Title: Charles W. Quantrell

a true history of his guerrilla warfare on the Missouri and Kansas border during the Civil War of 1861 to 1865

Author: Harrison Trow

John P. Burch

Release date: January 4, 2020 [eBook #61100]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by deaurider and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

By JOHN P. BURCH

ILLUSTRATED

AS TOLD BY

CAPTAIN HARRISON TROW

ONE WHO FOLLOWED QUANTRELL THROUGH

HIS WHOLE COURSE

Copyright, 1923

By J. P. Burch

Vega Texas

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | 11 |

| The False Jonah | 13 |

| Early Life of Quantrell | 15 |

| Why the Quantrell Guerrillas Were Organized | 23 |

| Quantrell’s First Battle in the Civil War | 29 |

| Fight at Charles Younger’s Farm | 35 |

| Fight at Independence | 37 |

| Second Fight at Independence | 39 |

| Flanked Independence | 41 |

| Fight at Tate House | 43 |

| Fight at Clark’s Home | 51 |

| Jayhawkers and Militia Murdered Old Man Blythe’s Son | 59 |

| The Low House Fight | 63 |

| Quantrell and Todd Go After Ammunition | 69 |

| A Challenge | 73 |

| The Battle and Capture of Independence | 77 |

| Lone Jack Fight | 85 |

| The March South in 1862 | 97 |

| Younger Remains in Missouri Winter of 1862 and 1863 | 105 |

| The Trip North in 1863 | 121 |

| Jesse James Joins the Command | 131 |

| Lawrence Massacre | 141 |

| Order Number 11, August, 1863 | 155 |

| Fights and Skirmishes, Fall and Winter, 1863–1864 | 159 |

| Blue Springs Fight, 1863 | 163 |

| Wellington | 165 |

| The Grinter Fight | 171 |

| The Centralia Massacre | 175 |

| Anderson | 187 |

| Press Webb, a Born Scout | 193 |

| Little Blue | 205 |

| Arrock Fight, Spring of 1864 | 207 |

| Fire Bottom Prairie Fight, Spring of 1864 | 209 |

| Death of Todd and Anderson, October, 1864 | 213 |

| Going South, Fall of 1864 | 223 |

| The Surrender | 229 |

| Death of Quantrell | 237 |

| The Youngers and Jameses After the War | 253 |

Do not loan this book out to

neighbors and friends

If You Do You Will Never Get It Back

Keep it in your Library

When You Are Not Reading It

If You Want One Send to

J. P. BURCH, VEGA, TEXAS

And He Will Mail You One At Once

11

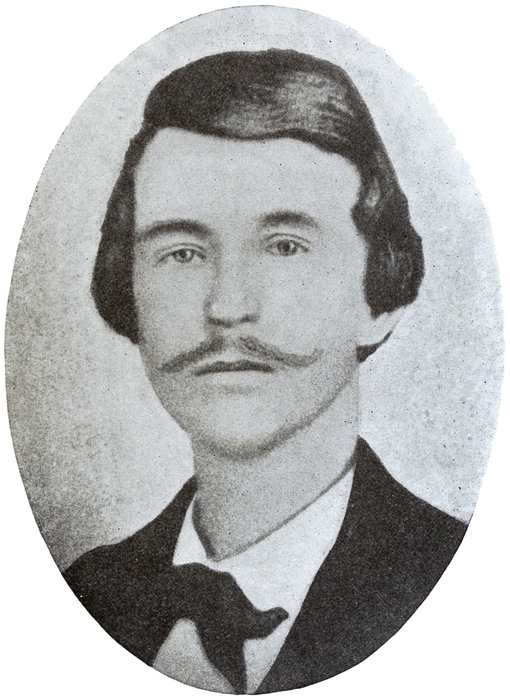

Captain Harrison Trow, who will be eighty years old this coming October, was with Quantrell during the whole of the conflict from 1861 to 1865, and for the past twenty years I have been at him to give his consent for me to write a true history of the Quantrell Band, until at last he has given it.

This narrative was written just as he told it to me, giving accounts of fights that he participated in, narrow escapes experienced, dilemmas it seemed almost impossible to get out of, and also other battles; the life of the James boys and Youngers as they were with Quantrell during the war, and after the war, when they became outlaws by publicity of the daily newspapers, being accused of things which they never did and which were laid at their feet.

Captain Trow identified Jesse James when the latter was killed at St. Joseph. He also was the last man to surrender in the State of Missouri.

John P. Burch.

12

Captain Harrison Trow was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, October 16, 1843, moved to Illinois in 1848, and thence to Missouri in 1850, and went to Hereford, Texas, in 1901, where he now resides. At the age of nine years, he, having one of the nicest, neatest and sweetest stepmothers (as they all are), and things not being as pleasant at home as they should be (which is often the case where there is a stepmother), and getting all the peach tree sprouts for the whole family used on him, he decided the world was too large for him to take such treatment, and one day he proceeded to give the stepmother a good flogging, such as he had been getting, and left for brighter fields.

In a few days he made his way to Independence, Missouri, got into a game of marbles, playing keeps, in front of a blacksmith shop, and won seventy-five cents. Then and there Uncle George Hudsbath rode up and wanted to hire a hand. Young Trow jumped at the job and talked to Mr. Hudsbath a few minutes and soon was up behind him and riding away to his new home. Young Trow proved to be the lad Uncle George was looking for and stayed with him until the war broke out.

13

Early in the year of 1861, about in January, Jim Lane sent a false Jonah down to Missouri to investigate the location of the negroes and stock, preparing to make a raid within a short time. This Jonah located first at Judge Gray’s house at Bone Hill, was fed by Judge Gray’s “niggers” and was secreted in an empty ice house where they kept ice in the summer time. He would come out in the night time and plan with the “niggers” for their escape into Kansas with the horses, buggies and carriages and other valuables belonging to their master that they could get possession of. But an old negro woman, old Maria by name, gave the Jonah away.

Chat Rennick, one of the neighbors, and two other men secreted themselves in the negroes’ cabin so as to hear what he was telling the negroes. After he had made all his plans for their escape Chat Rennick came out on him with the other two men and took him prisoner and started north to the Missouri River. Securing a skiff, they floated out into the river and when in about the center there came up a heavy gale, and one of these gentlemen thought it best to unload part of the cargo, so he was thrown overboard. As for the negroes, they repented in sack cloth and ashes and all stayed at home and took care of their master and mistress, as Jonah did in the olden times. As for the14 Jonah, I do not know whether the fish swallowed him or not, but if one did he did not get sick and throw him up. This took place at my wife’s uncle’s home, Judge James Gray.

15

The early life of Quantrell was obscure and uneventful. He was born near Hagerstown, Maryland, July 20, 1836, and was reared there until he was sixteen years of age. He remained always an obedient and affectionate son. His mother had been left a widow when he was only a few years old.

For some time preceding 1857, Quantrell’s only brother lived in Kansas. He wrote to his younger brother, Charles, to come there, and after his arrival they decided on a trip to California. About the middle of the summer of 1857 the two started for California with a freight outfit. Upon reaching Little Cottonwood River, Kansas, they decided to camp for the night. This they did. All was going well. After supper twenty-one outlaws, or Redlegs, belonging to Jim Lane at Lawrence, Kansas, rode up and killed the elder brother, wounded Charles, and took everything in sight, money, and even the “nigger” who went with them to do the cooking. They thought more of the d——d “nigger” than they did of all the rest of the loot. They left poor Charles there to die and be eaten later by wolves or some other wild animal that might come that way. Poor Charles lay there for three days before anyone happened by, guarding his dead brother, suffering near death from his wounds. After three days an old Shawnee Indian named Spye Buck came along,16 buried the elder brother and took Charles to his home and nursed him back to life and strength. After six months to a year Charles Quantrell was able to go at ease, and having a good education for those days, got a school and taught until he had earned enough money to pay the old Indian for keeping him while he was sick and to get him to Lawrence. He reached Lawrence and went to where Jim Lane was stationed with his company. He wanted to get into the company that murdered his brother and wounded himself. After a few days he was taken in and, from outward appearance, he became a full-fledged Redleg, but in his heart he was doing this only to seek revenge on those who had killed his brother and wounded him at Cottonwood, Kansas.

Quantrell, now known as Charles Hart, became intimate with Lane and ostensibly attached himself to the fortunes of the anti-slavery party. In order to attain his object and get a step nearer his goal, it became necessary for him to speak of John Brown. He always spoke of him to General Lane, who was at that time Colonel Lane, in command of a regiment at Lawrence, as one for whom he had great admiration. Quantrell became enrolled in a company that held all but two of the men who had done the deadly work at Cottonwood, Kansas. First as a private, then as an orderly and sergeant, Quantrell soon gained the esteem of his officers and the confidence of his men.

