![[Image of the book's cover unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: How to Study Architecture

Author: Charles H. Caffin

Release date: December 2, 2019 [eBook #60830]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

|

Contents. (In certain versions of this etext [in certain browsers] clicking on the image will bring up a larger version.) (etext transcriber's note) |

HOW TO STUDY ARCHITECTURE

BY

CHARLES H. CAFFIN

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

NEW YORK

DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY

1917

{iv}

Copyright, 1917

By DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY, Inc.

{v}

The author gratefully acknowledges the critical assistance given to him on certain points by Professor William H. Goodyear, W. Harmon Beers and William Warfield; and his indebtedness to Caroline Caffin for compiling the index and to Irving Heyl for several architectural drawings. For some of the illustrations he has put himself under obligations to the following publications, through the courtesy of the Librarian of the Metropolitan Museum of Art—“Histoire de l’Art,” by Perrot et Chipiez; “Assyrian Sculptures,” by Rev. Archibald Paterson; “Monuments Modernes de la Perse,” by Pascal Coste; “Ruins of the Palace of Diocletian at Spalato” by R. Adams, and “The Annual of the British School at Athens.{vii}{vi}”

Architecture, Sculpture, and Painting share the distinctive title of the Fine Arts, or, as the Italians and French more fitly call them, the Beautiful Arts; the arts, that is to say, of beautiful design. They are known by their beauty.

By their beauty they appeal to the eye and through the eye to the mind, stirring in us emotions or feelings of pleasure—a higher kind of pleasure than that which is derived solely from the gratification of the senses—the kind which is distinguished as æsthetic.

The term æsthetic is derived from a Greek word, meaning perception. Originally it described the act of perceiving “objects” by means of the senses—“objects” meaning anything that can be perceived through the senses. But the term æsthetic has come to have another meaning, especially in respect to sense-perceptions derived from seeing and hearing. It means that the perception gives us pleasure, because it stirs in us a sense of beauty. It may do so without any conscious activity on the part of our mind. We may be absorbed in the delight of the sensation; or it may appeal to our mind—to our memory or imagination—in such a way as to set us{4} thinking and feeling not only about the immediate “object” but also about something which our mind associates with it.

For example: by simple sense-perception we discover that one tree is taller than another, or that one tree is an elm, another a silver birch. Our perception may stop there; but not if we are in a mood to contemplate. Then the perception that one tree is taller than the other may be followed by the feeling that the taller tree gives us more satisfaction. It may seem to us to be a better proportioned tree: its parts are more pleasingly related to the whole mass; or it may seem to be in a fitter relation to the spot it occupies and to the other “objects” near it. Again, having ascertained by pure sense-impression that one tree is an elm and the other a silver birch, we may find ourselves thinking about the qualities of difference presented by the two trees. With what splendid assurance the elm trunk rears up! How majestically the branches radiate from it and bear their glorious masses of abundant foliage! On the other hand, how dainty are the stems and branches of the silver birch, how delicately graceful the sprays of tiny leaves! “How sensitive!” perhaps we say. For to our imagination the slender tree may seem to be endowed with senses that respond to every movement of the air, to every glancing of the sunlight.

In all these cases we have gone beyond mere sense-perception. We are no longer interested only in the “object.” Our interest has become subjective. We are interested in the subject not the object of the verb, to perceive—the subject who perceives, in this case, ourself; how the thing affects oneself; how it stirs in one a sense of beauty. By this time our thoughts may have been{5} withdrawn from the concrete object and have passed on to “abstract” ideas, suggested by the object. It is grandeur of growth, as embodied in the elm, fragile tenderness, as expressed in the birch, that absorb our thought; and the wonder also how qualities so different can survive the rude shocks of nature, and find, each its special function in the scheme of nature’s beauty.

In thus feeling external objects through our own experience of life and our own sense of beauty, we are employing the sense-perception that is specially called æsthetic. And it is in the degree to which objects of architecture, sculpture, or painting have the capacity of stimulating this æsthetic appreciation that they properly belong in the company of the Fine Arts.

Architecture is the science and art of building structures that, while in most cases they serve a useful purpose, are in all cases designed and built with a view to beauty. Their motive is beauty as well as utility.

In certain instances, as, for example, the triumphal arch, the motive may seem to have been solely one of beauty. On the other hand, when we recall that the arch was erected as a memorial to some great man or some great exploit—the Arch of Titus, for example, commemorating this general’s capture of Jerusalem—the imposing dignity of the structure, by compelling attention and exciting admiration, would actually serve the purpose for which it was erected.

Indeed, the distinction which people are apt to draw between the useful and the beautiful is not necessarily so sharp as is supposed and is largely founded upon ignorance or a mistaken attitude toward life. The tendency to be satisfied with the utility of a thing and to{6} regard beauty as a fad, impractical and wasteful, shows that, although our civilisation may have progressed in some respects, it has fallen back in others. For there is nothing more surely certain in the history of human progress, than that, while primitive man had to exercise his ingenuity in providing for the necessities of life and in the making of tools, implements, utensils, and so forth to achieve his needs, he was not satisfied that his work should be merely useful. He had a mind to make it pleasing in shape and by means of ornament. And this attention to beauty grew as men grew in civilisation, becoming most conspicuous as their civilisation reached its highest point; and continued through the ages, until machinery began to replace the individual craftsman.

For the individual craftsman, responsible for making a thing from start to finish, must, if he is worth a hill of beans, take a personal pride in making it as well as he can. As the Bible relates of the Supreme Creator, “And God saw everything that he had made and, behold, it was very good.” And the craftsman, so long as he is free to create out of his own knowledge and his own feeling, must be able to feel this, because there is an instinct in him, an imperative need of his own nature, that he shall be proud of his work. It is a wonderful fact of human nature that when it works freely, putting forth all its capacities, it is prompted by this instinct, not only to make useful things but also to make them well and as beautiful as may be.

But gradually machinery took away the workman’s control of his work. He ceased to design, lay out, and carry through all the details of his work to a finish. He has come to be intrusted with only a part of the opera{7}tion, and that is performed under the control of a machine that turns out the work with soulless uniformity. The craftsman has degenerated into a repeater of partial processes; he has become the servant of a machine; a cog in a vast mechanical system. And, with the development of high power machines the output of production has been increased, until quantity rather than quality has tended to become the ambition of the system.

It has followed as a logical result of this taking away from millions of men and women the privilege of being individual craftsmen, creators of their own handiwork, that they have grown indifferent to the quality of the work turned out; taste, which means the ability to discriminate between qualities, has diminished and a general indifference to the element of beauty has ensued.

Of all the Fine Arts, Architecture is closest to the life of man. It has been developed out of the primitive necessity of providing shelter from the elements and protection against the assaults of all kinds of aggressors. And chief among the aggressors against which primitive man sought to defend himself were the mysterious forces of nature which his imagination pictured as evil spirits. To ward off these and to enlist the support of kindly spirits represented a necessity of life that developed through fetish worship into some positive conception of religion. This need was embodied in structures, which, originating in the selection or erection of a single stone, gradually became composed of an aggregation of stones variously disposed, in heaps, in geometric groups of single stones, or in the placing of stones horizontally upon two or more vertical supporting stones.

In these crude devices to mark the burial places of{8} dead heroes and to provide for the necessities of religion, primitive man used the stones as he found them, with a preference for those of enormous size, to ensure permanency. Meanwhile, in the huts that he erected for the living, it is reasonable to suppose that, when available, the more perishable material of timber was employed. And here, again, he would use at first the smaller limbs, planting them in the ground in a circle or square and drawing them together at the top, so that they took the shape of a heap of stones; and covering them with skins, so that they became the prototype of the tent. Then gradually he would employ stouter timbers, planting them upright and keeping them in place at the top with horizontal timbers. On these would be laid transverse beams to form a roof; the spaces between the beams, as between the uprights of the walls, being filled in with wattles of twigs or reeds and rendered still more impervious to weather by a coating of clay or mud.

The efforts of primitive builders, it is true, are rather of archæological than of architectural significance, yet they have this much to do with architecture, that in them are to be discovered the rudiments of the art. For by the time that man had superimposed a stone horizontally upon two vertical ones, he had hit upon the principle of construction, now variously styled “post and lintel” or “post and beam” or “trabeated,” that is to say, “beam” construction. The embryo was conceived that in the fulness of time would be developed into the trabeated design of the Egyptian temple and the column-and-entablature design of Classic architecture. From the colossal, monolithic form, still preserved, for example, in Stonehenge, there is a direct progression to the highly organised perfection of the Parthenon.{9}

It is this fact that makes the study of architecture so vitally interesting. Its evolution has proceeded, stage by stage, with the evolution of civilisation. Having its roots in necessity, it has expressed the phases of civilisation more directly and intimately than have the other Fine Arts; while the comparative durability of the materials in which it has been embodied has caused more of its records to survive. Even out of the fragments of architecture it is possible for the imagination to visualise epochs of civilisation long since buried in the past; while the memorials that have been preserved in comparative integrity stand out through the misty pages of history as object lessons of distinct illumination.

