[In 1618 two unusually brilliant comets were

visible in the Philippines; their effects on the minds of the people

are thus described (fol. 5):]1 There was great variety and

inaccuracy of opinion about the comets; but through that general

although confused notion which the majority of people form, that comets

presage disastrous events, and that the anger of God threatens men by

them, they assisted greatly in awakening contrition in the people, and

inciting them to do penance. To this the preachers endeavored to

influence them with forcible utterances, for the Society had not been

behind [the other orders] in preparing the city for the entire success

of the jubilee;2 for there was one occasion when eleven Jesuits

were counted, who, distributed at various stations, cried out like

Jonah, threatening [28]destruction to impenitent and rebellious

souls. God giving power to their words, this preaching was like the

seed in the gospel story, scattered on good ground, which not only

brought forth its fruit correspondingly, but so promptly that those who

heard broke down in tears at hearing the eternal truths; and, like

thirsty deer, when the sermon was ended they followed the preacher that

he might hear their confessions, already dreading lest some emergency

might find them in danger of damnation. This harvest was not confined

within the walls of Manila, but extended to its many suburbs, and to

the adjacent villages, in which missions had been conducted. Not only

was there preaching to the Spaniards, but to the Tagálogs, the

Indian natives of the country—who, in token of their fervor, gave

from their own scanty supply food in abundance to the jails and

prisons, Ours aiding them to carry the food, to the edification of the

city. To the Japanese who were living in our village of San

Miguel—exiles from their native land, in order to preserve their

religion, who had taken refuge in Manila, driven out from that kingdom

by the tyrant Taycosama—our fathers preached, in their own

language. And it can be said that there was preaching to all the

nations, that which occurred to the apostles in Jerusalem on the day of

Pentecost being represented in Manila; for I believe that there is no

city in the world in which so many nationalities come together as here.

For besides the Spaniards (who are the citizens and owners of the

country) and the Tagálogs (who are the Indian natives of the

land), there are many other Indians from the islands, who speak

different tongues—such as the Pampangos, the Camarines

[29][i.e., the Bicols], the Bisayans, the

Ilocans, the Pangasinans, and the Cagayans. There are Creoles [Criollos], or Morenos, who are swarthy blacks, natives of the

country;3 there are many Cafres, and other negroes from

Angola, Congo, and Africa. There are blacks from Asia, Malabars,

Coromandels, and Canarins. There are a great many Sangleys, or

Chinese—part of them Christians, but the majority heathens. There

are Ternatans, and Mardicas (who took refuge here from Ternate); there

are some Japanese; there are people from Borney and Timor, and from

Bengal; there are Mindanaos, Joloans, and Malays; there are Javanese,

Siaos, and Tidorans; there are people from Cambay and Mogol, and from

other islands and kingdoms of Asia. There are a considerable number of

Armenians, and some Persians; and Tartars, Macedonians, Turks, and

Greeks. There are people from all the nations of Europa—French,

Germans, and Dutch; Genoese and Venetians; Irish and Englishmen; Poles

and Swedes. There are people from all the kingdoms of España,

and from all America; so that he who spends an afternoon on the

tuley4 or bridge of Manila will see all

these nationalities pass by him, behold their costumes, and hear their

languages—something which cannot be done in any other city in the

entire Spanish monarchy, and hardly in any other region in all the

world.

From this arises the fact that the confessional of

Manila is, in my opinion, the most difficult in all the [30]world;

for, as it is impossible to confess all these people in their own

tongues, it is necessary to confess them in Spanish; and each

nationality has made its own vocabulary of the Spanish language, with

which those people have intercourse [with us], conduct their affairs,

and make themselves understood; and without it Ours can understand them

only with great difficulty, and almost by divination. A Sangley, an

Armenian, and a Malabar will be heard talking together in Spanish, and

our people do not understand them, as they so distort the word and the

accent. The Indians have another Spanish language of their own; and the

Cafres have one still more peculiar, to which must be added that they

eat half of the words. No one save he who has had this experience can

state the labors which it costs to confess them; and even when the

fault is understood in general, to seek for a specific account of the

circumstances is to enter a labyrinth without a clue. For they do not

understand our orderly mode of speech, and therefore when they are

questioned they say “yes” or “no” as it occurs

to them, without rightly understanding what is asked from them—so

that in a short time they will utter twenty contradictions. It is

therefore necessary to accommodate oneself to their language, and learn

their vocabulary. Another of the very serious difficulties is the

little capacity of these people to distinguish and explain numbers,

incidents, and circumstances; add to this the unbridled licentiousness

of some, in accordance with the freedom and opportunities [for vice] in

this land, the continual backsliding, and the few indications of fixed

purpose. In others, who are capable and explain their meaning well, is

found a complication [31]of perplexities—with a thousand

reflections, and bargains, and frauds, and oaths all joined together;

and faults that are extraordinary and of new kinds, which keep even the

most learned man continually studying them. The heat of the country,

and the stench or foul odor of the Indians and the negroes, unite in

great part to make a hardship of the ministry, which in these islands

is the most difficult; and on this account I regard it as being very

meritorious. The annual confessions last from the beginning of Lent

until Corpus Christi. In our college of Manila the church is open from

daylight until eleven o’clock, and from two o’clock until

nightfall; and always some fathers are present to hear

confessions—for this is done not only by the active ministers,

but by the instructors, when their scholastic duties give them

opportunity; and I have known some fathers who remain to hear

confessions during seven, eight, or more hours a day.

It makes them bear all these annoyances patiently, and

even sweetens these, to see how many souls are kept pure by the grace

of God, in the midst of so many temptations, like the bramble in the

midst of the fire without being burned. There are many who are striving

for perfection, who frequent the sacraments, who maintain prayer and

spiritual reading, and who give much in alms and perform other works of

charity. And it is cause for the greatest consolation to see, at the

solemn festivals of the Virgin and other important feasts, the

confessional surrounded by Indians, Cafres, and negroes, men and women,

great and small, who are awaiting their turns with incredible patience,

kept there through the grace of God, against every impulse of their

natural dispositions [32]and their slothfulness. And at the season of

Lent it is heart-breaking to see the confessor, when he rises from his

seat, surrounded by more than a hundred persons of all colors, who go

away disconsolate because they have not obtained an opportunity to make

their confessions; and in this manner they go and come for eight or ten

days, or a fortnight, or even more, with unspeakable patience, but with

such eagerness that when the confessor rises they go following him

throughout the house, calling to him to hear their confessions. This is

done even by boys of seven to twelve years, and hardly with violence

can they be made to leave the father, and they continue to call after

him; and some remain in the passages, on their knees, asking for

confession, so great is the number of the penitents—to which that

of the confessors does not correspond by far, nor does their assiduity,

even if there were enough of them. The Society is not content with

aiding those who come to seek relief in our church, and attending the

year round all the sick, of various languages, who summon them to hear

confession; but its laborers go forth—as it were, gospel

hunters—to search for penitents. They assist almost all who are

executed in the city; every week they go to the jails and hospitals; in

Lent they hear confessions in all the prisons, and at the foundry,

those of the galley-slaves. And in the course of the year they hear

confessions in the college of Santa Ysabel—in which there are

more than a hundred students, who are receiving the most admirable

education—and in the seminary of Santa Potenciana, the students

frequenting the sacraments often; and, in fine, they go on a perpetual

round in pursuit of the impious. [33]

