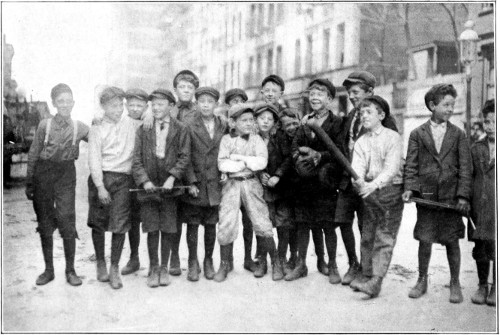

Just Boys!

Why not make them a community asset? ix

Title: West Side Studies: Boyhood and Lawlessness; The Neglected Girl

Other: Pauline Goldmark

Contributor: Ruth S. True

Photographer: Lewis Wickes Hine

Release date: August 17, 2019 [eBook #60116]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by ellinora, Wayne Hammond and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

i

ii

iii

In the summer of 1912 the field work was completed for the West Side studies published in these volumes. They are part of a wider survey of the neighborhood which it was proposed to make under the Bureau of Social Research of the New York School of Philanthropy with funds supplied by the Russell Sage Foundation. Dr. Samuel McCune Lindsay, director of the School, and I were in charge of the Bureau and together planned the scope and nature of the inquiry. To his inspiriting influence was due in large measure the enthusiasm and harmonious work of our staff.

The investigators in the Bureau were men and women who had been awarded fellowships by the School of Philanthropy. There were junior fellowships, given for one year only, and intended to provide training in social research for students without much previous experience, who were required to give part of their time to class work and special reading. There were also senior fellowships given to more advanced students who devoted full time to investigation. After two years’ work it was felt that to carry out the original plan satisfactorily would require the employment of a permanent staff of investigators who were well trained and equipped. The School, therefore, decided not to carry the survey further and reorganized the Bureau on a different basis. iv

This brief account of the Bureau is needed to explain the special topics dealt with in these volumes. The personal qualifications of the investigators as well as the available opportunities for investigation necessarily determined the choice of subjects.

A word must be said, too, as to the selection of this particular West Side district of New York City. These 80 blocks which border upon the Hudson River, between Thirty-fourth and Fifty-fourth Streets, contrast sharply with almost all other tenement neighborhoods of the city. They have as nearly homogeneous and stable a population as can be found in any part of New York. The original stock was Irish and German. In each generation the bolder spirits moved away to more prosperous parts of the city. This left behind the less ambitious and in many cases the wrecks of the population. Hence in this “backset” from the main current of the city’s life may be seen some of the most acute social problems of modern urban life—not the readjustment and amalgamation of sturdy immigrant groups, but the discouragement and deterioration of an indigenous American community.

The quarter which we studied is strangely detached from the rest of the city. Only occasionally an outbreak of lawlessness brings it to public notice. Its old reputation for violence and crime dates back many generations and persists to the present day. So true is this that we considered it essential at the beginning of our undertaking to ascertain the main facts of the district’s development. To Otho G. Cartwright was assigned the task of collecting this material. He did not make an exhaustive inquiry, but obtained from reliable sources sufficient information to give the historical v background of life in the district today. His work serves as a general introduction to the more intensive studies which follow.

The study of juvenile delinquency, Boyhood and Lawlessness, shows clearly the need of special intimate knowledge of social phenomena if their underlying causes are to be understood. It describes the inadequacies of the present system: the innumerable arrests for petty offenses or for playing in the streets, and the failure of the police to bring the ringleaders into court. All this seems so unreasonable to the neighborhood and has so often aroused its antagonism that the influence of the Children’s Court is seriously undermined. In fact, the fathers and mothers of its charges look upon it only as a hostile authority in league with the police, while its real purpose is entirely hidden from them. The evidence is clear, too, that both parents and community have failed to understand and provide for the most elementary physical needs of the boys.

The same tragic lack of opportunity and care characterizes the lives of the girls. Ruth S. True’s portrayal of these lives in The Neglected Girl rests upon close personal acquaintance with a special group of girls who, though they were not brought up on charges in the Children’s Court, yet were without question in grave need of probationary care.

In neither of these two studies was it possible to suggest adequate remedies for the evils described. It is true that steps have already been taken by the Children’s Court to make its probation staff more effective. But the more fundamental need for modification of the conditions of the child’s life and environment vi has still to be pondered. Clearly it is not the child alone who needs reformation.

Similarly, Katharine Anthony’s report, Mothers Who Must Earn, reveals much more than isolated cases of hardship and suffering due to accident or death. She has studied the social and economic causes which compel the mother of a family to become a wage-earner, and the consequences of such employment for her home and family. The occupations where her services are in demand were carefully examined. The underpayment of many of the husbands, which drives their already overburdened wives into wage-earning, is perhaps the most significant fact disclosed. To relieve such severe economic pressure there is certainly need of more radical and far-reaching readjustments than can be effected by any one remedial measure. Relief giving is at best only a temporary stop-gap. This is rather a labor problem of the utmost gravity, affecting whole classes of underpaid laborers.

Indeed, if there is any one truth which emerges from these studies, it is the futility of dealing with social maladjustments as single isolated problems. They are all closely interrelated, and the first step in getting order out of our complexities must be knowledge of what exists. To such knowledge these studies aim to make a contribution. They are not intended to prove preconceived ideas nor to test the efficacy of any special remedies. They aim to describe with sympathy and insight some of the real needs of a neglected quarter of our city—“to hold, as it were, the mirror up to nature.”

The various investigators who took part in the inquiry are given herewith: Edward M. Barrows, Clinton vii S. Childs, Eleanor H. Adler, Beatrice Sheets, and Ruth S. True contributed to the study of the West Side boy, here published under the title Boyhood and Lawlessness. Thomas D. Eliot, a junior fellow, also assisted. Associated with Ruth S. True in the study of the neglected girl, were Ann Campion and Dorothy Kirchwey. All three shared the responsibility of conducting the Tenth Avenue club for the observation of the girls described in their report. The volume Mothers Who Must Earn is the result of work done by Katharine Anthony, who was assisted in her field work by Ruth S. Waldo, a junior fellow.1

In the fall of 1912 practically the whole staff at that time employed devoted two months’ time to inspection of the industrial establishments of the district, under authority of the New York State Factory Investigating Commission. The results were published as Appendix V, to Volume I, of the Commission’s Preliminary Report, 1912.

Thanks are due to many persons who gave unstintedly of their time to the various investigators. Our indebtedness is especially great to the staff of the Clinton District office of the Charity Organization Society, who brought us in touch with many families in their care, and through their varied experience helped us in interpreting many aspects of neighborhood life. Among viii other agencies, Hartley House was particularly generous in making us acquainted with its Italian neighbors and in giving us the opportunity to visit them in their homes. The teachers of various local schools should also be mentioned with appreciation for the help they gave us in many ways.

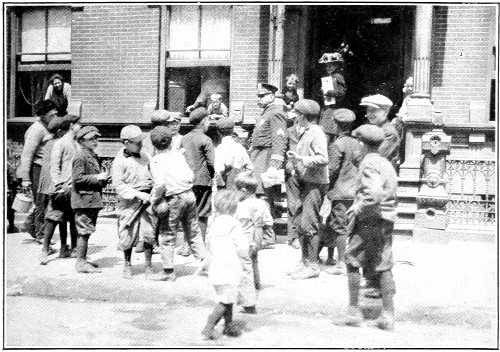

Just Boys!

Why not make them a community asset? ix

Copyright, 1914, by

The Russell Sage Foundation

THE TROW PRESS

NEW YORK

xi

When the Bureau of Social Research began, early in 1909, an investigation of the Middle West Side, it was soon realized that of all the problems presented by the district, none was more urgent and baffling, none more fundamental, than that of the boy and his gang. His anti-social activities have forced him upon public attention as an obstruction to law and business and a menace to order and safety. Because of this lawlessness and because of New York’s backwardness in formulating wise preventive measures to meet it, a special study of the West Side boy was begun.

In order to gain an intimate knowledge of neighborhood conditions which affect the boy, two men workers, Edward M. Barrows and Clinton S. Childs, went to live in the district, the former remaining for nearly two years. During their residence they came in close touch with several gangs and clubs of boys. Their experiences, while they yielded some of the most vital and significant material of our study, did not lend themselves to statistical treatment; they were not recorded in the form of family and individual histories, but as a running day-by-day diary, which formed the basis of the chapters dealing with the activities and the environment of the boys.

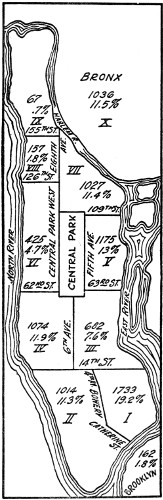

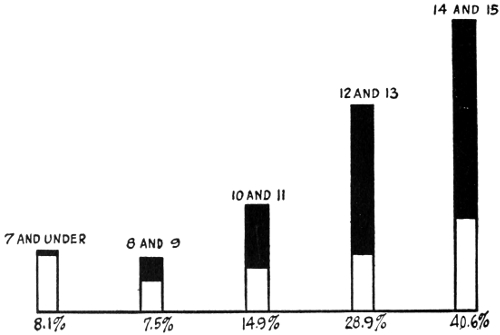

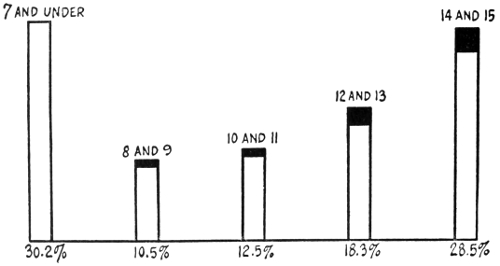

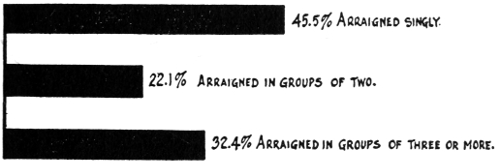

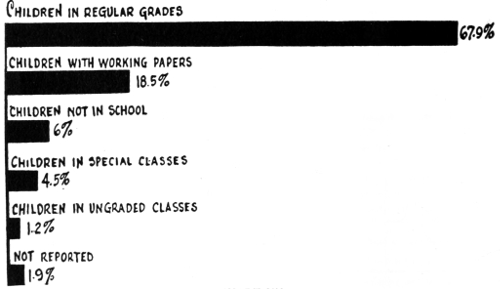

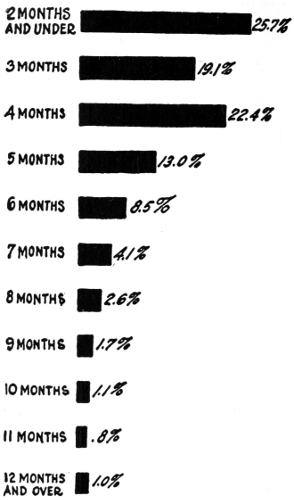

Since the West Side boy, either through personal contact or through association with gang leaders, is inseparable from the Children’s Court, attention was xii naturally drawn to the extent and the result of his relation to this institution. For this reason the Bureau made a special study of 294 boys2 selected from the district with particular reference to their delinquency and their court records.3

