Title: The Farmer's Veterinarian: A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of Farm Stock

Author: Charles William Burkett

Release date: August 16, 2017 [eBook #55366]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Charlene Taylor, Harry Lamé and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

FARM LIFE SERIES

THE FARMER’S VETERINARIAN

By Charles William Burkett

HANDY FARM DEVICES AND HOW TO MAKE THEM

By Rolfe Cobleigh

MAKING HORTICULTURE PAY

By M. G. Kains

FARM CROPS

By Charles William Burkett

PROFITABLE STOCK RAISING

By Clarence A. Shamel

PROFITABLE POULTRY PRODUCTION

By M. G. Kains

Other Volumes in Preparation

HEALTH

A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of Farm Stock: Containing Brief and Popular Advice on the Nature, Cause and Treatment of Disease, the Common Ailments and the Care and Management of Stock when Sick

By

CHARLES WILLIAM BURKETT

Editor of American Agriculturist

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

ORANGE JUDD COMPANY

1914

Copyright, 1909

Orange Judd Company

New York

Printed in U. S. A.

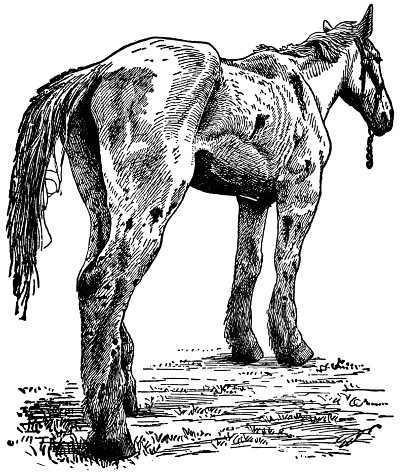

large class of people, by force of circumstances, are compelled to treat their own animals when sick or disabled. Qualified veterinarians are not always available; and all the ills and accidents incident to farm animals do not require professional attendance. Furthermore, the skilled stockman should be familiar with common diseases and the treatment of them. He should remember, too, that the maintenance of health and vigor in our farm stock is the direct result of well-directed management. Too frequently this is neither understood nor admitted, and an unreasonable lack of attention, when animals are ill or indisposed, works out dire mischief in the presence of physical disorder and infectious diseases. A fair acquaintance with the common ailments is helpful to the owner and to his stock. This leads to health, to prevention of disease, and to skill in attendance when disease is at hand.

The volume herewith presented abounds in helpful suggestions and valuable information for the most successful treatment of ills and accidents and disease troubles. It is an everyday handbook of disease and its treatment, and contains the best ideas gathered from the various authorities and the experience of a score of practical veterinarians in all phases of veterinary practice.

C. W. BURKETT.

New York, June, 1909.

[vi]

[vii]

| Page | |

|---|---|

| Introduction | |

| Facing Disease on the Farm | 1 |

| Chapter I. | |

| How the Animal Body is Formed | 9 |

| Chapter II. | |

| Some Physiology You Ought to Know | 21 |

| Chapter III. | |

| The Teeth as an Indication of Age | 34 |

| Chapter IV. | |

| Examining Animals for Soundness and Health | 39 |

| Chapter V. | |

| Wounds and Their Treatment | 54 |

| Chapter VI. | |

| Making a Post-Mortem Examination | 62 |

| Chapter VII. | |

| Common Medicines and Their Actions | 69 |

| Chapter VIII. | |

| Meaning of Disease | 82 |

| Chapter IX. | |

| Diagnosis and Treatment of Disease | 92 |

| Chapter X. | |

| Diseases of Farm Animals | 101 |

[viii]

[ix]

