THE HISTORY OF

PARLIAMENTARY TAXATION

IN ENGLAND

Williams College

DAVID A. WELLS PRIZE ESSAYS

Number 2

THE HISTORY OF

PARLIAMENTARY TAXATION

IN ENGLAND

BY

SHEPARD ASHMAN MORGAN, M.A.

PRINTED FOR THE

DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE

OF WILLIAMS COLLEGE

By Moffat, Yard and Company, New York

1911

HENRY LOOMIS NELSON

OLIM

PRECEPTORI

D. D. D.

DISCIPULUS

HAUD IMMEMOR

S. A. M.

PREFACE

This is the second volume in the series of “David A. Wells Prize Essays” established under the provisions of the bequest of the late David A. Wells. The subject for competition is announced in the spring of each year and essays may be submitted by members of the senior class in Williams College and by graduates of not more than three years’ standing. By the terms of the will of the founder the following limitation is imposed: “No subject shall be selected for competitive writing or investigation and no essay shall be considered which in any way advocates or defends the spoliation of property under form or process of law; or the restriction of Commerce in times of peace by Legislation, except for moral or sanitary purposes; or the enactment of usury laws; or the impairment of contracts by the debasement of coin; or the issue and use by Government of irredeemable notes or promises to pay intended to be used as currency and as a substitute for money; or which defends the[viii] endowment of such ‘paper,’ ‘notes’ and ‘promises to pay’ with the legal tender quality.”

The first essay, published in 1905, was “The Contributions of the Landed Man to Civil Liberty,” by Elwin Lawrence Page. The subject of the following essay was announced in 1906 by the late Henry Loomis Nelson, then David A. Wells Professor of Political Science. As first framed it read, “The Origin and Growth of the Power of the English National Council and Parliament to Levy Taxes, from the Time of the Norman Conquest to the Enactment of the Bill of Rights; Together with a Statement of the Constitutional Law of the United States Governing Taxation.” Mr. Nelson subsequently eliminated the last clause, thus restricting the field of the essay to English Constitutional History. The prize was awarded in 1907. Since the death of Mr. Nelson in 1908, the task of editing the successful essay has been given to the undersigned in coöperation with the author.

In publishing this volume occasion is taken to state the purpose of the competition. Since it is confined to students and graduates of a[ix] college which offers no post-graduate instruction, it is not intended to require original historical research but rather to encourage a thoughtful handling of problems in political science.

Theodore Clarke Smith,

J. Leland Miller Professor of

American History

Williams College,

Williamstown, Mass., December, 1910.

INTRODUCTION

In a chapter of Hall’s Chronicle having to do with the mid-reign history of Henry VIII occurs an instance of popular protest against arbitrary taxation. The people are complaining against the Commissions, says the Chronicler, bodies appointed by the Crown to levy taxes without consent of Parliament. “For thei saied,” so goes the passage, “if men should geue their goodes by a Commission, then wer it worse than the taxes of Fraunce, and so England should be bond and not free.” Hall’s naïve statement is scarcely less than a declaration of the axiomatic principle of politics that self-taxation is an essential of self-government.

Writers on the evolution of the taxing power are inclined to go a step farther and believe that the liberty of a nation can be gauged most readily by the power of the people over the public purse. With a view so extended a narrative of the growth of popular control in[xii] England might easily expand into a history of the English Constitution. In the present essay, however, an effort has been made to exclude all matters which were not of the strictest pertinency to the subject in hand. Feudal dues and incidents, the machinery of taxation, the Exchequer, the forces accounting for the shifting composition of the national assemblies, these and other matters have been treated of in outline rather than in detail, because they appeared to lie beyond the scope of this essay.

Only two matters have been taken to be of first rate importance,—the tax and the authority by which it was laid. Taxation has been construed broadly as being any contribution levied by the government for its own support. An endeavor has been made in each instance to find out who or what the taxing authority was, and whether the tax was laid in accordance with it. Under the Normans the taxing authority was unmistakably the king, and by the Bill of Rights it lay as unmistakably in Parliament, with the right of initiation in the House of Commons. The story of the shift from one position to the other[xiii] forms, of course, the major burden of the essay.

At the time when the subject was assigned, the power of the House of Commons over money bills had not been brought into question for more than two centuries, and the first drafts had been written and the prize awarded before the Asquith ministry was confronted with the problem of interference by the House of Lords. At this writing the question has not been settled. It has seemed advisable therefore to leave the essay within the bounds originally set for it, and what connection it has with the events of 1909 and 1910 consists chiefly in its consideration of the basic principles involved in that struggle.

To the late Henry Loomis Nelson, David A. Wells Professor of Political Science in Williams College, I owe the interest I have had in the preparation of this book. It is an outgrowth of his course in English Constitutional history, and some of the interpretations placed upon events are his interpretations. His death intervened before the second draft of the book was made, and the revisory work had to be done without his suggestions. To[xiv] my friend, Dr. Theodore Clarke Smith, Professor in Williams College, I am indebted for a painstaking examination of the manuscript and for much valuable advice in the work preliminary to publication. Acknowledgments in the footnotes to Bishop Stubbs, Mr. Medley, Mr. Taswell-Langmead and many others scarcely manifest my obligations. But the essay throughout is based upon original authorities.

Shepard Ashman Morgan.

New York, December, 1910.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER I | |

| The Saxons: Customary Revenues and Extraordinary Contributions |

1 |

| Evolutionary character of the English Constitution—Early ideas of taxation amongst the Germans and Anglo-Saxons—Revenues of the Anglo-Saxon kings—The Danegeld and the authority for it—The Witenagemot and its powers. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Feudal and Royal Taxation: The Norman and the Angevin Kings, 1066-1215 | 12 |

| William the Conqueror—His National Council and its part in taxation—Domesday Survey—William Rufus—Henry I and his Charter—Question of assent to taxation in the shire moots and the National Council—Stephen—Henry II—His controversy with Becket over the Sheriff’s Aid—Scutage—Theobald’s complaint—Early step toward a tax on movables—The Saladin Tithe and its assessment by juries of inquest—Richard I—His ransom—The king the authority for taxes—Refusal of Hugh of Lincoln—John—His scutages a cause leading to Magna Carta—Inquest of Service—John’s demand for a thirteenth of movables—Council at St. Alban’s, 1213—Summons to Oxford—Magna Carta—Chapters 12 and 14—Advance toward Parliamentary taxation. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Custom of Parliamentary Grants, 1215-1272 | 71 |

| Henry III—Reissues of the Charter—Assessment of a carucage by the Council—Conditional Grants—Rejected offer of [xvi]a disbursing commission—Supervision of expenditures—Representation as it was in Henry’s National Council—Knights of the shire called, 1254—Provisions of Oxford—Knights of the shire summoned by Henry and Simon de Montfort to national assemblies—In Parliament, 1264—Simon de Montfort’s Great Parliament, 1265—First instance of burgher representation—House of Commons foreshadowed. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Law of Parliamentary Taxation, 1272-1297 | 107 |

| Edward I—His first Parliament and its grant of a custom on wool—His second Parliament—Attendance of knights of the shire declared “expedient”—Provincial assemblies at Northampton and York grant taxes—Seizure of wool, 1294—Separate meeting of knights of the shire—The Model Parliament, 1295—“What affects all by all should be approved”—Parliament of 1296—Struggle with the barons over service in Gascony—Contumacy of Bohun and Bigod—Principle that grants must wait upon redress of grievances—Confirmatio Cartarum—De tallagio non concedendo. | |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Taxation by the Commons, 1297-1461 | 154 |

