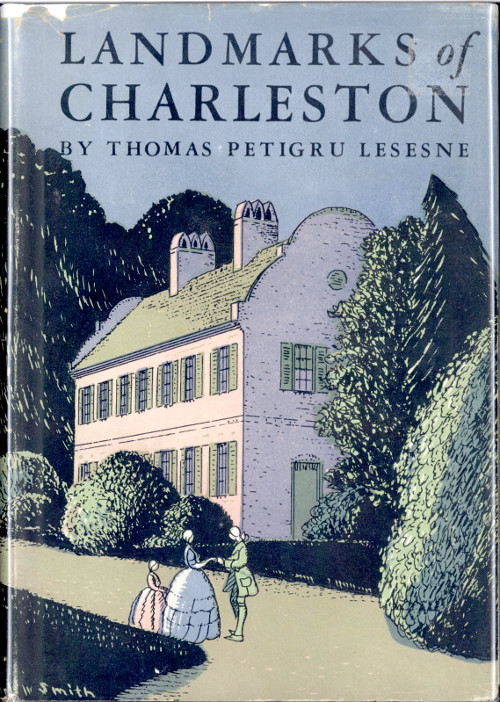

Title: Landmarks of Charleston

Author: Thomas Petigru Lesesne

Release date: February 20, 2019 [eBook #58921]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

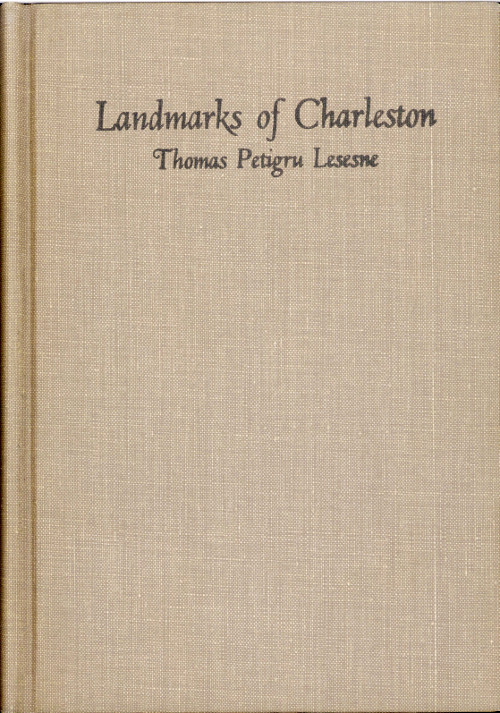

St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, Broad and Meeting Streets: its Steeple and Chimes Famous Courtesy of South Carolina National Bank

INCLUDING DESCRIPTION OF

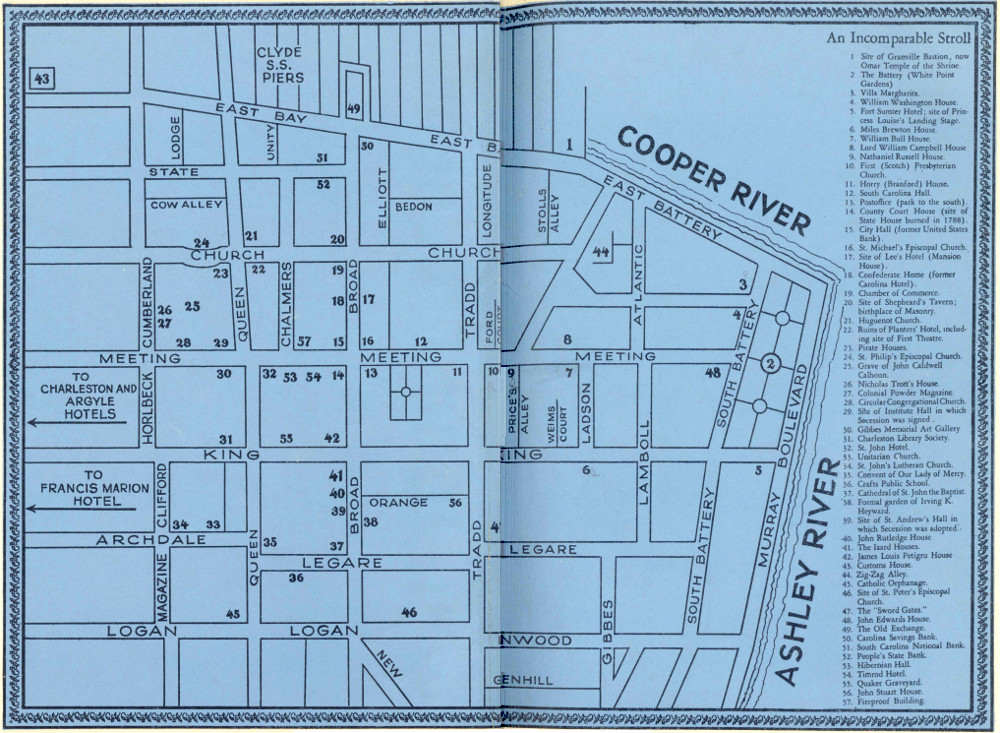

An Incomparable Stroll

BY

THOMAS PETIGRU LESESNE

AUTHOR OF

History of Charleston County

RICHMOND

GARRETT & MASSIE, INCORPORATED

MCMXXXIX

COPYRIGHT, 1939, BY

GARRETT & MASSIE, INCORPORATED

RICHMOND, VIRGINIA

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

One’s task in discussing Landmarks of Charleston is to describe the more outstanding from the beginning of Charles Town to this present year. It is an agreeable task, but it leaves undone some things one wishes he had done.

An Incomparable Stroll will give the visitor information of people and places of Charles Town under the Lords Proprietors, Charlestown under the Royal Government, and Charleston under the Republic.

The gardens which bring thousands of visitors to Charleston each spring are reached by excellent highways. Middleton Place and Magnolia-on-the-Ashley are on the Ashley River Road; Cypress off the Coastal Highway, United States 52. These gardens are so different that they are not competitive, and the visitor questing for beauty that baffles description should see all three, and, time permitting, journey toward Georgetown and enjoy the famous Belle Isle Gardens, on Winyah Bay.

In this work the index has been compiled with great care and should be consulted freely. Charleston’s points vi of interest are too scattered to be grouped on a single route. Near Charleston are traces of fortifications used in the Revolution and in the War for Southern Independence. They are too numerous for individual enumeration. Books have been written about them.

From the building of the Colonial Powder Magazine to the building of the Cooper River Bridge, the third highest vehicular bridge in the world, is a tremendous gap.

It is unnecessary to say that the author has consulted many authorities; his quotations suffice to reveal this.

Thomas Petigru Lesesne.

Charleston,

South Carolina.

Why Charleston? Three European nations were claiming this southern country—the Spaniards called it Florida, the French Carolina and the English Southern Virginia. The Spanish claim was through Ponce de Leon, 1512; the French through Verazzano, a Florentine, 1524, and the English, it is said, by virtue of a grant by the Pope of Rome, and through John Cabot and his son, Sebastian, both of them in the service of the English King Henry VII, 1497-98. To Edward, Earl of Clarendon, and his associates Charles II of England gave a charter in 1663—“excited by a laudable and pious zeal for the propagation of the Gospel.”

The Proprietors planted colonists on the Albemarle and the Cape Fear, North Carolina. Things did not go well and many of these people subsequently found their way to old Charles Town, which was established, not by English design, but through circumstances. Robert Sandford, “Secretary and Chiefe Register for the Lords Proprietors of their County of Clarendon,” had explored this coast in the summer of 1666, 2 and would have seen the site of Charles Town, but his Indian pilot confused his bearings “until it was too late.” Sandford however, renamed the River Kiawah the Ashley in honor of Ashley-Cooper, later the Earl of Shaftesbury, one of the Proprietors.

Sandford, off Edisto, near Charles Town, was sought by the Cassique, or Chief, of the Kiawah Indians and importuned to plant an English colony near the Kiawah village on the west bank of the Kiawah (Ashley) River. The Cassique, Sandford related, was known to the Clarendon colonists. Sandford agreed to investigate, but missed the entrance and chose to lose no further time by putting back. The Sandford report so impressed the Proprietors that they authorized the planting of a colony, not at Charles Town, but at Port Royal, to the south. Colonel William Sayle, soldier of fortune, was commissioned Governor when Sir John Yeamans, already Governor of the more northern colony, left the adventurers. Three ships were in the enterprise, but one of these was separated. The other two made land at present-day Bull’s Island in the spring of 1670. The Cassique of Kiawah was there and Governor Sayle was importuned to abandon Port Royal and bring his colonists to the Kiawah country.

Sayle, however, followed his instructions and proceeded to Port Royal, arriving in mid-April of 1670. The Cassique of Kiawah had told the colonists that the Indians were on the warpath and his story was confirmed. Carteret, who was in the “friggott” Carolina, flagship, says: “Wee weighed from Porte Royall and ran in between St. Hellena and Combohe (Combahee).” Here the first English election in Carolina was held, five men “to be of the Council.”

The sloop which had come with the Carolina was “despatched 3 to Keyawah to view that land soe much commended by the Casseeka,” and soon returned with “a report that ye land was much more fitt to plant than in St. Hellena which begott a question.... The Governour adhearing for Keyawah and most of us being of a temper to follow though we know noe reason for it, imitating ye rule of ye inconsiderate multitude, cryed out for Keyawah, yet some dissented from it being sure to make a new voyage, but difident of a better convenience, those that inclyned for Porte Royall were looked upon strangely, so thus wee came to Keyawah.”

So, it was the Cassique, or chief, of the Kiawahs, that was responsible for the choice of the site of old Charles Town. First the colonists named their settlement Albemarle Point, but in the fall of 1670 they renamed it Charles Town, in honor of their King, Charles II. Carolina they named for him also, but the French had previously called it Carolina for their King, Charles IX. However, there were no French in Carolina when the English colonists arrived; the French effort at colonization had ended in tragedy, a hundred years before.

No sooner were the colonists established at Albemarle Point (where the Seaboard Air Line Railroad touches the west shore of the Ashley) than they looked with favor on the peninsula between the Ashley and the Cooper (the Indians called this river the Etiwan), as much the more desirable for their town, and in 1680 the change was officially in force. The new town was facilitated by the voluntary action of Henry Hughes and of John Coming and “Affera, his Wife,” in surrendering land for the new town. John Culpeper was commissioned to plan it. “The Town is regularly 4 laid out into large and capacious streets,” said “T.A., Gent.,” clerk aboard H.M.S. Richmond, “in the year 1682.”

Charles Town on the peninsula prospered as a port and as the capital of the plantations. To ships in its commodious harbor came the things of the fields, the woods and the streams. Constantly new people were arriving and the outpost of civilization rapidly took on the appearance of European manners and customs, notwithstanding the incongruity of savages, red and black, and Indian traders in their bizarre garb. It was Charles Town under the Proprietors, Charlestown under the Royal Government, and Charleston since its incorporation in 1783.

This Carolina metropolis has had part in Indian, Spanish and French wars. It has had bold adventures with pirates. It was conspicuous in the Revolution and in the War for Southern Independence. It furnished men for the famous Palmetto Regiment in the Mexican War. The War of 1812 little affected it. Its men served in the Spanish-American War and the World War. It is said that from the tops of the highest buildings come under the eye more historic places than come under it from any other place in the United States, explaining the slogan, Charleston—America’s Most Historic City. It is in order to remind that William Allen White, in an address, said that “Charleston is the most civilized town in America,” and that William Howard Taft, then President of the United States, pronounced it, “the most convenient port to Panama.”

In Charleston survive buildings that were erected during the Proprietary Government, many buildings that were erected during the Royal Government. Survive scars of wars and storms and fires that raged in the long ago. Survive street 5 names that were bestowed when Charles Town was in its swaddling clothes. It is a far cry from old Charles Town, bounded on the south by Vanderhorst Creek (Water Street); on the west by earthworks and a moat (Meeting Street); on the north by earthworks (Cumberland Street), and on the east by the Cooper River. King, Queen and Princess Streets are reminiscent of the Royal Régime. St. Philip’s, St. Michael’s, St. Andrew’s, Berkeley, and St. James, Goose Creek, were of the Church of England, under the Bishop of London, albeit the present St. Philip’s was erected half a century after the Revolution, replacing the Proprietary building that was burned in 1835.

But this work is concerned, not with the history of Charleston, but with Landmarks of Charleston, and in the pages that follow are tales of prominent landmarks, places and buildings that are storied. Eminent Carolinian names pass in review. The greatness of the lustrous past is linked with the more convenient present. The Charles Town that was and the Charleston that is are brought before the reader. The author’s effort is to present the facts accurately.

Outstanding landmarks include Fort Sumter, Fort Moultrie, the Old Exchange Building, the Powder Magazine, the Rhett and Trott Houses for their antiquity, the Miles Brewton House as enemy headquarters in the Revolution and the War for Southern Independence.

Fort Sumter from the Air

Would you, guest within the gates of Charleston, see things reminiscent of old Charles Town rubbing elbows with things of modern Charleston? Take this stroll, a little more than a mile, and you will be abundantly compensated.

