Title: Miller's Mind training for children Book 1 (of 3)

Author: William Emer Miller

Release date: May 30, 2017 [eBook #54814]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by MFR, David E. Brown and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from images made available by the HathiTrust

Digital Library.)

A Practical Training

for Successful

Living

Educational Games

That Train

the Senses

William E. Miller

AUTHOR AND PUBLISHER

Alhambra, California.

BY

WILLIAM E. MILLER

ALHAMBRA, CALIFORNIA

AUTHOR OF

The Natural Method of Memory Training

Copyright 1920

Copyright 1921

WILLIAM E. MILLER

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

INCLUDING FOREIGN COPYRIGHTS

| Page | |

| A First Word to Readers | 7 |

| Training the Senses | 9 |

| Game of Hide the Watch | 11 |

| Results of Sense Training | 12 |

| To Develop the Sense of Touch | 16 |

| The Game of the Button Bag | 17 |

| The Game of Matching Cards | 18 |

| The Game of Insets | 18 |

| The Game of the Rag Bag | 19 |

| The Game of the Dry Goods Clerk | 19 |

| The Game of Who Is It? | 20 |

| The Game of Weighing | 20 |

| Measuring | 21 |

| Training the Ear | 22 |

| The Game of Whispering | 23 |

| The Game of Tapping | 23 |

| The Game Speak and I'll Name You | 23 |

| The Game of Silence | 24 |

| The Game of Drop It | 24 |

| A Musical Exercise | 25 |

| The Game of Blind Man's Ears | 25 |

| The Game of Telephoning | 26 |

| The Bell Game | 27 |

| The Game of Stop Thief | 27 |

| The Table Game | 28 |

| Care of the Ears | 28 |

| Training the Sense of Sight | 29 |

| Strive for More Detail | 30 |

| Training the Eye to Measure | 32 |

| The Game of Measuring | 33 |

| The Sense of Taste and Smell | 37 |

| Using Two of the Senses | 38 |

| Exercise for Two Senses | 38 |

| Improvement from Conscious Effort | 40 |

| The Faculty of Visualization | 41 |

| A Visual Test | 41 |

| Visual Process Natural | 42[Pg 4] |

| Training the Mind's Eye | 43 |

| The Picture Test | 43 |

| Test for Quick Reaction | 43 |

| Test for Color Reaction | 44 |

| Test for Order | 44 |

| The Letter Game | 45 |

| The Number Game | 47 |

| Practice with Geometrical Figures | 48 |

| Out of Door Game | 49 |

| Immediate Visualization | 50 |

| Training of Younger Children | 51 |

| Developing the Observation | 52 |

| Value of Observation | 55 |

| The Neglected Faculty | 56 |

| Picture Cards for Observation | 59 |

| Counting from Mind's Eye Pictures | 59 |

| The Game of Quick Counting | 61 |

| The Game of Visual Counting | 62 |

| Reproducing the Visual Picture | 63 |

| The Game of Color Cards | 63 |

| The Game of Picture Cards | 64 |

| The Seeing Game | 65 |

| The Game of Detective | 66 |

| A Game at the Dining Table | 66 |

| The Change About Game | 67 |

| The Game of Observation | 67 |

| Training the Sense of Location | 68 |

| The Game of Guide | 69 |

| The Game of Guiding Home | 69 |

| Make Play Profitable | 70 |

| Attention and Concentration | 72 |

| Exercise for Prolonging Attention | 73 |

| Divided Attention | 75 |

| The Degree of Attention | 77 |

| Expectant Attention | 77 |

| Cure for Diverted Attention | 78 |

| Parent Is Child's Interpreter | 79 |

| What Is Concentration? | 80 |

| Exercise for Concentration | 80[Pg 5] |

| The Construction of a Home | 81 |

| The Farmer and His Farm | 82 |

| The Farmer and His Crop | 83 |

| The Growing Plant | 83 |

| The Imagination | 85 |

| Test for Visual Reproduction | 86 |

| A Universally Useful Faculty | 87 |

| Children's Falsehoods | 88 |

| Reality of Illusions | 89 |

| Imagination a Curse or Blessing | 90 |

| Dissipating the Imagination | 90 |

| Exercises for the Imagination | 91 |

| The Story Games | 91 |

| The Game of Creation | 92 |

| The Picture Gallery | 94 |

| The Power of Suggestion | 97 |

| Indirect Suggestion | 101 |

| Indirect Positive Suggestion | 101 |

| Health Habits | 105 |

| Deep Breathing | 106 |

| Drinking Water | 107 |

| Rest and Sleep | 108 |

| Thinking Health | 109 |

| Ambition Pulls | 111 |

Many requests from parents for a simple method of training children to think and remember have prompted this series of books on "Mind Training for Children."

Play is the child's great objective and this is capitalized in the methods used in presenting this subject. There are over fifty interesting games and as many exercises, all of which are based upon scientific principles. These will not only interest and amuse the children, but will result in the development of their senses and faculties. This will lead naturally to the improvement of the memory.

In the last book all this advancement is applied to the child's studies and school problems. Parents should read these books and use the ideas according to the ages of the children. Older children can read and apply the principles for themselves, but should be encouraged and guided by the parents.

[Pg 8]Here is a great boon to mothers who need assistance in entertaining the children in the house or out of doors. For rainy days and children's parties there is a never-ending source of pleasure and continual profit in these Mind Training Games.

No equipment is required. All games and exercises are so planned that they are easily made of materials already in the home. The making of the games will interest the children for hours.

Sense training is fundamental to profitable education.

Memory is the storehouse of all knowledge—see that your child has a good one.

You can give your children a wonderful advantage by playing these games with them. They have the indorsement of educators. They are scientific, but simple and "lots of fun."

THE AUTHOR.

All through life you are accumulating knowledge, and storing it away for future usefulness. This knowledge becomes yours through one process, which is a series of impressions carried to your brain by the nerves connecting it with the sense organs of your body.

The future value of this knowledge will depend largely upon the accuracy of the first sense impression. If the sense impression is dim and indefinite the resulting knowledge will be uncertain and useless. If the sense impression is inaccurate the resulting knowledge will be an error and cause a mistake in judgment. The senses are the tools, by the use of which the mind accumulates the knowledge which it uses in memory, thought, judgment, imagination, and all the mental operations.

Professor W. Prior says: "The foundation of all mental development is the activity of the senses."

The first step in mental growth is the making of impressions on the brain by the senses. The senses are the instruments by the use of which all knowledge is acquired.

Sense training is the logical beginning of all Education.

You give your child an education to help him to succeed in life. First give him sharp tools—keen senses—that he may get the best results from the time spent in study.

An understanding of the proper use of the senses will enable you to make these impressions lasting—instead of fleeting.

Lack of ability to properly use the senses is a handicap in life and a subtle foe to success.

In the beginning all the brain does is to store the simple sense impressions. The baby sees his mother many times before he recognizes her. The eye nerve carries to the brain the picture of the mother's face and stores it there. Soon the brain perceives the similarity and the child recognizes her. The fact that in some way the brain retains the first, second, third, etc., impressions becomes the foundation of recognition.

If the sense nerve failed to carry the image of the face there would be no comparison and no recognition. Without sense impression there can be no knowledge. Imperfect sense impressions can only result in imperfect knowledge.

Each set of sense nerves carries its impressions to a different area of the brain. Each set has a distinct and localized memory. The ear memory is the auditory memory. There is the gustatory memory of[Pg 11] taste; the olfactory memory of smell, and the tactual memory of touch.