Of these boys 28 were under twelve years, 71 more were fourteen, and 102 more were under sixteen. In view of these significant facts it became necessary not only to examine the environment of the West Side boy, but also to estimate the influence of the Children’s Court and other institutions upon him when toughness, truancy, gambling, or other temptations had carried him over the brink into real delinquency. That society should feel itself compelled to resort continually to the arrest and trial of children is in itself a confession of defeat. But when even these resources fail, it becomes imperative to analyze all the factors in the situation; to set the destructive and the constructive elements over against each other, and to determine the chances which the boy and the various public and private agencies organized to regenerate him have of understanding one another.

To many the study may serve to show at their doors a world undreamed of; a world in which, through causes which are even now, removable, youth is denied the universal rights of life, liberty, and happiness. To the xiii court it may be of use in throwing light into dark places and in showing where old paths should be abandoned, as well as in offering suggestions at a critical period in its history.

And, indeed, every suggestion which will tend to lessen the troubles of the Middle West Side is peculiarly needed. The whole community—from molested property owners to the most disinterested social workers—are agreed that the worst elements rule the streets and that neither police nor court authority succeed in enforcing decency and order. And the center of the problem is the boy, for in him West Side lawlessness finds its most perennial and permanent expression.

The aim of this study, therefore, is to trace the principal influences which have formed the West Side boy; to consider some of the means which have heretofore been employed to counteract these influences; and to picture him as he is, exemplifying the results of circumstances for which not he but the entire community is responsible. xiv xv

