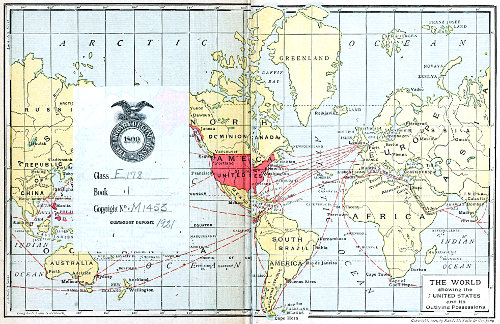

THE WORLD showing the UNITED STATES and its Outlying Possessions

Copyright, 1909, by Rand, McNally & Company.

Title: A Beginner's History

Author: William H. Mace

Illustrator: P. Raymond Audibert

Homer Wayland Colby

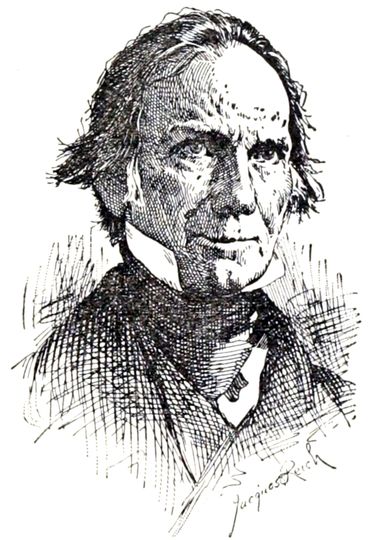

Jacques Reich

B. F. Williamson

Release date: November 25, 2015 [eBook #50548]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing, Richard Hulse and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

THE WORLD showing the UNITED STATES and its Outlying Possessions

Copyright, 1909, by Rand, McNally & Company.

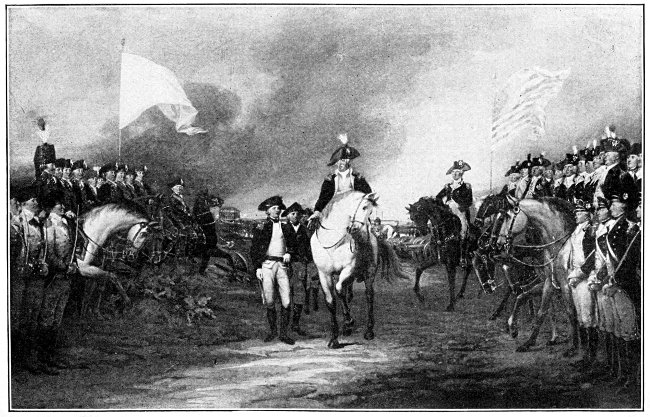

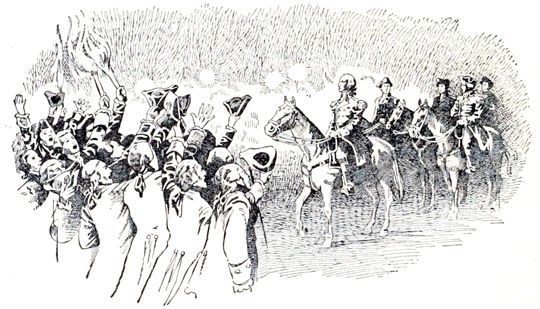

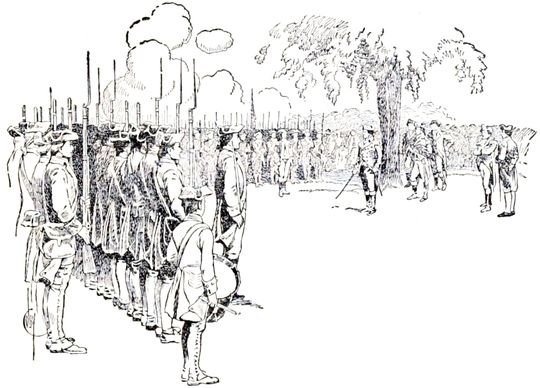

THE SURRENDER OF CORNWALLIS

by

WILLIAM H. MACE

Formerly Professor of History in Syracuse University, Author of

"Method in History," "A Working Manual of American

History," "A School History of the United

States," "Lincoln: The Man of the

People," and "Washington:

A Virginia Cavalier"

Illustrated by

HOMER W. COLBY

Portraits by

JACQUES REICH, P. R. AUDIBERT,

and B. F. WILLIAMSON

RAND McNALLY & COMPANY

Chicago New York London

Mace's Primary History

Copyright, 1909,

By William H. Mace

All rights reserved

Mace's Elementary History

Copyright, 1914,

By William H. Mace

Mace's Beginner's History

Copyright, 1914,

By William H. Mace

Copyright, 1916,

By William H. Mace

Copyright, 1921,

By William H. Mace

The Rand-McNally Press

Chicago

The material out of which the child pictures history lies all about him. When he learns to handle objects or observes men and other beings act, he is gathering material to form images for the stories you tell him, or those he reads. So supple and vigorous is the child's imagination that he can put this store of material to use in picturing a fairy story, a legend, or a myth.

From this same source—his observation of the people and things about him—he gathers simple meanings and ideas of his own. He weaves these meanings and ideas, in part, into the stories he reads or is told. From the cradle to the grave he should exercise this habit of testing the men and institutions he studies by a comparison with those he has seen.

The teacher should use the stories in this book to impress upon the pupil's mind the idea that life is a constant struggle against opposing difficulties. The pupil should be able to see that the great men of American history spent their lives in a ceaseless effort to conquer obstacles. For everywhere men find opponents. What a struggle Lincoln had against the twin difficulties of poverty and ignorance! What a battle Roosevelt waged with timidity and a sickly boyhood! And what a tremendously courageous and vigorous man he became!

In the fight which men wage for noble or ignoble ends the pupil finds his greatest source of interest. Here he forms his ideas of right and wrong, and deals out praise and blame among the characters. Hence the need of presenting true Americans—patriotic Americans—for his study.

This book of American history includes the stirring scenes of the world's greatest war. It shows how a vast nation, loving peace and hating war, worked to get ready to fight,[Pg iv] how it trained its soldiers and planned a great navy, and how, when all was ready, it hurled two million men against the Germans and helped our brave allies to crush the cruelest foe that war ever let loose.

With the knowledge of American men and events which the study of our history should give him, the pupil is ready to ask where the first Americans came from. To answer that question, and many others, we must go to European history. We must look at the great peoples of the world's earlier history, and see how their civilization finally developed into that which those colonists who pushed across the Atlantic to America brought with them.

But the civilization brought to this country by earlier or by later comers must not cease to grow. America has her part to add to its development. With the close of the World War we must not forget one fact which that conflict brought out—the vast number of people in the United States almost untouched by the spirit of American institutions. Teachers of history, the subject-matter of which is the story of American institutions and American leaders, can do much to change such conditions. This need for more thorough Americanization they can help to fill by teaching in their classes not a mechanical patriotism but a loyal understanding of American ideals.

William H. Mace

Syracuse University

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| The Northmen Discover the New World | |

| Leif Ericson, Who Discovered Vinland | 1 |

| Early Explorers in America | |

| Christopher Columbus, the First Great Man in American History | 2 |

| Ponce de Leon, Who Sought a Marvelous Land and Was Disappointed | 17 |

| Cortés, Who Found the Rich City of Mexico | 18 |

| Pizarro, Who Found the Richest City in the World | 23 |

| Coronado, Who Penetrated Southwestern United States but Found Nothing but Beautiful Scenery | 24 |

| De Soto, the Discoverer of the Mississippi | 24 |

| Magellan, Who Proved that the World Is Round | 28 |

| The Men Who Made America Known to England and Who Checked the Progress of Spain | |

| John Cabot also Searches for a Shorter Route to India and Finds the Mainland of North America | 34 |

| Sir Francis Drake, the English "Dragon," Who Sailed the Spanish Main and Who "Singed the King of Spain's Beard" | 37 |

| Sir Walter Raleigh, the Friend of Elizabeth, Plants a Colony in America to Check the Power of Spain | 42 |

| The Men Who Planted New France in America, Founded Quebec, Explored the Great Lake Region, and Penetrated the Mississippi Valley | |

| Samuel de Champlain, the Father of New France | 49 |

| Joliet and Marquette, Fur Trader and Missionary, Explore the Mississippi Valley for New France | 53 |

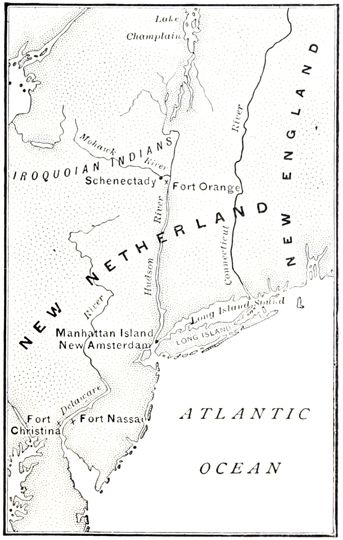

| What the Dutch Accomplished in the Colonization of the New World | |

| Henry Hudson, Whose Discoveries Led Dutch Traders to Colonize New Netherland | 54 |

| Famous People in Early Virginia | |

| John Smith the Savior of Virginia, and Pocahontas its Good Angel | 60[Pg vi] |

| Lord Baltimore, in a Part of Virginia, Founds Maryland as a Home for Persecuted Catholics and Welcomes Protestants | 68 |

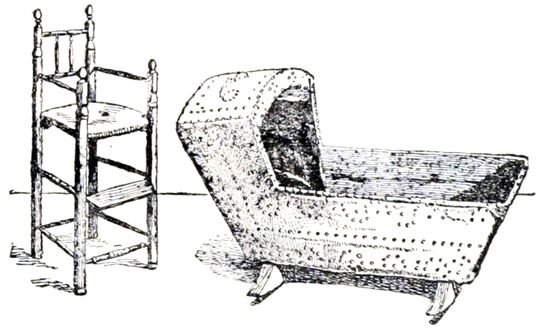

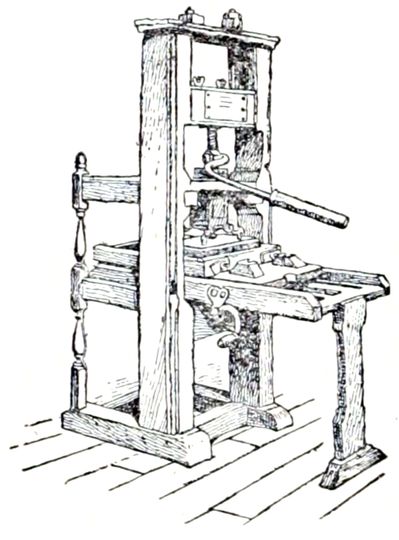

| Industries, Manners, and Customs of First Settlers of Virginia | 71 |

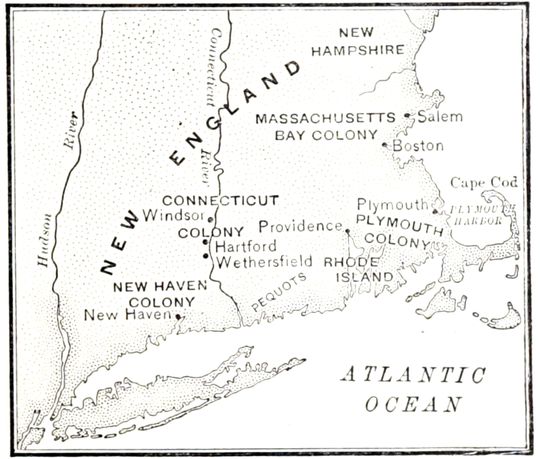

| Pilgrims and Puritans in New England | |

| Miles Standish, the Pilgrim Soldier, and the Story of "Plymouth Rock" | 73 |

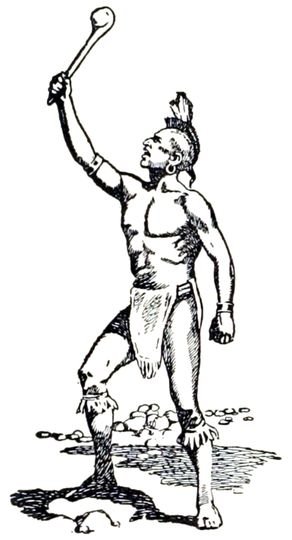

| John Winthrop, the Founder of Boston; John Eliot, the Great English Missionary; and King Philip, an Indian Chief the Equal of the White Man | 81 |

| Industries, Manners, and Customs | 85 |

| The Men Who Planted Colonies for Many Kinds of People | |

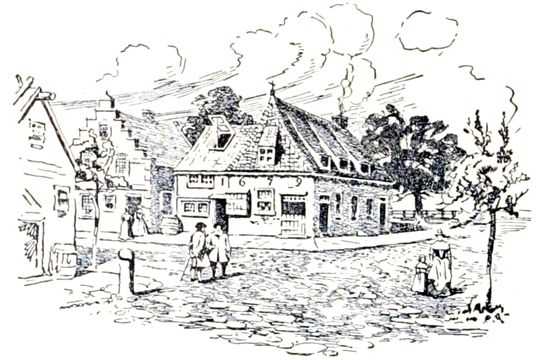

| Peter Stuyvesant, the Great Dutch Governor | 87 |

| Manners and Customs of New Netherland | 91 |

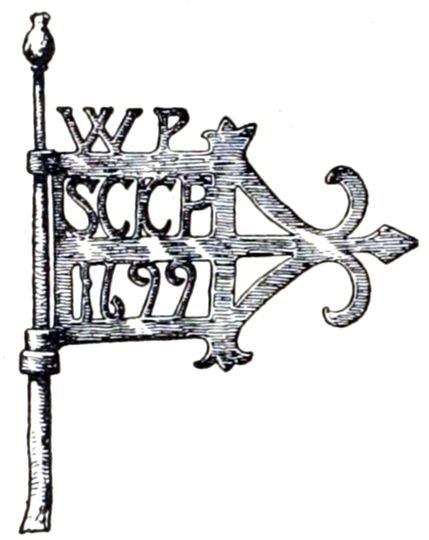

| William Penn, the Quaker, Who Founded the City of Brotherly Love | 92 |

| Quaker Ways in Old Pennsylvania | 98 |

| James Oglethorpe, the Founder of Georgia as a Home for English Debtors, as a Place for Persecuted Protestants, and as a Barrier against the Spaniards | 100 |

| Industries, Manners, and Customs of the Southern Planters | 103 |

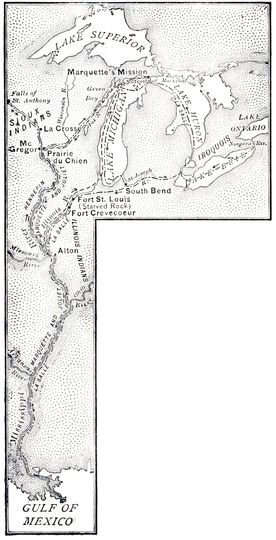

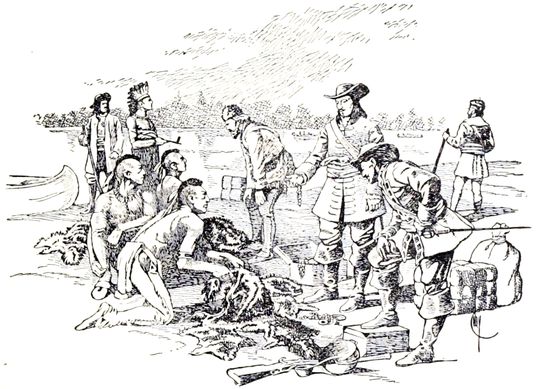

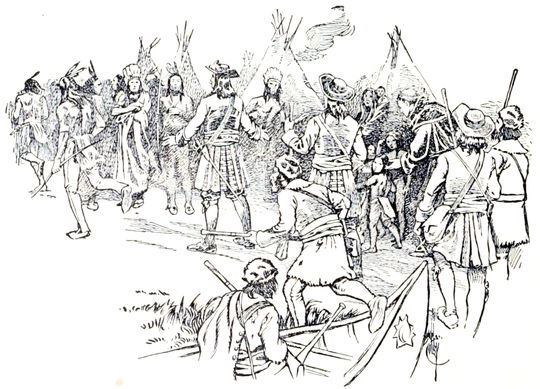

| Robert Cavelier de la Salle, Who Followed the Father of Waters to its Mouth, and Established New France from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico | |

| La Salle Pushed Forward the Work Begun by Joliet and Marquette | 106 |

| The Men of New France | 113 |

| George Washington, the First General and First President of the United States | |

| The "Father of His Country" | 115 |

| The Man Who Helped Win Independence by Winning the Hearts of Frenchmen for America | |

| Benjamin Franklin, the Wisest American of His Time | 147 |

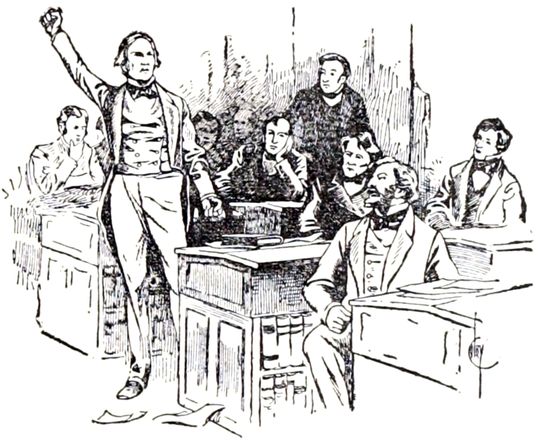

| Patrick Henry and Samuel Adams, Famous Men of the Revolution, Who Defended America with Tongue and Pen | |

| Patrick Henry, the Orator of the Revolution | 158 |

| Samuel Adams, the Firebrand of the Revolution | 167 |

| The Men Who Fought for American Independence with Gun and Sword | |

| Nathan Hale | 179[Pg vii] |

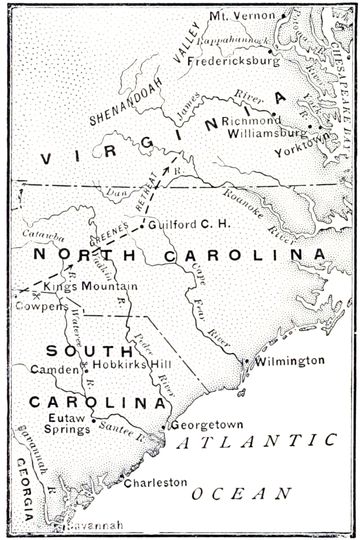

| Generals Greene, Morgan, and Marion, the Men Who Helped Win the South from the British | 182 |

| The Men Who Helped Win Independence by Fighting England on the Sea | |

| John Paul Jones, a Scotchman, Who Won the Great Victory in the French Ship, Bon Homme Richard | 194 |

| John Barry, Who Won More Sea Fights in the Revolution than Any Other Captain | 199 |

| The Men Who Crossed the Mountains, Defeated the Indians and British, and Made the Mississippi River the Western Boundary of the United States | |

