Walker & Boutall, Ph. Sc.

Title: The Tragedy of Fotheringay

Author: Mary Monica Maxwell-Scott

Contributor: Dominique Bourgoing

Release date: June 10, 2017 [eBook #54884]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by MWS, Linda Cantoni, and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Transcriber's Note

Obvious printer errors have been corrected without note; inconsistent and archaic spellings in quoted material have been retained as they appear in the original.

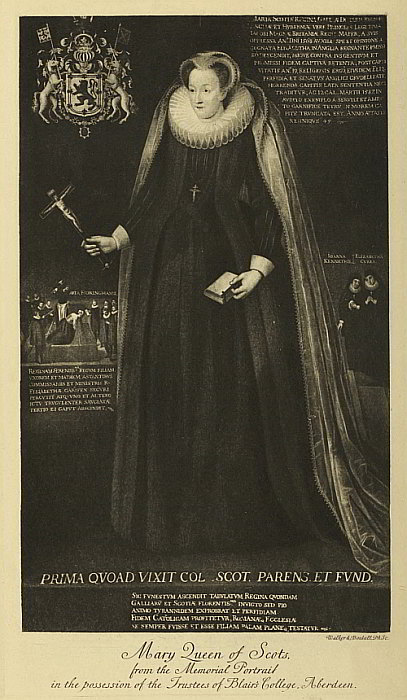

Mary Queen of Scots,

from the Memorial Portrait

in the possession of the Trustees of Blairs College, Aberdeen.

Enlarge

FOUNDED ON

THE JOURNAL OF D. BOURGOING,

PHYSICIAN TO MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS, AND

ON UNPUBLISHED MS. DOCUMENTS

BY THE

HON. MRS. MAXWELL SCOTT

OF ABBOTSFORD

LONDON

ADAM & CHARLES BLACK

1895

In compiling this book, my original intention was to deal with the material afforded by Bourgoing's Journal, supplemented by the Letters of Sir Amyas Paulet. Both narrate the events of the last few months of Queen Mary's prison life, the details of which have been hitherto little known. As time went on, however, and further new and valuable matter was offered to me by the kindness of friends, the scope of the work gradually expanded. Many details regarding the Queen's execution and burial have been added, and I feel that some apology is due for possible repetitions and other errors of style which almost necessarily follow such a change of plan. Many of the illustrative notes regarding Queen Mary's last moments are culled from original contemporary accounts of the execution, for the use of which I am indebted to the kindness of the Rev. Joseph Stevenson, S.J., LL.D. Some of these narratives are printed in the Appendix in their entirety. The-vi- valuable collection of the Calthorpe MSS. has furnished many interesting details, and I am especially indebted to the courtesy of the present Lord Calthorpe for permission to publish the two curious contemporary drawings of the trial and execution. The value of these drawings is materially increased by the annotations in Beale's handwriting. To him we owe several of the most interesting notes regarding the execution, etc., and the knowledge that these MSS. have come down to us under the direct guardianship of Beale's descendants lends additional value to their testimony.

Robert Beale, whose name occurs so frequently in my narrative, had long been employed in a subordinate position by Elizabeth's Government, and in 1576 was sent by the Privy Council on an embassy to the Prince of Orange. He was later appointed Clerk of Council to the Queen, the office in which he comes before us at the time of Queen Mary's trial and death, and his daughter Margaret married Sir Henry Yelverton, Attorney-General, the ancestor of the Calthorpe family, who thus became the possessors of the documents I have referred to.

The frontispiece, taken from what is known as the Blairs portrait of Queen Mary, has its own pedigree of-vii- unusual interest, although it cannot claim to be an original portrait. The following description of this picture is taken from the pen of the Right Rev. Bishop Kyle, Vicar Apostolic of the Northern district of Scotland:—

This large picture of Queen Mary belonged once to Mrs. Elizabeth Curle, wife and widow of Gilbert Curle, one of the Queen's secretaries during the last years of her life and at her death. Mrs. Curle herself was one of the attendants at her execution. When, and by whom it was painted, I have never learned. The attire and attitude of the principal figure being the same in which it is said Mary appeared on the scaffold, seem to testify decisively that the picture is not what can be called an original—that is traced from the living subject under the painter's eye. The adjuncts were evidently added by another and an inferior artist, but when, I have no means of knowing. Mrs. Curle survived her mistress long, at least thirty years. She had two sons, who both became Jesuits. Of one, John, there is little known. He died in Spain. The other, Hyppolytus, was long Superior, and a great benefactor of the Scotch College of Douai. To that College he bequeathed the property, not inconsiderable, which he derived from his mother, and among the rest the very picture now at Blairs. The picture remained in that College (Douai) till the French Revolution. At the wreck of the College it was taken from its frame, and being rolled up was concealed in a chimney, the fireplace of which was built up, and was so preserved. After the peace of 1815 it was taken from its place of concealment and conveyed first to Paris, but ultimately to Scotland, through the late Bishop Paterson and the Reverend John Farquharson,-viii- who being the latter Principal, the former Prefect of Studies in the Douai College at the time of the Revolution, identified it as the picture that had been kept there according to the tradition mentioned above.[1]—(From Annals of Lower Deeside, John A. Henderson.)

In the background of this picture the execution of the Queen at Fotheringay is represented, along with the portraits of Jane Kennedy and Elizabeth Curle, the two maids of honour who were present on the sad occasion. The royal arms of Scotland are painted on the right-hand corner of the picture, and there are three inscriptions in Latin, the translations of which are as follow:—

1. Mary Queen of Scotland, Dowager Queen of France, truly legitimate Sovereign of the Kingdoms of England and Ireland, mother of James, King of Great Britain, oppressed by her own Subjects in the year 1568, with the Hope and Expectation of Aid promised by her Cousin Elizabeth, reigning in England, went thither, and there, contrary to the Law of Nations and the Faith of a Promise, being retained Captive after 19 years of Imprisonment on Account of Religion by the Perfidy of the same Elizabeth and the Cruelty of the English Parliament, the horrible Sentence of Decapitation being passed upon her, is delivered up to Death, and on the 12th of the Kalends of March—such an Example being unheard of—she is beheaded by a vile and abject Executioner in the 45th year of her Age and Reign.

2. In the Presence of the Commissioners and Ministers of Queen Elizabeth, the Executioner strikes with his Axe the most serene Queen, the Daughter, Wife, and Mother of Kings, and after a first and second Blow, by which she was barbarously wounded, at the third cuts off her Head.

3. While she lived the chief Parent and Foundress of the Scotch College, thus the once most flourishing Queen of France and Scotland ascends the fatal Scaffold with unconquered but pious mind, upbraids Tyranny and Perfidy, professes the Catholic Faith, and publicly and plainly professes that she always was and is a Daughter of the Roman Church.

The reliquary containing a portrait of Queen Mary, of which Lady Milford kindly allows me to publish the photograph for the first time, is very interesting, and the date can be fixed as being not later than 1622, but unfortunately the history of the medallion is little known.[2] It was originally in the possession of the Darrell family, and as a Darrell was appointed to be Queen Mary's steward during her captivity, and a Marmaduke Darrell (presumably the same person) attended the funeral at Peterborough, I would fain see a connection between him and the miniature, but so far I have found no proof of this.

The two contemporary drawings of Queen Mary's trial and execution from the Calthorpe MSS. are now-x- also published for the first time. The lists of spectators written by Beale are of particular interest, and it is curious to compare the drawings of the trial with Bourgoing's description of the scene (see p. xiii.) and with that given in Appendix, p. 270.

In conclusion, I earnestly desire to express my grateful thanks for the constant and valuable help and encouragement given to me by the Rev. Joseph Stevenson, S.J., LL.D., to whose kindness I owe so much; to Mr. Leonard Lindsay, F.S.A., and to other kind friends.

M.M. MAXWELL SCOTT.

