London, Henry Colburn, 1846.

Title: Memoirs of the Reign of King George the Second, Volume 2 (of 3)

Author: Horace Walpole

Editor: Baron Henry Richard Vassall Holland

Release date: September 5, 2018 [eBook #57851]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by MWS, John Campbell and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

This is Volume 2 of 3. The first volume can be found in Project Gutenberg at: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/57016

The List of Illustrations has been copied from Volume I. This list describes six illustrations, two in each volume.

As the Editor notes in his Preface in Volume I, “Some, though very few, coarse expressions, have been suppressed by the Editor, and the vacant spaces filled up by asterisks.” There is one such occurrence in this volume (on page 205). Some omitted text is indicated by * * * (on page 416.)

The Editor has also inserted the occasional [word] in brackets, when that makes the passage more sensible.

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of each chapter.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

MEMOIRS

OF THE REIGN OF

KING GEORGE THE SECOND.

BY

HORACE WALPOLE,

YOUNGEST SON OF SIR ROBERT WALPOLE, EARL OF ORFORD.

EDITED, FROM THE ORIGINAL MSS.

WITH A PREFACE AND NOTES,

BY THE LATE

LORD HOLLAND.

Second Edition, Revised.

WITH THE ORIGINAL MOTTOES.

VOL. II.

LONDON:

HENRY COLBURN, PUBLISHER,

GREAT MARLBOROUGH STREET.

1847.

| CHAPTER I. | ||

| A. D. | PAGE | |

| 1755. | Endeavours for Peace with France in vain | 2 |

| Duke of Dorset removed; Lord Hartington made Lord-Lieutenant | 3 | |

| Debate on King Charles’s Martyrdom | ib. | |

| Affair of Sheriffs-Depute in Scotland, and Debates thereon | 4 | |

| Ireland | 10 | |

| History of the Mitchel Election | 11 | |

| Scotch Sheriff-Depute Bill | 14 | |

| History of Earl Poulet | 18 | |

| Preparations for War | 19 | |

| Ireland | ib. | |

| Preparations for War in France | 20 | |

| King’s Journey to Hanover | ib. | |

| Duke of Cumberland at head of Regency | 21 | |

| Prospects of War | 22 | |

| Affairs of Ireland | 23 | |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| 1755. | Commencement of the War | 27 |

| War with France | 28 | |

| War in America | 29 | |

| [vi] Author avoids detailing Military events minutely | 30 | |

| Defeat and Death of General Braddock | 31 | |

| Events at Sea | 32 | |

| Spain neutral | 33 | |

| Fears for Hanover | ib. | |

| Negotiations at Hanover. Treaties made there | 34 | |

| Dissensions in Ministry and Royal Family | 36 | |

| Disunion of Fox and Pitt | 37 | |

| Affairs of Leicester House | 39 | |

| King arrives | ib. | |

| Ministers endeavour to procure support in Parliament | 41 | |

| Fox made Secretary of State | 43 | |

| Resignations and Promotions | 44 | |

| Both Ministers insincere and discontented | 45 | |

| Sir William Johnson’s Victory | 46 | |

| Accession of Bedford Party | ib. | |

| The Parliament meets | 47 | |

| Address in Lords | 48 | |

| New Opposition of Pitt, &c. | 50 | |

| Debates on the Treaties | ib. | |

| Pitt &c. dismissed | 62 | |

| Sir George Lyttelton Chancellor of the Exchequer | 63 | |

| Complaint of Mr. Fox’s Circular to Members of Parliament | ib. | |

| Debate on Fox’s Circular Letter | 65 | |

| Debates on number of Seamen | 67 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| 1755. | Earthquake at Lisbon | 77 |

| Debates on a Prize Bill | 78 | |

| Death of the Duke of Devonshire | 86 | |

| Debates on the Army | ib. | |

| Remarks on the above Debate | 96 | |

| Debates on a new Militia Bill | 97 | |

| [vii] CHAPTER IV. | ||

| 1755. | Debates on the Treaties | 103 |

| Affair of Hume Campbell and Pitt | 107 | |

| Changes in the Administration settled | 139 | |

| Lord Ligonier and Duke of Marlborough | ib. | |

| Further Changes and new Appointments | 140 | |

| Lord Barrington and Mr. Ellis | 141 | |

| Pensions granted to facilitate Changes in Ministry | 143 | |

| Parliamentary Eloquence | ib. | |

| History of Oratory. Account and comparison of Orators | 144 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| 1756. | Parliament | 150 |

| Negotiations with France | ib. | |

| Accommodation with the King of Prussia | 152 | |

| Parliament | ib. | |

| Affair of Admiral Knowles | ib. | |

| Supplies | 153 | |

| Grants to North America | 154 | |

| Parliament and Parties | ib. | |

| Hessians sent for | 155 | |

| Mischiefs produced by Marriage Act | ib. | |

| Prevot’s Regiment | 156 | |

| Debate on Prevot’s Regiment | 157 | |

| Author’s Speech on Swiss Regiments | 163 | |

| Debate on Swiss Regiments continued | 170 | |

| Affair of Fox and Charles Townshend | 172 | |

| Divisions | 174 | |

| Swiss Regiment Bill opposed in all its stages | ib. | |

| Swiss Regiment Bill passed the Commons and Lords | 175 | |

| Anecdote of Madame Pompadour | 176 | |

| Debates on Budget and Taxes | 177 | |

| New Taxes | ib. | |

| [viii] CHAPTER VI. | ||

| 1756. | Tax on Plate | 179 |

| Tranquillity restored in Ireland | 183 | |

| Hessians and Hanoverians sent for | 184 | |

| Private Bill for a new Road, and Dissensions thereupon | 186 | |

| Hessians | 187 | |

| Hanoverians | 188 | |

| Debate on Hanoverians | ib. | |

| French attack Minorca | 190 | |

| Militia Bill | 191 | |

| Vote of Credit | ib. | |

| Debates on the Prussian Treaty | 197 | |

| War declared | 201 | |

| Militia Bill in Lords | ib. | |

| Parliament Prorogued | 202 | |

| Troops raised by Individuals | 203 | |

| The Prince of Wales of age | 204 | |

| History of Lord Bute’s favour | ib. | |

| Scheme of taking the Prince from his Mother | 206 | |

| CHAPTER VII. | ||

| 1756. | Minorca | 209 |

| Character of Richelieu and Blakeney | 210 | |

| Siege of Minorca | 212 | |

| Incapacity of Administration | 213 | |

| Reinforcements from Gibraltar refused | 214 | |

| French Reports from Minorca | 215 | |

| Public Indignation | ib. | |

| Admiral Byng’s Despatch | 217 | |

| Remarks on the Character of Government | 218 | |

| The Empress-Queen joins with France | 220 | |

| Conclusion of the Law-suit about New Park | 221 | |

| [ix] Continuation of the proceedings with the Prince of Wales | 221 | |

| Death of the Chief Justice Rider, and designation of Murray | 223 | |

| Loss of Minorca | 225 | |

| Proceedings on Loss of Minorca | 227 | |

| General Fowke tried | 229 | |

| Addresses on the Loss of Minorca | 230 | |

| Revolution in Sweden | 231 | |

| Deduction of the Cause of the War in Germany | 232 | |

| German Ministers | 233 | |

| Bruhl | ib. | |

| Kaunitz | 234 | |

| Views and Conduct of the Courts of Dresden and Vienna | 235 | |

| Character of the Czarina | 236 | |

| League of Russia, Austria, and Saxony | 238 | |

| King of Prussia apprized of the League against him | ib. | |

| King of Prussia endeavours to secure Peace | 240 | |

| Invasion of Saxony by the King of Prussia | 241 | |

| Dresden Conquered, and the Archives searched by the Prussians | 242 | |

| Campaign in Saxony | 243 | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | ||

