Title: The Young Emperor, William II of Germany

Author: Harold Frederic

Release date: June 26, 2017 [eBook #54989]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

THE YOUNG EMPEROR, WILLIAM II OF GERMANY

CHAPTER I.—THE SUPREMACY OF THE HOHENZOLLERNS.

CHAPTER III.—UNDER CHANGED INFLUENCES AT BONN

CHAPTER IV.—THE TIDINGS OF FREDERIC’S DOOM

CHAPTER V.—THROUGH THE SHADOWS TO THE THRONE

CHAPTER VI.—UNDER THE SWAY OF THE BISMARCKS

CHAPTER VII.—THE BEGINNINGS OF A BENEFICENT CHANGE

CHAPTER VIII.—A YEAR OF EXPERIMENTAL ABSOLUTISM

CHAPTER IX.—A YEAR OF HELPFUL LESSONS

CHAPTER X.—THE FALL OF THE BISMARCKS

CHAPTER XI—A YEAR WITHOUT BISMARCK

CHAPTER XII.—PERSONAL CHARACTERISTICS

In June of 1888, an army of workmen were toiling in the Champ de Mars upon the foundations of a noble World’s Exhibition, planned to celebrate the centenary of the death by violence of the Divine Right of Kings. Four thousand miles westward, in the city of Chicago, some seven hundred delegates were assembled in National Convention, to select the twenty-third President of a great Republic, which also stood upon the threshold of its hundredth birthday. These were both suggestive facts, full of hopeful and inspiring thoughts to the serious mind. Considered together by themselves they seemed very eloquent proofs of the progress which Liberty, Enlightenment, the Rights of Man, and other admirable abstractions spelled with capital letters, had made during the century.

But, unfortunately or otherwise, history will not take them by themselves. That same June of 1888 witnessed a spectacle of quite another sort in a third large city—a spectacle which gave the lie direct to everything that Paris and Chicago seemed to say. This sharp and clamorous note of contradiction came from Berlin, where a helmeted and crimson-cloaked young man, still in his thirtieth year, stood erect on a throne, surrounded by the bowing forms of twenty ruling sovereigns, and proclaimed, with the harsh, peremptory voice of a drill-sergeant, that he was a War Lord, a Mailed Hand of Providence, and a sovereign specially conceived, created, and invested with power by God, for the personal government of some fifty millions of people.

It is much to be feared that, in the ears of the muse of history, the resounding shrillness of this voice drowned alike the noise of the hammers on the banks of the Seine and the cheering of the delegates at Chicago.

Any man, standing on that throne in the White Saloon of the old Schloss at Berlin, would have to be a good deal considered by his fellow-creatures. Even if we put aside the tremendous international importance of the position of a German Emperor, in that gravely open question of peace or war, he must compel attention as the visible embodiment of a fact, the existence of which those who like it least must still recognize. This is the fact: that the Hohenzollerns, having done many notable things in other times, have in our day revivified and popularized the monarchical idea, not only in Germany, but to a considerable extent elsewhere throughout Europe. It is too much to say, perhaps, that they have made it beloved in any quarter which was hostile before. But they have brought it to the front under new conditions, and secured for it admiring notice as the mainspring of a most efficient, exact, vigorous, and competent system of government. They have made an Empire with it—a magnificent modern machine, in which army and civil service and subsidiary federal administrations all move together like the wheels of a watch. Under the impulse of this idea they have not only brought governmental order out of the old-time chaos of German divisions and dissensions, but they have given their subjects a public service, which, taken all in all, is more effective and well-ordered than its equivalent produced by popular institutions in America, France, or England, and they have built up a fighting force for the protection of German frontiers which is at once the marvel and the terror of Europe.

Thus they have, as has been said, rescued the ancient and time-worn function of kingship from the contempt and odium into which it had fallen during the first half of the century, and rendered it once more respectable in the eyes of a utilitarian world.

But it is not enough to be useful, diligent, and capable. If it were, the Orleans Princes might still be living in the Tuileries. A kingly race, to maintain or increase its strength, must appeal to the national imagination. The Hohenzollerns have been able to do this. The Prussian imagination is largely made up of appetite, and their Kings, however fatuous and limited of vision they may have been in other matters, have never lost sight of this fact. If we include the Great Elector, there have been ten of these Kings, and of the ten eight have made Prussia bigger than they found her. Sometimes the gain has been clutched out of the smoke and flame of battle; sometimes it has more closely resembled burglary, or bank embezzlement on a large scale; once or twice it has come in the form of gifts from interested neighbours, in which category, perhaps, the cession of Heligoland may be placed—but gain of some sort there has always been, save only in the reign of Frederic William IV and the melancholy three months of Frederic III.

That there should be a great affection for and pride in the Hohenzollerns in Prussia was natural enough. They typified the strength of beak, the power of talons and sweeping wings, which had made Prussia what she was. But nothing save a very remarkable train of surprising events could have brought the rest of Germany to share this affection and pride.

The truth is, of course, that up to 1866 most other Germans disliked the Prussians thoroughly and vehemently, and decorated those head Prussians, the Hohenzollerns, with an extremity of antipathy. That brief war in Bohemia, with the consequent annexation of Hanover, Hesse-Cassel, Nassau, and Frankfort, did not inspire any new love for the Prussians anywhere, we may be sure, but it did open the eyes of other Germans to the fact that their sovereigns—Kings, Electors, Grand Dukes, and what not—were all collectively not worth the right arm of a single Hohenzollern.

It was a good deal to learn even this—and, turning over this revelation in their minds, the Germans by 1871 were in a mood to move almost abreast of Prussia in the apotheosis of the victor of Sedan and Paris. To the end of old William’s life in 1888, there was always more or less of the apotheosis about the Germans’ attitude toward him. He was never quite real to them in the sense that Leopold is real in Brussels or Humbert in Rome. The German imagination always saw him as he is portrayed in the fine fresco by Wislicenus in the ancient imperial palace at Goslar—a majestic figure, clad in modern war trappings yet of mythical aspect, surrounded, it is true, by the effigies of recognizable living Kings, Queens, and Generals, but escorted also by heroic ancestral shades, as he rides forward out of the canvas. Close behind him rides his son, Fritz, and he, too, following in the immediate shadow of his father to the last, lives only now in pictures and in sad musing dreams of what might have been.

But William II—the young Kaiser and King—is a reality. He has won no battles. No antique legends wreathe their romantic mists about him. It has occurred to no artist to paint him on a palace wall, with the mailed shadows of mediaeval Barbarossas and Conrads and Sigismunds overhead.

The group of helmeted warriors who cluster about those two mounted figures in the Goslar picture, and who, in the popular fancy, bring down to our own time some of the attributes of mediaeval devotion and prowess—this group is dispersed now. Moltke, Prince Frederic Charles, Roon, Manteuffel, and many others are dead; Blumenthal is in dignified retirement; Bismarck is at Friedrichsruh. New men crowd the scene—clever organizers, bright and adroit parliamentarians, competent administrators, but still fashioned quite of our own clay—busy new men whom we may look at without hurting our eyes.

For the first time, therefore, it is possible to study this prodigious new Germany, its rulers and its people, in a practical way, without being either dazzled by the disproportionate brilliancy of a few individuals or drawn into side-paths after picturesque unrealities.

Three years of this new reign have shown us Germany by daylight instead of under the glamour and glare of camp fires and triumphal illuminations. We see now that the Hohenzollern stands out in the far front, and that the other German royalties, Wendish, Slavonic, heirs of Wittekind, portentously ancient barbaric dynasties of all sorts, are only vaguely discernible in the background. During the lifetime of the old Kaiser it seemed possible that their eclipse might be of only a temporary nature. Nowhere can such an idea be cherished now. Young William dwarfs them all by comparison even more strikingly than did his grandfather.

They all came to Berlin to do him homage at the opening of the Reichstag, which inaugurated his reign on June 25, 1888. They will never make so brave a show again; even then they twinkled like poor tallow dips beside the shining personality of their young Prussian chief.

