Title: Baled Hay: A Drier Book than Walt Whitman's "Leaves o' Grass"

Author: Bill Nye

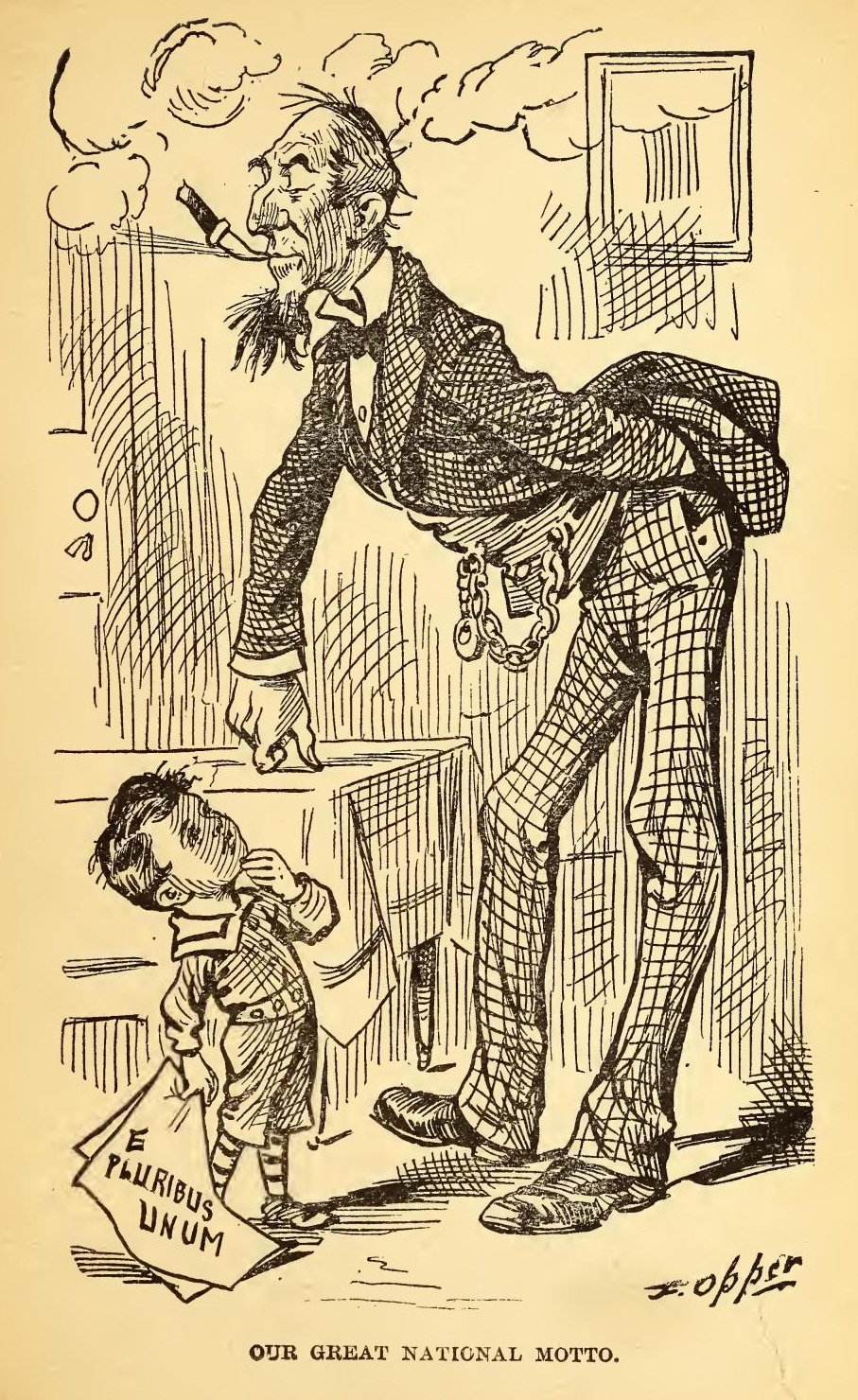

Illustrator: Frederick Burr Opper

Release date: December 15, 2015 [eBook #50699]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

CHIPETA'S ADDRESS TO THE UTES.

HUMAN' NATURE ON THE HALF-SHELL.

THE REVELATION RACKET IN UTAH.

WHAT THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY NEEDS.

Who has courteously and heroically laughed at my feeble and emaciated jokes, even when she did not feel like it; who has again and again started up and agitated successfully the flagging and reluctant applause, who has courageously held my coat through this trying ordeal, and who, even now, as I write this, is in the front yard warning people to keep off the premises until I have another lucid interval,

This Volume is Affectionately Inscribed,

There can really be no excuse for this last book of trite and beautiful sayings. I do not attempt, in any way, to palliate this great wrong. I would not do so even if I had an idea what palliate meant.

It will, however, add one more to the series of books for which I am to blame, and the pleasure of travel will be very much enhanced, for me, at least.

There is one friend I always meet on the trains when I travel. He is the news agent. He comes to me with my own books in his arms, and tells me over and over again of their merits. He means it, too. What object could he have in coming to me, not knowing who I am, and telling me of their great worth? Why would he talk that way to me if he did not really feel it?

That is one reason I travel so much. When 1 get gloomy and heartsick, I like to get on a train and be assured once more, by a total stranger, that my books have never been successfully imitated.

Some authors like to have a tall man, with a glazed grip-sack, and whose breath is stronger than his intellect, selling their works; but I do not prefer that way.

I like the candor and ingenuousness of the train-boy. He does not come to the front door while you are at prayers, and ring the bell till the hat-rack falls down, and then try to sell you a book containing 2,000 receipts for the blind staggers. He leans gently over you as you look out the car window, and he puts some pecan meats in your hand, and thus wins your trusting heart. Then he sells you a book, and takes an interest in you.

This book will go to swell the newsboy's armful, and if there be any excuse, under the sun, for its publication, aside from the royalty; that is it.

I have taken great care to thoroughly eradicate anything that would have the appearance of poetry in this work, and there is not a thought or suggestion contained in it that would soil the most delicate fabric.

Do not read it all at once, however, in order to see whether he married the girl or not. Take a little at a time, and it will cure gloom on the "similia simili-bus curanter" principle. If you read it all at once, and it gives you the heaves, I am glad of it, and you deserve it. I will not bind myself to write the obituary of such people.

Hudson, Wis., Sept, 5,1883.

I NEVER wrote a novel, because I always thought it required more of a mashed-rasp-berry imagination than I could muster, but I was the business manager, once, for a year and a half, of a little two-bit novelette that has never been published.

I now propose to publish it, because I cannot keep it to myself any longer.

Allow me, therefore, to reminisce.

Harry Bevans was an old schoolmate of mine in the days of and although Bevans was not his sure-enough name, it will answer for the purposes herein set forth. At the time of which I now speak he was more bashful than a book agent, and was trying to promote a cream-colored mustache and buff "Donegals" on the side.

Suffice it to say that he was madly in love with Fanny Buttonhook, and too bashful to say so by telephone.

Her name wasn't Buttonhook, but I will admit it for the sake of argument. Harry lived over at Kalamazoo, we will say, and Fanny at Oshkosh. These were not the exact names of the towns, but I desire to bewilder the public a little in order to avoid any harassing disclosures in the future. It is always well enough, I find, to deal gently will those who are alive and moderately muscular.

Young Bevans was not specially afraid of old man Buttonhook, or his wife. He didn't dread the enraged parent worth a cent. He wasn't afraid of anybody under the cerulean dome, in fact, except Miss Buttonhook; but when she sailed down the main street, Harry lowered his colors and dodged into the first place he found open, whether it was a millinery store or a livery stable.

Once, in an unguarded moment, he passed so near her that the gentle south wind caught up the cherry ribbon that Miss Buttonhook wore at her throat, and slapped Mr. Bevans across the cheek with it before he knew what ailed him. There was a little vision of straw hat, brown hair, and pink-and-white cuticle, as it were, a delicate odor of violets, the "swish" of a summer silk, and my friend, Mr. Bevans, put his hand to his head, like a man who has a sun-stroke, and fell into a drug store and a state of wild mash, ruin and helpless chaos.

His bashfulness was not seated nor chronic. It was the varioloid, and didn't hurt him only when Miss Buttonhook was present, or in sight. He was polite and chatty with other girls, and even dared to be blithe and gay sometimes, too, but when Frances loomed up in the distance, he would climb a rail fence nine feet high to evade her.

He told me once that he wished I would erect the frame-work of a letter to Fanny, in which he desired to ask that he might open up a correspondence with her. He would copy and mail it, he said, and he was sure that I, being a disinterested party, would be perfectly calm.

I wrote a letter for him, of which I was moderately proud. It would melt the point on a lightning rod, it seemed to me, for it was just as full of gentleness and poetic soothe as it could be, and Tupper, Webster's Dictionary and my scrap-book had to give down first rate. Still it was manly and square-toed. It was another man's confession, and I made it bulge out with frankness and candor.

