Title: Gettysburg: Stories of the Red Harvest and the Aftermath

Author: Elsie Singmaster

Release date: March 14, 2017 [eBook #54358]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Barry Abrahamsen and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Gettysburg, by Elsie Singmaster

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/gettysburgstorie00insing |

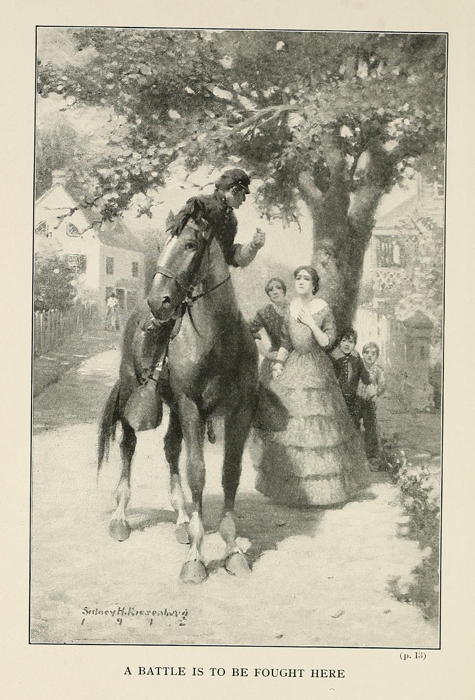

A BATTLE IS TO BE FOUGHT HERE

Four Score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty; and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate—we cannot consecrate—we cannot hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us, the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

Gettysburg, November 19, 1863.

| Page | |

| I. July the First | 1 |

| II. The Home-Coming | 21 |

| III. Victory | 45 |

| IV. The Battle-ground | 65 |

| V. Gunner Criswell | 87 |

| VI. The Substitute | 109 |

| VII. The Retreat | 133 |

| VIII. The Great Day | 157 |

| IX. Mary Bowman | 181 |

Note. Grateful acknowledgment is made to the editors for permission to reprint in this volume chapters that first appeared in Harper's, Lippincott's, McClure's, and Scribner's Magazines.

| A Battle is to be fought here Frontispiece | 13 |

| From the drawing by Sidney H. Riesenberg, reproduced by courtesy of Harper and Brothers | |

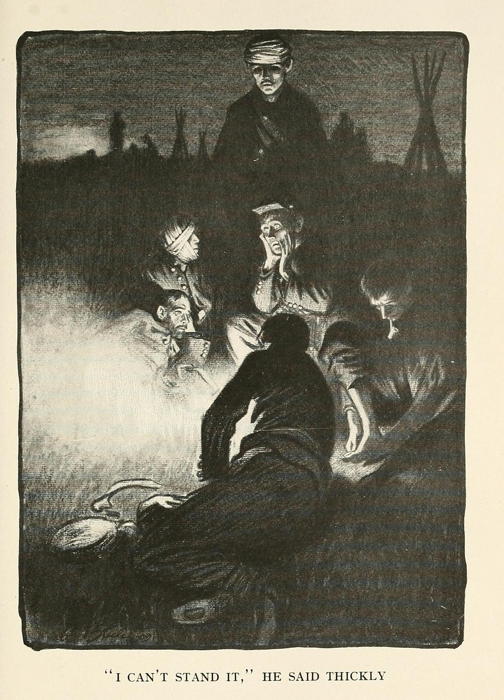

| "I can't stand it," he said thickly | 26 |

| From the drawing by Frederic Dorr Steele reproduced by courtesy of McClure's Magazine | |

| He stood where Lincoln had stood: | 104 |

| From the drawing by C. E. Chambers, reproduced by courtesy of Harper and Brothers | |

| They saw the Strange Old Figure on the Porch | 152 |

| From the drawing by F. Walter Taylor, reproduced by courtesy of Chas. Scribner's Sons |

From the kitchen to the front door, back to the kitchen, out to the little stone-fenced yard behind the house, where her children played in their quiet fashion, Mary Bowman went uneasily. She was a bright-eyed, slender person, with an intense, abounding joy in life. In her red plaid gingham dress, with its full starched skirt, she looked not much older than her ten-year-old boy.

Presently, admonishing herself sternly, she went back to her work. She sat down in a low chair by the kitchen table, and laid upon her knee a strip of thick muslin. Upon that she placed a piece of linen, which she began to scrape with a sharp knife. Gradually a soft pile of little, downy masses gathered in her lap. After a while, as though this process were too slow, or as though she could no longer endure her bent position, she selected another piece of linen and began to pull it to pieces, adding the raveled threads to the pile of lint. Suddenly, she slipped her hands under the soft mass, and lifted it to the table. Forgetting the knife, which fell with a clatter, she rose and went to the kitchen door.

"Children," she said, "remember you are not to go away."

The oldest boy answered obediently. Mounted upon a broomstick, he impersonated General Early, who, a few days before, had visited the town and had made requisition upon it; and little Katy and the four-year-old boy represented General Early's ragged Confederates.

Their mother's bright eyes darkened as she watched them. Those raiding Confederates had been so terrible to look upon, so ragged, so worn, so starving. Their eyes had been like black holes in their brown faces; they had had the figures of youth and the decrepitude of age. A straggler from their ranks had told her that the Southern men of strength and maturity were gone, that there remained in his village in Georgia only little boys and old, old men. The Union soldiers who had come yesterday, marching in the Emmittsburg road, through the town and out to the Theological Seminary, were different; travel-worn as they were, they had seemed, in comparison, like new recruits.

Suddenly Mary Bowman clasped her hands. Thank God, they would not fight here! Once more frightened Gettysburg had anticipated a battle, once more its alarm had proved ridiculous. Early had gone days ago to York, the Union soldiers were marching toward Chambersburg. Thank God, John Bowman, her husband, was not a regular soldier, but a fifer in the brigade band. Members of the band, poor Mary thought, were safe, danger would not come nigh them. Besides, he was far away with Hooker's idle forces. No failure to give battle made Mary indignant, no reproaches of an inert general fell from her lips. She was passionately grateful that they did not fight.

It was only on dismal, rainy days, or when she woke at night and looked at her little children lying in their beds, that the vague, strange possibility of her husband's death occurred to her. Then she assured herself with conviction that God would not let him die. They were so happy, and they were just beginning to prosper. They had paid the last upon their little house before he went to war; now they meant to save money and to educate their children. By fall the war would be over, then John would come back and resume his school-teaching, and everything would be as it had been.

She went through the kitchen again and out to the front door, and looked down the street with its scattering houses. Opposite lived good-natured, strong-armed Hannah Casey; in the next house, a dozen rods away, the Deemer family. The Deemers had had great trouble, the father was at war and the two little children were ill with typhoid fever. In a little while she would go down and help. It was still early; perhaps the children and their tired nurses slept.

Beyond, the houses were set closer together, the Wilson house first, where a baby was watched for now each day, and next to it the McAtee house, where Grandma McAtee was dying. In that neighborhood, and a little farther on past the new court-house in the square, which Gettysburg called "The Diamond," men were moving about, some mounted, some on foot. Their presence did not disturb Mary, since Early had gone in one direction and the Union soldiers were going in the other. Probably the Union soldiers had come to town to buy food before they started on their march. She did not even think uneasily of the sick and dying; she said to herself that if the soldiers had wished to fight here, the good men of the village, the judge, the doctor, and the ministers would have gone forth to meet them and with accounts of the invalids would have persuaded them to stay away!

Over the tops of the houses, Mary could see the cupola of the Seminary lifting its graceful dome and slender pillars against the blue sky. She and her husband had always planned that one of their boys should go to the Seminary and learn to be a preacher; she remembered their hope now. Far beyond Seminary Ridge, the foothills of the Blue Ridge lay clear and purple in the morning sunshine. The sun, already high in the sky, was behind her; it stood over the tall, thick pines of the little cemetery where her kin lay, and where she herself would lie with her husband beside her. Except for that dim spot, the whole lovely landscape was unshadowed.

Suddenly she put out her hand to the pillar of the porch and called her neighbor:—

"Hannah!"

The door of the opposite house opened, and Hannah Casey's burly figure crossed the street. She had been working in her carefully tended garden and her face was crimson. Hannah Casey anticipated no battle.

