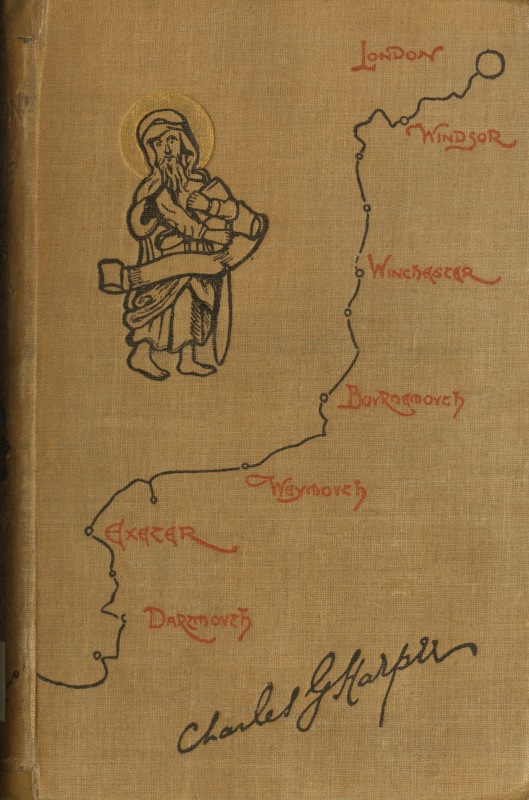

Title: From Paddington to Penzance

Author: Charles G. Harper

Release date: February 17, 2019 [eBook #58898]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Charlie Howard, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

By the Author of the Present Volume.

Demy 8vo, cloth extra, 16s.

THE BRIGHTON ROAD:

OLD TIMES AND NEW ON A CLASSIC HIGHWAY.

With a Photogravure Frontispiece and Ninety Illustrations.

“The revived interest in our long-neglected highways has already produced a considerable crop of books descriptive of English road life and scenery, but few have been more attractive than this substantial volume. The author has gathered together a great deal of amusing matter, chiefly relating to coaching and life on the road in the days of George IV., wherewith to supplement his own personal observations and adventures. He wields a clever pen on occasion—witness his graphic sketch of the ‘ungodly tramp’ whom he met between Merstham and Crawley. The book, in brief, is inspired by a genuine love of the road and all its associations, past and present, animate and inanimate. Its ninety illustrations, partly sketches made by the author on the way, and partly reproductions of old-time pictures and engravings, will add greatly to its attractions.”—Daily News.

“This is a book worth buying, both for the narrative and the illustrations. The former is crisp and lively, the latter are tastefully chosen and set forth with much pleasing and artistic effect.”—Scottish Leader.

“The Brighton Road was merry with the rattle of wheels, the clatter of galloping horses, the bumpers of hurrying passengers, the tipping of ostlers, the feats of jockeys and ‘whips’ and princes, the laughter of full-bosomed serving-wenches, and the jokes of rotund landlords, and all this Mr. Harper’s handsome and picturesque volume spreads well before its readers. To the author, Lord Lonsdale, with his great feat on the road between Reigate and Crawley, is the last of the heroes, and the Brighton Parcel Mail is the chief remaining glory of what was once the most frequented and fashionable highway of the world. As Mr. Harper sadly says, ‘the Brighton of to-day is no place for the travel-worn;’ but, with his book in hand, the pedestrian, the horseman, the coachman, or the cyclist, may find the road that leads to it from town one of the most interesting and entertaining stretches of highway to be found anywhere.”—Daily Chronicle.

“Space fails us to mention the many sporting events that have been decided upon, or near, the Brighton Road. They are duly recorded in this lively volume.... An old writer, speaking of Brighton shore, talks of the ‘number of beautiful women who, every morning, court the embraces of the Watery God;’ but these Mr. Harper found wanting, so he fled to Rottingdean.”—Spectator.

“This handsome book on the Brighton Road should be attractive to three classes in particular—those who like coaching, those who enjoy cycling, and the ‘general reader.’”—Globe.

“A pleasant gossiping account of a highway much trodden, ridden, driven, and cycled by the Londoner; a solid and handsome volume, with attractive pictures.”—St. James’s Gazette.

“The Brighton Road is the classic land, the Arcadia, of four-in-hand driving. An ideally smooth, hard, high road, with no more of uphill and down than a coach could travel over at a canter going up, and at a rattling trot, with the skid on, going downhill, it was a road that every sporting Londoner knew by heart, and many a London man and woman who cared nothing for sport.... The ancient glories of the road live for the author, and when he walks along the highway from London to Brighton, he seems to tread on holy ground. He would never have written so pleasant a book as ‘The Brighton Road’ had he been less of an idealist. He has, however, other qualifications for bookmaking besides a delight in coaching and its ancient palmy days. Something of an archæologist, he can speak learnedly of churches, both as ecclesiologist and artist, and has an eye for the human humours as well as the picturesque natural beauties of the road. His book is enriched with over ninety good illustrations, mainly from his own hand. Add to this, that Mr. Harper writes English pleasantly and well, with thorough love for and knowledge of his subject, and the reader of this review will see that ‘The Brighton Road’ that I am inviting him to buy or borrow is a thoroughly honest, good, and readable book.”—Black and White.

LONDON: CHATTO & WINDUS, PICCADILLY.

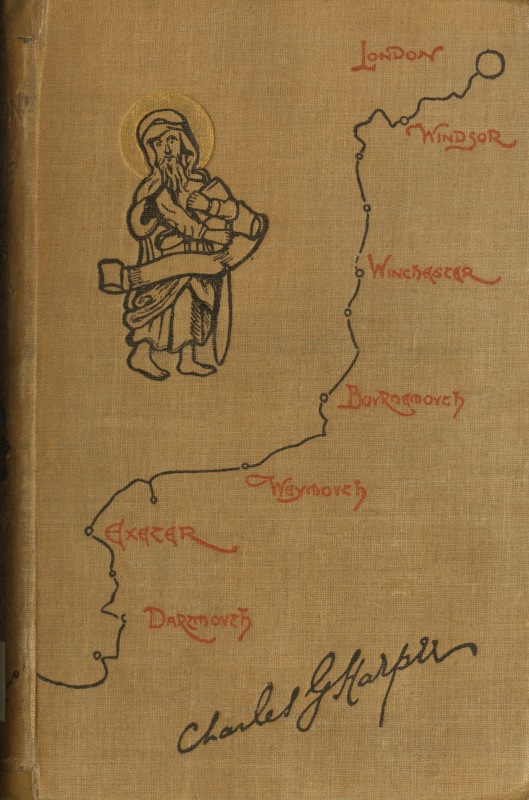

“GREAT SHIPS LAY ANCHORED.”

Frontispiece.

From Paddington

To Penzance

THE RECORD OF A SUMMER TRAMP FROM

LONDON TO THE LAND’S END

BY

CHARLES G. HARPER

AUTHOR OF “THE BRIGHTON ROAD,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY THE AUTHOR WITH ONE HUNDRED AND FOUR DRAWINGS

Done chiefly with a Pen

London

CHATTO & WINDUS, PICCADILLY

1893

v

To General Hawkes, C.B.

My Dear General,

Although we did not tour together, you and I, there is none other than yourself to whom I could so ardently desire this book to be inscribed—this by reason of a certain happening at Looe, and not at all for the sake of anything you may find in these pages, saving indeed that the moiety of them is concerned with your county of Cornwall.

I have wrought upon this work for many months, in storm and shine; and always, when this crowded hive was most dreary, the sapphire seas, the bland airs, the wild moors of that western land have presented themselves to memory, and at the same time have both cheered and filled with regrets one who works indeed amid the shoutings and the tumults ofvi the streets, but whose wish is for the country-side. You reside in mitigated rusticity; I, in expiation of some sin committed, possibly, in by-past cycles and previous incarnations, in midst of these roaring millions; and truly I love not so much company.

Yours very faithfully,

CHARLES G. HARPER.

vii

Before I set about the overhauling of my notes made on this tour—afoot, afloat, awheel—from London to Land’s End, I confided to an old friend my intention of publishing an account of these wanderings. Now, no one has such a mean idea of one’s capacities as an old friend, and so I was by no means surprised when he flouted my project. I have known the man for many years; and as the depth of an old friend’s scorn deepens with time, you may guess how profound by now is his distrust of my powers.

“Better hadn’t,” said he.

“And why not?” said I.

“See how often it has been done,” he replied. “Why should you do it again, after Elihu Burritt, after Walter White, and L’Estrange, and those others who have wearied us so often with their dull records of uneventful days?”

“I do it,” I said, “for the reason that poets writeviii poetry, because I must. Out upon your Burritts and the rest of them; I don’t know them, and don’t want to—yet. When the book is finished, then they shall be looked up for the sake of comparison; at present, I keep an open mind on the subject.”

And I kept it until to-day. I have just returned from a day with these authors at the British Museum, and I feel weary. Probably most of them are dead by this time, as dead as their books, and nothing I say now can do them any harm; so let me speak my mind.

First I dipped into the pages of that solemn Yankee prig, Burritt, and presently became bogged in stodgy descriptions of agriculture, and long-drawn parallels between English and American husbandry. Stumbling out of these sloughs, one comes headlong upon that true republican’s awkward raptures over titled aristocracy. The rest is all a welter of cheap facts and interjectional essays in the obvious.

Then I essayed upon Walter White’s “Londoners Walk to the Land’s End”—horribly informative, and with an appalling poverty of epithet. This dreadful tourist was used (he says) to sing and recite to the rustics whom he met.

“’Tis a dry day, master,” say the thirsty countrymen to him; while he, heedless of their artful formula, calls not for the flowing bowl, but strikes an attitude, and recites to them a ballad of Macaulay’s!

And yet those poor men, robbed of their beer, applauded (says our author), and, like Oliver Twist, asked for more.

ix Then an American coach-party had driven over part of our route, following the example of “An American Four-in-Hand in Britain,” by Citizen Carnegie. Indeed, we easily recognise the Citizen again, under the name of Mæcenas, among this party, which produced the “Chronicle of the Coach.”

The same Americanese pervades both books; the same patronage of John Bull, and the same laudation of those States, is common to them; but for choice, the Citizen’s own book is in the viler taste. Both jig through their pages to an abominable “charivari” of their own composing, an amalgam of “Yankee Doodle” and the “Marseillaise,” one with (renegade Scot!) a bagpipe “obbligato.”

They anticipate the time when we shall be blessed with a Republic after the model of their own adopted country; the Citizen (I think) commonly wears a cap of liberty for headgear, and a Stars and Stripes for shirt. This last may possibly be an error of mine. But at any rate I should like to see him tucking in the tails of such a star-spangled banner.

These were the works which were to forbid a newer effort at a book aiming at the same destination, but proceeding by an independent route, and (as it chanced) written upon different lines—written with what I take to be a care rather for personal impressions than for guide-book history.