Almost all of them are of royal lines older than that of the Hohenzollerns. Five of the principal personages among them—the King of Saxony, the Regent representing Bavaria’s crazy King, the heir-apparent representing the semi-crazy King of Wurtemberg, the Grand Duke of Baden, and the Grand Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt—owe their titles in their present form to Napoleon, who paid their ancestors in this cheap coin for their wretched treason and cowardice in joining with him to crush and dismember Prussia. Now they are at the feet of Prussia, not indeed in the posture of conquered equals, but as liveried political subordinates. No such wiping out of sovereign authorities and emasculation of sovereign dignities has been seen before since Louis XI consolidated France 500 years ago. Let us glance at some of these vanishing royalties for a moment, that we may the better measure the altitude to which the Hohenzollern has climbed.

There was a long time during the last century when people looked upon Saxony as the most powerful and important State in the Protestant part of Germany. It is an Elector of Saxony who shines forth in history as Luther’s best friend and resolute protector. For more than a hundred years thereafter Saxony led in the armed struggles of Protestantism to maintain itself against the leagued Catholic powers.

Then, in 1694, there ascended the electoral throne the cleverest and most showy man of the whole Albertine family, who for nearly thirty years was to hold the admiring attention of Europe. We can see now that it was a purblind and debased Europe which believed August der Starke to be a great man; but in his own times there was no end to what he thought of himself or to what others thought of him. It was regarded as a superb stroke of policy when, in 1697, he got himself elected King of Poland—a promotion which inspired the jealous Elector of Branden-berg to proclaim himself King of Prussia four years later. August abjured Protestantism to obtain the Polish crown, and his descendants are Catholics to this day, though Saxony is strongly Protestant. August did many wonderful things in his time—made Dresden the superb city of palaces and museums it is, among other matters, and was the father of 354 natural children, as his own proud computation ran. A tremendous fellow, truly, who liked to be called the Louis XIV of Germany, and tried his best to live up to the ideal!

Contemporary observers would have laughed at the idea that Frederick William, the surly, bearish Prussian King, with his tobacco orgies and giant grenadiers, was worth considering beside the brilliant, luxurious, kingly August. Ah, “gay eupeptic son of Belial,” where is thy dynasty now?

There is to-day a King of Saxony, descended six removes from this August, who is distinctly the most interesting and valuable of these minor sovereigns. He is a sagacious, prudent, soldierlike man, nominal ruler of over three millions of people, actual Field Marshal in the German Army which has a Hohenzollern for its head. Although he really did some of the best fighting which the Franco-German war called forth, nobody outside his own court and German military circles knows much about it, or cares particularly about him. The very fact of his rank prevents his generalship securing popular recognition. If he had been merely of noble birth, or even a commoner, the chances are that he would now be chief of the German General Staff instead of Count von Schlieffen. Being only a king, his merits as a commander are comprehended alone by experts.

There is just a bare possibility that this King Albert may be forced by circumstances out of his present obscurity. He is only sixty-three years old, and if a war should come within the next decade and involve defeat to the German Army in the field, there would be a strong effort made by the other subsidiary German sovereigns to bring him to the front as Generalissimo.

As it is, his advice upon military matters is listened to in Berlin more than is generally known, but in other respects his position is a melancholy one. Even the kindliness with which the Kaisers have personally treated him since 1870, cannot but wear to him the annoying guise of patronage. He was a man of thirty-eight when his father, King John, was driven out of Dresden by Prussian troops, along with the royal family, and when for weeks it seemed probable that the whole kingdom of Saxony would be annexed to Prussia. Bismarck’s failure to insist upon this was bitterly criticised in Berlin at the time, and Gustav Frey-tag actually wrote a book deprecating the further independent existence of Saxony. Freytag and the Prussians generally confessed their mistake after the young Saxon Crown Prince’s splendid achievement at Sedan; but that could scarcely wipe from his memory what had gone before, and even now, after the lapse of a quarter century, King Albert’s delicate, clear-cut, white-whiskered face still bears the impress of melancholy stamped on it by the humiliations of 1866.

Two other kings lurk much further back in the shadow of the Hohenzollern—idiotic Otto of Bavaria and silly Charles of Wurtemberg. Of the former much has been written, by way of complement to the picturesque literature evoked by the tragedy of his strange brother Louis’s death. In these two brothers the fantastic Wittelsbach blood, filtering down from the Middle Ages through strata of princely scrofula and imperial luxury, clotted rankly in utter madness.

As for the King of Würtemberg, whose undignified experiences in the hands of foreign adventurers excited a year or two ago the wonderment and mirth of mankind, he also pays the grievous penalty of heredity’s laws. Writing thirty years back, Carlyle commented in this fashion upon the royal house of Stuttgart: “There is something of the abstruse in all these Beutelsbachers, from Ulric downwards—a mute ennui, an inexorable obstinacy, a certain streak of natural gloom which no illumination can abolish; articulate intellect defective: hence a strange, stiff perversity of conduct visible among them, often marring what wisdom they have. It is the royal stamp of Fate put upon these men—what are called fateful or fated men.” * The present King Charles was personally an unknown quantity when this picture of his house was drawn. He is an old man now, and decidedly the most “abstruse” of his whole family.

* “History of Friedrich II, of Prussia,” book vii. chapter

vi.

Thus these two ancient dynasties of Southern Germany, which helped to make history for so many centuries, have come down into the mud. There is an elderly regent uncle in Bavaria who possesses sense and respectable abilities; and in Würtemberg there is an heir-apparent of forty-three, the product of a marriage between first cousins, who is said to possess ordinary intelligence. These will in time succeed to the thrones which lunacy and asininity hold now in commission, but no one expects that they will do more than render commonplace what is now grotesquely impossible.

Of another line which was celebrated a thousand years ago, and which flared into martial prominence for a little in its dying days, when this century was young, nothing whatever is left. The Fighting Brunswickers are all gone.

They had a fair right to this name, had the Guelphs of the old homestead, for of the forty-five of them buried in the crypt of the Brunswick Burg Kirche nine fell on the battlefield. This direct line died out seven years ago with a curiously-original old Duke who bitterly resented the new order of things, and took many whimsical ways of showing his wrath. In the sense that he scorned to live in remodeled Germany, and defied Prussia by ostentatiously exhibiting his sympathy for the exiled Hanoverian house, he too may be said to have died fighting. The collateral Guelphs who survive in other lands are anything but fighters. The Prince of Wales is the foremost living male of the family, and Bismarck’s acrid jeer that he was the only European Crown Prince whom one did not occasionally meet on the battlefield, though unjustly cruel, serves to point the difference between his placid walk of life and the stormy careers of his mother’s progenitors. Another Guelph, who is de jure heir to both Brunswick and Hanover—Ernest, Duke of Cumberland—has a larger strain of the ancestral Berserker blood, but alas! no weapon remains for him but obdurate sulkiness. He buries himself in his sullen retreat at Gmunden in uncompromising rage, and the powers at Berlin have left off striving to placate him with money—his relatives not even daring now to broach the subject to him.

And so there is an end to the Fighting Bruns-wickers, and a Hohenzollern has been put in their stead. Prince Albert of Prussia—a good, wooden, ceremonious man of large stature, who stands straight in jack boots and cuirass and is invaluable as an imposing family figure at christenings and funerals—reigns as Regent in Brunswick. So omnipotent are the Hohenzollerns grown that he was placed there without a murmur of protest—and when the time comes for the Prussian octopus to gather in this duchy, that also will be done in silence.

Of the sixteen remaining sovereigns-below-the-salt, the Grand Duke of Baden is a fairly-able and wholly-amiable man, much engrossed in these latter days in the fact that his wife is the Kaiser’s aunt. This makes him feel like one of the family, and he takes the aggrandizement of the Hohenzollerns as quite a personal compliment. The venerable Duke Ernest, of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, has an active mind and certain qualities which under other conditions might have made him a power in Germany. But Bismarck was far too rough an antagonist for him to cope with openly, and he fell into the feeble device of writing political pamphlets anonymously against the existing order of things, using the ingenuity of a jealous woman to circulate them and denying their authorship before he was accused. This has, of course, been fatal to his influence in the empire. Duke George, of Saxe-Meiningen, is another able and accomplished prince, who has devoted his energies and fortune to the establishment and perfecting of a very remarkable theatrical company. The rest are mere dead wood—presiding over dull little country Courts, wearing Prussian uniforms at parades and reviews, and desiring nothing else so much as the reception of invitations to visit Berlin and shine in the reflected radiance of the Hohenzollern’s smile.

