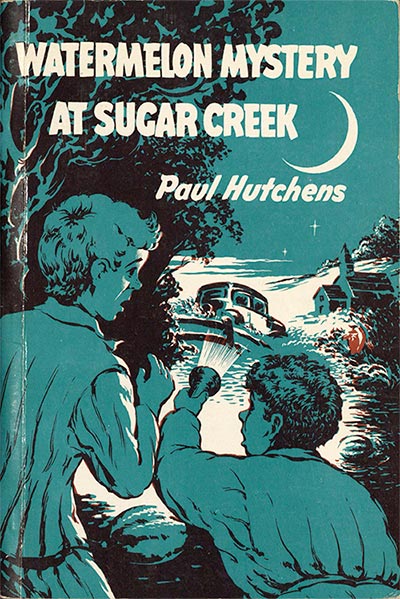

Title: Watermelon Mystery at Sugar Creek

Author: Paul Hutchens

Release date: January 6, 2019 [eBook #58628]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Sue Clark, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

WATERMELON MYSTERY

AT SUGAR CREEK

by

PAUL HUTCHENS

Published by

Scripture Press BOOK DIVISION

WHEATON, ILLINOIS

Watermelon Mystery at Sugar Creek

Copyright © 1955, by

Paul Hutchens

Third Printing

All rights in this book are reserved. No part may be reproduced in any manner without the permission in writing from the author, except brief quotations used in connection with a review in a magazine or newspaper.

Printed in the United States of America

| Chapter | Page |

| 1 | 5 |

| 2 | 15 |

| 3 | 27 |

| 4 | 37 |

| 5 | 45 |

| 6 | 52 |

| 7 | 65 |

| 8 | 76 |

| 9 | 84 |

| 10 | 97 |

IF I hadn’t been so proud of the prize watermelon I had grown from the packet of special seed Pop had ordered from the State Experiment Station, maybe I wouldn’t have been so fighting mad when somebody sneaked into our truck patch that summer night and stole it.

I was not only proud of that beautiful, oblong, dark green melon, but I was going to save the seed for planting next year. I was, in fact, planning to go into the watermelon-raising business.

Pop and I had had the soil of our truck patch tested, and it was just right for melons, which means it was well-drained, well-ventilated, with plenty of natural plant food. We would never have to worry about moisture in case there would ever be a dry summer, on account of we could carry water from the iron pitcher pump which was just inside the south fence. As you maybe know, our family had another pitcher pump not more than fifteen feet from the back door of our house—both pumps getting mixed up in the mystery of the stolen watermelon, which I’m going to tell you about right now.

Mom and I were down in the truck patch one hot day that summer, looking around a little, admiring my melon and guessing how many seeds she might have buried in her nice red inside. “Let’s give her a name,” I said to Mom—the Collins family, which is ours, giving names to nearly every living thing around our farm anyway—and Mom answered, “All right, let’s call her Ida.”

Mom caught hold of the iron pitcher pump handle and pumped it up and down quite a few fast, squeaking times to fill the pail I was holding under the spout.

“Why Ida?” I asked with a grunt, the pail getting heavier with every stroke of the pump handle.

Mom’s answer sounded sensible: “Ida means thirsty. I noticed it yesterday when I was looking through a book of names for babies.”

6 I had never seen such a thirsty melon in all my half-long life. Again and again, day after day, I had carried water to her, pouring it into the circular trough I had made in the ground around the roots of the vine she was growing on, and always the next morning the water would be gone. Knowing a watermelon is over ninety-two per cent water anyway, I knew if she kept on taking water like that, she’d get to be one of the fattest melons in the whole Sugar Creek territory.

Mom and I threaded our way through the open spaces between the vines, dodging a lot of smaller other melons grown from ordinary seed, till we came to the little trough that circled Ida’s vine, and while I was emptying my pail of water into it, I said, “Okay, Ida, my girl. That’s your name: Ida Watermelon Collins. How do you like it?”

I stooped, snapped my third finger several times against her fat green side and called her by name again, saying, “By this time next year you’ll be the mother of a hundred other melons. And year after next, you’ll be the grandmother of more melons than you can shake a stick at.”

I sighed a long noisy happy sigh, thinking about what a wonderful summer day it was and how good it felt to be alive, to be a boy and to live in a boy’s world. I carried another pail of water, poured it into Ida’s trough, then stopped to rest in the shade of the elderberry bushes near the fence. Pop and I had put up a brand new woven-wire fence there early in the spring, and at the top of it had stretched two strands of barbed wire, making it dangerous for anybody to climb over the fence in a hurry. In fact, the only place anybody would be able to get over real fast would be at the stile we were going to build near the iron pitcher pump half way between the pump and the elderberry bushes. We would have to get the stile built pretty soon, I thought, ’cause in another few weeks school would start, and I would want to do like I’d always done—go through or over the fence there to get to the lane, which was a short cut to school.

I didn’t have the slightest idea then that somebody would try to steal my melon, nor that the stealing of it would plunge me into7 the exciting middle of one of the most dangerous mysteries there had ever been in the Sugar Creek territory. Most certainly I never dreamed that Ida Watermelon Collins would have a share in helping the gang capture a fugitive from justice, an actual runaway thief the police had been looking for for quite a while.

We found out about the thief one hot summer night about a week later when Poetry, the barrel-shaped member of our gang, stayed all night with me in his green sportsman’s tent which my parents had let us pitch under the spreading branches of the plum tree in our yard.

The way it looks now it will take me almost a whole book to write it all for you. Boy oh boy, will it ever be fun remembering everything! Of course everything didn’t happen that very first night but one of the most exciting and confusing things did. It wouldn’t have happened though, if we hadn’t gotten out of our cots and started on a pajama-clad hike in the moonlight down through the woods to the spring—Poetry in his green striped pajamas and I in my red-striped ones, and Dragonfly in——!

But say! I hadn’t planned to tell you just yet that Dragonfly was with us that night—which he wasn’t at first. Dragonfly, as you probably know, is the spindle-legged, pop-eyed member of our gang, who is always showing up when we don’t need him or want him and when we least expect him and is always getting us into trouble—or else we have to help get him out of trouble.

Now that I’ve mentioned Dragonfly and hinted that he was the cause of some of our trouble—mine especially—I’d better tell you that he and I had the same kind of red-striped pajamas—our different mothers having seen the same ad in the Sugar Creek Times and had gone shopping the same afternoon in the same Sugar Creek Dry Goods Store and had seen the same bargains in boys’ night clothes—two pairs of red-striped pajamas being the only kind left when they got there.

Little Tom Till’s mother—Tom being the newest member of our gang—had seen the ad about the sale too, and his mother and mine had each bought for their two red-haired, freckle-faced8 sons a pair of blue denim western-style jeans exactly alike, also two maroon-and-gray-striped T-shirts exactly alike. When Tom and I were together anywhere, you could hardly tell us apart. So I looked like Little Tom Till in the daytime and like Dragonfly at night.

Poor Dragonfly! All the gang felt very sorry for him on account of he not only is very spindle-legged and pop-eyed, but in ragweed season—which it was at that time of the year—his crooked nose which turns south at the end, is always sneezing, and he also gets asthma.

Before I get into the middle of the stolen watermelon story, I’d better explain that my wonderful grayish-brown-haired mother had been having what is called “insomnia” that summer, so Pop had arranged for her to sleep upstairs in our guest bedroom—that being the farthest away from the night noises of our farm, especially the ones that came from the direction of the barn. Mom simply had to have her rest or she wouldn’t be able to keep on doing all the things a farm mother has to do every day all summer.

That guest room was also the farthest away from the tent under the plum tree—which Poetry and I decided maybe was another reason why Pop had put Mom upstairs.

Just one other thing I have to explain quick, is that the reason Poetry was staying at my house for a week was on account of his parents were on a vacation in Canada, and had left Poetry with us. He and I were going to have a vacation at the same time by sleeping in his tent which we pitched in our yard—as I’ve already told you, under the spreading branches of the plum tree.

Well, here goes, headfirst into our adventure! It was a very hot late-summer night, the time of year when the cicadas were as much a part of a Sugar Creek night as sunshine is part of the day. Cicadas, as you probably know, are broad-headed, protruding-eyed insects which some people call locusts and others “harvest flies.” In the late summer evenings, they set the whole country half crazy with their whirring sounds from the trees where thousands of them are like an orchestra with that many members, each member playing nothing but a drum.

