Title: Ethan Allen, the Robin Hood of Vermont

Author: Henry Hall

Release date: January 15, 2016 [eBook #50929]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, John Campbell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

Obvious typographical errors and punctuation errors have been corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within the text and consultation of external sources.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

More detail can be found at the end of the book.

BY

HENRY HALL

NEW YORK

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

1892

Copyright, 1892,

By D. APPLETON AND COMPANY.

At the time of the death of Mr. Henry Hall, in 1889, the manuscript for this volume consisted of finished fragments and many notes. It was left in the hands of his daughters to complete. The purpose of the author was to make a fuller life of Allen than has been written, and singling him from that cluster of sturdy patriots in the New Hampshire Grants, to make plain the vivid personality of a Vermont hero to the younger generations. Mr. Hall's well-known habit of accuracy and painstaking investigation must be the guaranty that this "Life" is worthy of a place among the volumes of the history of our nation.

Henrietta Hall Boardman.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| An Account of Allen's Family, | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Early Life, Habits of Thought, and Religious Tendencies, | 12 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Removal to Vermont.—The New Hampshire Grants, | 22 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Allen and the Green Mountain Boys.—Negotiations Between New York and the New Hampshire Grants, | 32 |

| [vi]CHAPTER V. | |

| The Raid upon Colonel Reid's Settlers.—Allen's Outlawry.—Crean Brush.—Philip Skene, | 46 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Preparations to Capture Ticonderoga.—Diary of Edward Mott.—Expeditions Planned.—Benedict Arnold.—Gershom Beach, | 61 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Capture of Ticonderoga, | 73 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Allen's Letters to the Continental Congress, to the New York Provincial Congress, and to the Massachusetts Congress, | 81 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Allen's Letters to the Montreal Merchants, to the Indians in Canada, and to the Canadians.—John Brown, | 89 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Warner Elected Colonel of the Green Mountain Boys.—Allen's Letter to Governor Trumbull.—Correspondence in Regard to the Invasion of Canada.—Attack on Montreal.—Defeat and Capture.—Warner's Report, | 98 |

| [vii]CHAPTER XI. | |

| Allen's Narrative.—Attack on Montreal.—Defeat and Surrender.—Brutal Treatment.—Arrival in England.—Debates in Parliament, | 110 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Life in Pendennis Castle.—Lord North.—On Board the "Solebay."—Attentions Received in Ireland and Madeira, | 128 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Rendezvous at Cape Fear.—Sickness.—Halifax Jail.—Letter to General Massey.—Voyage to New York.—On Parole, | 144 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Release from Prison.—With Washington at Valley Forge.—The Haldimand Correspondence, | 162 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Vermont's Treatment by Congress.—Allen's Letters to Colonel Webster and to Congress.—Reasons for Believing Allen a Patriot, | 173 |

| [viii]CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Allen with Gates.—At Bennington.—David Redding.—Reply to Clinton.—Embassies to Congress.—Complaint against Brother Levi.—Allen in Court, | 183 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Allen at Guilford.—"Oracles of Reason."—John Stark.—St. John de Crèvecœur.—Honors to Allen.—Shay's Rebellion.—Second Marriage, | 191 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Death.—Civilization in Allen's Time.—Estimates of Allen.—Religious Feeling in Vermont.—Monuments, | 198 |

ETHAN ALLEN.

AN ACCOUNT OF HIS FAMILY.

Ethan Allen is the Robin Hood of Vermont. As Robin Hood's life was an Anglo-Saxon protest against Norman despotism, so Allen's life was a protest against domestic robbery and foreign tyranny. As Sherwood Forest was the rendezvous of the gallant and chivalrous Robin Hood, so the Green Mountains were the home of the dauntless and high-minded Ethan Allen. As Robin Hood, in Scott's "Ivanhoe," so does Allen, in Thompson's "Green Mountain Boys," win our admiration. Although never a citizen of the United States, he is one of the heroes of the state and the nation; one of those whose names the people will not willingly let die. History and tradition, song and story, sculpt[2]ure, engraving, and photography alike blazon his memory from ocean to ocean. The librarian of the great library at Worcester, Massachusetts, told Colonel Higginson that the book most read was Daniel P. Thompson's "Green Mountain Boys." Already one centennial celebration of the capture of Ticonderoga has been celebrated. Who can tell how many future anniversaries of that capture our nation will live to see! Another reason for refreshing our memories with the history of Allen is the bitterness with which he is attacked. He has been accused of ignorance, weakness of mind, cowardice, infidelity, and atheism. Among his assailants have been the president of a college, a clergyman, editors, contributors to magazines and newspapers, and even a local historian among a variety of writers of greater or less prominence. If Vermont is careful of her own fame, well does it become the people to know whether Ethan Allen was a hero or a humbug.

Arnold calls history the vast Mississippi of falsehood. The untruths that have been published about Allen during the last hundred and fifteen years might not fill and overflow the Ohio branch of such a Mississippi, but[3] they would make a lively rivulet run until it was dammed by its own silt. The late Benjamin Disraeli, Lord Beaconsfield, fought a duel with Daniel O'Connell, because O'Connell declared it to be his belief that Disraeli was a lineal descendant of the impenitent thief on the Cross. Perhaps the libellers of Allen are descended from the Yorkers whom he stamped so ignominiously with the beech seal. The fierce light of publicity perhaps never beat upon a throne more sharply than for more than a hundred years it has beat upon Ethan Allen. His patriotism, courage, religious belief, and general character have been travestied and caricatured until now the real man has to be dug up from heaps of untruthful rubbish, as the peerless Apollo Belvidere was dug in the days of Columbus from the ruins of classic Antium.

Discrepancies exist even in regard to his age. On the stone tablet over his grave his age is given as fifty years. Thompson said his age was fifty-two. At the unveiling of his statue, he was called thirty-eight years old when Ticonderoga was taken. These three statements are erroneous, and, strange to say, Burlington is responsible for them all, Bur[4]lington, the Athens of Vermont, the town wherein rest his ashes, the town wherein most of the last two years of his life were passed, and the town that has done most to honor his memory.

However humiliating it may be to state pride, it is probable that the Allens, centuries ago, were no more respectable than the ancestors of Queen Victoria and the oldest British peers. The different ways of spelling the name, Alleyn, Alain, Allein, and Allen, seem to indicate a Norman origin. George Allen, professor in the University of Pennsylvania, says that Alain had command of the rear of William the Conqueror's army at the battle of Hastings in 1066.

Joseph Allen, the father of Ethan, comes to the surface of history about the year 1720, one year after the death of Addison and the first publication of "Robinson Crusoe," in the town of Coventry, in Eastern Connecticut, twenty miles east of Hartford. When he first appears to us he is a minor and an orphan. His widowed mother, Mercy, has several children, one of them of age. Their first recorded act is emigration fifty miles westward to Litchfield, famous for its scenery and ancient elms,[5] located between the Naugatuck and the Shepaug rivers, on the Green and Taconic mountain ranges; famous also as the place where the first American ladies' seminary was located, and most famous of all for its renowned law-school, begun over a century ago by Judge Tapping Reeve and continued by Judge James Gould. Chief Justice John Pierpoint and United States Senator S. S. Phelps were among its notable pupils. The widow, Mercy Allen, died in Litchfield, February 5, 1728. Her son Joseph bought one-third of her real estate. Within five years he sold two tracts, of 100 acres each, and fourteen years after his mother's death he sold the residue as wild land. On March 11, 1737, Joseph Allen was married to Mary Baker, daughter of John Baker, of Woodbury, sister of Remember Baker, who was father of the Remember Baker that came to Vermont. Thus Ethan Allen and Remember Baker were cousins.

Ethan Allen was born January 10, 1737, and died February 21, 1789, and consequently he has been said to have been fifty-two years, one month and two days old. In fact, he was fifty-one years, one month and two days old. The year 1737 terminated March 24. Had it[6] closed December 31, Allen would have been born in 1738. The first day of the year was March 25 until 1752 in England and her colonies. In 1751 the British Parliament changed New Year's Day from March 25 to January 1. The year 1751 had no January, no February, and only seven days of March. Allen was thirteen years old in 1750, and was fourteen years old in 1752.