| Page | ||

|---|---|---|

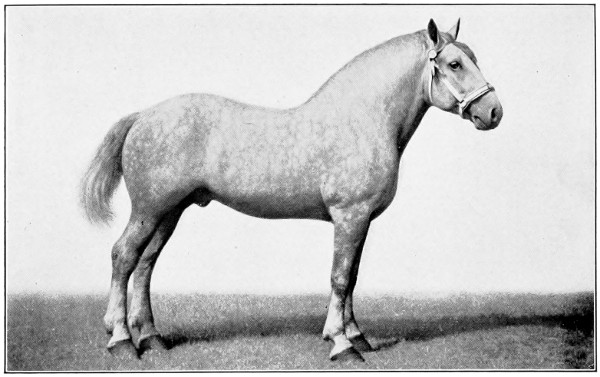

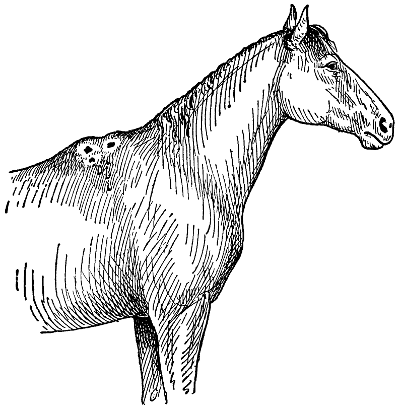

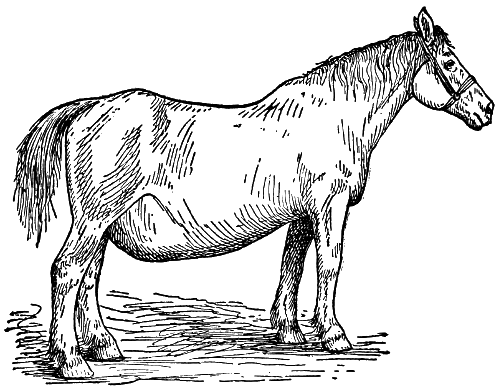

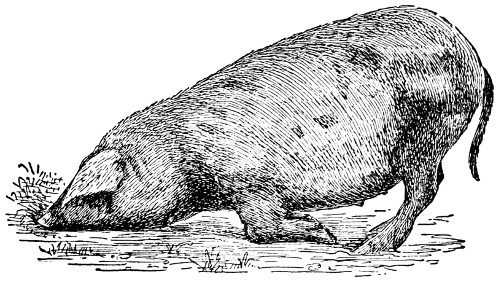

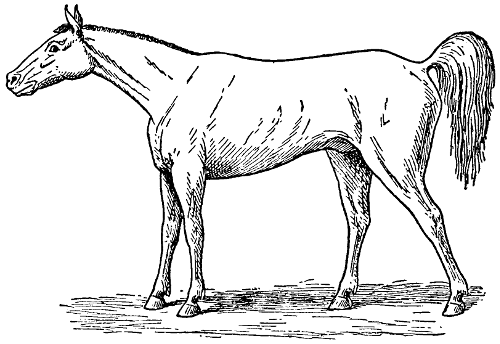

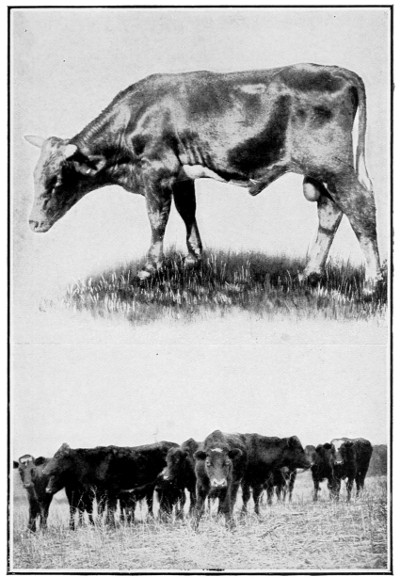

| 1. | Health | Frontispiece |

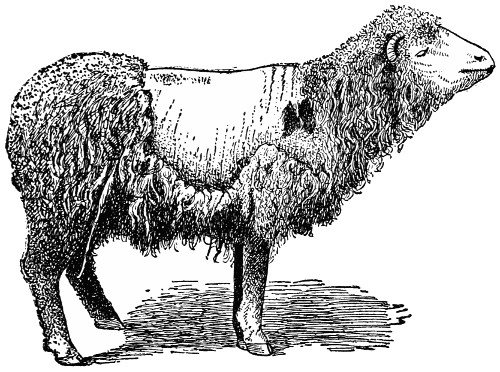

| 2. | Common Sheep Scab | 3 |

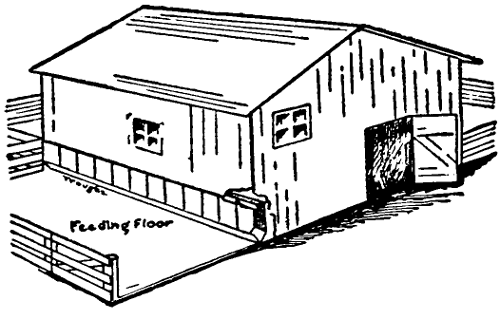

| 3. | Hog House and Feeding Floor | 5 |

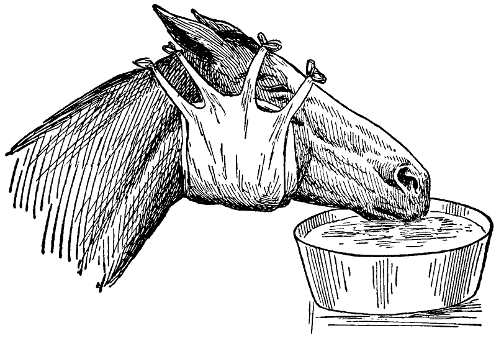

| 4. | Poulticing the Throat | 8 |

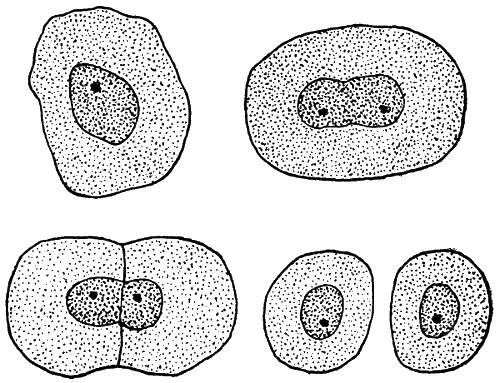

| 5. | How a Cell Divides | 10 |

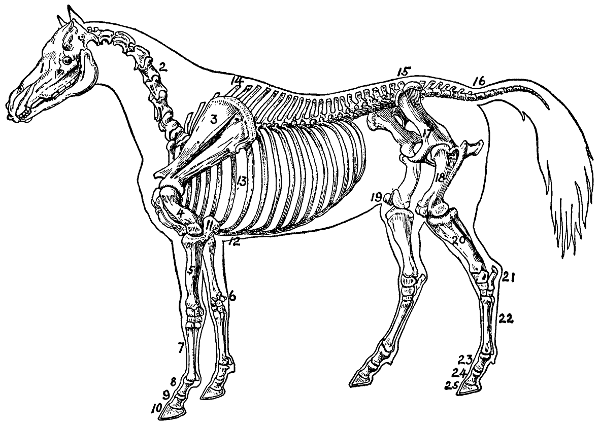

| 6. | Bones of Skeleton of a Horse | 16 |

| 7. | One of the Parasites of the Hog | 18 |

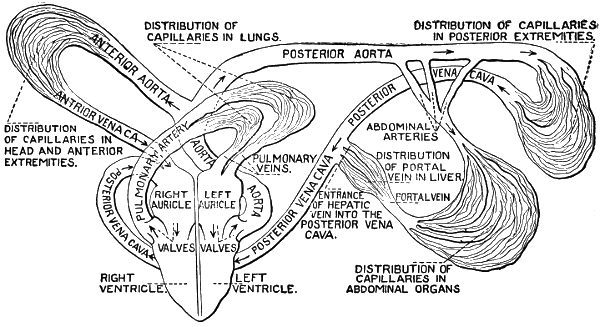

| 8. | Circulation and Digestion | 22 |

| 9. | Diseased Kidney | 25 |

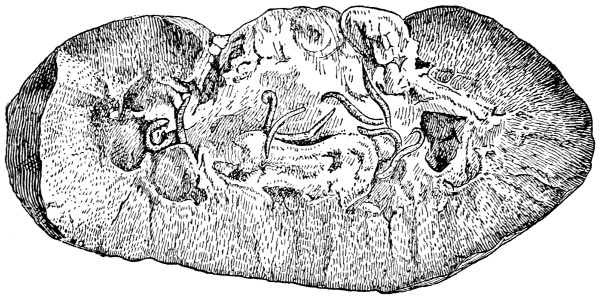

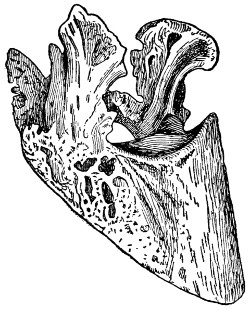

| 10. | Stomach of Ruminant | 27 |

| 11. | Circulation of Blood in Body | 30 |

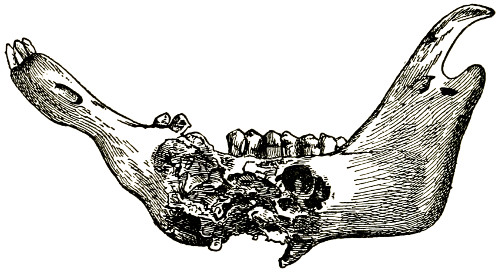

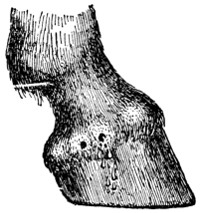

| 12. | Lumpy Jaw (jaw bone) | 36 |

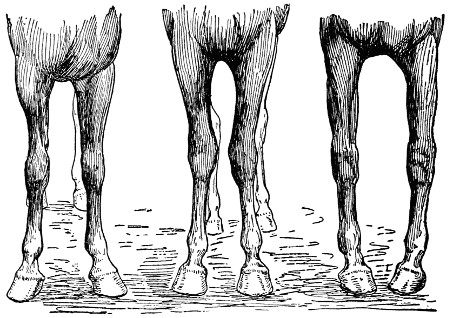

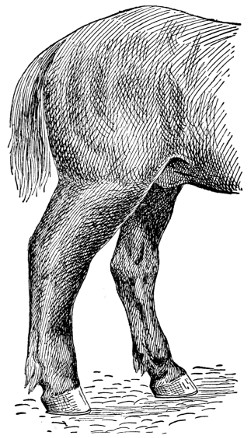

| 13. | Bad Attitude Due to Conformation | 41 |

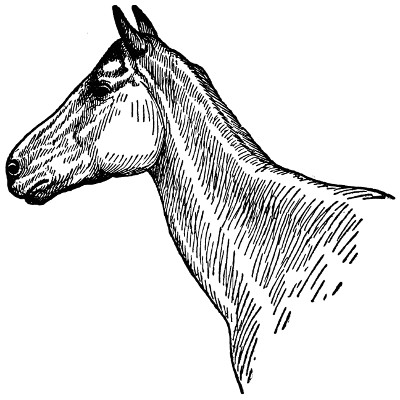

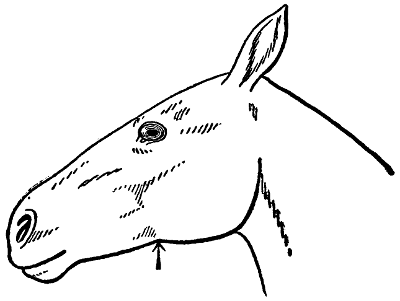

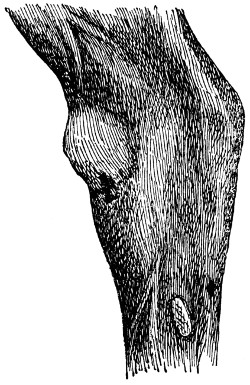

| 14. | Ewe Neck | 46 |

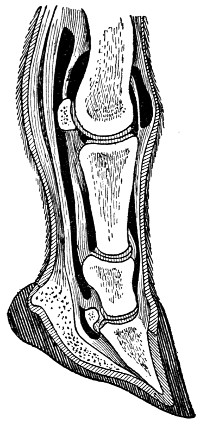

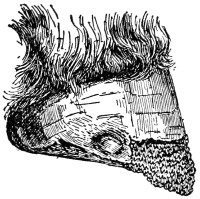

| 15. | Anatomy of the Foot | 49 |

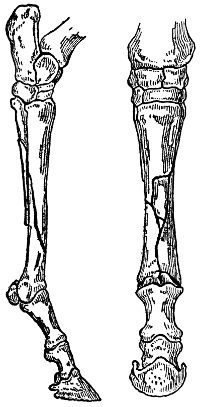

| 16. | Fractures | 54 |

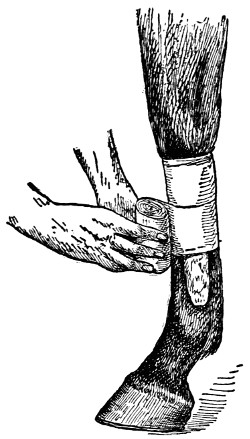

| 17. | Bandaging a Leg | 57 |

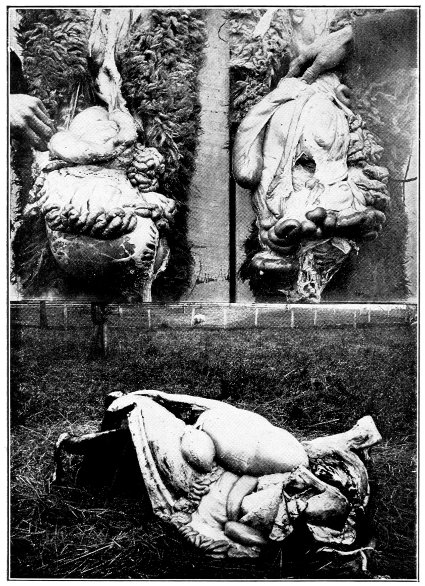

| 18. | Rickets in Pigs | 63 |

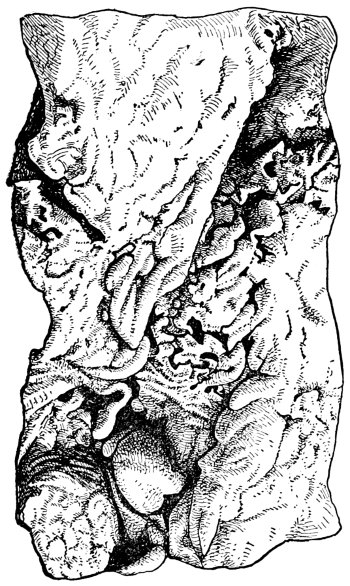

| 19. | Round Worms in Hog Intestines | 66 |

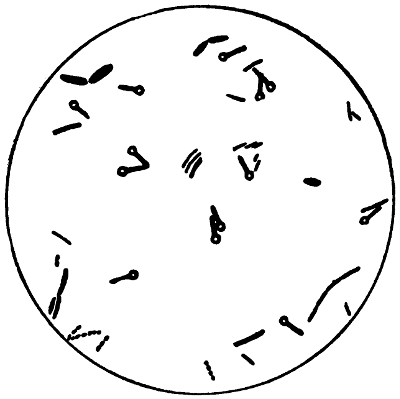

| 20. | Tetanus Bacilli | 71 |

| 21. | Ready for the Drench | 81 |

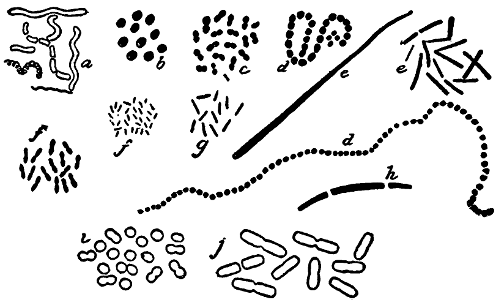

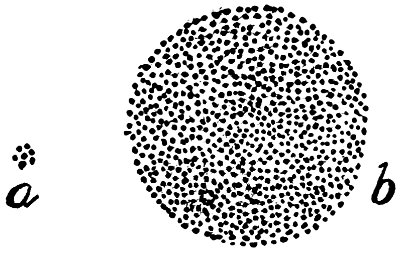

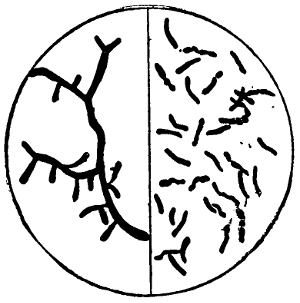

| 22. | Bacteria As Seen Under the Microscope | 85 |

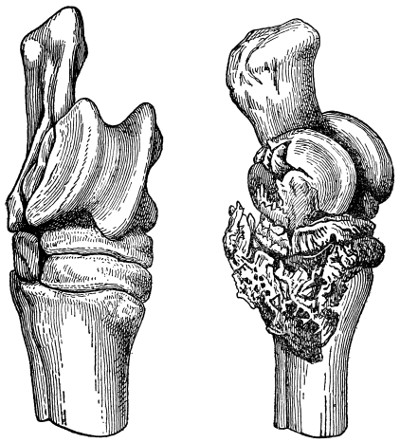

| 23. | Result of Bone Spavin | 90 |

| 24. | Feeling the Pulse | 94 |

| 25. | How Heat Affects Growth | 96 |

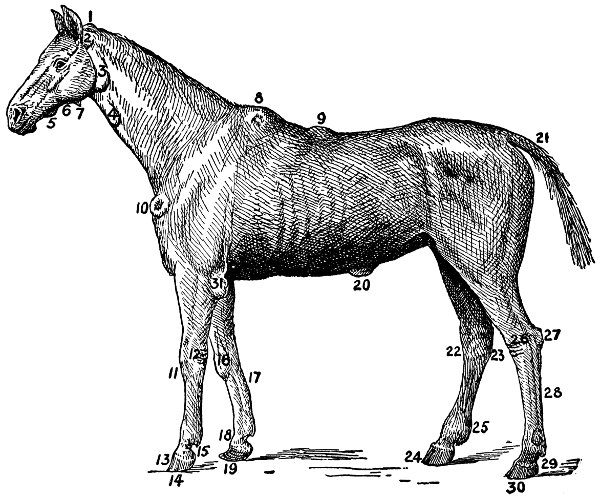

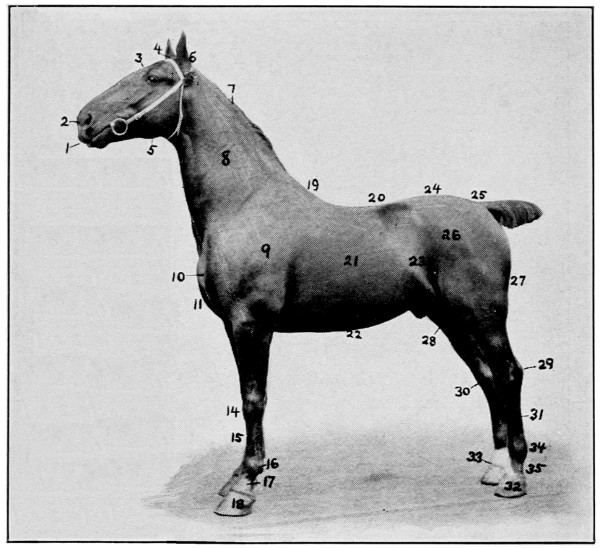

| 26. | Diseases of the Horse | 102 |

| 27. | Lumpy Jaw (external view) | 105 |

| 28. | Where to Tap in Bloating | 118 |

| 29. | Bog Spavin | 122 |

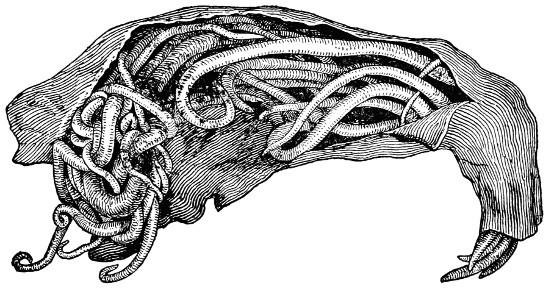

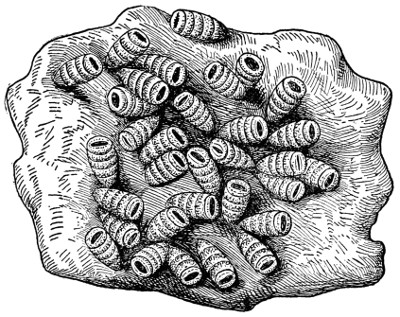

| 30. | Horse Bots in Stomach | 124 |

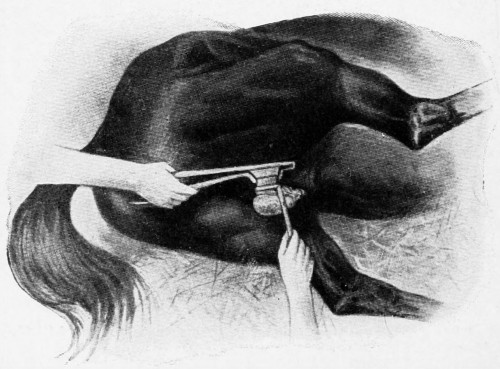

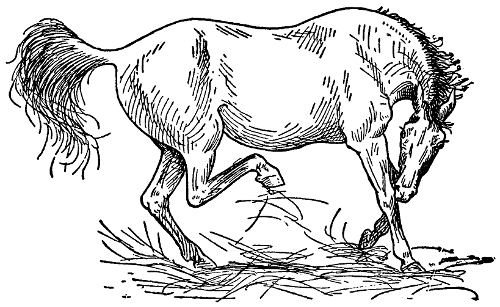

| 31. | Colic Pains | 138 |

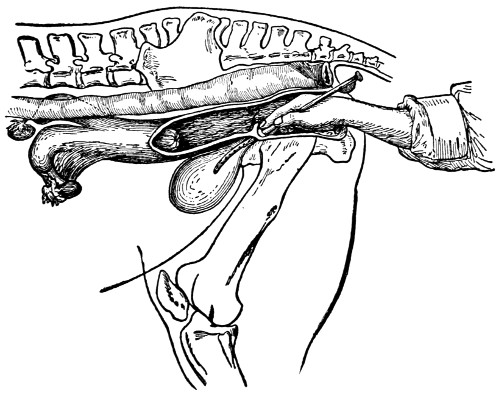

| 32. | Retention of the Urine | 141 |

| 33. | Curb | 145 |

| 34. | Fistulous Withers | 156 |

| 35. | Foot Rot in Sheep | 160 |

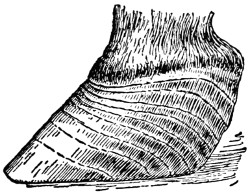

| 36. | Founder | 163 |

| 37. | Bad Case of Glanders | 170 |

| 38. | Ventral Hernia | 180 |

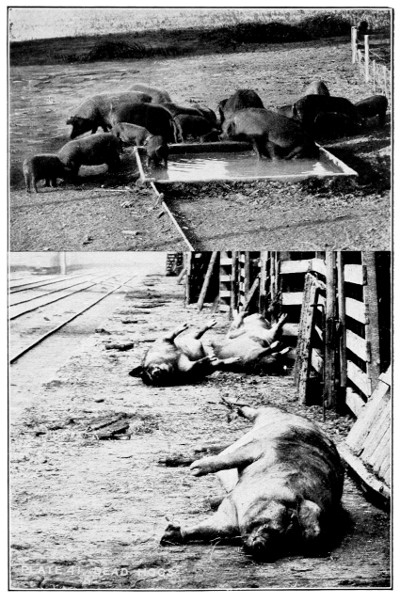

| 39. | An Attack of Cholera | 182 |

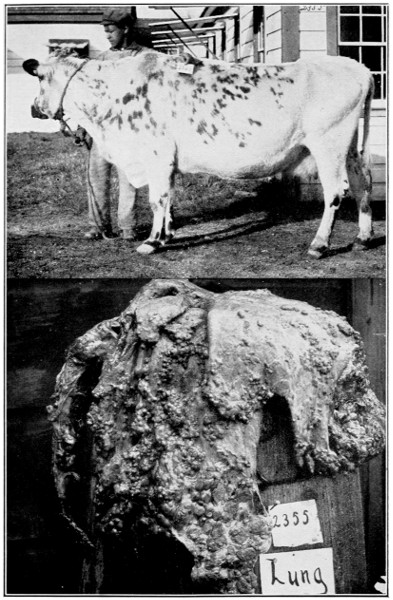

| 40. | The Result of Hog Cholera | 186 |

| 41. | Kidney Worms in the Hog | 205 |

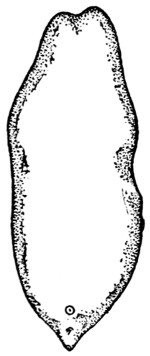

| 42. | Liver Fluke | 207 |

| 43. | Lockjaw | 209 |

| 44. | Lymphangitis | 215 |

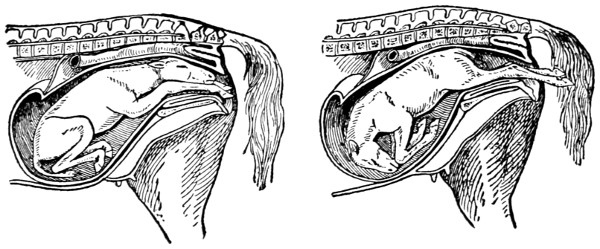

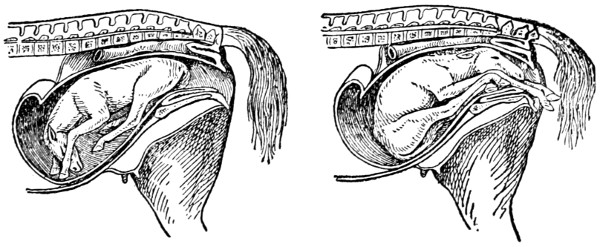

| 45. | Natural Presentation of the Foal | 225 |

| 46. | Abnormal Presentation of the Foal | 227 |

| 47. | Quittor | 235 |

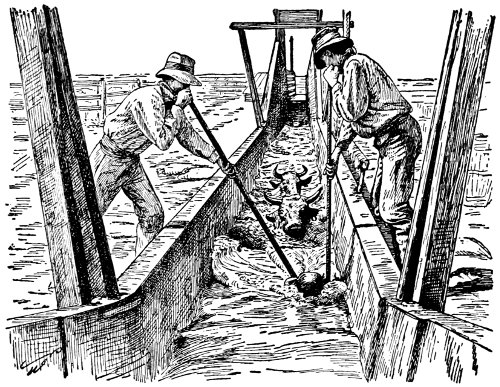

| 48. | A Cattle Bath Tub | 241 |

| 49. | Side Bones | 244 |

| 50. | Splint | 248 |

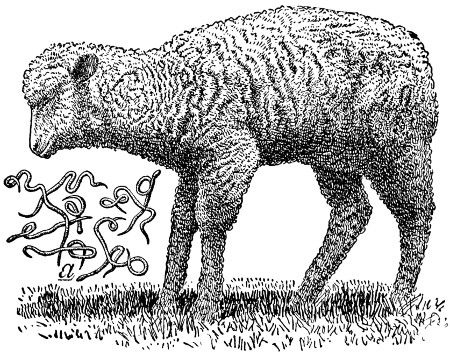

| 51. | Twisted Stomach Worms | 252 |