Accordingly, one purpose of this book represents an attempt to study the evolution of architecture in relation to the phases of civilisation that it immediately embodied; to find in the monuments of architecture so many “sermons in stone”—discourses upon the character, conditions of life, the methods and the ideals of the men who reared and shaped them.

And this involves the second purpose, that we shall try to study architecture as it actually evolved in practice. Remembering that it originated in the need of making provision for certain specific purposes, in a word, that its motive primarily was practical, moreover, that from the first it has been the product of invention, we will try to study it in relation to man’s gradual mastery of material and the processes of building. We will regard architecture in its fundamental significance as the science and art of building; tracing, as far as is possible, the stages by which man has met the problems imposed upon him by the purpose of the structure and by the{10} conditions of the material available; how he gradually surmounted the difficulties of building, step by step improving upon his devices and processes and thereby creating new principles of construction, and, further, how the practical operations of one race and period were carried on, modified, or developed by other races, under different conditions and in response to differences of needs and ideals.

And, while thus studying architecture as the gradual solution of practical problems of construction we will also keep constantly in mind the stages by which as man’s skill in building progressed, so also did his desire to make his structures more and more expressive of his higher consciousness of human dignity. How age after age built not only to meet the needs of living but also to embody its ideals of the present and the future life; how hand in hand with growing skill in workmanship was evolved superior achievement in artistic beauty.

Our methods of study shall follow, as far as possible, the architect’s order of procedure. Given a site and the commission of erecting thereon a building for a specific purpose, the architect first concerns himself with the plans: the ground plan, and, if the building be of more than one story, the several floor plans. He lays out in the form of a diagram the lines that enclose the building and those that mark the divisions and subdivisions; indicating by breaks in the lines the openings of doors and windows and by isolated figures the position of columns or piers which he may be going to use for support of ceilings and roofs. The disposition of all these particulars will be determined not only by the purpose of the building, but also by the character of the site and by the{11} nature of the materials and method of construction that the architect purposes to employ.

Then, having acquired the habit of thinking of a building as having originated in a plan, we will follow the building as it grows up out of the plan, taking vertical form in what the architect calls the elevation, or, when he is speaking specifically of the outside of the building, the façades. Sometimes we shall study one of the diagrams, which he calls a section, when he imagines his building intersected by a vertical plane that cuts the structure into two parts. The one between the spectator and the cutting plane is supposed to be removed, and thus is laid bare the system of the interior construction-work.

In studying the exterior of a building, therefore, we shall keep in mind the interior disposition, arising out of the planning, and acquire the habit of looking on the outside of a building as logically related to the interior. The design of a building will come to mean to us not a mere pattern of façade, arbitrarily invented, but an arrangement of vertical and horizontal features, of solid surfaces and open spaces, that has grown out of the interior conditions and proclaims them.

In a word, we shall regard a work of architecture as an organic growth; rooted in the plan, springing up in accordance with constructive principles; each part having its separate function, and all co-ordinated in harmonious relation to the unity of the whole. For we shall find that unity of design is a special element of excellence in architecture; a unity secured by the relations of proportion, harmony and rhythm established between the several parts and between the parts and the whole. And, since architecture is primarily an art of practical utility,{12} all these relations are equally determined by the principle of fitness; in order that each and every part may perform most efficiently its respective function in the combined purpose of the whole edifice. For this is the first and final criterion of organic composition.

The various remains that exist of prehistoric structures, though scattered widely over different parts of the world, present a general similarity of purpose and design.

The earliest examples of domestic buildings are the lake-dwellings which have been discovered at the bottom of some of the Swiss lakes, as well as in other countries both in the Eastern and Western hemispheres. They consist of huts, rudely constructed of timber, erected on piles, sometimes in such numbers as to form a fair-sized village. Their purpose was apparently to afford security against sudden attacks of enemies, the danger of wild beasts and snakes and the malaria and fever of the swampy shores, while bringing the inhabitants nearer to their food supply and offering a crude but ready means of sanitation. The system still survives among the natives of many tropical countries and has its analogy in the boat-houses that throng the Canton River in China.

More important, however, archæologically as well as in relation to the subsequent story of building, as it gradually developed into the art of architecture are: the single huge stone, known as a Menhir; the Galgal or Cairn of stones piled in a heap; the Tumulus or Barrow, composed of a mound of earth and the Cromlech.

The single stone seems to have been regarded as an object of veneration and a fetish to ward off evil spirits. It may have been the primitive origin of the Egyptian{14} obelisk, the Greek stele and the modern tombstone. From the galgal and barrow may have been developed the pyramids of Egypt and the truncated pyramid which we shall find to be the foundation platforms of temples in various parts of the world while the cromlech is the prototype of temples.

Two stones were set upright and a third was placed upon the top of them. This represents in rudimentary form the so-called “post and beam” principle of temple construction. Sometimes two or four uprights were surmounted by a large flat stone. It had the appearance of a gigantic table and is called a Dolmen. It is conjectured that this was a form of sepulchral-chamber, in which the corpse was laid, being thus protected from the earth that was heaped around the stones into a mound. If so, the Dolmen is the origin of the sepulchral chamber that was embedded in the Egyptian pyramid.

Meanwhile, an intermediary stage between the highly developed pyramids and the primitive dolmen is represented in the Altun-Obu Sepulchre, near Kertsch in the Crimea. Here the mound is faced with layers of shaped stones, with which also the chamber and the passage leading to it are lined. The ceilings of both are constructed of courses of stone, each of which projects a little beyond the one beneath it, until the diminishing space is capped by a single stone. In the angle of masonry thus formed is discoverable the rudimentary beginning of the arch.

It is also convenient here to note, though it anticipates our story, the more elaborate example of this principle of roofing which is shown in the so-called Treasury of Atreus at Mycenæ in Greece. In this instance, moreover, there is a farther approximation toward the arch, since the{15} projections of the stones have been cut so as to present a continuous line. And these contour lines are slightly concave and meet at the top in a point, for which reason this class of tomb is known as bee-hive.

Another form of this method of angular roofing is seen in an Arch at Delos, which is part of a system of masonry that is known as Cyclopean, after the name of the one-eyed giant whom Ulysses and his followers encountered in Sicily, during their return from Troy. For the masonry is composed of large blocks of unshaped stone, the interstices of which are filled in with smaller stones. Here, too, the actual arch is composed of a repetition of huge, upright monoliths, supporting a series of single blocks, set up one against the other at an angle.

While, however, these primitive forms of roof construction prefigure the later development of the true arch, the student is warned in advance that they represent rather a feeling of the need of some such method of construction than any approach to a solution of the problem. For the latter, as we shall find later, consisted in discovering how to counteract the thrust of the arch; its tendency, that is, to press outward and collapse; whereas in the primitive construction this danger was evaded by embedding the roof in a mass of masonry or earth that made lateral strains impossible. The system, in fact, was more like that employed in shoring up the excavations in modern tunnelling and mining.

Meanwhile, this rude method of spanning an opening with more than one piece of stone was the primitive germ of the later development of arch, vault, and dome construction, just as the placing of a single horizontal stone on two upright ones is the prototype of columns and entablature. Thus the instinct of man, in earliest times,{16} reached out toward the two fundamental principles of architectural construction.

The most interesting examples of primitive structure are the so-called Cromlechs, of which that of Stonehenge, in England, is the best preserved. The unit of this and like remains is the “post and beam” formation, composed of a block of stone, supported on two uprights. In the case of Stonehenge this formation was repeated so as to form a continuous circle one hundred feet in diameter. Within this was a concentric circle, composed of smaller slabs, which enclosed a series of five separate post and beam structures on a horse-shoe plan. The latter is repeated by another series of slabs and in the centre stands the flat altar stone. Seventeen stones of the outer circle, varying from sixteen to eighteen feet in height, are still standing and in part connected by their beam slabs.

This impressive memorial stands on Salisbury Plain, eight miles north of the cathedral city of Salisbury, in the neighbourhood of which are many barrows. Was it then the temple of a burying place of mighty chieftains or was it erected in memory of some great victory in honour of the dead heroes and the nation’s god? According to Geoffrey of Monmouth (A.D. 1154) who is supposed to have compiled much of his history from Celtic legends, Stonehenge is a Celtic Memorial, erected to the glory of the Celtic Zeus.