The confessional is, as it were, the harvesting of the

crop; and the pulpit is the sowing, in which the seed of the gospel is

scattered in the hearts of men, where with the watering of grace it

bears fruit in due time, according to the coöperation [of the Holy

Ghost?]. With great constancy and solicitude the Society contributes to

the cultivation of these fields of Christianity, with preaching. In

Manila the Society has, besides the sermons from the holy men of the

order, other endowed feasts, and the set sermons5 in the

cathedral and the royal chapel. When necessity requires it, a mission

is held, and the attendance is very large, although hardly a fifth of

those who hear understand the Spanish language; this to a certain

extent discourages the missionaries, as does even much more the fact

that they do not encounter those external demonstrations of excitement

and tears that they arouse in other places. This originates

[34]from the characteristic of a large part of the

audience, that these attend with due seriousness only to certain

undertakings; and the distractions of their disputes and business

affairs, and their indolence and the air of the country, dissipate

their attention beyond measure. Their imaginations, overborne with

foolish trifles, and accustomed to our voices, become so relaxed that

even the most forcible and persuasive discourses make little, if any,

impression. Nevertheless, there are many in whom the holy fear of God

reigns, and the seed of the gospel takes root—which they embrace

with seriousness and simplicity, as the importance of the subject

demands. The marvel is, that many Indians and a great many Indian

women, only by the sound of [the preaching in] the mission, and without

understanding what they hear, are stricken with contrition, confess

themselves, and receive communion, in order to gain the

indulgences—to their own great advantage, and to the unspeakable

consolation of their confessors at seeing the wonderfully loving

providence of God for these souls.

This fruit and this consolation are most evident in the

Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius,6 which are

explained through most of the year in our college. [35]The

principal citizens make their retreat there, and in the solitude of

that retirement God speaks to them within their hearts; and marvelous

results have been seen in various persons, in whom has been established

a tenor of life so Christian that they may be called the religious of

the laymen—in their minds those eternal truths, on which they

meditate with seriousness, remaining firm, for the orderly conduct of

their lives. The students in the college of San Joseph have their own

society, which meets every Sunday, in which they perform their

exercises of devotion and have their exhortations, during the course of

the year. Every Sunday the Christian doctrine is explained to the boys

in the school, and some example [for their imitation] is related to

them; and they walk in procession through the streets, chanting the

doctrine. The Indian servants of the college have their own assembly,

conducted in a very decorous manner, with continual instruction in the

doctrine. Every Saturday an address in Tagálog is given to the

beatas who attend our church; they have their own society, and exercise

themselves in frequent devotions, furnishing an excellent and useful

example to the community. Every year they perform the spiritual

exercises; and the topics therein are given to them in Tagálog,

in our church, by one of Ours. Many devout Indian and mestizo women

resort hither on this occasion, to perform these exercises, in various

weeks, for which purpose they make retreat in the beaterio during the

week required for that; and even Spanish women, including ladies of the

most distinguished position, perform their spiritual exercises, and the

topics for meditation are assigned to them in our church. This practice

is [36]very beneficial for their souls, of great

usefulness to the community, and remarkably edifying to all.

The Society also busies itself in the conversion and

reconciliation of certain heretics, who are wont to come from the East

(as has been observed in recent years), and in catechising and

baptizing the Moros or the heathens who sometimes reach the

islands—either driven from their route, or called by God in other

ways; and He draws them to himself, so that they obtain holy baptism,

as has been seen in late years in some persons from the Palaos and

Carolina islands, and from Siao. Another of the means of which the

Society avails itself for the good of souls is, to print and distribute

free many spiritual books in various languages, which are most

efficacious although mute preachers. These, removing from men their

erroneous ideas by clear exposition [of the truth], and leaving them

without the cloak of their own fantastic notions, persuade them,

without being wearisome, to abandon vice or error; and then they

embrace virtue and the Christian mode of life. In Lent, as being an

acceptable time and especially opportune for the harvest, the dikes are

opened, in order that the waters of the word of God may flow more

abundantly. On Tuesdays there is preaching to the Spaniards, and these

sermons usually have the efficacy of a mission, although not given

under that name. On Thursdays there is explanation of the doctrine, and

preaching, in Tagálog, to the Indians; the attendance is very

great, since many come, not only from the numerous suburbs of Manila,

but even from the more distant villages. On Saturdays some good example

of the Virgin is related, with a moral exhortation; the Spaniards who

are members of [37]fraternities attend these, and afterward visit the

altars. On Sundays there is preaching to the Cafres, blacks, creoles,

and Malabars—who through a sense of propriety are called Morenos,

although they are dark-skinned. The sermon is in Spanish, and the

greatest difficulty of the preacher is to adapt his language to the

understanding of the audience. Various poor Spaniards also attend these

sermons, as well as other people, of various shades of color, of both

sexes.

Every Sunday certain fathers are sent to preach at the

fort or castle, to the soldiers and the other men who live there. The

Christian doctrine is chanted through the streets, and in the

procession walk the boys of the school; it ends at the royal chapel,

where some part of the catechism is explained, and a moral sermon is

preached to the soldiers who live in their quarters in order to mount

guard. The doctrine is explained at the Puerta Real and at the Puerta

del Parián, and there is preaching in the guard-room—where

there is a large attendance, not only of soldiers, but of the many

people who, on entering or going out from the gates, stop to hear the

word of God. Another father goes to the royal foundry, in which the

galley-slaves live, where there is such a variety of

people—mestizos, Indians of various dialects, Cafres, negroes of

different kinds, and Sangleys or Chinese—that exceptional ability

and patience are necessary in order to make them understand. Other

fathers go to the college of Santa Isabel and the seminary of Santa

Potenciana, where they give addresses and exhortations to the students

of the former, and the women secluded in the latter. Others go to the

prisons of both the ecclesiastical and [38]secular jurisdictions, in

order that the prisoners may obtain the spiritual food of the doctrine.

On Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays there is in our church a

Miserere, with the discipline [i.e., scourging]; a

spiritual book is read to those who are present, and at least once a

week an exhortation is addressed to them.

Such is, in general, the distribution of work for our

college at Manila in Lent, and therein are engaged nearly all the men

in the college, whether priests or students; and in times when there is

a scarcity of workers I have seen some helping at two or three posts,

and not only ministers and instructors thus occupied, but even the

superiors, and men of seventy years old, to the great edification of

the community. At Lent is seen in Manila that which occurred at the

destruction of Jericho, where, when the priests sounded around the city

the trumpets of the jubilee, the walls immediately gave way and fell to

the ground. Thus in Manila do the Jesuits surround the walls, calling

to every class of people with the trumpets of the jubilee and offering

pardon; and at the sound, through the grace and mercy of the Highest,

the lofty walls of lawlessness, vice, and crime, fall in ruins. And

even the presence of the ark is not lacking to this marvelous success,

for it is not to be doubted that the Blessed Virgin, most merciful

mother of sinners, aids us with her intercession. [Our author here

relates various instances of miraculous aid from heaven, and other

edifying cases.]

[Fol. 13:] Father Juan de Torres, with another priest

and a brother, went from the college of Manila to conduct a mission at

a place which is called [39]Cabeza de Bondoc,7 about sixty

leguas from Manila, in the bishopric of Camarines—the bishop of

Nueva Cazeres at that time being his illustrious Lordship Don Fray

Diego de Guevara, of the Order of St. Augustine. As soon as that

zealous prelate took possession of his see, he began to ask for fathers

of the Society, in order that, commencing with the Indians who were

already peaceable who reside in Nueva Cazeres, they might establish

missions and continue their instructions in other villages which he

intended to give them. But the Society, who always have showed due

consideration to the other ministers in these islands, not attempting

to dispossess them from their ministries—although not always have

we found them respond in like spirit—thanked that illustrious

prelate for his kindness, without accepting those ministries; and in

order that he might see that [the cause of this action] was

consideration for the ministers, and not the desire to escape from the

labor, Ours consented to conduct a mission in Bondoc, the difficulty of

which, and its results, are explained by that prelate in a letter which

he wrote to Father Torres, in which he says: “I find that it is

true, what was told to me in Manila, when I gave that mission-field to

the Society, and I mention it with great consolation to myself; and

that is, that it was the Holy Ghost who inspired me to give

it—for I see the fruits which are steadily and evidently being

gathered therein. For in so many ages it has been impossible to unite

those villages, and the Indians in them were regarded as irreclaimable;

[40]and now in so short a time those villages have

been united, and the Indians, [who were like] wild beasts, appear like

gentle lambs. These are the works of God, who operates through the

ministers of the Society—who with so much mildness, affection,

and zeal are laboring for the welfare of those people.” Great

hardships were suffered by those of the Society in these missions, and

for several years that ministry was cared for by Ours, until it was

entrusted to the secular priests.