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Introduction | ix | |

| I. | His Background | 1 |

| II. | His Playground | 10 |

| III. | His Games | 24 |

| IV. | His Gangs | 39 |

| V. | His Home | 55 |

| VI. | The Boy and the Court | 79 |

| VII. | The Center of the Problem | 141 |

| Appendix. | ||

| Tables | 165 | |

| Excerpts from Report of Children’s Court, County of New York, 1913 | 177 | |

| Index | 201 | |

xvi

xvii

Photographs by Lewis W. Hine

| FACING | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

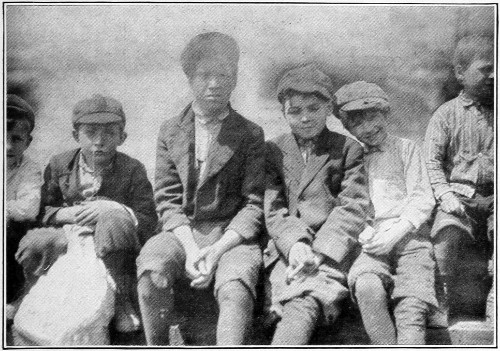

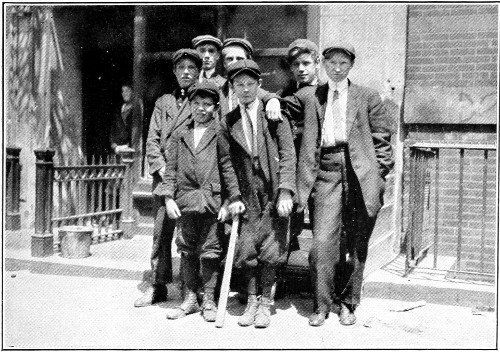

| Just Boys! Frontispiece | |

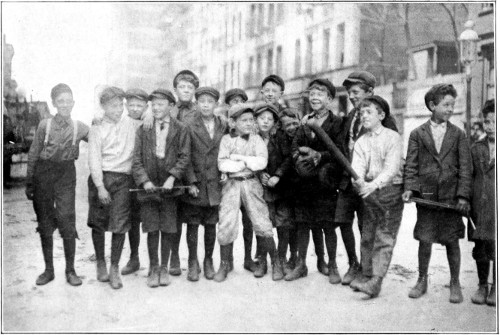

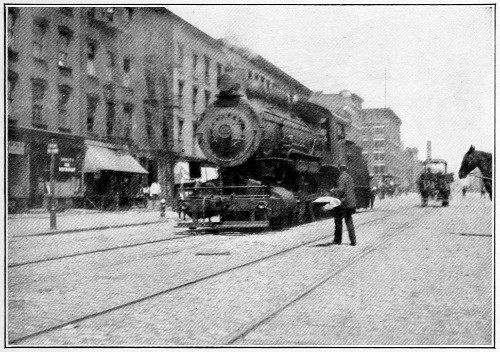

| Tenth Avenue | 4 |

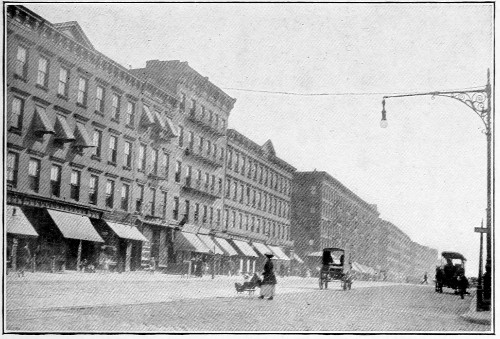

| Eleventh (“Death”) Avenue | 4 |

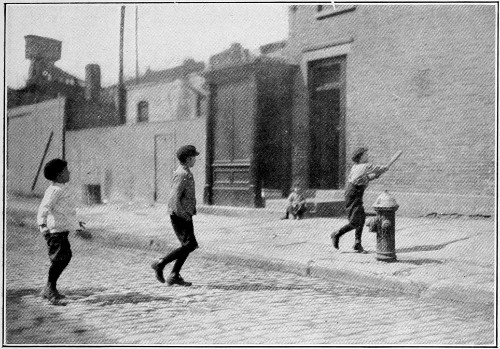

| Bounce Ball with Wall as Base. Property is Safe | 10 |

| Bounce Ball with Steps as Base. Windows in Danger | 10 |

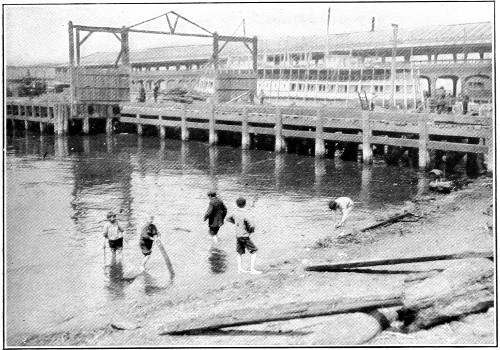

| Wading in Sewage-laden Water | 20 |

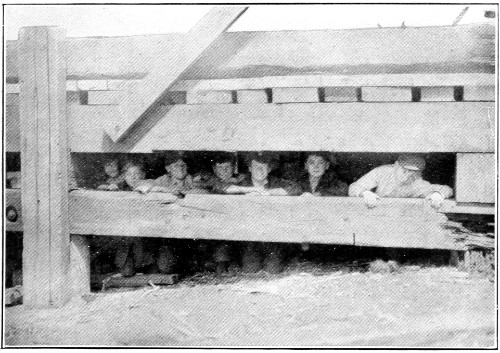

| A “Den” Under the Dock | 20 |

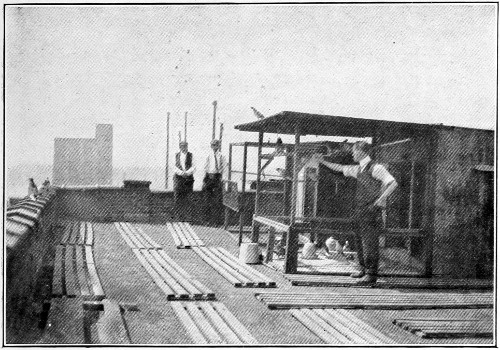

| Pigeon Flying. A Roof Game | 28 |

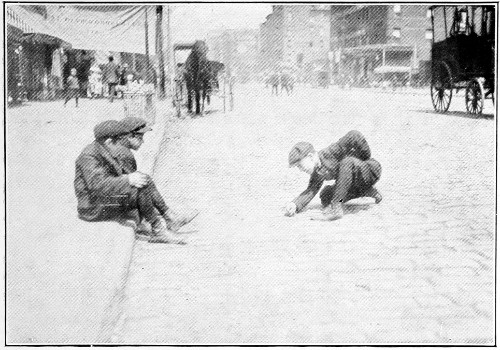

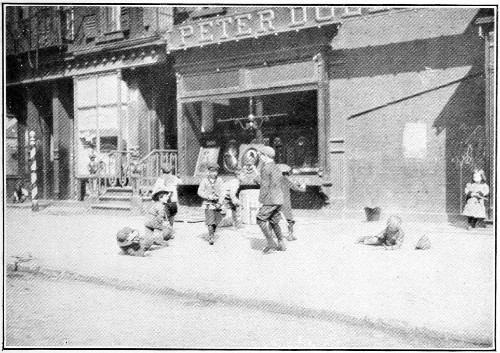

| Marbles. A Street Game | 28 |

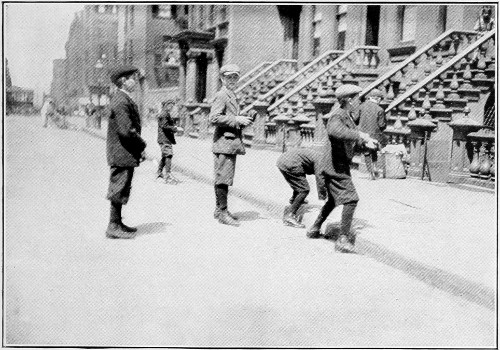

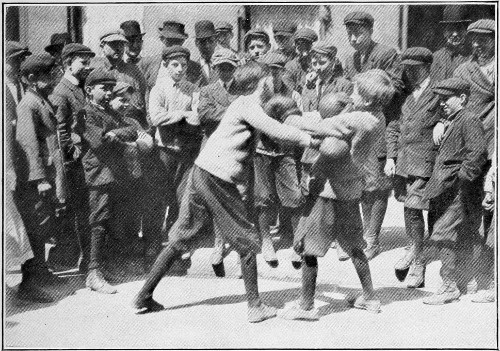

| Prize Fighters in Training | 34 |

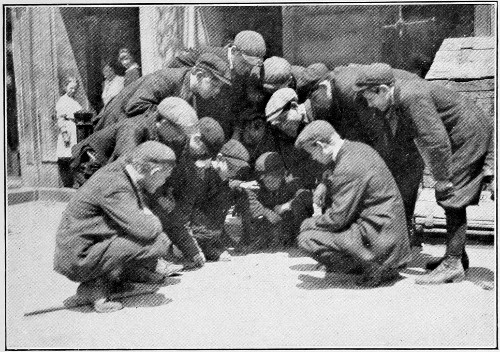

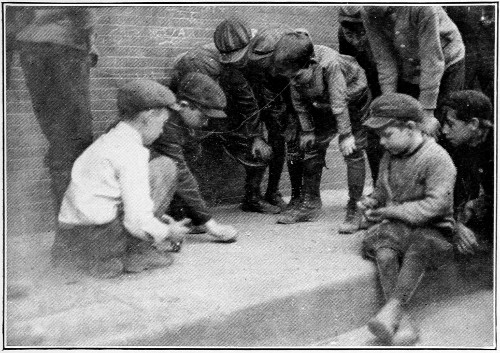

| Craps with Money at Stake | 34 |

| Boy Scouts and Soldiers | 40 |

| After the Battle | 40 |

| Resting. What Next? | 48 |

| Early Lessons in Craps | 48 |

| Approaching the “Gopher” Age | 64 |

| One Diversion of the Older Boys | 64 |

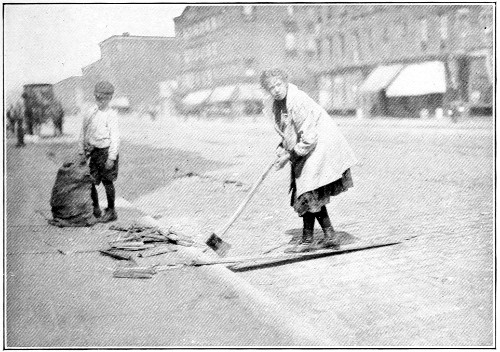

| Replenishing the Wood Box | 74 |

| A Rich Find | 74 |

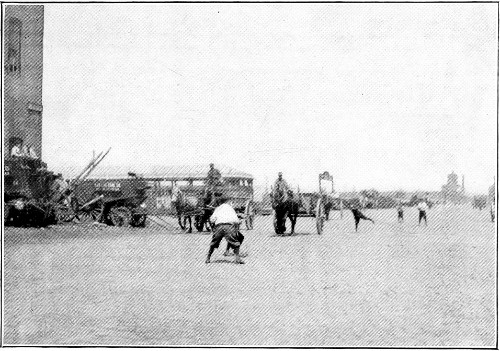

| A Ball Game Near the Docks | 82 |

| “Obstructing Traffic” on Twelfth Avenue | 82 |

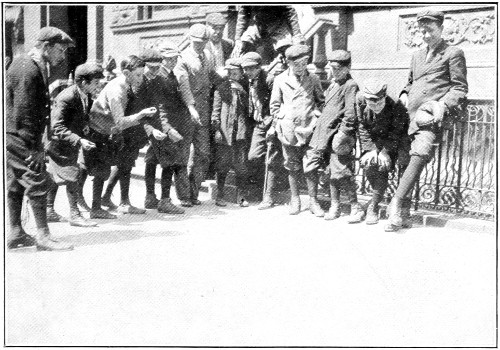

| “We Ain’t Doin’ Nothin’” | 98 |

| The Same Gang at Craps | 98 |

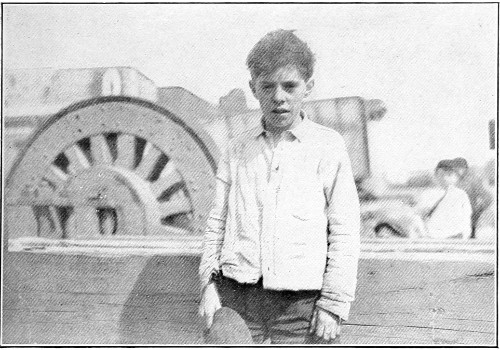

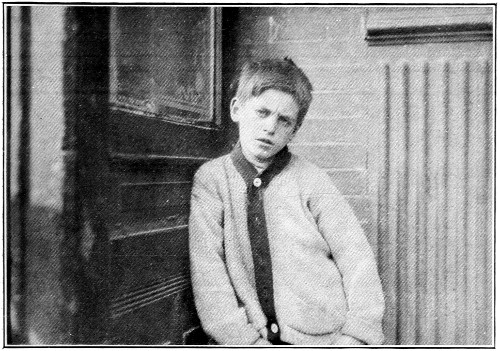

| An Embryo Gangster | 122 |

| The “Toughest Kid” on the Street | 122 |

| Carrying Loot from a Vacant Building | 142 |

| Closed by the Gangs | 142 |

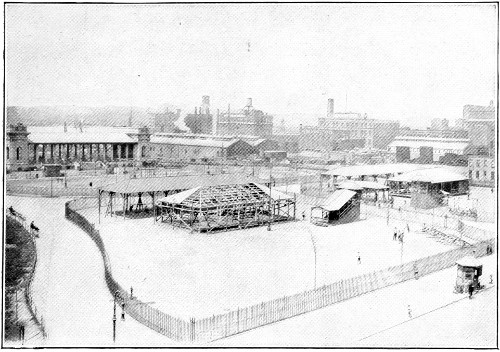

| De Witt Clinton Park | 146 |

| A Favorite Playground | 146 |

xviii xix

xx 1

The influence of environment on character is now so fully recognized that no study of juvenile offenders would be complete without a consideration of their background. In the lives of the boys with whom this study deals this background plays a very large part. One-third of the 241 families studied, 82, are known to have lived in the district from five to nineteen years, and a somewhat larger number, 88, for twenty years or more.4 This means that the boys belonged almost completely to the neighborhood. Most of them had lived there all their lives, and many of them always will live there. If they are to be understood aright, this neighborhood which has given them home, schooling, streets to play in, and factories to work in must also be pictured and understood.

In New York, owing perhaps to the shape of the island, the juxtaposition of tenement and mansion is unusually frequent. Walk five blocks along Forty-second Street west from Fifth Avenue and you are in the heart of the Middle West Side. The very suddenness of the change which these blocks present makes the contrast between wealth and poverty more striking and enables you to appreciate the particular form 2 taken by poverty in this part of the city. Eighth Avenue, at which our district begins, looks east for inspiration and west for patronage. It is the West Sider’s Broadway and Fifth Avenue combined. Here he promenades, buys his clothes, travels up and down town on the cars, or waits at night in the long queue before the entrance to a moving picture show. The pavement is flanked by rows of busy stores; saloons and small hotels occupy the street corners. There is plenty of life and movement, and as yet no obvious poverty. On Saturdays and “sale” days, the neighborhood department stores swarm with custom.

Ninth Avenue has its elevated railroad, and suffers in consequence from noise, darkness, and congestion of traffic. Here the storekeeper can no longer rely on his window to attract customers. He knows the necessity of forceful advertising, and his bedsteads and vegetables, wooden Indians and show cases, everywhere encroach upon the sidewalk. On Saturday nights “Paddy’s Market”5 flares in the open street, supplying for a few hours a picturesqueness which is greatly needed. Poor and untidy as this avenue is, the small tradesmen who live in it profess to look down on their less prosperous neighbors nearer the river.

