Title: Homer Martin, a Reminiscence, October 28, 1836-February 12, 1897

Author: Elizabeth Gilbert Martin

Release date: September 6, 2017 [eBook #55498]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive)

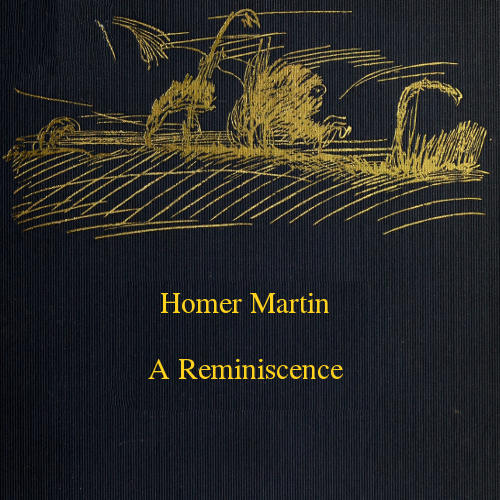

HOMER MARTIN

From a photograph taken in England in 1892

HOMER MARTIN

A REMINISCENCE

OCTOBER 28, 1836—FEBRUARY 12, 1897

NEW YORK

WILLIAM MACBETH

1904

Copyright, 1904, by William Macbeth

| PORTRAIT OF HOMER MARTIN | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| NORMANDY TREES | 6 |

| THE DUNES | 12 |

| ON THE HUDSON | 18 |

| BLOSSOMING TREES | 24 |

| THE HAUNTED HOUSE | 28 |

| THE CRIQUEBŒUF CHURCH | 32 |

| GOLDEN SANDS | 36 |

| ON THE SEINE (“HARP OF THE WINDS”) | 40 |

| TREES NEAR VILLERVILLE | 46 |

| CAPE TRINITY | 52 |

| A NEWPORT LANDSCAPE | 56 |

The publisher cordially thanks the friends who kindly lent the pictures which have been reproduced to illustrate these pages.

During the last year I have more than once been told that an authoritative biographical sketch of my husband ought to be written and I have never felt inclined to dispute the statement as an abstract proposition. But when it is followed by the direct question: “Who so capable of writing it as you?” the names of one or two of his personal friends inevitably present themselves as belonging to practised writers and connoisseurs of art, who might, perhaps, need the aid of dates or facts I could supply, but who, in more essential respects, would be altogether better equipped for the task. Homer Martin was so intensely masculine, so preëminently a man’s man, that he must necessarily have escaped thorough comprehension by any woman. And this, I think, is the chief reason why I have so long delayed, why I am even now inclined to shirk altogether, the fulfilment of my[viii] reluctant promise to put on paper some of my memories of the years we spent together.

The question made me smile when it was propounded more than a year ago, but since then it has often made me ponder. Doubtless no one else has had so long and intimate an acquaintance with various phases of his character and circumstances; doubtless, too, it was not merely as an artist that he commanded attention and attracted life-long friends. Yet I suppose it must be solely in this character that he appeals to the majority of those who are now attaining to a tardy appreciation of his achievement as a whole. It is not in my power to hasten that. When I first met him my ignorance of art—at any rate on its pictorial side—was dense; and if it has been somewhat mitigated since, that result is due solely to him and largely to his own works. Is not this tantamount to expressing my conviction that those who wish to increase their knowledge of Homer Martin as an artist can do so much more satisfactorily[ix] by studying the landscapes into which he has put as much of his best self as any man could part with and live, than by reading anything I find it possible to say about him? Aspects of external nature are inextricably blended in these with the mind, moods, and personality of the painter. Years before he had quite succeeded in mastering his material, I remember the late John Richard Dennett saying of them: “Martin’s landscapes look as if no one but God and himself had ever seen the places.” There is an austerity, a remoteness, a certain savagery in even the sunniest and most peaceful of them, which were also in him, and an instinctive perception of which had made me say to him in the very earliest days of our acquaintance that he reminded me of Ishmael. They formed, I think, the substratum of his personality. Needless to add, for those who knew him even slightly, that he had other phases. Though the human verb in him was one and singular, its moods were many.

Elizabeth Gilbert Martin.

Homer Dodge Martin, fourth child and youngest son of Homer Martin and Sarah Dodge, was born in Albany, N. Y., in a house on Park Street, October 28, 1836. That was my own native city, but although we must have lived for years in the same neighborhood, he was past twenty-two and I in my twenty-first year when we first became acquainted. But for the anti-slavery movement which split the Methodist body first into two great sections and then into minor subdivisions, we might have met much earlier, for, in our childhood, our parents had attended the same place of worship.

What I know, therefore, about his early years I learned chiefly from his mother. He was not of a reminiscent habit as a rule, and his recollections of childhood were not always pleasant. His father was one of the most upright and altogether the mildest-tempered of all the men that I have met. His mother was a woman of strong but uncultivated mind, keen wit, incisive speech and arbitrary will, from whom her son derived many of his own characteristics, including his innate bent toward pictorial expression. In her that inclination never took any but the crudest shape, but she had beyond all peradventure the instinct which under more propitious circumstances would have displayed itself more convincingly. Perhaps the very cramping of it in her was the cause of its appearance at so preternaturally early an age in him. She more than once told me that he began to draw as soon as he could hold a pencil, and that from his twentieth month to provide him with one and a piece of blank paper was the surest means of quieting his[5] most turbulent outbreaks. Years afterward, not long before our marriage, his first schoolmistress sent me a spirited drawing of a horse which she said he had made for her when not more than five years old.

This drawing was produced in one of the Albany ward schools, and it pretty accurately foreshadowed all that he was to accomplish in them thereafter. I doubt if he ever took kindly to lessons obviously given. Even in painting, his sole direct tuition was imparted by James Hart and extended over two weeks only. What he needed, what suited him, he then and always took in, so to say, through his pores, absorbing what he required, leaving other things untouched, and wrestling unaided with his personal problems. Greatly to his own after regret, his ordinary schooling ended when he was thirteen. But at the time his aversion to school-books and school routine dovetailed to a marvel with the persuasion of his relatives that it was time for him to begin earning his own livelihood. He once told me that his school-hours had been largely[6] spent in looking through the windows at the Greenbush hills on the other side of the Hudson, and in longing for the time to come when he could go over there in the horse-boat with paper and pencil to record a nearer view.

Nevertheless, it was only for school-books as such that he had an intimate aversion. In other lines all was fish that came to his net. How he obtained it I do not know, but a copy of Volney’s “Ruins” which he read at this period colored his opinions in a way that he afterward found reason to regret. But at the time it made him an irreverent, amused, and precocious critic of the talk he heard at Conference-time, when itinerant ministers thronged the family board.

