Title: When We Were Strolling Players in the East

Author: Louise Jordan Miln

Release date: December 27, 2017 [eBook #56262]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed

Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net from

page images generously made available by the Internet

Archive (https://archive.org)

WHEN WE WERE

STROLLING PLAYERS IN THE EAST

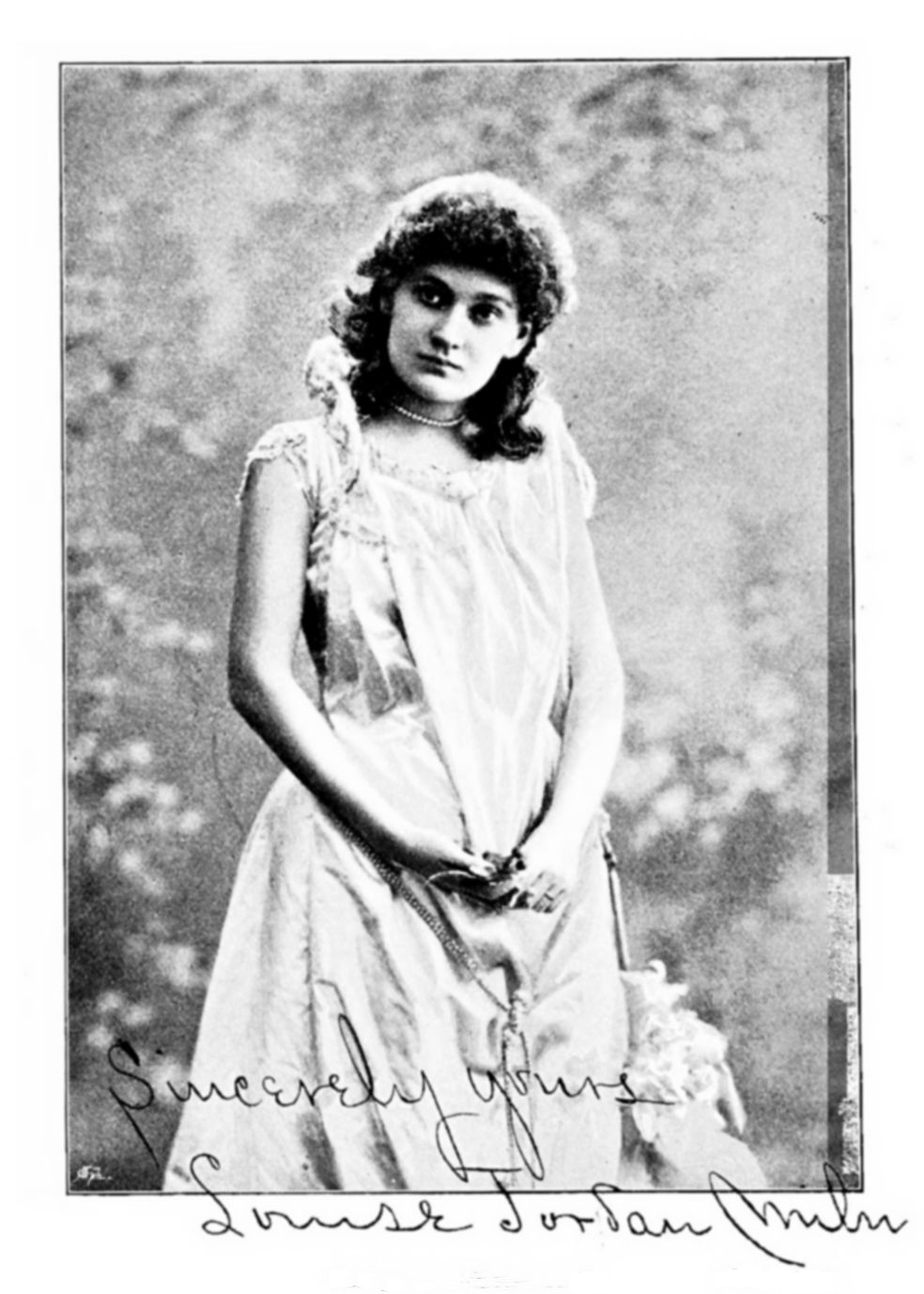

MRS. MILN AS DESDEMONA. Frontispiece.

WHEN WE WERE

STROLLING PLAYERS

IN THE EAST

BY

LOUISE JORDAN MILN

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

NEW YORK:

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

153-157 FIFTH AVENUE

1896

TO MY FATHER

WHOSE LOVE NEVER FAILED ME

AND WHO NEVER MISUNDERSTOOD ME

I dedicate this Volume

In connection with this volume I have several words of thanks to write.

My first and best thanks are due to the editors of the Pall Mall Gazette and of the Pall Mall Budget. Their kindness has enabled me to reprint here several articles that have previously appeared in one or both of their papers. And to the generosity of the editor of the Pall Mall Budget I owe five of the illustrations appearing here.

“Oriental Nuptials” have appeared in The Lady, the editor of which paper kindly allows me to here use them.

Messrs. Bourne and Shepherd of Calcutta have generously granted me permission to reproduce three of their copyrighted photographs.

Messrs. Skeen of Colombo have kindly permitted me to use two of their copyrighted views of Ceylon.

Several of the Burmese photographs have been collected for me in Burmah, and sent me by William Miller, Esq., of Rangoon. I am peculiarly obliged to Mr. Miller, because he found time in the press of grave official duties to take so much trouble for one who had not then the pleasure of his acquaintance.

L. J. M.

London, 31st May 1894.

| CHAPTER I | ||

| My First Glimpse of the Orient | 1 | |

| CHAPTER II | ||

| Andrew | 12 | |

| CHAPTER III | ||

| Our Day Out | 19 | |

| CHAPTER IV | ||

| My First ’Rickshaw Ride | 26 | |

| CHAPTER V | ||

| In the Burra Bazaar | 35 | |

| CHAPTER VI | ||

| A Christmas Dinner on a Roof | 55 | |

| CHAPTER VII | ||

| Oriental Obsequies—A Hindoo Burning Ghât | 62 | |

| CHAPTER VIII | ||

| Oriental Nuptials—A Hindoo Marriage | 70 | |

| CHAPTER IX | ||

| King Theebaw’s State Barge | 80 | |

| CHAPTER X | ||

| Oriental Obsequies—Burmese Burials | 87 | |

| CHAPTER XI | ||

| Oriental Nuptials—Burmese Bridals | 93 | |

| CHAPTER XII | ||

| A Jaunt in a House-boat through the Home of the Wild White Rose | 100 | |

| CHAPTER XIII | ||

| An Opium Den in Shanghai | 112 | |

| CHAPTER XIV | ||

| Memories of Hong-Kong | 120 | |

| CHAPTER XV | ||

| A Glimpse of Canton | 131 | |

| CHAPTER XVI | ||

| Chinese Prisoners | 151 | |

| CHAPTER XVII | ||

| The Chinese New Year | 157 | |

| CHAPTER XVIII | ||

| Oriental Obsequies—Chinese Coffins | 164 | |

| CHAPTER XIX | ||

| Oriental Nuptials—Chinese Espousals | 173 | |

| CHAPTER XX | ||

| Chinese Shoes | 180 | |

| CHAPTER XXI | ||

| Japanese Touch | 188 | |

| CHAPTER XXII | ||

| Four Women that I knew in Tokio—Mrs. Keutako | 196 | |

| CHAPTER XXIII | ||

| Four Women that I knew in Tokio—The Countess Oyama and Mrs. Uriu | 206 | |

| CHAPTER XXIV | ||

| Four Women that I knew in Tokio—Madame Sannomiya | 214 | |

| CHAPTER XXV | ||

| Tom Street | 223 | |

| CHAPTER XXVI | ||

| Oriental Obsequies—A Japanese Funeral | 235 | |

| CHAPTER XXVII | ||

| Oriental Nuptials—Japanese Wedlock | 241 | |

| CHAPTER XXVIII | ||

| Bamboo | 249 | |

| CHAPTER XXIX | ||

| On the Himalayas | 255 | |

| CHAPTER XXX | ||

| My Ayah | 265 | |

| CHAPTER XXXI | ||

| Sambo | 275 | |

| CHAPTER XXXII | ||

| How we kept House on the Hills | 288 | |

| CHAPTER XXXIII | ||

| Oriental Obsequies—The Parsi Towers of Silence | 298 | |

| CHAPTER XXXIV | ||

| Oriental Nuptials—A Parsi Wedding | 306 | |

| CHAPTER XXXV | ||

| At Subathu where the Bagpipes play and the Lepers hide | 315 | |

| CHAPTER XXXVI | ||

| In the Officers’ Mess | 322 | |

| CHAPTER XXXVII | ||

| At the Mouth of the Khyber Pass | 328 | |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII | ||