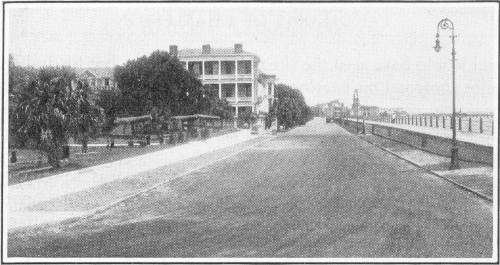

Begin at the Mosque of Omar Temple of the Mystic Shrine, on the site of the Granville Bastion, southeastern edge of Charles Town in 1680. Proceed, southward, along East (or High) Battery, washed by the Cooper River. You behold the harbor declared by Admiral Dickins capable of accommodating the fleets of the world at one time. Seaward you see gallant Fort Sumter. To its left, Sullivan’s Island, on which is Fort Moultrie of Revolutionary fame; to its right, by the Quarantine Station, Charles Town’s first fort, Johnson, named for a Proprietary Governor. On the west side are some of Charleston’s most desirable residences. You reach South Battery.

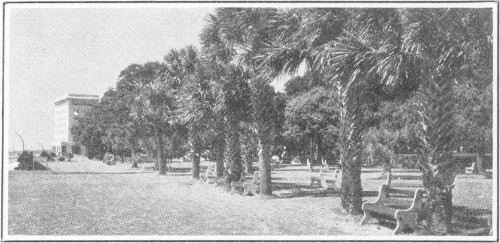

Here you see the monument to the brave Confederate defenders of Fort Sumter, to face that famous fortress. Continue on the promenade which has inspired extravagant phrases. In the park you see the capstan from the battleship Maine, blown up in Havana harbor in February, 1898; 7 monuments to the defenders of Fort Moultrie in 1776, and to William Gilmore Simms, novelist, historian, editor. Across the park, at the foot of Church Street, you see the home of Colonel William Washington, Virginian, who achieved a lustrous record as a Revolutionary officer in South Carolina; across Church Street is the Villa Margharita, built as the home of Andrew Simonds, banker. At the foot of Meeting Street, you see a memorial fountain to the gallant Confederates of the first submarine.

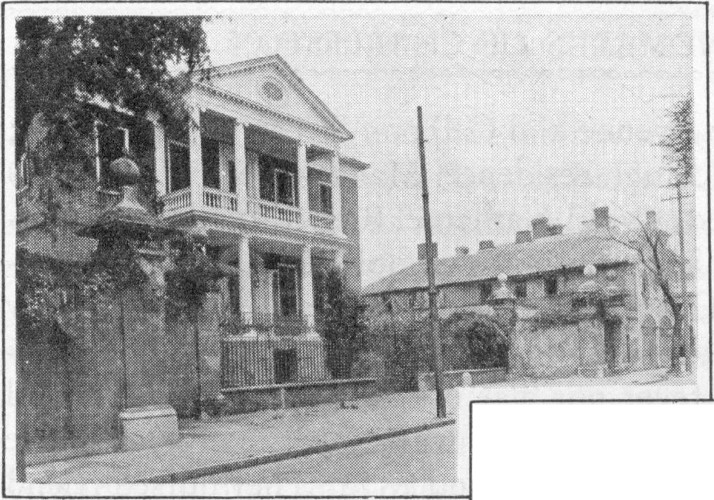

Stay on the promenade and enjoy the sight of stately palmettos bordering a beautiful park in which majestic oaks are many. At the foot of King Street, you come to the Fort Sumter Hotel. This building includes the site of the landing stage used by Queen Victoria’s daughter, the Princess Louise, in 1883; first member of the English royal family to visit the capital of the former English colony and province. Go north in King Street. At No. 27 is the celebrated Miles Brewton House, used by the British as headquarters in the Revolution and by the Union commanders in the War for Southern Independence. Note the picturesque old coach house.

Turn east and proceed through Ladson Street. At the northwest corner of Ladson and Meeting Streets is the home of the last Royal Lieutenant Governor, William Bull, and across Meeting Street (No. 34) the home of the last Royal Governor, Lord William Campbell, who escaped through Vanderhorst Creek (now Water Street) to H.M.S. Tamar, carrying with him the Great Seal of the Province. Next to the Bull House is the home of the late General James Conner, distinguished Confederate officer, and eminent for his work during Reconstruction. At Water Street you come to a corner of old Charles Town.

Continue north in Meeting Street. At No. 51 is the home of Governor Robert Francis Withers Allston, some time a convent of the Sisters of Mercy, now the home of Francis J. Pelzer. At the southwest corner of Meeting and Tradd Streets is the First (Scotch) Presbyterian Church, organized in 1731, an offspring of the old White Meeting House. On the northwest corner is the old Branford (also called Horry) home, the portico over the street being less ancient. On the east side (No. 72) is the hall of the South Carolina Society, which also houses the St. Andrew’s Society, founded in 1729; in this building are tables and chairs used in the Secession convention. On the west side is the post office park, including the site of the old Charleston Club, and of the United States courthouse that collapsed in the earthquake of August 31, 1886. On the southwest corner of Meeting and Broad Streets is the United States post office, completed in 1896; this houses the United States court. On the northwest corner is the county Court House, on the site of the old State House, burned in 1788. Behind the Court House is the Daniel Blake double house, one of the first of its kind in the country.

On the southeast corner is St. Michael’s Church, on the site of the original English church, St. Philip’s. In its yard sleep illustrious Charlestonians, including James Louis Petigru, the epitaph on whose grave is famous. On the northeast corner is the City Hall, with its great municipal art gallery, including John Trumbull’s renowned portrait of General George Washington. This was the building of the United States Bank, on the site of the early market place. Behind and beside the City Hall, Washington Park, in the northwest corner of which is the country’s first fireproof building.

Proceed east in Broad Street. No. 73 is the site of Lee’s Hotel, known also as the Mansion House, “kept by a dignified and distinguished looking mulatto, once the most fashionable hotel in the city and probably the best kept and most expensive,” said William G. Whilden in his Reminiscences. Across the street (No. 62) is the Confederate Home which before the War for Southern Independence was the Carolina Hotel, a noted caravansary. At the northwest corner of Broad and Church Streets, is the Chamber of Commerce, oldest in the country, organized in 1773; this was the old South Carolina Bank building, later the home of the Charleston Library Society, which moved into modern quarters, elsewhere on this stroll. At the northeast corner is the Citizens and Southern Bank, on the site of Shepheard’s Tavern, birthplace of Ancient Free Masonry in America, Solomon’s Lodge, No. 1, having been chartered by the Grand Lodge of England in 1735, and birthplace also of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Free Masonry, 1801. A block to the eastward, at the foot of Broad Street, is the Old Exchange, as historic a building as there is in all America.

Northward on Church Street, at the southeast corner of Church and Queen, the only Huguenot church in America! Opposite, on the southwest corner, the restored Planters’ Hotel (1803), including the reproduction of Charleston’s first regular theater (1735), the company of players coming direct from England. North of Queen Street, on the west side, the reputed Pirates’ houses. St. Philip’s graveyard is divided by Church Street, running through the foundations of the building burned in 1835. The first St. Philip’s was on the site now occupied by St. Michael’s and the present St. Philip’s is the third. In the graveyards sleep, Edward Rutledge, Signer 10 of the Declaration of Independence; William Rhett, captor of the notorious pirate, Stede Bonnet, 1718; Christopher Gadsden, Revolutionary patriot; John Caldwell Calhoun, eminent statesman.

Proceed through the western yard. You are paralleling the northern boundary of old Charles Town, a matter of yards away. You are in the Gateway Walk of the Garden Club. Midway of the yard, you are behind the first brick house in Charles Town, that of Judge Nicholas Trott; it was standing in 1719. Next to the Trott House is Charles Town’s oldest building, the Powder Magazine, 1703, owned and used by the Colonial Dames of America. Into the yard of the Circular Church, cradle of Presbyterianism in Carolina. Illustrious dead are buried here. The newspaper building to the south is on the site of the South Carolina Institute Hall, in which the Ordinance of Secession was signed December 20, 1860, and in which, several months before, the famous Democratic convention of 1860 was held. You come to Meeting Street, the Circular Church as the White Meeting House giving its name. Down Meeting Street, at the southwestern corner of Queen, is the St. John Hotel, on the site of the old St. Mary's Hotel, opened in 1801; General Robert E. Lee and President Theodore Roosevelt were of the notables who have been guests of this house.

At Meeting Street you are at the western edge of old Charles Town. Cross the street and pass through the yard of the Gibbes Memorial Art Gallery, a section of the old Schenking Square. Thence into the yard, of the Charleston Library Society, dating to 1748, among the oldest in the land. You come now to King Street. Down the street on the east side of the next block is the Quaker burial ground and 11 site of the meeting houses that were burned. Cross King Street into the walk of the Unitarian Church, its building used by the British during their occupation in the Revolution for stables, and, to the north, the first Lutheran church, St. John’s. You come to Archdale Street, named for pious John Archdale, Quaker, Proprietor and Governor. Go southward to Queen Street, at the corner of Legare (it used to be Friend, reminiscent of the early Quakers in the colony) is the convent of Our Lady of Mercy, a community of consecrated Sisters, now more than a hundred years old. Opposite the convent, in Legare Street, is the Crafts public school, memorial to William Crafts.

On the left, at the corner of Broad Street, is the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, on the site of the Cathedral of St. Finbar and St. John, burned in 1861; here Bishop John M. England built the first St. Finbar’s on the site of the Vauxhall gardens. Go east in Broad Street. No. 119 (south side) is the residence of Irving Keith Heyward with one of Charleston’s finest formal gardens. Next door, to the east, is a property once occupied by Edward Rutledge.

On the north side of Broad Street, No. 118, is the site of St. Andrew’s Society hall in which President James Monroe and the Marquis de Lafayette were guests of the city, Monroe in 1819 and Lafayette in 1825; in which the Ordinance of Secession was adopted December 20, 1860. Next door, No. 116, is the former house of John Rutledge, “The Dictator,” later Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States; here President William Howard Taft was the guest of Robert Goodwyn Rhett. No. 114, once the home of Colonel Thomas Pinckney, is the residence of the Bishop of Charleston, the Most Reverend Emmet Walsh. No. 112 12 is the Ralph Izard house; the coach house in the yard is one of the most picturesque in Charleston. This neighborhood was in Mr. Hollybush’s farm, just outside of old Charles Town. No. 100 Broad Street was at one time the residence of James Louis Petigru.

You come again to the intersection of Broad and Meeting Streets and remember that here in 1876 occurred violent Reconstruction riots; that in the Revolution, years before, the statue of William Pitt was in the center and that a British shell struck off an arm. You who have followed me on this incomparable walk have seen things of Charles Town, Charlestown and Charleston. You have seen things reminiscent of early English and early French. You have seen the evolution of a British outpost in a savage land into what William Allen White has called “the most civilized town in America.”

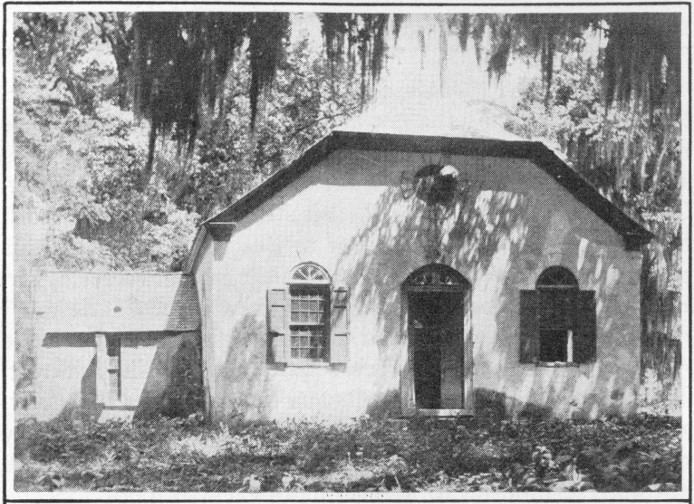

POWDER MAGAZINE, 23 Cumberland Street: In the early days of Charles Town this storehouse for ammunition was built of brick covered with “tabby.” It is known to have been in use in 1703. It continued as a storing place of gunpowder years after the town limits had been pushed northward of Cumberland Street. When the British were besieging Charlestown in 1780, a shell exploded near the magazine and attention was thus directed to its danger. It was abandoned as a magazine. Nowadays this ancient building is the property of the Charleston Society of the Colonial Dames of America. In it are many interesting and valuable relics. How this magazine escaped through the years is one of the mysteries.

NICHOLAS TROTT’S HOUSE, 25 Cumberland Street: Next door to the Powder Magazine is Charleston’s first brick house, standing in its old appearance until a few years ago when it was done over for business offices. It was the home of Nicholas Trott, one of the chief men of Charles Town. It is a large two-story building, its back to St. Philip’s western graveyard. Trott, born in England in 1663, came to Charles Town from the Bahamas about 1690. He was Attorney General in 1698, Speaker of the Assembly in 1700, 14 Councillor in 1703 and the Chief Judge after that. With the overthrow of the government of the Proprietors, Trott’s star waned. He revised and published Laws of South Carolina (two volumes, 1736) and Laws Relating to the Church and the Clergy (1721). He died in Charlestown in 1740. Dr. Shecut says that the Trott House was standing in 1719. “The great ability and legal attainments of Chief Justice Trott, who acted as Chief Justice in all for some fifteen or sixteen years,” Henry A. M. Smith wrote, drew all the business and litigation to it; his became practically the only court in the Province. The Proprietors sustained Trott when the people complained “and the response on the part of the people was to overthrow the Proprietary Government,” Judge Smith is quoted.

