Title: Morriña (Homesickness)

Author: condesa de Emilia Pardo Bazán

Translator: Mary J. Serrano

Release date: May 18, 2017 [eBook #54742]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

M O R R I Ñ A

(HOMESICKNESS)

![[Image of colophon unavailable.]](images/colophon.jpg)

CASSELL PUBLISHING COMPANY

NEW YORK

Copyright, 1891, by

CASSELL PUBLISHING COMPANY.

All rights reserved.

THE MERSHON COMPANY PRESS,

RAHWAY, N. J.

| Chapter I., II., III., IV., V., VI., VII., VIII., IX., X., XI., XII., XIII., XIV., XV., XVI., XVII., XVIII., XIX., XX., XXI., XXII., XXIII., EPILOGUE. |

If the apartment which Doña Nogueira de Pardiñas and her only son Rogelio occupied in Madrid was neither the sunniest nor the most spacious to be found in the city, it possessed, on the other hand, the inestimable advantage of being situated in the Calle Ancha de San Bernardo, so close to the Central University that to live in it was, as one might say, the same as living in the university itself.

Seated in her leather-covered easy-chair by the window, widening and narrowing the stocking she was{2}

knitting without once looking at it, Señora de Pardiñas would follow her adored boy with her gaze, which, traversing space and passing through the solid substance of the walls, accompanied him to the very lecture-room of the university. She saw him when he went in and when he came out—she noticed whether he stopped to chat{3} with any one, whom he talked to, whether he laughed; she knew who his companions were, whom he liked and whom he disliked; who were the industrious students and whom the idle ones; who were regular and who were irregular in their attendance. She was familiar, too, with the faces of the professors, and made a study of their expression and their manner of returning the salutations of the pupils, drawing from external signs important psychological deductions bearing on the problem of the examinations: “Ah, there comes old Contreras already, the Professor of Procedure. How amiable he looks! what a saint-like face he has. How slowly he walks, poor man. ’Tis easy to see that he suffers from rheumatism as I do. The more’s the pity! I like him on that account, and not on that account alone, but because I know that he is indulgent and that he will give Rogelio a good mark in his examination.{4} Now comes Ruiz del Monte, so stiff and so conceited. He looks as if he were made all in one piece. Poor us! Neither favor nor influence nor anything else is of any use with him. He would have the boys know the studies as well as he does himself. If he wants that let him give them his place in the college—and the pay as well. Ah, here we have Señor de Lastra. He stoops a little. What comical caricatures the boys make of him in the class! And he is familiar to a fault. There he is now clapping Benito Diaz, Rogelio’s great friend, on the back. He looks to me like a good easy-going man. My blessing upon him! I don’t know what there is to be gained by torturing poor boys and distressing their parents.”

Pausing in her soliloquy, the good lady ran her knitting needle through the coil of her hair, now turning gray, and scratched her head lightly with it.{5} Suddenly her withered cheek flushed brightly as if a breath of youth had blown across it.

“Ah, there is Rogelio,” she cried.

The student emerged from the building, wrapped in his crimson plush cloak, his low, broad-brimmed hat slightly tipped to one side, his glance fixed, from the first moment, on the window at which his mother was sitting. Generally he would give her a smile, but sometimes, assuming a serious air, he would raise his hand to his hat, and, with the stiff movement of a marionette, mimic the salutation of the dandies of the Retiro. The mother would return his salutation, shaking her hand threateningly at him, convulsed with laughter, as if this were not a jest of almost daily repetition. Then the boy would stop to chat for a few minutes with some of his fellow-students; he would exchange a word in passing with the match-vender, the ticket-vender, the{6} orange-girl at the corner, and the clerks of the neighboring shops, winding up with some half-jesting compliment to the servants who stood chatting at the doors; and finally he would ascend the steps of his own house, where Doña Aurora was already waiting for him in the hall. His first words were generally in the following strain:

“Mater amabilis, set quickly before your offspring corporeal sustenance. I have an appetite that I don’t know where I got it. Ah-h-h! If the beefsteak does not soon make its appearance, dreadful scenes of cannibalism will be enacted.”

“Yes,” his mother would answer, smiling, “and it will all amount to your eating a couple of olives and a morsel of meat. Go away with you, you humbug! You have the appetite of a bird.”

The room in which they liked best to sit was neither the parlor—which was almost always solitary and deserted,—{7}nor Rogelio’s study, nor his mother’s room; it was the dining-room, which adjoined the reception-room. Here was the clock which informed Rogelio, negligent about winding his watch, when it was time to go to college; here the little table on which stood the work-basket with the unfinished stocking buried under a pile of numbers of Madrid Comico, Los Madriles, and all the Ilustraciones that had ever been published; here the low, broad, comfortable sofa and the capacious easy-chairs; here, on the sideboard, refreshments for the inner man—a bottle of sherry and some biscuits, or, in summer, fruits, which the boy ate with enjoyment; here, in a glass, the branch of fresh lilacs, or the pinks which he wore in his button-hole; here the earthen water jar exuding moisture from its sides, and the bottle of syrup of iron, and the Japanese fan, and the unfinished novel, with the marker between{8} the leaves, and the text-book, worn more by the ill-humor and displeasure with which it was handled than by use; and finally, the little fireplace that had so good a draught, which made up for the icy class-rooms, and the dilapidated courts and passages of the temple of Minerva. With what enjoyment did Rogelio go to warm himself by the fire before taking off his cloak when he came in from college, stretching out his hands, cold as icicles, to the blaze. The genial heat thawed his stiffened muscles, quickened his impoverished blood, and gave him strength to ask, with a comical pretense at scolding and coaxing entreaties mingled, for his breakfast, almost regretting the promptness with which it was served, since it left him a subject the less for his humorous jests. Before it had crossed the threshold of the door, Doña Aurora was already crying out:{9}

“Fausta! Pepa! Here is the señorito; bring the breakfast. Quick! Hurry! Child, your syrup of iron. Shall I count your bitter drops for you!”

“What more bitterness do I want than the pangs of starvation! Here, you who preside over the culinary department, may I be permitted to know with what delicacies you intend to assuage to-day the pangs of hunger that are gnawing my vitals? Have you prepared for me celestial ambrosia, nectar from the calyxes of the flowers, or tripe and snails from the Petit Fornos? Relieve me from this cruel uncertainty?

(Suppressed laughter in the kitchen.)

“Bring this crazy boy his breakfast, so that he may hold his tongue!”

Mother and son being seated at the table, the drops counted out and drank, the steaming soup was set before them, followed by the couple of{10}

fried eggs, round and crisp-edged, and the beefsteak, invariably sent in from the neighboring café. Only on this condition would Rogelio eat it. No matter what pains Fausta, the Biscayan, might take, she could never succeed in supplanting the cook of the café. The succulent piece of underdone steak would come between two plates, with its accompaniment of fried potatoes, tender, juicy, and appetizing. While Rogelio cut and ate the meat,{11} his mother watched him eagerly and anxiously, as if she had never before seen this delicate youth, so different from the ideal of a Galician mother. Twenty summers run to seed, a pale, dull complexion, eyes black and sparkling, but with the eyelids drooping, and surrounded by purple rings, a sarcastic mouth, the lips delicately curved and somewhat pale, shaded by a light mustache, hair smooth and silky, a head narrow at the temples, a slender throat, the back of the neck slightly hollowed in, flat wrists and a graceful shape made up a figure still immature, interrupted in its development by the chlorosis which is the result of a hothouse existence in which the plant that requires the pure, free air, dwindles and wilts. So that Doña Aurora did not enjoy a moment’s peace of mind because of this son who, if not exactly sickly, was of a nervous and delicate constitution, as was evidenced by{12} his moods of childlike gayety followed by periods of causeless gloom. Therefore it was that she watched him at his meals as eagerly as if every mouthful he swallowed were entering her own stomach after a two days’ fast. In thought she said to the succulent meat: Go, strengthen the child. Give him muscle, give him blood, give him bone. Make him robust, manly, independent. Make him grow to be like a young bull—although he should have all the savageness of one. No matter, all the better, I only wish it might be so! Consider that all there is left me in the world now to love, is that puny boy. And she would say aloud to Rogelio:

“Eat, child, eat; flesh makes flesh.”{13}

Doña Aurora had her daily reception—and in the afternoon; nothing less, indeed, than a five o’clock tea, as a society reporter would say—only, without the tea or the wish for it, for if she had offered anything to her guests, the Señora de Pardiñas, who was very old-fashioned in her ideas, would undoubtedly have selected some good slices of ham or the like substantial nourishment. As her friends knew that she was accustomed to go out only in the morning wrapped in her mantle and her fur cape to make a few unceremonious calls or to do some shopping, and that she spent her afternoons at her dining-room window knitting, they attended these receptions punctually, attracted to{14} them by the cheerful fire, by the easy-chairs, by friendship, and by habit.