| 52. | Tuberculosis Germs | 264 |

| Health and Disease | Plate 1 | |

| Making Post Mortem Examinations | Plate 2 | |

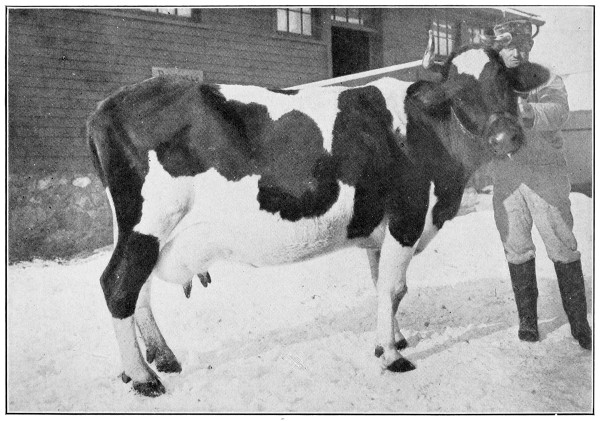

| A Victim of Tuberculosis | Plate 3 | |

| Exterior Points of the Horse; Castration | Plate 4 | |

| Texas Fever | Plate 5 | |

| A Typical Case of Foot and Mouth Disease | Plate 6 | |

[1]

To call a veterinarian or not—that is the question. Whether your horse or cow is sick enough for professional attendance, or just under the weather a little, is a problem you will always be called upon to face. And you must meet it. It has always faced the man who raises stock, and it is a problem that always will. Like human beings, farm stock have their ailments and troubles; and, in most cases, a little care and nursing are all that will be required. With these troubles all of us are acquainted; especially those who have spent much time with the flocks and the herds on the farm. Through experience we know that often with every reasonable care, some animals, frequently the healthiest-looking ones, in the field, or stable, give trouble at the most unsuspected times. So the fault is not always with the owner.

There is no reason, however, why an effort should not be made, just as soon as any trouble is noticed, to assist the sick animal to recover, and help nature in every way possible to restore the invalid to its usual normal condition. The average observing farmer, as a rule, knows just about what the trouble is; he usually knows if treatment is beyond him, and if not, what simple medical aid will be effective in bringing about a recovery with greater dispatch than nature unaided will effect.

Now, of course, this means that the farmer should be acquainted with his animals; in health and disease their actions should be familiar to him.[2] If he be a master of his business he naturally knows a great deal about his farm stock. No man who grows corn or wheat ever raises either crop extremely successfully unless he has an intimate knowledge of the soil, the seed, the details of fertilization and culture. He has learned how good soils look, how bad soils look; he knows if soils are healthy, whether they are capable of producing big crops or little crops.

So with his stock. He must know, and he does know, something as to their state of health or ill health. With steady observation his knowledge will increase; and with experience he ought to be able to diagnose the common ailments, and not only prescribe for their treatment, but actually treat many of them himself. Unfortunately, many farmers pass health along too lightly and the common disorders too seriously. This is wrong. The man who deals with farm animals should be well acquainted with them, just as the engineer is acquainted with his engine. If an engine goes wrong the engineer endeavors to ascertain the trouble. If it is beyond his experience and knowledge he turns the problem over to an expert. It should be so with the stock raiser. So familiar should the owner be with his animals in case of trouble he ought to know of some helpful remedy or to know that the trouble is more serious than ordinary, in which case the veterinarian should be called.

All of this means that the art of observing the simple functions should be acquired at the earliest possible moment—where to find the pulse of horse or cow, how many heart beats in a minute, how many respirations a minute, the color of the healthy nostril, the use of the thermometer and where to place it to get the information, the character of the[3] eye, the nature of the coat, the passage of dung and water, how the animal swallows, the attitude when standing, the habit of lying down and getting up—all of these should be as familiar to the true stockman as the simplest details of tillage or of planting or of harvesting.

