The Project Gutenberg eBook of Faery Lands of the South Seas

Title: Faery Lands of the South Seas

Author: James Norman Hall

Charles Nordhoff

Release date: April 2, 2017 [eBook #54479]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

Faery Lands

Of the South Seas

FAERY LANDS

OF THE SOUTH SEAS

By

James Norman Hall

and

Charles Bernard Nordhoff

Harper & Brothers Publishers

New York and London

FAERY LANDS OF THE SOUTH SEAS

Copyright, 1921, by Harper & Brothers

Printed in the United States of America

C-K

CONTENTS

CHAP.

PREFACE

The islands of the South Seas are places of an interest curiously limited. The ethnological problem presented by the native is interesting only to men of science, commerce is negligible, there is little real agriculture, and no industry at all. There remains the charm of living among people whose outlook upon life is basically different from our own; of living with a simplicity foreign to anything in one's experience, amid surroundings of a beauty unreal both in actuality and in retrospect.

It is impossible to write of the islands as one would write of France or Mexico or Japan—the accepted viewpoint of the traveler is not applicable here. A simple attempt to impart information would prove singularly monotonous, and one is driven to essay a different task; to pry into the life of the mingling races, hoping to catch something of its significance and atmosphere. In making such an attempt it is necessary at times to dig deeper than would be consistent with good taste if names were mentioned, and for this reason—in the case of certain small islands—the ancient Polynesian names have been used instead of those given on the chart. All of the islands described are to be found in the Paumotu, Society, and Hervey groups.

J.N.H.

C.B.N.

TAHITI, April 10, 1921.

Landfall

Faery Lands

Of the South Seas

CHAPTER I

A Leisurely Approach

I don't remember precisely when it was that Nordhoff and I first talked of this adventure. The idea had grown upon us, one might say, with the gradual splendor of a tropical sunrise. We were far removed from the tropics at that time. We were, in fact, in Paris and had behind us the greatest adventure we shall ever know. On the Place de la Concorde and along the Champs-Élysées stood rank on rank of German cannon, silent enough now, but still menacing, their muzzles tilted skyward at that ominous slant one came to know so well. For a month we had seen them so, children perched astride them on sunny afternoons, rolling pebbles down their smooth black throats; veterans in soiled and faded horizon blue, with the joy of this new quiet world bright on their faces, opening breech-blocks, examining mechanism with the skill of long use at such employment; with a kind of wondering hesitation in their movements too, as though at any moment they expected those sinister monsters in the fantastic colors of Harlequin to spring into life again.

Those were glorious days! Never again, I think, will there be such a happy time as that in Paris. The boulevards were crowded, the tables filled under every awning in front of the cafés; and yet there seemed to be a deep silence everywhere, a silence intensified by the faint rustling of autumn leaves and the tramping of innumerable feet. One heard the sound of voices, of laughter, of singing, the subdued, continuous rumble of traffic; but not a harsh cry, not a discordant note. All the world seemed to be making holiday at the passing of a solemn, happy festival.

Well, we had kept it with the others—Nordhoff and I—and have the memory of it now, to be enjoyed over and over again as the years pass. But there was danger that we might outstay the freshness of that period. We were anxious to avoid that for the sake of our memories, if for nothing else. While we were not yet free to order our movements as we chose, we pretended that we were, and so one rainy evening in the December following the armistice we decided to call that chapter of experience closed and to go forward with the making of new plans.

For we meant to have further adventure of one kind or another—adventure in the sense of unexpected incident rather than of hazardous activity. That had been a settled thing between us for a long time. We had no craving for excitement, but turned to plans for uneventful wanderings which we had sketched in broad outlines months before. They had been left, of necessity, vague; but now that any of them might be made realities, now that we had leisure and a reasonable hope for the fulfillment of plans—well, we had cause for a contentment which was something deeper than happiness.

The best of it was that the close of the war found us with nothing to prevent our doing pretty much as we chose. We might have had houses or lands to anchor us, or promising careers to drag us back into the bewilderments of modern civilization; but, fortunately or unfortunately, there were none of these things. The chance of war had given us a freedom far beyond anyone's desert. We had some misgivings about accepting so splendid a gift, which the event sometimes proves to be the most doubtful of benefits. Viewed in the light of our longings, however, our capacity for it seemed incalculable, and so, by degrees, we allowed our minds to turn to an old allurement—the South Pacific. It became irresistible the more we talked of it, longing as we then were for the solitude of islands. The objection to this choice was that the groups of islands which we meant to visit have been endowed with an atmosphere of pseudoromance displeasing to the fastidious mind.

But there was not the slightest chance of our being pioneers wherever we might go. We could not hope to see with the eyes of the old explorers who first came upon those far-off places. We must expect great changes. But much as we might regret for the purposes of this adventure that we had not been born two hundred years earlier, comfort was not wanting to our situation. Had we been contemporaries and fellow-explorers with De Quiros, or Cook, or Bougainville we should have missed the Great War.

We came within view of Tahiti one windless February morning—such a view as Pedro Fernandez de Quiros himself must have had more than three hundred years before. The sky to the west was still bright with stars and but barely touched with the very ghost of light, giving it the appearance of a great water, with a few clouds, like islands, immeasurably distant. Half an hour later the islands themselves lay in full sunlight, jagged peaks falling away in steep ridges to the sea. Against sheer walls still in shadow in upland valleys one could see a few terns; but there was no other movement, no sound, nor any sign of a human habitation—nothing to shatter the illusion of primitive loveliness. It was illusion, of course, but the reality was nothing like so disappointing as I had feared it would be. Outwardly, two hundred years of progress have wrought no great amount of havoc. There is a little port, a busy place on boat days. But when the steamer has emptied the town of her passengers, the silence flows down again from the hills. Off the main harbor-front thoroughfare streets lie empty to the eye for half hours at a time. Chinese merchants sit at the doorways of their shops, waiting for trade. Now and then broad pools of sunlight flow over the gayly flowered dresses of a group of native women, scarcely to be seen otherwise as they move slowly through tunnels of moist green gloom; or a small schooner, like a detail gifted with sudden mobility in a picture, will back away from shore, cross the harbor, bright with the reflections of clouds, and stand out to sea. In the stillness of the noon siesta one hears at infrequent intervals the resounding thud of ripe fruits as they tear their way to the ground through barriers of foliage; and at night the melancholy thunder of the surf on the reef outside the harbor, and the slithering of bare feet in the moonlit streets.

Coming from a populous exile, doubly attracted for that reason by the lure of unpeopled places, Nordhoff and I sought here an indication of what we might find later elsewhere. The few thousands of natives, whites, Orientals, half-castes, live in a charmed circle of low land fronting the sea, conscious of their mountains, no doubt, but the whites without curiosity, the Orientals without desire, the natives without remembrance. There must have been a maze of trails in the old days, leading down from the rich valleys. Now they are overgrown, untraveled, lost. Since the old life is no more than a memory, one is glad for the desolation, and grateful to the French lack of enterprise which surely is the only way to account for it.

No, we couldn't have chosen a better jumping-off place for our unpremeditated wanderings. We had the whole expanse of the Pacific before us, or, better, around us, and there was, as I have said, a harbor full of shipping. Boats with pleasing names, like the Curieuse, the Avarua, the Potii Ravarava, the Kaeo, the Liane—and self-confident, seagoing aspect. Some tidy and smart with new paint and rigging; others with decks warped and sides blistered, bottoms foul with the accumulation of a six months' cruise, reeking with the warm odor of copra. Boats newly arrived from remote islands, with crowds of bare-legged natives on their decks, their eyes beaming with pleasure in anticipation of the delights of the great capital; outward-bound to the Marquesas, the Australs, the Cooks, the Low Archipelago, despite the fact that it was the middle of the hurricane season. Among these latter there was one whose name was like a friendly hail from Gloucester, or Portland, Maine. But it was not this which attracted me to her, for all its assurance of Yankee hospitality. She was off to the Paumotus, the Cloud of Islands, and a longing to go there persisted in the face of a number of vague discouragements. There were no practical difficulties. Easy enough to get passage by one schooner or another. Paumotu copra is famous throughout the Southern Pacific. There is a good deal of competition for it, boats racing one another for cargo to the richer islands. The discouragements weren't so vague, either, now that I think of them. They came from men kindly disposed, interested in the islands in their own way. But their concerns were purely commercial. I heard a deal of talk about copra—in kilos, in tons, in shiploads; its market value in Papeete, in San Francisco, in Marseilles, until the stately trees which gave it lost for a time their old significance. Talk, too, of coconut oil and its richness in butter-fat. Butter-fat! There was a word to bring one back to a workaday world. To meet it at the outset of a long-dreamed-of journey was disheartening. It followed me with the shrill insistence of a creamery whistle, and I came very near giving up my plans altogether. Nordhoff did change his. He said that it was silly, no doubt, but he didn't like the idea of wandering, however lonely, in a cloud of butter-fat islands. Therefore we said good-by, having arranged for a rendezvous at a distant date, and set out on diverging paths.

