Title: Musical Instruments, Historic, Rare and Unique

Author: Alfred J. Hipkins

Illustrator: William Gibb

Release date: October 17, 2018 [eBook #58117]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Linda Cantoni, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note

Obvious printer errors have been corrected without note. For clarity, the frontispiece illustration (Plate I.) has been moved to its appropriate chapter.

Click on the music notation images to hear the music (this may not work in formats other than HTML).

THE SELECTION, INTRODUCTION AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES

BY

A.J. HIPKINS, F.S.A. Lond.

AUTHOR OF THE ARTICLE "PIANOFORTE" IN THE ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA

ILLUSTRATED BY

A SERIES OF FORTY-EIGHT PLATES IN COLOURS

DRAWN BY WILLIAM GIBB

A. AND C. BLACK, LTD.

4, 5 AND 6 SOHO SQUARE, LONDON, W.1

1921

First published in 1888.

Printed in Great Britain

| INTRODUCTION | Page vii. |

| BURGMOTE HORNS | Plate I. |

| QUEEN MARY'S HARP | II. |

| THE LAMONT HARP | III. |

| CORNEMUSE. CALABRIAN BAGPIPE. MUSETTE | IV. |

| BAGPIPES | V. |

| CLAVICYTHERIUM OR UPRIGHT SPINET | VI. |

| OLIPHANT | VII. |

| QUEEN ELIZABETH'S VIRGINAL | VIII. |

| QUEEN ELIZABETH'S LUTE | IX. |

| THE RIZZIO GUITAR | X. |

| POSITIVE ORGAN | XI. |

| REGAL | XII. |

| PORTABLE ORGAN AND BIBLE REGAL | XIII. |

| CETERA | XIV. |

| LUTE | XV. |

| THEORBO | XVI. |

| DULCIMER | XVII. |

| VIRGINAL | XVIII. |

| VIOLA DA GAMBA | XIX. |

| DOUBLE SPINET OR VIRGINAL | XX.-vi- |

| THREE CHITARRONI | XXI. |

| SPINET | XXII. |

| QUINTERNA AND MANDOLINE | XXIII. |

| WELSH CRWTH. RUSSIAN BALALÄIKA | XXIV. |

| VIOLIN—THE HELLIER STRADIVARIUS, and two old Bows noted for the Fluting | XXV. |

| VIOLINS—THE ALARD STRADIVARIUS, THE KING JOSEPH GUARNERIUS DEL GESÙ | XXVI. |

| VIOLA D'AMORE | XXVII. |

| CETERA, BY ANTONIUS STRADIVARIUS | XXVIII. |

| GUITAR, BY ANTONIUS STRADIVARIUS | XXIX. |

| BELL HARP AND HURDY-GURDY | XXX. |

| SORDINI | XXXI. |

| CLAVICHORD | XXXII. |

| THE EMPRESS HARPSICHORD | XXXIII. |

| PEDAL HARP | XXXIV. |

| STATE TRUMPET AND KETTLEDRUM | XXXV. |

| CAVALRY BUGLE. CAVALRY TRUMPET. TRUMPETS | XXXVI. |

| LITUUS AND BUCCINA. CORNET. TRUMPETS | XXXVII. |

| TWO DOUBLE FLAGEOLETS, A GERMAN FLUTE, AND TWO FLÛTES DOUCES | XXXVIII. |

| DOLCIANO. OBOE. BASSOON. OBOE DA CACCIA. BASSET HORN | XXXIX. |

| SITÁRS AND VÍNA | XL. |

| INDIAN DRUMS | XLI. |

| SAW DUANG AND BOW. SAW TAI AND BOW. SAW OO AND BOW. KLUI. PEE | XLII. |

| RANAT EK. KHONG YAI. TA'KHAY | XLIII. |

| HU-CH'IN AND BOW. SHÊNG. SAN-HSIEN. P'I-P'A | XLIV. |

| CHINESE TI-TZU, SO-NA, YUEH-CH'IN. JAPANESE HIJI-RIKI. CHINESE LA-PA | XLV. |

| JAPANESE KOTO | XLVI. |

| SIAMISEN, KOKIU, BIWA | XLVII. |

| MARIMBA OF SOUTH AFRICA | XLVIII. |

| INDEX | Page 117 |

The Woodcuts at the head of this page (from the British

Museum) represent Sir Michael Mercator,

of Venloo, Musical Instrument Maker to King Henry VIII.

IT is claimed for this book, intended to illustrate rare historical and beautiful Musical Instruments, that it is unique. Classical, Mediæval, Japanese, and other varieties of Decorative Art, Weapons, and Costumes, have found worthy illustration and adequate description, but hitherto no attempt has been made to represent in a like manner the grace and external charm of fine lutes and harps, of viols, virginals, and other instruments. Engravings have been produced, in historical or technical works; but the greater number of these are mere repetitions continued from one to the other, and have no specially æsthetic interest. Beauty of form and fitness of decoration demand more than the commonplace homage paid to simple use, and while we should never lose sight of the purpose of a musical instrument, its capacity to produce agreeable and various sounds, we can take advantage of its form and material, and, making it lovely to look upon, give pleasure to the eye as well as the ear. It is hardly necessary to say that the love of adornment or ornament is an attribute of the human race. It is to be found everywhere and in every epoch when life is, for the time being, safe and the means of existence secure. Some favourite manner of decoration is the characteristic stamp of a people, a period, or a country. The earliest monuments we can point to that represent musical instruments, show a tendency to adorn them or to place them with decorative surroundings. The Egyptians, the Assyrians, the ancient Greeks supply a record that has been continued by the Persians and Saracens, in the Gothic age and the Renaissance, always repeating, as it were, in an ineffaceable script, the precept that the hand should minister to the gratification of the eye, and satisfy it by alternating excitement with repose. And so it was, until the marvellous mechanical advance in the present century has not only caused us to forget, by its overwhelming power, what our predecessors so steadfastly continued, but-viii- has induced us to regard the ugly as sufficient if the mere practical end is served. By thus chilling the appreciation and pursuit of decorative invention, that faculty has been numbed for the time being, and there is danger of its being lost altogether. It may be answered that real artistic work is occasionally done, and there are examples of it to be found in musical instruments; a good organ case is sometimes made, sometimes a fine decoration for a piano case. If there is any hope of an awakening of the love for musical instruments that finds expression in their adornment, its promise lies in the beautiful designs that have been, of late years, so meritoriously carried out for pianos—the invention of Mr. Alma Tadema, Mr. Burne Jones, Mr. Fox, and Miss Kate Faulkner. Good decoration need not be a privilege of the rich; the old Antwerp clavecin-makers, who were all members of the guild of St. Luke, the artists' guild, knew how to worthily decorate their instruments at little cost, as may be seen in the Ruckers Virginal, Plate XVIII. They painted their sound-boards with appropriate ornamentation, and used bright colour to heighten the effect of their instruments when open. The Italians went even farther in richer details, and beautified other stringed instruments besides those with key-boards. The persistence of noble traditions is shown in the exquisite ornament of the Siamese instruments (Plates XLII. and XLIII.) and of the Japanese Koto (Plate XLVI.). It would be grievous if this Eastern inheritance were lost through the engrafting of Western ideas and reception of our material civilisation. The incentive to all such work is the pleasure found in it, and without pleasure in work the life of the worker is aimless and sad.

In describing musical instruments we can refer to no beginnings; those that may be discerned dimly in the glimmering of the historic dawn present a certain completeness that marks an intellectual advance already accomplished. The well-known Egyptian Nefer, a spade-like guitar, or rather tamboura, invited by its long neck the stopping of various notes upon its strings. As early as the Third Dynasty, it had already been so long in use as to have become incorporated in the pictorial language of the Hieroglyphics, in which its representation presented the concept or symbol of the-ix- attribute good. This stringed instrument, thus complex in its playing, must have been already grey with age when it was cut in stone in the monument of the beautiful Princess Nefer-t, now in the museum at Bulaq. We cannot conjecture when it was discovered that more tones than one could be got from a single string by taking advantage of the expedient of a long neck or finger-board, or from a single pipe by boring lateral holes in it, and closing those holes to produce different notes with the fingers. Even these remote inventions, certainly prehistoric, seem to require that there should be yet older inventions—those which placed pipes or strings of different lengths, or strings of the same length but of different thicknesses and tension, side by side, as in the syrinx or Pan's pipes, or the harp and lyre.