8th February 1895.[3]

| CHAP. | PAGE |

| I. Chartley | 1 |

| II. Fotheringay | 16 |

| III. The Trial—First Day | 44 |

| IV. The Trial—Second Day | 69 |

| V. Suspense | 83 |

| VI. After the Sentence | 107 |

| VII. Waiting for Death | 125 |

| VIII. Further Indignities | 145 |

| IX. The Death Warrant | 163 |

| X. The Last Day on Earth | 179 |

| XI. The End | 200 |

| XII. Peterborough | 225 |

| XIII. Westminster | 244 |

| Appendix | 249 |

| Mary Queen of Scots, reproduced from the Portrait at Blairs College, Aberdeen | Frontispiece | |

| Contemporary Drawing of the Trial, reproduced from the Calthorpe MS.[4] Facsimile Key to above | } } } | Facing each other at page 44 |

| Contemporary Drawing of the Execution, from The Calthorpe MS. Facsimile Key to above | } } } | Facing each other at page 200 |

| Enlargement of the Execution Scene, as given in the Background of the above | To face page 220 | |

| Reliquary containing Miniature of Mary Queen of Scots, and Relics, now in the possession of Lady Milford | To face page 244 |

THE

TRAGEDY OF FOTHERINGAY

"Ceux qui voudront jamais escrire de cette illustre Reine d'Ecosse en ont deux tres-amples sujets. L'un celui de sa vie y l'autre de sa mort, l'un y l'autre tres mal accompagnés de la bonne fortune."

Brantôme.

THREE hundred years have passed since Brantôme wrote these lines, and his prevision has been fully verified. Writers of every opinion—friends and foes—have taken as their theme the life and death of Mary Stuart, and it would now seem as if nothing further could be written on the subject, fascinating though it has proved. Fresh historical matter bringing new evidence, however, comes to light now and then, and the publication in France, some years ago, of such testimony is our excuse for adding a short chapter to the history of Queen Mary. That this evidence relates to her last days and death, is very welcome, for we hold-2- that in Queen Mary's case we may specially apply her own motto, "In my end is my beginning." Her death was the crown and meaning of her long trial, and the beginning of an interest which has continued to the present day.

The journal of Queen Mary's last physician, Dominique Bourgoing, published by M. Chantelauze in 1876, which recounts the events of the last seven months of Mary's life, informs us of many details hitherto unknown, while the report of the trial of which Bourgoing was an eye-witness is most valuable and interesting. Taken together with the Letters of Sir Amyas Paulet, which, although written in a very different spirit, agree in the main with Bourgoing's narrative, the journal presents us with a complete picture of the daily life of the captive Queen and the inmates of Fotheringay. In the preface to his valuable book M. Chantelauze tells us of his happy acquisition of the manuscript copy of Bourgoing's journal at Cluny, discusses the proofs of its authenticity, and refers us to the passage in Queen Mary's last letter to Pope Sixtus V., which we must consider as Bourgoing's "credentials."

"Vous aurez," writes Mary, "le vrai récit de la fasson de ma dernière prise, et toutes les procédures contre moy et par moy, affin qu'entendant la vérité, les calumnies que les ennemys de l'Eglise me vouedront-3- imposer puissent estre par vous réfutées et la vérité connue: et à cet effet ai-je vers vous envoyé ce porteur, requérant pour la fin votre sainte bénédiction."[5]

Bourgoing's Journal in effect begins from the moment specified by the Queen, at her "last taking," and contains, as she says, the full account of the proceedings taken against her. Although the interest of the narrative centres in Fotheringay, Bourgoing also gives new and interesting particulars of the way in which the Queen was removed from Chartley, the imprisonment at Tixall, and the return to Chartley before the journey to her last prison of Fotheringay.

Bourgoing begins his journal on Thursday, the 11th of August 1586, at Chartley, where the Queen had now been since the previous Christmas, and at a moment of the gravest importance for her safety. The fatal conspiracy known as the Babington Plot had been arrested, and the unhappy agents in it were awaiting their cruel doom. It was determined that Mary should be removed from Chartley, her secretaries sent to London, and her papers seized, while she was still ignorant of the fate of Babington and his companions. For this purpose-4- William Wade, a sworn enemy to Mary, was sent down to Staffordshire to take the necessary measures, and in order that this might be done secretly, he and Sir Amyas Paulet, Mary's keeper, met at some distance from the castle, and there arranged their plan of action.

The Queen's health had improved at Chartley, and she was now able to take exercise on horseback. Paulet therefore proposed to her to ride to Tixall, the house of Sir Walter Aston, which was situated a few miles off, to see a Buck hunt. This proposal Mary accepted with pleasure, and probably with some surprise at the unusual courtesy of Sir Amyas.

On 16th August the party set out. "Her Majesty," says Bourgoing, "arrayed herself suitably, hoping to meet some pleasant company, and was attended by M. Nau, who had not forgotten to adorn himself; Mr. Curle, Mr. Melvim, and Bourgoing, her physician; Bastien Pages, mantle-bearer; and Annibal, who carried the crossbows and arrows of Her Majesty. All were mounted and in good apparel, to do her and the expected company honour, and indeed every one was joyous at the idea of this fine hunt."[6]

The Queen, who was very cheerful, rode on for about a mile, till Nau observed to her that Sir Amyas was some-5- way behind. She stopped till he came up and spoke very kindly, saying she feared that, as he was in bad health, he could not go so fast; to which he replied courteously. The party proceeded a short way "without thinking more about it," says Bourgoing, "when Sir Amyas, approaching the Queen, said: 'Madame, here is one of the gentlemen pensioners of the Queen, my mistress, who has a message to deliver to you from her,' and suddenly M. George,[7] habited in green serge, embroidered more than necessary for such a dress, and, as it appeared to me, a man of about fifty years, dismounted from his horse, and coming to the Queen, who remained mounted, spoke to her as follows: 'Madame, the Queen, my mistress, finds it very strange that you, contrary to the pact and engagement made between you, should have conspired against her and her state, a thing which she could not have believed had she not seen proofs of it with her own eyes and known it for certain. And because she knows that some of your servants are guilty, and charged with this, you will not take it ill if they are separated from you. Sir Amyas will tell you the rest.'

"To which Her Majesty could only reply that, as for her, she had never even thought of such things, much less wished to undertake them, and that from-6- whatever quarter she (Elizabeth) had received her information, she had been misled, as she (Mary) had always shown herself her good sister and friend." A melancholy scene now took place. Nau and Curle, who wished to approach their mistress, were forced back, and taken off to a neighbouring village. They never saw Mary again. Melville was also removed.

The Queen's party now turned back and proceeded a mile or two, when Bourgoing, who, as he tells us, had placed himself as near as he could to his mistress, saw that they were following a new route; to this he drew the Queen's attention, and she called to Sir Amyas, who was ambling slowly in front, to know where they were going. On hearing that they were not to return to Chartley, Mary, "feeling very indisposed, and unable to proceed," dismounted from her horse and seated herself on the ground. She now implored Sir Amyas to tell her where she was to be taken; he replied that she would be in a good place, one finer than his, that she could not return to her former residence, and that it was mere loss of time to resist or remain where she was. She saying she would prefer to die there, he threatened to send for her coach and place her in it. The Queen remained inconsolable; and here it is very touching to observe Bourgoing's efforts to comfort and encourage his mistress, his entreaties to Paulet, his-7- affectionate remonstrances with the Queen herself, and even the very improbable ideas that he propounds to console her, such as that perhaps Elizabeth was dead and Mary's friends were taking these strange measures to place her person in safety. At last the Queen was persuaded to proceed, but first, aided by Bourgoing, she withdrew a few yards, and there under a tree she "made her prayer to God, begging Him to have pity on her people and on those who worked for her, asking pardon for her faults, which she acknowledged to be great and to merit chastisement. She begged Him to deign to remember His servant David, to whom He had extended His mercy, and whom He had delivered from his enemies, imploring Him to extend also His pity to her, though she was of use to no one, and to do with her according to His will, declaring that she desired nothing in this world, neither goods, honours, power, nor worldly sovereignty, but only the honour of His holy name and His glory, and the liberty of His Church and of the Christian people; ending by offering Him her heart, saying that He knew well what were her desires and intention."[8]

On the way to Tixall, where Mary was to be lodged, two more of her attendants were separated from her; one, Lawrence, who held her bridle rein, and was observed-8- to talk with her, and Elizabeth Pierpoint, one of her women.