The visual memory is the most accurate and lasting. The nerves connecting the eyes with the brain are many times larger than those of the other sense organs. Psychological tests have also proven the eye to be the most accurate of all the senses. Next to the eye comes the ear in both strength and exactness.

The training of the senses, important and necessary as it is, can be accomplished in a most entertaining and pleasant manner. The playing of games, so necessary in the life of children, can in most cases be used as the agency to gain this result.

You can entertain your children for an hour with this game and at the same time, even without their knowledge, be training one of their most important senses.

Go into a quiet room and hide a watch where it will be out of sight but in a place where the ticking will be plainly audible. If the children are small it will be well to start with a small clock, or a watch which ticks loudly. Now let the children come into the room and, standing perfectly still, try to locate the watch by hearing it tick. Let them move around, but very quietly, so as not to disturb the others; or let all move at one time.

When one of them has located the watch allow that child to remain and assist you in hiding it for the others. A record can be kept to see who finds the watch the most often. One child must not be allowed to move noisily, or in any way disturb the efforts of the others. See to it that they use their ears and not their eyes; it will even be well to blindfold them.

That the senses can be trained every one will at once admit. The world is full of examples, as the Indian savage with his keen sight and hearing. You may think this a natural born ability but there are many examples to prove the contrary. The American scouts, some of whom have gone into the Indian country when they were grown men, have become almost as proficient as the Indians themselves.

This fact of the unusual ability of the Indian is true today as well as in the story periods of the past. On a recent camping and canoeing trip through the lakes of Canada, it was a common occurrence for the Indian guide to say, "Washkeesh," meaning deer. No one in the party could see the animal, but the Indian would point out the exact spot, and as the party canoed silently along the shores the deer would soon become visible to all.

This training of the Indian was brought about largely by necessity. It was required for the preservation of his life. The same is true of the white man who has gone into the Indian's country. If we[Pg 13] were all driven by the same necessity we would have the same keenly developed senses.

Prof. Magnusson says: "There is affecting our senses what may be called the disease of civilization. Civilized man does not have to use his senses." Let the realization of the importance of the ability spur you to conscious effort to secure this result for your children. It can be done by playing the games which are to follow—it is of great value.

Prof. Gates has demonstrated that by exercising one of the senses we actually build up brain matter. A child who is helped to cultivate the sense of sight will not only make more brain cells in the visual areas but will also make more brain generally; for the sense of sight correlates with all other areas of the brain. This is a result well worth striving for.

There are many other examples in the different trades of today. The Tea and Wine tasters have a very fine sense of taste and smell. The jeweler has a well developed sense of hearing so that he can detect irregularities in the ticking of a clock that are imperceptible to most of us. Makers of telescope lenses complete the smoothing of the surface by rubbing them with the fingers, being able in this way to detect the slightest roughness. The blind have a very fine sense of feeling and hearing. Deaf people often have a keen sense of sight.

Necessity and Desire are the parents of all progress and development.

You[Pg 14] will notice that in all of these cases there are these two impelling motives which have caused this great improvement. Create in the child the desire to be unusual in this regard. Show him that the highest success of life necessitates this development. Also that in every case it comes as the result of individual effort. The one possessing this unusual capacity acquired it only as the result of his own continued practice. The senses cannot be developed in a day. They CAN be developed, however, if you will make any reasonable effort.

The child will attach most value to that which gives him the greatest pleasure.

This is a fact which you must keep in mind throughout all your efforts in child training. Whenever possible make the exercises into games and make them interesting. Do not work so long with one idea that it becomes tiresome or tedious to the child. Add anything that suggests itself to you that will give variety. When the child seems to be losing interest or paying only partial attention, vary the game or change to some other. In all the exercises it is helpful to note the results and keep careful watch of the progress made. Have competitive trials and championship records; always keep some incentive for further effort before him.

Each child should be a rule unto himself. Do not encourage or strive for uniformity of desire or result[Pg 15] in your children. Let them reveal those distinctive characteristics with which they are endowed and then encourage and assist them in their development.

A child will excel in some things and possibly be deficient in others. He will naturally wish to play most often that game in which he does best. Do not deny this game, but use it as a reward, when the child does well the thing he most needs. Use the promise to play it as an inducement to get him to do the more necessary or difficult exercise first.

Even in cases where the children are old enough to use these books themselves, parents should keep an oversight of the games used, to see that all of their senses, and especially the eye and the ear, are developed.

An all around development is most necessary. When parents join the game let it be an opportunity to introduce and encourage the most needed exercises.

Training the senses will result in greater ability in all mental operations throughout life.

A few moments' daily use of the games and exercises in these books will attain the result.

There is one principal instruction, that is—MAKE AN EFFORT—TRY.

Then persist, try again, let failure spur you to greater effort. Only he who continues to try, after others have tried and given up, will win the prize of success.

The child should be taught to determine the degree of smoothness, size, shape, quality (of cloth), and many other things of value by touch. You can give an experienced dry goods clerk a piece of cloth and he can tell without looking at it what kind it is, and about what grade. This is entirely a matter of development upon the part of the clerk. When he began this work he could not tell muslin from long-cloth.

Parents will get a good idea of what is going on in the child's mind, and the training he is receiving by watching the little fingers work in all these exercises for the development of the sense of touch. Try the exercises yourself and see what is required to do them accurately. In this way you will be better able to help the child. Washing the hands in tepid water before the exercises of touch will increase the sensitiveness of the fingers. Have the child touch lightly with the pads at the ends of the fingers. Increase the difficulty of the exercises as he progresses.

Exercise—Blindfold the child and hand him articles which are somewhat familiar and have him[Pg 17] tell, by feeling, what they are. Have him describe them. If a knife, what kind of a knife it is. If a box, what kind of a box it is—about how long? how wide? how high? If you ask the child to give these estimates in inches after removing the blindfold have him make the actual measurements. Have the child describe the article, giving all the details possible, and find any peculiarities or irregularities by feeling.

Exercise—Give the child an article with which he is not familiar and have him describe it. See how much he can learn by touch alone. Then let him see if he can learn any more by sound, by knocking the article against something to determine what it is made of, whether solid or hollow, etc.

Exercise—Give the child, while blindfolded, a book which he has recently read and see if he can identify it by the size, shape, thickness, and quality of paper.

From your button bag select a number of different buttons, two of each kind. Let the child sort out the pairs and thus become somewhat familiar with the sizes and shapes. Then mix the buttons, blindfold the child, and let him match the pairs entirely by feeling. Have him lay them out in pairs as he matches them. Then take off the blindfold and let him see them just as he has matched them, and count for himself how many are right and how many wrong.

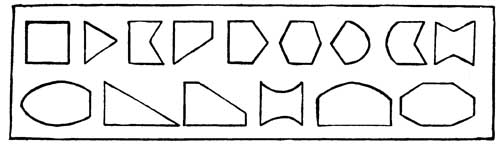

Take a piece of cardboard and cut it into many shapes, as suggested by the illustration below. Make two pieces of each figure exactly alike. Let the child match them and see that there are two of each kind. Then mix them, blindfold him and have him pick out the pairs by feeling. There should be at least 12 sets—more if desired.

A similar game to the one above can be played with a box of animal cookies. Pour the cookies out on a large plate. Blindfold the children and let them select pairs of animals or as many of a kind as possible. Let them name the animals by feeling.