| 1756. | Affairs at Home | 245 |

| Mr. Byng publishes a Defence | 246 | |

| Effect of Byng’s Pamphlet | 247 | |

| Loss of Oswego | 248 | |

| Affair of the Hanoverian Soldier at Maidstone | ib. | |

| The King admits Lord Bute into the Prince’s Family | 249 | |

| Fox discontented with Newcastle, and insists on resigning | 251 | |

| Precarious state of the Ministry | 252 | |

| [x] Lord Grenville takes Fox’s resignation to the King | 253 | |

| Fox, irresolute, applies to the Author | 254 | |

| Author’s motives in declining to interfere | 255 | |

| Fox has an Audience | 256 | |

| Pitt’s objections and demands | 257 | |

| Prince of Wales’s new Household | 258 | |

| Pitt visits Lady Yarmouth | 259 | |

| State of Parties | 260 | |

| Duke of Newcastle determines to resign | 262 | |

| Pitt declines acting with Fox | ib. | |

| Negotiations for the formation of a new Ministry | 263 | |

| Fox labours to obstruct the formation of a Ministry | 268 | |

| The designs of Fox defeated | 269 | |

| Duke of Devonshire accepts the Treasury | ib. | |

| New Ministry | 270 | |

| Duke of Newcastle resigns | 272 | |

| The Chancellor resigns | 273 | |

| The changes settled | 274 | |

| Pitt Minister | 275 | |

| Parliament meets | 276 | |

| CHAPTER IX. | ||

| 1757. | Character of the Times | 278 |

| Contest between the Parliament and Clergy in France | 279 | |

| France | 280 | |

| King of France stabbed | 281 | |

| Torture and execution of Damiens | 282 | |

| The King compliments Louis on his escape | 283 | |

| Trial of Admiral Byng | 284 | |

| Admiral Byng’s sentence, and the behaviour of the Court-Martial | 287 | |

| Author’s impressions | 288 | |

| Sentence of Court-Martial on Byng | 289 | |

| Representation of Court-Martial | 292 | |

| Remarks on Byng’s case | 293 | |

| [xi] Two Highland Regiments raised | 300 | |

| Ordnance Estimates | 301 | |

| Guinea Lottery | ib. | |

| Militia Bill | 302 | |

| Ordnance | 303 | |

| CHAPTER X. | ||

| 1757. | Baker’s Contract | 304 |

| Parliamentary Inquiries limited to Minorca | 305 | |

| Byng’s Sentence produces various impressions | 306 | |

| The Sentence of the Court-Martial referred to the Judges | 307 | |

| Conduct of the Judges on the Case referred to them | 308 | |

| Conduct of Fox | 309 | |

| The Admiralty sign the Sentence | 311 | |

| The Sentence notified to the House of Commons | 312 | |

| Mr. Pitt demands Money for Hanover | 313 | |

| Lord G. Sackville declares for Pitt | 314 | |

| Motives of Lord G. Sackville | 315 | |

| Approaching Execution of Byng | 317 | |

| House of Commons | 318 | |

| Sir Francis Dashwood animadverts on Byng’s Sentence | ib. | |

| Debate on Byng’s Sentence | ib. | |

| Some applications to the King for mercy | 326 | |

| Members of Court-Martial desirous to be absolved from their Oaths | 327 | |

| Author urges Keppel to apply to House of Commons | ib. | |

| Author promotes an application to House of Commons | 328 | |

| Sir Francis Dashwood applies for Mr. Keppel | ib. | |

| Keppel’s application to House of Commons | ib. | |

| Debate on Keppel’s application | 329 | |

| Keppel’s application considered in Cabinet | 331 | |

| [xii] The King’s Message on respiting Byng | 332 | |

| Breach of Privilege in the King’s Message | 332 | |

| Debate on the King’s Message | ib. | |

| Bill to release Court-Martial from Oath | 335 | |

| Sensations excited by proceedings in House of Commons | 341 | |

| Holmes and Geary disavow Keppel | 342 | |

| Further debate on Court-Martial Bill | 344 | |

| Court-Martial Bill passes House of Commons | 350 | |

| CHAPTER XI. | ||

| 1757. | Debate in Lords | 351 |

| Debate in Lords on proposal to examine the Members of Court-Martial | 354 | |

| Court-Martial ordered to attend House of Lords | 358 | |

| Examination of Court-Martial in House of Lords | 359 | |

| Bill debated and dropped in House of Lords | 366 | |

| Result of Proceedings in Parliament | 367 | |

| Petition for Mercy from City intended and dropped | 368 | |

| Death of Admiral Byng | 369 | |

| Reflections on Admiral Byng’s behaviour | 370 | |

| Rochester Election | 372 | |

| Death of Archbishop Herring | 374 | |

| Abolition of the Office of Commissioners of Wine-Licences | 375 | |

| Intrigues to dismiss Mr. Pitt, and form a new Ministry | 376 | |

| The Duke goes to Hanover to command the Army | 378 | |

| Change in Ministry | 379 | |

| ——— | ||

| Appendix | 383 | |

| VOL. I. | ||

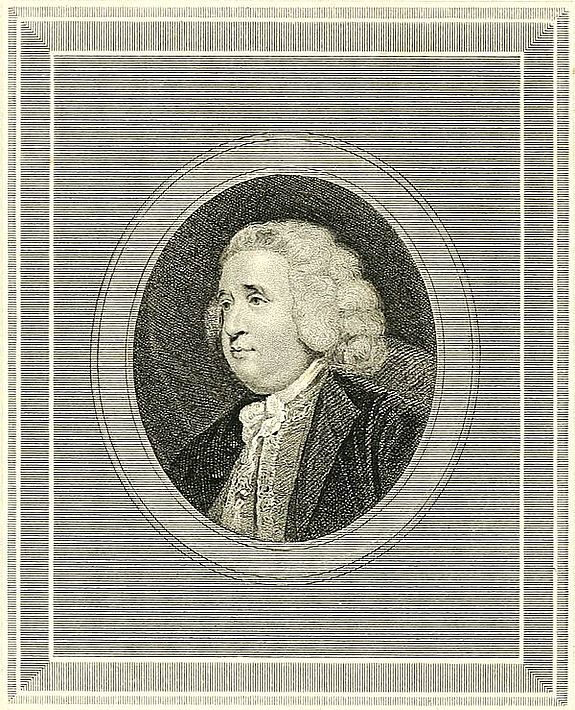

| George II. | Frontispiece. | |

| Mr. Pelham | p. 378 | |

| VOL. II. | ||

| Mr. Fox | Frontispiece. | |

| Duke of Bedford | 270 | |

| VOL. III. | ||

| Mr. Pitt | Frontispiece. | |

| Duke of Newcastle | 182 |

MEMOIRS

OF THE REIGN OF

KING GEORGE THE SECOND.

Invenies etiam disjecti membra.—Hor.

Fruitlessness of our efforts to maintain Peace with France at the commencement of the year 1755—Lord Hartington, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland—Debate on King Charles’s Martyrdom—Scotch Sheriff-Depute Bill—Speeches in the House of Commons—The St. Michael Election—History of Earl Powlett—Preparations for War—The King’s Journey to Hanover—Duke of Cumberland at the head of the Regency—Affairs of Ireland.

The tranquillity of the Administration continued to be disturbed by repeated accounts of great armaments preparing in France for the West Indies; of which General Wall was believed to have given us the first intimation. Their marine grew formidable, but their insults unwisely outstripped their increasing power. We took the alarm; two regiments were ordered from Ireland; and by the beginning of February a fleet of thirty ships of the line was[2] fitted out with equal spirit and expedition. Lord Anson had great merit in that province where he presided. The Earl of Hertford, a man of most unblemished morals, but rather too gentle and cautious to combat so presumptuous a Court, was named Embassador to Paris, whither Monsieur de Mirepoix was desired to write, that if they meaned well, we would send a man of the first quality and character.

The Duke of Marlborough succeeded Lord Gower in the Privy Seal, and the Duke of Rutland, a nobleman of great worth and goodness, returned to Court, which he had long quitted, yet without enlisting in any faction, though governed too much by a mercenary brother; and was appointed Lord Steward.

France sent a haughty answer, accompanied with these inadmissible proposals; that each nation should destroy all their forts on the south of the Ohio, which would leave them in possession of all the north side of that river; and whereas the Five Nations were allotted to the division of England by the Treaty of Utrecht, and the French had built forts amongst them contrary to that Treaty, and we agreeably to it, they demanded that we should destroy such forts, while they should be permitted to maintain theirs. Lord Hertford’s journey was suspended; at the same time that his brother, Colonel Conway, rose merely on the basis of his[3] merit to a distinguished situation, entirely unsought, uncanvassed. The Ministry had perceived that it was unsafe to venture Ireland again under the Duke of Dorset’s rule; and they had fixed on Lord Hartington to succeed, as the most devoted to their views, and as the least likely, from the wariness of his temper, to throw himself into the scale of either faction. He refused to accept so uncommon an honour, unless Mr. Conway, with whom he was scarce acquainted, would consent to accompany him as Secretary and Minister. Mr. Conway’s friends would not let him hesitate.