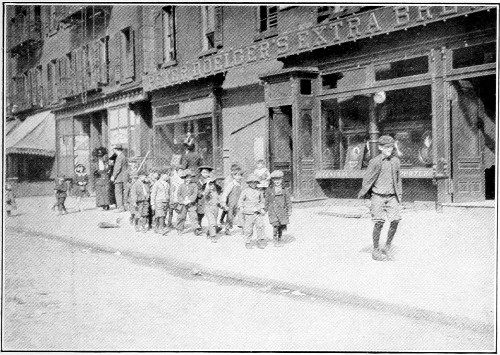

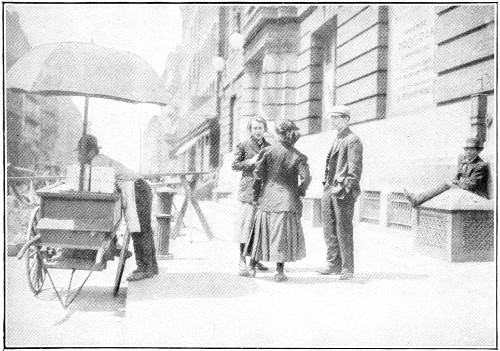

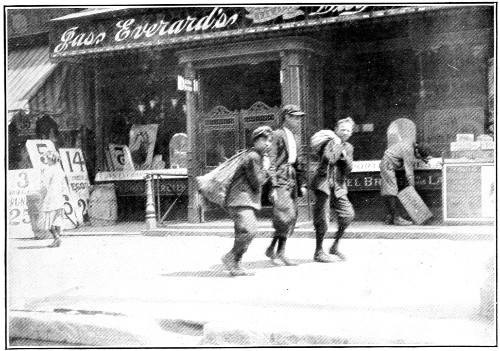

West of Ninth Avenue tenements begin and rents decrease. At Tenth Avenue, where red and yellow crosstown cars swing round the corner from Forty-second Street, you have reached the center of the West Side wage-earning community, and a street which on a bright day is almost attractive. Four stories of red 3 brick tenements surmount the plate glass of saloons and shops. Here and there immense colored advertisements of tobacco or breakfast foods flame from windowless side walls, and the ever-present three brass balls gleam merrily in the sunlight. But the poverty is unmistakable. You see it in the tradesman’s well-substantiated boast that here is “the cheapest house for furniture and carpets in the city.” You see it in the small store, eking out an existence with cigars and toys and candy. You see it in the ragged coats and broken shoes of the boys playing in the street; in the bareheaded, poorly dressed women carrying home their small purchases in oil-cloth bags; in the grocer’s amazing values in “strictly fresh” eggs; in the ablebodied loafers who lounge in the vicinity of the corner saloon, subsisting presumably on the toil of more conscientious brothers and sisters. And in one other feature besides its indigence Tenth Avenue is typical of this district. At the corner of Fiftieth Street stands the shell of what was once a flourishing settlement, and beside it a smaller building which was once a church. Both, as regards their original uses, are now deserted. Both are a concrete expression not merely of failure, but of failure acquiesced in. These West Side streets are more than poor. They have ceased to struggle in their slough of despond, and have forgotten to be dissatisfied with their poverty.

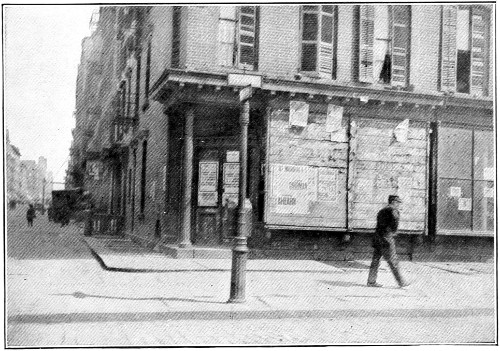

Eleventh Avenue is much more dirty and disconsolate. In its dingy tenements live some of the poorest and most degraded families of this district. On the west side of the avenue and lining the cross streets are machine shops, gas tanks, abattoirs, breweries, warehouses, piano factories, and coal and lumber yards 4 whose barges cluster around the nearby piers. Sixty years ago this avenue, in contrast to the fair farm land upon which the rest of the district grew up, was a stretch of barren and rocky shore, ending at Forty-second Street in the flat unhealthy desolation of the Great Kill Swamp. Land in such a deserted neighborhood was cheap and little sought for, and permission to use it was readily given to the Hudson River Railroad.6 Today the franchise, still continued under its old conditions, is an anomaly. All day and night, to and from the Central’s yard at Thirtieth Street, long freight trains pass hourly through the heterogeneous mass of trucks, pedestrians, and playing children; and though they now go slowly and a flagman stands at every corner, “Death Avenue” undoubtedly deserves its name.

De Witt Clinton Park, the only public play space in the district, lies westward between Fifty-second and Fifty-fourth Streets. It is better known as “The Lane” from days, not so long ago, when a pathway here ran down to the river, and on either side of it the last surviving farm land gave the tenement children a playground, and the young couples of the neighborhood a place to stroll in. The usual well kept and restrained air of a small city park is very noticeable here. There is almost no grass, the swings and running tracks are, perhaps necessarily, caged by tall iron fences, and uninteresting asphalt paths cover a considerable part of the limited area. A large stone pergola, though of course it has obvious uses, somehow deepens the impression that an opportunity was lost in the laying out of this 5 place. At one side of the pergola, however, lie the plots of the school farm in which small groups of boys and girls may often be seen at work. Little attempt has been made to develop a play center in the park. On a fine Saturday afternoon it is often practically empty.7

Tenth Avenue

Eleventh (“Death”) Avenue]

Twelfth Avenue adjoins the Hudson River, losing itself here and there in wharves and pier-heads. Two of the piers belong to the city, one being devoted to the disposal of garbage, the other to recreation. Factories and an occasional saloon are on the inland side, but there are almost no shacks or tenements.

At first sight there are no striking features about the Middle West Side. Hand-to-mouth existence reduces living to a universal sameness which has little time or place for variety. In street after street are the same crowded and unsanitary tenements; the same untended groups of playing children; the same rough men gathered round the stores and saloons on the avenue; the same sluggish women grouped on the steps of the tenements in the cross streets. The visitor will find no rambling shacks, no conventional criminal’s alleys; only square, dull, monotonous ugliness, much dirt, and a great deal of apathy.

The very lack of salient features is the supreme characteristic 6 of this neighborhood. The most noticeable fact about it is that there is nothing to notice. It is earmarked by negativeness. There is usually a lifelessness about the streets and buildings, even at their best, which is reflected in the attitude of the people who live in them. The whole scene is dull, drab, uninteresting, totally devoid of the color and picturesqueness which give to so many poor districts a character and fascination of their own. Tenth Avenue and the streets west of it are lacking in the crowds and bustle and brilliant lights of the East Side. Eleventh Avenue by night is almost dark, and throughout the district are long stretches of poorly lit cross streets in which only the dingy store windows shine feebly. Over the East River great bridges throw necklaces of light across the water; here the North River is dark and unspanned.

What is it that has brought about this condition? Why is this part of New York so utterly featureless and depressing? The answer lies primarily not with the present or past inhabitants, but in the isolation and neglect to which for years it has been subjected. Much of the Middle West Side was once naturally attractive, with prosperous homesteads and cottages with gardens.8 But while other parts of Manhattan were being developed as a city, the Middle West Side was left severely alone. It was one of the last sections of the city to become thickly populated. When the first factories arrived, they brought the tenements in their wake. The worst kinds of tenements were hastily built—anything was supposed to be good enough for the poor Irish who settled there; and these tenements 7 have long survived in spite of their dilapidated condition because until recently there has been no one who cared for the rough and dull West Sider. East Side problems were much more picturesque and inviting. So our district has grown up under a heritage of desolation and neglect, uninteresting to look at, unpleasant to live in, overlooked, unsympathized with, and neglected into aloofness, till today its static population is almost isolated from and little affected by the life of the rest of the city. The casual little horse car which jingles up Tenth Avenue four times an hour is typical of the West Sider’s home, just as the Draft Riots of 1863 were typical of his temper.

The nationalities which largely form the basis of the population on the Middle West Side are the German and the Irish, the latter predominating.9 Peculiar to the district is the large number of families of the second generation with parents who have been born and brought up in the immediate neighborhood.

The nationality of the American-born parents throws additional light on the subject of racial make-up of the population.10 There were 81 American-born fathers and 92 American-born mothers in the 241 families. The parentage of 67 American-born fathers for whom information was available was as follows: 28, German; 8 21, Irish; 15, American; and 3, English. The parentage of 73 American-born mothers was: 28, German; 25, Irish; 18, American; and 2, English. The country of birth of parents of 14 of the American-born fathers and 19 of the American-born mothers could not be ascertained.11

We are accustomed to regard the German as the best of European emigrants. He brings with him a thrift and solidity which have taught us to depend on him. He has been a welcome immigrant as he has become a successful citizen. Yet here are large numbers of Germans living in a wild no-man’s-land which has a criminal record scarcely surpassed by any other district in New York. Surely this is more than a case of the exception proving the rule. It shows that our estimate of the Middle West Side is correct.

The district is like a spider’s web. Of those who come to it very few, either by their own efforts, or through outside agency, ever leave it. Now and then a boy is taken to the country or a family moves to the Bronx, but this happens comparatively seldom. Usually those who come to live here find at first (like Yorick’s starling) that they cannot get out, and presently that they do not want to. It is not that conditions throughout the district are economically extreme, although greater misery and worse poverty cannot be found in other parts of New York. But there is something in the dullness of these West Side streets and the traditional apathy of their tenants that crushes the wish for anything better and kills the hope of change. It is as though decades of lawlessness and neglect have formed an atmospheric monster, beyond the power and 9 understanding of its creators, overwhelming German and Irish alike.

Such, in brief, is the background of the West Side boy. It is a gray picture, so gray that the casual visitor to these streets may think it over-painted. But this is because a superficial glance at the Middle West Side is peculiarly misleading. So much lies below the surface. It is obvious that this district has come to be singularly unattractive, and that its methods of life are extraordinarily rough. And it is equally true that hundreds of boys never know any other place or life than this, and that most of their offenses against the law are the direct result of their surroundings. The charges brought against them in court are only in part against the boys themselves. The indictment is in the main against the city which considers itself the greatest and most progressive in the New World, for allowing any of its children to start the battle of life so poorly equipped and so handicapped for becoming efficient American citizens. Not that these youngsters have not their share of “devilment” and original sin, but in estimating the work of the juvenile court with the boys of this neighborhood, it is absolutely essential to bear in mind not only the crimes they commit, but their chances for escaping criminality. If heredity and environment have any meaning, Tenth Avenue has much to answer for. 10

The boy himself is blissfully untroubled by any serious thoughts about his background; and to him these streets are as a matter of course a place to play in. This point of view is perfectly natural for several reasons:

In the first place, he has never known any other playground. At the earliest possible stage of infancy he is turned out, perhaps under an older sister’s supervision, to crawl over the steps of the tenement or tumble about in the gutter in front of it, watching with large eyes the new sights around him. Here he is put to play, and here he learns to imitate the street and sidewalk games of other boys and girls. He is scarcely to be blamed for a point of view so universally held that it never occurs to him to doubt it.