The word “invitations” does indeed suggest that the elderly Prince Henry XIV, of Reuss-Schleiz, should receive separate mention, as having but recently abandoned a determined feud with Prussia. It is true that Reuss-Schleiz has only 323 miles of territory and 110,000 people, but that did not prevent the feud being of an embittered, not to say menacing, character. When the invitations were sent out for the Berlin palace celebration of old Kaiser Wilhelm’s ninetieth birthday, in 1887, by some accident Henry of Reuss-Schleiz was overlooked. There are so many of these Reusses, all named Henry, all descended from Henry the Fowler, and all standing so erect with pride that they bend backward! The mistake was discovered in a day or two and a belated invitation sent, which Henry grumblingly accepted. On the appointed day he arrived at the palace in Berlin and went up to the banqueting hall with the other princes. Being extremely near-sighted, he made a tour of the table, peering through his spectacles to discover his name-card. Horror of horrors! No place had been provided for him, and everybody in the room had observed him searching for one! Trembling with wrath, he stalked out, brushing aside the chamberlains who essayed to pacify him, and during that reign he never came to Berlin again. Not death itself could mollify him, for when Kaiser Wilhelm died the implacable Henry XIV, who personally owns most of his principality, refused his subjects a grant of land on which to rear a monument to his memory. But even he is reconciled to Berlin now.

Thus with practical completeness had the ancient dynasties of old Germany been subordinated to and absorbed by the ascendency of the Hohenzollerns, when young William II stepped upon the throne. Thus, too, with this passing glance at their abasement or annihilation, the way is cleared for us to study the young chief of this mighty and consolidated Empire, to examine his personality and his power, and, by tracing their growth during the first three years of his reign, to forecast their ultimate mark upon the history of his time.

The young Emperor was born in the first month of 1859. The prolonged life of his grandfather, and the apparently superb physical vitality of his father, made him seem much further removed from the throne than fate really intended, and he grew up into manhood with only scant attention from the general public. There was an unexpressed feeling that he belonged to the twentieth century, and that it would be time enough then to study him. When of a sudden the world learned that the stalwart middle-aged Crown Prince had a mortal malady, and saw that it was a race toward the grave between him and his venerable father, haste was made to repair this negligent error, and find out things about the hitherto unconsidered young man who was to be so prematurely called upon the stage. Unfortunately, this swift and unexpected shifting of history’s lime-light revealed young William in extremely repellent colours. Many circumstances, working together in the shadows behind the throne, had combined to put him into a temporary attitude toward his parents, which showed very badly under this sudden and fierce illumination. “Ho, ho! He is a bad son, then, is he?” we all said, and made up our minds to dislike him on the spot. Three years have passed, and during that time many things have happened, many other things have come to light, calculated to convince us that this early judgment was an over-hasty one.

So far as I have been able to learn, the first hint given to the world that there was a young Prince in Berlin distinctly worth watching appeared in the book “Sociétiê de Berlin. Par le Comte Paul Vasili,” published at the end of 1883. This volume was, perhaps, the cleverest of the anonymous series projected by a Parisian publisher to make money out of the collected gossip and scandal of the chief European capitals, and utilized by more than one bright familiar of Mme. Adam’s salon to pay off old grudges and market afresh moss-grown libels. The authorship of these books was never clearly established. There is a general understanding in Berlin that the one about that city was for the most part written by a Parisian journalist named Gerard, then stationed in Germany. At all events, the evidence was regarded at the time as sufficient as to warrant his being chased summarily out of Berlin, while the book itself was prohibited, confiscated, almost burned by the common hangman. Perhaps Gerard, if he be still alive, might profitably return to Berlin now, for to him belongs the credit of having first put into type an intelligent character study of the young man who now monopolizes European attention.

“The Prince William,” said this anonymous writer, “is only twenty-four years of age. It is, therefore, difficult as yet to say what he will become; but what is clearly apparent even now is that he is a young man of promise in mind and head and heart. He is by far the most intellectual of the Princes of this royal family. Withal courageous, enterprising, ambitious, hot-headed, but with a heart of gold, sympathetic in the highest degree, impulsive, spirited, vivacious in character, and gifted with a talent for repartee in conversation which would almost make the listener doubt his being a German. He adores the army, by which he is idolized in return. He has known how, despite his extreme youth, to win popularity in all classes of society. He is highly educated, well read, busies his mind with projects for the welfare of his country, and has a striking keenness of perception for everything relating to politics.

“He will certainly, be a distinguished man, and very probably a great sovereign. Prussia will perhaps have in him a second Frederic II, but minus his scepticism. In addition, he possesses a fund of gaiety and good humour that will soften the little angularities of character without which he would not be a true Hohenzollern.

“He will be essentially a personal king—never allowing himself to be blindly led, and ruling with sound and direct judgment, prompt decision, energy in action, and an unbending will. When he attains the throne, he will continue the work of his grandfather, and will as certainly undo that of his father, whatever it may have been. In him the enemies of Germany will have a formidable adversary; he may easily become the Henri IV of his country.”

I have ventured upon this extended extract from a book eight years old because the prophecy seems a remarkable one—far nearer what we see now to be the truth than any of the later predictions have turned out to be. “Paul Vasili” continues his sketch with some paragraphs about the Prince’s vast penchant for lower-class dissipated females, concluding with the warning that if ever he comes under the influence of a’ really able woman “it will be necessary to follow his actions with great caution.” All this may be unhesitatingly put down to the French writer’s imagination.

There is no city where more frankness about talking scandal exists than in Berlin, yet I have sought in vain to find any justification for this view of the Kaiser’s character, either past or present. The impression brought from many talks with people who know him and his life intimately is that this special accusation is less true of him than of almost any other prince of his generation.

William’s boyhood was marked by one innovation in the family traditions of a Hohenzollern’s training, the importance of which it is not easy to exaggerate. His father had been the first of these royal heirs to be sent to a university. He in his turn was the first to go to a public school.

It is a solemn and portentous sort of thing—this training of a Hohenzollern. The progress of the family has been one long, sustained object lesson to the world on the value of education. No doubt it is in great part due to the influence of this standing example that Prussia leads the van of civilization in its proportion of scholars and teachers, and has made its name a synonym for all that is thorough and exhaustive in educational systems and theories. The dawn of this notion of a specially Spartan and severe practical schooling for his heir, in the primitive and curiously-limited brain of the first King Frederic William, really marked an era in the world’s conception of what education meant.

We have all read, with swift-chasing mirth, wonder, incredulity and wrath, the stories of the way in which this luckless heir, afterward to be Frederic the Great, got his education stamped, beaten, burned, frozen, almost strangled into him. The account reads like a nightmare of lunatic savagery—yet in it were the germs of a lofty idea. From the brutal cudgeling, cursing, and manacling of Frederic’s experience grew the tradition of a unique kind of training for a Hohenzollern prince. The very violence and wild barbarity of his treatment fixed the attention of the family upon the theory of education—with very notable results.

Historically we are all familiar with the excessive military twist given to this education of the youths born to be Kings of Prussia. The picture books are full of portraits of them—quaint little manikins dressed in officers’ uniforms—stepping from the cradle into war’s paraphernalia. The picture of the Great Fritz beating a drum at the age of three, of which the rapturous Carlyle makes so much, has its modern counterpart in the photographs of the present child Crown Prince, clad in regimentals and saluting the camera, which are in every Berlin shop window. But another element of this stern regimen, not so much kept in view, is the absolute dependence of the son upon the father, or rather the King, which is insisted upon.

We know to what abnormal lengths this ran in the youth and early manhood of Frederic the Great. It did not alter much in the next reign. In 1784, when this same Frederic was seventy-two years old, a travelling French noble was his guest at a great review in Silesia. There was also present the King’s nephew and heir, who two years later was to ascend the throne as Frederic William II, and who now was in his fortieth year. Yet of this forty-year-old Prince the Frenchman writes in his diary: “The heir presumptive lodges at a brewer’s house, and in a very mean way; is not allowed to sleep from home without permission from the King.”

The results in this particular instance were not of a flattering kind, and among the decaying forms of the dying eighteenth century—in an atmosphere poisoned by the accumulated putridities of that luxurious and evil epoch—even the Hohenzollern of the next generation was not a shining success. He was at least, however, much superior to the other German sovereigns of his time, and he had the unspeakable fortune, moreover, to be the husband of that Queen Louise who is enshrined as the patron saint of Prussian history. It was she who engrafted a humane spirit upon the rough drill-sergeant body of Hohenzollern education. She made her sons love her—and it seems but yesterday since the last of these sons, a tottering old man of ninety, used to go to the Charlottenburg mausoleum on the anniversary of her death, and pray and weep in solitude beside the recumbent marble effigy of the mother who had died in 1810.