Hitherto nothing has been known of the Queen's imprisonment at Tixall. Bourgoing, however, tells us a few facts. We learn that Paulet allowed Mary's apothecary, two of her women, and Martin, an equerry, to join her, and Bourgoing remained for one night before being sent back to Chartley. In the evening of her arrival at Tixall, Mary sent to ask for pen and paper to write to Queen Elizabeth; but this Paulet refused, saying he should allow no letter to be sent till he had authority from the Court.

"On the morrow, the 17th August," writes Bourgoing,[9] "Her Majesty being still in bed, I was sent for by Sir Amyas to speak with him. Before descending I asked Her Majesty if she had anything to acquaint him with, but she said I should first learn what he wanted of me; and afterwards I was not permitted to return to the Queen, but was taken to Chartley, where I remained a prisoner with the rest, awaiting the return of the Queen."

Bourgoing describes the search made at Chartley, and mentions the three coffers of papers of all sorts that were carried off by Wade and his companions. On 26th August the Queen was brought back to-9- Chartley. On leaving Tixall a crowd of beggars, attracted no doubt by her well-known charity, assembled at the park gate, but she was as poor as they. "I have nothing to give you," she said; "I am a beggar as well as you—all is taken from me."[10]

Bourgoing's Journal thus records this day: "Thursday the 26th Her Majesty was brought back to Chartley with a great company, after being strictly detained at the place of Tiqueshal; she was welcomed by each one of us, anxious to show our devotion, not without tears on both sides, and the same day she visited us, one after the other, as one who returns home." Then he adds briefly: "After that the tears were over (Her Majesty) found nothing to say except about the papers which had been taken away, as has been related above."[11] But here Paulet's correspondence with Walsingham gives us further details, in which he describes the Queen's very just indignation at the manner in which her drawers and cabinets had been ransacked and every paper carried off. Then, turning to Paulet, she said that there were two things which he could not take from her—her royal blood and her religion, "which both she would keep until her death."

Early in September Paulet received orders to take-10- possession of all the Queen's money. Bourgoing gives a long account of the way in which the commission was executed. Mary was ill in bed, but Paulet insisted on seeing her. He and Mr. Baquet[12] entered her apartment, leaving his son and a good number of other gentlemen and servants, all armed, in the anteroom. Paulet sent all the ladies and servants out of her room, "which made us all anxious," says Bourgoing, "not knowing what to expect from such an unusual proceeding and being unaccustomed to such words. The best I could do was to keep myself by the door, under the pretext that Her Majesty was alone, and two men with her, (where I remained) very sad and thoughtful." In the end Gervais, the surgeon, was also permitted to remain along with Bourgoing. When Paulet informed Mary that he must have her money, she at first absolutely refused to give it up. When at last Elspeth Curle had, at the Queen's bidding, opened the door of her cabinet, the Queen, "all alone in her room, which no one (of us) dared approach, and guarded by Sir Amyas's people, rose from her bed, crippled as she was, and without slipper or shoe followed them, dragging herself as well as she could to her cabinet, and told them that this money which they were taking was money which she had long put aside as a last resource-11- for the time when she should die, both for her funeral expenses and to enable her attendants to return each to his own country after her death." Mary pleaded for some time, but Sir Amyas, while assuring her she should want for nothing, refused to leave her any of the money.

Some days later Sir Amyas again visited the Queen, and interrogated her at length regarding her knowledge of Babington and the conspiracy, concluding by saying "that she would be spoken to more fully about it, as it was necessary that the whole thing should be cleared up. From this Her Majesty took occasion to think she would be examined, but no one imagined this would be in the manner we shall hereafter see."[13]

About 15th September Paulet began to speak to Mary of the intended move to Fotheringay; he did not tell her the name of the place, but said that it would be very beneficial for her health to move from Chartley, and that she should be taken to one of the Queen's castles situated thirty miles from London. He also informed Mary that he now understood why her money had been taken from her. He perceived, he said, that it was for fear she should give it away or use it for some dangerous purpose on the road, and he had been assured she would receive it back when-12- she should reach her journey's end. The Queen was quite willing to leave Chartley, and was anxious to take the journey before her indisposition should increase. Bourgoing thus continues:—

"From now they commenced to prepare the luggage and everything for the departure which was fixed for the Tuesday following, the 20th of the said month, but was deferred till the next day on account of the change in the appointed lodging, which was supposed to be Worcester or else Chazfort (?); but both were changed and Fotheringay was chosen, a castle of the (English) Queen's in Northamptonshire.... Of all these things we were only told secretly, and Her Majesty never knew for certain where they were taking her, not even on the day she reached her new dwelling, but used to think sometimes they were taking her one way, sometimes another. Before starting in the morning they would tell her whether she had a long or a short journey to make, sometimes the number of miles, but they would never tell her the place where she was to sleep that night."

On the Monday before the party left Chartley, Sir Thomas Gorges and Stallenge (Usher of Parliament) arrived "with their pistols in their belts." This arrival caused anxiety among Mary's followers, who were only reassured when they observed that Gorges-13- and Stallenge addressed her more courteously than they expected.

"The following Wednesday, which was St. Matthew's Day (21st September), Her Majesty being ready to start, the doors of all the rooms were locked where her servants were, who were to remain behind, and the windows were guarded for fear that they should speak to her, or even see her." Mary was carried to her coach, as she was still unable to walk. As the Queen started, Sir Thomas Gorges, who, together with Stallenge, accompanied the party, accosted her, and informed her that he had something to say to her from his mistress. "I pray God," replied Mary, "that the message is better and more agreeable than the one you recently brought me." To which Gorges answered, "I am but a servant." "With this Her Majesty was content, telling him that she could not consider him to blame."[14] It was not till the next day that the message was delivered.

The Queen and her escort spent the first night at Burton,[15] and the next morning before starting, Mary, who had been in great anxiety to know what he had to say, sent for Sir Thomas. The message, in part-14- similar to the previous one, was to the effect that Elizabeth was utterly surprised that Mary should have planned such enterprises, and even to have hands laid on her who was an anointed Queen. Gorges swore that his mistress had never been so astonished or distressed by anything that had ever happened. "My mistress knows well," he said, "that if your Majesty were sent to Scotland, you would not be in safety; your subjects there would do you an ill turn; and she would have been esteemed a fool had she sent you to France without any reason."

To this Mary replied very fully, declaring that she had never planned anything against the Queen of England or the State. "I am not so base," said she, "as to wish to cause the death or to lay hands on an anointed Queen like myself, and I have comported myself towards her as was my duty." Mary remarked that she had several times warned Elizabeth of things to her advantage, and then reverted to her own long imprisonment, and her many sufferings. "If all the Christian prelates, my relations, friends, and allies," continued she, "moved by pity, and having compassion for my fate, have made it their duty to comfort and aid me in my misery and captivity, I, seeing myself destitute of all help, could not do less than throw myself into their arms and trust to their mercy, but,-15- however, I do not know what were their designs, nor what they would have undertaken, nor what were their intentions. I have no part with this, and have not been the least in the world mixed up in it. If they have planned anything, let her (Elizabeth) look to them; they must answer for it, not I. The Queen of England," concluded Mary, "knows well that I have warned her to look to herself and her Council, and that perchance foreign kings and princes might undertake something against her, upon which she replied that she was well assured of both foreigners and her own subjects, and that she did not require my advice."[16]

Gorges' only reply was that he prayed God this was true, but he showed Mary every courtesy by the way, "as well for her lodgings as for requisite commodities for the journey." Nothing of any importance occurred during the remainder of the journey, and on 25th September the party reached Fotheringay.

| "In darkest night for ever veil the scene When thy cold walls received the captive Queen." Antona's Banks MSS., 17—. |

ON Sunday 25th September 1586 Mary Stuart reached the last stage of her weary pilgrimage. As she passed through the gloomy gateway of Fotheringay Castle the captive Queen bade farewell to hope and to life. Well read as she was in the history of England, Mary must have keenly realised the ominous nature of her prison. The name of Fotheringay had been connected through a long course of years with many sorrows and much crime, and during the last three reigns the castle had been used as a state prison. Catherine of Arragon, more fortunate than her great-niece, had flatly refused to be imprisoned within its fatal walls, declaring that "to Fotheringay she would not go, unless bound with cart ropes and dragged thither." Tradition, often kinder than history, asserts-17- that James VI., after his accession to the English throne, destroyed the castle;[17] and though it is no longer possible to credit him with this act of filial love or remorse, time has obliterated almost every trace of the once grim fortress. A green mound, an isolated mass of masonry, and a few thistles,[18] are all that now remain to mark the scene of Mary's last sufferings. Very different was the aspect of Fotheringay at the time of which we write. Then, protected by its double moat, it frowned on the surrounding country in almost impregnable strength. The front of the castle and the great gateway faced to the north, while to the north-west rose the keep. A large courtyard occupied the interior of the building, in which were situated the chief apartments, including the chapel and the great hall destined to be the scene of the Queen's death.