The mission of Bondoc gained such repute in the island

of Marinduque, distant more than forty leguas from Manila, that its

minister, who was a zealous cleric, wrote to the father rector at

Manila asking him very humbly and urgently to send there a mission,

from which he was expecting abundant fruit. So earnest were the

entreaties of this fervent minister that a mission was sent to the said

island; it had the results which were expected, and afterward the

Society was commissioned with its administration. In nearly all the

ministries of secular priests the Society was carrying on continual

missions, at the petition of the ministers or at the instance of the

bishops.... The Society was held in honor not only by the bishop of

Camarines, but equally by his illustrious Lordship Don Fray Miguel

Garzia Serrano, a son of the great Augustine and most worthy archbishop

of Manila. That most zealous father Lorenzo Masonio preached to the

negroes who are in this city and outside its walls, according to the

custom of this province, which distributes the bread of the gospel

doctrine to all classes of people and all nations. And that holy

prelate deigned to go to our church, and, taking a wand in his hand, as

[41]the Jesuits are accustomed to do, he walked

through the aisle of the church, asked questions, and explained the

Christian doctrine to the slaves and negroes. The community experienced

the greatest edification at seeing their pastor so worthily occupied in

instructing his sheep, not heeding the outer color of their bodies, but

looking only at their precious souls—for in the presence of God

there is no distinction of persons.

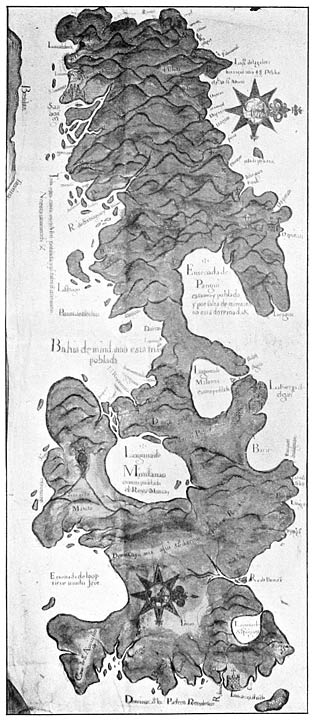

[Fol. 22:] The island of Malindig—named thus on

account of a high mountain that is in it, and which the Spaniards call

Marinduque—is more than forty leguas from Manila, extends north

and south, and is in the course which is taken by the galleons on the

Nueva España trade-route.8 There Ours carried on a

mission with much gain, at the instance of its zealous pastor, who was

a cleric; and in the year 1622 this island was transferred to the

Society by his illustrious Lordship Don Fray Miguel Garzia Serrano, the

archbishop of Manila, who was satisfied by the care with which the

Society administers its charges, and desirous that his sheep should

have the spiritual nourishment that is necessary for their

souls—for it was exceedingly difficult for him always to find a

secular priest to station there, on account of the distance from

Manila, the difficulty of administering that charge, and the loneliness

which one suffers there. The Society gladly overcame these difficulties

for the sake of the spiritual fruit which could be gathered among those

Indians; and our ministers, [42]applying themselves to the

cultivation [of that field], went about among those rugged

mountains—from which they brought out some heathens, and others

who were Christians, but who were living like heathen, without any

spiritual direction. They baptized the heathens and instructed the

Christians; and, in order that the results might be permanent, Ours

gradually settled them in villages which they formed; there are three

of these, Bovac, Santa Cruz, and Gasan, and formerly there was a visita

in Mahanguin. The language spoken there is generally the

Tagálog, although in various places there is a mixture of

Visayan, and of some words peculiar to the island. God chose to prove

those people by a sort of epidemic, of which many died; and the fathers

not only gave them spiritual assistance, but provided the poor with

food, and treated the sick. This trouble obliged them to resort for aid

to the Empress of Heaven, to whom they offered a fiesta under the title

of the Immaculate Conception, during the week before Christmas, with

great devotion; and the Virgin responded to them by aiding them in

their troubles and necessities.

[Fol. 27:] In Marinduque Ours labored very fervently to

reduce the Christians to a Christian and civilized mode of life; and

among them was abolished an abuse which was deeply rooted in that

island—which was, that creditors employed their debtors almost as

if they were slaves, without the debtor’s service ever

diminishing his debt. The wild Indians were reduced to settlement;

among them were some persons who for thirty years had not received the

sacraments of penance and communion. In the Pintados Islands there was

now much longing [43]for and attendance upon these holy sacraments,

when their necessity and advantage had been explained to the

natives.

[Fol. 29:] His illustrious Lordship Don Fray Miguel

Garzia Serrano had so much affection for the Society, and so high an

opinion of the zeal of its ministers, that he decided to entrust to it

the parish of the port of Cavite. This, one may say, is a parish of all

the nations, on account of the many peoples who resort to that port

from the four quarters of the world; it was especially so then, when

its commerce was more opulent, flourishing, and extensive [than now].

It did not seem expedient to the Society to accept this parish; but, in

order to show their gratitude for the favor, and to coöperate by

their labors with the zeal of that active prelate, they took upon

themselves for several months the administration of that port, in which

they gathered the fruit corresponding to the necessity—which,

with so great a concourse of different peoples there, and the freedom

from restraint which exists in this country, was very great. The

metropolitan was well satisfied, and very grateful; and he insisted

until the Society made itself responsible for the administration of one

of the three visitas which the said parish has. This was a village on

the shore of the river of Cavite, which on account of being older than

the settlement at the port is called Cavite el Viejo [i.e., Old

Cavite]; it afterward was located on the shore of the bay, about a

legua from the said port—which, in order to distinguish it from

this village, is called Cavite la Punta [i.e., Cavite on the

Point], because it is on the point of the hook formed by the land; from

this is derived the name Cavite, which means “a hook.” The

[44]ministry [at Old Cavite] was then small, but

difficult to administer, on account of the people being scattered, and

far more because of the corruption of morals; for, lacking the presence

of the pastor, and the wolves of the nations who come here from all

parts for trade, being so near, it might better be called a herd of

goats than a flock of sheep—this village being, as it were, the

public brothel [lupanar] of that port; and there was

hardly a house where this sort of commerce was not established. This

was a matter which at the beginning gave the ministers much to do, but

with invincible firmness they continued to correct this lawless

licentiousness; and by explaining the doctrine, preaching, and aiding

the people with the sacraments, they made Christians in morals those

who before only seemed to be such in outward appearance and name. Ours

continued to reclaim these people to the Christian life, and today this

village is one of the most Christian and best instructed communities in

all the islands; it has a beautiful and very capacious church of stone,

dedicated to St. Mary Magdalen, and a handsome house [for the

minister]. There are in this village, besides the Tagálogs (who

are the natives), some Sangleys and many mestizos, who live in

Binacayan, which is a sort of ward of the village.

[Fol. 31 b:] Ardently did the apostle of the Indias

desire to go over to China for its conversion; but he died, like

another Moses, in sight of the land which his desires promised to him.

