Title: The Cambridge, Ely, and King's Lynn Road: The Great Fenland Highway

Author: Charles G. Harper

Release date: September 1, 2019 [eBook #60205]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Alan and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

| The Brighton Road: Old Times and New on a Classic Highway. |

| The Portsmouth Road, and its Tributaries: To-day and in Days of Old. |

| The Dover Road: Annals of an Ancient Turnpike. |

| The Bath Road: History, Fashion, and Frivolity on an Old Highway. |

| The Exeter Road: The Story of the West of England Highway. |

| The Great North Road: The Old Mail Road to Scotland. Two Vols. |

| The Norwich Road: An East Anglian Highway. |

| The Holyhead Road: The Mail-Coach Road to Dublin. Two Vols. |

| Cycle Rides Round London. |

| The Oxford, Gloucester, and Milford Haven Road. [In the Press. |

THE CAMBRIDGE

ELY AND KING'S

LYNN ROAD THE

GREAT FENLAND HIGHWAY

BY CHARLES G. HARPER

AUTHOR OF "THE BRIGHTON ROAD" "THE PORTSMOUTH

ROAD" "THE DOVER ROAD" "THE BATH ROAD"

"THE EXETER ROAD" "THE GREAT NORTH ROAD"

"THE NORWICH ROAD" "THE HOLYHEAD ROAD" AND

"CYCLE RIDES ROUND LONDON"

ILLUSTRATED BY THE AUTHOR, AND FROM OLD-TIME PRINTS

AND PICTURES

London : CHAPMAN & HALL LTD. 1902.

(All Rights Reserved)

Preface

In the course of an eloquent passage in an eulogy of the old posting and coaching days, as opposed to railway times, Ruskin regretfully looks back upon "the happiness of the evening hours when, from the top of the last hill he had surmounted, the traveller beheld the quiet village where he was to rest, scattered among the meadows, beside its valley stream." It is a pretty, backward picture, viewed through the diminishing-glass of time, and possesses a certain specious attractiveness that cloaks much of the very real discomfort attending the old road-faring era. For not always did the traveller behold the quiet village under conditions so ideal. There were such things as tempests, keen frosts, and bitter winds to make his faring highly uncomfortable; to say little of the snowstorms that half smothered him and prevented [Pg viii]his reaching his destination until his very vitals were almost frozen. Then there were MESSIEURS the highwaymen, always to be reckoned with, and it cannot too strongly be insisted upon that until the nineteenth century had well dawned they were always to be confidently expected at the next lonely bend of the road. But, assuming good weather and a complete absence of those old pests of society, there can be no doubt that a journey down one of the old coaching highways must have been altogether delightful.

In the old days of the road, the traveller saw his destination afar off, and—town or city or village—it disclosed itself by degrees to his appreciative or critical eyes. He saw it, seated sheltered in its vale, or, perched on its hilltop, the sport of the elements; and so came, with a continuous panorama of country in his mind's eye, to his inn. By rail the present-day traveller has many comforts denied to his grandfather, but there is no blinking the fact that he is conveyed very much in the manner of a parcel or a bale of goods, and is delivered at his journeys end oppressed with a sense of detachment never felt by one who travelled the road in days of old, or even by the cyclist in the present age. The railway traveller is set down out of the void in a strange place, many leagues from his base;[Pg ix] the country between a blank and the place to which he has come an unknown quantity. In so travelling he has missed much.

The old roads and their romance are the heritage of the modern tourist, by whatever method he likes to explore them. Countless generations of men have built up the highways, the cities, towns, villages and hamlets along their course, and have lived and loved, have laboured, fought and died through the centuries. Will you not halt awhile and listen to their story—fierce, pitiful, lovable, hateful, tender or terrible, just as you may hap upon it; flashing forth as changefully out of the past as do the rays from the facets of a diamond? A battle was fought here, an historic murder wrought there. This way came such an one to seek his fortune and find it; that way went another, to lose life and fortune both. In yon house was born the Man of his Age, for whom that age was ripe; on yonder hillock an olden malefactor, whom modern times would call a reformer, expiated the crime of being born too early—there is no cynic more consistent in his cynicism than Time.

All these have lived and wrought and thought to this one unpremeditated end—that the tourist travels smoothly and safely along roads once rough and dangerous beyond belief, and that as he goes [Pg x]every place has a story to tell, for him to hear if he will. If he have no ears for such, so much the worse for him, and by so much the poorer his faring.

CHARLES G. HARPER.

Petersham, Surrey,

October 1902.

List of Illustrations

SEPARATE PLATES

| PAGE | |

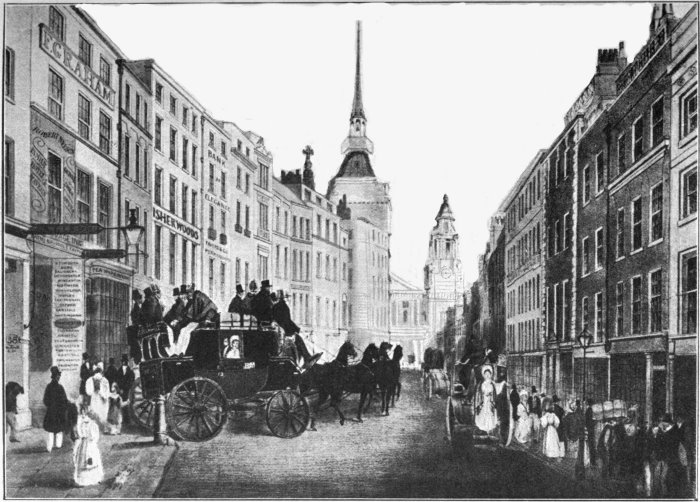

| The "Cambridge Telegraph" starting from the White Horse, Fetter Lane From a Print after J. Pollard. |

Frontispiece |

| The "Star of Cambridge" starting from the Belle Sauvage Yard, Ludgate Hill, 1816 From a Print after T. Young. |

17 |

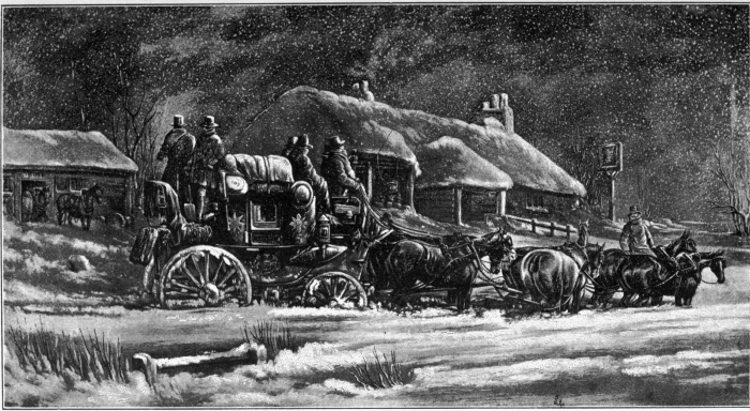

| "Knee-Deep": the "Lynn and Wells Mail" in a Snowstorm From a Print after C. Cooper Henderson. |