January 29th.—Mr. Fox having proposed that the House should sit the next day, to read some Bill for which the time pressed, the Speaker urged the Act of Parliament that sets apart that day for the commemoration of what is ridiculously termed King Charles’s Martyrdom. It occasioned a warm squabble between the Speaker and Fox, and between Sir George Lyttelton[1] and General Mordaunt; and though Sir Francis Dashwood talked of moving for a repeal of the Act, the Speaker prevailed for observing the solemnity. One can scarce conceive a greater absurdity than retaining the three holidays dedicated to the house of Stuart. Was the preservation of James the First a greater blessing to[4] England than the destruction of the Spanish Armada, for which no festival is established? Are we more or less free for the execution of King Charles? Are we at this day still guilty of his blood? When is the stain to be washed out? What sense is there in thanking Heaven for the restoration of a family, which it so soon became necessary to expel again? What action of Charles the Second proclaimed him the—Sent of God? In fact, does not the superstitious jargon, rehearsed on those days, tend to annex an idea of sainthood to a worthless and exploded race? and how easy to make the populace believe, that there was a divine right inherent in a family, the remarkable events of whose reigns are melted into our religion, and form a part of our established worship!

February 20th.—The new Lord Advocate of Scotland moved that the Bill, passed seven years before, for subjecting their Sheriffs-depute to the King’s pleasure during that term, and which was on the point of expiring, after which they were to hold their offices for life, should continue some time longer on the present foot. It was opposed with great eloquence and knowledge by one Elliot, a young Scotch civilian, lately chosen into Parliament. The measure had been one of the steps taken after the late Rebellion, to create greater dependence on the Crown, and to empower it to commit places of[5] trust to more loyal hands, as it should be found necessary.

26th.—The House went again upon the Scotch Bill. Charles Townshend warmly opposed the Ministerial plan, urged that the independence of the Sheriffs-depute was a case connected with every thing sacred, and hoped that the most habitually-attached to a Ministry, who are generally the most unfeeling, would think on this. What signifies the best constitution, if the Judges [are] not independent, and their judgments [not] impartial? If the people are oppressed, what matters it by whom? That this alteration was a breach of faith to Scotland—that these Sheriffs are formed according to the claim of right, and to the Act of Settlement; would not the King have sufficient power over them if they were to hold their offices only quam diù se benè gesserint? that he was sorry to see that basis shaken, on which this Administration stands, or it ought to stand on none. That this will be regarded with fear and amaze; with fear, for the people will not know what is to follow, or whether this is not an attempt to try how far they will bear: with amaze, for Murray had pronounced that there was not one Jacobite left in Scotland. That he neither meaned ambition nor courted popularity, but looked upon himself as an executor of those who had planned the Revolution.

Lord George Sackville replied well, and ridiculed the importance with which Mr. Townshend had treated so immaterial a business, the utmost extent of the jurisdiction of the Sheriffs not extending to decide finally upon property of above the value of 12l. Yet, whoever had come into the House, not knowing the subject, would have concluded that a question was agitating for taking away the Judges from Westminster-hall. The lawyers, he said, were not agreed as to the extent of their criminal jurisdiction: in cases of treason, it is agreed, they have none. That the Sheriffs-depute, if supported by military authority, might have suppressed the last Rebellion. With such resources for good, and so tied up from ill, would you not entrust the disposition of them with the Crown? The more this family encroaches illegally, the more they lessen their tenure in the Crown. But this measure was taken at the request of the people of Scotland; have any there petitioned against it? Nor is it a breach of faith, for one Parliament may correct the acts of a preceding.

The Attorney-General laboured, in a speech extremely artful, to convince the Speaker, whose Whig spirit had groaned over this attempt, that it was no breach of the principles of the Revolution; and he insisted that it was by no means the sense of Scotland, that these little magistrates should be for life. He owned, that Judges, who[7] are to decide on questions of State, should be for life, as in cases of treason, where it is not fit to trust the Crown with its own revenge; in cases of charters, &c.; but it is not necessary to be so strict in mere cases of meum and tuum. Even Charles, and James the Second, permitted other Judges to be for life, as the Master of the Rolls, the Judge of the Marshalsea, &c., because the Crown could remove trials into the King’s Bench.

This, with many more details of law, too long to rehearse, were poorly answered by Lord Egmont; by Pitt, with great fire, in one of his best-worded and most spirited declamations for liberty, but which, like others of his fine orations, cannot be delivered adequately without his own language; nor will they appear so cold to the reader, as they even do to myself, when I attempt to sketch them, and cannot forget with what soul and grace they were uttered. He did not directly oppose, but wished rather to send the Bill to the Committee, to see how it could be amended. Was glad that Murray would defend the King, only with a salvo to the rights of the Revolution; he commended his abilities, but tortured him on his distinctions and refinements. He himself indeed had more scruples; it might be a Whig delicacy—but even that is a solid principle. He had more dread of arbitrary power dressing itself in the long robe, than even of military power. When master principles are[8] concerned, he dreaded accuracy of distinction: he feared that sort of reasoning: if you class everything, you will soon reduce everything into a particular; you will then lose great general maxims. Gentlemen may analyze a question till it is lost. If I can show him, says Murray, that it is not My Lord Judge, but Mr. Judge, I have got him into a class. For his part, could he be drawn to violate liberty, it should be regnandi causâ, for this King’s reigning. He would not recur for precedents to the diabolic divans of the second Charles and James—he did not date his principles of the liberty of this country from the Revolution: they are eternal rights; and when God said, “let justice be justice,” he made it independent. The Act of Parliament that you are going to repeal is a proof of the importance of Sheriffs-depute: formerly they were instruments of tyranny. Why is this attempted? is it to make Mr. Pelham more regretted? He would have been tender of cramming down the throats of people what they are averse to swallow. Whig and Minister were conjuncts he always wished to see. He deprecated those, who had more weight than himself in the Administration, to drop this; or besought that they would take it for any term that may comprehend the King’s life; for seven years, for fourteen, though he was not disposed to weigh things in such golden scales.

Fox said, that he was undetermined, and would reserve himself for the Committee; that he only spoke now, to show it was not crammed down his throat; which was in no man’s power to do. That in the Committee he would be free, which he feared Pitt had not left it in his own power to be, so well he had spoken on one side. That he reverenced liberty and Pitt, because nobody could speak so well on its behalf.

Nugent made an impertinent and buffoon speech, though not without argument, the tenour of which was to impeach professors of liberty, who, he said, (and which he surely could say on knowledge,) always became bankrupts to the public. He perceived, he said, that the House was impatient to rise—they were not worthy of liberty!—yet, what were they to stay to hear? vague notions of liberty, which my Lord Egmont could even admire in Poland, and in the dungeons of the Barons! The Craftsman[2] and Common Sense, which had often very little common sense, had wound the notions of liberty too high. That he had read the Craftsman over again two years ago, and had found it poor stuff! that this was no more a breach of public faith, than the innovations which had been made in the Act of Settlement. Though the House sat till ten at night, no division ensued.

27th.—The Chancellor and Newcastle acquainted the Duke of Dorset that he was to return no more to Ireland. He bore the notification ill, and produced a letter from the Primate, which announced a calmer posture of affairs, and mentioned a meeting of the Opposition, at which no offensive healths had been suffered. Lord George Sackville, who was present, had more command of himself, and owned, that one temperate meeting did not afford sufficient grounds to say, that animosities were composed; and he agreed to the prudential measure of their not going over again. His father rejoined, that if the situation of affairs should prove to be mended, he hoped his honour might be saved, and he be permitted to return to his government. The next morning Andrew Stone conceded for his brother the Primate, who, he owned, was sufficiently elevated, and would be better without power. At last the Duke of Dorset begged a little respite, and that the King might not yet be acquainted with the scheme. He wanted to fill up Malone’s place of Prime Serjeant, and to obtain the dismission of Clements.

The next business in Parliament did not deserve to be noticed for any importance in itself; the scenes, to which it gave rise, made it very memorable. Lord Sandwich, who could never be unemployed, but to whose busy nature any trifle was food, and who was as indefatigable in the election[11] of an Alderman, as in a Revolution of State, had been traversed at Mitchel[3] in Cornwall, a borough belonging to his nephew, by the families of Edgecombe and Boscawen. His candidates were returned by his intrigues, but a petition was lodged against them. He had scarce effected their return, but he applied to all parties for support, against the cause should be heard in Parliament; and had even worked so artfully as to engage the Chancellor on his side; and having once engaged him, pleaded his countenance, as a proof that it was a private affair, unconnected with party. Mr. Fox eagerly supported him as a creature of the Duke, which soon threw the whole into a cause of faction. The Duke of Newcastle at first did not appear in it; but Lord Lincoln, pretending to espouse the Edgecombes, commanded all their dependents to vote against Lord Sandwich. The second hearing of the petition was on the 28th, when Mr. Fox, attacking and attacked by the law, of which body was Hussey, one of the petitioners, beat four lawyers and Nugent, and carried a division by 26; in which he was aided by Potter, one of the tellers, who counted five votes twice.