As luck would have it, I went over to Oshkosh about the time Harry's prize epistle reached that metropolis, and having been a confidant of Miss B's from early childhood, I had the pleasure of reading Bev's letter, and advising the young lady about the correspondence.

Finally a bright thought struck her. She went over to an easy chair, and sat down on her foot, coolly proposing that I should outline a letter replying to Harry's, in a reserved and rather frigid manner, yet bidding him dare to hope that if his orthography and punctuation continued correct, he might write occasionally, though it must be considered entirely sub rosa and abnormally entre nous on account of "Pa."

By the way, "Pa" was a druggist, and one of the salts of the earth—Epsom salts, of course.

I agreed to write the letter, swore never to reveal the secret workings of the order, the grips, explanations, passwords and signals, and then wrote her a nice, demure, startled-fawn letter, as brief as the collar to a party dress, and as solemn as the Declaration of Independence.

Then I said good-by, and returned to my own home, which was neither in Kalamazoo nor Oshkosh. There I received a flat letter from 'William Henry Bevans, inclosing one from Fanny, and asking for suggestions as to a reply. Her letter was in Miss Buttonhook's best vein. I remember having written it myself.

Well, to cut a long story short, every other week I wrote a letter for Fanny, and on intervening weeks I wrote one for the lover at Kalamazoo. By keeping copies of all letters written, I had a record showing where I was, and avoided saying the same pleasant things twice.

Thus the short, sweet summer scooted past. The weeks were filled with gladness, and their memory even now comes back to me, like a wood-violet-scented vision. A wood-violet-scented vision comes high, but it is necessary in this place.

Toward winter the correspondence grew a little tedious, owing to the fact that I had a large, and tropical boil on the back of my neck, which refused to declare its intentions or come to a focus for three weeks. In looking over the letters of both lovers yesterday, I could tell by the tone of each just where this boil began to grow up, as it were, between two fond hearts.

This feeling grew till the middle of December, when there was a red-hot quarrel. It was exciting and spirited, and after I had alternately flattered myself first from Kalamazoo and then from Oshkosh, it was a genuine luxury to have a row with myself through the medium of the United States mails.

Then I made up and got reconciled. I thought it would be best to secure harmony before the holidays so that Harry could go over to Oshkosh and spend Christmas. I therefore wrote a letter for Harry in which he said he had, no doubt, been hasty, and he was sorry. It should not occur again. The days had been like weary ages since their quarrel, he said—vicariously, of course—and the light had been shut out of his erstwhile joyous life. Death would be a luxury unless she forgave him, and Hades would be one long, sweet picnic and lawn festival unless she blessed him with her smile.

You can judge how an old newspaper reporter, with a scarlet imagination, would naturally dash the color into another man's picture of humility and woe.

She replied—by proxy—that he was not to blame. It was her waspish temper and cruel thoughtlessness. She wished he would come over and take dinner with them on Christmas day and she would tell him how sorry she was. When the man admits that he's a brute and the woman says she's sorry, it behooves the eagle eye of the casual spectator to look up into the blue sky for a quarter of an hour, till the reconciliation has had a chance and the brute has been given time to wipe a damp sob from his coat-collar.

I was invited to the Christmas dinner. As a successful reversible amanuensis I thought I deserved it. I was proud and happy. I had passed through a lover's quarrel and sailed in with whitewinged peace on time, and now I reckoned that the second joint, with an irregular fragment of cranberry jelly, and some of the dressing, and a little of the white meat please, was nothing more than right.

Mr. Bevans forgot to be bashful twice during the day, and even smiled once also. He began to get acquainted with Fanny after dinner, and praised her beautiful letters. She blushed clear up under her "wave," and returned the compliment.

That was natural. When he praised her letters I did not wonder, and when she praised his I admitted that she was eminently correct. I never witnessed better taste on the part of two young and trusting hearts.

After Christmas I thought they would both feel like buying a manual and doing their own writing, but they did not dare to do so evidently. They seemed to be afraid the change would be detected, so I piloted them into the middle of the succeeding fall, and then introduced the crisis into both their lives.

It was a success.

I felt about as well as though I were to be cut down myself, and married off in the very prime of life. Fanny wore the usual clothing adopted by young ladies who are about to be sacrificed to a great horrid man. I cannot give the exact description of her trousseau, but she looked like a hazel-eyed angel, with a freckle on the bridge of her nose. The groom looked a little scared, and moved his gloved hands as though they weighed twenty-one pounds apiece.

However, it's all over now. I was up there recently to see them. They are quite happy. Not too happy, but just happy enough. They call their oldest son Birdie. I wanted them to call him William, but they were headstrong and named him Birdie. That wounded my pride, and so I called him Earlie Birdie.

WHEN I visit Greeley I am asked over and over again as to the practical workings of woman suffrage in Wyoming, and when I go back to Wyoming I am asked how prohibition works practically in Greeley, Col. By telling varied and pleasing lies about both I manage to have a good deal of fun, and also keep the two elements on the anxious seat.

There are two sides to both questions, and some day when I get time and have convalesced a little more, I am going to write a large book relating to these two matters. At present I just want to say a word about the colony which bears the name of the Tribune philosopher, and nestles so lovingly at the chilly feet of the Rocky mountains. As I write, Greeley is apparently an oasis in the desert. It looks like a fertile island dropped down from heaven in a boundless stretch of buffalo grass, sage hens and cunning little prairie dogs. And yet you could not come here as a stranger, and within the colonial barbed wire fence, procure a bite of cold rum if you were President of the United States, with a rattlesnake bite as large as an Easter egg concealed about your person. You can, however, become acquainted, if you are of a social nature and keep your eyes open.

I do not say this because I have been thirsty these few past weeks and just dropped on the game, as Aristotle would say, but just to prove that men are like boys, and when you tell them they can't have any particular thing, that is the thing they are apt to desire with a feverish yearn. That is why the thirstful man in Maine drinks from the gas fixture; why the Kansas drinkist gets his out of a rain-water barrel, and why other miracles too numerous to mention are performed.

Whisky is more bulky and annoying to carry about in the coat-tail pocket than a plug of tobacco, but there have been cases where it was successfully done. I was shown yesterday a little corner that would hold six or eight bushels. It was in the wash-room of a hotel, and was about half full. So were the men who came there, for before night the entire place was filled with empty whisky bottles of every size, shape and smell. The little fat bottle with the odor of gin and livery stable was there, and the large flat bottle that you get at Evans, four miles away, generally filled with something that tastes like tincture of capsicum, spirits of ammonia and lingering death, is also represented in this great congress of cosmopolitan bottles sucked dry and the cork gnawed half up.

When I came to Greeley, I was still following the course of treatment prescribed by my Laramie City physician, and with the rest, I was required to force down three adult doses of brandy per day. He used to taste the prescription at times to see if it had been properly compounded. Shortly after my arrival here I ran out of this remedy and asked a friend to go and get the bottle refilled. He was a man not familiar with Greeley in its moisture-producing capacity, and he was unable to procure the vile demon in the town for love or wealth. The druggist even did not keep it, and although he met crowds of men with tears in their eyes and breath like a veteran bung-starter, he had to go to Evans for the required opiate. This I use externally, now, on the vagrant dog who comes to me to be fondled and who goes away with his hair off. Central Colorado is full of partially bald dogs who have wiped their wet, cold noses on me, not wisely but too well.

I HAVE just returned from a trip up the North Wisconsin railway, where I went to catch a string of codfish, and anything else that might be contagious. The trip was a pleasant one and productive of great good in many ways. I am hardening myself to railway traveling, like Timberline Jones' man, so that I can stand the return journey to Laramie in July.

Northern Wisconsin is the place where the "foreign lumber" comes from which we use in Laramie in the erection of our palatial residences. I visited the mill last week that furnished the lumber used in the Oasis hotel at Greeley. They yank a big wet log into that mill and turn it into cash as quick as a railroad man can draw his salary out of the pay car. The log is held on a carriage by means of iron dogs while it is being worked into lumber. These iron dogs are not like those we see on the front steps of a brown stone house occasionally. They are another breed of dogs.

The managing editor of the mill lays out the log in his mind, and works it into dimension stuff, shingle holts, slabs, edgings, two by fours, two by eights, two by sixes, etc., so as to use the goods to the best advantage, just as a woman takes a dress pattern and cuts it so she won't have to piece the front breadths, and will still have enough left to make a polonaise for the last-summer gown.

I stood there for a long time watching the various saws and listening to their monotonous growl, and wishing that I had been born a successful timber thief instead of a poor boy without a rag to my back.

At one of these mills, not long ago, a man backed up to get away from the carriage, and thoughtlessly backed against a large saw that was revolving at the rate of about 200 times a minute. The saw took a large chew of tobacco from the plug he had in his pistol pocket, and then began on him.