The year 1738 gave birth to three honest men—Ethan Allen, George III., and Benjamin West. In 1738 George Washington was six years old, John Adams three years old, John Stark ten years old, Israel Putnam twenty years old. Seth Warner and Jefferson were born five years later. In that year no claim had ever been made to Vermont by New York or New Hampshire. No one had ever questioned the right of Massachusetts to the English part of Vermont. New Hampshire was bounded on the west by the Merrimac. Colden, the surveyor-general of New York, in an official report bounded New York on the east by Connecticut and Massachusetts, on the north by Lake Ontario and Canada; Canada occupying Crown Point and Chimney Point.

If by waving a magician's wand the English-American colonies on the Atlantic slope, as they existed in 1738, could pass before us, wherein would the tableau differ from that of to-day? West of the Alleghanies there were the Indians and the French. On the north were 50,000 prosperous French, farmers chiefly along the valley of the St. Lawrence from Montreal to Quebec. On the east, Acadie, including Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and a part of Maine, was Scotch. Florida was Spanish. From Georgia to Maine were 1,500,000 English-Americans and 400,000 African-Americans. The colony of New York had a population of 60,100. New Hampshire, consisting of a few thousand settlers, was located north and east of the Merrimac, and had a legislature of its own, but no governor. Massachusetts, with its charters from James I. and Charles I., claimed the country to the Pacific Ocean, and exercised ownership between the Merrimac and Connecticut and west of the Connecticut, without a breath of opposition from any mortal. Massachusetts had sold land as her own which she found to be in Connecticut, and she paid that state for it by granting her many thousand acres in three of the southeast[8]ern townships of Vermont. She built and sustained a fort in Brattleboro', kept a garrison there with a salaried chaplain, salaried resident Indian commissioner, and she established a store supplied with provisions, groceries, and goods suitable for trade with frontiersmen and the Indians of Canada. Bartering was actively carried on along the Connecticut River, Black River, Otter Creek, and Lake Champlain. In 1737 a solemn ratification of the old treaty occurred there; speeches were made, presents given, and the healths of George II. and Governor Belcher, of Massachusetts, were duly drunk. There was no Anglo-Saxon settlement in Vermont outside of Brattleboro'. In Pownal were a few families of Dutch squatters. The Indian village of St. Francis, midway between Montreal and Quebec, peopled partly by New England refugees from King Philip's war of 1676, exercised supreme control over northeastern Vermont.

In all the land were only three colleges: Harvard, one hundred and two years old, Yale, thirty-seven, and William and Mary, forty-five.

Ethan Allen had five brothers, Heman, Heber, Levi, Zimri, and Ira, and two sisters,[9] Lydia and Lucy. Of all our early heroes, few glide before us with a statelier step or more beneficent mien than Heman Allen, the oldest brother of Ethan. Born in Cornwall, Connecticut, October 15, 1740, dying in Salisbury, Connecticut, May 18, 1778, his life of thirty-seven and a half years was like that of the Chevalier Bayard, without fear and without reproach. A man of affairs, a merchant and a soldier, a politician and a land-owner, a diplomat and a statesman, he was capable, intelligent, honest, earnest, and true. But fifteen years old when his father died, he was early engaged in trade at Salisbury. His home became the home of his widowed mother and her large family. Salisbury was his home and probably his legal residence, although he represented Rutland and Colchester in the Vermont Conventions, and was sent to Congress by Dorset.

Heber was the first town clerk of Poultney.

Ira was able, shrewd, and gentlemanly; a land surveyor and speculator, a lieutenant in Warner's regiment, a member of all the conventions of 1776 and 1777, of the Councils of Safety and of the State Council; state treasurer, surveyor-general, author of a "History of Vermont", and of various official papers and[10] political pamphlets. In 1796 he bought, in France, twenty-four brass cannon and twenty thousand muskets, ostensibly for the Vermont militia, which were seized by the English. After a lawsuit of seven or eight years he regained them, but the expense beggared him. He died in Philadelphia, January 7, 1814, aged sixty-three years.

Levi Allen joined in the expedition to capture Ticonderoga, became Tory, and was complained of by his brother Ethan as follows:

Bennington County, ss.:

Arlington, 9 January, 1779.

To the Hon. the Court of Confiscation, comes Col. Ethan Allen, in the name of the freemen of the state, and complaint makes that Levi Allen, late of Salisbury in Connecticut, is of Tory principles and holds in fee sundry tracts and parcels of land in this State. The said Levi, has been detected in endeavoring to supply the enemy on Long Island; and in attempting to circulate counterfeit continental money, and is guilty of holding treasonable correspondence with the enemy under cover of doing favors to me when a prisoner at New York and Long Island; and in talking and using influence in favor of the enemy, associating with inimical persons to this country, and with them monopolizing the necessaries of[11] life; in endeavoring to lessen the credit of the continental currency, and in particular hath exerted himself in the most fallacious manner to injure the property and character of some of the most zealous friends to the independence of the U. S. and of this State likewise: all which inimical conduct is against the peace and dignity of the freemen of this State. I therefore pray the Hon. Court to take the matter under their consideration and make confiscation of the estate of said Levi before mentioned, according to the laws and customs of this State, in such case made and provided.

Ethan Allen.

Levi died while in jail, for debt, at Burlington, Vermont, in 1801.

Zimri lived and died in Sheffield.

Lydia married a Mr. Finch, and lived and died in Goshen, Connecticut.

Lucy married a Dr. Beebee, and lived and died in Sheffield.

EARLY LIFE, HABITS OF THOUGHT, AND RELIGIOUS TENDENCIES.

The life of Allen may be divided into four periods: the first thirty-one years before he came to Vermont (1738-1769), the six years in Vermont before his captivity (1769-1775), the two years and eight months of captivity (1775-1778), and the eleven years in Vermont after his captivity (1778-1789).

When he was two years old the family moved into Cornwall. There his brothers and sisters were born, there his father died, there Ethan lived until he was twenty-four years old. When seventeen he was fitting for college with the Rev. Mr. Lee, of Salisbury. His father's death put an end to his studies. This was in 1755, when the French and Indian war was raging along Lakes George and Champlain, a war which lasted until Allen's twenty-third year. Some of the early settlers of Vermont, Samuel Robinson, Joseph Bowker, and others,[13] took part in this war. Not so Allen. There is no intimation that he hungered for a soldier's life in his youth. His usual means of earning a livelihood for himself and his widowed mother's family is supposed to have been agriculture.

William Cothrens, in his "History of Ancient Woodbury," tells us that in January, 1762, Allen, with three others, entered into the iron business in Salisbury, Connecticut, and built a furnace. In June of that year he returned to Roxbury, and married Mary Brownson, a maiden five years older than himself. The marriage fee was four shillings, or sixty-seven cents. By this wife he had five children: one son, who died at the age of eleven, while Ethan was a captive, and four daughters. Two died unmarried; one married Eleazer W. Keyes, of Burlington; the other married the Hon. Samuel Hitchcock, of Burlington, and was the mother of General Ethan Allen Hitchcock, U. S. A.

Allen resided with his family first at Salisbury and afterward at Sheffield, the southwest corner town of Massachusetts. For six miles the boundary line of the two states is the boundary line of the two towns. In these[14] towns the families of Ethan Allen and his brothers and sisters lived many years. Two years after moving to Salisbury he bought two and a half acres, or one-sixteenth part of a tract of land on Mine Hill, an elevation of 350 feet in Roxbury, containing, it is said, the most remarkable deposit of spathic iron ore in the United States. Immense sums of money were expended in vain attempts to work it as a silver mine. Two years after Allen began his Vermont life he still owned land in Judea Society, a part of the present town of Washington. The details and financial results of these business undertakings are not furnished us. They indicate enterprise, if nothing more. Carrying on a farm, casting iron ware, and working a mine, not military affairs, seem to have been the avenues wherein Allen developed his executive ability during his early manhood.

