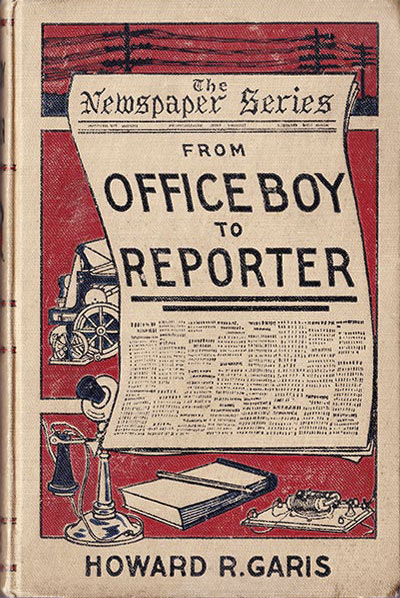

Title: From Office Boy to Reporter; Or, The First Step in Journalism

Author: Howard Roger Garis

Release date: October 8, 2019 [eBook #60456]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

FROM OFFICE BOY

TO REPORTER

OR

THE FIRST STEP IN JOURNALISM

BY

HOWARD R. GARIS

AUTHOR OF “THE WHITE CRYSTALS,” “THE ISLE OF BLACK FIRE,”

“WITH FORCE AND ARMS,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

New York

GROSSET & DUNLAP

Publishers

Copyright, 1907

BY

CHATTERTON-PECK COMPANY

From Office Boy to Reporter

My Dear Boys:—

I have tried to write for you a story of newspaper life and tell how a boy, who started in the lowest position,—that of a copy carrier,—rose to become a reporter. The newspaper covers a wide field, and enters into almost every home, telling of the doings of all the world, including that which takes place right in our midst.

There are many persons in the business, which is an interesting and fascinating one. I have been actively engaged in it for nearly sixteen years, and I have seen many strange happenings. Some of these I have set down in this book for you to read, and I hope you will like them.

There are many things which I had not the time or space to tell about, and which may be related in other books of this series. There have[Pg iv] been written many good stories of newspaper life and experiences. I trust I may have added one that will appeal especially to you boys. If I have, I will feel amply repaid for what I have done.

Yours with best wishes,

Howard R. Garis.

January 10, 1907.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Foreclosing the Mortgage | 1 |

| II. | Bad News | 9 |

| III. | Looking for Work | 18 |

| IV. | Larry and the Reporter | 26 |

| V. | Larry Secures Work | 36 |

| VI. | Larry Makes an Enemy | 46 |

| VII. | The Missing Copy | 53 |

| VIII. | Peter is Discharged | 62 |

| IX. | Larry Gets a Story | 70 |

| X. | Larry Meets His Enemy | 79 |

| XI. | Larry Has a Fight | 87 |

| XII. | A Strange Assignment | 95 |

| XIII. | Under the River | 104 |

| XIV. | Larry’s Success | 113 |

| XV. | Larry Goes to School | 121 |

| XVI. | Larry at a Strike | 130 |

| XVII. | Taken Prisoner | 139 |

| XVIII. | Held Captive | 148 |

| XIX. | Larry’s Movements | 156 |

| XX. | Back at Work | 165 |

| XXI. | Larry on the Watch | 173 |

| XXII. | Trapping a Thief | 181 |

| XXIII. | Bad Money | 189 |

| vi XXIV. | A Queer Capture | 197 |

| XXV. | A Big Robbery | 205 |

| XXVI. | The Men in the Lot | 214 |

| XXVII. | Larry is Rewarded | 222 |

| XXVIII. | The Renowned Doctor | 233 |

| XXIX. | The Operation | 241 |

| XXX. | The Flood | 249 |

| XXXI. | Days of Terror | 257 |

| XXXII. | The Flood Increases | 265 |

| XXXIII. | Dynamiting the Dam | 273 |

| XXXIV. | Under Water | 281 |

| XXXV. | The Race | 290 |

| XXXVI. | Larry Scores a Big Beat | 298 |

| XXXVII. | Larry’s Advancement | 306 |

FROM OFFICE BOY

TO REPORTER

“Now then,” began the shrill voice of the auctioneer, “we’ll start these proceedin’s, if ye ain’t got no objections. Step right this way, everybody, an’ let th’ biddin’ be lively!”

“Hold on a minute!” called a big man in the crowd. “We want to know what the terms are.”

“I thought everybody knowed ’em,” spoke Simon Rollinson, deputy sheriff, of the village of Campton, New York State. “This here farm, belongin’ in fee-simple to Mrs. Elizabeth Dexter, widow of Robert Dexter, containin’ in all some forty acres of tillable land, four acres of pasture an’ ten of woods, is about to be sold, with all stock an’ fixtures, consistin’ of seven cows an’ four horses, an’ other things, to th’ highest bidder, t’ satisfy a mortgage of three thousand dollars.”

“We know all that,” said the big man who had first spoken. “What’s the terms of payment?”

2 “Th’ terms is,” resumed Simon, “ten per cent. down, an’ the balance in thirty days, an’ the buyer has t’ give a satisfactory bond or——”

“That’ll do, go ahead,” called several.

“Now then, this way, everybody,” went on Mr. Rollinson. “Give me your attention. What am I bid to start this here farm, one of the finest in Onondaga County? What am I bid?”

There was a moment’s silence. A murmur went through the crowd of people gathered in the farmyard in front of a big red barn. Several wanted to bid, but did not like to be the first.

As the deputy sheriff, who acted as the auctioneer, had said, the farm was about to be sold. It was a fine one, and had belonged to Robert Dexter. With his wife Elizabeth, his sons, Larry, aged fifteen, a sturdy lad with bright blue eyes and brown hair, and James, aged eight, his daughters, Lucy, a girl of twelve, afflicted with a bad disease of the spine, and little Mary, just turned four, Mr. Dexter had lived on the place, and had worked it successfully, for several years.

Then he had become ill of consumption. He could not follow the hard life. Crops failed, and in order to get cash to keep his family he was obliged to borrow a large sum of money. He gave the farm as security, and agreed, in case he could not pay the money back in a certain time, that the farm should be forfeited.

He was never able to get the funds together,3 and this worry, with the ravages of the disease, soon caused his death. Mrs. Dexter, with Larry’s help, made a brave effort to stand up against the misfortune, but it was of no use. She could not pay the interest on the mortgage, and, finally, the holder, Samuel Mortland, foreclosed.

The matter was placed in the hands of the sheriff, whose duty it is to foreclose mortgages, and that official, being a busy man, delegated the unpleasant task to one of his deputies or assistants, who lived in the town of Campton. The sale had been advertised for several miles surrounding the village, and on the date set quite a crowd gathered.

There were farmers from many hamlets, a number of whom brought their wives and families, as a country auction is not unlike a fair or circus as an attraction. There they were sure to meet friends and acquaintances, and, besides, they might pick up some bargains.

“Who’ll make the first offer?” called Mr. Rollinson. “The upset or startin’ price is fifteen hundred dollars, an’ I’ll jest go ahead with that. Now who’ll make it two thousand?”

“I’ll go seventeen hundred,” called a short stout man in the front row.

“Huh! I should think ye would, Nate Jackson. Why, seventeen hundred dollars wouldn’t buy th’ house an’ barn. You’ll hev t’ do better than that!”

4 “I’ll say eighteen hundred,” cried a woman who seemed to mean business.

“Now you’re talkin’!” cried Mr. Rollinson. “That’s sumthin’ like. Why, jest think of th’ pasture, an’ woodland, an’ cows an’ horses an’——”

“I’ll make it two thousand dollars,” said a third bidder.

“I’m bid two thousand,” cried the deputy sheriff. “Who’ll make it twenty-two hundred?”

Then the auction was in full swing. The bidding became lively, though the advances were of smaller amounts than at first. By degrees the price crept up until it was twenty-nine hundred dollars.

“I’ve got to git at least thirty-one hundred to pay th’ mortgage an’ expenses,” the auctioneer explained. “If I don’t git more than this last bid Mr. Mortland will take the property himself. Now’s your last chance, neighbors.”

This seemed to stimulate the people, and several offers came in at once, until at last the bid was $3,090. There it seemed to stick, no one caring to go any higher, and each one hoping he might, by adding a few dollars more, get possession of the property, which was worth considerable above the figure offered.

While the auction was going on there sat, in the darkened parlor of the farmhouse, Mrs. Dexter and her three younger children. With them5 were some sympathizing neighbors, who had called to tell her how sorry they were that she had lost the farm.

“What do you intend to do?” asked Mrs. Olney, winding her long cork-screw curls about her fingers.

“I’m sure I don’t know,” Mrs. Dexter said. “If we have to leave here, and I suppose we will, I think the only thing to do is to go to my sister. She lives in New York.”

