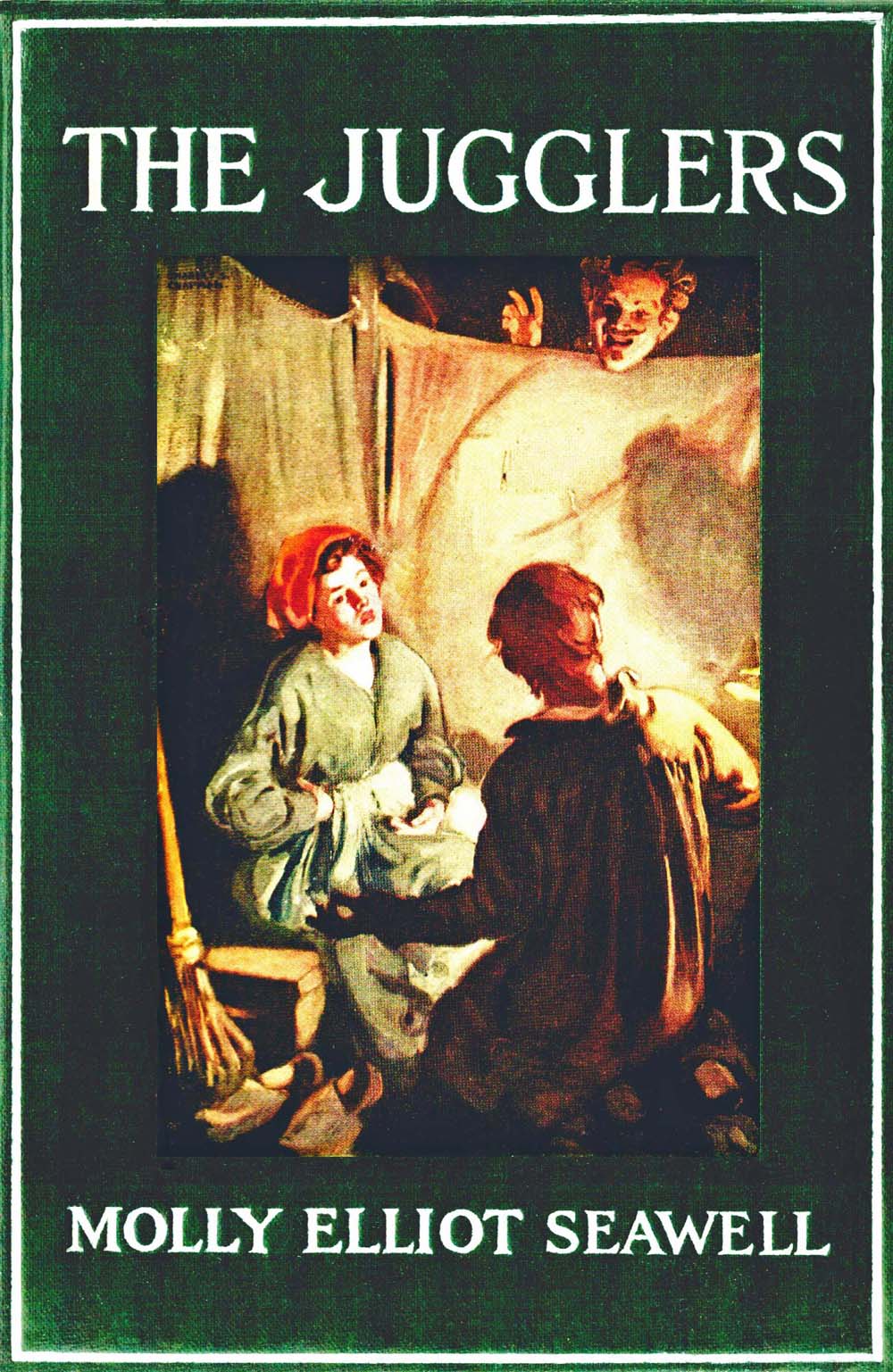

Title: The Jugglers: A Story

Author: Molly Elliot Seawell

Release date: August 14, 2020 [eBook #62927]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by D A Alexander, David E. Brown, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO

SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

“Think What It Is to Act When One Feels It.”

THE JUGGLERS

A Story

BY

MOLLY ELLIOT SEAWELL

WITH A FRONTISPIECE

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1911

Dramatic and all other rights reserved

Copyright, 1911,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up and electrotyped. Published October, 1911.