| An Impromptu Dinner Party in the Punjab | 335 | |

| CHAPTER XXXIX | ||

| Salaam! | 341 | |

| Glossary | 349 |

| Louise Jordan Miln | Frontispiece | ||

| Street Scene in Colombo | To face page | 9 | |

| Natives Weaving Mats in Ceylon | " | 25 | |

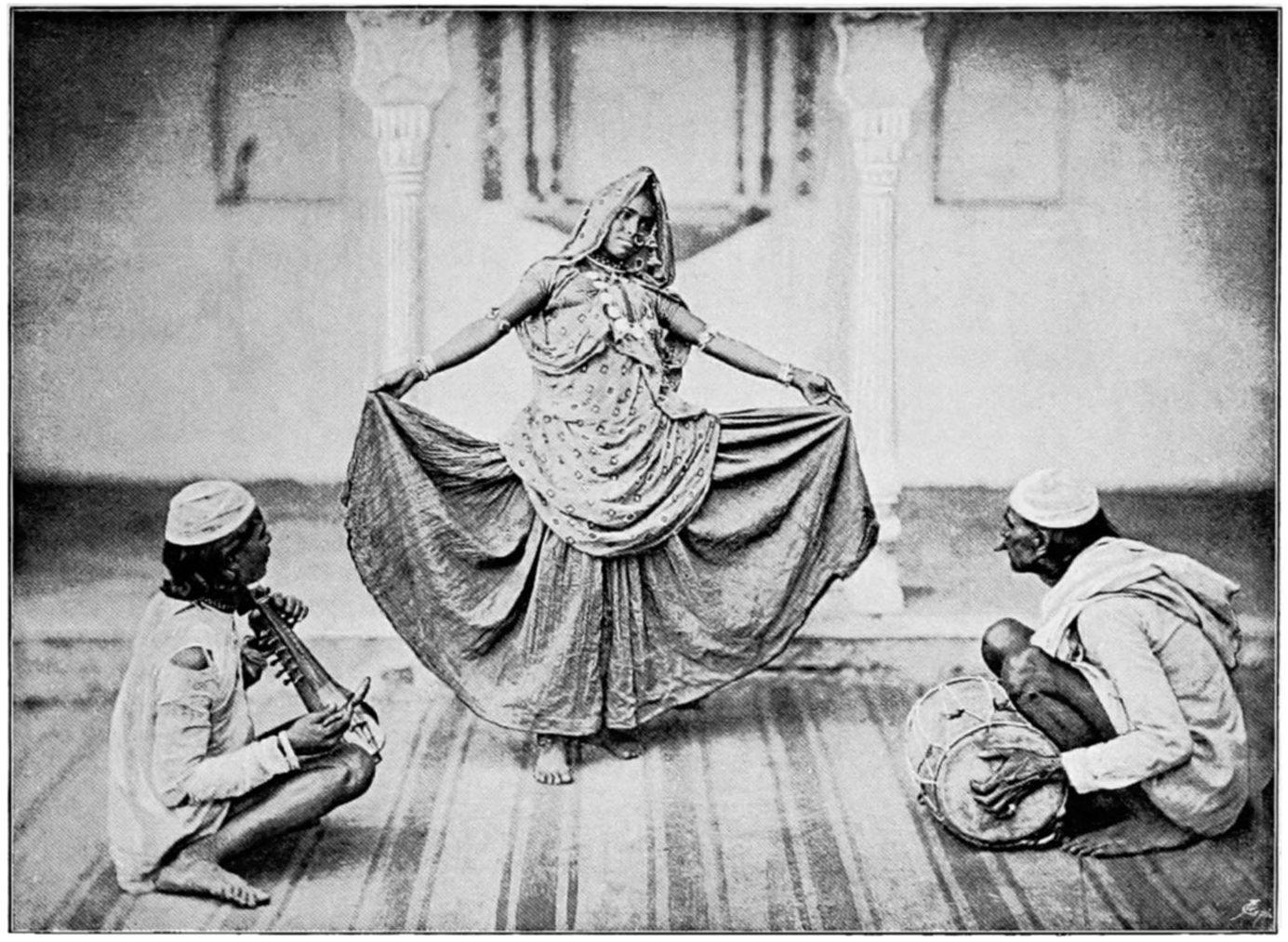

| Delhi Nautch Girl | " | 56 | |

| King Theebaw’s State Barge | " | 80 | |

| Burmese Posture Girls | " | 85 | |

| Pagoda near Mandalay | " | 88 | |

| Band at a Burmese Theatrical Performance | " | 90 | |

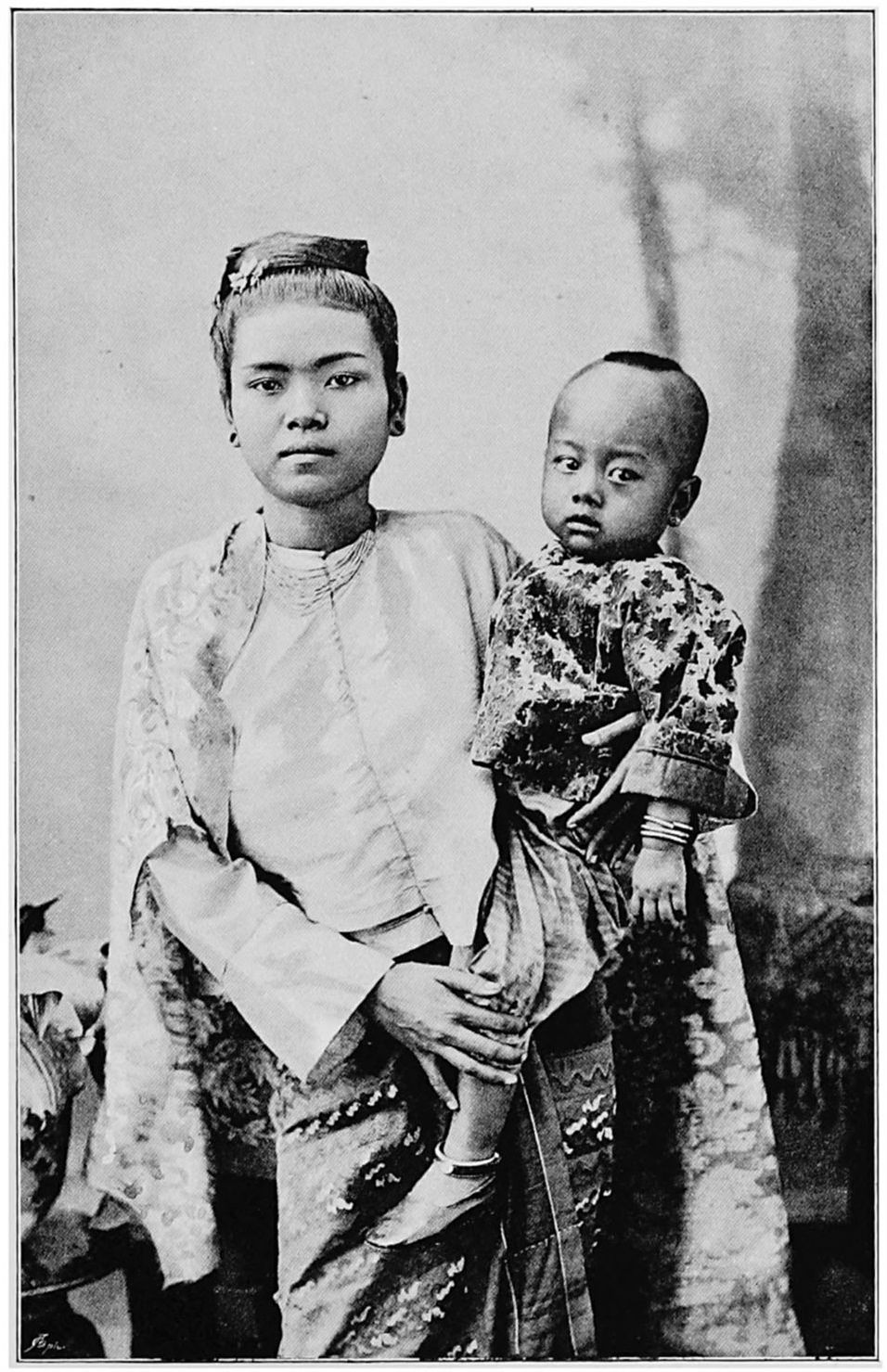

| Burmese Mother and Child | " | 94 | |

| Burmese Musicians | " | 97 | |

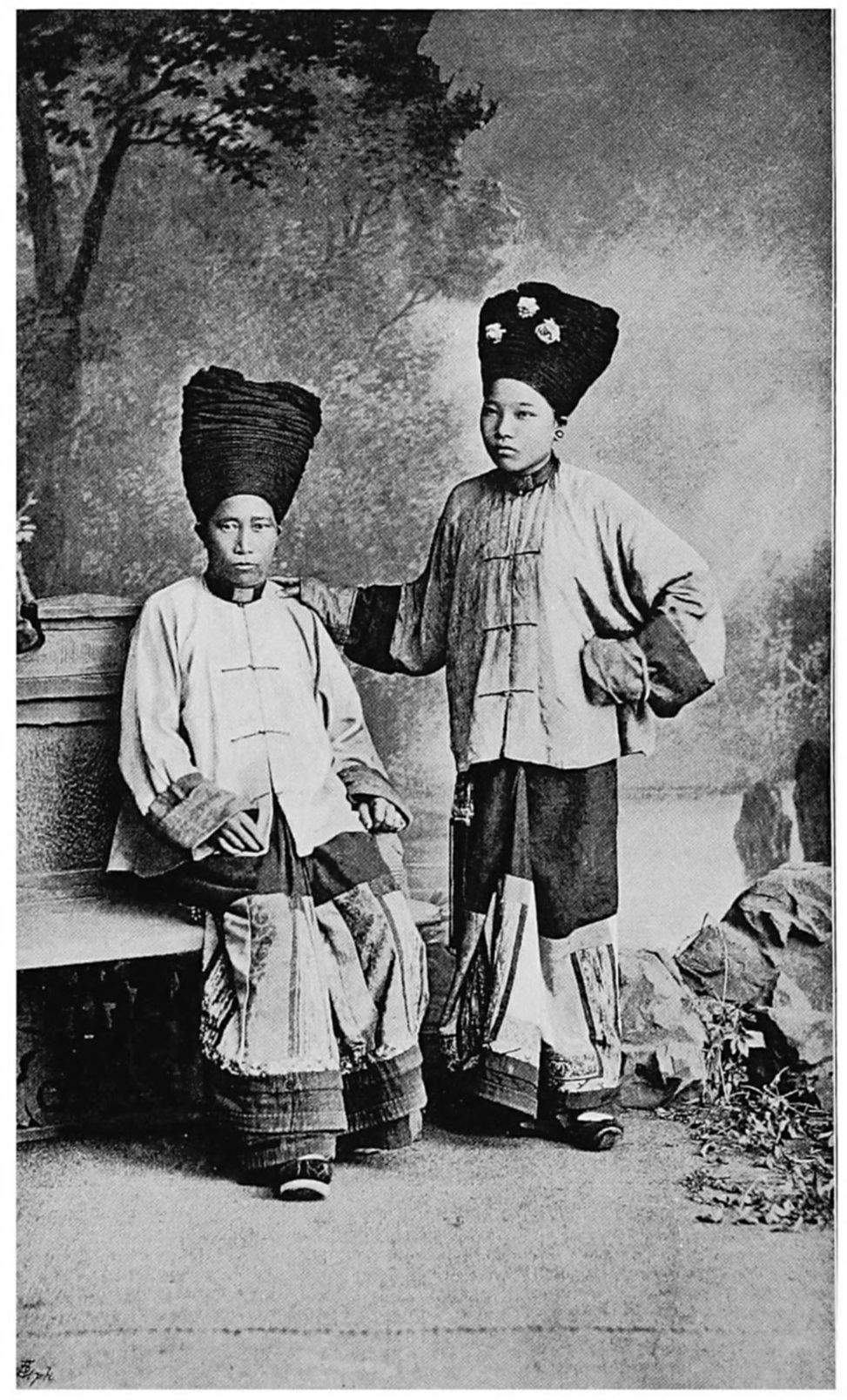

| Bhâmo Women | " | 99 | |

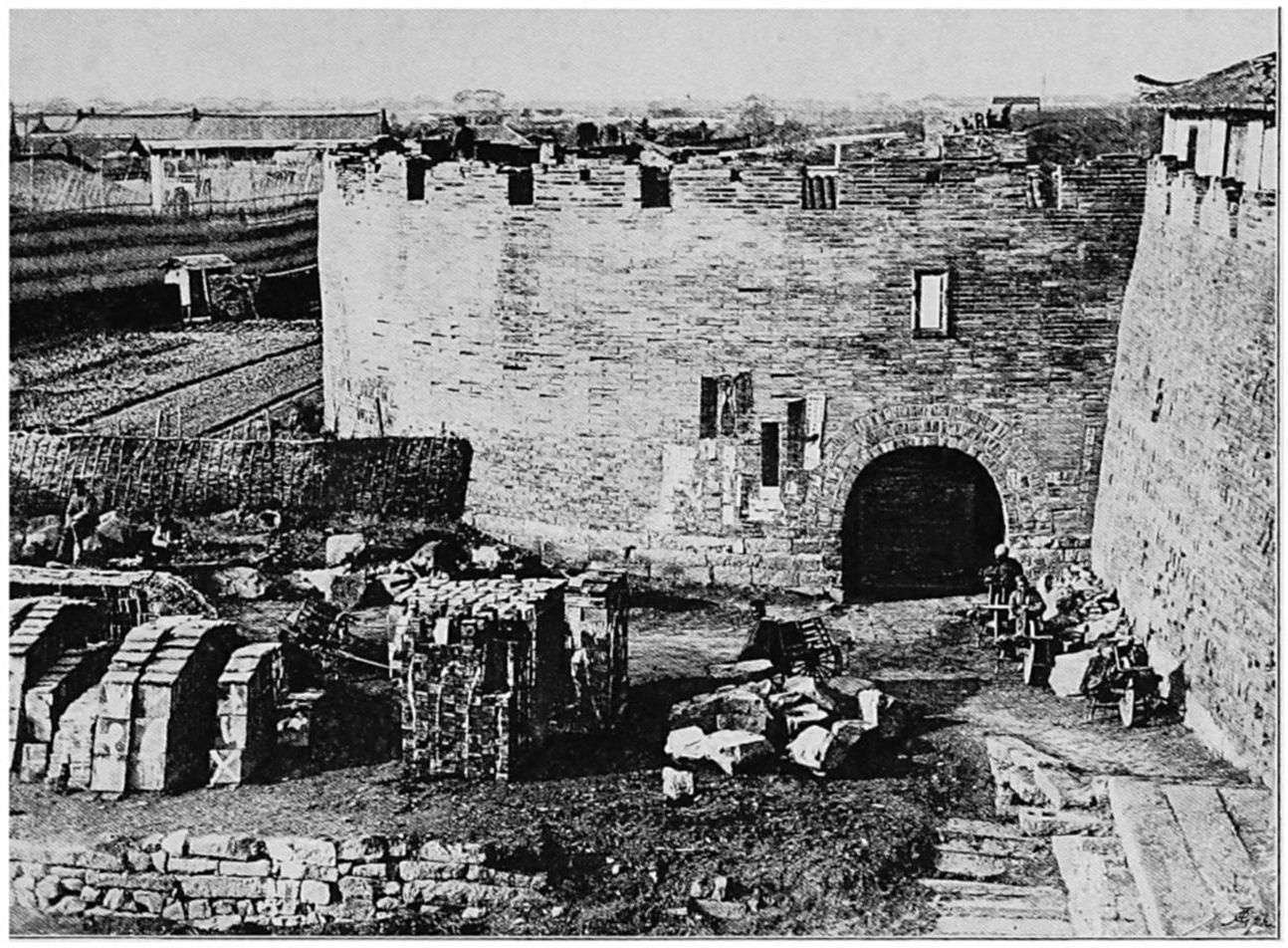

| City Wall, Old Shanghai | " | 112 | |

| Chinese Actors | " | 136 | |

| Foochow Singing Girls | " | 169 | |

| Chinese Musicians | " | 184 | |

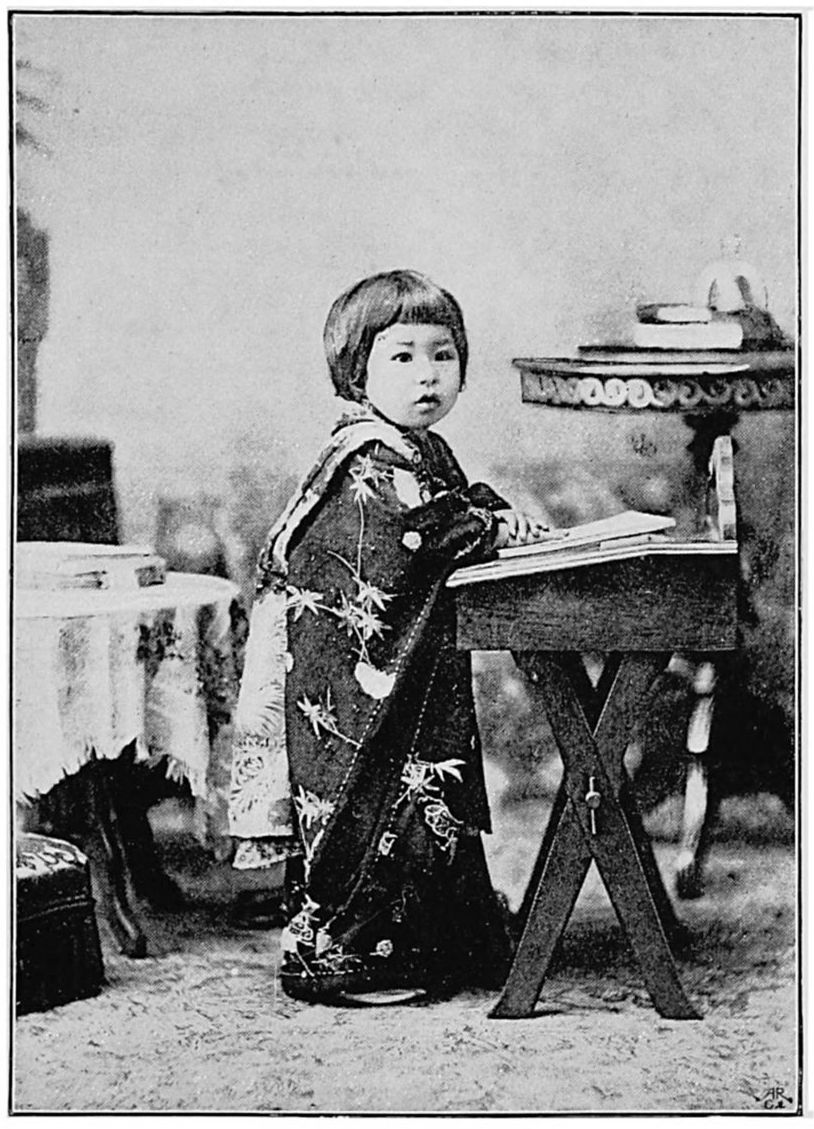

| Mrs. Keutako’s Daughter | " | 200 | |

| Danjero in his Favourite Rôle | |||

| Danjero in European Costume | } | 209 | |

| Danjero as I knew Him | |||

| Mrs. Keutako’s Baby | " | 224 | |