23 |

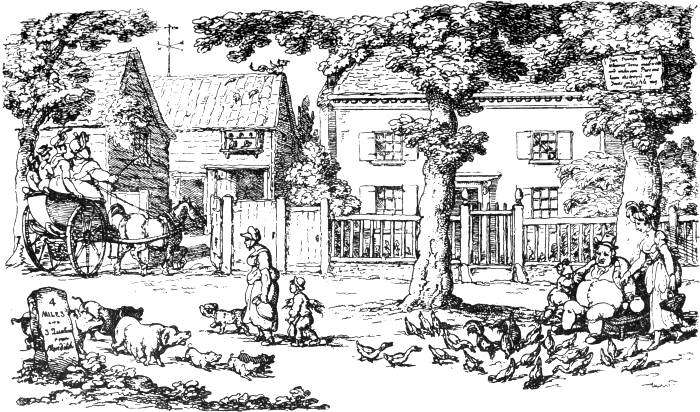

| A London Suburb in 1816: Tottenham From a Drawing by Rowlandson. |

39 |

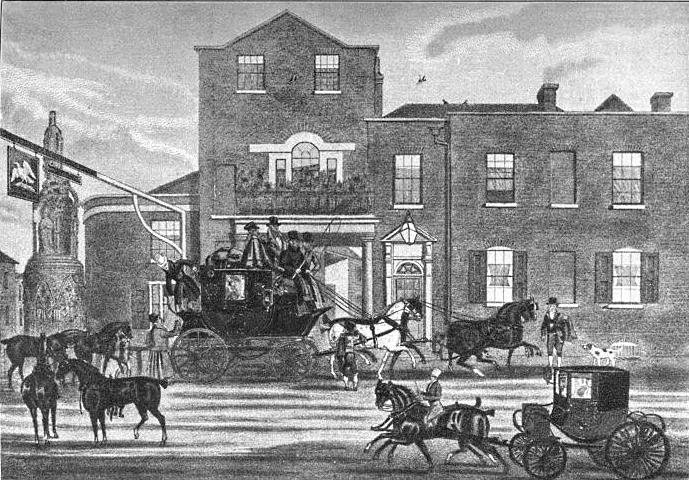

| Waltham Cross | 61 |

| The "Hull Mail" at Waltham Cross From a Print after J. Pollard. |

65 |

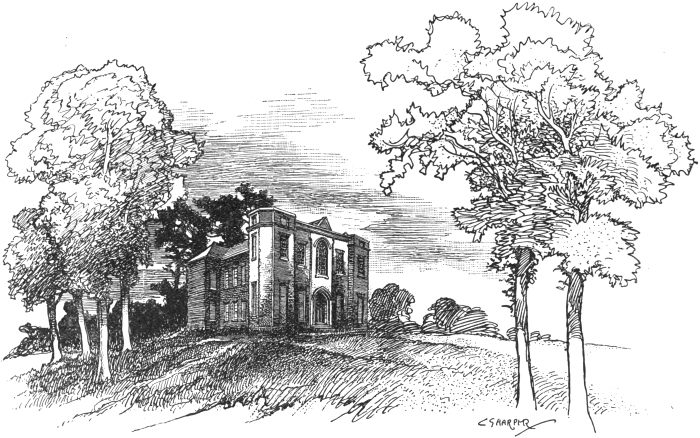

| Cheshunt Great House | 77 |

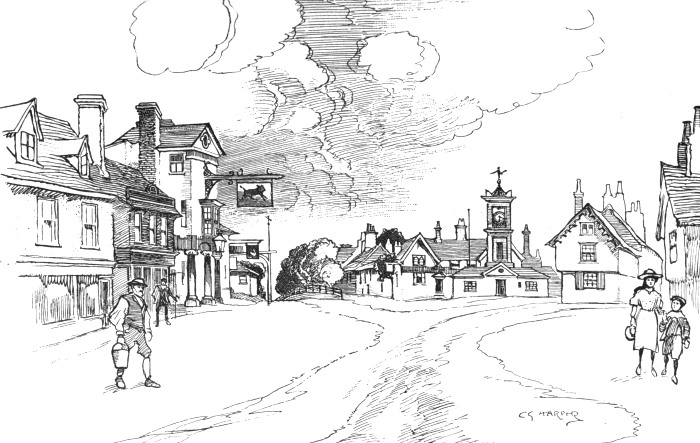

| Hoddesdon | 83 |

| Ware | 89 |

| Barley | 105 |

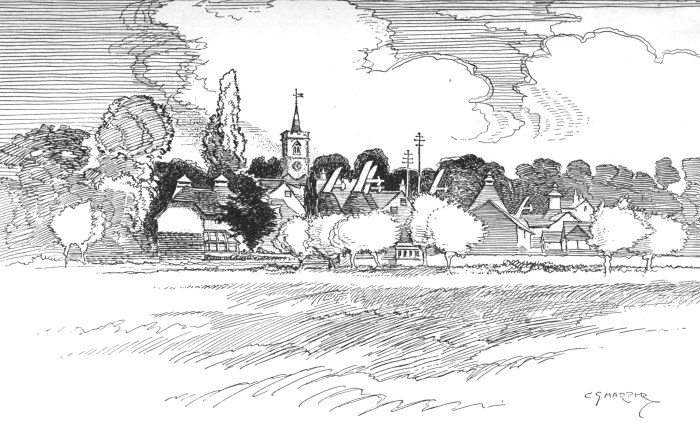

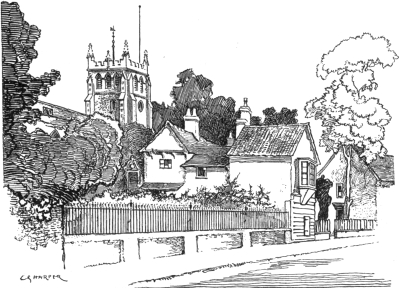

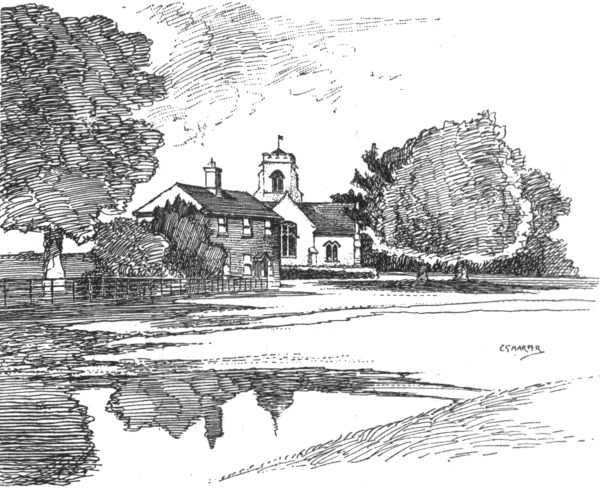

| Fowlmere: a typical Cambridgeshire Village | 113 |

| Melbourn | 129 |

| Trumpington Mill[Pg xii] | 137 |

| Trumpington Street, Cambridge | 145 |

| Hobson, the Cambridge Carrier | 159 |

| A Wet Day in the Fens | 203 |

| Aldreth Causeway | 219 |

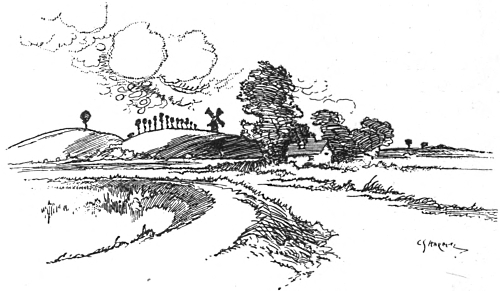

| A Fenland Road: the Akeman Street near Stretham Bridge |

245 |

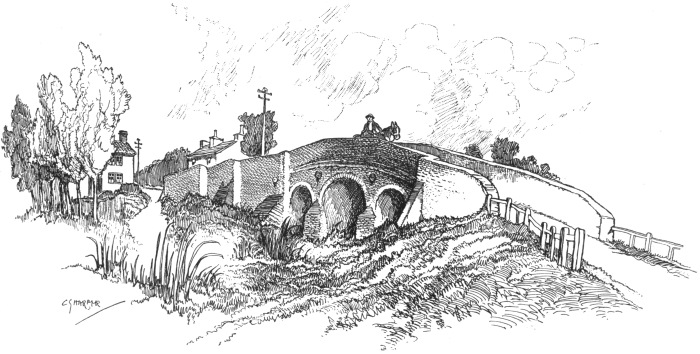

| Stretham Bridge | 249 |

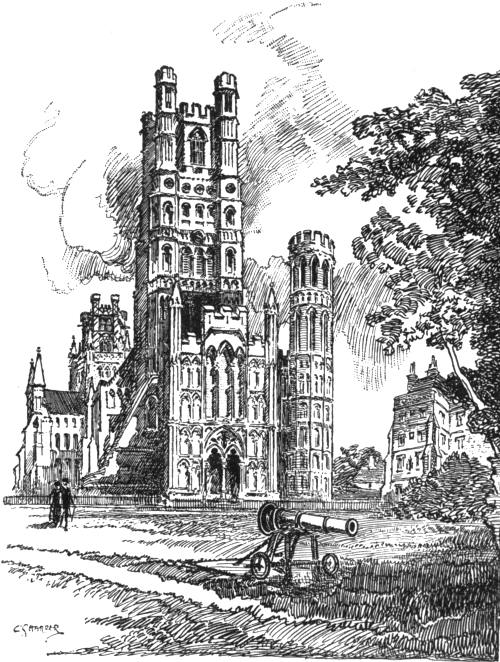

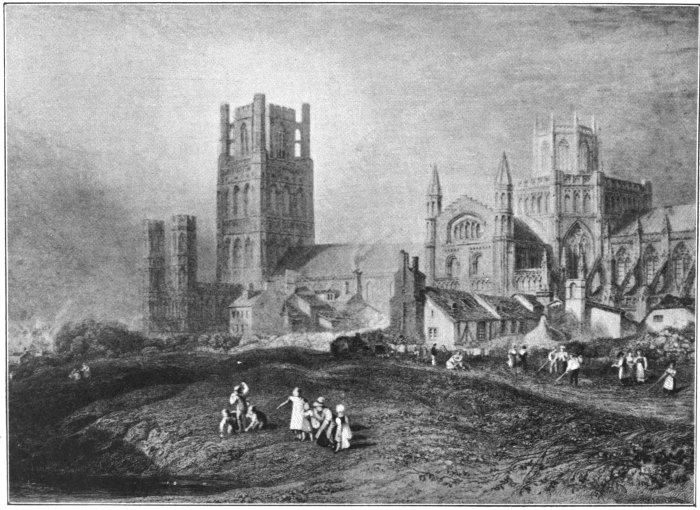

| Ely Cathedral After J. M. W. Turner, R.A. |

271 |

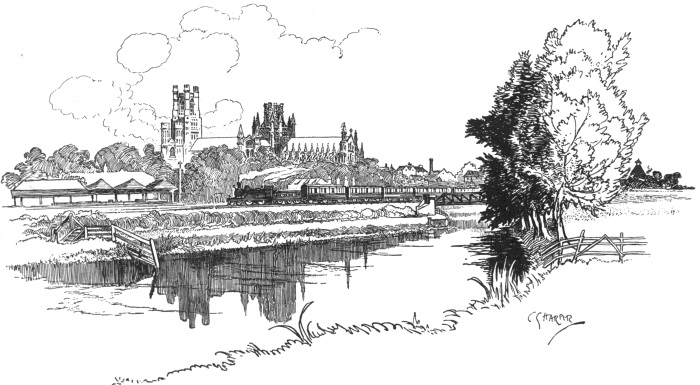

| Ely, from the Ouse | 277 |

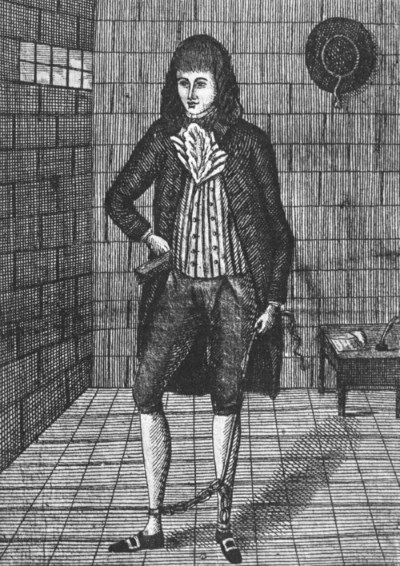

| Joseph Beeton in the Condemned Cell | 311 |

| The Town and Harbour of Lynn, from West Lynn | 317 |

| "Clifton's House" | 320 |

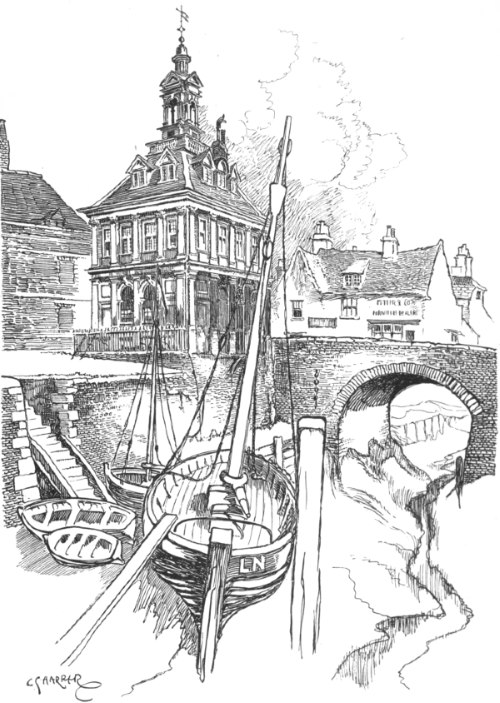

| The Custom-House, Lynn | 323 |

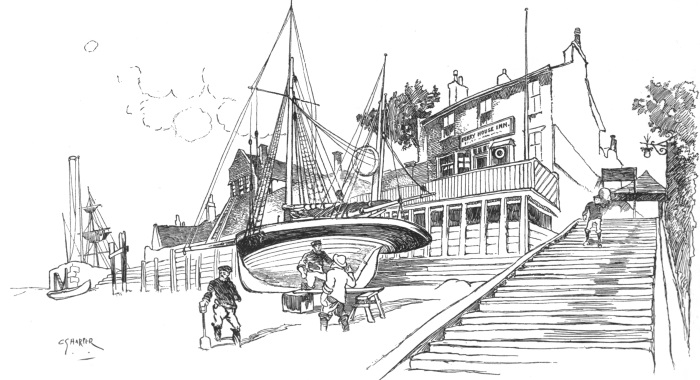

| The Ferry Inn, Lynn | 327 |

ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT

| PAGE | |

| Vignette: Eel-Spearing | Title-page |

| Preface | vii |

| List of Illustrations: Taking Toll | xi |

| The Cambridge, Ely, and King's Lynn Road | 1 |

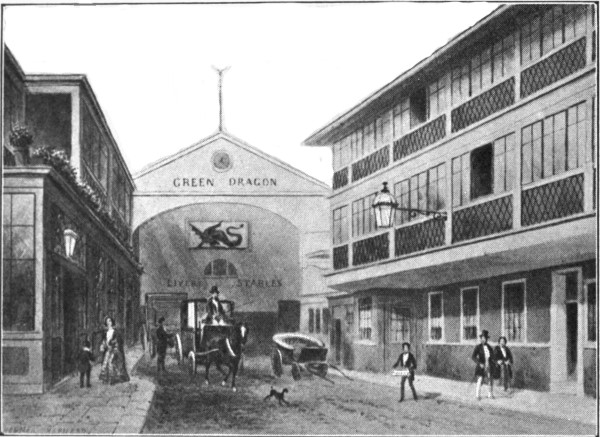

| The Green Dragon, Bishopsgate Street, 1856 From a Drawing by T. Hosmer Shepherd. |

8 |

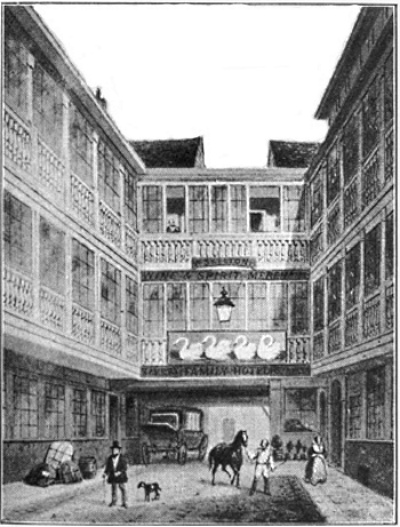

| The Four Swans, Bishopsgate Street, 1855 From a Drawing by T. Hosmer Shepherd. |

