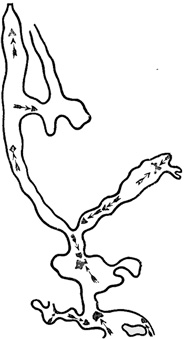

An eye draught of Madison's cave on a scale of 67 feet to the inch. The arrows show where it descends or ascends.

Title: The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 8 (of 9)

Author: Thomas Jefferson

Editor: H. A. Washington

Release date: January 5, 2018 [eBook #56313]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Melissa McDaniel, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

Inconsistent hyphenation and spelling in the original document have been preserved. Obvious typographical errors have been corrected.

Inconsistent or incorrect accents and spelling in passages in French, Latin and Italian have been left unchanged.

The Table of Contents references a Special Message dated Mar. 21, 1804. The corresponding entry itself is dated Mar. 20.

Accents in the table showing the geographical locations of the Indian confederacies seem to indicate pronunciation.

The section starting "Logan's family" has no closing quotation mark.

The section starting "An act of" has no closing quotation mark.

Prevôté and vicomté should possibly not have accents.

Soree. Ral-bird should possibly be Sora. Rail-bird.

bueltas y tortuosidades should possibly be vueltas y tortuosidades.

Cypriores should possibly be Cypriéres.

Aligators should possibly be Alligators.

[Sidenote: 43*] is missing.

Part II ends with an unfinished sentence, and an incomplete address. It has been left as printed.

The dated sidenote "1778, Sept. 5." is out of order, and may be an error.

The following possible inconsistencies/printer errors/archaic spellings/different names for different entities were pointed out by the proofers, and left as printed:

Chippewas and Chippawas

Muskingum and Muskinghum

Rappahanoc, Rappahannoc, Rappahànoc

Duponçeau and Duponceau

Pawtomac, Potomac, Potomak, Powtomac,

Pottawatomies, Powtawatamies, Powtewatamy

Monongalia, Monongahela

Mississippi, Missisipi

Miller, Millar

Maudan, Mandan

levee and levée

BEING HIS

AUTOBIOGRAPHY, CORRESPONDENCE, REPORTS, MESSAGES,

ADDRESSES, AND OTHER WRITINGS, OFFICIAL

AND PRIVATE.

PUBLISHED BY THE ORDER OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE OF CONGRESS ON THE LIBRARY,

FROM THE ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPTS,

DEPOSITED IN THE DEPARTMENT OF STATE.

WITH EXPLANATORY NOTES, TABLES OF CONTENTS, AND A COPIOUS INDEX

TO EACH VOLUME, AS WELL AS A GENERAL INDEX TO THE WHOLE,

BY THE EDITOR

H. A. WASHINGTON.

VOL. VIII.

NEW YORK:

PUBLISHED BY RIKER, THORNE & CO.

WASHINGTON, D.C.:—TAYLOR & MAURY.

1854.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1853, by

TAYLOR & MAURY,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court for the District of Columbia.

EZRA N. GROSSMAN, Printer,

211 & 213 Centre st., N.Y.

| Page | ||

| First Inaugural Address | March 4, 1801 | 1 |

| First Annual Message | Dec. 8, 1801 | 6 |

| Second Annual Message | Dec. 15, 1802 | 15 |

| Special Message | Jan. 28, 1802 | 21 |

| Special Message | Feb. 24, 1803 | 22 |

| Third Annual Message | Oct. 17, 1803 | 23 |

| Special Message | Oct. 21, 1803 | 29 |

| Special Message | Nov. 4, 1803 | 30 |

| Special Message | Nov. 25, 1803 | 31 |

| Special Message | Dec. 5, 1803 | 31 |

| Special Message | Jan. 16, 1804 | 32 |

| Special Message | Mar. 21, 1804 | 33 |

| Fourth Annual Message | Nov. 8, 1804 | 34 |

| Second Inaugural Address | Mar. 4, 1805 | 40 |

| Fifth Annual Message | Dec. 3, 1805 | 46 |

| Special Message | Jan. 13, 1806 | 54 |

| Special Message | Jan. 17, 1806 | 57 |

| Special Message | Feb. 3, 1806 | 58 |

| Special Message | Feb. 19, 1806 | 59 |

| Special Message | Mar. 20, 1806 | 60 |

| Special Message | April 14, 1806 | 61 |

| Sixth Annual Message | Dec. 2, 1806 | 62 |

| Special Message | Dec. 3, 1806 | 70 |

| Special Message | Jan. 22, 1807 | 71 |

| Special Message | Jan. 28, 1807 | 78 |

| Special Message | Jan. 31, 1807 | 78 |

| Special Message | Feb. 10, 1807 | 79 iv |

| Seventh Annual Message | Oct. 27, 1807 | 82 |

| Special Message | Nov. 23, 1807 | 89 |

| Special Message | Dec. 18, 1807 | 89 |

| Special Message | Jan. 20, 1808 | 90 |

| Special Message | Jan. 30, 1808 | 93 |

| Special Message | Jan. 30, 1808 | 94 |

| Special Message | Feb. 2, 1808 | 95 |

| Special Message | Feb. 4, 1808 | 95 |

| Special Message | Feb. 9, 1808 | 96 |

| Special Message | Feb. 15, 1808 | 97 |

| Special Message | Feb. 19, 1808 | 97 |

| Special Message | Feb. 25, 1808 | 98 |

| Special Message | Mar. 7, 1808 | 99 |

| Special Message | Mar. 17, 1808 | 100 |

| Special Message | Mar. 18, 1808 | 101 |

| Special Message | Mar. 22, 1808 | 101 |

| Eighth Annual Message | Nov. 8, 1808 | 103 |

| Special Message | Dec. 30, 1808 | 111 |

| Special Message | Jan. 6, 1809 | 111 |

| Appendix—Confidential Message recommending a Western Exploring Expedition | Jan. 18, 1803 | 241 |

PART I.

PART II.

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES OF DISTINGUISHED MEN.

PART III.

Friends and Fellow Citizens:—

Called upon to undertake the duties of the first executive office of our country, I avail myself of the presence of that portion of my fellow citizens which is here assembled, to express my grateful thanks for the favor with which they have been pleased to look toward me, to declare a sincere consciousness that the task is above my talents, and that I approach it with those anxious and awful presentiments which the greatness of the charge and the weakness of my powers so justly inspire. A rising nation, spread over a wide and fruitful land, traversing all the seas with the rich productions of their industry, engaged in commerce with nations who feel power and forget right, advancing rapidly to destinies beyond the reach of mortal eye—when I contemplate these transcendent objects, and see the honor, the happiness, and the hopes of this beloved country committed to the issue and the auspices of this day, I shrink from the contemplation, and humble myself before the magnitude of the undertaking. Utterly indeed, should I despair, did not the presence of many whom I here see remind me, that in the other high authorities provided by our constitution, I shall find resources of wisdom, of virtue, and of zeal, on which to rely under all difficulties. 2 To you, then, gentlemen, who are charged with the sovereign functions of legislation, and to those associated with you, I look with encouragement for that guidance and support which may enable us to steer with safety the vessel in which we are all embarked amid the conflicting elements of a troubled world.