Mary, as we know, reached Fotheringay under the care of Sir Amyas Paulet and Sir Thomas Gorges.[19] Sir William Fitzwilliam, castellan of the castle, whose constant courtesy and kindness obtained the Queen's ready gratitude, had also accompanied her. As soon as Mary was safely consigned to her prison Sir Thomas Gorges was despatched to inform Queen Elizabeth of-18- the fact. His report of the journey which he had made in company with the royal prisoner and the arrival at Fotheringay (which must have afforded him many opportunities of ascertaining Mary's sentiments regarding the position in which she was now placed) would be full of the deepest interest for us, but although, no doubt, Elizabeth eagerly inquired into every detail regarding her cousin, no record of this report has been discovered.

Very little is known of Mary's first days at Fotheringay. No letters of the Queen's relating to this time have been preserved, but from Bourgoing's Journal we gather a few facts. His mistress, he tells us, complained, and with justice, of the scanty and insufficient accommodation provided for her, especially as she had observed "many fine rooms unoccupied." As Paulet paid little attention to her demands, and it was rumoured that the vacant apartments were reserved for some noblemen, Mary at once suspected that she was about to be brought to trial. She had long foreseen this issue, and had spoken of it to her attendants. The prospect did not alarm her; to use Bourgoing's words, "she was not in the least moved; on the contrary, her courage rose, and she was more cheerful and in better health than before."

On October 1st Paulet sent a courteous message to the Queen requesting an interview with her. He had-19- received intelligence which he would "willingly" communicate to her. Experience had taught Mary and her followers to connect evil tidings with any unusual display of civility on Paulet's part, nor were they deceived. When he found himself in Mary's presence he brusquely informed her that Queen Elizabeth, having now received Sir Thomas Gorges' report, had expressed much surprise, and marvelled that her cousin dared to deny the charges brought against her, when she herself possessed proof of the facts. His mistress must now send some of her lords and counsellors to interrogate Mary, and of this he wished to warn her, so that she might not think she was to be taken by surprise. Then lowering his voice, Paulet added significantly that "the Queen would do better to beg pardon of Her Majesty, and confess her offence and fault, than to let herself be declared guilty (by law); and that if she would follow his advice, and agree to this, he would communicate her decision to Queen Elizabeth, being ready to write her reply, whatever it might be." Mary smiled at this proposal, saying that it reminded her of the way in which children are bribed to make them confess, and in reply said, "As a sinner I am truly conscious of having often offended my Creator, and I beg Him to forgive me, but as Queen and Sovereign I am aware of no fault or offence for which I have to render account to any one here below,-20- as I recognise no authority but God and His Church. As therefore I could not offend, I do not wish for pardon; I do not seek, nor would I accept it from any one living." Then assuming a lighter tone, the Queen further remarked that she thought Sir Amyas took much pains for but small result, and that he seemed to make little progress in this affair. Paulet here interrupted her, exclaiming that his mistress could show proof of what she asserted, and that the thing was notorious. Mary therefore would do well to confess, but he would report her answer. He then begged the Queen to listen while he repeated her answer word by word, and having written it down, he despatched it on the same day to the Court.

We may ask ourselves whether Elizabeth was sincere in her overtures to her cousin. If Mary had sued for mercy, would Elizabeth have granted it? It is more probable that any words which could have been extorted from Mary would have been used by the English Queen as a safeguard for her own honour. Armed with a confession of any sort, Elizabeth would have had no difficulty in ridding herself quietly of her cousin, and her own reputation would have suffered less. As we have seen, Mary at once perceived the trap prepared for her, and with her usual promptitude and courage she easily avoided it.

About this time a little ray of comfort came to cheer the Queen's imprisonment. Her faithful steward, Melville, who had of late been separated from her, was permitted to return, and he brought with him his daughter and the daughter of Bastien Pages, who was a goddaughter of the Queen's. The consolation which Mary received from their arrival was, however, soon allayed by the summary dismissal of her coachmen and some other servants, a proceeding which she rightly took to be a fresh sign of the gravity of her position.[20]

In London meanwhile events were proceeding rapidly. On October 8th the Commissioners appointed to judge the Scottish Queen assembled at Westminster. The Chancellor, Sir Thomas Bromley, having briefly related the history of the late conspiracy, read aloud copies of the letters addressed by Babington to Mary, her reputed answers, and the evidence said to have been extracted from Nau and Curle. At the conclusion nearly all present were of opinion that Mary should be brought to trial. The Commissioners were therefore summoned to meet at Fotheringay, and all the peers of the kingdom were invited to be there present, save those employed in offices of state. To the great displeasure of Elizabeth and Burleigh, Lord Shrewsbury evaded this summons on the plea of illness. The Queen herself-22- intimated the approaching trial to her faithful Paulet.[21] The crisis, therefore, had now come. No one familiar with the character of Elizabeth or the policy of her advisers could doubt the issue of the trial. It would have seemed only natural to suppose that France or Spain would effectively resent the outrage offered to a sister Queen; but the days of chivalry were past, and Philip of Spain could forsake an ally and Henry of France abandon a sister-in-law in her dire need. To the honour of France be it said, however, that Mary found an ardent defender in the French Ambassador, De Chateauneuf, who exerted himself to the utmost on her behalf; Elizabeth, however, treated his efforts with supreme contempt.

When Chateauneuf implored that the Queen of Scotland might at least have counsel to defend her, Elizabeth sent him word that she knew what she was doing, and did not require advice from strangers. She was aware that she need fear no active interference from Chateauneuf's master. Still less did she dread opposition on the part of the young King of Scotland. The disregard for his mother, in which Elizabeth had herself encouraged James, was her present safeguard, and she had determined that should he prove obstinate she would threaten him with exclusion from the succession to the English throne.

On Saturday, 11th October, the Commissioners-23- reached Fotheringay. Some were lodged in the castle, though the greater number found rooms in the village and neighbouring farmhouses and cottages. A duplicate copy of the Commission was at once transmitted to Mary. The act bore the names of forty-eight members, but of these nine or ten had refused to attend.