What were his educational facilities, his social privileges, and his religious views during this formative period of his life? Ira Allen, in 1795, writes to Dr. S. Williams, the early historian of Vermont, that when his father, Joseph Allen, died, his brother Ethan was preparing for college, and that the death of his[15] father obliged Ethan to discontinue his classical studies. Mr. Jehial Johns, of Huntington, told the Rev. Zadock Thompson that he knew Ethan Allen in Connecticut, and was very certain that Allen spent some time studying with the Rev. Mr. Lee, of Salisbury, with the view of fitting himself for college. The widow of Judge Samuel Hitchcock, of Burlington, told Mr. Thompson that Ethan's attendance at school did not exceed three months. Ira Allen writes General Haldimand in July, 1781, that his brother Ethan has resigned his Brigadier-Generalship in the Vermont militia, and "returned to his old studies, philosophy." To what period in Ethan's life does the phrase "old studies" refer? It could not be his life after the captivity, during his five years' collisions with the Yorkers, but the period we are now considering. Heman Allen's widow, when Mrs. Wadhams, told Zadock Thompson that one summer when he was residing in her house he passed almost all the time in writing. She did not know what was the subject of his study, but on one occasion she called him to dinner, and he said he was very sorry she had called him so soon, for he had "got clear up into the upper regions." Allen himself says:

In my youth I was much disposed to contemplation, and at my commencement in manhood I committed to manuscript such sentiments or arguments as appeared most consonant to reason, lest through the debility of memory, my improvement should have been less gradual. This method of scribbling I practised for many years, from which I experienced great advantages in the progression of learning and knowledge; the more so as I was deficient in education and had to acquire the knowledge of grammar and language, as well as the art of reasoning, principally from a studious application to it; which after all, I am sensible, lays me under disadvantages, particularly in matters of composition; however, to remedy this defect I have substituted the most unwearied pains.... Ever since I arrived at the state of manhood and acquainted myself with the general history of mankind, I have felt a sincere passion for liberty. The history of nations doomed to perpetual slavery in consequence of yielding up to tyrants their natural-born liberties, I read with a sort of philosophical horror.

In Allen's youth great revivals were inaugurated, organized, and continued mainly by the preaching of Whitefield, who roused and electrified audiences of several thousands, as men have rarely been moved since the days of Peter the Hermit. Even Franklin, Bolingbroke, and Chesterfield were fascinated by him.[17] As for Allen, baptized in his infancy, in the days when no Sabbath-school blessed the race, when the Westminster Catechism and Watts' Hymns were in use throughout New England (Isaac Watts died when Allen was eleven years old), living in and near northwest Connecticut in as democratic and religious community as the world had ever seen, reading none of the books of the Deists, he was fond of discussion and delighted in writing out his arguments. Having been brought up an Armenian Christian, in contradistinction to a Calvinistic Christian, his views in early manhood began to change. One picture of this gradual evolution he gives us in the following description:

The doctrine of imputation according to the Christian scheme consists of two parts. First, of imputation of the apostasy of Adam and Eve to their posterity, commonly called original sin; and secondly, of the imputation of the merits or righteousness of Christ, who in Scripture is called the second Adam to mankind or to the elect. This is a concise definition of the doctrine, and which will undoubtedly be admitted to be a just one by every denomination of men who are acquainted with Christianity, whether they adhere to it or not.

I therefore proceed to illustrate and explain the doctrine by transcribing a short but very perti[18]nent conversation which in the early days of my manhood I had with a Calvinistic divine; but previously remark that I was educated in what are commonly called the Armenian principles; and among other tenets to reject the doctrine of original sin; this was the point at issue between the clergyman and me. In my turn I opposed the doctrine of original sin with philosophical reasonings, and as I thought had confuted the doctrine. The Reverend gentleman heard me through patiently: and with candor replied:

"Your metaphysical reasonings are not to the purpose, inasmuch as you are a Christian and hope and expect to be saved by the imputed righteousness of Christ to you; for you may as well be imputedly sinful as imputedly righteous. Nay," said he, "if you hold to the doctrine of satisfaction and atonement by Christ, by so doing you presuppose the doctrine of apostasy or original sin to be in fact true;" for, said he, "if mankind were not in a ruined and condemned state by nature, there could have been no need of a Redeemer; but each individual of them would have been accountable to his Creator and Judge, upon the basis of his own moral agency. Further observing that upon philosophical principles it was difficult to account for the doctrine of original sin, or of original righteousness; yet as they were plain, fundamental doctrines of the Christian faith we ought to assent to the truth of them; and that from the divine authority of revelation. Notwithstanding," said he,[19] "if you will give me a philosophical explanation of original imputed righteousness, which you profess to believe and expect salvation by, then I will return you a philosophical explanation of original sin; for it is plain," said he, "that your objections lie with equal weight against original imputed righteousness, as against original imputed sin."

Upon which I had the candor to acknowledge to the worthy ecclesiastic, that upon the Christian plan I perceived the argument had clearly terminated against me. For at that time I dared not to distrust the infallibility of revelation; much more to dispute it. However, this conversation was uppermost in my mind for several months after; and after many painful searches and researches after the truth, respecting the doctrine of imputation, resolved at all events to abide the decision of rational argument in the premises; and on a full examination of both parts of the doctrine, rejected the whole; for on a fair scrutiny, I found that I must concede to it entirely or not at all; or else believe inconsistently as the clergyman had argued.

He relates also a change from his juvenile views of biblical history:

When I was a boy, by one means or other, I had conceived a very bad opinion of Pharaoh; he seemed to me to be a cruel, despotic prince; he would not give the Israelites straw, but nevertheless, demanded of them the full tale of brick; for[20] a time he opposed God Almighty; but was at last luckily drowned in the Red Sea; at which event, with other good Christians, I rejoiced, and even exulted at the overthrow of the base and wicked tyrant. But after a few years of maturity and examination of the history of that monarch given by Moses, with the before recited remarks of the apostle, I conceived a more favorable opinion of him; inasmuch as we are told that God raised him up and hardened his heart, and predestinated his reign, his wickedness, and his overthrow.

In 1782 he says:

In the circle of my acquaintance (which has not been small), I have generally been denominated a Deist, the reality of which I never disputed; being conscious I am no Christian, except mere infant baptism makes me one; and as to being a Deist, I know not, strictly speaking, whether I am one or not, for I have never read their writings.

We are told that Allen in his early life was very intimate with Dr. Thomas Young, the man who supplied the state with its name, "Vermont," in April, 1777, and who so strongly encouraged it to assert its independence. One of the most noted characteristics of Ethan, his fondness for the society of able men, is illustrated in his association with Young.

Dr. Young, who was a distinguished citizen of[21] Philadelphia, was on most of the Whig committees in Boston, before the Revolution, with James Otis, Samuel Adams, Joseph Warren, and others. He and Adams addressed the great public meeting on the day "when Boston harbor was black with unexpected tea." He was a neighbor of Allen, living in the Oblong, in Dutchess County, while Allen lived in Salisbury. Afterward he lived in Albany, and died in Philadelphia in the third year of Allen's captivity. He was influential in causing Vermont to adopt the constitution of Pennsylvania.

The Oblong, Salisbury and vicinity, abounded in free thinkers. Young and Allen opposed President Edwards' famous theological tenets, the latter spending much time in Young's house, and it was generally understood that they were preparing for publication a book in support of sceptical principles; the two agreeing that the one that outlived the other should publish it. Allen, on going to Vermont, left his manuscripts with Young, and on his release from captivity after Young's death obtained from the latter's family, who had gone back to Dutchess County, both his own and Young's manuscripts, and these were the originals of his "Oracles of Reason."

REMOVAL TO VERMONT.—THE NEW HAMPSHIRE GRANTS.

Allen came to Vermont, probably, in 1769, a year memorable for the founding of Dartmouth College and for the birth of four of earth's renowned men: two soldiers, Wellington and Napoleon; two scholars, Cuvier and Humboldt.

In the early history of Vermont, one of its prominent judges speculated extensively in Green Mountain wild lands. The aggregate result of these speculations was disastrous. Attending a session of the legislature, the judge was called upon by a committee for his advice in reference to suitable penalties for some crime. He replied, advising for the first offence a fine; for the second, imprisonment; and if the criminal should prove such a hardened offender, such a veteran in vice as to be guilty the third time, he recommended that the scoundrel should be compelled to receive[23] a deed of a mile square of wild Vermont lands. Speculation in wild lands is a feature of pioneer society. Vermont was once the agricultural Eldorado of New England. Emigration first rolled northward. Since that time a certain star, erroneously supposed to belong to Bishop Berkeley, has been travelling westward.