I ought to leave Crichton, the English planter, out of this story altogether. He doesn't belong in a commonplace record of travel such as this one set out to be. He had very little to do with the voyage of the Caleb S. Winship among the atolls. But when I think of that vessel he comes inevitably into mind. I see him sitting on the cabin deck with his freckled brown hands clasped about his knees, looking across a solitude of waters; and in my mental concept of the Low Archipelago he is always somewhere in the background, standing on the sun-stricken reef of a tiny atoll, his back to the sea, almost as much a part of the lonely picture as the sea itself.

But one can't be wholly matter of fact in writing of these islands. They are not real in the ordinary sense, but belong, rather, to the realm of the imagination. And it is only in the imagination that you can conceive of your ever having been there, once you are back again in a well-plowed sea track. As for the people, whether native or alien, in order to focus them in a world of reality it is necessary to remember what they said or did; what they ate; what sort of clothing they wore. Otherwise they elude you just as the islands do.

This point of view isn't, perhaps, commonly held among the few white men who know them—captains of small schooners, managers of trading companies, resident agents, whose interest, as I have said, is in what they produce rather than in what they are. As one old skipper of my acquaintance put it, in speaking of the atolls, "Take them by and large, they are as much alike as the reef-points on that sail." Findlay's South Pacific Directory, a supposedly competent authority, bears him out in this: "They are all of similar character," adding, for emphasis, no doubt, "and they exhibit very great sameness in their features." He does, however, make certain slight concessions to what may be his own private conception of their peculiar fascination, "This vast collection of coral islands; one of the wonders of the Pacific," and later, in his account of them, "The native name, 'Paumotu,' signifies a Cloud of Islands, an expressive term." But he doesn't forget that he is writing for practical-minded mariners who want facts and not fancies, however truthful these may be to reality.

"Now, there's Tikehau," one of them said to me before I had been out there. "That's a round atoll; and Rahiroa is sort o' square like, an' so on. Some with passes and a good anchorage inside the lagoon. Others you got to lay outside an' take your cargo off the reef in a small boat."

But, to go back to Crichton, no one knew who he was or where he came from. The manager of the Inter-Island Trading Company had lived in Papeete for years and had never seen him until the day when he turned up at the water front trundling a wheelbarrow loaded with four crates of chickens and an odd lot of plantation tools and fishing tackle. Following him were two native boys carrying a weather-blackened sea chest, and an old woman with an enormous roll of bedding tied loosely in a pandanus mat. That was about an hour before the schooner weighed anchor. He stacked his gear neatly on the beach and then went on board, asking for passage to Tanao.

"No, sir," the manager said, in telling about it afterward, "I never laid eyes on him until that moment, and I don't know anyone who had. Where's he been hiding himself? And why in the name of common sense does he want to go to Tanao? There's no copra or pearl shell there—not enough, anyway, to make it worth a man's while going after it."

Tino, the supercargo, was equally puzzled.

"I know Tanao from the sea," he said. "Passed it once coming down from the Marquesas when I was supercargo of the Tiare Tahiti. We were blown out of our course by a young hurricane. Didn't land. There's no one on the God-forsaken place. Now here's this Englishman, or Dane, or Norwegian—whatever he is—asking to be set down there with four crates of chickens and an old Kanaka woman for company!" He shook his head with a give-it-up expression, adding a moment later: "Well, you meet some queer people down in this part of the world. I don't believe in asking them their business, but it beats me sometimes, trying to figure out what their business is."

He was not able to figure it out in this case. The old woman was talkative; but the information he gathered from her only stimulated his curiosity the more. She owned Tanao, an atom of an atoll miles out of the beaten track even of the Paumotu schooners. There had never been more than a score of people living on it, she said, and now there was no one. Crichton had taken a long lease on it, and was going out there—as he told me afterward—"to do my writing and thinking undisturbed."

I didn't know this until later, however. When I first heard him spoken of we were only a few hours out from Papeete. We had left the harbor with a light breeze, but at four in the afternoon the schooner was lying about fifteen miles offshore, lazy jacks flapping against idle sails with a mellow, crusty sound. After a good deal of fretting at the fickleness of land breezes, talk had turned to Crichton, who was up forward somewhere looking after his chickens. I didn't pay much attention then to what was being said, for I had just had one of those moments which come rarely enough in a lifetime, but which make up for all the arid stretches of experience. They give no forewarning. There comes a flood of happiness which brings tears to the eyes, the sense of it is so keen. The sad part of it is that one refuses to accept it as a moment. You say, "By Jove! I'm not going to let this pass!" and it has gone as unaccountably as it came, half lost through foreboding of its end. One prepares for it unknowingly, I suppose, through months, sometimes years, of longing for something remote and beautiful—such as these islands, for example. And when you have your islands, the moment comes, sooner or later, and you see them in the light which never was, as the saying goes, but which is the light of truth for all that. Brief as it is, no one can say that the reward isn't ample. And it leaves an afterglow in the memory, tempering regret, fading very slowly; which one never wholly loses since it takes on the color of memory itself, becoming a part of that dim world of worth-while illusions.

All of which has very little to do with what was passing aboard the Caleb S. Winship, except that I was prevented from taking an immediate interest in my fellow passengers; but this being my first near view of a Polynesian trading schooner, the scene on deck had all the charm of the unusual. Our skipper was a Paumotuan, a former pearl diver, and the sailors—six of them, including the mate—Tahitian boys. In addition to these there were Crichton, the planter; the supercargo, master of three major languages and half a dozen Polynesian dialects; the manager of the Inter-Island Trading Company; William, the engineer; Oro, the cabin boy; a Chinese cook and two Chinese storekeepers—evidence of the leisurely, persistent Oriental invasion of French Polynesia; thirty native passengers; a horse in an improvised stall amidships; a monkey perched in the mainmast rigging; Crichton's four crates of chickens, and five pigs. In addition to the passengers and live stock, we were carrying out a cargo of lumber, corrugated iron, flour, rice, sugar, canned goods, clothing, and dry goods. Each of the native passengers brought with him as much dunnage as an Englishman carries when he goes traveling, and his food for the voyage—limes, oranges, bananas, breadfruit, mangoes, canned meat. With all of this, a two months' supply of gasoline for the engines, and fresh water and green coconuts for both passengers and crew, we made a snug fit. Even the space under the patient little native horse was used to stow his fodder for the long journey.

The women, with one exception, were barefooted, bareheaded, but otherwise conventionally dressed according to European or American standards. This, I suppose, is an outrageous betrayal of a trade secret, if one may say that writers of South Sea narratives belong to a trade. Those seriously interested in the islands have, of course, known the truth about them for years; but I believe it is still a popular misconception that the women who inhabit them—no one seems to be interested in the men—are even to this day half-savage, unself-conscious creatures who display their charms to the general gaze with naïve indifference. Half-savage they may still be, but not unself-conscious in the old sense. There are a few, to be sure, who, by means of the bribes or the entreaties of itinerant journalists and photographers, may be persuaded to disrobe before the camera for a moment's space; and in this way the primitive legend is preserved to the outside world. But, as I told Nordhoff, although we are itinerant, we may as well be occasionally truthful and so gain, perhaps, a certain amount of begrudged credit.

