Title: Harper's Round Table, February 16, 1897

Author: Various

Release date: November 21, 2019 [eBook #60755]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

Copyright, 1897, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 16, 1897. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xviii.—no. 903. | two dollars a year. |

When I was a boy I belonged to a small company of young fellows, all under fourteen, who had banded themselves together for the purpose of practising archery. Our company owed its name to our great admiration for Major Ringgold, about whose valiant exploits in the Mexican war we had often read and talked. He was a romantic man, and romance always has a charm for the young, even when they do not understand it. The Major was a brave cavalryman, and we had seen pictures of him charging at the head of his horsemen, with his long hair floating in the wind. In this long hair lay his romance; for we had heard the story that, having been crossed in love, he vowed he would never again cut his hair. The point of this resolution we did not then understand, nor can I say that I fully[Pg 378] comprehend it now, but I am quite sure that each one of us would have been perfectly willing to be crossed in love if the result should be that we would charge at the head of some brave cavalrymen, with our sword drawn and our long hair floating in the breeze.

When we had decided upon the name of our company, and had elected officers, we considered that the next most important thing was to provide ourselves with a uniform dress. This subject did not occasion very much discussion. The color for an archer could be nothing else than green; and as to the cut and general make-up of the dress, it would have to be very simple, for none of us were able to afford an elaborate uniform, so it was decided that a blouse long enough to cover our ordinary coats and fasten around the waist with a belt would be quite sufficient. As to our head-gear—we all wore straw hats, and if we chose to put feathers in them we could do so, but this was left for future consideration.

The material of our uniform was determined by the state of our finances. When each one of us had put into the treasury all the money he could afford, it was plain to see that our blouses must be made of some cheap stuff.

One of our members had some family connection with the dry-goods business, and he informed us that the best thing to do would be to buy a whole piece of goods, for in that way we could get it cheaper, and he was sure that our money would be sufficient to buy a piece of cotton cloth good enough for our purposes.

It was early in the afternoon of a summer day that the meeting was held at which the matter of the uniform was decided upon, and as it was still light, we thought it well to go immediately and buy our material. If we delayed, something might happen to our money.

Therefore in a body we repaired to a dry-goods store, and it was not long before we found a piece of goods which we thought would suit us. It was a little glittering upon one side, and it was rather stiffer than we thought an archer's dress should be, but if we made our blouses with the wrong side of the material out, they would look well enough, and we had no doubt that the stiffness would come out after we had worn them for a time, especially if we were obliged to encounter storms, which true archers should never fear.

Triumphantly we carried our piece of goods to the house of one of the members, and having found out how much of the material would be necessary to make a blouse, we cut it up into suitable portions, one of which was given to each member, and he was expected to take it home and have some one of his family cut it out and make it for him.

There was a very early meeting the next morning at the house of our Captain, and every boy brought with him his allotted portion of goods. We were all horrified—the stuff was blue, and not green! The gas had been lighted in the store when we bought it, and instead of Robin Hood green we had picked out a piece of bright blue material! This mistake would have been a matter of no importance had we not been in such haste to divide the stuff among the members. If the piece had been left entire, we could have easily exchanged it, but now this was impossible.

We had a long meeting and much discussion; but as we had bought our material, and as we had no money to buy more, we at last regretfully concluded that the best thing we could do would be to make up our blouses of the blue, and try to forget that they ought to be green.

Vacation was passing, and there was no time to be lost if we expected to make a successful summer campaign, and our uniforms were immediately put into the hands of our mothers, sisters, and aunts. In most cases there was but little trouble in inducing these good relatives to make the blouses, although I think we were all of us told that it would have been a great deal better if we had asked some lady to buy our goods for us. But as this would have deprived us of a great and independent pleasure, it should hardly have been expected.

There was an exception, however, to the ready consent of our families to do our tailoring-work. The mother of one of our members objected to her son's wearing a uniform of any sort, and although she did not actually forbid his doing so, she would have nothing to do with the fabrication of it. Therefore it was that the poor boy, in the seclusion of his chamber, set to work to make it himself. Some of us found him at this work just as he was about to cut it out; we took it from him, and one of us carried it home, where it was properly made.

While work was going on upon our uniforms we thought it well to attend to the armament of our company, and those who did not possess bows and arrows were ordered to get them as soon as possible, no matter what family assessments might be necessary. Our archery weapons were not of a fancy sort. We had no bows of yew, nor arrows pointed with steel and tipped with fine feathers; but we had good bows, made by a cooper of our acquaintance, and our blunt-headed arrows often sped well to the mark, although they did not stick there. We had discussed the propriety of inserting pieces of sharpened iron into the heads of these arrows, but this improvement having been made known to some of our parents had been strictly forbidden.

As soon as our garments were finished we held a full meeting, in which we all appeared in our new uniforms, and to say that the result was satisfactory would be to make a misstatement. In the city in which we lived there was a great deal of charcoal used, and this fuel was carried about the streets in wagons with high sides, each accompanied by two men, one of whom marched in front, ringing a bell and crying, "Charcoal!" while the other attended to the horse, and shovelled out the charcoal whenever a purchaser hailed him from a house. These men invariably dressed in long blue gowns, and when we were gathered together, attired in our uniforms, there was not one of us who was not immediately reminded of the charcoal-men.

Some were disgusted, and some laughed, but there was no remedy. There were but two things we could do: we must wear our blue blouses, or we must go out on our archery expeditious in our ordinary clothes. In the latter case we would be a mere party of boys, whereas if we marched forth in our uniforms—no matter what color they might be—we were the Ringgold Archers. We chose to stand by our name, our purpose, and our organization.

On the outskirts of our city there were open country, woods, and streams, and it was here that we were to begin our life of "Merrie men under the green-wood tree," and our first expedition was made without delay. Early one afternoon we marched forth into the streets—seven of us—each wearing his blue blouse, his arrows stuck in his belt, and his unstrung bow in his hand. We attracted a good deal of attention. There were people who looked at us and laughed, there were others who wondered, and during our march through town we frequently met with youngsters who cried "Charcoal!" and then ran away. Seven boys—no matter how they might be dressed—were not to be trifled with.

When we reached the country we had a fine time. The birds did not laugh at us, the wild flowers and bushes took no notice of us, except when some sociable blackberry bush endeavored to detain us by seizing the skirts of our flowing robes, and the trees which we used as targets did not always refuse to be hit, whether they represented men or deer, or even an on-coming bear—for there were bold fellows in our company, with good imaginations.

But I cannot tell all the bloodless pleasures of our chase, for I must hasten to relate how this first expedition of the Ringgold Archers was its last. Toward the close of the day, well satisfied with our afternoon's sport, we were returning along a quiet and almost deserted country road, when we met two rough-looking young men.

These fellows, when they beheld the strange procession of blue-clad boys appearing around a turn in the road, were greatly impressed, and they burst into the most vociferous laughter. Of course we did not like this, and we would have been content to pass on, treating the disrespectful fellows with silent contempt; but this the young men did not permit. They stopped us and wanted to know why we were dressed in these blue shirts, and what we intended to do with our bows and arrows. When our organization and our purposes had been explained, they were not satisfied. They examined our arms, and ridiculed them, as they[Pg 379] were sure they would not kill anything. They laughed again at our uniform, making those allusions to charcoal which had become familiar to us, and in other ways treated our band with the discourtesy which, although good-humored, was extremely disagreeable to us. When they had jeered at us to their satisfaction, they went their way.

There were two members of our company whose proud souls could not brook this treatment, and they determined that they would give these impudent fellows a taste of their quality. They followed the young men a little way, and then ran up a low bank on the side of the road. There they fitted arrows to their bows, and prepared to shoot at the fellows who had insulted them.

As soon as the rest of us saw what our companions proposed to do, we hurried to them, and urged them to come down and let the young men alone; it would not do to rouse the anger of such fellows, who looked as if they might be very rough customers if they chose to be. But our bold companions were not to be restrained; their souls chafed under their injuries, and before we could stop them, each had drawn an arrow to its head and let it fly at the young men, who were now barely within range. One of the arrows struck its mark, and the other fell near by.

