Title: The Red Cross Girls on the French Firing Line

Author: Margaret Vandercook

Release date: September 8, 2019 [eBook #60265]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Demian Katz, Craig Kirkwood, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Villanova University Digital Library (https://digital.library.villanova.edu/)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Red Cross Girls on the French Firing Line, by Margaret Vandercook

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Villanova University Digital Library. See https://digital.library.villanova.edu/Item/vudl:382657# |

THE RED CROSS GIRLS ON

THE FRENCH FIRING

LINE

BOOKS BY MARGARET VANDERCOOK

THE RANCH GIRLS SERIES

The Ranch Girls at Rainbow Lodge

The Ranch Girls’ Pot of Gold

The Ranch Girls at Boarding School

The Ranch Girls in Europe

The Ranch Girls at Home Again

The Ranch Girls and their Great Adventure

THE RED CROSS GIRLS SERIES

The Red Cross Girls in the British Trenches

The Red Cross Girls on the French Firing Line

The Red Cross Girls in Belgium

The Red Cross Girls with the Russian Army

The Red Cross Girls with the Italian Army

The Red Cross Girls Under the Stars and Stripes

STORIES ABOUT CAMP FIRE GIRLS

The Camp Fire Girls at Sunrise Hill

The Camp Fire Girls Amid the Snows

The Camp Fire Girls in the Outside World

The Camp Fire Girls Across the Sea

The Camp Fire Girls’ Careers

The Camp Fire Girls in After Years

The Camp Fire Girls in the Desert

The Camp Fire Girls at the End of the Trail

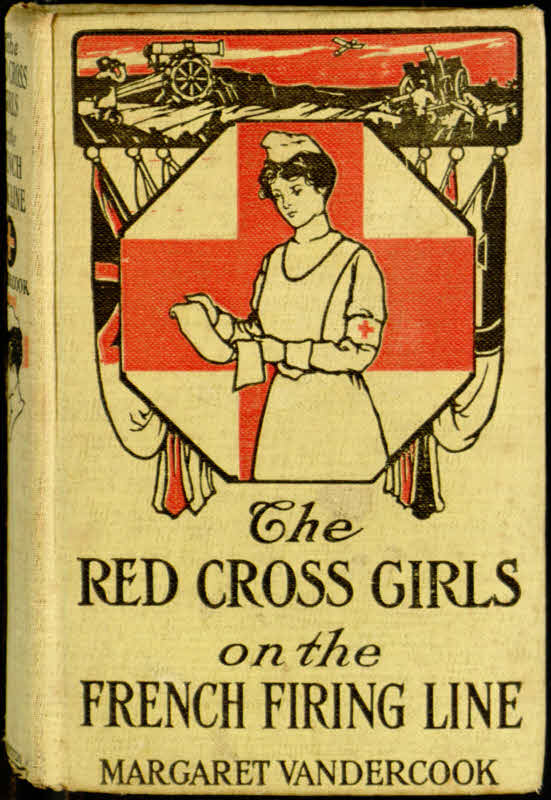

Captain Castaigne Lay Hidden Under a Pile of Bed Clothes—(See page 225)

By

MARGARET VANDERCOOK

Author of “The Ranch Girls Series,” “Stories

about Camp Fire Girls Series,” etc.

Illustrated

The John C. Winston Company

Philadelphia

Copyright, 1916, by

The John C. Winston Co.

[5]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Place de l’Opera | 7 |

| II. | Another Meeting | 23 |

| III. | The Cross of the Legion of Honor | 38 |

| IV. | On the Roof | 54 |

| V. | Other Fields | 69 |

| VI. | The Chateau | 78 |

| VII. | Nicolete | 89 |

| VIII. | Who Goes There? | 103 |

| IX. | A Conversation | 116 |

| X. | Chateau d’Amélie | 126 |

| XI. | The Prejudice Deepens | 139 |

| XII. | Not Peace But War | 150 |

| XIII. | Danger | 164 |

| XIV. | The Parting of the Ways | 177 |

| XV. | The Other Two Girls | 192 |

| XVI. | The Discovery | 202 |

| XVII. | Recognition | 214 |

| XVIII. | Out of the Depth | 227 |

| XIX. | Eugenia | 240 |

| XX. | The Pool of Truth | 250 |

[7]

THE RED CROSS GIRLS ON

THE FRENCH FIRING

LINE

Not long after the beginning of the war in Europe four American girls set sail from New York City to aid in the Red Cross nursing.

When they boarded the “Philadelphia” they were almost strangers to one another. And never were girls more unlike.

Eugenia Peabody, the oldest of the four, hailed from Massachusetts and appeared almost as stern and forbidding as the rock-bound coasts. Privately the others insisted in the early part of their acquaintance that this same Eugenia must have been born an “old maid.”

[8]

Mildred Thornton was the daughter of a distinguished New York judge and her mother a prominent society woman. But Mildred herself cared little for a butterfly existence. With the call of the suffering sounding in her ears she had given up a luxurious existence for the hardships and perils of a Red Cross nurse.

The youngest of the four girls, Barbara Meade, was a very small person with a large store of energy and unexpectedness. And the last girl, Nona Davis, was a native of the conservative old city of Charleston, South Carolina. Although a mystery shadowed her mother’s history, Nona had been brought up by her father, a one-time Confederate general, with all the ideas and traditions of the old South.

Yet in spite of these contrasts in their natures and lives, the four American Red Cross girls had spent more than six months caring for the wounded British soldiers in the Sacred Heart Hospital in northern France.

With the closing of the last story the news had come that the headquarters of the[9] hospital must be changed at once. At any hour the German invaders might swarm into the countryside.

There had been but little time to remove the wounded. So, not wishing to add to the responsibilities and finding themselves more in the way than of service, the four girls had escaped together to a small town in France farther away from the enemy’s line.

Here they concluded to offer their aid to the Croix de Rouge, or the Red Cross Society of France.

But this was in the spring, and now another autumn has come round.

One wonders what the four American girls are doing and where they are living.

The great square in front of the Grand Opera House in Paris surged with excited people.

Automobiles and carriages crowded with men and women, waving tri-colored flags, filled the streets. It was a warm October night with a brilliant canopy of stars overhead.

[10]

“Vive la France! Vive l’Armée!” the throng shouted, swaying backward and forward in its effort to draw closer to the great palace.

There must have been between five and ten thousand persons in the neighborhood, for tonight France was celebrating her greatest achievement of the war. At last the news had come that the victorious French army had driven the Germans back across the frontiers of Alsace-Lorraine. Once again the French flag was planted within their lost provinces.

In the crowd a woman had started the singing of the Marseillaise. Immediately thousands of voices joined in the song, while thousands of feet kept time upon the paving stones to this greatest of all marching measures.

Six broad streets in Paris converge into a triangular square which is known as the Place de l’Opera. From here one looks upward to the opera house itself, a splendid[11] building three stories in height and approached by a broad flight of stone steps.

Standing within the crowd, a little to the left of the opera, was a group of five persons, four of them girls, while the fifth was a young man whose coat was buttoned in such a fashion that he appeared to have but one arm. However, the other arm hung limp and useless underneath his coat.

Although their appearance and accents were those of foreigners, two of the girls in the little party were singing along with the French crowd. The other two were silent, although their faces expressed equal interest and animation.

Suddenly the singing of the street crowd ceased. The central door of the opera house had been thrown open and a young woman came out upon the portico. She was dressed in a clinging white robe and wore upon her head a diadem of brilliants, while in her hands she carried the French flag. So skilfully had the lights been arranged behind her that she could be seen for a great distance. To the onlookers she represented the symbolic female figure of the great[12] French Republic, “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité.”

For a moment after her appearance there was a breathless silence, then the next even more enthusiastic shouts resounded:

“Vive Chenel! Vive Chenel!” Hats were thrown into the air, thousands of flags waved, while myriads of handkerchiefs fluttered like white doves.

It was a night to be always remembered by the people who shared its rapture.