Rhys, in his “Celtic Heathendom,” accepts the probability of this account and adds: “What sort of temple could have been more appropriate for the primary god of light and of the luminous heavens than a spacious open-air enclosure of a circular form like Stonehenge? Nor{17} do I see any objection to the old idea that Stonehenge was the original of the famous temple of Apollo in the island of the Hyperboreans, the stories about which were based in the first instance most likely on the journal of Pytheas’ travels.” Pytheas was a Greek navigator and astronomer of the second half of the fourth century B.C., who was a native of the Greek colony of Massilia (Marseilles) and visited the coasts of Spain, Gaul, and Britain.

Situated some twenty miles to the north of Stonehenge is the Abury or Avebury monument. Its remains comprise two circles, formed of menhirs, which are enclosed within a large outer circle of monoliths, about 1250 feet in diameter. This was further surrounded by a moat and rampart, which suggest that the structure may have served at once the purposes of a place of assembly and a stronghold.

At Carnac, in the old territory of Brittany, in France, are the remains of about 1000 menhirs, some of which reach a height of 16 feet, disposed in parallel straight rows, forming avenues nearly two miles long. They are unworked blocks of granite, set in the ground at their smaller ends. The neighbourhood also abounds with tumuli, dolmens, and later monuments that belong to the Polished Stone Age.

Furthermore, remains of such monuments as we have been describing are found in Scandinavia, Ireland, North Germany (in Hannover and the Baltic Provinces); also in India and Asia Minor, in Egypt, on the northwest of Africa and in the region about the Atlas Mountains. This fact, assuming that the monuments are of Celtic origin, testifies to the wide-spread migrations of this im{18}portant branch of the Indo-European family which in prehistoric times swept westward in successive waves. It is known that this race also overflowed into Northern Italy and Spain. That none of their monuments of the Rough Stone and Polished Stone ages exist in these countries seems to point to the migration thither having been made at a later period.

From the time that the Celtic race finds its way into recorded history it has been recognised as pre-eminently characterised by artistic genius. The rude menhirs, under the combined influences of Christianity and art were in time replaced by Stone Crosses that in form closely approximate the thickset simplicity of the monolith, but are embellished with carved ornament. And the latter in its detail is evidently akin to the motives of decoration found upon the weapons and earthenware of the Bronze Age, combined with the interlace of lines, suggested by the example of weaving, and the use of motives derived from plant forms. These same principles of decoration were applied to the metal-work in which the Celt excelled and later to the decorated manuscripts in which he reached so high a degree of artistry. The Celtic artists in time also introduced human and animal figures into their designs, but always treated them solely as motives of decoration and never with the purpose of representing them naturally.

The prevalence of these decorative motives in ancient Asiatic and European ornament may have been due to the extended migrations of the Celts. But not necessarily; for they are equally to be found in the primitive ornament of the South Sea Islanders, North American Indians, and the inhabitants of Peru, Mexico, and Central America. Primitive man, in fact, shows a tendency to{19} similarity of motives and methods at corresponding stages of his evolution.

In the last three countries have been discovered some of the most remarkable remains of the Polished Stone Age and the Bronze Age. For it was to this stage—after how many centuries of development is only a matter of conjecture—that the mighty nations of the Incas, Aztecs, and others had attained, when the Spanish invaders in the sixteenth century overcame them and wiped out their civilisations.

Hitherto the most famous example has been the ruins of Cuzco, the imperial city of the Incas in Peru, which was captured by Pizarro; but the exploration of Professor Hiram Bingham has recently unearthed, also in Peru, Machu Picchu, a city of refuge, perched almost inaccessibly on the heights of the Andes. It is the belief of the explorer that this is the traditional city of Tampu Tocco, to which a highly civilised tribe retreated, when they were hard pressed by barbarian enemies and from which, legend says, they descended later to conquer Peru and found the city of Cuzco, under the leadership of “three brothers who went out from three windows.” Now Tampa means a place of temporary abode and Tocco means windows; and in the principal plaza of this newly discovered city has been found a temple with three windows.

Thus it is possible that it was actually a deserted city at the time of the Spanish invasion, held in reverence as the cradle city of the Incas. Anyhow, it escaped the knowledge and the ravages of the Spaniards and retains to-day its primitive state, unmixed with the additions of any subsequent civilisation.{20}

It occupies an immense area, only rivalled by that of Cuzco, and is constructed of stones, many of which weigh several tons, hewn into shape with stone hammers. Large portions of the mountain sides are built up with terraces, which were used for agricultural purposes and suggest an analogy with the “hanging gardens” of Babylon. No less than a hundred flights of steps connect the various parts of the city, which is divided into wards or “clan groups” by walled enclosures, enclosing houses and sometimes a central place of worship. The typical design of the houses is much like that of an Irish cabin—a ground story and a half story with gabled ends, each pierced by a small window. The wooden roofs have disappeared, but the stones, bored with a hole, to which the timbers were lashed, are still in place. In the burial caves bronze objects of fine workmanship have been discovered.

Among other noted remains of early buildings is the Teocalli or “House of the God” of Guatusco in Costa Rica. It shows a truncated pyramid of masonry, rising in steps, the top forming a platform on which the temple stands. A still more important example of this form of structure must have been the Teocalli of Tenochtitlan, the ancient name of Mexico City. Built about 1446, it was destroyed by the Spaniards and part of its site is now occupied by the Cathedral. According to accounts it comprised a truncated pyramid, measuring at the top, which was 86 feet from the ground, 325 by 250 feet. In the ascent it was necessary to pass five times round the structure by a series of terraces. On the platform were several ceremonial buildings, the terrible image of the god Huitzilopochtli, supposed to be the one that is now in the Museum of Mexico City, and the sacrificial stone.{21} Upon the latter were sacrificed immense numbers of human victims; report saying, though no doubt with exaggeration, that at the dedication of the temple seventy thousand were slaughtered to appease the sanguinary appetite of this hideous idol.

The exteriors of the latest remains of Central America and Mexican primitive civilisation are embellished with ornament, the motives of which exhibit curved and rectangular meanders and interlacings, derived from the example of weaving and plaiting, as well as vegetable and animal forms. Often, as in the Casa de Monjas in Yucatan, the ornament is so profuse that it obscures the character of the structure, while the forms are fantastic and extravagant and in some instances horribly grotesque. Their intention apparently was to strike awe into the spectator.

Most of what we have been studying in this chapter comes under the head of archaeology rather than of art. Nevertheless, since it represents the gradual approach of civilisation toward the artistic conception, it is well worth attention.{23}{22}

The most ancient civilisation known to us is that of Egypt, and the knowledge of it is mainly derived from its architectural remains and the sculpture, painting, and inscriptions with which they are decorated. In addition, there are the records written upon papyri, the Biblical books of Exodus, and the history of Manetho, an Egyptian priest, who lived about 250 B.C. By this time Egypt had been subdued by Alexander the Great and had passed under the rule of the Ptolemies. So Manetho wrote in Greek, but only fragments of his work have survived, through quotations made from it by Eusebius, Josephus, and other historians.

It is from all these materials that scholars have endeavoured to piece together some sort of connected history of the period covered by Manetho; the difficulty being increased by the fact that the Egyptian system of chronology reckoned by dynasties and computed the time by the years of the reigning sovereign, beginning anew with each succession. Furthermore, the inscriptions omit references to any interruptions that occurred in the sequence of the dynasties; recording only the periods of Egyptian supremacy and leaving out those in which the country suffered from the domination, short or long, of foreign conquerors.

Accordingly, while Manetho names the first ruler of the First Dynasty as Menes, there is nothing but the conjecture of scholars as to the date; and the latter has been{26} variously estimated as from 3892 to 5650 years before Christ.

It will be a help at the outset to summarise the Dynasties under two heads: (A) those of Independent Egypt; (B) those of Subject Egypt.

A. Dynasties of Independence.

1. I-X—The Ancient Empire; Capital, Memphis in Lower Egypt. Lasted about 1500 years.

2. XI-XIII—The Middle Empire, or First Theban Monarchy; Capital, Thebes in Upper Egypt. Lasted about 900 years.

3. XIV-XVII—Hyksos Invaders occupy Lower Egypt; the Egyptian princes rule as vassal princes in Upper Egypt: from 400-500 years.

4. XVIII-XX—The New Empire or Second Theban Monarchy. The Great Epoch of Egyptian power and art. Lasted about 600 years and ended about 1000 B.C.