The Tories, who had promised their votes indiscriminately as their affections led them, perceiving that this election was to decide whether Fox or Newcastle should carry the House of Commons,[12] and that at least in this affair the members were nearly balanced, came to a sudden resolution of giving their little body importance, and at once, as if to add to their weight, threw all their passions and resentments into the scale. Northey, the representative of their anger, proposed to the Duke of Newcastle, that if he would give up the Oxford election, and dismiss both Fox and Pitt, they would support him without asking a single reward. The proposal was tempting—the Tories did not hate Fox and Pitt, the one for always attacking, the other for having deserted them, more than the Duke of Newcastle hated both for acting with him. The defect of the proposal was, that besides disgusting the whole body of Whigs by sacrificing the Oxford election, the Jacobites would deprive his Grace of the two ablest speakers in the House, with all their followers, and could replace them with nothing but about a hundred of the silentest and most impotent votes. Though his Grace would have embraced a whole majority of mutes, he took care not to fling himself away on such a forlorn hope. This notable project being evaporated, the Tories were summoned, on the 5th of March, to the Horn Tavern. Fazakerley informed them that they were to take measures for acting in a body on the Mitchel election: he understood that it was not to be decided by the merits, but was a contest for power between Newcastle and Fox: whoever carried[13] it, would be Minister: that he for every reason should be for the former. Beckford told him, he did not understand there was any such contest: that he did not love to nominate Ministers: were he obliged to name, he would prefer Mr. Fox. The meeting, equally unready at speeches and expedients, broke up in confusion. This business, however remarkable, does not deserve to be dwelt upon too long; and therefore I shall finish it at once, though it spun out near a month longer. Mr. Fox, who apprehended these Tory cabals, proposed to Murray a compromise of one and one; but Admiral Boscawen, the most obstinate of an obstinate family, refused it. Murray’s friends suspected, that the Chancellor’s unnatural support of Lord Sandwich was only calculated to inflame a division between Murray and Fox.

7th.—Sixty-two Tories met again at the Horn, where they agreed to secrecy, though they observed it not; and determined to vote, according to their several engagements, on previous questions, but not on the conclusive question in the Committee.

12th.—The last day in the Committee Lord Sandwich triumphed by 158 to 141. Of the Tories all retired but eight, who were equally divided. Forty of them, having omitted to summon twenty-nine, had met again to consider if they should adhere to their last resolution.

24th.—The morning of the report, the Tories[14] met again at the Horn, and here took the shameless resolution of cancelling all their engagements, in order to defeat Fox. The merits of elections have long been out of the question: promises, private friendships, reasons of party, have almost always influenced in their decision. However, a decency was observed, and conscience always pretexted. It was reserved to the wretched remnant of the Tories, who having suffered most by, had been most clamorous against, engagements and bias in elections, to throw off the mask entirely, and crown their profligacy by breach of promises. Only twelve of them stood to their engagements; the Duke of Newcastle, assisted by the deserters, ejected Lord Sandwich’s members, by 207 to 183; the House, by a most unusual proceeding, and indeed by an absurd power, as the merits are only discussed in the Committee, setting aside what in a Committee they had decided.

I return to the Scotch Bill, which was finished in the foregoing month, after another long Debate, though the Ministry had given up the point of its being durante benè placito. Sir Francis Dashwood pronounced that the Revolution had not gone half far enough; and proposed to suspend the Act for seven years more. General Mordaunt, with his usual frankness, attacked the Scotch principles, and would extend the suspension for fifteen. Campbell, of Calder, a worthy man, and formerly of the Treasury,[15] would have moderated for nine, lest it should seem that the suspension was perpetually to be renewed for seven years. His son warmly defended the Highlanders, and said, (what perhaps was no very great hyperbole,) that Middlesex contained more Jacobites than the Highlands. Elliot defended them still better, and called on Mordaunt for a local remedy, as he affirmed that twenty-five counties of thirty-three know nothing of, have nothing in common with, the Highlands: and he asked how it happened, that when the Duke could suppress the Rebellion pending the jurisdictions, the Ministry, with those and other impediments demolished, could not quash Jacobitism, though seven years had rolled away since the Rebellion? The Attorney-General said, he would yield to great authority, (the Speaker’s,) would agree, though not convinced, as he saw everybody meaned the same end, though by different means.

The Speaker uttered one of his pompous pathetics couched in short sentences; declared he was against the principle, as it was against the Revolution. It was against the principle of the constitution, of society, of liberty. No farther against the Revolution, than as it is against liberty. It always was true, it always will be. What is liberty, but that the people may be sure of justice? Other officers of justice should be for life like this; not this at pleasure, like others. If the Judge of Gibraltar[16] decided on property, he should be for life. Shall the accidental union of the ministerial office and of police reduce this to their standard, and have the preference? We are all united with regard to the principle. If he thought that these last seven years had united Scotland, he would not give a day more to this suspension. Would not have it thought that this Act is ever to be renewed; but when this additional term shall be expired, that the Sheriffs-depute are to be for life. Would say with that great man, Lord Somers, what I cannot have to-day I will be contented to have to-morrow. The people of Scotland are within our patronage; it is generous to make no distinction between them and our countrymen. Whoever thinks to preserve justice here by denying it there, is unjust. He would be content with suspending the Act for fifteen years for this once.

Fox replied, laughing at the Speaker, that he could not think these Judges of such a magnitude. If they were within the Speaker’s description, he would not consent to subject them to the Crown for any term. That the Lord Chancellor is not for life, and yet nobody is discontent with his decisions on that account. That he was content to get to-day what he might have to-morrow too. That this was the truest triumph of Revolution principles, for it was the sound that triumphed, not the sense. That perhaps it was honourable deceit in[17] those who opposed this; they made it serious, as they thought no harm could come from their opposition. That his deference for the Speaker was such, that he should even malle cum Platone errare, quam cum cæteris rectè sentire; but that if Plato did not err, if sense and reason were with him and his sect, it would be following sense and reason with so few, that for his part he chose to follow them no farther.

Pitt talked on the harmony of the day, and wished that Fox had omitted anything that looked like levity on this great principle. That the Ministry giving up the durante benè placito was an instance of moderation. That two points of the Debate had affected him with sensible pleasure, the admission that judicature ought to be free, and the universal zeal to strengthen the King’s hands. That liberty was the best loyalty; that giving extraordinary powers to the Crown, was so many repeals of the Act of Settlement. Fox said shortly, that if he had honoured the fire of liberty, he now honoured the smoke. Dr. Hay, a civilian, lately come into Parliament with great character, began to open about this time: his manner was good; as yet he shone in no other light. Nugent declared that liberty was concerned in this question, just as Christianity had been in the Jew Bill—Oswald replied rudely, “If he will define to what species of Christianity he chooses to belong,”—but Nugent[18] calling him to order, Oswald said, “My very expression admitted that he was a Christian.” No division following, the Committee resolved that the suspension should be enacted for seven years.

March 6th.—The Marquis of Hartington was declared Lord Lieutenant of Ireland; and the same day, the Earl of Rochford, Minister at Turin, having been appointed to succeed the late Lord Albemarle, as Groom of the Stole; Earl Poulet, First Lord of the Bed-chamber, resenting that a younger Lord had, contrary to custom, been preferred to him, resigned his employment. He had served the King twenty years in that station; and yet his disgrace was not lamentable, but ridiculous. He did not want sense, but that sense wanted every common requisite. He had dabbled in factions, but always when they were least creditable; he had lived in a Court, without learning the very rudiments of mankind; and was formal upon the topics which of all others least admit solemnity. For about two months the town was entertained with the episode of his patriotism: it vented itself in reams of papers without meaning, and of verses without metre, which were chiefly addressed to the Mayor of Bridgewater, where the Earl had been dabbling in an opposition. His fury died in the fright of a measure which I shall mention presently.