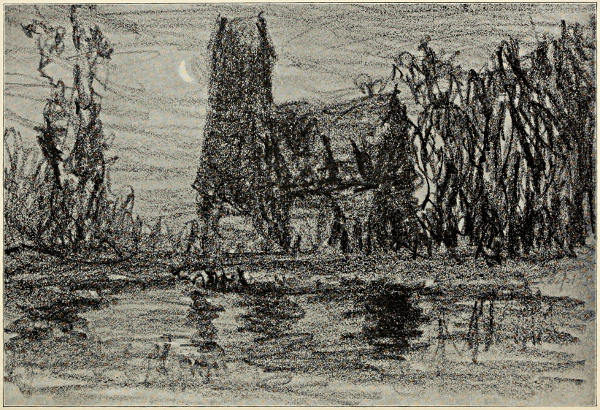

NORMANDY TREES

Reproduced from the original painting in the Wilstach Collection, Philadelphia

Poetry of certain kinds attracted him throughout his life, and verse that greatly pleased him would stamp itself indelibly on his memory. Once in a great while, almost to the last, I could persuade him to repeat to me Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” with a lingering enunciation and a[7] melancholy charm of accent which a few of his most intimate friends may likewise recall. I especially remember one night in Villerville, when we were alone out-of-doors in the late moonlight, awaiting in vain the advent of a nightingale said to have been heard in the neighborhood, that he more than compensated me for its absence by reciting the whole of the same poet’s lines to that “light-wingèd Dryad of the trees.” Reciting, I say, but the word is ill chosen. It was rather a barely audible yet perfectly distinct breathing out of the ineffable melancholy and remoteness of those perfect lines.

Homer was transferred to his father’s carpenter shop on leaving school; but even that most patient of men came at last to the reluctant conclusion that the long, slender fingers which could not refrain from ornamenting smoothly planed boards with irrelevant trees and mountains were of no use at all in handling saws and chisels. A shopkeeper with whom he was next placed as clerk, much against the boy’s own[8] will, soon discharged him for incorrigible—perhaps premeditated—rudeness to customers. One of these, who was a young cleric in the Episcopalian Seminary in Ninth Avenue, New York City, when he told me the story, described in words too graphic to quote, the manner in which, as a child, he had once been driven out of the shop and all memory of what he was sent for out of his mind, by the thunderous scowl and wrath-freighted tone and terms in which Homer inquired what he wanted.

He was next introduced into the architect’s office of a relative, whence he was eliminated, partly because his cousin thought the inevitable landscapes that decorated his plans totally superfluous, but also on account of Homer’s congenital inability to see perpendicular lines distinctly. I think I never saw him draw an upright of any sort without first laying his paper or canvas on its side. When the Civil War broke out, shortly before our marriage, and he presented himself for the draft, it was[9] this defect of vision which caused the examiners to reject him.

Every attempt at harnessing him to a beaten track of obvious utility and present productiveness having terminated disastrously, from the paternal point of view, E. D. Palmer, the Albany sculptor, finally succeeded in persuading the elder Homer Martin that his son’s talent and inclination for art were too marked and exclusive to permit of his success in any other pursuit. Thenceforward—he was perhaps sixteen—he was left free to follow the bent of his genius. I do not know where he painted at first; perhaps at home. Later on, he had a studio in the old Museum Building, at the junction of State Street and Broadway. James Hart had previously occupied it, and it was probably there that for a fortnight he acted as Homer’s instructor.

There were other painters in Albany at the time: William Hart, George Boughton, Edward Gay, perhaps one or two others, with all of whom he was intimate and whose studios he frequented. Boughton went[10] abroad not long after, and, when he was in France, once wrote to Launt Thompson in most enthusiastic terms concerning the landscapes of Corot, whose great vogue had hardly yet begun, but with whose work Boughton was at once enchanted. And, in describing it, he remarked that “if Homer Martin had been his pupil he could hardly paint more like him.” It was not until long years after that Thompson had the grace to repeat the observation to Homer, and when at last he did so, the only reply he got was: “Why did you not tell me that years ago, when it would have been of some service to me?” For Homer, too, was one of the Corot worshipers from the first.

It was in the Museum studio that I first saw Homer Martin. It was not until long afterward that I learned—and not from him—that having seen me in the street, he deliberately sought acquaintance with my eldest brother, like himself a lover of music and a frequenter of the local Philharmonic Society. An invitation to visit the studio and bring his sisters soon followed. To the[11] end of his days, I suppose, Homer had reticences of that sort with me. At the time I speak of he was already locally known as a colorist of no mean capacity and a man of genius. I had heard his name, but only in connection with that of a dear friend and schoolmate of my own, a beautiful, golden-haired little creature, with a voice as delightful as her person, whom he was said to be following everywhere she went. They never met until after our marriage, which preceded her own.

I went one afternoon with my brother to see his pictures and his studio. The latter struck me as the most untidy room I had ever entered. I remember his rushing to throw things behind a large screen. I was not used to paintings. Such as I had seen had seemed to me mere daubs to which any good engraving would be altogether preferable. But on that afternoon there was a large unfinished landscape on the easel, which even to my unpractised eye conveyed the promise of beauty. It was a commission, painted for a Mr. Thomas of Albany,[12] if I do not mistake. There were two great boulders lifting their heads out of a shallow foreground brook, and one day, much later, when I was there, he painted his own initials on one of them and mine on the other, but—as was always his habit when he remembered to sign his pictures at all—in tints differing so slightly from that of the surface on which he inscribed them as to be scarcely distinguishable from it.