In the second place, the street is the place that he must play in, whether he wants to or not. There is no room for him in the house; the janitor usually chases him off the roof. Excepting De Witt Clinton Park, which, as has been shown, is small, restricted, and inadequate, there is no park on the West Side between Seventy-second and Twenty-eighth Streets. Central Park and New Jersey are too inaccessible to be his regular playgrounds. And besides, not only will a boy not go far afield for his games, but he cannot. He is often needed at home after school hours to run 11 errands and make himself generally useful. Moreover, to go any distance involves a question of food and transportation; so that except at times of truancy and wanderlust, or when he is away on some baseball or other expedition, the street inevitably claims him.

Bounce Ball with Wall as Base

Property is safe

Bounce Ball with Steps as Base

Windows in danger

And in the third place, just because this playground is so natural and so inevitable, he becomes attached to it. It is the earliest, latest, and greatest influence in his life. Long before he knew his alphabet it began to educate him, and before he could toddle it was his nursery. Every possible minute from babyhood to early manhood is spent in it. Every day, winter and summer, he is here off and on from early morning till 10 o’clock at night. It gives him a training in which school is merely a repressive interlude. From the quiet of the class room he hears its voice, and when lessons are over it shouts a welcome at the door. The attractions that it offers ever vary. Now a funeral, now a fire; “craps” on the sidewalk; a stolen ride on one of Death Avenue’s freight trains; a raid on a fruit stall; a fight, an accident, a game of “cat”—always fresh incident and excitement, always nerve-racking kaleidoscopic confusion.

No wonder, then, that the streets are regarded by the boy as his rightful playground. They are the most constant and vivid part of his life. They provide companionship, invite to recklessness, and offer concealment. Every year their attraction grows stronger, till their lure becomes irresistible and his life is swallowed up in theirs.

But unfortunately for the boy everyone does not agree with him as to his right of possession. The storekeeper, for instance, insists on the incompatibility 12 of a vigorous street ball game with the safety of his plate glass windows. Drivers not unreasonably maintain that the road is for traffic rather than for marbles or stone throwing. Property owner, pedestrian, the hardworking citizen, each has a point of view which does not altogether favor the playground theory. At the very outset of his career, therefore, in attempting to exercise childhood’s inalienable right to play, the boy finds himself colliding with the rights of property; the maintenance of public safety, the enforcement of law and order, and other things equally puzzling and annoying, all apparently united in being inimical to his ideas of amusement. He is too young to understand that in his city’s scheme children were forgotten. No one can explain to him that he has been born in a congested area where lack of play space must be accepted patiently; that life is a process of give and take in which the rights of others demand as much respect as his own. He does not know that his dilemma is the problem which eternally confronts the city child. But he does know that he must play. He has a store of nervous energy and animal spirits which simply must be let loose. Yet when he tries to play under the only conditions possible to him he is hampered and repressed at every turn. Inevitably he revolts; and long before he is old enough to learn why most of his street games are illegal, fun and law-breaking have become to him inseparable, and the policeman his natural enemy.

So far the boy’s attitude is normal. Childish antagonism to arbitrary authority is natural. In any large town it extends to the police. All over New York games are played with one eye on the corner and often with a small scout or two on the watch for the “cop.” 13 But at this point two facts differentiate the Middle West Side from the rest of the city, and make its situation peculiar. On the one hand, the parents and older people of the district, instead of showing the usual indifference or at most a passive antipathy toward the police, openly conspire against and are actively hostile to them. On the other, the police, largely because of this neighborhood feeling, are utterly unable to cope with the lawless conditions which they find around them.

This state of things has been brought about in various ways. The lurid record of criminals in the district has for years necessitated methods of policing which have not made the Irish temper any less excitable. Public sentiment here is almost static, and hatred of the police has become a tradition. No one has a good word for them; everyone’s hand is against them. The boys look on them as spoil-sports and laugh at their authority. The toughs and gangsters are at odds with them perforce. Fathers and mothers, resenting the trivial arrests of their children, consign the “cop,” the “dinny” (detective), and “the Gerrys” to outer darkness together. The better class of residents and property owners, though their own failure to properly support them is partly to blame for the failure of the police to do their duty, frankly distrust them for being so completely incompetent and ineffective. And now perhaps no one would dare to support them. For the toughs of the district have taken the law into their own hands, and with the relentlessness and certainty of a Corsican vendetta every injury received by them is repaid, sooner or later, by some act of pitiless retaliation. Honest or dishonest, successful or otherwise, 14 the policeman certainly has a hard time of it. Wherever he goes he is dangerously unpopular. He cannot be safely active or inactive, and whatever he does seems to add to his difficulties. Hectored on duty, frequently bullied in court, misunderstood and abused by press and public alike, he stands out solitary, the butt and buffer of the neighborhood’s disorder.

It is scarcely remarkable that under these circumstances the guardian of the law is bewildered, and tends to become unreasonably touchy and suspicious. “I tried to start a club in a saloon on Fiftieth Street a while ago,” said a young Irishman of twenty-five. “After we had had the club running one night, a policeman came in and asked me for my license. I told him I didn’t have any. He said he would have to break up the club then. I kicked about this and he pinched me. They brought me up for trial next morning, and the judge told me I would have to close up my club. I asked him why, and said the club was perfectly orderly and was just made up of young fellows in the neighborhood; and he said, ‘Well, your club has a bad reputation, and you’ve got to break it up.’ Now, how could a club have a bad reputation when it had only been running one day? Tell me that? But that’s the way of it. Those cops will give you a bad reputation in five minutes if you never had one before in your life.” “The cops are always arresting us and letting us go again,” said a small West Sider. “I’ve been taken up two or three times for throwing stones and playing ball, but they never took me to the station house yet. You can’t play baseball anywhere around here without the cops getting you.” And so it has come about that relations between police and people 15 in this section of New York are abnormally strained. Provocation is followed by reaction, and reaction by reprisal and a constant aggravation of annoyances, till the tension continually reaches breaking point.

This situation shows very definite results in the boy. Gradually his play becomes more and more mischievous as he finds it easier to evade capture. Boylike, his delight in wanton and malicious destruction is increased by the knowledge that he will probably escape punishment. Six-year-old Dennis opens the door of the Children’s Aid Society school and throws a large stone into the hall full of children. Another youngster of about the same age recently was seen trying for several minutes to break one of the street lamps. He threw stone after stone until finally the huge globe fell with a crash that could have been heard a block. Then he ran off down the street and disappeared around the corner. No one attempted to stop him; no one would tell who he was. Later on, the boy begins to admire and model himself on the perpetrators of picturesque crimes whom he sees walking unarrested in the streets around him. And by the time that he reaches the gang age he is usually a hardened little ruffian whom the safety of numbers encourages to carry his play to intolerable lengths. He robs, steals, gets drunk, carries firearms, and his propensity for fighting with stones and bottles is so marked that for days whole streets have been terrorized by his feuds. Insurance companies either ask prohibitive rates for window glass in this neighborhood or flatly refuse to insure it at all.

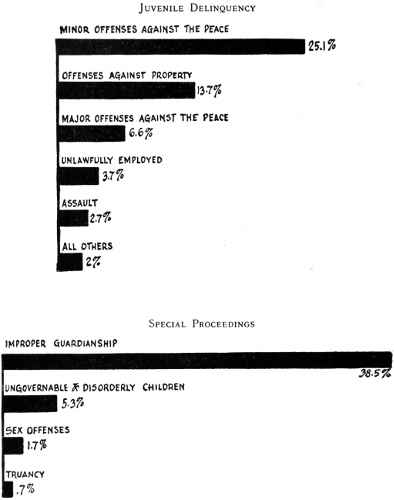

Meanwhile the police are not idle. Public opinion and their own records at the station house demand a certain amount of activity, and every week the playground 16 sees its arrests. In the following table we have classified by causes, from our own intimate knowledge of each individual case, the arrests which took place during 1909 among the boys of our 241 families. The court’s legal system of classification has been discarded here in favor of the classification made to show the real nature of each offense. The result illustrates how entirely police intervention has failed to meet the issue in the district, and consequently explains in part why the work of the children’s court with boys from this neighborhood has not proved more effectual.

| Offenses of vagrancy and neglect: | |

| Truancy | 38 |

| Begging | 3 |

| Selling papers at ten | 18 |

| Selling papers without a badge | 5 |

| Run-away | 7 |

| Sleeping in halls and on roofs | 6 |

| Improper guardianship | 12 |

| General incorrigibility | 23 |

| Total | 112 |

| Offenses due to play: | |

| Playing ball | 20 |

| Playing cat | 3 |

| Playing shinny | 2 |

| Pitching craps | 26 |

| Pitching pennies | 9 |

| Throwing stones and other missiles | 44 |

| Building fires in the street | 15 |

| Fighting | 6 |

| Total | 12517 |

| Offenses against persons: | |

| Assault | 5 |

| Stabbing | 4 |

| Use of firearms | 3 |

| Immorality | 0 |

| Intoxication | 1 |

| Total | 13 |

| Offenses against property: | |

| Illegal use of transfers | 1 |

| Petty thievery | 58 |

| Serious thievery | 18 |

| Burglary, i. e., breaking into houses and theft | 36 |

| Forgery | 0 |

| Breaking windows | 4 |

| Picking pockets | 2 |

| Total | 119 |

| Offenses of mischief and annoyance: | |

| Upsetting ash cans | 2 |

| Shouting and singing | 6 |

| Breaking arc lights | 3 |

| Loitering, jostling, etc | 12 |

| Stealing rides on cars | 4 |

| Profanity | 1 |

| Total | 28 |

| Unknown | 73 |

| Total | 470 |

| Deducting duplicates | 7 |

| Grand Total | 463 |

a For the classification of these arrests according to the court charges see Chapter VI, The Boy and the Court, p. 82.