9 |

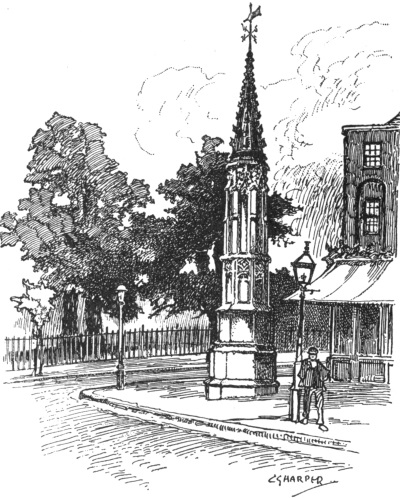

| Tottenham Cross | 38 |

| Balthazar Sanchez' Almshouses, Tottenham | 41 |

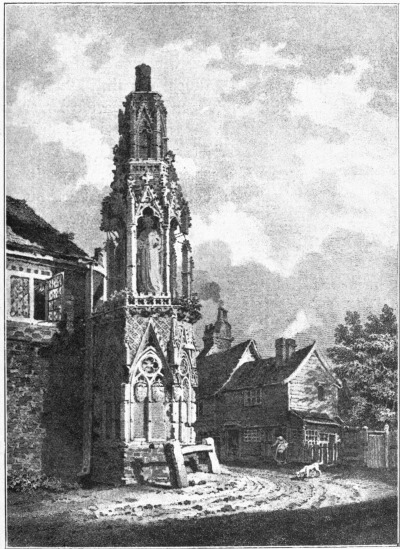

| Waltham Cross a hundred years ago | 59 |

| The Roman Urn, Cheshunt | 76 |

| Charles the First's Rocking-Horse | 79 |

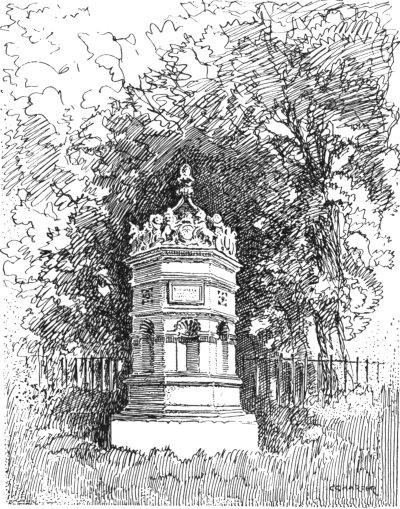

| Clarkson's Monument | 99 |

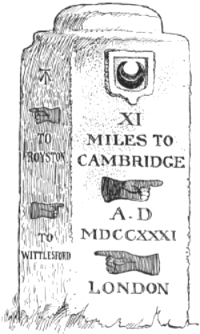

| A Monumental Milestone | 111 |

| The Chequers, Fowlmere | 115 |

| West Mill | 118 |

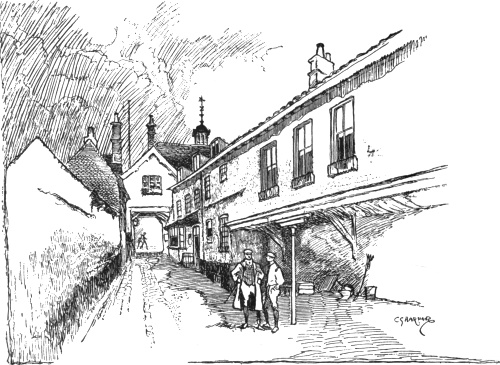

| A Quaint Corner in Royston | 125 |

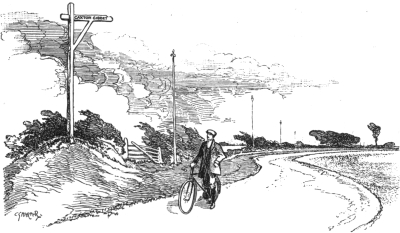

| Caxton Gibbet | 127 |

| The First Milestone from Cambridge | 139 |

| Hobson's Conduit | 141 |

| Hobson From a Painting in Cambridge Guildhall. |

162 |

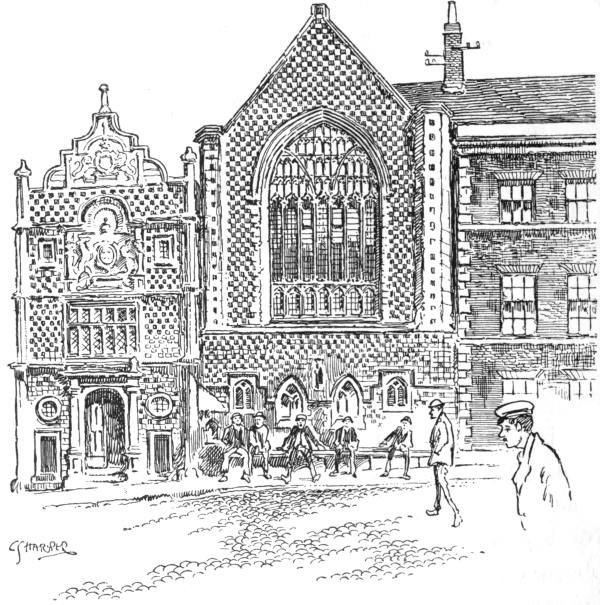

| Market Hill, Cambridge | 167 |

| The Falcon, Cambridge | 168 |

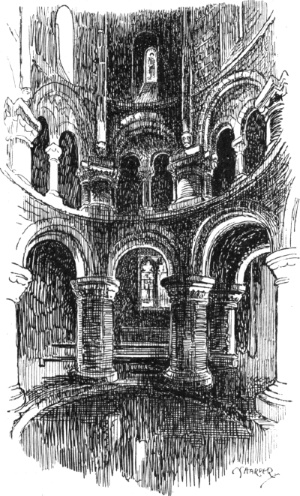

| Interior of St. Sepulchre's Church[Pg xiv] | 169 |

| Cambridge Castle a hundred years ago | 171 |

| Landbeach | 181 |

| The Fens After Dugdale. |

191 |

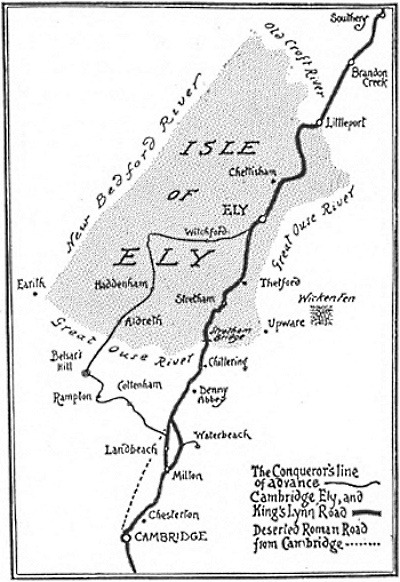

| The Isle of Ely and district | 215 |

| Aldreth Causeway and the Isle of Ely | 218 |

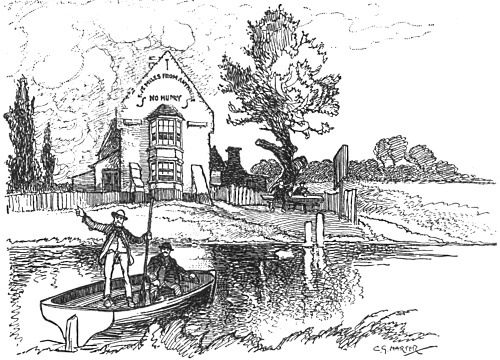

| Upware Inn | 237 |

| Wicken Fen | 241 |

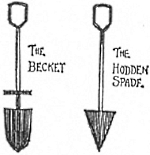

| Hodden Spade and Becket | 248 |

| Stretham | 254 |

| The West Front, Ely Cathedral | 265 |

| Ely Cathedral, from the Littleport Road | 289 |

| Littleport | 291 |

| The River Road, Littleport | 293 |

| The Ouse | 295 |

| Southery Ferry | 296 |

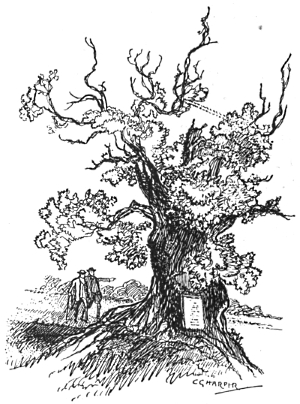

| Kett's Oak | 300 |

| Denver Hall | 301 |

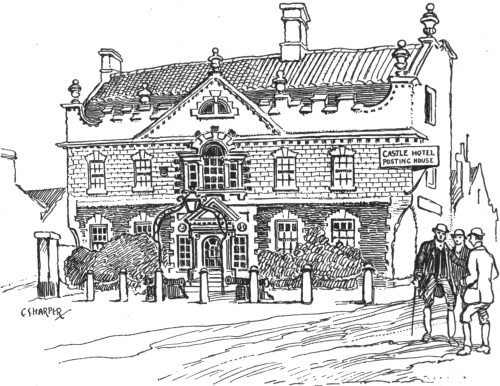

| The Crown, Downham Market | 302 |

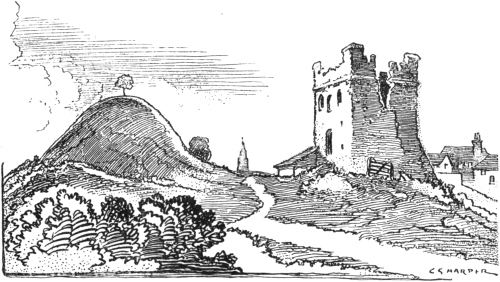

| The Castle, Downham Market | 303 |

| Hogge's Bridge, Stow Bardolph | 305 |

| The Lynn Arms, Setchey | 306 |

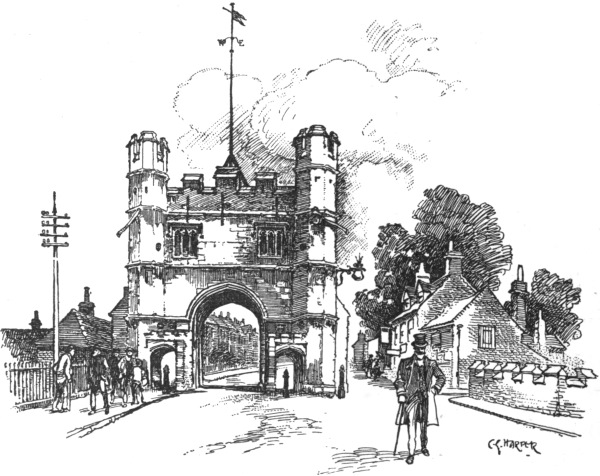

| The South Gates, Lynn | 308 |

| The Guildhall, Lynn | 314 |

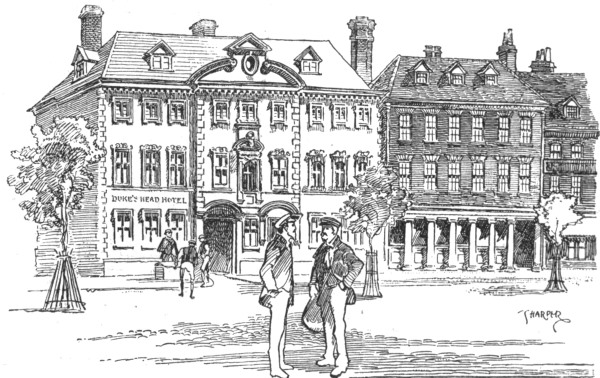

| The Duke's Head, Lynn | 321 |

| Islington | 329 |

THE ROAD TO CAMBRIDGE, ELY,

AND

KING'S LYNN

| London (Shoreditch Church) to— | MILES | ||

| Kingsland | 1 | ½ | |

| Stoke Newington | 2 | ½ | |

| Stamford Hill | 3 | ¼ | |

| Tottenham High Cross | 4 | ¼ | |

| Tottenham | 5 | ¼ | |

| Upper Edmonton | 6 | ||

| Lower Edmonton | 6 | ¾ | |

| Ponder's End | 8 | ½ | |

| Enfield Highway | 9 | ¼ | |

| Enfield Wash | 10 | ||

| Waltham Cross | 11 | ½ | |

| Crossbrook Street | 12 | ||

| Turner's Hill | 13 | ||

| Cheshunt | 13 | ¼ | |

| Cheshunt Wash | 13 | ¾ | |

| Turnford | 14 | ||

| Wormley (cross New River) | 14 | ¾ | |

| Broxbourne | 15 | ¾ | |

| Hoddesdon | 17 | ||

| Great Amwell (cross New River and the Lea) | 19 | ¼ | |

| Ware | 21 | ||

| Wade's Mill (cross River Rib) | 23 | ||

| High Cross | 23 | ½ | |

| Collier's End | 25 | ||

| Puckeridge (cross River Rib) | 26 | ¾ | |

| Braughing | 27 | ¾ | |

| Quinbury | 28 | ¾ | |

| Hare Street | 30 | ¾ | |

| Barkway | 35 | ||

| Barley | 36 | ¾ | |

| Fowlmere | 42 | ||

| Newton | 44 | ¼ | |

| [Pg xvi]Hauxton (cross River Granta) | 47 | ¾ | |

| Trumpington | 48 | ½ | |

| Cambridge (Market Hill) | 50 | ¾ | |

| To Cambridge, through Royston— | |||

| Puckeridge (cross River Rib) | 26 | ¾ | |

| West Mill | 29 | ¾ | |

| Buntingford | 31 | ||

| Chipping | 32 | ½ | |

| Buckland | 33 | ¾ | |

| Royston | 37 | ¾ | |

| Melbourn | 41 | ¼ | |

| Shepreth | 43 | ¼ | |

| Foxton Station and Level Crossing | 44 | ||

| Harston | 45 | ½ | |

| Hauxton (cross River Granta) | 46 | ½ | |

| Trumpington | 48 | ¾ | |

| Cambridge (Market Hill) | 51 | ||

| Milton | 54 | ||

| Landbeach | 54 | ¾ | |

| Denny Abbey | 58 | ||

| Chittering | 58 | ¾ | |

| Stretham Bridge (cross Great Ouse River) | 61 | ¾ | |

| Stretham | 63 | ¼ | |

| Thetford Level Crossing | 64 | ½ | |

| Ely | 67 | ½ | |

| Chettisham Station and Level Crossing | 69 | ½ | |

| Littleport | 72 | ½ | |

| Littleport Bridge (cross Great Ouse River) | 73 | ½ | |

| Brandon Creek (cross Little Ouse River) | 76 | ¾ | |

| Southery | 78 | ¾ | |

| Modney Bridge (cross Sams Cut Drain) | 80 | ¼ | |

| Hilgay (cross Wissey River) | 81 | ¾ | |

| Fordham | 82 | ¾ | |

| Denver | 84 | ||

| Downham Market | 85 | ¼ | |

| Wimbotsham | 86 | ½ | |

| Stow Bardolph | 87 | ¼ | |

| South Runcton (cross River Nar) | 89 | ¼ | |

| Setchey | 92 | ¼ | |

| West Winch | 93 | ¾ | |

| Hardwick Bridge | 95 | ¼ | |

| King's Lynn | 97 | ¼ | |

The Cambridge Ely and King's Lynn Road

I

"Sister Anne, Sister Anne, do you see anyone coming?" asks Fatima in the story of Bluebeard. Clio, the Muse of History, shall be my Sister Anne. I hereby set her down in the beginnings of the Cambridge Road, bid her be retrospective, and ask her what she sees.

"I see," she says dreamily, like some medium or clairvoyant,—"I see a forest track leading from the marshy valley of the Thames to the still more marshy valley of the Lea. The tribes who inhabit the land are at once fierce and warlike, and greedy for trading with merchants from over the narrow channel that separates Britain from Gaul. They are fair-haired and blue-eyed, they are dressed in the skins of wild animals, and their chieftains wear many ornaments of red gold." Then she is silent, for Clio, like her eight sisters, is a very ancient personage, and like the aged, although she knows much, cannot recall sights and scenes without a deal of mental fumbling.

"And what else do you see?"

"There comes along the forest track a great concourse of soldiers. Never before were such seen in the land. They form the advance-guard of an invading army, and the tribes presently fly from them, for these are the conquering Romans, whose fame has come before them. There are none who can withstand those soldiers."

"Many a tall Roman warrior, doubtless, sleeps where he fell, slain by wounds or disease in that advance?"

Clio is indignant and corrective. "The Romans," she says, "were not a race of tall men. They were undersized, but well built and of a generous chest-development. They are, as I see them, imposing as they march, for they advance in solid phalanx, and their bright armour, their shields and swords, flash like silver in the sun.

"I see next," she says, "these foreign soldiers as conquerors, settled in the land. They have an armed camp in a clearing of the forest, where a company of them keep watch and ward, while many more toil at the work of making the forest track a broad and firm military way. Among them, chained together like beasts, and kept to their work by the whips and blows of taskmasters, are gangs of natives, who perform the roughest and the most unskilled of the labour.

"And after that I see four hundred years of Roman power and civilisation fade like a dream, and then a dim space of anarchy, lit up by the fitful glare of fire, and stained and running red with blood. Many strange and heathen peoples come and go in[Pg 3] this period along the road, once so broad and flat and straight, but now grown neglected. The strange peoples call themselves by many names,—Saxons, Vikings, Picts, and Scots and Danes,—but their aim is alike: to plunder and to slay. Six hundred years pass before they bring back something of that civilisation the Romans planted, and the land obtains a settled Christianity and an approach to rest. And then, when things have come to this pass, there comes a stronger race to make the land its own. It is the coming of the Normans.