In 1749 Benning Wentworth, Governor of New Hampshire, issued a patent of a township, six miles square, near the northwest angle of Massachusetts and corresponding with its line northward, and in this township of Bennington the Allens bought lands and made their home. This grant caused a remonstrance from the governor and council of New York. Similar remonstrances had been made in the cases of Connecticut and Massachusetts, each of whom claimed that their territory extended to the Connecticut River. But that question had been settled in the former cases between New York and New England by agreeing upon a line from the southwest corner of Connecticut northerly to Lake Champlain as the boundary between the provinces. Wentworth urged in justification of his course that the boundary line was well known, and that New Hampshire had the same right as the other colonies of New[24] England, and he persevered in his own course. In 1754 fourteen new townships had been granted, when the French war broke out and the settlers were deterred from occupying their lands by the incursions of the French and Indians on the frontier and the uncertainty of the termination of the contest; but when Canada was reduced by the English and peace concluded, there was a new rush for the possession of the fertile lands by the hardy and adventurous sons of the old New England colonies. In four years Governor Wentworth granted one hundred and thirty-eight townships, and the territory included was called the New Hampshire Grants. Then began in bitter earnest the long controversy between New York and New Hampshire for the ownership of all the territory now known as Vermont.

In order to make clear the circumstances of the time when Ethan Allen came to the front, it is necessary to explain something of the origin of the strife. The New York claim was founded on a charter given by Charles II. to his brother, the Duke of York, in 1664, for the country lying between the Connecticut and Delaware rivers. But that charter had long[25] been considered as practically a nullity, for when the Duke of York succeeded to the throne of England, it all became public property subject to the king's divisions; and there are strong reasons for believing that the mention of the Connecticut was merely a formality, not intended as a definite boundary, and that the design was to take in the whole of the New Netherlands. The geography of the country was little known, and the wording of the charter was ambiguous and vague. Allen at once espoused the cause of the settlers. But for him the State of Vermont would probably have never existed. But for Allen, Albany, not Montpelier, might have been the capital of Vermont. Allen's most illustrious achievement for the benefit of the nation was the capture of Ticonderoga. His great work for Vermont was successful resistance to the Yorkers.

Before entering upon this period of litigation, one of the stories of Allen, illustrating his honesty, may fitly find a place. Having given a note which he was unable to pay when it became due, he was sued. Allen employed a lawyer to attend to his case and postpone payment. But the lawyer could not[26] prevent the rendering a judgment against Allen at the first term of court, unless he filed a plea alleging some real or fictitious ground of defence. Accordingly, quite innocently he put in the usual plea denying that Allen signed the note. The effect of this was to continue the case to the next term of court, exactly what Allen wanted; but Allen was present and was indignant that he should be made to appear to sanction a falsehood. He rose in court and vehemently denounced his lawyer, telling him that he did not employ him to tell a lie; he did sign that note; he wanted to pay it; he only wanted time!

It was in June, 1770, that Allen first became prominent in Vermont public affairs. Then it was that the lawsuits brought by Yorkers for Vermont lands were tried before the Supreme Court at Albany. Robert R. Livingston was the presiding judge; Kempe and Duane, attorneys for plaintiffs; Silvester, of Albany, and Jared Ingersoll, of New Haven, attorneys for defendants. Ethan Allen was active in preparing the defence. But of what avail was defence when the court was virtually an adverse party to the suit? Not only did Duane claim 50,000 acres of[27] Vermont lands, but, to the disgrace of English jurisprudence, Livingston, the presiding judge, was interested directly or indirectly in 30,000 acres. The farce was soon played out; the court refused to hear the New Hampshire charter read; one trial was sufficient; the plaintiffs won all the cases. Duane and others called on Allen and reminded him that "might makes right," advising him to go home and counsel compromise. Allen observed: "The gods of the valleys are not the gods of the hills!" Duane asked for an explanation, and Allen replied: "If you will come to Bennington the meaning shall be made clear to you."

Allen went home and no compromise was thought of. The great seal of New Hampshire being disregarded, the "Beech Seal" was invented as a substitute. A military organization was formed with several companies, Seth Warner, Remember Baker, and others as captains, and Ethan Allen as colonel.

In July, 1771, on the farm of James Breakenridge, in Bennington, the State of Vermont was born. Ten Eyck, the sheriff, with 300 men, including mayor, aldermen, lawyers, and others, issued forth from Albany, as did De Soto to[28] capture Florida, as Don Quixote essayed to conquer the windmills. Breakenridge's family were wisely absent. In his house were eighteen armed men provided with a red flag to run up the chimney as a signal for aid. The house was barricaded and provided with loop-holes. On the woody ridge north were 100 armed men, their heads and the muzzles of their guns barely visible amid the foliage. To the southeast, in plain sight, was a smaller body of men within gunshot of the house. Six or seven guarded the bridge half a mile to the west. Mayor Cuyler and a few others were allowed to cross the bridge and a parley ensued. The mayor returned to the bridge, and in half an hour the sheriff was notified that possession would be kept at all hazards. He ordered the posse to advance, and a small portion reluctantly complied. Another parley followed, while lawyer Yates expounded New York law and the Vermonters justified their position. The sheriff seized an axe, and going toward the door, threatened to break it open. In an instant an array of guns was aimed at him; he stopped, retired to the bridge, and ordered the posse to advance five miles into Bennington. But the Yorkers stampeded for home, and the[29] bubble burst. The "star that never sets" had begun to glimmer upon the horizon.

In the winter of 1771-72 Governor Tryon, of New York, issued proclamations heavy with ponderous logic and shotted with offers of money for the arrest of Allen and others. To the arguments Allen replied through a newspaper, the Connecticut Courant, of Hartford. To the premium for his arrest he returned a Roland for an Oliver in the following placard:

£25 Reward.—Whereas James Duane and John Kempe, of New York, have by their menaces and threats greatly disturbed the public peace and repose of the honest peasants of Bennington and the settlements to the northward, which are now and ever have been in the peace of God and the King, and are patriotic and liege subjects of Geo. the 3d. Any person that will apprehend those common disturbers, viz: James Duane and John Kempe, and bring them to Landlord Fay's, at Bennington, shall have £15 reward for James Duane and £10 reward for John Kempe, paid by

Ethan Allen.

Remember Baker.

Robert Cochran.

Dated Poultney,

Feb. 5, 1772.

Duane and Kempe were prominent lawyers of New York, and also prominent as advocates of New York's claim to Vermont lands. Duane[30] was the son-in-law of Robert Livingston and Kempe was attorney-general. The idea of their being kidnapped for exhibition at a log tavern in the wilderness was slightly grotesque. But this did not satisfy Allen. He would fain visit the enemy in one of his strongholds.

Albany was emphatically a Dutch city, for it was two centuries old before it had 10,000 inhabitants. In 1772 it might have had half that number. While the country was flooded with proclamations for his arrest, Allen rode alone into the city. Slowly passing through the streets to the principal hotel he dismounted, entered the bar-room, and called for a bowl of punch. The news circulated; the Dutch rallied; the crowd centred at the hotel; the officers of the court, the valiant sheriff, Ten Eyck, and the attorney-general were present. Allen raised the punch-bowl, bowed courteously to the crowd, swallowed the beverage, returned to the street, remounted his horse, rose in his stirrups and shouted "Hurrah for the Green Mountains!" and then leisurely rode away unharmed and unmolested. The incident illustrates Allen's shrewd courage, and sustains Governor Hall's theory that the people of New York sympathized more with the Green Moun[31]tain Boys than with their own land-gambling officers.

At the Green Mountain tavern in Bennington was a sign-post, with a sign twenty-five feet from the ground. Over the sign was the stuffed skin of a catamount with large teeth grinning toward New York. A Dutchman of Arlington who had been active against the Green Mountain Boys was punished by being tied in an arm-chair, hoisted to this sign, and there suspended for two hours, to the amusement of the juvenile population and the quiet gratification of their seniors.

ALLEN AND THE GREEN MOUNTAIN BOYS.—NEGOTIATIONS BETWEEN THE NEW YORK AND THE NEW HAMPSHIRE GRANTS.

During the six years preceding the Revolution, Allen was the most prominent leader of the Green Mountain Boys in all matters of peace, and also in political writing. When the Manchester Convention, October 21, 1772, sent James Breakenridge, of Bennington, and Jehiel Hawley, of Arlington, as delegates to England, perhaps Allen could not be spared, for if any New York document needed answering Allen answered it; if any handbill, proclamation or counter-statement, or political or legal argument was to be written, Allen wrote it; if New England was to be informed of the Yorkers' rascalities, Allen sent the information to the Connecticut Courant and Portsmouth Gazette, Vermont having no newspaper. Rarely was force or threat used or a rough joke played on a Yorker, but Allen was first in the[33] fray. In Bennington County Allen with others told a Yorker that they had "that morning resolved to offer a burnt sacrifice to the gods of the woods in burning the logs of his house." They did burn the logs and the rafters, and told him to go and complain to his "scoundrel governor."