"Good morning to you," she called. "What is it you want?"

"Come here," bade Mary Bowman.

The Irishwoman climbed the three steps to the little porch.

"What is it?" she asked again. "What is it you see?"

"Look!—Out there at the Seminary! You can see the soldiers moving about, like black specks under the trees!"

Hannah squinted a pair of near-sighted eyes in the direction of the Seminary.

"I'll take your word for it," she said.

With a sudden motion Mary Bowman lifted her hand to her lips.

"Early wouldn't come back!" she whispered. "He would never come back!"

Hannah Casey laughed a bubbling laugh.

"Come back? Those rag-a-bones? It 'ud go hard with them if they did. The Unionists wouldn't jump before 'em like the rabbits here. But I didn't jump! The Bateses fled once more for their lives, it's the seventeenth time they've saved their valuable commodities from the foe. Down the street they flew, their tin dishes and their precious chiny rattling in their wagon. 'Oh, my kind sir!' says Lillian to the raggedy man you fed,—'oh, my kind sir, I surrender!' 'You're right you do,' says he. 'We're goin' to eat you up!'—'Lady,' says that same snip to me, 'you'd better leave your home.' 'Worm!' says I back to him, 'you leave my home!' And you fed him, you soft-heart!"

"He ate like an animal," said Mary; "as though he had had nothing for days."

"And all the cave-dwellers was talkin' about divin' for their cellars. I wasn't goin' into no cellar. Here I stay, aboveground, till they lay me out for good."

Mary Bowman laughed suddenly, hysterically. She had laughed thus far through all the sorrows war had brought,—poverty, separation, anxiety. She might still laugh; there was no danger; Early had gone in one direction, the Union soldiers in the other.

"Did you see him dive into the apple-butter, Hannah Casey? His face was smeared with it. He couldn't wait till the biscuits were out of the oven. He—" She stopped and listened, frowning. She looked out once more toward the ridge with its moving spots, then down at the town with its larger spots, then back at the pines, standing straight and tall in the July sunshine. She could see the white tombstones beneath the trees.

"Listen!" she cried.

"To what?" demanded Hannah Casey.

For a few seconds the women stood silently. There were still the same faint, distant sounds, but they were not much louder, not much more numerous than could be heard in the village on any summer morning. A heart which dreaded ominous sound might have been set at rest by the peace and stillness.

Hannah Casey spoke irritably. "What do you hear?"

"Nothing," answered Mary Bowman. "But I thought I heard men marching. I believe it's my heart beating! I thought I heard them in the night. Could you sleep?"

"Like a log!" said Hannah Casey. "Sleep? Why, of course, I could sleep! Ain't our boys yonder? Ain't the Rebs shakin' in their shoes? No, they ain't. They ain't got no shoes. Ain't the Bateses, them barometers of war, still in their castle, ain't—"

"I slept the first part of the night," interrupted Mary Bowman. "Then it seemed to me I heard men marching. I thought perhaps they were coming through the town from the hill, and I looked out, but there was nothing stirring. It was the brightest night I ever saw. I—"

Again Hannah Casey laughed her mighty laugh. There were nearer sounds now, the rattle of a cart behind them, the gallop of hoofs before. Again the Bateses were coming, a family of eight crowded into a little springless wagon with what household effects they could collect. Hannah Casey waved her apron at them and went out to the edge of the street.

"Run!" she yelled. "Skedaddle! Murder! Help! Police!"

Neither her jeers nor Mary Bowman's laugh could make the Bateses turn their heads. Mrs. Bates held in her short arms a feather bed, her children tried to get under it as chicks creep under the wings of a mother hen. Down in front of the Deemer house they stopped suddenly. A Union soldier had halted them, then let them pass. He rode his horse up on the pavement and pounded with his sword at the Deemer door.

"He might terrify the children to death!" cried Mary Bowman, starting forward.

But already the soldier was riding toward her.

"There is sickness there!" she shouted to his unheeding ears; "you oughtn't to pound like that!"

"You women will have to stay in your cellars," he answered. "A battle is to be fought here."

"Here?" said Mary Bowman stupidly.

"Get out!" said Hannah Casey. "There ain't nobody here to fight with!"

The soldier rode his horse to Hannah Casey's door, and began to pound with his sword.

"I live there!" screamed Hannah. "You dare to bang that door!"

Mary Bowman crossed the street and looked up at him as he sat on his great horse.

"Oh, sir, do you mean that they will fight here?"

"I do."

"In Gettysburg?" Hannah Casey could scarcely speak for rage.

"In Gettysburg."

"Where there are women and children?" screamed Hannah. "And gardens planted? I'd like to see them in my garden, I—"

"Get into your cellars," commanded the soldier. "You'll be safe there."

"Sir!" Mary Bowman went still a little closer. The crisis in the Deemer house was not yet passed, even at the best it was doubtful whether Agnes Wilson could survive the hour of her trial, and Grandma McAtee was dying. "Sir!" said Mary Bowman, earnestly, ignorant of the sublime ridiculousness of her reminder, "there are women and children here whom it might kill."

The man laughed a short laugh.

"Oh, my God!" He leaned a little from his saddle. "Listen to me, sister! I have lost my father and two brothers in this war. Get into your cellars."

With that he rode down the street.

"He's a liar," cried Hannah Casey. She started to run after him. "Go out to Peterson's field to do your fighting," she shouted furiously. "Nothing will grow there! Go out there!"

Then she stopped, panting.

The soldier took time to turn and grin and wave his hand.

"He's a liar," declared Hannah Casey once more. "Early's went. There ain't nothing to fight with."

Still scolding, she joined Mary Bowman on her porch. Mary Bowman stood looking through the house at her children, playing in the little field. They still played quietly; it seemed to her that they had never ceased to miss their father.

Then Mary Bowman looked down the street. In the Diamond the movement was more rapid, the crowd was thicker. Women had come out to the doorsteps, men were hurrying about. It seemed to Mary that she heard Mrs. Deemer scream. Suddenly there was a clatter of hoofs; a dozen soldiers, riding from the town, halted and began to question her. Their horses were covered with foam; they had come at a wild gallop from Seminary Ridge.

"This is the road to Baltimore?"

"Yes."

"Straight ahead?"

"Yes."

Gauntleted hands lifted the dusty reins.

"You'd better protect yourself! There is going to be a battle."

"Here?" asked Mary Bowman again stupidly.

"Right here."

Hannah Casey thrust herself between them.

"Who are you goin' to fight with, say?"

The soldiers grinned at her. They were already riding away.

"With the Turks," answered one over his shoulder.

Another was kinder, or more cruel.

"Sister!" he explained, "it is likely that two hundred thousand men will be engaged on this spot. The whole Army of Northern Virginia is advancing from the north, the whole Army of the Potomac is advancing from the south, you—"

The soldier did not finish. His galloping comrades had left him, he hastened to join them. After him floated another accusation of lying from the lips of Hannah Casey. Hannah was irritated because the Bateses were right.

"Hannah!" said Mary Bowman thickly. "I told you how I dreamed I heard them marching. It was as though they came in every road, Hannah, from Baltimore and Taneytown and Harrisburg and York. The roads were full of them, they were shoulder against shoulder, and their faces were like death!"

Hannah Casey grew ghastly white. Superstition did what common sense and word of man could not do.

"So you did!" she whispered; "so you did!"

Mary Bowman clasped her hands and looked about her, down the street, out toward the Seminary, back at the grim trees. The little sounds had died away; there was now a mighty stillness.

"He said the whole Army of the Potomac," she repeated. "John is in the Army of the Potomac."

"That is what he said," answered the Irishwoman.

"What will the Deemers do?" cried Mary Bowman. "And the Wilsons?"

"God knows!" said Hannah Casey.

Suddenly Mary Bowman lifted her hands above her head.

"Look!" she screamed.

"What?" cried Hannah Casey. "What is it?"

Mary Bowman went backwards toward the door, her eyes still fixed on the distant ridge, as though they could not be torn away. It was nine o'clock; a shrill little clock in the house struck the hour.

"Children!" called Mary Bowman. "Come! See!"

The children dropped the little sticks with which they played and ran to her.

"What is it?" whined Hannah Casey.