I was lying on my hot cot just across the tent from Poetry in9 his own hot cot, each of us having tried about seven times to go to sleep, which Pop had ordered us to do about seventy-times-seven times that very night, barking out his orders from the back door or from the living room window.

Poetry, being in a mischievous mood, was right in the middle of quoting one of his favorite poems, “The Village Blacksmith,” quoting aloud to an imaginary audience out in the barnyard, when Pop called to us again to keep still. His voice came bellowing out through the drumming of the cicadas, saying, “Bill Collins, if you boys don’t stop talking and laughing and go to sleep, I’m coming out there and put you to sleep!”

A few seconds later, Pop added in a still-thundery voice, “I’ve told you boys for the last time! You’re keeping Charlotte Anne awake—and you’re liable to wake up your mother, too!” When Pop says anything like that, like that, I know he really means it, especially when he has already said it that many times.

I knew it was no time of night for my two-year-old cute little brown-haired sister, Charlotte Ann, to be awake, and certainly my nice friendly-faced, grayish-brown-haired mother would need a lot of extra sleep, ’cause tomorrow was Saturday and there would be the house to clean, pies and cookies to bake for Sunday, and a million chores a farm woman has to do on Saturday, every Saturday there is.

“Wonderful!” Poetry whispered across to me. “He won’t tell us any more; he’s told us for the last time. We can laugh and talk now as much as we want to!”

“You don’t know Pop,” I said. “When he says he has said anything for the last time he means he won’t say it again with just words—he’ll use a switch or his old razor strap.”

You see, Poetry didn’t know as well as I did what an expert Pop was in the way he could handle a switch—beech, willow, cherry or any kind that happened to be handy—and he could handle a razor strap better than any father a boy ever felt.

Poetry ignored my warning and tried to be funny by saying, “Does your father still use an old-fashioned razor that has to be stropped?”

10 I tried to think of something funny myself which was, “He still has an old-fashioned boy that has to be—when that boy is too dull to understand.” But maybe what I said wasn’t very humorous, ’cause Poetry ignored it.

“I’m thirsty,” he said. “Let’s go get a drink,” his voice coming across the darkness like the voice of a duck with laryngitis.

Right away there was a squeaking of the springs of his cot as he rolled himself into a sitting position. He swung his feet out of bed, set them with a ker-plop on the canvas floor of the tent. I could see him sitting there like the shadow of a fat grizzly in the light of the moonlight that filtered in through the plastic-netted window just above my cot.

A split jiffy later, he was across the three feet of space between us, sitting on the edge of my cot, making it groan almost loud enough for Pop to hear.

“Let’s go!” he said, using a businesslike tone.

I certainly didn’t want to get up and go outside with him to get a drink. Besides, I knew the very minute we would start to pump the iron pitcher pump at the end of the board walk not more than fifteen feet from our kitchen door, Pop would hear the pump pumping and the water splashing into the big iron kettle under the spout and would come storming out, with or without words, and would start saying again something he had already said for the last time.

I yawned the laziest longest yawn I could, sighed the longest drawn-out sigh I could, saying to Poetry, “I’m too sleepy. You go and get a drink for both of us.”

Then I sighed once more, turned over, and began to breathe heavily like I was sound asleep.

But Poetry couldn’t be stopped by sighs and yawns. He shook me awake and hissed, “Come on, treat a guest with a little politeness, will you?”—meaning I had to wake up and get up and go out with him to pump a noisy pump and run the risk of stirring up Pop’s already stirred-up temper.

When I kept on breathing like a sleeping baby, Poetry said with a disgruntled grunt, “Give me one little reason why you won’t help me get a drink!”

11 “One little reason?” I yawned up at his shadow. “I’ll give you a big one—five feet, eleven inches tall, one-hundred-seventy-two pounds, bushy-eyebrowed, reddish-brown mustached, and with a razor strap in his powerful right hand!”

“You want me to die of thirst?” asked Poetry.

“Thirst, or something; whatever you want to do it of. But hurry up and do it, and get it over with, ’cause I’m going to sleep.”

I certainly wasn’t going to get up and go out in the moonlight and run into Pop’s razor strap for anybody.

That must have stirred up Poetry’s temper a little, ’cause he said, “Okay, Chum, I’ll go by myself!”

Quicker than a firefly’s fleeting flash, he had zipped open the zipper of the plastic screened door of the tent, whipped the canvas curtain aside and stepped out into the moonlight.

I was up and out and after him in a nervous hurry. I grabbed him by the sleeve of his green-striped pajamas, but he wouldn’t stay stopped. He whispered a half-growl at me, “If you try to stop me, I’ll scream and you’ll get a licking.”

With that he started off on the run across the moonlit yard—not toward the pump but in a different direction toward the front gate, saying over his shoulder, “I’m going down to the spring to get a drink.”

That idea was even crazier, I thought—crazier than pumping the iron pitcher pump and waking up Pop, who, in turn, would start pumping his right arm up and down with a razor strap on either Poetry or me, or both.

But you might as well try to start a balky mule as to stop Leslie Thompson from doing what he has made up his stubborn mind he is going to do, so a jiffy later the two of us were hurrying past “Theodore Collins” on our mailbox—Theodore Collins being Pop’s name. A second later, we were across the gravel road and over the rail fence, following the path made by barefoot boys’ bare feet through the woods to the spring, Poetry using his flashlight every few seconds to light the way.

And that is where we ran into our mystery!

Zippety-zip-zip, swishety-swish-swish, clomp-clomp-clomp, dodge, swerve, gallop ... It’s nearly always one of the happiest12 times of my life when I am running down that little brown path to the spring, where the gang has nearly all its meetings and where so many interesting and exciting things have happened through the years. Generally, my barefoot gallop through the woods is in the daytime, and I feel like a frisky young colt turned out to pasture. But I had never run down that path in red-striped pajamas at night when I was sleepily disgruntled like I was right that minute for having to follow a dumpish barrel-shaped boy. So when we had passed the black widow stump and the linden tree and had dashed down the steep grade to the spring itself and found the dark green watermelon floating in the cement pool which Pop had built there as a reservoir for the water, it was as easy as anything for me to get fighting angry at most anything or anybody. A watermelon there could mean only one thing—especially when right beside it was a glass fruit jar with a pound of butter in it. It meant there were campers somewhere nearby—and campers in the Sugar Creek woods was something the Sugar Creek Gang would rather have most anything else than. It meant our peace and quiet would be interrupted; that we would have to wear bathing suits when we went in swimming, and we couldn’t yell and scream to each other like we liked to do.

Poetry, who was on his haunches beside the spring, surprised me by saying, “Look! It’s plugged! Let’s see how ripe it is!”

Before I could have stopped him even if I had thought of trying to do it, he was working the extra large rectangular plug out of the middle of the extra large melon’s long fat side.

It was one of the prettiest watermelons I had ever seen—in fact, it was as pretty as Ida Watermelon Collins, herself.

Poetry had the plug out in a jiffy and was holding it up for me to see.

Somebody had bitten off what red there had been on the end of the plug, I noticed. Then Poetry said, “Well, what do you know! The melon’s green. See, it’s all white inside!”

That didn’t make sense, ’cause this time of year even a watermelon that wasn’t more than half ripe would be at least pink inside. My eyes flashed off the rectangular plug and into the hole in the13 melon, and Poetry was right—it was white inside! Then his mind came to life and he said, “Look, there is something in it! There’s a ball of paper or something stuffed in it!”

I felt curiosity creeping up and down my spine and was all set for a mystery. Hardly realizing that I was trespassing on other people’s property and most certainly didn’t have a right to, even if the melon was in our spring, I quick stooped and with nervous fingers pulled out the folded piece of paper, which is what it was—the kind that comes off a loaf of bakery bread—and which at our house, when the loaf is all eaten, I nearly always toss into the woodbox or the wastebasket unless Mom sees me first and stops me. Sometimes Mom wants to save the paper and use it for wrapping sandwiches for Pop’s or my lunches, mine especially during the school year.

The melon was ripe, though, I noticed. The inside was a deep dark red.

While my mind was still trying to think up a mystery, something started to happen. From up in the woods at the top of the incline there was the sound of running feet and laughing voices, and flashlights, and flickering shadows, and it sounded like a whole flock of people coming. People, mind you! Only there weren’t any boys’ or men’s voices, but girls’ voices. GIRLS’! They were giggling and laughing and coming toward the base of the linden tree just above us. In another brain-whirling second, they would be where they could see us, and we’d be caught.