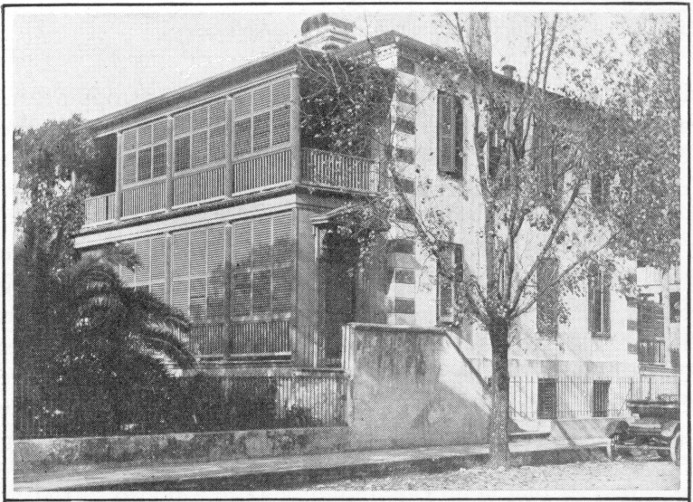

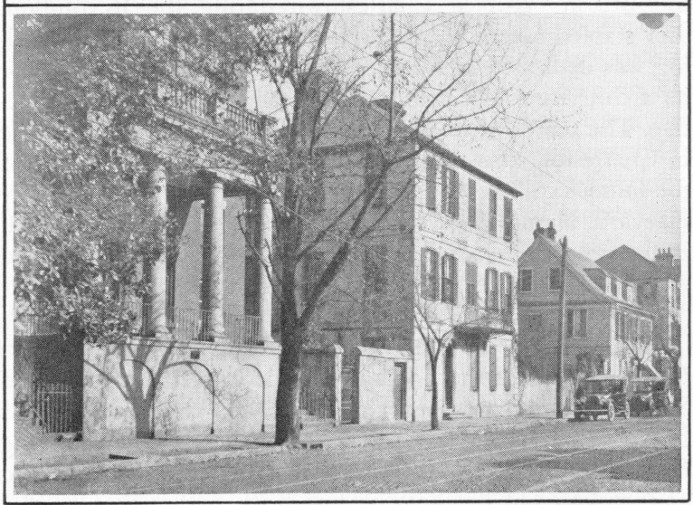

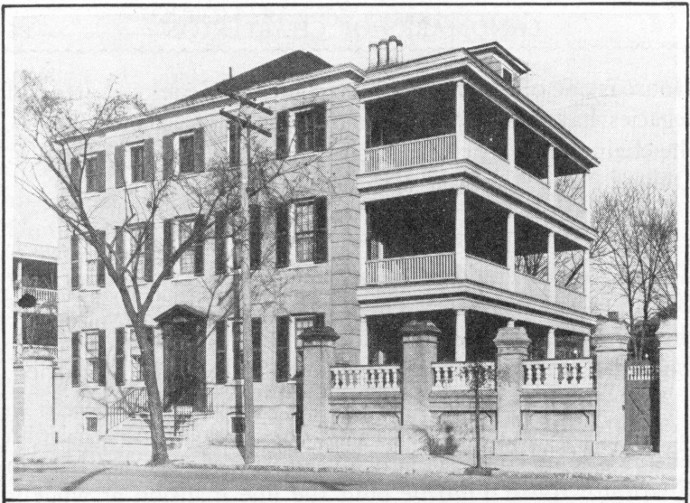

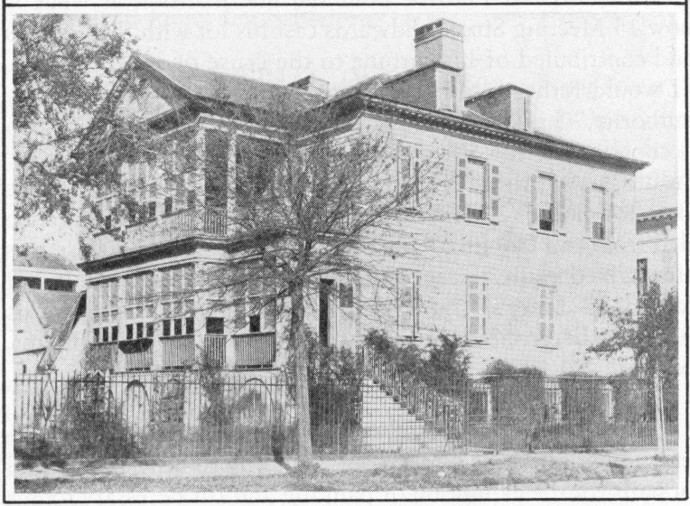

WILLIAM RHETT’S HOUSE, 58 Hasell Street: Wade Hampton, South Carolina hero of the Reconstruction period after the War for Southern Independence, acclaimed as the savior of his state, was born in the house wherein lived William Rhett, captor of Stede Bonnet, notorious pirate, and his fellows, who were hanged, in 1718. William Rhett was a great man in the early Carolina and Wade Hampton in the later. Rhett’s large square house was in excellent condition in 1722, says Joseph Johnson, M.D., in his Traditions of the Revolution. It is in good condition in this year, 1939. It is entered through a broad piazza on the west side and contains four large rooms on each floor. Colonel Rhett is remembered chiefly for his capture of the pirates, but other marks in his record are lustrous. He commanded the little fleet that in 1706 put down the harbor against a hostile French fleet under Le Feboure: the Frenchman 15 weighed his anchors and went to sea without offering a single shot. A few days later Rhett’s flotilla, a short distance up the coast, captured a French vessel; among his prisoners was the chief land officer, Arbouset. Rhett was born in London, September 4, 1666, and came to Charles Town in November of 1694; he died here in June of 1722. On his tomb in St. Philip’s western graveyard, it is chiseled that “he was a person that on all occasions promoted the public good of this colony and several times generously and successfully ventured in defense of the same.... A kind husband, a tender father, a faithful friend, a charitable neighbour.”

QUAKER GRAVEYARD, 138 King Street: Graves among the oldest in Carolina are in the yard of the old Quaker Meeting House property. The first Quaker house of worship was built on this site in 1694. John Archdale, Quaker, Proprietor and Governor, came to Charles Town in 1695, and attended services with his fellow Friends. The property is a parcel of the old Archdale Square, nowadays bounded by King, Queen, Meeting and Broad Streets. It was just outside the town in those early years. This building was blown up in July, 1837, to stop a fire. The rebuilt Meeting House was destroyed in the conflagration of 1861. Quakers came to Charles Town while it was across the Ashley River. A letter from Shaftesbury, dated June 9, 1675, said: “There come now in my dogger Jacob Waite and two or three other familys of those who are called Quakers. These are but the Harbingers of a greater number that intend to follow. ’Tis theire purpose to take up a whole colony for themselves and theire Friends here, they promised me to build a Town of 30 Houses. I have writ to the Gov’r and 16 Council about them and directed them to set them out 12,000 acres.” The Society of Friends owns this property, but there is now no meeting house in Charleston. The name of Governor Archdale is preserved in the street of that name, on which are the Unitarian and St. John’s Lutheran Churches.

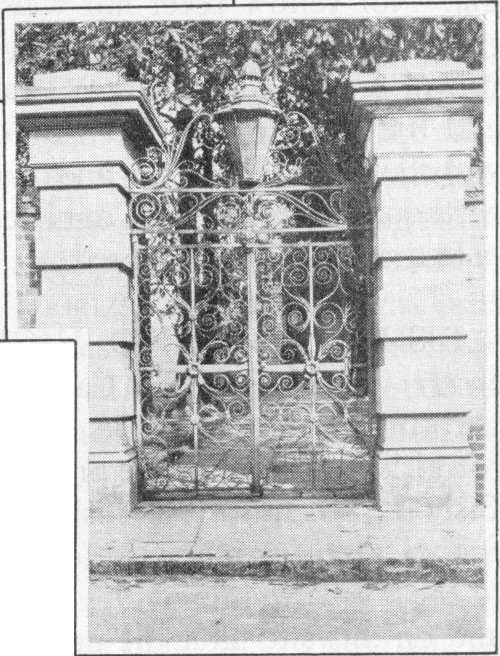

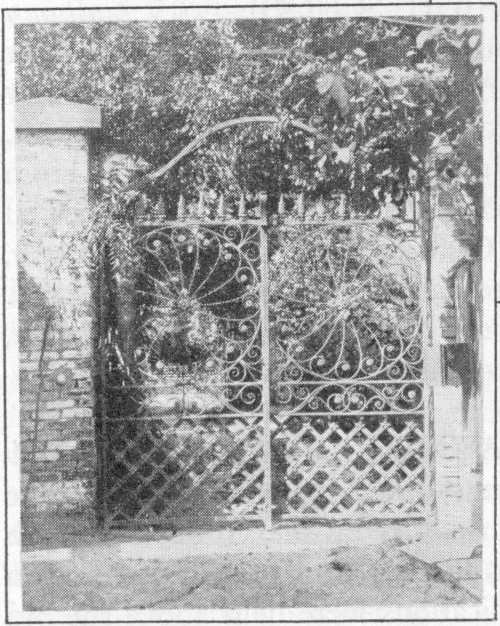

THE GATEWAY WALK, from Church to Archdale: No visitors to Charleston should forego the pleasure of using the Gateway Walk of the Garden Club. A bronze plate on a gate at the Charleston Library says:

Through hand-wrought gates alluring paths

Lead on to pleasant places,

Where ghosts of long-forgotten things

Have left elusive traces.

This verse speaks eloquently for it. East to west, the walk is through St. Philip’s graveyard, through the yard of the Circular Congregational Church, thence across Meeting Street, through the yard of the Gibbes Memorial Art Gallery, through that of the Charleston Library Society, across King Street, through the yards of the Unitarian and St. John’s Lutheran Churches. There are two graceful wrought-iron gateways between the Gallery and the Library which formerly had place at the home of William Aiken, King and Ann Streets, used nowadays by the Southern Railway System for offices. Mr. Aiken was president of the South Carolina Canal and Railroad Company from 1828 to 1831. Aiken, near Augusta, popular winter resort, was named in his honor. The railroad company a hundred years ago built the world’s longest steam railroad. In the large yard behind the Gibbes 17 Gallery is an attractive pool with growing water plants. To describe the Gateway Walk at length would operate to rob a visitor of the tranquil pleasure of moving through it leisurely. In the yards of St. Philip’s and the Circular Church are graves of early citizens of Charles Town. It is enough to say that the Garden Club has achieved a unique and worthwhile project. Elsewhere in this book is found information of the six properties traversed by the walk.

ST. ANDREWS HALL SITE, 118 Broad Street: The St. Andrew’s Society of Charleston was organized by Scots in 1729. It is Charleston’s oldest benevolent society, active and flourishing into this season. Its hall was built in 1814 and here the Marquis de Lafayette was entertained in March, 1825. The distinguished Frenchman was the guest of the city and was showered with attentions. Here he met his friend, Colonel Francis K. Huger, who some years before had engaged in the frustrated scheme of aiding Lafayette to escape from an Austrian prison. Here on Tuesday, March 15, 1825, he “received the salutations of the reverend clergy, the officers of the militia, judges and gentlemen of the Bar, and many citizens, after which he visited Generals Charles C. and Thomas Pinckney, Mrs. Shaw, the daughter of General Greene, and Mrs. Washington, relict of the late General William Washington.” In this hall was passed the Ordinance of Secession December 20, 1860 (it was signed in the Institute Hall, however). It was among the many buildings razed by the flames in 1861. The St. Andrew’s Society is housed in these seasons with the South Carolina Society, certain of the chairs and tables used in the Secession convention being preserved. In the years before the War for Southern Independence St. Andrew’s Hall was the scene of many brilliant social entertainments, including balls of that eminent Charleston order, the Saint Cecilia Society, which had its beginning as a musical society, presenting concerts.

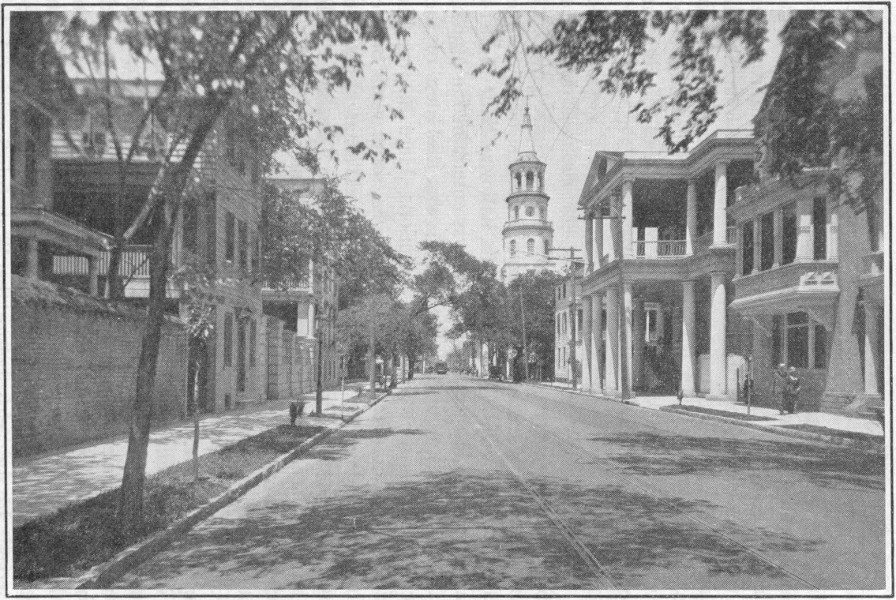

Looking North on Meeting Street

Right Middleground, Portico of South Carolina Hall; Background, St. Michael’s Church

JOHN STUART’S HOUSE, 104 Tradd Street: John Stuart, born in England in 1700, came through Charlestown with General James Oglethorpe, founder of Georgia, in 1733. Thirty years later he was appointed the British general agent for Indian affairs in the South. Captured by the Cherokees, he was saved by Attakullakulla (the Little Carpenter). With the breaking of the Revolution he engaged to incite Cherokees, Chickasaws and Creeks (Muscogees) to war against the whites. The Indian outbreak was to coincide with Sir Peter Parker’s attack on Charlestown in the spring of 1776. It was foiled by alert Kentucky settlers. His plot being exposed Colonel Stuart fled to Florida, thence to England where he died in 1779. His property was confiscated by the independent government. To escape the British, it is related that General Francis Marion leaped from a window. His coattails caught and his liberty was in peril. (That’s the story, but the house from which Marion fled is at the northeast corner of Legare and Tradd.) Certain of the interior of this house has been reset up in Minneapolis which has broadcast its pride in the accession.