During the contest of opinion through which we have passed, the animation of discussion and of exertions has sometimes worn an aspect which might impose on strangers unused to think freely and to speak and to write what they think; but this being now decided by the voice of the nation, announced according to the rules of the constitution, all will, of course, arrange themselves under the will of the law, and unite in common efforts for the common good. All, too, will bear in mind this sacred principle, that though the will of the majority is in all cases to prevail, that will, to be rightful, must be reasonable; that the minority possess their equal rights, which equal laws must protect, and to violate which would be oppression. Let us, then, fellow citizens, unite with one heart and one mind. Let us restore to social intercourse that harmony and affection without which liberty and even life itself are but dreary things. And let us reflect that having banished from our land that religious intolerance under which mankind so long bled and suffered, we have yet gained little if we countenance a political intolerance as despotic, as wicked, and capable of as bitter and bloody persecutions. During the throes and convulsions of the ancient world, during the agonizing spasms of infuriated man, seeking through blood and slaughter his long-lost liberty, it was not wonderful that the agitation of the billows should reach even this distant and peaceful shore; that this should be more felt and feared by some and less by others; that this should divide opinions as to measures of safety. But every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle. We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all republicans—we are federalists. If there be any among us who would wish to dissolve this Union or to change its republican form, let them stand undisturbed as 3 monuments of the safety with which error of opinion may be tolerated where reason is left free to combat it. I know, indeed, that some honest men fear that a republican government cannot be strong; that this government is not strong enough. But would the honest patriot, in the full tide of successful experiment, abandon a government which has so far kept us free and firm, on the theoretic and visionary fear that this government, the world's best hope, may by possibility want energy to preserve itself? I trust not. I believe this, on the contrary, the strongest government on earth. I believe it is the only one where every man, at the call of the laws, would fly to the standard of the law, and would meet invasions of the public order as his own personal concern. Sometimes it is said that man cannot be trusted with the government of himself. Can he, then, be trusted with the government of others? Or have we found angels in the forms of kings to govern him? Let history answer this question.

Let us, then, with courage and confidence pursue our own federal and republican principles, our attachment to our union and representative government. Kindly separated by nature and a wide ocean from the exterminating havoc of one quarter of the globe; too high-minded to endure the degradations of the others; possessing a chosen country, with room enough for our descendants to the hundredth and thousandth generation; entertaining a due sense of our equal right to the use of our own faculties, to the acquisitions of our industry, to honor and confidence from our fellow citizens, resulting not from birth but from our actions and their sense of them; enlightened by a benign religion, professed, indeed, and practiced in various forms, yet all of them including honesty, truth, temperance, gratitude, and the love of man; acknowledging and adoring an overruling Providence, which by all its dispensations proves that it delights in the happiness of man here and his greater happiness hereafter; with all these blessings, what more is necessary to make us a happy and prosperous people? Still one thing more, fellow citizens—a wise and frugal government, which shall restrain men from injuring 4 one another, which shall leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement, and shall not take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned. This is the sum of good government, and this is necessary to close the circle of our felicities.

About to enter, fellow citizens, on the exercise of duties which comprehend everything dear and valuable to you, it is proper that you should understand what I deem the essential principles of our government, and consequently those which ought to shape its administration. I will compress them within the narrowest compass they will bear, stating the general principle, but not all its limitations. Equal and exact justice to all men, of whatever state or persuasion, religious or political; peace, commerce, and honest friendship, with all nations—entangling alliances with none; the support of the state governments in all their rights, as the most competent administrations for our domestic concerns and the surest bulwarks against anti-republican tendencies; the preservation of the general government in its whole constitutional vigor, as the sheet anchor of our peace at home and safety abroad; a jealous care of the right of election by the people—a mild and safe corrective of abuses which are lopped by the sword of the revolution where peaceable remedies are unprovided; absolute acquiescence in the decisions of the majority—the vital principle of republics, from which there is no appeal but to force, the vital principle and immediate parent of despotism; a well-disciplined militia—our best reliance in peace and for the first moments of war, till regulars may relieve them; the supremacy of the civil over the military authority; economy in the public expense, that labor may be lightly burdened; the honest payment of our debts and sacred preservation of the public faith; encouragement of agriculture, and of commerce as its handmaid; the diffusion of information and the arraignment of all abuses at the bar of public reason; freedom of religion; freedom of the press; freedom of person under the protection of the habeas corpus; and trial by juries impartially selected—these principles form the bright constellation which has gone before us, and 5 guided our steps through an age of revolution and reformation. The wisdom of our sages and the blood of our heroes have been devoted to their attainment. They should be the creed of our political faith—the text of civil instruction—the touchstone by which to try the services of those we trust; and should we wander from them in moments of error or alarm, let us hasten to retrace our steps and to regain the road which alone leads to peace, liberty, and safety.

I repair, then, fellow citizens, to the post you have assigned me. With experience enough in subordinate offices to have seen the difficulties of this, the greatest of all, I have learned to expect that it will rarely fall to the lot of imperfect man to retire from this station with the reputation and the favor which bring him into it. Without pretensions to that high confidence reposed in our first and great revolutionary character, whose preëminent services had entitled him to the first place in his country's love, and destined for him the fairest page in the volume of faithful history, I ask so much confidence only as may give firmness and effect to the legal administration of your affairs. I shall often go wrong through defect of judgment. When right, I shall often be thought wrong by those whose positions will not command a view of the whole ground. I ask your indulgence for my own errors, which will never be intentional; and your support against the errors of others, who may condemn what they would not if seen in all its parts. The approbation implied by your suffrage is a consolation to me for the past; and my future solicitude will be to retain the good opinion of those who have bestowed it in advance, to conciliate that of others by doing them all the good in my power, and to be instrumental to the happiness and freedom of all.

Relying, then, on the patronage of your good will, I advance with obedience to the work, ready to retire from it whenever you become sensible how much better choice it is in your power to make. And may that Infinite Power which rules the destinies of the universe, lead our councils to what is best, and give them a favorable issue for your peace and prosperity. 6

[In communicating his first message to Congress, President Jefferson addressed the following letter to the presiding officer of each branch of the national legislature.]

December 8, 1801.

Sir: The circumstances under which we find ourselves placed rendering inconvenient the mode heretofore practised of making by personal address the first communication between the legislative and executive branches, I have adopted that by message, as used on all subsequent occasions through the session. In doing this, I have had principal regard to the convenience of the legislature, to the economy of their time, to their relief from the embarrassment of immediate answers on subjects not yet fully before them, and to the benefits thence resulting to the public affairs. Trusting that a procedure founded in these motives will meet their approbation, I beg leave, through you, sir, to communicate the enclosed message, with the documents accompanying it, to the honorable the senate, and pray you to accept, for yourself and them, the homage of my high respect and consideration.

The Hon. the President of the Senate.

Fellow Citizens of the Senate and House of Representatives:

It is a circumstance of sincere gratification to me that on meeting the great council of our nation, I am able to announce to them, on the grounds of reasonable certainty, that the wars and troubles which have for so many years afflicted our sister nations have at length come to an end, and that the communications of peace and commerce are once more opening among them. While we devoutly return thanks to the beneficent Being who has been pleased to breathe into them the spirit of conciliation and forgiveness, we are bound with peculiar gratitude to be thankful to him that our own peace has been preserved through so perilous a season, and ourselves permitted quietly to cultivate the earth and to practice and improve those arts which tend to 7 increase our comforts. The assurances, indeed, of friendly disposition, received from all the powers with whom we have principal relations, had inspired a confidence that our peace with them would not have been disturbed. But a cessation of the irregularities which had affected the commerce of neutral nations, and of the irritations and injuries produced by them, cannot but add to this confidence; and strengthens, at the same time, the hope, that wrongs committed on unoffending friends, under a pressure of circumstances, will now be reviewed with candor, and will be considered as founding just claims of retribution for the past and new assurance for the future.