Since then, without looking for them, thousands of heathen Chinese have

settled in these islands. As soon as the Society came to these shores,

Ours applied themselves, in the best manner that they could, to the

conversion and [45]instruction of those people—and even more in

recent times, on account of the Society possessing near Manila some

agricultural lands, which the Chinese (or Sangleys, as they are

commonly called) began to cultivate. Ours were unwilling to lose the

opportunity of converting them to our holy faith, so various persons

were actually baptized; and, to render this result more permanent, a

minister was stationed there, belonging to this field, who catechised

them, preached in their own language, baptized them, and administered

the sacraments—with permission from the vice-patron, Don Juan

Niño de Tabora, and from the archbishop, Don Fray Miguel Garzia

Serrano—and it is called the village of Santa Cruz. Their

language is very difficult; the words are all monosyllables, and the

same word, according to its various intonations, has many and various

significations; on this account not only patience and close study, but

a correct ear, are required for learning this language. Don Juan

Niño de Tabora was the godfather of the first Sangley who was

baptized; the most distinguished persons in the city attended the

ceremony; and this very solemn pomp had much influence on the Chinese

(who are very material), so that, having formed a high idea of the

Catholic religion, many of them embraced it. Some were baptized a

little while before they died, leaving behind many tokens of their

eternal felicity, through the concurrence of circumstances which were

apparently directed by a very special providence.

In Marinduque Father Domingo de Peñalver had just

induced some hamlets of wild Indians to settle down; he traveled

through the bed of the river, getting his clothing wet, stumbling

frequently over the [46]stones, and often falling in the water. He

went to take shelter in a hut, where there were so many and so fierce

mosquitoes, that he remained awake all night, without being able to rid

himself of the insects, notwithstanding all his efforts. He reached a

hill so inaccessible that it was necessary that some Indians, going

ahead and ascending by grasping the roots [of trees], should draw them

all up the ascent with bejucos. There he set up a shed, where,

preaching to them morning and afternoon, he prepared them for

confession, and persuaded them to go down and settle in one place, as

actually they did, to live as Christians. For lack of laborers, the

Society resigned the district of Bondoc and several visitas, although

Ours went there at various times on missionary trips. The people of

Hingoso called upon Father Peñalver to assist them, because many

in their village were sick, and the cura was at Manila; the father went

there, gave the sacraments to the sick, and preached to the rest twice

a day in the church. Three times a week they repaired to the church for

the discipline, and he offered for them the act of contrition, and

almost all the people in the village confessed. Afterward, at the

urgent request of the archbishop of Manila, Father Peñalver went

to Mindoro, to see if he could reconcile those Indians and their cura,

which the archbishop had not been able to secure by various means; the

said father went there, and preached various sermons, with so much

earnestness and efficacy (on account of his proficiency in the

Tagálog language) that in a short time they were reconciled

together, the causes of the dispute bring entirely forgotten. This

mission lasted two months; he preached twice every day, and heard some

two thousand five [47]hundred confessions; at this the illustrious

prelate (who was Don Fray Miguel Garzia Serrano) was greatly pleased,

and thoroughly confirmed in the extraordinary esteem which he deigned

to show the Society.... One of the greatest hardships and dangers

experienced by the ministers of Bisayas (or Pintados), in which are the

greater part of our ministries, is that they are journeying on the

water all their lives; for, as the villages are many and the ministers

few, one father regularly takes care of two villages, and sometimes of

three or four; and as these are in different islands, he is continually

moving from one to another, for their administration. I have known some

fathers who formerly had six or seven visitas, and spent nearly all the

year traveling from one to another. Nevertheless, so paternal and

benignant is the providence of God that it is not known that any

minister in Bisayas has been drowned—which, considering the many

hurricanes, tempests, storms, currents, and other dangers in which

every year many perish and are drowned, seems a continual miracle. To

this it must be added that at various times vessels have capsized in

the midst of the sea, and the fathers have fallen into the water; but

God succored them by means of the Indians, who are excellent swimmers,

or by other special methods of His paternal providence.

[Fol. 38 b:] In this year [1628] Manila and the

adjoining villages were grievously afflicted with a sort of epidemic

pest, from which many people died—some suddenly, but even he who

lingered longest died within twelve hours. Some attributed this pest to

the many blacks who had been brought here from India to be sold, and

who, sick from ill-usage, communicated [48]their disease to others;

and some thought that it arose from an infection in the fish, which is

the usual food of the poor. Various corpses were anatomized [se hizo anatomia], and the origin of the disease could not be

discovered, although it was considered certain that it arose from a

poisonous condition, since the only remedy that was found was

theriac.9 In a city where there are so few Spaniards, it is

easy to understand the affliction which was felt at seeing the

suddenness with which they were dying, since the colony was placed in

so great danger of extinction, and the islands of being ruined at one

stroke—besides the grief of individual persons at seeing

themselves bereft, the wife without a husband, the husband without a

wife, the father without children, the children deprived of their

parents. All search was made for remedies. Our priests did not cease,

day or night, to hear confessions, and to aid the sick and dying; and

at the request of the cura they carried with them the consecrated oils,

to administer these in case of need. They also carried theriac, after

this was discovered to be a remedy, for the relief of the sick; so they

exercised their charity at the same time on the souls and on the bodies

of men, to the great edification of all.

At San Miguel, one of those attacked by the pest told

the father who was hearing his dying confession that he had seen near

him two figures in the guise of ministers of justice, who seized

people; and that when he had received absolution they went away from

him, leaving behind a pestilential odor. The [49]father

published this information throughout the village, commanding the

people to prepare themselves for confession on the following day, under

the patronage of the Blessed Mary and St. Michael. A novenary was

offered, and the litanies recited; and in the church the discipline was

taken, with other prayers and penances, by which the Lord was moved to

have especial mercy on this village—as God showed to a devout

soul, in the figure of a ship which sailed through the air, the pilot

of which was the common enemy; but he could not enter San Miguel, since

there were powers greater than he, who prevented him. Also there were

seen in the neighborhood of Manila malign spirits, in the appearance of

horrible phantoms, who struck with death those who only looked at them.

In the face of a danger so near, many amended their lives, and were

converted to God in earnest, making a good confession. Then was seen

the charity with which the poor Indians, despising the danger to their

own lives, assisted the sick. Among others were two pious married

persons, who devoted themselves entirely to aiding the sick, never

leaving their bedsides until they either died or recovered; and God

most mercifully chose to bring them out unscathed from so continual

dangers. With the same kindness He chose to reward Brother Antonio de

Miranda, who had charge of the infirmary in our college at Manila, who,

on account of his well-known charity and solicitude in caring for the

sick, had been commissioned by the father provincial, Juan de Bueras,

to devote himself to the care of the sick Indians. But the poison of

the pest infected him, so violent being the attack that hardly had he

time to receive the sacraments; [50]and he died at Manila on October

15, 1628.... He was a native of Ponferrada, and of a very well known

family; he was an exemplary religious, and had been ten years in the

Society.

[Fol. 44 b:] In the years 1628 and 1629, at the request

of the bishops and of some Indians the Society was placed in charge of

various villages of converts. Don Juan Niño de Tabora gave us

the chaplaincy of the garrison of Spanish soldiers which is at Iloylo

in the island of Panay, and the instruction of the natives and the

people from other nations who are gathered there. Also were given to us

Ilog in the island of Negros, and Dapitan in Mindanao—of which

afterward more special mention will be made.