| Character of the period—Parliament of Lincoln—Tunnage and poundage and other customs—Tallage—Edward II—Tentative abolition of the New Customs—The Lords Ordainers—Abolition of the New Customs—Tallage of 1312—Deposition of Edward II—Edward III—Tallage of 1332 and its withdrawal—New Customs a regular means of revenue—The wool customs—Statutory abolition of the Maletolt and of all unauthorized taxation—Parliament the sole taxing authority in law—Checkered history of the wool customs—Appropriation of Supplies—Examination of Accounts—Death of Edward III—Separate sessions of the houses—Richard II—Trouble over audit of accounts—Special treasurers—The Rising of the Villeins—Richard’s despotism and dethronement—Henry IV—Initiation of tax levies in the House of Commons, 1407—Henry V—Henry VI—Declaration for appropriation of supplies—Accession of the Yorkists. | |

| CHAPTER VI[xvii] | |

| Extra-Parliamentary Exaction, 1461-1603 | 213 |

| Edward IV—Benevolences and forced loans—Richard III—Prohibition of benevolences—The Tudors—Henry VII—The “New-found Subsidy”—Morton’s Crotch—Early taxation of Henry VIII—Cardinal Wolsey’s breach of privilege—Henry’s commissions and benevolences—Forced loans—Profits of the Reformation—Parliament the confirming authority in clerical grants—Elizabeth—Liberality of her Parliaments—Assertion by the commons of their right to originate money bills. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| The Stuarts, 1603-1689 | 236 |

| Divine right as against Parliamentary supremacy—James I dictates the composition of the House of Commons—Tunnage and poundage for life—Royal poverty—The Bate Case—Opinions of the Barons in the Bate Case—The position of Parliament—The Book of Rates—Remonstrance from the Commons—Cowel’s “Interpreter”—The Great Contract—Petty extortion after the dissolution of Parliament—The “Addled” Parliament—Case of Oliver St. John—James’s Third Parliament—Delay of a supply pending redress of grievances—Revival of impeachment by the Commons—James’s last Parliament—Charles I—His early Parliaments—Forced loans—Threats of non-Parliamentary exaction—The Petition of Right—Omission of the customs—Tunnage and poundage—Charles’s eleven years without Parliament—His financial expedients—Ship Money—Extra-judicial opinions—Hampden’s Case—Judgment for the Crown—The Short Parliament—The Long Parliament—Royal exaction of tunnage and poundage declared illegal—The Ship Money Act—The Grand Remonstrance—The Puritan Revolution—Charles II—Appropriation of Supplies—James II—William and Mary—The Bill of Rights. | |

| Index | 309 |

PARLIAMENTARY TAXATION

I

THE SAXONS: CUSTOMARY REVENUES AND EXTRAORDINARY CONTRIBUTIONS

The English Constitution looks ever backward. Precedent lies behind precedent, law behind law, until fact shades off into legend and that into a common beginning, the Germanic character. Standing upon the eminence of 1689, one sees the Petition of Right, and then in deepening perspective, Confirmatio Cartarum and Magna Carta. The crisis of 1215 points to the Charter of Henry I, and behind that are the good laws of Edward the Confessor. The Anglo-Saxon polity looks back of the era of Alfred, to the times when Hengist and Horsa were yet unborn, and the German tribesmen were still living in their forests beyond the Rhine without thinking of migrating westward. And there, behind the habits of those barbaric ancestors of[2] Englishmen, lies the national character, the Anglo-Saxon sense of right and wrong, of loyalty, justice, and duty. The growth of the English Constitution has been as subject to the laws of evolution as the development of man himself. The germ of national character evolved habits of thought and action, and these habits, or as they are better termed, institutions, were beaten upon by conditions and fused with the institutions of another people, until at last they took on the shape of free government.

An account of the advance toward the laying of taxes by representatives of the people must begin with some notice of the idea of taxation which actuated the German tribesmen. Tacitus writing of them as they were at the beginning of the Second Century A. D. makes this remark:Amongst the Germans “It is customary amongst the states to bestow on the chiefs by voluntary and individual contribution a present of cattle or of fruits, which, while accepted as a compliment, supplies their wants.”[1] Here, [3]then, is the earliest idea of a tax, a voluntary contribution for the support of the princeps. It was prompted by the essentially personal relationship existent between people and chieftain, the sense of attachment of the people to the leader. Direct taxation laid by the princeps upon the tribe, was as unknown in Germany as it was foreign to the Germanic spirit.

When the conquering Saxons, therefore, swept westward across the German Ocean, they carried with them scarcely more than a semblance of taxation. Between men and leader the personal relationship still subsisted, but as time went on, the Anglo-Saxon king became less the father of the people, and more their lord.Amongst the Anglo-Saxons Lord of the national land he was as well, but he did not rule by reason of that fact. The two claims upon popular support were therefore distinct, the one as personal leader, the other as lord of the national land; and during the major part of the Anglo-Saxon era they afforded a sufficient means for the maintenance of the king and his government. Until the moment of a supreme emergency the king did not have to seek extraordinary sources of income.

As lord of the national land, the king had a double source of revenue. The folkland, or land subject to national regulation[2] and Revenue of the Anglo-Saxon kings alienable only by the consent of the Witenagemot, presented the king with its proceeds, much of which went for the maintenance of the royal armed retainers and servants. Deducible from this right to the public lands, was the claim of the king to tolls, duties, and customs accruing from the harbors, landing-places, and military roads of the realm, and to treasure-trove. Aside from this, the king was one of the largest private landowners in the kingdom, and from it he derived rents and profits which were disposable at will.

The other sources of the royal revenue, which at least in the beginning may be said to have accrued to the king by reason of personal obligation, were the military, the judicial, and the police powers. By reason of the military power vested in him, the king could demand the services of all freemen to fulfill the trinoda necessitas,—service in the militia, repair of bridges, and the maintenance of fortifications. Further, in accordance [5]with the system of vassalage incident to his military power, he had the right of heriot,[3] according to which the armor of a deceased vassal became the property of the king. The judicial authority, also, was a fruitful source of income; from it the king adduced a right to property forfeited in consequence of treason, theft, or similar crimes, and to the fines which were payable upon every breach of the law. The third great power vested in the royal person was the police control; under it the king turned to account the privilege of market by reserving to himself certain payments; also the protection offered to Jews and merchants was paid for, and the king pocketed the bulk of the tribute. Beyond these,—and here we have the analogy of the later royal claim to purveyance,—the districts through which [6]the king passed or those traversed by messengers upon the king’s business, lay under obligation to supply sustenance throughout the extent of the royal sojourn.

It is apparent that an extraordinary occasion had to arise before this large ordinary revenue should prove to be inadequate to meet all reasonable royal necessities. The whole matter is shrouded in obscurity, yet it is unlikely that this extraordinary occasion arrived before the onslaught of the Danes. There is no record of an earlier instance.

It was in 991[4] that the Saxon army under Brihtnoth, Ealdorman of the East Saxons, suffered decisive defeat at the hands of Danish pirates. King Ethelred the Unready found himself at the mercy of foreign enemies, and his only recourse was bribery. Under this necessity, a levy[5] of £10,000 was made, [7]and secured momentary peace from the truculent Danes. But it was only momentary; they returned in 994 and took away £16,000. They repeated, under various pretexts, their profitable incursions in 1002, 1007, and 1011.[6] In 1012, having been bought off for the last time, the Danes entered English pay, and the Danegeld instead of being an extraordinary charge, became a regularly recurrent tax. It continued until 1051, when Edward the Confessor succeeded in paying off the last of the Danish ships.[7] The chronicler[8] accounts for the abolition of the Danegeld after the manner of his time. Edward the Confessor, so goes the story, entered his treasure-house one day to find the Devil sitting amongst the money bags. It so happened that the wealth which was being thus guarded was that which had accrued from a recent levy of the Danegeld. To the pious Confessor the sight was sufficient to demonstrate the evil of the tax and he straightway abolished it.

