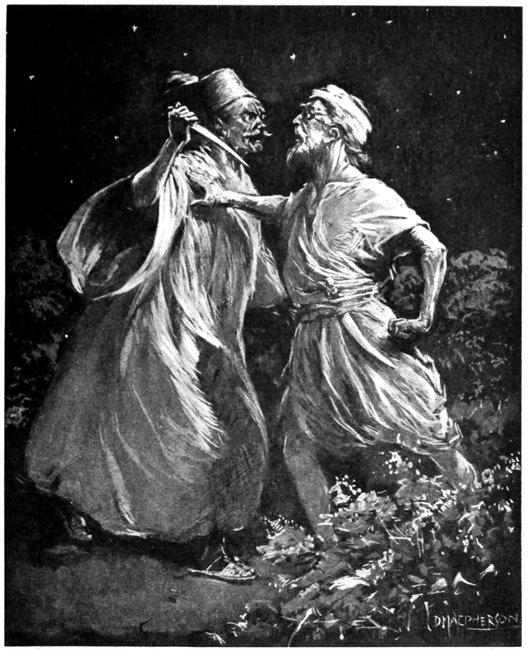

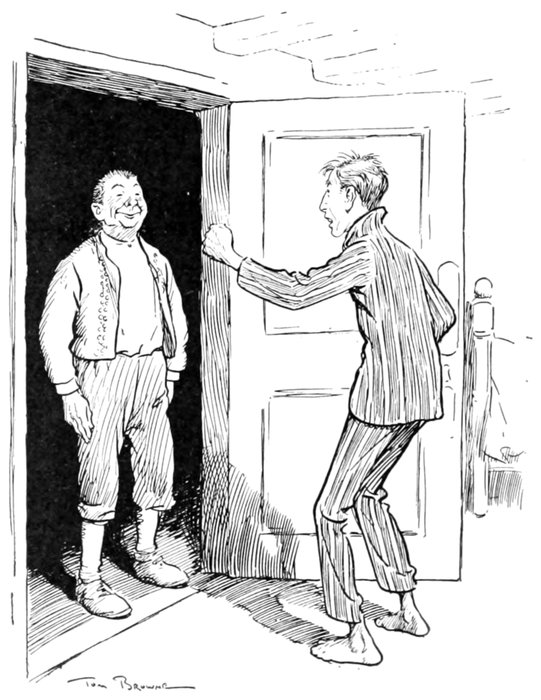

"'MY DEAR FELLOW', EXCLAIMED THE YOUNGER OF THE TWO, 'WHAT ON EARTH IS THE MEANING OF ALL THIS?'"

The two policemen, their last doubts dissipated by the promptitude with which the officers claimed their charge's acquaintance, acquiesced readily enough. A cab was procured and Petroff and his new-found friends installed therein, while the coachman was directed to drive to an address in a fashionable neighbourhood.

As the vehicle started off, Petroff looked at his deliverers with fresh wonder.

"Where have I met you before?" he murmured. "I don't seem to remember. Did you ever come to my boot-shop? If so, I mush have been drunk!"

The officer thus addressed shook his head gravely. "We had the honour of meeting your Excellency when you served in the army."

Petroff looked more puzzled than ever.

"The army?" he repeated. "What do you mean? I'm not a soldier. I'm a bootmaker."

The two officers exchanged glances.

"I beg your pardon for venturing to contradict you, sir, but the Czar has just been pleased to promote you to major-general in appreciation of your distinguished services."

Petroff smiled happily.

"It's the first I've heard of it," he murmured.

"I fancied, sir, that you might have been celebrating the appointment already," was the grave response. "We shall, however, be[Pg 120] honoured if you will join us in a little refreshment. Our house is close at hand."

"Certainly, my friends. I was going to have a drink when those rude policemen interfered just now."

As the old man spoke the cab drew up at the door of a handsome building. The next moment Petroff found himself being ushered into a beautifully-furnished room. Here the first thing upon which his eyes fell was a sideboard covered with bottles and glasses.

"How perfectly lovely!" he exclaimed, clasping his hands in ecstasy. "You don't know how thirsty I am. But what house is this?"

"It is your house, general."

The bootmaker's eyes blinked.

"Who's a general?" he demanded, truculently. "I won't have you make fun of me."

The senior of the two officers bowed deferentially.

"Your Excellency is pleased to jest. Of course you are a general. As, however, it is only to-day that you were appointed one, it is quite possible that the fact has escaped your memory."

Petroff's momentary anger evaporated at the speaker's apologetic tone. After all, it was much better to be a major-general than a bootmaker, and he was not going to quarrel with his good fortune.

"I did forget it for the moment," he returned, "but I'll remember it now. If I'm a major-general, though, I must have something to drink, eh?"

"Certainly, your Excellency," replied the other, as he uncorked a bottle of vodka and poured out a brimming glass. Petroff sat sipping it happily, when the second officer came over to his chair and saluted.

"Will your Excellency be pleased to dress now?" he remarked. "It is time to get into uniform." Then, without waiting for the old man to recover from the surprise which this announcement created, he brought forward a richly ornamented tunic, together with the remaining items of a general's uniform. Petroff gazed at the clothes in awe; he had never seen so much magnificence in his life.

As his two companions proceeded to make his toilet for him he could do nothing but murmur, "I'm a general." At last he had repeated the statement so often that, in his befuddled condition, he almost came to believe in it.

