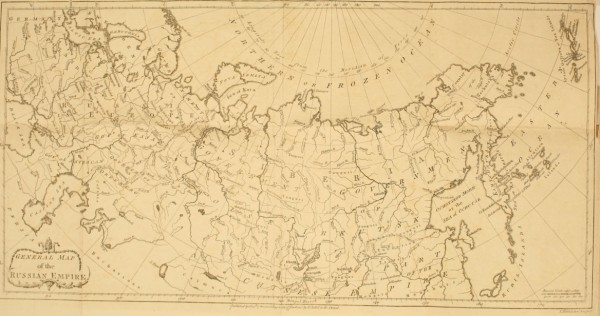

General Map of the Russian Empire.

General Map of the Russian Empire.

Title: Account of the Russian Discoveries between Asia and America

Author: William Coxe

Release date: August 6, 2015 [eBook #49637]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Judith Wirawan and The Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

TO WHICH ARE ADDED,

THE CONQUEST OF SIBERIA,

AND

THE HISTORY OF THE TRANSACTIONS AND

COMMERCE BETWEEN RUSSIA AND CHINA.

By WILLIAM COXE, A. M.

Fellow of King's College, Cambridge,

and Chaplain to his Grace the

Duke of Marlborough.

LONDON,

PRINTED BY J. NICHOLS,

FOR T. CADELL, IN THE STRAND.

MDCCLXXX.

TO

JACOB BRYANT, ESQ.

AS A PUBLIC TESTIMONY

OF

THE HIGHEST RESPECT FOR

HIS DISTINGUISHED LITERARY ABILITIES,

THE TRUEST ESTEEM FOR

HIS PRIVATE VIRTUES,

AND THE MOST GRATEFUL SENSE OF

MANY PERSONAL FAVOURS,

THE FOLLOWING PAGES ARE INSCRIBED,

BY

HIS FAITHFUL AND AFFECTIONATE

HUMBLE SERVANT,

WILLIAM COXE.

Cambridge,

March 27, 1780.

The late Russian Discoveries between Asia and America have, for some time, engaged the attention of the curious; more especially since Dr. Robertson's admirable History of America has been in the hands of the public. In that valuable performance the elegant and ingenious author has communicated to the world, with an accuracy and judgement which so eminently distinguish all his writings, the most exact information at that time to be obtained, concerning those important discoveries. During my stay at Petersburg, my inquiries were particularly directed to this interesting subject, in order to learn if any new light had been thrown on an article of knowledge of such consequence to the history of mankind. For this purpose I endeavoured to collect the respective journals of the several voyages subsequent to the expedition of Beering and Tschirikoff in 1741, with which the celebrated Muller concludes his account of the first Russian navigations.

During the course of my researches I was informed, that a treatise in the German language, published at Hamburg and Leipsic in 1776, contained a full and exact narrative of the Russian voyages, from 1745 to 1770[1].

As the author has not prefixed his name, I should have paid little attention to an anonymous publication, if I had not been assured, from very good authority, that the work in question was compiled from the original journals. Not resting however upon this intelligence, I took the liberty of applying to Mr. Muller himself, who, by order of the Empress, had arranged the same journals, from which the anonymous author is said to have drawn his materials. Previous to my application, Mr. Muller had compared the treatise with the original papers; and he favoured me with the following strong testimony to its exactness and authenticity: "Vous ferès bien de traduire pour l'usage de vos compatriotes le petit livre sur les isles situées entre le Kamtchatka et l'Amerique. II n'y a point de doute, que l'auteur n'ait eté pourvu de bons memoires, et qu'il ne s'en foit fervi fidelement. J'ai confronté le livre avec les[Pg vii] originaux." Supported therefore by this very respectable authority, I considered this treatise as a performance of the highest credit, and well worthy of being more generally known and perused. I have accordingly, in the first part of the present publication, submitted a translation of it to the reader's candour; and added occasional notes to such passages as seemed to require an explanation. The original is divided into sections without any references. But as it seemed to be more convenient to divide it into chapters; and to accompany each chapter with a summary of the contents, and marginal references; I have moulded it into that form, without making however any alteration in the order of the journals.

The additional intelligence which I procured at Petersburg, is thrown into an appendix: It consists of some new information, and of three journals[2], never before given to the public. Amongst these I must particularly mention that of Krenitzin and Levasheff, together with the chart of their voyage, which was communicated to Dr. Robertson, by order of the Empress of Russia; and which that justly admired historian has, in the politest and most obliging manner,[Pg viii] permitted me to make use of in this collection. This voyage, which redounds greatly to the honour of the sovereign who planned it, confirms in general the authenticity of the treatise above-mentioned; and ascertains the reality of the discoveries made by the private merchants.

As a farther illustration of this subject, I collected the best charts which could be procured at Petersburg, and of which a list will be given in the following advertisement. From all these circumstances, I may venture, perhaps, to hope that the curious and inquisitive reader will not only find in the following pages the most authentic and circumstantial account of the progress and extent of the Russian discoveries, which has hitherto appeared in any language; but be enabled hereafter to compare them with those more lately made by that great and much to be regretted navigator, Captain Cooke, when his journal shall be communicated to the public.

As all the furs which are brought from the New Discovered Islands are sold to the Chinese, I was naturally led to make enquiries concerning the commerce between Russia and China; and finding this branch of traffic much more important than is commonly imagined, I thought that a general sketch of its present state,[Pg ix] together with a succinct view of the transactions between the two nations, would not be unacceptable.

The conquest of Siberia, as it first opened a communication with China, and paved the way to all the interesting discoveries related in the present attempt, will not appear unconnected, I trust, with its principal design.

The materials of this second part, as also of the preliminary observations concerning Kamtchatka, and the commerce to the new-discovered islands, are drawn from books of established and undoubted reputation. Mr. Muller and Mr. Pallas, from whose interesting works these historical and commercial subjects are chiefly compiled, are too well known in the literary world to require any other vouchers for their judgement, exactness, and fidelity, than the bare mentioning of their names. I have only farther to apprize the reader, that, besides the intelligence extracted from these publications, he will find some additional circumstances relative to the Russian commerce with China, which I collected during my continuance in Russia.

I cannot close this address to the reader without embracing with peculiar satisfaction the just occasion, which the ensuing treatises upon the Russian discoveries and commerce afford me, of joining with every friend of science in the warmest admiration of that enlarged and liberal spirit, which so strikingly marks the character of the present Empress of Russia. Since her accession to the throne, the investigation and discovery of useful knowledge has been the constant object of her generous encouragement. The authentic records of the Russian History have, by her express orders, been properly arranged; and permission is readily granted of inspecting them. The most distant parts of her vast dominions have, at her expence, been explored and described by persons of great abilities and extensive learning; by which means new and important lights have been thrown upon the geography and natural history of those remote regions. In a word, this truly great princess has contributed more, in the compass of only a few years, towards civilizing and informing the minds of her subjects, than had been effected by all the sovereigns her predecessors since the glorious æra of Peter the Great.

In order to prevent the frequent mention of the full title of the books referred to in the course of this performance, the following catalogue is subjoined, with the abbreviations.

Müller's Samlung Russischer Geschichte, IX volumes, 8vo. printed at St. Petersburg in 1732, and the following years; it is referred to in the following manner: S. R. G. with the volume and page annexed.

From this excellent collection I have made use of the following treatises:

vol. II. p. 293, &c. Geschichte der Gegenden an dem Flusse Amur.

There is a French translation of this treatise, called Histoire du Fleuve Amur, 12mo, Amsterdam, 1766.

vol. III. p. 1, &c. Nachrichten von See Reisen, &c.

There is an English and a French translation of this work; the former is called "Voyages from Asia to America for completing the Discoveries of the North West Coast of America," &c. 4to, London, 1764. The title of the latter is Voyages et Decouvertes faites par les Russes, &c. 12mo, Amsterdam, 1766. p. 413. Nachrichten Von der Hanlung in Sibirien.

Vol. VI. p. 109, Sibirische Geshichte.

Vol. VIII. p. 504, Nachricht Von der Russischen Handlung nach China.

Pallas Reise durch verschiedene Provinzen des Russischen Reichs, in Three Parts, 4to, St. Petersburg, 1771, 1773, and 1776, thus cited, Pallas Reise.

Georgi Bemerkungen einer Reise im Russischen Reich in Jahre, 1772, III volumes, 4to, St. Petersburg, 1775, cited Georgi Reise.

Fischer Sibirische Geschichte, 2 volumes, 8vo, St. Petersburg, cited Fis. Sib. Ges.

