Title: Claudian, volume 1 (of 2)

Author: Claudius Claudianus

Translator: Maurice Platnauer

Release date: March 14, 2016 [eBook #51443]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English, Latin

Credits: Produced by Ted Garvin and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber’s Note:

Volume 2 is available as Project Gutenberg ebook number 51444.

THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY

FOUNDED BY JAMES LOEB, LL.D.

EDITED BY

| † T. E. PAGE, C.H., LITT.D. | |

| † E. CAPPS, PH.D., LL.D. | † W. H. D. ROUSE, LITT.D. |

| L. A. POST, L.H.D. | E. H. WARMINGTON, M.A., F.R.HIST.SOC. |

CLAUDIAN

I

CLAUDIAN

WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY

MAURICE PLATNAUER

SOMETIME HONORARY SCHOLAR OF NEW COLLEGE, OXFORD

ASSISTANT MASTER AT WINCHESTER COLLEGE

IN TWO VOLUMES

I

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

LONDON

WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD

MCMLXIII

First printed 1922

Reprinted 1956, 1963

Printed in Great Britain

Claudius Claudianus may be called the last poet of classical Rome. He was born about the year 370 A.D. and died within a decade of the sack of the city by Alaric in 410. The thirty to forty odd years which comprised his life were some of the most momentous in the history of Rome. Valentinian and Valens were emperors respectively of the West and the East when he was born, and while the former was engaged in constant warfare with the northern tribes of Alamanni, Quadi and Sarmatians, whose advances the skill of his general, Theodosius, had managed to check, the latter was being reserved for unsuccessful battle with an enemy still more deadly.

It is about the year 370 that we begin to hear of the Huns. The first people to fall a victim to their eastward aggression were the Alans, next came the Ostrogoths, whose king, Hermanric, was driven to suicide; and by 375 the Visigoths were threatened with a similar fate. Hemmed in by the advancing flood of Huns and the stationary power of Rome this people, after a vain attempt to ally itself with the latter, was forced into arms against her. An indecisive battle with the generals of Valens (377) was followed by a crushing Roman defeat in the succeeding year (August 9, 378) at Adrianople, where[viii] Valens himself, but recently returned from his Persian war, lost his life.

Gratian and his half-brother, Valentinian II., who had become Augusti upon the death of their father, Valentinian I., in 375, would have had little power of themselves to withstand the victorious Goths and Rome might well have fallen thirty years before she did, had it not been for the force of character and the military skill of that same Theodosius whose successes against the Alamanni have already been mentioned. Theodosius was summoned from his retirement in Spain and made Augustus (January 19, 379). During the next three years he succeeded, with the help of the Frankish generals, Bauto and Arbogast, in gradually driving the Goths northward, and so relieved the barbarian pressure on the Eastern Empire and its capital. In 381 Athanaric, the Gothic king, sued in person for peace at Constantinople and there did homage to the emperor. In the following year the Visigoths became allies of Rome and, for a time at least, the danger was averted.

Meanwhile the West was faring not much better. Gratian, after an uneasy reign, was murdered in 383 by the British pretender, Magnus Maximus. From 383 to 387 Maximus was joint ruler of the West with Valentinian II., whom he had left in command of Italy rather from motives of policy than of clemency; but in the latter year he threw off the mask and, crossing the Alps, descended upon his colleague whose court was at Milan. Valentinian fled to Thessalonica and there threw himself on the mercy of Theodosius. Once more that general was to save the situation.

Maximus was defeated by him at Aquileia and put to death, while Arbogast recovered Gaul by means of an almost bloodless campaign (388).

The next scene in the drama is the murder at Vienne on May 15, 392, of the feeble Valentinian at the instigation of Arbogast. Arbogast’s triumph was, however, short-lived. Not daring himself, a Frank, to assume the purple he invested therewith his secretary, the Roman Eugenius, intending to govern the West with Eugenius as a mere figure-head. Once more, and now for the last time, Theodosius saved the cause of legitimacy by defeating Eugenius at the battle of the Frigidus[1] in September 394. Eugenius was executed but Arbogast made good his escape, only to fall a few weeks later by his own hand.

Theodosius himself died on January 17, 395, leaving his two sons, Arcadius and Honorius, emperors of the East and West respectively. Arcadius was but a tool in the hands of his praetorian prefect, Rufinus, whose character is drawn with such venomous ferocity in Claudian’s two poems. Almost equally powerful and scarcely less corrupt seems to have been that other victim of Claudian’s splenetic verses, the eunuch chamberlain Eutropius, who became consul in the year 399. Both these men suffered a violent end: Eutropius, in spite of the pleadings of S. John Chrysostom, was put to death by Gainas, the commander of the Gothic troops in the East; Rufinus was torn to pieces in the presence of Arcadius himself by his Eastern troops.[2] The instigator of[x] this just murder was Claudian’s hero, Stilicho the Vandal.

Stilicho, who had been one of Theodosius’ generals, had been put in command of the troops sent to oppose Alaric, the Visigoth, when the latter had broken away from his allegiance to Rome and was spreading devastation throughout Thrace, Macedonia and Thessaly. He was successful in his campaign, but, upon his marching south into Greece, in order to rid that country also of its Gothic invaders, he was forbidden by Rufinus to advance any farther. There can be little doubt that the murder of Rufinus was Stilicho’s answer.

In spite of a subsequent victory over Alaric near Elis in the year 397, Stilicho’s success can have been but a partial one, for we find the Visigoth general occupying the post of Master of the Soldiery in Illyricum, the withholding of which office had been the main cause of his defection. Possibly, too, the revolt of Gildo in Africa had something to do with the unsatisfactory termination of the Visigothic war. It is interesting to observe the dependence of Italy on African corn, a dependence of which in the first century of the Christian era Vespasian, and right at the end of the second the pretender Pescennius Niger, threatened to make use. If we can credit the details of Claudian’s poem on the war (No. xv.), Rome was very shortly reduced to a state of semi-starvation by Gildo’s holding up of the corn fleet, and, but for Stilicho’s prompt action in sending Gildo’s own brother, Mascezel, to put down the rebellion, the situation might have become even more critical. The poet, it may be remarked, was in an awkward position with regard to the war for,[xi] though the real credit of victory was clearly due to Mascezel (cf. xv. 380 et sqq.), he nevertheless wished to attribute it to his hero Stilicho, and, as Stilicho had Mascezel executed[3] later in that same year (Gildo had been defeated at Tabraca July 31, 398), he prudently did not write, or perhaps suppressed, Book II.

Stilicho, who had married Serena, niece and adoptive daughter of Theodosius, still further secured his position by giving his daughter, Maria, in marriage to the young Emperor Honorius in the year 398. This “father-in-law and son-in-law of an emperor,” as Claudian is never wearied of calling him, did the country of his adoption a signal service by the defeat at Pollentia on Easter Day (April 6), 402, of Alaric, who, for reasons of which we really know nothing, had again proved unfaithful to Rome and had invaded and laid waste Italy in the winter of 401-402.

The battle of Pollentia was the last important event in Claudian’s lifetime. He seems to have died in 404, four years before the murder of Stilicho by the jealous Honorius and six before the sack of Rome by Alaric—a disaster which Stilicho[4] alone, perhaps, might have averted.

So much for the historical background of the life of the poet. Of the details of his career we are not well informed. Something, indeed, we can gather from the pages of the poet himself, though it is not much, but besides this we have to guide us only Hesychius of Miletus’ short[xii] article in Suidas’ lexicon, a brief mention in the Chronicle of 395, and (a curious survival) the inscription[5] under the statue which, as he himself tells us,[6] emperor and senate had made in his honour and set up in the Forum of Trajan. We are ignorant even of the date of his birth and can only conjecture that it was about the year 370. Of the place of his birth we are equally uninformed by contemporary and credible testimony, but there can be little doubt that he came from Egypt,[7] probably from Alexandria itself. We have, for what it is worth, the word of[xiii] Suidas and the lines of Sidonius Apollinaris,[8] which clearly refer to Claudian and which give Canopus as the place of his birth. (Canopus is almost certainly to be taken as synonymous with Egypt.) But besides these two statements we have only to look at his interest in things Egyptian, e.g. his poems on the Nile, the Phoenix, etc., at such passages as his account of the rites at Memphis,[9] at such phrases as “nostro cognite Nilo,”[10] to see that the poet is an Egyptian himself. It is probable that, whether or not he spent all his early life in Egypt, Claudian did not visit Rome until 394. We know from his own statement[11] that his first essays in literature were all of them written in Greek and that it was not until the year 395 that he started to write Latin. It is not unlikely, therefore, that his change of country and of literary language were more or less contemporaneous, and it is highly probable that he was in Rome before January 3, 395, on which day his friends the Anicii (Probinus and Olybrius) entered upon their consulship. Speaking, moreover, of Stilicho’s consulship in 400 Claudian mentions a five years’ absence.[12] Not long after January 3, 395, Claudian seems to have betaken himself to the court at Milan, and it is from there that he sends letters to Probinus and Olybrius.[13] Here the poet seems to have stayed for five years, and here he seems to[xiv] have won for himself a position of some importance. As we see from the inscription quoted above, he became vir clarissimus, tribunus et notarius, and, as he does not continue further along the road of honours (does not, for instance, become a vir spectabilis) we must suppose that he served in some capacity on Stilicho’s private staff. No doubt he became a sort of poet laureate.