The late Carl Engel, Music of the Most Ancient Nations (London, 1864), has formed a kind of Development theory for musical instruments, giving the earliest place to the drum, and the latest to the stringed instruments; those of the latter with key-boards having been invented almost in our own time. This theory has lately been reconstructed upon a more scientific basis by Mr. Rowbotham (History of Music, vol. i., London, 1885). The drum and tambourine, and other clashing and mere time-marking instruments, as sistrums, cymbals, castagnettes, and triangles, are on the limit of musical sound and noise, inclining, for the most part, to the latter. The drum is widely used in religious services in different parts of the world, and to play the sistrum was in ancient Egypt the prerogative of a high order of priesthood. The various Buddhist gongs resemble the kettledrums in this respect, that they have a more definable musical element in them, and we find these sonorous metal instruments widely used in China and the Indo-Chinese countries, in Java, and the Indian Archipelago. The Indian drums (Plate XLI.), according to the theory just mentioned, should be aboriginal, but the most ancient, the M'ridang, is attributed to the god S'iva, and is therefore Aryan. Her Majesty the Queen's State Kettledrum (Plate XXXV.) here adorned with a richly embroidered silk banneret, serves to show the highest point the drum has yet attained in estimation and use. On a much higher-x- level is that arrangement of wooden or metal bars in those instruments classed generally as Harmonicons, which are especially at home in Java, Siam, and Burma, and are known to be used from the Hill country of India in the one direction, to Africa in the other. The beautiful Siamese Ranat and Khong (Plate XLIII.) and the Zulu Marimba (Plate XLVIII.) are examples of this wide distribution, and in the latter the gourd resonators attached to the bars show the simplest form of sound reinforcers, which, perfected in various Eastern instruments, such as the Indian Vínas and Sitárs (Plate XL.) has in Europe attained its crowning artistic development in the beautiful pear-shaped Resonance bodies of the Lute and Mandoline. We find also varieties of this beautiful form in the Georgian and Turcoman tambouras, the Colascione of Southern Italy and similar instruments, the migrations of which may here and there be traced along the lines of religious movements, as in Central Asia and Hindostan, in China, the Corea, and Japan. For instance, the shorter-necked lutes and guitars, the rebec, rebab, and other precursors of the viols and violins, which, borrowed from the Arabic population of the Holy Land, actually came to Europe upon the reflex wave of the Crusades. The Saracenic occupation of Spain had, however, its share in the transmission of these instruments, and of a taste for the pizzicato, and also of an elaboration of vocal and instrumental ornament, which has remained in the popular airs and dances of that country, and, an important characteristic of the music of the Troubadours and Trouvères, has left its mark upon our modern music everywhere. The Arab blood in Spain may have tended to preserve the use of the guitar as a national instrument in that country. A Guitar (Plate XXIX.) and a Cetera (Plate XXVIII.) made by Stradivarius, as he usually signed his name, are of especial interest as showing that he was not above making more simple instruments than violins. The beautiful tortoiseshell Guitar (Plate X.) has a tradition that connects it with Mary of Scots and the unfortunate Rizzio. In all these guitar and lute instruments, the roses in the sound-boards show a wealth of invention in design that is truly astonishing. A work of this kind would not be without interest if it were devoted only to these roses, and to those of spinets and-xi- harpsichords. Guitars have flat backs, and lutes shell or pear-shaped resonance bodies, and the former are again divided into the guitar proper with catgut strings, and cithers with wire strings necessitating the employment of a plectrum. The Cetera is the Italian name of the cither, and the one drawn in Plate XIV. is of remarkable, although not unusual, beauty. The cither to which the name of Queen Elizabeth is traditionally attached, belongs to the English family of the Pandore, Orpheoreon, and Penorcon; it is not exactly one of these instruments, but it most nearly resembles the last named. As a fine specimen of English work, in no way ceding to the Italian, this beautiful instrument, commonly known as Queen Elizabeth's Lute (Plate IX.), cannot be too highly extolled. The description accompanying this drawing, and in fact the descriptions of all the drawings, must be referred to for those special particulars that are more conveniently given separately. The Lute (Plate XV.) is one of the finest existing examples of its kind. It bears the label of Vvendelio Venere, Padua, dated 1600, and marks the culmination of that once most favourite instrument. The large bass lutes—the theorboes and chitarroni—that came into use about that date, were rendered necessary through the weakness in the bass of the contemporary harpsichord, which was insufficient as a sub-structure for the Continuo, or Thorough Bass, intended to accompany the Recitativo, then recently introduced at Florence, and forming an essential part of that Monody that was the latest blooming of the Renaissance, as applied to the latest art, harmonised music. The Venetian Theorboes (or Tiorbe) and Chitarroni (Plates XVI. and XXI.) are of great beauty and historical interest. But the lute, even when diapasons or extra bass strings were added to it, went out, being superseded by the more useful, although less beautifully toned, spinet. The latest lute instruments are the pleasing Mandolines to which fashion may possibly grant a new lease of popularity. These instruments are drawn in Plate XXIII. Both ear and eye are equally gratified in that culmination of qualities attained in a violin, in which the sound and shape are so intimately and inseparably connected that we fail to conceive the one without some mental reference to the other. The form and colour of a fine-xii- violin are in themselves so beautiful that it seems scarcely possible to enhance their effect by adding any kind of decoration, but in Plate XXV. it will be seen that Antonio Stradivari, with whom the instrument reached perfection, has successfully inlaid one of his masterpieces with an appropriate design. Another violin by the same illustrious master, in this instance without adornment, is drawn in Plate XXVI. The particular characteristics of another famous Cremona maker, Giuseppe Guarneri, who signed himself "Del Gesù," and is accounted Stradivari's only rival, are also illustrated in this plate. With forty-eight plates, however, to which this work is limited, no complete scheme can be offered of the rich varieties of musical instruments that exist, but the pictorially interesting Viola d'Amore (Plate XXVII.) and the Viola da Gamba (Plate XIX.) have not been overlooked.

Wind instruments, although they may be of earlier invention in their

rudimentary forms than those with strings, as in the old-world fable

of Apollo and Marsyas, are always placed second. But they have an

equal interest intrinsically and historically, and like drums and

gongs, have an especial connection with the sacred rites of various

nations. The Jewish Shophar, a simple ram's horn, a woodcut of which,

drawn from an interesting example preserved at the great Synagogue,

Aldgate, London, figures at the end of this Introduction, is the

oldest wind instrument in present use in the world. It is first named

in the Bible as sounding when the Lord descended upon Mount Sinai,

and there seems to be little doubt that it has been continuously

used in the Mosaic Service from the time it was established until

now. It is sounded in the synagogues at the New Year and on the Fast

of the Day of Atonement. The Talmud gives ten reasons for sounding

the Shophar at the New Year, which may be summed up as reminding

those who hear it of the Creation, Penitence, and the Law, of the

Prophets, who were as watchmen blowing trumpets, of the Temple and

the Binding of Isaac, of Humility, the gathering together of Israel,

the Resurrection, and the day of Judgment, when the trumpet shall

sound for all. The embouchure of the Shophar is very difficult, and

but three proper tones are usually obtained from it, although in some

instances-xiii- higher notes can be got. The short rhythmic flourishes

are common, with unimportant differences, to both the German and

Portuguese Jews, and consequently date from before their separation.

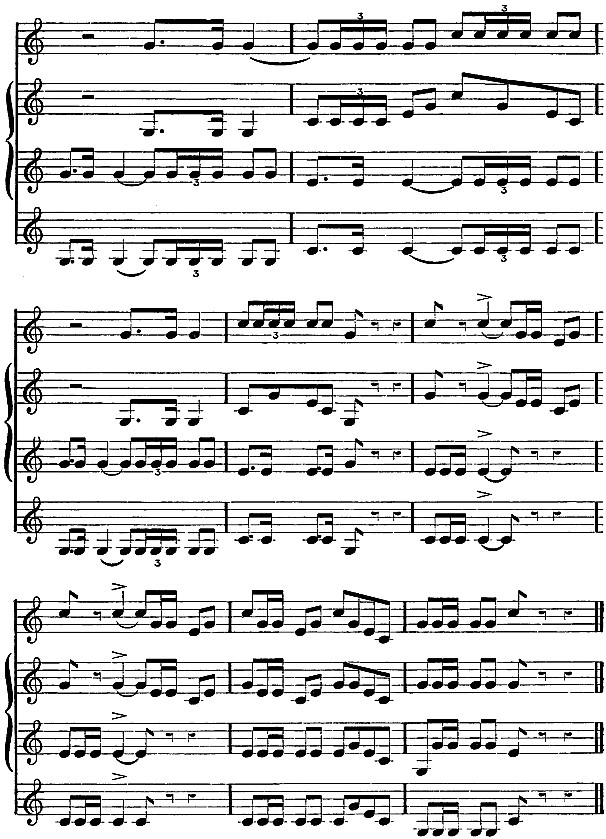

These flourishes as used in the Ritual are the Tekiah (T'qia̓h)

![]() Shebarim (Sh'bharim)

Shebarim (Sh'bharim)

![]() and Teruah (T'rua̓h)

and Teruah (T'rua̓h)

![]() usually a tongued vibrato of the lower note. The Gedolah

usually a tongued vibrato of the lower note. The Gedolah

![]() is the great Tekiah concluding the flourishes. The shophar is usually

a ram's horn flattened by heat, the bore being a cylindrical tube

of very small calibre, which opens into a kind of bell of parabolic

form. The notes here given are those usually produced, but from

the empirical formation of the embouchure and a peculiarity of the

player's lips, an octave is occasionally produced instead of the

normal fifth. The fundamental, if obtained, is not regarded as a true

shophar note. Through the mediation of a friend, whose assistance

has enabled me to gather this information, I have heard the shophar

flourishes played by a competent performer, and am enabled to give

an authoritative notation of these strangely interesting historical

phrases, for the final correction of which I have to thank the Rev.

