Title: Letters from a Son to His Self-Made Father

Author: Charles Eustace Merriman

Illustrator: Fred Kulz

Release date: June 10, 2017 [eBook #54880]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Garcia, Larry B. Harrison, Martin Pettit

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

A Table of Contents has been added.

The Girl the son Married.

By

CHARLES EUSTACE MERRIMAN

Being the Replies to

Letters from a Self-Made

Merchant to his Son

Illustrations by

FRED KULZ

London: G. P. Putnam's Sons

Boston: Robinson, Luce Company

1904

Copyright, 1903

by

HENRY G. PAGANI.

Entered at

Stationers Hall.

All Rights Reserved.

TO

Mark Twain

A READY-MADE WIT

| PAGE | |

| LETTER No. I. | 9 |

| LETTER No. II. | 21 |

| LETTER No. III. | 33 |

| LETTER No. IV. | 45 |

| LETTER No. V. | 57 |

| LETTER No. VI. | 69 |

| LETTER No. VII. | 83 |

| LETTER No. VIII. | 97 |

| LETTER No. IX. | 113 |

| LETTER No. X. | 127 |

| LETTER No. XI. | 141 |

| LETTER No. XII. | 157 |

| LETTER No. XIII. | 173 |

| LETTER No. XIV. | 187 |

| LETTER No. XV. | 203 |

| LETTER No. XVI. | 217 |

| LETTER No. XVII. | 233 |

| LETTER No. XVIII. | 249 |

| LETTER No. XIX. | 265 |

| LETTER No. XX. | 279 |

| "The Son" in College. |

| His College Girl. |

| "The Son" as a Travelling Salesman. |

| His Society Girl. |

| "The Son" as Manager of His Father's Pork-packing Establishment. |

| The Girl He Marries. |

LETTER NO. I.

Pierrepont Graham, a newly fledged Freshman

at Harvard, writes his

father, John, in

Chicago, how he and the University

are getting along together.

Cambridge, Oct. 10, 189—

Dear Father:

I know you will accuse me of lack of the business promptness which is the red label on your brand of success, but I really couldn't answer your letter before. I have been trying to reconcile your maxims of life with the real thing, and I had to get busy and keep so. Reconciliation has not yet come, leastwise not so as you would notice it.

I'm glad Ma got back safe to the stock-yards, for when she left Cambridge that morning she didn't quite feel as if she would. I thought she had too large a roll to be travelling around the country with, and convinced her that she ought to leave all but $8 and her return ticket with me. Its a great thing to have a good mother.

I have already taken quite a course in art, fitting up my new flat; the fellows go in quite strong for art here, and it really is one of the most expensive courses in the curriculum, for although the photographers make special rates to the students, models come high.

You will be glad to hear that I shook the room in College Hall that Ma picked out for me, and by extraordinary luck secured a small apartment of five rooms and bath in one of the big dormitories. The dingy hole in "College" was so horribly noisy that I found it impossible to do my best work. The building was fairly infested with "pluggers," whose grinding made day and night hideous. Here I can work in peace and get a raft of culture from my art studies and other beautiful surroundings. I have had the bill for fitting up forwarded to you. Please settle within thirty days, or I shall be terribly disturbed in my course.

Tell Ma not to worry about my over-studying. I have too much inherited common sense for that. It's a wise pig that knows when he is being crammed for John Graham's lightning sausage developer; I've heard the squeal. As for under-study[Pg 11]—well, as Kip says, that's another floor to the building.

I fail to find education as "good and plenty" at Harvard as you seem to think it. Some of it may be good, but it certainly isn't plenty, and it isn't passed around with the term bills. There's a fellow in our dormitory—one of the "pluggers" who escaped from College Hall—who is hot after education, and they say he has to dig for it. I haven't dug yet, although I had a spade given me last night. Unfortunately, what I needed just then was a club.

You will be pleased to hear that I have already added several extra elective courses to my studies. I am especially interested in the topography course, in which we are making a careful study of Boston streets. I am glad to say that I am making rapid strides in the same. For this no text-books are required, but the experimental apparatus is quite expensive. On our last tour of inspection we all required lanterns. I paid $10 and costs for mine, and it stood me $5 more to square things with the driver of the herdic for a window broken while making a particularly interesting experiment.

I feel that I am learning rapidly. I know [Pg 12]the value of money as never before. Money talks here quite as much as in Chicago; not so loudly, perhaps, but faster. As you have always advised me to be sociable, I find it pretty lively work keeping up my share in the pecuniary conversation, especially as in all our little gatherings there are always several fellows whose money doesn't talk even in signs.

Taking it by and large, as you say so often, Harvard seems all right, although the fellows say the term hasn't really opened, as there's nothing doing yet in the legitimate drama in the Boston theatres. They have a queer custom of colloquial abbreviation here—they call it "leg. drama," or "leg. show." Curious, isn't it?

If you value my peace of mind, dear father, don't write any more educated pig stories to me. Such anecdotes strike me as verging close on personalities. In fact, the whole pig question just now hits me in a tender spot. Even the pen I am using makes me shudder. I hate to look a gift hog in the mouth, but I wish you had made your money in coal or patent medicine, or anything that wasn't porcine. Fact is, I've got a nickname out of your business, and [Pg 13]it'll stick so that even your boss hogman, Milligan, couldn't scald it off.

You see, I board at Memorial Hall with about 1199 other hungry wretches, and let me tell you that your yarns about old Lem Hostitter and his skin-bruised hams wouldn't go for a cent here. Memorial is the limit for bad grub, and thereby hangs a curly tail. The other day at dinner, things were so rotten that an indignation meeting was held on the spot, and a committee of investigation was appointed to go to the kitchen and see what kind of vile stuff was being shovelled at us.

There must have been a rough-house in the culinary cellar, for we heard a tremendous racket in which the crash of crockery and the banging of tin predominated. Pretty soon the committee came back bringing a dozen or so of cans, waving them about and yelling like Indians. When they got near enough for me to see, I shuddered, for on every blessed can of them was your label, father—that old red steer pawing the ground as if he smelt something bad.

Just one table away from me the gang stopped, and a fat senior they call "Hippo" Smith rapped for order. Even the girls in the gallery quit gabbling.

"Gentlemen," yelled the senior, "your committee begs leave to report that it has discovered the abominable truck that has been ruining our palates and torturing our vitals. It's these cans of trichinated pork, unclassable sausages and mildewed beef that have made life a saturnalia of dyspepsia for us, and every one of 'em bears the label 'Graham & Company, Chicago.'"

Then you ought to have heard the roaring.

"Down with Graham & Co.!" "Let's go to Chicago and lynch Graham." "Confounded old skinflint!" the fellows shouted. I turned pale and thought what a narrow escape I was having.

Just then up got little "Bud" Hoover, old Doc's grandson, whom you have always held up to me as a model of truth-telling you know. Bud's a sophomore, and thinks he's a bigger man than old Eliot.

"Here's Graham's son," he piped in his rat-tail-file voice that you could hear over all the rumpus, and pointing right at me, "Ask him about it."

There was nothing for it for me but to get up and defend the family honor. As I was about to speak I saw another fellow running in from the kitchen with a big ham,[Pg 15] yellow covered and bearing a big red label,—your label. I had a great inspiration. I felt that ham would prove our salvation.

"Gentlemen, I am the son of John Graham," I said haughtily, "and glad of it, for he has got more dough than this whole blamed college is worth; and, to show that you're all wrong, I'm going to quote something that he wrote me last week. Just you listen:

"'If you'll probe into a thing which looks sweet and sound on the skin to see if you can't fetch up a sour smell from around the bone, you'll be all right.'"

That hit 'em in great shape, and "Hippo" Smith took a big carver and slashed the ham into shoe-strings in about thirty seconds. Then he lifted the bone to his nose and let out a yell that sent all the girls upstairs flying. The other fellows sniffed and bellowed with him.

The next thing I knew the bone landed violently on my neck and the air was full of tin cans, four of which met splendid interference from my head. When I came to I could hear four hundred voices shouting "Piggy, piggy, oowee, oowee oowee," at me, and I knew I had passed through a[Pg 16] baptism of rapid fire. They were the "roast beef and blood-gravy boys" you mentioned in your letter, for sure.