Of all the towns of Western Vermont, Clarendon had been most noted for its Tories and its Yorkers. Settled as early as 1768, its settlers founded their claims to land titles on grants from three different powers: Colonel Lydius, New York, and New Hampshire. The New York patent of Socialborough, covering Rutland and Pittsford substantially, was dated April 3, 1771, and issued by Governor Dunmore. The New York patent of Durham, dated January 7, 1772, issued by Governor Tryon, covered Clarendon. Both were in direct violation of the royal order in council, July, 1767, and therefore illegal and void. The new county of Charlotte, created March 12, 1772, extended from Canada into Arlington and Sunderland and west of Lake George and Lake Champlain. Benjamin Spencer, of Durham, was a justice and judge of the new county; Jacob Marsh, of Socialborough, a justice; and Simeon Jenny,[34] who lived near Chippenhook, coroner. These three officers were zealous New York partisans. The Green Mountain Boys in council passed resolutions to the effect that no citizen should do any official act under New York authority; that all persons holding Vermont lands should hold them under New Hampshire laws, and if necessary force should be used to enforce these resolves.

In the early part of the fall of 1773, a large force of Green Mountain Boys, under Ethan Allen and other leaders, visited Clarendon and requested the Yorkers to comply with these resolutions, informing them if this were not done within a reasonable time the persons of the Durhamites would suffer. Justice Spencer absconded. No violence was used except on one poor innocent dog of the name of Tryon, and Governor Tryon was so odious that the dog was cut in pieces without benefit of clergy. This display of force and the threats that were very freely used, it was hoped, would be enough to secure submission, but the justices still issued writs against the New Hampshire settlers; other New York officials acted, and all were loud in advocating the New York title.

A second visit to Durham was made. Saturday, November 20, at 11 P.M., Ethan Allen, Remember Baker, and twenty to thirty others surrounded Spencer's house, took him prisoner, and carried him two miles to the house of one Green, where he was kept under a guard of four men until Monday morning, and then taken "to the house of Joseph Smith, of Durham, innkeeper." He was asked where he preferred to be tried; he replied that he was not guilty of any crime, but if he must be tried, he should choose his own door as the place of trial. The Green Mountain Boys had now increased in number to about one hundred and thirty, armed with guns, cutlasses, and other weapons. The people of Clarendon, Rutland, and Pittsford hearing of the trial, gathered to witness the proceedings. A rural lawsuit still has a wonderful fascination for a rural populace. Allen addressed the crowd, telling them that he, with Remember Baker, Seth Warner, and Robert Cochran, had been appointed to inspect and set things in order; that "Durham had become a hornets' nest" which must be broken up. A "judgment seat" was erected; Allen, Warner, Baker, and Cochran took seats thereon as judges, and Spencer was ordered to stand[36] before this tribunal, take off his hat, and listen to the accusations. Allen accused him of joining with New York land jobbers against New Hampshire grantees and issuing a warrant as a justice. Warner accused him of accepting a New York commission as a magistrate, of acting under it, of writing a letter hostile to New Hampshire, of selling land bought of a New York grantee, and of trying to induce people to submit to New York. He was found guilty, his house declared a nuisance, and the sentence was pronounced that his house be burnt, and that he promise not to act again as a New York justice. Spencer declared that if his house were burned, his store of dry-goods and all his property would be destroyed and his wife and children would be great sufferers. Thereupon the sentence was reconsidered. Warner suggested that his house be not destroyed, but that the roof be taken off and put on again, provided Spencer should acknowledge that it was put on under a New Hampshire title and should purchase a New Hampshire title. The judges so decided. Spencer promised compliance, and "with great shouting" the roof was taken off and replaced, and this pioneer dry-goods store of 1773 was preserved.

At another time twenty or thirty of Allen's party visit the house of Coroner Jenny. The house was deserted; Jenny had fled, and they burned the house to the ground. The other Durhamites were visited and threatened, and they agreed to purchase New Hampshire titles. Some of the party returning from Clarendon met Jacob Marsh in Arlington, on his way from New York to Rutland. They seized him and put him on trial. Warner and Baker were the accusers. Baker wished to apply the "beech seal," but the judges declined. Warner read the sentence that he should encourage New Hampshire settlers, discourage New York settlers, and not act as a New York justice, "upon pain of having his house burnt and reduced to ashes and his person punished at their pleasure." He was then dismissed with the following certificate:

Arlington, Nov. 25, A.D. 1773. These may sertify that Jacob Marsh haith been examined, and had a fare trial, so that our mob shall not meadel farther with him as long as he behaves.

Sertified by us as his judges, to wit,

Nathaniel Spencer,

Saml. Tubs,

Philip Perry.

On reaching home, Marsh found that the roof of his house had been publicly taken off by the Green Mountain Boys.

Spencer in his letter to Duane, April 11, 1772, wrote: "One Ethan Allen hath brought from Connecticut twelve or fifteen of the most blackguard fellows he can get, double-armed, in order to protect him." This same Spencer, after acting as a Whig and one of the Council of Safety, deserted to Burgoyne in 1777, and died a few weeks after at Ticonderoga.

Benjamin Hough, of Clarendon, was a troublesome New York justice. His neighbors seized him and carried him thirty miles south in a sleigh. After three days, January 30, 1775, he was tried in Sunderland before Allen and others. His punishment was two hundred lashes on the naked back while he was tied to a tree. Allen and Warner signed a written certificate as a burlesque passport for Hough to New York, "he behaving as becometh."

At this time the following open letters from the Green Mountain Boys were published:

An epistle to the inhabitants of Clarendon: From Mr. Francis Madison of your town, I under[39]stand Oliver Colvin of your town has acted the infamous part by locating part of the farm of said Madison. This sort of trick I was partly apprised of, when I wrote the late letter to Messrs. Spencer and Marsh. I abhor to put a staff into the hands of Colvin or any other rascal to defraud your letter. The Hampshire title must, nay shall, be had for such settlers as are in quest of it, at a reasonable rate, nor shall any villain by a sudden purchase impose on the old settlers. I advise said Colvin to be flogged for the abuse aforesaid, unless he immediately retracts and reforms, and if there be further difficulties among you, I advise that you employ Capt. Warner as an arbitrator in your affairs. I am certain he will do all parties justice. Such candor you need in your present situation, for I assure you, it is not the design of our mobs to betray you into the hands of villainous purchasers. None but blockheads would purchase your farms, and they must be treated as such. If this letter does not settle this dispute, you had better hire Captain Warner to come simply and assist you in the settlement of your affairs. My business is such that I cannot attend to your matters in person, but desire you would inform me, by writing or otherwise relative thereto. Captain Baker joins with the foregoing, and does me the honor to subscribe his name with me. We are, gentlemen, your friends to serve.

Ethan Allen,

Remember Baker.

To Mr. Benjamin Spencer and Mr. Amos Marsh, and the people of Clarendon in general:

Gentlemen:—On my return from what you called the mob, I was concerned for your welfare, fearing that the force of our arms would urge you to purchase the New Hampshire title at an unreasonable rate, tho' at the same time I know not but after the force is withdrawn, you will want a third army. However, on proviso, you incline to purchase the title aforesaid, it is my opinion, that you in justice ought to have it at a reasonable rate, as new lands were valued at the time you purchased them. This, with sundry other arguments in your behalf, I laid before Captain Jehiel Hawley and other respectable gentlemen of that place (Arlington) and by their advice and concurrence, I write you this friendly epistle unto which they subscribe their names with me, that we are disposed to assist you in purchasing reasonably as aforesaid; and on condition Colonel Willard, or any other person demand an exorbitant price for your lands we scorn it, and will assist you in mobbing such avaricious persons, for we mean to use force against oppression, and that only. Be it in New York, Willard, or any person, it is injurious to the rights of the district.

From yours to serve.

Ethan Allen,

Jehiel Hawley,

Daniel Castle,

Gideon Hawley,

Reuben Hawley,

Abel Hawley.

