Title: Fighting Joe; Or, The Fortunes of a Staff Officer. A Story of the Great Rebellion

Author: Oliver Optic

Release date: May 4, 2019 [eBook #59429]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Richard Hulse, Barry Abrahamsen, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/fightingjoe00adamiala |

AT THE BATTLE OF ANTIETAM.—Page 143.

This volume, the fifth of “The Army and Navy Stories,” is not a biography of the distinguished soldier whose sobriquet in the army has been chosen as its principal title, though the prominent incidents of his military career are noticed in its pages. The writer offers his humble tribute of admiration to the energetic and devoted general who will be recognized under the appellation given to this work; but perhaps the object of the volume may be better represented by the second title. It follows Tom Somers, “The Soldier Boy” and “The Young Lieutenant,” in his brilliant and daring career as a staff officer, through some of the most stormy and trying scenes of the late war.

As in the volumes of the series which have preceded it, the best sources of information upon military events have been carefully consulted; and to the extent to which the book is properly historical, it is intended to be faithful in its delineations. But the work is more correctly a record of personal adventure, no more complicated, daring, and romantic than may be found in the experience of many, who, through trial and tribulation, through victory and defeat, have passed from the inception to the gigantic failure of this gigantic rebellion.

More earnest than any other purpose in the production of the book, it has been the object of the writer to exhibit a character in his hero worthy the imitation of the boy and the man who may read it; and if it does not inculcate a lofty patriotism, and a noble and Christian morality, it will have failed of the highest aim of the author.

With the still stronger expression of gratitude which the increasing favor bestowed upon previous efforts demands of me, I pass the fifth volume of the series into the hands of my indulgent friends, hoping that it will not fall short of their reasonable expectations.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | A Fighting Man. | 11 |

| II. | A Skirmish on the Road. | 22 |

| III. | Fighting Joe. | 33 |

| IV. | Miss Maud Hasbrouk. | 44 |

| V. | The Boot on One Leg. | 55 |

| VI. | The Boot on the Other Leg. | 66 |

| VII. | South Mountain. | 77 |

| VIII. | Before the Great Battle. | 88 |

| IX. | Between the Pickets. | 98 |

| X. | Major Riggleston. | 109 |

| XI. | Shot in the Head. | 120 |

| XII. | The Council of Officers. | 131 |

| XIII. | The Battle of Antietam. | 141 |

| XIV. | The Battle on the Right. | 151 |

| XV. | After the Battle. | 161 |

| XVI. | The Mystery explained. | 171 |

| XVII. | Down in Tennessee. | 181 |

| XVIII. | The Guerillas at Supper. | 191 |

| XIX. | Tippy the Scout. | 202 |

| XX. | Skinley the Texan. | 213 |

| XXI. | The House of the Union Man. | 223 |

| XXII. | The Greenback Train. | 234 |

| XXIII. | The Battle in the Clouds. | 244 |

| XXIV. | Peach-Tree Creek. | 254 |

| XXV. | The Monkey and the Cat’s Paw. | 264 |

| XXVI. | Supper for Seven. | 274 |

| XXVII. | The Cat’s Paw too sharp for the Monkey. | 284 |

| XXVIII. | The Blood-Hounds on the Track. | 294 |

| XXIX. | The Pilgrimage to the Sea. | 303 |

| XXX. | Major Somers and Friends. | 314 |

“WELL, Alick, I don’t know where I am,” said Captain Thomas Somers, of the staff of the major general commanding the first army corps of the Army of the Potomac, then on its march to repel the invasion of Maryland, which had been attempted by the victorious rebels under General Lee.

“Well, massa, I’m sure I don’t know,” replied Alick, his colored servant. “If you was down ’bout Petersburg, I reckon I’d know all ’bout it.”

“We must find out very soon,” added Captain Somers, as he reined in his horse at a point where two roads branched off, one to the north-west and the other to the south-west.

“Day ain’t no house ’bout here, massa.”

“I don’t want to lose my way, for I have no time to spare.”

“Dar’s somebody comin’ up behind, massa,” said Alick, who first heard the sounds of horses’ feet approaching in the direction from which they had just come.

Captain Somers, after receiving the agreeable intelligence of his appointment on the staff of the general, in whose division he had served on the Peninsula, hastened to Washington to report for duty. He had hardly time to visit his friends, and was obliged to content himself with a short call on Miss Lilian Ashford, though he had an invitation to spend the evening with the family, extended for the purpose of enabling the young gentleman to cultivate an acquaintance with the beautiful girl’s grandmother!

Lilian’s father’s mother was certainly a very estimable old lady, and her granddaughter loved and reverenced her with a fervor which was almost enthusiastic. It was quite natural, therefore, that she should wish Captain Somers,—for whom she had knit a pair of socks, which had been no small portion of his inspiration in the hour of battle, and for whom she had contracted a friendship,—it was quite natural that she should wish to have the captain well acquainted with her grandmother. She loved the old lady herself, and of course so brave, handsome, and loyal a person as her friend had proved to be, must share her reverence and respect. Besides, the venerable woman remembered all about the last war with Great Britain. Her husband had been one of the firemen sent out with axes to cut away the bridges which connect Boston with the surrounding country, when an invasion of the town was expected. She could tell a good story, and as Somers was a military man, it was highly important that he should know all about the dreaded invasion which did not take place.

Captain Somers was obliged to deprive himself of the pleasure of listening to the old lady’s history of those stirring events, for more exciting ones were in progress on the very day of which we write. He was sorry, for he anticipated a great deal of pleasure from the visit, though whether he expected to derive the whole of it from the presence of the grandmother, we are not informed; and it would be wicked to pry too deeply into the secrets of the young man’s heart. We are not quite sure that Lilian was entirely unselfish when she described what a rich treat the old lady’s narrative would be; but we are certain that she was entirely sincere, and that it was quite proper to offer some extra inducement to secure the gallant captain’s attendance.

The captain did not need any extraordinary inducements, beyond the presence of the fair Lilian herself. We even believe that he would have cheerfully spent the evening at No. — Rutland Street, if there had been no one but herself to give him a welcome, and aid him in passing away the hours. Nothing but a high sense of duty could have led him to break the engagement. The rebel hordes, victorious before Washington, and elated by the signal successes they had won, were pouring into Maryland, menacing Washington, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. It was a time which tried the souls of patriotic men—a time when no man who loved his country could rest in peace while there was a work which his hands could do.

The young staff officer called upon the lady and stated his situation. She blushed, as she always did in his presence, and gave him a God-speed on his patriotic mission. She hoped he would not be killed, or even wounded; that his feeble health would be restored; and that God would bless him as he went forth to do battle for his treason-ridden land. She was pale when he took her hand at parting; her bosom heaved with emotions, to which Somers found a response in his own heart, but which he could not explain.

He went to Washington; but the gallant army, still suffering from the pangs of recent defeat, but yet strong in the cause they had espoused, had marched to the scene of new battles. Somers had already provided himself with his staff uniform, and he remained in Washington only long enough to purchase two horses, one of which he mounted himself, while Alick rode the other, and started for the advance of the army. The roads were so cumbered with artillery trains and baggage wagons that his progress was very slow, and the corps to which he now belonged was several days in advance of him. By the advice of a general officer, he had made a détour from the direct road, and passed through a comparatively quiet country.

The rebels were at Frederick City, and their cavalry, in large and small bodies, was scattered all over the region, gathering supplies for the half starved, half clothed men of Lee’s army. Thus far Somers had met none of these marauders, nor any of the guerillas, who, without a license from either side, were plundering soldiers and civilians who could offer no resistance. Somers had ridden as rapidly as his feeble state of health would permit; but his enthusiasm had urged him forward until his horse was more in danger of giving out than the rider. But when he reached the cross-roads, at which we find him, doubtful about the right way, he had slept the preceding night at a farm-house, and horse and rider were now in excellent condition.

“Are your pistols ready for use, Alick?” asked Somers, as he heard the sounds of the horses’ feet.

“Yes, sar; always keep the pistols ready. But what you gwine to do wid pistols here?” replied the servant, as he took his weapon from his pocket.

“The country is full of rebels and guerillas; they may want our horses, and perhaps ourselves. I can’t spare my coat and boots very well at present.”

“Guess not, massa,” laughed Alick, as he examined the lock of his pistol.