The surgeon's bill is $75, which I know you will pay cheerfully for my gallant defense of the house. But I wish you'd put up better stuff. Your label is a dandy, but couldn't you economize in lithographs and buy better pigs? By the way, the fellows have nicknamed you the "Ham-fat Philosopher." The letter did it. But don't feel hurt; I've already almost got used to being called "Piggy" myself.

I am appreciating more and more the golden truths of your cold storage precepts. As you say "Right and wrong don't need to be labelled for a boy with a good conscience." Good consciences must be scarce around here, for on the other side of Harvard Bridge they label wrong with red lights, and I've failed to find a fellow yet who is color blind.

In my pursuit of knowledge I have made the acquaintance of quite a number of the police force. They seem to me to be an undiscerning lot. For instance, I heard one of them say the other day that Harvard turned out fools. This isn't true, for, to[Pg 17] my certain knowledge, there are quite a number of fools who have been in the University several years.

I am unable to write at any further length this evening, as I must attend a lecture in Course XIII. on Banks and Banking, by Professor Pharo.

Your affectionate son,

Pierrepont Graham.

P.S. I am trying hard to be a good scholar, and am really learning a thing or two. But I respect your anxiety that I should also be "a good, clean man," and almost every Sunday morning I wake up in a Turkish bath.

LETTER NO. II.

Pierrepont's University progress along rather

unique lines is duly

chronicled for the paternal

information, and some rather thrilling

experiences are noted.

Cambridge, May 7, 189—

Dear Dad:

I am sincerely sorry my last expense account has made you round-shouldered. I should think you pay your cashier well enough to let him take the burden of this sort of thing. Better try it when next month's bills come in, for I should hate to have a hump-backed father.

You haven't the worst end of this expense account business, by any means. If it makes you round-shouldered to look it over, as you say, you can just gamble a future in the short ribs of your dutiful son that it made me cross-eyed to put it together. You see there are so many items that a Philistine—that's what Professor Wendell calls men who haven't been to Harvard—couldn't be expected to [Pg 22]understand. I was afraid that $150 for incidental expenses in the Ethnological course wouldn't be quite clear to you. It may be necessary to tell you that Ethnology is the study of races, and the text-books are very costly and hard to procure. But the fellows are very fond of the course; it is so full of human interest that it is a real pastime for them. In fact, they sportively call it "playing the races," to the great delight of dear old Professor Bookmaker, our instructor.

Your suggestion that I appear to be trying to buy Cambridge proves you are not posted on conditions here. I am, and I may say en passant, the conditions are also posted on me—the Dean sees to that. I wouldn't buy Cambridge if it were for sale. I never had any taste for antiques. There are purchasable things in Boston far more attractive; if you will come on I'll be glad to let you look 'em over. I like Cambridge well enough daytimes, but the most interesting thing in it is the electric car that runs to Boston.

I realize that my expenses grow heavier each month, but money not only has wings, but swims like a duck, and the fashionable[Pg 23] fluid to float it is costly. I'm really beginning to believe that a man who can read, write and speak seven or eight languages may be an utter failure unless he's able to say "No" in at least one of them.

The problem of how to get rich has not yet been reached in the Higher Mathematics course and so it's not worrying me, as you seem to think. But of course I don't want to cast reflections on the solvency of the house of Graham & Co., so I try to keep my end up. It's expensive, for there are fellows here who've got bigger fools than I have for—but this wasn't what I started to say. All men may be born equal, but they get over it a good sight easier than they do the measles; and while some of the fellows have to study in cold rooms, others have money to burn. Poverty may not be a crime, but it's a grave misdemeanor in Cambridge.

I am grieved, my dear father, to have you say that you haven't noticed any signs of my taking honors here at Cambridge. You cannot have read the society columns of the Boston papers, or you would have seen that I have already a degree from the Cotillion Society, as being a proficient[Pg 24] student of the German; am entitled to the letters B.A.A. after my name—a privilege granted by a learned Boston organization after very severe tests, and have been extended the freedom of Boston Common by the aldermen of the city. If these things don't justify the inking up of a few pink slips, you can souse my knuckles. It grieves me to have you fail to appreciate what I've accomplished. I am trying to do your credit,—what a foolish little slip; rub the "r" from "your" and you'll see my meaning.

Another thing that proves my high standing in college is the fact that I've been admitted to the D.K.E., playfully known here as the "Dicky," a very exclusive and high-toned literary and debating society, specially patronized by the Faculty. The initiation ceremonies are very curious, and I really believe you would laugh to see some of the innocent little pranks the new men cut up. They are sent around town and over into Boston dressed in quaint garb and instructed to ask roguish questions of any they meet. This is to give them self-possession in debate and calmness in facing the battles of life. It would meet with your hearty approval, I am sure.

For my little trial I was compelled to wear a yellow Mother Hubbard, with a belt of empty Graham & Co. tin cans fastened around my waist and a double rope of your sausages hanging from my neck. A silk hat completed the rig. Thus accoutred I was told to promenade up and down Tremont street over in Boston, a swell walk opposite the Common, and bark like a dog. Every five minutes I had to buttonhole some one and shout "Buy Graham & Co.'s pork products and you'll never use any others."

Well, the long and short of it is that I became a marked man on the gay boulevard. Small boys tendered me a free escort and made insulting remarks, which I endured cheerfully for the cause. It vexed me a bit, though, to find that one of the persons I advised as to our meats was Miss Vane of Chicago. She looked unutterable things and murmured something to her escort at which he smiled pityingly. If you hear that I drink, you will know exactly how the rumor started, and discredit it accordingly.

Finally the crowd around me became so dense that street traffic was blocked,[Pg 26] and I was taken in charge by a policeman for disorderly conduct. In another minute I was arrested by a meat inspector for exposing adulterated foods for sale. Between the two of them it was a simple little cot that night and a frugal breakfast next morning for Pierrepont. I was discharged on the disorderly conduct count, but fined $100 and costs on the bad meat item. The judge ordered all the windows opened when it came into court. Father, it's up to Graham & Co. to make good the deficit in my month's allowance. As a philosopher, you will see the point, I am sure. Perhaps a little bonus for mental suffering will suggest itself to you.

I simply mention this in a general way to let you know how your pork products are regarded in the east, where the health laws are stricter than in Chicago. I would advise you to play harder for the Klondike trade and cut Boston off your drummers' maps. This is a bit of "thinking for the house" that I'm not charging anything for. It's sense, though, and you can coin it into dollars if you see fit.

Dear old father, always planning for my comfort and pecuniary welfare! You wrote[Pg 27] that when I have had my last handshake with John the Orangeman, I am to enter the Graham packing plant to lick postage stamps as a mailing clerk at $8 a week. Honestly, dad, I don't feel worthy of so much. Make me an office boy at three per and let me grow up with the business. And I can't lick a postage stamp—really, I can't. Professor Plexus, our instructor in calisthenics, told me so the other day. He is a coarse and brutal man and I think I shall cut his elective out next semester.

But of course I shall accept your offer, although I should prefer a partnership, no matter how silent; for I shall be glad to be on hand in case anything should happen to you. Despite the law of averages you never can tell, you know.

As you say, there's plenty of room at the top. But that's where I'd like to start. I'd take all the chances of falling down the elevator well. Even if one starts at the bottom, he's not safe. The elevator may fall on him.

You say that Adam invented all the different ways in which a young man can make a fool of himself. If he did—which, with all due respect to you, pater, I[Pg 28] doubt—it's a wonder to me that Beelzebub didn't quit his job in Adam's favor. I have no doubt it pays to be good, but you know better than I do that it often takes a long time to get a business well established. Misdeeds may be sure to find you out, but if they do they'll call again.

I've devoted a good deal of thought to your maxims, which I realize to be sensible if homely, but, after all, if people practiced what other people preached, the preachers would have to take on a new line of goods. At all events I won't allow myself to worry. The man who's long on pessimism is usually short on liver pills. Misanthropy is only an aristocratic trade-mark for biliousness.