Francis Cohen.

is the great Tekiah concluding the flourishes. The shophar is usually

a ram's horn flattened by heat, the bore being a cylindrical tube

of very small calibre, which opens into a kind of bell of parabolic

form. The notes here given are those usually produced, but from

the empirical formation of the embouchure and a peculiarity of the

player's lips, an octave is occasionally produced instead of the

normal fifth. The fundamental, if obtained, is not regarded as a true

shophar note. Through the mediation of a friend, whose assistance

has enabled me to gather this information, I have heard the shophar

flourishes played by a competent performer, and am enabled to give

an authoritative notation of these strangely interesting historical

phrases, for the final correction of which I have to thank the Rev.

Francis Cohen.

Bronze horns are also of very ancient use, and existing specimens, chiefly of Celtic or Scandinavian origin, are frequently richly ornamented. Their employment appears to have been for war, for hunting, and the feast. In more recent times, their possession has been attached to feudal customs, as the transfer and holding of land, and at last through the growth of large cities they became associated, as the interesting Dover and Canterbury Horns (Plate I.) were, with municipal customs. Horns were sounded for the curfew, and an especially characteristic example of such horn-blowing is a dramatic feature introduced by Wagner at the close of-xiv- the second act of his Shakespearean Music Drama, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Earl Spencer's very beautiful ivory horn or Oliphant (Plate VII.) was most likely intended for the chase. Of other simple wind instruments depending upon the player's lips, the ancient Roman Lituus and Buccina (Plate XXXVII.) are eminently interesting examples. The Roman horse-soldier bore the Lituus, so called from its resemblance to an Augur's staff, and the foot-soldier, the Tuba and circular Buccina. They marched to the sound of instruments, the tones of which were produced exactly as they are in the trumpet and bugle we are familiar with—from the vibration of the lips, varying with the pressure and force of wind within a cup-like mouthpiece. These tones, being from natural harmonics, are not different now from what they were when Cæsar first landed in Britain, or, indeed, the first notes from a horn that were ever produced. Of modern brass instruments drawn, there are two possessing historical interest—the Cavalry Bugle in Plate XXXVI. which belongs to H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, and sounded the moonlight charge of the Household Cavalry at Kassassin in Egypt, and a trumpet that sounded the famous charge at Salamanca. By way of contrast there is the silver State Trumpet (Plate XXXV.), one of ten that were employed in peaceful service for Her Majesty Queen Victoria during her long and gracious rule.

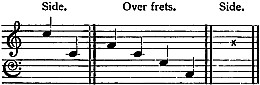

The Syrinx, or Pan's pipes, has been already referred to, and may be described as composed of a certain number of flute-pipes, the sounds being produced by directing the breath against the sharp edge of each pipe. Plato considered the use of the Syrinx lawful in rural life, but he condemned the more richly-toned flute. The shepherd's pipe belongs to the Oboe family, inasmuch as it is sounded by means of a reed, an artifice of great antiquity. We do not know anything about its early development, but Chaldean shepherds played upon similar instruments nearly 2000 years ago, while watching their flocks by night, and Neapolitan peasants still play, in memory of those shepherds, upon similar rustic reed pipes, the Zampogna or Cennamella, for nine days preceding the great Church festivals of the Madonna Immaculata and the Nativity. These primitive oboes must be of very great antiquity. It is probable,-xv- the shepherd's pipe was at first a smaller reed inserted in a larger one, or the larger one was slit for a reed vibrator, as boys cut them now. The lowland Scotch shepherd's pipe is made of horn, the cover for the reed being also horn. The principle of a reservoir of air to furnish a supply for pipes, the primitive conception of the organ, was known to the Romans and the original form of bagpipe was the Tibia Utricularis. In course of time no instrument was more popular throughout Europe than the bagpipe. Varieties of it (Plates IV. and V.), including specimens of the Cornemuse and Musette, show the modern forms of this now despised instrument. The principle of the drone-bass, common to the Bagpipe and Hurdy-gurdy (Plate XXX.), must have been of universal acceptance in Europe before the knowledge of counterpoint became general. The peculiar scale of intervals of the great Highland bagpipe adds much to what is characteristic in the tones of the instrument. Its divergence of intonation may be due to the incompetency of the instrument-maker to determine the true distances for boring the lateral holes. If so, we must be lenient with him, for even now, with our perfection of mechanical appliances, the boring is not above question. But, of course, accuracy is more nearly attained than it has been at any previous time, even the earlier years of the present century. Another and a more attractive hypothesis for the Highland bagpipe scale, derives its mean or neuter thirds, neither major nor minor, from a Syrian scale, still found at Damascus, and attributes its presence in Europe to the pipes having been brought, like rebecs, rebabs, and lutes, by returning Crusaders, whose wondering admiration for Saracenic Art is well known. It seems scarcely likely that the music would not also have touched them, possessed as it was of a special charm due to ages of Persian and Arabic cultivation. There is abundant evidence in the present day as to the favour shown in the East for those indefinite thirds, which may originate from an ideally equal scale of seven intervals of the same extent, such as the Siamese accept, instead of five of larger and two of smaller, such as obtains with us; or they may be due to an alteration in tuning the lute, attributed by the Arabian philosopher Al Fārābi to a lutenist named Zalzal, who changed one of the frets of the lute to-xvi- obtain it. It is not necessary to do more than refer to the peculiarities of these Eastern divisions of the scale or the possible survival of one in the Highland bagpipe; the inquirer will find information carried to the limits of our present knowledge in Recherches sur l'Histoire de la Gamme Arabe, par J.P.N. Land (Leyden, 1884), and On the Musical Scales of Various Nations, by Alexander J. Ellis, a paper read before the London Society of Arts, and published in that Society's Journal, 27th March, 1885. It is sufficient to add that while the neuter third remains a favourite interval in some Eastern countries, as far as investigation has been possible it is known in Europe only among the mountains and in the bagpipe music of the Scottish Gael. The latest development of flute and reed pipes is to be found in the flute, oboe, clarinet, and bassoon of the modern orchestra. Plates XXXVIII. and XXXIX. represent instruments that have been the immediate precursors of or are identical with the instruments named. One, the Dolciano or Tenoroon with a clarinet reed, is of unusual importance as possibly anticipating the invention of the Saxophone. It would require a volume to describe the transformations wind instruments have undergone in the present century, particularly that of the Flute by the late Theobald Boehm. The clarinet and oboe have been less altered because the completely refashioned instruments that have been intended to replace them, the saxophone and the sarrusophone, have not retained those special qualities of tone colour required for the palette of the orchestral composer. But for the brass instruments there has been as yet no halting-place. Furnished early in this century with keys, that important revolution was succeeded by another no less complete—the introduction of the valve or piston system, the gain of which, now almost universally acknowledged, has been largely taken advantage of by Wagner and other recent composers.

The familiar Organ is shown in the Positive and Portable organs (l'orgue positif et portatif), small instruments representing reduced front portions of the Montre, the visible speaking pipes of the mediæval church organ, which was neither more nor less than a large mixture register; that is to say, each key when put down-xvii- sounded the octave, twelfth, super-octave, and other notes simultaneously with the fundamental note. The movement of the Plain Song, or of any melody with this harmonic structure upon it, was in progressions that no modern musically trained ear could tolerate. Not more than one key of the large church organ could, however, be put down by either hand, as the keys were as broad as the palm, and to press one down required an attack with the player's fist. But the keys of the Portable organ, a processional instrument, were narrow—one hand manipulating the bellows while the player touched the keys with the other. The positive was a chapel or chamber organ, intended to be stationary, and also with narrow keys, admitting of the grasp of an octave. The key-board shown in the Van Eyck St. Cecilia panel of the famous altar-piece at Ghent—the Adoration of the Lamb—has already the complete arrangement of chromatic keys, exactly as in our modern key-board instruments. The date of this panel could not have been later than A.D. 1426. Among the numerous portable organs depicted in paintings of earlier date, the addition of the ficti, as the chromatic notes were called, excepting perhaps the B flat, or the B flat and E flat, does not appear. The B flat, however, was not a chromatic, but an essential note in the ecclesiastical scale. Another early instance in a painting by Hans Memling, preserved in the Hospital of St. John at Bruges, is subsequent in date to the Ghent altar-piece, but is still within the fifteenth century. The chromatic keys are here put farther back than in our usual key-boards, as they were also in the fourteenth-century Halberstadt organ. The fourteenth-century portable organ drawn in Critical and Bibliographical Notes on Early Spanish Music, by Don Juan F. Riaño (Quaritch, London), 1887, p. 127, shows the B flat only, and figured as an upper key, apparently not raised, but level with the natural keys, which agrees with contemporary representations of the instrument by Fra Angelico. The Portable Organ (Plate XIII.) here drawn is of comparatively late date, these small instruments having remained in use until after the Reformation. The Positive Organ (Plate XI.) is of earlier date, and is so far developed as to have registers and drawstops to govern them; in this example they are an octave apart, but an unimpeachable authority, Praetorius, speaks of a register in a-xviii- positive organ a fifth from the fundamental one! Our ancestors were evidently not affected by a progression of fifths as we are.