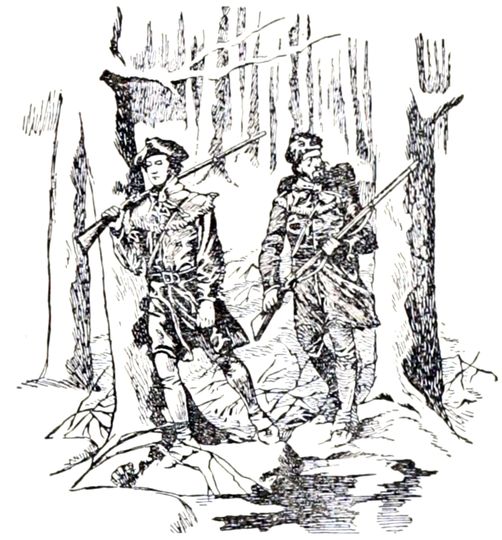

| Daniel Boone, the Hunter and Pioneer of Kentucky | 202 |

| John Sevier, "Nolichucky Jack" | 210 |

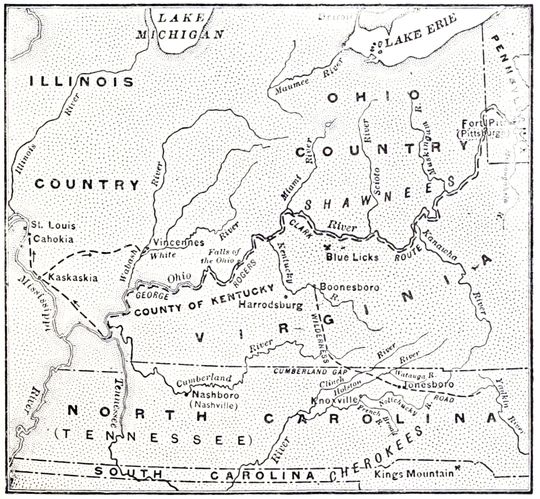

| George Rogers Clark, the Hero of Vincennes | 216 |

| Development of the New Republic | |

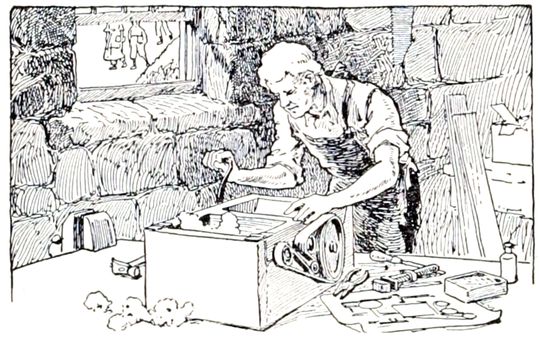

| Eli Whitney, Who Invented the Cotton Gin and Changed the History of the South | 226 |

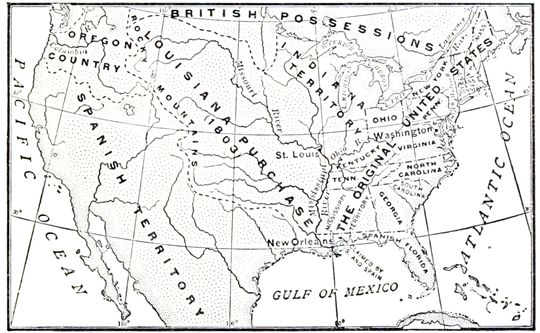

| Thomas Jefferson, Who Wrote the Declaration of Independence, Founded the Democratic Party, and Purchased the Louisiana Territory | 229 |

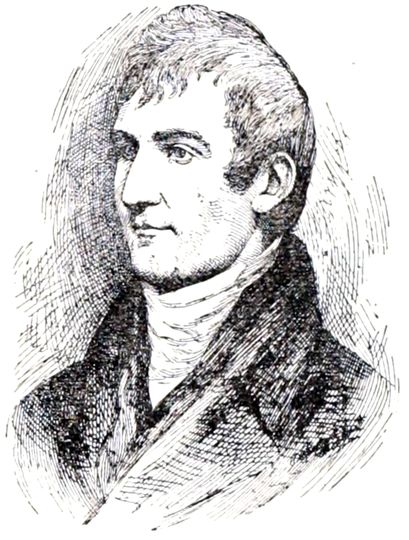

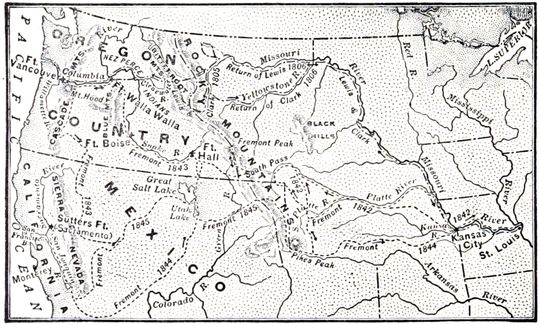

| Lewis and Clark, American Explorers in the Oregon Country | 238 |

| Oliver Hazard Perry, Victor in the Battle of Lake Erie | 244 |

| Andrew Jackson, the Victor of New Orleans | 245 |

| The Men Who Made the Nation Great by Their Inventions and Discoveries | |

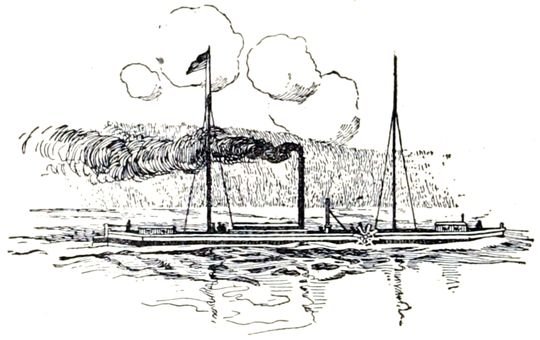

| Robert Fulton, the Inventor of the Steamboat | 257 |

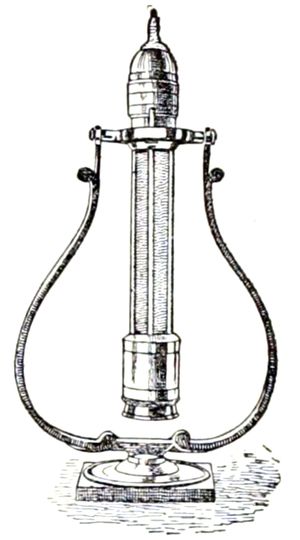

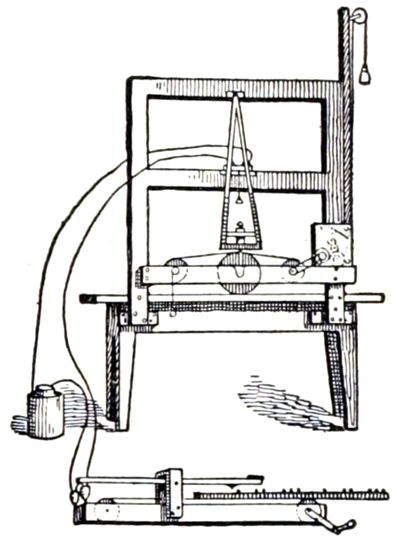

| Samuel F. B. Morse, Inventor of the Telegraph | 264 |

| Cyrus West Field, Who Laid the Atlantic Cable between America and Europe | 268 |

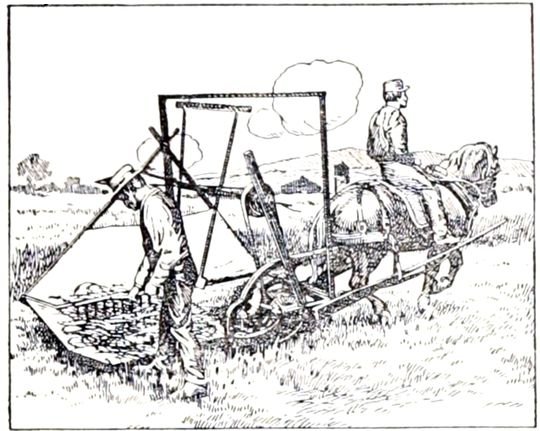

| Cyrus McCormick, Inventor of the Reaper | 272 |

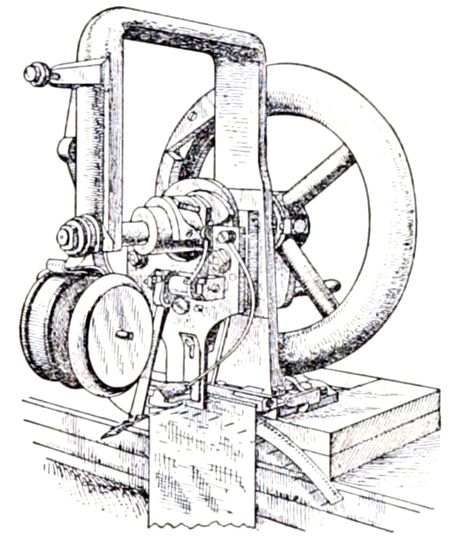

| Elias Howe, Inventor of the Sewing Machine | 274 |

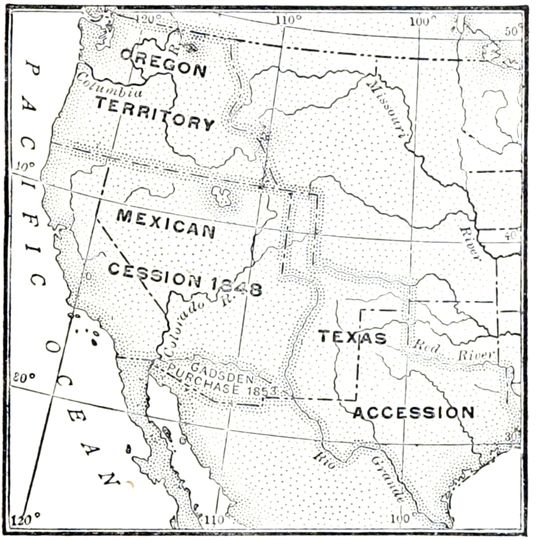

| The Men Who Won Texas, the Oregon Country, and California | |

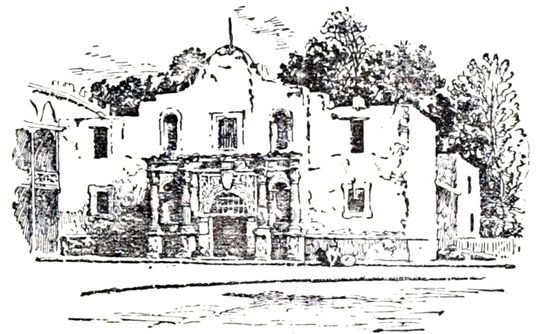

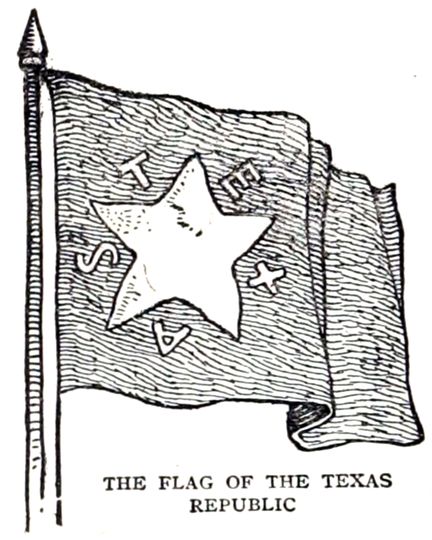

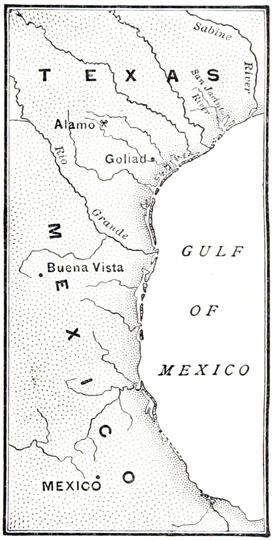

| Sam Houston, Hero of San Jacinto | 277 |

| David Crockett, Great Hunter and Hero of the Alamo | 282 |

| John C. Fremont, the Pathfinder of the Rocky Mountains | 283 |

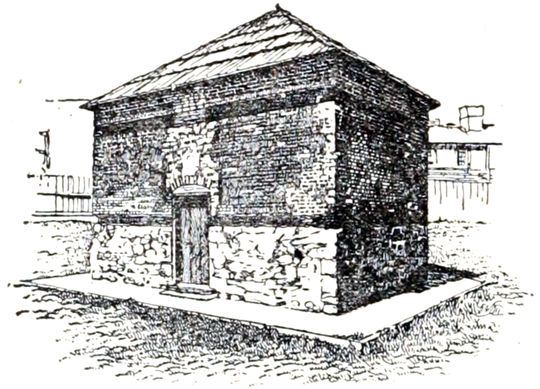

| Spanish Missions in the Southwest | 290 |

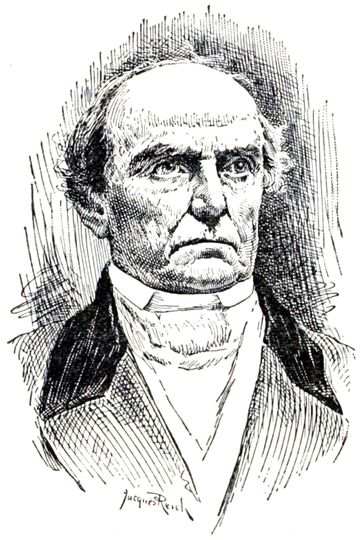

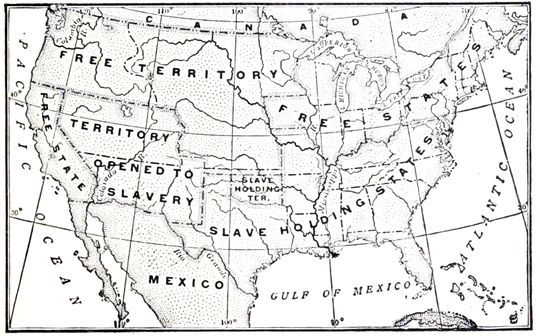

| The Three Greatest Statesmen of the Middle Period | |

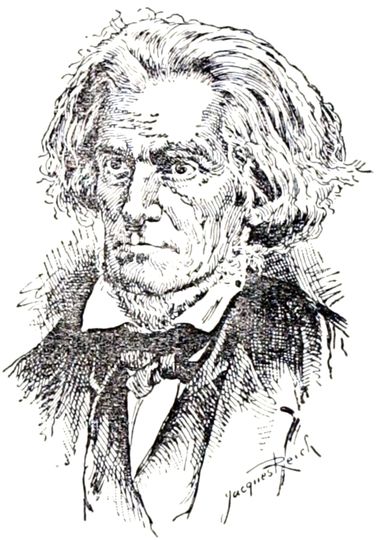

| Henry Clay, the Founder of the Whig Party and the Great Pacificator | 294[Pg viii] |