B. Dynasties of Subjection.

5. XXI-XXXII—The Period of Decadence under various foreign rulers; sometimes called the Saitic Period, because the first conquerors, the Libyans, made their capital at Sais. Lasted from about 1000-324 B.C.

6. XXXIII—The Ptolemaic Period of Greek rule, following the Conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great; 324-31 B.C.

7. XXXIV—The Roman Rule: Egypt a Province of the Roman Empire; 31 B.C. to 395 A.D. At the latter date it became a part of the Eastern Roman Empire.

In 389 the emperor, Theodosius, issued an edict proclaiming that Christianity was to be recognised as the religion of Egypt. In consequence of this change all knowledge of the old form of writing gradually disappeared and the antiquities of Egypt remained a sealed book for some fourteen centuries.

The commencement of the modern interest in Egypt, as a mine of historical, archæological, and artistic lore, dates from Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion, for he took with him a body of savants to explore the topography and nature of the country and its antiquities. The results of their labours were published in 1809-13 in twenty-five volumes, illustrated with 900 engravings.

Meanwhile, in 1799, Captain Boussard, an engineer under Bonaparte, had discovered in the trenches a tablet of black basalt, inscribed with three kinds of writing, one of which was Greek. From the name of the village near which it was found it is called the Rosetta Stone and is now in the British Museum. Various attempts were made to decipher through the Greek the other two scripts, which were, respectively, hieroglyphic and the demotic or popular writing-form of ancient Egypt.

Finally, the clue was discovered by the French scholar, Champollion. He found there had been three kinds of characters which represented successive developments of one system of writing: that in the hieroglyphic each letter was represented by a picture-form; that in the hieratic or priestly writing, these forms were represented in a freer and more fluent way, which was further simplified in the demotic characters, used generally by the scribes. Two of these had been repeated as nearly as possible in the Greek text. It is out of this discovery that Egyp{28}tology, or the science which concerns itself with the writing, language, literature, monuments, and history of ancient Egypt, is being gradually developed. Yet the subject is still involved in great uncertainty, owing to the difficulty in discovering principles of grammar, so that the translations of one scholar vary from those of others and all reach only the general sense, without assurance of accuracy.

The civilisation of a country is always largely determined by its geographical character and the latter, in the case of Egypt, is of exceptional significance. Herodotus called Egypt the “Gift of the Nile.” The great river created it and has continued to preserve it. For the country comprises a narrow strip of soil varying from 4 to 16 miles in width, bordering the two sides of the stream, and extending in ancient times, as far as the second cataract, a distance of some 900 miles; approximating, that is to say, the distance from New York to Chicago or from London to Florence. It is bounded by rocky hills, and, as it reaches the Mediterranean, fans out into a delta of flat lands, the various streams being kept in place by dykes. The only thing that has saved this country from being swallowed up in the desert is the annual rise of the river, succeeding the tropical rains in the interior and the melting of the snow in the mountains of Abyssinia. This floods the lowlands and leaves behind an alluvial deposit, so richly fertile that the soil, warmed by constant sunshine, yields three harvests annually. Meanwhile, it is a remarkable fact that the records of ancient times tally with those of to-day, both showing that the amount of the rise varies but little from year to year.{29}

Before considering how these natural features of the country affected the civilisation of its inhabitants, a fact is to be noted. At the point of time when Manetho commenced his history of the Egyptians, variously estimated from about 4000 to about 6000 years before the Christian Era, they appear as a people already possessed of a high degree of civilisation, surrounded by inferior races. An immense interval of progress separates them from the earliest conditions that we considered in the previous chapter. By what stages did they reach this footing of superiority and through what length of time; moreover, what was the origin of their race? To these questions of profound interest there is no answer forthcoming. Some recent scholars are disposed to believe that the civilisation of Egypt, as we first meet with it, had been preceded by a still more remote civilisation in Babylonia; but as yet they have not shaken the accepted view that priority in civilisation belongs to the Land of the Nile. So far as knowledge exists, civilisation appeared first in Egypt and by a wonderful combination of circumstances, continued up to historic times.

The tenacity of the civilisation of the Egyptians is a counterpart of the tenacity of character of the people, as a result primarily of their natural surroundings. Within the limits of Upper and Lower, that is to say of Southern and Northern Egypt, the Nile has no tributaries. Consequently, there was at first no urge to the inhabitants to push outward; and every inducement to cling to their own strip of territory. Moreover, since the periodic river floods were constant, there was every inducement, nay almost necessity, that they should cling to the methods by which they had learned to utilise them. Hence, conservatism was forced upon them and became ingrained{30} in their character and institutions. It was further encouraged by their isolation; for the adjoining country was desert, meagrely occupied by nomad tribes. Accordingly, that tendency of every nation to consider itself the salt of the earth and especially favoured of the gods seemed justified abundantly in their case.

Again, their dependence on the Nile early taught them the habit of noting the seasons, while the necessity of husbanding the water in reservoirs and by irrigation made them skilled in engineering and generally resourceful. And these characteristics of method and constructiveness were reflected in the social organisation.

The King was the supreme head of the whole system, descendant of the Sun-god, Ra, the individual embodiment of the nation’s greatness, while beneath him the people were divided into the official class, middle class, and slaves. The first included generals, high-priests, officers, physicians, overseers, district-chiefs, judges, master-builders, scribes, and many others—officialdom being spun like a web over the life of the people. The middle class, composed of merchants, traders, ordinary priests, artisans, free working potters, carpenters, joiners, smiths, and agriculturists, enjoyed many of the privileges of the upper classes, but were not permitted to erect tombs, though their place of burial might be marked by a stele with inscriptions. The slaves were mere hewers of wood and drawers of water.

Title to all land, except that attached to the temples, was vested in the King and the land was worked for the State by slaves or let out at an annual rental. In connection with this subject compare the story of Joseph, especially Genesis xli.

Each administrative department had its own {31}troops—or, to use the modern word, corvée—of slaves, under an overseer who kept tally of work done and rations distributed. It was the troop, not the individual, that constituted the unit. Agriculturists ranked higher than the artisans; although the work of the latter was highly esteemed. The weavers made baskets, mats, and boats of papyrus leaves and produced linen of the finest quality as well as coarser grades. The carpenter, notwithstanding the scarcity of timber, did creditable work with the simplest kind of tools. Little variation was attempted by the potters in the forms of vessels, which were crude but often finished with fine glazes. The metal workers used gold, silver, bronze, iron, and tin; silver exceeding gold in value. Whence they procured tin is unknown, but the other metals came from the mines of Sinai and Nubia.

The processes of agriculture were of the simplest. The plough was formed of a sharpened stake, dragged by oxen; the crops were cut with sickles, and the grain was winnowed by casting it in the air, after which it was stored in large, tunnel-shaped receptacles, filled from the top by a ladder. While the Egyptians prided themselves on their immense herds of cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, and asses, the shepherds, living in the remote marshes, were “an abomination unto the Egyptians” (Genesis xlvi, 34).

Their recreations included the hunting of wild animals with dogs, while the men were armed with lasso and spear and occasionally a bow and arrows. In the marshy districts birds were brought down with a boomerang or caught in nets and traps. The people indulged in wrestling matches, gymnastics, ball-playing, quoits, and juggling, while work was performed to the accompaniments of music and singing, and music and dancing enlivened{32} the feasts. The instruments comprised the flute and a kind of whistle, the guitar, harp, and lyre, the last two having sometimes twenty strings.

The school, “bookhouse” or “house of instruction,” was presided over by a scribe and attended by children of all classes. The curriculum included orthography, calligraphy, and the rules of etiquette, together with practice in the technical work of the department for which the children were being trained.

The uniform male garment for all classes was an apron fastened around the loins. To this in early times the King added a lion’s tail and the noble a panther-skin. In the Middle Empire the apron took a pointed, triangular shape in front and became longer, while by degrees a single apron gave way to a short, opaque under-apron with a long, transparent one over it. The short apron, however, continued to be the sole garment of the priest. In time, the costume of the King included garments covering the upper part of the body, a practice which dates from the Eighteenth Dynasty, when the vigorous Queen Hatasu adopted the male costume. The uniform dress of women was a transparent robe hung from the shoulders by straps and reaching from the breasts to the ankles. In later times it was supplemented with a sleeved or sleeveless mantle.