SITE OF FORT JOHNSON, James Island: The first fortification erected for the defense of old Charles Town was at the northeast end of James Island, within the present-day Quarantine reservation. It was devised to meet the threatened invasion by the French under Le Feboure and was 20 named Fort Johnson in honor of the then Governor, Sir Nathaniel Johnson. In 1759 a second fort of tabby (or tapia) was built on the site and this was the Fort Johnson of the Revolution—“in plan triangular, with salients bastioned and priestcapped, the gorge closed, the gate protected by an earthwork, a defensible sea wall of tapia extended the fortification to the west and southwest.” In 1765 stamped paper was transferred from a British sloop-of-war and stored in Fort Johnson while in Charlestown excitement prevailed, resulting in seizure of the stamped paper by three companies of volunteers under Captains Marion, Pinckney and Elliott. The British garrison was placed under guard and preparations made to resist any attack from the sloop-of-war. At this time was displayed the first form of the South Carolina State flag—a blue field with three white crescents. The naval commander agreed to carry the stamped paper from Charlestown and the incident passed off without clash at arms. This was ten years before the Battle of Concord. In 1775, the spirit of liberty gaining strength, Fort Johnson was again seized by order of the Council of Safety, as a precaution against the last of the Royal Governors, Lord William Campbell, British troops being expected. In November of this year (1775) three shots were fired from Fort Johnson on the British sloops-of-war Tamar and Cherokee, which were engaged in blocking Hog Island Channel. June 28, 1776, Fort Johnson was commanded by Colonel Christopher Gadsden, but had no opportunity of engaging Sir Peter Parker’s fleet, which was repulsed by soldiers under Colonel William Moultrie at Fort Sullivan, known afterward and now as Fort Moultrie, on Sullivan’s Island. In 1780 Sir Henry Clinton reported Fort Johnson “destroyed.” In 1793 the third work at this 21 site was built, but in 1800 a tropical storm so damaged it that it was abandoned, being restored in the War of 1812. At the site of Fort Johnson the Confederate forces defending Charleston located a mortar battery from which to bombard Fort Sumter. It now became “an extensive entrenched camp of considerable strength and capacity.” The Confederates evacuated this fort February 17, 1865, and the works were allowed to fall into decay. Latterly there has been an earnest effort at restoration.

FORT MOULTRIE, Sullivan’s Island: A glorious day in the annals of South Carolina was the twenty-eighth of June, 1776. A partially built fort of palmetto logs repulsed the proud British fleet under Sir Peter Parker. Above this rude fort floated a South Carolina flag with a blue field in which was one crescent and the word LIBERTY. It was this flag that Sergeant Jasper rescued, his gallant deed commemorating his name. The first government of any of the thirteen American colonies was established at Charlestown, March, 1776, with John Rutledge as president, Henry Laurens as vice-president and William Henry Drayton as chief justice. Against Colonel William Moultrie’s rude fort on that June day in 1776 was pitted a trained fleet of eleven armed vessels carrying 270 guns. Moultrie’s garrison comprised 435 men. While Moultrie was engaged with Sir Peter Parker, Colonel William Thomson with 800 men and two cannons prevented Sir Henry Clinton from landing his soldiery. In the Battle of Fort Moultrie the defenders suffered only thirty-seven casualties while the fleet suffered more than 200, and the loss of a frigate. It was from Fort Moultrie that Major Robert Anderson on the night of December 26, 1860, removed his Union 22 garrison into Fort Sumter. The Confederates used Fort Moultrie against the invading Union forces until Fort Sumter was abandoned by the South’s defenders. Before Anderson left Moultrie, he had spiked the guns and burned their carriages. Fort Moultrie helped make Morris Island an unhappy place for Union troops under General Gilmore. At the entrance to the old fort is the grave of Osceola, chief of the Seminoles, who was brought a captive after the war in Florida a hundred years ago. In these years the fort gives name to a reservation which is the headquarters of the Eighth Infantry, a small detail of Coast Artillerymen being on duty with the coast defense guns.

FORT SUMTER, at the Entrance to the Harbor: Facing the open sea stands gallant Fort Sumter. No fortress in all America awakens greater memories. It is a shining emblem of Secession, enduring monument to the incomparable defense of Charleston by the Confederates. The bravest of the brave served within this shell-torn fortress, withstanding the siege of Union land and sea forces. Sumter is not alone a proud fortress, but a landmark invested with a wealth of patriotic sentiment. It is stirring American drama. “In the annals of the Federal army and navy, there is no exploit comparable to the defense of Charleston harbor. It would not be easy to match it in the records of European warfare”—the Rev. John Johnson, D.D., quoted an English historian. In skeleton, Fort Sumter’s great story includes: April 7, 1863, it had part in the repulse of the United States armored squadron after a severe engagement. In August it “suffered its first great bombardment of sixteen days, ending in the demolition and silencing of the fort, chiefly by land 23 batteries of Morris Island.” Confederates effected immediate repairs. While these were making, the defenders of Sumter beat off a night attack by small boats. Then came the “second and third great bombardments, one of forty-one days, and the other, and last, of sixty days and nights continuously, both being borne without any thought of failure or surrender.” The quotations are from an article by Dr. Johnson in The News and Courier. In all, the siege lasted until Charleston was evacuated February 17-18, 1865, “after 567 days of continuous military and naval operations.” The famous fortress of Sumter, named for the Revolutionary hero, General Thomas Sumter, the “Game Cock,” was built upon a shoal, the Secretary of War approving the plans in December, 1828. It is about a mile southwest of Fort Moultrie, Sullivan’s Island, and the same distance northeast of Fort Johnson, James Island. It was nearing completion when on the night of December 26, 1860, Major Robert Anderson removed the Union garrison of Fort Moultrie to it. On the twelfth and thirteenth of April, 1861, it was bombarded by the Confederates for about thirty hours, Major Anderson surrendering. He evacuated the following day, embarking his men for the north. The Confederates at once put the fortress in order for defense. There had been no casualties on either side. Lieutenant Colonel R. S. Ripley was the first Confederate commander of Fort Sumter and Major Thomas A. Huguenin the last, the Confederate occupation extending from April 14, 1861, to February 17, 1865. Fort Sumter nowadays is without a garrison. It is part of the defenses of Charleston. A military caretaker lives within the battle-scarred walls. Modern coast defense guns are mounted. As a grim sentinel, Sumter still faces the open seas.

SITE OF FIRST THEATER, 43 Queen Street: Plays were performed in Charles Town in 1703, according to Sonneck. However, the first regular theater was the Play House in Dock (now Queen) Street. Here in the winter of 1735, a company, “direct from England,” presented its repertory. Members of Solomon’s Lodge of the Ancient Free Masons, the oldest Masonic lodge in the United States, attended, in a body, the performance of “The Recruiting Officer” May 28, 1737. The Federal government has reproduced this theater; it was reopened officially November 26, 1937.

