Vespas. MS. A VIII.

Title: Early London: Prehistoric, Roman, Saxon and Norman

Author: Walter Besant

Release date: March 28, 2018 [eBook #56865]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Les Galloway and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME

PRICE 30/ NET EACH

LONDON

IN THE TIME OF THE TUDORS

With 146 Illustrations and a Reproduction of Agas’ Map

of London in 1560.

“For the student, as well as for those desultory readers who are drawn by the rare fascination of London to peruse its pages, this book will have a value and a charm which are unsurpassed by any of its predecessors.”—Pall Mall Gazette.

“A vivid and fascinating picture of London life in the sixteenth century—a novelist’s picture, full of life and movement, yet with the accurate detail of an antiquarian treatise.”—Contemporary Review.

LONDON

IN THE TIME OF THE STUARTS

With 116 Illustrations and a Reproduction of Ogilby’s Map

of London in 1677.

“It is a mine in which the student, alike of topography and of manners and customs, may dig and dig again with the certainty of finding something new and interesting.”—The Times.

“The pen of the ready writer here is fluent; the picture wants nothing in completeness. The records of the city and the kingdom have been ransacked for facts and documents, and they are marshalled with consummate skill.”—Pall Mall Gazette.

LONDON

IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

With 104 Illustrations and a Reproduction of Rocque’s Map

of London in 1741-5.

“The book is engrossing, and its manner delightful.”—The Times.

“Of facts and figures such as these this valuable book will be found full to overflowing, and it is calculated therefore to interest all kinds of readers, from the student to the dilettante, from the romancer in search of matter to the most voracious student of ‘Tit-Bits.’”—The Athenæum.

MEDIÆVAL LONDON

VOL. I. HISTORICAL AND SOCIAL

With 108 Illustrations, mostly from contemporary prints.

VOL. II. ECCLESIASTICAL

With 108 Illustrations, mostly from contemporary prints.

“The book is at once exact and lively in its statements; there is no slovenly page in it—everywhere there is the sense of movement and colour, and the charm which belongs to a living picture.”—Standard.

“One is struck by the admirable grouping, the consistency and order of the work throughout, and in none more than in this latest instalment.”—Pall Mall Gazette.

The Survey of London

EARLY LONDON

AGENTS

| America | The Macmillan Company |

| 64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, New York | |

| Australasia | The Oxford University Press, Melbourne |

| Canada | The Macmillan Company of Canada, Ltd. |

| 27 Richmond Street West, Toronto | |

| India | Macmillan & Company, Ltd. |

| Macmillan Building, Bombay | |

| 309 Bow Bazaar Street, Calcutta |

BY

SIR WALTER BESANT

LONDON

ADAM & CHARLES BLACK

1908

v

| BOOK I | ||

| PREHISTORIC LONDON | ||

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| 1. | The Geology | 3 |

| 2. | The Site | 17 |

| 3. | The Earliest Inhabitants | 33 |

| BOOK II | ||

| ROMAN LONDON | ||

| 1. | The Coming of the Romans | 53 |

| 2. | The Roman Rule | 57 |

| 3. | The Aspect of the City | 79 |

| 4. | Remains of Roman London | 95 |

| 5. | The Building of the Wall | 112 |

| 6. | London Bridge | 128 |

| 7. | London Stone | 133 |

| 8. | The Desolation of the City | 135 |

| BOOK III | ||

| SAXON LONDON | ||

| 1. | The Coming of the Saxons | 153 |

| 2. | Early History | 161 |

| 3. | The Danes in London | 169 |

| 4. | The Second Saxon Occupation | 176 |

| 5. | The Second Danish Occupation | 190 |

| 6. | Town and People | 196 |

| 7. | Thorney Island | 231 |

| 8. | Saxon Remains | 243 vi |

| BOOK IV | ||

| NORMAN LONDON | ||

| 1. | William the Conqueror | 249 |

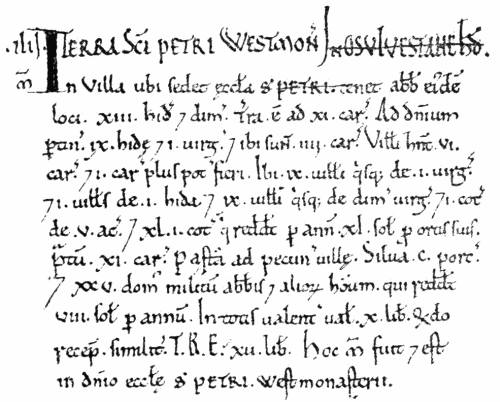

| 2. | Domesday Book | 262 |

| 3. | William Rufus | 272 |

| 4. | Henry I. | 275 |

| 5. | The Charter of Henry I. | 279 |

| 6. | Stephen | 289 |

| 7. | FitzStephen the Chronicler | 301 |

| 8. | The Streets and the People | 321 |

| 9. | Social Life | 337 |

| 10. | A Norman Family | 345 |

| APPENDICES | ||

| 1. | The River Embankment | 351 |

| 2. | The Riverside Discoveries | 353 |

| 3. | Strype on Roman Remains | 356 |

| 4. | The Clapton Sarcophagus | 361 |

| 5. | 363 | |

| INDEX | 365 | |

vii

| PAGE | |

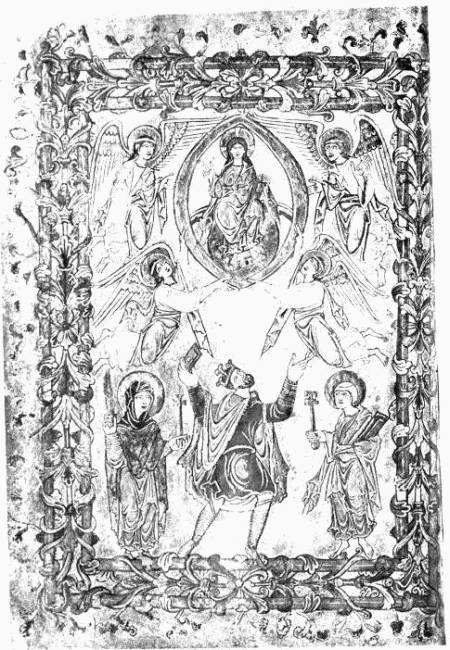

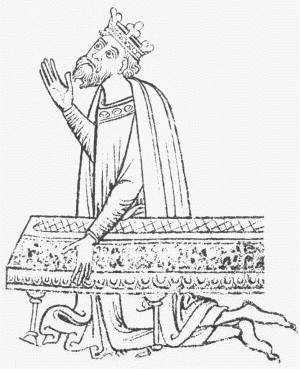

| King Edgar adoring the Saviour | Frontispiece |

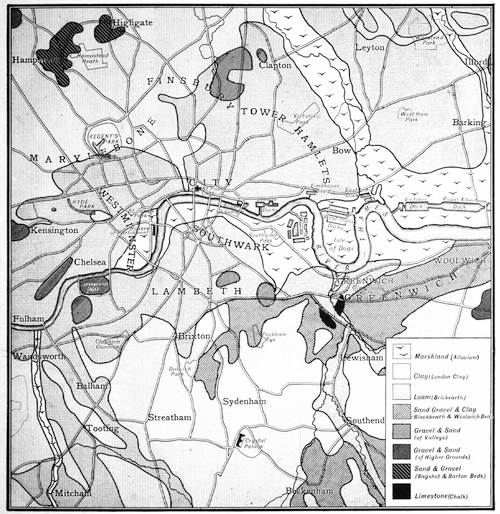

| Geological Map of the Site | 7 |

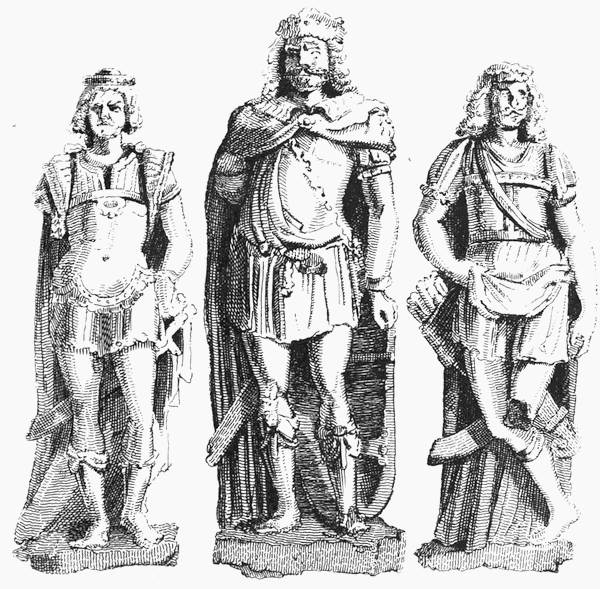

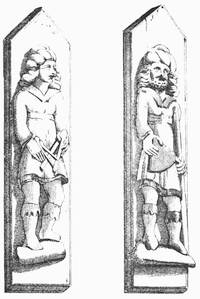

| Statues of King Lud and his two Sons, Androgeus and Theomantius | 19 |

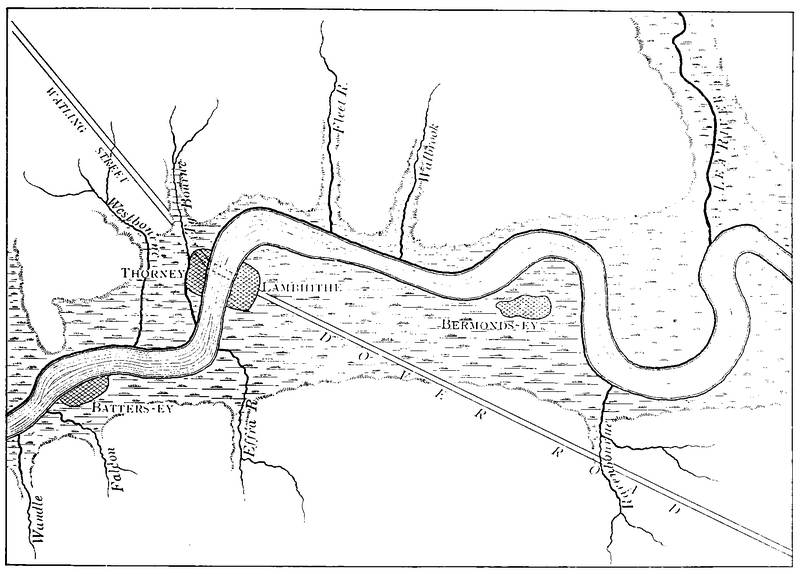

| The Marshes of Early London | 25 |

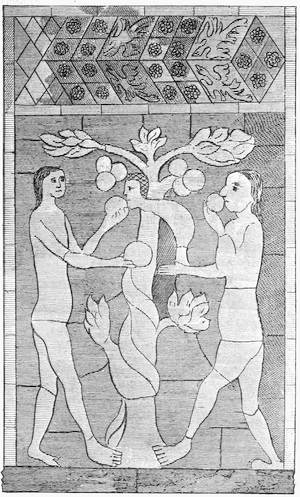

| Side of Font, East Meon Church, Hampshire | 36 |

| Side of Font, East Meon Church, Hampshire | 37 |

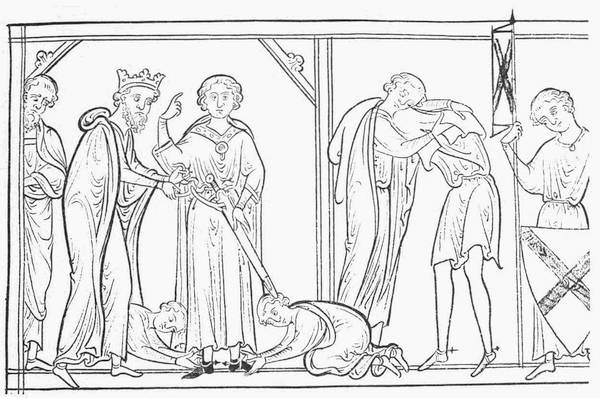

| Offa being invested with Spurs | 39 |

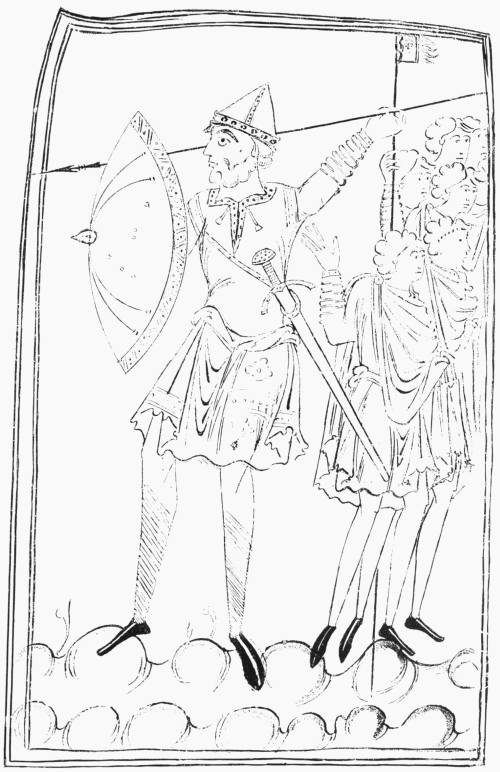

| An Archer | 42 |

| Figures reconstructed from Ancient Clothes and Remains found in a Bog | 43 |

| Figures in Wood at Wooburn in Buckinghamshire, supposed to represent Itinerant Masons | 45 |

