TRANSCRIBER’S NOTES:

—Obvious print and punctuation errors were corrected.

—The transcriber of this project created the book cover image using the title page of the original book. The image is placed in the public domain.

A BOOK OF

THE RIVIERA

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

A BOOK OF CORNWALL

A BOOK OF DARTMOOR

A BOOK OF DEVON

A BOOK OF NORTH WALES

A BOOK OF SOUTH WALES

A BOOK OF THE RHINE

A BOOK OF THE PYRENEES

THE LIFE OF NAPOLEON BONAPARTE

THE TRAGEDY OF THE CÆSARS

A BOOK OF FAIRY TALES

THE VICAR OF MORWENSTOW

OLD COUNTRY LIFE

A GARLAND OF COUNTRY SONG

SONGS OF THE WEST

A BOOK OF NURSERY SONGS AND RHYMES

STRANGE SURVIVALS

YORKSHIRE ODDITIES

DEVON

BRITTANY

A BARING-GOULD SELECTION READER

A BARING-GOULD CONTINUOUS READER

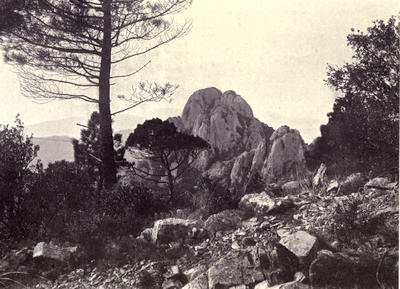

CAP ROUX, ESTÉREL

A BOOK OF

THE RIVIERA

BY S. BARING-GOULD

“ON OLD HYEMS’ CHIN, AND ICY CROWN,

AN ODOROUS CHAPLET OF SWEET SUMMER BUDS

IS SET.”

Midsummer Night’s Dream, ii. 2.

WITH FORTY ILLUSTRATIONS

SECOND EDITION

METHUEN & CO.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

First Published November 1905

Second Edition December 1909

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Provence | 1 |

| II. | Le Gai Saber | 24 |

| III. | Marseilles | 39 |

| IV. | Aix | 55 |

| V. | Toulon | 72 |

| VI. | Hyères | 84 |

| VII. | Les Montagnes des Maures | 97 |

| VIII. | S. Raphael and Fréjus | 113 |

| IX. | Draguignan | 130 |

| X. | L’Estérel | 147 |

| XI. | Grasse | 157 |

| XII. | Cannes | 180 |

| XIII. | Nice | 205 |

| XIV. | Monaco | 227 |

| XV. | Mentone | 255 |

| XVI. | Bordighera | 264 |

| XVII. | San Remo | 276 |

| XVIII. | Alassio | 288 |

| XIX. | Savona | 296 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| Cap Roux, L’Estérel | Frontispiece | |