COMMON SHEEP SCAB

Here is an advanced case and shows how serious the trouble may become. A very small itch mite is the cause. The mites live and multiply under the scurf and scab of the skin.

Moreover, the stockman should be a judge of external characters, whether natural or temporary. He should have a knowledge of animal conformation. If to know a good plow is desirable, then to know a good pastern or foot is desirable. If the art of selecting wheat is a worthy acquisition, then the art of comparing hocks of different horses is a worthy accomplishment also. If experience tells the grower that his corn or potatoes or cotton is strong, vigorous and healthy or just the reverse,[4] observation and experience ought also to tell him when his stock are in good health or when they lack thrift or are sick and need treatment.

Few farmers there are, indeed, who are not acquainted with crop diseases. Smut is readily recognized when present in the wheat or corn or oat field; so colic, too, should be recognized when your horse is affected by it. The peach and the apple have their common ailments; so have the cow and pig. In either case the facts ought to be familiar. So familiar that as soon as diagnosed and recognized prompt measures for treatment should be followed that the cure may be effected before any particular headway is at all made. Handled in this way, many cases that are now passed on to the veterinarian would never develop into serious disturbances at all.

The old saying, “Prevention is better than cure,” is both wisdom and a splendid platform on which to build any branch of live stock work. Every disease is the result of some disturbance, somewhere. It may be improper food; the stockman must know. Moldy fodder causes nervous troubles in the horse. Cottonseed meal, if fed continuously to pigs, leads to their death. Hence, food has much to do with health and disease. Ventilation of the stable plays its part. Bad air leads to weakness, favors tuberculosis, and, if not remedied, brings about loss and death. Fresh air in abundance is better than medicine; and the careful stockman will see that it be not denied.

[5]

Good sanitation, including cleanly quarters, wholesome water and dry stables, has its reward in more healthy animals. When not provided, the animals are frequently ill, or are in bad health more or less. As these factors—proper food, good ventilation, and effective sanitation—are introduced in stable accommodations, diseases will be lessened and stock profits will increase.

HOG HOUSE AND FEEDING FLOOR

This convenient hog house is inexpensive, and the feeding floor at the side insures cleanliness and thorough sanitary conditions. A sanitary hog house should be one of the chief improvements of the farm.

As disease is better understood it becomes more closely identified with germs and bacteria. Hence, to lessen disease we must destroy, so far as possible, the disease-producing germs. For this purpose nothing is better than sunlight and disinfectants. Sunlight is itself death to all germs; therefore, all stables, and the living quarters for farm animals, should be light and airy, and free from damp corners and lodgment places for dust, vermin, and bacteria. Even when animals are in good[6] health, disinfection is a splendid means for warding off disease. For sometimes with the greatest care germs are admitted in some manner or form. By constantly disinfecting, the likelihood of any encroachment by germs is greatly lessened.

Fortunately we have disinfectants that are easily applied and easily obtained at small cost. One of these disinfecting materials is lime, just ordinary slaked lime, the lime that every farmer knows. While it does not possess the disinfecting power of many other agents, it is, nevertheless, very desirable for sprinkling about stables and for whitewashing floors, walls, and partitions. When so used the cracks and holes are filled and the germs destroyed. Ordinary farm stables should be whitewashed once or twice each year, and the crumbled lime sprinkled on the litter or open ground. It is not desirable to use lime with bedding and manure, for the reason that it liberates the nitrogen contained therein. Hence the bedding and manure should be removed to the fields as frequently as possible, where it can be more helpful to the land. Thus scattered, the sunlight and purifying effects of the soil will soon destroy the disease bacteria, if any are present in the manure.

Another splendid disinfectant is corrosive sublimate, mercuric chloride, as it is often called. Use one ounce in eight gallons of water. This makes one-tenth of one per cent solution. In preparing this disinfectant, allow the material to stand for several hours, so as to permit the chemical to become entirely dissolved. This solution should be carefully guarded and protected, since it is a poison and, if drunk by animals, is liable to cause death. If infected quarters are to be disinfected, see that[7] the loose dirt and litter is first removed before applying the sublimate.

Carbolic acid is another satisfactory disinfectant. Usually a five per cent solution is recommended. It can be easily applied to mangers, stalls, and feed boxes. Enough should be applied so that the wood or iron is made wet and the cracks and holes more or less filled. Chloride of lime is a cheap and an easily prepared disinfectant. Use ten ounces of chloride of lime to two gallons of water. This makes a four per cent solution, and should be applied in the same way as the corrosive sublimate.

Formalin has come into prominence very recently as a desirable disinfectant. A five per cent solution fills the bill. Floors and cracks should be made thoroughly wet with it. By using one or more of these agents the living quarters of farm animals can be kept wholesome, sweet, and free from germ diseases. In fact, the use of disinfectants is one of the best aids of the farmer in warding off disease and in lessening its effects when once present.

Many diseases are introduced into a herd or flock by thoughtlessness on the part of the owner. I have known distemper to be introduced into stables and among horses, Texas fever and tuberculosis into herds of cattle, and hog cholera among hogs, because diseased animals, when purchased, were not separated off by themselves, for a short time at least. If this were done, farmers would lessen the chance of an introduction of disease into their healthy herds. Consequently quarantine quarters should be provided; especially is this true if new[8] animals are frequently purchased and brought to the farm where many animals are raised and handled. These quarantine quarters need not be expensive, and they ought to be removed far enough from the farm stock so that there may be no easy means of infection. When newly purchased animals are placed in the quarantine quarters they should be kept there long enough to determine if anything strange or unusual is taking place.

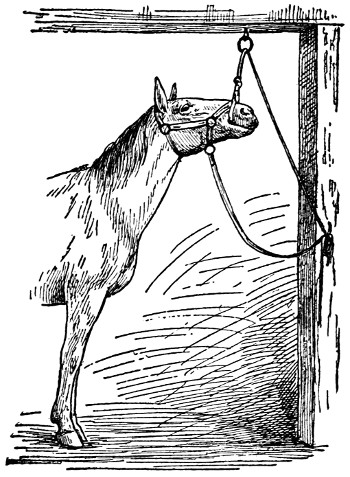

POULTICING THE THROAT

The picture shows how to apply a poultice to the throat.

[9]

The cell is the unit of growth. It is so with all forms of life—plant or animal, insect or bacterium. In the beginning the start is with a single cell, an egg, if you please. After fertilization has taken place, this single cell enlarges or grows. Many changes now occur, all rather rapidly, until the cell walls become too small, when it breaks apart and forms two cells just like the first used to be. This is known as cell division. As growth increases, the number of cells increases also—until in the end there are millions.

—The cell is very small. In most cases it cannot be seen with the naked eye. The microscope is necessary for a study of the parts, the nature and the character of the cell.

In the first place the cell is a kind of inclosed sac, in which are found the elements of growth and life. Surrounding the cell is a thin wall known as the cell membrane. In plants this cell wall is composed of cellulose, a woody substance, which is thin and tender in green and growing plants, but hard and woody when the plant is mature.

Within the limits of the cell is the protoplasm, the chief constituent of the cell; locked up in this protoplasm is life, the vital processes that have to do with growth, development, individual existence.

Embedded within the protoplasm is another part known as the nucleus and recognized under the microscope by its density. Around the nucleus is[10] centered the development of new cells or reproduction—for the changes that convert the mother-cell into offspring-cells are first noted in this place.

HOW A CELL DIVIDES

The simple steps in cell division are pictured here. Starting with a single cell, growth and enlargement take place, ending finally in cell division or the production of two individual cells.

So much for plant cells. Is this principle different in animals? For a long time it was thought that plants and animals were different. But upon investigation it was discovered that animals were comprised of cells just as plants. And not only was this discovered to be true, but also that animal cells corresponded in all respects to plant cells. Hence in animals are to be found cells possessing the cell walls formed of a rather thick membrane, the granular protoplasm or yoke, and the nucleus established in the yoke.

[11]

The ovum, known as the female egg, is composed of the parts just described. If it is not fertilized when ripe it passes away and dies. If fertilized in a natural way, it enlarges in size and subsequently divides into two cells; and these, passing through similar changes, finally give rise to the various groups of cells from which the body is developed.

—The body is, therefore, a mass of cells; not all alike, of course, but grouped together for the purpose of doing certain special kinds of work. In this way we have various groups, with each group a community performing its own function. The brain forms one community; and these cells are concerned with mind acts. The muscle cells are busy in exerting force and action. Another group looks after the secretions and digestive functions, while another group is concerned solely with the function of generation and reproduction. And so it is throughout the body.

Both individual cells and group cells are concerned with disease. One cell may be diseased or destroyed, but the surrounding ones may go on just the same. It is when the group is disturbed that the greatest trouble results.

—The cell always possesses its three parts—membrane, protoplasm, and nucleus. But there is no rule as to the size or shape. Cells may be round or oblong, any shape. Substances pass in and out of the cell walls; and they are in motion, many of them, especially those that line the intestines and the air passages, and the white corpuscles of the blood. More than this, some cells, Dr. Jekyl-like, change their appearance and shape, send out finger-like bodies to catch[12] enemies or food, and even travel all around in the body, often leaving it altogether.

The animal body contains five forms of tissues: Epithelial, in which the cells are very compact, forming either thin or thick plates; the connective tissue, by which many organs are supported or embedded; muscle tissue, either smooth or striated, and in which the cells are in fibers that contract and shorten; nerve-tissue, that has to do with nerve and ganglion cells by which mental impulses are sent; and blood and lymph tissue or fluid tissues.

The first group is intimately connected with the secretory organs, or those organs which secrete certain substances essential for the proper work of the body. Thus we have salivary glands, mucous glands, sweat glands, and the liver and pancreas. Connective tissue includes fibrous tissue, fatty tissue, cartilage and bone. The fibrous connective tissue is illustrated when the skin is easily picked up in folds. Fatty tissue occurs where large amounts of fat are deposited in the cells. Cartilage is found where a large amount of firm support is required. With muscle we are all familiar; it is the real lean meat of the body.

—The blood is a fluid in which many cells are to be found. The fluid is known as serum or blood-plasma and the cells as corpuscles, and are both red and white. The red cells give the characteristic color. When observed under a microscope, they appear as small, round disks. They are of great importance to the body work. Because of the coloring matter in them the oxygen of the air is attracted when it comes in[13] contact with the blood in the lungs. Oxygen is in reality absorbed, and on the blood leaving the lungs it is distributed to all parts of the body. The oxygen supply of the body is, therefore, in the keeping of the red corpuscles.

White corpuscles have a different work; they guard the body by picking up poison, bacteria, and other undesirable elements and cast these out through the natural openings of the body. Compared with the red cells, they exist in far less numbers and may wander about through all parts of the body.

Lymph is a fluid in which a few cells, lymph corpuscles, are suspended. These cells are very much like the colorless corpuscles of the blood, only no red blood cells are present. But the lymph attends to its own business; it bathes the tissues and endeavors to keep them in a healthy condition.

—Without a covering the delicate muscles would be unprotected. The skin serves in this capacity. It does still more; out of it is exuded poisonous substances, perspiration, and, at the same time, the skin is a sort of respiratory organ, through which much of the carbonic acid formed in the body escapes.

The skin possesses two general layers, the cutis and sub-cutis; in the first is contained also epidermis. Developed in the skin are the outer coverings like hair, wool, feathers, horns, claws, and hoofs.

The framework of the body undergoes a gradual development from birth to maturity. It represents the bony structure of the body; and on it all other[14] parts depend for support and protection. The brief summary of its parts and work that follows here has been adapted from Wilcox and Smith.

—This consists of a backbone, skull, shoulder girdle, pelvic girdle, and two pairs of appendages. The backbone may be conveniently divided into regions, each comprising a certain number of vertebræ. The cervical vertebræ include those from the skull from the first rib. In all mammals except the sloth and sea cow the number of cervical vertebræ is seven, being long or short, according as the neck of the animal is relatively long or short. The first and second cervical vertebræ, known as the atlas and axis, are especially modified so as to allow free turning movements of the head.