But there's no use going into details. Such things are not cheerful. They gathered him up out of the sawdust and put him in a nail keg and carried him away, but he did not speak again. Life was quite extinct. Whether it was the nervous shock that killed him, or the concussion of the cold saw against his liver that killed him, no one ever knew.

The mill shut down a couple of hours so that the head sawyer could file his saw, and then work was resumed once more.

We should learn from this never to lean on the buzz saw when it moveth itself aright.

A RECENT article in a dairy paper is entitled, "Experiments with Old Cheese." We have experimented some on the venerable cheese, too. One plan is to administer chloroform first, then perform the operation while the cheese is under its influence. This renders the experiment entirely painless, and at the same time it is more apt to keep quiet. After the operation the cheese may be driven a few miles in the open air, which will do away with the effects of the chloroform.

WITH the threatened eruption of the rag carpet as a kind of venerable successor to the genuine Boston-made Turkish rug, there comes a wail on the part of the male portion of humanity, and a protest on the part of all health-loving humanity.

I rise at this moment as the self-appointed representative of poor, down-trodden and long-suffering man. Already lady friends are looking with avaricious and covetous eyes on my spring suit, and, in fancy, constructing a stripe of navy blue, while some other man's spring clothes are already spotted for the "hit-or-miss" stripe of this time-honored humbug.

It does seem to me that there is enough sorrowing toil going for nothing already; enough of back ache and delirium, without tearing the shirts off a man's back to sew into a big ball, and then weave into a rag carpet made to breathe death and disease, with its prehistoric perspiration and its modern drug store dyes.

The rug now commonly known as the Turkish prayer rug, has a sad, worn look, but it does not come up to the rag carpet of the dear old home.

Around it there clusters, perhaps, a tradition of an Oriental falsehood, but the rag carpet of the dear old home, rich in association, is an heir-loom that passes down from generation to generation, like the horse blanket of forgotten years or the ragbag of the dear, dead past. Here is found the stripe of all-wool delaine that was worn by one who is now in the golden hence, or, stricken with the Dakota fever, living in the squatter's home; and there is the fragment of underclothes prematurely jerked from the back of the husband and father before the silver of a century had crept into his hair. There is no question but the dear old rag carpet, with poisonous greens and sickly yellows and brindle browns and doubtful blacks, is a big thing. It looks kind of modest and unpretending, and yet speaks of the dead past, and smells of the antique and the garret.

It represents the long months when aching fingers first sewed the garments, then the first dash of gravy on the front breadth, the maddening cry, the wild effort to efface it with benzine, the sorrowful defeat, the dusty grease-spot standing like a pork-gravy plaque upon the face of the past, the glad relinquishment of the garment, the attack of the rag-carpet fiend upon it, the hurried crash as it was torn into shreds and sewn together, then the mad plunge of the dust-powdered mass into the reeking bath of Paris green or copperas, then the weaver's gentle racket, and at last the pale, consumptive, freckled, sickly panorama of outrageous coloring, offending the eye, the nose, the thorax and the larynx, to be trodden under feet of men, and to yield up its precious dose of destroying poisons from generation even unto generation.

It is not a thing of beauty, for it looks like the colored engraving of a mortified lung. It is not economical, for the same time devoted to knocking out the brains of frogs and collecting their hams for the metropolitan market would yield infinitely more; and it is not worth much as an heirloom, for within the same time a mortgage may be placed upon the old homestead which will pass down from father to son, even to nations yet unborn, and attract more attention in the courts than all the rag carpets that it would require to span the broad, spangled dome of heaven.

I often wonder that Oscar Wilde, the pale patron of the good, the true and the beautiful, did not rise in his might and knock the essential warp and filling out of the rag carpet. Oscar did not do right, or he would have stood up in his funny clothes and fought for reform at so much per fight. While he made fun of the Chicago water works, a grateful public would have buried him in cut flowers if, instead, he had warped it to the rag carpet and the approaching dude.

THERE are a great many things in life which go to atone for the disappointments and sorrows which one meets," but when a young man's rival takes the fair Matilda to see the baseball game, and sits under an umbrella beside her, and is at the height of enjoyment, and gets the benefit of a "hot ball" in the pit of his stomach, there is a nameless joy settles down in the heart of the lonesome young man, such as the world can neither give nor take away.

I AM always sorry to see a youth get irritated and pack up his clothes, in the heat of debate, and leave the home nest. His future is a little doubtful, and it is hard to prognosticate whether he will fracture limestone for the streets of a great city, or become President of the United States; but there is a beautiful and luminous life ahead of him in comparison with that of the boy who obstinately refuses to leave the home nest.

The boy who cannot summon the moral courage some day to uncoil the tendrils of his heart from the clustering idols of the household, to grapple with outrageous fortune, ought to be taken by the ear and led away out into the great untried realm of space.

While the great world throbs on, he sighs and refuses to throb. While other young men put on their seal-brown overalls and wrench the laurel wreath and other vegetables from cruel fate, the youth who dangles near the old nest, and eats the hard-earned groceries of his father, shivers on the brink of life's great current and sheds the scalding tear.

He is the young-man-afraid-of-the-sawbuck, the human being with the unlaundried spinal column. The only vital question that may be said to agitate his pseudo brain is, whether he shall marry and bring his wife to the home nest, or marry and tear loose from his parents to live with his father-in-law. Finally he settles it and compromises by living alternately with each.

How the old folks yearn to see him. How their aged eyes light up when he comes with his growing family to devour everything in sight and yawn through the space between meals. This is the heyday of his life; the high noon of the boy who never ventured to ride the yearling colt, or to be yanked through the shimmering sunlight at the tail of a two-year-old. He never dared to have any fun because he might bump his nose and make it bleed on his clean clothes. He never surreptitiously cut the copper wire off the lightning rod to snare suckers with, and he never went in swimming because the great, rude boys might duck him or paint him with mud. He shunned the green apple of boyhood, and did not slide down hill because he would have to pull his sled back to the top again.

Now, he borrows other people's newspapers, eats the provisions of others, and sits on the counter of the grocery till the proprietor calls him a counter irritant.

There can be nothing more un-American than this flabby polyp, this one-horse tadpole that never becomes a frog. The average American would rather burst up in business six times in four years, and settle for nine cents on the dollar, than to lead such a life. He would rather be an active bankrupt than a weak and bilious barnacle on the clam-shell of home.

The true American would rather work himself into luxury or the lunatic asylum than to hang like a great wart upon the face of nature. This young man is not in accordance with the Yankee schedule, and yet I do not want to say that he belongs to any other nation. Foreign powers may have been wrong; trans-Atlantic nations may have erred, and the system of European government may have been erroneous, but I would not come out and charge them with this horrible responsibility. They never harmed me, and I will not tarnish their fair fame with this grave indictment.

He will breathe a certain amount of atmosphere, and absorb a given amount of feed for a few years, and then the full-grown biped will leave the home nest at last. The undertaker will come and get him and take what there is left of him out to the cemetery. That will be all. There can be no deep abiding sorrow for him here; public buildings will not be draped in mourning, and you can get your mail at the usual hour when he dies. The band will not play a sadder strain because the fag-end of a human failure has tapered down to death, and the soft and shapeless features are still. You will have no trouble getting a draft cashed on that day, and the giddy throng will join the picnic as they had made arrangements to do.

LARAMIE has the champion mean man. He has a Sunday handkerchief made to order with scarlet spots on it, which he sticks up to his nose just before the plate starts round, and leaves the church like a house on fire. So after he has squeezed out the usual amount of gospel, he slips around the corner and goes home ten cents ahead, and has his self-adjusting nose-bleed handkerchief for another trip.

I HAVE just returned from a little two-handed tournament with the gloves. I have filled my nose with cotton waste so that I shall not soak this sketch in gore as I write.

I needed a little healthful exercise and was looking for something that would be full of vigorous enthusiasm, and at the same time promote the healthful flow of blood to the muscles. This was rather difficult. I tried most everything, but failed. Being a sociable being (joke) I wanted other people to help me exercise, or go along with me when I exercised. Some men can go away to a desert isle and have fun with dumb-bells and a horizontal bar, but to me it would seem dull and commonplace after a while, and I would yearn for more humanity.

Two of us finally concluded to play billiards; but we were only amateurs and the owner intimated that he would want the table for Fourth of July, so we broke off in the middle of the first game and I paid for it.

Then a younger brother said he had a set of boxing-gloves in his room, and although I was the taller and had longer arms, he would hold up as long its he could., and I might hammer him until I gained strength and finally got well.

I accepted this offer because I had often regretted that I had not made myself familiar with this art, and also because I knew it would create a thrill of interest and fire me with ambition, and that's what a hollow-eyed invalid needs to put him on the road to recovery.