| From a photograph by G. Richard. | ||

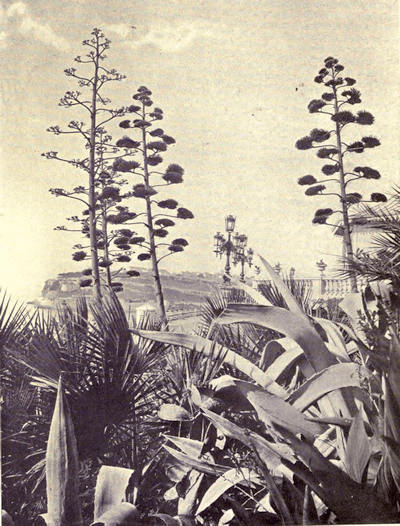

| God’s Candelabra | To face page | 1 |

| From a photograph by J. Giletta. | ||

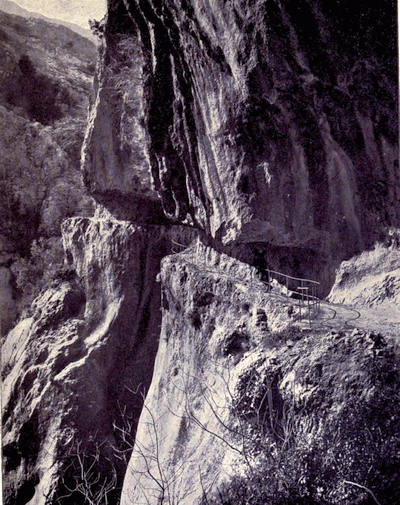

| A Passage in the Gorge du Loup | ” | 4 |

| From a photograph by Neurdein frères. | ||

| Palms at Cannes | ” | 7 |

| From a photograph by J. Giletta. | ||

| La Rade, Marseilles | ” | 39 |

| From a photograph by Neurdein frères. | ||

| King Réné | ” | 63 |

| From the triptych of the Burning Bush, at Aix. | ||

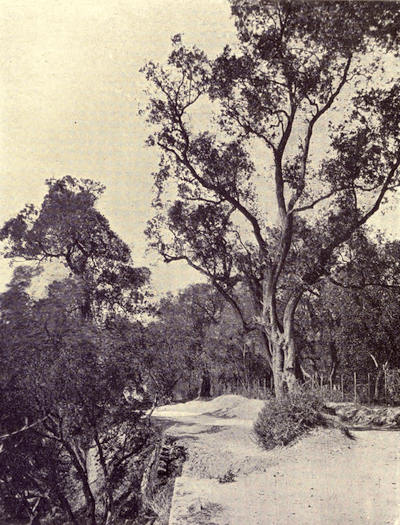

| Olive Trees | ” | 85 |

| From a photograph by J. Giletta. | ||

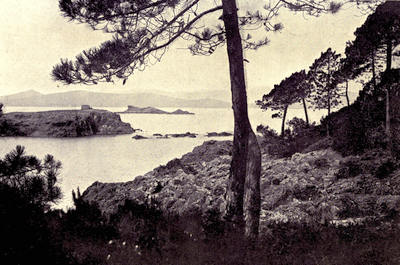

| Pines near Hyères | ” | 89 |

| From a photograph by Neurdein frères. | ||

| A Carob Tree | ” | 97 |

| From a photograph by Neurdein frères. | ||

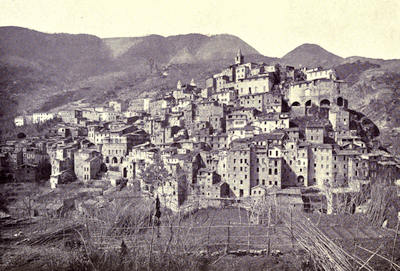

| Grimaud | ” | 109 |

| From a photograph by Neurdein frères. | ||

| An Umbrella Pine, S. Raphael | ” | 113 |

| From a photograph by Neurdein frères. | ||

| Le Lion de Terre, S. Raphael | ” | 115 |

| From a photograph by A. Bandieri. | ||

| Théoule | ” | 147 |

| From a photograph by J. Giletta. | ||

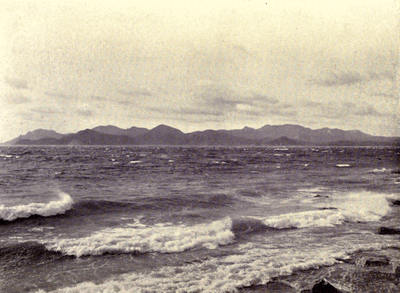

| L’Estérel from Cannes | ” | 153 |

| From a photograph by G. Richard. | ||

| Grasse, Les Blanchiseuses | ” | 157 |

| From a photograph by J. Giletta. | ||

| Carros | ” | 167 |

| From a photograph by Neurdein frères. | ||

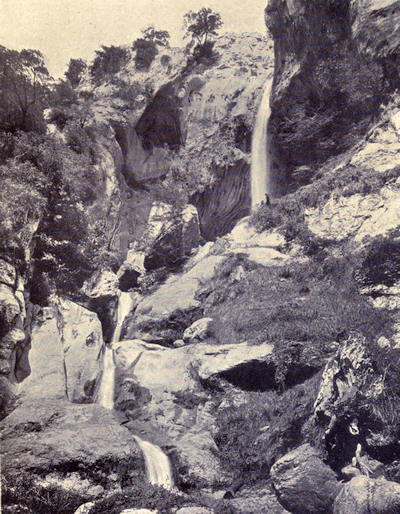

| The Cascade of the Loup | ” | 172 |

| From a photograph by J. Giletta. | ||

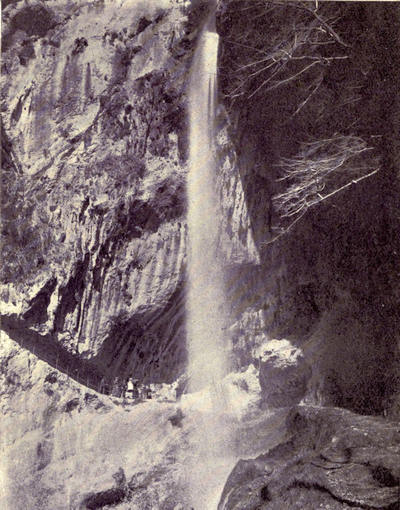

| Fall in the Gorge of the Loup | ” | 173 |

| From a photograph by Neurdein frères. | ||

| Interior of the Château Saint Honorat[vii] | ” | 180 |

| From a photograph by J. Giletta. | ||

| The Prison of the Man with the Iron Mask | ” | 190 |

| From a photograph by J. Giletta. | ||

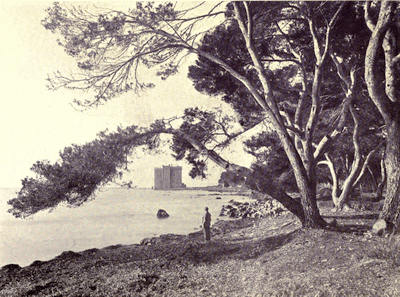

| The Castle of S. Honorat | ” | 195 |

| From a photograph by J. Giletta. | ||

| La Napoule | ” | 203 |

| From a photograph by J. Giletta. | ||

| The Cascade of the Château, Nice | ” | 205 |

| From a photograph by J. Giletta. | ||

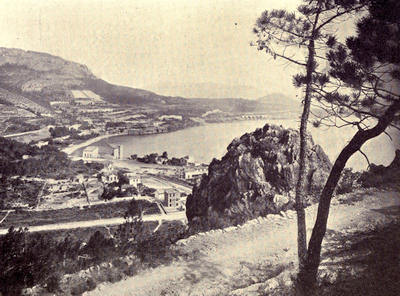

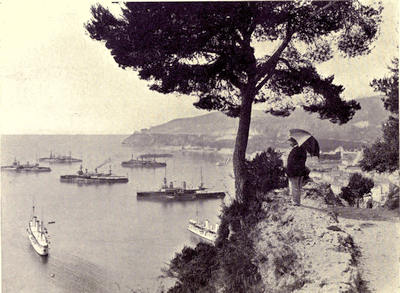

| Villefranche | ” | 225 |

| From a photograph by J. Giletta. | ||

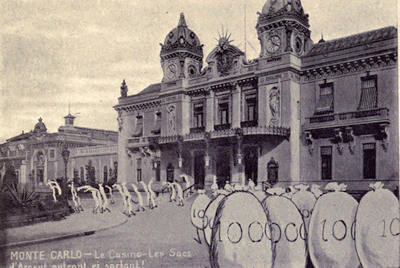

| The Theatre, Monte Carlo | ” | 237 |

| From a photograph by J. Giletta. | ||

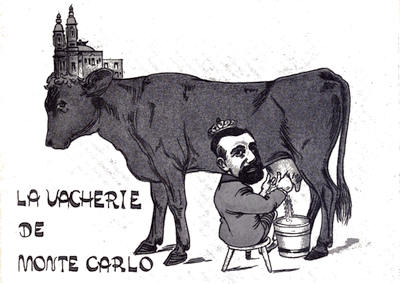

| Postcards Prohibited at Monaco | ” | 244 |

| The Gaming Saloon, Monte Carlo | ” | 248 |

| From a photograph by J. Giletta. | ||

| The Concert Hall, Monte Carlo | ” | 252 |

| From a photograph by J. Giletta. | ||

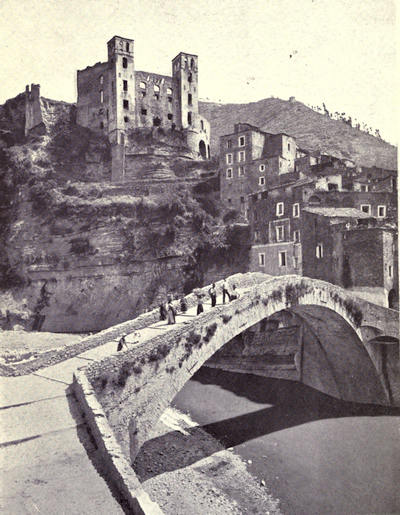

| Dolce acqua | ” | 273 |

| From a photograph by Alinari. | ||

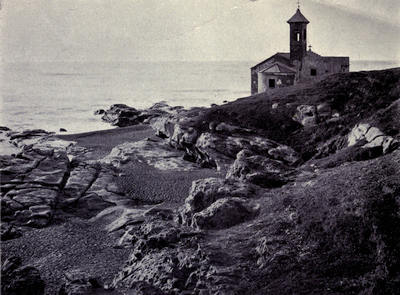

| San Ampelio, Bordighera | ” | 274 |

| From a photograph by Alinari. | ||

| Arches in Street, Bordighera | ” | 276 |

| From a photograph by J. Giletta. | ||

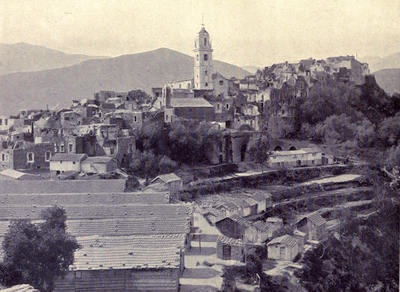

| Ceriana | ” | 279 |

| From a photograph by G. Brogi. | ||

| Bussana | ” | 280 |

| From a photograph by J. Giletta. | ||

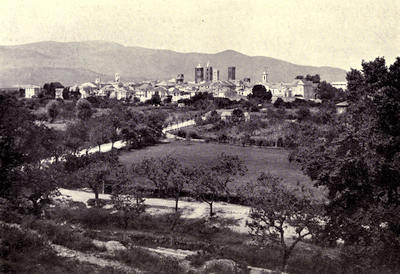

| Albenga | ” | 293 |

| From a photograph by Alinari. | ||

| Savona | ” | 301 |

| From a photograph by Alinari. | ||

| Pope Sixtus IV | ” | 304 |

| From an old engraving. | ||

PREFACE

THIS little book has for its object to interest the many winter visitors to the Ligurian coast in the places that they see.

A consecutive history of Provence and Genoese Liguria was out of the question; it would be long and tedious. I have taken a few of the most prominent incidents in the history of the coast, and have given short biographies of interesting personages connected with it. The English visitor calls the entire coast—from Marseilles to Genoa—the Riviera; but the French distinguish their portion as the Côte d’Azur, and the Italians distinguish theirs as the Riviera di Ponente. I have not included the whole of this latter, so as not to make the book too bulky, but have stayed my pen at Savona.

GOD’S CANDELABRA

THE RIVIERA

CHAPTER I

PROVENCE

Montpellier and the Riviera compared—The discovery of the Riviera as a winter resort—A district full of historic interest—Geology of the coast—The flora—Exotics—The original limit of the sea—The formation of the craus—The Mistral—The olive and cypress—Les Alpines—The chalk formation—The Jura limestone—Eruptive rocks—The colouring of Provence—The towns and their narrow streets—Early history—The Phœnicians—Arrival of the Phocœans—The Roman province—Roman remains—Destruction of the theatre at Arles—Visigoths and Burgundians—The Saracens—When Provence was joined to France—Pagan customs linger on—Floral games—Carnival—The origin of the Fauxbourdon—How part-singing came into the service of the church—Reform in church music—Little Gothic architecture in Provence—Choirs at the west end at Grasse and Vence.

WHEN a gambler has become bankrupt at the tables of Monte Carlo, the Company that owns these tables furnish him with a railway ticket that will take him home, or to any distance he likes, the further the better, that he may hang or shoot himself anywhere else save in the gardens of the Casino. On much the same principle, at the beginning of last century, the physicians of England recommended their consumptive patients to go to Montpellier, where they might die out of sight,[2] and not bring discredit on their doctors. As Murray well puts it:—

“It is difficult to understand how it came to be chosen by the physicians of the North as a retreat for consumptive patients, since nothing can be more trying to weak lungs than its variable climate, its blazing sunshine alternating with the piercingly cold blasts of the mistral. Though its sky be clear, its atmosphere is filled with dust, which must be hurtful to the lungs.”

The discovery of a better place, with equable temperature, and protection from the winds, was due to an accident.

In 1831, Lord Brougham, flying from the fogs and cold of England in winter, was on his way to Italy, the classic land of sunshine, when he was delayed on the French coast of the Mediterranean by the fussiness of the Sardinian police, which would not suffer him to pass the frontier without undergoing quarantine, lest he should be the means of introducing cholera into Piedmont. As he was obliged to remain for a considerable time on the coast, he spent it in rambling along the Gulf of Napoule. This was to him a veritable revelation. He found the sunshine, the climate, the flowers he was seeking at Naples where he then was, at Napoule. He went no farther; he bought an estate at Cannes, and there built for himself a winter residence. He talked about his discovery. It was written about in the papers. Eventually it was heard of by the physicians, and they ceased to recommend their patients to go to Montpellier, but rather to try Cannes. When Lord Brougham settled there, it was but a fishing village; in thirty years it was transformed; and from Cannes stretches a veritable[3] rosary of winter resorts to Hyères on one side to Alassio on the other; as white grains threaded on the line from Marseilles to Genoa. As this chain of villas, hotels, casinos, and shops has sprung up so recently, the whole looks extremely modern, and devoid of historic interest. That it is not so, I hope to show. This modern fringe is but a fringe on an ancient garment; but a superficial sprinkling over beds of remote antiquity rich in story.

Sometimes it is but a glimpse we get—as at Antibes, where a monument was dug up dedicated to the manes of a little “boy from the North, aged twelve years, who danced and pleased” in the theatre. The name of the poor lad is not given; but what a picture does it present! Possibly, of a British child-slave sent to caper, with sore heart, before the Roman nobles and ladies—and who pined and died. But often we have more than a hint. The altar piece of the Burning Bush at Aix gives up an authentic portrait of easy-going King Réné, the luckless wearer of many crowns, and the possessor of not a single kingdom—Réné, the father of the still more luckless Margaret, wife of our Henry VI.