We won to the West by no known route, but followed the inclinations of irresponsible tourists, with a strong disinclination for martyrdom on dusty highways and in uninteresting places. This, too, is explanatory of our taking the train at certainx points and our long lingering at others. If, unwittingly or by intent, I have here or there in these pages dropped into history, I beg your pardon, I’m sure; for all I intended was to show you personal impressions in two media, pictures and prose.

CHARLES G. HARPER.

London, October 1893.

xi

| I. | |

| PAGES | |

| Leaving London—The Spirit of the Silly Season—An Unimportant Residuum—The Direct Road—And the Indirect—To Richmond by Boat | 1–5 |

| II. | |

| Radical Richmond and its Royal Memories—The Poets’ Chorus—The Social Degradation implied by Tea and Shrimps—No Water at Richmond | 6–9 |

| III. | |

| Rural Petersham—The Monuments of Petersham Church—Ham House—Beer, Beauty, and the Peerage—The Earls of Dysart and their Curious Preferment—Village Hampdens and Litigation—Ham and the Cabal—Horace Walpole and his Trumpery Ghosts—Kingston—The Dusty Pother anent Coway Stakes—The Author “drops the Subject”—The King’s Stone—The Reader is referred to the Surrey Archæological Society, and the Tourists pursue their Journey—The Philosophy of the Thames—To Shepperton | 9–17 |

| IV. | |

| Windsor and Eton—The Terrific Keate—Persuasions of Sorts—Bray and its Most Admirable Vicar—Taplow Bridge—Boulter’s Lock—Cookham | 17–23 |

| V.xii | |

| An Indignant Man—Advantages of Indignation and a Furious Manner—Al fresco Meals—Medmenham Abbey—Those unkind Topographers—The Hell Fire Club—From Hambledon to Henley | 23–28 |

| VI. | |

| Regatta Island—Its Shoddy Temple—The Preposterous Naiads and River Nymphs of the Eighteenth Century Poets—Those Improper Creatures v. County Councils—A Poignant Individual—Mary Blandy, the Slow Poisoner | 28–33 |

| VII. | |

| Picturesque Wargrave—The Loddon River and Patricksbourne—Sonning—A Typical Riverside Inn—Filthy Kennet Side—Reading to Basingstoke | 33–35 |

| VIII. | |

| Hampshire Characteristics—White of Selborne as a Vandal—Holy Ghost Chapel | 35–38 |

| IX. | |

| A Dreary Road—Micheldever—Hampshire Literary Lights—The Worthies—“Johēs Kent de Redying” | 38–41 |

| X. | |

| Winchester—The City Lamps—The Cathedral—Saint Swithun | 41–48 |

| XI.xiii | |

| Wykeham—The Renaissance in the Cathedral—The Puritans—Winchester Castles, Royal and Episcopal—A Graceless Corporation—The Military—Saint Catherine’s Hill | 48–55 |

| XII. | |

| A Literary Transfiguration—Wyke—An Unique Brass—The Romance of Lainston—Sparsholt | 56–59 |

| XIII. | |

| A Rustic Symposium | 60–64 |

| XIV. | |

| Camping-out of Necessity—The Tramp en amateur—Soapless Britons—The Livelong Day | 64–65 |

| XV. | |

| Restoration at Romsey—Prout justified—An Unsportsmanlike Palmerston | 66–68 |

| XVI. | |

| The New Forest—The Woodman’s Axe—The coming Social Storm—Lyndhurst—Brockenhurst—Avon Water | 68–74 |

| XVII. | |

| A Superior Pedestrian—Christchurch—An Enigmatical Epitaph | 74–76 |

| XVIII.xiv | |

| Bournemouth—The Interesting Invalid—Languorous Romances—Bournemouth, the Paradise of the Unbeneficed | 76–79 |

| XIX. | |

| Our Encounter with an American | 79–81 |

| XX. | |

| By the Sea to North Haven—Studland—Our Coldest Welcome at an Inn—To Swanage | 82–83 |

| XXI. | |

| The Isle of Purbeck—Purbeck Marble—Domesticated Swanage—The Rush for Ground-rents | 83–86 |

| XXII. | |

| Corfe—Corfe Castle—Those Ubiquitous Roundheads | 86–88 |

| XXIII. | |

| Lulworth Castle—The Dorset Coast—Osmington | 88–90 |

| XXIV. | |

| Weymouth and George the Third—An Old-time Jubilee—A Gorgeous Individual—Railways and Derivatives—Hotel Snobbery | 91–93 |

| XXV.xv | |

| Abbotsbury—The Abbey Ruins—Saint Catherine’s Chapel—Historic Wessex—The Chesil Beach—West Bay, Bridport—A Hilly Country | 93–97 |

| XXVI. | |

| Chideock—One who fared at Dead of Night—Early Rising | 97–99 |

| XXVII. | |

| Charmouth—Concerning Rainy Days by the Sounding Sea—The Devon Borders—A Humorous Wheelman | 99–101 |

| XXVIII. | |

| Axminster—The Battle of Brunenburgh—The “Book of Remembrance”—Axminster Carpets | 102–104 |

| XXIX. | |

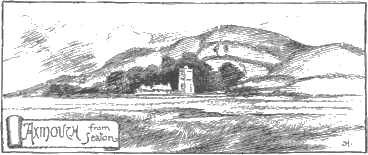

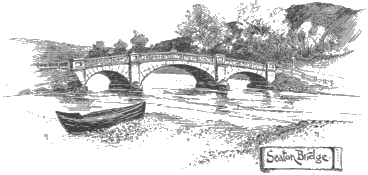

| Drakes of Ashe—Axmouth—The Fearful Joys of the Day-tripper—Seaton | 105–107 |

| XXX. | |

| Exeter, a Busy City—Richard the Third—A Chivalric Myth—Northernhay—The Cathedral: Black but Comely—St. Mary Steps | 108–111 |

| XXXI. | |

| The Suburb of Saint Thomas—Alphington—Exminster | 112–116 |

| XXXII.xvi | |

| A Grotesque Saint—The Pious Editor | 116–118 |

| XXXIII. | |

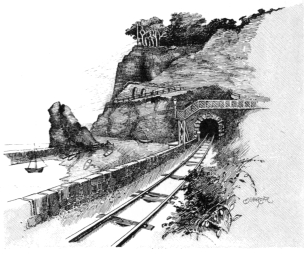

| Beside the Exe to Powderham—The Courtenays—The Atmospheric Railway | 118–120 |

| XXXIV. | |

| Starcross and its Aspirations—The Warren—Langstone Point—Mount Pleasant—The Limitations of Dawlish | 120–124 |

| XXXV. | |

| The Legend of the Parson and Clerk | 124–127 |

| XXXVI. | |

| Teignmouth—The Sad Tale of the Market House—Doleful Ratepayers—Teignmouth Harbour—Devon Weather—Society—To Shaldon | 127–133 |

| XXXVII. | |

| The (more or less) True Story of an Artist—Labrador Tea-gardens—Peripatetic Organ-grinders—The Author’s Indignation moves him poetically—And he reflects upon Comic Songs | 133–137 |

| XXXVIII. | |

| Devon Combes—Maidencombe—Where the Devil died of the Cold—Who was Anstey, of Anstey’s Cove?—“Thomas” of Anstey’s | 137–140 |

| XXXIX.xvii | |

| Torquay—Still growing—The Witchery of Tor Bay Scenery—Charter Day—Napoleon on board the “Billy Ruffian” | 140–144 |

| XL. | |

| Teutonic Paignton—Thoughts on German Bands—The Present Author loves a Comely Falsehood, but destroys a Lying Tradition—Berry Pomeroy and the Seymours | 144–149 |

| XLI. | |

| Totnes—Brutus the Trojan—“Oliver, by the Grace of God”—To Dartmouth | 149–153 |

| XLII. | |

| Down the Dart—Nautical Terms | 153–154 |

| XLIII. | |

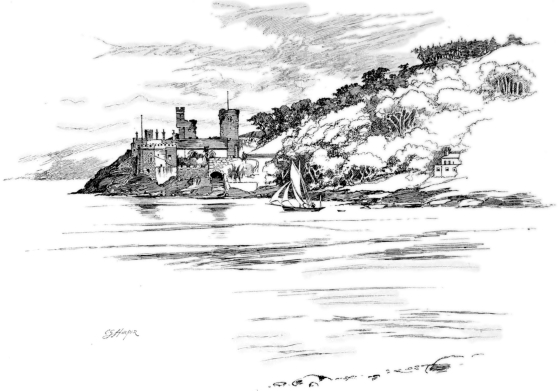

| Dartmouth—Castles of Dartmouth and Kingswear—Fighting the Foreigner—An Unrestored Church—Paternal Government | 154–159 |

| XLIV. | |

| Dittisham and the Dart—Tea at Dittisham, and so “Home” | 159–162 |

| XLV. | |

| Stoke Fleming—A Country Coach—Slapton Sands—To Kingsbridge | 163–165 |

| XLVI.xviii | |

| Kingsbridge—Its one Literary Celebrity—“Peter Pindar” upon his Barn—Kingsbridge Grammar School | 165–171 |

| XLVII. | |

| Salcombe River—Voyage to Salcombe—Hotel hunting—Salcombe Shops—The Castle | 171–176 |

| XLVIII. | |

| Voyage to Plymouth—The Tourists are Extremely Ill—Land at last—The Hoe and its Memorials—Politics and Patriotism—The Hamoaze—Saltash | 176–183 |

| XLIX. | |

| An Old Author on the Characteristics of Cornwall—Saint Budeaux—The Three Towns—Stained Glass extraordinary | 184–187 |

| L. | |

| Antony—Richard Carew: a Seventeenth Century Poet—The Tourists are entreated despitefully, and quarrel | 187–190 |

| LI. | |

| Carew’s Epitaph at Antony—Downderry | 191–192 |

| LII. | |

| A Lovely Valley, a Moorland Stream, and what befell there | 193–195 |

| LIII. | |

| Looe—Stage-like Picturesqueness—Hotel Visitors’ Books | 195–201 |

| LIV.xix | |

| Talland—Humorous Memorials of the Dead—Epitaph on a Smuggler—“John Bevyll of Kyllygath”—A Notable Devil-queller | 201–207 |

| LV. | |

| The Road to Polperro—The “Three Pilchards” Inn—Saturday Night at Polperro—John Wesley’s Experiences of that Place | 207–213 |

| LVI. | |

| Lanteglos-juxta-Fowey—A Cornish Cross—Polruan—Again the Comic Song!—Fowey—Tourists’ Lumber | 214–218 |

| LVII. | |

| Par: a Cornish Seaport | 219–220 |

| LVIII. | |

| An Old-time Adventure—Deserted Mining Fields—Saint Austell | 220–225 |

| LIX. | |

| By Carrier’s Cart to Mevagissey—John Taylor, the “Water Poet,” on his Adventure there—Exceptional Britons | 225–228 |