The one exception was a girl of about nineteen. She came on board balancing unsteadily on high French heels, her brown legs darkening the sheen of her white-cotton stockings. I had seen her the day before as she passed below the veranda of Le Cercle Bougainville, the everyman's club of the port. She walked with the same air of precarious balance, and her broad-brimmed straw hat was set at the jaunty angle American women affect.

"Voilà! L'indigène d'aujourd'hui," my French companion said. Then, breaking into English: "The old Polynesia is dead. Yes, one may say that it is quite, quite dead." A memory he called it. "Maintenant je vous assure, monsieur, ce n'est rien que ça." He rang changes on the word, in a soft voice, with an air of enforced liveliness.

I was rather saddened at the time, picturing in my mind the scene on the shore of that bright lagoon two hundred years ago, before any of these people had been forced to accept the blessings of an alien civilization. But the girl with the French heels wasn't a good illustration of l'indigène d'aujourd'hui, even in the matter of surface changes. Most of the women dress much more simply and sensibly, and it was amusing as well as comforting to see how quickly she got rid of her unaccustomed clothing once we had left the harbor. She disappeared behind a row of water casks and came out a moment later in a dress of bright-red material, barefooted and bareheaded like the rest of them. She had a single hibiscus flower in her hair, which hung in a loose braid. I don't believe she had ever worn shoes before. At any rate, as she sat on a box, husking a coconut with her teeth, I could see her ankle calluses glinting in the sun like disks of polished metal.

There was another girl sitting on the deck not far from me, with an illustrated supplement of an American paper spread out before her. It was an ancient copy. There were pictures of battlefields in France; of soldiers marching down Fifth Avenue; a tennis tournament at Longwood; aeroplanes in flight; motor races at Indianapolis; actresses, society women, dressmakers' models making a display of corsets and other women's equipment—pictures out of the welter of modern life. The little Paumotuan girl appeared to be deeply interested. With her chin resting on her hands and her elbows braced against her knees, she went from picture to picture, but looked longest at those of the women who smiled or posed self-consciously, or looked disdainfully at her from the pages. I would have given a good deal to know what, if anything, was passing in her mind. All at once she gave a little sigh, crumpled the paper into a ball, and threw it at the monkey, who caught it and began tearing it in pieces. She laughed and clapped her hands at this, called the attention of the others, and in a moment men, women, and children had gathered round, laughing and shouting, throwing bits of coconut shell, mango seeds, banana skins, faster than the monkey could catch them.

The spontaneity of the merriment did one's heart good. Even the old men and women laughed, not in the indulgent manner of parents or grandparents, but as heartily as the children themselves. Unconscious of the uproar, one of the Chinese merchants was lying on a thin mattress against the cabin skylight. Although he was sound asleep, his teeth were bare in a grin of ghastly suavity, and his left eye was partly open, giving him an air of constant watchfulness. He was dreaming, I suppose, of copra, of pearl shell—in kilos, tons, shiploads; of its market value in Papeete, in San Francisco, in Marseilles, etc. Well, the whites get their share of these commodities and the Chinamen theirs; but the natives have a commodity of laughter which is vastly more precious, and as long as they do have it one need not feel very sorry for them.

Dusk gathered rapidly while I was thinking of these things. Heavy clouds hung over Tahiti and Moorea, clinging about the shoulders of the mountains whose peaks, rising above them, were still faintly visible against the somber glory of the sky. They seemed islands of sheer fancy, looked at from the sea. It would have been worth all that one could give to have seen them then as De Quiros saw them, or Cook, or the early missionaries; to have added to one's own sense of their majesty, the solemn and more childlike awe of the old explorers, born of their feeling of utter isolation from their kind with the presence of the unknown on every hand. It is this feeling of awe rarely to be known by travelers in these modern days, which pervades many of the old tales of wanderings in remote places; which one senses in looking at old sketches made from the decks of ships, of the shores of heathen lands.

The wind freshened, then came a deluge of cool water, blotting out the rugged outlines against the sky. When it had passed it was deep night. The forward deck was a huddle of shelters made of mats and bits of canvas, but these were being taken down now that the rain had stopped. I saw an old woman sitting near the companionway, her head in clear relief against a shaft of yellow light. She was wet through and the mild misfortune broke the ice between us, if one may use a metaphor very inapt for the tropics. With her face half in shadow she reminded me of the typical, Anglo-Saxon grandmother, although no grandmother of my acquaintance would have sat unperturbed through that squall and indifferent to her wet clothing afterward. She didn't appear to mind it in the least, and now that it was over fished a paper of tobacco and a strip of pandanus leaf out of the bundle on which she was sitting. She rolled a pinch of tobacco in the leaf, twisting it into a tight corkscrew, and lit it at the first attempt. Then she began talking in a deep, resonant voice, and by a simplicity and an extraordinary lucidity of gesture conveyed the greater part of her meaning even to an alien like myself. It was not, alas! a typical accomplishment. I have not since found others similarly gifted.

She was Crichton's landlady, the owner of Tanao. "Pupure" she called him, because of his fair hair. I couldn't make out what she was driving at for a little while. I understood at last that she wanted to know about his family—where his father was, and his mother. I suppose she thought I must know him, being a white man. They have queer ideas of the size of our world. He was young. He must have people somewhere. She, too, couldn't understand his wanting to go to Tanao; and I gathered from her perplexity that he hadn't confided his purposes to her to any extent. I couldn't enlighten her, of course, and at length, realizing this, she wrapped herself in her mat to preserve the damp warmth of her body, and dozed off to sleep.

I went below for a blanket and some dry clothing, for the night air was uncomfortably cool after the rain. The cabin floor was strewn with sleeping forms. Three children were curled up in a corner like puppies in a box of sawdust. Little brown babies lay snugly bedded on bundles of clothing, the mothers themselves sleeping in the careless, trustful attitudes of children. The light from a swinging lamp threw leaping shadows on the walls; flowed smoothly over brown arms and legs; was caught in faint gleams in masses of loose black hair. And to complete the picture and make it wholly true to fact, cockroaches of the enormous winged variety ran with incredible speed over the oilcloth of the cabin table, or made sudden flying sallies out of dark corners to the food lockers and back again.

On deck no one was awake except Maui at the wheel. There was very little unoccupied space, but I found a strip against the engine-room ventilator where I could stretch out at full length. By that time the moon was up and it was almost as light as day. I was not at all sleepy, and my thoughts went forward to the Paumotus, the Cloud of Islands. We ought to be making our first landfall within thirty-six hours. I didn't go beyond that in anticipation, although in the mind's eye I had seen them for months, first one island and then another. I had pictured them at dawn, rising out of the sea against a far horizon; or at night, under the wan light of stars, lonely beyond one's happiest dreams of isolation; unspoiled, unchanged, because of their very remoteness. Well, I was soon to know whether or not they fulfilled my hopeful expectations.

Some one came aft, walking along the rail in his bare feet. It was Oro, the cabin boy, who is taken with an enviable kind of madness at the full of the moon. He looked carefully around to make sure that everyone was asleep, then stood clasping and unclasping his hands in ecstasy, carrying on a one-sided conversation in a confidential undertone. Now and then he would smile and straightway become serious again, gazing with rapt, listening attention at the world of pure light; nodding his head at intervals in vigorous confirmation of some occult confidence. At length his figure receded, blurred, took on the quality of the moonlight, and I saw him no more.