Instantly the enemy stopped and turned, and beholding the two boys standing on the bank with their bows in their hands, had no reason to ask who had shot at them. But instead of hurrying away to avoid another discharge of arrows from these bold archers, the young men made use of some very violent language, and without the slightest hesitation ran towards the two boys, who turned and fled across a field.

The chase was short, for the young men were powerful runners. The valiant archers were caught by the collars of their blue uniforms, their bows were wrenched from their hands, and the next moment each one of them was receiving a sound drubbing with his own weapons. The arrows which they had in their belts were taken and broken, and they were told in very strong language that if they did not get out of sight as fast as they could they would have another whipping. This advice was taken, and the disarmed archers fled.

All this happened so quickly that the other members of the Ringgold Archers had no chance to do anything in defence of their comrades, even if they had felt able. But now we perceived that we must do something to defend ourselves, for the young men—still speaking angrily—advanced towards us. We stood our ground, for we had seen that there was no use in running; and, besides, why should we run? We had done no wrong to any one.

The young men jumped down from the bank, and without delay or explanation ordered all of us to surrender our arms. To this we vehemently objected. We had committed no offence towards them; we had even advised our comrades to refrain from their attack, and there was no reason why we should give up our bows and arrows. But the young men were in no mood to consider reasons. They seized our bows, forced them from our hands, and jerked our arrows from our belts. I can remember now how stoutly I held on to my bow, and how soon I became convinced of the superiority of a man's strength over that of a boy.

Our disarmament was complete; not a bow or arrow was left to us. We continued to expostulate against the injustice that had been done to us, but the two fellows paid not the slightest attention to our words. Pleased with their easy victory, they began to amuse themselves. Standing at a little distance from us, they discharged our arrows at various marks. They were miserable shots, and could not hit anything, and so, on concluding that this was no fun, they shot our arrows far and wide into the thickets, where it would be almost impossible to find them again.

This exercise seemed to dissipate their anger, and when the arrows were all gone they came to us and threw all our bows on the ground.

"There!" said one of them. "You can take them and go home with them, and the best thing you can do is to give up coming out here with your bows and arrows and stick to your charcoal!"

Sadly the Ringgold Archers resumed their homeward march, and it was not long before they were joined by their two comrades, who had been hiding in the bushes. Some of us were inclined to give the young scamps another whipping for getting us into such a scrape, and we were the more angry because they did not seem in the least sorry for what they had done; but finally the matter was smoothed over, and we marched peaceably on together.

Before they reached the outskirts of the city the Ringgold Archers halted and took off their uniforms. Most of these were sadly bedraggled and torn in the struggles with the young men, and, furthermore, they seemed more like the gowns of the charcoal-men than they had done before. Each of us rolled his uniform around his bow and carried them home under his arm, and such of us as had feathers in our hats took them out and threw them away.

That was the last expedition of the Ringgold Archers. Although we gave up the idea of emulating the deeds of Robin Hood, Little John, and Friar Tuck, some of us became very good amateur archers.

As to Major Ringgold, his blighted affections and his flowing hair, they faded out of our minds with the memory of our torn and discarded uniforms of blue.

When the snow falls in the city,

Oh, it seems a dreadful pity!

And it costs a lot to cart it all away;

But the boys who on the side-

Walk make the dangerous slide

Would like to have the snow come every day.

Oh, it's fun to hear them shout,

As they slip and slide about,

Like some eerie, cheery spirits of the storm;

But just call out, "Cheese the cop!"

And how suddenly they stop!

For the "copper" has a duty to perform.

"Now yous fellies git a gait,"

He exclaims, and, if they wait,

"Come, now, yous, jus' chase yourselves right off de block!"

But I should not be surprised

If he often sympathized

With his victims, and his heart were not a rock.

For 'twas but the other night,

When no roundsman was in sight,

That I saw a "copper" running down the street.

Was he chasing of a thief?

Don't you err in that belief—

He was sliding on each slide along his beat.

nce a gentleman reproved his negro servant for serving a duck for dinner to which there was only one leg. He suspected Sam of having eaten the missing limb.

"Oh, no, sir," replied Sam; "these ducks have only one leg!"

"Indeed!" said the master. "I must see them."

So the next morning he told Sam to show him the one-legged ducks. Sam conducted his master to the poultry-yard, and pointed to half a dozen ducks, each standing on one leg near the pond.

"There, sah!" he exclaimed.

The master waved his arms, and cried out, "Shoo! shoo!" and the ducks scampered away.

"How about that?" he said, turning to Sam.

"That's right, sah," returned Sam, calmly; "but why didn't yo' shoo de oder duck, las' night?"

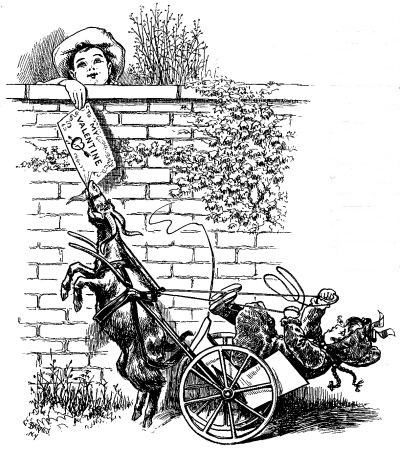

he Chadwick girls, one February morning, were deep in consultation as to the best way in which to entertain their friend Dorothy Adams, who was coming the next week to make them a two days' visit.

"Why not have a valentine party instead of a tea?" suggested Catharine. "Teas are so stiff and poky when one is not acquainted with any of the other guests, and Dorothy is one that likes a thoroughly good time."

"A valentine party would be much more lively, of course," said Helen; "but where in the world could we find enough valentines to go round?"

"Write them, the same as the girls did in Grandmother Livingston's day," answered Catharine. "Even if we haven't any especial gift for verse-making, we can string some passable rhymes together, I hope."

"How would it do," asked stately Elizabeth, beginning to be interested, "to have bows or rosettes of ribbon—two of each color—distributed, and let each person take for a partner the one that wears the corresponding badge? Then, of course, there would have to be two sets of Valentines. For example— Here, give me your pencil, Catharine, please, and that empty envelope. How would this do?

"Blue No. 1, fastening her badge to the lapel of her partner's coat:

"As ladies fair, in days of old,

To chosen knights their colors gave,

This ribbon blue

I give to you;

And this, dear Valentine, I crave,

That you the little badge will take,

And bravely wear it for my sake.

"And something like this for an answer:

"Blue No. 2 (fastening his own badge on his lady's gown):

"Of all the merry throng to-night,

With colors rich and rare bedight,

Believe me, none will prove more true

Than he who wears this bonny blue."

"Bravo, Beth!" cried the others.

"Verily I believe it's catching," exclaimed Helen. "I too have an idea. Quick, give me a pencil!" And straightway all three fell to scribbling, each taking a different color for her subject.

And when they had made an end of cudgelling their brains, the following rhymes were ready to be copied:

Red, No. 1—

Red as my own is the badge I seek,

And red as a rose is the wearer's cheek.

Why art thou thrilling, heart of mine?

Ah, if I knew they were both for me,

The badge and the blush, on bended knee

I would sue for the love of my Valentine.

No. 2.—

This ruddy bow for thee I bind.

Be true, and thou wilt ever find

Warm is the heart that wears the red;

No scorn nor coldness needst thou dread.

Pink, No. 1—

My lady fair doth wear the tint

That deep within the sea-shell glows,

But, like the shell beneath the pink,

Her heart is white as Alpine snows.

No. 2—

I would this little knot of pink

Might be, dear Valentine, the link,

Where'er the lines for us be cast,

To hold our friendship firm and fast.

Yellow, No. 1—

Dear Valentine, one boon I ask—

Pray make it not a loveless task,

Nor think me somewhat overbold—

When you this yellow knot espy,

Ask not to-night the reason why,

Within your own my hand enfold.

No. 2—

Oh, maiden fair, whose badge is yellow,

Let heart and hand

Together band,

And find in me your happy fellow.

Green, No. 1—

Green as the larch's bursting buds

When spring is everywhere afield,

This pledge of all my heart's desire

To thee, sweet Valentine, I yield.

No. 2—

Leal throbs the heart beneath the sheen

That mates thy knot of tender green.

If thou, dear knight, that heart wouldst woo,

Be this thy motto, "Brave and true."