“I have never seen you in a fight, Alick. Do you think you can stand up to it?”

“Well, massa. I don’t want to say much about that, but I reckon I won’t run away no faster’n you do.”

“If I get into trouble with these ruffians, I shall want to know whether I can depend on you, or not.”

“Golly, massa! You can depend on me till the cows come home!” exclaimed Alick. “I doesn’t like to say much about it, but if these yere hossmen wants to fight, I’m not the chile to run away.”

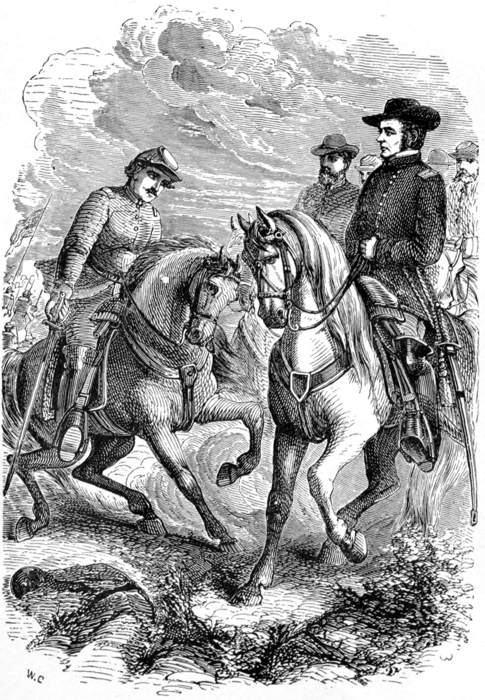

“They don’t look much like rebels or guerillas,” added Somers, as he obtained his first view of the approaching horsemen. “But you can’t tell much by the looks in these times, for the villains have robbed us till half of them wear our own colors. Those people certainly wear the uniform of our army.”

“Dar’s only two of ’em, massa. I reckon they don’t want to fight much.”

“I only wished to be cautious; very likely they are loyal and true men,” replied Somers, as the strangers came too near to permit any further remarks in regard to their probable character.

Both the travellers were evidently officers of the army, though, as Somers had suggested, it was impossible to tell what anybody was by the looks, or even if he was seen to take the oath of allegiance. As they came round a bend of the road, and discovered the captain and his servant, they reined up their steeds, and seemed to be disturbed by the same doubts which had troubled the first party. But they advanced, after a cautious survey, and each of them touched his cap, when they came within speaking distance. Somers politely returned the salute, and moved his horse towards them.

“Good morning, gentlemen,” said he. “Can you inform me which is the road to Frederick City?”

“The left, sir. If you are going in that direction, we shall be glad of your company,” replied one of the officers.

“Thank you; I shall be glad to go with you.”

“I see by your uniform that you belong on the staff,” added the officer who had done the talking.

“Yes, sir;” and Somers, without reserve, informed him who and what he was.

“Somers!” exclaimed the stranger. “I have heard of you before. Perhaps you remember one Dr. Scoville, of Petersburg?”

“Perfectly,” laughed Somers.

“Well, sir, he is an uncle of mine.”

“Indeed? I took you to be an officer of the United States army.”

“So I am; but my father married a sister of Dr. Scoville.”

“Dr. Scoville is a very good sort of man, but he is an awful rebel. I suppose he bears no good will towards me and my friend Major de Banyan.”

“Perhaps not; but the affair was a capital joke on the doctor. And since he is a rebel, and a very pestilent one too, I enjoyed it quite as much as you did.”

“I feel very grateful to him for what he did for me. I went into his house without an invitation; he dressed my wound, and nearly cured me. When the soldiers came upon us, he promised to give us up at the proper time, and pledged himself for our safety. We left him, one day, rather shabbily, I confess; but we had no taste for a rebel prison, for the rebs don’t always manage their prisons very well.”

“I have heard the whole story. It’s rich. If you please, we will move on.”

“With all my heart, major,” replied Somers, who read his rank from his shoulder-straps.

“I am Major Riggleston, of the —nd Maryland Home Brigade, on detached duty, just now.”

“I am glad to know you, Major Riggleston, especially as you are a relative of my friend Dr. Scoville, and on the right side.”

“This is Captain Barkwood, of the regulars.”

Somers saluted the quiet gentleman, who had hardly spoken during the interview. Major Riggleston was dressed in an entirely new uniform, and rode a splendid horse, which led Somers to believe that he belonged to one of the wealthy and aristocratic families of the state which so tardily embraced the cause of the Union. On the other hand, Captain Barkwood looked as though he had seen hard service; for his uniform was rusty, and his face was bronzed by exposure beneath the fervid sun of the south.

The party were excellently well acquainted with each other before they had ridden a mile. After the topics suggested by the first meeting had been exhausted, Somers mentioned his fear of the guerillas and rebel marauders, who kept a little way in advance of the invading army. The travellers were now farther north than Frederick, and some distance from the advancing line of the Union army. The road they had chosen was not one of the great thoroughfares of the state; consequently it was but little frequented.

“I don’t object to meeting a small party of guerillas,” said Major Riggleston; “for, gentlemen, if you are of the same mind that I am, we should show them the quality of true Union steel.”

“I hope we shall not meet any; but if we do, I am in no humor to lose my horse or my boots,” replied Somers. “But we may meet so many of them that it would be better to trust to our horses’ heels than to the quality of our steel.”

“True—too many would not be agreeable; but, say a dozen or twenty of them. We could whip that number without difficulty. The fact is, gentlemen, I am a fighting man. There has been too much of this looking at the enemy, and then running away. I repeat, gentlemen, I am a fighting man.”

“I am glad to hear it, and glad to have met you, for I am told there are a good many of these small plundering parties loose about this region; and I would rather fight than lose my boots,” laughed Somers.

“Three of us can do a good thing,” added the major.

“Four,” suggested Somers.

“Four?”

“My man can fight.”

“But he is a nigger; niggers won’t fight.”

“He will. By the way, he came from your uncle’s, at Petersburg.”

“Alick!” exclaimed the major, glancing back at the servant.

He did not seem to be well pleased to discover one of his uncle’s contrabands at this distance from home; for, with many other chivalrous southrons, he believed it would be a good thing to preserve the Union, if slavery could be preserved with it. He spoke a few words to Alick, but did not seem to enjoy the interview.

“Yes, we can whip at least twenty of the villains,” added the major, as he resumed his place between Somers and Captain Barkwood. “What do you think?” he continued, turning to the regular.

“I hope we shall not meet any. I am a coward by nature. I would rather run than fight, any time,” replied the captain. “Of all things I dislike these small skirmishes, these hand-to-hand fights.”

“I like them; I’m a fighting man,” said the major.

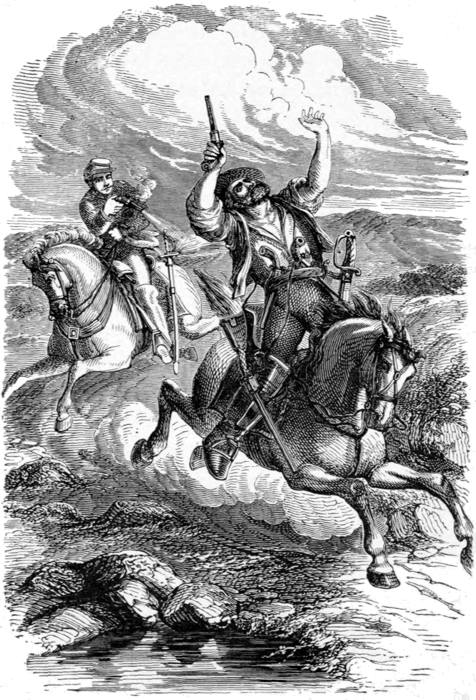

“I’m afraid you will have a chance to test your mettle,” said Somers. “Those fellows are guerillas, if I mistake not,” added he, pointing to half a dozen horsemen who were approaching them.

THE horsemen who had attracted the attention of Captain Somers were hard-looking fellows. They were dressed in a miscellaneous manner, their clothes being partly civilian and partly military. Portions of their garb were new, and probably at no distant period had been part of the stock in trade of some industrious clothier in one of the invaded towns; and portions were faded and dilapidated, bearing the traces of a severe march through the soft mud of Virginia. It was not easy to mistake their character.

