Title: When Santiago Fell; or, The War Adventures of Two Chums

Author: Edward Stratemeyer

Release date: April 19, 2016 [eBook #51798]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Tom Cosmas and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

OR

THE WAR ADVENTURES OF

TWO CHUMS

BY

CAPTAIN RALPH BONEHILL

AUTHOR OF “A SAILOR BOY WITH DEWEY,” “OFF FOR HAWAII,”

“GUN AND SLED,” “LEO, THE CIRCUS BOY,”

“RIVAL BICYCLISTS,” ETC.

CHATTERTON-PECK COMPANY

NEW YORK, N. Y.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

WITH CUSTER IN THE BLACK HILLS;

Or, A Young Scout among the Indians.

BOYS OF THE FORT;

Or, A Young Captain’s Pluck.

THE YOUNG BANDMASTER;

Or, Concert Stage and Battlefield.

WHEN SANTIAGO FELL;

Or, The War Adventures of Two Chums.

A SAILOR BOY WITH DEWEY;

Or, Afloat in the Philippines.

OFF FOR HAWAII;

Or, The Mystery of a Great Volcano.

12mo, finely illustrated and bound in cloth.

Price, per volume, 60 cents.

NEW YORK

CHATTERTON-PECK COMPANY

1905

Copyright, 1899, by

THE MERSHON COMPANY

“When Santiago Fell,” while a complete story in itself, forms the first volume of a line to be issued under the general title of the “Flag of Freedom Series” for boys.

My object in writing this story was to present to American lads a true picture of life in the Cuba of to-day, and to show what a fierce struggle was waged by the Cubans against the iron-handed mastery of Spain previous to the time that our own glorious United States stepped in and gave to Cuba the precious boon of liberty. The time covered is the last year of the Cuban-Spanish War and our own campaign leading up to the fall of Santiago.

It may be possible that some readers may think the adventures of the two chums over-drawn, but this is hardly a fact. The past few years have been exceedingly bitter ones to all living upon Cuban soil, and neither life nor property has been safe. Even people who were peaceably inclined were drawn into the struggle [Pg iv] against their will, and the innocent, in many cases, suffered with the guilty.

This war, so barbarously carried on, has now come to an end; and, under the guiding hand of Uncle Sam, let us trust that Cuba and her people will speedily take their rightful place among the small but well-beloved nations of the world—or, if not this, that she may join the ever-increasing sisterhood of our own States.

Once more thanking my numerous young friends for their kind reception of my previous works, I place this volume in their hands, trusting that from it they may derive much pleasure and profit.

Captain Ralph Bonehill.

January 1, 1899.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Off for the Interior | 1 |

| II. | The Escape from the Gunboat | 8 |

| III. | In the Wilds of the Island | 15 |

| IV. | In a Novel Prison | 22 |

| V. | Lost among the Hills | 30 |

| VI. | From One Difficulty to Another | 37 |

| VII. | Fooling the Spanish Guerrillas | 45 |

| VIII. | Andres | 52 |

| IX. | Across the Canefields | 59 |

| X. | A Council of the Enemy | 66 |

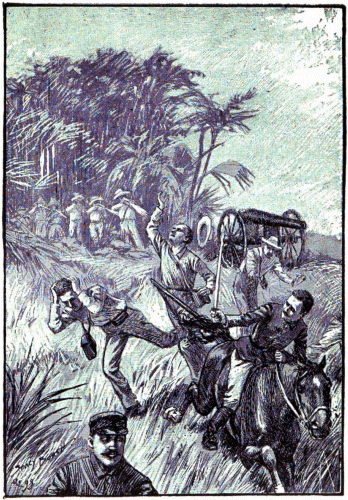

| XI. | A Wild Ride on Horseback | 74 |

| XII. | A Daring Leap | 81 |

| XIII. | Friends in Need | 87 |

| XIV. | General Calixto Garcia | 95 |

| XV. | A Prisoner of War | 102 |

| XVI. | A Rescue under Difficulties | 108 |

| XVII. | A Treacherous Stream to Cross | 116 |

| XVIII. | Alone | 123 |

| XIX. | The Cave in the Mountain | 130 |

| XX. | Señor Guerez | 137 |

| XXI. | The Attack on the Old Convent | 145 |

| XXII. | The Routing of the Enemy | 154 |

| XXIII. | On the Trail of My Father | 161 |

| XXIV. | In the Belt of the Firebrands | 168 |

| XXV. | Escaping the Flames [Pg vi] | 176 |

| XXVI. | A Disheartening Discovery | 184 |

| XXVII. | Gilbert Burnham | 191 |

| XXVIII. | A Battle on Land and Water | 198 |

| XXIX. | Looking for my Cuban Chum | 205 |

| XXX. | Once More among the Hills | 212 |

| XXXI. | The Battle at the Railroad Embankment | 220 |

| XXXII. | A Leap in the Dark | 229 |

| XXXIII. | Captain Guerez Makes a Discovery | 238 |

| XXXIV. | The Dogs of Cuban Warfare | 244 |

| XXXV. | The Last of the Bloodhounds | 252 |

| XXXVI. | Cast into a Santiago Dungeon | 261 |

| XXXVII. | The Fall of the Spanish Stronghold | 271 |

OFF FOR THE INTERIOR.

“We cannot allow you to leave this city.”

It was a Spanish military officer of high rank who spoke, and he addressed Alano Guerez and myself. I did not understand his words, but my companion did, and he quickly translated them for my benefit.

“Then what are we to do, Alano?” I questioned. “We have no place to stop at in Santiago, and our money is running low.”

Alano’s brow contracted into a perplexing frown. He spoke to the officer, and received a few curt words in reply. Then the Spaniard turned to others standing near, and we felt that we were dismissed. A guard conducted us to the door, and saluted us; and we walked away from the headquarters.

The reason for it all was this: Less than a month before we had left the Broxville Military Academy in upper New York State to join « 2 » Alano’s parents and my father in Cuba. Alano’s father was a Cuban, and owned a large sugar plantation some distance to the eastward of Guantanamo Bay. He was wealthy, and had sent Alano to America to be educated, as many rich Cubans do. As my father and Señor Guerez were well acquainted and had strong business connections, it was but natural that Alano should be placed at the boarding school which I attended, and that we should become firm friends. For a long time we played together, ate together, studied together, and slept together, until at last as chums we became almost inseparable.

Some months back, and while the great struggle for liberty was going on between the Cubans and their rulers in Spain, certain business difficulties had taken my father to Cuba. During his stop in the island he made his home for the greater part with Señor Guerez, and while there was unfortunate enough during a trip on horseback to fall and break his leg.

This accident placed him on his back longer than was first expected, for the break was a bad one. In the meantime the war went on, and the territory for many miles around Santiago de Cuba was in a state of wild excitement.

Not knowing exactly what was going on, Alano wrote to his parents begging that he be « 3 » allowed to come to them, and in the same mail I sent a communication to my father, asking if I could not accompany my Cuban chum. To our delight the answer came that if we wished we might come without delay. At the time this word was sent neither Señor Guerez nor my father had any idea that the war would assume such vast proportions around Santiago, involving the loss of many lives and the destruction of millions of dollars of property.

Alano and I were not long in making our preparations. We left Broxville two days after permission was received, took the cars to the metropolis, and engaged immediate passage upon the Esmeralda for Santiago de Cuba.

We had heard of the war a hundred times on the way, but even on entering the harbor of the city we had no thought of difficulty in connection with our journey on rail and horseback outside of the city. We therefore suffered a rude awakening when the custom-house officials, assisted by the Spanish military officers, made us stand up in a long row with other passengers, while we were thoroughly searched from head to foot. Each of us had provided himself with a pistol; and these, along with the cartridges, were taken from us. Our baggage, also, was examined in detail, and everything in the way of a weapon was confiscated.

“War means something, evidently,” was the remark I made, but how much it meant I did not learn until later. Our names were taken down, and we were told to remain in the city over night and report at certain headquarters in the morning. We were closely questioned as to where we had come from; and when I injudiciously mentioned the Broxville Military Academy, our questioner, a swarthy Spanish lieutenant, glared ominously at us.

“I’m afraid you put your foot into it when you said that,” was Alano’s comment at the hotel that evening, when we were discussing our strange situation. “They are on the watch for people who want to join the insurgents.”

“Perhaps your father has become a rebel,” I ventured.

“It is not unlikely. He has spoken to me of Cuban independence many times.”