| Pavement before the Altar of the Prior’s Chapel at Ely | 49 |

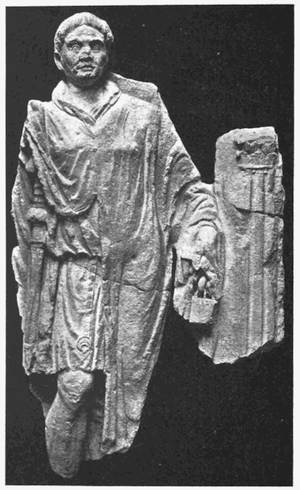

| Statue of a Roman Warrior found in a Bastion of the London Wall | 58 |

| Roman Knife-handle—Figure of Charioteer, Bronze | 60 |

| Carausius | 61 |

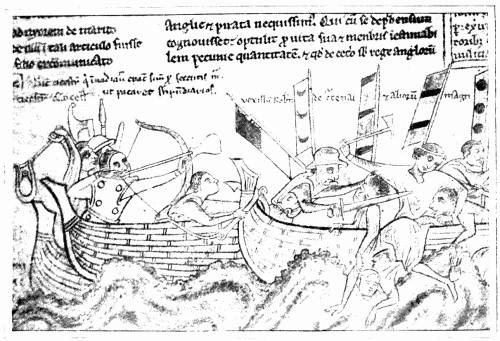

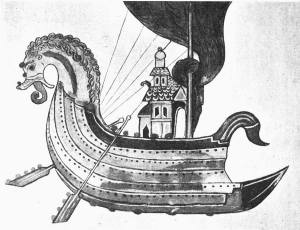

| A Sea Fight | 66 |

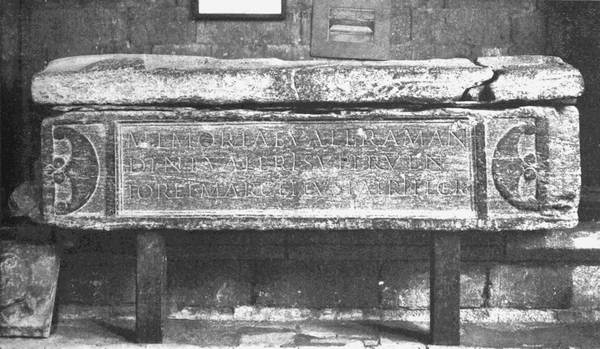

| Tomb of Valerius Amandinus (A Roman General) | 67 |

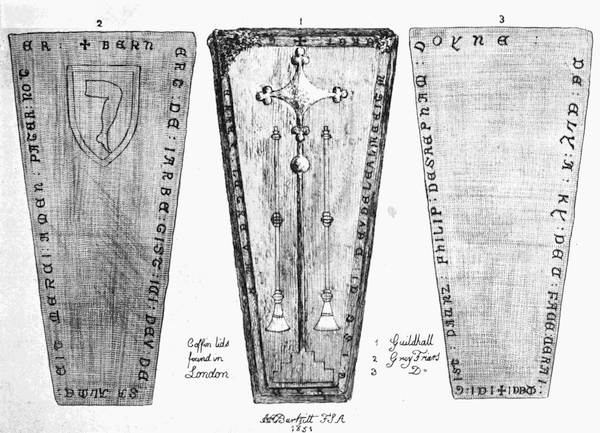

| Coffin Lids found in London | 71 |

| Bronze Roman Lamp found in Cannon Street | 75 |

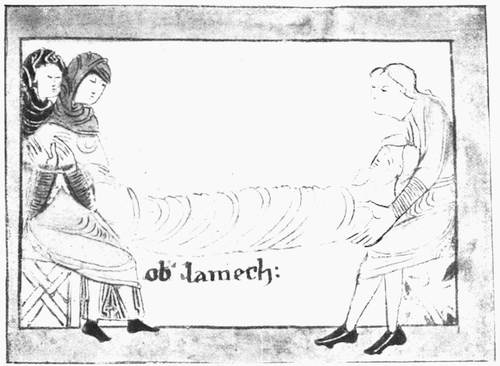

| Method of Swathing the Dead | 77 |

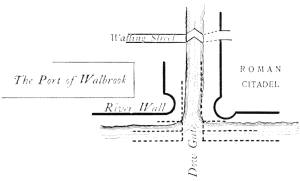

| Dow Gate | 79 |

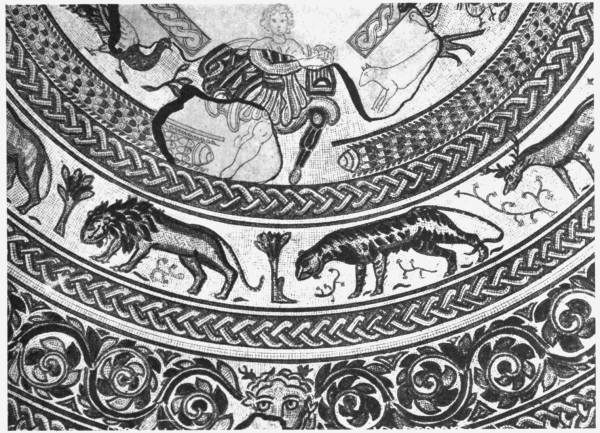

| Tessellated Pavement | 81 |

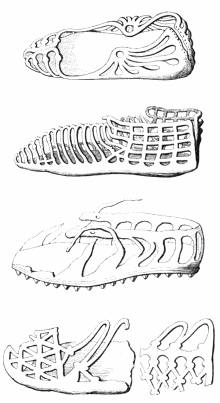

| Roman Sandals taken from the Bed of the Thames | 89 |

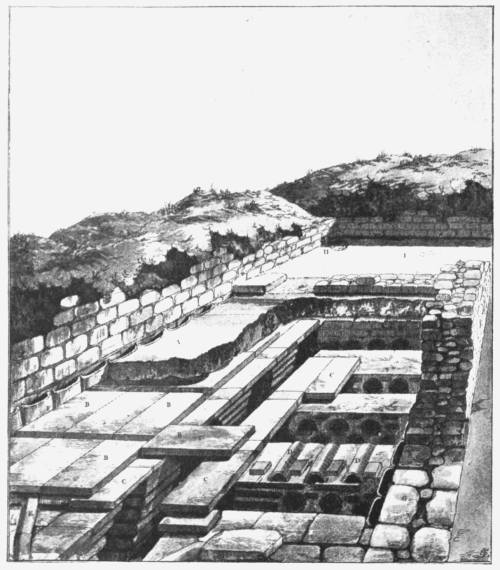

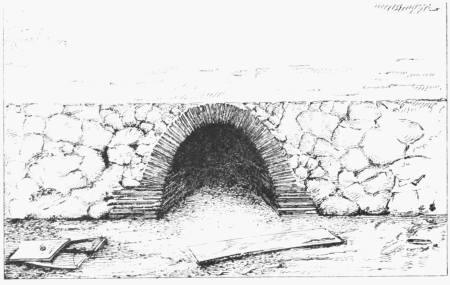

| The Laconicum, or Sweating Bath | 90 |

| Tessellated Pavement | 91 |

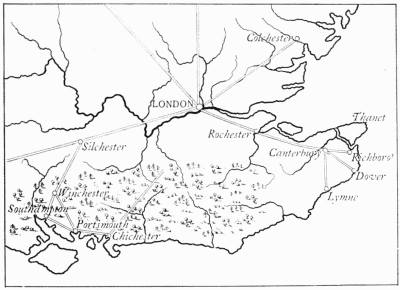

| Roman Roads radiating from London | 93 |

| Roman Altar to Diana found in St. Martin’s-le-Grand | 95 |

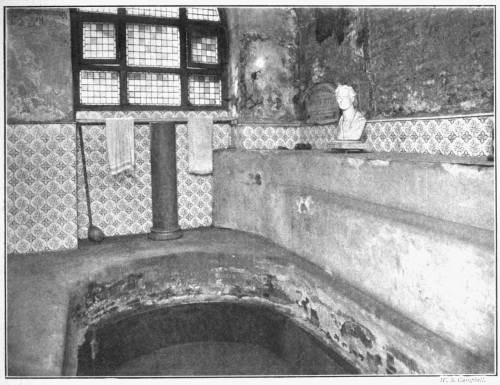

| Roman Bath, Strand Lane | 97 |

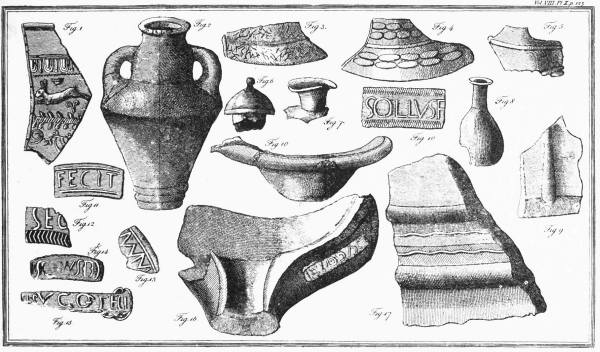

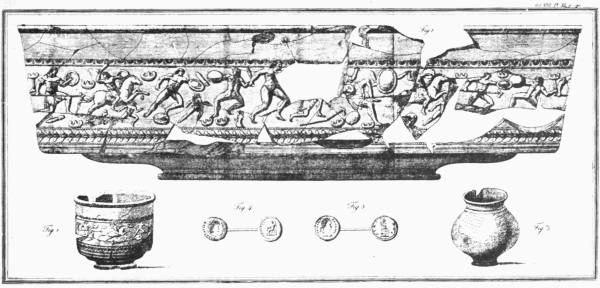

| Roman Antiquities found in London, 1786 | 101 |

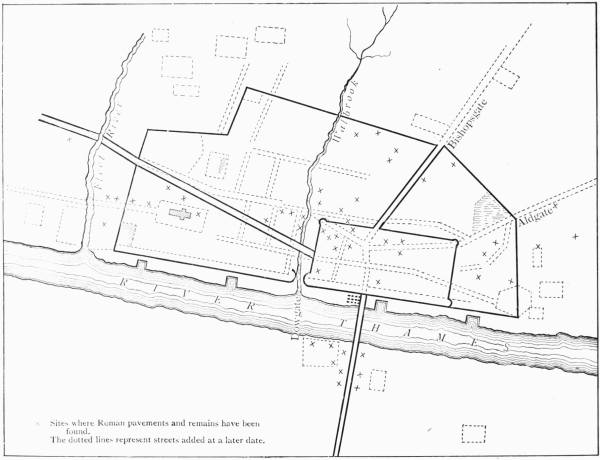

| Roman London | 102 |

| Statuettes of Roman Deities | 103 |

| Roman Sepulchral Stone found at Ludgate by Sir Christopher Wren | 107 |

| Roman Statue discovered at Bevis Marks | 108 |

| Roman Antiquities found in London in 1786 | 109 |

| Roman Remains found in a Bastion of London Wall | 113 |

| Roman Arch, London Wall | 122 |

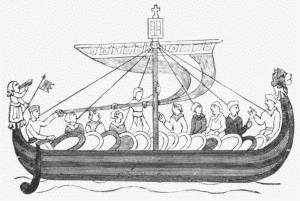

| A Ship | 126 viii |

| An Anglo-Saxon Warrior | Facing 136 |

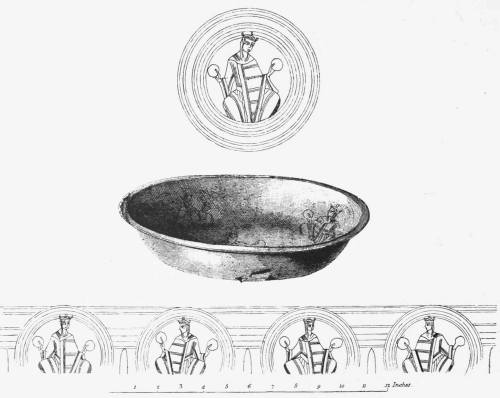

| Ancient Copper Bowl found in Lothbury | 138 |

| The Ark | 142 |

| King and Courtiers | 146 |

| A Group of Anglo-Saxon Spearmen | 154 |

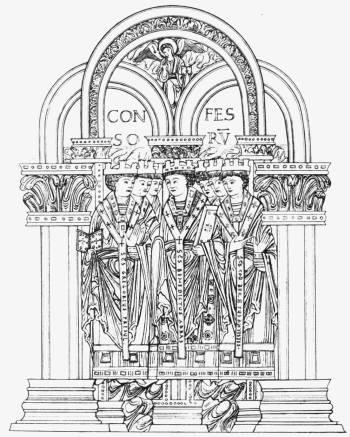

| Gregory the Great, St. Benedict, and St. Cuthbert | 156 |

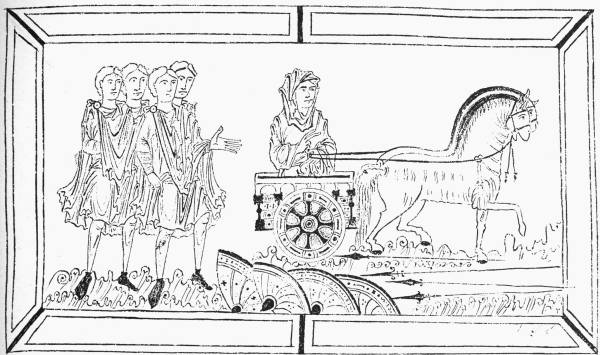

| Lady in a Chariot | 157 |

| Family Life | 159 |

| Aelfwine | 161 |

| The Coronation of a King | 162 |

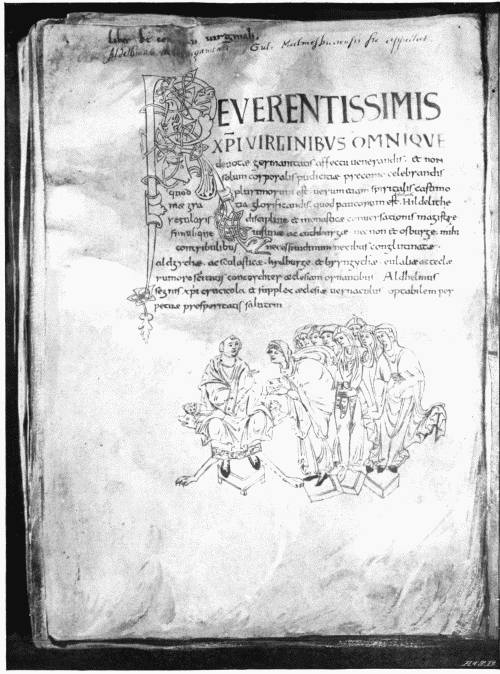

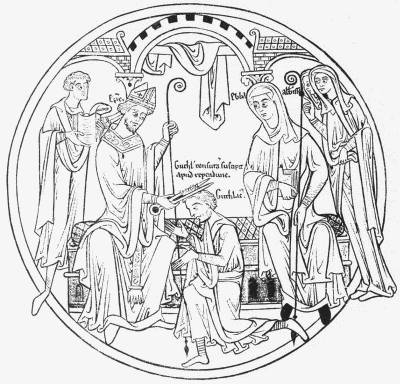

| Aldhelm presenting “De Virginitate” to Hildelida, Abbess of Barking, and her Nuns | Facing 162 |