A badge of two colors, violet and orange, No. 1—

Who wears to-night

The colors bright

That in this radiant badge entwine,

I single from the lovely ranks,

And claim her for my Valentine.

No. 2—

A happy Valentine is she

Whose fortune in this badge is told,

For violet for heart's ease stands,

And orange for the heart of gold.

Brown, No. 1—

Ah me! no golden gift have I

To offer to my lady fair,

And much I fear she will not deign

This tawny gift of mine to wear.

Accepting his and fastening hers to his lapel.

No. 2—

Though sombre-hued this badge may seem,

Disdain it not, for oft, I deem,

Those forced to wear life's thrifty brown

Are worthy of love's brightest crown.

A white satin star, No. 1—

The bravest knight in Arthur's train

Was he who wore with ne'er a stain

The shining badge of purity;

And since I know that thou art true,

And that my trust I ne'er shall rue,

This token white I yield to thee.

No. 2—

Thy gift, as pure as thy radiant brow,

I take, dear heart, with the reverent vow

That whether the way be near or far,

I'll follow the lead of my lady's star.

"There!" said Helen. "Counting in the first two, we have sixteen, and the two sets must be put in separate baskets and drawn for. The next question is, what are the people to do after they find their partners?"

"We must seat each couple at a table and give them[Pg 381] some puzzle or problem to work out together," said Catharine, promptly. "How would 'An Astronomical Wedding-Journey' answer? You can get that up, Beth—you are so fond of star-gazing; but don't make it too prosy."

"I'll attempt it only on one condition," answered Elizabeth: "neither of you must see it until it is given to the rest."

"Very well, Beth; we'll leave you to yourself while we copy the valentines."

And this is what Elizabeth set them to pondering over on St. Valentine's eve:

Once upon a time it chanced that the —— in the —— (satellite of the earth) fell desperately in love with a certain fair —— (sixth sign of the zodiac), and the latter, having first dutifully asked her ——' (one of the primary planets) permission, readily consented to marry him. For bridemaids they chose —— (one of the Northern constellations who was noted for her shining hair), and —— (a Northern constellation, a princess who had once been chained to a rock on the sea-shore); while for groomsmen they had the twin brothers —— and —— (third sign of the zodiac).

At the wedding-breakfast the bride sat in ——'s chair (a Northern constellation), and as they were fond of sea-food, they had on the menu deviled —— (fourth sign of the zodiac) and broiled —— (twelfth sign of the zodiac), with —— (eleventh sign of the zodiac) for their water-carrier.

After breakfast they had a game of —— and —— (Northern constellation) with their guests; and the bride, being a fine musician, entertained them by playing the —— (Northern constellation).

As there were no railroads in the country, they harnessed —— (Northern constellation) to Charles's —— (Northern constellation), and took the route known as 'The —— ——.'

"It seems very selfish to be seeking only our own pleasure," suggested the bride, who, like every truly happy bride, wanted all the world to share her joy; and the groom, being a sworn knight, decided that they would go in search of the lost ——. Becoming thirsty on the journey, they stopped at a farm-house well.

"You can drink from the little ——," said the groom, "and I from the big ——."

But a great —— (a Southern constellation) began barking at them, and before they could get back to the wagon they were butted by a vicious —— (first sign of the zodiac), and came near being tossed by an angry —— (second sign of the zodiac). A little later, in passing through a thicket, they met a roaring —— (fifth sign of the zodiac). But the groom, being a fine —— (ninth sign of the zodiac), slew him with an —— (Northern constellation), and when shortly afterward they encountered a great grizzly —— and a little one (Northern constellations), he made an end of the old one in the same way. But the little one was too bright for him, and chasing the tip of his tail, they presently reached that long-sought —— around which the —— are the only dancers on May-day. For the remainder of the journey there was nothing to mar their pleasure; but after they reached the groom's palace, the trail of the —— (Northern constellation) soon made a change, for the groom in his own house, like many another husband, was as eccentric as a ——, flying off in a —— on the slightest provocation, and though he had always been reputed to be made of gold, he proved so poor that he could afford no —— except what he borrowed from his generous father, the ——, whom he disrespectfully called "Old ——."

The bride in her disappointment declared that he had been weighed in the —— (seventh sign of the zodiac) and found wanting, and also charged him with having become so infatuated with —— (the most beautiful of the planets), that she herself was totally ——. And though he protested that she was still his morning and his evening ——, and that he would willingly endure for her the labors of —— (Northern constellation), she refused to be reconciled. Whereupon he made way with himself by taking an overdose of —— (one of the planets), and the bride in a fit of remorse hid a —— (eighth sign of the zodiac) in her bosom, and suffered the fate of —— (Egyptian queen).

A copy of this puzzle having been given to each couple, half an hour was allowed for the filling of the blank spaces, after which prizes were awarded to those who had made out the papers correctly.

EACH COUPLE HAD A COPY OF THE PUZZLE.

EACH COUPLE HAD A COPY OF THE PUZZLE.

t was four o'clock in the morning before the household began to settle down into its accustomed quiet. Miss Joanna was at last sleeping quietly, and the doctor assured the sisters that they need fear no further danger. He begged them to go to their rooms and try to get some rest, for he saw that the four ladies were in a state of nervous excitement which was almost alarming. Miss Middleton declared that she should not leave her sister Joanna, but she begged the others to follow the doctor's advice. Miss Thomasine, as she passed Theodora's room, opened the door quietly and looked in. She intended to tell her niece, if she were awake, that her aunt Joanna was decidedly better.

But when Miss Thomasine peeped into the room, which was but dimly lighted, she was astonished to find that Theodora was not there. She stepped inside and looked again. The bed was empty, as was also the lounge. The room was not large, and one could see at a glance that it was not occupied.

Miss Thomasine felt a shock similar to the one which she had experienced when she was told that Joanna "had one of her attacks." Where could the child be?

In the hall she met Miss Dorcas and Miss Melissa.

"Theodora is not in her room," she whispered. "Where do you suppose she is, sisters? And what had we better do?"

The three stood and looked at one another. Without their two ruling spirits Adaline and Joanna, whose words were always law, the three younger sisters felt much as if they were a ship deprived of both captain and pilot in a stormy sea.

They drew a step nearer to one another.

"Perhaps," said Miss Melissa—"perhaps—there's no knowing; she might do anything!—she went again—"

"Went where?" asked Miss Dorcas. "Do you mean on the—the—"

"Do you mean the bicycle?" asked Miss Thomasine, courageously uttering the obnoxious word.

Miss Melissa nodded.

"Oh, it could not be!" said Miss Dorcas.

"Certainly not!" exclaimed Miss Thomasine. "The child is somewhere in the house, and we must look for her."

They investigated the rooms on the second floor with no success, and then they descended the broad stairs, one behind the other, each clad in a flowered dressing-gown and enveloped in a worsted shawl, and each one carrying a lighted candle in a tall silver candlestick.

Over their heads, shorn of the additional braids which adorned them by day, and in no state to be seen by the doctor or even by the servants, each sister had tied a white knit "cloud." Even Miss Melissa, when she removed her bonnet after her futile attempt to summon the doctor, had again adjusted her cloud.

And now they crept down their own staircase feeling strangely ill at ease. Never before had they been downstairs at this hour and in this costume, but Theodora must be found.

THEODORA LAY ON THE SOFA ASLEEP.

THEODORA LAY ON THE SOFA ASLEEP.

The parlor door stood open at the foot of the stairs. It was dark there now, for the moon had set and it was not yet dawn. The three ladies gathered at the threshold, and holding their candles on high, peered into the room. There, on the sofa, lay Theodora, one arm hanging over the side, the other tossed above her head. As the aunts drew nearer she moved a little, and murmured in her sleep: "Of course I believe you. It's dreadful not to be believed."

Then the gleam of the three candles shone full in her face and she wakened, her eyes blinking in the light.

"Why, what is it?" she cried, starting up in terror and gazing at the three odd figures. "Where am I, and who are you? Who are you, I say?"

"My dear Teddy," said Miss Thomasine, "do not be alarmed! Do you not know us?"

"Why, it's Aunt Tom," said their niece, wonderingly, "and Aunt Dorcas, and Aunt Melissa! You don't know how funny you look! Have you been out to walk?"