Among our Indian neighbors, also, a spirit of peace and friendship generally prevails; and I am happy to inform you that the continued efforts to introduce among them the implements and the practice of husbandry, and of the household arts, have not been without success; that they are becoming more and more sensible of the superiority of this dependence for clothing and subsistence over the precarious resources of hunting and fishing; and already we are able to announce, that instead of that constant diminution of their numbers, produced by their wars and their wants, some of them begin to experience an increase of population.

To this state of general peace with which we have been blessed, one only exception exists. Tripoli, the least considerable of the Barbary States, had come forward with demands unfounded either in right or in compact, and had permitted itself to denounce war, on our failure to comply before a given day. The style of the demand admitted but one answer. I sent a small squadron of frigates into the Mediterranean, with assurances to that power of our sincere desire to remain in peace, but with orders to protect our commerce against the threatened attack. The measure was seasonable and salutary. The bey had already declared war in form. His cruisers were out. Two had arrived at Gibraltar. Our commerce in the Mediterranean was blockaded, and that of the Atlantic in peril. The arrival of our squadron dispelled the danger. One of the Tripolitan 8 cruisers having fallen in with, and engaged the small schooner Enterprise, commanded by Lieutenant Sterret, which had gone as a tender to our larger vessels, was captured, after a heavy slaughter of her men, without the loss of a single one on our part. The bravery exhibited by our citizens on that element, will, I trust, be a testimony to the world that it is not the want of that virtue which makes us seek their peace, but a conscientious desire to direct the energies of our nation to the multiplication of the human race, and not to its destruction. Unauthorized by the constitution, without the sanction of Congress, to go beyond the line of defence, the vessel being disabled from committing further hostilities, was liberated with its crew. The legislature will doubtless consider whether, by authorizing measures of offence, also, they will place our force on an equal footing with that of its adversaries. I communicate all material information on this subject, that in the exercise of the important function confided by the constitution to the legislature exclusively, their judgment may form itself on a knowledge and consideration of every circumstance of weight.

I wish I could say that our situation with all the other Barbary states was entirely satisfactory. Discovering that some delays had taken place in the performance of certain articles stipulated by us, I thought it my duty, by immediate measures for fulfilling them, to vindicate to ourselves the right of considering the effect of departure from stipulation on their side. From the papers which will be laid before you, you will be enabled to judge whether our treaties are regarded by them as fixing at all the measure of their demands, or as guarding from the exercise of force our vessels within their power; and to consider how far it will be safe and expedient to leave our affairs with them in their present posture.

I lay before you the result of the census lately taken of our inhabitants, to a conformity with which we are to reduce the ensuing rates of representation and taxation. You will perceive that the increase of numbers during the last ten years, proceeding in geometrical ratio, promises a duplication in little more 9 than twenty-two years. We contemplate this rapid growth, and the prospect it holds up to us, not with a view to the injuries it may enable us to do to others in some future day, but to the settlement of the extensive country still remaining vacant within our limits, to the multiplications of men susceptible of happiness, educated in the love of order, habituated to self-government, and valuing its blessings above all price.

Other circumstances, combined with the increase of numbers, have produced an augmentation of revenue arising from consumption, in a ratio far beyond that of population alone, and though the changes of foreign relations now taking place so desirably for the world, may for a season affect this branch of revenue, yet, weighing all probabilities of expense, as well as of income, there is reasonable ground of confidence that we may now safely dispense with all the internal taxes, comprehending excises, stamps, auctions, licenses, carriages, and refined sugars, to which the postage on newspapers may be added, to facilitate the progress of information, and that the remaining sources of revenue will be sufficient to provide for the support of government, to pay the interest on the public debts, and to discharge the principals in shorter periods than the laws or the general expectations had contemplated. War, indeed, and untoward events, may change this prospect of things, and call for expenses which the imposts could not meet; but sound principles will not justify our taxing the industry of our fellow citizens to accumulate treasure for wars to happen we know not when, and which might not perhaps happen but from the temptations offered by that treasure.

These views, however, of reducing our burdens, are formed on the expectation that a sensible, and at the same time a salutary reduction, may take place in our habitual expenditures. For this purpose, those of the civil government, the army, and navy, will need revisal.

When we consider that this government is charged with the external and mutual relations only of these states; that the states themselves have principal care of our persons, our property, and 10 our reputation, constituting the great field of human concerns, we may well doubt whether our organization is not too complicated, too expensive; whether offices and officers have not been multiplied unnecessarily, and sometimes injuriously to the service they were meant to promote. I will cause to be laid before you an essay toward a statement of those who, under public employment of various kinds, draw money from the treasury or from our citizens. Time has not permitted a perfect enumeration, the ramifications of office being too multiplied and remote to be completely traced in a first trial. Among those who are dependent on executive discretion, I have begun the reduction of what was deemed necessary. The expenses of diplomatic agency have been considerably diminished. The inspectors of internal revenue who were found to obstruct the accountability of the institution, have been discontinued. Several agencies created by executive authority, on salaries fixed by that also, have been suppressed, and should suggest the expediency of regulating that power by law, so as to subject its exercises to legislative inspection and sanction. Other reformations of the same kind will be pursued with that caution which is requisite in removing useless things, not to injure what is retained. But the great mass of public offices is established by law, and, therefore, by law alone can be abolished. Should the legislature think it expedient to pass this roll in review, and try all its parts by the test of public utility, they may be assured of every aid and light which executive information can yield. Considering the general tendency to multiply offices and dependencies, and to increase expense to the ultimate term of burden which the citizen can bear, it behooves us to avail ourselves of every occasion which presents itself for taking off the surcharge; that it never may be seen here that, after leaving to labor the smallest portion of its earnings on which it can subsist, government shall itself consume the residue of what it was instituted to guard.

In our care, too, of the public contributions intrusted to our direction, it would be prudent to multiply barriers against their 11 dissipation, by appropriating specific sums to every specific purpose susceptible of definition; by disallowing all applications of money varying from the appropriation in object, or transcending it in amount; by reducing the undefined field of contingencies, and thereby circumscribing discretionary powers over money; and by bringing back to a single department all accountabilities for money where the examination may be prompt, efficacious, and uniform.

An account of the receipts and expenditures of the last year, as prepared by the secretary of the treasury, will as usual be laid before you. The success which has attended the late sales of the public lands, shows that with attention they may be made an important source of receipt. Among the payments, those made in discharge of the principal and interest of the national debt, will show that the public faith has been exactly maintained. To these will be added an estimate of appropriations necessary for the ensuing year. This last will of course be effected by such modifications of the systems of expense, as you shall think proper to adopt.

