Title: The Quest of the Golden Pearl

Author: J. R. Hutchinson

Illustrator: Hume Nisbet

Release date: January 11, 2016 [eBook #50897]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

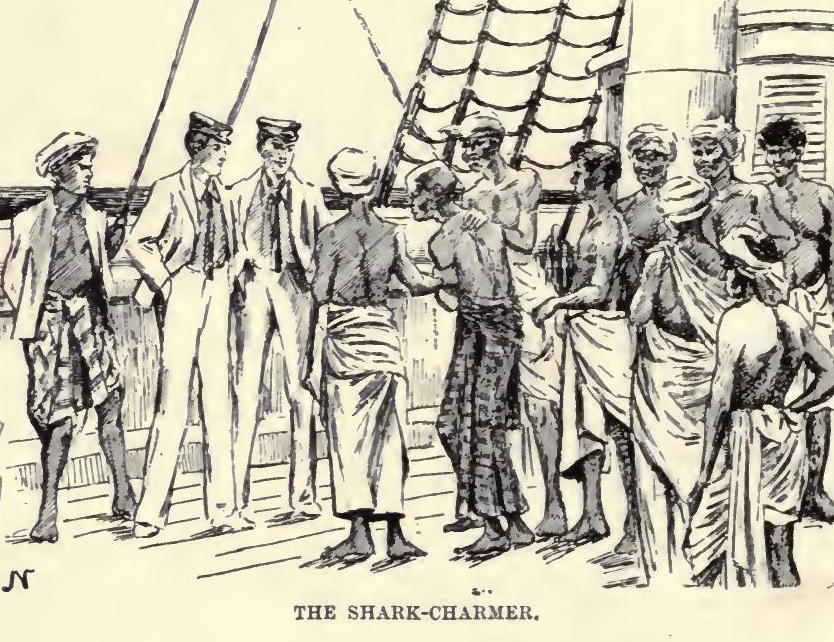

CHAPTER I.—THE SHARK-CHARMER WALKS THE PLANK.

CHAPTER II. A STROKE OF LUCK AND AN AFTER-STROKE.

CHAPTER III.—THE QUEST BEGINS.

CHAPTER IV.—INTRODUCES BOSIN, AND TELLS HOW CAPTAIN MANGO PROVED HIMSELF A TRUMP.

CHAPTER V.—THE LASCAR GETS HIS KNIFE BACK.

CHAPTER VI.—IN THE THICK OF IT.

CHAPTER VII.—“FUN OR FIGHTING, I'M READY, ANYHOW!”

CHAPTER VIII.—AT THE HAUNTED PAGODAS.

CHAPTER XI.—INTO THE HEART OF THE HILL.

CHAPTER XII.—RELATES HOW A WRONG ROAD LED TO THE RIGHT PLACE.

CHAPTER XIII.—CAPTAIN MANGO “GOES ALOFT.”

CHAPTER XIV.—SHROUDED IN A HAMMOCK.

CHAPTER XV.—THE CROCODILE PIT.

CHAPTER XVI.—DON SETS A DEATH-TRAP FOR THE LASCAR.

CHAPTER XVII.—THE BLAST OF A CONCH-SHELL.

CHAPTER XVIII.—BETWEEN LIFE AND DEATH.

CHAPTER XIX.—ONE-TO-TWENTY GIVES TWENTY-TO-ONE THE WORST OF IT.

CHAPTER XXI. RIVALS FOR THE HONOURS OF DEATH.

CHAPTER XXII.—A REPORT FROM THE SEA.

CHAPTER XXIII.—DON RUNS THE GAUNTLET.

CHAPTER XXIV.—IN THE NICK OF TIME.

CHAPTER XXV.—THE SHARK-CHARMER IS CAUGHT IN HIS OWN TRAP.

CHAPTER XXV.—BRINGS THE QUEST TO AN END.

Jack! I say, Jack! there's a row among the boatmen.”

A sturdy, thick-set young fellow of seventeen was Jack, with low-hung fists of formidable size, and a love for anything in the shape of a row that constantly led him into scrapes. Hot-headed though he was, he was one of the most good-humoured, well-meaning young fellows in the world, who, while he would not hurt a fly if he could help it, was always ready to fight in defence of his own or another's rights.

His chum, Roydon Leigh—“Don” for short—was of an altogether different type of young manhood. Jack's senior by a year, he was tall for his age, standing five feet ten in his stockings. His lithe, wiry frame contrasted strongly with Jack's sturdier build, as did his Scotch “canniness” with that young gentleman's headlong impetuosity.

“A row!” cried Jack delightedly, as he rushed to the taffrail. “Time, too; four weeks we've lain here, and never a hand in a single shindy!”

His companion laughed.

“As for that,” said he, “you're not likely to have a hand in this, unless you take the boat and row off to the diving grounds. All the same, there's a jolly row on—look yonder.”

The schooner Wellington rode at anchor at the northern extremity of the Strait of Manaar, on the famous pearl-fishing grounds of Ceylon. On her larboard bow lay the coast—a string of low, white sand-hills, dotted with the dark-brown thatch of fisher huts and the vivid green of cocoa-nut palms. The hour was eight o'clock in the morning of a cloudless March day; the fitful land-breeze had died away, leaving the whole surface of the sea like billowy glass. Half-a-dozen cable's-lengths distant on the schooner's starboard quarter, a score or-more of native dhonies or diving-boats rose and dipped to the regular motion of the long ground-swell.

It was towards these boats that Don pointed.

That something unusual had occurred was evident enough. Angry shouts floated across the placid water; and the native boatmen could be seen hurriedly pulling the boats together into a compact group about one central spot where the clamour was loudest.

“I say,” cried Jack, after watching the boats for some time in silence, “they're making for the schooner.”

“I don't half like the look of it,” replied Don uneasily; “they shouldn't leave the diving grounds, you know, until the signal gun's fired. I wish the guv was here.”

“Wishing's no good when he's ashore,” said Jack philosophically. “You're the skipper pro tem., and you must make the most of your promotion, old fellow. We'll have some fun, anyhow. Whew! how those niggers pull, and what a jolly row they're making!”

By this time the excited cries, which had first attracted the attention of those upon the schooner's deck, had been exchanged by the boatmen for a weird chant, to which every oar kept time. Erect in the stern of the foremost boat an old whiteheaded tyndal or “master” led the song, while at the end of each measure a hundred voices raised a chorus that seemed fairly to lift the boats clear of the water.

“What are they singing, anyway?” demanded Jack. “There's something about a diver and a shark in it, but I can't half make it out, can you?”

“We'll call Puggles—he'll be able to tell us. Pug! Hi, Pug! come here.”

“Coming, sa'b!” answered a voice from the cook's galley; and almost simultaneously there appeared on deck the plumpest, shiniest, most good-natured looking black boy that ever displayed two raws of pearly teeth. Nature had, apparently, pulled him into the world by the nose, and then, as a sort of finishing touch to the job, had given that organ a sharp upward tweak and left it so. It was to this feature that Puggles owed his name.

“Pug,” said his master, “tell us what those boatmen yonder are singing.”

The black boy cocked his ears and listened for a moment with parted lips. “Boat-wallahs this way telling, sa'b,” said he; and, catching the strain of the chant, he repeated the words of each line as it fell from the lips of the old tyndal:

“Salambo selling the diver one charm,

Salaam, Alii kum!

Old shark, he telling, then do no harm,

Salaam, Alii kum!

One spotted shark come out the south,

Salaam, Alii kum!

He taking diver's leg in his mouth,

Salaam, Alii kum!

Me big liking got, he telling, for you,

Salaam, Alii kum!

So he biting diver clean in two,

Salaam, Alii kum!

The lying charmer we take to the ship,

Salaam, Alii kum!

There he feeling bite of the sahib's whip,

Salaam, Alii kum!”

“Why, this Salambo must be the chap the guv had whipped off the grounds last season, eh, Pug?” cried Don excitedly.

“Same black rascal, sa'b. His skin getting well, he coming back. Dey bring him 'board ship, make his skin sore two times,” explained Puggles, grinning.

“Ha, ha!” laughed Jack. “We'll oblige 'em! We'll trice the fellow up! Hullo, here they come!”

The boats having now reached the schooner, the chant ceased abruptly, the heavy oars were noisily shipped, and, amid a perfect Babel of voices, the boatmen came swarming up the sides, until the deck was one mass of wildly gesticulating, dusky humanity. The uproar was terrific.

The old tyndal, who towered a full head and shoulders above his comrades, pushed his way to the front, and commanding silence among his followers, addressed himself to Don, who was always-recognised as master in his fathers absence.

“Sab.” said he in pigeon English, “one year back big sa'b ordering Salambo eat plenty blows for selling charm to diver-man. All same, this season he done come back and sell plenty charm, telling diver-man he put charm round neck, shark no eat him up. He telling plenty lie—this morning one shark done come, eat diver, charm, all!”

“Let him stand forward,” said Don, beginning to enter as much into the novelty of the thing as Jack himself.

The culprit, a sleek old fellow with shaven head, crafty eyes, and a rosary of wooden beads about his neck, was shoved to the front.

“Are you the chap who was whipped off the grounds last year for selling chaims?” demanded Don.

“Your honour speaking true words.” whined the shark-charmer, salaaming until his shaven head almost touched the deck; “I same rascal.”