Among the Montagnes des Maures, on a height are the cisterns and foundations of the stronghold of the Saracens, their last stronghold on this side of the Pyrenees, whence they swept the country, burning and slaying, till dislodged in 972 by William, Count of Provence. Again, the house at Draguignan of Queen Joanna, recalls her tragic story; the wife of four husbands, the murderess of the first, she for whose delectation Boccaccio collected his merry, immoral tales; she, who sold Avignon to the Popes, and so brought about their migration from Rome,[4] the Babylonish captivity of near a hundred years; she—strangled finally whilst at her prayers.

The Estérel, now clothed in forest, reminds us of how Charles V. advancing through Provence to claim it as his own, hampered by peasants in this group of mountains, set the forests on fire, and for weeks converted the district into one great sea of flame around the blood-red rocks.

Marseilles recalls the horrors of the Revolution, and the roar of that song, smelling of blood, to which it gave its name. At Toulon, Napoleon first drew attention to his military abilities; at S. Raphael he landed on his return from Egypt, on his way to Paris, to the 18th Brumaire, to the Consulate, to the Empire; and here also he embarked for Elba after the battle of Leipzig.

But leaving history, let us look at what Nature affords of interest. Geologically that coast is a great picture book of successions of deposits and of convulsions. There are to be found recent conglomerates, chalk, limestone, porphyry, new red sandstone, mica schist, granite. The Estérel porphyry is red as if on fire, seen in the evening sun. The mica schist of the Montagnes des Maures strews about its dust, so shining, so golden, that in 1792 a representative of the Department went up to Paris with a handful, to exhibit to the Convention as a token of the ineptitude of the Administration of Var, that trampled under foot treasures sufficient to defray the cost of a war against all the kings of the earth.

The masses of limestone are cleft with clus, gorges through which the rivers thunder, and foux springs of living water bursting out of the bowels of the mountains.

THE GORGE OF THE LOUP

Consider what the variety of geologic formation implies: an almost infinite variety of plants; moreover, owing to the difference of altitudes, the flora reaches in a chromatic scale from the fringe of the Alpine snows to the burning sands by the seas. In one little commune, it is estimated that there are more varieties to be found than in the whole of Ireland.

But the visitor to the seaboard—the French Côte d’azur and the Italian Riviera—returns home after a winter sojourn there with his mind stored with pictures of palms, lemons, oranges, agaves, aloes, umbrella pines, eucalyptus, mimosa, carob-trees, and olives. This is the vegetation that characterises the Riviera, that distinguishes it from vegetation elsewhere; but, although these trees and shrubs abound, and do form a dominant feature in the scenery, yet every one of them is a foreign importation, and the indigenous plants must be sought in mountain districts, away from towns, and high-roads, and railways.

These strangers from Africa, Asia, Australia and South America have occupied the best land and the warmest corners, just as of old the Greek and Roman colonists shouldered out the native tribes, and forced them to withdraw amidst the mountains.

The traveller approaching the Riviera by the line from Lyons, after passing Valence, enters a valley that narrows, through which rolls the turbid flood of the Rhone. Presently the sides become steeper, higher, more rocky, and draw closer; on the right appears Viviers, dominated by its cathedral and tower, square below, octagonal above, and here the Rhone becomes more rapid as it enters the Robinet de Donzère, between calcareous rocks full of caves and rifts. Then, all at[6] once, the line passes out of the rocky portal, and the traveller enters on another scene altogether, the vast triangular plain limited by the Alps on one side and the Cevennes on the other, and has the Mediterranean as its base. To this point at one time extended a mighty gulf, seventy miles from the present coast-line at the mouth of the Rhone. Against the friable limestone cliffs, the waves lapped and leaped. But at some unknown time a cataclysm occurred. The Alps were shaken, as we shake a tree to bring down its fruit, and the Rhone and the Durance, swollen to an enormous volume, rolled down masses of débris into this gulf and choked it. The Durance formed its own little crau along the north of the chain of the Alpines, and the Rhone the far larger crau of Arles, the pebbles of which all come from the Alps, in which the river takes it rise. But, in fact, the present craus represent but a small portion of the vast mass of rubbish brought down. They are just that part which in historic times was not overlaid with soil.

PALMS, CANNES

When this period was passed, the rivers relaxed their force, and repented of the waste they had made, and proceeded to chew into mud the pebbles they rolled along, and, rambling over the level stretches of rubble, to deposit upon it a fertilising epidermis. Then, in modern times, the engineers came and banked in the Rhone, to restrain its vagaries, so that now it pours its precious mud into the sea, and yearly projects its ugly muzzle further forwards. When we passed the rocky portal, we passed also from the climate of the North into that of the South, but not to that climate without hesitations. For the sun beating on the level land heats the pebble bed, so that the air above it quivers as over a lime-kiln, and, rising, is replaced by a rush of icy winds from the Alps. This downrush is the dreaded Mistral. It was a saying of old:—

“Parlement, Mistral, et Durance

Sont les trois fléaux de Provence.”

The Parliament is gone, but the Mistral still rages, and the Durance still overflows and devastates.

The plain, where cultivated, is lined and cross-lined as with Indian ink. These lines, and cross-lines, are formed of cypress, veritable walls of defence, thrown up against the wind. When the Mistral rages, they bow as whips, and the water of the lagoons is licked up and spat at the walls of the sparsely scattered villages. Here and there rises the olive, like smoke from a lowly cottage. It shrinks from the bite of the frost and the lash of the wind, and attains its proper height and vigour only as we near the sea; and is in the utmost luxuriance between Solliès Pont and Le Luc, growing on the rich new red sandstone, that skirts the Montagnes des Maures.

Presently we come on the lemon, the orange, glowing golden, oleanders in every gully, aloes (“God’s candelabra”), figs, mulberries, pines with outspread heads, like extended umbrellas, as the cypress represents one folded; cork trees, palms with tufted heads; all seen through an atmosphere of marvellous clearness, over-arched by a sky as blue as that of Italy, and with—as horizon—the deeper, the indigo blue, of the sea.

On leaving Arles, the train takes the bit between its teeth and races over the crau, straight as an arrow, between lines of cypresses. It is just possible to catch glimpses to the north, between the cypresses, of a chain[8] of hills of opalescent hue. That chain, Les Alpines, gives its direction to the Durance. This river lent its aid to Brother Rhone to form this rubble plain, the Campus lapideus of the Romans, the modern crau. This was a desert over which the mirage alternated with the Mistral, till Adam de Craponne, in the sixteenth century, brought a canal from the Durance to water the stony land, and since then, little by little, the desert is being reclaimed. This vast stony plain was a puzzle to the ancients, and Æschylus, who flourished B.C. 472, tells us that Heracles, arriving at this plain to fight the Ligurians, and being without weapons, Heaven came to his aid and poured down great stones out of the sky against his foes. This is much like the account in Joshua of the battle against the Kings in the plain of Esdraelon.

At length, at Miramas, we escape from between the espalier cypresses and see that the distant chain has drawn nearer, that it has lost its mother-of-pearl tints, and has assumed a ghastly whiteness. Then we dash among these cretaceous rocks, desolate, forbidding and dead. They will attend us from Marseilles to Toulon.

The cretaceous sea bed, that once occupied so vast an area, has been lifted into downs and mountains, and stretched from Dorset and Wiltshire to Dover. We catch a glimpse of it at Amiens. A nodule that has defied erosion sustains the town and cathedral of Laon. It underlies the Champagne country. It asserts itself sullenly and resolutely in Provence, where it overlies the Jura limestone, and is almost indistinguishable from it at the junction, for it has the same inclination, the same fossils, and the same mineralogical constituents.

In England we are accustomed to the soft skin of thymy turf that covers the chalk on our downs. Of this[9] there is none in Provence. The fierce sun forbids it. Consequently the rock is naked and cadaverously white, but scantily sprinkled over with stunted pines.

The Jura limestone is the great pièce de resistance in Provence: it is sweeter in colour than the chalk, ranging from cream white to buff and salmon; it has not the dead pallor of the chalk. Any one who has gone down the Cañon of the Tarn knows what exquisite gradations and harmonies of tone are to be found in Jura limestone. Here this formation stands up as a wall to the North, a mighty screen, sheltering the Riviera from the boreal winds. It rises precipitously to a plateau that is bald and desolate, but which is rent by ravines of great majesty and beauty, through which rush the waters from the snowy Alps. The chalk and the limestone are fissured, and allow the water flowing over their surface to filter down and issue forth in the valleys, rendering these fertile and green, whereas the plateaux are bare. The plateaux rise to the height of 3,000 or 4,500 feet.

The tract between the mountain wall of limestone and the sea is made up of a molass of rolled fragments of the rock in a paste of mud. This forms hills of considerable height, and this also is sawn through here and there by rills, or washed out by rivers.

Altogether different in character is the mass of the Montagnes des Maures, which is an uplifted body of granite and schist.

Altogether different again is the Estérel, a protruded region of red porphyry.

About these protruded masses may be seen the new red sandstone.

When we have mastered this—and it is simple enough[10] to remember—we know the character of the geology from the mouths of the Rhone to Albenga.

“The colouring of Provence,” says Mr. Hammerton, “is pretty in spring, when the fields are still green and the mulberry trees are in leaf, and the dark cypress and grey olive are only graver notes in the brightness, while the desolation of the stony hills is prevented from becoming oppressive by the freshness of the foreground; but when the hot sun and the dry wind have scorched every remnant of verdure, when any grass that remains is merely ungathered hay, and you have nothing but flying dust and blinding light, then the great truth is borne in upon you that it is Rain which is the true colour magician, though he may veil himself in a vesture of grey cloud.”