With the closing of the final verse of the Marseillaise, in the midst of the wild applause, the smallest of the four girls in the little group placed her hand gently upon the armless sleeve of her young man companion.

“Tonight makes up for a good deal, doesn’t it, Dick?” she queried a little wistfully. As she spoke her blue eyes were shining with excitement, while a warm color flooded her cheeks.

The young fellow nodded. “It is the greatest spectacle I ever saw and one we[13] shall never forget,” he replied. “Yet there will be a greater night to come when this war is finally over, though when that night will be no one can foretell.”

Dick Thornton spoke gravely and seemed weary from the evening’s excitement. But then something of what he had passed through in the last six months showed in other ways than in his empty coat sleeve.

Without his knowledge, the girl who had been speaking continued to study him for another moment. Then she turned to Mildred Thornton, who was on her other side, and whispered:

“Mill, Dick is tired, but would rather die than confess it. Can’t you think of some way to get us out of this crowd before the breaking up begins? The jam then will be awful and we may not be able to keep together.”

Up to the instant of Barbara Meade’s suggestion, Mildred had forgotten all personal matters in her interest in the music and the vivid beauty of the scene surrounding them. Now she too glanced toward her brother.

[14]

“Dick,” she suggested at once, “don’t you think we had best start back toward our pension? Madame Chenel is to sing an encore and I’m sorry we must miss it, but I really think it would be more sensible to go.”

With the closing of the Marseillaise the celebrated singer had disappeared. Now in the midst of Mildred’s remark she returned to the balcony of the Opera House. No longer was she wearing her crown of brilliants, nor carrying the immense French flag. Instead her head was uncovered, showing her dark hair and eyes and the flag she bore was British, not French.

Then she began singing in English, but with a delicious French accent:

The crowd joined in the chorus. There were soldiers on the street, who had returned to Paris on leaves of absence, after learning English from the Tommies in the trenches. Others had only a faint knowledge of a few English words. But everybody sang, and[15] because some of the voices were French and others English the effect was all the more thrilling and amusing.

Naturally Dick hesitated for a moment, then he remembered his own condition. Certainly he would be powerless to push their way through the great throng. Then if by chance rioting should break out from sheer excitement, it would be impossible for him to protect four girls. True, the American Red Cross girls were fairly well able to look after themselves in most emergencies. But Dick Thornton did not like the idea of having them put to the test at such a time and under the present circumstances.

“I am afraid you are right, Mildred,” he agreed reluctantly. “Let’s form a single file; I’ll go first and all of you follow me. Tell the others.”

Mildred at once put her arm inside a young woman’s who was standing near her, apparently oblivious of the past conversation. Yet one would have expected Eugenia Peabody to have been first to have made the sensible suggestion of the past few moments.[16] Yet it was Barbara Meade with whom it had actually originated.

But Eugenia too had been swept off her feet with enthusiasm. Moreover, she could scarcely make up her mind now to agree to leave, although plainly appreciating the situation. Eugenia looked surprisingly handsome tonight.

In the first place, she wore a new Paris frock, which after long insistence the other three girls had persuaded her to buy. It was an inexpensive dress of dark-blue cloth and silk, but it was stylishly made and extremely becoming. Above all, Eugenia had at last discarded the unattractive hat in which she had set sail, and which she had resolutely worn until this day. The new one had only cost five francs, but one should see the character of hat that can be bought in Paris for one dollar!

Eugenia, it is true, had begrudged even that small amount for her own adornment, until Nona and Barbara had refused to appear upon the street with her still in her ancient “Alpine.” However, although she rebelled against the unnecessary extravagance,[17] so far Eugenia had not regretted her purchases.

At the present moment she was standing next to Nona Davis and turned to speak to her.

“Nona, I am sorry when it’s all so wonderful, but we must start back to the pension at once. Please come on,” she insisted authoritatively.

And Eugenia had every reason to believe that Nona heard her words and agreed with her. She even thought that Nona moved on a few paces behind her. Moreover, this is exactly what she did. Nevertheless, Nona afterwards insisted that her act must have been purely involuntary, since she was not conscious of having heard or obeyed her companion.

If the little group of five Americans had been enthralled by the night’s excitement, it was Nona Davis who was most completely swept off her feet. Never had she even dreamed of such beauty and glamour as this gala night in Paris offered!

So little even of her own land had Nona seen, nothing save Charleston and the[18] surrounding neighborhood and the view from her car window on her way to New York City.

The few days in London had been overhung with the thought of the work ahead. But here in Paris for the past week the four Red Cross girls had been enjoying a brief holiday and were completely under the spell of the fascinating and beautiful city.

Upon persons with a far wider experience of life and places than Nona Davis, Paris frequently casts this same spell. Indeed, it sometimes seems impossible that a city can be so beautiful and yet suited to the uses of everyday life. Both in Paris and in Venice one often expects to wake up and find the city a dream and not a reality.

Certainly Nona had turned automatically to do as Eugenia had commanded her. But unfortunately, at the same moment Madame Chenel finished her English song and began at once on another which by an odd chance had a reminiscent quality for Nona. Instinctively she paused to listen and remember.

Her impression of the song was one of long ago. Nona’s mother had once been in[19] New Orleans. Now the vision came to her daughter of an old-fashioned spinet at one end of the drawing room in her home in Charleston, and of a young woman in a white dress with blue ribbons sitting there singing this same French verse.

For the moment everything else was forgotten. The girl simply stood spellbound until the great artist finished. Only when she began bowing her thanks to the applauding crowd, did Nona turn again to look for Eugenia and her other friends. But as more than five minutes had passed since their warning, and as they had believed Nona following them, no one of the four could be seen.

Moreover, at this same moment the great crowd began to break up. Then, as is always the case, everybody struggled to get away at the same moment.

Just at first Nona was not alarmed at finding herself alone; she was simply bewildered. However, because she was endeavoring to stand still while every one else was moving, she was constantly being shoved from side to side.

[20]

Her first intention was to remain in the same place for a few moments. Then Dick or one of the girls would probably return for her. However, she soon appreciated that no human being could push their way back through the thronging multitude. Moreover, she too must move along or be trampled upon.

Fortunately, the fact that she was alone did not seem to have been observed. For although the people in her neighborhood were not rough and ugly, as an English or Teutonic crowd might have been, nevertheless, Nona knew that for a young girl to be alone at night in the streets of Paris was an unheard-of thing. Besides, later on the crowd might indulge in noisier ways of celebrating the German defeat than by listening to the singing of the great prima donna.

What had she best do? As she was being pushed along, Nona was also thinking rapidly, although somewhat confusedly. She had not been on the street alone since her arrival. Both Mildred and Dick Thornton were familiar with Paris and had been acting as the others’ escorts.

[21]

Their little French pension happened to be over on the other side of Paris. Fortunately, Nona remembered that she could find a bus near the Madeleine, the famous church not more than a dozen blocks away from the neighborhood of the opera. But how to reach this destination and what bus to take after her arrival? These were problems still to be dealt with. First of all, she must keep her forlorn condition a secret from observers in order not to be spoken to by an impertinent stranger.

Naturally Nona appreciated that it was impossible for all Frenchmen to be equally courteous. Therefore, one of them might misunderstand her present predicament.

However, as there was nothing else to do she continued moving with the crowd. In the meantime she kept assuring herself that it was absurd to be so nervous over an ordinary adventure. Think what experiences she had so lately passed through as a Red Cross nurse!

But if she had only been wearing her nurse’s uniform, always it served as a protection! Yet naturally when one was[22] off duty and merely a holiday visitor in a city, it was pleasanter to dress like other persons.

Like Eugenia, Nona was also wearing a new frock. Hers was of black silk with a hat of black tulle, making her fair hair and skin more conspicuous by contrast. Certainly she would be apt to attract attention among the darker, more vividly colored French girls.

But Nona had gone half the distance to the Madeleine before she was annoyed. Then just as she was about to cross the street at one of the corners, an arm was unexpectedly slipped through hers.