It is probable that the “De raptu” was written during the first two years of his sojourn at the court of Milan. The poem is dedicated, or addressed, to Florentinus,[14] who was praefectus urbi from August 395 to the end of 397 when he fell into disgrace with Stilicho. It is to this circumstance that we are to attribute the unfinished state of Claudian’s poem.

The Emperor Honorius became consul for the third time on January 3, 396, and on this occasion Claudian read his Panegyric in the emperor’s presence.[15]

Some five weeks before this event another of greater importance had occurred in the East. This was the murder of Rufinus, the praetorian prefect, amid the circumstances that have been related above. The date of the composition of Claudian’s two poems “In Rufinum” is certainly to be placed within the years 395-397, and the mention of a “tenuem moram”[16] makes it probable that Book II. was written considerably later than Book I.; the references, moreover, in the Preface to Book II. to a victory of Stilicho clearly point to that general’s defeat of the Goths near Elis in 397.

To the year 398 belong the Panegyric on the[xv] fourth consulship of Honorius and the poems celebrating the marriage of the emperor to Stilicho’s daughter, Maria. We have already seen that the Gildo episode and Claudian’s poem on that subject are to be attributed to this same year.

The consuls for the year 399 were both, in different ways, considered worthy of the poet’s pen. Perhaps the most savage of all his poems was directed against Eutropius, the eunuch chamberlain, whose claim to the consulship the West never recognized,[17] while a Panegyric on Flavius Manlius Theodorus made amends for an abusive epigram which the usually more politic Claudian had previously levelled at him.[18]

At the end of 399, or possibly at the beginning of 400, Claudian returned to Rome[19] where, probably in February,[20] he recited his poem on the consulship of Stilicho; and we have no reason for supposing that the poet left the capital from this time on until his departure for his ill-starred journey four years later. In the year 402,[21] as has already been mentioned, Stilicho defeated Alaric at Pollentia, and Claudian recited his poem on the Gothic war sometime during the summer of the same year. The scene of the recitation seems to have been the Bibliotheca Templi Apollinis.[22] It was in this year, too, that the poet reached the summit of his greatness[xvi] in the dedication of the statue which, as we have seen, was accorded to him by the wishes of the emperor and at the demand of the senate.

The last of Claudian’s datable public poems is that on the sixth consulship of Honorius. It was composed probably towards the end of 403 and recited in Rome on (or after) the occasion of the emperor’s triumphant entry into the city. The emperor had just returned after inflicting a defeat on the Goths at Verona in the summer of 403. It is reasonable to suppose that this triumphant entry (to which the poem refers in some detail, ll. 331-639) took place on the day on which the emperor assumed the consular office, viz. January 3, 404.

In the year 404 Claudian seems to have married some protégée of Serena’s. Of the two poems addressed to her the “Laus Serenae” is clearly the earlier, and we may take the other, the “Epistola ad Serenam,” to be the last poem Claudian ever wrote. It is a poem which seems to have been written on his honeymoon, during the course of which he died.[23]

It is not easy to arrive at any just estimate of Claudian as a writer, partly because of an inevitable tendency to confuse relative with absolute standards, and partly (and it is saying much the same thing in other words) because it is so hard to separate Claudian the poet from Claudian the manipulator of the Latin language. If we compare his latinity with that of his contemporaries (with the possible exception of Rutilius) or with that of such a poet as Sidonius Apollinaris, who came not much more[xvii] than half a century after him, it is hard to withhold our admiration from a writer who could, at least as far as his language is concerned, challenge comparison with poets such as Valerius Flaccus, Silius Italicus, and Statius—poets who flourished about three centuries before him.[24] I doubt whether, subject matter set aside, Claudian might not deceive the very elect into thinking him a contemporary of Statius, with whose Silvae his own shorter poems have much in common.

Even as a poet Claudian is not always despicable. His descriptions are often clever, e.g. the Aponus, and many passages in the “De raptu.”[25] His treatment of somewhat commonplace and often threadbare themes is not seldom successful—for example, the poem on the Phoenix and a four-line description of the horses of the dawn in the Panegyric on Honorius’ fourth consulship[26]—and he has a happy knack of phrase-making which often relieves a tedious page:

he says of the pander Eutropius.

But perhaps Claudian’s forte is invective. The panegyrics (with the doubtful exception of that on[xviii] Manlius, which is certainly brighter than the others) are uniformly dull, but the poems on Rufinus and Eutropius are, though doubtless in the worst of taste, at least in parts amusing.

Claudian’s faults are easy to find. He mistook memory for inspiration and so is often wordy and tedious, as for instance in his three poems on Stilicho’s consulship.[28] Worse than this he is frequently obscure and involved—witness his seven poems on the drop of water contained within the rock crystal.[29] The besetting sin, too, of almost all post-Virgilian Roman poets, I mean a “conceited” frigidity, is one into which he is particularly liable to fall. Examples are almost too numerous to cite but the following are typical: “nusquam totiensque sepultus”[30] of the body of Rufinus, torn limb from limb by the infuriated soldiery; “caudamque in puppe retorquens Ad proram iacet usque leo”[31] of one of the animals brought from Africa for the games at Stilicho’s triumph; “saevusque Damastor, Ad depellendos iaculum cum quaereret hostes, Germani rigidum misit pro rupe cadaver”[32] of the giant Pallas turned to stone by the Gorgon’s head on Minerva’s shield. Consider, too, the remarkable[xix] statement that Stilicho, in swimming the Addua, showed greater bravery than Horatius Cocles because, while the latter swam away from Lars Porsenna, the former “dabat … Geticis pectora bellis.”[33]

Two of the poems are interesting as touching upon Christianity (Carm. min. corp. xxxii. “De salvatore,” and l. “In Iacobum”). The second of these two poems can scarcely be held to be serious, and although the first is unobjectionable it cannot be said to stamp its author as a sincere Christian. Orosius[34] and S. Augustine[35] both declare him to have been a heathen, but it is probable that, like his master Stilicho, Claudian rendered the new and orthodox religion at least lip-service.

It seems likely that after the death of Claudian (404) and that of his hero, Stilicho, the political poems (with the exception of the Panegyric on Probinus and Olybrius,[36] which did not concern Stilicho) were collected and published separately. The “Carmina minora” may have been published about the same time. The subsequent conflation of these two portions came to be known as “Claudianus maior,” the “De raptu” being “Claudianus minor.”

The MSS. of Claudian’s poems fall into two main classes:

(1) Those which Birt refers to as the Codices[xx] maiores and which contain the bulk of the poems but seldom the “De raptu.”

(2) Those which Birt calls the Codices minores and which contain (generally exclusively) the “De raptu.”

Class (1) may be again divided into (a) MSS. proper; (b) excerpts. I give Birt’s abbreviations.

(a) The most important are:

Besides these are many inferior MSS. referred to collectively by Birt as ς.

(b) Consists of:

Each of them resembles the other closely and both come from a common parent.

Under (b) may further be mentioned the Basel edition of Isengrin (1534), which preserves an independent tradition.

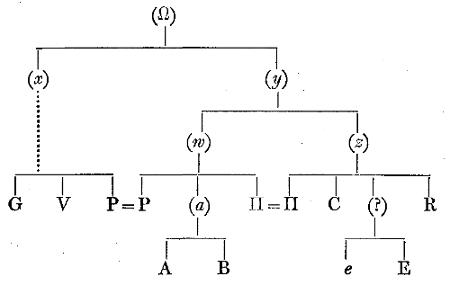

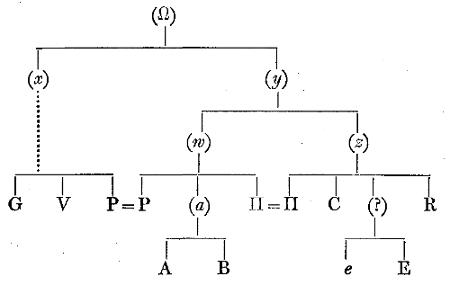

Birt postulates an archetype (Ω), dating between 6th and 9th centuries, and two main “streams,” x and y; y being again subdivided into w and z.

The following is the family “tree.” Letters enclosed in brackets refer to non-existent MSS.

Of class (2) may be mentioned:

It is to be observed that in Birt’s edition, and in any other that accepts his “sigla,” A B C and V stand for different MSS. according to whether they refer, or do not refer, to the “De raptu.”