25th.—Sir Thomas Robinson, by the King’s command, acquainted the Commons with the preparations[19] of France for war, and demanded assistance. He did not inform them that there were actually then but three regiments in England, and that the Duke of Newcastle, from jealousy of the Duke’s nomination, would not suffer any more to be raised. Lord Granby and George Townshend moved the Address and a vote of credit. Doddington spoke with much applause on the insignificance into which Parliaments were dwindled, and of the inattention to public affairs. Every sentence trimmed between satire on, and a disposition towards, the Court: he concluded, “Let us carry the zeal of the people to St. James’s, with such spirit, that it may be heard at Versailles!” The torrent was for revenge; even Sir John Philipps felt against the French. Prowse desired it might be observed that we were advising a war. It was a puerile Debate. In the House of Lords, the Duke of Bedford attacked the inadvertence of the Ministry. The next day the Committee of Supply gave a million.

The Duke of Dorset was made Master of the Horse; but his faction did not fall without a convulsive pang. The primate and Lord Besborough sent a violent letter, to deny the report of their having quarrelled, and to demand some more sacrifices. As Lord Besborough’s son, Lord Duncannon, had married the new Lord Lieutenant’s sister, the latter resented this symptom of attachment to the disgraced cabal. The King said, “It was the work[20] of that ambitious priest, the Primate.” And the Duke of Newcastle, to mark his own sacrifice of the Stones, solemnized their condemnation with a Latin quotation—Quos Deus vult perdere, prius dementat.

On the 10th, came advice that 20,000 French were ready to embark at the Isle of Rhee. Lord Rothes, and the officers on the Irish establishment, were ordered to their posts in that kingdom; whither Lord Hartington and Mr. Conway went, without ceremony, at the end of the month.

23rd.—At midnight was finished the Oxfordshire election, after hearings of near fifty days: the Jacobite members were set aside by 231 to 103.

It was the year in turn for the King to go to Hanover. The French armaments, the defenceless state of the kingdom, the doubtful faith of the King of Prussia, and, above all, the age of the King, and the youth of his heir at so critical a conjuncture, everything pleaded against so rash a journey. But, as his Majesty was never despotic but in the single point of leaving his kingdom, no arguments or representations had any weight with him. When all had failed, so ridiculous a step was taken to dissuade him, that it almost grew a serious measure to advise his going. Earl Poulet notified an intention of moving the House of Lords to Address against the Hanoverian journey. However, as the Motion would not be merely ridiculous, but offensive[21] too, Mr. Fox dissuaded him from it. He was convinced; and though he had been disgraced as much as he could be, he took a panic, and intreated Mr. Fox and Lady Yarmouth to make apologies for him to the King. Before they were well delivered, he relapsed, and assembled the Lords, and then had not resolution enough to utter his Motion. This scene was repeated two or three times: at last, on the 24th, he vented his speech, extremely modified, though he had repeated it so often in private companies, that half the House could have told him how short it fell of what he had intended. Lord Chesterfield, not famous heretofore for tenderness to Hanover, nor called on now by any obligations to undertake the office of the Ministers, represented the impropriety of the Motion, and moved to adjourn. Lord Poulet cried, “My Lords, and what is to become of my Motion?” The House burst into a laughter, and adjourned, after he had divided it singly. The next day the Lord Chamberlain forbade him the entrées; the Parliament was prorogued; and on the 28th, the King went abroad, leaving the Duke at the head of the Regency. This was thought an artful stroke of the Newcastle faction, as it would tie up Fox, who, by being a Cabinet Councillor, became a Regent too, from censuring, in the ensuing session, the measures of the summer, in which the Duke and he would necessarily be involved: but the truth was, that the[22] Duke of Devonshire, terrified by old Horace Walpole at the thoughts of the King’s going abroad, had proposed the Duke for sole Regent. The Duke of Newcastle, in a panic for his power, hurried to the King, and besought him to place the Duke only first in the Regency. In fact, the nomination of him for sole Regent might have been attended with this absurdity; had the King died abroad, the sole Regent must have descended from his dignity, to be at the head of the Council to the parliamentary sole Regent, the Princess.

On the 29th, it was known that the French squadron was sailed, and that our fleet was ordered to follow and attack them, if they went to the Bay of St. Lawrence, even though they designed for Louisbourg. It was a hardy step, and not expected by France: our tameness and connivance at their encroachments had drawn them into a false security; they could not believe us disposed to war, nor had calculated that it would arrive so soon: their debts were not paid, their fleets not re-established, their Ministry was divided, and the spirit of their Parliaments not abashed. These were advantages in our scale; but our incumbrances were not inferior nor dissimilar to theirs. Our debts were weighty, not to be wiped out by a De-par-le-Roy; our troops, our sailors were disbanded; our Ministry was weak and factious, if not divided; and, headed by the Duke of Newcastle’s jealousy, how long[23] could it preserve any stability?—Our Parliament, indeed, was not mutinous; it was ready to receive any impression.

Our state at home was most naked and defenceless: the Stuart party in Scotland was humbled, not extirpated; Ireland was in a state of confusion, swarming with Papists, and the Whigs ready to burst into a civil war—a single circumstance will show how little attention had been paid to the security of so considerable a dominion: the few muskets in the hands of the King’s troops had been purchased, in the Duke of Devonshire’s Regency, at Hanover, and were so carelessly or knavishly made, that the men dared not fire them at a common review, lest they should burst in their hands: a supply was forced to be sent at this juncture from the Tower. Lord Hartington and Mr. Conway set out in haste for that kingdom, without awaiting the preparations for a new Lord Lieutenant’s entry. He was received coolly, though visited by each party: the Speaker and Malone made him great promises of not obstructing the King’s measures, and of even acquiescing to the litigated clause of the King’s consent to the disposal of the surplus money; though they wished the question, if possible, might be avoided. Lord Hartington replied, he could not engage it should. For the Primate, he would impart only a proper share of power to him. The Opposition determined to pursue that[24] Prelate; and the difficulty of appointing him of, or omitting him in, the Regency, prevented Lord Hartington from returning immediately to England, as was intended. Mr. Conway was sent alone, commissioned to obtain concessions to the Irish patriots, and to state the posture of affairs in such a light, as should force the Duke of Newcastle to withdraw his protection from the Primate. This was not to be demanded in form, though, unless conceded, Lord Hartington determined to resign the government: if obtained, the Lord Lieutenant proposed to deal more haughtily and sparingly with the Speaker’s party on other points.

During Mr. Conway’s absence, Lord Hartington was made to expect a conference with the Speaker, who kept in the country—several delays were invented—at last he came. The Marquis told him he should expect and had understood three things: that the supplies should be raised; the previous question dropped on both sides; that no censures should be passed on the late Administration. On his side, he would obtain the restoration of the Speaker to his employments, and of the rest, as occasion should offer: he engaged that the Primate should have no obnoxious power; and that all proper communication of Government should be made to the discontented. The Speaker professed that these offers would content himself, but feared would have no effect on his friends, unless they[25] were promised that the Primate should not be left in the Regency. “That,” replied the Marquis, “is more than I have authority to promise.” The Speaker desired till next day to consult his friends. He returned with Malone; but no acquiescence could be drawn from them without such a promise. The Primate made a specious offer of sacrificing himself for the tranquillity, if it would not be prejudicial to the dignity, of the Government. How sincere this interlude of self-denial was on either side, will appear hereafter.

Mr. Conway prevailed on the Chancellor and the Duke of Newcastle to consent to this sacrifice, which Lord Kildare, through Mr. Fox, assured Mr. Conway would content him. Newcastle wrote to the Primate, to desire he would ask his own exclusion. He was thunderstruck: he had offered it, while depending on support from England—it was the last thing he was ready to do, if his resignation was to be accepted. As he neither wanted arts nor engines, and had so fair a field to exercise his abilities on, as the Lord Lieutenant, now destitute of Mr. Conway’s advice, and beset by Lord Besborough, Mr. Ponsonby, and Lady Elizabeth, his wife, the Marquis’s sister, the junto instilled a thousand fears into the Lord Lieutenant of falling into the power of the Speaker; and drove him to write, not only to his father and Mr. Conway, to object against discarding the Primate, but even to[26] the Duke of Newcastle, and to propose the nomination of a Lord Deputy. This childish and contradictory step confounded Mr. Conway, and transported the Duke of Newcastle. The father-Duke and Mr. Fox wrote earnestly to the Marquis to persuade him to abandon the Primate: he yielded to their advice; yet was again whirled round to the interests of that faction; for, on Lord Kildare’s returning to Ireland, and assuring Lord Hartington that his sole object was the disgrace of the Primate; the Marquis replied, that, as the Primate had supported the King’s measures, and the Speaker had defeated them, he would not give up the one, and leave the other in the Regency; but offered to omit the Primate, provided Lord Kildare would come to him in form, and offer to relinquish the Speaker too. This was a master-stroke of the Churchman: he knew Lord Kildare did not love the Speaker: yet, being punctilious, the Earl replied, he could not take such a step on his own authority. I have chosen to throw these transactions together, though they took up some months in discussion, lest the reader should be perplexed by the frequent interruption of the narrative.