"I see the Conqueror, lord of all this land but the Isle of Ely, coming to vanquish the English remnant. I see him, his knights and men-at-arms, his standard-bearers and his bowmen, marching where the Romans marched a thousand years before, and in three years I see the shrunken remains of his army return, victorious, but decimated by those conquered English and their allies, the agues and fevers, the mires and mists of the Fens."

"And then—what of the Roman Road, the Saxon 'Ermine Street'? tell me, why does it lie deserted and forgot?"

But Clio is silent. She does not know; it is a question rather for archæology, for which there is no Muse at all. Nor can she tell much of the history of the road, apart from the larger national concerns in which it has a part. She is like a wholesale trader, and deals only in bulk. Let us in these pages seek to recover something from the past to illustrate the description of these many miles.

II

The coach-road to Cambridge, Ely, and King's Lynn—the modern highway—follows in general direction, and is in places identical with, two distinct Roman roads. From Shoreditch Church, whence it is measured, to Royston, it is on the line of the Ermine Street, the great direct Roman road to Lincoln and the north of England, which, under the names of the "North Road" and the "Old North Road," goes straight ahead, past Caxton, to Alconbury Hill, sixty-eight miles from London, where it becomes identical with our own Great North Road, as far as Stamford and Casterton.

From Royston to Cambridge there would seem never to have been any direct route, and the Romans apparently reached Cambridge either by pursuing the Ermine Street five miles farther, and thence turning to the right at Arrington Bridge; or else by Colchester, Sudbury, and Linton. Those, at anyrate, are the ways obvious enough on modern maps, or in the Antonine Itinerary, that Roman road-book made about A.D. 200-250. We have, however, only to exercise our own observation to find that the Antonine Itinerary is a very inaccurate piece of work, and that the Romans almost certainly journeyed to Camboricum, their Cambridge, by way of Epping, Bishop's Stortford, and Great Chesterford, a route taken by several coaches sixty years ago.

From Cambridge to Ely and King's Lynn the[Pg 5] coach-road follows with more or less exactness the Akeman Street, a Roman way in the nature of an elevated causeway above the fens.

The Ermine Street between London and Lincoln is not noted by the Antonine Itinerary, which takes the traveller to that city by two very indirect routes: the one along the Watling Street as far as High Cross, in Warwickshire, and thence to the right, along the Fosse Way past Leicester; the other by Colchester. The Ermine Street, leading direct to Lincoln, is therefore generally supposed to be a Roman road of much later date.

We are not to suppose that the Romans knew these roads by the names they now bear; names really given by the Saxons. Ermine Street enshrines the name of Eorman, some forgotten hero or divinity of that people; and the Akeman Street, running from the Norfolk coast, in a south-westerly direction through England, to Cirencester and Bath, is generally said to have obtained its name from invalids making pilgrimage to the Bath waters, there to ease them of their aches and pains. But a more reasonable theory is that which finds the origin of that name in a corruption of Aquæ Solis, the name of Bath.

No reasonable explanation has ever been advanced of the abandonment of the Ermine Street between Lower Edmonton and Ware, and the choosing of the present route, running roughly parallel with it at distances ranging from half a mile to a mile, and by a low-lying course much more likely to be flooded than the old Roman highway.[Pg 6] The change must have been made at an early period, far beyond the time when history dawns on the road, for it is always by the existing route that travellers are found coming and going.

Few know that the Roman road and the coaching road are distinct; and yet, with the aid of a large-scale Ordnance map, the course of the Ermine Street can be distinctly traced. Not only so, but a day's exploration of it, as far as its present condition, obstructed and diverted in places, will allow, is of absorbing interest.

It makes eleven miles of, in places, rough walking, and often gives only the satisfaction of being close to the actual site, and not actually on it. A straight line drawn from where the modern road swerves slightly to the right at Northumberland Park, Edmonton, to Ware, gives the direction the ancient road pursued.

The exact spot where the modern road leaves the Roman way is found at Lower Edmonton, where a Congregational Church stands in an open space, and the houses on the left hand are seen curving back to face a lane that branches off at this point. This, bearing the significantly ancient name of "Langhedge Lane," goes exactly on the line of the Ermine Street; but it cannot be followed for more than about a hundred yards, for it is cut through by railways and modern buildings, and quite obliterated for some distance. Where lanes are found near Edmonton Rectory on the site of the ancient way, names that are eloquent of an antiquity closely allied with Roman times begin to appear. "Bury[Pg 7] Hall," and, half a mile beyond it, "Bury Farm," neighboured by an ancient moat, are examples. "Bury" is a corruption of a Saxon word meaning anything, from a fortified camp to a settlement, or a hillock; and when found beside a Roman road generally signifies (like that constantly recurring name "Coldharbour") that the Saxons found deserted Roman villas by the wayside. Beyond Bury Farm the cutting of the New River in the seventeenth century obscured some length of the Ermine Street. A long straight lane from Forty Hill Park, past Bull's Cross, to Theobalds, represents it pretty accurately, as does the next length, by Bury Green and Cheshunt Great House. Cold Hall and Cold Hall Green mark its passing by, even though, just here, it is utterly diverted or stopped up. "Elbow Lane" is the name of it from the neighbourhood of Hoddesdon to Little Amwell. Beyond that point it plunges into narrower lanes, and thence into pastures and woods, descending steeply therefrom into the valley of the Lea by Ware. In those hillside pastures, and in an occasional wheatfield, a dry summer will disclose, in a long line of dried-up grass or corn, the route of that ancient paved way below the surface. A sepulchral barrow in one of these fields, called by the rustics "Penny loaf Hill," is probably the last resting-place of some prehistoric traveller along this way. A quarter of a mile from Ware the Ermine Street crossed the Lea to "Bury Field," now a brickfield, where many Roman coins have been found. Thenceforward it is one with the present highway to Royston.

III

THE GREEN DRAGON, BISHOPSGATE STREET, 1856.