Some MSS. contain scholia but none of these go back before the 12th or even the 13th century.

The chief editions of Claudian are as follows:

Like Bentinus, Claverius used certain MSS. (in his case those of the library of Cuiacius) unknown to us.[xxiii][38]

These last three have good explanatory notes.

The first critical edition is that of L. Jeep (Leipzig, 1876-79).

In 1892 Birt published what must be considered as the standard edition of Claudian—vol. x. in the Monumenta Germaniae historica series. Birt was the first to put the text of Claudian on a firm footing, and it is his edition that I have followed, appending critical notes only where I differ from him.[39]

The latest edition of Claudian is that of Koch (Teubner, Leipzig, 1893). Koch was long associated with Birt in his researches into textual questions connected with Claudian, and his text is substantially the same as that of Birt.

So far as I know, there is no English prose translation of Claudian already in the field, though various of his poems, notably the “De raptu,” have found many verse translators, and in 1817 his complete works were put into English verse by A. Hawkins. An Italian version was published by Domenico Grillo in Venice in 1716, a German one by Wedekind in Darmstadt in 1868, and there exist two French prose translations, one by MM. Delatour and Geruzez (éd. Nisard, Paris, 1850) and one by M. Héguin de Guerle (Garnier frères, Collection Panckoucke, Paris, 1865).

Of Claudiana may be mentioned Vogt, De Claudiani carminum quae Stilichonem praedicant fide historica (1863); Ney, Vindictae Claudianeae (1865); T. Hodgkin’s Claudian, the last of the Roman Poets (1875); E. Arens’ Quaestiones Claudianae (1894); two studies by A. Parravicini, (1) Studio di retorica sulle opere di Claudio Claudiano (1905), and (2) I Panegirici di Claudiano (1909); J. H. E. Crees’ Claudian as an Historical Authority (Cambridge Historical Essays, No. 17, 1908); Professor Postgate’s article on the editions of Birt and Koch in the Class. Rev. (vol. ix. pp. 162 et sqq.), and the same scholar’s Emendations in the Class. Quarterly of 1910 (pp. 257 et sqq.). Reference may also be made to Professor Bury’s appendix to vol. iii. of his edition of Gibbon (1897, under “Claudian”) and to Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, vol. xxx. The Encomiums of Claudius Claudianus. Vollmer’s article in Pauly-Wissowa’s Lexicon is a mine of information, but for completeness Birt’s introduction (over 200 pp. long) stands alone.

The curious may find an interesting light thrown[xxv] on Claudian and his circle by Sudermann’s play, Die Lobgesänge des Claudian (Berlin, 1914).

All Claudian’s genuine works are translated in the present volumes with the exception of the two-line fragment “De Lanario” (Birt, c.m.c. lii [lxxxviii.]). The appendix “vel spuria vel suspecta continens” has been rejected both by Birt and Koch, and I have in this followed their example. The eight Greek poems attributed to Claudian are at least of doubtful authenticity, though Birt certainly makes out a good case for the “Gigantomachia” (a fragment of 77 lines). The remainder consists of short epigrams, two on the well-worn theme of the water enclosed in the crystal and two Christian ones. These last are almost certainly not the work of Claudius Claudianus but of Claudianus Mamertus, presbyter of Vienne circ. 474 A.D. We know from Sidonius (Ep. iv. 3. 8) that this Claudian was a writer of sacred poetry both in Greek and Latin—indeed the famous “Pange lingua” is attributed to him.

A word should perhaps be said as to the numbering of the poems.

It is much to be regretted that Birt did not cut adrift from Gesner’s system, or at least that he only did so in the “Carmina minora.” The resultant discrepancy in his (and Koch’s) edition between the order of the poems and their numbering is undoubtedly a nuisance, but I have not felt justified, in so slight a work as the present one, in departing from the now traditional arrangement.

I wish, in conclusion, to express my thanks to my colleagues, Mr. R. L. A. Du Pontet and Mr. E. H. Blakeney: to the first for valuable suggestions on several obscure points, and to the second for help in reading the proofs.

MAURICE PLATNAUER.

Winchester, September 1921.

[1] Cf. vii. 99 et sqq.

[2] v. 348 et sqq. S. Jerome (Ep. lx.) refers to his death and tells how his head was carried on a pike to Constantinople.

[3] Or at least connived at his death; see Zosimus v. 11. 5.

[4] For an adverse (and probably unfair) view of Stilicho see Jerome, Ep. cxxiii. § 17.

[5] C.I.L. vi. 1710 (=Dessau 2949). Now in the Naples Museum.

[Cl.] Claudiani v.c. | [Cla]udio Claudiano v.c., tri|[bu]no et notario, inter ceteras | [de]centes artes prae[g]loriosissimo | [po]etarum, licet ad memoriam sem|piternam carmina ab eodem | scripta sufficiant, adtamen | testimonii gratia ob iudicii sui | [f]idem, dd. nn. Arcadius et Honorius | [fe-]licissimi et doctissimi | imperatores senatu petente | statuam in foro divi Traiani | erigi collocarique iusserunt.

v.c. = vir clarissimus, i.e. (roughly) The Rt. Hon. dd. nn. = domini nostri. The inscription may be translated:—To Claudius Claudianus v.c., son of Claudius Claudianus v.c., tribune and notary (i.e. Permanent Secretary), master of the ennobling arts but above all a poet and most famous of poets, though his own poems are enough to ensure his immortality, yet, in thankful memory of his discretion and loyalty, their serene and learned majesties, the Emperors Arcadius and Honorius have, at the instance of the senate, bidden this statue to be raised and set up in the Forum of the Emperor Trajan of blessed memory.

[6] xxv. 7.

[7] John Lydus (De magistr. i. 47) writes οὖτος ὁ Παφλαγών, but this, as Birt has shown, is merely an abusive appellation.

[8] Sid. Ap. Carm. ix. 274.

[9] viii. 570 et sqq.

[10] Carm. min. corp. xix. 3: cf. also Carm. min. corp. xxii. 20.

[11] Carm. min. corp. xli. 13.

[12] xxiii. 23.

[13] Carm. min. corp. xl. and xli.; see ref. to Via Flaminia in xl. 8.

[14] Praef. ii. 50.

[15] vi. 17.

[16] iv. 15.

[17] Cf. xxii. 291 et sqq.

[18] Carm. min. xxi.

[19] xxiii. 23.

[20] So Birt, Praef. p. xlii. note 1.

[21] It should perhaps be mentioned that this date is disputed: see Crees, Claudian as an Historical Authority, pp. 175 et sqq.

[22] xxv. 4 “Pythia … domus.”

[23] This suggestion is Vollmer’s: see his article on Claudian in Pauly-Wissowa, III. ii. p. 2655.

[24] Still more striking is the comparison of Claudian’s latinity with that of his contemporary, the authoress of the frankly colloquial Peregrinatio ad loca sancta (see Grandgent, Vulgar Latin, p. 5: Wölfflin, “Über die Latinität der P. ad l. sancta,” in Archiv für lat. Lexikographie, iv. 259).

[25] It is not impossible that this poem is a translation or at least an adaptation of a Greek (Alexandrine) original. So Förster, Der Raub und die Rückkehr der Persephone, Stuttgart, 1874.

[26] viii. 561-4 (dawns seem to suit him: cf. i. 1-6).

[27] xviii. 82, 83.

[28] Honourable exception should be made of xxi. 291 et sqq.—one of the best and most sincere things Claudian ever wrote.

[29] It is worth observing that not infrequently Claudian is making “tentamina,” or writing alternative lines: e.g. Carm. min. corp. vii. 1 and 2, and almost certainly the four lines of id. vi. v. is quite likely “a trial” for some such passage as xv. 523.

[30] v. 453.

[31] xxiv. 357-8.

[32] Carm. min. corp. liii. 101-3.

[33] xxviii. 490.

[34] vii. 35 “Paganus pervicacissimus.”

[35] Civ. dei, v. 26 “a Christi numine alienus.”

[36] This poem does not seem to have been associated with the others till the 12th century.

[37] See section on MSS.

[38] Koch, De codicibus Cuiacianis quibus in edendo Claudiano Claverius usus est, Marburg, 1889.

[39] I should like if possible to anticipate criticism by frankly stating that the text of this edition makes no claims to being based on scientific principles. I have followed Birt not because I think him invariably right but because his is at present the standard text. Where I differ from him (and this is but in a few places) I do so not because I prefer the authority of another MS. or because I am convinced of the rightness of a conjecture, but because Birt’s conservatism commits him (in my opinion) to untranslatable readings, in which cases my choice of a variant is arbitrary. Of the principle of difficilior lectio I pragmatically take no account.