“I say, Jack,” whispered Don, “I shan't have him whipped, you know. We'll, make him walk the plank.”

“Capital! Hell funk, certain, and there'll be no end of fun.”

“Well do it, then,” said Don decidedly. “Go forward and order two of the lascars to take the boat and lie under the schooner's quarter—-this side, you know—ready to pick him up.”

In high glee Jack departed to execute this commission, while Don again turned to the shark-doctor.

“Do you happen to have one of those charms about you?” he asked.

“One here got, sa'b,” said the fellow, producing from the folds of his waist-cloth an ola or fragment of palm-leaf, covered with cabalistic characters. “Sa'b no look at him?”

“Keep it yourself,” said Don; “you'll soon need it. Hi, lascar!” to one of the schooner's crew who stood near. “Fetch a plank here and run it out over the side.”

By the time the plank was brought and run out until one-half its length projected over the water, Jack came up chuckling, and by a sign intimated that the boat was in readiness. The crowd of natives, guessing that something unusual was afoot, craned their necks eagerly, while Puggles executed a comic pas seul in his delight. But the shark-charmer, as Jack had predicted, “funked” miserably.

Knowing that with the boat in waiting there was absolutely no danger to the shark-charmer's life, Don turned a deaf ear to his pleadings, and made a signal to the lascars to proceed.

Willing hands seized the quaking wretch and dragged him to the schooner's side, where he was placed upon, the plank, Puggles standing on the deck-end to keep it down.

“Steady, Puggles!” cried Don. “One, two, three—let him slide!”

Puggles jumped aside, the deck-end of the plank rose high in air, then descended with a crash; and with a scream of terror the shark-charmer disappeared over the side.

A tremendous shout rose from the natives on deck, and with a common impulse they one and all rushed to the schooner's side, which they reached just as the shark-charmer's head reappeared above the surface. Another moment, and he was dragged into the boat, where, catching sight of the laughing faces ranged along the rail above, he shook his fist in mute menace, and so was rowed to shore.

“Teach the beggar a lesson he won't forget in a hurry,” said Don, as he watched the boat recede. “Good-bye, old boy; we're not likely to meet again.”

But in this sanguine forecast of the future he was mistaken, as events speedily proved.

It was the afternoon of the day on which the shark-charmer so unwillingly walked the plank. The breeze was so light and fitful that it barely ruffled the surface of the sea about the schooner. Weary of the narrow limits of the deck, Don and his chum dropped into the boat and rowed ashore—Puggles, as a matter of course, bearing them company.

“These beastly sands are like an oven!” growled Don, lifting his helmet to cool his dripping forehead. “Where shall we go, Jack?”

“Bazaar,” replied Jack laconically; “always some fun to be had there. Pug, point for the bazaar.”

“Me pointing, sar,” puffed the black boy, setting his dumpy legs in motion.

Puggles was never so much in his element as when thus strutting pompously in advance, warning common nigger humanity of the white sahibs' approach. At such times the disdainful tilt of his nose, the supreme self-complaisance of his expansive grin, were as good as a show.

A gay and animated scene did the bazaar present. Back and forth through the temporary street surged an endless throng of natives of every shade of complexion and variety of costume—buying, selling, shouting, jabbering, drinking with friends or fighting with enemies.

“Much cry and little wool,” laughed Jack. “There's a big black fellow yonder auctioning off some pearl oysters; let's have a go at the next lot.”

“All right,” assented Don; “perhaps we'll have a stroke of luck. The guv knew a poor half-caste once who bid in just such a chance lot as this, and in one of them he found sixty-eight thumping big pearls. Cleared thousands of pounds by that one bid, the guv says. Pug! here, Pug!”

“Coming, sa'b,” gasped a faint voice, and Puggles wriggled his way from amongst the bystanders, shining with abundant perspiration and squeezed well-nigh flat by the pressure of the crowd.

“Pug,” said his master, “up on this creel with you, and when that big black fellow yonder puts up his next lot, bid 'em in.”

Up went Puggles, nothing loth to escape further squeezing, and up went the auctioneer's next lot. In five minutes' time the few dozens of oysters composing the lot were knocked down to the black boy at an absurdly low figure.

“Here you are,” said Don, handing him the coin. “Pass that over, and fetch the things away till we see what's inside them.”

Making a dive for the oysters, Puggles scrambled them into his cloth, and followed the sahibs to the outskirts of the crowd, blowing like a porpoise. Finding a convenient patch of shade beneath a banyan tree within a few yards of the lazy surf, they proceeded to ascertain, without further delay, whether the shells contained anything of value.

“Him plenty smell got, anyhow,” commented Puggles, as he arranged the oysters, which had been several days out of the water, in a small pyramid.

Jack threw himself on the sand, and surveyed the rough, discoloured heap with unqualified disgust. “They don't look very promising, I must say,” he cried. “Try that big one on top, Don.”

Inserting the blade of his pocket-knife between the shells of the bivalve, Don prized it open and carefully examined its contents. It contained nothing of any value.

Jack looked listlessly on, while his companion opened shell after shell with no other result than the finding of two or three miserable specimens of pearls, so small that, as Jack laughingly said, “one might stick them in ones eye and forget the moment after where one had put them.”

Only three or four shells now remained unopened, and Don was on the point of abandoning the search in disgust, when Jack, who had edged himself on his elbow as close to the heap as the villainous odour of the decomposed oysters would allow, snatched up a shell of large size, and said:

“Let me have the knife a moment, will you? This looks promising—it's the biggest of the whole lot, anyhow.”

“There you are, then; I've had enough of them myself,” said Don, tossing him the knife and walking off.

He had not proceeded half-a-dozen yards, however, when a loud shout brought him back at a run. Jack and Puggles were eagerly bending over the opened oyster.

“What is it?” he asked breathlessly, going down on his knees beside them.

Jack thrust the half-shell towards him. It was literally filled with magnificent pearls. *

* In 1828 no less than sixty-seven pearls were taken from a

single oyster on these grounds.—J. K. H.

Not a word was spoken as the glistening, priceless globules were carefully abstracted from their unsightly case and laid upon Pug's coffee-coloured palm. Twenty-five pearls of matchless size and brilliancy did Jack count out ere the store was exhausted. So taken up were they with their good fortune that not one of the three observed a native creep stealthily towards them under cover of the tree.

“There's been nothing like it known on the grounds for years!” cried Don excitedly. “Any more, Jack?”

“No more,” said Jack, and was about to throw the shell away, when Puggles caught his arm.

“Stop, sar, stop! Me see something yellow in shell. Stick knife in the meat, sar, that side.”

With the point of the blade Jack prodded the substance of the oyster at the point indicated, and presently laid bare the queen of the royal family of pearls on which they had stumbled. Larger by far than any of the twenty-five already taken from the shell, this latest addition to the number was in shape like a pear, in lustre of the purest pale yellow.

“Him gold pearl, sa'b!” cried Puggles gleefully, grinning from ear to ear. “Other only silver. Gold pearl plenty price fetching.”

“Jack, old fellow,” cried Don, thumping his companion on the back, “Puggles is right; we're in luck. I've heard the guv say that a golden pearl isn't found once in twenty years. The priests are ready to give simply any sum you like for a really fine specimen.”

The native who had concealed himself behind the trunk of the banyan tree, leaned eagerly forward. So close was he to the absorbed group that he could distinctly hear every word of their conversation. As he listened, an avaricious glitter shone in his crafty eyes, and he rubbed his hands unctuously together, as though he were rubbing pearls between them.

“How much do you suppose the lot is worth; Don?” Jack inquired.

“Some thousands of pounds, I should say. But the guv will be able to tell us. Say, I'd better put them in this.”

Taking out his watch, he drew off the soft chamois leather case, and carefully transferred the output of the mammoth oyster from Pugs palm to this temporary receptacle.

“Now,” cried Jack, leaping to his feet, “let's make for the schooner. The sun's set, and besides, I shan't feel easy until the golden 'un is in a safer place than a waistcoat pocket.”

“That's so,” assented Don. “Point, Pug!”

When they had disappeared in the crowded bazaar, the shark-charmer emerged from behind the tree, and took the road to that part of the beach where the boats lay.

By the time Don and his companions reached the schooner, the brief twilight had deepened into the gray darkness of early night. The pearls were at once shown to Captain Leigh, who confirmed his son's estimate of their value. It would, he said, run well into four figures, if not into five. The golden pearl he pronounced to be of special value.

“Not that it would fetch anything in England,” said he; “but wealthy natives—and more especially priests—stop at nothing to secure a pearl like that. I mean that in a double sense, my lads; so you had better stow your find away in a safe place.”

In the locker under the cabin clock, accordingly, the chamois leather bag with its precious contents was placed. On closing the locker, however, to his annoyance Don found the key to be missing.

“I shall put it in the little locker under the cabin clock,” said Don. “It locks, and there isn't a safer place on board the schooner.”

“Wrap your handkerchief round the bag, so it won't be noticed if any one opens the locker,” suggested Jack. “It will be safe enough then, especially as nobody ever comes here except ourselves and Pug.”

But on quitting the cabin, to their amazement they came face to face with the shark-charmer! He stood at the very bottom of the companionway, within a yard of the cabin door, and directly opposite the clock and locker.

“What are you doing here?” cried Don, advancing upon him angrily.

“Nothing, sab, nothing!” protested the native, dropping a running salvo of salaams as he backed up the steps. “Me only wanting to see big sa'b.”