I don't do things just because the other fellows do, as you suggest, but for the sake of the family name I must observe the proprieties. Even in this I do not go to such extremes as the Afro-American gentleman who sells hot corn and "hot dogs" in Harvard Square in their respective seasons. His wife died a few weeks ago and he found it pretty hard to get a living and crap stakes without a laundress in the family. So he married a stout wench about[Pg 29] ten days ago. Last Sunday, says our janitor, who tells the story, his new wife asked him to go to church with her. "Go to church wid you, chile," he cried; "Bress de Lord, be'ent you got no moh sense ob de propri'ties dan to think dat I'd go to church wid annuder woman so soon after de death ob my wife?"

It is nearly midnight and I must close, for at twelve the art class meets at Soldiers Field to go and paint the John Harvard statue.

Your affectionate son,

Pierrepont Graham.

P.S. I wired you to-day for $50. I couldn't explain by telegraph, but the fact is it cost me that sum to keep your name out of the police court records.

LETTER NO. III.

Pierrepont, about to forsake Harvard, supplies

his father with some reasons for agreeing

with him that a post-graduate

course is not advisable.

Cambridge, June 4, 189—

My Dear Father:

No, you certainly need not get out a meat ax to elaborate your arguments against my taking a post-graduate course. What you have already said makes me feel as if a ham had fallen on me from the top of Pillsbury's grain elevator. There I go again with my similes derived from trade! It's exasperating how home associations will cling to a fellow even after four years of college life! But it's worse when these stock-yard phrases bulge out in polite conversation. It's a case of head-on collision with your pride, when you are doing your very neatest to impress some sugar-cured beauty that you are the flower of the flock, to make a break like a Texas steer. The[Pg 34] social circle was pretending to tell ages the other night. When it came my next, a pert little run-about, in a cherry waist and a pair of French shoes that must have come down to her from the original Cinderella, spoke up.

"And you, Mr. Graham, how old are you?"

"I was established in 187—" I said, with one of my fervid I'll-meet-you-in-the-conservatory-after-the-next-dance glances. But I never added the odd figure. Everybody laughed. Fortunately they thought I intended a joke. I'll bet you a new hat—if you are still sporting your old friend you need one—that you couldn't say "born." I caught the "established" from you.

I trust my education will do all that you hope for my advancement in business. I've read somewhere—perhaps in one of your meaty letters—that "good schooling is good capital." It may be, but the chances for investment are pretty poor hereabouts. Money is certainly more generally current. It may be the root of all evil, but I've noticed that it is a root that some very good people plant in the sunniest corner of their intellectual garden and keep well[Pg 35] watered. While it may not be true that every man has his price, I note that many of those who do are ready to cut rates and give long time with discounts.

With your customary capacity for banging the spike on its topknot, you diagnose my future correctly. I admit that I'm "not going to be a poet or a professor." Even the Lampoon rejects my verses—though I am bound to say that if I wrote such hogwash as your street-car ad-smith grinds out, I would never dare criticise Alfred Austin again—while as for the professorial calling, there is nothing I could possibly teach except anatomy. We have had a splendid course in that at the various Boston amphitheatres, and the fellows say I'm way up on the subject. But I hardly think it serious enough for a life calling, so, as you so pleasantly intimate, I believe I will accept your offer to join fortunes with the packing-house. I think I know enough of Latin to decline pig—and I always do when it's our label—but circumstances of a strictly pecuniary nature make it advisable for me to close with you at once. Better an eight-dollar job and six o'clock dinner than a post-graduate course and free[Pg 36] lunch. While I'm not prepared to admit that my soul soars to the azure at the thought of being a pork packer, perhaps it is just as well. When I was a boy my ambition oscillated between keeping a candy store and being a hero. Now candy makes my teeth ache and I've seen two or three heroes.

I spent some time thinking what I had better do about meeting your desire that I desert literature for liver, but your last letter soldered my aspirations into a pretty small can. My chum doesn't like pork or relish my imminent intimate connection with it. Every day for a month he's asked me whether I had decided. To-day I answered him with a story that Deacon Skinner used to tell about a young minister he once knew. He was parson of a small country church that paid a pretty skimpy salary, mostly in vegetables his flock could not eat themselves. There was precious little marrying and everybody that died seemed to be on the funeral free list. Altogether it was a case of labouring in a vineyard that had gone to seed, and the young preacher was more often full of inspiration than of roast turkey and fixin's. But an[Pg 37] empty stomach made a clear head and the eloquence of his sermons would have given Demosthenes a hard run for first money.

You can't always hide away talent so that it can't be dug up, and one Sunday the outlook committee from a fashionable church came down to D— and listened to the minister. His text that day happened to be one of those which permit of much oratory without enough orthodoxy to set the soul into convulsions. The sermon made a hit with a regular Harvard "H" and in a day or two the pastorate of the Wabash avenue church, whose steeple is nearer heaven than the majority of the congregation are likely to get, was offered to the young man, who told the committee that he must weigh the matter carefully.

The news spread through the village instantly, as it always does—for any country town has Marconi beat to a custard on wireless telegraphy—and on the afternoon of the day on which the call to the new field of labor came, the young minister's parishioners inaugurated a special pilgrimage to find out the prospects. The first arrival was a woman. (Strange, isn't it, that for all a[Pg 38] woman takes so long to dress, she can always give a man a killing handicap and beat him from scratch to the scene of a scandal or a bargain sale?) She was ushered into the parlor by the clergyman's little girl. No one else seemed to be visible. The Mother Eve in her wouldn't let the visitor wait long, so she put the little girl in the quiz box.

"I've heerd tell, Cicely, that your pa's been asked to go to a big church up to the city."

"Yes'm," answered Cicely, discreetly.

"Well, child, tell me, hev you heerd him say if he's a-goin'?"

"No, mam, I haven't."

"Nor your mother neither?"

"No, mam."

"Waal, my dear, you must know somethin' abaout it. Dew you think he's a-goin' to leave us?"

The child squirmed about uneasily and twisted her fingers.

"Speak right out naow, that's a good girl. Be he a-goin' to go or stay?" urged the inquisitor.

"I don't know, mam, really. Papa's in his study praying for Divine guidance."

"Where's your mother?"

"Upstairs packing the trunks."

I simply mention this in a general way, father, and would note in addition that in the absence of mother the janitor has helped me do my packing. I decided it was best to agree with you, for I realize that it never pays a man to act like a fool; there are too many doing it as a regular business. While I should have liked a post-graduate course, with an elective or two from Radcliffe, I realize that the difference between firmness and obstinacy is that the first is the exercise of will power and the second of won't power. Give me a little vacation in Europe and I'll come home and let you can me as devilled ham if you want to.

I don't want to brag about myself, but I'll bet you'll be surprised in me. We've all been cured of bragging by a New Yorker in my class who spends all his spare time proving why Gotham should be the only real splash on the map. To hear him, you'd think the good Lord moved the sun up and down simply to accommodate New York's business hours. A fellow from Dublin who's here studying home rule took him down the other day. Gotham[Pg 40] was boasting of New York's high buildings when Dublin spoke up.

"Hoigh buildings, is it? Begorra, we've buildings in Dublin so tall that we have to put hinges on the four upper stories."

"What in the world is that for?" asked Gotham.

"To let the sun by so it can reach New York, av coorse."

By the way, you say that some men learn all they know from Life. If you refer to the New York publication, you must have met some very gloomy and dyspeptic individuals of late. I'm not of that sort, nor, on the other hand, am I bound up in books, although, if I do say it, I have the finest set of the Decameron in college, and am considered quite an authority on the poetry of Rabelais. While on the subject of literature, I ought to state that the extra $100 in this month's expense account is for initiation fee and dues in the new Reading Club that a lot of us seniors have organized. We have for our motto Lord Bacon's great phrase "Reading maketh a full man," and it is wonderful to see how accurately the old philosopher hits our case. Owing to lack of accommodations here, we usually meet[Pg 41] in some Boston hotel where we are safe from interruption. You would laugh to see how hot some of the fellows get arguing fine points. The other night I become so exercised myself discussing Schenck's "Theory of Straights" that I walked plumb into a pier glass, thinking I was up against another chap. I think the hotel man stuck us on the damages, but the Club chipped in and paid like little men. Despite such occasional drawbacks, the club meetings are very popular. In fact, we have full houses every time we get together.