Sun, that encirclest the world with reins of flame and rollest in ceaseless motion the revolving centuries, scatter thy light with kindlier beams and let thy coursers, their manes combed and they breathing forth a rosy flame from their foaming bits, climb the heavens more jocund in their loftier drawn chariot. Now let the year bend its new steps for the consul brothers and the glad months take their beginning.

Thou wottest of the Auchenian[40] race nor are the powerful Anniadae unknown to thee, for thou oft hast started thy yearly journey with them as consuls and hast given their name to thy revolution. For them Fortune neither hangs on uncertain favour nor changes, but honours, firmly fixed, pass to all their kin. Select what man thou wilt from their family, ’tis certain he is a consul’s son. Their ancestors are

[40] Probinus and Olybrius, the consuls for 395 (they were brothers), both belonged to the Anician gens, of which Auchenius became an alternative gentile name, Anicius becoming, in these cases, the praenomen. Many members of this family had been, and were to be, consuls: e.g. Anicius Auchenius Bassus in A.D. 408. The Annian gens was related by intermarriage to the Anician: e.g. Annius Bassus (cos. 331) who married the daughter of Annius Anicius Iulianus (cos. 322).

counted by the fasces (for each has held them), the same recurring honours crown them, and a like destiny awaits their children in unbroken succession. No noble, though he boast of the brazen statues of his ancestors, though Rome be thronged with senators, no noble, I say, dare boast himself their equal. Give the first place to the Auchenii and let who will contest the second. It is as when the moon queens it in the calm northern sky and her orb gleams with brightness equal to that of her brother whose light she reflects; for then the starry hosts give place, Arcturus’ beam grows dim and tawny Leo loses his angry glint, far-spaced shine the Bear’s stars in the Wain, wroth at their eclipse, Orion’s shafts grow dark as he looks in feeble amaze at his strengthless arm.

Which shall I speak of first? Who has not heard of the deeds of Probinus of ancient lineage, who knows not the endless praise of Olybrius?

The far-flung fame of Probus[41] and his sire lives yet and fills all ears with widespread discourse: the years to come shall not silence it nor time o’ercloud or put an end to it. His great name carries him beyond the seas, beyond Ocean’s distant windings and Atlas’ mountain caverns. If any live beneath the frozen sky by Maeotis’ banks, or any, near neighbours of the torrid zone, drink Nile’s stripling stream, they, too, have heard. Fortune yielded to his virtues, but never was he puffed up with success that engenders pride. Though his life was surrounded with luxury he knew how to preserve his uprightness uncorrupted. He did not hide his wealth in dark cellars nor condemn his riches to the nether gloom, but in showers more abundant than rain would ever enrich countless numbers of

[41] Probus was born about 332 and died about 390. He was (among many other things) proconsul of Africa and praefectus of Illyricum.

[42] MSS. si quis; Birt suggests sic vix; possibly ecquis should be read. Postgate (C. Q. iv. p. 258) quae vix … miretur … Astur.

men. The thick cloud of his generosity was ever big with gifts, full and overflowing with clients was his mansion, and thereinto there poured a stream of paupers to issue forth again rich men. His prodigal hand outdid Spain’s rivers in scattering gifts of gold (scarce so much precious metal dazzles the gaze of the miner delving in the vexed bowels of the earth), exceeding all the gold dust carried down by Tagus’ water trickling from unsmelted lodes, the glittering ore that enriches Hermus’ banks, the golden sand that rich Pactolus in flood deposits over the plains of Lydia.

Could my words issue from a hundred mouths, could Phoebus’ manifold inspiration breathe through a hundred breasts, even so I could not tell of Probus’ deeds, of all the people his ordered governance ruled, of the many times he rose to the highest honours, when he held the reins of broad-acred Italy, the Illyrian coast, and Africa’s lands. But his sons o’ershadowed their sire and they alone deserve to be called Probus’ vanquishers. No such honour befell Probus in his youth: he was never consul with his brother. You ambition, ever o’ervaulting itself, pricks not; no anxious hopes afflict your minds or keep your hearts in long suspense. You have begun where most end: but few seniors have attained to your earliest office. You have finished your race e’er the full flower of youth has crowned your gentle cheeks or adolescence clothed your faces with its pleasant down. Do thou, my Muse, tell their ignorant poet what god it was granted such a boon to the twain.

When the warlike emperor had with the thunderbolt of his might put his enemy to flight and freed

the Alps from fear, Rome, anxious worthily to thank her Probus, hastened to beg the Emperor’s favour for that hero’s sons. Her slaves, Shock and horrid Fear, yoked her winged chariot; ’tis they who ever attend Rome with loud-voiced roar, setting wars afoot, whether she battle against the Parthians or vex Hydaspes’ stream with her spear. The one fastens the wheels to the hubs, the other drives the horses beneath the iron yoke and makes them obey the stubborn bit. Rome herself in the guise of the virgin goddess Minerva soars aloft on the road by which she takes possession of the sky after triumphing over the realms of earth. She will not have her hair bound with a comb nor her neck made effeminate with a twisted necklace. Her right side is bare; her snowy shoulder exposed; her brooch fastens her flowing garments but loosely and boldly shows her breast: the belt that supports her sword throws a strip of scarlet across her fair skin. She looks as good as she is fair, chaste beauty armed with awe; her threatening helm of blood-red plumes casts a dark shadow and her shield challenges the sun in its fearful brilliance, that shield which Vulcan forged with all the subtlety of his skill. In it are depicted the children Romulus and Remus, and their loving father Mars, Tiber’s reverent stream, and the wolf that was their nurse; Tiber is embossed in electrum, the children in pure gold, brazen is the wolf, and Mars fashioned of flashing steel.

And now Rome, loosing both her steeds together, flies swifter than the fleet east wind; the Zephyrs shrill and the clouds, cleft with the track of the wheels, glow in separate furrows. What matchless speed! One pinion’s stroke and they reach their

goal: it is there where in their furthermost parts the Alps narrow their approaches into tortuous valleys and extend their adamantine bars of piled-up rocks. No other hand could unlock that gate, as, to their cost, those two tyrants[43] found; to the Emperor only they offer a way. The smoke of towers o’erthrown and of ruined fortresses ascends to heaven. Slaughtered men are piled up on a heap and bring the lowest valley equal with the hills; corpses welter in their blood; the very shades are confounded with the inrush of the slain.

Close at hand the victor, Theodosius, happy that his warfare is accomplished, sits upon the green sward, his shoulders leaning against a tree. Triumphant earth crowned her lord and flowers sprang up from prouder banks. The sweat is still warm upon his body, his breath comes panting, but calm shines his countenance beneath his helmet. Such is Mars, when with deadly slaughter he has devastated the Geloni and thereafter rests, a dread figure, in the Getic plain, while Bellona, goddess of war, lightens him of his armour and unyokes his dust-stained coursers; an outstretched spear, a huge cornel trunk, arms his hand and flashes its tremulous splendour over Hebrus’ stream.

When Rome had ended her airy journey and now stood before her lord, thrice thundered the conscious rocks and the black wood shuddered in awe. First to speak was the hero: “Goddess and friend, mother of laws, thou whose empire is conterminous with heaven, thou that art called the consort of the Thunderer, say what hath caused thy coming: why leavest thou the towns of Italy and thy native clime? Say, queen of the world. Were it thy

[43] Maximus and Eugenius. See Introduction, p. ix.

wish I would not shrink from toiling neath a Libyan sun nor from the cold winds of a Russian midwinter. At thy behest I will traverse all lands and fearing no season of the year will hazard Meroë in summer and the Danube in winter.”

Then the Queen answered: “Full well know I, far-famed ruler, that thy victorious armies toil for Italy, and that once again servitude and furious rebels have given way before thee, overthrown in one and the same battle. Yet I pray thee add to our late won liberty this further boon, if in very truth thou still reverest me. There are among my citizens two young brothers of noble lineage, the dearly loved sons of Probus, born on a festal day and reared in my own bosom. ’Twas I gave the little ones their cradles when the goddess of childbirth freed their mother’s womb from its blessed burden and heaven brought to light her glorious offspring. To these I would not prefer the noble Decii nor the brave Metelli, no, nor the Scipios who overcame the warlike Carthaginians nor the Camilli, that family fraught with ruin for the Gauls. The Muses have endowed them with full measure of their skill; their eloquence knows no bounds. Theirs not to wanton in sloth and banquets spread; unbridled pleasure tempts them not, nor can the lure of youth undermine their characters. Gaining from weighty cares an old man’s mind, their fiery youth is bridled by a greybeard’s wisdom. That fortune to which their birth entitles them I beg thee assure them and appoint for them the path of the coming year. ’Tis no unreasonable request and will be no unheard-of boon. Their birth demands it should be so. Grant it; so may Scythian Araxes be our vassal

and Rhine’s either bank; so may the Mede be o’erthrown and the towers that Semiramis built yield to our standards, while amazèd Ganges flows between Roman cities.”