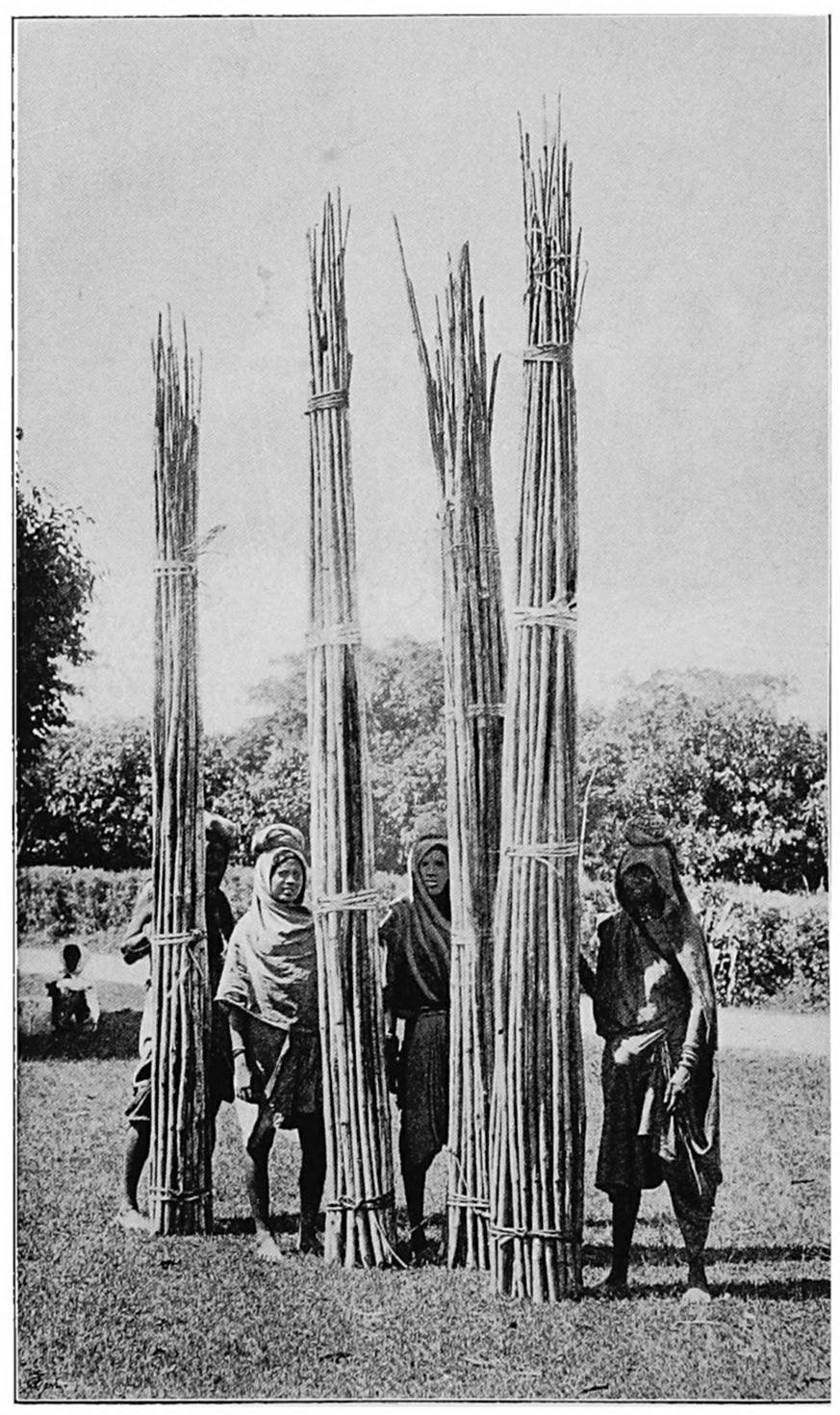

| Hindoo Coolie Women with Loads of Bamboo | " | 249 | |

| Fan Palm at Singapore | " | 255 | |

| Natives Reading at Penang | " | 256 | |

| Hill People—Bhooteas and Nepaulese | " | 264 | |

| A Thornless Black Blossom | " | 273 | |

| H.H. The Maharajah of Patiala on his Favourite Racer | " | 320 | |

| Afredeeds at the Khyber Pass | " | 329 | |

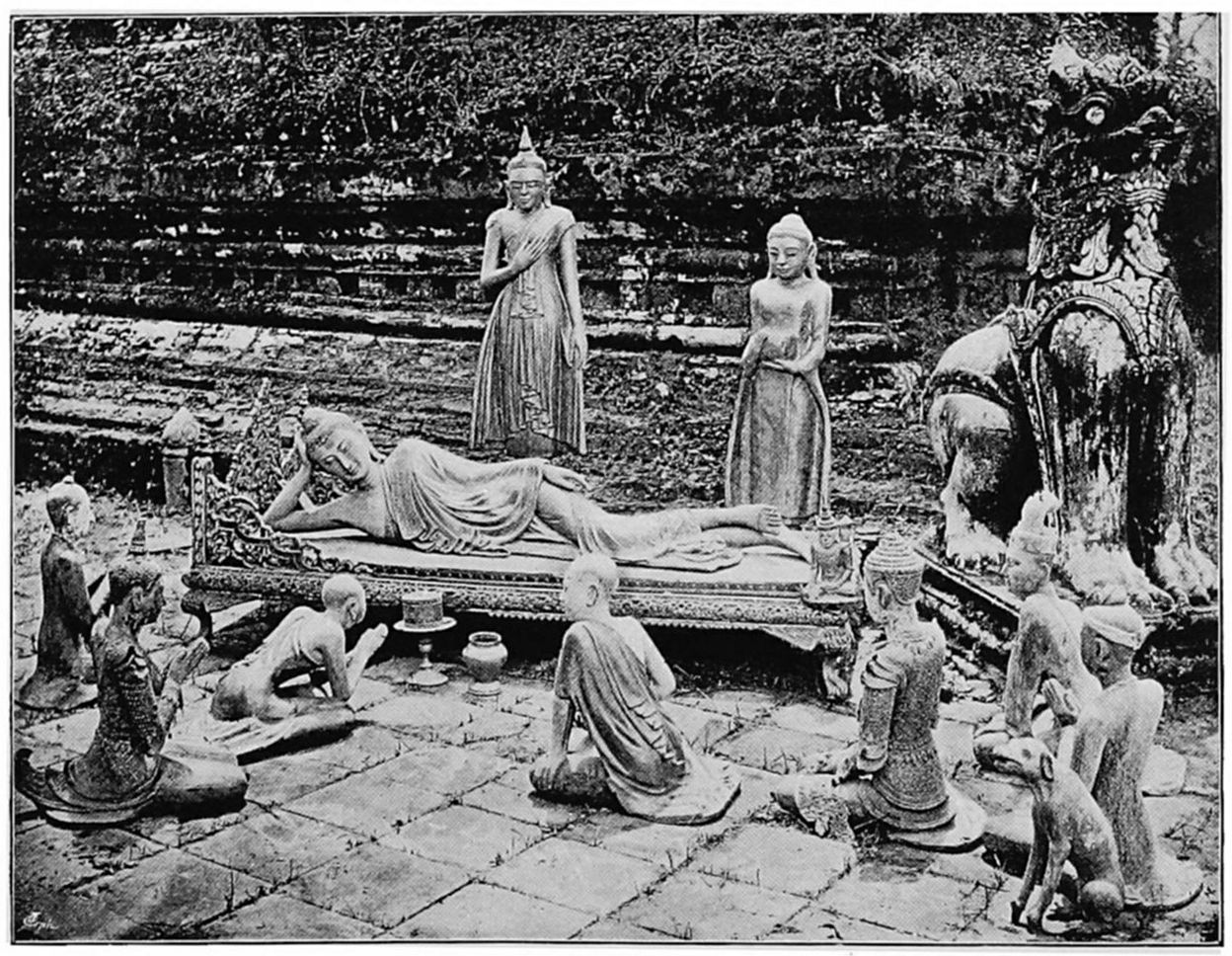

| Idols in a Siamese Pagoda | " | 341 | |

MY FIRST GLIMPSE OF THE ORIENT

To travel far and wide—out of the beaten paths, and to enjoy it, is to have a great career. I know no other impersonal delight that is so endless as the delight of learning new places. To see new flora, a new type of people having new customs, and then to realise that it is Damascus or Kabul, Calcutta or Canton,—a place which has been to you all your life a meaningless dot on a map, but is now—and for ever will be to you—a vivid, vital reality,—that is an exquisite pleasure, a twofold pleasure, for while it fires your intellect, it feeds your artistic sense, your love of the picturesque.