With her heart pounding with terror and every bit of color drained from her cheeks, Nona looked up into the eyes of an impertinent youth.

“La belle Americaine!” he announced insolently.

[23]

The next instant Nona recovered her poise. She was, however, both frightened and angry. Yet if it were possible to avoid it, she did not wish to raise an alarm nor create any kind of commotion upon the street.

At first quietly and firmly she attempted removing her arm, at the same time regarding the Frenchman with an expression of scorn and disapproval.

“Let me go at once,” she said, speaking excellent French, so there was no possibility of being misunderstood.

But the young man only shrugged his shoulders, looking, if she had but known it, more mischievous than wicked.

But Nona was now gazing despairingly about her. There were numbers of persons near by, stout mothers and fathers, the respectable tradespeople of Paris, with[24] the usual French family of two children. Nona could, of course, appeal to any one of them. But just at the instant no one was sufficiently near to accost without raising her voice. This would, of course, attract public attention, which, if possible, Nona did not wish to do.

So she waited another second, hoping her tormentor would release her of his own accord. Finding he did not intend this, she glanced about for assistance a second time. Then she discovered two young officers passing within a few feet of her. One of them wore a British uniform and the other French.

Nona spoke quickly, knowing instinctively that the men were gentlemen.

“Stop a moment, please!” she asked. “I am a stranger and have lost my friends in the crowd. This man is annoying me.”

Then in spite of her efforts the girl’s voice shook with nervousness while her eyes filled with humiliated tears.

With her first words the two officers whirled around. At the same moment Nona’s persecutor started to run. However,[25] he was not quick enough, for the young French officer managed to slip his scabbard between the fellow’s feet. At once he was face down on the ground and only brought upright again by the officer’s hand on his collar.

In the interval the other young man was gazing at Nona Davis in surprise and perhaps with something like pleasure.

“Miss Davis,” he began, lifting his officer’s cap formally, “are we never to meet except under extraordinary circumstances? You may not remember me, but I am Lieutenant Hume, Colonel Dalton’s aide. Perhaps you recall that unfortunate affair in which Miss Thornton was concerned at the Sacred Heart Hospital? But before that you know there was our first meeting at the gardener’s cottage in Surrey.”

It was unnecessary for Lieutenant Hume to present Nona with all his credentials of acquaintance. For at this instant she was too unreservedly glad to see him. To have discovered some one whom she knew at such a trying time was an unexpected boon.

[26]

“I am, you see—oh, I can’t explain now,” Nona protested. “But, Lieutenant Hume, if you have nothing very important to do, won’t you be kind enough to put me on the right bus. I am trying to get back to our pension. And though I am sorry to be so stupid, I am lost and dreadfully frightened.”

The hand that Nona now extended to her English acquaintance was cold with nervousness.

Lieutenant Hume took it and bowed courteously. “Of course I will take you home with the greatest pleasure,” he returned. At the same time he smiled to himself:

“Girls are indeed strange creatures, say what you will! Here is a young American girl who has been doing Red Cross work near the battlefield. She has been able to keep her head and remain cool and collected among war’s horrors, but because she has been spoken to on the street by a young ruffian she is terrified and confused.” Possibly she would have scorned his protection in the face of an artillery charge, when[27] under the present conditions a masculine protector was fairly useful.

Now for the first time the young French officer spoke. He had just given his captive a rough shake and then straightened him up again after a second attempt to get away.

“What shall I do with this fellow, Mademoiselle?” he asked, speaking English with difficulty, but showing extraordinarily white, even teeth under a small, dark moustache. Indeed, Nona decided that she had never seen a more charming and debonair figure than the young French officer, when he finally engaged her attention. He could scarcely have been more than five feet, four inches tall, yet his figure was perfectly built. He was slender, but from the casual fashion in which he gripped the other man, who was several inches taller and far heavier, he must have been extraordinarily strong.

“Oh, let the man go, please,” Nona murmured weakly. “Yes, I know I should have you turn him over to a gendarme and appear against him in court, but really I should hate doing it.”

[28]

The girl smiled at the young French officer’s evident disappointment. He made no protest, however; only he gave the man another half-savage shake and said rapidly in French:

“Why aren’t you with the army, you miserable loafer? Your name at once?” Then, when the offender mumbled something indistinguishable: “Report to me at the barracks tomorrow. Oh, I shall find you again, never fear, and it will then be imprisonment for you.”

The moment after the man had run away the French officer stood at attention with his shoulders erect and his feet together. The next he bowed to Nona in an exquisitely correct fashion, as Lieutenant Hume introduced him.

“Miss Davis, my friend, Captain Henri Castaigne, one of the youngest captains in the French army.” Lieutenant Hume then added boyishly: “Tomorrow he is to be presented with the Cross of the Legion of Honor.”

Nona was naturally impressed by such an introduction. But evidently the young[29] officer preferred not having his praises sung to a complete stranger. He pretended not even to have heard his friend’s last remark.

“I will say au revoir,” he returned graciously. “Since you and Lieutenant Hume are old acquaintances, he will prefer to take you to your friends unaccompanied by me.”

He was about to withdraw when Nona interposed.

“But you must have had some engagement together for the evening. Now if you separate on my account your evening will be spoiled. So please don’t trouble to take me all the way to the pension; just find my omnibus and——”

Both young men laughed. The idea of leaving a girl alone in such an extremity was of course an absurdity.

“Oh, come along, Henri, Miss Davis will be able to endure your society for a few moments as long as I was braced to endure it all evening.” Lieutenant Hume added: “Besides, it may help your education to talk to an American girl. Castaigne does not know a thing except military tactics;[30] he is rather a duffer,” the English officer continued half proudly and half with a pretense of contempt. It was not difficult to discover that there was a good deal of affection existing between the two young officers of the Allied armies.

Nona wondered how they happened to know each other so intimately.

“By the way, Lieutenant Hume,” she asked, when they had finally reached the desired square and stood waiting their turn on the overcrowded omnibus. “How in the world do you chance to be in Paris instead of at the front? The last time I heard of you, you were in the midst of desperate fighting.”

The young man answered so quietly that no one except his two companions could hear. “I am in Paris on a private mission for the British Government. I am not at liberty to say anything more.”

Nona flushed, a little confused at having appeared to be curious when she had only meant to be friendly. But immediately Lieutenant Hume inquired:

“May I ask the same question of you?[31] How do you chance to be in Paris? Did you come here after the Sacred Heart Hospital was closed? I knew that one side of it had been struck by a shell and partly destroyed.”

Nona nodded. “Yes, but let us not talk of that now, if you don’t mind. We had to move the wounded soldiers, the supplies and everything in a tremendous hurry. So we are resting now for a short time and afterwards mean to go into southern France to help with the hospital work there. But hasn’t tonight’s celebration been too wonderful? It is the very first victory I have ever helped to celebrate and it has made me very happy.”

“Then you are not entirely neutral, as you Americans are supposed to be?” Lieutenant Hume queried, waiting with more interest than was natural for his companion’s reply. “I thought Red Cross doctors and nurses were expected to have no feeling about the war.”

Nona hesitated. “Of course, that is true so far as our nursing goes,” she replied. “Naturally I would nurse any soldier without[32] its making the least difference what his nationality might be. But when it comes to a question of my own personal feeling, well, that is a different matter.”

Nona’s answer was a little incoherent; nevertheless, her companion seemed to find it satisfactory.

On arriving at the pension Eugenia herself opened the door. The concierge had previously admitted the girl and her two escorts to the ground floor.

The apartment where the four girls and Dick Thornton were at present boarding occupied the third floor of an old house that had once belonged to an ancient French family and had afterwards been converted into an apartment building. Such houses are common in Paris. The atmosphere of this one was gloomy and imposing and the hallway very dark.

At first Eugenia only saw Nona outside or she might have been more amiable. However, she had been so frightened for the past hour that she was thoroughly angry, an effect fright often has upon people.