Gmelin Reise durch Sibirien, Tome IV. 8vo. Gottingen, 1752, cited Gmelin Reise.

There is a French translation of this work, called Voyage en Siberie, &c. par M. Gmelin. Paris, 1767.

Neueste Nachrichten von Kamtchatka aufgesetst im Junius des 1773ten Yahren von dem dasigen Befehls-haber Herrn Kapitain Smalew.

Aus dem abhandlungen der freyen Russischen Gesellschaft Moskau.

In the journal of St. Petersburg, April, 1776.—cited Journal of St. Pet.

Baidar, a small boat.

Guba, a bay.

Kamen, a rock.

Kotche, a vessel.

Krepost, a regular fortress.

Noss, a cape.

Ostrog, a fortress surrounded with palisadoes.

Ostroff, an island.

Ostrova, islands.

Quass, a sort of fermented liquor.

Reka, a river.

The Russians, in their proper names of persons, make use of patronymics; these patronymics are formed in some cases by adding Vitch to the christian name of the father; in others Off or Eff: the former termination is applied only to persons of condition; the latter to those of an inferior rank. As, for instance,

| Among persons | of condition | Ivan Ivanovitch, | } Ivan the son of Ivan. |

| of inferior rank, | Ivan Ivanoff | ||

| Michael Alexievitch, | } Michael the son of Alexèy. | ||

| Michael Alexeeff, | |||

| Sometimes a surname is added, Ivan Ivanovitch Romanoff. | |||

A pood weighs 40 Russian pounds = 36 English.

16 vershocks = an arsheen.

An arsheen = 28 inches.

Three arsheens, or seven feet = a fathom[3], or sazshen.

500 sazshens = a verst.

A degree of longitude comprises 104-1/2 versts = 69-1/2 English miles. A mile is therefore 1,515 parts of a verst; two miles may then be estimated equal to three versts, omitting a small fraction.

A rouble = 100 copecs.

Its value varies according to the exchange from 3s. 8d. to 4s. 2d. Upon an average, however, the value of a rouble is reckoned at four shillings.

| P. | 23, | Reference, for Appendix I. No I. read No II. |

| 24, | for Appendix I. No II. read No III. | |

| 30, | for Rogii read Kogii. | |

| 46, | for Riksa read Kiska. | |

| 96, | for Korovin read Korelin. | |

| 186, | Note—for Tobob read Tobol. | |

| 154, | Note—Line 2, after handpauken omitted von verschiedenen Klang. | |

| 119, | for Saktunk read Saktunak. | |

| 134, | Line 6, for were read was. | |

| 188, | l. 16. for pretection read protection. | |

| 190, | l. 5. for nor read not. | |

| 195, | for Sungur read Sirgut. | |

| 225, | l. 13. read other has an. | |

| 226, | for harlbadeers read halberdiers. | |

| 234, | Note—line 3, dele See hereafter, p. 242. | |

| 246, | for Marym read Narym. | |

| 256, | Note—for called by Linnæus Lutra Marina read Lutra Marina, called by Linnæus Mustela Lutris, &c. | |

| 257, | Line 5, for made of the bone, &c. read made of bone, or the stalk, &c. | |

| 278, | Note 2—line 2, for Corbus read Corvus. | |

| 324, | Note—line 4, dele was. | |

| 313, | Note—line 3, dele that. | |

| Ibid. | Note—line 10, "I should not" &c. is a separate note, and relates to the extract in the text beginning "In 1648," &c. |

Omitted in the ERRATA.

| P. 242. | l. 9. r. 18, 215. |

| l. 11. r. 1, 383, 621. 35. |

As no astronomical observations have been taken in the voyages related in this collection, the longitude and latitude ascribed to the new-discovered islands in the journals and upon the charts cannot be absolutely depended upon. Indeed the reader will perceive, that the position[4] of the Fox Islands upon the general map of Russia is materially different from that assigned to them upon the chart of Krenitzin and Levasheff. Without endeavouring to clear up any difficulties which may arise from this uncertainty, I thought it would be most satisfactory to have the best charts engraved: the reader will then be able to compare them with each other, and with the several journals. Which representation of the new-discovered islands deserves the preferance, will probably be ascertained upon the return of captain Clerke from his present expedition.

| CHART | I. | A reduced copy of the general map of Russia, published by the Academy of Sciences at St. Petersburg, 1776. | to face the title-page. |

| II. | Chart of the voyage made by Krenitzin and Levasheff to the Fox Islands, communicated by Dr. Robertson, | to face p. 251. | |

| III. | Chart of Synd's Voyage towards Tschukotskoi-Noss, | p. 300. | |

| IV. | Chart of Shalauroff's Voyage to Shelatskoi-Noss, with a small chart of the Bear-Islands, | p. 323. | |

| View of Maimatschin, Communicated by a gentleman who has been upon the spot. |

p. 211. | ||

| Dedication, | p. iii. |

| Preface, | p. v. |

| Catalogue of books quoted in this work, | p. xi. |

| Explanation of some Russian words made use of, | p. xiii. |

| Table of Russian Weights, Measures of Length, and Value of Money, | p. xiv. |

| Advertisement, | p. xv. |

| List of Charts, and Directions for placing them, | p. xvi. |

| PART I. | |

| Containing Preliminary Observations concerning Kamtchatka, and Account of the New Discoveries made by the Russians, | p. 3—16. |

| Chap. I. Discovery and Conquest of Kamtchatka—Present state of that Peninsula—Population—Tribute—Productions, &c. | p. 3. |

| Chap. II. General idea of the commerce carried on to the New Discovered Islands—Equipment of the vessels—Risks of the trade, profits, &c. | p. 8. |

| Chap. III. Furs and skins procured from Kamtchatka and the New Discovered Islands, | p. 12. |

| Account of the Russian Discoveries, | p. 19. |

| Chap. I. Commencement and progress of the Russian Discoveries in the sea of Kamtchatka—General division of the New Discovered Islands, | ibid. |

| Chap. II. Voyages in 1745—First discovery of the Aleütian Isles, by Michael Nevodsikoff, | p. 29. |

| Chap. III. Successive voyages, from 1747 to 1753, to Beering's and Copper Island, and to the Aleütian Isles—Some account of the inhabitants, | p. 37. |

| Chap. IV. Voyages from 1753 to 1756. Some of the further Aleütian or Fox Islands touched at by Serebranikoff's vessel—Some account of the natives, | p. 48. |

| Chap. V. Voyages from 1756 to 1758, | p. 54. |

| Chap. VI. Voyages in 1758, 1759, and 1760, to the Fox Islands, in the St. Vladimir, fitted out by Trapesnikoff—and in the Gabriel, by Bethshevin—The latter, under the command of Pushkareff, sails to Alaksu, or Alachshak, one of the remotest Eastern Islands hitherto visited—Some account of its inhabitants, and productions, which latter are different from those of the more Western islands, | p. 61. |

| Chap. VII. Voyage of Andrean Tolstyk, in the St. Andrean and Natalia—Discovery of some New Islands, called Andreanoffsky Ostrova—Description of six of those islands, | p. 71 |

| Chap. VIII. Voyage of the Zacharias and Elizabeth, fitted out by Kulkoff, and commanded by Dausinin—They sail to Umnak and Unalashka, and winter upon the latter island—The vessel destroyed, and all the crew, except four, murdered by the islanders—The adventures of those four Russians, and their wonderful escape, | p. 80. |

| Chap. IX. Voyage of the vessel called the Trinity, under the command of Korovin—Sails to the Fox Islands—Winters at Unalashka—Puts to sea the spring following—The vessel is stranded in a bay of the island Umnak, and the crew attacked by the natives—Many of them killed—others carried off by sickness—-They are reduced to great streights—Relieved by Glottoff, twelve of the whole company only remaining—Description of Umnak and Unalashka, | p. 89. |

| Chap. X. Voyage of Stephen Glottoff—He reaches the Fox Islands—Sails beyond Unalashika to Kadyak—Winters upon that island—Repeated attempts of the natives to destroy the crew—They are repulsed, reconciled, and prevailed upon to trade with the Russians—Account of Kadyak—Its inhabitants, animals, productions—Glottoff sails back to Umnak—winters there—returns to Kamtchatka—Journal of his voyage, | p. 106. |

| Chap. XI. Solovioff's voyage—He reaches Unalashka, and passes two winters upon that island—Relation of what passed there—fruitless attempts of the natives to destroy the crew—Return of Solovioff to Kamtchatka—Journal of his voyage in returning—Description of the islands of Umnak and Unalashka, productions, inhabitants, their manners, customs, &c. &c. | p. 131. |