The boxing-glove is a large fat mitten, with an abnormal thumb and a string at the wrist by which you tie it on, so that when you feed it to your adversary he cannot swallow it and choke himself. I had never seen any boxing-gloves before, but my brother said they were soft and wouldn't hurt anybody. So we took off some of our raiment and put them on. Then we shook hands. I can remember distinctly yet that we shook hands. That was to show that we were friendly and would not slay each other.

My brother is a great deal younger than I am and so I warned him not to get excited and come for me with anything that would look like wild and ungovernable fury, because I might, in the heat of debate, pile his jaw up on his forehead and fill his ear full of sore thumb. He said that was all right and he would try to be cool and collected.

Then we put our right toes together and I told him to be on his guard. At that moment I dealt him a terrific blow aimed at his nose, but through a clerical error of mine it went over his shoulder and spent itself in the wall of the room, shattering a small holly-wood bracket, for which I paid him $3.75 afterward. I did not wish to buy the bracket because I had two at home, but he was arbitrary about it and I bought it.

We then took another athletic posture, and in two seconds the air was full of poulticed thumb and buckskin mitten. I soon detected a chance to put one in where my brother could smell of it, but I never knew just where it struck, for at that moment I ran up against something with the pit of my stomach that made me throw up the sponge along with some other groceries, the names of which I cannot now recall.

My brother then proposed that we take off the gloves, but I thought I had not sufficiently punished him, and that another round would complete the conquest, which was then almost within my grasp. I took a bismuth powder and squared myself, but in warding off a left-hander, I forgot about my adversary's right and ran my nose into the middle of his boxing-glove. Fearing that I had injured him, I retreated rapidly on my elbows and shoulder-blades to the corner of the room, thus giving him ample time to recover. By this means my younger brother's features were saved, and are to-day as symmetrical as my own.

I can still cough up pieces of boxing-gloves, and when I close my eyes I can see calcium lights and blue phosphorescent gleams across the horizon; but I am thoroughly convinced that there is no physical exercise which yields the same amount of health and elastic vigor to the puncher that the manly art does. To the punchee, also, it affords a large wad of glad surprises and nose bleed, which cannot be hurtful to those who hanker for the pleasing nervous shock, the spinal jar and the pyrotechnic concussion.

That is why I shall continue the exercises after I have practiced with a mule or a cow-catcher two or three weeks, and feel a little more confidence in myself.

PEOPLE of my tribe! the sorrowing widow of the dead Ouray speaks to you. She comes to you, not as the squaw of the dead chieftain, to rouse you to war and victory, but to weep with you over the loss of her people and the greed of the pale face.

The fair Colorado, over whose Rocky mountains we have roamed and hunted in the olden time, is now overrun by the silver-plated Senator and the soft-eyed dude.

We are driven to a small corner of the earth to die, while the oppressor digs gopher holes in the green grass and sells them to the speculator of the great cities toward the rising sun.

Through the long, cold winter my people have passed, in want and cold, while the conqueror of the peaceful Ute has worn $250 night-shirts and filled his pale skin with pie.

Chipeta addresses you as the weeping squaw of a great man whose bones will one day nourish the cucumber vine. Ouray now sleeps beneath the brown grass of the canyon, where the soft spring winds may stir the dead leaves, and the young coyote may come and monkey o'er his grave. Ouray was ignorant in the ways of the pale face. He could not go to Congress, for he was not a citizen of the United States. He had not taken out his second papers. He was a simple child of the forest, but he stuck to Chipeta. He loved Chipeta like a hired man. That is why the widowed squaw weeps over him.

A few more years and I shall join Ouray—my chief, Ouray the big Injun from away up the gulch. His heart is still open to me. Chipeta could trust him, even among tire smiling maidens of her tribe. Ouray was true. There was no funny business in his nature. He loved not the garb of the pale face, but won my heart while he wore a saddle-blanket and a look of woe.

Chipeta looks to the north and the south, and all about are the graves of her people. The refinement of the oppressor has come, with its divorce and schools and gin cocktails and flour bread and fall elections, and we linger here like a boil on the neck of a fat man.

Even while I talk to you, the damp winds of April are sighing through my vertebras, and I've got more pains in my back than a conservatory.

Weep with the widowed Chipeta. Bow your heads and howl, for our harps are hung on the willows and our wild goose is cooked.

Who will be left to mourn at Chipeta's grave? None but the starving pappooses of my nation. We stand in the gray mist of spring like dead burdocks in the field of the honest farmer, and the chilly winds of departing winter make us hump and gather like a burnt boot.

All we can do is to wail. We are the red-skinned wailers from Wailtown.

Colorado is no more the home of the Ute. It is the dwelling place of the bonanza Senator, who doesn't know the difference between the plan of salvation and the previous question.

Chipeta cannot vote. Chipeta cannot pay taxes to a great nation, but you will be apt to hear her gentle voice, and her mellow racket will fill the air till her tongue is cold, and they tuck the buffalo robe about her and plant her by the side of her dead chieftain, where the south wind and the sage hen are singing.

I AM not fond of cats, as a general rule. I never yearned to have one around the house. My idea always was, that I could have trouble enough in a legitimate way without adding a cat to my woes. With a belligerent cook and a communistic laundress, it seems to me most anybody ought to be unhappy enough without a cat.

I never owned one until a tramp cat came to our house one day during the present autumn, and tearfully asked to be loved. He didn't have anything in his make-up that was calculated to win anybody's love, but he seemed contented with a little affection,—one ear was gone and his tail was bald for six inches at the end, and he was otherwise well calculated to win confidence and sympathy. Though we could not be madly in love with him, we decided to be friends, and give him a chance to win the general respect.

Everything would have turned out all right if the bobtail waif had not been a little given to investigation. He wanted to know more about the great world in which he lived, so he began by inspecting my house. He got into the store-room closet and found a place where the carpenter had not completed his job. This is a feature of the Laramie artisan's style. He leaves little places in unobserved corners generally, so that he can come back some day and finish it at an additional cost of fifty dollars. This cat observed that he could enter at this point and go all over the imposing structure between the flooring and the ceiling. He proceeded to do so.

We will now suppose that a period of two days has passed. The wide halls and spacious façades of the Nye mansion are still. The lights in the banquet-hall are extinguished, and the ice-cream freezer is hushed to rest in the wood-sned. A soft and tearful yowl, deepened into a regular ring-tail-peeler, splits the solemn night in twain. Nobody seemed to know where it came from.

I rose softly and went to where the sound had seemed to well up from. It was not there.

I stood on a piece of cracker in the diningroom a moment, waiting for it to come again. This time it came from the boudoir of our French artist in soup-bone symphonies and pie—Mademoiselle Bridget O'Dooley. I went there and opened the door softly, so as to let the cat out without disturbing the giant mind-that had worn itself out during the day in the kitchen, bestowing a dry shampoo to the china.

Then I changed my mind and came out. Several articles of vertu, beside Bridget, followed me with some degree of vigor.

The next time the tramp cat yowled he seemed to be in the recesses of the bath-room. I went down stairs and investigated. In doing so I drove my superior toe into my foot, out of sight, with a door that I encountered. My wife joined me in the search. She could not do much, but she aided me a thousand times by her counsel. If it had not been for her mature advice I might have lost much of the invigorating exercise of that memorable night.

Toward morning we discovered that the cat was between the floor of the children's play-room and the ceiling of the dining-room. We tried till daylight to persuade the cat to come out and get acquainted, but he would not.

At last we decided that the quickest way to get the poor little thing out was to let him die in there, and then we could tear up that portion of the house and get him out. While he lived we couldn't keep him still long enough to tear a hole in the house and get at him.

It was a little unpleasant for a day or two waiting for death to come to his relief, for he seemed to die hard, but at last the unearthly midnight yowl was still. The plaintive little voice ceased to vibrate on the still and pulseless air. Later, we found, however, that he was not dead. In a lucid interval he had discovered the hole in the store-room where he entered, and, as we found afterward a gallon of coal-oil spilled in a barrel of cut loaf-sugar, we concluded that he had escaped by that route.

That was the only time that I ever kept a cat, and I didn't do it then because I was suffering for something to fondle. I've got a good deal of surplus affection, I know, but I don't have to spread it out over a stump-tail orphan cat.

IN the Rocky mountains now the eternal whiteness is stealing down toward the foot-hills and the brown mantle of October hangs softly on the swelling divide, while along the winding streams, cottonwood and willow are turned to gold, and the deep green of the solemn pines lies farther back against the soft blue of the autumn sky. The sigh of the approaching storm is heard at eventide, and the hostile Indian comes into the reservation to get some arnica for his chilblain, and to heal up the old feeling of intolerance on the part, of the pale face.

He leaves the glorious picture of mountain and glen; the wide sweep of magnificent nature, where a thousand gorgeous dyes are spread over the remains of the dead summer, and folding his tepee, he steals into the home of the white man that he may be once more at peace with the world.