The guerillas perceived the approaching party almost as soon as they were themselves perceived. They adopted no uncertain tactics, but instantly put spurs to their horses and galloped up to the little squad of officers. They appeared to have no doubts whatever in regard to the issue of the meeting, for they resorted to no cautionary movements, and made no prudential halts. They had evidently had everything their own way in previous encounters of this description, and seemed to be satisfied that they had only to demand an unconditional surrender in order to find their way at once to the pockets of the travellers, or to appropriate their coats and boots to the use of the rebel army.

“Halt!” said the nondescript gentleman at the head of the guerillas.

“Your business?” demanded Major Riggleston.

“Sorry to trouble you, gentlemen, but you are my prisoners,” said the chief guerilla, as blandly as though he had been in a drawing-room.

“Who are you, gentlemen?” asked the major.

“I don’t like to be uncivil to a well-dressed gentleman like yourself; but I haven’t learned my catechism lately, and can’t stop to be questioned. In one word, do you surrender?”

“Allow me a moment to consult my friends.”

“Only one moment.”

“Don’t you think we had better surrender, Captain Somers?”

“I thought you were a fighting man,” replied Somers.

“I am, when circumstances will admit of it; but they are two to our one.”

“Just now you thought we were a match for at least twenty of these fellows.”

“Time’s up, gentlemen,” said the dashing guerilla.

“What do you say, Captain Somers?”

“You can do as you please; I don’t surrender, for one.”

“But this is madness.”

“I don’t care what it is; I am going to fight my way through.”

“Do you surrender?” demanded the impatient chief of the horsemen.

“No!” replied Somers, in his most decided tone.

“Then you are a dead man!” And the guerilla raised his pistol.

Somers already had one of his revolvers in his hand, and before the villain had fairly uttered the words, he presented his weapon and fired, as quick as the flash of the lightning. The leader dropped from his horse, and his pistol was discharged in the act, but the ball went into the ground. Almost at the same instant the quiet captain of the regulars fired, and wounded another of the banditti. The others, apparently astonished at this unexpected resistance, discharged their pistols, and pressed forward, with their sabres in hand, to avenge the fall of their comrades.

Somers rapidly fired the other barrels of his revolver, and so did Captain Barkwood, but without the same decisive effect as before, though two of the assailants appeared to be slightly wounded. There was no further opportunity to use firearms, and the officers drew their swords, as they fell back before the impetuous charge of the savage guerillas. Major Riggleston followed their example, and for a moment the sparks flew from the well-tempered steel of the combatants. Our officers were accomplished swordsmen, but the furious rebels appeared to be getting the better of them. Major Riggleston contrived to wheel his horse, and was so fortunate as to get out of the mêlée with a whole skin.

At this point, when victory seemed about to perch on the rebel standard, Alick, who had thus far been ignored, brought down a third guerilla with his pistol. The negro was cool, collected, and self-possessed. He had not fired before, because the officers stood between him and the assailants. Now, as he had no sword, he stood off, and took deliberate aim at his man.

Captain Barkwood, who was a man of immense muscle, succeeded, after a desperate hand-to-hand conflict, in wounding his opponent in the sword arm. The fellow dropped his weapon, and turning his horse, fled with the utmost precipitation. The only remaining one, finding himself alone, immediately followed his example. The battle was won, and the coats and boots were evidently saved.

“Why don’t you follow them?” cried Major Riggleston, rushing madly up to the spot at this decisive moment. “Hunt them down! Tear them to pieces.”

“We’ll leave that for our fighting man to do,” replied Somers, with a smile, though he was so much out of breath with the violence of his exertions that he could scarcely articulate the words.

“Don’t let them escape,” added the major, furiously. “Cut them down! Don’t let them plunder the country any more.”

As he spoke, he put spurs to his horse, and dashed madly up the road in pursuit of the defeated guerillas.

“Your hand, Captain Somers,” said the regular. “You are a trump.”

“Thank you; and I am happy to reciprocate the compliment,” replied the young staff officer, as he took the proffered hand of Captain Barkwood.

“As a general rule, I don’t think much of volunteer officers,” continued the regular; “but you are a stunning good fellow, and as plucky as a hen that has lost one of her chickens.”

“I am obliged to you for your good opinion, and especially for your ornithological simile,” laughed Somers, who, we need not add, was delighted with the conduct of his companion.

“My what?”

“Your ornithological simile.”

“My dear fellow, you must have swallowed a quarto dictionary. If you had only used that expression before the fight, the rebels would certainly have run away, and declined to engage a man who used words of such ominous length. No matter; you can fight.”

“I can when I am obliged to do so. You remarked, a little while ago, that you were a coward by nature.”

“So I am; but it was safer to fight than it was to run.”

“You did not behave like a man who is a coward by nature.”

“But I am a coward; and I dislike these hand-to-hand encounters.”

“You didn’t appear to dislike them very much just now,” added Somers, who was filled with admiration at the gallant bearing of the regular.

“I do; war is a science. I play at it just as I do at chess. By the way, Captain Somers, do you play chess?”

“Only a little.”

“Well, it’s a noble game; and I may have the pleasure of letting you beat me some time. War is like chess; it’s a great game. I like to see a well-planned battle, and even to take a part in it. But these little affairs, where everything depends on brute force, are my particular abomination. There is no science about them—no strategy—no chance to flank, or do any other smart thing.”

“Here comes the major; he didn’t catch his man,” said Somers, as the “fighting man” was seen galloping towards them.

“He’s a prudent man,” replied the regular, hardly betraying the contempt he felt for this particular volunteer.

“He’s a Maryland man.”

“So am I,” promptly returned Captain Barkwood, as though he feared that something might be said against the bravery of the men of his state. “I was born and brought up not ten miles from the spot where we now stand.”

“Why didn’t you follow me?” demanded the major, in a reproachful tone, as he reined in his panting steed.

“We had got enough of it,” answered the regular.

“We might have brought them down if you had joined me in the pursuit.”

“We might, if you had stuck by us in the fight,” said Somers, with a gentle smile, to break the force of the rebuke.

“Stood by you?” exclaimed Major Riggleston, his face flushed with anger. “Do you intend to insinuate that I did not stand by you?”

“You did, but at a safe distance.”

“Didn’t I do all the talking with the villains?” foamed the major.

“Certainly you did,” replied the regular.

“Didn’t I bear the whole brunt of the assault at the beginning?”

“Undoubtedly you did,” responded Captain Barkwood, before Somers could speak a word.

“Didn’t I fight like a tiger, till—”

“Unquestionably you did.”

“Till my rein got entangled in my spur, and whirled my horse round?”

“My dear major, you behaved like a lion,” said Barkwood, in tones so soothing that the anger of Riggleston passed away like the shadow of a summer cloud.

“I am a fighting man.”

“That’s so.”

“And I dislike this marching and countermarching in the face of an enemy.”

“There we unfortunately disagree for the first time. That is strategy,—the art of war,—and all that makes war glorious.”

“I believe in pitching into an enemy, and, when he is beaten, in following him up till there is nothing left of him. I regret, gentlemen, that you did not join in the pursuit of the two miscreants with me. We might have annihilated them as well as not.”

Somers did not understand the humor of the regular, and could not fathom his object in permitting the coward still to believe that he was a fighting man. While the conversation was in progress, Alick had removed the bodies of the two dead rebels from the road, and placed the other two, who were severely wounded, in a comfortable position under a tree. He had filled their canteens with water from the brook which ran across the road a short distance from the spot, and left them to live or die, as the future might determine. He had also transferred a good saddle from one of the guerillas’ horses to his own animal, which had not before been provided with one.

The party moved on again. Major Riggleston talked about the fight; for some reason or other he could speak of nothing else. He still called himself a fighting man, and still talked as though he had fired the most effective shots and struck the hardest blows which had been given. The regular agreed with him in all things, except when he impugned the sacred claims of strategy.

“Never cross a fool in his folly, nor ruin a man in his own estimation,” said Captain Barkwood, when Somers, at a favorable moment, asked an explanation of his singular commendation of the poltroon.

“But he is a coward.”

“Call no man a coward but yourself. There is hardly an officer in the army, from the general-in-chief down to the corporal of the meanest regiment in the service, that has not been called a coward. You don’t know who are cowards, and who are not.”

“Perhaps you are right.”