| Chap. XII. Voyage of Otcheredin—He winters upon Umnak—Arrival of Levasheff upon Unalashka—Return of Otcheredin to Ochotsk, | p. 156. |

| Chap. XIII. Conclusion—General position and situation of the Aleütian and Fox Islands—their distance from each other—Further description of the dress, manners, and custom of the inhabitants—their feasts and ceremonies, &c. | p. 164. |

| PART II. | |

| Containing the Conquest of Siberia, and the History of the Transactions and Commerce between Russia and China, | p. 175. |

| Chap. I. First irruption of the Russians into Siberia—second inroad—Yermac driven by the Tzar of Muscovy from the Volga, retires to Orel, a Russian settlement—Enters Siberia, with an army of Cossacs—his progress and exploits—Defeats Kutchum Chan—conquers his dominions—cedes them to the Tzar—receives a reinforcement of Russian troops—is surprized by Kutchum Chan—his defeat and death—veneration paid to his memory—Russian troops evacuate Siberia—re-enter and conquer the whole country—their progress stopped by the Chinese, | p. 177. |

| Chap. II. Commencement of hostilities between the Russians and Chinese—disputes concerning the limits of the two empires—treaty of Nershinsk—embassies from the court of Russia to Pekin—treaty of Kiachta—establishment of the commerce between the two nations. | p. 197. |

| Chap. III. Account of the Russian and Chinese settlements upon the confines of Siberia—description of the Russian frontier town Kiachta—of the Chinese frontier town Maitmatschin—its buildings, pagodas, &c. | p. 211. |

| Chap. IV. Commerce between the Chinese and Russians—list of the principal exports and imports—duties—average amount of the Russian trade. | p. 231. |

| Chap. V. Description of Zuruchaitu—and its trade—transport of the merchandize through Siberia. | p. 244. |

| PART III. | |

| Appendix I. and II. containing Supplementary Accounts of the Russian Discoveries, &c. &c. | |

| Appendix I. Extract from the journal of a voyage made by Captain Krenitzin and Lieutenant Levasheff to the Fox Islands, in 1768, 1769, by order of the Empress of Russia—they sail from Kamtchatka—arrive at Beering's and Copper Islands—reach the Fox Islands—Krenitzin winters at Alaxa—Levasheff upon Unalashka—productions of Unalashka—description of the inhabitants of the Fox Islands—their manners and customs, &c. | p. 251. |

| No II. Concerning the longitude of Kamtchatka, and of the Eastern extremity of Asia, as laid down by the Russian geographers. | p. 267. |

| No III. Summary of the proofs tending to shew, that Beering and Tschirikoff either reached America in 1741, or came very near it. | p. 277. |

| No IV. List of the principal charts representing the Russian Discoveries. | p. 281. |

| No V. Position of the Andreanoffsky Isles ascertained—number of the Aleutian Isles. | p. 288. |

| No VI. Conjectures concerning the proximity of the Fox Islands to the continent of America. | p. 291. |

| No VII. Of the Tschutski—reports of the vicinity of America to their coast, first propagated by them, seem to be confirmed by late accounts from those parts. | p. 293. |

| No VIII. List of the New Discovered Islands, procured from an Aleütian chief—catalogue of islands called by different names in the account of the Russian discoveries. | p. 297. |

| No IX. Voyage of Lieutenant Synd to the North East of Siberia—he discovers a cluster of islands, and a promontory, which he supposes to belong to the continent of America, lying near the coast of the Tschutski. | p. 300. |

| No X. Specimen of the Aleütian language. | p. 303. |

| No XI. Attempts of the Russians to discover a North East passage—voyages from Archangel towards the Lena—from the Lena towards Kamtchatka—extract from Muller's account of Deshneff's voyage round Tschukotskoi Noss—narrative of a voyage made by Shalauroff from the Lena to Shelatskoi Noss. | p. 304. |

| Appendix II. Tartarian rhubarb brought to Kiachta by the Bucharian merchants—method of examining and purchasing the roots—different species of rheum which yield the finest rhubarb—price of rhubarb in Russia—exportation—superiority of the Tartarian over the Indian rhubarb. | p. 332. |

| Table of the longitude and latitude of the principal places mentioned in this work. | p. 344. |

The Peninsula of Kamtchatka was not discovered by the Russians before the latter end of the last century. The first expedition towards those parts was made in 1696, by sixteen Cossacs, under the command of Lucas Semænoff Morosko, who was sent against the Koriacks of the river Opooka by Volodimir Atlafsoff commander of Anadirsk. Morosko continued his march until he came within four days journey of the river Kamtchatka, and having rendered a Kamtchadal village tributary, he returned to Anadirsk[5].

The following year Atlafsoff himself at the head of a larger body of troops penetrated into the Peninsula, took possession of the river Kamtchatka by erecting a cross upon its banks; and built some huts upon the spot, where Upper Kamtchatkoi Ostrog now stands.

These expeditions were continued during the following years: Upper and Lower Kamtchatkoi Ostrogs and Bolcheretsk were built; the Southern district conquered and colonised; and in 1711 the whole Peninsula was finally reduced under the dominion of the Russians.

During some years the possession of Kamtchatka brought very little advantage to the crown, excepting the small tribute of furs exacted from the inhabitants. The Russians indeed occasionally hunted in that Peninsula foxes, wolves, ermines, sables, and other animals, whose valuable skins form an extensive article of commerce among the Eastern nations. But the fur trade carried on from thence was inconsiderable; until the Russians discovered the islands situated between Asia and America, in a series of voyages, the journals of which will be exhibited in the subsequent translation. Since these discoveries, the variety of rich furs, which are procured from those Islands, has greatly encreased the trade of Kamtchatka, and rendered it a very important branch of the Russian commerce.

The Peninsula of Kamtchatka lies between 51 and 62 degrees of North latitude, and 173 and 182 of longitude from the Isle of Fero. It is bounded on the East and South by the Sea of Kamtchatka, on the West by the Seas of Ochotsk and Penshinsk, and on the North by the country of the Koriacs.

It is divided into four districts, Bolcheresk, Tigilskaia Krepost, Verchnei or Upper Kamtchatkoi Ostrog, and Nishnei or Lower Kamtchatkoi Ostrog. |Government| The government is vested in the chancery of Bolcheresk, which depends upon and is subject to the inspection of the chancery of Ochotsk. The whole Russian force stationed in the Peninsula consists of no more than three hundred men[6].

The present population of Kamtchatka is very small, amounting to scarce four thousand souls. Formerly the inhabitants were more numerous, but in 1768, that country was greatly depopulated by the ravages of the small-pox, by which disorder five thousand three hundred and sixty-eight persons were carried off. There are now only seven hundred and six males in the whole Peninsula who are tributary, and an hundred and fourteen in the Kuril Isles, which are subject to Russia.

The fixed annual tribute consists in 279 sables, 464 red foxes, 50 sea-otters with a dam, and 38 cub sea-otters. All furs exported from Kamtchatka pay a duty of 10 per cent. to the crown; the tenth of the cargoes brought from the new discovered islands is also delivered into the customs.

Many traces of Volcanos have been observed in this Peninsula; and there are some mountains, which are at present in a burning state. The most considerable of these Volcanos is situated near the Lower Ostrog. In 1762 a great noise was heard issuing from the inside of that mountain, and flames of fire were seen to burst from different parts. These flames were immediately succeeded by a large stream of melted snow water, which flowed into the neighbouring valley, and drowned two Kamtchadals, who were at that time upon an hunting party. The ashes, and other combustible matter, thrown from the mountain, spread to the circumference of three hundred versts. In 1767 there was another discharge, but less considerable. Every night flames of fire were observed streaming from the mountain; and the eruption which attended them, did no small damage to the inhabitants of the Lower Ostrog. Since that year no flames have been seen; but the mountain emits a constant smoke. The same phænomenon is also observed upon another mountain, called Tabaetshinskian.

The face of the country throughout the Peninsula is chiefly mountainous. It produces in some parts birch, poplars, alders, willows, underwood, and berries of different sorts. Greens and other vegetables are raised with great facility; such as white cabbage, turneps, radishes, beetroot, carrots, and some cucumbers. Agriculture is in a very low state, which is chiefly owing to the nature of the soil and the severe hoar frosts; for though some trials have been made with respect to the cultivation of corn, and oats, barley and rye have been sown; yet no crop has ever been procured sufficient in quality or quality to answer the pains and expence of raising it. Hemp however has of late years been cultivated with great success[7].