| LX. | |

| Mevagissey—Gorran Haven—The Inhospitable Hamlet of Saint Michael Caerhayes—In the Dark to Veryan—Hospitality of the Village Inn | 228–234 |

| LXI.xx | |

| Treworlas—Philleigh by the Fal—Truro City—Truro Cathedral | 234–239 |

| LXII. | |

| A “Lift” to Redruth—Local Tales—Saint Day—Redruth—The Tourists are taken for “Hactors,” and are sorrowfully obliged to disclaim the Honour | 239–242 |

| LXIII. | |

| A Rainy Day—Available Literature of the Hotel—The Cornishman and the Church—Cornish Livings | 242–245 |

| LXIV. | |

| Cam Brea—The Disillusionments of Exploration—Pool v. Poole—Dolcoath Mine—Squalid Camborne | 246–249 |

| LXV. | |

| The Hamlet of Barrepper—Cornish Names—Marazion | 249–252 |

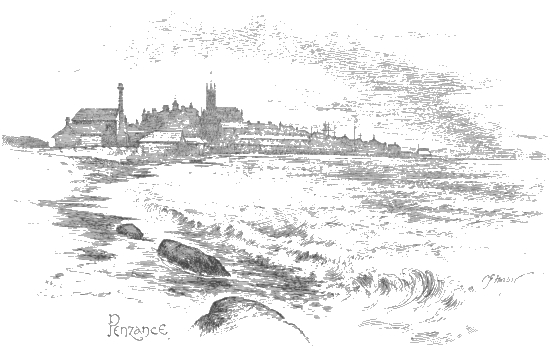

| LXVI. | |

| Alverton—Mount’s Bay—Penzance—German Band-itti—Pellew’s Birthplace—Saint Michael’s Mount, and the Loyal Saint Aubyns—The Newlyn School—Bridges, Potsherds, and Old Boots | 252–262 |