“Then be off about your business, or you'll get the whipping you missed this morning. Do you hear?” And, without further ado, Salambo made for the deck, where they saw him disappear over the side.

“Do you think he saw us at the locker, Jack?” Don asked uneasily.

“I should think not. But even if he did he wouldn't be any the wiser. He knows nothing about the pearls.”

“True enough,” said Don, and so the subject dropped.

The cabin clock indicated the hour of ten when they turned in for the night. Somehow Don found himself unable to sleep. In spite of every effort he could make to the contrary, his thoughts would run on the pearls. At last he could stand it no longer. Leaping out of his berth, he struck a light and crept noiselessly into the main cabin. The companion door stood open to admit the night air, and his candle flared in the draught.

“I'll get to sleep, perhaps, if I take a look at them,” he said to himself as he made his way to the locker.

An exclamation of alarm burst from his lips. His hand shook so violently that it was with difficulty he could hold the candle. The lid of the locker stood wide open!

Advancing the light, he peered into the receptacle. It contained nothing. Handkerchief, bag, pearls—all had disappeared!

For a moment the discovery paralysed him, body and mind. Then he turned and hurried to Jack's cabin. Jack was snoring. Don shook him fiercely by the shoulder.

“Wake up! The pearls are gone!”

Jack was awake and on his feet in a twinkling. “You're dreaming, old fellow,” said he, seeing Don in his night-clothes. “You're only half awake.” Don did not argue the matter. He simply seized Jack by the arm and dragged him into the main cabin. There the empty locker placed the truth of his assertion beyond dispute.

“What's to be done?” gasped Jack.

“Let us call Pug,” suggested Don. “He may know something about this.”

Puggles slept on deck. In two minutes they were by his side, and he was stretching his jaws in a mighty yawn. Great was his astonishment when he heard of the loss. But he could throw no light on the matter. He had neither seen nor heard anything suspicious. As for Puggles himself, he was above suspicion.

“Come down and let us have another look,” said Jack. “It's just possible, you know, that some one may have been to the locker and accidentally dropped or knocked the case out upon the floor. I can't believe it's gone.”

Just as they reached the bottom of the companion-way, Puggles, who was slightly in advance of his master, stopped short, and called their attention to an object dangling from the handle of the door. Jack caught it up and ran to the table, where the lighted candle stood.

“Merely a string of wooden beads,” said he, tossing the object on the table.

“A native rosary!” cried Don, snatching it up. “I've seen this before somewhere.”

“Sa'b,” broke in Puggles, his eyes the size and colour of Spanish onions, “him shark-charmer rosilly, sa'b!”

“The very same!” cried Don. “I recollect seeing it round his neck this morning.”

“And I recollect seeing it there this evening,” added Jack.

“When we bundled him out of the companionway?”

“Yes.”

“Then how do you account for our finding it on the door-knob, and for its being broken as it is now?”

“Don't you see? The fellow returned, of course.”

“Returned? When?”

“After we saw him over the side; he never went ashore. He sneaked back, and then made off in a tremendous hurry. The position, not to say the condition, in which we found the rosary proves that. Jove! what a pair of fools we've been. That rascally shark-charmer has diddled us out of the pearls.”

Don stared at his friend open-mouthed, yet unable to utter a single word either of assent or doubt, so great was the consternation produced in his mind by Jack's daring theory as to the disappearance of the pearls, and the consequences which must follow if it held good.

“You may take it to be a dead certainty,” resumed Jack, following up his idea, “that when Salambo actually left the ship, the pearls went with him. We made the rascal walk the plank this morning, and he's bound to resent that, of course. In fact, the way in which he shook his fist at us when he went off in the boat shows that he did resent it. Very well, then, there's a readymade motive for you—revenge.”

“That's all right,” said Don, finding his tongue at last, “I'm not boggling over the motive: the value of the pearls is enough motive for any nigger. What puzzles me is this: How did he know we had them in our possession at all?”

“Why, that's as plain as the nose on your face,” replied Jack; “the fellow was on shore at the same time we were, was he not?”

“He was.”

“Well, then, suppose he saw us buy the shells, watched us open them, and, in short, discovered that we had met with a stroke of luck. Then he follows us back here—you saw him yourself, didn't you?”

“I did,” said Don.

“And you see this, don't you?” dangling the rosary before Don's eyes.

“I do; I'm not blind.”

“Then what the dickens more do you want?”

“The pearls,” said Don, laughing. “I'm convinced, old fellow, so no more palaver. Our business now is to run the shark-charmer down. What's the time?”

“Eleven o'clock to the minute.”

“And what start of us do you think he has got?”

“It was about nine when we caught him sneaking, and we turned in at ten.”

“And out again half an hour later. Then the locker must have been rifled between ten and halfpast. That would give him, say, forty-five minutes' start if we were on his track at this identical moment, which we——— What was that? I heard a noise overhead.”

“Some one at the skylight,” said Jack in a whisper. “S-s-sh! I'll slip on deck and see who it is.”

The skylight referred to was situated directly over the cabin table, so that, its sash being then raised some six inches to admit the night air, it afforded a ready means of eavesdropping. Springing lightly up the cabin steps in his stocking feet, Jack took a cautious survey of the deck. The awning had been taken in at nightfall, and a full moon shone overhead, making the whole deck as light as day. Close beside the skylight, lashed against the cabin, stood a water-butt; and bending carelessly over this he saw one of the native crew. Calling out sharply, he bade him go forward, and the fellow, muttering some half-audible excuse about wanting a drink, slunk away.

“A lascar after water; I don't think he was spying,” said Jack, diving below again. “All the same, we'll keep an eye aloft; that rascally Salambo may have an accomplice among the crew.”

“Very likely; but as I was saying,” resumed Don, in a lower key, “the thief has had ample time to make himself scarce. Now the thing is—how are we to nab him?”

“There are the peons. * Why not get the guv to set them on the fellow's track?”

* Native attendants; pronounced pewns.—J..R. H.

“Why, there's just the difficulty,” said Don, with a despairing gesture. “They all sleep ashore except one or two; and by the time we woke the governor, explained matters to him, and got the fellows started, there'd be no end of delay. Besides, the rascal would naturally be on the look-out for the peons, and either give them the slip or bribe them to let him off.”

“That's so; whatever's done must be done sharp.”

“Just what I was going to say,” continued Don. “The schooner, you see, sails for Colombo in two or three days' time at the most, and it would put the governor to no end of inconvenience to despatch half-a-dozen peons on an errand like this just now. Fact is, I doubt if he'd do it at all, and we might go whistle for our pearls. No, I've a better plan than that to propose. There's no need to trouble the guv at all; we'll go ashore and capture the thief ourselves.”

“Capital!” cried Jack; “I'd like nothing better. When shall we start?”

“At once. There's a bright moon, the fellow has only about an hour's start, and with ordinary luck we ought to run him down by daybreak at the very——”

“Hist!” said Jack suddenly; “there's some one at the skylight again. Wait a minute—I'll soon put an end to his spying.”

Clearing the ladder at a bound, he emerged upon the deck before the listener was aware of his approach. The spy was actually bending over the open skylight. He was there for no good or friendly purpose—that was evident.

“You're not after water this time, anyhow,” said Jack, hauling him off the cabin with scant ceremony. “Didn't I tell you to go forward? You'll obey orders next time, perhaps;” and drawing off, he felled him to the deck with a single blow.

The lascar picked himself up and scuttled forward, muttering curses beneath his breath.

“There,” said Jack quietly, as he rejoined those below, “we'll not be spied upon again to-night, I fancy. Now, Don, for the rest of your plan.”

“That's soon told. I propose that we follow the thief at once. The only difficulty will be to get on his track.”

“Marster going take me?” queried Puggles anxiously.

“Why, of course,” said Don; “we couldn't manage without you, Pug.”

“Then,” said Puggles, grinning, “me soon putting on track; me knowing place Salambo sleeping plenty nights.”

“Good; there's something in that,” said Don. “He is sure to go straight to his den on leaving the schooner, though it's hardly likely he'll remain there to sleep. Still, he might. 'Twill give us a clue to his whereabouts, at all events. And now, Jack, ready's the word.”

No time was to be lost, and quietly and quickly their preparations were completed. These were by no means extensive: they fully expected to return to the schooner by break of day. A revolver, half-a-dozen rounds of ammunition, and a few rupees-disposed in their pockets, they stole noiselessly on deck. The night was one of breathless calm, and the watch lay stretched upon their backs, snoring away the sultry hours of duty. Save our three adventurers, not a living thing was astir; not a sound broke the stillness of the night; and high overhead the moon floated in ghostly splendour.

The boat, as it chanced, lay on that side of the schooner farthest from the shore; and in order to shape their course for the beach it was necessary to round the vessel's bows. Puggles held the tiller-ropes, but in doing this he miscalculated his distance, and ran the boat full tilt against the schooners cable.

“Keep her off, Pug!” cried his master in suppressed, half-angry tones. “Can't you see where you're steering?”

In the momentary confusion a figure appeared for a moment above the schooner's bulwarks. Then a glittering object hurtled through the moonlit air and struck the gun'le of the boat immediately abaft the thwait on which Jack sat. Jack uttered a stifled cry and dropped his oar.

“What's the matter?” said Don impatiently, as the boat swung clear of the cable. “Pull, old fellow; we've no time to lose.”