Dramatic and all other rights reserved.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing Co.—Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

TO

NELLIE AND ISABEL

WHO HAVE A GENIUS FOR FRIENDSHIP

THIS BOOK IS INSCRIBED

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Diane, the Dreamer | 1 |

| II. | The Marquis Egmont of the Holy Angels | 31 |

| III. | The Splendid Events that Happened at Bienville | 65 |

| IV. | The Bridal Veil | 95 |

| V. | The Deluge | 122 |

| VI. | The Day of Glory has Arrived | 158 |

The lazy blue river and the wide, brown plains of Picardy lay basking in the still splendor of the November afternoon. The mysterious hush of the autumn lay upon the fields and the farmsteads. A flock of herons in a near-by marsh meditated gravely, standing one-legged, and watching the cows kneedeep in the muddy meadows. High in the sunny air, a vulture sailed, majestically evil, watching both the cows and the herons. The world was saying farewell softly to the sunny hours.

The only sound that broke the deep silence was the steady trot of the big Normandy horses on the flinty towpath, as they drew a covered boat along the narrow and shallow stream, and the faint echo of the voices of five persons sitting[2] on the roof of the boat in the sunshine. The herons cocked their eyes toward the boat, and listened attentively, though they could not understand a word of these strange, noisy, laughing, weeping, fighting, dancing, talking creatures, called men and women. Sometimes, so the herons thought, these odd beings were a little kind; sometimes they were very cruel, but always they were formidable, and were masters of life and death.

The great question under discussion on the roof of the boat was, where the theatrical company of jugglers and singers should spend the winter. Grandin, the proprietor of the show, a tall, handsome, boastful man, with a big voice like a church organ and a backbone made of brown paper, always gave his opinion first, but was generally overruled by Madame Grandin, also tall, handsome, easily wheedled or bullied, but inexorably truthful. Decisions really rested with the three subordinates, Diane Dorian, the prima donna, Jean Leroux, her partner, and the individual known as François le Bourgeois, juggler.

“I have determined upon Bienville,” roared Grandin, in his big, rich voice. “We wintered[3] there nine years ago, and my lithograph was in some of the best shops in the place.”

“Oh, what a lie!” cried Madame Grandin, amiably. “They only put your picture in three butcher shops and the bake shop across the street, and I am sure you paid enough for it. But Bienville is my choice too.”

Grandin took this with the utmost good nature. Between his propensity to tell agreeable lies, and Madame Grandin’s natural inability to let a lie go uncontradicted, the couple struck a very good average of truth.

The manager and his wife having spoken, the real discussion was now on.

“I should say Bienville,” said Jean Leroux, quietly.

He, too, was big—an ugly, resolute man with an indomitable eye, and as honest as the day was long.

He looked at Diane as he spoke. She was dark haired and dark eyed, with a skin milk white in spite of grease paint, and had a vivid, irregular, theatrical beauty, in great contrast to the big, Juno-like manager’s wife. Also, she was so slight and thin as to deserve the name of[4] “Skinny,” which was freely applied to her by François, and she had a voice like the flute of Pan. In spite of her soft voice and gently drooping head, Diane had ten times the resolution of the resolute Jean Leroux. She was also the vainest of women, and in order to protect her matchless complexion wore, over her scarlet hood, a transparent veil of a misty grey, through which her eyes shone as the flash of stars is seen through a drifting cloud. Jean Leroux, who frankly adored her, sat at her right, and François, who always laughed at her, sat on the other side. This François had the clear cut, highbred features, the slim hands and feet, that indescribable air of the aristocrat which marks a man who can trace his descent through many lines of greatness, back to those who shone at the court of Philippe le Bel. Yet François was a frowzy person, and his small feet had burst through his shoes; but he had the same glorious and ineffable impudence of his ancestors who bullied their kings and princes.

“What do you say, Diane?” he asked, giving Diane a friendly kick.

“I say Bienville,” replied Diane in her lovely[5] stage voice. “I was born and brought up five miles from Bienville, in a little hole of a house, for my father, the village hatter, and my mother had a hard time to keep body and soul together. When I was a little, little girl, I used to look in clear days toward Bienville where I could see the tall spires of the cathedral making a dark line against the sky, and I used to imagine I could hear the bells on the clear December days, and in the soft summer nights. I yearned with all my heart to go to Bienville on market day, and to see the wonderful things that I had heard of there. My mother and father were always promising me that when they had enough money they would take me to Bienville on a market day, but, poor souls, they never had enough. So then, when they died and I was twelve years old, I was taken far away by my uncle. I never saw Bienville, and tended geese until I was sixteen and begun to sing at the village festivals.”