“Let’s see, she married a Jimson, didn’t she?” asked Mrs. Peterkins, another neighbor.

“No, her husband’s name is Edward Ralston,” replied Mrs. Dexter. “He is a conductor on a street car, in New York. My sister wrote to me to come to her if I could find no other place.”

“That would be a wise thing to do,” spoke Mrs. Olney. “New York is such a big place. Perhaps Larry could find some work there.”

“I hope he can,” said Larry’s mother. “He is getting to be a strong boy, but I would rather see him in school.”

“Of course, knowledge is good for the young,” admitted Mrs. Peterkins, “but you’ll need the money Larry can earn.”

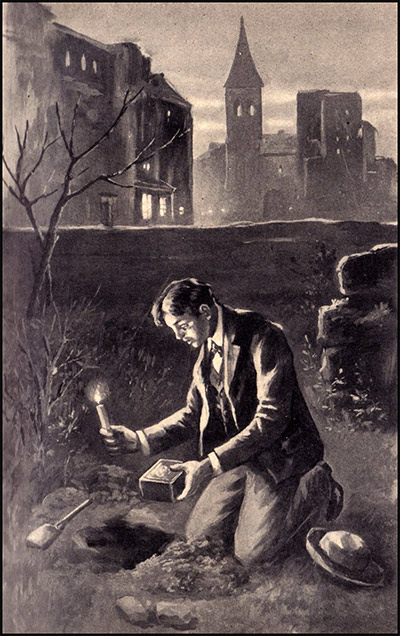

“I’m goin’ to earn money when I go to New York!” exclaimed James. “I’m goin’ to the end of the rainbow, where there’s a pot of gold, an’ I’m goin’ to dig it up an’ give it all to mommer.”

“Good for you!” exclaimed Mrs. Olney, clasping6 the little fellow to her and kissing him. “You’ll be a great help to your mother when you grow up.”

“Kisses is for girls!” exclaimed James, struggling to free himself, whereat even his mother, who had been saddened by the thought of leaving her home, smiled.

“Will—will you have any money left after the place is sold?” asked Mrs. Peterkins.

“I hope it will bring in at least a few hundred dollars above the mortgage,” answered Mrs. Dexter. “If it does not I don’t know what I’ll do. We would have to sell some of the house things to get money enough to travel.”

Outside, the shrill voice of the auctioneer could be heard, for it was summer and the windows were open.

“Third an’ last call!” cried Mr. Rollinson.

“Oh, it’s going to be sold!” exclaimed Mrs. Dexter, with a sound that seemed like a sob in her throat. “The dear old farm is going.”

“Third an’ last call!” the deputy sheriff went on. “Last call! Last call! Going! Going! Gone!”

With a bang that sounded like the report of a rifle, Mr. Rollinson brought his hammer down on the block.

“I declare this farm sold to Jeptha Morrison fer th’ sum of thirty-two hundred and seventy-five dollars,” he cried. “Step this way, Mr. Morrison,7 an’ I’ll take yer money an’ give ye a receipt. Allers willin’ t’ take money,”—at which sally the crowd laughed.

“Only thirty-two hundred and seventy-five dollars,” repeated Mrs. Dexter. “Why, that will leave scarcely anything for me. The sheriff’s fees will have to be paid, and some back interest. I will have nothing.”

She looked worried, and the two neighbors, knowing what it meant to be a widow without money and with little children to support, felt keenly for her.

“Mother!” exclaimed a voice, and a lad came into the room somewhat excitedly. “Mother, the farm’s sold!”

“Yes, Larry, I heard Mr. Rollinson say so,” said Mrs. Dexter.

“It wasn’t fair!” the boy went on. “We should have got more for it!”

“Hush, Larry. Don’t say it wasn’t fair,” said his mother. “You should accuse no one.”

“But I heard Mr. Mortland going around and telling people not to bid on it, as the title wasn’t good,” the boy declared. “He wanted to scare them from bidding so he could get the property cheap.”

“But he didn’t buy it,” said Mrs. Dexter. “It went to Mr. Morrison.”

“Yes, and he bought it with the money Mr. Mortland supplied him,” Larry cried. “I saw8 through the whole game. It was a trick of Mr. Mortland’s to get the farm, and he’ll have it in a few weeks. Oh, how I wish I was a man! I’d show them something!”

“Larry, dear,” said his mother reprovingly, and then the boy noticed, for the first time, that others were in the room.

“Of course I haven’t any proof,” Larry continued, “for I only saw Mr. Mortland hand Mr. Morrison some money and heard him tell him to make the last bid. But I have my suspicions, just the same. Why, mother, there will be nothing left for us.”

“That’s what I was telling Mrs. Olney and Mrs. Peterkins,” said Mrs. Dexter with a sigh. “I don’t know how we can get to New York, when railroad fares are so high.”

“I’ll tell you what we must do, mother!” exclaimed Larry.

“What, son?”

“We must sell the furniture.”

“Oh, I could never do that.”

“But we must,” the boy went on. “We cannot take it with us to New York, and we may get money enough from it to help us out. It is the best thing to do.”

“I believe Larry is right,” said Mrs. Olney. “The furniture would only be a trouble to you, Mrs. Dexter. Now would be a good chance to sell it, while the crowd is here. You ought to get pretty good prices, as much of the stuff is new.”

“Perhaps you are right,” assented the widow, “though I hate to part with the things. Suppose you tell Mr. Rollinson, Larry.”

The boy hurried from the room to inform the auctioneer there was more work for him, and Mrs. Dexter, with her two friends, came from the parlor, for they knew the place would soon be overrun by curious persons looking for bargains.

Mr. Rollinson, anxious to make more commissions, readily undertook to put the furniture up for auction. With the exception of a few articles that she prized very highly, and laying aside only the clothes of herself and children, Mrs. Dexter permitted all the contents of the house to be offered for sale.

Then, having reached this decision, she went off in a bedroom and cried softly, for she could10 not bear to think of her home being broken up, and strangers using the chairs and tables which, with the other things, had made such a nice place while Mr. Dexter was alive.

Larry had hard work to keep back the tears when he saw some article of furniture, with which were associated happy memories, bid for by some farmer.

When, at length, Mr. Rollinson reached the old armchair, in which Mr. Dexter used to sit and tell his children stories, and where, during the last days of his life he had rested with his little family gathered about him, Larry could stand it no longer. He felt the hot scalding tears come to his eyes, and ran out behind the big red barn, where he sobbed out his grief all alone.

He covered his face with his hands and, as he thought of the happy days that seemed to be gone forever, his grief grew more intense. All at once he heard a voice calling:

“Hello, cry-baby!”

At first Larry was too much occupied with his troubles to pay any attention. Then someone called again:

“Larry Dexter cries like a girl!”

Larry looked up, to meet the laughing gaze of a boy about his own size and age, with bright red hair and a face much covered with freckles.

“I’m not a cry-baby!” Larry exclaimed.

“You be, too! Didn’t I see you cryin’?”

11 “I’ll make you cry on the other side of your mouth, Chot Ramsey!” Larry exclaimed, making a spring for his tormentor.

Chot doubled up his fists. To do him credit he had no idea that Larry was crying because he felt so badly at the prospect of leaving the farm that had been his home for many years. Chot was a good-hearted boy, but thoughtless. So, when he saw one of his playmates weeping, which act was considered only fit for girls, Chot could not resist the temptation to taunt Larry.

“Do you want t’ fight?” demanded Chot.

“I’ll punch you for calling me names!” exclaimed Larry, his sorrow at the sale of his father’s armchair dispersed at the idea of being laughed at and called a cry-baby.

“You will, hey?” asked Chot. “Well, I dare you to touch me!”

“I’ll make you sing a different tune in a minute!” cried Larry, rushing forward.

Then, like two game roosters, both wishing to fight, yet neither desiring to begin the battle, the boys faced each other. Their eyes were angry and all tears had disappeared from Larry’s face.

“Will you knock a chip off my shoulder?” demanded Chot.

“Sure,” replied Larry.

Chot stooped down, found a little piece of wood and carefully balanced it on the upper part of his arm.

12 “I dare you to!” he taunted.

This time-honored method of starting hostilities was not ignored by Larry. He sprang forward, and with a quick motion sent the fragment of wood flying through the air. Then he doubled up his fists, imitating the example Chot had earlier set, and stood ready for the fracas.

But at that instant, when, in another second Chot and Larry would have been involved in a rough-and-tumble encounter, James, Larry’s little brother, came running around the corner of the barn. He seemed greatly excited.

“Larry! Larry!” he exclaimed. “They’re sellin’ my nice old rockin’ horse, an’ my high chair what I used to have when I was a baby! Please stop ’em, Larry!”