Every year a vessel, belonging to the crown, sails from Ochotsk to Kamtchatka laden with salt, provisions, corn, and Russian manufactures; and returns in June or July of the following year with skins and furs.

Since the conclusion of Beering's voyage, which was made at the expence of the crown, the prosecution of the New Discoveries began by him has been almost entirely carried on by individuals. These persons were principally merchants of Irkutsk, Yakutsk, and other natives of Siberia, who formed themselves into small trading companies, and fitted out vessels at their joint expence.

Most of the vessels which are equipped for these expeditions are two masted: they are commonly built without iron, and in general so badly constructed, that it is wonderful how they can weather so stormy a sea. They are called in Russian Skitiki or sewed vessels, because the planks are sewed together with thongs of leather. Some few are built in the river of Kamtchatka; but they are for the most part constructed at the haven of Ochotsk. The largest of these vessels are manned with seventy men, and the smallest with forty. The crew generally consists of an equal number of Russians and Kamtchadals. The[Pg 9] latter occasion a considerable saving, as their pay is small; they also resist, more easily than the former, the attacks of the scurvy. But Russian mariners are more enterprising and more to be depended upon in time of danger than the others; some therefore are unavoidably necessary.

The expences of building and fitting out the vessels are very considerable: for there is nothing at Ochotsk but timber for their construction. Accordingly cordage, sails, and some provisions, must be brought from Yakutsk upon horses. The dearness of corn and flour, which must be transported from the districts lying about the river Lena, renders it impossible to lay-in any large quantity for the subsistence of the crew during a voyage, which commonly lasts three or four years. For this reason no more is provided, than is necessary to supply the Russian mariners with quass and other fermented liquors.

From the excessive scarcity of cattle both at Ochotsk and[8]Kamtchatka very little provision is laid in at either of those places: but the crew provide themselves[Pg 10] with a large store of the flesh of sea animals, which are caught and cured upon Beering's Island, where the vessels for the most part winter.

After all expences are paid, the equipment of each vessel ordinarily costs from 15,000 to 20,000 Roubles. And sometimes the expences amount to 30,000. Every vessel is divided into a certain number of shares, generally from thirty to fifty; and each share is worth from 300 to 500 Roubles.

The risk of the trade is very great, as shipwrecks are common in the sea of Kamtchatka, which is full of rocks and very tempestuous. Besides, the crews are frequently surprised and killed by the islanders, and the vessels destroyed. |Profits.|In return the profits arising from these voyages are very considerable, and compensate the inconveniencies and dangers attending them. For if a ship comes back after having made a profitable voyage, the gain at the most moderate computation amounts to cent. per cent. and frequently to as much more. Should the vessel be capable of performing a second expedition, the expences are of course considerably lessened, and the shares are at a lower price.

Some notion of the general profits arising from this trade (when the voyage is successful), may be deduced from the sale of a rich cargo of furs, brought[Pg 11] to Kamtchatka, on the 2d of June, 1772, from the new-discovered islands, in a vessel belonging to Ivan Popoff.

The tenth part of the skins being delivered to the customs, the remainder was distributed in fifty-five shares. Each share consisted of twenty sea-otters, sixteen black and brown foxes, ten red foxes, three sea-otter tails; and such a portion was sold upon the spot from 800 to 1000 Roubles: so that according to this price the whole lading was worth about 50,000 Roubles[9].

The principal furs and skins procured from the Peninsula of Kamtchatka and the New Discovered Islands are sea-otters, foxes, sables, ermines, wolves, bears, &c.—These furs are transported to Ochotsk by sea, and from thence carried to[10]Kiachta upon the frontiers of Siberia; where the greatest part of them are sold to the Chinese at a very considerable profit.

Of all these furs the skins of the sea-otters are the richest and most valuable. Those animals resort in great numbers to the Aleutian and Fox Islands: they are called by the Russians Bobry Morski or sea-beavers, and sometimes Kamtchadal beavers, on account of the resemblance of their fur to that of the common beaver. From these circumstances several authors have been led into a mistake, and have supposed that this animal is of the beaver species; whereas it is the true sea-otter[11].

The female are called Matka or dams; and the cubs till five months old Medviedki or little bears, because their coat resembles that of a bear; they lose that coat after five months, and then are called Koschloki.

The fur of the finest sort is thick and long, of a dark colour, and a fine glossy hue. They are taken four ways; struck with darts as they are sleeping upon their backs in the sea, followed in boats and hunted down till they are tired, surprised in caverns, and taken in nets.

Their skins fetch different prices according to their quality.

| At Kamtchatka[12] the best sell for per skin from | 30 to 40 Roubles. |

| Middle sort | 20 to 30 |

| Worst sort | 15 to 25 |

| At Kiachta[13] the old and middle-aged sea-otter skins are sold to the Chinese per skin from |

80 to 100 |

| The worst sort | 30 to 40. |

As these furs fetch so great a price to the Chinese, they are seldom brought into Russia for sale: and several, which have been carried to Moscow as a tribute, were purchased for 30 Roubles per skin; and sent from thence to the Chinese frontiers, where they were disposed of at a very high interest.

There are several species of Foxes, whose skins are sent from Kamtchatka into Siberia and Russia. Of these the principal are the black foxes, the Petsi or Arctic foxes, the red and stone foxes.

The finest black foxes are caught in different parts of Siberia, and more commonly in the Northern regions between the Rivers Lena, Indigirka, and Kovyma: the black foxes found upon the remotest Eastern islands discovered by the Russians, or the Lyssie Ostrova, are not so valuable. They are very black and large; but the coat for the most part is as coarse as that of a wolf. The great difference in the fineness of the fur, between these foxes and those of Siberia, arises probably from the following circumstances. In those islands the cold is not so severe as in Siberia; and as there is no wood, the foxes live in holes and caverns of the rocks; whereas in the abovementioned parts of Siberia, there are large tracts of forests in which they find shelter. Some black foxes however[Pg 15] are occasionally caught in the remotest Eastern Islands, not wholly destitute of wood, and these are of great value. In general the Chinese, who pay the dearest for black furs, do not give more for the black foxes of the new-discovered islands than from 20 to 30 Roubles per skin.

The arctic or ice foxes are very common upon some of the New-Discovered Islands. They are called Petsi by the Russians, and by the Germans blue foxes. |Pennant's Synopsis.| Their natural colour is of a bluish grey or ash colour; but they change their coat at different ages, and in differerent seasons of the year. In general they are born brown, are white in winter, and brown in summer; and in spring and autumn, as the hair gradually falls off, the coat is marked with different specks and crosses.

| At Kiachta[14] all the several varieties sell upon an average to the Chinese per skin from 50 copecs to | 2-2/3 Roubles. |

| Stone Foxes at Kamtchatka per skin from | 1 to 2-1/2 |

| Red Foxes from 80 copecs to | 1 80 copecs. |

| At Kiachta from 80 copecs to | 9 |

| Common wolves skins at per skin | 2 |

| Best sort per skin from | 8 to 16 |

| Sables per ditto | 2-1/2 to 10 |

| A pood of the best sea-horse teeth[15] sells At Yakutsk for |

10 Roubles. |

| Of the middling | 8 |

| Inferior ditto | from 5 to 7. |

Four, five, or six teeth generally weigh a pood, and sometimes, but very rarely, three. They are sold to the Chinese, Monguls, and Calmucs.

TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN.

WITH NOTES BY THE TRANSLATOR.

A Thirst after riches was the chief motive which excited the Spaniards to the discovery of America; and which turned the attention of other maritime nations to that quarter. The same passion for riches occasioned, about the middle of the sixteenth century, the discovery and conquest of Northern Asia, a country, before that time, as unknown to the Europeans, as Thule to the ancients. |Conquest of Siberia.| The first foundation of this conquest was laid by the celebrated Yermac[16], at the head of a band of adventurers, less civilized, but at the same time, not so inhuman as the conquerors of America. By the accession of this vast territory, now known by the name of Siberia, the Russians have acquired an extent of empire never before attained by any other nation.

The first project[17] for making discoveries in that tempestuous sea, which lies between Kamtchatka and America, was conceived and planned by Peter I. the greatest sovereign who ever sat upon the Russian throne, until it was adorned by the present empress. The nature and completion of this project under his immediate successors are well known to the public from the relation of the celebrated Muller. |Their progress.| No sooner had [18]Beering and [Pg 21] Tschirikoff, in the prosecution of this plan, opened their way to islands abounding in valuable furs, than private merchants immediately engaged with ardour in similar expeditions; and, within a period of ten years, more important discoveries were made by these individuals, at their own private cost, than had been hitherto effected by all the expensive efforts of the crown.

