Title: A Cadet of the Black Star Line

Author: Ralph Delahaye Paine

Illustrator: George Varian

Release date: December 31, 2019 [eBook #61064]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Martin Pettit and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, A Cadet of the Black Star Line, by Ralph Delahaye Paine, Illustrated by George Varian

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/cadetofblackstar00painiala |

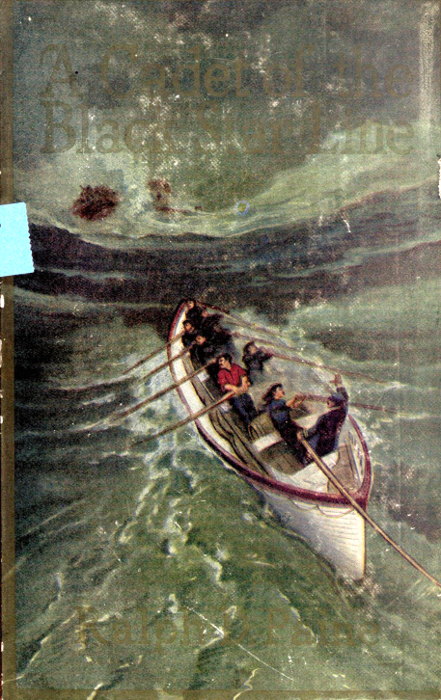

"She can't last much longer. Lay into it, my buckos!" [Page 22]

A CADET OF THE

BLACK STAR LINE

By

RALPH D. PAINE

Author of "College Years," "The Head Coach,"

"The Fugitive Freshman," etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY

GEORGE VARIAN

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

1922

Copyright, 1910, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

———

Printed in the United States of America

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | Oil Upon the Waters | 3 |

| II. | The Sea Waifs | 23 |

| III. | The Fire-Room Gang | 43 |

| IV. | Mr. Cochran's Temper | 63 |

| V. | Mid Fog and Ice | 83 |

| VI. | The Missing Boat | 102 |

| VII. | The Bonds of Sympathy | 121 |

| VIII. | Yankee Topsails | 140 |

| IX. | Captain Bracewell's Ship | 161 |

| X. | The Call of Duty | 179 |

| "She can't last much longer. Lay into it, my buckos!" | Frontispiece |

| Facing Page |

|

| Some one was kneeling on his chest, with a choking grip on his neck | 50 |

| It was easy work to get alongside and pass them a line | 110 |

| David gazed down at the white deck of the Sea Witch | 194 |

A CADET OF THE BLACK

STAR LINE

A CADET OF THE BLACK

STAR LINE

The strength of fifteen thousand horses was driving the great Black Star liner Roanoke across the Atlantic toward New York. Her promenade decks, as long as a city block, swarmed with cabin passengers, while below them a thousand immigrants enjoyed the salty wind that swept around the bow. Far above these noisy throngs towered the liner's bridge as a little world set apart by itself. Full seventy feet from the sea this airy platform spanned the ship, so remote that the talk and laughter of the decks came to it only as a low murmur. The passengers were forbidden to climb to the bridge, and they seldom thought of the quiet[Pg 4] men in blue who, two at a time, were always pacing that canvas-screened pathway to guide the Roanoke to port.

Midway of the bridge was the wheel-house, in which a rugged quartermaster seemed to be playing with the spokes set round a small brass rim while he kept his eyes on the swaying compass card before him. The huge liner responded like a well-bitted horse to the touch of the bridle rein, for the power of steam had been set at work to move the ponderous rudder, an eighth of a mile away.

A lad of seventeen years was cleaning the brasswork in the wheel-house. Trimly clad in blue, his taut jersey was lettered across the chest with the word CADET. When in a cheerful mood he was as wholesome and sailorly a youngster to look at as you could have found afloat, but now he was plainly discontented with his task as with sullen frown and peevish haste he finished rubbing the speaking-tubes with cotton waste. Then as he caught up his kit he burst out:

"If my seafaring father could have lived to watch me at this fool kind of work, he'd have[Pg 5] been disgusted. I might better be a bell-boy in a hotel ashore at double the wages."

The quartermaster uneasily shifted his grip on the wheel and growled:

"The old man's on the bridge. No talkin' in here. Go below and tell your troubles to your little playmates, sonny."

Young David Downes went slowly down the stairway that led to the boat deck, but his loafing gait was quickened by a strong voice in his ear:

"Step lively, there. Another soft-baked landsman that has made up his mind to quit us, eh?"

The youth flushed as he flattened himself against the deck house to make room for the captain of the liner who had shrewdly read the cadet's thoughts. As he swung into the doorway of his room the brown and bearded commander flung back with a contemptuous snort: "Like all the rest of them—no good!"

It was the first time that Captain Thrasher had thought it worth while to speak to the humble cadet who was beneath notice among the four hundred men that made up the crew of the Roanoke. From afar, David had viewed[Pg 6] this deep-water despot with awe and dislike, thinking him as brutal as he was overbearing. Even now, as he scurried past the captain's room, he heard him say to one of the officers:

"Take the irons off the worthless hounds, and if they refuse duty again I will come down to the fire room and make them fit for the hospital."

The cadet shook his fist at the captain's door and moved on to join his companions in the fore part of the ship. He was in open rebellion against the life he had chosen only a month before. Bereft of his parents, he had lived with an uncle in New York while he plodded through his grammar-school years, after which he was turned out to shift for himself. He had found a place as a "strong and willing boy" in a wholesale dry-goods store, but his early boyhood memories recalled a father at sea in command of a stately square-rigger, and the love of the calling was in his blood. There were almost no more blue-water Yankee sailing ships and sailors, however, and small chance for an ambitious American boy afloat.

Restlessly haunting the wharves in his leisure hours, David had happened to discover that the famous Black Star Line steamers were compelled by act of Congress to carry a certain number of apprentices or "cadets," to be trained until they were fit for berths as junior officers. The news had fired him with eagerness for one of these appointments. But for weeks he faced the cruel placard on the door of the marine superintendent's office:

NO CADETS WANTED TO-DAY

At last, and he could hardly believe his eyes, when he hurried down from the Broadway store during the noon hour, the sign had been changed to read:

TWO CADETS WANTED

Partly because he was the son of a ship-master and partly because of his frank and manly bearing, David Downes was asked for his references, and a few days later he received orders to join the Roanoke over the heads of thirty-odd applicants. Now he was completing his first round voyage and, alas! he had almost[Pg 8] decided to forsake the sea. He was ready to talk about his grievances with the four other cadets of his watch whom he found in their tiny mess room up under the bow.

"I just heard the old man threaten to half kill a couple of firemen," angrily cried David. "He is a great big bully. Why, my father commanded a vessel for thirty years without ever striking a seaman. Mighty little I'll ever learn about real seafaring aboard this marine hotel. All you have to do is head her for her port and the engines do the rest. Yet the captain thinks he's a little tin god in brass buttons and gold braid."

An older cadet, who was in his second year aboard the liner, eyed the heated youngster with a grim smile, but only observed:

"You must stay in steam if you want to make a living at sea, Davy. And as for Captain Stephen Thrasher—well, you'll know more after a few voyages."

A chubby, rosy lad dangled his short legs from a bunk and grinned approval of David's mutiny as he broke in:

"There won't be any more voyages for this[Pg 9] bold sailor boy. Acting as chambermaid for paint and brasswork doesn't fill me with any wild love for the romance of the sea. We were led aboard under false pretences, hey, David?"

"Me, too," put in another cadet. "I'm going to make three hops down the gangway as soon as we tie up in New York."

"So I am the only cadet in this watch with sand enough to stick it out," said their elder. "You are a mushy lot, you are. I'm going on deck to find a man to talk to."

As the door slammed behind him, David Downes moodily observed:

"He has no ambition, that's what's the matter with him." But after a while David grew tired of the chatter and horse-play of the mess room and went on deck to think over the problem he must work out for himself. Was it lack of "sand" that made him ready to quit the calling he had longed for all his life? Would he not regret the chance after he had thrown it away? But the life around him was nothing at all like the pictures of his dreams, and he was too much of a boy to look beyond the present. His ideas of the sea were[Pg 10] colored through and through by the memories of his father's career. He had come to hate this ugly steel monster crammed with coal and engines, which ate up her three thousand miles like an express train.