But the history of the origin of the Danegeld and the mythical tale of its abolition are of trifling importance as compared with the authority whereby the impost was laid. In 991 it was apparently the Witenagemot, acting upon the advice of the Archbishop Sigeric, which issued the decree levying the tax.[9] Three years later it was “King Ethelred by the advice of his chief men” who promised the Danes tribute.[10] Similarly in 1002, 1007, and 1011 it is Ethelred “cum consilio primatum” who fixes the amount of money to be raised.[11]

The deduction is not hard to make: it was at least usual if indeed it was not felt to be a necessity for the king to take counsel with the Witenagemot before he went about the preliminaries of taxation. It is not unlikely, however, [9]that in practice the assent of the Witan was less or more of a formality varying according to the weakness or strength of the king. A strong king’s will would dominate the Witan, whereas a weak king would be subservient to its desires and interest.

In order to arrive at a clear comprehension of the taxing power of the Witan as compared with that subsequently exercised by the English Parliament, The Witenagemot and its powers it is essential that one understands the make-up of the Anglo-Saxon body. As its name implies, the Witan was an assembly of the wise. Its organization was not based upon the ownership of land, nor was there any rule held to undeviatingly which prescribed qualifications for membership. Generally speaking it was composed of the king and his family, who were known as the Athelings; the national officers, both ecclesiastical and civil, a group which included the bishops and abbots, the ealdormen or chief men of the shires, and the ministri or administrative officers; and finally, the royal nominees, men who are not comprehensible in the above classes, but who recommended themselves to the king by reason of unusual or expert[10] knowlege.[12] It is observable, then, that this assembly was by the nature of its composition aristocratic. That it was not representative in the modern sense of the term is as readily apparent. With certain restrictions the official members—the bishops, ealdormen, the ministri—were coöpted by the existing members, while the remainder were either present by right of birth or invited to attend by reason of peculiar attainment. Nevertheless, the Witenagemot was commonly believed to be capable of expressing the national will. It had the power of electing the king and the complementary power of deposition, and exercised every power of government, making laws, administering them, adjudging cases arising under them, and levying taxes for the public need.[13]

Such in brief was the body which in 991 assented to the levy of the Danegeld. The act was of great importance; by it the Witan both exercised a right which was not to be vindicated in its completeness for the space of seven hundred years, but it laid a trap for [11]those who, in the time of Charles the First, should be struggling for the attainment of that right, for in their action lay the precedent which the Stuart lawyers should warp into a pretext for the levy of ship-money.

II

FEUDAL AND ROYAL TAXATION

THE NORMAN AND THE ANGEVIN KINGS

1066-1215

Under the Saxon kings the structure of government was only half built. The foundation, laid in the shire and hundred moots, the townships, and the incidental organisms of local government, was solid and capable of upholding a heavy superstructure. But the Saxons scarcely built further. They left to the Norman kings, peculiarly fitted to their work by temperament and habit, the task of setting up a strong central government. The price which the nation paid for it was the loss of what right it had possessed of assenting to taxation.

During the whole period from the coming of the Normans in 1066 to the signing of Magna Carta in 1215 there can be brought forward only two or three instances of assent by the National Council to taxes levied by the[13] king, and these few instances are at best equivocal. They are insufficient to justify the belief that the National Council had any final power over the levying of taxation. But the period is not altogether gray; it concludes with the enunciation in Magna Carta of rights which cast a halo of color over the whole subsequent narrative of the struggle for parliamentary taxation.

William the Conqueror was precisely the man most likely to exercise supreme control over taxation. Elected to the kingship according to the Saxon forms and with his title to the crown backed up by force of arms, he created a system of government of which he himself was the center and in which his authority, even to the vassals of vassals, was supreme.[14] With his thirst for power thus satisfied he was given a free hand to indulge his besetting sin of avarice. Small wonder was it therefore that he clung to the revenues of his predecessors and added new imposts of his own.

Nevertheless, notwithstanding the absolutist character of the king, William retained the theory and for the most part the form of the Saxon Witan. Never, however, did the Norman assemblies exercise independent legislative or executive functions.[15] The holding of land,His National Council as a prerequisite to membership in the National Council, was under William an uncertain factor; the membership continued to include, generally speaking, the same officers, ecclesiastics, and nobles as composed the Witenagemot. The powers of this assembly were probably not great; at any rate, the magnates of the period considered attendance not as a right or a privilege or even as an advantage, but merely as a necessary duty toward the royal person. The king consulted the magnates on almost every piece of legislation, and stated in the subsequent promulgation of the laws that he had obtained their advice. But in the case of a strong king, such as was the Conqueror, the consultation must have been scarcely more than a statement of the royal will and a formal acquiescence. The holding of these assemblies [15]took place at the crowning days of the king, at Christmas, Easter, and Whitsuntide, generally in London, Winchester, and Gloucester.

In the matter of taxation, it is probable as in the case of other legislation that the Conqueror advised with his Council, though the evidence pointing toward such a conclusion is entirely of a later date. But in so far as practical advantage to the payers of the taxes was concerned, the power might quite as well have lain solely in the hands of the king; if indeed the Conqueror did secure the assent of the Council, it was no more than an instance of his policy of adhering to the forms of law while making the practices under it serve his own purposes. The reimposition in 1084 of the Danegeld which William revived as an occasional instead of a regular tax, is not stated by the chronicler as receiving assent from the Council; the king is said to have “received six shillings from every hide.”[16] Roger of Wendover’s Chronicle of the same [16]year brands this exaction as an “extortion,”[17] by which we are scarcely to understand a tax granted in any modern sense by the chief legislative body of the kingdom.Instance of the Danegeld, 1084 The Saxon Chronicler speaking of the same imposition says, “The king caused a great and heavy tax to be raised throughout England, even seventy-two pence on every hide of land.”[18] The amount of such an impost, if drawn from two-thirds of the hidage of the kingdom, would be a sum approximating £20,000.[19] It is unlikely that an exaction of so great magnitude could have been levied without the assent of the Council if the Conqueror was under any obligation to obtain their consent or even their advice; and it is still more unlikely that four chroniclers of the events of that year should have let pass unnoted a vote of assent if it had been passed by the National Council. We are therefore to conclude that either the Conqueror levied the tax without consulting his Council at all, or that he did consult them, [17]and that their assent was of so formal and valueless a nature as not to deserve notice in the records of the year.[20]

The year 1086 witnessed the Domesday Survey. By it William obtained a detailed register of the land and its capacity for taxation. To the administrative side of taxation the Survey is of supreme importance, since the valuation of land thus arrived at was never entirely superseded as a definite and fair basis for the laying of taxes; to the actual granting of the tax, however, its importance is of much less degree. In such light the interest centers chiefly on the fact that representatives were elected from every hundred upon whose sworn depositions the information that William wanted was obtained.

The unlucky thirteen years of the reign of William Rufus, who succeeded to the throne upon the death of the Conqueror in 1087, are almost negligible in considering the progress toward parliamentary taxation. William [18] Rufus, or more particularly his brilliant and perverted justiciar, Ranulf Flambard, determined upon the profitable program of getting together as much money as possible by whatever means seemed most convenient. In the nature of things the church and the great feudatories were the most available sources for extortion and toward them Flambard chiefly directed his energies. He did not, however, overlook the Danegeld and he seems to have levied it with perfect absolutism. The chronicler Florence gives an instance of the petty extortion which the justiciar practiced upon the people. Flambard was in the habit of enforcing military service from the shires. On one occasion, so says Florence, he met the array, informed the militiamen that there was no necessity for their appearance, and then proceeded to mulct them of the ten shillings which their shires had given to each by way of providing for their maintenance.[21] Against plunderings of that sort the people were too weak and too disunited to make resistance. In such a reign, with one side unwilling to progress and the other unable, it is apparent [19]that no steps could be taken toward the granting of taxes by a responsible body.

The reign of Henry I is of greater importance, not only because of the long forward strides which the king and his justiciar Roger of Salisbury took in the direction of judicial and financial organization, but because we find in the records of his time certain pieces of evidence which seem to support the contention that the Council gave some measure of consent to taxation. The former is palpably beyond the scope of this essay, but the latter is more pertinent.