17 One day Quantrell and three men were sent down in the neighborhood of Wyandotte to meet a wagon load of “niggers” coming up to Missouri under the pilotage of Jack Winn, a somewhat noted horse thief and abolutionist. One of the three men failed to return with Quantrell, nor could any account be given of his absence until his body was found near a creek several days afterwards. In the center of his forehead was the round, smooth hole of a navy revolver bullet. Those who looked for Jack Winn’s safe arrival were also disappointed. People traveling the road passed the corpse almost daily and the buzzards found it first, and afterwards the curious. There was the same round hole in the forehead and the same sure mark of the navy revolver bullet. This thing went on for several months, scarcely a week passing but that some sentinel was found dead at his post, some advance picket surprised and shot at his outpost watch station.

The men began to whisper, one to another, and to cast about for the cavalry Jonah who was in their midst. One company alone, that of Captain Pickins, the company to which Quantrell belonged, had lost thirteen men between October, 1859 and 1860. Other companies had lost two to three each. A railroad conductor named Rogers had been shot through the forehead. Quantrell and Pickens became intimate, as a captain and lieutenant of the same company should, and confided many things to each other. One night the story of the Cottonwood18 River was told and Pickens dwelt with just a little relish upon it. Three days later Pickens and two of his most reliable men were found dead on Bull Creek, shot like the balance, in the middle of the forehead. For a time after Pickens’ death there was a lull in the constant conscription demanded by the Nemesis. The new lieutenant bought himself a splendid uniform, owned the best horse in the territory and instead of one navy revolver, now had two. Organizations of all sorts now sprang up, Free Soil clubs, Men of Equal Rights, Sons of Liberty, Destroying Angels, Lane’s Loyal Leaguers, and everyone made haste to get his name signed to both constitution and by-laws.

Lawrence especially effected the Liberator Club, whose undivided mission was to found freedom for all the slaves now in Missouri.

Quantrell persevered in his efforts to kill all of the men who had had a hand in the killing of his brother and the wounding of himself. With this in view, he induced seven Liberators to co-operate with him in an attack on Morgan Walker. These seven men whom Quantrell picked were the last except two of the men he had sworn vengeance upon when left to die at Cottonwood River, Kansas. He told them that Morgan Walker had a lot of “niggers,” horses and cattle and money and that the sole purpose was to rob and kill him. Quantrell’s only aim was to get these seven men. Morgan Walker was an old citizen of Jackson County,19 a venerable pioneer who had settled there when buffalo grazed on the prairie beyond Westport and where, in the soft sands beyond the inland streams, there were wolf and moccasin tracks. This man, Morgan Walker, was the man Quantrell had proposed to rob. He lived some five or six miles from Independence and owned about twenty negroes of various ages and sizes. The probabilities were that a skillfully conducted raid might leave him without a “nigger.”

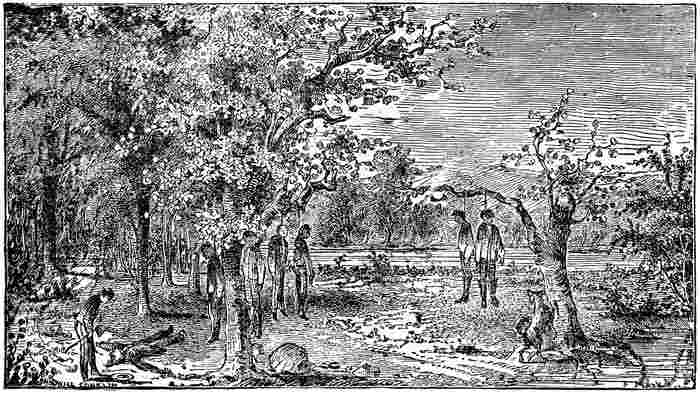

Well mounted and armed, the little detachment left Lawrence quietly, rode two by two, far apart, until the first rendezvous was reached, a clump of timber at a ford on Indian Creek. It was the evening of the second day, and they tarried long enough to rest their horses and eat a hearty supper.

Before daylight the next morning the entire party were hidden in some heavy timber about two miles west of Walker’s house. There these seven men stayed, none of them stirring, except Quantrell. Several times during the day, however, he went backwards and forwards, apparently to the fields where the negroes were at work, and whenever he returned he brought something either for the horses or the men to eat.

Mr. Walker had two sons, and before it was yet night, these boys and their father were seen putting into excellent order their double-barrel shotguns, and a little later three neighbors who likewise carried double-barrel shotguns rode up to the house. Quantrell,20 who brought news of many other things to his comrades, brought no note of this. If he saw it he made no sign. When Quantrell arranged his men for the dangerous venture they were to proceed, first to the house, gain access to it, capture all the male members of the family and put them under guard, assemble all the negroes and make them hitch up the horses to the wagons and then gallop them for Kansas. Fifty yards from the gate the eight men dismounted and fastened their horses, and the march to the house began. Quantrell led. He was very cool and seemed to see everything. The balance of his men had their revolvers in their hands while he had his in his belt. Quantrell knocked loudly at the oaken panel of the door. No answer. He knocked again and stood perceptibly at one side. Suddenly the door flared open and Quantrell leaped into the hall with a bound like a red deer. A livid sheet of flame burst out through the darkness where he had disappeared, followed by another as the second barrels of the guns were discharged and the tragedy was over. Six fell where they stood, riddled with buckshot. One staggered to the garden and died there. The seventh, hard hit and unable to mount his horse, dragged himself to a patch of timber and waited for the dawn. They tracked him by the blood upon the leaves and found him early in the morning. Another volley, and the last Liberator was liberated.

21 Walker and his two sons, assisted by three of the stalwart and obliging neighbors, had done a clean night’s work, and a righteous one. This being the last of the Redlegs, except two, who murdered Quantrell’s brother and wounded him in Cottonwood, Kansas, in 1857, he closed his eyes and ears from ever being a scout for old Jim Lane any more.

In a few days after the ambuscade at Walker’s, Charles W. Quantrell, instead of Charles Hart, as he was known, then was not afraid to tell his name on Missouri soil. He wrote to Jim Lane, telling him what had happened to the scouts sent out by him, and as the war was on then, Quantrell told Lane in his letter that he was going to Richmond, Virginia, to get a commission from under Jeff Davis’ own hand, which he did (as you will read further on in this narrative), to operate on the border at will. So Quantrell, being fully equipped with all credentials, notified Jim Lane of Missouri, telling him he would treat him with the same or better courtesy than he (Lane) had treated him and his brother at Cottonwood River, Kansas, in 1857. This made Jim Lane mad, and he began to send his roving, robbing, and thieving bands into Missouri, and Charles W. Quantrell, having a band of well organized guerrillas of about fifty men, began to play on their golden harps. Every time they came in sight, which was almost every day, they would have a fight to the finish.

23

It all came about from the Redlegs or Kansas Jayhawkers. For two years Kansas hated Missouri and at all times during these two years there were Redlegs from old Jim Lane’s army crossing to Missouri, stealing everything they could get their hands on, driving stock, insulting innocent women and children, and hanging and killing old men; so it is the province of history to deal with results, not to condemn the phenomena which produce them. Nor has it the right to decry the instruments Providence always raises up in the midst of great catastrophes to restore the equilibrium of eternal justice. Civil War might well have made the Guerrilla, but only the excesses of civil war could have made him the untamable and unmerciful creature that history finds him. When he first went into the war he was somewhat imbued with the old-fashioned belief that soldiering meant fighting and that fighting meant killing. He had his own ideas of soldiering, however, and desired nothing so much as to remain at home and meet its despoilers upon his own premises. Not naturally cruel, and averse to invading the territory of any other people, he could not understand the patriotism of those who invaded his own territory. Patriotism, such as he was required to profess, could not spring up in the market place at24 the bidding of Redleg or Jayhawker. He believed, indeed, that the patriotism of Jim Lane and Jennison was merely a highway robbery transferred from the darkness to the dawn, and he believed the truth. Neither did the Guerrilla become merciless all of a sudden. Pastoral in many cases by profession, and reared among the bashful and timid surroundings of agricultural life, he knew nothing of the tiger that was in him until death had been dashed against his eyes in numberless and brutal ways, and until the blood of his own kith and kin had been sprinkled plentifully upon things that his hands touched, and things that entered into his daily existence. And that fury of ideas also came to him slowly, which is more implacable than the fury of men, for men have heart, and opinion has none. It took him likewise some time to learn that the Jayhawkers’ system of saving the Union was a system of brutal force, which bewailed not even that which it crushed; and it belied its doctrine by its tyranny, stained its arrogated right by its violence, and dishonored its vaunted struggles by its executions. But blood is as contagious as air. The fever of civil war has its delirium.