Larry lost all desire to fight. He didn’t mind if all the boys in Campton called him cry-baby. He had too many sorrows to mind that.

“Don’t worry, Jimmie,” he said to the little fellow. “I’ll buy you some new ones.”

But little James was not to be comforted, and burst into a flood of tears. Chot, who had looked on in some wonder at what it was all about, for he did not understand that the household goods were being sold, unclosed his clenched fists. Underneath a somewhat rough exterior he had a warm heart.

“Say,” he began, coming up awkwardly to Larry, “I didn’t know you was bein’ sold out. I—I13 didn’t mean t’ make fun of ye. I—I was only foolin’ when I said ye was a cry-baby. Ye can have my best fishhook, honest ye can!”

“Thanks, Chot,” replied Larry, quick to feel the change of feeling. “I couldn’t help crying when I saw some of the things dad used to have going under the hammer. But I feel worse for mother and the others. I can stand it.”

“Are ye goin’ away from here?” asked Chot, for that anyone should leave Campton, where he had lived all his life, seemed too strange a thing to be true.

“I think we will go to New York,” replied Larry. “Mother’s sister lives there. I expect to get some work, and help support the folks.”

“I wish I was goin’ off like that!” exclaimed Chot. “They could sell everything in my house, an’ everything I’ve got, except my dog, if they’d let me go t’ New York.”

“You don’t know when you’re well off,” spoke Larry, who, in the last few months, under the stress of trouble, had become older than his years indicated.

By this time James, who saw a big yellow butterfly darting about among the flowers which grew in an old-fashioned garden below the barn, rushed to capture it, forgetting his troubles. Larry, whose grief-stricken mood had passed, returned to the house, to find it a place of confusion.

14 Men and women were in almost every room, going through and looking at the different articles. The loud voice of the auctioneer rang out, and Larry felt another pang in his heart as he saw piece after piece of furniture being knocked down to the highest bidder.

The boy found his mother in the bedroom, where she had sought a quiet place to rest.

“Have you really made up your mind to go to New York, mother?” Larry asked.

“I think it is the best thing to do,” was the answer. “We can stay with your aunt Ellen until I can find some work to do.”

“Are you going to work, mother? I hate to think of it. I’ll work for you.”

“I know you will do what you can,” replied Mrs. Dexter, “but I’m afraid boys do not earn much in big cities, so we will need all we both can get. It is going to be a hard struggle.”

“Don’t worry!” exclaimed Larry, assuming a cheerfulness he did not feel. “It will all come out right, somehow, you see if it doesn’t.”

“I hope so,” sighed Mrs. Dexter.

The auctioneering of the goods went on rapidly, and, toward the close of the afternoon, all that were not to be kept were disposed of. Mr. Rollinson cried his last “Going! Going! Gone!” brought his hammer down for the last time with a loud bang, and then announced that the sale was over.

15 “Where’s your mother, Larry?” he asked of the boy.

“I’ll call her.”

In a few minutes Larry had brought Mrs. Dexter to where the deputy sheriff waited for her in the parlor.

“Wa’al, everthing’s sold,” Mr. Rollinson began. “Didn’t bring as much as I cal’lated on, but then ye never can git much at a forced sale.”

“How much will I have left after all expenses are paid?” asked Mrs. Dexter.

“Allowin’ for everything,” said the auctioneer, figuring up on the back of an envelope, “you’ll have jest four hundred and three dollars and forty-five cents, the odd cents bein’ for some pictures.”

“It is very little to begin life over again on,” said Mrs. Dexter.

“But it’s better than nothin’,” said Mr. Rollinson, who seldom looked on the dark side of things. “Now I made the sale of these household things dependent on you. You can stay here two weeks if ye want t’, an’ nothin’ will be taken away. Them as bought it understands it.”

“I would like t’ get away as soon as possible,” said the widow.

“Wa’al, there’s nothin’ t’ hinder ye.”

“Then I shall start for New York day after to-morrow.”

“All right, Mrs. Dexter. I’ll settle up th’ accounts an’ have all th’ money ready by then.”

16 Mr. Rollinson was as good as his word. On the third day after the sale, having written to her sister that she was coming, but not waiting for a reply, Mrs. Dexter, with Larry, Lucy, Mary and James, boarded a train for the big city where they were all hoping their fortunes awaited them. Little James was full of excitement. He was sure they were going at last to the end of the rainbow. Mary was delighted with the new and strange sights along the way. Larry was very thoughtful. As for Lucy her spine hurt her so that she got very little enjoyment from the trip. But she did not say anything about it, for fear of worrying her mother.

It was a long journey, but it came to an end at last. The train reached Hoboken, on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River, and, though somewhat bewildered by the lights, the noise and confusion, Larry managed to learn which ferryboat to take to land them nearest to his aunt’s house, who lived on what is called the “East Side” of New York.

The trip across the river on the big boat was a source of much delight to the younger children, but Mrs. Dexter was too worried to be interested. Lucy was very tired, but Larry kept up his spirits.

Once landed in New York, in the evening, the confusion, the noise, the shouts of the cabmen, the rattle of the cars, the clanging of gongs and the ringing of bells, was so great that poor Mrs. Dexter,17 who had been so long used to the quiet of the country, felt her head ache.

By dint of many inquiries Larry found out which car to take and, marshaling his mother and the children ahead of him, he directed them where to go. A long ride brought them to the street where Mrs. Ralston lived.

Here was more confusion. The thoroughfare swarmed with children, and the noise was almost as great as down at the ferry. A man directed the travelers to the house, which was an apartment or tenement one, inhabited by a number of families. Larry, his mother, and the children climbed the stairs to the third floor, where Mrs. Ralston lived. A knock on the door brought a woman who was surprised at her visitors.

“Does Mrs. Ralston live here?” asked Larry, thinking he might have made a mistake.

“She did, but she moved away yesterday,” was the answer.

“Moved away?”

“Yes, didn’t you hear? Her husband was killed in a street-car accident a few days ago, and after the funeral Mrs. Ralston said she could not afford to keep these rooms. So she moved away. I came in last night. Are you relatives of hers?”

“I am her sister,” said Mrs. Dexter, and then, at the news of Mr. Ralston’s death, coming on top of all the other troubles, the poor woman burst into tears.

“Now there, don’t you worry one mite,” said the woman who had come to the door. “I know jest how you feel. Come right in. We haven’t much room, but there’s only my husband, and he can sleep on the floor to-night. I’ll take care of you until you can find some place to stay. Bring the children in. Well, if there isn’t a little fellow who’s jest the image of my little Eddie that died,” and the good woman clasped James in her arms and hugged him tightly.

“I’m afraid we’ll be too much trouble for you,” spoke Larry, seeing that his mother was too overcome to talk.

“Not a bit of it,” was the hearty reply. “Come right along. I was jest gittin’ supper, an’ there’s plenty for all of you. Come in!”

Confused and alarmed at the sudden news, and hardly knowing what she did, Mrs. Dexter entered the rooms where she had expected to find her sister. She was almost stunned by the many troubles coming all at once, and was glad enough to find any sort of temporary shelter.

19 “I’m Mrs. Jackson,” the woman went on. “We’re a little upset, but I know you won’t mind that.”

“No indeed,” replied Mrs. Dexter. “We are only too glad to come in.”

The apartment, which consisted of four small rooms, was in considerable confusion. Chairs and tables stood in all sorts of positions, and there were two beds up.

“We’ll manage somehow,” said Mrs. Jackson. “My goodness! The potatoes are burning!” and she ran to the kitchen, where supper was cooking.

While she was busy over the meal her husband came in, and, though he was much surprised to see so many strangers in the house, he quickly welcomed them when his wife explained the circumstances. Supper was soon ready, and the travelers, except Mrs. Dexter, ate with good appetites. Then, after she had told something of her troubles it was decided that the two younger children should sleep in a bed with their mother. Lucy shared Mrs. Jackson’s room, and Larry and Mr. Jackson had beds made up on the floor in the parlor.

“We’ll pretend we’re camping out,” said Mr. Jackson. “Did you ever camp, Larry?”

“Sometimes, with the boys in Campton,” was the reply. “But we never stayed out all night.”

“I have when I was a young man,” said Mr. Jackson. “I used to be quite fond of hunting.”

20 Larry was tired enough to fall off to sleep at once, but, for a time, the many unusual noises bothered him. There was an elevated railroad not far off, and the whistle of the trains, the buzz and hum of the motors, kept him awake. Then, too, the streets were full of excitement, boys shouting and men calling, for it was a warm night, and many stayed out until late.

At length, however, the country boy fell asleep, and dreamed that he was engineer on a ferryboat which collided with an elevated train, and the whole affair smashed into a balloon and came shooting earthward, landing with a thump, which so startled Larry that he awoke with a spring that would have rolled him out of bed had he not been sleeping on the floor.