The expensive Insets used by the Montessori School can be satisfactorily made out of heavy cardboard and accomplish the desired result. Take a piece of cardboard of good thickness and draw on it some of the figures illustrated above. After they are cut out with a sharp knife, smooth the edges so that they will fit easily into the places from which[Pg 19] they came. The cardboard from which they are cut may be fastened to another or tacked to a thin board. The game is to blindfold the child, give him the cutouts and by the sense of touch let him find the proper hole and fit the piece into it. As the pieces are fitted into their places they may be left there until the board is filled. This exercise is a little more difficult than most of the others. Encourage the child to keep at it.

Cut a number of pieces of different kinds of cloth. Show them to the child and have him feel of them and become acquainted with the pieces so as to know them by name. Blindfold him and give him one of the pieces of cloth and have him tell by feeling what kind it is. Put all the pieces in the rag bag (any large bag will do). Blindfold the child again and let him pick out the kind of cloth you name. See how many he can get correctly. Have him choose velvet, silk, satin, calico, muslin, broadcloth, etc., using all the common varieties of cloth. Children need not be blindfolded if the bag is held so they cannot see. Blindfolding increases the curiosity and thus the interest in the games.

Cut from the scraps in your rag bag two pieces each of all the different kinds of cloth that can be found there. Make the pieces about two by four inches and have them all of one size and shape. Let[Pg 20] the child examine them and match them in pairs. Have him feel of them and see that they all feel different. Do not have more than two pieces of any one kind of cloth. Pay no attention to color. Now mix the pieces in a pile on the table, blindfold the child and seat him in front of them. Have him match the pieces by feeling and lay each aside. When finished, have the child look at the pairs as matched, counting for himself the points won.

Blindfold two or three children. Silently select one of the others to be identified by the blindfolded children by means of touch. Let the blindfolded ones feel of the child—his hair, face, clothes and shoes. In this way see which one will first be able to name him. To win this game depends a great deal on the child's observation of what the other children are wearing. The game of Blind Man's Buff is similar and good, but usually has a good deal of sound to assist the one guessing.

Get a pair of scales and let the child weigh anything he wishes. Let him learn to accurately judge a pound, then to estimate the weight of an article before placing it upon the scales. Teach the child comparative weights by lifting articles and determining which is the heavier. Encourage him to make a pair of balances with which he can balance one object against the other after he has compared them[Pg 21] by holding one in each hand. Many variations can be easily made of these ideas, to help the child to become accurate in estimating weights. All practice will be more interesting if there is a record made, and the spirit of competition is introduced.

Give the child a measure—quart or pint—and let him learn to estimate the capacity of the different utensils of the kitchen. He should in this manner become able to judge accurately the contents of different containers. The child should learn to estimate in pecks, bushels, etc. This is good exercise and a valuable ability for later life.

Let the games given here suggest new ones to be used; any factor which will vary or add to the game is valuable. Keep always in mind the fact that the highest usefulness of the games is training the senses to be more accurate.

This is a very important sense; consider its relation to memory and how your decisions and judgments are based upon things you have heard or thought you heard.

Psychological tests have revealed the fact that the ear of the average person is mistaken thirty-four per cent of the time. Think of it—one-third of your ear impressions are mistaken. The resulting memory, judgment and action must suffer. This is true largely because of lack of a conscious effort to develop this important sense.

Have the child stand across the room and listen for the tick of a watch which you hold in your hand. If he cannot hear the tick, advance slowly toward him and keep track of the distance at which the child first distinguishes the ticking. It will be interesting to test each ear separately. Any physical defect in the child's hearing can be found by this test. Encourage him to make a deliberate effort to hear the watch. Do not be too hasty in moving towards him as he will have to concentrate his attention before the tick can be heard. This exercise is[Pg 23] a good one for the development of attention. Practice with this yourself. You will find as your attention wanders that you will lose the consciousness of the ticking of the watch.

Have the child stand across the room or several feet away. Whisper a word and see if he can repeat it. Encourage him to try a little more and to be more quiet; then whisper the same word but no louder. Work with this exercise, increasing the tone gradually until the child distinguishes what is said. Then whisper other words and sentences. This exercise can be lengthened and is excellent for the development of attention and memory as well as of hearing.

Sit at a table and with a pencil or your finger tap upon it a certain number of times, during which there are irregular intervals, for example—four taps—interval—two taps—interval—five taps—interval—one tap.

Now see if the child can reproduce the correct number of taps and intervals. This can be varied in innumerable ways. For older children tap a familiar tune and see who can recognize it. Let the winner tap a tune for the others to recognize.

Blindfold one child and have the others sit or stand around him in a circle. Turn the blindfolded[Pg 24] one around a few times and let him point to anyone, saying: "Speak and I'll name you." The child designated, in a natural voice says, "Yes, sir." The one blindfolded has two chances to guess from the sound of the voice who the person is. If he guesses correctly he is released, if not, he must pay a forfeit. The person pointed out must be blindfolded and take the next turn. Forfeits may be redeemed in any manner desired. The game "Ruth and Jacob," familiar to everyone, is a good game of sound.

For developing self-control and relaxation, have the children practice silence. Have them relax and show them that the movement of a foot or a hand makes a slight noise. Have them listen to their breathing, and then breathe just as quietly as they can. Drop a pin and have those who heard it put up their hands. Let them become perfectly quiet again and drop several pins for them to count. See who is the most accurate. In all your instructions to them only whisper. Do not allow them to talk or whisper at all during this exercise. As you use it prolong the periods of silence and attention to one sound or idea. This is a wonderful exercise for the development of the power of concentration and should be played often.

Have the children sit quietly in a room; have several different articles in your hands and drop them[Pg 25] one at a time, on the table. Have the children sitting with their backs to the table and determine by the sound what you have dropped. For this exercise you can use a bunch of keys, coins, pencil, knife, books, ball—anything that is available.

After they have become somewhat acquainted with the articles by sound, drop the different objects in different places, moving quietly about so that the children can only determine from the sound what you have dropped, and where you dropped it. For example, drop the book on the rug, the keys on the floor, the pencil on the tiles of the hearth, the coin on the table, the keys on the mantel. After each object is dropped, see which child can tell what was dropped and where. This will teach them to recognize the object and its location by sound. Do not overlook the value of competition—keep a score.

The child should be taught to recognize tones, and the spaces between tones of the scale. Have him stand with his back to the piano and learn to tell the difference in the tones that are played. First, use the octave, then the one-five-eight. Next the one-three-five eight; then the one-two three, etc. Then introduce the half-tones. This exercise can be made more difficult according to age and musical ability.

Have the child blindfolded and sitting quietly on the porch and tell all the sounds he hears. The[Pg 26] blindfold will add to the interest and fun, at the same time insure his dependence upon the sense of hearing. Let him tell what is approaching; if persons are walking, how many? If a vehicle is coming, how many horses, and what kind of a vehicle? Let him learn to distinguish automobiles by sound, large cars from small ones, trucks from pleasure cars.

Strive for recognition of the slightest sound, a distant bird, etc. Try to estimate the distance from which the sound is coming.

Take the child into the woods, teach him to distinguish the sounds of the different animals, and if possible to locate the distance and to estimate the location. On the ground, in a bush, or up a tree?

Anything which stimulates the child to hear keenly and accurately is of value. Let the exercise be adapted to the time and place. When he remarks "How quiet it is here," it is a good time for him to realize how many sounds are actually going on around him.

Give each child a pencil and paper and have them sit in a row or in different parts of the room equally distant from the spot selected for the "operator."

Make a list of words; later on short sentences can be used; have the operator take these and sit about twelve feet from the children. Let the operator whisper "Hello," just loud enough for the children to hear distinctly. The children can raise their hands when they "get the connection," or hear the "Hello,"[Pg 27] but should not be allowed to speak during the game.