The first of these instances is the eleventh section of the Charter of Liberties which Henry I issued at the moment of his accession. The significant passage is this: “To those knights who hold their lands by the cuirass, of my own gift I grant the lands of their demesne ploughs free from all payments and all labor.”[22] The king goes on to state [20]the reason; it was “so they may readily provide themselves with horses and arms for my service and for the defense of my kingdom.” The relief thus granted was by way of protection against the extortionate demands which Ranulf Flambard had laid upon the lands of vassals in the time of William Rufus. But Henry did not grant the liberty freely out of hand. He appended the clause that for his service and the defense of the kingdom, the vassals should supply themselves with horses and arms. Thus remotely and in effect rather than in fact did the Charter touch upon taxation. It contained no reference to assent by the vassals, either individually or in the National Council. In accordance with the feudal theory of individual contribution for the support of the lord, and in view of the provision in the Charter against payments, the inference can be drawn that individual assent would be in order. But to find an answer to the question as to where the collective assent of the barons was obtained, if at all, one must look further.

In a letter addressed to “Samson the Bishop and Urso d’Abitat,” who were respectively the bishop of the diocese and the sheriff of the county of Worcester, Henry says, in speaking of the county courts, “I will cause those courts to be summoned when I will for my own proper necessities at my pleasure.”[23] That these county courts were utilized by the Norman kings for purposes of extortion, is attested by the reluctance of the suitors to attend their sessions,[24] and in the light of that fact, the “proper necessities” of the king are apparently none other than the royal need for money. But why, if the assent of the taxed was not required, should the courts be summoned to meet the “proper necessities” of the crown? In the Shire Moots Would that purpose be subserved merely by making a demand for money? Had that been the fact, the courts might well have been left to carry on their peculiar functions untroubled, for extortion can be the more readily practiced king to man than [22]king to people. The conclusion is reasonable, notwithstanding the very large part which conjecture plays in it, that some form of assent was usual in the county courts in response to the royal demands.

But there is another piece of evidence which points to the National Council itself giving assent to taxation. In the Chronicle of the Monastery of Abingdon occurs a quotation of an order from Henry to his officers exempting the lands of a certain abbot from the payment of an “aid which my barons have given me.”[25] Whether or not this statement can be taken as substantiating the theory of assent depends upon a point of time; was the gift of the barons before or after the laying of the tax?In the National Council If the gift was indeed prior to the levy, then the evidence is conclusive that the barons assented to taxation; if, on the other hand, the barons gave the aid after the levy [23]had been made, the statement refers solely to the actual payment of the tax. The tense of the Latin verb, however, and the circumstances in which the king writes, seem to point to the former alternative; Henry directs that the Exchequer exempt the abbot’s lands from the collection of an aid, not which the barons were giving him, but which they have given him. It is possible to infer, then, that sometimes, at least, the barons formally assented to the levying of an extraordinary aid.

But this assent must not be taken as proof that the barons discussed taxation in formal session or that they had any generally recognized power of choice. None of the records of the time, though they speak emphatically of the oppressiveness of the taxes,[26] suggest [24]that at any time the barons refused to give the king what he asked for. The probability is that Henry I sought baronial assent merely as a matter of form, and that he did it out of respect, more or less conscious, for the theory that contributions of a feudatory toward the support of the crown should be of a nature voluntary. The perfunctory character of the assent, together with the absence of evidence looking to a refusal, points to nothing so much as the firmness of the royal grip upon the purses of the nation.

During the major part of King Stephen’s nineteen turbulent years, feudalism and anarchy ran hand in hand. Such progress as had been making toward parliamentary taxation ceased. Stephen showed himself an adept at misgovernment and succeeded in nothing so well as in his own discomfiture.

Things went by contraries. Stephen allowed the nobles to make themselves impregnable[25] in the royal castles and then sought to dislodge them by raising up a new and hostile baronage. The nobles, needing money to carry on war amongst themselves and against the king, extorted it from the people. “Those whom they suspected to have any goods they took by night and by day, seizing both men and women,” says the Saxon Chronicle,[27] “and they put them in prison for their gold and silver, and tortured them with pains unspeakable, for never were martyrs tormented as these were.” And then, “They were continually levying an exaction from the towns, which they called Tenserie (a payment to the superior lord for protection), and when the miserable inhabitants had no more to give, then plundered they and burnt all the towns, so that well mightest thou walk a whole day’s journey nor ever shouldest thou find a man seated in a town, or its lands tilled.”

Henry of Huntingdon adds a detail which fills out the picture of wretchedness. Speaking of Stephen’s promise to abolish the Danegeld in 1135, shortly after his accession, the chronicler says, “The king promised that the Danegeld, [26]that is two shillings for a hide of land, which his predecessors had received yearly, should be given up forever. These ... he promised in the presence of God; but he kept none of them.”[28]

By the treaty of Wallingford in 1153, Stephen agreed that the crown should descend at his death to Henry of Anjou,[29] Henry II, 1154-1189 the son of the Empress Matilda, and great-grandson of the Conqueror. The treaty provided, also, for comprehensive reforms which Stephen, a melancholy figure in contrast with the vigorous Henry, tried to work out. Stephen died at the end of a year’s attempt to put in operation the new programme and Henry came to the throne. Henry’s reign was marked by a regular and peaceful administration of the government which had its rise in the genius of the king for organization. It witnessed too the struggle with Thomas à Becket, a [27]conflict which has been pointed to as “the first instance of any opposition to the king’s will in the matter of taxation which is recorded in our national history.”[30]

The story of it is full of dramatic interest. At the Council of Woodstock in 1163, “the question was moved,” Controversy with Becket over the Sheriff’s Aid so goes the Latin narrative, “concerning a certain custom.” This custom, which amounted to two shillings from each hide, had previously fallen to the sheriffs, but this “the king,” so continues the Latin account, “wished to enroll in the treasury and add to his own revenues.”[31]

In response to this, Becket is recorded as saying, “Not as revenue, my lord king, saving your pleasure, will we give it: but if the sheriffs and servants and ministers of the shires will serve us worthily and defend our dependents, we will not fail in giving them their aid.”[32]

This was from the chancellor turned archbishop. In his former estate Becket had not shrunk from pressing money composition for military service from prelates holding land of the crown on the ground that they were tenants-in-chief and therefore owed service of arms to the king. But now he had changed his masters and stood champion of the church.

To him Henry returned, “By the eyes of God, it shall be given as revenue, and it shall be entered in the king’s accounts; and you have no right to contradict; no man wishes to oppress your men against your will.”

“My lord king,” Becket declared, “by the reverence of the eyes by which you have sworn, it shall not be given from my land and from the rights of the church not a penny.”

Apparently for the moment the archbishop won his point, but from that time on, Becket and the king stood apart. The continuation of the struggle between them at Westminster the following October; the Constitutions of Clarendon, sweeping away much of the exclusive authority which previously had characterized[29] ecclesiastical jurisdiction; the flight of Becket into France; the coronation of the young Henry by the Archbishop of York to the prejudice of Becket, and the latter’s declaration of illegality; these and the martyrdom of the archbishop, are parts of another story.

Exactly what were the motives of Becket in making his stand against the king at the Council of Woodstock, are somewhat difficult of determination. The interest of the king was obvious; he wished to increase his revenue by annexing the “auxilium vicecomitis” or “Sheriff’s aid,” which had not gone into the royal treasury at all but had served to swell the private income of the sheriffs. Whether Becket, “standing on the sure ground of existing custom,”[33] objects to change merely because it was a change; or whether he had in mind some lofty democratic principle, and took his stand against the royal power in favor of the lesser folk through some flush of democratic fervor, is not only impossible of being decided, but the decision would not be of strict relevance to the subject. The two [30]points to observe, and they are perfectly evident, are that Becket’s stand against the king did not concern a new levy of taxes, but an imposition already customary; and that the king asserted Becket’s incompetency to interfere. Becket had presumed to take a hand in a matter connected with taxation; the king had denied him that right, though the archbishop was the chief member of his National Council. Therein lay a great issue.