"I suppose I am really a general?" he remarked, as his companions assisted him to buckle on his sword.

"There is no doubt of it, your Excellency," replied the senior. "Let me introduce myself as Major Romanoff, and my colleague here as Captain Marckovitch. We have been appointed to act as your adjutants, and shall be pleased to carry out any orders you may give us."

Petroff laughed delightedly. This was a thousand times better than being a bootmaker and getting locked up for taking too much vodka.

"Very well, then; if I'm a general I must have another drink," he declared, stretching out his hand towards the table.

The fiery spirit seemed to touch a chord of memory.

"But what about my wife?" he demanded, suddenly. "Does she know I'm a—hic—general?"

"Certainly, sir. In fact, she has been trying to find you all day."

Petroff's face paled.

"What does she want?" he gasped.

"Merely to offer your Excellency her congratulations."

Here was a new mystery.

"That's very strange. She never wanted to—hic—congratulate me before."

"But she has only just heard of your promotion, sir."

The look of dismay faded from the old man's countenance, and a placid smile took its place.

"I must buy her a present," he declared.

"Yes, sir. That is why we are going out. Your wife will have to be presented at His Majesty's next reception, and you must accordingly order her some suitable jewels. Captain Marckovitch and I will be very pleased to conduct you to a firm where you can obtain such diamonds and other articles as will be necessary."

Petroff gulped down another glass of vodka. Under its stimulus his mind was working rapidly.

"That's all very well, my friends, but how am I going to get the money to pay for them? I spent my last rouble in the inn where the policemen found me."

Major Romanoff nodded.

"We have not yet had time to draw any funds from the Treasury on your behalf. Everything will be all right by to-morrow, though. In the meantime my colleague and myself will see that you are supplied with whatever you may be pleased to order at any shop. As the afternoon is drawing in, I would propose that we set out for a drive at once in your carriage."

Petroff rubbed his eyes in amazement. It seemed that surprises would never cease.

"But I haven't got a carriage," he protested.

"Pardon me," said Captain Marckovitch, "but your Excellency's establishment includes[Pg 121] a carriage and pair. It is already waiting at the door. Will it please you to make a start just now?"

"All right! I suppose I can't say anything better than that, can I?"

Captain Marckovitch bowed.

"Certainly, that will do admirably. In fact, sir, it's the only thing you need say while you are with us. Perhaps you will graciously pardon me if I take this opportunity of once more reminding you that, as your appointment is so—er—recent, it would perhaps be best if you permitted yourself to be guided by Major Romanoff and myself."

Petroff wagged his grey head with an air of profound wisdom. "Quite so. You tell me what to say, and I'll say it."

The senior adjutant bowed gravely.

"I was going to suggest that, sir. We are now all going out together to make some purchases for your Excellency's wife. While we are in the different shops it will not be necessary for you to say anything but 'All right' whenever your opinion is asked. You see, sir, your previous experience has almost entirely been gained on the field of battle. In fact, you have only just returned from a campaign."

"Have I?" interrupted the old man. "'Pon my word, I don't recollect it very clearly."

"Your Excellency was wounded in action," observed Captain Marckovitch, suavely. "Your memory may not return for a day or two. Still, you have only to say 'All right.'"

"Yes, I can remember that."

There was only time for a parting glass of vodka, and as Petroff drained the last drop in the bottle all his qualms disappeared. He felt determined to show the whole of St. Petersburg that he was as fine a major-general as any that the army of the Czar contained. The whole way down the stairs and out into the courtyard he kept repeating to himself, "I'm a general. All right."

A splendidly-appointed carriage was in waiting at the doorway. As the trio entered it, Major Romanoff gave the liveried coachman the address of a jewellery establishment in the Nevski Prospect. A few minutes' drive brought them to the door. The moment they alighted the manager and his assistants, dazzled by the magnificent equipage and uniforms of the party, came forward to receive their illustrious patrons with deferential bows.

Major Romanoff went up to Petroff, who had sunk heavily into a chair.

"Shall I explain your Excellency's wishes to Mr. Gorshine?" he inquired.

The manager rubbed his hands briskly. The unknown patron was an Excellency, then!

"All right," said Petroff.

"Perhaps I might be permitted to show his Excellency a selection from my stock," suggested Mr. Gorshine.

"Quite so," said Captain Marckovitch, hastily. "You must, however, please understand that his Excellency does not wish to spend more than two hundred thousand roubles this afternoon. The general," he added, sinking his voice a little, "is not feeling very well, so perhaps you had better make all the arrangements with Major Romanoff and myself."

Mr. Gorshine nodded comprehendingly.

"I understand perfectly, sir. His Excellency shall not be inconvenienced at all. Now, what can I have the pleasure of showing you?"

"His Excellency wishes to buy a diamond tiara and other jewellery for his wife. He would also like some rings and bracelets. Show us the best that your stock contains."

The manager beamed with delight, and, hastily unlocking a large safe, produced tray after tray covered with beautiful gems. The two adjutants inspected their contents hastily, and put aside the finest for a more detailed examination.

"How will this suit?" inquired Captain Marckovitch, picking up a magnificent tiara.

Petroff, who was feeling drowsy after his plentiful consumption of vodka, pushed it away with a lordly gesture.

"All right," he exclaimed.

"Then his Excellency approves of it?" inquired the delighted manager.