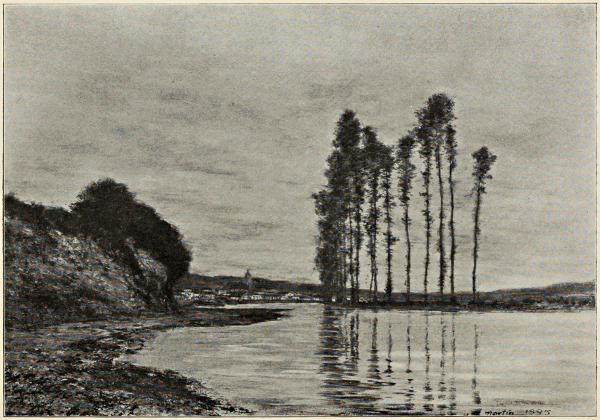

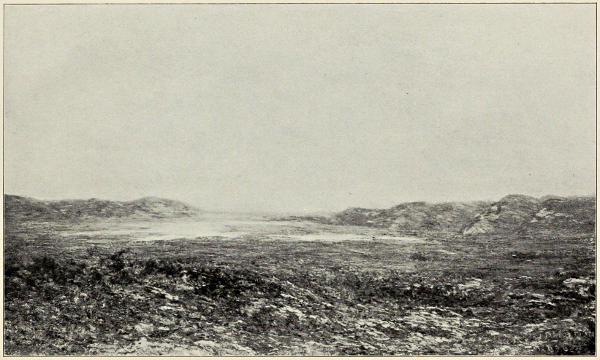

THE DUNES

Reproduced from the original water color in the collection of Mr. Wm. Macbeth

We were married in my father’s house during the first year of the Civil War, on the twenty-fifth of June, 1861, and went off the same day to Twin Lakes, Connecticut. I still have the first sketch in oils which he made out-of-doors that season: a barley-field, meadow land in the middle distance, gray-green trees beyond. Two or three brown boulders, others merely penciled in, lie on the left of the foreground. The delicate heads of grain are swaying in a light breeze. Perhaps he did not do much in the way of visible work that summer. At all events, I do not now recall any. But in some subsequent winter he embodied his[13] recollections of the place and time in a delightful landscape. All his life long, I think, his results were arrived at more by means of a slow, only half deliberate absorption when out-of-doors than by a wilful effort to record them at the time. Yet the one exception to that statement which I distinctly recall is a very great one: the Westchester Hills, which is thought by many to be his most perfect landscape. It was painted entirely en plein air, and many a day I sat close by, reading aloud or knitting while it was in progress. He never got so much as an offer for it, nor was it until more than two years after his death that a purchaser was found sufficiently venturesome to end a long hesitation by paying $1,000 to obtain it. He was presently rewarded for his temerity, I am happy to say, for when he put it up at auction a few months later, it brought him $4,750. The second purchaser was still more fortunate, reselling it for $5,300.

Neither of us ever revisited Twin Lakes. Later in the season we went to the farmhouse[14] of Mr. Thaddeus Dewey, near Fort Ann, N. Y., where we remained until late in the autumn.

My husband retained his Albany studio until the winter of 1862-63, when he went to New York and for some months painted in the studio of Mr. James Smillie. It could hardly have been earlier than the winter of 1864-65 that after many efforts he succeeded in finding an empty studio in the Tenth Street Studio Building—a little, skylighted room on the top corridor which he occupied continuously until he resigned it before sailing for England the second time in the fall of 1881. His forty-fifth birthday came while he was on shipboard. I followed him to London in the succeeding June.

His nearest neighbors in the Studio Building for many years were Sanford R. Gifford, Richard Hubbard, C. C. Griswold, and J. G. Brown. Jervis McEntee and his charming wife were on the corridor next below; so was Julian Scott. Eastman[15] Johnson and Launt Thompson were on the ground floor. I think that John La Farge must have come a little later. At any rate, I do not remember him before the winter of 1867-68. Failing, as often happened, to find my husband in his own studio, I went one day to that of Mr. La Farge on the same corridor in search of him. He was not there either, but I still retain a very distinct recollection of Mr. La Farge, face and characteristic attitude of doubtful welcome for intruders quickly changing as he divined my identity, asked me to enter, and so began a friendship still unbroken. Of course, Homer had talked a good deal to me about him. Certain questions which had been pressing on my mind with increasing persistence ever since my father’s death in 1866, very speedily found expression in a sort of personal catechism concerning his hereditary faith which he, perhaps, may likewise recall.

We were fairly prosperous in those early years, or might have been if we had been constituted differently. “There is much[16] virtue in If.” Homer’s landscapes were often commissioned, and seldom remained long on his easel in any case after they were finished. But it was never possible to count on any definite term as that of their probable completion. He was a man of many moods, and that one of them in which he could paint and be satisfied after a fashion with what he painted, was the most irregular and uncertain of them all. He did not possess his genius but was possessed by it. His fallow periods were many. When they passed away, the first sign that seeds had begun to sprout again was often the entire scraping out of a landscape that to others had seemed to need only the final touches. I asked him once in later years, at a time when there was every need for exertion were it possible, why he did not paint. It was in 1881. “I cannot paint,” said he. “I do not know where the impulse comes from, nor why it stays away. All I know is that when it comes I can do nothing else but paint; when it goes I can do nothing but dawdle.” That was absolutely true. It was also very inconvenient.

But in that earlier period with which I am still concerned, his pictures for years brought him an income which averaged between two and three thousand dollars, sometimes more than that. It was war-time and after. Prices were high for everything. Money came at irregular intervals, often so prolonged that, when it did come, it had to be chiefly employed in the process he once described as “mopping up debts;” a kind of industry to which he found me persistently addicted. Neither of us took as much thought for the morrow as perhaps we might have done had not the morrows themselves seemed so uncertain a quantity. Life used to present itself to me at that time as a narrow path leading between precipices, across turbulent brooks, over stones that were slippery as well as sharp, and whose end was nowhere in sight. In fact, it never did become visible until, turning at some unexpected angle, our cul-de-sac would prove to have had a hidden outlet after all. Perhaps this was why our frequently recurring difficulties troubled us more and taught us less than they might[18] have done under different circumstances. In the complex of life we ourselves were circumstances. Once, in later years, he casually remarked that I had never given him a chance to get tired of me, because he never knew what I would do next. Can any one give what one has not got?

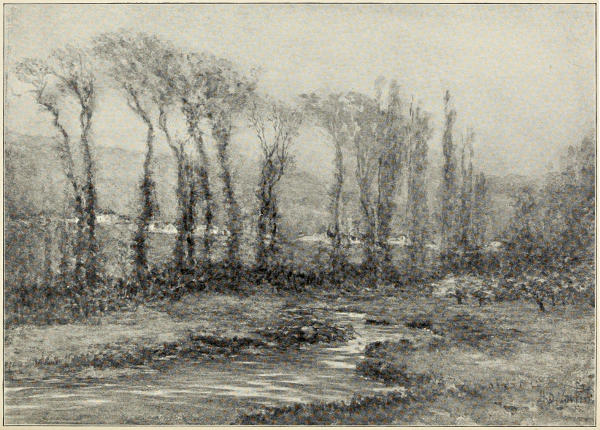

ON THE HUDSON

Reproduced from the original painting through the courtesy of John M. Robertson, Esq.

Meantime, we found life entertaining as well as perplexing and difficult. Our little boys were healthy, intelligent and good-tempered. Homer’s work, when he could once settle down to it, was always able to divert his mind from every other preoccupation. I had been writing book reviews occasionally ever since the early spring of 1861 for the “Leader,” to which paper an article of mine concerning Mrs. Rebecca Harding Davis’s first novel had been sent under a pseudonym by the brother I have already referred to, who was a friend of that eccentric genius, Henry Clapp. Later on, I wrote once in a while for the “Round Table,” and, after some date in 1866, when Auerbach’s “On the Heights” was sent me from the “Nation” editorial rooms for[19] review, pretty steadily for that periodical. Our friends were interesting to both of us. If Homer ever “talked shop,” at least I never heard him, and the men whose company he instinctively sought were never painters; or, since I must make an exception in the case of John La Farge, they were never merely that. He had a great capacity for love, and the two men whom he loved best were critics in the large sense: John Richard Dennett, from the first time they met until his untimely death in 1874; and William C. Brownell from that period, or perhaps before it, until the end.