As might be expected, we passed an almost sleepless night, so anxious were we to learn what action the Spanish authorities would take in our case. When the decision came, as noted at the opening of this story, I was almost dumb-founded.

“We’re in a pickle, Alano,” I said, as we walked slowly down the street, lined upon either side with quaint shops and houses. “We can’t stay here without money, and we can’t get out.”

“We must get out!” he exclaimed in a low tone, so as not to be overheard. “Do you suppose I am going to remain here, when my father and mother are in the heart of the war district, and, perhaps, in great danger?”

“I am with you!” I cried. “For my father is there too. But how can we manage it? I heard at the hotel last night that every road leading out of the city is well guarded.”

“We’ll find a way,” he rejoined confidently. “But we’ll have to leave the bulk of our baggage behind. The most we can carry will be a small valise each. And we must try to get hold of some kind of weapons, too.”

We returned to our hotel, and during the day Alano struck up an acquaintanceship with a Cuban-American who knew his father well. Alano, finding he could trust the gentleman, took him into his confidence, and, as a result, we obtained not only a good pistol each,—weapons we immediately secreted in our clothing,—but also received full details of how to leave Santiago de Cuba by crossing the bay in a rowboat and taking to the woods and mountains beyond.

“It will be rough traveling,” said the gentlemen who gave us the directions, "but you’ll find your lives much safer than if you tried one of the regular roads—that is, of course, after you « 6 » have passed the forts and the gunboats lying in the harbor."

Both Alano and I were much taken with this plan, and it was arranged we should leave the city on the first dark night. Two days later it began to rain just at sunset, and we felt our time had come. A small rowboat had already been procured and was secreted under an old warehouse. At ten o’clock it was still raining and the sky was as black as ink, and we set out,—I at the oars, and Alano in the bow,—keeping the sharpest of lookouts.

We had agreed that not a word should be spoken unless it was necessary, and we moved on in silence. I had spent many hours on the lake facing Broxville Academy, and these now stood me in good stead. Dropping my oars without a sound, I pulled a long, steady stroke in the direction I had previously studied out.

We were about halfway across the bay when suddenly Alano turned to me. “Back!” he whispered, and I reversed my stroke as quickly as possible.

“There is a gunboat or something ahead,” he went on. “Steer to the left. See the lights?”

I looked, and through the mists made out several signals dimly. I brought the boat around, and we went on our way, only to bring up, a few seconds later, against a huge iron chain, « 7 » attached to one of the war vessels' anchors, for the vessel had dragged a bit on the tide.

The shock threw Alano off his feet, and he tumbled against me, sending us both sprawling. I lost hold of one of the oars, and at the same moment an alarm rang out—a sound which filled us both with fear.

THE ESCAPE FROM THE GUNBOAT.

“We are lost!” cried Alano, as he sought to pick himself up. “Oh, Mark, what shall we do?”

“The oar—where is that oar?” I returned, throwing him from me and trying to pierce the darkness.

“I don’t know. I—— Oh!”

Alano let out the exclamation as a broad sheet of light swept across the rain and the waters beneath us—light coming from a search-lantern in the turret of the gunboat. Fortunately the rays were not lowered sufficiently to reach us, yet the light was strong enough to enable me to see the missing oar, which floated but a few feet away. I caught it with the end of the other oar, and then began pulling at the top of my speed.

But all of this took time, and now the alarm on board of the war vessel had reached its height. A shot rang out, a bell tolled, and several officers came rushing to the anchor chains. They began shouting in Spanish, so volubly I « 9 » could not understand a word; and now was no time to question Alano, who was doing his best to get out a second pair of oars which we had, fortunately, placed on board at the last moment. He had often rowed with me on the lake at Broxville; and in a few seconds he had caught the stroke, and away we went at a spinning speed.

“They are going to fire on us!” he panted, as the shouting behind increased. “Shall we give up?”

“Not on my account.”

“Nor on mine. If we give up, they’ll put us in prison, sure. Pull on!”

And pull we did, until, in spite of the cold rain, each of us was dripping with perspiration and ready to drop with exhaustion.

Boom! a cannon shot rang out, and involuntarily both of us ducked our heads. But the shot flew wide of its mark—so wide, in fact, that we knew not where it went.

“They’ll get out a boat next!” I said. “Pull, Alano; put every ounce of muscle into the stroke.”

“I am doing that already,” he gasped. “We must be getting near the shore. What about the guard there?”

“We’ll have to trust to luck,” I answered.

Another shot came booming over the misty « 10 » waters, and this time we heard the sizz of the cannon ball as it hit the waves and sank. We were now in the glare of the searchlight, but the mist and rain were in our favor.

“There is the shore!” I cried, on looking around a few seconds later. “Now be prepared to run for it as soon as the boat beaches!”

With a rush our craft shot in between a lot of sea grass and stuck her bow into the soft mud. Dropping our oars, we sprang to the bow and took long leaps to solid ground. We had hardly righted ourselves when there came a call out of the darkness.

“Quien va?” And thus challenging us, a Spanish soldier who was on guard along the water’s edge rushed up to intercept our progress. His bayonet was within a foot of my breast, when Alano jumped under and hurled him to the ground.

“Come!” he cried to me. “Come, ere it is too late!” and away we went, doing the best sprinting we had ever done in our lives. Over a marsh and through a thorny field we dashed, and then struck a narrow path leading directly into a woods. The guard yelled after us and fired his gun, but that was the last we saw or heard of him.

Fearful, however, of pursuit, we did not slacken our pace until compelled to; and then, coming to a thick clump of grass at the foot of a half-decayed banana tree, we sank down completely out of breath. I had never taken such fearful chances on my life before, and I trusted I would never have to do so again, little dreaming of all the perils which still lay before us.

“I believe we are safe for the present,” said Alano, when he could get his breath. “I wonder where we are?”

“We’re in a very dark, dirty, and wet woods,” I returned gloomily. “Have we got to remain here all night?”

“It’s better than being in a Spanish prison,” replied my Cuban chum simply. “We can go on after we are a bit rested.”

The rain was coming down upon the broad leaves of the banana tree at a lively rate, but Alano said he thought it must be a clearing shower, and so it soon proved to be. But scarcely had the drops ceased to fall than a host of mosquitoes and other insects arose, keeping us more than busy.

“We must get out of this!” I exclaimed, when I could stand the tiny pests no longer. “I’m being literally chewed up alive. And, see, there is a lizard!” And I shook the thing from my arm.

“Oh, you mustn’t mind such things in Cuba!” said Alano, laughing shortly. "Why, « 12 » we have worse things than that—snakes and alligators, and the like. But come on, if you are rested. It may be we’ll soon strike some sort of shelter."

Luckily, through all the excitement we had retained our valises, which were slung across our backs by straps thrown over the shoulder. From my own I now extracted a large handkerchief, and this served, when placed in my broad-brimmed hat, to protect my neck and ears from the insects. As for Alano, he was acclimated and did not seem to be bothered at all.

We pursued our way through the woods, and then ascended a steep bank of clay, at the top of which was a well-made road leading to the northward. We looked up and down, but not a habitation or building of any kind was in sight.

“It leads somewhere,” said Alano, after a pause. “Let us go on, but with care, for perhaps the Spanish Government has guards even as far out as this.”

On we went once more, picking our way around the numerous pools and bog-holes in the road. The stars were now coming out, and we could consequently see much better than before.

“A light!” I cried, when quarter of a mile had been traversed. “See, Alano.”

“It must be from a plantation,” he answered. « 13 » “If it is, the chances are that the owner is a Spanish sympathizer—he wouldn’t dare to be anything else, so close to the city.”

“But he might aid us in secret,” I suggested.

Alano shrugged his shoulders, and we proceeded more slowly. Then he caught my arm.

“There is a sugar-house back of that canefield,” he said. “We may find shelter there.”

“Anywhere—so we can catch a few hours' nap.”

We proceeded around the field with caution, for the plantation house was not far away. Passing a building where the grinding was done, we entered a long, low drying shed. Here we struck a match, and by the flickering light espied a heap of dry husks, upon which we immediately threw ourselves.

“We’ll have to be up and away before daybreak,” said my chum, as he drew off his wet coat, an example which I at once followed, even though it was so warm I did not suffer greatly from the dampness. “We would be sorry fellows to give an explanation if we were stopped in this vicinity.”

