NARRATIVE AND CRITICAL

HISTORY OF AMERICA

| Aboriginal America |

|

NARRATIVE AND CRITICAL

HISTORY OF AMERICA

EDITED

By JUSTIN WINSOR

LIBRARIAN OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY

CORRESPONDING SECRETARY MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL SOCIETY

VOL. I

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

Copyright. 1889,

By HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY.

All rights reserved.

The Riverside Press, Cambridge, Mass., U. S. A.

Electrotyped and Printed by H. O. Houghton & Company.

To

CHARLES WILLIAM ELIOT, LL. D.

President of Harvard University.

Dear Eliot:

Forty years ago, you and I, having made preparation together, entered college on the same day. We later found different spheres in the world; and you came back to Cambridge in due time to assume your high office. Twelve years ago, sought by you, I likewise came, to discharge a duty under you.

You took me away from many cares, and transferred me to the more congenial service of the University. The change has conduced to the progress of those studies in which I hardly remember to have had a lack of interest.

So I owe much to you; and it is not, I trust, surprising that I desire to connect, in this work, your name with that of your

Obliged friend,

CONTENTS AND ILLUSTRATIONS.

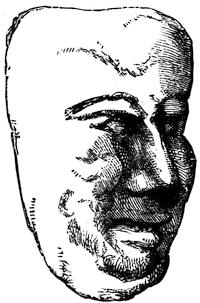

[The cut on the title represents a mask, which forms the centre of the Mexican Calendar Stone, as engraved in D. Wilson’s Prehistoric Man, i. 333, from a cast now in the Collection of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.]

| INTRODUCTION. | |

| Part I. Americana in Libraries and Bibliographies. The Editor | i |

| Illustrations: Portrait of Professor Ebeling, iii; of James Carson Brevoort, x; of Charles Deane, xi. | |

| Part II. Early Descriptions of America, and Collective Accounts of the Early Voyages Thereto. The Editor |

xix |

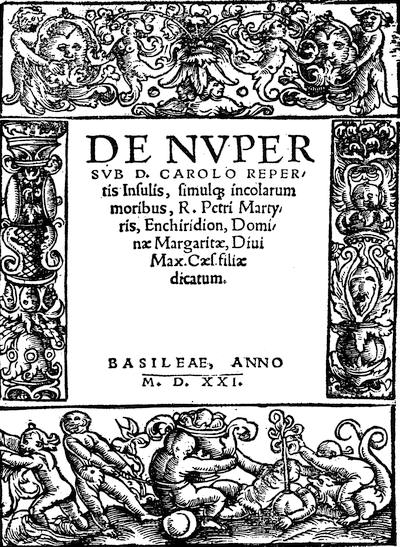

| Illustrations: Title of the Newe Unbekanthe Landte, xxi; of Peter Martyr’s De Nuper sub D. Carolo repertis insulis (1521), xxii; Portrait of Grynæus, xxiv; of Sebastian Münster, xxvi, xxvii; of Monardes, xxix; of De Bry, xxx; of Feyerabend, xxxi. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The Geographical Knowledge of the Ancients Considered in Relation To The Discovery of America. William H. Tillinghast |

1 |

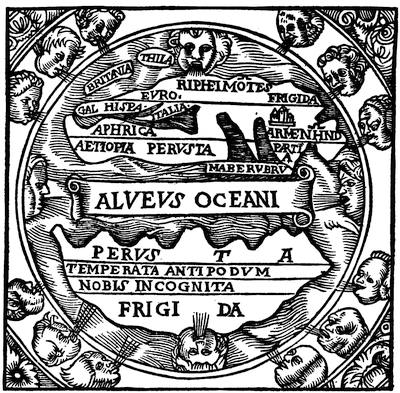

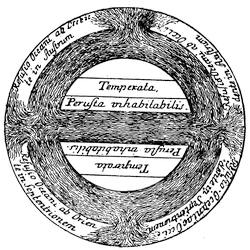

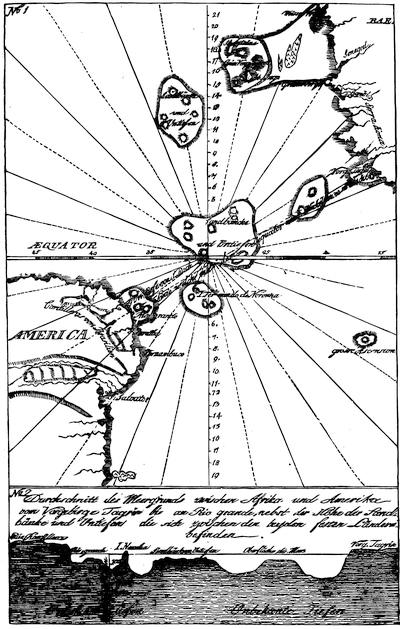

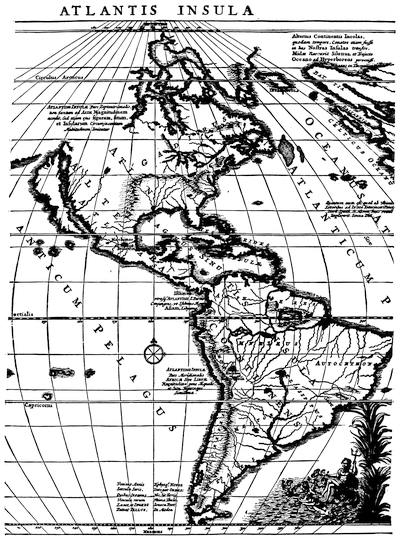

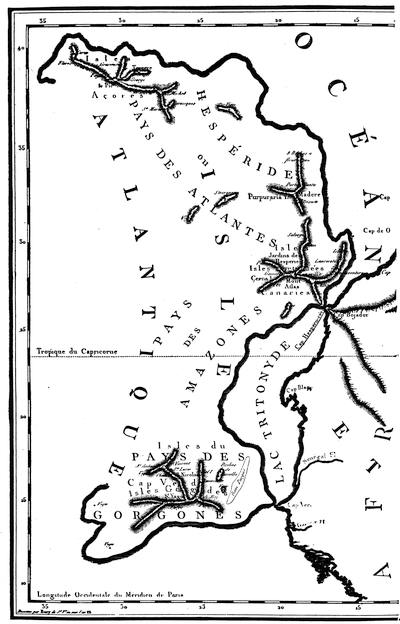

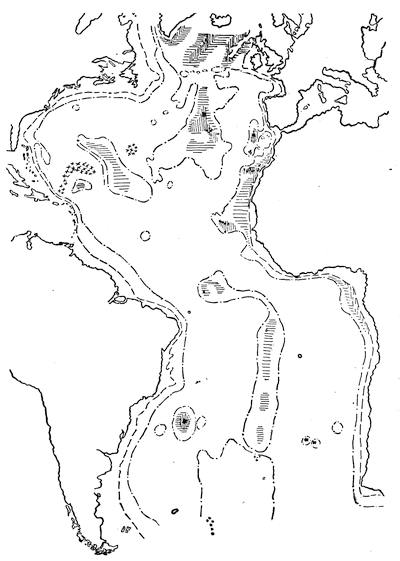

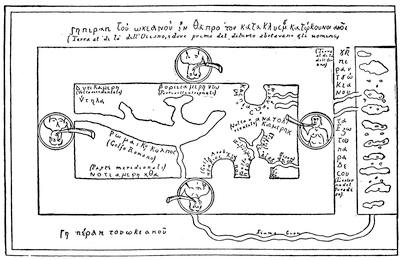

| Illustrations: Maps by Macrobius, 10, 11, 12; Carli’s Traces of Atlantis, 17; Sanson’s Atlantis Insula, 18; Bory de St. Vincent’s Carte Conjecturale de l’Atlantide, 19; Contour Chart of the Bottom of the Atlantic Ocean, 20; The Rectangular Earth, 30. | |

| Critical Essay | 33 |

| Notes | 38 |

| A. The Form of the Earth, 38; B. Homer’s Geography, 39; C. Supposed References to America, 40; D. Atlantis, 41; E. Fabulous Islands of the Atlantic in the Middle Ages, 46; F. Toscanelli’s Atlantic Ocean, 51. G. (By the Editor.) Early Maps of the Atlantic Ocean, 53. | |

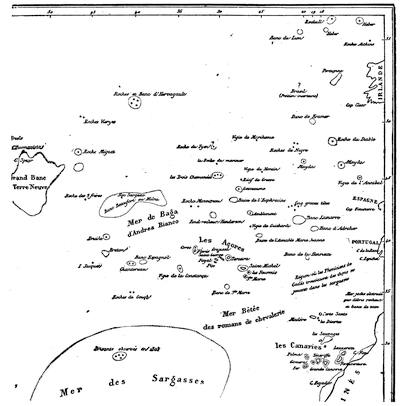

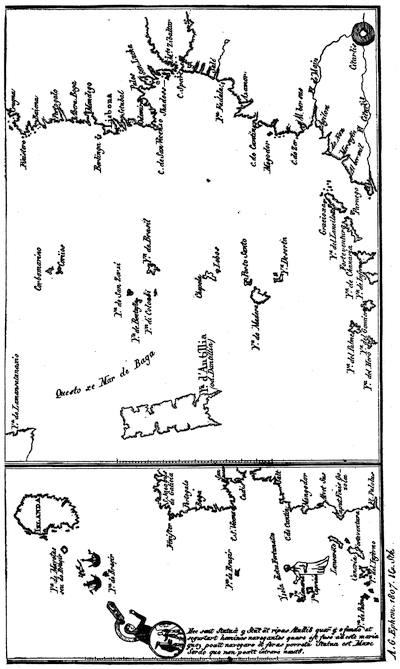

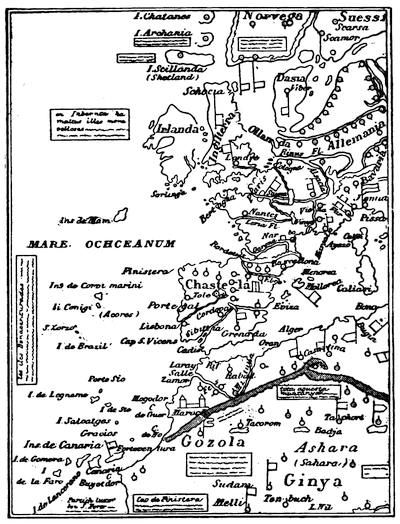

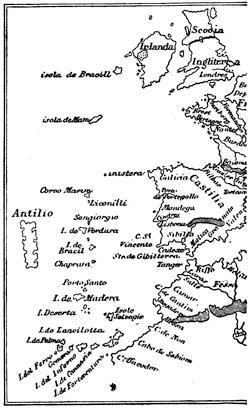

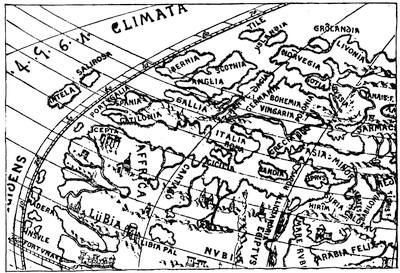

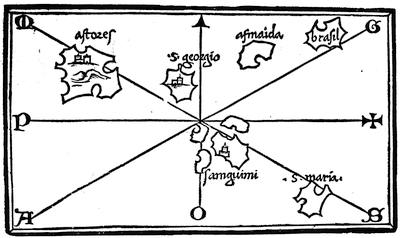

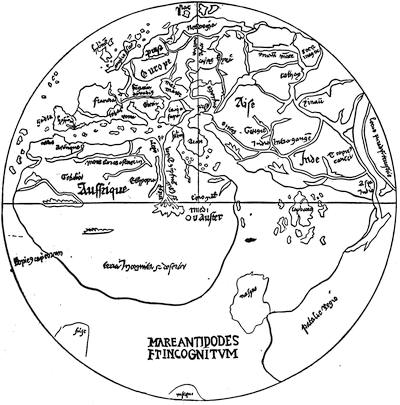

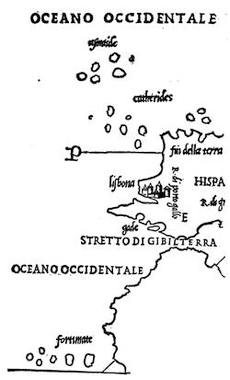

| Illustrations: Map of the Fifteenth Century, 53; Map of Fr. Pizigani (a.d. 1367), and of Andreas Bianco (1436), 54; Catalan Map (1375), 55; Map of Andreas Benincasa (1476), 56; Laon Globe, 56; Maps of Bordone (1547), 57, 58; Map made at the End of the Fifteenth Century, 57; Ortelius’s Atlantic Ocean (1587), 58. | |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Pre-Columbian Explorations. Justin Winsor | 59 |

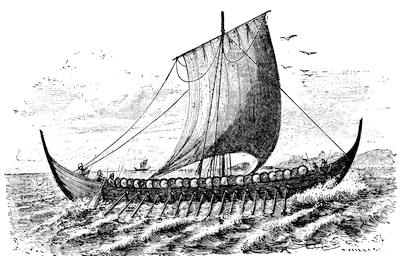

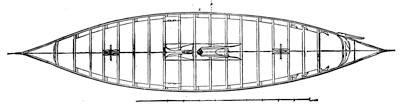

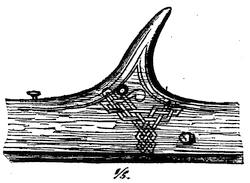

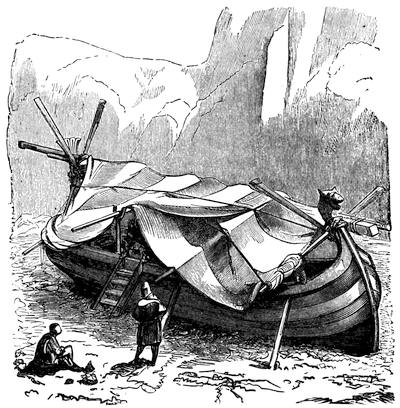

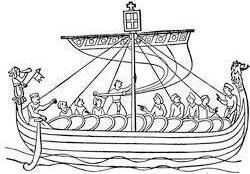

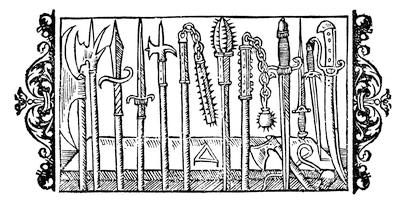

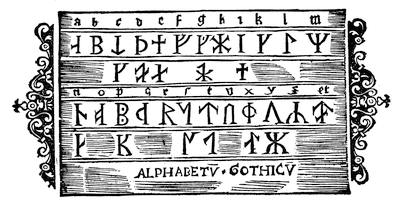

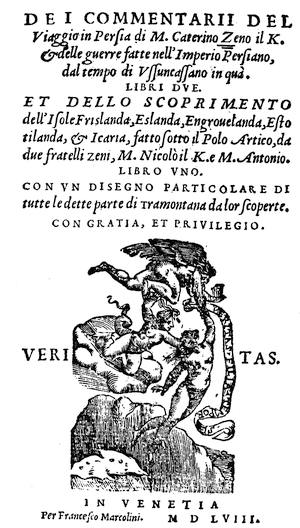

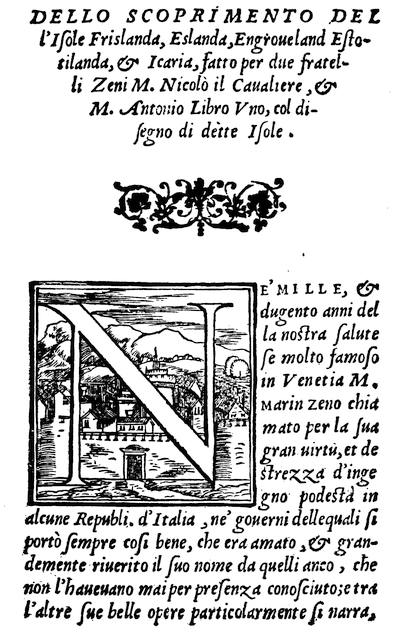

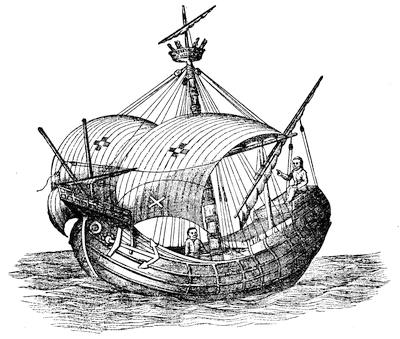

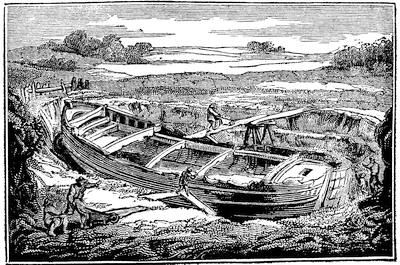

| Illustrations: Norse Ship, 62; Plan of a Viking Ship 63, and her Rowlock, 63; Norse [viii]Boat used as a Habitation, 64; Norman Ship from the Bayeux Tapestry, 64; Scandinavian Flags, 64; Scandinavian Weapons, 65; Runes, 66, 67; Fac-simile of the Title of the Zeno Narrative, 70; Its Section on Frisland, 71; Ship of the Fifteenth Century, 73; The Sea of Darkness, 74. | |