| LXVII. | |

| To Land’s End—Saint Buryan—The First and Last House in England | 262–268 |

| LXVIII. | |

| Home again | 268–269 |

xxi

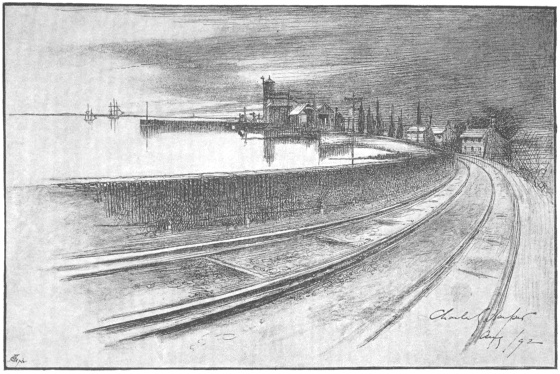

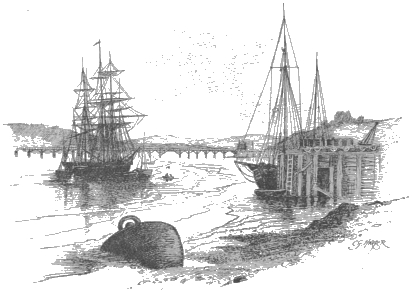

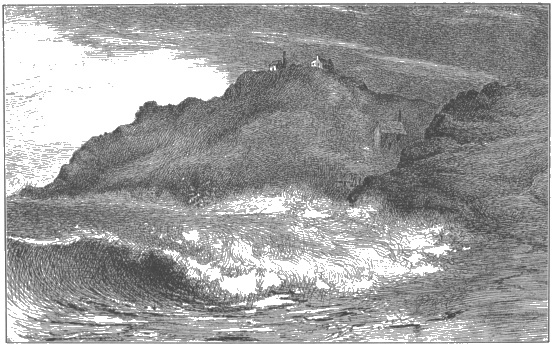

| “Great Ships Lay Anchored” | Frontispiece |

| Vignette | Title-page |

| Page | |

| Decoration | v |

| Preface Heading | vii |

| Decoration | xi |

| List of Illustrations | xxi |

| The Wreck | 1 |

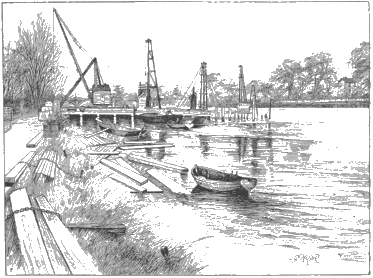

| Richmond Lock Works | 5 |

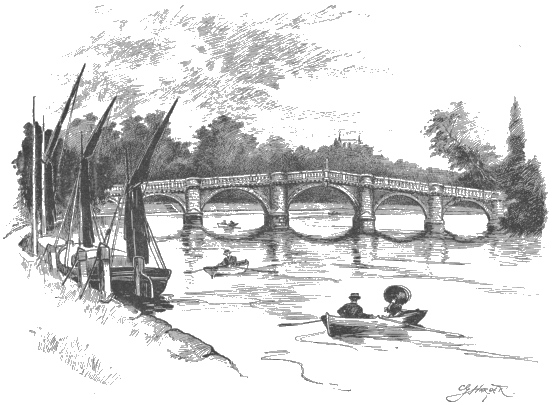

| Richmond Bridge | 6 |

| New Inn, Ham | 11 |

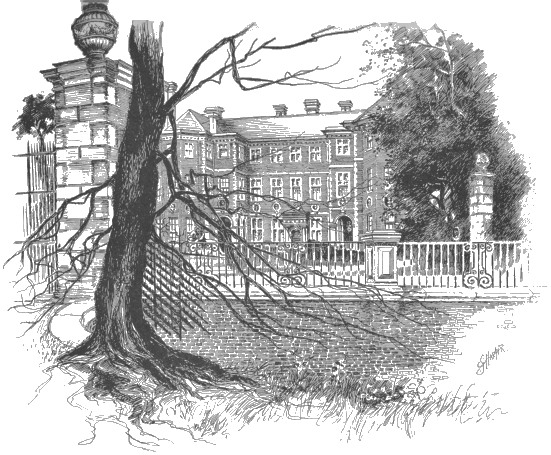

| Ham House | 14 |

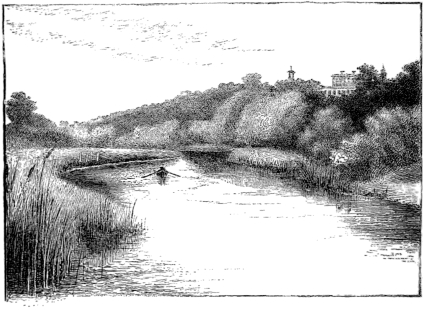

| Below Kingston | 15 |

| “Her Henry” | 18 |

| “W. E. Gladstone” | 19 |

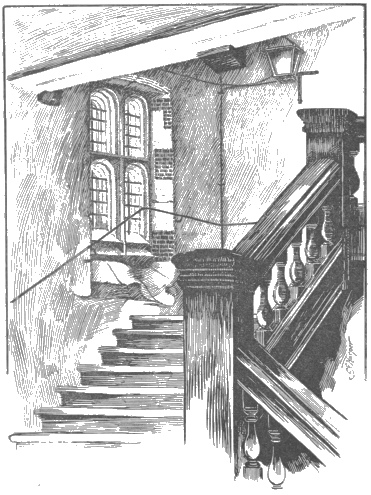

| Staircase in Eton College | 20 |

| Windsor: Early Morning | 20 |

| Clieveden | 22 |

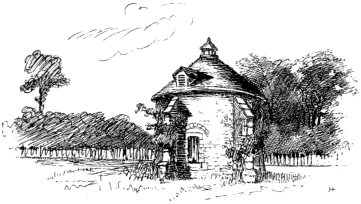

| Dove Cote, Hurley | 25xxii |

| Above Hurley | 26 |

| Medmenham Abbey | 27 |

| Poignant Individual | 29 |

| Evening at Henley | 33 |

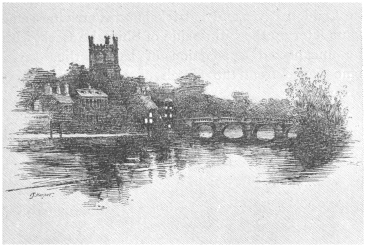

| Sonning Bridge | 34 |

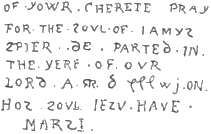

| Inscription: Sherborne Saint John | 36 |

| Holy Ghost Chapel, Basingstoke | 37 |

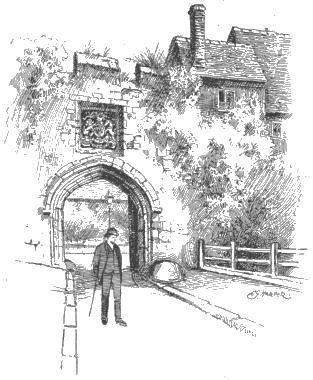

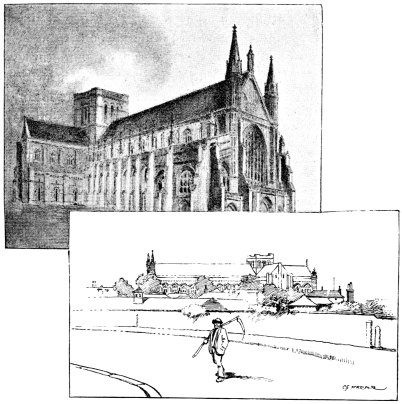

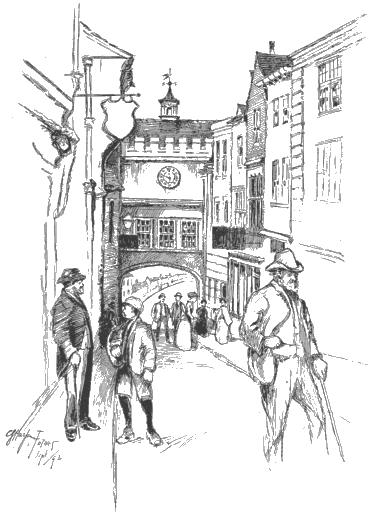

| Entrance to the Close, Winchester | 43 |

| Winchester Cathedral | 45 |

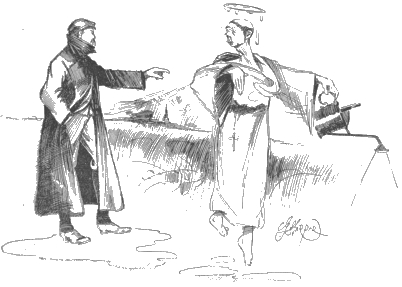

| St. Swithun and the Indignant Tourist | 47 |

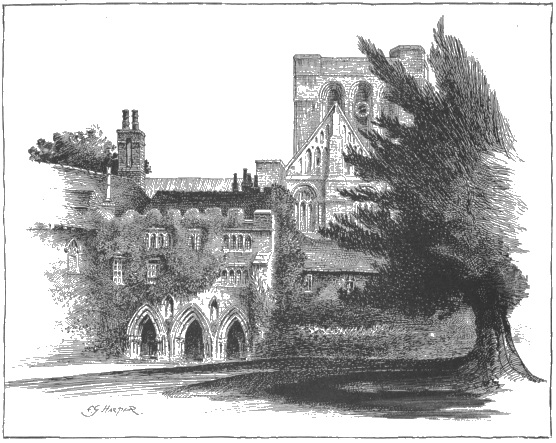

| The Deanery, Winchester | 50 |

| Bishop Morley’s Palace | 52 |

| High Street, Winchester | 52 |

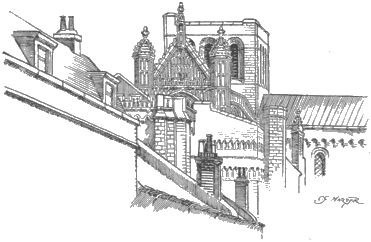

| A Peep over Roof-tops, Winchester | 54 |

| Saint Catherine’s Hill from Itchen Meads | 55 |

| “Ad Portas,” Winchester College | 56 |

| Brass, Weeke | 58 |

| Interior, Sparsholt Church | 59 |

| Romsey Abbey | 66 |

| Lyndhurst | 71 |

| A Ford in the New Forest | 73 |

| “Flashed Past” | 75 |

| Corfe Castle | 86 |

| “Politics and Agriculture” | 89 |

| “Gazed after us” | 90 |

| “Extremely Amusing, I do assure you” | 92 |

| “Humorous Wheelman, Garbed Fearfully” | 101 |

| Axmouth, from Seaton | 105 |

| Seaton Bridge | 106 |

| “Loathly Worm” | 107 |

| Exeter Cathedral: West Front | 110 |

| Saint Thomas | 112 |

| Exeter, from the Dunsford Road | 112 |

| Alphington | 113xxiii |

| An Exminster Monument | 115 |

| Exminster Saint | 116 |

| Turf | 119 |

| Starcross | 120 |

| Langstone Point | 122 |

| Mount Pleasant | 123 |

| Lee Mount, Dawlish | 124 |

| Sea Wall, Teignmouth | 126 |

| Railway and Sea-wall, Night | 128 |

| Railway and Sea-wall, from East Cliff, Teignmouth | 128 |

| The Teign | 130 |

| Teignmouth Harbour | 131 |

| Maidencombe | 138 |

| Berry Pomeroy Castle | 147 |

| From a Monument, Berry | 149 |

| Eastgate, Totnes | 151 |

| Dartmouth Castle | 156 |

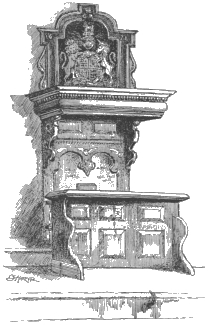

| Ancient Ironwork, South Door of Saint Saviour’s Church, Dartmouth | 158 |

| Arms of Dartmouth on the Old Gaol | 159 |

| Fore Street, Kingsbridge | 166 |

| Headmaster’s Desk, Kingsbridge | 170 |

| Kingsbridge Quay: Evening | 172 |

| Bolt Head | 178 |

| Drake’s Statue | 181 |

| Saltash Station | 186 |

| Guildhall, East Looe, and Borough Seal | 197 |

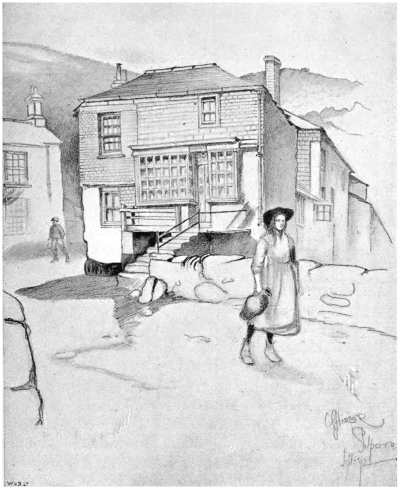

| “Comparatively Prosaic Fisherman” | 198 |

| The “Jolly Sailor” | 200 |

| Seal of West Looe | 201 |

| Talland Cherubs | 203 |

| An Old Shop, Polperro | 211 |

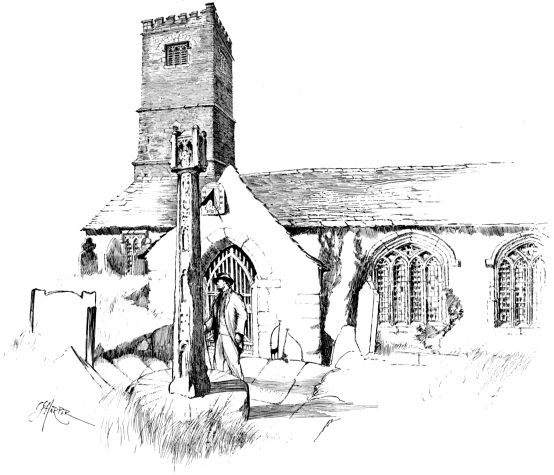

| Lanteglos-juxta-Fowey | 214 |

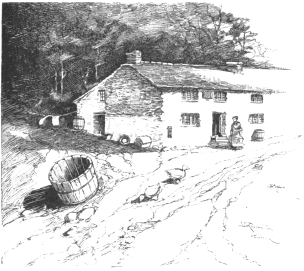

| A Cornish Moor | 220xxiv |

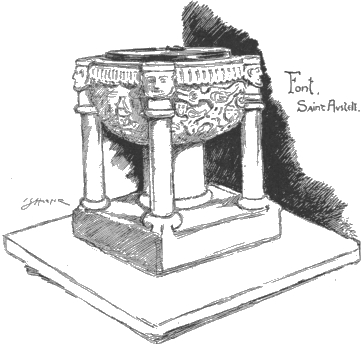

| Font, Saint Austell | 224 |

| A Note at Gorran | 229 |

| Roseland Inn, Philleigh | 236 |

| Lander | 237 |

| Carn Brea | 246 |

| Druidical Altar, Carn Brea | 248 |

| Saint Michael’s Mount | 253 |

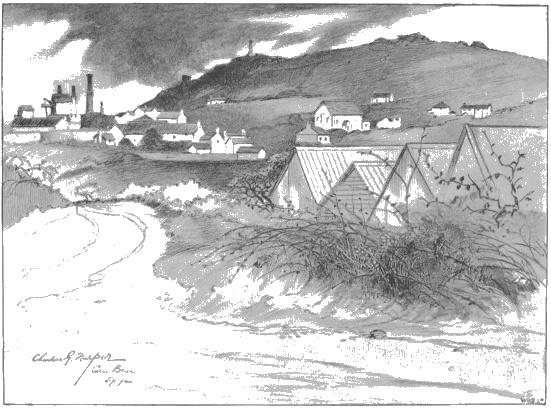

| Penzance, from above Gulval | 254 |

| Saint Michael’s Mount: Entrance to the Castle | 256 |

| Penzance Harbour: Night | 256 |

| Chevy Chase Hall | 259 |

| Penzance | 260 |

| Ludgvan Leaze | 261 |

| Saint Buryan | 262 |

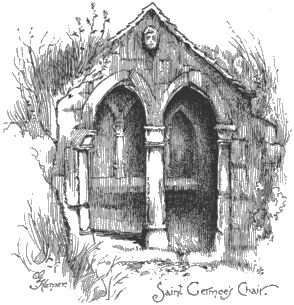

| Saint Germoe | 263 |

| The Longships Lighthouse | 264 |

| Carn Kenidjack | 266 |

| Saint Levan | 267 |

| Saint Germoe’s Chair | 268 |

1

There were two of us: myself, the narrator, the artist-journalist of these truthful pages, and my sole companion, the Wreck. Why I call him by this unlovely title is our own private business, our exclusive bone of contention; not for untold gold would I disclose the identity of that man, the irresponsible, the nerveless, mute, inglorious fellow-wayfarer in this record of a summer’s tour. Let him, nameless save by epithet, go down with this book to a more or less extended posterity. But I give you some slight portraiture of him,2 so that you shall see he was not so very ill-favoured a Wreck, at any rate.

This man, willing to be convinced of the pleasure and the healthful profit of touring afoot, yet loth to try so grand a specific for varied ills, delayed long and faltered much between yea and nay ere he was finally pledged to the trip; but a time for decision comes at last, even to the most vacillating, and at length we set out together on this leisured tour.

It was time. When we left London the spirit of the silly season roamed abroad, and made men mad: the novelists were explaining diffusely in the columns of the public press why they wrote no plays; the playwrights were giving the retort discourteous (coram publico) to the effect that the novelists had all the will but didn’t know how, and the factions between them made any amount of copy for the enterprising editor who looked on and, so to speak, winked the other eye while the combatants contended. Unsuccessful Parliamentary candidates were counting the cost of their electoral struggles, and muttering melodramatic prophecies of “a time will come”; the eager journalist wandered about Fleet Street, seeking news and finding none, for the Building Societies had not yet begun to collapse; and the chiefest streets of town were “up.”

Those happy men, the layers of wood-paving, had created a delightful Rus in Urbe of their own in Piccadilly, and enjoyed a prolonged sojourn amid such piney odours as Bournemouth itself never knew: here was health-giving balsam for them that had no cash to spend in holiday-making! But3 indeed almost every one had left town; only an unimportant residuum of some four millions remained, and wide-eyed emaciated cats howled dismally in deserted areas of the West End, while evening breezes blew stuffily across the Parks and set the Londoner sighing for purer air where blacks were not, nor the shouting of the streets annoyed the ear.

If you take the reduced ordnance map of England, and rule a straight line upon it from Paddington to Penzance and the Land’s End, you will find that the distance by this arbitrary measurement is some 265 miles, and that the line passes through or near Staines, Basingstoke, Salisbury, Exeter, Truro, and Redruth, to Penzance and Sennen Cove, by Penwithstart, touching the sea at three places en route—Fowey, Par, and Charlestown, neighbouring towns in Cornwall.

The most direct coach-road is given by Cary, of the New Itinerary, as 297 miles 5 furlongs. It was measured from Hyde Park Corner, and went through Brentford, Hounslow, Staines, Egham, Bagshot, Hartford Bridge, Basingstoke, Whitchurch, Andover, Salisbury, Blandford, Dorchester, Bridport, Axminster, Honiton, Exeter, Crockernwell, Okehampton, Launceston, Bodmin, Redruth, Pool, Camborne, Hayle River, and Crowlas. The route, it will be seen from this breathless excerpt, was commendably direct, thirty-two miles only being added by way of deviation from the measured map. On this road, so far as Exeter at least, much might be gleaned of moving interest in matters of coaching times, but beyond the Ever Faithful City no first-class4 nor very continuous service seems to have been maintained: the Royal Mail, Defiance, Regulator, Traveller, Celerity, and Post coaches finding little custom farther west.

