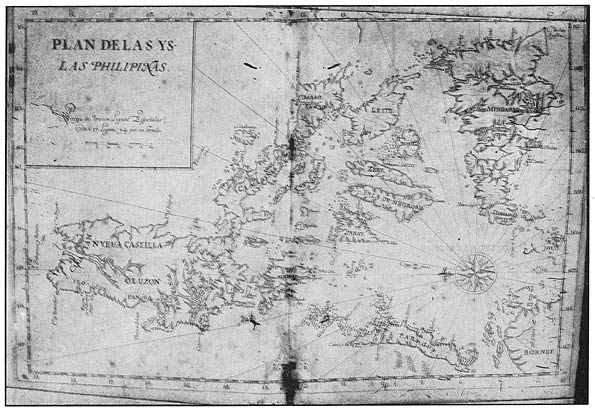

Map of the Philippine Islands (ca. 1742)

[Photographic facsimile of original MS. map in Museo-Biblioteca de Ultramar, Madrid]

Cleveland, Ohio

MCMVII

[iii]

CONTENTS OF VOLUME XLVII

| Preface | 11 | |||||||

| Documents of 1728–1759 | ||||||||

| The Santa Misericordia of Manila. Juan Bautista de Uriarte; Manila, 1728 | 23 | |||||||

| Survey of the Filipinas Islands. Fernando Valdés Tamón; Manila, 1739. (To this is added, “The ecclesiastical estate in the aforesaid Philipinas islands,” by Pablo Francisco Rodriguez de Berdozido; [Manila], 1742.) | 86 | |||||||

| The Order of St. John of God. Juan Maldonado de Puga; Granada, 1742 | 161 | |||||||

| Letter to the president of the India Council. Pedro Calderon y Enriquez; Manila, July 16, 1746 | 230 | |||||||

| Letter of a Jesuit to his brother. Antonio Masvesi; Cavite, December 2, 1749 | 243 | |||||||

| Commerce of the Philipinas Islands. Nicolas Norton Nicols; Manila, [1759] | 251 | |||||||

| Bibliographical Data | 285 | |||||||

| Appendix: Relation of the Zambals. Domingo Perez, O.P.; Manila, 1680 | 289 | |||||||

[v]

ILLUSTRATIONS

| Map of the Philippine Islands; photographic facsimile of original MS. map (ca. 1742) in Museo-Biblioteca de Ultramar, Madrid | Frontispiece | |||||||

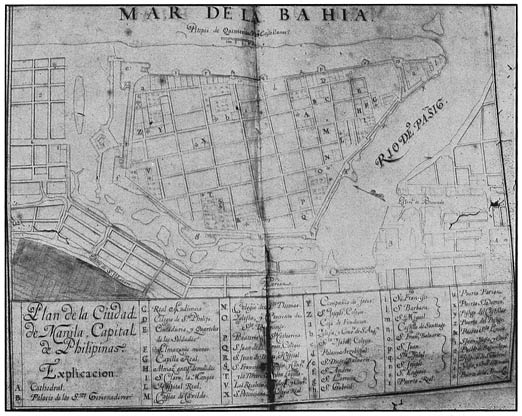

| Plan of Manila, ca. 1742; photographic facsimile from original manuscript in Museo-Biblioteca de Ultramar, Madrid | 89 | |||||||

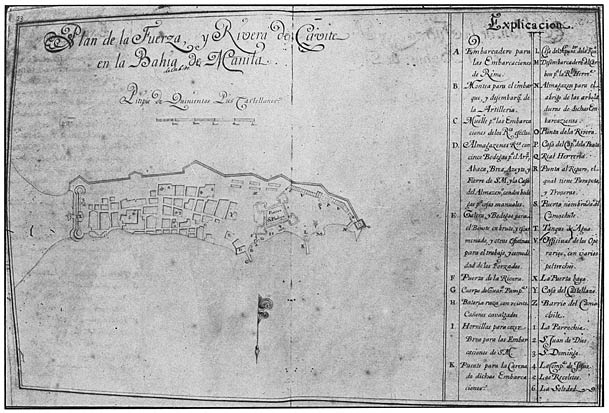

| Plan of Cavite and its fortifications, (ca. 1742); photographic facsimile from original manuscript in Museo-Biblioteca de Ultramar, Madrid | 107 | |||||||