"Out to walk!" repeated Miss Dorcas, severely. "Do you know that it is the middle of the night?"

"Is it, really? Then how did I get here? Oh, I remember! Aunt Joanna was ill, and I went on Arthur's wheel, and then I came down here and found Andy Morse. Oh, it has been such an exciting night! I gave him something to eat in the kitchen. I hope you won't mind, but he was so hungry. And he has promised to be good after this."

The three aunts looked at one another and then at Teddy's flushed face. Miss Thomasine felt her pulse and asked to see her tongue.

"You have been dreaming, I suppose. Come up stairs and go to bed, my dear."

"But I didn't dream that, Aunt Tom. Andy Morse was really here, and I gave him some money to go away with. I had some in my bank, you know, so I could do what I liked with it."

"She grows more and more incoherent," said Miss Dorcas.

"I think, sisters," murmured Miss Melissa, "that—that—it would be as well—the doctor right here—"

"I agree with you," said Miss Thomasine; "she most certainly is not well, and the doctor had better see her. Teddy dear, come up stairs. Lean on me if you feel at all giddy."

"I'm not a bit giddy," cried Theodora, springing to her feet, "and I don't know what you are talking about. Why must I see the doctor? I am not sick, and oh, I do want to tell you about Andy Morse!"

Again the sisters looked significantly at one another. Then Miss Thomasine took one of Teddy's hands and Miss Dorcas possessed herself of the other, while Miss Melissa walked in front with two of the candles.

"We must get her to bed as quietly as possible," said Miss Thomasine. "Oh, what a night this has been!"

"I was sure that ride would be too much for her," said Miss Dorcas.

"Is it—do you think it can be? I have heard of it—brain fever?" whispered Miss Melissa, turning in affright.

"What do you all mean?" exclaimed Teddy, wrenching her hands away from her aunts. "I tell you I'm not a bit sick, and I do wish you would let me go up stairs alone! And I don't see why you won't believe what I say. Are you never going to believe me again? I wish you would let me tell you about Andy Morse. He hid behind the big sofa, and I heard him there, and asked him to come out. Do you know, that poor boy hadn't had a thing to eat for two days! Just think of it! And he was so desperate he came here to steal something. I don't wonder—do you?"

The sisters had again looked at one another meaningly, and during this speech Miss Dorcas had left the room. Presently she returned with the doctor.

"What's all this?" he asked. "Teddy ill, after saving her aunt's life, as she did? She doesn't look very ill."

"Of course I'm not ill, Dr. Morton! They won't believe me when I say that Andy Morse was hiding here and I gave him something to eat and the money out of my bank. If you go into the kitchen you will see the plates and things on the table, and if you go up to my room you will see the empty bank. I do wish my father and mother were here!" she added. "I'm just tired of not being believed."

The doctor felt her pulse and looked at her.

"I believe you, my child," he said. "You are as well as I am, and I have no doubt Andy Morse was here. He is quite capable of anything. I am sorry you gave him your money, for he doesn't deserve it, but I quite believe you."

Theodora glanced at him gratefully, and from that moment she considered Dr. Morton one of her best friends.[Pg 383] He asked her more particularly about the occurrences of the night, and she gave him a detailed history of it from the time when she returned from her ride.

"Well, well," he said, when he heard how she had stood in the moonlight and invited the intruder to come forth—"well, well! you're the girl for my mind. And didn't you feel afraid?"

"Why, yes, I suppose I was afraid," said she. "But there was nothing else to be done that I could think of, and so I had to do it."

At which the doctor chuckled more appreciatively than ever.

Miss Joanna was much better in the morning, and in a few days was quite convalescent. The sisters were all more or less prostrated by this thrilling night, and it was a week before the household affairs were running with their accustomed smoothness, and before the Misses Middleton could turn their thoughts and their conversation to the ordinary concerns of life.

A new idea and a very startling one had been presented to them, too. Dr. Morton, upon each of his visits to Miss Joanna, had made some remark upon Theodora's courage, upon her presence of mind, upon her general excellence. He declared that she, and she alone, had been the means of saving her aunt's life, and in his opinion she should be rewarded not only for that, but for having prevented a bold and startling robbery.

Undoubtedly Andy Morse, if left to himself, would have carried away the greater part of the Misses Middleton's treasures. According to Dr. Morton, if it had not been for Teddy, her aunts, when they descended in the morning, would have found their large drawing-room absolutely bare and empty. The girl should certainly be rewarded, and no better token of her aunts' gratitude and regard could be found than a bicycle. Not only would it give her pleasure, but it would also be of benefit to her health.

Never before did Dr. Morton discourse so long and so earnestly, and the result was that he gained his point. The ladies held out as long as they could, but he was too much for them.

As Miss Joanna remarked, "When we feel that Theodora really did us such a service, it seems as if we should waive our prejudices."

And for Miss Joanna to acknowledge this, and to call "prejudices" the feelings which had hitherto been designated as "principles" meant a great deal. Miss Thomasine had from the first been in favor of buying the wheel, and had strongly urged it; but not until Miss Joanna thus expressed herself did Miss Middleton actually give her consent.

John, the old coachman, now fortunately recovered from his attack of rheumatism, could scarcely believe his ears when Miss Middleton ordered him to drive to the large bicycle-shop on Main Street.

The carriage with its four occupants reached the shop in due time, and the ladies entered. They looked about in some bewilderment at the vast number of bicycles that were stacked in the place, and the thought that they could all whirl, as wheels will, made them positively dizzy. Miss Melissa was glad that she had brought her salts, and she held them first to one nostril, then to the other.

"What can I do for you, ladies?" asked the salesman, as he came forward.

"We wish to look at bi-cy-cles," said Miss Middleton, wondering if it could be really she who was making this request, and wishing more than ever that Miss Joanna were there to take the lead.

"Ah, indeed? Something for yourselves, no doubt?"

"Not by any means," said Miss Middleton, coldly, and with all the "Middleton manner" that she could summon to her aid. "We are about to purchase a bi-cy-cle for our niece."

"Oh, certainly! I didn't see her at first. So many ladies do ride, that I thought— However, here is one that I am sure your niece will like—light weight, not more than twenty pounds; improved chain and skirt guards; made in such a way that there is a minimum degree of weight with a maximum amount of safety; small narrow sweep of handle-bar; latest invention in pedals; small adjustable saddle—most comfortable that is made—though if your niece prefers one of the new anatomical saddles, that can easily be arranged; bell, brake, lantern, and cyclometer thrown in if you pay cash down, together with a full supply of cement, patches, plugs, twine, and needle for a punctured tire, also oil-can, pump, and wrench. Or, if you don't fancy this model, here is another—twenty-one pounds, self-mending tires in case of punctures—"

"Oh, please stop a moment!" cried Miss Middleton. "My dear sisters, I scarcely know what to think. If only Joanna were here! I never dreamed that there were so many accessories to a bi-cy-cle. It seems as if we were getting a great deal for the money."

"A great deal, madam, I do assure you, and at the same time very light weight. To be sure, the tendency this year is to make heavier machines, but this being a miss's wheel, it is absolutely strong, while being at the same time exceedingly light. Just lift it yourself, madam, and you will see."

And before she realized what she was doing, Miss Middleton had laid aside her little satchel and her sunshade, and was actually lifting a bicycle. Each sister in turn, not to be outdone, went through the same form.

One wheel after another was brought forward, and each one seemed to possess more virtues than its predecessor. The three Misses Middleton grew more and more bewildered, while Theodora began to think that the matter would never be settled. She had no opportunity for stating her preference, if she had any, for her aunts appeared to think that she knew nothing at all on the subject.

Their interest increased with their bewilderment, and they soon found themselves conversing with ease about gear and ball-bearings, and the salesman did not allow himself even to smile when Miss Thomasine examined the chain-guard, and said it seemed like an excellent brake. He had begun to hope that he might dispose of four wheels instead of one, so enthusiastic were his customers becoming.

So it might have gone on for some time longer, and there is no knowing what might have transpired, had not Paul Hoyt, greatly to Teddy's relief, appeared in the doorway. He had heard rumors of the intended purchase, and he had at once mounted his own wheel and ridden in search of his neighbors, knowing that it would be an entertaining sight, to say the least, and thinking that he might find an opportunity for giving his opinion and lending the weight of his experience.