[33]

“Nona, what does this mean?” she demanded, speaking like an outraged school-marm. “You have given us one of the worst hours any one of us has ever spent. Why did you not come along with the rest of us? Of course, no one wished to leave; it was quite as much of a sacrifice for us as for you. Now Mildred and Barbara and Dick have had to go back to look for you and to inform the police of your disappearance. I have waited here, hoping for a message from them or you.”

“Yes, I know. I am dreadfully sorry,” Nona replied more apologetically than she actually felt. Naturally regretting the trouble she had given, yet she did not enjoy being scolded before entire strangers.

“Eugenia,” she protested, changing the tone of her voice in an effort to stem the tide of her friend’s resentment, “I was so fortunate as to meet Lieutenant Hume on the street. You may recall he was Colonel Dalton’s companion when he visited the Sacred Heart Hospital. He and his friend have been good enough to bring me home. I should like to have you meet them.”

[34]

Certainly Eugenia was somewhat nonplussed on discovering that there had been an audience to overhear her reproaches. Still she was no less offended. However, she could not exactly make up her mind to refuse to be introduced to Nona’s acquaintances, who had undoubtedly been kind.

The result was that she was stiffer and colder than ever before as she stalked ahead into the pension drawing room, leaving the younger girl and the two men to follow her.

Moreover, Eugenia undoubtedly looked plain, partly as the result of her severe mood and partly of her fatigue and anxiety. She had removed her street suit and was wearing a gray frock that might have been cut out by the village carpenter, so free was it from any possible grace or prettiness. The dress had been intended to be useful and undoubtedly had been, for Eugenia must have been wearing it for the past five years.

But Eugenia really believed that she was fairly gracious to the two young officers. She shook hands with both of them and[35] asked them to be seated. She even thanked them for escorting the scapegrace home, yet all in a manner that suggested ice trying to thaw on an impossibly cold day.

Lieutenant Hume paid but little attention to her, being frankly too much interested in Nona Davis to do more than be polite to Miss Peabody, whom he regarded strictly in the light of a chaperon.

But to Captain Castaigne Eugenia was at once a puzzle and an amusement. In his life he had never seen any one in the least like her.

The young French officer belonged to an old and aristocratic French family. Had France remained a monarchy instead of becoming a republic, he would have held a distinguished title. He was not a native of Paris, for he had been brought up in the country with his mother upon their impoverished estate. Later, as she considered a soldier’s life the only one possible for her son, he had attended a military school for officers. So it was true that he knew but little of women. However, those he had met previously had been his mother’s[36] friends and their daughters. They were women with charming, gracious manners, of unusual culture and refinement. Moreover, they had always been extremely kind to him. Now this remarkable young American woman paid no more attention to him than if he had been a wooden figure, and perhaps not so much. Her appearance and manner recalled an officer whom he had once had as a teacher. His colonel had been just such a tall, stern person, who having given his orders expected them to be obeyed without demur. So the young French officer was torn between his desire to laugh, which of course his perfect manners made impossible, and his desire to offer this Miss Peabody a military salute.

She spoke the most extraordinary French he had ever heard in his life. Her grammar was possibly correct, but such another accent had never been listened to on sea or land. Captain Castaigne was not familiar with Americans, so how could he know that Eugenia spoke French with a Boston intonation?

[37]

Ten, fifteen minutes elapsed, while conversation between Eugenia and the French officer became more and more impossible. Nevertheless his friend failed to regard Captain Castaigne’s imploring glances.

At last the English officer realized that their call was becoming unduly long under the circumstances. Yet before saying farewell he managed a few moments of confidential conversation with Nona.

“You will persuade your friends to come to the Review tomorrow? I shall call for you more than an hour ahead of time. President Poincaré himself is to present decorations to a dozen soldiers. I say it would be rotten for you to miss it.”

Undoubtedly Nona agreed with him. “You are awfully kind. I accept for us all with pleasure and shall look forward then to tomorrow,” she returned. “Thank you again for tonight, and good-by.”

[38]

That night just before falling asleep Nona Davis had an unexpected flash of thought. It was odd that Lieutenant Hume, who had been a friend in need, should turn out to be such a well-educated and attractive fellow. Moreover, how did it happen that he was a British officer? Now and then for some especial act of valor, or for some especial ability, a man was raised from the ranks. Yet Nona did not believe either of these things to have happened in Lieutenant Hume’s case.

What was the answer to the puzzle? He was the son of a gardener and she herself had seen his mother Susan, a comfortable old lady with twinkling brown eyes, red cheeks, a large bosom and a round waist to match. Surely it was difficult to conceive of her as the mother of such a son![39] And especially in England where it was so difficult to rise above one’s environment.

Although tired and sleepy, Nona devoted another ten minutes to her riddle. Then all at once the answer appeared plain enough. Lieutenant Hume had doubtless been brought up as the foster brother of a boy of nobler birth and greater riches than he himself possessed. Then, doubtless, seeing his unusual abilities, he had been given unusual opportunities. Nona had read English novels in which just such interesting situations occurred, so she felt rather pleased with her own discernment. However, if it were possible to introduce the subject without being rude, she intended to make sure of her impression by questioning Lieutenant Hume. One might so easily begin by discussing English literature, a subject certainly broad enough in itself. Then one could mention a particular book, where a foster brother played a conspicuous part. But while trying to recall a story with just the exact situation she required, Nona went to sleep.

She and Barbara shared the same room.[40] But fortunately no one of her other friends had been so severe as Eugenia. However, after the departure of the two young men, realizing that she had been tiresome, Nona had been sufficiently contrite to appease even Eugenia.

The next morning at déjeuner Dick Thornton declared that Nona’s adventure had really resulted in good fortune for all of them. More than most things he had desired to attend the review of the fresh troops about to leave Paris for the firing line. Moreover, it would be uncommonly interesting to see the presentation of the decorations by the French President. And if Nona had not chanced to meet Lieutenant Hume and his friend, neither of these opportunities would have been theirs. Dick had no chance of securing the special invitations and tickets necessary for seats in the reviewing stand. Privately Dick had intended escaping from the four girls to witness the scene alone. But now as Lieutenant Hume had invited all of them it would be unnecessary to make this confession.

[41]

The review was to take place on a level stretch of country just outside Paris between St. Cloud and the Bois.

Having in some magical fashion secured two antiquated taxicabs, Lieutenant Hume arrived next day at the pension. He and Nona and Eugenia started off in one of them, with Barbara, Mildred and Dick in the other.

During the ride into the country Lieutenant Hume talked the greater part of the time about his friend, Captain Castaigne, whom Nona and Eugenia had met the evening before. The two men had only known each other since the outbreak of the war, yet a devoted friendship had developed between them.

Indeed, Nona smiled to herself over Lieutenant Hume’s enthusiasm; it was so unlike an Englishman to reveal such deep feeling. But for the time being Captain Henri Castaigne was one of the idols of Paris. The day’s newspapers were full of the gallant deed that had won him the right to the military order France holds most dear, “The Cross of the Legion of Honor.”

[42]

Nevertheless, during the early part of the conversation Eugenia scarcely listened. She was too busily and happily engaged in watching the sights about her. Paris was having a curious effect upon the New England girl, one that she did not exactly understand. She was both shocked and fascinated by it.

In the first place, she had not anticipated liking Paris. She had only consented to make the trip because they were in need of rest and the other girls had chosen Paris. Everything she had ever heard or read concerning Paris had made her feel prejudiced against the city. Moreover, it was totally unlike Eastport, Massachusetts, where Eugenia had been born and bred and where she had received most of her ideas of life.

Yet there was no denying that there was something about Paris that took hold even of Eugenia Peabody’s repressed imagination.

It was a brilliant autumn afternoon. The taxicab rattled along the Champs Elysées, under the marvelous Arc de Triomphe[43] and then turned into the wooded spaces of the Bois.

Every now and then Eugenia found a lump rising in her throat and her heart beating curiously fast. It was all so beautiful, both in art and nature. Surely it was impossible to believe that there could be an enemy mad enough to destroy a city that could never be restored to its former loveliness.