A statement has been formed by the secretary of war, on mature consideration, of all the posts and stations where garrisons will be expedient, and of the number of men requisite for each garrison. The whole amount is considerably short of the present military establishment. For the surplus no particular use can be pointed out. For defence against invasion, their number is as nothing; nor is it conceived needful or safe that a standing army should be kept up in time of peace for that purpose. Uncertain as we must ever be of the particular point in our circumference where an enemy may choose to invade us, the only force which can be ready at every point and competent to oppose them, is the body of neighboring citizens as formed into a militia. On these, collected from the parts most convenient, in numbers proportioned to the invading foe, it is best to rely, not only to meet the first attack, but if it threatens to be permanent, to maintain the defence until regulars may be engaged to relieve them. These considerations render it important that we should 12 at every session continue to amend the defects which from time to time show themselves in the laws for regulating the militia, until they are sufficiently perfect. Nor should we now or at any time separate, until we can say we have done everything for the militia which we could do were an enemy at our door.

The provisions of military stores on hand will be laid before you, that you may judge of the additions still requisite.

With respect to the extent to which our naval preparations should be carried, some difference of opinion may be expected to appear; but just attention to the circumstances of every part of the Union will doubtless reconcile all. A small force will probably continue to be wanted for actual service in the Mediterranean. Whatever annual sum beyond that you may think proper to appropriate to naval preparations, would perhaps be better employed in providing those articles which may be kept without waste or consumption, and be in readiness when any exigence calls them into use. Progress has been made, as will appear by papers now communicated, in providing materials for seventy-four gun ships as directed by law.

How far the authority given by the legislature for procuring and establishing sites for naval purposes has been perfectly understood and pursued in the execution, admits of some doubt. A statement of the expenses already incurred on that subject, shall be laid before you. I have in certain cases suspended or slackened these expenditures, that the legislature might determine whether so many yards are necessary as have been contemplated. The works at this place are among those permitted to go on; and five of the seven frigates directed to be laid up, have been brought and laid up here, where, besides the safety of their position, they are under the eye of the executive administration, as well as of its agents, and where yourselves also will be guided by your own view in the legislative provisions respecting them which may from time to time be necessary. They are preserved in such condition, as well the vessels as whatever belongs to them, as to be at all times ready for sea on a short warning. Two others are yet to be laid up so soon as they shall have received 13 the repairs requisite to put them also into sound condition. As a superintending officer will be necessary at each yard, his duties and emoluments, hitherto fixed by the executive, will be a more proper subject for legislation. A communication will also be made of our progress in the execution of the law respecting the vessels directed to be sold.

The fortifications of our harbors, more or less advanced, present considerations of great difficulty. While some of them are on a scale sufficiently proportioned to the advantages of their position, to the efficacy of their protection, and the importance of the points within it, others are so extensive, will cost so much in their first erection, so much in their maintenance, and require such a force to garrison them, as to make it questionable what is best now to be done. A statement of those commenced or projected, of the expenses already incurred, and estimates of their future cost, so far as can be foreseen, shall be laid before you, that you may be enabled to judge whether any attention is necessary in the laws respecting this subject.

Agriculture, manufactures, commerce, and navigation, the four pillars of our prosperity, are the most thriving when left most free to individual enterprise. Protection from casual embarrassments, however, may sometimes be seasonably interposed. If in the course of your observations or inquiries they should appear to need any aid within the limits of our constitutional powers, your sense of their importance is a sufficient assurance they will occupy your attention. We cannot, indeed, but all feel an anxious solicitude for the difficulties under which our carrying trade will soon be placed. How far it can be relieved, otherwise than by time, is a subject of important consideration.

The judiciary system of the United States, and especially that portion of it recently erected, will of course present itself to the contemplation of Congress; and that they may be able to judge of the proportion which the institution bears to the business it has to perform, I have caused to be procured from the several States, and now lay before Congress, an exact statement of all the causes decided since the first establishment of the courts, and 14 of those which were depending when additional courts and judges were brought in to their aid.

And while on the judiciary organization, it will be worthy your consideration, whether the protection of the inestimable institution of juries has been extended to all the cases involving the security of our persons and property. Their impartial selection also being essential to their value, we ought further to consider whether that is sufficiently secured in those States where they are named by a marshal depending on executive will, or designated by the court or by officers dependent on them.

I cannot omit recommending a revisal of the laws on the subject of naturalization. Considering the ordinary chances of human life, a denial of citizenship under a residence of fourteen years is a denial to a great proportion of those who ask it, and controls a policy pursued from their first settlement by many of these States, and still believed of consequence to their prosperity. And shall we refuse the unhappy fugitives from distress that hospitality which the savages of the wilderness extended to our fathers arriving in this land? Shall oppressed humanity find no asylum on this globe? The constitution, indeed, has wisely provided that, for admission to certain offices of important trust, a residence shall be required sufficient to develop character and design. But might not the general character and capabilities of a citizen be safely communicated to every one manifesting a bonâ fide purpose of embarking his life and fortunes permanently with us? with restrictions, perhaps, to guard against the fraudulent usurpation of our flag; an abuse which brings so much embarrassment and loss on the genuine citizen, and so much danger to the nation of being involved in war, that no endeavor should be spared to detect and suppress it.

These, fellow citizens, are the matters respecting the state of the nation, which I have thought of importance to be submitted to your consideration at this time. Some others of less moment, or not yet ready for communication, will be the subject of separate messages. I am happy in this opportunity of committing the arduous affairs of our government to the collected wisdom 15 of the Union. Nothing shall be wanting on my part to inform, as far as in my power, the legislative judgment, nor to carry that judgment into faithful execution. The prudence and temperance of your discussions will promote, within your own walls, that conciliation which so much befriends rational conclusion; and by its example will encourage among our constituents that progress of opinion which is tending to unite them in object and in will. That all should be satisfied with any one order of things is not to be expected, but I indulge the pleasing persuasion that the great body of our citizens will cordially concur in honest and disinterested efforts, which have for their object to preserve the general and State governments in their constitutional form and equilibrium; to maintain peace abroad, and order and obedience to the laws at home; to establish principles and practices of administration favorable to the security of liberty and property, and to reduce expenses to what is necessary for the useful purposes of government.

To the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States:—

When we assemble together, fellow citizens, to consider the state of our beloved country, our just attentions are first drawn to those pleasing circumstances which mark the goodness of that Being from whose favor they flow, and the large measure of thankfulness we owe for his bounty. Another year has come around, and finds us still blessed with peace and friendship abroad; law, order, and religion, at home; good affection and harmony with our Indian neighbors; our burdens lightened, yet our income sufficient for the public wants, and the produce of the year great beyond example. These, fellow citizens, are the circumstances under which we meet; and we remark with special satisfaction, those which, under the smiles of Providence, result 16 from the skill, industry and order of our citizens, managing their own affairs in their own way and for their own use, unembarrassed by too much regulations, unoppressed by fiscal exactions.

On the restoration of peace in Europe, that portion of the general carrying trade which had fallen to our share during the war, was abridged by the returning competition of the belligerent powers. This was to be expected, and was just. But in addition we find in some parts of Europe monopolizing discriminations, which, in the form of duties, tend effectually to prohibit the carrying thither our own produce in our own vessels. From existing amities, and a spirit of justice, it is hoped that friendly discussion will produce a fair and adequate reciprocity. But should false calculations of interest defeat our hope, it rests with the legislature to decide whether they will meet inequalities abroad with countervailing inequalities at home, or provide for the evil in any other way.