Painting was his own sole means of adequate expression. Perhaps I ought not to say that. I may not be an adequate judge, and certainly I have heard great things about his reputation as a talker at the Century Club. But to me, from first to last, he never talked about impersonal subjects—perhaps because he could not consider anything that affected me in a purely impersonal light. I always read aloud to him a great deal, but the books and topics[20] which interested me most after 1870 never interested him at all. Until then we had both been turning our intellectual searchlights in every conceivable intellectual direction. At that period mine steadied on its proper centre and veered no more. But to the very end I continued to read to him whatever he desired to hear.

Nevertheless, even though he was too many-sided not to find issue in more than one direction, his pictures are the only permanent result of his imperative need for self-expression. He always detested what he called literary pictures—pictures, that is, that told or tried to tell a story. And yet I think it true to say that if he is supreme as a colorist it is largely because color was to him an instrument, not an end. He used it as a poet uses words. He made it reflect not so much what is obvious in nature as that duplex image into which external nature fused itself with him, who was also a part of nature. To me, this is what individualizes his pictures. I think it impossible to mistake them. When he was[21] in England the second time, I went to the art rooms of Mr. Lanthier, whom I had authorized to obtain from William Schaus a landscape I had never seen, and which had been for some months tucked away in an upper room inaccessible to visitors. I, at least, had been refused a sight of it when I went to the Schaus gallery for that purpose. The attendant told me they did not exhibit American pictures. Lanthier obtained possession of it, and when I saw it I remarked that, as usual, it was unsigned. “Unsigned!” protested he. “It is signed from the top of the canvas to the bottom. No one in the world could have painted it but Homer Martin.” He sold it a few days later to Mr. Sidney de Kay, whose family, I believe, still possesses it.

Homer went abroad for the first time in 1876, in company with the late Dr. Jacob S. Mosher, an Albany friend of both of us since before our marriage, and at that period quarantine physician of the port of New York. They went to France and Holland, perhaps to Belgium, as well as to England.[22] How far they penetrated into France I do not remember, but I do recall—though when Mr. Charles de Kay wrote to ask the question some three years since I had forgotten—that they visited Barbizon and probably some of the painters whose classic ground it was, and that Homer made some pencilings both there and at Saint-Cloud. They were absent for some considerable time, and it was at this period that he made acquaintance with the late James McNeill Whistler.

He sailed for England the second time in October, 1881, and I joined him in London early in the next July. On the “glorious Fourth” we visited Mr. Whistler’s studio, where Homer had occasionally painted. I think it must have been there that he painted, late in the previous autumn, a delightful Newport landscape which was bought at the Artist Fund sale of that season by Mr. Lanthier for Mr. Charles de Kay. Whistler’s beautiful portrait of his mother—which I afterward saw in Paris at the Salon—was on the easel, and it is[23] the only one of his pictures which I distinctly recollect. There were some “nocturnes” on the walls, and they were doubtless worth remembering. But I never went there again, and on this occasion my attention was riveted by the artist and his surroundings, alike spectacular and bizarre, the man grotesque as a caricature in attitude and aspect, the rooms all pale blue and lemon-yellow, even to the many vases and the flowers therein contained. He said a good many things, not one of which was I able to recall, so lost was I in contemplation of the general oddity of him and his chosen environment. “What did you think of him?” asked Homer after we came away. “Why didn’t you talk? You never said a thing.” “I was afraid to open my lips,” said I, “lest I should involuntarily tell him to shake that feather out of his hair. He must have had his head buried in a pillow before we went in.” “I wish you had!” said he with a laugh. “That is Jimmy’s feather. He delights in having it noticed.” I had observed that he bowed profoundly[24] on our introduction and so brought it into staring evidence; but I could scarcely believe, even on testimony, that the premeditated effect was produced by a quite unpremeditated lock of gray hair.

BLOSSOMING TREES

Reproduced from the original painting through the courtesy of Mrs. Charles O. Gates

The especial occasion for this second visit to England was the making of some drawings illustrative of places mentioned in the novels of Thackeray and George Eliot. He had been there for some months and they were hardly more than begun, but after I came he worked at them pretty steadily. It was an undertaking which he did not at all enjoy, but which circumstances had made imperative. When he first told me of it in the previous summer, he made it evident that he thought such a commission derogatory to his dignity as a painter. Whether it was that his pictures were selling less readily, or because the painting mood came with less imperative frequency, I do not know, but he was unusually despondent. The idea of the voyage was pleasant in itself. One of his never fulfilled longings was to cross[25] the ocean in a sailing vessel. His Artist Fund picture was nearly due and could be painted on the other side; he thought the price of the drawings would pay all his other expenses. And when an unexpected stroke of good fortune made it possible for me to join him, his sky cleared up. I do not remember whether the English drawings were successful; I do know that they were tardy in reaching the New York office of The Century Company, for whose magazine they had been destined, and that when, in the ensuing year, he sent the same publishers a set of Villerville drawings, accompanied by a sketch he had suggested my writing about that delightful haunt of painters, Mr. Gilder wrote me, after some delay, that they had been much interested in my article, but that their art department was not satisfied with the drawings. It was subsequently published in the “Catholic World,” unaccompanied by the illustrations, that magazine not then having begun to produce any.

In October of that year, the completion[26] of the last drawing coincided with the arrival in London of an old New York friend, the late Mr. Bryant Godwin, and an invitation to spend some weeks in Normandy with the family of another, W. J. Hennessy, the well-known artist and illustrator. There was no further reason for delay in England, and the three of us crossed the Channel one night by the Southampton boat. I have never forgotten my first sight of the French shore next morning. “I don’t wonder now at Rousseau’s color,” I said to Homer; “how could he help it?”

It had been our intention to return to New York after a brief visit with the Hennessys, who had been living for years in a picturesque and pleasant way at Pennedepie, an agricultural hamlet on the road between Honfleur and Trouville, where they occupied a roomy and quaintly furnished old manor just opposite the village church. But we found the place, the people, and the neighboring views alike delightful, and when news arrived, early in our stay, of a considerable sum to his credit which had[27] been lying for some months uncalled for at the American Exchange, London, where it had been sent to his first address by Mr. James Stillman, Homer decided on remaining in Normandy. To have returned to New York just then would have been a distinct loss to both of us in many ways. I look back on the time we spent in Villerville as the most tranquil and satisfactory period of our life together.