I take it for granted that you have a love of the picturesque. If I am wrong, you would better close my little book, and try to change it for another. For you will think me a bit mad, and we shan’t get on together at all.

I love the East—genuinely and intensely—I love every inch of it. There are occasional bits of the landscape that are uninteresting, but the people are always charming. They are often lovable. They are invariably quaint and interesting.

I remember saying to my husband, when we had been in the East two days, “I can never be grateful enough for having come to this wonderful Orient.” Days passed into weeks. Weeks stretched into months. Months lengthened into years. With every passing hour my gratitude grew. We are back in London now, and the East is a memory; but I am grateful still, and shall be always.

For people who long to see the Eastern wonderland and can’t, I have a big pity. For people who could go, but don’t care to, I have a huge contempt.

My father—a delightful fellow-traveller, and the dear chum of my girlhood—my father and I had planned to see the East together. But we never did. My husband and I saw all the East together. Every day as we went farther and farther into those wonderful countries we said one to the other, “If he were only with us!”

We had been playing some time in Australia, and when we began to fear lest we had worn out our welcome, our thoughts turned to London, the actor’s Mecca. But I begged that we might go to dear old England by a very roundabout way. It turned out a very roundabout way indeed. We were tempted to go from place to place. We were detained in Japan by business. We were held in India by illness. We went all over the East. And when we “came home” a year ago, my boy knew a little Chinese, a little Japanese, and very much Hindustani.

We reached Colombo at daylight. When I woke I had that strange sensation to which, become as old a traveller as one may, one never gets quite used—the sensation of being in a boat that is at anchor after weeks of incessant motion. The noise was indescribable. The Valetta was going on to London, and they were already coaling. I climbed up to the port-hole and looked out. The coaling was going on farther down. As far as I could see, were native boats that would have made Venice gaudier when Venice was gay with the glory of coloured gondolas. Some of them reminded me of the birch-bark canoes that dart up and down the St. Lawrence, some were shaped like Spanish caravels, some were Egyptian in outline. But all were Oriental in colour; and all were manned by Cingalese—the first Oriental people I had ever seen en masse.

The stewardess knocked. “Would I come into the nursery?” (as we called our children’s cabin), “the children absolutely refused to be dressed.” I threw on a dressing-gown and crossed the narrow passage. My two elder babies were crowding each other from the port-hole, and the four-month-old bairn was kicking and clutching at the kind hands that were trying to dress her. Outside, beneath the port-hole, was a small native boat. It was full of fruit which the natives were reaching up to my eager-handed children. Another boat, laden with shells, was trying to push the fruit boat away. A dozen other boats were crowded about these two, and fifty Cingalese were crying—“Buy, buy, buy!” I threw out a bit of silver in payment for the bananas and oranges my infants were devouring. I took a firm clutch of their night gowns and pulled them down. The stewardess closed the port-hole, and we three women gradually persuaded the three babies into their different costumes. The children were taken on deck, where their father was. I went back to my cabin to dress. A Cingalese man had his head thrust well inside my port-hole. His fine aquiline features were covered-with a rich brown skin. His long black hair was twisted into a small but prominent knob at the back of his square head. In the knob was thrust eight inches of convex tortoise-shell, which in the bright sunshine of the early morning sparkled like a queen’s coronet.

“Salaam, beautiful English lady!” he cried before my astonishment had let me speak; “I bring you many beautiful silk—much beautiful sapphire, pearls, not white as your neck, but white as the neck of another.” He threw a square foot of morocco at my naked feet. I picked it up to throw it back, but it opened and I held it a moment. I had seen the Mediterranean when it was good-humoured, and the sky in Italy. I never saw blue until I looked into that leather casket of rings. Oh! those sapphires, cunningly relieved here and there by a glinting cat’s-eye, or a gleaming pearl!

“Go away,” I said, handing up the box, “I’m not dressed.”

“Beautiful English lady, buy,” he replied, ignoring his gems. I glanced into the diminutive P. and O. mirror. My nose was sunburnt; my hair was in curl papers. I have seen uglier women, but not many. That naturally annoyed me.

“Take your rubbish away,” I said sharply. “I don’t want. I’ve no money.”

The first statement was untrue. I did want them. Only a blind woman could look on Ceylon sapphires without longing to wear them. With the poetic sense peculiar to the East, it was my last and true statement that he disregarded.

“Lady take one ring, two ring, six ring. I come hotel get money.”

“I’m going to London,” I said, lying glibly. I was anxious to get on deck. I wanted to dress.

“Lady send me money from London. I trust. No English sir, no English madame, cheat poor native man.”

I have heard English honour upheld in Westminster. I have heard it praised directly and indirectly by almost all the peoples in Europe and in America. But, to me, this was the establishment of English honour. And it was so all over the East. I was not an Englishwoman, but I was the next best thing, the wife of an Englishman, and I could buy on credit half the curios in the East, if I wished.

At last I induced my Cingalese friend to carry his sapphires to a more hopeful port-hole. I dressed and went on deck. One of my little ones crept to me. She had a huge bunch of blossom in her wee hands. Some of the flowers I had seen in famous conservatories. Half of them I had never seen. They were massed together—white, red and yellow, no half colours! They were tightly bound into a stupid graceless bunch, stiffly bordered by thick leaves, but from them rose a perfume heavy as incense, sweet as sandal-wood. One of my baby’s many admirers had given them to her. He had bought them for two annas. The vendor had cheated him into paying double price.

The deck was thronged with native merchants and was vocal with hubbub. At a short distance from the Valetta a dozen native boys were paddling a frail little craft. “Throw away, sir; throw money, sir. I dive, sir—I dive.” And dive they did, invariably bringing up the silver in their triumphant mouths. They dived and swam and rose like nimble, black flying-fish. Hundreds of coolies were bringing big baskets of coal up the ship’s sides. They were as quick as monkeys and far noisier.

I sank into my steamer chair. In a moment I was surrounded. Three Cingalese men planted themselves complacently at my feet. Their attendant coolies followed with their wares. One man had photographs. One had Point de Galle lace and chicken work. One had tortoise-shell and ebony. All had sapphires, cat’s-eyes, and moonstones. Every passenger on deck was surrounded by just such a brown coterie.

Colombo itself we saw but indifferently. A few houses and myriad cocoanut trees, that was all; but around us were anchored the ships of a dozen flags. If I remember, the only men-of-war were three or four funny little Japanese warships.

After a hasty breakfast, which even the children were too excited to eat, we went on shore. What a wonderland! The grass was the crisp green of eternal summer. The intense sunshine was pouring mercilessly down. But native men and women were walking leisurely along, with bare heads, and apparently cool skins. A horribly deformed boy rushed at us with a prayer for bukshish. My husband sprang between him and me. But, though I did not know it, I had, for the first time, seen a leper. I was destined to see lepers all over India, and a year or more later, in Subathu, I learned to go among them quietly if not quite calmly. As for the cry of bukshish, which was the first native word I heard in the East, it was also the last. I heard it incessantly for two years and more. The peoples among whom we went spoke Hindustani, Gujarati, Tamul, Marahti, and a dozen other tongues, but they all cried “Salaam, memsahib. Bukshish! Bukshish!”

It was only a stone’s throw to the large, pleasant hotel. The manager was waiting for us; and with him was an ayah, who had been engaged as an assistant nurse, by our advance agent. What a splendidly handsome woman she was! A long, straight piece of striped silk was wrapped about her hips and fell nearly to her ankles. A short Cingalese jacket, made of white lawn and edged with lace, covered her bosom. Her arms and neck and feet were gleaming, black and bare. And between her short white jacket and her low red skirt was an interspace of four or more inches of black plumpness. Her magnificent black hair was carefully braided, and the long braids were artistically gathered together by a beautiful silver pin, which also fastened a red rose. She wore a string of big gold beads about her neck. She gave a shrewd look at my sturdy little flock. “Salaam, memsahib,” she cried, showing all her large perfect teeth. “Two baba not walk!” She seized upon the smaller of the two and led the way to our rooms. That very afternoon the elder baby walked, for the first time, and after that very rarely asked to be carried. If the ayah repented her choice of babies she gave no sign, but abode by her first selection.

It was in Colombo that I first ate curry that was nearly perfect. In Colombo I ate a dozen fruits I had never eaten before. The hotel was very pleasant. The rooms were large and shady, and they were—what, alas! we were not always to find them in the East—sweetly clean. There was a wonderful garden at the back of the hotel, from which the mallie used to gather me a great bunch of strange, graceful, scarlet flowers. And yet there never seemed a flower the less. Alas! the flowers of the East

spring up, bloom, bear, and wither

In the same hour.

The quiet, respectful, ready Oriental service was delightful. And it was adequate, which Eastern service is not always, for it was under efficient European supervision.

The verandah of the hotel was a great cool place. It was pleasant to sit there when the heat of the day had broken a bit—to sit there and write chits for iced lemon drinks or claret cup, and watch the deft Indian jugglers, and barter with the persistent natives for lace and embroideries, for silks and pongées, for silver belts and for gems. Two Mahommedans had the privilege of spreading their wares on one end of the verandah. And the others were allowed to come upon the verandah with a small quantity of things. They were not allowed to over-pester you, which made shopping on the hotel verandah far pleasanter than shopping in the shops.

But the hotel, pleasant as it was, was merely a European incident,—it was no part of Colombo the native, Colombo the picturesque, though some of the native colour and bits of the native picture were necessarily included in its background.

The first thing we did in Colombo, after we had had a rest and interviewed a dhobie, was to inspect the theatre. The second was to take a long drive.

We drove some distance, indeed, to the theatre. We drove by the barracks, and the bagpipes of the Gordon Highlanders squeaked out that the Campbells were coming. We drove by native shops, where tiger skins from the thick jungles and rich rugs from Persia were hung outside, and where delicately wrought gold and silver ware gleamed in the windows. The proprietors of these shops invariably rushed out and threw themselves in front of our steed, who was, by the way, far from fiery. The gharri wallah and the sais gave us no help. They sat and waited developments as patiently as did the horse itself. We tried abusing the over-solicitous merchants. But they were impervious to abuse. We found that there was one way and one way only of effecting our escape, namely, by committing perjury. We took their cards and vowed we would return in one hour, to their particular shop and to none other.

STREET SCENE IN COLOMBO. Page 9.

And so we, at last, escaped—escaped into a native street. Shall I ever forget it! Hut huddled against hut, where the streets were thick with dwellings. In the front of almost every hut was a booth—a booth piled with grains or fruits or any of a hundred other articles of diet, all equally unknown to us. Potatoes and bananas were the only things I recognised. Oh yes! and pumpkins. In each booth sat a salesman or woman. Sometimes it was a nearly naked coolie—as often it was a carefully dressed Cingalese woman. In every instance there was a pair of primitive scales, and, usually, a customer or two. Farther out, the streets grew more sylvan. There were more cocoanut trees and fewer houses. There were no more shops. Here and there a native squatted upon the ground, waiting to sell a trayful of violently coloured cakes and sweetmeats, or drinks from greasy-looking bottles that were filled with crudely-hued liquids.

We passed a thousand-stemmed banyan tree. A pretty Tamul mother sat in its shade nursing a rolly-poly black baby. A few feet from her were two yellow-clad priests of Buddha, telling their beads.

We drove by a quiet, irregular, silver lake. We drove through a tangle of tropical undergrowth and Eastern flowers. Here and there the cocoanut trees lifted their supreme heads, and now and again the laughing faces of brown babies peeped out at us from the thick of the bamboo.

We came to the theatre all too soon, for our delight with this old world, so new to us, had quite superseded our professional anxiety. But the theatre was a pleasant surprise.