| Critical Notes | 76 |

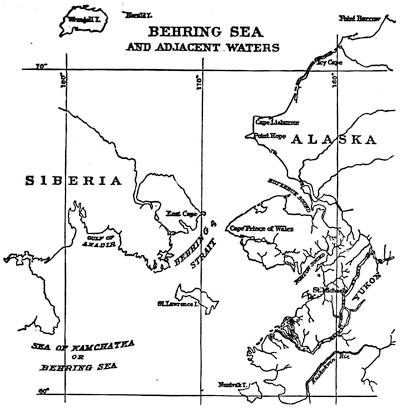

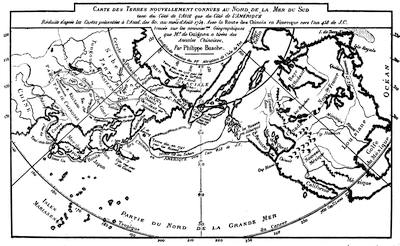

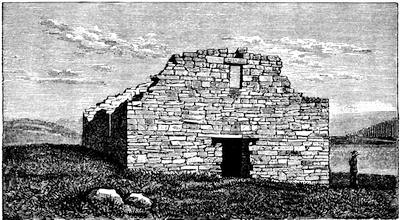

| A. Early Connection of Asiatic Peoples with the Western Coast of America, 76; B. Ireland the Great, or White Man’s Land, 82; C. The Norse in Iceland, 83; D. Greenland and its Ruins, 85; E. The Vinland Voyages, 87; F. The Lost Greenland Colonies, 107; G. Madoc and the Welsh, 109; H. The Zeni and their Map, 111; I. Alleged Jewish Migration, 115; J. Possible Early African Migrations, 116. | |

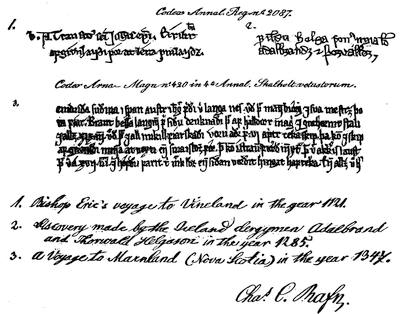

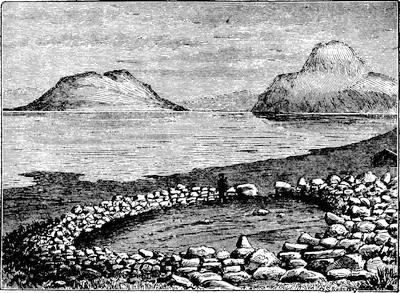

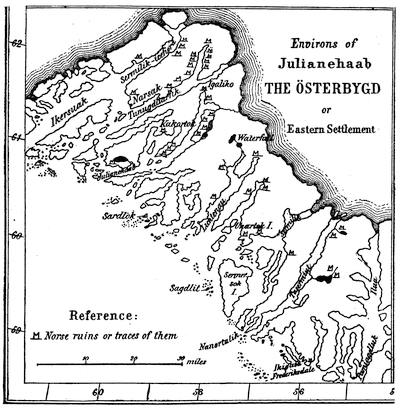

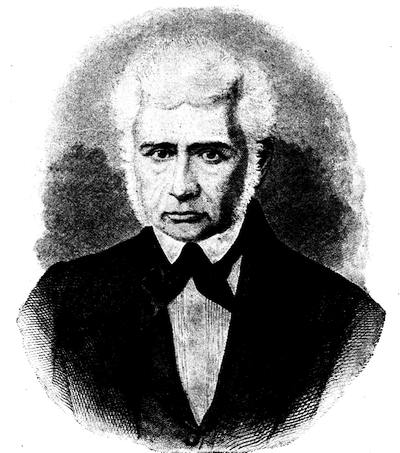

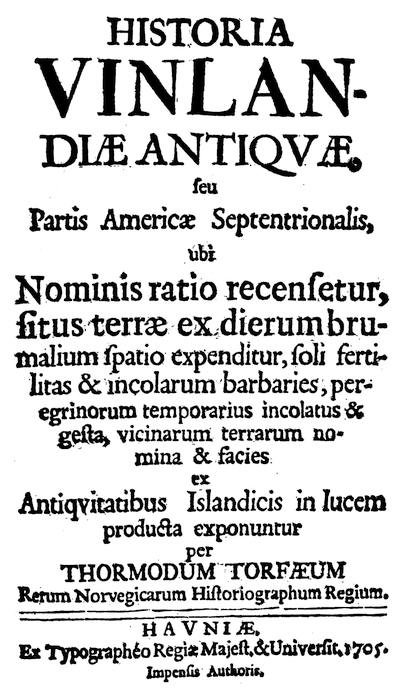

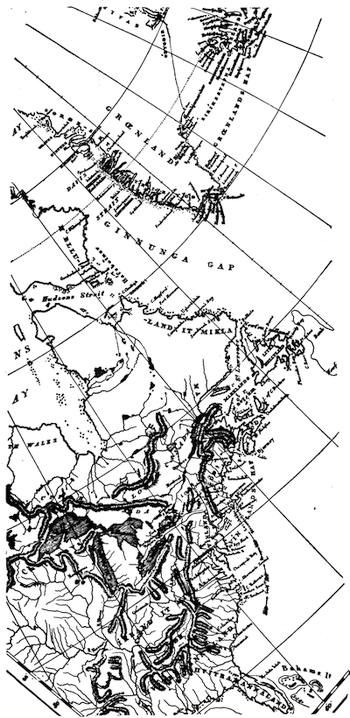

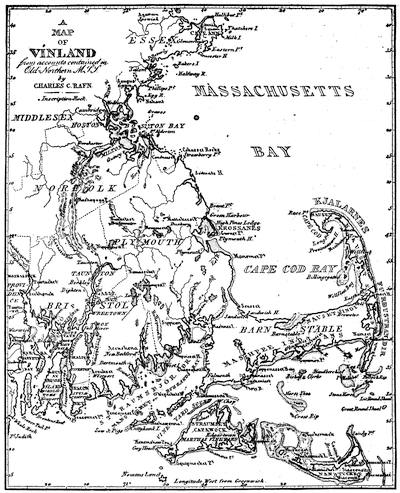

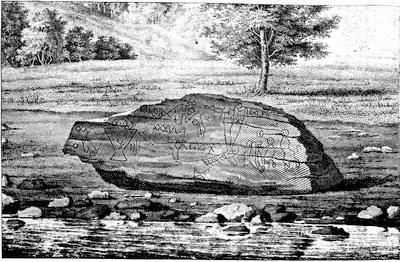

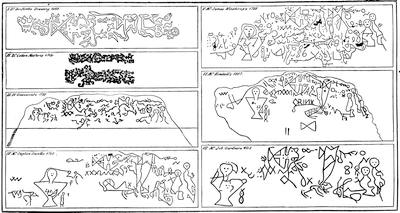

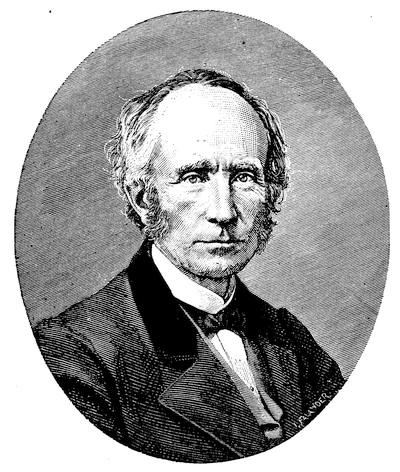

| Illustrations: Behring’s Sea and Adjacent Waters, 77; Buache’s Map of the North Pacific and Fusang, 79; Ruins of the Church at Kakortok, 86; Fac-simile of a Saga Manuscript and Autograph of C. C. Rafn, 87; Ruin at Kakortok, 88; Map of Julianehaab, 89; Portrait of Rafn, 90; Title-page of Historia Vinlandiæ Antiguæ per Thormodum Torfæum, 91; Rafn’s Map of Norse America, 95; Rafn’s Map of Vinland (New England), 100; View of Dighton Rock, 101; Copies of its Inscription, 103; Henrik Rink, 106; Fac-simile of the Title-page of Hans Egede’s Det gamle Gronlands nye Perlustration, 108; A British Ship of the Time of Edward I, 110; Richard H. Major, 112; Baron Nordenskjöld, 113. | |

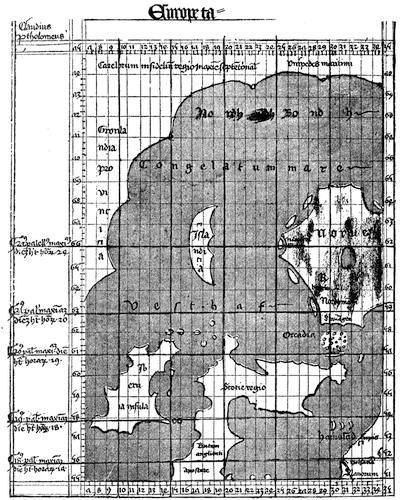

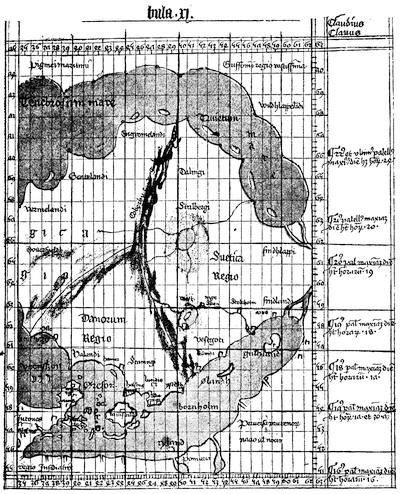

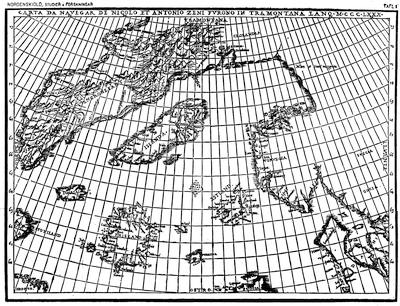

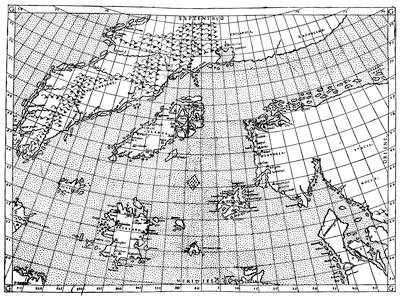

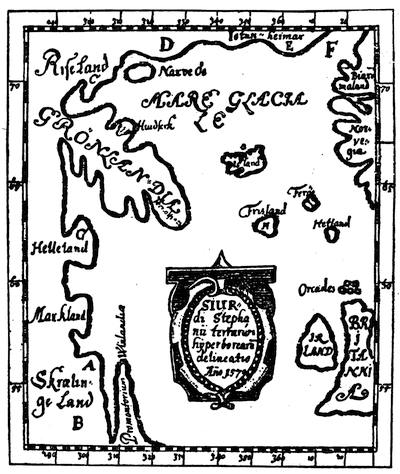

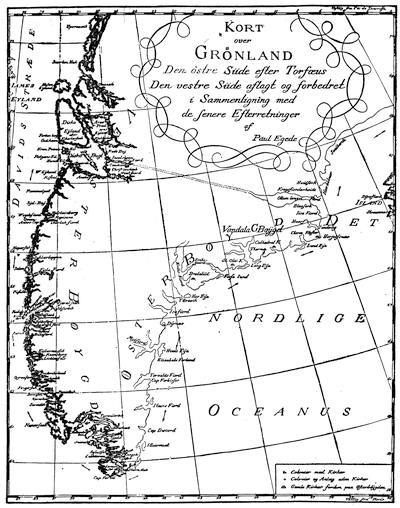

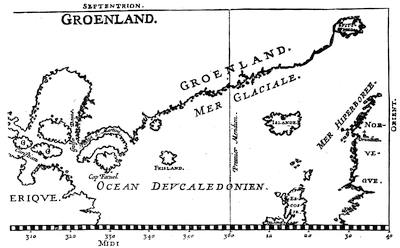

| The Cartography of Greenland. The Editor | 117 |

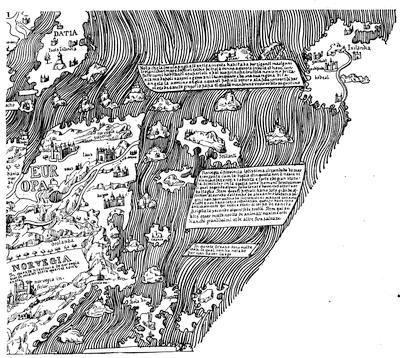

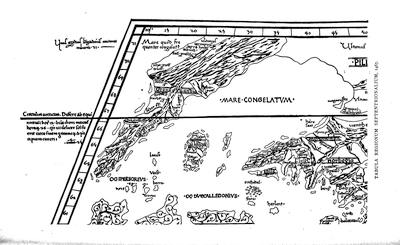

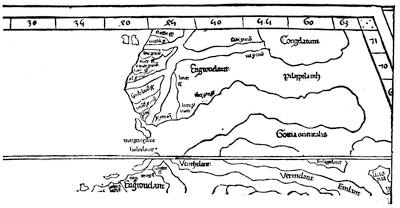

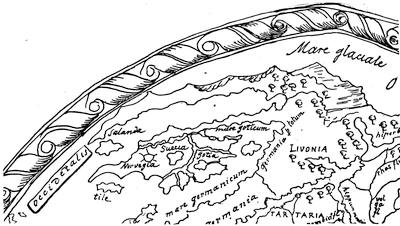

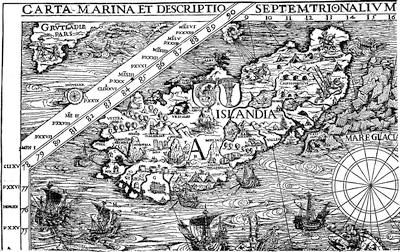

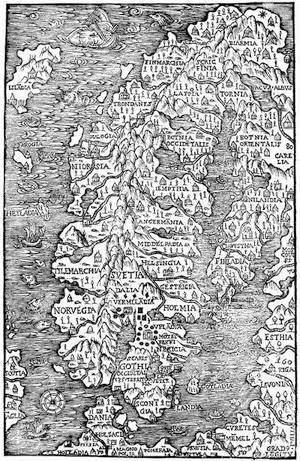

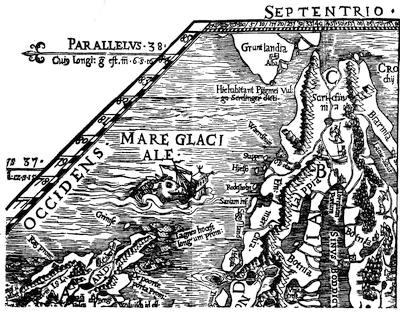

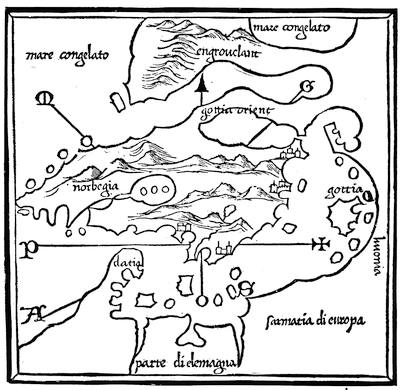

| Illustrations: The Maps of Claudius Clavus (1427), 118, 119; of Fra Mauro (1459), 120; Tabula Regionum Septentrionalium (1467), 121; Map of Donis (1482), 122; of Henricus Martellus (1489-90), 122; of Olaus Magnus (1539), 123; (1555), 124; (1567), 125; of Bordone (1547), 126; The Zeno Map, 127; as altered in the Ptolemy of 1561, 128; The Map of Phillipus Gallæus (1585), 129; of Sigurd Stephanus (1570), 130; The Greenland of Paul Egede, 131; of Isaac de la Peyrère (1647), 132. | |