“Better lose a little time than one's life,” muttered Jack through his set teeth. “Look here!”

Turning in his seat Don saw, still quivering in the gun'le of the boat where its point had stuck, a sailor's heavy sheath-knife. In its passage it had slashed open the shoulder of Jack's coat, grazing the flesh so closely as to draw blood—the first shed in the quest of the golden pearl.

Jack passed it off with an air of indifference.

“A mere scratch,” said he; “but a close shave all the same. The work of that treacherous lascar I knocked down a while back. Saw his ugly head-piece above the rail just now, don't you know. There's no time to pay him out now, but if ever he interferes with me again he'll get his knife back, anyhow!” and wrenching the formidable weapon free of the plank, he thrust it into his belt and again bent to his oar.

“If that fellow's an accomplice of the shark-charmer, it looks as though they meant business,” commented Don, seconding his companion's stroke.

“So do we, if it comes to that,” was Jacks significant retort,

For some time they pulled in silence, the creaking of the oars in the rowlocks and the soft purling of the water about the boat's prow being the only sounds audible. When within a couple of hundred yards of the gleaming surfline, Don suddenly broke the silence.

“Hold hard, Jack! Do you make out anything astern there—anything black on the water?”

“Nothing,” said Jack, after a moment's hesitation.

“It's gone now, but I saw it quite plainly. Struck me it looked like a man's head. Must have been a dugong.”

“Or the lascar,” suggested Jack. “He's safe to follow us if he's an accomplice.”

“Hardly safe with so many sharks about,” rejoined Don, “unless his master has provided him with an extra potent charm.”

Five minutes later, the boat having meanwhile been beached upon the deserted sands, Puggles was rapidly “pointing” for the bazaar, where the shark-charmer slept o' nights. That they should find him there to-night, however, was almost too much to hope. He had probably “made tracks” with all speed after securing the pearls. All the same, a visit to the bazaar might furnish some clue to his present whereabouts.

“Stop!” said Don, when within fifty yards of the spot. “The whole place will be astir in two minutes if we show ourselves, Jack. We'd better send Pug on ahead to reconnoitre while we wait here. Do you know the hut he usually sleeps in, Pug?”

“Me finding with me eyes shut, sa'b.”

“Good! Now listen. Make your way to this hut as quietly as you can, and ascertain whether he's there or not. If he's there, don't wake him, but come back here as fast as your legs can carry you. If he's not there, try and find out where he's gone.”

“Put your cloth over your head so he won't recognise you, and say you've come on business,” put in Jack. “Pretend you want a charm, or something of that sort.”

“Not a bad idea,” assented Don. “You understand, Pug?”

“Me understanding, sa'b.”

“Then be off with you, sharp!”

Puggles promptly disappeared.

In the course of ten minutes he returned, accompanied by a native muffled from head to heel in a blanket.

“Surely he can't have induced the old fellow to return with him!” whispered Jack excitedly.

But in this surmise he was wrong. It was not the shark-charmer.

“Dis one bery nice black man; plenty talk got,” said Puggles, by way of introduction, when he reached the spot where his master and Jack were waiting. “Him telling shark-charmer no here; he going one village.”

“Just as I feared,” said Don. “How far is it to this village, Pug!”

“Him telling one two legs,” replied Puggles, meaning leagues. “Village 'long shore; marster giving one rupee, dis'black man showing way.”

Without further parley the rupee was transferred from Don's pocket to the stranger's outstretched palm, and off they started. After following the beach for about a mile, their guide turned his back upon the sea and struck inland, leading them a tortuous course amid ghostly, interminable sand-hills, where the mournful sighing of the night-wind through the tall silver-grass, and the howling of predatory jackals, added to the weird loneliness of the scene. A blurred furrow in the yielding sand formed the only footpath. So slow was their progress that when at last the guide pointed out the village a halfmile ahead, Don, on consulting his watch, found it to be three o'clock. They had wasted fully two hours in walking six miles.

While they were still some little distance short of the village, the guide stopped, and pointing out a pool of water which shone like a boss of polished silver amid the sand-hills, asked leave to go and slake his thirst. His request granted, he disappeared amid the dunes.

“Do you know,” said Jack, while they were impatiently awaiting his return, “I fancy I've seen that fellow before, though I can't for the life of me recall where.”

The guide not returning, they at length went in search of him. But Pug's “bery nice black man” was nowhere to be seen.

“Looks as if he meant to leave us in the lurch,” Jack began, when a shout of “Him here got, sa'b!” from Puggles, brought them back to the footpath at a run.

The new-comer, however, was not the missing guide, but a stranger. He had been belated at the bazaar, he told them, and was now making his way home to the village close by. In answer to inquiries concerning the shark-charmer, he imparted a startling piece of news.

The shark-charmer had indeed taken his departure from the bazaar, but not to this village. He had, the stranger asserted, embarked in a coasting vessel bound for the opposite side of the Strait.

Don uttered an exclamation of impatience and dismay.

“He will be safe on the Madras coast by daybreak!” he cried.

“Him there coming from, sa'b,” put in Puggles.

“And that lying guide,” added Jack savagely, “was an accomplice, left behind to throw us off the scent. Don't you remember you saw some one swimming after the boat? I'll lay any odds 'twas the lascar. He got to the bazaar ahead of us—he could easily manage that, you know, by running along the sands—muffled himself up so that I shouldn't recognise him, and then led us on this fool's errand while his master made off. Well, good-bye to the golden pearl!”

“Not a bit of it!” cried Don resolutely. “I, for one, shan't relinquish the quest, come what may. Back we go to the schooner! Then, with the governor's consent, we'll go further. Point, Pug!”

Jack seconding this proposal heartily, they rewarded the communicative native, and with unflagging determination retraced their steps. By four o'clock they had traversed something more than half the distance. The dawn star was now high above the eastern horizon. A rosy flush in the same quarter warned them that day was rapidly approaching. Suddenly, out of the gray distance ahead, a dull booming sound floated to their ears.

“The schooner's signal gun!” exclaimed Don. “Why, it's too early yet by a good hour for the boats to put out. What's the governor about, I wonder?”

“There it goes again!” cried Jack. “I never knew it to be fired twice of a morning, did you?”

“Never,” said Don uneasily. “Come, let us get on!”

Off again at their best speed, until at length the heavy path was exchanged for the smooth, hard sand of the beach. On this it was possible to make better time, and by five o'clock they were within half a mile or so of the bazaar. It was now daylight; but a sharp bend in the coast-line, and the sand-hills which here rose steeply from the beach on their left, as yet concealed both the landing-place and the schooner from view.

Puggles, who in spite of his shortness of limb had throughout maintained the lead by several rods, suddenly stopped, and fell to shouting and gesticulating wildly. Breaking into a run, Don and Jack speedily came up with him.

“Look, sa'b, look!” gasped Puggles, pointing down the coast with shaking hand.

Far away on the horizon appeared the white canvas of a vessel bowling along before the fresh land breeze, with a fleet of fishing-boats spreading their fustian-hued wings in her wake.

The spot where our adventurers had last seen the schooner at anchor was deserted. She was gone!

The schooner had sailed!

When the dismay caused by this unlooked-for turn of events had somewhat abated, Jack, catching sight of the black boy's lugubrious face, fell to laughing heartily.

“After all,” said Don, following his chum's example, “it's no use crying over spilt milk. I'm not sure but this is the best thing that could have happened, Jack.”

“My opinion exactly. We began the quest without the guv's knowledge, and nolens volens we must continue it without his consent. What's the next piece on the programme, old fellow?”

Don pondered for a moment.

“Why, first,” said he, “we must ascertain whether that fellow told us the truth about the shark-charmer's having gone across the Strait. If it turns out that he has, then I'm not exactly clear yet as to what our next move will be, though I've an idea. You shall hear what it is later on.”

“All right,” said Jack “whatever course you decide on, I'm with you heart and fist, anyhow.”

Arrived in the vicinity of the bazaar, Puggles was at once despatched to learn what he could of the shark-charmer's movements. In half an hour he returned. His report confirmed that which they had already heard. The shark-charmer had undoubtedly sailed for the opposite side of the Strait.

Throwing himself upon his back in the shade of the banyan tree which had witnessed the discovery of the pearls, Don drew his helmet over his eyes, and pondered long and deeply.

“Jack,” said he at length, “how much money have you?”

Jack turned out his pockets.

“Barely a rupee and a half,” said he,

“And I,” added Don, turning out his own, “have four and a half.”

“Here one rupee got, sa'b,” cried Puggles, tugging at his waist-cloth. “Me giving him heart and fist, anyhow.”

“That makes seven rupees, then,” said his master, laughing; “not much to continue the quest on, eh, Jack?”

“We'll manage,” said Jack hopefully. “But, I say, you haven't told us your plans yet, old fellow.”

“Oh, our course is as plain as a pikestaff. We'll hire a native boat, and follow the shark-charmer across the Strait. The only question is, where's enough money to come from?”

“Don't know,” said Jack, “unless we try to borrow it in the bazaar.”

At this juncture there occurred an interruption which, unlikely though it may seem, was destined to lead to a most satisfactory solution of this all-important and perplexing question.

While this conversation was in progress Puggles had seated himself at a short distance behind his master, and throwing his turban aside, proceeded to untie and dress the one tuft of hair which adorned the back of his otherwise cleanly shaven head.