The next region includes the dorsal or thoracic vertebræ, which are characterized by having ribs movably articulated with them. The number is 13 in the cat, dog, ox, sheep, and goat; 14 in the hog; 18 or 19 in the horse and ass, and six or seven in domestic poultry. In mammals they are so joined together as to permit motion in several directions, but in poultry the dorsal vertebræ are more rigidly articulated, those next to the sacrum often being grown together with the sacrum. The spines are high and much flattened in all ungulates, long and slender in dogs and cats. They slope backward, forming strong points of attachment for the back muscles. Several ribs, varying in number in different animals, meet and become articulated with the breast bone or sternum. The sternum consists of seven to nine articulated segments in our domestic mammals, while in fowls the sternum is one thin high bone furnished with a keel of varying depth. The lumbar vertebræ lie between the dorsal[15] vertebræ and the sacrum. The number is five in the horse, six in the hog, ox and goat, and seven in the sheep. The sacrum is made up of a certain number of vertebræ, which are rigidly united and serve as an articulation for the pelvic arch. The number of sacral vertebræ is five in the ox and horse, four in sheep and hogs, and 12 to 17 in birds. The caudal or tail vertebræ naturally vary in number according to the length of the tail (7 to 10 in sheep, 21 in the ox, 23 in hogs, 17 in the horse, 22 in the cat, 16 to 23 in the dog).

In ungulates the anterior ribs are scarcely curved, the chest being very narrow in front. The number of pairs of ribs is the same as the number of dorsal vertebræ with which they articulate.

—This part of the skeleton is really composed of a number of modified vertebræ, just how many is not determined. The difference in the shape of the skulls of different animals is determined by the relative size of the various bones of the skull. In hogs, for example, the head has been much shortened as a result of breeding, thus giving the skull of the improved breeds a very different appearance from that of the razorback.

The shoulder girdle consists of a shoulder blade, collar bone and coracoid on either side. The fore leg (or wing, in case of birds) articulates with the socket formed by the junction of these three bones. In all the ungulates the shoulder blade is high and narrow, the coracoid is never much developed, and the collar bone is absent. In fowls all three bones of the shoulder girdle are well developed, the collar bone being represented by the “wish bone.”

—This consists of three bones

on either side, viz., ilium, ischium, and pubis. The

first two are directly articulated to the spinal[16]

[17]

column, while the pubic bones of either side unite

below to complete the arch. The three bones of

each side of the pelvis are present in all our

domestic animals, including the fowls.

BONES OF THE SKELETON OF A HORSE

1 Face Bones, 2 Neck Bones or Cervical Vertebræ, 3 Scapula or Shoulder Blade, 4 Humerus or Arm Bone, 5 Radius or Bone of Forearm, 6 Carpus or Knee, 7 Shank Bone or Cannon, 8 Upper Pastern, 9 Lower Pastern, 10 Coffin Bone, 11 Ulna or Elbow, 12 Cartilages of the Rib, 13 Costæ or Ribs, 14 Dorsal Vertebræ or Bones of Back, 15 Lumbar Vertebræ or Bones of Loin, 16 Candal Vertebræ or Bones of Tail, 17 Haunch, 18 Femur or Thigh Bone, 19 Stifle Joint, 20 Tibia, 21 Tarsus or Hock, 22 Metatarsal Bones, 23 Upper Pastern Bone, 24 Lower Pastern Bone, 25 Coffin Bone.

—There is one formula for the bones of the fore and hind legs of farm animals. The first segment is a single bone, the humerus of the fore leg, femur of the hind leg. In the next segment there are two bones, radius and ulna in the fore leg, tibia and fibula in the hind leg. In the dog, cat, and Belgian hare the radius and ulna are both well developed and distinct. In ungulates the humerus is short and stout, while the ulna is complete in the pig, rudimentary and behind the radius in ruminants and firmly united with the radius in the horse. Similarly with the hind leg the fibula is a complete bone in the pig, while in the horse there is merely a rudiment of it, attached to the tibia.

—The mammalian skeleton has undergone the greatest modification in the bones of the feet. In the horse there are only six of the original ten wrist or carpal bones, and, since there is but one of the original five toes, the horse has also but one metacarpal or cannon bone. Splint-like rudiments of two other metacarpal bones are to be found at the upper end of the cannon bone, or at the “knee” joint. Below the cannon bone, and forming the shaft of the foot, we have the small cannon bone, coronary bone, and coffin bone—the last being within the hoof with the navicular bone behind it. The stifle joint of the horse corresponds to the knee of man. The “knee” of the horse’s fore leg corresponds to the hock of the hind leg, both being at the upper end of the cannon bone. The fetlock joint is between the large and small cannon bones,[18] the pastern joint between the small cannon or large pastern bones, and the coffin joint between the coronary and coffin bones. The horse walks upon what corresponds to the nail of the middle finger and middle toe of man.

In pigs four digits touch the ground, the first being absent and the third and fourth larger and in front of the second and fifth. In ruminants the third and fourth digits reach the ground, while the second and fifth do not. In dogs the first digit appears on the side of the leg, not in contact with the ground.

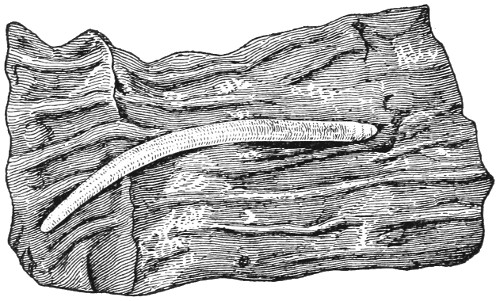

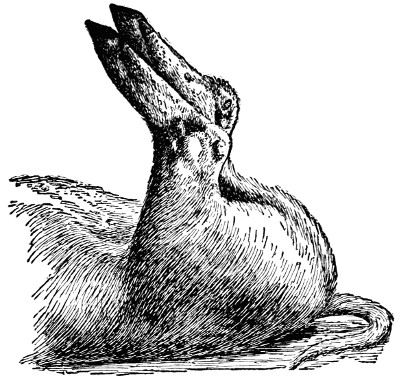

ONE OF THE PARASITES OF THE HOG

The thorn-headed worm attached to the anterior part of the small intestine often causes death. Not more than five or six are usually found in a single animal.

In fowls the wing, which corresponds to the fore leg of mammals, shows a well-developed humerus, radius and ulna, while only one carpal and one metacarpal bone remain, along which the wing feathers are attached. In the leg the femur and tibia are strong bones, but the fibula is a mere splint. The tarsal bones are absent, while the shank consists of a metatarsal bone (really three bones fused together), to which the four toes are articulated.

[19]

—The muscular system is too elaborate, the number of muscles too great, and their modifications for different purposes too complex for consideration in detail in the present volume. All muscles are either striped or unstriped (as examined under the microscope), according as they are under the immediate control of the will or not. The heart muscle forms an exception, for it is striped though involuntary. The essential characteristic of muscle fibers is contractility, which they possess in high degree. The typical striped muscles are concerned in locomotion, being attached at either end to a bone and extending across some movable joint. The most important unstriped muscles are found in the walls of the intestines and blood vessels.

—In so far as our present purposes are concerned, the nervous system may be disposed of in a few words. The central nervous system consists of a brain and spinal cord. The microscopic elements of this tissue are peculiarly modified cells, consisting of a central body, from which fibers run in two or more directions. The cell bodies constitute the gray matter, and the fibers the white matter of the brain and spinal cord. The gray substance is inside the spinal cord and on the surface of the brain, constituting the cortex. The most important parts of the brain are the cerebrum, optic lobes, cerebellum, and medulla. There are twelve pairs of cranial nerves originating in the brain and controlling the special senses, movements of the face, respiration, and pulse rate. From each segment of the spinal cord a pair of spinal nerves arises, each of which possess both sensory and motor roots. The sympathetic nervous system consists of a trunk on either side, running[20] from the base of the skull to the pelvis, furnished with ganglionic enlargements and connected with the spinal nerves by small fibers.

—These include the nose, larynx, trachea or windpipe, and lungs. The trachea forks into bronchi and bronchioles of smaller and smaller size, ending in the alveoli or blind sacs of the lungs. In fowls there are numerous extensions of the respiratory system known as air sacs, and located in the body cavity and also in the hollow bones. The air sacs communicate with the lungs, but not with one another.

—These consist of kidneys connecting by means of ureters with a bladder from which the urethra conducts the urine to the outside. In the male the urethra passes through the penis and in the female it ends just above the opening of the vagina. The kidneys are usually inclosed in a capsule of fat. The right kidney of the horse is heart-shaped, the left bean-shaped. Each kidney of the ox shows 15 to 20 lobes, and is oval in form. The kidneys of sheep, goats, and swine are bean-shaped and without lobes.

—This consists of ovaries, oviducts, uterus or womb, and vagina in the female; the testes, spermatic cords, seminal vesicle and penis, together with various connecting glands, especially prostate gland and Cowper’s gland, in the male. In fowls there is no urinary bladder, but the ureters open into the cloaca or posterior part of the rectum. The vagina and uterus are also wanting in fowls, the oviducts opening directly into the rectum. The male copulating organ is absent except in ducks, geese, swan, and the ostrich.

[21]

A close relation exists between the soil, plant, and the animal. One really cannot exist without the other to fulfill its destiny. A soil without plant or animal growth is barren, devoid of life. The soil comes first; the elements contained in it and the air are the basis of plant and animal life. The body of the animal is made up of the identical elements found in the plant, yet the growth of the plant is necessary to furnish food for animal life. The plant takes from the soil and from the air the simple chemical elements, and with these builds up the plant tissue which, in its turn, is the food of the animal.

The animal cannot feed directly from the soil and air; it requires the plant first to take the elements and to build them into tissue. From this tissue animals get their food for maintenance and growth. Then the animal dies; with its decay and decomposition comes change of animal tissue, back to soil and air again; back to single simple elements, that new plants may be grown, that new plant tissue may be made for another generation of animal life.

Thus the plant grows out of the soil and air, and the decay of the animal plant life furnishes food for the plant that the plant may furnish food for the animal. Thus we see the cycle of life; from the soil and air come the soil constituents.

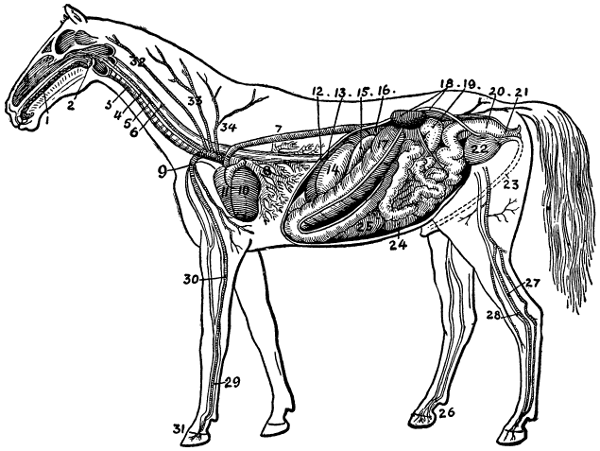

CIRCULATION AND DIGESTION

1 Mouth, 2 Pharynx, 3 Trachea, 4 Jugular Vein, 5 Carotid Artery, 6 Œsophagus, 7 Posterior Aorta, 8 Lungs, 9 External Thoracic Artery, 10 Left Auricle, 11 Right Auricle, 12 Diaphragm, 13 Spleen, 14 Stomach, 15 Duodenum, 16 Liver, upper extremity, 17 Large Colon, 18 Left Kidney and its Ureter, 19 Floating Colon, 20 Rectum, 21 Anus, 22 Bladder, 23 Urethra, 24 Small Intestine, 25 Cæcum, 26 Venous Supply to the Foot, 27 Posterior Tibial Artery, 28 Internal Metatarsal Vein, 29 Internal Metatcarpal Vein, 30 Posterior Radial Artery, 31 Metacarpal Artery, 32 Vertebral Artery, 33 Superior Cervical Artery, 34 Anterior Dorsal Artery.