| CHAPTER III. | |

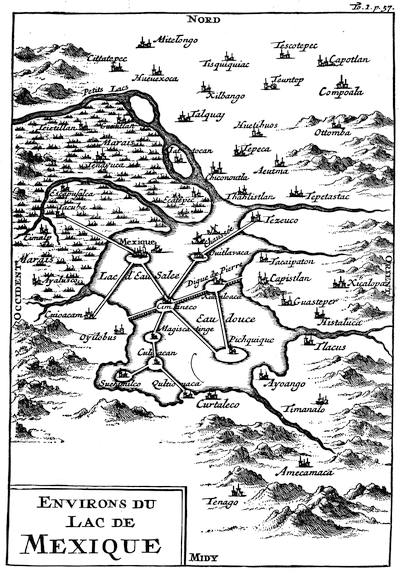

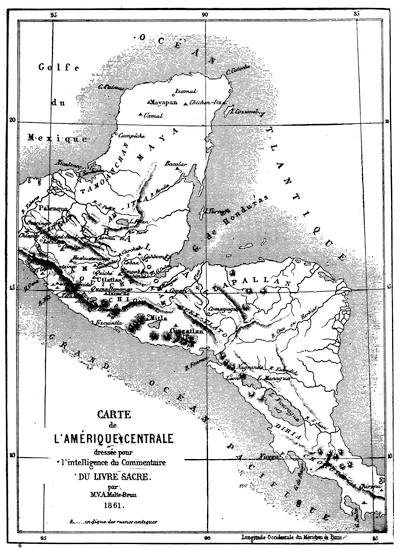

| Mexico and Central America. Justin Winsor | 133 |

| Illustrations: Clavigero’s Plan of Mexico, 143; his Map of Anahuac, 144; Environs du Lac de Méxique, 145; Brasseur de Bourbourg’s Map of Central America, 151. | |

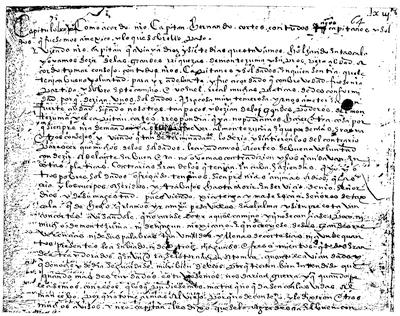

| Critical Essay | 153 |

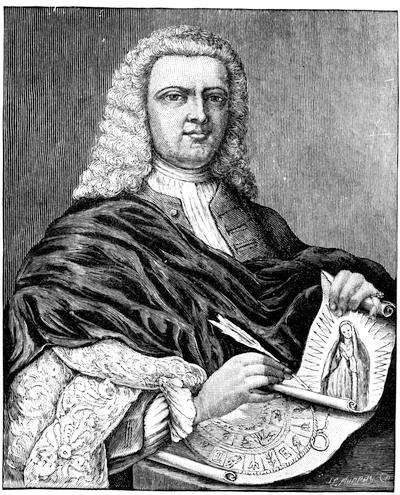

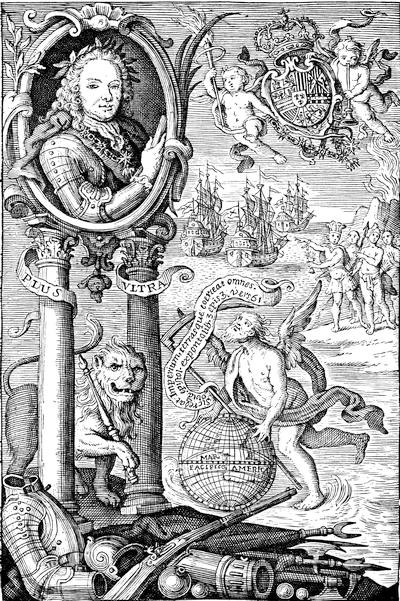

| Illustrations: Manuscript of Bernal Diaz, 154; Sahagún, 156; Clavigero, 159; Lorenzo Boturini, 160; Frontispiece of his Idea, with his Portrait, 161; Icazbalceta, 163; Daniel G. Brinton, 165; Brasseur de Bourbourg, 170. | |

| Notes | 173 |

| I. The Authorities on the so-called Civilization of Ancient Mexico and Adjacent Lands, and the Interpretation of such Authorities, 173; II. Bibliographical Notes upon the Ruins and Archæological Remains of Mexico and Central America, 176; III. Bibliographical Notes on the Picture-Writing of the Nahuas and Mayas, 197. | |

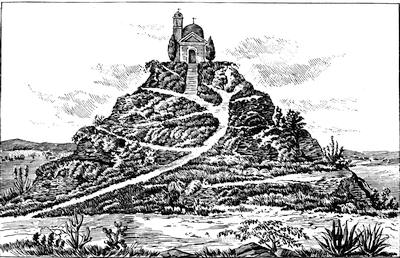

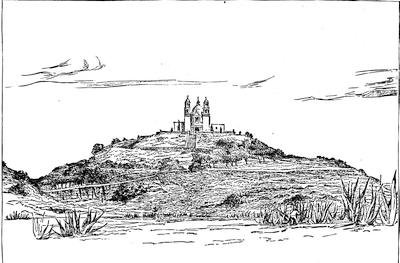

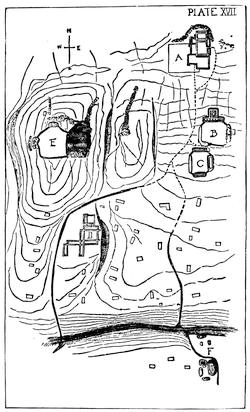

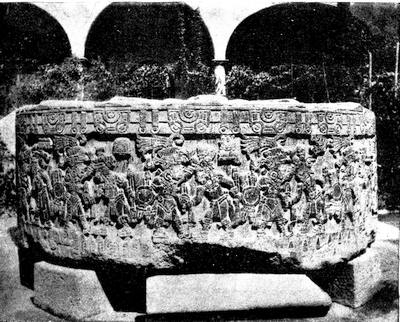

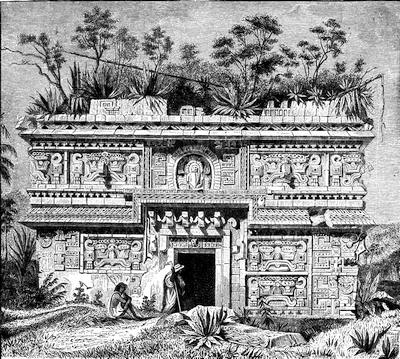

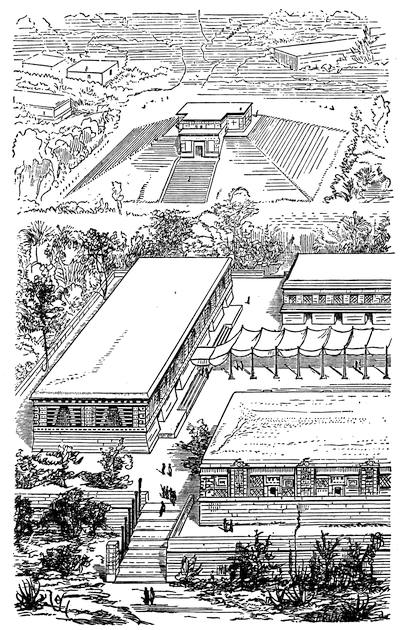

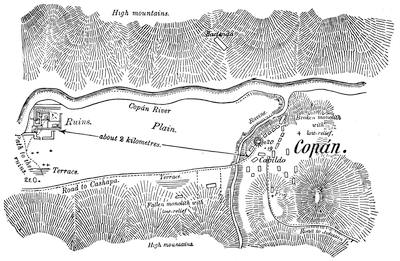

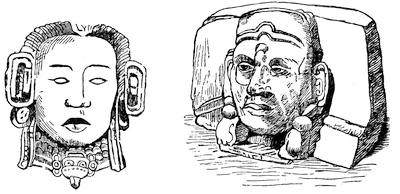

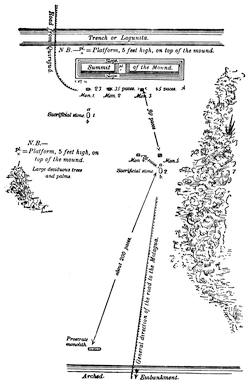

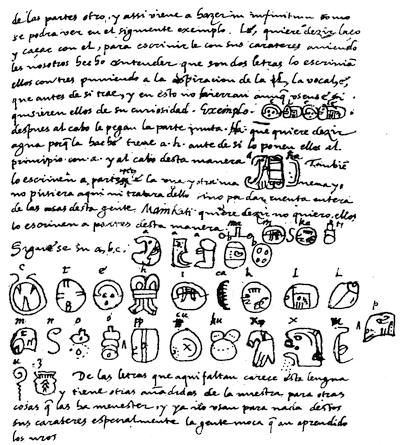

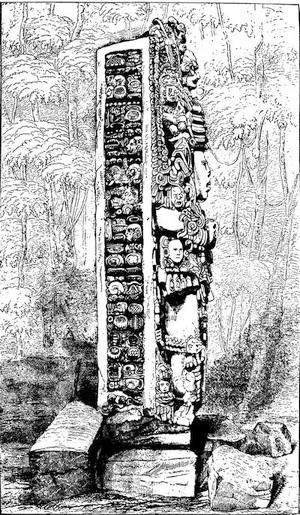

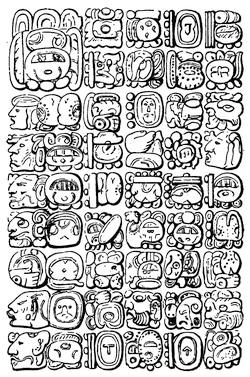

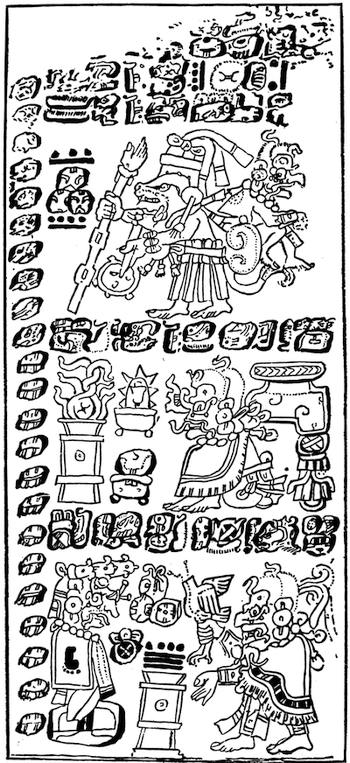

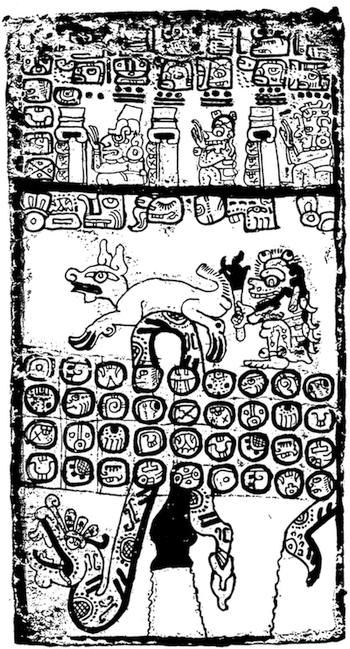

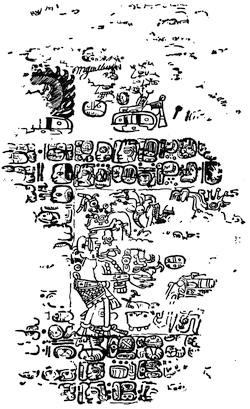

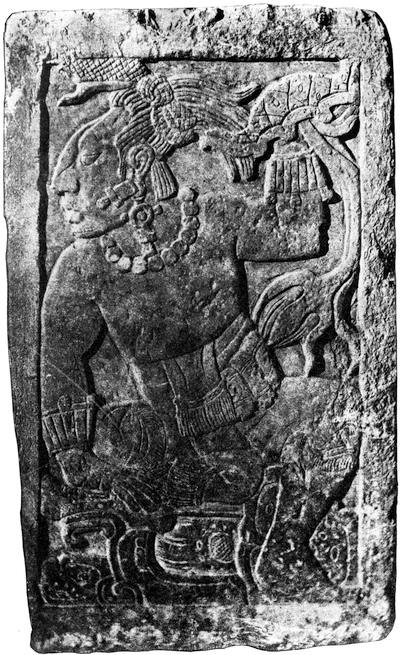

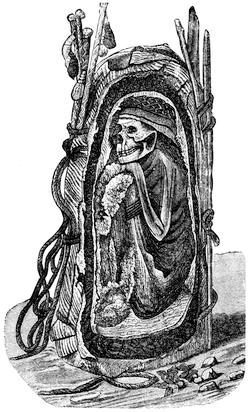

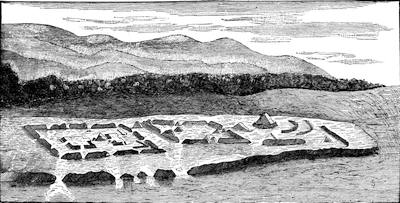

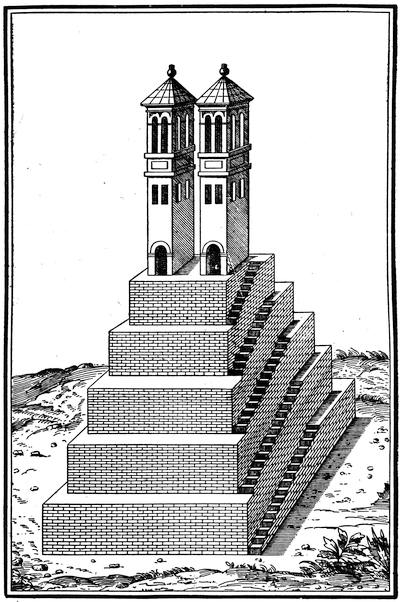

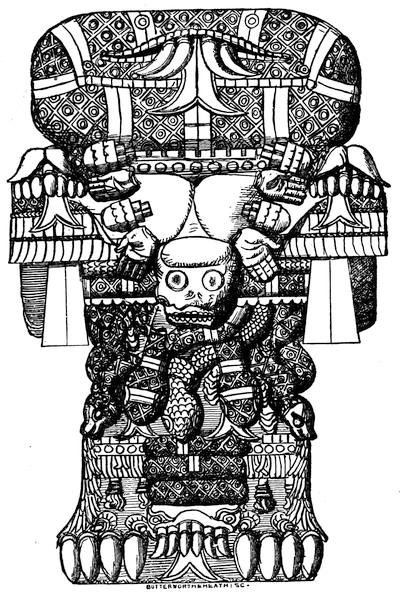

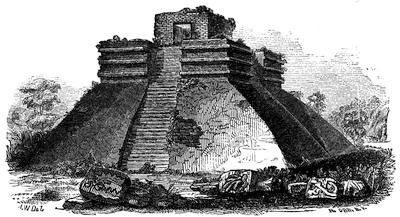

| Illustrations: The Pyramid of Cholula, 177; The Great Mound of Cholula, 178; Mexican Calendar Stone, 179; Court of the Mexico Museum, 181; Old Mexican Bridge near Tezcuco, 182; The Indio Triste, 183; General Plan of Mitla, 184; Sacrificial Stone, 185; Waldeck, 186; Désiré Charnay, 187; Charnay’s Map of Yucatan, 188; Ruined Temple at Uxmal, 189; Ring and Head from Chichen-Itza, 190; Viollet-le-Duc’s Restoration of a Palenqué Building, 192; Sculptures from the Temple of the Cross at Palenqué, 193; Plan of Copan, 194; Yucatan Types of Heads, 195; Plan of Quirigua, 196; Fac-simile of Landa’s Manuscript, 198; A Sculptured Column, 199; Palenqué Hieroglyphics, 201; Léon de Rosny, 202; The Dresden Codex, 204; Codex Cortesianus, 206; Codex Perezianus, 207, 208. | |