The larger part of the circle of Doña Aurora’s friends was composed of the companions of her deceased husband, magistrates, or, as she called them in professional parlance, “Señores.” Some few of these, who had already retired from active official life, were the most constant in their attendance. Certain seats in the dining-room were regarded as belonging of right to certain persons—the broad-backed easy-chair was set apart for Don Nicanor Candás, the Crown Solicitor, who loved his ease; the leather-covered arm-chair with the soft seat was for Don Prudencio Rojas; the arm-chair covered with flowered cretonne by the chimney corner—let no one attempt to dispute its possession with the patriarch Don Gaspar Febrero. This venerable personage was the soul of the company, the most active, the most imposing in appearance, and the{15}

gayest of the assemblage, notwithstanding his eighty odd years and his lame leg, broken by jumping from a horse-car. The first quarter of an hour’s conversation was generally devoted to a discussion of the weather and the health of the company; there was not one of these worthy people who was not afflicted with some ailment or other.{16} Some of them, indeed, were full of ailments, so that neither their complaints nor the remedies they discussed were of merely abstract interest. There an account was kept of the fluctuations in the chronic catarrhs, the rheumatic pains, the flatulent attacks, and the heartburns of each one of the assemblage, and they discussed as solemnly as they had formerly discussed a judgment the virtues of salycilic acid or of pectoral lozenges.

The sanitary question being exhausted—for everything exhausts itself—they passed on, almost always following the lead of Señor Febrero, to treat of less agreeable matters. The amiable old man could not bear to hear all this talk of drugs, prescriptions, and potions. “Any one would suppose one had one foot in the grave,” he would say, smiling and showing his brilliant artificial teeth. The subject of the conversation was changed, but it{17} scarcely ever turned on questions of the day. Like a gavotte played by a grandmother on an antiquated harpsichord, the ritornello of souvenirs and reminiscences of the past resounded here. The conversation usually began somewhat as follows:

“Do you remember when I received my appointment to the Canary Islands during the ministry of Narvaez?”

Or:

“What times those were! At least ten years before the celebrated Fontanellas case. My eldest son was not yet born.”

Señor de Febrero interposed to restrain them in these sorrowful reminiscences of bygone days also, exclaiming with youthful vivacity:

“Why, that took place only yesterday, as one might say. In the life of a nation what is a paltry twenty-five or thirty years?”

“Yes, but in a man’s life—{18}—”

“Or in a man’s life either, if it comes to that. Forty or fifty I call the prime of life.”

“Speak for yourself. You have discovered the elixir of youth. You are as fresh as a lettuce. But the rest of us look like parchment; we are only fit to be wheeled out in the sun.”

With his crutch between his knees Don Gaspar laughed, and as he shook his head the silvery curls of his wig shone in the light. I regret to be obliged to pay tribute to descriptive truth by stating that Señor de Febrero wore a wig and false teeth; but it must be added that their falseness was so true that they were superior to the genuine articles and would deceive the sharpest eye. With exquisite taste and consummate art, the old man had had his wig made of hair as white as snow, and the coronet of light white curls that encircled his ivory brow was like a majestic aureole, very different{19} from the thick forest of hair with which would-be young old men persist in striving to repair the irreparable ravages of time. In the same way the teeth, skillfully imitating his own, somewhat uneven and worn, with a gap on the left side, would have deceived anybody. With his beautiful hair, his smooth-shaven face, his regular and still very expressive features, with his pulchritude and dignity of mien, Don Gaspar reminded one of the heads of the eighteenth century as they have come down to us in miniatures. It seemed a pity that he should not wear an embroidered satin coat; the cloth coat did not suit him. Even the ebony crutch, with its blue velvet cushion, served to enhance and complete the commanding dignity of his presence. With the gallantry of a bygone age, Don Gaspar, the moment a woman appeared in sight, was all ardor, and honied speeches flowed from his lips.{20} Even to Señora Pardiñas, who was altogether out of the lists, he did not neglect to pay attentions that were lover-like and gallant, rather than merely polite.

It gratified the vanity of this old man, who wore his old age so serenely and so gracefully, to hear his companions, all infirm, all asthmatic, all with their chronic colds and coughs, all visibly bald, say of him enviously:

“This Don Gaspar is wonderful. He will live to bury us all.”

It was also a gratification to his vanity to prove to them the strength and clearness of his memory, and it was one which he often enjoyed, for at the reception of the Señora de Pardiñas the thread of memory was constantly spun, and intermingled with it was a strand of gold, but of tarnished gold like that of an antique chasuble. Don Gaspar’s memory was a sort of wardrobe in which were stored away among{21} perfumes, duly labeled and classified, events, names, dates, and even words. “This Señor de Febrero is an old record-book,” Doña Aurora would say. When there was a difference of opinion regarding the date of some past event, Don Gaspar was appealed to as umpire.

“Isn’t it true, Señor de Febrero, that the Zaldivar case, at Seville, was decided in the winter of ’56.”

“No, Señor, the winter of ’57. I remember it was on the 15th of December—I mean the 16th, the birthday of our friend Don Nicanor Candás.”

“But, good Heavens!” exclaimed Don Nicanor, when this was related to him. “It is not right that any one should be endowed with a memory like that. If that infernal Galician does not remember even the date of my birth, a thing that I can never remember myself! As nobody is going to steal any of my years away from{22} me, I don’t see the use of keeping so exact an account of them.”

Don Nicanor Candás, a retired Asturian, from Oviedo, suspicious and conceited like all his townspeople, as biting as pepper and as sharp as a thorn, afforded much amusement to the assemblage through his disputes with Señor de Febrero, whom he opposed systematically, without consideration for his patriarchal privileges or respect for his honorable seniority. The better to confound his adversary Candás adopted a singular method, which was not without humor. He pretended to be as deaf as a post, and he always carried in the pocket of his coat a little silver trumpet, which he put to his ear whenever he was able to answer and refute his opponent’s arguments, but which he would say he had forgotten to bring with him when, not being able to do this, he wished to change the subject of conversation. Such a stratagem{23} could not fail to succeed, and by the help of it he was always enabled to avoid being worsted in a dispute. In his language Señor de Candás was as rude and ill-bred as Don Gaspar was choice, polite and mellifluous, and for this reason he was out of harmony with the other habitués of the house. Nor was he so for this reason alone, but also because he was the only one of them who preferred the news of the day to reminiscences of the past, the only one who brought to this musty senate a breath of out-door air, of real life.

The portentous memory of the octogenarian grew confused and uncertain when recent events were concerned, and Candás, profiting by this defect in the admirable faculties of the patriarch, was always trying to trip him up. “Let us see,” he would say, “how our Don Gaspar would set about proving an alibi. He is impregnable in all that{24} relates to the Calomarde ministry or the regency of Espartero, yet he does not remember what he was doing this morning.” And imitating Don Gaspar’s voice, he would add, “What did I do yesterday? Let me see. Did I go to see Rojas? I think so. What am I saying? No, no. I was walking in Recoletos. Yet I would not swear to that, either.”