Say! when you are wearing a pair of red-striped pajamas and your barrel-shaped friend is wearing a pair of green-striped pajamas, and it is night, and you hear a flock of girls running in your direction and you are half scared of girls even in the daytime, you all of a sudden forget about a plugged watermelon floating in the nice fresh cool water of your spring, and you look for the quickest place you can find to hide yourself!

We couldn’t make a dash up either side of the incline to the top, ’cause that’s where the girls were, and we couldn’t escape in the opposite direction ’cause there was a barbed wire fence there separating us and the creek, but we had to do something! If it had14 been a gang of boys coming, we could have stood our ground and fought if we had to—but not when it was a bevy of girls, which sounded like a flock of blackbirds getting ready to fly south for the winter, only they weren’t getting ready to fly south, but north, which was in our direction.

“Quick!” Poetry’s faster-thinking mind cried to me. “Let’s beat it!” He showed me what he wanted us to do, by scrambling to his awkward feet and making a dive east toward the place where I knew we could get through a board fence, on the other side of which was a path that wound through a forest of giant ragweeds leading to Dragonfly’s Pop’s cornfield in the direction of the Sugar Creek Gang’s swimming hole.

In another jiffy I would have been following Poetry through the fence and we would have escaped being seen, but my right bare foot which was standing on a thin layer of slime on the cement lip of the pool where the melon was, slipped out from under me, and I felt myself going down.

Down, mind you, and I couldn’t stop myself! I struggled to regain my balance, and couldn’t—couldn’t even fall where my mixed-up mind told me would be a better place to fall than into the pool, which was in a mud puddle on the other side. Then thuddety-whammety, slip-slop-splashety—I was half sitting and half lying in the middle of the pool of ice cold spring water astride that long green watermelon, like a boy astride a bucking bronco at a Sugar Creek rodeo!

From above and all around and from every direction, it seemed, there were the voices of happy-go-lucky girls with flashlights, probably coming to get the watermelon, or the butter in the glass jar, or maybe a pail of drinking water for their camp.

THERE wasn’t any sense to what I did then, because of the confusion in my mixed-up mind—if I had any mind at all—but the very minute the light of those three or four—or maybe there were seventeen—flashlights dropped over the edge of the hill and all of them at the same time splashed down upon me, hitting me in the face and all over my red-striped pajamas, I let loose with a wild, trembling-voiced cry like a loon’s eery, half-scared-half-to-death ghostlike quaver, loud enough to be heard as far away as the Sugar Creek bridge. I began to wave my arms wildly, to splash around in the water, and to yell to my watermelon-bronco, “Giddap!... Giddap! You great big green good-for-nothing bronco!”

I let out a whole series of those wild loon calls, splashed myself off the watermelon and out of the cement pool and made a fast, wet dash down the path to the opening in the board fence, through which Poetry had already gone ahead of me. I quickly shoved myself through, and a jiffy later was making a wild moonlit run up the winding barefoot boy’s trail through the forest of giant ragweeds toward the swimming hole, crying like a loon all the way until I knew I was out of sight of all those excited girls.

Even as I ran, flopping along in my wet pajamas, I had the memory of flashlights splashing in my eyes and some of the things I heard while I was going through the fence. Some of the excited words were, “Help! Help! There’s a wild animal down there in the spring!” Others of the girls had simply screamed like girls do when they are scared, but one of them had shrieked an unearthly shriek, crying, “There’s a zebra down there—a wild zebra, taking a bath in our drinking water!”

That, I thought, as I dodged my way along the path, was almost funny. In fact, sometimes a boy feels fine inside if something he has done makes a gang of girls let out an unearthly explosion of screams—most girls screaming not because they’re really scared16 anyway, but because they like to make people think they are.

Where, I wondered as I zig-zagged along, was Poetry?

I didn’t have to wonder long. By the time I was through the tall weeds and at the edge of Dragonfly’s Pop’s cornfield I had caught up to where he was. His flashlight hit me in the face as he exclaimed in his duck-like voice, “Help! Help! A zebra! A wild zebra!”

I stopped stock-still with my wet pajama sleeve in front of my eyes to shield them from the blinding glare of his flashlight. “It’s all your fault!” I half-screamed at him. “If you hadn’t had the silly notion you had to have a drink!”

His voice in answer was saucy as he said back, “What a mess you made of things—falling into that water and yelling like a wild Indian! Now those girl scouts will tell your folks, and your father will really sharpen you up with his razor strap!”

“Girl scouts?” I exclaimed to him with chattering teeth from being so cold and still all wet with spring water. Also for some reason I didn’t feel very brave—most certainly not very happy.

“Sure,” he said, “didn’t you know it? A bunch of girl scouts have got their tents pitched up there by the pawpaw bushes for a week. Old Man Paddler gave them permission; it’s his woods, you know.”

And then I was sad. Girl scouts were supposed to be some of the nicest people in the world—even if they were girls, I thought. What would they think of a red-haired freckle-faced creature of some kind that was part loon and part zebra, splashing around in their drinking water, riding like a cowboy on a watermelon and acting absolutely crazy? I would never dare show my face where any of them could see me, or some of them would remember me from having seen me in the light of their flashlights, and they would ask my mother whose boy I was. I knew that one of the very first things some of those girl scouts would do this week would be to come to the Collins’ house to buy eggs and milk and such things as sweet corn and new potatoes. Some of them would be bound to recognize me.

“We had better get back to the tent and into bed quick, before17 somebody comes running up to use your telephone to call the police, or the marshal, or the sheriff, to tell them some wild boys have been causing a disturbance at the camp!” Poetry said.

It was a good idea even if it was a worried one, so away we went—not the way we had come, but lickety-sizzle straight up through Dragonfly’s Pop’s cornfield, swinging around the east end of the bayou and back down the south side of it until we came to the fence that goes south to Bumblebee Hill. Once we got to Bumblebee Hill we would swing southwest to the place where we always went over the rail fence, which was across the road from our house. Then we would scoot across the road and past “Theodore Collins” on our mailbox, hoping we wouldn’t wake up Theodore Collins himself in the Collins’ west bedroom, and a jiffy after that would be safe in our tent once more!

The very thought of safety and the security of Poetry’s nice green tent under the spreading plum tree gave me a spurt of hope, and put wings on my feet, as I followed my lumbering barrel-shaped friend, not realizing there would be more trouble when I got home on account of my very wet red-striped night clothes.

We didn’t even bother to stop at Bumblebee Hill where the fiercest fastest fist-fight that ever was had taken place—and which you already know about if you’ve read the story called We Killed a Bear. At the bottom of the hill, you know, is the Little-Jim tree near which Little Jim, the littlest member of our Gang, killed the fierce old mad old mother bear; and at the top of the hill is the abandoned cemetery where the Gang has so many of its meetings. The wind I was making as I ran was blowing against my very wet 89-pounds of red-haired boy, making me feel chilly all over in spite of it being such a hot night.

It was a shame not to be able to enjoy such a pretty Sugar Creek summer night—the almost most-wonderful thing in the world. I guess there isn’t anything in the whole wide world that sounds better than a Sugar Creek night when you are down along the creek fishing and you hear the bullfrogs bellowing in the riffles, the katydids rasping voices calling to one another: “Katy-did, Katy-she-did;18 Katy-did, Katy-she-did!” the crickets singing away, vibrating their forewings together, making one of the friendliest lonesome sounds a boy ever hears. Every now and then, you can hear a screech owl crying “Shay-a-a-a-a!” like a baby loon learning to loon.

Oh, there are a lot of sounds that make a boy feel good all over, such as Old Topsy, our favorite horse, in her stall crunching corn, the queer sound the chickens make in their sleep, the wind sighing through the pine trees along the bayou, with every now and then somebody’s rooster turning loose with a “Cocka-doodle-do!” like he is so proud of himself he can’t wait until morning to let all the sleeping hens know about it—like it was a waste of good time to sleep when you could listen to such nice noisy music. From across the fields you sometimes hear the sound of a nervous dog barking, and somebody else’s dog answering from across the creek. You even like to listen to the corn blades whispering to each other as the wind blows through them.

Summer nights on our farm smell good, too—nearly always there being the smell of new-mown hay or fresh pine-tree fragrance which is always sweeter at night. If you are near the creek you can smell the fish that don’t want to bite, the wild peppermint, the sweet clover and a thousand other half friendly, half lonely smells that make you feel sad and glad at the same time.