As he leaned against the rail, staring sadly out to sea, the sunlight flashed into snowy whiteness the distant royals and top-gallant sails of a square-rigger beating to the westward under a foreign flag. The boy's eyes filled with tears of genuine homesickness. Yonder was a ship worthy of the name, such as he longed to be in, but there was no place in her kind for him or his countrymen. A brown paw smote David's shoulder, and he turned to see the German bos'n. The cadet brushed a hand across his eyes, ashamed of his emotion, but the kind-hearted old seaman chuckled:

"Vat is it, Mister Downes? You vas sore on the skipper and the ship, so?"

David answered with a little break in his voice:

"It is all so different from what I expected, Peter."

"You stay mit us maybe a dozen or six voyages," returned the other, "and you guess again, boy. I did not t'ink you vas a quitter."

"But this isn't like going to sea at all," protested David.

"You mean it ist not a big man's work?" shouted the bos'n. "Mein Gott, boy, it vas full up mit splendid kinds of seamanship, what that old bundle of sticks and canvas out yonder never heard about. I know. I vas in sailin' vessels twenty years."

The bos'n waved a scornful hand at the passing ship. But David could not be convinced by empty words, and long after the bos'n had left him, he wistfully watched the square-rigger slide under the horizon, like a speck of drifting cloud.

There had been bright skies and smooth seas during the outward passage to Dover and Antwerp, and although the season was early spring the Roanoke had reached mid-ocean on her return voyage before the smiling weather shifted. When David was roused out to stand his four-hour watch at midnight, the liner was plunging into head seas which broke over the[Pg 12] forward deck and were swept aft by a gale that hurled the spray against her bridge like rain. The cadet had to fight his way to the boat deck to report to the chief officer. Climbing to the bridge he found Captain Thrasher clinging to the railing, a huge and uncouth figure in dripping oil-skins. It was impossible to see overside in the inky darkness, while the clamor of wind and sea and the pelting fury of spray made speech impossible.

The cadet crouched in the lee of the wheel-house while the night dragged on, now and then scrambling below on errands of duty until four o'clock sounded on the ship's bell. Then he went below, drenched and shivering, to lie awake for some time and feel the great ship rear and tremble to the shock of the charging seas.

When he went on deck in daylight, he was amazed to find the Roanoke making no more than half speed against the storm. The white-crested combers were towering higher than her sides, and as he started to cross the well deck a wall of green water crashed over the bow, picked him up, and tossed him against a hatch,[Pg 13] where he clung bruised and strangling until the torrent passed. It was the sturdy bos'n who crawled forward and fetched the boy away from the ring-bolt to which he was hanging like a barnacle. As soon as he had gained shelter, David gasped:

"Did you ever see a storm as bad as this, Peter?"

"It is a smart gale of wind," spluttered the bos'n, "and two of our boats vas washed away like they vas chips already. But maybe she get worse by night."

On his reeling bridge Captain Thrasher still held his post, after an all-night vigil. The cadet was cheered at the sight of this grim and silent figure, no longer a "fair-weather sailor," but the master of the liner, doing his duty as it came to him, braced to meet any crisis. The men were going about their work as usual, and David began cleaning the salt-stained brass in the wheel-house.

When he looked out again, the chief officer was waving his arm toward the dim, gray skyline, and at sight of David he beckoned the lad to fetch him his marine glasses. Captain[Pg 14] Thrasher also clawed his way to the windward side of the bridge and stared hard at the sea. The two men shouted in each other's ears, then resumed their careful scrutiny of the tempest-torn ocean in which David could see nothing but the racing billows. Presently the chief officer shook his head and folded his arms as if there was nothing more to be said or done.

After a while David made out a brown patch of something which was tossed into view for an instant and then vanished as if it would never come up again. If it were a wreck it seemed impossible that any one could be left alive in such weather as this. As the Roanoke forged slowly ahead, the drifting object grew more distinct. With a pair of glasses from the rack in the wheel-house, David fancied he could make out some kind of a signal streaming from the splintered stump of a mast. Captain Thrasher was pulling at his brown beard with nervous hands, but he did not stir from his place on the bridge. Presently he asked David to call the third officer. There was a consultation, and fragments of speech were blown[Pg 15] to the cadet's eager ears: "No use in trying to get a boat out.... God help the poor souls ... she'll founder before night...."

Could it be that the liner would make no effort to rescue the crew of this sinking vessel, thought David. Was this the kind of seamanship a man learned in steamers? He hated Captain Thrasher with sudden, white-hot anger. He was only a youngster, but he was ready to risk his life, just as his father would have done before him. And still the liner struggled on her course without sign of veering toward the wreck whose deck seemed level with the sea.

The forlorn hulk was dropping astern when Captain Thrasher buffeted his way to the wheel-house and stood by a speaking-tube. As if he were working out some difficult problem with himself, he hesitated, and said aloud:

"It is the only chance. But I'm afraid the vessel yonder can't live long enough to let me try it."

The orders he sent below had to do with tanks, valves, pipes, and strainers. David could not make head or tail of it. What had the engineer's department to do with saving[Pg 16] life in time of shipwreck? Stout-hearted sailors and a life-boat were needed to show what Anglo-Saxon courage meant. The cadet ran to the side and looked back at the wreck. He was sure that he could make out two or three people on top of her after deck house, and others clustered far forward. They might be dead for all he knew, but the pitiful distress signal beckoned to the liner as if it were a spoken message. When David went off watch he found a group of cadets as angry and impatient as himself.

"He ought to have sent a boat away two hours ago," cried one.

"I'd volunteer in a minute," exclaimed another. "The old man's lost his nerve."

The bos'n was passing and halted to roar:

"Hold your tongues, you know-noddings, you. A boat would be smashed against our side like egg-shells and lose all our people. If the wedder don't moderate pretty quick, it vas good-by and Davy Jones's locker for them poor fellers."

But the cadets soon saw that Captain Thrasher was not running away from the wreck, even though he was not trying to send aid. The[Pg 17] Roanoke was hovering to leeward as if waiting for something to happen. It was heart-breaking to watch the last hours of the doomed vessel. At last Captain Thrasher was ready to try his own way of sending help. The oldest cadet who was in charge of the signal locker came on deck with an armful of bunting. One by one he bent the bright flags to a halliard; they crept aloft, broke out of stops, and snapped in the wind. David, who had studied the international code in spare hours, was able to read the message:

Will stand by to give you assistance.

Only the iron discipline that ruled the liner from bridge to fire room kept the cadets from cheering. David expected to see a boat dropped from the lofty davits, but there were no signs of activity along the liner's streaming decks. It looked as if Captain Thrasher would let those helpless people drown before his eyes.

After a little the Roanoke began to swing very slowly off her course. Then as the seas began to smash against her weather side, she rolled until it seemed as if her funnels must be jerked out by the roots. Inch by inch, however, she[Pg 18] crept onward along the arc of a mile-wide circle of which the wreck was the centre. Even now David did not at all understand what the captain was trying to do. The great circle had been half-way covered before the cadet happened to notice that a band of smoother water was stretching to leeward of the steamer, and that as if by a miracle the huge combers were ceasing to break. An eddying gust brought him a strong smell of oil, and he went to the rail and stared down at the sea. The Roanoke heaved up her black side until he saw smears of a yellow liquid trickle from several pipes, and spread out over the frothing billows in shimmering sheets.

Slowly the Roanoke plunged and rolled on her circular course until she had ringed the wreck with a streak of oily calm. But still no efforts were made to attempt a rescue. The night was not far off. The gray sky was dusky and the horizon was shutting down nearer and nearer in mist and murk. Once more the liner swung her head around as if to steer a smaller circle about the helpless craft. In an agony of impatience David was praying that she might[Pg 19] stay afloat a little longer. Clear around this second and smaller circuit the liner wallowed until two rings of oil-streaked calm were wrapped around the wreck. Now surely, Captain Thrasher would risk sending a boat. But the bearded commander gave no orders and only shook his head now and then, as if arguing with himself.