“I know I am. I am a coward myself, but I know nothing about anybody else.”

“I differ with you.”

“You don’t know anything about it. The major don’t love you over much now for what you hinted. Never make an enemy when there is no need of it.”

The approach of Major Riggleston put an end to this conversation. Somers could not help noticing that the major treated him rather cavalierly; but as he was not particularly anxious to secure the esteem of such a man, the manner of his companion did not disturb him.

In the afternoon the party reached Frederick, which had just been abandoned by Lee’s rear guard, and was now occupied by a portion of McClellan’s advance.

“Gentlemen, we have had a hard ride, and I know you must be tired as well as myself,” said Major Riggleston, as they entered the city. “You will permit me to offer you the hospitalities of my father’s house.”

“Thank you; I accept, for one,” replied Captain Barkwood. “I am not tired, but I am half starved.”

“And you, Somers?” added the major, with a degree of cordiality in his manner which he had not exhibited since the skirmish on the road.

The young captain had been in the saddle all day; his health was feeble, and he was very much exhausted by the journey. He had hoped to reach the headquarters of the first army corps that night; but he was still several miles distant from his destination, and his physical condition did not admit of this addition to his day’s travel. With many thanks he accepted the invitation, apparently so cordially extended, and the little party halted, soon after, in the grounds of an elegant mansion. The tired horses were given into the keeping of the servants, and Major Riggleston led the way into the house.

They were ushered into the drawing-room, where the major excused himself to inform the family of their arrival. He left the door open behind him.

“They are Yankee officers!” exclaimed a female voice. “What did Fred bring them here for? Get out of sight, Ernest, as fast as you can.”

A door leading from the entry closed, and the visitors heard no more. The regular paid no attention to the remark, and Somers followed his example.

CAPTAIN SOMERS, though he said nothing to his companion about the remark to which they had listened, could not help thinking about it. The regular and himself had been alluded to as Yankee officers. It was evident that some one was present who ought not to be present; but as a guest in the house, it was not competent for him to investigate the meaning of the suspicious words.

Major Riggleston presently returned to the drawing-room, attended by an elderly gentleman, whom he introduced as his father, and a beautiful but majestic and haughty young lady of eighteen, whom he introduced as Miss Maud Hasbrouk. When Somers heard her voice, which was as musical as the rippling of a mountain rill, he recognized the tones of the person who had used the doubtful words in the adjoining room.

The old gentleman was happy to see the visitors, especially as they belonged to the Union army, whose presence was welcome to him after the visit of the rebels. He hoped that General McClellan would be able to drive the invaders from the soil—conquer, capture, and exterminate them. His words were certainly strong enough to vouch for his loyalty; and these, added to the fact that the major was an officer in the Maryland Home Brigade, satisfied Somers that he had not fallen into a nest of rebels and traitors, as the obnoxious remark, not intended for his ears, had almost led him to believe.

“The more true men we have here the better; for we have been completely overrun by traitors,” said the old gentleman, alluding to the visit of Lee’s army.

“You use strong words, Mr. Riggleston,” added the lady, whose bright eyes flashed as she spoke.

“I say what I mean,” continued the host.

“Is there any doubt of the fact that the state has been invaded by the rebels?” asked Somers, with a smile.

“None whatever; but Mr. Riggleston called them traitors,” replied Miss Hasbrouk.

“Is there any doubt of that fact?”

“Are men who are fighting for the dearest rights of man traitors?” demanded she, warmly.

“Undoubtedly not. But the rebels are not fighting for any such thing.”

“I beg your pardon, Captain Somers. I think they are. Permit me to add, that I am a rebel.”

“I am very sorry to hear it,” laughed Somers, pleased with the spirit, no less than the beauty, of the lady.

“I suppose you are,” replied she. “The South is fighting for the right of self-government—for its own existence. The right of secession is just as evident to me as the right to live.”

The question of secession was fully discussed by the lady and Somers, but both of them were in the best of humor. Neither contestant succeeded in convincing the other on a single point; and when the party were called to supper, they had advanced just about as far as the statesmen had when the momentous issue was handed over to the arbitrament of arms. It was a matter to be adjusted by hard fighting; and as Miss Hasbrouk and Somers did not intend to settle the question in this rude manner, the subject was dropped.

The family, so far as Somers could judge, were loyal people. The imperial young lady, who was a fit type of the southern character, was only a visitor. In spite of her proud and haughty bearing, she was a very agreeable person, and the guests enjoyed her society.

“I am a rebel,” said she, as they sat down to supper; “but I am, sorely against my will, I confess, a non-combatant, and we are now on neutral ground. We will bury our differences, then, Captain Somers, and be friends.”

“With all my heart,” replied the gallant young captain.

A very pleasant evening was spent in the drawing-room, during which Miss Hasbrouk affected the company of Somers rather than that of the regular, who appeared to be as stoical in society as he was on the road. She was lively, witty, and fascinating, and seemed to be very much delighted with the society of the young staff officer. He was an exceedingly good-looking fellow, it is true; but he was a Yankee, and she made no secret of her aversion to Yankees in general. He was an exception to the rule, and she compelled him to relate the history of his brief campaign at Petersburg. She laughed at the chagrin of Dr. Scoville, when his invalid took to himself wings and flew away; but she took no pains to conceal her sympathy with the cause of the Confederacy.

At an early hour the officers retired; and as they announced their intention to depart at daylight in the morning, they took leave of the ladies. Miss Hasbrouk was so kind as to hope she might meet the captain again; for notwithstanding his vile political affinities, he was a sensible person.

Before the sun rose, Somers and the regular were in the saddle. The major, whose route lay in a different direction, was no longer their companion. The headquarters of the first army corps were on the Monocacy; and thither the travellers wended their way through a beautiful country, which excited the admiration even of the stoical captain of the regulars, though it was no new scene to him.

The reveille was sounding in the camps of the Pennsylvania Reserves as they passed through on their way to the tent of the commanding general. They reached their destination, and their names were sent in by an orderly in attendance.

“Captain Somers, I am glad to see you,” said the general, at a later hour, when they obtained an audience.

“Thank you, general; I am very grateful for the kindness and consideration you have bestowed upon me,” replied Somers.

“You are an aid-de-camp now; but I ought to say that I gave you the appointment because you are a good fellow on a scout.”

“I will do my best in whatever position you may place me.”

“You were rather unfortunate in your last trip, but you accomplished the work I gave you to do. We shall do some hard fighting in a day or two, and there will be sharp work for you before that comes off.”

“I am ready, general. Every man is ready to march or fight as long as he can stand while you are in command.”

“I will see you again in an hour, Somers,” said the general, as he turned to Captain Barkwood, who belonged to the engineers, and had been assigned to a position on the staff.

Somers soon made the acquaintance of the general’s “military family.” His position and rank were defined in the general orders, and duly promulgated. From those around him he obtained all the current knowledge in regard to the situation of the rebel army, which was posted in the Catoctin valley, with the South Mountain range in the rear, whose gaps and passes it was to defend.

At the time appointed Captain Somers again stood in the presence of the general, who was his beau-ideal of all that was grand and heroic in the military chieftain. He was a tall, straight, well-formed man, with a ruddy complexion, flecked with little thready veins, and a muscular frame. His eye was full of energy; he spoke with his eye as much as with his voice. His military history was familiar to the nation. He was a decided man, and his decision had won him his first appointment in the army. He said what he meant, and meant what he said. His energy of character had made him a success from the beginning. His faith in himself and his faith in the loyal army were unbounded. He fought and conquered by the force of his mighty will. He attempted only what was possible, and triumphed through the faith of an earnest soul. His military judgment was of the highest order, and when he had decided what could be done, he did it. His conclusions, however suddenly reached, were not the offspring of impulse; they were carefully drawn from well-founded premises. His quick eye and his solid judgment rapidly collated all the facts in regard to an enemy’s strength, relative situation, and advantage of position; and from them he promptly deduced the conclusion whether to fight or not—how, when, and where to fight.

The general’s pet name was “Fighting Joe;” and by this appellation he was known and loved in the army. But he was not a rash man; he made no unconsidered movements. If the term implies rashness and blundering impetuosity, it is a misnomer; but, after Williamsburg, Glendale, Malvern, South Mountain, Antietam, Lookout Mountain, who could mistake its meaning? for his battles were too uniformly successful to be the issues of merely headlong courage and unmatured strategy. All his operations on the splendid fields where he has so gloriously distinguished himself, exhibit a head as well as an arm; carefully considered plan, as well as bold and determined execution.