It is with satisfaction I lay before you an act of the British parliament anticipating this subject so far as to authorize a mutual abolition of the duties and countervailing duties permitted under the treaty of 1794. It shows on their part a spirit of justice and friendly accommodation which it is our duty and our interest to cultivate with all nations. Whether this would produce a due equality in the navigation between the two countries, is a subject for your consideration.

Another circumstance which claims attention, as directly affecting the very source of our navigation, is the defect or the evasion of the law providing for the return of seamen, and particularly of those belonging to vessels sold abroad. Numbers of them, discharged in foreign ports, have been thrown on the hands of our consuls, who, to rescue them from the dangers into which their distresses might plunge them, and save them to their country, have found it necessary in some cases to return them at the public charge.

The cession of the Spanish province of Louisiana to France, which took place in the course of the late war, will, if carried into effect, make a change in the aspect of our foreign relations 17 which will doubtless have a just weight in any deliberations of the legislature connected with that subject.

There was reason, not long since, to apprehend that the warfare in which we were engaged with Tripoli might be taken up by some others of the Barbary powers. A reinforcement, therefore, was immediately ordered to the vessels already there. Subsequent information, however, has removed these apprehensions for the present. To secure our commerce in that sea with the smallest force competent, we have supposed it best to watch strictly the harbor of Tripoli. Still, however, the shallowness of their coast, and the want of smaller vessels on our part, has permitted some cruisers to escape unobserved; and to one of these an American vessel unfortunately fell a prey. The captain, one American seamen, and two others of color, remain prisoners with them unless exchanged under an agreement formerly made with the bashaw, to whom, on the faith of that, some of his captive subjects had been restored.

The convention with the State of Georgia has been ratified by their legislature, and a repurchase from the Creeks has been consequently made of a part of the Tallahassee county. In this purchase has been also comprehended part of the lands within the fork of Oconee and Oakmulgee rivers. The particulars of the contract will be laid before Congress so soon as they shall be in a state for communication.

In order to remove every ground of difference possible with our Indian neighbors, I have proceeded in the work of settling with them and marking the boundaries between us. That with the Choctaw nation is fixed in one part, and will be through the whole in a short time. The country to which their title had been extinguished before the revolution is sufficient to receive a very respectable population, which Congress will probably see the expediency of encouraging so soon as the limits shall be declared. We are to view this position as an outpost of the United States, surrounded by strong neighbors and distant from its support. And how far that monopoly which prevents population should here be guarded against, and actual habitation made 18 a condition of the continuance of title, will be for your consideration. A prompt settlement, too, of all existing rights and claims within this territory, presents itself as a preliminary operation.

In that part of the Indian territory which includes Vincennes, the lines settled with the neighboring tribes fix the extinction of their title at a breadth of twenty-four leagues from east to west, and about the same length parallel with and including the Wabash. They have also ceded a tract of four miles square, including the salt springs near the mouth of the river.

In the department of finance it is with pleasure I inform you that the receipts of external duties for the last twelve months have exceeded those of any former year, and that the ratio of increase has been also greater than usual. This has enabled us to answer all the regular exigencies of government, to pay from the treasury in one year upward of eight millions of dollars, principal and interest, of the public debt, exclusive of upward of one million paid by the sale of bank stock, and making in the whole a reduction of nearly five millions and a half of principal; and to have now in the treasury four millions and a half of dollars, which are in a course of application to a further discharge of debt and current demands. Experience, too, so far, authorizes us to believe, if no extraordinary event supervenes, and the expenses which will be actually incurred shall not be greater than were contemplated by Congress at their last session, that we shall not be disappointed in the expectations then formed. But nevertheless, as the effect of peace on the amount of duties is not yet fully ascertained, it is the more necessary to practice every useful economy, and to incur no expense which may be avoided without prejudice.

The collection of the internal taxes having been completed in some of the States, the officers employed in it are of course out of commission. In others, they will be so shortly. But in a few, where the arrangement for the direct tax had been retarded, it will still be some time before the system is closed. It has not yet been thought necessary to employ the agent authorized by 19 an act of the last session for transacting business in Europe relative to debts and loans. Nor have we used the power confided by the same act, of prolonging the foreign debts by reloans, and of redeeming, instead thereof, an equal sum of the domestic debt. Should, however, the difficulties of remittances on so large a scale render it necessary at any time, the power shall be executed, and the money thus unemployed abroad shall, in conformity with that law, be faithfully applied here in an equivalent extinction of domestic debt. When effects so salutary result from the plans you have already sanctioned, when merely by avoiding false objects of expense we are able, without a direct tax, without internal taxes, and without borrowing, to make large and effectual payments toward the discharge of our public debt and the emancipation of our posterity from that moral canker, it is an encouragement, fellow citizens, of the highest order, to proceed as we have begun, in substituting economy for taxation, and in pursuing what is useful for a nation placed as we are, rather than what is practiced by others under different circumstances. And whensoever we are destined to meet events which shall call forth all the energies of our countrymen, we have the firmest reliance on those energies, and the comfort of leaving for calls like these the extraordinary resources of loans and internal taxes. In the meantime, by payments of the principal of our debt, we are liberating, annually, portions of the external taxes, and forming from them a growing fund still further to lessen the necessity of recurring to extraordinary resources.

The usual accounts of receipts and expenditures for the last year, with an estimate of the expenses of the ensuing one, will be laid before you by the secretary of the treasury.

No change being deemed necessary in our military establishment, an estimate of its expenses for the ensuing year on its present footing, as also of the sums to be employed in fortifications and other objects within that department, has been prepared by the secretary of war, and will make a part of the general estimates which will be presented to you.

Considering that our regular troops are employed for local purposes, 20 and that the militia is our general reliance for great and sudden emergencies, you will doubtless think this institution worthy of a review, and give it those improvements of which you find it susceptible.

Estimates for the naval department, prepared by the secretary of the navy for another year, will in like manner be communicated with the general estimates. A small force in the Mediterranean will still be necessary to restrain the Tripoline cruisers, and the uncertain tenure of peace with some other of the Barbary powers, may eventually require that force to be augmented. The necessity of procuring some smaller vessels for that service will raise the estimate, but the difference in their maintenance will soon make it a measure of economy.

Presuming it will be deemed expedient to expend annually a sum towards providing the naval defence which our situation may require, I cannot but recommend that the first appropriations for that purpose may go to the saving what we already possess. No cares, no attentions, can preserve vessels from rapid decay which lie in water and exposed to the sun. These decays require great and constant repairs, and will consume, if continued, a great portion of the money destined to naval purposes. To avoid this waste of our resources, it is proposed to add to our navy-yard here a dock, within which our vessels may be laid up dry and under cover from the sun. Under these circumstances experience proves that works of wood will remain scarcely at all affected by time. The great abundance of running water which this situation possesses, at heights far above the level of the tide, if employed as is practised for lock navigation, furnishes the means of raising and laying up our vessels on a dry and sheltered bed. And should the measure be found useful here, similar depositories for laying up as well as for building and repairing vessels may hereafter be undertaken at other navy-yards offering the same means. The plans and estimates of the work, prepared by a person of skill and experience, will be presented to you without delay; and from this it will be seen that scarcely more than has been the cost of one vessel is necessary to save the 21 whole, and that the annual sum to be employed toward its completion may be adapted to the views of the legislature as to naval expenditure.