I keep all love for high-roads for those times (rare indeed) when I go a-wheel on cycles; it is better to fare by lanes and by-ways when you go afoot, and then to please yourself as to your route, caring little for a consistent line of march: consistency is the bugbear of little minds. So swayed by impulse and circumstances were we, that I should indeed fear to set about the computation of mileage in this our journey from East to West: for our somewhat involved course, your attention, dear reader, is invited to the map.

We packed our knapsacks overnight, and the next morning

we had taken a hansom from Paddington, bound for Westminster Bridge, thence to voyage by steamer to Richmond.

Set down at Westminster Pier, we waited for the Richmond boat, while the growls and grumblings of the streets sounded loudly from the Bridge overhead, and mingled with the hoarse thunder of trains crossing the abominable squat cylinders and giant trellis-work that go to make the railway-bridge of Charing Cross.

I am not going to weary you with a description of how we slowly paddled up stream in the5 Richmond boat, past the Houses of Parliament on one hand, and Lambeth Palace and Doulton’s on the other; under Vauxhall and other London bridges, into suburban reaches, the shoals of Kew, and past the dirty town of Brentford (noted for possessing the ugliest parish church in all England), until at length we came off the boat at Richmond town. No: if I were to commence with this I know not where I should stop, and so, perhaps, the best way to treat the voyage would be by a masterly display of “reserved force.” Assume, then, that we are at length (for this steamboat journey is an affair of considerable time though few miles)—at length arrived at Richmond.

6

What semi-suburb so pleasant as Richmond, quite unspoilable, though jerry-buildings and shoddy hotels conspire to oust its old-world air; though the Terrace elms are doomed; though on Saturdays and Sundays of summer, Halberts and Arrys, Halices and Hemmers, crowd George Street, and shout and sing and exchange hats, and row upon the river, where, from the bridge, you may see them waving their sculls windmill fashion, and colliding, one boat with another, so that, their little hour upon the water being finished, the boatowners levy extra charges for scraped paint and broken scull-blades.

How many towns or neighbourhoods can show such courtly concourse of old: kings and queens, statesmen, nobles, poets, and wits? Palaces so many and various have been builded here, that the historian’s brain reels with the reading of them: eulogistic verse, blank and rhymed, has been written by the yard, on place and people, chiefly by eighteenth century poets, who then thronged the banks of Thames and constituted themselves, virtually, a Mutual Admiration Society. Thomson wrote and died here; near by, Gay, protected by a Duke and Duchess of Queensberry, lapped milk, wrote metrical fables, grew sleek, and presently died; Cowley, Pope, and a host of others contributed to the flood of verse, commonly in such journalistic tricklings as these:—

7

Literary ladies, and blue-stockings too, have thronged Richmond, and to this day there stands on the Green a row of charming old houses, fronted with gardens and decaying wrought-iron gates, called Maid of Honour Row, where were lodged such maids of rank whom interest or favour could admit to that honoured, though hard-worked and thankless guild. Madame D’Arblay, who, as Fanny Burney, was a domestic martyr to the royal household, has shown us how empty was the title and painful the place of “Maid of Honour.”

But despite royal associations, perhaps, indeed, on account of them, the Richmond of to-day is Radical: it has been distinguished, or notorious, for its Radical tradesmen any time these last hundred and forty years, from the time when the institution of “Tea and shrimps, 9d.” may be said to date. Tea, by itself, is not distinctly Radical, but I confess I see the germs of Republicanism in shrimps, and I should not be surprised at hearing of red-capped revolts originating at any of those places—Herne Bay, Margate, Ramsgate, Greenwich, Gravesend, Kew, and Richmond, where the shrimp is (so to speak) rampant.

Time was, indeed, when a “dish of tea” was distinctly exclusive and aristocratic: it has been, with the constant reductions of duty, rendered less and8 less respectable. The first step in its downward career was taken when the “dish” was substituted for the “cup,” and its final degradation is reached in the company of the unholy shrimp. The “cup of coffee and two slices” of the early morning coffee-stall is vulgar, but seems not to sound the depths of the other institution.

Let Chancellors of the Exchequer be warned ere it is yet too late; with the disappearance of the last halfpenny of the duty upon tea will come the final crash. Tea and shrimps will be obtainable for sixpence, and monarchy will no longer rule the land; perchance Chancellors of the Exchequer themselves will be obsolete and dishonoured officers of State. Perhaps, too, in some far distant period, Richmond will succeed in obtaining a water supply. Now she stands on one of the charmingest reaches of Thames, and yet, within constant sight of his silver flood, drinkable water is hardly come by in Richmond households. This is the penalty (or one of them) of popularity; the wells that were all-sufficient for Richmond of the past do not suffice for the population of to-day, which has gained her a charter of incorporation, and lost her an aristocratic prestige. The rateable value of Richmond must be very large indeed, but what does it avail when hundreds of thousands of pounds are continually being spent in fruitless borings for water? Richmond folk, nowadays, have all of them a species of hydrophobia, induced by a tax of too many pence in the pound for the water rate. Uneasy sits the Mayor, and the way of the Council is hard.

9

Thames, too, has been shockingly inclined to run dry at Richmond, so that there is building, even now, a lock that is to supersede that of Teddington in its present fame of largest and lowest on the river.

We looked into Richmond church and noted its many tablets to bygone actors and actresses, chief among them Edmund Kean, who died at the theatre here, so recently rebuilt. Then we hied to a restaurant and lunched, and partook (as in duty bound) of those cakes peculiar to the town. Then we set forth upon our walk.

To continue on the highroad that leads out of populous Richmond toward the “Star and Garter,” is to find one’s self presently surrounded with rustic sights and sounds altogether unexpected of the stranger in these gates. To take the lower road is to come directly into Petersham, wearing, even in these days, an air of retirement and a smack of the eighteenth century, despite its close neighbourhood to the Richmond of District Railways and suburban aspects.

The little church of Petersham is interesting despite (perhaps on account of) its bastard architecture10 and singular plan, but the feature that gives distinction is its cupola-covered bell turret, quaintly designed and louvre-boarded. The interior is small and cramped, and crowded with monuments. Among these the most interesting, so it seemed to us, was that to the memory of Captain George Vancouver, whose name is perpetuated in the christening of Vancouver Island.

Others of some note, very great personages in their day, but now half-forgotten, are buried in the churchyard and have weighty monuments within the church. Among these are an Earl of Mount Edgcumbe, a vice-admiral, a serjeant-at-law, Lauderdales, Tollemaches, and several dames and knights of high degree. Perhaps more interesting still, Mortimer Collins, author of, among other novels, that charming story, “Sweet and Twenty,” lies buried here.

And from here it is well within three miles to the little village of Ham, encircling, with its scattered cottages and mansions of stolid red brick of legitimate “Queen Anne” design, that common whose name has within the last two years been so familiar in the mouths of men. You may journey into the county’s depths and not find so quiet a spot as this out-of-the-world corner, nor one so altogether behind these bustling times. It has all the makings of the familiar type of an old English village, even to its princely manor-house. Ham House is magnificent indeed, and thereby hangs a tale.

Its occupiers have been for many generations the Earls of Dysart, whose family rose to noble rank by11 sufficiently curious means in the time of Charles I., an era when the peerage was reinforced by methods essentially romantic and irregular. Beauty (none too strictly strait-laced) secured titles for its bar-sinistered descendants in those times: in our own it is commonly Beer that performs the same kindly office.

The first Earl of Dysart had in his time fulfilled the painful post of “whipping-boy”—a species of human scapegoat—to his sacred Majesty, and by his stripes was his preferment earned.

I am told that it is not to be supposed this house and manor are the property of the Dysarts: they pay and have paid, time almost out of mind, an12 annual rent into the Court of Chancery for the benefit of the lost owners.

“But yet,” said my informant at Ham—the strenuous upholder of public rights in that notorious Ham Common prosecution,—“but yet, although this is their only local status, the Dysart Trustees have endeavoured, from time to time, to assume greater rights over Ham Common and public rights-of-way, than even might be claimed by the veritable lord of the manor.”

In the early part of 1891, the Trustees placed notice-boards at different points of the Common, setting forth the pains and penalties and nameless punishments that would be incurred by any who should cut turf or cart gravel, exceeding in this act (it seems) their rights, even had they possessed the title, for there is extant a deed executed by Charles I., in favour of the people of Ham, giving the Common to their use for ever.

Fortunately there was sufficient public spirit in Ham for the resisting of illegal encroachments, and eventually the notice-boards were sawn down by village Hampdens. Thereupon followed a prosecution at the instance of the Dysart Trustees, with the result that the defendants were all triumphantly acquitted.

It were indeed a pity had this, one of the largest and most beautiful commons near London, been gradually drawn within the control of family trustees. It is now a breezy open space of some seventy-eight acres, stretching away from Richmond Park to near Teddington, and pleasingly wild with gorse and sandpits and ancient elms.

13 Here, almost to where the Kingston road bisects the Common, the avenue leading to Ham House stretches its aisle of greenery, its length nearly half-a-mile. To pursue this walk to the wrought-iron gates of the House is to be assured of interest. Erected in the early years of the seventeenth century, it remains a splendid specimen of building ere yet the day of contracts had set in. The red-brick front faces toward the river, and includes a spacious courtyard in whose centre is placed a semi-recumbent stone figure of Thames with flowing urn. Along the whole extensive frontage of the House, placed in niches, runs a series of busts, cast in lead and painted to resemble stone—a quaint conceit.

But it is not only the splendour of design and execution that renders Ham House so interesting. It was, in the time of Charles II., a meeting-place of the notorious Cabal—that quintette of unscrupulous Ministers of State whose doings were a shame to their country. Here they plotted together, and under this roof the liberties of the lieges were schemed away. Those were stirring times at Ham. Now the place wears almost a deserted look. The courtyard is grass-grown between the joints of its paving, and it is many years since the massive iron gates enclosing the grounds were used. It seems to have been lonely and decayed, even in Horace Walpole’s time. He says, “Every minute I expected to see ghosts sweeping by—ghosts that I would not give sixpence to see—Lauderdales, Tollemaches, and Maitlands.” For my part I think I would give a great many sixpences not to see14 them, either by night or by day, whether or not they carried their heads in the place where heads should be, or under their arms, an exceedingly uncomfortable position, even for ghosts, one would think. I have not that horrid itching (which I suppose characterises the membership of the Psychical Research Society) for the society of wraiths and bogeys, and hold ghosts, apparitions, spooks, and spunkies of every kind in a holy horror.