Perchance the war had purified Paris, taking away its uglier side in the healing influence of patriotism. For even Eugenia’s New England eyes and conscience could find but little to criticize. Naturally many of the costumes worn by the young women she considered reprehensible. The colors were too bright, the skirts were too short. French women were really too stylish for her severer tastes. For there was little black to be seen. This was a gala afternoon, so whatever one’s personal sorrow, today Paris honored the living.

Before Eugenia consented to listen Lieutenant Hume had arrived in the middle of his story, and then she listened only half-heartedly.[44] She was interested chiefly because the young Captain she had met the evening before was so far from one’s idea of a hero. He was more like a figure of a manikin dressed to represent an officer and set up in a shop window. His features were too perfect, he was too graceful, too debonair! But in truth Eugenia’s idea of a soldier must still have been represented by the type of man who, shouldering a musket and still in his farmer’s clothes, marched out to meet the enemy at Bunker Hill.

Some day Eugenia would learn that it takes all manner of men and women to make a world. And that there are worthwhile people and things that do not come from Boston.

“He was in the face of the enemy’s fire when a shell exploded under his horse,” Lieutenant Hume explained. “He and the horse were shot twenty feet in the air. When they came down to earth again there was an immense hole in the ground beneath them and both man and horse were plunged into it. Rather like having one’s grave dug ahead of time, isn’t it?”

[45]

Nona nodded, leaning across from her seat in the cab with her golden brown eyes darkening with excitement and her hands clasped tight together in her lap.

Eugenia kept her eyes upon her even while giving her attention to the narrative. Personally she considered Nona unusually pretty and attractive and the idea worried her now and then. For there were to be no romances if she could prevent them while the four American Red Cross girls were in Europe. If they wished such undesirable possessions as husbands they must wait and marry their own countrymen.

“But Captain Castaigne was not hurt? So he still managed to carry the messages to his General?” Nona demanded. She was much interested in getting the details of the story before seeing its hero again.

Robert Hume was talking quietly. Nevertheless it was self-evident that he was only pretending to his casual tone.

“Of course Captain Castaigne was injured. There would have been no reason why any notice should have been taken of him if he had only done his ordinary duty.[46] Fact is, when he crawled out he was covered with blood and nearly dead. The horse was killed outright and Henri almost so. Nevertheless he managed to run on foot under heavy fire to headquarters with his message. No one knows how he accomplished it and he knows least of all. He simply is the kind of fellow who does the thing he starts out to do. We Anglo-Saxons don’t always understand the iron purpose under the charm and good looks these French fellows have. But fortunately we don’t often use cavalrymen now for carrying despatches. Motor cars do the work better when there is no telephone connection.”

“Yes, and I’m truly glad,” Nona murmured softly. She was thinking of how many gallant young cavalry officers both in France and England those first terrible months of the war had cut down, before the lessons of the new warfare had been learned.

But Eugenia had now awakened to a slight interest in the conversation.

“Your young friend looks fit enough now,” she remarked dryly.

[47]

The English officer was not pleased with Eugenia’s tone. “Nevertheless, Captain Castaigne has been dangerously ill in a hospital for many months, although he is returning to his regiment tomorrow.”

After this speech there was no further opportunity for conversation. The two cabs had driven through the Bois and were now in sight of the field where the review was to be held.

Drawn up at the left were two new regiments about to depart for the front. Most of the soldiers were boys of nineteen who would have finished their terms of military service in the following year, but because of necessity were answering France’s call today. They were wearing the new French uniform of gray, which is made for real service, and not the old-fashioned one with the dark-blue coat and crimson trousers. These too often formed conspicuous targets for the enemy’s guns.

Across from the recruits stood another line of about fifty men. They were old men with gray hair. If their shoulders were still erect and their heads up it was not[48] because this was now their familiar carriage. It was because this great day had inspired them. For they were the old soldiers who had been gallant fighters in 1870, when France had fought her other war with Germany. Now they were too old to be sent to the firing line. Nevertheless, each one of them was privately armed and ready to defend his beloved Paris to the last gasp should the enemy again come to possess it.

Between the two lines and on horseback were President Poincaré, France’s new war minister and half a dozen other members of the Cabinet.

Then standing in a small group separated from the others were the soldiers who were about to be decorated for especial bravery.

While Lieutenant Hume was struggling to find places for his guests, Nona was vainly endeavoring to discover the young French officer whom she had met so unexpectedly the evening before. She was anxious to point him out to Mildred and Dick and Barbara.

But after they were seated it was Eugenia[49] who found him first. Captain Castaigne was wearing an ordinary service uniform with no other decorations besides the emblems of his rank.

Then a few moments later President Poincaré and his staff dismounted.

The four American girls were distinctly disappointed by the French President’s appearance. He is a small, stout man with a beard, very middle class and uninteresting looking. Yet he has managed to hold France together in times of peace and of war.

This was indeed a great day for Paris. Rarely are medals for bravery bestowed upon the soldiers save near the scene of battle by the officers in command. Yet there was little noise and shouting among the crowd as there had been the evening before. They were unusually silent, the women and girls not trying now to keep back the tears.

Sixty-four buglers sounded a salute. Then President Poincaré marched forward and shook hands with every soldier in the group of twelve. Eleven of them were to[50] receive the new French decoration which is known as the “Croix de Guerre.” This is a medal formed of two crossed swords and having a profile of a figure representing the French Republic in the center. But Captain Castaigne alone was to be honored with the Cross of the Legion of Honor.

First President Poincaré pinned the medal on the breast of a boy sentry. He had stood at the mouth of a trench as the Germans approached, and though wounded in half a dozen places had continued to fire until his companions had been warned of the attack.

Then one after the other each soldier received his country’s thanks and the recognition of his especial bravery until at length President Poincaré came to young Captain Castaigne.

One does not know exactly what it was in the young man’s appearance that touched the older man. Perhaps when you learn to know more of his character you will be better able to understand. For after the President had bestowed the higher decoration upon the young captain, he leaned over and kissed him.

[51]

Eugenia Peabody had an excellent view of the entire proceeding. Though her lips curled sarcastically, strangely enough her eyes felt absurdly misty. She much disliked this French custom of the men kissing each other, for Eugenia believed very little in kissing between either men or women. Nevertheless, she did feel disturbed by the whole performance, and hoped that her friends were too much engaged to pay attention to her. Above all things Eugenia desired that Barbara Meade should not observe her weakness. She knew Barbara would never grow weary hereafter of referring to the amazement of Eugenia’s giving way to tears in public and without any possible excuse.

Ten minutes later the review began with a blare of trumpets. Then gravely the new regiments passed before the President and his officers. Afterwards they marched away until a cloud of dust hid them and there was nothing for the spectators to do but return to their own homes.

Nevertheless, the young French Captain managed to make his way to his English[52] friend. He appeared as indifferent and as debonair as he had the evening before. One could never have guessed that he had just received the greatest honor of his life, and an honor given to but few men.

Reference to his decoration he pretended not to be able to understand, although Mildred, Barbara and Dick tried to compliment him with their best school French.

But beyond inclining her head frostily, Eugenia made no attempt at a further acquaintance with the young soldier.

However, several times when he believed no one was observing him, Captain Castaigne stole a furtive glance at Eugenia.

She was somewhat better looking than she had been the evening before, yet she was by no means a beauty. Moreover, she was still a puzzle.

Then the boy—for after all he was only twenty-three—swallowed a laugh. At last he had found a real place for Eugenia. No wonder he had thought of his former colonel. Recently he had learned that a regiment of women in Paris were in training as soldiers. He could readily behold Eugenia in command.

[53]

The other three American girls were charming and he was glad to have met them. But Eugenia he trusted he might never see again. He was glad to be returning to the firing line next day. Let heaven preserve him from further acquaintance with such an unattractive person!

[54]

One week longer the American Red Cross girls remained in Paris. They were only tourists for these brief, passing days. Yet all the while they were waiting for orders. After having nursed the British soldiers for a number of months, when the Sacred Heart Hospital was no longer in existence, they had concluded to offer their services to France.