The operator will then whisper the words in the list slowly, using the same volume of sound as in the "Hello," giving time between words for each child to write them. At the conclusion correct the lists, each child being scored for the number of words heard correctly. During this game all instructions should be given in whisper, and perfect quiet maintained among the children.

Have all the children sit quietly in one room while some one takes a small bell and goes to some other room, hall or any other part of the house and rings the bell softly, just loud enough to be heard in the room where the children are seated. See which child can tell most accurately the location where the bell was rung. Allow the child making the closest guess to go out and ring the bell.

Place a table in the center of the room, preferably one with doors on two sides, or at least more than one door. On the table place a bell, bunch of keys or other article difficult to pick up without making a noise.

Have all but one of the children blindfolded and seated at the end of the room farthest from the doors. The child not blindfolded is the Thief and leaves the room. When everything is perfectly quiet the Thief tries to enter the room, get the article from[Pg 28] the table and get out without being heard.

If a child hears the Thief, he calls "Stop Thief," and if he accurately locates the position of the thief he takes his place.

This game will teach the children to move quietly as well as to improve their hearing.

After the meal and while enjoying a few minutes around the table have the children close their eyes while you take a spoon or fork and tap softly upon some dish or article on the table. See who can tell by hearing what the article is and where it is. See who is most accurate in locating the spot where the sound is made.

Other interesting games to be played at the table will be found under the sense of Sight and faculty of Observation.

Remember it is the effort that counts—just to listen will tend to sharpen the sense of hearing. Well developed senses are the result of repeated efforts upon the part of their possessor. Try—keep on trying.

Teach the child to respect and value the sense organs as possessions of great worth and to care for them properly. Do not allow any kind of abuse, especially of the ears and eyes. Do not try to wash too far into the ears, the inner ear is fully protected by nature and does not need cleansing. Wash as far as the child's finger will reach and no farther.

This sense has been endowed by nature with special ability and capacity. The nerves connecting the eye with the brain are eighteen times larger than those of any other sense. Their capacity to impress the brain is therefore many times greater. At the same time nature has duplicated the sense of sight and we have the mind's eye, or the faculty of visualization, by which we can reproduce the visual impression, or picture, of the thing which we have seen. This faculty is one of the important foundations of memory development as you will see in future chapters.

We are probably more conscious of defects in the operation of the sense of sight because of the many opportunities for comparison with others. Children may differ considerably in their vision but any unusual condition should prompt a consultation with a specialist.

Because of the movement possible in this sense organ and the delicate muscles which control it, there is the possibility of improvement by muscular exercise which does not exist in the other senses.[Pg 30] The following exercises will strengthen the eye muscles. They should be practiced by persons of all ages. It has been found during operations that some of the eye muscles have been exercised so little that they have become almost incapable of use.

These exercises are simple, and can be practiced at odd moments, that would otherwise be wasted.

First—Move the eye horizontally as far as you can to the left and then to the right. Continue this until there is a feeling of fatigue. No physical exercise should be continued beyond that point.

Second—Move the eyes vertically as far as you can, up and then down, trying to extend the range of vision. Continue this alternately until you feel fatigue.

Third—Roll the eyes from right to left and then from left to right in as large a circle as possible.

These exercises will keep the eye muscles in a healthy condition. See to it that the child does not abuse his eyes; that he does not strain them; always has plenty of light and that it falls upon the page, or work, that he is doing. Do not overlook indications of eye trouble, eye pains, inflamed lids, continued recurrence of styes, blood-shot eyeballs, or pain back of the eyes, all should have the attention of a doctor. "A stitch in time saves nine."

There is the greatest difference in the amount of detail which the eyes of different persons gather from a glance at an object. Some will only see a[Pg 31] tree; others in the same time will see a tree with spreading branches, small irregularly shaped leaves, with small black berries and a rough vertically marked bark. Children should be trained to notice as much detail as possible. Development along this line becomes a basis for many other mental operations which will be discussed later on.

Place yourself with the child where you can look out on the landscape. Pick out some object, tell him what it is, and have him look until he finds it. Then let the child pick out some object that he thinks will be difficult for you to find. It may be a bird, a red flower, or a hoop. As he develops pick objects farther away, smaller or partially hidden.

Have the child look at a house and give you all the detail that he can see. Call the child's attention to the things missed so that he sees the reason for making an additional effort. The same exercise can be followed with any object, a tree, an automobile, or an animal. When in the house use a picture on the wall, a table, a book case or a coin. You will find that the longer the child looks at the object the more detail he will see. The aim is to get him to notice and mention the details as quickly as possible. After some practice he will be able to mention them as rapidly as he can speak. This can be made into a competitive game when there are several children.[Pg 32] Keep score of the number of the details each can write on a slip of paper in a given length of time.

The ability to accurately measure with the eye is a thing that a great many people find very difficult, if not almost impossible. You are continuously finding opportunity to use such an ability. A little conscious effort will work wonders in this regard and children should not be allowed to grow up without being trained to intelligently estimate measurements. In this training begin with larger measurements and from that work to the finer ones as rapidly as the child can progress.

Have the child determine which of two trees in the distance is the closest or use any other objects in the landscape. Walk towards the trees to prove the matter. Point out things of interest to encourage the child's observation of nature.

Give the child a foot rule and let him become acquainted with its length. Then with his fingers on the table have him indicate the distance which he believes to equal that of the length of the rule. Lay it between the child's fingers. Practice until he knows accurately how long a foot is. At the same time and for variety he can practice with a half foot and an inch. Have him compare objects with a foot rule and determine whether they are longer or[Pg 33] shorter. Then let him measure the objects. Allow the child to check the measurements himself, this will increase his definite conception of the length of a foot.

Let the child with his eye, and without a rule, measure the length of the table, of the book case, the side of the room, or the height of a door. Have him do this by eye measurement and not by guess work. Teach him to start at one end and select a point which he judges to be one foot from the end and then to advance the eye to a point one foot from that and so on, counting as he goes, "one, two, three and a half"—whatever he believes is right. Then have him take the foot rule and check his measurements accurately.

In the same manner the child should be taught to know and to be able to measure with the yard stick. With it, of course, measure larger objects, as the length of the house, the width of the porch, the distance from the house to the sidewalk, the width of the street, the height of the shed, etc. Teach the child to recognize the distance of a block, a half mile or a mile, and the size of an acre.

Unless you have had some practice in work of this kind, you will find yourself busy keeping ahead of the child. You can get excellent practice and development which will be of value to you, by entering into these exercises. Make it a point to become thoroughly interested in the work yourself, as it will[Pg 34] insure continuation and increased good for the child. Remember the interest increasing value of competition.

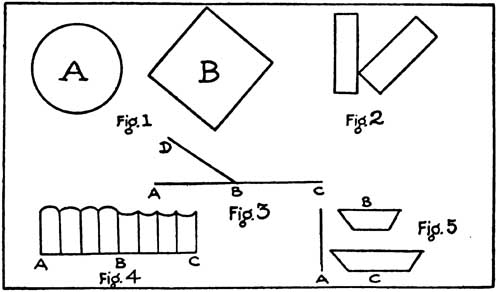

While training the child's eye to measure, excellent practice will be found in determining comparative length of lines. The illustrations below will show some of the ways in which the lines can be made confusing. The child should be given enough drill in this exercise so that he learns to judge the things as they are, and not as they seem.

Have him look at Figure 1 and decide which is the longer line, a side of the square B or the diameter of the circle A. Then have him measure carefully.

In like manner compare the height of the two rectangles in Figure 2. Which line is longest in Figure 3—AB, CB, or BD? Which vertical lines are tallest in Figure 4—those between AB or BC?