"Certainly, Mr. Gorshine; you have just heard him say so," declared Major Romanoff. "Pack it up."

"I'm feeling very thirsty," murmured Petroff. "Why doesn't somebody give me a drink?"

The obsequious jeweller rushed forward.

"Pray allow me to send for refreshments," he begged.

Captain Marckovitch nodded meaningly towards the chair where Petroff was sitting.

"Perhaps I ought to have told you that the general has a little weakness," he said. "His Excellency has only lately returned from a hot climate, and—well—you understand, no doubt."

The jeweller bowed.

"Entirely so, sir," he whispered. "In fact, a brother of mine, who is also in the army, cannot stand the slightest——"

"Besides," interrupted the adjutant, "we must make every allowance for so distinguished an officer. Apart from his bravery in action, it is well known that his kindness of heart, his thoughtfulness, and his generosity are proverbial. All the presents that he is buying now are intended for his wife."

"Yes, I'm going to give them to my wife,"[Pg 122] said Petroff, sharply. "She'll be so pleased that she'll forgive me. Now bring out some more. It's all right."

Mr. Gorshine wanted nothing better. Here was a customer who showed a lordly indifference to price, and who approved of everything set before him. Clearly a profitable afternoon was in store. Accordingly, he exerted himself to ransack the shelves and show-cases of their finest gems. These, after being critically inspected by the two adjutants, were passed over to their companion, who, for his part, contented himself with drowsily murmuring "All right."

At last, when goods to the estimated value of two hundred thousand roubles had been set aside, Major Romanoff declared that enough had been exhibited.

Mr. Gorshine bowed again. He had done a very fine day's work and nothing was to be gained by being too greedy.

"Might I venture to inquire his Excellency's name?" he hazarded.

Captain Marckovitch looked at him haughtily.

"I am surprised that you do not recognise the general," he remarked. "This is his Highness the Prince Savanoff, who has just returned from special service in the Caucasus. He is at present occupying an appointment at the Imperial Court."

"That's all right," murmured Petroff.

The jeweller was almost overcome with confusion at the slip he had made. Not to be familiar with the name of Prince Savanoff—the illustrious soldier whom all Russia was honouring just then on account of his distinguished services in the Caucasus—indicated a quite abysmal ignorance.

"Of course, I recognise his Excellency's name," he protested, humbly. "I had not, however, seen a photograph of the Prince."

Major Romanoff bent his brows.

"The Prince is as modest as he is brave. On this account he has never permitted his portrait to appear in the papers."

"Ten thousand apologies," exclaimed the contrite Mr. Gorshine. "And now, sir, is there anything else I can have the honour of showing you?"

"I will inquire," said the other, as he shook Petroff by the shoulder. "Is your Highness satisfied with what you have already chosen? If so, perhaps I had better take the jewels to the palace and let her Highness, your wife, decide which she will retain. Then, when I return, you can pay Mr. Gorshine for what she wishes to keep."

"All right," muttered Petroff.

The adjutant turned to the smiling jeweller.

"Very well, then. As time presses, I will start at once. His Excellency and Captain Marckovitch will remain here to await my return. The carriage is outside, and I can get to the palace and back in less than half an hour. Please pack everything up very carefully."

"Certainly, sir. If her Highness would like me to change any of these ornaments for others I shall be only too pleased to do so. Might I also beg, sir, that you will use your influence with the Prince to secure me an appointment as jeweller to the Court? Perhaps his Excellency would sign my application now?"

The major shrugged his shoulders and glanced at the somnolent Petroff.

"I'm really afraid," he answered, in a low tone, "that his Highness is scarcely in a condition to sign anything at this moment. Still, I will remember the matter. I should prefer, however, to speak to the Princess about it first. After all, these jewels are for her, you know."

"Quite so," was the prompt reply. "I will not detain you any longer."

As he spoke the manager picked up the velvet-lined cases and followed the adjutant to the carriage. When it disappeared from sight he went back into the shop, full of delight at the excellent stroke of business he had accomplished.

"A charming afternoon, your Excellency," he remarked.

Petroff gave vent to a long-drawn-out snore and dropped his head on the counter.

"The Prince is a little fatigued," observed Captain Marckovitch, apologetically. "He is not used to buying jewels. Perhaps you will be good enough to make out your bill, and it can be settled when my brother adjutant returns with her Excellency's decision."

"Certainly, sir. I will see about it at once."

Withdrawing to the counting-house, Mr. Gorshine spent a pleasant quarter of an hour totalling up the cost of the various articles which had been selected on approval. A smile of content spread over his features as he saw the substantial amount to which it came. Even if Major Romanoff brought back half the goods there would still be a handsome profit on the transaction. Certainly, Prince Savanoff was the sort of customer he would like to see in his shop every day in the week.

Presently he returned and handed the itemized account to the adjutant. Captain Marckovitch cast a cursory glance over it, and then put it down with a careless gesture.

"I expected it to be a good deal larger," he said, airily.

Mr. Gorshine began to reproach himself for not having added twenty-five per cent. to every item. The Prince would have paid it, he[Pg 123] felt sure. However, it was no good wasting time on vain regrets. Accordingly, he began to speculate what would be the best position in his showroom for displaying the coveted certificate appointing him Court jeweller. A quarter of an hour passed in this fashion. Mr. Gorshine looked at the clock pointedly. The evening was coming on, and it would soon be time to close the premises for the night.