It was just getting daylight, and Larry at first could not recall where he was. Then he sat up, and his movement awakened Mr. Jackson.

“Is it time to get up?” asked the latter.

“I—I don’t know,” said Larry.

Mr. Jackson reached under his pillow, drew out his watch, and looked at the time.

“Guess I’d better be stirring if I want to get to work to-day,” he remarked. Then he began to dress and Larry did likewise. Mrs. Jackson was already up, and breakfast was soon served.

“Make yourselves at home,” was Mr. Jackson’s remark, as he left the house to go to the office where he was employed.

21 Mrs. Dexter insisted on helping Mrs. Jackson with the housework, and, while the two women were engaged Mary and James went down to the street to see what, to them, were many wonderful sights. Lucy, whose spine hurt her very much because of the long journey, remained in bed, and Larry made himself useful by going to the store for Mrs. Jackson, after receiving many cautions from his mother not to get lost in New York.

Mrs. Dexter was worrying over what she should do. She wanted to find her sister, but she realized that if Mr. Ralston was dead his widow would not be in a position to give even temporary shelter to Mrs. Dexter and her family. She knew her sister must have written to her, but the letter had probably reached Campton after Mrs. Dexter had left.

“Why don’t you take a few rooms in this house?” suggested Mrs. Jackson. “There are some to be had cheap on the floor above, and it’s a respectable place. Then you will have time to hunt up your sister. Maybe the janitor knows where she moved to.”

“I believe I will do that,” said the widow. She knew what little money she had would not last long and she wanted to make a home for her children where they could stay while she went out to work.

When Larry returned Mrs. Dexter talked the matter over with him, for she had come to depend22 on her son very much of late. The matter was decided by their engaging four rooms on the floor above. They were unfurnished except for an attractive gas range on which cooking could be done.

“I’m afraid I wouldn’t know how to work it,” said Mrs. Dexter.

“I know,” said Larry. “Mrs. Jackson showed me this morning.”

From a secondhand store some beds, a table, and a few chairs were purchased, and thus, on a very modest scale, compared with their former home, the Dexters began housekeeping in New York.

They ate supper in their new rooms that night. The younger children were delighted, but Mrs. Dexter could not but feel that it was a poor home compared to the one she had been compelled to leave. Larry saw what was troubling his mother.

“Don’t worry,” he said. “I’ll soon be working and we will have a better place.”

“I wish I was strong enough to work,” said Lucy in a low tone, her eyes filling with tears as she thought of her helplessness.

“Don’t you wish anything of the kind!” exclaimed Larry. “I’m going to work for all of us.”

He made up his mind to start out the first thing in the morning and hunt for a job. He carried this plan out. After a simple breakfast which23 was added to by some nice potatoes and meat which Mrs. Jackson sent up, Larry hurried off.

“Be very careful,” cautioned his mother. “Don’t let anyone steal your pocketbook.”

Larry thought a thief would not make a very good haul, as he only had twenty-five cents in it, but he did not say so to his mother.

The boy did not know where to start to look for work. He had had no experience except on a farm, and there is not much call for that sort of labor in the city. Still he was strong, quick, and willing, and, though he didn’t know it, those qualities go a great way in any kind of work.

Larry started out from the apartment house, and walked slowly. He had the address of his new home written down, in case he got lost, but he determined to walk slowly, note the direction of the streets, and so acquaint himself with the “lay-out” of the big city.

He had two plans in mind. One was to go along the streets looking for a sign “Boy Wanted.” The other was to look at the advertisements in the newspapers. He resolved to try both.

Purchasing one of the big New York daily newspapers, which bore on the front page the name The Leader, Larry turned to the page where the dealer who sold it to him had said he would find plenty of want advertisements. There were a number of boys wanted, from those to run errands24 to the variety who were expected to begin in a wholesale house at a small salary and work their way up. In nearly every one were the words “experience necessary.”

Now Larry had had no experience, and he felt that it would be useless to try the places where that qualification was required. He marked several of the advertisements that he thought might provide an opening for him, and asked the first policeman he met how to get to the different addresses.

The bluecoat was a friendly one, who had boys of his own at home, and he kindly explained to Larry just how to get to the big wholesale and retail places that needed lads.

But luck seemed to be against Larry that day. At every place he went he was told that he was just too late.

“You’ll have to get up earlier in the morning if you want to get a job,” said one man where he inquired. “There were ten boys here before breakfast after this place. This is a city where you can’t go to sleep for very long.”

Larry was beginning to think so. He had tried a number of places that advertised, without success, when he saw a sign hanging out in front of a shoe store. It informed those who cared to know that a boy was needed.

Larry made an application. Timidly he asked the proprietor of the store for work.

25 “I hired a boy this morning about seven o’clock,” was the reply.

“Your sign is out yet,” spoke Larry.

“I forgot to bring it in,” said the man.

He did not seem to think it minded that he had caused disappointment to one lad, and might to others. Larry walked from the place much discouraged.

It was now noon, and Larry, who had a healthy boy’s appetite, began to feel hungry. He had never eaten in one of the big city restaurants, and he felt somewhat timid about going in. Besides, he had only a quarter, and he thought that he could get very little for that. He also felt that he had better save some of the money for car-fare, and so he made up his mind that fifteen cents was all he could afford for dinner.

He walked down several streets before he saw a restaurant that seemed quiet enough for him to venture in.

The place was kept by an old German, and while it was neat and clean did not seem to be very prosperous, as Larry was the only customer at that particular hour.

“Vat you want, boy?” asked the old man, as Larry entered. “I don’t have noddings to gif away to beggars. I ain’t buying noddings. You had better git out.”

“I’m not selling anything and I’m not a beggar,” said Larry sharply. “I came in here to27 buy a meal,—er—that is a small one,” he added as he thought of his limited finances.

“Ach! a meal, eh!” exclaimed the German, smiling instead of frowning. “Dot’s different alretty yet! Sid down! I have fine meals!”

“I guess I only want something plain,” spoke Larry. “A cup of coffee and some bread and butter.”

“We gif a plate of soup, a piece of meat, coffee und rolls yet by a meal,” said the restaurant keeper, and Larry wondered how much such a meal would cost. “It’s fifteen cents alretty,” the German went on, and Larry breathed a sigh of relief, for he was very hungry.

He had gone, by chance, into one of the cheap though good restaurants of New York, where a few cents buys plenty of food, though it is not served with as much style as in more expensive places.

The restaurant keeper motioned Larry to sit down at one of the oilcloth-covered tables, and then, having brought a glass of water, hurried away. Soon his voice was heard giving orders, and in a little while he came back, bringing a bowl of hot soup. Larry thought he had never tasted anything so fine.

By this time several other persons had come into the place and the German was kept busy filling orders. A young woman came out from the rear of the shop to help him and she served Larry28 with the rest of his meal. When he had finished he was given a red square of pasteboard, with the figures “15” on it, and he guessed that this was his meal check and that he was to pay at the desk, over which a fat woman presided. It was near the door, and walking up to it Larry laid down his quarter, getting his ten cents in change and going out.

He felt that he was getting on in the world, since he had eaten all by himself in a public restaurant, and he was encouraged now to go on with his search for work. A meal often puts a strong heart into a man, or boy either, for that matter.

“Now for a job!” exclaimed Larry as he started off briskly.

He consulted the paper which he still had and went to several places that had advertised. But that day must have brought forth an astonishing crop of boys out of work, or else all places were quickly filled, for at every establishment where Larry called he was told that there was no need for his services.

Signs of “Boy Wanted” became “as scarce as hen’s teeth,” Larry said afterward, which are very scarce indeed, as no one ever saw a hen with teeth. About four o’clock in the afternoon he found himself at the junction of Fifth Avenue and Broadway, where the big Flatiron Building, as it is called, stands. Larry had walked several miles and he was tired and discouraged.

29 The day, which had been pleasant when Larry started out, had become cloudy, and a dark bank of clouds rolling up in the west indicated that a thunderstorm was about to break. As Larry stood there, amid all the bustle and excitement of the biggest city in the United States, he felt so lonely and worried that he did not know what to do. He thought of his mother and the children at home, and wondered whether he would ever get work so that he could take care of them.

Suddenly, from out of the western sky, there came a dazzling flash of lightning. It was followed by a crashing peal of thunder, and then the storm, which had been gathering for some time, burst. There was a deluge of rain, and people began running for shelter.

Larry looked about, and, seeing that many were making for the open doorway of the Flatiron Building, on the Fifth Avenue side, ran in that direction. He had hardly reached the friendly shelter when there came a crash that sounded like the discharge of a thirteen-inch gun, and a shock that seemed to make the very ground tremble.