Soon after the return of Beering's crew from the island where he was ship-wrecked and died, and which is called after his name, the inhabitants of Kamtchatka ventured over to that island, to which the sea-otters and other sea-animals were accustomed to resort in great numbers. Mednoi Ostroff, or Copper Island, which takes that appellation from large masses of native copper found upon the beach, and which lies full in sight of Beering's Isle, was an easy and speedy discovery.

These two small uninhabited spots were for some time the only islands that were known; until a scarcity of land and sea-animals, whose numbers were greatly diminished by the Russian hunters, occasioned other expeditions. Several of the vessels which were sent out upon these voyages were driven by stormy weather to the South-east; and discovered by that means the Aleütian Isles, situated about the 195th[19] degree of longitude, and but moderately peopled.

From the year 1745, when it seems these islands were first visited, until 1750, when the first tribute of furs was brought from thence to Ochotsk, the government appears not to have been fully informed of their discovery. In the last mentioned year, one Lebedeff was commander of Kamtchatka. From 1755 to 1760, Captain Tsheredoff and Lieutenant Kashkareff were his successors. In 1760, Feodor Ivanovitch Soimonoff, governor of Tobolsk, turned his attention to the abovementioned islands; and, the same year, Captain Rtistsheff, at Ochotsk, instructed Lieutenant Shmaleff, the same who was afterwards commander in Kamtchatka, to promote and favour all expeditions in those seas. Until this time, all the discoveries subsequent to Beering's voyage were made, without the interposition of the court, by private merchants in small vessels fitted out at their own expence.

The present Empress (to whom every circumstance which contributes to aggrandize the Russian empire is an object of attention) has given new life to these discoveries. The merchants engaged in them have been animated by recompences. The importance and true position of the Russian[Pg 23] islands have been ascertained by an expensive voyage[20], made by order of the crown; and much additional information will be derived from the journals and charts of the officers employed in that expedition, whenever they shall be published.

Meanwhile, we may rest assured, that several modern geographers have erred in advancing America too much to the West, and in questioning the extent of Siberia Eastwards, as laid down by the Russians. It appears, indeed, evident, that the accounts and even conjectures of the celebrated Muller, concerning the position of those distant regions, are more and more confirmed by facts; in the same manner as the justness of his supposition concerning the form of the coast of the sea of Ochotsk[21] has been lately established. With respect to the extent of Siberia, it appears almost beyond a doubt from the most recent observations, that its Eastern extremity is situated beyond[22] 200 degrees of longitude. In regard to the Western coasts of America, all the navigations to the New Discovered Islands evidently shew, that, between 50[Pg 24] and 60 degrees of latitude, that Continent advances no where nearer to Asia than the[23]coasts touched at by Beering and Tschirikoff, or about 236 degrees of longitude.

As to the New Discovered Islands, no credit must be given to a chart published in the Geographical Calendar of St. Petersburg for 1774; in which they are inaccurately laid down. Nor is the antient chart of the New Discoveries, published by the Imperial Academy, and which seems to have been drawn up from mere reports, more deserving of attention[24].

The late navigators give a far different description of the Northern Archipelago. From their accounts we learn, that Beering's Island is situated due East from Kamtchatkoi Noss, in the 185th degree of longitude. Near it is Copper Island; and, at some distance from them, East-south-east, there are three small islands, named by their inhabitants, Attak, Semitshi, and Shemiya: these are properly the Aleütian Isles; they stretch from West-north-west towards East-south-east, in the same direction as Beering's and Copper Islands, in the longitude of 195, and latitude 54.

To the North-east of these, at the distance of 600 or 800 versts, lies another group of six or more islands, known by the name of the Andreanoffskie Ostrova.

South-east, or East-south, of these, at the distance of about 15 degrees, and North by East of the Aleütian, begins the chain of Lyssie Ostrova, or Fox Islands: this chain of rocks and isles stretches East-north-east between 56 and 61 degrees of North latitude, from 211 degrees of longitude most probably to the Continent of America; and in a line of direction, which crosses with that in which the Aleütian isles lie. The largest and most remarkable of these islands are Umnak, Aghunalashka, or, as it is commonly shortened, Unalashka, Kadyak, and Alagshak.

Of these and the Aleütian Isles, the distance and position are tolerably well ascertained by ships reckonings, and latitudes taken by pilots. But the situation of the Andreanoffsky Isles[25] is still somewhat doubtful, though probably their direction is East and West; and some of them may unite with that part of the Fox Islands which are most contiguous to the opposite Continent.

The main land of America has not been touched at by any of the vessels in the late expeditions; though possibly[Pg 26] the time is not far distant when some of the Russian adventurers will fall in with that coast[26]. More to the North perhaps, at least as high as 70 degrees latitude, the Continent of America may stretch out nearer to the coast of the Tschutski; and form a large promontory, accompanied with islands, which have no connection with any of the preceding ones. That such a promontory really exists, and advances to within a very small distance from Tschukotskoi Noss, can hardly be doubted; at least it seems to be confirmed by all the latest accounts which have been procured from those parts[27]. That prolongation, therefore, of America, which by Delisle is made to extend Westward, and is laid down just opposite to Kamtchatka, between 50 and 60 degrees latitude, must be entirely removed; for many of the voyages related in this collection lay through that part of the ocean, where this imaginary Continent was marked down.

It is even more than probable, that the Aleütian, and some of the Fox Islands, now well known, are the very same which Beering fell-in with upon his return; though, from the unsteadiness of his course, their true position could not be exactly laid down in the chart of that expedition[28].

As the sea of Kamtchatka is now so much frequented, these conjectures cannot remain long undecided; and it is only to be wished, that some expeditions were to be made North-east, in order to discover the nearest coasts of America. For there is no reason to expect a successful voyage by taking any other direction; as all the vessels, which have steered a more southerly course, have sailed through an open sea, without meeting with any signs of land.

A very full and judicious account of all the discoveries hitherto made in the Eastern ocean may be expected from the celebrated Mr. Muller[29]. Meanwhile, I hope the following account, extracted from the original papers, and procured from the best intelligence, will be the more acceptable to the public; as it may prove an inducement to the Russians to publish fuller and more circumstantial relations. Besides, the reader will find here a narrative more authentic and accurate, than what has been pub[Pg 28]lished in the abovementioned calendar[30]; and several mistakes in that memoir are here corrected.

A voyage made in the year 1745 by Emilian Bassoff is scarce worth mentioning; as he only reached Beering's Island, and two smaller ones, which lie South of the former, and returned on the 31st of July, 1746.

The first voyage which is in any wise remarkable, was undertaken in the year 1745. The vessel was a Shitik named Eudokia, fitted out at the expence of Aphanassei Tsebaefskoi, Jacob Tsiuproff and others; she sailed from the Kamtchatka river Sept. 19, under the command of Michael Nevodtsikoff a native of Tobolsk. |Discovers the Aleütian Islands.| Having discovered three unknown islands, they wintered upon one of them, in order to kill sea-otters, of which there was a large quantity. These islands were undoubtedly the nearest[31] Aleütian Islands: the language of the inhabi[Pg 30]tants was not understood by an interpreter, whom they had brought with them from Kamtchatka. For the purpose therefore of learning this language, they carried back with them one of the Islanders; and presented him to the chancery of Bolcheretsk, with a false account of their proceedings. This islander was examined as soon as he had acquired a slight knowledge of the Russian language; and as it is said, gave the following report. He was called Temnac, and Att was the name of the island of which he was a native. At some distance from thence lies a great island called Sabya, of which the inhabitants are denominated Rogii: these inhabitants, as the Russians understood or thought they understood him, made crosses, had books and fire-arms, and navigated in baidars or leathern canoes. At no great distance from the island where they wintered, there were two well-inhabited islands: the first lying E. S. E. and S. E. by South, the second East and East by South. The above-mentioned Islander was baptised under the name of Paul, and sent to Ochotsk.

As the misconduct of the ship's crew towards the natives was suspected, partly from the loss of several men, and partly from the report of those Russians, who were not concerned in the disorderly conduct of their companions, a strict examination took place; by which the following circumstances relating to the voyage were brought to light.

According to the account of some of the crew, and particularly of the commander, after six days sailing they came in sight of the first island on the 24th of September, at mid-day. They sailed by, and towards evening they discovered the second island; where they lay at anchor until the next morning.