Mary Bowman lifted the little boy to her shoulder. A strange, unaccountable excitement possessed her, she hardly knew what she was doing. She wondered what a battle would be like. She did not think of wounds, or of blood or of groans, but of great sounds, of martial music, of streaming flags carried aloft. She sometimes dreamed that her husband, though he had so unimportant a place, might perform some great deed of valor, might snatch the colors from a wounded bearer, and lead his regiment to victory upon the field of battle. And now, besides, this moment, he was marching home! She never thought that he might die, that he might be lost, swallowed up in the yawning mouth of some great battle-trench; she never dreamed that she would never see him again, would hunt for him among thousands of dead bodies, would have her eyes filled with sights intolerable, with wretchedness unspeakable, would be tortured by a thousand agonies which she could not assuage, torn by a thousand griefs beside her own. She could not foresee that all the dear woods and fields which she loved, where she had played as a child, where she had picnicked as a girl, where she had walked with her lover as a young woman, would become, from Round Top to the Seminary, from the Seminary to Culp's Hill, a great shambles, then a great charnel-house. She lifted the little boy to her shoulder and held him aloft.

"See, darling!" she cried. "See the bright things sparkling on the hill!"

"What are they?" begged Hannah Casey, trying desperately to see.

"They are bayonets and swords!"

She put the little boy down on the floor, and looked at him. Hannah Casey had clutched her arm.

"Hark!" said Hannah Casey.

Far out toward the shining cupola of the Seminary there was a sharp little sound, then another, and another.

"What is it?" shrieked Hannah Casey. "Oh, what is it?"

"What is it!" mocked Mary Bowman. "It is—"

A single, thundering, echoing blast took the words from Mary Bowman's lips.

Stupidly, she and Hannah Casey looked at one another.

Parsons knew little of the great wave of protest that swept over the Army of the Potomac when Hooker was replaced by Meade. The sad depression of the North, sick at heart since December, did not move him; he was too thoroughly occupied with his own sensations. He sat alone, when his comrades would leave him alone, brooding, his terror equally independent of victory or defeat. The horror of war appalled him. He tried to reconstruct the reasons for his enlisting, but found it impossible. The war had made of him a stranger to himself. He could scarcely visualize the little farm that he had left, or his mother. Instead of the farm, he saw corpse-strewn fields; instead of his mother, the mutilated bodies of young men. His senses seemed unable to respond to any other stimuli than those of war. He had not been conscious of the odors of the sweet Maryland spring, or of the song of mocking-birds; his nostrils were full of the smell of blood, his ears of the cries of dying men.

Worse than the recollection of what he had seen were the forebodings that filled his soul. In a day—yes, an hour, for the rumors of coming battle forced themselves to his unwilling ears—he might be as they. Presently he too would lie, staring, horrible, under the Maryland sky.

The men in his company came gradually to leave him to himself. At first they thought no less of him because he was afraid. They had all been afraid. They discussed their sensations frankly as they sat round the camp-fire, or lay prone on the soft grass of the fields.

"Scared!" laughed the oldest member of the company, who was speaking chiefly for the encouragement of Parsons, whom he liked. "My knees shook, and my chest caved in. Every bullet killed me. But by the time I'd been dead about forty times, I saw the Johnnies, and something hot got into my throat, and I got over it."

"And weren't you afraid afterwards?" asked Parsons, trying to make his voice sound natural.

"No, never."

"But I was," confessed another man. His face was bandaged, and blood oozed through from the wound that would make him leer like a satyr for the rest of his life. "I get that way every time. But I get over it. I don't get hot in my throat, but my skin prickles."

Young Parsons walked slowly away, his legs shaking visibly beneath him.

Adams turned on his side and watched him.

"Got it bad," he said shortly. Then he lay once more on his back and spread out his arms. "God, but I'm sick of it! And if Lee's gone into Pennsylvania, and we're to chase him, and old Joe's put out, the Lord knows what'll become of us. I bet you a pipeful of tobacco, there ain't one of us left by this time next week. I bet you—"

The man with the bandaged face did not answer. Then Adams saw that Parsons had come back and was staring at him.

"Ain't Hooker in command no more?" he asked.

"No; Meade."

"And we're going to Pennsylvania?"

"Guess so." Adams sat upright, the expression of kindly commiseration on his face changed to one of disgust. "Brace up, boy. What's the matter with you?"

Parsons sat down beside him. His face was gray; his blue eyes, looking out from under his little forage-cap, closed as though he were swooning.

"I CAN'T STAND IT," HE SAID THICKLY

"I can't stand it," he said thickly. "I can see them all day, and hear them all night, all the groaning—I—"

The old man pulled from his pocket a little bag. It contained his last pipeful of tobacco, the one that he had been betting.

"Take that. You got to get such things out of your head. It won't do. The trouble with you is that ever since you've enlisted, this company's been hanging round the outside. You ain't been in a battle. One battle'll cure you. You got to get over it."

"Yes," repeated the boy. "I got to get over it."

He lay down beside Adams, panting. The moon, which would be full in a few days, had risen; the sounds of the vast army were all about them—the click of tin basin against tin basin, the stamping of horses, the oaths and laughter of men. Some even sang. The boy, when he heard them, said, "Oh, God!" It was his one exclamation. It had broken from his lips a thousand times, not as a prayer or as an imprecation, but as a mixture of both. It seemed the one word that could represent the indescribable confusion of his mind. He said again, "Oh, God! Oh, God!"

It was not until two days later, when they had been for hours on the march, that he realized that they were approaching the little Pennsylvania town where he lived. He had been marching almost blindly, his eyes nearly closed, still contemplating his own misery and fear. He could not discuss with his comrades the next day's prospects, he did not know enough about the situation to speculate. Adams's hope that there would be a battle brought to his lips the familiar "Oh, God!" He had begun to think of suicide.

It was almost dark once more when they stumbled into a little town. Its streets, washed by rains, had been churned to thick red mud by thousands of feet and wheels. The mud clung to Parsons's worn shoes; it seemed to his half-crazy mind like blood. Then, suddenly, his gun dropped with a wild clatter to the ground.

"It's Taneytown!" he called wildly. "It's Taneytown."

Adams turned upon him irritably. He was almost too tired to move.

"What if it is Taneytown?" he thundered. "Pick up your gun, you young fool."

"But it's only ten miles from home!"

The shoulder of the man behind him sent Parsons sprawling. He gathered himself up and leaped into his place by Adams's side. His step was light.

"Ten miles from home! We're only ten miles from home!"—he said it as though the evil spirits which had beset him had been exorcised. He saw the little whitewashed farmhouse, the yellowing wheat-fields beside it; he saw his mother working in the garden, he heard her calling.

Presently he began to look furtively about him. If he could only get away, if he could get home, they could never find him. There were many places where he could hide, holes and caverns in the steep, rough slopes of Big Round Top, at whose foot stood his mother's little house. They could never find him. He began to speak to Adams tremulously.

"When do you think we'll camp?"

Adams answered him sharply.

"Not to-night. Don't try any running-away business, boy. 'Tain't worth while. They'll shoot you. Then you'll be food for crows."

The boy moistened his parched lips.

"I didn't say anything about running away," he muttered. But hope died in his eyes.

It did not revive when, a little later, they camped in the fields, trampling the wheat ready for harvest, crushing down the corn already waist-high, devouring their rations like wolves, then falling asleep almost on their feet.

Well indeed might they sleep heavily, dully, undisturbed by cry of picket or gallop of returning scout. The flat country lay clear and bright in the moonlight; to the north-west they could almost see the low cone of Big Round Top, to which none then gave a thought, not even Parsons himself, who lay with his tanned face turned up toward the sky. Once his sunken eyes opened, but he did not remember that now, if ever, he must steal away, over his sleeping comrades, past the picket-line, and up the long red road toward home. He thought of home no more, nor of fear; he lay like a dead man.

It was a marvelous moonlit night. All was still as though round Gettysburg lay no vast armies, seventy thousand Southerners to the north, eighty-five thousand Northerners to the south. They lay or moved quietly, like great octopi, stretching out, now and then, grim tentacles, which touched or searched vainly. They knew nothing of the quiet, academic town, lying in its peaceful valley away from the world for which it cared little. Mere chance decreed that on the morrow its name should stand beside Waterloo.