[Fol. 50:] In this time [about 1630] the Christian faith

made great advances in Maragondong, Silang, and Antipolo, bringing many

Cimarrons (or wild Indians) from their lurking-places. A very fruitful

mission was carried on in Mindoro, and on the northern coast of

Mindanao; and Father Pedro Gutierrez went along those rivers,

converting the Subanos. In Ilog, in the island of Negros, the fathers

labored much in removing an inhuman practice of those barbarians, which

was, to abandon entirely the old people, as being useless and only a

burden on them; and these poor wretches were going about through the

mountains, without knowing where to go, since even their own children

drove them away. The fathers gave them shelter, fed them, and

instructed them in order to baptize them; and there they converted many

heathens.

[Fol. 52:] In the year 1631 the cura of Mindoro, who was

a secular priest, gave up that ministry to the Society, and Ours began

to minister in that island, [53]making one resilience of this and one

of the island of Marinduque, and the superior lived at Nauhan in

Mindoro; and they began to preach, and to convert the Manguianes, the

heathen Indians of that island.

In the year 1631 was begun the residence of Dapitan, in

the great island of Mindanao. The first Jesuit who preached in that

island was the apostle of the Indias, St. Francis Xavier, as appears

from the bull for his canonization. Ruy Lopez de Villalobos came to

these islands with his ships, sent by the viceroy of Nueva

España, and gave them the name of Philipinas in honor of Phelipe

II; and, driven by storms, he went to Amboyno, where the saint then

was, in whose care Villalobos died. At the news of these islands thus

obtained by the holy apostle, he came to them. The circumstance that

this island was consecrated by the labors of that great apostle has

always and very rightly commended it to the Society; and Ours have

always and persistently endeavored to occupy themselves in converting

the Mindanaos; and Father Valerio de Ledesma and others had begun to

form missions on the river of Butuan. In the year 1596 the cabildo of

Manila, in sede vacante—in whose charge was then

the spiritual government of all the islands, as there was no division

into bishoprics—gave possession of Mindanao to the Society in due

form; and in 1597 this was confirmed by the vice-patron, Don Francisco

Tello, the governor of these islands. Possession of it was taken by

Father Juan del Campo, who, going as chaplain of the army, accompanied

the adelantado, Estevan Rodriguez de Figueroa, when he set out for the

conquest of that kingdom.

The first who began to minister to the Subanos in

[54]the coasts of Dapitan was Father Juan Lopez;

afterward Father Fabricio Sarsali, and then Father Francisco de Otazo,

and various other fathers followed, who made their incursions sometimes

from Zebu, sometimes from Bohol. In the year 1629 this ministry was

entrusted to the Society by the bishop of Zebu, Don Fray Pedro de Arze.

The venerable Father Pedro Gutierrez went through those coasts,

carrying the gospel of Christ to the rivers of Quipit, Mucas, Telinga,

and others; and in the year 1631 a permanent residence was formed, its

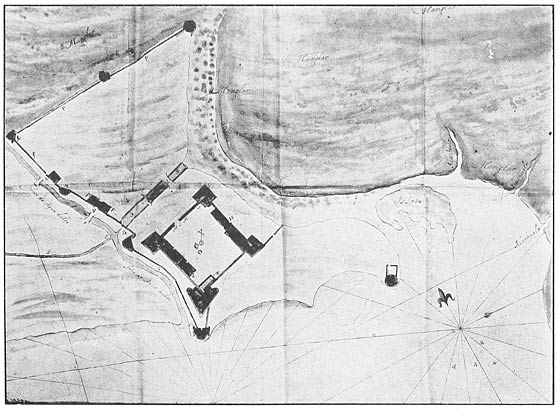

rector being Father Pedro Gutierrez. The village of Dapitan is at the

foot of a beautiful bay with a good harbor (in which the first

conquistadors anchored), on the northern coast of Mindanao; it is south

from the island of Zebu, and to the northeast of Samboangan, which is

on the opposite coast [of Mindanao]. It lies at the foot of a hill, at

the top of which there is a sort of fortress, so inaccessible that it

does not need artillery for its defense. Above it has a parapet, and

near the hill is an underground reservoir for collecting water, besides

a spring of flowing water. Maize and vegetables can be planted there,

in time of siege; and the minister and all the people retire to this

place in time of invasions. I was there in the year 1737

[misprinted 1637], and it seemed to me that it might be called

the Aorno10 of Philipinas.

[Fol. 60:] In the year 1631 and in part of 1632 this

province experienced so great a scarcity of laborers that the father

provincial wrote to our father general that he would have been obliged

to abandon [55]some of the ministries if the fervor of the few

ministers had not supplied the lack of the many, their charity making

great exertions. Our affliction was increased by the news that the

Dutch had seized Father Francisco Encinas, the procurator of this

province, who was going to Europa to bring a mission band

here—for which purpose they had sent Father Juan Lopez, who was

appointed in the second place11 in the congregation of 1626. But

soon God consoled this province, the mission arriving at Cavite on May

26, 1632. On June 18, 1631, they sailed from Cadiz, and on the last day

of August arrived at Vera Cruz; they left Acapulco on February 23,

1632, and on May 15 sighted the first land of these islands. Every

mission that goes to Indias begins to gather abundant fruit as soon as

it sails from España; I will set down the allotment of work in

which this band of missionaries was engaged, since from this may be

gathered what the others do, since there is very little difference

among them all. In the ship a mission was proclaimed which lasted

eleven days, closing with general communion on the day of our father

St. Ignatius; in this mission, through the sermons, instructions given

in addresses, and individual exhortations, the fathers succeeded in

obtaining many general confessions, besides the special ones which the

men on the ship made, in order to secure the jubilee. Ours assisted the

dying, consoled the sick and the afflicted, and established peace

between those who were enemies. In Nueva España the priests were

distributed in various colleges, in which they continued the exercises

of preaching and hearing confessions. [56]They went to Acapulco a

month before embarking, by the special providence of God; for there

were many diseases at that port, so that they were able to assist the

dying. Thirty religious of St. Dominic were there, waiting to come over

to these islands; all of them were sick, and five died; and, in order

to prevent more deaths, they decided to remove from their house in

which they were, on account of its bad condition. It was necessary, on

account of their sick condition, to carry them in sedan-chairs; and

although many laymen charitably offered their services for this act of

piety, Ours did not permit them to do it, but took upon themselves the

care of conveying the sick, their charity making this burden very

light. In the ship “San Luys” they continued their

ministries, preaching, and hearing the confessions of most of the

people on the ship—in which the functions of Holy Week were

performed, as well as was possible there. Twenty-one Jesuits left

Cadiz, and all arrived at Manila except Father Matheo de Aguilar, who

died near these islands on May 12, 1632; he was thirty-three years old,

and had been in the Society sixteen years—most of which time he

spent in Carmona, in the province of Andalusia, where he was an

instructor in grammar, minister, and procurator in that college.... The

rest who are known to have come in that year with Father Francisco de

Encinas, procurator, and Brother Pedro Martinez are: The fathers

Hernando Perez (the superior), Rafael de Bonafe, Luys de Aguayo, Magino

Sola, and Francisco Perez; and the brothers Ignacio Alcina, Joseph

Pimentél, Miguel Ponze, Andres de Ledesma, Antonio de Abarca,

Onofre Esbri, Christoval de Lara, Amador Navarro, Bartholome

[57]Sanchez; also Brother Juan Gazera, a coadjutor,

and Diego Blanco and Pedro Garzia, candidates [for the priesthood].