The Son in College.

Yes, that being elected president of my class was a good thing, for at last I can get my name on programmes and things without any reference to pigs tacked to it. But I don't know as it proves any overwhelming popularity on my part, for it was a dull season and I just slid in. Of course I would have liked to be marshal, but as I hadn't made any home runs and you wouldn't let me kick goals through your check-book, I was put on the mourners' bench so far as that ambition went.

I am glad to be able to write you the cheerful news that I shall graduate; up to last week there seemed to be considerable[Pg 42] doubt about it in certain high quarters not far removed from Prexy's mansion. But I went over to see one of the influential overseers, a Boston Brahmin with moss on his front steps, and plead with him. I was finally obliged to promise him that you would leave Harvard $100,000 by your will if he would see that I graduated. Of course it's a pretty stiff price, but as you won't have to pay it you ought not to mind. Besides, dad, think of the pleasure to Ma and the girls to have one real Commencement in their lives. It's cheap all round.

Your affectionate son,

Pierrepont.

P.S. If my dream comes out and I get a diploma, I'll bring it home. It may be useful to you as a by-product. It's sheepskin, you know.

LETTER NO. IV.

From the Waldorf-Astoria, Pierrepont gives his

father some inside information as to life

and manners in New York and

cites some experiences.

Waldorf-Astoria, June 30, 189—

My Dear Father:

I used to think you had a strong sense of fun, but I am beginning to fear that long connection with such essentially un-humorous animals as hogs condemned to the guillotine, has dulled it. I say this because it is evident that you didn't take my little joke about wanting to go to Europe in the spirit I intended. The idea of suggesting to you, dear old practical pig-sticker that you are, that Europe was in it for a minute with a pork-packing house as a means of culture seemed so irresistibly comic to me that I thought you would roar with laughter also, and perhaps put another dollar on that eight per I am going to receive so soon. I can catch echoes of your roar even here, but I get no suggestion of cachinnation.[Pg 46] Really, the laugh is on me for attempting such a feeble joke. When I get fairly into the pork emporium, I shall confine my witty sallies to Milligan.

On the whole, and seriously, I'm glad you drew a red line through my scheme of letting the Old World see what a pork-packer's only looks like after his bristles have been scraped through college. Since I've been at the Waldorf-Astoria I've seen so many misguided results of a few days in London that I never want to cross the duck pond. Montie Searles, who graduated when I was a soph, was a tip-topper at Cambridge, but he unfortunately got the ocean fever. I met him in the palm room last night and the way he "deah boy"-ed me and worked his monocle overtime was pitiful. He's just got back and took the fastest steamer, for fear his British dialect would wear off before he got a chance to air it on Broadway. If I should borrow his clothes and come home in 'em you'd swap 'em for a straight-jacket. They are so English that boys play tag with him in the streets waiting to see the H's drop, and so loud that every time he goes out of the hotel an auto gets frightened and runs[Pg 47] away. After I left him last night I had to sing myself to sleep with "Hail Columbia."

Familiarity breeds contempt; no man is a hero to his own valet, and I'm afraid no son is taken seriously by his own father. For instance, you draw a pretty strong inference that I've never earned a dollar which is hardly fair. I have earned considerable at times as a dealer in illustrated cards, and have picked up a tenner here and there by successfully predicting the results of various official speed tests. These things require hard labor and mental application. But the pay is sometimes uncertain, and on the whole I think your plan for me is better.

I told Searles about the packing-house job, and he pooh-poohed the idea. "Ma deah boy," he cried, "why don't you be independent? Try writing for money, old chap. That's what you were always doing in college." I'll bet he read that joke in Punch.

This is the greatest hotel in the world for one thing—in it you can meet a more varied assortment of people than under any one roof on earth. Billionaires jog elbows with impecunious upstarts who saunter[Pg 48] about the hotel corridors in evening clothes, and live on some cross street in hall-rooms way up under the eaves. There is one young fellow who haunts the hotel and looks like a swell, who is said to be only a few dress shirts shy of being a pauper. But he actually believes he's the real thing, and the story goes that to keep up his self-deception he goes home every afternoon, sits on his trunk and toots a horn, after cleaning his trousers with gasoline, and thinks he's been automobiling.

It's a long shot that you can't tell anything about a man in New York until you find out his business. He may look like a tramp and have curvature of the spine from carrying around certified checks, or he may seem the real thing in lords and only have a third interest in an ash collecting industry. I had an illustration last Sunday of how impossible it is to judge a man's motives until you know his business. I went to church—fact, I assure you. I saw a new style hat and followed its wearer into the sacred edifice, as I wanted to fix its details in my mind to tell mother. She—I mean it—was very pretty. On second thought I guess you'd better not mention[Pg 49] this to mother. In the course of his sermon the minister—one of those preachers who seem to think it necessary to shout out an occasional sentence to keep his congregation awake—declared in stentorian tones, "Wonders will never cease." A fat, bald-headed man in front of me nodded and murmured audibly, "Thank Heaven!" I wondered and asked the sexton who he was. It appears that he runs a dime museum on Sixth avenue.

Here's a straight tip for Sis. If she must marry a title let it be an American one, a Coal or Ice Baron. Counts and earls are thicker than sand fleas here and about as useless and annoying.

Speaking of straight tips, I've got a sure one on the horses sewed into the lining of my vest: If you want to go to the races without losing money don't take any money with you. The subject of money reminds me that your old Kansas friend, "Uncle" Seth Slocum was in town a day or two ago. With all due respect to him and his, you must admit that with his particularly flourishing facial lawn he looks more like a hayseed than a wheat king. At all events the head clerk tipped off a house detective to[Pg 50] keep an eye on him. They don't want any one robbed in the hotel—by outsiders. Seth hadn't been in town an hour, most of which he spent in telling me how he once got you into a corner on July wheat, when he remembered that he had an appointment down town and started out for the L. I went with him as far as the door, and as I stood there waiting for a cab, I saw a burly, flashily dressed man step up and grab Seth by the hand.

"How do you do, my dear Mr. Haymaker. How are all the folks at the Corners?" he cried.

Uncle Seth looked at him a moment and said, "Haven't you made a mistake?"

"In the name, perhaps, in the face, no," said the big chap, suavely. "Can it be possible that you are—"

Seth took hold of the fellow's lapel and drew him closer to him. "No, my name's not Haymaker nor am I from the Corners. Come closer. I've heerd tell a lot about those bunker men and I don't want any one to know my name, except you; you're such a likely chap."

The burly man laughed and inclined his head. Then, in a stage whisper that could[Pg 51] be heard a block, Uncle Seth said, solemnly, "Sh, don't breathe it. I'm Sherlock Holmes, disguised as the real thing in gold-brick targets, but don't give me away."

Uncle Seth nearly started a riot one day at luncheon. It had been very hot in the morning, but the wind changed and the temperature went down rapidly. Seth saw me at a table in the palm room and came over. "Well, Ponty," he shouted, in that grain-elevator voice of his, "quite a tumble, wasn't it? Dropped 15 points in half an hour." You ought to have seen 'em. It seemed as if every one in the room jumped to his feet in wild excitement. You see they thought he was talking stocks instead of thermometer.

By the way, Uncle Seth is infringing on your territory. He's going in for philosophy and gave me a little advice. "If you ever want to build up a big trade, Ponty," he said, "mix up a little soft soap with your business life. Flattery counts. There's a man here in New York who's made his pile as a barber because it is his invariable rule to ask every bald-headed man that he shaves if he'll have a shampoo."

I gather from your statement that my[Pg 52] allowance dies a violent death on July 15, that you are very anxious to see me on or about that date. You will. I have no desire to walk to Chicago, and my general mode of life trends toward Pullmans rather than freight cars. Ad interim, as we used to say in our debating societies, I think I shall run down to one of those jaw-twisting lakes in Maine to get some of New York soaked out of my system before dropping in on you. Billy Poindexter, a classmate of mine, has a camp there, and he writes me that hornpouts are biting like sixty, and mosquitoes like seventy. But I don't mind that, for I believe a little blood-letting will do me good after my stay here.