| Daniel Webster, the Defender of the Constitution | 300 |

| John C. Calhoun, the Champion of Nullification | 306 |

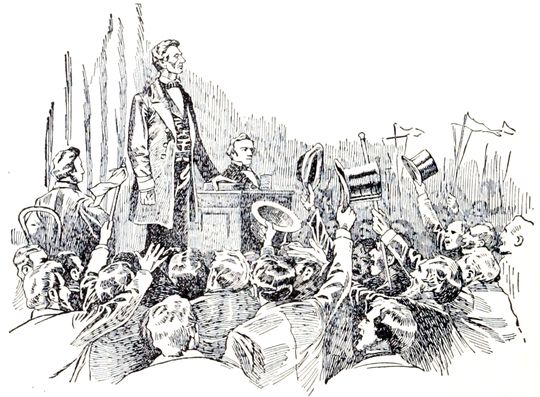

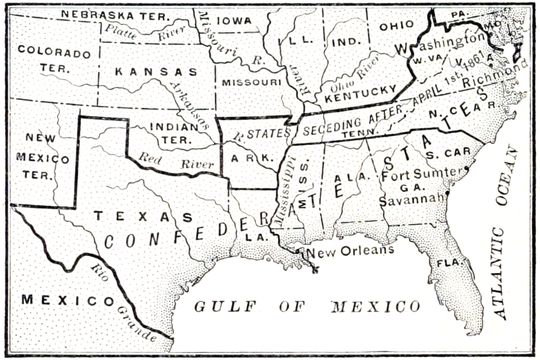

| Abraham Lincoln, the Liberator and Martyr | |

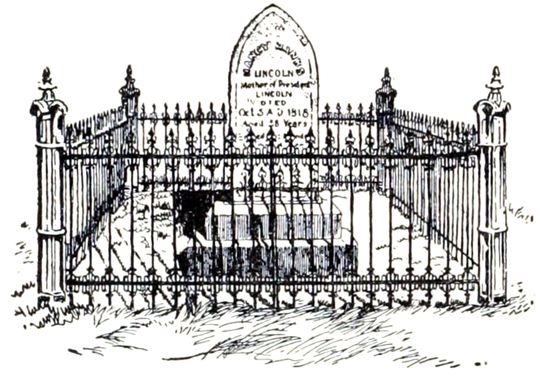

| A Poor Boy Becomes a Great Man | 313 |

| Andrew Johnson and the Progress of Reconstruction | 328 |

| Two Famous Generals | |

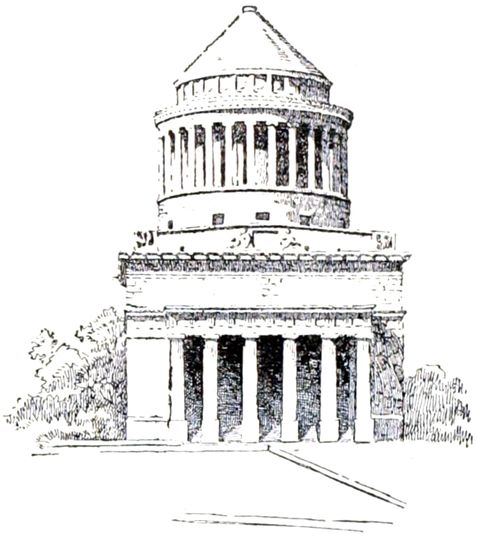

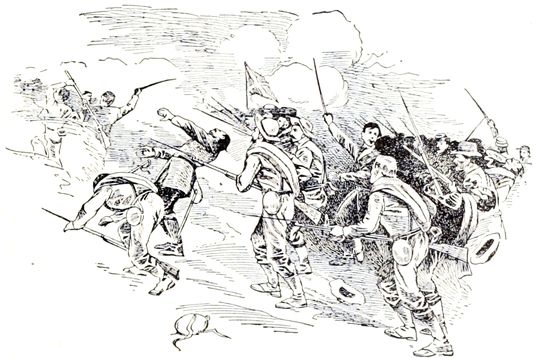

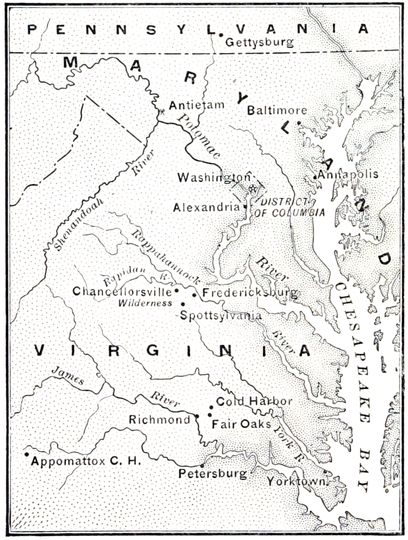

| Ulysses S. Grant, the Great General of the Union Armies | 331 |

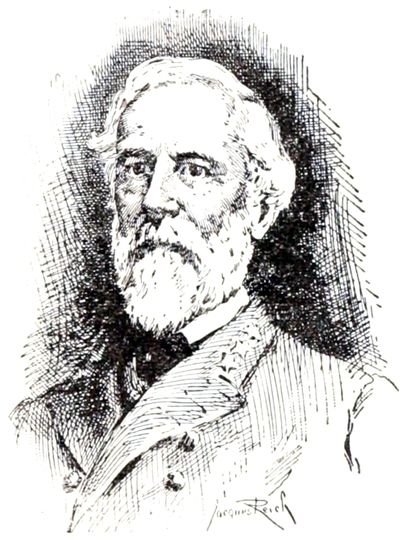

| Robert Edward Lee, the Man Who Led the Confederate Armies | 337 |

| Men Who Helped Determine New Political Policies | |

| Rutherford B. Hayes | 342 |

| James A. Garfield | 345 |

| Chester A. Arthur | 346 |

| Grover Cleveland | 347 |

| Benjamin Harrison | 349 |

| The Beginning of Expansion Abroad | |

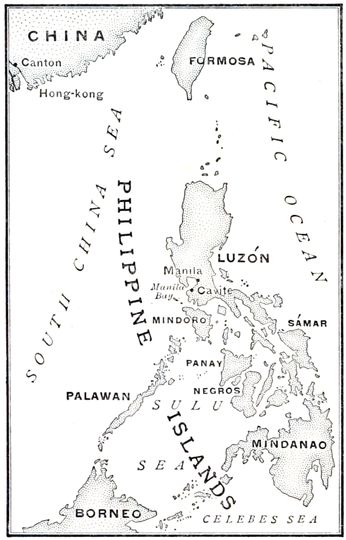

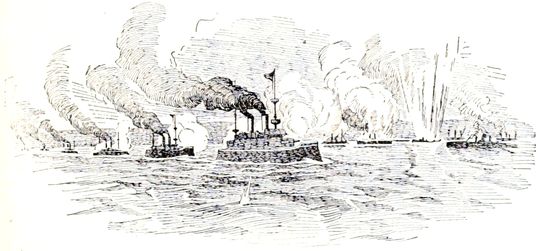

| William McKinley and the Spanish-American War | 352 |

| The Man Who Was the Champion of Democracy | |

| Theodore Roosevelt, the Typical American | 360 |

| William Howard Taft | 369 |

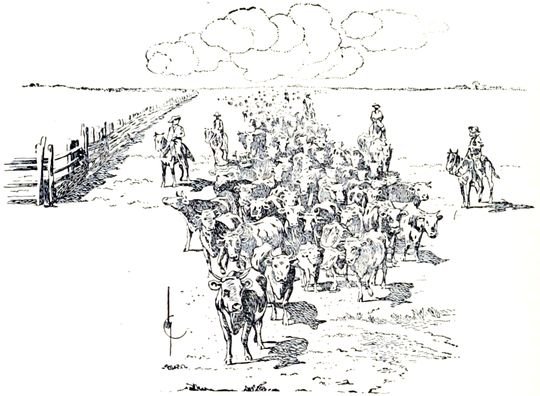

| Westward Expansion and Development | |

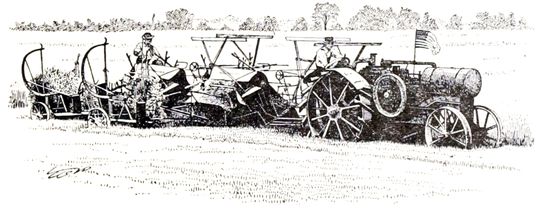

| The Westward Movement of Population and the Development of Transportation | 372 |

| George Washington Goethals, Chief Engineer of the Panama Canal | 376 |

| Men of Recent Times Who Made Great Inventions | |

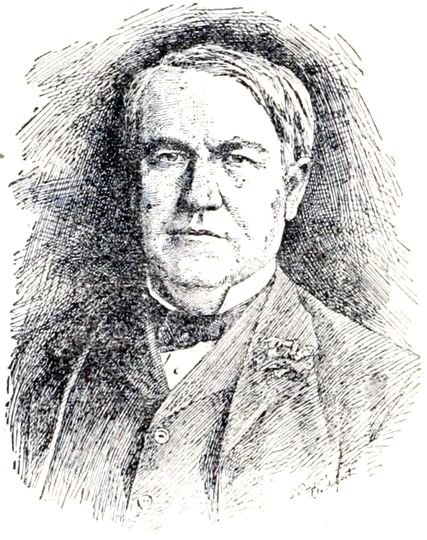

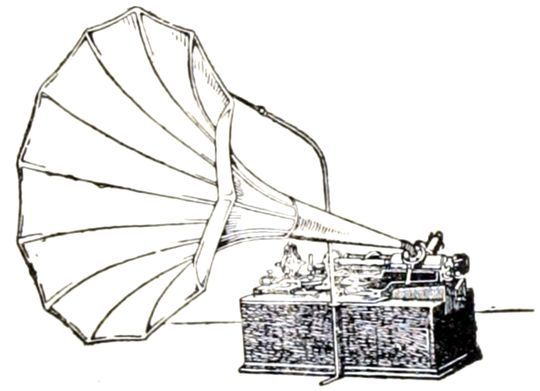

| Thomas A. Edison, the Greatest Inventor of Electrical Machinery in the World | 380 |

| Two Inventions Widely Used in Business | 386 |

| Automobile Making in the United States | 388 |

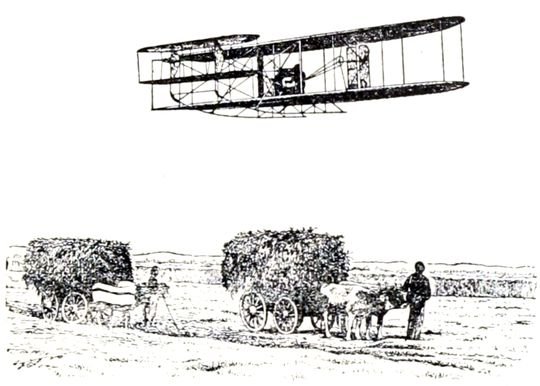

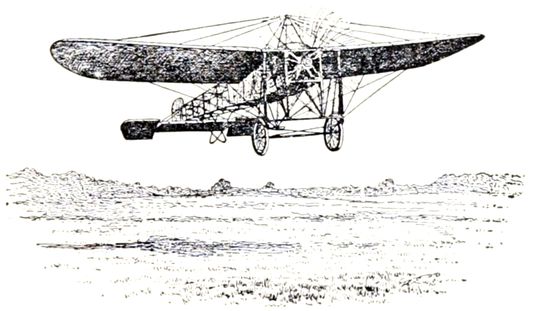

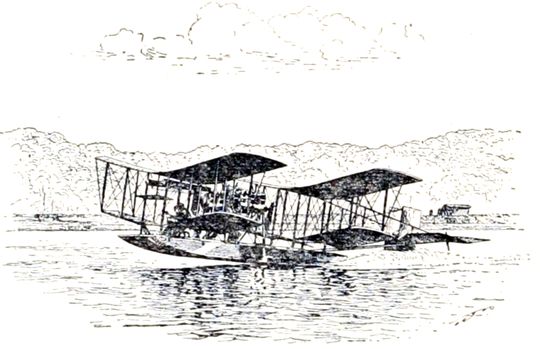

| Wilbur and Orville Wright, the Men Who Gave Humanity Wings | 390 |

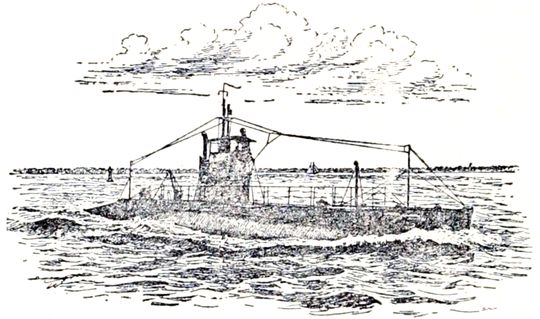

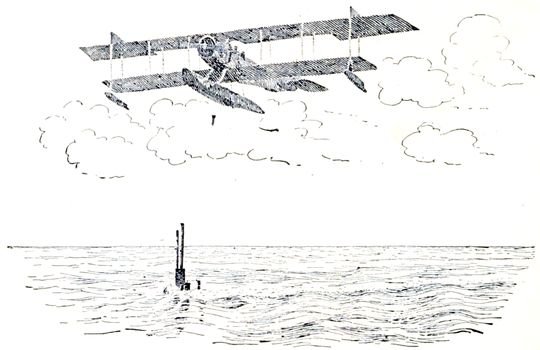

| John P. Holland, Who Taught Men to Sail Under the Sea | 395 |

| Heroines of National Progress | |

| Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, Who Were the first to Struggle for the Rights of Women | 400 |

| Julia Ward Howe, Author of "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," and Harriet Beecher Stowe, Who Wrote Uncle Tom's Cabin | 404 |

| [Pg ix] | |

| Frances E. Willard, the Great Temperance Crusader; Clara Barton, Who Founded the Red Cross Society in America; and Jane Addams, the Founder of Hull House Social Settlement in Chicago | 408 |

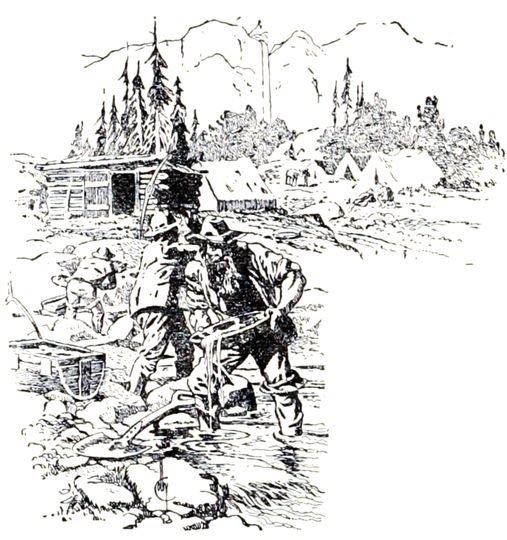

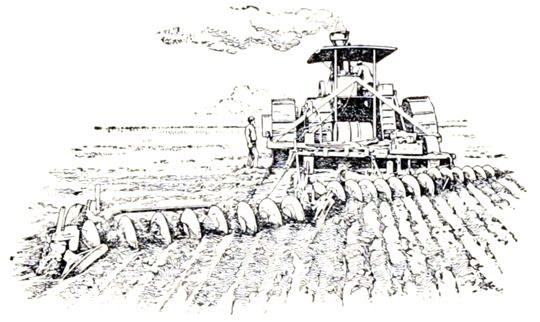

| Resources and Industries of Our Country | |

| How Farm and Factory Helped Build the Nation | 416 |

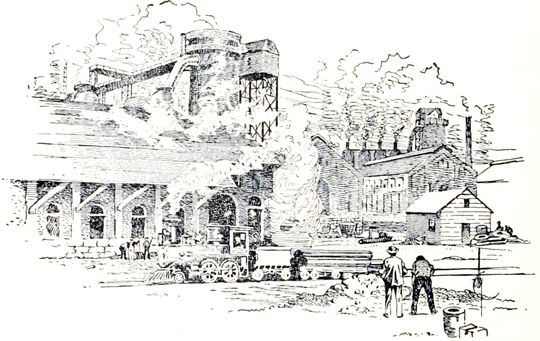

| Mines, Mining, and Manufactures | 421 |

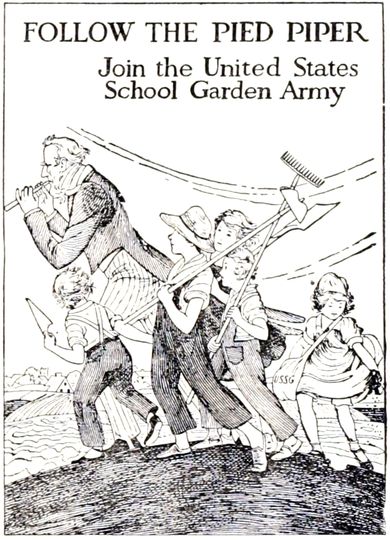

| America and the World War | |

| Early Years of the War | 424 |

| America Enters to Win | 431 |

| The Conclusion of the War | 437 |

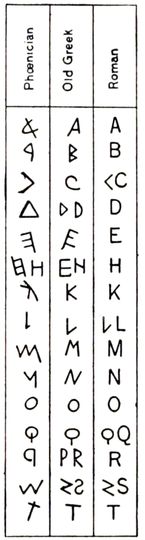

| Where the American People and Their Civilization Came From | |

| Introduction | 445 |

| The Oldest Nations | 446 |

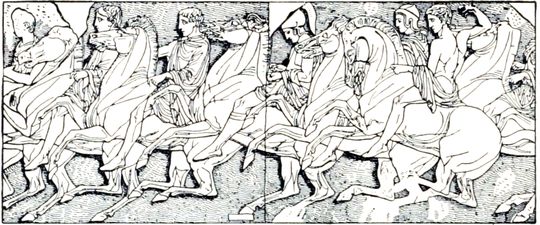

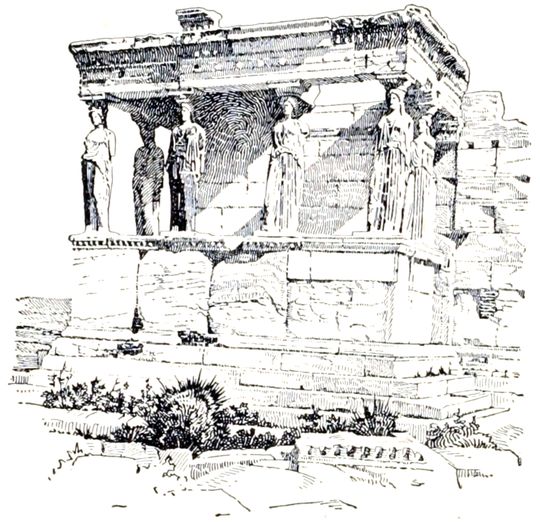

| Greece, the Land of Art and Freedom | 450 |

| How the Greeks Taught Men to be Free | 456 |

| Spread of Greek Civilization | 461 |

| When Rome Ruled the World | 464 |

| Hannibal Tries to Conquer Rome | 467 |

| Rome Conquers the World, but Grows Wicked | 469 |

| The Roman Republic Becomes the Roman Empire | 471 |

| What Rome Gave to the World | 473 |

| The Downfall of Rome | 476 |

| The Angles and Saxons in Great Britain | 478 |

| Charles the Great, Ruler of the Franks | 479 |

| The Coming of the Northmen | 483 |

| Alfred the Great | 484 |

| The Norman Conquest | 488 |

| The Struggle for the Great Charter | 490 |

| A Pronouncing Index | xi |

| The Index | xv |

MACE'S BEGINNER'S HISTORY

1. The Voyages of the Northmen. The Northmen were a bold seafaring people who lived in northern Europe hundreds of years ago. Some of the very boldest once sailed so far to the west that they reached the shores of Iceland and Greenland, where many of them settled. Among these were Eric the Red and his son Leif Ericson.

Now Leif had heard of a land to the south of Greenland from some Northmen who had been driven far south in a great storm. He determined to set out in search of it. After sailing for many days he reached the shore of this New World (A. D. 1000). There he found vines with grapes on them growing so abundantly that he called the new land Vinland, a country of grapes.

Leif's discovery caused great excitement among his people. Some of them could hardly wait until the winter was over, and the snow and ice broken up, so as to let their ships go out to this new land.

This time Thorvald, one of Leif's brothers, led the expedition. On reaching land, as they stepped ashore, he exclaimed: "It is a fair region and here I should like[Pg 2] to make my home." But Thorvald was killed in a battle with the Indians and was buried where he had wanted to build his home. The Northmen continued to visit the new land, but finally the Indians became so unfriendly that the Northmen went away and never came again.

The Leading Facts. 1. The Northmen, bold sailors, settled Iceland and Greenland. 2. Leif Ericson reached the shores of North America and called the country Vinland. 3. The Northmen continued to visit the new land, but finally ceased to come on account of the Indians.

Study Questions. 1. In what new countries did the Northmen settle? 2. Tell the story of Leif Ericson's voyage. 3. What did he call the new land, and why?

Suggested Readings. The Northmen: Glascock, Stories of Columbia, 7-9; Higginson, American Explorers, 3-15; Old South Leaflets, No. 31.