“Yes, and for the matter of that, we had better sleep with one eye open,” I rejoined. And then we turned in, and both presently fell asleep through sheer exhaustion.

How long I had been sleeping I did not know. « 14 » I awoke with a start, to find a cold nose pressing against my face.

“Hi! get out of here!” I cried, and then the owner of the nose leaped back and uttered the low, savage, and unmistakable growl of a Cuban bloodhound!

IN THE WILDS OF THE ISLAND.

To say that I was alarmed when I found that the intruder in our sleeping quarters was a bloodhound would be to put the fact very mildly. I was truly horrified, and a chill shook my frame as I had a momentary vision of being torn to pieces by the bloodthirsty animal.

My cry awoke Alano, who instantly asked what was the matter, and then yelled at the beast in Spanish. As the creature retreated, evidently to prepare for a rush upon us, I sprang to my feet and grasped a short ladder which led to the roof of the shed.

“Come!” I roared to my chum, and Alano did so; and both of us scrambled up, with the bloodhound snarling and snatching at our feet. He even caught the heel of my boot, but I kicked him off, and we reached the top of the shed in temporary safety. Baffled, the dog ran out of the shed and began to bay loudly, as though summoning assistance.

“We’re in for it now!” I groaned. "We « 16 » can’t get away from the dog, and he’ll arouse somebody before long."

“Well, we can’t help ourselves,” replied Alano, with a philosophical shrug of his shoulders. “Ha! somebody is coming now!”

He pointed through the semi-darkness, for it was close to sunrise. A Cuban negro was approaching, a huge fellow all of six feet tall and dressed in the garb of an overseer. He carried a little triangular lantern, and as he drew closer he yelled at the bloodhound in a Cuban patois which was all Greek to me, but which Alano readily understood. The dog stopped baying, but insisted upon leading his master to the very foot of the shed, where he stood with his nose pointed up at us.

There was no help for it, so Alano crawled to the edge of the roof and told the overseer what was the trouble—that the dog had driven us hither and that we were afraid of being killed. A short conversation followed, and then my chum turned to me.

“We can go down now,” he said. “The overseer says the dog will not touch us so long as he is around.”

We leaped to the ground, although I must admit I did not do so with a mind perfectly at ease, the bloodhound still looked so ugly. However, beyond a few sniffs at my trousers-leg and a « 17 » deep rumble of his voice, he offered no further indignities.

“He wants to know who we are,” said Alano, after more conversation. “What shall I tell him?”

“Tell him the truth, and ask him for help to reach your father’s plantation, Alano. He won’t know we escaped from Santiago de Cuba without permission.”

Alano did as directed. At the mention of Senor Guerez' name the overseer held up his hands in astonishment. He told Alano that he knew his father well, that he had met the señor only two weeks previously, and that both Alano’s father and my own had thrown in their fortunes with the insurgents!

“Is it possible!” I ejaculated. “My father, too! Why, he must be still lame!”

“He is,” said Alano, after further consultation with the newcomer. “My father, it seems, had to join the rebels, or his plantation would have been burned to the ground. There was a quarrel with some Spanish sympathizers, and in the end both your father and mine joined the forces under General Calixto Garcia.”

“And where are they now?”

“The overseer does not know.”

“What of your mother and sisters?”

“He does not know about them either;” and « 18 » for a moment Alano’s handsome and manly face grew very sober. “Oh, if I was only with them!”

“And if I was only with my father!” I cried. My father was all the world to me, and to be separated from him at such a time was more than painful. “Do you think he will help us?” I went on, after a moment of silence.

The overseer agreed to do what he could for us, although that would not be much. He was an insurgent at heart, but his master and all around him were in sympathy with the Spanish Government.

“He says for us to remain here and he will bring us breakfast,” said Alano, as the man turned and departed, with the bloodhound at his side. “And after that he will set us on a road leading to Tiarriba and gave us a countersign which will help us into a rebel camp if there is any around.”

We secreted ourselves again in the cane shed, and it was not long before the overseer returned, bringing with him a kettle of steaming black coffee, without which no Cuban breakfast seems complete, and some fresh bread and half a dozen hard-boiled eggs. He had also a bag of crackers and a chunk of dried beef weighing several pounds.

“Put those in your bags,” he said to Alano, « 19 » indicating the beef and crackers. “You may find it to your interest to keep out of sight for a day or two, to avoid the Spanish spies.”

The breakfast was soon dispatched, the provisions stored in our valises, and then the overseer took us up through the sugar-cane fields to where a brook emptied into a long pond, covered with green weeds, among which frogs as broad as one’s hand croaked dismally. We hurried around the pond, and our guide pointed out a narrow, winding path leading upward through a stony woods. Then he whispered a few words to Alano, shook us both by the hand, and disappeared.

“He says the countersign is ‘Sagua’—after the river and city of that name,” explained my chum as we tramped along. “You must wave your hand so if you see a man in the distance,” and Alano twirled his arm over his head.

Stony though it was in the woods, the vegetation was thick and rank. On every side were the trunks of decaying trees, overgrown with moss—the homes of beetles, lizards, and snakes innumerable. The snakes, most of them small fellows not over a foot long, at first alarmed me, but this only made Alano laugh.

“They could not harm you if they tried,” he said. “And they are very useful—they eat up so many of the mosquitoes and gnats and lizards.”

“But some of the snakes are dangerous,” I insisted.

“Oh, yes; but they are larger.”

“And what of wild animals?”

“We have nothing but wild hogs and a few deer, and wild dogs too. And then there are the alligators to be found in the rivers.”

The sun had risen clear and hot, as is usual in that region after a shower. Where the trees were scattered, the rays beat down upon our heads mercilessly, and the slippery ground fairly steamed, so rapid was the evaporation. By noon we had reached the top of a hill, and here we rested and partook of several crackers each and a bit of the beef, washing both down with water from a spring, which I first strained through a clean handkerchief, to get clear of the insects and tiny lizards, which abounded everywhere.

“I can see a house ahead,” announced Alano, who had climbed a palm tree to view the surroundings. “We’ll go on and see what sort of a place it is before we make ourselves known.”

Once again we shouldered our traps and set out. The way down the hill was nearly as toilsome as the upward course on the opposite side had been, for gnarled roots hidden in the rank grasses made a tumble easy. Indeed, both of « 21 » us went down several times, barking our shins and scratching our hands. Yet we kept on, until the house was but a short distance off.

It was set in a small clearing; and as we approached we saw a man come out of the front door and down the broad piazza steps. He was dressed in the uniform of a captain in the Spanish army.

“Back!” cried Alano; but it was too late, for by pure accident the military officer had caught sight of us. He called out in Spanish to learn who we were.

“He is a Spanish officer!” I whispered to Alano. “Shall we face him and trust to luck to get out of the scrape?”

“No, no! Come!” and, catching me by the arm, Alano led the way around the clearing.

It was a bad move, for no sooner had we turned than the officer called out to several soldiers stationed at a stable in the rear of the house. These leaped on their horses, pistols and sabers in hand, and, riding hard, soon surrounded us.

“Halte!” came the command; and in a moment more my Cuban chum and myself found ourselves prisoners.

IN A NOVEL PRISON.

I looked with much foreboding upon the faces of the soldiers who had surrounded us. All were stern almost to the verge of cruelty, and the face of the captain when he came up was no exception to the rule. Alano and I learned afterward that Captain Crabo had met the day previous with a bitter attack from the insurgents, who had wounded six of his men, and this had put him in anything but a happy frame of mind.

“Who are you?” he demanded in Spanish, as he eyed us sharply.

Alano looked at me in perplexity, and started to ask me what he had best say, when the Spanish captain clapped the flat side of his sword over my chum’s mouth.

“Talk so that I can understand you, or I’ll place you under arrest,” he growled. And then he added, “Are you alone?”

“Yes,” said Alano.

“And where are you going?”

"I wish to join my father at Guantanamo. « 23 » His father is also with mine," and my chum pointed to me.

“Your name?”

Seeing there was no help for it, Alano told him. Captain Crabo did not act as if he had heard it before, and we breathed easier. But the next moment our hearts sank again.

“Well, we will search you, and if you carry no messages and are not armed, you can go on.”

“We have no messages,” said Alano. “You can search us and welcome.”

He handed over his valise, and I followed suit. Our pistols we had placed in the inner pockets of our coats. By his easy manner my chum tried to throw the Spaniards off their guard, but the trick did not work. After going through our bags, and confiscating several of my silk handkerchiefs, they began to search our clothing, even compelling us to remove our boots, and the weapons were speedily brought to light.