This humorous criticism of the patriarch, might, to a certain extent, be applied with equal justice to all the other “Señores.” It would seem as if the present did not exist for them, as if the past only had life and color. They discussed the news of the reporter, Don Nicanor, for a few minutes with the pessimism that is characteristic of old age; then they resumed their progress up the stream of time, plunging with supreme satisfaction into the fogs of vanished years. Perhaps, along with old age, they were influenced in this to{25} some extent by the character acquired in the practice of the law, a profession based on scientific notions already stratified, a science purely historical, in which the spirit of innovation is a heresy, and in which the judicial problems of to-day are solved according to the standard of the Roman law or the jurisdiction of the Visigoths. Thus it was that the reunions in the house of the Señora de Pardiñas might be likened to a rock standing motionless amid the ceaseless surge of the sea of life. The worthy “Señores” did not see that among dusty and worm-eaten parchments, too, living germs palpitate and the spirit of progress lives. Clinging to vain formulas, they fancied they were the custodians of a sacred liquor, when only the empty vase remained in their hands, and, treating of innovations, they placed in the same category of heterodoxy the use of the beard, inferior courts, trial by jury, and the revision of the Codes.{26}

This assembly of sleep-walkers awakened to life and became animated at the entrance Rogelio, who, before taking his afternoon drive or walk, was in the habit of showing himself for a moment at the meeting, laughing at what took place there, but good-naturedly, with the mischievousness of a spoiled child. He had nicknamed it, “The Idle Club.” Candás, on account of his bald yellow skull, he called “Lain Calvo,” and the smooth-shaven and gallant Señor de Febrero, Nuño Rasura. The servants called them by these names among themselves. Even the Señora de Pardiñas laughed in secret, although she pretended to be vexed and would say to the boy:

“It is very wrong for you to turn{27} them into ridicule, in that way—those poor gentlemen who are all so fond of you!”

And they were indeed fond of him. The moment Rogelio appeared it was as if a ray of warm, golden sunlight had entered a closed and darkened room where furniture, hangings, paper, and pictures have all acquired the faded hue imparted by the dust and the damp. All the old men loved the boy; one of them remembered him when he was a child in arms, another had been present at his first communion; this one had brought him toys when he had the scarlet-fever; that other, a professional colleague and the intimate friend of his father, became a child again when he thought of the baptismal sweetmeats. If they had acted according to their feelings, notwithstanding the black fringe that adorned Rogelio’s upper lip, they would have showered kisses on him, and brought him caramels and{28} peanuts. For them he was always the little one, the boy. It was true that by a curious illusion the worthy guests of Señora de Pardiñas were disposed to regard the young as children and those of mature years as young. They would say, for instance; “So Valdivieso is dead! Why, he was in the prime of life, he was only a boy!” And it was necessary for the malicious Asturian, putting his ear-trumpet, or his hand as a substitute, to his ear, to interpose, “A boy indeed! a pretty sort of children you are dreaming of, truly. Valdivieso was past fifty.” “He was not so old as that, not so old as that!” “What do you mean? And the time he was in his nurse’s arms and learning to walk, does that count for nothing?”

Where Rogelio was concerned, they carried to an extreme this whim of forgetting the passage of time, and turning a deaf ear to the striking of the clock. Every additional year he spent{29} in the study of the law, was for them a fresh wonder; they could not fancy him a lawyer: they would have had him still at school learning to read. Once, on his return from a summer excursion to San Sebastián, Señor de Rojas had said to him with the utmost good faith:

“What a fine time you must have had, eh? Running about and playing on the beach all day, I suppose?”

And the boy answered without betraying any annoyance, but with a grimace of mischievous drollery:

“Yes, indeed, splendid! I made holes in the sand, and built little houses with it. I never enjoyed myself so much.”

In reality the good heart of the young man had grown attached to the assemblage of worthy old oddities who frequented the house. This very Señor de Rojas, for example, inspired him with a feeling of affectionate respect,{30} on account of the justness of his views, and his unquestioned probity. If Themis should descend to this lower sphere, she might take up her abode in the house of Señor Rojas and she would find there an altar erected to her and her image (of wood, according to Candás). A jealous interpreter of the law in its literal signification, Rojas walked along the narrow path that lay before him, without turning to the right hand or to the left, with head erect, and with a tranquil conscience. Convinced of the exalted dignity of his position, he complied with the requirements of social decorum at the expense of incredible privations in his house, sympathized with and seconded in this heroic conduct by his wife. In the exercise of his functions he was influenced neither by considerations of politics nor of friendship. Interests involving millions had been intrusted to him, without awakening in him the{31} faintest touch of cupidity, which is only the instinct of conservation expressing itself in the guise of acquisitiveness. For this reason the honorable name of Prudencio Rojas was pronounced, sometimes with veneration, sometimes with the disguised and caustic irony which vice employs to discredit virtue. The sarcastic Don Nicanor called Rojas a “puppet of the law.” He said that everything about him, mind and character alike, was wooden, neither seeing nor wishing to see that this kind of men, if laws were perfect as far as it is possible for human laws to be, might, by their firmness and integrity in applying them, bring back the golden age.

Often, of an afternoon, especially if it was very cold, or if it snowed or rained, Rogelio, instead of going out, would settle himself comfortably in a corner of the broad sofa and listen to the drowsy chat of the old people. Whenever{32} he could he tried to turn the conversation toward a subject for him full of interest, and one of which he never tired—his native Galicia, which he had left when he was very young. Almost all the party were either natives of that province or had spent long periods of time there, filling positions in the court of Marineda, and they expatiated on the benignity and salubrity of the climate, the cheapness and the excellent quality of the food, the easy and cordial manners of the people and the extraordinary beauty of the scenery.

“I cannot understand why our amiable friend, Doña Aurora, does not take the child to see his native place,” Señor de Febrero would say, stroking the cushion of his crutch.

“I am always intending to do so,” Señora Pardiñas would answer, “but it is one of those plans that something always happens to interfere with. The truth is, as you know, that up to the{33} present there has always been some difficulty or other in the way.”

“Say that you are very fond of your ease, mater amabilis,” her son would interpose. “If it had depended upon you, you would have been a tree that you might have taken root where you had happened to be planted.”

“Just as I take you to San Sebastián I might have taken you to Galicia, child, but it has not been possible to do so. Do you think I don’t often long myself to see my native place again? We who were born there—it is foolishness—but our dearest wish is to go back to the old spot, and our love for it never changes.”

“And we who were not born there love it too,” added Don Nicanor Candás, armed with his trumpet. “I would give my little finger now to spend a year in Marineda; I would rather go there than to Oviedo or to Gijón.

“But with me,” continued Señora{34} Pardiñas, “something always occurred to prevent me from carrying out my plan, as if the witches had interfered in the matter. Do you long to see your native place again, before you die? Well, wear yourself out with waiting until you are bent double with old age. You shall hear the causes of my never going back there”—and she would count them upon her fingers: “First, the difficulties in the way of doing so. You leave your family, your home, your possessions, to wander about the world, with a young child who is always delicate—from Oviedo to Saragossa, then, on account of the Regency, to Barcelona, then to the Supreme Court here. I was always saying to Pardiñas, ‘Resign your position, man, resign your position, and let us return to the old land and not leave our bones in a foreign soil. With what we have, we have more than enough to live, and our family is not so large as to be a burden to{35} us.’ But you know what my poor husband was, there is no need for me to tell you.”

(A murmur of sympathy in the audience.)

“He believed it was his duty to continue at his post to the end. And whenever duty was in question—at any rate, that was his idea, and it was necessary to respect it. And afterward, his health became so wretched——”

Here Señora Pardiñas’ voice grew slightly husky. She put her hand into her pocket, and taking out her handkerchief blew her nose and then wiped her eyes.

“So that,” she repeated, with a sigh and a shrug of the shoulders, “when the time came—And afterward you know how I was with my sisters-in-law, the law-suits and the difficulties I was involved in. I thought I should never be able to extricate myself from them. From home my old friends wrote to{36} me, ‘Come back, come back; in a day you will accomplish more here than you could in a year there. What would you have?’ I was afraid of the undertaking. With my rheumatism, to think of shutting myself up in one of those coaches that you couldn’t open a window in if it was to save your life! And when, well or ill, things were at last settled and the tangle of the will was straightened out, lo and behold, they put a railroad direct to Marineda. But by that time I had lost the wish to go, for to return home to find myself at variance with all my connections——”

“Not with all of them, mamma; according to your own account there are several who have taken our part.”

“Bah, how can I tell? In our place, child, it is hard to know who is for and who is against you. On that point I have had terrible disappointments. When you least expect it, your friends betray you and drive the knife into{37} you up to the handle. To speak the truth, there we are not frank and loyal, so to say, like the old Castillians.”