The convention had decreed that no officer from New York should attempt to take any person out of its territory, on penalty of a severe punishment, and it forbade any surveyor to run lines through the lands or inspect them with that purpose. This edict enlarged the powers of the military commanders, and it was their duty to search out such offenders. The Committees of Safety which were chosen were entrusted with powers for regulating local affairs, and the conventions of delegates representing the people, which assembled from time to time, adopted measures tending to harmony and concentration of effort.

May 19, 1772 (the year in which occurred Poland's first dismemberment), Governor Tryon wrote to Bennington and vicinity, inviting the citizens to send delegates to him and explain the causes of their opposition to New York rule. Could anything be fairer or more politic and wise? He promised safety to any and all sent, except four of their leaders, Allen, Warner, Cochran, and Sevil, and suggested sending their pastor, J. Dewey, and Mr. Fay. Dewey answered on June 5:

We, his Majesty's leal and loyal subjects of the Province of New York.... First, we hold[42] fee of our land by grants of George II., and George III., the lands reputed then in New Hampshire. Since 1764, New York has granted the same land as though the fee of the land and property was altered with jurisdiction, which we suppose was not.... Suits of law for our lands rejecting our proof of title, refusing time to get our evidence are the grounds of our discontent.... Breaking houses for possession of them and their owners, firing on these people and wounding innocent women and children.... We must closely adhere to the maintaining our property with a due submission to Your Excellency's jurisdiction.... We pray and beseech Your Excellency would assist to quiet us in our possessions, till his Majesty in his royal wisdom shall be graciously pleased to settle the controversy.

Allen, not being allowed to go to New York, wrote to Tryon in conjunction with Warner, Baker, and Cochran, stating the case as follows:

No consideration whatever, shall induce us to remit in the least of our loyalty and gratitude to our most Gracious Sovereign, and reasonably to you; yet no tyranny shall deter us from asserting and vindicating our rights and privileges as Englishmen. We expect an answer to our humble petition, delivered you soon after you became Governor, but in vain. We assent to your jurisdiction, because it is the King's will, and always[43] have, except where perverse use would deprive us of our property and country. We desire and petition to be reannexed to New Hampshire. That is not the principal cause we object to, but we think change made by fraud, unconstitutional exercise of it. The New York patentees got judgments, took out writs, and actually dispossessed several by order of law, of their houses and farms and necessaries. These families spent their fortunes in bringing wilderness into fruitful fields, gardens and orchards. Over fifteen hundred families ejected, if five and one-quarter persons are allowed to each family.... The writs of ejectment come thicker and faster.... Nobody can be supposed under law if law does not protect.... Since our misfortune of being annexed to New York, law is a tool to cheat us.... Fatigued in settling a wilderness country.... As our cause is before the King, we do not expect you to determine it.... If we don't oppose Sheriff, he takes our houses and farms. If we do, we are indicted rioters. If our friends help us, they are indicted rioters. As to refugees, self-preservation necessitated our treating some of them roughly. Ebenezer Cowle and Jonathan Wheat, of Shaftsbury, fled to New York, because of their own guilt, they not being hurt nor threatened. John Munro, Esq., and ruffians, assaulting Baker at daybreak, March 22, was a notorious riot, cutting, wounding and maiming Mr. Baker, his wife and children. As Baker is alive he has no cause of complaint. Later he (Munro) assaulted Warner[44] who, with a dull cutlass, struck him on the head to the ground. As laws are made by our enemies, we could not bring Munro to justice otherwise than by mimicing him, and treating him as he did Baker, and so forth. Bliss Willoughby, feigning business, went to Baker's house and reported to Munro, thus instigating and planning the attack.... The alteration of jurisdiction in 1764 could not affect private property.... The transferring or alienation of property is a sacred prerogative of the true owner. Kings and Governors cannot intermeddle therewith.... We have a petition lying before his Majesty and Council for redress of our grievances for several years past. In Moore's time, the King forbid New York to patent any lands before granted by New Hampshire. This a supercedeas of Common Law. King notifying New York he takes cognizance and will settle and forbids New York to meddle: common sense teaches a common law, judgment after that, if it prevailed, would be subversive of royal authority. So all officers coming to dispossess are violaters of law. Right and wrong are externally the same. We are not opposing you and your Government, but a party chiefly attorneys. We hear you applied to assembly for armed force to subdue us in vain. We choose Captain Stephen Fay and Mr. Jonas Fay, to treat with you in person. We entreat your aid to quiet us in our farms till the King decides it.[1]

The embassy was successful. The council advised that all legal processes against Vermont should cease. If Bennington was happy in May over the invitation, Bennington was jubilant in August over the kindly advice. The air rang with shouts; the health of governor and council was drunk and cannon and small-arms were heard everywhere. No part of New York colony was happier or more devotedly British. Two years had passed since the New York Supreme Court had adjudged all the Vermont legal documents null and void: one year had passed since New York had sent a sheriff and posse with hundreds of citizens to force Vermont farmers from their farms, but both of these affairs occurred under Governor Clinton. Now perhaps, the Vermonters thought, the new governor was going to act fairly: there would be no more fights; no more watching and guarding against midnight attacks; no more need of fire-arms; and wives and babes would be safe. There would be no more kidnapping of Green Mountain Boys and hurrying them away to Albany jail; no more foreign surveying of the lands they tilled and loved.

THE RAID UPON COLONEL REID'S SETTLERS.—ALLEN'S OUTLAWRY.—CREAN BRUSH.—PHILIP SKENE.

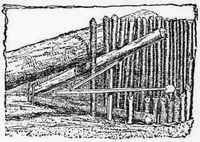

But "best laid schemes of mice and men gang aft agley." While these negotiations were pending, New Yorkers were quietly doing the necessary work for stealing more Vermont lands. Cockburn, the Scotch New York surveyor, was surveying land along Otter Creek. The Green Mountain Boys heard of it, rallied, and overtook him near Vergennes, and found Colonel Reid's Scotchmen enjoying mills and farms. For three years these foreigners had been there. In 1769, with no legal title, they had found, seized, and enjoyed the land, with a mill. Vermonters had then rallied and dispossessed these dispossessors, but a second raid of Reid's men redispossessed them. In the summer of 1772, Vermont, seizing Cockburn, turned out Reid's tenants, broke up mill-stones and threw them over the falls, razed houses, and burned crops.

The Scotch story is as follows: John Cameron made affidavit that he and some other families from Scotland arrived at New York in the latter part of June, and a few days afterward agreed with Lieutenant-Colonel Reid to settle as tenants on his lands on Otter Creek, in Charlotte County. Reid went with them to Otter Creek, some miles east from Crown Point, and was at considerable expense in transporting them, their wives, children, and baggage. The day after their arrival at Otter Creek they were viewing the land, where they saw a crop of Indian corn, wheat, and garden stuff, and a stack of hay and two New England men. Reid paid these two men $15 for their crops, the men agreeing to leave until the king's pleasure should be known. Reid made over these crops to his new tenants, gave them possession of the land in presence of two justices of the peace of Charlotte County, and bought some provisions and cows for his tenants. On or about the 11th of August, armed men from different parts of the country came and turned James Henderson and others out of their homes, burnt the houses to the ground, and for two days pastured fifty horses which they had brought with them in a field of[48] corn which Reid had bought. They also burnt a large stack of hay, purchased by Reid. The next day the rioters, headed by their captains, Allen, Baker, and Warner, came to Cameron's house, destroyed the new grist-mill, built by Reid (Baker insisting upon it), broke the mill-stones in pieces and threw them down a precipice into the river. The rioters then turned out Cameron's wife and two small children, and burnt the house, having in the two days burnt five houses, two corn shades, and one stack of hay. When Cameron, much incensed, asked by what authority of law they committed such violences, Baker replied that they lived out of the bounds of law, and holding up his gun said that was his law. He further declared that they were resolved never to allow any persons claiming under New York to settle in that part of the province, but if Cameron would join them, they would give him lands for nothing. This offer Cameron rejected. While the rioters were destroying his house and mill on the Crown Point (west) side of Otter Creek, he heard six men ordered to go with arms and stand as sentinels on a rising ground toward Crown Point, to prevent any surprise from the troops in the garrison there.[49] Having destroyed Cameron's house and the mill, the rioters recrossed the river. Cameron reports that he saw among the rioters Joshua Hide, who had agreed in writing with Reid not to return, and had received payment for his crop. Hide was very active in advising the destruction of Cameron's house and the mill.