When the Guerrilla awoke he was a giant! He took in, as it were, and at a single glance, all the immensity of the struggle. He saw that he was hunted and proscribed; that he had neither a flag nor a government; that the rights and the amenities of civilized warfare were not to be his; that a25 dog’s death was certain to be his if he surrendered even in the extremest agony of battle; that the house which sheltered him had to be burned; the father who succored him had to be butchered; the mother who prayed for him had to be insulted; the sister who carried him food had to be imprisoned; the neighborhood which witnessed his combats had to be laid waste; the comrade shot down by his side had to be put to death as a wild beast—and he lifted up the black flag in self-defense and fought as became a free man and a hero.

Much obloquy has been cast upon the Guerrilla organization because in its name bad men plundered the helpless, pillaged the friend and foe alike, assaulted non-combatants and murdered the unresisting and the innocent. Such devils’ work was not Guerrilla work. It fitted all too well the hands of those cowards crouching in the rear of either army and courageous only where women defended what remained to themselves and their children. Desperate and remorseless as he undoubtedly was, the Guerrilla saw shining upon his pathway a luminous patriotism, and he followed it eagerly that he might kill in the name of God and his country. The nature of his warfare made him responsible, of course, for many monstrous things he had no personal share in bringing about. Denied a hearing at the bar of public opinion, of all the loyal journalists, painted blacker than ten devils, and given a countenance that was made to retain some shadow of all26 the death agonies he had seen, is it strange in the least that his fiendishness became omnipresent as well as omnipotent? To justify one crime on the part of a Federal soldier, five crimes more cruel were laid at the door of the Guerrilla. His long gallop not only tired, but infuriated his hunters. That savage standing at bay and dying always as a wolf dies when barked at by hounds and dudgeoned by countrymen, made his enemies fear and hate him. Hence, from all their bomb-proofs his slanderers fired silly lies at long range, and put afloat unnatural stories that hurt him only as it deepened the savage intensity of an already savage strife. Save in rare and memorable instances, the Guerrilla murdered only when fortune in open and honorable battle gave into his hands some victims who were denied that death in combat which they afterward found by ditch or lonesome roadside. Man for man, he put his life fairly on the cast of the war dice, and died when the need came as the red Indian dies, stoical and grim as a stone.

As strange as it may seem, the perilous fascination of fighting under a black flag—where the wounded could have neither surgeon nor hospital, and where all that remained to the prisoners was the absolute certainty of speedy death—attracted a number of young men to the various Guerrilla bands, gently nurtured, born to higher destinies, capable of sustaining exertion in any scheme or enterprise, and fit for callings high27 up in the scale of science or philosophy. Others came who had deadly wrongs to avenge, and these gave to all their combats that sanguinary hue which still remains a part of the Guerrilla’s legacy. Almost from the first a large majority of Quantrell’s original command had over them the shadow of some terrible crime. This one recalled a father murdered, this one a brother waylaid and shot, this one a house pillaged and burned, this one a relative assassinated, this one a grievous insult while at peace at home, this one a robbery of all his earthly possessions, this one the force that compelled him to witness the brutal treatment of a mother or sister, this one was driven away from his own like a thief in the night, this one was threatened with death for opinion’s sake, this one was proscribed at the instance of some designing neighbor, this one was arrested wantonly and forced to do the degrading work of a menial; while all had more or less of wrath laid up against the day when they were to meet, face to face and hand to hand, those whom they had good cause to regard as the living embodiment of unnumbered wrongs. Honorable soldiers in the Confederate army—amenable to every generous impulse and exact in the performance of every manly duty—deserted even the ranks which they had adorned and became desperate Guerillas because the home they had left had been given to the flames, or a gray-haired father shot upon his own hearthstone. They wanted to avoid28 the uncertainty of regular battle and know by actual results how many died as a propitation or a sacrifice. Every other passion became subsidiary to that of revenge. They sought personal encounters that their own handiwork might become unmistakably manifest. Those who died by other agencies than their own were not counted in the general summing up of the fight, nor were the solacements of any victory sweet to them unless they had the knowledge of being important factors in its achievement.

As this class of Guerrilla increased, the warfare of the border became necessarily more cruel and unsparing. Where at first there was only killing in ordinary battle, there came to be no quarter shown. The wounded of the enemy next felt the might of this individual vengeance—acting through a community of bitter memories—and from every stricken field there began, by and by, to come up the substance of this awful bulletin: Dead, such and such a number; wounded, none. The war had then passed into its fever heat, and thereafter the gentle and the merciful, equally with the harsh and the revengeful, spared nothing clad in blue that could be captured.

29

Quantrell, together with Captain Blunt, returned from Richmond, Virginia, in the fall of 1861, with his commission from under the hand of Jeff Davis, to operate at will along the Kansas border. He began to organize his band of Guerrillas. His first exploits were confined to but eight men. These eight men were William Haller, James and John Little, Edward Koger, Andrew Walker, son of Morgan Walker, at whose farm Quantrell got rid of the last but two of the band that murdered his brother at Cottonwood River, Kansas, and left himself to die; John Hampton James Kelley and Solomon Bashman.

This little band knew nothing whatever of war, and knew only how to fight and shoot. They lived on the border and had some old scores to settle with the Jayhawkers.

These eight men, or rather nine—for Quantrell commanded—encountered their first hereditary enemies, the Jayhawkers. Lane entered Missouri only on grand occasions; Jennison only once in a while as on a frolic. One was a collossal thief; the other a picayune one. Lane dealt in mules by herds, horses by droves, wagons by parks, negroes by neighborhoods, household effects by the ton, and miscellaneous plunder by the cityful; Jennison contented himself with the pocketbooks of his prisoners, the pin money of the30 women, and the wearing apparel of the children. Lane was a real prophet of demagogism, with insanity latent in his blood; Jennison a sans coulotte, who, looking upon himself as a bastard, sought to become legitimate by becoming brutal.

It was in the vicinity of Morgan Walker’s that Quantrell, with his little command, ambushed a portion of Jennison’s regiment and killed five of his thieves, getting some good horses, saddles and bridles and revolvers. The next fight occurred upon the premises of Volney Ryan, a citizen of Jackson County, with a company of Missouri militia, a company of militia notorious for three things—robbing hen roosts, stealing horses, and running away from the enemy. The eight Guerrillas struck them just at daylight, charged through it, charged back again, and when they returned from the pursuit they counted fifteen dead, the fruits of a running battle.

An old man by the name of Searcy, claiming to be a Southern man, was stealing all over Jackson County and using violence here and there when he could not succeed through persuasion. Quantrell swooped down upon him one afternoon, tried him that night and hanged him the next morning, four Guerrillas dragging on the rope. Seventy-five head of horses were found in the dead man’s possession, all belonging to the citizens of the county, and any number of deeds to small tracts of land, notes and mortgages, and private31 accounts. All were returned. The execution acted as a thunder-storm. It restored the equilibrium of the moral atmosphere. The border warfare had found a chief.

The eight Guerrillas had now grown to fifty. Among the new recruits were David Poole, John Jarrette, William Coger, Richard Burns, George Todd, George Shephers, Coleman Younger, myself and several others of like enterprise and daring. An organization was at once effected, and Quantrell was made captain; William Haller, first lieutenant; William Gregg, second; George Todd, third, and John Jarrette, orderly sergeant. The eagles were beginning to congregate.