The Misses Middleton paid more attention to him than they did to Theodora, and at last a wheel was chosen and paid for, and the three ladies, with their niece, left the shop.

They drove away still full of their subject, and when the new bicycle came home it was brought directly to them. The three Misses Middleton who had made the purchase explained to the two who were still in ignorance of its merits the great advantages which this bi-cy-cle possessed over every other make of machine, while Teddy looked on, wondering when the happy moment would arrive that she could take the beloved object and go forth for a ride upon her own, own wheel. Indeed she could scarcely express her gratitude to her aunts, so engrossed were they in all the technicalities of the subject.

About ten days after this, Mrs. Hoyt, accompanied by Arthur, called upon the Misses Middleton. The ladies came down to the drawing-room and greeted their guests with their usual formal courtesy. There was a moment's pause after all had seated themselves, and then Mrs. Hoyt began the conversation.

"I have come," she said, "to speak once more on the subject of the bowl. Have you found yet any clew to the person who broke it?"

"No," said Miss Middleton, "we have not."

"But we still have our suspicious," interposed Miss Joanna.

"And what are they?"

"We did think that it was either Arthur or Theodora. Now we are convinced that it was Arthur, and that our[Pg 384] niece, from a mistaken feeling of honor, helped him to hide it. Nothing can change us in this opinion."

"I have come to tell you," said Mrs. Hoyt, quietly but with great firmness, "that Mr. Hoyt and I are perfectly convinced that Arthur did not do it. The evidence is very strong against him, we admit, but he has always been a truthful boy, and we feel very sure that he is so still. The child has been made so unhappy by the affair that I felt it necessary to bring him here, and let him hear me tell you that his father and I do not think he did it."

She rose to go in the pause that followed this speech. The sisters were silent until they also had risen, and then Miss Joanna spoke.

"Our opinion is unchanged," said she, "and always will be."

At this moment the parlor door flew open and Theodora ran into the room.

"I have just met the postman," she cried, "and he gave me this letter! Look at it!" and she held it up for her aunts' inspection.

The envelope was exceedingly soiled, and the stamp was placed upside down on the lower left-hand corner. It was addressed to "miss tedy middleton."

"It is from Andy Morse," she continued; "and—oh, Arthur, he tells it all!" And this was what she read aloud:

"'miss tedy middleton, dear miss.

"'i Rite you theese few lines Hopping thay will find you in Good helth i want too tell you ive got work ime goin on a Ship i wont make mutch yet butt its Better nor nothin and i Hopp ile make more soon its all Bekorse you gave me That Monny and sum day ime goin to pay it Back.

"And i want to tell you i broke that bole'" (Teddy paused in the reading and looked about upon her audience. Her five aunts sank into their chairs, and Miss Melissa vigorously applied her salts, while, much to Arthur's amazement, his mother began to cry. Teddy continued) "'i was that Mad the day you give me the Black i that i ran to your house and the dore was open and i went in and sore the bole and i herd of that bole and that hoite Boy was in the parler and i skeered him most to deth and i asked him if that was the middleton bole and he said yes and i smashed it and made him promise not to tell on me and if he did ide kill him i fritened him orful bad and i have ever since.

"'i was going to tell you about it that nite i was thare only you Was so good to me i diddent Like to and you sed it Cost so mutch i was afraid, butt i remember you sed thay Thort you did it and you beleeved me wen i sed i was going to be onnest so thats the Reeson ive rote this,

"yours truly andy morse

"'thay cant ketch me About the bole bekorse ile be to see wen you read this.'"

When Teddy had finished the letter, Miss Joanna settled her spectacles more firmly upon her aristocratic, aquiline nose. Then she held out her hand for the paper, which she took and examined with care. It was passed from one sister to another as they sat in an impressive silence, which was broken as usual by Miss Joanna.

She rose from her chair, and going to Mrs. Hoyt, she took her by the hand.

"We beg your pardon, Ellen Hoyt," said she, "and we beg your son's pardon. He is a truthful boy, after all, as Theodora is a truthful girl. Is it not so, sisters?"

"It is indeed so," replied they all, as they also rose and gathered about their guests.

Thus Arthur was at last cleared from suspicion and relieved from the state of dread and anxiety in which he had lived since the accident, for Morse had not only threatened him at the time, should he give any information as to what he had done, but had constantly found means since then of frightening the boy, which accounted for his nervous condition.

And the Misses Middleton were at last convinced that neither Arthur nor Theodora had broken the Middleton bowl.

suppose if I were writing a tale of invention, I could imagine no stranger happenings than those I have recorded in the last few pages of this old ledger. But as almost everything has an explanation and can be sifted down to the why and wherefore, when we keep off the subject of religion and beliefs, I can make plain in a few words the situation. If "a ship without a captain is a man without a soul," truly a ship without a compass is a man without an eye. And that was what was the matter with the topsail schooner Yankee, of New Bedford. Four days before I had come on board she had had an encounter with an English ship that had offered resistance. During the course of the action the binnacle of the Yankee had been shot away, and the compass smashed to flinders. But the English ship had been taken, and was the Yankee's seventh prize in a cruise of less than four months. Captain Gorham had manned her and sent her home. The only compass left on board the Yankee was a small-boat's needle in a wooden box. But, as Plummer told me, it was all out of kilter, and as useless to steer by as a twirled sheath-knife. Now for three days after the last capture there had been such thick weather that they had not been able to get a sight of the sun, moon, or stars, and had sailed not by dead-reckoning, as the wind had blown from all quarters, but by sheer guesswork and the lead.

How it came about that Captain Gorham knew the French cockswain was simple. Although the Captain was an American born and raised, only a few years previous to the outbreak of the war he had done a little smuggling on his own account between Dunquerque and the coast of England. So what appeared at first to be most mysterious is really simple when we come to look at it.

But now to tell of what we did. It had been Captain Gorham's intention, I take it, to run into Dunquerque Harbor, but owing to the representations of Pierre Burron, who stated that he might never leave it if we did so, this idea was given up; and keeping the lead going, we took the wind on our quarter, and made off to the southward, the Captain promising to put the little Frenchman on board the first vessel hound for his country, and pay him well for his services.

While we had been coming about, I, to show my willingness, had hauled lustily on the mainsheet and pitched in with the crew, and as soon as everything was going well, Plummer and I sat down against the bowsprit and began to spin our respective yarns. Of course there was much to tell. Mine is known already, and Plummer's was but[Pg 386] the recounting of the most unusual good luck that had ever attended the career of a cruiser in any service, I suppose.

It seems that finding the Young Eagle had sailed before he expected she would be ready, Plummer had delayed a long time before he had found a berth to suit his fancy, and then he had shipped in the Yankee from New Bedford. From the day of their sailing they had had fair winds and good fortune, capturing two English vessels off the American coast, laden with supplies for the English army in Canada, two more on the high seas, and three, of all places in the world but almost under the nose of the British Admiralty, at the entrance to their own private Channel. In all these encounters they had lost but two men killed and three slightly wounded.

The manning of so many prizes had reduced the crew of one hundred and twenty men to twenty-six all told. Being a fore-and-aft vessel, this was more than sufficient to run her properly, and, although it was considered foolhardiness in the forecastle, old Smiley, or Smiler, as they called Gorham, had determined to make one more attempt before he started for the States. Besides, the necessity of speaking some vessel and securing a compass had now become imperative.

"Tell me something of your skipper, Plummer," I asked. "He is of a certainty the strangest-looking man I ever met."

"Well, if you want to know the truth," Plummer answered, in a whisper, "he's as mad as the King of Bedlam—that is, to my thinking. In fact, on shore they say he is in league with the devil. But whether it is the devil or the powers above, he certainly carries a fair pinch of good luck 'twixt his thumb and his forefinger. You haven't heard him sing yet. Wait till you hear him at that. It will make the flesh crawl on your back, my lad. But, mark ye, he's a good seaman, for all of his vagaries. And he can man-handle any two of us."

The only other officer capable of navigation left on board the schooner was the third Lieutenant, Mr. Carter, who had been one of the slightly wounded, and who yet carried his right arm in a sling. As Plummer and I were talking, the Lieutenant came on deck, and ordered us to shake out the reef in the mainsail that we had taken in some time back, and set the topsail and flying jib.