2. Old Trade Routes to Asia. More than four hundred fifty years ago Christopher Columbus spent his boyhood in the queer old Italian town of Genoa on the shore of the Mediterranean Sea. Even in that far-away time the Mediterranean was dotted with the white sails of ships busy in carrying the richest trade in the world. But no merchants were richer or had bolder sailors than those of Columbus' own town.

Genoa had her own trading routes to India, China, and Japan. Her vessels sailed eastward and crossed the Black Sea to the very shores of Asia. There they found[Pg 3] stores of rich shawls and silks and of costly spices and jewels, which had already come on the backs of horses and camels from the Far East. As fast as winds and oars could carry them, these merchant ships hastened back to Genoa, where other ships and sailors were waiting to carry their goods to all parts of Europe.

THE BOY COLUMBUS

After the statue by Giulio Montverde in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Every day the boys of Genoa, as they played along the wharves, could see the ships from different countries and could hear the stories of adventure told by the sailors. No wonder Christopher found it hard to work at his father's trade of combing wool; he liked to hear stories of the sea and to make maps and to study geography far better than he liked to comb wool or study arithmetic or grammar. He was eager to go to sea and while but a boy he made his first voyage. He often sailed with a kinsman, who was an old sea captain. These trips were full of danger, not only from storms but from sea robbers, with whom the sailors often had hard fights.

While Columbus was growing to be a man, the wise and noble Prince Henry of Portugal was sending his sailors to brave the unknown dangers of the western coast of Africa to find a new way to India. The Turks, by capturing Constantinople, had destroyed Genoa's overland trade routes.

The bold deeds of Henry's sailors drew many seamen[Pg 4] to Lisbon, the capital of Portugal. Columbus went, too, where he was made welcome by his brother and other friends. Here he soon earned enough by making maps to send money home to aid his parents, who were very poor.

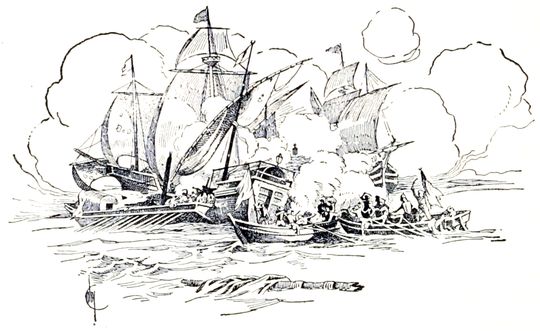

A SEA FIGHT BETWEEN GENOESE AND TURKS

The Genoese were great seamen and traders. When the Turks tried to ruin their trade with the Far East by destroying their routes many fierce sea fights took place

Columbus was now a large, fine-looking young man with ruddy face and bright eyes, so that he soon won the heart and the hand of a beautiful lady, the daughter of one of Prince Henry's old seamen. Columbus was in the midst of exciting scenes. Lisbon was full of learned men, and of sailors longing to go on voyages. Year after year new voyages were made in the hope of reaching India, but after many trials, the sailors of Portugal had explored only halfway down the African coast.

THE HOME OF COLUMBUS, GENOA

It is said that one day while looking over his father-in-law's maps, Columbus was startled by the idea of reaching[Pg 5] India by sailing directly west. He thought that this could be done, because he believed the world to be round, although all people, except the most educated, then thought the world flat. Columbus also believed that the world was much smaller than it really is.

The best map of that time located India, China, and Japan about where America is. For once, a mistake in geography turned out well. Columbus, believing his route to be the shortest, spent several years in gathering proof that India was directly west. He went on long voyages and talked with many old sailors about the signs of land to the westward.

Finally Columbus laid his plans before the new King of Portugal, John II. The king secretly sent out a ship to test the plan. His sailors, however, became frightened and returned before going very far. Columbus was[Pg 6] indignant at this mean trick and immediately started for Spain (1484), taking with him his little son, Diego.

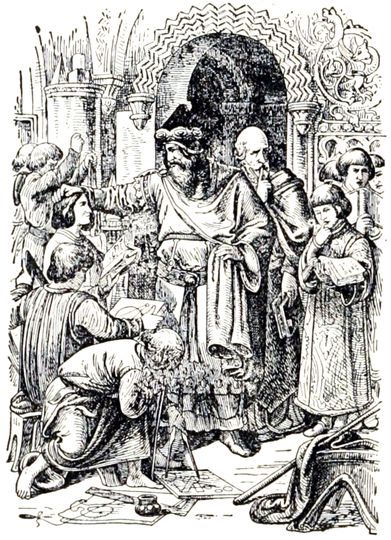

3. Columbus at the Court of Spain. The King and Queen of Spain, Ferdinand and Isabella, received him kindly; but some of their wise men did not believe the world is round, and declared Columbus foolish for thinking that countries to the eastward could be reached by sailing to the westward. He was not discouraged at first, because other wise men spoke in his favor to the king and queen.

COLUMBUS SOLICITING AID FROM ISABELLA

From the painting by the Bohemian artist, Vaczlav Brozik, now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York

It was hard for these rulers to aid him now because a long and costly war had used up all of Spain's money. Columbus was very poor and his clothes became threadbare. Some good people took pity on him and gave him money but others made sport of the homeless stranger and insulted him. The very boys in the street,[Pg 7] it is said, knowingly tapped their heads when he went by to show that they thought him a bit crazy.

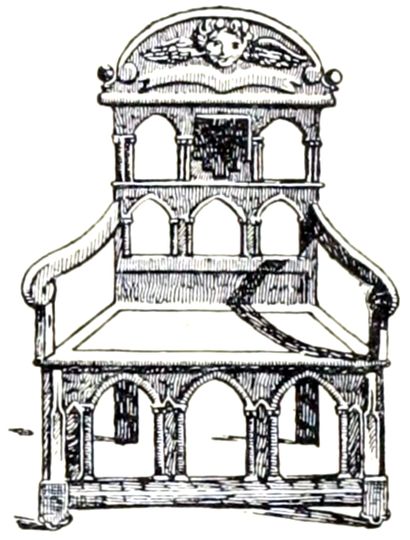

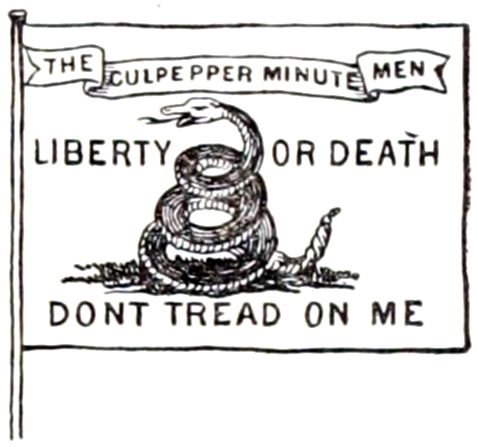

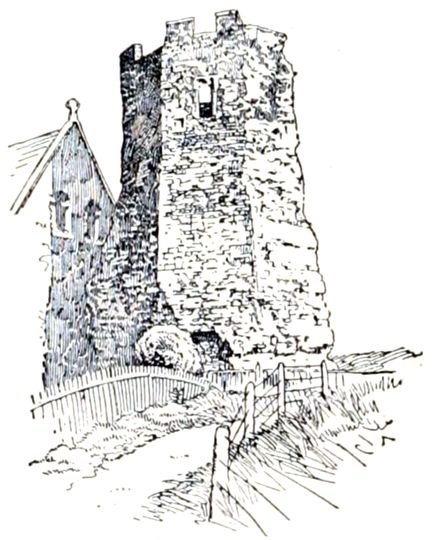

LA RABIDA CONVENT NEAR PALOS

At this monastery, on his way to France, Columbus met the good prior

4. New Friends of America. Disappointed and discouraged, after several years of weary waiting, Columbus set out on foot to try his fortunes in France. One day while passing along the road, he came to a convent or monastery. Here he begged a drink of water and some bread for his tired and hungry son, Diego, who was then about twelve years of age. The good prior of the monastery was struck by the fine face and the noble bearing of the stranger, and began to talk with him. When Columbus explained his bold plan of finding a shorter route to India, the prior sent in haste to the little port of Palos, near by, for some old seamen, among them a great sailor, named Pinzón. These men agreed with Columbus, for they had seen proofs of land to the westward.

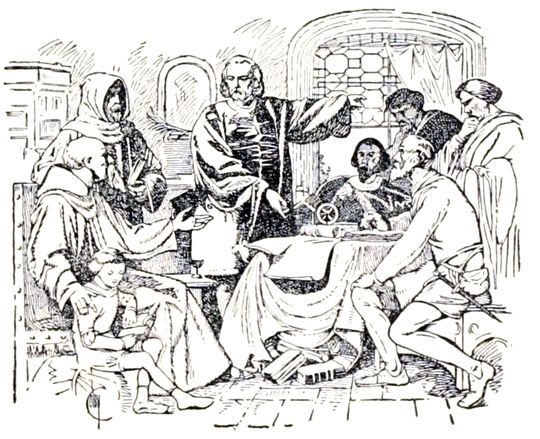

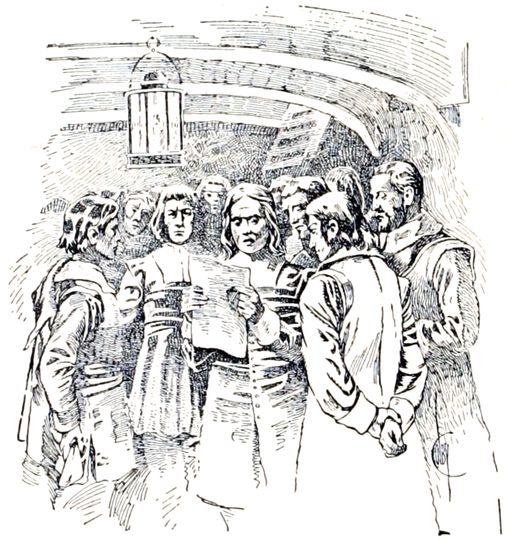

COLUMBUS AT THE CONVENT OF LA RABIDA

Columbus explaining his plan for reaching India to the prior and to Pinzón, the great sailor

The prior himself hastened with all speed to his[Pg 8] good friend, Queen Isabella, and begged her not to allow Columbus to go to France, for the honor of such a discovery ought to belong to Isabella and to Spain. How happy was the prior when the queen gave him money to pay the expenses for Columbus to visit her in proper style! With a heart full of hope, once more Columbus hastened to the Spanish Court, only to find both king and queen busy in getting ready for the last great battle of the long war. Spain won a great victory, and while the people were still rejoicing, the queen's officers met Columbus to make plans for the long-thought-of voyage. But because the queen refused to make him governor over all the lands he might discover, Columbus mounted his mule and rode away, once more bent on seeking aid from France.

CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS

From the portrait by Antonis van Moor, painted in 1542, from two miniatures in the Palace of Pardo. Reproduced by permission of C. F. Gunther, Chicago

Some of the queen's men hastened to her and begged her to recall Columbus. Isabella hesitated, for she had but little money in her treasury. Finally, it is said, she declared that she would pledge her jewels, if necessary, to raise the money for a fleet. A swift horseman overtook Columbus, and brought him back. The great man cried with joy when[Pg 9] Isabella told him that she would fit out an expedition and make him governor over all the lands he might discover.

COLUMBUS BIDDING FAREWELL TO THE PRIOR

From the painting by Ricardo Balaca

Columbus now took a solemn vow to use the riches obtained by his discovery in fitting out a great army which should drive out of the holy city of Jerusalem those very Turks who had destroyed the greatness of his native city.

5. The First Voyage. Columbus hastened to Palos. What a sad time in that town when the good queen commanded her ships and sailors to go with Columbus on a voyage where the bravest seamen had never sailed! When all things were ready for the voyage, Columbus' friend, the good prior, held a solemn religious service, the sailors said good-by to sorrowing friends, and the little fleet of three vessels and ninety stout-hearted men sailed bravely out of the harbor, August 3, 1492.

Columbus commanded the Santa Maria, the largest[Pg 10] vessel, only about ninety feet long. Pinzón was captain of the Pinta, the fastest vessel, and Pinzón's brother of the Niña, the smallest vessel. The expedition stopped at the Canary Islands to make the last preparations for the long and dangerous voyage. The sailors were in no hurry to go farther, and many of them broke down and cried as the western shores of the Canaries faded slowly from their sight.

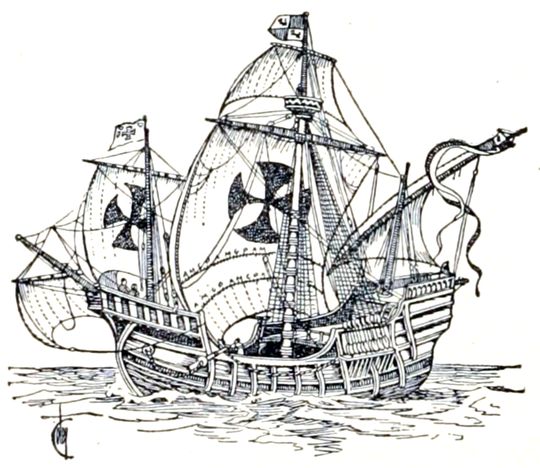

THE SANTA MARIA, THE FLAGSHIP OF COLUMBUS

From a recent reconstruction approved by the Spanish Minister of Marine

After many days, the ships sailed into an ocean filled with seaweed, and so wide that no sailor could see the end. Would the ships stick fast or were they about to run aground on some hidden island and their crews be left to perish? The little fleet was already in the region of the trade winds whose gentle but steady breezes were carrying them farther and farther from home. If these winds never changed, they thought, how could the ships ever make their way back?

The sailors begged Columbus to turn back, but he encouraged them by pointing out signs of land, such as flocks of birds, and green branches floating in the sea. He told them that according to the maps they were near Japan, and offered a prize to the one who should first see land. One day, not long after, Pinzón shouted, "Land! Land! I claim my prize." But he had seen only a dark bank of clouds far away on the horizon. The sailors,[Pg 11] thinking land near, grew cheerful and climbed into the rigging and kept watch for several days. But no land came into view and they grew more downhearted than ever. Because Columbus would not turn back, they threatened to throw him into the sea, and declared that he was a madman leading them on to certain death.

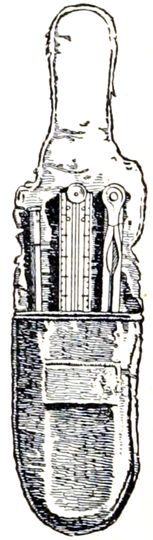

THE ARMOR OF COLUMBUS

Now in the Royal Palace, Madrid

6. Columbus the Real Discoverer. One beautiful evening, after the sailors sang their vesper hymn, Columbus made a speech, pointing out how God had favored them with clear skies and gentle winds for their voyage, and said that since they were so near land the ships must not sail any more after midnight. That very night Columbus saw, far across the dark waters, the glimmering light of a torch. A few hours later the Pinta fired a joyful gun to tell that land had been surely found. All was excitement on board the ships, and not an eye was closed that night. Overcome with joy, some of the sailors threw their arms around Columbus' neck, others kissed his hands, and those who had opposed him most, fell upon their knees, begged his pardon, and promised faithful obedience in the future.

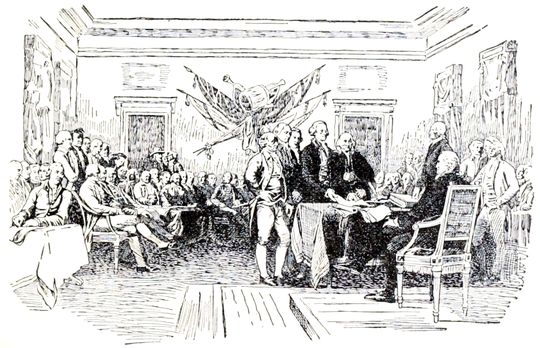

On Friday morning, October 12, 1492, Columbus, dressed in a robe of bright red and carrying the royal flag of Spain, stepped upon the shores of the New World. Around him were gathered his officers and sailors, dressed in their best clothes and carrying flags, banners, and crosses. They fell upon their knees, kissed the earth, and with tears of joy, gave thanks. Columbus then[Pg 12] drew his sword and declared that the land belonged to the King and Queen of Spain.

THE LANDING OF COLUMBUS

From the painting by Dioscoro Puebla, now in the National Museum, Madrid

7. How the People Came to be Called "Indians." When the people of this land first saw the ships of Columbus, they imagined that the Spaniards had come up from the sea or down from the sky and that they were beings from Heaven. They, therefore, at first ran frightened into the woods. Afterwards, as they came back, they fell upon their knees as if to worship the white men.

Columbus called the island on which he landed San Salvador and named the people Indians because he believed he had discovered an island of East India, although he had really discovered one of the Bahama Islands, and, as we suppose, the one known to-day as San Salvador. He and his men were greatly disappointed at the appearance of these new people, for[Pg 13] instead of seeing them dressed in rich clothes, wearing ornaments of gold and silver, and living in great cities, as they had expected, they saw only half-naked, painted savages living in rude huts.

8. Discovery of Cuba. After a few days Columbus sailed farther on and found the land now called Cuba, which he believed was Japan. Here his own ship was wrecked, leaving him only the Niña, for the Pinta had gone, he knew not where. He was now greatly alarmed, for if the Niña should be wrecked he and his men would be lost and no one would ever hear of his great discovery. He decided to return to Spain at once, but some of the sailors were so in love with the beautiful islands and the kindly people that they resolved to stay and plant the first Spanish colony in the New World. After collecting some gold and silver articles, plants, animals, birds, Indians, and other proofs of his discovery, Columbus spread the sails of the little Niña for the homeward voyage, January 4, 1493.

9. Columbus Returns to Spain. On the way home a great storm knocked the little vessel about for four days. All gave up hope, and Columbus wrote two accounts of his discovery, sealed them in barrels, and set them adrift. A second storm drove the Niña to Lisbon, in Portugal, where Columbus told the story of his great voyage. Some of the Portuguese wished to imprison Columbus, but the king would not, and in the middle of March the Niña sailed into the harbor of Palos.

What joy in that little town! The bells were set ringing and the people ran shouting through the streets to the wharf, for they had long given up Columbus and his crew as lost. To add to their joy, that very night[Pg 14] when the streets were bright with torches, the Pinta, believed to have been lost, also sailed into the harbor.

Columbus immediately wrote a letter to the king and queen, who bade him hasten to them in Barcelona. All along his way, even the villages and the country roads swarmed with people anxious to see the great discoverer and to look upon the strange people and the queer products which he had brought from India, as they thought.