It was pretty—decidedly pretty, and new. We opened it, if I remember—at least professionally. The auditorium was a large high room, beautifully finished with teak-wood. I sat down while my husband gave some directions about scenery. At least fifty coolies were working in their slow, noisy way. They ought to have worked more quickly, for they were encumbered by an absolute minimum of clothing.

We went back to the gharri. We drove through some pretty, unkept gardens, where the air reminded me of my grandmother’s best cupboard, it was so heavy with the smell of cinnamon and nutmegs, and of cloves. That is one of the disadvantages of having lived in the West. Such vulgar utilitarian comparisons suggest themselves.

Children ran after us, throwing flowers and fruit into my lap and screaming to my husband for bukshish. It was amusing at first; but it grew wearying. If they had varied it a bit, by offering him a flower or begging from me a pice. But that never occurred to them. It is a very sophisticated Cingalese indeed who ever suspects a woman of having any money. The late gloaming fell upon us, and we could no longer see the full details of the beauty that surrounded us. As the last of the colour faded with which the sunset echoed the beauty of Ceylon, we found ourselves at the door of a Buddhist temple. As my husband lifted me out of the gharri, I noticed that he was softly quoting a lovely line from The Light of Asia. He was interrupted by a sudden rush of humanity. Three buxom girls had dashed from an adjacent hut. They threw themselves literally upon him, with a nice Oriental disregard of my presence. My husband shook himself, but not free, and used a word that is not in the purists’ lexicon. I must own I felt a little perturbed. Andrew (my husband’s Cingalese boy, of whom more anon) relieved the embarrassment. “No harm, sahib—no harm,” he said. “Hers want bukshish.”

The Buddhist temple was novel, and weird in the dim light. The grotesque figures of Buddha were huge, crudely shaped, glaringly coloured, and shockingly disproportioned. But the priest who constituted himself our cicerone was very wonderful. He spoke only fairish English. But he explained Buddhism so clearly, so concisely, and withal so picturesquely, that we felt we had learned more of it in that one hour spent with him than we had learned before from many earnestly read books.

We drove home through the tender starlight. The flowers were hidden, like high-caste Hindoo women, behind the purdah of the dark. But the damp night dews had distilled the tender leaves of the cinnamon trees, and the air was superlatively sweet.

We went into the hotel a little tired, but very pleased with our first day in the Orient, and very content that it was almost dinner time.

ANDREW

We are poor sometimes, we two Nomads, but we are never without a retinue. There are two reasons for this. I am a helpless, incapable woman, with an acute need of servants. My husband, on the other hand, is phenomenally good to servants. They seem to know this instinctively. They flock to him, and install themselves in his service, and he always feels it difficult to dislodge them. We went into Colombo a party of six. I am not speaking of our company of twenty odd artists (more or less), but of our family party, in which were ourselves, our three children, and their European nurse. We left Colombo a party of eight. A Madrassi boy had attached himself to my husband, and I took the Cingalese ayah for Baby. We left Andrew weeping and wailing on the wharf, and doing it in the most approved and vigorous style. My husband was half inclined to take Andrew with him, but we did not need him; and I had rather discouraged the idea for two other reasons. I should perhaps be ashamed of them both; but this is a true history as far as it goes; so here they are:—Andrew was not good-looking. Now one must put up with ill-looking relatives, but I can never bring myself to be contented with positively plain servants. My other objection to Andrew was that he was a “Cold Water Baptist.” I don’t in the least know what cold water Baptists are. Were I to meet them in Europe, it is of course possible that I should like and respect them intensely; but I must own to a prejudice against native converts. Not so much because I believe that they are usually insincere, as because they are almost invariably hybrid. I believe in the suitability of all things, even in the suitability of religion. Andrew was lank and hungry-looking; he wrapped the native skirt about his legs; he pinned his long hair up with the orthodox tortoise-shell comb; but he wore a European coat over a dirty European shirt. Could anything have looked worse? I think not.

Andrew called himself a guide. He discovered my husband before we had fairly arrived, and insisted upon being engaged. We found him very useful, because he could speak English. And that was a comfort, though he never had any exact information and very rarely spoke the rigid truth. He never lost sight of his master for an instant, unless he was peremptorily sent on an errand to the other end of the town. My husband used to try to escape him. Once or twice we would really have enjoyed a short walk or a drive, alone. But we never had either. There were many exits from our hotel. We tried them all. Sometimes we would get as far as the corner. Then we would hear the plunk—plunk—plunk—of Andrew’s flying feet. “Salaam, sahib,” he would gasp breathlessly, “where are we going?”

He never would tell us his real name. I used to try to bribe him. His master would threaten him. He had but one reply for threat or bribe: “Andrew is my Christian name. I am a Cold Water Baptist.” He never seemed able to lessen my dense ignorance re the interesting subject of Cold Water Baptists. But he could talk glibly enough about the faith he had forsworn. And I observed that he seemed on intimate terms with the priests at all the native temples, and never failed to drop a copper in the temple box. I concluded that his conversion had been purely commercial. He told me that the “Padre Sahib” had given him three coats. It is easier to give a native a coat than a belief.

When we drove in the chill early morning, Andrew used to wrap his head in a Gordon tartan. If we chanced to pass the barracks, he promptly unwound his shawl, folded it up, and sat upon it. Doubtless he did not wish to embarrass me by having the sentry mistake him for the Colonel.

My husband often used, when he was too busy to go with me on my long afternoon drives, to send Andrew—partly for my convenience, as I always went into the densest native quarters, where English was not spoken, and partly, I think, to get rid of Andrew.

One afternoon I looked behind to speak to Andrew, who with the sais was perched on the back of the gharri. He was smoking a not bad cigar. I flew at him, verbally.

“No harm,” he said, with insolence that was, I am sure, unconscious. “No harm. The sahib is not here. I no smoke before my master.”

“You won’t smoke before me!” I said with undignified warmth. “Your master would not smoke in a gharri with me. And I won’t allow any other man to do so—black or white.”

Andrew looked at me stupidly and smiled. Then a thought flashed from my eyes to his. He knocked the fire from his cigar, and put the stump in his pocket. I had recognised my husband’s favourite Havanna, and Andrew knew it.

One day I bought some trifle from an itinerant native. We were driving, and I was wearing a pocketless dress.

“Give the man six annas for me, Andrew,” I said; “I have no money.”

“No,” he said smoothly, “a woman wouldn’t.”

I had one other experience with Andrew, when driving. My husband sent me to capture a scene-painter, and bring him, if possible, to the theatre. The man was that despised unhappy thing, a Eurasian. He was poor; and he drank too much. But I had seen a fan he had painted, and some water-colour sketches of Kandy which he had done. I knew that he was—in part at least—a genius. We found him after a great deal of trouble. He came out to my gharri, and I greeted him, as I would always greet an artist, and stated my business. He took off his shabby sombrero and climbed up to the seat I indicated beside me. Andrew broke into excited vernacular. The man beside me flushed, and started to move.

“What is the matter?” I asked.

“I tell him I no let Eurasian man sit beside my master’s wife. He must come back here with me and Sais.”

I was in a fine rage. I made Andrew get out and walk the several miles that stretched between us and the theatre. That night I had my husband tell him that, when he went out with me, he was, under no circumstances, to speak, unless I spoke to him.

But it was the day of our first performance that I really established myself in Andrew’s mind as a person of importance. I went to the theatre about four o’clock to see if the ayah I had engaged to help me at the theatre had put my dressing-room into proper trim. As I passed in, I noticed Andrew sitting on the lowest rung of a bamboo ladder. He was looking very vicious. He muttered “Salaam” rather than said it, and didn’t rise. I went into my dressing-room, and then marched on to the stage, to attack the poor stage manager.

“Am I to dress in that fearful hole?” I asked him sweetly.

Some one laughed. I turned round.

“I beg your pardon,” said Jimmie M‘Allister, “but do come and see the governor’s quarters.” Jimmie was, of all the boys in our company, my first favourite.

I followed him downstairs, and the stage manager followed me. I looked into my husband’s quarters.

“Do you want to see where the other ladies dress?” asked the stage manager softly.

“I say, do come and see our palace behind the scenes,” cried Jimmie triumphantly.

But I had seen quite enough. The artists’ quarters at the Colombo theatre did not compare favourably with the front of the house. I went meekly back to my dressing-room, wondering what could be done to make my husband’s den a little more comfortable.

“Would you mind speaking to this young imp of your husband’s?” said the stage manager. “He won’t let us take the governor’s things into the dressing-room.” My heart warmed to Andrew.

“Quite right,” I said; “the room certainly must be cleaned out first.”

“Oh! he doesn’t in the least mind the dirt,” explained Jimmie. “He’s offended because your dressing-room is better than the governor’s.”

I had known a prominent actor in—well never mind where—who used to dress luxuriously off the stage, while his wife climbed up a flight of narrow stairs, and wandered down a dark corridor to a gruesome little closet. But that any one would ever expect my husband to be brute enough to allow me to do anything of that kind had never occurred to me. I felt vexed for the moment. Then we came upon Andrew, sitting on the ladder, doggedly guarding his master’s luggage. I realised that Andrew was quite right from his point of view; and for a moment I felt tempted to gratify him by ordering my things to be put into my husband’s room. Then I remembered that we were to play the Merchant of Venice that night. Shylock wore one dress; Portia wore five. And then too, had I changed rooms, my husband would have changed back again. I sent for some coolies; I called my ayah, and superintended the cleaning of that room myself. Jimmie M‘Allister and the stage manager helped me. Andrew stood by sullenly. His master came in. Andrew sprang to him.

“The memsahib has a more nice room,” he said impressively.

“The memsahib has a beastly hole. Go and tell that Madrassi out in front that I want a carpet and a sofa and some nice chairs, here in half an hour, for the memsahib’s room—mind you.”

Poor Andrew gasped and went out. But his manner to me changed from that moment. An hour later Jimmie and I went to the bazaar and got the furniture for my husband’s room. I think Andrew forgave me when I came back with it. I took some curtains from a property box, and told him to tack them up at his master’s window. He answered me quite pleasantly.

I never had another encounter with Andrew; but I never could teach him to knock. He would walk into my dressing-room, and coolly pick up my hare’s-foot, or my scissors, without vouchsafing me one poor word of explanation. If I ventured to ask “What are you doing?” he replied, “Master want,” and went out. I used to beg him to knock; but I don’t remember that he ever did knock. Nor did he ever beat a retreat, no matter in what state of deshabille he found me. Finally, we used to turn the key in the door, if I had an entire change to make. Then he would pound on the door and cry so loudly that the people in front heard—“Open, open; Master want your red paint.”

Andrew and I grew better friends. He used to bring me some little present every morning. Three or four flowers, or a basket of cocoanuts, or a spray of cinnamon.

He said one day to my nurse—“The master like the memsahib. I want please the master—I must please the memsahib. When the memsahib grow old and her teeth drop out, the master will sell her and buy a new wife.” We overheard this remark of Andrew’s. My husband was delighted, and to this day often holds the threat over my silvering head. But I grew to really like Andrew, he was so unmistakably fond of his master. I believe that he grew to really like me, for the same reason.

OUR DAY OUT

Three Grecian cities strove for Homer dead

Where Homer living begged his daily bread.

And the locale of the Garden of Eden is claimed by at least three of the Eastern islands that we have visited. The island of Penang appealed the most seductively to my credulity; but before I saw Penang, I was convinced that Ceylon was in reality the site of the Garden of Eden. Colombo impressed me; Mount Lavinia convinced me.

Mount Lavinia is the Richmond of Colombo. The Mount Lavinia Hotel is the Star and Garter of Ceylon. But ’Arry and ’Arriet never go there. The demi-monde never goes there. The world and his wife don’t flock there. The European population of Colombo is so limited that it does not embrace either ’Arry or ’Arriet—it has no demi-monde, at least no palpable one; and the world and his wife are not numerous enough to flock. Mount Lavinia is a Paradise à deux. Nature is superlatively beautiful there. At the hotel there is an ideal chef.