Poole, an unschooled Aristophanes of the Civil War, laughed at calamity, and mocked when any man’s fear came. But for its picturesqueness, his speech would have been comedy personified. He laughed loudest when he was deadliest, and treated fortune with no more dignity in one extreme than in another. Gregg, a grim Saul among the Guerrillas, made of the Confederacy a mistress, and like the Douglass of old, was ever tender and true to her. Jarrette, the man who never knew fear, added to fearlessness and immense activity an indomitable will. He was a soldier in the saddle par excellence. John Coger never missed a battle nor a bullet. Wounded thirteen times, he lived as an exemplification of what a Guerrilla could endure—the amount of lead he could comfortably get along32 with and keep fat. Steadfastness was his test of merit—comradeship his point of honor. He who had John Coger at his back had a mountain. Todd was the incarnate devil of battle. He thought of fighting when awake, dreamed of it at night, mingled talk of it in laxation, and went hungry many a day and shelterless many a night that he might find his enemy and have his fill of fight. Quantrell always had to hold him back, and yet he was his thunderbolt. He discussed nothing in the shape of orders. A soldier who discusses is like a hand which would think. He only charged. Were he attacked in front—a charge; were he attacked in the rear—a charge; on either flank—a charge. Finally, in a desperate charge, and doing a hero’s work upon the stricken rear of the Second Colorado, he was killed. This was George Todd. Shepherd, a patient, cool, vigilant leader, knew all the roads and streams, all the fords and passes, all modes of egress and ingress, all safe and dangerous places, all the treacherous non-combatants, and all the trustworthy ones—everything indeed that the few needed to know who were fighting the many. In addition, there were few among the Guerrillas who were better pistol shots. It used to do Quantrell good to see him in the skirmish line. Coleman Younger, a boy having still about his neck the purple marks of a rope made the night when the Jayhawkers shot down his old father and strung him up to a blackjack, spoke rarely, and33 was away a great deal in the woods. “What was he doing?” his companions began to ask one of another. He had a mission to perform—he was pistol practicing. Soon he was perfect, and then he laughed often and talked a good deal. There had come to him now that intrepid gaiety that plays with death. He changed devotion to his family into devotion to his country, and he fought and killed with the conscience of a hero.

35

The new organization was about to be baptized. Burris, raiding generally along the Missouri border, had a detachment foraging in the neighborhood of Charles Younger’s farm. This Charles Younger was an uncle of Coleman, and he lived within three miles of Independence, Missouri, the county seat of Jackson County. The militia detachment numbered eighty-four and the Guerrillas thirty-two. At sunset Quantrell struck their camp. Forewarned of his coming, they were already in line. One volley settled them. Five fell at the first fire and seven more were killed in the chase. The shelter of Independence alone, where the balance of the regiment was as a breakwater saved the detachment from utter extinction. On this day—the 10th of November, 1861—Cole Younger killed a militiaman seventy-one measured yards. The pistol practice was bearing fruit.

Independence was essentially a city of fruits and flowers. About every house there was a parterre and contiguous to every parterre there was an orchard. Built where the woods and the prairies met, when it was most desirable there was sunlight, and when it was most needed there was shade. The war found it rich, prosperous and contented, and it left it as an orange that had been devoured. Lane hated it because it was a hive of secession, and Jennison preyed upon36 it because Guerrilla bees flew in and out. On one side the devil, on the other the deep sea. Patriotism, that it might not be tempted, ran the risk very often of being drowned. Something also of Spanish intercourse and connection belonged to it. Its square was a plaza; its streets centered there; its courthouse was a citadel. Truer people never occupied a town; braver fathers never sent their sons to war; grander matrons never prayed to God for right, and purer women never waited through it all—the siege, the sack, the pillage and the battle—for the light to break in the East at last, the end to come in fate’s own good and appointed time.

37

Quantrell had great admiration for Independence; his men adored it. Burris’ regiment was still there—fortified in the courthouse—and one day in February, 1862, the Guerrillas charged the town. It was a desperate assault. Quantrell and Poole dashed down one street. Cole Younger and Todd down another, Gregg and Shepherd down a third, Haller, Coger, Burns, Walker and others down the balance of the approaches to the square. Behind heavy brick walls the militia, of course, fought and fought, besides, at a great advantage. Save seven surprised in the first moments of the rapid onset and shot down, none others were killed, and Quantrell was forced to retire from the town, taking some necessary ordnance, quartermaster and commissary supplies from the stores under the very guns of the courthouse. None of his men were killed, though as many as eleven were wounded. This was the initiation of Independence into the mysteries as well as the miseries of border warfare, and thereafter and without a month of cessation, it was to get darker and darker for the beautiful town.

Swinging back past Independence from the east the day after it had been charged, Quantrell moved up in the neighborhood of Westport and put scouts upon the roads leading to Kansas City. Two officers belonging to Jennison’s regiment were picked up—a lieutenant,38 who was young, and a captain, who was of middle age. They had only time to pray. Quantrell always gave time for this, and had always performed to the letter the last commissions left by those who were doomed. The lieutenant did not want to pray. “It could do no good,” he said. “God knew about as much concerning the disposition it was intended to be made of his soul as he could suggest to him.” The captain took a quarter of an hour to make his peace. Both were shot. Men commonly die at God’s appointed time, beset by Guerrillas, suddenly and unawares. Another of the horrible surprises of Civil War.

At first, and because of Quantrell’s presence, Kansas City swarmed like an ant hill during a rainstorm; afterwards, and when the dead officers were carried in, like a firebrand had been cast thereon.

39

While at the house of Charles Cowherd, a courier came up with the information that Independence, which had not been garrisoned for some little time, was again in possession of a company of militia. Another attack was resolved upon. On the night of February 20, 1862, Quantrell marched to the vicinity of the town and waited there for daylight. The first few faint streaks in the East constituted the signal. There was a dash altogether down South Main Street, a storm of cheers and bullets, a roar of iron feet on the rocks of the roadway, and the surprise was left to work itself out. It did, and reversely. Instead of the one company reported in possession of the town, four were found, numbering three hundred men. They manned the courthouse in a moment, made of its doors an eruption and of its windows a tempest, killed a noble Guerrilla, young George, shot Quantrell’s horse from under him, held their own everywhere and held the fort. As before, all who were killed among the Federals, and they lost seventeen, were those killed in the first few moments of the charge. Those who hurried alive into the courthouse were safe. Young George, dead in his first battle, had all the promise of a bright career. None rode further nor faster in the charge, and when he fell he fell so close to the fence about the fortified building that it was with difficulty his comrades took40 his body out from under a point blank fire and bore it off in safety.

It was a part of Quantrell’s tactics to disband every now and then. “Scattered soldiers,” he argued, “make a scattered trail. The regiment that has but one man to hunt can never find him.” The men needed heavier clothing and better horses, and the winter, more than ordinarily severe, was beginning to tell. A heavy Federal force was also concentrating in Kansas City, ostensibly to do service along the Missouri River, but really to drive out of Jackson County a Guerrilla band that under no circumstances at that time could possibly have numbered over fifty. Quantrell, therefore, for an accumulation of reasons, ordered a brief disbandment. It had hardly been accomplished before Independence swapped a witch for a devil. Burris evacuated the town; Jennison occupied it. In his regiment were trappers who trapped for dry goods; fishermen who fished for groceries. At night passers-by were robbed of their pocketbooks; in the morning, market women of their meat baskets. Neither wiser, perhaps, nor better than the Egyptians, the patient and all-suffering citizens had got rid of the lean kine in order to make room for the lice.

41

At the appointed time, and at the place of David George, the assembling was as it should be. Quantrell meant to attack Jennison in Independence and destroy him if possible, and so moved in that direction as far as Little Blue Church. Here he met Allen Parmer, a regular red Indian of a scout, who never forgot to count a column or know the line of march of an enemy, and Parmer reported that instead of three hundred Jayhawkers being in Independence there were six hundred. Too many for thirty-two men to grapple, and fortified at that, they all said. It would be murder in the first degree and unnecessary murder in addition. Quantrell, foregoing with a struggle the chance to get at his old acquaintance of Kansas, flanked Independence and stopped for a night at the residence of Zan Harris, a true Southern man and a keen observer of passing events. Early the next morning he crossed the Big Blue at the bridge on the main road to Kansas City, surprised and shot down a detachment of thirteen Federals watching it, burned the structure to the water, and marched rapidly on in a southwest direction, leaving Westport to the right. At noon the command was at the residence of Alexander Majors.

43

After the meal at Major’s Quantrell resumed his march, sending Haller and Todd ahead with an advance guard and bringing up the rear himself with the main body of twenty-two men. Night overtook him at the Tate House, three miles east of Little Santa Fe, a small town in Jackson County, close to the Kansas line, and he camped there. Haller and Todd were still further along, no communication being established between these two parts of a common whole. The day had been cold and the darkness bitter. That weariness that comes with a hard ride, a rousing fire, and a hearty supper, fell early upon the Guerrillas. One sentinel at the gate kept drowsy watch, and the night began to deepen. In various attitudes and in various places, twenty-one of the twenty-two men were sound asleep, the twenty-second keeping watch and ward at the gate in freezing weather.