Therefore, we presently departed hence, and came, in course of time, to Kingston. Whether or not Kingston can be identified as the place where Cæsar crossed the ford across the Thames in pursuit of Cassivelaunus and his cerulean-dyed hordes of Britons, our ancestors, is, I take it, of not much concern nowadays, although antiquaries of our fathers’ time made a great pother about the conflicting claims of Kingston and Coway Stakes, at Shepperton, to the honour, if honour it be, of affording passage to the victorious general and his legions. I like something of more human interest than these dry bones, and, I doubt not, you who endeavour to read these pages are of the same mind; so, to make your pilgrimage through this book the lighter, I think “we had better” do like Boffin, in the presence of Mrs. Boffin—that is, “drop the subject.”

But the subject to which we must come (for no one who writes upon Kingston can avoid it) is only one remove nearer. I refer to that bone of contention (excuse the confusion of ideas) the King’s Stone, now set up and railed round in Kingston market-place, and carven with the names of the seven15 Saxon kings crowned here. It is this stone which has caused many pretty controversies as to whether or not it confers the name upon the town, or whether or not the place was the King’s Town.

You may, doubtless, if you are greedy of information on these heads, find all conceivable arguments set forth in the pages of the Surrey Archæological Society’s Transactions. I confess my curiosity does not carry me to such lengths. The stone is there, and, like good tourists, we accepted as so much gospel the facts set forth on it, and cared nothing as to the etymology of Kingston. Instead, we busied ourselves in hiring a boat which should take us to Reading, a journey which we estimated of a week’s duration.

Geographers, physical and political, tell us that Thames drains and waters all that great district which lies between the estuary of the Severn and the seaward sides of Essex and Kent; that it is the fertiliser of square miles innumerable, and the potent source of London’s pre-eminent rank amongst the cities of the earth. This is all very true, but the geographers take no note of Thames’ other functions; the inspiration of the poets and the painters, the enrichment of innkeepers and boat-proprietors, and the pleasuring of all them that delight in bathing and the rowing of boats. Everywhere in summer-time are boats and16 launches and canoes, punts and houseboats, and varieties innumerable of floating things; for when the sun shines, and the incomparable river scenery of the Thames is at its best, the heart of man desireth nothing more ardently than to lie in a boat upon the quiet mirrored depths of a shady backwater, or better still, to sit within the roaring of the weir, where the swell of the tumbling water acts like a tonic upon the spirits, and the sunlight fashions rainbows in the smoke-like suspended moisture of its foam. These are modern pleasures. For centuries the Thames has flowed through a well-peopled country, yet the delights of the river are new-found, and only in the eighteenth century did the poets’ chorus break forth in flood of praise. But to-day every one who can string rhymes makes metrical essays upon the Thames, and writers without number have written countless books upon it. From Kingston to Oxford, houseboats make populous all its banks, and the quantity of paint and acres of canvas that have been expended upon artistic efforts along its course, from Trewsbury Mead to the Nore, must ever remain without computation.

For these reasons ’tis better to say little of our journey this afternoon to Shepperton, past Hampton Court, the Cockney’s paradise, to Hampton, Sunbury, Walton, and Halliford. The river was crowded with boating parties, with those who raced and with others who paddled lazily, and when night was come the houseboats hung out their paper lanterns, all red and yellow, that streaked every little ripple with waving colour.

17 That night saw the first unpacking of our knapsacks, and the irrevocable disappearance of their orderly arrangement. Chaos reigned ever afterward within their ostensibly waterproof sides, for to man is not given the gift of packing up, and we were not superior to the generality of our sex. I remember perfectly the shower of things that always befell o’ nights when I came to the ordeal of unpacking my knapsack: how razors, comb and brush, pencils, and neckties and other articles dropped from it; and, I make no doubt, it was the same with the other man.

Chertsey we passed this morning, heated with rowing, but between this and Laleham we were so far fortunate as to fall in with some acquaintances on a steam-launch who took us in tow so far as Old Windsor Lock, where we cast off and proceeded alone, landing at one of the many slips by Eton Bridge.

Windsor and Eton claimed us for the remainder of the day for the due pursuance of some desultory sight-seeing, but Eton chiefly, for the sake of its College, where “her Henry,” that unhappy pious founder, Henry VI., stands in effigy in the great quadrangle, and casts a “holy shade,” according to Grey.

The “College of the Blessed Mary of Eton beside Windsor” has numbered among its scholars a18 goodly proportion of our famous men; and many of their names, carved on the woodwork of the schools in their schoolboy days, remain to this day. On the doorway leading from the Upper School into that place of dread, the headmaster’s room, may be seen carved, in company with other well-known names, that of “W. E. Gladstone;” and once within that apartment, your attention is drawn to the block whereon many have suffered, in less heroic wise, and by no means so tragically, as the martyrs of Tower Hill, but perhaps more painfully, for birch twigs, with the buds on them, must sting dreadfully. But these things are become historical relics rather than engines of contemporary punishment: they belong to the days of the terrific Keate and his19 robustious predecessors, who were wont to regard the fortiter in re as more convincing and a better preservative of discipline than the suaviter in modo.

It seems that everywhere the iron gauntlet gives way to the kid glove in our times; persuasion is to-day more a mental than a physical process. There are relics in plenty at Windsor and Eton of those times, only at Windsor these things take higher ground: there for persuasion read diplomacy in this era, where it had used to be a performance requiring the assistance of axe and chaplain. The Castle survives, its mediæval defences restored, for appearance sake, but its State apartments filled with polite furniture, dreadfully gilded and (we thought) tawdry. It makes a picture, this historic warren of kings and princes, and its Round Tower commands a glorious view, altogether an imposing range of turrets, battlements, and loopholed walls; but, alas! Henry the Eighth’s massive gateway was guarded by a constable of that singularly unromantic body—the Police, and his presence there made everything save the gas-lamps and the shop-fronts of Windsor streets seem of paste-board fashion and unreal.

20

The river is the proper place from whence to view the Castle: the time, early morning; for then, when the mists cling about the water, and the meadows are damp with them, that palace and stronghold,21 that court and tomb of royalty bulks larger than at any other time, both on sight and mind.

Thus we thought, when the early hours of the morning found us afloat again. Boveney, Monkey Island, were passed, and now arose above all the trees, the tall poplars that identify Bray to the distant view more surely than church or anything contrived at the hands of man. They range in rows, and are at once formal and touched with a delightful note of distinction. The village, too, is of the quaintest, with almshouses that should make the poverty housed within them dignified with a dignity that we who live in London’s hutches of brick and mortar, and are numbered with a plebeian number, may never know.

And at this Bray (we are told) lived that weathercock vicar, who twirled with every political wind, and by his dexterity kept his benefice and earned immortality. O most sensible Vicar of Bray: wholly admirable and right reverend exponent of expediency!

When once the bend of the river just above Bray is reached there is an end, for the time, of beauty, for the reach runs straight, and on either bank the encroachments of villadom are forming a continuous frontage of houses on to Taplow and Maidenhead, and three parts of the way to Cookham. Taplow Railway Bridge, brick-built, with bricks of a jaundiced hue, straddles over the water in two strides, an unlovely bridge, but remarkable for the great span of its arches, and for their extreme depression. So flat are the two arches of Taplow22 Bridge, that it seems scarcely credible they can bear the weight of the heavy trains constantly crossing. Yet fifty years have passed, and still the constant traffic of the Great Western Railway passes unharmed.

Beyond Taplow comes Maidenhead, most favoured of riverside towns, and, at the far end of Maidenhead, Boulter’s Lock, the busiest on the river, filled from morn to eve of summer days with boats full of the smartest frocks and prettiest girls one would wish to see. No more charming sight than Boulter’s on a busy day, when the boats are going up stream to Clieveden and Cookham. Clieveden woods on the right hand, and Ray Mead level on the left,23 with the river between, green with the reflections of the trees, and splashed here and there with the bright-coloured blazers of the rowers, make a sight to be remembered.

We came late round the bend to Cookham Lock, and into Cookham village from the landing-place, as the moon rose in a cloudless sky.

This morning there was an indignant man to breakfast at Cookham. Nothing pleased the creature, and the crowded coffee-room was well advised of his discontent, for he took care to proclaim it to all and sundry. He had begun the morning badly, so it seemed, and was like to continue thus throughout the day. The birds began it by arousing him from sleep at dawn, and surely never had birds of any sort been so anathematised since the time of that famous jackdaw of Rheims. The rooks and crows, the sparrows and pigeons, that cawed and chattered and murmured with the coming of day in neighbouring elms and hedgerows, on roof-tops and in pigeon-cots, had awakened him and kept him counting the dawning hours, and that was why the toast, the tea, the eggs and the butter were all at fault to this man. He badgered the coffee-room waiter, who—poor fool!—respected him the more for it at the expense of the less contentious of the guests, and he plied all that waiter’s attention with a grumbling commentary, that went far to show him24 in the character of the fault-finder on principle. You see, that man who has a great capacity for indignation, with a voice of roaring and words of fury, is the man who gets on in this world. He who takes the world by the throat, and grips it hard and shakes it violently, and kicks it where honour is the more readily wounded, is the man who, at the end of the struggle, comes out “upper dog.” But the cultivation of the furious manner is a wearing cult, and besides, does not sit well on a man of little chest, small voice, and gentle eye. Other things, too, are wanting to a complete success. Let me put them all together, like Mrs. Glass, the historic, the well-beloved:—

Take a goodly presence, one pair of sound lungs, some original sin, and a small pinch of merit. Throw them all into your avocation, and, adding some impudence to taste, let the whole boil vigorously until public attention is attracted. Then serve up hot.1

Possibly that reader of a frankness so unmistakable, who annotates the margins of books from his Mudie (or even, goodness knows! from his Public Library), may disagree with these views, and fill these fair margins with criticisms of this view of life; but (a word in your ear, my friend) consider awhile, the view is sound.

This by the way. Excuse, if you please, the digression.

At Cookham we were bitten with a fancy for taking our meals al fresco, so when the time came25 for departure, imagine us stowing away into what I suppose are called the “stern sheets” of our boat sufficient provender for the day. There was a loaf and a pot of raspberry jam, some butter and a tin of some sort of meat. A couple of plates furnished us luxuriantly in the crockery department, and as for a table-knife, why, we forgot all about it, and when, in a quiet backwater, the time came for luncheon, we did our little best, which indeed was little enough, with a pocket-knife.

That meal was a gruesome orgie. Try to cut a new loaf with a pocket-knife, and you will find it much better to tear your bread straight away without further ado, a discovery we presently made; but don’t try to open a tin with such a knife, as you value your cutlery. This from experience, which we gained at the expense of a broken blade. Eventually we burst the tin open by stamping on it, and then the Wreck scooped out some of the contents26 with a piece of stick, as clean as might be, but still scarcely the ideal substitute for a knife. With this we spread the lumps of bread, and ate precariously. It should be said that the plates had already come to grief, and their fragments were now reposing in the river bed. For dessert we dipped the bread into the jam-pot, and thus circumvented the necessity for spoons.