[1] He had formerly written a letter against a Bishop’s sermon, which had carried very high the respect due to that day.

[2] Two Papers published weekly by the Opposition against Sir R. Walpole.

[3] [St. Michael, Cornwall.] E.

Commencement of the War with France—War in America—Defeat and Death of General Braddock—Events at Sea—Fears for Hanover—Treaties made there—Dissensions in the Royal Family and in the Ministry—Disunion of Fox and Pitt—Ministers endeavour to procure support in Parliament—Fox made Secretary of State—Resignations and Promotions—Accession of the Bedford Party—Meeting of Parliament—New Opposition of Pitt—Debates on the Treaties—Pitt dismissed—Mr. Fox’s Circular to Members of Parliament—Debates on the number of Seamen.

July 15th, came news that three of Admiral Boscawen’s fleet, under the command of Captain Howe, had met, engaged, and taken three French men-of-war. The circumstances of this action were, that the three Frenchmen, on coming up with Howe, had demanded if it was, Peace or war? He replied, he waited for his Admiral’s signal; but advised them to prepare for war. The signal soon appeared for engaging: Howe attacked, and was victorious; but one of the French ships escaped in a fog: nine more were in sight, but, to the great disappointment of England, got safe into the harbour of Louisbourg. The Duke de Mirepoix had[28] still remained in England, writing letters to his Court of our pacific disposition. The Duke of Newcastle, having nobody left at home undeceived, had applied himself to deceive this Minister; and had succeeded. On this hostile action, Monsieur de Mirepoix departed abruptly, without taking leave, and suffered a temporary disgrace at his own Court for his credulity. The Abbé de Bussy, formerly resident here, had been sent after the King to Hanover, with the civilest message that they had hitherto vouchsafed to dictate. Two days after he had delivered it, a courier was dispatched in haste to prevent it, and to recall him, upon the notice of our capture of the two French ships. They had meditated the war; we began it. They affected to call us pirates; their King was made to say, “Je ne pardonnerai pas les pirateries de cette insolente nation.” The point was tender, as we had at least prepared no alliances to give strength to such alertness. However, the stroke was struck; and it was deemed policy to follow up the blow. The Martinico fleet was returning: it occasioned great Debates in the Council, whether this too was not to be attacked; but the danger of giving pretence to Spain to declare against us, if we opened the scene of war in Europe, preponderated for the negative. In America we were not so delicate: the next advices brought a conquest from Nova Scotia. About three thousand of our[29] troops, under the command of Colonel Monckton, had laid siege to the important fort of Beau-sejour, and carried it in four days, with scarce any loss: two other small forts surrendered immediately.

These little prosperities were soon balanced by the miscarriage of our principal operation in that part of the world. A resolution had been taken here to possess ourselves of the principal French forts on the Ohio, and in those parts; and the chief execution was to be entrusted to two regiments sent from hence. The Duke, who had no opinion but of regular troops, had prevailed for this measure. Those who were better acquainted with America and the Indian manner of fighting, advised the employment of irregulars raised on the spot. Unhappily, the European discipline preponderated; and to give it all its operation, a commander was selected, who, though remiss himself, was judged proper to exact the utmost rigour of duty. This was General Braddock, of the Guards, a man desperate in his fortune, brutal in his behaviour, obstinate in his sentiments, intrepid, and capable. To him was entrusted the execution of an enterprise on Fort Duquesne. His appointments were ample; the troops allotted to him most ill chosen, being draughts of the most worthless in some Irish regiments, and disgusted anew by this species of banishment.

As I am now opening some scenes of war, I must[30] premise that it is not my intention to enter minutely into descriptions of battles and sieges: my ignorance in the profession would lead me certainly, the reader possibly, into great mistakes; nor, had I more experience, would such details fall within my plan, which is rather to develope characters, and the grounds of councils, and to illuminate other histories, than to complete a history myself. Indeed, another reason would weigh with me against circumstantial relations of military affairs: I have seldom understood them in other authors. The confusion of a battle rarely leaves to any one officer a possibility of embracing the whole operation: few are cool enough to be preparing their narrative in the heat of action. Historians collect relations from these disjointed or supplied accounts; and, as different historians glean from different relations, and add partialities of their own or of their country, it is seldom possible to reconcile their contradictions. The events of battles and sieges are certain; for of the Te Deums which are sometimes chanted on both sides, the mock one vanishes long before it can usurp a place in history. The decision of actions and enterprises shall suffice me.

At the beginning of July, Braddock began his march at the head of two thousand men. Having reached the Little Meadows, which are about twenty miles beyond Fort Cumberland, at Will’s Creek, he found it necessary to leave the greatest part of his[31] heavy baggage at that place, under Colonel Dunbar, with orders to follow, as he should find it practicable; himself, with about twelve hundred men and ten pieces of artillery, advanced and encamped on the 8th, within ten miles of Fort Duquesne. He was warned against ambuscades and sudden attacks from the Indians: as if it were a point of discipline to be only prepared against surprises by despising them, he treated the notice as American panics, and advanced, with the tranquillity of a march in Flanders, into the heart of a country where every little art of barbarous war was still in practice. Entering on the 9th into a hollow vale, between two thick woods, a sudden and invisible fire put his men into confusion; they fired disorderly and at random against an enemy whom they did not see, and with so little command of themselves, that the greater part of the officers fell by the shot of their own men, who, having given one discharge, retreated precipitately. In vain were they attempted to be rallied by their officers, who behaved like heroes, and by Braddock, who, finding his generalship exerted too late, pushed his valour to desperation; he had five horses killed under him, and fell. Of sixty officers, near thirty perished; as many were wounded. Three hundred men were left on the field. The General was brought off by thirty English, bribed to that service by Captain Orme, his Aide-de-camp, for a guinea and a bottle[32] of rum a-piece. He lived four days, a witness to the effects of his own rashness and to his erroneous opinion of the American troops, who alone had stood their ground. He dictated an encomium on his officers, and expired. In one respect it was a singular battle, even in that country; there was no scalping, no torture of prisoners, no pursuit; our men never descried above fifty enemies. The cannon was fetched off by the garrison of Fort Duquesne; and among the spoil were found the Duke’s instructions to Braddock, which the French published as a confirmation of our hostile designs. Colonel Dunbar hurried back in great precipitation with the heavier artillery on the first alarm from the fugitives.

What a picture was this skirmish of the vicissitude of human affairs! What hosts had Cortez and a handful of Spaniards thrown into dismay, and butchered, by the novel explosion of a few guns! Here was a regular European army confounded, dispersed by a slight band of those despised Americans, who had learned to turn those very fire-arms against their conquerors and instructors!

These enterprises on land were accompanied on our part by seizing great numbers of French vessels. Sir Edward Hawke was reprimanded for letting two East Indiamen pass; and repaired his fault by sending in two Martinico and two other ships; and these were followed by three rich captures[33] from St. Domingo. The French with folded arms beheld these hostilities; and though our Admiralty issued Letters of Marque and Reprisal on the 29th of August, they immediately released the Blandford man-of-war, which, conveying Mr. Lyttelton to his new government of South Carolina, had been taken by some of their ships, who had not conceived that war on England and from England was not war with England. As late as the beginning of November, they persisted in their pacific civility, sending home ten of the crew of the Blandford, who had remained sick in France, and promising to dispatch another as soon as he should be recovered. Lord Anson, attentive to, and, in general, expert in maritime details, selected with great care the best officers, and assured the King that in the approaching war he should at least hear of no Courts-Martial. One happy consequence appeared of Sir Benjamin Keene’s negotiations: the Spanish court refused positively to embark in the war, having, as they declared, examined the state of the question, and found that the French were the aggressors. Had Ensenada remained in power, it is obvious with what candour the examination would have been made.

But, in the midst of all this ostentation of national resentment, symptoms of great fear appeared in the Cabinet: while Britain dared France, its Monarch was trembling for his Hanover.[34] As we had given so fatal a blow to the navy of France in the last war; as we were undoubtedly so superior to them in America; as we had no Austrian haughtiness to feed and defend; no Dutch to betray and counteract us, we had a reasonable presumption of carrying on a mere naval war with honour—perhaps with success. As all our force was at home; as our fleet was numerous; as Jacobitism had been so unnerved by the late Rebellion, we were much less vulnerable in our island than ever: Ireland was the only exposed part, and timely attention might secure it. The King apprehended that he should be punished as Elector, for the just vengeance that he was taking as King,—the supposition was probable, and the case hard—but how was England circumstanced? was the necessary defence of her colonies to be pretermitted, lest her Ally, the Elector of Hanover, should be involved in her quarrel? While that is the case, do not the interests of the Electorate annihilate the formidable navies of Great Britain?