[Fol. 63 b:] In the islands of Pintados those first

laborers made such haste that by this time [1633] there remained no

heathens to convert, and they labored perseveringly in ministering to

the Christians, with abundant results and consolation.... In the island

of Negros and that of Mindanao, which but a short time before had been

given up to the Society, the fathers were occupied in catechising and

baptizing the heathens and especially in the island of Mindoro, where

besides the Christian convents, were the heathen Manguianes, who lived

in the mountains, and, according to estimate, numbered more than six

thousand souls. These people wandered through the mountains and woods

there like wild deer, and went about entirely naked, wearing only a

breech-clout [bahaque] for the sake of decency; they had no

house, hearth, or fixed habitation; and they slept where night overtook

them, in a cave or in the trunk of some tree. They gathered their food

on the trees or in the fields, since it was reduced to wild fruits and

roots; and as their greatest treat they ate rice boiled in water. Their

furnishings were some bows and arrows, or javelins for hunting, and a

jar for cooking rice; and he who secured a knife, or any iron

instrument, thought that he had a Potosi. They acknowledged no deity,

and when they had any good fortune the entire barangay (or family

connection) killed and ate a carabao, or buffalo; and what was left

they sacrificed to the souls of their ancestors. In order to convert

these heathens, a beginning was made by the reformation and instruction

[58]of the Christians; and by frequent preaching they

gradually established the usage of confession with some frequency, and

many received the Eucharist—a matter in which there was more

difficulty then than now. Many came down from the mountains, and

brought their children to be instructed; various persons were baptized,

and even some, who, although they had the name of Christians, had never

received the rite of baptism. After the fathers preached to the

Christians regarding honesty in their confessions, the result was

quickly seen in many general confessions, which were made with such

eagerness that the crowds resorting to the church lasted more than two

months.

[Fol. 69:] In Maragondong various trips were made into

the mountains [by Ours], and although many were reclaimed to a

Christian mode of living, yet, as the mountains are so difficult of

access and so close by, those people returned to their lurking-places

very easily, and it was with difficulty that they were again brought

into a village—so that the number of Indians was greatly

diminished, not only in Maragondong, but in Looc, which was a visita of

the former place, and contained very rugged mountains. In order to

encourage the Indians thus settled to make raids on the Cimarrons and

wild Indians and punish them, Don Juan Cerezo de Salamanca, the

governor ad interim, granted that those wild Indians

should for a certain time remain the slaves of him who should bring

them out of the hills; and by this means they succeeded in bringing out

many from their caverns and hiding-places. Some of these were seventy

or eighty years old, of whom many died as soon as they were instructed

and baptized. [59]Once the raiders came across an old woman about a

hundred years old, near the cave in which those people performed their

abominable sacrifices; she was alone, flung down on the ground, naked,

and of so horrible aspect that she made it evident, even in external

appearance, that she was a slave of the devil. Moved by Christian pity,

those who were making the raid carried her to the village, where it was

with difficulty that the father could catechise her, on account of her

age and her stupidity. He finally catechised and baptized her, and she

soon died; so that it seems as if it were a mercy of God that she thus

waited for baptism, in order that her soul might not be lost—and

the same with the other souls, their lives apparently being preserved

in order that they might be saved through the agency of baptism.

Blessed be His mercy forever! In Ilog, in the island of Negros, several

heathens of those mountains were converted to the faith. An Indian

woman was there, so obstinate in her blindness and so open in her

hatred to holy baptism that, in order to free herself from the

importunities of the minister, she feigned to be deaf and mute. Some of

her relatives notified the father to come to baptize her. The father

went to her, and began to catechise her, but she, keeping up the

deceit, pretended that she did not hear him, and he could not draw a

word from her. The father cried out to God for the conversion of that

soul, and, at the same time, he continued his efforts to catechise her,

suspecting that perhaps she was counterfeiting deafness. God heard his

prayers, and, after several days, the first word which that woman

uttered was a request for baptism—to the surprise of all who knew

what horror of it she had felt. The father catechised and baptized

[60]her, and this change was recognized as caused by

the right hand of the Highest; for she who formerly was like a wild

deer, living alone in the thickets, after this could not go away from

the church, and continued to exercise many pious acts until she rested

in the Lord.

[Fol. 74 b:] In the year 1596 Father Juan del Campo and

Brother Gaspar Gomez went with the adelantado Estevan Rodriguez de

Figueroa, who set out for the conquest of this island [Mindanao]. After

the death of Father Juan del Campo, Father Juan de San Lucar went to

assist that army, performing the functions of its chaplain, and also of

vicar for the ecclesiastical judge. Fathers Valerio de Ledesma and

Manuel Martinez preached to the Butuans, and afterward they were

followed, although with some interruptions, by others, who announced

the gospel to the Hadgaguanes—a people untamed and

ferocious—to the Manobos, and to other neighboring peoples.

Afterward this ministry was abandoned, on account of the lack of

laborers for so great a harvest as God was sending us. Secular priests

held it for some time, and finally it was given to the discalced

Augustinian [i.e., Recollect] religious, who are ministering in

that coast, and in Caraga as far as Linao—an inland region, where

there is a small fort and a garrison. When Father Francisco Vicente was

ministering in Butuan the cazique [meaning the headman] of Linao

went to invite him to go to his village; and even the blacks visited

him, and gave him hopes for their submission. Thus all those peoples

desired the Society, as set aside for the preaching in that

island—which work was assigned to the Society by the

ecclesiastical judge in the year 1596, and confirmed [61]to them

in 1597 by the governor Don Francisco Tello, as vice-patron. And when

some controversy afterward occurred over [the region of] Lake Malanao,

sentence was given in favor of the Society by Governors Don Juan

Niño de Tabora and Don Sebastian Hurtado de Corcuera, as Father

Combés states in book iii of his History of Mindanao.

These decisions were finally confirmed by Don Fernando Valdès

Tamon, in the year 1737.

In the year 1607 Father Pasqual de Acuña, going

thither with an armada of the Spaniards, began to preach with great

results to the heathens of the hill of Dapitan, where he baptized more

than two hundred. He also administered the sacraments to some

Christians who were there, who with Pagbuaya, a chief of Bohol, had

taken refuge in that place. Afterward, Father Juan Lopez went to supply

the Subanos of Dapitan with more regular ministrations. He was

succeeded by Father Fabricio Sarsali, and he by Father Francisco Otazo

and others, as a dependency of Zebu or of Bohol—until, in the

year 1629, his illustrious Lordship the bishop of Zebu, Don Fray Pedro

de Arze, governor of the archbishopric of Manila, again assigned this

mission to the Society; and in 1631 the residence of Dapitan was

founded, its first rector being the venerable Father Pedro Gutierrez;

and in those times the Christian faith was already far advanced, and

was extending through the region adjoining that place, and making great

progress.

[Fol. 92:] The island of Basilan, or Taguima, is three

or four leguas south of Samboangan, east from Borney, and almost

northeast from Joló. It is a fertile and abounding land, and on

this account they call [62]it the storehouse or garden of Samboangan.

Its people are Moros and heathens, and almost always they follow the

commands received from Joló. The Basilans, who inhabit the

principal villages, are of the Lutaya people; those who dwell in the

mountains are called Sameacas. Three chiefs had made themselves lords

of the island, Ondol, Boto, and Quindinga; and they formed the greatest

hindrance to the reduction of that people, who, as barbarians, have for

an inviolable law the will of their headmen, [which they follow]

heedlessly—that being most just, therefore, which has most

following. Nevertheless, the brave constancy of Father Francisco Angel

was not dismayed at such difficulties, or at the many perils of death

which continually threatened him; and his zeal enabled him to secure

the baptism of several persons, and to rescue from the captivity of

Mahoma more than three hundred Christians, whom he quickly sent to

Samboangan. Moreover, the fervor of the father being aided by the

blessing of God, he saw, with unspeakable consolation to his soul, the

three chiefs who were lords of the island baptized, with almost all the

inhabitants of the villages in it; and in the course of time the

Sameacas, or mountain-dwellers, were reduced—in this way mocking

the strong opposition which was made by the panditas, who are their

priests and doctors. [Here follows an account of the conquest of

Joló in 1638, and of affairs there and in Mindanao, in which the

Jesuits (especially Alexandro Lopez) took a prominent part; these

matters have already been sufficiently recounted in VOLS. XXVIII and XXIX].