The weather was clearing up and the wind going down at the same time. The sun now broke through the clouds, and by noon it was fine, clear weather. To the eastward we could see the low-lying shores of France, while to the westward the white cliffs of England shone plain to sight. A number of sail could be seen skirting the English coast, but nothing in the way of shipping could we make out on the other hand. But after we had altered our course slightly to the eastward, at three o'clock in the afternoon we made out a brown sail hugging the east shore, and evidently endeavoring to make the entrance to a small port not far from the mouth of a little bay. We could see the houses and steeples plainly.

It was evidently our intention to head off this little brown sail, and soon we saw that in this we should be successful, as the latter turned about, and started to run for it; but a point of land made her take quite an offing, and in two hours we were almost within hailing distance.

One of the 18-pound carronades was loaded, and a shot fired across the little vessel's bow. Down came the brown sail, and she lay there swinging and dipping like a wild fowl too frightened to escape. I have seen some clumsy craft in my day, but I think these vessels are the strangest-looking. She was a French lugger, only half decked over, with a great leeboard swung alongside, and had a comformation somewhat like the shape of the boat which boys whittle out with their jack-knives. There were five men in her, who appeared scared out of their wits, but their relief was great when Captain Gorham hailed them in French.

They had no compass, but agreed to set our pilot on shore, and he left us, grinning and delighted. Now we cleared away again, and left the Strait of Dover behind us, steering a course somewhat to the eastward of the middle of the English Channel.

I noticed that the armament of the Yankee was very similar to that of the Young Eagle, except she carried one less gun on a side.

In the evening, as I was talking to some of the crew below, a cabin-boy came into the forecastle in search of me, with an order for me to repair aft at once—the Captain wished me. I was thinking of exchanging my citizen's clothes for some that Plummer had offered me, but I had not done so when the message was given me, so I hastened up. Captain Gorham was pacing up and down the little quarter-deck; he halted as he saw me approaching.

"You will dine with me this evening, Mr. Hurdiss," he said. "And if my nose does not deceive me, dinner is on the table."

I bowed and thanked him, and we went down into the little cabin. Mr. Carter was on deck, and the Captain and I sat down vis-à-vis. No sooner had he seated himself than he began to hum, or chant better, only without using words, beneath his breath. This he kept up even while he was feeding himself. As I was very hungry, I did not interrupt the music, and so for full five minutes not a word was said. At last Gorham pushed back a little ways from the table, and sang a few words to the same air he had been humming.

"And-now,-Mr.-Hurdiss, spin-us-your-yarn," he chanted.

So I began at once with the cruise of the Young Eagle and the fight with the frigate, for I did not consider it necessary to tell of my earlier life. It was the second time that I had told the story this day, and I probably hastened it. When I came to the more exciting parts, dealing with my prison life and escape, Captain Gorham hummed a little bit louder, and this continuous accompaniment urged me to speak faster, so I covered ground in great fashion. He played an obligato to my solo, as it were piano, fortissimo, and all of it. When I had finished he arose and hushed his noise, as if he had been forced to bite the end off the tune against his will.

"Mr. Hurdiss," he said, "we need some one here aft with us, and there's a berth for you. Take it. I shall tell the men to obey your orders, as you will obey mine. You will act as third Lieutenant, sir."

Then, as if this settled matters, he began to hum again, and went up the ladder to the deck, leaving me sitting there in amazement. Here was another false position! How fate had forced such situations upon me! It seemed a long time ago that I was supposed to be a French nobleman (mark you, I was one), and I could scarce bring myself to believe that my rescue had happened only the very morning of this day. "Now," said I to myself, "if I refuse to accept this honor thrust upon me, I may do the very worst thing for myself that may happen." It behooved me to balance matters carefully, to weigh and measure possible results.

I knew enough to give the orders under ordinary circumstances for the making and taking in of sail. I could, at a pinch, have stood my trick at the wheel. I could use enough sea terms to lead one to suppose that I knew more, but I knew none of the methods used in determining a ship's position at sea. I had no inkling of how to prick a course on the chart, and what a navigator did when he squinted at the sun through a sextant I could not imagine; but yet, I reasoned, the Captain and Mr. Carter would probably do all of that that was necessary. I could get on with the men, I felt sure, and why not undertake it? Thus I convinced myself that I could become a Lieutenant. I had learned to box the compass while in prison; and thinking of this accomplishment made me smile, for surely we would have given something to have possessed one to box.

The good ten-knot breeze held in the same direction all night long. I took the midnight watch, and felt quite proud of myself as the men moved to obey my orders to ease off the sheets when I thought occasion demanded it.

Plummer appeared quite pleased at my promotion, and the other men had not appeared to take any dislike to their new officer; so I became quite tickled with the idea of my importance, and stopped my misgivings.

The next day was Sunday. I think I detected that Captain Gorham hummed psalm tunes during breakfast. Surely it was Old Hundred that he was repeating when I joined him on deck in the afternoon.

But it was no Sunday breeze, and we skipped along lively. In my opinion the Yankee would have been no match for the Young Eagle in sailing, but she would have shown a clean pair of heels to almost any English or French cruiser.

During the day we had passed within some miles of a number of vessels, but they had paid no attention to us, and it was not until half past five that we had anything that approached an interesting situation. We were somewhere off the island of Alderney, for the Captain knew his position to a nicety, and was steering a little to the north, "to give the Casquet Rocks a wide berth," he told me, when we made out a vessel bearing down to meet us, and carrying the wind so that if we kept on as we were we would pass near to her.

In an hour it could be seen that she was a frigate, but Captain Gorham held the same course undisturbed.

It reminded me a little of my voyage in the Minetta to note the anxiety among the crew. The vessel was to windward, and had evidently been reconnoitring the French coast; but she did not show any suspicion, and we approached one another as peaceably as were we two friendly merchantmen. All at once the frigate tossed out her flag, and up went ours in answer.

Needless to say ours was the same as hers—the cross of St. George.

Mr. Carter had brought up from the cabin a canvas bag and a book, the edges of which were weighted with lead. "There she goes, sir," he said, turning to the Captain; and as he spoke a little line of streamers crept up the Britisher's mast-head. The Captain, humming carelessly, opened the book.

"Give them four, one, nine, three, seven, Mr. Carter," he said, in a singsong.

Five little flags that the Lieutenant had picked out rose on our color halyards. To this day I do not know what they meant, but it was apparently satisfactory to the frigate, for she took in her signals, and we did likewise. Plummer gave me a wink as he gathered the colors in as they fluttered to the deck.

"We caught these aboard the last prize," he said, "and just saved the book from going overboard. There's luck for you!"

I noticed that Captain Gorham's eyes were dancing as we passed by the frigate, about a quarter of a mile astern of her, but I was totally unprepared for what he did, and stood aghast at his orders.

"Stand by to cast loose and provide the long twelve!" he shrieked in his high voice.

Mr. Carter made as if to offer some remonstrance; but the men, grinning, jumped to obey. We had the windward place now, and every advantage, besides it would soon be dusk.

"Teedle, dee, dumpty, di-do," sang Captain Gorham as he sighted the long gun himself.

As soon as he had trained it to his satisfaction there was a roar, and we all bent forward to watch the shot. I gave a squeal of delight as I saw the frigate's mizzen-topsail yard break square in two and, with the sail, slam over against the stays. The Captain of that vessel must have been a most surprised individual. He yawed about and succeeded in getting taken all aback and generally mixed up.

"Show our colors!" cried Gorham, and I dare say the sight of them surprised the Englishman still more. It was full five minutes, however, before he got upon our track or fired a gun. Then two of his shot went over us, and the rest fell short; but as we sailed three points closer in the wind almost, and legged two feet for his one, he gave up after half an hour's sailing; and I wonder if he made a report of all this to their lordships!

A pitch-dark night came on. I went on watch at ten o'clock, and did a great deal of thinking while I paced the deck; but my wandering thoughts were soon called back. At eleven the lookout reported to me that he thought there was land dead ahead, as he could make out lights.

I ran forward, and sure enough I could see flashes here and there, and two or three steady points of light off our weather beam. I jumped below and called the Captain.