CHAPTER II

In the Cloud of Islands

Ruau, the old Paumotuan woman, and the owner of Tanao, was the last of her family. There were relatives by marriage, but none of them would consent to live on so poor an atoll; and the original population, never large, had diminished, through death and migration, until at last she was left alone, living in her memories of other days, awed by the companionship of spirits present to her in strange and terrible shapes. At last she felt that she could endure it no longer; but it was many months before the smoke of one of her signal fires was seen by a passing schooner. She returned with it to Tahiti, and if she had been lonely before, she was tenfold lonelier there, so far from the graves of her husband and children. It was at this time that Crichton met her. He had been living at Tahiti for more than a year, on the lookout for just such an opportunity as Ruau offered him. Although only twenty-eight, he was in the tenth year of his wanderings, and had almost despaired of finding the place he had so long dreamed of and searched for. During that period he had been moving slowly eastward, through Borneo, New Guinea, the Solomons, the New Hebrides, the Tongas, the Cook Group. In some of these islands the climate was too powerful an enemy for a white man to contend with; in others there was no land available, or they lacked the solitude he wanted. This latter embarrassment was the one he had met at Tahiti. The fact is an illuminating commentary on his character. Most men would find exceptional opportunities for seclusion there; not on the seaboard but in the mountains; in the valleys winding deeply among them, where no one goes from year's end to year's end. Even those leading out to the sea are but little frequented in their upward reaches. But Crichton was very exacting in his requirements in this respect. He was one of those men who make few or no friends—one of those lonely spirits without the ties or the kindly human associations which make life pleasant to most of us. They wander the thinly peopled places of the earth, interested in a large way at what they see from afar or faintly hear, but looking on with quiet eyes; taking no part, being blessed or cursed by nature with a love of silence, of the unchanging peace of great solitudes. One reads of them now and then in fiction, and if they live in fiction it is because of men like Crichton, their prototypes in reality, seen for a moment as they slip apprehensively across some by-path leading from the outside world.

He had a little place at Tahiti, a walk of two hours and a quarter, he said, from the government offices in the port. He had to go there sometimes to attend to the usual formalities, and I have no doubt that he knew within ten seconds the length of the journey which would be a very distasteful one to him. I can imagine his uneasiness at what he saw and heard on those infrequent visits. An after-the-war renewal of activity, talk of trade, development, progress, would startle him into a waiting, listening attitude. Returning home, maps and charts would be got out and plans made against the day when it would be necessary for him to move on. He told me of his accidental meeting with Ruau, as he called the old Paumotuan woman. It came only a few days after the arrival from San Francisco of one of the monthly steamers. A crowd of tourists—stop-over passengers of a day—had somehow discovered the dim trail leading to his house. "They were much pleased with it," he said, adding, with restraint: "They took a good many pictures. I was rather annoyed at this, although, of course, I said nothing." No doubt they made the usual remarks: "Charming! So quaint!" etc.

It was the last straw for Crichton. So he made another visit to the government offices where he had his passport viséed. He meant to go to Maketea, a high phosphate island which stands like a gateway at the northwestern approach to the Low Archipelago. The phosphate would be worked out in time and the place abandoned, as other islands of that nature had been, to the seabirds. But on that same evening, while he was having dinner at a Chinaman's shop in town, he overheard Ruau trying to persuade some of her relatives to return with her to Tanao. He knew of the island. He is one of the few men who would know of it. He had often looked at it on his charts, being attracted by its isolated position. The very place for him! And the old woman, he said, when she learned that he wanted to go there, that he wanted to stay always—all his life—gripped his hands in both of hers and held them, crying softly, without saying anything more. The relatives made some objections to the arrangement at first. But the island being remote, poverty-stricken, haunted, they were soon persuaded to consent to a ten years' lease, with the option of renewal. Crichton promised, of course, to take care of Ruau as long as she lived, and at her death to bury her decently beside her husband.

He proceeded at once with his altered plans. There were government regulations to be complied with and these had taken some time. On the day when he was at last free to start he learned that the Caleb S. Winship was about to sail on a three months' voyage in the Low Archipelago. He had no time to ask for passage beforehand. He had to chance the possibility of getting it at the last moment. It is not to be supposed that either the manager of the Inter-Island Trading Company or the supercargo of the Winship would have consented to carry him to such an out-of-the-way destination had they known his reason for wanting to be set down there. It amuses me now to think of those two hard-headed traders, men without a trace of sentiment, going one hundred and fifty miles off their course merely to carry the least gregarious of wanderers on the last leg of his long journey to an ideal solitude. It was their curiosity which gained him his end. They believed he had some secret purpose, some reason of purely material self-interest in view. They had both seen Tanao from a distance and knew that it had never been worth visiting either for pearl shell or copra. It is hard to understand what miracle they believed might have taken place in the meantime. During the voyage I often heard them talking about the atoll, about Crichton—wondering, conjecturing, and always miles off the track. It was plain that he was a good deal disturbed by their hints and furtive questionings. He seemed to be afraid that mere talk about Tanao on the part of an outsider might sully the purity of its loneliness. He may have been a little selfish in his attitude, but if that is a fault in a man of his temperament it is one easily forgiven. And what could he have said to those traders? It was much better to keep silent and let them believe what they liked.

It must not be thought that Crichton poured out his confidences to me like a schoolgirl. On the contrary, he had a very likable reserve, although a good half of it, I should say, was shyness. Then, too, he had almost forgotten how to talk except in the native dialects of several groups of widely scattered islands. In English he had a tendency to prolong his vowels and to omit consonants, which gave his speech a peculiar exotic sound. He made no advances for some time. Neither did I. For more than three weeks we lived together on shipboard, went ashore together at islands where we had put in for copra, and all that while we did not exchange above two hundred words in conversation. There was so little talk that I can remember the whole of it, almost word for word. Once while we were walking on the outer beach at Raraka, an atoll of thirty-five inhabitants, he said to me:

"I wish I had come out here years ago. They appeal to the imagination, don't you think, all these islands?"

His volubility startled me. It was a shock to the senses, like the crash of a coconut on a tin roof heard in the profound stillness of an island night. There was my opportunity to throw off reserve and I lost it through my surprise. I merely said, "Yes, very much." An hour later we saw the captain, no larger than a penny doll, at the end of a long vista of empty beach, beckoning us to come back. We went aboard without having spoken again. It was an odd sort of relationship for two white men thrown into close contact on a small trading schooner in the loneliest ocean in the world, as Nordhoff put it. We were no more companionable in the ordinary sense than a pair of hermit crabs.

But the need for talking drops away from men under such circumstances and neither of us found the long silences embarrassing. The spell of the islands was upon us both. I can understand Crichton's speaking of their appeal to the imagination while we were in the midst of them; for our presence there seemed an illusion—a dream more radiant than any reality could be. In fact, my only hold upon reality during that voyage was the Caleb S. Winship, and sometimes even that substantial old vessel suffered sea changes; was metamorphosed in a moment; and it was hard to believe that she was a boat built by men's hands. Often as she lay at anchor in a lagoon of dreamlike beauty I paddled out from shore in a small canoe, and, making fast under her stern, spent an afternoon watching the upward play of the reflections from the water and the blue shadows underneath, rippling out and vanishing in the light like flames of fire. For me her homely, rugged New England name was a pleasant link with the past. I liked to read the print of it. The word "Boston," her old home port, was still faintly legible through a coat of white paint. It brought to mind old memories and the faces of old friends, hard to visualize in those surroundings without such practical help. Far below lay the floor of the lagoon where all the rainbows of the world have authentic end. The water was so clear, and the sunlight streamed through it with so little loss in brightness that one seemed to be suspended in mid-air above the forests of branching coral, the deep, cool valleys, and the wide, sandy plains of that strange continent.

Crichton, I believe, was beyond the desire to keep in touch with the world he had left so many years before. His experiences there may have been bitter ones. At any rate, he never spoke of them, and I doubt if he thought of them often. People had little interest for him, not even those of the atolls which we visited. When on shore I usually found him on the outer beaches, away from the villages which lie along the lagoon. In most of the atolls the distance from beach to beach is only a few hundred yards, but the ocean side is unfrequented and solitary. On calm days when the tide begins to ebb the silence there is unearthly. The wide shore, hot and glaring in the sun, stretches away as far as the eye can reach, empty of life except for thousands of small hermit crabs moving into the shade of the palms. They snap into their shells at your approach and make fast the door as their houses fall, with a sound like the tinkling of hailstones, among heaps of broken coral. We waded along the shallows at low tide. When the wind was onshore and a heavy surf breaking over the outer edge of the reef, we sat as close to it as we could, watching the seas gathering far out, rising in sheer walls fringed with wind-whipped spray, which seemed higher than the island itself as they approached. It was a fascinating sight—the reef hidden in many places in a perpetual smoke of sunlight-filtered mist, through which the oncoming breakers could be seen dimly as they swept forward, curled, and fell. But one could not avoid a feeling of uneasiness, of insecurity, thinking of what had happened in those islands—most of them only a meter or two above sea level—in the hurricanes of the past; and of what would happen again at the coming of the next great storm.