[Fol. 111:] [After the Spanish expeditions to Lake

Lanao, in 1639–40, the fort built there was abandoned,

[63]and soon afterward burned by the natives. On May

7, 1642, the Moros of that region killed a Spanish officer, Captain

Andres de Rueda, with three men and a Jesuit, Father Francisco de

Mendoza, who accompanied him.] Much were the hopes of the gospel

ministers cast down at seeing our military forces abandon that country,

since they were expecting that with that protection the Christian

church would increase. Notwithstanding, his faith thereby planted more

firmly on God, Father Diego Patiño began to catechise the Iligan

people—with so good effect that in a few months the larger (and

the best) part of the residents in that village were brought under the

yoke of Christ; this work was greatly aided by the kindness of the

commandant of the garrison, Pedro Duran de Monforte. At this good news

various persons of the Malanaos came down [from the mountains], and in

the shelter of the fort they formed several small villages or hamlets,

and heard the gospel with pleasure. The conversions increasing, it was

necessary to station there another minister; this was Father Antonio de

Abarca. They founded the village of Nagua, and others, which steadily

and continually increased with the people who came down from the lake

[i.e., Lanao], where the villages were being broken up.12

This angered a brother of Molobolo, [64]and he tried to avert his own

ruin by the murder of the father; and for this purpose his treacherous

mind [led him to] pretend that he would come down to the new villages,

in order to become a Christian, intending to carry out then his treason

at his leisure. [65]But the father, warned by another Malanao, who was

less impious, escaped death. The traitor did not desist from his

purpose, and, when Father Abarca was in one of those villages toward

Layavan, attacked the village; but he was discovered by the blacks of

[66]the hill-country, and they rained so many arrows

upon the Moros that the latter abandoned their attempt. Another effort

was a failure—the preparation of three joangas which the traitor

had upon the sea, in order to capture and kill the father when he

should return to Iligan; but in all was displayed the special

protection with which God defends His ministers. However great the

efforts made by the zeal of the gospel laborers, the result did not

correspond to their desires, on account of the obstinacy of the

Mahometans—although in the heathens they encountered greater

docility for the acceptance of our religion. The life of the ministers

was very toilsome, since to the task of preaching must be added the

vigils and weariness, the heat and winds and rains, the dangers of

[travel by] the sea, and the scarcity of food. In a country so poor,

and at that time so uncultivated, it was considered a treat to find a

few sardines or other fish, some beans, and a little rice; and many

times they hardly could get boiled rice, and sometimes they must get

along with sweet potatoes, gabes,13 or [other] roots. But God

made amends for these privations and toils with various inner

pleasures; for they succeeded in obtaining some conversions that they

had not expected, and even among the blacks, from whom they feared

death, they found help and sustenance. [The author here relates a

vision which appeared to an Indian chief, of the spirit of Father

Marcelo Mastrilli as the director [67]and patron of Father Abarca; and

the renunciation of a mission to Europe which was vowed by Father

Patiño in order to regain his health—which accomplished,

he returns to his missionary labors at Iligan.]

He returned to the ministry, where he encountered much

cause for suffering and tears; because the [military] officers

[cabos] who then were governing that jurisdiction,

actuated by arrogance and greed of gain, had committed such acts of

violence that they had depopulated those little villages, many fleeing

to the hills, where among the Moros they found treatment more

endurable. The only ones who can oppose the injustice of such men are

the gospel ministers. These fathers undertook to defend the Indians,

and took it upon themselves to endure the anger of those men—who,

raised from a low condition to places of authority, made their mean

origin evident in their coarse natures and lawless passions; and the

license of some of them went to such extremes that it was necessary for

the soldiers to seize them as intolerable; and, to revenge themselves

for the outrageous conduct of the officials, they accused the latter as

traitors. Not even the Malanao chief Molobolo, who always had been firm

on the side of the Spaniards, could endure their acts of violence, and,

to avoid these, went back to the lake. This tempest lasted for some

time, but afterward some peace was secured, when those officers were

succeeded by others who were more compliant. The venerable Father Pedro

Gutierrez went to Iligan, and with his amiable and gentle disposition

induced a chief to leave the lake, who, with many people, became a

resident of Dapitan; and another chief, still more powerful, was

[68]added to Iligan with his people. These results

were mainly seemed by the virtue of the father, the high opinion which

all had of his holy character, and the helpful and forcible effects of

his oratory. The land was scorched by a drouth, which was general

throughout the islands, from which ensued great losses. The father

offered the Indians rain, if they would put a roof on the church; they

accepted the proposal, and immediately God fulfilled what His servant

had promised—sending them a copious rain on his saying the first

mass of a novenary, which he offered to this end. With this the Indians

were somewhat awakened from their natural sloth, and the church was

finished, so that the fathers could exercise in it their ministries.

The drouth was followed by a plague of locusts, which destroyed the

grain-fields; the father exorcised them, and, to the wonder of all, the

locusts thrust their heads into the ground, and the plague came to an

end. This increased the esteem of the natives for our religion, and

many heathens and Moros were brought into its bosom; and Father

Combés says that when he ministered there he found more than

fifty old persons of eighty to a hundred years, and baptized them all,

with some three hundred boys this being now one of the largest

Christian communities in the islands. The village is upon the shore, at

the foot of the great Panguil,14 between Butuan and Dapitan, to

the south of Bohol, and north from Malanao, at the mouth of a river

with a dangerous bar. The fort is of good stone, dedicated to St.

Francis Xavier, in the shape of a star; the wall [69]is two

varas high, and half a vara thick, and it has a garrison, with

artillery and weapons. The Moros have several times surrounded it, but

they could not gain it by assault.

[Fol. 116 b:] In Sibuguey Father Francisco Luzon was

preaching, a truly apostolic man, who spent his life coming and going

in the most arduous ministries of the islands. The Sibugueys are

heathens, of a gentler disposition and more docile to the reception of

the gospel than are the Mahometans; therefore this mission aroused

great hopes. One Ash Wednesday Father Luzon went to the fort, and he

was received by a Lutao of gigantic stature who gave him his hand. The

father shook hands with him, supposing that that was all for which he

stopped him; but the Lutao trickily let himself be carried on, and with

his weight dragged the father into the water, with the assurance that

he could not be in danger, on account of his dexterity in swimming. The

father went under, because he could not swim, and the captain and the

soldiers hastened from the fort to his aid—but so late that there

was quite enough time for him to be drowned, on account of having sunk

so deep in the water; they pulled him out, half dead, and the first

thing that he did was to secure pardon for the Lutao. He gained a

little strength and went to the fort; he gave ashes to the Spaniards,

and preached with as much fervor as if that hardship had not befallen

him. The principal of Sibuguey was Datan, and, to make sure of him, the

Spaniards had carried away as a hostage his daughter Paloma; and love

for her caused her parents to leave Sibuguey and go to Samboangan to

live, to have the company of their daughter. Father Alexandro Lopez

went to minister at Sibuguey, and he saw that without the [70]authority of Datan he could do almost nothing

among the Sibugueys; this obliged him to go to Samboangan to get him,

and he succeeded [in persuading them] to give him the girl. The father

went up toward the source of the river, and found several hamlets of

peaceable people, and a lake with five hundred people residing about

it; and their chief, Sumogog, received him as a friend, and all

listened readily to the things of God. He went so far that he could see

the mountains of Dapitan, which are so near that place that a messenger

went [to Dapitan] and returned in three days. These fair hopes were

frustrated by the absence of Datan, who went with all his family to

Mindanao; and on Ascension day in 1644 that new church disappeared, no

one being left save a boy named Marcelo. Afterward the Moros put the

fort in such danger, having killed some men, that it was necessary to

dismantle it and withdraw the garrison.