—Before the single

simple elements were taken into the plant, they[22]

[23]

were of little value. The animal could not use

them for food, they could not be burned to furnish

heat, and they stored up no energy to carry on any

of the world’s work. What a change the plant

makes of them! So used, they become the source

of the animal food, and, as food, they contain five

principal groups with which the animal is nourished.

These five groups are the air, water, the

protein compounds, the nitrogen free compounds,

such as starch, crude fiber, sugar and gums, and

the fat or ether extract, as it is called.

Before these different constituents of the plant can be used as food for animals, they must be prepared for absorption into the system of the animal. This preparation takes place in the mouth, œsophagus tube, the stomach, and the intestines, aided by the various secretions incident to digestion and absorption. Any withholding of any essential constituent has its result in inefficiency or illness of the animal.

Withhold ash materials, for instance, from the food, or supply an insufficient quantity, and the fact will be evidenced by poor teeth, deficient bone construction and poor health in general. Let the feeding ration be short in protein, and the result will be shown in the flesh and blood. Let the carbohydrates and fat be withheld or supplied insufficiently, and energy will be denied and a thrifty condition will not be possible.

The supply of these different constituents in the proper proportion gives rise to the balanced ration; and is concerned in a treatise of this kind only in so far as it has to do with disease or health. For,[24] remember this fact: live stock are closely associated with right feeding. If foods be improperly prepared, or improperly supplied, or the rations poorly balanced, with too much of one constituent and too little of another, the effect will be manifest in an impoverished condition of the system. That means either disease, or disease invited.

Not only must these facts be considered, but other matters given recognition also. The greater part of the trouble of the stockman in the way of animal diseases is due to some disturbance of the digestive system, or to the water supply, or to ventilation, or to the use to which the animal is put from day to day. Attention to the details of digestion has its reward in thrifty, healthy stock; a lack of this attention brings trouble and either a temporary ailment or a permanent disease.

—Food is taken in the mouth, where it is masticated by means of the teeth, lips, cheeks, and the tongue. While the process of mastication is taking place there is being poured into the mouth large quantities of saliva, which softens the food and starts the process of digestion. The active principle of saliva is a soluble ferment, called ptyalin, that converts the starch of food into sugar. The amount of saliva that is poured into the food is very great, being often as much as one-tenth of the weight of the animal. This ferment is active after the teeth have been formed, which explains why it is not advisable to feed much starchy food to children before their teeth have begun development.

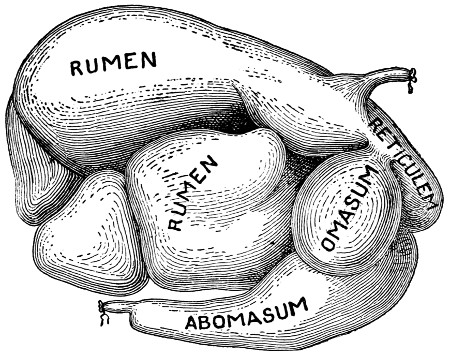

The food, after being ground and mixed with the saliva fluid, goes to the stomach. With the horse and hog the stomach is a single sac not capable of holding very large quantities of food; with the[25] cow and sheep, on the other hand, we find a large storehouse for holding food—a storehouse that is divided into four compartments, the rumen or paunch, reticulum, omasum, and the abomasum. The first three communicate with the gullet by a common opening. The cud is contained in the first and second stomachs, and, after it has been masticated a second time, it passes to the third and fourth, and to the bowels, where the process of digestion is continued.

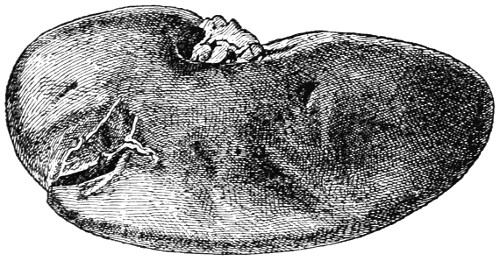

DISEASED KIDNEY

The kidney of the hog is pictured here. As a rule it is usually impossible to diagnose kidney troubles in hogs and similar lower animals.

—From this it will be noticed that chewing the cud is an act in the process of digestion; it refers only to rechewing the food so as to get it finer and better ground for digestion. While in the stomach the saliva continues the digestion of the starchy matter and is assisted by the gastric fluid that pours in from the lining of the stomach, which converts the protein or albuminoids into peptones. The fatty matter is not acted upon at this point. There are three constituents of gastric juice, which affect the changes in the food. These are pepsin, rennet, and acid. With rennet you are acquainted. It is used in the kitchen, in the making of cheese, and is obtained from the stomach of[26] calves or other young animals. Pepsin, also obtained directly from the stomach, is now a conspicuous preparation in medicine. The food, after leaving the stomach, goes into the bowels and is acted upon by secretions of the liver and pancreas or sweetbreads. It should be noted in passing that no secretion enters the first three divisions of the ruminant’s stomach. It is only in the fourth or true stomach that the gastric juice is found.

—While food is in the stomach it is subjected to a constant turning movement that causes it to travel from the entrance to the exit or intestines. When it passes into the small intestines it is subjected to the action of bile and pancreatic juices, which have principally to do with the breaking up of the fat compounds. Both resemble, to a certain extent, saliva in their ability to change starch into sugar.

The secretion of the bile comes from the liver and the pancreatic juice from the pancreas or sweetbreads, and both are poured into the intestines near the same point, so that they act together. The ferments they contain act in the following ways: They change starch into sugar, fat into fatty compounds, they curdle milk, and convert protein compounds into soluble peptones.

The process of digestion is finally ended in the intestines, where absorption into the system takes place. There is no opening at all from the bowels into the body, but the digestive nutriment is picked up by the blood when handed into the body from the intestines by means of countless little cells called villi, that line the walls of the intestines. These villi cells have little hair-like projections extending into the intestines, which constantly move; these protrusions, as they move about, catch on to[27] the digested nutriment, draw it into the cells themselves, where it is handed on to the blood, when it is later on distributed to all parts of the body. You can realize that an immense number of these absorption cells are present when the length of the intestine is considered. In the ox the intestine is nearly 200 feet long. After the nutriment is drawn from the food the undigested portions are voided periodically as feces or dung.

STOMACH OF RUMINANT

The four main divisions of the ruminant’s stomach are pictured here. The first three divisions are the store-houses for food until it is fully prepared for the fourth stomach or abomasum.

—Digestion, therefore, is a dissolving process; food is admitted to the system by means of cells. You remember that[28] all plant food first passes into a soluble state before it can enter the roots and be conveyed to the parts of the plants that require additional food for growth. In the case of plants the entrance is by means of the root hairs. In the case of the animal, entrance in the body is by means of the villi cells that line the intestines. From this we see that digestion is both an intricate and delicate process. Any loss of appetite, any disturbance of the digestion work, and any irregularity of the bowels bear decided results, one way or the other, to the rest of the system; and any disturbance of the body at other points, although having no direct relation to the digestion system, sooner or later affects the digestion and in so doing causes additional trouble.

Directly affecting digestion may be improper food, either liquid or solid; and over-exercise or not enough of it may prove troublesome, for exercise is clearly related to digestion. When the digestion process is disturbed, air or gas may accumulate in the stomach or bowels and give rise to colic or hoven. A watery action of the intestines, due to inflammation or irritation, may lead to dysentery and enteritis; or some obstruction like a hair-ball or a clover fuzzy ball, or the knotting of the intestines, may occur, temporarily or permanently impairing digestion so seriously often as to cause death itself.

As water in the plant is the carrier of plant food throughout the plant, so is blood the carrier and distributor of food in the animal. When food is absorbed, it either passes into the lymphatic system or into the capillaries of the blood system.[29] If in the former, it is carried to the thoracic duct, which extends along the spinal column and enters one of the main blood vessels. If collected by the capillary system, it is carried to the portable vein, thence to the liver and finally to the heart, where it meets with the blue blood collected from all parts of the body.

At this point, the blood contains both the nutriment and the waste matter of the body. Before it can be sent through the body again the waste material must be thrown out of the system by means of the lungs. This is accomplished by the heart forcing to the lungs the impure blood with its impurities collected from all parts of the body and also the nutriment collected from the digestive tract.

The chief organs, therefore, of the circulatory system are the blood and lymphatic vessels containing respectively blood and lymph. The only difference between these two materials is in the fact that lymph is blood without the red-blood corpuscles. The body, after all, really depends upon this lymph for nourishment, since it wanders to all parts of the body, surrounds all the cells in all of the tissues and in this way carries to the cells the very kinds of food that they need.

—The blood vessels have no openings into the body at all. In this respect the blood system is like the digestive system; it is separate and distinct in itself. The blood, however, does creep through the walls of the blood vessels. In so doing the blood corpuscles are left behind and lymph is the result.

HOW THE BLOOD CIRCULATES THROUGH THE BODY

The center of the blood system is the heart. It

is the engine of the body. Going out from it is the

great aorta, which subdivides into arteries and[30]

[31]

farther away further subdivides until there is a

great network of little arteries; these in turn become

very tiny and take the name of capillaries.

Thus the red blood, by means of arteries and capillaries,

is carried to all parts of the body. This

plan of distribution would not be complete unless

some way were provided for the return of the blood

to the heart and lungs for purification. And just

such an arrangement has been provided. Another

kind of network collects this scattered blood at the

extremities into separate vessels, which gradually

increase in size and finally empty their possessions

into the heart. These are the veins of the body,

and have to do with the impure blood of the body.

—The power back of blood distribution is the heart. It is an automatic pump, as it were, that sends blood to the lungs and through the arteries to all parts of the body. The heart is divided into four divisions: the left and right ventricles and the right and left auricles. The right auricle receives the blood from the upper half of the body through a large vein and the lower half of the body through another large vein, and the blood from both lungs empties into the left auricle through two left and two right pulmonary veins. The large arteries of the heart which carry the blood from the heart to the different organs arise from the ventricle.

The blood always flows in the same direction. It goes into the auricle from the veins, and from this into the ventricle. It then passes into the arteries, then to the veins and then to the capillaries.

The action of the heart is very much like a force pump; the dark blood flows into the right auricle, which contracts; when this is done, the blood is[32] forced into the right ventricle; this in turn contracts and forces the blood into the lungs, where oxygen is taken on and carbonic acid gas and other impurities are thrown off. From the lungs the blood, now red and pure, passes into the left auricle and thence into the left ventricle, from which it is forced into the aorta to be distributed to all parts of the body.

We now see the close connection existing between the digestive system and the circulatory system. The digested food in the intestines is gathered in by villi cells. The question can now be asked, What do these cells do with this nutriment or digested food? They pour it into the absorbent vessels or lymphs, as they are called; these in turn empty the assimilated stores of food into larger and still larger vessels, which continues until the whole of the nutritive fluid is collected into one great duct or tube, which pours its contents into the large veins at the base of the neck, from whence it is carried into the circulatory system, the very basis of which is the blood.

The dark and impure blood, after returning to the heart, is sent to the lungs. It is, when collected from the body, just before being sent to the lungs dark, dull and loaded with worn-out matter. It must now be sent to the lungs, where it may be spread over the delicate thin walls of millions of vesicles, to be exposed to the air, which is inhaled by the acts of breathing. The blood gives off the broken-down material and carbonic acid gas very readily. It is both unpleasant and disagreeable, and the blood cells find it very unattractive.