We made landfalls at dawn, in midafternoon, late at night—saw the islands in aspects of beauty exceeding one's strangest imaginings. We penetrated farther and farther into a thousand-mile area of atoll-dotted ocean, discharging our cargo of lumber and corrugated iron, rice and flour and canned goods; taking on copra; carrying native passengers from one place to another. Sometimes we were out of sight of land for several days, beating into head winds under a slowly moving pageantry of clouds which alone gave assurance of the rotundity of the earth. When at last land appeared it seemed inaccessibly remote, at the summit of a long slope of water which we would never be able to climb. Sometimes for as long a period we skirted the shore line of a single atoll, the water deepening and shoaling under our keel in splotches of vague or vivid coloring. From a vantage point in the rigging one could see a segment of a vast circle of islands strung at haphazard on a thread of reef which showed a thin, clear line of changing red and white under the incessant battering of the surf. Several times upon going ashore we found the villages deserted, the inhabitants having gone to distant parts of the atoll for the copra-making season. In one village we came upon an old man too feeble to go with the others, apparently, sitting in the shade playing a phonograph. He had but three records: "Away to the Forest," "The Dance of the Nymphs Schottische," and "Just a Song at Twilight." The disks were as old as the instrument itself, no doubt, and the needles so badly worn that one could barely hear the music above the rasping of the mechanism. There was a groove on the vocal record where the needle caught, and the singer, a woman with a high, quavery voice, repeated the same phrase, "when the lights are low," over and over again. I can still hear it, even at this distance of time and place, and recall vividly to mind the silent houses, the wide, vacant street bright with fugitive sunshine, the lagoon at the end of it mottled with the shadows of clouds.

The sense of our remoteness grew upon me as the weeks and months passed. Once, rounding a point of land, we came upon two schooners lying inside the reef of a small atoll. One of them had left Papeete only a short while before. Her skipper gave us a bundle of old newspapers. Glancing through them that evening, I heard as in a dream the far-off clamor of the outside world—the shrieking of whistles, the roar of trains, the strident warnings of motors; but there was no reality, no allurement in the sound. I saw men carrying trivial burdens with an air of immense effort, of grotesque self-importance; scurrying in breathless haste on useless errands; gorging food without relish; sleeping without refreshment; taking their leisure without enjoyment; living without the knowledge of content; dying without ever having lived. The pictures which came to mind as I read were distorted, untrue, no doubt; for by that time I was almost as much attracted by the lonely life of the islands as my friend Crichton. My old feeling of restlessness was gone. In its place had come a certitude of happiness, a sense of well-being for which I can find no parallel this side of boyhood.

It was largely the result of living among people who are as permanently happy, I believe, as it is possible for humankind to be. And the more remote the island, the more slender the thread of communication with civilization as we know it, the happier they were. It was not in my imagination that I found this true, or that I had determined beforehand to see only so much of their life as might be agreeable and pleasant to me. On the contrary, if I had any bias at first, it was on the other side. Disillusionment is a sad experience and I had no desire to lay myself open to it. Therefore I listened willingly to the less favorable stories of native character which the traders, and others who know them, had to tell. But summed up dispassionately later, in the light of my own observations, it seemed to me that the faults of character of which they were accused were more like the natural shortcomings of children. In many respects the Paumotuans, like other divisions of the Polynesian family, are children who have never grown up, and one can't blame them for a lack of the artificial virtues which come only with maturity. They are without guile. They have little of the shrewdness or craftiness of some primitive peoples. At least so it appeared to me, making as careful a judgment of them as I could. I have often noticed how like children they are in their amazing trustfulness, their impulsive generosity, and in the intensity and briefness of their emotions.

The more I saw of their life, the more desirable it seemed that they might continue to escape any serious encroachments of European or American civilization. They have no doctors, because illness is almost unknown in their islands. Crime, insanity, feeble-mindedness, evils all too common with us, are of such rare occurrence that one may say they do not exist. It may be said, too, without overstatement, that their community life very nearly approaches perfection. Every atoll is a little world to itself with a population varying from twenty-five to perhaps three hundred inhabitants. The chief, who is chosen informally by the men, serves for a period of four years under the sanction of the French government. He has very little to do in the exercise of his authority, for the people govern themselves, are law-abiding without law.

When I first learned that there are no schools throughout the islands I thought the French guilty of criminal neglect, but later I reversed this opinion. Alter all, why should they have schools? No education of ours could make them more generous, more kindly disposed to one another, more hospitable and courteous toward strangers, happier than they are now. Certainly it could not make them less selfish, covetous, rapacious, for most of them are as innocent of those vices as their own children. In a few of the richer, more accessible islands they are slowly changing in these respects, owing to the example set them by men of our own race. In another fifty years, perhaps, they may have learned to believe that material wealth is the only thing worth striving for. Then will come pride in their possessions, envy of those who have greater, contempt and suspicion for those who have less, and so an end to their happiness.

I had never before seen children growing up in a state of nature and I made full use of the rare opportunity. I spent most of my time with them; played on shore with them; went fishing and swimming with them; and found in the experience something better than a renewal of boyhood because of a keener sense of beauty, a more conscious, mature appreciation of the happiness one has in the simplest kinds of pleasures. Sometimes we started on our excursions at dawn; sometimes we made them by moonlight. I became a collector of shells in order to give some purpose to our expeditions along the reef. I couldn't have chosen a better interest, for they knew all about shells, where and when to find the best ones, and they could indulge their love of giving to a limitless extent. In the afternoons we went swimming in the lagoon. There I saw them at their best and happiest, in an element as necessary and familiar to them as it is to their parents. It is always a pleasure to watch children at play in the water, but those Paumotuan youngsters with their natural grace at swimming and diving put one under an enchantment. Many of the boys had water glasses and small spears of their own and went far from shore, catching fish. They lay face down on the surface of the water, swimming easily, with a great economy of motion, turning their heads now and then for a breath of air; and when they saw their prey they dived after it as skillfully as their fathers do and with nearly as much success. Seen against the bright floor of the lagoon, with swarms of brilliantly colored fish scattering before them, they seemed doubtfully human, the children of some forsaken merman rather than creatures who have need of air to breathe and solid earth to stand on. If education is the suitable preparation for life, the children of the atolls have it at its best and happiest without knowing that it is education. They are skillful in the pursuits and learned in the interests which touch their lives, and one can wish them no better fortune than that they may remain in ignorance of those which do not.

Their parents, as I have said, are but children of mature stature, with the same gift of frank, generous laughter, the same delight in the new and strange. Very little is required to amuse them. I had a mandolin which I used to take ashore with me at various atolls, after I had become convinced that their enjoyment of my music was not feigned. At first I was suspicious, for I had no illusions about my virtuosity, and even when I thought of it in the most flattering way their pleasure seemed out of all proportion to the quality of the performance. But there was no doubting the genuineness of it. The whole village would assemble to hear me play. I had a limited repertoire, but that seemed to matter very little. They liked to hear the same tunes played over and over again. I learned some of the old missionary hymns which they knew: "From Greenland's Icy Mountains," "Oh, Happy Day," "We're Marching to Zion," and others.

It was strange to find those songs, belonging, fortunately, to a bygone period in English and American life, living still in that remote part of the world, not because of anything universal in their appeal, but merely because they had been carried there years ago by representatives of the missionary societies. Many eccentric changes had been made in both the rhythm and melody, greatly to the improvement of both, but no amount of changing could make them other than what they are—the uncouth expression of a narrow and ugly kind of religious sentiment. I don't think the Paumotuans care much for them, either. They always seemed glad to turn from them to their own songs, which have nothing either of modern or old-time missionary feeling. A woman usually began the singing, in a high-pitched, nasal, or throaty voice, which she modulated in an extraordinary way. Immediately other women joined in, then several men whose voices were of tenor quality, followed by other men in basses and barytones, chanting in two or three tones which, for rhythm and tone, quality, were like the beating of kettledrums. The weird blending of harmonics was unlike anything I had ever heard before. There is nothing in our music which even remotely resembles theirs, so that it is impossible to describe the effect of the full chorus. Some of the songs make a strong appeal to savage instincts. The less resolute of the early missionaries, hearing them, must have thrown up their hands in despair at the thought of the long, difficult task of conversion awaiting them. But if there were any irresolute missionaries, they were evidently overruled by their sterner brothers and sisters.