[From a Drawing by T. Hosmer Shepherd]

Although Shoreditch Church marks the beginning of the Cambridge Road, of the old road to the North, and of the highways into Lincolnshire, it was always to and from a point somewhat nearer the City of London that the traffic along these various ways came and went. Bishopsgate Street was of old the great centre for coaches and vans, and until quite modern times—until, in fact, after railways had come—those ancient inns, the Four Swans, the Vine, the Bull, the Green Dragon, and many another, still faced upon the street, as for many centuries they had done. Coaches were promptly withdrawn on the opening of the railways, but the [Pg 9]lumbering old road-waggons, with their vast tilts, broad wheels, swinging horn-lanterns, and long teams of horses, survived for some years later. Now everything is changed; inns, coaches, waggons are all gone. You will look in vain for them; and of the most famous inn of all—the Bull, in Bishopsgate Street Within—the slightest memory survives. On its site rises that towering block of commercial offices called "Palmerston House," crawling abundantly, like some maggoty cheese, with companies and secretaries, clerks and office-boys, who seem,[Pg 10] like mites, to writhe out of the interstices of the stone and plaster. Overhead, on the dizzy roof, are the clustered strands of the telegraph-wires, resembling the meshes of some spider's web, exquisitely typical of much that goes forward in those little cribs and hutches of offices within. It is a sorry change from the old Bull—the Black Bull, as it was originally named—with its cobble-stoned courtyard and surrounding galleries, whence audiences looked down upon the plays of Shakespeare and others of the Elizabethans, and so continued until the Puritans came and stage-plays were put under interdict. When plays were not being enacted in that old courtyard, it was crowded with the carriers' vans out of Cambridgeshire and the Eastern Counties generally. "The Black Bull," we read in a publication dated 1633, "is still looking towards Shoreditch, to see if he can spy the carriers coming from Cambridge." Would that it still looked towards Shoreditch!

THE FOUR SWANS, BISHOPSGATE STREET, 1855.

[From a Drawing by T. Hosmer Shepherd.]

It was to the Bull that old Hobson, the Cambridge carrier of such great renown, drove on his regular journeys, between 1570 and 1631. Hobson was the precursor, the grand original, of all the Pickfords and Carter Patersons of this crowded age, and lives immortal, though his body be long resolved to dust, as the originator of a proverb. That is immortality indeed! No deed of chivalry, no great achievement in the arts of peace and war, shall so surely render your name imperishable as the linking of it with some proverb or popular saying. Who has not heard of "Hobson's[Pg 11] Choice"? Have you never been confronted with that "take it or leave it" offer yourself? For, in truth, Hobson's Choice is no choice at all; and is, and ever was, "that or none." The saying arose from the livery-stable business carried on by Thomas Hobson at Cambridge, in addition to his carrying trade. He is, indeed, rightly or wrongly, said to have been the first who made a business of letting out saddle-horses. His practice, invariably followed, was to refuse to allow any horse in his stables to be taken out of its proper turn. "That or none" was his unfailing formula, when the Cambridge students, eager to pick and choose, would have selected their own fancy in horseflesh. Every customer was thus served alike, without favour. Hobson's fame, instead of flickering out, has endured. Many versified about him at his death, but one of the best rhymed descriptions of his stable practice was written in 1734, a hundred and three years later, by Charles Waterton, as a translation from the Latin of Vincent Bourne—

IV

Who was that man, or who those associated adventurers, to first establish a coach between London and Cambridge, and when was the custom first introduced of travelling by coach, instead of on horseback, along this road? No one can say. We can see now that he who first set up a Cambridge coach must of necessity have been great and forceful: as great a man as Hobson, in whose time people were well content to hire horses and ride them; but although University wits have sung the fame of Hobson, the greater innovator and the date of his innovation alike remain unknown. It is vaguely said that the first Cambridge coach was started in the reign of Charles the Second, but Pepys, who might have been trusted to mention so striking a novelty, does not refer to such a thing, and, as on many other roads, we hear nothing definite until 1750, when a Cambridge coach went up and down twice a week, taking two whole days each way, staying the night at Barkway going, and at Epping returning. The same team of horses dragged the coach the whole way. There was in this year a coach through to Lynn, once a week, setting out on Fridays in summer and Thursdays in winter.

In 1753 a newer era dawned. There were then two conveyances for Cambridge, from the Bull and the Green Dragon in Bishopsgate: one leaving Tuesdays and Fridays, the other Wednesdays and Saturdays, reaching the Blue Boar and the Red Lion, Cambridge,[Pg 13] the same night and returning the following day, when that day did not happen to be Sunday.

Each of these stage-coaches carried six passengers, all inside, and the fares were about twopence-halfpenny a mile in summer and threepence in winter. The cost of a coach journey between London and Cambridge was then, therefore, about twelve shillings.

Hobson's successors in the carrying business had by this time increased to three carriers, owning two waggons each. There were thus six waggons continually going back and forth in the mid-eighteenth century. They took two and a half days to perform the fifty-one miles, and "inned" at such places as Hoddesdon, Ware, Royston, and Barkway, where they would be drawn up in the coachyards of the inns at night, and those poor folk who travelled by them at the rate of three-halfpence a mile would obtain an inexpensive supper, with a shakedown in loft or barn.

The coaches at this period did by much effort succeed in performing the journey in one day, but it was a long day. They started early and came late to their journey's end; setting out at four o'clock in the morning, and coming to their destination at seven in the evening; a pace of little more than three miles an hour.

In 1763, owing partly to the improvements that had taken place along the road, and more perhaps to the growing system of providing more changes of horses and shorter stages, the "London and Cambridge Diligence" is found making the journey daily, in eight hours, by way of Royston, "performed by J. Roberts of the White Horse, Fetter Lane;[Pg 14] Thomas Watson's, the Red Lyon, Royston; and Jacob Brittain, the Sun, Cambridge." The "Diligence" ran light, carrying three passengers only, at a fare of thirteen shillings and sixpence. There were in this same year two other coaches; the "Fly," daily, from the Queen's Head, Gray's Inn Lane, by way of Epping and Chesterford, to the Rose on the Market Hill, Cambridge, at a fare of twelve shillings; and the "Stage," daily, to the Red Lion, Petty Cury, carrying four passengers at ten shillings each.

We hear little at this period of coaches or waggons on to Ely and King's Lynn. Cambridgeshire and Norfolk roads were only just being made good, after many centuries of neglect, and Cambridge town was still, as it always had been (strange though it may now seem), something of a port. The best and safest way was to take boat or barge by Cam and Ouse, rather than face the terrors of roads almost constantly flooded. Gillam's, Burleigh's, and Salmon's waggons, which at this time were advertised to ply between London and Cambridge, transferred their loads on to barges at the quays by Great Bridge. Indeed it was not until railways came that Cambridge ceased to depend largely upon the rivers, and the coals burnt, the wine drank, and the timber used were water-borne to the very last. Hence we find the town always in the old days peculiarly distressed in severe winters when the waterways were frozen; and hence, too, the remonstrance made by the Mayor and Corporation when Denver Sluice was rebuilt in 1745, "to the hindering of the navigation to King's Lynn."

In 1796, the roads now moderately safe, a stage-coach is found plying from Cambridge to Ely and back in one day, replacing the old "passage-boats"; but Lynn, as far as extant publications tell us, was still chiefly approachable by water. In this year Cambridge enjoyed a service of six coaches between the town and London, four of them daily; the remaining two running three times a week. The Mail, on the road ten years past, started at eight o'clock every night from the Bull and Mouth, London, and, going by Royston, arrived at the Sun, Cambridge, at 3.30 the following morning. The old "Diligence," which thirty-three years before had performed the journey in eight hours, now is found to take nine, and to have raised its fares from thirteen shillings and sixpence to one guinea, going to the Hoop instead of the Sun. The "Fly," still by Epping and Great Chesterford, has raised its fares from twelve shillings to eighteen shillings, and now takes "outsides" at nine shillings. It does not, however, fly very swiftly, consuming ten hours on the way. "Prior's Stage" is one of the new concerns, leaving the Bull, Bishopsgate Street, at eight in the morning on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, and, going by Barkway, arriving at some unnamed hour at the Red Lion, Petty Cury. It conveys six passengers at fifteen shillings inside and eight shillings out, like its competitor, "Hobson's Stage," setting out on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Saturdays from the Green Dragon, Bishopsgate Street, for the Blue Boar, Cambridge. "Hobson's" is another new-comer, merely trading on the glamour of the old name.[Pg 16] The "Night Post Coach" of this year, starting from the Golden Cross, Charing Cross, every afternoon at 5.30, went by Epping and Great Chesterford. It carried only four passengers inside, at fifteen shillings each, and a like number outside at nine shillings. Travelling all night, and through the dangerous glades of Epping Forest, the old advertisement especially mentions it to be "guarded." Passing through many nocturnal terrors, the "Night Post Coach" finally drew up in the courtyard of the still-existing Eagle and Child (now called the Eagle) at Cambridge, at three o'clock in the morning.

The next change seems to have been in 1804,

when the "Telegraph" was advertised to cover the

fifty-one miles in seven hours,—and made the promise

good. People said it was all very well, but shook

their heads and were of opinion that it would not

last. In 1821, however, we find the "Telegraph"

still running, and actually in six hours, starting

every morning at nine o'clock from the White Horse

in Fetter Lane, going by Barkway, and arriving at

the Sun at Cambridge at 3 p.m. This is the coach

shown in Pollard's picture in the act of leaving the

White Horse. In the meanwhile, however, in 1816

another and even faster coach, the "Star of

Cambridge," was established, and, if we may go so

far as to believe the statement made on the rare old

print showing it leaving the Belle Sauvage Yard

on Ludgate Hill in that year, it performed the

journey in four hours and a half! Allowing for

necessary stops for changing on the way, this would

give a pace of over eleven miles an hour; and we may

[Pg 17]

[Pg 18]

[Pg 19]perhaps, in view of what both the roads and coaching

enterprise were like at that time, be excused from

believing that, apart from the special effort of any

one particular day, it ever did anything of the kind;

even in 1821, five years later, as already shown, the

"Telegraph," the crack coach of the period on this

road, took six hours!

THE "STAR OF CAMBRIDGE" STARTING FROM THE BELLE SAUVAGE YARD, LUDGATE HILL, 1816.

[From a Print after T. Young.]

Let us see what others there were in 1821. To Cambridge went the "Safety," every day, from the Boar and Castle, Oxford Street, and the Bull, Aldgate, leaving the Bull at 3 p.m. and arriving at Cambridge, by way of Royston, in six hours; the "Tally Ho," from the Bull, Holborn, every afternoon at two o'clock, by the same route in the same time; the "Royal Regulator," daily, from the New Inn, Old Bailey, in the like time, by Epping and Great Chesterford; the old "Fly," daily, from the George and Blue Boar, Holborn and the Green Dragon, Bishopsgate, at 9 a.m., by the same route, in seven hours; the "Cambridge Union," daily, from the White Horse, Fetter Lane and the Cross Keys, Wood Street, at 8 a.m., by Royston, in eight hours, to the Blue Boar, Cambridge; the "Cambridge New Royal Patent Mail," still by Royston, arriving at the Bull, Cambridge, in seven and a half hours; the "Cambridge and Ely" coach, every evening at 6 p.m., from the Golden Cross and the White Horse, arriving at the Eagle and Child, Cambridge, in ten hours; and the "Cambridge Auxiliary Mail," and two other coaches, which do not appear to have borne any distinctive names, the duration of whose pilgrimage is not specified.

Cambridge was therefore provided in 1821 with no fewer than twelve coaches a day, starting from London at all hours, from a quarter to eight in the morning until half-past six in the afternoon. There were also the "Lynn and Wells Mail," every evening, reaching Lynn in twelve hours thirty-three minutes; and the "Lynn Post Coach," through Cambridge, starting every morning from the Golden Cross, Charing Cross, and reaching Lynn in thirteen hours. The "Lynn Union" ran three days a week, in thirteen and a half hours, through Barkway. Other Lynn stages were the "Lord Nelson," "Lynn and Fakenham Post Coach," and two not dignified by specific names.