Things you think at night are wonderful, too. You can lie on the grass in the yard and, in the summertime, look up at the purplish blue sky that is like a big upside-down sieve with a million yellow holes in it and in your mind go sailing out across the Milky Way like a boy skating on the bayou pond, dodging this way and that so you won’t run into any of the stars....

But this wasn’t the right time to hear or see or smell how wonderful a night it was. It was, instead, a time for two worried boys, including a red-haired freckle-faced one to get inside the tent and into bed and to sleep.

Pretty soon Poetry and I were at the rail fence across from “Theodore Collins” on our mailbox. There we stopped stock-still and stood and studied the situation, keeping ourselves in the shadow19 of the elderberry bush that grew there. It seemed like the moonlight was never brighter and we couldn’t afford to let ourselves be seen or heard by anybody who hadn’t used a razor strap for a long time but who perhaps hadn’t forgotten how—and not on his razor, either.

I was shivering with the cold, and just that second I sneezed. Just that second also, Poetry shushed me with a shush that was almost louder than my sneeze, as he whispered, “Hey, don’t wake anybody up! Do you want your guest to get a licking? Your father has told us for the last time to—”

“Shush, yourself!” I ordered him.

We decided to go back up the fence, cross the road by the hickory nut trees, climb over into our cornfield and sneak down between the rows to arrive at the tent from the opposite side so nobody could see us from the house, which we did.

We had to pass Old Red Addie’s apartment hog house on the way, which is the kind of place on a farm that doesn’t have a nice, clean, sweet farm smell. Pretty soon, still shivering and wishing I had dry night clothes to sleep in, we were behind the tent waiting and listening to see if we could get in without being seen or heard.

Right then I sneezed again, and also again, and I knew I was either going to catch a cold or I already had one. I quick lifted the tent flap, swished through the plastic screen door, expecting Poetry to follow me, but he didn’t and wouldn’t. He stood for a second in the clear moonlight that came slanting through a branchless place in the plum tree overhead, then he said, “I’ll be back in a minute.” He started to start toward the house—in the moonlight, mind you, where he could be seen!

“Wait!” I called to him, in as quiet a whisper as I could. “Where are you going?”

“I’m thirsty,” he whispered back. “I forgot to get a drink at the spring.”

“You’ll wake up my father!” I exclaimed to him. “Don’t you dare pump that pump handle!”

Poetry couldn’t be stopped. I knew that if Pop ever waked up and came to prove he had meant what he said when he had said20 what he said, there’d really be trouble. Pop would hear me sneeze, or see my wet night clothes and wonder what on earth, and why.

So in a jiffy, like the story in one of our school books about a man named Mr. McGregor chasing Peter Rabbit who was all wet from having jumped in a can of water to hide—and Peter Rabbit sneezing—I was acting out that story backwards: I myself was a very wet, very dumb bunny chasing Leslie Poetry Thompson to try to stop him from getting us into even more trouble than we were already in.

We arrived at the iron pitcher pump platform at the same time, where I hissed to him not to pump the pump, pushing in between him and the pump, blocking him from doing what his stubborn mind was driving him to do.

“I’m thirsty,” he squawked to me.

“The pump handle squeaks!” I hissed back to him and shoved him off the pump platform. My left wet pajama sleeve pressed against his face.

What happened after that happened so fast and with so much noise it would have wakened seventeen fathers, as Poetry, my almost best friend who had always stood by me when I was in trouble, who was always on my side, all of a sudden didn’t act like he was my friend at all.

We weren’t any more than three feet from the large iron kettle filled with innocent water, which up to that moment had been reflecting the moon as clearly as if it had been a mirror—clearly enough, in fact, for you to see the man in the moon in it.

The next second Poetry’s powerful arms were around me and he was dragging me toward that big kettle. The next second after that, he swooped my 89 pounds up and with me kicking and squirming and trying to wriggle out of his grasp and not being able to, he sat me down kerplop-splash, double-splashety-slump right in the center of that large kettle of water.

“What on earth!” I exclaimed, my voice trembling with temper, my teeth chattering with the cold and my mind whirling.

My words exploded out of my mouth at the very minute Pop came out the back door. “‘What on earth!’ is right,” he exclaimed21 in his big father-sounding voice. “What on earth are you doing in the water?”

Poetry answered for me, saying politely like he was trying to save somebody from a razor strap, “It’s all my fault, Mr. Collins. We were getting a drink and I—I shouldn’t have done it—but I pushed him. I—.” Then Poetry’s voice took on a mischievous tone, as he said, “The water was so clear and the man in the moon reflected in it was so handsome, I wanted to see what a good-looking boy would look like in it. I couldn’t resist the temptation.”

Such an innocent voice! So polite! I was boiling inside as I splashed myself out of the kettle and stood dripping on the pump platform.

Then I did get a surprise. Pop’s voice, instead of being like black thunder, which it sometimes is at a time like that, was a sort of husky whisper: “Let’s keep quiet—all of us. We wouldn’t want to wake up your mother, Bill. You boys get back into the tent quick, while I slip into the house and get Bill a pair of dry pajamas. Hurry up! QUICK, into the tent!”

Pop turned, tiptoed to the back screen door, opened it quietly, while Poetry and I scooted to the tent. A second later, we were inside in the shadowy moonlight which oozed in through the plastic window above my cot.

Pop was back out of the house almost before I was out of my wet pajamas. He whispered to us at the tent door, “Here’s a towel. Dry yourself good. Put these fresh pajamas on—but, BE QUIET!” He whispered the last two words almost savagely.

“Here, let me have your old wet ones. I’ll hang them on the line behind the house to dry—and remember, not a word of this to your mother, Bill. Do you hear me?”

“Don’t worry,” I said. It was easy to hear anything as easy to listen to as that.

And Pop was gone.

In only a few jiffies I was dry and had on my nice fresh clean-smelling, Mom-washed stripeless yellow pajamas, and there wasn’t even a sniffle in my nose to hint that maybe I would catch cold.

Boy oh boy, was it ever quiet in the tent—the only sounds being22 those in my mind. Everything had happened so fast, it seemed as if it had taken only a minute. It also seemed like a year had passed—so many exciting things had happened—crazy things, too, such as a boy galloping around in a pool of cold water on a green watermelon, and a gang of girls screaming like wild hyenas that there was a zebra taking a bath in the spring.

“Wait,” Poetry ordered, as I sat down on the edge of my cot and started to crawl in. “We can’t get in between your mother’s nice clean sheets with feet that have waded through mud and dusty cornfields. I’ll go get the wash pan from the grape arbor, fill it with water, and bring it back.”

“You stay here!” I ordered. “I don’t trust you outside this tent one minute! I’ll get the water myself.”

Say, do you know what that dumb bunny of a fat boy answered me? He said in his very polite voice, “But I’m thirsty—I haven’t had a chance to get a drink—I—”

“Stay here!” I ordered. “I’ll bring you a drink.”

“After all I’ve done for you, you won’t even let me go with you?” he begged.

“What have you done for me, I’d like to know? You—with your plunking me into the middle of that kettle of water?”

Poetry’s strong fat hands grabbed me by the shoulders and shook me. “Listen, Chum,” he said fiercely; “I saved you from getting a licking, didn’t I? I heard your father opening the back door, and I knew he’d be there in a jiffy. If he found you all wet with that spring water, he’d have asked you how come, and you’d really have been in a pretty kettle. So I pushed you in with my bare hands, don’t you see? Besides—look at this!” Poetry turned on his flashlight, reached over to the foot of his cot and picked up a long black something-or-other with a handle on it, and extended it to me. AND IT WAS POP’S RAZOR STRAP!

“He had it in his hand when he came out the door,” Poetry told me. “He accidentally left it on the pump platform when he went in for the fresh pajamas. Now, am I your friend, or not?”

Looking at the eighteen-inch-long blackish-brown leather razor strap in Poetry’s hand, and remembering the last time Pop had23 given me a few interesting strokes with it, I decided maybe Poetry really had been my friend. Besides, if I let him go to get a pan of water for washing our feet, and if Pop saw and heard him, Pop would probably not say a word—he not wanting to wake Mom up.

“All right,” I said to Poetry, “but hurry back.” Which he did.