This was at Hurley, after we had passed beautiful Marlow and Bisham, where the ghost of Lady Hoby walks in the abbey, and before we had come to Medmenham.

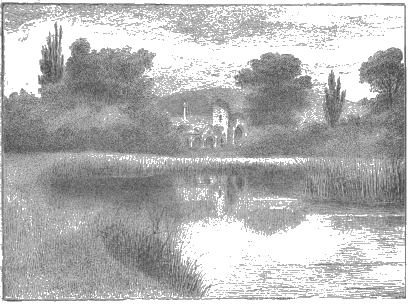

Here the notorious Medmenham Abbey stands by the waterside, where the river winds and rushes grow thick, and a lovely view it makes, close-hemmed27 with tall trees, the hills rising in the background and the level meads spreading out, emerald green, in front.

They tell us—those unkind topographers—that the picturesque ruins of the Abbey are a sham; that possibly one single pillar may be a genuine relic of the old religious house that once stood here, but that the arcading, the Tudor windows and the ivy-covered tower, are “ruins” deliberately built. Perhaps they are, but, even so, they are excellent, and those purists are not to be thanked for setting us right, where we might gladly have erred.

They would, too, assuage by exact inquiry the28 romantic legends of the Hell Fire Club, those “Monks of St. Francis,” as Wilkes and his jolly companions who rioted here were pleased to call themselves. Their horrid rites, their orgies and debauchery, the license of the place, typified by their motto, still extant, “Fay ce que voudras,” are, perhaps, better “taken as read.”

We crept up stream against a swift current, and between heavy rain showers that soaked us and diluted the remains of our picnic to a revolting mess: bread and water, tinned meat and raspberry jam, both sufficiently saturated, are not appetising items. It would perhaps be an exaggeration to say there was more jam on the seats and our clothes than in its native pot, but this was at least an open question.

At Hambledon, the lock-keeper let us through in a pelting shower, which ceased directly we were freed from the unsheltered imprisonment of the lock. Have you ever noticed how wet the river looks after rain? how much more watery the water appears? Thus looked Henley Reach as we rowed up it this evening, past that singular eyot called Regatta Island.

Regatta Island is scarcely a place of beauty. There is a brick and plaster pseudo-temple affair on it that records the most strenuous days of the classic29 fallacy, when eighteenth-century poets peopled the country side and the river banks with preposterous naiads and other galvanised reproductions of the beautiful and mystic mythology of the ancients. Alas! this is not Arcadia: Great Pan is dead long since, and his nymphs have danced away to an enduring Götterdämmerung. It is well it should be so, for had Pan survived he would have hidden his hairy legs with check trousers, and changed his “woodnotes wild” for the democratic strains of the concertina. In these days of prim and proper County Councils, whose internal rottenness is varnished over with a shiny varnish of prudery, such improper creatures are impossible. This is an age when everything must be properly breeched or sufficiently skirted, and, though the constitution of our Councils be revolutionary, a revolution sans culottes could not hope to win their approval.

A poignant individual, whose melancholy look touched time and place to a deeper pathos, stood by the water’s side, and vulgarised that shoddy temple with an air of one who had drunk too much beer, and was in the lachrymose stage.

We passed him by with flashing sculls that sent the watery shadows dancing madly in our wake, and crept up the quiet30 reach, past the poetically-named Phillis Court; the Wren-built bulk of Fawley; modern-built, yet historical Greenlands, residence of the late Mr. W. H. Smith, that unromantic but sufficiently strenuous upholder of “duty to Queen and country,” and presently came off the slip where many boats lay moored. Henley was quiet enough, not to say dull. Except when the midsummer madness of the Regatta sets all the riverside agog, and sends even garret lodgings up to fabulous prices, the broad stony streets of the town loom blankly to the stranger. The great church of Henley, whose tower, picturesquely turreted, shows to greater advantage at a distance, is of equally generous proportions. It is scarcely interesting, but there is in the graveyard a tomb of a sombre and darkling interest. Here lies, beside her father and mother, Mary Blandy, who, at the time of her trial and execution, was probably the most notorious person within the compass of these islands. The daughter of Mr. Francis Blandy, an attorney-at-law, who in 1750 lived in Henley town, close by the Angel Inn, she became acquainted with a Captain Cranston, who, being in charge of a recruiting party stationed here, was received into the society of the place. Now, Mr. Blandy was a widower, and dotingly fond of his daughter, his only child. Being a rich man as times went, he was anxious to secure for her a footing in county society, then more difficult of access than now. To this end he caused it to be understood that his Molly would have £10,000 by way of dowry, and the prospect of securing this large sum led the captain, who was a married man,31 to pretend love for her. Although he sprang from an old Scots family, Cranston was a man of extremely dissolute and evil character, and the lawyer, although he knew little or nothing of this, and nothing of the wife in Scotland, disliked and distrusted him, and forbade the engagement into which he and his daughter had entered.

However, Mary Blandy was so infatuated with the man, and so influenced by him, that, to get rid of her father, and to obtain at once both husband and her dowry, she set in train a scheme of slow poisoning that for heartlessness rivals Brinvilliers herself. In November 1750, she began to poison her father, under the instructions of Cranston, who, returning to Scotland, had sent her some pebbles, and powders ostensibly to clean them withal. The powders were composed of arsenic, and were administered in her father’s tea. By March of the following year the poison had its effect in causing her father’s teeth to drop out, whereupon this exceptional daughter “damned him for a toothless old rogue and wished him at hell.”

Several times the servants were nearly killed by having accidentally drunk of the tea prepared for the master of the house, and on each occasion this extraordinary woman nursed them back to health with the tenderest solicitude. At length their suspicions were sufficiently aroused to inform Mr. Blandy secretly. He told his daughter that he suspected he was being poisoned. She confessed to him, and he, incredible as it may appear, forgave her, with admonitions to amend her life, and, above all, to conceal everything,32 saying, “Poor girl, what will not a love-sick woman do for the man she loves!”

He died the next day, and Mary Blandy escaped the same night from the house, after having vainly attempted to bribe the servants to smuggle her off to London in a post-chaise. Half-way across Henley Bridge she was discovered, and would have been lynched by the inhabitants had she not taken shelter within the Angel Inn, where she was promptly arrested. Taken thence to Oxford, she was tried, found guilty, and condemned to death on the 29th February 1752. She was executed on the 6th April, begging not to be hanged high, “for the sake of decency.”

She asserted her innocence to the last, saying Cranston had told her the powders would do her father no harm. The same mob that had hunted her to the doors of the “Angel,” attended her body from the scene of execution at Oxford Castle, regarding her as a saint. She was buried here in a coffin lined with white satin. Cranston, it is scarcely necessary to add, fled the country.

This slow poisoner, if painter and mezzotinter lie not who have handed down her portraiture to our times, was peculiarly beautiful, with an eighteenth-century grace, a swan neck, and a sweetness of expression that, if any truth there be in views that take the face as index to the mind, would seem to shadow forth nothing but virtues minor and major.

At the “Red Lion” by the bridge we supped and slept, possibly attracted to this particular hostelry by Shenstone’s famous lines—

33

Boating men comprised almost the whole of the company at the Red Lion, and the talk was solely aquatic, dealing with races—past, present, and to come—with sculls and sliding-seats, and all the minutiæ of water pastimes.

This morning we rowed through Marsh Lock, struggled through the mazes, snags, and shallows of Hennerton Backwater, and lazed in the sunshine34 at Wargrave, that picturesque beach and village set over against the flat green meadows of the Oxfordshire bank. Then (for the spirit of exploration grew strong again) we laboriously shoved, rather than rowed, our craft through the esoteric windings of the Loddon River and Patricksbourne, arriving some hours later on the hither side of Shiplake Lock, with the unexpected satisfaction of having thus saved some pence from the clutch of the Thames Conservancy.

At the Bull at Sonning we dined in a parlour gay with geraniums, with windows shaded by vines and creepers, with old-fashioned fire-place surmounted by a huge stuffed fish—a typical river-side inn—and thereafter rowed up from Sonning to Reading, where, by the filthy Kennet side, we left our boat for return to its owner, in the usual Thames-side practice.

We came to Reading prepared for anything but35 charm in that town of biscuits, and we were not inclined to alter our ready-made opinion upon sight of it. We passed through “double-quick,” leaving the last of the town as late as 8.30. He who runs may read, perhaps, if the type be sufficiently large; but I don’t think he would find it possible to write: we did not, and so this book must go forth lacking a description of Reading.

The train that carried us from this town of almost metropolitan savour jogged along in most leisurely fashion past Mortimer Stratfield, and finally brought up at Basingstoke, where we went to bed with what haste we might.

And so we came into Hampshire. A weary county this, for those who know not where to seek its beauties—a county of flint-bestrewn roads, a county, too, of unconscionable distances and sad, lonely, rolling downs. Hampshire, indeed, seems ever attuned to memories in a minor key. It is, possibly, but a matter of individual temperament, but so it seems that this county of pine woods and bleak hills—bare, save for some crowning clump of eerie trees, whose branches continually whisper in sobbing breezes—shall always restrain your boisterous spirits, however bright the day, with a sense of foreboding. How much more, then, shall you be impressed of eventide, should you be still abroad, to see how weirdly the sun goes down36 behind those hill-tops, which then grow black beside his dying glory, while the water-meadows below grow blurred and indistinct, as the night mists rise in ghostly swirls. These thoughts can never find adequate expression, charged as they are with a latent superstition which, despite the lapse of centuries, lingers yet, perhaps unreasonably.

Such are the emotions conjured up by Nature in Hampshire. You may test their force readily at sundown, outside Winchester, when the huge mass of St. Catherine’s Hill looms awfully above the water-meadows of the Itchen, etched in deepest black upon the radiant evening sky. Gazing thus, and presently possessed of a fine thrill of superstitious dread, or artistic admiration—what you will—you may turn and encounter, full to the gaze, the twinkling lamps of the City—prosaic indeed.

But we anticipate, as the artless novelist of another generation was used to remark, with a painful frequency. Before Winchester, Basingstoke. This morning, we took an early walk to Sherborne St. John, an outlying village, now suburban to37 Basingstoke, a village, as it proved, uninteresting. The church, as was to be expected at 8 a.m., was locked: our only reminiscence of the place, then, is this problematic inscription from the doorway. Returning, we made a nearer acquaintance with that ruined chapel—the chapel of the Holy Ghost—familiar to all travellers by the South-Western Railway, standing as it does beside the Station. Here was established the lay Fraternity of the Holy Ghost, founded at that late period when Gothic architecture began to feel the influence of the Renaissance. The mixed details are very interesting, though, unfortunately, much mutilated. Gilbert White, the historian of Selborne, says he was, when38 a schoolboy, “eye-witness, perhaps a party concerned”—observe the grace of later years that made him ashamed of the occasion, and willing to doubt his participance—“in the undermining a vast portion of that fine old ruin at the north end of Basingstoke town.” The motive for this destruction (he says) does not appear, save that boys love to destroy what men venerate and admire; the more danger the more honour, and the notion of doing some mischief gave a zest to the enterprise.