Directly above the spot where he sat there extended far out from the trunk of the banyan a branch of great size, from which dangled numerous rope-like air-roots, which, reaching to-within a few feet of the ground, swayed to and fro in the morning breeze. Out along this branch crept a large black monkey, which, after taking a cautious survey of Puggles and his unconscious neighbours, glided noiselessly down one of the swinging roots, and from its extremity dropped lightly to the ground within a yard of the discarded turban. Cautiously, with his cunning ferret-eyes fastened on the preoccupied Puggles, the monkey approached the coveted prize, snatched it up, and with a shrill cry of triumph turned tail and fled.

Looking quickly round at the cry, Puggles took in the situation at a glance.

“Sa'b! Sar!” he shouted, invoking the aid of both his master and Jack in one breath, “one black debil monkey me turban done hooking;” and leaping to his feet he gave chase.

“Why,” said Jack, “the little beast is making a bee-line for the old fort. It must be Bosin, Captain Mango's pet monkey.”

“Captain Mango!” cried Don, as though seized with some sudden inspiration. “Never thought of him until this minute!” and, clapping on his helmet, he set off at a run after Puggles and the monkey.

Away like the wind went the monkey, the stolen turban trailing after him through the sand like a great serpent; and away went Puggles, his back hair flying. But while Puggles was short of wind, the monkey was nimble of foot. The race was, therefore, unequal from the start, its finish more summary than satisfactory; for as Puggles ran, with his eyes glued upon the scurrying monkey, and his mouth wide-stretched, his foot unluckily came in contact with a tree-root, which lay directly across his path. Immediately beyond was a bed of fine soft sand, and into this he pitched, head foremost. Just then his master came up, with Jack at his heels.

“Sa'b! Sar!” spluttered Puggles, knuckling his eyes and spitting sand right and left, “debil monkey done stole turban. Where him going, sa'b?”

“Come on, Pug,” his master called out as he ran past; “your headgear's all right—the monkey's taken it into the fort.”

The structure known as “the fort” occupied the summit of a sandy knoll, about which grew a thick plantation of cocoanut palms, seemingly as ancient as the fort itself. The walls of the enclosure had so crumbled away in places as to afford glimpses of the buildings within. These were two in number—one an ancient godown, as dilapidated as the surrounding wall; the other, a bungalow in excellent repair, blazing in all the glory of abundant whitewash.

Towards this building, after passing the tumble-down gateway, with its turreted side-towers alive with pigeons, Don and his companion shaped their course; for this was by no means their first visit to the fort. A broad, low-eaved verandah shaded the front of the bungalow, and upon this opened two or three low windows and a door. As they drew near a shadow suddenly darkened the doorway, and there emerged upon the verandah an individual whose pea-jacket and trousers of generous nautical cut unmistakably proclaimed him to be a seafaring man. About his throat a neckerchief of a deep marine blue was tied in a huge knot; while from beneath the left leg of his wide pantaloons there projected the end of a stout wooden substitute for the real limb.

On catching sight of his visitors an expression of mingled astonishment and pleasure overspread his honest, bronzed features.

“Shiver my binnacle!” roared he, advancing with a series of hitches and extended hand to meet them. “Shiver my binnacle if it ain't Master Don and Master Jack made port again! An' split my topsails, yonder's the little nigger swab a-bearin' down under full sail out o' the offin! Lay alongside the old hulk, my hearties, an' tell an old shipmate what may be the meaning of it all. Where away might the schooner be, I axes?”

“To tell you the truth, Captain Mango,” said Don, shaking the old sailor by the hand in hearty fashion, “on that point we're as much at sea as yourself. We pulled ashore last night on a little matter of business of our own—without the skipper's knowledge, you understand—and when we returned here this morning the schooner had sailed.”

“Shiver my figger-head if ever I hear'd any yarn to beat that!” roared the captain, gripping Jack by the hand in turn. “An' d'ye mean to say now, as ye ain't atween decks, sound asleep in your bunks, when the wessel gets under weigh?”

“Not we,” cried Jack, laughing at the captain's puzzled face and earnest manner; “we were miles down the coast just then.”

“Belay there!” sang out the captain, rubbing his stubbly chin in greater perplexity than ever. “Blow me if I'm able to make out what tack you're on, lad. For, d'ye see, I lays alongside o' the wessel somewheres about eight bells—arter they fires the signal gun, d'ye see—to pay my 'specks to the master like, and shiver my bulk-head, when I axes what might your bearin's be, lads, he ups an' says, 'The younkers be below decks,' says he; an' so he weighs anchor, an' shapes his course for Colombie.”

“It's plain there's been a double misunderstanding,” said Don; “we knew nothing of the guv's intention to sail this morning, and he knew nothing of our absence from the schooner. He, of course, thought we were below, and so sailed without us. As I hinted just now, we're ashore on business of our own. Fact is, we're in a fix, and we want your advice.”

“Adwice is it?” cried the captain, leading his visitors indoors; “fire away, lads, till I hears what manner o' stuff you wants, and the wery best a water-logged old seaman can give ye, ye shall have—shiver my figger-head if ye shan't! Howsomedever, afore we lays our heads together like, I'll pipe the cook and order ye some wittles.” This hospitable duty performed, the captain threw himself into a chair with his “main-brace,” as he jocosely termed his wooden leg, extended before him, and, bidding Don proceed with what he had to say, composed himself to listen. Whereupon Don recounted the cause and manner of the shark-charmer's punishment, the discovery and subsequent loss of the pearls, together with their reasons for suspecting the shark-charmer of the theft, as well as how they had been tricked by the latter's supposed accomplice, and on making their way back to the beach had found, not the schooner as they expected, but a deserted roadstead.

“The thief has crossed the Strait, there's no doubt about that,” he concluded. “We want to hire a boat and go in pursuit of him; but the governor's sudden departure has placed us in a dilemma. The fact is, captain, we haven't enough cash to——”

“Belay there!” roared the captain, stumping across the room to a side-table. “Hold hard, lads, till I has a whiff o' the fragrant! Shiver my maintop! there's nothing like tobackie for ilin' up a seaman's runnin' gear, says you!”

Filling a meerschaum pipe of high colour and huge dimensions from a pouch almost as large as a sailor's bag, the captain reseated himself, and for some minutes puffed away in silence.

“Shiver my smokestack!” cried he at last, slapping his thigh energetically with his disengaged hand, “the thing's as easy as boxin' the compass, lads! You axes me for adwice: my adwice is, up anchor and away as soon as ye can. Supplies is low, says you. What o' that? I axes. There's a canvas bag in the old sea-chest yonder as'll charter all the boats hereabouts, if so be as they're wanted, which they ain't, d'ye mind me. Ye can dror on the canvas bag, lads, an' welcome—why not? I axes. An' there's as tight a leetle cutter in the boat-house below as ever ye clapped eyes on—which the Jolly Tar's her name—what's at your sarvice, shiver my main-brace if it ain't! An' blow me, as the fog-horn says to the donkey-engine, I'll ship along with ye, lads!”

“An' a-sailin' we'll go, we'll go;

An' a-sailin' we will go-o-o!”

he concluded, with a stave of a rollicking old sea-song.

“Hurrah! You're a trump, captain, and no mistake!” cried Jack, while Don sprang forward and gripped the old sailor's hand with a heartiness that showed how thoroughly he appreciated this generous offer.

“Why, y'see, lads,” explained the captain apologetically, “'twould be ekal to a-sendin' of ye to Davy Jones if I was to let ye go pokin” round this 'ere Strait alone. Now me—rope-yarn an' marlin-spikes!—there ain't a reef, nor a shool, nor yet a crik atween Colombie an' Jafna P'int but what's laid down on this 'ere old chart o' mine,” tapping his forehead significantly. “An' besides I'm a-spilin' for a bit o' the briny, so with you I ships—an' why not? I axes.”

“And right glad of your company and assistance we'll be, captain,” said Don. “The main difficulty will be, of course, to discover to what part of the Indian coast the thief has gone.”

The captain puffed thoughtfully at his pipe.

“Why, as for that,” said he at length, “I've an idee as I knows his reckonin', shiver my binnacle if I ain't! But that's neither here nor there at this present speakin'. Ballast's the first consideration, lads; so dror up your cheers an' tackle the perwisions.”

When they had complied with this welcome invitation to the entire satisfaction of the captain and their own appetites, “Now, lads,” said the old sailor gaily, “do ye turn in an' snatch a wink o' sleep, whiles I goes an' gets the cutter ready for puttin' to sea. For, says you, look alive's the word if so be as we wants to overhaul the warmint as took the treasure in tow. Spike my guns!—we'll make him heave to in no time!

“For all things is ready, an' nothing we want,

To fit out our ship as rides so close by;

Both wittles an' weapons, they be nothing scant,

Like worthy sea-dogs ourselves we will try!”

Trolling this ditty, the captain stumped away, while his guests made themselves as comfortable as they could, and sought the slumber of which they stood so much in need.

It was late in the afternoon when they woke. Puggles had disappeared. Proceeding to the beach, they found the captain, assisted by a small army of native servants, busily engaged in putting the-finishing touches to his preparations for the proposed voyage. Just above the surf-line lay the Jolly Tar—a trim little craft, fitted with mast-and sprit, whose sharp, clean-cut lines betokened possibilities in the way of speed that promised well for the issue of their enterprise. In the cuddy, amid a bewildering array of pots, pans, and pannkins, Puggles had already installed himself, his shining face a perfect picture of self-complacent good-nature, whilst Bosin, newly released from durance vile, sat in the stern-sheets, cracking nuts-and jabbering defiance at his black rival.