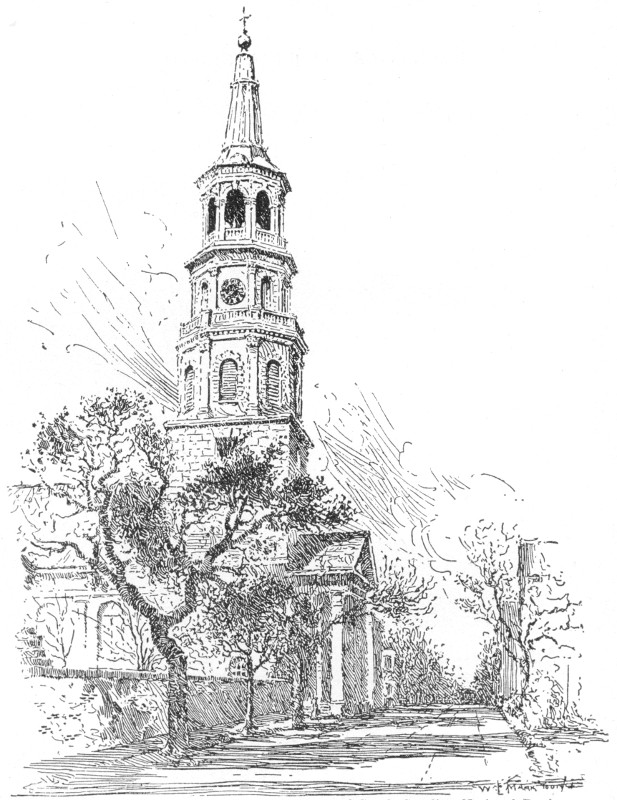

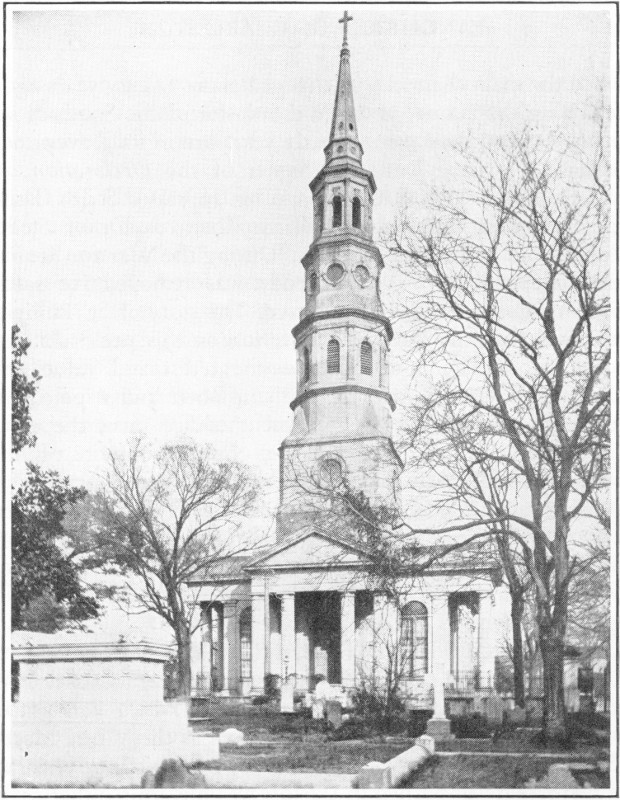

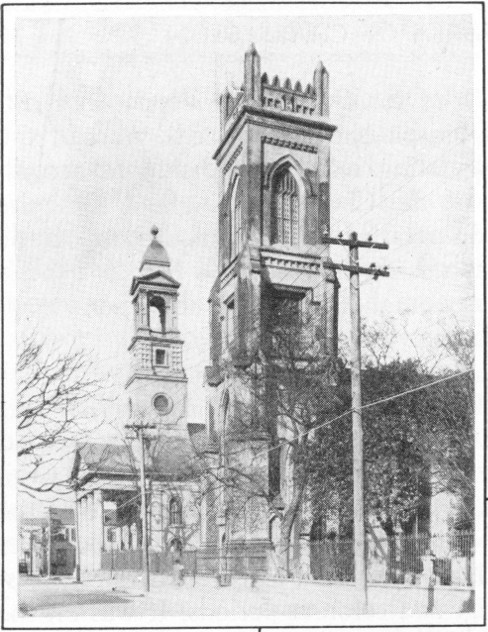

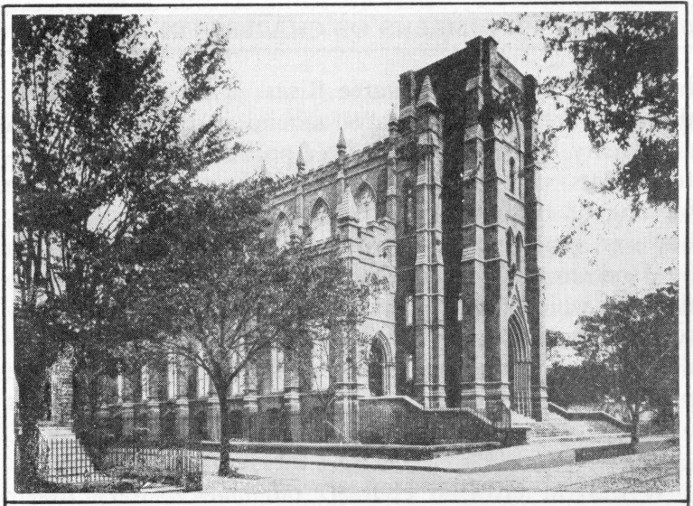

ST. PHILIP’S CHURCH, 144 Church Street: St. Philip’s is the oldest Protestant Episcopal congregation south of Virginia. The first edifice was built on the site now occupied by St. Michael’s (southeast corner of Meeting and Broad Streets). The second and third were built at the present site. The first St. Philip’s was erected in 1681-82. It was of wood, but little is known of it. Early maps designate it as the English Church. The second St. Philip’s was opened for divine worship Easter Sunday, 1723. It faced the west and its steeple was eighty feet high. John Wesley, founder of Methodism, preached in this church two hundred years ago. The first Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina was the Right Reverend Robert Smith, rector of St. Philip’s. This edifice was known far and wide for its great beauty. It was burned February 15, 1835. The third St. Philip’s was used for service May 3, 1838. Its chimes, cast into Confederate cannon, have never been replaced. During twenty-two years an important mariners’ light glowed in the steeple, the other light of this range having been on historic Fort Sumter. The light above St. Philip’s was discontinued when the main channel was changed about twenty years ago. St. Philip’s is known as the Westminster of the South as so many distinguished men of early years are in its graveyards, including Edward Rutledge, Signer of the Declaration of Independence; John C. Calhoun, often appraised South Carolina’s greatest statesman; William Rhett, captor of Stede Bonnet and his associate pirates. During the War for Southern Independence Calhoun’s body was removed for safekeeping, but it was later reinterred. The story of St. Philip’s is coeval with the story of Charleston on this peninsula. Its communion plate is of uncommon interest and value, including pieces presented by William Rhett and a paten of unquestioned antiquity. The present edifice faces the east. The curve in Church Street passes through the site of the body of the edifice that was burned in 1835. President George Washington attended services in the second St. Philip’s May 8, 1791, and President James Monroe May 2, 1819. The present St. Philip’s is accounted one of the beautiful churches of America.

St. Philip’s Episcopal Church

CRADLE OF PRESBYTERIANISM, 138 Meeting Street: The congregation of the Circular Church dates to 1681. The small wooden building in the erection of which Landgrave Joseph Blake was influential was known as the White Meeting House and was replaced in 1804 by a brick edifice circular in form, that was burned in 1861. It was this church that gave name to Meeting Street. From this congregation sprang two other congregations, the First (Scotch) Presbyterian and the Unitarian. Some of the earliest graves in Charles Town are in the Circular Churchyard. David Ramsay, physician, statesman and historian, is buried in it. Some of the early Huguenots 27 (French Protestants) are also buried in it. The chapel in the rear of the yard was built after the fire of 1861. The present edifice is without a great portico over the street.

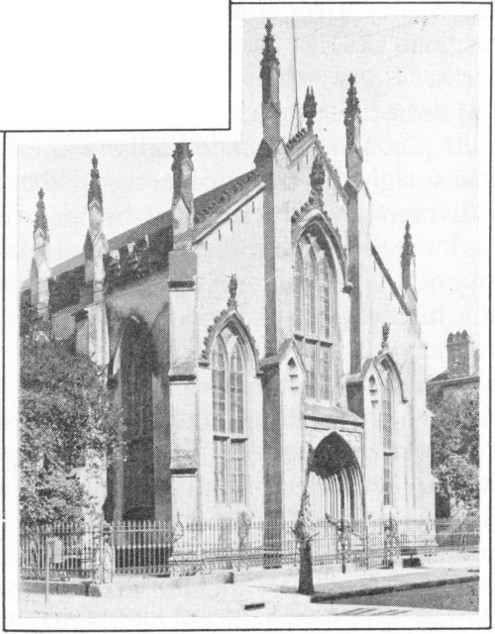

HUGUENOT CHURCH, 136 Church Street: The only Huguenot Church in America! This is the proud and unique distinction of the French Protestant Church in Charleston. Its congregation holds to the old Huguenot litany. It dates to 1681. The first recognized and regular pastor of the French Church was the Reverend Elias Prioleau, who came with the “great Huguenot immigration” about 1687; he died in 1699. Alluding to the Huguenots of Charles Town Bancroft said: “Their Church was in Charles Town and thither every Lord’s Day, gathering from their plantations upon the banks of the Cooper, and taking advantage of the ebb and flow of the tide, they might all regularly be seen, the parents with their children, whom no bigot could now wrest from them, making their way in light skiffs through scenes so tranquil, that silence was broken only by the rippling of oars and the hum of the flourishing village at the confluence of the rivers.” The first Huguenot Church was burned in 1740. The second church was also burned, in 1797. It was at once rebuilt and in 1845 it was remodeled to the form it now presents. “The church edifice is of great architectural beauty, being of pure Gothic, and its walls are adorned with mural tablets, commemorating the names and memories of the first Huguenot emigrants to Carolina.” It is the boast of this congregation that it has had a church on the same site for more years than has any other Charleston congregation. For more than one hundred and fifty years the services were in the French language.

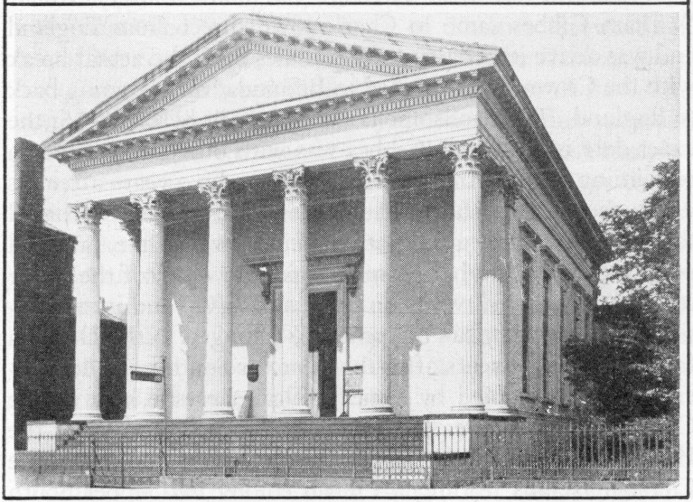

FIRST BAPTIST CHURCH, 61 Church Street: When Charles Town on the peninsula was about three years old the first congregation of Baptists was formed. Some of these Baptists came from New England, with the Reverend William Screven, their pastor, and others came from England. Old records show that for several years the Baptists worshipped in the home of Mrs. William Chapman. Lady Blake, and her mother, Lady Axtell, were both Baptists and members of this congregation; their official rank lent strength to the church. William Elliott, a member, gave the site of the First Baptist Church in 1699. A wooden building was erected. The present building was on the site before 1826 and of it Mills says it showed “the best specimen of correct taste in architecture of the modern buildings in the city.” There are many old graves in its yard.

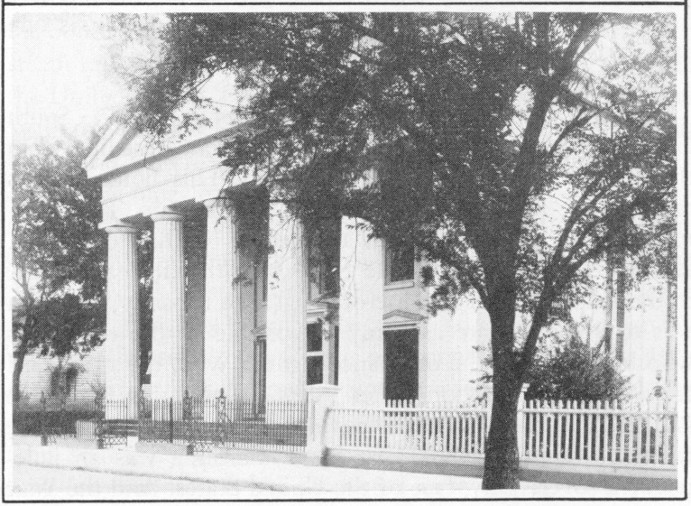

SCOTCH PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH, 53 Meeting Street: Sprung from the White Meeting House, the First (Scotch) Presbyterian Church dates to 1731. The Reverend Hugh Stewart, a native Scot, was its first pastor. The present edifice was dedicated in 1814. It was severely damaged in the earthquake of August 31, 1886, but fully restored. It has one of the finest auditoriums in the country. When the Marquis of Lorne (later the Duke of Argyle) and his wife, the Princess Louise, daughter of Queen Victoria, were in Charleston in January, 1883, they visited the Scotch Church to inspect a memorial tablet to their cousin, Lady Anne Murray. The Duke of Sutherland also made a trip to Charleston expressly to see it. May 2, 1819, President James Monroe attended service in the Scotch Church, hearing a sermon by the Reverend Mr. Reid, the pastor. This 29 church celebrated its bicentennial in March, 1931. During 100 years it has had three pastors—the Reverend John Forrest, D.D., forty-seven years, the Reverend W. Taliaferro Thompson, D.D., twenty years and the Reverend Alexander Sprunt, D.D., thirty-three years. Prominent Charlestonians sleep the sleep eternal in its yard.

TRINITY METHODIST CHURCH, 273 Meeting Street: As its congregation springs from the old Cumberland Church, the first Methodist group in Charleston (1786), Trinity may be called Charleston’s oldest Methodist congregation, but the building it now occupies was recently acquired from the Westminster Presbyterian Church (which combined the abandoned Third Presbyterian in Archdale Street and the Glebe Street Presbyterian Church). Through years Trinity Church was at 57 Hasell Street. Here the first church was erected before 1813. For a short time the church was used by an Episcopal congregation. The story goes that some of the congregation were not agreeable to occupancy by Episcopalians and sought legal counsel. They were informed that possession was “nine points in the law.” So, after an Episcopalian service, the Methodist brothers and sisters, when the congregation was dismissed, locked the doors from the inside, fastened the windows and mounted guard within the edifice, women assisting, until the case was returned in their favor. During this peaceful siege, a lad was born in the building; he years later became a bishop of the church. The Methodist church was planted in Charleston when Bishop Asbury and his associates came here in 1785. The first church building was erected in Cumberland Street in 1787, and within it the first Methodist Conference in South Carolina was held the 30 same year. This building was destroyed in the fire of 1861. John and Charles Wesley had visited Charlestown in 1736. John Wesley preached in St. Philip’s Episcopal Church in 1737. The Wesleys came with General James Oglethorpe’s Georgia colonists. Charles Wesley was the general’s secretary and John Wesley was to be a missionary among the Indians.

ST. JOHN’S LUTHERAN CHURCH, 10 Archdale Street: The Lutheran congregation of St. John’s was organized in 1757 with the Reverend John George Fredichs as pastor. Lacking a building of their own the Lutherans used the French Huguenot Church. June 24, 1764, the first St. John’s was dedicated. The present brick building was dedicated January 18, 1818, the Reverend Dr. John Bachman, friend and associate of J. J. Audubon, the celebrated naturalist, being the pastor. This congregation was influential in the organization of Newberry College and the Lutheran Theological Seminary in South Carolina. Prominent persons of German origin or descent are buried in the yard. But the Lutheran story goes back to March, 1734. In his Sketch of St. John’s, the Reverend E. T. Horn says: “In March, 1734, while the ship containing the exiled Salzburgers lay off the harbor of Charleston, Governor Oglethorpe brought their Commissary, the Baron von Reck, and their pastor, the Reverend John Martin Bolzius, with him to the city. Here they found a few Germans, firm in their attachment to the Lutheran faith, and hungering and thirsting for the Holy Supper. In May, therefore, Bolzius was glad to accompany von Reck as far as Charleston, that he might minister to this little company, and on Sunday, May 26th, 1754, at five o’clock in the morning, most probably in the inn where Bolzius was stopping, he administered the Holy Communion to those whom on the day before he had examined and absolved according to the usages of the Lutheran Church.”

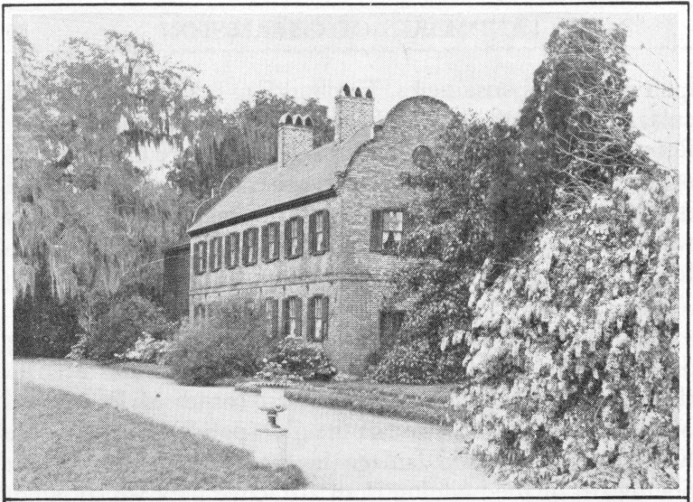

William Rhett House, 58 Hasell Street

The Izard Houses; Nearer, Home of Bishop of Charleston; Other is the Older—110 and 114 Brand Street

UNITARIAN CHURCH, 6 Archdale Street: Just before the American Revolution, the Circular Church on Meeting Street, cradle of Presbyterianism in Charles Town, found it necessary to use an additional building. Thus another church with another pastor was established in Archdale Street. One of the pastors espoused Unitarianism and by amicable agreement the part of the congregation following his teachings took over the Archdale Street church. While the British occupied Charlestown during the Revolution, they stabled horses in this edifice. The present church building was dedicated in April of 1854, and is much praised for its architecture. The ceiling of the nave is peculiarly attractive. The pastor of this Unitarian congregation, the only one in Charleston, was the Reverend Samuel Gilman, author of the famous college song, “Fair Harvard,” and in his memory Harvard alumni arranged the Samuel Gilman Memorial Room in the church tower; the ceremony was performed April 16, 1916.