The Chapel stands within the cemetery known locally as the Liten. Within its walls are two mutilated effigies on altar-tombs, the sole remains of a building long preceding the present ruin, hacked and carven with many penknives.

Modern Basingstoke—“name of hidden and subtle meaning,” as Mr. Gilbert says in “Ruddigore”—is prosperous, cheerful with the ruddy mellowness of red-brick, and loyal with a lofty Jubilee belfry-tower to its Town Hall; and that is all the spirit moves me to set down here of the town.

No more dreary road than that sixteen miles between Basingstoke and Winchester; a road that goes in a remorseless straight line through insignificant scenery, passing never a village for twelve39 or more weary miles, a road upon which every turning leads to Micheldever. Sign-posts one and all conspire to lead you thither, with an unanimity perfectly surprising. We made certain that something entirely out of the common run was to be found at that place of the peculiar name, and so we were ill enough advised to visit it by turning aside for the matter of a mile.

And yet, when we were arrived at the place, there was nothing to be seen; nay, worse than that indeed: there is a church at Micheldever whose architectural enormities would make any sane ecclesiologist flee the neighbourhood on the instant. Of the scenery, I will remark only that the village is overhung with funereal pines and firs, a setting that depresses beyond the power of words to express.

We retraced our steps toward the high road to Winchester, with anathemas upon those sign-posts, varied by a consideration of Hampshire as a county prolific in what Mr. Gilbert calls, “that curious anomaly”—the lady novelist. For, look you, at Micheldever resides Mrs. Mona Caird, the heroine of the “Marriage a Failure” correspondence, and the authoress of the “Wing of Azrael”; and Sparkford, Haslemere, and the New Forest shelter respectively, Miss Yonge, Mrs. Humphry Ward, and Miss Braddon; others, doubtless, there be within these gates who help to swell the output of the familiar three volumes, for almost every woman of leisure and scribbling propensities writes romances nowadays. Hampshire, indeed, seems decidedly a40 literary county, for Tennyson and Tyndall and Kingsley (Keble, too) have lived and worked within its borders.

For the next five miles we passed, I think, but one house, Lunways Inn, and then came upon modified civilisation in the shape of the village of King’s Worthy. There is quite a cluster of villages here with the generic name of Worthy, with prefixes by which we can generally identify the old-time lords of the respective manors. There are beside King’s Worthy, Abbot’s Worthy, Martyr Worthy, and Headbourne Worthy, “Headbourne,” conjecturally from the brook that rises by the village churchyard. This village lies on the road to Winchester, directly after King’s Worthy is passed, and is about a mile and a half from the city.

The church is interesting for itself, but it contains a charming little monumental brass to a Winchester scholar that alone is worth journeying to see, both from its unique character and by reason of its technical excellence. It was formerly let into the flooring of the chancel, and was in danger of being trampled out of recognition, until the vicar caused it to be fixed on the north wall of the church, where it now remains.

The brass consists of the kneeling figure of a boy in the act of prayer, habited in the time-honoured Winchester College gown, of the same pattern, with slight modifications, as that worn to-day. He wears, suspended from his collar, a badge, probably that of a patron saint; his hair is short, and exhibits the small first tonsure customarily performed on scholars41 upon completing their first year. A scroll issuing from his mouth is inscribed “Misericordias dni inetnū cantabo”—The mercies of the Lord I will sing for ever. The curiously contracted Latin of the inscription beneath is, Englished, “Here lies John Kent, sometime scholar of the New College of Winchester, son of Simon Kent of Reading, whose soul God pardon.”

It is supposed that he was removed to Headbourne from the College by his parents, to escape an epidemic prevalent there in the year of his death, 1434, when several other scholars died. The “College Register” records the death of John Kent: “Johēs Kent de Redyng de eadem com. adm. XXIII. die August obiit ulto die Augusti anno Regni Reg. H. VI. XIII.”

Within the space of another half-hour we had reached the city and discovered an hostelry after our own heart. We remained three whole days at Winchester.

The ancient capital of all England lies in the quiet valley of the River Itchen, a small stream which, some twelve miles lower down, empties into Southampton Water. The naïve remark of the schoolboy upon the “coincidence” of great cities always being situated upon the banks of large rivers did not, when Winchester was the metropolis, have any application here, but in the light of subsequent42 history it may show the reason of the city’s decadence.

From the earliest times Winchester was a city of importance; Briton and Roman, Saxon, Dane, and Norman alike made it a place of strength. Under Cerdic, first king of the West Saxons, the city became the capital of that kingdom, and at the dissolution of the Heptarchy, capital of united England.

But it was under the rule of the early Plantagenet kings that Winchester attained the zenith of its prosperity as the seat of government and as a centre of the woollen trade. Now the court has departed, and the manufacture utterly died out; but Winchester is a prosperous city still—gay with the rubrical gaiety of a cathedral city—the centre of an agricultural district, and the capital of a diocese.

Of feudal Winchester much has been destroyed; but from the remains of its two great castles, and of the city gates and walls, one may conjure up the city of the two first Norman kings, held under stern repressive rule, when despotic power lay in the hands of alien king and noble. Then the New Forest lying near was a newly created desolation; and the country-side, now dotted with villages, a sparsely settled tract. And even in the city itself there were long hours when all was silent and lonely; for when the curfew rang out, who dared to disobey its warning note? Then the city was given up to darkness, the watchmen at the closed and guarded gates, and the sentinels pacing the walls; for though, mayhap, there were no danger threatening from without,43 it must perchance be watched for and combated from within.

The curfew bell has been sentimentally revived, and tolling nightly from the old Guildhall, awakens dim vistas of social history. The custom has, of course, lost all its harsh significance, but it is one not lost upon him who cares for tradition in an age that makes for novelty; when vaunting soaps affront the eye of the wayfarer in their garish advertisements, and the voice of the touter (commercial, social, political,44 and religious) is heard in the land crying new lamps (of the sorriest) for old.

But the word “lamps” reminds me that Winchester public lamps have long been lighted with oil, for the Corporation and the Gas Company have agreed to differ; so, pending wiser counsel in the Company’s ranks, the City Fathers, good souls, put back the clock of social history some sixty years by re-adopting paraffin as an illuminant.

Thus local history wags at Winchester, with but few excitements, and those magnified to things of greatest import, by reason of their rarity.

To attempt to give here the briefest outline of Winchester’s long and stirring story were indeed vain; but a succinct account of its Cathedral may be of interest, as therein lies in these days most of the charm of the place. It is an epitome of architectural history unsurpassed in England.

One might, as a stranger, wander through the city for some while without finding the Cathedral, and then, perhaps, be compelled to inquire the way, for it is not possessed of soaring spire nor lofty towers, to guide the pilgrim from afar.

The first impression one gets of the building is of its great length: it is, indeed, the longest cathedral in England. The exterior, seen from the north-west corner of the close, is, perhaps, disappointing, with its long, unbroken, roof-line and low central tower, showing an almost entire absence of that picturesque grouping which is the charm of many others. But Winchester Cathedral has an interior equalling, if not surpassing, all others in beauty and interest.

45 The present cathedral is not the first nor second building of its kind erected here. Even before the Christian era its site held buildings devoted to worship; for the old chroniclers, the monks, to whom we owe most of our early history, have stated that the temple to Dagon stood on this spot.

Up to the time of the Norman Conquest the history of the Cathedral is one long account of building, destruction, and rebuilding—for those were troublous46 times, and religious institutions fared no better than secular.

Walkelin, the first Bishop of Winchester after the Conquest, was appointed in 1070. In the year 1079 he began to rebuild the existing Saxon cathedral from its foundations; and in 1086, the king, for its completion granted him as much wood from a certain forest as his workmen could cut and carry in the space of four days and nights. But the wily bishop brought together an innumerable troop of workmen who, within the prescribed time, felled the entire wood and carried it off. For this piece of sharp practice Walkelin had to humbly implore pardon of the enraged William.

In 1093 the new building was completed, and was dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul.

The Cathedral is now (or, at least, part of it is) dedicated to Saint Swithun. Now, Swithun was a holy man who died in the odour of sanctity and the Saxon era. He was Bishop of Winchester, but lowly minded indeed, for he desired his body to be buried without the building, under the eaves, where the rain might always drip upon his grave; but disregarding the spirit of the saint’s injunctions, the monks “howked” his corpse up again, after first complying with the letter of them by burying him for awhile in the cathedral yard. They proposed to enshrine the body within the Cathedral, but the saint, who had apparently obtained in the meantime an appointment as a sort of celestial turncock, brought about a continuous rainfall of forty days and nights. After this manifestation, the monks concluded to47 leave Swithun alone, and he lies in the close to this day. Unfortunately, the saint seems to have ever after made an annual commemoration of the event, commencing with July 15th. This would be a comparatively small matter did he confine himself to that period alone; but unlike the gyrating turncocks of our water companies, he is constantly on duty, more particularly when holiday folk most do fare abroad. Perhaps Swithun is offended at his name being so continually spelled wrongly—Swithin: perhaps—but, no matter. Anyhow, he is more addicted to water than (if all tales be true) holy friars were wont to be, either for external or inward application. What does Ingoldsby say of one typical friar—I quote from memory (a shocking habit):—

48

But no more frivolity: let us, pray, be serious.

Of Walkelin’s building we have preserved to us unaltered the transepts, tower, crypt, and exterior of the south aisle. The plan, like that of most Norman cathedrals, was cruciform, with an apsidal east end. This plan remains almost the same; but the apse has disappeared, and in its place we have the usual termination, with the addition of a thirteenth century Lady Chapel.

The tower, low and yet so massive, has a curious history. In the year 1110, William, the Red King, was killed in the New Forest, slain by the arrow of Walter Tyrrell. It is a familiar tale in history, how the body of the feared and hated king was carried to Winchester in a cart and buried in the choir, beneath the tower, mourned by none. Seven years later the tower fell in utter ruin, because, according to popular superstition, one had been buried there who had not received the last rites of the Church. The tower was rebuilt in its present form, and the result of the fall may be seen in the massive piers which now support it. The tomb of Rufus is here, covered with a slab of Purbeck marble, without inscription.

The first alteration to the plan of the Norman cathedral was made by De Lucy, commencing in49 1202. His work may be seen in part of the Lady Chapel and in the retrochoir. The Norman choir was taken down by Edingdon, and replaced by him in the transitional style from Decorated to Perpendicular. But the greatest feat was the transformation of the Norman nave into one of the Perpendicular style. This was carried out by William of Wykeham, one of the greatest architects our country can boast. Succeeding Bishop Edingdon in 1367, he carried on the alteration of the nave which the late bishop had but begun.

What makes this work the more remarkable is that the Norman walls were not removed; the ashlar facing was stripped off them and replaced by masonry designed in the prevailing style.