Pretty soon we had our feet washed and dried on the towel, which I noticed when we got through might also have to be washed in the morning. In only a little while we were in our bunks again and sound asleep, and right away I began dreaming a crazy mixed-up dream in which I was running in red-striped pajamas through the woods, leaving the path made by barefoot boys’ bare feet and working my way around to the left along the crest of the hill where the pawpaw bushes were, just to see how many girl campers there were. Then it seemed like I was in the spring again, galloping around on a green no-legged bronco which somebody had stolen and plugged and maybe sold to the girls—or even given to them—or maybe some of the girls had invaded our melon patch that very night and stolen it themselves.

I hated to think that, though, ’cause any girl who is a girl scout is supposed to be like a boy who is a boy scout, which is absolutely honest. Besides as much as I didn’t like girls—not most of them anyway—and was scared of them a little—it seemed like there was a small voice inside of me which all my life had been whispering that girls are kind of special—and anybody couldn’t help it if she happened to be born one. Mom had been a girl for quite a few years herself, and it hadn’t hurt her a bit. She had grown up to become one of the most wonderful people in the world.

But who had stole my watermelon? And how had it gotten down there in the spring? It was my melon, of course!

The idea woke me up. Or else my own voice did, when I heard myself hissing to Poetry:

“Hey, you! Poetry! Come on, wake up!”

He groaned, turned over in his cot, and groaned again. “Let me sleep, will you?”

“No,” I whispered, “wake up! Come on and go with me. I’ve got to go down into our watermelon patch to see—”

24 “I don’t want any more water,” he mumbled, “and I wouldn’t think you would either.”

“That melon in the spring,” I said. “I just dreamed it was my prize melon! I think somebody stole it. I want to go down to our truck patch to see if it’s gone.”

Poetry showed he hadn’t been asleep at all then, ’cause he rolled over, sat up, swung his feet out over the edge of his cot and onto the canvas floor, and I knew we were both going outside once more—just once more.

What we were going to do was one of the most important things we had ever done—even if it might not seem so to a boy’s father if he should happen to wake up and see us in the melon patch and think we were two strange boys out there actually stealing watermelons.

Poetry and I were pretty soon outside the tent again in the wonderful moonlight where now most of the cicadas had stopped their wild whirrings and the crickets had begun to take over for the rest of the night. Fireflies were everywhere, too. It seemed like there were thousands of fireflies flashing their green lights on and off in every tree in our orchard and in all the open spaces everywhere. The lights of those that were flying were like short yellowish green chalk marks being made on a schoolhouse blackboard.

Poetry, with his flashlight, was leading the way as he and I moved out across our barnyard. When we were passing Old Red Addie’s apartment hog house, I was reminded again that all the smells around a farm are not the kind to write about in a story, so I won’t even mention it but will let you imagine what it was like.

At the wooden gate near the barn, Poetry said, “Listen, will you?”

I listened, but all I could hear was the sound of pigeons cooing in the haymow, which is one of the friendliest sounds a boy ever hears—the low lonesome cooing of pigeons.

There are certainly a lot of different sounds around our farm, nearly all of which I have learned to imitate so well I actually sound like a farmyard full of animals sometimes, Pop says. Mom also says25 that sometimes I actually look like a red-haired freckle-faced pig—which I probably don’t.

Say, did you ever stop to think about all the different kinds of sounds a country boy gets to enjoy?

While you are imagining Poetry and me cutting across the south pasture to the east side of our melon patch, I’ll mention just a few that we get to hear a hundred times a year, such as the wind roaring in a winter blizzard, Dragonfly’s Pop’s bulls bellowing, Circus’s Pop’s hounds baying or bawling or snarling or growling; Mixy, our black and white cat, meowing or purring; mice squeaking in the corncrib; Old Topsy neighing; Poetry’s Pop’s sheep bleating; all the old setting-hens clucking; the laying hens singing or cackling; Big Jim’s folks’ ducks quacking; honey and bumblebees droning and buzzing; crows cawing; and our old red rooster crowing at midnight or just at daybreak; screech owls screeching; hoot-owls hooting; the cicadas drumming, and the crickets chirping. Yes, and Dragonfly sneezing, especially in ragweed season, which it already was in the Sugar Creek territory.

There are a lot of interesting sounds, too, down along the creek and the bayou, such as water singing in the riffles, the big night herons going “Quoke-quoke,” cardinals whistling, bob-whites calling, squirrels barking—and when the gang is together, the happiest sounds of all with everybody talking at once and nobody listening to anybody.

There are also a few sounds that hurt your ears, such as Pop filing a saw, Old Red Addie’s family of red-haired pigs squealing, the death squawk of a chicken just before it gets its head chopped off for the Collins’ family dinner, and the wild screams of a bevy of girls calling an innocent boy in red-striped pajamas, a zebra!

In only a few jiffies we were out in the middle of our truck patch looking to see if any of the melons were missing. I was just sure that when I came to Ida’s vine, I’d find a long oval indentation where she had been—the dream I had had about her being stolen was so real in my mind.

“All this walk for nothing,” Poetry exclaimed all of a sudden,26 when his flashlight landed ker-flash right on the green fat side of Ida Watermelon Collins, as peaceful and quiet as an old setting hen on her nest.

I stood looking down at her proudly, then I said in a grumpy voice, “What do you mean, making me get up out of a comfortable bed and drag myself all the way out here for nothing! You see to it that you don’t make me dream such a crazy dream again—do you hear me!”

I felt better after saying that, then Poetry beside me grunted grouchily, and said, “And don’t ever rob me of my good night’s rest again either!”

With that, we started to wend our barefoot pajama-clad way back across the field of vines and other melons in the direction of the barn again. We hadn’t gone more than fifteen yards when what to my wondering ears should come but the strange sound of something running—that is, that’s what I thought it sounded like at first. I stopped stock-still and looked around in a fast moonlit circle of directions, and saw away over by the new woven-wire fence not more than twenty feet from the iron pitcher pump, something dark about the size of a long, low-bodied extra-large raccoon, moving toward the shadows of the elderberry bushes.

I could feel the red hair on the back of my neck and on the top of my head beginning to crawl like the bristles on a dog’s or a cat’s or a hog’s back do when it’s angry—only I wasn’t angry—not yet, anyway.

A little later, I was not only angry but my mind was going in excited circles. If you had been me and seen what I saw, and found out what I found out, you’d have felt the way I felt, which was all mixed up in my thoughts, worried and excited and stormy-minded, and ready for a headfirst dive into the middle of one of the most thrilling mysteries that ever started in the middle of a dog day’s night.

YOU don’t have to wait long to decide what to do at a time like that, when you have mischievous-minded, quick-thinking Poetry along with you, even when you are in the middle of a muddle in the middle of a melon patch, watching something the size of a long, very fat raccoon hurrying in jerky movements toward the shadows of the elderberry bushes.

If things hadn’t been so exciting, it would have been a good time to let my imagination put on its wings and fly me around in my boy’s world awhile—what with a million stars all over the sky and fireflies writing on the blackboard of the night and rubbing out all their greenish-yellow marks as fast as they made them, and with the crickets singing and the smell of sweet clover enough to make you dizzy with just feeling fine.

But it was no time for dreaming. Instead, it was a time for acting—and QUICK!

“Come on!” Poetry hissed to me. “Let’s give chase!” and he started running and yelling, “Stop, thief! Stop!”

And away we both went, out across that truck patch, dodging melons as we went, leaping over them or swerving aside like we do when we are on a coon chase at night with Circus’s Pop’s long-eared, long-nosed, long-voiced hounds leading the way, trying to catch up with the dark-brown, long, low, very-fat animal—something I had never seen around Sugar Creek before in all my life.

Then, all of a disappointing sudden, the brown whatever-it-was disappeared into the shadow of the elderberry bushes, and I heard an exciting whirring noise in the lane on the other side of the fence. A fast jiffy later, an automobile came to noisy-motored life, a pair of head-lamps went on, and an oldish-sounding car went rattling down the lane, headed in the direction of the Sugar Creek school, which is at the end of the lane where it meets the county line road.

28 Poetry’s long 3-batteried flashlight shot a straight white beam through the firefly-spattered night. It landed ker-flash right on that oldish-looking car as it swished past the iron pitcher pump and disappeared down the hill. A few seconds later, we heard the car go rattlety-crash across the board floor of the branch bridge, the head-lamps lighting up the lane as it sped up the hill on the other side in the direction of the schoolhouse.

What on earth!

My mind was still on the car and who might be in it, when I heard Poetry say, “Look! There is our wild animal! He stopped right at the fence! Let’s get him!”