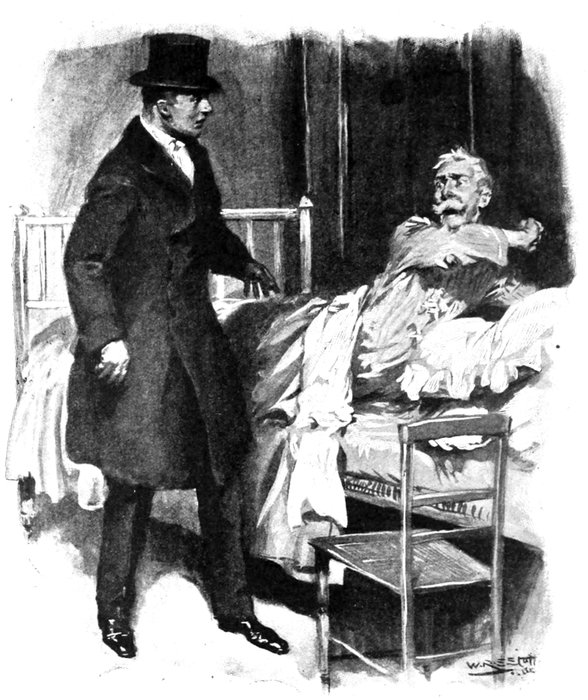

"'THE PRINCE IS A LITTLE FATIGUED,' OBSERVED CAPTAIN MARCKOVITCH."

"Major Romanoff is longer than I expected," observed Captain Marckovitch, taking out his watch.

"Perhaps he has not found her Excellency at home," suggested the other.

"I dare say you're right. It is quite possible, too, that her Excellency was out shopping when the major reached the palace. In this case he will naturally have decided to wait until she returns."

"Oh, naturally," agreed the jeweller.

Another twenty minutes went by. Despite all his efforts to appear at ease Mr. Gorshine began to feel a little disturbed. Several possible explanations of the delay occurred to him, the most likely one being that the Princess might have decided to see the general before making up her mind.

The adjutant interrupted his train of thought.

"I'm afraid it's not very far off your usual closing time," he remarked.

"We generally close at seven, sir."

The captain glanced at his watch again.

"It is now half-past six. If I start at once I can get to the palace and back by seven. Would you like me to drive there and explain that his Highness the Prince wishes her Excellency to make an immediate decision? Then, if by any chance I find she has not arrived, I will come back with Major Romanoff and the jewels."

Mr. Gorshine felt almost overwhelmed at such condescension.

"I could not think of troubling you, sir," he protested. "I will send one of my assistants."

"I'm afraid that won't do," returned the other, with a laugh. "You see, only an officer of the Guards would be admitted to the palace at this hour, and as I feel that I ought to relieve your very natural anxiety I will go myself. By the way, on no account disturb his Excellency[Pg 124] during my absence. It would make him very angry, and he might cancel his order."

"Certainly not, sir."

"Very well, then, I'll start at once. Be good enough to call a cab with a fast horse."

Secretly overjoyed at having the matter thus settled, but volubly protesting his disinclination to trouble his illustrious patron, the jeweller escorted the captain to the door and saw him into a cab. Then he returned to the showroom, where a group of assistants, with smiling faces, were watching the still snoring Petroff. As the manager came up to his chair he opened his eyes sleepily.

"It's all right," he murmured.

Darkness began to fall. It was too late to expect any more customers. In fact, the usual closing hour had already gone by and the assistants were beginning to get restless. Mr. Gorshine went to the doorway a dozen times and peered out into the street. On each occasion, however, he returned to his desk in disappointment. There was no sign of either Major Romanoff or Captain Marckovitch.

"What can have happened to his Excellency's adjutants?" he said. "They ought to have been back here long ago."

The principal assistant blew his nose thoughtfully.

"It's a long way after closing time, sir. I really think we ought to awaken his Excellency."

Mr. Gorshine, mindful of Captain Marckovitch's injunction, would not hear of such a thing.

"On no account," he exclaimed. "If we did so, his Highness would be certain to cancel the order he has given us."

At the end of another half-hour, however, the jeweller decided that it would perhaps be better to take his assistant's advice after all. There was just a possibility, too, that the Prince might catch cold. Besides, he ought to be back in the palace by this time for dinner. Accordingly he went up to him deferentially and laid a respectful hand upon his epauletted shoulder.

"I beg your Excellency's pardon," he said, "but your adjutants have not yet returned, and we wish to close the establishment now. If you will graciously permit me, I will see you back to the palace."

"All right," muttered Petroff. "I'm a general."

"Certainly, your Highness; but this is closing time."

The vodka mounted to Petroff's brain, and he began to get angry.

"Go to the devil!" he shouted, rising unsteadily to his feet. "I'm a general, I tell you. I want a drink. If you don't let me have one I'll put you all in prison!"

"Oh, pray forgive me!" exclaimed the manager, regretting his boldness. "I did not mean to inconvenience your Excellency. I merely wished to point out that it is closing time, and that perhaps you would like to return home."

A gleam of intelligence crept into Petroff's eyes.

"Yes, I want to go home," he murmured. "I want to see my wife."

"Then pray permit me to escort you. I will send for a carriage at once."

"All right," was the sulky response.

Although the keen night air sweeping up the open street sobered him a little, Petroff was still somewhat unsteady on his feet. Mr. Gorshine and a couple of assistants, however, managed to get him into a cab.