In winter and early spring it is that the coast is enjoyable. In winter there is the evergreen of the palms, the olive, the ilex, the cork tree, the carob, the orange and lemon and myrtle. Indeed, in the Montagnes des Maures and in the Estérel, it is always spring.

The resident in winter can hardly understand the structure of the towns, with streets at widest nine feet, and the houses running up to five and six storeys; but this is due to necessity. The object is double: by making the streets so narrow, the sun is excluded, and the sun in Provence is not sought as with us in England; and secondly, these narrow thoroughfares induce a draught down them. In almost every town the contrast between the new and the old is most marked, for the occupants of the new town reside there for the winter only, and therefore court the sun; whereas the inhabitants of the old town dwell in it all the year round, and consequently endeavour to obtain all protection possible from the sun. But this shyness of basking in the sun was not[11] the sole reason why the streets were made so narrow. The old towns and even villages were crowded within walls; a girdle of bulwark surrounded them, they had no space for expansion except upwards.

What Mr. Hammerton says of French towns applies especially to those of Provence:—

“France has an immense advantage over England in the better harmony between her cities and towns, and the country where they are placed. In England it rarely happens that a town adds to the beauty of a landscape; in France it often does so. In England there are many towns that are quite absolutely and hideously destructive of landscape beauty; in France there are very few. The consequence is that in France a lover of landscape does not feel that dislike to human interference which he so easily acquires in England, and which in some of our best writers, who feel most intensely and acutely, has become positive hatred and exasperation.”

It was fear of the Moors and the pirates of the Mediterranean which drove the inhabitants of the sea-coast to build their towns on the rocks, high uplifted, walled about and dominated by towers.

I will now give a hasty sketch of the early history of Provence—so far as goes to explain the nature of its population.

The earliest occupants of the seaboard named in history are the Ligurians. The Gulf of Lyons takes its name from them, in a contracted form. Who these Ligurians were, to what stock they belonged, is not known; but as there are megalithic monuments in the country, covered avenues at Castelet, near Arles, dolmens at Draguignan and Saint Vallier, a menhir at Cabasse, we may perhaps conclude with some probability[12] that they were a branch of that great Ivernian race which has covered all Western Europe with these mysterious remains. At an early period, the Phœnicians established trading depôts at Marseilles, Nice, and elsewhere along the coast. Monaco was dedicated to their god, Melkarth, whose equivalent was the Greek Heracles, the Roman Hercules. The story of Heracles fighting the gigantic Ligurians on the crau, assisted by Zeus pouring down a hail of pebbles from heaven, is merely a fabulous rendering of the historic fact that the Phœnician settlers had to fight the Ligurians, represented as giants, not because they were of monstrous size, but because of their huge stone monuments.

The Phœnicians drew a belt of colonies and trading stations along the Mediterranean, and were masters of the commerce. The tin of Britain, the amber of the Baltic, passed through their hands, and their great emporium was Marseilles. It was they who constructed the Heraclean Road, afterwards restored and regulated by the Romans, that connected all their settlements from the Italian frontier to the Straits of Gibraltar. They have left traces of their sojourn in place names; in their time, Saint Gilles, then Heraclea, was a port at the mouth of the Rhone; now it is thirty miles inland. Herculea Caccabaria, now Saint Tropez, recalls Kaccabe, the earliest name of Carthage. One of the islets outside the harbour of Marseilles bore the name of Phœnice.

This energetic people conveyed the ivory of Africa to Europe, worked the lead mines of the Eastern Pyrenees, and sent the coral and purple of the Mediterranean and the bronze of the Po basin over Northern Europe. The prosperity of Tyre depended on its trade.

“Inventors of alphabetical writing, of calculation, and of astronomy, essential to them in their distant navigations, skilful architects, gold-workers, jewellers, engravers, weavers, dyers, miners, founders, glass-workers, coiners, past-masters of all industries, wonderful sailors, intrepid tradesmen, the Phœnicians, by their incomparable activity, held the old world in their grip; and from the Persian Gulf to the Isles of Britain, either by their caravans or by their ships, were everywhere present as buyers or sellers.”[1]

Archæological discoveries come to substantiate the conclusions arrived at from scanty allusions by the ancients. The Carthaginians had succeeded to the trade of Tyre; but Carthage was a daughter of Tyre. At Marseilles have been found forty-seven little stone chapels or shrines of Melkarth, seated under an arch, either with his hands raised, sustaining the arch, or with them resting on his knees; and these are identical in character with others found at Tyre, Sidon, and Carthage. Nor is this all. An inscription has been unearthed, also at Marseilles, containing a veritable Levitical code for the worship of Baal, regulating the emoluments of his priests.

In the year B.C. 542 a fleet of Phocœans came from Asia Minor, flying from the Medes; and the citizens of Phocœa, abandoning their ancient homes, settled along the coast of the Riviera. Arles, Marseilles, Nice—all the towns became Greek. It was they who introduced into the land of their adoption the vine and the olive. They acquired the trade of the Mediterranean after the fall of Carthage, B.C. 146.

The Greeks of the coast kept on good terms with Rome. They it was who warned Rome of the approach[14] of Hannibal; and when the Ambrons and Teutons poured down a mighty host with purpose to devastate Italy, the Phocœan city of Marseilles furnished Marius with a contingent, and provisioned his camp at the junction of the Durance with the Rhone.

The Romans were desirous of maintaining good relations with the Greek colonies, and when the native Ligurians menaced Nice and Antibes, they sent an army to their aid, and having defeated the barbarians, gave up the conquered territory to the Greeks.

In B.C. 125, Lucius Sextius Calvinus attacked the native tribes in their fastness, defeated them, and founded the town of Aquæ Sextiæ, about the hot springs that rise there—now Aix. The Ligurians were driven to the mountains and not suffered to approach the sea coast, which was handed over entirely to the Greeks of Marseilles.

So highly stood the credit of Marseilles, that when, after the conclusion of the Asiatic War, the Senate of Rome had decreed the destruction of Phocœa, they listened to a deputation from Marseilles, pleading for the mother city, and revoked the sentence. Meanwhile, the Gauls had been pressing south, and the unfortunate Ligurians, limited to the stony plateaux and the slopes of the Alps, were nipped between them and the Greeks and Romans along the coast. They made terms with the Gauls and formed a Celto-Ligurian league. They were defeated, and the Senate of Rome decreed the annexation of all the territory from the Rhone to the Alps, to constitute thereof a province. Thenceforth the cities and slopes of the coast became places of residence for wealthy Romans, who had there villas and gardens. The towns were supplied with amphitheatres and baths.[15] Theatres they possessed before, under the Greeks; but the brutal pleasures of the slaughter of men was an introduction by the Romans. The remains of these structures at Nîmes, Arles, Fréjus, Cimiez, testify to the crowds that must have delighted in these horrible spectacles. That of Nîmes would contain from 17,000 to 23,000 spectators; that of Arles 25,000; that of Fréjus an equal number.

Wherever the Roman empire extended, there may be seen the same huge structures, almost invariable in plan, and all devoted to pleasure and luxury. The forum, the temples, sink into insignificance beside the amphitheatre, the baths, and the circus. Citizens of the empire lived for their ease and amusements, and concerned themselves little about public business. In the old days of the Republic, the interests, the contests, of the people were forensic. The forum was their place of assembly. But with the empire all was changed. Public transaction of business ceased, the despotic Cæsar provided for, directed, governed all, Roman citizens and subject peoples alike. They were left with nothing to occupy them, and they rushed to orgies of blood. Thus these vast erections tell us, more than the words of any historian, how great was the depravity of the Roman character.

But with the fifth century this condition of affairs came to an end. The last time that the circus of Arles was used for races was in 462. The theatre there was wrecked by a deacon called Cyril in 446. At the head of a mob he burst into it, and smashed the loveliest statues of the Greek chisel, and mutilated every article of decoration therein. The stage was garnished with elegant colonnets; all were thrown down and broken, except a few that were carried off to decorate churches.[16] All the marble casing was ripped away, the bas-reliefs were broken up, and the fragments heaped in the pit. There was some excuse for this iconoclasm. The stage had become licentious to the last degree, and there was no drawing the people from the spectacles. “If,” says Salvian, “as often happens, the public games coincide with a festival of the Church, where will the crowd be? In the house of God, or in the amphitheatre?”

During that fifth century the Visigoths and the Burgundians threatened Provence. When these entered Gaul they were the most humanised of the barbarians; they had acquired some aptitude for order, some love of the discipline of civil life. They did not devastate the cities, they suffered them to retain their old laws, their religion, and their customs. With the sixth century the domination of the Visigoths was transferred beyond the Pyrenees, and the Burgundians had ceased to be an independent nation; the Franks remained masters over almost the whole of Gaul.

In 711 the Saracens, or Moors, crossed over at Gibraltar and invaded Spain. They possessed themselves as well of Sicily, Sardinia, and the Balearic Isles. Not content with this, they cast covetous eyes on Gaul. They poured through the defiles of the Pyrenees and spread over the rich plains of Aquitaine and of Narbonne. Into this latter city the Calif Omar II. broke in 720, massacred every male, and reduced the women to slavery. Béziers, Saint Gilles, Arles, were devastated; Nîmes opened to them her gates. The horde mounted the valley of the Rhone and penetrated to the heart of France. Autun was taken and burnt in 725. All Provence to the Alps was theirs. Then in 732 came the most terrible of their invasions. More than 500,000 men, according to the[17] chroniclers, led by Abdel-Raman, crossed the Pyrenees, took the road to Bordeaux, which they destroyed, and ascended the coast till they were met and annihilated by Charles Martel on the field of Poitiers.