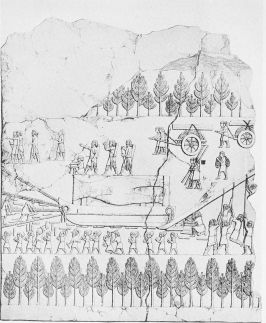

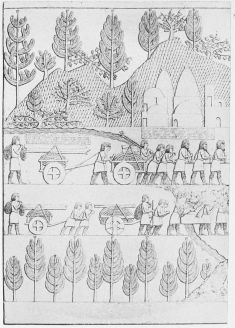

These, and countless other particulars of daily life, are pictured with precise details, in coloured carvings and in paintings on the walls of tombs, so as to continue after death, for the benefit of the Ka or double, the conditions which the deceased had been accustomed to in life. This Ka was believed to be separate from the body, mind, or soul of the individual; an independent spiritual existence which, as long as it was present, ensured “protection, life,{33} continuance, purity, health, and joy.” Hence the care with which provision was made to induce it to remain with the individual when dead. For continuance of life after death was the cardinal principle of Egyptian religion. It was the spiritualised expression of the people’s intense conservatism; and the preservation of the body as a mummy and the taking of measures to ensure that the Ka would abide with it or, at least, visit it frequently, were the chief duties of the priesthood. The homes of the living, therefore, were considered of less importance than those of the dead; and, while few traces remain of dwellings or even of palaces, Egypt abounds with Tombs. These are the memorials of individuals, while the Temples embody the pride and glory of the national, collective life. Indeed, it would seem that during life the individual, except only the King, who represented the union of all, was regarded simply as a factor in the collective organisation of the community, the splendour and power of which was visualised in the Temples.

Hence the importance which was attached to size and beauty of colour in the Temple architecture. Evidence shows the Egyptians were not an intellectual race. That is to say, they were not given to speculation; nor did they carry their mathematical or scientific studies beyond the point at which they were needed for material and practical purposes. And equally devoid of abstract qualities was their imagination. It conceived of “better” in terms of “bigger,” and “best” in terms of “biggest.” Through all their centuries of civilisation they did not progress beyond the crude stage of finding sufficient satisfaction in constructing or possessing “the biggest thing on earth.” And the biggest was constructed by sheer force of numbers of slave-workers, at an immense human{34} sacrifice. It has been computed that every stone in the huge Temples cost at least one life.

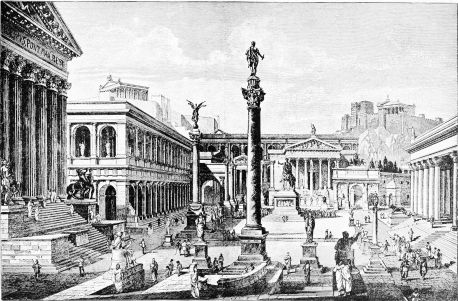

Accordingly, the distinguishing features of their Temple architecture are colossal height and the spreading out over vast areas, as succeeding kings added to the original building another Court or Hall to demonstrate the grandeur of his reign.

And, to repeat once more, it was the conservatism, characteristic of the race, that encouraged this repetition of motives, while at the same time establishing conventionalised forms for the details. Individuality of artistic expression was curbed by the canons of form that the priests had laid down and enforced age after age. Meanwhile, in the scenes of life with which they decorated the walls, some latitude was allowed the painters and sculptors in the direction of naturalistic representation; and it was increased when, in later times, the influence of Cretan civilisation penetrated to Egypt.

We will conclude with a brief summary of the part played by the several Dynasties in the art which is discussed in the following chapter.

It is to be noted that no inscriptions survive from the first three Dynasties; but that with the Fourth commence the records which have been recovered from the Tombs or Mastabas.

To Snofru (Greek Soris, as given by Manetho) is attributed the stepped-pyramid at Sakkarah, while the four pyramids at Gizeh are known by the names of their builders Khufu or Cheops; Khafra or Chephren, and Menkara or Mycerinus. The Sixth Dynasty closed with the reign of Queen Nitocris, who is supposed to have faced with granite the Pyramid of Menkara, in which it is believed{35} her funeral chamber was constructed. After her reign a period of darkness intervened during which the power of the monarchy was gradually developed, until, with the beginning of the Eleventh Dynasty, the Government was established in Thebes.

The Kings of the Middle Empire, Usertesen I, II, and III, signalised their rule by reaching out beyond the limits of Lower and Upper Egypt. They conquered Ethiopia to the south and opened up trade to the eastward with Syria, and recovered possession of the mines of Sinai. Temples were built and great public works of irrigation carried out, while changes were inaugurated in writing and education. The process of development seems to have been continued even during the Hyksos usurpation. For these Asiatic invaders, whose race and origin are unknown—the term Hyksos meaning Shepherd Kings or Bedouin Chiefs—confined their occupation to Lower Egypt, while the Egyptian Kings continued to govern Upper Egypt as vassal princes.

It was an attempted interference with Egyptian self-rule that precipitated the expulsion of the Hyksos. The latter’s chief had demanded of the “Prince of the South” that he abandon the worship of Ra-Ammon for that of the Hyksos god. A refusal led to war which was brought to a successful end by Amasis or Ahmes I, first King of the Eighteenth Dynasty.

With the commencement of the New Empire Egypt entered upon an era of prosperity and power that were reflected in the grandeur of her art. It corresponded in Egyptian history to the age of Pericles in Athens; the Imperial Epoch of Rome, and the High Renaissance of the sixteenth century in Italy. Amenophis subdued the Libyans to the westward of the Delta. His successor,{36} Thothmes I, carried conquest as far south as the third cataract and annexed the land of Cush as a province. Having thus consolidated authority in the neighbourhood of Egypt, he invaded Palestine and Syria as far as the Euphrates. His daughter, Queen Hatasu, fitted out an expedition to the land of Punt (South Arabia) and brought back incense, wood, and animals, such as the dog-headed ape; all of which is duly recorded on the walls of her temple at Deir-el-Bahri. But the acme of power was reached by her half-brother, Thothmes III; for this monarch made fifteen expeditions, in the course of which he reduced the rising power of the Hittites and made himself master of the countries west of the Euphrates and south of Amanus. His two successors managed to hold together this great empire; but in time these foreign entanglements necessitated frequent expeditions.

By the time of the Nineteenth Dynasty the federation of the Hittites had been consolidated and Seti I advanced against them, claiming a victory which was at least not final, for they threatened his successor, Rameses II, who, however, made a treaty of peace with them and married the daughter of the Hittite king. Rameses II also invaded Palestine and afterwards penetrated as far as the Orontes. He reigned sixty-six years and it has been estimated that half the buildings in Egypt bear his cartouche; although in many cases he probably followed the practice of adding his own cartouche to buildings already existing.

It was during the reign of his son, Meneptah, that the Hebrew Exodus is supposed to have taken place; an event that indicates the weakening of the central authority, which was continued under this king’s successors. Finally, during the reign of Rameses III, of the Twen{37}tieth Dynasty, mercenaries were not only employed but allowed to settle in the country and during the remainder of the Rameseide Dynasty the monarchs became the tools of mercenaries and priests. Thus set in the decadence of power and art, which marked the Saitic Dynasty.

Then followed a short period of Persian domination, which was so hateful to the Egyptians that they welcomed Alexander as a liberator. He appointed as king one of his generals, Ptolemy, in whose family the succession continued through sixteen rulers of the same name. During this period Egypt became an intellectual centre, its splendid library being the nucleus of scholarship. It was by order or at least permission of Ptolemy Philadelphos, about 270 or 280 B.C., that the Hebrew scriptures were translated into Greek by seventy scholars, whence the version is known as the Septuagint. The Ptolemies signalised their rule by the restoration of the old temples and monuments, which had suffered from the havoc of invasions.

After the victory of Augustus Cæsar at Actium in B.C. 31 and the death of Cleopatra the following year, Egypt became, as we have already noted, a Roman province.{38}

The remains of monumental architecture in Egypt afford a remarkable opportunity of studying the development from primitive types of structure. The earliest, which comprise the pyramids, mastabas, and two examples of temples, represent developed forms of the tumulus and dolmen, while the later temples, which began to appear in the Twelfth Dynasty, exhibit their origin in the primitive hut of the country.

Great Sphinx.—Meanwhile among the earliest monuments, of uncertain date and origin, is the Great Sphinx of Gizeh. It is the prototype of the sphinxes that were afterwards used to form avenues of approach to the temples, being distinguished from the Greek type of Sphinx by the fact that the recumbent lion body is wingless and carries a male instead of female head and bust. The heads of the later sphinxes represented portraits of the reigning kings, the conception symbolised in the whole figure being the royal power. An inscription, however, upon a small temple, which was erected between the paws of the Great Sphinx in the Eighteenth Dynasty, records that it was made in honour of Harmachis, one of the forms of the Sun-god, Ra.