That little fishing village, dominated by the tower of a church erected when the eleventh century was young, in thanksgiving because the foreboded end of the world had not come in the year 1000, lies about midway between Honfleur and Trouville, at an easy walk from Pennedepie. Equidistant from either place stands the ivy-grown church of Criquebœuf, beloved of artists, and made by Homer the theme of one of his best pictures. In the same grassy enclosure on the right of the pond into which this old church dips its foot, he found two more delightful subjects. One of them is embodied on one of his last canvases, the[28] “Normandy Farm,” now owned, I believe, by Mr. Bloomingdale of New York. It was bought in the first place by Mr. W. T. Evans, a week or so before my husband’s death. The other, a view of a deserted manor, showing dimly through a veil of ghostly trees, which Mrs. Hennessy declared ought to be called “The Haunted House,” was finished in New York after his return for an early friend, Dr. D. M. Stimson, to whom for many years he had been greatly attached. I think it was exhibited at the Chicago World’s Fair.

THE HAUNTED HOUSE

Reproduced from the original painting through the courtesy of Dr. D. M. Stimson

Villerville had for years been thronged in summer and fall by painters, French, English, and American; perhaps it is so still. Guillemet had been there for twenty consecutive seasons; Duez had built himself a house and studio with a Norman tower. Stanley Reinhart came both summers while we were there, with that most sweet wife of his and their pretty little children. The Forbes-Robertsons had a little villa for a while,—the parents, that is, and Miss Frances, then a girl of sixteen; and the[29] actor son must have spent some considerable part of his vacation with them, for I recall a rather animated discussion we had one night, pacing up and down the estacade in the moonlight, when he declaimed in so ardent a fashion about the intrinsic and extrinsic glories of England, that a mere sense of equilibrium made the interjection of a “What about Ireland? What about India?” seem to me inevitable. “Oh! unjust, if you insist,” said he. “But I am an Englishman—Scotch as a matter of fact, I suppose. And you must admit that a man is bound to stand up for his country, right or wrong.” It is a sentiment I have never been able to understand. Some of us, I suppose, are born cosmopolitans, or else look forward to “an abiding city wherein dwelleth justice,” since not even patriotism can insist that it has a local abiding place here.

And that reminds me of another incident belonging to the winter time, when, as there was not an English-speaking soul in the entire neighborhood except ourselves, our[30] landlord one day brought me in despair a lady whose vernacular it was, accompanied by a French bonne and two little children as apple-faced and ruddy as Polly Toodles’ babies. She explained that she was the wife of a major in the English army, and had but just returned with him from India; also, that while there she had read such a glowing description of the beauties of Villerville in a copy of “The Queen,” that she had determined to examine them for herself. I did what I could for her in the way of finding a furnished apartment, and before they had removed to it, went one morning to return her call at one of the hotels. I found her and the major at a late breakfast, with the English newspapers lying about. The period antedated Mr. Joseph Chamberlain’s change of his political coat, the Irish question was well to the front, and my new acquaintances spoke English with one of the most sonorous brogues that had ever greeted my ear. Here was a case in which my own sympathies and the presumable ones of my audience[31] seemed naturally to invite a moderate expression of views on a current topic. Dead silence fell for a moment after I had stopped speaking. Then the major said with an accent that positively projected: “Excuse me, but I am English: that is to say, I am Irish, but of the landlord class!” It was simply a matter of the point of view.

It was this question of the seasons, I think, which chiefly necessitated my learning the language which was afterward of so much use to both of us up to the very end. It also necessitated a more incessant companionship than at any period was ever possible in the city of the Century Club. It was easy to pick up French enough to carry on such intercourse as was absolutely necessary with the people about us, but my serious study of it was undertaken in the first place in order that I might continue to read aloud to Homer in the evenings after the available supply of English novels and periodicals had been exhausted. I began with About’s “Roi des Montagnes,” my method being to read a sentence to[32] accustom his ear and my tongue to the unfamiliar sounds, and forthwith to translate it literally. Of course, I had teachers, one of whom had taught this, her native language, in a London private school, while a second was at the time professor of English in the College of Honfleur. Curious English it must have been! But he was praiseworthily anxious to increase his own knowledge as well as mine. But the best one of the three was a delightful woman, Mademoiselle Lemonnier, the village postmistress, who did not know a word of English although her mother had been an Englishwoman. She was very well read and intelligent as well as companionable and kindly. I had applied to her, when my first instructress found it impossible to come any longer, to find me another. We already knew each other pretty well, and when she said, “If you will let me teach you for love, I will do it myself, but if you insist on paying, I will inquire for some one else,” it was simply a new version of Hobson’s choice. I could not have done better[33] in any case. When Homer went abroad for the last time, he made a point of crossing the Channel to visit Mademoiselle Lemonnier. Slender as were their means of communication, they had managed to understand and sympathize with each other very completely, a strong sense of humor on either side helping greatly to that consummation.

THE CRIQUEBŒUF CHURCH

Reproduced from the original drawing through the courtesy of Dr. D. M. Stimson

We lived in Villerville for nineteen months. An excellent studio with two adjacent rooms had been arranged for us before our arrival, and we lunched and dined at Madame Cornu’s hotel, providing our breakfast in our own quarters. A quaint old English priest whom I knew in London, and who had to the full the hereditary prejudice against “Johnny Crapaud,” had warned me not merely of what he believed to be the prevalent Jansenism which would prevent so frequent an approach to the sacraments as I had been accustomed to, but against the cheating, the conscienceless thievery to which he assured me we would be subjected on all sides. “I[34] would not spend a farthing in France!” said he. Well, in Paris, perhaps, though I had no personal experience of it even there. But in Villerville, and afterward in Honfleur, there was absolutely no exception to the perfect cordiality, absolute trust, and gentle politeness which greeted us on all sides. I have never met anything like it elsewhere save in the parish of the Paulist Fathers in New York. I speak from what may be called exhaustive knowledge, since there was a period, before we left the former place, when we were out of money for so long that when at last we were able to settle Madame Cornu’s bill it amounted to the considerable sum of two thousand francs. I had asked her some time previously if she were not in need of it, but only to receive the smiling answer: “When Madame pleases. We are neither of us robbers.” So in Honfleur, where, after we had been domiciled for a month or so, and had found our fresh bread and rolls on the kitchen-window ledge every morning, I went to the baker to inquire for and[35] settle his account. “But, Madame,” objected the fresh-cheeked young woman in charge, “we have kept no account. Does not Madame know how much it is herself?” “Why, yes,” said I; “you have brought so much for so many days at such a price.” “C’est ça” she smiled. “Whatever Madame says.” And this, again, reminds me of Madame Cornu and her remarkable bill. There had been a price set in the first place of so much a day for our two meals, which were always abundant and well-cooked. I knew the dates and was ready with the exact sum. But when my tally was placed beside her bill there was a discrepancy arising from the fact that Homer would sometimes be absent from the midday meal by reason of a sketching excursion or something of the sort, and she was never notified beforehand. Yet on every such occasion a deduction had been scrupulously made. Such an experience never befell us elsewhere.