| CHAPTER IV.[ix] | |

| The Inca Civilization in Peru. Clements R. Markham | 209 |

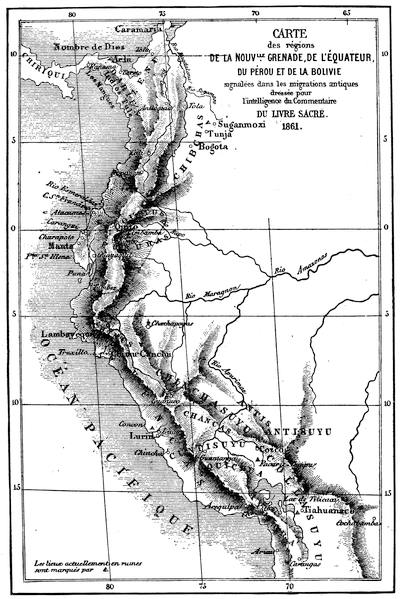

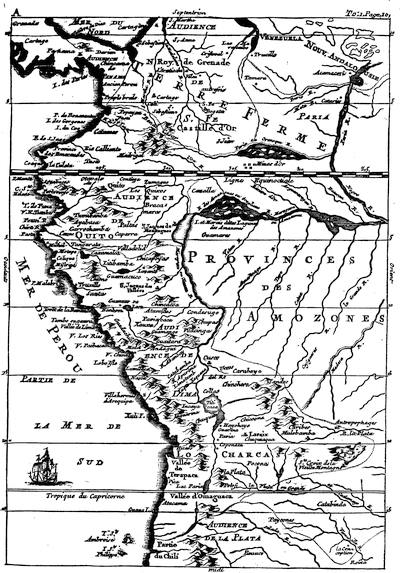

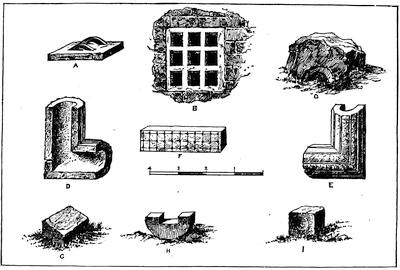

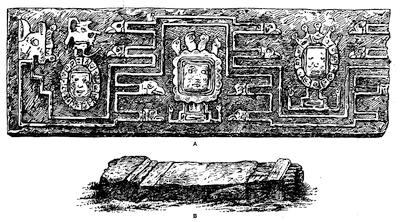

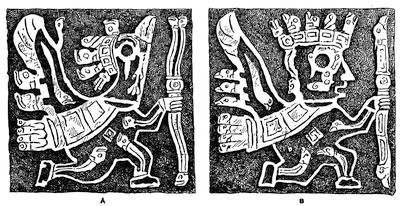

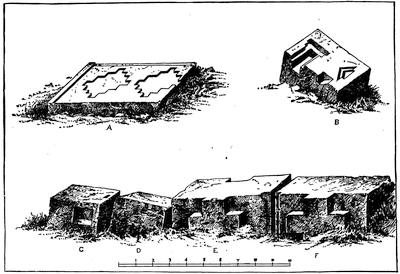

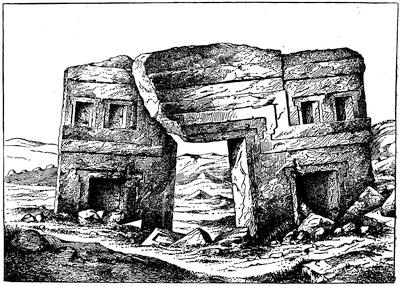

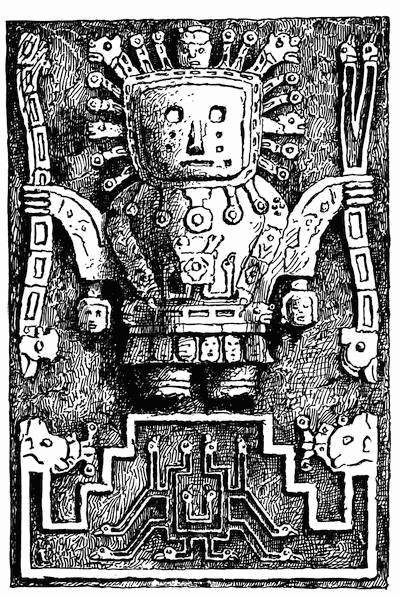

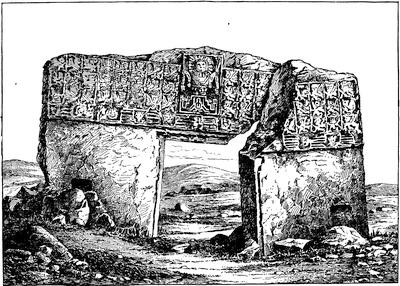

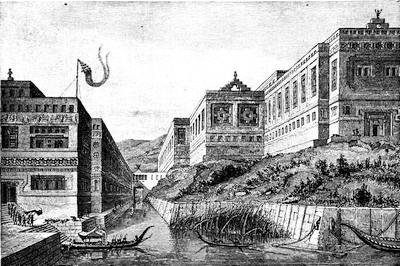

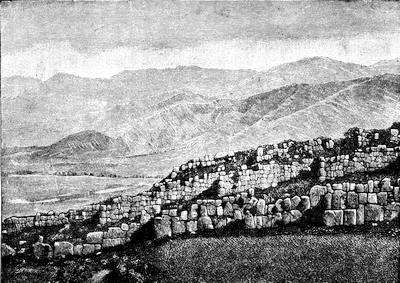

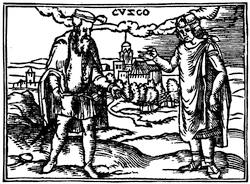

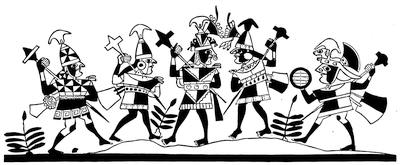

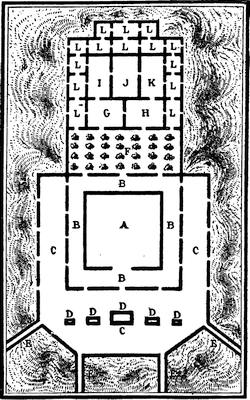

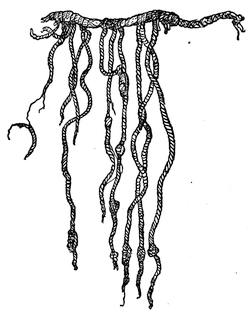

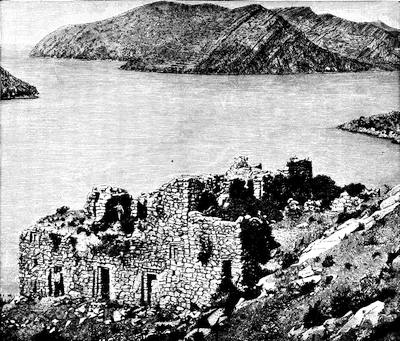

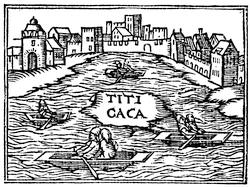

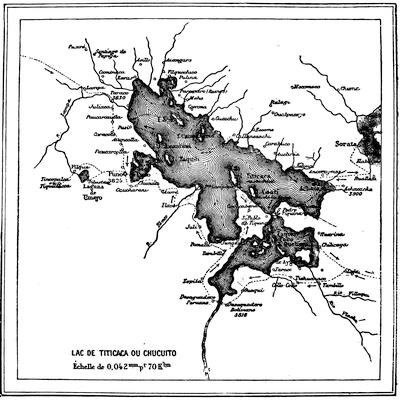

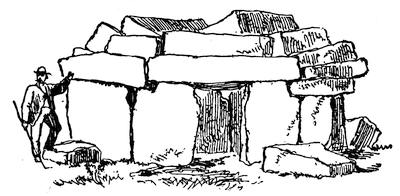

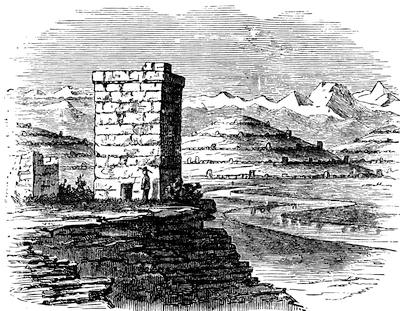

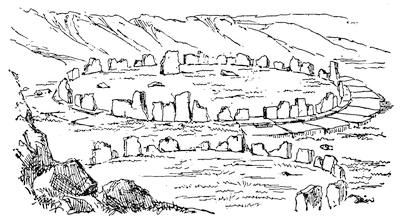

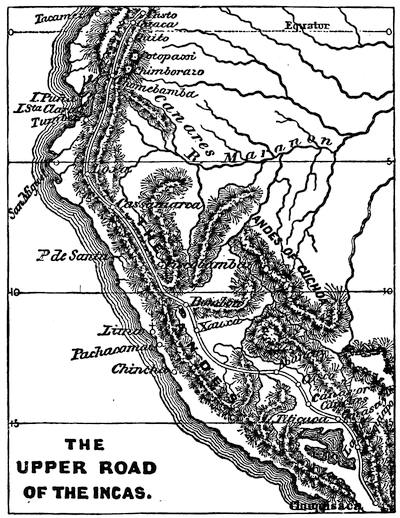

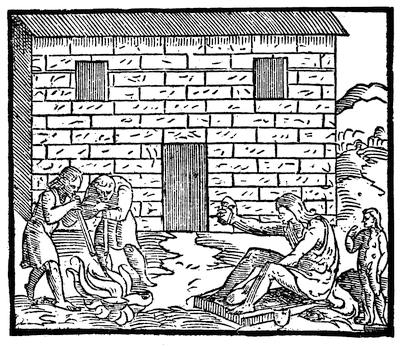

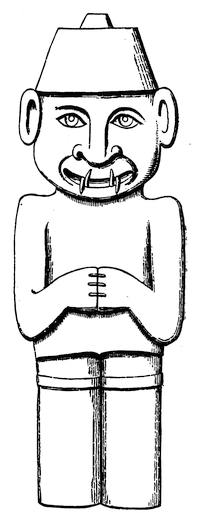

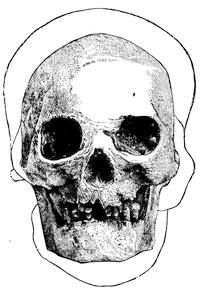

| Illustrations: Brasseur de Bourbourg’s Map of Northwestern South America, 210; Early Spanish Map of Peru, 211; Llamas, 213; Architectural Details at Tiahuanaca, 214; Bas-Reliefs, 215; Doorway and other Parts, 216; Image, 217; Broken Doorway, 218; Tiahuanaca Restored, 219; Ruins of Sacsahuaman, 220; Inca Manco Ccapac, 228; Inca Yupanqui, 228; Cuzco, 229; Warriors of the Inca Period, 230; Plan of the Temple of the Sun, 234; Zodiac of Gold, 235; Quipus, 243; Inca Skull, 244; Ruins at Chucuito, 245; Lake Titicaca, 246, 247; Map of the Lake, 248; Primeval Tomb, Acora, 249; Ruins at Quellenata, 249; Ruins at Escoma, 250; Sillustani, 250; Ruins of an Incarial Village, 251; Map of the Inca Road, 254; Peruvian Metal-Workers, 256; Peruvian Pottery, 256, 257; Unfinished Peruvian Cloth, 258. | |

| Critical Essay | 259 |

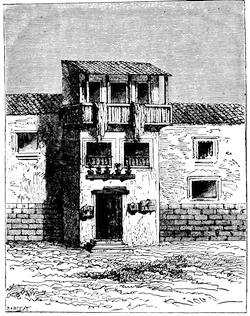

| Illustrations: House in Cuzco in which Garcilasso was born, 265; Portraits of the Incas in the Title-page of Herrera, 267; William Robertson, 269; Clements R. Markham, 272; Márcos Jiménez de la Espada, 274. | |

| Notes | 275 |

| I. Ancient People of the Peruvian Coast, 275; II. The Quichua Language and Literature, 278. | |

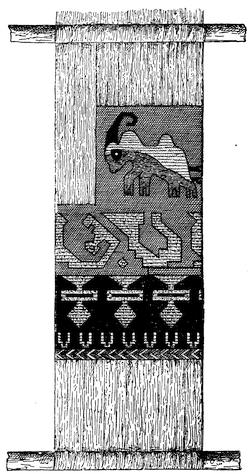

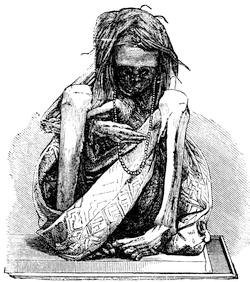

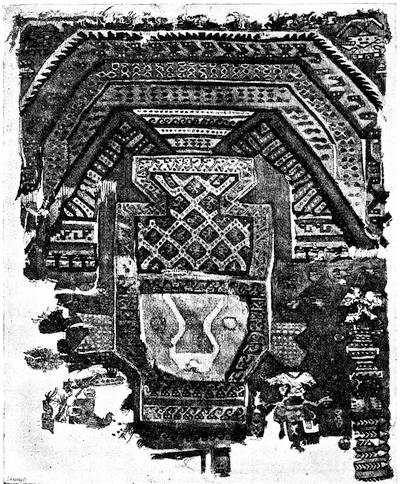

| Illustrations: Mummy from Ancon, 276; Mummy from a Huaca at Pisco, 277; Tapestry from the Graves of Ancon, 278; Idol from Timaná, 281. | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The Red Indian of North America in Contact with the French and English. George E. Ellis | 283 |

| Critical Essay. George E. Ellis and the Editor | 316 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| The Prehistoric Archæology of North America. Henry W. Haynes | 329 |

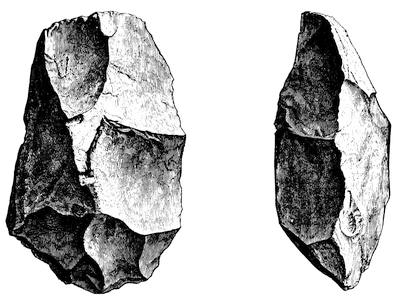

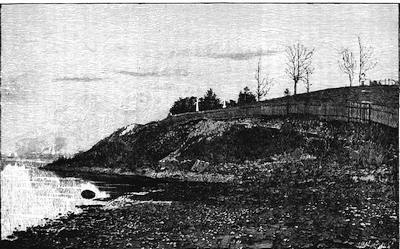

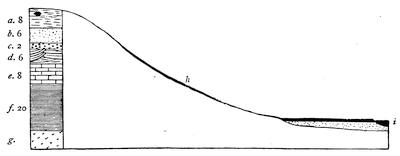

| Illustrations: Palæolithic Implement from the Trenton Gravels, 331; The Trenton Gravel Bluff, 335; Section of Bluff near Trenton, 338; Obsidian Spear Point from the Lahontan Lake, 349. | |

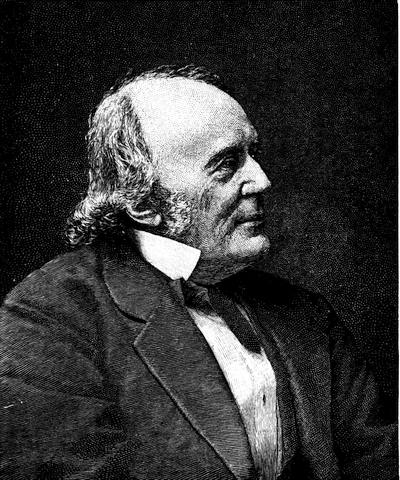

| The Progress of Opinion respecting the Origin and Antiquity of Man in America. Justin Winsor | 369 |