Cameron stayed about three weeks at Otter Creek, after the rioters dispersed, hoping to hear from Reid, and hoping also that New York would protect him and his fellow-settlers, but having no house, and being exposed to the night air, the fever and ague soon compelled him to retire. Some of his companions went before, the rest were to follow. What became of his wife and children he does not state. Cameron stayed one night at the house of a Mr. Irwin, on the east shore of the lake, five miles north of Crown Point. Irwin, an elderly man, holding a New Hampshire title, told Cameron that Reid had a narrow escape, for Baker with eight men had laid in wait for him a whole day, near the mouth of Otter Creek, determined to murder him, and the men in the boat with him, on their way back to Crown Point, so that none might remain to tell tales.[50] Fortunately Reid had left the day before. Irwin disapproved of such bloody intentions, and said if his land was confirmed to a Yorker, he would either buy the Yorker's title or move off.

James Henderson, settler under Colonel Reid, deposed that on Wednesday, August 11, he and three others of Colonel Reid's settlers were at work at their hay in the meadow, when twenty men, armed with guns, swords, and pistols, surprised them. They inquired if Henderson and his companions lived in the house some time before occupied by Joshua Hide. They replied no, the men who lived in that house were about their business. The rioters then told Henderson and his companions that they must go along with them (as they could not understand the women), and marched them prisoners, guarded before and behind like criminals, to the house, where they joined the rest of the mob, in number about one hundred or more, all armed as before, and who, as Henderson was told by the women, had let their horses loose in the corn and wheat that Reid had bought for his settlers. The mob desired the things to be taken out of the house, and then set the house on fire. Ethan[51] Allen, the ringleader or captain, then ordered part of his gang to go with Henderson to his own house (formerly built and occupied by Captain Gray) in order to prepare it for the same fate. Henderson and his wife earnestly requested the mob to spare their house for a few days, in order to save their effects and protect their children from the inclemency of the weather, until they could have an opportunity of removing themselves to some safe place; but Captain Allen, coming up from the fore-mentioned house, told them that his business required haste; for he and his gang were determined not to leave a house belonging to Colonel Reid standing. Then the mob set fire to and entirely consumed Henderson's house. Henderson took out his memorandum book and desired to know their ringleader's or captain's name. The captain answered: "Who gave you authority to ask for my name?" Henderson replied that as he took him to be the ringleader of the mob, and as he had in such a riotous and unlawful manner dispossessed him, he had a right to ask his name, that he might represent him to Colonel Reid, who had put him, Henderson, in peaceable possession of the premises as his just[52] property. Allen answered, he wished they had caught Colonel Reid; they would have whipped him severely; that his name was Ethan Allen, captain of that mob, and that his authority was his own arms, pointing to his gun; that he and his companions were a lawless mob, their law being mob law. Henderson replied that the law was made for lawless and riotous people, and that he must know it was death by the law to ringleaders of rioters and lawless mobs. Allen answered that he had run these woods in the same manner these seven years past [this would carry it back to the year 1766, when Zadoc Thompson says Allen's family was living in Sheffield] and never was caught yet; and he told Henderson that if any of Colonel Reid's settlers offered hereafter to build any house and keep possession, the Green Mountain Boys, as they call themselves, would burn their houses and whip them into the bargain. The mob then burnt the house formerly built and occupied by Lewis Stewart, and remained that night about Leonard's house. The next day, about seven A.M., August 12, Henderson went to Leonard's house. The mob were all drawn up, consulting about destroying the mill.[53] Those who were in favor of it were ordered to follow Captain Allen. In the mean time Baker and his gang came to the opposite side of the river and fired their guns. They were brought over at once, and while they were taking some refreshment, Allen's party marched to the mill, but did not break up any part of it until Allen joined them. The two mobs having joined (by their own account one hundred and fifty in number), with axes, crow-bars, and handspikes tore the mill to pieces, broke the mill-stones and threw them into the creek. Baker came out of the mill with the bolt-cloth in his hands. With his sword he cut it in pieces and distributed it among the mob to wear in their hats like cockades, as trophies of the victory. Henderson told Baker he was about very disagreeable work. Baker replied it was so, but he had a commission for so doing, and showed Henderson where his thumb had been cut off, which he called his commission.

Angus McBean, settler under Colonel Reid, deposed that between seven and eight A.M., Thursday, August 12 last, he met a part of the New England mob about Leonard's house, sixty men or thereabouts, he supposed, armed[54] with guns, swords, and pistols. One of them asked Angus if he were one of Colonel Reid's new settlers, and having been told he was, asked him what he intended to do. McBean replied he intended to build himself a house and keep possession of the land. He was then asked if he intended to keep possession for Colonel Reid. He replied yes, as long as he could. Soon after their chief leader, Allen, came and asked him if he was the man that said he would keep possession for Colonel Reid. McBean said yes. Allen then damned his soul, but he would have him, McBean, tied to a tree and skinned alive, if he ever attempted such a thing. Allen and several of the mob said, if they could but catch Colonel Reid, they would cut his head off. Joshua Hide, one of the persons of whom Colonel Reid bought the crop, advised the mob to tear down or burn the houses of Donald McIntosh and John Burdan, as they both had been assisting Colonel Reid. Soon after several guns were fired on the other side of the creek. Some of the mob said that was Captain Baker and his party coming to see the sport. Soon Baker and his party joined the mob, and all went to tear down the grist-mill. McBean thought[55] Baker was one of the first that entered the mill.

However strong our indignation at the New York usurpations, we cannot read of the violent ejectment of families without a feeling of repugnance to such a method. Turn to the vivid and romantic account of Colonel Reid's settlement in "The Tory's Daughter," and remember that in civil strife the innocent must often suffer. The Green Mountain Boys' immunity from the penalty of the law for their riotous acts shows not only their adroitness, but suggests half-heartedness in their pursuit. Laws not supported by public sentiment are rarely enforced.

John Munroe wrote to Duane during the Clarendon proceedings:

The rioters have a great many friends in the county of Albany, and particularly in the city of Albany, which encourages them in their wickedness, at the same time hold offices under the Government, and pretend to be much against them, but at heart I know them to be otherwise, for the rioters have often told me, that be it known to me, that they had more friends in Albany than I had, which I believe to be true.

Hugh Munro lived near the west line of[56] Shaftsbury. He took Surveyor Campbell to survey land in Rupert for him. He was seized by Cochran, who said he was a son of Robin Hood, and beaten. Ira Allen says Munro fainted from whipping by bush twigs. Munro had not a savory reputation with the Vermonters. After Tryon's offer of a reward for the arrest of Allen, Baker, and Cochran, he, with ten or twelve other men, had seized Baker, who lived ten or twelve miles from him, a mile east of Arlington. After a march of sixteen miles, they were met by ten Bennington men, who arrested Munro and Constable Stevens, the rest of the party fleeing. Later Warner and one man rode to Munro's and asked for Baker's gun. Munro refused, and seizing Warner's bridle ordered the constable to arrest Warner, who drew his cutlass and felled Munro to the ground. For this act of Warner's, Poultney voted him one hundred acres of land April 4, 1773.

In 1774 Allen published a pamphlet of over two hundred pages, in which he rehearsed many historical facts tending to show that previous to the royal order of 1764, New York had no claim to extend easterly to the Connecticut River. He portrayed in strong[57] light the oppressive conduct of New York toward the settlers. This pamphlet also contained the answer of himself and of his associates to the Act of Outlawry of March, 1774. Another man was busy this year drawing up reports of the trouble in Vermont.

Crean Brush, the first Vermont lawyer, was a colonel, a native of Dublin. In 1762 he came to New York and became assistant secretary of the colony; in 1771-74 he practised law in Westminster, Vt. He claimed thousands of Vermont acres under New York titles, and became county clerk, surrogate, and provincial member of Congress. He was in Boston jail nineteen months for plundering Boston whigs, and finally escaped in his wife's dress. The British commander in New York told him his conduct merited more punishment. A Yorker, always fighting the Green Mountain Boys; a tory, always fighting the whigs; with fair culture and talent, he became a sot, and, at the age of fifty-three, in 1778, he blew his brains out, in New York City. He left a step-daughter who became the second wife of Ethan Allen.