“You talk like a book,” assented Señor de Candás, who never let slip an opportunity of showing his claws. “The Galicians may have all the good qualities you please, but so far as being tricky and slippery and deceitful is concerned, there is no one who can beat them. Don’t trust to the word of a Galician, for they have no faith; or, if they have, it is Punic faith. What must the Galicians be when the gypsies don’t venture to pass through their country lest they should be cheated by them?”

“Take care how you insult the old land,” said Rogelio.

“Why, that is a well-known fact. No gypsy will go to Galicia. They are trickier and more crafty than all the gypsies put together. And as for going to law—Good Lord! They are born litigants. And they will be sure{38} to get the best of you; the most ignorant peasant there could wind you around his finger.”

“That is a proof,” responded Señor de Febrero, “that we are an intelligent race; you will not deny that?”

Señor de Candás, removing the silver tube from his ear so as not to find himself in the necessity of replying to this observation, and, in order to finish his argument to his own satisfaction, continued:

“And there are simpletons, who call the Galicians clever! I call them crafty. If they were clever, they would not be always sunk in poverty, eaten up with envy, without ever making an effort to be anything better than beggars and grumblers. They are more given to complaining than any people I know. They are always crying and groaning about something.”

The ivory skin of Señor de Febrero flushed a little, for he found it impossible{39} to accustom himself to the malignant rudeness of Lain Calvo.

“You are a little severe, Señor Don Nicanor,” he said, “remember that we Galicians are in the majority here. How would you like it if I were to repeat to you now the vulgar saying, ‘Asturian, vain, bad Christian, insane’?”

“There are plenty of fools,” continued the imperturbable Crown Solicitor, “who make a great show of surprise when they hear these things, but every one knows them so well that no one thinks it necessary to repeat them. The Galician, it is true, possesses some shrewdness, especially when the question is how to cheat his neighbor, but for all that he can neither cultivate any industry nor better his miserable condition. There he is, contented with his crust of corn bread, a poor creature, without clothes to his back, who never eats meat and who does not drink a{40} glass of wine even once in the year. With all his reputation for smartness, he sometimes seems more stupid than the Aragonese themselves. He is stingy and he would save an ochavitu even if he had to scrape it from his skin with a file; but you need not fear that he will ever think of investing this ochavo, or that he will have the energy to work in earnest in the hope of saving a dollar. Nothing of the kind. All he asks is to be let go on undisturbed in his lazy ways. See, for instance, the network of railroads they have, and what use do they make of them? They would not move a finger to attract summer visitors. None of that desire to please, that neatness of the people of our country.”

“One must either choke this Don Nicanor or take no notice of what he says,” exclaimed Nuño Rasura, furious, “for he won’t listen to argument. Where is that network of railroads he{41} talks about? A pretty network! Full of holes. He wants everything to be done in a day; no one but God can work miracles! Everything needs time and patience. Let Don Nicanor take note of the growing importance of beautiful Vigo. Its cool climate, its coasts and rivers are the admiration of the newspapers. And the women—always excepting those present, but then my good friend is from there, too. And the fish, the like of which is to be found nowhere else, what do you say of that? My dear Doña Aurora, I have eaten neither sardines nor soles since I left there. Just before the downfall of O’Donnell, I remember we were taking baths in Marin, and they brought a turbot to the door that——”

Here the old man went on spinning the thread of memory, and Rogelio, leaning with his elbow on the sofa, his cheek in the palm of his hand, listened absorbed. It seemed to him as if he{42}

were listening to some family tradition. The apartment, and the people in it assumed an air of friendly intimacy; the atmosphere, moral and material, was genial; the world was as comfortable and easy for him as the cushion against which he leaned. Each of the company was for him, if not a father, at the least an uncle. Around him reigned sweet security; and as in certain{43} luxurious abodes embarrassment and privation betray themselves, so in this modest dining-room was plainly visible domestic comfort, the most perfect golden mediocrity that poet could dream or philosopher desire. Harmony and moderation are always beautiful, and Rogelio, without being able to define this beauty that surrounded him, felt it and sheltered himself in it as the bird shelters itself among the feathers of its nest. And while the blazing logs crackled in the fireplace, and the sounds of the mortar came softened from the kitchen, and the old men chatted and his mother knitted her stocking, the boy, plunged in vague reverie, tried to picture to himself what that beautiful country, that green Galicia, abounding in rivers, in flowers, and in lovely girls was like.{44}

The whole street—shopkeepers, peddlers, servants, and inhabitants—all knew Rogelio; as the saying is, every one had some account to settle with him. He was familiar with all the establishments, or rather, the modest little shops for the sale of crockery, imported provisions, novelties, cordage and periodicals, interspersed among the ancient and imposing ancestral houses of the Calle Ancha, which was animated by the presence of the students and by the passing up and down of the street cars.

But those with whom Rogelio was most intimate were the drivers of the hackney coaches, of which there was a stand in the little square of Santo Domingo. Doña Aurora seldom went out{45} that a twinge of her rheumatism or the cold or the heat did not decide her to send for one of those vehicles, so shabby in appearance but so comfortable and convenient. She called them, emphatically, her “equipages,” and declared laughingly that her coach stood always waiting at the door with so punctual a driver that he had never once kept her waiting. Rogelio, as the only son of wealthy parents, indulged in a more luxurious mode of conveyance; his mother allowed him to keep a dashing brougham and a pair of spirited horses at the livery stable of Augustin Cuero, so that on feast days he might drive in the Retiro, or wherever he might like. She would not consent to his keeping a saddle horse, through fear of an accident. But nothing in the world would have induced Señora Pardiñas herself to make use of that toy equipage. She was perfectly satisfied with her quiet hacks. Except on some special occasion{46}—to make visits of ceremony or the like—she cared not a jot whether her carriage had a little extra varnish or her coachman wore gloves or a goat-skin cape. Owing to the frequency with which she employed them and to judicious tips all the drivers of the square were devoted to Doña Aurora, as well as greatly attached to the Señorito, though he loved to torment them, especially his compatriots, the Galicians, whom he was never tired of teasing. He ridiculed their native land, he sang the Muñeira for them, he spoke to them in the Galician dialect, like the servants in Ayála’s comedies, and if by a miracle they were vexed, he would say:

“I too, swift charioteer, am a Galician, a Galician of the Galicians.”

To which they would answer:

“What a droll señorito!”

Whenever he went to engage a carriage for his mother the moment they caught sight of him, if he was a league{47} away, they would laugh and lower the sign. And he would appear upon the scene addressing them something in this fashion:

“Winged Automedon, touch your fiery courser with the whip that he may fly to my enchanted palace. Already the generous steed, impatient, champs the golden bit. Behold him flecked with snowy foam. Buloniu, of what were you thinking, that you did not perceive my approach?”

“I was reading La Correspondencia, Señorito.”

“La Correspondencia! What name have thy sacrilegious lips pronounced? La Correspondencia! By the tail of Satan! A revolutionary, an anarchical, a nihilistic sheet. Quick! Cast away that venom before thou comest near the honorable dwelling of peaceful citizens. Hasten, run, fly, coachman! Hurrah, Cossack of the desert! On, drunkard, demagogue!”{48}

The more extravagant the absurdities he strung together the more delighted were the drivers.

One morning Rogelio left the house wrapped up to the eyes in his cloak, for these closing days of October were bitterly cold, although the bright Madrid sun was shining in all its splendor. As usual, his errand was to go in search of a carriage for Doña Aurora. On reaching the corner of the square he caught sight of one of his favorite equipages—a landau whose lining of Abellano shagreen was less soiled and worn than that of the generality of those vehicles. The driver, a stout man, fair and ruddy, answering to the name of Martin, was a Galician. Rogelio made signs to him as he approached, crying:

“Martin, Martin of the cape! Ho, with the imperial chariot!”

The driver was conversing with a {49}woman whose face was hidden from the student, but at the sound of Rogelio’s voice she turned around and he saw that she was young and not ill-looking, of humble appearance and dressed in mourning.

“Señorito, what a coincidence!” exclaimed Martin, as he recognized Rogelio. “This young girl is looking for the señorito’s house and she was just asking me the way there. She is a country-woman of ours. She brings a letter——”

“Will you let me look at the direction?” said the student, changing his manner and the tone of his voice completely, as he addressed the young girl.

The girl handed him the note, for it was only a note.