The hectic of the dying year saddens and depresses him, for is it not an emblem to him of the death of his race? Is it not to him an assurance that in the golden ultimately, the red man will be sought for on the face of the earth and he will not be able to represent. He will not be there either in person or by proxy. Here and there may be found the little silent mounds with some glass beads and teeth in them, but the silent warrior with the Roman nose will not be there.

The Indian agent will have a large, conservative cemetery on his hands, and the brave warrior will be marching single file through the corridors of the hence.

At this moment he does not look romantic. Clothed in a coffee sack and a little brief authority, he would not make a good vignette on a $5 bill. His wife, too, looks careworn, and the old glad light is not in her eye. Pier gunny-sack dolman is not what it once was, and her beautifully arched foot has spread out over the reservation more than it used to. Her step has lost its old elasticity, and so have her suspenders.

Autumn brings to her nothing but regret for the past and hopelessness for the future. The cold and cruel winter will bring her nothing but bitter memories and condemned government grub. The solemn hush of nature and the gorgeous coloring of the forest do not awake a thrill in her wild heart. She cares not for the dead summer or the mellow mist of the grand old mountains.

She doesn't care two cents. She knows that no sealskin sacque will come to her on the Christmas trees, and the glad welcome of the placid and select oyster is not for her.

Is it surprising, then, that to this decaying belle of an old family the sparkle of hope is unknown? Can we wonder, as we contemplate her history, that to her the soldier pantaloons of last year, and the bullwhacker's straw hat of '79, are obnoxious?

She is like her sex, and her joy is fractured by the knowledge that her moccasins are down at the heel, and her stockings existing in the realms of fancy. We should not look with scorn upon Mrs. Rise-up-William-Riley, for hope is dead in her breast, and the wigwam is desolate in the sage-brush.

Daughter of a great nation, we are not mad at you. You are not to be blamed because the republican party has busted your crust. We do not hate you because you eat your steak-rare and wear your own hair. It is your own right to do so if you wish. Brace up, therefore, and take a tumble, as it were, and try to be cheerful. We will not massacre you if you will not massacre us. All we want is peace, and you can wear what you like, only wear something, if you please, when you come into our society. We do not ask you to conform strictly to our false and peculiar costumes, but wear something to protect you from the chilling blasts of winter and you will win our respect. You needn't mingle in our society much if you do not choose to, but wrap yourself up in most any kind of clothing that will silence the tongue of slander, and try to quit drinking. You would get along first-rate if you would only let liquor alone. Do not try to drown your sorrows in the flowing bowl. It's expensive and unsatisfactory. Take our advice and swear off. We have tried it, and we know what we are talking about.

You have a glorious future before you, if you will cease to drink the vintage of the pale face, and monkey with petty larceny. Look at Pocahontas and Mrs. Tecumseh. They didn't drink. They were women of no more ability than you have, but they were high-toned, and they got there, Eli. Now they are known to history along with Cornwallis and Payne. You can do the same if you choose to. Do not be content to lead a yellow dog around by a string and get inebriated, but rise up out of the alkali dust, and resolve that you will shun the demon of drink.

You ought to be ashamed of yourself.

I DO not, as a rule, thirst for the blood of my fellow-man. I am willing that the law should in all ordinary cases take its course, but when we begin to discuss the man who breaks into a conversation and ruins it with his own irrelevant ideas, regardless of the feelings of humanity, I am not a law and order man. The spirit of the "Red Vigilanter" is roused in my breast and I hunger for the blood of that man.

Interrupters are of two classes: First, the common plug who thinks aloud, and whose conversation wanders with his so-called mind. He breaks into the saddest and sweetest of sentiment, and the choicest and most tearful of pathos, with the remorseless ignorance that marks a stump-tail cow in a dahlia bed. He is the bull in my china shop, the wormwood in my wine, and the kerosene in my maple syrup. I am shy in conversation, and my unfettered flights of poesy and sentiment are rare, but this man is always near to mar all with a remark, or a marginal note, or a story or a bit of politics, ready to bust my beautiful dream and make me wish that his name might be carved on a marble slab in some quiet cemetery, far away.

Dear reader, did you ever meet this man—or his wife? Did you ever strike some beautiful thought and begin to reel it off to your friends only to be shut off in the middle of a sentence by this choice and banner idiot of conversation? If so, come and sit by me, and you may pour your woes into my ear, and I in turn will pour a few gallons into your listening ear.

I do not care to talk more than my share of the time, but I would be glad to arrive at a conclusion just to see how it would seem. I would be so pleased and so joyous to follow up an anecdote till I had reached the "nub," as it were, to chase argument home to conviction, and to clinch assertion with authority and evidence.

The second class of interrupters is even worse. It consists of the man—and, I am pained to state, his wife also—who see the general drift of your remarks and finish out your story, your gem of thought or your argument. It is very seldom that they do this as you would do it yourself, but they are kind and thoughtful and their services are always at hand. No matter how busy they may be, they will leave their own work and fly to your aid. With the light of sympathy in their eyes, they rush into the conversation, and, partaking of your own zeal, they take the words from your mouth, and cheerfully suck the juice out of your joke, handing back the rind and hoping for reward. That is where they get left, so far as I am concerned. I am almost always ready to repay rudeness with rudeness, and cold preserved gall with such acrid sarcasm as I may be able to secure at the moment. No one will ever know how I yearn for the blood of the interrupter. At night I camp on his trail, and all the day I thirst for his warm life's current. In my dreams I am cutting his scalp loose with a case-knife, while my fingers are twined in his clustering hair. I walk over him and promenade across his abdomen as I slumber. I hear his ribs crack, and I see his tongue hang over his shoulder as he smiles death's mirthful smile.

I do not interrupt a man no more than I would tell him he lied. I give him a chance to win applause or decomposed eggs from the audience, according to what he has to say, and according to the profundity of his profund. All I want is a similar chance and room according to my strength. Common decency ought to govern conversation without its being necessary to hire an umpire armed with a four-foot club, to announce who is at the bat and who is on deck.

It is only once in a week or two that the angel troubles the waters and stirs up the depths of my conversational powers, and then the chances are that some leprous old nasty toad who has been hanging on the brink of decent society for two weeks, slides in with a low kerplunk, and my fair blossom of thought that has been trying for weeks to bloom, withers and goes to seed, while the man with the chilled steel and copper-riveted brow, and a wad of self-esteem on his intellectual balcony as big as an inkstand, walks slowly away to think of some other dazzling gem, and thus be ready to bust my beautiful phantom, and tear out my high-priced bulbs of fancy the next time I open my mouth.

THE attention of the Rocky Mountain Detective Association is respectfully called to a large bay cow, who is hanging around this place under an assumed name. She has no visible means of support, and has been seen trying to catch the combination to the safes of several of our business men here. She has also stolen into our lot several times and eaten two or three lengths of stovepipe that we neglected to lock up.

THE Scientific American gives this as an excellent mode of preserving eggs: "Take fresh, ones, put a dozen or more into a small willow basket, and immerse this for five seconds in boiling water, containing about five pounds of common brown sugar per gallon, then pack, when cool, small ends down, in an intimate mixture of one part of finely powdered charcoal and two of dry bran. In this way they will last six months or more. The scalding water causes the formation of a thin skin of hard albumen near the inner surface of the shell, and the sugar of syrup closes all the pores."

The Scientific American neglects, however, to add that when you open them six months after they were picked and preserved, the safest way is to open them out in the alley with a revolver, at sixteen paces. When you have succeeded in opening one, you can jump on a fleet horse and get out of the country before the nut brown flavor catches up with you.

I AM up here in River Falls, Wisconsin, and patiently waiting for the snow-banks to wilt away and gentle spring to come again. Gentle spring, as I go to press, hath not yet loomed up. Nothing in fact hath loomed up, as yet, save the great Dakota boom. Everybody, from the servant girl with the symphony in smut on her face and the boundless waste of freckles athwart her nose, up to the normal school graduate, with enough knowledge to start a grist mill for the gods, has "a claim" in the promised land, the great wild goose orchard and tadpole aquarium of the new Northwest.

The honest farmer deserts his farm, around which clusters a thousand memories of the past, and buckling on his web feet, he flees to the frog ponds of the great northern watershed, to make a "tree claim," and be happy.

Such is life. We battle on bravely for years, cutting out white-oak grubs, and squashing army worms on a shingle, in order that we may dwell beneath our own vine and plum tree, and then we sell and take wings toward a wild, unknown country, where land is dirt cheap, where the wicked cease from troubling and the weary are at rest.

That is where we get left, if I may be allowed an Americanism, or whatever it is. We are never at rest. The more we emigrate the more worthless, unsatisfied and trifling we become. I have seen the same family go through Laramie City six times because they knew not of contentment. The first time they went west in a Pullman car "for their health." The husband rashly told a sad-eyed man that he lied, and in a little while the sun was obscured by loose teeth and hair. The ground was torn up and vegetation was killed where the discussion was held.