Not only is this table extraordinarily interesting in itself, but its importance to our investigation is inestimable, because it brings out certain features of the problem with a vividness which could not be equaled in pages of discussion or narrative.

On the one hand, it is noticeable how large a proportion 18 of the arrests are for offenses which are more or less excusable in these boys. Almost every one of their offenses is due to one of four causes: neglect on the part of the parent, the pressure of poverty, the expression of pure boyish spirits, or the attempt to play. Thievery, for instance, particularly the stealing of coal from the docks or railroad tracks, is quite often encouraged at home. “Johnnie is a good boy,” said one mother quite frankly. “He keeps the coal and wood box full nearly all the time. I don’t have to buy none.” And her attitude is typical. Shouting and singing too, and even loitering, do not seem on the face of them overwhelmingly wicked. Of course, boys sometimes choose the most impossible times and places in which to shout and sing, but is no allowance to be made for “the spirit of youth”? And as for the arrests for play, they speak for themselves. Some of these games, played when and where they are played, are unquestionably dangerous to passersby and property, while others are simply forms of gambling. But it must be remembered that the West Side boy has nowhere else to play; that his games are the games which he sees around him, and he plays them because no one has taught him anything better. The policeman, however, has no interest in the responsibility of the boys for their offenses; he is concerned merely with offenses as such, and his arrests must be determined chiefly by opportunity and by rule. All that we can ask of him is to be tolerant, broad-minded, and sympathetic—a request with which he will find it difficult enough to comply if only because of the atmosphere of hostility against him.

On the other hand, it is remarkable how seldom the 19 boys are caught for very serious offenses.12 Most of the arrests shown here are for causes which are comparatively trifling. Yet the whole neighborhood seethes with the worst kinds of criminality, and many of the boys are almost incredibly vicious. Stabbing, assault, the use of firearms, acts of immorality, do not appear in this table to an extent remotely approximating the frequency with which they occur. In other words, the police absolutely fail to cover the ground. Although a large proportion of arrests does take place, they are mostly on less important charges, and often involve any one but the young criminal whose capture is really desirable. The little sister of one boy who was “taken” expressed the position exactly when she said, “The only time Jimmy was caught was when he wasn’t doin’ anything bad.”

In this way it happens that the fact of a boy’s arrest is no clue to his character. Again and again boys “get away with” their worst crimes, secretly committed, in which they are protected from discovery by the neighborhood’s code of ethics; whereas for minor offenses, of which they are openly guilty, they are far more likely to be arrested. Some of the worst offenders may never be caught at all. And if one of them is taken, it is probably for some technical misdemeanor which the officer has used less for its own importance than as a pretext for getting the boy into court. What is the result? The policeman is lectured by the judge for being an oppressor of the poor, and the boy is discharged, though his previous record would entitle him to a severe sentence, as both boy and policeman know.

Not unnaturally, respect for the court is soon lost, 20 and an arrest quickly comes to be treated with indifference, or is looked upon merely as a piece of bad luck, like a licking or a broken window. One boy recounted recently with amusement how he moved the judge to let him off: “I put on a solemn face and says, ‘Judge, I didn’t mean to do it; I’ll promise not to do it again,’ and a lot of stuff like that, and the judge gives me a talkin’ to and lets me go.” “Gee, that court was easy!” was the comment of another. “You can get away with anything down there except murder.” Experiences in the juvenile court are invariably related with a boyish contempt for the judges, who are looked upon either as “easy guys to work” or as “a lot of crooks” who “get theirs” out of their jobs. And so the boy comes back to the streets, and plays there more selfishly and more recklessly than ever.

His activities are not confined to the block in which he lives or even to the streets of his neighborhood. Any kind of space, from a roof or an area to a cellar or an empty basement, is utilized as an addition to the playground. But two places attract him particularly. All the year around at some time of day or night you can find him on the docks. In summer they provide a ball ground, in winter, coal for his family, and always a hiding place from the truant officer or the police. Here along the river front he bathes in the hot weather, encouraged by the city’s floating bath which anchors close by, and regardless of the fact that the water is filthy with refuse and sewage. In the stifling evenings, too, when the band plays on the recreation pier and there are lights and crowds and “somethin’ goin’ on,” he is again drawn toward the water.

Wading in Sewage Laden Water

A “Den” Under the Dock

And next to the streets and docks he loves the hallways. 21 There is something about those dark, narrow passages which makes them seem built for gangs to meet or play or plot in. The youth of the district and his girl find other uses for them, but the boy and his playmates have marked them for their games. Neighbors who have no other place to “hang around in” may protest, but the boys play on. They dirty the floors, disturb the tenements by their noises, run into people, and if they are lying here in wait are apt to chip away the wainscoting or tear the burlap off the walls. But what do they care! It’s all in the day’s play; and if the janitor objects, so much the better, for he can often be included in a game of chase.

Streets, roofs, docks, hallways,—these, then, are the West Side boy’s playground, and will be for many years to come. And what a playground it is! Day and night, workdays and holidays alike, the streets are never quiet, from the half-hour before the factory whistles blow in the early morning, when throngs of men and boys are hurrying off to work, to still earlier morning hours when they echo with the footsteps of the reveler returning home. All day long an endless procession of wagons, drays, and trucks, with an occasional automobile, jolts and clatters up and down the avenue. Now and then an ambulance or undertaker’s cart arrives, drawing its group of curious youngsters to watch the casket or stretcher carried out. Drunken men are omnipresent, and drunken women are seen. Street fights are frequent, especially in the evening, and, except for police annoyance or when “guns” come into play, are generally regarded as diversions. Every crime, every villainy, every form of sexual indulgence and perversion is practiced in the district and talked 22 of openly. The sacredness of life itself finds no protecting influence in these blocks. There is no rest, no order, no privacy, no spaciousness, no simplicity; almost nothing that youth, the city’s everlasting hope, should have, almost everything that it should not.

A family from another state moved recently into one of these tenements. The only child, a boy of fifteen, after several tentative efforts to reconcile himself to street life, came in and announced his intention of staying in the flat in leisure time thereafter, as he was shocked and his finer feelings were hurt by what he saw of the street life around him. His mother tried to persuade him to go out, but the boy told her she had no idea what she was doing, and refused to go. He attempted to take his airings on the roof, but was ordered down by the janitor. Finally he yielded to his mother’s persuasion and went back to the street. Within three months this boy, a type of the bright, clean boyhood of our smaller towns, had become marked by dissipation and had once even come home intoxicated.

What chance has the best of boys who must spend two-thirds of his school days in such a playground? What wonder that he becomes a callous young criminal, when the very conditions of his play lead him to crime? The whole influence of such conditions on a child’s life can never be gauged. But just as apart from his traditions and background he is incomprehensible as a boy, so, as a wanton little ruffian, he is unintelligible apart from his playground. This develops his play into mischief and his mischief into crime. It educates him superficially in the worst sides of life, and makes him cynical, hard, and precocious. It takes 23 from him everything that is good; almost everything that it gives him is bad. Its teachings and tendencies are not civic but anti-social, and the boy reflects them more and more. Every year he adds to a history of lawless achievement which the court, police, and institutions alike have proved powerless to prevent. And every day the Middle West Side bears witness to the truth of the saying that “a boy without a playground is the father of the man without a job.” 24

It would be impossible to describe the thousand and one uses to which the West Side boy puts his playground. After all, the street is not such a bad place to play in if you have known nothing better; and as you tumble out of school on a fine afternoon, ready for mischief, it offers you almost anything, from a fight with your best friend to a ride on the steps of an ice wagon. But certain games and sports are so universal in this district as to deserve separate mention.

Spring is the season for marbles. On any clear day in March or February you may find the same scene on roadway and sidewalks of every block—a huddle of multicolored marbles in the middle of a ring, and a group of excited youngsters, shrieking, quarreling, and tumbling all over each other, just outside the circle. Instead of the time-honored chalk ring the boys often use the covers of a manhole, whose corrugated iron surface offers obstacles and therefore gives opportunity for unusual skill. Another game consists in shooting marbles to a straight line drawn along the middle of the sidewalk; thus one such game may be continued through the whole length of the block. In another the marbles are pitched against a brick wall or against the curbstone, and the boy whose marbles stop closest to a chalked mark wins the marbles of all competitors. 25

As the fall days grow shorter and the afternoons more crisp, bonfires become the rage. The small boy has an aptitude for finding wood at need in places where one would suppose that no fuel of any kind would be obtainable. A careless grocer leaves a barrel of waste upon the sidewalk. In five minutes’ time that barrel may be burning in the middle of the street with a group of cheering youngsters warming their hands at the blaze, or watching it from their seats on the curbstone. The grocer may berate the boys and threaten disaster to the one who lit the barrel, but he is seldom able to find the culprit. Before the barrel is completely burned some youngster produces a stick or two which he has found in an areaway or pulled from a passing wagon, and adds it to the fire. Stray newspapers, bits of excelsior, rags, and even garbage are contributed to keep the fire going, regardless of the effect on the olfactory nerves of the neighborhood. The police extinguish these fires whenever they can, but the small boy meets this contingency by posting scouts, and on the alarm of “Cheese it!” the fire is stamped out and the embers are hastily concealed. The “cop” sniffs at the smoke and looks at the boys suspiciously, but suspicions do not bother the boys—they are used to them—and when he has passed on down the street the fragments of the fire are reassembled and lighted again. On a cold evening one may see half a dozen of these bonfires flaming in different directions, each with a group of small figures playing around them. Sticks are thrust into the fire and waved in figures in the air; and among them very often circle larger and brighter spots of light which glow into a full flame when the motion ceases. These are fire pots, an 26 ingenious invention consisting of an empty tomato can with a wire loop attached to the top by which to swing it, and filled with burning wood. This amusement might seem harmless enough if it were not for the fact that these fire pots, being of small boy construction, have an unfortunate habit of slipping from the wire loop just as they are being most rapidly hurled.