“Why, it is for mamma!” he said, as he looked at the superscription. “Come with me; I will show you where the house is. Do you, driver, follow in our resplendent wake with{50} your imperial chariot, drawn by that stately swan.”

“Many thanks, Señorito,” said the girl in a sweet and well modulated voice, and with the sing-song accent peculiar to the Galicians of the coast. “There is no need for you to trouble yourself. I can see the door of the house from here; the driver pointed it out to me.”

“It is no trouble; I am going that way,” replied the young man.{51}

Without offering any further objection the girl walked with him in the direction of the house. Rogelio instinctively took her left as he would have done with a lady. He had not gone a dozen steps, however, before he repented of his gallantry. In the first place, his companions would ridicule him unmercifully if they should chance to meet him accompanying so politely a girl wearing a shawl over her head and dressed in a plain merino skirt. In the second place, Rogelio was at the age when a boy brought up under maternal influence in the pure atmosphere of home cannot avoid a feeling of painful shyness when brought in contact with persons of the other sex with whom he is unacquainted. It is true that women of an inferior station did not confuse him so much; young ladies were like death to him; he always fancied they were making fun of him, that everything they said to him was only in sport; to draw him{52} out, enjoy his confusion, and ridicule him afterward among themselves with malicious and pitiless irony. Walking at the side of this girl dressed in mourning, however, he experienced the same sort of confusion, for, notwithstanding her humble dress, neither in her manner nor in her appearance was there a trace of vulgarity. “Shall I speak to her?” he said to himself. “Will she laugh at me? She will laugh at me more if I say nothing. No, I must say something to her.” What he said—and with the utmost seriousness, was:

“Do you know whom that letter is from that you are taking to mamma?”

“Why, certainly;” she replied; “it is from the young ladies at General Romera’s. Don’t you know them?”

“Of course I do. General Romera was a friend of papa’s. We have not seen them for a long time.”{53}

“Doña Pascuala, the elder, has been sick. She had something they call tonsilitis. Ah, she was very ill!”

“And is she better now?” asked Rogelio, for the sake of saying something, for anxiety for Doña Pascuala’s tonsils would never have deprived him of his sleep.

“She is entirely well now. If she was not well I should not have left her.”

“Were you—living there?” (Rogelio did not venture to say at service.)

“Yes, Señor, ever since I came from the old land.”

“Ah, you are a Galician, then?”

“There is no reason why I should be ashamed of it.”

“Nor I either, caramba!”

“No, Señor, no indeed. It is a very good country, better than Madrid or than any other place in the world.”

Rogelio smiled, pleased with the girl’s patriotism, and beginning to feel{54} at home with her, for she seemed to him incapable of ridiculing any one. They were now near the house; Martin, who had gone on in advance, stopped his hack, a task which was easier than to make him start, and at the door stood Doña Aurora, making signs to her son.{55}

“Mamma, here is some one with a love-letter for you.”

“Who? This girl?”

“Yes, Señora—from the Señoritas Romera,” said the young Galician.

“Come here, let me see. Perhaps it is something that requires immediate attention.”

But no sooner had she torn open the envelope than she burst into a laugh.

“How crazy I am! Without my glasses—Here, child, read it you.”

Rogelio unfolded the missive and began in a pompous voice:

“High and mighty and most tormented lady: if your beauty——”

“See, child; have sense and read what is set down there; there is a terrible{56} draught and the rheumatism in my joints won’t allow me to stand here listening to nonsense.”

In his natural tone of voice Rogelio read as follows:

“Most respected friend: Esclavita Lamas, the bearer, will inform you of the favor she desires; all we can say is that during the time she was with us, she was most exemplary in her conduct and fulfilled her duties faithfully; so much so that we are very sorry to lose her, as we have no fault to find with her; quite the contrary.

“Your old and affectionate friends,

“Pascuala and Mercedes Romera.”

“Is there nothing more, child?”

“There is a foolish postscript that it is not necessary to read.”

“A foolish postscript?”

“Yes; asking why no one ever sees me now and saying that I must be grown a fine-looking young fellow. The stereotyped, silly compliments—{57}—”

“I am always telling you so, child!” exclaimed his mother, with vexation. “You never go to spend ten minutes at the house of these poor ladies, who are so fond of you. They have seen you so petted that they will think it is all my fault. Well, I speak to you often enough about them. Pascuala and Mercedes! If you don’t go, I shall.”

“But, mater terribilis, when I put my foot in that reception room, I get so sleepy that I can do nothing but yawn!”

“Well, they are a pair of saints.”

“Amen; I don’t dispute their sanctity; I am only saying that they are very tiresome and that they never stop talking. They keep up a duet like the Germans in La Diva. ‘Rogelio, how is mamma?’ ‘And how are you getting on with your studies?’” And he imitated the husky voice and Malagan accent of the old maids.

“What nonsense you talk,” said Señora de Pardiñas, repressing a smile,{58} “I don’t know why Pascuala and Mercedes should make you sleepy.”

“Unfathomable mysteries of the human heart. Profound arcana. In that dimora casta e pura a fatal narcotic pervades the atmosphere.”

“Humbug!”

During this skirmish between mother and son the girl stood waiting, motionless, with her eyes fixed upon the ground. Doña Aurora, at last remembering her presence, turned toward her:

“Excuse me, child; this letter says that you will tell me what you have come to see me about. Will you come upstairs?”

“No, Señora. Don’t put yourself to any trouble on my account. Here will do just as well.”

“Well, let me hear. Is it some favor you wish to ask of me?”

“Favor? No, Señora. I would like to enter into service in your house—or{59} in the house of some other Galician family,” she added, after a pause.

Doña Aurora looked fixedly at the petitioner and fancied she reddened slightly under her gaze.

“You—were not contented at the Señoritas de Romera’s, then?”

“Yes, Señora, I was contented enough—and I think they were pleased with me, too. You can see that from the letter they gave me. As far as the Señoritas are concerned I would be in glory, for they are as good as they can be, not belittling others. God grant them every prosperity! Only that sometimes—there are good people that one doesn’t find one’s self at home with. Those ladies are from Malaga, in the Andalusian country, and they have customs and dishes that I don’t understand. Even their way of talking is strange to me. When they tell me to do a thing and I don’t understand, I feel as if I had heard my death sentence.{60} And, then, Señora, the truth before all—not to be among people of one’s own country, never to hear it mentioned, even, makes one’s heart very sad. For the half of the wages and with double the work I would rather serve a person from my own place.”

All this she said with an air of so much sincerity that Doña Aurora’s good-will toward her increased, prepossessed in her favor as she already was by the respectable and decorous bearing of the girl, so different from the bold manners of the Madrid Menegildas. Only there was something in the girl’s story that was not altogether clear to her. There must be some mystery in all this. Before the door the driver was smoking his cigarette, while the hack, with drooping head and projecting lower lip, was dreaming of abundant fodder and delightful meadows.{61}

“Child,” said Señora Pardiñas. “I am going to sit down in the carriage. As I am not as young as you are I feel tired standing, and my legs are bending under me. If you don’t want to go upstairs, come over to the carriage with me.”

The little Galician helped Doña Aurora to settle herself in the vehicle, and the latter when she was seated said:

“Tell me, if you were so greatly attached to your country how was it that you came here?”

Ah, this time there was not the slightest doubt of it; it was a blush, and a vivid blush, that dyed the girl’s cheeks. And when she answered one must be deaf, and very deaf, not to perceive that she stammered, especially at the first words.

“Sometimes—one has—to do what one’s heart least prompts one to do, Señora. We are children of fate. I{62} was brought up by my uncle, the parish priest of Vimieiro. It was the will of God to take him to himself and I was left without a protector. To get one’s bread one must work. I was a queen in my own house; now I am a servant. God be praised, and may we never lose the power of our hands or our health.”

“Why did you not go out to service there?” persisted Señora Pardiñas, who had a keener scent than a bloodhound where a secret was concerned. And that the secret was there she could not doubt on seeing that it was not now a blush but a hot flame that passed over Esclavita’s face.

“I—I couldn’t find a place,” she answered, in choking accents. “And then, as everybody there knows me, I was ashamed.”