“Ha! armed!” cried Captain Crabo. “They are not so innocent as they seem. We will look into their history a little closer ere we let them go. Take them to the smoke-house until I have time to make an investigation to-night. We must be off for Pueblo del Cristo now.”

Without ceremony we were marched off across the clearing and around the back of the stable, where stood a rude stone building evidently « 24 » built many years before. Alano told me what the captain had said, and also explained that the stone building was a smoke-house, where at certain seasons of the year beef and other meat were hung up to be dried and smoked, in preference to simple drying in the sun.

As might be expected, the smoke-house was far from being a clean place; yet it had been used for housing prisoners before, and these had taken the trouble to brush the smut from the stones inside, so it was not so dirty as it might otherwise have been.

We were thrust into this building minus our pistols and our valises. Then the door, a heavy wooden affair swinging upon two rusty iron hinges, was banged shut in our faces, a hasp and spike were put into place, and we were left to ourselves.

“Now we are in for it,” I began, but Alano stopped me short.

“Listen!” he whispered, and we did so, and heard all of our enemies retreat. A few minutes later there was the tramping of horses' feet, several commands in Spanish, and the soldiers rode off.

“They have left us to ourselves, at any rate,” said my chum, when we were sure they had departed. "And we are made of poor stuff indeed « 25 » if we cannot pick our way out of this hole."

At first we were able to see nothing, but a little light shone in through several cracks in the roof, and soon our eyes became accustomed to the semi-darkness. We examined the walls, to find them of solid masonry. The roof was out of our reach, the floor so baked it was like cement.

“We are prisoners now, surely, Mark,” said Alano bitterly. “What will be our fate when that capitan returns?”

“We’ll be sent back to Santiago de Cuba most likely, Alano. But we must try to escape. I have an idea. Can you balance me upon your shoulders, do you think?”

“I will try it. But what for?”

“I wish to examine the roof.”

Not without much difficulty I succeeded in reaching my chum’s broad shoulders and standing upright upon them. I could now touch the ceiling of the smoke-house with ease, and I had Alano move around from spot to spot in a close inspection of every bit of board and bark above us.

“Here is a loose board!” I cried in a low voice. “Stand firm, Alano.”

He braced himself by catching hold of the stone wall, and I shoved upward with all of my « 26 » strength. There was a groan, a squeak; the board flew upward, and the sun shone down on our heads. I crawled through the opening thus made, and putting down my hand I helped Alano to do likewise.

“Drop out of sight of the house!” he whispered. “Somebody may be watching this place.”

We dropped, and waited in breathless silence for several minutes, but no one showed himself. Then we held a consultation.

“They thought we couldn’t get out,” I said. “More than likely no one is left at the homestead but a servant or two.”

“If only we could get our bags and pistols,” sighed Alano.

“We must get them,” I rejoined, “for we cannot go on without them. Let us sneak up to the house and investigate. I see no dogs around.”

With extreme caution we left the vicinity of the smoke-house, and, crawling on hands and knees, made our way along a low hedge to where several broad palms overshadowed a side veranda. The door of the veranda was open, and, motioning to Alano to follow, I ascended the broad steps and dashed into the house.

“Now where?” questioned my Cuban chum, as we hesitated in the broad and cool hallway. « 27 » “Here is a sitting room,” and he opened the door to it.

A voice broke upon our ear. A negro woman was singing from the direction of the kitchen, as she rattled among her earthenware pots. Evidently she was alone.

“If they left her on guard, we have little to fear,” I said, and we entered the sitting room. Both of us uttered a faint cry of joy, for there on the table rested our valises and provisions, just as they had been taken from us. Inside of Alano’s bag were the two pistols with the cartridges.

“Now we can go at once,” I said. “How fortunate we have been! Let us not waste time here.”

“They owe us a meal for detaining us,” replied my chum grimly. “Let me explore the pantry in the next room.”

He went through the whip-end curtains without a sound, and was gone several minutes. When he came back his face wore a broad smile and he carried a large napkin bursting open with eatables of various kinds, a piece of cold roast pork, some rice cakes, buns, and the remains of a chicken pie.

“We’ll have a supper fit for a king!” he cried. “Come on! I hear that woman coming.”

And coming she was, in her bare feet, along « 28 » the polished floor. We had just time left to seize our valises and make our escape when she entered.

“Qué quiere V.? [What do you want?]” she shouted, and then called upon us to stop; but, instead, we ran from the dooryard as fast as we could, and did not halt until the plantation was left a good half mile behind.

“We are well out of that!” I gasped, throwing myself down under the welcome shade of a cacao tree. “Do you suppose she will send the soldiers in pursuit?”

“They would have hard work to find us,” replied Alano. “Here, let us sample this eating I brought along, and then be on our way. Remember we have still many miles to go.”

We partook of some of the chicken pie and some buns, the latter so highly spiced they almost made me sneeze when I ate them, and then went on our way again.

Our run had warmed us up, and now the sun beat down upon our heads mercilessly as we stalked through a tangle where the luxurious vegetation was knee-high. We were glad enough when we reached another woods, through which there was a well-defined, although exceedingly poor, wagon trail. Indeed, let me add, nearly all of the wagon roads in « 29 » Cuba, so I have since been told, are wretched affairs at the best.

“We ought to be in the neighborhood of Tiarriba,” said Alano about the middle of the afternoon.

“We won’t dare enter the town,” I replied. “Those soldiers were going there, you must remember.”

“Oh, the chances are we’ll find rebels enough—on the quiet,” he rejoined.

On we went, trudging through sand and shells and not infrequently through mire several inches to a foot deep. It was hard work, and I wished more than once that we were on horseback. There was also a brook to cross, but the bridge was gone and there was nothing left to do but to ford the stream.

“It’s not to our boot-tops,” said Alano, after an examination, “so we won’t have to take our boots and socks off. Come; I fancy there is a good road ahead.”

He started into the water, and I went after him. We had reached the middle of the stream when both of us let out a wild yell, and not without reason, for we had detected a movement from the opposite bank, and now saw a monstrous alligator bearing swiftly down upon us!

LOST AMONG THE HILLS.

Both Alano and I were almost paralyzed by the sight of the huge alligator bearing down upon us, his mouth wide open, showing his cruel teeth, and his long tail shifting angrily from side to side.

“Back!” yelled my Cuban chum, and back we went, almost tumbling over each other in our haste to gain the bank from where we had started.

The alligator lost no time in coming up behind, uttering what to me sounded like a snort of rage. He had been lying half-hidden in the mud, and the mud still clung to his scaly sides and back. Altogether, he was the most horrible creature I had ever beheld.

Reaching the bank of the brook, with the alligator not three yards behind us, we fled up a series of rocks overgrown with moss and vines. We did not pause until we were at the very summit, then both of us drew our pistols and fired at the blinking eyes. The bullets glanced from the “'gator’s” head without doing much harm, « 31 » and with another snort the terrifying beast turned back into the brook and sank into a pool out of sight.

“My gracious, Alano, supposing he had caught us!” I gasped, when I could catch my breath.

“We would have been devoured,” he answered, with a shudder, for of all creatures the alligator is the one most dreaded by Cubans, being the only living beast on the island dangerous to life because of its strength.

“He must have been lying in wait for somebody,” I remarked, after a moment’s pause, during which we kept our eyes on the brook, in a vain attempt to gain another look at our tormentor.

“He was—it is the way they do, Mark. If they can, they wait until you are alongside of them. Then a blow from the tail knocks you flat, and that ends the fight—for you,” and again Alano shuddered, and so did I.

“We can’t cross,” I said, a few minutes later, as all remained quiet. “I would not attempt it for a thousand dollars.”

“Nor I—on foot. Perhaps we can do so by means of the trees. Let us climb yonder palm and investigate.”

We climbed the palm, a sloping tree covered with numerous trailing vines. Our movements « 32 » disturbed countless beetles, lizards, and a dozen birds, some of the latter flying off with a whir which was startling. The top of the palm reached, we swung ourselves to its neighbor, standing directly upon the bank of the brook. In a few minutes we had reached a willow and then a cacao, and thus we crossed the stream in safety, although not without considerable exertion.

The sun was beginning to set when we reached a small village called by the natives San Lerma—a mere collection of thatched cottages belonging to some sheep-raisers. Before entering we made certain there were no soldiers around.