The introduction of filial affection into the relation between Hohenzollern parents and children dates from this Queen Louise, and belongs to our own century. Before that it was the rule for the heirs of Prussia to detest their immediate progenitors. From the time of the Great Elector, every rising generation of this royal house sulked, cursed under its breath, went into opposition as far as it dared, and every fading generation disliked and distrusted those who were coming after it. Nor were these harsh relations confined to sovereign and heir. Wilhelmine, Margravine of Baireuth, records in her memoirs how, at the age of six, she was so much surprised at being fondled and caressed by her mother, on the latter’s return from a prolonged journey, that she broke a blood vessel. * It seems safe to say that down to the family of Frederic William III and Louise, no other reigning race in Europe had ever managed to engender so much bitterness and bad blood between elders and juniors within its domestic fold. The change then was abrupt. The two older boys of this family, Frederic William IV and William I, lived lives as young men which were poems of filial reverence and tenderness. The cruel misfortunes of the Napoleonic wars made the mutual affection within this hunted and homeless royal family very sweet and touching. Perhaps the most interesting of all the reminiscences called forth by the death of the old Kaiser was furnished by the publication of the letters he wrote as a young man to his father—that strange correspondence which reveals him resolutely breaking his own heart and tearing from it the image of the Princess Radziwill, in loving obedience to his father’s wish.

* “Memoirs of Wilhelmine, Margravine of Baireuth,”

translated by H.R.H. Princess Chri of Wilhelmine, Margravine

of Baireuth, translated by H.R.H. Princess Christian,

London, 1887

This trait of filial piety did not loom so largely in William’s son, the late Frederic III, as one or two random allusions in his diary show. And in his son, in turn, its pulse beats with such varying and intermittent fervour that sometimes one misses it altogether.

Young William, as has been said, was the first of his race to be sent to a public school, the big gymnasium at Cassel being selected for the purpose. The innovation was credited at the time to the eccentric liberalizing notions of his mother, the English Crown Princess. The old Kaiser did not like the idea, and Bismarck vehemently opposed it, but the parents had their way, and at the age of fifteen the lad went, along with his twelve-year-old brother Henry, and their tutor, Dr. Hinzpeter. They were lodged in an old schloss, which had been one of the Electoral residences, and out of school hours maintained a considerable seclusion. But in the school itself William was treated quite like any ordinary citizen’s son.

It may have been a difficult matter for some of the teachers to act as if they were unconscious that this particular pupil was the heir of the Hohenzollerns, but men who were at the school at the time assure me they did so, with only one exception. This solitary flunkey, knowing that William was more backward in his Greek than most of his class, sought to curry favour with the Prince by warning him that the morrow’s examination was to be, let us say, upon a certain chapter of Xenophon. The boy William received this hint in silence, but early the next morning went down to the classroom and wrote upon the blackboard in big letters the information he had received, so that he might have no advantage over his fellows. This struck me when I heard it as a curious illustration of the boy’s character. There seems to have been no excited indignation at the meanness of the tutor—but only the manifestation of a towering personal and family pride, which would not allow him to win a prize through profiting by knowledge withhold from the others.

During his three years at Cassel William was very democratic in his intercourse with the other boys. He may have been helped to this by the fact that he was one of the worst-dressed boys in the school—in accordance with an ancient family rule which makes the Hohenzollern children wear out their old clothes in a way that would astonish the average grocer’s progeny. He was only an ordinary scholar so far as his studies went. At that time his brother Henry, who went to a different school, was conspicuously the brighter pupil of the two. Those who were at Cassel with the future Emperor have the idea that he was contented there, but he himself, upon reflection, is convinced that he did not like it. At all events, he gathered there a very intimate knowledge of the gymnasium system which, as will be seen later on, he now greatly disapproves.

At the age of eighteen William left Cassel and entered upon his university course at Bonn. Here his tutor, Hinzpeter, who had been his daily companion and mentor from childhood, parted company with him, and the young Prince passed into the hands of soldiers and men of the world. The change marks an important epoch in the formation of his character.

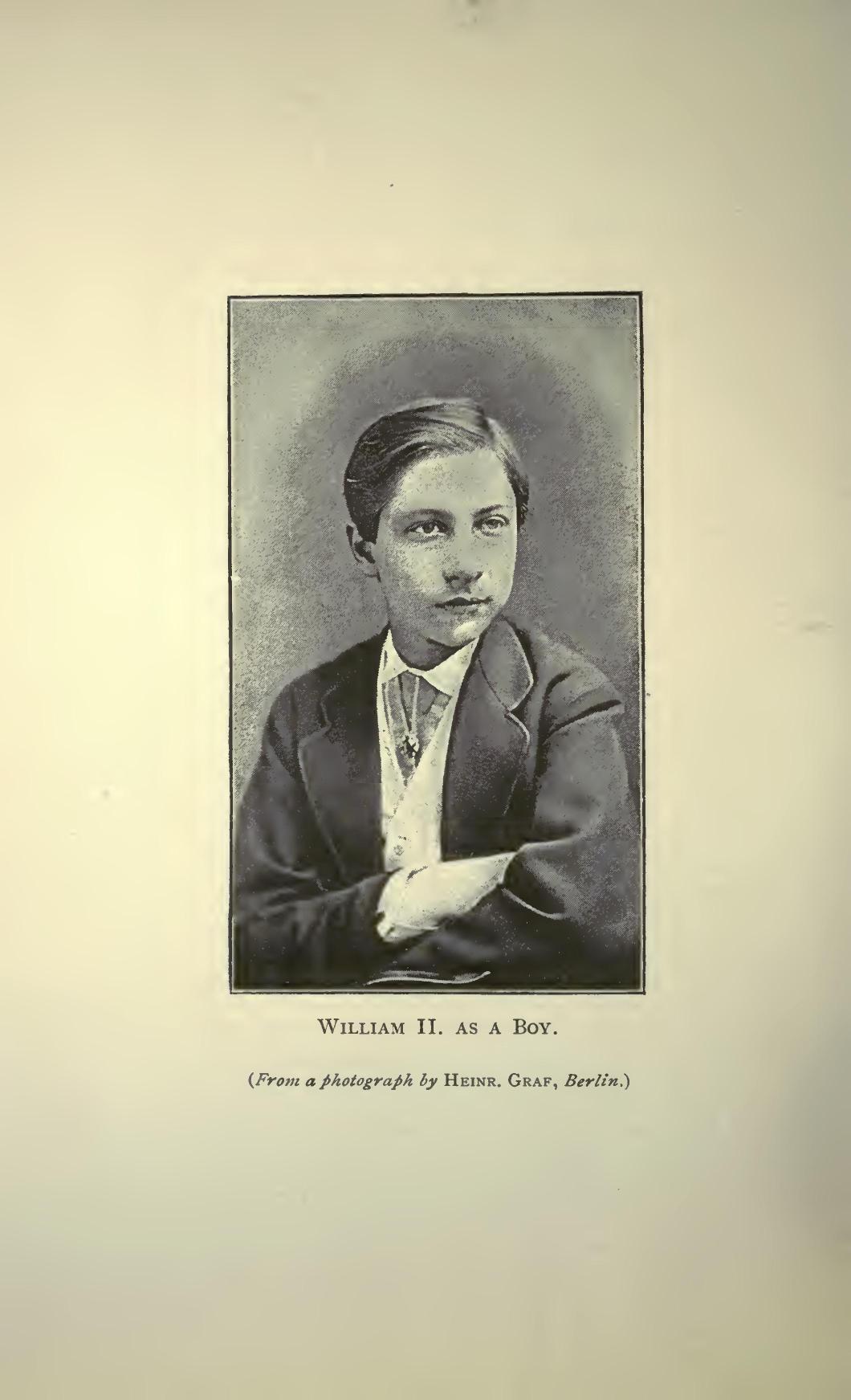

There is a photograph of him belonging to the earlier part of this Cassel period which depicts a refined, gentle, dreamy-faced German boy, with a soft, girlish chin, small arched lips with a suggestion of dimples at the corners, and fine meditative eyes. The forehead, though not broad, is of fair height and fulness. The dominant effect of the face is that of sweetness. Looking at it, one instinctively thinks “How fond that boy’s parents must have been of him!” And they were fond in the extreme.