ST. MARY’S CATHOLIC CHURCH, 79 Hasell Street: Mother parish of the Roman Catholic Church in North and South Carolina and Georgia, St. Mary’s congregation was organized in 1794, and in 1798 bought a frame building from a Protestant congregation. In 1836 this was burned and on the site the present fine brick edifice was erected being completed in 1838. In the late 1890’s the interior was 33 improved. Memorial stained-glass windows were emplaced. Of its interesting graveyard Bishop John M. England who came to Charleston in 1820 (finding two Catholic churches occupied and two priests doing duty) wrote: “The cemetery of this church which is now in the center of the city affords in the inscriptions of its monuments the evidence of the Catholicity of those whose ashes it contains. You may find the American and the European side by side.... The family of the Count de Grasse, who commanded the fleets of France near the Commodore of the United States and his partner, sleep in the hope of being resuscitated by the same trumpet.” According to David Ramsay, “prior to the American Revolution in 1776, there were very few Roman Catholics in Charleston, and these had no ministry, but of all other countries none has furnished the Province with so many inhabitants as Ireland.” About 1786 a vessel bound for South America, having an Italian priest aboard, put into Charleston. This priest celebrated mass for a congregation of about twelve persons. It was “the first Mass celebrated in Charleston and may be regarded as the introduction of the Catholic religion to the States of North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia which afterward constituted the See of Charleston.” The history of St. Mary’s is coeval with the history of the Roman Catholic religion in the Southeast, excluding the Florida possessions of the Spanish.

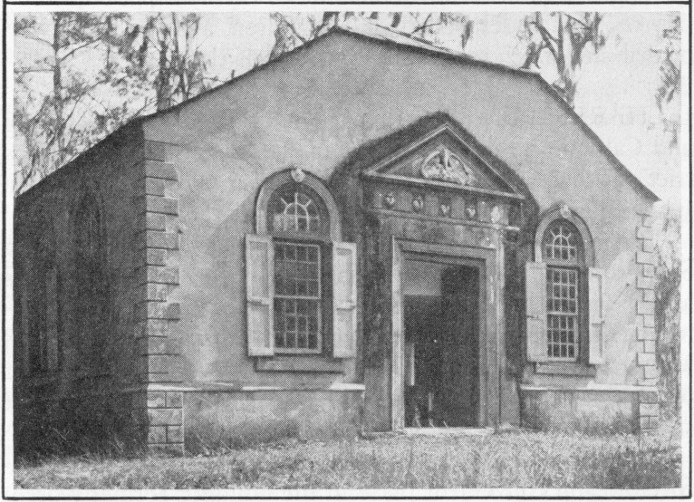

ST. JAMES, GOOSE CREEK, off the Coastal Highway: The British Royal Arms still stand in South Carolina! The British yoke was thrown off one hundred and sixty years ago, but in St. James Church, Goose Creek, sixteen miles from 34 the city hall of Charleston the Royal Arms have never come down! The ancient edifice stands in a tranquil woodland, quite near The Oaks, home of Arthur Middleton in early years. At the foot of the altar is a tomb with this inscription: “Here lyeth the body of the Reverend Francis Le Jau, Doctor in Divinity, of Trinity College, Dublin, who came to this Province October, 1706, and was one of the first missionaries sent by the honourable society to this Province, and was the first Rector of St. James, Goose Creek, Obijt. 15th September, 1717, ætat 52, to whose memory this stone is fixed by his only Son, Francis Le Jau.” In the records left by Dr. Le Jau is mentioned that he christened Indians. Four acres for the old parsonage were the gift of Arthur Middleton, and another pioneer gave the Glebe of one hundred acres. The cherubs in stucco over each of the keystones are famous and so is the pelican feeding her young, over the west door. Interesting memorial tablets have places. In the present day this picturesque and historic church is easily reached by automobile. Each year at Easter divine services are held in the church, the congregation invariably overflowing the building. The original church was built soon after Dr. Le Jau’s arrival.

ST. ANDREW’S, BERKELEY, on the Ashley River Road: The parish of St. Andrew’s, Berkeley (the district about Charles Town was Berkeley in olden times), was founded in 1706 and a simple brick building erected. Seventeen years later this was enlarged, taking the form of a cross. The gallery was intended for non-pewholders and was later set aside for negroes. Destroyed by fire it was rebuilt in 1764 and is one of the few rural churches that has survived the 35 Revolution and the War for Southern Independence. St. Andrew’s was one of ten parishes authorized by act of the Assembly in 1706 regulating religious worship in accordance with the forms of the Church of England. In quite recent years a question relative to the jurisdiction of the Bishop of London was raised! St. Andrew’s had its genesis when the colony had a population of 9,000, “of whom 5,000 were Negro and Indian slaves.”

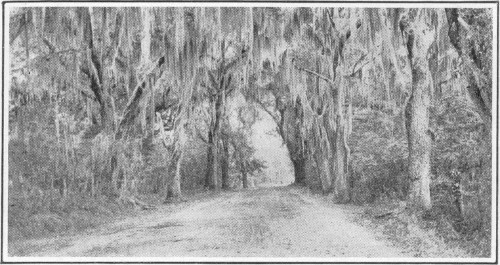

ASHLEY RIVER ROAD, Leading to Famous Gardens: St. Andrew’s Church is but one of many interesting and historic places on the Ashley River Road. Two miles from the Ashley River Bridge the road passes near the site of the original Charles Town in South Carolina and three miles farther is the Ashley Hall plantation of the Bull family, distinguished in provincial and colonial periods. It was on the Bull place that Attakullakulla, a chief of the Cherokee Indians, signed a treaty of peace in the 1760’s after his tribe had been severely humbled by the whites. Just across the highway were the lovely Magwood Gardens, now the property of a granddaughter of President Abraham Lincoln. Here the highway passes through a grove of majestic live oaks festooned with Spanish moss. Seven miles from the bridge one passes St. Andrew’s Church and a short distance farther through old Fort Bull, the moat about which has been filled. Next, on the right, is the entrance to Drayton Hall, then Magnolia Gardens, Runnymede, home of John Julius Pringle, Speaker of the House of the Assembly in 1787, and later the property of Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, of the famous Pinckney family; Middleton Place (gardens) where is buried Arthur Middleton, Signer of the Declaration of Independence; the seat of the old Wragg barony; the Ashley River is crossed at Bacon’s Bridge near which stands an ancient oak beneath the spreading boughs of which General Francis Marion is alleged to have entertained a British officer (it is a pretty legend, but its site is severally located). Half a mile beyond the bridge is the road leading down to the ruins of old Dorchester, established in 1696 by colonists from Dorchester, Massachusetts, led by the Reverend Joseph Lord. In this year ruins of fort and churches are mute reminders of a brave village in a primeval wilderness infested with savage Indians. From Bacon’s Bridge the distance to Summerville is five miles. It is a drive every visitor to this section should follow. In the season, the Middleton Place and Magnolia Gardens are open to visitors.

Foreground, Unitarian Church; Background, St. John’s Lutheran Church

Huguenot Church. Only One in America

CASTLE PINCKNEY, in Charleston Harbor: Stand on the incomparable Battery and look seaward. Fort Sumter is in plain view, of course, but nearer the gaze is Castle Pinckney, holding the status nowadays of a government monument. It is to be reached only by boat. The fort at the edge of the sand bank known as Shute’s Folly was built after the Revolution, in 1797-1804. Later, it was enlarged. In the War for Southern Independence, it lacked opportunity to contribute materially to the defense of Charleston. Really there is more legend than history about Castle Pinckney, but long it has been a well-known landmark. The government used it as a depot for aids for navigation until the depot was established at the foot of Tradd Street, on the Ashley River, site of the old Chisolm’s rice mill. An excuse for including it among Landmarks of Charleston is that many strangers 38 promenading on the High Battery wish to know what Castle Pinckney is.

ST. MICHAEL’S CHURCH, 78 Meeting Street: Five times have the bells of St. Michael’s crossed the Atlantic ocean. They came from England in 1764 and returned there after the British evacuated the town in 1784. Repurchased for Charleston, they came back to their steeple. During the War for Southern Independence they were taken for safekeeping to Columbia and in the burning of that town charged to General William Tecumseh Sherman (who had been a social favorite in Charleston before the war) they were so damaged that they were shipped to England. There they were recast in the original molds. Brought back they are still in the steeple, pealing on occasions. When Charles Town on the peninsula was laid out, a lot was designed for the English church, St. Philip’s. A wooden building was erected. This being outgrown a brick church was built on Church Street, on the present site of St. Philip’s. By act of the Assembly, June, 1751, Charlestown was divided into two parishes; the lower, St. Michael’s, and the upper, St. Philip’s. February 17, 1752, the corner stone was laid with much ceremony, the South Carolina Gazette carrying an account. The reputed successor of Sir Christopher Wrenn was the architect and the edifice is declared to resemble St. Martin’s-in-the-Field, London, near Trafalgar Square. From the pavement to the ball of the steeple is 182 feet. During the War for Southern Independence, the steeple, and that of St. Philip’s, offered shining marks for the Union artillerists. Cannon balls struck the church, but not with serious results. Heavy damage was done by the earthquake of August 31, 1886. The old clock in the 39 steeple, with four dials, began the keeping of Charlestown time in 1764. President George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette have worshipped in St. Michael’s. In the taxed tea excitement of 1774, the assistant rector of St. Michael’s preached a sermon that aroused his congregation and he received his walking papers. In the yard of this church are illustrious dead, including James Louis Petigru, eminent South Carolina lawyer, an opponent of Nullification in the 1830’s and of Secession in 1860; however, when his state had seceded, Mr. Petigru cast his fortune with the Confederacy. The incumbent Bishop of South Carolina, the Right Reverend Albert S. Thomas was rector of St. Michael’s when he was elected to this high office.

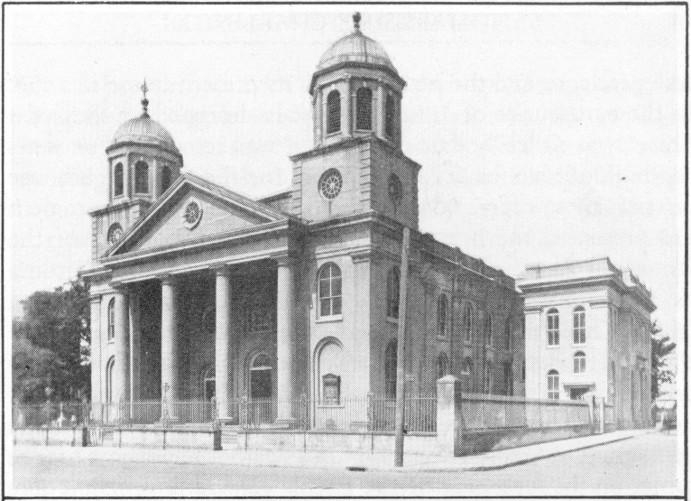

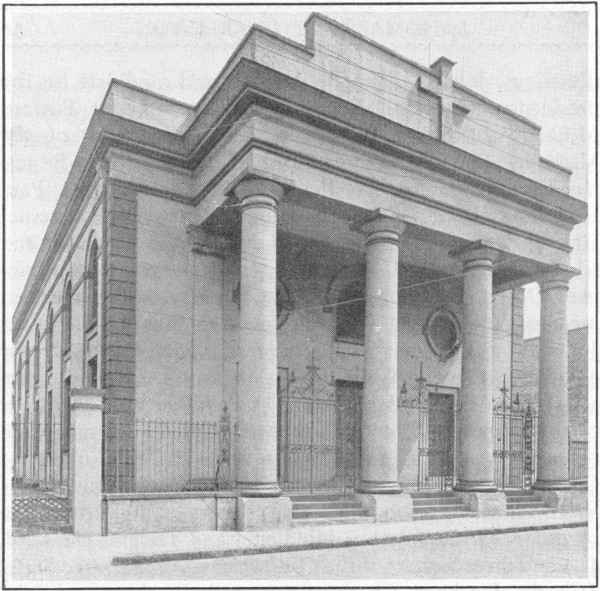

CATHEDRAL OF ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST, 122 Broad Street: John Morica England, first Bishop of Charleston, arrived in Charleston December 30, 1820, and the Cathedral of St. Finbar was dedicated by him a year later. It was a plain frame structure. Thirty years it stood. Then it was razed for the building of the St. John and St. Finbar Cathedral, burned in 1861; it was similar in design to the present Cathedral of St. John the Baptist on the same site, the northeast corner of Broad and Legare Streets. This handsome Gothic edifice of brown stone was begun late in 1888 by the Right Reverend Henry Pinckney Northrop, Bishop of Charleston. April 14, 1907, it was consecrated, Cardinal Gibbons being one of the celebrants. The site is that of the Vauxhall Gardens. Between December, 1861, and the occupancy of the new cathedral, the congregation worshipped in the pro-cathedral in Queen Street, built by the Right Reverend Patrick Nielsen Lynch, then Bishop of Charleston. St. John the Baptist’s is 200 feet 40 long from the entrance to the rear of the vestry, the nave being 150 feet long by eighty feet wide; from the floor to the top of clerestory is sixty feet. The interior is beautifully decorated and contains fine paintings and stained-glass windows. To the north of the Cathedral is the Convent of Our Lady of Mercy. Graves of bishops are under the cathedral. The edifice is one of Charleston’s cardinal show places.