Parsons whimpered the next morning when he heard the sound of guns. He knew what would follow. In a few hours the firing would cease; then they would march, wildly seeking an enemy that seemed to have vanished, or covering the retreat of their own men; and there would be once more all the ghastly sounds and cries. But the day passed, and they were still in the red fields.

It was night when they began to march once more. All day the sounds of firing had echoed faintly from the north, bringing fierce rage to the hearts of some, fear to others, and dread unspeakable to Parsons. He did not know how the day passed. He heard the guns, he caught glimpses now and then of messengers galloping to headquarters; he sat with bent head and staring eyes. Late in the afternoon the firing ceased, and he said over and over again, "Oh, God, don't let us go that way! Oh, God, don't let us go that way!" He did not realize that the noise came from the direction of Gettysburg, he did not comprehend that "that way" meant home, he felt no anxiety for the safety of his mother; he knew only that, if he saw another dead or dying man, he himself would die. Nor would his death be simply a growing unconsciousness; he would suffer in his body all the agony of the wounds upon which he looked.

The great octopus of which he was a part did not feel in the least the spark of resistance in him, one of the smallest of the particles that made up its vast body. When the moon had risen, he was drawn in toward the centre with the great tentacle to which he belonged. The octopus suffered; other vast arms were bleeding and almost severed. It seemed to shudder with foreboding for the morrow.

Round Top grew clear before them as they marched. The night was blessedly cool and bright, and they went as though by day, but fearfully, each man's ears strained to hear. It was like marching into the crater of a volcano which, only that afternoon, had been in fierce eruption. It was all the more horrible because now they could see nothing but the clear July night, hear nothing but the soft sounds of summer. There was not even a flag of smoke to warn them.

They caught, now and again, glimpses of men hiding behind hedge-rows, then hastening swiftly away.

"Desertin'," said Adams grimly.

"What did you say?" asked Parsons.

He had heard distinctly enough, but he longed for the sound of Adams's voice. When Adams repeated the single word, Parsons did not hear. He clutched Adams by the arm.

"You see that hill, there before us?"

"Yes."

"Gettysburg is over that hill. There's the cemetery. My father's buried there."

Adams looked in under the tall pines. He could see the white stones standing stiffly in the moonlight.

"We're goin' in there," he said. "Keep your nerve up there, boy."

Adams had seen other things besides the white tombstones, things that moved faintly or lay quietly, or gave forth ghastly sounds. He was conscious, by his sense of smell, of the army about him and of the carnage that had been.

Parsons, strangely enough, had neither heard nor smelled. A sudden awe came upon him; the past returned: he remembered his father, his mother's grief at his death, his visits with her to the cemetery. It seemed to him that he was again a boy stealing home from a day's fishing in Rock Creek, a little fearful as he passed the cemetery gate. He touched Adams's arm shyly before he began to sling off his knapsack and to lie down as his comrades were doing all about him.

"That is my father's grave," he whispered.

Then, before the kindly answer sprang from Adams's lips, a gurgle came into Parsons's throat as though he were dying. One of the apparitions that Adams had seen lifted itself from the grass, leaving behind dark stains. The clear moonlight left no detail of the hideous wounds to the imagination.

"Parsons!" cried Adams sharply.

But Parsons had gone, leaping over the graves, bending low by the fences, dashing across an open field, then losing himself in the woodland. For a moment Adams's eyes followed him, then he saw that the cemetery and the outlying fields were black with ten thousand men. It would be easy for Parsons to get away.

"No hope for him," he said shortly, as he set to work to do what he could for the maimed creature at his feet. Dawn, he knew, must be almost at hand; he fancied that the moonlight was paling. He was almost crazy for sleep, sleep that he would need badly enough on the morrow, if he were any prophet of coming events.

Parsons, also, was aware of the tens of thousands of men about him, to him they were dead or dying men. He staggered as he ran, his feet following unconsciously the path that took him home from fishing, along the low ridge, past scattered farmhouses, toward the cone of Round Top. It seemed to him that dead men leaped at him and tried to stop him, and he ran ever faster. Once he shrieked, then he crouched in a fence-corner and hid. He would have been ludicrous, had the horrors from which he fled been less hideous.

He, too, felt the dawn coming, as he saw his mother's house. He sobbed like a little child, and, no longer keeping to the shade, ran across the open fields. There were no dead men here, thank God! He threw himself frantically at the door, and found it locked. Then he drew from the window the nail that held it down, and crept in. He was ravenously hungry, and his hands made havoc in the familiar cupboard. He laughed as he found cake, and the loved "drum-sticks" of his childhood.

He did not need to slip off his shoes for fear of waking his mother, for the shoes had no soles; but he stooped down and removed them with trembling hands. Then a great peace seemed to come into his soul. He crept on his hands and knees past his mother's door, and climbed to his own little room under the eaves, where, quite simply, as though he were a little boy, and not a man deserting from the army on the eve of a battle, he said his prayers and went to bed.

When he awoke, it was late afternoon. He thought at first that he had been swinging, and had fallen; then he realized that he still lay quietly in his bed. He stretched himself, reveling in the blessed softness, and wondering why he felt as though he had been brayed in a mortar. Then a roar of sound shut out possibility of thought. The little house shook with it. He covered his ears, but he might as well have spared himself his pains. That sound could never be shut out, neither then, nor for years afterward, from the ears of those who heard it. There were many who would hear no other sound forevermore. The coward began again his whining, "Oh, God! Oh, God!" His nostrils were full of smoke; he could smell already the other ghastly odors that would follow. He lifted himself from his bed, and, hiding his eyes from the window, felt his way down the steep stairway. He meant, God help him! to go and hide his face in his mother's lap. He remembered the soft, cool smoothness of her gingham apron.

Gasping, he staggered into her room. But his mother was not there. The mattress and sheets from her bed had been torn off; one sheet still trailed on the floor. He picked it up and shook it. He was imbecile enough to think she might be beneath it.

"Mother!" he shrieked "Mother! Mother!" forgetting that even in that little room she could not have heard him. He ran through the house, shouting. Everywhere it was the same—stripped beds, cupboards flung wide, the fringe of torn curtains still hanging. His mother was not there.

His terror drove him finally to the window overlooking the garden. It was here that he most vividly remembered her, bending over her flower-beds, training the tender vines, pulling weeds. She must be here. In spite of the snarl of guns, she must be here. But the garden was a waste, the fence was down. He saw only the thick smoke beyond, out of which crept slowly toward him half a dozen men with blackened faces and blood-stained clothes, again his dead men come to life. He saw that they wore his own uniform, but the fact made little impression upon him. Was his mother dead? Had she been killed yesterday, or had they taken her away last night or this morning while he slept? He saw that the men were coming nearer to the house, creeping slowly on through the thick smoke. He wondered vaguely whether they were coming for him as they had come for his mother. Then he saw, also vaguely, on the left, another group of men, stealing toward him, men who did not wear his uniform, but who walked as bravely as his own comrades.

He knew little about tactics, and his brain was too dull to realize that the little house was the prize they sought. It was marvelous that it had remained unpossessed so long, when a tiny rock or a little bush was protection for which men struggled. The battle had surged that way; the little house was to become as famous as the Peach Orchard or the Railroad Cut, it was to be the "Parsons House" in history. Of this Parsons had no idea; he only knew, as he watched them, that his mother was gone, his house despoiled.

Then, suddenly, rage seized upon him, driving out fear. It was not rage with the men in gray, creeping so steadily upon him—he thought of them as men like himself, only a thousand times more brave—it was rage with war itself, which drove women from their homes, which turned young men into groaning apparitions. And because he felt this rage, he too must kill. He knelt down before the window, his gun in his hand. He had carried it absently with him the night before, and he had twenty rounds of ammunition. He took careful aim: his hand, thanks to his mother's food and his long sleep, was quite steady; and he pulled the trigger.