On February 5, 1774, Brush reported to the New York Legislature resolutions to the effect[58] "that riotousness exists in part of Charlotte County and northeast Albany County, calling for redress; that a Bennington mob has terrorized officers, rescued debtors, assumed military command and judicial power, burned houses, beat citizens, expelled thousands, stopped the administration of justice; that anti-rioters are in danger in person and property and need protection. Wherefore the Governor is petitioned to offer fifty pounds reward for the apprehension and lodgment in Albany jail of Ethan Allen, Seth Warner, Remember Baker, Robert Cochran, Peleg Sunderland, Silvanus Brown, James Breakenridge, and John Smith, either or any of them." It was ordered that Brush and Colonel Ten Eyck report a bill for the suppression of riotous and disorderly proceedings. Captain Delaney and Mr. Walton were appointed to present the address and resolutions to the governor.

A committee met March 1, 1774, at Eliakim Weller's house in Manchester, adjourning to the third Wednesday at Captain Jehial Hawley's in Arlington. Nathan Clark was chairman of the committee and Jonas Clark clerk. The New York Mercury, No. 1,163, with the foregoing report in it, was produced and read.[59] Seven of the committee were chosen to examine it and prepare a report, which was adopted and ordered published in the public papers. They speak of their misfortune in being annexed to New York, and hope that the king will adopt the report of the Board of Trade, made December 3, 1772. In consequence, hundreds of settled families, many of them comparatively wealthy, resolved to defend the outlawed men. All were ready at a minute's warning. They resolved to act on the defensive only, and to encourage the execution of law in civil cases and in real criminal cases. They advised the General Assembly to wait for the king's decision. The committee declared that they were all loyal to their political father; but that as they bought of the first governor appointed by the king, on the faith of the crown, they will maintain those grants; that New York has acted contrary to the spirit of the good laws of Great Britain. This declaration was certified by the chairman and clerk, at Bennington, April 14, 1774.

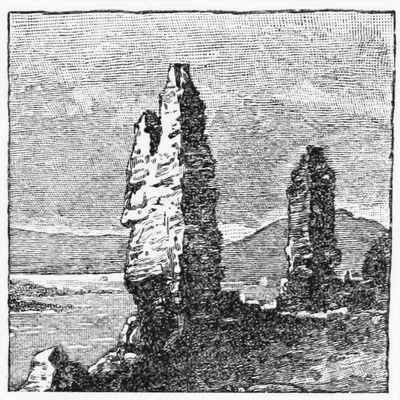

It was in 1774 that a new plan was formed for escaping from the government of New York; a plan that startles us by its audacity and its comprehensiveness. This was to establish[60] a new royal colony extending from the Connecticut to Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence, from forty-five degrees of north latitude to Massachusetts and the Mohawk River. The plan was formed by Allen and other Vermonters. At that time Colonel Philip Skene, a retired British officer, was living at Whitehall on a large patent of land. To him the Vermonters communicated the project. Whitehall was to be the capital and Skene the governor of the projected colony. Skene, at his own expense, went to London, and was appointed governor of Ticonderoga and Crown Point, but the course of public events prevented the completion of this scheme.

PREPARATIONS TO CAPTURE TICONDEROGA.—DIARY OF EDWARD MOTT.—EXPEDITIONS PLANNED.—BENEDICT ARNOLD.—GERSHOM BEACH.

On March 29, 1775, John Brown, a Massachusetts lawyer, wrote from Montreal to Boston:

The people on the New Hampshire Grants have engaged to seize the fort at Ticonderoga as soon as possible, should hostilities be committed by the king's troops.

The most minute account of the preparations to capture Ticonderoga is furnished by the diary for April, 1775, of Edward Mott, of Preston, Conn., a captain in Colonel S. H. Parson's regiment. He had been at the camp of the American army beleaguering Boston; took charge of the expedition to seize Ticonderoga; reported its success to Governor Trumbull at Hartford; was sent by Trumbull to Congress at Philadelphia with the news; resumed the command of his company[62] at Ticonderoga in May; was with the Northern army during the campaign; was at the taking of Chambly and St. Johns; and became a major in Colonel Gray's regiment next year.

Preston, Friday, April 28, 1775.

Set out for Hartford, where I arrived the same day. Saw Christopher Leffingwell, who inquired of me about the situation of the people at Boston. When I had given him an account, he asked me how they could be relieved and where I thought we could get artillery and stores. I told him I knew not unless we went and took possession of Ticonderoga and Crown Point, which I thought might be done by surprise with a small number of men. Mr. Leffingwell left me and in a short time came to me again, and brought with him Samuel H. Parsons and Silas Deane, Esqrs. When he asked me if I would undertake in such an expedition as we had talked of before, I told him I would. They told me they wished I had been there one day sooner; that they had been on such a plan; and that they had sent off Messrs. Noah Phelps and Bernard Romans, whom they had supplied with £300 in cash from the treasury, and ordered them to draw for more if they should need; that said Phelps and Romans had gone by the way of Salisbury, where they would make a stop. They expected a small number of men would join them, and if I would go after them they would give me an order or letter to them to join with them and[63] to have my voice with them in conducting the affair and in laying out the money; and also that I might take five or six men with me. On which I took with me Mr. Jeremiah Halsey, Mr. Epaphras Bull, Mr. Wm. Nichols, Mr. Elijah Babcock, and John Bigelow joined me; and Saturday, the 29th of April, in the afternoon, we set out on said expedition. Mr. Babcock tired his horse. We got another horse of Esq. Humphrey in Norfolk, and that day arrived at Salisbury; tarried all night, and the next day, having augmented our company to the number of sixteen in the whole, we concluded it was not best to add any more, as we meant to keep our business a secret and ride through the country unarmed till we came to the New Settlements on the Grants. We arrived at Mr. Dewey's in Sheffield, and there we sent off Mr. Jer. Halsey and Capt. John Stevens to go to Albany, in order to discover the temper of the people in that place, and to return and inform us as soon as possible.

That night (Monday the 1st of May) we arrived at Col. Easton's in Pittsfield, where we fell in company with John Brown, Esq., who had been at Canada and Ticonderoga about a month before; on which we concluded to make known our business to Col. Easton and said Brown and to take their advice on the same. I was advised by Messrs. Deane, Leffingwell, and Parsons not to raise our men till we came to the New Hampshire Grants, lest we should be discovered by having too long a[64] march through the country. But when we advised with the said Easton and Brown they advised us that, as there was a great scarcity of provisions in the Grants, and as the people were generally poor, it would be difficult to get a sufficient number of men there; therefore we had better raise a number of men sooner. Said Easton and Brown concluded to go with us, and Easton said he would assist me in raising some men in his regiment. We then concluded for me to go with Col. Easton to Jericho and Williamstown to raise men, and the rest of us to go forward to Bennington and see if they could purchase provisions there.

We raised twenty-four men in Jericho and fifteen in Williamstown; got them equipped ready to march. Then Col. Easton and I set out for Bennington. That evening we met with an express for our people informing us that they had seen a man directly from Ticonderoga and he informed them that they were re-enforced at Ticonderoga, and were repairing the garrison, and were every way on their guard; therefore it was best for us to dismiss the men we had raised and proceed no further, as we should not succeed. I asked who the man was, where he belonged, and where he was going, but could get no account; on which I ordered that the men should not be dismissed, but that we should proceed. The next day I arrived at Bennington. There overtook our people, all but Mr. Noah Phelps and Mr. Heacock, who were gone forward to reconnoitre the fort: and Mr.[65] Halsey and Mr. Stevens had not got back from Albany.

The following account of expenses incurred on this expedition is amusing, pitiful, and interesting, as evidence of the small beginnings of the Revolution, and as compared with the machinery of transportation and the wealth of the nation in its Civil War:

Account of Captain Edward Mott for his expenses going to Ticonderoga and afterwards against the Colony of Connecticut:

| £ | s. | d. | |

| April 26th.—To expenses from Preston to Hartford | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Expenses at Hartford while consulting what plan to take, or where it would be best to raise the men | 0 | 15 | 0 |

| April 30th.—To expenses of six men at New Hartford on our way to New Hampshire Grants to raise men ($3) | 0 | 18 | 0 |

| May 1st.—To expenses at Norfolk ($2.50) | 0 | 15 | 0 |

| To expenses at Shaftsbury | 0 | 7 | 8 |

| To expenses in Jericho while raising men | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| To expenses of marching men from Jericho to Williamstown | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| [66] May 1st.—To expenses at Allentown | 0 | 6 | 8 |

| To expenses at Massachusetts | 2 | 4 | 6 |