I like New York, even if it is a bit commonplace and straight-laced compared with Chicago. They are great on Sunday observance in this town, and I find I am gathering a little of the same spirit myself. For instance, at an auditorium called the Haymarket, there is always a devotional service very early on Sunday mornings. I attended yesterday, and was much attracted by the ceremonies and the music. You would be surprised to see the number of ladies who are willing to be absent from[Pg 53] their comfortable homes at such an inconvenient hour.

Say what you will, father, New York is a hospitable place. Although an utter stranger, I was invited the other night to the house of Mr. Canfield, a very wealthy gentleman who lives in great style. Mr. Canfield is well known as a philosopher who devotes a great deal of his time to the working out of the laws of chance and sequence. Beautiful experiments are made at his home every evening before a number of invited guests, among whom are some of the most prominent men in the city. It seems that it is the custom to have the youngest and least known guest contribute largely for the evening's entertainment, so naturally I went pretty deep into my available funds. I think I have just about enough to settle my hotel bill and buy my transportation to Lake Moose-something-or-other. It will be quite necessary that I hear from you at that point, and to the point, if you don't want me to become a lumberman or a Maine guide.

By the way, I've been observant and I've discovered something, though you'll doubtless not credit it. I see at last how so many[Pg 54] dunderheads marry pretty girls. Two of them—pretty girls, not dunderheads—were talking at the next table to me the other day.

"So she's going to marry Dick Rogers, is she?" said one. "Poor thing! He's awfully flat."

"Well," replied her companion, "he's got a steam yacht, an auto, a string of saddle horses and his own golf links."

"Ah, I see," murmured her companion, "a flat with all the modern improvements." Not bad for a New York girl, is it?

Your affectionate son,

P.

P.S. I met Colonel Blough the other evening and he invited me to sit in at a poker game. Of course I refused. He was surprised, said he supposed it ran in the family, and related the details of a little business transaction he and some other gentlemen had with you when you were last in New York. I hope mother is well. I am very anxious to see her. I think you'd be in line for repute as a philanthropist if you would send me a check for a hundred.

LETTER NO. V.

Pierrepont goes fishing and writes his father

some of his experiences, not all of which,

however, seem directly identified

with the piscatorial art.

Lake Moose, etc., Me., July 11, 189—

Dear Dad:

Here I am in a little hut by the water, writing on the bottom of a canned meat box—not our label, for I gave Billy a bit of wholesome advice as to packing foods, which he accepted on the ground that mine was expert testimony—a tallow candle flickering at my side, and the hoarse booming of bullfrogs outside furnishing an obligato to my thoughts. One particular bullfrog who resides here can make more noise than any Texas steer that ever struck Chicago. It isn't always the biggest animal that can make the loudest rumpus, as I sometimes fear you think. I simply mention this in passing that you may see that all the Graham philosophy isn't on one side of the house.

As a spot for rest this place has even Harvard skinned to death. It is so quiet here—when the frogs are out of action—that you can hear the march of time. Besides Billy Poindexter and our guide, Pete Sanderson, I don't believe there's another human being within a hundred miles. It's a great change from the Waldorf-Astoria, where you couldn't walk into the bar without getting another man's breath. The commissary department is different, too. The canned goods Billy bought are as bad as yours, dad, upon my soul, while as for fish, there's nothing come to the surface yet but hornpouts, and they'll do for just about once.

We have fried salt pork for a change and Pete makes biscuits that would make excellent adjuncts to deep sea fishing tackle. Altogether, this is great preparation for the packing-house, for I shall be so hungry by July 15 that I'll do anything to get a square meal. By the way, you haven't said anything on the subject of board—whether I could live at home on a complimentary meal ticket or be landed in a boarding-house and made to pay. I am going to write to Ma on this subject, for I think she[Pg 59] is a good deal stronger on the fatted calf business than you.

I think you would like to meet Pete Sanderson, for he's a veteran of the Civil War with a pension for complete disability, which he was awarded a little while ago. There isn't anything the matter with Pete except a few little scars, which he came by in a curious manner. It seems that he was examined by the pension board down at Bangor a few weeks back for complete paralysis. His home doctor swore that Pete couldn't move nor feel, and two strapping sons brought him to the office in their arms.

The other doctors punched and pounded him nearly to a jelly, but Pete never yipped. As a last resort they jabbed him with pins in a dozen different places, yet he didn't budge. Complete paralysis, they declared, but they didn't know that Pete had been stuffed so full of opium that he couldn't see nor feel, either. But he says he helped just as hard to save the nation as any one else, and ought to be recognized. At any rate his case is quite as worthy as that of the man who visited a Washington pension agency and sought government aid on the[Pg 60] ground that he had contracted gout from high living, due to his profits on army contracts.

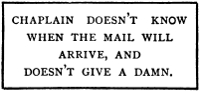

Pete is a great hand to spring stories of the war on us, and some of them are pretty good. One he tells about the chaplain of the —— Mass., when that regiment was lying on the Rappahannock or Chickahominy, or some other river during the summer of '62. It seems that the chaplain was acting as postmaster for the men, and had been much bothered by requests for the mail, which had got tangled up with the Rebs somewhere. One hot afternoon he allowed to himself that he'd like a good snooze free from interruption, so he affixed to the front of his tent a placard that read thus:

This worked like a charm, and the reverend soldier had a fine sleep and came out several hours later, greatly refreshed in body and mind. He was just a bit surprised to find a row of grinning privates[Pg 61] sitting outside his canvas residence, their eyes fixed on his warning in so noticeable a fashion that he himself turned to look at it. There, to his horror, mixed with amusement—for he was a very human sort of chaplain—he found that some wag had got at his card so that it now read:

I merely mention this anecdote as evidence that a man cannot always be judged by what appear to be his deeds, as you seem to think, and that the devil often gives him a side wallop when he's engaged in perfectly innocent recreation.

Thanks to your kind little remembrance I shall be able to be officially introduced to Milligan on the 15th. I note that, through your customary forethought, the check is just sufficient to land me in Chicago with eleven cents in my pocket, provided I practice strict economy en route. Permit me to compliment you on being the most skillful promoter of labor any son ever had.

I have racked my brain in vain to think what I could have said in the letter of the Fourth of July to arouse your encomiums. Your assertion that it "said more to the number of words" than any letter you ever received from me suggests that it was brief. As it was written on the Fourth, a day that, as a good American, I always celebrate, its brevity may be accounted for. The same explanation, however, will scarcely answer for the condensed power of expression you note.

By the way, Poindexter isn't going to marry old Conway's widow, spite her millions. I quizzed him about it and he finally put me wise. "Yes, I could have married her," he said. "In fact, we agreed, but I squirmed out of it. The truth is I proposed by mail—I didn't have the nerve to do it face to face—and she accepted me on a postal card. Her evident economy was a bit too much for me."

I've done a lot of thinking (this word is not written very plainly, but it is thinking and nothing else) since I have been in the woods. Billy says I only think I'm thinking, but he's a cynic. There's been little to do but think. The hunting is worse[Pg 63] than the fishing and the only thing I've bagged is my trousers. The sum total of my thoughts seems to be a few resolutions. Although I know resolutions are not ripe till Jan. 1, I've had time to make them here and I'll have plenty of chance to get accustomed to them before I write them down in the Russia leather diary that I know you will be glad to include among my Christmas gifts.

My resolutions may not be original, they may not even be good ones, but such as they are I am going to write them out for you, for you have often told me that it was every man's duty to himself to set himself a goal and mark out the course by which to reach it. For this and a perfect wealth of other advice I can never thank you enough. Perhaps, however, the knowledge that I am really taking life seriously, as shown by my resolutions, will be some recompense to you for the midnight oil you have burned in the coinage of succinct sayings and meaty metaphors. (I flatter myself that is pretty well expressed, although my English professor would object, as he often did, to my employment of trade terms as illustrations and similes.)