By 1828 the average speed was greatly improved, for although no coach reached Cambridge in less than six hours, there was, on the other hand, only one that took so long a time as seven hours and a half. The Mail had been accelerated by one hour, throughout to Lynn, and was, before driven off the road, further quickened, the post-office schedule of time for the London, Cambridge, King's Lynn, and Wells Mail in 1845 standing as under:—

| London (G.P.O.) | 8.0 | p.m. |

| Wade's Mill | 10.32 | " |

| Buckland | 11.43 | " |

| Melbourn | 12.32 | a.m. |

| Cambridge | 1.36 | " |

| Ely | 3.31 | " |

| Brandon Creek | 4.27 | " |

| Downham Market | 5.21 | " |

| Lynn | 6.33 | " |

| Wells | 10.43 | " |

In the 'forties, up to 1846 and 1847, the last[Pg 21] years of coaching on this road, the number of coaches does not seem to have greatly increased. The "Star" was still, meteor-like, making its swift daily journey to the Hoop at Cambridge, and the "Telegraph," "Regulator," "Times," and "Fly," and the "Mail," of course, were old-established favourites; but new names are not many. The "Regulator," indeed,—the daily "Royal Regulator" of years before,—is found going only three times weekly. The "Red Rover," however, was a new-comer, between London and Lynn daily; with the "Norfolk Hero" (which was probably another name for Nelson) three days a week between London, Cambridge, Ely, Lynn, and Wells. Recently added Cambridge coaches were the Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday "Bee Hive," and the daily "Rocket"; while one daily and two triweekly coaches through Cambridge to Wisbeach—the daily "Rapid"; the Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday "Day"; and the Monday, Wednesday, and Friday "Defiance," make their appearance.

How do those numbers compare with the number of trains run daily to Cambridge in our own time? It is not altogether a fair comparison, because the capacities of a coach and of a railway train are so radically different. Twenty-nine trains run by all routes from London to Cambridge, day by day, and they probably, on an average, set down five hundred passengers between them at the joint station. Taking the average way-bill of a coach to contain ten passengers, the daily arrivals at Cambridge were a hundred and sixty, or, adding twenty post-chaises daily with two passengers each, a hundred and[Pg 22] eighty. These are only speculative figures, but, unsupported by exact data though they must be, they give an approximation to an idea of the growth of traffic between those times and these. The imagination refuses to picture this daily host being conveyed by road. It would have meant some thirty-five coaches, fully laden, and as for goods and general merchandise, the roads could not possibly have sufficed for the carrying of them.

V

Coaching on the road from London to Lynn has

found some literary expression in the Autobiography

of a Stage Coachman, the work of Thomas Cross,

published in 1861. Cross was a remarkable man.

Born in 1791, he may fairly be said to have been

born to the box-seat, his father, John Cross, having

been a mail-contractor and stage-coach proprietor

established at the Golden Cross, Charing Cross.

The Cross family, towards the end of the eighteenth

century, claimed to rank with the county families

of Hampshire, and John Cross was himself a man

of wealth. He had inherited some, and had made

more by fetching and carrying for the Government

along the old Portsmouth Road in the romantic days

of our long wars with France. He not only had his

establishment in London and a town house in Portsmouth,

but also the three separate and distinct

country seats of Freeland House and Stodham, near

[Pg 23]

[Pg 24]

[Pg 25]Petersfield, and the house and grounds of Qualletes,

at Horndean, purchased in after years by Admiral Sir

Charles Napier, and renamed by him "Merchistoun."

John Cross was always headstrong and reckless, and

made much money—and lost much. The story of

how he would fill his pockets with gold at his bank

at Portsmouth and then ride the lonely twenty miles

thence to Horndean explains his making and his losing.

No cautious traveller in those times went alone by that

road, and the highwaymen tried often to bag this particularly

well-known man, who carried such wealth on

him. "Many a shot I've had at old John Cross of

Stodham," said one of these gentry when lying, cast

for execution, in Portsmouth Gaol; adding regretfully,

"but I couldn't hit him: he rode like the

devil."

"KNEE-DEEP": THE "LYNN AND WELLS MAIL" IN A SNOWSTORM.

[From a Print after C. Cooper Henderson.]

This fine reckless character lived to dissipate everything in ill-judged speculations, and misfortunes of all kinds visited the family. We are told but little of them in the pages of his son's book, but it was entirely owing to one of these visitations that Thomas Cross found his whole career changed. Destined by his father for the Navy, he was entered as a midshipman, but he had been subject from his birth to fits, and coming home on one occasion and going into the cellars of a wine business his father had in the meanwhile taken, he was seized by one of these attacks, and falling on a number of wine-bottles, was so seriously injured that the profession of the Navy had to be abandoned. We afterwards find him as a farmer in Hampshire, and then, involved in the financial disasters that[Pg 26] overtook the family, reduced to seeking an engagement as coachman in the very yard his father had once owned. It is curious that, either intentionally or by accident, he does not mention the name of the coach he drove between London and Lynn, but calls it always "the Lynn coach." There were changes on the road between 1821, when he first drove along it, and 1847, when he was driven off, but he is chiefly to be remembered as the driver of the "Lynn Union." He tells how he came to the box-seat, how miserably he was shuttlecocked from one to the other when in search of employment, and how, when the whip who drove the "Lynn coach" on its stage between Cambridge and London had taken an inn and was about to relinquish his seat, he could obtain no certain information that the post would be vacant. The bookkeeper of the coach-office said it would; the coachman himself told a lie and said he was not going to give up the job. In this condition of affairs Cross did not know what to do, until a kindly acquaintance gave him the date upon which the lying Jehu must take possession of his inn and of necessity give up coaching, and advised him to journey down to Cambridge, meet the up coach there as it drove into the Bull yard, and present himself as the coachman come to take it up to London. Cross scrupulously carried out this suggestion, and when he made his appearance, with whip and in approved coaching costume, at the Bull, and was asked who he was and what he wanted, replied as his friend had indicated. No one offered any objection, and no other coachman had appeared[Pg 27] by the time he drove away, punctual to the very second we may be quite sure. An old resident of Lynn, who has written his recollections of bygone times in that town, tells us that Thomas Cross "was not much of a whip," a criticism that seems to be doubly underscored in Cross's own description of this first journey to London, when he drove straight into the double turnpike gates that then stretched across the Kingsland Road, giving everyone a good shaking, and cause, in many bruises, to remember his maiden effort.

Cross had a long and varied experience, extending to twenty-eight years, of this road. At different times he drove between London and Cambridge, on the middle ground between Cambridge and Ely, and for a while took the whole distance between Ely and Lynn. He drove in his time all sorts and conditions of men, and instances some of his experiences. Perhaps the most amusing was that occasion when he drove into Cambridge with a choleric retired Admiral on the box-seat. The old sea-dog was come to Cambridge to inquire into the trouble into which a scapegrace son had managed to place himself. He confided the whole story to the coachman. By this it seemed that the Admiral had two sons. One he had designed to make a sailor; the other was being educated for the Church. It was the embryo parson who had got into trouble: very serious trouble, too, for he had knocked down a Proctor, and was rusticated for that offence. The Admiral, in fact, had made a very grave error of judgment. His sons had very opposite characters:[Pg 28] the one was wild and high-spirited, and the other was meek and mild to the last degree of inoffensiveness. Unfortunately it was this good young man whom he had sent to sea, while his devil's cub he had put in the way of reading for Holy Orders.

"I have committed a great mistake, sir," he said. "I ought to have made a sailor of him and a parson of the other, who is a meek, unassuming youth aboard ship, with nothing to say for himself; while this, sir, would knock the devil down, let alone a Proctor, if he offended him."

The Admiral was a study in the mingled moods of offended dignity and of parental pride in this chip of the old block; breathing implacable vengeance one moment and admiration of a "d——d high-spirited fellow" the next. When Thomas Cross set out on his return journey to London, he saw the Admiral and his peccant son together, the best of friends.

Cross was in his prime when railways came and spoiled his career. In 1840, when the Northern and Eastern line was opened to Broxbourne, and thence, shortly after, to Bishop Stortford, he had to give up the London and Cambridge stage and retire before the invading locomotive to the Cambridge and Lynn journey. In 1847, when the Ely to Lynn line was opened, his occupation was wholly gone, and all attempts to find employment on the railway failed. They would not have him, even to ring the bell when the trains were about to start. Then, like many another poor fellow at that time, he presented an engrossed petition to Parliament, setting forth how[Pg 29] hardly circumstances had dealt with him, and hoping that "your honourable House" would do something or another. The House, however, was largely composed of members highly interested in railways, and ordered his petition, with many another, to lie on the table: an evasive but well-recognised way of utterly ignoring him and it and all such troublesome and inconvenient things and persons. Alas! poor Thomas! He had better have saved the money he expended on that engrossing.

What became of him? I will tell you. For some years he benefited by the doles of his old patrons on the "Union," sorry both for him and for the old days of the road, gone for ever. He then wrote a history of coaching, a work that disappeared—type, manuscript, proofs and all—in the bankruptcy proceedings in which his printers were presently involved. Then he wrote his Autobiography. He was, you must understand, a gentleman by birth and education, and if he had little literary talent, had at least some culture. Therefore the story of his career, as told by himself, although discursive, is interesting. He had some Greek and more Latin, and thought himself a poet. I have, however, read his epic, The Pauliad, and find that in this respect he was mistaken. That exercise in blank verse was published in 1863, and was his last work. Two years later he found a place in Huggens' College, a charitable foundation at Northfleet, near Gravesend; and died in 1877, in his eighty-sixth year, after twelve years' residence in that secure retreat. He lies in Northfleet churchyard, far away from that place where he would[Pg 30] be,—the little churchyard of Catherington beside the Portsmouth Road, where his father and many of his people rest.

VI

Few and fragmentary are the recollections of the old coachmen of the Cambridge Road. A coloured etching exists, the work of Dighton, purporting to show the driver of the "Telegraph" in 1809; but whether this represents that Richard Vaughan of the same coach, praised in the book on coaching by Lord William Pitt-Lennox as "scientific in horseflesh, unequalled in driving," is doubtful, for the hero of Dighton's picture seems to belong to an earlier generation. Among drivers of the "Telegraph" were "Old Quaker Will" and George Elliott, just mentioned by Thomas Cross; himself not much given to enlarging upon other coachmen and their professional skill. Poor Tommy necessarily moved in their circle; but although with them, he was not of them, and nursed a pride both of his family and of his own superior education that grew more arrogant as his misfortunes increased. As for Tommy himself, we have already heard much of him and his Autobiography of a Stage Coachman. The "Lynn Union," however, the coach he drove down part of the road one day and up the next, was by no means one of the crack "double" coaches, but started from either end only three times a week, and although upset every now and again, was a jog[Pg 31]trot affair that averaged but seven miles an hour, including stops. That the "Lynn Union" commonly carried a consignment of shrimps one way and the returned empty baskets another was long one of Cross's minor martyrdoms. He drove along the road, his head full of poetry and noble thoughts, and yearning for cultured talk, while the shrimp-baskets diffused a penetrating odour around, highly offensive to those cultured folk for whose society his soul longed. People with a nice sense of smell avoided the "Lynn Union" while the shrimp-carrying continued.

Contemporary with Cross was Jo Walton, of the "Safety," and later of the "Star." He was perhaps one of the finest coachmen who ever drove on the Cambridge Road, and it was possibly the knowledge of this skill, and the daring to which it led, that brought so many mishaps to the "Star" while he wielded the reins. He has been described as "a man who swore like a trooper and went regularly to church," with a temper like an emperor and a grip like steel. This fine picturesque character was the very antithesis of the peaceful and dreamy Cross, and thought nothing of double-thonging a nodding waggoner who blocked the road with his sleepy team. Twice at least he upset the "Star" between Royston and Buntingford when attempting to pass another coach. He, at last, was cut short by the railway, and his final journeys were between Broxbourne and Cambridge. "Here," he would say bitterly, as the train came steaming into Broxbourne Station, "here comes old Hell-in-Harness!"

Of James Reynolds, of Pryor, who drove the[Pg 32] "Rocket," of many another, their attributes are lost and only their names survive. That William Clark, who drove the "Bee Hive," should have been widely known as "the civil coachman" is at once a testimonial to him and a reproach to the others; and that memories of Briggs at Lynn should be restricted to the facts that he was discontented and quarrelsome is a post-mortem certificate of character that gains in significance when even the name of the coach he drove cannot be recovered.