In the Crown Prince Frederic’s diary, written while the German headquarters were at Versailles, are these words:—

“This is William’s thirteenth birthday. May he grow up to be an able, honest, and upright man, a true German, prepared to continue without prejudice what has now been begun! Heaven be praised; between him and us there is a simple, hearty, and natural relationship, which we shall strive to preserve, so that he may thus always look upon us as his best and truest friends. It is really an oppressive reflection when one realizes what hopes have already been placed on the head of this child, and how great is our responsibility to the nation for his education, which family considerations and questions of rank, and the whole Court life at Berlin and other things will tend to make so much more difficult.”

The retirement of Dr. Hinzpeter from his charge was an event the significance of which recent occurrences have helped us to appreciate. When history is called upon to make her final summing up upon William’s character and career, she will allot a very prominent place to the influence of this relatively unknown man. A curious romance of time’s revenge hangs about Dr. Hinzpeter. He is a native of the Westphalian manufacturing town, Bielefeld, and was a poor young tutor at Darmstadt when he was recommended to the parents of William as one exceptionally fitted to take charge of their son. The man who gave this recommendation was the then Mr. Robert Morier, British Minister at Darmstadt. Nearly a quarter of a century later Sir Robert Morier was able to see his ancient and implacable enemy, Bismarck, tripped, thrown, and thrust out of power, and to sweeten the spectacle by reflecting that he owed this ideal vengeance to the work of the tutor he had befriended in the old Darmstadt days.

It is more than probable that the idea of sending the young Prince to the Cassel gymnasium originated with Dr. Hinzpeter. At all events, we know that he held advanced and even extreme views as to the necessity of emphasizing the popular side of the Hohenzollern tradition.

This Prussian family has always differed radically from its other German neighbours in professing to be solicitous for the poor people rather than for the nobility’s privileges and claims. Sometimes this has sunk to be a profession merely; more often it has been an active guiding principle. The lives of the second and third Kings of Prussia are filled with the most astonishing details of vigilant, ceaseless intermeddling in the affairs of peasant farmers, artisans, and wage-earners generally, hearing complaints, spying out injustice, and roughly seeing wrongs righted. When Prussia grew too big to be thus paternally administered by a King poking about on his rounds with a rattan and a taker of notes, the tradition still survived. We find traces of it all along down to our times in the legislation of the Diet in the direction of what is called State Socialism.

Dr. Hinzpeter felt the full inspiration of this tradition. He longed to make it more a reality in the mind of his princely pupil than it had ever been before. Thus it was that the lad was sent to Cassel, to sit on hard benches with the sons of simple citizens, and to get to know what the life of the people was like. Years afterwards this inspiration was to bear fruit.

But in 1877 the work of creating an ideally democratic and popular Hohenzollern was abruptly interrupted. Dr. Hinzpeter went back to Bielefeld, and young William entered the University of Bonn. The soft-faced, gentle-minded boy, still full of his mother’s milk, his young mind sweetened and strengthened by the dreams of clemency, compassion, and earnest searchings after duty which he had imbibed from his teacher, suddenly found himself transplanted in new ground. The atmosphere was absolutely novel. Instead of being a boy among boys, he all at once found himself a prince amongst aristocratic toadies. In place of Hinzpeter, he had a military aide given him for principal companion, friend, and guide.

These next few years at the Rhenish university did not, we see now, wholly efface what Dr. Hinz-peter had done. But they obscured and buried his work, and reared upon it a superstructure of another sort—a different kind of William, redolent of royal pretensions and youthful self-conceit, delighting in the rattle and clank of spurs and swords and dreaming of battlefields.

Poor Hinzpeter, in his Bielefeld retreat, could have had but small satisfaction in learning of the growth of the new William. The parents at Potsdam, too, who had built such loving hopes upon the tender and gracious promise of boyhood—they could not have been happy either.

The act of matriculation at Bonn meant to young William many things apart from the beginning of a university career. In fact, it was almost a sign of his emancipation from academic studies. He was a student among students in only a formal sense. The theory of a complete civic education was respected by his attendance at certain lectures, and by his perfunctory compliance with sundry university regulations. But, in reality, he now belonged to the army. He had attained his majority, like other Prussian princes, at the age of eighteen, and thereupon had been given his Second Lieutenant’s commission in the First Foot Regiment of the Guards, where his father had been trained before him. The routine of his military service, and the exigencies of the martial education which now supplanted all else, kept him much more in Berlin than at Bonn.

Both at the Prussian capital and Rhenish university town he now wore his uniform, his sword, and his epaulets, and, chin well in air, sniffed his fill of the incense burned before him by the young men of the army. The glitter and colour of the parade ground, the peremptory discipline, the sense of power given by these superb wheeling lines and walls of bayonets and exact geometrical movements as of some mighty machine, fascinated his imagination. He threw himself into military work with feverish eagerness. Pacific Cassel, with its gymnasium and the kindly figure of the tutor, Hinzpeter, faded away into a remote memory of childhood.

Public events, meanwhile, had been working out a condition of affairs which gave a marked importance to this change in William’s character. The German peoples, having got over the first rapt enthusiasm at beholding their ancient Frankish enemy rolled in the dust at their feet, and at finding themselves once more all together under an imperial German flag, began to devote attention to domestic politics. It was high time that they did so.

Prussia had roared as gently as any sucking dove the while the question was still one of enticing the smaller German States into the federated empire. But once the Emperor-King felt his footing secure upon the imperial throne, the old hungry Hohenzollern blood began stirring in his veins. His great Chancellor, Prince Bismarck, needed no prompting; every fibre of his bulky frame responded intuitively to this inborn Prussian instinct of aggrandisement. Together these two began putting the screws upon the minor States. “Solidifying the Empire” was what they called their work. The Hohenzollerns were always notable “solidifiers,” as their neighbours have had frequent occasion to observe tearfully during the last three centuries.

The humiliation and expulsion of Austria had been the pivot upon which the creation of the new Germany turned. In its most obvious aspect this had appeared to all men to be the triumph of a Protestant over a Catholic power. Later events had contributed to associate Prussia’s ascendency with the religious issue. The great OEcumenical Council at Rome had been followed by a French declaration of war, which every good Lutheran confidently ascribed to the dictation of the Jesuits.

These things grouped themselves together in the public mind just as similar arguments did in England in the days of the Armada. To be a Catholic grew to seem synonymous with being a sympathizer with Austria and France. It is an old law of human action that if you persistently impute certain views to a man, and persecute him on account of them, the effect is to reconcile his mind to those views. The melancholy history of theologico-political quarrels is peculiarly filled with examples of this. The Catholics of Germany were in the main as loyal to the idea of imperial unity as their Protestant neighbours, and they had shed their blood quite as freely to establish it as a fact. Their bishops and priests had over and over again testified by deeds their independence of Rome in matters which affected them as Germans. But when they found Bismarck ceaselessly insisting that they were hostile to Prussia, it was natural enough that they should discover that they did dislike his kind of a Prussia, and that some of the least cautious among them should say so.

Prussia’s answer—coming with the promptness of deliberate preparation—was the Kulturkampf, Into the miserable chaos which followed we need not go. Bishops were exiled or imprisoned; schools were broken up and Catholic professors chased from the universities; a thousand parishes were bereft of their priests; the whole empire was filled with angry suspicions, recriminations, and violence, hot-tempered roughness on one side, grim obstinacy of hate on the other—to the joy of all Germany’s enemies outside and the confusion of all her friends.

Despotism begets lawlessness, and Bismarck and old William, busy with their priest hunt, suddenly discovered that out of this disorder had somehow sprouted a strange new thing called Socialism. They halted briefly to stamp this evil growth out—and lo! from an upper window of the beer house on Unter den Linden, called the Three Ravens, the Socialist Nobiling fired two charges of buckshot into the head and shoulders of the aged Emperor, riddling his helmet like a sieve and laying him on a sick bed for the ensuing six months.

As a consequence, the Crown Prince Frederic was installed as Regent from June till December of 1878, and from this period dates young William’s public attitude of antagonism to the policy of his parents.