“A purty craft!” chuckled the captain, checking for a moment the song that was always on his lips, as he led his visitors to the cutters side; “stave my water-butt if there's anything can pull ahead of her in these 'ere parts. Everything shipshape 'an' ready to hand, d'ye see—wittles for the woyage, an' drink for the woyagers. Likewise ammunitions o' war,” cried he proudly, pointing out a number of muskets and shining cutlasses, which a servant just then brought up and placed on board.

“Bath, wittles an' weapons, they be nothing scant,

So like worthy sea-dogs ourselves we will try.”

“What with the cutlasses and guns, and the captain's wooden leg, to say nothing of our small-arms, Don,” said Jack, “we'd better set up for buccaneers at once.”

“Shiver my main-brace! a wooden leg ain't sich a bad article arter all,” rejoined the captain; “specially when a seaman falls overboard. With a life-buoy o' that nater rove on to his starn-sheets, he's sartin to keep one leg above water, says you.”

“No doubt of that, even if he goes down by the head,” assented Don, laughing. “But, I say, captain, what's in the keg—spirits?”

“Avast there!” replied the captain, half shutting one eye and contemplating the keg with the other, “that 'ere keg, lads, has stuff in its hold what's a sight better'n spurts. Gunpowder, lads, that's what it is; and spike my guns if we don't broach the same to the health of old Salambo when we falls in with him. What say you, lads?

“We always be ready,

Steady, lads, steady;

We'll fight an' we'll conquer agin an' agin.”

“I hope we shan't have to do that, captain,” said Jack gravely. “But powder or no powder, we'll pay the beggar out, anyhow.”

“Right, lad; so we'll just take the keg along with us in case of emargencies like. Shiver my compass, there's no telling aforehand what this 'ere wenture may lead to.”

To whatever the venture was destined to lead, preparations for its successful inception went on apace, and by nightfall all was in readiness. The captain declaring that he “couldn't abide the ways o' them 'ere jabbering nigger swabs when afloat,” the only addition to their numbers was a single trusty servant of the old sailor's, who was taken along rather with a view to the cutter's safety when they should be ashore than because his assistance was required in sailing her.

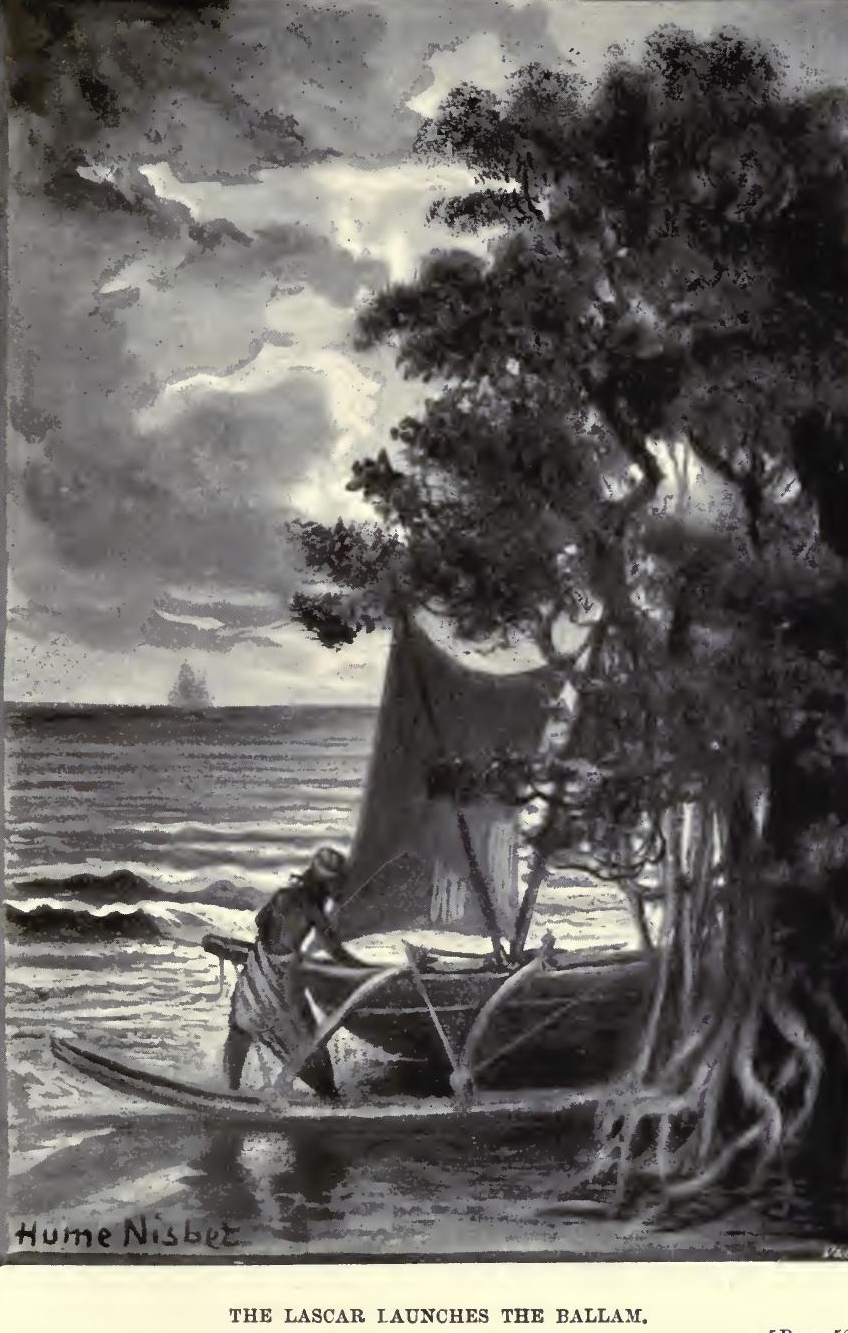

Don having despatched an overland messenger with a letter to his father, explaining their absence and proposed undertaking, as the full moon rose out of the eastern sea the cutter was launched.

Half an hour later, with her white sails bellying before the freshening land-breeze, she bore away for the opposite shore of the Strait, on that quest from which one at least of those on board was destined never to return.

While her sails were yet visible in the moonlit offing, a native crept down to the deserted beach. He was a dark-skinned, evil-featured fellow; and the moonlight, falling upon his face, showed his left temple to be swollen and discoloured as from a recent blow. On his shoulder he carried a paddle-and a boathook.

“The wind will drop just before dawn,” he muttered, as he stood a moment noting the strength and direction of the breeze. “Then, you white-devil, then!” and he patted the boathook affectionately, as if between him and it there existed some secret, dark understanding.

Selecting a ballam or “dug-out” from amongst a number that lay there, he placed the boathook carefully in the bottom of the frail skiff, and launched it almost in the furrow which the cutter's keel had ploughed in the yielding sand. Then springing in, and plying his paddle with rapid strokes, he quickly disappeared in the cutter's wake.

Her light sails winged to catch every breath of the light but steady breeze that chased her astern, the cutter for some hours bowled through the water merrily. In the cabin Puggles and the captain's Black servant snored side by side; whilst Don and Jack lolled comfortably just abaft the mast-, where the night wind, soft and spicy as the breath of Eden, would speedily have lulled them to slumber but for the excitement that fired their blood. The Captain was at the tiller, Bosin curled up by his side.

“If this 'ere wind holds, lads,” exclaimed the old sailor abruptly, after a prolonged silence on his part, “we'd orter make the island agin sunrise, shiver my forefoot if we don't!”

Don looked up with half-sleepy interest. “Island, captain? I thought we were heading straight for the Indian coast.”

“Ay, so we be, straight away. But, y'see, lad, as I hinted a while back, I has a sort o' innard idee, so to say, as the old woman ain't on the mainland.”

“What old woman?” queried Jack, yawning. “Didn't know there was one in the case, captain.”

The old sailor burst into a roar of laughter. “An' no more there ain't, lad,” chuckled he; “an' slit my hammock if we wants one, says you. Forty odd year has I sailed the seas, an' hain't signed articles with any on 'em yet. A tight leetle wessel's the lass for me, lads; for, unship my helm! she never takes her own head for it, says you.”

“Then what about the old woman you mentioned captain?” said Don banteringly.

“Avast there now! An' d'ye mean to say,” demanded the captain incredulously, “as you ain't ever hear'd tell o' the fish what sails under that 'ere name? And a wicious warmint he is, too, shiver my keelson! Hysters is his wittles, an' pearls his physic; he lives on 'em, so to say; an' so I calls the cove as took them pearls o' your'n in tow an old woman; an' why not, I axes?”

“But what about the island you spoke of just now, captain?”

“Why, d'ye see, it's this way, lads; there's an island off the coast ahead, a sort o' holy place like, where them thievin' natives goes once a year an' gets salwation from their sins. Howsomedever, that's neither here nor there, says you; the p'int's this, lads: Somewheres about the month o' March, which is this same month, says you, here the priests flocks from all parts, an' here they stays until they gets a purty pocketful o' cash. Now, my idee's this, d'ye see: the old woman—which I means Salambo—lays alongside the schooner an' takes them pearls o' your'n in tow. What for? says you. Cash, says I. An' so, shiver my main-brace, he shapes his course for this 'ere island, an' sells 'em to the priests.”