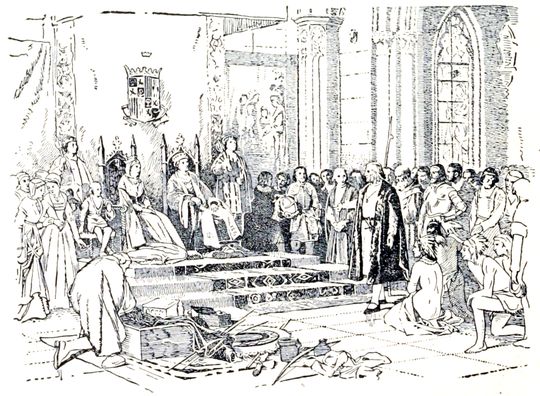

THE RECEPTION OF COLUMBUS AT BARCELONA

From the celebrated painting by the distinguished Spanish artist, Ricardo Balaca

As he came near the city, a large company of fine people rode out to give him welcome. He entered the city like a hero. The streets, the balconies, the doors, the windows, the very housetops were crowded with happy people eager to catch sight of the great hero.

COLUMBUS IN CHAINS

After the clay model by the Spanish sculptor, Vallmitjiana, at Havana

In a great room of the palace, Ferdinand and Isabella had placed their throne. Into this room marched Columbus surrounded by the noblest people of Spain, but none more noble looking than the hero. The king and queen arose and Columbus fell upon his knees and kissed their hands. They gave him a seat near them and bade him tell the strange story of his wonderful voyage.

When he finished, the king and queen fell upon their knees and raised their hands in thanksgiving. All the people did the same, and a great choir filled the room with a song of praise. The reception was now over and the people, shouting and cheering, followed Columbus to his home. How like a dream it must have seemed to Columbus, who only a year or so before, in threadbare clothes, was begging bread at the monastery near Palos!

10. The Second Voyage. But all Spain was on fire for another expedition. Every seaport was now anxious to furnish ships, and every bold sailor was eager to go. In a few months a fleet of seventeen fine ships and fifteen hundred people sailed away under the command of Columbus (1493) to search for the rich cities of their dreams. After four years of exploration and discovery among the islands that soon after began to be called the West Indies, Columbus sailed back to Spain greatly disappointed. He had found no rich cities or mines of gold and silver.

THE HOUSE IN WHICH COLUMBUS DIED

This house is in Valladolid, Spain, and stands in a street named after the great discoverer

11. The Third and Fourth Voyages. On his third voyage (1498) Columbus sailed along the northern shores of South America, but when he reached the West Indies the Spaniards who had settled there refused to obey him, seized him, put him in chains, and sent him back to Spain. But the good queen set Columbus free and sent him on his fourth voyage (1502). He explored the coast of what is now Central America, but afterward met shipwreck on the island of Jamaica. He returned to Spain a broken-hearted man because he had failed to find the fabled riches of India. He died soon afterward, not knowing that he had discovered a new world.

In 1501 Amerigo Vespucci made a voyage to South America. He was sent out by Portugal. It was thought that Vespucci had discovered a different land than that seen by Columbus. Without intending to wrong Columbus, the country he saw, and afterward all land to the northward, was called America.

Spain was too busy exploring the new lands to give proper heed to the death of the man whose discoveries would, after a few years, make the kingdom richer even than India. But it was left to the greatest nation in all the western world to do full honor to the memory of Columbus in the World's Columbian Exposition at Chicago (1892-1893).

12. Ponce de Leon. When the Spaniards came to America they were told many strange stories by the Indians about many marvelous places. Perhaps most wonderful of all was the story of Bimini, where every day was perfect and every one was happy. Here was also the magic fountain which would make old men young once more, and keep young men from growing old.

When Columbus sailed to America for the second time he brought with him a brave and able soldier, named Ponce de Leon. De Leon spent many years on the new continent fighting for his king against the Indians. After a while he was made governor of Porto Rico. While thus serving his country he too heard the story of this wonderful land which no white man had explored. Like most Spaniards, he loved adventure. Also he was weary of the cares of his office, and soon resolved to find this land and to explore it.

In the spring of 1513 De Leon set sail with three ships from Porto Rico. Somewhere to the north lay this land of perfect days. Northward he steered for many days, past lovely tropical islands. At last, on Easter Sunday, an unknown shore appeared. On its banks were splendid trees. Flowers bloomed everywhere, and clear streams came gently down to the sea. De Leon named the new land Florida and took possession of it for the King of Spain.

Various duties kept him away from the new land for eight years after its discovery. In 1521 he again set out from Porto Rico, with priests and soldiers, and amply provided with cattle and horses and goods. He wrote[Pg 18] to the King of Spain: "Now I return to that island, if it please God's will, to settle it." He was an old man then and hoped to found a peaceful and prosperous colony of which he was to be governor. But Indians attacked his settlement and sickness laid low many of his men. He had been in Florida only a short time when he himself was wounded in a fight with the Indians. Feeling that he would soon die, he hastily set sail with all his men for Cuba, where he died shortly after.

De Leon had failed to find the wonderful things of which the Indians had told him. He had failed even to establish the colony of which he was to be governor. But De Leon did discover a new and great land which now forms one of the states of the Union. To him also goes the honor of having been the first man to make a settlement in what is now a part of the United States.

THE ARMOR OF CORTÉS

Now in the museum at Madrid

13. Cortés Invades Mexico. Columbus died disappointed because he had not found the rich cities which everybody believed were somewhere in India. Foremost among Spanish soldiers was Hernando Cortés, who, in 1519, sailed with twelve ships from Cuba to the coast of what is now Mexico. His soldiers and sailors were hardly on land before he sank every one of his ships. His men now had to fight. They wore coats of iron, were armed with swords and guns, and they had a few cannon and horses. Every few miles they saw villages and now and then cities. The Indians wore cotton clothes, and in their ears and around their necks and their ankles they had gold and silver ornaments. The Spaniards could hardly keep their hands off these ornaments, they[Pg 19] were so eager for gold. They were now sure that the rich cities were near at hand, which Columbus had hoped to find, and which every Spaniard fully believed would be found.

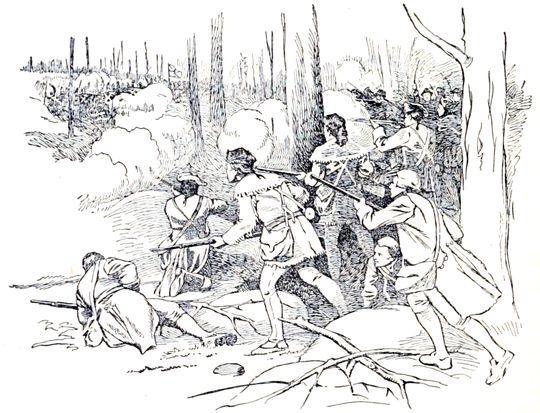

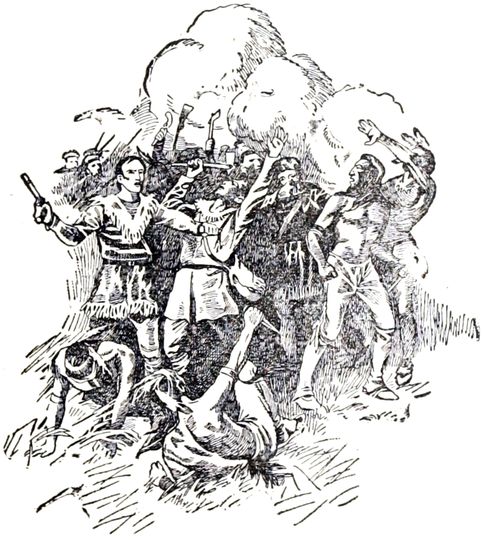

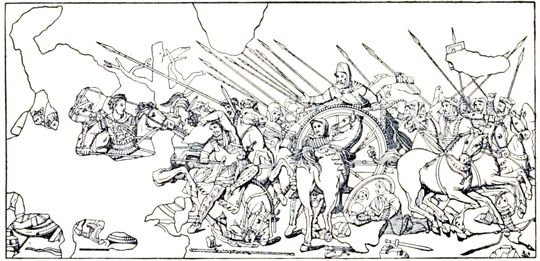

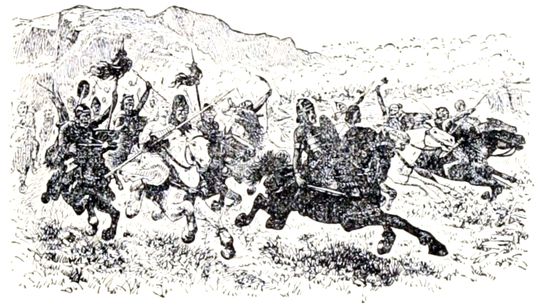

The people of Mexico had neither guns nor swords, but they were brave. Near the first large city, thousands upon thousands of fiercely painted warriors wearing leather shields rushed upon the little band of Spaniards. For two days the fighting went on, but not a single Spaniard was killed. The arrows of the Indians could not pierce iron coats, but the sharp Spanish swords could easily cut leather shields. The simple natives thought they must be fighting against gods instead of men, and gave up the battle.

HOUSE OF CORTÉS, COYOACAN, MEXICO

Over the main doorway are graven the arms of the Conqueror, who lived here while the building of Coyoacan, which is older than the City of Mexico, went on

Day after day Cortés marched on until a beautiful valley broke upon his view. His men now saw a wonderful sight: cities built over lakes, where canals took the place of streets and where canoes carried people from place to place. It all seemed like a dream. But they hastened forward to the great capital city. It, too, was built over a lake,[Pg 20] larger than any seen before, and it could be reached only along three great roads of solid mason work.

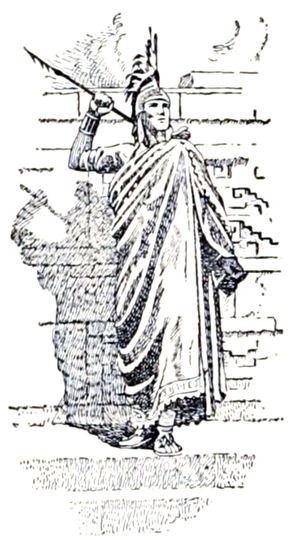

GUATEMOTZIN

The nephew of Montezuma and the last Indian emperor of Mexico. After the statue by Don Francisco Jimenes

These roads ran to the center of the city where stood, in a great square, a wonderful temple. The top of this temple could be reached by one hundred fourteen stone steps running around the outside. The city contained sixty thousand people, and there were many stone buildings, on the flat roofs of which the natives had beautiful flower gardens.

AN INDIAN CORN BIN, TLAXCALA

These are community or public bins, stand in the open roadway, and are still fashioned as in the days of Cortés

Montezuma, the Indian ruler, received Cortés and his men very politely and gave the officers a house near the great temple. But Cortés was in danger. What if the Indians should rise against him? To guard against this danger, Cortés compelled Montezuma to live in the Spanish quarters. The people did not like to see their beloved ruler a prisoner in his own city.

But no outbreak came until the Spaniards, fearing an attack, fell upon the Indians, who were holding a religious festival, and killed hundreds of them. The Indian council immediately chose Montezuma's brother to be their ruler and the whole city rose in great fury to drive out the now hated Spaniards. The streets and even the housetops were filled with angry warriors. Cortés[Pg 21] compelled Montezuma to stand upon the roof of the Spanish fort and command his people to stop fighting.

HERNANDO CORTÉS

From the portrait painted by Charles Wilson Peale, now in Independence Hall, Philadelphia

But he was ruler no longer. He was struck down by his own warriors, and died in a few days, a broken-hearted man. After several days of hard fighting, Cortés and his men tried to get out of the city, but the Indians fell on the little army and killed more than half of the Spanish soldiers before they could get away.

14. Cortés Conquers Mexico. Because of jealousy a Spanish army was sent to bring Cortés back to Cuba. By capturing this army Cortés secured more soldiers. Once more he marched against the city. What could bows and arrows and spears and stones do against the terrible horsemen and their great swords, or against the Spanish foot soldiers with their muskets and cannon? At length the great Indian city was almost destroyed, but thousands of its brave defenders were killed before the fighting ceased (1521). From this time on, the country gradually filled with Spanish settlers.

15. Cortés Visits Spain. After several years, Cortés longed to see his native land once more. He set sail, and reached the little port of Palos from which, many[Pg 22] years before, the great Columbus had sailed in search of the rich cities of the Far East. Here, now, was the very man who had found the splendid cities and had returned to tell the wonderful story to his king and countrymen. All along the journey to the king the people now crowded to see Cortés as they had once crowded to see Columbus.

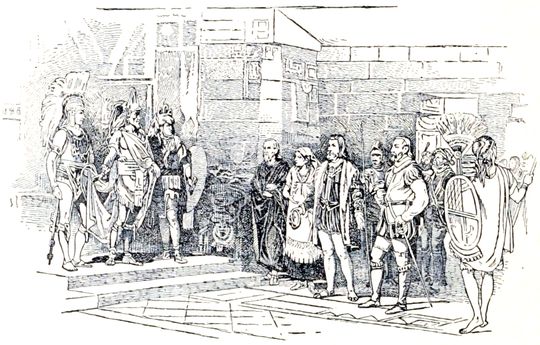

CORTÉS BEFORE MONTEZUMA

After the original painting by the Mexican artist, J. Ortega; now in the National Gallery of San Carlos, Mexico

Cortés afterwards returned to Mexico, where he spent a large part of his fortune in trying to improve the country. The Spanish king permitted great wrong to be done to Cortés and, like Columbus the discoverer, Cortés the conqueror died neglected by the king whom he had made so rich. For three hundred years the mines of Mexico poured a constant stream of gold and silver into the lap of Spain.

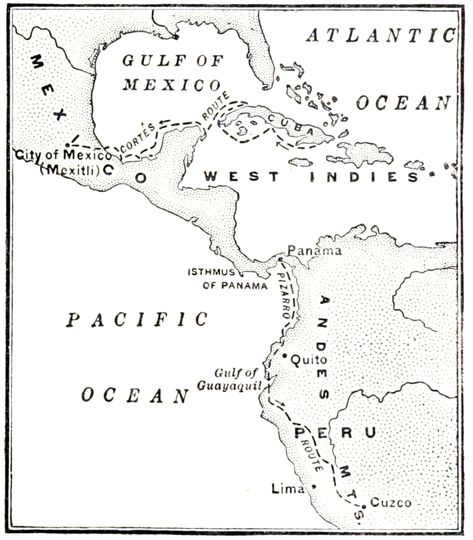

ROUTES OF THE CONQUERORS, CORTÉS AND PIZARRO

Their conquests of Mexico and of Peru brought untold stores of riches to Spain

16. Pizarro's Voyages. Another Spaniard, Francisco Pizarro, dreamed of finding riches greater than De Leon or Cortés had ever heard of. He set out for Peru with an army of two hundred men. Reaching the coast, he started inland and in a few days came to the foot of the Andes. They crossed the mountains and, marching down the eastern side, the Spaniards came upon the Inca, the native ruler, and his army. By trickery they made the Inca a prisoner, put him to death, and then subdued the army. The Spaniards then marched on to Cuzco, the capital of Peru, where they found enormous quantities of gold and silver. Never before in the history of the world had so many riches been found. This great wealth was divided among the Spaniards according to rank. But the greedy Spaniards fell to[Pg 24] quarreling and fighting among themselves, and Pizarro fell by the hand of one of his own men.

17. Coronado's Search for Rich Cities. Stories of rich cities to the north of Mexico led Francisco Coronado with a thousand men into the rocky regions now known as New Mexico and Arizona. They looked with wonder at the Grand Cañon of the Colorado, but they found no wealthy cities or temples ornamented with gold and silver.

They pushed farther north into what is now Kansas and Nebraska, into the great western prairies with their vast seas of waving grass and herds of countless buffalo. "Crooked-back oxen" the Spaniards named the buffalo.

But Coronado was after gold and silver, and cared nothing for beautiful and interesting scenes. Disappointed, he turned southward and in 1542, after three years of wandering, reached home in Mexico. He reported to the King of Spain that the region he had explored was too poor a place for him to plant colonies.

18. The Expedition to Florida. While Coronado and his men were searching in vain for hidden cities with golden temples, another band of men was wandering through the forests farther to the eastward. Hernando de Soto had been one of Pizarro's bravest soldiers. The news that this bold adventurer was to lead an expedition to Florida stirred all Spain. Many nobles sold their lands to fit out their sons to fight under so great a leader.

HERNANDO DE SOTO

After an engraving to be found in the works of the great Spanish historian, Herrera

The Spanish settlers of Cuba gave a joyful welcome[Pg 25] to De Soto and to the brave men from the homeland. After many festivals and solemn religious ceremonies, nine vessels, carrying many soldiers, twelve priests, six hundred horses, and a herd of swine, sailed for Florida (1539).

What a grand sight to the Indians as the men and horses clad in steel armor landed! There were richly colored banners, beautiful crucifixes, and many things never before seen by the Indians. But this was by far the most cruel expedition yet planned.

Wherever the Spaniards marched Indians were seized as slaves and made to carry the baggage and do the hard work. If the Indian guides were false, they were burned at the stake or were torn to pieces by bloodhounds. Hence the Indians feared the Spaniards, and Indian guides often misled the Spanish soldiers on purpose to save the guides' own tribes from harm.

De Soto fought his way through forests and swamps to the head of Apalachee Bay, where he spent the winter. In the spring a guide led the army into what is now Georgia, in search of a country supposed to be rich in gold and ruled by a woman. The soldiers suffered and grumbled, but De Soto only turned the march farther northward.