The mention of “Fighting Joe” warmed the hearts of the soldiers. He was more popular than any other general in the army. Our soldiers were thinking men, as well as brave ones. They could not love and honor a general who led them into the forefront of battle to be entrapped and sacrificed. They could not believe in a man whose highest recommendation was brute courage. “Fighting Joe” was one of the ablest strategists in the army; and, wherever he has justified his title as a fighting man, he has also displayed the highest skill and judgment, and a profound knowledge and appreciation of the science of war.

Somers stood before the general with a certain feeling of awe and reverence, which one experiences in the presence of a truly great man. There was no time to talk of the past, for the present and the future were full of trials and cares—were full of a nation’s life and hope. Fighting Joe was cool and self-possessed, as he always was, even in the mad rage of the hottest fight; but he was earnest and anxious. He was even now doing that work which wins battles quite as much as the fiery onslaught.

Burnside was in command of the right wing of the army, which occupied the vicinity of Frederick. The rebels had just been driven out of Middletown, and the cannon was roaring beyond Catoctin Creek; but it was evident to the general that no pitched battle could take place that day. He wanted certain information, which he thought Captain Somers was smart enough to procure for him. A map lay on the table in the tent, and in a few telling words he explained what he wanted.

“Don’t be rash, Somers,” said he, as the aid-de-camp rose to depart. “Intelligent courage is what we want. I shall depend upon you for skill and discretion as well as dash and boldness.”

“I will do the best I can,” replied the captain, as he left the tent and mounted his horse.

He dashed off towards Middletown, as the army commenced its march in the same direction. He reached this place before noon, and agreeably to his instructions, pursued a northerly course, until he reached a point beyond the active operations of Pleasanton’s cavalry, which was scouring the country. Leaving his horse at a farm-house, he advanced on foot to the westward of the creek, until he discovered the outposts of the rebel army. Small squads of Confederate cavalry were beating about this region, and Somers was obliged to dodge them several times. But he obtained his information, and fully acquainted himself with the nature of the country, and the situation of the rebels to the north of the Cumberland road.

It was three o’clock in the afternoon when he had completed his reconnaissance, and he was nearly exhausted by the long walk he had taken, and the excitement of his occupation. He was at least two miles from the farm-house where he had left his horse. He had eaten nothing since breakfast, and he was faint for the want of food. He walked one mile, and stopped to rest near an elegant mansion, which evidently belonged to one of the grandees of Maryland. He was tempted to visit the house and procure some refreshment; but, as he was alone, and knew nothing of the political status of the occupants, he did not deem it prudent to do so.

After resting a short time, he rose and continued his weary walk towards the farm-house. As he passed the door of the elegant mansion, a chaise stopped at the gate, and a young officer handed a lady from the vehicle. A servant led the horse away. The lady paused at the gate, and appeared to be observing him. Somers could think of no reason why the lady should watch him, and he continued on his course till he came within a few feet of the spot where she stood.

“Captain Somers!” exclaimed she; “I am delighted to see you again so soon.”

“Miss Hasbrouk,” replied he, not a little surprised to find in her his rebel friend, whom he had met in Frederick the preceding evening.

“This is an unexpected pleasure,” added she, extending her hand, which the young man took.

“I should hardly have expected to meet you at this distance from Frederick.”

“O, I reside here; this is my father’s house. You are some distance from the Yankee army.”

“As you are a rebel, it is hardly proper for me to inform you why I happen to be here,” laughed he. “I am an invalid, and am walking for my health.”

“It is well you are away from your army, for they will all be captured in a few days.”

“Perhaps not; but I shall be with the army before night.”

“This is Major Riggleston,” said she, turning to the gentleman, who had followed the servant to the stable, and had just returned.

“How do you do, again, major?” said Somers.

“Happy to meet you, Captain Somers,” replied the major, not very cordially.

“Now you must come into the house, Captain Somers. It is just dinner time with us,” continued the lady.

Somers was too faint and hungry to refuse.

THE lady conducted Captain Somers to the sitting-room of the house. He was followed by Major Riggleston, who, judging by his looks and actions, regarded the staff officer with no special favor. Miss Hasbrouk did all the talking, however, and seemed to do it for the purpose of keeping the major in the shade, for she carefully turned aside two or three observations he made, as though they were of no consequence, or as though they might provoke an unpleasant discussion.

“I am particularly delighted to meet you again, Captain Somers,” said the imperial beauty, as they entered the apartment.

“Thank you,” replied he; though he could see no good reason why Miss Maud Hasbrouk should be particularly delighted to see him.

He was a Union man and a loyal soldier, while she was a rebel, with strength of mind enough to regret that her sex compelled her to be a non-combatant. She was a magnificent creature, even to Somers, whose knowledge of the higher order of beauties that float about in the mists of fashionable society was very limited. She was fascinating, and he could not resist the charm of her society; albeit in the present instance he was too much exhausted by ill health and over-exertion to be very brilliant himself.

“This is very unexpected, considering the distance from the place at which I met you last evening,” said he.

“O, it isn’t a very great distance to Frederick. The major drove me over in three hours,” replied she.

“Three and a half, Maud,” interposed the major, apparently because he felt the necessity of saying something to avoid being regarded as a mere cipher.

“How do you feel to-day, after the little brush we had yesterday, major?” added Somers, turning to the gentleman.

“What brush do you refer to?” asked Major Riggleston, rather coldly.

“The little rub we had with the guerillas.”

“Really, you have—”

“Now, gentlemen, will you excuse me for a few moments?” said Miss Hasbrouk, very impolitely breaking in upon the major’s remark.

“Certainly,” replied Somers, with his politest bow. “You are a fighting man, Major Riggleston; and the affair of yesterday was pretty sharp work for a few minutes.”

“Of course I’m a fighting man; but—”

“Major, you promised me something, you will remember,” said the lady, who still lingered in the room; “and now is the best time in the world to redeem your promise.”

“What do you mean, Maud?” demanded the major.

“Why, don’t you remember?”

“Upon my life I don’t.”

“Perhaps Captain Somers will excuse you for a few moments, while I refresh your memory.”

“Certainly; to be sure,” added the polite staff officer.

He moved towards the door at which the lady stood. Somers saw her whisper something to him as she took him familiarly by the arm.

“O, yes, I remember all about it now!” exclaimed he, with sudden vivacity. “I will return in a few moments, Captain Somers, if you will excuse me.”

“By all means; don’t let me interfere with any arrangement you have made.”

They retired, and the door closed behind them. Somers was not a little befogged by the conduct of both the lady and the gentleman. Several times she had interrupted him, and the major had an astonishingly bad memory. He seemed not to remember even the skirmish on the road; and he was equally unmindful of what had passed between him and the lady at some period antecedent to the present.

They were quite intimate; and, slightly versed as the young officer was in affairs of love and matrimony, he had no difficulty in arriving at the conclusion that the interesting couple who had just left him were more than friends; and though he had not the skill to determine what particular point in the courtship they had reached, he ventured to believe they were engaged. Though it was rather a rash and unauthorized conclusion, it was a correct one; showing that young men know some things by intuition.

Somehow Major Riggleston did not appear exactly as he had appeared the preceding day. His uniform did not look quite so bright; his manner was more brusque and less polished; and he spoke with a heavier and more solid tone. But men are not always the same on one day that they are on another; and it was quite probable that the major was suffering for the want of his dinner, or from some vexation not apparent to the casual observer.

Somers wanted his dinner; not as an epicure is impatient for the feast which is to tickle his palate, but as a man who knows and feels that meat is strength. His health was not yet sufficiently established to enable him to endure the hardship of an empty stomach; for his muscles seemed, in his present weak state, to derive their power more directly than usual from that important organ. He did not, therefore, worry himself to obtain a solution of what was singular in the conduct of the lady and her lover.

They were absent but a few moments before the major returned. If he had been gone seven years, and passed through a Parisian polishing school in the interim, his tone and his manner could not have been more effectually changed. He looked and acted more like the Major Riggleston of yesterday. He was all suavity now; and, what was vastly more remarkable, his memory was as perfect as though he had made mnemonics the study of a lifetime. He remembered all about the skirmish on the road, and even recalled incidents connected with that affair of which Somers was profoundly ignorant.