As the King’s Ministers had resolved on war, his Majesty, now at Hanover, precipitated every measure for the defence of his private dominions. He had no English Minister with him, at least only Lord Holderness, who was not likely to soar at once from the abject condition of a dangling Secretary to the dignity of a remonstrating patriot. One subsidiary treaty was hurried on with Hesse; another[35] with Russia, to keep the King of Prussia in awe: while to sweeten him again, a match was negotiated for his niece, the Princess of Brunswick, with the Prince of Wales; in short, a factory was opened at Herenhausen, where every petty Prince that could muster and clothe a regiment, might traffic with it to advantage: let us turn our eyes and see how these negotiations were received at home. There the Duke of Newcastle was absolute. He had all the advice from wise heads that could make him get the better of rivals, and all the childishness in himself that could make them ashamed of his having got the better. If his fickleness could have been tied down to any stability, his power had been endless. Yet, as it often happens, the puny can shake, where the mighty have been foiled—nor Pitt, nor Fox, were the engines that made the Duke of Newcastle’s power totter. I have mentioned how early his petulant humour had humbled Legge—never was revenge more swiftly gratified. The treaties came over: as acquiescence to all Hanoverian measures was the only homage which the Duke of Newcastle paid to his master, he consented to ratify them. Being subsidiary, it was necessary that the Treasury should sign the warrants: he could not believe his eyes, when Legge refused to sign. He said, the contents had not been communicated to him, nay, not to Parliament: he dared not set his name to[36] what the Parliament might disapprove. Nugent beseeched him to sign; he continued firm. The step was most artful; as he saw he must fall, and knew his own character, it was necessary to quit with éclat. If popularity could be resuscitated, what so likely to awaken it, as refusing to concur in a measure of profusion for interests absolutely foreign? Some coincident circumstances tended to confirm his resolution, and perhaps had the greatest share in dictating it.

I have mentioned the projected match with Brunswick: the suddenness of the measure, and the little time left for preventing it, at once unhinged all the circumspection and prudence of the Princess. From the death of the Prince, her object had been the government of her son; and her attention had answered. She had taught him great devotion, and she had taken care that he should be taught nothing else. She saw no reason to apprehend from his own genius that he would escape her; but bigotted, and young, and chaste, what empire might not a youthful bride (and the Princess of Brunswick was reckoned artful) assume over him? The Princess thought that prudence now would be most imprudent. She immediately instilled into her son the greatest aversion to the match: he protested against it: but unsupported as they were, how to balance the authority of a King who was beloved by his people, who had heaped every possible[37] obligation on the Princess, who, in favour of her and her children, had taught himself to act with paternal tenderness, and who, in this instance, would be blindly obeyed by a Ministry that were uncontrolled? Here Legge’s art stepped in to her assistance; and weaving Pitt’s disgusts into the toils that they were spreading for the Duke of Newcastle, they had the finesse to sink all mention of the Brunswick union, while they hoisted the standard against subsidiary treaties.

Mr. Pitt, who had never contentedly acquiesced in remaining a cipher after the death of Mr. Pelham, and who was additionally inflamed at Mr. Fox’s being preferred to the Cabinet, had sent old Horace Walpole to the Duke of Newcastle the day before the King went abroad, with a peremptory demand of an explicit answer, whether his Grace would make him Secretary of State on the first convenient opportunity; not insisting on any person’s being directly removed to favour him. The response was not explicit; at least, not flattering. From that moment, it is supposed, Pitt cast his eyes towards the successor. Early in the summer Pitt went in form to Holland-house, and declared to Mr. Fox, that they could have no farther connexions; that times and circumstances forbad. Fox asked, if he had suspected him of having tried to rise above him. Pitt protested he had not. “Yet,” said Fox, “are we on incompatible lines?”[38] “Not on incompatible,” replied Pitt, “but on convergent: that sometime or other they might act together: that for himself, he would accept power from no hands.” To others, Pitt complained of Fox’s connexion with Lord Granville; and dropped to himself a clue that led to an explanation of this rupture. “Here,” said Pitt, “is the Duke King, and you are his Minister!” “Whatever you may think,” replied Fox, “the Duke does not think himself aggrandized by being of the Regency, where he has no more power than I have.”

In fact, the Duke of Newcastle, as was mentioned before, had prevailed to have his Royal Highness named a Regent, without acquainting him or asking his consent. When Mr. Fox discovered the intention, and informed the Duke, he would not believe it, and said, “Mr. Fox, I beg your pardon, as you are to be of the number, but I shall not think myself aggrandized.” And it was so little considered as flattery to him, that the King did not name it to him, but sent Lord Holderness with the notification. After this interview and separation, Pitt and Fox imputed the rupture to each other. The truth seemed to be this: Pitt had learned, and could not forgive, Fox’s having disclaimed him; and being united with the Princess, he sought this breach; which was so little welcome to Fox, that, soon after it, a rumour prevailing that Pitt was to be Chancellor of the Exchequer, Fox[39] desired Legge to advise Pitt to accept it, offering himself to take the Paymastership. Legge was suspected of not having reported this message, to which he affirmed Pitt had not listened. What seemed to confirm the Princess’s favour being the price of Pitt’s rupture with Fox, and consequently of his disclaiming the Duke, was Pitt’s appearing to pin it down to the individual day of his visit at Holland-house, as the date from whence his connexion with Fox was to cease. It was discovered, that the very day before he had had a private audience of the Princess. The only spy in the service of the Ministry was a volunteer; Princess Amelie, who traced and unravelled the mystery of this new faction.

However, the little junto forming at Leicester House would have made small impression, if the Duke of Newcastle, in a fit of folly and fear, had not dashed down his own security. Hearing that the Duke of Devonshire, Sir George Lee, Mr. Legge, and some others, declared their disapprobation of the treaties, his Grace took a panic, which with full as little sense he poured into the King the moment he returned. To soften the Duke of Devonshire, they consented to whatever Lord Hartington should ask as terms for treating with the Irish patriots; which disposition had such immediate effect, that the Address of the House of Commons of Ireland was voted without a negative, and the body of the[40] Opposition there manifested their readiness to sell themselves, the moment they knew that the Lord Lieutenant had authority to buy them. Some faint efforts towards tumults were made by little people, who had no chance of being included in the purchase; and the face of Lord Kildare, one of the mollifying demagogues, was blackened on sign-posts; but when chiefs capitulate, they seldom recede for such indignities. But more material was, who should defend the treaties in the English Parliament? Murray shrunk from the service—what! support them against Pitt! perhaps against Fox! They looked down to Lord Egmont—he was uncertain, fluctuating between the hopes of serving under the Princess in opposition, and jealous at the prospect of serving under Pitt too. No resource lay, but in prevailing on either Pitt or Fox to be the champion of the new negotiations. When either was to be solicited, it was certain that the Chancellor and the Duke of Newcastle would not give the preference to the latter.

In this dilemma, his Grace sent for Mr. Pitt, offered him civilities from the King, (for to that hour his Majesty had never spoken to him but once,) a Cabinet Counsellor’s place, and confidence. He, who had crowded the whole humility of his life into professions of respect to the King, was not wanting now to strain every expression of duty, and of how highly he should think himself honoured[41] by any ray of graciousness beaming upon him from the Throne—for the Cabinet Counsellor’s place, he desired to be excused. The Duke of Newcastle then lisped out a hint of the Hessian treaty—“would he be so good as to support it?” “If,” said Pitt, “it will be a particular compliment to his Majesty, most undoubtedly.”—“The Russian?” “Oh! no,” cried Pitt, hastily; “not a system of treaties.” When the Duke of Newcastle could not work upon him, he begged another meeting in presence of the Chancellor, who, being prepared with all his pomp, and subtilties, and temptations, was strangely disconcerted by Pitt’s bursting into the conversation with great humour by a panegyric on Legge, whom he termed the child, and deservedly the favourite child, of the Whigs. A conference so commenced did not seem much calculated for harmony; and accordingly it broke up without effect. Nothing remained but to have recourse to Fox: not expecting the application, he[4] too had dropped intimations of his dislike to the treaties; and he knew they had tried all men ere they could bend their aversion to have recourse to him: yet he was not obdurate: he had repented his former[42] refusal; and a new motive, that must be opened, added irresistible weight to the scale of ambition.