To cultivate peace and maintain commerce and navigation in all their lawful enterprises; to foster our fisheries and nurseries of navigation and for the nurture of man, and protect the manufactures adapted to our circumstances; to preserve the faith of the nation by an exact discharge of its debts and contracts, expend the public money with the same care and economy we would practise with our own, and impose on our citizens no unnecessary burden; to keep in all things within the pale of our constitutional powers, and cherish the federal union as the only rock of safety—these, fellow-citizens, are the landmarks by which we are to guide ourselves in all our proceedings. By continuing to make these our rule of action, we shall endear to our countrymen the true principles of their constitution, and promote a union of sentiment and of action equally auspicious to their happiness and safety. On my part, you may count on a cordial concurrence in every measure for the public good, and on all the information I possess which may enable you to discharge to advantage the high functions with which you are invested by your country.

Gentlemen of the Senate and House of Representatives:—

I lay before you the accounts of our Indian trading houses, as rendered up to the first day of January, 1801, with a report of the secretary of war thereon, explaining the effects and the situation of that commerce, and the reasons in favor of its farther extension. But it is believed that the act authorizing this trade expired so long ago as the 3d of March, 1799. Its revival, therefore, as well as its extension, is submitted to the consideration of the legislature.

The act regulating trade and intercourse with the Indian 22 tribes will also expire on the 3d day of March next. While on the subject of its continuance, it will be worthy the consideration of the legislature, whether the provisions of the law inflicting on Indians, in certain cases, the punishment of death by hanging, might not permit its commutation into death by military execution, the form of the punishment in the former way being peculiarly repugnant to their ideas, and increasing the obstacles to the surrender of the criminal.

These people are becoming very sensible of the baneful effects produced on their morals, their health and existence, by the abuse of ardent spirits, and some of them earnestly desire a prohibition of that article from being carried among them. The legislature will consider whether the effectuating that desire would not be in the spirit of benevolence and liberality which they have hitherto practised toward these our neighbors, and which has had so happy an effect toward conciliating their friendship. It has been found too, in experience, that the same abuse gives frequent rise to incidents tending much to commit our peace with the Indians.

It is now become necessary to run and mark the boundaries between them and us in various parts. The law last mentioned has authorized this to be done, but no existing appropriation meets the expense.

Certain papers, explanatory of the grounds of this communication, are herewith enclosed.

Gentlemen of the Senate and House of Representatives:—

I lay before you a report of the secretary of state on the case of the Danish brigantine Henrick, taken by a French privateer in 1799, retaken by an armed vessel of the United States, carried into a British island and there adjudged to be neutral, but under an allowance of such salvage and costs as absorbed nearly the 23 whole amount of sales of the vessel and cargo. Indemnification for these losses, occasioned by our officers, is now claimed by the sufferers, supported by the representation of their government. I have no doubt the legislature will give to the subject that just attention and consideration which it is useful as well as honorable to practise in our transactions with other nations, and particularly with one which has observed toward us the most friendly treatment and regard.

To the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States:—

In calling you together, fellow citizens, at an earlier day than was contemplated by the act of the last session of Congress, I have not been insensible to the personal inconveniences necessarily resulting from an unexpected change in your arrangements. But matters of great public concernment have rendered this call necessary, and the interest you feel in these will supersede in your minds all private considerations.

Congress witnessed, at their last session, the extraordinary agitation produced in the public mind by the suspension of our right of deposit at the port of New Orleans, no assignment of another place having been made according to treaty. They were sensible that the continuance of that privation would be more injurious to our nation than any consequences which could flow from any mode of redress, but reposing just confidence in the good faith of the government whose officer had committed the wrong, friendly and reasonable representations were resorted to, and the right of deposit was restored.

Previous, however, to this period, we had not been unaware of the danger to which our peace would be perpetually exposed while so important a key to the commerce of the western country remained under foreign power. Difficulties, too, were presenting 24 themselves as to the navigation of other streams, which, arising within our territories, pass through those adjacent. Propositions had, therefore, been authorized for obtaining, on fair conditions, the sovereignty of New Orleans, and of other possessions in that quarter interesting to our quiet, to such extent as was deemed practicable; and the provisional appropriation of two millions of dollars, to be applied and accounted for by the president of the United States, intended as part of the price, was considered as conveying the sanction of Congress to the acquisition proposed. The enlightened government of France saw, with just discernment, the importance to both nations of such liberal arrangements as might best and permanently promote the peace, friendship, and interests of both; and the property and sovereignty of all Louisiana, which had been restored to them, have on certain conditions been transferred to the United States by instruments bearing date the 30th of April last. When these shall have received the constitutional sanction of the senate, they will without delay be communicated to the representatives also, for the exercise of their functions, as to those conditions which are within the powers vested by the constitution in Congress. While the property and sovereignty of the Mississippi and its waters secure an independent outlet for the produce of the western States, and an uncontrolled navigation through their whole course, free from collision with other powers and the dangers to our peace from that source, the fertility of the country, its climate and extent, promise in due season important aids to our treasury, an ample provision for our posterity, and a wide-spread field for the blessings of freedom and equal laws.

With the wisdom of Congress it will rest to take those ulterior measures which may be necessary for the immediate occupation and temporary government of the country; for its incorporation into our Union; for rendering the change of government a blessing to our newly-adopted brethren; for securing to them the rights of conscience and of property; for confirming to the Indian inhabitants their occupancy and self-government, establishing friendly and commercial relations with them, and for ascertaining 25 the geography of the country acquired. Such materials for your information, relative to its affairs in general, as the short space of time has permitted me to collect, will be laid before you when the subject shall be in a state for your consideration.

Another important acquisition of territory has also been made since the last session of Congress. The friendly tribe of Kaskaskia Indians with which we have never had a difference, reduced by the wars and wants of savage life to a few individuals unable to defend themselves against the neighboring tribes, has transferred its country to the United States, reserving only for its members what is sufficient to maintain them in an agricultural way. The considerations stipulated are, that we shall extend to them our patronage and protection, and give them certain annual aids in money, in implements of agriculture, and other articles of their choice. This country, among the most fertile within our limits, extending along the Mississippi from the mouth of the Illinois to and up the Ohio, though not so necessary as a barrier since the acquisition of the other bank, may yet be well worthy of being laid open to immediate settlement, as its inhabitants may descend with rapidity in support of the lower country should future circumstances expose that to foreign enterprize. As the stipulations in this treaty also involve matters within the competence of both houses only, it will be laid before Congress as soon as the senate shall have advised its ratification.

With many other Indian tribes, improvements in agriculture and household manufacture are advancing, and with all our peace and friendship are established on grounds much firmer than heretofore. The measure adopted of establishing trading houses among them, and of furnishing them necessaries in exchange for their commodities, at such moderated prices as leave no gain, but cover us from loss, has the most conciliatory and useful effect upon them, and is that which will best secure their peace and good will.

The small vessels authorized by Congress with a view to the Mediterranean service, have been sent into that sea, and will be able more effectually to confine the Tripoline cruisers within 26 their harbors, and supersede the necessity of convoy to our commerce in that quarter. They will sensibly lessen the expenses of that service the ensuing year.