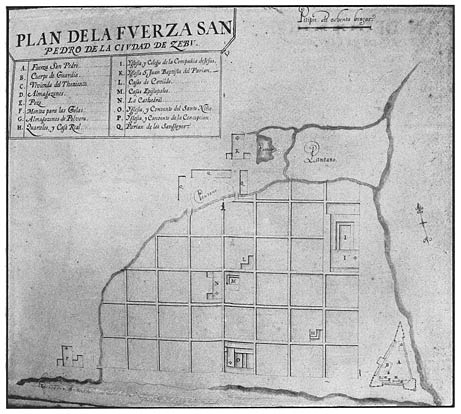

| Cebú and its fortifications, ca. 1742; photographic facsimile from original manuscript in Museo-Biblioteca de Ultramar, Madrid | 115 | |||||||

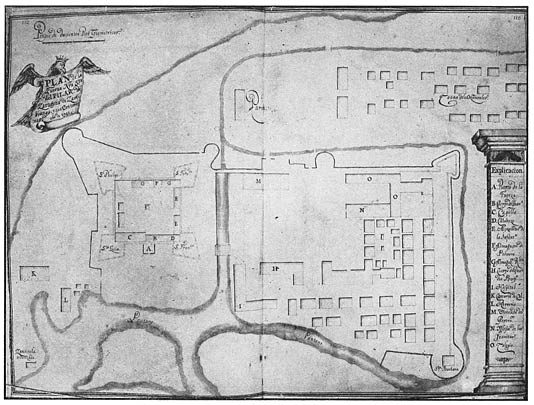

| Plan of fort at Zamboanga, 1742; photographic facsimile from original manuscript in Museo-Biblioteca de Ultramar, Madrid | 121 | |||||||

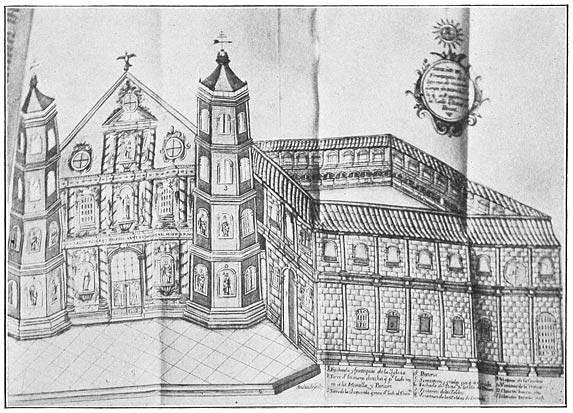

| Church of San Juan de Dios, Manila, in Religiosa hospitalidad, by Juan M. Maldonado de Puga (Granada, 1742), facing p. 148; photographic facsimile from copy in collection of Eduardo Navarro, O.S.A., at Colegio de Filipinas, Valladolid | 177 | |||||||

[11]

PREFACE

The documents presented in this volume (which covers the years 1728–59) form a comprehensive and interesting survey of the islands and their condition—social, religious, military, and commercial—during the middle portion of the eighteenth century; and the writers of these are prominent in their respective spheres of action. The appendix furnishes a valuable description of the savage Zambals of western Luzón, written by a Dominican missionary among that people in 1680.