The stain on this sheet of paper is due to Poindexter, who shied a slice of fat pork at my head while I was writing. That was yesterday and he absolutely refused to let me finish my letter. He said a man who couldn't find anything better to do in the woods than write was several unpleasant sounding things. As he emphasized his remarks by war-whoops, Comanche dances and the beating together of tin plates, I was forced to forsake my literary pursuits till this morning. Billy is asleep. He absolutely refused to rise without a pick-me-up and, as our canoe was upset last night, we lost all our camp utensils, including that indispensable adjunct to camp life, the pick-me-up.

Billy is up and insists that we must go to the nearest settlement for a new camp kit. He misses the splendid assortment of pick-me-ups with which we started out and swears he won't know north from south till he gets one. The resolutions will have to wait till we return.

July 13.

We did not get back till to-day. We found a fine collection of camp necessities at the settlement and what we selected[Pg 65] proved such a heavy burden that we were unable to start on the return trip till this morning. Billy is asleep again. I never knew he was such a heavy sleeper. It must be the bracing air of the woods. In Cambridge he had the reputation of never sleeping.

I have re-read the resolutions and I think it best not to send them to you until I am out of the woods. Surveyed in the light of this particular morning they seem to need as many amendments as the Constitution of the United States.

Just a word of warning not to be surprised when I show up for work in hunting costume. I was compelled to leave all my other clothes in New York for safe keeping. Storage rates are very high there; the tickets call for a payment of $150. I shall call at the Waldorf on my way through the city and shall get any letters—with enclosures—that may be there.

Your hopeful son,

P.

P.S. Do you think that when a man finds he is catching two fish on one hook every time he hauls in his line it is time for him to stop using bait? Billy assures me that it is.

LETTER NO. VI.

The seat at his father's mailing desk does not

appear especially comfortable to the Junior

Graham, if we may judge by the

tone of his correspondence.

Chicago, Aug. 30, 189—

My Dear Father:

Permit me to say, most respectfully of course, that you are overdoing the emotional business as to my mistake in mailing a note of invitation to the theatre to Jim Donnelly in place of a letter denying his claim of shortage on hams, and denouncing him as a double-distilled prevaricator for venturing the same. As a matter of fact, it was a great stroke, and I've ordered the cashier in your name to put a two-dollar ell on my financial structure. Donnelly came in to-day and gave us a thousand-dollar order for short ribs; said he was devilish glad to find a bit of humanity and sentiment in the house of Graham, and that if you had more blood and less lard in your veins, Chicago would be a better place to live in. He's fond of[Pg 70] the old burgh, at that, for he licked a Boston drummer last week for claiming that the Boston Symphony Orchestra was better than Theodore Thomas'. You see Jim has just become engaged and my little break struck him in a tender spot.

I note with pain, dear dad, that you make a great hullabaloo over my robbing you of your time by writing that note. Theoretically you may be right, but practically your kick is so small that a respectable jack-rabbit would be ashamed of it. Let's see; I work—theoretically—from 8 to 6, one hour out for lunch. Under your munificent system of payment I get about 15 cents an hour, or a quarter of a cent a minute. It took me two minutes to write the note. Ergo, I owe you half a cent, whereas you owe me the profit on the thousand-dollar order of short ribs, which Donnelly says must be something immense. Let's square up on that basis.

But even had results been worse, absent-mindedness is a fault, not a crime. Literature is full of well-authenticated instances of that perversity of wit which makes one do the wrong thing instead of the much easier right one. The poet Cowper's feat[Pg 71] of boiling his watch while he timed it by an egg is really a very commonplace illustration of the vagaries of the human mind.

It was surpassed by Dean Stanley and Dr. Jowett, who were both extremely absent-minded and very fond of tea. One morning they breakfasted together and in their chat each of them drank seven or eight cups of tea. As the session broke up, Dr. Jowett happened to glance at the table. "Good gracious!" he exclaimed, "I forgot to put in the tea." Neither had noticed it.

Even this, I think, is excelled by the case of a remarkably absent-minded man in the western part of Massachusetts, whose freaks of memory made him the sport of the country for miles around. He once went for days without sleeping because he was very busy in his library and didn't leave it, so did not see his bed as a reminder. He capped the climax, however, when he came home one night and hanged himself to the bed-post by his suspenders. As he was wealthy and cheerful, with much to live for, it is generally believed that he mistook himself for his own pants. At all events absent-mindedness, like bad penmanship, is a sign of[Pg 72] genius, and, as a loving father, you should be glad that I have one of the symptoms.

I must frankly admit that the addressing of envelopes is not the most fascinating of pursuits. If I must write in order to earn my salary from the house, I should much prefer to do it across the bottom of checks. I would then feel that the business was more dependent upon me and also that it might mean more to me. It has got so that the sight of a U. S. stamp after business hours gives me a bilious attack. Let me at least fill out the checks if I don't sign 'em. Then I'll be better able to imagine that I'm the real thing around here, even if my salary's attenuation continues to eat a big hole in my sainted mother's pin money. The next best thing to owning an auto, you know, is to wear an auto coat.

Of course Milligan made a noisy, braying, Hibernian ass of himself when he came around to take your cussing of him out on me. He swore and danced and waved his arms, and got still madder when I asked him what he was Donnybrooking around in Chicago for. He didn't seem to like it a bit when I told him that one little finger of the girl I wrote to, was worth a[Pg 73] thousand times as much as himself and the hogs he associated with, put together. He allowed that I was an impudent young jackass and the dead copy of my father; went on to say that if he hadn't started the firm and kept his weather-eye on it ever since, you would have been in the bankruptcy court or jail years ago. When I got mad and told him that I'd have him bounced, he said you didn't dare to fire him because he knew the secret of—but really I don't think it safe to entrust it to paper.

Milligan is a dirty beast who belongs to the Shy-of-Water tribe and smokes a horror of a clay pipe. To think that I, who have mingled with gentlemen for the past four years, should be compelled to breathe his air is too much. I won't work under a man who habitually insults my honored father. If you haven't pride enough to rebel, I have. He is vulgar enough to call you the "ould man," and I am morally certain he is a pretty liberal toucher of that private stock you keep in your inner office. For heaven's sake, throw him out and purify the place.

Jim Donnelly seems to have taken quite a shine to me, and last night he invited me[Pg 74] to his club for dinner. This was a great relief for yours truly, for between you and me, Ma has got pretty stingy with the table since you left, and is trying to use up a box of our products she found down cellar. (By the way, I notice from a slip Milligan gave me to file to-day, that you crossed off all the Graham foods the steward of your private car had picked out for your trip—wise old dad!) So Jim's invite was like an early cocktail to Col. R. E. Morse. After dinner we hied ourselves to a vaudeville show, which I simply mention in a business way. I see you've an "ad" on the drop curtain at the Hyperion, and if you won't kill the poet who wrote those verses, I must. Such awful rot as:

may appeal to you as A1 inspiration, but trust an humble member of your family when he says that you simply nauseate the public by such tomfool stuff. You're rich enough to hire Howells if you like, so there's no excuse for this.

Wish I was with you on the car instead[Pg 75] of being compelled to hear Milligan blart about "our house" like an Irish Silas Wegg. They say around the office that the car is bully well stocked with things and things, and they even hint that you have been taking to it pretty regular of late to change climates with Ma. I don't encourage such idle talk.

I've worried a lot since you went away. The business seems to have got on my nerves. Of course I realize that all I have to do is to lick stamps and try to look as if I enjoyed it, but as the family heir I can't help worrying about the firm. Several matters have come to my attention, in the way of business, that make me fearful that perhaps you made a mistake in going away without leaving one of the family at the helm here. The Celtic gentleman who signs himself "Supt." and whom the boys call "Soup," does not take kindly to my advice. When I told him yesterday that I feared that a carload of lard that was shipped to Indiana was not first chop and would be returned, he looked me over curiously for a minute and said:

"Don't let that worry ye, me bye; the toime to fret is when they sind it back."

And then, in a very loud voice, so that everybody in the office could hear, he told me a story.