For years we have had a habit of periodically escaping from every one and everything. Our life has been a busy one; it has been full of friction; but when the friction has threatened to make us forget each other a bit, we have usually managed to shake the dust of the high road from our tired feet, and to snatch a quiet breathing spell, alone, and together.

The second Sunday we were in Colombo we were up very early,—we were going to Mount Lavinia for the day. When we left the hotel the sun was just rising. I had a new frock on, and my husband was good enough to say that it was pretty. I tore it badly getting into the gharri, but it didn’t matter—he found a pin and pinned it for me. We had a long wait at the little station. We stood outside, and tried to guess which of the hieroglyphics painted in black on the white station was “Colombo” in Tamul, and which was “Colombo” in Cingalese.

The funny little train came sizzing into the station; in five minutes we had started. We looked at each other and smiled; our little holiday had begun. Critics might rail, and actors might snarl; it was nothing to us; this was our day out.

We sped through miles of cocoanut trees. Except near the little settlements, through which we passed every ten or fifteen minutes, we saw nothing but cocoanuts. Here and there the natives were gathering the ripe nuts. Here and there agile boys were stealing them, slipping up and down the trees like squirrels. The thousands, nay tens of thousands, of tall straight trees became impressive from their very numbers. It was very Oriental, very graphic; and just before it became the least bit monotonous, the train slackened a little. Then we passed a broken line of native huts.

Every Cingalese mother bathes her children on Sunday. Weather permitting (and in Ceylon the weather almost always does permit), every Cingalese ablution takes place out of doors, and in as conspicuous a place as possible. We must have seen some hundreds of native children drenched with soapsuds, swashed with icy water, or rubbed with oil that morning. Many of the adults bathe as publicly, but not so often. We saw one woman bathing eleven children, and they were all crying. The huts thickened, and we had reached a station. It was a pretty low brown building. It reminded me—though I don’t know why—of Anne Hathaway’s cottage. Brilliant flowering vines hung from the sloping roof. In the doorway was gathered a motley group. Two dirty Buddhist priests sat on the ground counting pice. A group of Cingalese women were eating cocoanuts, drinking the milk, and scraping the soft young meat out with their nails and teeth. The Cingalese women are most beautifully formed. They are upright and supple, and every beauty-line of the human figure is emphasised upon their persons. Their invariable white jackets contrast so splendidly with their dusky skin that one almost catches oneself wondering if black is not the desirable complexion-colour after all. Their brilliant lips, their tawny eyes, their gay petticoats, save the sharp black and white contrast from being too abrupt or too emphatic. A few feet from the women stood a group of Cingalese men, doing nothing. Their long hair was in every instance nicely pinned up with a big tortoise-shell comb, and their parti-coloured skirts hung in straight, listless folds.

A small detachment of the Salvation Army was singing “From Greenland’s icy mountains, From India’s coral strand,” very badly. No one was paying the least attention to them, however. The women were dressed in the Cingalese costume, with some slight additions where the genuine Cingalese dress is rather abbreviated. I thought it rather nice of them not to disfigure the picture by the introduction of clumsy blue frocks and big pokebonnets.

We went slowly on, passing a quaint string of native carts. The oxen were necklaced with roses, and most of them were surmounted by at least one small black boy. The carts were peculiarly shaped of course, gaily painted, and more or less embellished by nondescript draperies. Each cart was incredibly full. But the oxen were crawling along and seemed very comfortable. None of the natives seemed in the least hurry.

When we reached Mount Lavinia, Andrew, whom we had thought in Colombo, opened the carriage door. We gave him a rupee and told him to go home. He looked very indignant; but he went away.

What a day of days! The air was sweet and strong—you could drink it. Indeed, breathing was drinking in this paradise place. A few steps on, and the blue water laughed at our feet. A few yards up, and we saw the rambling old hotel, where we had been told that we would get the best dinner in India.

But before dinner, we had a long lounge on the vined verandah. We didn’t talk; we rested. My companion was very radiant over a cigar, and I sipped bravely at a glass of sherry. I don’t like sherry; but we had been advised to leave ourselves absolutely in the hands of the khansamah. He, I think, had spied the rent in my frock, for he eyed us rather dubiously and asked sadly, but evidently without hope, if we wanted champagne with our tiffin. We confessed that we did, and he brightened up wonderfully. He gave me a long verandah chair, and my husband another, and trotted off, without waiting for any further orders. He came back soon, with a tray of cigars, two glasses, and some milk biscuits. He gave my husband the cigars and the wee glass that held a thimbleful of something that looked deadly. Upon me he bestowed the glass of sherry and the innocent milk biscuits. I am no more devoted to milk biscuits than I am to sherry, but I nibbled and sipped obediently. It was my day out, and I meant to enjoy it, and everything it brought. My comrade was very happy with his cigar, and said that the mysterious thimbleful was very good, but he didn’t think I’d better taste it. That was apparently the opinion also of the khansamah; so I abode by the united decision of two superior intellects.

I felt a soft tug at my gown. I looked down. An ayah was seated at my feet; she was calmly taking the pin from my rent skirt. Then she produced needle and cotton and mended my tatters. Verily, the khansamah had taken us in hand.

The tiffin, even as a pale memory, defies description. We had a little flower-decked table in a window; we could look across the gorgeous garden to the purple sea; sea and garden were shimmering with golden glints of sunshine.

The khansamah waited upon us himself. He apparently knew that the tiffin was perfect, for he allowed us to decline nothing. He gave us soft-shell crabs, as I had never hoped to eat them out of Boston; and the memory of the mayonnaise haunts me still. I often dream of the curry. Some day I am going all the way to Ceylon to get such another tiffin; and if the cook is dead—“I’ll have a suit of sables.”

When the khansamah thought that we had had enough to eat, he marched us out on to one of the terraces of the garden. There he brought us our coffee and liqueurs. He brought out three cigarettes; and my husband, who doesn’t care for cigarettes, took them meekly.

We lazed a bit, and then employed a young gentleman of about five, to roll down hill at an anna a roll. He was really very interesting. The hill was steep but grassy. He started at the top, and brought up in the surf. He swam about for a few moments, and then came back to us, and did it over again. He did not wet his garments, for he wore none. We grew satiated before he grew tired. We paid him, and he carried his dripping person off, to offer his services to some officer sahibs that were in another part of the gardens.

We went for a long, slow walk. I went into three or four native huts, while my husband smoked outside and called in to me what wild risks I was running. The huts were built of mud, of dried banana stalks, of bits of wood, and of white-washed manure. The interiors were very clean. The Cingalese are scrupulously clean. The only exceptions are the priests and the lepers. I bought a piece of coarse embroidery from one woman. I did not want it, but she had given us milk and plantains. I bought sweetmeats from a wayside seller, and sat under a banyan tree to eat them. While we were there, an old decrepit man hobbled to us. He untied his well-worn pouch and took out a gray soapy-looking stone, about the size of a small marble. He laid it in my lap and asked for bukshish. We gave him a rupee, to get rid of him. I quite forgot about the stone until a year or more after, when I came across it one day. We were in Patiala at the time, and a famous lapidarian was there from Calcutta. I showed him the bit of stone. It was an uncut sapphire. And it turned out a very fair gem.

We concluded to be very extravagant, and drive back to Colombo through the moonlit cocoanut groves. We went back to the hotel to order a gharri and to pay our bill. Our happy holiday was nearly over; but still the best of it was to come,—the long delightful drive was to come.

That drive home was so beautiful that I almost forgot to be sorry that our pleasant jaunt was ending.

NATIVES WEAVING MATS IN CEYLON. Page 25.

The weird shadows of the cocoanut trees fell softly on the white road. The native huts we passed were dark and silent. The natives, one and all, had eaten their evening rice, and gone to sleep. The Cingalese have not learned that it is sometimes economy to burn night oil. In their cities, torches of splintered wood sometimes help them to lengthen their day’s work; but in the country they go to bed with the birds.

I looked behind me, to impress my memory with the outlines of some unusually peculiar hut. Andrew was clinging to the back of the gharri with the sais.

As we neared Colombo, we drove through unbroken miles of pungent cinnamon groves. The moonlight was vivid. We were content and silent.

Colombo was wide awake. The officers’ mess was aflame with light. Government House showed a hundred lights through the mass of surrounding shrubberies.

“What a perfect night it is!” said one of us.

“What a perfect day it has been!” sighed the other.

“We will try to go to Mount Lavinia again before we leave,” said my companion.

“I wonder if the children have been good,” said I, as we drew up at our hotel door.

MY FIRST ’RICKSHAW RIDE

My husband would not ride in a jinrickshaw, nor did he wish me to do so. Of course, I was curious—very curious—to know how it felt to be rushed along, drawn by a “human horse.” He thought it wrong to use men in that fashion, and would neither step into a jinrickshaw nor countenance my doing so.

The night before we left Colombo it rained furiously. I suppose every one feels caged, once in a while. I felt caged that night. I remember walking up and down our long sitting-room, up and down, until my husband laid aside his book and said, “What is the matter?”

“I want to go for a ’rickshaw ride,” I cried.

“In all this rain?”

“You know I love to be out in the rain——”

“I can’t let you go alone, and I will not ride in one of those cruel carts.”

“I’ll take Nurse with me, if you’ll see that the ayah minds the children.”

“All right. I don’t think it’s right; but if you do, I’ll go and get the ’rickshaws.”

I flew into the nursery, and encountered another obstacle. My nurse did not approve of ’rickshaws either. She proposed a gharri ride. I told her that I was going in a ’rickshaw, and that, if she didn’t come, I’d go alone. She was incapable of letting me go alone; so she sighed and put on her things.

Does every one in England know what a ’rickshaw is? Almost every one ought by this. A ’rickshaw is not unlike a bath-chair. It is higher, lighter, more comfortable. It is not pushed; it is pulled. A jinrickshaw coolie runs between the two shafts, which he holds firmly in his hands.

We took two ’rickshaws. The manager of the hotel told the coolies that they were to run for an hour, and bring us back at the end of that time.

How it poured! but I was delighted with the motion, and never ceased to like it. They were very swift; they ran with an easy even gait. There was all the pleasure of driving behind a spirited horse and none of the responsibility. There were no reins to hold, no control to exercise. I leaned back on my cushions and enjoyed myself. They were sure of foot those brown runners; and I knew that though they ran never so swiftly they would never run away. As for their personalities, they have less personality than a horse. Their presence a few feet in front was no intrusion. They were merely the naked steaming means toward an exhilarating end of entrancing motion.

We rushed on and on, through the dark and the storm—such a soft, warm, pleasant storm. At last the coolies stopped. They had brought us into the cinnamon grove. I was glad to be there upon my last night in Ceylon. While we sat and sniffed the sweet, languid, scented air, the coolies rubbed each other down. Each carried over his shoulder a long towel-like rag. With these they gave each other a good shampooing. They did not withdraw into the shade or the shelter of the cinnamon trees. They stayed where they were, as pet horses might have browsed by the near way-side. The night was black; but the well-trimmed ’rickshaw lamps flashed steadily upon the clearly revealed coolies, showing their brown bodies red.

The rain fell in torrents. They seemed to like it; and as they towelled off each other’s sweat, they lifted their faces to the descending drench as tired horses might push their steaming flanks into a well found stream.

They halted three minutes perhaps—perhaps fifteen. I don’t know. I was thinking new thoughts, and one can’t measure thought with a tape measure.

They wrung the human rain and the rain of heaven from their rags, and started on their homeward run. My homeward run I should say, for they slept beside their ’rickshaws beneath the stars, or, if it chanced to rain, beneath their rickshaws. And I, who slept mostly in hotels, could hear, if I woke in the watches of the night, the peaceful breathings of my babies as they slumbered in an adjacent room.

The ’rickshaw coolies are not, I believe, blessed, or burdened, with many babies. They rarely have means justifiant of marriage. And in the Orient, marriage is more honoured in the observance than in the breach. Then too they die young as a rule, these “human horses” of the East. Consumption, in some one of its many deadly forms, cuts short their perpetual racing after the petty cash of listless-legged Europeans.