The Regal (Plate XII., and as Bible Regal, Plate XIII.), was equally a part of the old church organ taken out and played by itself. It is the beating-reed register, so called because the reed overlaps its frame, and when vibrating produces a more or less jarring or strident quality of tone. As the free reed does not touch its frame it is less harsh in quality. But the latter variety of reed is of very recent introduction into Europe. Strangely enough, it has been taken from a Chinese mouth organ of great antiquity, the Shêng! This Chinese instrument has seventeen sounding pipes, each furnished with a small brass or copper free reed, and is usually sounded by drawing in the wind, not blowing, being in this respect followed by the present American organ. The adoption in Europe of the principle of the Shêng was due to an application of it at St. Petersburg by an organ-builder named Kirsnick, about 1780, and the enthusiastic advocacy of the Abbé Vogler. (Sir George Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Art. "Vogler," by the Rev. J.H. Mee.) From it are derived our accordion and concertinas, harmonium and American organ, as well as sundry musical toys. The Shêng is drawn in Plate XLIV. It is familiar in Japan, with some variation, as the Sho, and a larger instrument on the same principle used in the Lao States of Siam is there called Phān. In nearly all instances it is retained as a solo instrument. The Siamese musicians, whom H.M. the King of Siam very generously sent at his own expense to the London Inventions Exhibition, and who performed there, in the music room and in the Royal Albert Hall, had among them a Phān player, who always played alone.

Harp-like instruments, but with resonance bodies beneath the strings, appear in their oldest, but a yet highly developed form, in the Chinese Ch'in, or Scholar's Lute. The Japanese Sono Koto (Plate XLVI.) is derived from a modification of the Ch'in, known in China as the Sê, the difference being that while the Ch'in has fixed bridges and a system of stopping, the Sê, and consequently the Koto, have movable bridges and no stops. The Koto is tuned according to the five notes in the octave system that prevails in Japan and, with a-xix- difference in the division of the scale, in China, named, by the late Carl Engel, pentatonic. The player kneels upon the ground beside the instrument, and resting or sitting upon his heels, touches the shorter lengths of the strings, as divided by the bridges, with plectra on the thumb and first two fingers, but, at the same time, makes constant use of the longer lengths to press upon or relieve the strings so as to alter the tension and produce intermediate tones. The Koto drawn is one of great beauty. The four characteristic popular instruments of Japan are the Koto, the Siamisen, the Biwa, and the Kokiu (see Plates XLVI. and XLVII.) The Siamisen is allied to the Chinese San-hsien and the Biwa to the Chinese P'i-p'a (see Plate XLIV.). The very curious Siamese Ta'khay, or crocodile (Plate XLIII.), is of the same genus as the Koto and Ch'in, but has been changed into its present form by Siamese ingenuity, which has found a rich field for employment in the decoration of musical instruments, the Siamese, in this respect, bearing the palm in the East, as the Italians have done in the West.

As to the principle of the harp or rather of the psaltery embodied in these parallel strung instruments, it differs from the Egyptian and Assyrian conceptions, which placed the resonance bodies of their harps in a curved disposition, the one below, the other above the strings. Greek lyres had their sound bodies directly underneath the strings. The origin of the Greek lyre is unknown, the name not being Hellenic; it may possibly have been Asiatic, but was not originally Egyptian. It would solve an interesting problem could we know what was the Hebrew kinnor, the harp of the Authorised Version, the most prominent stringed instrument occurring in the richest collection of sacred poetry the world has known, the Hebrew Psalms. Dr. Stainer, who has made a complete analysis of the text, has not got beyond conjecture. It is only certain that the kinnor was a stringed instrument. It is recorded that it was made by Tubal Cain, played upon by Laban the Syrian and by the shepherd boy David. It is mentioned in the Book of Job, and the captive Hebrews in Babylon hung their kinnors on the trees. Whether with or without finger-board, whether a lyre, a trigonon, or a harp, its tones had power over the feelings to produce similar-xx- effects to those with which music touches us now, as surely as that the physical law of sympathetic vibration was as active then in Syria, or by the waters of Babylon, as it is to-day in Edinburgh or London.

The forms of Harp drawn in this work (Plates II., III., and XXXIV.) differ from the ancient harps which had no forearm or front pillar, and could therefore have endured but little strain. Yet an old Celtic monument represents a harp-like instrument with this Eastern peculiarity. The extremely interesting Celtic harps here drawn, the Queen Mary and the Lamont harps, have forearms or bows of a constructive strength that would, with the rest of the framing, bear a considerable draught of wire. The Celts and Germanic nations appear to have long cultivated the harp. The word itself is German, but the Celtic people of these islands have different names for it, according to whether they are of the Gaelic or Cymric branch. The common Gaelic name was Cruit (Crot), which comes from a root meaning vibration, but this name has been superseded by Clarsach, which is derived from the resounding board. The Welsh name, Telyn, implies strain or tension. It must be remembered that the triple-strung Welsh Harp is a comparatively modern instrument, and so also is the Welsh Crwth (Plate XXIV.), in the only form in which it has come down to us, as a bowed instrument with extra strings off the finger-board, a peculiarity belonging to the theorbo and lyra-viol. The origin of the Crwth would appear to have been the classical lyre submitted to changes that had come with time, and, as the Continental Rote or Rotta, it was a very common form of instrument in the Middle Ages. It had to give way before Eastern stringed instruments, such as the rebec and lute. The Vína (Plate XL.) is the characteristic Hindu stringed instrument, and has a great antiquity attributed to it. The string is theoretically said to be divided into twenty-two small intervals in the octave, of equal extent, called s'ruti, by which the tones and semitones are determined; but recent observation shows that the Hindus are satisfied with a division of twelve semitones in the octave—in fact, our chromatic scale. Smaller intervals are only used for grace notes, and are produced by deflecting the string. Gourd resonators have been mentioned as of probably very ancient use, and the employment of sympathetic-xxi- strings, in vogue in Europe only in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, may be added as also of remote origin in India. The Hindus and Persians have both used gourds attached to the Vínas and Sitárs (Plate XL.) for resonance. In Southern India, where the use of the original Hindu Vína prevails, although the scale now used is at least heptatonic, there is still a leaning towards pentatonic forms of melody. The accordances are in fourths or fifths and octaves. The Sitár of Northern India and greater use of the interval of the third may be attributed to Persian introduction; but throughout India, and more intensely in the south, music is felt as a poetic art, and has a development in its own way, that still remains unrecognised in Europe, although we now have scholars from whose researches and zeal this ignorance may be in time, at least partially, dispelled. Music is acutely felt as a means of expression in India unknown in China or among the Indo-Chinese races.

The vexed question of the introduction of the bow to stringed instruments, upon which the most eminent authorities are not yet disposed to agree, is one that needs only to be mentioned here. Whether of Asiatic or European introduction, it would appear at first to have been only one of the ways by which sounds could be drawn from strings, and that it gradually became victorious over the plectrum, with instruments of the viol kind, which thereby gained a great development. It is even now permitted to use the fingers to a bowed instrument in the pizzicato of the violin and violoncello.

The Psaltery was a plectrum instrument derived from the Arab Qanūn; it is rarely absent in paintings of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries where musical instruments are represented. The same instrument, increased in the weight of stringing to resist the impact of hammers, is the familiar dulcimer, which, like the hurdy-gurdy and the bagpipe, has seen better days. What was once thought of the dulcimer is shown by the painting that adorns the one drawn in Plate XVII. It seems almost vexatious that we do not know who first adjusted a key-board to a psaltery, and thus constructed a spinet. It was not earlier than the fifteenth century, but the name of the meritorious inventor has not come down to us, or where he lived. It seems most likely from the earliest name, clavicymbalum, being Latin,-xxii- that the instrument was first contrived in a monastery. But we have, fortunately, in Plate VI., in an upright Spinet or Clavicytherium, one of the earliest existing specimens of the kind. It is a question not yet decided whether this rare instrument is of South German or North Italian origin. The reason is given for the former attribution in the description accompanying the drawing. Yet the Mantegnesque feeling is so strong in the decoration of the interior that we pause before accepting the Swabian origin as conclusively settled.