"Your anticipation av trouble reminds me," he said, "av an ould maid up in York state twinty years ago. She was so plaguey homely that if she'd been the lasht woman on earth the lasht man wud a jumped off it whin he met her. Arethusa Prudence Smylie—I've niver forgot the name, how cud I?—was as full av imagination as a Welsh rarebit is av nightmare, and ye niver cud tell phwat her nixt break wud be. She was sittin' in the kitchen one winter's day, radin' po'try and toastin' her fate in the open oven door, while her good ould slob av a mother was rollin' out pie crust, whin all av a suddint she burst out cryin'. This startled her mother so that she dropped her rollin' pin and rushed to her daughter's side. She thought she'd had a warnin' or cramps or somethin'. It was a long toime before she cud squeeze a worrd out edgewise bechune the wapes.

"'Phwat is the matter?' she cried, agin and agin. Finally, wid the tears a streamin' down her chakes an' the sobs wrestlin wid her breath, Arethusa tuk her mother into[Pg 77] her confidence. 'I was sittin' here, radin',' she said, 'whin the po'try suggisted somethin' to me an' thin I got to thinkin',' and here her gab trolley was trun off by sobs.

"'Thinkin' of phwat, darlint?' cried her mother.

"'Oh, mother, I was thinkin', as I sot here wid my feet in the open oven door, that if I should get married and a little baby should come and—and—' Agin she stopped to put on brakes wid her handkerchief, and thin wint on rapidly, 'I was thinkin' how terrible it would be if I should git married and should leave the baby here in the kitchin' and go out and—and it should crawl into the oven an' you should shut it up wid the pies and—and—boo-hoo, hoo!'"

The point of this yarn appeared clear enough to the boys in the office, for they laughed like hyenas and looked at me as if I were the latest thing in tailor-mades. Strange how everybody knows when to laugh when the boss makes a joke! This morning one of the boys had the nerve to call me Arethusa. When I got through with him, in the vacant lot back of the hog pens, he couldn't have said "Arethusa" to[Pg 78] save his life. You will commend this, I know, for the dignity of the family name must be upheld. I found long ago that in order to maintain the respect of the world it is sometimes necessary to give it a few drop kicks.

I am disappointed in Milligan. Until recently I thought he really felt an interest in me. For instance, a day or two ago he expressed surprise that you had not established me in the real estate business, and said that it struck him that I was better suited for it than for the coarse details of pork-packing. After that I went round like a pouter pigeon. But I have since learned that he followed his remark about the real estate business with a side speech to one of the clerks: "He certainly knows more about the real estate business than he is likely to ever learn of this. He can tell the difference between a house and lot."

Milligan is so full of jokes that it's safe betting that if he had the shaking up I'd like to give him he'd shed comic operas, end-men's gags and "side-walk conversation" enough to keep the show business running for years to come. Do you wonder that I have written you several letters[Pg 79] demanding his resignation or acceptance of my own? You will not receive any of those letters, however, for home, although humble, is a place of shelter. I must say, though, that Milligan's penchant for presenting the naked truth without even the traditional fig leaf is annoying.

Your chafing son,

Pierrepont.

P.S. I have just learned that Milligan is at home, sick. I wish him well, of course, but if he should find a change of climate necessary I will gladly hunt up the timetables for him.

LETTER NO. VII.

Pierrepont writes of "independent work for the

house" and its results; of the methods of

"guide-books-to-success" philosophers,

and of divers other topics.

Chicago, Sept. 10, 189—

Dear Father:

What a clever, indulgent, far-seeing old boy you are, to be sure. Your ultimatum that I must continue to be subject to Milligan sounds harsh at first reading, but I see your motive. You think by keeping me under him for a while I shall work like a fiend to get promotion, and thus escape his Celtic cussedness. I shall. No greater incentive to rise was ever offered a poor young man. In fact, you couldn't keep me down with Mike if you gave me ten thousand a year. My lacerated feelings are worth much more than that.

Ma is a pretty good Samaritan these days. I told her that Milligan was my bête noir, and she said it was a mean shame for a grandson of her father to have to affiliate[Pg 84] with such an animal. Her sympathy cost her ten, but I feel that it was worth that to have her wellsprings of emotion tapped once more.

I see the logic of what you said in your last. True it is that if it isn't a Milligan over us, it's some one else—I won't say worse, for that would be lying. I have Mike, Mike has you, you have Ma, and Ma has Mrs. Grundy. We are all travelling over the ocean of life in the same boat, but I'm hanged if I wouldn't prefer to be in the first cabin drinking champagne, than down in the stoke-hole sweating like a galley slave.

I am sincerely glad you are coming home. The old adage about the mice playing when the cat's away is away off. Since you've been gone, except for the half day that your Brian Boru-descended super was sick, I've not even had time enough in office hours to devote an occasional few moments' thought to how I will improve methods here when you elect to add "retired" to your recital of personal facts for the city directory. The way Milligan keeps me jumping would have pinned all the Mott Haven medals on me, had his system[Pg 85] of training been adopted in Harvard athletics. I've lost seven pounds in three weeks, and if this thing keeps on I'll be so far under weight that I'll be sent out to pasture or to the boneyard.

I used to think Milligan a well-balanced man, but I was wrong,—no man whose lungs are so out of proportion to his brains can be. I'm getting used to being bossed, but I shall never be broke to being roared at in the fashion of the Bull of Bashan. I don't object to being told that it is necessary to have a state as a component part of the superscription on a letter,—but is it essential to the business code that the people in East Saginaw should have full particulars of my dereliction shouted at them?

Milligan takes especial delight in introducing me to all the visitors who inspect the works, but never by any chance does he tell who I am. Not a bit of it. "This is our new mailing clerk: he is just from Harvard," is the neat way he puts it. And then they look me over and say, "Harvard? Oh, indeed!" and the look passed out with it—you'd think I was a new line of prize pig. I've come to believe that I'm[Pg 86] under suspicion here in Chicago; and I've locked up all my college pins and insignia in a closet down cellar, and couldn't be roped into confession of my alma mater with a lariat. Education is evidently not a thing to brag of in Chicago.

I can't quite get on to what it is, but Milligan is up to some game. He's very chummy with the visitors and insists upon showing them about himself. An English lord who was here the other day, chatted with him for fully half an hour in your private office. Think of it—in your private office. I shall have it deodorized before you return. As usual, Milligan boasted and, as the door was open, we all heard. Something was said of the Irish land bill, and this opened the throttle of the super's conversation.

"It's no more than roight to do somethin' for Ireland. Who won the Boer War for ye? Kitchener, Lord Roberts,—both Irish."

"Really, you don't tell me?" drawled his lordship. "And were all our great fighters Irishmen? Was—was Wellington?"

"Certainly," said Milligan.

"And Nelson?"

"Shure. All great fightin' min were Irish."

"How about Alexander?" asked the Englishman.

"Celtic, for shure."

"So? And say now, how about—well, Balaam?" lisped the peer.

"Irish," cried Milligan, "Irish to the backbone. But—an' I asks ye to note this, your lordship—but the ass was English."

I hate Milligan, but I love a joke, and I joined in the laugh that went up. Then I heard his lordship pipe up, "How delightful, don't yer know, that your clarks are so merry. I do wonder what they are laughing at."

Just then he toddled out and surveyed us through his monocle. As Milligan joined him he turned to him and said: "So Balaam was Irish, too, Mr. Milligan? But I really didn't know the ass was a native animal in my country."

Milligan certainly possesses self-control. He was as grave as a government inspector opening a Graham tin can as he replied, "Those laugh best who laugh last, your lordship."

By the way, there was a little excitement[Pg 88] in the packing house yesterday which you may hear of in some other way. I'll tell you the straight facts. I happened to be over in the refining house during the noon hour, to get some butterine for a sandwich, when a fellow with some sort of monkey togs blew in and acted in a very suspicious manner. He nosed around into the vats, poked a queer glass machine plumb through a keg of butterine, broke open some tins and raised particular Ned in the olive oil department When he started to put some stuff in his pockets, I remembered your oft-repeated injunctions to occasionally do some independent work for the house—to get out of the ruts, as it were—and I came an old-time Soldier's Field tackle on his jiglets which resulted in his complete disappearance from the interior of the plant, and a compound fracture of the left shoulder-blade where he landed on the cobblestones of the yard. He cursed me as he was being carried away on a stretcher, and said the concern would hear from him to its sorrow.