Therefore, like soldiers, they also were ready upon short notice to start for the front. But in the meantime there was Paris to be investigated, where the October days were like jewels. One saw all that it was humanly possible to see of pictures and people and parks and then came home to dream of the statues in the Luxembourg, or of Venus in her shaded corner in the Louvre, or else of the figure of Victory midway up the Louvre’s central staircase.

[55]

To one another the girls confessed that it was difficult to think of war so near at hand, or of the experiences through which they had so lately passed. Yet one saw the streets full of soldiers and knew that a great line of fortifications encircled Paris, such as few cities have ever had in the world’s history. Also, there were always guns mounted on high towers waiting for the coming of the Zeppelin raid.

“Then one night, as luck would have it,” Barbara insisted, “the raid came just in the nick of time. For how could the Germans have dreamed that we were leaving for southern France the next morning?”

Nevertheless, the luggage of the Red Cross girls was actually packed and in spite of war times the girls had added to the amount. Moreover, they were due to take the ten o’clock train next day at the Gare de Lyons. So because they were weary, a little sorry at having to leave Paris, and yet curious of the new adventures ahead, the four girls retired early.

In one way Paris has conspicuously changed since the outbreak of the war.[56] She has become an early-to-bed city and except on special occasions her cafés are all closed after dark.

So Dick Thornton, although not leaving with the girls the next day, found little to amuse him on the same evening. He had said good-night soon after dinner and then gone for a long walk. For in truth he did not wish to have an intimate farewell talk with his sister or any one of her friends.

The hazards of war had used Dick pretty severely. He had not come to Europe to act as a soldier; nevertheless, in a tragically short time, before he had even begun to be fairly useful, he had paid a cruel penalty. Dick believed that he would never again be able to use his right arm.

He did not intend, however, to allow this to make him morose or disagreeable and so seldom spoke of it. But now and then he used to desert his four feminine companions and walking through the semi-darkened streets of Paris try to work out a solution for his future.

So by chance it was Dick who gave the alarm to the household on the night of Paris’ long-anticipated Zeppelin raid.

[57]

He had just come home and was standing idly before the door waiting to awaken the concierge who presides over the destinies of all Parisian apartment houses. A beautiful night, the sky was thickly studded with stars, although there was no moon.

Suddenly Dick heard a tremendous explosion. Naturally his first thought was a bomb and then he smiled at himself. In war times every noise suggested a bomb. This noise may have been nothing but an unusually loud automobile tire explosion. However, Dick was not particularly convinced by his own suggestion. He remained quiet for another moment with all his senses acute. The streets in his neighborhood had been well-nigh deserted at the moment of the shock. If it were nothing they would still continue so. A brief time only was necessary for finding out. For an instant later windows were thrown open and every variety of heads thrust forth with eyes upturned toward the sky.

Then a fire engine rattled by and afar off a bugle call sounded.

[58]

That moment Dick pounded at the closed door of their house, but the concierge was already awake and let him in at once. Then with a few bounds he cleared the steps and stood knocking at his sister’s bedroom door.

“Something startling is happening, I don’t know exactly what,” he announced hurriedly. “But you girls had best get on some clothes and come out. I am going up on the roof. If it is a Zeppelin raid the city officials have warned people to go down to the cellars. I’ll let you know in half a minute.”

But in half a minute Dick did not return. There seemed to be no danger for the present at least, and besides he had a masculine contempt for the length of time it takes girls to put on their clothes, even in times of emergency. Moreover, he kept staring up at the heavens too entranced by the spectacle to think of danger.

Five Zeppelins were passing over Paris, the projectiles which they dropped in passing leaving long trails of light behind them.

[59]

Soon after a small voice spoke at Dick’s elbow: “It’s wonderful, isn’t it? When I was a little girl I could never have believed that I should see real fireworks like these.”

Without glancing around Dick naturally recognized the voice. It always amused him to hear Barbara talk of the days when she was little, as she appeared so far from anything else even now.

“You had better go downstairs, little girl, with the other girls;” he commanded. “Yes, it is a wonderful spectacle, but this is no place for you.”

Then hearing her laugh lightly, he did turn around. Assuredly Barbara could not go down to the other girls, since they were assembled on the roof with her, and not only the girls but a third of the people in the pension. They were all talking at once in French fashion.

Dick felt rather helpless.

“I thought I told you to go to the cellar,” he protested. But Barbara paid not the slightest attention to him and the other girls were out of hearing.

[60]

She was clutching his left arm excitedly.

Now they could see the aeroplanes that had come out for the defense of Paris circling overhead and firing upon the Zeppelins and farther off in the distance the thunder of cannon could be heard.

“Paris is being wonderfully good to us, isn’t she?” Barbara whispered. “We keep seeing more and more amazing things.”

Dick scoffed. “I thought you pretended to be a coward, Barbara, though it is difficult for me to think of you as one.”

And to this the girl made no answer except, “I don’t believe any one in Paris is seriously frightened. A raid is not the terrible thing everybody feared, at least not one like this.”

But Dick was not so readily convinced. There was a chance that these first air raiders were but scouts of the great army of German Zeppelins that London and Paris have both been dreading since the outbreak of the war.

Moreover, Dick was not alone in this idea. He could see now that the tops of all the large houses and hotels in the[61] neighborhood, as far as one could discern, were thronged with as curious a crowd as his own. And from the streets below chatter and laughter and now and then cries of terror or admiration floated upward.

Of course, there were many persons in Paris that night wiser or at least more prudent than the four American Red Cross girls, and there were a number of places where proper precautions were taken. However, no one thought of going to bed again.

By and by the three other girls joined Barbara and Dick. But now there was nothing more to be seen save the stars in the sky which were too eternal to be appreciated. So when the noise of the cannonading had at last died away, Madame Raffet, who had charge of the pension, asked her guests to come down into the drawing room for coffee.

The girls were cold and dismal now that the excitement had passed and were glad enough of the invitation. Dick Thornton, however, resolutely declined to join them. He was still not in the mood for cheerful[62] society, although he did not offer this excuse. He merely said that he always had wished to see the dawn steal over Paris and here was the opportunity of a lifetime, since the dawn must break now in a short while.

It may be that Barbara Meade guessed something of her friend’s humor, for she went quietly away with the other girls, not joining her protests with theirs over Dick’s unusual obstinacy.

An hour and a half passed, perhaps longer. Dick had found a seat on a stone ledge between two tall chimney stacks. It was a long, cold bench and he was growing rather tired of his bargain. Still, there was a grayness over things now and daylight must soon follow. Yet he was sorry he had not gone downstairs with the others; it would have been an easy enough business to have returned to his perch later and coffee would undoubtedly have been a boon.

He was kicking his feet rather more like a disconsolate small boy, who had been sent upstairs to his room alone for punishment,[63] than like a romantic youth about to pay tribute to his Mistress Paris, when Barbara Meade joined him for the second time that evening.

However, this time he saw her coming and her welcome was far more enthusiastic.

The girl had put on her long gray-blue nursing coat, but wore a ridiculous little blue silk cap pulled down over her curls. Moreover, Dick Thornton had to rush forward to meet her to keep her from tripping, since she was dragging his neglected overcoat with her and also trying to carry a thick mug of coffee.

Dick snatched at the mug none too politely.

“I say, you are a trump!” he remarked with such fervor, however, that any girl would have forgiven him.

Then Barbara sat down beside him on the stone ledge and after seeing that he had put on the overcoat, watched him drink the coffee. She even added two rolls for his refreshment from the depth of her pocket.

“I made the coffee for you myself. I[64] think it rather good of me,” she remarked placidly. “The other girls are lying down. But I had a fancy to see the dawn over Paris myself and I thought if I brought you a present you would not send me away.”

Dick smiled, for the dawn had broken when Barbara came. From their tall roof they had a marvelous view of the city and the long line of beautiful bridges crossing the Seine. And there, not far away, looking as if she were built half upon the water and half upon land, the Church of Notre Dame.