Queen Elizabeth's Virginal (Plate VIII.), which has at last found a resting-place in the splendid collection of old musical instruments in South Kensington Museum, is not a virginal proper, but apparently an Italian spinet. It has been gloriously decorated, and it awakens an intense feeling of interest to reflect upon who may have played upon it and who may have stood by and heard the pleasing tones of an instrument once so much cared for. The Spinet was at that time beginning to gain upon the Lute. The power to perform part music with two hands, which the lute-player, having only one hand to stop with, could but imperfectly approach, was an endowment there was no gainsaying. We may see the contemporary prosperity of the great Venetian republic in the lutes, theorboes, and spinets that are now dispersed throughout Europe; and almost at the same time such instruments as the Ruckers Virginal (Plate XVIII.) and the Ruckers double Spinet (Plate XX.) bear witness for Antwerp as to the favour successful commerce has ever shown the Arts. The great English spinet-makers belong to the second half of the seventeenth century, and the first quarter of the eighteenth. Among them, Stephen Keene was in the foremost rank, and his work will still bear examination in the spinet drawn in Plate XXII. The eighteenth century was marked by a great advance in making the expressive Clavichord, which although perhaps the oldest key-board stringed instrument, had always had to give way before the louder and more graceful-looking spinet. Plate XXXII. displays the clavichord at its culmination, and the Chinese Lac decoration shows that, in this specimen at least, its intimate charm of tone, capable, as no other key-board instrument was, of the vibrato, was deemed worthy of an elaborate setting.

The latest improvements of which the Spinet genus was capable,-xxiii- including the Venetian Swell, are founded in the Double Harpsichord (Plate XXXIII.) made by Burkat Shudi (Burkhard Tschudi) and John Broadwood in 1773, for the Empress Maria Theresa. It is a question whether some musical instruments of special character should not be retained for use or be made again when that character cannot be expressed by any existing instrument. If this were done the Viola d'Amore, the Viola da Gamba, the Harpsichord, the Clavichord, and the old German flute, in the last instance with some concession to defective intonation, would find their places and be sometimes heard with pleasure.

With regard to the selection and drawing of the subjects represented in the following Plates, it may be mentioned that the present writer had the important advantage of a free use of the remarkable Loan Collection of Musical Instruments exhibited at the Royal Albert Hall, Kensington, in 1885. Extraordinary facilities for drawing the selected subject were obtained through his official connection with the Music Division of the Exhibition, and through the gracious permission of the respective owners of the instruments, including H.M. the Queen, H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, H.R.H. the Siamese Minister, and the Japanese Commission. He has also utilised some sketches of instruments selected and drawn by Mr. Robert Glen of Edinburgh, to whom belongs the credit of originating the idea of this publication.

The pictorial representation of the subjects was undertaken by Mr. William Gibb, and the plates in this volume have been successfully reproduced from his admirable drawings. The book gains, moreover, a special and unexpected value from the fact that no illustrated Catalogue Raisonné was compiled of the Music Loan Collection of 1885, which combined the most beautiful and valuable Manuscripts, Books, Paintings, etc., as well as Musical Instruments, which were ever brought together. There were no funds available, nor was there time to permit of such a work being carried out before the Collection was dispersed. By those who deplore the loss of that opportunity, the illustrations of this work may be regarded as a valuable memento of that unrivalled Collection.

A.J.H.

JEWISH SHOPHAR.

BEAUTIFUL horns of hammered and embossed bronze belonging to the Corporations of Canterbury and Dover. The right-hand one is from Dover, where it was formerly used for the calling together of the Corporation at the order of the mayor. The minutes of the town proceedings were constantly headed "At a common Horn blowing" (comyne Horne Blowying). This practice continued until the year 1670, and is not yet entirely done away with, as it is still blown on the occasion of certain Municipal ceremonies. The motto on this horn is:—

JOHANNES DE · ALLEMAINE · ME · FECIT ·

preceded by the talismanic letters A·G·L·A, which stand for the Hebrew

אַתָּה גִּבּוֹר לְעוֹלָם אֲדֹנָי

and mean, "Thou art mighty for ever, O Lord!" The horn, which is 31¾ inches long, with a circumference at the larger end of 15½ inches, is of brass, and is deeply chased with a spiral scrollwork of foliage chiefly on a hatched ground. The inscription is on a band that starts four inches from the mouth and continues spirally. The maker's name is now nearly effaced, but the inscription shows that he was a German, and the date is assigned to the thirteenth century. A paper in the Antiquary (vol. 1. pp. 253-55), written by the late Llewellyn Jewitt, F.S.A., of which some use has here been made, states that there are on the obverse of the oldest Seal of Dover, said to have been made in 1305, two horn-blowers in the stern of a ship, each blowing a horn similar to this example.

The left-hand Burgmote Horn belongs to the Corporation of Canterbury, and records of its use for calling meetings of the Corporation are extant from 1376, down to the year 1835. The chord measurement of the arc of this Horn is 36 inches.

The antiquity of horns, whether natural or of metal, as instruments for sounding is well known. Their employment in some-2- religious services points to customs that were already old when the oldest historical monuments we possess were raised. The Hebrew formulary upon the Dover horn reminds us of the Jewish Shophar, referred to particularly in the Introduction (page xii)—a ram's horn, usually straightened and flattened, which is not only the solitary ancient musical instrument actually preserved in the Mosaic ritual, but is the oldest wind instrument known to be retained in present use in the world. It is still sounded by Jews on the New Year and on the Fast of the Day of Atonement.

In England, horns have been used amongst the various methods of transferring inheritances. They were adopted for instruments of conveyance either in Frank Almoigne, in Fee, or in Serjeantry, and from this cause have been often preserved.

THIS venerable instrument, the least impaired Gaelic Harp existing, is known as Queen Mary's Harp, and belongs to C. Durrant Steuart, Esq., of Dalguise, near Dunkeld. Of Gaelic Harps we can only reckon seven that may be dated earlier than the eighteenth century, the oldest being the Queen Mary and Lamont Harps, now in Edinburgh, and the harp named after Brian Boru (Boromha), preserved at Trinity College, Dublin; these three dating anterior, perhaps long anterior, to the fifteenth century. The Queen Mary and Brian Boru Harps are the two most nearly resembling one another. They are small, the Queen Mary Harp being only 31 inches high and 18 inches from back to front. They were played resting upon the left knee and against the left shoulder of the performer, whose left hand touched the upper strings. The comb is from 2½ to 3¼ inches high. It is inserted obliquely in the sound chest, and projects about 14 inches. The sound chest, in shape a truncated triangle hollowed out of the solid, is 5 inches wide at the top and 12 at the bottom, the depth being 4½ inches. The bow or forearm measures in a straight line 27½ inches, the chord of the arc of the inner curve being 23 inches. The front of it is expanded so as to form a convenient hold for the hand; it tapers slightly above and below, and ends both ways in boldly carved heads of animals of a symbolical character. The strings were of brass and twenty-nine in number, and were made to sound by the player's finger-nails, which were allowed to grow long for the purpose. The Queen Mary Harp has had another (the lowest) string attached later. This string measured 24 inches, the highest treble string 2½ inches; what compass the harp had it is now impossible to decide, but, following the tradition of Irish harpers, the accordance was based upon the old diatonic scale-4- with the minor seventh, sometimes replaced by the major seventh. We learn by the lectures of the late Dr. Eugene O'Curry that the ancient Irish had three modes in their music, the "Crying," the "Laughing," and the "Sleeping." Whatever these tunings were, and probably the Highland Scotch had the same, their secret is locked up in the wood of the harps that once responded to them. In this, and frequent instances in these Plates, the instruments are not represented as strung. It is impossible to keep old instruments with that strain continually upon them, and to string them only to have them drawn would have been attended with many disadvantages.