To Homer also Villerville was as delightful as any place could be while lacking[36] that social intercourse with men of brains and cultivation which was always his chief pleasure and relaxation. Years afterward, Mr. Brownell said one evening when we were all dining together in those pleasant apartments of theirs on Fifty-sixth Street, that the three weeks which he and his wife had spent there with us seemed to him more like his idea of heaven than anything he remembered. And he asked me whether I would not like to live it all over again. In retrospect, yes; as I have just been proving. But, were it possible in reality? O no! Never have I seen a day that has tempted me to say to it: “Stay, thou art fair!”

GOLDEN SANDS

Reproduced from the original painting through the courtesy of Mrs. Wm. Macbeth

Our sojourn in Villerville was a particularly important one for both of us, but in different ways. For him it was a period of absorption rather than of production, while, on that very account, exactly the reverse process went on in me. I have already said it was at his suggestion that I accompanied his Villerville drawings with an article which, Mr. Brownell afterward wrote me,[37] was like “a Martin landscape put into words.” Homer perhaps thought so himself, for he had already said: “I see that you can paint with words. I wonder if you can set people in action. Why not try?” Whereupon I made a character sketch which Mr. Alden, of “Harper’s Magazine,” declined because “it was too painful,” but which the then editor of “Lippincott’s”—I think his name was Kirk—found too short, and wrote me that if I would lengthen it out so that it should bear less resemblance to a truncated cone, he would be glad to avail himself of it. Whereupon I recalled it, fished up my heroine out of an earthquake on the island of Capri which I had allowed to swallow her, but whom I now unearthed, none the worse except in the matter of a broken wrist,—I think it was a wrist,—and in a month or so received a very fair-sized check for the tale of her experiences.

The same sort of exterior pressure, not any interior need of expression, was what led to the production of a tale which ran[38] for eighteen months as a serial in the “Catholic World” under the title of “Katharine,” and during that period provided for our necessary expenditures. Henry Holt republished it with a new name which he himself suggested. I liked the first one better, but it made too little difference to me to make it worth while to adhere to my own views. Mr. Kirk, by the way, had also renamed my sketch: that seems to be a privilege with literary sponsors, the literary parent not being present. Almost an entire chapter was also eliminated from the book, because the reader, whose name I never knew, objected to it on the ground that it showed too plainly that “Mrs. Martin really believed” that a certain tenet of her faith was absolutely true.

I began a second story on the heels of this one, but when it had run to some thirty thousand words, Homer objected to it as certain to split upon the same dogmatic rock as its predecessor, and I laid it aside for a third one which attained the same[39] proportions and pleased every one who then or thereafter read it better than either of its predecessors. But it had the misfortune of not specially interesting me; and yet there was a baby in it with the second sight, who bade fair to develop into something “mystic, wonderful,” in course of time, if not interfered with. Meantime, the imperative need for production on my part having ended, I put the unfinished manuscript in the fire some three years ago. The second one I completed after our return to New York, and it was published under the title of “John Van Alstyne’s Factory,” in the “Catholic World.”

To Homer our life in France was chiefly seed-time. There germinated his “Low Tide at Villerville,” the “Honfleur Lights,” the “Criquebœuf Church,” the “Normandy Trees,” the “Normandy Farm,” the “Sun Worshipers,” and the landscape known in the Metropolitan Gallery of New York, where it now hangs, as a “View on the Seine,”—which, in strictness, it is not,—but for which his own[40] title was “The Harp of the Winds.” I had asked him what he meant to call it, and, with his characteristic aversion to putting his deeper sentiments into words, he answered that he supposed it would seem too sentimental to call it by the name I have just given, but that was what it meant to him, for he had been thinking of music all the while he was painting it. And this reminds me of a commission given him by a music-lover among his friends during our early days in New York to “paint a Beethoven symphony” for him. He did it, too, and to the utmost satisfaction of its possessor.

ON THE SEINE (“HARP OF THE WINDS”)

Reproduced from the original painting in the Metropolitan Museum, New York

He used to carry about with him in those days a pocket sketch-book in which he noted his impressions in water-color. Mr. Brownell must remember it, and so, I think, must Mr. Russell Sturgis, for, being at our rooms during my husband’s last sojourn on the other side of the Atlantic, when he was known to be afflicted with an incurable malady, he said to me that if Homer’s things were ever put up for sale, he would like to[41] become the purchaser of this book. My husband never got over his chagrin when it became evident that it must have fallen a prey to some unscrupulous packer of our household goods at the time when he concluded to follow me to St. Paul, in June, 1893. He had a suspicion that it might have found its way to a pawnbroker, and never gave up hoping for its ultimate recovery. It had in it some delightful miniature bits of character and color.

It was in Villerville also that he began the “Sand Dunes on Lake Ontario,” now hanging in the Metropolitan Museum, New York, with the intention of sending it to the Salon. But before it was completed he got into one of those hobbles which were not uncommon in his experience, when the more he tried to hurry the less he was in reality accomplishing. It was in no condition to be seen when the last day for sending came, as we both agreed, yet he sent it. Naturally enough, it was rejected. I think that result surprised him less than it momentarily annoyed him. He put the[42] canvas aside and for months never touched it. But one day during the next season, while he was painting on it, a French landscapist and his wife came to call upon us. I forget his name. He studied it in silence for a long time. Then turning to me, he said: “Your husband’s work reminds me strongly of that of Pointelin. He must send this canvas to the next Salon.” “It has been there once,” said I, “and the jury rejected it,” adding, because of his evident surprise, “It was not then in its present condition.” “Nevertheless,” he replied, “I cannot understand a French jury rejecting such a picture in any state in which Mr. Martin would have sent it in at all.”

I do not remember just why we removed from Villerville. Perhaps because Homer was able to obtain in Honfleur a roomy and well-lighted studio apart from our dwelling-place, an arrangement which he always preferred. The little city from which William the Norman set out on his conquering expedition in 1066 had not the picturesque[43] charm of the village we left, but possessed compensating features in the way of English and American neighbors. Our whole sojourn in France was, in fact, delightful, and perhaps even more so to me than to my husband. Through my mother there was a good deal of French blood in my veins, and in its ancestral environment it throbbed with a rhythmic atavism unknown elsewhere to my pulses.