Then for the third and last time the Roanoke began to weave a path around the water-logged hulk, which was so close at hand that the castaways could be counted. One, two, three aft, and three more sprawled up in the bow. One or two of them were waving their arms in feeble signals for help. A great sea washed over them, and one vanished forever. It was cruel beyond words for those who were left alone to have to watch the liner circle them time after time.

The stormy twilight was deepening into night when this third or inner circle was completed. The onset of the seas was somewhat broken when it met the outside ring of oil. Then rushing onward, the diminished breakers came to the second protecting streak and their menace[Pg 20] was still further lessened. Once more the sea moved on to attack the wreck, and coming to the third floating barrier the combers toppled over in harmless surf, such as that which washes the beach on a summer day when the wind is off shore.

It was possible now for the first time to launch a boat from the lee side of the liner, if the help so carefully and shrewdly planned had not come too late. Landlubber though he was, and convinced beforehand that there was no room for seamanship aboard a steamer, David Downes began to perceive the fact that Captain Thrasher knew how to meet problems which would have baffled a seaman of the old school. But even while the third officer was calling the men to one of the leeward boats, the sodden wreck dove from view and rose so sluggishly that it was plain to see her life was nearly done. The hearts of those who looked at her almost ceased to beat. It could not be that she was going to drown with help so near. As the shadows deepened across the leaden sea, David forgot that he was only a cadet, forgot the discipline that had taught him to think only[Pg 21] of his own duties, and rushing toward the boat he called to the third officer:

"Oh, Mr. Briggs, can't I have an oar? I can pull a man's weight in the boat. Please let me go with you."

The ruddy mate spun on his heel and glared at the boy as if about to knock him down. Just then a Norwegian seaman hung back, muttering to himself as if not at all anxious to join this forlorn hope. The mate glanced from him to the flushed face and quivering lip of the stalwart lad. Mr. Briggs was an American, and in this moment blood was thicker than water.

"Pile in amidships," said he. "You are my kind, youngster."

Mr. Briggs shoved the Norwegian headlong, and David leaped into the boat just as the creaking falls began to lower her from the davits. The boat swung between sea and sky as the liner rolled far down to leeward and back again. Then in a smother of broken water the stout life-boat met the rising sea, the automatic tackle set her free, and she was shoved away in the nick of time to escape being shattered against the steamer.

As the seven seamen and the cadet tugged madly at the sweeps and the boat climbed the slope of a green swell, Mr. Briggs shouted:

"She can't last much longer. Lay into it, my buckos. Give it to her. There's a woman on board, God bless her. I can see her skirt. No, it's a little girl. She's lashed aft with the skipper. Now break your backs. H-e-a-v-e a-l-l!"

As the liner's life-boat drew nearer the foundering hulk, the men at the oars could see how fearful was the plight of the handful of survivors. The arms of a gray-haired man were clasped around a slip of a girl, whose long, fair hair whipped in the wind like seaweed. They were bound fast to a jagged bit of the mizzen-mast and appeared to be lifeless. Far forward amid a tangle of rigging and broken spars, three seamen sprawled upon the forecastle head. If any of them were alive, they were too far gone to help save themselves.

Just beyond the innermost ring of oil-streaked sea there was a patch of quiet water, and as the boat hovered on the greasy swells, the third officer called to his men:

"One of us must swim aboard with a line."

The excited cadet, straining at his sweep,[Pg 24] yelled back that he was ready to try it, but the officer gruffly replied:

"This is a man's job. Bos'n, you sung out next. Over you go."

The bos'n was already knotting the end of a heaving line around his waist, and without a word he tossed the end to the officer in the stern. David Downes bent to his oar again with bitter disappointment in his dripping face. He was a strong swimmer and not afraid of the task, for this was the kind of sea life he had fondly pictured for himself. But he had to watch the bos'n battle hand-over-hand toward the wreck, the line trailing in his wake. Then a sea picked up the swimmer and flung him on the broken deck that was awash with the sea. Those in the boat feared that he had been killed or crippled by the shock, and waited tensely until his hoarse shout came back to them. They could see him creeping on hands and knees across the poop, now and then halting to grasp a block or rope's end until he could shake himself clear of the seas that buried him.

At length he gained the cabin roof, and his shadowy figure toiled desperately while he[Pg 25] wrenched the little girl from the arms of her protector and tied the line about her. The life-boat was warily steered under the stern as the bos'n staggered to the bulwark with his burden. With a warning cry he swung her clear. A white-backed wave caught her up and bore her swiftly toward the boat as if she were cradled. Two seamen grasped her as she was swept past them and lifted her over the gunwale.

Again the bos'n shouted, and the master of the vessel was heaved overboard and rescued with the same deft quickness. Mr. Briggs rejoiced to find that both had life in them, and forced stimulants between their locked and pallid lips, while his men rowed toward the bow of the wreck. The three survivors still left on board could no longer be seen in the gray darkness.

David Downes, fairly beside himself with pity and with anger at the sea which must surely swallow the wreck before daylight could come again, had tied the end of a second line around his middle while the boat was waiting under the stern. Now, as the mate hesitated[Pg 26] whether to attempt another rescue, the cadet called out:

"It's my turn next, sir. I know I can make it. Oh, won't you let me try?"

"Shut your mouth and sit still," hotly returned Mr. Briggs.

He had no more than spoken when David jumped overboard and began to swim with confident stroke toward the vague outlines of the vessel's bow. The whistle of the liner was bellowing a recall, and her signal lamps twinkled their urgent message from aloft. It was plain to read that Captain Thrasher was troubled about the safety of his boat's crew, but they doggedly hung to their station.

As for David, his strength was almost spent before he was able to fetch alongside his goal. He had never fought for his life in water like this which clubbed and choked him. By great good luck he was tossed close to a broken gap in the vessel's waist, and gained a foothold after barking his hands and knees. Half stunned, he groped his way forward until a feeble cry for help from the gloom nerved him to a supreme effort. He found the man whose[Pg 27] voice had guided him, and was trying to pull him toward the side when the wreck seemed to drop from under their feet. Then David felt the bow rise, rearing higher and higher, until it hung for a moment and descended in a long, sickening swoop as if it were heading straight for the bottom. There was barely time to make fast a bight of the line under the sailor's shoulders before, clinging to each other, the two were washed out to sea.

The men in the boat discerned the wild plunge of the sinking craft, and guessing that she was in the last throes, they hauled on the line with might and main. Their double burden was dragged clear, just as the bark rose once more as if doing her best to make a brave finish of it, and a few moments later there was nothing but seething water where she had been.

When David came to himself he was slumped on the bottom boards beside the groaning seaman he had saved. They were close to the Roanoke and her passengers were cheering from the promenade deck. It was a dangerous task to hoist the boat up the liner's side, but cool-headed seamanship accomplished it without[Pg 28] mishap. Several stewards and the ship's doctor were waiting to care for the rescued, and as David limped forward he caught a glimpse of the slender girl being borne toward the staterooms of the second cabin.

Men and women passengers hurried after the cadet, for the bos'n had lost no time in telling the story, winding up with the verdict:

"A cadet vas good for somethings if you give him a chance."

Wobbly and water-logged, David dodged the ovation and steered for his bunk as fast as he was able. The other cadets of his watch shook his hand and slapped him on the back until he feebly cried for mercy, and brought him enough hot coffee and food to stock a schooner's galley.

"There will be speeches in the first cabin saloon, and the hat passed for the heroes, and maybe a medal for your manly little chest," said one of the boys. "You are a lucky pup. How did you get a chance to kick up such a fuss?"

David was proud that he had been able to play a part in a deed of real seafaring, such as[Pg 29] he had thought was no longer to be found in steamers. He had changed his mind. He was going to stick by the Roanoke and Captain Thrasher, by Jove, and with swelling heart he answered:

"I just did it, that's all, without waiting for orders. I tell you, fellows, that's the kind of thing that makes going to sea worth while, even in a tea-kettle."

"You did it without orders?" echoed the oldest cadet with a whistle of surprise. "Um-m-m! wait till the old man gets after you. You may wish you hadn't."

"What! When I saved a man's life in the dark from a vessel that went down under us? I did my duty, that is all there is to it."

"It wasn't discipline. It was plain foolishness," was the unwelcome reply. "I am mighty well pleased with you myself, but—well, there's no use spoiling your fun."