“Captain Somers, that was the hardest fight for a little one I ever happened to be in,” said the major, after the event had been thoroughly rehearsed.

“It was sharp for a few moments. By the way, major, what is your opinion of Alick now?” asked Somers.

“Well, I was rather surprised to see him go in as he did. He is a brave fellow.”

“So he is; I did not know whether he would fight or not; but I thought he would.”

“O, I was sure of it.”

“Were you? Before the fight you seemed to be of the opinion that he was of no account.”

“That was said concerning niggers in general. I always had a great deal of confidence in Alick. When he fired his gun I knew what the boy meant.”

“His pistol, you mean; he had no gun.”

“You are right; it was a pistol,” said the major, with more confusion than this trifling inaccuracy justified.

“In the pursuit of the guerillas—”

“Yes, in the pursuit Alick was splendid,” continued Riggleston, taking the words out of Somers’s mouth.

“You forget, major; you conducted the pursuit alone,” mildly added the staff officer.

“O, yes! so I did. I am mixing up this matter with another affair, in which my boy Mingo chased the Yankees—”

“Chased the what?” interposed Somers, confounded by this singular and inappropriate remark.

“The guerillas, I said,” laughed the major. “What did you think I said?”

“I understood you to say the Yankees.”

“O, no! Yankees? No; I am one myself. I said guerillas.”

“If you did, I misunderstood you.”

“Of course I didn’t say Yankees. That is quite impossible.”

Somers was disposed to be polite, even at the sacrifice of the point of veracity; therefore he did not contradict his companion, though he felt entirely certain in regard to the language used.

“Of course you could not have meant Yankees, whatever you said,” added Somers.

“Certainly not. Do you know why I didn’t catch those—those guerillas?” continued the major.

“I do not,” replied Somers; but he had a strong suspicion that it was because he did not want to catch them; because it would have been imprudent for him to catch them; because it would have been in the highest degree dangerous for him to catch them.

“I’ll tell you why I didn’t catch them,” added the major, rubbing his hands as a man does when he has a point to make. “It was because their horses went faster than mine.”

“Good!” exclaimed Somers, who had the judgment to perceive that this answer was intended as a joke, and who was politic enough to render the homage due to such a tremendous effort—a laugh, as earnest as the circumstances would permit.

“Or possibly it was because my horse went slower than theirs,” added the major, with the evident design of perpetrating a joke even more stupendous than the last.

We beg to suggest to our readers, young and old, that a person lays himself open more by his jokes, his puns, and his witticisms, than by any other means of communication between one soul and another with which we are acquainted. Hear a man talk about business, politics, morality, or religion, and you have a very inadequate idea of his moral and mental resources. Hear him jest, hear him make a pun, hear him indulge in a witticism, and you have his brains mapped out before you. We have heard a man get off a witticism, and felt an infinite contempt for him; we have heard a man get off a witticism, and felt a profound respect for him. It is not the thing said; it is not the manner in which it is said; it is not the look with which it is said. It is all three combined. He who would conceal himself from those around him should neither get drunk nor attempt to be funny.

Major Riggleston had revealed himself to Captain Somers more completely in that unguarded joke than in all that had passed between them before. The young staff officer was not a moral nor a mental philosopher; but that agonizing jest had given him a poorer opinion of his companion than he had before entertained. It was fortunate for the major that Miss Hasbrouk returned before he had an opportunity to launch another witticism upon the sea of the captain’s charity, or the latter might have prematurely learned to despise him.

“We have not lately been honored by the voluntary presence of gentlemen at dinner, Captain Somers; and you will pardon me for lingering an extra moment before my glass,” said the merry lady.

“Happy glass!” replied Somers.

“Thank you, captain; that was very pretty.”

“Excellent!” added the major, who seemed to be hungering and thirsting for something funny or smart.

A bell rang in the hall, which Somers took to be the summons for dinner; and he was thankful, and took courage accordingly; for however much he enjoyed the society of the fascinating Maud, he could not forget that he owed a solemn duty to the outraged member of his body corporate, which had been kept fasting since an early breakfast hour.

“Now, gentlemen, shall I have the pleasure of conducting you to the dining-room?” continued Miss Hasbrouk.

“Thank you.”

“Your arm, if you please, Captain Somers,” said the brilliant lady.

Of course Somers complied with this reasonable request, though he had not been in the habit of observing these little courtesies at the cottage in Pinchbrook, nor even in some of the best regulated families at the Harbor, making no little pretensions to gentility. It seemed to him that it would have been more proper, in the present instance, and with the supposed relation between them, for the lady to take the arm of the gentleman to whom she was engaged; but he had not very recently read any book on the etiquette of good society, and he was utterly unable to settle the difficult question.

They passed through the hall and entered the dining-room. The table was laid for only three; and while Somers was wondering where the rest of the family were, a tremendous knocking was heard at the front door.

“Somebody is in earnest,” said Maud. “He knocks like a sheriff who comes with authority. Take this seat, if you please, captain.”

“Thank you, Miss Hasbrouk,” replied Somers, as he took the appointed place.

“I hope that isn’t any one after me,” added the major, as he seated himself opposite to Somers. “I don’t want to lose my dinner.”

“You shall not lose it, major,” answered Maud, as a colored servant entered the room with a salver in his hand, on which lay a letter.

“For Major Riggleston,” said the man, as he presented the salver to him.

The major took the letter and broke the seal, apologizing to Somers for doing so. His eyes suddenly opened wider than their natural spread, and his chin dropped till mouth and eyes were both eloquent with astonishment. He sprang out of his chair, and assumed an attitude in the highest degree dramatic. Somers almost expected to hear him perpetrate a witticism.

“What is it, major?” demanded Maud, who seemed to be enduring the most agonizing suspense.

“I must go this instant!” exclaimed the major, still gazing at the momentous letter.

“What has happened?”

“Don’t ask me, Maud,” answered he, in excited tones. “I will be back before night; perhaps in an hour. You will excuse me, Captain Somers.”

“Certainly,” replied Somers.

The major rushed to the door, cramming the letter into his pocket, or attempting to do so, as he moved off. The document fell on the floor without the owner’s notice.

“What can it mean?” said Maud, with a troubled look.

Somers did not know what it meant; if he had, it is doubtful whether he would have had the temerity to stop to dinner.

“WHAT can have happened?” said Maud, apparently musing on the event which had just transpired. “The major is not often moved so deeply as he appeared to be just now.”

“Something of importance, evidently,” said Somers. “He has dropped the letter on the floor.”

“So he has,” said she, glancing at the document. “Thus far I have resisted the propensity of Mother Eve to know more than the law allows; and I think I will not yield to it now. It would hardly be honorable for me to read the letter after the major has declined to inform me what has occurred. But, whatever it may be, we will have some dinner.”

Whatever opinions Somers may have entertained on some of the other points suggested by the fair hostess, he had none in regard to the last proposition. He was absolutely and heartily in favor of the dinner, without regard to Mother Eve’s curiosity, or her favored representative then before him. The dinner was a good one, though the rebels had so recently gathered up all the provision which the country appeared to contain. With every mouthful that he ate Somers’s strength seemed mysteriously to return to him.

The dinner was not so formal as might have been expected in the house of a Maryland grandee, and did not occupy over half an hour; but in that half hour he had grown strong and vigorous again, and felt equal to any emergency which might occur. However agreeable the society of the fascinating Maud had proved, he began to be very impatient for the moment when he could, without outraging the laws of propriety, break the spell which bound him. He had faithfully discharged his duty to the inner man, and he bethought him that he owed another and higher obligation to his country; that the commanding general of the first army corps was expecting to hear from him, though the time given him to complete his mission had not yet expired.

While he was considering some fit excuse with which to tear himself away from his interesting companion,—for it was not prudent to inform an avowed rebel lady that he had been engaged in collecting information for the use of a Union general, and must return to report the result of his mission,—while he was thinking what he should say to her, he heard something which sounded marvellously like the tramp of horses’ feet on the walks which surrounded the mansion. These sounds might have been sufficient to create a tempest of alarm in his mind if he had not believed that he was far enough from the camps of the rebels to insure the estate from a visit of their cavalry. He did not know exactly where he was in relation to the line of either army; but he felt a reasonable assurance that he was out of the reach of danger from the enemy.