My mind came back to the long brown low very-fat something-or-other we had been chasing a minute before. My eyes got to it at about the same time Poetry’s flashlight socked it ker-wham-flash right in the middle of its fat side.

My feet got there almost as quick as my eyes did.

“What is it?” I exclaimed, looking about for a stick or a club to protect myself, in case I had to.

My imagination had been yelling to me, “It’s some kind of animal, different from anything you’ve ever seen!” so I was terribly disappointed when Poetry let out a disgusted grunt with a surprise in it, saying, “Aw, it’s only an old gunny sack.”

And it was. An old brownish—or rather, new, light-brown—gunny sack, with something large inside of it. Fastened to one end was a plastic rope which stretched from the gunny sack back into the elderberry bushes.

We kept on standing stock-still and staring at the thing. Whatever was in the sack wasn’t moving at all, not even breathing, I thought, as we stood studying it and wondering, “What on earth!”

It was large and long and round and very fat and—!

Then like a light turning on in my mind, I knew what was in that brown burlap bag. I knew it as well as I knew my name was Bill Collins, Theodore Collins’ only son. “There’s a watermelon in that bag!” I exclaimed.

Whoever was in that car had probably crawled out into our melon patch, picked the melon, slipped it into this burlap bag, tied the rope to it, and had been hiding here in the bushes, pulling the29 rope and dragging the melon to him! Doing it that way so nobody would see him walking, carrying it!

Was I ever stirred up in my mind! Yet, there wasn’t any sense in getting too stirred up. A boy couldn’t let himself waste his perfectly good temper in one big explosion, ’cause, as my Pop has told me many a time, you can’t think straight when you are angry. Pop was trying to teach me to use my temper, instead of losing it.

“A temper is a fine thing, if you control it, but not if it controls you,” he has told me maybe five hundred times in my half-long life. As you maybe already know if you’ve read some of the other Sugar Creek Gang stories, my hot temper had gotten me into trouble many a time by shoving me headfirst into an unnecessary fight with somebody who didn’t know how to control his own temper.

In a flash I was down on my haunches beside the burlap bag. “Here,” I said to Poetry, “lend me your knife a minute. Let’s get this old burlap bag off and see if it’s a watermelon!”

“Goose!” Poetry answered me. “I’m wearing my night clothes!” Both of us were, as you already know. His were green-striped, and mine yellow, as I’ve already told you. We both looked ridiculous there in the moonlight.

“Look!” Poetry exclaimed. “Here’s how they were going to get it through the fence!”

My eyes fastened onto the circle of light his flashlight made on a spot back under the elderberry bushes and I noticed there was a hole cut in Pop’s new woven-wire fence, large enough to let a boy through. Boy oh boy, would Pop ever have a hard time using his temper when he saw that tomorrow morning!

But we had to do something with the melon. “Let’s leave it for the gang to see tomorrow,” Poetry suggested. “Let Big Jim decide what to do about it.”

“What to do with Bob Till, you mean,” I said grimly. Already my temper was telling me it was Bob Till himself, the Sugar Creek Gang’s worst enemy, who had been trying to steal one of our melons.

Just thinking that started my blood to running faster in my veins. How many times during the past two years we had had trouble with John Till’s oldest boy, Bob, and how many times Big30 Jim, the Sugar Creek Gang’s fierce-fighting leader, had had to give Bob a licking—and always Bob was just as bad a boy afterward, and maybe even worse.

I was remembering that only last week at our very latest Gang meeting, Big Jim had told us: “I’m through fighting Bob Till. I’m going to try kindness. We’re all going to try it. Let’s show him that a Christian boy doesn’t have to fight every time somebody knocks a chip off his shoulder—and let’s not put the chip on our shoulder in the first place.”

At that meeting, which had been at the spring, Dragonfly had piped up and asked, “What’s a ‘chip on your shoulder’ mean?”

Poetry had answered for Big Jim by saying, “It’s a doubled-up fist, shaking itself under somebody else’s nose—daring him to hit you first!”

Big Jim ignored Poetry’s supposed-to-be-funny answer and said, “Bob is on probation, you know, and he has to behave, or the sentence that is hanging over him will go into effect and he’ll have to spend a year in the reformatory. We wouldn’t want that. We have got to help him prove that he can behave himself. If he thinks we are mad at him, he will be tempted to do things to get even with us. As long as this sentence is hang—”

Dragonfly cut in, then, with one of his dumbish questions, at the same time trying to show how smart he was in school, asking, “What kind of a sentence—declarative, or interrogative, or imperative, or exclamatory?”

Big Jim’s jaw set, and he gave Dragonfly an exclamatory look. Then he went on, shocking us almost out of our wits when he told us something not a one of us knew yet: “One of the conditions of his being on probation instead of in the reformatory is that he go to church at least once a week for a year. That means he’ll probably come to our church, and that means he’ll be in our Sunday school class, and—”

I got one of the queerest feelings I ever had in my life. Whirlwindlike thoughts were spiraling in my mind. I just couldn’t imagine Bob Till in church and Sunday school. It would certainly seem funny to have him there with nice clothes on and his hair combed, listening to our preacher preach from the Bible. What if31 I had to sit beside him myself—I, who could hardly think his name without feeling my muscles tighten and my fists start to double up?

Another thing Big Jim said at that meeting was, “You guys want to promise that you will stick with me and all of us try to help him?”

And we had promised.

And now here was Bob already doing something that would make the sentence drop on his head. Whoever was in that car just had to be Bob Till on account of he had a car just like that—the car being what people call a “hot rod.”

“Listen!” Poetry exclaimed. I listened in every direction there is, then I heard and saw at the same time a car coming back up the lane, its head-lamps hitting us full in the face.

“Quick!” Poetry cried. “Down!”

We stooped low behind the elderberry bushes and waited for the car to pass.

“Hey!” I said to us. “It’s slowing down. It’s going to stop,” which it did. The same rattling old jalopy. In a split jiffy we were scooting along the fence row to a spot about twenty-five feet farther up the lane. And there we crouched behind some giant ragweeds and goldenrod and orange-rayed, black-eyed Susans—Pop having ordered me a week ago to cut down the ragweeds with our scythe, and I hadn’t done it yet. I nearly always cut the goldenrod too, on account of Dragonfly, the pop-eyed member of our Gang, is allergic to them as well as to the ragweeds and he nearly always uses this lane going to and from school.

My heart was pounding in my ears as I crouched there with Poetry, he in his green-striped pajamas and I in my plain yellow ones.

“Get down!” I hissed to him.

“I am down,” he whispered.

“Flatter!” I ordered him, “so you won’t be seen! Can’t you lie flat?”

“I can only lie round,” he answered saucily, which, under any32 other circumstances, would have sounded funny, he being so extra large around.

“Somebody is getting out,” Poetry whispered.

“How many are there?”

“Only one, I think.”

Then I felt Poetry’s body grow tense. “There goes one of your watermelons,” he hissed to me.

I saw it at the same time he did—the brown burlap bag being pulled deeper into the elderberry bushes—and I knew somebody was actually stealing one of our melons. In a jiffy it would be gone!

“Let’s jump him,” I exclaimed to Poetry. My blood was tingling for battle. I started to my feet, but he stopped me, saying, “Sh!” in a subdued but savage whisper. “Detectives don’t stop a man from stealing; they let him do it first, then they capture him.”

It wasn’t an easy thing to do—to do nothing, watching that watermelon being hoisted into the back seat of that car. My muscles were aching to get into some new kind of action that was different from hoeing potatoes, milking cows, gathering eggs, and other things any ordinary boy’s muscles could do. I was straining to go tearing up the fence row to the elderberry bushes, dive through the hole in the fence, make a football-style tackle on that thief’s hind legs and bring him down. I was pretty sure, if all the Gang had been there, one or the other of us wouldn’t have been able to stay stopped stock-still. He would have rushed in, and the rest of us would be like Jack, in the poem about “Jack and Jill”—we would go tumbling after, even if some of us got knocked down and got our crowns cracked.

But the rest of the Gang wasn’t there. Besides it was already too late to do anything. In less time than it has taken me to write it, the melon in the gunny sack was in the car. The thief was in the driver’s seat, and the hot rod was shooting like an arrow with two blazing heads down the moonlit lane.

Poetry shot a long powerful beam from his flashlight straight toward the car, socking it on the license plate, and I knew his mind—which is so good it’s almost like what is called a “photographic mind”—would remember the number if he had been able to see it.