Hewn out of the living rock, it faces eastward, as if on guard over the pyramids and the entrance to the Nile Valley. The dimensions, when the sand was cleared from

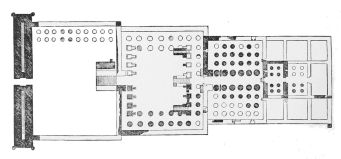

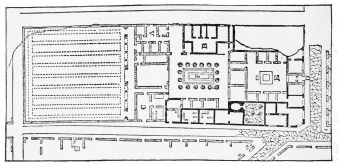

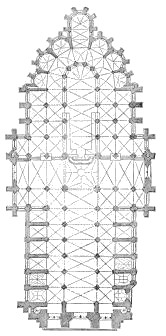

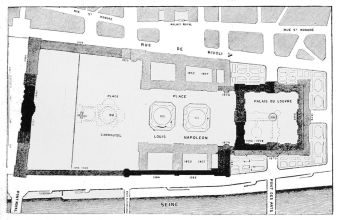

PLAN OF RAMESSEUM OR TEMPLE-TOMB OF RAMESES II

Near Deir-el-Bahri. Showing Pylons, Two Forecourts with Colonnades; Hypostyle Hall or Hall of Columns, and the Sanctuary and Ritual Chambers. Type of all Egyptian Temple Plans. P. 46

the body in the nineteenth century, were found to be: length, 189 feet; height, 66 feet. The face, which was originally painted red, has lost part of the nose and beard, as the result of being used as a target by the Mameluke cavalry.

Pyramids.—The Pyramids, numbering over a hundred, were the sepulchres of the kings of the first twelve Dynasties. Some, for example, the one at Sakkarah, attributed to Senefrou of the Third Dynasty, are of the form known as stepped-pyramids, their sides ascending in six bold steps; there is one at Dashour which slopes steeply from the ground and then breaks to a gentler slope; but the usual type is an unbroken pyramid on a square base.

Three of these, situated at Gizeh, are of surprising size and known by the names of their builders: Cheops or Khufu; Chephren or Khafra, and Mycerinus or Menkara; all of the Fourth Dynasty. The largest of these, that of Cheops, known as the Great Pyramid, is 482 feet high, with a side length of 764 feet. It is, in fact, 150 feet higher than St. Paul’s Cathedral, 50 feet higher than St. Peter’s, while it covers an area nearly three times that of the latter.

The evolution of the pyramid form has been traced from the method of burial. In prehistoric times the body was laid in a square pit which was roofed over with poles and brushwood, covered with sand. The kings of the First Dynasty lined the pit with wood. Later a wooden chamber with a beam roof was erected within the pit, descent to which was by a stairway on one side. Still later, the whole was covered by a pile of earth, held in place by dwarf walls. Then, in the Third Dynasty, the earth was replaced by a mass of brickwork with a sloping passage leading down to the mummy chamber,{40} and subsequently stone was employed. The completed development is represented in the pyramids of Gizeh.

They are constructed of limestone upon a foundation of levelled rock and were originally finished on the outside with massive blocks of polished stone. The entrance is on the north side by a passage, which first descends and then rises to the principal chamber, which contained the king’s sarcophagus. This was lined on the east and west sides with immense stones, supporting several layers of horizontal blocks, crowned with a gable, formed of stones, which are so placed that they exert no thrust upon the stones below. A similar gable formed the ceiling of the Queen’s Chamber, which is situated at a lower level, while at a still lower level is a third chamber.

The statues and sculptured reliefs, discovered in the pyramids and mastabas of the Fourth to Sixth Dynasties, exhibit not only a highly developed skill in the cutting of hard and soft stone, and ivory and wood and in beating copper but also remarkable expression of character. The minute statuette in ivory of Cheops, though the face is only about a quarter of an inch in length, is a portrait of extraordinary force, and the life-size figure of Chephren, carved in hard diorite, is equally distinguished for its serenity and power. The character of all the sculpture, even of low-reliefs of everyday scenes, is but little naturalistic, being impressed with a certain grandeur, as of something inevitable and immutable.

The earliest example of wall-painting appears at Sakkarah in the Pyramid of Onas, the last king of the Fifth Dynasty; where, amid the record of ritual observances, is depicted the grinding of the god’s bones to make bread.

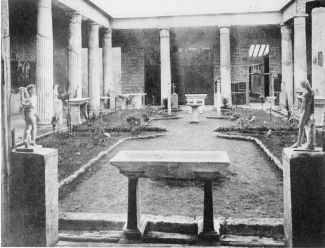

Mastabas.—From the methods of burial were also de{41}veloped the type of the mastabas or tombs of the royal family, priests, and chieftains, which were erected at Sakkarah, near Memphis, during the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Dynasties. The name is derived from the Arabian term for a bench, the familiar type of which is a seat, supported upon boards that slope inward. Similarly the tomb has a flat roof and battered, or inward sloping, walls of masonry. It is entered usually on the east side, by a passage that descends to the Chamber of Offering, which contains, to hold the offerings, a sculptured table. Near it a vertical pit, or well, from forty to fifty feet deep, is sunk in the solid rock, communicating with the mummy chamber. Another hidden chamber, often connected with the Chamber of Offering, is known as the Serdab, which was intended to serve as a home for the deceased’s Ka or “double.” It contained a statue of the deceased and sometimes a model of his home and representations of his occupations during life. Thus, in the Mastaba of Thy, with a view to inducing the Ka to overlook the break that has occurred in the life of the deceased, the reliefs depict harvest operations, ship-building scenes, the arts and crafts of the period, the slaughtering of sacrificial animals and Thy himself traversing the marshes in a boat.

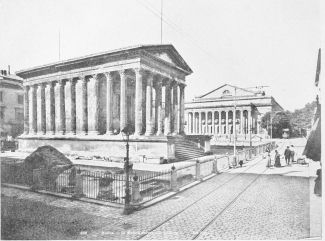

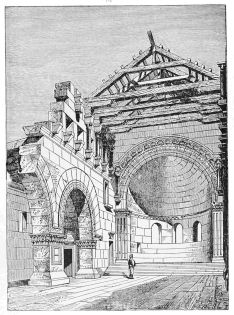

Sphinx Temple.—Akin to the mastaba is the earliest type of temple, such as the so-called Sphinx Temple, which although near the Great Sphinx is now attributed to Chephren. Partially excavated out of rock, it is T shaped in plan, with two rows of square piers in the longitudinal portion and one row in the transverse, supporting the stone beams of the roof. The piers are monoliths of polished granite, while the interior walls are veneered with slabs of alabaster. The whole was em{42}bedded in a rectangular mass of masonry. Another temple of the Fourth or Fifth Dynasty is represented as restored in a model in the Metropolitan Museum, New York.

With the removal of the seat of government from Memphis to Thebes commenced the First Theban Monarchy or Middle Empire, comprising the Eleventh, Twelfth, and Thirteenth Dynasties. Abydos and Beni Hassan now became the place of tombs.

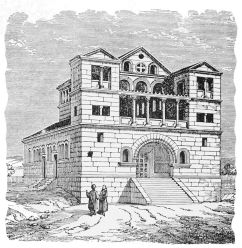

Two types of tomb distinguish this period. One, frequently found at Abydos, consists of a pyramidal structure with a cubical porch on one side, entered by an arched portal. The latter feature proves that the Egyptians were familiar with the principle of the arch, although they did not employ it in their monumental buildings. It appears later in the elliptical barrel-vaultings which crowned the long tunnel-like cellars that Rameses I (The Great) erected for the storage of grain. The above mentioned tombs were structural, whereas those of the second type were excavated in the vertical rock-wall that forms the west bank of the Nile; their entrance thus being toward the east. At Beni Hassan is a group of thirty-nine such tombs which show a marked progress in architectural design.

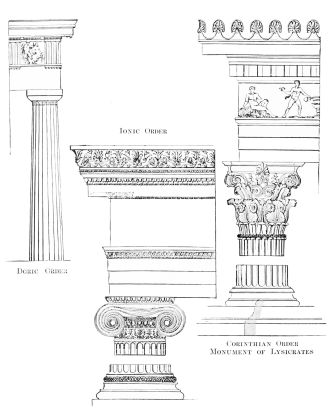

The front of each presents a porch, composed of columns supporting a cornice, the latter being surmounted by a row of projections or dentils that resemble the ends of beams. The shafts of the columns are polygonal, with eight, sixteen, or thirty-two faces, and are surmounted by a square abacus. It has been conjectured that these columns may be the prototype of the Doric{43} column and accordingly their type has been designated as proto-Doric. Meanwhile the columns inside the tomb exhibit a stage in the development of the lotus column; the motive of their design having been derived from a post around the top of which had been fastened the decoration of a cluster of lotus buds. The interior walls of these tombs are decorated with pictorial scenes, executed in red, yellow, and blue.