On nearly every island there is now a church, either Protestant or Catholic. In the Protestant ones the native population practice the only true faith, largely to the accompaniment of this old barbaric music. Those unsightly little structures rock to the sound of exultant choruses which ought never to be sung withindoors. The Paumotuans themselves know best the natural setting for their songs—the lagoon beach with a great fire of coconut husks blazing in the center of the group of singers. I liked to hear them from a distance where I could get their full effect; to look on from the schooner lying a few hundred yards offshore. All the inhabitants of the village would be gathered within the circle of the firelight, which brought their figures and the white, straight stems of the coconut palms into clear relief against a background of deep shadow. The singing continued far into the night, so that I often fell asleep while listening, and heard the music dying away, mingling at last with the interminable booming of the surf.

By degrees we worked slowly through the heart of the archipelago, pursuing a general southeasterly course, the islands becoming more and more scattered, until we had before us an expanse of ocean almost unbroken to the coast of South America. But Tanao lay at the edge of it, and at length, on a lowering April day, we set out on that last leg of our outward journey. The Caleb S. Winship lay very low in the water. By that time she had a full cargo of copra, one hundred tons in the hold and twelve, sacked, on deck. A portion of the deck cargo was lost that same afternoon, during a gale of wind and rain which burst upon us with fury and followed us with a seeming malignity of intent. We ran before it, far out of our course, for three hours. To me the weight of air was something incredible, an unusually vigorous flourish of the departing hurricane season. Water spouted out of the scuppers in a continuous stream, and loose articles were swept clear of the ship, disappearing at once in a cloud of blinding rain. There was a fearful racket in the cabin of rolling biscuit tins and smashing crockery. Then an eight-hundred-pound safe broke loose and started to imitate Victor Hugo's cannon. Luckily it hadn't much scope and no smooth runway, so that it was soon brought to a halt by Ruau, the old Paumotuan woman, who was the only one below at the time. She made an effective barricade of copra sacks and bedding, dodging the plunging monster with an agility surprising in a woman of sixty. But what I remember best was Tané, a monkey belonging to one of the sailors, skidding along the cabin deck until he was blown against the engine-room whistle, which rose just clear of the forward end of it. He wrapped arms and legs around it in his terror, opening the valve in some way, and the shrill blast rose high above the mighty roar of wind, like the voice of man lifted with awe-inspiring impudence in defiance of the mindless anger of nature.

The storm blew itself out toward sundown and the night fell clear—a night for stars to make one wary of thought; but the moon rose about nine, softening the pitiless distances, throwing a veil of mild light across the black voids in the Milky Way, seen so clearly in those latitudes. The schooner was riding a heavy swell, and, burdened as she was, rose clumsily to it, sticking her nose into the slope of every sea. Ruau was at her accustomed place against the cabin ventilator, unmindful of the showers of spray, maintaining her position on the slanting deck with the skill of three months' practice. The thought that I must soon bid her good-by saddened me, for I knew there was small chance that I should ever meet her again. I envied Crichton his opportunity for friendship with that noble old woman, so proud of her race, so true to her own beliefs, to her own way of living. Her type is none too common among Polynesians in these days. One gets all too frequently an impression of a consciousness of inferiority on their part, a sense of shame because of their simple way of living as compared with ours. Ruau was not guilty of it. She never could be, I think, under any circumstances. I learned afterward of an attempt which had been made to convert her to Christianity during her stay at Tahiti. Evidently she had not been at all convinced by the priest's arguments, and when he made some slighting remark about the ghosts and spirits which were so real to her, she refused to listen any longer. Frightened though she was of spirits, she was not willing that they should be ridiculed.

We sighted her atoll at dawn, such a dawn as one rarely sees outside the tropics. The sky was overcast at a great height with a film of luminous mist through which the sun shone wanly, throwing a sheen like a dust of gold on the sea. Masses of slate-colored cloud billowed out from the high canopy, overhanging a black fringe of land which lay just below the line of the horizon. The atoll was elliptical in shape, about eight miles long by five broad. There were seven widely separated islands on the circle of reef and one small motu in the lagoon. We came into the wind about a half mile offshore and put off in the whaleboat. The sea was still running fairly high, and the roar of the surf came across the water with a sound as soothing as the fall of spring rain; but it increased in volume as we drew in until the ears were stunned by the crash of tremendous combers which toppled and fell sheer, over the ledge of the reef. It was by far the most dangerous-looking landing place we had seen on the journey. There was no break in the reef; only a few narrow indentations where the surf spouted up in clouds of spray. Between the breaking of one sea and the gathering of the next, the water poured back over a jagged wall of rock bared for an instant to an appalling depth. Only a native crew could have managed that landing. We rode comber after comber, the sailors backing on their oars, awaiting the word of the boat steerer, who stood with his feet braced on the gunwales, his head turned over his shoulder, watching the following seas. All at once he began shouting at the top of his voice. I looked back in time to see a wall of water, on the point of breaking, rising high above us. It fell just after it passed under us, and we were carried forward across the edge of the reef, through the inner shallows to the beach.

The two traders started off at once on a tour of inspection and we saw nothing more of them until late in the evening. Meanwhile I went with Ruau and Crichton across the island to the lagoon beach where her house was. As in most of the atolls, the ground was nearly free from undergrowth, the soil affording nourishment only to the trees and a few hardy shrubs. Coconuts and dead fronds were scattered everywhere. A few half-wild pigs, feeding on the shoots of sprouted nuts, gazed up with an odd air of incredulity, of amazement as we approached, then galloped off at top speed and disappeared far in the distance. Ruau stopped when we were about halfway across and held up her hand for silence. A bird was singing somewhere, a melodious varied song like that of the hermit thrush. I had heard it before and had once seen the bird, a shy, solitary little thing, one of the few species of land birds found on the atolls.

While we were standing there, listening to the faint music, Crichton took me by the arm. He said nothing, and in a moment withdrew his hand. I was deeply moved by that manifestation of friendliness, an unusual one for him to make. He had some unaccountable defect in his character which kept him aloof from any relationship approaching real intimacy. I believe he was constantly aware of it, that he had made many futile attempts to overcome it. It may have been that which first set him on his wanderings, now happily at an end. It was plain to me the moment we set foot on shore that he would have to seek no farther for asylum. Tanao is one of the undoubted ends of the earth. No one would ever disturb him there. He himself was not so sure of this. Once, I remember, when we were looking at the place on the chart, he spoke of the island of Pitcairn, the old-time refuge of the Bounty mutineers. Before the opening of the Panama Canal it had been as far removed from contact with the outside world as an island could be. Now it lies not far off the route through the Canal to New Zealand and is visited from time to time by the crews of tramp steamers and schooners. Tanao, however, is much farther to the north, and there is very slight possibility that its empty horizons will ever be stained by a smudge of smoke. As for an actual visit, one glance at the reef through the binoculars would convince any skipper of the folly of the attempt.

Even our own crew of natives, skilled at such hazardous work, came to grief in their second passage over it. They had gone out to the schooner for supplies Crichton had ordered—a few sacks of flour, some canned goods, and kerosene oil; in coming back the boat had been swept, broadside, against a ledge of rock. It stuck there, just at the edge of the reef, and the sailors jumped out with the line before the next wave came, capsizing the boat and carrying it inshore, bottom up. All the supplies were swept into deep water by the backwash and lost. There had been a similar accident at the other atoll—flour and rice brought so many thousands of miles having been spoiled within a few yards of their destination. I remember the natives plunging into the water at great risk to themselves to save a few sacks of soggy paste in the hope that a little of the flour in the center might still be dry; and a Chinese storekeeper, to whom it was consigned, standing on the shore, wringing his hands in dumb grief. It was the first time I had ever seen a Chinaman make any display of emotion, and the sight brought home to me a conception of the tragic nature of such accidents to the inhabitants of those distant islands.