A number of other incidents of the reign of Henry II, though they lack the color of a controversy between archbishop and monarch, are nevertheless worthy of consideration. Scutage The imposition in 1159 of the Great Scutage, despite the fact that it came as a feudal charge rather than as a form of regular taxation, assumes great importance in view of the part that scutage played in the evolution of the taxing power.

Scutage is generally considered as one of the forms of “commutation for personal service,” and commutation was undoubtedly the underlying idea of the imposition.[34] The payment was made for every knight owing [31]military service. Each knight holding of the king was expected to serve in the field for forty days. Eight pence a day in the reign of Henry II was the usual wages of a knight, and for forty days the wages would amount to two marks, which was the sum most commonly paid in lieu of personal service. It was in its earlier phase distinctly a feudal charge.

Payment of scutage, like most of the other forms of feudal and general taxation, struck its roots far into the past. Bishop Stubbs fixes 1156 as the year in which the term scutage was first employed.[35] Others find counterparts in various payments to the sovereign in the time before and shortly after the Conquest. In the reign of Henry I the practice of allowing ecclesiastics to compound at a fixed rate for the knight-service due from their estates was generally followed. The privilege was sometimes extended to mesne tenants.[36] One writer[37] points to Ranulf Flambard’s [32]device in 1093, when he took from the men of the fyrd the money which had been given them for the purchase of supplies while on the march. Others[38] suggest the Anglo-Saxon fyrdwite, the payment made by the king’s men when they were absent from the royal train in war time as the analogy and precedent for scutage. It seems more likely that the king and his vassals adopted a money payment in lieu of service because it was convenient for both of them.[39] The king thereby got the means for the enlistment of a body of mercenaries, subject to his absolute will, and the barons were relieved, if so they pleased, of the burden of military service.

The levy commonly spoken of as the Great Scutage was made in 1159. Henry II was considering an expedition into France against the Count of Toulouse. He had a claim to the latter’s lands through the inheritance of his wife, the Duchess of Aquitaine. The English baronage, by the terms of their feudal tenure, were bound to follow their lord into the field. Nevertheless a distaste had arisen [33]of late among them for service abroad, and it was natural enough, therefore, that they should fall in with the scheme of Henry and his adviser, Thomas à Becket, for a commutation in money. Henry levied a charge of two marks (£1, 6s. 8d.) on the knight’s fee of £20, annual value, from such of his vassals as chose not to follow him into France.[40]

The authority by which this payment was demanded was apparently solely that of the king. It is probable that the levy was unquestioned. In view of the facts that this was merely a change, and possibly no very great change, in the method of meeting a regular feudal obligation, and that many of the barons were willing to avail themselves of a means of escaping the burden of foreign service, the want of a recorded protest is not to be wondered at. The chronicler puts it plainly and probably with accuracy when he says that Henry “received” a scutage.[41] It [34]was profitable for the king. The chronicler puts the proceeds at “one hundred and twenty-four pounds of silver.”

Three years previously, however, an ecclesiastical complaint was raised against a similar imposition. In 1156 such prelates as held their lands by military tenure were directed to compound for soldierly service which their character of churchmen precluded them from rendering.[42] Some thirty-five bishops and abbots paid the assessment, but Archbishop Theobald raised vigorous protest.[43] He objected, apparently, not out of principle, but because he could not see that the exaction was necessary.[44] This probability, together with the further considerations that the demand was not a demand for a new tax but merely that the prelates compound for an obligation long recognized as lawful, and that there were precedents for precisely this sort of commutation, [35]makes Theobald’s protest not of great importance. He did not question, strictly speaking, the right of the king to levy taxes at all.

The remainder of the reign of Henry II, aside from the fact that it witnessed the temporary passing of the Danegeld,[45] derives its chief importance by reason of the extension of taxation to cover personal property. By the Assize of Arms in 1181, “every free layman who had in chattels or in revenue to the value of sixteen marks” was to “have a coat of mail and a helmet and a shield and a lance;” and “every free layman who had in chattels or revenue ten marks should have a hauberk and a head-piece of iron and a lance.”[46] Here was a step toward laying movables and personal property open to taxation. Seven years later, when Saladin had cut his way into Jerusalem, personal property was forced to contribute toward the Crusade. The Saladin Tithe, 1188 This tax, the so-called “Saladin tithe,” was laid at the Council [36]of Geddington on the 11th February, 1188. Present at it were archbishops and bishops and the greater and lesser barons,[47] but it is not stated whether or not they gave a formal consent to the levy. “This year,” so goes the Ordinance, “each one shall give in alms a tenth part of his revenues and movables, except the arms and horses and clothing of the knights; likewise excepting the horses and books and clothing and vestments and articles required in divine service of whatever sort of the clerks, and the precious stones both of clerks and laymen.” This is the earliest recorded instance of a general tax upon movables. For the assessment and collection of the Saladin tithe, Henry adopted a scheme favorite with him, which had been utilized in England for national purposes at least since the time of the Domesday Survey.Assessment by Juries of Inquest It was ordained that the assessment be done by juries of inquest; thus the taxpayers themselves were instruments in the determination of how much each should pay, even though the determination of how much the gross payment should be was as yet far beyond their power.

Henry II closed his reign in 1189. His taxation[48] had never been exceptionally heavy, though it had been the occasion for protest and had served as the pretext in 1174 for a little warring with his barons. In the matter of royal authority over taxation, the power of the king to levy taxes was not much diminished. The instances of opposition that have been cited do not prove much more than that now and then complaining voices were raised in the Great Council; nowhere is it shown that the objections had more than passing value, much less that they were conclusive.

The year after the laying of the Saladin tithe, Henry died. Of his four sons, two were dead and two had taken up arms against him. His first son, who he had hoped would succeed him as Henry III, was dead, and so too was Geoffrey, the father of the luckless Arthur; Richard, his second son, was for the moment the ally of Philip of France; and John, whom the king had loved above the others, now as [38]afterward seeking his own advantage, had recently taken his place amongst the rebellious barons who had made common cause with the king of France. This blow, coming on top of his unfavorable peace with Philip, struck the old king to the heart, and cleared the throne for Richard.

Richard was not, in the fullest sense of the word, an English king. His heart was on the Continent; England he regarded as a treasure-house, and he left the administration of it to his justiciars. Along with the exaction of feudal incidents and other and more special forms of taxation, Richard worked the machinery of the laws to its maximum capacity for what money it would bring him. He sold bishoprics and ministries, and released malefactors from prison for a consideration; sometimes, as in the case of Ranulf Glanville, his father’s treasurer, he threw men into prison on shadowy charges and forced them to buy their release. But all was under the guise of legality; Richard, unlike John, and much like Henry VIII, knew how to gain his end and yet adhere to the letter of the law.

On his way back from the Crusade near the close of the year 1192, Richard fell into the hands of his enemy, Leopold, Duke of Austria. Leopold turned him over to his feudal superior, the Emperor Henry VI, and he held Richard for a ransom of £100,000. The levy of the king’s ransom was one of the three regular feudal aids[49] for which the subjects were responsible. The magnitude of Richard’s ransom, however, brings it out of strictly feudal history into the domain of taxation. In the letter which Richard wrote from his German prison to his mother, the Queen Eleanor, and to his justiciars, he said, “For becoming reasons it is that we are prolonging our stay with the Emperor, until his business and our own shall be brought to an end, and until we shall have paid him seventy thousand marks of silver.” The amount of the ransom was subsequently raised to one hundred thousand marks, with an additional fifty thousand exacted as the price of not assisting the Emperor in his war to regain Apulia. Thus [40] England became liable for the payment of a sum aggregating £100,000.