For the present we need examine this only in its outer and political phases. It is too much, perhaps, to say that heretofore there had been no divisions inside the Hohenzollern family. The Crown Prince and his English wife had been in tacit opposition to the Kaiser-Chancellor régime for many years. But this opposition took on palpable form and substance during the Regency of 1878.

A new Pope—the present Leo XIII—had been elected only a few months before, and with him the Regent Frederic opened a personal correspondence, with a view to compromising the unhappy religious wrangles which were doing such injury to Germany. The letters written from Berlin were models of gentle firmness and wise statesmanship, and they laid a foundation of conciliatory understanding upon which Bismarck afterward gladly reared his superstructure of partial settlement when the time came for him to need and bargain for the Clerical vote in the Reichstag. But at the time their friendly tone gave grave offence to the Prussian Protestants, and was peculiarly repugnant to the Junker court circles of Berlin.

It is no pleasant task to picture to one’s self the grief and chagrin with which the Regent and his wife must have noted that their elder son ranged himself among their foes. The change which had been wrought in him during the year in the regiment and at Bonn revealed itself now in open and unmistakable fashion. Prince William ostentatiously joined himself with those who criticised the Regent. He assiduously cultivated the friendship of the men who led hostile attacks upon his parents. He had his greatest pride in being known for a staunch supporter of Bismarck, a firm believer in divine right, Protestant supremacy, and all the other catchwords of the absolutist party. The praises which these reactionary people sang in his honour mounted like the fumes of spirits to his young brain. Instinctively he began posing as the Hope of the Monarchy—as the providential young prince, handsome, wise and strong, who was in good time to ascend the throne and gloriously undo all that the weak dreamer, his father, had done toward liberalizing the institutions of Prussia and Germany.

A lamentable and odious attitude this, truly! Yet, which of us was wholly wise at nineteen? And which of us, it may be added fairly, has encountered such magnificent and overpowering temptations to foolishness as these that beset young William?

Remember that all his associates, alike in his daily routine with his regiment or at the University and in his larger intercourse among the aristocratic social circles of Berlin, took only one view of this subject. At their head were Bismarck, the most powerful and impressive personality in Europe, and the aged Emperor, the one furiously inveighing against the manner in which the Protestant religion and political security were being endangered, the other deploring from his sick-bed the grievous inroads which were threatened upon the personal rights and prerogatives of the Hohenzollerns.

It is not strange that young William adopted the opinion of his grandfather and of Bismarck, chiming as it did with the new impulses of militarism that had risen so strongly within him, and being re-echoed, as it was, from the lips of all his friends.

But the event of this brief Regency which most clearly marked the chasm separating the Crown Prince from the Junker circles of his son’s adoption, was the appointment of Dr. Friedberg to high office. And this is particularly worth studying, because its effects are still felt in German social and political life.

Dr. Friedberg was then a man of sixty-five, and one of the most distinguished jurists of Germany. He had adorned a responsible post in the Ministry of Justice for over twenty years, and had written numerous valuable works, those relating to his special subject of prison reform and the efficacy of criminal law in social improvement standing in the very front rank of literature of that kind. His promotion, however, had been hopelessly blocked by two considerations; he was professedly a Liberal in politics and a close friend of the Crown Prince and Princess, and, what was still worse, he was a Jew.

On the second day of his Regency, Frederic astounded and scandalized aristocratic Berlin by appointing Dr. Friedberg to the highest judicial-administrative post in the kingdom. To glance forward for a moment, it may be noted that when old Kaiser Wilhelm returned to active power in December, he refused to remove Friedberg, out of a feeling of loyalty to his son’s actions as Regent. But he vented his wrath in another way by conspicuously neglecting to give Friedberg the Black Eagle after he had served nine years in the Ministry, though all his associates obtained the decoration upon only six years’ service. This slight upon the Hebrew Minister explains the well-remembered action of Frederic, when he was on his journey home from San Remo to ascend the throne after his father’s death:—as the Ministerial delegation met his train at Leipsic, and entered the carriage, he took the Black Eagle from his own neck and placed it about that of Friedberg.

This action of the emotional sick man, returning through the March snowstorm to play his brief part of phantom Kaiser, created much talk in Germany three years ago, and Friedberg, upon the strength of it, plumed himself greatly as the chief friend of the new monarch. He was the first Jew ever decorated by that exalted and exclusive Black Eagle—and during the short reign of ninety-nine days he held himself like the foremost man in the Empire.

It is a melancholy reflection that this mean-spirited old man, as soon as Frederic died, made haste to lend himself to the work of blackening his benefactor’s memory. He had owed more to Frederic’s friendship and loyalty than any other in Germany, and he requited the debt to the dead Kaiser with such base ingratitude that even Frederic’s enemies were disgusted, and, under the pressure of general disfavour, he had soon to quit his post. But enough of Friedberg’s unpleasant personality. Let us return to 1878.

The Regent’s action in giving Prussia a Jewish Minister lent an enormous original impulse to the anti-Semitic movement in Berlin, which soon grew into a veritable Judenhetze. This Jewish question, while it ran its course of excitement in Germany, completely dwarfed the earlier clerical issue, just as it in turn has been submerged by the rising tide of Socialistic agitation. But though the anti-semitic party has ceased to exert any power at the polls the feeling back of it is still a potent factor in Berlin life.

In the new Berlin, of which I shall speak presently, the Jews occupy a more commanding and dominant position than they have ever had in any other important city since the fall of Jerusalem. For this the Germans have themselves largely to blame. The military bent of the ascendant Prussians has warped the whole Teutonic mind toward unduly glorifying the army. The prizes of German upper-class life are all of a military sort. Every nobleman’s son, every bright boy in the wealthier citizens’ stratum, aspires to the uniform. The tacit rule which excludes the Jews from positions in this epauletted aristocracy drives them into the other professions. They may not wear the sword: they revenge themselves by owning the vast bulk of the newspapers, by writing most of the books, by almost monopolizing law, medicine, banking, architecture, engineering, and the more intellectual branches of the civil service.

This preponderance of Hebrews in the liberal professions seems unnatural to the Tory German, who has vainly tried to break it down by political action and by social ostracism. These attempts in turn have thrown the Jews into opposition. Of the seven Israelites in the present Reichstag six are Socialist Democrats and one is a Freisinnige leader. Every paper in Germany owned or edited by a Jew is uncompromisingly Radical in its politics. This in turn further exasperates the German Tories and keeps alive the latent fires of hatred which bigots like Stocker from time to time fan into flame.

In finance, too, the German aristocrats find themselves getting more and more helplessly into Jewish hands. Their wonderful new city of Berlin not only acts as a sieve for the great wave of Hebrew migration steadily moving westward from Russia, but it is becoming the Jewish banking and money centre of Europe. The grain trade of Russia is concentrated in Berlin. To buy wheat from Odessa you apply to one of the three hundred Jewish middleman firms at Berlin. To borrow money in Europe you go with equal certainty to Berlin. The German nobleman was never very rich; he has of late years become distinctly poor—and all the mortgages which mar his sleep o’ nights are locked in Jewish safes at Berlin.

To revenge himself the German aristocrat can only assume an added contempt for literature and the peaceful professions generally because they are Jewish; insist more strongly than ever that the army is the only place for German gentlemen because it is not Jewish, and dream of the time when a beneficent fate shall once more hand Jerusalem over to conquest and rapine.

This German nobleman, however, does not disdain in the meanwhile to lend himself to the spoliation of the loathed tribes when chance offers itself. There is a famous Jewish banker in Berlin, who, in his senile years, is weak enough to desire social position for his children. One of his sons, a stupid and debauched youngster, is permitted to associate with sundry fashionable German officers—just up to the point where he loses his money to them with sufficient regularity—and, of course, never gets an inch beyond that point.

A daughter of this old banker had an even more disastrous experience. She was an ugly girl, but with her enormous dower the ambitious parents were able to buy a titled husband in the person of a penniless German Baron. Delighted with this success, the banker settled upon the couple a handsome estate in Silesia, The Baron and his bride were provided with a special train to convey them to their future home, and in that very train the Baron installed his mistress, and with her a lawyer friend who had already arranged for the sale of the estate. The Jewish bride arrived in Silesia to find herself contemptuously deserted by her husband and robbed of her estate. She returned to Berlin, obtained a divorce, and as soon as might be was married again—this time to a diamond merchant of her own race.