The 25th several inhabitants appeared on the coast, and the pilot was making towards shore in the small boat, with an intention of landing; but observing their numbers increase to about an hundred, he was afraid of venturing among them, although they beckoned to him. He contented himself therefore with flinging some needles amongst them: the islanders in return threw into the boat some sea-fowl of the cormorant kind. He endeavoured to hold a conversation with them by means of the interpreters, but no one could understand their language. And now the crew endeavoured to row the vessel out to sea; but the wind being contrary, they were driven to the other side of the same island, where they cast anchor.

The 26th, Tsiuproff having landed with some of the crew in order to look for water, met several inhabitants: he gave them some tobacco and small Chinese pipes; and received in return a present of a stick, upon which the head of a seal was carved. They endeavoured to wrest his[Pg 32] hunting gun from him; but upon his refusing to part with it and retiring to the small boat, the islanders ran after him; and seized the rope by which the boat was made fast to shore. This violent attack obliged Tsiuproff to fire; and having wounded one person in the hand, they all let go their hold; and he rowed off to the ship. The Savages no sooner saw that their companion was hurt, than they threw off their cloaths, carried the wounded person naked into the sea, and washed him. In consequence of this encounter the ship's crew would not venture to winter at this place, but rowed back again to the other island, where they came to an anchor.

The next morning Tsiuproff, and a certain Shaffyrin landed with a more considerable party: they observed several traces of inhabitants; but meeting no one they returned to the ship, and coasted along the island. The following day the Cossac Shekurdin went on shore, accompanied by five sailors: two of whom he sent back with a supply of water; and remained himself with the others in order to hunt sea-otters. At night they came to some dwellings inhabited by five families: upon their approach the natives abandoned their huts with precipitation, and hid themselves among the rocks. Shekurdin no sooner returned to the ship, than he was again sent on shore with a larger company, in order to look out for a proper place to lay up the vessel during winter: In their way they observed fifteen islanders upon an height;[Pg 33] and threw them some fragments of dried fish in order to entice them to approach nearer. But as this overture did not succeed, Tsiuproff, who was one of the party, ordered some of the crew to mount the height, and to seize one of the inhabitants, for the purpose of learning their language: this order was accordingly executed, notwithstanding the resistance which the islanders made with their bone spears; the Russians immediately returned with their prisoner to the ship. They were soon afterwards driven to sea by a violent storm, and beat about from the 2d to the 9th of October, during which time they lost their anchor and boat; at length they came back to the same island, where they passed the winter.

Soon after their landing they found in an adjacent hut the dead bodies of two of the inhabitants, who had probably been killed in the last encounter. In their way the Russians were met by an old woman, who had been taken prisoner, and set at liberty. She was accompanied with thirty-four islanders of both sexes, who all came dancing to the sound of a drum; and brought with them a present of coloured earth. Pieces of cloth, thimbles, and needles, were distributed among them in return; and they parted amicably. Before the end of October, the same persons, together with the old woman and several children, returned dancing as before, and brought birds, fish, and other provision. Having passed the night with[Pg 34] the Russians, they took their leave. Soon after their departure, Tsiuproff, Shaffyrin, and Nevodsikoff, accompanied with seven of the crew, went after them, and found them among the rocks. In this interview the natives behaved in the most friendly manner, and exchanged a baidar and some skins for two shirts. They were observed to have hatchets of sharpened stone, and needles made of bone: they lived upon the flesh of sea-otters, seals, and sea-lions, which they killed with clubs and bone lances.

So early as the 24th of October, Tsiuproff had sent ten persons, under the command of Larion Belayeff, upon a reconnoitring party. The latter treated the inhabitants in an hostile manner; upon which they defended themselves as well as they could with their bone lances. This resistance gave him a pretext for firing; and accordingly he shot the whole number, amounting to fifteen men, in order to get at their wives.

Shekurdin, shocked at these cruel proceedings, retired unperceived to the ship, and brought an account of all that had passed. Tsiuproff, instead of punishing these cruelties as they deserved, was secretly pleased with them; for he himself was affronted at the islanders for having refused to give him an iron bolt, which he saw in their possession. He had, in consequence of their refusal, committed several acts of hostilities against them; and had even formed the horrid design of poisoning them with a mixture of corrosive sublimate. In order[Pg 35] however to preserve appearances, he dispatched Shekurdin and Nevodsikoff to reproach Belayeff for his disorderly conduct; but sent him at the same time, by the above-mentioned persons, more powder and ball.

The Russians continued upon this island, where they caught a large quantity of sea otters, until the 14th of September, 1746; when, no longer thinking themselves secure, they put to sea with an intention of looking out for some uninhabited islands. Being however overtaken by a violent storm, they were driven about until the 30th of October, when their vessel struck upon a rocky shore, and was shipwrecked, with the loss of almost all the tackle, and the greatest part of the furs. Worn out at length with cold and fatigue, they ventured, the first of November, to penetrate into the interior part of the country, which they found rocky and uneven. Upon their coming to some huts, they were informed, that they were cast away upon the island of Karaga, the inhabitants of which were tributary to Russia, and of the Koraki tribe. The islanders behaved to them with great kindness, until Belayeff had the imprudence to make proposals to the wife of the chief. The woman gave immediate intelligence to her husband; and the natives were incensed to such a degree, that they threatened the whole crew with immediate death: but means were found to pacify them, and they continued to live with the Russians upon the same good terms as before.

The 30th of May, 1747, a party of Olotorians made a descent upon the island in three baidars, and attacked the natives; but, after some loss on both sides, they went away. They returned soon after with a larger force, and were again forced to retire. But as they threatened to come again in a short time, and to destroy all the inhabitants who paid tribute, the latter advised the Russians to retire from the island, and assisted them in building two baidars. With these they put to sea the 27th of June, and landed the 21st of July at Kamtchatka, with the rest of their cargo, consisting of 320 sea-otters, of which, they paid the tenth into the customs. During this expedition twelve men were lost.

In the year 1747[32] two vessels sailed from the Kamtchatka river, according to a permission granted by the chancery of Bolckeretsk for hunting sea-otters. One was fitted out by Andrew Wsevidoff, and carried forty-six men, besides eight Cossacs: the other belonged to Feodor Cholodiloff, Andrew Tolstyk, and company; and had on board a crew, consisting of forty-one Russians and Kamtchadals, with six Cossacs.

The latter vessel sailed the 20th of October, and was forced, by stress of weather and other accidents, to winter at Beering's Island. From thence they departed May the 31st, 1748, and touched at another small island, in order to provide themselves with water and other necessaries. They then steered S. E. for a considerable way without[Pg 38] discovering any new islands; and, being in great want of provisions, returned into Kamtchatka River, August 14, with a cargo of 250 old sea-otter-skins, above 100 young ones, 148 petsi or arctic fox-skins, which were all slain upon Beering's Island.

We have no sufficient account of Wsevidoff's voyage. All that is known amounts only to this, that he returned the 25th of July, 1749, after having probably touched upon one of the nearest Aleütian Isles which was uninhabited: his cargo consisted of the skins of 1040 sea-otters, and 2000 arctic foxes.

Emilian Yugoff, a merchant of Yakutsk, obtained from the senate of St. Petersburg the permission of fitting out four vessels for himself and his associates. He procured, at the same time, the exclusive privilege of hunting sea-otters upon Beering's and Copper Island during these expeditions; and for this monopoly he agreed to deliver to the customs the tenth of the furs.

October 6, 1750, he put to sea from Bolcheresk, in the sloop John, manned with twenty-five Russians and Kamtchadals, and two Cossacs: he was soon overtaken by a storm, and the vessel driven on shore between the mouths of the rivers Kronotsk and Tschasminsk.

October 1751, he again set sail. He had been commanded to take on board some officers of the Russian[Pg 39] navy; and, as he disobeyed this injunction, the chancery of Irkutsk issued an order to confiscate his ship and cargo upon his return. The ship returned on the 22d of July, 1754, to New Kamtchatkoi Ostrog, laden with the skins of 755 old sea-otters, of 35 cub sea-otters, of 447 cubs of sea-bears, and of 7044 arctic fox-skins: of the latter 2000 were white, and 1765 black. These furs were procured upon Beering's and Copper Island. Yugoff himself died upon the last-mentioned island. The cargo of the ship was, according to the above-mentioned order, sealed and properly secured. But as it appeared that certain persons had deposited money in Yugoff's hand, for the purpose of equipping a second vessel, the crown delivered up the confiscated cargo, after reserving the third part according to the original stipulation.

This kind of charter-company, if it may be so called, being soon dissolved for misconduct and want of sufficient stock, other merchants were allowed the privilege of fitting out vessels, even before the return of Yugoff's ship; and these persons were more fortunate in making new discoveries than the above-mentioned monopolist.