At the same time Larry felt a queer tingling in the ends of his fingers, and several persons near him jumped.

“That struck near here!” a man at his side exclaimed.

“Guess you’re right,” another man said. “Lucky we’re in out of the wet.”

30 By this time the rain was coming down in torrents, and several more persons crowded into the lobby of the big building. Larry stayed near the door, for he liked to watch the storm and was not afraid.

Suddenly, down the street, there sounded a shrill whistle, mingled with a rumbling and a clang of bells.

“It’s a fire!” cried several.

“Lightning struck!” exclaimed one or two.

“It was that last smash!” said the man Larry had noticed first. “I thought it did some damage. Here come the engines!”

Up Fifth Avenue dashed the steamers, hose carts, and hook-and-ladder wagons.

“There’s the fire! In that building across the street!” someone said.

Larry looked and saw, coming out of the top story of a big piano warehouse on the opposite side of Fifth Avenue, a volume of black smoke. A number of men, unmindful of the rain, ran out to see the firemen work, and after a little hesitation Larry, who did not mind a wetting, followed.

It was the first time he had ever seen a fire in a big city, and he did not want to miss it. He worked his way through the crowds that quickly gathered until he was almost in front. There he held his place, not minding the rain, which was still falling hard, though not as plentifully as at first.

31 He saw the firemen run out long lengths of hose, attach them to the steamers, which had already started to pump, and watched the ladder men run out the long runged affairs up which they swarmed to carry the hose to the top stories, where the lightning had started the fire.

Then the water tower was brought into play. Under the power of compressed air the long slender pole of latticed ironwork rose high, carrying several lengths of hose with it. Then the nozzle was pointed toward the top windows, and soon a powerful stream of water was being sent in on the flames, that were making great headway among wood and shavings in the piano place.

The street was filled with excited men who were running back and forth. Many of them were persons who had come from near-by buildings to see the fire. Some were from the burning building, trying to save their possessions. The firemen themselves were the coolest of the lot, and went about their tasks as if there was nothing unusual the matter. Soon the police patrol dashed up and the blue-coats piled out and began to establish fire lines. Larry, like many others, was forced to get back from the middle of the street.

The boy, however, managed to keep his position in the front rank. He watched with eager eyes the firemen at work, and never thought how wet he was.

32 “It’s going to be a bad blaze,” remarked a man near Larry. “The fire department’s going to have its hands full this time.”

It certainly seemed so, for flames were spouting from all the windows on the top story and the one below it. More engines dashed up, and the excitement, noise, and confusion grew.

In front of Larry a big policeman was standing, placed there by the sergeant in charge of the reserves to maintain the fire lines. The officer had his back toward the crowd, and enjoyed a good vantage point from which to watch the flames. A young fellow, with his coat collar and trousers turned up, and carrying an umbrella, worked his way through the crowd until he was beside Larry.

“Let me pass, please,” he said, and then, slipping under the rope which the police had stretched, he was about to pass the policeman and get closer to the fire.

“Here, come back, you!” the officer exclaimed.

“It’s all right; I’m a reporter from the Leader,” said the young fellow, and he turned, showing a big shining metal star on his coat.

“Go ahead,” spoke the policeman. “You’ll have a good story, I’m thinking.”

“Anybody hurt?” asked the reporter, pausing to ask the first question that a newspaper man puts when he gets to a fire.

“Wouldn’t wonder. Saw the Roosevelt Hospital33 ambulance taking a man away when we came up. Jumped from the roof, I heard.”

“Gee! I’ll have to get busy! Say, it ain’t doin’ a thing but rain, is it? I can’t take notes and hold my umbrella too, and I certainly hate to get wet. I wish I had a kid to manage the thing for me.”

“I’ll hold the umbrella for you,” volunteered Larry, quick to take advantage of the situation, and realizing that, by aiding the reporter, who seemed to be a sort of favored person at fires, he might see more of the blaze.

“All right, kid, come along,” spoke the newspaper man, and, at a nod from the policeman to show it was all right, Larry slipped under the rope and followed the reporter, who made off on a run toward the burning building. Many men wished they were in Larry’s place.

“Come on, youngster. What’s your name?” asked the reporter of Larry.

The boy told him.

“Mine’s Harvey Newton,” volunteered the newspaper man. “We’ll have to look lively. Here, you hold the umbrella over me, while I make a few notes.”

Larry did so, screening the paper which the reporter drew from his pocket as much as possible from the rain. Mr. Newton, who, as Larry looked at him more closely, appeared much older than he had at first, made what looked like the34 tracks of a hen, but which were in reality a few notes setting down the number of the building, the height, the size, the location of the fire. Then the reporter jotted down the number of engines present, a few facts about the crowd, the way the police were handling it, and something of how the firemen were fighting the blaze.

“This is better than getting wet through,” Mr. Newton said, as he returned his paper to his pocket and waited for new developments.

“Say, why don’t you bring the city editor out with you when you cover fires?” asked another reporter, from a different paper, addressing Mr. Newton, and noticing Larry’s occupation.

“I would if he’d come,” replied Mr. Newton. “Don’t you wish you had an umbrella and a rain-shield bearer?”

“Don’t know but what I do,” rejoined the other, who was soaking wet. “Say, this is a corker, ain’t it? Got much?”

“Not yet. Just arrived.”

Suddenly, with a report like that of a dynamite blast, the whole top of the building seemed to rise in the air. An explosion of oils and varnishes used on pianos had occurred. For an instant there was deep silence succeeding the report. Then came cries of fear and pain, mingled with the shouts of men in the fiercely burning structure.

“I’ll need help on this story!” exclaimed Mr.35 Newton. “I wonder—— Say, Larry,” he went on, turning to the boy, “can you use a telephone?”

“Yes,” replied Larry, who had used one several times at Campton.

“Then call up the Leader office. The number’s seventeen hundred and eighty-four. Ask for the city editor, and tell him Newton said to send down a couple of men to help cover the fire. Run as if you were in a race!”

Larry handed over the umbrella and darted toward the sidewalk. He wiggled his way through the crowd, and went back to the lobby of the Flatiron Building, where he had noticed a telephone booth. Dashing inside he took off the receiver, and gave central the number of the Leader office. Then the girl in the exchange, after making the connection, told him to drop ten cents in the slot, for the telephone was of the automatic kind. In a few seconds Larry, in a somewhat breathless voice, was talking with the city editor of one of New York’s biggest newspapers.

“What’s that?” Larry heard the voice at the other end of the wire ask. “Newton told you to call me up? Who are you? Larry Dexter, eh? Well, what is it? Big fire, eh? Explosion? Fifth Avenue and Broadway? All right. I’ll attend to it.”

Then, before the city editor hung up the receiver of his instrument Larry heard him call in sharp tones:

“Smith, Robinson! Quick! Jump up to that37 fire and help Newton. Telephone the stuff in! We’ll get out an extra if it’s worth it!”

Then came a click that told that the connection was cut off, and Larry knew that help for his friend, the reporter, was on the way.

The boy hurried from the booth and ran again toward the crowd that was watching the fire. There were more people than ever now on the scene, but Larry managed to make his way through them to where the same policeman stood that had let himself and the reporter through the lines once before. Larry resolved to find his new friend. He slid close up to the officer.

“I’m helping Mr. Newton, the reporter for the Leader,” the boy said to the bluecoat.

The policeman looked down, recognized Larry, and said:

“All right, youngster, go ahead. Only get a fire badge next time or I’ll have to shut you out.”

But Larry was not worrying about the next time. He was rejoicing that he had gained admittance through the lines, and was close to the fire, which was now burning furiously.

More engines arrived with the sending in of the third alarm, and several ambulances were on the scene, as a number of men had been hurt in the explosion. Within the space made by the ropes there was plenty of room to move about, but there was much confusion. Larry spied Mr. Newton as close to the blaze as the reporter could get.38 Then he saw him dart over to an ambulance to which they had carried a wounded man.

Larry ran after his new friend, and found him getting the name of the injured piano worker, who was badly burned. The poor fellow was being swathed in cotton and oil by the ambulance surgeon, but the reporter did not seem to think of this. He asked the man for his name and address, got them, and jotted them down on his paper, which was now quite wet, since he had furled the umbrella.

“Back on the job, eh?” questioned Mr. Newton, stopping a moment in his rush to notice Larry. “Did Mr. Emberg say he’d send me some help?”

“Mr. Emberg?” asked Larry.

“Yes. The city editor you telephoned to?”

“Oh yes, I heard him tell someone to ‘jump out on the fire.’”

“Then they’ll come. Now, youngster, let’s see—what’s your name? Oh yes,—Larry. Well, I’m going to have my hands full now. Never mind about holding the umbrella. But drop in the Leader office and see me some day, say about five o’clock in the afternoon, after we go to press.”