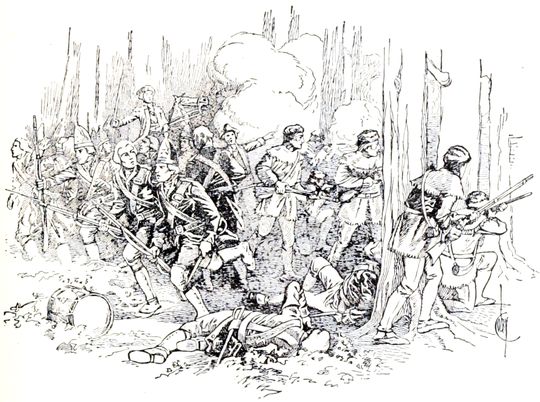

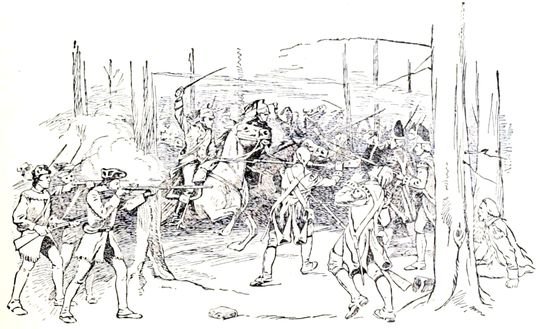

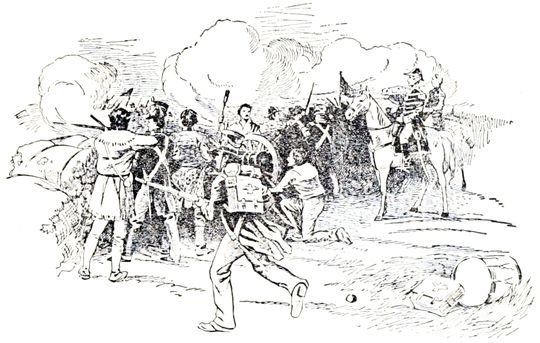

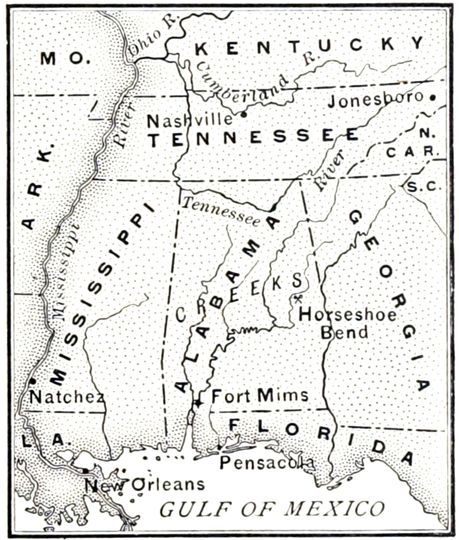

The Appalachian Mountains caused them to turn[Pg 26] south again until they reached the village of Mavilla (Mobile), where the Indians rushed on them in great numbers and tried to crush the army. But Spanish swords and Spanish guns won the day against Indian arrows and Indian clubs. De Soto lost a number of men, at least a dozen horses, and the baggage of his entire army, yet he boldly refused to send to the coast for the men and supplies waiting for him there.

19. The Discovery of the Mississippi. Again De Soto's men followed him northward, this time into what we know as northern Mississippi, where the adventuring army spent the second winter in a deserted Indian village. In the spring, in 1541, De Soto demanded two hundred Indians to carry baggage, but the chief and his men one night stole into camp, set fire to their own rude houses, gave the war whoop, frightened many horses into running away, and killed a number of the Spaniards.

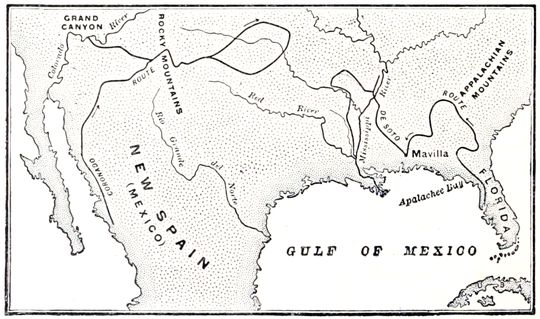

THE ROUTES OF CORONADO AND DE SOTO

Following these pathways, the soldier-explorers discovered the Grand Cañon of the Colorado and the great Mississippi River

DE SOTO DISCOVERS THE MIGHTY MISSISSIPPI

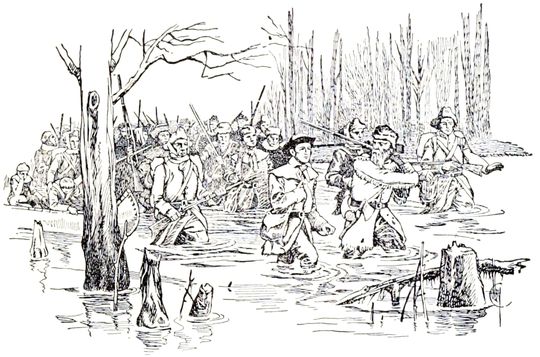

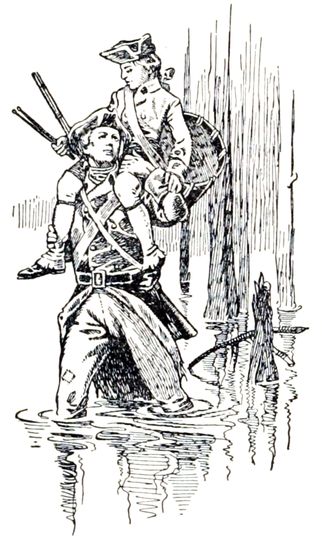

The army then marched westward for many days, wading swamps and wandering through forests so dense that at times they could not see the sun. At last, a river was reached greater than any the Spaniards had ever seen. It was the Mississippi, more than a mile wide, rushing on at full flood toward the Gulf.

On barges made by their own hands, De Soto and his men crossed to the west bank of the broad stream. There they marched northward, probably as far as the region now known as Missouri, and then westward two hundred miles. Nothing but hardships met them on every hand. In the spring of 1542, the little army came upon the Mississippi again.

De Soto was tiring out. He grew sad and asked the Indians how far it was to the sea. But it was too far for the bold leader. A fever seized him, and after a few days he died. At dead of night his companions buried him in the bosom of the great river he had discovered.

20. Only Half the Army Returns to Cuba. There were bold leaders still left in the army. They turned westward again, but after finding neither gold nor silver, they returned to the Mississippi and spent the winter on its banks. There they built boats, and then floated down to the Gulf. Only one half of the army returned[Pg 28] to tell the sad tales of hardships, battles, and poverty.

Thus it came about that Coronado and De Soto proved that northward from Mexico there were no rich cities, such as Columbus had dreamed about, and such as Cortés and Pizarro had really found. Hence it was that the King of Spain and his brave adventurers took less interest in that part of North America which is now the United States, and more in Mexico and in South America.

FERDINAND MAGELLAN

From the portrait designed and engraved by Ferdinand Selma in 1788

21. Magellan's Task. Columbus died believing that he had discovered a part of India. But he had not proved that the earth is round by sailing around it. This great task was left for Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese sailor. Columbus' great voyage had stirred up the Portuguese. One of their boldest sailors, Vasco da Gama, had reached India in 1498 by rounding Africa, and Magellan had made voyages for seven years among the islands of the East.

MAGELLAN'S FIRST VIEW OF THE PACIFIC OCEAN

Beyond the stormy strait he found the waters of the ocean smooth and quiet; hence its name Pacific, meaning peaceful

After returning to Portugal, Magellan sought the king's aid, but without success; then, like Columbus, he went to Spain, and in less than two years his fleet of five vessels sailed for the coast of South America (1519).[Pg 29] Severe storms tossed the vessels about for nearly a month. Food and water grew scarce. The sailors threatened to kill Magellan, but the brave captain, like Columbus, kept boldly on until he reached cold and stormy Patagonia.

It was Easter time, and the long, hard winter was already setting in. Finding a safe harbor and plenty of fish, Magellan decided to winter there. But the captains of three ships refused to obey, and decided to kill Magellan and lead the fleet back to Spain. Magellan was too quick for them. He captured one of the ships, turned the cannon on the others, and soon forced them to surrender.

There were no more outbreaks that winter. One of the ships was wrecked. How glad the sailors were when, late in August, they saw the first signs of spring! But they were not so happy when Magellan commanded the ships to sail still farther south in search of a passage to the westward.

In October, his little fleet entered a wide, deep channel and found rugged, snow-clad mountains rising high on both sides of them. Many of the sailors believed they[Pg 30] had at last found the westward passage, and that it was now time to turn homeward.

But Magellan declared that he would "eat the leather off the ship's yards" rather than turn back. The sailors on one ship seized and bound the captain and sailed back to Spain. Magellan with but three ships sailed bravely on until a broad, quiet ocean broke upon his sight. He wept for joy, for he believed that now the western route to India had indeed been found. This new ocean, so calm, so smooth and peaceful, he named the Pacific, and all the world now calls the channel he discovered the Strait of Magellan.

No man had yet sailed across the Pacific, and no man knew the distance. Magellan was as bold a sailor as ever sailed the main, and he had brave men with him. In November (1520) the three little ships boldly turned their prows toward India. On and on they sailed. Many of the crew, as they looked out upon a little island, saw land for the last time. Many thousand miles had yet to be sailed before land would again be seen. After long weeks their food supply gave out and starvation stared them in the face. Many grew sick and died. The others had to eat leather taken from the ship's yards like so many hungry beasts.

How big the world seemed to these poor, starving sailors! But the captain never lost courage. Finally they beheld land. It was the group of islands now known as the Marianas (Ladrones). Here the sailors rested and feasted to their hearts' content.

Then Magellan pressed on to another group of islands which were afterwards called the Philippines, from King Philip of Spain.

Here in a battle with the inhabitants, while bravely defending his sailors, Magellan was killed. Their great commander was gone and they were still far from Spain. Sadly his sailors continued the voyage, but only one of the vessels, with about twenty men, ever reached home to tell the story of that wonderful first voyage around the world.

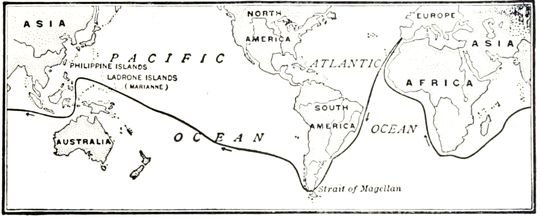

MAGELLAN'S ROUTE AROUND THE WORLD

Magellan, the bold Portuguese sailor, discovered the strait that bears his name and planned the first successful trip made around the world

Thus Magellan proved that Columbus was right in thinking the world round and that India could be reached by sailing west, while other men like Cortés and Pizarro found rich cities like those Columbus had dreamed of finding.

The Leading Facts. 1. Columbus was born near the shores of the Mediterranean and trained for the sea by study and by experience. 2. The people of Europe traded with the Far East, but the Turks destroyed their trade routes. 3. Columbus was drawn to Portugal because of Prince Henry's great work. 4. Columbus thought he could reach the rich cities of the East by sailing west. 5. After many discouragements he won aid from Isabella and discovered the Bahama Islands, Cuba, and Haiti. 6. The king and queen of Spain received Columbus with great ceremony. 7. Columbus made three more voyages, but was disappointed in not finding the rich[Pg 32] cities of India. 8. Ponce de Leon sailed from Porto Rico to find a land of which strange stories had been told of riches and of a fountain of eternal youth. 9. He reached Florida on Easter Sunday, 1513. 10. Eight years later he returned to found a settlement. 11. He was attacked by the Indians, wounded, and forced to return to Porto Rico, where he died of his wounds. 12. His is the distinction of being the first white man to plant a settlement in the United States after the discovery of America by Columbus. 13. Cortés marched against a rich city, afterward called Mexico, captured the ruler, and fought great battles with the people. 14. Cortés captured the city and ruled it for several years. 15. From this time on Mexico gradually filled with Spanish settlers. 16. Pizarro invaded Peru, the richest of all countries, and captured and put to death the ruler. 17. Pizarro was killed by his own men. 18. Coronado marched north from Mexico into Arizona and New Mexico, but found no rich cities. 19. He wandered into the great prairies and the rocky country of Colorado but finally turned back in disappointment. 20. De Soto wandered over the country east of the Rocky Mountains in search of rich cities, but found a great river, the Mississippi, and later was buried in its waters. 21. Hence the Spaniards, eager for gold, went to Mexico and South America rather than farther to the north. 22. Columbus thought the world was round, but Magellan proved it. 23. Magellan sailed around South America into the Pacific Ocean, and across this new sea to the Philippine Islands, where he was killed. 24. His ship reached Spain—the first to sail around the world.

Study Questions. 1. Make a list of articles which the caravans (camels and horses) of the East brought to the Black Sea. 2. What studies fitted Columbus for the sea? 3. Why were there so many sailors in Lisbon? 4. How did Columbus get his idea of the earth's shape? 5. What did men in Portugal and Spain think of this idea? 6. Tell the story of Columbus in Spain. 7. What is the meaning of the vow taken by him? 8. Make a picture in your mind of the first voyage of Columbus. Read the poem "Columbus," by Joaquin Miller. 9. Shut your eyes and imagine you see Columbus land and take possession of the country. 10. Why was Columbus so disappointed? 11. How did the people of Palos act when Columbus returned? 12. Picture the reception of Columbus[Pg 33] by the people, and by the king and queen. 13. Why was Columbus disappointed in the second expedition? 14. What did Columbus believe he had accomplished? 15. What had he failed to do that he hoped to do? 16. Why did Ponce de Leon go in search of the new land? 17. What was the strange tradition about the country? 18. What did Ponce de Leon set out to do on his second trip? 19. Did he succeed? 20. What is his distinction? 21. Why did Cortés sink his ships? 22. How were Spaniards armed and how were Indians armed? 23. Describe the city of Mexico. 24. Who began the war, and what does that show about the Spaniards? 25. How did Cortés get more soldiers? 26. How did the people and king receive Cortés in Spain? 27. How was he treated on his return to Mexico? 28. What did Pizarro find in Peru? 29. How did he treat the Inca? 30. What was Pizarro's fate? 31. What was Coronado searching for, and why were the Spaniards disappointed? 32. What things did the Spaniards see that they never before had seen? 33. What report did Coronado make? 34. Why were De Soto's Indian guides false? 35. Show that De Soto was a brave man. 36. How far north did the Spaniards go both east and west of the Mississippi? 37. Tell the story of De Soto's death and burial. 38. What proof can you give to show that the Spaniards were more cruel than necessary? 39. What part of the problem of Columbus did Magellan solve? 40. What was Magellan's preparation? 41. Where is Patagonia, and how could there be signs of spring late in August? 42. What did Magellan's voyage prove, and what remained of Columbus' plans yet to be accomplished? 43. Who accomplished this?

Suggested Readings. Columbus: Hart, Colonial Children, 4-6; Pratt, Exploration and Discovery, 17-32; Wright, Children's Stories in American History, 38-60; Higginson, American Explorers, 19-52; Glascock, Stories of Columbia, 10-35; McMurry, Pioneers on Land and Sea, 122-160; Brooks, The True Story of Christopher Columbus, 1-103, 112-172.

Ponce de Leon: Pratt, Explorations and Discoveries, 17-23.

Cortés: McMurry, Pioneers on Land and Sea, 186-225; Hale, Stories of Adventure, 101-126; Ober, Hernando Cortés, 24-80, 82-291.

Pizarro: Hart, Colonial Children, 12-16: Towle, Pizarro, 27-327.

[Pg 34]Coronado: Griffis, Romance of Discovery, 168-182; Hale, Stories of Adventure, 136-140.

De Soto: Hart, Colonial Children, 16-19; Higginson, American Explorers, 121-140.

Magellan: McMurry, Pioneers on Land and Sea, 186-225; Butterworth, Story of Magellan, 52-143; Ober, Ferdinand Magellan, 108-244.

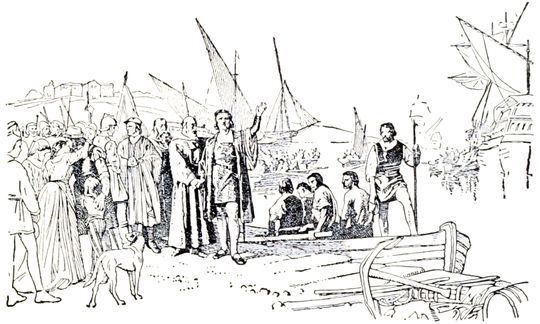

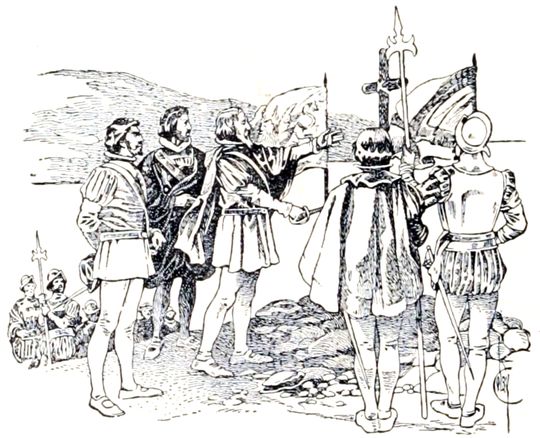

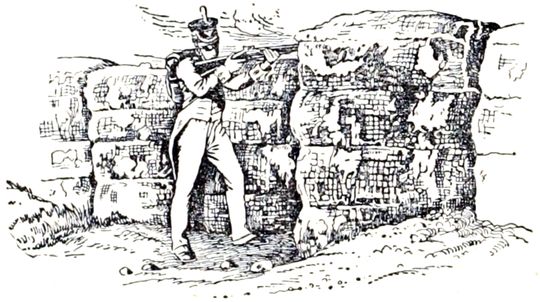

CABOT TAKING POSSESSION OF NORTH AMERICA FOR THE KING OF ENGLAND

On the spot where he landed Cabot planted a large cross and beside it flags of England and of St. Mark

22. Cabot's Voyages. When the news of Columbus' great discovery reached England, the king was sorry, no doubt, that he had not helped him. The story is that Columbus had gone to Henry VII, King of England, for aid to make his voyage. But England had a brave sailor of her own, John Cabot, an Italian, born in Columbus' own town of Genoa, who also had learned his lessons in voyages on the Mediterranean. Cabot had gone to live in the old town of Venice. Afterward he made[Pg 35] England his home and lived in the old seaport town of Bristol, the home of many English sailors.

JOHN CABOT AND HIS SON SEBASTIAN

From the statue modeled by John Cassidy, Manchester, England

He, too, believed the world to be round, and that India could be reached by sailing westward. King Henry VII gave Cabot permission to try, providing he would give the king one fifth of all the gold and silver which everybody believed he would find in India.