VII

Bishopsgate Street Within and Without, and Norton Folgate of to-day, would astonish old Hobson, not only with their press of ordinary traffic, but with the vast number of railway lorries rattling and thundering along, to and from the great Bishopsgate Goods Station of the Great Eastern Railway; the railway that has supplanted the coaches and the carriers' waggons along the whole length of this road. That station, once the passenger terminus of Shoreditch, before the present huge one at Liverpool Street was built, remains as a connecting-link between the prosperous and popular "Great Eastern" of to-day and the reviled and bankrupt "Eastern Counties" of fifty years ago. The history of the Great Eastern Railway is a complicated story of amalgamations of many lines with the original Eastern Counties Railway. The line to Cambridge,[Pg 33] with which we are principally concerned, was in the first instance the project of an independent company calling itself the Northern and Eastern Railway, opened after many difficulties as far as Broxbourne in 1840, and thence, shortly afterwards, to Bishop Stortford. Having reached that point and the end of its resources simultaneously, it was taken over by the Eastern Counties and completed in 1847, the line going, as the Cambridge expresses do nowadays, viâ Audley End and Great Chesterford.

Having thus purchased and completed the scheme of that unfortunate line, the Eastern Counties' own difficulties became acute. Locomotives and rolling stock were seized for debt, and it fell into bankruptcy and the Receiver's hands. How it emerged at last, a sound and prosperous concern, this is not the place to tell, but many years passed before any passenger whose business took him anywhere along the Eastern Counties' "system" could rely upon being carried to his destination without vexatious delays, not of minutes, but of hours. Often the trains never completed their journeys at all, and came back whence they had started. Little wonder that this was then described as "that scapegoat of companies, that pariah of railways."

"On Wednesday last," said Punch at this time, "a respectably-dressed young man was seen to go to the Shoreditch terminus of the Eastern Counties Railway and deliberately take a ticket for Cambridge. He has not since been heard of. No motive has been assigned for the rash act."

The best among the Great Eastern Cambridge[Pg 34] expresses of to-day does the journey of 55¾ miles in 1 hour 13 minutes. Onward to Lynn, 97 miles, the best time made is 2 hours 25 minutes.

VIII

It is a far cry from Shoreditch Church to the open country. Cobbett, in 1822, journeying from London to Royston, found the suburbs far-reaching even then. "On this road," he says, "the enormous Wen" (a term of contempt by which he indicated the Metropolis) "has swelled out to the distance of above six or seven miles." But from the earliest times London exhibited a tendency to expand more quickly in this direction than in others, and Edmonton, Waltham Cross, and Ware lay within the marches of Cockaigne long before places within a like radius at other points of the compass began to lose their rural look. The reason is not far to seek, and may be found in the fact that this, the great road to the North, was much travelled always.

But where shall we set the limits of the Great Wen in recent times? Even as these lines are written they are being pushed outwards. It is not enough to put a finger on the map at Stamford Hill and to say, "here, at the boundary of the London County Council's territory," or "here at Edmonton, the limit of the 'N' division of the London Postal Districts," or, again, "here, where the Metropolitan Police Area meets the territories of the Hertfordshire[Pg 35] and the Essex Constabulary at Cheshunt"; for those are but arbitrary bounds, and, beyond their own individual significances, tell us nothing. Have you ever, as a child, looking, large-eyed and a little frightened it may be, out upon the bigness of London, wondered where the houses ended and Gods own country began, or asked where the last house of the last street looked out upon the meadows, and the final flag-stone led on to the footpath of the King's Highway?

I have asked, and there was none to tell, and if you in turn ask me where the last house of the ultimate street stands on this way out of London—I do not know! There are so many last houses, and they always begin again; so that little romantic mental picture does not exist in plain fact. The ending of London is a gradual and almost insensible process. You may note it when, leaving Stoke Newington's continuous streets behind, you rise Stamford Hill and perceive its detached and semi-detached residences; and, pressing on, see the streets begin again at Tottenham High Cross, continuing to Lower Edmonton. Here at last, in the waste lands that stretch along the road, you think the object of your search is found. As well seek that fabled pot of gold at the foot of the rainbow. The pot and the gold may be there, but you will never, never reach the rainbow.

The houses begin again, absurdly enough, at Ponder's End. You will come to an end of them at last, but only gradually, and when, at fifteen and three-quarter miles from Shoreditch Church, Brox[Pg 36]bourne and the first glimpse of "real country" are reached, the original quest is forgotten.

Very different was the aspect of these first miles out of London in the days of Izaak Walton, Cowper, and Lamb. Cowper's Johnny Gilpin rode to Edmonton and Ware, and Walton and Lamb—the inspired Fleet Street draper and the thrall of the Leadenhall Street office—are literary co-parceners in the valley of the Lea.

"You are well overtaken, gentlemen," says Piscator, in the Compleat Angler, journeying from London; "a good morning to you both. I have stretched my legs up Tottenham Hill to overtake you, hoping your business may occasion you towards Ware, whither I am going this fine, fresh May morning." He meant that suburban eminence known as Stamford Hill, where, in the beginning of May 1603, the Lord Mayor and Sheriffs of London, having ridden out in State for the purpose, met James the First travelling to London to assume the Crown of England.

Stamford Hill still shadows forth a well-established prosperity. It was the favoured suburban resort of City merchants in the first half of the nineteenth century, and is still intensely respectable and well-to-do, even though the merchants have risen with the swelling of their bankers' pass-books to higher ambitions, and though many of their solid, stolid, and prim mansions know them no more, and are converted not infrequently into what we may bluntly call "boys' and girls' schools," termed, however, by their respective Dr. Blimber's and Miss Pinkerton's[Pg 37] "scholastic establishments for young ladies and young gentlemen." The old-time City merchant who resided at Stamford Hill when the nineteenth century was young (a period when people began to "reside" in "desirable residences" instead of merely living in houses), used generally, if he were an active man, to go up to his business in the City on horseback, and return in the same way. If not so active, he came and went by the "short stage," a conveyance between London and the adjacent towns, to all intents and purposes an ordinary stage-coach, except that it was a two-horsed, instead of a four-horsed, affair. The last City man who rode to London on horseback has probably long since been gathered to his fathers, for the practice naturally was discontinued when railways came and revolutionised manners and customs.

As you top Stamford Hill, you glimpse the valley of the Lea and its factory-studded marshes, and come presently to Tottenham High Cross. No need to linger nowadays over the scenery of this populous road, lined with shops and villas and crowded with tramways and omnibuses; no need, that is to say, except for association's sake, and to remark that it was here Piscator called a halt to Venator and Auceps, on their way to the Thatched House at Hoddesdon, now going on for two hundred and fifty years ago. "Let us now" (he said) "rest ourselves in this sweet, shady arbour, which Nature herself has woven with her own fine fingers; it is such a contexture of woodbines, sweet briars, jessamine, and myrtle, and so interwoven as[Pg 38] will secure us both from the sun's violent heat and from the approaching shower." And so they sat and discussed a bottle of sack, with oranges and milk.

TOTTENHAM CROSS.

So gracious a "contexture" is far to seek from Tottenham nowadays. If you need shelter from the approaching shower you can, it is true, obtain it more securely in the doorway of a shop than under a hedgerow in May, when Nature has not nearly finished her weaving; but there is something lacking in the exchange.

Tottenham High Cross that stands here by, over

against the Green, is a very dubious affair indeed;

[Pg 39]

[Pg 40]an impostor that would delude you if possible into

the idea that it is one of the Eleanor Crosses; with

a will-o'-wisp kind of history, from the time in

1466, when it is found mentioned only as existing,

to after ages, when it was new-built of brick and

thereafter horribly stuccoed, to the present, when

it is become a jibe and a jeer in its would-be Gothic.

A LONDON SUBURB IN 1816: TOTTENHAM.

[From a Drawing by Rowlandson.]

Much of old Tottenham is gone. Gone are the "Seven Sisters," the seven elms that stood here in a circle, with a walnut-tree in their midst, marking, as tradition would have you believe, the resting-place of a martyr; but in their stead is the beginning of the Seven Sisters' Road: not a thoroughfare whose romance leaps to the eye. What these then remote suburbs were like in 1816 may be seen in this charming sketch of Rowlandson's, where he is found in his more sober mood. The milestone in the sketch marks four and three-quarter miles from Shoreditch: this is therefore a scene at Tottenham, where the tramway runs nowadays, costermongers' barrows line the gutters, and crowds press, night and day. Little enough traffic in Rowlandson's time, evidently, for the fowls and the pigs are taking their ease in the very middle of the footpath.

Yet there are still a few vestiges of the old and the picturesque here. Bruce Grove, hard by, may be but a name, reminiscent of Robert Bruce and other Scottish monarchs who once owned a manor and a castle where suburban villas now cluster plentifully, and where the modern so-called "Bruce Castle" is a school; but there are dignified old[Pg 41] red-brick mansions here still, lying back from the road behind strong walls and grand gates of wrought iron. The builder has his eye on them, an Evil Eye that has already blasted not a few, and with bulging money-bags he tempts the owners of the others: even as I write they go down before the pick and shovel.

BALTHAZAR SANCHEZ' ALMSHOUSES, TOTTENHAM.

Old almshouses there are, too, with dedicatory tablet, complete. The builder and his money-bags cannot prevail here, you think. Can he not? My good sirs, have you never heard of the Charity Commissioners, whose business it is to sit in their snug quarters in Whitehall and to propound "schemes" whereby such old buildings as these are torn down, their sites sold for a mess of[Pg 42] pottage, and the old pensioners hustled off to some new settlement? "But look at the value of the land," you say: "to sell it would admit of the scope of the charity being doubled." No doubt; but what of the original testator's wishes? I think, if it were proposed to remove these old almshouses, the shade of Balthazar Sanchez, the founder, somewhere in the Beyond, would be grieved.

One Bedwell, parson of Tottenham High Cross circa 1631, and a most diligent Smelfungus, tells us Balthazar was "a Spanyard born, the first confectioner or comfit-maker, and the grand master of all that professe that trade in this kingdome"; and the tablet before-mentioned, on the front of the old almshouses themselves, tells us something on its own account, as thus—

Long may the queer old houses, with their monumental chimney-stalks and forecourt gardens remain: it were not well to vex the ghost of the good comfit-maker.

"Scotland Green" is the name of an odd and haphazard collection of cottages next these almshouses, looking down into Tottenham Marshes. Its name derives from the far-off days when those Scottish monarchs had their manor-house near by,[Pg 43] and though the weather-boarded architecture of the cottages by no means dates back to those times, it is a queer survival of days before Tottenham had become a suburb; each humble dwelling law to itself, facing in a direction different from those of its neighbours, and generally approached by crazy wooden footbridges over what was probably at one time a tributary of the Lea, now an evil-smelling ditch where the children of the neighbourhood enjoy themselves hugely in making mud-pies, and by dint of early and constant familiarity become immune from the typhoid fever that would certainly be the lot of a stranger.

IX

Edmonton, to whose long street we now come, has many titles to fame. John Gilpin may not afford the oldest of these, and he may be no more than the purely imaginary figure of a humorous ballad, but beside the celebrity of that worthy citizen and execrable horseman everything else at Edmonton sinks into obscurity.

Izaak Walton himself, of indubitable flesh and blood, forsaking his yard-measure and Fleet Street counter and tramping through Edmonton to the fishful Lea,[Pg 44] has not made so great a mark as his fictitious fellow-tradesman, the draper of Cheapside.