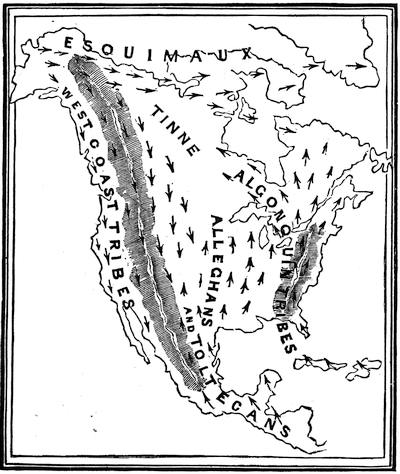

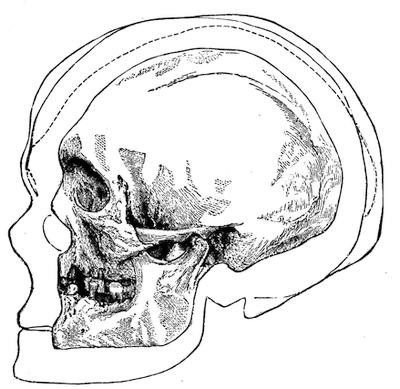

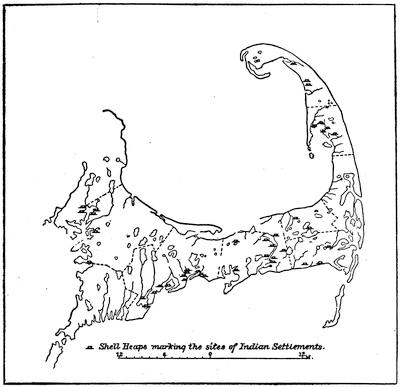

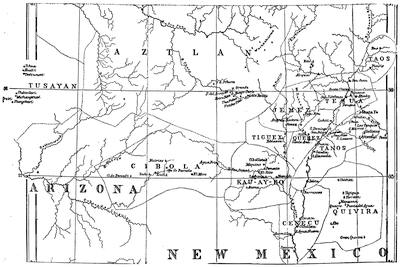

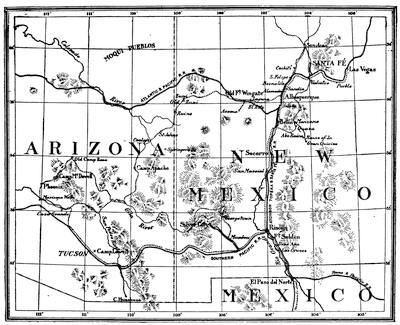

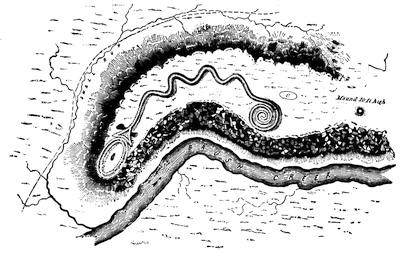

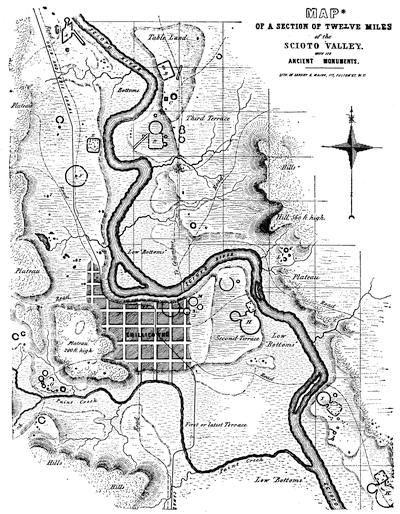

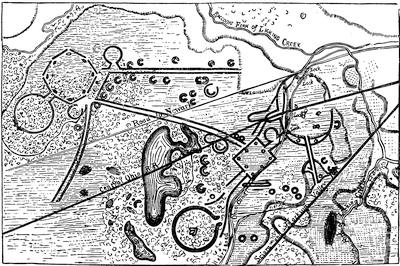

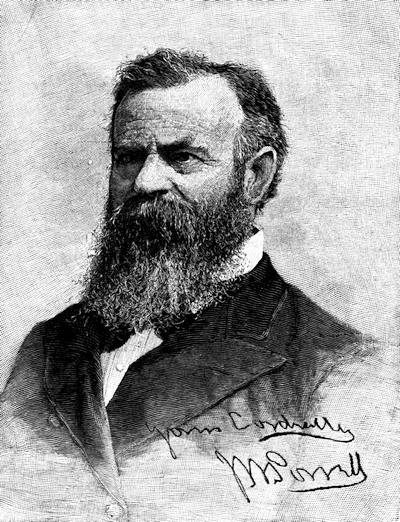

| Illustrations: Benjamin Smith Barton, 371; Louis Agassiz, 373; Samuel Foster Haven, 374; Sir Daniel Wilson, 375; Professor Edward B. Tylor, 376; Hochelagan and Cro-magnon Skulls, 377; Theodor Waitz, 378; Sir John Lubbock, 379; Sir John William Dawson, 380; Map of Aboriginal Migrations, 381; Calaveras Skull, 385; Ancient Footprint from Nicaragua, 386; Cro-magnon, Enghis, Neanderthal, and Hochelagan Skulls, 389; Oscar Peschel, 391; Jeffries Wyman, 392; Map of Cape Cod, showing Shell Heaps, 393; Maps of the Pueblo Region, 394, 397; Col. Charles Whittlesey, 399; Increase A. Lapham, 400; Plan of the Great Serpent Mound, 401; Cincinnati Tablet, 404; Old View of the Mounds on the Muskingum (Marietta), 405; Map of the Scioto Valley, showing Sites of Mounds, 406; Works at Newark, Ohio, 407; Major J. W. Powell, 411. | |

| APPENDIX.[x] | ||

| Justin Winsor. | ||

| I. | Bibliography of Aboriginal America | 413 |

| II. | The Comprehensive Treatises on American Antiquities | 415 |

| III. | Bibliographical Notes on the Industries and Trade of the American Aborigines | 416 |

| IV. | Bibliographical Notes on American Linguistics | 421 |

| V. | Bibliographical Notes on the Myths and Religions of America | 429 |

| VI. | Archæological Museums and Periodicals | 437 |

| Illustrations: Mexican Clay Mask, 419; Quetzalcoatl, 432; The Mexican Temple, 433; The Temple of Mexico, 434; Teoyaomiqui, 435; Ancient Teocalli, Oaxaca, Mexico, 436. | ||

| Index | 445 | |

INTRODUCTION.

By the Editor.

PART I. AMERICANA IN LIBRARIES AND BIBLIOGRAPHIES.

HARRISSE, in the Introduction of his Bibliotheca Americana Vetustissima, enumerates and characterizes many of the bibliographies of Americana, beginning with the chapter, “De Scriptoribus rerum Americanarum,” in the Bibliotheca Classica of Draudius, in 1622.[1] De Laet, in his Nieuwe Wereldt (1625), gives a list of about thirty-seven authorities, which he increased somewhat in later editions.[2] The earliest American catalogue of any moment, however, came from a native Peruvian, Léon y Pinelo, who is usually cited by the latter name only. He had prepared an extensive list; but he published at Madrid, in 1629, a selection of titles only, under the designation of Epitome de la biblioteca oriental i occidental,[3] which included manuscripts as well as books. He had exceptional advantages as chronicler of the Indies.

In 1671, in Montanus’s Nieuwe weereld, and in Ogilby’s America, about 167 authorities are enumerated.

Sabin[4] refers to Cornelius van Beughem’s Bibliographia Historica, 1685, published at Amsterdam, as having the titles of books on America.

The earliest exclusively American catalogue is the Bibliothecæ Americanæ Primordia of White Kennett,[5] Bishop of Peterborough, published in London in 1713. The arrangement of its sixteen hundred entries is chronological; and it enters under their respective dates the sections of such collections as Hakluyt and Ramusio.[6] It particularly pertains to the English colonies, and more especially to New England, where, in the eighteenth century, three distinctively valuable American libraries are known to have existed,—that of the Mather family, which was in large part destroyed during the battle of Bunker Hill, in 1775; that of Thomas Prince, still in large part existing in the Boston Public Library; and that of Governor Hutchinson, scattered by the mob which attacked his house in Boston in 1765.[7]

In 1716 Lenglet du Fresnoy inserted a brief list (sixty titles) in his Méthode pour étudier la géographie. Garcia’s Origen de los Indias de el nuevo mundo, Madrid, 1729, shows a list of about seventeen hundred authors.[8]

In 1737-1738 Barcia enlarged Pinelo’s work, translating all his titles into Spanish, and added[ii] numerous other entries which Rich[9] says were “clumsily thrown together.”

Charlevoix prefixed to his Nouvelle France, in 1744, a list with useful comments, which the English reader can readily approach in Dr. Shea’s translation. A price-list which has been preserved of the sale in Paris in 1764, Catalogue des livres des ci-devant soi-disans Jésuites du Collége de Clermont, indicates the lack of competition at that time for those choicer Americana, now so costly.[10] The Regio patronatu Indiarum of Frassus (1775) gives about 1505 authorities. There is a chronological catalogue of books issued in the American colonies previous to 1775, prepared by S. F. Haven, Jr., and appended to the edition of Thomas’s History of Printing, published by the American Antiquarian Society. Though by no means perfect, it is a convenient key to most publications illustrative of American history during the colonial period of the English possessions, and printed in America. Dr. Robertson’s America (1777) shows only 250 works, and it indicates how far short he was of the present advantages in the study of this subject. Clavigero surpassed all his predecessors in the lists accompanying his Storia del Messico, published in 1780,—but the special bibliography of Mexico is examined elsewhere. Equally special, and confined to the English colonies, is the documentary register which Jefferson inserted in his Notes on Virginia; but it serves to show how scanty the records were a hundred years ago compared with the calendars of such material now. Meuzel, in 1782, had published enough of his Bibliotheca Historica to cover the American field, though he never completed the work as planned.

In 1789 an anonymous Bibliotheca Americana of nearly sixteen hundred entries was published in London. It is not of much value. Harrisse and others attribute it to Reid; but by some the author’s name is differently given as Homer, Dalrymple, and Long.[11]

An enumeration of the documentary sources (about 152 entries) used by Muñoz in his Historia del nuevo mundo (1793) is given in Fustér’s Biblioteca Valenciana (ii. 202-234) published at Valencia in 1827-1830.[12]

There is in the Library of Congress (Force Collection) a copy of an Indice de la Coleccion de manuscritos pertinecientes a la historia de las Indias, by Fraggia, Abella, and others, dated at Madrid, 1799.[13]

In the Sparks collection at Cornell are two other manuscript bibliographies worthy of notice. One is a Biblioteca Americana, by Antonio de Alcedo, dated in 1807. Sparks says his copy was made in 1843 from an original which Obadiah Rich had found in Madrid.[14]

Harrisse says that another copy is in the Carter-Brown Library; and he asserts that, excepting some additions of modern American authors, it is not much improved over Barcia’s edition of Pinelo. H. H. Bancroft[15] mentions having a third copy, which had formerly belonged to Prescott.

The other manuscript at Cornell is a Bibliotheca Americana, prepared in twelve volumes by Arthur Homer, who had intended, but never accomplished, the publication of it. Sparks found it in Sir Thomas Phillipps’s library at Middlehill, and caused the copy of it to be made, which is now at Ithaca.[16]

In 1808 Boucher de la Richarderie published at Paris his Bibliothèque universelle des voyages,[17] which has in the fifth part a critical list of all voyages to American waters. Harrisse disagrees with Peignot in his favorable estimate of Richarderie, and traces to him the errors of Faribault and later bibliographers.

The Bibliotheca Hispano-Americana of Dr. José Mariano Beristain de Souza was published in Mexico in 1816-1821, in three volumes. Quaritch, pricing it at £96 in 1880, calls it the rarest and most valuable of all American bibliographical works. It is a notice of writers who were born, educated, or flourished in Spanish America, and naturally covers much of interest to the historical student. The author did not live to complete it, and his nephew finished it.

In 1818 Colonel Israel Thorndike, of Boston, bought for $6,500 the American library of Professor Ebeling, of Germany, estimated to contain over thirty-two hundred volumes, besides an extraordinary collection of ten thousand maps.[18] The library was given by the purchaser to Harvard College, and its possession at once put the library of that institution at the head of all libraries in the United States for the illustration of American history. No catalogue of it was ever printed, except as a part of the General Catalogue of the College Library issued in 1830-1834, in five volumes.

Another useful collection of Americana added to the same library was that formed by David B. Warden, for forty years United States Consul at Paris, who printed a catalogue of its twelve hundred volumes at Paris, in 1820, called Bibliotheca Americo-Septentrionalis. The collection in 1823 found a purchaser at $5,000, in Mr. Samuel A. Eliot, who gave it to the College.[19]

EBELING.[20]

The Harvard library, however, as well as several of the best collections of Americana in the United States, owes more, perhaps, to Obadiah Rich than to any other. This gentleman, a native of Boston, was born in 1783. He went as consul of the United States to Valencia in 1815, and there began his study of early Spanish-American history, and undertook the gathering of a remarkable collection of books,[21] which he threw open generously, with his own kindly assistance, to every investigator who visited Spain for purposes of study. Here he won the respect of Alexander H. Everett, then American minister to the court of Spain. He captivated Irving by his helpful nature, who says of him: “Rich was one of the most indefatigable, intelligent, and successful bibliographers in Europe. His house at Madrid was a literary wilderness, abounding with curious works and rare editions.[iv] ... He was withal a man of great truthfulness and simplicity of character, of an amiable and obliging disposition and strict integrity.” Similar was the estimation in which he was held by Ticknor, Prescott, George Bancroft, and many others, as Allibone has recorded.[22] In 1828 he removed to London, where he established himself as a bookseller. From this period, as Harrisse[23] fitly says, it was under his influence, acting upon the lovers of books among his compatriots, that the passion for forming collections of books exclusively American grew up.[24] In those days the cost of books now esteemed rare was trifling compared with the prices demanded at present. Rich had a prescience in his calling, and the beginnings of the great libraries of Colonel Aspinwall, Peter Force, James Lenox, and John Carter Brown were made under his fostering eye; which was just as kindly vigilant for Grenville, who was then forming out of the income of his sinecure office the great collection which he gave to the British nation in recompense for his support.[25] In London, watching the book-markets and making his catalogue, Rich continued to live for the rest of his life (he died in February, 1850), except for a period when he was the United States consul at Port Mahon in the Balearic Islands. His bibliographies are still valuable, his annotations in them are trustworthy, and their records are the starting-points of the growth of prices. His issues and reissues of them are somewhat complicated by supplements and combinations, but collectors and bibliographers place them on their shelves in the following order:

1. A Catalogue of books relating principally to America, arranged under the years in which they were printed (1500-1700), London, 1832. This included four hundred and eighty-six numbers, those designated by a star without price being understood to be in Colonel Aspinwall’s collection. Two small supplements were added to this.

2. Bibliotheca Americana Nova, printed since 1700 (to 1800), London, 1835. Two hundred and fifty copies were printed. A supplement appeared in 1841, and this became again a part of his.

3. Bibliotheca Americana Nova, vol. i. (1701-1800); vol. ii. (1801-1844), which was printed (250 copies) in London in 1846.[26]

It was in 1833 that Colonel Thomas Aspinwall, of Boston, who was for thirty-eight years the American consul at London, printed at Paris a catalogue of his collection of Americana, where seven hundred and seventy-one lots included, beside much that was ordinarily useful, a great number of the rarest of books on American history. Harrisse has called Colonel Aspinwall, not without justice, “a bibliophile of great tact and activity.” All but the rarest part of his collection was subsequently burned in 1863, when it had passed into the hands of Mr. Samuel L. M. Barlow,[27] of New York.

M. Ternaux-Compans, who had collected—as Mr. Brevoort thinks[28]—the most extensive library of books on America ever brought together, printed his Bibliothèque Américaine[29] in 1837 at Paris. It embraced 1,154 works, arranged chronologically, and all of them of a date before 1700. The titles were abridged, and accompanied by French translations. His annotations were scant; and other students besides Rich have regretted that so learned a man had not more benefited his fellow-students by ampler notes.[30]

Also in 1837 appeared the Catalogue d’ouvrages sur l’histoire de l’Amérique, of G. B. Faribault, which was published at Quebec, and was more specially devoted to books on New France.[31]

With the works of Rich and Ternaux the bibliography of Americana may be considered to have acquired a distinct recognition; and the succeeding survey of this field may be[v] more conveniently made if we group the contributors by some broad discriminations of the motives influencing them, though such distinctions sometimes become confluent.