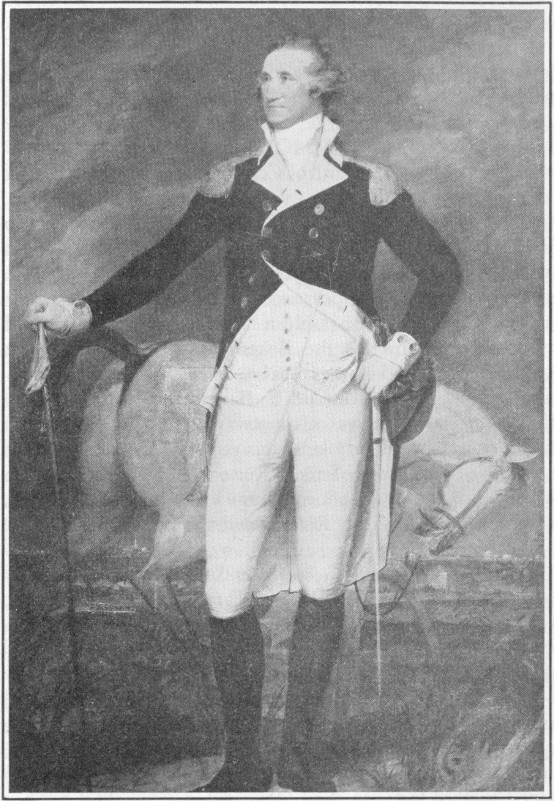

TRUMBULL’S WASHINGTON, in Charleston City Hall: One of the most famous and valuable portraits of General George Washington hangs in the City Hall, northeast corner of Meeting and Broad Streets. It was done by John Trumbull on the order of the City Council in honor of President Washington’s visit in 1791. It is reputed to be worth a million dollars! Art connoisseurs have come long distances to inspect this great portrait. Washington is shown full length, with his horse near him. While this is Charleston’s most valuable painting, there are other fine paintings in the Municipal Gallery, including President James Monroe, commemorating his visit in 1819, by Samuel F. B. Morse (inventor of the telegraph); the damage done by a Union shell in the 1860’s does not show; President Andrew Jackson, in uniform after the Battle of New Orleans, by Vanderlyn, student under the celebrated Gilbert Stuart; General Zachary Taylor, with spyglass in hand in Mexico, by Beard; John Caldwell Calhoun, eminent statesman, addressing the United States senate, by Healy; General William Moultrie, defender of Fort Moultrie against Sir Peter Parker’s British fleet in 1776, by Fraser; Marquis de Lafayette, miniature, by Fraser, commemorating the Frenchman’s visit in 1825; General Francis Marion, the “Swamp Fox,” in Revolutionary uniform, 41 by John Stolle (here the famous coonskin cap is replaced by a brigadier’s hat, by order of William A. Courtenay, then Mayor); Queen Anne, of England, by Sir Godfrey Kneller, a fragment of the original cherished as a relic; Joel Roberts Poinsett, statesman, by Jarvis; William Campbell Preston, statesman, by Jarvis; General and Governor Wade Hampton, the hero of Reconstruction, by Prescott; General P. G. T. Beauregard, Confederate Chieftain, by Carter; General Thomas A. Huguenin, the last Confederate commander of Fort Sumter; statuary busts of James Louis Petigru, Robert Young Hayne, Christopher Gustavus Memminger, Robert Fulton, and others. An informing sketch of this gallery by Joseph C. Barbot, Clerk of Council, is recommended. In Colonial years the site of the City Hall was the town’s market place. On it the United States Bank was housed about 1802 and this building became the City Hall. It is related that the money for the purchase came from the sale of the Exchange to the United States government. The interior has been rearranged.

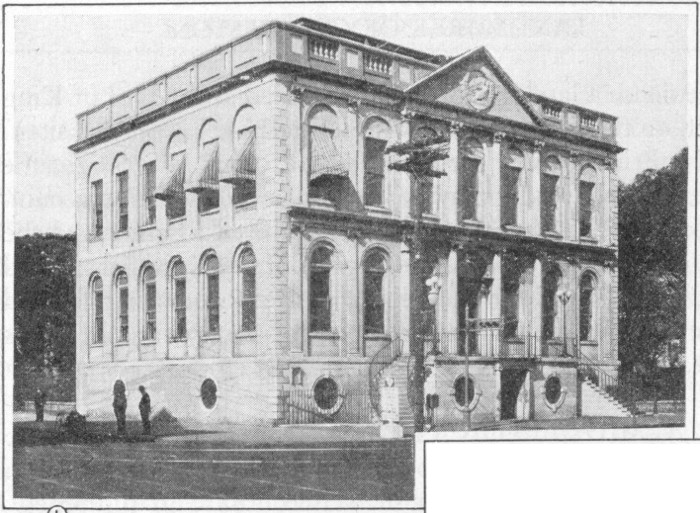

THE OLD EXCHANGE, East End of Broad Street: From the standpoint of history, this building is incomparably the most interesting in South Carolina and one of the most interesting in America, the Rev. William Way, D.D., told the Rebecca Motte Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, whose property it is by gift of the United States. When Charles Town was laid out in 1680 this site was the Court of Guards, the place of arms for the early colonists. Here were imprisoned Stede Bonnet and other pirates in 1718 when South Carolina was putting down piracy after its previous years of friendship and fraternizing. The Exchange 42 and Custom House was built in 1767 at a cost of 44,016 pounds. Most of the material was brought from England in sailing vessels. The date of completion was 1771. Taxed tea from England was stored in the Exchange in 1774 and citizens prevented its sale. A second cargo, arriving November 3, 1774, was dumped by merchants of Charlestown into the Cooper River. In July, 1774, delegates to the Provincial Congress gathered in this building and set up the first independent government established in America; the congress also elected delegates to the General Congress meeting in Philadelphia. Patriotic men and women of Charlestown were incarcerated in the Exchange by the British during the Revolution; it was from the Exchange that the martyr Colonel Isaac Hayne was led to his execution in 1781. President George Washington was entertained in the building, Charles Fraser writing in his Reminiscences: “Amidst every recollection that I have of that most imposing occasion, the most prominent is the person of that great man as he stood upon the steps of the Exchange uncovered, amidst the enthusiastic acclamation of the citizens.” Saturday, May 7, 1791, General Washington was guest of honor at a “sumptuous entertainment” given by the merchants of Charleston in the Exchange. During the War of 1812 patriotic meetings were held in the Exchange. In 1818 the city of Charleston sold the Exchange to the United States government for the sum of $60,000 and a week later the city government paid the sum of $60,000 for the building of the United States Bank, to be converted into the City Hall. The following year President James Monroe was in the Exchange. The federal government used the building for a customhouse and post office, the customhouse transferring to its own building after the War for Southern Independence and the post office to its present home in 1896. In the earthquake of 1886, the cupola designed by the artist Fraser was so badly damaged that it was removed. For years the building has been headquarters for the Sixth lighthouse district; these offices continue in it although the government has presented the historic building to the Daughters of the American Revolution in and of the State of South Carolina as an historical memorial, to be occupied by the Rebecca Motte Chapter; this was effective in March of 1913. When the United States entered the World War the Exchange by unanimous vote of the D.A.R. was tendered the Federal government which it used to the end of the conflict. On the centennial of George Washington’s death a handsome bronze tablet on the west side of the Exchange was unveiled. There is no question that this ante-Revolutionary building is one of Charleston’s greatest landmarks.

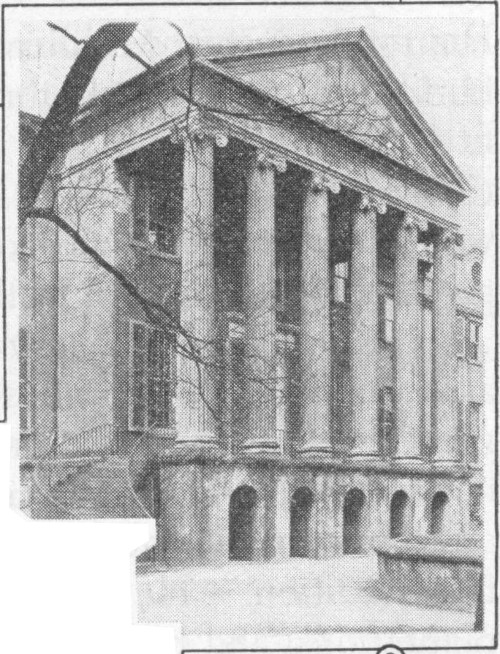

First (Scotch) Presbyterian Church

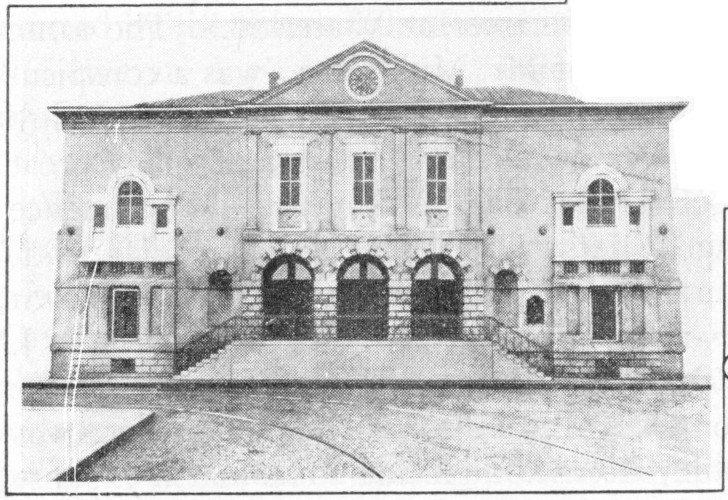

Bethel Methodist Church

SITE OF INSTITUTE HALL, 134 Meeting Street: South Carolina declared itself free and independent, seceding from the United States, December 20, 1860. This bold act was taken in the hall of the South Carolina Institute. The Ordinance of Secession had been adopted in the hall of the St. Andrew’s Society, 118 Broad Street, but the delegates came to the Institute Hall because of its greater capacity; the wish was to accommodate as many as possible of the thousands who hoped to see the ordinance signed. With the great hall crowded to suffocation, after all the signatures had been affixed, President Jamison advanced to the front of the rostrum and announced, that South Carolina was an independent sovereignty, free of the United States. And the War for Southern Independence was nascent. In this hall several 45 months before had been held the famous Democratic National Convention that adjourned without decision with respect to candidates for President and Vice President. On the site are published The News and Courier, one of the oldest daily newspapers in the United States, founded in 1803, with its roots going back to 1786, and the Charleston Evening Post. They carry on the traditions of the South.

CONFEDERATE MUSEUM, at the Head of the Market: Valuable relics of the Confederacy are preserved in their hall at the head of Market Street, at Meeting Street, by the Charleston Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. A gun on the porch was fashioned from Swedish wrought iron from one of the first locomotives operated by the South Carolina Railroad, the world’s oldest long-distance steam railroad. It was among the first rifled cannon made in the United States. This piece was in Columbia when General William Tecumseh Sherman’s Union troops occupied that town, and Union soldiers tried to burst the cannon, cracking it near the muzzle. During riots in the period of Reconstruction the Washington Light Infantry manned the gun. The Confederate Museum is in a hall over the west end of the old City Market established between 1788 and 1804, extending from East Bay Street to Meeting Street. Through many years all household marketing was done in the stalls. Into recent years it was a common sight to see a gentleman doing the marketing, a negro with a large basket following him from stall to stall. There survive stalls in the Market, but the long low building is not congested as it was in other years. The telephone has contributed much toward the discontinuance 46 of the good old Charleston custom of marketing in person.