“All right,” said Larry, dimly wondering how he was to get home, since he had spent his last ten cents for the telephone. But Mr. Newton was thoughtful to remember that item, and taking a quarter from his pocket he handed it to Larry.

39 “That’s for the message and your trouble,” he said.

Larry was glad enough to take it, though he would have been satisfied with ten cents.

“Don’t forget to call and see me!” said Mr. Newton.

The next instant there came loud cries of warning, and looking up Larry saw the whole upper front of the building toppling outward, and ready to fall over.

“Back! Back for your lives!” cried police and firemen in a shrill chorus.

Larry turned and ran, as did scores of others who were in the path of the crumbling masonry. A moment later the crash came. Then followed a rush of the frightened crowd, in which Larry was borne from his feet and carried along, until he found himself two blocks from the fire.

He turned to make his way back to within the fire lines, but found it too hard a task, as the crowd was now enormous. Then he decided to give it up as a bad job, and go home. Inquiry of a policeman showed him which car to take, and an hour later he was in the small apartment, where he was met by his mother and the children, who were much alarmed over his absence.

“No luck, mother,” Larry said, in answer to a look from Mrs. Dexter. “But I earned fifteen cents, anyhow, by helping at a fire.”

“Helping at a fire?”

40 Then Larry told his experience to the no small wonderment of them all.

“Maybe Mr. Newton will help me get a job,” he said hopefully.

“I wish he would,” said Mrs. Dexter. “I have some work to do, Larry,” she added.

“You, mother?”

“Yes, a lady on the floor above does sewing for a factory. It happened that one of the women who works in the place is sick, and our neighbor thought of me. I went to the shop, and I got something to do.”

“But I don’t like to have you work in a shop, mother,” objected Larry.

“I am to do the sewing at home,” went on Mrs. Dexter. “I cannot earn much, but it is better than nothing, and it may improve in time.”

“Maybe I can get a job diggin’ gold somewhere,” put in James. “If I do I’ll give you a million dollars, mommer.”

“I’m sure you will,” said his mother, giving him a hug.

“Maybe I could sew some,” spoke Lucy, from the chair where she was sitting, propped up in cushions.

“I’d like to see us let you!” exclaimed Larry. “You just wait, I’ll get a job somehow!”

But, though he spoke boldly, the boy was not so certain of his success. He was in a big city, where thousands are seeking work every hour,41 and where opportunities to labor do not go long unappropriated. But Larry was hopeful, and, though he worried somewhat over the prospect of the little family coming to grief in New York, he had not given up yet, by any means, for this was not his way.

Late that night Larry went out and bought a copy of the Leader. On the front page, set off by big headlines, was the story of the fire and explosion. The boy felt something of a part ownership in the account, and was proud to think he had helped, in some small measure, to provide such a thrilling tale.

For the fire proved a disastrous one, in which three men were killed and a number seriously hurt. The papers, for two days thereafter, had more stories about the blaze, and there was some talk of an investigation to see who was responsible for having so much oil and varnish stored in the place, which, it was decided by all, was the cause of the worst features of the accident.

During those two days Larry made a vain search for work. But there never seemed to be such a small number of positions and so many boys to fill them.

The third day, after a fruitless tramp about the city, Larry found himself down on Park Row, near the Post Office. He looked at one of the many tall buildings in that locality, and there staring42 him in the face, from the tenth story of one, were the words:

New York Leader.

“That’s my paper,” Larry thought with a sense of pride. Then the idea came to him to go up and see Mr. Newton, the reporter. It was nearly five o’clock, and this was the hour Mr. Newton had mentioned. Larry did not exactly know why he was going in to see the reporter. He had some dim notion of asking if there was not some work he might get to do.

At any rate, he reasoned, it would do no harm to try. Accordingly he entered the elevator, and asked the attendant on what floor the reporters of the Leader might be found.

“Twelfth,” was the reply, and then, before Larry could get his breath, he was shot upward, and the man called out:

“Twelfth floor. This express makes no stop until the twenty-first now.”

Larry managed to get out, somewhat dizzy by the rapid flight.

Before him the boy saw a door, marked in gilt letters:

City Room.

“I wonder where the country room is,” mused Larry. “I guess I’d feel more at home in a country room than I would in a city one.”

43 Then the door opened and several young men came out.

“Did you get any good stories to-day?” asked one.

“Pretty fair suicide,” was the answer. “How’d you make out?”

“Pretty decent murder, but they cleared it up too soon. No mystery in it.”

Rightly guessing that they were reporters, Larry approached them and asked for Mr. Newton. He was directed to walk into the city room, and there he saw his friend, with his feet perched upon a desk, smoking a pipe.

“Hello, youngster!” greeted Mr. Newton. “Been to any more fires?”

“No,” said Larry with a smile. “That one was enough.”

“I should say so. Well, you helped me considerable on that. We beat the other papers.”

“Beat them?” asked Larry.

“Yes, got out quicker, and had a heap better story, if I do say it myself. You helped some. Want to go down and see the presses run?”

“I came in to see if there was any chance of getting work,” answered Larry, determined to plunge at once into the matter that most interested him. “My mother and I and the rest of the family came to New York a few days ago, and I need work. Is there any chance at all of a job here?”

44 “Well, if that isn’t luck!” exclaimed Mr. Newton, without any apparent reference to Larry’s question. “Say,” he called to someone in the next room, “weren’t you asking me if I knew of someone who wanted to run copy, Mr. Emberg?” he asked.

“Yes,” replied the city editor, coming out into the reporter’s room. “Why?”

“Nothing, only here’s a friend of mine who wants the job, that’s all,” said Mr. Newton, as if such coincidences happened every day.

“Ever run copy?” asked the city editor, after a pause.

“I—I don’t know,” replied Larry, wondering what sort of work it was.

“It’s like being an office boy in any other establishment,” said Mr. Newton. “You carry the stuff from the reporters’ desks to the editors’ and copy readers’, and you carry it from them,—that is, what’s left of it—to the tube that shoots it to the composing room.”

“I guess I could do it, I’m pretty strong,” replied Larry, whereat the two men laughed, though Larry could not see why.

“You’ll do,” said the city editor pleasantly. “I’ll give you a trial, anyhow. When can you come in?”

“Right now!” exclaimed Larry, hardly believing the good news was true.

“To-morrow will do,” said the editor with a45 smile. “We’re all through for to-day. Come in at eight o’clock to-morrow morning.”

“I will!” almost gasped Larry, and then, as the two men nodded a kind good-night, he sped from the room.

Larry thought he would never get home that evening to tell the good news. He fairly burst into the room where his mother was sewing and cried out:

“Hurrah, mother! I’ve got a job!”

“Good, Larry!” exclaimed Mrs. Dexter. “I’m so glad. What is it?”

Talking so rapidly he could hardly be understood, Larry narrated all that had occurred on his visit to the newspaper office.

“I’m to go to work to-morrow morning,” he finished.

“Will they give you a thousand dollars, Larry?” asked little James, coming up to his brother.

“I’m afraid not, Jimmy. I really forgot to ask how much they pay, but it will be something for a start, anyhow.”

“Maybe they’ll let you write stories for the paper,” went on James, who was a great reader of fairy tales.

“Oh, wouldn’t that be fine!” spoke Lucy.

47 “They don’t have many stories in newspapers,” said Larry, who had begun to consider himself somewhat of an authority in the matter. “At least they call the things they print stories, for I heard Mr. Newton say he had a good story of the fire, but they’re not what we call stories. I wish I could get to writing, though; but I’m afraid I don’t know enough.”

“Why don’t you study nights?” suggested Lucy. “I’ll help you.”

“I believe I will,” replied Larry, for his sister had been very bright in her studies before the spinal trouble took her from school. “But first I want to see what sort of work I have to do. My, but I’m hungry!”

“We were waiting with supper for you,” said Larry’s mother. “I’ll get it right away.”

Then, while Mrs. Dexter set the table and started to serve the meal, Larry took little Mary on his knee and told her over again the story of the big fire he had seen, a tale which James also listened to with great delight. The little boy declared it was better than the best fairy story he had ever read.

Half an hour before the appointed time next morning Larry was at the office of the Leader. Neither the city editor, the copy readers, nor any of the reporters were on hand yet, but there were two boys in the room. At first they paid no attention to Larry, but stood in one corner, conversing.48 One of the boys, a rather thin chap, with a face that seemed older than it should have on a boy of his size, took out a cigarette and lighted it.

“If Mr. Emberg catches you, Peter, you’ll get fired,” cautioned the other fellow, who had a shock of light hair, blue eyes, and seemed a good-natured sort of chap.

“A heap I care for Emberg,” was Peter Manton’s reply. “I can get another job easy. The Rocket needs a good copy boy. Besides Emberg won’t be here for an hour,” and he began to puff on his cigarette.