Our coming brought half a dozen men, women, and children to our side. They were mainly of negro blood, and the children were but scantily clothed. They commenced to ask innumerable questions, which Alano answered as well as he could. One of the negroes had heard of Señor Guerez' plantation, and immediately volunteered to furnish us with sleeping accommodations for the night.

“Many of us have joined the noble General Garcia,” he said, in almost a whisper. “I would join too, but Teresa will not hear of it.” Teresa was his wife—a fat, grim-looking wench who ruled the household with a rod of iron. She « 33 » grumbled a good deal at having to provide us with a bed, but became very pleasant when Alano slipped a small silver coin into her greasy palm.

Feeling fairly secure in our quarters, we slept soundly, and did not awaken until the sun was shining brightly. The inevitable pot of black coffee was over the fire, and the smoke of bacon and potatoes frying in a saucepan filled the air. Breakfast was soon served, after which we greased our boots, saw to our other traps and our bag of provisions, which we had not opened, and proceeded on our way—the husband of Teresa wishing us well, and the big-eyed children staring after us in silent wonder and curiosity.

“That is a terrible existence,” I said to Alano. “Think of living in that fashion all your life!”

“They know no better,” he returned philosophically. “And I fancy they are happy in their way. Their living comes easy to them, and they never worry about styles in clothing or rent day. Sometimes they have dances and other amusements. Didn’t you see the home-made guitar on the wall?”

On we went, past the village and to a highway which we had understood would take us to Tiarriba, but which took us to nothing of the sort. As we proceeded the sun grew « 34 » more oppressive than ever, until I was glad enough to take Alano’s advice, and place some wet grass in my hat to keep the top of my head cool.

“It will rain again soon,” said Alano, “and if it comes from the right quarter it will be much cooler for several days after.”

The ground now became hilly, and we walked up and down several places which were steep enough to cause us to pant for breath. By noon we reckoned we had covered eight or nine miles. We halted for our midday rest and meal under some wild peppers, and we had not yet finished when we heard the low rumble of thunder.

“The storm is coming, sure enough!” I exclaimed. “What had we best do—find some shelter?”

“That depends, Mark. If the lightning is going to be strong, better seek the open air. We do not want to be struck.”

We went on, hoping that some village would soon be found, but none appeared. The rain commenced to hit the tree leaves, and soon there was a steady downpour. We buttoned our coats tightly around the neck, and stopped under the spreading branches of an uncultivated banana tree, the half-ripe fruit of which hung within easy reach.

The thunder had increased rapidly, and now from out of the ominous-looking clouds the lightning played incessantly. Alano shook his head dubiously.

“Do you know what I think?” he said.

“Well?”

“I think we have missed our way. If we were on the right road we would have come to some dwelling ere this. I believe we have branched off on some forest trail.”

“Let us go on, Alano. See, the rain is coming through the tree already.”

It was tough work now, for the road was uphill and the clayey ground was slippery and treacherous. It was not long before I took a tumble, and would have rolled over some sharp rocks had Alano not caught my arm. At one minute the road seemed pitch-dark, at the next a flash of lightning would nearly blind us.

Presently we gained the crest of a hill a little higher than its fellows, and gazed around us. On all sides were the waving branches of palms and other trees, dotted here and there with clearings of rocks and coarse grasses. Not a building of any kind was in sight.

“It is as I thought,” said my Cuban chum dubiously. “We have lost our way in the hills.”

“And what will we have to do—retrace our steps?” I ventured anxiously.

“I don’t know. If we push on I suppose we’ll strike some place sooner or later.”

“Yes, but our provisions won’t last forever, Alano.”

“That is true, Mark, but we’ll have to—— Oh!”

Alano stopped short and staggered back into my arms. We had stepped for the moment under the shelter of a stately palm. Now it was as if a wave of fire had swept close to our face. It was a flash of lightning; and it struck the tree fairly on the top, splitting it from crown to roots, and pinning us down under one of the falling portions!

FROM ONE DIFFICULTY TO ANOTHER.

How we ever escaped from the falling tree I do not fully know to this day. The lightning stunned me almost as much as my companion, and both of us went down in a heap in the soft mud, for it was now raining in torrents. We rolled over, and a rough bit of bark scraped my face; and then I knew no more.

When I came to my senses I was lying in a little gully, part of the way down the hillside. Alano was at my side, a deep cut on his chin, from which the blood was flowing freely. He lay so still that I at first thought him dead, but the sight of the flowing blood reassured me.

A strong smell of sulphur filled the air, and this made me remember the lightning stroke. I looked up the hill, to see the palm tree split as I have described.

“Thank God for this escape!” I could not help murmuring; and then I took out a handkerchief, allowed it to become wet, and bound up Alano’s cut. While I was doing this he came to, gasped, and opened his eyes.

“Què—què——” he stammered. “Wha—what—was it, Mark?”

I told him, and soon had him sitting up, his back propped against a rock. The cut on his chin was not deep, and presently the flow of blood stopped and he shook himself.

“It was a narrow escape,” he said. “I warned you we must get out into the open.”

“We’ll be more careful in the future,” I replied. And then I pointed to an opening in the gully. “See, there is a cave. Let us get into that while the storm lasts.”

“Let us see if it is safe first. There may be snakes within,” returned Alano.

With caution we approached the entrance to the cave, which appeared to be several yards deep. Trailing vines partly hid the opening; and, thrusting these aside, we took sticks, lit a bit of candle I carried, and examined the interior. Evidently some wild animal had once had its home there, but the cave was now tenantless, and we proceeded to make ourselves at home.

“We’ll light a fire and dry our clothing,” suggested Alano. “And if the rain continues we can stay here all night.”

“We might as well stay. To tramp through the wet grass and brush would be almost as bad as to have it rain—we would be soaked from our waists down.”

“Then we’ll gather wood and stay,” said he.

Quarter of an hour later we had coaxed up quite a respectable fire in the shadow of a rock at the entrance to the cave, which was just high enough to allow us to stand upright, and was perhaps twelve feet in diameter. We piled more wood on the blaze, satisfied that in its damp condition we could not set fire to the forest, and then retired to dry our clothing and enjoy a portion of the contents of the provision bag Alano had improvised out of the purloined napkin.

As we ate we discussed the situation, wondering how far we could be from some village and if there were any insurgents or Spanish soldiers in the vicinity.

“The rebels could outwit the soldiers forever in these hills,” remarked Alano—“especially those who are acquainted in the vicinity.”

“But the rebels might be surrounded,” I suggested.

“They said at Santiago they had too strong a picket guard for that, Mark.”

“But we have seen no picket guard. Supposing instead of two boys a body of Spanish soldiers had come this way, what then?”

“In that case what would the Spanish soldiers have to shoot at?” he laughed. “We have as yet seen no rebels.”

“But we may meet them—before we know it,” I said, with a shake of my head.

Scarcely had I uttered the words than the entrance to our resting-place was darkened by two burly forms, and we found the muzzles of two carbines thrust close to our faces.

“Who are you?” came in Spanish. “Put up your hands!”

“Don’t shoot!” cried Alano in alarm.

“Come out of that!”

“It’s raining too hard, and we have our coats off, as you see. Won’t you come in?”

At this the two men, bronzed and by no means bad-looking fellows, laughed. “Only boys!” murmured one, and the carbines were lowered and they entered the cave.

A long and rapid conversation with Alano, which I could but imperfectly understand, followed. They asked who we were, where we were going, how we had managed to slip out of Santiago, if we were armed, if we carried messages, if we had the countersign, how we had reached the cave, and a dozen other questions. Both roared loudly when Alano said he thought they were rebels.

“And so we are,” said the one who appeared to be the leader. “And we are proud of it. Have you any objections to make?”

“No,” we both answered in a breath, that « 41 » being both English and Spanish, and I understanding enough of the question to be anxious to set myself right with them.

“I think our fathers have become rebels,” Alano answered. “At least, we were told so.”

“Good!” said the leader. “Then we have nothing to fear from two such brave lads as you appear to be. And now what do you propose to do—encamp here for the night?”

“Unless you can supply us with better accommodations,” rejoined my chum.

“We can supply you with nothing. We have nothing but what is on us,” laughed the second rebel.