"Will your Highness have the goodness to give me the address to which you wish to be driven?" inquired the manager, deferentially, as he took the opposite seat.

With some little difficulty Petroff remembered the obscure quarter of the city in which he lived, and repeated the name and number of the street. Mr. Gorshine heard the answer in amazement, convinced that there must be some mistake. His companion, however, showed such an inclination to become argumentative that he finally decided to humour him, and they set off for the address indicated.

At the end of half an hour's drive the cab stopped in front of a squalid-looking house in a mean little side-street, far removed from the fashionable quarter of the city.

"It's all right," declared Petroff, glancing out of the window. "Here we are. Don't let my wife get angry with me. Tell her it wasn't my fault."

The jeweller smiled reassuringly, as the other clung to his arm and led the way up a steep flight of stairs. At the top floor Petroff stopped and fumbled with his latch-key.

"Don't wake my wife," he whispered.

As he spoke, however, the door was flung suddenly open, and an elderly woman, brandishing a stick, rushed out into the passage.

"There you are, then, you wicked old drunkard!" she exclaimed, shrilly. "I'll give you something for stopping out all this time. See if I don't!"

"Please don't let her hit me," shrieked Petroff, trying to hide behind his companion.

"Pardon me, madam, but his Highness is unwell," protested the jeweller, quite at a loss to account for this extraordinary reception.

Mme. Petroff burst into a peal of derisive laughter.

"Unwell, is he?" she retorted. "He'll be[Pg 125] worse presently, I can promise you!" Then her eyes fell on the magnificent uniform her husband was wearing.

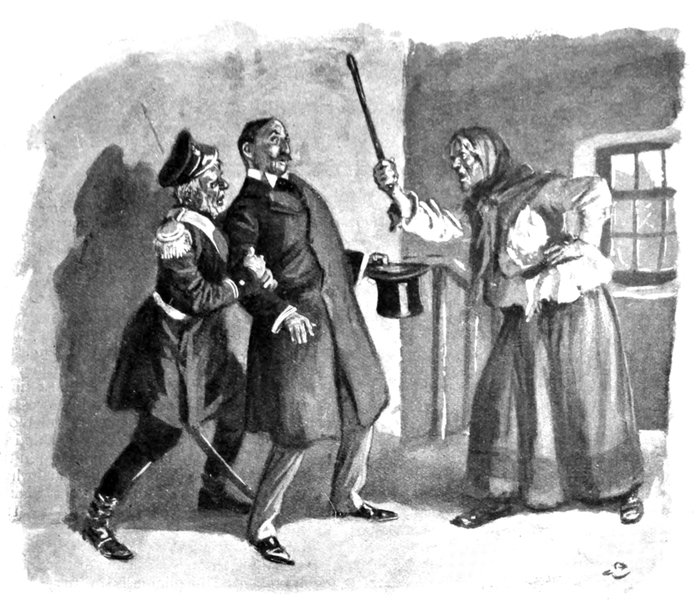

"'PLEASE DON'T LET HER HIT ME,' SHRIEKED PETROFF, TRYING TO HIDE BEHIND HIS COMPANION."

"What drunken freak is this?" she cried. "How dare you dress up as an officer, you silly old guy?"

Mr. Gorshine's face grew suddenly pale.

"I beg you not to be angry with his Highness," he exclaimed. "His adjutants, Major Romanoff and Captain Marckovitch, will probably be here directly."

Mme. Petroff snorted indignantly.

"I believe you're drunk, too. Since when, pray, has my husband been a Highness? He was Petroff, the bootmaker, this morning."

Mr. Gorshine sank into a chair, overwhelmed with horror.

"What?" he gasped, as soon as he found his breath. "Is not this his Highness Prince Savanoff, the famous general?"

"The famous fiddlestick," returned the other. "He's no more a Highness, and a Prince, and a general than you are yourself. He's a rascally, drunken old bootmaker, who disgraces the name of Petroff."

With the angry woman's shrill laughter ringing in his ears the unhappy jeweller staggered from the room and rushed down the stairs. He could think of nothing but the loss he had just sustained. By reporting the matter to the police at once there was a bare chance that some of the property might yet be recovered.

The superintendent of police, however, to whom he poured out his story, could not offer him much encouragement. It was clear that he had been made the victim of a singularly audacious robbery. The only thing that the authorities could do was to arrest Petroff as an accomplice. As, however, there was no evidence to connect him with the theft, he was, after a week's enforced sobriety, permitted to return to his wife.

This was comforting for Petroff, perhaps, but it was anything but pleasant for the hapless Mr. Gorshine, who never saw his jewels or the two "adjutants" again.