In Figure 5 which line is longest, A, B or C?

Good practice can be had in judging the size of boxes by comparing the length of one box with the width of another, or any similar measurements. In each case the measurements should actually be made so that all error can be corrected.

In the same way practice with size and thickness of books. Let the child estimate them by inches so that he learns to determine accurately the difference in thickness. The carpenter can readily tell the full inch board from the seven-eights boards by looking at it or by feeling. His ability to do this is the result of practice.

The size of type is a good thing to practice with, as the irregular outlines of the type make it quite confusing. A sample book of type can be gotten from any printer. From this the child can also be taught to become familiar with the common type faces. This knowledge he can use to good advantage in later years.

The child should be taught a definite length of step for the purpose of measurement. In proportion to his size he can learn to step off two feet or a yard. He should also know the length in inches of his shoe for the purpose of checking shorter measurements.

Have the child know his height and estimate the height of trees, buildings, etc. These estimates can be checked by computing the proportion of the length of the shadow thrown by the tree and using the proportion.

Example—If the child is five feet tall and his shadow measures three feet, the shadow is three-fifths of his height. If the shadow of the tree measures fifteen feet, the height of the tree is twenty-five feet.

There are two important faculties which are dependent upon the operation of the eye for usefulness and accuracy. They are Visualization and Perception. The games which are given later for the improvement of these important mental operations will also develop the sense of sight.

It will be better to use these later exercises where double results can be accomplished. Give all the time possible to the games on pages 59 to 69.

For most of the mental operations the three senses already treated are the more important ones. There are some trades in which the senses of taste and smell are also important. These can be cultivated readily by exercises of any nature that stimulate an effort on the part of the children. Many ideas will suggest themselves to you from those given for the other senses.

It is advisable to do a good deal of the practice blindfolded so as to separate entirely the sense of sight, and force dependence upon the senses of taste and smell.

These two senses are very closely allied. Try the experiment of determining the difference in tea, coffee, milk and water while the eyes are covered and the nose held tightly closed.

The degree to which these two senses can be developed is illustrated by the proficiency which is shown by experts and testers who grade tea, coffee and tobacco.

The usefulness of their development is to a large degree only of value to those engaged in these lines of trade. The opportunity for their development comes rarely except in connection with work in the trades, and for that reason will not be dealt with at any length here.

There are times when the ability to use two of the senses with reasonable accuracy at the same time will be of value. It is not possible for either of the senses to produce perfect attention while working in conjunction with one another. We can attend to only one thing at a time and do it well, but "Divided Attention" is possible. Under the chapter on Attention and Concentration, on page 75, you will find an explanation of "Divided Attention," which should be read before going farther with these exercises.

Combine any of the previous exercises for Eye and Ear, Ear and Feeling, Eye and Feeling, etc., but do not attempt two exercises of the same sense or use two of the same order.

At first the attention will alternate between the two exercises, but by persistence the child can learn to carry on two exercises at the same time.

Watch an operator in the central phone stations, she listens to the party calling, watches the board over which other conversations are passing, and pulls and shifts the plugs, all at the same time. Operators of many machines in factories learn to carry on two and more separate operations at one time.

Combine the Insets for the sense of feeling on page 18 with the Number Game or the Letter Game on page 45, or with the exercises for visual counting on page 59. Let the Insets be held close to the body so as not[Pg 39] to be easily seen, or have them worked under the table, or covered by a cloth.

Use a similar combination of any of the sense exercises or games. Try many variations of the idea given on page 75 under Divided Attention, using different verses and problems to suit the age of the child.

Have the child write a familiar verse while listening to the reading of a story and see how much he can tell after the verse is finished. See that the writing continues during the reading, that is, that he does not stop writing to listen, then write again.

Take the letter cards of the Letter Game, page 45, and arrange a series of six, having these covered. Give the child a paper and pencil, uncover the series of letters and simultaneously read an equal series of digits. After the reading cover the letters and have him write as many as possible, first the letters and immediately following the digits. Next time write the digits first and the letters second. The result of this test will reveal the comparative quality of the child's eye and ear memory, as memory must of course enter into this exercise. If the sounds of the digits are lost before the pictures of the letters, the eye memory is strongest. This is usually the case, but some children will retain the sounds easily and lose the picture of the letters.

The sense which proves most useful should be depended upon for accuracy, but there should be a continuous effort to develop and strengthen the weaker one.

The child may be normal in all his senses and able to gain an average success in life without much conscious effort given to improving them. It will require very little effort, however, to greatly develop the capacity of the different senses and thus increase the success which he will gain, and greatly reduce the effort necessary to attain it. While effort and use develop, neglect causes disintegration.

The fact that the eye, for example, needs development is illustrated by the limited usefulness of this organ in infants. Professor Compayre tells us that babies see only objects in front of them, not to the right or to the left, and only objects that are at short range.

Your present capacity in the use of this sense organ, and the accuracy with which you use it, is the result of the development of past years. Conscious effort upon the part of your children will lead them to more rapid development, and to the possibility of far greater power and usefulness.

The value of this improvement is apparent to you, but not to the child. The benefits to be derived will be largely dependent upon your leadership and encouragement in making the effort. While the children are seeking amusement, see that they combine it with these games and exercises which will accomplish some improvement that will be permanent and valuable to them later on.

The sense of sight has been wonderfully endowed with a duplicate power which we have come to call the mind's eye. With this visual faculty we produce some very important mental operations. We must first become conscious of this faculty and learn to use it intelligently and then to broaden its scope and increase its power to deal with details.

Visualization is the mind's eye reproduction of an impression made by the sense of sight.

When the name of Abraham Lincoln is mentioned you can see his face in your mind's eye. Hesitate a moment and become really conscious of this reproduction of Lincoln's face in your mind. See the details of the picture, the deep set eyes, the furrowed skin, the sad expression, etc.

In the same manner your mind can reproduce an unlimited number of pictures. Anything which you have once seen with the physical eye can be reproduced again in the mind's eye.

Make a few tests of this fact, if it is not well known to you. For example,—

See a pasture with a creek flowing through, willows hanging over the water, the green grass on the banks, and the stock grazing there. See several different kinds and sizes of animals, note their color, what they are doing. Add to the detail of the picture.

To close the eyes and thus to eliminate the more distinct impressions of the physical eye, will assist you in visualizing any picture.

We are all born with this ability to visualize or see imaginary mental reproductions of things which we have seen before. By the use of the imagination we combine parts of these pictures into new ones and thus are able to construct a mind's eye picture which may never have existed in fact.

Children possess this faculty in a marked degree; they use it continuously and unconsciously. They can also see their visual picture much more clearly than their parents can, unless they have continued to use the faculty consciously. Many children amuse themselves by the hour in playing with imaginary playmates, and will talk to them as interestedly as if they were really present. To the child they are present, he actually sees them and also visualizes the conditions under which he is playing.

The child should be given a conscious understanding of the mind's eye picture and what is meant by visualization. Teach him that when you ask him to visualize, you mean for him to see clearly the mind's eye picture of the thing referred to. The first exercises in visualization are for the purpose of developing a clear visual picture.

The following tests and games will reveal the lack of speed and accuracy in the operation of the visual faculty. The repetition of the tests will result in an improved ability; vary and continue them and you can quickly experience improvement in the availability of the faculty.

Exercises which tend to quicken the action, broaden the range of vision, and increase the amount of detail retained, are most valuable.