Crichton took his own loss calmly, concealing whatever disappointment he may have felt. Ruau was not at all concerned about it, and, while we were making an examination of the house, went out on the lagoon in a canoe and caught more than enough fish for supper. Then we found that all of our matches had been spoiled by sea water, so we could make no fire. Judging by the way Crichton brightened up at his discovery, one would have thought the loss a piece of luck. He set to work at once to make an apparatus for kindling fire, but before it was finished Ruau had the fish cleaned and spread out on a coverlet of green leaves. We ate them raw, dipping them first into a sauce of coconut milk, and for dessert had a salad made of the heart of a tree. I don't remember ever having eaten with heartier appetite, but at the same time I couldn't imagine myself enjoying an unrelieved diet of coconuts and fish for a period of ten years—not for so long as a year, in fact. Crichton, however, was used to it, and Ruau had never known any other except during her three months' stay at Tahiti, where she had eaten strange hot food which had not agreed with her at all, she said.

Dusk came on as we sat over our meal. Ruau sat with her hands on her knees, leaning back against a tree, talking to Crichton. I understood nothing of what she was saying, but it was a pleasure merely to listen to the music of her voice. It was a little below the usual register of women's voices, strong and clear, but softer even than those of the Tahitians, and so flexible that I could follow every change in mood. She was telling Crichton of the tupapaku of her atoll which she dreaded most, although she knew that it was the spirit of one of her own sons. It appeared in the form of a dog with legs as long and thick as the stem of a full-grown coconut tree, and a body proportionally huge. It could have picked up her house as an ordinary dog would a basket. Once it had stepped lightly over it without offering to harm her in any way. Her last son had been drowned while fishing by moonlight on the reef outside the next island, which lay about two miles distant across the eastern end of the lagoon. She had seen the dog three times since his death, and always at the same phase of the moon. Twice she had come upon it lying at full length on the lagoon beach, its enormous head resting on its paws. She was so badly frightened, she said, that she fell to the ground, incapable of further movement; sick at heart, too, at the thought that the spirit of the bravest and strongest of all her sons must appear to her in that shape. It was clear that she was recognized, for each time the dog began beating its tail on the ground as soon as it saw her. Then it got up, yawned and stretched, took a long drink of salt water, and started at a lope up the beach. She could see it very plainly in the bright moonlight. Soon it broke into a run, going faster and faster, gathering tremendous speed by the time it reached the other end of the island. From there it made a flying spring, and she last saw it as it passed, high in air, across the face of the moon, its head outstretched, its legs doubled close under its body. She believed that it crossed the two-mile gap of water which separated the islands in one gigantic leap.

That is the whole of the story as Crichton translated it for me, although there must have been other details, for Ruau gave her account of it at great length. Her earnestness of manner was very convincing; and left no doubt in my mind of the realness to her of the apparition. As for myself, if I could have seen ghosts anywhere it would have been at Tanao. Late that night, walking alone on the lagoon beach, I found that I was keeping an uneasy watch behind me. The distant thunder of the surf sounded at times like a wild galloping on the hard sand, and the gentle slapping of little waves near by like the lapping tongue of the ghostly dog having its fill of sea water.

We left Tanao with a fair wind the following afternoon, having been delayed in getting away because of the damaged whaleboat, which had to be repaired on shore. Tino, the supercargo, insisted on pushing off at once, the moment the work was finished. Crichton and Ruau were on the other beach at the time, so that I had no opportunity to say good-by; but as we were getting under way I saw him emerge from the deep shadow and stand for a moment, his hand shading his eyes, looking out toward the schooner. I waved, but evidently he didn't see me, for there was no response. Then he turned, walked slowly up the beach, and disappeared among the trees. For three hours I watched the atoll dwindling and blurring until at sunset it was lost to view under the rim of the southern horizon. Looking back across that space of empty ocean, I imagined that I could still see it dropping farther and farther away, down the reverse slope of a smooth curve of water, as though it were vanishing for all time beyond the knowledge and the concern of men.

My first packet of letters from Nordhoff was brought by the skipper of the schooner Alouette. He had been carrying it about for many weeks, and had it in the first place from the supercargo of another vessel, met at Rurutu, in the Austral group. The envelope, tattered and weather-stained, spoke of its long journey in search of me.

Before separating at Papeete we had arranged for a rendezvous, but at that time we still possessed American ideas of punctuality and well-ordered travel. Now we know something of the casual movements of trading schooners and have learned to regard the timely arrival of a letter as an event touching on the miraculous—the keeping of a rendezvous, a possibility too remote for consideration. One hears curious tales, in this part of the world, of the outcome of such temporary leave-takings as ours was meant to be—husbands seeking their wives and wives their husbands; families scattered among these fragments of land and striving for many months to reunite.

I witnessed, not long ago, the sequel of one of these unsuccessful quests. A native from a distant group of islands set out for one of the atolls of the Low Archipelago, the home of his sweetheart. Arrangements for the marriage had been made long before, but letters had gone astray, and upon his arrival the young man found that the family of his prospective father-in-law had gone to another atoll for the diving season. With no means of following, he submitted to the inevitable, and married another girl. Months later, the woman of his first choice returned with her second choice of a husband; and the former lovers met, for the young man had not yet been able to return to his own island. Neither made any question of the other's decision—life is too short; and from the native point of view, it is foolish to spend it in wanderings which, at the last, may never fulfill their purpose.

Nevertheless, I shall make a search for Nordhoff—a leisurely search, with some expectation of finding him. Our islands, like those of Mr. Conrad's enchanted Heyst, are bounded by a circle two thousand or more miles across, and it is likely that neither of us will ever succeed in breaking through to the outside world—if, indeed, there is an outside world. I am beginning to doubt this, for the enchantment is at work. As for Nordhoff, his letters, which follow, may speak for themselves.

Eaters of the Lotos

CHAPTER III

Marooned on Mataora

The sun was low when the Faaite steamed out through the pass and headed for the Cook group, six hundred miles west and south. Dark clouds hung over Raiatea—Rangi Atea of Maori tradition, the Land of the Bright Heavens—but the level sunlight still illuminated the hillsides of Tahaa, the lovely sister island, protected by the same great oval reef. Far off to the north, the peak of Bora Bora towered abruptly from the sea.

It was not yet the season of the Trades, and the northeast breeze which followed us brought a sweltering heat, intolerable anywhere but on deck. Worthington was sitting beside me—a lean man, darkly-tanned, with very bright blue eyes. His feet were bare; he wore a singlet, trousers of white drill, and a Manihiki hat—beautifully plaited of bleached pandanus leaf—a hat not to be bought with money. The dinner gong sounded.

"I'm not going down," he remarked; "too hot below. I had something to eat at Uturoa. How about you?"

I shook my head—it needed more than a normal appetite to drive one to the dining saloon. Banks of squall cloud, shading from gray to an unwholesome violet, were gathering along the horizon, and the air was so heavy that one inhaled it with an effort.

"This is the worst month of the hurricane season," Worthington went on; "it was just such an evening as this, last year, that the waterspout nearly got us—the night we sighted Mataora. I was five months up there, you know—marooned when Johnson lost the old Hatutu.

"I was pretty well done up last year, and when I heard that the Hatutu was at Avarua I decided to take a vacation and go for a six weeks' cruise with Johnson. Ordinarily he would have been laid up in Papeete until after the equinox, but the company had sent for him to make a special trip to Penrhyn. We had a wretched passage north—a succession of squalls and broiling calms. The schooner was in bad shape, anyway: rotten sails, rigging falling to pieces, and six inches of grass on her bottom. On a hot day she had a bouquet all her own—the sun distilled from her a blend of cockroaches and mildewed copra that didn't smell like a rose garden. On the thirtieth day the skipper told me we were two hundred miles from Penrhyn and so close to Mataora that we might sight the palm tops. I'd heard a lot about the place (it has an English name on the chart)—how isolated it was, what a pleasant crowd the natives were, and how it was the best place in the Pacific to see old-fashioned island life.