"Have you held the same course?" he asked.

"I think so, sir, unless the wind has changed."

"Oh, confound it, we must get a compass!" Gorham grumbled, as he ran up the ladder ahead of me.

He ascended a short ways into the weather shrouds.

"That's no shore," he cried to Mr. Carter, who had come on deck barefooted. "That's a big fleet bound out for the Indies—that's what it is. By Jupiter, we'll stop and get a compass! Port your helm!" he roared to the man at the wheel, and the booms swung out as we got before the wind.

We bore straight down upon the lights, that had now increased in number and vividness. We slackened our speed by taking in our topsails one after another, and hauling all sheets well aft. By one o'clock we were almost within speaking distance of the two rearmost ships, whose lights we could make out very plainly. As we displayed none of our own, we were probably invisible, owing to the blackness of the night. The crew had all been called on deck, and the carronades and the midship guns were loaded. And we came closer and closer, until it was only a question of time when a lookout should discern our presence.

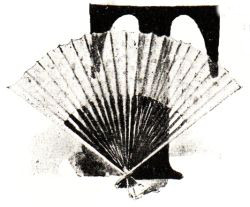

"Get out the whale-boat, Mr. Carter," said Gorham, quietly, (he had been squinting through a night-glass). "The nearest vessel is a merchant brig! Now, Mr. Hurdiss," he added, turning to me and dropping his singsong for a moment, "see what you're made of. Take the carpenter and nine men, and board that brig. They're all asleep on her. Do it quietly, and fire no shot unless you have to. Here, take this cutlass—a slit throat stops a shout."

Almost before I knew it the whale-boat was ready, the men sitting on the thwarts with their cutlasses and pistols in their belts, and we had shoved off. I confess that I was trembling so from excitement that my breath came in short gasps, and I could not swallow for the life of me. The carpenter was sitting close to me on the gun-wale.

"Old Smiler is going to see what that other chap is made of," he said, pointing to the faint glimmer a half a mile or so down the wind.

The last instructions I had received on leaving the Yankee were, if I took the vessel successfully, to douse all lights, make off to the eastward for an hour, and then crack on all sail, holding a course southwest-by-west. That would carry me, as I was told, clear of Lizard Head and out into the Atlantic, where Gorham would try to pick me up. The men, of their own accord, were taking quick short strokes, with no noise in the row-locks. And in a few minutes we were under the stern of the vessel, that I made out to be a brig, as Gorham said.

The breeze was much lighter than it had been, and we swung under the stern and backed up to her, the better to run away if necessary, and took in our oars quietly without any danger of capsizing. The man in the stern caught the chains that run down to the rudder, and whispered back, "All's well!"

I stood up, and straining my eyes, saw that within reach of a man's hand overhead was a row of four cabin windows; the middle one was open.

I CAUGHT THE COMBING OF THE WINDOW AND WORMED MYSELF

INSIDE.

I CAUGHT THE COMBING OF THE WINDOW AND WORMED MYSELF

INSIDE.

Thinking that it befitted my position best to be the first on board, I got to my feet, and then by standing on the shoulders of the two men on the afterthwart, I caught the combing of the window and wormed myself inside. I could see that I was in a fair-sized cabin, that a dim light came from a lantern hanging in a passageway forward; but my heart almost stood still after a tremendous thump against my ribs.

Not more than an arm's-length from me, I heard the sound of heavy breathing! I had unshipped my cutlass to make my entrance more easy, and now I drew the pistol from my belt and stood there, peering to one side, with every muscle stiff as a harp-string. The deep breathing went on without an interruption.

he most dreaded implement of war in these days is the torpedo. One of these darting fishes of death, costing a little more than $3000, can almost instantly send the most powerful battle-ship, costing as much as $5,000,000, to the bottom of the sea. This shark of war has a destructive charge of guncotton in its nose. When it strikes the war-ship it destroys itself and the ship also. No ship has ever been built stout enough to withstand an attack by one of these artificial monsters of the sea. They are made to leap from the side of a vessel into the water, and after they are once released they go with the speed of an express train to the place where they are aimed to go. They propel themselves through the water, and they keep exactly at a depth which is fixed before they are fired. Nowadays they dive from the ship into the water. It is probable that soon they will be sent into the water below the surface and out of sight of the enemy. Then no captain of a ship in battle will know when to expect an attack by a torpedo, and perhaps when he fancies that he has beaten his enemy, and has the other ship at his mercy, a torpedo may be darting at him, unseen and unerring in its track, that will send him and his ship to the bottom before any one on board can save himself.

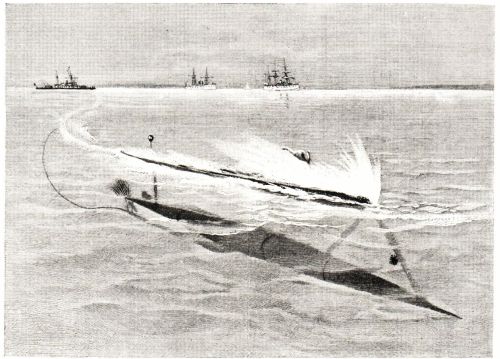

A CONTROLLABLE TORPEDO IN ACTION.

A CONTROLLABLE TORPEDO IN ACTION.

Torpedoes are of two general kinds. One is the automobile type and the other is the controllable type. The first goes its own way, that is, controls itself. The second may be steered or controlled from the place of its discharge. This country and most other countries use the automobile torpedoes, and we have two kinds of them. One is the Whitehead torpedo, and the other is the Howell. The Whitehead is practically a submarine boat, intended to destroy itself and anything else it hits after a limited run under the water. It has its own engine for propulsion, and uses compressed air as the motive power. The Howell is also intended to cause as much destruction as the Whitehead, and is also a submarine vessel. It is propelled by the rotation of a centrifugal wheel, which has been turned by machinery up to about 10,000 revolutions. As this wheel unwinds itself, so to speak, it sets the machinery of the torpedo in motion, and it goes on its errand of destruction. The Whitehead is a foreign invention, and the Howell is the invention of one of our own naval officers. This government has favored the Whitehead for the equipment of most of the ships of the navy, and for the purposes of this article we may take that as a type.

These torpedoes require as much delicacy in their manufacture as a watch. They are boats, and must be fashioned in their outlines so as to glide through the water without the slightest deviation. Any inequality of shape would send a torpedo flying off in some other direction than that in which it was intended it should go. Inside, the complex machinery must act as accurately as the machinery of a watch, or the torpedo will fail of its purpose. It would be tiresome to go into the full details of the machinery of a torpedo, and, besides, it is practically a government secret; but we may tell about the general features of these engines of war.

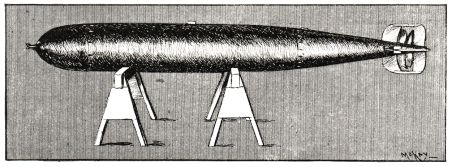

A WHITEHEAD TORPEDO.

A WHITEHEAD TORPEDO.

The Whitehead torpedo consists of several well-defined parts. The first is the head, where the guncotton is placed for explosion. This part is what is called "ogival" in shape, and is bluntly rounded. Then comes quite a long straight part. That is the chamber for the compressed air. Then there is what is called a buoyancy chamber, in which is placed the diving apparatus. Then follows the engine-room, to which the water is admitted through little slits in the torpedo. Then comes another buoyancy chamber, in which the important parts of the steering apparatus are placed, and then comes the tail with its two screws and rudders and fins.

The war-heads of the torpedoes of the largest size contain 220 pounds of guncotton. Most of this guncotton is kept in a damp condition. The rest is dry. The dry guncotton is exploded by a small charge of fulminate of mercury, and that in turn explodes the wet guncotton. About the only thing that will explode wet guncotton is dry guncotton. The war-heads of the torpedoes are so arranged that until they travel at least eighty yards from a ship the firing apparatus is locked. This saves the ship from being destroyed by its own weapon in case of accident. When the nose of the war-head strikes an object, it pushes a pin through a copper partition into the fulminate of mercury, and the explosion follows.