| King Ethelbald | 164 |

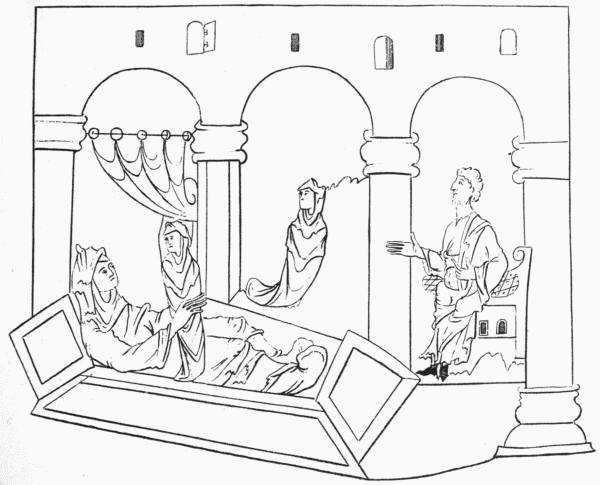

| King in Bed | 166 |

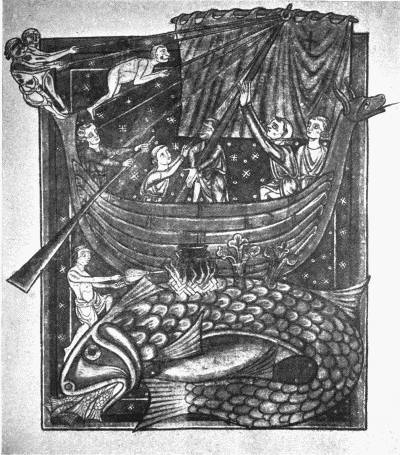

| The Perils of the Deep | 167 |

| Slaves waiting on a Household | 171 |

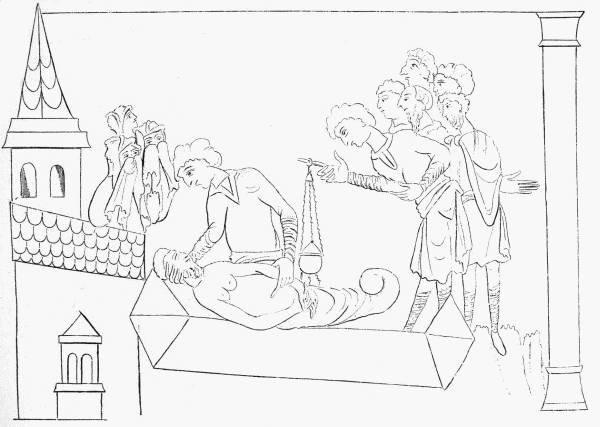

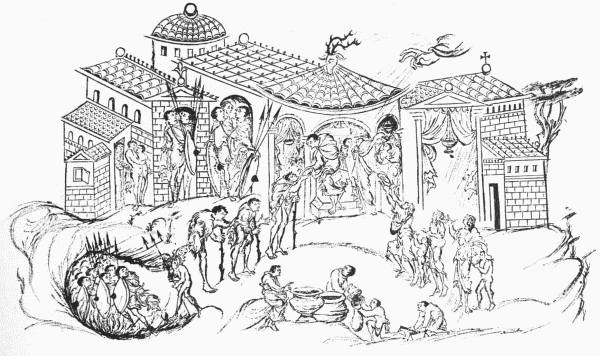

| Guthlac carried away by Devils | 172 |

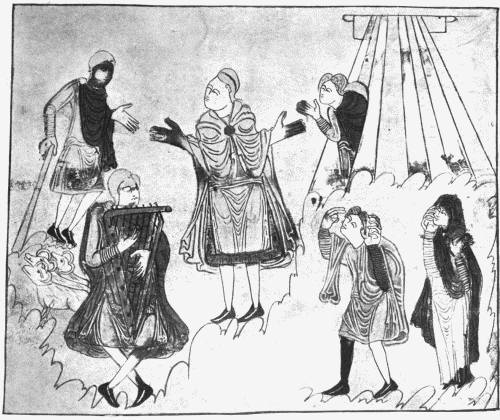

| Saxon Minstrels | 174 |

| Playing Draughts | 175 |

| The Alfred Jewel (Reverse) The Alfred Jewel (Obverse) | 177 |

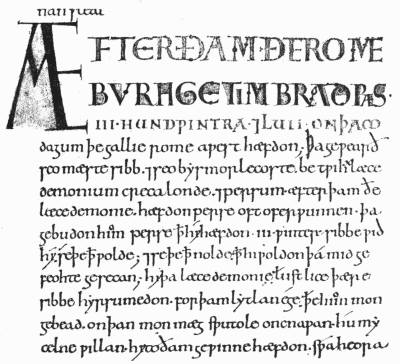

| Page from Gospel Book given by Otho I. to Athelstan, Grandson of Alfred the Great; on it the Anglo-Saxon Kings took the Coronation Oath | 178 |

| From King Alfred’s “Orosius” | 179 |

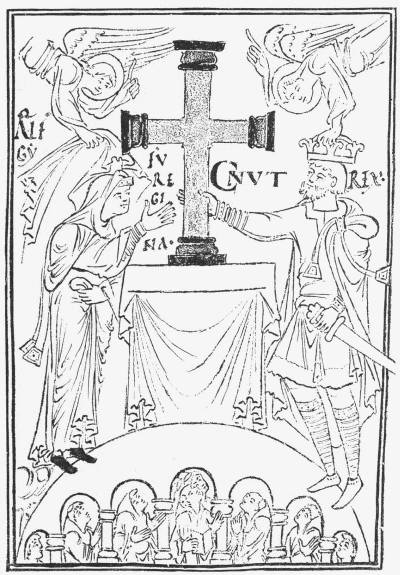

| King Cnut and his Queen, Emma, presenting a Cross upon the Altar of Newminster (Winchester) | 181 |