33 It’s like having a big blown-up balloon suddenly burst in your face to have your excited adventure come to an end like that; kinda like a fish must feel when it’s nibbling on a fat fishing worm down in Sugar Creek and, all of a disappointing sudden, having its nice juicy dinner jerked away from it by the fisherman who is on the other end of the line.

There wasn’t anything left to do except go back to the tent and to bed and to sleep.

Just thinking that reminded me of the fact that I probably would need another pair of pajamas to sleep in, the yellow pair I had on having gotten soiled while I was lying in the grass behind the goldenrod and ragweed and black-eyed Susans. “We’ll have to wash our feet again before we can crawl into Mom’s nice clean sheets,” I said, as we started to start back to the tent.

“Maybe it would be easier and cause less worry for your mother if we just climbed into our cots and went to sleep, and tomorrow if your mother gets angry at us we can explain about the watermelon and that will get her angry at the thief instead of at us. We could offer to help her wash the sheets, anyway.”

It was a pair of very sad, very mad boys that threaded their way through the watermelon patch to the pasture and across it to the gate at the barn and on toward the tent. There were still a few cicadas busy with their drums, I noticed, in spite of the fact that I was all stirred up in my mind about the watermelon. Thinking about the seeds in their long, straight rows, buried in the dark red flesh of the watermelon, like seeds always are, just like somebody had planted them, reminded me of the stars in the sky overhead, and I was wishing I could actually look up and see the Dog Star, which is the brightest star in all the Sugar Creek sky but which, during dog days—which are the hot and sultry days of July and August—you have to get up in the morning to see—on account of the Dog Star always comes up with the sun in July and August and, in a very little while, fades out of sight.

In the winter, in February, the Dog Star is almost straight overhead at night and is like a shining star at the top of a Christmas tree—but who wants to go out in the middle of a zero-cold night just to look at a star, even if it is the brightest one that ever shines?

34 “Are you sleepy?” Poetry asked me, when we reached the plum tree.

“Not very,” I said, “but I’m still so mad I can’t see straight.”

“You want to go back down to the spring with me?” he asked, his hand on the tent awning, about to lift it for us to go in.

“Are you crazy?” I asked.

“I’m a detective. I want to go down there and see if we can find the oiled paper you threw away when we heard those girls at the top of the hill.”

“My mother has dozens of old bread wrappers,” I told him. “I’ll ask her for one for you in the morning.”

“Listen, Chum,” Poetry whispered, as he let the tent awning drop into place and grabbed me by the arm, “I said I’m a detective, and I’m looking for a clue! I’ve a hunch there was something in that paper—something whoever put it in that melon, didn’t want to get wet!”

I knew, from having studied about watermelons that summer, that the edible part of a watermelon is made up of such things as protein, and fat, and ash, and calcium, and sugar and water and just fibre. Six per cent of the melon is sugar and over ninety-two per cent is water. You could eat a piece of watermelon the size of Charlotte Ann’s head and it would be like drinking more than a pint of sweetened water. I could understand that anything anybody put on the inside of the melon would get wet, almost as wet as if you had dunked it in a pail of water. “Look,” I said to Poetry, “I don’t want to show my face or risk my neck anywhere near a campful of excitable girls who can’t tell a boy in a pair of red-striped pajamas from a zebra and who might start screaming bloody murder if they happened to see us again.”

“I’ll have to go alone, then,” Poetry announced firmly, and in a jiffy, his fat green-striped back was all I could see of him as he waddled off across the moonlit lawn toward the walnut tree and the gate.

It was either let him go alone on a wild goose chase, or go with him and run the risk of stumbling into a whirlwind of honest-to-goodness trouble.

35 I caught up to him by the time he had reached “Theodore Collins” on our mailbox, and whispered to him, “What do you think might have been wrapped up in it?”

Poetry’s voice sounded mysterious, and also very serious, as he answered, “Didn’t you read the paper this morning?”

I nearly always read the daily paper, part of it anyway, almost as soon as it landed in the mailbox, sometimes racing to get to the box before Pop did. Pop himself always read the editorials and Mom, the fashions and the new recipes and the accidents, and also worried about the accidents outloud to Pop a little. Mom always felt especially sad whenever anything had happened to a little baby.

“Sure,” I puffed to Poetry as I loped along after him in the shadowy moonlight. “What’s that got to do with a wad of oiled paper in a plugged watermelon?”

His answer as it came panting back over his fat shoulder, started the shivers vibrating in my spine again—and if I had been a cicada with a sound-producing organ inside me somewhere, my shaking thoughts would have filled the whole woods with noise.

Here are Poetry’s gasping words, “Whoever broke into the Super Market last week might be hiding out in this part of the county—maybe even along the creek here somewhere!”

“The paper didn’t say that,” I said.

“It didn’t have to,” Poetry shouted back. “It didn’t say where he was hiding, did it? I’ve got a hunch he’s right here in our territory. Maybe in the swamp or——”

I’d had a lot of experiences with Poetry’s hunches, and he’d been right so many times, that whenever he said he had one, I felt myself getting all of a sudden in a mood for a big surprise of some kind.

But this time his idea didn’t seem to make sense—not quite, anyway, so I said, “Who on earth would want to stuff a lot of money inside a watermelon?”

Poetry’s answer was a grouchy grunt, followed by a scolding: “I said I had a hunch! I know we’ll find something important going on around here ... Now, stop asking dumb questions and hurry up!” With that, that barrel-shaped, detective-minded boy set a still faster pace for me as we dashed down the hill to the place where I36 had just had the humiliating experience of riding a wild green, legless bronco in a reservoir full of cold water.

The red-striped pajamas I had been wearing must have made me look ridiculous to those girl scouts, I thought. I hoped they wouldn’t come back to the spring again while Poetry and I were looking for what he called a “clue.”

SEVERAL times, before that night was finally over, I thought how much more sensible we had been if we had curled ourselves up in our cots in the tent and gone sound asleep.

It’s better to be in bed when you have your night clothes on than scouting a watermelon patch or splashing in a pool of spring water or crouching shivering behind ragweeds and goldenrod and black-eyed Susans in a fence row, or searching with a flashlight for a wad of oiled paper which somebody has stuffed into a watermelon.

Especially is it better to be in bed, like any decent boy should be, than to be lying on your stomach under an evergreen tree with pine needles pricking you and you don’t dare move or you’ll be heard by somebody you are straining your eyes to see, while he does the most ridiculous thing you ever heard of at the very spring where you yourself were just an hour ago.

Boy oh boy, let me tell you about what happened, the second time Poetry and I went to the spring that night.

When we came to the beech tree, on whose close-grained gray bark the Gang and maybe thirty other people had carved their initials through the years, we stopped to look the situation over. There was a stretch of moonlit open space about twenty yards wide between us and the leaning linden tree which is at the top of the incline leading down to the spring.

The shadowy hulk of the old black widow stump in the middle of the moonlit space looked like a black ghost. I kept straining my ears in the direction of the linden tree wondering if there might be anybody down at the spring; also I kept my ears and my eyes focused in the direction of the pawpaw bushes away off to the left where the girls’ camp was. I could smell the odor of wet ashes and I knew that the girls had had a campfire near the black widow stump—there being an outdoor fireplace there for picnickers to38 use for wiener roasts, steak fries, and for making coffee—and also for giving a picnic a friendly atmosphere. I was only half glad to notice that the girls had put out the very last spark of their fire, ’cause I hated to have to admit that a flock of girls knew one of the most important safety rules of a good camper, which is: “Never leave a campfire burning, but put it out before you go.”

From the beech tree we moved east maybe a hundred feet, then made a moonlit dash for the row of evergreens which border the rail fence that skirts the top of the hill above the bayou.

“Okay,” Poetry panted when we got there. “We’ll work our way down from here. As soon as we get to the bottom, we’ll turn on the light and start looking for our clue.”

And then I heard something—a noise out in the creek somewhere, as plain as a Dog Star sunrise. It was the sound of an oar in a rowlock.

Poetry and I shushed each other at the same time, straining our ears in the shadowy direction the sound had come from.

At the same instant, we dropped down onto the pine needles under the tree.

“It’s somebody in a boat,” Poetry whispered. “He’s pulling in at the spring.”

I could see the boat now, emerging from the shadow of the trees down the shore. It had come up the creek from the direction of the Sugar Creek bridge.