The Primate of England headed the list, and among the most important names occurred those of Cecil, Lord Burleigh, Walsingham, Sir Christopher Hatton, the Earls of Leicester and Warwick, Davison, Elizabeth's Secretary, Beale, and others.[22]

On the following day, Sunday, the lords attended service in the castle chapel. They afterwards sent a deputation to Mary, composed of Sir Walter Mildmay, Sir Amyas Paulet, Barker (Elizabeth's notary), and Stallenge, Usher of Parliament. They were the bearers of a letter from their mistress, couched in brief and imperious terms. This epistle, which was addressed simply to "The Scotish," without any other title or expression of courtesy, stated that Elizabeth having heard that Mary had denied participation in the plot against her person, notwithstanding that she herself possessed proofs of the fact, she now considered it well to send some of her peers and legal counsellors to examine Mary and judge the case, adding that as the Queen of-24- Scotland was in England, and under her protection, she was subject to the laws of the country.[23]

In reply to this document, which, as she observed, read as a command addressed to a subject, Queen Mary replied with dignity. "I am myself a queen," said she, "daughter of a king, a stranger, and the true kinswoman of the Queen of England. I came into England on my cousin's promise of assistance against my enemies and rebel subjects, and was at once imprisoned. I have thus remained for eighteen years, always ill-treated and suffering constant trials at the hands of Queen Elizabeth. I have several times offered to treat with the Queen with good and honest intentions, and have often wished to speak with her. I have always been willing to do her service and give her pleasure, but I have always been prevented by my enemies. As a queen I cannot submit to orders, nor can I submit to the laws of the land without injury to myself, the King my son, and all other sovereign princes. As I belong to their estate, majesty, and dignity, I would rather die than betray myself, my people, or my kingdom, as a certain person has done. I decline my judges," continued Mary, "as being of a contrary faith to my own. For myself, I do not recognise the laws of England, nor do I know or-25- understand them, as I have already often asserted. I am alone, without counsel, or any one to speak on my behalf. My papers and notes have been taken from me, so that I am destitute of all aid, taken at a disadvantage, commanded to obey, and to reply to those who are well prepared and are my enemies, who only seek my ruin. I have made several offers to the Queen of England which have not been accepted, and now I hear that she has again entered into a league with my son, thus separating mother from child. I am a Catholic, and have placed myself under the protection of those Catholic kings and princes who have offered me their services. If they have planned any attempt against Queen Elizabeth, I have not been cognisant of it, and therefore it is wrong to treat me as if I were guilty." Mary concluded by demanding that reference should be made to her former protestation.[24]

Mildmay and Paulet carried Mary's reply to the Commissioners, who were assembled in the large apartment which had been prepared for them, near the Queen's rooms. After a consultation had been held, Sir Amyas, Barker, and Stallenge returned to the Queen's presence, in order to obtain her sanction to the copy of her answer to Elizabeth, which had been committed to writing.

Barker knelt before Mary and read aloud the letter, which, Bourgoing tells us, was reported in "good style," and with no omission save the passage in which Mary expressed her desire to see Elizabeth. Mary signified her approval of the letter, and observed that she wished now to reply to those points of her cousin's letter which in her trouble and agitation had before escaped her. She repeated that she did not consider herself under the protection of the Queen; that she had not come into England for refuge, but to obtain assistance; and that, notwithstanding the promise of help from Elizabeth, she had been made prisoner and detained by force. She was not, she said, subject to the laws of England, which are made for the English and such as come to reside in England, whereas she had always been dealt with as a captive and had had no advantage from the laws, nor had she been in subjection to them. She had always kept her own religion, which was not that of England, and she had lived according to her own usages, to all of which no objection had been made.

Here Sir Amyas, "appearing to show himself more considerate," bade the Queen remember that he had no orders either to listen to her or to report her words; but Barker, "whispering in his ear," assured him that he could let her speak, and add her words and anything else he wished to the report. Paulet did not, however,-27- avail himself of this piece of advice, and thus the interview ended.

On the following morning, about ten o'clock, just as the Queen was seated at table for her early dinner, Sir Amyas, Barker, and Stallenge came to inquire whether she would be pleased to see the Commissioners, as they desired to speak with her. Mary expressed her willingness to receive them, and accordingly several members, chosen from the different orders of peers, privy-councillors, and lawyers, entered her presence, one by one, with great ceremony, preceded by an usher bearing the great seal of England.

The Lord Chancellor, Sir Thomas Bromley, speaking in the name of all, announced that they had come by command of the Queen of England their mistress, who, being informed that the Queen of Scotland was charged with complicity in a conspiracy against her person and state, had commissioned them to examine her on several points concerning this matter. He further reminded Mary that the Commission was authorised by letters patent thus to interrogate her; and concluded by remarking that as neither her rank as sovereign nor her condition as prisoner could exempt her from obedience to the laws of England, he recommended Her Majesty to listen in person to the accusations about to be brought against her, as, should she refuse, the Commissioners-28- would be obliged in law to proceed against her in her absence.

Mary, who was much moved by this arrogant speech, replied with tears that she had received Elizabeth's letter, and that she would rather die than acknowledge herself her subject. "By such an avowal," continued she, "I should betray the dignity and majesty of kings, and it would be tantamount to a confession that I am bound to submit to the laws of England, even in matters touching religion. I am willing to reply to all questions, provided I am interrogated before a free Parliament, and not before these Commissioners, who doubtless have been carefully selected, and who have probably already condemned me unheard." In conclusion Mary bade them consider well what they were doing. "Look to your consciences," said she, "and remember that the theatre of the world is wider than the realm of England." Noble and pathetic words, to the truth of which the history of three hundred years bears ample testimony.

Burleigh (whom Bourgoing designates as "Homme plus véhement")[25] here interrupted the Queen, and-29- informed her that the council, after receiving her former reply, had taken the advice of several learned doctors of canon and civil law; and that the latter, after mature deliberation, had decided that the Court could, despite her protest, proceed in the execution of their Commission. "Will you therefore," continued Burleigh rudely, "hear us or not? If you refuse, the assembled council will continue to act according to the Commission."

The Queen reminded Burleigh that she was a queen, and not a subject, and could not be treated as one. He retorted that Queen Elizabeth recognised no other queen but herself in her kingdom. He and his colleagues, he said, had no wish to treat Mary as a subject; they were well aware of her rank, and were prepared to treat her accordingly; but they were bound to fulfil the line of duty laid down for them by the Commission, and to ascertain whether she was subject to the laws of England. He ended by declaring that she was assuredly subject to the civil and canon law as it was observed abroad. The Queen remaining unconvinced by these-30- arguments, the Commissioners were forced to retire for a time.

Before leaving her Burleigh made a curious speech, bidding Mary recall to her memory the benefits which had been heaped upon her by her cousin! insisting in especial upon some remarkable instances of her clemency. "The Queen, my mistress," said he, "has punished those who contested your pretensions to the English crown. In her goodness she saved you from being judged guilty of high treason at the time of your projected marriage with the Duke of Norfolk, and she has protected you from the fury of your own subjects."

Mary replied to this extraordinary speech with a sad smile.

As soon as she had dined, the Queen, who, as Bourgoing tells us, had not been able to write for a long time, owing to rheumatic pains in her arm, set to work to make notes, to assist her when the Commissioners should return; fearing, as she said, that her memory might fail her. As was usual with her, however, the very danger of her position inspired her with fresh vigour and courage, and when the moment came she defended herself as "valiantly as she was rudely assailed, importuned, and pursued by the Commissioners; and she ended by saying far more than she had prepared in writing."

In the course of the afternoon Sir Amyas and three others were deputed to wait on Mary with a duplicate copy of the Commission, which she had requested to see. They proceeded to explain this document, which was chiefly founded on two Acts of Parliament passed two years previously. By the former of these it was declared high treason for any one to speak of Mary's succession to the crown of England during the lifetime of Elizabeth. The second decreed that should any one, of whatsoever rank, in the kingdom or abroad, conspire against the life of Elizabeth, or connive at such conspiracy, it should be lawful for an extraordinary jury comprised of twenty-four persons to adjudge that case. These laws (which the Queen justly felt to have been framed specially for her destruction) were now to be applied. She was accused of "consenting" to the "horrible fact of the destruction of Elizabeth's person and the invasion of the kingdom," and she was now called upon to submit to the interrogations of the appointed judges. To the energetic protests offered by Mary the deputies made no reply, but withdrew to consult with the other Commissioners; and later in the day the attack was renewed.

On this occasion Bourgoing says that the lords came in fewer numbers than in the morning, but with the same ostentatious ceremony.