Select a good sized picture which is strange to the child, in which there are several persons surrounded by the furniture of a room, or any similar setting where there are a number of objects. Allow him to give one quick glance at the picture and then see whether he can recall definitely just how many persons were in the picture? Whether they were men, women or children; and locate definitely the position of each person. The first glance should not exceed one second. Now let him look at the picture again for not more than five seconds. See how many objects he can name, check them up to see that he is accurate. Also notice how many objects are mentioned which are not in the picture.

Prepare a strip of cardboard about three inches wide and fourteen inches long. Get as many colors of paper as possible, cut them into strips of unequal width and[Pg 44] paste them on the cardboard so that each color will be from one to three inches wide, according to the number secured.

Stand across the room holding the back of the strip towards the children, then turn it over so that they get one clear glance. This glance should not exceed the length of time it takes you to count rapidly one-half the number of colors. There should not be less than six colors on the slip, in which case you count from one to three. After this first quick glance see who can tell accurately HOW MANY colors there are on the slip. Let each write down the number his mind registered without checking up to see if he is correct.

Now turn the paper over again so that they see the colors about twice as long as the first test. Then have them write a list of the colors that are on the paper. After they have written all the colors that they saw, have them take the following tests, before checking up the lists.

Allow a third glance at the color strip while you count ten, and have each begin at the left hand end of the strip, noting the arrangement of the colors, and see if they can write accurately the order in which the colors appear on the card.

The first test is for quick reaction of the mind. The amount that they are able to observe in a given length of time will depend upon the rapidity with which their[Pg 45] minds react. This test is designed to determine the rapidity of the mental reaction. About thirty-five per cent of those who take it are able to get the correct number, where the number of colors is not more than seven.

The second test is designed to determine the ability of the mind to hold the color impressions. About twenty-five per cent are able to retain the impression of the seven colors.

The third test combines the power to retain the color impression with the ability to retain the correct order. Experience shows that not over ten per cent are able to give the order accurately.

Similar tests repeated will give a great amount of exercise and soon result in a perceptible increase in the power to accomplish the desired results.

Prepare a series of white cards about 2 X 3 inches, larger for larger groups, on which are painted the letters of the alphabet in large black type.

For this test select a convenient spot, such as the mantel, window sill, or table edge, and place six letters upright and side by side, but do not have the letters spell a word.

Each child should be supplied with paper and pencil. All should hold the pencil above their heads. Upon a signal allow the children a five-second glance at the letters. When the five seconds have elapsed give the command "Write," at which each child will write the[Pg 46] letters in proper sequence. When they have had ten seconds in which to write, give the command "stop." During the time for writing the letters the cards should be covered. Now the cover can be removed and each allowed to check the result.

Begin with the arrangement of about six letters and gradually increase the number and complexity of arrangement so as always to give the child something to strive for.

Only that which requires effort results in growth. Those things for which we strive are of most value to us.

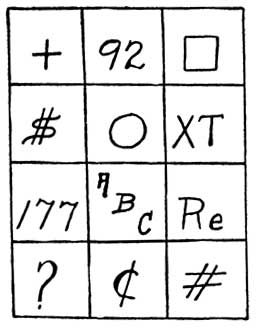

A few examples for the letter game—

Later arrange some double line combinations, and increase the complexity as the ability develops.

In some combinations use letters which make the semblance of a word and later some which spell a word. Notice how quickly and easily the combination is re[Pg 47]membered when it conveys sense or something definite which the mind can grasp. For example—

In the same manner in which you made the cards for the Letter Game prepare a set on which are numbers instead of letters. Follow the same rules for the Number Game, using rows of numbers instead of letters.

First use a row of single digits, increasing it until you have used nine or ten. Then change and arrange a column of two digits, as illustrated below.

Later for variety you can combine letters and numbers. In some arrangements leave blank spaces requiring the child to leave the blank in its proper location when reproducing his mental picture.

A series of squares, circles, triangles, etc., can be used. These exercises can be varied in any manner and made as long and as complicated as is necessary to keep the child striving to make an effort to accomplish more. Keep a time limit, remember the value of competition, championship scores, etc.

Have the child look at one side of the room, then look away and tell all the colors he saw there in pictures, draperies, etc. Have him look at a certain picture for about five seconds and turn away and see how many of the colors in it he can recall.

Use a row of books on the shelf for another test. Have the child tell how many colors he saw in the row, and, if possible, how many books.

First secure some geometrical figures. Take for example a five-pointed star, have the child look at it carefully, then close his eyes and reproduce its form and size in a clear, visual picture. Let him look at the drawing and see if he can improve the clearness and definite proportion of his mind's eye picture. Now have him take a sheet of paper and draw this picture as he sees it in his mind, and when complete compare it with the original for accuracy in size and proportion. Let him close his eyes several times and get just as definite a mind's eye picture as possible before he attempts the[Pg 49] drawing of the figure. Practice with figures of this kind, gradually increasing their complexity.

Instead of the geometrical figures of the previous exercise, take some simple object, such as a coin, a key, a watch charm, or a book. Follow the same plan as above. Have the child make a complete mind's eye picture, then try to draw it.

Secure a number of colored objects, such as sheets of paper, or book covers, or candy boxes, anything which is colored. Let the child study the color carefully, then reproduce it in his mind's eye. First he must work with single colors, then combine two or three in a group, and reproduce them in his mind's eye. In following this exercise he will develop an accurate color memory.

Select a certain tree and let the child look at it intently for a few seconds, then ask him to close his eyes, or look away, and describe the tree to you. Try to get him to see clearly all the detail in his mind's eye picture, as you did in the former exercises for the physical eye.

In the same way have the child visualize the landscape. Let him look at it intently for a few moments, and then, with his eyes closed, describe it. The descrip[Pg 50]tion which the child gives will reveal the amount of detail in his mind's eye picture. Try again, and see how much he can add at the second trial.

The rapidity of visualization can be greatly increased by effort and training. There is great value in this ability, and it can be attained by shortening the interval during which the object or exercise is visible to the eye.

After the children have learned to form a definite, accurate picture, try to shorten the time in which they see the objects. Strive until they can take in the whole at a glance. The detail will continue to develop after the eyes are closed. In the Letter and Number Games gradually shorten the time given until they can reproduce the entire row at a glance. Such effort will quicken the action of the brain area of sight.

The story is told of a woman who so developed this ability that she could secure a picture of the page of a letter in one glance and read it from the visual image. She became a well-known government agent in a foreign country, an internationally known spy.

All of the exercise given for the development of the sense of sight can be used for visualization and later for observation. These two important faculties are closely related to each other and both dependent upon the eye. Later on you will see that the most used of all the faculties—Memory—is in turn largely dependent upon all three.

Up to eight years of age the child should be trained principally in the use of his senses and in making clear mind's eye pictures. The parent should have the definite aim in mind of increasing the child's stock of knowledge, and of the later value of these efforts. Show him everything you can, and take time to explain. Things are new to the child, even though they are very common to you. This is the age when he acquires his knowledge of things without being so much interested in their relationship to each other.

A great deal which is explained to children is forgotten, because they did not sense it—that is, they do not impress it upon the mind by many and varied sense impressions. Simply to hear the answer to the question is not sufficient. You can tell a child what a rectangle is, but he is very apt to forget. If, after you have explained a rectangle to the child, you have him go around the room and find all the rectangles that he can—such as windows, doors, books, etc., and then draw different sizes of them, he will never forget.

The next step of development, after forming clear visual impressions, and closely allied to it, is the development of the faculty of observation. The eyes see, but the brain perceives. The sense organs bring a sensation to the brain where, by the act of perception, it is classified or identified as being like certain other objects and filed away in its proper place.