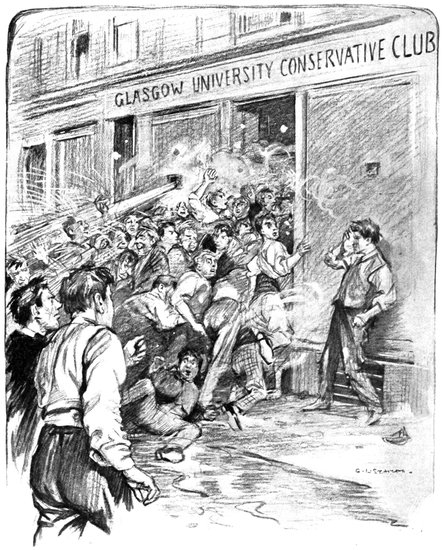

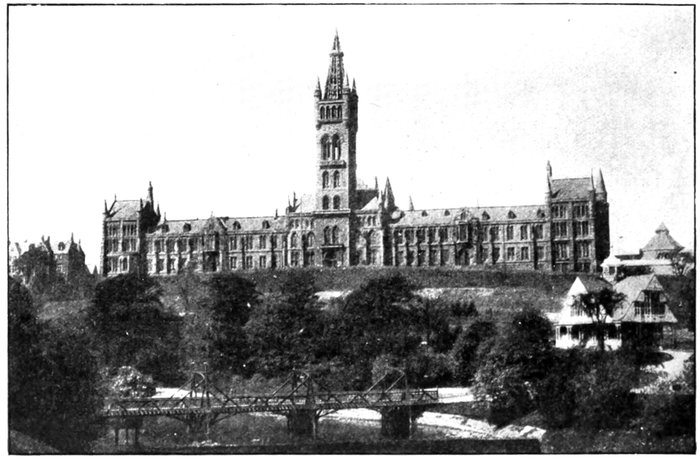

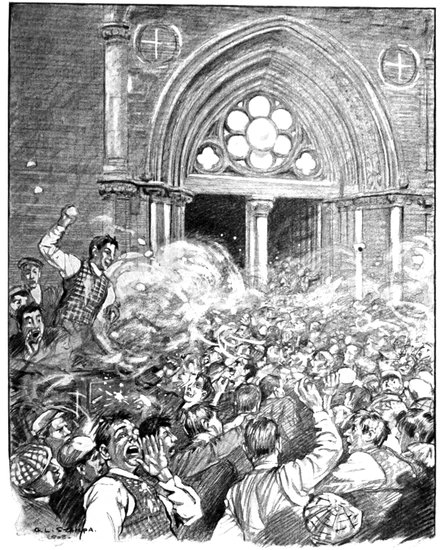

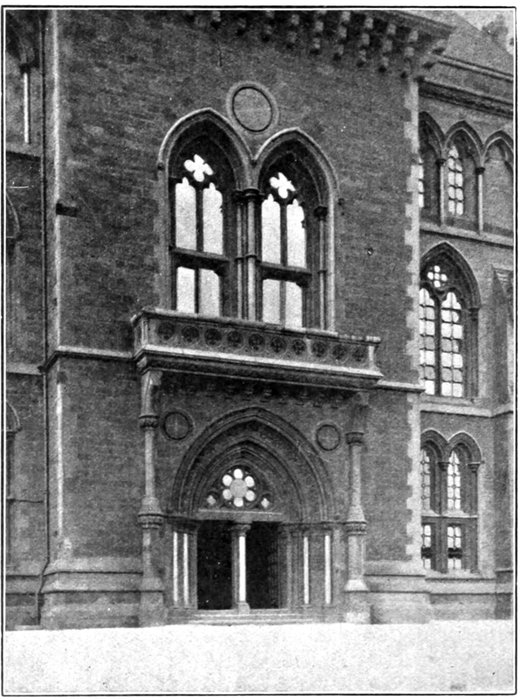

Some of the customs in vogue at American Universities are startling enough, but it comes as a surprise to learn that the authorities of an ancient Scottish foundation, aided and abetted by the police, countenance such extraordinary doings as are chronicled in this topical article. The writer describes the Glasgow University Rectorial Election of 1905, in which he took part as an official of one of the clubs concerned.

On October 24th of this year the students of Glasgow University will choose for themselves a new Lord Rector. Already announcements have appeared in the Press that the candidates are Lord Curzon (Conservative), Mr. Lloyd George (Liberal), and Mr. Keir Hardie (Socialist).

Triennially the public reads in some obscure corner in its newspapers that a Rectorial election is in progress in a Scotch University, that the fighting is fiercer than ever before, and that damage has been done amounting to hundreds of pounds. The reader, according to his viewpoint, either swiftly ejaculates a condemnation of such barbarous practices or grins as he detects what he takes to be newspaper exaggerations. The real facts behind all this the general public never learn; they never realize what a strange anachronism a Rectorial election is.

Fancy carefully-organized fighting, with a hundred or two hundred young men on either side, ending in the wrecking of the premises of the losers—to the breaking down the plaster of the walls and the tearing up of the floor—all countenanced by staid University authorities and countenanced, too, by the police department of a municipality that prides itself on being the most up-to-date in the country! Indeed, the police not only countenance the business but actually assist by sending forces of men to the scene of operations to ring round the arena, keep back the crowd, and often to hold up the electric cars and other street traffic while the rival parties push the claims of their respective candidates vi et armis! In the exigencies of the campaign, moreover, many deeds are done with perfect impunity by the students which would be seriously visited on less favoured mortals—for example, the cutting through of main water-pipes, carrying the supplies of whole blocks of buildings.

The good people of Glasgow are, for the most part, not at all inclined to withdraw this licence. They are, on the contrary, rather proud of the sacrifices they make in order that old customs may be kept up, and their complacency and good-humoured tolerance are almost inconceivable to people of non-University towns.

That the readers of The Wide World Magazine may realize what lies behind the fragmentary reports which they will find in their newspapers this month I shall relate what I know of Glasgow Rectorial elections, and particularly of the last election in November, 1905, in which I was specially concerned.