The effort to raise so great a sum revived all the forms of taxation known to England in earlier years, and laid the basis for certain methods of acquiring money previously unknown. The justiciars took “from every knight’s fee twenty shillings,[50] and the fourth part of all the incomes of the laity, and all the chalices of the churches, besides the other treasures of the church. Some of the bishops, also, took from the clergy the fourth part of their revenues, while others took a tenth for the ransom of the king.”[51] In addition to the property there stated as having been levied upon, the lands of tenants in socage yielded two shillings on the hide or carucate,[52] personal property to the amount of a fourth of its value, and the wool of the Cistercians and[41] Gilbertines. Thus every person in the kingdom, was laid under contribution. Later kings found all of these means of raising revenue exceedingly fruitful, and some of them served as precedents for taxes which played great parts in the struggle for the control of the public purse.[53]

The authority by which the impositions were laid was apparently solely that of the king. Speaking of the letter which Richard addressed to his mother and the justiciars, urging upon them the necessity for raising money for the ransom, the Chronicler says, “Upon the authority of this letter the king’s mother and the justiciars of England determined that all the clergy as well as the laity ought to give ... for the ransom of our lord the king.” He speaks of the exactions having been taken. The fact that there is no definite record of deliberation or even of assent by the National Council to the enormous demand which the ransom of the king laid upon England, and that no serious objection was raised to the collection, ordered upon the authority of queen and justices, is a comment [42]both upon the weariness of the nation and its respect for the ancient feudal aid.

When Richard was finally released from durance in Austria, he returned to England. Remembering the success which met his first visit to the island at the time of his coronation, he proceeded to set his machinery going despite the financial decrepitude of the nation. The account of his Great Council at Nottingham, called near the last of March, 1194, illustrates not only his ingenious methods of making extra-customary feudal exactions but also the manner in which he levied his non-feudal impositions. The Council, which was not very fully attended, was composed of the archbishops, bishops, and earls. On the first day, he removed from office all the sheriffs of Lincolnshire and Yorkshire, and proceeded to sell their places to Archbishop Geoffrey of York, who paid 3000 marks[54] on the spot with a promise of 100 marks by way of annual increment. Having thus spent his first day, on the second he contented himself with issuing orders against his contumacious brother John. But on the third day he demanded [43]the third part of the service of the knights, the wool of the Cistercians for which he was willing to accept a composition, and a carucage of two shillings.[55] This last, which was the lineal descendant of the Danegeld, a land tax on the carucate, he apparently did not exact upon any other authority than his own. The king “determined that there should be granted to him out of every carucate of land through out the whole of England, the sum of two shillings.”[56] His action carries out the theory that the voice of the king in his Council was supreme in matters of taxation, and that the promulgation of a tax levy was rather accepted in the character of an edict than as inviting discussion. The deduction, however, that the individuals composing that Council were barred from objecting to a tax or even refusing to pay it, is not well founded; the time had not yet come when the individual felt himself bound by the tacit acquiescence [44]of the Council. If he were strong enough to withstand the royal displeasure, he could refuse payment.

Richard levied a second carucage in 1198, “from each carucate or hide of land throughout all England five shillings.” Here, too, he acted upon his own authority, and the Chronicler does not refer to the summons of a Council, or the participation of the magnates in the laying of the tax. The assessment of it followed the plan pursued by Henry II, in that the liability of the taxpayer was determined by means of a jury of inquest. Against the payment of the imposition the men of the religious orders demurred, whereupon an edict of outlawry came immediately from Richard. Esteeming the payment of the tax the lighter burden, the friars yielded.

The same year, 1198, furnishes us with what is by far the most noteworthy and interesting incident of the reign of King Richard, an event which is taken to be “a landmark of constitutional history.”[57] Through his efficient justiciar, Archbishop Hubert Walter, the king laid before his Council at Oxford a [45]plan whereby he “required that the people of the kingdom of England should find for him three hundred knights to remain in his service one year, or else give him so much money as to enable him therewith to retain in his service three hundred knights for one year, namely three shillings per day, English money, as the livery of each knight.”[58] The way in which Hubert Walter’s proposition was met throws light upon the subservience of the National Council. “While all the rest were ready to comply with this,” the Chronicler proceeds, “not daring to oppose the king’s wishes, Hugh, Bishop of Lincoln, a true worshipper of God, who withheld himself from every evil work, made answer that for his part he would never in this one matter acquiesce in the king’s desires.” Now, if it could be established that the bishop raised the question as to whether the king had a right to lay an imposition upon the baronage and to require their assent, then we would be justified in saying that Hugh’s refusal went far toward anticipating future history. But the evidence does not uphold so generous an inference. In [46]the first place, it seems highly questionable whether Hubert Walter really offered the alternative of a money payment,[59] a conclusion which reduces the debate to one on foreign service. But Hugh even here did not raise the general question. “I know,” he is quoted as saying, “that the see of Lincoln is held by military service to our lord the king, but it has to be furnished in this land alone; beyond the boundaries of England nothing of the kind is due from it.”[60] Hugh, therefore, refused to comply with the royal request on purely feudal grounds. Basing his objection on ecclesiastical privilege, he registered his refusal for the see of Lincoln alone; he did not take his stand in behalf of the barons or even of the whole body of churchmen. The issue as to their relative powers to tax was not raised between king and Council, and the withdrawal of Hubert Walter’s demand did not constitute one of the first victories over arbitrary taxation. The withdrawal itself [47]seems to have had its disagreeable consequences. Herbert, Bishop of Salisbury, who stood shoulder to shoulder with Hugh of Lincoln in his opposition, had to pay a heavy fine for his part in the contest, and the Abbot of St. Edmund’s was obliged to win back royal favor with a gift of a hundred pounds which he made in addition to the pay of four knights for forty days.

Richard’s reign covered only a decade, six months of which he spent in England.[61] Notwithstanding his long absence, during which the National Council began in some small degree to feel itself able to get along without the royal presence, the authority of the king as the supreme initiator of taxation remained unquestioned. In the assessing of taxes, [48]however, the taxpayers had more participation. The justiciars of Richard continued Henry II’s practice of assessment through a representative jury.

John, the youngest son of Henry II, the thinnest figure that ever sat upon the English throne, succeeded to the crown some six weeks after the tragic passing of Richard. Richard was the creation of his own times, the incarnation of the mediæval spirit, and where it fell short he fell short. To attribute the meanness of his brother to any conditions of environment would be to perpetrate a slander upon the times. Yet, notwithstanding the vileness of the king, there eventuated from his reign the first of the three books in what Lord Chatham denominated “the Bible of the English Constitution.” The progress toward the finished writing of Magna Carta, especially in so far as the events concern laying of taxes, is the next step in this history.

An interregnum of six weeks elapsed between the death of Richard and the coming to England of John. Then Archbishop Hubert Walter set the crown upon his head and[49] declared him elected to the kingship. John’s stay in England was necessarily brief, because Philip II of France was already in a fair way to win his possessions on the far side of the Channel. For his expedition into Normandy John exacted a scutage of two marks on the knight’s fee; the rate was unusually high, almost without precedent.

Being unable to make head against Philip, John concluded a truce for which he had to pay 30,000 marks. The Jews had to pay a good deal of it and in addition John took a carucage of three shillings on the carucate, which, like the charge of scutage, was an exceedingly high rate. John laid this imposition, apparently, solely upon his own authority; Roger Hoveden says that he “took” the carucage and makes no mention of a Council.[62] He demanded the aid, and the justices issued the edicts. In 1201 John contributed, at the instance of a papal delegate, a fortieth of his revenues for the Crusade; from his barons he urged a similar offering, not “as a matter of right or of custom or of compulsion.” Freeholders and tenants by knight’s service [50]paid at a similar rate; just what liberty they had in refusal is shown in the direction of Geoffrey Fitz-Peter, the justiciar, at the end of his address to the sheriffs: “And if any persons shall refuse to give their consent to the said collection, their names are to be entered in the register, and made known to us at London.”[63] In the same year he exacted a scutage at the high rate of two marks on the knight’s fee.