To this the king: “Goddess, thou biddest me do what I would fain do and askest a boon that I wish to grant: thy entreaties were not needed for this. Does forgetfulness so wholly cloud my mind that I will not remember Probus, beneath whose leadership I have seen all Italy and her war-weary peoples come again to prosperity? Winter shall cause Nile’s rising, hinds shall make rivers their element, dark-flowing Indus shall be ice-bound, terror-stricken once again by the banquet of Thyestes the sun shall stay his course and fly for refuge back into the east, all this ere Probus can fade from my memory.”

He spake, and now the speedy messenger hies him to Rome. Straightway the choirs chant and the seven hills re-echo their tuneful applause. Joy is in the heart of that aged mother whose skilled fingers now make ready gold-embroidered vestment and garments agleam with the thread which the Seres comb out from their delicate plants, gathering the leafy fleece of the wool-bearing trees. These long threads she draws out to an equal length with the threads of gold and by intertwining them makes one golden cord; as fair Latona gave scarlet garments to her divine offspring when they returned to the now firm-fixèd shrine of Delos their foster-island, Diana leaving the forest glades and bleak Maenalus, her unerring bow wearied with much hunting, and Phoebus bearing the sword still dripping with black venom from the slaughtered Python. Then their dear island laved the feet of its acknowledged

deities, the Aegean smiled more gently on its nurslings, the Aegean whose soft ripples bore witness to its joy.

So Proba[44] adorns her children with vestment rare, Proba, the world’s glory, by whose increase the power of Rome, too, is increased. You would have thought her Modesty’s self fallen from heaven or Juno, summoned by sacred incense, turning her eyes on the shrines of Argos. No page in ancient story tells of such a mother, no Latin Muse nor old Grecian tale. Worthy is she of Probus for a husband, for he surpassed all husbands as she all wives. ’Twas as though in rivalry either sex had done its uttermost and so brought about this marriage. Let Pelion vaunt no more that Nereid bride.[45] Happy thou that art the mother of consuls twain, blessed thy womb whose offspring have given the year their name for its own.

So soon as their hands held the sceptres and the jewel-studded togas had enfolded their limbs the almighty Sire vouchsafes a sign with riven cloud and the shaken heavens, projecting a welcoming flash through the void, thundered with prosperous omen. Father Tiber, seated in that low valley, heard the sound in his labyrinthine cave. He stays with ears pricked up wondering whence this sudden popular clamour comes. Straightway he leaves his couch of green leaves, his mossy bed, and entrusts his urn to his attendant nymphs. Grey eyes flecked with blue shine out from his shaggy countenance, recalling his father Oceanus; thick curlèd grasses cover his neck and lush sedge crowns his head.

[44] Anicia Faltonia Proba. She was still alive in 410 and according to Procopius (Bell. Vand. i. 2) opened the gates of Rome to Alaric.

[45] Thetis, daughter of Nereus, was married to Peleus on Mount Pelion in Thessaly.

[46] Birt, following MSS., unanimes; Koch unanimos.

This the Zephyrs may not break nor the summer sun scorch to withering; it lives and burgeons around those brows immortal as itself. From his temples sprout horns like those of a bull; from these pour babbling streamlets; water drips upon his breast, showers pour down his hair-crowned forehead, flowing rivers from his parted beard. There clothes his massy shoulders a cloak woven by his wife Ilia, who threaded the crystalline loom beneath the flood.

There lies in Roman Tiber’s stream an island where the central flood washes as ’twere two cities parted by the sundering waters: with equal threatening height the tower-clad banks rise in lofty buildings. Here stood Tiber and from this eminence beheld his prayer of a sudden fulfilled, saw the twin-souled brothers enter the Forum amid the press of thronging senators, the bared axes gleam afar and both sets of fasces brought forth from one threshold. He stood amazed at the sight and for a long time incredulous joy held his voice in check. Yet soon he thus began:

“Behold, Eurotas, river of Sparta, boastest thou that thy streams have ever nurtured such as these? Did that false swan[47] beget a child to rival them, though ’tis true his sons could fight with the heavy glove and save ships from cruel tempests? Behold new offspring outshining the stars to which Leda gave birth, men of my city for whose coming the Zodiac is now awatch, making ready his hollow tract of sky for a constellation that is to be. Henceforth let Olybrius rule the nightly sky, shedding his ruddy light where Pollux once shone, and where glinted Castor’s fires there let glitter Probinus’

[47] Jupiter, who courted Leda in the form of a swan, becoming by her the father of Helen, Clytemnestra, Castor and Pollux. These latter two were the patrons of the ring—hence “decernere caestu” (l. 238); and of sailors—hence “arcere procellas” (l. 239).

flame. These shall direct men’s sails and vouchsafe those breezes whereby the sailor shall guide his bark o’er the calm ocean. Let us now pour libation to the new gods and ease our hearts with copious draughts of nectar. Naiads, now spread your snowy bands, wreath every spring with violets. Let the woods bring forth honey and the drunken river roll, its waters changed to wine; let the watering streams that vein the fields give off the scent of balsam spice. Let one run and invite to the feast and banquet-board all the rivers of our land, even all that wander beneath the mountains of Italy and drink as their portion the Alpine snows, swift Vulturnus and Nar infected with ill-smelling sulphur, Ufens whose meanderings delay his course and Eridanus into whose waters Phaëthon fell headlong; Liris who laves Marica’s golden oak groves and Galaesus who tempers the fields of Sparta’s colony Tarentum. This day shall always be held in honour and observed by our rivers and its anniversary ever celebrated with rich feastings.”

So spake he, and the Nymphs, obeying their sire’s behest, made ready the rooms for the banquet, and the watery palace, ablaze with gleaming purple, shone with jewelled tables.

O happy months to bear these brothers’ name! O year blessed to own such a pair as overlords, begin thou to turn the laborious wheel of Phoebus’ four-fold circle. First let thy winter pursue its course, sans numbing cold, not clothed in white snow nor torn by rough blasts, but warmed with the south wind’s breath: next, be thy spring calm from the outset and let the limpid west wind’s gentler breeze flood thy meads with yellow flowers.

May summer crown thee with harvest and autumn store thee with luscious grapes. An honour that no age has ever yet known, a privilege never yet heard of in times gone by, this has been thine and thine alone—to have had brothers as thy consuls. The whole world shall tell of thee, the Hours shall inscribe thy name in various flowers, and age-long annals hand thy fame down through the long centuries.

(II.)

(II.)

When Python had fallen, laid low by the arrow of Phoebus, his dying limbs outspread o’er Cirrha’s heights—Python, whose coils covered whole mountains, whose maw swallowed rivers and whose bloody crest touched the stars—then Parnassus was free and the woods, their serpent fetters shaken off, began to grow tall with lofty trees. The mountain-ashes, long shaken by the dragon’s sinuous coils, spread their leaves securely to the breeze, and Cephisus, who had so often foamed with his poisonous venom, now flowed a purer stream with limpid wave. The whole country echoed with the cry, “hail, Healer”: every land sang Phoebus’ praise. A fuller wind shakes the tripod, and the gods, hearing the Muses’ sweet song from afar off, gather in the dread caverns of Themis.

A blessed band comes together to hear my song, now that a second Python has been slain by the weapons of that master of ours who made the rule of the brother Emperors hold the world steady, observing justice in peace and showing vigour in war.

(III.)

(III.)

My mind has often wavered between two opinions: have the gods a care for the world or is there no ruler therein and do mortal things drift as dubious chance dictates? For when I investigated the laws and the ordinances of heaven and observed the sea’s appointed limits, the year’s fixed cycle and the alternation of light and darkness, then methought everything was ordained according to the direction of a God who had bidden the stars move by fixed laws, plants grow at different seasons, the changing moon fulfil her circle with borrowed light and the sun shine by his own, who spread the shore before the waves and balanced the world in the centre of the firmament. But when I saw the impenetrable mist which surrounds human affairs, the wicked happy and long prosperous and the good discomforted, then in turn my belief in God was weakened and failed, and even against mine own will I embraced the tenets of that other philosophy[48] which teaches that atoms drift in purposeless motion and that new forms throughout the vast void are shaped by chance and not design—that philosophy which believes in God in an ambiguous sense, or holds that there be no gods, or that they are careless of our doings. At

[48] Epicureanism.

last Rufinus’ fate has dispelled this uncertainty and freed the gods from this imputation. No longer can I complain that the unrighteous man reaches the highest pinnacle of success. He is raised aloft that he may be hurled down in more headlong ruin. Muses, unfold to your poet whence sprang this grievous pest.