A sudden glory of red and gold bathed its two perfect towers and the cross above. Slipping down between the grinning gargoyles along its sides it dipped into the river below. In another direction Montmartre was shimmering like a rainbow, steeped in the colors and the glories of romance.

Barbara shivered over the strange beauty after the excitement of the night before. And although Dick was there and they were good friends, she wished that one of the girls had also been her companion. It[65] was a time when she would have liked to put her hand inside a friend’s just for the sense of warm human companionship.

But Dick was not at the moment looking or thinking of her. It was hardly to be wondered at, the girl thought with the old grace of a smile at herself. There were so many better things to see. Yet it gave her the chance for a farewell study of him. They were to part now in a short time, for how long neither of them knew.

The next instant Barbara regretted her decision. For how wretchedly Dick Thornton was looking! Could any one believe that only a little over a year had passed since their first meeting on the March night when she had arrived so unceremoniously at his father’s house. Certainly Dick had been more than kind to her even then.

A moment later when Dick did chance to glance toward his companion she was crying hard but silently.

Once or twice before Dick had been surprised at Barbara Meade’s unexpected tears, but now he understood them at once.

[66]

He offered her the comfort she had wished a little while before. Gently he took her hand inside his left one.

“I know you are thinking of me, Barbara, and this tiresome old arm of mine. It is tremendously kind of you,” he protested. “But I want you to promise me not to worry and to keep Mill from fretting if you can. I hate you girls to go off to work again without me, but I’ve made up my mind to stay around Paris for a few months. I’m rather glad to have this chance to explain things to you. Of course, you know that when that shell shattered my shoulder it seemed to paralyze my arm. Well, I have not given up hope that something may yet be done for it. So as soon as I can get hold of one of the big surgeons here in Paris I want him to have a try at me. They are fairly busy these days with people who are of more account, but if I hang around long enough some one will find time to look after me. You know I have never told, nor let Mildred tell mother and father just how serious things are with me. But if[67] nothing can be done I’ve made up my mind to go home and find out what a one-armed man can do to be useful. He isn’t much good over here at present. You see, Barbara, I have not yet forgotten your New York lectures on the duty and beauty of usefulness.”

Dick said this in a laughing voice, with no intention of attempting the heroic, so Barbara did her best to answer in the same spirit.

Nevertheless, she had never gotten over her sense of responsibility and might always continue to feel it.

“Oh, I am sure something can be done,” she answered, forcing herself to speak bravely. “But in any case you will come and say good-by to Mill and the rest of us before you sail, won’t you?” she concluded.

Dick nodded, but by this time they had both gotten up and were walking across the roof top side by side.

“I say, Barbara,” Dick added shyly just at the moment of parting, “however things turn out, promise me you won’t take it[68] too seriously. Somehow I can’t say things as well as other fellows, but I’m not sorry I came over, in spite of this plagued arm of mine. I don’t know why exactly, but this war business makes a man of one. Then when one thinks of what other fellows are having to give up—oh well, I read a poem by an Englishman who was killed the other day. Would you mind my reciting the last lines to you?”

Then taking the girl’s consent for granted, Dick went on in a grave young voice that had much of the beauty which Barbara remembered in his song the year before.

“His name was Rupert Brooke and he wrote of the men who were going to die as he did:

[69]

The work which the American girls were to do for the French Croix de Rouge (Red Cross) was to be accomplished under entirely different circumstances.

They traveled southeast nearly an entire day and toward evening were driven through a thickly wooded country to the edge of the Forest of Le Prêtre.

An American field hospital, an exact duplicate of those used in America, had recently been presented to the French Government by three Americans who desired that their identity be kept a secret. The hospital was made up of twenty tents; six of them large enough to take care of two hundred wounded men. And these hospital tents could be put up in fifteen minutes and taken down in six by the American ambulance volunteers, many of[70] them students from Columbia, Harvard, Williams and other American universities.

So it was thought fitting that the four American Red Cross girls, who had lately offered their services to France, should assist in the nursing at these new hospitals. They had been located in southern France near the lines and just beyond the reach of the enemy’s guns.

Therefore it was self-evident that different living arrangements would have to be made for the nurses. So Nona, Barbara, Mildred and even Eugenia were unfeignedly glad when they learned that they were to live together in a tiny French farmhouse within short walking distance of the field hospital. There they were to do their own housekeeping, with the assistance of an old man who would take charge of the outdoor work.

The farmhouse had been offered for their use by the French countess who was the owner of an ancient chateau about a mile away. Indeed, the farmhouse lay within the boundaries of her lands.

When the girls first tumbled out of the[71] carriage they were too tired to be more than half-way curious over their new abode. But half an hour later they were investigating the entire place with delight.

This was because they had already rested and eaten a supper that would have served for all the good little princesses in the fairy stories.

Naturally the girls had expected to find their little house empty. But no sooner had they started up the cobblestone path to the blue front door when an old man appeared on the threshold, bowing with the grace of an eighteenth century courtier. He was only François, the old French peasant who was to be of what service he could to them.

There in the clean-scrubbed dining room stood a round oak table set with odd pieces of china, white and blue and gold, hundreds of years old and more valuable than any but a connoisseur could appreciate.

François himself waited to serve supper. The Countess, whose servant he had been for fifty years, had sent over the food—a pitcher of new milk, a square of golden[72] honey, petit fromage, which is a delicious cream cheese that only the French can make, and a great bowl of wild strawberries, which ripen in autumn in southern France. Besides this there was a big loaf of snowy bread.

Barbara straightway threw her bonnet and coat aside. Then as she found the first place at the table she exclaimed, “So this is what one has to eat in France in war times!”

A few moments later Mildred took her place at what was hereafter to be known as the head of the table, with Eugenia just across and Barbara and Nona on either side. For so almost unconsciously the little family of four girls arranged themselves. Although it was not until later that Mildred Thornton was to prove the real authority in domestic matters, while Eugenia continued to regard herself as intellectual head of the family, with Nona and Barbara as talented but at times tiresome children.

However, after thanks and good-byes were said to old François, the girls started[73] on their tour of the little house. Evidently it had belonged to real farmer people who must have worked some of the land of the countess. Doubtless the men had gone to war and the women found employment elsewhere.

The farmhouse was only one story and a half high, with the kitchen and dining room below, but above there were four small bedrooms with a single window each and sloping ceilings. But the charming thing was that the walls were of rough plaster painted in beautiful colors—one rose, one blue, one yellow and the other lavender.

So the girls chose each the color she most loved—Barbara the blue, Nona the pink, Mildred the lavender, and Eugenia, professing not to care, the yellow.

It was just about dusk when they finally came outdoors again for a better view of the house itself. They had scarcely done more than glanced at it on entering.

The farmhouse was built of wood which had once been white but was now a light gray with the most wonderful turquoise blue door and shutters.

[74]

Indeed, the girls were to find out later that the little place was known in the neighborhood roundabout as “The House with the Blue Front Door.”

But though the house was so delightful that the girls had almost forgotten the sadness of their errand to the country, the landscape was far less cheerful.

A row of poplar trees, already half stripped of their leaves, formed a windbreak at one side of the house. Growing close on the farther side were a dozen pine trees, suggesting gloomy sentinels left to guard the deserted place.

There were no other houses in sight.

“I wonder where the chateau is?” Barbara asked a trifle wistfully. “I suppose if our services are not required at the hospital at once we might go in the morning to call on the Countess to thank her for her kindness.”

Immediately Eugenia frowned upon the suggestion. She was a little depressed by the neighborhood, now that evening was coming on, and she still found it difficult to agree often with Barbara.

[75]

“Of course we shall do no such thing,” she answered curtly. “Exchanging friendly visits with new and unknown neighbors may be a western custom, but so far as I have been told it is assuredly not the custom in France. Why, there are no such exclusive persons in the world as the old French nobility, of which this countess is a member. Can’t you just imagine what she would think of the forwardness of American girls if we should intrude upon her in such a fashion?”