[33]

The cells of the blood, however, have a great attraction for oxygen, consequently the cells absorb oxygen with greediness, so that when the blood returns to the heart it is fresh and bright and ready to take its journey back over the body again. This is done just about every three minutes. This endless round continues until stopped forever by death.

The relation existing between the animal and plant functions is brought to light in another way. When the plant was building tissue it released oxygen and exhaled it into the air. At the same time, by means of leaves, it gathered in the carbonic acid to use in plant building. Of course this was got from the air. The animal in performing its functions and in building its tissue inhales oxygen from and exhales carbonic acid gas into the air. Thus it is that animals take up what is unnecessary to the plant and the plant uses what is waste and poison to the animal.

[34]

When a colt is born the first and second temporary molars, three on each jaw, are to be seen. These are large when compared with the size of those that later replace them. In from five to ten days after birth the two central incisors or nippers make their appearance. In three or four weeks the third temporary molars appear, followed within a couple of months by an additional incisor on each side of the first two, both above and below. The corner incisors appear between the ninth and twelfth months after birth. This makes the full set of teeth—twenty-four in number.

There is now no change in number, although there is considerable change taking place all the time; the incisor teeth, in rubbing against each other, are more or less worn, giving rise to the expression “losing the mark.”

The two molars present at birth remain until the animal is about three years old, at which time they fall out of their sockets by the protrusion of the second set, or permanent molars.

This change from temporary to permanent teeth takes place usually without difficulty and without trouble. The permanent teeth push their way up from below crowding those in view. While this pushing and crowding is going on the temporary teeth are losing ground, for the reason their roots are being absorbed, and a time comes when the cap only is left attached to the gums. This cap drops[35] out and the new or permanent tooth soon is established in its place.

According to the observation of Mayo, the temporary incisors are replaced by permanent teeth as follows: “The two central incisors are shed at about two and a half years, and the permanent ones are up ‘in wear’ at three years. The lateral incisors are shed at three and a half and the permanent ones are up and in wear at four years. The corner incisors are shed at four and a half and the permanent ones are up and in wear at five.

“The molars are erupted and replaced as follows: The fourth molar on each jaw (which is always a permanent molar) is erupted at ten to twelve months; the fifth permanent molar at two to two and a half years, and the sixth usually at four and a half to five. The first and second molars, which are temporary, are shed and replaced by permanent ones at two to three years of age. The third temporary molar is replaced by a permanent one at three and a half years. In males, the canine or bridle teeth are erupted at about four and a half years of age. At about five years of age a horse is said to have a full mouth of permanent teeth.”

Horsemen make use of the “mark in the tooth” for determining the age between five and eleven. In examining teeth you observe that two bands of enamel are to be seen; one exterior, that surrounds the tooth, the other interior, which is termed the casing enamel. It is this latter, or “date cavity,” that is used to tell the age.

[36]

The mark in the tooth is occasioned by the food blackening the hollow pit. This is formed on the surface by the bending in of the enamel, which passes over the surface of the teeth, and, by the gradual wearing down of the enamel from friction, and the consequent disappearance of it, the age can be determined for a period of several years.

LUMPY JAW

The disease is caused by the ray fungus. The result is local tumors in the bones and other tissues.

When a horse has attained his sixth year the mark on the central or middle incisors or nippers of the lower jaw will be completely worn off, leaving, however, a little difference of color in the center of the teeth. The cement which fills the hole produced by the dipping in of the enamel will be somewhat browner than that of the other portions of the tooth, and will exhibit evident proofs of the edge being surrounded by enamel.

At seven years the marks in the four middle incisors are worn out and are speedily disappearing in the corner ones. These disappear entirely at the[37] age of eight; thus all marks are obliterated at this age on the lower jaw; the surface of the teeth are level and the form of the teeth changes to a more oval form.

The marks on the upper jaw are still present, since there has been less friction and wear on them. At nine the marks disappear from the central upper incisors, at ten from the adjoining two, and at eleven from the corner teeth.

To tell the age of the horse beyond this period is difficult and uncertain, except by those very much experienced in performing the undertaking. The shape of the teeth, the color and the condition all enter into the determination but there is no fast and fixed rules after the marks have disappeared.

Cattle have no incisor teeth on the upper jaw. They have eight incisors on the lower jaw. According to Mayo, the temporary incisors are as follows: “The central incisors or nippers are up at birth, the internal lateral at one week old, the external lateral at two weeks, and the corner incisors at three weeks old. They are replaced by permanent incisors approximately as follows, though they vary much more than in the colt: The central incisors are replaced at 12 to 18 months; the internal laterals at about two and a half years; the external laterals at three to three and a half years; and the corner incisors at about three and a half years. In the horned cattle, a ring makes its appearance at three years of age, and a new ring is added annually thereafter.”

[38]

Sheep, like cattle, have no incisor teeth on the upper jaw. Like cattle, they have eight incisors on the lower jaw when the mouth has reached full age. The change of the teeth occurs as follows: At birth the lamb has two incisors, followed by two more very soon. At the end of two weeks two more are out, making six incisors in all. At three weeks of age two more have appeared, completing the appearance of the temporary or milk teeth.

The permanent begin to replace the temporary teeth between one and one and a half years. The two central milk teeth are first replaced by two longer and stronger teeth. The lamb is now known as a yearling.

At two years the two teeth adjoining the central incisors are replaced by permanent ones; at three the two adjoining these are replaced, making now six permanent incisors.

Between four and four and a half the last two permanent incisors appear and the sheep then has a full mouth.

[39]

In purchasing farm stock, it is a good plan to deal with reputable people only. Leave the horse trader alone. He knows too many tricks, and if you are a stranger to him you can be pretty certain that he will try one on you—just for fun.

Fortunately farmers sell to strangers more frequently than they buy of them, and when they seek new stock they deal largely with breeders, who, like themselves, are farmers and not given to the tricks of low and disreputable methods; nevertheless, every purchaser of stock should be familiar with animal form and able to recognize defects and faults when he sees them. This is as much his business as to breed, raise or feed the stock on his farm.

Know what form you want; draft and speed represent different types, so do dairy and beef. With all classes of farm stock there are a few points that are desirable in all stock. One of these is width between the eyes. No animal of any breed or class possessed of a narrow forehead is at all perfect. A wide forehead is one of the absolute beauties.

These are desirable characters of all farm animals; they represent culture and refinement and good breeding. The purchaser or breeder, therefore, should not only know conformation, but he should know quality.

[40]

Our breeds of horses may be divided into three general classes. Those used for speed, those for draft and those with a mixture of the two—a general purpose sort of horse. The speed or trotting horse has its distinct type; it has been evolving and developing through a long series of years.

Briefly, its conformation may be described as follows: A wide forehead, fairly long head, a long neck that is thin and agile, a narrow chest as you look at it from the front, but very deep as you look from the side, long sloping shoulders, rather long back, a long horizontal croup, small barrel, fairly long forearm, long cannon bones and feet that are well shaped and perfect in every respect. Looking at the animal from the side it should be as high over the hips or higher than over the withers.

The draft horse, on the other hand, has a different conformation. There is not that elongation of his parts, although there is a symmetry of parts and of proportion. There should be the width between the eyes; the clean, neat face; a graceful neck, which should be shorter and more heavily muscled than that of the speed horse. The chest should be wide, both from the front and side, the back short but heavily muscled, the croup strong and not so horizontal as with the speed type, the quarters heavily muscled and the cannon bone short.

The feet should be as perfect as those of the speed horse. In both types the knee should be thick, deep, and broad and the hocks wide. The narrow hock is not so well able to stand heavy strain, consequently curb diseases readily follow[41] where the conformation shows narrow hocks. Another difference between the two types is found in the muscles. The speed type throughout has long, thin, narrow muscles—muscles that stretch a long way and contract quickly.

BAD ATTITUDES DUE TO CONFORMATION

In the first, the toes are turned out. The middle picture shows in-kneed attitude and the third shows in-turned toes. Whether standing or traveling, the appearance is unpleasant and mitigates against the value of the animals.

With the draft horse it is different: the muscles are shorter, but they are heavy; they are less quick in their action, but they are more powerful. In both types good proportions are always desirable. The width between the eyes should be as much or more than one-third the length of the head. The distance from the point over the shoulders to the ground should be about equal to the distance from the point over the hips to the ground; and in turn this distance, whatever it is, should be about equal[42] to the length of the horse from the point of the shoulder to the point of the buttock.

Looking at the horse in front if a line be dropped from the point of the shoulder it should halve the fore leg, the knee, the cannon, and the hoof. And the width of the third hoof, if placed between the two front feet, should give the attitude that is desirable.

Looking at the horse from the rear, the same attitude is to be observed. Of course, many horses do not possess these qualities and proportions; and because they do not is the very reason that their beauty, efficiency, and value are less.

In going into the stable look the animals over quietly. Observe how they stand, breathe, eat, and act generally. Are they nervous? Does one swing his head from side to side? Does he kick, paw, put back his ears, or does he have any of the other common stable vices that are unpleasant and undesirable? As you look about and pass back and forth, you will get the evidence of these stable vices, if such are to be found.

Look particularly for cribbing, wind sucking, kicking and crowding. Pawing is just as bad. If you want animals with good stable manners pass by those possessing these ugly faults. The next step is to examine the animals individually; those that “look good” to you. No doubt you will find some that do not interest you for one reason or another. These need no further attention, unless you have overlooked some fact, in which case your attention will likely be called to it.

[43]

In making the individual examination, go up to the animal in the stall, place your hand on the hip, and gently press it. If no stringhalt afflicts the horse, he will move over, allowing you to pass into the stall. The same applies to the cow. If well trained, she will make room for you by moving over at the same time, if you do this on the proper side, and she will put back her hind foot, as if she were about to be milked.

This casual observation would not be possible if force were used or the animal excited by loud commands or by a whip or strap. The halter teaches its lesson also. A heavy rope or leather suggests that the animal has a pulling back vice, a habit you want to avoid. Light halters for horses and cattle are to be preferred to chains, heavy leather, or ropes.

Now that you have seen all of the animals for sale, ask the owner to lead them out of doors for a more careful examination. In this you will inspect the animal very carefully in order to be certain of the conformation, defects, and blemishes, and to acquaint yourself specifically as to health and disposition.

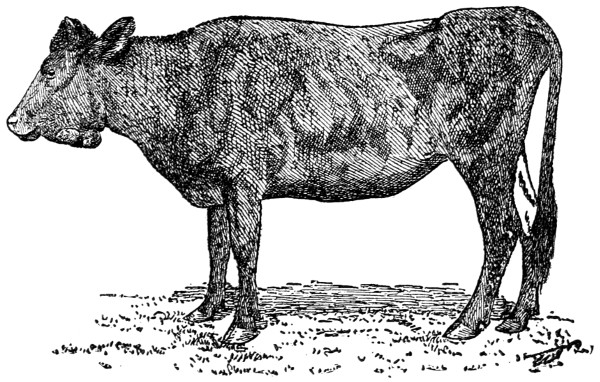

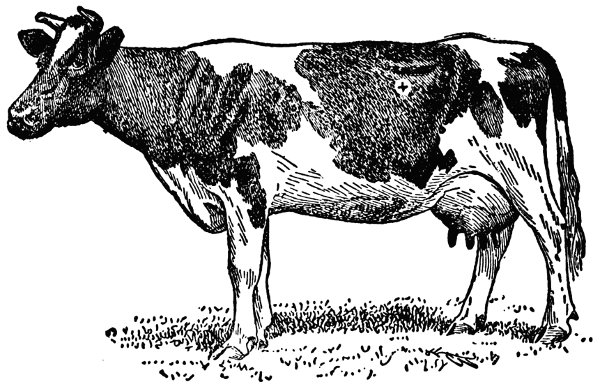

Cast your eyes over the animal, front, side, and rear. Pass around the animal, keeping some distance away. By so doing you can judge of type and conformation, of proportions and attitudes; for each of these is important. A beefy-looking cow, with a thick neck, square body and small udder will not suit you for milk. Neither will a cow with a long, thin neck, open, angular body, thin thighs, and[44] heavy, deep paunch meet your needs if you are seeking breeding stock for beef production.