Now the boat was being steered toward the shore. I knew if it was anybody who knew the shoreline, he wouldn’t stop directly in front of the spring, ’cause the overflow drained into the creek there and it would be a muddy landing. Below it, or just above it, was a good place.

“There’s only one man in it,” Poetry said. Even in the shadowy moonlight, I could tell it was a red boat and one we’d never seen before.

Then I did get a startled surprise, and my whole mind began whirling with wondering what on earth in a gunny sack! No sooner had the prow of the boat touched the gravelled shore than whoever was in it was up and out and beaching the boat, wrapping the guy39 rope, which is called a “painter,” around the small maple that grew there. Then he stepped back into the boat, stooped, picked up something in both hands—something dark and long and——!

“Hey!” my mind’s voice was screaming, while my actual voice was keeping still. “It’s a gunny sack! It’s the old brown burlap bag we saw in the watermelon patch a half hour ago!”

In a minute the man was out of the boat and disappearing in the path in the shadow of the trees we knew about. A second later, he emerged at the opening in the board fence, worked his way through, and moved straight toward the spring, lugging the burlap bag with the melon in it.

“Let’s jump him!” I whispered to Poetry.

Poetry put his lips to my ear and whispered back, “Nothing doing. Detectives don’t capture a criminal before he commits a crime. They let him do it first, then they capture him!”

“He’s already done it,” I said, “at the melon patch!”

“If you’ll be patient,” Poetry whispered back, “we’ll find out what we want to know.”

We kept on watching from behind the evergreen while the man at the spring hoisted his burlap bag over the cement lip of the pool and let it down inside. He stayed in a stooping, stock-still position for several jiffies, then began doing something with his hands.

“He’s about the size of Big Jim,” I whispered to Poetry.

“Or Circus,” he answered.

“Big Jim,” I insisted—only I knew that neither of them would steal a watermelon and bring it here by night in a boat.

Just then I shifted my position a little on account of I had been sitting on my foot and it was beginning to hurt. It was a crazy time to lose my balance and have to struggle awkwardly to keep from sliding down the incline, but that is what I did, and for a few anxious seconds I was looking after myself instead of watching the mysterious movements at the spring.

When, a jiffy later, I was focusing my vision in his direction, the man or extra large boy—whichever he was—had left the spring and was on his way back to the boat. For a split second we lost sight of him in the shadows, then we saw him again with his40 back to us at the boat, heard the painter being unwrapped from the tree.

In only a few more seconds the boat was gliding out into the creek—but only a few feet, for right away the oarsman steered it toward the shore and it became only a dim outline in the shadow of the trees that grew along the steep incline.

Poetry, beside me, sighed an exasperated sigh and said, “Well, it wasn’t any of our Gang, anyway. Look!”

I had already seen—first the flash of a match or a cigarette lighter, then a reddish glow in the dark, and I knew somebody was smoking a cigarette or a cigar. That’s how I knew for sure it wasn’t any of the Gang.

“I’d like to get my hands on him, for just one minute,” I said to Poetry. “Both hands—twenty times—in fast succession.”

“You wouldn’t strike a woman or a girl, would you?” he answered.

“What? Who said it was a woman or a girl? He had on a pair of trousers, didn’t he?”

“Girls wear slacks, don’t they? And lots of girls smoke, too.”

“And shouldn’t,” I answered.

We crept from our hiding place, scrambled down to where the boat had been beached and looked to be sure the oarsman—or oarswoman or oarsgirl—was out of sight. Then we slipped through the fence to look into the cement pool to see the melon and also to look around for the wad of paper I had tossed away when I had been here before.

I tell you it was an interesting minute—or three minutes, I should say—’cause that’s all the time it took us to discover some thing very important—very, very important!

Say, did you ever have a flashlight strike you full in the face and blind you for a few seconds? Well, the white light from the match or cigarette lighter and the reddish glow from the cigarette or cigar fifty yards down the shore, sort of blinded me—not my eyes, but my mind. I couldn’t think straight for a minute. It was Poetry’s suggestion, though—that the thief might be a woman or a girl—that really confused me.

41 I guess all the time I had had it in the back of my mind that the thief was Bob Till—but what if the person in the boat was a girl! No wonder I couldn’t think, I thought.

It was the perfume that sent my mind whirling. We noticed it the very second we had crawled through the fence. It was so strong it made the whole place smell as if somebody had upset the perfume counter in the Sugar Creek Dime Store and half the bottles of cologne and fancy perfumes had been broken.

If Dragonfly had been with us, I thought, he’d have sneezed and sneezed and sneezed, on account of he is allergic to almost every perfume there is.

Well, that was our chance to make a quick search for the wad of oiled paper which is what we had come there for in the first place. I remembered just about where I had tossed it and in only a few seconds Poetry hissed, “Here it is! Here’s our clue!”

His excitement about the thing and his being so sure, had built up my mind to expect to see something wonderful inside that oiled paper. Anybody who would go to the trouble to steal and deliver a watermelon secretly in a boat at night, would probably leave something in the melon worth a hundred times more than the melon itself.

There in the shadow of the linden tree, to the music of the bubbling water in the spring, and the singing of the crickets, Poetry held the flashlight while my trembling fingers unfolded that crumpled piece of oiled paper, and spread it out.

“There’s printing on it!” Poetry exclaimed under his breath.

And there was—actually was!

“What does it say?” I exclaimed.

“It says—it says, ‘Eat more Eatmore Bread. It’s better for you. The more Eatmore you eat, the more you like it.’”

It was disgusting; very disappointing also.

“Smell it,” Poetry exclaimed, which I did, and say!

Boy oh boy, there was really a perfume odor around the place now! If Dragonfly had been there, I thought again—or rather, started to think and didn’t get to finish, ’cause all of a sudden from the crest of the hill I heard a rustling of last year’s dry leaves, saw42 a flashlight leading the way and a spindle-legged barefoot boy in red-striped pajamas coming down the incline to the spring. Imagine that! Dragonfly in his night clothes! What on earth!

Poetry and I slipped behind an undergrowth of small elms where we couldn’t be seen, and listened and watched as Dragonfly came all the way down, went straight to the cement pool, shined his flashlight inside, then his hands began to work fast like he was in a big hurry and also like he was scared, and wanted to do what he was doing and get it over quick. He certainly was nervous and he seemed to be having trouble getting what he wanted to do, done.

Poetry’s fat face was close to mine. I decided I could whisper into his ear and only he would hear me, so I said, “Look! He’s got a knife! He’s going to plug the melon. He—”

Poetry jammed his fat elbow into my ribs so hard it made me grunt outloud.

Dragonfly jumped like he was shot, dropped his knife into the spring, started to straighten up, lost his balance, staggered in several moonlit directions, then ker-whammety-swish-splash—into the water he went just like I myself had done an hour or so ago.

And there he was, like I myself had been—a very wet boy in some very wet, very cold water, struggling to get onto his feet and out of the pool, and sneezing and spluttering because he had probably gotten some of the water into his mouth, or nose, and maybe even into his lungs.

And now what should we do?

We didn’t have time to decide, ’cause right that second there was a sound of running steps at the top of the incline and two shadowy figures with flashlights came flying down that leaf-strewn path, and somebody’s voice that was as plain as day a girl’s voice cried, “We’ve got you, you little rascal!”

Those two girls swooped down upon Dragonfly, seized him by the collar and started dunking him in the pool of very cold water, dunking and splashing water over him, and saying, “Take that—and that—and that! We knew if we waited here, you’d be back!”

Then all of a sudden, there was a hullabaloo of other girls’ voices at the top of the incline and a shower of flashlights and excited43 words came tumbling down with them. It seemed like there must have been a dozen girls, only there probably weren’t. Like a herd of stampeding calves, all of them swarmed around our little half-scared-half-to-death Dragonfly who was shivering and probably wondering what on earth. They were pulling him this way and that, as if they would tear him to pieces.

Things like those I was seeing and hearing that minute just don’t happen. Yet they were happening, and to one of the grandest little guys that ever sneezed in hayfever season—our very own Dragonfly himself.

I didn’t know what he had done, nor why, but it seemed like anybody with that many people swarming all over him like a colony of angry bumblebees, ought to have somebody to stand up for him. If it had been a gang of boys beating up on that innocent little spindle-legged guy, I probably would have made a headfirst dive, football style, into the thick of them and bowled half a dozen of them over into the cement pool. Then I’d have turned loose my two double-up experienced fists on them, windmill fashion, and Poetry would have come tumbling after.