Larry advanced further into the room, and, at the sound of his steps, the other boys turned quickly. Peter was the first to speak.

“Hello, kid,” he said rather familiarly, considering Larry was as old and about as large as himself. “What do you want?”

“I’m waiting for Mr. Emberg,” replied Larry.

“Lookin’ for a job?” sneered Peter. “If you are you can fade away. We got all the help we need. What right you got buttin’ in?”

“Mr. Emberg told me to come here and see him,” said Larry quietly, and then he sat down in a chair.

“Look a-here,” began Peter, crossing the room quickly and coming close to Larry, “if you think you can come in here and git a job over my head you’re goin’ to get left. Do you hear?”

49 Larry thought it best not to answer.

“I’ve a good mind to punch your face,” went on Peter, doubling up his fist. He seemed half inclined to put his threat into execution when the door suddenly opened and Mr. Newton walked into the city room.

“Hello, Larry!” he exclaimed cordially. “You’re on time, I see.”

“Yes, sir,” replied the new copy boy.

At the sight of the reporter Peter had dropped his cigarette to the floor and stepped on it. At the same time he slunk away from Larry, though the look in Peter’s face was not pleasant.

“Who’s been smoking cigarettes?” asked Mr. Newton, sniffing the air suspiciously. “Don’t you boys know the orders?”

While it was permitted for the men in the room to smoke there were stringent rules against the boys indulging in the habit.

“There was a feller come in to see the editor,” replied Peter. “He was smokin’ real hard. But he didn’t stay long. I guess that’s what you smell.”

Mr. Newton gave a quick look at Peter, and then at the still smouldering cigarette end on the floor. However, if he had any suspicions he did not mention them.

Several other reporters came in now, and there was much laughter and joking among them. Some had work to do on the stories they had been50 out on the night before, and soon half a dozen typewriters were clicking merrily.

Mr. Emberg arrived about half-past eight o’clock and began sending the men out on their different duties, or assignments as they are called in a newspaper office. He greeted Larry with a smile and told him to wait until the morning’s rush was over, when the lad would be told what his work was.

Larry was much interested in watching and listening to all that went on. He heard the men talking about fires, robberies, suicides, and political matters. The place seemed like a hive full of busy bees with men and boys constantly coming and going. Larry felt a thrill of excitement when he realized that he was soon to have a part in this.

In about half an hour, when most of the men had gone out to various places, some to hospitals, some to police stations, some to the courts, and some to fire headquarters, the room was comparatively quiet.

“Now then, you new boy—what’s your name?” began Mr. Emberg, motioning to Larry. “Oh yes, I remember it now, it’s Harry.”

“No, sir, it’s Larry,” corrected the new boy.

“Oh yes, Larry. Well, I’ll tell you what you are to do.”

Thereupon the city editor instructed Larry how, whenever he heard “Copy!” called, to hurry51 to the desk, get the sheets of paper on which the articles for the paper were written, and carry them to a room down the hall. There he was to put them in a sort of brass tube, or carrier, drop the carrier into a pipe, and pull a lever, which sent compressed air into the pipe and shot the tube of copy to the composing room. There it would be taken out and set up into type. But Larry’s duties, for the time, ended when he had put the copy in the tube.

There were many other little things to do, and errands to run, Mr. Emberg said, but Larry would pick them up in time.

“Now then, Peter,” called Mr. Emberg—“or never mind, I guess you had better do it, Bud,” to the tow-headed office boy. “You show Larry around a bit, so he’ll know where to go when I send him.”

“Come ahead,” said Bud with a smile.

As they passed Peter, who seemed to be sulking in a corner, Larry heard him utter:

“You wait, Larry, or whatever your name is, I’ll fix you for buttin’ in here. You’ll wish you’d never come.”

“Don’t mind him,” said Bud. “He’s afraid he’ll lose his job.”

“Why?” asked Larry.

“Oh, he’s made two or three bad mistakes here lately, and I guess he’s afraid they got you in his place. But don’t let that worry you, only look52 out for Pete, that’s all, or he may do something you won’t like.”

“I will,” replied Larry, as he followed his friend to learn something about the mysteries of a big newspaper office.

Bud first showed Larry how to work the pneumatic or compressed-air tube. Around it stood several other boys who seemed to be quite busy. Now and then one would dash in with a bunch of paper, grab a tube, stuff the copy in, and yank the lever over. A hissing, as the imprisoned air rushed into the pipe, told that the copy was on its way to the composing room.

“Where are those boys from; other papers?” asked Larry.

“Gosh, no!” exclaimed Bud. “No boy from another paper would dare come in here; that is while he worked for another paper. We’d think he was trying to get wind of some exclusive story we had. Those boys are from the different departments. One carries copy from the state department, another from the sporting room, and another from the telegraph desk.”

Then Bud briefly explained that there were several editors on the paper. One took charge of all the news in the city, and this was Mr. Emberg. Another handled all the foreign news that came in54 over the telegraph. Still another took charge of all matters that happened in the state outside of the city and the immediate surrounding territory. Then there was the sporting editor, who looked after all such things as football and baseball games, racing, wrestling, and so on. Each editor had a separate room, and there were one or two boys in each department to carry copy to the tube room, whence it was sent up to the printers.

“But our room’s the best,” finished Bud, with an air of conscious pride.

Larry was shown where the offices of the different editors were, so that he would know where to go if sent with messages to them. He was also taken to the composing room.

There he stood for a while bewildered by the noise and seeming confusion. A score of typesetting machines were at work, clicking away while the men sat at the keyboards, which were almost like those of typewriters. Larry saw where the tubes with copy in them bounced from the air pipe into a box. From that they were taken to a table by a boy, whose face was liberally covered with printer’s ink.

There a man rapidly numbered them with a blue pencil, and gave the sheets out to the compositors.

“Sometimes you have to come up here for proofs of a story,” Bud explained. “Then go over to that man there,” pointing to a tall thin55 individual, “and repeat whatever Mr. Emberg or whoever sends you, says. You see there are several different kinds of type in the heads of a story and each story is called according to the kind of a head it has.”

“I’m afraid I’ll never learn,” said Larry, who was beginning to feel confused.

“Oh yes, you will. I’ll explain it all to you. You probably won’t have to go for proofs for several days. You’ll only have to carry copy.”

They stayed up in the composing room for some time, and every second Larry wondered more and more how out of so much seeming confusion any order could ever come.

Boys with long galleys, like narrow brass pans that corresponded in size to columns of the newspaper, and set full of type, were hurrying with them to a big machine where they were placed on a flat table, and a roller covered with ink passed over them. Then a boy placed a long narrow slip of paper on the inky type, passed another roller over it, and lifted off the paper.

“That’s what they calling pulling or taking a proof,” said Bud. “But come on now, we’ll go back to the city room and rush copy. I guess there’s some by this time.”

There was quite a bit, for a number of stories had been handed in by the reporters, had been looked over by Mr. Emberg, his assistant, or the copy readers, and were ready for the compositors.56 Peter had been kept busy running back and forth and was in no gentle humor.

“I’ll fix you for this,” muttered Peter to Larry and Bud. “I’ll get even for running off and letting me do all the work. You jest wait an’ see wot I do!”

He spoke in a low tone, for he did not want the city editor to hear.

“Cut it out,” advised Bud with a grin. “I was sent to show Larry about the plant and you know it. Besides, if you try any of your tricks I know something I can do.”

“What?” asked Peter.

“Who was smoking cigarettes?” asked Bud in a whisper.

“If you squeal on me I’ll—I’ll do you up brown,” threatened Peter.

“It will take two like you,” boasted Bud.

“Well, I can get somebody to help me,” sputtered Peter.

“Copy!” called Mr. Emberg at that instant, and, at a nod from Bud, Larry sprang forward to carry it to the tube. It was his first actual work in the newspaper office, and quite proud he felt as he put the story in the case and sent it up the pipe.

From then on all three boys were kept busy, for as the morning wore on several reporters came in with stories, long or short, that they had gathered on their various assignments, and these57 were quickly corrected and edited, and ready for the typesetters.

Back and forth, from the city room desk to the pneumatic tube, the three boys ran. Larry noticed that Peter was in the sulks and that he did not seem to care very much about doing the work. Once or twice he lagged down the hall instead of hurrying back from the tube after more copy as he should have done, once Mr. Emberg remarked sharply to him:

“Peter, if you don’t want to work here, there are lots of other boys I can get.”

“My foot hurts me,” whined the boy, as he limped slightly.

“Why didn’t you say so before?” inquired the city editor. “If it is very bad you can go home and come in to-morrow.”

“Oh, it’s not as bad as that,” replied Peter, fearing lest he should be found out in his deceit. “I guess I can stand it.”