On election night, until recently, the boys’ traditional right of making bonfires has been observed. These bonfires are sometimes elaborate. As early as the middle of October the youngsters begin hoarding wood for the great occasion. They pile the fuel in the rear of a tenement or in the areaway or basement of some friendly grocer, or perhaps in a vacant lot or at the rear of a factory. Frequently to save their plunder they find it necessary to post guards for the few days preceding election, and even so, bonfire material often becomes the center of a furious gang fight. A few of the stronger gangs have a settled policy of letting some other gang collect their fuel for them, and then raiding them at the last minute. The victors carry the wood back triumphantly to their own block, and the vanquished are left either to collect afresh or to make reprisal on a still weaker gang. This kind of warfare continues even while the fires are burning on election night. A gang will swoop down unawares on a rival bonfire, scatter the burning material, and retire with the unburnt pieces to their own block.13 A recent election time, however, proved a gloomy one for the little West Siders. Wagons appeared in the streets, filled with fire hose and manned by firemen and police. The police scattered the boys while the firemen drenched the fires, 27 and by 8 o’clock the streets, formerly so picturesque and so dangerous, presented a sad and sober appearance. The tenement lights shone out on heaps of blackened embers and on groups of despairing youngsters who were not even permitted to stand on the corners and contemplate the destruction of their evening’s festivities.

In the winter the shortcomings of the street as a playground are especially evident. Frost and sleet and a bitter wind give few compensations for the discomfort which they bring. Traffic, the street cleaning department, and the vagaries of the New York climate, make most ways of playing in the snow impossible. But snowballing continues, in spite of the efforts of the police to prevent it. It is open to the same objections as baseball in the street, for the freedom which is possible in the small towns or in the country cannot be tolerated in a crowded district where a snowball which misses one mark is almost certain to hit another. Moreover, owing to the facility with which these boys take to dangerous forms of sport, the practice of making snowballs with a stone or a piece of coal in the middle and soaking them in ice water is even more prevalent here than in most other localities. Of course, snowballing is forbidden and abhorred by the neighborhood, and everyone takes a hand in chastising the juvenile snowball thrower. Nevertheless, the afternoon of the first fall is sure to bring a snow fight, and the innocent passerby is likely to be involuntarily included in the game.

Marbles and bonfires and snowballs are the sports of the smaller boys exclusively, but other games which are less seasonal are played by old and young alike. 28 “Shooting craps,” for instance, and pitching or matching pennies, are occupations which endure all the year round and are participated in by grown men as well as by boys. On a Sunday morning dozens of crap games are usually in full swing along the streets. Only two players handle the dice, but almost any number of bystanders can take part by betting amongst themselves on the throw—“fading,” as it is called. Pennies, dimes, or dollar bills, according to the prosperity of the bettor, will be thrown upon the sidewalk, for craps is one of the cheapest and most vicious forms of gambling, since there is absolutely no restriction in the betting. Perfect strangers may join in at will if the players will let them, and there are innumerable opportunities for playing with crooked dice. It is one of the chief forms of sidewalk amusements in this neighborhood.

Up above the sidewalks, on the roofs of the tenements, there is some flying of small kites, but pigeon flying is the chief sport. It provides an occupation less immediately remunerative, perhaps, than games of chance, but developed by the same unmoral tendencies which seem to turn all play in the district into vice. Some boys, through methods of accretion peculiar to this neighborhood, have a score or more of pigeons which are kept in the house, and taken up to the roof regularly every Sunday, and oftener during the summer, for exercise. The birds are tamed and carefully taught to return to their home roofs after flight, but ingenious boys have discovered many ways of luring them to alien roofs, so that now the sport of pigeon flying is as dangerously exciting as a commercial venture in the days of the pirates. Pigeon owners also train their birds to circle about the neighborhood and 29 bring back strangers. These strangers are taken inside, fed, and accustomed to the place before they are released again. On Sunday mornings and Sunday evenings the pigeons are to be seen flying around the neighborhood, while behind the chimneys of every fourth or fifth tenement house are crouched one or two small boys armed with long sticks, occasionally giving a low peculiar whistle to attract the pigeons coming from distant roofs. The sticks have a triple use. Pigeon owners use them to force their pigeons to fly for exercise; the little pigeon thieves on the roofs have a net on the end of their sticks for catching the bird when it alights; and most pigeons are trained to remain passive at the touch of the stick so that they may be picked up easily by their owner. This training, of course, operates to the advantage of the thief as well as of the owner, and valuable birds are sometimes lured away and held for ransom.

Pigeon Flying. A Roof Game

Marbles. A Street Game

The two chief sports of the Middle West Side—baseball and boxing—are perennial. The former, played as it always is, with utter carelessness and disregard of surroundings, is theoretically intolerable, but it flourishes despite constant complaints and interference. The diamond is marked out on the roadway, the bases indicated by paving bricks, sticks, or newspapers. Frequently guards are placed at each end of the block to warn of the approach of police. One minute a game is in full swing; the next, a scout cries “Cheese it!” Balls, bats, and gloves disappear with an alacrity due to a generation of practice, and when the “cop” appears round the corner the boys will be innocently strolling down the streets. Notwithstanding these precautions, as the juvenile court records 30 show, they are constantly being caught. In a great majority of these match games too much police vigilance cannot be exercised, for a game between a dozen or more boys, of from fourteen to eighteen years of age, with a league ball, in a crowded street, with plate glass windows on either side, becomes a joke to no one but the participants. A foul ball stands innumerable chances of going through the third-story window of a tenement, or of making a bee line through the valuable plate glass window of a store on the street level, or of hitting one of the passersby. And if the hit is a fair one, it is as likely as not to land on the forehead of a restive horse, or to strike some little child on the sidewalk farther down the street. When one sees the words “Arrested for playing with a hard ball in a public street” written on a coldly impersonal record card in the children’s court one is apt to become indignant. But when you see the same hard ball being batted through a window or into a group of little children on this same public street, the matter assumes an entirely different aspect.

Clearly, from the community’s point of view, the playing of baseball in the street is rightly a penal offense. It annoys citizens, injures persons and property, and interferes with traffic. But for all that, it is not abolished, and probably under present municipal conditions never will be, simply because there is another point of view, that of the boy, and his protest against its suppression is almost equally unanswerable. The store windows are filled with a tempting array of baseball gloves and bats offered at prices as close as possible to his means, and every effort is made by responsible business men, who themselves know the law 31 and the need for order on the streets, to induce him to buy them. Selling the boy those bats and balls is a form of business and is perfectly legal. And the boy cannot see why, after having paid his money for them, the merchant should have all the benefit of the transaction. The game is in itself perfectly harmless; and childhood has an abiding resentment against apparently inexplicable injustice. Perhaps the small boy believes that except for the odds against him his right to make use of the street in his own way is as assured as that of anyone else. Perhaps he reflects that he too has to make sacrifices; that a broken window means usually a lost ball, and a damaged citizen, a ruined game. At any rate he continues to play, and as things are, has a fairly good case for doing so.

This neighborhood is also full of regularly organized ball teams, ranging in the age of players from ten to thirty years. Many of the large factories have teams made up of their own employes. Almost every street gang has its own team, as has almost every social club. These teams meet in regularly matched games, on the waterfront, in the various city parks, or over in New Jersey. Practically all the teams, old and young alike, play for stakes, ranging from two to five dollars a side. When they do not, they call it simply a “friendly” game. There is no organization among them; one team challenges another, and the two will decide on some place to play the game. A few of the adult teams lease Sunday grounds in New Jersey, but most of them trust to the chance of finding one. The baseball leaders of the neighborhood usually have uniforms, and to belong to a uniformed team is one of the great ambitions of the West Side boy. 32

Down on the waterfront the broad, smooth quays offer a tempting place for baseball, especially on Sundays and summer evenings, when they are generally bare of freight. But it has one serious drawback, that a foul ball on one side invariably goes into the river, and the players must have either several balls or a willing swimmer if the game is to continue long. One Sunday game, for instance, between two fourteen-year-old teams, played near the water, cost five balls, varying in price from 50 cents to $1.00 each. The game was played before a scrap-iron yard, the high fence of which was used as a backstop. Fifty feet to the right was the Hudson River. Within a hundred feet of second base, in the center field, a slip reached from the line of the river to the street, which was just beyond third base on the other side. Behind the sixteen-foot fence of the scrap-iron yard were a savage dog at large and a morose watchman to keep out river thieves. Thus hemmed in by water on two sides, a street car line and a row of glass windows on the third side, and a high fence, a savage dog, and a watchman on the fourth, the boys started the game. In the first inning a new dollar ball was fouled over the fence into the scrap-iron yard and the watchman refused to let the boys in to hunt for it. The game was stopped while a deputation of boys from both sides walked up to a nearby street to buy a new fifty-cent ball. The first boy up when the game was resumed batted this ball into the Hudson River, where a youthful swimmer got it, and climbing ashore down the river, made away with it. A third ball was secured, and before the game was half over this ball was batted into the river, where it lodged underneath a barge full of paving stones which 33 was made fast to the dock, and could not be recovered. Then a fourth ball was produced. This lasted till the game was almost finished, though it was once batted deep into center field, where it bounced into the slip and stopped the game while it was being fished out. Finally it followed the first ball into the scrap-iron yard, and neither taunts nor pleas could move the obdurate watchman to let the boys in to find it. The game was finished with a fifth ball which was the personal property of one of the boys. On the occasion of another game in this same place two balls were batted into the scrap-iron yard and lost while the teams were warming up before the match began. A third ball was batted into the river twice but both times it was recovered. Baseball is played on the docks unmodified, but in the streets the boys make use of various adaptations, some of which dispense with the bat and in consequence lessen the dangers of the game.