Next day the Roanoke was steaming full speed ahead toward the Newfoundland banks, the storm left far behind her. David Downes, every muscle stiff and sore, went on duty, still hoping that his deed would be applauded by[Pg 30] the ship's officers. While he scoured, cleaned, and trotted this way and that at the beck and call of the bos'n, a bebuttoned small boy in a bob-tailed jacket hailed him with this brief message:

"He wants to see you in his room, right away."

The cadet followed the captain's cabin boy in some fear and trembling. He found the sea lord of the Roanoke stretched in an arm-chair, while a steward was cutting his shoes from his feet with a sailor's knife. The captain tried to hide the pitiable condition of his swollen feet as if ashamed of being caught in such a plight, and grumbled to the steward:

"Thirty-six hours on the bridge ought not to do that. But those shoes never did fit me."

To David he exclaimed more severely:

"So you are the cadet that jumped overboard without orders. Don't do it again. If you are going to sail with us next voyage, the watch officer will see that you have no shore leave in New York. You will be on duty at the gangway while the ship is in port. What kind of a vessel would this be if all hands did as they pleased?"

Standing very stiffly in the middle of the cabin, David chewed his lip to hold back his grief and anger. Overnight he had come to love the sea and to feel that he was ready to work and wait for the slow process of promotion. But this punishment fairly crushed him. He could only stammer:

"I did the best I could to be of service, sir."

The captain's stern face softened a trifle and there was a kindly gleam in his gray eye as he said:

"I put Mr. Briggs in charge of the boat, not you. That is all now. Hold on a minute. I hope you are going to sail with us next voyage."

The cadet tried to speak but the words would not come, and he hurried on deck. After the first shock he found himself repeating the captain's final words:

"I hope you are going to sail with us next voyage."

Said David to himself a little more cheerfully:

"That means he wants me to stay with him. It is a whole lot for him to say, and more than he ever told the other fellows. Maybe I did wrong, but I'm glad of it."

He would have been in a happier frame of mind could he have overheard Captain Thrasher say to Mr. Briggs after the boy had gone forward:

"I don't want the silly passengers to spoil the boy with a lot of heroics. He has the right stuff in him. He is worth hammering into shape. I guess I knocked some of the hero nonsense out of his noddle, and now I want you to work him hard and watch how he takes his medicine."

As soon as he was again off watch, David was very anxious to go in search of the castaways, but he was forbidden to be on the passenger deck except when sent there. The captain's steward had told him that the captain of the lost bark, the Pilgrim, was able to lie in a steamer chair on deck, but that the little girl could not leave her berth. The bos'n was quick to read the lad's anxiety to know more about these two survivors, and craftily suggested in passing:

"Mebbe I could use one more hand mit the awnings on the promenade deck, eh?"

David was more than willing, and as he[Pg 33] busied himself with stays and lashings he cast his eye aft until he could see the gray-haired skipper of the Pilgrim huddled limply in a chair, a forlorn picture of misery and weakness. David managed to work his way nearer until he was able to greet the haggard, brooding ship-master who was dwelling more with his great loss than with his wonderful escape, as he tremulously muttered in response:

"Ten good men and a fine vessel gone. My mate and four hands went when the masts fell. The others were caught forrud. And all I owned went with her, all but my little Margaret. If it wasn't for her I'd wish I was with the Pilgrim."

"Is she coming around all right?" asked David, eagerly. "We were afraid we were too late."

"She's too weak to talk much, but she smiled at me," and the ship-master's seamed face suddenly became radiant. "So you were in the boat. It was a fine bit of work, and your skipper ought to be proud of you, and proud of himself. That three-ringed oil circus he invented was new to me. I thank you all from the bottom of my heart."

The cadet grinned at thought of Captain Thrasher's "pride" in him, but said nothing about his own part in the rescue and inquired in an anxious tone:

"Does the doctor think she will be able to walk ashore? Had you been dismasted and awash very long?"

"Two days," was the slow reply. "But I don't want to think of it now. My mind kind of breaks away from its moorings when I try to talk about it, and my head feels awful queer. John Bracewell is my name. I live in Brooklyn when ashore. You must come over and see us when I feel livelier."

"But about the little girl," persisted David. "Is she your granddaughter?"

"Yes, my only one, and all I have to tie to. My boy was lost at sea and his wife with him. And she is all there is left. She's sailed with me since she was ten years old. She's most thirteen now, and I never lost a man or a spar before."

The broken ship-master fell to brooding again, and there was so much grief in his tired eyes and uncertain voice that David forbore to[Pg 35] ask him any more questions. When he went forward again, David sought the forecastle to learn what he could about the lone seaman of the Pilgrim's crew. A group of Roanoke hands were listening to the story of the loss of the bark as told by the battered man with bandaged head and one arm in a sling who sat propped in a spare bunk. The cadets were forbidden to loaf in the forecastle, and after a word or two David lingered in the doorway, where he could hear the sailor's voice rise and fall in such fragments of his tale as these:

"Broke his heart in two to lose her ... American-built bark of the good old times, the Pilgrim was ... me the only Yankee seaman aboard, too ... I'll ship out of New York in one of these tin pots, I guess.... No, the old man ain't likely to find another ship.... He's down and out.... I'm sorry for him and the little girl. She's all right, she is."

The Roanoke was nearing port at a twenty-knot gait, and the cadets were hard at work helping to make the great ship spick and span for her stately entry at New York. Now and then David Downes found an errand to the[Pg 36] second cabin deck, hoping to find Captain Bracewell's granddaughter strong enough to leave her room. But he had to content himself with talking to the master of the Pilgrim, who was like a man benumbed in mind and body. He was all adrift and the future was black with doubts and fears. He had lived and toiled and dared in his lost bark for twenty years. David could understand something of his emotions. His father had been one of this race of old-fashioned seamen, and the boy could recall his sorrow at seeing the American sailing ships vanish one by one from the seas they had ruled. Captain Bracewell was fit for many active years afloat, but he was too old to begin at the foot of the ladder in steam vessels, and there was the slenderest hope of his finding a command in the kind of a ship he had lost.

These thoughts haunted David and troubled his sleep. But he did not realize how much he was taking the tragedy to heart until the afternoon of the last day out. He was overjoyed to see the "little girl" snuggled in a chair beside her grandfather. She was so slight and delicate by contrast with the ship-master's[Pg 37] rugged bulk that she looked like a drooping white flower nestled against a rock. But her eyes were brave and her smile was bright, as her grandfather called out:

"David Downes, ahoy! Here's my Margaret that wants to know the fine big boy I've been telling her so much about."

Boy and girl gazed at each other with frank interest and curiosity. Even before David had a chance to know her, he felt as if he were her big brother standing ready to help her in any time of need. Margaret was the first to speak:

"I wish I could have seen you swimming off to the poor old Pilgrim. Oh, but that was splendid."

David blushed and made haste to say:

"I haven't had a chance to do anything for you aboard ship. I wish I could hear how you are after you get ashore."

"You are coming over to see us before you sail, aren't you?" spoke up Captain Bracewell, with a trace of his old hearty manner.

"I'd be awful glad to," David began, and then he remembered that if he intended sticking to the Roanoke he must stay aboard as[Pg 38] punishment for trying to do his duty. So he finished very lamely. "I—I can't see you in port this time."

Margaret looked so disappointed that he stumbled through an excuse which did not mean much of anything. He had made up his mind to stay in the ship as a cadet, even though he was forbidden to be a hero. He realized, for one thing, how ashamed he would be to let these two know that he had almost decided to quit the sea. He had played a man's part and the call of the deep water had a new meaning. But it would never do to let Margaret know that his part in the Pilgrim rescue had got him into trouble with his captain.

David was called away from his friends, and did not see them again until evening. A concert was held in the first-class dining saloon, and the president of a great corporation, a famous author, and a clergyman of renown made speeches in praise of the heroism of the Roanoke's boat crew. Then the prima donna of a grand-opera company volunteered to collect a fund which should be divided among the heroes and the castaways. She returned from[Pg 39] her quest through the crowded saloon with a heaping basket of bank-notes and coin. There was more applause when Captain Bracewell was led forward, much against his will. But instead of the expected thanks for the generous gift, he squared his slouching shoulders and standing as if he were on his own quarter-deck, his deep voice rang out with its old-time resonance:

"You mean well, ladies and gentlemen, but my little girl and I don't want your charity. I expect to get back my health and strength, and I'm not ready for Sailor's Snug Harbor yet. We thank you just the same, though, but there's those that need it worse."