Doña Aurora Pardiñas reflected for some two minutes, and speaking gently to soften the harshness of the words:{63}

“Let us see,” she said. “You can refer only to the Señoritas de Romera who—knew nothing about you before you went to their house. Isn’t it so? It would be well, then,—you will see that yourself,—if you could find some one here who knew you at home who would recommend you.”

The girl hesitated for an instant, and then said:

“The Señorito Gabriel Pardo de la Lage and his sister know who I am.”

“Rita Pardo? The wife of the engineer? I am very well acquainted with her. And you say that she knows you?”

The girl answered by raising her hand and shrugging her shoulders as much as to say, “Why, ever since I was born!”

“Well, child,” rejoined Señora Pardiñas, frankly, “I am sorry that you should leave the Romeras. You could{64} not find a better house or better ladies.”

“I do not deny that,” replied Esclavita with greater emphasis than before, if possible; “only that I have told you the truth, Señora, as if I were talking to my dead mother or to the confessor. I was seized with homesickness, and if I hadn’t left them I think I should have lost my reason or have gone straight to my grave. I couldn’t eat. I would go off by myself to a corner to think. I grew paler and paler every day, and so thin that my clothes hung loose on me. At night I had fits of choking, as if some one was tightening a rope about my neck. But in spite of all that I was loth to say anything to the Señoritas. They saw it themselves, though, and they were the first to advise me, if I did not go back home, to look for a place with some family from there! ‘Child, you are so altered that you{65} don’t look like the same person,’ were the very words they used.”

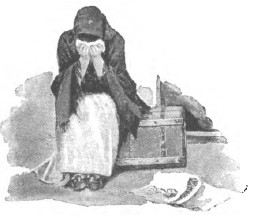

As she said this, Esclavita’s chin trembled like a child’s when it is making an effort to keep from bursting into sobs. Her eyes could not be seen, as she had cast them down, according to her wont.

“Calm yourself,” Señora Pardiñas said kindly. She was beginning to conceive an irresistible sympathy for this girl, whose bearing was so modest and whose heart was apparently so tender. How different she was from the impudent servants of Madrid, the gadabouts of the suburbs, shameless termagants who could not stay in any decent house. It was not two hours ago that Pepa, the house-maid, for a mere nothing had thrown aside all decency and scolded like a fishwoman. This little Galician might have had—well, some slip—for the reasons she gave for leaving her native place did{66} not seem all clear; but her whole appearance was so—well, so like that of an honest woman—God alone knew how the poor thing had been tempted.

“See,” she said, putting her head out of the carriage door, “for the present I cannot give you a decided answer as to whether I will take you or{67} not. Come to the house to see me to-morrow morning about this time. I should be glad to—but I must think the matter over. If I should not be able to take you myself, I will look for a place for you with some other Galician family. Tell me your conditions, in case any one else should want to know.”

Esclavita, meantime, stood rolling an end of her black silk handerchief between her thumb and forefinger.

“May God reward you!” she answered. “As for the wages, a dollar more or a dollar less makes no difference to me. Work does not frighten me. I would not engage as a cook, for I don’t know how to make those fine dishes that are the fashion now. I understand simple dishes like those of my native place. In everything else I think I could give satisfaction—in the cleaning, the mending, and the ironing. All I ask is that in the family you look{68} for there should not be—well, men, who——”

“I understand, I understand,” interrupted Doña Aurora. And she added jestingly, “But in that case, tell me why you want to come to my house. Haven’t you seen that there is a man in it?”

And she pointed to Rogelio who, relieved from his embarrassment by his mother’s presence, stood leaning against the carriage door, looking at the girl. Esclavita followed the direction of Señora Pardiñas’ hand; for the first time her eyes, green, changeful, sincere, rested on the student. After a pause she said with a smile:

“Is that young gentleman your son? May God spare him to you for many years. That isn’t the kind of man I mean, he is only a boy.”

Rogelio changed countenance as if he had received the most outrageous insult. He tried to disguise his annoyance{69} by a laugh, but the laugh died away in his throat. It must be confessed that he even felt his eyes fill with tears of vexation. It was one of those moments of insensate and profound rage which must come at one time or another to the man whose childhood has been unduly prolonged; moments in which he desires, as if it were the highest good, to possess the bitter treasure of experience—sorrows, disappointments, trials, struggles, sickness, gray hairs, wrinkles, calamities, betrayal of friendship and of love—all, all, so that he may hear the supreme word, so that he may taste the fruit of good and evil, the immortal apple, golden on the one side, blood-red on the other. All, so that he may fulfill the destiny of humanity, all, so that he may pass through the cycle of life.{70}

When the driver whipped up his horse, Señora Pardiñas called out to her son, who was on the box:

“Give him Rita Pardo’s direction.”

Rogelio obeyed; but when they reached the house in the dingy Calle del Pez, in which the engineer’s wife lived, he jumped down and opening the carnage door, said to his mother:

“I won’t go in. To make your inquiries you have no need of me.”

“And where are you going now?”

“Oh, to take a turn,” responded the student, indifferently, with a farewell gesture of the hand which betrayed the impatience of the boy growing into manhood to assert his manly independence, something like the nervous fluttering of the wings of the bird{71} when his cage door is opened to him. Without further explanation he drew his cloak more closely about him and disappeared around the nearest corner. His mother followed him with her eyes as long as he remained in sight, then she sighed to herself and half smiled. “It must come some day,” she thought. “He is at an age when the reins cannot be held too tightly. Of course, the poor boy does not impose upon me, that is only to show his independence; he will look in at a few shop-windows, buy half-a-dozen periodicals, and take a turn or two with any friend he chances to meet, and then go to the apothecary’s. If I could only see him strong, robust, burly—there are boys at his age that are perfect giants that have a beard like a forest. He is so delicate, and so puny! Our Lady of Succor, bring me safely through!”

These maternal anxieties had calmed down by the time Señora Pardiñas,{72} releasing her grasp on the banister of the stairs, had rung the bell of Rita Pardo’s apartment—a third floor with the pretensions of a first. The door was opened by a girl of eleven or twelve, pale, black-eyed, with her hair in disorder, her dress in still greater disorder, who as soon as she saw the visitor ran away, crying:

“Mamma! Mamma! Señora de Pardiñas!”

“Show her into the parlor; I will come directly,” answered a woman’s voice from the inner regions of kitchen or pantry. Doña Aurora, without waiting for the permission, was already entering the parlor, a perfect type of middle-class vulgarity, full of showy objects, and without a single solid or artistic piece of furniture. There were three or four chairs covered with plush of various colors, an étagère on which were some cast-metal statuettes; several trumpery ornaments{73} and silver articles which were there only because they were silver; two oil-paintings in oval frames, portraits of the master and the mistress of the house, dressed in their Sunday finery; on the floor was a moquette carpet, badly swept. It was evident that the parlor was seldom cleaned or aired, and the carpet gave unmistakable indications of the presence of children in the house.

At the end of ten minutes, Rita Pardo, the engineer’s wife, made her appearance. She came in fastening the last button of a morning gown, too fine for the occasion, of pale blue satin trimmed with cream-colored lace, which she had put on without changing her undergarments soiled in her household tasks. She had powdered her face, and put on her bracelets. Although she was no longer young and her figure had lost its trimness, neither maternity nor time had been able to{74} dim her piquant beauty, but the coquette whom we remember laying her snares for her cousin, the Marquis of Ulloa, had been transformed into a circumspect matron, with that veneering of decorum under which only the keen eye of the student of human nature could discover the real woman, such as she was, and would ever remain; for the real man and the real woman, however they may disguise themselves, do not change. She greeted Señora de Pardiñas cordially, with her usual, “What a pleasure to see you, Aurora! Heavens! in this life of Madrid months may pass without seeing one’s friends or knowing whether they are living or dead. You have caught me like a fright. The mornings are terrible—they slip away in listening to idle chatter and sending and receiving messages. How sorry Eugenio will be——”

No sooner had Doña Aurora{75} broached the subject of her visit than Rita Pardo suspended the flow of her talk and waited to hear further, with evident curiosity depicted in her voluptuous black eyes, and on her hard, fresh mouth. A series of ambiguous gestures and malicious little laughs was the prelude to the following commentary:

“What do you tell me? What do you tell me? Esclavita Lamas. The rector of Vimieiro’s Esclavita Lamas! Ta, ta, ta, ta, ta! And how has Esclavita Lamas happened to come across you?—Isn’t she a girl with auburn hair?”