Recognition goes a step farther and places this object alongside of one particular mental image, which it resembles.

Standing by the gate in the twilight you see an object coming down the road. As it approaches you Perceive that it is a cow. As it comes closer you Recognize it as Neighbor Jones' cow. You Perceive that it is a cow, but you Recognize her as a certain cow, different from all others.

It is a fact that the eye may be perfect, and the nerve connecting it with the brain may be in good working order, and yet no impression may be received by the brain. Injury to that area of the brain which receives the impression from the eye may cause total blindness;[Pg 53] at the same time the eye and nerves connecting it with the brain may be physically perfect.

When the brain is not injured, the same result is brought about by lack of Attention. The eye can look straight at an object and you do not perceive it. The brain does not accept any impression of it.

Attention is necessary that the sense impressions may be properly perceived and recognized; and this completed mental operation is commonly called Observation. Trained senses that react quickly make possible quick perception and recognition. The result is quick, accurate, and complete observation. Observation requires knowledge and it develops definite knowledge, but most people are poor observers. Help your children to be definite in their knowledge and to know what they know. How many can tell the different trees by name? How many legs has a spider, a fly, a bee, a butterfly?

It is a strange fact that the poorly educated are the best observers. Do not lose sight of the necessity of helping the child to form the habit of observation. It is the basis of common sense. Do not let him grow up ignorant of the common knowledge and experiences.

The faculty of observation is also the basis of science and of the success of specialists in every line. The story is told of a young man, who, having made up his mind to become a naturalist, went to a celebrated teacher in that line of study. The professor set the young man at work drawing a picture of a fish. The picture was soon[Pg 54] finished and carried to the teacher for inspection, who, without looking up, said: "Draw it again." This seemed foolish to the young man, but he sat down and drew a new and better picture, which he again carried to the teacher for approval. This time the professor told him to go back and improve it and to wait until he should come to inspect it. The young scholar returned, did some more work on the picture and then pushed it back and waited. The professor did not come and so he started wandering restlessly around the room, thinking he had been forgotten.

Soon he became interested in studying the fish he had been drawing; he noticed several peculiarities of the eye which he added to his picture. This led him to a more careful study, and other details were noted and added. He then decided he could draw a better picture, so started all over again. After days had passed, the professor came in and glanced at the picture which the young man then realized was still only partially complete. For one year this young scholar was kept busy studying and drawing the fish, then the old professor told him: "You have learned the greatest lesson of the scientist, observation." This young man was Agassiz, who became America's foremost naturalist.

Observation usually occurs where there is a motive. Do not ask the child to develop it, but induce him to play games and to strive to excel in contests which require observation.

This is one of the faculties which we use continuously, but have given very little thought to its conscious improvement. Every judgment rendered in business life is largely dependent for accuracy upon this faculty.

You may intend investing money in a piece of real estate. You go out to look at it. What you see on this trip of inspection is a large factor in your decision. Your ability to observe all existing conditions will go a long way towards determining whether or not your judgment in buying this property is correct. If the surrounding land is higher, and you do not observe this fact, you will probably discover, when winter comes, that you have purchased a mud hole.

Two men go to inspect a piece of mining property. Mr. A decides to invest, while Mr. B decides not to. In talking over the situation later on A inquires of B why he did not invest, and finds that B saw many things about the location of the property which he did not see at all.

In every decision of life we depend largely upon our observation; upon the things we see. A keen observation is of great help to the salesman in finding a point of contact with the prospective buyer. When he enters the man's office his eyes are keen and alert. He sees the golf bag or tennis racquet in the corner, or a book on the man's desk, the title of which he can read at a[Pg 56] glance. These things reveal to him the things in which this man is interested.

If all faces look alike to you you will of course call them all by the same name. Your friends are all different in their appearance. It is your observation which detects this difference. You may have thought that Mr. Jones and Mr. Smith look very much alike, but when you see the two side by side you are surprised that you ever thought they resembled each other. Such cases are not at all rare, and show that the observation has not been as keen and accurate as it should have been.

Observation can be improved easily and quickly. This is one of the faculties which is used so habitually that we have overlooked its importance and almost entirely neglected its improvement. The following pages will give some tests by which you can determine the child's power of observation and which will convince you of the need of its development, and also suggest some simple games by means of which you and your children can improve this important mental faculty.

It is a great aid to observation to have the ability to place upon the brain a physical eye picture which is so clear and distinct that later, when you reproduce the picture in the mind's eye, you still see the details accurately. To develop this power of visualization will help to develop the ability to observe. The exercises in the development of observation which follow will also improve the visual power of the mind's eye.

The story is told how the French magician Houdin trained the observation of his son. They would go down the street together and stop in front of a shop window. The father and son would both take a good look at the contents of the window, and then walk on a little farther and stop and write on a pad all the objects they could recall. Then they would go back to the window and compare the lists, and go on to a second window and do the same thing. This exercise was followed until the boy had developed an unusual ability to remember what he saw.

When the father was performing his magical feats on the stage of Paris he would ask people from the audience to come up onto the stage and deposit any articles which they chose upon the table until there were forty in all. The boy, blindfolded, was then brought onto the stage, led up to the table, and, after the blindfold was removed, allowed one glance. He was then blindfolded again and led to the front of the stage with his back to the table. He would without hesitation name each of the forty objects. This was considered magic, mental telepathy, etc. It was magic—the magic of practice.

Practice will work wonders for you and your children. The method followed by this magician is one of the best exercises for developing this faculty. The time you put in walking the streets is mostly wasted as far as mental development is concerned. As you and the[Pg 58] children pass a store window look closely at the articles in it and as you walk along see how many each of you can recall definitely. At first you will not be able to name very many. Practice in this way several times a day will soon enable you to recall the majority of things that you see. Continual practice will result in your becoming an adept.

The same kind of practice can be indulged in on streets where there are no store windows. Look at the front of a house and see how definitely you can describe it after you are by. How many windows has it? Can you see the color, trimmings, the style of windows, doors, porches, and all the details clearly? Practice until all can do this. Then observe the yard until you can describe the approximate size, the arrangement of the shrubbery, walks, flower beds and trees. While walking with the children continuously use these ideas. Call their attention to a certain house and when you have passed ask questions regarding what they have observed.

An excellent method of developing observation is to recall the definite location of the furniture in the different rooms of the home, the articles that are on the top of the dresser or library table.

In going to the home or office of a friend look around the room once carefully, then look out of the window or at the floor, and recall the furniture and other details of the furnishings. How many pictures are on the walls, where are they and what are they?

Secure a group of pictures which have considerable detail and a variety of objects such as often appear on calendars, large magazine pictures, and advertisements, etc.

Put a single picture upon the wall for observation for a period of a few seconds. Let each child write the answers to a series of questions, each being numbered. They can be answered verbally if the group is small.

Have the list of questions prepared and numbered. If the picture is of a house and yard have questions like the following: How many chimneys? How many windows upstairs, downstairs? How many porches? What color is the house? the trimmings? How many trees, bushes, flower beds? Is there a fence? Is the door open or closed? Is there any person in the picture? Any animal?

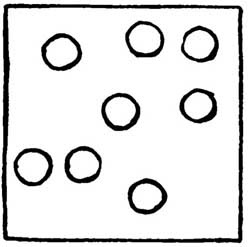

GROUP 1.

Take a piece of paper, or a child's slate, place a simple group of small circles, as illustrated in Group One. Let the child look at this group for five seconds. Turn the slate over and have him count from his mind's eye picture and tell how many circles are in the group. Then have the child draw on the other side of the slate or on[Pg 60] another piece of paper the circles as nearly in the same position as possible.