The Queen Mary Harp has a history based upon the family tradition of its former owners, the Robertsons of Lude in Perthshire, but in passing through several mediums it has become unreliable. It was long believed to have been Mary Stuart's, and, according to the Lude tradition, it had golden and jewelled ornaments attached to the right upper circle of the bow including her portrait and the Royal Arms of Scotland, which were stolen about 1745. The historical inquiry containing the information respecting this Harp is by John Gunn, F.S.A.E., and was published in 1807, under the auspices of the Highland Society. A paper read before the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland by Mr. Charles D. Bell, F.S.A. Scot., and published in their Proceedings for 1880-81, from which I have made extracts, thoroughly sifts the facts that can be deduced from it, and which may be thus accepted:—Queen Mary of Lorraine, the mother of Mary Queen of Scots, gave this harp to Beatrix Gardyn of Banchory, Aberdeenshire. Beatrix Gardyn was married to Finla Mór, and from this marriage the family of Farquharson of Invercauld, in Braemar, is descended. Finla Mór was killed at the battle of Pinkie in A.D. 1547. John Robertson, the eleventh in succession to Lude, married Margaret Farquharson, the only daughter of the then Laird of Invercauld. He was fifty-six years in possession of Lude, and died in A.D. 1730. The last performer on this ancient harp was his great-grandson, General Robertson, who lent both the Lude harps for examination by the Highland Society in 1805. It appears to have been General Robertson's belief that this harp was acquired for Lude by the marriage of John, the eleventh Laird, with a direct descendant of Beatrix Gardyn, but, following Burke's genealogy of the family, it would appear that it came to Lude-5- with Beatrix Gardyn herself, on her marriage with John, seventh Laird. The Robertsons of Lude are now, in the direct line, extinct, but the family of Gardyn is represented by Francis Garden-Campbell, Esq., of Troup and Glenlyon.

Queen Mary's and the Lamont Harps are on loan (1887) in the Museum of the Scottish Society of Antiquaries, Edinburgh, and it may be mentioned that when exhibited in the Music Loan Collection, South Kensington, the former was insured for £1500 and the latter for £1000.

THE Highland Harp, known as the Clarsach Lumanach, or Lamont Harp, belongs to the owner of the Queen Mary Harp, C. Durrant Steuart, Esq., of Dalguise, Perthshire. Both harps were sent to Edinburgh in 1805 by General Robertson of Lude, who owned them at that time, at the request of the Highland Society, and a book was published in 1807 under the patronage of the Society, entitled An Historical Enquiry respecting the Performance on the Harp in the Highlands of Scotland from the earliest times until it was discontinued about the year 1734, by John Gunn, F.A.S.E., in which they were described, and a version of the family tradition of Lude given, compiled from letters written by General Robertson, now unfortunately not forthcoming. Although Mr. Gunn's story of the Queen Mary Harp is coloured in order to attach the gift of it to Mary Queen of Scots, that of the Lamont Harp appears to be according to the simple statement of the original narrator, and may be thus epitomised from a paper published in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 1880-81, by Mr. C.D. Bell, F.S.A. Scot.: "The family tradition of Lude alleges that for several centuries past the larger of these harps has been known as the Clarsach Lumanach or Lamont Harp, and that it was brought from Argyllshire by a daughter of the Lamont family on her marriage with Robertson of Lude in 1464. It is said to be the older of the two. If the probably quiet place in the house of Lude be considered, and that it was likely to be valued and cared for there, also that the repairs appear to be of very old date, then the Clarsach Lumanach may have already, before 1464, been an old broken and mended instrument with a pre-traditional story we can never hope to hear." From Burke's Landed Gentry, "Lineage of the Robertsons of Lude," we learn that Charles, fifth Laird of Lude, married Lilias, daughter of Sir John Lamont of-8- Lamont, chief of that clan, and that "it was with this lady, Lilias Lamont, there came one of those very curious old harps which have been in the family for several centuries."

The drawing shows the harp as it is, and may have been for centuries, but Mr. M'Intyre North, in his Book of the Club of True Highlanders, London, 1880, proposes, by the substitution of a longer bow or forearm, to bring this harp to the lines of the Queen Mary Harp and that of Brian Boru. It is sufficient here to observe that the present bow agrees in measurement with that of the Queen Mary and Brian Boru Harps, and is certainly very old. Against its originality is the fact that the Lamont Harp appears to have always had thirty-two strings, and for the three extra treble strings a longer bow ought to have been required.

The extreme length of the Lamont Harp is 38 inches, and the extreme width 18½ inches. The sound chest, as with other ancient harps, is hollowed out of one piece of wood, but the back has been in this instrument renewed, although probably a long time ago. The sound chest is 30 inches long, 4 inches in breadth at the top, and 17 at the bottom. The comb projects 15½ inches. The broken parts of the bow are held together by iron clamps.

As to the musical effect of a Gaelic or Irish harp when well played, the impression of such a performance recorded by Evelyn in his Diary is worth quoting. He says: "Came to see me my old acquaintance and the most incomparable player on the Irish harp, Mr. Clarke, after his travells. He was an excellent musitian, a discreete gentleman, borne in Devonshire (as I remember). Such musiq before or since did I never heare, that instrument being neglected for its extraordinary difficulty; but in my judgment it is far superior to the Lute itselfe, or whatever speakes with strings." Elsewhere he speaks of a Mr. Clark (probably the same performer) as being from Northumberland, and says of the instrument, "Pity 'tis that it is not more in use; but indeede to play well takes up the whole man, as Mr. Clark has assur'd me, who, tho' a gent of quality and parts, was yet brought up to that instrument from 5 yeares old, as I remember he told me."

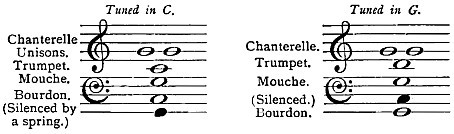

THE Bagpipe (Cornemuse and Musette) and the hurdy-gurdy (Vielle) were, after the thirteenth century, banished to the lower orders, to the blind and to the wandering mendicant class. But polite society in France resumed these instruments again in the modern Arcadia of Louis XIV. and XV.—not the Cornemuse, it is true, for that has ever remained a rustic instrument, as may be observed in the glowing pages of George Sand's Les Maîtres Sonneurs. The Cornemuse, as formerly used in France and the Netherlands, is derived from the Roman tibia utricularis, and is provided with a bag, inflated by the mouth of the player, while a double reed is attached to the melody pipe or chanter. In recent times it is furnished with two drones—le grand, et le petit bourdon, which are made to sound also by reeds, and an octave apart. The Musette, which has practically displaced the Cornemuse in use, is a softer, sweeter instrument, with a double reed to a very narrow cylindrical pipe, the effect of which is to make it sound like a stopped pipe, an octave lower. This accounts for the short appearance of the instrument. The drones, as it will be seen, are on a more artificial principle than those of the Cornemuse. Another difference is that the bag is always inflated by a small pair of bellows worked by the player's left arm. The Northumbrian and modern Irish bagpipes are also inflated by means of bellows, and have taken the place in northern England and Ireland of the large bagpipe inflated with the mouth which is now regarded as distinctly Highland Scotch. The Musette in the drawing is made of ebony and ivory with keys of silver, and has a bag adorned with needlework. The small bellows are made of walnut inlaid with marqueterie. The melody pipe (le grand chalumeau) is bored with eight finger-holes, and fitted-10- with seven keys for the chromatic notes. To the left of the melody pipe or chanter there is a small flask-shaped pipe furnished with six keys (le petit chalumeau) containing the additional compass upwards. There are four drones contrived in a barrel pierced with thirteen bores in juxtaposition, of from 5 to 35 inches in length. The barrel is furnished with five stops sliding in grooves and regulating the length of the apertures for tuning the drones. Bach's musettes, the alternatives to his gavottes, always imply a drone bass.

It will be observed the Cornemuse here drawn has a chanter and drone fixed parallel in one stock. The former has eight finger-holes, and, like that of the Scotch bagpipe, has a vent-hole not fingered. The bag covered with crimson plush is furnished with a short mouthpiece near the neck for the purpose of inflation.

The Calabrian Bagpipe or Zampogna is a rudely carved instrument of the eighteenth century. It has four drones attached to one stock, hanging downwards from the end of the bag: two of them are furnished with finger-holes. The reeds are double like those of the oboe and bassoon. The bag is large; it is inflated by the mouth and pressed by the left arm against the chest of the performer. The Zampogna is chiefly used as an accompaniment to a small reed melody pipe called by the same name, and played by another performer. The quality of the tone produced is not unpleasing. It has five holes only, and consequently the seventh of the scale is absent, but this can be easily got by octaving the open note of the pipe and covering part of the lower opening of the chanter with the little finger.

The Musette, Zampogna, and Cornemuse here shown are from specimens belonging to Messrs. J. & R. Glen, Edinburgh.