“Oh,” Barbara replied in a rather crestfallen voice as Nona put her arm across her shoulder. Then they started into the house together. A little later, however, she regained a part of her spirit, which Eugenia and the coming of night had crushed.

“I wonder, Eugenia,” she inquired in the soft tones in which she was most dangerous, “how you have learned so much concerning the customs of the old French nobility. Was it because you were introduced to Captain Castaigne the other day? I believe Lieutenant Hume said that he really belonged to the aristocracy, but preferred not to use his title in Republican France.”

[76]

Eugenia flushed and was about to answer curtly when Mildred Thornton interposed good-naturedly:

“For goodness sakes, children, don’t quarrel on our first evening, or you may bring us bad luck! Remember, we have got to prove that girls can live and work together. But I don’t want to preach. Let’s go to bed so we can get up early in the morning and unpack and get used to things about the house. I have no doubt some one from the field hospital will come over to tell us what they wish us to do. I am afraid I don’t know much about housekeeping or cooking except for the sick, but I am certainly going to try and learn.”

So the girls went in and each one lighted a candle and retired to her own room.

When she was nearly asleep, however, Barbara was startled by a head being thrust inside her door. Then by her flickering light she discovered Eugenia’s face looking uncommonly handsome with two long braids of dark hair framing her clear-cut features.

[77]

“Sorry I was so cross, Barbara,” she whispered. “You know, child, sometimes I feel that I must have been born an old maid.”

[78]

Next morning Mildred and Eugenia went over the field hospital with a French officer who had been sent to receive them.

Barbara and Nona, therefore, undertook the unpacking and arranging of their belongings and also the task of preparing lunch, which was to be a light one. Indeed, all the household arrangements must be of the simplest, so that the girls might have their strength and enthusiasm to give to the work of nursing.

But because they had gotten up soon after daylight, Nona and Barbara found that they had two hours of freedom which might be spent in investigating the neighborhood. So putting on ordinary clothes instead of their nursing uniforms, they set out for a walk.

“I suppose,” Barbara suggested, making[79] an odd grimace, “that there is no special harm in our walking through the estate of the countess and possibly looking at the chateau if we chance to be in the vicinity. I don’t believe that we can do much strolling about here without encroaching on her place. From what François told us yesterday she owns most of the countryside.”

Nona laughed. “That is possibly an exaggeration. Still, I would like to see the old chateau immensely. In spite of Eugenia, I agree with you that we may be permitted to humbly gaze upon it without attempting to speak to any one. I wonder in which direction we ought to go to discover it?”

The girls had gone several yards now and Barbara stopped and wheeled about.

“There is a pine forest over there to the left that is so lovely it won’t matter if it brings us out at the end of nowhere. Only we ought to drop bits of paper behind us like Hop o’ My Thumb for fear of getting lost.”

“I have a fairly good bump of locality,” the other girl answered.

[80]

Then in spite of the fact that they were two feminine persons, neither of the girls spoke again until they had walked at least a mile. Having come unexpectedly upon a shining pool of water, it was then impossible not to utter exclamations of delight.

Nona dropped down on her knees and stared into the depth of it. “Have you read ‘Peleas and Melisande,’ Barbara?” she asked. “It opens in the most exquisite fashion with Melisande gazing down into the depth of the pool and crying over something she has lost. One never knows exactly what it is, but I always thought the entire story meant a reaching after the light. I suppose that is what war is, though it is a cruel and horrible way of searching for it.”

Barbara nodded, although she did not know exactly what her friend was talking about. There was a poetic streak in Nona Davis that no other one of the four girls possessed. During her lonely childhood she seemed to have read an odd assortment of books. Of course she had not the real information that Eugenia had, but what she[81] knew was more fascinating, at least according to Barbara Meade’s ideas.

“Well, I hope that war may never cross the border line into these forests,” Nona added thoughtfully, “although I can imagine any one who knew them could play hide and seek with an enemy for a long time. There is a little hut over there that seems deserted; let’s go and see it.”

As Barbara had been standing she of course had a better view than her companion, but Nona obediently followed her.

The little hut was empty. It was merely a tumbledown shack of logs and stones. However, some one must have inhabited it at one time or another, because there were signs of a fire and a few old pots and pans, weather beaten and rusty, that had been left about. Moreover, there was a moth-eaten fur rug that may have formed a bed.

Yet it was lonely and uncomfortable looking, so the girls did not care to linger. Besides, if they were to see the old French chateau during the morning they must find a place where it was more likely to be.

[82]

Discovering a path that appeared to have been more used than any other, they followed it. In ten minutes after they came to the edge of the clearing and there about a quarter of a mile beyond was the outline of the chateau.

“I suppose it is intruding to go nearer,” Barbara said plaintively, “but I can’t get the least satisfaction from this bird’s-eye view.”

“No doubt of it,” Nona answered, “yet I propose that we take the risk. These are war times and very few servants are left about any of the old places, so we may escape without being seen. I feel it is our duty, as long as Eugenia is not along, to see all that we can before our work begins. Then we’ll have no chance.”

The chateau was in a measure a disappointment, because after all it looked more like an old-time fortress than a dwelling house, and besides was dreadfully dilapidated.

“But once one was accustomed to this idea, it really became more interesting,” Nona finally argued.

[83]

A part of the chateau must have been erected in the fourteenth or fifteenth century when feudal warfare was still carried on in France. The stone tower had loopholes for windows with iron bars across, so that the approach of an enemy could be discovered and he might be attacked with slight danger to the inmates of the castle. This tower was in a fairly good state of preservation, but the rest of the house, where the living apartments were situated, was almost a ruin. There were signs of poverty everywhere. The servants’ quarters were deserted, there were no stables, nothing to suggest the prosperity that should accompany so famous a possession as the old chateau represented.

Indeed, the two American girls were so engaged in discussing the situation that they were not aware of anyone approaching. Unexpectedly they found a woman past middle age moving slowly toward them. She was alone save that she was accompanied by an immense silver-gray dog, which to Nona’s gratification she held by a leash. For in spite of her bravery in other[84] matters, Nona was ridiculously and unreasonably fearful of dogs.

“Gracious!” Barbara whispered, half amused and half terror-stricken. “That must be the mythical countess herself. Shades of Eugenia, what shall we say or do?”

But the older woman gave them little opportunity for a decision.

She was small and slender, dressed in black, with a lace shawl over her head coming down into a point upon her forehead. Underneath were masses of carefully arranged snow-white hair. The Countess’ face was almost as white as her hair; there was nothing that gave it color save her lips and a pair of somber dark eyes. Her expression was sad and aloof.

She must have recognized the two girls as Americans and known for what purpose they had just come to the neighborhood. Nevertheless, she passed by them without speaking, save for a slight inclination of her head. In spite of her kindness the evening before, assuredly she had no desire for further acquaintance.

When she was out of hearing Barbara[85] and Nona gazed at each other like two forward children.

Then Barbara took off the small silk cap she was so fond of wearing.

“I am taking it off to Eugenia, Nona,” she explained. “Thank fortune, I did not intrude my western personality upon the great lady. I can just imagine how she would have treated me if I had undertaken to thank her for her kindness and what she would have thought about American girls in general. Eugenia put it mildly. Well, as a greater person than I am once remarked, ‘it takes all kinds of people to make a world.’ And methinks before this war nursing experience is over we shall have met a good many varieties. But let us get back to the little blue and gray farmhouse as soon as possible. Goodness knows, I would rather live in it than in a tumble-down chateau! Besides, I wish to apologize to Eugenia.”

However, the girls had only started on their return journey when some one came hobbling along behind them.

It was François and he carried a basket on his arm.

[86]

Nona inquired a shorter way home and the old man explained that as he was on the way to their house, he would like to be permitted to accompany them. There was a road that was only half as long as the route they had taken.

Naturally the girls were glad enough for the old man’s escort, especially as he was full of reminiscences of the neighborhood which he loved dearly to impart.