He listened, therefore, with tolerable coolness, to the clatter of the horses’ feet, and finally concluded that the animals belonged to the estate. This conclusion, however, was soon unpleasantly disturbed by other and more suspicious sounds than the tramp of horses—sounds like the clatter and clang of cavalry equipments. More than this, Maud looked anxious and excited, when there appeared to be not the least reason for anxiety and excitement on her part.

“Won’t you take another peach, captain?” said she glancing uneasily at the window, and then at the door.

“No more, I thank you, Miss Hasbrouk,” replied Somers. “You seem to be having more visitors.”

“No, I think not,” answered she, with assumed carelessness.

“What is the meaning of those sounds, then?”

“They are nothing; perhaps some of the servants leading the horses down to the meadow.”

“Do your horses wear cavalry trappings, Miss Hasbrouk?”

“Not that I am aware of. Do you think there is any cavalry around the house?”

“I am decidedly of that opinion; and, with your permission, I will step out and learn the occasion of this visit,” said he, rising from the table, and making sure that the two revolvers he wore in his belt were in working order.

“I beg you will not leave me, Captain Somers,” remonstrated Maud.

“I only wish to ascertain what the cavalry are.”

“I depend upon you for protection, captain,” said she, as she rose from her seat at the table. “Ah, here comes some one, who will explain it all to you,” she added, as the front door was heard to open rather violently.

“I think it won’t need much explanation,” replied Somers, as through the window he discovered two gray-back cavalrymen. “It is quite evident that the house is surrounded by rebel cavalry.”

At this moment the door of the dining-room opened, and Major Riggleston stalked into the apartment. He looked at Somers, and then at the lady. The troubled, astonished expression on his face when he went away had disappeared, and he wore what the staff officer could not help interpreting as a smile of triumph.

“Well, Maud, how is it now?” asked the major, as for the sixth time, at least, he glanced from Somers to her.

The brilliant beauty made no reply to this indefinite question. Instead of speaking as a civilized lady should when addressed by her accepted lover, she threw herself into a chair with an abandon which would have been creditable in a first lady in a first-class comedy, but which was highly discreditable in a first-class lady discharging only the duties of the social amenities in refined society. She threw herself into a chair, and laughed as though she had been suddenly seized with a fit of that playful species of hysterics which manifests itself in the cachinnatory tendency of the patient.

Somers was surprised. A less susceptible person than himself would have been surprised to see an elegant and accomplished lady laugh so violently, when there was apparently nothing in the world to laugh at. He could not understand it; a wiser and more experienced person than Somers could not understand it. He knew about Œdipus, and the Sphinx’s riddle which he solved; but if Œdipus had been there, in that mansion of a Maryland grandee, Somers would have defied him to solve the riddle of Miss Maud Hasbrouk’s inordinate, excessive, hysterical laughter. If Major Riggleston, from the great depository of unborn humor in his subtle brain, had launched forth one of the most tremendous of his thunderbolts of wit, the mystery would have solved itself. If the major had uttered anything but the most commonplace and easily interpreted remark, Somers might have believed that he had perpetrated a joke which he was not keen enough to perceive.

The house was surrounded by rebel cavalry; that was no joke to him; it could be no joke to the major, for he was an officer in the Maryland Home Brigade, “on detached service,” and what proved dangerous or fatal to one must prove dangerous or fatal to the other. But Riggleston did not seem to be in the least disturbed by the circumstance that the house was environed by Confederate cavalry. He stood looking at his lady-love, as though he was waiting her next move in the development of the game.

“What are you laughing at, Maud?” asked he, when he had watched her until his own patience was somewhat tried, and that of Somers had become decidedly shaky.

“Isn’t it funny?” gasped she, struggling for utterance between the spasms of laughter.

“Yes, it is, very funny,” replied he, obediently, though it was quite plain that he did not regard the scene as so excruciatingly amusing as the lady did.

“Why don’t you laugh, then?”

“I would if I had time; but I must proceed to business.”

“Don’t spoil the scene yet,” said she, with difficulty.

“Hurry it up, then, Maud.”

“Captain Somers,” added she, repressing her laughter to a more reasonable limit, “I am your most obedient servant.”

“Thank you, Miss Hasbrouk,” replied he, beginning to apprehend, for the first time, that he was individually and personally responsible for the joke which had so excited the lady’s risibles. “If you are, you will oblige me by informing me what you are laughing at.”

The lady broke forth anew, and peal on peal of laughter rang through the room. Somers tried to think what he had said or done that was so astoundingly funny, satisfied that his humor would certainly make his fortune when given a wider field of operations. It was evident that it would not do for him to be as funny as he could thereafter in the presence of ladies, or one of them might yet die of hysterics.

“Do you really wish to know what I am laughing at, Captain Somers?” asked she, at another brief interval of apparent sanity.

“That is what I particularly desire.”

“I am laughing at the situation. Do you know that there is something irresistibly ludicrous in situations, captain? I delight in situations—funny situations I mean.”

“Really, I don’t see anything very amusing in the present situation,” replied the puzzled staff officer.

“Don’t you, indeed? Well, I’m afraid you won’t appreciate the situation from your stand-point. What a pity we haven’t a photographer to give us the scene for future inspection!”

“Well, Miss Hasbrouk, you seem to be making yourself very merry at my expense. I am happy to have afforded you so much amusement; but I fear I am still your debtor for the bountiful hospitality of your house.”

“Don’t mention it, captain; and you won’t wish to mention it a few hours hence.”

“I assure you I shall ever gratefully remember your kindness to me.”

“Perhaps not,” laughed the maiden.

“Captain Somers,” interposed the major, “I think we have carried the joke far enough; and we will now proceed to the serious part of the business. In one word, you—”

“Stop, Major Riggleston, if you please,” interrupted Maud. “This is my affair.”

“Hurry it along a little faster, then, if you will, Maud. The people outside will get tired of waiting.”

“Don’t you interfere, major. You forget that you are a Union officer, belonging to the Maryland Home Brigade. Captain Somers insists that you are; and of course you are.”

“Of course I am; I had almost forgotten that little circumstance,” laughed the major.

“Well, Miss Hasbrouk, since you are to manage the affair, I will thank you to inform me what it all means,” demanded Somers, with the least evidence of impatience in his tones.

“With the greatest pleasure; with a pleasure which you cannot yet appreciate, I will inform you all about it. But, my dear Captain Somers, in deference to a lady who has admired you, fêted you, dined you, you will answer a few questions which I shall propose to you, before I proceed to the explanation.”

“Be in haste, Maud,” said the major.

“Major Riggleston, if you hurry me, I shall be obliged to ask you to leave the room,” answered she, with a resumption of the imperial dignity she had partially abandoned.

“I’m dumb, Maud.”

“Keep so, then. Now, Captain Somers, you are one of the heroes of the Yankee army; a down-east pink of chivalry. At Petersburg you were within the Confederate lines doing duty as a spy. First question: Is this so?”

“That would be for a rebel court-martial to prove, if I should happen to be captured.”

“First question evaded. Taking advantage of the hospitality and kindness of Dr. Scoville, who had pledged his honor that you should be delivered up to the proper authorities as soon as you were able to be moved, you escaped from his custody. Second question: Is this true?”

“I was under no pledge, and was not paroled.”

“Second question evaded. You are on the staff of the general of the first army corps, and you have been sent out to procure information. Third question: Is this true?”

“You have said it; not I.”

“Third question evaded. By your own confession, made to me yesterday, within the Federal lines, you are a spy. You have resorted to certain Yankee tricks to escape the penalty of your misdeeds. Now—fourth question: Would it not be fair to capture you by resorting to a trick such as those you have practised?”

“It would depend on the trick.”

“Fourth question evaded. You have abused the sacred rites of hospitality at the mansion of Dr. Scoville, in Virginia. Should you regard it as anything more—fifth question—than diamond cut diamond, if you should be captured in Maryland by a similar abuse of the sacred rites of hospitality?”

“That would depend on circumstances.”

“Fifth question evaded. All of them evaded, as I supposed all of them would be; for a Yankee can no more avoid prevarication than he can avoid talking through his nose.”

“Thank you for the handsome compliment. I cannot forget that I am speaking to a lady, and therefore I can make no answer,” replied Somers, with gentle dignity, as he bowed to the tormentor.