In most other Universities in these days the Rectorship is a purely academic distinction, probably conferred unanimously by the students. In Glasgow, however, it is still decided on political grounds.

In the University there exist two permanent clubs: the Glasgow University Conservative Club and the Glasgow University Liberal Club, the constitutional purpose of each of which is to effect the election of a Lord Rector of its own political colour.

For three years—since the last election—these clubs have been scraping money together. The election will cost each side from two to four hundred pounds, and the size of the fight they put up and their output of election literature will be on the scale of the funds in hand. Needless to say, most of the money comes from party sources and private subscriptions outside the University, but owing to the extraordinary nature of the campaign no accounts are ever made public. Like Tammany Hall and other efficient political "machines," a despotism is absolutely necessary. The entire control of the money is vested in four, or three, or even two students, and no questions are ever asked as to the uses to which they think best to put it.

At the beginning of the session preceding the election the presidents of the clubs, with great[Pg 127] secrecy, approach various leading men of their parties, and finally fix on candidates. In the second half of the session, about February, the candidates are announced, and soon afterwards the Conservative and Liberal Rectorial Committees are formed. These committees are large, numbering, perhaps, fifty in each, though, as I have said, the actual executives are very small. Each committee is divided into three sections—the canvassing, the literature, and the physical force.

The conveners of these sub-committees are busy all through the summer vacation with preparations for the coming fray, forming their plans, inventing ruses, and intriguing for various advantages.

The campaign commences in earnest as soon as college reassembles in the third week of October, and continues in a wild whirl of excitement for a fortnight, until the day of election. Then all the leading men, haggard and nearly dead with fatigue and the incessant strain, go to bed and sleep for twenty-four hours. The day after the election the 'Varsity is as quiet and peaceful as the most select young ladies' seminary.

This is the invariable course of events. On the particular occasion I am about to describe—the election of 1905—the candidates announced in the spring were Lord Linlithgow (Conservative) and Mr. Asquith (Liberal). The Liberals had lost the last election badly, but the reaction against the Government gave them high hopes of pulling their man through on this occasion.

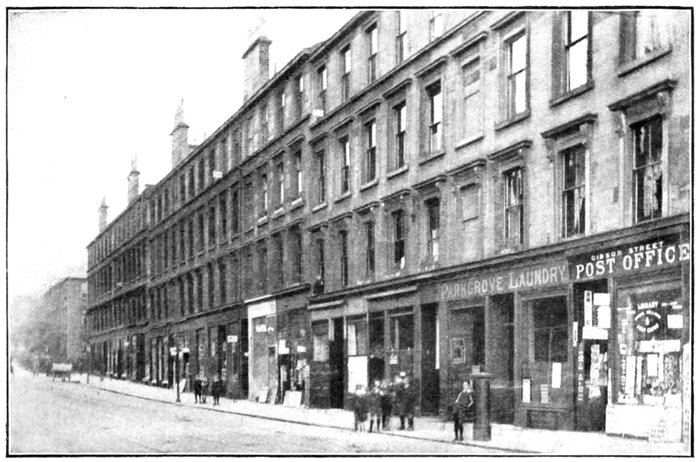

The summer, apart from the publishing of one magazine by the Liberals, was, as usual, a time of public inaction, but secret preparations. The clubs rented two large shops—almost next door to one another, by mutual arrangement—in a street near the University. These were the "committee rooms," and were practically the head-quarters from which the fighting was done. They were prepared for occupation by (1) removing all partitions and throwing the shop itself and the rooms behind into one large, bare apartment. (2) Taking out all fittings, even to the fire-grates. (3) Taking out the windows and filling their place with very massive, buttressed barricades, having loopholes high up. (4) Leading in special water supplies and fitting hydrants for hoses. In addition, the cellars are stocked with great cases of pease-meal, made up into paper packets of convenient size for throwing. A piano was also placed in each of the committee rooms.

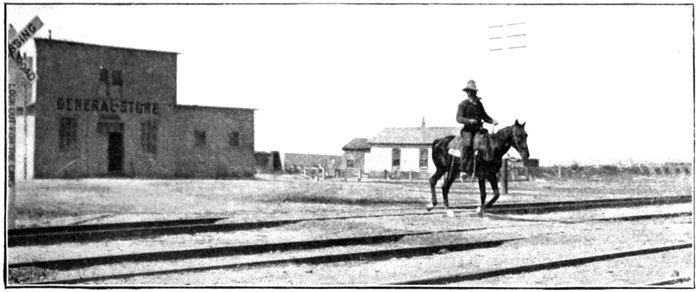

GIBSON STREET, GLASGOW, WHERE BOTH COMMITTEE-ROOMS ARE INVARIABLY SITUATED—IN THE LAST ELECTION THE CONSERVATIVES USED THE PREMISES OF THE LAUNDRY SHOWN AT THE RIGHT OF THE PHOTOGRAPH, WHILE THE INTERNAL ROOMS WERE TWO SHOPS HIGHER UP THE STREET.

From a Photograph.

About the 20th of October students rattled back to their Alma Mater from all parts of the country with an eager lust for the coming fray. For myself I can solemnly say that the ensuing fortnight was the happiest time I have ever had. The abandon, the madness of it; the fiercest possible fighting and raiding, with a minimum[Pg 128] of serious injury; and behind it all, on both sides, the greatest good-humour—all these are impossible to describe. Only students, I imagine, could fight such wild, lunatic fights with never a lost temper.