The Queen began by referring to a passage in Elizabeth's letter, and demanded to know what the word "protection" there signified. "I came into England," said she, "to seek assistance, and I was immediately imprisoned. Is that 'protection'?" Burleigh, always the spokesman, and who invariably seemed animated with a wish to attack Mary, was puzzled to reply to this simple question, and endeavoured to evade it. He had "read the letter in question," he said, "but neither he nor his colleagues were so presumptuous as to dare to interpret their mistress's letter. She, no doubt, knew well what she wrote; but it was not for subjects to interpret the words of their sovereign."

"You are too much in the confidence of your mistress," returned Mary, "not to be aware of her wishes and intentions, and if you are armed with such authority by your Commission as you describe, you have surely the power to interpret a letter from the Queen." Burleigh denied that he and his companions had known anything of the letter; adding, however, that he was aware that his mistress considered that every person living in her kingdom was subject to its laws. "This letter," continued Mary, "was written by Walsingham; he confessed to me that he was my enemy, and I well know what he has done against me and my son." At this point the Commissioners "dis-33-cussed among themselves as to whether Walsingham had been in London at the time when the letter was written or not, but could not decide the question." Mary then again protested against the injustice of being tried by the laws of a country in which she had lived only as a prisoner.

"If your Majesty," retorted one of the lords, "was reigning peacefully in your own kingdom, and some one were to conspire against you, would you not proceed against him, were he the greatest king in the world?"

"Never," replied Mary, "never would I act in such a manner; however, I see well that you have already condemned me—all you do now is merely for form's sake. I do not value my life, but I strive for the preservation of my own honour, and the honour of my relatives and of the Church. You frame laws according to your own wishes," continued the Queen; "and as in former days the English refused to recognise the salique law in France, so I do not feel bound to submit to your laws. If you wish to proceed according to the common law of England, you must produce examples and precedents. If you follow the canon law, those only who framed it can interpret it. Roman Catholics alone have the right to explain and apply it." To this Burleigh replied that the canon law was used ordinarily in England, especially regarding marriages and kindred-34- matters, but not in what touched the authority of the Pope, which they neither desired nor approved. "In consequence then," continued Mary, "you cannot avail yourselves of the privilege of him whose authority you deny. The Pope and his delegates alone can interpret the canon law, and I know of no one in England who has received this authority from the sovereign pontiff. As for the civil laws, they were made by the Catholic Emperors of old, or in any case, sanctioned by them; and these laws can only be applied by such as approve their authors, and would wish to imitate them. As these laws were often obscure and difficult, and people wished to interpret them, each according to his own idea, universities were established in Italy, France, and Spain. Here in England, where none such exist, you do not possess the knowledge of the true spirit and interpretation of these laws, but you interpret them according to your own wishes, and in such a way as to serve the law, and the police law of your country. If you wish to try me by the true civil law, I demand that some members of the universities be allowed to judge my case, so that I may not be left to the judgment of such lawyers as are subservient to the laws of England alone. But I see that you wish to prevent me from benefiting either by the canon or the civil law. You wish to reduce me to subject myself to the law of this country; but,"-35- continued the Queen earnestly, "I have no knowledge of this law. It is not my profession, and you have taken from me all power of studying it. Kings and princes usually have around them such persons as are versed in these matters, but I have no one. I therefore beg you to give me information in order that I may know how those in my position have been treated in the time past, and what has been admitted by law or precedent, either favourable to my case or not."

Mary's hearers eagerly seized the opportunity afforded them, and suggested that she should see the judges and lawyers then present at Fotheringay, who would explain the matter to her. At first the Queen seemed as if she were inclined to favour this proposal. "Her Majesty, very well pleased, at first agreed, till she perceived by some words of the Treasurer (Burleigh) that by this suggestion they had no intention but to make her aware by them (the judges) that her cause was bad, that she was subject to the laws of England, and that there was a just case against her, so that consequently she might in the end be judged by them. So Her Majesty, perceiving that she could not communicate with the judges about her business without humbling herself, refused to hear them."[26]

The envoys now proposed to the Queen to hear the-36- new Commission. After listening to it attentively, Mary observed that she saw it referred to laws which she must refuse to recognise, as she suspected that they had been framed expressly for her ruin by those persons who were her enemies, and who aimed at dispossessing her of her right to the kingdom. Elizabeth's emissaries replied that even though the laws were new, they were as just and equitable as those of other countries. Her Majesty, they added, knew well that it was necessary on occasion to abrogate certain laws and frame new ones.

"These new laws," returned Mary, "cannot be used to my prejudice. I am a stranger, and consequently not subject to them, and the more especially as I belong to a different religion. I confess to being a Catholic, and for this religion I would wish to die, and shed my blood to the last drop. In this matter do not spare me; I am ready and willing, and shall esteem myself very happy if God grants me the grace to die in this quarrel." The Queen's hearers, amazed at her courage, refrained from pressing her further, and reserved—as Bourgoing tells us—their reply for a future occasion.

Mary now demanded to see the former protestation which she had made at Sheffield. "I have not changed since then," she remarked, "being the same person still, my rank and quality remaining undiminished, and my sentiments unaltered, while the circumstances were then-37- almost identical with those of the present crisis." Being thus pressed, Sir Thomas Bromley and Lord Burleigh read aloud the protestation, refusing at the same time either to approve or accept it. Bromley acknowledged, however, that he had on the previous occasion received it from Mary and presented it to his mistress. "Her Majesty," continued he, "neither approved nor accepted it, and we are not at liberty to receive it, nor you to make use of it. The Queen of England has power in her own kingdom over all persons who conspire against her without respect to quality or degree. As your rank is, however, well known, the Queen is treating you very honourably, having selected so worthy a company of the great men of her kingdom as her Commissioners in this matter. We have taken no step against you; we are not judges, but have only come to examine you."

The day passed thus in mutual discussion until dusk, when Sir Christopher Hatton, seeing that no progress was being made, interposed, and adopting a conciliatory tone, observed that to his mind many unnecessary matters were being discussed. He and his colleagues were there simply to ascertain whether the Queen of Scots was, or was not, guilty of having participated in the plot against their mistress. He was of opinion, he said, that the Queen should not refuse to be examined,-38- as in that case people would take her to be guilty, whereas were she to consent to be interrogated she could prove her innocence, which would bring honour to herself and rejoice Queen Elizabeth. Hatton added that in his parting interview with his mistress she had protested to him with tears that nothing had ever so wounded her as the thought that her cousin should have sought to injure her,—a thing which she could not have believed of her.

"What favour can I look for when I shall have established my innocence?" demanded Mary; "and what reparation will be made to me for being brought here by force, treated as a criminal and a subject, and convoked before an assembly of judges in an apartment specially prepared for my trial?"

"Your honour will suffer no injury," returned Hatton persuasively, "and my mistress will be satisfied. As for the place of your trial, that is of no consequence; any place would do equally well. This castle was chosen as being the Queen's property and suitable for the occasion. If any of your people have alarmed you, be reassured, there is no danger for you. We have chosen the large hall close to your own apartment, as being more commodious for you in your weak health, and as it is Her Majesty's presence-chamber, we have there erected her dais. To us, who are sent here as her Commissioners,-39- this attribute of state represents our Queen, as if she were here in person." Burleigh here impatiently interrupted Hatton by exclaiming that it was time to retire, and demanded once more of Mary whether she would be examined or not. "The Commissioners are determined to proceed in any case," said he, "and the council will assemble to-morrow."

"I am not obliged to answer you," replied Mary. "May God inspire you, and may you be directed to do right according to God and to reason. I beseech you, think well of what you are about."

The Commissioners then withdrew.

Elizabeth had been at once informed of the previous day's interview, of Mary's refusal to be interrogated, and of the resolution of the Commissioners to proceed with the trial and sentence, even in the absence of the prisoner. Alarmed at this decision, the Queen sent a courier post-haste to urge Burleigh and his companions not to pronounce sentence until they should return, and give her a complete report of the proceedings. The same messenger was the bearer of a letter to Mary, the reception of which must have added bitterness to this day of trial.[27] The letter ran as follows:—

You have planned in divers ways and manners to take my life and to ruin my kingdom by the shedding of blood. I never proceeded so harshly against you; on the contrary, I have maintained you and preserved your life with the same care which I use for myself. Your treacherous doings will be proved to you, and made manifest in the very place where you are. And it is my pleasure that you shall reply to my Nobles and to the Peers of my kingdom as you would to myself were I there present. I have heard of your arrogance, and therefore I demand, charge, and command you to reply to them. But answer fully, and you may receive greater favour from us.