“Very likely,” assented Don. “He's bound to carry them to the best market, of course.”

“And equally of course the best market is where the most priests are. By Jove, you have a headpiece, captain!” put in Jack.

“I'm afraid, though,” resumed Don, after a moment's silence, “I'm afraid it's not going to be so easy to come at the old fellow as we think. You say this island's a sort of holy place; well, it's bound to be packed with natives to the very surf-line in that case. Rather ticklish work, I should think, taking the old fellow among so many pals. There's the getting ashore, too; what's to prevent their sighting us?”

“Belay there!” roared the captain, vigorously thumping the bottom of the boat with his wooden leg. “Shiver my main-brace! what sort o' craft do ye take me for, I axes? A island's a island the world over—a lump o' land what's floated out to sea. Wery good, that bein' so—painters an' boathooks!—ain't it as easy a-boardin' of her through the starn-ports as along o' the forechains?”

“Oh, you mean to make the back of the island, and steal a march on old Salambo from the rear, then?” cried Don. “A capital idea!”

“You're on the right tack there, lad,” assented the captain. “There's as purty a leetle cove at the backside o' that island as ever wessel cast anchor in, an' well I knows it, shiver my binnacle! Daylight orter put us into it, if so be—— Split my sprit-sail, lads, if it ain't a-fallin' calm!”

An ominous flapping of the cutter's sails confirmed the captain's words. During the half-hour over which this conversation extended the wind had gradually died away until scarcely a movement of the warm night air could be felt. The cutter, losing her headway, rolled lazily to the motion of the long, glassy swell. Consulting his watch, Don announced it to be three o'clock.

“This 'ere's the lull at ween the sea-breeze an' the land-breeze,” observed the captain complacently, working the tiller from side to side as if trying to coax renewed life into the cutter. “How-somedever, it hadn't orter last long. Stow my sea-chest!—we'll turn in an' catch a wink o' sleep atween whiles. Here, Master Jack, lad! take a turn at the tiller, will 'ee?”

Settling himself in the captain's place, with instructions to call that worthy sea-dog should the wind freshen, Jack began his first watch. Becalmed as they were, the tiller was useless, so he let it swing, contenting himself with keeping a bright look-out. But soon he concluded even this to be an unnecessary precaution. Not a sail was to be seen on the moonlit expanse of ocean; and even had a score been in sight, there would still have been no danger whatever, in the absence of wind, of their interfering with the cutter. In fine, so secure did he consider their position, and so soporific an influence did the comfortable snoring of Don and the captain exercise upon him, that in a very short time his head sank upon his breast, and he fell asleep.

He had slept soundly for perhaps an hour, when a cold, touch upon the cheek startled him into consciousness.

Rousing himself, he found Bosin at his elbow. The monkey for some reason had left his masters side, and it was his clammy paw, Jack now perceived, that had awakened him. It almost looked as if the monkey had purposely interrupted his slumber. But what had roused the monkey? Jack rose to his feet, stretched himself, and looked about him.

The night was, if anything, more breathlessly calm than when he had relieved the captain. Upon the unruffled, deserted sea the moonlight shimmered with a brilliancy uncanny in its ghostliness. From the cutter straight away to and around the horizon not an object, so far as he could make out, darkened the surface of the water, except under the cutter's larboard bow, where the moon-cast shadow of the sail fell. He fancied he saw something move there, close under the bow where the shadow lay blackest. The next instant it had disappeared.

“All right, Bosin, old chap,” said he, stroking the monkeys back; “a false alarm this time—back to your quarters, old fellow!”

The monkey, as if reassured by these words, crept away to his master's side, whilst Jack resumed his seat, and again dozed off.

Not for long, however. It was not the monkey this time, but a sudden and by no means gentle thud against the cutters side that roused him. Awake in an instant, he sprang to his feet with a startled exclamation. Close under the cutter's quarter lay a canoe, and in the canoe there stood erect a native, with what appeared to be a boathook poised above his head. All this Jack took in at a glance.

“Boat ahoy! Who's that?” he cried sharply, his hand instinctively seeking the knife at his belt.

For answer came a savage, muttered imprecation; and the boathook, impelled with all the strength of the native's muscular arms, descended swiftly through the air. Starting aside, Jack received the blow' upon his left arm, off which the heavy, iron-shod weapon glanced, striking the gun'le of the boat with a resounding crash.

“The lascar!” muttered Jack between his teeth, as he stepped back a pace and whipped out his knife in anticipation of a renewal of the attack.

But the lascar, baffled in his attempt to take his enemy by surprise, did not repeat the blow. Instead, he drew off, and with all his strength drove the iron point of the boathook through the cutter's side below the water-line.

“By Heaven!” cried Jack, as he perceived his intention, “I'll soon settle scores with you, my fine fellow.”

Springing lightly upon the gunle, at a single bound he cleared the few yards of open water intervening between the cutter and the canoe, and with all the impetus of his leap drove the knife into the lascar's shoulder up to the very hilt.

The lascar went overboard like a log. The canoe overturning at the same instant, Jack followed him.

The noise of the scuffle having roused the sleepers, all was now wild commotion on board the cutter; Captain Mango roaring out his strange nautical oaths, and stumping hither and thither in search of something with which to stop the leak; Don shouting wildly at Jack, as he hastily threw off shoes and coat to swim to his assistance. Before either well knew what had actually happened, Jack was alongside.

“What's the matter? Are you hurt?” Don inquired anxiously, giving him a hand over the side.

“Hurt? No, not a scratch,” said Jack lightly, scrambling inboard, and proceeding to wring the water from his dripping garments. “A narrow squeak, though. That lascar villain has got his knife back, anyhow.”

“Who?” cried Don in amazement; for, amid the confusion, neither he nor the captain had seen the native.

“The lascar. What else do you suppose I went over the side for? I dozed off, you see, captain,” said Jack, as the old sailor came stumping up with extended hand, “and that lascar dog, who must have seen us sail and paddled after us, stole a march on me, and tried to crack my nut with a boathook. Lucky for me, he ran his canoe against the side and woke me up. Got on my feet just in time to dodge the blow. Then he smashed the boathook through the side. By Jove! I forgot that. We must stop the leak, or we'll fill in no time.”

“Stave my quarter!” roared the captain, detaining him as he was about to rush aft. “The leak's stopped, lad; but blow me if ever I hear'd anything to beat this 'ere yarn o' your'n, so spin us the rest on it.”

“That's soon done,” resumed Jack. “When I found the fellow wouldn't give me a fair show, I boarded him, captain, and treated him to a few inches of cold steel. He won't trouble us again, I reckon!”

Scarcely had he finished speaking when Don gripped his arm and pointed to where, a dozen yards away, the bottom of the canoe glistened in the moonlight. A dark object had suddenly appeared alongside the overturned skiff. Presently a surging splash was heard.

“Shiver my keelson if he ain't righted the craft!” roared the captain, snatching up one of the muskets as the lascar was seen to scramble into the canoe and paddle slowly away.

Don laid a quick hand upon the old sailor's arm.

“Let the beggar go,” said he. “He'll never reach land with that knife in him.”

“Maybe not, lad,” replied the captain, shaking off the hold upon his arm and taking the best aim he could, considering the motion of the boat. “Bloodshed's best awoided, says you. Wery good; all' the best way to awoid it, d'ye mind me, is to send yon warmint to Davy Jones straight away. Consequential, the quality o' marcy shan't be strained on this 'ere occasion, as the whale says when he swallied the school o' codlings.” And with that he fired.

The lascar was seen to discontinue the use of his paddle for a moment, and then to make off faster than before.

The old sailor's face fell.

“Spike my guns, I've gone and missed the warmint!” said he. “Howsomedever, we'll meet again, as the shark's lower jaw says to the upper 'un when they parted company to accomidate the sailor. An' blow me, lads, here comes the wind!

“Ay, here's a master excelleth in skill,

An' the master's mate he is not to seek;

An' here's a Bjsin ull do our good will,

An' a ship, d'ye see, lads, as never had leak.

So lustily, lustily, let us sail forth!

Our sails he right trim an' the wind's to the north!”

It was now five o'clock, and as day broke the cutter, with a freshening breeze on her starboard quarter, bore away for the island, now in full view. When about a mile short of it, however, the captain laid the boat's head several points nearer the wind, and shaped his course as though running past it for the mainland, which lay like a low bank of mist on the horizon. In the cuddy Puggles was busy with preparations for breakfast, whilst Don lolled on the rail, watching the shore, and idly trailing one hand in the water.

“Hullo! what's this?” he exclaimed suddenly, examining with interest a fragment of dripping cloth that had caught on his hand. “Jack, come here!”

Jack happened to be forward just then, hanging out his drenched clothes to dry upon an improvised line, but hearing Don's exclamation, he sprang aft. Somehow he was always expecting surprises now.

“Look here,” said Don, rapidly spreading out the soaked cloth upon his knee, “have you ever seen this before?”

“Not likely!—a mere scrap of rag that some greasy native——” Jack began, eyeing the said scrap of rag contemptuously. But suddenly his tone changed, and he gasped out: “By Jove, old fellow, it's not the handkerchief, is it?”