Both told us later that they were on special picket duty in that neighborhood. They had been duly enlisted under General Garcia, but were not in uniform, each wearing only a wet and muddy linen suit, thick boots, and a plain braided palm hat. Around his waist each had strapped a leather belt, and in this stuck a machete—a long, sharp, and exceedingly cruel-looking knife. Over the shoulder was another strap, fastened to a canvas bag containing ammunition and other articles of their outfit.

These specimens of the rebels were hardly what I had expected to see, yet they were so earnest in their manner I could not help but admire them. One of them had brought down a « 42 » couple of birds, and these were cooked over our fire and divided among all hands, together with the few things we had to offer. After the meal each soldier placed a big bite of tobacco in his mouth, lit a cigarette, and proceeded to make himself comfortable.

“The Spaniards will not move in this weather,” said one. “They are too afraid of getting wet and taking cold.”

Darkness had come upon us, and it was still raining as steadily as ever. Our clothing was dry; and, as the cave was warmed, the rebel guards ordered us to put out the fire, that it might not attract attention during the night.

We were told that we had made several mistakes on the road and were far away from Tiarriba. If we desire to go there, the rebels said they would put us on the right road.

“But if you are in sympathy with us, you had better pass Tiarriba by,” said one to Alano. “The city is filled with Spanish soldiers, and you may not be able to get away as easily as you did from Santiago.”

Alano consulted with me, and then asked the rebel what we had best do.

“That depends. Do you want to join the forces under General Garcia?”

“We want to join our fathers at or near Guantanamo.”

“Garcia is pushing on in that direction. You had best join the army and stay with it until Guantanamo is reached.”

“But we will have to fight?” said my Cuban chum.

The guard smiled grimly, exhibiting a row of large white teeth.

“As you will. The general will not expect too much from boys.”

There the talk ended, one of the rebels deeming it advisable to take a tramp over to the next hill and back, and the other crouching down in a corner for a nap. With nothing else to do, we followed the example of the latter, and were soon in dreamland.

A single call from the man who had slept beside us brought us to our feet at daybreak. The storm had cleared away, and now it was positively cool—so much so that I was glad enough to button my coat up tightly and be thankful that the fire had dried it so well. The second rebel was asleep, and had been for two hours. We followed one out of the cave without arousing the other.

A tramp of half a mile brought us to a high bank, and here our rebel escort left us.

“Across the bank you will find a wagon-road leading to the west,” he said. "Follow that, and you cannot help but meet some of our party « 44 » sooner or later. Remember the new password, ‘Maysi,’ and you will be all right," and then he turned and disappeared from sight in the bush.

The climb to the top of the bank was not difficult, and, once over it, the road he had mentioned lay almost at our feet. We ran down to it with lighter hearts than we had had for some time, and struck out boldly, eating a light breakfast as we trudged along.

“I hope we strike no more adventures until the vicinity of Guantanamo is reached,” I observed.

“We can hardly hope for that, Mark,” smiled my chum. “Remember we are journeying through a country where war is raging. Let us be thankful if we escape the battles and skirmishes.”

“And shooting down by some ambitious sharpshooter,” I added. “By the way, I wonder if our folks are looking for us?”

“It may be they sent word not to come, when they saw how matters were going, Mark. I am sure your father would not want you to run the risk that——Look! look! We must hide!”

Alano stopped short, caught me by the arm, and pointed ahead. Around a turn in the road a dozen horsemen had swept, riding directly toward us. A glance showed that they were Spanish guerrillas!

FOOLING THE SPANISH GUERRILLAS.

“Halte!”

It was the cry of the nearest of the Spanish horsemen. He had espied us just as Alano let out his cry of alarm, and now he came galloping toward us at a rapid gait.

“Let us run!” I ejaculated to my Cuban chum. “It is our only chance.”

“Yes, yes! but to where?” he gasped, staring around in bewilderment. On one side of the road was a woods of mahogany, on the other some palms and plantains, with here and there a great rock covered with thick vines.

“Among the rocks—anywhere!” I returned. “Come!” And, catching his hand, I led the way from the road while the horseman was yet a hundred feet from us.

Another cry rang out—one I could not understand, and a shot followed, clipping through the broad leaves over our heads. The horseman left the road, but soon came to a stop, his animal’s progress blocked by the trees and rocks. He yelled to his companions, and all of the guerrillas came up at topmost speed.

“They will dismount and be after us in a minute!” gasped Alano. “Hark! they are coming already!”

“On! on!” I urged. “We’ll find some hiding-place soon.”

Around the rocks and under the low-hanging plantains we sped, until the road was left a hundred yards behind. Then we came to a gully, where the vegetation was heavy. Alano pointed down to it.

“We can hide there,” he whispered. “But we will be in danger of snakes. Yet it is the best we can do.”

I hesitated. To make the acquaintanceship of a serpent in that dense grass was not pleasant to contemplate. But what else was there to do? The footsteps of our pursuers sounded nearer.

Down went Alano, making leaps from rock to rock, so that no trail would be left. I followed at his heels, and, coming to a rock which was partly hollowed out at one side and thickly overgrown, we crouched under it and pulled the vines and creepers over us.

It was a damp, unwholesome spot, but there was no help for it, and when several enormous black beetles dropped down and crawled around my neck I shut my lips hard to keep from crying out. We must escape from the enemy, no matter what the cost, for even if they did not make « 47 » us prisoners we knew they would take all we possessed and even strip the coats from our backs.

Peering from between the vines, we presently caught sight of three of the Spaniards standing at the top of the gully, pistols in hand, on the alert for a sight of us. They were dark, ugly-looking fellows, with heavy black mustaches and faces which had not had a thorough washing in months. They were dressed in the military uniform of Spain, and carried extra bags of canvas slung from their shoulders, evidently meant for booty. That they were tough customers Alano said one could tell by their vile manner of speech.

“Do you see them, Carlo?” demanded one of the number. “I thought they went down this hollow?”

“I see nothing,” was the answer, coupled with a vile exclamation. “They disappeared as if by magic.”

“They were but boys.”

“Never mind, they were rebels—that is enough,” put in the third guerrilla, as he chewed his mustache viciously. “I wish I could get a shot at them.”

At this Alano pulled out his pistol and motioned for me to do the same.

“We may as well be prepared for the worst,” « 48 » he whispered into my ear. “They are not soldiers, they are robbers—bandits.”

“They look bad enough for anything,” I answered, and produced my weapon, which I had not discharged since the brush with the alligator.

“If they are in the hollow it is odd we do not see them on their trail,” went on one of the bandits. “Perhaps they went around.”

His companions shook their heads.

“I’ll thrash around a bit,” said one of them; and, leaving the brink of the gully, he started straight for our hiding-place.

My heart leaped into my throat, and I feared immediate discovery. As for Alano, he shoved his pistol under his coat, and I heard a muffled click as the hammer was raised.

When within ten feet of us the ugly fellow stopped, and I fairly held my breath, while my heart appeared to beat like a trip-hammer. He looked squarely at the rock which sheltered us, and I could not believe he would miss discovering us. Once he started and raised his pistol, and I imagined our time had come; but then he turned to one side, and I breathed easier.

“They did not come this way, capitan!” he shouted. “Let us go around the hollow.”

In another moment all three of the bandits « 49 » were out of sight. We heard them moving in the undergrowth behind us, and one of them gave a scream as a snake was stirred up and dispatched with a saber. Then all became quiet.

“What is best to do now?” I asked, when I thought it safe to speak.

“Hush!” whispered Alano. “They may be playing us dark.”

A quarter of an hour passed,—it seemed ten times that period of time just then,—and we heard them coming back. They were very angry at their want of success; and had we been discovered, our fate would undoubtedly have been a hard one. They stalked back to the road, and a moment later we heard the hoof-strokes of their horses receding in the distance.

“Hurrah!” I shouted, but in a very subdued tone. “That’s the time we fooled them, Alano.”

My Cuban chum smiled grimly. “Yes, Mark, but we must be more careful in the future. Had we not been so busy talking we might have heard their horses long before they came into view. However, the scare is over, so let us put our best foot forward once again.”

“If only we had horses too!” I sighed. “My feet are beginning to get sore from the uneven walking.”

“Horses would truly be convenient at times. But we haven’t them, and must make the best of it. When we stop for our next meal you had best take off your boots and bathe your feet. You will be astonished how much rest that will afford them.”

I followed this advice, and found Alano was right; and after that I bathed my feet as often as I got the chance. Alano suffered no inconvenience in this particular, having climbed the hills since childhood.