Dire Allecto once kindled with jealous wrath on seeing widespread peace among the cities of men. Straightway she summons the hideous council of the nether-world sisters to her foul palace gates. Hell’s numberless monsters are gathered together, Night’s children of ill-omened birth. Discord, mother of war, imperious Hunger, Age, near neighbour to Death; Disease, whose life is a burden to himself; Envy that brooks not another’s prosperity, woeful Sorrow with rent garments; Fear and foolhardy Rashness with sightless eyes; Luxury, destroyer of wealth, to whose side ever clings unhappy Want with humble tread, and the long company of sleepless Cares, hanging round the foul neck of their mother Avarice. The iron seats are filled with all this rout and the grim chamber is thronged with the monstrous crowd. Allecto stood in their midst and called for silence, thrusting behind her back the snaky hair that swept her face and letting it play over her shoulders. Then with mad utterance she unlocked the anger deep hidden in her heart.

“Shall we allow the centuries to roll on in this even tenour, and man to live thus blessed? What novel kindliness has corrupted our characters? Where is our inbred fury? Of what use the lash with none to suffer beneath it? Why this purposeless girdle of smoky torches? Sluggards, ye,

whom Jove has excluded from heaven, Theodosius from earth. Lo! a golden age begins; lo! the old breed of men returns. Peace and Godliness, Love and Honour hold high their heads throughout the world and sing a proud song of triumph over our conquered folk. Justice herself (oh the pity of it!), down-gliding through the limpid air, exults over me and, now that crime has been cut down to the roots, frees law from the dark prison wherein she lay oppressed. Shall we, expelled from every land, lie this long age in shameful torpor? Ere it be too late recognize a Fury’s duty: resume your wonted strength and decree a crime worthy of this august assembly. Fain would I shroud the stars in Stygian darkness, smirch the light of day with our breath, unbridle the ocean deeps, hurl rivers against their shattered banks, and break the bonds of the universe.”

So spake she with cruel roar and uproused every gaping serpent mouth as she shook her snaky locks and scattered their baneful poison. Of two minds was the band of her sisters. The greater number was for declaring war upon heaven, yet some respected still the ordinances of Dis and the uproar grew by reason of their dissension, even as the sea’s calm is not at once restored, but the deep still thunders when, for all the wind be dropped, the swelling tide yet flows, and the last weary winds of the departing storm play o’er the tossing waves.

Thereupon cruel Megaera rose from her funereal seat, mistress she of madness’ howlings and impious ill and wrath bathed in fury’s foam. No blood her drink but that flowing from kindred slaughter and forbidden crime, shed by a father’s, by a brother’s

sword. ’Twas she made e’en Hercules afraid and brought shame upon that bow that had freed the world of monsters; she aimed the arrow in Athamas’[49] hand: she took her pleasure in murder after murder, a mad fury in Agamemnon’s palace; beneath her auspices wedlock mated Oedipus with his mother and Thyestes with his daughter. Thus then she speaks with dread-sounding words:

“To raise our standards against the gods, my sisters, is neither right nor, methinks, possible; but hurt the world we may, if such our wish, and bring an universal destruction upon its inhabitants. I have a monster more savage than the hydra brood, swifter than the mother tigress, fiercer than the south wind’s blast, more treacherous than Euripus’ yellow flood—Rufinus. I was the first to gather him, a new-born babe, to my bosom. Often did the child nestle in mine embrace and seek my breast, his arms thrown about my neck in a flood of infant tears. My snakes shaped his soft limbs licking them with their three-forked tongues. I taught him guile whereby he learnt the arts of injury and deceit, how to conceal the intended menace and cover his treachery with a smile, full-filled with savagery and hot with lust of gain. Him nor the sands of rich Tagus’ flood by Tartessus’ town could satisfy nor the golden waters of ruddy Pactolus; should he drink all Hermus’ stream he would parch with the greedier thirst. How skilled to deceive and wreck friendships with hate! Had that old generation of men produced such an one as he, Theseus had fled Pirithous, Pylades deserted Orestes in wrath, Pollux hated Castor. I confess myself his inferior: his quick genius has outstripped

[49] Athamas, king of Orchomenus, murdered his son Learchus in a fit of madness.

his preceptress: in a word (that I waste not your time further) all the wickedness that is ours in common is his alone. Him will I introduce, if the plan commend itself to you, to the kingly palace of the emperor of the world. Be he wiser than Numa, be he Minos’ self, needs must he yield and succumb to the treachery of my foster child.”

A shout followed her words: all stretched forth their impious hands and applauded the awful plot. When Megaera had gathered together her dress with the black serpent that girdled her, and bound her hair with combs of steel, she approached the sounding stream of Phlegethon, and seizing a tall pine-tree from the scorched summit of the flaming bank kindled it in the pitchy flood, then plied her swift wings o’er sluggish Tartarus.

There is a place where Gaul stretches her furthermost shore spread out before the waves of Ocean: ’tis there that Ulysses is said to have called up the silent ghosts with a libation of blood. There is heard the mournful weeping of the spirits of the dead as they flit by with faint sound of wings, and the inhabitants see the pale ghosts pass and the shades of the dead. ’Twas from here the goddess leapt forth, dimmed the sun’s fair beams and clave the sky with horrid howlings. Britain felt the deadly sound, the noise shook the country of the Senones,[50] Tethys stayed her tide, and Rhine let fall his urn and shrank his stream. Thereupon, in the guise of an old man, her serpent locks changed at her desire to snowy hair, her dread cheeks furrowed with many a wrinkle and feigning weariness in her gait she enters the walls of Elusa,[51] in search of the house she had long known so well. Long

[50] Their territory lay some sixty miles S.E. of Paris. Its chief town was Agedincum (mod. Sens).

[51] Elusa (the modern Eauze in the Department of Gers) was the birthplace of Rufinus (cf. Zosim. iv. 51. 1).

[52] gramina E: other codd. gramine. Birt conjectures toxica, Heinsius carmina. I take Postgate’s crimina.

she stood and gazed with jealous eyes, marvelling at a man worse than herself; then spake she thus: “Does ease content thee, Rufinus? Wastest thou in vain the flower of thy youth inglorious thus in thy father’s fields? Thou knowest not what fate and the stars owe thee, what fortune makes ready. So thou wilt obey me thou shalt be lord of the whole world. Despise not an old man’s feeble limbs: I have the gift of magic and the fire of prophecy is within me. I have learned the incantations wherewith Thessalian witches pull down the bright moon, I know the meaning of the wise Egyptians’ runes, the art whereby the Chaldeans impose their will upon the subject gods, the various saps that flow within trees and the power of deadly herbs; all those that grow on Caucasus rich in poisonous plants, or, to man’s bane, clothe the crags of Scythia; herbs such as cruel Medea gathered and curious Circe. Often in nocturnal rites have I sought to propitiate the dread ghosts and Hecate, and recalled the shades of buried men to live again by my magic: many, too, has my wizardry brought to destruction though the Fates had yet somewhat of their life’s thread to spin. I have caused oaks to walk and the thunderbolt to stay his course, aye, and made rivers reverse their course and flow backwards to their fount. Lest thou perchance think these be but idle boasts behold the change of thine own house.” At these words the white pillars, to his amazement, began to turn into gold and the beams of a sudden to shine with metal.

His senses are captured by the bait, and, thrilled beyond measure, he feasts his greedy eyes on the sight. So Midas, king of Lydia, swelled at first

with pride when he found he could transform everything he touched to gold: but when he beheld his food grow rigid and his drink harden into golden ice then he understood that this gift was a bane and in his loathing for the gold cursed his prayer. Thus Rufinus, overcome, cried out: “Whithersoever thou summonest me I follow, be thou man or god.” Then at the Fury’s bidding he left his fatherland and approached the cities of the East, threading the once floating Symplegades and the seas renowned for the voyage of the Argo, ship of Thessaly, till he came to where, beneath its high-walled town, the gleaming Bosporus separates Asia from the Thracian coast.

When he had completed this long journey and, led by the evil thread of the fates, had won his way into the far-famed palace, then did ambition straightway come to birth and right was no more. Everything had its price. He betrayed secrets, deceived dependents, and sold honours that had been wheedled from the emperor. He followed up one crime with another, heaping fuel on the inflamed mind and probing and embittering the erstwhile trivial wound. And yet, as Nereus knows no addition from the infinitude of rivers that flow into him and though here he drains Danube’s wave and there Nile’s summer flood with its sevenfold mouth, yet ever remains his same and constant self, so Rufinus’ thirst knew no abatement for all the streams of gold that flowed in upon him. Had any a necklace studded with jewels or a fertile demesne he was sure prey for Rufinus: a rich property assured the ruin of its own possessor: fertility was the husbandman’s bane. He drives them from their homes, expels them from the lands their sires had

left them, either wresting them from the living owners or fastening upon them as an inheritor. Massed riches are piled up and a single house receives the plunder of a world; whole peoples are forced into slavery, and thronging cities bow beneath the tyranny of a private man.