Obelisks.—To the Twelfth Dynasty belongs the earliest Obelisk still in position; that of Usertesen I, in the necropolis of Memphis, its companion having fallen. For these developed forms of the monolithic menhir, regarded by the Egyptians as symbols of royalty and of the Sun-god, Ra, were placed in pairs, usually before the entrance of a temple. Their design was of great refinement, the taper being regulated very carefully in proportion to the width and height. The top was crowned with a small pyramid which in certain instances, at any rate, was capped with metal. The sides of the shaft were given a slight convex curve, or entasis, to offset the effect of concavity which they might have produced if rectilinear, and also to relieve the rigidity of the design. It is one of the instances which prove that the Egyptians understood and practised the principle of asymmetry, or deviation from strictly geometrical formality—a subject we shall study more fully in Hellenic and Gothic architecture.

The two obelisks now known as Cleopatra’s Needles, one of which is on the Thames Embankment, London, the other in Central Park, New York, were removed from Heliopolis to Alexandria by the Romans. They were originally erected by Thothmes III of the Eighteenth Dynasty, whose half-sister, Queen Hatasu, numbered{44} among her achievements the completion and erection of an obelisk, 100 feet high, in the short space of seven months.

From this period of the Middle Empire survive the fragments of three temples. Amid the ruins of Bubastis have been found examples of the type of clustered lotus columns, while portions of polygonal columns, discovered among the ruins of the Great Temple at Karnak, have been identified as belonging to a temple of the Twelfth Dynasty. The evidence which these remains afford of the fact that such columns were employed in actual construction as well as in rock-cut form, has been corroborated by the recent discovery of a sepulchral temple on the south side of the Temple of Deir-el-Bahri—to be mentioned later—of which it is the prototype. For the earlier was reached by steps that led up to a solid mass of masonry, which in the opinion of some authorities was crowned by a pyramid. It was surrounded by a peristyle, composed of an outer range of square piers and an inner one of octagonal columns.

It is surmised, in fact, that during the Middle Empire, which was a period of great development in the arts of peace, many of the architectural problems were worked out in temples, afterwards destroyed, to make way for the superior developments that were achieved under the Second Theban Empire.

No architectural monuments mark the period of Hyksos usurpation. But the expulsion of the invaders and the restoration of the power alike of the monarchy and of the national religion produced an outburst of patriotic ardour that was fostered by rulers of exceptional great{45}ness. The Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth Dynasties are brilliant with the prowess and architectural creations that are associated with such names as Thothmes, Amenophis, Queen Hatasu, Seti and Rameses.

The Tombs of the New Theban Empire comprised both the structural and the excavated types. The rock-cut royal tombs are distinguished by the extent and complexity of their shafts, passages, and chambers, designed to baffle the efforts of any possible marauder, while notwithstanding the darkness which fills all the spaces, the walls are brilliantly decorated with coloured reliefs for the propitiation of the Ka. In contrast with the interior is the extreme simplicity of the entrance, of which the main features are the majestic colossal seated figures of the Monarch, which take the place of the statue within the tomb. The grandest example is the Temple-Tomb of Rameses II at Abou Simbel.

An exception to this external simplicity is the Temple-Tomb of Queen Hatasu at Deir-el-Bahri, which, however, presents a combination of the structural and excavated types, for projecting from the face of the rock was an extensive portico, from which steps seem to have descended to a terrace bounded by a peristyle and communicating by another flight of steps with the lower ground—an impressive architectural ensemble, designed, apparently, for ritual ceremonies.

The most magnificent examples of the purely structural Tomb are the Ramesseum or Tomb of Rameses II, near Deir-el-Bahri, and that of Rameses III at Medinet Abou. They may have been rivalled by the Amenopheum or Tomb of Amenophis III, of which, however, scarce a trace remains except the colossal seated figures, fifty-six feet high, of the King and his Queen. The former is{46} known as the “Vocal Memnon,” a name given to it by the Greeks, after that of the son of Eos (Dawn), because of the legend, that when the statue was smitten by the rays of the rising sun, it gave forth a sound as of a broken chord.

The Ramesseum is a sepulchral temple and its plan, involving a sanctuary and ritual chambers, a hall of columns entered between pylons, and forecourts, presents the typal form of Temple plan.

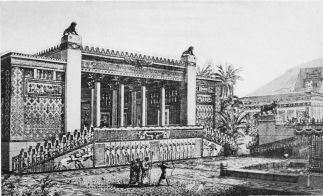

Temples.—The New Theban Empire was the great age of Temple Building. It is characteristic of the conservatism of the Egyptians not only that the style of their monumental architecture was evolved from the rude primitive hut-construction but also that it preserved features of the latter, even though the necessity for them no longer existed. And so persistent was the adherence to these features, now transformed into elements of beauty, that they were continued even in the later temples, built during the period of Roman domination.

It has been suggested that the origin of the style can be discovered in the modelled and sculptured reliefs of the house of the deceased, found in the earliest rock-cut tombs. The house represents a developed stage of the still earlier hut, the character of which was determined by the scarcity of wood. Instead, therefore, of employing poles, connected by wattled twigs or reeds and covered with mud, the Egyptians fashioned the alluvial deposit into bricks, dried in the sun, which they laid in horizontal courses, each layer projecting inwards, until the walls met at the top. Gradually this beehive form of construction was modified in the better class of dwellings, by the adoption of a square plan and the use of the trunks of palm trees to form the lintel of the door and to support{47} a flat mud-covered roof. The representations at Gizeh show that bundles of reeds were used to reinforce the angles of the structure and were also laid along the top of the walls, so as to form a rolled border, corresponding to what is later called a torus. This, through the weight of the roof, had a tendency to be forced outward, so that it formed what was practically a concave cornice along the top of the wall. Hence the so-called cavetto cornice which is one of the marked distinctions of the Egyptian monumental style. Moreover, while the sun-dried bricks acquire a hardness and compactness, they are unable to sustain much pressure, so that it was necessary to make the walls thicker at the bottom than at the top. From this resulted the batter of the walls, which is another distinctive characteristic of the Egyptian style. Further, owing to the intense heat, windows were dispensed with and the walls in consequence were unbroken except by the entrance. To this day the houses of the poorer classes are built as of old and present the rudiments out of which was developed the style of the stone-built temples, so vastly impressive in the embodied suggestion of elemental grandeur and eternal durability.

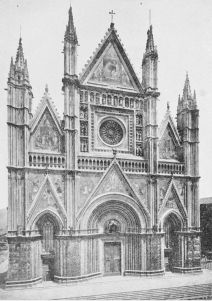

From the outside were visible only the walls and portal of the rectangular temple enclosure. The walls sloped backward, like the glacis of a fortification. A clustered torus moulding, as of reeds bound together at intervals, so as to produce alternate hollows and swells, ran up each of the angles of the masonry and along the top of the walls, where it was surmounted by a cavetto cornice, terminating in a square moulding. A similar finish crowned the entrance door and its flanking pylons. The door, framed at the sides and top with squared blocks of stone, frankly proclaimed the post and beam principle{48} that also governed the interior construction of the temple.

The door was flanked by pylons, each a truncated pyramid with oblong base; the form, in fact, of a hut grandiosely enlarged into a decorative feature of immense impressiveness. Set into its walls were rings to hold flag-staffs, and the surface of the pylon, like that of the walls, was resplendent with coloured reliefs, extolling the prowess of the King who had erected the temple. His statue flanked the doorway, in front of which soared two obelisks, while the roadway that led to the temple was embellished with an avenue of sphinxes. These avenues were of great length, the one from Karnak to Luxor extending a mile and a half.

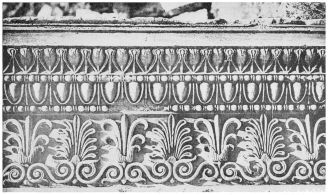

On the lintel over the door was the winged globe, symbol of the Sun’s flight through the sky to conquer Night. Other symbolic ornaments adorned the jambs and the various cornices, while historic pictures, recording the achievements of the monarch’s rule, covered the surfaces of walls and pylons. All were executed in the same way as the symbolic ornament and the pictures in honour of the deity, which covered the walls, columns, beams, and ceiling of the interior of the temple. The forms were either cut down in very low relief or enclosed by incised lines, the edges of which on the side nearer to the form were slightly rounded, in order to give a sense of modelling. In both cases the designs were filled in with the primary colours, blue, red, and yellow. Thus the decoration, derived from the method of drawing patterns in the mud of a wall while it was still damp, was inset, its higher parts being in the same plane as the wall’s surface—a method distinctively mural which also maintained the avoidance of projections. This avoidance of{49} projecting members, except in the cornice, was a marked characteristic of the Egyptian use of the post and beam principle, as compared with the use of it by the Greeks and Romans.