Elizabeth.[28]

In this epistle Elizabeth, as we see, once more held out hopes of clemency to her cousin, but it seems probable that Mary paid little heed to promises which she had so often found to be delusive. Bourgoing makes no allusion to this letter, but he says that his mistress, seeing the determination of the Commissioners to proceed in any case, "remained all the night in perplexity." On one side she dreaded being obliged to appear "in a public place against her duty, her state, and her quality," while on the other she foresaw that should she persist in her refusal to answer their interrogations, the Commissioners would assert her silence to be proof of her guilt, and would pronounce sentence against her, and declare "as an assured fact that in her conscience she knew herself to be guilty." Towards-41- morning the Queen determined to send word to the lords that she desired to say a few words to them before they assembled.

On the morning of the 14th, accordingly, the Commissioners delegated some of their number to wait upon the Queen. Among these was Walsingham, whom Mary now saw for the first time. We subjoin the dignified address made by the Queen on this occasion. It seems evident that Bourgoing wrote down this speech either from Mary's dictation, or from notes supplied by herself, as, unlike the other speeches recorded by him, it is given throughout in the first person:—

"When I remember that I am a queen by birth," said Mary, "a stranger and a near relation of the Queen, my good sister, I cannot but be offended at the manner in which I have been treated, and could do nothing other than refuse to attend your assembly and object to your mode of procedure. I am not subject either to your laws or your Queen, and to them I cannot answer without prejudice to myself and other kings and princes of the same quality. Now, as always heretofore, I will not spare my life in defence of my honour; and rather than do injury to other princes and my son, I am prepared to die, should the Queen, my good sister, have such an evil opinion of me as to believe that I have attempted aught against her person.-42- In order to prove my goodwill towards her, and to show that I do not refuse to answer to the charges of which I am accused, I am prepared to answer to that accusation only, which touches on the life of Queen Elizabeth, of which I swear and protest that I am innocent. I say nothing upon any other matter whatsoever as to any friendship or treaty with any other foreign princes. And making this protestation, I demand an act in writing."[29]

The Commissioners, "very happy to have brought the Queen to this point,"[30] assured her that their only desire was to ascertain whether she was guilty or not, and thus to satisfy their mistress, who would be well content to see her innocence proved. Mary then once more inquired if it was necessary for her to appear in the hall of council. They replied that it must be so; repeating that the apartment had been prepared expressly for the purpose, and that they would there hear her as if she were in the presence of Elizabeth herself, in order that they might address their report to their sovereign in due form. The delegates then withdrew to consult together over Mary's last protestation. Shortly afterwards they sent word that they had committed it to writing, and once again summoned her to appear before them. This the Queen consented to do "as soon as she-43- had broken her fast by taking a little wine, as she felt weak and ill."[31]

The die was now cast. To us the Queen's decision seems a fatal error. Had she persisted in claiming her royal prerogative of inviolability, the trial would have lost that semblance of legal justice which her present assent—though made under protest—lent to it; and her accusers would have been unable to extricate themselves from the difficulty. It is, however, very questionable whether Mary's life would have been saved in any case. Had she refused to be tried, other means would have been found. Private assassination was the one and only form of death which was dreaded by the Queen. She knew that were she to die without witnesses, every effort would be made to blacken her fame and, if possible, to throw doubt on her fidelity to her faith. It is to this fear that we may probably attribute Mary's final decision to face her judges.

THE large room destined for the trial was situated, as we have said, in close proximity to Mary's apartments, and immediately over the great hall of the castle. According to Bourgoing it was "very spacious and convenient." At the upper end stood the dais of estate, emblazoned with the arms of England, and surmounting a throne the emblem of sovereignty. In front of the dais, and at the side of the throne, a seat had been prepared for Queen Mary, "one of her crimson velvet chairs, with a cushion of the same" for her feet.

Contemporary Drawing of the Trial of Mary Queen of Scots at Fotheringay.

From the Calthorpe MS.

Enlarge

List of Names, in Beale’s handwriting, of those

present at the Trial.

Accompanying the Calthorpe Drawing.

Enlarge

Benches were placed on each side of the room: those on the right were occupied by the Lord Chancellor Bromley, the Lord Treasurer Burleigh, and the Earls; on the left the Barons and Knights of the Privy Council, Sir James Crofts, Sir Christopher Hatton, Sir Francis-45- Walsingham, Sir Ralph Sadler, and Sir Walter Mildmay. In front of the Earls sat the two premier judges and the High Baron of the Exchequer, while in front of the Barons were placed four other judges, and two doctors of civil law.

At a large table, which was placed in front of the dais, sat the representatives of the Crown: Popham, Attorney-General; Egerton, Solicitor-General; Gawdy, the Queen's sergeant; and Barker, the notary: also two clerks, whose duty it was to draw up the official report of the proceedings. The documentary evidence, such as it was, was arranged on the table. A movable barrier with a door divided the room into two parts, and at the lower end were assembled as spectators the gentlemen attendants and the servants of the Lords of Commission.

At nine o'clock the Queen made her entrance, escorted by a guard of halberdiers. She wore a dress and mantle of black velvet, and over her pointed widow's cap fell a long white gauze veil. Her train was borne by one of her maids of honour, Renée Beauregard. Mary was supported on each side by Melville and Bourgoing; and although, owing to the want of exercise and the severe rheumatism from which she suffered, she walked with great difficulty, it was with undiminished dignity of mien. She was followed by her surgeon, Jacques Gervais;-46- her apothecary, Pierre Gorion; and three waiting-women, Gillis Mowbray, Jane Kennedy, and Alice Curle.

As the Queen advanced the Commissioners uncovered before her, and she saluted them with a majestic air; then, perceiving that the seat prepared for her was placed outside the dais and in a lower position, she exclaimed—

"I am a queen by right of birth, and my place should be there, under the dais;" but quickly recovering her serenity, she took her seat, and looking round at the assembled dignitaries, whose faces bore no sign of sympathy for their victim, she said mournfully to Melville—

"Alas! here are many counsellors, but not one for me."[32]

Her desolate position, without counsel to defend her, without secretary to take notes for her, despoiled even of her papers, must have seemed strange to Mary's generous nature. In Scotland the poorest of her subjects would have enjoyed the privileges now denied to herself.

Among the noblemen assembled to judge the Queen were some of her former partisans, such as my Lords Rutland, Cumberland, and others, who had taken a-47- share in the late undertaking, and whose letters had been seized at Chartley, yet who now, to save their estates if not their lives, were forced to appear among her enemies. Very few of the English nobles were known to Mary by sight, and it was noticed that she often questioned Paulet, who was stationed behind her, regarding them. They on their side were doubtless eager to see this princess, whose beauty was renowned, and who with courage equal to her sorrows now faced her judges with all the dignity of her happier days.