Meanwhile Larry was kept on the jump. He soon got the knack of his duties and resolved to make himself as useful as possible. With this in view he kept close watch on the desk, and, as soon as he saw Mr. Emberg, the assistant city editor, or any of the readers, fold up copy, preparatory to handing it to one of the boys, Larry hurried up without waiting for the cry “Copy!”

“That’s the way to do it,” said Mr. Emberg58 encouragingly, as he noticed Larry’s remarkable quickness.

“Don’t be so fresh,” muttered Peter on one of these occasions, as he passed Larry in the long and deserted hall. “There’s no use rushin’ so, and the union won’t stand for it. I’ll punch your head if you don’t look out!”

“I’m going to do my work right, and I don’t care what you say!” exclaimed Larry. “And if there’s any head punching to be done, I can do my share!”

“Um,” grunted Peter. “I’ll get square with you all right!”

It was now noon, and the paper went to press for the first edition shortly after one o’clock. So there was considerable excitement and hurry in all the departments, to get the important news set up and ready to be printed.

Reporters were hurrying in and out, the readers and editors were using their pencils rapidly, correcting and changing copy, and the three boys in the city room were kept on the jump all the time.

Shortly before one o’clock a reporter came in all out of breath.

“Man—killed—himself—in—the—Post Office just—now!” he gasped.

“Quick!” shouted Mr. Emberg. “We’ve only got ten minutes to catch the edition. Write as fast as you can. Short paragraphs. Here, one59 of you boys bring me the sheets as fast as Mr. Steifert finishes them.”

The reporter sat down to a typewriter, rapidly inserted a piece of paper and began to click out copy so fast that Larry wondered how he could see the keys.

“I’ll carry the sheets to Mr. Emberg,” said Bud to Larry, “and you get ready to rush them to the tube.”

This was done. As soon as Mr. Steifert had one paragraph written he pulled it from the machine and handed it to Bud, who ran with it to the city editor. The latter quickly glanced at it, corrected one or two slight errors, and passed it over to Larry, who fairly raced down the hall.

When he came back another page was ready, and this was kept up until the story was all upstairs. Then Mr. Emberg proceeded to write a head for it and Larry carried that copy to the tube.

“Just made that in time,” said the city editor, as Larry came back. “Now, Mr. Steifert, get ready a better and longer story for the next edition. You can take a little more time.”

Matters became more quiet in the office after the first edition had gone to press. There were to be two more editions, and there still remained plenty of work to do. Once or twice Larry was sent to get proofs from the composing room and luckily he made no errors.

60 It was getting on toward four o’clock when the last edition was getting ready to close.

“Copy!” called Mr. Emberg, holding out a bunch of paper and not looking up to see who answered his summons.

Larry ran and grabbed it and sped down the hall. Halfway down he was met by Peter, who also had some papers in his hand.

“I’ll put that in the tube for you,” said Peter. “I’ve got some more to go in.”

At first Larry hesitated. Then, thinking perhaps Peter wanted to make up for his recent unkind remarks, Larry gave him the copy and returned to the city room.

A little later the big presses began thundering in the sub-cellar, and soon the first copies of the last edition were off and a boy brought several to the city room.

“Here! What’s this?” cried Mr. Emberg suddenly, after a hasty glance over the paper. “Where’s that story about Alderman Murphy?”

“I handed it to you,” said one of the reporters.

“I know you did, Reilly. I handled it and put a display head on it. It went up in time, but it isn’t in. Who took that copy?” he asked, turning to the three boys who stood to one side of the room. No one answered for a second or two.

“It was written on yellow paper,” went on Mr. Emberg.

61 “I—I did,” replied Larry, wondering what was going to happen.

“What did you do with it?”

“I—I gave it to Peter,” faltered Larry.

“You did not!” cried the other office boy, in an angry voice.

“Yes, I did,” replied Larry firmly. “I started down the hall with it as soon as Mr. Emberg gave it to me. You stood near the tube with some other copy and you said you’d send mine up for me.”

“How about that, Peter?” asked Mr. Emberg.

“I—I don’t remember anything about it,” said Peter. “I sent up my own copy; that’s all I’m supposed to do.”

“No, it is not,” said the city editor. “You are supposed to do what we are all doing here, work for the interests of the paper, no matter in what way. Larry did wrong if he let anyone else take any copy that was intrusted to him. Never do it again, Larry. When you get copy put it in the tube yourself. Then you will be sure it goes upstairs.”

“But he asked me for it,” said the new boy, feeling quite badly over the matter.

“No matter if he did.”

“I didn’t do it. He’s just tryin’ to get out of it,” spoke Peter.

63 “We’ll soon see who’s to blame,” came from the city editor. “You boys come with me.”

Secure in the sense that he was right, Larry followed. As for Peter he would a good deal rather not have gone, only he dared not disobey. Up to the composing room Mr. Emberg led the two boys. There he asked the boy whose duty it was to take copy from the tubes whether he had received any on yellow paper, for it was on sheets of that hue that the missing story was written.

“No yellow copy came up this afternoon,” said the tube boy. “The last batch I took out was a story about the new monument, and that was all.”

“That’s the copy you took, Peter, about the same time I sent the story about Alderman Murphy up,” said Mr. Emberg.

“I don’t know nothin’ about no yellow copy,” said Peter sullenly.

“I’ll inquire in the copy room downstairs,” said the city editor. With the boys following him, he went to the apartment where the pipe was located, in which the copy was sent upstairs. It was the duty of one boy to remain here all the while the paper was going to press to see that the machinery was in order.

“Who sent up the last copy, Dudley?” asked Mr. Emberg.

“Peter Manton,” replied Dudley. “There was some other fellow that ran in the last minute, but64 Peter took the copy from him and said he’d send it up.”

“What kind of copy was it?” asked the city editor.

“On red—no—it was on yellow paper,” replied Dudley.

“And did you see Peter put it in the pipe?” asked Mr. Emberg.

“No, sir. I didn’t look at him closely. I had to turn on a little more compressed air then, and I was too busy to take much notice.”

“Peter, you never sent that copy up!” exclaimed the city editor suddenly, turning to the sulking office boy. “You are up to some trick. Tell me what you did with it.”

“I didn’t——” began Peter.

But Mr. Emberg, with a quick motion, leaned forward and tore open Peter’s coat. Out on the floor tumbled a number of yellow sheets of paper. Mr. Emberg picked some of them up.

“There’s the missing copy,” he said. “Peter, you can go downstairs, get what money is coming to you, and go. We don’t want you here any more.”

“All right,” growled Peter sullenly.

He turned to leave. As he passed Larry he muttered in a low turn:

“This is all your fault. Wait until I get a chance! I’ll pay you back all right, all right!”

Then, before Larry could answer, Peter shuffled65 down the hall. And that was the end of Peter on the Leader, though it was by no means the last Larry saw of him.

Thus the first day of Larry’s life on a big newspaper came to a close and it was with considerable pride that he started for home. He felt he had done well, though he had made one or two mistakes. He was a little worried about what pay he was going to get, and he had a little fear lest he might be paid nothing while learning.

His fears were set at rest, however, when, as he was going out of the door, Mr. Emberg called to him.

“Well, Larry, how do you like it?”

“First-rate,” said Larry heartily.

“I forgot to tell you about your money,” the city editor went on. “You will get five dollars a week to start, and, as you improve, you will be paid more. Perhaps you’ll become a reporter some day.”

“I’d like to, but I’m afraid I never can,” said the boy wistfully.

“Why not?”

“I haven’t a good enough education.”

“It doesn’t always take education to make a good reporter,” said Mr. Emberg kindly. “Some of our best men would never take a prize at school. Yet they have a nose for news that makes them more valuable than the best college educated chaps.”

66 “A nose for news?” asked Larry, wondering what sort of a nose that was.

“Yes; to know a good story when they hear about it, and know how to go about getting it. That’s what counts. I hope you’ll have a nose for news, Larry.”

“I hope so,” replied the boy, yet he did not have much anticipation.

He was thinking more about the five dollars he was to earn every week than about his prospects as a reporter. He knew the money would be much needed, and he resolved to do all he could to merit a raise.

There was much rejoicing in the humble home that night when Larry told about his salary. Mrs. Dexter also had good news, for the firm for which she sewed had given her a finer grade of work, at which she could earn more money.

“We’ll get along fine, mother,” said Larry.

“Ain’t you afraid that mean boy Peter will hurt you?” asked little James, who had listened to Larry’s recital of the discharge of the other office boy.

“No, I guess I can take care of myself,” said Larry, feeling of the muscles of his arm, which were not small for a lad of his age. “And how are you, Lucy?” the boy went on, going over to where his sister was propped up in a big chair.