When we reached the hotel, they whined for bukshish with the usual mingling of cringing and of bullying. They were placidly oblivious of all the fine thoughts they had enkindled in my mind. They were not even curious as to what manner of woman I was, that I elected to ride through the rushing rain. I have so often seen the wonder-look upon the stupid face of a European coachman who has driven me aimlessly through the dark or the wet. But on the intelligent faces of my first ’rickshaw coolies, I saw nothing. Their feelings, their thoughts, were as locked from me as mine from them. And not one of their thoughts was of me. To them, I meant two rupees eight annas. No more, no less.

“Well?” said my husband.

“Well!” said I.

“Did you enjoy it?”

“Oh yes! so much.”

“Didn’t you feel wicked?”

“A little. But that will wear off, I think.”

Wear off it did. I became an inveterate jinrickshawist.

Did I shorten the life of any coolie? I don’t know. I provided many a coolie with an overflowing bowl of rice and curry, that made his life momentarily very endurable.

Would they better live longer and be hungrier?

Can we give them other, better work?

Ah! those are questions for statesmen, not for women.

The next day, when we left our rooms in the early morning, we found John, the Madrassi, waiting for us. We were taking him to Calcutta with us, and he was all anerve to start. John was, with one exception, the handsomest native man I ever saw. He was nearly six feet tall, and carried himself with superb dignity. He was fastidiously devoted to his own personal appearance, and we took great delight in his toilets. I remember him so well, as he stood outside our door, in the pale November dawn. He was dressed in the sheerest of white robes, or rather draperies; the upper cloth was of soft native silk; he wore a huge turban, snowy white, with one thin line of gold running through it; and in his ears he wore two hoops of flashing rubies. John never developed a desire to carry parcels, but it was his delight to carry our almost two-year-old baby. What pictures they used to make! She was a big dimpled baby, very white, with bright blue eyes and gleaming yellow curls. John was as black as a Madrassi can be, which is very black indeed; but he was always as spotless in his attire as baby Mona herself.

A man said to my husband, “You must not allow your servant to wear such turbans, nor, above all, to wear jewelry; and then at night he wraps a really valuable cashmere shawl about his miserable shoulders. It is shocking form.”

“My wife would be greatly annoyed if John dressed less picturesquely—” began my husband.

“But it’s most disrespectful, my dear boy, don’t you know.”

“My wife is very disrespectful. That I know.”

I came along in time to hear the last few sentences.

“Dear Sir——,” I said, “don’t you know that wherever MacGregor sits is the head of the table?”

“The natives must be kept down,” was all the reply vouchsafed me.

The Kaiser-i-Hind sailed at eleven in the morning. I had a good cry at nine o’clock—not because we were leaving Colombo, but because the dhobie had left us no underclothing but rags. It was my first experience with an Oriental washerman, and it grieved me. All the pretty, dainty things that my babies had worn during the long voyage from Adelaide to Colombo were ruined. Thorns and rocks had had more to do with that washing than had soap and water.

As we were leaving the hotel, Andrew, who had been paid in full the night before, and whom we had not expected to see again, arrived. He had begged to go with us and had been refused. Now he had made one heroic effort to carry his point. He had cut off his hair and broken his comb. Having Europeanised himself so far, he seemed to feel that we were in honour bound to take him with us. He even said to my husband that he would put on trousers when we reached Calcutta. He couldn’t do so in Colombo, because his wife was coming to see him off. He was broken-hearted when he learned that we really would not take him. He wept piteously on the pier and beat his breast. But his wife (she looked about sixteen) seemed very happy that he was not to accompany us. I thought that greatly to his credit, and gave her a rupee for no reason at all, save that I had so few that one less did not matter.

The ship was very crowded,—she had just come from London. The native merchants made the deck-crowd denser, and buzzed like flies in their last frantic efforts to sell us something—anything. Each rupee that we were taking away they felt a stain upon the record of their ingenuity and salesmanship.

As Colombo faded from our sight, we planned to return there on our homeward journey. But we said it doubtfully—we had learned that the plans of nomads are uncertain and changeable; and we have not yet seen Colombo again.

The Kaiser-i-Hind was full of English people,—army people, civil servants, and their contingent of memsahibs.

There were three Americans aboard beside myself.

I am often called a bad American. I certainly am not a rabid American. At times I am a bitter American. When I am among a lot of nice English people, and have the misfortune to meet the worst type of travelling American, I wince.

One of the Americans on board was a man of whom all Americans are justly proud; he is a soldier (with a great record), a gentleman, and a scholar. But not all the soldiers that have ever come from West Point, not all the scholars that have ever come from Harvard, not all the gentlemen that have ever come from Virginia, could have wiped out our national disgrace upon a boat that numbered among its passengers Mr. and Mrs. Frank Hunter.

They had been married two months. Whatever inspired Americans of their type to select the Orient as the scene of their honeymoon was, is, and always will be, a dark mystery. But there they were, glittering caricatures of our national life. There they were, amid a boat-load of nice English folk.

Mr. Frank Hunter did not wear quite such loud clothes as many of the Englishmen. But he wore them far more noisily. A magnified chess-board is nothing to a certain type of English officer in “mufti.” But though they make mistakes about their coats, they never blunder in their behaviour, those English officers—English and Irish, Scotch and Welsh, are they. But they are all gentlemen, in public at least.

Mr. Frank Hunter’s tailors were irreproachable; but his manners were simply shocking,—and English people are so easily shocked. The English people on the Kaiser-i-Hind quite forgot that there was a nasty something, called mal-de-mer. They were as sick as sick could be from the unavoidable proximity of the Hunters. I say “sick” advisedly; no other word would convey what I mean. Mrs. Hunter, on the whole, was worse than her husband. He sometimes smoked—rather frequently, in fact. When he smoked he was silent. Mrs. Hunter did not smoke. She was never silent, or, if ever, then only in the still watches of the night, and no one had the benefit of it—no one but Mr. Frank Hunter.

Mrs. Frank Hunter wore more diamonds at breakfast than all the other women in the boat put together wore at dinner. She dressed for dinner, but she dressed very high at the neck, which I thought a great pity,—the dimples in her chin told me that her neck was sweetly pretty. She gazed with prudish horror at the well controlled décollete of the English women. They gazed less openly, but quite as disapprovingly, at her vulgar display of jewelry. The abuse hurled by Mr. and Mrs. Frank Hunter upon the Kaiser-i-Hind Commissariat was positively indecent. I have been better fed at sea, several times. But the ceaseless comments of the Hunters were far worse than the food. There was no escape from the perpetual clatter of their tongues; but we were not forced to eat the food. “Won’t I just be glad to see my nice new brown stone bungalow on Fifth Avenue!” exclaimed the bride one night at dinner. “Won’t I have something to eat though! Don’t your mouth water for batter cakes every morning? And aren’t you half dead for butter-milk?” She was speaking to me. I felt very angry, because she had hit upon something we had in common. I am excessively fond of butter-milk; and, when we were housekeeping in Australia, every Sunday morning that was cold enough, my husband used to make me “batter cakes” if I were good. But I could not bring myself to confess that I agreed with that horrid little American in anything. So I said nothing. She persisted, “Isn’t America the nicest place on earth? Don’t you just love it?”

“America is very nice in some respects,” I said softly; “and I should love my native land dearly, if there were fewer Americans.”

Mrs. Hunter did not say much to me after that. But the relief was slight. She talked incessantly to some one—to her husband if to no one else, and her sharp little voice pierced to the utmost corner of the deck. Oh! my sisters, can’t we be free without being vulgar? Can’t we travel without becoming a reproach to our beautiful land?

One night I left the dinner table early. If I had stayed longer I should have thrown something at Mrs. Frank Hunter, and that would not have enhanced the women of America in the eyes of that boat-load of people. I went on deck. The gentleman of whom I have spoken—the American soldier who was the peer, at least, of any Englishman on board—was leaning sadly over the rail. “Are you ill, General?” I asked him.

“No,” he said, “but I am ashamed of being an American! Did you hear that dreadful person trying to pick a quarrel with Colonel Montmorency, about the relative merits of West Point and Sandhurst? I stood it until she told him that her Uncle Silas was a major of militia and one of the best soldiers in the States. Then I left.”

We sat down and tried to console each other. We planned to petition Congress to regulate the class of Americans who travel. We have not yet done so, but I do believe that it was a good idea.

Mrs. Hunter kept up her vulgar, impertinent, irritating remarks until we anchored in Diamond Harbour.

The last time I ever saw her, she and her husband were standing on Chowringhee, gazing at the maidan. She was ablaze with gems, as usual. The natives doubtless thought her the European wife of a Rajah. They are, I believe, the only class of European ladies who in India in the day overload themselves with jewels.

“Frank darling,” she was saying, “it ain’t a patch to Central Park, is it? And their old Government House, as they call it—it can’t hold a tallow candle to the Capitol at Washington, can it now?”

I fled down Dhurrumtollah.

IN THE BURRA BAZAAR

We all grumbled when we were put off the boat at Diamond Harbour, and were told that we must go to Calcutta by train. The treacherous Hooghly was at the moment unsafe for so large a vessel. Of course, every one blamed the Steamship Company. But the very contretemps at which we grumbled gave us a first view of Bengal—a view that was extremely lovely. Our little train went slowly through the peaceful Bengali country. It was early sunset. Strange scarlet flowers hung from the tall trees. Now and again a graceful bending limb almost threw the long vine trails against our window frames,—for the windows were open, and we were pressing against the ledge as eagerly as our children. Here and there, half hidden by the thick green trees and by the deepening twilight, were square white tanks. Natives were bathing in them. Their gleaming black shoulders emphasised the silver water and the marble tanks. We passed cornfields that, with a strange heart-throb, took us back to Illinois. But the corn was not high for all that, and the gaily-clad Hindoos, who were working in it, were as unlike American darkies as they were unlike western farm hands.

“Come, come quickly!” cried my husband, from the other end of the carriage. I went very quickly, for it takes wondrous much to make him “cry out.” A few yards to our left lay a smooth sheet of water. It was quite a purple in the fast-fading sunset; and on its drowsy, blushing bosom lay great masses of dappled water-lily leaves, and on each leaf a great pink lily pressed. Thin lines of crimson, great patches of pale golden green, broke the purple sky. Tropical trees, heavy with white and yellow bloom, hung over the little lake; and on its white and purple surface rested the pink water-lilies, amid their green and gleaming leaves.

We passed great open spaces, and came to small huddled villages. Little mud huts were squeezed together in marvellous fashion. Men, women, and children sat outside their low doorways, and the more prosperous of the family groups included a calf. One had a long wreath of orange marigolds about his pinky-white neck; and a jet-black baby, who lay asleep a few feet off, was similarly adorned. The women were cooking the all-important evening meal; and none of them looked up to see our unimportant European selves.

What a bedlam when we reached Calcutta! It was dark now, and the station was badly lighted. Our advance agent met us, of course; and when he had assured my husband that everything was all right, that he had done everything he had been told to do, he bundled me and my babies into a gharri, the native servants clambered on to the box, the roof, or caught on behind, and we started slowly, if not decorously, for the Great Eastern Hotel.

A steady drizzling rain had begun, and I could see nothing through the misty gharri windows save indistinct masses of oddly-clad and unclad humanity and dim backgrounds of gray walls.

We stopped at a huge white building. The servants at the door took our arrival as a matter of course—if I can say that they took it at all, for they paid not the slightest attention to us. Mr. Paulding left his bearer to wrangle with our charioteer, and we followed him up to our rooms. An incredible number of coolies followed us, carrying our small luggage. I remember one great giant who groaned and wiped his brow when he unloaded himself; and yet he had only carried a cardboard box, and it was empty but for an apology for a bonnet that was made of two crape roses and half a yard of Maltese lace.

My first discovery was that our rooms were large and clean and cool. Then I made myself very comfortable in an immense cane chair, and took my bairns into it with me, all three of them.

Our native servants did not seem to do anything; but somehow I found my hat and gloves were off, slippers had replaced my shoes, baby was drinking hot milk, my boy and girl were munching spongecake, the luggage seemed rapidly to be unpacking itself, and some one had given me a glass of port wine and a plate of vanilla wafers.

“I wonder how they knew that I hate tea,” I said to Mr. Paulding. “They have wonderful intuitions, haven’t they?”

“John told dem,” said my small son briefly, very briefly, for the spongecake was good.