The Lord Chancellor opened the proceedings by a speech, in which he declared that the Queen of England, having been surely informed, to her great grief, that the destruction of her person and the downfall of her kingdom had been lately planned by the Queen of Scots, and that in spite of her long tolerance and patience, this same Queen continued her bad practices and had made herself the disturber of religion and the public peace, Her Majesty felt impelled to convoke this present assembly to examine into these accusations. In thus acting Her Majesty was actuated by no unkind feeling, or desire of vengeance, but solely by a sense of the duty imposed upon her by her position as sovereign and her duty to her subjects. Bromley stated that the Queen of Scots should be heard in declaring fully all that should-48- seem good to her for her defence and to establish her innocence. Then turning to Mary, he concluded with these words: "Madame, you have heard why we have come here; you will please listen to the reading of our Commission, and I promise you that you shall say all that you wish."[33]

Mary replied in the following terms: "I came into this kingdom under promise of assistance, and aid, against my enemies, and not as a subject, as I could prove to you had I my papers; instead of which I have been detained and imprisoned. I protest publicly that I am an independent sovereign and princess, and I recognise no superior but God alone. I therefore require that before I proceed further, it be recorded that whatever I may say in replying here to the Commissioners of my good sister, the Queen of England (who, I consider, has been wrongly and falsely prejudiced against me), shall not be to my prejudice, nor that of the princes my allies, nor the King my son, or any of those who may succeed me. I make this protestation not out of regard to my life, or in order to conceal the truth, but purely for the preservation of the honour and dignity of my royal prerogative, and to show that in consenting to appear before this Commission I do so, not as a subject to Queen Elizabeth, but only from my desire to clear myself, and-49- to show by my replies to all the world that I am not guilty of this crime against the person of the Queen, with which it seems I am charged. I wish to reply to this point alone, I desire this protest to be publicly recorded, and I appeal to all the lords and nobles present to bear me testimony, should it one day be necessary."[34]

Bromley, in reply, utterly denied that Mary had come into the kingdom of England under promise of assistance from his mistress. He declared that he and his colleagues were willing to record the protest of the Queen of Scots, but without accepting or approving it. He affirmed that it was void and null in the eyes of the law, and should in no way be to the prejudice of the dignity and supreme power of the English sovereign, or to the prerogative or jurisdiction of the Crown. To this he called all present to bear witness.[35]

The Commission, which was drawn up in Latin, was now read aloud. At the end Mary protested energetically against the Commission and the laws upon which it was based,—laws which, she observed, had been framed expressly to destroy her just claims to the English throne and to bring about her death.

Gawdy, the Queen's sergeant, now rose, "having a blue robe, a red hood on the shoulder, and a round cap à l'antique," and with head uncovered, made a discourse-50- explaining the Commission and the occasion which had caused it to be summoned. He discussed several points, namely, the seizure of Babington, the suspected correspondence between him and the Queen of Scots, and further details of the plot, mentioning the names of the six men who (as he declared) had conspired to murder Queen Elizabeth.

As soon as Mary had replied that she had never spoken to Babington, that, although she had heard him spoken of, she did not know him and had never "trafficked" with him, and that she knew nothing of the six men whom they had alluded to, another lawyer, in the same dress as Gawdy, rose and read "certain letters which they said Babington had dictated of his own free will before his death, from memory." These, and other copies of letters said to have passed between the Queen and Babington, were also shown, together with the confessions of the conspirators, and the depositions of Curle and Nau, which were declared to be signed by them.

The Queen protested against this second-hand evidence brought against her, and demanded to see the originals of the letters. "If my enemies possess them," said she, "why do they not produce them? I have the right to demand to see the originals and the copies side by side. It is quite possible that my ciphers have been tampered with by my enemies. I cannot reply to this-51- accusation without full knowledge. Till then I must content myself with affirming solemnly that I am guiltless of the crimes imputed to me. I do not deny," continued the Queen, "that I have earnestly wished for liberty and done my utmost to procure it for myself. In this I acted from a very natural wish; but I take God to witness that I have never either conspired against the life of your Queen, nor approved a plot of that design against her. I have written to my friends, I confess; I appealed to them to assist me to escape from these miserable prisons in which I have languished for nearly nineteen years. I have also, I confess, often pleaded the cause of the Catholics with the Kings of Europe, and for their deliverance from the oppression under which they lie, I would willingly have shed my blood. But I declare formally that I never wrote the letters that are produced against me. Can I be responsible for the criminal projects of a few desperate men, which they planned without my knowledge or participation?"

The whole morning from about ten o'clock was occupied in reading the depositions and letters of Babington, the accusers doing their utmost to make Mary appear guilty, "without any one saying a single word for her."[36]

During the reading of the confession attributed to Babington, Mary was much moved by the allusion made-52- therein to the Earl of Arundel and his brothers, as also to the young Earl of Northumberland; and she exclaimed with tears, "Alas! why should this noble house of Howard have suffered so much for me? Is it likely," continued she, "that I should appeal for assistance to Lord Arundel, whom I knew to be in prison? or to Lord Northumberland, who is so young, and whom I do not know? If Babington really confessed such things, why was he put to death without being confronted with me? It is because such a meeting would have brought to light the truth, that he was executed so hastily."

About one o'clock the Queen retired to take her dinner, after which she returned to the hall and the proceedings were resumed. Bourgoing describes so graphically the position of the Queen and her judges, that we give his own words:—

"Her Majesty having dined and returned to the same place, they continued to read aloud letters tending to the same end, the deposition and confession of M. Nau and M. Curle written on the back of a certain letter and signed by them, and also some others touching her intelligence with them. Her Majesty replied first to one and then to another without any order, but on hearing any point read, would, without being interrogated by them, say whether it were true or not. For their manner of proceeding was always to read or speak to-53- persuade the lords that the Queen was guilty. They always addressed the lords, accusing the Queen in her presence, with confusion and without any order, and without any one answering them a word, in suchwise that when we returned to her room the poor Princess told us that it reminded her of the Passion of Jesus Christ, and that it seemed to her that, without wishing to make a comparison, they treated her as the Jews treated Jesus Christ when they cried, 'Tolle, Tolle, Crucifige'; and that she felt assured that there were those in the company who pitied her, and did not say what they thought."

In spite, however, of the vehemence of those "Messieurs les Chicaneux," as Bourgoing terms them, Mary preserved her calmness; and the hotter they grew, the more courageous and constant was she in her replies. She now recapitulated much of what she had before said to the Commissioners in her own room, in order that the assembly might know her sentiments; and after pointing out the injustice of her long imprisonment, she thus continues: "I have, as you see, lost my health and the use of my limbs. I cannot walk without assistance, nor use my arms, and I spend most of my time confined to bed by sickness. Not only this, but through my trials I have lost the small intellectual gifts bestowed on me by God, such as my memory, which would have aided me to recall those things which I have seen and-54- read, and which might be useful to me in the cruel position in which I now find myself. Also the knowledge of matters of business which I formerly had acquired for the discharge of those duties in the state to which God called me, and of which I have been treacherously despoiled. Not content with this, my enemies now endeavour to complete my ruin, using against me means which are unheard of towards persons of my rank, and unknown in this kingdom before the reign of the present Queen, and even now not approved by rightful judges, but only by unlawful authority. Against these I appeal to Almighty God, to all Christian princes, and to the estates of this kingdom duly and lawfully assembled. Being innocent and falsely suspected, I am ready to maintain and defend my honour, provided that my defence be publicly recorded, and that I make it in the presence of some princes or foreign judges, or even before my natural judges; and this without prejudice to my mother the Church, to kings, sovereign princes, and to my son. With regard to the pretensions long put forward by the English (as their Chronicles testify) to suzerainty over my predecessors the Kings of Scotland, I utterly deny and protest against them, and I will not, like a femme de peu de cœur, admit them, nor by any present act, to which I may be constrained, will I fortify such a claim, whereby I should dishonour those-55- princes my ancestors as well as myself, and acknowledge them to have been traitors or rebels. Rather than do this, I am ready to die for God and my rights in this quarrel, in which, as in all others, I am innocent.

"By this you can see that I am not ambitious, nor would I have undertaken anything against the Queen of England through a desire to reign. I have done with all that; and as regards myself, I wish for nothing but to pass the remainder of my life in peace and tranquillity of mind. My advancing age and my bodily weakness both prevent me from wishing to resume the reins of government. I have perhaps only two or three years to live in this world, and I do not aspire to any public position, especially when I consider the pain and désésperance which meet those who wish to do right, and act with justice and dignity in the midst of so perverse a generation, and when the whole world is full of crimes and troubles."[37]

Burleigh, "no longer able to contain himself," here interrupted the Queen, reproaching her with having assumed the name and arms of England, and of having aspired to the Crown. "What I did at that time," replied Mary, "was in obedience to the commands of Henry the Second, my father-in-law, and you well know the reason."

"But," retorted Burleigh, "you did not give up these practices even after we signed the peace with King Henry."