The first document is a translation and condensation of the Manifiesta y resumen historico de la fundacion de la venerable hermandad de la Santa Misericordia (Manila, 1728), by Juan Baptista de Uriarte. This poorly-constructed work is chiefly valuable, not for the direct historical facts that it gives, but for the social and economic deductions that can be made from those facts. For instance, in spite of the great poverty prevailing among certain classes of Manila, it is apparent that the city possessed much wealth, else it would have been quite impossible for the brotherhood of Santa Misericordia to carry on its beneficent work to so great an extent. The brotherhood is founded April 16, 1594, after the model of the brotherhood of the same name [12]in Lisboa, its first establishment being in the school of Santa Potenciana. The rules of the new organization are ordained January 14, 1597, and first printed in 1606. The favor and protection accorded it in the beginning by Luis Perez Dasmariñas is continued by many succeeding governors and ecclesiastics, many of whom act as purveyors. As might be expected, the first attempts toward charitable aid are weak, but strength is gradually attained, and the noble work of the brotherhood receives due recognition. Certain pious funds are gradually established; the brotherhood executes many wills; a hospital is early founded, under the spiritual charge of the Franciscans. In 1597, the royal hospital is taken in charge by the Misericordia at the request of Governor Tello, in order that it may be managed better. Amid all the many disasters from the time of its foundation to 1728—shipwrecks, other sea accidents, invasions by the Dutch, earthquakes, etc.—the brotherhood ever lends a helping hand cheerfully. The city is divided into three parts, for the greater good of the poor and destitute. The various amounts of the alms distributed, which are given throughout the work, show how well the brotherhood discharged the purpose of its foundation. Christianity is debtor to this organization through the aid furnished to the religious orders at various times. Generous aid has been given to the prisons, to poor widows, to orphan girls (for whom a school is founded), and to noble destitute families, and others. Its activities extend even to the ransoming of Spanish and Portuguese prisoners from the Dutch; to the care of the native, Spanish, and foreign soldiers who fight under the banners of Spain; and even to Japan. A productive [13]rule of the brotherhood is the one compelling all the brothers at death to leave something to the association. From 1619 on, many loans are made from the coffers of the Misericordia to the royal treasury, which is generally in a state of exhaustion; and these loans are always cheerfully given, even in the midst of the depressions that the association experiences. That the brotherhood has enemies is shown by citations from a manifesto which charges it with neglect and poor business management. These charges are, however, disproved by our author. Indeed, the Manila house exceeds in the amount of its alms, those given by the Lisbon or mother house. Elections are annual, and are made by ten members chosen by the brotherhood as a unit. The board is composed of thirteen brothers, chief of whom is the purveyor; his duties, as well as those of the secretary, treasurer, and three stewards, are stated. The remaining brothers of the board are known as deputies. Royal decrees of 1699 and 1708 exempt the association from visitation by either ecclesiastical or civil officials, a concession that had been long before conferred upon it by Tello. An important event in the history of the brotherhood is the completion in 1634 of its church and school of Santa Isabel, whereby it does much good, especially among the orphan girls under its charge. Confessions in the school are in charge of the Jesuits. Many of the girls of the school enter the religious life, but others marry, and to all such a generous dowry is provided. Regular devotions are prescribed for the girls; and for the brothers of the association various church duties are ordained. The girls are also required to help in the kitchen and to learn the duties of housekeeping, so that at marriage [14]they are quite ready to assume the position of wife. The number of girls and women aided in this school and church reaches into the thousands, and the expenses of the church have been considerably over 100,000 pesos. In 1656, the brotherhood makes a transfer of its hospital to the hospital order of St. John of God. Chief among the funds established for the use of the brotherhood are those by Governor Manuel de Leon of 50,000 pesos, and by the famous Archbishop Pardo of 13,000. Notwithstanding the many disasters that have occurred in the islands, many of which affect the brotherhood, the latter has never been in a better condition than at the time when this manifesto is written. In his final chapter, Uriarte gives a list of the members of the board of the brotherhood, of which he is secretary. He also gives in full various documents which he has mentioned in the body of his relation. Under charge of the association is the appointment of twenty-nine chaplaincies (apparently among the religious orders, for ten chaplaincies for lay priests are also mentioned); and a certain number of fellowships are supported in San José college. The brotherhood is composed of 250 members, whose qualifications and duties are given. The work ends with an account of the annual alms given by the association.

The condition of the islands in 1739 is well depicted in the relation furnished in that year to the home government by Governor Valdés Tamón. Brief descriptions are given of the city of Manila, and the port of Cavite, with their fortifications, gates, artillery, garrisons, and military supplies; the document contains similar accounts of all the other military posts in the Philippines, and short descriptions [15]of the various provinces in which the islands are governed. Lack of space, however, obliges us to omit the greater part of these accounts, presenting only those concerned with Manila, Cavite, Cebú, and Zamboanga.

In 1742 an additional report was made for the king in regard to the status of the ecclesiastical estate in the islands; this is here given in full. The four cathedral churches are first mentioned, with the jurisdiction, incumbent, expenses, and sources of income of each. The other religious and the educational institutions of Manila, and its hospitals, are enumerated, with statements of the aid given to each by the royal treasury. A list is given of all the encomiendas in the islands granted for such purposes, also of those granted to private persons. Another section is devoted to the missions which are carried on by the religious orders, and to the expenditures made for them by the government of the islands, tabulated statements of which are given, as in the other sections of this report. There is also a table of the amounts collected by the religious who are in charge of the mission villages as offerings on feast days. At the close are found some remarks eulogistic of the friars’ labors in the islands, with an expression of regret that they have not carried out the king’s orders to have the Castilian language taught to the Filipino natives.