At first, both groups of men halted. The shot had gone wide. They had seen the puff of smoke, but they had no way of telling whether it was friend or foe who held the little house. There was another puff, and a man in gray fell. The men in blue hastened their steps, even yet half afraid, for the field was broad, and to cross it was madness unless the holders of the house were their own comrades. Another shot went wide, another man in gray dropped, and another, and the men in blue leaped on, yelling. Not until then did Parsons see that there were more than twice as many men in gray as men in blue. The men in gray saw also, and they, too, ran. The little house was worth tremendous risks. Another man bounded into the air and rolled over, blood spurting from his mouth, and the man behind him stumbled over him. There were only twelve now. Then there were eleven. But they came on—they were nearer than the men in blue. Then another fell, and another. It seemed to Parsons that he could go on forever watching them. He smiled grimly at the queer antics that they cut, the strange postures into which they threw themselves. Then another fell, and they wavered and turned. One of the men in blue stopped at the edge of the garden to take deliberate aim, but Parsons, grinning, also leveled his gun once more. He wondered, a little jealously, which of them had killed the man in gray.

The six men, rushing in, would not believe that he was there alone. They looked at him, admiringly, grim, bronzed as they were, the veterans of a dozen battles. They did not think of him for an instant as a boy; his eyes were the eyes of a man who had suffered and who had known the hot pleasures of revenge. It was he who directed them now in fortifying the house, he who saw the first sign of the creeping Confederates making another sally from the left, he who led them into the woods when, reinforced by a hundred of their comrades, they used the little house only as a base toward which to retreat. They had never seen such fierce rage as his. The sun sank behind the Blue Ridge, and he seemed to regret that the day of blood was over. He was not satisfied that they held the little house; he must venture once more into the dark shadows of the woodland.

From there his new-found comrades dragged him helpless. His enemies, powerless against him by day, had waited until he could not see them. His comrades carried him into the house, where they had made a dim light. The smoke of battle seemed to be lifting; there was still sharp firing, but it was silence compared to what had been, peace compared to what would be on the morrow.

They laid him on the floor of the little kitchen, and looked at the wide rent in his neck, and lifted his limp arm, not seeing that a door behind them had opened quietly, and that a woman had come up from the deep cellar beneath the house. There was not a cellar within miles that did not shelter frightened women and children. Parsons's mother, warned to flee, had gone no farther. She appeared now, a ministering angel. In her cellar was food in plenty; there were blankets, bandages, even pillows for bruised and aching heads. Heaven grant that some one would thus care for her boy in the hour of his need!

The men watched Parsons's starting eyes, thinking they saw death. They would not have believed that it was Fear that had returned upon him, their brave captain. They would have said that he never could have been afraid. He put his hand up to his torn throat. His breath came in thick gasps. He muttered again, "Oh, God! Oh, God!"

Then, suddenly, incomprehensibly to the men who did not see the gracious figure behind them, peace ineffable came into his blue eyes.

"Why, mother!" he said softly.

1. From the narrative of Colonel Frank Aretas Haskell, Thirty-sixth Wisconsin Infantry. While aide-de-camp to General Gibbon he was largely instrumental in saving the day at Gettysburg to the Union forces. His brilliant story of the battle is contained in a series of letters written to his brother soon after the contest.

Sitting his horse easily in the stone-fenced field near the rounded clump of trees on the hot noon of the third day of battle, his heart leaping, sure of the righteousness of his cause, sure of the overruling providence of God, experienced in war, trained to obedience, accustomed to command, the young officer looked about him.

To his right and left and behind him, from Culp's Hill to Round Top, lay the Army of the Potomac, the most splendid army, in his opinion, which the world had ever seen, an army tried, proved, reliable in all things. The first day's defeat, the second day's victory, were past; since yesterday the battle-lines had been re-formed; upon them the young man looked with approval, thanking Heaven for Meade. The lines were arranged, except here in the very centre near this rounded clump of trees where he waited, as he would have arranged them himself, conformably to the ground, batteries in place, infantry—there a double, here a single line—to the front. There had been ample time for such re-formation during the long, silent morning. Now each man was in his appointed place, munition-wagons and ambulances waited, regimental flags streamed proudly; everywhere was order, composure. The laughter and joking which floated to the ears of the young officer betokened also minds composed, at ease. Yesterday twelve thousand men had been killed or wounded upon this field; the day before yesterday, eleven thousand; to-day, this afternoon, within a few hours, eight thousand more would fall. Yet, lightly, their arms stacked, men laughed, and the young officer heard them with approval.

Opposite, on another ridge, a mile away, Lee's army waited. They, too, were set out in brave array; they, too, had re-formed; they, too, seemed to have forgotten yesterday, to have closed their eyes to to-morrow. From the rounded clump of trees, the young officer could look across the open fields, straight to the enemy's centre. Again he wished for a double line of troops here about him. But Meade alone had power to place them there.

The young officer was cultivated, college-bred, with the gift of keen observation, of vivid expression. The topography of that varied country was already clear to him; he was able to draw a sketch of it, indicating its steep hills, its broad fields, its tracts of virgin woodland, the "wave-like" crest upon which he now stood. He could not have written so easily during the marches of the succeeding weeks if he had not now, in the midst of action, begun to fit words to what he saw. He watched Meade ride down the lines, his face "calm, serious, earnest, without arrogance of hope or timidity of fear." He shared with his superiors in a hastily prepared, delicious lunch, eaten on the ground; he recorded it with humorous impressions of these great soldiers.

The evening before he had attended them in their council of war; he has made it as plain to us as though we, too, had been inside that little farmhouse. It is a picture in which Rembrandt would have delighted,—the low room, the little table with its wooden water-pail, its tin cup, its dripping candle. We can see the yellow light on blue sleeves, on soft, slouched, gilt-banded hats, on Gibbon's single star. Meade, tall, spare, sinewy; Sedgwick, florid, thick-set; young Howard with his empty sleeve; magnificent Hancock,—of all that distinguished company the young officer has drawn imperishable portraits.

He heard their plans, heard them decide to wait until the enemy had hurled himself upon them; he said with satisfaction that their heads were sound. He recorded also that when the council was over and the chance for sleep had come, he could hardly sit his horse for weariness, as he sought his general's headquarters in the sultry, starless midnight. Yet, now, in the hot noon of the third day, as he dismounted and threw himself down in the shade, he remembered the sound of the moving ambulances, the twinkle of their unsteady lamps.

Lying prone, his hat tilted over his eyes, he smiled drowsily. It was impossible to tell at what moment battle would begin, but now there was infinite peace everywhere. The young men of his day loved the sounding poetry of Byron; it is probable that he thought of the "mustering squadron," of the "marshaling in arms," of "battle's magnificently-stern array." Trained in the classics he must have remembered lines from other glorious histories. "Stranger," so said Leonidas, "stranger, go tell it in Lacedæmon that we died here in defense of her laws." "The glory of Miltiades will not let me sleep!" cried the youth of Athens. A line of Virgil the young officer wrote down afterwards in his account, thinking of weary marches: "Forsan et hæc olim meminisse juvabit."—"Perchance even these things it will be delightful hereafter to remember."

Thus while he lay there, the noon droned on. Having hidden their wounds, ignoring their losses, having planted their guidons and loaded their guns, the thousands waited.

Still dozing, the young officer looked at his watch. Once more he thought of the centre and wished that it were stronger; then he stretched out his arms to sleep. It was five minutes of one o'clock. Near him his general rested also, and with them both time moved heavily.

Drowsily he closed his eyes, comfortably he lay. Then, suddenly, at a distinct, sharp sound from the enemy's line he was awake, on his feet, staring toward the west. Before his thoughts were collected, he could see the smoke of the bursting shell; before he and his fellow officers could spring to their saddles, before they could give orders, the iron rain began about the low, wave-like crest. The breast of the general's orderly was torn open, he plunged face downward, the horses which he held galloped away. Not an instant passed after that first shot before the Union guns answered, and battle had begun.

It opened without fury, except the fury of sound, it proceeded with dignity, with majesty. There was no charge; that fierce, final onrush was yet hours away; the little stone wall near that rounded clump of trees, over which thousands would fight, close-pressed like wrestlers, was to be for a long time unstained by blood. The Confederate aggressor, standing in his place, delivered his hoarse challenge; his Union antagonist standing also in his place, returned thunderous answer. The two opposed each other—if one may use for passion so terrible this light comparison—at arm's length, like fencers in a play.