I think that notwithstanding the excellent lighting arrangements of his studio, my husband did not complete much work in Honfleur. “The Mussel Gatherers,” to me one of the most impressive of his later canvases, was finished there, and though I do not recall another for the Artist Fund Sale, I suppose there must have been one. A never-completed studio interior with a portrait of me, and reproductions in miniature of the studies hanging on the walls; still another small portrait, a number of panels, one of which, “Wild Cherry Trees,” was in the Clarke Sale in 1897, and various water-colors belong likewise to this[44] period. Meanwhile his note-books were filling up with material for future use.

I sailed for New York at the end of August, 1886, and Homer, who had remained to finish some of the things I have just named, followed me three months later, arriving December 12th of that year. In the following spring he secured one of the studios in Fifty-fifth Street, having previously utilized for that purpose a room with a north light in an apartment we had in Sixty-third Street. In his more convenient quarters he painted a few great pictures, among them the “Low Tide at Villerville,” the “Sun Worshipers,” and still another, the title of which I never knew, and which I never saw until much later, when going one day with the late Miss a’Becket to the Eden Musée,—I think to see something of her own in an exhibition then in progress, of paintings belonging to private owners,—this great canvas faced me on the line of the opposite wall, and startled me into the exclamation: “That must be one of Homer’s!” It was full of[45] light and color. The land on the left sloped gradually down nearly to the middle of the foreground, and the wonderful sheet of water behind and beyond it that fairly rippled out of the frame, was dazzling. What he called it I do not know. To each other we never gave his landscapes any name, nor did he to any one else unless a purchaser required a title, or there was question of a catalogue. I think, however, that this canvas may be one which was completed in January, 1889, while I was in Toledo, and which was bought almost as soon as finished by Mr. Thomas B. Clarke. If so, it changed hands very soon, and was possibly taken away from New York. Homer wrote me at the time about the sale. From all I could learn of the Memorial Exhibition at the Century Club in the spring of 1897—an exhibition which, to my lasting regret, closed just before I was able to reach New York—this picture was not included in it.

TREES NEAR VILLERVILLE

Reproduced from the original water color in the collection of Mr. Wm. Macbeth

His last studio in New York—occupied from 1890 until he went to St. Paul in[46] June, 1893—was in a house belonging to the Paulist Fathers and adjoining their Convent in Fifty-ninth Street. There he painted the “Normandy Trees,” the “Haunted House” I have already referred to as belonging to Dr. D. M. Stimson, the “Honfleur Lights” now owned by the Century Club, and began the “Criquebœuf Church,” afterward completed in St. Paul. In that house I first observed that his eyesight, always imperfect, was becoming still more dim. Never till then had I known him to ask any one to trace an outline for him. He thought, moreover, that some serious internal trouble threatened him, and consulted both an oculist and a physician. In the early summer of 1892, believing that an ocean voyage would benefit him, he availed himself of the opportunity afforded by the sale to the Century Club of the “Honfleur Lights” and sailed for the last time to England. He spent a very considerable part of his absence at Bournemouth, where resided the family of Mr. George Chalmers, friendship[47] with whom must, I think, have been coeval with his entire life in New York, and lasted, on the part of the survivor, far beyond it. Concerning this visit, Mr. Chalmers wrote me a few years later, in reply to my request that he should tell me about it: “I do not feel that I can do Homer the justice he deserves. Certainly that visit greatly endeared him to me and to my wife, and even to our Harold, who was then a little mite, but who remembers him well. I wish I could remember some of Homer’s talk, always so charming, on our various outings during that happy time—especially about pictures, a subject with which he was eminently so familiar. Two visits to the National Gallery in London I recall in a general sort of way, to be sure. I remember how stirred he was as we stood before the two Turners in the National Gallery, presented by the artist on condition that they should be placed next to the Claudes. Homer regarded Turner’s challenging comparison with the great Frenchman as the sheerest audacity, and called attention[48] to the fussiness and labored work of the Turners compared with the ease and serene dignity and splendor of the Claudes.”

Curiously enough, Mr. Chalmers arrived in New York from London the next day after my own arrival from St. Paul, in April, 1897, and took what I am sure could not have been altogether agreeable pains in order to render me a very important service.

During this last absence of my husband from America, I spent a part of my own vacation in Ottawa, and while there received a letter in which he asked me to write to the oculist who had examined him—I think it was Dr. Bull—and find out from him precisely what was the condition of his eyes. I did so, and received the painful verdict that the optic nerve of one of them was dead, while the other was partially clouded by a cataract. I mention these facts in order that my readers may get an adequate conception of the enormous difficulties under which his latest paintings were begun and finished. Among these is the autumnal known as “The Adirondacks,” exhibited at[49] the Century Club Memorial Exhibition, and bought shortly afterward by Mr. Untermyer at the sale of Mr. T. B. Clarke’s collection. Looking at it when he was giving his final touches, I said to him: “Homer, if you never paint another stroke, you will go out in a blaze of glory!” “I have learned to paint, at last,” he answered. “If I were quite blind now, and knew just where the colors were on my palette, I could express myself.” Another belonging to this period is the “View on the Seine” already referred to, and which in an earlier stage was, to my mind, still more beautiful than it is at present. In its primitive condition—and, indeed, from the moment when it was first charcoaled on the canvas, the trees so grouped that they suggested by their very contour the Harp to which he was inwardly listening—it was supremely elegant. Elegance is still its characteristic feature, but I wish he had left it as I saw it first. “The trees were about four hundred feet high!” he objected, when I told him so, and I did not then, and do not now, see[50] the force of the objection. It was a thing of beauty, anyhow, and who but a pedant measures those except by the optical illusion and spiritual impression they produce?

It was I who went first to St. Paul, where our elder son resided, hoping to recover by means of a long rest from the fatigue entailed by incessant mental labor. I had been editing, reviewing, translating, finishing a novel, besides keeping house, and began to feel as if my own mainspring were liable to snap at any moment. This was at the end of December, 1892. I went, intending to return, and to continue the writing of book reviews during my absence. But in February I broke down completely, gave up all work and all expectation of resuming it in New York. In the following June, Homer resigned his studio and followed me, stopping on the way to see the Chicago Exposition, where several of his paintings were on view.

In St. Paul he had for a while a very good studio in one of the life insurance buildings, and while there completed several[51] pictures, among them that of the “Criquebœuf Church,” selling it, almost as soon as it reached New York, to Mr. William T. Evans. This building was sold, soon afterward, and converted to uses which made it impossible as a studio.