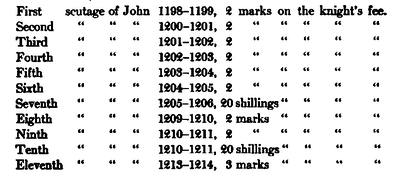

The importance of the part which scutage played in the tragedy of John can hardly be overestimated; it was the great moving cause which brought about the crisis of 1215 and Magna Carta. Scutage, a cause leading to the Charter Not only did John raise scutage to an amount which had not been equalled since the Scutage of Toulouse in 1159, but he levied it as though it were a regular and almost annual obligation. Previously understood as a commutation arranged at the pleasure of the king for knight’s service not rendered, as an extraordinary impost reserved for extraordinary occasions, John changed its character and used it as a means of supplying his heavy financial needs, irrespective of customary right or of shrewd policy.

John began with a demand of two marks on the knight’s fee.[64] The barons had accustomed themselves, during the reigns of Henry and Richard, to expect at the outside a demand of twenty shillings; sometimes indeed the imposition had fallen to a single mark or even as low as ten shillings. His second scutage came in the third year of his reign, two marks on the fee. Then for four successive years John kept his barons on edge with annual scutages of two marks each. In 1205-06, apparently fearing a storm, he reduced his imposition to twenty shillings, and then waited for three years before laying another. The three years of relief, however, were not as innocent as they seem; it was in 1207 that John broke [52]with the Pope, and the freedom to plunder ecclesiastics which this quarrel gave him, made unnecessary for the moment any further demands upon the baronage. But this source of revenue shortly proved insufficient, and John turned again toward scutage. In the two financial years from 1209 to 1211, he laid three scutages which aggregated some seventy-three shillings on the knight’s fee. Then for the space of two years John paused.

But it was only a pause. On June 1, 1212, he caused to be taken the Inquest of Service, Inquest of Service, 1212 by which he sought to bind the cord more tightly upon his demesne tenants by ascertaining in the now familiar manner of the local jury, how great was the return which he might expect from the lands of each crown vassal. It is easy to see in this Inquest, recalling in its nature Domesday Survey and the Inquest of 1166, the intended basis for another imposition of scutage.[65] It came in 1213-14, when John made the wholly unprecedented levy of three marks on the knight’s fee. Apparently he was doing all he could to hurry [53]the crisis which should lead him to Runnymede.

There were two features of John’s use of scutage aside from the magnitude and frequency of his levies Attendant abuses of John’s levies of Scutage which made them particularly onerous. The first had to do with the fines which he exacted from such of the baronage as were delinquent in paying the imposts of Richard, some of which had been in arrears since 1190. Miss Norgate notes an instance which illustrates John’s habit, and throws light upon his character. Two men of Devon in 1201 were charged with fines by reason of their absence from the train of Richard in 1193, and the cause of their failure was this, that “they had been with Count John.” At the moment John was in rebellion against Richard, but now that he was become king in Richard’s place, he exacted fines for service the nonperformance of which he himself had been the cause of.[66] The collection of fines owing to Richard bore with special heaviness upon the northern baronage and these, it will be remembered, were the leaders in the assault upon John in 1215.

The other great abuse which John introduced into the levying of scutage was his subversion of the theory that the payment of it by the vassal wholly acquitted him of his obligation to the king for that occasion. John endeavored in a number of instances to make him liable for personal service in addition, and for fines in case he failed to be present in his train. In 1199 John exacted fines from those who did not accompany him to Normandy; in 1201 he accepted money-payment as a substitute for service; in 1205 he fined the tenants-in-chivalry after he dismissed them from service in the host. In these years scutages were laid as well.[67]

Thus did John make over scutage; it had become a heavy impost upon the lands of demesne tenants, an almost annual charge, and a tax foreign to its original character as a commutation for personal service. A rebellion culminating in the exaction from John of a written contract between him and the baronage, detailing their mutual relations was the natural consequence.

But the knights were by no means the only [55]body of Englishmen whom John alienated by his frequent levy of taxes. Antagonism of the clergy The clergy, already irritated by John’s quarrel with the Pope and his seizures of ecclesiastical property, were ready to combat the king in any further attempt to tax them. At a Great Council at London on the 8th January, 1207, the king asked “the bishops and abbots to permit the parsons and the beneficed clergy to give to the king a fixed sum from their revenues.”[68] The prelates did not consent, and John brought the matter up again at a second Great Council which he convened at Oxford on the 9th February. There were present an “infinite multitude of prelates of the church and magnates of the realm,” and John again addressed the ecclesiastics. The bishops “unanimously answered that the English church could in no wise sustain what was unheard of in all the ages before.” The king, “taking wise council,” withdrew his demand, but he did not abandon his project.General demand of a thirteenth of movables “Afterward he ordained generally throughout the kingdom that every man ... give a thirteenth part to the king” of revenue and movables. The [56]demand applied to all men, no matter from whom they held their lands.[69] Against the imposition, the earlier analogues of which were the Saladin Tithe and Richard’s ransom, “all murmured, but none dared to contradict” the king, except Geoffrey of York; he did not consent, but openly refused, and then had to fly from England to escape John’s anger.[70] The writ for the assessment of the thirteenth has it that the tax was provided “by the common advice and assent of our Council at Oxford.”[71] How whole-souled was the assent is revealed by the Chronicler; “none dared to contradict.”

The time was at hand when men would not longer endure the extortionate exercise of an unchallenged royal right. Normandy is lost There were a number of conditions and circumstances aside from the burdensome taxes which were pointing toward Runnymede and Magna Carta. By 1204 John had come to the end of his day in France. Normandy was lost. The effect [57]upon England was marked; the Norman baronage was obliged to choose between England and the Continent. Hereafter tyranny and good-rule of the English kings were alike felt solely at home, and the barons cast their eyes not across the Channel, but upon their lands in England. The English were for England and the nation was born, the first conscious act of which was to be the enactment of Magna Carta.

During the seven years from 1206-1213 John had his disgraceful quarrel with the pope, a quarrel which ended in the enfeoffment of England with Innocent as feudal overlord. The matter is foreign to the subject in hand, save as the struggle, especially in the early development of it, gave John a pretext for confiscating the ecclesiastical holdings and thereby relieving the barons of a scutage for the space of about four years.

John, conceiving that peace with the Pope meant full mastery of affairs, was seized with an ambition to reconquer Normandy. To this end he tried to induce the barons to follow him into Poictou. They refused, first on the ground that John was not yet fully absolved[58] from his excommunication; and then, after this objection was removed by Stephen Langton on the 20th July, 1213, they raised the old plea that they were not bound by their tenure to follow the king abroad. John determined to enforce their attendance upon him by show of arms.

Before he started to the north, where the seditious movement had its center, an assembly was held at St. Albans on the 4th August by Archbishop Langton, and the justiciar Geoffrey Fitz-Peter. Its purpose was to assess the amount due to the ecclesiastics in consequence of the damage sustained by church property during the quarrel with the Pope. But its great importance lay in the body of men who made it up. It is in so far as we have record, the first occasion that representatives of the lesser folk were summoned to a National Council.[72] Beside the bishops and barons who attended, there were present the reeve and four men from each township on the royal demesne. The Council advanced somewhat beyond the simple purpose for which it was summoned; the justiciar issued an edict [59]against unjust exactions, to be observed as the sheriffs valued their lives and limbs, and commanded the observance of the good laws of Henry I.[73]

Later in the year to Oxford, the non-noble representatives were again called, and at the initiation of John himself. John hoped to win to himself by this act of respect the support of the smaller landowners against the threatening barons. The sheriffs were to send up, beside the knights holding from the king, four discreet men from each county “to talk with us,” as the writ had it, “concerning the business of our realm.”[74] This, provided subsequent events had kept pace with it, was an immensely long step forward; indeed the provisions of Magna Carta themselves do not advance to the point thus falteringly and unworthily reached by John. It provided a precedent for the representation of the third estate in the councils of the nation; and though it is not known whether or not any action was taken relative to the levying of taxes, or even whether the council was held [60]at all, nevertheless the fact that representation for the moment was provided for, marks the step in the light of the present, as of great, almost of profound, importance in the consideration of parliamentary taxation.