We were again on rising ground, and now passed through a heavy wood of cedars, the lower branches sweeping our hats as we passed. This thick shade was very acceptable, for the glare of the sun had nearly blinded me, while more than once I felt as if I would faint from the intense heat.

“It’s not such a delightful island as I fancied it,” I said to my chum. “I much prefer the United States.”

“That depends,” laughed Alano. “The White Mountains or the Adirondacks are perhaps nicer, but what of the forests and everglades in Florida?”

“Just as bad as this, I suppose.”

“Yes, and worse, for the ground is wetter, I believe. But come, don’t lag. We must make several more miles before we rest.”

We proceeded up a hill and across a level space which was somewhat cleared of brush and trees. Beyond we caught sight of a thatched hut. Hardly had it come into view than from its interior we heard a faint cry for help.

ANDRES.

“What is that?” ejaculated Alano, stopping short and catching my arm.

“A cry of some kind,” I answered. “Listen!”

We stepped behind some trees, to avoid any enemies who might be about, and remained silent. Again came the cry.

“It is a man in distress!” said Alano presently. “He asks us not to desert him.”

“Then he probably saw us from the window of the hut. What had we best do?”

“You remain here, and I will investigate,” rejoined my Cuban chum.

With caution he approached the thatched hut, a miserable affair, scarcely twelve feet square and six feet high, with the trunks of palm trees as the four corner-posts. There were one tiny window and a narrow door, and Alano after some hesitation entered the latter, pistol in hand.

“Come, Mark!” he cried presently, and I ran forward and joined him.

A pitiable scene presented itself. Closely bound to a post which ran up beside the window was a Cuban negro of perhaps fifty years of age, gray-haired and wrinkled. He was scantily clothed, and the cruel green-hide cords which bound him had cut deeply into his flesh, in many places to such an extent that the blood was flowing. The negro’s tongue was much swollen, and the first thing he begged for upon being released was a drink of water.

We obtained the water, and also gave him what we could to eat, for which he thanked us over and over again, and would have kissed our hands had we permitted it. He was a tall man, but so thin he looked almost like a skeleton.

“For two days was I tied up,” he explained to Alano, in his Spanish patois. “I thought I would die of hunger and thirst, when, on raising my eyes, I beheld you and your companion. Heaven be praised for sending you! Andres will never forget you for your goodness, never!”

“And how came you in this position?” questioned my chum.

“Ah, dare I tell, master?”

“You are a rebel?”

The negro lowered his eyes and was silent.

“If you are, you have nothing to fear from us,” continued Alano.

“Ah—good! good!” Andres wrung his hand. « 54 » “Yes, I am a rebel. For two years I fought under our good General Maceo and under Garcia. But I am old, I cannot climb the mountains as of yore, and I got sick and was sent back. The Spanish soldiers followed me, robbed me of what little I possessed, and, instead of shooting me, bound me to the post as a torture. Ah, but they are a cruel set!” And the eyes of the negro glowed wrathfully. “If only I was younger!”

“Were the Spaniards on horseback?” asked Alano.

“Yes, master—a dozen of them.”

Alano described the bandits we had met, and Andres felt certain they must be the same crowd. The poor fellow could scarcely stand, and sank down on a bed of cedar boughs and palm branches. We did what we could for him, and in return he invited us to make his poor home our own.

There was a rude fireplace behind the hut, and here hung a great iron pot. Rekindling the fire, we set the pot to boiling; and Andres hobbled around to prepare a soup, or rather broth, made of green plantains, rice, and a bit of dried meat the bandits had not discovered, flavoring the whole mess with garlic. The dish was not particularly appetizing to me, but I was tremendously hungry and made way with a fair « 55 » share of it, while Alano apparently enjoyed his portion.

It was dark when the meal was finished, and we decided to remain at the hut all night, satisfied that we would be about as secure there as anywhere. The smoke of the smoldering fire kept the mosquitoes and gnats at a distance, and Andres found for us a couple of grass hammocks, which, when slung from the corner-posts, made very comfortable resting-places.

During the evening Alano questioned Andres closely, and learned that General Garcia was pushing on toward Guantanamo, as we had previously been informed. Andres did not know Señor Guerez, but he asserted that many planters throughout the district had joined the rebel forces, deserting their canefields and taking all of their help with them.

“The men are poorly armed,” he continued. “Some have only their canefield knives—but even with these they are a match for the Spanish soldiers, on account of their bravery”—an assertion which later on proved, for the greater part, to be true.

The night passed without an alarm of any kind, and before sunrise we were stirring around, preparing a few small fish Alano had been lucky enough to catch in a near-by mountain stream. These fish Andres baked by rolling them in a « 56 » casing of clay; and never have I eaten anything which tasted more delicious.

Before we left him the Cuban negro gave us minute directions for reaching the rear guard of the rebel army. He said the password was still “Maysi.”

“You had better join the army,” he said, on parting. “You will gain nothing by trying to go around. And you, master Alano—if your father has joined the forces, it may be that will gain you a horse and full directions as to just where your parent is,” and as we trudged off Andres wished us Godspeed and good luck over and over again, with a friendly wave of his black bony hand.

The cool spell, although it was really only cool by contrast, had utterly passed, and as the sun came up it seemed to fairly strike one a blow upon the head. We were traveling along the edge of a low cliff, and shade was scarce, although we took advantage of every bit which came in our way. The perspiration poured from our faces, necks, and hands; and about ten o’clock I was forced to call a halt and throw myself on my back on the ground.

“I knew it would be so,” said my chum. "That is why I called for an early start. We might as well rest until two or three in the afternoon. « 57 » Very few people travel here in the heat of the day."

“It is suffocating,” I murmured. “Like one great bake-oven and steam-laundry combined.”

“That is what makes the vegetation flourish,” he smiled. “Just see how it grows!”

I did not have far to look to notice it. Before us was a forest of grenadillo and rosewood, behind us palms and plantains, with an occasional cacao and mahogany tree. The ground was covered with long grass and low brush, and over all hung the festoons of vines of many colors, some blooming profusely. A smell of “something growing green” filled the hot air, and from every side arose the hum of countless insects and the occasional note of a bird.

“I wouldn’t remain on the ground too long,” remarked Alano presently. “When one is hot and lies down, that is the time to take on a fever. Better rest in yonder tree—it is more healthy; and, besides, if there is any breeze stirring, there is where you will catch it.”

“We might as well be on a deserted island as to be in Cuba,” I said, after both of us had climbed into a mahogany tree. “There is not a building nor a human soul in sight. I half believe we are lost again.”

Alano smiled. "Let us rather say, as your « 58 » Indian said, 'We are not lost, we are here. The army and the towns and villages are lost,'" and he laughed at the old joke, which had been the first he had ever read, in English, in a magazine at Broxville Academy.

“Well, it’s just as bad, Alano. I, for one, am tired of tramping up hill and down. If we could reach the army and get a couple of horses, it would be a great improvement.”

My chum was about to reply to this, when he paused and gave a start. And I started, too, when I saw what was the trouble. On a limb directly over us, and ready to descend upon our very heads, was a serpent all of six feet in length!

ACROSS THE CANEFIELDS.

“Look, Mark!” ejaculated Alano.

“A snake!” I yelled. “Drop! drop!”

I had already dropped to the limb upon which I had been sitting. Now, swinging myself by the hands, I let go and descended to the ground, a distance of twelve or fifteen feet.

In less than a second my Cuban chum came tumbling after me. The fall was no mean one, and had the grass under the tree been less deep we might have suffered a sprained ankle or other injury. As it was, we both fell upon our hands and knees.

Gazing up at the limb we had left, we saw the serpent glaring down at us, its angry eyes shining like twin diamonds. How evil its intention had been we could but surmise. It was possible it had intended to attack us both. It slid from the upper limb to the lower, and stretched out its long, curling neck, while it emitted a hiss that chilled my blood.

“It’s coming down! Run!” I began; when bang! went Alano’s pistol, and I saw the serpent give a quiver, and coil and uncoil itself around « 60 » the limb. The bullet had entered its neck, but it was not fatally wounded; and now it came for us, landing in the grass not a dozen feet from where we stood.

Luckily, while traveling along the hills, we had provided ourselves with stout sticks to aid us in climbing. These lay near, and, picking one up, I stood on the defensive, certain the reptile would not dare to show much fight. But it did, and darted for me with its dull-colored head raised a few inches out of the grass.