Nikiphor Trapesnikoff, a merchant of Irkutsk, obtained the permission of sending out a ship, called the Boris and Glebb, upon the condition of paying, besides the tribute which might be exacted, the tenth of all the furs. The Cossac Sila Sheffyrin went on board this[Pg 40] vessel for the purpose of collecting the tribute. They sailed in August, 1749, from the Kamtchatka river; and re-entered it the 16th of the same month, 1753, with a large cargo of furs. In the spring of the same year, they had touched upon an unknown island, probably one of the Aleütians, where several of the inhabitants were prevailed upon to pay a tribute of sea-otter skins. The names of the islanders who had been made tributary, were Igya, Oeknu, Ogogoektack, Shabukiauck, Alak, Tutun, Ononushan, Rotogèi, Tschinitu, Vatsch, Ashagat, Avyjanishaga, Unashayupu, Lak, Yanshugalik, Umgalikan, Shati, Kyipago, and Oloshkot[33]; another Aleütian had contributed three sea-otters. They brought with them 320 best sea-otter skins, 480 of the second, and 400 of the third sort, 500 female and middle aged, and 220 medwedki or young ones.

Andrew Tolstyk, a merchant of Selenginsk, having obtained permission from the chancery of Bolsheretsk, refitted the same ship which had made a former voyage; he sailed from Kamtchatka August the 19th, 1749, and returned July the 3d, 1752.

According to the commander's account, the ship lay at anchor from the 6th of September, 1749, to the 20th[Pg 41] of May, 1750, before Beering's Island, where they caught only 47 sea-otters. From thence they made to those Aleütian Islands, which were[34] first discovered by Nevodsikoff, and slew there 1662 old and middle-aged sea-otters, and 119 cubs; besides which, their cargo consisted of the skins of 720 blue foxes, and of 840 young sea-bears.

The inhabitants of these islands appeared to have never before paid tribute; and seemed to be a-kin to the Tschuktski tribe, their women being ornamented with different figures sewed into the skin in the manner of that people, and of the Tungusians of Siberia. They differed however from them, by having two small holes cut through the bottom of their under-lips, through each of which they pass a bit of the sea-horse tush, worked into the form of a tooth, with a small button at one end to keep it within the mouth when it is placed in the hole. They had killed, without being provoked, two of the Kamtchadals who belonged to the ship. Upon the third Island some inhabitants had payed tribute; their names were reported to be Anitin, Altakukor, and Aleshkut, with his son Atschelap. The weapons of the whole island consisted of no more than twelve spears pointed with flint, and one dart of bone pointed with the same; and the Russians observed in the possession of the natives two figures, carved out of wood, resembling sea-lions.

August 3, 1750, the vessel Simeon and John, fitted out by the above-mentioned Wsevidoff, agent for the Russian merchant A. Rybenskoi, and manned with fourteen Russians (who were partly merchants and partly hunters) and thirty Kamtchadals, sailed out for the discovery of new islands, under the command of the Cossac Vorobieff. They were driven by a violent current and tempestuous weather to a small desert island, whose position is not determined; but which was probably one of those that lie near Beering's Island. The ship being so shattered by the storm, that it was no longer in a condition to keep the sea, Vorobieff built another small vessel with drift-wood, which he called Jeremiah; in which he arrived at Kamtchatka in Autumn, 1752.

Upon the above-mentioned island were caught 700 old and 120 cub sea-otters, 1900 blue foxes, 5700 black sea-bears, and 1310 Kotiki, or cub sea-bears.

A voyage made about this time from Anadyrsk deserves to be mentioned.

August 24, 1749, Simeon Novikoff of Yakutsk, and Ivan Bacchoff of Ustyug, agents for Ivan Shilkin, sailed from Anadyrsk into the mouth of the Kamtchatka river. They assigned the insecurity of the roads as their reason for coming from Anadyrsk to Kamtchatka by sea; on this account, having determined to risk all the dangers[Pg 43] of a sea voyage, they built a vessel one hundred and thirty versts above Anadyr, after having employed two years and five months in its construction.

The narrative of their expedition is as follows. In 1748, they sailed down the river Anadyr, and through two bays, called Kopeikina and Onemenskaya, where they found many sand banks, but passed round them without difficulty. From thence they steered into the exterior gulph, and waited for a favourable wind. Here they saw several Tschutski, who appeared upon the heights singly and not in bodies, as if to reconnoitre; which made them cautious. They had descended the river and its bays in nine days. In passing the large opening of the exterior bay, they steered between the beach, that lies to the left, and a rock near it; where, at about an hundred and twenty yards from the rock, the depth of water is from three to four fathoms. From the opening they steered E. S. E. about fifty versts, in about four fathom water; then doubled a sandy point, which runs out directly against the Tshuktshi coast, and thus reached the open sea.

From the 10th of July to the 30th, they were driven about by tempestuous winds, at no great distance from the mouth of the Anadyr; and ran up the small river Katirka, upon whose banks dwell the Koriacs, a people [Pg 44]tributary to Russia. The mouth of the river is from sixty to eighty yards broad, from three to four fathoms deep, and abounds in fish. From thence they put again to sea, and after having beat about for some time, they at length reached Beering's Island. |Shipwreck upon Beering's Island.| Here they lay at anchor from the 15th of September to the 30th of October, when a violent storm blowing right from the sea, drove the vessel upon the rocks, and dashed her to pieces. The crew however were saved: and now they looked out for the remains of Beering's wreck, in order to employ the materials for the constructing of a boat. They found indeed some remaining materials, but almost entirely rotten, and the iron-work corroded with rust. Having selected however the best cables, and what iron-work was immediately necessary, and collected drift-wood during the winter, they built with great difficulty a small boat, whose keel was only seventeen Russian ells and an half long, and which they named Capiton. In this they put to sea, and sailed in search of an unknown island, which they thought they saw lying North-east; but finding themselves mistaken, they tacked about, and stood far Copper Island: from thence they sailed to Kamtchatka, where they arrived at the time above-mentioned.

The new constructed vessel was granted in property to Ivan Shilkin as some compensation for his losses, and with the privilege of employing it in a future expedition[Pg 45] to the New Discovered Islands. Accordingly he sailed therein on the 7th of October, 1757, with a crew of twenty Russians, and the same number of Kamtchadals: he was accompanied by Studentzoff a Cossac, who was sent to collect the tribute for the crown. An account of this expedition will be given hereafter[35].

August, 1754, Nikiphor Trapesnikoff fitted out the Shitik St. Nicholas, which sailed from Kamtchatka under the command of the Cossac Kodion Durneff. He first touched at two of the Aleütian Isles, and afterwards upon a third, which had not been yet discovered. He returned to Kamtchatka in 1747. His cargo consisted of the skins of 1220 sea-otters, of 410 female, and 665 cubs; besides which, the crew had obtained in barter from the islanders the skins of 652 sea-otters, of 30 female ditto, and 50 cubs.

From an account delivered in the 3d of May, 1758, by Durneff and Sheffyrin, who was sent as collector of the tributes, it appears that they sailed in ten days as far as Ataku, one of the Aleütian Islands; that they remained there until the year 1757, and lived upon amicable terms with the natives.

The second island, which is nearest to Ataku, and which contains the greatest number of inhabitants, is[Pg 46] called Agataku; and the third Shemya: they lie from forty to fifty versts asunder. |Account of inhabitants.| Upon all the three islands there are (exclusive of children) but sixty males, whom they made tributary. The inhabitants live upon roots which grow wild, and sea animals: they do not employ themselves in catching fish, although the rivers abound with all kinds of salmon, and the sea with turbot. Their cloaths are made of the skins of birds and of sea-otters. The Toigon or chief of the first island informed them by means of a boy, who understood the Russian language, that Eastward there are three large and well peopled islands, Ibiya, Ricksa, and Olas, whose inhabitants speak a different language. Sheffyrin and Durneff found upon the island three round copper plates, with some letters engraved upon them, and ornamented with foliage, which the waves had cast upon the shore: they brought them, together with other trifling curiosities, which they had procured from the natives, to New Kamtchatkoi Ostrog.

Another ship built of larchwood by the same Trapesnikoff, which sailed in 1752 under the conduct of Alexei Drusinin a merchant of Kursk, had been wrecked at Beering's Island, where the crew constructed another vessel out of the wreck, which they named Abraham. In this vessel they bore away for the more distant islands; but being forced back by contrary winds to the same island, and meeting with the St. Nicholas upon the point of sailing for the Aleütian Isles, they embarked on that ship, after having left the new constructed vessel under the care of[Pg 47] four of their own sailors. The crew had slain upon Beering's Island five sea-otters, 1222 arctic foxes, and 2500 sea-bears: their share of the furs, during their expedition in the St. Nicholas, amounted to the skins of 500 sea-otters, and of 300 cubs, exclusive of 200 sea-otter-skins, which they procured by barter.