Ball playing continues sporadically all the year round, and never loses popularity, but it is, of course, mainly a game for the summer. During the winter among the small boys, youths, and men alike, boxing is the all-absorbing sport. It is hard for an outsider to understand the tremendous hold which prize fighting has upon the boys in a neighborhood of this kind. Fights are of course of common occurrence, not only among children but among grown men. This in itself gives a great impetus to the study of the art of self-defense. Good fighters become known early in this district. Professional prize fighters are everywhere; and for every boy who has actually succeeded in getting into the prize ring on one or more occasions, there are a dozen who are eager and anxious for an opportunity. 34 The various athletic clubs of the city always offer chances to boys from fourteen to sixteen years old to appear in the “preliminaries,” as the boxing contests which precede the main bout of the evening are called. A boy who gains a reputation as a street fighter and boxer will be recommended to the manager of an athletic club as a likely aspirant. He is given a chance to box in one or two rounds with another would-be prize fighter in a “preliminary.” If he makes a good showing, he is paid from five to fifteen dollars according to his ability and experience, and is given another chance. If he can continue to make favorable appearances in these preliminaries, he will soon be given a chance of taking part in a six or eight-round bout at one of the smaller athletic clubs, and from that time on he takes regular status as a prize fighter, and accordingly becomes a hero in his circle of youthful acquaintances. There are many such small prize fighters in our district, none of them over twenty-one years of age, and all earning just enough to make it possible to lead a life of indolence. If they can make ten or fifteen dollars by appearing in a ring once a week, they are quite content.

But boxing and street fighting by no means always go together on the Middle West Side. The real professional boxers of the neighborhood dissociate them in practice as well as in theory; they take their profession for what it is—a game to be played in a sportsmanlike manner—and they are usually good-natured. One of the best known prize fighters of the city, who lives on the Middle West Side, states that it is years since he was mixed up in a fight of any kind. “I box 35 because I like the game,” he said, “but I’ve no use for fighting.”

Prize Fighters in Training

Craps with Money at Stake

Another man, an exceedingly clever lightweight boxer, who has appeared several times in the ring in New York City clubs, was boxing one night with a rather crude amateur. The bout was really for the instruction of the amateur, and both boxers were going very easily by agreement. Suddenly the amateur landed an unintentionally hard blow upon the eye of his opponent, just as the latter was stepping forward. The eye became fearfully discolored and the whole side of the boxer’s face swelled. But in spite of his evident feeling that the amateur had taken an unfair advantage in striking so hard when his opponent was off his guard, the lightweight fighter laughed and submitted to treatment for the eye without losing his temper in the least, and freely accepted the apologies of the other.

This is boxing at its best, but unfortunately its tendencies are more usually toward unfairness and brutality than otherwise. Boys are taught to box early in this district. It is not uncommon to see a bout between youngsters of seven or eight being watched by a crowd of young men, who encourage the combatants by cheering every successful blow, but pay no attention to palpable fouls or obvious attempts to take a dishonest advantage. Even some of the best of the prize fighters frankly say that once in the ring the extent to which they foul is only a question of how much they can deceive the referee. And when this questionable code of ethics is passed on by these heroes and leaders of sentiment to the boys who have no referee and no thought beyond that of winning by disabling 36 an opponent as much as possible, the sport degenerates into an unfair and tricky test of endurance. Striking with the open hand, kicking, tripping, hitting in a clinch, all these unfair practices are considered a great advantage if one can “get away with it.” The West Side youngster sees very little of the real professional boxers who, from the very nature of their somewhat strenuous employment, must keep in good condition, as a rule retire early, drink little, and do a great deal of hard gymnastic work. But of their brutalized hangers-on, the “bruisers,” who frequent the saloons and street corners and pose as real fighters, he sees a great deal; consequently, as a whole, prize fighting must be classed as one of the worst influences of the neighborhood. It is too closely allied with street fighting, and too easily turned to criminal purposes. The bully who learns to box will use his acquired knowledge as a means of enforcing his superiority on the street, and if he is beaten will have recourse to weapons or any other means of maintaining his prestige.

Baseball and boxing bring to a close the list of common outdoor games played by boys on the Middle West Side,—just ordinary games, modified by a particular environment and played in a shifting and spasmodic way which is characteristic of it. It remains to emphasize the lesson taught by their effects on boy life as they are practiced in this neighborhood.

The philosophy of the West Side youngster is practical and not speculative. Otherwise he could not fail to notice very early in his career that the world in general, from the mother who bundles him out of an overcrowded tenement in the morning, to the grown-ups in the street playground where most of his time is spent, 37 seem to think him very much in the way. All day long this fact is borne in upon him. If a wagon nearly runs over him the driver lashes him with the whip as he passes to teach him to “watch out.” If he plays around a store door the proprietor gives him a cuff or a kick to get rid of him. If he runs into someone he is pushed into the gutter to teach him better. And if he is complained of as a nuisance the policeman whacks him with hand or club to notify him that he must play somewhere else. Moreover, everything that he does seems to be against the law. If he plays ball he is endangering property by “playing with a hard ball in a public place.” If he plays marbles or pitches pennies he is “obstructing the sidewalk,” and craps, quite apart from the fact that it is gambling, constitutes the same offense. Street fighting individually or collectively is “assault,” and a boy guilty of none of these things may perforce be “loitering.” In other words he finds that property or its representatives are the great obstacles between him and his pleasure in the streets. And in considering our problem neither the principal cause of this situation nor its results must be lost sight of.

The great drawback to normal life on the Middle West Side is that it is a dual neighborhood. Tenements and industrial establishments are so inextricably mixed that the demands of the family and the needs of industry and commerce are eternally in conflict. The same streets must be used for all purposes; and one of the chief sufferers is the boy. More obvious, however, than this cause of a complex situation are the results of it, two of which are especially noticeable. The first is the inevitableness with which the boy 38 accepts—and must accept—illegal and immoral amusements as a matter of course. The spirit of youth is forced to become a criminal tendency, and sport and the rights of property are forced into antagonism. And in the second place, partly because of this, partly because their association with the toughs of the street predisposes them to imitate vice and rowdyism, the boys come to take a positive pleasure in such activities as retaliation by theft and destruction of property. Stores and basements in this district are sometimes completely abandoned owing to the stone throwing and persecution of a youthful gang which has found their occupants too strenuously hostile or defensive. Undoubtedly the street is the most inadequate of playgrounds and throws many difficulties of prevention and interruption in the path of sport. But these obstacles are from their nature provocative of contest, and sport flourishes with a Hydra-like vitality. Nothing short of impossibility will keep the boy and his game apart. 39

It is frequently necessary in these chapters to consider the boy of the Middle West Side as a type; and in discussing the causes and possible solution of the conditions which have produced him it is easy to forget that what the individual boy actually is at the moment is also of very real importance. But as a matter of fact it is not the boy individually but the boy collectively that is the policeman’s bane and the district’s despair. Once on the street the boy is no longer an individual but a member of a gang; and it is with and through the gang that he justly earns a reputation which provoked an irate citizen recently to suggest that for the New York street urchin boiling in burning oil was too good a fate. The court finds him a little villain, and newspapers tell the public that he is a little desperado; but those who know him best know that he is probably worse than either court or public suppose, and that for this the development of the gang on the West Side is primarily responsible.

The formation of “sets” or “gangs” is almost a law of human nature, and boyhood one of its most constant exponents, for a boy is gregarious naturally as well as by training. And over here, where the sociable Irish-American element predominates and children rarely mention the word “home,” it is inevitable that the gang should flourish and its members try to find in 40 its activities the rough affection, comfort, and amusement which a dirty and overcrowded tenement room has failed to give.

The West Side gang is in its origin perfectly normal. In the words of one of the boys, “De kids livin’ on de street jist naturally played together, an’ stuck together w’en anything came up about kids from any other street.” Nothing is more entirely natural and spontaneous, and it is exasperating to reflect that nothing could be a more persuasive and uplifting power in the boy’s life than the gang’s development when given proper scope and direction. Its influence is strong and immediate. The gang contains the friends to whose praise and criticism he is most keenly sensitive, its standards are his aims, and its activities his happiness. Untrammeled by the perversion of special circumstances it might encourage his latent interests, train him to obedience and loyalty, show him the method and the saving of co-operation, and teach him the beauty of self-sacrifice. Gang life at its best does so. The universal endorsement and success of the Boy Scout movement, for instance, in almost every country living under Western civilization, shows this most clearly. Association and rivalry should bring out what is best in a boy; but on the Middle West Side it almost invariably brings out what is worst. Practically, under present conditions, it is inevitable that this should be so; but with the first movement toward amelioration such a result becomes less necessary.

Boy Scouts and Soldiers

After the Battle

Take the case of a certain gang typical of this neighborhood. This gang is now several years old, but its membership is almost exactly what it was four or five years ago. Its members singled each other out from 41 the throng of children in their immediate neighborhood and first made for themselves a cave between two lumber piles in a neighboring yard. All one summer they met in this “hang-out”; here they brought the “loot,” as they call the product of their marauding expeditions, threw craps, pitched pennies, played cards, smoked, told stories, and fought. But they were disturbed by early disaster in the shape of the business needs of the lumber company, which one day caused their shack to be torn down over their heads. They made their headquarters next in the empty basement of a tenement, but soon moved at the well reinforced request of the landlord. After an exiled period of meeting on the street corners, the boys conceived the idea of building their own habitation in the protection of their own homes. They began a small wooden structure in the areaway of the tenement in which the leader lived. But civil war broke out, and in one unhappy culmination the leader of the gang chased his own little brother up two flights of stairs with a hatchet. The little brother promptly “squealed,” and the projected headquarters was destroyed by parental decree.

There followed another interval of meeting on the streets, and then one of the workers in a neighboring settlement became interested. She arranged to have the boys hold meetings in the settlement once a week. They were given certain privileges in the gymnasium and game rooms also, which kept them happily occupied and away from the street influences. But the settlement was closed suddenly and the gang went back to the streets once more. Here is a case in which a gang were from the outset driven from pillar to post 42 by the deficiencies of their surroundings as a playground, and made to feel that every man’s hand was against them. When kindness was shown to them they responded at once. And scores of other gangs, if they were given the chance, would respond in the same way.