First, as regards what may be termed professional bibliography. One of the earliest workers in the new spirit was a Dresden jurist, Hermann E. Ludewig, who came to the United States in 1844, and prepared an account of the Literature of American local history, which was published in 1846. This was followed by a supplement, pertaining wholly to New York State, which appeared in The Literary World, February 19, 1848. He had previously published in the Serapeum at Leipsic (1845, pp. 209) accounts of American libraries and bibliography, which were the first contributions to this subject.[32] Some years later, in 1858, there was published in London a monograph on The Literature of the American Aboriginal Linguistics,[33] which had been undertaken by Mr. Ludewig but had not been carried through the press, when he died, Dec. 12, 1856.[34]

We owe to a Franco-American citizen the most important bibliography which we have respecting the first half century of American history; for the Bibliotheca Americana Vetustissima only comes down to 1551 in its chronological arrangement. Mr. Brevoort[35] very properly characterizes it as “a work which lightens the labors of such as have to investigate early American history.”[36]

It was under the hospitable roof of Mr. Barlow’s library in New York that, “having gloated for years over second-hand compilations,” Harrisse says that he found himself “for the first time within reach of the fountain-heads of history.” Here he gathered the materials for his Notes on Columbus, which were, as he says, like “pencil marks varnished over.” These first appeared less perfectly than later, in the New York Commercial Advertiser, under the title of “Columbus in a Nut-shell.” Mr. Harrisse had also prepared (four copies only printed) for Mr. Barlow in 1864 the Bibliotheca Barlowiana, which is a descriptive catalogue of the rarest books in the Barlow-Aspinwall Collection, touching especially the books on Virginian and New England history between 1602 and 1680.

Mr. Barlow now (1864) sumptuously printed the Notes on Columbus in a volume (ninety-nine copies) for private distribution. For some reason not apparent, there were expressions in this admirable treatise which offended some; as when, for instance (p. vii), he spoke of being debarred the privileges of a much-vaunted public library, referring to the Astor Library. Similar inadvertences again brought him hostile criticism, when two years later (1866) he printed with considerable typographical luxury his Bibliotheca Americana Vetustissima, which was published in New York. It embraces something over three hundred entries.[37] The work is not without errors; and Mr. Henry Stevens, who claims that he was wrongly accused in the book, gave it a bad name in the London Athenæum of Oct. 6, 1866, where an unfortunate slip, in making “Ander Schiffahrt”[38] a personage, is unmercifully ridiculed. A committee of the Société de Géographie in Paris, of which M. Ernest Desjardins was spokesman, came to the rescue, and printed a Rapport sur les deux ouvrages de bibliographie Américaine de M. Henri Harrisse, Paris, 1867. In this document the claim is unguardedly made that Harrisse’s book was the earliest piece of solid erudition which America had produced,—a phrase qualified later as applying to works of American bibliography only. It was pointed out that while for the period of 1492-1551 Rich had given twenty titles, and Ternaux fifty-eight, Harrisse had enumerated three hundred and eight.[39]

Harrisse prepared, while shut up in Paris during the siege of 1870, his Notes sur la Nouvelle France, a valuable bibliographical essay referred to elsewhere.[40] He later put in shape the material which he had gathered for a supplemental volume to his Bibliotheca Americana Vetustissima, which he called Additions,[41] and published it in Paris in 1872. In his introduction to this latter volume he shows how thoroughly he has searched the libraries of Europe for new evidences of interest in America during the first half century after its discovery. He notes the depredations upon the older libraries which have been made in recent years, since the prices for rare Americana have ruled so high. He finds[42] that the Biblioteca Colombina[vi] at Seville, as compared with a catalogue of it made by Ferdinand Columbus himself, has suffered immense losses. “It is curious to notice,” he finally says, “how few of the original books relating to the early history of the New World can be found in the public libraries of Europe. There is not a literary institution, however rich and ancient, which in this respect could compare with three or four private libraries in America. The Marciana at Venice is probably the richest. The Trivulgiana at Milan can boast of several great rarities.”

For the third contributor to the recent bibliography of Americana, we must still turn to an adopted citizen, Joseph Sabin, an Englishman by birth. Various publishing enterprises of interest to the historical student are associated with Mr. Sabin’s name. He published a quarto series of reprints of early American tracts, eleven in number, and an octavo series, seven in number.[43] He published for several years, beginning in 1869, the American Bibliopolist, a record of new books, with literary miscellanies, largely upon Americana. In 1867 he began the publication (five hundred copies) of the most extensive American bibliography yet made, A Dictionary of books relating to America, from its discovery to the present time. The author’s death, in 1881,[44] left the work somewhat more than half done, and it has been continued since his death by his sons.[45]

In the Notas Para una bibliografia de obras anonimas i seudonimas of Diego Barros Arana, published at Santiago de Chile in 1882, five hundred and seven books on America (1493-1876), without authors, are traced to their writers.

As a second class of contributors to the bibliographical records of America, we must reckon the students who have gathered libraries for use in pursuing their historical studies. Foremost among such, and entitled to be esteemed a pioneer in the modern spirit of research, is Alexander von Humboldt. He published his Examen critique de l’histoire de la géographie du nouveau continent,[46] in five volumes, between 1836 and 1839.[47] “It is,” says Brevoort,[48] “a guide which all must consult. With a master hand the author combines and collates all attainable materials, and draws light from sources which he first brings to bear in his exhaustive investigations.” Harrisse calls it “the greatest monument ever erected to the early history of this continent.”

Humboldt’s library was bought by Henry Stevens, who printed in 1863, in London, a catalogue of it, showing 11,164 entries; but this was not published till 1870. It included a set of the Examen critique, with corrections, and the notes for a new sixth volume.[49] Harrisse, who it is believed contemplated at one time a new edition of this book, alleges that through the remissness of the purchaser of the library the world has lost sight of these precious memorials of Humboldt’s unperfected labors. Stevens, in the London Athenæum, October, 1866, rebuts the charge.[50]

Of the collection of books and manuscripts formed by Col. Peter Force we have no separate record, apart from their making a portion of the general catalogue of the Library of Congress, the Government having bought the collection in 1867.[51]

The library which Jared Sparks formed during the progress of his historical labors was sold about 1872 to Cornell University, and is now at Ithaca. Mr. Sparks left behind him “imperfect but not unfaithful lists of his books,[vii]” which, after some supervision by Dr. Cogswell and others, were put in shape for the press by Mr. Charles A. Cutter of the Boston Athenæum, and were printed, in 1871, as Catalogue of the Library of Jared Sparks. In the appendix was a list of the historical manuscripts, originals and copies, which are now on deposit in Harvard College Library.[52]

In 1849 Mr. H. R. Schoolcraft[53] printed, at the expense of the United States Government, a Bibliographical Catalogue of books, etc., in the Indian tongues of the United States,—a list later reprinted with additions in his Indian Tribes (in 1851), vol. iv.[54]

In 1861 Mr. Ephraim George Squier published at New York a monograph on authors[viii] who had written in the languages of Central America, enumerating one hundred and ten, with a list of the books and manuscripts on the history, the aborigines, and the antiquities of Central America, borrowed from other sources in part. At the sale of Mr. Squier’s library in 1876, the catalogue[55] of which was made by Mr. Sabin, the entire collection of his manuscripts fell, as mentioned elsewhere,[56] into the hands of Mr. Hubert Howe Bancroft of San Francisco.

Probably the largest collection of books and manuscripts[57] which any American has formed for use in writing is that which belongs to Mr. Bancroft. He is the organizer of an extensive series of books on the antiquities and history of the Pacific coast. To accomplish an examination of the aboriginal and civilized history of so large a field[58] as thoroughly as he has unquestionably made it, within a lifetime, was a bold undertaking, to be carried out in a centre of material rather than of literary enterprise. The task involved the gathering of a library of printed books, at a distance from the purely intellectual activity of the country, and where no other collection of moment existed to supplement it. It required the seeking and making of manuscripts, from the labor of which one might well shrink. It was fortunate that during the gathering of this collection some notable collections—like those of Maximilian,[59] Ramirez, and Squier, not to name others—were opportunely brought to the hammer, a chance by which Mr. Bancroft naturally profited.

Mr. Bancroft had been trained in the business habits of the book trade, in which he had established himself in San Francisco as early as 1856.[60] He was at this time twenty-four years old, having been born of New England stock in Ohio in 1832, and having had already four years residence—since 1852—in San Francisco as the agent of an eastern bookseller. It was not till 1869 that he set seriously to work on his history, and organized a staff of assistants.[61] They indexed his library, which was now large (12,000 volumes) and was kept on an upper floor of his business quarters, and they classified the references in paper bags.[62] His first idea was to make an encyclopædia of the antiquities and history of the Pacific Coast; and it is on the whole unfortunate that he abandoned the scheme, for his methods were admirably adapted to that end, but of questionable application to a sustained plan of historical treatment. It is the encyclopedic quality of his work, as the user eliminates what he wishes, which makes and will continue to make the books that pass under his name of the first importance to historical students.

In 1875 the first five volumes of the series, denominated by themselves The Native Races of the Pacific States, made their appearance. It was[ix] clear that a new force had been brought to bear upon historical research,—the force of organized labor from many hands; and this implied competent administrative direction and ungrudged expenditure of money. The work showed the faults of such a method, in a want of uniform discrimination, and in that promiscuous avidity of search, which marks rather an eagerness to amass than a judgment to select, and give literary perspective. The book, however, was accepted as extremely useful and promising to the future inquirer. Despite a certain callowness of manner, the Native Races was extremely creditable, with comparatively little of the patronizing and flippant air which its flattering reception has since begotten in its author or his staff. An unfamiliarity with the amenities of literary life seems unexpectedly to have been more apparent also in his later work.

In April, 1876, Mr. Lewis H. Morgan printed in the North American Review, under the title of “Montezuma’s Dinner,” a paper in which he controverted the views expressed in the Native Races regarding the kind of aboriginal civilization belonging to the Mexican and Central American table-lands. A writer of Mr. Morgan’s reputation commanded respect in all but Mr. Bancroft, who has been unwise enough to charge him with seeking “to gain notoriety by attacking” his (Mr. B.’s) views or supposed views. He dares also to characterize so well-known an authority as “a person going about from one reviewer to another begging condemnation for my Native Races.” It was this ungracious tone which produced a divided reception for his new venture. This, after an interval of seven years, began to make its appearance in vol. vi. of the “Works,” or vol. i. of the History of Central America, appearing in the autumn of 1882.

The changed tone of the new series, its rhetoric, ambitious in parts, but mixed with passages which are often forceful and exact, suggestive of an ill-assorted conjoint production; the interlarding of classic allusions by some retained reviser who served this purpose for one volume at least; a certain cheap reasoning and ranting philosophy, which gives place at times to conceptions of grasp; flippancy and egotism, which induce a patronizing air under the guise of a constrained adulation of others; a want of knowledge on points where the system of indexing employed by his staff had been deficient,—these traits served to separate the criticism of students from the ordinary laudation of such as were dazed by the magnitude of the scheme.

Two reviews challenging his merits on these grounds[63] induced Mr. Bancroft to reply in a tract[64] called The Early American Chroniclers. The manner of this rejoinder is more offensive than that of the volumes which it defends; and with bitter language he charges the reviewers with being “men of Morgan,” working in concert to prejudice his success.

But the controversy of which record is here made is unworthy of the principal party to it. His important work needs no such adventitious support; and the occasion for it might have been avoided by ordinary prudence. The extent of the library upon which the work[65] is based, and the full citation of the authorities followed in his notes, and the more general enumeration of them in his preliminary lists, make the work pre-eminent for its bibliographical extent, however insufficient, and at times careless, is the bibliographical record.[66]

The library formed by the late Henry C. Murphy of Brooklyn to assist him in his projected history of maritime discovery in America, of which only the chapter on Verrazano[67] has been printed, was the creation of diligent search for many years, part of which was spent in Holland as minister of the United States. The earliest record of it is a Catalogue of an American library chronologically arranged, which was[x] privately printed in a few copies, about 1850, and showed five hundred and eighty-nine entries between the years 1480 and 1800.[68]

JAMES CARSON BREVOORT.

There has been no catalogue printed of the library of Mr. James Carson Brevoort, so well known as a historical student and bibliographer, to whom Mr. Sabin dedicated the first volume of his Dictionary. Some of the choicer portions of his collection are understood to have become a part of the Astor Library, of which Mr. Brevoort was for a few years the superintendent, as well as a trustee.[69]

The useful and choice collection of Mr. Charles Deane, of Cambridge, Mass., to which, as the reader will discover, the Editor has often had recourse, has never been catalogued. Mr. Deane has made excellent use of it, as his tracts and papers abundantly show.[70]

A distinct class of helpers in the field of American bibliography has been those gatherers of libraries who are included under the somewhat indefinite term of collectors,—owners of books, but who make no considerable dependence[xi] upon them for studies which lead to publication. From such, however, in some instances, bibliography has notably gained,—as in the careful knowledge which Mr. James Lenox sometimes dispensed to scholars either in privately printed issues or in the pages of periodicals.

CHARLES DEANE.

Harrisse in 1866 pointed to five Americana libraries in the United States as surpassing all of their kind in Europe,—the Carter-Brown, Barlow, Force, Murphy, and Lenox collections. Of the Barlow, Force (now in the Library of Congress), and Murphy collections mention has already been made.

The Lenox Library is no longer private, having been given to a board of trustees by Mr. Lenox previous to his death,[71] and handsomely housed, by whom it is held for a restricted public use, when fully catalogued and arranged. Its character, as containing only rare or unusual books, will necessarily withdraw it from the use of all but scholars engaged in recondite studies. It is very rich in other directions than American history; but in this department the partial access which Harrisse had to it while in Mr. Lenox’s house led him to infer that it would hold the first rank. The wealth of its alcoves, with their twenty-eight thousand volumes, is becoming known gradually in a series of bibliographical monographs, printed as contributions to its catalogue, of which six have[xii] thus far appeared, some of them clearly and mainly the work of Mr. Lenox himself.

Of these only three have illustrated American history in any degree,—those devoted to the voyages of Hulsius and Thévenot, and to the Jesuit Relations (Canada).[72]

The only rival of the Lenox is the library of the late John Carter Brown, of Providence, gathered largely under the supervision of John Russell Bartlett; and since Mr. Brown’s death it has been more particularly under the same oversight.[73] It differs from the Lenox Library in that it is exclusively American, or nearly so,[74] and still more in that we have access to a thorough catalogue of its resources, made by Mr. Bartlett himself, and sumptuously printed.[75] It was originally issued as Bibliotheca Americana: A Catalogue of books relating to North and South America in the Library of John Carter Brown of Providence, with notes by John Russell Bartlett, in three volumes,—vol. i., 1493-1600, in 1865 (302 entries); vol. ii., 1601-1700, in 1866 (1,160 entries); vol. iii., 1701-1800, in two parts, in 1870-1871 (4,173 entries).

In 1875 vol. i. was reprinted with fuller titles, covering the years 1482[76]-1601, with 600 entries, doubling the extent of that portion.[77] Numerous facsimiles of titles and maps add much to its value. A second and similarly extended edition of vol. ii. (1600-1700) was printed in 1882, showing 1,642 entries. The Carter-Brown Catalogue, as it is ordinarily cited, is the most extensive printed list of all Americana previous to 1800, more especially anterior to 1700, which now exists.[78]

Of the other important American catalogues, the first place is to be assigned to that of the collection formed at Hartford by Mr. George Brinley, the sale of which since his death[79] has been undertaken under the direction of Dr. J. Hammond Trumbull,[80] who has prepared the catalogue, and who claims—not without warrant—that it embraces “a greater number of volumes remarkable for their rarity, value, and interest to special collectors and to book-lovers in general, than were ever before brought together in an American sale-room.”[81]

The library of William Menzies, of New York, was sold in 1875, from a catalogue made by Joseph Sabin.[82] The library of Edward A. Crowninshield, of Boston, was catalogued in Boston in 1859, but withdrawn from public sale, and sold to Henry Stevens, who took a portion of it to London. It was not large,—the catalogue shows less than 1,200 titles,—and was not exclusively American; but it was rich in[xiii] some of the rarest of such books, particularly in regard to the English Colonies.[83]

The sale of John Allan’s collection in New York, in 1864, was a noteworthy one. Americana, however, were but a portion of the collection.[84] An English-American flavor of far less fineness, but represented in a catalogue showing a very large collection of books and pamphlets,[85] was sold in New York in May, 1870, as the property of Mr. E. P. Boon.