From this moment the struggle changed its character. The Christians assumed the offensive. Charles Martel pursued the retreating host, and took from them the port of Maguelonne; and when a crowd of refugees sought shelter in the amphitheatre of Arles, he set fire to it and hurled them back into the flames as they attempted to escape. Their last stronghold was Narbonne, where they held out for seven years, and then in 759 that also fell, and the Moorish power for evil in France was at an end; but all the south, from the Alps to the ocean, was strewn with ruins.

They were not, however, wholly discouraged. Not again, indeed, did they venture across the Pyrenees in a great host; but they harassed the towns on the coast, and intercepted the trade. When the empire of Charlemagne was dismembered, Provence was separated from France and constituted a kingdom, under the administration of one Boso, who was crowned at Arles in 879. This was the point of departure of successive changes, which shall be touched on in the sequel. The German kings and emperors laid claim to Provence as a vassal state, and it was not till 1481 that it was annexed to the Crown of France. Avignon and the Venaissin were not united to France till 1791.

In no part of Europe probably did pagan customs linger on with such persistence as in this favoured land of Provence, among a people of mixed blood—Ligurian, Phœnician, Greek, Roman, Saracen. Each current of uniting blood brought with it some superstition, some[18] vicious propensity, or some strain of fancy. In the very first mention we have of the Greek settlers, allusion is made to the Floral Games. The Battle of Flowers, that draws so many visitors to Nice, Mentone, and Cannes, is a direct descendant from them; but it has acquired a decent character comparatively recently.

At Arles, the Feast of Pentecost was celebrated throughout the Middle Ages by games ending with races of girls, stark naked, and the city magistrates presided over them, and distributed the prizes, which were defrayed out of the town chest. It was not till the sixteenth century, owing to the remonstrances of a Capuchin friar, that the exhibition was discontinued. Precisely the same took place at Beaucaire. At Grasse, every Thursday in Lent saw the performance in the public place of dances and obscene games, and these were not abolished till 1706 by the energy of the bishop, who threatened to excommunicate every person convicted of taking part in the disgusting exhibition of “Les Jouvines.”

A native of Tours visited Provence in the seventeenth century, and was so scandalised at what he saw there, that he wrote, in 1645, a letter of remonstrance to his friend Gassendi. Here is what he says of the manner in which the festival of S. Lazarus was celebrated at Marseilles:—

“The town celebrates this feast by dances that have the appearance of theatrical representations, through the multitude and variety of the figures performed. All the inhabitants assemble, men and women alike, wear grotesque masks, and go through extravagant capers. One would think they were satyrs fooling with nymphs. They hold hands, and race through the town, preceded by flutes and violins. They form an unbroken chain, which winds and wriggles in and out[19] among the streets, and this they call le Grand Branle. But why this should be done in honour of S. Lazarus is a mystery to me, as indeed are a host of other extravagances of which Provence is full, and to which the people are so attached, that if any one refuses to take part in them, they will devastate his crops and his belongings.”

The carnival and micarême have taken the place of this exhibition; and no one who has seen the revelries at these by night can say that this sort of fooling is nearing its end. Now these exhibitions have become a source of profit to the towns, as drawing foreigners to them, and enormous sums are lavished by the municipalities upon them annually. The people of the place enter into them with as much zest as in the centuries that have gone by.

Dancing in churches and churchyards lasted throughout the Middle Ages. The clergy in vain attempted to put it down, and, unable to effect this, preceded these choric performances by a sermon, to deter the people from falling into excesses of extravagance and vice. At Limoges, not indeed in Provence, the congregation was wont to intervene in the celebration of the feast of their apostle, S. Martial, by breaking out into song in the psalms, “Saint Martial pray for us, and we will dance for you!” Whereupon they joined hands and spun round in the church.[2]

This leads to the mention of what is of no small interest in the history of the origin of part-singing. Anyone familiar with vespers, as performed in French churches, is aware that psalms and canticles are sung in one or other fashion: either alternate verses alone are[20] chanted, and the gap is filled in by the organ going through astounding musical frolics; or else one verse is chanted in plain-song, and the next in fauxbourdon—that is to say, the tenor holds on to the plain-song, whilst treble and alto gambol at a higher strain a melody different, but harmonious with the plain-song. In Provence at high mass the Gloria and Credo are divided into paragraphs, and in like manner are sung alternately in plain-song and fauxbourdon. The origin of this part-singing is very curious. The congregation, loving to hear their own voices, and not particularly interested in, or knowing the Latin words, broke out into folk-song at intervals, in the same “mode” as that of the tone sung by the clergy. They chirped out some love ballad or dance tune, whilst the officiants in the choir droned the Latin of the liturgy. Even so late as 1645, the Provençals at Christmas were wont to sing in the Magnificat a vulgar song—

“Que ne vous requinquez-vous, Vielle,

Que ne vous requinquez, donc?”

which may be rendered—

“Why do you trick yourself out, old woman?

O why do you trick yourself so?”

In order to stop this sort of thing the clergy had recourse to “farcing” the canticles, i.e. translating each verse into the vernacular, and interlarding the Latin with the translation, in hopes that the people, if sing they would, would adopt these words; but the farced canticles were not to the popular taste, and they continued to roar out lustily their folk-songs, often indelicate, always unsuitable. This came to such a pass[21] that either the organ was introduced to bellow the people down, or else the system was accepted and regulated; and to this is due the fauxbourdon. But in Italy and in the South of France it passed for a while beyond regulation. The musicians accepted it, and actually composed masses, in which the tenor alone sang the sacred words and the other parts performed folk-songs.

As Mr. Addington Symonds says:—

“The singers were allowed innumerable licences. Whilst the tenor sustained the Gregorian melody, the other voices indulged in extempore descant, regardless of the style of the main composition, violating time, and setting even the fundamental tone at defiance. The composers, to advance another step in the analysis of this strange medley, took particular delight in combining different sets of words, melodies of widely diverse character, antagonistic rhythms, and divergent systems of accentuation, in a single piece. They assigned these several ingredients to several parts, and for the further exhibition of their perverse skill, went even to the length of coupling themes in the major and the minor. The most obvious result of such practice was that it became impossible to understand what was being sung, and that instead of concord and order in the choir, a confused discord and anarchy of dinning sounds prevailed. What made the matter, from an ecclesiastical point of view, still worse, was that these scholastically artificial compositions were frequently based on trivial and vulgar tunes, suggesting the tavern, the dancing-room, or even worse places, to worshippers assembled for the celebration of a Sacrament. Masses bore titles adopted from the popular airs on which they were founded; such, for example, as Adieu, mes amours, À l’ombre d’un buissonnet, Baise moi, Le vilain jaloux. Even the words of love ditties and obscene ballads were being squalled out by the tenor (treble?) while[22] the bass (tenor?) gave utterance to an Agnus Dei or a Benedictus, and the soprano (alto?) was engaged upon the verses of a Latin hymn. Baini, who examined hundreds of the masses and motetts in MS., says that the words imported into them from vulgar sources ‘make one’s flesh creep, and one’s hair stand on end.’ He does not venture to do more than indicate a few of the more decent of these interloping verses. As an augmentation of this indecency, numbers from a mass which started with the grave rhythm of a Gregorian tone were brought to their conclusion on the dance measure of a popular ballata, so that Incarnatus est or Kyrie eleison went jigging off into suggestions of Masetto and Zerlina at a village ball.”[3]

The musicians who composed these masses simply accepted what was customary, and all they did was to endeavour to reduce the hideous discords to harmony. But it was this superposing of folk-songs on Gregorian tones that gave the start to polyphonic singing. The state of confusion into which ecclesiastical music had fallen by this means rendered it necessary that a reformation should be undertaken, and the Council of Trent (Sept. 17, 1562) enjoined on the Ordinaries to “exclude from churches all such music as, whether through the organ or the singing, introduces anything impure or lascivious, in order that the house of God may truly be seen to answer to its name, A House of Prayer.” Indeed, all concerted and part music was like to have been wholly banished from the service of the church, had not Palestrina saved it by the composition of the “Mass of Pope Marcellus.”

A visitor to Provence will look almost in vain for churches in the Gothic style. A good many were built after Lombard models. There remained too many[23] relics of Roman structures for the Provençals to take kindly to the pointed arch. The sun had not to be invited to pour into the naves, but was excluded as much as might be, consequently the richly traceried windows of northern France find no place here. The only purely Gothic church of any size is that of S. Maximin in Var. That having been a conventual church, imported its architects from the north.

One curious and indeed unique feature is found in the Provençal cathedral churches: the choir for the bishop and chapter is at the west end, in the gallery, over the narthex or porch. This was so at Grasse; it remains intact at Vence.

CHAPTER II

LE GAI SABER

The formation of the Provençal tongue—Vernacular ballads and songs: brought into church—Recitative and formal music—Rhythmic music of the people: traces of it in ancient times: S. Ambrose writes hymns to it—People sing folk-songs in church—Hymns composed to folk-airs—The language made literary by the Troubadours—Position of women—The ideal love—Ideal love and marriage could not co-exist—William de Balaun—Geofrey Rudel—Poem of Pierre de Barjac—Boccaccio scouts the Chivalric and Troubadour ideals.