With all of the strength at my command I swung the stick around the instant it came within reach. It tried to dodge, but failed; and, struck in the neck, turned over and over as though more than half stunned.

By this time Alano had secured the second stick, and now he rushed in and belabored the serpent over the head and body until it was nearly beaten into a jelly. I turned sick at the sight, and was glad enough when it was all over and the reptile was dead beyond all question.

“That was a narrow escape!” I panted. “Alano, don’t you advise me to rest in a tree again. I would rather run the risk of fever ten times over.”

“Serpents are just as bad in the grass,” he replied simply. “Supposing he had come up when you were flat on your back!”

“Let us get away from here—there may be more. And throw away that stick—it may have poison on it.”

“That serpent was not poisonous, Mark. But I will throw it away,—it is so covered with blood,—and we can easily cut new ones.”

The excitement had made me forget the heat, and we went on for over a mile. Then, coming to a mountain stream, we sat down to take it easy until the sun had passed the zenith and it was a trifle cooler.

About four o’clock in the afternoon, or evening, as they call it in Cuba, we reached the end of the woods and came to the edge of an immense sugar-cane field. The cane waved high over our heads, so that what buildings might be beyond were cut off from view. There was a rough cart-road through the field, and after some hesitation we took to this, it being the only road in sight.

We had traveled on a distance of half a mile when we reached a series of storehouses, each silent and deserted. Beyond was a house, probably belonging to the overseer of the plantation, and this was likewise without occupant, the windows and doors shut tightly and bolted.

“All off to the war, I suppose,” I said. “And I had half an idea we might get a chance to sleep in a bed to-night.”

“We might take possession,” Alano suggested.

But to this proposition I shook my head. “We might be caught and shot as intruders. Come on. Perhaps the house of the owner is further on.”

Stopping for a drink at an old-fashioned well, we went on through the sugar cane until we reached a small stream, beyond which was a boggy spot several acres in extent.

“We’ll have to go around, Alano,” I said. “Which way will be best?”

“The ground appears to rise to our left,” he answered. “We’ll try in that direction.”

Pushing directly through the cane, I soon discovered, was no mean work. It was often well-nigh impossible to break aside the stout stalks, and the stubble underfoot was more than trying to the feet. We went on a distance of a hundred yards, and then on again to the stream, only to find the same bog beyond.

“We’ll have to go further yet,” said Alano. “Come, Mark, ere the sun gets too low.”

“Just a few minutes of rest,” I pleaded, and pulled down the top of a cane. The sweet juice was exceedingly refreshing, but it soon caused a tremendous thirst, which I gladly slaked at the not over clear stream. Another jog of « 63 » quarter of an hour, and we managed to cross at a point which looked like solid ground.

“How far do you suppose this field extends?” I asked.

“I have no idea; perhaps but a short distance, and then again it may be a mile or more. Some of the plantations out here are very large.”

“Do you think we can get back to the road? I can’t go much further through this stubble.”

“I’ll break the way, Mark. You follow me.”

On we went in the direction we imagined the trail to be, but taking care to avoid the bog. I was almost ready to drop from exhaustion, when Alano halted.

“Mark!”

“What now, Alano?”

“Do you know where we are?”

“In a sugar-cane field,” I said, trying to keep up my courage.

“Exactly, but we are lost in it.”

I stared at him.

“Can one become lost in a sugar-cane field?” I queried.

“Yes, and badly lost, for there is nothing one can climb to take a view of the surroundings. Even if you were to get upon my shoulders you could see but little.”

“I’ll try it,” I answered, and did so without delay, for the sun was now sinking in the west.

But my chum had been right; try my best I could not look across the waving cane-tops. We were hedged in on all sides, with only the setting sun to mark our course.

“It’s worse than being out on an open prairie,” I remarked. “What shall we do?”

“There is but one thing—push on,” rejoined Alano gravely; “unless you want to spend a night here.”

Again we went on, but more slowly, for even my chum was now weary. The wet ground passed, we struck another reach of upland, and this gave us hope, for we knew the sugar cane would not grow up the hills. But the rise soon came to an end, and we found ourselves going down into a worse hollow than that we had left. Ere we knew it, the water was forming around our boots.

“We must go back!” I cried.

“I think it is drier a few yards beyond,” said Alano. “Don’t go back yet.”

The sun had set, so far as we were concerned, and it was dark at the foot of the cane-stalks. We plowed on, getting deeper and deeper into the bog or mire. It was a sticky paste, and I could hardly move one foot after another. I called to Alano to halt, and I had scarcely done so when he uttered an ejaculation of disgust.

“What is it?” I called.

“I can’t move—I am stuck!”

I looked ahead and saw that he spoke the truth. He had sunk to the tops of his boots, and every effort to extricate himself only made him settle deeper.

I endeavored to gain his side and aid him, but it was useless. Ere I was aware I was as deep and deeper than Alano, and there we stood,—and stuck,—unable to help ourselves, with night closing rapidly in upon us.

A COUNCIL OF THE ENEMY.

“Well, this is the worst yet,” I said, after a minute of silence. Somehow, I felt like laughing, yet our situation was far from being a laughing matter.

“We have put our foot into it, and no mistake,” rejoined Alano dubiously.

“Say feet, Alano,—and legs,—and you’ll be nearer it. What on earth is to be done?”

“I don’t know. See, I am up to my thighs already. In an hour or so I’ll be up to my neck.”

To this I made no reply. I had drawn my pistol, and with the crook of the handle was endeavoring to hook a thick sugar-cane stalk within my reach. Several times I had the stalk bent over, but it slipped just as I was on the point of grasping it.

But I persevered,—there was nothing else to try,—and at last my eager fingers encircled the stalk. I put my pistol away and pulled hard, and was overjoyed to find that I was drawing myself up out of my unpleasant position.

“Be careful—or the stalk will break,” cautioned my Cuban chum, when crack! it did split, but not before I was able to make a quick leap on top of the clump of roots. Here I sank again, but not nearly as deeply as before.

The leap I had taken had brought me closer to Alano, and now I was enabled to break down a number of stalks within his reach. He got a firm hold and pulled with all of his might, and a moment later stood beside me.

“Oh, but I’m glad we’re out of that!” were his first words. “I thought I was planted for the rest of my life.”

“We must get out of the field. See, it will be pitch dark in another quarter of an hour.”

“Let us try to go back—it will be best.”

We turned around, and took hold of each other’s hands, to balance ourselves on the sugar-cane roots, for we did not dare to step in the hollows between. Breaking down the cane was slow and laborious work, and soon it was too dark to see our former trail. We lost it, but this was really to our advantage, for, by going it blindly for another quarter of an hour, we emerged into an opening nearly an acre square and on high and dry ground.

Once the patch was reached, we threw ourselves down on the grass panting for breath, the heavy perspiration oozing from every pore. « 68 » We had had another narrow escape, and silently I thanked Heaven for my deliverance.

Toward the higher end of the clearing was a small hut, built of logs plastered with sun-baked clay. We came upon it by accident in the dark, and, finding it deserted, lit our bit of candle before mentioned and made an examination.

“It’s a cane-cutter’s shanty,” said Alano. “I don’t believe anybody will be here to-night, so we might as well remain and make ourselves comfortable.”

“We can do nothing else,” I returned. “We can’t travel in the darkness.”

Both of us were too exhausted to think of building a fire or preparing a meal. We ate some of our provisions out of our hands, pulled off our water-soaked boots, and were soon asleep on the heaps of stalks the shanty contained. Once during the night I awoke to find several species of vermin crawling around, but even this was not sufficient to make me rouse up against the pests. I lay like a log, and the sun was shining brightly when Alano shook me heartily by the shoulder.

“Going to sleep all day?” he queried.

“Not much!” I cried, springing up. “Hullo, if you haven’t got breakfast ready!” I added, glancing to where he had built a fire.

“Yes; I thought I’d let you sleep for a while,” « 69 » he answered. “Fall to, and we’ll be on our way. If we have good luck we may strike a part of General Garcia’s army to-day.”

“If we can get out of this beastly canefield.”

“I’ve found a way out, Mark. Finish your meal, and I’ll show you.”

Breakfast was speedily dispatched, and, having put on my boots, which were stiff and hard from the wetting received, and taken up my valise, I followed Alano to the extreme southwest end of the clearing. Here there was an ox-cart trail, leading in a serpentine fashion through the canefield to still higher ground. Beyond were the inevitable rocks and woods.