David Downes was outside, peering through an open port, for he knew that the concert was no place for a Roanoke "hero." He could not hear all that the captain of the Pilgrim had to say, but the ship-master's manner told the story. The cadet had a glimpse of Margaret sitting in a far corner of the great room. She clapped her hands when her grandfather was done speaking, and there was the same proud independence in the poise of her head. David[Pg 40] sighed, and as he turned away bumped into the lone seaman of the Pilgrim who had been gazing over his shoulder.

"He's a good skipper," said the sailor. "But he's an old fool. He's goin' to need that cash, and need it bad. All he ever saved at sea his friends took away from him ashore. My daddy and him was raised in the same town, and I know all about him."

"Do you mean they'll have to depend on his getting to sea again?" asked David.

"That's about the size of it. He's worked for wages all his life, and knowin' no more about shore-goin' folks and ways than a baby, he never risked a dollar that he didn't lose. Here's hopin' he lands a better berth than he lost."

"Aye, aye," said David.

Next morning the Roanoke steamed through the Narrows with her band playing, colors flying from every mast, and her passengers gay in their best shore-going clothes. David had no chance to look for Captain Bracewell and Margaret. It was sad to think of them amid this jubilant company which had scattered its wealth over Europe with lavish hand. The[Pg 41] contrast touched David even more as he watched Captain Thrasher give orders for swinging the huge steamer into her landing. With voice no louder than if he were talking across a dinner table, the master of the liner waved away the tugs that swarmed out to help him, and with flawless judgment turned the six hundred feet of vibrant steel hull almost in its own length and laid her alongside her pier as delicately as a fisherman handles a dory. The strength of fifteen thousand horses and the minds of four hundred men, alert and instantly obedient, did the will of this calm man on the bridge. David thrilled at the sight, and thought of Captain Bracewell, as fine a seaman in his way, but belonging to another era of the ocean.

The cadet was on duty at the gangway when the happy passengers streamed ashore to meet the flocks of waiting friends. The decks were almost deserted when the skipper of the Pilgrim and Margaret came along very slowly. David ran to help them. They were grateful and glad to see him, but the "little girl," could not hide her disappointment that her boy hero[Pg 42] was not coming to see them before he sailed. She could not understand his refusal, and when she tried to thank him for what he had done for them, there were tears in her eyes. Her grandfather had fallen back into the hopeless depression of his first day aboard. Weak and unnerved as he was, it seemed to frighten him to face the great and roaring city, in which he was only a stranded ship-master without a ship.

David tried to be cheery at parting, but his voice was unsteady as he said:

"I'll see you both again, as soon as ever I can get ashore. And you must write to me, won't you?"

Margaret's last words were:

"You will always find us together, David Downes. And we'll think of you every day and pray for you at sea."

They went slowly down the gangway and were lost in the crowd on the pier. The cadet stood looking after them and said to himself:

"I can never be really happy till he has another ship. But what in the world can I do about it?"

Cadet David Downes was on watch with the fourth officer of the Roanoke at the forward gangway. It was their duty, while the liner lay at her pier in New York, to see that nobody came on board except on the ship's business, and to prevent attempts at smuggling by the crew. David had heard nothing from Captain Bracewell and Margaret since they went ashore three days before. They had taken such a strong hold on his affection and sympathy that he was wondering how it fared with these friends of his, when a quartermaster, returning from an evening visit to the offices ashore, handed the cadet two letters from the bundle of ship's mail.

One envelope was bordered with black and he opened it first. The letter told him of the sudden death of his uncle, who had gone to live in a Western city. This guardian had[Pg 44] shown little fondness for and interest in the motherless boy, and David felt more surprise than grief. But the loss made him think himself left so wholly alone that it seemed as if all his shore moorings were cut. More than ever he longed for some place to call home, and for people who would be glad to see him come back from the sea. It was with a new interest, therefore, that he read his other letter, which was signed in a very precise hand, "Margaret Hale Bracewell." In it the "little girl" told him:

Dear David Downes:

Grandfather wants me to write you that we are as well as could be expected and hoping very much to see you. We are boarding in the house with an old shipmate, Mr. Abel Becket, who used to sail with us. When are you coming to see us? I am most as well as ever. We have not found a ship, but Grandfather is looking round and maybe we will have good news for you next voyage. He tries to be cheerful, but is very restless and worried. I wish we were in steam instead of sail, don't you? Good luck, and I am

Your Sincere and Respectful Friend.

David smiled at the "we" of this stanch partnership of the Pilgrim, and as soon as he[Pg 45] was off watch he wrote a long reply, in which he told Margaret that his uncle's death made him feel as if he kind of belonged to their little family, for he had nobody else to care for and be of service to. Once or twice he thought of asking permission to leave the ship long enough to run over to Brooklyn, but new notions of discipline had been pounded into him by the events of the homeward voyage, and he decided to take his detention on board as part of the routine which made good sailors "in steam."

Two nights before sailing he happened to be left alone at the gangway, for the watch officer had been called to another part of the ship. A drizzling fog filled the harbor, and the arc lights on the pier were no more than vague blobs of sickly yellow. The cadet's attention was roused by a confused noise of shouting, singing, and swearing out toward the end of the pier shed. After making sure that the racket did not come from the ship he concluded that a riotous lot of Belgian firemen and roustabouts were making merry. When the watch officer returned, the cadet reported the unseemly noise.

A few minutes later a louder clamor arose, as if the revellers had fallen to fighting among themselves. Then a quartermaster came running forward from the after gangway.

"Dose firemen vill kill each odder," he reported. "They tries to come aboard ship and I can't stop 'em."

The officer told David to stay at his post, and hurried aft in the wake of the quartermaster. The cadet could hear seamen running from the other side of the ship to re-enforce the peace party, and presently one of them dashed up the pier as if to call the police patrol boat, which lay at the next dock. The cadet had seen enough of the fire-room force, a hundred and fifty strong, to know that the coal-passers and firemen were as brutal and disorderly men ashore as could be found in the slums of a great seaport. But such an uproar as this right alongside the ship was out of the ordinary.

While the cadet listened uneasily to the distant riot, his alert ears caught the sound of a splash, as if some heavy object had been dropped from a lower deck. On the chance that one of the crew might have fallen over, he[Pg 47] ran to the other side and looked down at the fog-wreathed space of water between the liner and the next pier. He could see nothing and heard no cries for help. A little later there came faintly to his ears a second splash. It somehow disquieted him. The galley force was asleep. Nothing was thrown overboard from the kitchens at this time of night and the ash-hoists were never dumped in port.

Firemen sometimes deserted ship, but no deserter would be foolish enough to swim for it in the icy water of early spring. David dared not leave his gangway more than a minute or two at a time. He wanted very much to know what was going on overside in this mysterious fashion, but there was no one in hailing distance, and the watch officer, judging by the noise in the pier, had his hands full.

David had quick hearing, and in the still, fog-bound night small sounds travelled far. Presently he fancied he heard words of hushed talk, and a new noise as if an oar had been let fall against a thwart. It was his business to see that the ship was kept clear of strangers, and[Pg 48] without knowing quite why, he felt sure that something wrong was going on. Finally, when he could stand the suspense no longer, he tiptoed across the deck, moved aft until he was amidships between the saloon deck houses, and crouched on a bench against the rail.

Cautiously poking his head over, he could dimly discern the outline of a small boat riding close to the ship as if she were waiting for something. She was hovering under one of the lower ports, which had been left open to resume coaling at daylight. Two or three men were moving like dark blots in the little craft. Presently a bulky object loomed above their heads and slowly descended. As if suddenly alarmed, the boat did not wait for it, but shot out in the stream, and there was the quick "lap, lap" of muffled oars. It was not long before the boat stole back, however, and seemed to be trying to pick up something adrift.