| The King receiving a Deputation | 183 |

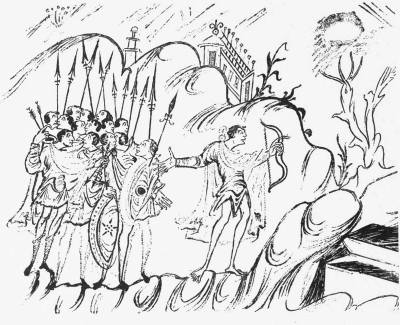

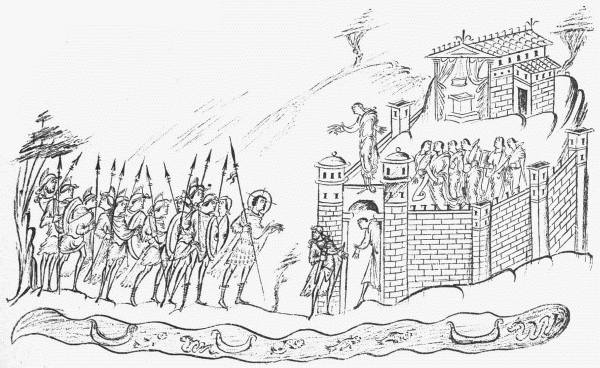

| Anglo-Saxon Warriors approaching a Fort | 185 |

| A Fight | 186 |

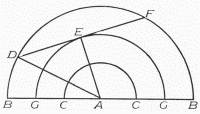

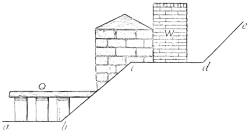

| Diagram of Canal | 188 |

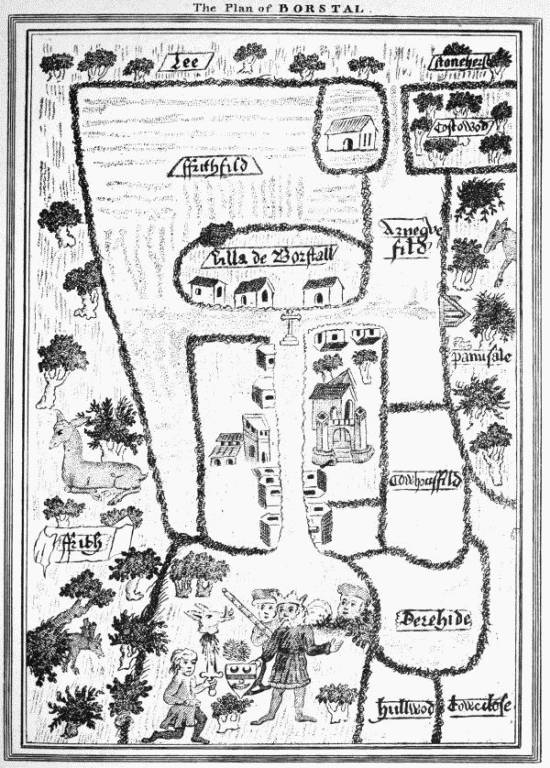

| King Edward the Confessor’s Palace at Borstal (Brill) | 193 |

| A Solar | 196 |

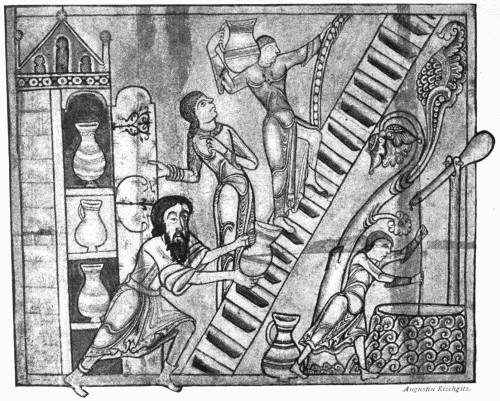

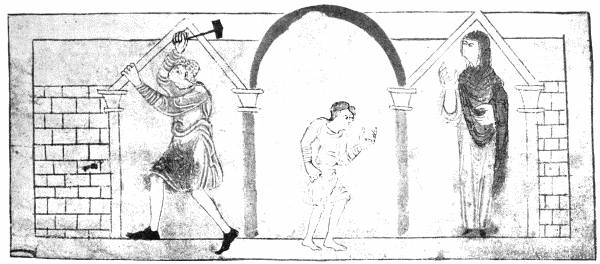

| Building a House | 197 |

| October. Hawking | 198 |

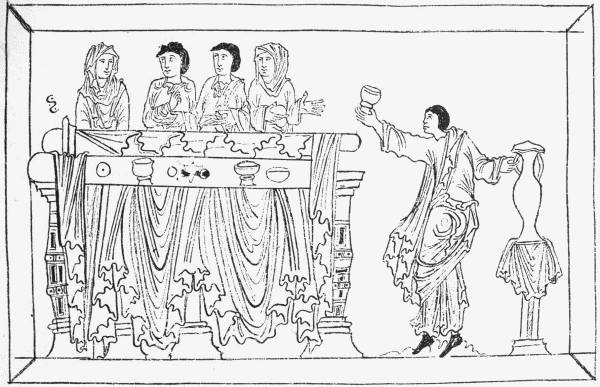

| A Banquet | 199 |

| Saxon Ladies | 201 |

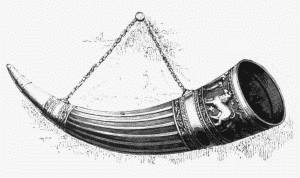

| Saxon Horn | 202 |

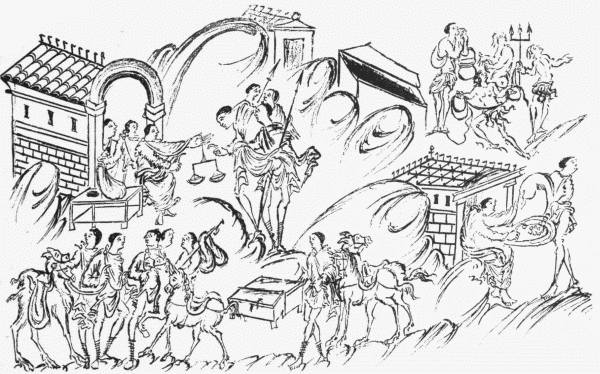

| Merchantmen with Horses and Camels | 203 |

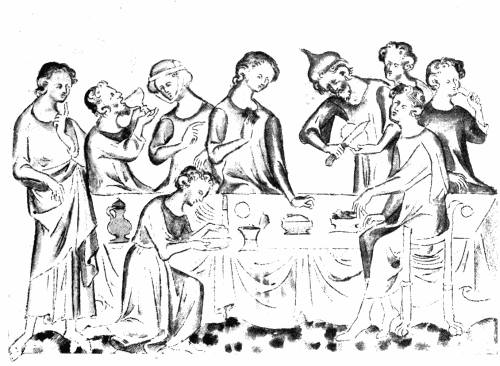

| A Banquet | 205 |

| Glastonbury Abbey | 206 |

| Anglo-Saxon Nuns | 207 |

| Conferring the Tonsure | 208 |

| A Burial | 209 |

| Saxon Church at Greenstead | 211 |

| St. Dunstan | 213 |

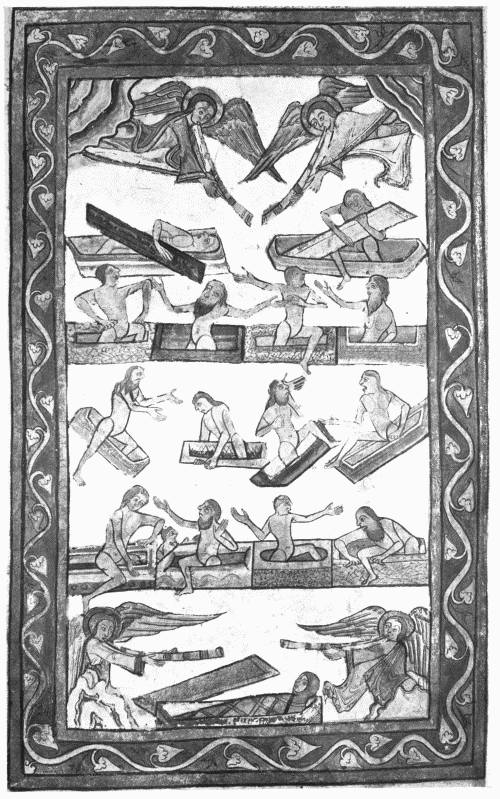

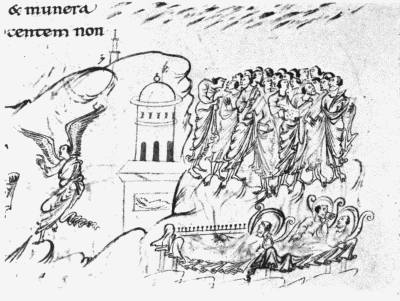

| The Last Day | Facing 214 |

| Anglo-Saxon Modes of Punishment | 216 |

| The Flogging of a Slave | 216 |

| Three Men in Bed | 218 ix |

| Mother and Child | 219 |

| Drawing Water | 220 |

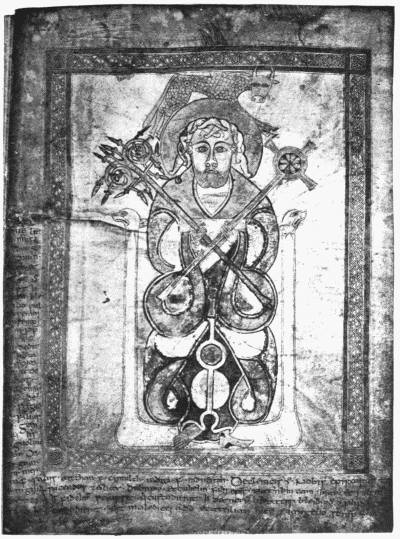

| St. Luke, from St. Chad’s Gospel Book, date about 700 A.D. | 221 |

| Anglo-Saxon Husbandman and his Wife | 223 |

| Feeding the Hungry | 225 |

| Going to the Chase | 226 |

| The Hawk Strikes | 226 |

| Feasting | 227 |

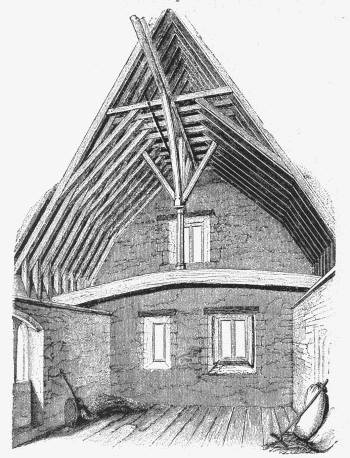

| Anglo-Saxon House | 229 |

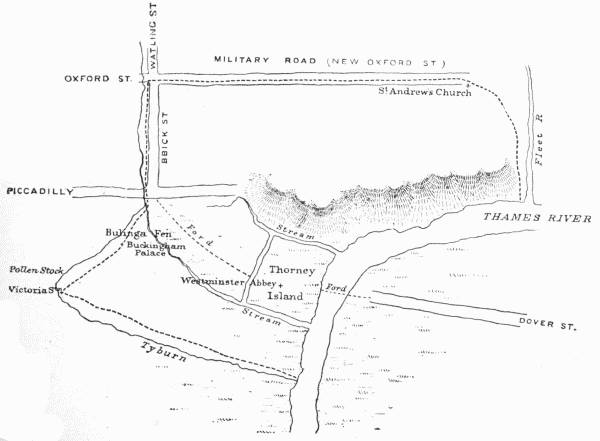

| The Situation of Westminster | 231 |

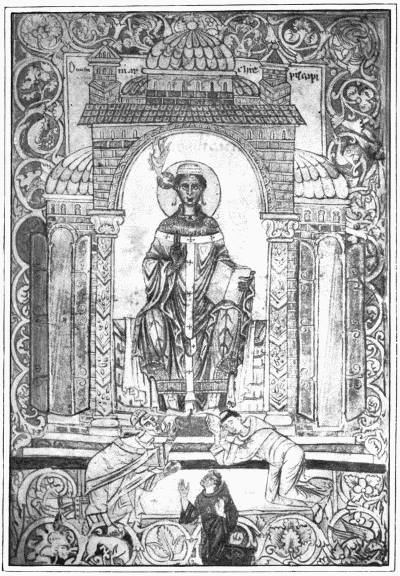

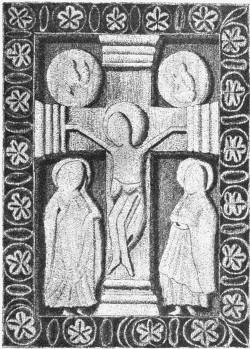

| St. Dunstan at the Feet of Christ | 233 |

| Monks | 235 |

| The Famous “Book of Kells” MS. of the Gospels in Latin, written in Ireland (A.D. 650-690) | 237 |

| Rood over the South Door of Stepney Church | 239 |

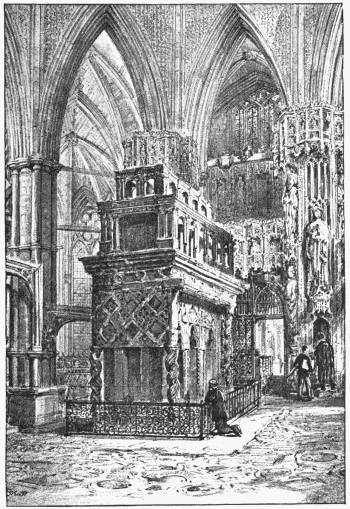

| Edward the Confessor’s Chapel | 241 |

| Ancient Enamelled Ouche in Gold discovered near Dowgate Hill; probably Ninth Century | 243 |

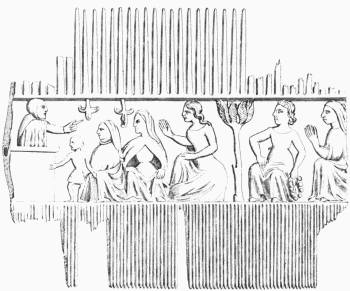

| An Ancient Comb found in the Ruins of Ickleton Nunnery | 244 |

| Duke William comes to Pevensey | 249 |

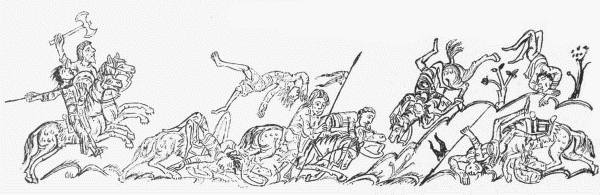

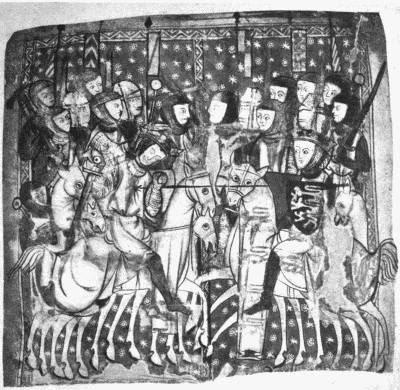

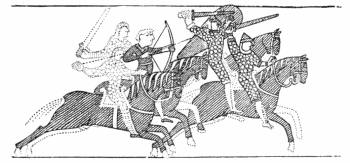

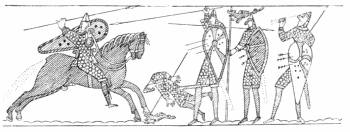

| King Harold shown in a Mêlée of Fighting-Men | 251 |

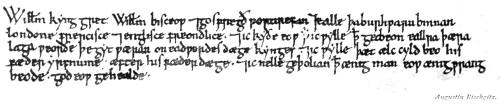

| Charter of the City of London given by William the Conqueror | 252 |

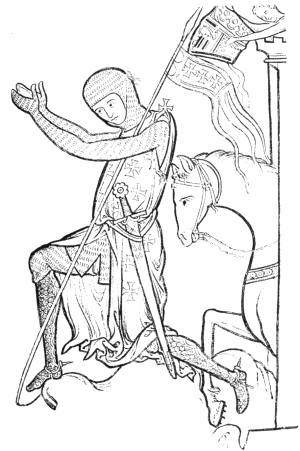

| A Norman Knight | 253 |

| Norman Horsemen | 255 |

| Harold trying to pull the Arrow from his Eye | 255 |

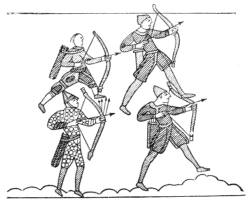

| Norman Archers | 255 |

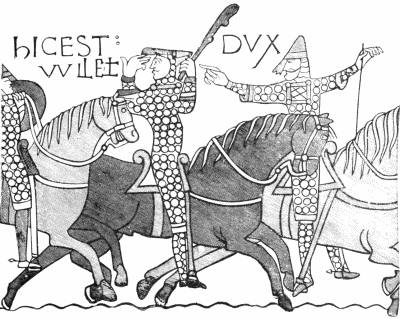

| William the Conqueror and his Knights (from the Bayeux Tapestry) | 257 |

| Bishops | 258 |

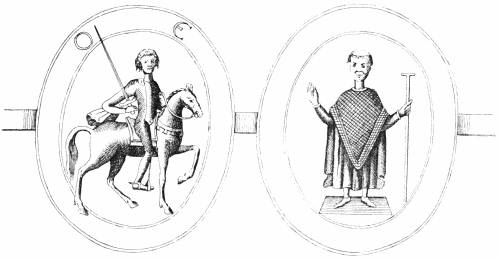

| The Seal of Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, Half-brother of William I. | 259 |

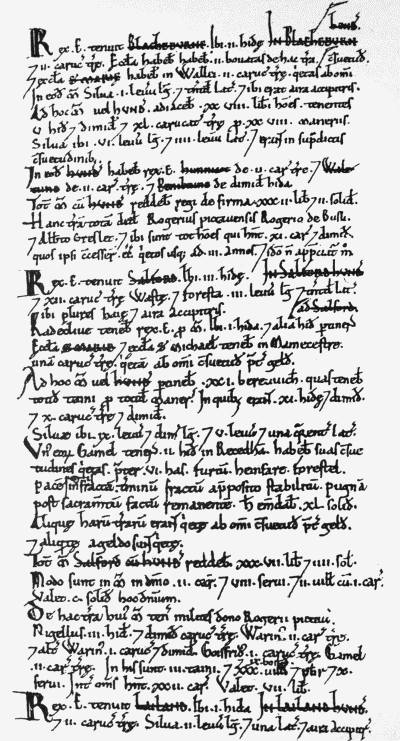

| Part of a Page of Domesday Book | 263 |

| William I. and II., Henry I. and Stephen | Facing 264 |

| Norman Soldiers | 267 |

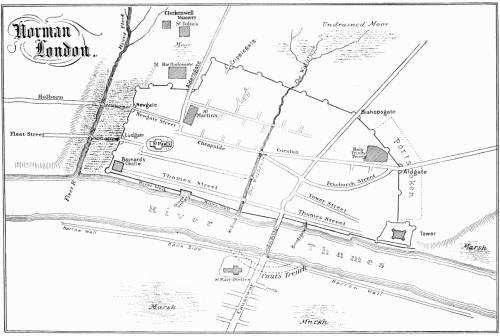

| Norman London | 269 |

| Norman Capitals from Westminster Hall | 273 |

| Seal of St. Anselm | 275 |

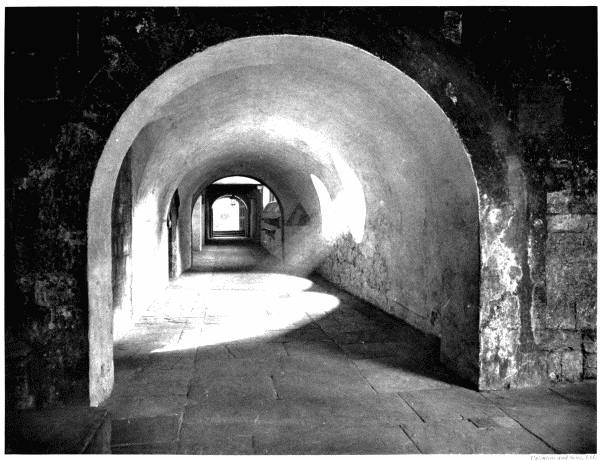

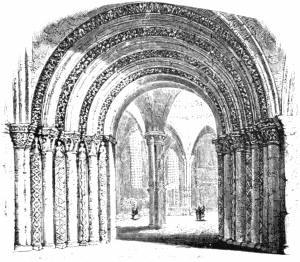

| Norman Arch, in the Cloisters, Westminster Abbey | Facing 276 |

| Coronation of Henry I. | 279 |

| An Ancient Seal of Robert, Fifth Baron FitzWalter | 281 |

| The Temple Church | 283 |

| A Fight | 291 |

| Costume of English Kings of the Eleventh Century. Anglo-Norman Ladies of High Degree | Facing 292 |