Then the family went home to Toledo. They went in a day coach and said a Pullman car was full of malaria and death. Their relatives made sport of them and lifted up their yawp and yawped at them insomuch that the yawpness thereof was as the town caucus for might. Then the tourists on the following spring packed up two pillows, and a pink comforter, and a change of raiment, and gat them onto the emigrant train and journeyed into the land which is called Arizona, where the tarantula climbeth up on the innerside of the pantaloon and tickleth the limb of the pilgrim as he journeyeth, and behold he getteth in his work, and the leg of that man is greater than it was aforetime, even like unto the leg of a piano.

THERE'S no doubt but that the Fort Collins route to the North Park, is a good, practicable route, but the only man who has started out over it this spring fetched up in the New Jerusalem.

The trouble with that line of travel is, that the temperature is too short. The summer on the Fort Collins route is noted mainly for its brevity. It lasts about as long as an ordinary eclipse of the sun.

The man who undertook to go over the road this spring on snow shoes, with a load consisting of ten cents' worth of fine cut tobacco, has not been heard from yet at either end of the line, and he is supposed to have perished, or else he is still in search of an open polar sea.

It is hoped that dog days will bring him to the surface, but if the winter comes on as early this fall as there are grave reasons to fear, a man couldn't get over the divide in the short space of time which will intervene between Decoration day and Christmas.

We hate to discourage people who have an idea of going over the Fort Collins road to North Park, but would suggest that preparations be made in advance for about five hundred St. Bernard dogs and a large supply of arctic whisky, to be placed on file where it can be got at without a moment's delay.

THERE is a firm on Coyote creek, in New Jersey, that would like to advertise in The Boomerang, and the members of the firm are evidently good square men, although they are not large. They lack about four feet in stature of being large enough to come within the range of our vision.

They have got more pure gall to the superficial foot than anybody we ever heard of. It seems that the house has a lot of vermifuge to feed plants, and a bedbug tonic that it wants to bring before the public, and it wants us to devote a quarter of a column every day to the merits of these bug and worm discouragers, and then take our pay out of tickets in the drawing of a brindle dog next spring.

We might as well come right out end state that we are not publishing this paper for our health, nor because we like to loll around in luxury all day in the voluptuous office of the staff. We have mercenary motives, and we can't work off wheezy parlor organs and patent corn plasters and threshing machines very well. We desire the scads. We can use them in our business, and we are gathering them in just as fast as we can. At the present time we are pretty well supplied with rectangular churns and stem-winding mouse traps. We do not need them, It takes too much time to hypothecate them.

In closing, we will add, that New Jersey people will not be charged much more for advertising space than Wyoming people. We have made special rates so that we can give the patrons of the East almost as good terms as our home advertisers.

IT is rather interesting to watch the manner by which old customs have been slightly changed and handed down from age to age. Peculiarities of old traditions still linger among us, and are forked over to posterity like a wappy-jawed teapot or a long-time mortgage.. No one can explain it, but the fact still remains patent that some of the oddities of our ancestors continue to appear from time to time, clothed in the changing costumes of the prevailing fashion.

Along with these choice antiquities, and carrying the nut-brown flavor of the dead and relentless years, comes the amende honorable. From the original amende in which the offender appeared in public clothed only in a cotton-flannel shirt, and with a rope about his neck as an evidence a formal recantation, down to this day when (sometimes) the pale editor, in a stickful of type, admits that "his informant was in error," the amende honorable has marched along with the easy tread of time. The blue-eyed moulder of public opinion, with one suspender hanging down at his side, and writing on a sheet of news-copy paper, has a more extensive costume, perhaps, than the old-time offender who bowed in the dust in the midst of the great populace, and with a halter under his ear admitted his offense, but he does not feel any more cheerful over it.

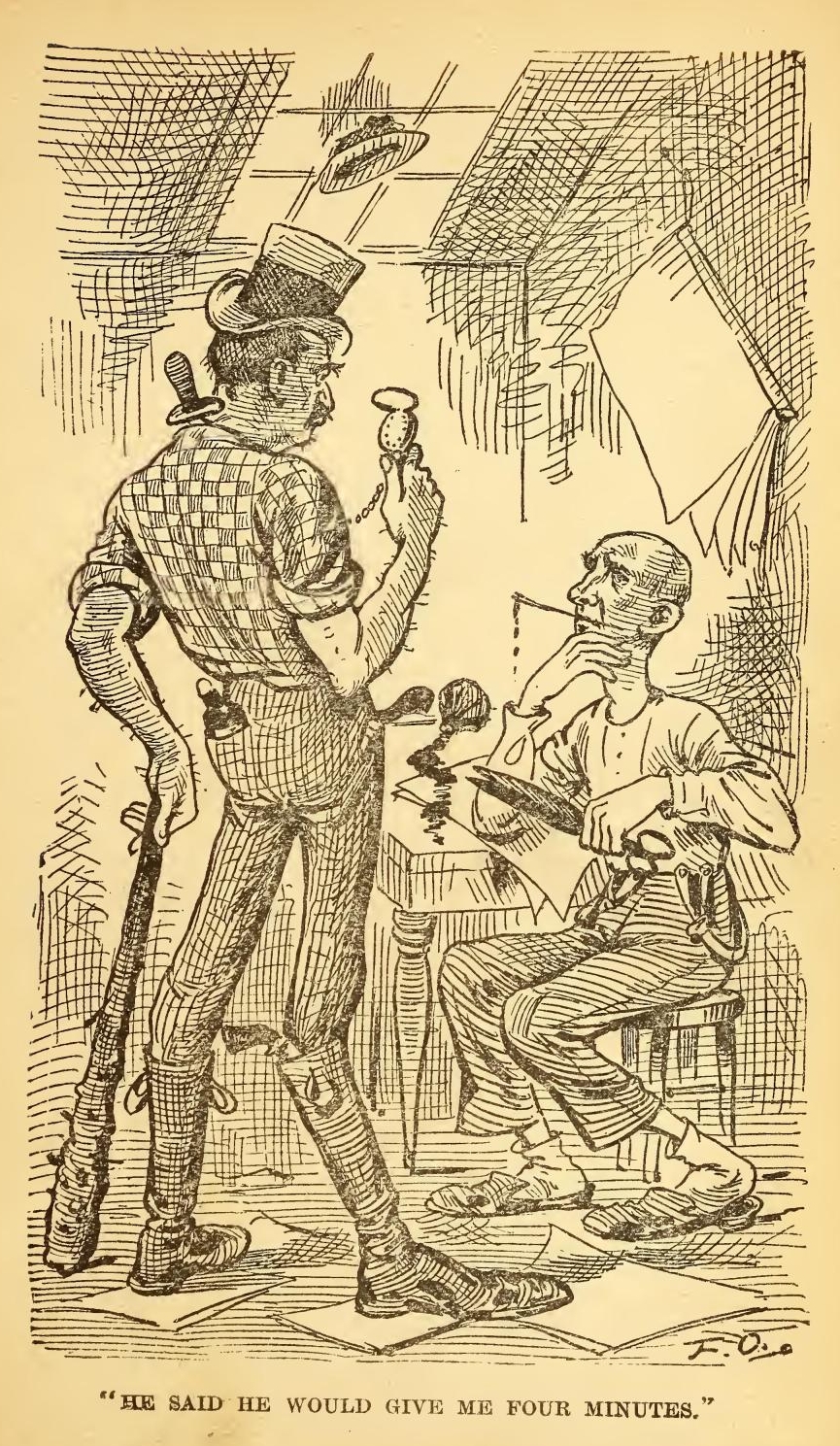

I have been called upon several times to make the amende honorable, and I admit that it is not an occasion of mirth and merriment. People who come into the editorial office to invest in a retraction are generally very healthy, and have a stiff, reserved manner that no cheerfulness of hospitality can soften..

I remember of an accident of this kind which occurred last summer in my office, while I was writing something scathing. A large map with an air of profound perspiration about him, and a plaid flannel shirt, stepped into the middle of the room, and breathed in the air that I was not using. He said he would give me four minutes in which to retract, and pulled out a watch by which to ascertain the exact time.

I asked him if he would not allow me a moment or two to go over to the telegraph office and to wire my parents of my awful death. He said I could walk out of that door when I walked over his dead body. Then I waited a long time, until he told me my time was up, and asked what I was waiting for. I told him I was waiting for him to die, so that I could walk over his dead body. How could I walk over a corpse until life was extinct?

He stood and looked at me first in astonishment, afterward in pity. Finally tears welled up in his eyes, and plowed their way down his brown and grimy face. Then he said that I need not fear him. "You are safe," said he. "A youth who is so patient and so cheerful as you are—who would wait for a healthy man to die so that you could meander over his pulseless remnants, ought not to die a violent death. A soft-eyed seraph like you, who is no more conversant with the ways of this world than that, ought to be put in a glass vial of alcohol and preserved. I came up here to kill you and throw you into the rain-water barrel, but now that I know what a patient disposition you have, I shudder to think of the crime I was about to commit."