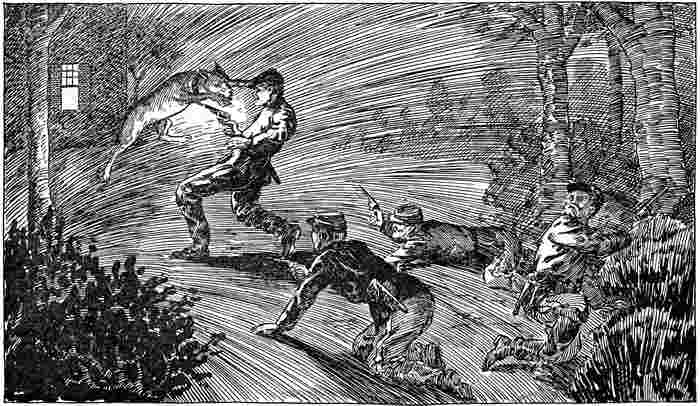

It was just twelve o’clock and the fire in the capacious fireplace was burning low. Suddenly a shout was heard. The well known challenge of “Who are you?” arose on the night air, followed by a pistol shot, and then a volley. Quantrell, sleeping always like a cat, shook himself loose from his blankets and stood erect in the glare of the firelight. Three hundred Federals, following all day on his trail, had marked him take cover at night and went to bag him, boots and breeches. They had44 hitched their horses back in the brush and stole upon the dwelling afoot. So noiseless had been their advance, and so close were they upon the sentinel before they were discovered, that he had only time to cry out, fire, and rush for the timber. He could not get back to his comrades, for some Federals were between him and the door. As he ran he received a volley, but in the darkness he escaped.

The house was surrounded. To the men withinside this meant, unless they could get out, death by fire and sword. Quantrell was trapped, he who had been accorded the fox’s cunning and the panther’s activity. He glided to the window and looked out cautiously. The cold stars above shone, and the blue figures under them and on every hand seemed colossal. The fist of a heavy man struck the door hard, and a deep voice commanded, “Make a light.” There had been no firing as yet, save the shot of the sentinel and its answering volley. Quantrell went quietly to all who were still asleep and bade them get up and get ready. It was the moment when death had to be looked in the face. Not a word was spoken. The heavy fist was still hammering at the door. Quantrell crept to it on tip-toe, listened a second at the sounds outside and fired. “Oh,” and a stalwart Federal fell prone across the porch, dying. “You asked for a light and you got it, d——n you,” Quantrell ejaculated, cooler than his pistol barrel. Afterwards there was no more45 bravado. “Bar the doors and barricade the windows,” he shouted; “quick, men!” Beds were freely used and applicable furniture. Little and Shepherd stood by one door; Jarrette, Younger, Toler and Hoy barricaded the other and made the windows bullet-proof. Outside the Federal fusilade was incessant. Mistaking Tate’s house for a frame house, when it was built of brick, the commander of the enemy could be heard encouraging his men to shoot low and riddle the building. Presently there was a lull, neither party firing for the space of several minutes, and Quantrell spoke to his people: “Boys, we are in a tight place. We can’t stay here, and I do not mean to surrender. All who want to follow me out can say so. I will do the best I can for them.” Four concluded to appeal to the Federals for protection; seventeen to follow Quantrell to the death. He called a parley, and informed the Federal commander that four of his followers wanted to surrender. “Let them come out,” was the order. Out they went, and the fight began again. Too eager to see what manner of men their prisoners were, the Federals holding the west side of the house huddled about them eagerly. Ten Guerrillas from the upper story fired at the crowd and brought down six. A roar followed this, and a rush back again to cover at the double quick. It was hot work now. Quantrell, supported by James Little, Cole Younger, Hoy and Stephen Shores held the upper story, while Jarrette,46 Toler, George Shepherd and others held the lower. Every shot told. The proprietor of the house, Major Tate, was a Southern hero, gray-headed, but Roman. He went about laughing. “Help me get my family out, boys,” he said, “and I will help you hold the house. It’s about as good a time for me to die, I reckon, as any other, if so be that God wills it. But the old woman is only a woman.” Another parley. Would the Federal officer let the women and children out? Yes, gladly, and the old man, too. There was eagerness for this, and much of veritable cunning. The family occupied an ell of the mansion with which there was no communication from the main building where Quantrell and his men were, save by way of a door which opened upon a porch, and this porch was under the concentrating fire of the assailants. After the family moved out the attacking party would throw skirmishers in and then—the torch. Quantrell understood it in a moment and spoke up to the father of the family: “Go out, Major. It is your duty to be with your wife and children.” The old man went, protesting. Perhaps for forty years the blood had not coursed so rapidly and so pleasantly through his veins. Giving ample time for the family to get safely beyond the range of the fire of the besieged, Quantrell went back to his post and looked out. He saw two Federals standing together beyond revolver range. “Is there a shotgun here?” he asked. Cole Younger brought him one47 loaded with buckshot. Thrusting half his body out the nearest window, and receiving as many volleys as there were sentinels, he fired the two barrels of his gun so near together that they sounded as one barrel. Both Federals fell, one dead, the other mortally wounded. Following this daring and conspicuous feat there went up a yell so piercing and exultant that even the horses, hitched in the timber fifty yards away, reared in their fright and snorted in terror. Black columns of smoke blew past the windows where the Guerrillas were, and a bright red flame leaped up towards the sky on the wings of the wind. The ell of the house had been fired and was burning fiercely. Quantrell’s face—just a little paler than usual—had a set look that was not good to see. The tiger was at bay. Many of the men’s revolvers were empty, and in order to gain time to reload them, another parley was held. The talk was of surrender. The Federal commander demanded immediate submission, and Shepherd, with a voice heard above the rage and the roar of the flames, pleaded for twenty minutes. No. Ten? No. Five? No. Then the commander cried out in a voice not a whit inferior to Shepherd’s in compass: “You have one minute. If, at its expiration, you have not surrendered, not a single man among you shall escape alive.” “Thank you,” said Cole Younger, soto voce, “catching comes before hanging.” “Count sixty, then, and be d——d to you”! Shepherd shouted as a parting48 volley, and then a strange silence fell upon all these desperate men face to face with imminent death. When every man was ready, Quantrell said briefly, “Shot guns to the front.” Six loaded heavily with buck shot, were borne there, and he put himself at the head of the six men who carried them. Behind these those having only revolvers. In single file, the charging column was formed in the main room of the building. The glare of the burning ell lit it up as though the sun was shining there. Some tightened their pistol belts. One fell upon his knees and prayed. Nobody scoffed at him, for God was in that room. He is everywhere when heroes confess. There were seventeen about to receive the fire of three hundred.

Ready! Quantrell flung the door wide open and leaped out. The shotgun men—Jarrette, Younger, Shepherd, Toler, Little and Hoy, were hard behind him. Right and left from the thin short column a fierce fire beat into the very faces of the Federals, who recoiled in some confusion, shooting, however, from every side. There was a yell and a grand rush, and when the end had come and all the fixed realities figured up, the enemy had eighteen killed, twenty-nine badly wounded; and five prisoners, and the captured horses of the Guerrillas. Not a man of Quantrell’s band was touched, as it broke through the cordon on the south of the house and gained the sheltering timber beyond. Hoy, as he rushed out the third from Quantrell49 and fired both barrels of his gun, was so near to a stalwart Federal that he knocked him over the head with a musket and rendered him senseless. To capture him afterwards was like capturing a dead man. But little pursuit was attempted. Quantrell halted at the timber, built a fire, reloaded every gun and pistol, and took a philosophical view of the situation. Enemies were all about him. He had lost five men—four of whom, however, he was glad to get rid of—and the balance were afoot. Patience! He had just escaped from an environment sterner than any yet spread for him, and fortune was not apt to offset one splendid action by another exactly opposite. Choosing, therefore, a rendezvous upon the head waters of the Little Blue, another historic stream of Jackson County, he reached the residence of David Wilson late the next morning, after a forced march of great exhaustion. The balance of the night, however, had still to be one of surprises and counter-surprises, not alone to the Federals, but to the other portion of Quantrell’s command under Haller and Todd.

Encamped four miles south of Tate House, the battle there had roused them instantly. Getting to saddle quickly, they were galloping back to the help of their comrades when a Federal force, one hundred strong, met them full in the road. Some minutes of savage fighting ensued, but Haller could not hold his own with thirteen men, and he retreated, firing, to the brush.

50 Afterwards everything was made plain. The four men who surrendered so abjectly at the Tate house imagined that it would bring help to their condition if they told all they knew, and they told without solicitation the story of Haller’s advance and the whereabouts of his camp. A hundred men were instantly dispatched to surprise it or storm it, but the firing had roused the isolated Guerrillas, and they got out in safety after a rattling fight of some twenty minutes.