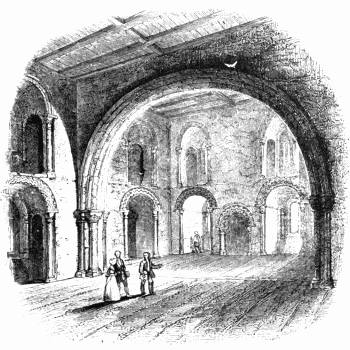

| St. John’s Chapel, Tower of London, Norman Architecture | 295 |

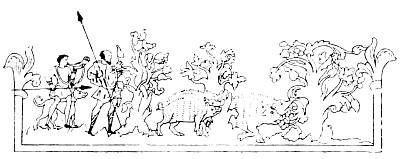

| March. Field Work. September. Boar-Hunting | 303 |

| Matron and Maid | 305 |

| A Horseman | 308 |

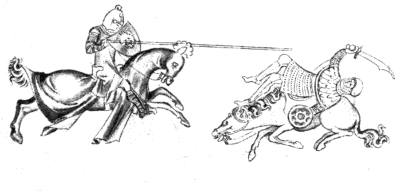

| Tilting | 313 |

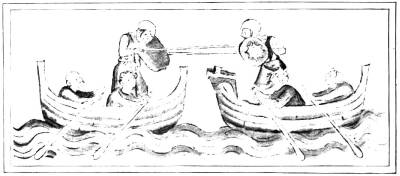

| Tilting in Boats | 314 |

| Dancing | 315 x |

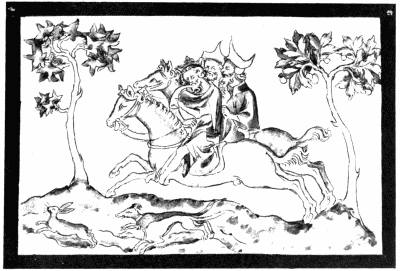

| The Chase | 317 |

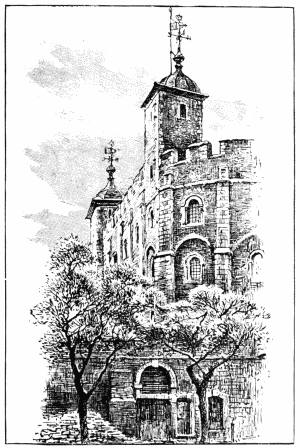

| The White Tower | 319 |

| Representation of Orion | 322 |

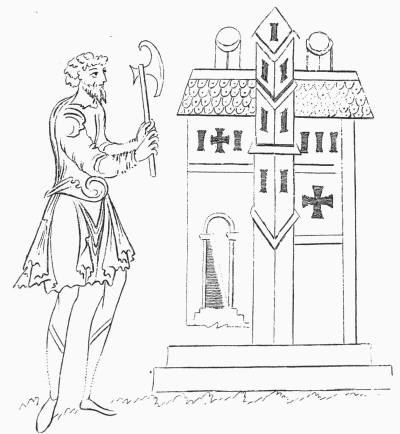

| Craftsman at work on a House | 323 |

| London Wall | 325 |

| A Norman Hall | 327 |

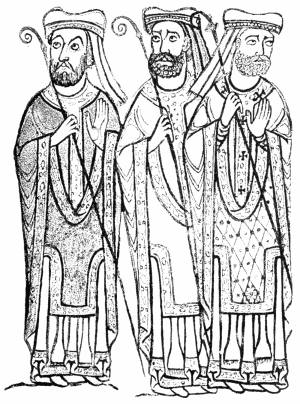

| Three Bishops | 329 |

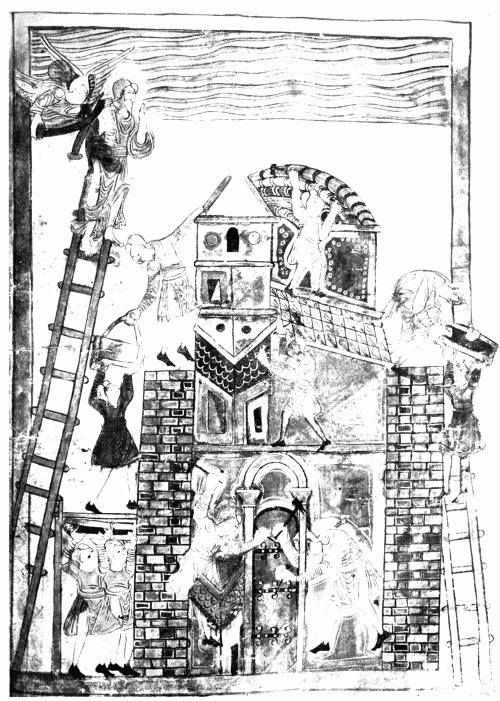

| Building a House | Facing 338 |

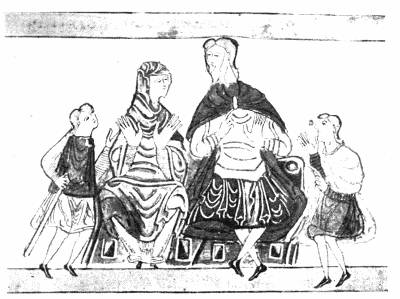

| A Family Group | 339 |

| Lady saving a Stag from the Hunters | 341 |

| Saxon Doorway, Temple Church | 343 |

1

3

By Prof. T. G. Bonney, F.R.S.

The buildings of a town often succeed in masking the minor physical features of its site—irregularities are levelled, brooks are hidden beneath arches and find ignominious ends in sewers; canals, quays, and terrace walls may be wholly artificial. To realise completely the original contours of the ground is often a laborious process, demanding inductive reasoning on the evidence obtained in sinking wells, in digging the foundations of the larger buildings, or in making cuttings and tunnels. Still the broader and bolder features cannot be obscured, however thick the encrusting layer of masonry may be. What, then, are these in the case of Greater London? Its site is a broad valley, along the bed of which a tidal river winds in serpentine curves as its channel widens and deepens towards the sea. On either side of this valley the ground slopes upwards, though for a while very gently, towards a hilly district, which rises, sometimes rather steeply, to a height of about 400 feet above sea-level. Towards the north this district passes into an undulating plateau, the chalky uplands of Hertfordshire; on the south it ends in a more sharply defined range, which occasionally reaches an elevation of about 800 feet above the sea—the North Downs. The upland declines a little, the valley broadens towards the sea, as the river changes into an estuary. Between the one and the other there is no very hard and fast division; the ground by the side of each is low, but as a rule by the river it is just high enough to be naturally fit for cultivation, while by the estuary it is a marsh. But as the ground becomes more salubrious, the channel becomes more shallow, and at one place, a short distance above the confluence of a tributary stream from the north—the Lea—this change in the character of the valley is a little more rapid than elsewhere.

These conditions seem to have determined the site of the city—the original nucleus of the vast aggregate of houses which forms the London of to-day. Air and water are among the prime requisites of life; no important settlement is likely to be established where the one is insalubrious, the other difficult to obtain. Thus men, in the days before systems of drainage had been devised, would shun the marshes of Essex and Kent, and, in choosing a less malarious site, would seek one where they4 could get water fit to be drunk, either from brooks which descended from the uplands, or from shallow wells. These conditions, as we shall see, were fulfilled in the site of ancient London; these for long years determined its limits and regulated its expansion.

Let us imagine London obliterated from the valley of the Thames; let us picture that valley as it was more than two thousand years ago, when the uplands north of the river were covered by a dense forest, and the Andreds Wald (as it was afterwards named) extended from the Sussex coast to the slopes of the Kentish Downs. We gaze, as we have said, upon a broad valley, through which the tidal Thames takes its winding course, receiving affluents from either side. These are sometimes mere brooks, sometimes rivers up which the salt water at high tide makes its way for short distances. The brooks generally rise among the marginal hills; the rivers on the northern side start far back on the undulating plateau; but on the southern the more important have cut their way completely through the range of the North Downs and are fed by streams which began their course in the valley of the Weald. Of the latter, however, probably not one is directly connected with the earliest history of London; of the former, only the Fleet, which, rising on the southern scarp of Hampstead Heath, ultimately enters the Thames near Blackfriars Bridge. But both the one and the other at later stages in the development of London may require a passing word of notice.

What, then, do we see at this earliest phase in the history of the future metropolis? At once we are impressed with the fact that the Thames formerly must have flowed in a channel broader but straighter than its present one; a channel which is now indicated by a tract of alluvial land a few feet below the general level of the valley, and but little above high-water mark. Traces of this may be seen here and there between Chelsea and London Bridge, in the low ground about Millbank and along the river-side at Westminster, and in that which runs from Lambeth along the right bank of the Thames. But the most marked indication of this alluvial plain begins about a mile below London Bridge. Here the left bank of the river is formed, as it has been from the bend at Hungerford Bridge, by a terrace ranging at first from about 25 feet to 40 feet above mean tide level, a most important physical feature, for it determined, as we shall see, the site of London. But on the opposite shore, the strip of lower ground—often about four or five hundred yards wide—on which river-side Southwark is built, continues until, at Bermondsey, it widens rather suddenly to about a mile and a half. So it goes on past the junction of the Lea, now widening, now contracting slightly, as, for instance, opposite to Purfleet and above Greenwich, but always a broad lowland through which the present tidal river takes a wholly independent and sinuous course. This plain is formed of silt which the Thames itself has deposited over the debatable region where river and sea begin to meet. It is but little above high-water mark; much of it less than a dozen feet5 above ordnance datum. A similar low plain, about half a mile wide, may be traced for a few miles up the valley of the Lea, and indications of this may be found here and there by the side of the Thames above Chelsea; but commonly they are wanting, and always are limited in extent. In their absence, the river bank is higher, for it is formed by the scarp of that terrace to which we have already referred. The difference in elevation between these plains is not great, for the second begins at about 20 to 25 feet above ordnance datum; but it shelves from this gently upwards, forming the remainder of the more obvious bed of the valley, till it reaches a height of about 100 feet. At about this level, though it is impossible to be quite precise, the steeper slopes, more especially on the northern side of the river, and the hills, continue to rise till sometimes—as at Hampstead and at Highgate—they reach an elevation of rather over 400 feet. We cannot, however, do more than speak in general terms, for in a valley like that of the Thames—mainly excavated in a soft and tenacious clay—a large part of the rainfall runs off, forming numerous brooklets and small streams, which carve out many minor undulations and shallow ramifying valleys.

The lowest alluvial plain, in olden days, must have been a desolate marshland, the haunt of wildfowl and the home of ague; so we pass it by, to describe more particularly the ground which overlooks it. The valley as a whole—in the neighbourhood of London—is carved out of strata assigned by geologists to the earlier part of the Tertiary era, the period called the Eocene. These rest upon a mass of chalk some 650 feet thick beneath the junction of Tottenham Court Road with Oxford Street—which rises to the surface towards the Kentish Downs on the one side and in the Hertfordshire hills on the other. Near London this rock is not exposed, but it begins to show itself near Deptford and Charlton, and is yet more conspicuous about Dartford and Purfleet, so that it evidently forms a true basin beneath London. Of what lies beneath it we shall speak hereafter, for this is a matter of more importance to the future history of London than at first might be supposed. The Eocene strata take the same basin-like form as the underlying chalk, so that while the lowest of them rises to the surface north and south of London, it is rather more than 200 feet below sea-level at Hungerford Bridge. This rock, called the Thanet Sand, is a marine deposit; it is a very light grey or buff-coloured sand, formed almost entirely of quartz grains, and it occupies a more limited area than the overlying strata, its thickness beneath London commonly varying from about 20 to 40 feet. The Thanet Sand seldom, if ever, reaches the surface to the north or the south-west of London, but it may be seen to the south-east, as about Woolwich and Croydon.

Over the Thanet Sand comes a rather variable group of clays and sands called the Woolwich and Reading Beds. They extend over a larger area and generally run a little thicker than it does, for beneath London they are usually about 50 or 60 feet,6 and occasionally rather more. The fossils are sometimes fresh-water forms, sometimes estuarine or marine, so that the deposit probably marks the embouchure of one or possibly two large rivers. Next comes that brownish clay which is so constantly turned up in digging sewers or foundations, especially on the lower slopes of the hills. Its name—the London Clay—is taken from the metropolis; but it covers, or at any rate has covered, a much more extensive area, for it can be traced at intervals (large masses having been removed by denudation in some districts) as far as Marlborough on the west, the Isle of Wight on the south, and Great Yarmouth on the north. The same cause has reduced its thickness in parts of the metropolitan districts. Beneath Trafalgar Square, for example, it is 142 feet, and in some wells even less, but the total thickness must have been—indeed in some places it still is—rather more than 400 feet. At the base a band of pebbles commonly occurs. This, under the central part of London, is inconspicuous; but farther away, especially towards the south and the east, it is often 20 to 30 feet thick, and sometimes more. It consists of well-rounded flint pebbles, generally not so big as a hen’s egg, mixed with quartz sand. This gravel lies at or near the surface over a considerable area about Blackheath, Charlton, and Chiselhurst, and is now generally distinguished from the London Clay by a separate name—the Blackheath or the Oldhaven Beds. Both this formation and the London Clay contain fossils, sometimes rather abundantly, which indicate a marine origin, though the deposit cannot have been formed at a long distance from land, for estuarine species occur in it; while fossil fruits and pieces of wood are sometimes common in the London Clay, the latter being often riddled by the borings of teredines (a bivalve mollusc which still exists and makes great havoc in timber). So that in all probability both the gravel and the clay were connected with the rivers already mentioned.

Above the London Clay comes a group of sands, occasionally containing intercalated beds of clay, which once must have had almost as wide an extent as it, but in the London area it is reduced to isolated fragments, capping the clay hills at Hampstead, Highgate, and Harrow. Here the deposit is less than 100 feet in thickness, for so much has been washed away, but it often reaches quite 300 feet on the dry moorland about Chobham, Aldershot, and Weybridge.

Then comes a great gap in the geological record. The beds just mentioned belong to the Eocene, but after these nothing more is found till we are very near the end, if not actually out of, the Pliocene period. This long interval, in the district with which we are concerned, was occupied by earth-movements, the result of which was denudation rather than deposition. As we have already said, the chalk and the overlying Eocene strata are bent into the form of an elongated basin, which is related to the long dome-like elevation from which the hills and valleys of the Weald have been sculptured. Basin and dome alike are the results of wave-like movements which began to affect a large portion of Europe soon after the7 latest Eocene deposits in the London area were formed, movements of which the Alps and the Pyrenees are more conspicuous monuments. But these folds first began at a still earlier epoch—that which separates the newest part of the chalk from the oldest beds of the Eocene. Even then the London basin and the Wealden dome must have been outlined, though less boldly than now; for beneath the City the Thanet Sand and the Woolwich and Reading Beds are pierced in borings, and are together about 90 feet in thickness. But high up on the North Downs the pebble bed at the bottom of the London Clay may be seen resting on the chalk. So this district in early Eocene times must have been higher than the former one by at least the above-named amount; or, in other words, the basin of the Thames and the dome of the Weald must have been already indicated.

8

The later earth-movements, however, were on a much grander scale. Under London Bridge the base of the London Clay is about 90 feet below the sea-level, while on the North Downs it is about 750 feet above it, so the displacement since it was laid down has been at least 840 feet. The uplift in the central part of the Weald was doubtless much greater, but as denudation must have begun as soon as ever dry land appeared, we cannot say to what height the hills in this part may have risen. Still, when we remember that the valleys of the Wey, the Mole, and the Medway, which drain the northern half of the Weald, have cut completely through the range of the North Downs on their course towards the Thames, and are the makers of the valleys in which they flow, we can understand the magnitude of the work of denudation. But that work was far too complicated, the subject is far too difficult and full of controversies, to be discussed in these pages; we must content ourselves with mentioning a few facts which have more or less affected the history of the metropolis.