David did not know what to do. He guessed that this might be some kind of a bold smuggling enterprise, but it seemed hardly possible that anybody would risk capture in this rash and wholesale way. He was afraid of being laughed[Pg 49] at for his pains if he should raise an alarm. He really knew so little of this vast and complex structure called a steamship that almost any surprising performance might happen among her eight decks. It was duty to report this singular visit, however, and the officers could do the rest.

Some one was kneeling on his chest, with a choking grip on his neck.

He rose from his seat and turned to recross the deck, when he was tripped and thrown on his back so suddenly that there was no time to cry out before some one was kneeling on his chest, with a choking grip on his neck. His eyes fairly popping from his head, David could only gurgle, while he tried to free himself from this attack. The man above him wore the uniform of a Roanoke seaman, this much the cadet could make out, but the shadowy face so close to his own was that of a stranger. He was saying something, but the lad was too dazed to understand it. At length the repetition of two or three phrases beat a slow way into David's brain:

"Forget it. Forget it. It'll be worth your while. You get your piece of it. Forget it, or overboard you go, with your head stove in."

Forget what? It was like a bad dream without head or tail, that such a thing could happen on the deck of a liner in port. Twisting desperately, for he was both quick and strong, David managed to sink his teeth in the arm nearest him. The grip on his throat weakened and he yelled with a volume of sound of which the whistle of a harbor tug might have been proud. The assailant pulled himself free, kicked savagely at the boy's head, missed it, and closed with him again as if trying to heave him overboard. But he had caught a Tartar, and David shouted lustily while he fought.

It was Captain Thrasher who came most unexpectedly to the rescue. He was on his way back from an after-theatre supper party ashore, and he launched his two hundred and thirty pounds of seasoned brawn and muscle at the intruder before the pair had heard him coming. Then his great voice boomed from one end of the ship to the other:

"On deck! Bring a pair of irons! Are all hands asleep? What's all this devil's business?"

The watch officer came running up with a quartermaster and two seamen. Without [Pg 51]waiting for explanations they fell upon the captive whom Captain Thrasher had tucked under one arm, and handcuffed him in a twinkling. Swift to get at the heart of a matter, the captain snapped at David:

"How did it happen? Anybody with him? I know the face of that dirty murdering scoundrel."

"I was just going to report a boat alongside," gasped David.

Captain Thrasher sprang to the rail. The fog had begun to lift, and a black blotch was moving out toward the middle of the river.

"After 'em, Mr. Enos," roared the captain to the fourth officer. "Jump for the police patrol. It's the Antwerp tobacco smuggling gang. I thought we were rid of 'em."

The officer took to his heels, and in a surprisingly short time the captain saw a launch dart out from the pier beyond the Roanoke, her engines "chug chugging" at top speed. Making a trumpet of his hands, Captain Thrasher shouted:

"I just now lost sight of them, but the boat[Pg 52] was headed for the Hoboken shore. They can't get away if you look sharp."

Then the captain ordered his men to lock the captive in the ship's prison until the police came back. The chief officer was roused out and told to search the ship and to put double watches on the decks and gangways. Having taken steps to get at the bottom of the mischief, Captain Thrasher fairly picked up David and lugged him to his cabin. Dumping the lad on a divan, the master of the liner pawed him over from head to foot to make sure no bones were broken, and then remarked with great severity:

"You are more trouble than all my people put together. Disobeying orders again?"

"I guess I was, sir," faltered the cadet. "Mr. Enos told me not to budge from the gangway, and I went over to see what was going on."

"What was it? Speak up. I won't bite you," growled the captain. David told him in detail all that happened, but he did not have the wit to put two and two together. This was left for the big man with the wrathful gray eye, who fairly exploded:

"Mr. Enos is a good seaman, but his brain needs oiling. It is all as plain as the nose on your face. That row on the dock was all a blind, put up by two or three of those fire-room blackguards from Antwerp, who stand in with the gang of tobacco smugglers. They figured it out that all hands on deck would be pulled over to the port side and kept there by their infernal row, while their pals dumped the tobacco out of the starboard side. It was hidden in the coal bunkers, wrapped in rubber bags. And because the police patrol boat berths close by us, they even decoyed the whole squad away for a little while. Oh, Mr. Enos, but you were soft and easy."

The captain was not addressing David so much as the world in general, but the cadet could not help asking:

"How about the man that jumped on top of me?"

"He was one of them, the head pirate of the lot," said the captain. "He sneaked up from below as soon as the coast was clear, to signal his mates if anybody caught them at work with the boat."

It was worth being choked and thumped a little to be here in the captain's cabin, thought David, and to be taken into the confidence of the great man. The guest risked another question:

"Did they ever try it before, sir?"

"Every ship in the line has had trouble for years with these tobacco-running firemen. But this is the biggest thing they ever tried. Do you expect me to sit here yarning all night with a tuppenny cadet? Go to your bunk and report to me in the morning. You are a young nuisance, but you can go ashore to-morrow night, if you want to. Punishment orders are suspended. Get along with you."

David turned in with his mind sadly puzzled. One thing at least was certain. There was more in the life of a cadet than cleaning paint and brass, but was he always going to be in hot water for doing the right thing at the wrong time? Before he went to sleep he heard the police launch return, and stepped on deck long enough to see four prisoners hauled on to the landing stage.

When David went on duty next morning he noticed a little group of ill-favored and [Pg 55]unkempt-looking men talking together on the end of the pier. One of them made a slight gesture, and the others turned and stared toward the cadet. Then they moved toward the street without trying to get aboard ship. Mr. Enos called David aft and told him:

"The police are watching that bunch of thugs. Two of them used to be in our fire room. All four ought to be in jail. They had something to do with the ruction last night, but they can't be identified. The bos'n tells me he thinks they got wind that you were the lad who spoiled the game for their pals. If you go ashore after dark, keep a sharp eye out. They'd love to catch you up a dark street."

David looked solemn at this, but it was too much like playing theatricals to let himself believe that he was in any kind of danger along the water front of New York. It was early evening before he was free to get into his one suit of shore-going clothes and head for Brooklyn to look for his friends, Captain Bracewell and Margaret. The bridge cars were blockaded by an accident, and after fidgeting for half an hour David decided to walk across.[Pg 56] There was more delay on the other side in trying to find the right street, and it was getting toward nine o'clock before he rang the bell of a small brick house in a solid block of them so much alike that they suggested a row of red pigeon-holes. A sturdy man with hair and mustache redder than his house front opened the door, and to David's rather breathless inquiry answered in a tone of dismay:

"Why, Captain John and the little girl left here this very afternoon. Bless my soul, are you the lad from the Roanoke they think so much of? Come aboard and sit down. No, they ain't coming back that I know of. My name is Abel Becket and I'm glad to meet you."

David followed Mr. Becket into the parlor, feeling as if the world had been turned upside down. The sympathetic sailor man hastened to add:

"They didn't expect to see you this voyage and they was all broke up about it. The old man is kind of flighty and I couldn't ha' held him here with a hawser. They could have berthed here a month of Sundays, for he has been like a daddy to me."

"But where did they go?" implored David.

"All I know is," said Mr. Becket, rubbing his chin, "that the old man came home this noon mighty glum and fretty after visitin' some ship-brokers' offices. He told me that he heard how an old ship of his, the Gleaner, had been cut down to a coal-barge. He was mighty fond of her, and it upset him bad. And I think he was sort of hopin' to get her again. Then he said he was going to move over to New York to be close to the shipping offices in case anything turned up, and with that him and Margaret packed up and away they flew."

"But why didn't they stay here with you, Mr. Becket? I can't understand it."

Mr. Becket laid a large hand on David's knee and exclaimed:

"Captain John is a sudden and a funny man. For one thing, I suspicion he was afraid of being stranded, and that I'd offer to lend him money or something like that. He is that touchy about taking favors from anybody that it's plumb unnatural. I'm worried that he will go all to pieces if he don't get afloat again. I[Pg 58] wish I could drag him back here so as to look after him."

"And how about Margaret?" David asked.

"Oh, she's feelin' fairly chirpy, and she went off with granddaddy as proud and cocksure as if they were expectin' to be offered command of a liner to-morrow."

Despite Mr. Becket's explanations, the flight of Captain Bracewell remained a good deal of a mystery to David. He could not bear to think of them adrift in New York, and he declared with decision:

"If you will give me their address, I'll look them up to-night."