The business of the young officer was not with these cannon, but with the infantry, who, crouching before the guns, hugging the ground, were to bide their time in safety for two hours. Therefore, sitting on his horse, he still fitted words to his thoughts. The conflict before him is not a fight for men, it is a fight for mighty engines of war; it is not a human battle, it is a storm, far above earthly passion. "Infuriate demons" are these guns, their mouths are ablaze with smoky tongues of livid fire, their breath is murky, sulphur-laden; they are surrounded by grimy, shouting, frenzied creatures who are not their masters but their ministers. Around them rolls the smoke of Hades. To their sound all other cannonading of the young officer's experience was as a holiday salute. Solid shot shattered iron of gun and living trunk of tree. Shot struck also its intended target: men fell, torn, mangled; horses started, stiffened, crashed to the ground, or rushed, maddened, away.

Still there was nothing for the young officer to do but to watch. Near him a man crouched by a stone, like a toad, or like pagan worshiper before his idol. The young officer looked at him curiously.

"Go to your regiment and be a man!" he ordered.

But the man did not stir, the shot which splintered the protecting stone left him still kneeling, still unhurt. To the young officer he was one of the unaccountable phenomena of battle, he was incomprehensible, monstrous.

He noted also the curious freaks played by round shot, the visible flight of projectiles through the air, their strange hiss "with sound of hot iron, plunged into water." He saw ambulances wrecked as they moved along; he saw frantic horses brought down by shells; he calls them "horse-tamers of the upper air." He saw shells fall into limber-boxes, he heard the terrific roar which followed louder than the roar of guns; he observed the fall of officer, of orderly, of private soldier.

After the first hour of terrific din, he rode with his general down the line. The infantry still lay prone upon the ground, out of range of the missiles. The men were not suffering and they were quiet and cool. They professed not to mind the confusion; they claimed laughingly to like it.

From the shelter of a group of trees the young officer and his general watched in silence. For that "awful universe of battle," it seemed now that all other expressions were feeble, mean. The general expostulated with frightened soldiers who were trying to hide near by. He did not reprove or command, he reminded them that they were in the hands of God, and therefore as safe in one place as another. He assured his young companion of his own faith in God.

Slowly, after an hour and a half, the roar of battle abated, and the young officer and his general made their way back along the line. By three o'clock the great duel was over; the two hundred and fifty guns, having been fired rapidly for two hours, seemed to have become mortal, and to suffer a mortal's exhaustion. Along the crest, battery-men leaned upon their guns, gasped, and wiped the grime and sweat from their faces.

Again there was deep, ominous silence. Of the harm done on the opposite ridge they could know nothing with certainty. They looked about, then back at each other questioningly. Here disabled guns were being taken away, fresh guns were being brought up. The Union lines had suffered harm, but not irreparable harm. That centre for which the young officer had trembled was still safe. Was the struggle over? Would the enemy withdraw? Had yesterday's defeat worn him out; was this great confusion intended to cover his retreat? Was it—

Suddenly, madly, the young officer and his general flung themselves back into their saddles, wildly they galloped to the summit of that wave-like crest.

What they saw there was incredible, yet real; it was impossible, yet it was visible. How far had the enemy gone in the retreat which they suspected? The enemy was at hand. What of their speculations about his withdrawal, of their cool consideration of his intention? In five minutes he would be upon them. From the heavy smoke he issued, regiment after regiment, brigade after brigade, his front half a mile broad, his ranks shoulder to shoulder, line supporting line. His eyes were fixed upon that rounded clump of trees, his course was directed toward the centre of that wave-like crest. He was eighteen thousand against six thousand; should his gray mass enter, wedge-like, the Union line, yesterday's Union victories, day before yesterday's Union losses would be in vain.

To the young officer, enemies though they were, they seemed admirable. They had but one soul; they would have been, under a less deadly fire, opposed by less fearful odds, an irresistible mass. Before them he saw their galloping officers, their scarlet flags; he discerned their gun-barrels and bayonets gleaming in the sun.

His own army was composed also; it required no orders, needed no command; it knew well what that gray wall portended. He heard the click of gun-locks, the clang of muskets, raised to position upon the stone wall, the clink of iron axles, the words of his general, quiet, calm, cool.

"Do not hurry! Let them come close! Aim low and steadily!"

There came to him a moment of fierce rapture. He saw the color-sergeant tipping his lance toward the enemy; he remembered that from that glorious flag, lifted by the western breeze, these advancing hosts would filch half its stars. With bursting heart, blessing God who had kept him loyal, he determined that this thing should not be.

He was sent to Meade to announce the coming of the foe; he returned, galloping along the crest. Into that advancing army the Union cannon poured shells; then, as the range grew shorter, shrapnel; then, canister; and still the hardy lines moved on. There was no charging shout, there was still no confusion, no halt under that raking fire. Stepping over the bodies of their friends, they continued to advance, they raised their muskets, they fired. There was now a new sound, "like summer hail upon the city roofs."

The young officer searched for his general, and could not find him. He had been mounted; now, probably wounded, possibly killed, he was down from his horse.

Then, suddenly, once more, the impossible, the incredible became possible, real. The young officer had not dreamed that the Confederates would be able to advance to the Union lines; his speculation concerned only the time they would be able to stand the Union fire. But they have advanced, they are advancing still farther. And there in that weak centre—he cannot trust his own vision—men are leaving the sheltering wall; without order or reason, a "fear-stricken flock of confusion," they are falling back. The fate of Gettysburg, it seemed to his horrified eyes, hung by a spider's single thread.

"A great, magnificent passion"—thus in his youthful emotion he describes it—came upon the young man. Danger had seemed to him throughout a word without meaning. Now, drawing his sword, laying about with it, waving it in the air, shouting, he rushed upon this fear-stricken flock, commanded it, reproached it, cheered it, urged it back. Already the red flags had begun to thicken and to flaunt over the deserted spot; they were to him, he wrote afterwards, like red to a maddened bull. That portion of the wall was lost; he groaned for the presence of Gibbon, of Hays, of Hancock, of Doubleday, but they were engaged, or they were too far away. He rushed hither and yon, still beseeching, commanding, praying that troops be sent to that imperiled spot.

Then, in joy which was almost insanity, he saw that gray line begin to waver and to break. Tauntingly he shouted, fiercely his men roared; than their mad yells no Confederate "Hi-yi" was ever more ferocious. This repelling host was a new army, sprung Phœnix-like from the body of the old; to him its eyes seemed to stream lightning, it seemed to shake its wings over the yet glowing ashes of its progenitor. He watched the jostling, swaying lines, he saw them boil and roar, saw them dash their flamy spray above the crest like two hostile billows of a fiery ocean.

Once more commands are few, men do not heed them. Clearly once more they see their duty, magnificently they obey. This is war at the height of its passion, war at the summit of its glory. A color-sergeant rushed to the stone wall, there he fell; eagerly at once his comrades plunged forward. There was an instant of fierce conflict, of maddening, indistinguishable confusion. Men wrestled with one another, opposed one another with muskets used as clubs, tore at each other like wolves, until spent, exhausted, among heaps of dead, the conquered began to give themselves up. Back and forth over twenty-five square miles they had fought, for three interminable days. Here on this little crest, by this little wall, the fight was ended. Here the high-water mark was reached, here the flood began its ebb. Laughing, shouting, "so that the deaf could have seen it in their faces, the blind have heard it in their voices," the conquerors proclaimed the victory. Thank God, the crest is safe!

Are men wounded and broken by the thousands, do they lie in burning thirst, pleading for water, pleading for the bandaging of bleeding arteries, pleading for merciful death? The conquerors think of none of these things. Is night coming, are long marches coming? Still the conquerors shout like mad. Is war ended by this mammoth victory? For months and months it will drag on. Is this conquered foe a stranger, will he now withdraw to a distant country? He is our brother, his ills are ours, these wounds which we have given, we shall feel ourselves for fifty years. Is this brave young officer to enjoy the reward of his great courage, to live in fame, to be honored by his countrymen? At Cold Harbor he is to perish with a bullet in his forehead. Is not all this business of war mad?

It is a feeble, peace-loving, fireside-living generation which asks such questions as these.

Now, thank God, the crest is safe!