As the rivers flowed, they transported and deposited the débris of the land, and if ever a submergence occurred, the same work would be done by tides and currents of the sea. The earliest deposits, obviously, would be formed in places which are far above the present beds of the streams. Most of these deposits would be washed away, their materials would be sorted out and transferred to lower levels, as the valleys were widened and deepened, and as the surface of the ground approached more nearly to its present contours. Thus gravels, sands, and clays are found at various levels down nearly to the present level of the Thames. The oldest of them, deposited within a radius of about ten miles from London Stone, lie rather more than 300 feet above the sea.1 These last are probably connected with similar sands and gravels which cover considerable areas in the Eastern Counties, and may have been deposited at an epoch when even the outline of the present valley system of the Thames had not been delineated. Upon this question, however, it is needless to enter. The next deposit, supposing these patches of sand and gravel to be of one age—a very doubtful matter,—is the Boulder Clay—a stiff, tenacious clay, often studded with pieces of chalk, from minute grains to biggish lumps, which commonly are fairly well rounded, together with flints, both rounded and angular, and fragments of other rocks. These have been derived, generally speaking, from the north and from various places, often at long distances, either on the eastern side of England, or in Scotland, or occasionally even in Norway. The clay also appears to have been formed from materials which came9 from the same direction. But little of this Boulder Clay now remains in the neighbourhood of London; the nearest patch is found on the higher ground on either side of the 300 feet contour-line between Whetstone, Finchley, and Muswell Hill—perhaps also at Hendon. To what extent the valley system of the Thames was sculptured when the Boulder Clay was formed; why the latter stops short on the northern slopes; under what circumstances it was deposited—are all subjects of controversy which it is impossible to discuss in these pages. Suffice it to say that the clay indicates, to some extent at least, the action of ice; and that as the patches of it and of the associated gravels occur at different levels (a fact which is still more obvious in other districts) and appear to exhibit a general correspondence in distribution with the present contours of the ground, several valleys must have been by then partially, if not completely, defined. In the main valley—as, for example, near Erith—fine sandy clays or “brick earth” occur, which some geologists consider to be at least as old as this clay. The climate, when this “brick earth” was deposited, certainly must have been much colder than it is at present, for remains of the musk-sheep have been found in it, and at that time the valley of the Thames must have been excavated nearly to its present depth. But on the slopes of this valley, and of its tributaries, beds of gravel are found, containing stones which must have been washed out of the Boulder Clay; and as these gravels often extend to more than a hundred feet above the present level of the river, the changes since they were deposited must have been considerable. They contain the bones of extinct mammals, such as the woolly rhinoceros and the mammoth, with others indicative of a climate distinctly colder than at present. But as these also have been found almost at the present level of the river, the animals must have remained in this country till it had assumed very nearly its present outlines. For instance, the tooth of a mammoth was discovered in 1731, 28 feet below the surface, when a sewer was dug in Pall Mall. Many bones of this and other animals have been found in the “brick earth” of Ilford; and a splendid pair of tusks, obtained in 1864, is now preserved in the British Museum, South Kensington. Here “the ground forms a low terrace, bordering the small river Roding on the one side, and on the other it slopes gradually down to the Thames. The height of the surface at the pits is about 28 feet above the Thames.”2 It is therefore certain that the river valley was cut down nearly to its present level while the climate was still much colder than it is at present, and very probable that its depth was much increased after the chalky Boulder Clay had been deposited; for these gravels, as has been said, are strewn over the lower slopes up to about a hundred feet above the present river. At Highbury Terrace they even reach 154 feet, and at Wimbledon 190 feet.

These gravels have yielded the remains, not only of the mammoth, but also of10 man. His bones indeed have hardly ever been discovered, but stones chipped into shape by his hands are far from rare. They are almost always made of flint, a material which was abundant, could be readily trimmed, and afforded a good and durable cutting edge. These implements are never smoothed or polished, and exhibit many varieties of form. They range from mere flakes, the artificial origin of which cannot always be proved, but which in all probability were used as knives and scrapers, to instruments which could only have been made at the cost of considerable time and some skill. Similar remains have been found elsewhere in the more eastern and southern counties of England and on the Continent. The people, however, who fashioned such implements hardly can have been so far advanced in civilisation as the wandering tribes of Esquimaux in Northern Greenland.

These worked flints are very rarely found either below 20 or above 100 feet from the sea-level, but between these heights they are not uncommon. About two centuries ago a well-worked flint, something like a spear-head in shape, was found with an elephant’s (mammoth’s) tusk “opposite black Mary’s, near Grayes Inn Lane.”3 Implements of various shapes have been obtained from the gravel near Acton, Ealing, Hackney, Highbury, and Erith, as well as at Tottenham Cross, Lower Edmonton, and other places in the valley of the Lea. But the most interesting localities hitherto investigated are in the neighbourhood of Stoke Newington and of Crayford. The worked flints at the former place are found at more than one level, and indicate a progress in manual skill sufficient to lead observers to the conclusion that they belong to more than one epoch. The newest of these implements, flint flakes with occasional more elaborate specimens, were so abundant and have occurred in such a manner as to suggest to their discoverer (Mr. Worthington Smith) that they lay on the actual surface where they were fashioned by the workers of olden time. “The floor upon which this colony of men lived and made their implements has remained undisturbed till modern times, and the tools, together with thousands of flakes, all as sharp as knives, still rest on the old bank of the brook just as they were left in Palæolithic times. In some places the tools are covered with sand, but usually with four or five feet of brick earth.... That (the floor) was really a working place where tools were made in Palæolithic times is proved by the fact of my replacing flakes on to the blocks from which they were originally struck.”4 At Crayford also, a layer of flint chips was found by Mr. F. C. J. Spurrell in “brick earth” at the foot of a buried cliff of chalk. The circumstances under which these flakes occurred led him to the conclusion that this also was the site of an old “workshop” of flint implements.5

These gravels may be assigned to a time—probably towards the conclusion of11 the Glacial epoch—when the climate of Britain was still cold, when the higher hills were permanently capped by snow, and when glaciers may have lingered in the more mountainous regions. All through the spring and early summer the rivers would be swollen with melting snow, the torrents from the highland districts would be full and strong, and thus denudation would be comparatively rapid—the more rapid because the latest deposits, the Boulder Clay with its associated gravelly sands, would be incoherent and in many places still unprotected by vegetation. Very different would be the brooks and the rivers which then traversed the valley of the Thames from those which now creep through lush water-meadows or glide “by thorpe and town.” The final sculpturing of the valleys—all that has been effected since the date of the Chalky Boulder Clay—may have been accomplished with comparative quickness. Still, since the time when the oldest of these flint implements were lost by their owners, the beds of the valleys have been lowered, in some places by not less than a hundred feet. The district also, until the greater part of this final sculpturing was accomplished, was inhabited by men whose habits of life were throughout substantially the same.

The alluvial deposits, as already stated, rise but little above the surface of the river at high tide. Their thickness varies, but commonly it is from about 12 to 20 feet. The lowest part is generally gravel and sand—materials indicating that the conditions which produced the older deposits of a like nature passed away gradually. This is followed by river silt, with occasional thin beds of peat or with indications of old land surfaces on which flourished woods of oak or even of yew. Below the Port of London, marine shells are rather abundant in the lower part of the silt; these indicate that the general level of the land was a little lower than it had been during the preceding age, perhaps even than it is at present. These alluvial deposits have yielded implements of smoothed or polished stone, of bronze and of iron; also canoes, and even relics of the Roman occupation of Britain. In other words, they have yielded antiquities belonging mainly to prehistoric times, though the record is continued up to a comparatively recent date. Marshy or peaty ground occurs even within the limits of the city,6 as at one corner of St. Paul’s Cathedral, in Finsbury Crescent, and near London Wall, as well as at Westminster. Thorney—the “Isle of Thorns”—the site of the Abbey, was formerly a low insular bank of gravel among marshes. The lake in St. James’s Park indicates the track of the Tyburn, which traversed one of these swamps. It was a brook of some size, and traces of it may be found in the names Marylebone (le-bourne7), and Brook Street. One branch of it passed “through Dean Street and College Street till it fell into the Thames by Millbank Street.”8 The water from the slopes north of Hyde Park made12 another stream called the Westbourne; this, after following a path still suggested by the Serpentine, found its way to the Thames through a fenny district which is now Belgravia (see also p. 26).

Such, then, is the structure of the valley of the Thames; such are the deposits which form its surface on either side, and on which the metropolis has been built. But we must now look a little more closely at their distribution, for by this the growth of London in ancient times was largely determined. The broad terrace already mentioned on the left bank of the Thames, the site of mediæval London, consists, for a couple of miles or so inland, mainly of a flint gravel more or less sandy, seldom exceeding 20 feet in thickness, and commonly rather less, which rests upon the tenacious London Clay. Here and there this gravel may be traversed by a small stream, but the most marked break in its level is formed by a brook which, flowing from the slopes of Hampstead and Highgate, at last has cut its bed down to the clay and has broadened out into a creek as it joins the Thames. It was known in its lower reaches as the Fleet (see p. 27). This gravel terrace made London possible; this stream formed its first boundary on the west. The rain-water is readily absorbed by the gravel, but is arrested by the underlying clay. It can escape in springs wherever a valley has been cut down to the level of saturation, but if it is not tapped in this way the gravel will be full of water to within a few feet of the surface, so that a shallow well will yield a good supply. The first settlement was placed upon this gravel, by the river-side, where the channel is still deep at high tide; it was limited on the west by the slopes descending to the Fleet, on the east by the lower ground which shelves downwards towards the mouth of the Lea. From this nucleus, enclosed within the Roman fortification, the town expanded, as times became more peaceful, along the lines of the great roads; and at an early date a tête-du-pont would undoubtedly be formed at Southwark.

But without entering into the details of this development, let us pass over some centuries and see how the growth of London was for a long time conditioned and limited by this gravel. The metropolis spread13 “eastward towards Whitechapel, Bow, and Stepney; north-eastward towards Hackney, Clapton, and Newington; and westward towards Kensington and Chelsea; while northward it came for many years to a sudden termination at Clerkenwell, Bloomsbury, Marylebone, Paddington, and Bayswater: for north of a line drawn from Bayswater, by the Great Western Station, Clarence Gate, Park Square, and along the side of the New Road to Euston Square, Burton Crescent, and Mecklenburg Square, this bed of gravel terminates abruptly, and the London Clay comes to the surface and occupies all the ground to the north. A map of London, as recent as 1817, shows how well defined was the extension of houses arising from this cause. Here and there only beyond the main body of the gravel there were a few outliers, such as those at Islington and Highbury, and there habitations followed. In the same way, south of the Thames, villages and buildings were gradually extended over the valley-gravels to Peckham, Camberwell, Brixton, and Clapham; while, beyond, houses and villages rose on the gravel-capped hills of Streatham, Denmark Hill, and Norwood. It was not until facilities were afforded for an independent water-supply by the rapid extension of the works of the great Water Companies that it became practicable to establish a town population in the clay districts of Holloway, Camden Town, Regent’s Park, St. John’s Wood, Westbourne, and Notting Hill.”9

It is possible that the position of the older parks—St. James’s, the Green Park—and Hyde Park may have been indirectly determined by the fact that over much of them the gravel is thin or the clay actually rises to the surface.

Every old settlement outside the earlier limits of the metropolis marks the presence of sand or gravel. Hampstead and Highgate, which early in the nineteenth century were severed from London by nearly a couple of miles of open fields, stand upon large patches of Bagshot Sand, which caps the London Clay and is sometimes as much as 80 feet thick. This yellowish or fawn-coloured sand may be seen almost anywhere in the old excavations at the top of Hampstead Heath, and the difference of the vegetation on this material and on the clay of the lower slopes cannot fail to be noticed. On the latter, grass abounds; on the former, fern, furze, and even heather. The junction of the sand and the clay is indicated by springs which supply the various ponds. These are occasionally chalybeate, like the once-noted spring which may still be seen in Well Walk, Hampstead. Harrow stands on another outlying patch of Bagshot Sand. Enfield, Edmonton, Barnet, Totteridge, Finchley, Hendon, and other old villages are built upon the high-level gravels which have been already mentioned.

The shallow wells are no longer used in London itself. Infiltration of sewage, in some cases of the drainage from churchyards, had rendered many of them actually poisonous; clear, sparkling, even palatable, though the water might be, there was often “death in the cup.” There was a terrible illustration of this fact during the visitation of the cholera in 1854. A pump, the water of which was much esteemed, stood by the wall of the churchyard in Broad Street (south of Oxford Street). The water became infected, and the cholera ravaged the immediate neighbourhood. But though most of these pumps were closed barely sixty years ago, some, like that in Great Dean’s Yard, Westminster, were in use for quite another quarter of a century. It has now disappeared, but that within the precincts of the Charterhouse is still standing. Thus London was limited to the gravel till it was able to obtain water from other sources.10

The first step in this direction was early in the seventeenth century, when the14 New River Company had its origin, and for many years this was the only Company by which water was supplied to London; but seven others were subsequently founded.11

The New River Company obtains its water from the Lea, the original source being nearly forty miles from London, but the supply has been since increased by sinking wells. The East London draws upon the same river. Five of the other Companies get their water from the Thames, some miles above London, augmenting their supply by means of wells, and the Kent Company draws exclusively from deep wells in the chalk. As these Companies were founded the metropolis began to spread rapidly over the areas which they supplied, but it did so in a regular and systematic fashion. Houses fed by the mains of a Water Company must keep, as it were, in touch with their base of supply, because of the cost of laying a long line of pipes to supply a solitary house. Thus a town which draws its water from mains advances block by block into the surrounding country, and is not encircled by a wide fringe of scattered dwellings.

In the London area, however, there is a way in which the occupant of an isolated house can obtain a supply of water, though it is not a cheap one. He may bore through the London Clay into the underlying sands and gravels. When a porous stratum rests on one that is impervious, the former becomes saturated with water up to a certain level, dependent on local circumstances, and in this case a well sunk sufficiently deep into it will be filled. But if the porous stratum be also covered by one which is impervious; if all three be bent into a basin-like form; and if the porous one crop out at a considerably higher level than the place where a well is needed, then it may be water-logged to a height sufficient to force the water up the bore-hole, perhaps even to send up a jet like a fountain. Wells of this kind are termed Artesian, from Artois in France, where they have been in use for several centuries, and they began to be sunk in England about a century ago. The London Clay was pierced, and the water-logged sands and gravels belonging to the lowest part of the Tertiary series were tapped. These basin-formed beds crop out at an elevation generally of about one hundred feet above the Thames; thus they were charged with water to a considerable height above the level of the river, and it very commonly at first spouted up above the surface of the ground; but as the wells increased in number, its level was gradually lowered, for the area over which these beds are exposed is not very extensive, and a stratum cannot supply more water than it receives by percolation from the rainfall. At first everything went well; consumers were like heirs who had succeeded to the savings of a long minority, for water had been accumulating in this subterranean basin-like reservoir during myriads15 of years; but after a time the expenditure began to exceed the income, and the water-level sank slowly, till now it is many yards below the surface of the ground.