51

In April, 1862, Quantrell, with seventeen men, was camped at the residence of Samuel Clark, situated three miles southeast of Stony Point, in Jackson County. He had spent the night there and was waiting for breakfast the next morning when Captain Peabody, at the head of one hundred Federal cavalry, surprised the Guerrillas and came on at the charge, shooting and yelling. Instantly dividing the detachment in order that the position might be effectively held, Quantrell, with nine men, took the dwelling, and Gregg, with eight, occupied the smoke house. For a while the fighting was at long range, Peabody holding tenaciously to the timber in front of Clark’s, distant about one hundred yards, and refusing to come out. Presently, however, he did an unsoldierly thing—or rather an unskillful thing—he mounted his men and forced them to charge the dwelling on horseback. Quantrell’s detachment reserved fire until the foremost horseman was within thirty feet, and Gregg permitted those operating against his position, to come even closer. Then, a quick, sure volley, and twenty-seven men and horses went down together. Badly demoralized, but in no manner defeated, Peabody rallied again in the timber, while Quantrell, breaking out from the dwelling house and gathering up Gregg as he went,52 charged the Federals fiercely in return and with something of success. The impetus of the rush carried him past a portion of the Federal line, where some of their horses were hitched, and the return of the wave brought with it nine valuable animals. It was over the horses that Andrew Blunt had a hand-to-hand fight with a splendid Federal trooper. Both were very brave.

Blunt had just joined. No one knew his history. He asked no questions and he answered none. Some said he had once belonged to the cavalry of the regular army; others, that behind the terrible record of the Guerrillas he wished to find isolation. Singling out a fine sorrel horse from among the number fastened in his front, Blunt was just about to unhitch him when a Federal trooper, superbly mounted, dashed down to the line and fired and missed. Blunt left his position by the side of the horse and strode out into the open, accepting the challenge defiantly, and closed with his antagonist. The first time he fired he missed, although many men believed him a better shot than Quantrell. The Federal sat on his horse calmly and fired the second shot deliberately and again missed. Blunt went four paces toward him, took a quick aim and fired very much as a man would at something running. Out of the Federal’s blue overcoat a little jet of dust spurted up and he reeled in his seat. The man, hit hard in the breast, did not fall, however. He gripped his saddle with his knees, cavalry fashion,53 steadied himself in his stirrups and fired three times at Blunt in quick succession. They were now but twenty paces apart, and the Guerrilla was shortening the distance. When at ten he fired his third shot. The heavy dragoon ball struck the gallant Federal fair in the forehead and knocked him dead from his horse.

While the duel was in progress, brief as it was, Blunt had not watched his rear, to gain which a dozen Federals had started from the extreme right. He saw them, but he did not hurry. Going back to the coveted steed, he mounted him deliberately and dashed back through the lines closed up behind him, getting a fierce hurrah of encouragement from his own comrades, and a wicked volley from the enemy.

It was time. A second company of Federals in the neighborhood, attracted by the firing, had made a junction with Peabody and were already closing in upon the houses from the south. Surrounded now by one hundred and sixty men, Quantrell was in almost the same straits as at the Tate house. His horses were in the hands of the Federals, it was some little distance to the timber, and the environment was complete. Captain Peabody, himself a Kansas man, knew who led the forces opposed to him and burned with a desire to make a finish of this Quantrell and his reckless band at one fell sweep. Not content with the one hundred and sixty men already in positions about the house, he sent off posthaste to Pink Hill for additional54 reinforcements. Emboldened also by their numbers, the Federals had approached so close to the positions held by the Guerrillas that it was possible for them to utilize the shelter the fences gave. Behind these they ensconced themselves while pouring a merciless fusillade upon the dwelling house and smoke house in comparative immunity. This annoyed Quantrell, distressed Gregg and made Cole Younger—one of the coolest heads in council ever consulted—look a little anxious. Finally a solution was found. Quantrell would draw the fire of this ambuscade; he would make the concealed enemy show himself. Ordering all to be ready and to fire the very moment the opportunity for execution was best, he dashed out from the dwelling house to the smoke house, and from the smoke house back again to the dwelling house. Eager to kill the daring man, and excited somewhat by their own efforts made to do it, the Federals exposed themselves recklessly. Then, owing to the short range, the revolvers of the Guerrillas began to tell with deadly effect. Twenty at least were shot down along the fences, and as many more wounded and disabled. It was thirty steps from one house to the other, yet Quantrell made the venture eight different times, not less than one hundred men firing at him as he came and went. On his garments there was not even the smell of fire. His life seemed to be charmed—his person protected by some superior presence. When at last55 even this artifice would no longer enable his men to fight with any degree of equality, Quantrell determined to abandon the houses and the horses and make a dash as of old to the nearest timber. “I had rather lose a thousand horses,” he said, when some one remonstrated with him, “than a single man like those who have fought with me this day. Heroes are scarce; horses are everywhere.”

In the swift rush that came now, fortune again favored him. Almost every revolver belonging to the Federals was empty. They had been relying altogether upon their carbines in the fight. After the first onset on horseback—one in which the revolvers were principally used—they had failed to reload, and had nothing but empty guns in their hands after Quantrell for the last time drew their fire and dashed away on the heels of it into the timber. Pursuit was not attempted. Enraged at the escape of the Guerrillas, and burdened with a number of dead and wounded altogether out of proportion to the forces engaged, Captain Peabody caused to be burned everything upon the premises which had a plank or shingle about it.

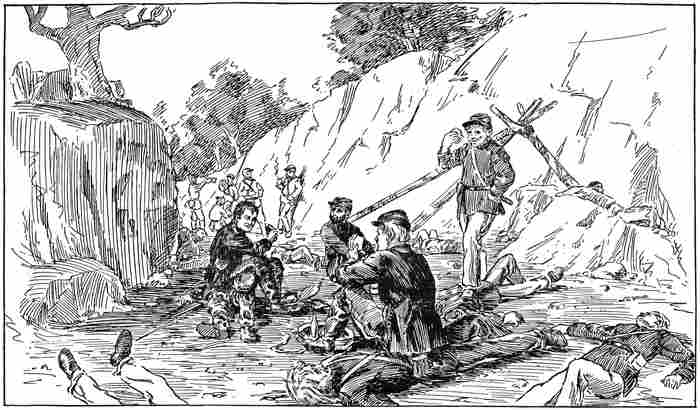

Something else was yet to be done. Getting out afoot as best he could, Quantrell saw a company of cavalry making haste from toward Pink Hill. It was but a short distance to where the road he was skirting crossed a creek, and commanding this crossing was a perpendicular bluff inaccessible to56 horsemen. Thither he hurried. The work of ambushment was the work of a moment. George Todd, alone of all the Guerrillas, had brought with him from the house a shotgun. In running for life, the most of them were unencumbered. The approaching Federals were the reinforcements Peabody had ordered up from Pink Hill, and as Quantrell’s defense had lasted one hour and a half, they were well on their way.

As they came to the creek, the foremost riders halted that their horses might drink. Soon others crowded in until all the ford was thick with animals. Just then from the bluff above a leaden rain fell as hail might from a cloudless sky. Rearing steeds trampled upon wounded riders; the dead dyed the clear water red. Wild panic laid hold of the helpless mass, cut into gaps, and flight beyond the range of the deadly revolvers came first of all and uppermost. There was a rally, however. Once out from under the fire the lieutenant commanding the detachment called a halt. He was full of dash, and meant to see more of the unknown on the top of the hill. Dismounting his men and putting himself at their head, he turned back for a fight, marching resolutely forward to the bluff. Quantrell waited for the attack to develop itself. The lieutenant moved right onward. When within fifty paces of the position, George Todd rose up from behind a rock and covered the young Federal with his unerring shotgun. It seemed a pity to kill him, he was so brave and collected,57 and yet he fell riddled just as he had drawn his sword and shouted “Forward!” to the lagging men. At Todd’s signal there succeeded a fierce revolver volley, and again were the Federals driven from the hills and back towards their horses.

Satisfied with the results of this fight—made solely as a matter of revenge for burning Clark’s buildings—Quantrell fell away from the ford and continued his retreat on towards his rendezvous upon the waters of the Sni. Peabody, however, had not had his way. Coming on himself in the direction of Pink Hill, and mistaking these reinforcements for Guerrillas, he had quite a lively fight with them, each detachment getting in several volleys and killing and wounding a goodly number before either discovered the mistake.