[Fol. 121 (sc. 120):] The Joloans having been

subjected by the bravery of Don Pedro de Almonte, they began to listen

to the gospel, and they went to fix their abodes in the shelter of our

fort. But, [divine] grace accommodating itself to their nature, as the

sect of Mahoma have always been so obstinate, it was necessary that God

should display His power, in order that their eyes might be opened to

the light. The fervent father Alexandro Lopez was preaching in that

island, to whose labors efficacy was given by the hand of God with many

prodigies. The cures which the ministers made were frequent, now with

benedictions, now with St. Paul’s earth,15 in many

[71]cases of bites from poisonous serpents, or of

persons to whom poison was administered. Among other cures, one was

famous, that of a woman already given up as beyond hope; having given

her some of St. Paul’s earth, she came back from the gates of

death to entire health. With this they showed more readiness to accept

the [Christian] doctrine, which was increased by a singular triumph

which the holy cross obtained over hell in all these islands; for,

having planted this royal standard of our redemption in an island

greatly infested by demons, who were continually frightening the

islanders with howls and cries, it imposed upon them perpetual silence,

and freed all the other [neighboring] islands from an extraordinary

tyranny. For the demons were crossing from island to island, in the

sea, in the shape of serpents of enormous size, and did not allow

vessels to pass without first compelling their crews to render

adoration to the demon in iniquitous sacrifices; but this ceased, the

demon taking flight at sight of the cross. [Several incidents of

miraculous events are here related.] With these occurrences God opened

their eyes, in order that they might see the light and embrace baptism,

and in those islands a very notable Christian church was formed; and

almost all was due to the miraculous resurrection of Maria Ligo [which

our author relates at length]. Many believed, and thus began a

flourishing Christian community; and as ministers afterward could not

be kept in Joló on account of the wars, [these converts] exiled

themselves from their native land, and went to live at Samboangan, in

order that they might be able to live as Christians. [This prosperous

beginning is spoiled by the lawless conduct of [72]the

commandant Gaspar de Morales, which brings on hostilities with the

natives, and finally his own death in a fight with them.] Father

Alexandro Lopez went to announce the gospel at Pangutaran, (an island

distant six leguas east from Joló), and as the people were a

simple folk they received the law of Christ with readiness ... The

Moros of Tuptup captured a discalced religious of St. Augustine, who,

to escape from the pains of captivity, took to flight with a negro.

Father Juan Contreras (who was in Joló) went out with some

Lutaos in boats to rescue him, calling to him in various places from

the shore; but the poor religious was so overcome with fear that,

although he heard the voices and was near the beach, he did not dare to

go out to our vessels, despite the encouragement of the negro; and on

the following day the Joloans, encountering him, carried him back to

his captivity, with blows. He wrote a letter from that place, telling

the misfortunes that he was suffering; all the soldiers, and even the

Lutaos, called upon the governor [of Joló], to ransom that

religious at the cost of their wages, but without effect. Then Father

Contreras, moved by fervent charity, went to Patical, where the

fair16 was [73]held, and offered himself to remain

as a captive among the Moros, in order that they might set free the

poor religious, who was feeble and sick. Some Moros agreed to this; but

the Orancaya Suil, who was the head chief of the Guimbanos, said that

no one should have anything to do with that plan—at which the

hopes of that afflicted religious for ransom were cut off. Seeing that

he must again endure his hardships, from which death would soon result,

he asked Father Contreras to confess him; the latter undertook to set

out by water to furnish him that spiritual consolation, but the Lutaos

would not allow him to leave the boat, even using some violence, in

order not to endanger his person. All admired a charity so ardent, and,

having renewed his efforts, he so urgently persuaded the governor, Juan

Ruiz Maroto, to ransom him that the latter gave a thousand pesos in

order to rescue the religious from captivity. Twice Father Contreras

went to the fair, but the Moros did not carry the captive there with

them. Afterward he was ransomed for three hundred pesos by Father

Alexandro Lopez, the soldiers aiding with part of their pay a work of

so great charity.

[Fol. 123:] [The Society of Jesus throughout the world

celebrates the centennial anniversary of its foundation; the official

order for this does not reach Manila in time, so the Jesuits there

observe the proper anniversary (September 27, 1640) with solemn

[74]religious functions, besides spending a week in

practicing the “spiritual exercises” and various works of

charity. “On one day of the octave all the members of the Society

went to the prisons, and carried to the prisoners an abundant and

delicious repast. The same was done in the hospitals, to which they

carried many sweetmeats to regale the sick; they made the beds, swept

the halls, and carried the chamber-vessels to the river to clean them;

and afterward they sprinkled the halls with scented water. Throughout

the octave abundance of food was furnished at the porter’s lodge

to the beggars; and a free table was set for the poor Spaniards, who

were served with food in abundance and neatness. It was a duty, and a

very proper manner of celebrating the [virtues of the] men who have

rendered the Society illustrious, to imitate them in humility,

devotion, and charity.”]

[Fol. 123 b:] In the Pintados Islands and other

ministries Ours labored fervently in ministering to the Christians and

converting the infidels. Nor was the zeal of the Society content with

laboring in its own harvest-field; it had the courage to go to the

ministers of the secular priests to conduct missions. Two fathers went

on a mission to Mindoro and Luban, and when they were near the village

their caracoa was attacked by three joangas of Borneans and Camucones.

The caracoa, in order to escape from the enemies, ran ashore; and the

fathers, leaving there all that they possessed—books, missal, and

the clothing that they were carrying to distribute as alms to the poor

Indians—took to the woods, through which they made their way to

Naujan. On the road it frequently rained, and they had no change of

[75]clothing, nor any food save some buds of the wild

palm-tree; they suffered weariness, hunger, and thirst, and to slake

this last they drank the water which they found in the pools there.

After twenty days of this so toilsome journeying they reached the chief

town [of the island], their feet covered with wounds, themselves faint

and worn out with hunger, and half dead from fatigue; but they were

joyful and contented, because God was giving them this opportunity to

suffer for love of Him. One of the fathers went back to Marinduque,

where he found other troubles, no less grievous than those which had

gone before; for the Camucones had robbed the church, ravaged the

grain-fields, captured some Indians, and caused the rest to flee to the

hills. The father felt deep compassion for them, and at the cost of

much toil he again assembled the Indians and brought them back to their

villages.

[Fol. 134:] In the fifth provincial congregation, which

was held in the year 1635, Father Diego de Bobadilla was chosen

procurator to Roma and Madrid. He embarked in the year 1637, and while

he was in España the disturbances in Portugal and

Cataluña occurred. The news of these events was very afflicting

to this province, considering the difficulty in its securing aid.

Besides the usual fields of Tagalos and Bisayas, the province occupied

the new missions of Buhayen, Iligan, Basilan, and Jolo; and there were

several years when it found itself with only forty priests, who with

the utmost difficulty provided as best they could for needs so great.

Phelipe IV—whom we may call “the Great,” on account

of his unconquerable, signal, and unusual patience, which God chose to

prove by great and [76]repeated misfortunes—was so zealous for

the Catholic religion, its maintenance, and its progress that even in

times so hard he did not grudge the grant of forty-seven missionaries

for this province. He also gave orders that they should be supplied at

Sevilla with a thousand and forty ducados, and at Mexico with thirteen

thousand pesos—a contribution of the greatest value in those

circumstances, and which could only be dictated by a heart so Catholic

as that of this prince, who every day renewed the vow that he had taken

that he would not make friends with the infidels, to the detriment of