As for the Baron who perpetrated this unspeakably brutal and callous outrage, I did not learn that he had lost caste among his friends by the exploit. Indeed, the story was told to me as a merry joke on the Jews.

Prince Bismarck, almost alone among the Junker group, did not associate himself with this anti-Semitic agitation. In the work which he was carrying forward Jewish bankers were extremely useful. Both in a visibly regular way, and by subterranean means, capitalists like Bleichroder played a most important part in his performance of the task of centralizing power at Berlin. Hence he always held aloof from the movement against the Jews, and on occasions made his dislike for it manifest.

Doubtless it was his counsel which restrained the impetuous young William from openly identifying himself with this bigoted and proscriptive demonstration. At all events, the youthful Prince avoided any overt sign of his sympathy with the anti-Jewish outcry, yet continued to find all his friends among the class which supported the Judenhetze. It seems a curious fact now that in those days he created the impression of a silent and reserved young man—almost taciturn. As to where his likes and dislikes lay, no uncertainty existed. He was heart and soul with the aristocratic Court party and against all the tendencies and theories of the small academic group attached to his father. He made this obvious enough by his choice of associations, but kept a dignified curb on his tongue.

In addition to his course of studies at Bonn and his practical labours with his regiment, the Prince devoted a set amount of time each week to instruction of a less common order. He had regular weekly appointments with two very distinguished professors—the Emperor William, who spoke on Kingcraft, and Chancellor Bismarck, whose theme was Statecraft. The former series of discourses was continued almost without intermission, even during the old Kaiser’s period of retirement after Nobiling’s attempt on his life. The Prince saw these eminent instructors regularly, but it did not enter into their scheme of education that he should profess to learn anything from his father.

Among the ideas which the impressionable young man imbibed from Bismarck there could be nothing calculated to increase his filial affection or respect. Bismarck had cherished a bitter dislike for the English Crown Princess, conceived even before her marriage, at a time when she represented to him only the girlish embodiment of an impolitic matrimonial alliance, and strengthened year by year after she came to Berlin to live. He did not scruple to charge to a conspiracy between her and the Empress Augusta all the political obstacles which from time to time blocked his path. He not only believed, but openly declared, that the Crown Princess was responsible for the whole Arnim episode; and it is an open secret that even the State papers emanating from the German Foreign Office during his Chancellorship contain the grossest and most insulting allusions to her. As for the Crown Prince, Bismarck was at no pains to conceal his contempt for one of whom he habitually thought as a henpecked husband.

Enough of this feeling about his parents must have filtered through into young William’s mind, from his intercourse with the powerful Chancellor, to render any reassertion of parental influence impossible.

In the summer of 1880 the Emperor and his Chancellor decided that it was time for their pupil to marry, and they selected for his bride an amiable, robust and comely-faced German princess of the dispossessed Schleswig-Holstein family. I gain no information anywhere as to William’s parents having been more than formally consulted in this matter—and no hint that William himself took any deep personal interest in the transaction. The marriage ceremony came in February of 1881, and William was now installed in a residence of his own—the pretty little Marble Palace at Potsdam. His daily life remained otherwise unaltered. He worked hard at his military and civil tasks, and continued to pose—not at all through mere levity of character, but inspired by a genuine, if misguided, sense of duty—as the darling of all reactionary elements in modern Germany.

Six years of married and semi-independent life went by, and left Prince William of Prussia but little changed. He worked diligently up through the grades of military training and responsibility, fulfilling all the public duties of his position with exactness, but showing no inclination to create a separate rôle in the State for himself. The young men of the German upper and middle classes, alive with the new spirit of absolutism and lust for conquest with which boyish memories of 1870 imbued their minds, looked toward him and spoke of him as their leader that was to be when their generation should come into its own—but that seemed something an indefinite way ahead. He could afford to wait silently.

His summer home at Marmorpalais, charmingly situated on the shore of the Heiligen Sea at Potsdam, did not in any obvious sense become a political centre. The men who came to it were chiefly hard-working officers, and the talk of their scant leisure, over wine and cigars, was of military tasks, hunting experiences, and personal gossip rather than of graver matters. The library, which was William’s workroom in these days, has most of its walls covered with racks arranged to hold maps, presumably for strategic studies and Kriegspiel work. The next most important piece of furniture in the room is a tall cabinet for cigars. The bookcase is much smaller.

When winter came Prince William and his family returned to their apartments in the Schloss at Berlin. Nurses clad in the picturesque Wendish dress of the Spreewald bore an increasing prominent part in this annual exodus from Potsdam—for almost every year brought its new male Hohenzollern.

Thus the early spring of 1887 found William, now past his twenty-eighth year, a major, commanding a battalion of Foot guards, the father of four handsome, sturdy boys, and two lives removed from the throne.

Then came, without warning, one of those terrible, world-changing moments wherein destiny reveals her face to the awed beholder—moments about which the imagination of the outside public lingers with curiosity forever unsatisfied. No one will ever tell what happens in that soul-trying instant of time, We shall never know, for example, just what William felt and thought one March day in 1887, when somebody—identity unknown to us as well—whispered in his ear that the Crown Prince, his father, had a cancer in the throat.

The world heard this sinister news some weeks later, and was so grieved at the intelligence that for over a year thereafter it fostered the hope of its falsity, and was even grateful to courtier physicians and interested flatterers who encouraged this hope. Civilization had elected Frederic to a place among its heroes, and clung despairingly to the belief that his life might, after all, be saved.

But in the inner family circle of the Hohenzollerns there was from the first no illusion on this point. The old Emperor and his Chancellor and the Prince William knew that the malady was cancerous. Their information came from Ems, whither Frederic went upon medical advice in the spring of 1887, to be treated for “a bad cold with bronchial complications.” Later a strenuous and determined attempt was made to represent the disease as something else, and out of this grew one of the most painful and cruel domestic tragedies known to history. At this point it is enough to say that the Emperor and his grandson knew about the cancer before even rumours of it reached the general public, and that their belief in its fatal character remained unshaken throughout.

To comprehend fully and fairly what followed, it will be necessary to try to look at Frederic through the eyes of the Court party. The view of him which we of England and America take has been, beyond doubt, of great and lasting service to the human race—in much the same sense that the world has been benefited by the idealized purities and sweetnesses of the Arthurian legend. We are helped by our heroes in this practical, work-a-day, modern world as truly as were our pagan fathers who followed the sons of Woden. Every one of us is the richer and stronger for this image of Frederic the Noble which the English-speaking peoples have erected in their Valhalla.

But it is fair to reflect, on the other hand, that this fine, handsome, able, and good-hearted Prince could not have created for himself such hosts of hostile critics in his own country, could not have continually found himself year by year losing his hold upon even the minority of his fellow-countrymen, without reason. It is certain that in 1886—the year before his illness befell—he had come to a minimum of usefulness, influence, and popularity in the Empire. Deplore this as we may, it would be unintelligent to refuse to inquire into its causes.

Moreover, we are engaged upon the study of a living man, holding a great position, possibly destined to do great things. All our thoughts of this living man are instinctively coloured by prejudices based upon his relations with his father, who is dead. Justice to William demands that we shall strive fairly to get at the opinions and feelings which swayed him and his advisers in their attitude of antagonism to our hero, his father.

His critics say that Frederic was an actor. They do not insist upon his insincerity—in fact, for the most part credit him with honesty and candour—but regard him as the victim of hereditary histrionism. His mother, the late Empress Augusta, had always impressed Berliners in the same way—as playing in the rôle of an exiled Princess, with her little property Court accessories, her little tea-party circle of imitation French littérateurs, and her “Mrs. Haller” sighs and headshakings over the coarseness and cruelty of the big roaring world outside. And her grandfather was that play-actor gone mad, Czar Paul of Russia, who tore the passion so into tatters that his own sons rose and killed him.

Once given the key to this view of Frederic’s character, a strange cloud of corroborative witnesses are at hand. Take one example. Most of the pictures of him drawn at the period of his greatest popularity—during and just after the Franco-German war—pourtray him with a long-bowled porcelain pipe in his hand. The artists in the field made much of this: every war correspondent wrote about it. The effect upon the public mind was that of a kindly, unostentatious, pipe-loving burgher—and so lasting was it that when, seventeen years later, he was attacked by cancer, many good people hastened to ascribe it to excessive smoking. I had this same notion, too, and therefore was vastly surprised, in Berlin, years after, when a General Staff officer told me that Frederic rather disliked tobacco. I instanced the familiar pictures of him with his pipe. The instant reply was: “Ah, yes, that was like him. He always carried a pipe about at headquarters to produce an impression of comradeship on the soldiers, although it often made him sick.”