Madman, what shall be the end? Though thou possess either Ocean, though Lydia pour forth for thee her golden waters, though thou join Croesus’ throne to Cyrus’ crown, yet shalt thou never be rich nor ever contented with thy booty. The greedy man is always poor. Fabricius, happy in his honourable poverty, despised the gifts of monarchs; the consul Serranus sweated at his heavy plough and a small cottage gave shelter to the warlike Curii. To my mind such poverty as this is richer than thy wealth, such a home greater than thy palaces. There pernicious luxury seeks for the food that satisfieth not; here the earth provides a banquet for which is nought to pay. With thee wool absorbs the dyes of Tyre; thy patterned clothes are stained with purple; here are bright flowers and the meadow’s breathing charm which owes its varied hues but to itself. There are beds piled on glittering bedsteads; here stretches the soft grass, that breaks not sleep with anxious cares. There a crowd of clients dins through the spacious halls, here is song of birds and the murmur of the gliding stream. A frugal life is best. Nature has given the opportunity of happiness to all, knew they but how to use it. Had we realized this we should now have been enjoying a simple life, no trumpets would be sounding, no whistling spear would speed, no ship be buffeted by the wind, no siege-engine overthrow battlements.

Still grew Rufinus’ wicked greed, and his impious passion for new-won wealth blazed yet fiercer; no feeling of shame kept him from demanding and extorting money. He combines perjury with ceaseless cajolery, ratifying with a hand-clasp the bond he purposes to break. Should any dare to refuse his demand for one thing out of so many, his fierce heart would be stirred with swelling wrath. Was ever lioness wounded with a Gaetulian’s spear, or Hyrcan tiger pursuing the robber of her young, was ever bruisèd serpent so fierce? He swears by the majesty of the gods and tramples on his oath. He reverences not the laws of hospitality. To kill a wife and her husband with her and her children sates not his anger; ’tis not enough to slaughter relations and drive friends into exile; he strives to destroy every citizen of Rome and to blot out the very name of our race. Nor does he even slay with a swift death; ere that he enjoys the infliction of cruel torture; the rack, the chain, the lightless cell, these he sets before the final blow. Why, this remission is more savage, more madly cruel, than the sword—this grant of life that agony may accompany it! Is death not enough for him? With treacherous charges he attacks; dazed wretches find him at once accuser and judge. Slow to all else he is swift to crime and tireless to visit the ends of the earth in its pursuit. Neither the Dog-star’s heat nor the wintry blasts of the Thracian north wind detain him. Feverish anxiety torments his cruel heart lest any escape his sword, or an emperor’s pardon lose him an opportunity for injury. Neither age nor youth can move his pity: before their father’s eyes his bloody axe severs boys’ heads

from their bodies; an aged man, once a consul, survived the murder of his son but to be driven into exile. Who can bring himself to tell of so many murders, who can adequately mourn such impious slaughter? Do men tell that cruel Sinis of Corinth e’er wrought such wickedness with his pine-tree, or Sciron with his precipitous rock, or Phalaris with his brazen bull, or Sulla with his prison? O gentle horses of Diomede! O pitiful altars of Busiris! Henceforth, compared with Rufinus thou, Cinna, shalt be loving, and thou, Spartacus, a sluggard.

All were a prey to terror, for men knew not where next his hidden hatred would break forth, they sob in silence for the tears they dare not shed and fear to show their indignation. Yet is not the spirit of great-hearted Stilicho broken by this same fear. Alone amid the general calamity he took arms against this monster of greed and his devouring maw, though not borne on the swift course of any wingèd steed nor aided by Pegasus’ reins. In him all found the quiet they longed for, he was their one defence in danger, their shield out-held against the fierce foe, the exile’s sanctuary, standard confronting the madness of Rufinus, fortress for the protection of the good.

Thus far Rufinus advanced his threats and stayed; then fell back in coward flight: even as a torrent swollen with winter rains rolls down great stones in its course, overwhelms woods, tears away bridges, yet is broken by a jutting rock, and, seeking a way through, foams and thunders about the cliff with shattered waves.

How can I praise thee worthily, thou who

sustainedst with thy shoulders the tottering world in its threatened fall? The gods gave thee to us as they show a welcome star to frightened mariners whose weary bark is buffeted with storms of wind and wave and drifts with blind course now that her steersman is beaten. Perseus, descendant of Inachus, is said to have overcome Neptune’s monsters in the Red Sea, but he was helped by his wings; no wing bore thee aloft: Perseus was armed with the Gorgons’ head that turneth all to stone; the snaky locks of Medusa protected not thee. His motive was but the love of a chained girl, thine the salvation of Rome. The days of old are surpassed; let them keep silence and cease to compare Hercules’ labours with thine. ’Twas but one wood that sheltered the lion of Cleonae, the savage boar’s tusks laid waste a single Arcadian vale, and thou, rebel Antaeus, holding thy mother earth in thine embrace, didst no hurt beyond the borders of Africa. Crete alone re-echoed to the bellowings of the fire-breathing bull, and the green hydra beleaguered no more than Lerna’s lake. But this monster Rufinus terrified not one lake nor one island: whatsoever lives beneath the Roman rule, from distant Spain to Ganges’ stream, was in fear of him. Neither triple Geryon nor Hell’s fierce janitor can vie with him nor could the conjoined terrors of powerful Hydra, ravenous Scylla, and fiery Chimaera.

Long hung the contest in suspense, but the struggle betwixt vice and virtue was ill-matched in character. Rufinus threatens slaughter, thou stayest his hand; he robs the rich, thou givest back to the poor; he overthrows, thou restorest; he sets wars afoot, thou winnest them. As a pestilence, growing from day

to day by reason of the infected air, fastens first upon the bodies of animals but soon sweeps away peoples and cities, and when the winds blow hot spreads its hellish poison to the polluted streams, so the ambitious rebel marks down no private prey, but hurls his eager threats at kings, and seeks to destroy Rome’s army and overthrow her might. Now he stirs up the Getae[53] and the tribes on Danube’s banks, allies himself with Scythia and exposes what few his cruelties have spared to the sword of the enemy. There march against us a mixed horde of Sarmatians and Dacians, the Massagetes who cruelly wound their horses that they may drink their blood, the Alans who break the ice and drink the waters of Maeotis’ lake, and the Geloni who tattoo their limbs: these form Rufinus’ army. And he brooks not their defeat; he frames delays and postpones the fitting season for battle. For when thy right hand, Stilicho, had scattered the Getic bands and avenged the death of thy brother general, when one section of Rufinus’ army was thus weakened and made an easy prey, then that foul traitor, that conspirator with the Getae, tricked the emperor and put off the instant day of battle, meaning to ally himself with the Huns, who, as he knew, would fight and quickly join the enemies of Rome.[54]

These Huns are a tribe who live on the extreme eastern borders of Scythia, beyond frozen Tanais; most infamous of all the children of the north. Hideous to look upon are their faces and loathsome their bodies, but indefatigable is their spirit. The chase supplies their food; bread they will not eat. They love to slash their faces and hold it a

[53] Here and throughout his poems Claudian refers to the Visigoths as the Getae.

[54] Cf. Introduction, p. x.

righteous act to swear by their murdered parents. Their double nature fitted not better the twi-formed Centaurs to the horses that were parts of them. Disorderly, but of incredible swiftness, they often return to the fight when little expected.

Fearless, however, against such forces, thou, Stilicho, approachest the waters of foaming Hebrus and thus prayest ere the trumpets sound and the fight begins: “Mars, whether thou reclinest on cloud-capped Haemus, or frost-white Rhodope holdeth thee, or Athos, severed to give passage to the Persian fleet, or Pangaeus, gloomy with dark holm-oaks, gird thyself at my side and defend thine own land of Thrace. If victory smile on us, thy meed shall be an oak stump adorned with spoils.”

The Father heard his prayer and rose from the snowy peaks of Haemus shouting commands to his speedy servants: “Bellona, bring my helmet; fasten me, Panic, the wheels upon my chariot; harness my swift horses, Fear. Hasten: speed on your work. See, my Stilicho makes him ready for war; Stilicho whose habit it is to load me with rich trophies and hang upon the oak the plumed helmets of his enemies. For us together the trumpets ever sound the call to battle; yoking my chariot I follow wheresoever he pitch his camp.” So spake he and leapt upon the plain, and on this side Stilicho scattered the enemy bands in broadcast flight and on that Mars; alike the twain in accoutrement and stature. The helmets of either tower with bristling crests, their breastplates flash as they speed along and their spears take their fill of widely dealt wounds.

Meanwhile Megaera, more eager now she has got her way, and revelling in this widespread

calamity, comes upon Justice sad at heart in her palace, and thus provokes her with horrid utterance: “Is this that old reign of peace; this the return of that golden age thou fondly hopedst had come to pass? Is our power gone, and no place now left for the Furies? Turn thine eyes this way. See how many cities the barbarians’ fires have laid low, how vast a slaughter, how much blood Rufinus hath procured for me, and on what widespread death my serpents gorge themselves. Leave thou the world of men; that lot is mine. Mount to the stars, return to that well-known tract of Autumn sky where the Standard-bearer dips towards the south. The space next to the summer constellation of the Lion, the neighbourhood of the winter Balance has long been empty. And would I could now follow thee through the dome of heaven.”