JOAQUIN MILLER has just published a new book called "The Shadows of Shasta." It is based on the Hiawatha, Blue Juniata romance, which the average poet seems competent to yank loose from the history of the sore-eyed savage at all times.

Whenever a dead-beat poet strikes bedrock and don't have shekels enough to buy a bowl of soup, he writes an inspired ode to the unfettered horse-thief of the west.

It is all right so far as we know. If the poet will wear out the smoke-tanned child of the forest writing poetry about him, and then if the child of the forest will rise up in his death struggle and mash the never-dying soul out of the white-livered poet, everything will be O.K., and we will pay the funeral expenses.

If it could be so arranged that the poet and the bright Alfarita bug-eater and the bilious wild-eyed bard of the backwoods could be shut up in a corral for six weeks together, with nothing to eat but each other, it would be a big thing for humanity. We said once that we wouldn't dictate to this administration, but let it flicker along alone. We just throw out the above as a suggestion, however, hoping that it will not be ignored.

SPRING, gentle, touchful, tuneful, breezeful, soothful spring is here. It has not been here more than twenty minutes, and my arctics stand where I can reach them in case it should change its mind.

The bobolink sits on the basswood vines, and the thrush in the gooseberry tree is as melodious as a hired man. The robin is building his nest—or rather her nest, I should say, perhaps—in the boughs of the old willow that was last year busted by thunder—I beg your pardon—by lightning, I should say. The speckled calf dines teat-a-teat with his mother, and strawberries are like a baldheaded man's brow—they come high, but we can't get along without them.

I never was more tickled to meet gentle spring than I am now. It stirs up my drug-soaked remains, and warms the genial current of life considerably. I frolicked around in the grass this afternoon and filled my pockets full of 1000-legged worms, and other little mementoes of the season. The little hare-foot boy now comes forth and walks with a cautious tread at first, like a blind horse; but toward the golden autumn the backs of his feet will look like a warty toad, and there will be big cracks in them, and one toe will be wrapped up in part of a bed quilt, and he will show it with pride to crowded houses.

Last night I lay awake for several hours thinking about Mr. Sherrod and how long we had been separated, and I was wondering how many weary days would have to elapse before we would again look into each other's eyes and hold each other by the hand, when the loud and violent concussion of a revolver shot near West Main street and Cascade avenue rent the sable robe of night. I rose and lit the gas to see if I had been hit. Then I examined my pockets to see if I had been robbed of my led pencil and season pass. I found that I had not.

This morning I learned that a young doctor, who had been watching his own house from a distance during the evening, had discovered that, taking advantage of the husband's absence, a blonde dry goods clerk had called to see the crooked but lonely wife. The doctor waited until the young man had been in the house long enough to get pretty well acquainted, and then he went in himself to see that the youth was making himself perfectly comfortable.

There was a wild dash toward the window, made by a blonde man with his pantaloons in his hand, the spatter of a bullet in the wall over the young man's head and then all was still for a moment save the low sob of a woman with her head covered up by the bed clothes. Then the two men clinched and the doctor injected the barrel of a thirty-two self-cocker up the bridge of the young man's nose, knocked him under the wash stand, yanked him out by the hem of his garment and jarred him into the coal bucket, kicked him up on a corner bracket and then swept the quivering ruins into the street with a stub-broom. He then lit the chandelier and told his sobbing wife that she wasn't just the temperament for him and he was afraid that their paths might diverge. He didn't care much for company and society while she seemed to yearn for such things constantly. He came right out and admitted that he was of a nervous temperament and quick tempered. He loved her, but he had such an irritable, fiery disposition that he guessed he would have to excuse her; so he escorted her out to the gate and told her where the best hotel was, came in, drove out the cat, blew out the light and retired.

Some men seem almost like brutes in their treatment of their wives. They come home at some eccentric hour of the night, and because they have to sleep on the lounge, they get mad and try to shoot holes in the lambrequins, and look at their wives in a harsh, rude tone of voice. I tell you it's tough.

You are an youmorist, are you not?" queried a long-billed pelican addressing a thoughtful, mental athlete, on the Milwaukee & St. Paul road the other day.

"Yes, sir," said the sorrowful man, brushing away a tear. "I am an youmorist. I am not very much so, but still I can see that I am drifting that way. And yet I was once joyous and happy as you are. Only a few years ago, before I was exposed to this malady, I was as blithe as a speckled yearling, and recked not of aught—nor anything else, either. Now my whole life is blasted. I do not dare to eat pie or preserves, and no one tells funny stories when I am near. They regard me as a professional, and when I get in sight the 'scrub nine' close up and wait for me to entertain the crowd and waddle around the ring."

"What do you mean by that?" murmured the purple-nosed interrogation point.

"Mean? Why, I mean that whether I'm drawing a salary or not, I'm expected to be the 'life of the party.' I don't want to be the life of the party. I want to let some one else be the life of the party. I want to get up the reputation of being as cross as a bear with a sore head. I want people to watch their children for fear I'll swallow them. I want to take my low-cut-evening-dress smile and put it in the bureau drawer, and tell the world I've got a cancer in my stomach, and the heaves and hypochondria, and a malignant case of leprosy."

"Do you mean to say that you do not feel facetious all the time, and that you get weary of being an youmorist?"

"Yes, hungry interlocutor. Yes, low-browed student, yes. I am not always tickled. Did you ever have a large, angry, and abnormally protuberent boil somewhere on your person where it seemed to be in the way? Did you ever have such a boil as a traveling companion, and then get introduced to people as an youmorist? You have not? Well, then, you do not know all there is of suffering in this sorrow-streaked world. When wealthy people die why don't they endow a cast-iron castle with a draw-bridge to it and call it the youmorists' retreat? Why don't they do some good with their money instead of fooling it away on those who are comparatively happy?"

"But how did you come to git to be an youmorist?"

"Well, I don't know. I blame my parents some. They might have prevented it if they'd taken it in time, but they didn't. They let it run on till it got established, and now its no use to go to the Hot Springs or to the mountains, or have an operation performed. You let a man get the name of being an youmorist and he doesn't dare to register at the hotels, and he has to travel anonymously, and mark his clothes with his wife's name, or the public will lynch him if he doesn't say something youmorous.

"Where is your boy to-night?" continued the gloomy humorist. "Do you know where he is? Is he at home under your watchful eye, or is he away somewhere nailing the handles on his first little joke? Parent, beware. Teach your boy to beware. Watch him night and day, or all at once, when he is beyond your jurisdiction, he will grow pale. He will have a far-away look in his eye, and the bright, rosy lad will have become the flatchested, joyless youmorist.

"It's hard to speak unkindly of our parents, but mingled with my own remorse I shall always murmur to myself, and ask over and over, why did not my parents rescue me while they could? Why did they allow my chubby little feet to waddle down to the dangerous ground on which the sad-eyed youmorist must forever stand?

"Partner, do not forget what I have said to-day. 'Whether your child be a son or daughter, it matters not. Discourage the first sign of approaching humor. It is easier to bust the backbone of the first little, tender jokelet that sticks its head through the virgin soil, than it is to allow the slimy folds of your son's youmorous lecture to be wrapped about you, and to bring your gray hairs with sorrow to the grave."

I HAVE made a small collection of wild, western things during the past seven years, and have put them together, hoping some day, when I get feeble, to travel with the aggregation and erect a large monument of kopecks for my executors, administrators and assigns forever.

Beginning with the skull of old Hi-lo-Jack-and-the-game, a Sioux brave, the collection takes in my wonderful bird, known as the Walk-up-the-creek, and another vara avis, with carnivorous bill and web feet, which has astonished everyone except the taxidermist and myself. An old grizzly bear hunter—who has plowed corn all his life and don't know a coyote from a Maverick steer—looked at it last fall and pronounced it a "kingfisher," said he had killed one like it a year ago. Then I knew that he was a pilgrim and a stranger, and that he had bought his buckskin coat and bead-trimmed moccasins at Niagara Falls, for the bird is constructed of an eagle's head, a canvas back duck's bust and feet, with the balance sage hen and baled hay.

Last fall I desired to add to my rare collection a large hornet's nest. I had an embalmed tarantula and her porcelain-lined nest, and I desired to add to these the gray and airy home of the hornet. I procured one of the large size after cold weather and hung it in my cabinet by a string. I forgot about it until this spring. When warm weather came, something reminded me of it. I think it was a hornet. He jogged my memory in some way and called my attention to it. Memory is not located where I thought it was. It seemed as though whenever he touched me he awakened a memory—a warm memory with a red place all around it.

Then some more hornets came and began to rake up old personalities. I remember that one of them lit on my upper lip. He thought it was a rosebud. When he went away it looked like a gladiola bulb. I wrapped a wet sheet around it to take out the warmth and reduce the swelling so that I could go through the folding doors and tell my wife about it.