In his earlier life Mr. Fox had wasted his fortune in gaming; it had been replaced by some family circumstances, but was small, and he continued profuse. Becoming a most fond father, and his constitution admonishing him, he took up an attention to enrich himself precipitately. His favour with the Duke, and his office of Secretary at War, gave him unbounded influence over recommendations in the Army. This interest he exerted by placing Calcraft in every lucrative light, and constituting him an Agent for regiments. Seniority or services promoted men slowly, unless they were disposed to employ Mr. Calcraft; and very hard conditions were imposed on many, even of obliging them to break through promises and overlook old friendships, in order to nominate the favourite Agent. This traffic, so unlimited and so lucrative,[5] would have mouldered to nothing, if Mr. Fox had gone into Opposition; his inclination not prompting him to that part, his interest dissuading and the Duke forbidding it; when the new overtures arrived from the Duke of Newcastle, he took[43] care not to consult his former counsellors, who had been attentive only to his honour, but listened to men far less anxious for it. Stone and Lord Granville were the mediators; the latter, at once the victim, the creature, and the scourge of the Duke of Newcastle, undertook the negotiation. The Duke in his fright had offered to resign his power to him; Lord Granville, not weak enough to accept the boon, laughed, and said with a bitter sneer, “he was not fit to be First Minister.” He proposed that Fox should be Chancellor of the Exchequer—to that the Duke, still as jealous as timid, would not listen.

At last Lord Granville settled the terms; that Fox should be Secretary[6] of State, with a notification to be divulged, that he had power with the King to help or hurt in the House of Commons; and a conference being held to ratify the conditions, Fox said, “My Lord, is it not fit that this should be the last time that we should meet to try to agree?” “Yes,” replied the Duke, “I think it is.” “Then,” said Fox, “if your Grace thinks so, it shall be so.” His other terms were moderate, for[44] not intending to be more scrupulous than he knew the Duke of Newcastle would be, in the observance of the articles of their friendship, he insisted on the preferment or promotion of only five persons, Mr. Ellis, Sir John Wynne, George Selwyn, Mr. Sloper, and a young Hamilton,[7] who, in the preceding spring, though connected with the Chancellor’s family, had gone with a frank abruptness, and offered his service to Mr. Fox, telling him “that he foresaw he must one day be very considerable; that his own fortune was easy and not pressing; he did not disclaim ambition, but was willing to wait.” His father had been the first Scot who ever pleaded at the English bar, and, as it was said of him, should have been the last; the son had much more parts. The only impediment to the new accommodation was no obstruction; Sir Thomas Robinson cheerfully gave up the Seals, with more grace from the sense of his unfitness, than from the exorbitant indemnification he demanded. “He knew,” he said, “a year and a half before, why he was selected for that office; for the business of it, he had executed it to the best of his abilities; for the House of Commons he had never pretended capacity.” He desired to be restored to his old office, the Great Wardrobe, in which he had been placed to reform it, and had succeeded. He asked it for his own life and his son’s. They gave it him[45] during pleasure, with a pension of 2000l. a year on Ireland for thirty-one years. When he thanked the Duke of Newcastle, he added, with a touching tenderness, “I have seven children, and I never looked at them with so much pleasure as to-day.” As Lord Barrington was to be removed from the Wardrobe to make room for Sir Thomas, he had the good fortune to find the Secretaryship at War vacant, and slipped into it.

Lord Chesterfield hearing of this new arrangement, said, “The Duke of Newcastle had turned out every body else, and now he has turned out himself.” The whole was scarce adjusted before Mr. Fox had cause to see what an oversight he had committed in extending a hand to save the Duke of Newcastle, when he should have pushed him down the precipice; asking Stone what they would have done if he had not come into them, Stone owned that they would have gone to the King and told him they could carry on his business no longer, and that he must compose a new Ministry. How sincere the coalition was, even on Mr. Fox’s side, appeared by his instantly dispatching an express for Mr. Rigby, the Duke of Bedford’s chief counsellor, to concert measures for prevailing on that Duke to return to Court, and contribute to balance, and then to overthrow, the Duke of Newcastle’s influence.

While the Ministry was in this ferment, they received[46] accounts of a victory, little owing to their councils, and which at once repaired and contrasted Braddock’s defeat. The little Army assembled by some of our West Indian governments, and composed wholly of irregulars, had come up with the French forces to the number of 2000, and defeated them near the Lake St. Sacrament, with slight loss on our part, with considerable on theirs. What enhanced the glory of the Americans was, taking prisoner the Baron de Dieskau, the French General, an able élève of Marshal Saxe, lately dispatched from France to command in chief, while the English Commander was a Colonel Johnson, of Irish extraction, settled in the West Indies, and totally a stranger to European discipline. Both Generals were wounded, the French one dangerously. Sir William Johnson was knighted for this service; and received from Parliament a reward of 5000l.

Mr. Fox’s great point was to signalize his preferment by the accession of the Duke of Bedford and his party; the faction were sufficiently eager for such a junction, the Duke himself most averse to it; especially as the very band of concord was to be an approbation of the treaties; the tenour of his opposition had run against such measures; these were certainly not more of English stamp. When the Duchess and his connexion could not prevail on him to give up his humour and his honour, to gratify their humour and necessities, Mr. Fox and[47] Lord Sandwich employed Lord Fane, whom the Duke of Bedford esteemed as the honestest man in the world, to write him a letter, advising his Grace to vote for the treaties; and they were careful to prevent his conversing with Mr. Pitt, which he wished, or with any other person, who might confirm him in a jealousy of his honour; indeed, he did not want strong sensations of it; they drew tears from him before they could draw compliance. Fox would have engaged him to accept the Privy Seal, which he had prepared the Duke of Marlborough to cede; but the Duke of Bedford had resolution enough to refuse any employment for himself—acquiescing to the acceptance of his friends, they rushed to Court—what terms they obtained will be seen at the conclusion of the year.

November 12th.—The night before the opening of the Parliament, Mr. Fox presided at the meeting at the Cockpit, instead of Mr. Legge, who, with Mr. Pitt, the Grenvilles, and Charles Townshend, did not appear there. They were replaced by the Duke of Bedford’s friends. From thence Mr. Rigby was sent to his Grace with a copy of the Address; and to indulge him, an expression was softened that promised too peremptory defence of Hanover.

13th.—The Houses met. The expectation of men was raised; a new scene was ready to disclose. The inactivity of the late sessions was dispelled; a formidable Opposition, with the successor and his[48] mother at the head, was apprehended: the Ministers themselves had, till the eve of Parliament, trembled for the event of the treaties. Legge, indefatigable in closet applications and assiduity, had staggered many; the promotion of Fox, it was supposed, had revolted many more. A war commenced with France; factions, if not parties, reviving in Parliament, were novel sights to a lethargic age. The immensity of the Debates during this whole session would, if particularized, fatigue the reader, and swell these cursory Memoirs to a tedious compilation: I shall select the heads of the most striking orations, and only mark succinctly the questions and events.

The King’s Speech acquainted the Houses with the outlines of the steps he had taken to protect and regain his violated dominions in America; of the expedition used in equipping a great Maritime Force; of some land forces sent to the West Indies; of encouragement given to the Colonies; of his Majesty’s disposition to reasonable terms of accommodation; of the silence of France on that head; of the pacific disposition of the King of Spain—it very briefly touched on the tender point of the new treaties. In the House of Lords, the Duke of Marlborough and Lord Marchmont moved the Address. Lord Temple, the incendiary of the new Opposition, and Lord Halifax, who could not endure any measure that diverted attention or treasure from[49] the support of our American Settlements, dissented from the Address on the article of the treaties. The Duke of Bedford decently and handsomely excused his approbation of them: the Chancellor, the Duke of Newcastle, and Lord Bathurst, defended them; and no division ensued; yet Lord Temple protested: he had, unwarranted, expressed the Duke of Devonshire’s concern at being prevented by ill health from appearing against the treaties. His Grace was offended at, and disavowed, Lord Temple’s use of his name: he was more hurt at the property he had been made by old Horace Walpole, who no sooner snuffed the scent of new troubles on German measures, than he felt the long wished-for moment approach of wrenching a coronet from the unwilling King. He immediately worked up the Duke of Devonshire to thwart the treaties, declared against them himself, talked up the Whigs to dislike them; and then deserted the Duke and his Whigs, by compounding for a Barony, in exchange for a public defence of the negotiations.