The goddess made answer: “Thou shalt rage no further, mad that thou art. Now shall thy creature receive his due, the destined avenger hangs over him, and he who now wearies land and the very sky shall die, though no handful of dust shall cover his corpse. Soon shall come Honorius, promised of old to this fortunate age, brave as his father Theodosius, brilliant as his brother Arcadius; he shall subdue the Medes and overthrow the Indians with his spear. Kings shall pass under his yoke, frozen Phasis shall bear his horses’ hooves, and Araxes submit perforce to be bridged by him. Then too shalt thou be bound with heavy chains of iron and cast out from the light of day and imprisoned in the nethermost pit, thy snaky locks overcome and shorn from thy head. Then the world shall be owned by all in common, no field marked off from another

by any dividing boundary, no furrow cleft with bended ploughshare; for the husbandman shall rejoice in corn that springs untended. Oak groves shall drip with honey, streams of wine well up on every side, lakes of oil abound. No price shall be asked for fleeces dyed scarlet, but of themselves shall the flocks grow red to the astonishment of the shepherd, and in every sea the green seaweed will laugh with flashing jewels.”

(IV.)

(IV.)

Return, ye Muses, and throw open rescued Helicon; now again may your company gather there. Nowhere now in Italy does the hostile trumpet forbid song with its viler bray. Do thou too, Delian Apollo, now that Delphi is safe and fear has been dispelled, wreath thy avenger’s head with flowers. No savage foe sets profane lips to Castalia’s spring or those prophetic streams. Alpheus’[55] flood ran all his length red with slaughter and the waves bore the bloody marks of war across the Sicilian sea; whereby Arethusa, though herself not present, recognized the triumphs freshly won and knew of the slaughter of the Getae, to which that blood bore witness.

Let peace, Stilicho, succeed these age-long labours and ease thine heart by graciously listening to my song. Think it no shame to interrupt thy long toil and to consecrate a few moments to the Muses. Even unwearying Mars is said to have stretched his tired limbs on the snowy Thracian plain when at last the battle was ended, and, unmindful of his wonted fierceness, to have laid aside his spear in gentler mood, soothing his ear with the Muses’ melody.

[55] A reference to Stilicho’s campaign against Alaric in the Peloponnese in 397 (see Introduction, p. x).

(V.)

(V.)

After the subjugation of the Alpine tribes and the salvation of the kingdoms of Italy the heavens welcomed the Emperor Theodosius[56] to the place of honour due to his worth, and so shone the brighter by the addition of another star. Then was the power of Rome entrusted to thy care, Stilicho; in thy hands was placed the governance of the world. The brothers’ twin majesty and the armies of either royal court were given into thy charge. But Rufinus (for cruelty and crime brook not peace, and a tainted mouth will not forgo its draughts of blood), Rufinus, I say, began once more to inflame the world with wicked wars and to disturb peace with accustomed sedition. Thus to himself: “How shall I assure my slender hopes of survival? By what means beat back the rising storm? On all sides are hate and the threat of arms. What am I to do? No help can I find in soldier’s weapon or emperor’s favour. Instant dangers ring me round and a gleaming sword hangs above my head. What is left but to plunge the world into fresh troubles and draw down innocent peoples in my ruin? Gladly will I perish if the world does too; general destruction shall console me for

[56] Theodosius died in January 395, not long after his defeat of Eugenius at the Frigidus River (near Aquileia), September 5-6, 394 (see Introduction, p. ix).

mine own death, nor will I die (for I am no coward) till I have accomplished this. I will not lay down my power before my life.”

So spake he, and as if Aeolus unchained the winds so he, breaking their bonds, let loose the nations, clearing the way for war; and, that no land should be free therefrom, apportioned ruin throughout the world, parcelling out destruction. Some pour across the frozen surface of swift-flowing Danube and break with the chariot wheel what erstwhile knew but the oar; others invade the wealthy East, led through the Caspian Gates and over the Armenian snows by a newly-discovered pass. The fields of Cappadocia reek with slaughter; Argaeus, father of swift horses, is laid waste. Halys’ deep waters run red and the Cilician cannot defend himself in his precipitous mountains. The pleasant plains of Syria are devastated, and the enemy’s cavalry thunders along the banks of Orontes, home hitherto of the dance and of a happy people’s song. Hence comes mourning to Asia, while Europe is left to be the sport and prey of Getic hordes even to the borders of fertile Dalmatia. All that tract of land lying between the stormy Euxine and the Adriatic is laid waste and plundered, no inhabitants dwell there; ’tis like torrid Africa whose sun-scorched plains never grow kindlier through human tillage. Thessaly is afire; Pelion silent, his shepherds put to flight; flames bring destruction on Macedonia’s crops. For Pannonia’s plain, the Thracians’ helpless cities, the fields of Mysia were ruined but now none wept; year by year came the invader, unsheltered was the countryside from havoc and custom had robbed suffering of its sting. Alas, in how swift ruin perish

even the greatest things! An empire won and kept at the expense of so much bloodshed, born from the toils of countless leaders, knit together through so many years by Roman hands, one coward traitor overthrew in the twinkling of an eye.

That city,[57] too, called of men the rival of great Rome, that looks across to Chalcedon’s strand, is stricken now with terror at no neighbouring war; nearer home it observes the flash of torches, the trumpet’s call, and its own roofs the target for an enemy’s artillery. Some guard the walls with watchful outposts, others hasten to fortify the harbour with a chain of ships. But fierce Rufinus is full of joy in the leaguered city and exults in its misfortunes, gazing at the awful spectacle of the surrounding country from the summit of a lofty tower. He watches the procession of women in chains, sees one poor half-dead wretch drowned in the water hard by, another, stricken as he fled, sink down beneath the sudden wound, another breathe out his life at the tower’s very gates; he rejoices that no respect is shown to grey hairs and that mother’s breasts are drenched with their children’s blood. Great is his pleasure thereat; from time to time he laughs and knows but one regret—that it is not his own hand that strikes. He sees the whole countryside (except for his own lands) ablaze, and has joy of his great wickedness, making no secret of the fact that the city’s foes are his friends. It is his boast, moreover, that to him alone the enemy camp opened its gates, and that there was allowed right of parley between them. Whene’er he issued forth to arrange some wondrous truce his companions thronged him round and an armed band of dependents

[57] Constantinople.

danced attendance on a civilian’s standards. Rufinus himself in their midst drapes tawny skins of beasts about his breast (thorough in his barbarity), and uses harness and huge quivers and twanging bows like those of the Getae—his dress openly showing the temper of his mind. One who drives a consul’s chariot and enjoys a consul’s powers has no shame to adopt the manners and dress of barbarians; Roman law, obliged to change her noble garment, mourns her slavery to a skin-clad judge.

What looks then on men’s faces! What furtive murmurs! For, poor wretches, they could not even weep nor, without risk, ease their grief in converse. “How long shall we bear this deadly yoke? What end shall there ever be to our hard lot? Who will free us from this death-fraught anarchy, this day of tears? On this side the barbarian hems us in, on that Rufinus oppresses us; land and sea are alike denied us. A pestilence stalks through the country: yes, but a deadlier terror haunts our houses. Stilicho, delay no more but succour thy dying land; of a truth here are thy children, here thy home, here were taken those first auspices for thy marriage, so blessed with children, here the palace was illumined with the torches of happy wedlock. Nay, come even though alone, thou for whom we long; wars will perish at thy sight and the ravening monster’s rage subside.”

Such were the tempests that vexed the turbulent East. But so soon as ever winter had given place to the winds of spring and the hills began to lose their covering of snow, Stilicho, leaving the fields of Italy in peace and safety, set in motion his two armies and hastened to the lands of the sunrise, combining

the so different squadrons of Gaul and of the East. Never before did there meet together under one command such numerous bands, never in one army such a babel of tongues. Here were curly-haired Armenian cavalry, their green cloaks fastened with a loose knot, fierce Gauls with golden locks accompanied them, some from the banks of the swift-flowing Rhone, or the more sluggish Saône, some whose infant bodies Rhine’s flood had laved, or who had been washed by the waves of the Garonne that flow more rapidly towards, than from, their source, whenever they are driven back by Ocean’s full tide. One common purpose inspires them all; grudges lately harboured are laid aside; the vanquished feels no hate, the victor shows no pride. And despite of present unrest, of the trumpet’s late challenge to civil strife, and of warlike rage still aglow, yet were all at one in their support of their great leader. So it is said that the army that followed Xerxes, gathered into one from all quarters of the world, drank up whole rivers in their courses, obscured the sun with the rain of their arrows, passed through mountains on board ship, and walked the bridged sea with contemptuous foot.