The work carried on by the Misericordia was well supplemented by that of the hospital order of St. John of God, an account of which was published (Granada, 1742) by one of its brethren in Manila, Juan Manuel Maldonado de Puga. He describes the urgent need of aid for the sick there, the efforts [16]made in early years (chiefly by the Misericordia) to supply this want, and the coming of the hospitalers of St. John (1641) to Manila. The government places in their charge the royal hospital at Cavite (1642), and the Misericordia surrender to them their hospital in Manila (1656); and for a time they conduct a hospital for convalescents at Bagumbaya. A full account is given of the transfer of the Misericordia hospital, and of its history up to 1740. Some difficulties arise between the hospitalers and the Misericordia, which are decided in favor of the former by the Jesuit university. Maldonado presents a careful description of the new church and convent erected in 1727 by the hospitalers, and narrates the leading events in their history. An interesting digression by our author describes the system of weighing in use by the Sangley traders in the islands, and the substitution therefor (1727) of the Castilian steelyard and standards of weight; he states that he is the first to explain the Chinese system, and we know of no other writer who has done so. He proceeds to give an account of the manner in which the Filipinas province of the hospital order is governed, with lists of its provincials and of its present officers and members; and then enumerates the incomes and contributions of the order in the islands, relating the history of these, and similarly the grants of royal aid to its work there. In this connection is described the personal service called reserva or polo, which is imposed on the natives. Another chapter enumerates and describes the charitable foundations [obras pias] from which the hospital receives aid. Maldonado describes the present condition of the other hospitals in the islands, those outside Manila being mainly for [17]special classes—the lepers, the Chinese, the soldiers, etc.; and few of them are properly managed or served. He ends with an apology for numerous errors in his text, due to the blunders of native amanuenses.

A letter from Manila (July 16, 1746) to the president of the India Council recounts the difficulties and dangers with which the islands are threatened by the Dutch and English, who are sending goods from their Eastern factories to America, lying in wait to seize the Spanish galleons, and even menacing Manila. The writer suggests that the former trade between Luzón and the Malabar coast be resumed, and that more effective measures be taken to overawe the Dutch and English in Eastern waters.

The Jesuit Antonio Masvesi informs his brother (December 2, 1749) of the failure of the Joló and Mindanao missions, and severely criticises the governor, Bishop Arrechedera, for his infatuation with the sultan of Joló, and his lavish entertainment of that treacherous and crafty Moro, against the advice of the Jesuits. Masvesi sends also an account of these matters by a brother Jesuit, these letters being intended to counteract the influence of Arrechedera’s reports to the home government.

A curious memorial to the king, by an Englishman named Norton but naturalized in Spain, urges that that country open up a direct commerce with the Philippine Islands by way of the Cape of Good Hope, and that mainly in cinnamon. He enumerates the products and exports of the islands, and urges that these be cultivated more than they are—above all, the cinnamon, which is now purchased by Spain and her colonies from the Dutch, at exorbitant [18]prices. The finest quality of this spice could be produced in Mindanao, and Norton recommends that plantations of cinnamon be made there, thus furnishing it to Spain and the colonies at a lower price, and retaining their silver for their own use instead of allowing their enemies to get possession of it. He recapitulates the great advantages which will accrue to Spain, to her people and colonists, and to the Indian natives, from the execution of this project; and he would cultivate in the islands not only cinnamon but pepper. He cites figures from the Amsterdam Gazette to show how great quantities of commodities which might be produced by the Philippines are brought to Europe from the Dutch factories in the East; and he points out how Spain might profitably exchange cinnamon and pepper for the lumber, cordage, etc., which she now purchases for cash from Norway and Russia. He urges that Spain should no longer submit to the tyranny of the Dutch and other heretics, who are really in her power, since they must depend on her for silver. He asks that the king will appoint a commission to examine and report on his project, and enumerates various conditions which he requires in order to establish the direct commerce between Spain and Filipinas. At the end are stated the numerous advantages which would accrue to Spain and the colonies from the execution of Norton’s plan.

Appendix: Domingo Perez, one of the most noted of the seventeenth century Dominican missionaries, writes an account in 1680, from personal experience, of the newly-acquired Dominican province of Zambales, in which he describes that province, and the people in their manifold relations. He gives much [19]interesting information, for the truth of which he vouches, concerning the Malayan race of the Zambals, whose peculiar characteristics he describes, from the standpoints of their religion and superstitions, and their social and economic life; describes the changes effected by the softening influences of the Christian religion; and gives various suggestions as to their management. They are seen to possess a religion somewhat vague in its general concept, but quite specific and complex in its individual points, with a graded priesthood, to all of which, however, not too great importance must be attached. In their superstitious beliefs, they approach quite closely to the other peoples of the Philippines. Birds are a good or bad omen according to circumstances; sneezing is always a bad omen; great credence is given to dreams. Marriage is an important ceremony, and chastity is general among the women, who exercise great power among the people. Feasts are occasions for intoxication. Above all, they are fierce headhunters, and strive to cut off as many heads as possible, although they are a cowardly race. The Dominican policy of governing the Zambals is one of concentration, in which they are well aided by the garrison of Spanish soldiers stationed in the Zambal country.

The Editors

December, 1906. [21]