WHAT the language of the Ligurians was we do not know. Among them came the Phœnicians, then the Greeks, next the Romans. The Roman soldiery and slaves and commercials did not talk the stilted Latin of Cicero, but a simple vernacular. Next came the Visigoths and the Saracens. What a jumble of peoples and tongues! And out of these tongues fused together the Langue d’oc was evolved.

It is remarkable how readily some subjugated peoples acquire the language of their conquerors. The Gauls came to speak Latin. The Welsh—the bulk of the population was not British at all; dark-haired and dark-eyed, they were conquered by the Cymri and adopted their tongue. So in Provence, although there is a strong strain of Ligurian blood, the Ligurian tongue is gone[25] past recall. The prevailing language is Romance; that is to say, the vernacular Latin. Verna means a slave; it was the gabble of the lower classes, mainly a bastard Latin, but holding in suspense drift words from Greek and Gaulish and Saracen. In substance it was the vulgar talk of the Latins. Of this we have curious evidence in 813. In his old age Charlemagne concerned himself much with Church matters, and he convoked five Councils in five quarters of his empire to regulate Church matters. These Councils met in Mainz, Rheims, Châlons, Tours, and Arles. It was expressly laid down in all of these, save only in that of Arles, that the clergy should catechise and preach in the vulgar tongue; where there were Franks, in German; where there were Gauls, in the Romance. But no such rule was laid down in the Council of Arles, for the very reason that Latin was still the common language of the people, the simple Latin of the gospels, such as was perfectly understood by the people when addressed in it.

The liturgy was not fixed and uniform. In many secondary points each Church had its own use. Where most liberty and variety existed was in the hymns. The singing of hymns was not formally introduced into the offices of the Church till the tenth century; but every church had its collection of hymns, sung by the people at vigils, in processions, intercalated in the offices. In Normandy it was a matter of complaint that whilst the choir took breath the women broke in with unsuitable songs, nugacis cantalenis. At funerals such coarse ballads were sung that Charlemagne had to issue orders that where the mourners did not know any psalm they were to shout Kyrie eleison, and nothing else. Agobard, Bishop of Lyons, A.D. 814-840, says that when he entered on[26] his functions he found in use in the church an antiphonary compiled by the choir bishop, Amalric, consisting of songs so secular, and many of them so indecent, that, to use the expression of the pious bishop, they could not be read without mantling the brow with shame.

One of these early antiphonaries exists, a MS. of the eleventh century belonging to the church of S. Martial. Among many wholly unobjectionable hymns occurs a ballad of the tale of Judith; another is frankly an invocation to the nightingale, a springtide song; a third is a dialogue between a lover and his lass.

It is in the ecclesiastical hymns, religious lessons, and legends couched in the form of ballads, coming into use in the eighth and ninth centuries, that we have the germs, the rudiments, of a new literature; not only so, but also the introduction of formal music gradually displacing music that is recitative.

Of melodies there are two kinds, the first used as a handmaid to poetry; in it there is nothing formal. A musical phrase may be repeated or may not, as required to give force to the words employed. This was the music of the Greek and Roman theatre. The lyrics of Horace and Tibullus could be sung to no other. This, and this alone, was the music adopted by the Church, and which we have still in the Nicene Creed, Gloria, Sanctus, and Pater Noster. But this never could have been the music of the people—it could not be used by soldiers to march to, nor by the peasants as dance tunes.

Did rhythmic music exist among the ancients side by side with recitative? Almost certainly it did, utterly despised by the cultured.

When Julius Cæsar was celebrating his triumph at Rome after his Gaulish victories, we are informed that the soldiery marched singing out:—

“Gallias Cæsar subegit

Mithridates Cæsarem.

Ecce Cæsar nunc triumphat,

Qui subegit Gallias,

Nicomedes non triumphat,

Qui subegit Cæsarem.”

This must have been sung to a formal melody, to which the soldiers tramped in time.

So also Cæsar, in B.C. 49, like a liberal-minded man, desired to admit the principal men of Cisalpine Gaul into the Senate. This roused Roman prejudice and mockery. Prejudice, because the Gauls were esteemed barbarians; mockery, because of their peculiar costume—their baggy trousers. So the Roman rabble composed and sang verses, “illa vulgo canebantur.” These may be rendered in the same metre:—

“Cæsar led the Gauls in triumph,

Then to Senate-house admits.

First must they pull off their trousers,

Ere the laticlavus fits.”

Now, it may be noted that in both instances the rhythm is not at all that of the scientifically constructed metric lines of Horace, Tibullus, and Catullus, but is neither more nor less than our familiar 8.7. time. The first piece of six lines in 8.7. is precisely that of “Lo! He comes in clouds descending.” The second of four lines is that of the familiar Latin hymn, Tantum ergo,[28] and is indeed that also of our hymn, “Hark! the sound of holy voices.”[4]

Nor is this all. Under Cæsar’s statue were scribbled the lines of a lampoon; that also was in 8.7. Suetonius gives us another snatch of a popular song relative to Cæsar, in the same measure. Surely this goes to establish the fact that the Roman populace had their own folk-music, which was rhythmic, with tonal accent, distinct from the fashionable music of the theatre.

Now, it is quite true that in Latin plays there was singing, and, what is more, songs introduced. For instance, in the Captivi of Plautus, in the third act, Hegio comes on the stage singing—

“Quid est suavius quam

Bene rem gerere bono publico, sicut feci

Ego heri, quum eius hosce homines, ubi quisque

Vident me hodie,” etc.

But I defy any musician to set his song to anything else but recitative; the metre is intricate and varied.

Now of rhythmic melody we have nothing more till the year A.D. 386, when, at Milan, the Empress Justina ordered that a church should be taken from the Catholics and be delivered over to the Arians.

Thereupon S. Ambrose, the bishop, took up his abode within the sacred building, that was also crowded by the faithful, who held it as a garrison for some days. To occupy the people Ambrose hastily scribbled down some hymns—not at all in the old classic metres, but[29] in rhythmic measure—and set them to sing these, no doubt whatever, to familiar folk-airs. Thirteen of the hymns of S. Ambrose remain. His favourite metre is—

“Te lucis ante terminum,”

our English Long Measure. And what is more, the traditional tunes to which he set these hymns have been handed down, so that in these we probably possess the only ascertainable relics of Roman folk-airs of the fourth century, and who can tell of how much earlier?

Now, in ancient days the people were wont to crowd to church on the vigils of festivals and spend the night in or outside the churches in singing and dancing. To drive out the profane and indelicate songs, the clergy composed hymns and set them to the folk-airs then in vogue. These hymns came into use more and more, and at length simply forced their way into the services of the Church—but were not recognised as forming a legitimate part of it till the tenth century.

The ecclesiastical hymns for the people, after having been composed in barbarous Latin, led by a second step to the vernacular Romance. The transition was easy, and was, indeed, inevitable. And in music, recitative fell into disfavour, and formal music, to which poetry is the handmaid, came into popular usage exclusively; recitative lingering on only in the liturgy of the Church. The Provençal language was now on its way to becoming fixed and homogeneous; the many local variations found in the several districts tending to effacement.

Then came the golden age of the Troubadours, who did more than any before to fix the tongue. In the twelfth century the little courts of the Provençal[30] nobles were renowned for gallantry. In fact, the knights and barons and counts of the South plumed themselves on setting the fashion to Christendom. In the South there was none of that rivalry existing elsewhere between the knights in their castles and the citizens in the towns. In every other part of Western Europe the line of demarcation was sharp between the chivalry and the bourgeoisie. Knighthood could only be conferred on one who was noble and who owned land. It was otherwise in the South; the nobility and the commercial class were on the best of terms, and one great factor in this fusion was the Troubadour, who might spring from behind a counter as well as from a knightly castle.

The chivalry of the South, and the Troubadour, evolved the strange and, to our ideas, repulsive theory of love, which was, for a time, universally accepted. What originated it was this:

In the south of France women could possess fiefs and all the authority and power attaching to them. From this political capacity of women it followed that marriages were contracted most ordinarily by nobles with an eye to the increase of their domains. Ambition was the dominant passion, and to that morality, sentiment, inclination, had to give way and pass outside their matrimonial plans. Consequently, in the feudal caste, marriages founded on such considerations were regarded as commercial contracts only, and led to a most curious moral and social phenomenon.

The idea was formed of love as a sentiment, from which every sensual idea was excluded, in which, on the woman’s side, all was condescension and compassion, on the man’s all submission and homage. Every[31] lady must have her devoted knight or minstrel—her lover, in fact, who could not and must not be her husband; and every man who aspired to be courteous must have his mistress.

“There are,” says a Troubadour, “four degrees in Love: the first is hesitancy, the second is suppliancy, the third is acceptance, and the fourth is friendship. He who would love a lady and goes to court her, but does not venture on addressing her, is in the stage of Hesitancy. But if the lady gives him any encouragement, and he ventures to tell her of his pains, then he has advanced to the stage of Suppliant. And if, after speaking to his lady and praying her, she retains him as her knight, by the gift of ribbons, gloves, or girdle, then he enters on the grade of Acceptance. And if, finally, it pleases the lady to accord to her loyal accepted lover so much as a kiss, then she has elevated him to Friendship.”