“The only prisoner I ever shot during the war,” relates Captain Trow, “was a ‘nigger’ I captured on guard at Independence, Missouri, who claimed that he had killed his master and burned his houses and barns. The circumstances were these: Captain Blunt and I one night went to town for a little spree and put on our Federal uniforms. While there we came in contact with the camp guard, which was a ‘nigger’ and a white man. They did not hear us until we got right up to them, so we, claiming to be Federals, arrested them for not doing their duty in hailing us at a distance. We took them prisoners, disarmed them, took them down to the Fire58 Prairie bottom east of Independence about ten miles, and there I thought I would have to kill the ‘nigger’ on account of his killing his master and burning his property. I shot him in the forehead just above the eyes. I even put my finger in the bullet hole to be sure I had him. The ball never entered his skull, but went round it. To make sure of him, I shot him in the foot and he never flinched, so I left him for dead. He came to, however, that night and crawled out into the road, and a man from Independence came along the next morning and took him in his wagon. This I learned several years afterwards at Independence in a saloon when one day I chanced to be taking a drink. There I met the ‘nigger’ whom I thought dead. He recognized me from hearing my name spoken and asked if I remembered shooting a ‘nigger.’ I said ‘Yes.’ I had the pleasure of taking a drink with him.”

59

Quantrell and His Company Were on Foot Again and Jackson County was filled with troops. At Kansas City there was a large garrison, with smaller ones at Independence, Pink Hill, Lone Jack, Stoney Point and Sibley. Peabody caused the report to be circulated that a majority of Quantrell’s men were wounded, and that if the brush were scoured thoroughly they might be picked up here and there and summarily disposed of. Raiding bands therefore began the hunt. Old men were imprisoned because they could give no information of a concealed enemy; young men murdered outright; women were insulted and abused. The uneasiness that had heretofore rested upon the county gave place now to a feeling of positive fear. The Jayhawkers on one side and the militia on the other made matters hot. All traveling was dangerous. People at night closed their eyes in dread lest the morrow should usher in a terrible awakening. One incident of the hunt is a bloody memory yet with many of the older settlers of Jackson County.

An aged man by the name of Blythe, believing his own house to be his own, fed all whom he pleased to feed, and sheltered all whom it pleased him to shelter. Among many of his warm personal friends was Cole Younger. The colonel commanding the fort at Independence sent a60 scout one day to find Younger, and to make the country people tell where he might be found. Old man Blythe was not at home, but his son was, a fearless lad of twelve years. He was taken to the barn and ordered to confess everything he knew of Quantrell, Younger, and their whereabouts. If he failed to speak truly he was to be killed. The boy, in no manner frightened, kept them some moments in conversation, waiting for an opportunity to escape. Seeing at last what he imagined to be a chance, he dashed away from his captors and entered the house under a perfect shower of balls. There, seizing a pistol and rushing through the back door towards some timber, a ball struck him in the spine just as he reached the garden fence and he fell back dying, but splendid in his boyish courage to the last. Turning over on his face as the Jayhawkers rushed up to finish him he shot one dead, mortally wounded another, and severely wounded the third. Before he could shoot a fourth time, seventeen bullets were put into his body.

It seemed as if God’s vengeance was especially exercised in the righting of this terrible wrong. An old negro man who had happened to be at Blythe’s house at the time, was a witness to the bloody deed, and, afraid of his own life, ran hurriedly into the brush. There he came unawares upon Younger, Quantrell, Haller, Todd, and eleven of his men. Noticing the great excitement under which the negro labored, they forced him to tell61 them the whole story. It was yet time for an ambuscade. On the road back to Independence was a pass between two embankments known as “The Blue Cut.” In width it was about fifty yards, and the height of each embankment was about thirty feet. Quantrell dismounted his men, stationed some at each end of the passageway and some at the top on either side. Not a shot was to be fired until the returning Federals had entered it, front and rear. From the Blue Cut this fatal spot was afterwards known as the Slaughter Pen. Of the thirty-eight Federals sent out after Cole Younger, and who, because they could not find him, had brutally murdered an innocent boy, seventeen were killed while five—not too badly shot to be able to ride—barely managed to escape into Independence, the avenging Guerrillas hard upon their heels.

62

The next rendezvous was at Reuben Harris’, ten miles south of Independence, and thither all the command went, splendidly mounted again and eager for employment. Some days of preparation were necessary. Richard Hall, a fighting blacksmith, who shot as well as he shod, and knew a trail as thoroughly as a piece of steel, had need to exercise much of his handiwork in order to make the horses good for cavalry. Then there were several rounds of cartridges to make. A Guerrilla knew nothing whatever of an ordnance master. His laboratory was in his luck. If a capture did not bring him caps, he had to fall back on ruse, or strategem, or blockade-running square out. Powder and lead in the raw were enough, for if with these he could not make himself presentable at inspection he had no calling as a fighter in the brush.

It was Quantrell’s intention at this time to attack Harrisonville, the county seat of Cass County, and capture it if possible. With this object in view, and after every preparation was made for a vigorous campaign, he moved eight miles east of Independence, camping near the Little Blue, in the vicinity of Job Crabtree’s. He camped always near or in a house. For this he had two reasons. First, that its occupants might gather up for him all the news possible; and, second, that in the event of a surprise a sure rallying63 point would always be at hand. He had a theory that after a Guerrilla was given time to get over the first effects of a sudden charge or ambushment the very nature of his military status made him invincible; that after an opportunity was afforded him to think, a surrender was next to impossible.

Before there was time to attack Harrisonville, however, a scout reported Peabody again on the war path, this time bent on an utter extermination of the Guerrillas, and he well-nigh kept his word. From Job Crabtree’s, Quantrell had moved to an unoccupied house known as the Low house, and then from this house he had gone to some contiguous timber to bivouac for the night. About ten o’clock the sky suddenly became overcast, a fresh wind blew from the east, and rain fell in torrents. Again the house was occupied, the horses being hitched along the fence in the rear of it, the door on the south, the only door, having a bar across it in lieu of a sentinel. Such soldiering was perfectly inexcusable, and it taught Quantrell a lesson to remember until the day of his death.

In the morning preceding the day of the attack Lieutenant Nash, of Peabody’s regiment, commanding two hundred men, had struck Quantrell’s trail, but lost it later on, and then found it again just about sunset. He was informed of Quantrell’s having gone from the Low house to the brush and of his having come back to it when the rain began falling heavily. To a certain extent this64 seeking shelter was a necessity on the part of Quantrell. The men had no cartridge boxes, and not all of them had overcoats. If once their ammunition were damaged, it would be as though sheep should attack wolves.

Nash, supplied with everything needed for the weather, waited patiently for the Guerrillas to become snugly settled under shelter, and then surrounded the house. Before a gun was fired the Federals had every horse belonging to the Guerrillas, and were bringing to bear every available carbine in command upon the only door. At first all was confusion. Across the logs that once had supported an upper floor some boards had been laid, and sleeping upon them were Todd, Blunt and William Carr. Favored by the almost impenetrable darkness, Quantrell determined upon an immediate abandonment of the house. He called loudly twice for all to follow him and dashed through the door under a galling fire. Those in the loft did not hear him, and maintained in reply to the Federal volleys a lively fusillade. Then Cole Younger, James Little, Joseph Gilchrist and a young Irish boy—a brave new recruit—turned back to help their comrades. The house became a furnace. At each of the two corners on the south side four men fought, Younger calling on Todd in the intervals of every volley to come out of the loft and come to the brush. They started at last. It was four hundred yards to the nearest shelter, and the ground was very muddy. Gilchrist was shot65 down, the Irish boy was killed, Blunt was wounded and captured, Carr surrendered, Younger had his hat shot away, Little was unhurt, and Todd, scratched in four places, finally got safely to the timber. But it was a miracle. Twenty Federals singled him out as well as they could in the darkness and kept close at his heels, firing whenever a gun was loaded. Todd had a musket which, when it seemed as if they were all upon him at once, he would point at the nearest and make pretense of shooting. When they halted and dodged about to get out of range, he would dash away again, gaining what space he could until he had to turn and re-enact the same unpleasant pantomime. Reaching the woods at last, he fired point blank, and in reality now, killing with a single discharge one pursuer and wounding four. Part of Nash’s command were still on the track of Quantrell, but after losing five killed and a number wounded, they returned again to the house, but returned too late for the continued battle. The dead and two prisoners were all that were left for them.

Little Blue was bank full and the country was swarming with militia. For the third time Quantrell was afoot with unrelenting pursuers upon his trail in every direction. At daylight Nash would be after him again, river or no river. He must get over or fare worse. The rain was still pouring down; muddy, forlorn, well-nigh worn out, yet in no manner demoralized,66 just as Quantrell reached the Little Blue he saw on the other bank Toler, one of his own soldiers, sitting in a canoe. Thence forward the work of crossing was easy, and Nash, coming on an hour afterwards, received a volley at the ford where he expected to find a lot of helpless and unresisting men.