"Bless my stars and buttons, I'll go along with you and make my own mind easy," announced Mr. Becket. "I won't sleep sound unless I know how they're fixed. I'm so used to thinkin' of Cap'n John as fit and ready to ride out any weather, that I don't realize he's so broke up and helpless. And I've got to go to sea before long."

The twisted streets of old Greenwich village in down-town New York proved to be a puzzle to this pair of nautical explorers, partly because[Pg 59] Mr. Becket had so much confidence in his ability to steer a straight course to Captain Bracewell's new quarters that he positively refused to ask his bearings of policemen or wayfarers. After they had lost themselves several times, the red-headed pilot of the expedition announced with an air of certainty:

"It's here or hereabouts. I saw the name of the street on a corner sign three or four years ago, and my memory is a wonder."

This was more cheering than definite, and David meekly suggested that he inquire at the next corner store.

"Do you think I'm scuppered yet?" snorted Mr. Becket. "Not a bit of it. Bear off to starboard at the next turn."

But once again they fetched up all standing, and Mr. Becket was obliged to confess as he meditated with hands in his pockets:

"They've gone and moved the street. That's what they've done. It's a trick they have in New York."

"You wait here and I'll go back to the cigar store around the last corner," volunteered David.

Mr. Becket was left to shout his protests while David ran up the dark and narrow street. But the cigar store was not where he expected to find it, and certain that it must be in the next block beyond, he hurried on. Two crooked streets joined in the shape of the letter Y at the second corner, and the cadet failed to notice which of these two courses he had traversed with Mr. Becket. Without knowing it, David began to head into a district filled with sailors' drinking places and cheap eating-houses. As soon as he was sure that the street was unfamiliar he slowed his pace, looked around him, and not wishing to enter a saloon, went over to a gaudily placarded "oyster house."

There were screens in front of the tables, and finding no one behind the cigar-counter David started for the rear of the room. Three rough-looking men jumped up from a table littered with bottles, and one of them cried out with an oath:

"It's the very kid himself. Leave him to me."

David dodged a chair that was flung at him like lightning, and fled for the street amid a[Pg 61] shower of dishes and bottles. He had recognized the unlovely face of the man who yelled at him as that of one of the Roanoke firemen who had stared at him from the pier in the morning. He knew he could expect no mercy at the hands of these ruffians.

The three men were at his heels as he blindly doubled the nearest corner, hoping that Mr. Becket might hear his shouts for help. But the silent, shadowy street gave back only the echoes of his own voice and the sound of furious running. The fugitive had lost all sense of direction. He was still stiff from the bruising ordeal of the Pilgrim wreck, and his legs felt benumbed, while the panting firemen seemed to be overhauling him inch by inch. One of them whipped out a revolver and fired. The whine of the bullet past his head made David leap aside, stumble, and lose ground. Were there no policemen in New York? It was beyond belief, thought David, that a man could be hunted for his life through the streets of a great city.

Far away David heard the rapping of nightsticks against the pavement. Help was coming,[Pg 62] but it might be too late, and where, oh where, was Mr. Becket? To be stamped on, kicked, and crippled by the boots of these ruffians—this was how they fought, David knew, and this was what he feared.

Two of his pursuers were lagging, but the pounding footfalls of the third were coming nearer and nearer. The street into which he had now come was lined with warehouses, their iron doors bolted, their windows dark. There was no refuge here. He must gain the water front, whose lights beckoned him like beacons. Then, as he tried to clear the curb, he tripped and fell headlong. He heard a shout of savage joy almost in his ear, just before his head crashed against an iron awning post. A blinding shower of stars filled his eyes, and David sprawled senseless where he fell.

David Downes stared at the ceiling, blinked at the long windows, and squirmed until he saw a sweet-faced woman smiling at him from the doorway. She wore a blue dress and white apron, but she was not a Roanoke stewardess nor was this place anything like the bunk-room on shipboard. The cadet put his hands to his head and discovered that it was wrapped in bandages. Then memory began to come back, at first in scattered bits. He had been running through dark and empty streets. Men were after him. How many of his bones had they broken? He raised his knees very carefully and wiggled his toes. He was sound, then, except for his head. Oh, yes, he had banged against something frightfully hard when he fell. But why was he not aboard the Roanoke? She sailed at eight o'clock in the[Pg 64] morning. He tried in vain to sit up, and called to the nurse:

"What time is it, ma'am? Tell me, quick!"

"Just past noon, and you have been sleeping beautifully," said she. "The doctor says you can sit up to-morrow and be out in three or four days more."

"Oh! oh! my ship has sailed without me," groaned David, hiding his face in his hands. "And Captain Thrasher will think I have quit him. He knew I had a notion of staying ashore."

"You must be quiet and not fret," chided the nurse. "You got a nasty bump, that would have broken any ordinary head."

"But didn't you send word to the ship?" he implored. "You don't know what it means to me."

"You had not come to, when you were brought in, foolish boy, and there were no addresses in your pockets."

"But the captain probably signed on another cadet to take my place, first thing this morning," quavered the patient, "and—and I—I'm adrift and dis—disgraced."

The nurse was called into the hall and presently returned with the message:

"A red-headed sailor man insists upon seeing you. If you are very good you may talk to him five minutes, but no more visitors until to-morrow, understand?"

The anxious face of Mr. Becket was framed in the doorway, and at a nod from the nurse he crossed the room with gingerly tread and patted David's cheek, as he exclaimed:

"Imagine my feelin's when I read about it in a newspaper, first thing this morning. They didn't know your name, but I figured it out quicker'n scat. You must think I'm the dickens of a shipmate in foul weather, hey, boy?"

"You couldn't help it, Mr. Becket, and I'm tickled to death to see you. Please tell me what happened to me. I feel as if I was somebody else."

"Well, it was quick work, by what I read," began Mr. Becket. "And as close a shave as there ever was. Accordin' to reports, you, being a well-dressed and unknown young stranger, was rescued from a gang of drunken[Pg 66] roustabouts by two policemen, a big red automobile, and a prominent citizen whose name was withheld at his request, as the bright reporter puts it. The machine was coming under full power from a late ferry, and making a short cut to Broadway. It must have bowled around the corner, close hauled, just as you landed on your beam ends, and it scattered the enemy like a bum-shell. They never had a chance to see it coming. The skipper of the gasolene liner, he being the aforesaid prominent citizen, hopped out to pick you up, and had you aboard just as the police came up. So you came to the hospital in the big red wagon, the gentleman taking a fancy to your face, as far as I can make out. And so you've been turned into a regular mystery that ought to be in a book."

"But did you find Captain Bracewell?" was David's next spoken thought.

"Of course I did, after I got tired waitin' for you," and Mr. Becket's tone was aggrieved. "It was mistrustin' my judgment that landed you in a hospital. Captain John and Margaret will be over to pay their respects[Pg 67] as soon as the doctors will let 'em pass the hospital gangway. I just came from telling them about you."

But David's mind had harked back to his own ship, and his face was so troubled and despairing that Mr. Becket tugged at his red mustache and waited in a gloomy silence.

"I've lost my ship," said David at length. "Captain Bracewell and I are on the beach together."

"Why didn't I think to telephone the dock as soon as I guessed it in the newspaper?" mourned Mr. Becket, beating his head with his fists. "But Captain Thrasher or some of 'em aboard will read it."

"They won't know it's me," wailed David. "All I can do now is to report to the dock as soon as I can, but I am afraid it will do no good."

The boy's distress was so moving that Mr. Becket had to look out of the window to hide his own woe. Then he spun around and announced with a shout that brought nurses and orderlies hurrying from the near-by wards:

"I have it, my boy. Abel Becket's intellect is on the mend. Send old Thrasher a [Pg 68]wireless, do you hear? Get the hospital folks to sign it."

With that Mr. Becket jerked a roll of bills from his waistcoat and demanded a telegraph blank with so commanding an air that an orderly rushed for the office. The sailor-man and David put their heads together and composed this message to the Roanoke, which was speeding hull down and under, far beyond Sandy Hook:

Cadet Downes hurt on shore leave. Unable report because senseless. Anxious to rejoin ship.