The Glasgow University Conservative and Liberal Clubs hereby agree to the following arrangements for the conduct of the Rectorial Election.

1. The Rooms of the Clubs shall be used for Fighting on and after October 25th, with the exceptions hereafter mentioned.

2. Pianos shall be held inviolable.

3. There shall be no Battering Rams used or similar appliances whose use is dangerous.

4. Matriculation and Class Tickets shall not be taken.

5. Fighting shall be with "open doors," i.e., no insuperable obstacles shall be placed in the doorway.

6. Gas fittings shall be inviolable.

7. Canvassers and Canvass Sheets shall be inviolable.

8. The evenings on which Smokers are held by either Club shall be truces.

9. Truces shall exist till half-an-hour after all other meetings.

JOSEPH DAVIDSON,

Hon. Secy.,

G.U. Conservative Club.

J. C. WATSON,

Hon. Secy.,

G.U. Liberal Club.

The atmosphere was something different from the rest of life; it was like a slice out of the Middle Ages. Up all night and sleeping during the day, life became for us a complicated mass of plottings and intrigues, ambushes, wild chases in cabs, men spying on other men and in turn being shadowed themselves. Last, but by no means least, there was the unholy but very real joy that comes of the unlicensed destruction of property. A Rectorial election is the shortest road to romance in this prosaic modern life that I know of.

The canvass, though very efficient, is comparatively routine work, and naturally neither particularly novel nor interesting. I shall pass it over and deal mainly with the fighting. There were four chief features in the fighting—"painting raids," "regular battles," "magazine captures," and "bus fights."

At this election some attempt was made for the first time to restrain and organize the fighting. It was thought that it would be better to have something in the way of fixed battles by mutual agreement rather than or in addition to the constant running fight. Consequently truces were frequently arranged, except at the times fixed on for battles. These truces, however, were technically held not to inhibit painting raids.

The front of each of the committee-rooms was, of course, loudly painted with the party colour—red for the Liberals, blue for the Conservatives. A painting raid meant stealing out at dead of night, with paint-buckets and brushes, and daubing the enemy's rooms your own colour.

Our opponents, however, sometimes received information beforehand in some mysterious way. The painters would be softly busy, with a whish-whish of brushes, chuckling to one another, when suddenly, without a whisper of warning, two deadly streams of water would pour an irresistible cross-fire from the loopholes and sweep painters, chairs, and ladders to the ground in a confused, dripping mass. Then there was much spluttering and vociferation, and, if possible, the contents of the paint-buckets were made to shoot through the loopholes. The barricades, however, were invulnerable, and the hoses could not be withstood. If the enemy are prepared for a painting raid there is little to do but retire.

In this sort of work it was pretty well give-and-take; both sides painted and were painted. The raids, however, ceased once the regular fighting commenced.

This happened a few days later, when the "articles of war," here reproduced, were published by both clubs in their magazines.

The "open doors" article was new. It came of past experience. If the massive doors of a committee-room were closed, obviously the only way of getting at those inside was with axes and heavy rams, with results and risks, in excited hands, rather more serious than the clubs were prepared to face. It turned out a wise step, for it had the effect of making the fights more physical and good-humoured, and in all probability prevented a great deal of serious injury and wounding.

The article about pianos was, strangely enough, strictly kept. It was a striking sight at the end of a "wrecking" to see the piano standing unhurt and immaculate amid a chaos of torn flooring and broken plaster.

The matriculation and class tickets of a student are what make him eligible to vote, and would cost at least four guineas to replace. To make war on these would be a shabby way of winning an election.

Though it was the "open season," so to speak, after October 25th very little fighting was done by the rank and file except at the battles. The clubs concentrated all their energies on these. The occasions were arranged beforehand, and there were four altogether.

On the evening of the first battle students arrived in the oldest rags they could lay hands on. A great crowd of spectators also turned up, the time of the engagement having leaked out. The crowd was kept back by a force of policemen. Inside the rooms busy preparations were going on. Boxes of pease-meal bags were hauled up from the cellar and served out to all hands—if you were clever you might manage to carry ten of these most effective missiles. The hoses were fixed up and tested, while men who were not willing to submit even the worst clothes they had to the combined effect of pease-meal and water stripped until they were clad only in the sparsest of underwear.

The Liberals—of whom I may as well confess at once I was one—divided their force. About two-thirds were detailed for attack, and the remainder had to stay by the rooms and defend them in case of need. This boldness was because we had been assured by our scouts that we were largely in the majority. The Conservatives, realizing their weakness, only threw perhaps a quarter of their number outside.

A few minutes before the hour the attacking forces lined up opposite their doors, facing one another. They looked a queer lot, in most grotesque attire—the first pease-meal bag ready in each man's right hand, their figures bulging with the remainder. In the rooms the defending forces were massed at the open doors, while at each loophole were two men controlling the nozzle of a hose. These waited anxiously, for the result of the collision of the outside forces determined whose rooms were to be attacked.

On this occasion, however, there was little doubt. The odds were so clearly against the Conservatives that, unless they had some stratagem up their sleeve (which was always very possible), it was decidedly to be the Liberals' night.

The good-natured and even sympathetic police-inspector in charge capped the official sanction by consenting to blow his whistle to start us. He stood, watch in hand, with the whistle between his lips and his eyes on the minute-hand. Dead silence prevailed all around.