In the life of a knight the contracting of such an union was a most solemn moment. The ceremony by which it was sealed was formulated on that in which a vassal takes oath of fealty to a sovereign. Kneeling before the lady, with his hands joined between hers, the knight devoted himself and all his powers to her, swore to serve her faithfully to death, and to defend her to the utmost of his power from harm and insult. The lady, on her side, accepted these services, promised in return the tenderest affections of her heart, put a gold ring on his finger as pledge of union, and then raising him gave him a kiss, always the first, and often the only one he was to receive from her. An incident in the Provençal romance of Gerard de Roussillon shows us just what were the ideas prevalent as to marriage and love at this time. Gerard was desperately in love with a lady, but she was moved by[32] ambition to accept in his place Charles Martel, whom the author makes into an Emperor. Accordingly Gerard marries the sister of the Empress on the same day. No sooner is the double ceremonial complete than,—

“Gerard led the queen aside under a tree, and with her came two counts and her sister (Gerard’s just-acquired wife). Gerard spoke and said, ‘What will you say to me now, O wife of an Emperor, as to the exchange I have made of you for a very inferior article?’ ‘Do not say that,’ answered the Queen; ‘say a worthy object, of high value, Sir. But it is true that through you I am become Queen, and that out of love for me you have taken my sister to wife. Be you my witnesses, Counts Gervais and Bertelais, and you also, my sister, and confidante of all my thoughts, and you, above all, Jesus, my Redeemer; know all that I have given my love to duke Gerard along with this ring and this flower. I love him more than father and husband!’ Then they separated; but their love always endured, without there ever being any harm come of it, but only a tender longing and secret thoughts.”

The coolness of Gerard, before his just-received wife, disparaging her, and swearing everlasting love to the new-made Queen, the moment after they have left church, is sufficiently astounding.

So completely was it an accepted theory that love could not exist along with marriage, that it was held that even if those who had been lovers married, union ipso facto dissolved love. A certain knight loved a lady, who, however, had set her affections on another. All she could promise the former was that should she lose her own true love, she would look to him. Soon after this she married the lord of her heart, and at once the discarded lover applied to be taken on as her servitor.[33] The lady refused, saying that she had her lover—her husband; and the controversy was brought before the Court of Love. Eleanor of Poitiers presided, and pronounced against the lady. She condemned her to take on the knight as her lover, because she actually had lost her own lover, by marrying him.

We probably form an erroneous idea as to the immorality of these contracts, because we attach to the idea of love a conception foreign to that accorded it by the chivalry of Provence in the twelfth century. With them it was a mystic exaltation, an idealising of a lady into a being of superior virtue, beauty, spirituality. And because it was a purely ideal relation it could not subsist along with a material relation such as marriage. It was because this connexion was ideal only that the counts and viscounts and barons looked with so much indifference, or even indulgence, on their wives contracting it. There were exceptions, where the lady carried her condescension too far. But the very extravagance of terms employed towards the ladies is the best possible evidence that the Troubadours knew them very little, and by no means intimately. Bertram, to Helena, was “a bright particular star,” but only so because he was much away from Roussillon, and—

“So high above me

In his bright radiance and collateral light

Must I be computed, not in his sphere.”

When she became his wife she discovered that he was a mere cub. Cœlia was no goddess to Strephon. So the privileged “servant,” worshipped, and only could frame his mind to worship, because held at a great distance, too far to note the imperfections in temper, in person, in mind, of the much-belauded lady.

A friend told me that he was staggered out of his posture of worship to his newly acquired wife by seeing her clean her teeth. It had not occurred to him that her lovely pearls could need a toothbrush.

William de Balaun, a good knight and Troubadour, loved and served Guillelmine de Taviac, wife of a seigneur of that name. He debated in his mind which was the highest felicity, winning the favour of a lady, or, after losing it, winning it back again. He resolved to put this question to the proof, so he affected the sulks, and behaved to the lady with rudeness—would not speak, turned his back on her. At first she endeavoured to soothe him, but when that failed withdrew, and would have no more to say to him. De Balaun now changed his mood, and endeavoured to make her understand that he was experimentalising in the Gai Saber, that was all. She remained obdurate till a mutual friend intervened. Then she consented to receive William de Balaun again into her favour, if he would tear out one of his nails and serve it up to her on a salver along with a poem in praise of her beauty. And on these terms he recovered his former place.

Geofrey Rudel had neither seen the Countess of Tripoli nor cast his eyes on her portrait, but chose to fall in love with her at the simple recital of her beauty and virtue. For long he poured forth verses in her honour; but at last, drawn to Syria by desire of seeing her, he embarked, fell mortally ill on the voyage, and arrived at Tripoli to expire; satisfied that he had bought at this price the pleasure of casting his eyes on the princess, and hearing her express sorrow that he was to be snatched away.

In a great many cases, probably in the majority of[35] cases, there was no amorous passion excited. It was simply a case of bread and butter. The swarm of knights and Troubadours that hovered about an exalted lady, was drawn to her, not at all by her charms, but by her table, kitchen, and cellar—in a word, by cupboard love.

In their own little bastides they led a dull life, and were very impecunious. If they could get some lady of rank to accept their services, they obtained free quarters in her castle, ate and drank of her best, and received gratuities for every outrageously flattering sonnet. If she were elderly and plain—that mattered not, it rather favoured the acceptance, for she would then not be nice in selecting her cher ami. All that was asked in return was, that he should fetch her gloves, hold her stirrup, fight against any one who spoke a disparaging word, and turn heels over head to amuse her on a rainy day.

A little poem by Pierre de Barjac is extant. He loved and served a noble lady De Javac. One day she gave him to understand that he was dismissed. He retired, not a little surprised and mortified, but returned a few days later with a poem, of which these are some of the strophes:—

“Lady, I come before you, frankly to say good-bye for ever. Thanks for your favour in giving me your love and a merry life, as long as it suited you. Now, as it no longer suits you, it is quite right that you should pick up another friend who will please you better than myself. I have naught against that. We part on good terms, as though nothing had been between us.

“Perhaps, because I seem sad, you may fancy that I am speaking more seriously than usual; but that you are mistaken[36] in this, I will convince you. I know well enough that you have some one else in your eye. Well, so have I in mine—some one to love after being quit of you. She will maintain me; she is young, you are waxing old. If she be not quite as noble as yourself, she is, at all events, far prettier and better tempered.

“If our mutual oath of engagement is at all irksome to your conscience, let us go before a priest—you discharge me, and I will discharge you. Then each of us can loyally enter on a new love affair. If I have ever done anything to annoy you, forgive me; I, on my part, forgive you with all my heart; and a forgiveness without heart is not worth much.”

During the winter these professional lovers resided at the castles of the counts and viscounts. In the spring they mounted their horses and wandered away, some in quest of a little fighting, some to loiter in distant courts, some to attend to their own farms and little properties. Each as he left doubtless received a purse from the lady he had served and sung, together with a fresh pair of stockings, and with his linen put in order.

“Love,” says Mr. Green, in his History of the English People, “was the one theme of troubadour and trouveur; but it was a love of refinement, of romantic follies, of scholastic discussions, of sensuous enjoyment—a plaything rather than a passion. Nature had to reflect the pleasant indolence of man; the song of the minstrel moved through a perpetual May-time; the grass was ever green; the music of the lark and the nightingale rang out from field and thicket. There was a gay avoidance of all that is serious, moral, or reflective in man’s life. Life was too amusing to be serious, too piquant, too sentimental, too full of interest and gaiety and chat.”

That this professional, sentimental love-making went[37] beyond bounds occasionally is more than probable, for human nature cannot be controlled by such a spider-web system. It will break through. Every one knows the story of William de Cabestaing, who loved and served among others—for he was to one thing constant never—Sermonde, wife of Raymond de Roussillon, whereupon the husband had him murdered, and his heart roasted and dished up at table. When Sermonde was told what she had eaten, she threw herself out of a window. But is the story true? Much the same tale occurs thrice in Boccaccio; once of Sermonde, something of the same in the Cup, and again in the Pot of Basil; moreover, the same tale is told of others.

This artificial theory of love was carried to the Court of Naples, and to that of Frederick II. at Palermo. It brought after it an inevitable reaction, and this found its fullest expression in Boccaccio.

“All the mediæval enthusiasms,” says Mr. Addington Symonds, “are reviewed and criticised from the standpoint of the Florentine bottega and piazza. It is as though the bourgeois, not content with having made nobility a crime, were bent upon extinguishing its spirit. The tale of Agilult vulgarises the chivalrous conception of love ennobling men of low estate, by showing how a groom, whose heart is set upon a queen, avails himself of opportunity. Tancred burlesques the knightly reverence for a stainless scutcheon, by the extravagance of his revenge. The sanctity of the Thebaid, that ascetic dream of purity and self-renunciation for God’s service, is made ridiculous by Ailbech. Sen Ciappelletto brings contempt upon the canonisation of saints. The confessional, the worship of relics, the priesthood, and the monastic orders, are derided with the deadliest persiflage. Christ Himself is scoffed at in a jest which points the most[38] indecent of these tales. Marriage offers a never-failing theme for scorn; and when, by way of contrast, the novelist paints an ideal wife, he runs into such hyperboles that the very patience of Griselda is a satire on its dignity.”[5]

LA RADE, MARSEILLES

CHAPTER III

MARSEILLES

The arrival of the Phocœans—The story of Protis and Gyptis—Siege of Marseilles by Cæsar—Pythias the first to describe Britain—The old city—Encroachment of the sea—S. Victor—Christianity: when introduced—S. Lazarus—Cannebière—The old galley—Siege by the Constable de Bourbon—Plague—The Canal de Marseilles—The plague of 1720—Bishop Belzunce—The Revolution—The Marseillaise—The Reign of Terror at Marseilles—The Clary girls.

AS has been already stated, Massilia, or Marseilles, was originally a Phœnician trading station. Then it was occupied by the Phocœans from Asia Minor. It came about in this fashion.