This fight at the Low house occurred the first week in May, 1862, and caused the expedition against Harrisonville to be abandoned. Three times surprised and three times losing all horses, saddles, and bridles, it again became necessary to disband the Guerrillas in this instance as in the preceding two. The men were dismissed for thirty days with orders to remount themselves, while Quantrell—taking Todd into his confidence and acquainting him fully with his plans—started in his company for Hannibal. It had become urgently necessary to replenish the supply of revolver caps. The usual trade with Kansas City was cut off. Of late the captures had not been as plentiful as formerly. Recruits were coming in, and the season for larger operations was at hand. In exploits where peril and excitement were about evenly divided, Quantrell took great delight. He was so cool, so calm; he had played before such a deadly game; he knew so well how to smile when a smile would win, and when to frown when a frown was a better card to play, that something in this expedition appealed to every quixotic instinct of his intrepidity. Todd was all iron; Quantrell67 all glue. Todd would go at a circular saw; Quantrell would sharpen its teeth and grease it where there was friction. One purred and killed, and the other roared and killed. What mattered the mode, however, only so the end was the same?

68

Clad in the full uniform of Federal majors—a supply of which Quantrell kept always on hand, even in a day so early in the war as this—Quantrell and Todd rode into Hamilton, a little town on the Hannibal & St. Louis Railroad, and remained for the night at the principal hotel. A Federal garrison was there—two companies of Iowa infantry—and the captain commanding took a great fancy to Todd, insisting that he should leave the hotel for his quarters and share his blankets with him.

Two days were spent in Hannibal, where an entire Feneral regiment was stationed. Here Quantrell was more circumspect. When asked to give an account of himself and his companion, he replied promptly that Todd was a major of the Sixth Missouri Cavalry and himself the major of the Ninth. Unacquainted with either organization, the commander at Hannibal had no reason to believe otherwise. Then he asked about that special cut-throat Quantrell. Was it true that he fought under a black flag? Had he ever really belonged to the Jayhawkers? How much truth was there in the stories of the newspapers about his operations and prowess? Quantrell became voluble. In rapid yet picturesque language he painted a perfect picture of the war along the border. He told of Todd, Jarrette, Blunt, Younger, Haller, Poole, Shepherd,69 Gregg, Little, the Cogers, and all of his best men just as they were, and himself also just as he was, and closed the conversation emphatically by remarking: “If you were here, Colonel, surrounded as you are by a thousand soldiers, and they wanted you, they would come and get you.”

From Hannibal—after buying quietly and at various times and in various places fifty thousand revolver caps—Quantrell and Todd went boldly into St. Joseph. This city was full of soldiers. Colonel Harrison B. Branch was there in command of a regiment of militia—a brave, conservative, right-thinking soldier—and Quantrell introduced himself to Branch as Major Henderson of the Sixth Missouri. Todd, by this time, had put on, in lieu of a major’s epaulettes, with its distinguishing leaf, the barred ones of a captain. “Too many majors traveling together,” quaintly remarked Todd, “are like too many roses in a boquet: the other flowers don’t have a chance. Let me be a captain for the balance of the trip.”

Colonel Branch made himself very agreeable to Major Henderson and Captain Gordon, and asked Todd if he were a relative of the somewhat notorious Si Gordon of Platte, relating at the same time an interesting adventure he once had with him. En route from St. Louis, in 1861, to the headquarters of his regiment, Colonel Branch, with one hundred and thirty thousand dollars on his person, found that he would have to remain70 in Weston over night and the better part of the next day. Before he got out of the town Gordon took it, and with it he took Colonel Branch. Many of Gordon’s men were known to him, and it was eminently to his interest just then to renew old acquaintanceship and be extremely complaisant to the new. Wherever he could find the largest number of Guerrillas there he was among them, calling for whiskey every now and then, incessantly telling some agreeable story or amusing anecdote. Thus he got through with what seemed to him an interminably long day. Not a dollar of his money was touched, Gordon releasing him unconditionally when the town was abandoned and bidding him make haste to get out lest the next lot of raiders made it the worse for him.

For three days, off and on, Quantrell was either with Branch at his quarters or in company with him about town. Todd, elsewhere and indefatigable, was rapidly buying caps and revolvers. Branch introduced Quantrell to General Ben Loan, discussed Penick with him and Penick’s regiment—a St. Joseph officer destined in the near future to give Quantrell some stubborn fighting—passed in review the military situation, incidently referred to the Guerrillas of Jackson County and the savage nature of the warfare going on there, predicted the absolute destruction of African slavery, and assisted Quantrell in many ways in making his mission thoroughly successful. For the first and last71 time in his life Colonel Branch was disloyal to the government and the flag—he gave undoubted aid and encouragement during those three days to about as uncompromising an enemy as either ever had.

From St. Joseph Quantrell and Todd came to Kansas City in a hired hack, first sending into Jackson County a man unquestionably devoted to the South with the whole amount of purchases made in both Hannibal and St. Joseph.

72

Quantrell with his band of sixty-three men were being followed by a force of seven hundred cavalrymen under Peabody. Peabody came up in the advance with three hundred men, while four hundred marched at a supporting distance behind him. Quantrell halted at Swearington’s barn and the Guerrillas were drying their blankets. One picket, Hick George, an iron man, who could sleep in his saddle and eat as he ran and who suspected every act until he could fathom it, watched the rear against an attack. Peabody received George’s fire, for George would fire at an angel or devil in the line of his duty, and drove him toward Quantrell at a full run. Every preparation possible under the circumstances had been made and if the reception was not as cordial as expected, the Federals could attribute it to the long march and the rainy weather.

Quantrell stood at the gate calmly with his hand on the latch; when George entered he would close and fasten it. Peabody’s forces were within thirty feet of the fence when the Guerrillas delivered a crashing blow and sixteen Federals crashed against the barricade and fell there. Others fell and more dropped out here and there before the disorganized mass got back safe again from the deadly revolver range. After them Quantrell himself dashed hotly, George Maddox,73 Jarrette, Cole Younger, George Morrow, Gregg, Blunt, Poole and Haller following them fast to the timber and upon their return gathering all the arms and ammunition of the killed as they went. At the timber Peabody rearranged his lines, dismounted his men and came forward again at a quick run, yelling. Do what he would, the charge spent itself before it could be called a charge.

Peabody arranged his men, dismounted them, and came forward again at a double-quick, and yelling. Do what he would, the charge again spent itself before it could be called a charge. Never nearer than one hundred yards of the fence, he skirmished at long range for nearly an hour and finally took up a position one mile south of the barn, awaiting reinforcements. Quantrell sent out Cole Younger, Poole, John Brinker and William Haller to “lay up close to Peabody,” as he expressed it, and keep him and his movements steadily in view.

The four daredevils multiplied themselves. They attacked the pickets, rode around the whole camp in bravado, firing upon it from every side, and finally agreed to send a flag of truce in to Peabody with this manner of a challenge:

“We, whose names are hereunto affixed, respectfully ask of Colonel Peabody the privilege of fighting eight of his best men, hand to hand, and that he himself74 make the selection and send them out to us immediately.”

This was signed by the following: Coleman Younger, William Haller, David Poole and John Brinker.

Younger bore it. Tieing a white handkerchief to a stick he rode boldly up to the nearest picket and asked for a parley. Six started towards him and he bade four go back. The message was carried to Peabody, but he laughed at it and scanned the prairie in every direction for the coming reinforcements. Meanwhile Quantrell was retreating. His four men cavorting about Peabody were to amuse him as long as possible and then get away as best they could. Such risks are often taken in war; to save one thousand men, one hundred are sometimes sacrificed. Death equally with exactness has its mathematics.

The reinforcements came up rapidly. One hundred joined Peabody on the prairie, and two hundred masked themselves by some timber on the north and advanced parallel with Quantrell’s line of retreat—a flank movement meant to be final. Haller hurried off to Quantrell to report, and Peabody, vigorous and alert, now threw out a cloud of cavalry skirmishers after the three remaining Guerrillas. The race was one for life. Both started their horses on a keen run. It was on the eve of harvest, and the wheat, breast high to the horse, flew away from before the feet of75 the racers as though the wind were driving through it an incarnate scythe blade. As Poole struck the eastern edge of this wheat a very large jack, belonging to Swearingen, joined in the pursuit, braying loudly at every jump, and leading the Federals by a length. Comedy and tragedy were in the same field together. Carbines rang out, revolvers cracked, the jack brayed, the Federals roared with merriment, and looking back over his shoulder as he rode on, Poole heard the laughter and saw the jack, and imagined the devil to be after him leading a lot of crazy people.

76