"No, that doesn't sound right," objected David. "He thinks I have no sense anyhow. I can just hear him saying that he isn't in the least surprised. Try it again, Mr. Becket."

"Time is up," put in the nurse. "And I ought to have cut it shorter, with your friend bellowing at you as if he were in a storm at sea."

Mr. Becket looked repentant, as he whispered to David:

"Sit tight and keep your nerve. I'll get the wireless off all shipshape. Good-by, and God bless you."

The patient soon fell asleep. It was late in the afternoon when he awoke, hungry and refreshed. The nurse informed him:

"A dear old man and a sweet mite of a girl called to ask after you, and I told them to come back in the morning and they might see you. Mr. Cochran had you put in this private room and left orders that you were to be made as comfortable as possible. So we will have to stretch the rules a bit, I suppose, and let your friends call out of visiting hours to-morrow."

David asked who the mysterious Mr. Cochran might be, but he could learn nothing from the nurse, except that he was the wealthy gentleman who had brought him to the hospital in his automobile. David tried to be patient overnight, and was mightily cheered by the arrival of a wireless message, which read:

S.S. Roanoke. At sea.

Have cadet repaired in first-class shape to join ship next voyage. He is a nuisance.

Thrasher, Master.

The news that he still belonged in the liner braced David like a strong tonic. What did a[Pg 70] cracked head-piece amount to now? Being called a nuisance only made him smile. It was Captain Thrasher's way of trying to cover every kindly deed he did. Next forenoon he was rereading this message for something like the tenth time when Captain Bracewell was shown into the room. Margaret followed rather timidly, as if she feared to find her hero in fragments. The skipper looked even older than when he had left the Roanoke, but the "little girl" looked more like a June rose than a white violet, so swiftly had her sparkling color returned. She had both her hands around one of David's as she cried:

"Are you always going to get banged up, you poor sailor boy? And we were to blame for it again, weren't we?"

"You had no business to run away from me," returned the beaming patient. "The worst of it was that I almost lost my own ship."

These were thoughtless words said in fun, but they stung Captain Bracewell with remembrance of his own misfortune, and he stood staring beyond David with troubled eye.[Pg 71] Margaret was quick to read his unhappiness, and brought him to himself with a fluttering caress. The derelict shipmaster smiled, and said to David:

"Glad to find you doing so well, boy. You just take it that you are one of our family while you are ashore. There is an extra room in our—in our—" He hesitated, and a bit of color came into his leathery cheek as he finished: "We can find a room for you close by us."

"He means that just now we can't afford to hire more than three rooms to live in," explained Margaret without embarrassment. "But it will be different when we get our ship."

They chatted for a few minutes longer and David promised to find a room as near them as he could, while he waited for the return of the Roanoke. It was easy to see that they wanted to take care of him, but, for his own part, he felt a kind of guardian care for the welfare of the two "Pilgrims," and he was very glad of the chance to be with them at a time when Captain Bracewell was so pitifully unlike his reliant self. After they had gone, David fell[Pg 72] to wondering anew about this unknown Mr. Cochran who had so lavishly befriended him. It was enough to make even a sound head ache, and when the nurse brought his dinner, David begged her:

"If you don't tell me something more about Mr. Cochran, I'll blow up."

"He telephoned about you this morning," she answered, "and wanted to call, but you had visitors enough. The doctors have told him who you are, of course, and he seemed very much interested. He said he would bring his son to see you this afternoon. No, not another word. What must you be when you are well and sound? I'd sooner take care of a young cyclone."

Some time later the motherly nurse came in to say, with an air of excitement that she could not hide:

"Mr. Cochran and his boy to see you. It is the great Stanley P. Cochran. I knew him from his pictures in the newspapers and magazines."

The portly gentleman with the bald brow, gold-rimmed glasses, and close-cropped gray[Pg 73] mustache who entered the room with quick step looked oddly familiar to David. Why, of course, he had seen his portrait and his name as the head of a great Trust, and a director in railroads, banks, and corporations by the dozen. He spoke with curt, clean-clipped emphasis, as if his minutes were dollars:

"Pretty fit for a lad that looked as dead as a mackerel when I picked him up. Sailors have no business ashore, but they are hard to kill. Lucky I was so late in getting back from my country place the other night. Wish I'd run over the scoundrels, but the police got two of them. This is my boy, Arthur."

The delicate-looking lad, who had been hanging back, shook hands with David and smiled with such an air of shy friendliness and admiration that David liked him on the spot. He looked to be a year or two younger than the strapping cadet, and lacked the hale and rugged aspect of which his illness had not robbed him. Mr. Cochran resumed, as if expecting no reply:

"I liked your looks and there was no sense in waiting for the confounded ambulance. I[Pg 74] told them to treat you right. If they haven't, I'll get after the hospital, doctors, nurses, and all. When I found out that you were a cadet from the Roanoke, my boy had to come along. He is crazy about ships and sailors. Reads all the sea stories he can lay his hands on. Well, I must be off. Arthur, you may stay, but not long, mind you."

Mr. Stanley P. Cochran clapped on his silk hat and vanished as if he had dropped through a trap-door. His son said to David, with his shy smile:

"He is the best father that ever was, but he never has time to stay anywhere. I wish you would tell me all about your scrape. It sounds terribly interesting. Will it make your head hurt?"

The cadet had forgotten all about that hard and damaged head of his, and he plunged into the heart of his adventure without bringing in Captain Bracewell and Margaret. Their fortunes were too personal and intimate to be lugged out for the diversion of strangers. Arthur Cochran followed the flight from the sailors' eating-house with the most breathless[Pg 75] attention, and when David wound up with his head against the iron post and a ship's fireman about to kick his brains out, his audience sighed:

"Is that all? Things never happen to me. I am not very strong, you know, and they sort of coddle me, and trot me around to health resorts like a set of china done up in cotton. It makes me tired. Tell me all about being a cadet."

David fairly ached to spin the yarn of the Pilgrim wreck, but the cruel nurse cut the visit short, and Arthur Cochran had to depart with the assurance that he would come back next day "to hear the rest of it."

He was true to his word and found David so much stronger that the unruly patient was sitting up in bed and loudly demanding his clothes. It was the patient's turn to ask questions this time, and he was eager to know all about the occupations of a millionaire's son. The heir of the Cochran fortune had to do most of the talking. David demanded to know all about his automobiles, his horses, and his yacht, his trips to Florida and California, his[Pg 76] private tutors, and his several homes among which he flitted to and fro like an uneasy bird. Before they realized how time had fled Mr. Cochran came to take Arthur home. The Trust magnate was in his usual hurry, and he volleyed these commands as if argument were out of the question:

"I have looked you up, Downes. The Black Star office speaks very well of you. Also the store in which you used to work. I sent a man out this morning. My boy has taken a great fancy to you. He seldom finds a boy he likes. I think it might do him good to have you around. I have told the people here that you are to be moved to my house to-night. You will stay there until you feel all right. If you wear well, and you are as capable as you look, I shall find something better for you to do than this dog's life at sea. Come along, Arthur. You shall see David this evening."

David's head was in a whirl. A gentleman who belonged in the "Arabian Nights" was bent upon kidnapping him. It seemed as rash to question the orders of this lordly parent as to disobey Captain Thrasher, but there[Pg 77] was a look of stubborn resolution in the suntanned jaw of the young sailor and he was not to be so easily driven. He wavered in silence for a minute or two while Mr. Stanley P. Cochran eyed him with rising impatience. Visions of an enchanted land of wealth and pleasure danced before David's eyes, but even more clearly he saw the appealing figures of Captain Bracewell and Margaret. They needed him and he had promised to go to them. He looked up and shook his head as he said with much feeling:

"I don't know what makes you so good to me, sir. I never heard anything like it. But I can't accept your invitation. I can never thank you enough, but I belong somewhere else."

"You have no kinfolk here. I found out all that," exclaimed Mr. Cochran with a very red face. "Why can't you do as I tell you? Of course you can. Not another word! Come along, Arthur."

"I mean it," cried David. "I promised to stay with friends I met on shipboard."

He wanted to tell him about these friends, but the manner of Mr. Cochran stifled [Pg 78]explanation. The magnate was not used to such astonishing rebellion, and it galled him the more because he felt that he was stooping to do an uncommonly good deed.