Mercifully, Mary Bowman, a widow, whose husband had been missing since the battle of Gettysburg, had been warned, together with the other citizens of Gettysburg, that on Thursday the nineteenth of November, 1863, she would be awakened from sleep by a bugler's reveillé, and that during that great day she would hear again dread sound of cannon.

Nevertheless, hearing again the reveillé, she sat up in bed with a scream and put her hands over her ears. Then, gasping, groping about in her confusion and terror, she rose and began to dress. She put on a dress which had been once a bright plaid, but which now, having lost both its color and the stiff, out-standing quality of the skirts of '63, hung about her in straight and dingy folds. It was clean, but it had upon it certain ineradicable brown stains on which soap and water seemed to have had no effect. She was thin and pale, and her eyes had a set look, as though they saw other sights than those directly about her.

In the bed from which she had risen lay her little daughter; in a trundle-bed near by, her two sons, one about ten years old, the other about four. They slept heavily, lying deep in their beds, as though they would never move. Their mother looked at them with her strange, absent gaze; then she barred a little more closely the broken shutters, and went down the stairs. The shutters were broken in a curious fashion. Here and there they were pierced by round holes, and one hung from a single hinge. The window-frames were without glass, the floor was without carpet, the beds without pillows.

In her kitchen Mary Bowman looked about her as though still seeing other sights. Here, too, the floor was carpetless. Above the stove a patch of fresh plaster on the wall showed where a great rent had been filled in; in the doors were the same little round holes as in the shutters of the room above. But there was food and fuel, which was more than one might have expected from the aspect of the house and its mistress. She opened the shattered door of the cupboard, and, having made the fire, began to prepare breakfast.

Outside the house there was already, at six o'clock, noise and confusion. Last evening a train from Washington had brought to the village Abraham Lincoln; for several days other trains had been bringing less distinguished guests, until thousands thronged the little town. This morning the tract of land between Mary Bowman's house and the village cemetery was to be dedicated for the burial of the Union dead, who were to be laid there in sweeping semicircles round a centre on which a great monument was to rise.

But of the dedication, of the President of the United States, of his distinguished associates, of the great crowds, of the soldiers, of the crape-banded banners, Mary Bowman and her children would see nothing. Mary Bowman would sit in her little wrecked kitchen with her children. For to her the President of the United States and others in high places who prosecuted war or who tolerated war, who called for young men to fight, were hateful. To Mary Bowman the crowds of curious persons who coveted a sight of the great battle-fields were ghouls; their eyes wished to gloat upon ruin, upon fragments of the weapons of war, upon torn bits of the habiliments of soldiers; their feet longed to sink into the loose ground of hastily made graves; the discovery of a partially covered body was precious to them.

Mary Bowman knew that field! From Culp's Hill to the McPherson farm, from Big Round Top to the poorhouse, she had traveled it, searching, searching, with frantic, insane disregard of positions or of possibility. Her husband could not have fallen here among the Eleventh Corps, he could not lie here among the unburied dead of the Louisiana Tigers! If he was in the battle at all, it was at the Angle that he fell.

She had not been able to begin her search immediately after the battle because there were forty wounded men in her little house; she could not prosecute it with any diligence even later, when the soldiers had been carried to the hospitals, in the Presbyterian Church, the Catholic Church, the two Lutheran churches, the Seminary, the College, the Court-House, and the great tented hospital on the York road. Nurses were here, Sisters of Mercy were here, compassionate women were here by the score; but still she was needed, with all the other women of the village, to nurse, to bandage, to comfort, to pray with those who must die. Little Mary Bowman had assisted at the amputation of limbs, she had helped to control strong men torn by the frenzy of delirium, she had tended poor bodies which had almost lost all semblance to humanity. Neither she nor any of the other women of the village counted themselves especially heroic; the delicate wife of the judge, the petted daughter of the doctor, the gently bred wife of the preacher forgot that fainting at the sight of blood was one of the distinguishing qualities of their sex; they turned back their sleeves and repressed their tears, and, shoulder to shoulder with Mary Bowman and her Irish neighbor, Hannah Casey, they fed the hungry and healed the sick and clothed the naked. If Mary Bowman had been herself, she might have laughed at the sight of her dresses cobbled into trousers, her skirts wrapped round the shoulders of sick men. But neither then nor ever after did Mary laugh at any incident of that summer.

Hannah Casey laughed, and by and by she began to boast. Meade, Hancock, Slocum, were non-combatants beside her. She had fought whole companies of Confederates, she had wielded bayonets, she had assisted at the spiking of a gun, she was Barbara Frietchie and Moll Pitcher combined. But all her lunacy could not make Mary Bowman smile.

Of John Bowman no trace could be found. No one could tell her anything about him, to her frantic letters no one responded. Her old friend, the village judge, wrote letters also, but could get no reply. Her husband was missing; it was probable that he lay somewhere upon this field, the field upon which they had wandered as lovers.

In midsummer a few trenches were opened, and Mary, unknown to her friends, saw them opened. At the uncovering of the first great pit, she actually helped with her own hands. For those of this generation who know nothing of war, that fact may be written down, to be passed over lightly. The soldiers, having been on other battle-fields, accepted her presence without comment. She did not cry, she only helped doggedly, and looked at what they found. That, too, may be written down for a generation which has not known war.

Immediately, an order went forth that no graves, large or small, were to be opened before cold weather. The citizens were panic-stricken with fear of an epidemic; already there were many cases of dysentery and typhoid. Now that the necessity for daily work for the wounded was past, the village became nervous, excited, irritable. Several men and boys were killed while trying to open unexploded shells; their deaths added to the general horror. There were constant visitors who sought husbands, brothers, sweet-hearts; with these the Gettysburg women were still able to weep, for them they were still able to care; but the constant demand for entertainment for the curious annoyed those who wished to be left alone to recover from the shock of battle. Gettysburg was prostrate, bereft of many of its worldly possessions, drained to the bottom of its well of sympathy. Its schools must be opened, its poor must be helped. Cold weather was coming and there were many, like Mary Bowman, who owned no longer any quilts or blankets, who had given away their clothes, their linen, even the precious sheets which their grandmothers had spun. Gettysburg grudged nothing, wished nothing back, it asked only to be left in peace.

When the order was given to postpone the opening of graves till fall, Mary began to go about the battle-field searching alone. Her good, obedient children stayed at home in the house or in the little field. They were beginning to grow thin and wan, they were shivering in the hot August weather, but their mother did not see. She gave them a great deal more to eat than she had herself, and they had far better clothes than her blood-stained motley.

She went about the battle-field with her eyes on the ground, her feet treading gently, anticipating loose soil or some sudden obstacle. Sometimes she stooped suddenly. To fragments of shells, to bits of blue or gray cloth, to cartridge belts or broken muskets, she paid no heed; at sight of pitiful bits of human bodies she shuddered. But there lay also upon that field little pocket Testaments, letters, trinkets, photographs. John had had her photograph and the children's, and surely he must have had some of the letters she had written!

But poor Mary found nothing.

One morning, late in August, she sat beside her kitchen table with her head on her arm. The first of the scarlet gum leaves had begun to drift down from the shattered trees; it would not be long before the ground would be covered, and those depressed spots, those tiny wooden headstones, those fragments of blue and gray be hidden. The thought smothered her. She did not cry, she had not cried at all. Her soul seemed hardened, stiff, like the terrible wounds for which she had helped to care.

Suddenly, hearing a sound, Mary had looked up. The judge stood in the doorway; he had known all about her since she was a little girl; something in his face told her that he knew also of her terrible search. She did not ask him to sit down, she said nothing at all. She had been a loquacious person, she had become an abnormally silent one. Speech hurt her.

The judge looked round the little kitchen. The rent in the wall was still unmended, the chairs were broken; there was nothing else to be seen but the table and the rusty stove and the thin, friendless-looking children standing by the door. It was the house not only of poverty and woe, but of neglect.

"Mary," said the judge, "how do you mean to live?"

Mary's thin, sunburned hand stirred a little as it lay on the table.

"I do not know."

"You have these children to feed and clothe and you must furnish your house again. Mary—" The judge hesitated for a moment. John Bowman had been a school-teacher, a thrifty, ambitious soul, who would have thought it a disgrace for his wife to earn her living. The judge laid his hand on the thin hand beside him. "Your children must have food, Mary. Come down to my house, and my wife will give you work. Come now."