In the year B.C. 599 a few Phocœean vessels, under the guidance of an adventurer called Eumenes, arrived in the bay of Marseilles. The first care of the new arrivals was to place themselves under the protection of the Ligurians, and they sent an ambassador, a young Greek named Protis, with presents to the native chief, Nann, at Arles. By a happy coincidence Protis arrived on the day upon which Nann had assembled the warriors of his tribe, and had brought forth his daughter, Gyptis, to choose a husband among them. The arrival of the young Greek was a veritable coup de théâtre. He took his place at the banquet. His Greek beauty, his graceful form and polished manners, so different from the ruggedness and uncouthness of the Ligurians, impressed the damsel,[40] and going up to him, she presented him with the goblet of wine, which was the symbol of betrothal. Protis put it to his lips, and the alliance was concluded.

The legend is doubtless mythical, but it shows us, disguised under the form of a tale, what actually took place, that the Ionian settlers did contract marriages with the natives. But the real great migration took place in B.C. 542, fifty-seven years later.

Harpagus, the general of Cyrus, was ravaging Asia Minor, and he invested Phocœa. As the Ionians in the town found that they could hold out no longer, their general, Dionysos, thus addressed them:

“Our affairs are in a critical state, and we have to decide at once whether we are to remain free, or to bow our necks in servitude, and be treated as runaway slaves. Now, if you be willing to undergo some hardships, you will be able to secure your freedom.”

Then he advised that they should lade their vessels with all their movable goods, put on them their wives and children, and leave their native land.

Soon after this Harpagus saw a long line of vessels, their sails swelled with the wind, and the water glancing from their oars, issue from the port and pass away over the blue sea towards the western sun. All the inhabitants had abandoned the town. Dionysos had heard a good report of the Ligurian coast, and thither he steered, and was welcomed by his countrymen who had settled there half a century before.

But the Ligurians did not relish this great migration, and they resolved on massacring the new arrivals, and of taking advantage of the celebration of the Floral Games for carrying out their plan. Accordingly they[41] sent in their weapons through the gates of Marseilles, heaped over with flowers and boughs, and a party of Ligurians presented themselves unarmed, as flocking in to witness the festival. But other Ligurian girls beside Gyptis had fallen in love with and had contracted marriages with the Greeks, and one of these betrayed the plot. Accordingly the Phocœans closed their gates, and drawing the weapons from under the wreaths of flowers, slaughtered the Ligurians with their own arms.

From Marseilles the Greeks spread along the coast and founded numerous other towns, and, penetrating inland, made of Arles a Greek city.

In the civil war that broke out between Cæsar and Pompey, Marseilles, unhappily for her, threw in her lot with the latter. Cæsar, at the head of his legions, appeared before the gates, and found them closed against him. It was essential for Cæsar to obtain possession of the town and port, and he invested it. Beyond the walls was a sacred wood in which mysterious rites were performed, and which was held in the highest veneration by the Massiliots. Cæsar ordered that it should be hewn down; but his soldiers shrank from profaning it. Then snatching up an axe, he exclaimed, “Fear not, I take the crime upon myself!” and smote at an oak. Emboldened by his words and action, the soldiers now felled the trees, and out of them Cæsar fashioned twelve galleys and various machines for the siege.

Obliged to hurry into Spain, he left some of his best troops under his lieutenants C. Trebonius and D. Brutus to continue operations against Marseilles; the former was in command of the land forces, and Brutus was admiral of the improvised fleet. The people of Marseilles were now reinforced by Domitius, one of[42] Pompey’s most trusted generals, and they managed to scrape together a fleet of seventeen galleys.

This fleet received orders to attack that of Brutus, and it shot out of the harbour. Brutus awaited it, drawn up in crescent form. His ships were cumbrous, and not manned by such dextrous navigators as the Greeks. But he had furnished himself with grappling irons, and when the Greek vessels came on, he flung out his harpoons, caught them, and brought the enemy to the side of his vessels, so that the fight became one of hand to hand as on platforms, and the advantage of the nautical skill of the Massiliots was neutralised. They lost nine galleys, and the remnant with difficulty escaped back into port.

The besieged, though defeated, were not disheartened. They sent to friendly cities for aid, they seized on merchant vessels and converted them into men of war, and Pompey, who knew the importance of Marseilles, sent Nasidius with sixteen triremes to the aid of the invested town.

Again their fleet sallied forth. This time they were more wary, and backed when they saw the harpoons shot forth, so that the grappling irons fell innocuously into the sea. Finding all his efforts to come to close quarters with the enemy unavailing, Brutus signalled to his vessels to draw up in hollow square, prows outward.

Nasidius, who was in command of the Massiliot fleet, had he used his judgment, should have waited till a rough sea had opened the joints of the opposed ranks, and broken the formation. Instead of doing this, he endeavoured by ramming the sides to break the square, with the result that he damaged his own vessels, which were the lightest and least well protected at the bows,[43] far more than he did the enemy. Seeing that his plan was unsuccessful, he was the first to turn his galley about and fly. Five of the Massiliot vessels were sunk, four were taken, and those that returned to the port were seriously damaged.

On land the besieged had been more successful; they had repelled all attempts of Trebonius to storm the place. When he mined, they countermined, or let water into his galleries, and drowned those working in them. When he rolled up his huge wooden towers against the walls, the besieged rushed forth and set them on fire.

But now a worse enemy than Cæsar’s army appeared against them—the plague. Reduced to the utmost extremity, the Massiliots saw that their only hope was in the clemency of the conqueror. Nasidius had fled. Now Domitius departed; but not till he saw that surrender was inevitable. Cæsar had arrived in the camp of the besiegers. Marseilles opened her gates, and Cæsar treated the city with great magnanimity. But, ruined by the expenses of the long siege, without a fleet, its commerce gone, depopulated by war and disease, long years were required for the effacement of the traces of so many misfortunes.

Now I must go back through many centuries to speak of a most remarkable man, “the Humboldt of Antiquity,” who was a native of Marseilles, and who was the first to reveal to the world the existence of the Isle of Britain. His name was Pythias, and he lived four centuries before the birth of Christ. The Greeks had vague and doubtful traditions of the existence, far away in the North, of a land where the swans sang, and where lived a people “at the back of the north wind,” in perpetual sunshine, and worshipped[44] the sun, offering to it hecatombs of wild asses, and whence came the most precious of metals—tin, without which no bronze could be fabricated. The way to this mysterious land was known only to the Carthaginians, and was kept as a profound secret from the Phocœan Greeks, who had occupied their colony at Marseilles, and were engrossing their commerce. The Phœnicians of Tyre and Sidon, and of Carthage, had secured a monopoly of the mineral trade. Spain was the Mexico of the antique world. It was fabled that the Tagus rolled over sands of gold, and the Guadiana over a floor of silver. The Phœnician sailors, it was reported, replaced their anchors of iron with masses of silver; and that the Iberians employed gold for mangers, and silver for their vats of beer; that the pebbles of their moors were pure tin, and that the Iberian girls “streamed” the rivers in wicker cradles, washing out tin and gold, lead and silver. But as more was known of Spain, it was ascertained that these legends were true only in a limited degree; tin and silver and lead were there, but not to the amount fabled. Therefore it was concluded that the treasure land was farther to the north. Not by any means, by no bribery, by no persuasion, not by torture, could the secret be wrung from the Phœnicians whence they procured the inestimable treasure of tin. Only it was known that much of it came from the North, and by a trade route through Gaul to the Rhone; but also, and mainly, by means of vessels of the Phœnicians passing through the Straits into the unknown ocean beyond.

Accordingly, the merchants of Marseilles resolved on sending an expedition in quest of this mysterious Hyperborean land, and they engaged the services of Pythias, an eminent mathematician of the city, who had already[45] made himself famous by his measurement of the declination of the ecliptic, and by the calculation of the latitude of Marseilles. At the same time the merchants despatched another expedition to explore the African coast, under the direction of one Euthymes, another scientist of their city. Unhappily, the record of the voyage of this latter is lost; but the diary of Pythias, very carefully kept, has been preserved in part, quoted by early geographers who trusted him, and by Strabo, who poured scorn on his discoveries because they controverted his preconceived theories.

Pythias published his diary in two books, entitled The Circuit of the World and Commentaries concerning the Ocean. From the fragments that remain we can trace his course. Leaving Marseilles, he coasted round Spain to Brittany; from Brittany he struck Kent, and visited other parts of Britain; then from the Thames he travelled to the mouths of the Rhine, passed round Jutland, entered the Baltic, and went to the mouth of the Vistula; thence out of the Baltic and up the coast of Norway to the Arctic Circle; thence he struck west, and reached the Shetlands and the North of Scotland, and coasted round the British Isles till again he reached Armorica; and so to the estuary of the Garonne, whence he journeyed by land to Marseilles.

Pythias remained for some time in Britain, the country to which, as he said, he paid more attention than to any other which he visited in the course of his travels; and he claimed to have investigated all the accessible parts of the Island, and to have traced the eastern side throughout. He arrived in Kent early in the summer, and remained there until harvest time, and he again returned after his voyage to the Arctic Circle. He says[46] that there was plenty of wheat grown in the fields of Britain, but that it was thrashed out in barns, and not on unroofed floors as in the sunny climate of Marseilles. He says that a drink to which the Britons were partial was composed of wheat and honey—in a word, metheglin. It is greatly to be regretted that of this interesting and honestly written diary only scraps remain.[6]