Mr. Thomas W. Field issued in 1873 An Essay towards an Indian Bibliography, being a Catalogue of books relating to the American Indians, in his own library, with a few others which he did not possess, distinguished by an asterisk. Mr. Field added many bibliographical and historical notes, and gave synopses, so that the catalogue is generally useful to the student of Americana, as he did not confine his survey to works dealing exclusively with the aborigines. The library upon which this bibliography was based was sold at public auction in New York, in two parts, in May, 1875 (3,324 titles), according to a catalogue which is a distinct publication from the Essay.[86]

The collection of Mr. Almon W. Griswold was dispersed by printed catalogues in 1876 and 1880, the former containing the American portion, rich in many of the rarer books.

Of the various private collections elsewhere than in the United States, more or less rich in Americana, mention may be made of the Bibliotheca Mejicana[87] of Augustin Fischer, London, 1869; of the Spanish-American libraries of Gregorio Beéche, whose catalogue was printed at Valparaiso in 1879; and that of Benjamin Vicuña Mackenna, printed at the same place in 1861.[88]

In Leipsic, the catalogue of Serge Sobolewski (1873)[89] was particularly helpful in the bibliography of Ptolemy, and in the voyages of De Bry and others. Some of the rarest of Americana were sold in the Sunderland sale[90] in London in 1881-1883; and remarkably rich collections were those of Pinart and Bourbourg,[91] sold in Paris in 1883, and that of Dr. J. Court,[92] the first part of which was sold in Paris in May, 1884. The second part had little of interest.

Still another distinctive kind of bibliographies is found in the catalogues of the better class of dealers; and among the best of such is to be placed the various lists printed by Henry Stevens, a native of Vermont, who has spent most of his manhood in London. In the dedication to John Carter Brown of his Schedule of Nuggets (1870), he gives some account of his early bibliographical quests.[93] Two years after graduating at Yale, he says, he had passed “at Cambridge, reading passively with legal Story, and actively with historical Sparks, all the while sifting and digesting the treasures of the Harvard Library. For five years previously he had scouted through several States during his vacations, prospecting in out-of-the-way places for historical nuggets, mousing through town libraries and country garrets in search of anything old that was historically new for Peter Force and his American Archives.... From Vermont to Delaware many an antiquated churn, sequestered hen-coop, and dilapidated flour-barrel had yielded to him rich harvests of old papers, musty books, and golden pamphlets. Finally, in 1845, an irrefragable desire impelled him to visit the Old World, its libraries and book-stalls. Mr. Brown’s enlightened liberality in those primitive years of his bibliographical pupilage contributed largely towards the boiling of his kettle.... In acquiring con amore these American Historiadores Primitivos, he ... travelled far and near. In this labor of love, this journey of life, his tracks often become your tracks, his labors your works, his [xiv]libri your liberi,” he adds, in addressing Mr. Brown.

In 1848 Mr. Stevens proposed the publication, through the Smithsonian Institution, of a general Bibliographia Americana, illustrating the sources of early American history;[94] but the project failed, and one or more attempts later made to begin the work also stopped short of a beginning. While working as a literary agent of the Smithsonian Institution and other libraries, in these years, and beginning that systematic selection of American books, for the British Museum and Bodleian, which has made these libraries so nearly, if not quite, the equal of any collection of Americana in the United States, he also made the transcriptions and indexes of the documents in the State Paper Office which respectively concern the States of New Jersey, Rhode Island, Maryland, and Virginia. These labors are now preserved in the archives of those States.[95] Perhaps the earliest of his sale catalogues was that of a pseudo “Count Mondidier,” embracing Americana, which were sold in London in December, 1851.[96] His English Library in 1853 was without any distinctive American flavor; but in 1854 he began, but suspended after two numbers, the American Bibliographer (100 copies).[97] In 1856 he prepared a Catalogue of American Books and Maps in the British Museum (20,000 titles), which, however, was never regularly published, but copies bear date 1859, 1862, and 1866.[98] In 1858—though most copies are dated 1862[99]—appeared his Historical Nuggets; Bibliotheca Americana, or a descriptive Account of my Collection of rare books relating to America. The two little volumes show about three thousand titles, and Harrisse says they are printed “with remarkable accuracy.” There was begun in 1885, in connection with his son Mr. Henry Newton Stevens, a continuation of these Nuggets. In 1861 a sale catalogue of his Bibliotheca Americana (2,415 lots), issued by Puttick and Simpson, and in part an abridgment of the Nuggets with similarly careful collations, was accepted by Maisonneuve as the model of his Bibliothèque Américaine later to be mentioned.[100]

In 1869-1870 Mr. Stevens visited America, and printed at New Haven his Historical and Geographical Notes on the earliest discoveries in America, 1453-1530, with photo-lithographic facsimiles of some of the earliest maps. It is a valuable essay, much referred to, in which the author endeavored to indicate the entanglement of the Asiatic and American coast lines in the early cartography.[101]

In 1870 he sold at Boston a collection of five thousand volumes, catalogued as Bibliotheca Historica[102] (2,545 entries), being mostly Americana, from the library of the elder Henry Stevens of Vermont. It has a characteristic introduction, with an array of readable notes.[103] His catalogues have often such annotations, inserted on a principle which he explains in the introduction to this one: “In the course of many years of bibliographical study and research, having picked up various isolated grains of knowledge respecting the early history, geography, and bibliography of this western hemisphere, the writer has thought it well to pigeon-hole the facts in notes long and short.”

In October, 1870, he printed at London a Schedule of Two Thousand American Historical Nuggets taken from the Stevens Diggings in September, 1870, and set down in Chronological Order of Printing from 1490 to 1800 [1776], described and recommended as a Supplement to my printed Bibliotheca Americana. It included 1,350 titles.

In 1872 he sold another collection, largely Americana, according to a catalogue entitled Bibliotheca Geographica & Historica; or, a Catalogue of [3,109 lots], illustrative of historical geography and geographical history. Collected, used, and described, with an Introductory Essay on Catalogues, and how to make them upon the Stevens system of photo-bibliography. The title calls it a first part; but no second part ever appeared. Ten copies were issued, with about four hundred[xv] photographic copies of titles inserted. Some copies are found without the essay.[104]

The next year (1873) he issued a privately printed list of two thousand titles of American “Continuations,” as they are called by librarians, or serial publications in progress as taken at the British Museum, quaintly terming the list American books with tails to ’em.[105]

Finally, in 1881, he printed Part I. of Stevens’s Historical Collections, a sale catalogue showing 1,625 titles of books, chiefly Americana, and including his Franklin Collection of manuscripts, which he later privately sold to the United States Government, an agent of the Boston Public Library yielding to the nation.[106]

One of the earliest to establish an antiquarian bookshop in the United States was the late Samuel G. Drake, who opened one in Boston in 1830.[107] His special field was that of the North American Indians; and the history and antiquities of the aborigines, together with the history of the English Colonies, give a character to his numerous catalogues.[108] Mr. Drake died in 1875, from a cold taken at a sale of the library of Daniel Webster; and his final collections of books were scattered in two sales in the following year.[109]

William Gowans, of New York, was another of the early dealers in Americana.[110] The catalogues of Bartlett and Welford have already been mentioned. In 1854, while Garrigue and Christern were acting as agents of Mr. Lenox, they printed Livres Curieux, a list of desiderata sought for by Mr. Lenox, pertaining to such rarities as the letters of Columbus, Cartier, parts of De Bry and Hulsius, and the Jesuit Relations. This list was circulated widely through Europe, but not twenty out of the 216 titles were ever offered.[111]

About 1856, Charles B. Norton, of New York, began to issue American catalogues; and in 1857 he established Norton’s Literary Letter, intended to foster interest in the collection of Americana.[112] A little later, Joel Munsell, of Albany, began to issue catalogues;[113] and J. W. Randolph, of Richmond, Virginia, more particularly illustrated the history of the southern parts of the United States.[114] The most important Americana lists at present issued by American dealers are those of Robert Clarke & Co., of Cincinnati, which are admirable specimens of such lists.[115]

In England, the catalogues of Henry Stevens and E. G. Allen have been already mentioned.[xvi] The leading English dealer at present in the choicer books of Americana, as of all other subjects—and it is not too much to say, the leading one of the world—is Mr. Bernard Quaritch, a Prussian by birth, who was born in 1819, and after some service in the book-trade in his native country came to London in 1842, and entered the service of Henry G. Bohn, under whose instruction, and as a fellow-employé of Lowndes the bibliographer, he laid the foundations of a remarkable bibliographical acquaintance. A short service in Paris brought him the friendship of Brunet. Again (1845) he returned to Mr. Bohn’s shop; but in April, 1847, he began business in London for himself. He issued his catalogues at once on a small scale; but they took their well-known distinctive form in 1848, which they have retained, except during the interval December, 1854,-May, 1864, when, to secure favorable consideration in the post-office rates, the serial was called The Museum. It has been his habit, at intervals, to collect his occasional catalogues into volumes, and provide them with an index. The first of these (7,000 entries) was issued in 1860. Others have been issued in 1864, 1868, 1870, 1874, 1877 (this with the preceding constituting one work, showing nearly 45,000 entries or 200,000 volumes), and 1880 (describing 28,009 books).[116] In the preface to this last catalogue he says: “The prices of useful and learned books are in all cases moderate; the prices of palæographical and bibliographical curiosities are no doubt in most cases high, that indeed being a natural result of the great rivalry between English, French, and American collectors.... A fine copy of any edition of a book is, and ought to be, more than twice as costly as any other.”[117] While the Quaritch catalogues have been general, they have included a large share of the rarest Americana, whose titles have been illustrated with bibliographical notes characterized by intimate acquaintance with the secrets of the more curious lore.

The catalogues of John Russell Smith (1849, 1853, 1865, 1867), and of his successor Alfred Russell Smith (1871, 1874), are useful aids in this department.[118] The Bibliotheca Hispano-Americana of Trübner, printed in 1870, offered about thirteen hundred items.[119] Occasional reference can be usefully made to the lists of George Bumstead, Ellis and White, John Camden Hotten, all of London, and to those of William George of Bristol. The latest extensive Americana catalogue is A catalogue of rare and curious books, all of which relate more or less to America, on sale by F. S. Ellis, London, 1884. It shows three hundred and forty-two titles, including many of the rarer books, which are held at prices startling even to one accustomed to the rapid rise in the cost of books of this description. Many of them were sold by auction in 1885.

In France, since Ternaux, the most important contribution has come from the house of Maisonneuve et Cie., by whom the Bibliotheca Americana of Charles Leclerc has been successively issued to represent their extraordinary stock. The first edition was printed in 1867 (1,647 entries), the second in 1878[120] (2,638 entries, with an admirable index), besides a first supplement in 1881 (nos. 2,639-3,029). Mr. Quaritch characterizes it as edited “with admirable skill and knowledge.”

Less important but useful lists, issued in France, have been those of Hector Bossange, Edwin Tross,[121] and the current Americana series of Dufossé, which was begun in 1876.[122]

In Holland, most admirable work has been done by Frederik Muller, of Amsterdam, and by Mr. Asher, Mr. Tiele, and Mr. Otto Harrassowitz under his patronage, of which ample accounts[xvii] are given in another place.[123] Muller’s catalogues were begun in 1850, but did not reach distinctive merit till 1872.[124] Martin Nijhoff, at the Hague, has also issued some American catalogues.

In 1858 Muller sold one of his collections of Americana to Brockhaus, of Leipsic, and the Bibliothèque Américaine issued by that publisher in 1861, as representing this collection, was compiled by one of the editors of the Serapeum, Paul Trömel, whom Harrisse characterizes as an “expert bibliographer and trustworthy scholar.” The list shows 435 entries by a chronological arrangement (1507-1700). Brockhaus again, in 1866, issued another American list, showing books since 1508, arranged topically (nos. 7,261-8,611). Mr. Otto Harrassowitz, of Leipsic, a pupil of Muller, of Amsterdam, has also entered the field as a purveyor of choice Americana. T. O. Weigel, of Leipsic, issued a catalogue, largely American, in 1877.

So well known are the general bibliographies of Watt, Lowndes, Brunet, Graesse, and others, that it is not necessary to point out their distinctive merits.[125] Students in this field are familiar with the catalogues of the chief American libraries. The library of Harvard College has not issued a catalogue since 1834, though it now prints bulletins of its current accessions. An admirable catalogue of the Boston Athenæum brings the record of that collection down to 1871. The numerous catalogues of the Boston Public Library are of much use, especially the distinct volume given to the Prince Collection. The Massachusetts Historical Society’s library has a catalogue printed in 1859-60. There has been no catalogue of the American Antiquarian Society since 1837, and the New England Historic Genealogical Society has never printed any; nor has the Congregational Library. The State Library at Boston issued a catalogue in 1880. These libraries, with the Carter-Brown Library at Providence, which is courteously opened to students properly introduced, probably make Boston within easy distance of a larger proportion of the books illustrating American history, than can be reached with equal convenience from any other literary centre. A book on the private libraries of Boston was compiled by Luther Farnham in 1855; but many of the private collections then existing have since been scattered.[126] General Horatio Rogers has made a similar record of those in Providence. After the Carter-Brown Collection, the most valuable of these private libraries in New England is probably that of Mr. Charles Deane in Cambridge, of which mention has already been made. The collection of the Rev. Henry M. Dexter, D.D., of New Bedford, is probably unexampled in this country for the history of the Congregational movement, which so largely affected the early history of the English Colonies.[127]

Two other centres in the United States are of the first importance in this respect. In Washington, with the Library of Congress (of which a general consolidated catalogue is now printing), embracing as it does the collection formed by Col. Peter Force, and supplementing the archives of the Government, an investigator of American history is situated extremely favorably.[128] In New York the Astor and Lenox libraries, with those of the New York Historical Society and American Geographical Society, give the student great opportunities. The catalogue of the Astor Library was printed in 1857-66,[xviii] and that of the Historical Society in 1859. No general catalogue of the Lenox Library has yet been printed. An account of the private libraries of New York was published by Dr. Wynne in 1860. The libraries of the chief importance at the present time, in respect to American history, are those of Mr. S. L. M. Barlow in New York, and of Mr. James Carson Brevoort in Brooklyn. Mr. Charles H. Kalbfleisch of New York has a small collection, but it embraces some of the rarest books. The New York State Library at Albany is the chief of the libraries of its class, and its principal characteristic pertains to American history.

The other chief American cities are of much less importance as centres for historical research. The Philadelphia Library and the collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania are hardly of distinctive value, except in regard to the history of that State. In Baltimore the library of the Peabody Institute, of which the first volume of an excellent catalogue has been printed, and that of the Maryland Historical Society are scarcely sufficient for exhaustive research. The private library of Mr. H. H. Bancroft constitutes the only important resource of the Pacific States;[129] and the most important collection in Canada is that represented by the catalogue of the Library of Parliament, which was printed in 1858.

This enumeration is intended only to indicate the chief places for ease of general investigation in American history. Other localities are rich in local helps, and accounts of such will be found elsewhere in the present History.[130]

INTRODUCTION.

By the Editor.

Part II. THE EARLY DESCRIPTIONS OF AMERICA AND COLLECTIVE ACCOUNTS OF THE EARLY VOYAGES THERETO.

OF the earliest collection of voyages of which we have any mention we possess only a defective copy, which is in the Biblioteca Marciana, and is called Libretto de tutta la navigazione del Rè di Spagna delle isole e terreni nuovamente scoperti stampato per Vercellese. It was published at Venice in 1504,[131] and is said to contain the first three voyages of Columbus. This account, together with the narrative of Cabral’s voyage printed at Rome and Milan, and an original—at present unknown—of Vespucius’ third voyage, were embodied, with other matter, in the Paesi novamente retrovati et novo mondo da Alberico Vesputio Florentino intitulato, published at Vicentia in 1507,[132] and again possibly at Vicentia in 1508,—though the evidence is wanting to support the statement,—but certainly at Milan in that year[xx] (1508).[133] There were later editions in 1512,[134] 1517,[135] 1519[136] (published at Milan), and 1521.[137] There are also German,[138] Low German,[139] Latin,[140] and French[141] translations.