See that he gets the advantage of two tests from this exercise, one the counting from his mind's eye picture and the other to be able to reproduce the group in the same positions as shown on the other side of the slate.

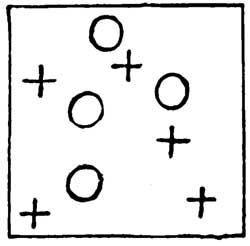

GROUP 2.

Make another group of mixed crosses and circles as shown in Group Two. After looking at it for five seconds, have the child tell you how many circles and how many crosses there are. Have him draw a picture of them.

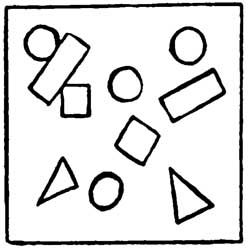

GROUP 3.

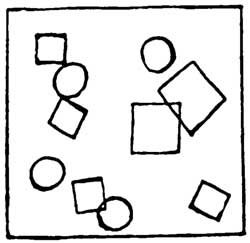

Use a group of combined circles and squares as illustrated in Groups Three and Four. As the child becomes able to count and reproduce accurately, increase the difficulty and complexity of the exercises. For variety use triangles, rectangles, octagons, stars, etc., as in Group Four.

GROUP 4.

Divide a slate or a sheet of paper into four, six, nine or twelve sections. Beginning with four and increasing the number as the child progresses. Draw in each section some picture, number, letter or object, as illus[Pg 61]trated. Let the child look at those which you have arranged and then close his eyes and look away and tell what is in each of the squares. If he is old enough, let him take a piece of paper and reproduce the squares and their contents. For variety the squares can contain all letters, all numbers, or all objects.

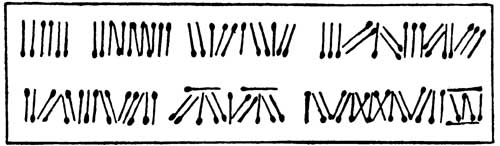

Have a handful of small sticks or matches and lay a number in a row on the table. Let the children stand with their backs to the table and a few feet away from it. After you have arranged the sticks go several feet away from the table and say, "Ready!" The children then go to the table, count the sticks, run to you and whisper their answer. The object in your being away from the table is to keep the others from repeating the answer of the first child when they have not finished the count for themselves. From a simple beginning of a straight row of a few sticks, the game can be developed to any degree of complexity, so that it will tax the powers of the most alert and developed mind. The children will soon be able to glance at the group of sticks and count them from their mind's eye picture while they are coming to you and not have to stand at the table while counting them.

Lay the sticks in groups, make them into figures, into small piles, double lines of different length, etc. A few different groups are illustrated below—use matches, tooth picks, or any small articles.

Take the same game described above for Quick Counting and have the children see the figure or pile of sticks for just a moment, then cover them and let them count from their visual picture and tell the number, rather than by the actual count as before. They can also have a handful of sticks in their hands and each try to arrange a group of sticks which is the duplicate of the one they have been observing.

The game of dominoes is good for small children in helping them to count quickly and accurately. Use a row of dominoes instead of sticks and have the children count the number of spots from their mind's eye picture.

For variety use any objects, let the child look at a flag and count the stars. Have him count the number of squares in a colonial window; the number of books on a shelf; the number of sections in the radiator. Anything of this kind can be easily used. Give him only a[Pg 63] glance, do not allow time enough for an actual count. In each case let the time allowed for each exercise be less than required to count the objects.

Show the child a vase, or the picture of one that is odd in shape, a water pitcher, or an Egyptian water bottle. Let him have a good look at the object, then take it away and let him describe it in detail, or, better still, have him draw it. Drawing is an excellent exercise for the development of muscular control and will-power.

In the same way let children observe the decorations of a building, the design of the windows, the design and style of the caps and bases of the pillars, and then draw them.

Older girls should be taught to observe so as to be able to describe accurately, and to draw in detail, suits and dresses; draperies and furnishings. This is also an excellent opportunity for color study. Boys can observe, describe and draw the outlines of boats, automobiles, and furniture, and anything that interests them. An excellent book to help the child in learning to draw is one entitled, "When Mother Lets Us Draw," by E. R. Lee Thayer.

To develop Observation and Memory of location, and relation of objects, get eight cards of any size, from one to three inches square, each of a different color. Colors[Pg 64] of decided contrast are best. Number the cards on the back from one to eight. While the child is not looking arrange the cards in a double row, writing the number of each card on a slip of paper. The numbers should be in two rows and in the exact order in which the color cards are to be arranged. Call the child and let him look twenty seconds at these cards. The time can be shortened as the ability develops. Now mix the cards and let him try to arrange them as they were.

The one taking the test should do this by making a picture of the colors as they appear, holding them in mind as he arranges the cards. This is excellent practice for persons of all ages. Some can do it accurately at the first trial, others will have a poor record at the beginning, but as usual persistence will win and the ability will grow rapidly.

The Score.—The numbers, as you have previously written them on the slip, will give the original order. After they have been arranged by the one taking the test, turn the cards and check by the numbers. Each card in its correct place entitles him to one point. Any number can be decided upon as a game. The first one reaching that number of points by correct arrangement wins.

If colored cardboard is not handy the cards can easily be made by painting one side with a child's water color paints or by using crayolas.

This game will develop observation and location. Make a series of eight, ten, or twelve cards about 2x3[Pg 65] inches in size, on one side number them as in the color game, and on the other side draw the outlines of simple objects, as a hat, tea kettle, shears, box, fan, book, owl, hen, dog, etc. These pictures can be cut from a paper and pasted on the cards; small picture cards, or picture postals may be used.

Arrange the cards in two rows. You can begin with four or six cards and later, after these have been used with comparative accuracy, add more. Keep a record of the arrangement by the numbers on the back of the cards as in the Color Game. Allow about twenty seconds for the observation of the cards and their positions, then shuffle them and arrange them in the original position if possible. Score the same as in the Color Game.

Take the child into some room with which he is not familiar, and let him walk through the room slowly, then go out and make a list of everything he can remember. Now let him look through again and see what he can add to the list.

Walk a block down the street and have him make a list or tell you of as many of the things which he saw as possible. Whenever possible return for a second look so that the child may see and realize the many things that he has omitted.

The story of the experience of the magician Houdin and the method which he used for developing the observation of his son can easily suggest a number of in[Pg 66]teresting, and as you have learned, very profitable games.

Place a dozen objects on a table and let the child look at the table from twenty to thirty seconds and then leave the room. While gone change the position of two objects. Have him return and tell what changes were made. Where there are two or more children let the one who first observes the change remain and make the change for the others. The number of objects changed can be varied. But those out of the room should know how many changes are being made. At first the objects changed should be returned to their original positions, before the second change, so that the mental picture is the same each time. Later they can remain in the position to which they were changed so that there is a new relationship to be retained in mind each time.

After a meal, while sitting at the table, let the children take a careful look at what is upon it and then close their eyes. Ask the location of different things and see how many they can remember accurately. While their eyes are closed take something off the table and hide it. See which one can first tell what is removed. Return it and next remove some other article. Let the child first telling what was removed be the one to remove the next article, and so on, or take turns around the table.

Let all the persons playing the game look over the furnishings of the room and then all, but one, go out. The person remaining can change the location of one article but nothing must be removed. When the alteration is made the others may return. The first one to detect the change must remain and make the change for the others. At first the changes should be made of larger articles as the chairs, pictures, pillows, etc. Later smaller ones can be used as vases, doilies, books, bric-a-brac.