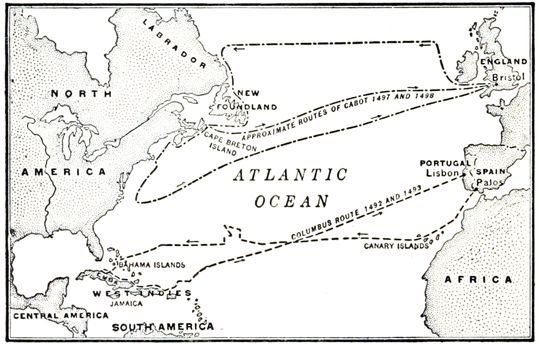

Accordingly, John Cabot, and it may be his son, Sebastian, set out on a voyage in May, 1497. After many weeks, Cabot discovered land, now supposed to be either a part of Labrador or of Cape Breton Island. He landed and planted the flag of England, and by its side set up that of Venice, which had been his early home.

Later, he probably saw parts of Newfoundland, but nowhere did he see a single inhabitant. He did, however, find signs that the country was inhabited, but he found no proof of rich cities or of gold and silver. In the seas all around Cabot saw such vast swarms of fish that he told the people of England they would not need to go any more to cold and snowy Iceland to catch fish.

How John Cabot was treated by the king and people of England when he came back is seen in an old letter written from England by a citizen of Venice to his friends at home. "The king has promised that in the spring[Pg 36] our countryman shall have ten ships, armed to his order. The king has also given him money wherewith to amuse himself till then, and he is now at Bristol with his wife, who is also a Venetian, and with his sons. His name is John Cabot, and he is called the great admiral. Vast honor is paid to him; he dresses in silk, and the English run after him like mad people, so that he can enlist as many of them as he pleases, and a number of our own rogues besides. The discoverer of these places planted on his new-found land a large cross, with one flag of England and another of St. Mark, by reason of his being a Venetian."

THE FINDING OF AMERICA

The first voyages of Columbus, the discoverer of the New World, and of Cabot, the first man to reach the mainland of North America

Again, in May, 1498, John Cabot started for India by sailing toward the northwest. This time the fleet was larger, and filled with eager English sailors. But Cabot could not find a way to India, so he altered his[Pg 37] course and coasted southward as far as the region now called North Carolina.

Now because of these two voyages of Cabot, England later claimed a large part of North America, for he had really seen the mainland of America before Columbus. Spain also claimed the same region, but we have seen how Mexico and Peru drew Spaniards to those countries.

If England had been quick to act and had made settlements where Cabot explored, she would have had little trouble in getting a hold in North America. But she did not do so. Henry VII was old and stingy. Cabot had twice failed to find India with its treasures of gold and silver, so little attention was given to the new lands.

23. The Quarrel between Spain and England. After John Cabot failed to find a new way to India, King Henry did nothing more to help English discovery. His son, Henry VIII, got into a great quarrel with the King of Spain. He was too busy with this quarrel to think much about America. But during this very time, Cortés and Pizarro were doing their wonderful deeds. Spain grew bold, seized English seamen, threw them into dungeons, and even burned them at the stake. Englishmen robbed Spanish ships and killed Spanish sailors in revenge.

24. Sir Francis Drake. A most daring English seaman was Sir Francis Drake. From boyhood days he had been a sailor. His cousin, Captain Hawkins, gave him command of a ship against Mexico, but the Spaniards fell upon it, killed many of the sailors, and took all they had. Drake came back ruined, and eager to take revenge.[Pg 38] Besides, he hated the Spaniards because he thought they were plotting to kill Elizabeth, the Queen of England.

In 1573 Drake returned to England with his ship loaded with gold and precious stones, captured from the Spaniards on the Isthmus of Panama.

25. Drake's Voyage around the World. After four years Drake, with four small but fast vessels, sailed direct for the Strait of Magellan. He was determined to sail the Pacific, which he had seen while on the Isthmus of Panama. In June his fleet entered the harbor of Patagonia where Magellan had spent the winter more than fifty years before.

SIR FRANCIS DRAKE

From the original portrait attributed to Sir Antonis van Moor, in the possession of Viscount Dillon, at Ditchly Park, England

After destroying his smallest vessel, which was leaky, Drake sailed to the entrance of the Strait. Here he changed the name of his ship from the Pelican to the Golden Hind, with ceremonies fitting the occasion.

The fleet passed safely through the Strait, but as it sailed out into the Pacific a terrible storm scattered the ships. One went down, and one returned to England, believing that Drake's ship, the Golden Hind, had been destroyed.

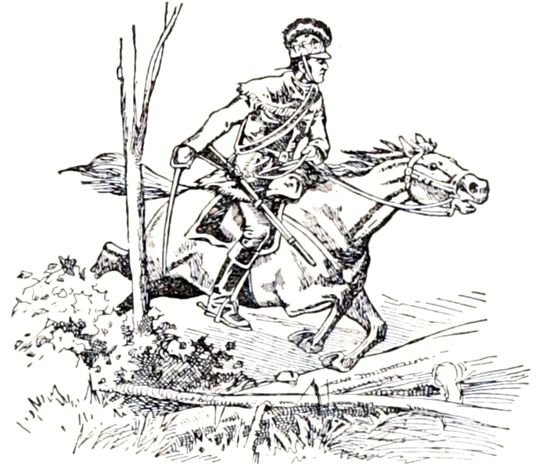

But Drake had a bold heart, good sailors, and a stout ship. After the storm he sailed north to Valparaiso, where his men saw the first great treasure ship. The Spanish sailors jumped overboard, and[Pg 39] left four hundred pounds of gold to Drake and his men. Week after week Drake sailed northward until he reached Peru, the land conquered by Pizarro.

DRAKE'S CHAIR, OXFORD UNIVERSITY

It was made from the timbers of the "Golden Hind"

Another great treasure ship had just sailed for Panama. Away sped the Golden Hind in swift pursuit. For a thousand miles, day and night, the chase went on. One evening, just at dark, the little ship rushed upon the great vessel, and captured her. What a rich haul! More than twenty tons of silver bars, thirteen chests of silver coin, one hundredweight of gold, besides a great store of precious stones.

The little ship continued northward. Hoping for a northeast passage to the Atlantic, Drake sailed along the coast as far as what was afterward known as the Oregon country. But the increasing cold and fog and the strong northwest winds made him turn southward again. Sailing close inshore, he found a small harbor, just north of the great bay of San Francisco. Here his stout little ship came to anchor. The natives believed that Drake and his men were gods, and begged them to remain with them always. Drake named the country New Albion and took possession in the name of the queen, Elizabeth. When he had refitted his ship for the long voyage home, Drake set sail, to the great sorrow of the natives.

Week after week went by, until he saw the very islands where Magellan had been. He made his way among the islands and across the Indian Ocean until the Cape of Good Hope was rounded, and the Golden Hind spread her sails northward toward England.

Drake reached home in 1580, the first Englishman to sail around the world. The people, who had given him up as lost, shouted for joy when they heard he was safe. Queen Elizabeth visited his ship in person, and there gave him a title, so that now he was Sir Francis Drake. Years after, a chair was made from the timbers of the famous Golden Hind and presented to Oxford University, where it can now be seen.

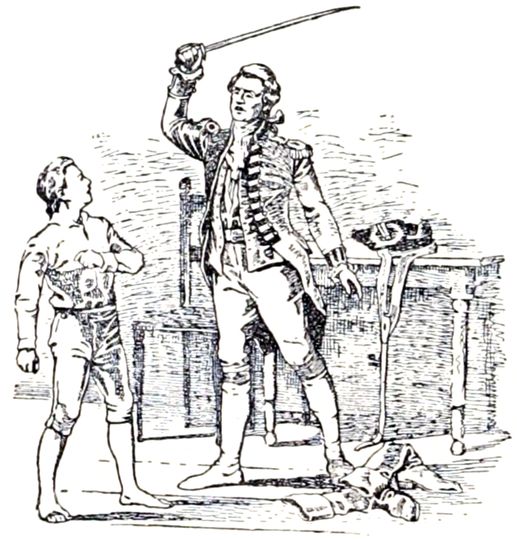

QUEEN ELIZABETH MAKING DRAKE A NOBLEMAN

After the drawing by Sir John Gilbert. It pictures the scene that took place on board the "Golden Hind" at the close of the great voyage. Queen Elizabeth visited Drake in his ship and conferred knighthood on him for his great services to England

26. Drake Again Goes to Fight the Spaniards. Drake soon took command of a fleet of twenty-five vessels and two thousand five hundred men, all eager to fight the Spaniards (1585). He sailed boldly for the coast of[Pg 41] Spain, frightened the people, and then went in search of the Gold Fleet, which was bringing shipload after shipload of treasure from America to the King of Spain.

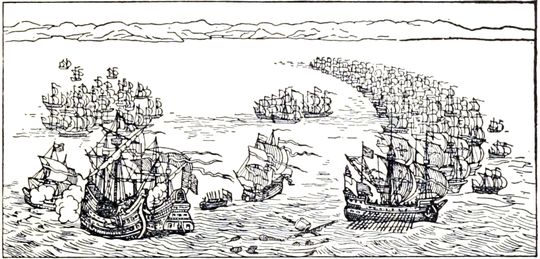

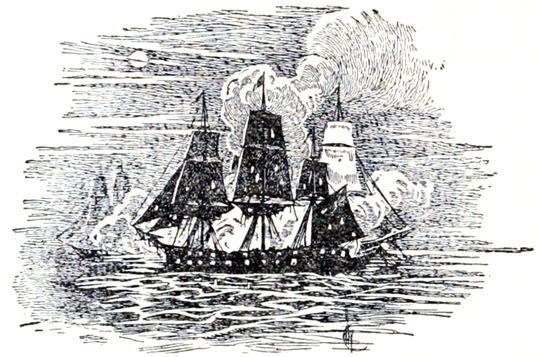

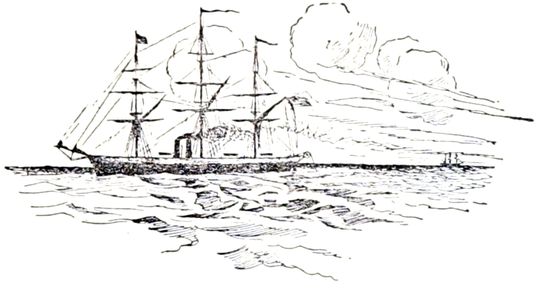

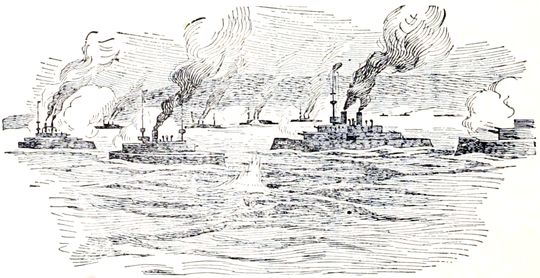

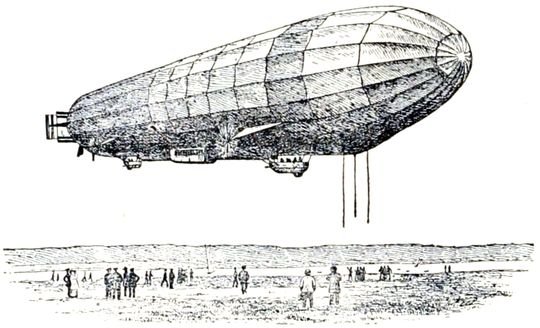

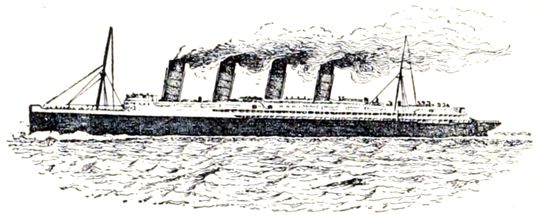

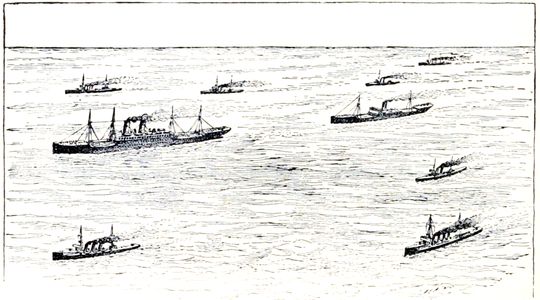

THE SPANISH ARMADA

More than one hundred twenty-five vessels sailed from Lisbon to conquer England, but only about fifty returned to the home port

No sooner had Drake missed the fleet than he made direct for the West Indies, where he spread terror among the islands. The Spaniards had heard of Drake, the "Dragon." He attacked and destroyed three important towns, and intended to seize Panama itself, but the yellow fever began to cut down his men, so he sailed to Roanoke Island, and carried back to England the starving and homesick colony which Raleigh had planted there.

The Spanish king was angry. He resolved to crush England. More than one hundred ships, manned by thousands of sailors, were to carry a great army to the hated island. Drake heard about it, and quickly gathered thirty fast ships manned by sailors as bold as himself. His fleet sailed right into the harbor of Cadiz, past cannon and forts, and burned so many Spanish ships that it took Spain another year to get the great fleet[Pg 42] ready. Drake declared that he had "singed the King of Spain's beard."

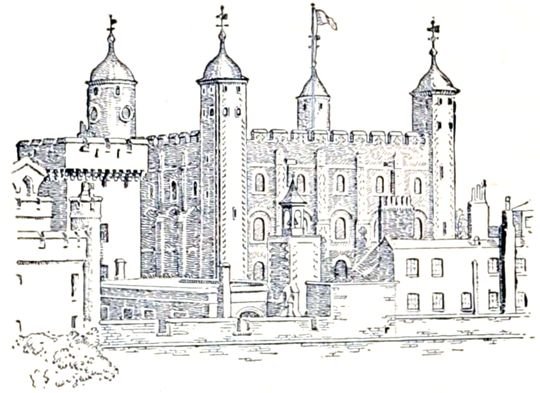

27. The Spanish Armada. The King of Spain was bound to crush England at one mighty blow. In 1588 the Spanish Armada, as the great fleet was called, sailed for England. There were scores of war vessels manned by more than seven thousand sailors, carrying nearly twenty thousand soldiers. Almost every noble family in Spain sent one or more of its sons to fight against England.

When this mighty fleet reached the English Channel, Drake and other sea captains as daring as himself dashed at the Spanish ships, and by the help of a great storm that came up, succeeded in destroying almost the whole fleet. No such blow had ever before fallen upon the great and powerful Spanish nation.

From that time on her power grew less and less, while England's power on the sea grew greater and greater. Englishmen could now go to America without much thought of danger from Spaniards.

28. Sir Walter Raleigh. Born (1552) near the sea, Raleigh fed his young imagination with stories of the wild doings of English seamen. He went to college at Oxford at the age of fourteen, and made a good name as a student.

In a few years young Raleigh went to France to take part in the religious wars of that unhappy country. At the time he returned home all England was rejoicing over Drake's first shipload of gold. When Queen Elizabeth sent an army to aid the people of Holland against the Spaniards, young Raleigh was only too glad to go.

THE BOYHOOD OF RALEIGH

After the painting by Sir John E. Millais

On his return from this war he went with his half-brother, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, on two voyages to America, at the very same time Drake was plundering the Spanish treasure ships in the Pacific Ocean. Afterward Raleigh turned soldier again and, as captain, went to Ireland, where Spain had sent soldiers to stir up rebellion. Thus, before he was thirty years old, he had been a seaman and a soldier, and had been in France, Holland, America, and Ireland.

At this time Raleigh was a fine-looking man, about six feet tall, with dark hair and a handsome face. He had plenty of wit and good sense, although he was fond, indeed, of fine clothes. He was just the very one to catch the favor of Queen Elizabeth.

One day Elizabeth and her train of lords and ladies were going down the roadway from the royal castle to the river. The people crowded both sides of the road to see their beloved queen and her beautiful ladies go by. Raleigh pressed his way to the front.

SIR WALTER RALEIGH

From the original portrait painted by Federigo Zuccaro

As Elizabeth drew near, she hesitated about passing over a muddy place. In a moment the feeling that every true gentleman has in the presence of ladies told Raleigh what to do, and the queen suddenly saw his beautiful red velvet cloak lying in the mud at her feet.[Pg 44] She stepped upon it, nodded to its gallant owner, and passed on. From this time forward Raleigh was a great favorite at the court of Queen Elizabeth.

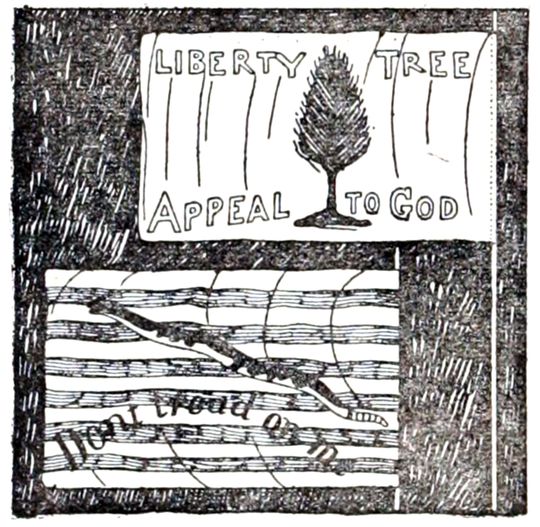

29. Trying to Plant English Colonies. In 1584 Raleigh caused a friend to write a letter to the queen, explaining that English colonies planted on the coast of North America would not only check the power of Spain but would also increase the power of England. That very year the queen gave him permission to plant colonies. Thus a better way of opposing Spain was found than by robbing treasure ships and burning towns.

Raleigh immediately sent a ship to explore. The captain landed on what is now Roanoke Island. The Indians came with a fleet of forty canoes to give them a friendly welcome. After a few days an Indian queen with her maidens came to entertain the English. "We found the people most gentle, loving, and faithful, void of all guile and treason," said Captain Barlow. His glowing account of the land and people so pleased Elizabeth that she named the country Virginia, in honor of her own virgin life.

Raleigh next sent out a kinsman, Sir Richard Grenville, with a fleet of seven vessels and one hundred settlers, under Ralph Lane as governor. But the settlers[Pg 45] were bent on finding gold and silver, instead of making friends with the Indians.

An Indian stole a silver cup from the English. Because of this theft Lane and his men fell upon the Indian village, drove out men, women, and children, burned their homes, and destroyed their crops. This was not only cruel but also foolish, for the story of his cruelty spread to other tribes, and after that wherever the English went they were always in danger from the Indians.

INDIAN CORN

When Drake came along the next spring with his great fleet, the settlers were only too glad to get back to England, and be once more among friends. They took home from America the turkey and two food plants, the white potato and Indian corn—worth more to the world than all the gold and silver found in the mines of Mexico and Peru!