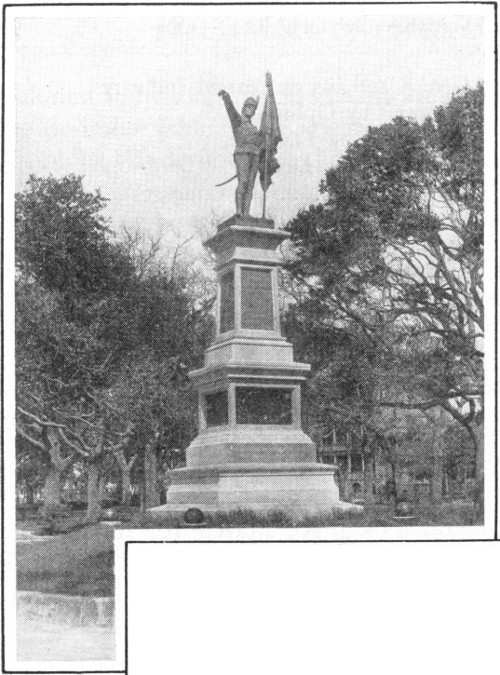

MARION SQUARE, King, Meeting and Calhoun Streets: Named in honor of General Francis Marion, hero of the Revolution, affectionately called the “Swamp Fox,” this six-acre square in the very heart of Charleston was from 1882 to 1921 the parade ground of The Citadel, the military college of South Carolina, giving rise to the nickname, Citadel Green. The Citadel is now at Hampton Park, on the Ashley River, but its main building and four wings stand as reminders. In Lowndes Street, from Calhoun to the Citadel sally port, is a statue of John Caldwell Calhoun, eminent South Carolina statesman, atop a tall granite shaft. On the Meeting Street side is a monument to General and Governor Wade Hampton, savior of his State in Reconstruction, and on the west side a section of “horn work,” part of the Revolutionary line of fortifications for the defense of Charlestown against the invading British. It was just outside the town, Boundary Street becoming Calhoun Street after the town limits were extended to their present line in 1849. Before the purchase by the now defunct Fourth Brigade, the square was solidly built. After the evacuation of Charleston until 1882 the United States army was in possession of the Citadel buildings. On the east side and on the west side are fountains fed by a great artesian well near King and Calhoun Streets, formerly in the waterworks system.

THE OLDEST DRUG STORE, 125 King Street: America’s oldest drug store business is in Charleston. It has had a career antedating 1781 as in that year Dr. Andrew Turnbull 47 bought the business and began the dispensing of his own remedies. In 1792 Joseph Chouler was the proprietor, in 1806 William Burgoyne, in 1816 Jacob De La Motta. The mortar and pestle he displayed over his Apothecary’s Hall is still extant, and in the store now used. Felix l’Herminier took over the business in 1845 and soon afterward it was in the name of William G. Trott who in 1870 sold it to C. F. Schwettmann. In 1894 the style was C. F. Schwettmann & Son. This continues with John F. Huchting as proprietor. In 1920 Mr. Huchting presented much of the old Apothecary’s Hall to the Charleston Museum which has reset it and where it may be seen. More than one hundred and fifty years for a drug business is a worth-while record!

CHARLESTON LIGHTHOUSE, on Morris Island: During Colonial years the only coastal light south of the Delaware capes was the Charleston Lighthouse on Morris Island, built in 1767. The present tower was built in 1876; it is of brick, 161 feet high. The earthquake of 1886 cracked the tower and threw the lens out of adjustment. From the first Charleston Light came a copper plate in the corner stone, reading: “The first stone of this Beacon was laid on the 30th of May 1767 in the seventh year of His Majesty’s reign, George the III,” and so on. December 18, 1860, the first incident of the War for Southern Independence affecting the lighthouse service occurred at the Charleston Light. The Secretary of the Treasury was told by the Secretary of the Lighthouse Board that he would not recommend that the coast of South Carolina “be lighted by the Federal Government against her will.” December 30, the lighthouse inspector reported that “the Governor of the State of South Carolina 48 has requested me to leave the State.” By the latter part of April, 1861, the Confederates had extinguished this and other lights; they were furnishing no aids to navigation for Union mariners. Morris Island is at the left entrance to the harbor of Charleston. From the eastern end of the Folly Beach, accessible by automobile, a clear view of the Charleston Light may be had.

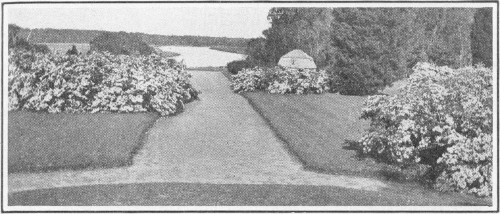

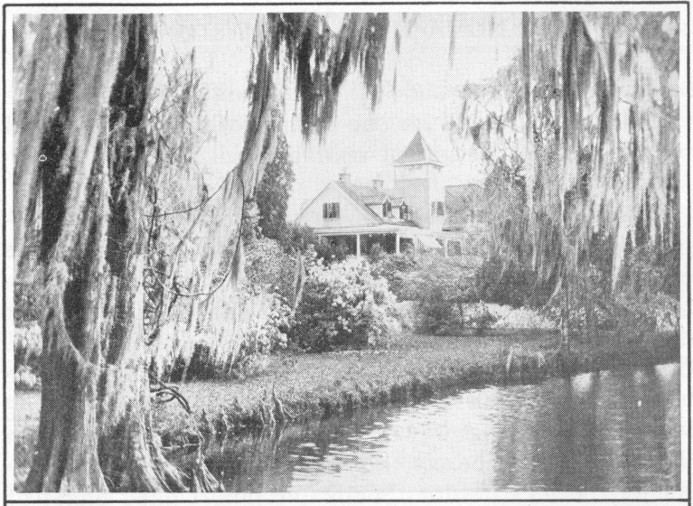

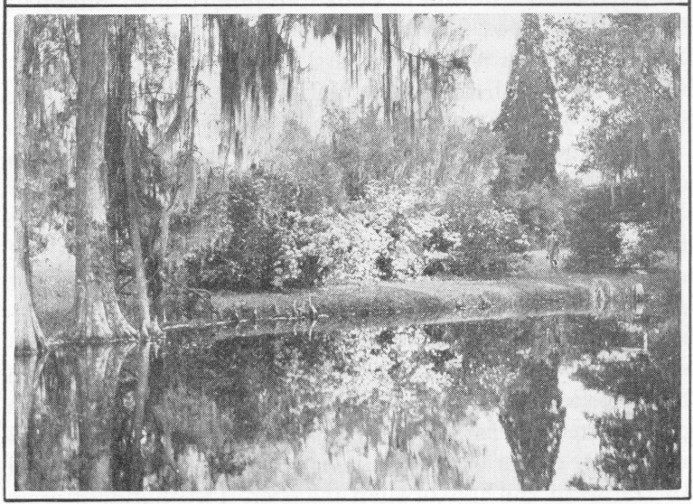

MIDDLETON PLACE, Gardens on the Ashley River: This was the seat of Arthur Middleton, Signer of the Declaration of Independence. Henry Middleton, of The Oaks, president of the Continental Congress, obtained the land through his wife. Two English landscape gardeners were brought oversea to fashion the show place, which was completed about 1740. The fine Tudor house was put to the torch late in the War for Southern Independence. Only the left wing stands, and in it the owner, J. J. Pringle Smith, descendant of the Signer, lives. The old steps to the main building are in place, and from them a commanding view of the broad formal terraces and the winding Ashley River is had. The first japonicas brought into this country were transplanted at Middleton Place about 1805 and one of the original plants was alive in 1939. Middleton Place is famous not only for its gorgeous azalea show in spring, but for the wide variety of plants. It has been praised with lavish enthusiasm by distinguished visitors. Annually thousands of people travel many miles to walk about these wonderful gardens, a living reminder of the beauty wrought before the Revolution. The grave of the Signer is at Middleton Place. The Gardens are on the Ashley River Road, about fourteen miles from the Ashley River Bridge. If one would see gardens, terraces and hedges substantially as they were in 1740; if one would see one of the world’s most beautiful places, he should be sure of visiting Middleton Place.

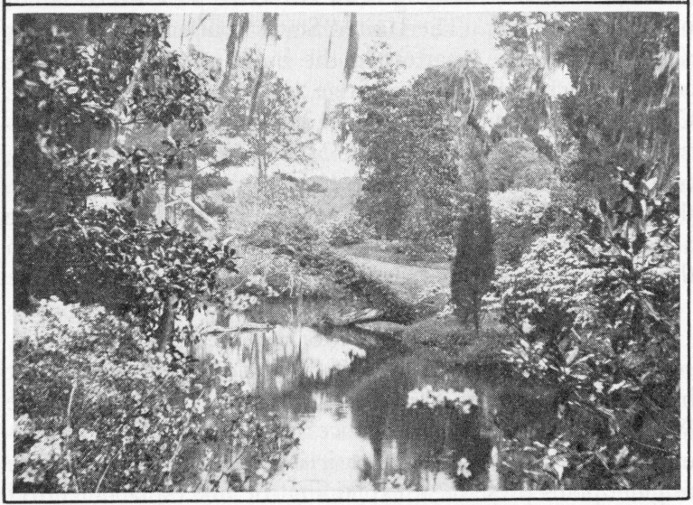

Alluring Views of Magnolia-on-the-Ashley

MAGNOLIA GARDENS, on the Ashley River: Distinguished authors have heaped glowing compliments on the enchantment that is Magnolia-on-the-Ashley, “a sight unrivalled,” said a writer in the Chicago Tribune. The fame of these gardens has gone wide and far. Thomas P. Lesesne, of Charleston, was in the great Kew Gardens, London. Coming to the azalea section he was surprised to find a sign declaring to all who came that way that if one would see the azalea in the zenith of its beauty, he should visit Magnolia-on-the-Ashley, near Charleston, South Carolina, United States of America! In Kew! Think of that! John Galsworthy, Owen Wister and other notables have shed superlatives in describing the gardens. In this show place on the Ashley River, the Reverend John Grimke Drayton planted the first Azalea Indica. They had been imported from the East to Philadelphia in 1843, but, the Pennsylvania climate being too rigorous for them, Mr. Drayton was invited to see what he could do with them. And what he has done with them brings thousands of people from distant places each spring when the azaleas are in the full glory of their bloom! The gardens, about twenty-five acres in extent, have what is declared to be the most valuable collection of the Camellia Japonica; there are more than 250 varieties. They come into bloom in the winter, and the gardens are open for their inspection. Carlisle Norwood Hastie, present owner of Magnolia, is grandson of the Reverend Mr. Drayton, an Episcopalian minister. Two hundred years the property has been in possession of the Drayton family. 51 During the Revolution the Colonial mansion was burned and a second building was burned during the War for Southern Independence. Mr. Hastie has purchased the old Tupper house in Charleston (its site on Meeting Street) for rëerection at Magnolia-on-Ashley. Moss-covered oak and cypress trees, bordering mirroring lagoons, furnish a bewitching background for the gardens, with the Ashley River in front.

ASHLEY RIVER BRIDGE, on the Coastal Highway (17): Until the first of July, 1921, the bridge over the Ashley River at the head of Spring Street was privately owned. At that time the county of Charleston acquired it by purchase and at once the toll was taken off. In the spring of 1926, the present handsome and commodious concrete bridge was formally opened. It is slightly down-stream from the rather ramshackle wooden bridge. It cost a million and a quarter dollars. It is wide enough for four vehicles abreast and on each side is a sidewalk for pedestrians. Its huge bascule leaves provide plenty of clearance for the greatest seagoing vessels. This bridge, a memorial to Charleston soldiers who lost their lives in the World War, is an essential link in the Coastal Highway between the provinces of eastern Canada and the keys of Florida, thence by “ferry” to Havana, Cuba. It connects the city of Charleston with all the trans-Ashley region. From the town it leads to James Island (on which are the Country Club and the Municipal Links, Riverland Terrace and Wappoo Hall) and the popular Folly Beach; by way of James Island to the Stono River bridge which is near the famous Fenwick Hall, a great estate in pre-Revolutionary years; it leads to Walterboro, Beaufort, Port Royal (site of the earliest French colony) and Savannah and Jacksonville; it leads to the Ashley 52 River Road for St. Andrew’s Church, Middleton Place, Magnolia-on-the-Ashley, Drayton Hall, Runnymede, Wragg Barony and Bacon’s Bridge over the upper Ashley River. In the War Between the States the old bridge was burned and after Appomattox more than fifteen years elapsed before it was restored. Near the Ashley River Bridge in St. Andrew’s Parish are sites of the earliest English plantations. Quite near it Eliza Lucas, daughter of the Governor of Antigua and mother of the Generals Charles Cotesworth and Thomas Pinckney, carried forward her indigo experiments. David Ramsay says that the indigo planters doubled their capital every three or four years.

COOPER RIVER BRIDGE, on the Old King’s Highway: Coming to Charleston President George Washington, President James Monroe and the Marquis de Lafayette traveled over the old King’s Highway. Washington was here in 1791, Monroe in 1819 and Lafayette in 1825. From the Mount Pleasant shore to the City of Charleston they crossed by primitive ferry. To August of 1929 ferries over the broad Cooper River were continued. In that month the great bridge over the Cooper River was opened to traffic. This is the world’s third highest vehicular bridge! Its span over Town Creek affords vertical clearance of 132 feet, as much as that of the famous Brooklyn Bridge, and the span over the Cooper River a vertical clearance of 152 feet at mean high water. From the crest of this engineering achievement are provided commanding views. In the distance to the right is Fort Sumter, looking for all the world like a toy fortress in a toy pool. From this coign of vantage one sees the many bold and little creeks that flow into the Cooper. To the middle left one sees 53 the heavy woods of Christ Church Parish. Give the imagination rein and appear ghosts of almost naked Indians, of early English, French, Irish, Scotch; of bitter conflicts of man against man; of Sir Peter Parker and his naval armada smiting the little palmetto fort with shot and shell. At Charleston, over the Cooper River Bridge the old Kings Highway makes junction with the Coastal Highway. It is the short route from Charleston to Georgetown, Wilmington, Norfolk, crossing the lower Santee and other bold coastal streams almost within sight of the sea. There is every promise that the old King’s Highway, paved, will develop into a paramount route between East and Southeast, an important alternate to the Coastal Highway. No visitor to Charleston should forego the opportunity of passing over the three-mile Cooper River Bridge. It is a sensation well worth the trivial Journey.