Hornets lit ah over me and walked around on my person. I did not dare to scrape them off because they are so sensitive. You have to be very guarded in your conduct toward a hornet.

I remember once while I was watching the busy little hornet gathering honey and June bugs from the bosom of a rose, years ago, I stirred him up with a club, more as a practical joke than anything else, and he came and lit in my sunny hair—that was when I wore my own hair and he walked around through my gleaming tresses quite awhile, making tracks as large as a watermelon all over my head. If he hadn't run out of tracks my head would have looked like a load of summer squashes. I remember I had to thump my head against the smoke-house in order to smash him, and I had to comb him out with a fine comb, and wear a waste-paper basket two weeks for a hat.

Much has been said of the hornet, but he has an odd, quaint way after all, that is forever new.

WHILE trying to reconstruct a telescoped spine and put some new copper rivets in the lumbar vertebrae, this spring, I have had occasion to thoroughly investigate the subject of so-called health food, such as gruels, beef tea inundations, toasts, oat meal mush, bran mash, soups, condition powders, graham gem, ground feed, pepsin, laudable mush, and other hen feed usually poked into the invalid who is too weak to defend himself.

Of course it stands to reason that the reluctant and fluttering spirit may not be won back to earth, and joy once more beam in the leaden eye unless due care be taken relative to the food by means of which nature may be made to assert herself.

I do not care to say to the world through the columns of the Free Press, that we may woo from eternity the trembling life with pie. Welsh rabbit and other wild game will not do at first. But I think I am speaking the sentiments of a large and emaciated constituency when I say, that there is getting to be a strong feeling against oat meal submerged in milk and in favor of strawberry short cake.

I almost ate myself into an early grave in April by flying into the face of Providence and demoralizing old Gastric with oat meal. I ate oat meal two weeks, and at the end of that time my friends were telegraphed for, but before it was too late, I threw off the shackles that bound me. With a desperation born of a terrible apprehension, I rose and shook off the fatal oat meal habit and began to eat beefsteak. At first life hung trembling in the balance and there was no change in the quotations of beef, but later on there was a slight, delicate bloom on the wan cheek, and range cattle that had barely escaped a long, severe winter on the plains, began to apprehend a new danger and to seek the secluded canyons of the inaccessible mountains.

I often thought while I was eating health food and waiting for death, how the doctor and other invited guests at the post mortem would start back in amazement to find the remnants of an eminent man filled with bran!

Through all the painful hours of the long, long night and the eventless day, while the mad throng rushed onward like a great river toward eternity's ocean, this thought was uppermost in my mind. I tried to get the physician to promise that he would not expose me, and show the world what a hollow mockery I had been, and how I had deceived my best friends. I told him the whole truth, and asked him to spare my family the humiliation of knowing that though I might have led a blameless life, my sunny exterior was only a thin covering for bran and shorts and middlings, cracked wheat and pearl barley.

I dreamed last night of being in a large city where the streets were paved with dry toast, and the buildings were roofed with toast, and the soil was bran and oat meal, and the water was beef tea and gruel. All at once it came over me that I had solved the great mystery of death, and had been consigned to a place of eternal punishment. The thought was horrible! A million eternities in a city built of dry toast and oat meal! A home for never-ending cycles of ages, where the principal hotel and the post-office building and the opera house were all built of toast, and the fire department squirted gruel at the devouring element forever!

It was only a dream, but it has made me more thoughtful, and people notice that I am not so giddy as I was.

A NEW and dazzling literary star has risen above the horizon, and is just about to shoot athwart the starry vault of poesy. How wisely are all things ordered, and how promptly does the new star begin to beam, upon the decline of the old.

Hardly had the sweet singer of Michigan commenced to wane and to flicker, when, rising above the western hills, the glad light of the rising star is seen, and adown the canyons and gulches of the Rocky mountains comes the melodious cadences of the poet of the Greeley Eye.

Couched in the rough terms of the west; robed in the untutored language of the Michael Angelo slang of the miner and the cowboy, the poet at first twitters a little on a bough far up the canyon, gradually waking the echoes, until the song is taken up and handed back by every rock and crag along the rugged ramparts of the mighty mountain barrier.

Listen to the opening stanza of "The Dying Cowboy and the Preacher:"

``So, old gospel shark, they tell me I must die;

``That the wheels of life's wagon have rolled into their last rut,

``Well, I will "pass in my checks" without a whimper or a cry,

``And die as I have lived—"a hard nut."=

This is no time-worn simile, no hackneyed illustration or bald-headed decrepit comparison, but a new, fresh illustration that appeals to the western character, and lifts the very soul out of the kinks, as it were.

"Wheels of life's wagon have rolled into their last rut."

Ah! how true to nature and yet how grand. How broad and sweeping. How melodious and yet how real. Hone but the true poet would have thought to compare the close of life to the sudden and unfortunate chuck of the off hind wheel of a lumber wagon into a rut.

In fancy we can see it all. We hear the low, sad kerplunk of the wheel, the loud burst of earnest, logical profanity, and then all is still.

How and then the swish of a mule's tail through the air, or the sigh of the rawhide as it shimmers and hurtles through the silent air, and then a calm falls upon the scene. Anon, the driver bangs the mule that is ostensibly pulling his daylights out, but who is, in fact, humping up like an angle worm, without pulling a pound.

Then the poet comes to the close of the cowboy's career in this style:

```"Do I repent?" No—of nothing present or past;

```So skip, old preach, on gospel pap I won't be fed;

```My breath comes hard; I—am going—but—I—am game to

`````the—last.

```And reckless of the future, as the present, the cowboy was

`````dead.=

If we could write poetry like that, do you think we would plod along the dreary pathway of the journalist? Do you suppose that if we had the heaven-born gift of song to such a degree that we could take hold of the hearts of millions and warble two or three little ditties like that, or write an effigy before breakfast, or construct an ionic, anapestic twitter like the foregoing, that we would carry in our own coal, and trim our own lamps, and wear a shirt two weeks at a time?

No, sir, he would hie us away to Europe or Salt Lake, and let our hair grow long, and we would write some obituary truck that would make people disgusted with life, and they would sigh for death that they might leave their insurance and their obituaries to their survivors.

IT might be well in closing to say a word in defense of myself.

The varied and uniformly erroneous notions expressed recently as to my plans for the future, naturally call for some kind of an expression on this point over my own signature. In the first place, it devolves upon me to regain my health in full if it takes fourteen years. I shall not, therefore, "publish a book,"

"prepare an youmorous lecture,"

"visit Florida,"

"probate the estate of Lydia E. Pinkham, deceased," nor make any other grand break till I have once more the old vigor and elasticity, and gurgling laugh of other days.

In the meantime, let it be remembered that my home is in Laramie City, and that unless the common council pass an ordinance against it, I shall return in July if I can make the trip between snow storms, and evade the peculiarities of a tardy and reluctant spring. Bill Nye.

TOM FAGAN, of this city, has a wild horse that don't seem to take to the rush and hurry and turmoil of a metropolis. He has been so accustomed to the glad, free air of the plains and mountains that the hampered and false life of a throbbing city, with its myriad industries, makes him nervous and unhappy. He sighs for the boundless prairie and the pure breath of the lifegiving mountain atmosphere. So taciturn is he in fact, and so cursed by homesickness and weariness of an artificial and unnatural horse society here in Laramie, that he refuses to eat anything and is gradually pining away. Sometimes he takes a light lunch out of Mr. Fagan's arm, but for days and days he utterly loathes food. He also loathes those who try to go into the stable and fondle him. He isn't apparently very much on the fondle. He don't yearn for human society, but seems to want to be by himself and think it over.

The wild horse in stories soon learns to love his master and stay by him and carry him through flood or fire, and generally knows more than the Cyclopedia Brittanica; but this horse is not the historical horse that they put into wild Arabian falsehoods. He is just a plain, unassuming wild horse of Wyoming descent, whose pedigree is slightly clouded, and who is sensitive on the question of his ancestry. All he wants is just to be let alone, and most everybody has decided that he is right. They came do that conclusion after they had soaked their persons in arnica and glued themselves together with poultices.

Perhaps, after a while, he will conclude to eat hay and grow up with the country, but now he sighs for his native bunch-grass and the buffalo wallow wherein he has heretofore made his lair. We don't wonder much, though, that a horse who has lived in the country should be a little rattled here when he finds the electric light, and bicycles, and lawn mowers, and Uncle Tom's Cabin troupes, and baled hay at $20 per ton. It makes him as wild and skittish as it does an eighteen-year-old girl the first time she comes into town, and for the first time is met by the blare of trumpets, and the oriental wealth of the circus with its deformed camels and uniformed tramps driving its miles of cages with no animals in them. The great natural world and the giddy maelstrom of seething, perspiring humanity, peculiar to the city world, are two separate and distinct existences.