It would be wandering far afield to trace the final struggles of John with his infuriated barons. It is sufficient to note that it was an unauthoritative demand of taxation which pulled the structure of John’s misgovernment crashing down upon his head.Events leading to Runnymede On the 26th May, 1214, John issued writs for the collection of a scutage at the quite unprecedented rate of three marks on the knight’s fee, for which there was not a shadow of consent. The northern barons, the same who had refused personal service, now refused likewise to pay scutage. In the face of precedent to the contrary, they denied their liability to follow him, not merely to Poictou but to any district beyond the Channel, or to pay him composition for not doing so.[75] At his interview with the contumacious barons in November at [61] Bury St. Edmunds, he reiterated his demand, but they remained steadfast in their refusal.

From that time until King and Barons met on the meadow near the Thames called Runnymede, John’s sky was darkening. He did his best to avoid the tempest, but with no success. He attempted to break the union of his enemies by giving the church and the people of London special charters; it was the church, headed by Stephen Langton, which stood shoulder to shoulder with the barons in unending hostility to John, and it was the citizens of London whose adherence to the baronial cause determined the final contest against the king. John bought the services of mercenaries to fight his battles for him, but when he became penniless, they fell away. With every expedient he could summon in his extremity, he tried to avoid the breaking of the storm. But the whole nation was against him. The men of the North, who had been steadfast from the beginning in their opposition to John, were joined by barons of similar mettle throughout the rest of England. The citizens of London when they joined the ranks of John’s enemies were followed by the earlier[62] partisans of the king, save only those few who were attached by interest or necessity. He signed the Charter the 15th June, 1215, in the full hope that with the passing of the tempest he might forget his promises.

The Great Charter, in form granted by John as a voluntary gift to the nation, was in reality a treaty concluded between him and his barons. That its provisions relative to taxation are important has already been hinted at; as a matter of history, the recurrence of references to these particular sections of the Charter proves the esteem in which Englishmen of later generations regarded this early book of their Bible of Liberties. Whether this veneration, displayed by the framers of subsequent and perhaps equally important instruments, was based upon the intrinsic value of the Charter or upon nothing firmer than sentiment, is somewhat of a mooted question.[76] The fact that it was held in such esteem is for us the important and sufficient reason for considering it in detail. It is essential to understand upon what the later champions of parliamentary taxation [63]based their arguments, even though those arguments presumed interpretations of Magna Carta which the framers of the Charter would have been far from admitting.

The twelfth chapter,[77] taken with the fourteenth,[78] serves as the legal basis for much of the eloquence against arbitrary taxation from the time of John to the acceptance of the United States Constitution. It has been taken to admit “the right of the nation to ordain taxation”[79] and even as the surrender of the “royal claim to arbitrary taxation.”[80] An analysis of the contents and application of the twelfth chapter together with additional comment on the fourteenth may throw some light on the substance for these assertions.[81]

The impositions which are specified in the chapter are “scutage” and “aid.” The arbitrary levy of scutage upon the lands of his tenants was the chief moving cause which brought John to Runnymede, and this chapter undertook the correction of the abuse of abuses. The aids mentioned are to be distinguished from the incidents of feudal tenure, reliefs, marriages, primer seisins, and similar payments which are dealt with elsewhere in the Charter and belong to the peculiar history of feudalism. The twelfth chapter provides that the three ordinary aids—for ransoming the king, for knighting his eldest son, and for the marriage of his eldest daughter—should be reasonable in amount. These might be exacted by the king as a matter of course, without the common council of the realm. The extraordinary aids, which the Charter places in the same category with scutages, include all other arbitrary feudal exactions levied to meet some particular emergency and in an unusual manner. The Charter places both these extraordinary aids and the obnoxious scutages beyond the pale of royal imposition; hereafter they are leviable[65] only “by common counsel” of the kingdom. That they were to be laid by the body known as the Common Council is indicated by the provisions of Chapter Fourteen.

The people of London rightfully expected to benefit by the granting of the Charter. According to the last clause of the Twelfth Chapter, it was to “be done concerning the aids of the city of London” in the “same way.” The provision is indefinite; whether the “aids” were also to include in their category the more arbitrary and therefore more obnoxious tallage[82] is unknown. The aids were for the most part free-will offerings of the city itself, whereas the tallages were exacted by the king upon his own arbitrary authority as one having the power of a demesne lord over London. And whether or not the phrase “in the same way” means that aids shall be levied by the common counsel of the realm, or merely that they shall be of “reasonable” amount, is difficult of determination. If indeed the former idea was in the minds of the framers of the Charter, when [66]they came to the section providing for the composition of the Common Council, they made no provision for the attendance of any member of the corporation of London, or even for securing their consent. At all events, the king continued to tallage London at not infrequent intervals and almost without question until 1340, when Parliament took the privilege away from Edward III.

Before we advance to a consideration of the true importance of the Twelfth Chapter, in order to have a complete understanding of its position in the line of progress toward parliamentary taxation, we are obliged to look at the method by which the common counsel of the kingdom was to be taken. Chapter Fourteen[83] lays down the rule according to which the assembly was to be called that should hold this power of assenting to scutages [67]and aids. The method of summons was simple; it involved the issuance of writs, individually to the archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls, and the greater barons, and collectively to the lesser barons through the agency of the royal sheriffs and bailiffs. The writs gave at least forty days’ notice as to the place and time of meeting, and specified the business which furnished the occasion for the Council. As for its composition, the answer is very simple; it was a gathering of tenants-in-chief of the king, of crown vassals. The line between the greater and the lesser barons was ill-defined. Roughly, however, it divided the baronage into classes, one of which included the baron whose holdings embraced the major part of a county, and the other the tenant of the king whose dwelling was a cottage set in his dozen acres. It is probable that the lesser barons played no[68] considerable part in the assembly, and that their attendance or non-attendance was of little consequence. The light of the lesser folk was as yet hid under the bushel.

It is a conclusion easily drawn from the text of the two chapters that this was a body of feudatories called together for the purpose of making feudal payments. The members of the Commune Concilium were the vassals of the crown and, save in rare instances, none other; the taxation to which they were to give their consent according to the terms of the Charter, included no carucage or other general tax, but only the scutages and aids which feudal tenants of the king by military service were expected to pay him as overlord. Furthermore, the idea of representation in the strictly technical sense into which present usage has frozen the word, was quite wanting. It is true that a consent by the barons gathered in the Council to an imposition levied in accordance with the notice stated in the summons, was binding upon the barons who did not attend, but this was on the principle that absence gave consent, not that the consent of the majority was binding upon a dissentient[69] minority. The instance is quoted of the Bishop of Winchester who in Henry III’s time was relieved of his assessment because he had opposed the levy in the Council. John had introduced definite representation in his summons to the Oxford Council in 1213, by directing the sheriffs to send up “four discreet knights” from their counties to treat with him “concerning the business of his realm.” In respect of this, looking at it in the light of later progress, the Great Charter is positively retrogressive.

The conclusion is thus forced upon us that save in the two cases of scutages and extraordinary aids, with possibly the addition of a third in the shape of tallaging the city of London, supreme authority over general taxation remained in the hands of the king. The Charter provides solely for the financial incidents of the feudal relation, and that in the somewhat narrower aspect of tenure by chivalry. The only true taxes, carucage and John’s levy on movables known as the thirteenth, were not referred to. It is an anticipation of later history to read into the provisions of Magna Carta either a definite inauguration[70] of national consent to taxation or of the representative principle.