“That is more than I expected of a Yankee,” said Maud, a slight flush upon her fair cheek assuring her victim that his rebuke had been felt. “I am a lady; but before the lady, I am the Confederate woman, having a cause dearer to my heart than anything save only a woman’s honor.”

She spoke proudly, and her head rested with imperial grandeur on her neck as she uttered her impressive words.

“Now, Captain Somers, you understand my position, and you understand your own position,” she continued. “I invited you to dine with me for a purpose. That purpose is now reached. The house is surrounded by Confederate cavalry. Captain Somers, you are a prisoner!”

LONG before the imperial, and now imperious, lady announced the conclusion of the whole matter, Somers realized that he was the victim of a conspiracy; that he had been invited to dinner in order to procure his capture. He had listened to the fallacious argument embodied in the five questions, and was prepared to refute it if occasion required. He had no difficulty in perceiving that he had got into trouble. The house was surrounded by a squad of rebel cavalry, and it would be folly to attempt to fight his way through them.

Nevertheless, Somers had coolly and decisively made up his mind not to be a prisoner. He had been invited into the house under the guise of friendship. The lady had pretended to cherish an excellent feeling, amounting almost to admiration, towards him; had treated him as a friend, and detained him until the cavalry could be sent for. The trap had been set, and he had certainly fallen into it. The circumstances were not at all like those under which he had entered the house of Dr. Scoville; he had not been invited there; he had gone in as a hunted fugitive, and the host had received and taken care of him without any pledge, expressed or implied, on his part, or that of Captain de Banyan, who accompanied him. His conscience, therefore, did not reproach him for any violation of the law of hospitality.

“You are a prisoner, Captain Somers, I repeat,” said Maud—“my prisoner, if you please.”

“Miss Hasbrouk, I have always cherished a feeling of admiration and regard for the ladies; but I regret, in the present instance, to be compelled to contradict you. I am not a prisoner, if you will excuse me for saying so,” replied Somers, calmly.

“The house is surrounded by Confederate cavalry,” added she. “It only remains for me to call them in and end this scene.”

“Allow me to observe that the part which remains will be infinitely more difficult than the part already performed.”

“Am I to understand, Captain Somers, that you propose to resist twenty men, who stand ready to capture you?” demanded the lady, with a triumphant smile.

“Excuse me if I evade that question also for the present. Perhaps you will still further pardon me, if, in this delicate and difficult business, I venture to ask you a few questions, which you will answer or evade, as you please.”

“With great pleasure I submit to be questioned, Captain Somers,” answered she, with a merry twinkle in her eyes, which told how much she still enjoyed the “situation.”

“Thank you, Miss Hasbrouk. You are one of those brawling rebel women who have done so much to keep up the spirits of the chivalry in this iniquitous rebellion. You are one of the feminine Don Quixotes who have unsexed themselves in the cause of treason and slavery.”

“I will not hear this, if you will, Maud. Sir!” exclaimed the major, advancing towards the bold and ungallant speaker, “your foul mouth—”

“Stand where you are, Major Riggleston!” said Somers, fiercely, as he pointed a pistol at his head. “If you stir a step, or open your mouth again, you are a dead man!”

The major seemed to be taken all aback by this decided demonstration. He had no pistol about him; and though he was a “fighting man,” Somers was pretty well satisfied that he would “hold still” until it was safe for him to move. Judging from her looks, Maud seemed to be taking a slightly different view of the situation.

“Excuse my rude words, Miss Hasbrouk,” continued the captain, with a gentle inclination of the head. “As this is your affair, I will thank this gentleman not to interfere. Shall I repeat what I said before?”

“It is not necessary,” replied she, coldly.

“Then we will proceed. First question: Did I correctly state your position?”

“Is a woman who strengthens the hearts of those who are fighting for the right to exist—”

“First question evaded,” interposed Somers. “You invited me to this house; and, by the laws of hospitality, which even the heathen respect, you were impliedly pledged to treat me as a friend, and not as a foe. Second question: Is this so?”

“Did you learn to respect the law of hospitality at Dr. Scoville’s?” sneered she.

“Second question evaded. Dr. Scoville made no pledges to me, nor I to him. No person can blame me for leaving his house when I got ready. Accepting his hospitality and his kindness did not pledge me to go to a Confederate dungeon, where prisoners are systematically murdered. To proceed: By your own confession you invited me to dine in order to make me a prisoner, and take my life by having me hanged as a spy. If you sought to capture me by a trick, would it not—third question—be equally fair for me to escape by a trick?”

“But it is utterly impossible for you to escape,” replied she, glancing through the window at the cavalry on the lawn.

“Third question evaded. You are a lady; and as such, under ordinary circumstances, you are entitled to be treated with the delicacy and consideration due to your sex. But as you have ceased to be a non-combatant,—which you were sorely against your will, and are now actively engaged in the war, conducting the business of capturing a prisoner,—under these circumstances, would it not be entirely fair for me to treat you as a combatant, precisely the same as though you had not unsexed yourself, and were a man?”

“You seem to have already forgotten what is due to a lady,” replied she, her cheek flushed with anger.

“Fourth question evaded.”

“Sir, I decline to hear any more of this coarse abuse!” exclaimed she, stamping her foot.

“Indulge me for one moment more, and I will endeavor as much as possible to avoid talking through my nose, and making pretensions as a hero of the Yankee army, or a down-east pink of chivalry.”

Perhaps the imperial beauty thought that these expressions, borrowed from her own elegant discourse, were not especially refined for a lady to use; it may be that they sounded coarse on a repetition, but she made no acknowledgment to that effect.

“Your silence consents: thank you. Miss Hasbrouk, you speak with chivalrous contempt of what you are pleased to term ‘Yankee tricks;’ at the same time, you were thrown into spasms of laughter by the apparent success of one of your own tricks. Now, permit me to ask whether you would equally appreciate—fifth question—a trick quite as smart as your own?”

“You have insulted me long enough, sir!” replied she, haughtily. “Now, sir—”

“Fifth question evaded. I have no more to ask.”

“Now, sir, I will hand you over to your masters,” said she, moving a step towards the door.

“Excuse me if I take the liberty to decline being handed over to my masters,” said Somers, stepping between her and the door, and now occupying a position between the lady and the discomfited major.

“Sir, what do you mean?” demanded the lady, her bosom heaving with angry emotions, as she found herself confronted by the young officer, who looked as firm and immovable as a mountain of granite.

“I mean all that I say, and much more,” answered he, with an emphasis which she could not fail to understand.

“Sir, I desire to pass out at that door.”

“I positively forbid your passing out at that door.”

“Sir!” gasped she, almost overcome by her angry passions.

“Miss Hasbrouk!” replied he, bowing.

“You are no gentleman!”

“When I came here I regarded you as a lady, and one of the brightest ornaments of your sex. What I think now I shall keep to myself.”

“I shall go mad!”

“I hope not; though I fear you have been tending in that direction for the last hour.”

“Major Riggleston!” cried she, turning to her lover, “will you stand there and permit me to be insulted in this manner?”

“Major Riggleston will stand there. If he moves hand or foot, or opens his mouth to speak, I will blow his brains out. He is a villain and a traitor, and of course he is a coward!”

The major winced under these strong words; but there was death in the sharp, snapping eye of the young officer, and he dared not move hand or foot, or even speak. Perhaps he thought that, as the lady had insisted on managing the affair herself, it was quite proper that she should be indulged to the end.

“I can endure this no longer!” exclaimed Maud, as she took another step towards the door for the purpose of calling in the troopers.

“Stop, Miss Hasbrouk!” said Somers, pointing a pistol at her head with his right hand, while that in his left was ready to dispose of the major.

THE BOOT ON THE OTHER LEG.—Page 73.

“Is it possible that you can raise your weapon against a woman?” cried she, shrinking back from the gaping muzzle of the pistol.

“Let us understand each other, Miss Hasbrouk. I am not to be captured. If you attempt to leave the room, or to call in the rebel soldiers, I will shoot you, as gently and considerately as the deed can be done; but I will shoot you, as surely as you stand there and I stand here.”

He cocked the pistol. She heard the click of the hammer. She stood in mortal terror of her life.

“You forget that I am a woman,” said she, in tones of alarm.