"We had been working to windward against a light, northerly breeze, but the wind began to drop at noon, and by three o'clock it was glassy calm. There was a wicked-looking mass of clouds moving toward us from the west, but the glass was high and Johnson said we were in for nothing worse than a squall. As the clouds drew near I could see that they had a sort of purplish-black heart, broad at the top, pointed at the bottom, and dropping gradually toward the water. There was something queer about it; the mate was pointing, and Johnson's Kanakas were all standing up. Suddenly I heard a rushing sound, like a heavy squall passing through the bush; the point of the funnel had touched the sea three or four hundred yards away from us—a waterspout! There wasn't a breath of air, and the Hatutu had no engine. It was moving straight for us, so slowly that I could watch every detail of its formation. The boys slid our boat overboard; the mate sang out something about all hands being ready to leave the schooner.

"I've heard of waterspouts ever since I was a youngster, but I never expected to see one as close as we did that day. As the point of cloud dropped toward the sea it was ragged and ill defined; but when it touched the water and the noise began I saw its shape change and its outlines grow hard. It was now a thin column, four or five feet in diameter, rising a couple of hundred feet before it swelled in the form of a flat cone, to join the clouds above. Curiously enough, it was not perpendicular, but had a decided sagging curve. Nearer and nearer it came, until I could make out the great swirling hole at its base, and see the vitreous look of this column of solid water, revolving at amazing speed. It hadn't the misty edges of a waterfall. The outside was sharply defined as the walls of a tumbler. I wondered what would happen when it struck the Hatutu. The mate was shouting again, but just then the skipper pushed a rifle into my hands. 'Damned if I leave the old hooker,' he swore. 'Shoot into the thing—maybe we can break it up.' And, believe me or not, we did break it up.

"It didn't come down with a crash, as one might have expected. When we had pumped about twenty shots into it, and it was not more than fifty yards away, it began to dwindle. The column of water became smaller and drew itself out to nothing; the rushing noise ceased; the hole in the sea disappeared in a lazy eddy; the dark funnel rose and blended with the clouds above.

"A fine southeast breeze sprang up as the clouds dispersed, and we were reaching away for Penrhyn when a boy up forward gave a shout and pointed to the northwest. Sure enough there was a faint line on the horizon—the palms of Mataora. A sudden idea came to me. I was fed up with the schooner. Why not ask to be put ashore and picked up on the Hatutu's return from Penrhyn? She would be back in a fortnight, and it was only a few miles out of her way to drop me and pick me up.

"Johnson is a good fellow; his answer to my proposition was to change his course at once and slack away for the land twelve miles to leeward. 'You'll have a great time,' he said; 'I wish I were going with you. Old Tari will put you up—I'll give you a word to him. Take along two or three bags of flour and a few presents for the women.'

"At five o'clock we were off the principal village, with canoes all about us and more coming out through the surf. The men were a fine, brawny lot, joking with the crew, and eager for news and small trade. I lowered my box, some flour, tobacco, and a few bolts of calico, into the largest canoe, and said good-by to Johnson.

"It was nearly a year before I saw him again; as you know, he lost the Hatutu on Flying Venus Shoal. They made Penrhyn in the boat and got a passage to Tahiti two months later. Everyone knew I was on Mataora, but it was five months before a schooner could come to take me off.

"There is no pass into the lagoon. As we drew near the shore I saw that the easy, deceptive swell reared up to form an ugly surf ahead of us. At one point, where a crowd of people was gathered, there was a large irregular fissure in the coral, broad and deep enough to admit the passage of a small boat, and filled with rushing water each time a breaker crashed on the reef. My two paddlers stopped opposite this fissure and just outside the surf, watching over their shoulders for the right wave. They let four or five good-sized ones pass, backing water gently with their paddles; but at last a proper one came, rearing and tossing its crest till I thought it would break before it reached us. My men dug their paddles into the water, shouting exultantly as we darted forward. The shouts were echoed on shore. By Jove! it was a thriller! Tilting just on the break of the wave, we flew in between jagged walls of coral, up the fissure, around a turn—and before the water began to rush back, a dozen men and women had plunged in waist deep to seize the canoe.

"Mataora is made up of a chain of low islands—all densely covered with coconut palms—strung together in a rough oval to inclose a lagoon five miles by three. Though there is no pass, the surf at high tide breaches over the gaps between the islands. The largest island is only a mile and a half long, and none of them are more than half a mile across. Dotted about the surface of the lagoon are a number of motu—tiny islets—each with its flock of sea fowl, its clump of palms, and shining beach of coral sand. Set in a lonely stretch of the Pacific, the place is almost cut off from communication with the outside world; twice or three times in the course of a year a trading schooner calls to leave supplies and take off copra. Undisturbed by contact with civilization, the life of Mataora flows on—simple, placid, and agreeably monotonous—very little changed, I fancy, since the old days. It is true that they have a native missionary, and use calico, flour, and tobacco when they can get them; but these are minor things. The great events in their annals are the outrage of the Peruvian slavers in eighteen sixty-two, when many of the people were carried off to labor and die in the Chinchas Islands, and the hurricane of nineteen thirteen.

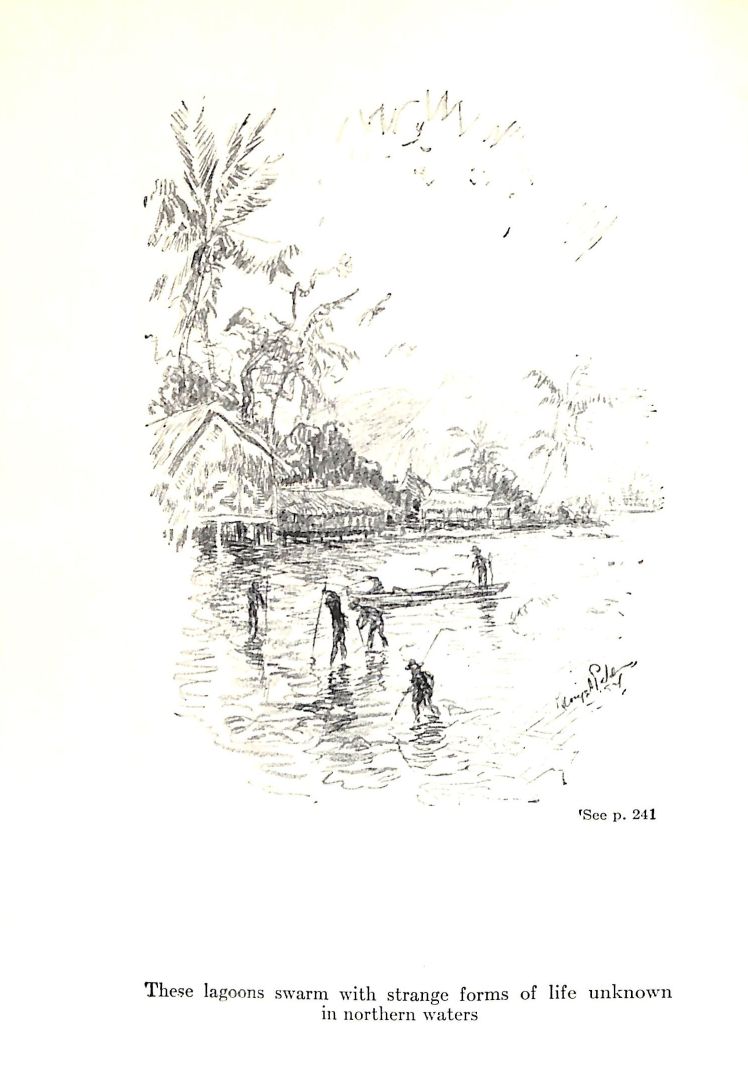

"After presenting myself to the missionary and the chief I was escorted by a crowd of youngsters to the lagoon side of the island, where Tairi lived, in a spot cooled by the trade wind and pleasantly shaded by coconuts. The old chap was a warm friend of Johnson's and made me welcome; I soon arranged to put up with him during my stay on the island. His house, like all the Mataora houses, was worth a bit of study.