A further knowledge of the ground in the north-eastern and north-western angles of the United States has evinced that the boundaries established by the treaty of Paris, between the British territories and ours in those parts, were too imperfectly described to be susceptible of execution. It has therefore been thought worthy of attention, for preserving and cherishing the harmony and useful intercourse subsisting between the two nations, to remove by timely arrangements what unfavorable incidents might otherwise render a ground of future misunderstanding. A convention has therefore been entered into, which provides for a practicable demarkation of those limits to the satisfaction of both parties.

An account of the receipts and expenditures of the year ending 30th September last, with the estimates for the service of the ensuing year, will be laid before you by the secretary of the treasury so soon as the receipts of the last quarter shall be returned from the more distant States. It is already ascertained that the amount paid into the treasury for that year has been between eleven and twelve millions of dollars, and that the revenue accrued during the same term exceeds the sum counted on as sufficient for our current expenses, and to extinguish the public debt within the period heretofore proposed.

The amount of debt paid for the same year is about three millions one hundred thousand dollars, exclusive of interest, and making, with the payment of the preceding year, a discharge of more than eight millions and a half of dollars of the principal of that debt, besides the accruing interest; and there remain in the treasury nearly six millions of dollars. Of these, eight hundred and eighty thousand have been reserved for payment of the first instalment due under the British convention of January 8th, 1802, and two millions are what have been before mentioned as placed by Congress under the power and accountability of the president, toward the price of New Orleans and other territories 27 acquired, which, remaining untouched, are still applicable to that object, and go in diminution of the sum to be funded for it.

Should the acquisition of Louisiana be constitutionally confirmed and carried into effect, a sum of nearly thirteen millions of dollars will then be added to our public debt, most of which is payable after fifteen years; before which term the present existing debts will all be discharged by the established operation of the sinking fund. When we contemplate the ordinary annual augmentation of imposts from increasing population and wealth, the augmentation of the same revenue by its extension to the new acquisition, and the economies which may still be introduced into our public expenditures, I cannot but hope that Congress in reviewing their resources will find means to meet the intermediate interests of this additional debt without recurring to new taxes, and applying to this object only the ordinary progression of our revenue. Its extraordinary increase in times of foreign war will be the proper and sufficient fund for any measures of safety or precaution which that state of things may render necessary in our neutral position.

Remittances for the instalments of our foreign debt having been found practicable without loss, it has not been thought expedient to use the power given by a former act of Congress of continuing them by reloans, and of redeeming instead thereof equal sums of domestic debt, although no difficulty was found in obtaining that accommodation.

The sum of fifty thousand dollars appropriated by Congress for providing gun-boats, remains unexpended. The favorable and peaceful turn of affairs on the Mississippi rendered an immediate execution of that law unnecessary, and time was desirable in order that the institution of that branch of our force might begin on models the most approved by experience. The same issue of events dispensed with a resort to the appropriation of a million and a half of dollars contemplated for purposes which were effected by happier means.

We have seen with sincere concern the flames of war lighted up again in Europe, and nations with which we have the most 28 friendly and useful relations engaged in mutual destruction. While we regret the miseries in which we see others involved, let us bow with gratitude to that kind Providence which, inspiring with wisdom and moderation our late legislative councils while placed under the urgency of the greatest wrongs, guarded us from hastily entering into the sanguinary contest, and left us only to look on and to pity its ravages. These will be heaviest on those immediately engaged. Yet the nations pursuing peace will not be exempt from all evil. In the course of this conflict, let it be our endeavor, as it is our interest and desire, to cultivate the friendship of the belligerent nations by every act of justice and of incessant kindness; to receive their armed vessels with hospitality from the distresses of the sea, but to administer the means of annoyance to none; to establish in our harbors such a police as may maintain law and order; to restrain our citizens from embarking individually in a war in which their country takes no part; to punish severely those persons, citizen or alien, who shall usurp the cover of our flag for vessels not entitled to it, infecting thereby with suspicion those of real Americans, and committing us into controversies for the redress of wrongs not our own; to exact from every nation the observance, toward our vessels and citizens, of those principles and practices which all civilized people acknowledge; to merit the character of a just nation, and maintain that of an independent one, preferring every consequence to insult and habitual wrong. Congress will consider whether the existing laws enable us efficaciously to maintain this course with our citizens in all places, and with others while within the limits of our jurisdiction, and will give them the new modifications necessary for these objects. Some contraventions of right have already taken place, both within our jurisdictional limits and on the high seas. The friendly disposition of the governments from whose agents they have proceeded, as well as their wisdom and regard for justice, leave us in reasonable expectation that they will be rectified and prevented in future; and that no act will be countenanced by them which threatens to disturb our friendly intercourse. 29 Separated by a wide ocean from the nations of Europe, and from the political interests which entangle them together, with productions and wants which render our commerce and friendship useful to them and theirs to us, it cannot be the interest of any to assail us, nor ours to disturb them. We should be most unwise, indeed, were we to cast away the singular blessings of the position in which nature has placed us, the opportunity she has endowed us with of pursuing, at a distance from foreign contentions, the paths of industry, peace, and happiness; of cultivating general friendship, and of bringing collisions of interest to the umpirage of reason rather than of force. How desirable then must it be, in a government like ours, to see its citizens adopt individually the views, the interests, and the conduct which their country should pursue, divesting themselves of those passions and partialities which tend to lessen useful friendships, and to embarrass and embroil us in the calamitous scenes of Europe. Confident, fellow citizens, that you will duly estimate the importance of neutral dispositions toward the observance of neutral conduct, that you will be sensible how much it is our duty to look on the bloody arena spread before us with commiseration indeed, but with no other wish than to see it closed, I am persuaded you will cordially cherish these dispositions in all discussions among yourselves, and in all communications with your constituents; and I anticipate with satisfaction the measures of wisdom which the great interests now committed to you will give you an opportunity of providing, and myself that of approving and carrying into execution with the fidelity I owe to my country.

To the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States:—

In my communication to you of the 17th instant, I informed you that conventions had been entered into with the government 30 of France for the cession of Louisiana to the United States. These, with the advice and consent of the Senate, having now been ratified, and my ratification exchanged for that of the first consul of France in due form, they are communicated to you for consideration in your legislative capacity. You will observe that some important conditions cannot be carried into execution, but with the aid of the legislature; and that time presses a decision on them without delay.

The ulterior provisions, also suggested in the same communication, for the occupation and government of the country, will call for early attention. Such information relative to its government, as time and distance have enabled me to obtain, will be ready to be laid before you within a few days. But, as permanent arrangements for this object may require time and deliberation, it is for your consideration whether you will not, forthwith, make such temporary provisions for the preservation, in the meanwhile, of order and tranquillity in the country, as the case may require.

To the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States:—

By the copy now communicated of a letter from Captain Bainbridge of the Philadelphia frigate, to our consul at Gibraltar, you will learn that an act of hostility has been committed on a merchant vessel of the United States by an armed ship of the Emperor of Morocco. This conduct on the part of that power is without cause and without explanation. It is fortunate that Captain Bainbridge fell in with and took the capturing vessel and her prize; and I have the satisfaction to inform you, that about the date of this transaction such a force would be arriving in the neighborhood of Gibraltar, both from the east and the west, as leaves less to be feared for our commerce from the suddenness of the aggression. 31

On the 4th of September, the Constitution frigate, Captain Preble, with Mr. Lear on board, was within two days' sail of Gibraltar, where the Philadelphia would then be arrived with her prize, and such explanations would probably be instituted as the state of thing required, and as might perhaps arrest the progress of hostilities.