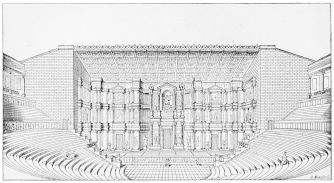

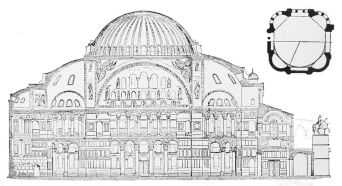

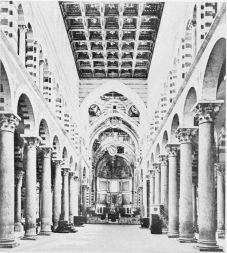

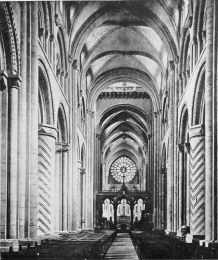

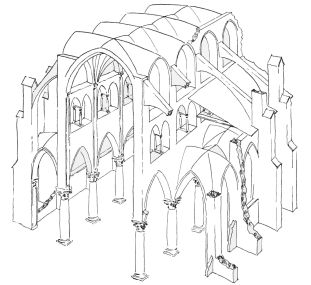

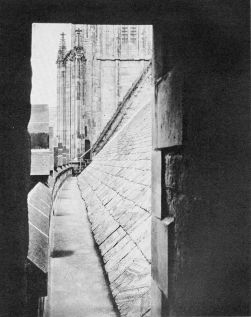

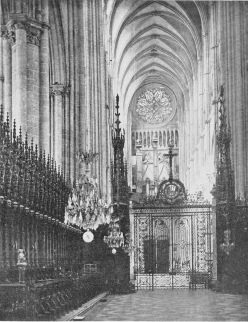

The essential feature of the temple within the enclosure was the sanctuary of the deity to whom the temple was dedicated, around which were grouped chambers for the service of the priests in connection with the ritual. Entrance to this Holy of Holies and its subsidiary cells was through a hypostyle hall, so called because its ceiling of slabs of stone was supported upon stone beams that rested upon columns. The latter, to withstand the weight of the superincumbent mass, were of great girth and closely ranged, so that an effect as of the depths of a forest was produced, rendered more mysterious and apparently limitless by the dim and fitful light. This penetrated through clerestory windows, covered with pierced stonework and set in the sides of the central portion of the roof, which, supported on higher columns, rose above the side roofs, as the nave of a Gothic cathedral rises above the level of the aisles. When one recollects that the interior was completely covered with symbolic ornament and pictures, one can imagine no mode of lighting better adapted to produce a phantasy of effect, to preclude distinctness of vistas and promote a suggestion of limitless immensity, according with the idea of the eternal continuity of the soul’s existence, on which the religion of the Egyptians was founded.

The only approximation in architecture to the mysterious grandeur of the hypostyle hall, leading to the sanctuary, is the nave and aisles and choir of a Gothic cathedral. But the latter presents a great difference, since it was arranged for the congregational service of{50} crowds of worshippers and, partly for this reason and partly because it was a product of the comparatively sunless north, it is flooded through its numerous and large stained-glass windows more abundantly with “dim religious light.”

It remains to note the approach to this hall through an open court which was surrounded on two or three sides by a colonnade or peristyle, while an avenue of columns frequently led through the centre from the main entrance of the pylons to the portal of the hall.

This combination of Court, Hall, and Sanctuary with its Chambers, already present in the Ramesseum, formed the essential of every temple plan, even during the period of Roman occupation. But while the nucleus of the plan was organically complete, unity of effect was abandoned in actual practice owing to the additions made to the original temple by successive kings, who would contribute another hall of columns or another court and sometimes erect another temple as an annex. The most remarkable example of this gradual accretion of additional features is to be found at Karnak; a group of temples in honour of the Sun-god Ra-Ammon, the building of which extended throughout the period of the New Empire.

Temples of Karnak.—The nucleus of the scheme was the granite sanctuary and chambers erected by Usertesen I of the Twelfth Dynasty. In the Eighteenth Dynasty Thothmes I added to the west front of this a columned hall with pylon entrances, surrounding the interior wall with Osirid statues, seated statues of Osiris, the wise and beneficent ruler of the Second Dynasty, who after his death was honoured as the King of the Dead in the nether world. Later a third pair of pylons was built by Rameses I; and this was utilised as one of the sides{51} of the Great Hypostyle Hall begun by Seti I and completed by Rameses II. It communicated through another pair of immense pylons with the Great Court of Sheshonk.

In the northwest corner of the latter Seti II of the Nineteenth Dynasty erected a small temple, while, protruding into the court on the opposite side was the temple of Ammon, built by Rameses III of the Twentieth, who also built the adjacent temple of Chons, connected with the main group of buildings by an avenue of Sphinxes. It was from this temple that the long avenue of sphinxes, already mentioned, extended to the Temple of Luxor.

Meanwhile, during the Eighteenth Dynasty, Thothmes III had erected at some distance to the eastward of Usertesen’s original sanctuary, a large hall and adjoining chambers. These are supposed to have been his palace, though it is urged to the contrary that they offered but little accommodation for the retinue of servants and officials which distinguished an oriental court, besides being gloomy as a residence. Possibly, however, Thothmes under the spell of religious feeling may have used this palace for occasional occupation, even as Philip II of Spain built a palace in connection with a monastery, a school of priests and a great church and mausoleum—the aggregate of functions represented in the Escoriál.

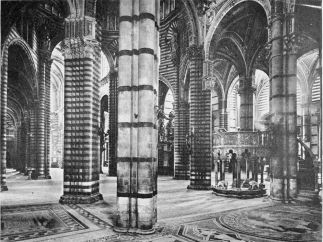

The climax of the architectural ensemble at Karnak is Seti’s Great Hypostyle Hall, the most imposing example known of post and beam construction. It is 338 feet wide with a depth of 170. A double row of six mighty columns 70 feet high and nearly 12 in diameter support the central nave, on each side of which the flat roof is supported by 61 columns, each about 42 feet high and 9 wide. The capitals of the taller columns are of{52} the so-called bell type; those of the lower ones, lotus bud.

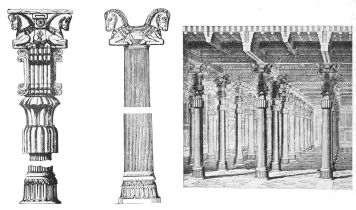

Column Types.—Reference already has been made to the lotus-bud type of columns found in the interior of some of the tombs at Beni Hassan. These represented a conventionalised design as of four buds with long stems bound around a circular post. The later columns, however, of the lotus-bud type were no longer only a decorative feature but had to support the immense weight of the beams and ceiling slabs, consequently the diameter was increased to about one sixth of the height. The capital suggests either one bud with numerous petals crowning a smooth circular shaft or a cluster of buds and stalks bound at intervals with rows of fillets; the design in both cases being more conventionalised than in the early examples.

The bell, or campaniform type is distinguished by a smooth shaft crowned with a conventionalised single blossom of the lotus, the petals of which flare or curve outward so as to resemble the shape of an inverted bell.

Another example of the flaring capital is that of the palm column, the fronds of which are bound by fillets to a smooth shaft. It is a type that appears in the later temples and was varied by the architects of the Ptolemaic period, who substituted for the palm other motives derived from river plants.

An exceptional form, which appears in Temples of Isis, as at Denderah, Edfou, and Esneh, is the so-called Hathor-headed column, which has a cubical capital, embellished on each side with a face of the goddess and surmounted by a miniature temple. The latter takes the place of the impost block which in the other types of column sustains the weight of the beam and protects the carving of the capital.{53}

In certain instances the columns were superseded by piers with rectangular shafts, which sometimes were unadorned in their impressive simplicity, at other times ornamented with lotus flowers and stalks or heads of Hathor. In the so-called Osirid pier a colossal statue of the god projects from the face of the pier, being the only example of a feature added to a pier or column for purposes solely of symbolic ornament and without any structural function.

Next to Karnak in magnificence and extent is the neighbouring Temple of Luxor. Another important example of the period is the temple erected at Abydos by Seti I dedicated to Osiris and other deities. In consequence it is distinguished by seven sanctuaries, ranged side by side and roofed over with horizontal courses of stonework, each of which projects inward over the one below it, until they meet at the top, the undersides being chiselled into the form of a vault.