I have known men more industrious than my husband’s picturesque Madrassi servant, John; but I never knew any man with a more considerate memory. He was not indefatigable in doing hard work; but he was infallible in remembering what I liked to have done, and in making other people do it. I sipped my wine, and sighed. It was raining now in dense torrents; and my husband was still at the station, struggling with two of the great problems of a strolling player’s life—scenery and heavy luggage. I released Mr. Paulding with the assurance that we were entirely comfortable, and he rushed off through the storm to help his chief.

John had found where the nursery was; and he marshalled the pretty procession of my babies and their household out with a great deal of dignity. I sat alone in the dim, cool room, and dreamed, and rested. Visions of wild American plains came back—memories of Australia, of Europe, and Canada; I dreamed and dozed; and then I sprang up at the welcome sound of a footstep I knew, in whatever quarter of the globe I heard it. America, Europe, Australasia—they were behind me; Asia was before me. Another phase of our fascinating nomadic life had begun. My husband came in at one door, very, very wet. John came in at another. Behind him walked a half-grown Mahommedan boy, carrying a tray of the steaming tea my husband liked as much as I loathed it.

“Salaam, sahib,” exclaimed the newcomer.

John said something hastily, and the boy added:

“Burra salaam, memsahib.”

In Europe I am more than indifferent to all the woman’s-rights movement. We have so many more privileges than men; and I am sure that I have all my rights, for I never missed one of them. But in the East I waged a long war for the equality of the sexes. Not that I believe that women are men’s equals—I don’t; my observation has been to the contrary; but I wish women to be treated as men’s superiors. Clever John had fathomed my vulnerable narrowness; and so he prompted the boy, and the boy cried, “Burra salaam, memsahib.”

“His name is Abdul,” said John, as he drew an easy chair near mine. “He will be our khitmatgar. We will pay him fifteen rupees a month. To-morrow I will find a bearer, an ayah for the other missie baba, and an ayah for memsahib.”

“Haven’t we enough servants?” pleaded my husband feebly. John shook his handsome turbaned head.

“No sir,” he said, “we want many. One does very little here.”

John, like all Madrassis, was a natural linguist. But he spoke unusual English, even for a Madrassi. He left us to the ministration of Abdul. More than half the servants we had in the East were called Abdul. This was our first Abdul. He was a frightened looking child, with long, lean, awkward legs, and great, lovely, brown eyes. Presently John came back with three or four nondescript-looking, almost garmentless coolies. They carried on their heads chattees of steaming water. In a few moments John came back again.

“The hot bath,” he said. “It will be dinner in an hour.”

When I went to dress I found John laying out a gown for me.

“What are you doing?” I asked him.

“Miss Wadie” (i.e. my nurse) “is tired,” was all he said, and he began to sew a loose bow on to one of my slippers.

They gave us an excellent dinner, for which we were unfeignedly thankful. The room was crowded, and there was, of course, a babel of tongues. But the servants were fairly quiet and only fairly slow, and the gravies were distinctly good. As we left the dining-room, I saw a strangely familiar black face peering at me through the square window of a queer house-like place that was erected in the hall. I paused involuntarily. It was a glimpse of home.

“I’se right proud to see you, lady,” said the dear old black.

I nodded to him and went on without speaking to him. There was a ridiculous something in my foolish throat. He had found me, and I had found him. How he knew me for one of the countrywomen of his adoption I shall never know, but to me every thread of his curly white wool was eloquent of “de ole Virginie state.”

I made friends with him the next day. His name was “Uncle Peter Washington,” and he had come to Calcutta, as I had, with a “trabbling show.” The Ethiopian histrionic combination of which Uncle Pete had been a bright black star, had, after two brilliant performances, succumbed to the tropical heat and the non-appreciation of the public. Uncle Pete, like most Virginian darkies, was versatile, and we found him installed as a Steward at the Great Eastern. He used to send me dainties, not on the bill of fare, and beg continually for “passes.”

After dinner, although we were a little tired, we went with Mr. Paulding to see the Corinthian Theatre, where we were to play. We found it a surprisingly nice play-house—a little dirty, and rather empty of scenery; but it could be cleaned; we had brought our scenery with us; and altogether it was an encouragingly possible place. We went up the outer stairs of the adjacent house, and met the local manager—a vivacious Frenchwoman. It was late when we left her, but I coaxed for a little drive through the streets, like the spoiled woman I was. The rain had ceased; the stars were almost dancing in the sky; and so, at night, I had my first good look at Calcutta.

We had strange half glimpses of odd, weird sights; we caught snatches of plaintive native songs, sung in the monotonous Hindoo treble.

Hamlet was to be our opening bill, and we were very busy. But I, who am usually rather lucky, found time to see a great deal of Calcutta. I ran errands, or rather drove them, and that took me to a number of strange places. I found my way to the native lumber yards. I learned to bargain, in the vernacular, for timber. Moreover, I learned that the only way to ensure its delivery at the theatre, in time for the carpenters, was to see it loaded myself; to see the bullock carts start, and to follow them every inch of the way, until we passed up Dhurrumtollah, and I halted my unique procession triumphantly at the door of the Corinthian Theatre. I learned to descend into the quarters of the dhursies and to return to the theatre with a gharri load of sewing machines and tailors. I even grew so expert in the Calcutta highways and byways that I more than once pounced upon our dhobie in his lair, and wrestled with him for the proper laundrying of some treasured garment.

Best of all, I came to know the Burra Bazaar as few Europeans have ever known it. We first drove there one brilliant Sunday afternoon. A lady, who lived in Calcutta, and Jimmie M‘Allister went with me. My husband refused to go to the place, which he had been told was aswarm with evil smells and more evil natives. He was rather a dilettante sight-seer was my lord and master; and he regarded my inveterate prowlings as something to be permitted on broad principles of personal liberty, but never to be countenanced, much less encouraged. I was an old habitué of the Burra Bazaar before I could induce him to go there with me; and he never went but once.

The Burra Bazaar fascinated me powerfully. Day after day I went there, when I should have been performing sacred social duties. The more I went to the Burra Bazaar, the more I wanted to go. It held me—called me in a thousand ways. What a drive it was from the hotel to the outskirts of the Bazaar. We started in Europe, and stopped in the heart of Asia! Through China the liberal into China the conservative, on to India the wily, into India the tolerant, into India the dense—the real! Through Bentick Street, where the Chinese shoemakers “most do congregate,” into “Old China Bazaar,” where Fan Man sold silks that had been made in the wonderful bamboo looms of Canton, dipped in the huge vats of Chinese colour, beflowered by the deft needles of the incomprehensible Mongolians. Fan Man was not the proprietor of the only silk shop in “Old China Bazaar Street.” He had some dozen rivals. But national consanguinity is more to a Chinaman than trade vigilance—I can say nothing more emphatic of Heathen John’s love for his Heathen brother man. While I sat in one Chinese silk shop, the retainers of all the other adjacent silk shops clustered about the apparently doorless doorway; they manifested every appearance of surprise at the unprecedented bargains offered me by their fellow past grand master of the brotherhood of selling. When I shook my head, pushed aside the coveted masses of silken beauty, and returned to my gharri (with a reluctance that was disgracefully ill-disguised for an actress), they scurried back to their shops with an agility that was more rabbit-like than Chinese. A Chinaman does not unduly urge you to enter his shop. He is too dignified—too Chinese; but once in!—Ah! well, their wares were very lovely, and very cheap, compared with all my preconceived standards of price. Silk and such fabrics were not the only commodities of the Old China Bazaar. Carved ivories, painted porcelains, and bamboo everythings were in emphatic evidence. And there were lesser stores of many other articles.

After Old China Bazaar we came upon the stronghold of the nondescript Parsi merchants. What had they for sale?—What hadn’t they? A few among many of their for-sale-offered commodities were second-hand American cook-stoves, tin boxes, topees, cardigan jackets, broken sewing-machines, pickles, dried-fish, hand punkahs, umbrellas, rusty music-boxes, artificial orange-blossoms, Bibles, cigars, gin, toys, lamps, portières, mildewed books in every known and unknown tongue, cod-liver oil, and a few thousand other things. I even saw a pair of skates there once, not roller skates, but really true skates.

Then the streets grew narrower; they wound and twisted in and out of each other and themselves. Great gray houses towered thinly up toward the glittering sky. Low, narrow doorways led into uninviting, windowless booths. Fat, greasy babus squatted on the filthy little verandahs, making up their books. Our gharri caught and stopped. The street was too narrow. An incredible number of natives were wedged in between our wheels and the adjacent doorways. Beyond were multitudes of black and brown humans—seemingly eternal multitudes! The gharri wallah and the sais got down, and a few dozen of the crowd helped them to extricate our equipage. The proprietors of the pitiful little shops clung desperately to the wheels, shouting the praises of their wares into my bewildered ears, and cursed the charioteers for not leaving me for ever glued where I was, or, at least, until I had emptied my purse and depleted their emporiums. We went slowly and difficultly on, through the sickening, pungent fumes of condiment shops, past great heaps of chillies that made me sneeze and sneeze again. We saw tons of buttons, miles of tinsel, crates of cheap wax beads, infinities of shawls. The saries were without number; the piece-goods shops were numberless, and the varieties of the other shops were as bewildering as the differing wares they held, and the differing castes of the tradesmen who shrieked the superiority of their merchandise with all the frenzy of mad dervishes. Now and anon we caught, through a narrow gateway, a glimpse of a dirty, spacious courtway, where liveried servants slept on empty boxes, and snored their allegiance to His Highness the Rajah.

Pigeons, thousands and tens of thousands, fluttered over our heads, or flew down to demand the corn which was never refused them. They looked at me confidently with their clear red eyes. One fat fellow, I vow, was an old friend of mine, in the days when I spent many sous for corn to scatter on the Square of St. Mark. Perhaps my head was a little dizzy with the crowd, the babel, and the stench. I thought the pigeon spoke to me. This is what I thought he said: “We’re both grown since we met in Venice. You have changed for the worse. You used to wear bright blue plumage and bronze feet, and you had long shiny ropes of hair down your back. Now you’ve black feathers, and you seem a very ordinary sort of person. But with me, everything has changed for the better. ‘How did I get here?’ Oh! a missionary brought me over. But the missionary’s wife was too fond of pigeon-pie, so I flew from Alipore to here, the Burra Bazaar. I am sacred here; I can do what I like, and have what I like. It will be a cruel day for me when the missionaries convert all the Burra Bazaar.” And then the pigeon laughed, and added, as he winged away, “But it won’t be in my day—oh no!”

When I had penetrated into some two or three of the tall, empty-looking houses, and learned how packed with treasure they were, I experienced an added delight in merely driving by them, and thinking what silken, embroidered, bepearled loveliness lay in great piles within those silent buildings.

The tortuous complications of the Catacombs at Rome are nothing compared with the winding mazes of the Burra Bazaar. I believe that I have seen every corner of the Burra Bazaar. I know my way into it. But my way out of it I never knew; and I always shall regard the natives who do know their way out as exceptionally clever.

I have done a great many foolhardy things in Asia. Proper European memsahibs looked askance at me, and even my long-suffering husband remonstrated. One of the two exploits which gained me the greatest disrepute as a wild unladylike woman was going into the Burra Bazaar at night. My husband was playing Rob Roy. I was not quite strong, and my Scotch accent was not considered safe. Consequently I was out of the Bill. That was a rare event in my professional life. And I made much of it. We were preparing for the Lady of Lyons. That was a play that my husband had always declared that he would never under any circumstances play. He did play it in Calcutta, as a concession to the local management. He now meanly says that he played it to please me, but that is not accurate; and, at all events, he was in a fine rage over the whole business. Claude Melnotte was not a gentleman he admired; and he used to say some very unkind things re the whole play, which a more sensitive Pauline might have resented as personal.

“What are you going to wear, dear?” I asked him sweetly, at what I thought a propitious moment. My gentle husband frowned.

“Wear!” said he. “I shall wear anything John lays out,—a Roman toga, or Ingomar’s furs, or Shylock’s gown, or anything else. You didn’t for one moment suppose I was going to buy anything for that fool of a part, did you?” I sighed.