Who has not read of John Gilpin's ride to Edmonton, in Cowper's deathless verse? Cowper, most melancholy of poets, made the whole English-speaking world laugh with the story of Gilpin's adventures. How he came to write the ballad it may not be amiss to tell. The idea was suggested to him at Olney, in 1782, by Lady Austen, who, to rouse him from one of his blackest moods, related a merry tale she had heard of a London citizen's adventures, identical with the verses into which he afterwards cast the story. He lay awake all that night, and the next morning, with the idea of amusing himself and his friends, wrote the famous lines. He had no intention of publishing them, but his friend, Mrs. Unwin, sent a copy to the Public Advertiser. Strange to say, it did not attract much attention in those columns, and it was not until three years later, when an actor, Henderson by name, recited the ballad at Freemasons' Hall that (as modern slang would put it) it "caught on." It then became instantly popular. Every ballad-printer printed, and every artist illustrated it; but the author remained unknown until Cowper included it in a collection of his works.

There are almost as many originals of John Gilpin as there are of Sam Weller. There used to be numbers of respectable and ordinarily dependable people who were convinced they knew the original of Sam Weller, in dozens of different persons and in[Pg 45] widely-sundered towns, and the literary world is even now debating as to who sat as the model for Squeers. So far back as the reign of Henry the Eighth the ludicrous idea of a London citizen trying to ride horseback to Edmonton made people laugh, and on it Sir Thomas More based his metrical "Merry Jest of the Serjeant and the Frère." It would be no surprise to discover that Aristophanes or another waggish ancient Greek had used the same idea to poke fun at some clumsy Athenian, and that, even so, it was stolen from the Egyptians. Indeed, I have no doubt that the germ of the story is to be found in the awkwardness of one of Noah's sons in trying to ride an unaccustomed animal into the Ark.

The immediate supposititious originals of John Gilpin were many. Some identified him with a Mr. Beger, a Cheapside draper, who died in 1791, aged one hundred. Others found him in Commodore Trunnion, in Peregrine Pickle, and a John Gilpin lies in Westminster Abbey. The Gentleman's Magazine in 1790, five years after Cowper's poem became the rage, records the death at Bath of a Mr. Jonathan Gilpin, "the gentleman who was so severely ridiculed for bad horsemanship under the title of 'John Gilpin.'" All accidental resemblances and odd coincidences, without doubt.

But if John had no corporeal existence, the Bell at Edmonton—at Upper Edmonton, to be precise—was a very real place, and, in an altered form, still is. Who could doubt of the man who ever saw the house? Is not the present Bell[Pg 46] real enough, and, for that matter, ugly enough? and is not the picture of John, wigless and breathless, and his coat-tails flying, sufficiently prominent on the sign? The present building is the third since Cowper's time, and is just an ordinary vulgar London "public," standing at the corner of a shabby street (where there are no trees), called, with horrible alliteration, "Gilpin Grove."

Proceed we onwards, having said sufficient of Gilpin. Off to the right hand turned old Izaak, to Cook's Ferry and the Bleak Hall Inn by the Lea, that "honest ale-house, where might be found a cleanly room, lavender in the windows, and twenty ballads stuck about the wall." Ill questing it would be that should seek nowadays for the old inn. Instead, down by Angel Road Station and the Lea marshes, you find only factories and odours of the Pit, horrent and obscene. We have yet to come to the kernel, the nucleus of this Edmonton. Here it is, at Lower Edmonton, at the end of many houses, in a left-hand turning—Edmonton Green; the green a little shorn, perhaps, of its old proportions, and certainly by no means rural. On it they burnt the unhappy Elizabeth Sawyer, the Witch of Edmonton, in 1621, with the full approval of king and council: Ahriman perhaps founding one of his claims to Jamie for that wicked deed. It was well for Peter Fabell, who at Edmonton deceived the devil himself, that he practised his conjuring arts before Jamie came to rule over us, else he had gone the way of that unhappy Elizabeth; for James was of a logical turn of mind, and would[Pg 47] have argued the worst of one who could beat the Father of Lies at his own game. Peter flourished, happily for him, in the less pragmatical days of Henry the Seventh. We should call him in these matter-of-fact days a master of legerdemain, and he would dare pretend to no more; but he was honoured and feared in his own time, and lies somewhere in the parish church, his monument clean gone. On his exploits Elizabethan dramatists founded the play of the Merry Devil of Edmonton.

The railway and the tramway have between them played the very mischief with Edmonton Green and the Wash—

that here used to flow athwart the road, and does actually still so flow, or trickle, or stagnate; if not always visible to the eye, at least making its presence obvious at all seasons to the nose. In the first instance, the railway planted a station and a level crossing on the highway, practically in the Wash; and then the Tramway Company, in order to carry its line along the road to Ponders End, constructed a very steeply rising road over the railway. Add to these objectionable details, that of another railway crossing over the by-road where Lamb's Cottage and the church are to be found, and enough will have been said to prove that the Edmonton of old is sorely overlaid with sordid modernity.

Charles Lamb would scarce recognise his Edmonton if it were possible he could revisit the spot, and[Pg 48] it seems—the present suburban aspect of the road before us—a curious ideal of happiness he set himself: retirement at Edmonton or Ponder's End, "toddling about it, between it and Cheshunt, anon stretching on some fine Izaak Walton morning to Hoddesdon or Amwell, careless as a beggar, but walking, walking ever, till I fairly walked myself off my legs, dying walking."

Everyone to his taste, of course, but it does not seem a particularly desirable end. It is curious, however, to note that this aspiration was, in a sense, realised, for it was in his sixtieth year that, taking his customary walk along the London road one day in December 1834, he stumbled against a stone and fell, cutting his face. It seemed at the time a slight injury, but erysipelas set in a few days later, and on the twenty-seventh of the same month he died. It was but a fortnight before, that he had pointed out to his sister the spot in Edmonton churchyard where he wished to be buried.

Lamb's last retreat—"Bay Cottage" as it was named, and "Lamb's Cottage" as it has since been re-christened, "the prettiest, compactest house I ever saw," says he—stands in the lane leading to the church; squeezed in between old mansions, and lying back from the road at the end of a long narrow strip of garden. It is a stuccoed little house, curiously like Lamb himself, when you come to consider it: rather mean-looking, undersized, and unkempt, and overshadowed by its big neighbours, just as Lamb's little talents were thrown into insignificance by his really great contemporaries. The[Pg 49] big neighbours of the little cottage are even now on the verge of being demolished, and the lane itself, the last retreat of old-world Edmonton, is being modernised; so that those who cultivate their Lamb will not long be able to trace these, his last landmarks. Already, as we have seen, the Bell has gone, where Lamb, "seeing off" his visitors on their way back to London, took a parting glass with them, stutteringly bidding them hurry when the c-cu-coach c-came in.

One of the most curious of literary phenomena is this Lamb worship. Dingy, twittering little London sparrow that he was, diligent digger-up of Elizabethan archaisms with which to tune his chirpings, he seems often to have inspired the warmest of personal admiration. As the "gentle Elia" one finds him always referred to, and a halo of romance has been thrown about him and his doings to which neither he nor they can in reality lay much claim. Romance flies abashed before the picture of Lamb and his sister diluting down the poet of all time in the Tales from Shakespeare: Charles sipping gin between whiles, and Mary vigorously snuffing. Nor was his wit of the kindly sort readily associated with the epithet "gentle." It flowed the more readily after copious libations of gin-and-water, and resolved itself at such times into the offensive, if humorous, personalities that were the stock in trade of early nineteenth-century witlings. His famous witticism at a card-party on one who had hands not of the cleanest ("If dirt were trumps, what a hand you'd have") must have been bred of the juniper berry.[Pg 50] Stuttering and blue-lipped the next morning, he was an object of pity or derision, just according to the charity of those who beheld him. Carlyle, who knew Lamb in his latter days, draws him as he was, in one of those unmerciful pen-portraits he could create so well:—"Charles Lamb and his sister came daily once or oftener; a very sorry pair of phenomena. Insuperable proclivity to gin in poor old Lamb. His talk contemptibly small, indicating wondrous ignorance and shallowness, even when it was serious and good-mannered, which it seldom was, usually ill-mannered (to a degree), screwed into frosty artificialities, ghastly make-believe of wit, in fact more like 'diluted insanity' (as I defined it) than anything of real jocosity, humour, or geniality. A most slender fibre of actual worth in that poor Charles, abundantly recognisable to me as to others, in his better times and moods; but he was Cockney to the marrow; and Cockneydom, shouting 'glorious, marvellous, unparalleled in nature!' all his days had quite bewildered his poor head, and churned nearly all the sense out of the poor man. He was the leanest of mankind, tiny black breeches buttoned to the knee-cap, and no further, surmounting spindle-legs also in black, face and head fineish, black, bony, lean, and of a Jew type rather; in the eyes a kind of smoky brightness or confused sharpness; spoke with a stutter; in walking tottered and shuffled; emblem of imbecility bodily and spiritual (something of real insanity I have understood), and yet something too of human, ingenuous, pathetic, sportfully much enduring. Poor Lamb! he was infinitely[Pg 51] astonished at my wife and her quiet encounter of his too ghastly London wit by a cheerful native ditto. Adieu, poor Lamb!"

Edmonton Church has lain too near London in all these years to have escaped many interferences, and the body of it was until recently piteous with the doings of 1772, when red brick walls and windows of the factory type replaced its ancient architecture. These have now in their turn been swept away, and good modern Gothic put in their stead, already densely covered with ivy. The ancient tower still rises grandly from the west end, looking down upon a great crowded churchyard; a very forest of tombstones. Near by is the grave of Charles and Mary Lamb, with a long set of verses inscribed upon their headstone.

There was once in this churchyard of Edmonton a curious epitaph on one William Newberry, ostler to the Rose and Crown Inn, who died in 1695 from the effects of unsuitable medicine given him by a fellow-servant acting as an amateur doctor. The stone was removed by some clerical prude—

The feelings of Sue Bellamy will not be envied, but Sue, equally with William, has long reached beyond all such considerations, and the Rose and Crown of that day is no more. There is still, however, a Rose and Crown, and a very fine building[Pg 52] it is, with eleven windows in line and wearing a noble and dignified air. It is genuine Queen Anne architecture; the older house being rebuilt only ten years after the ostler was cut off untimely, as may be seen by the tablet on its front, dated not only 1705, but descending to the small particular of actual month and day of completion.

X

The tramway line, progressing through Edmonton in single track, goes on in hesitating fashion some little distance beyond Edmonton Green, and terminates in a last feeble, expiring effort on the open road, midway between Edmonton and Ponder's End; like the railhead of some African desert line halting on the edge of a perilous country. Where it ends there stands, solitary, a refreshment house, so like the last outpost of civilisation that the wayfarer whimsically wonders whether he had not better provision himself liberally before adventuring into the flats that lie so stark and forbidding before him.

It is indeed an uninviting waste. On it the gipsy caravans halt; here the sanguine speculative builder projects a street of cheap houses and generally leaves derelict "carcases" of buildings behind him; here the brick-maker and the market-gardener contend with one another, and the shooters of rubbish bring their convoys of dust, dirt, and old tins from afar. On the skyline ahead are factory[Pg 53] chimneys, and to the east—the only gracious note in the whole scene—the wooded hills of Essex, across the malodorous Lea.

This desolate tract is bounded by the settlement of Ponder's End, an old roadside hamlet. "Ponder's End," says Lamb, "emblematic name, how beautiful!" Sarcasm that, doubtless, for of what it is emblematic, and where lies the beauty of either place or name, who shall discover? The name has a heavily ruminative or contemplative sound, a little out of key with its modern note. For even Ponder's End has been rudely stirred up by the pitchfork of progress and bidden go forward, and new terraces of houses and shops—no, not shops, nothing so vulgar; "business premises" if you please—have sprung up, and the oldest inhabitant is distraught with the changes that have befallen. Where he plodded in the mud there are pavements; the ditch into whose unsavoury depths he has fallen many a time when returning late from the old Two Brewers is filled up, and the Two Brewers itself has changed from a roadside tavern to something resplendent in plate-glass and brilliant fittings. Our typical ancient and his friends, the market-gardening folk and the loutish waggoners, are afraid to enter. Nay, even the name of the village or hamlet, or urban district, or whatever the exact slang term of the Local Government Board for its modern status may be, is not unlikely to see a change, for to the newer inhabitants it sounds derogatory to be a Ponder's Ender.