Slowly Mary had risen from her chair, and smoothed down her dress and obeyed him. Down the street they went together, seeing fences still prone, seeing walls torn by shells, past the houses where the shock of battle had hastened the deaths of old persons and little children, and had disappointed the hearts of those who longed for a child, to the judge's house in the square. There wagons stood about, loaded with wheels of cannon, fragments of burst caissons, or with long, narrow, pine boxes, brought from the railroad, to be stored against the day of exhumation. Men were laughing and shouting to one another, the driver of the wagon on which the long boxes were piled cracked his whip as he urged his horses.

Hannah Casey congratulated her neighbor heartily upon her finding work.

"That'll fix you up," she assured her.

She visited Mary constantly, she reported to her the news of the war, she talked at length of the coming of the President.

"I'm going to see him," she announced. "I'm going to shake him by the hand. I'm going to say, 'Hello, Abe, you old rail-splitter, God bless you!' Then the bands'll play, and the people will march, and the Johnny Rebs will hear 'em in their graves."

Mary Bowman put her hands over her ears.

"I believe in my soul you'd let 'em all rise from the dead!"

"I would!" said Mary Bowman hoarsely. "I would!"

"Well, not so Hannah Casey! Look at me garden tore to bits! Look at me beds, stripped to the ropes!"

And Hannah Casey departed to her house.

Details of the coming celebration penetrated to the ears of Mary Bowman whether she wished it or not, and the gathering crowds made themselves known. They stood upon her porch, they examined the broken shutters, they wished to question her. But Mary Bowman would answer no questions, would not let herself be seen. To her the thing was horrible. She saw the battling hosts, she heard once more the roar of artillery, she smelled the smoke of battle, she was torn by its confusion. Besides, she seemed to feel in the ground beneath her a feebly stirring, suffering, ghastly host. They had begun again to open the trenches, and she had looked into them.

Now, on the morning of Thursday, the nineteenth of November, her children dressed themselves and came down the steps. They had begun to have a little plumpness and color, but the dreadful light in their mother's eyes was still reflected in theirs. On the lower step they hesitated, looking at the door. Outside stood the judge, who had found time in the multiplicity of his cares, to come to the little house.

He spoke with kind but firm command.

"Mary," said he, "you must take these children to hear President Lincoln."

"What!" cried Mary.

"You must take these children to the exercises."

"I cannot!" cried Mary. "I cannot! I cannot!"

"You must!" The judge came into the room. "Let me hear no more of this going about. You are a Christian, your husband was a Christian. Do you want your children to think it is a wicked thing to die for their country? Do as I tell you, Mary."

Mary got up from her chair, and put on her children all the clothes they had, and wrapped about her own shoulders a little black coat which the judge's wife had given her. Then, as one who steps into an unfriendly sea, she started out with them into the great crowd. Once more, poor Mary said to herself, she would obey. She had seen the platform; by going round through the citizen's cemetery she could get close to it.

The November day was bright and warm, but Mary and her children shivered. Slowly she made her way close to the platform, patiently she stood and waited. Sometimes she stood with shut eyes, swaying a little. On the moonlit night of the third day of battle she had ventured from her house down toward the square to try to find some brandy for the dying men about her, and as in a dream she had seen a tall general, mounted upon a white horse with muffled hoofs, ride down the street. Bending from his saddle he had spoken, apparently to the empty air.

"Up, boys, up!"

There had risen at his command thousands of men lying asleep on pavement and street, and quietly, in an interminable line, they had stolen out like dead men toward the Seminary, to join their comrades and begin the long, long march to Hagerstown. It seemed to her that all about her dead men might rise now to look with reproach upon these strangers who disturbed their rest.

The procession was late, the orator of the day was delayed, but still Mary waited, swaying a little in her place. Presently the great guns roared forth a welcome, the bands played, the procession approached. On horseback, erect, gauntleted, the President of the United States drew rein beside the platform, and, with the orator and the other famous men, dismounted. There were great cheers, there were deep silences, there were fresh volleys of artillery, there was new music.

Of it all, Mary Bowman heard but little. Remembering the judge, whom she saw now near the President, she tried to obey the spirit as well as the letter of his command; she directed her children to look, she turned their heads toward the platform.

Men spoke and prayed and sang, and Mary stood still in her place. The orator of the day described the battle, he eulogized the dead, he proved the righteousness of this great war; his words fell upon Mary's ears unheard. If she had been asked who he was, she might have said vaguely that he was Mr. Lincoln. When he ended, she was ready to go home. There was singing; now she could slip away, through the gaps in the cemetery fence. She had done as the judge commanded and now she would go back to her house.

With her arms about her children, she started away. Then someone who stood near by took her by the hand.

"Madam!" said he, "the President is going to speak!"

Half turning, Mary looked back. The thunder of applause made her shiver, made her even scream, it was so like that other thunderous sound which she would hear forever. She leaned upon her little children heavily, trying to get her breath, gasping, trying to keep her consciousness. She fixed her eyes upon the rising figure before her, she clung to the sight of him as a drowning swimmer in deep waters, she struggled to fix her thoughts upon him. Exhaustion, grief, misery threatened to engulf her, she hung upon him in desperation.

Slowly, as one who is old or tired or sick at heart, he rose to his feet, the President of the United States, the Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy, the hope of his country. Then he stood waiting. In great waves of sound the applause rose and died and rose again. He waited quietly. The winner of debate, the great champion of a great cause, the veteran in argument, the master of men, he looked down upon the throng. The clear, simple things he had to say were ready in his mind, he had thought them out, written out a first draft of them in Washington, copied it here in Gettysburg. It is probable that now, as he waited to speak, his mind traveled to other things, to the misery, the wretchedness, the slaughter of this field, to the tears of mothers, the grief of widows, the orphaning of little children.

Slowly, in his clear voice, he said what little he had to say. To the weary crowd, settling itself into position once more, the speech seemed short; to the cultivated who had been listening to the elaborate periods of great oratory, it seemed commonplace, it seemed a speech which any one might have made. But it was not so with Mary Bowman, nor with many other unlearned persons. Mary Bowman's soul seemed to smooth itself out like a scroll, her hands lightened their clutch on her children, the beating of her heart slackened, she gasped no more.

She could not have told exactly what he said, though later she read it and learned it and taught it to her children and her children's children. She only saw him, felt him, breathed him in, this great, common, kindly man. His gaze seemed to rest upon her; it was not impossible, it was even probable, that during the hours that had passed he had singled out that little group so near him, that desolate woman in her motley dress, with her children clinging about her. He said that the world would not forget this field, these martyrs; he said it in words which Mary Bowman could understand, he pointed to a future for which there was a new task.

"Daughter!" he seemed to say to her from the depths of trouble, of responsibility, of care greater than her own,—"Daughter, be of good comfort!"

Unhindered now, amid the cheers, across ground which seemed no longer to stir beneath her feet, Mary Bowman went back to her house. There, opening the shutters, she bent and solemnly kissed her little children, saying to herself that henceforth they must have more than food and raiment; they must be given some joy in life.

On an afternoon in late September, 1910, a shifting crowd, sometimes numbering a few score, sometimes a few hundred, stared at a massive monument on the battle-field of Gettysburg. The monument was not yet finished, sundry statues were lacking, and the ground about it was trampled and bare. But the main edifice was complete, the plates, on which were cast the names of all the soldiers from Pennsylvania who had fought in the battle, were in place, and near at hand the platform, erected for the dedicatory services on the morrow, was being draped with flags. The field of Gettysburg lacks no tribute which can be paid its martyrs.

The shifting crowd was part of the great army of veterans and their friends who had begun to gather for the dedication; these had come early to seek out their names, fixed firmly in enduring bronze on the great monument. Among them were two old men. The name of one was Criswell; he had been a gunner in Battery B, and was now blind. The explosion which had paralyzed the optic nerve had not disfigured him; his smooth-shaven face in its frame of thick, white hair was unmarred, and with his erect carriage and his strong frame he was extraordinarily handsome. The name of his friend, bearded, untidy, loquacious, was Carolus Depew.