If you are examining a horse, keep in mind the purpose for which you are selecting. Remember the long, thin neck, very oblique shoulder, long cannon, long back, and long thin muscles are not adequate for draft. On the other hand, if you want a horse for road purposes, avoid the heavy muscles, the short neck, the heavy croup, and the heavy thighs. These mean draft—an animal for heavy work.

The milk cow should have a very soft, mellow skin, and fine, silky hair. The head should be narrow and long, with great width between the eyes. This last-mentioned characteristic is an indication of great nervous force, an important quality for the heavy milker. The neck of the good dairy cow is long and thin, the shoulders thin and lithe and narrow at the top. The back is open, thin, and tapering toward the tail. The hips are wide apart and covered with little meat.

The good cow is also thin in the regions of the thigh and flank, but very deep through the stomach girth, made so by long open ribs. The udder is large, attached well forward on the abdomen, and high behind. It should be full, but not fleshy. The lacteal or milk veins ought also to be large and extend considerably toward the front legs.

The beef cow is altogether different: she is square in shape, full and broad over the back and loins, and possesses depth and quality, especially in these regions. The hips are even with flesh, the legs full and thick, the under line parallel with[45] the straight back. The neck is full and short, the eyes bright, the face short, the bones of fine texture, the skin soft and pliable, and the flesh mellow, elastic, and rich in quality.

In other words, a beef cow is square and blocky, while the dairy cow is wedge-shaped and angular. The one stores nutriment in her body; the other gives it off. The one is a miser, and stores all that she gets into her system; the other is a philanthropist and gives away all that comes into her possession.

It will be seen, therefore, that the two types are radically different. This difference is due to breeding, not to feeding, nor to management. If you are seeking good milk cows, you must look for form and conformation. If you are looking for beef cows, you must also look for form and conformation, but of a different kind. With this knowledge to back you up and to guide you, you are now ready to make an examination of animals that will meet your purpose.

After making these general observations you are now ready to examine the animal. Begin with the head. How is the eye? Dull, weak, without animation? If so, be on your guard. The good eye shows brightness, intelligence, and it must be free from specks. By placing the hand over the eye for a few moments you will be able to detect its sensitiveness to light. Do you find any discharge of any kind from the eye? If so, some inflammation is present. Try to ascertain the cause.

—A large, open nostril is desirable. Look for that character first. Now[46] observe the color of the lining. To be just right, it should be healthy-looking, of a bright rose-pink color, and it should be moist. A healthy nostril is one free from sores, ulcers, pimples, and any unpleasant odor. Be careful here; an unscrupulous dealer can very easily remove discharges and odors by sponging and washing, and you may be deceived.

EWE NECK

The neck is one of the beauty points of the horse. In purchasing animals look carefully to conformation and quality. Let these also be guiding principles in breeding.

—Always look in the mouth; you have the tongue, teeth, jaws, and glands to see. Naturally, you, like every other person, consider the teeth first; you want to be certain of the age. This feature is discussed elsewhere in this book, and all in addition that needs to be said is in reference to the shape of the teeth,[47] whether or not they are diseased or worn away by age or by constant cribbing of the manger. Of course these facts you will think of as you examine the mouth.

Give the tongue a second of your time. If it is scarred and shows rough treatment a harsh bit is likely the cause, due to its need in driving and handling.

Then give a thought to the glands while here. Enlarged glands may indicate some scrofulous or glanderous condition of the system.

—A beautiful neck and throat is an absolute beauty in the horse or cow. The skin should be thin, mellow, and soft, and the hair not over thick nor coarse. Look for poll-evil at the top of the neck and head. See if swellings, lumps or hard places are to be found at the sides of the neck, or underneath joining the throat. I have found such very frequent with dairy cattle; and cases are not unusual with horses.

Frequently scars are to be found on the sides or bottom of the neck. These may be due to scratches caused by nails, barb-wire or some similar accident, and again they may have been caused by sores, tumors, or other bad quality of the blood.

—Passing the side, look over the withers for galls or fistulæ, the shoulders for tumors, collar puffs, and swellings. Observe at the same time if there is any wasting of the muscles on the outside along the shoulder.

Now the back. Is it right as to shape? Do you find any evidence of sores or tumors? Look for these along the sides and belly. Now stoop a bit and look under; do you find anything different from what is natural? In males look for tumor or disease of the penis; do the same with the scrotum,[48] and, in case of geldings scrutinize carefully to see if they be ridgelings.

While making this examination, if the animal is nervous and fretful, you can help matters along if an assistant holds up a fore leg. Take the same precaution when examining the hind quarters and legs. By doing so, you will avoid being kicked and can run over the parts more quickly and satisfactorily.

Before leaving the body observe if the hips are equally developed, and the animal evenly balanced in this region. Both horses and cattle are liable to hip injury, one of the hips being frequently knocked down. Make sure that both are sound and natural.

—Now step to the front again for a careful examination of the front legs and feet. Starting with the elbow, examine for capped elbow; now the knee. It should be wide, long, and deep, and at the same time free from any bony enlargements. The knees must stand strong, too. Is the leg straight? Do you observe any tendency of the knee to lean forward out of line, showing or indicating a “knee sprung” condition? Just below the knee, do you find any cuts or bunches or scars due to interference of the other foot in travel? Look here also for splints; follow along with the fingers to see if splints are present—on the inside of the leg.

Be particular about the cannon. The front should be smooth—you want no bunches or scars. Just above the fetlock feel for wind puffs; and note if about the fetlock and pastern joints there are any indications of either ringbones, bunches, or puffs. Now look for side bones; if present, you will find them just at the top of the hoof. They may be on either side. Sidebones are objectionable, and are[49] the lateral cartilages changed into a bony structure.

ANATOMY OF THE FOOT

The delicate nature of the foot is readily recognized when the various parts are considered in their relation to each other.

Give the foot considerable attention. The old law of the ancients, “no feet, no horse,” is certainly true in our day. You can overlook many other imperfections and troubles in the horse, but if the feet are bad you do not have much of a horse. A good foot is well shaped, with a healthy-looking hoof and no indication of disease either now or ever before.

See that the shape is agreeable. A concave wall is not to be desired, and the heels are not to be contracted. The wall should be perfect—no sand cracks, quarter crack, or softening of the wall at the toe of the foot.

—These are both troublesome and cause much lameness. A healthy frog, uninjured by the knife or the blacksmith or other cause is very much to be preferred.

—In examining these regions give the hocks of the horse special attention. No defect is more serious than bone spavin. You can, as a rule, detect this by standing in front of the horse just a little to the side. If there is[50] any question about the matter, step around to the other side and view the opposite leg. This comparison will let you out of the difficulty, as it is very unusual that this defect should be upon both legs at the same point and developed to the same degree.

A spavin is undesirable for the reason that it often produces serious lameness, which frequently is permanent. As it is a bone enlargement, it is something that cannot be remedied. If you are seeking good horses, better reject such as have any spavin defect.

In this same region between the hock and the fetlock curbs troubles are located. They appear at the lower part of the hock, directly behind. You can readily detect any enlargement if you will step back five or six feet. The curb, while it may not produce lameness, is altogether undesirable. It looks bad; it shows a weakness in the hock region and often is caused by overwork, consequently the animal with curb disease is one that has not measured up to the work demanded of him.

Just above and to the rear of the hock the thorough-pin disease appears, and just in front of and slightly toward the inner side of the hock bog spavin is sometimes to be found. Lameness may come from either of these diseases. Small tumors, puffs and other defects frequently show themselves on the hind legs and the best way is to reject animals having them. While some of these may be caused by accident, the most of them are the result of bad conformation, due to heredity, unimproved blood and bad ancestors.

Lameness comes from many causes; maybe from[51] soreness, from disease or from wounds. And lameness is hard to detect. Frequently it seems to be in the shoulder, when in fact it is a puncture in the foot. Again it may seem to be in the fetlock, but the trouble is in the shoulder or fore leg. You must examine for lameness both in the stable and out of the stable. If you find the horse standing squarely upon three feet and resting the fourth foot, you should be suspicious. If you move the horse about and he assumes the same attitude again and still again, you can be certain that he is assuming that position because he wants to rest some part of that member.

In testing out the horse for lameness, let no excitement prevail. Under such excitement the horse forgets his lameness or soreness for the time being, and you do not note the trouble. A quiet, slow walk or trot on as hard a road as possible is a desirable sort of examination to give.

The free breathing of a horse may be interfered with, and for two reasons. Roaring or whistling, as it is called, is a serious disease of the throat, and, at the same time, an incurable disease. The second disease is known as heaves or bellows, and is also a most serious disease, because it is also incurable. By the use of drugs relief may be given temporarily, but no permanent cure follows. Unscrupulous dealers will resort to dosing for the time being, or until a sale is made.

You should guard against this trouble, however, for it is one of the most serious that a horse can have. Upon this subject, Butler has the following to say: “To test the wind and look for two serious conditions and others which may be present,[52] the animal should be made to run at the top of his speed for some considerable distance—a couple hundred yards or more. Practically this run or gallop should be up hill, which will make the test all the better. After giving the horse this gallop, stop him suddenly, step closely up to him and listen to any unusual noise, indicating obstruction of the air passages, and also observe the movements of the flanks for any evidence of the big double jerky expulsion of the air from the lungs characteristic of heavers.”

No examination is complete that does not make a test of the paces. You want to know how fast the horse can walk, how he trots or paces or how he takes some other gait. Some horses make these movements very gracefully; others very unmannerly. A well-acting horse is one that moves smoothly, regularly, who picks up his feet actively and who places them firmly in their position regardless of the ground or gait. Some horses have a rolling movement of the legs. Avoid these. Others step on the toe or heel. These, too, should be avoided. They suggest some defect or bad conformation.

The testing of the paces brings all parts of the body into play and assists in catching other blemishes or defects that you may have overlooked in your previous examination. It gives you another opportunity to examine the wind, to observe the respiration, the heart beatings, the condition of the nostril after work; it shows you also how the animal takes his pace and how he stands. All of this will be of value as indicating the soundness and health of the individual under observation.

[53]

Now, as a last factor of your examination, consider the uses to which the animal is put. If you are looking for breeding animals be sure to know that the udder is not injured. Of what use is a cow with a bad udder? How often do we find a quarter of the udder destroyed or a teat cut or so badly mangled as to be of little use! Some udders are dead, heavy, fleshy; some are diseased, lumpy; and even though the animal is otherwise good you must reject her.

If the udder is good, superior in many respects, and shows great milk production, you can often afford to overlook other defects, especially if the result of accident.

In the case of horses, a disease or blemish due to accident may be overlooked, if the work to which the animal will be subjected does not interfere, let us say, for breeding purposes. The horse has good conformation, good quality, is healthy and very superior, but unfortunately a leg was broken. Shall she be rejected as a breeder? No heavy work will be required of her—she is wanted for colt raising. Take her; of course you will pay less for her. This accident interferes in no way with her value for breeding purposes. Many cases of accidental injuries are similar to this example among cattle and horses.

A good rule is to reject those having defects or blemishes that interfere with functional activity or the work to which you wish to put them. Then, as breeders, reject all with constitutional defects, as bad feet, narrow hocks, coarse disease-appearing bones, and bad conformation and scrubby character.

[54]

FRACTURES

When a bone is broken into two or more parts it is said to be fractured. These may be straight across, up and down, or oblique. Ordinary fractures are easily treated by splints, but sometimes fractures are so serious as to destroy the value of the animal.