“I don’t know whether her hair is auburn or not. She wears a shawl over her head. She is in deep mourning and looks very neat. Her appearance is greatly in her favor.”

“Well, well, well! Esclavita Lamas! Who would have thought it! Yes, she is, as we say in our part of the{76} country, very demure, very mannerly; she talks so soft and low that at times you can scarcely hear her. She smells a hundred leagues off of the sacristy and of incense. A little saint!”

Doña Aurora was more discouraged than was reasonable by this preamble; she resolved, however, to disguise her feelings and to find out the truth, the whole truth, even though it should grieve her to the heart to hear any ill{77} of the girl, in whom she was deeply interested.

“So that you know her very well?” she said.

“Heavens! As well as I know my own fingers. Indeed I know her! Lamas Tarrío was a great friend of the family even while he was in the other parish in the mountains before papa presented him for Vimieiro. He always lived in our house, and he was very fond of making presents. What lard, what cheese, what eggs at Easter and what capons at Christmas he used to give us! Papa thought a great deal of him, for in the mountains he took charge of the collecting of the rents. In short, he was devoted to us. He was indebted to papa, too, for a great many favors, important favors, Doña Aurora.”

“Well, what I want to know is what relates to the girl. If her antecedents are good, and I can admit her into my{78} house, I shall be glad of it. I am not satisfied with Pepa, and I have taken a liking to this girl.”

Rita Pardo smiled maliciously, as she smoothed out the lace of her left sleeve, a little crumpled with use. She arched her eyebrows, and made a grimace difficult of interpretation.

“Um! Good antecedents may mean much or little, as you know. What is good for one is only middling for another. In that matter, some people are more particular than others. If the girl pleases you so much——”

“No, not so fast!” exclaimed Señora de Pardiñas, alarmed. “For me good antecedents are good antecedents, neither more nor less. Be frank and tell me all you know, for that is what I have come for; and now with the thorn of suspicion you have planted in my mind, I would not take the girl, not if she were crowned with glory, unless you explain to me—{79}—”

Rita smoothed out her lace again, and gave a little sigh of embarrassment as she answered:

“Aurora, there are certain things that, no matter how public they may be, one cannot have it on one’s conscience to reveal them. You know nothing about the matter, eh? Then it would be very ugly on my part to enlighten you. So much the better if it has not reached your ears; it is an advantage for Esclavita. And you can take her without any hesitation; I am certain she will turn out an excellent servant.”

“You are jesting, Rita,” said Señora de Pardiñas, letting her growing irritation get the better of her, “You envelop the affair in mystery, you make a mountain out of it, and then you tell me that I may take Esclavita. No, child; in my house people are not received in that way, without knowing{80} anything about them. Explain what you mean——”

When the interview had reached this point Rita assumed a manner that was almost discourteous; she threw herself back, her nostrils dilated, her bosom swelled, and she began to excuse herself from answering with an air of offended dignity and wounded modesty.

When, after exhausting all her arguments, Doña Aurora obtained for her sole response, “I am very sorry, but it is impossible,” she rose, without troubling herself to conceal the annoyance this impertinent affectation of modesty had given her. She was just saying angrily, “Excuse my having come to trouble you,” when after a loud ring at the bell, followed by exclamations in a childish voice in the hall, the eldest girl—the twelve-year-old madcap, rushed joyfully into the parlor, crying:{81}

“Mamma! mamma! Uncle Gabriel!”

Then, the widow Pardiñas, with sudden inspiration, planted her feet firmly on the floor, saying to herself:

“Now I shall have my revenge. Now you shall see, hypocritical cat, impostor, humbug!”{82}

The commandant, dressed in the costume of a peasant, unceremoniously entered the room with his niece, who was the apple of his eye, his arm encircling her waist as if he was going to dance a waltz with her. In the salutation he exchanged with his sister, however, Doña Aurora could detect a shade of coldness, not far removed from dislike, a feeling which can sometimes be dissimulated where strangers are concerned, but never where its object is a member of one’s family. After the customary salutations and compliments, Señora de Pardiñas, who did not belie her race so far as wiliness and obstinacy were concerned, said tentatively:

“Well, I will leave you now. After all, I did not find out what I had {83}come to learn, and consequently—— Your sister is very reserved, Señor de Pardo.”

“Upon my faith, I have never thought so,” answered the artilleryman bluntly, almost rudely.

“Well, every one speaks of the fair according to the bargain he has made. With me she has shown herself extraordinarily reticent.” And without heeding the gesture or the glance of Rita, she continued undaunted: “For the last quarter of an hour I have been asking information from her in vain about a young countrywoman of ours, Esclavita Lamas, the niece of the rector of Vimieiro.”

Pardo listened like one in whose memory some vague recollection has been awakened.

“Stay—let me think—Vimieiro—Lamas—Lamas Tarrío. He was an intimate friend of papa’s. Rita knows all about him; she has the whole story at{84} her fingers’ ends.—What objection have you to tell it to Doña Aurora?”

A caricaturist desiring to represent bourgeois dignity in its most exaggerated form might have copied with exactness the features and expression of Rita as, arching her brows and pointing to her eldest daughter leaning against the commandant’s knees, she exclaimed impressively:

“The child!”

“Well, what of the child?” responded Don Gabriel, imitating his sister’s tragic tone. “Is it one of those shocking things that innocent ears must not hear—that the cat has had kittens, for instance?”

“Gabriel, you are dreadful,” groaned Rita, casting up her beautiful southern eyes. “When one is killing one’s self, trying to make your nieces what they ought to be in society, you must do your best to—there is no use in trying to struggle against people’s dispositions.”{85}

“Well,” insisted the obstinate Doña Aurora, “I come back to my complaint. Rita, don’t say that it was for the child’s sake that you refused to give me the information I asked. The child was not present, and even if she had been, by sending her out of the room——”

“Which is what I am going to do now. Eugenita, child, go practice your Concone.”

The girl left the room, much against{86} her will, casting on her uncle, as she went, a couple of affectionate farewell glances; but no scale or study was heard to tell that she had shut herself in the musical torture-chamber in which our young ladies, worthy of a better fate, are condemned to dislocate their fingers daily.

“You shall hear,” said Doña Aurora, emphatically, “now that we can speak freely. The question is that that girl, Esclavita Lamas, wants to enter my service; and that I, for my part, am greatly pleased with what I have seen of her. But I know nothing about her past, nor why she left her native place. There seems something odd in the whole affair. Your sister knows the story, and neither for God’s sake nor the saints’ will she tell it to me. There you have the cause of our dispute. It was beginning to grow serious when you came in.”

“The story,” said Gabriel, nervously{87} wiping his gold-rimmed spectacles, and putting them on again carefully. “Wait a moment, Señora; for if my treacherous memory does not deceive me—Rita, is not that the Father Lamas who took a poor girl off the street into his house for charity? Tell the truth, or I shall write this very day to Galicia to inquire.”

“Heavens! What notions you have! You are growing more unbearable every day—Was I not going to tell you the truth? Yes, that was the Lamas, and since you insist upon opening his grave, and dragging him out to public shame, do it you, for I don’t want to have such a thing on my conscience.”

“It should weigh more heavily upon your conscience,” replied Gabriel, with vehemence, “to try to prevent the girl getting her place on account of the sins of others. Now I can tell you the whole story, Doña Aurora, by an end I have unwound the{88} skein; it is the same with stories as with an old tune—if one remembers the first bar, one can sing the whole of it through without a mistake. And I can tell you that it is a novel, a real novel.”

“It may seem so to you,” said Rita, venomously, pulling the lace of her sleeves again. “As for me—there are certain things—— Well, I wash my hands of it.”

Doña Aurora concealed the satisfaction her victory gave her, but, a woman after all, she said to herself, casting a side glance at Rita:

“I’ve got the best of you, hypocrite!”