IN continuation of the Bagpipes, this Plate shows, in the instrument with a crimson bag, the modern Northumbrian Bagpipe. The four drones, proceeding from one stock, are mounted with brass and ivory. The chanter, or melody pipe, has seven finger-holes in front and one behind; also, seven brass keys. As there is only one hole open at a time when the instrument is played, this manner of playing is called close fingering. The chanter and drones are furnished with stops at the ends. The instrument with a blue bag is the ancient Northumbrian bagpipe. It has three drones, mounted with silver and ivory, of different sizes; the longest being tuned an octave and the middle one a fourth lower than the shortest. The chanter is of ivory, with seven holes in front and one behind. The large bagpipe with a green bag is the Lowland Scotch. It is of boxwood, with three drones placed in one stock. The two shorter drones sound in unison, the long one an octave lower, the same as in the Highland Bagpipe. They are mounted with carved horn. The chanter has seven finger-holes and a vent-hole, also the same as in the Highland Bagpipe, with which the Lowland agrees in fingering and other particulars, except that it is inflated by bellows attached to the bag by a short blow-pipe, a peculiarity that it has in common with the other Bagpipes in this Plate. The bellows of the modern Northumbrian Bagpipe are also drawn.

The Bagpipe is, as Mr. Henri Lavoix has justly said in his La Musique au Siècle de Saint Louis, the organ reduced to its most simple expression. It is of great antiquity, and in the Middle Ages was generally popular in Europe. It was as well known in England as in Scotland, in France as in Italy and Germany. Shakspeare makes out Falstaff in Part I. of Henry IV. to be as melancholy as a lover's lute or the drone of a Lincolnshire Bagpipe. If we may-12- judge by the peculiar scale of the Scotch Bagpipe, it would appear almost certain that the instrument, in its modern forms, has come from the East, and was most likely brought by the Crusaders. This would not of course apply to the ancient principle of a pipe and air reservoir, which is traced back to the Romans, but to the boring of the finger-holes of the chanter, the reed pipe by which the melody is played. By their position and size the intervals are so regulated that the thirds are neither major nor minor, but give a neutral or mean interval that is neither the one nor the other. This mean third, of a tone and three-quarters, has not been elsewhere observed in Europe, but in the East, in Syria and Egypt, and in other parts, it is of common occurrence, and gives a peculiar character to the music, not to be explained, but felt. An historical origin of the mean third is to be found in Mr. A.J. Ellis's paper "On the Musical Scales of Various Nations" (p. 498), published in the Journal of the Society of Arts, London, March, 1885. Modern Bagpipes that have keys are, of course, different.

As to the antiquity of existing Bagpipes, Messrs. Glen of Edinburgh own one, carved with the initials R. Mc.D., and the Hebridean galley, that bears the date of 1409. But this is not considered to be the oldest existing, as the M'Intyre pipe, belonging to N. Robertson M'Donald, Esq., of Kinlochmoidart, is reputed to have been played at Bannockburn. Possessing one drone only, it has the peculiarity of two vent-holes, instead of one, on each side of the chanter to accommodate a right or left handed player; in either case one hole is temporarily stopped. Messrs. Glen's pipe has two drones set in one stock. The name M'Intyre, by which Mr. Robertson M'Donald's pipe is distinguished, is derived from the hereditary pipers of the Chiefs of Menzies and Clanranald. Both these ancient Bagpipes are figured in Mr. M'Intyre North's Book of the Club of True Highlanders. The Bagpipes here drawn are from specimens belonging to Messrs. J. & R. Glen, Edinburgh.

THIS singularly interesting and rare key-board instrument, now the property of Mr. Donaldson, belonged to the collection of Count Correr of Venice. There is no maker's name or any date upon the instrument, which is of the kind named Clavicytherium by the earliest writer on musical instruments, Virdung (Musica getutscht und auszgezogen, Basle, 1511), who gives a drawing of one. It is in fact a spinet, set upright. The internal decoration, as old as the instrument itself, may be North Italian or South German, authorities differ, but a piece of paper pasted over a split in the inside of the wooden back, possibly by the maker, proves to be a fragment of a lease or agreement contracted at Ulm, which is in favour of the Swabian origin. The instrument can hardly be of later date than the first years of the sixteenth century, and is probably the oldest spinet or key-board stringed instrument existing. The earliest date that can be given for the introduction of the Spinet must be within the second half of the fifteenth century.

The key-board is of narrow compass—three octaves and a minor

third—from the second E below, to the second G above, middle C,

this note being the ledger-line C between the bass and treble clefs

—an extent about the compass of the human voice, which long

ruled that of key-board instruments. In Virdung's time their compass

was being extended. It is, however, more than likely that the lowest

E key was here tuned down to the still lower C, according to the

so-called "short octave" arrangement, which altered the lowest E,

F♯, and G♯, to make fourths below F, G, and A, instead

of semitones, and thus get deep dominant basses for cadences.

Examination of the-14- plectra or "jacks" of this instrument shows

they were furnished with little tongues of wire, and not quills or

leather, as in later spinet instruments. It is in a painted pine

case, the inside being also painted. An unusual feature of the

interior is the Calvary below the narrow sound-board, in which the

sound holes, judging by the ornament that remains in one, have been

Flamboyant windows. There must also have originally been figures,

perhaps the Transfiguration or the Crucifixion, but there is no trace

of them left. The treatment of the landscape, without other evidence,

nearly determines the epoch when the instrument was made.

—an extent about the compass of the human voice, which long

ruled that of key-board instruments. In Virdung's time their compass

was being extended. It is, however, more than likely that the lowest

E key was here tuned down to the still lower C, according to the

so-called "short octave" arrangement, which altered the lowest E,

F♯, and G♯, to make fourths below F, G, and A, instead

of semitones, and thus get deep dominant basses for cadences.

Examination of the-14- plectra or "jacks" of this instrument shows

they were furnished with little tongues of wire, and not quills or

leather, as in later spinet instruments. It is in a painted pine

case, the inside being also painted. An unusual feature of the

interior is the Calvary below the narrow sound-board, in which the

sound holes, judging by the ornament that remains in one, have been

Flamboyant windows. There must also have originally been figures,

perhaps the Transfiguration or the Crucifixion, but there is no trace

of them left. The treatment of the landscape, without other evidence,

nearly determines the epoch when the instrument was made.

The stand and the paintings on the door, one of which represents a figure holding a mirror and a serpent, are of later date.

The dimensions of this truly remarkable spinet are—height of instrument, 4 feet 10½ inches, and extreme width, 2 feet 3 inches—the key-board being 2 feet wide. The depth of the case at base, 11 inches, diminishes in ascending to 55/8 inches. The table upon which it stands is 2 feet high and 2 feet 11 inches wide.

AN ivory Hunting Horn belonging to Earl Spencer, called Oliphant because it is of ivory, and bearing in the ornament the arms and badges of Ferdinand and Isabella of Portugal, may be regarded as belonging to the first half of the sixteenth century, the strap and buckle being evidently an addition of later date. The beautiful carving, so conspicuous in this horn, is supposed to have been executed by negroes of the West Coast of Africa, who carved ivory for the Portuguese; the arms of Portugal, with the supporters, two angels, holding the shield upside down, often appearing on their work.

Philip II. of Spain married Mary, daughter of the King of Portugal, in 1543. She died in 1545. The carving of the Horn was probably completed within that interval, and when Philip came to England to marry Mary Tudor, he may have brought the horn with him.

Besides the uses named under Burgmote Horns (Plate I.) horns were blown to give alarm in circumstances of danger, to announce the arrival of visitors of distinction, and, as Mr. M'Intyre North informs us respecting the horn in Drummond Castle, for summoning the household and guests to dinner. But horns were not restricted to winding, there were also drinking and powder horns, often beautifully adorned.

The extreme length of this Horn, measuring along the outside of the curve and including the mouthpiece, is 28¼ inches. The greatest circumference is 11½ and the least 2¾ inches.

THIS beautiful Spinet is, in the drawing, placed upon a stand, which served for its support in the Tudor Historical Room appertaining to the Music Loan Collection of 1885. I believe this instrument to be Italian, not Flemish or English, and Italian spinets had no stands or legs, but when required for use were withdrawn from an outer case, as this one would be, and placed upon a table, or some other convenient position. They were even taken in Gondolas, as Evelyn records, for pleasure and the performance of serenades.

We may assume 1570 to be approximately the date of this instrument. The green and gold decoration, including a border of gold two and a half inches broad round the inside of the top, is of later date, perhaps by nearly one hundred years. An indistinct number on the back of the case, inside, appears to be 1660. The Royal Arms of Elizabeth are emblazoned on one end to the left of the key-board; to the right a dove is seen rising crowned. The dove holds in its right foot a sceptre; beneath it is an oak tree. This decoration, whether original in 1660 or the copy of a former one, goes far to support the claim for this Spinet having been Queen Elizabeth's. Her musical taste, inherited from Elizabeth of York, and skill as a performer upon the spinet, need no more than a passing reference.

I characterize the instrument as a spinet because a true virginal is a parallelogram, not a trapeze-shaped instrument. The attribution of virginal is, however, not incorrect as a generic term; for all key-board stringed instruments with jacks were known in England as virginals from the Tudor epoch to that of the Commonwealth.