Three vessels were fitted out for the islands in 1753, one by Cholodiloff, a second by Serebranikoff agent for the merchant Rybenskoy, and the third by Ivan Krassilnikoff a merchant of Kamtchatka.

Cholodiloff's ship sailed from Kamtchatka, the 19th of August, manned with thirty-four men; and anchored the 28th before Beering's Island, where they proposed to winter, in order to lay-in a flock of provisions: as they were attempting to land, the boat overset, and nine of the crew were drowned.

June 30, 1754, they stood out to sea in quest of new discoveries: the weather however proving stormy and foggy, and the ship springing a leak, they were all in danger of perishing: in this situation they unexpectedly reached one of the Aleütian islands, were they lay from the 15th of September until the 9th of July, 1755. In[Pg 49] the autumn of 1754 they were joined by a Kamtchadal, and a Koriac: these persons, together with four others, had deserted from Trapesnikoff's crew; and had remained upon the island in order to catch sea-otters for their own profit. Four of these deserters were killed by the islanders for having debauched their wives: but as the two persons above-mentioned were not guilty of the same disorderly conduct, the inhabitants supplied them with women, and lived with them upon the best terms. The crew slew upon this island above 1600 sea-otters, and came back safe to Kamtchatka in autumn 1755.

Serebranikoff's vessel sailed in July 1753, manned also with thirty-four Russians and Kamtchadals: they discovered several new islands, which were probably some of the more distant ones; but were not so fortunate in hunting sea-otters as Cholodiloff's crew. They steered S. E. and on the 17th of August anchored under an unknown island; whose inhabitants spoke a language they did not understand. Here they proposed looking out for a safe harbour; but were prevented by the coming on of a sudden storm, which carried away their anchor. The ship being tost about for several days towards the East, they discovered not far from the first island four others: still more to the East three other islands appeared in sight; but on neither of these were they able to land. |Shipwrecked upon one of the more distant Islands.| The vessel continued driving until the 2d of September, and was considerably shattered, when they fortunately came[Pg 50] near an island and cast anchor before it; they were however again forced from this station, the vessel wrecked upon the coast, and the crew with difficulty reached the shore.

This island seemed to be right opposite to Katyrskoi Noss in the peninsula of Kamtchatka, and near it they saw three others. Towards the end of September Demitri Trophin, accompanied with nine men, went out in the boat upon an hunting and reconnoitring party: they were attacked by a large body of inhabitants, who hurled darts from a small wooden engine, and wounded one of the company. The first fire however drove them back; and although they returned several times to the attack in numerous bodies, yet they were always repulsed without difficulty.

These savages mark and colour their faces like the Islanders above-mentioned; and also thrust pieces of bone through holes made in their under-lips.

Soon afterwards the Russians were joined in a friendly manner by ten islanders, who brought the flesh of sea-animals and of sea-otters; this present was the more welcome, as they had lived for some time upon nothing but small shell-fish and roots; and had suffered greatly from hunger. Several toys were in return distribut[Pg 51]ed among the savages. |The Crew construct another Vessel, and return to Kamtchatka.| The Russians remained until June, 1754, upon this island: at that time they departed in a small vessel, constructed from the remains of the wreck, and called the St. Peter and Paul: in this they landed at Katyrskoi Noss; where having collected 140 sea-horse teeth, they got safe to the mouth of the Kamtchatka river.

During this voyage twelve Kamtchadals deserted; of whom six were slain, together with a female inhabitant, upon one of the most distant islands. The remainder, upon their return to Kamtchatka, were examined; and from them the following circumstances came to light. The island, where the ship was wrecked, is about 70 versts long, and 20 broad. Around it lie twelve other islands of different sizes, from five to ten versts distant from each other. Eight of them appear to be no more than five versts long. All these islands contain about a thousand souls. The dwellings of the inhabitants are provided with no other furniture than benches, and mats of platted grass[36]. Their dress consists of a kind of shirt made of bird-skins, and of an upper garment of intestines stitched together; they wear wooden caps, ornamented with a small piece of board projecting forwards, as it seemed, for a defence against the arrows. They are all provided with stone knives, and a[Pg 52] few of them possess iron ones: their only weapons are arrows with points of bone or flint, which they shoot from a wooden instrument. There are no trees upon the island: it produces however the cow-parsnip[37], which grows at Kamtchatka. The climate is by no means severe, for the snow does not lie upon the ground above a month in the year.

Krassilnikoff's vessel sailed in 1754, and anchored on the 18th of October before Beering's Island; where all the ships which make to the New Discovered Islands are accustomed to winter, in order to procure a stock of salted provisions from the sea-cows and other amphibious animals, that are found in great abundance. Here they refitted the vessel, which had been damaged by driving upon her anchor; and having laid in a sufficient store of all necessaries, weighed the 1st of August, 1754. The 10th they were in sight of an island, whose coast was lined with such a number of inhabitants, that they durst not venture ashore. Accordingly they stood out to sea, and being overtaken by a storm, they were reduced to great distress for want of water; at length they were driven upon Copper Island, where they landed; and having taken in wood and water, they again set sail. |Shipwrecked upon Copper Island.| They were beat back however by contrary winds, and dropped both their anchors near the shore; but the storm increasing at night, both the cables were broken, and the ship dashed to pieces upon the coast. All the[Pg 53] crew were fortunately saved; and means were found to get ashore the ship's tackle, ammunition, guns, and the remains of the wreck; the provisions, however, were mostly spoiled. Here they were exposed to a variety of misfortunes; three of them were drowned on the 15th of October, as they were going to hunt; others almost perished with hunger, having no nourishment but small shell-fish and roots. On the 29th of December great part of the ship's tackle, and all the wood, which they had collected from the wreck, was washed away during an high sea. Notwithstanding their distresses, they continued their hunting parties, and caught 103 sea-otters, together with 1390 blue foxes.

In spring they put to sea for Beering's Island in two baidars, carrying with them all the ammunition, fire-arms, and remaining tackle. Having reached that island, they found the small vessel Abraham, under the care of the four sailors who had been left ashore by the crew of Trapesnikoff's ship: but as that vessel was not large enough to contain the whole number, together with their cargo of furs, they staid until Serebranikoff's and Tolstyk's vessels arrived. These took in eleven of the crew, with their part of the furs. Twelve remained at Beering's Island, where they killed great numbers of arctic foxes, and returned to Kamtchatka in the Abraham, excepting two, who joined Shilkin's crew.

September 17, 1756, the vessel Andrean and Natalia, fitted out by Andrean Tolstyk, merchant of Selenginsk, and manned with thirty-eight Russians and Kamtchadals, sailed from the mouth of the Kamtchatka river. The autumnal storms coming on, and a scarcity of provisions ensuing, they made to Beering's Island, where they continued until the 14th of June 1757. As no sea-otters came on shore that winter, they killed nothing but seals, sea-lions, and sea-cows; whose flesh served them for provision, and their skins for the coverings of baidars.

June 13, 1757, they weighed anchor, and after eleven days sailing came to Ataku, one of the Aleütian isles discovered by Nevodsikoff. Here they found the inhabitants, as well of that, as of the other two islands, assembled; these islanders had just taken leave of the crew of Trapesnikoff's vessel, which had sailed for Kamtchatka. The Russians seized this opportunity of persuading them to pay tribute; with this view they[Pg 55] beckoned the Toigon, whose name was Tunulgasen: the latter recollected one of the crew, a Koriac, who had formerly been left upon these islands, and who knew something of their language. A copper kettle, a fur and cloth coat, a pair of breeches, stockings and boots, were bestowed upon this chief, who was prevailed upon by these presents to pay tribute. Upon his departure for his own island, he left behind him three women and a boy, in order to be taught the Russian language, which the latter very soon learned.

The Russians wintered upon this island, and divided themselves, as usual, into different hunting parties: they were compelled, by stormy weather, to remain there until the 17th of June, 1758: before they went away, the above-mentioned chief returned with his family, and paid a year's tribute.

This vessel brought to Kamtchatka the most circumstantial account of the Aleütian isles which had been yet received.

The two largest contained at that time about fifty males, with whom the Russians had lived in great harmony. They heard of a fourth island, lying at some distance from the third, called by the natives Iviya, but which they did not reach on account of the tempestuous weather.