“You shall hear,” began the commandant. “This Father Lamas was a simple-minded man, illiterate as all the rural clergy were at that time,—now they are much more enlightened,—and not over-intelligent; but he performed all his parochial duties faithfully, and if{89} he committed faults he succeeded in hiding them. If you cannot be chaste, be cautious, as the saying is. Well, one night there came to the door of the rectory a girl, about tea years old, an orphan, who lived upon charity; in one house they gave her a piece of corn bread, in another a bundle of corn leaves to sleep upon, here a ragged shawl, there a pair of old shoes. In this way the wretched girl managed to live. The rector took pity upon her and said to her: ‘Stay here; you can learn housework; you will have clothes to wear, a bed to sleep in, and good hot soup to nourish you.’ And so it was decided—the girl stayed.”

“The girl was Esclavita?”

“No, Señora, no Señora. Wait a while. The girl turned out bright and capable; she put away from her her melancholy, as they say in our country, and she even grew rosy and handsome. And—” here the voice of the commandant{90} took a sarcastic tone—“when the flower of maidenhood bloomed—”

“Oh, Gabriel,” remonstrated Rita, “certain things should be spoken of in a different way. There is no need of entering into details that——”

“Bah!” said Doña Aurora. “We are all of us married and I am an old woman. We know all about it and are not to be so easily shocked as that comes to, my dear. Go on. What came afterward?”

“Afterward came Esclavita.”

Although Señora Pardiñas had affirmed that she knew all about it, this piece of information, given thus suddenly, almost made her jump in her chair.

“Ah!” she exclaimed, and then looked very thoughtful. “That is why the poor girl—well, and afterward?”

“Afterward,” cried Rita impetuously, unable to keep silent any longer, “papa{91} had the greatest difficulty to pacify Señor Cuesta, the Cardinal Archbishop. As the Archbishop himself was so virtuous he maintained strict discipline and permitted no misconduct. If it were not for all papa’s efforts with his eminence, to-day one entreaty and to-morrow another, Lamas Tarrío would have been deprived of his license and would have been left to rot in the ecclesiastical prison. For it is one thing for a priest to commit a fault that no one knows anything about, and another to scandalize his parishioners, bringing up the child in his own house, outraging public opinion, petting and indulging her——”

“My father,” said Gabriel, interrupting his sister, “with one hand smoothed down the Archbishop and with the other hammered away at the sinner. By dint of exhortations he succeeded in having the siren sent away from the rectory; but Lamas{92} continued to see her. At last papa took a firm stand and prevailed on him to allow the mother to be sent to Montevideo, on condition that he was permitted to keep the child.”

“Yes,” again interposed Rita, “a fine remedy that was, worse than the disease. The man became wilder and more reckless than he had been before. He spent night after night without closing an eye, crying and screaming. He had a rush of blood to the head—he was in our house at the time—so that they were obliged to apply more than forty leeches to him at once, and the blood that came was as black as pitch. We thought he would go mad; he would go about the corridors tearing his hair, calling on the woman’s name with maudlin expressions of endearment.”

As Rita said this her brother observed that the curtains of the adjoining room moved as if they had been stirred by a breath of hoydenish curiosity, and the{93} outlines of an inquisitive little nose were vaguely defined against them.

“See,” he said, “now it is you who are getting beyond your depth. All that has nothing whatever to do with the case. Let us end the story at once, and let me tell it in my own way. Poor{94} Lamas became so ill that the Archbishop himself was sorry for him, and sent for him to cheer him and inspire him with thoughts of penitence. And in effect, in process of time he grew calmer and even behaved himself very well afterward. The only fault to be found with him was that he brought up the child with extraordinary indulgence; but as the feelings of a father, even when they contravene both human and divine laws, have something sacred, people shut their eyes to this. He introduced the girl as his niece. As such children do not inherit, the priest saved up money, ounce upon ounce, which he put into Esclavita’s own hand; but the girl, who had turned out very discreet and very devout, and, in addition to that, very unselfish, when Lamas died, gave all this money, in gold as she had received it, for masses and prayers for the soul of the sinner. This act alone will give you an idea of the{95} girl’s character. There are not many girls who would do so much even if they had been born in a better station and in a more orthodox manner.”

“As my brother is of a romantic turn he sees things in that way,” interposed Rita.

“Señora de Pardiñas, I give you my word as a gentleman that I neither add nor diminish. That girl, in my opinion, would be capable of going bare-footed on a pilgrimage to any part of the world in order to get the soul of the rector of Vimieiro out of purgatory.”

“And well he would need it,” said Rita, “and her mother too, who, by all accounts, does not lead the life of a saint over there in America.”

“Good Heavens! How merciless you women can be, who have never had to suffer for the want of consideration or of bread,” exclaimed Pardo, now really angry. “I do not err on the side of philanthropy, but there are certain{96} things that I cannot understand in people who make a boast of being good Christians and who go to mass and say their prayers. Fine prayers those are! Is that what you understand by charity? Well, my dear, I declare that Esclavita is worth more than——”

Fortunately he restrained himself in time and ended:

“Than some other people. How is she to blame for her parents’ faults? Tell me that! And she is expiating them as if she had committed them. She even left her native place, it seems, so as not to be where people know and remember and discuss——”

“I would swear the same thing,” asserted Doña Aurora warmly. “Now I know why it was that she became so confused when she was asked certain questions. I am of the same opinion as you, Pardo, that she is good, that she has noble sentiments, and that those traits do her honor.”{97}

“Yes, be guided by my brother, admit her into your house,” exclaimed Rita, with a spiteful and insolent laugh. “For giving advice, Gabriel has a special gift. I tremble when he and my husband get together. If Eugenio were to be led by him we should be living on charity. Take that girl on your hands, and you will see how it will end. Then you will say, ‘Rita Pardo was right after all.’”

Señora Pardiñas thought within herself:

“I will take her if only to spite you, hypocrite, impostor. I have taken your measure, now.”

When Gabriel was going out, he found his eldest niece waiting for him in the reception room. He caught her by the waist, and lifting her up to a level with his mouth, whispered in her ear:

“Good little girls, if they want Uncle Gabriel to love them, must not{98} go peeping and spying and hiding themselves behind portières. They must obey mamma because she is mamma, and she will not tell them to do anything wrong. Take care and don’t bite, little lizard. Good little girls—are good. Ah-h-h! my cravat!”

“Uncle Gabriel, will you take me with you?” coaxed the little madcap. “With you, yes; with you, no; with{99} you, yes, I will go. Come, take me with you!”

“To Leganes it is that I will take you. Be good now! Study your French lesson! Comb that mane of yours! Run into the kitchen to see what the girl is about there! Papa likes his roast beef well done! See to papa’s roast beef!”

As he crossed the threshold the commandant threw a kiss to the girl, which she promptly returned.{100}

Doña Aurora was in the habit of taking her son his chocolate every morning before he was out of bed, for, old-fashioned in many other respects, the household was old-fashioned also in the matter of early rising. Those were delightful moments for the doting mother.

The boy, as she called him, felt on awakening that causeless joy peculiar to the springtime of life, that season when each new day seems to come fresh from the hands of time, golden and beautiful, and embellished with delights, before painful memories have begun to weigh down the fluttering wings of hope. Rogelio, who in the afternoon suffered from occasional fits of nervous depression, in the morning{101} was as gay and sprightly as a bird. Even his chatter resembled the chirping of birds or the cooing of infants when they open their eyes in the morning. His mother, after removing the articles of clothing and the books lying about, would seat herself at his bed-side and hold the tray, so that the chocolate might not spill as the boy dipped the golden biscuits into it, while a glass of pure fresh milk stood beside it waiting its turn.

And what anxiety and trouble this glass of milk cost Doña Aurora! She knew more on the subject than the entire municipal board of chemists; without analysis or instruments or other nonsense of the kind, she could distinguish, simply by looking at it, by its color and its odor, every grade and quality of milk that is consumed in Madrid. For her hopes of seeing Rogelio grow robust were all centered in that glass of milk drank before going to college, and in the beefsteak eaten after returning from it.

While he was taking his chocolate, it was that all the events of the preceding day were discussed, the amusing skirmishes between Nuño Rasura and Lain Calvo, the college jokes, the latest crime, last night’s fire, together with all the trifling incidents of that home so truly peaceful like many another in the capital, notwithstanding the provincial superstition that Madrid{103} is a perpetual whirlpool or vortex, Rogelio’s first words on the morning following the day of the Galician’s application were to ask his mother with ill-disguised interest:

“Well, what did they tell you about the fair maid—of all work?”