Although Raleigh had already spent thousands of dollars, he would not give up. He immediately sent out a second colony of one hundred fifty settlers, a number of whom were women. John White was governor. Roanoke was occupied once more, and there, shortly afterwards, was born Virginia Dare, the first white child of English parents in North America. Before a year went by, the governor had to go to England for aid.

A WILD TURKEY

But Raleigh and all England had little time to think of America. The Armada was coming, and every English ship and sailor was needed to fight the Spaniards. Two years went by before Governor White reached America with supplies. When he did reach there practically no trace of the colony could be found. Not a settler was left to tell the tale.

POTATO PLANT AND TUBERS

The only trace of Raleigh's "lost colony" was the word "Croatoan" cut in large letters on a post. Croatoan was the name of an island near by. White returned home, but Raleigh sent out an old seaman, Samuel Mace, to search for the lost colony. It was all in vain. Many years later news reached England that a tribe of Indians had a band of white slaves, but the mystery of the lost colony never was cleared up.

Raleigh had now spent his great fortune. But he did not lose heart, for he said that he would live to see Virginia a nation. He was right. Before he died a great colony had been planted in Virginia, and a ship loaded with the products of Virginia had sailed into London port and an Indian "princess" had married a Virginian and had been received with honor by the King and Queen of England.

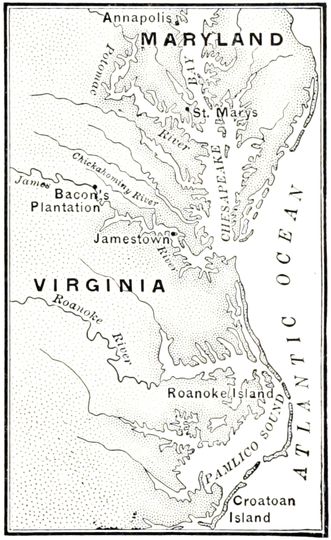

EARLY SETTLEMENTS IN VIRGINIA AND MARYLAND

30. The Death of Raleigh. But the great Elizabeth was dead, and an unfriendly king, James I, was on the throne. He threw Raleigh into prison, and kept him there thirteen years. The Spaniards urged the king to put Raleigh to death. He had been a life-long enemy of Spain and they knew they were not safe if he lived.

At last Spanish influence was too strong, and Sir Walter faced death on the scaffold as bravely as he had faced the Spaniards in battle.

Thus died a noble man who gave both his fortune and his life for the purpose of planting an English colony in America.

The Leading Facts. 1. John Cabot, trying for a short route to India, discovered what is supposed to be Labrador, or Cape Breton. 2. On a second voyage he coasted along eastern North America as far south as the Carolinas. 3. Later, England claimed all North America. 4. Francis Drake sailed to the Pacific in the Pelican and then turned northward after the Spanish gold ships. 5. He wintered in California, and then started across the Pacific—the first Englishman to cross. 6. Drake reached England, and was received with great joy. 7. Once more Drake went to fight the Spaniards,[Pg 48] until the Great Armada attacked England. 8. Walter Raleigh, a student, a soldier, and a seaman, won the favor of the queen. 9. He hated the Spaniards, and planted settlements in what is now North Carolina. 10. What was Raleigh's prophecy?

Study Questions. 1. Tell the story of John Cabot before he came to England. 2. What did Cabot want to find when he sailed away and what did he find? 3. How was Cabot treated by King Henry VII, according to a "Citizen of Venice," after he returned? 4. Why was little attention given to the new lands by the English?

5. Prove that Spanish and English sailors did not like each other. 6. Who was Francis Drake? 7. What was Magellan after and what was Drake after? 8. Find out why Drake renamed his ship the Golden Hind. 9. Tell the story of Drake's voyage from Valparaiso to Oregon. 10. Tell the story of the voyage across the Pacific and how he was received at home. 11. What did Drake do when he missed the "Gold Fleet"? 12. What did Drake mean when he said he had "singed the King of Spain's beard"? 13. What became of the Spanish Armada, and what effects did its failure produce?

14. What other brave man went to America before the Armada was destroyed? 15. Give the early experiences of Raleigh before he was thirty. 16. Make a mental picture of the cloak episode. 17. Explain how kind the Indians were; how did the English repay the Indians? 18. What did the colonists take home with them? 19. Who was the first white child of English parents born in America? 20. How did the destruction of the Armada affect Englishmen who wanted to go to America? 21. Read in other books about Raleigh's death. 22. How did the English treatment of the Indians compare with that of the Spaniards?

Suggested Readings. Cabot: Hart, Colonial Children, 7-8; Griffis, Romance of Discovery, 105-111.

Drake: Hart, Source Book of American History, 9-11; Hale, Stories of Discovery, 86-106; Frothingham, Sea Fighters, 3-44.

Raleigh: Hart, Colonial Children, 165-170; Pratt, Early Colonies, 33-40; Wright, Children's Stories in American History, 254-258; Higginson, American Explorers, 177-200; Bolton, Famous Voyagers, 154-234.

31. The French in North America. France was the slowest of the great nations in the race for North America. Not until 1534 did Jacques Cartier, a French sea captain searching for a shorter route to India, sail into the mouth of the St. Lawrence River. He reached an Indian village where Montreal now stands and took possession of the country for his king.

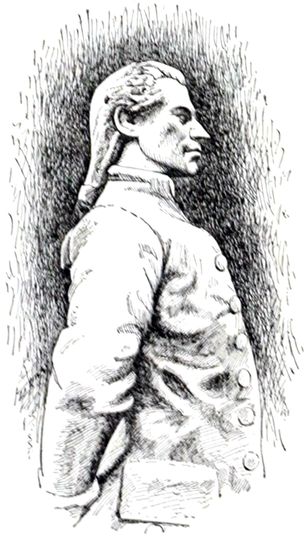

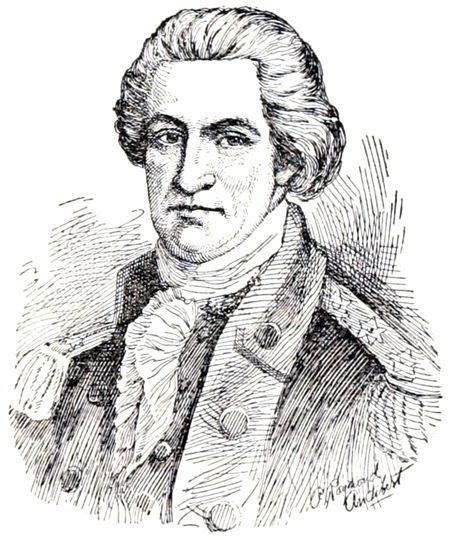

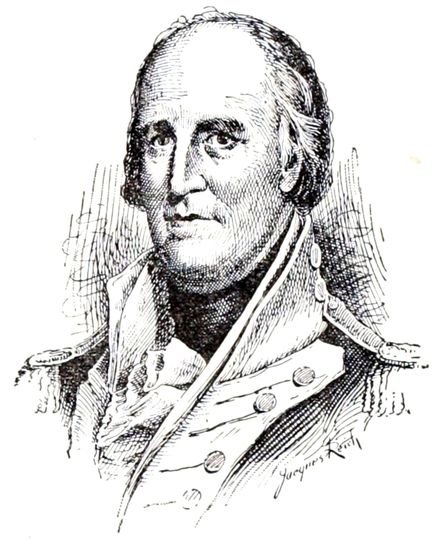

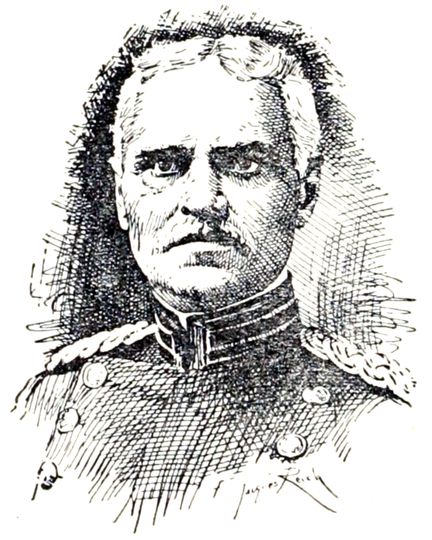

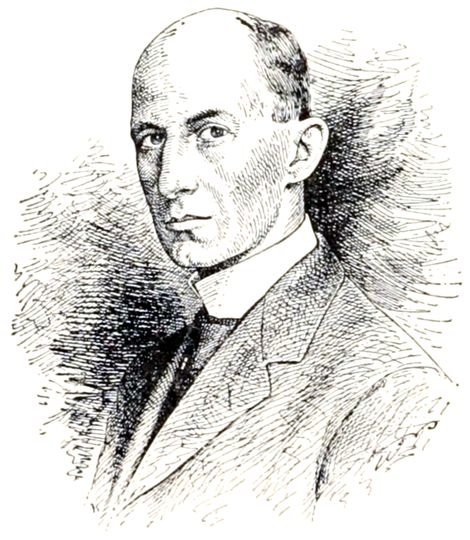

SAMUEL DE CHAMPLAIN

From the portrait painting in Independence Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

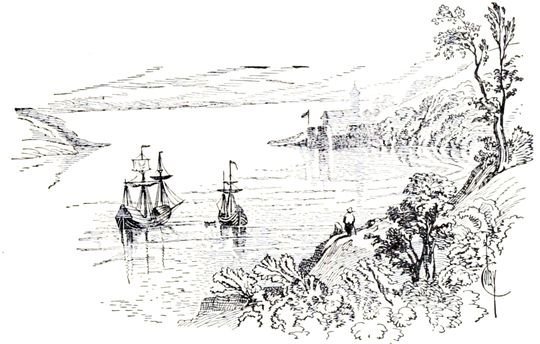

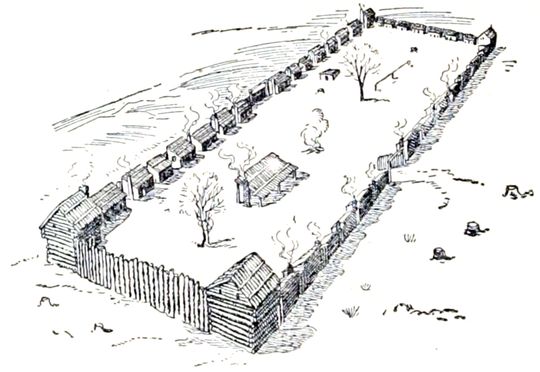

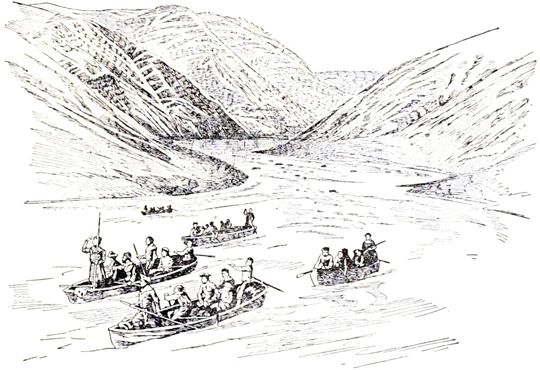

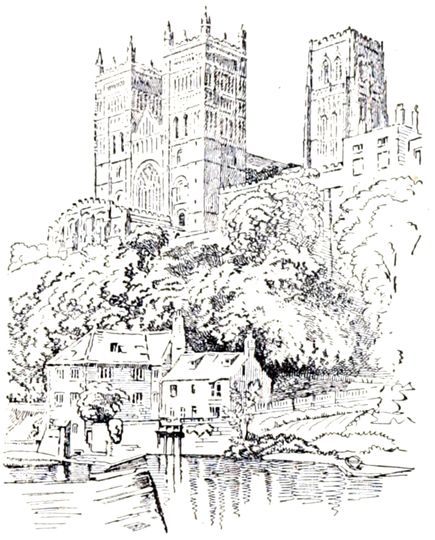

One year after Jamestown was settled, and one year before the Half Moon sailed up the Hudson, Samuel de Champlain laid the foundations of Quebec (1608). Champlain was of noble birth, and had been a soldier in the French army. He had already helped found Port Royal in Nova Scotia.

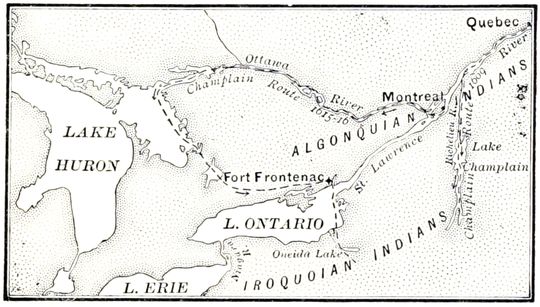

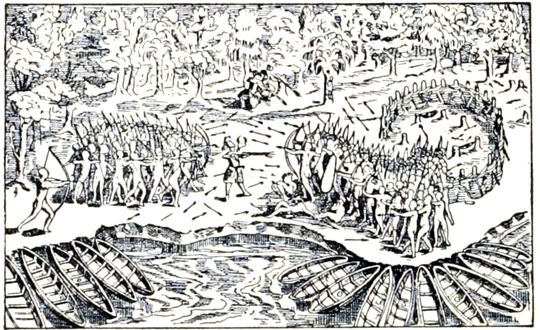

Wherever he went, Champlain made fast friends with the Algonquin Indians, who lived along the St. Lawrence. He gave them presents and bought their skins of beaver and of other animals. In the fur trade he saw a golden stream flowing into the king's[Pg 50] treasury. Champlain certainly made a good beginning in winning over these Indians, but he also made one great blunder out of which grew many bitter enemies among other Indian tribes.

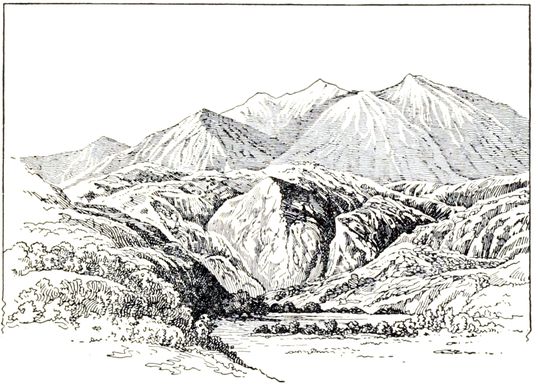

THE SITE OF QUEBEC

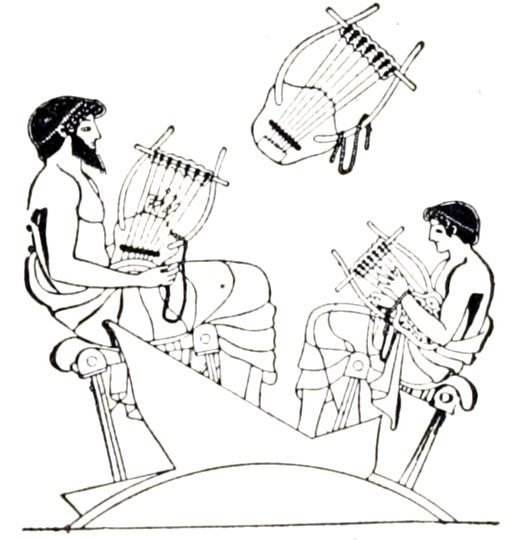

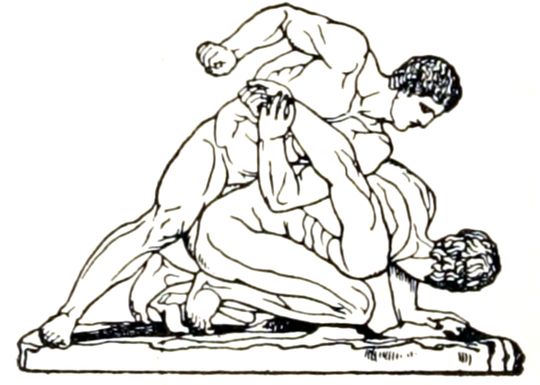

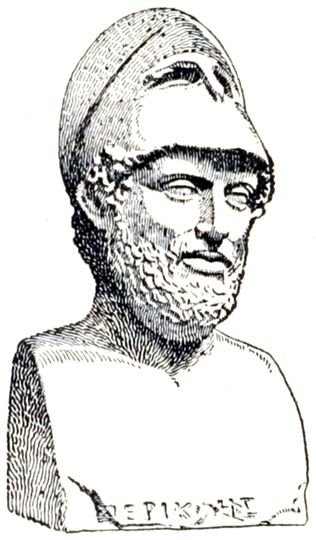

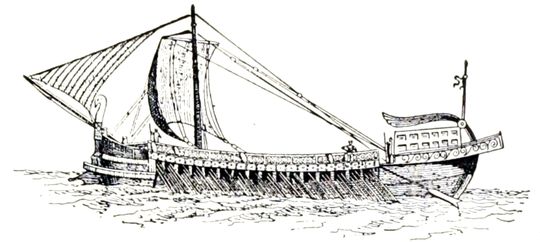

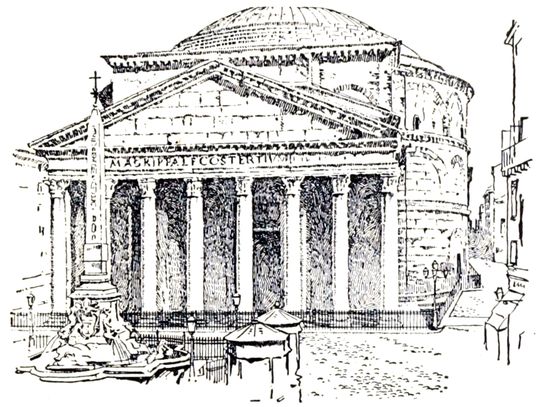

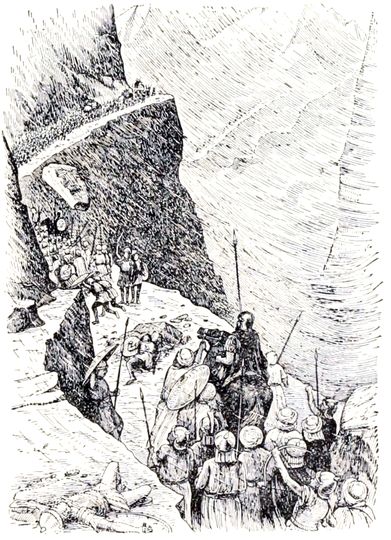

Here, 1608, on a narrow belt of land at the foot of the high bluff, Champlain laid out the city of Quebec