But when this source of supply evidently was becoming overtaxed, another was found in the underlying chalk. This rock absorbs water rapidly, but parts with it very slowly. Professor Prestwich found by experiment that a slab of chalk measuring 63 cubic inches drank up 26 cubic inches of water (all it could hold) in a quarter of an hour; yet when left to drain for twelve hours it parted with only one-tenth of a cubic inch.12 So that an ordinary well is useless. But the upper part of the chalk, generally to a depth of rather more than 300 feet, is traversed by fissures, and these are full of water. So a bore-hole is carried down till one of them is struck, and they are so abundant that failures are rare. In this way the water-supply of London is materially augmented.

This source also—at any rate in the immediate neighbourhood of London—is becoming overtaxed, so an effort has been made to obtain water from yet greater depths. Below the chalk is an impervious clay (Gault), and beneath this comes a brownish sand, followed by some other beds not quite so porous (called the Lower Greensand), which are succeeded by thick clays. These sandy rocks crop out at the surface to the north of London in Buckinghamshire and Bedfordshire, and to the south in Surrey and Kent. So they reasonably might be expected to pass beneath the metropolis, to be saturated with water, and to yield a large supply as they do at Paris, the geological position of which bears a considerable resemblance to that of London. Bore-holes have been put down in search of these sands at Kentish Town, Meux’s Brewery (Tottenham Court Road), Richmond, Streatham, and Crossness. They have also been sunk beyond the metropolitan area at Ware, Cheshunt, Harwich, and Chatham. At the last place the Lower Greensand is only about 40 feet thick, instead of 400 feet as it is south of the North Downs.13 It was expected to occur under London at a depth of about 1000 feet in round numbers, but in every case it was found to be either wholly absent or so thin as to be worthless. This is true even so far away as Ware and Harwich on the northern side, and perhaps as Croydon on the southern. In the days when this Lower Greensand, and even a considerable thickness of strata which elsewhere comes beneath it, were deposited, a large island or peninsula composed of much older rocks must have risen above the sea in the region over which London and all its environs now stand. So there is no hope of increasing the supply of water from any beds older than the upper part of the chalk. But a good deal more may be obtained from this rock, if it be tapped at longer distances from the metropolis. To this process, however, there are two objections: one, that the number of wells and of16 conduits which will be required in order to collect the water will probably make it a rather costly source of supply; the other, that if large demands be made on the water stored up beneath the chalk hills, the level of the surface of saturation in this rock will be appreciably lowered, many springs will be dried up, and the streams will be seriously diminished, which will greatly injure thousands of acres of water-meadows and many important industries. Large sums would have to be paid as compensation, and this would add greatly to the cost of any scheme. It is doubtful whether more water ought to be withdrawn from the Thames and its tributaries; and rivers which flow through a thickly populated country can hardly be regarded as safe from sewage contamination. It is therefore not improbable that, within a few years, the metropolis will have to follow the example of Liverpool and of Manchester, and seek another source of water-supply at a yet greater distance than has been done by those cities.

T. G. Bonney.

17

It is due to the respect with which all writers upon London must regard the first surveyor and the collector of its traditions and histories that we should quote his words as to the origin and foundation of the City. He says (Strype’sStow, vol. i. book i.):—

“As the Roman Writers, to glorify the City of Rome, drew the Original thereof from Gods, and Demi-gods, so Geoffrey of Monmouth, the Welsh historian, deduceth the Foundation of this famous City of London, for the greater Glory thereof, and Emulation of Rome, from the very same original. For he reporteth, that Brute, lineally descended from the Demi-god Eneas, the son of Venus, Daughter of Jupiter, about the Year of the World 2855, and 1108 before the Nativity of Christ, builded the City near unto the River now called Thames, and named it Troynovant, or Trenovant. But herein, as Livy, the most famous Historiographer of the Romans, writeth, ‘Antiquity is pardonable, and hath an especial Privilege, by interlacing Divine Matters with Human, to make the first Foundations of Cities more honourable, more Sacred, and as it were of greater Majesty.’

This Tradition concerning the ancient Foundation of the City by Brute, was of such Credit, that it is asserted in an ancient Tract, preserved in the Archives of the Chamber of London; which is transcribed into the Liber Albus, and long before that by Horn, in his old Book of Laws and Customs, called Liber Horn. And a copy of this Tract was drawn out of the City Books by the Mayor and Aldermen’s special Order, and sent to King Henry the VI., in the Seventh year of his reign; which Copy yet remains among the Records of the Tower. The Tract is as followeth:—

18

‘Inter Nobiles Urbes Orbis, etc. 1. Among the noble Cities of the World which Fame cries up, the City of London, the only Seat of the Realm of England, is the principal, which widely spreads abroad the Rumour of its Name. It is happy for the Wholesomeness of the Air, for the Christian religion, for its most worthy Liberty, and most ancient Foundation. For according to the Credit of Chronicles, it is considerably older than Rome: and it is stated by the same Trojan Author that it was built by Brute, after the Likeness of Great Troy, before that built by Romulus and Remus. Whence to this Day it useth and enjoyeth the ancient City Troy’s Liberties, Rights, and Customs. For it hath a Senatorial Dignity and Lesser Magistrates. And it hath Annual Sheriffs instead of Consuls. For whosoever repair thither, of whatsoever condition they be, whether Free or Servants, they obtain there the refuge of Defence and Freedom. Almost all the Bishops, Abbots, and Nobles of England are as it were Citizens and Freemen of this City, having their noble Inns here.’

These and many more matters of remark, worthy to be remembered, concerning this most noble City, remain in a very old Book, called Recordatorium Civitatis; and in the Book called Speculum.

King Lud (as the same Geoffrey of Monmouth noteth) afterward (about 1060 Years after) not only repaired this City, but also increased the same with fair Buildings, Towers, and Walls; which after his own Name called it Caire-Lud, or Luds-Town. And the strong Gate which he builded in the west Part of the City, he likewise, for his own honour, named Ludgate.

And in Process of Time, by mollifying the Word, it took the Name of London, but some others will have it called Llongdin; a British word answering to the Saxon word Shipton, that is, a Town of Ships. And indeed none hath more Right to take unto itself that Name of Shipton, or Road of Ships, than this City, in regard of its commodious situation for shipping on so curious a navigable River as the Thames, which swelling at certain Hours with the Ocean Tides, by a deep and safe Channel, is sufficient to bring up ships of the greatest Burthen to her Sides, and thereby furnisheth her inhabitants with the Riches of the known World; so that as her just Right she claimeth Pre-eminency of all other Cities. And the shipping lying at Anchor by her Walls resembleth a Wood of Trees, disbranched of their Boughs.

This City was in no small Repute, being built by the first Founder of the British Empire, and honoured with the Sepulchre of divers of their Kings, as Brute, Locrine, Cunodagius, and Gurbodus, Father of Ferrex and Porrex, being the last of the Line of Brute.

Mulmutius Dunwallo, son of Cloton, Duke of Cornwall, having vanquished his Competitors, and settled the Land, caused to be erected on, or near the Place, where now Blackwell-Hall standeth (a Place made use of by the Clothiers for the sale of their Cloth every Thursday), a Temple called the Temple of Peace; and after his Death was there interred. And probably it was so ordered to gratify the Citizens, who favoured his Cause.

Belinus (by which Name Dunwallo’s Son was called) built an Haven in this Troynovant, with a Gate over it, which still bears the Name of Belingsgate [now Billingsgate]. And on the Pinnacle was a brazen Vessel erected, in which was put the ashes of his Body burnt after his Death.

The said Belinus is supposed to have built the Tower of London, and to have19 appointed three Chief Pontiffs to superintend all Religious Affairs throughout Britain; whereof one had his See in London, and the other Sees were York and Carleon. But finding little on Record concerning the actions of those Princes, until we come to the reign of King Lud, it is thought unnecessary to take any further Notice of them. He was eldest son of Hely, who began his Reign about 69 years before the Birth of Jesus Christ. A Prince much praised by Historians for his great Valour, noble Deeds, and Liberality (for amending the Laws of the Country, and forming the State of his Common-weal). And in particular, for repairing this City, and erecting many fair Buildings, and encompassing it about with a strong stone Wall. In the west Part whereof he built a strong Gate, called Ludgate, as was shewed before, where are now standing in Niches, over the said Gate, the Statues of this good King, and his two Sons on each side of him, as a lasting Monument of his Memory, being, after an honourable Reign, near thereunto Buried, in a Temple of his own Building.

This Lud had two Sons, Androgeus and Theomantius [or Temanticus], who being not of age to govern at the death of their father, their Uncle Cassivelaune took upon him the Crown; about the eighth Year of whose reign, Julius Cæsar arrived in this Land, with a great power of Romans to conquer it. The Antiquity20 of which conquest, I will summarily set down out of his own Commentaries, which are of far better credit than the Relations of Geoffrey of Monmouth.

The chief Government of the Britons, and Administration of War, was then by common advice committed to Cassivelaune, whose borders were divided from the Cities on the sea coast by a river called Thames, about fourscore miles from the sea. This Cassivelaune before had made continual Wars with the other Cities; but the Britons, moved with the coming of the Romans, had made him their Sovereign and General of their Wars (which continued hot between the Romans and them). [Cæsar having knowledge of their intent, marched with his army to the Thames into Cassivelaune’s Borders. This River can be passed but only in one place on Foot, and that with much difficulty. When he was come hither, he observed a great power of his enemies in Battle Array on the other side of the River. The Bank was fortified with sharp stakes fixed before them; and such kind of Stakes were also driven down under water, and covered with the river. Cæsar having understanding thereof by the Prisoners and Deserters, sent his Horse before, and commanded his Foot to follow immediately after. But the Roman Soldiers went on with such speed and force, their Heads only being above water, that the Enemy not being able to withstand the Legions, and the Horse, forsook the Bank and betook themselves to Flight. Cassivelaune despairing of Success by fighting in plain battle, sent away his greater forces, and keeping with him about Four Thousand Charioteers, watched which way the Romans went, and went a little out of the way, concealing himself in cumbersome and woody Places. And in those Parts where he knew the Romans would pass, he drove both Cattle and People out of the open Fields into the Woods. And when the Roman Horse ranged too freely abroad in the Fields for Forage and Spoil, he sent out his Charioteers out of the Woods by all the Ways and Passages well known to them, and encountered with the Horse to their great Prejudice. By the fear whereof he kept them from ranging too far; so that it came to this pass, that Cæsar would not suffer his Horse to stray any Distance from his main Battle of Foot, and no further to annoy the enemy, in wasting their Fields, and burning their Houses and Goods, than their Foot could effect by their Labour or March.]

But in the meanwhile, the Trinobants, in effect the strongest City of those Countries, and one of which Mandubrace, a young Gentleman, that had stuck to Cæsar’s Party, was come to him, being then in the Main Land [viz. Gaul], and thereby escaped Death, which he should have suffered at Cassivelaune’s Hands (as his Father Imanuence who reigned in that city had done). The Trinobants, I say, sent their Ambassadors, promising to yield themselves unto him, and to do what he should command them, instantly desiring him to protect Mandubrace from the furious tyranny of Cassivelaune, and to send some into the City, with authority to take the Government thereof. Cæsar accepted the offer and appointed them to21 give him forty Hostages, and to find him Grain for his Army, and so sent he Mandubrace to them. They speedily did according to the command, sent the number of Hostages, and the Bread-Corn.

When others saw that Cæsar had not only defended the Trinobants against Cassivelaune, but had also saved them harmless from the Pillage of his own Soldiers, the Cenimagues, the Segontiacs, the Ancalites, the Bibrokes, and the Cassians, by their Ambassies, yield themselves to Cæsar. By these he came to know that Cassivelaune’s Town was not far from that Place, fortified with Woods and marshy Grounds; into the which a considerable number of Men and Cattle were gotten together. For the Britains call that a Town, saith Cæsar, when they have fortified cumbersome Woods, with a Ditch and a Rampire; and thither they are wont to resort, to abide the Invasion of their Enemies. Thither marched Cæsar with his Legions. He finds the Place notably fortified both by Nature and human Pains; nevertheless he strives to assault it on two sides. The Enemies, after a little stay, being not able longer to bear the Onset of the Roman Soldiers, rushed out at another Part, and left the Town unto him. Here was a great number of Cattle found, and many of the Britains were taken in the Chace, and many slain.

While these Things were doing in these Quarters, Cassivelaune sent Messengers to that Part of Kent, which, as we showed before, lyeth upon the Sea, over which Countries Four Kings, Cingetorix, Caruil, Taximagul, and Segorax, reigned, whom he commanded to raise all their Forces, and suddenly to set upon and assault their Enemies in their Naval Trenches. To which, when they were come, the Romans sallied out upon them, slew a great many of them, and took Cingetorix, an eminent Leader among them, Prisoner, and made a safe Retreat. Cassivelaune, hearing of this Battle, and having sustained so many Losses, and found his Territories wasted, and especially being disturbed at the Revolt of the Cities, sent Ambassadors along with Comius of Arras, to treat with Cæsar concerning his Submission. Which Cæsar, when he was resolved to Winter in the Continent, because of the sudden insurrection of the Gauls, and that not much of the Summer remained, and that it might easily be spent, accepted, and commands him Hostages, and appoints what Tribute Britain should yearly pay to the People of Rome, giving strait Charge to Cassivelaune, that he should do no Injury to Manubrace, nor the Trinobants. And so receiving the Hostages, withdrew his Army to the Sea again.