I understand he's a government inspector, but I rely on your little way of settling such things. However, I think it[Pg 89] would be just as well that you cut your expedition in two and get around here by the time the plot thickens. If you don't care to go home so much sooner than you intended, you can live in the private car right here in the railroad yard, and I won't let Ma know. You would enjoy the surroundings immensely. Think of being lulled to sleep by the squealing of your own hogs and awakened in the morning by the music of Texas steers that are going into Graham cans.

Billy Poindexter is here for a day or two on a little trip from New York. He cut up horribly when I told him I couldn't get out to air myself all day long. But I pointed out to him that I was in training to carry Graham & Co. around on my shoulders one of these days, and he admitted that it looked like a good game to follow. I showed him one or two of your letters, and he said they were too clever for a pork-packer and too greasy for a philosopher. Asked if you weren't over-doing the "Beyond-the-Alps-lies-Italy" business a trifle, and allowed that too much watering has killed many a promising plant. However, I don't believe water will be the death[Pg 90] of me. Billy says my occupation would drive him to drink, but I guess he isn't on to my salary or else doesn't know the price of cabs out here. Besides, he doesn't need driving.

Billy has developed quite a philosophical streak lately. I guess the girl he really wanted for better or worse decided it a long shot for worse and scratched Billy in the running. I taxed him with it.

"Young man," said he—he's only fourteen months older than I, but how he does swell up over it—"Young man, the pursuit of a girl is like running after a street car and missing it. You're never quite sure that it was the right car, after all."

That's all I could coax out of him, but I guess he got the stuffed glove all right. The other night, after we had spent several hours in the Palmer House examining some very curiously shaped glasses and some quaintly embossed steins, Billy became pathetically confidential and imparted a secret to me.

"Piggy, my boy," he said, "I once cherished rainbow visions of being a great man some day, but I've given it up. After all, the only sure guarantee that you are a[Pg 91] great man is to have a five-cent cigar named after you and see them sold at the drug stores at seven for a quarter." The thought affected him so that he tried to conceal his emotion by hiding his face behind one of a couple of glasses that were just then submitted to our inspection.

If Billy only could set his mind on any thing he'd be sure to make a success at it; but the only thing he has ever tried to do is to help spend his governor's money, and he is certainly the entire ping-pong at that. He is of a companionable nature, however, and is not averse to assistance in his pecuniary labors. I help him all I can, and, to square things up a bit, I invited him to be my guest at the house during his stay here. He doesn't eat much, so the family exchequer will not be lowered materially. He never has any appetite for breakfast. Mother has cottoned to him as if he were an orphan. She likes me to be with him for his good example, for she knows that he doesn't drink, he's always so thirsty in the morning.

The other night at dinner Billy was very loquacious. He had been playing billiards all the afternoon, and there is something[Pg 92] connected with the game that always loosens his tongue. Somebody mentioned success, and that started William, for he always spells it with a big "S."

"Success is much easier to talk about than to discover," he said. "The man of affairs who undertakes to point out the path to it to a young man anxious to tread it, is like the average man of whom you ask directions in a large city, and who says, 'Well, but it's hard to tell a stranger. You'd better go up this street till you come to the City Hall, then take the first street to the right and the second to the left and—and then ask some one else.'"

"I've noticed," said Billy, without a pause in his eloquence, "that the prominent men who write magazine and newspaper articles on 'How to Succeed,' always tell their yearning readers to save part of each dollar they receive, but never tell them how to get the dollar. Fact is, if they knew where the dollar was they'd go get it themselves. And they never tell how they themselves succeeded. That would be betraying a business secret. 'Work, work hard,' they say, 'do more than you're paid for doing, and you will soon be appreciated by your[Pg 93] employer. Do two dollars' worth of work for one dollar and you'll soon be getting three dollars.'"

Here Billy leaned over the table and spoke more impressively than I thought he was able to. "Search the career of one of these self-advisory boards for the community," he said, "and you'll find that these men succeeded by hiring men to do two dollars' worth of work for one dollar and then getting themselves incorporated and selling the work for $5."

When Billy got through, Ma smiled across to me and said, "How much Mr. Poindexter talks like your father!"

Your hopeful son,

P.

P.S.—We are going to a masquerade ball to-night at the De Porques. Old De P. offers a prize of $100 for the most hideous make-up. I'm going as Milligan.

LETTER NO. VIII.

His governor's visit to Hot Springs, a contretemps

with a British Lord, together with

experiences with a few physicians,

inspire Pierrepont's pen.

Chicago, Jan. 23, 189—

Dear Pa:

There's no doubt that the Hot Springs are great for a good many ailments, and I'm glad you are improving. Professor Plexus, our old instructor in calisthenics at Harvard, used to take the trip to Arkansas with John L. Sullivan, twice a year, and they both said the treatment was fine. I don't think Sullivan had rheumatism, but your case may not be the same as his, and the scalding process will probably do you more good than it does a regular Graham hog. The boys around the office laugh considerably when they mention you and the Hot Springs, which makes me rather warm under the collar, for I can't stand having a father of mine misapprehended. I know you for what you are, but they[Pg 98] know you for what they think you are, and provisional knowledge, you know, goes a long ways in the provision business.

Speaking of the Hot Springs reminds me of a story Professor Plexus used to tell about the Arkansas boiling vats. According to him, there used to be a morgue connected with the establishment, for the use of those who were unlucky enough to succumb to the treatment. An old Irishman was the general factotum of the place, and it happened that he was afflicted with a bronchial disturbance that was the envy of every cougher who visited the spot. Meeting him one day in the abode of the departed, one of the doctors remarked to him, on hearing a particularly sepulchral wheeze:

"Pat, I wouldn't have your cough for five hundred dollars."

"Is thot so, sorr?" retorted the son of Erin. "Well," pointing with his thumb to the inner room where the departed patients lay on slabs covered with sheets, "they's a felly in there who wud give five t'ousand uf he cud hav ut."

I simply mention this little incident in passing to show that all of us prefer the ills[Pg 99] we have to those we know not of. I would rather be a mailing clerk at eight per than a free man working freight trains for transportation and relying on hand-outs for sustenance in place of Ma's frugal, but certain table d'hôte.

I sincerely trust, sir, that your trip to the Springs will do you the anticipated good. Billy Poindexter says—(by the way, I guess you didn't know he was back from the Klondike. Not exactly that, either, for he didn't reach the Klondike. The nearest he got to it was on the map he bought while he was here. He went no farther than San Francisco. His only object in starting for the Yukon, he says, was to see if he couldn't pick up a good thing or two, and as he found them in 'Frisco he stayed there.) He was much concerned about you when I told him you had gone to the Springs.

"Too bad for your governor," he said. "He must suffer terribly with them."

"With them?" I asked. "With what?"

"Why, boils, of course. What would he go to the Hot Springs for, if not for boils?"

It cost me five minutes' time in a very busy evening to find out that he had made[Pg 100] a very bad joke, a paranomasia as we called it in college; in other words, a pun or play upon words. I've advised Billy to publish a chart of this joke. If he does I'll send you one. He says I'm as dense as that English lord who visited the works while you were away last fall.

Apropos, we met him—the lord—the other night. We were having a bite to eat at a rathskeller after the theatre when "his ludship" wandered in. He was built up regardless, with an Inverness coat with grey plaids, that looked like a country-bred rag carpet. It was the real thing, of course, and I made up my mind to save the four dollars that have been added to my stipend until I could get one like it. I decided, however, that I shall not make my possession of it public until he has left the country. I should really hate to be mistaken for him. I even prefer to be known as connected with your business.

Strange to say, when "his ludship" reached our table, he halted uncertainly as he saw me, and then stepped forward.

"You'll—aw—pawdon me, doncherknow, but—aw—is not this—aw—young Mr.—aw—Graham?"

I pleaded guilty, with a mental plea for mercy, and the next thing I knew his dukelets had made his monocle a part of the set-up of our table. I was very much embarrassed, for I didn't know how to introduce him to Billy. But his earlship quickly backed me out of that corner by calling Billy by name.

"Yaas, old chap," he was saying, "I met you—aw—at the Ring Club, doncherknow."

Billy didn't know, because his sight is often very bad, especially at the Ring Club. So the Marquis gave his memory a push.

"I'm Fitz-Herbert," he said.