While this Zorzi-Montalboddo compilation was flourishing, an Italian scholar, domiciled in Spain, was recording, largely at first hand, the varied reports of the voyages which were then opening a new existence to the world. This was Peter Martyr, of whom Harrisse[142] cites an early and quaint sketch from Hernando Alonso de Herrera’s Disputatio adversus Aristotelez (1517).[143] The general historians have always made due acknowledgment of his service to them.[144]

Harrisse could find no evidence of Martyr’s First Decade having been printed at Seville as early as 1500, as is sometimes stated; but it has been held that a translation of it,—though no copy is now known,—made by Angelo Trigviano into Italian was the Libretto de tutta la navigazione del Rè di Spagna, already mentioned.[145] The earliest unquestioned edition was that of 1511, which was printed at Seville with the title Legatio Babylonica; it contained nine books and a part of the tenth book of the First Decade.[146] In 1516 a new edition, without map, was printed at Alcalá in Roman letter. The part of the tenth book of the First Decade in the 1511 edition is here annexed to the ninth, and a new tenth book is added, besides two other decades, making three in all.[147]

There exists what has been called a German version (Die Schiffung mitt dem lanndt der Gulden Insel) of the First Decade, in which the supposed author is called Johan von Angliara; and its date is 1520, or thereabout; but Mr. Deane, who has the book, says that it is not Martyr’s.[148] Some Poemata, which had originally been included in the publication of the First Decade, were separately printed in 1520.[149]

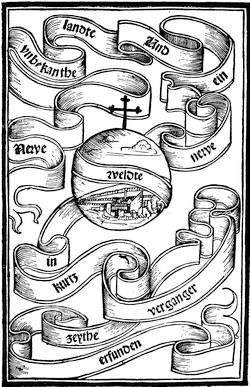

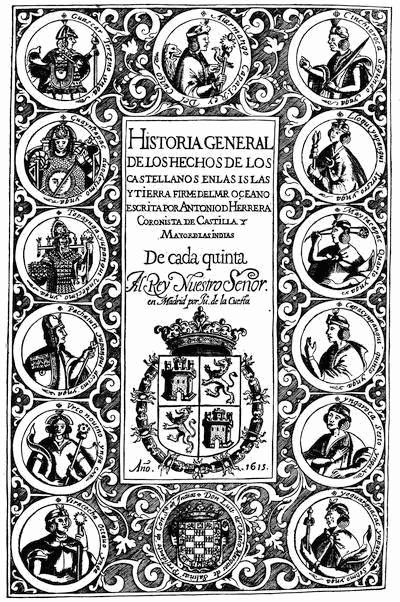

TITLE OF THE NEWE UNBEKANTHE LANDTE (REDUCED).

At Basle in 1521 appeared his De nuper sub D. Carolo repertis insulis, the title of which is annexed in fac-simile. Harrisse[150] has called it an extract from the Fourth Decade; and a similar statement is made in the Carter-Brown Catalogue (vol. i. no. 67). But Stevens and other authorities define it as a substitute for the lost First Letter of Cortes, touching the expedition of Grijalva and the invasion of Mexico; and it supplements, rather than overlaps, Martyr’s other narratives.[151] Mr. Deane contends that if the Fourth Decade had then been written, this might well be considered an abridgment of it.

The first complete edition (De orbe novo) of all the eight decades was published in 1530 at Complutum; and with it is usually found the map (“Tipus orbis universalis”) of Apianus, which originally appeared in Camer’s Solinus in 1520. In this new issue the map has its date changed to 1530.[152]

In 1532, at Paris, appeared an abridgment in French of the first three decades, together with an abstract of Martyr’s De insulis (Basle, 1521), followed by abridgments of the printed second and third letters of Cortes,—the whole bearing the title, Extraict ov Recveil des Isles nouuellemēt trouuees en la grand mer Oceane[xxii] en temps du roy Despaigne Fernād & Elizabeth sa femme, faict premierement en latin par Pierre Martyr de Millan, & depuis translate en languaige francoys.[153]

In 1533, at Basle, in folio, we find the first three decades and the tract of 1521 (De insulis) united in De rebus oceanicis et orbe novo.[154]

At Venice, in 1534, the Summario de la generale historia de l’Indie occidentali was a joint issue of Martyr and Oviedo, under the editing of Ramusio.[155] An edition of Martyr, published at Paris in 1536, sometimes mentioned,[156] does not apparently exist;[157] but an edition of 1537 is noted by Sabin.[158] In 1555 Richard Eden’s Decades of the Newe Worlde, or West India, appeared in black-letter at London. It is made up in large part from Martyr,[159] and was the basis of Richard Willes’ edition of Eden in 1577, which included the first four decades, and an abridgment of the last four, with additions from Oviedo and others,—all under the new name, The History of Trauayle.[160]

There was an edition again at Cologne in 1574,—the one which Robertson used.[161] Three decades and the De insulis are also included in a composite folio published at Basle in 1582, containing also Benzoni and Levinus, all in German.[162] The entire eight decades, in Latin, which had not been printed together since the Basle edition of 1530, were published in Paris in 1587 under the editing of Richard Hakluyt, with the title: De orbe novo Petri Martyris Anglerii Mediolanensis, protonotarij, et Caroli quinti senatoris Decades octo, diligenti temporum obseruatione, et vtilissimis annotationibus illustratæ, suôque nitori restitutæ, labore et industria Richardi Haklvyti Oxoniensis Angli. Additus est in vsum lectoris accuratus totius operis index. Parisiis, apud Gvillelmvm Avvray, 1587. With its “F. G.” map, it is exceedingly rare.[163]

GRYNÆUS.

Fac-simile of cut in Reusner’s Icones (Strasburg, 1590), p. 107.

As illustrating in some sort his more labored work, the Opus epistolarum Petri Martyris was first printed at Complutum in 1530.[164] The letters were again published at Amsterdam, in 1670,[165] in an edition which had the care of Ch. Patin, to which was appended other letters by Fernando del Pulgar.[166]

The most extensive of the early collections was the Novus orbis, which was issued in separate editions at Basle and Paris in 1532. Simon Grynæus, a learned professor at Basle, signed the preface; and it usually passes under his name. Grynæus was born in Swabia, was a friend of Luther, visited England in 1531, and died in Basle, in 1541. The compilation, however, is the work of a canon of Strasburg, John Huttich (born about 1480; died, 1544), but the labor of revision fell on Grynæus.[167] It has the first three voyages of Columbus, and those of Pinzon and Vespucius; the rest of the book is taken up with the travels of Marco Polo and his successors to the East.[168] It[xxv] next appeared in a German translation at Strasburg in 1534, which was made by Michal Herr, Die New Welt. It has no map, gives more from Martyr than the other edition, and substitutes a preface by Herr for that of Grynæus.[169] The original Latin was reproduced at Basle again in 1537, with 1536 in the colophon.[170] In 1555 another edition was printed at Basle, enlarged upon the 1537 edition by the insertion of the second and third of the Cortes letters and some accounts of efforts in converting the Indians.[171] Those portions relating to America exclusively were reprinted in the Latin at Rotterdam in 1616.[172]

Sebastian Münster, who was born in 1489, was forty-three years old when his map of the world—which is preserved in the Paris (1532) edition of the Novus orbis—appeared. This is the first time that Münster significantly comes before us as a describer of the geography of the New World. Again in 1540 and 1542 he was associated with the editions of Ptolemy issued at Basle in those years.[173] It is, however, upon his Cosmographia, among his forty books, that Münster’s fame chiefly rests. The earliest editions are extremely rare, and seem not to be clearly defined by the bibliographers. It appears to have been originally issued in German, probably in 1544 at Basle,[174] under the mixed title: Cosmographia. Beschreibūg aller lender Durch Sebastianum Munsterum. Getruckt zü Basel durch Henrichum Petri, Anno MDxliiij.[175] He says that he had been engaged upon it for eighteen years, keeping Strabo before him as a model. To the section devoted to Asia he adds a few pages “Von den neüwen inseln” (folios[xxvi] dcxxxv-dcxlij).

MÜNSTER.

Fac-simile of the cut in the Ptolemy of 1552.

This account was scant; and though it was a little enlarged in the second edition in 1545,[176] it remained of small extent through subsequent editions, and was confined to ten pages in that of 1614. The last of the German editions appeared in 1628.[177] The earliest[xxvii] undoubted Latin text[178] appeared at Basle in 1550, with the same series of new views, etc., by Manuel Deutsch, which were given in the German edition of that date.[179] With nothing[xxviii] but a change of title apparently, there were reissues of this edition in 1551, 1552, and 1554,[180] and again in 1559.[181] The edition of 1572 has the same map, “Novæ insulæ,” used in the 1554 editions; but new names are added, and new plates of Cusco and Cuba are also furnished.[182]

MÜNSTER.

Fac-simile of a cut in Reusner’s Icones (Strasburg, 1590), p. 171.

The earliest French edition, according to Brunet,[183] appeared in 1552; and other editions followed in that language.[184] Eden gave the fifth book an English dress in 1553, which was again issued in 1572 and 1574.[185] A Bohemian edition, made by Jan z Puchowa, Kozmograffia Czieská, was issued in 1554.[186] The first Italian edition was printed at Basle in 1558, using the engraved plates of the other Basle issues; and finally, in 1575, an Italian edition, according to Brunet,[187] appeared at Colonia.

MONARDES.

The best-known collection of voyages of the sixteenth century is that of Ramusio, whose third volume—compiled probably in 1553, and printed in 1556—is given exclusively to American voyages.[188] It contains, however, little regarding Columbus not given by Peter Martyr and Oviedo, except the letter to Fracastoro.[189] In Ramusio the narratives of these early voyages first got a careful and considerate editor,[xxix] who at this time was ripe in knowledge and experience, for he was well beyond sixty,[190] and he had given his maturer years to historical and geographical study. He had at one time maintained a school for topographical studies in his own house. Oviedo tells us of the assistance Ramusio was to him in his work. Locke has praised his labors without stint.[191]

Monardes, one of the distinguished Spanish physicians of this time, was busy seeking for the simples and curatives of the New World plants, as the adventurers to New Spain brought them back. The original issue of his work was the Dos Libros, published at Seville in 1565, treating “of all things brought from our West Indies which are used in medicine, and of the Bezaar Stone, and the herb Escuerçonera.” This book is become rare, and is priced as high as 200 francs and £9.[192] The “segunda parte” is sometimes found separately with the date 1571; but in 1574 a third part was printed with the other two,—making the complete work, Historia medicinal de nuestras Indias,—and these were again issued in 1580.[193] An Italian version, by Annibale Briganti, appeared at Venice in 1575 and 1589,[194] and a French, with Du Jardin, in 1602.[195] There were three English editions printed under the title of Joyfull Newes out of the newe founde world, wherein is declared the rare and singular virtues of diverse and sundry Herbes, Trees, Oyles, Plantes, and Stones, by Doctor Monardus of Sevill, Englished by John Frampton, which first appeared in 1577, and was reprinted in 1580, with additions from Monardes’ other tracts, and again in 1596.[196]

The Spanish historians of affairs in Mexico, Peru, and Florida are grouped in the Hispanicarum rerum scriptores, published at Frankfort in 1579-1581, in three volumes.[197] Of Richard Hakluyt and his several collections,—the Divers Voyages of 1582, the Principall Navigations of[xxx] 1589, and his enlarged edition, of which the third volume (1600) relates to America,—there is an account in Vol. III. of the present work.[198]

PORTRAIT OF DE BRY.

This follows a print given in fac-simile in the Carter-Brown Catalogue, i. 316.

The great undertaking of De Bry was also begun towards the close of the same century. De Bry was an engraver at Frankfort, and his professional labors had made him acquainted with works of travel. The influence of Hakluyt and a visit to the English editor stimulated him to undertake a task similar to that of[xxxi] the English compiler.

FEYERABEND.

Sigmund Feyerabend was a prominent bookseller of his day in Frankfort, and was born about 1527 or 1528. He was an engraver himself, and was associated with De Bry in the publications of his Voyages.

He resolved to include both the Old and New World; and he finally produced his volumes simultaneously in Latin and German. As he gave a larger size to the American parts than to the others, the commonly used title, referring to this difference, was soon established as Grands et petits voyages.[199] Theodore De Bry himself died in March, 1598; but the work was carried forward by his widow, by his sons John Theodore and John Israel, and by his sons-in-law Matthew Merian and William Fitzer. The task was not finished till 1634, when twenty-five parts had been printed in the Latin, of which thirteen pertain to America; but the German has one more part in the American series. His first part—which was Hariot’s Virginia—was printed not only in Latin and German, but also in the original English[200] and in French; but there seeming to be no adequate demand in these languages, the subsequent issues were confined to Latin and German. There was a gap in the[xxxii] dates of publication between 1600 (when the ninth part is called “postrema pars”) and 1619-1620, when the tenth and eleventh parts appeared at Oppenheim, and a twelfth at Frankfort in 1624. A thirteenth and fourteenth part appeared in German in 1628 and 1630; and these, translated together into Latin, completed the Latin series in 1634.

Without attempting any bibliographical description,[201] the succession and editions of the American parts will be briefly enumerated:—

I. Hariot’s Virginia. In Latin, English, German, and French, in 1590; four or more impressions of the Latin the same year. Other editions of the German in 1600 and 1620.

II. Le Moyne’s Florida. In Latin, 1591 and 1609; in German, 1591, 1603.

III. Von Staden’s Brazil. In Latin, 1592, 1605, 1630; in German, 1593 (twice).

IV. Benzoni’s New World. In Latin, 1594 (twice), 1644; in German, 1594, 1613.

V. Continuation of Benzoni. In Latin, 1595 (twice); in German, two editions without date, probably 1595 and 1613.

VI. Continuation of Benzoni (Peru). In Latin, 1596, 1597, 1617; in German, 1597, 1619.

VII. Schmidel’s Brazil. In Latin, 1599, 1625; in German, 1597, 1600, 1617.

VIII. Drake, Candish, and Ralegh. In Latin, 1599 (twice), 1625; in German, 1599, 1624.

IX. Acosta, etc. In Latin, 1602, 1633; in German, probably 1601; “additamentum,” 1602; and again entire after 1620.

X. Vespucius, Hamor, and John Smith. In Latin, 1619 (twice); in German, 1618.

XI. Schouten and Spilbergen. In Latin, 1619,—appendix, 1620; in German, 1619,—appendix, 1620.

XII. Herrera. In Latin, 1624; in German, 1623.

XIII. Miscellaneous,—Cabot, etc. In Latin, 1634; in German, the first seven sections in 1627 (sometimes 1628); and sections 8-15 in 1630.

Elenchus: Historia Americæ sive Novus orbis, 1634 (three issues). This is a table of the Contents to the edition which Merian was selling in 1634 under a collective title.

The foregoing enumeration makes no recognition of the almost innumerable varieties caused by combination, which sometimes pass for new editions. Some of the editions of the same date are usually called “counterfeits;” and there are doubts, even, if some of those here named really deserve recognition as distinct editions.[202]

While there is distinctive merit in De Bry’s collection, which caused it to have a due effect in its day on the progress of geographical knowledge,[203] it must be confessed that a certain meretricious reputation has become attached to the work as the test of a collector’s assiduity, and of his supply of money, quite disproportioned to the relative use of the collection in these days to a student. This artificial appreciation has no doubt been largely due to the engravings, which form so attractive a feature in the series, and which, while they in many cases are the honest rendering of genuine sketches, are certainly in not a few the merest fancy of some designer.[204]

There are several publications of the De Brys sometimes found grouped with the Voyages as a part, though not properly so, of the series. Such are Las Casas’ Narratio regionum Indicarum; the voyages of the “Silberne Welt,” by Arthus von Dantzig, and of Olivier van Noort;[205] the Rerum et urbis Amstelodamensium historia of Pontanus, with its Dutch voyages to the north; and the Navigations aux Indes par les Hollandois.[206]

Another of De Bry’s editors, Gasper Ens, published in 1680 his West-unnd-Ost Indischer Lustgart, which is a summary of the sources of American history.[207]