There are in this instrument fifty quilled jacks (plectra). The natural keys, thirty in number, are of ebony with gold arcaded fronts, and the compass is of four octaves and apparently a semitone, from B to C. But the lowest natural key was tuned G when the instru-18-ment was in use. The semitone keys, twenty in number, begin apparently as C♯, but this was tuned A to continue the "short octave" arrangement. They are very elaborate, being inlaid with silver, ivory, and different woods, each consisting, it is said, of about two hundred and fifty pieces. The painting of the case of the instrument is done upon gold with carmine and ultramarine, the metal ornaments being minutely engraved. The outer case is of cedar, covered with crimson Genoa velvet, and lined inside with yellow tabby silk. There are three gilt locks, finely engraved. The entire case is five feet long, sixteen inches wide, and seven inches deep. Queen Elizabeth's Virginal was bought, at Lord Spencer Chichester's sale at Fisherwick in 1803, by Mr. Jonas Child, a painter at Dudley. The Rev. J.M. Gresley acquired it in 1840. It has since (1887) been obtained from the Rev. Nigel Gresley, for South Kensington Museum.

STRINGED instruments with a finger-board, touched with the fingers or a plectrum, may be divided, as stated in the Introduction, into two principal types: the lute and the guitar, the former with a rounded back, the latter with a flat back. Both are derived from the East. According to this division, the beautiful instrument called Queen Elizabeth's Lute must resign the name of lute and be considered a Guitar. As a wire-strung instrument it belongs to that species of guitar known as Cither, and from the incurvations of the ribs, but that the bridge is not set obliquely, I should be disposed to specialize the instrument as a Pandore or Penorcon. Praetorius regarded the Pandore and its varieties, the Orpheoreon and Penorcon, as of English invention. This instrument, the property of Lord Tollemache, was made in London by John Rose, as the label bears witness:—

Johannes Rosa, Londini fecit,

In Bridwell, the 27th of July, 1580.

It is infinitely more graceful than any Pandore, and is perhaps best described by the maker's designation, "Cymbalum Decachordum," carved on the ribs. It had, as this name indicates, ten strings, which were of wire, to be tuned in five pairs of unisons, and played with a plectrum.

The carving is surpassingly lovely, and bears comparison with contemporary Italian work. The jewelled centre of the rose in the sound-hole is so beautiful that an enlarged drawing of it has been made to show it to advantage. The shell at the back is a characteristic feature deserving attention.

The extreme length of this instrument is 2 feet 11 inches. The length of the body is 1 foot 4 inches. The extreme breadth, beneath the rose and near the string-holder, is 12 inches. The breadth, measuring across the centre of the rose, is 10 inches. The depth of the ribs varies from 1½ to 3 inches, the greatest depth being near the finger-board.

The traditions that attach themselves to instruments of this character require to be carefully tested. Queen Mary's Harp, for instance, could not have been the gift to Beatrix Gardyn from Mary Stuart of Scots, although her portrait and coat of arms are said to have, at one time, adorned it. The attribution to Queen Elizabeth also of a spinet or virginal rests entirely upon such evidence as can be gathered from the instrument itself. This so-called lute has no doubt the support of a family tradition, and the story is thus told in Burke's Peerage ("Lineage of the Dysart Family," 1884): "Sir Lionel Tollemache, of Helmingham, high sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk in 1567. In 1561 Queen Elizabeth honoured Helmingham with her presence, and remained there from the 14th to the 18th of August inclusive, being most hospitably and sumptuously entertained. During Her Majesty's visit she stood sponsor to Sir Lionel's son, and presented the child's mother with her lute, which is still preserved at Helmingham Hall, county Suffolk, the seat of Lord Tollemache of Helmingham." Unfortunately the dates do not fit. John Rose's Lute, made in 1580, although it might possibly have belonged to Queen Elizabeth, could not have been the lute given in 1561. It is the tradition, however, that may have gone astray, and a fault in it does not do away entirely with a plausible attribution.

THIS beautiful Guitar of tortoiseshell, combined with ivory, mother-o'-pearl, and ebony (the property of Mr. George Donaldson, London), has ten pegs representing fleur-de-lys, and the ornament round the rose is formed with the same emblematic flower. To this, no doubt, it owes its romantic reputation of having belonged to David Rizzio. The apparent age of the Guitar would agree with a supposed gift of it from Mary Stuart to Rizzio, and the fleur-de-lys might connect it with the French or Scotch Royal Families; but this slender suggestion of the fleur-de-lys, to which the guitar owes its special interest, unsupported by other evidence, is scarcely sufficient to uphold the fascinating attribution. Mr. Donaldson, however, informs me that this instrument was bought in Scotland, nearly forty years ago, from an old family that had possessed it for generations with this tradition of its former ownership.

This Guitar had ten strings, forming five notes, in pairs of unisons, instead of six single strings, as in the modern guitar, giving six notes. It is the lowest note E that is here wanting. The instrument is 3 feet 1 inch in extreme length; the body being 18¾ inches in length, and 10 inches across. The ribs are 3¾ inches deep.

This Spanish guitar may have first come to England in the reign of Henry VIII., as there is occasional mention, at that time, of the Spanish viol, a bowed instrument which may have been accompanied by the true Spanish guitar. There is no doubt, however, about the Spanish guitar having been here in the reign of Elizabeth, and it might have been brought by attendants of Philip II. when he married Mary Tudor. In the latter half of the sixteenth century it was already known, valued, and highly decorated in Venice; and it was also known in France, so that, as an instrument, it would not be strange to Mary Stuart, or Rizzio either. The lute, however, was the most in vogue at that time, excepting perhaps in Spain. The character of the design of this so-called Rizzio guitar is undoubtedly Moorish.

A CHAMBER Organ formerly in the Tolbecque Collection, and belonging to the epoch of Louis XIII. The Positive Organ, as the name implies, was intended to remain in a fixed place, while the smaller portable organ (orgue portatif) was made to be carried about. The disposition of the pipes was usually the same in both organs,—what may be called the natural order,—ascending from the longest pipe in the bass to the shortest in the treble, but some positive organs had the pipes arranged in a circular disposition, perhaps for a more equal distribution of the weight upon what is known as the sound-board. The instrument admits of more than one register. There are authentic representations of positives in several old pictures, one of the best known being that in the St. Cecilia panel, by Hubert Van Eyck, in the famous altar-piece of the Adoration of the Lamb at Ghent. The original St. Cecilia panel, now at Berlin, was not painted later than 1426, but the panel at Ghent is a good copy. Another St. Cecilia panel (date about 1484), with a positive organ, by an unknown painter, is not of such universal fame, but is nevertheless of very great merit. It is in the palace of Holyrood, Edinburgh, and is of equal value with the Van Eyck panel as a faithful representation of the instrument, and of the chromatic arrangement of the keys, thus early introduced.

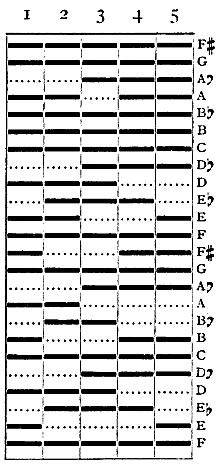

The Positive Organ drawn in this volume has been intended for chamber, not choir, use. It has three registers, and the drawstops which control them project at the right-hand side of the case the same as in the old Flemish harpsichords. The principal register, that of the show pipes of gilt tin, is called the Montre; and the compass of it is from the E below, to the third C above, middle C—three octaves and a sixth. The second register, also of tin, is an octave higher in pitch, but extends only from the first E below, to the second C above, middle C; the remainder of the key-board compass is borrowed from the-24- Montre. The third register is the Bourdon—wooden pipes stopped at the upper ends, an octave lower in pitch than the Montre. The Bourdon extends in compass from E an octave and sixth below, to the second C above, middle C. The three registers in this instrument are consequently at octave distances, but Praetorius (1619) describes an old positive in which the registers were in the relation of the fifth and octave to the lowest!—a combination the modern musical ear rejects. The boxwood natural keys with gilded paper fronts, as seen in this specimen, were common to the earliest known key-board instruments. The dimensions of this Positive Organ, including the stand, are—height, 6 feet 4 inches; width, 2 feet 6 inches; and depth, 1 foot 4 inches. The paintings inside the doors are, to the left, St. Cecilia playing upon a positive organ, while three angels sing and a fourth blows the bellows; to the right, a warrior crowned with laurel is in the attitude of listening; outside the doors there are panels with paintings of a woman playing on an instrument of the viol kind, and another playing a flute. There is a crowing cock upon the apex of the cornice. This Positive Organ is the property of the Conservatoire Royal, Brussels.