If my memory serves me correctly, it was in the spring of 1894 that the Century Club had a reunion of more than ordinary importance. The special date and occasion I do not recall, but I know that Homer’s presence was so urgently desired by some of his friends that he then paid his last visit to New York, and to the place and associates in it which had given him most satisfaction. He was absent some six weeks, possibly more, and I have since been told that when he left, his physical condition was such that his friends not merely gave up hope of seeing him again, but expected speedy tidings of his death. But the end was not so near. It was to be preceded by such a conquest of mind over matter, of sheer will over propensities both inherited and acquired, of triumphant performance[52] in the face of physical obstacles apparently insurmountable as is altogether unique in my experience. Such efforts are never made, I take it, except under the stimulus of hope, and even that sheet-anchor often fails when the soul is pusillanimous. But Homer Martin was no coward. Moreover, he had always been his own severest critic. Mr. Montgomery Schuyler has quoted him as saying in earlier years when the hangmen exalted him “above the line” in exhibitions, and buyers accepted that verdict as conclusive: “If I could only do it, they would see it fast enough.” Mr. Schuyler adds: “But this was more modest than exact. Even after he had attained the capacity to ‘do it,’ to make canvas palpitate with light and color, as the visitors to the Memorial Exhibition know, the picture-buyers of twenty years ago still failed to ‘see it.’”

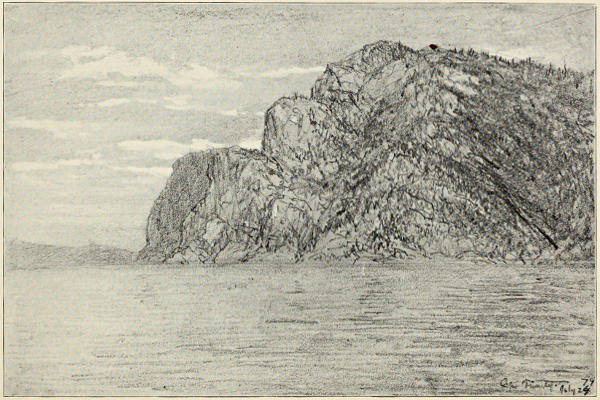

CAPE TRINITY

Reproduced from the original drawing in the collection of Mr. Wm. Macbeth

But, at the period of his life with which I am now concerned, he was not only conscious that he had attained full mastery of his own power of artistic expression by means of color, but he had reason to believe[53] that an opportunity had been afforded him to make that mastery triumphantly evident. Although his faith turned out to be ill-founded, yet his belief to the contrary was sufficient to make him rise at once to his full strength and shake off without apparent effort whatever other shackles had hitherto confined him. He was like nothing so much as blind Samson after his hair had grown, and he carried off the gates of old habits and flung them aside as easily as if he had never felt their weight. In the late spring of that year he went away alone to a quiet farm, taking with him the canvases on which “The Adirondacks,” the “Seine View,” and the “Normandy Farm” were already charcoaled, and set to work at their development and completion. From time to time he would come into the city, his step alert and his physical improvement so apparent in every way, that my apprehension that his health was already shattered irreparably gave way to confidence that years of life and successful achievement were still before him. As[54] for him, I think he never fully believed that the doctors were right in considering his bodily condition hopeless until a short time before his death. He had always looked confidently forward to such length of days as both of his parents and others of his more remote forbears had attained. “I never thought,” he said to me one night, a week or two before his death, “that I was shortening my life in this way.” As to his blindness, it never became entire, and having been accustomed from the beginning to defective vision while yet absorbing his material through the eye and appealing to it in his production, he had, in a measure bewildering to hear of and barely credible to us who beheld it in its final efforts, learned to rely almost entirely on his inward vision and the hand which responded as it were instinctively to its impulse and suggestion.

The pictures I have named went to New York in the late autumn of 1895, and were at once acknowledged with hearty words of praise and a preliminary check. My husband[55] was back at home by this time, and, full of vigor and the anticipation of assured success, had begun three or four other landscapes. Only one of these was ever completed, but that was so present to his imagination, and his steady hand moved in such obedience to his will, that it took visible shape almost without an effort. He had begun making plans for the future and seemed to have renewed his youth. And then, when the year was nearly ended, his hopes were shattered by the tidings that the pictures were found to be unsalable, and had been, or were to be, transferred to other hands which might or might not be more successful in finding purchasers for them.

This was the end, so far as further work was concerned. My Samson fell once more into the hands of the Philistines, and this time not to rise again.

A NEWPORT LANDSCAPE (The Artist’s Last Work)

Reproduced from the original painting through the courtesy of Frank L. Babbott, Esq.

Over those final days, I have not the heart to linger. In all ways, they were inexpressibly painful. In August of the following year, a growth in his throat made[56] its appearance. Although it never caused him intense physical anguish until a few days before his death, when it seemed to have made its way to the brain, it caused him great discomfort. So long as hope remained that it was not malignant and might be removed, he felt and expressed an irritation which, under the precise circumstances, was only natural. But when, late in October, about the time of his sixtieth birthday, the specialist who was attending him pronounced it cancerous, his mood changed. Certain thoughts, certain memories, certain injustices of which he had felt himself the victim, would still move him to indignation when the recollection of them recurred, but he bore his physical trials with wonderful and unalterable patience. A Unitarian clergyman in the neighborhood began calling on him in the early winter and contributed much to his entertainment in some of my unavoidable absences. But, as Christmas was approaching, my husband asked me to request the Reverend Doctor Shields, now Professor of Psychology in[57] the Catholic University at Washington, D. C., to pay him a visit. Said he: “L⸺ is a good fellow; he thinks just as I do about the tariff and the civil service, and he likes good books. But, what all that has to do with his profession, considered as a profession, I do not clearly see.” Therefore I preferred his request to Dr. Shields, who might reasonably have refused it, as he was not doing parish duty but employed in laboratory work at the Ecclesiastical Seminary in St. Paul. He came, nevertheless, a number of times, paying his last visit on the Saturday evening before Homer died. And then, before leaving, he said to me: “There is not the ghost of a hope that your husband will do just exactly what you wish him to do. And, for my part, I am content to leave him in the hands of God just as he is. He is absolutely honest. If he could take another step forward, he would do it.” And, on his part, Homer said to me, “Father Shields has the clearest mind of any man I ever met. I wish I had known him three years ago. But now my head is[58] in such anguish that I can no longer keep three or four threads of argument in my mind at the same time.”

One day in Honfleur, Homer broke a protracted silence by saying, “I hope that I shall die before you do.” To which I answered, “I hope so too.” “You think that you could get along better without me than I could without you?” he asked, and I said, “I know I could.” And now, two days before he died, he said, “I am glad that I am going first”; adding a few more words which it pleases me to remember, but which I shall not repeat. And again I told him that I was glad also. Later still, he asked me what I meant to do when he was gone, and when I said I hoped to enter a convent, he replied, “That is just what I supposed. Well, it is a beautiful life.”