Thus far out of Cæsar’s Commentaries concerning this History, which happened in the year before Christ’s Nativity LIV. In all which Process, there is for this Purpose to be noted, that Cæsar nameth the City of the Trinobantes; which hath a Resemblance with Troynova or Trenovant; having no greater Difference in the Orthography than the changing of [b] into [v]. And yet maketh an Error, which I will not argue. Only this I will note, that divers learned Men do not think Civitas Trinobantum to be well and truly translated The City of the Trinobantes: but that22 it should rather be The State, Communalty, or Seignory of the Trinobants. For that Cæsar, in his Commentaries, useth the Word Civitas only for a People living under one and the self-same Prince and Law. But certain it is, that the Cities of the Britains were in those Days neither artificially builded with Houses, nor strongly walled with Stone, but were only thick and cumbersome Woods, plashed within and trenched about. And the like in effect do other the Roman and Greek authors directly affirm; as Strabo, Pomponius Mela, and Dion, a Senator at Rome (Writers that flourished in the several Reigns of the Roman Emperors, Tiberius, Claudius, Domitian, and Severus): to wit, that before the Arrival of the Romans, the Britains had no Towns, but called that a Town which had a thick entangled Wood, defended, as I said, with a Ditch and Bank; the like whereof the Irishmen, our next Neighbours, do at this day call Fastness. But after that these hither Parts of Britain were reduced into the Form of a Province by the Romans, who sowed the Seeds of Civility over all Europe, this our City, whatsoever it was before, began to be renowned, and of Fame.

For Tacitus, who first of all Authors nameth it Londinium, saith, that (in the 62nd year after Christ) it was, albeit, no Colony of the Romans; yet most famous for the great Multitude of Merchants, Provision and Intercourse. At which time, in that notable Revolt of the Britains from Nero, in which seventy thousand Romans and their Confederates were slain, this City, with Verulam, near St. Albans, and Maldon, then all famous, were ransacked and spoiled.

For Suetonius Paulinus, then Lieutenant for the Romans in this Isle, abandoned it, as not then fortified, and left it to the Spoil.

Shortly after, Julius Agricola, the Roman Lieutenant in the Time of Domitian, was the first that by exhorting the Britains publickly, and helping them privately, won them to build Houses for themselves, Temples for the Gods, and Courts for Justice, to bring up the Noblemen’s Children in good Letters and Humanity, and to apparel themselves Roman-like. Whereas before (for the most part) they went naked, painting their Bodies, etc., as all the Roman Writers have observed.

True it is, I confess, that afterward, many Cities and Towns in Britain, under the Government of the Romans, were walled with Stone and baked Bricks or Tiles; as Richborough, or Rickborough-Ryptacester in the Isle of Thanet, till the Channel altered his Course, besides Sandwich in Kent, Verulamium besides St. Albans in Hertfordshire, Cilcester in Hampshire, Wroxcester in Shropshire, Kencester in Herefordshire, three Miles from Hereford Town; Ribchester, seven Miles above Preston, on the Water of Rible; Aldeburg, a Mile from Boroughbridge, on Watheling-Street, on Ure River, and others. And no doubt but this our City of London was also walled with Stone in the Time of the Roman Government here; but yet very latewardly; for it seemeth not to have been walled in the Year of our Lord 296. Because in that Year, when Alectus the Tyrant was slain in the Field,23 the Franks easily entered London, and had sacked the same, had not God of his great Favour at that very Instant brought along the River of Thames certain Bands of Roman Soldiers, who slew those Franks in every Street of the City.”

We need not pursue Stow in the legendary history which follows. Let us next turn to the evidence of ancient writers. Cæsar sailed for his first invasion of Britain on the 26th of August B.C. 55. He took with him two legions, the 7th and the 10th. He had previously caused a part of the coast to be surveyed, and had inquired of the merchants and traders concerning the natives of the island. He landed, fought one or two battles with the Britons, and after a stay of three weeks he retired.

The year after he returned with a larger army—an army of five legions and 2000 cavalry. On this occasion he remained four months. We need not here inquire into his line of march, which cannot be laid down with exactness. After his withdrawal certain British Princes, when civil wars drove them out, sought protection of Augustus. Strabo says that the island paid moderate duties; that the people imported ivory necklaces and bracelets, amber, and glass; that they exported corn, cattle, gold and silver, iron, skins, slaves, and hunting-dogs. He also says that there were four places of transit from the coast of Gaul to that of Britain, viz. the mouths of the Rhine, the Seine, the Loire, and the Garonne.

The point that concerns us is that there was before the arrival of the Romans already a considerable trade with the island.

Nearly a hundred years later—A.D. 43—the third Roman invasion took place in the reign of the Emperor Claudius under the general Aulus Plautius. The Roman fleet sailed from Gesoriacum (Boulogne), the terminus of the Roman military road across Gaul, and carried an army of four legions with cavalry and auxiliaries, about 50,000 in all, to the landing-places of Dover, Hythe, and Richborough.

No mention of London is made in the history of this campaign. Colchester and Gloucester were the principal Roman strongholds.

Writing in the year A.D. 61, Tacitus gives us the first mention of London. He says, “At Suetonius mirâ constantiâ medios inter hostes Londinium perrexit cognomento quidem coloniâ non insigne sed copiâ negotiatorum et commeatuum maxime celebre.”

This is all that we know. There is no mention of London in either of Cæsar’s invasions; none in that of Aulus Plautius. When we do hear of it, the place is full of merchants, and had been so far a centre of trade. The inference would seem to be, not that London was not in existence in the years 55 B.C. or 43 A.D., or that neither Cæsar nor Aulus Plautius heard of it, but simply that they did not see the town and so did not think it of consequence.

If we consider a map showing the original lie of the ground on and about the site of any great city, we shall presently understand not only the reasons why the24 city was founded on that spot, but also how the position of the city has from the beginning exercised a very important influence on its history and its fortunes. Position affects the question of defence or of offence. Position affects the plenty or the scarcity of supplies. The prosperity of the city is hindered or advanced by the presence or the absence of bridges, fords, rivers, seas, mountains, plains, marshes, pastures, or arable fields. Distance from the frontier, the proximity of hostile tribes and powers, climate—a seaport closed with ice for six months in the year is severely handicapped against one that is open all the year—these and many other considerations enter into the question of position. They are elementary, but they are important.

We have already in the first chapter considered this important question under the guidance of Professor T. G. Bonney, F.R.S. Let us sum up the conclusions, and from his facts try to picture the site of London before the city was built.

Here we have before us, first, a city of great antiquity and importance; beside it a smaller city, practically absorbed in the greater, but, as I shall presently prove, the more ancient; thirdly, certain suburbs which in course of time grew up and clustered round the city wall, and are now also practically part of the city; lastly, a collection of villages and hamlets which, by reason of their proximity to the city, have grown into cities which anywhere else would be accounted great, rich, and powerful. The area over which we have to conduct our survey is of irregular shape, its boundaries following those of the electoral districts. It includes Wormwood Scrubbs on the west and Plaistow on the east. It reaches from Hampstead in the north to Penge and Streatham in the south. Roughly speaking, it is an area seventeen miles in breadth from east to west, and eleven from north to south. There runs through it from west to east, dividing the area into two unequal parts, a broad river, pursuing a serpentine course of loops and bends, winding curves and straight reaches; a tidal river which, but for the embankments and wharves which line it on each side, would overflow at every high tide into the streets and lanes abutting on it. Streams run into the river from the north and from the south: these we will treat separately. At present they are, with one or two exceptions, all covered over and hidden.

Remove from this area every house, road, bridge, and all cultivated ground, every trace of occupation by man. What do we find? First, a broad marsh. In the marsh there are here and there low-lying islets raised a foot or two above high tide; they are covered with rushes, reeds, brambles, and coarse sedge; some of them are deltas of small affluents caused by the deposit of branches, leaves, and earth brought down by the stream and gradually accumulating till an island has been formed; some are islands formed in the shallows of the river by the same process. These islands are the haunt of innumerable wild birds. The river, which now runs between strong and high embankments, ran through this vast marsh.25 The marsh extended from Fulham at least, to go no farther west, as far as Greenwich, to go no farther east; from west to east it was in some places two miles and a half broad. The map shows that the marsh included those districts which are now called Fulham, West Kensington, Pimlico, Battersea, Kennington, Lambeth, Stockwell, Southwark, Newington, Bermondsey, Rotherhithe, Deptford, Blackwall, Wapping, Poplar, the Isle of Dogs. In other words, the half at least of modern London is built upon this marsh. At high tide the whole of this vast expanse was covered with water, forming exactly such a lovely lake as one may now see, standing at the water-gate of Porchester Castle and looking across the upper stretches of Portsmouth harbour, or as one may see from any point in Poole harbour when the tide is high. It was a lake bright and clear; here and there lay the islets, green in summer, brown in winter; there were wild duck, wild geese, herons, and a thousand other birds flying over it in myriads with never-ending cries. At low tide the marsh was black mud, and on a day cloudy and overcast a dreary and desolate place. How came a city to be founded on a marsh? That we shall presently understand.

Many names still survive to show the presence of the islets I have mentioned.26 For instance, Chelsea is Chesil-ey—the Isle of Shingle (so also Winchelsea). Battersea has been commonly, but I believe erroneously, supposed to be Peter’s Isle; Thorney is the Isle of Bramble; Tothill means the Hill of the Hill; Lambeth is the “place of mud,” though it has been interpreted as the place where lambs play; Bermondsey is the Isle of Bermond. Doubtless there are many others, but their names, if they had names, and their sites have long since been forgotten.

Several streams fell into the river. Those on the north were afterwards called Bridge Creek, the Westbourne, the Tybourne, the Fleet or Wells River, the Walbrook, and the Lea. Those on the south were the Wandle, the Falcon, the Effra, the Ravensbourne, and other brooks without names. Of the northern streams the first and last concern us little. The Bridge Creek rose near Wormwood Scrubbs, and running along the western slope of Notting Hill, fell into the Thames a little higher up than Battersea Bridge. The Westbourne, a larger stream, is remarkable for the fact that it remains in the Serpentine. Four or five rills flowing from Telegraph Hill, at Hampstead, unite, and after running through West Hampstead receive the waters of another stream formed of two or three rills rising at Frognal. The junction is at Kilburn. The stream, thus increased in volume, runs south and enters Kensington Gardens at the head of the Serpentine, into which it flows, passing out at the south end. It crosses Knightsbridge at Albert Gate, passes along Cadogan Place, and finally falls into the Thames at Chelsea Embankment. Of the places which it passed, especially Kilburn Priory, we shall have more to say later on. Meantime we gather that Kilburn, Westbourne Terrace, Knightsbridge, and Westbourne Street, Chelsea, owe their names to this little stream.

The Tyburn, a smaller stream, but not without its importance, took its rise from a spring called the Shepherd’s Well, which formed a small pool in the midst of the fields called variously the Shepherd’s Fields, or the Conduit Fields, but later on the Swiss Cottage Fields. The site is marked by a drinking-fountain on the right hand rather more than half way up FitzJohn’s Avenue. The water was remarkable for its purity, and as late as fifty or sixty years ago water-carts came every morning to carry off a supply for those who would drink no other. The stream ran down the hill a little to the east of FitzJohn’s Avenue, crossed Belsize Lane, flowed south as far as the west end of King Henry’s Road, then turning west, crossed Avenue Road, and flowed south again till it came to Acacia Road. Here it received an affluent from the gardens and fields of Belsize Manor and Park. Thence south again with occasional deflections, east and west, across the north-west corner of Regent’s Park, receiving another little affluent in the Park; then down a part of Upper Baker Street, Gloucester Road, taking a south-easterly course from Dorset Street to Great Marylebone Lane. It crossed Oxford Street at the east corner of James Street, ran along the west side of South Molton Street, turned again to the south-west, crossed Piccadilly at Brick Street, and running across Green Park it27 passed in front of Buckingham Palace. Here the stream entered upon the marsh, which at high tide was covered with water. Then, as sometimes happens with marshes, the stream divided. One—the larger part—ran down College Street into the Thames; the other, not so large, turned to the north-east and presently flowed down Gardener’s Lane and across King’s Street to the river.

The principal interest attaching to this little river is that it actually created the island which we now call Westminster. The island was formed by the detritus of the Tyburn. How many centuries it took to grow one need not stop to inquire: it is enough to mark that Thorney Island, like the Camargue, or the delta of the Nile, was created by the deposit of a stream.

The Fleet River—otherwise called the River of Wells, or Turnmill Brook, or Holebourne—the fourth of the northern streams, was formerly, near its approach to London, a very considerable stream. Its most ancient name was the “Holebourne,” i.e. the stream that flows in a hollow. It was called the River of Wells on account of the great number of wells or springs whose waters it received; and the “Fleet,” because at its mouth it was a “fleet,” or channel covered with shallow water at high tide. The stream was formed by the junction of two main branches, one of which rose in the Vale of Health, Hampstead, and the other in Ken Wood between Hampstead and Highgate. There were several small affluents along the whole course of the stream. The spot where the two branches united was in a place now called Hawley Road, Kentish Town Road. Its course then led past old St. Pancras Church, on the west, between St. Pancras and King’s Cross Stations on the east side of Gray’s Inn Road, down Farringdon Road, Farringdon Street, and New Bridge Street, into the Thames. The wells which gave the stream one of its names were—Clerkenwell, Skinnerswell, Fagswell, Godwell (sometimes incorrectly spelt Todwell), Loderswell, Radwell, Bridewell, St. Chad’s Well. At its mouth the stream was broad enough and deep enough to be navigable for a short distance. It became, however, in later times nothing better than an open pestilential sewer. Attempts were made from time to time to cleanse the stream, but without success. All attempts failed, for the simple reason that Acts of Parliament without an executive police and the goodwill of the people always do fail. Three hundred years later Ben Jonson describes its condition:—

The banks continued to be encumbered with tenements, lay-stalls, and “houses of office,” until the Fire swept all away. After this they were enclosed by a stone28 embankment on either side, and the lower part of the river became a canal forty feet wide, and, at the upper end, five feet deep, with wharves on both sides. Four bridges were built over the canal—viz. at Bridewell, at Fleet Street, at Fleet Lane, and at Holborn. But the canal proved unsuccessful, the stream became choked again and resumed its old function as a sewer. Everybody remembers the Fleet in connection with the Dunciad—

In the year 1737 the canal between Holborn and Fleet Street was covered over, and in 1765 the lower part between Fleet Street and the Thames was also covered.

So much for the history of the stream. Its importance to the city was very great. It formed a natural ditch on the western side. Its eastern bank rose steeply, much more steeply than at present, forming originally a low cliff; its western bank was not so steep. Between what is now Fleet Lane and the Thames there was originally a small marsh covered with water at high tide, part, in fact, of the great Thames marsh; above Fleet Lane the stream became a pleasant country brook meandering among the fields and moors of the north. The Fleet determined the western boundary, and protected the city on that side.