In the meanwhile it is for Congress to consider the provisional authorities which may be necessary to restrain the depredations of this power, should they be continued.

To the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States:—

The treaty with the Kaskaskia Indians being ratified with the advice and consent of the Senate, it is now laid before both houses, in their legislative capacity. It will inform them of the obligations which the United States thereby contract, and particularly that of taking the tribe under their future protection; and that the ceded country is submitted to their immediate possession and disposal.

To the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States:—

I have the satisfaction to inform you that the act of hostility mentioned in my message of the 4th of November to have been committed by a cruiser of the emperor of Morocco on a vessel of the United States, has been disavowed by the emperor. All difficulties in consequence thereof have been amicably adjusted, and the treaty of 1786, between this country and that, has been recognized and confirmed by the emperor, each party 32 restoring to the other what had been detained or taken. I enclose the emperor's orders given on this occasion.

The conduct of our officers generally, who have had a part in these transactions, has merited entire approbation.

The temperate and correct course pursued by our consul, Mr. Simpson, the promptitude and energy of Commodore Preble, the efficacious co-operation of Captains Rodgers and Campbell of the returning squadron, the proper decision of Captain Bainbridge that a vessel which had committed an open hostility was of right to be detained for inquiry and consideration, and the general zeal of the other officers and men, are honorable facts which I make known with pleasure. And to these I add what was indeed transacted in another quarter—the gallant enterprise of Captain Rodgers in destroying, on the coast of Tripoli, a corvette of that power, of twenty-two guns.

I recommended to the consideration of Congress a just indemnification for the interest acquired by the captors of the Mishouda and Mirboha, yielded by them for the public accommodation.

To the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States:—

In execution of the act of the present session of Congress for taking possession of Louisiana, as ceded to us by France, and for the temporary government thereof, Governor Claiborne, of the Mississippi territory, and General Wilkinson, were appointed commissioners to receive possession. They proceeded with such regular troops as had been assembled at Fort Adams, from the nearest posts, and with some militia of the Mississippi territory, to New Orleans. To be prepared for anything unexpected, which might arise out of the transaction, a respectable body of militia was ordered to be in readiness, in the States of Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee, and a part of those of Tennessee 33 was moved on to Natchez. No occasion, however, arose for their services. Our commissioners, on their arrival at New Orleans, found the province already delivered by the commissaries of Spain to that of France, who delivered it over to them on the twentieth day of December, as appears by their declaratory act accompanying it. Governor Claiborne being duly invested with the powers heretofore exercised by the governor and intendant of Louisiana, assumed the government on the same day, and for the maintenance of law and order, immediately issued the proclamation and address now communicated.

On this important acquisition, so favorable to the immediate interests of our western citizens, so auspicious to the peace and security of the nation in general, which adds to our country territories so extensive and fertile, and to our citizens new brethren to partake of the blessings of freedom and self-government, I offer to Congress and the country, my sincere congratulations.

To the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States:—

I communicate to Congress, a letter received from Captain Bainbridge, commander of the Philadelphia frigate, informing us of the wreck of that vessel on the coast of Tripoli, and that himself, his officers, and men, had fallen into the hands of the Tripolitans. This accident renders it expedient to increase our force, and enlarge our expenses in the Mediterranean beyond what the last appropriation for the naval service contemplated. I recommend, therefore, to the consideration of Congress, such an addition to that appropriation as they may think the exigency requires. 34

To the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States:—

To a people, fellow citizens, who sincerely desire the happiness and prosperity of other nations; to those who justly calculate that their own well-being is advanced by that of the nations with which they have intercourse, it will be a satisfaction to observe that the war which was lighted up in Europe a little before our last meeting has not yet extended its flames to other nations, nor been marked by the calamities which sometimes stain the footsteps of war. The irregularities too on the ocean, which generally harass the commerce of neutral nations, have, in distant parts, disturbed ours less than on former occasions. But in the American seas they have been greater from peculiar causes; and even within our harbors and jurisdiction, infringements on the authority of the laws have been committed which have called for serious attention. The friendly conduct of the governments from whose officers and subjects these acts have proceeded, in other respects and in places more under their observation and control, gives us confidence that our representations on this subject will have been properly regarded.

While noticing the irregularities committed on the ocean by others, those on our own part should not be omitted nor left unprovided for. Complaints have been received that persons residing within the United States have taken on themselves to arm merchant vessels, and to force a commerce into certain ports and countries in defiance of the laws of those countries. That individuals should undertake to wage private war, independently of the authority of their country, cannot be permitted in a well-ordered society. Its tendency to produce aggression on the laws and rights of other nations, and to endanger the peace of our own is so obvious, that I doubt not you will adopt measures for restraining it effectually in future.

Soon after the passage of the act of the last session, authorizing the establishment of a district and port of entry on the waters 35 of the Mobile, we learnt that its object was misunderstood on the part of Spain. Candid explanations were immediately given, and assurances that, reserving our claims in that quarter as a subject of discussion and arrangement with Spain, no act was meditated, in the meantime, inconsistent with the peace and friendship existing between the two nations, and that conformably to these intentions would be the execution of the law. That government had, however, thought proper to suspend the ratification of the convention of 1802. But the explanations which would reach them soon after, and still more, the confirmation of them by the tenor of the instrument establishing the port and district, may reasonably be expected to replace them in the dispositions and views of the whole subject which originally dictated the conviction.

I have the satisfaction to inform you that the objections which had been urged by that government against the validity of our title to the country of Louisiana have been withdrawn, its exact limits, however, remaining still to be settled between us. And to this is to be added that, having prepared and delivered the stock created in execution of the convention of Paris, of April 30, 1803, in consideration of the cession of that country, we have received from the government of France an acknowledgment, in due form, of the fulfilment of that stipulation.

With the nations of Europe in general our friendship and intercourse are undisturbed, and from the governments of the belligerent powers especially we continue to receive those friendly manifestations which are justly due to an honest neutrality, and to such good offices consistent with that as we have opportunities of rendering.

The activity and success of the small force employed in the Mediterranean in the early part of the present year, the reinforcement sent into that sea, and the energy of the officers having command in the several vessels, will, I trust, by the sufferings of war, reduce the barbarians of Tripoli to the desire of peace on proper terms. Great injury, however, ensues to ourselves as well as to others interested, from the distance to which 36 prizes must be brought for adjudication, and from the impracticability of bringing hither such as are not seaworthy.

The bey of Tunis having made requisitions unauthorized by our treaty, their rejection has produced from him some expressions of discontent. But to those who expect us to calculate whether a compliance with unjust demands will not cost us less than a war, we must leave as a question of calculation for them, also, whether to retire from unjust demands will not cost them less than a war. We can do to each other very sensible injuries by war, but the mutual advantages of peace make that the best interest of both.

Peace and intercourse with the other powers on the same coast continue on the footing on which they are established by treaty.

In pursuance of the act providing for the temporary government of Louisiana, the necessary officers for the territory of Orleans were appointed in due time, to commence the exercise of their functions on the first day of October. The distance, however, of some of them, and indispensable previous arrangements, may have retarded its commencement in some of its parts; the form of government thus provided having been considered but as temporary, and open to such improvements as further information of the circumstances of our brethren there might suggest, it will of course be subject to your consideration.