It was hard work to credit this theory—until it was confirmed by a passage in Sir Morell Mackenzie’s book. In response to the physician’s question, Frederic said the report of his being a great smoker was “quite untrue, and that for many years he had hardly smoked at all.” He added that probably this report, coming from soldiers who had seen him sometimes solacing himself after a hard-fought battle with a pipe, had given him his “perfectly undeserved reputation” as a devotee of tobacco.*

* “The Fatal Illness of Frederic the Noble,” p. 20.

But the most striking illustrations of this trait, which Germans suspected in Frederic, are given in Gustav Freytag’s interesting book, “The Crown Prince and the Imperial Crown.” It may be said in passing that even among Conservatives in Berlin there is a feeling that Freytag should not have published this book. No doubt it tells the truth, but then Freytag owed very much to the tender friendship and liking of Frederic, who conspicuously favoured him above other German writers, and wrote kindly things about him in his diary—and, if the truth had to be told, some other than Freytag should have told it. Coupled as it is in the public mind with Dr. Friedberg’s desertion, heretofore spoken of, this behaviour of another of the dead Prince’s friends is felt to help justify the low opinion of German gratitude held among scoffing neighbours. As a Berlin official said in comment to the writer: “When men like Friedberg and Freytag do these things to the memory of their dead patron, it is no wonder that foreigners call us Prussians a pack of wolves, ready always to leap upon and devour any comrade who is down.”

Freytag was the foremost correspondent attached to Frederic’s headquarters in 1870-71, and enjoyed the confidence of the Crown Prince in extraordinary measure. Thus he is able to give us a detailed picture of the man’s moods and mental workings, day by day, during that eventful time. And this picture is a perfect panorama of varying phases of histrionism.

The Crown Prince was sedulously cultivating the popular impression of himself as a plain, hail-fellow-well-met, friendly Prince. But Freytag says: “The traditional conception of rank and position dwelt ineradicably in his soul; when he had occasion to remember his own claims, he stood more vehemently on his dignity than others of his class.... Had destiny allowed him a real reign, this peculiarity would probably have shown itself in a manner unpleasantly surprising to his contemporaries.” *

* “The Crown Prince and the German Imperial Crown,” by

Gustav Freytag, p. 27.

More important still is this remark on the following page: “The idea of the German Empire grew out of princely pride in his soul; it became an ardent wish, and I think he was the originator and motive power of this innovation.”

The fact that it was Frederic who conceived the idea of the Empire first came to the world when Dr. Geffcken printed that famous portion of the Crown Prince’s diary which led to prosecutions and infinite scandal. Freytag’s subsequent publication surrounds the fact with most curious minutiae of detail.

As early as August 1st, before his Third Army had even crossed the Rhine, Frederic had broached the idea of an empire, with Prussia at its head. All through the campaign which followed his head was full of it. He busied his mind with questions of titles, precedence, &c., to grow out of the new creation. One afternoon—August 11th—he strolled on the hillside with Freytag for a talk. “He had put on his general’s cloak so that it fell around his tall figure like a king’s mantle, and had thrown around his neck the gold chain of the Hohenzollern order, which he was not wont to wear in the quiet of the camp—and paced elated along the village green. Filled with the importance which the emperor idea had for him, he evidently adapted his external appearance to the conversation.” During this talk he asked what the new title of the King of Prussia should be, and the anti-imperialist Freytag suggested Duke of Germany. Then “the Crown Prince broke out with emphasis, his eyes flashing: ‘No! he must be Emperor!’” * To create this empire Frederic was quite ready to forcibly coerce the Southern German States. Bismarck and William I., whom we think of as rough, hard, arbitrary men, shrank from even considering such a course. To the enthusiastic and slightly unreal Frederic it seemed the most natural thing in the world. The account in his diary of the long interview of Nov. 16, 1870, with Bismarck makes all this curiously clear. “What about the South Germans? Would you threaten them, then?” asks the Chancellor. “Yes, indeed!” answers our ideal constitutional Frederic, with a light heart. The interview was protracted and stormy, Bismarck ending it by resort to his accustomed trick of threatening to resign, a well-worn device which twenty years later was to be used just once too often.

* Freytag, p. 20.

In this same diary, under date of the following March (1871), Frederic writes: “I doubt whether the necessary uprightness exists for the free development of the Empire, and think that only a new epoch, which shall one day come to terms with me, will see that.... More especially I shall be the first Prince who has to appear before his people after having honourably declared for constitutional methods without any reserve.”

One feels that these two passages from his own diary—the utterances of November and the reflections of March—show distinctly why the practical rulers, soldiers, and statesmen of Prussia distrusted Frederic. They saw him more eager and strenuous about grasping the imperial dignity than any one else—willing even to break treaties and force Bavaria, Saxony, and Würtemberg into the empire at the cannon’s mouth, and then they heard him lamenting that until he came to the throne there would not be enough “uprightness” to insure The Empress Frederic “constitutional methods.” Candidly, it is impossible to wonder at their failure to reconcile the two.

An even more acute reason for this suspicion and dislike lay in Frederic’s relations with the English Court. To begin with, there was a sensational and fantastic uxoriousness about his attitude toward his wife which could not command sympathy in Germany. Freytag tells of his lying on his camp bed watching the photographs of his wife and children on the table before him, with tears in his eyes, and rhapsodizing about his wife’s qualities of heart and intellect to the newspaper correspondent, until Freytag promised to dedicate his next book to her. “He gave me a look of assent and lay back satisfied.” This in itself would rather pall on the German taste.

Worse still, Frederic used to write long letters home to his wife every day—often the work of striking the camp would be delayed until these epistles could be finished—and then the Crown Princess at Berlin would as regularly send the purport of these to her royal relatives in England and thence it would be telegraphed to France. Bismarck always believed, or professed to believe, that there was concerted treachery in this business. No one else is likely to credit this assumption. But at all events the fact is that this embarrassing diffusion of news was discovered and complained of at the time, and charged against Frederic, and was the reason, as Bismarck bluntly declared during the discussion over the diary, why the Crown Prince was not trusted by his father or allowed to share state secrets.

As for the Empire itself, though the original idea of it was his, Frederic suffered the fate of many other inventors in having very little to do with it after it was put into working order. He presented a magnificently heroic figure on horseback in out-of-door spectacles, and his cultured tastes made the task of presiding over museums and learned societies congenial. But there his participation in public affairs ended.

The Empire he had dreamed of was of a wholly different sort from this prosaic, machine-like, departmental structure which Bismarck and Delbruck made. Frederic’s vision had been of some splendid, picturesque, richly-decorated revival of the Holy Roman Empire. There are a number of delightful pages in Freytag’s book giving the Crown Prince’s romantic views on this point. * When the first Reichstag met in 1871, to acclaim the new Emperor in his own capital, Frederic introduced into the ceremony the ancient throne chair of the Saxon Emperors, which may now be seen in Henry’s palace at Goslar, and which, having lain unknown for centuries in a Harz village, was discovered by being offered for sale by a peasant as old metal some seventy years ago.

* Fryetag, pp. 115-130.

Among practical Germans this attempt to link their new Empire with the discredited and disreputable old fabric, which had been too rotten for even the Hapsburgs to hold together, was extremely distasteful. Yet Frederic clung to this pseudo-mediævalism to the last. When he came to the throne as Kaiser his first proclamation spoke of “the re-established Empire.” And those who were in Berlin at the time know how a whole day’s delay was caused by the dissension over what title the new ruler should assume—the secret of which was that he desired to call himself Kaiser Friedrich IV, thus going back for imperial continuity to that Friedrich III who died while Martin Luther was a boy, and who is remembered only because he was the father of the great Max and was the original possessor of the Austrian under lip.

Freytag indeed says that to that first proclamation Frederic did affix a signature with an IV—the assumption being that Bismarck altered it.

The reader has been shown this less satisfying aspect of Frederic, as his associates saw him, because without understanding it the attitude of both his father and his son towards him would be flatly unintelligible. They did not believe that he would make a safe Emperor for Germany.