The torpedo's air-chamber consists of forged steel about an inch thick. It must be very strong, for it must be charged with compressed air to a pressure of 1350 pounds to the square inch. Expensive machinery is used in finishing off this part of the torpedo. The lathes, that work on the inside can produce steel shavings of the thickness of a thousandth of an inch. The long after-part of the torpedo is made of thin steel, but strongly braced so that the machinery can do its work.

We probably can best understand how these little ships are made by studying what they do. Suppose the battle-ship Kentucky wants to sink an antagonist in war. The air-compressor is set at work. A large-size torpedo is swung[Pg 389] on a rack and lowered to a tube in the side of the ship, and slid in place. A valve is attached to an opening in the torpedo, and the air is compressed into the air-chamber. By means of a measuring device the observer has fixed the exact time and direction when to discharge the torpedo so as to hit the enemy. Four ounces of powder have been inserted in the torpedo-tube back of the torpedo, and the word to fire is given.

By a simple arrangement the air-valves are closed, the machinery in the torpedo unlocked so that after it strikes the water the air will flow into the engine and start the screws going. The gauges and springs have also been so arranged that the torpedo will remain at a fixed depth. With a speed of about a mile in two minutes the 16-foot torpedo rushes through the water. If it strikes the enemy, a great naval catastrophe happens. If it misses, it is so arranged as to sink after it has spent its force, and to disappear out of the way of doing harm to shipping. If practice work is being done with the torpedo at any time, the mechanism is so arranged beforehand that when the torpedo has run its course it rises to the surface and is recovered.

How does a torpedo keep at a certain distance under water? Well, there are two bits of machinery to accomplish that. One is a pendulum. If the nose of the torpedo raises itself, the pendulum swings backward and depresses the rudders at the stern, and brings down the nose. If the torpedo begins to dive, the pendulum moves forward, and the opposite result follows. The torpedo remains at the required depth through the pressure of the water that comes into the engine-room on a rubber diaphragm, to which is attached a delicate spring. The pressure of the water and the strength of the spring offset each other when the torpedo is at the depth wanted. If the torpedo sinks or rises, the harmony between the spring and the pressure of water is disturbed and the steering-engine is affected, and the rudders moved so as to keep the weapon at a certain depth. Slight changes up or down are regulated by this machinery; but if the plunge or rise is of a serious nature, the pendulum begins to swing, and the torpedo corrects its course at once.

Another most delicate part of the torpedo's machinery is what is called a "valve group." This is a set of valves used for various purposes, the chief of which is to restrain violent action from the compressed air during changes in direction of the little craft or during its run. They have such names as the "controlling valve," the "reducing valve," the "regulating valve." The flow of air into the little three-cylinder engine must be constant and of a certain pressure. The screws at the stern of the boat must be turned at the rate of about one thousand revolutions a minute, and the control of the force that propels them must be most efficient.

Another piece of important machinery is known as the "locking gear." When a torpedo is shot into the water from a ship the pendulum may lag a little in its swing forward. This would put the rudder down and make the torpedo take a deep dive. In shallow water this might mean contact with the bottom, and of course that would never do. The locking gear prevents any action by the rudder until the torpedo has travelled about a hundred yards. By that time the craft has settled to its work, and has ceased to make any skipping motions in the water. Thus we see that the torpedo is not ready for full duty until it has gone a considerable distance from the ship. It cannot explode nor steer itself until it is darting through the water under its own power at a certain depth and at a certain speed. If it does the work expected of it, it will strike its target in probably less than one minute. It therefore does appalling destruction in almost an instant.

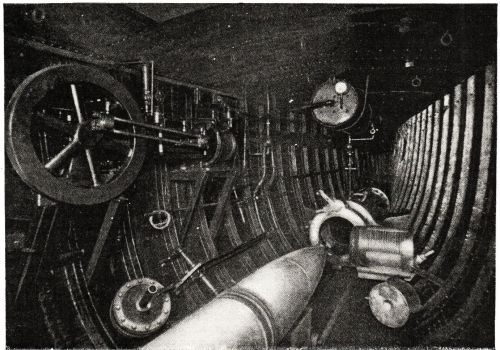

TORPEDO AND LAUNCHING TUBE.

TORPEDO AND LAUNCHING TUBE.

The reason that there are two screws at the stern is to make sure of propelling the torpedo in a straight line. One screw turns to the right, and one to the left. The tendency to go to the right or left which would occur if there were only one screw is thus equalized. The fin part of the tail also serves to keep the torpedo on a straight course. There is a great deal of variety in the machinery which is crowded into one of these torpedoes, but with that we need not concern ourselves. There is almost as much delicate machinery necessary to place the torpedoes in the water as to keep them going after they get into the water. The launching tube and air-compressors look like simple affairs, but in reality they have to be adjusted most delicately and most carefully to the torpedoes.

Great care is bestowed not only on this machinery on shipboard, but also on the torpedoes. The torpedoes are smothered with grease, and every precaution is taken to prevent rust from accumulating in any spot outside or inside. Every torpedo is tested most thoroughly before it is accepted by the government, and a careful record is kept of the performance of each in practice on the ship to which it is sent.

No one knows the full power of one of these missiles. In recent times two large war-ships, the Aquidaban in the Brazilian civil war, and the Blanco Encalada in the Peruvian-Chilian war, were sunk by torpedoes. Several smaller craft were sent to the bottom in the war between China and Japan. When we think of their power of destruction, and the extreme care and skill required to make them, it seems wonderful that such implements of war can be made for about $3200 each. That is the sum which the government pays for each of the 16-foot torpedoes. For those that are 11 feet 8 inches long the cost is, in round numbers, $2500 each.

verybody has seen tumble-bugs rolling their dust-covered balls along some path or highway in the country, but few people are aware that these little insects are the lineal descendants, so to speak, of a deity—the sacred scarabæus of the Egyptians, of which we have read so much. The little fellows, in seeming indifference to their fall from high estate, are still rolling their balls as industriously as they did on the banks of the Nile in Moses's time.

The coleoptera, or beetles, form the highest division of insects. They all have six legs, and a distinctly marked head, thorax, and abdomen. The body is covered with a horny envelope, which takes the place of the skeleton in higher creatures, protecting and holding the organs in place. The beetle has also four wings, one pair over the other. The lower ones are of a parchmentlike substance, while the upper ones are horny.

Beetles are of various kinds, some of which are useful to man, and others harmful. Scavenger-beetles belong to the former class, and no one variety is more interesting than the pellet-beetle or tumble-bug.

This little fellow, of one species or another, is found all over the United States, in Europe, and in northern Africa. With us he is from half to three-quarters of an inch in length, and coal-black.

The most remarkable thing about tumble-bugs, and one which excites the curiosity of every one who observes them, is the manner in which the egg is developed into the perfect insect. This egg is laid in manure, which is mixed with a little clay, and then rolled into a ball about the size of a marble, and left to dry. For the work that is to follow, the powerful legs and jaws of the insect are well adapted. No better proof of its strength may be obtained than by putting one or two bugs under a candlestick on a table, and noticing the ease with which they move it along.

When the ball is dry, the bugs, usually two in number, commence rolling it to a suitable place of deposit, which is not, apparently, selected in advance. Whether these two bugs are the parents or not is unknown, but at any rate one places himself in the front, with his hind feet on the ground and the others on the ball, while the other goes in the rear, with his body reversed—that is, his four front legs are planted firmly on the ground, with his head bent low in the dust, while his hinder parts are raised high on the ball, which he pushes with the two remaining legs and the extremity of the body.

The duty of the bug in front seems to be either to guide the ball or to pull it forward, possibly both. Although he has the most natural position, and seems to have less to do than the other bug, he really has the harder time, for when the ball gets rolling down a slope it frequently goes over him entirely, or pushes him sprawling by the way-side. But he is soon on his feet again, and scrambling into place, makes believe he is having the jolliest time in the world.

If obstructions occur in the path, the tumble-bug is not easily discouraged. You may frighten him away, or even push him aside with your stick, but if you keep quiet for a few moments he will return to his work. If a tuft of grass or a stone intervene, he leaves his work and goes in search of help, and his comrades rarely fail to respond. If, however, after repeated efforts to move it, the bugs leave their ball in despair, it often happens that a new party comes across it and rolls it merrily to its destination. The whole community seem to take an interest in every ball, and are willing to do their utmost to help it along.