“The very same!” replied-Don, rising and hurrying aft to where the captain stood at the tiller. “I say, captain, you remember my telling you how I tied a handkerchief round that bag of pearls? Well, here's the identical 'wipe.' with my initials on it as large as life. Just fished it out of the water.”

For full a minute the old sailor stared at him open-mouthed. Then: “Flush my scuppers,” roared he, “if this 'ere ain't the tidiest piece o' luck as ever I run agin. We've got the warmint safe in the maintop, so to say, where he can't run away—shiver my main-brace if we ain't!”

“Thanks to your clear head, captain,” said Don. “It certainly does look as if he had come straight to the island here.”

“We'll purty soon know for sartin; we're a-makin' port hand over fist,” rejoined the captain, bringing the cutter's head round, and running under the lee of the island.

This side, unlike the wind-swept seaward face, was thickly clad in jungle, above which at intervals towered a solitary palm like a sentinel on duty. No traces of human habitation were to be seen; for a rocky backbone or ridge, running lengthwise of the island, isolated its frequented portion from this jungly half. Midway between the extremities of this ridge rose two hills: one a symmetrical, cone-shaped elevation, clad in a mantle of jungle green; the other a vast mass of naked rock, towering hundreds of feet in air, and in its general-outline somewhat resembling a colossal kneeling elephant. As if to heighten the resemblance, there was perched upon the lofty back a native temple, which looked for all the world like a gigantic howdah.

“D'ye see them elewations, lads?” cried the captain, heading the cutter straight for what-appeared to be an unbroken line of jungle. “A. brace o' twins, says you. Wery good; atween 'em lies as purty a leetle cove as wessel ever cast anchor in—slip my cable if it ain't!”

“Are you sure you're not out of your reckoning, captain?” said Jack, scanning the shore-line with dubious eye. “It's no thoroughfare, so far as I can see.”

“Avast there! What d'ye say to that, now?” chuckled the captain, as the cutter, in obedience to a movement of the tiller, swept round a tiny eyot indistinguishable in its mantle of green from, the shore itself, and entered a narrow, land-locked creek, whose precipitous sides were completely covered from summit to water-line with a rank growth of vegetation. “Out with the oars, lads! a steam-whistle couldn't coax a wind into the likes o' this place, says you.”

The oars run out, they pulled for some distance through this remarkable rift in the hills, the cutter's mast in places sweeping the overhanging jungle; until at last a spot was reached where a side ravine cleft the cliff upon their left, terminating at the water's edge in a strip of sandy beach, thickly shaded with cocoa-nut palms.

“Stow my cargo!” chuckled the captain, as he ran the cutter bow-on into the sand, “a nautical sea-sarpent himself couldn't smell us out here, says you. So here we heaves to, and here we lies until——swabs an' slush-buckets, what's this?”

For the captain had already scrambled ashore, and as he uttered these words he stooped and intently examined the sand at his feet. In it were visible recent footprints, and a long trailing furrow that started from the water's edge and ran for several yards straight up the beach. Where the furrow terminated there lay a native ballam.

Jack was first to espy the canoe. Guessing the cause of the captain's sudden excitement, he ran up the sands to the spot where the rude vessel lay. The ballam was still dripping sea-water; and in it, amid a pool of blood, lay a sailors sheath-knife.

“The lascar!” he shouted, snatching up the blood-stained weapon, and holding it out at arms length, as Don and the captain hurried up; “we've landed in his very tracks!”

Either the lascar's wound had not proved as serious as Jack surmised, or the fellow was endowed with as many lives as a cat. At all events, he had reached land before them, and in safety.

“Sharks an' sea-sarpents!” fumed the captain, Stumping excitedly round and round the canoe. “The warmint had orter been sent to Davy Jones as I ad wised. Howsomedever, bloodshed's best awoided, says you, Master Don, lad; an' so, shiver my keelson! here we lies stranded. What's the course to be steered now, I axes? That's a matter o' argyment, says you; so here's for a whiff o' the fragrant!”

Bidding his servant fetch pipe and tobacco, the captain seated himself upon the canoe and fell to puffing meditatively, his companions meanwhile discussing the situation and a project of their own, with many anxious glances in the direction of the adjacent jungle, where, for anything they knew to the contrary, the lascar might even then be stealthily watching their movements.

“Shiver my smokestack! d'ye see that, now?” exclaimed the captain at last, following with half-closed eye and tarry finger the ascent of a perfect smoke-ring that had just left his lips. “An' what's a ring o' tobackie smoke? says you. A forep'intin' to ewents to come, says I. A ring means surrounded, d'ye see; an'—grape-shot an' gun-swabs!—surrounded means fightin', lads!”

“Fun or fighting, I'm ready, anyhow!” cried Jack, flourishing his knife.

“Ay, ay, lad; an' me, too, for the matter o' that,” replied the old sailor, presenting his pipe at an imaginary foe like a pistol; “but when our situation an' forces is beknownst to the enemy, we're sartin to be surprised, d'ye mind me. An' so I gets an idee!

“Go palter to lubbers an' swabs, d'ye see?

'Bout danger, an' fear, an' the like;

A tight leetle boat an' good sea-room give me,

An' it ain't to a leetle I'll strike!”

“Out with the idea then, captain!” cried Don.

“Shiver my cutlass, lads!—we must carry the war into the camp o' the enemy, dye see'. Wery good, that bein' so, what we wants, d'ye mind me, is a safe, tidy place to fall back on, as can't be took, or looted, or burnt, like the cutter here, whiles we're away on the rampage, so to say.”

“Why not entrench ourselves on the hill just above?” suggested Jack.

“Stow my sea-chest!—the wery identical plan I perposes,” promptly replied the captain. “An' why? you naterally axes. Because it's ha'nted, says I.”

“Because it's what?” cried the two young men in chorus. “Haunted?”

“Ay, the abode o' spurts,” continued the captain. “There's a old ancient temple aloft on yon hill, d'ye see, as they calls the 'Ha'nted Pagodas'—which they say as it's a tiger-witch or summat inhabits it, d'ye see—an' shiver my binnacle if a native'll go a-nigh it day or night!”

“Admirable! But what about the cutter, captain?” said Don.

The captain sucked for a moment at his pipe as if seeking to draw a suitable idea therefrom.

“What o' the cutter? you axes,” said he presently. “Why, we'll wrarp her down the crik a bit, d'ye see, an' stow her away out o' sight where the wegitation's thickish-like on the face o' the cliff; copper my bottom if we won't!”

“The stores, of course, must be carried up the hill,” said Jack, entering readily into the captain's plans. “We should set about the job at once.”

“Avast there, lad! What's to perwent the jungle hereabouts a-usin' of its eyes? I axes. The wail o' night, says you. So, when the wail o' night unfurls, as the poic says, why, up the hill they goes.”

This being unanimously agreed to, and Puggles at that moment announcing breakfast, our trio of adventurers adjourned to the cutter.

“Captain,” said Don, after delighting the black boy's heart by a ravenous attack upon the eatables, “like you, I've got an idee—Hullo, you, Pug! What are you grinning at?”

“Nutting, sa'b,” replied Puggles, clapping his hand over his mouth; “only when marster plenty eating, he sometimes bery often one idee getting. Plenty food go inside, he kicking idee out!”

“Just double reef those lips of yours, Pug, and tell us where do your ideas come from?” said Jack, laughing.

“Me tinking him here got, sar,” said Puggles, gravely patting his waistband, at which the old sailor nearly choked.

“And a pretty stock of them you have, too, judging by the size of your apple-cart!” said his master, shying a biscuit at his head. “Well, as I was saying, captain, I have an idea——”

“Flush my scuppers!” gasped the old sailor, swallowing a brimming pannikin of coffee to clear his throat. “Let's hear more on it then, lad.”

“Well, it's this. Jack and I are going over to the town—where the temples are, you understand—to see if we can't sight old Salambo. A bit of reconnoitring may be of use to us later, you see.”

“A-goin'—over—to—the—town!” roared the captain in amazement, separating the words as though each were a reluctant step in the direction proposed. “Scuttle my cutter, lads! ye'll have the whole pack o' waimints down on ye in a brace o' shakes!”

“You won't say so when you see us in full war-paint,” retorted Jack, as he and Don rose and disappeared in the cuddy.

In the course of half an hour the cuddy door was thrown open, and two stalwart young natives, in full country dress, confronted the old sailor. With the assistance of Puggles and the captain's “boy,” not to mention soot from the cuddy pots, the two young fellows had cleverly “made up” in the guise of Indian pilgrims. At first sight of them, the captain, thinking old Salambo's crew were upon him, seized a musket and threw himself into an attitude of defence.

“Blow me!” he roared, when a loud burst of laughter apprised him of his mistake, “if this ain't the purtiest go as ever I see. Scrapers an' holystones, ye might lay alongside the old woman himself, lads, an' him not know ye from a reglar, genewine brace o' lying niggers. What tack are ye on now, lads? I axes.”

“Off to the town, captain,” replied Don, “to search for old Salambo among his idols. That is, if you'll let Spottie here come with us as pilot.”

“Spottie” was the nickname with which they had dubbed the captain's black servant, whose face was deeply pitted from smallpox.

“Right, lads; he's been here afore, an' knows the lay o' the land; so take him in tow, and welcome,” was the captain's hearty rejoinder. “An' stow your knives away amidships, in case of emargency like; though blow me if they ever take ye for aught but genewine lying niggers!”