“How interesting!” cried François, who had heard the story forty times before. “When you are prima donna at the Paris Opera, and your noble lineage is acknowledged by the proudest[6] houses in France, it will be so romantic to hear ‘The Tale of the Goose Girl’!”

This was an old joke of François’, at which everybody was expected to laugh, but Diane remained sullenly silent. François had told her by way of a gibe that her name, Dorian, was undoubtedly a corruption of the noble name of D’Orian, and the ridiculous story had taken possession of Diane, who was as ambitious as Julius Cæsar, and not without repartee.

“Anyhow,” she answered tartly, “it is better to rise from being a goose girl to being a singer in a nice company like this, than—” Diane stopped, but François finished the sentence for her.

“Than to be born in a chateau and come down to being general utility man in a nice, though small, theatrical company. But I tell you, ladies and gentlemen, that the fault is in the stars, not in me. God is a great showman, and arranges many highly dramatic events in certain lives. He has a little string, which He calls Life, and when He pulls it, we walk, talk, and sin. And when He cuts that string, we walk, talk, and sin no more. To return to the concrete, however—I[7] give my voice for Bienville too, because the Bishop is a friend of mine, and so is the major general commanding the district.”

Now, François had never before been known to mention any great people he had ever known in his former life, claiming acquaintance only with organ-grinders, ratcatchers, and the like. So all present pricked up their ears at this.

“When I was a little lad five years old,” continued François, “they wanted to teach me to read, but I did not want to read, so then I was taken into the meadows and shown two big boys, twelve and fourteen years old, who watched the cows, and meanwhile each carried a book which he read every moment he could. One of those boys has become Bishop of Bienville, and the other, I tell you, is a major general commanding. I suppose they will turn up their noses at me, as indeed they should. But Bienville is the place for the winter.”

The three subordinates having spoken, the question of spending the winter in Bienville was considered settled, provided they could get a cheap hall in which to give performances three times a week. The horses were to be sold, as[8] they always were at the end of a season, and the boat tied up at the quay, because it could not be heated for winter weather.

“I am sorry,” said Diane, “that the summer is over, and this is the last time for this year that we shall travel by water.”

Diane did not suspect that it was the last time she should ever travel in that way again.

The horses trotted on steadily toward the far-off steeples and roofs of Bienville coming within clear sight. By that time it was nearly dusk, and a great golden, smoky moon hung in the heavens. The boat was stopped on the river bank where the streets of the little town ran down to the waterside. The horses were taken out, rubbed down, and fed, while the Juno-like manager’s wife and the future prima donna of the Paris Opera cooked supper. Presently they were all assembled around a little table in the small, stuffy cabin, lighted by a kerosene lamp hung on the beam over their heads. They were very humble people, and poor, but they were not unhappy, and lived in a singular harmony together, in spite of the fact that the three ruling spirits, Diane, Jean Leroux, and François[9] were all made on a special model. But each had that strange, artistic conscience which begets the iron discipline of the stage. Apart from the stage, François was frankly an outlaw, and submitted to things because there was always a strong and relentless world against him.

When supper was over and everything settled for the night, Grandin and his wife were soon snoring loudly in the little coop which was their room. Diane was not in her little coop, nor was Jean Leroux huddled in his blanket in the large cabin which he shared with François. Both Diane and Jean were sitting on the roof of the cabin watching the moon and stars reflected in the black river, and listening to the sounds brought to them upon the wandering breeze of a merry little town at night. Jean Leroux, a taciturn man, was, as usual, on or off the stage, watching Diane.

“At last I am in Bienville,” murmured Diane. “After so many years of longing and yearning! I feel that something will happen to me here, something great and splendid.”

“Now, Diane,” said Leroux, “don’t let François’ jokes get into your head as serious things.[10] Nothing is going to happen here. You sing pretty well, but you have no more chance of being a great opera singer than I have of being an archbishop. You haven’t the voice, my dear, for opera at all. You will never get beyond a good music hall artist.”

“You are so discouraging, Jean,” complained Diane. “You have a fine voice and know how to act too, but you never aspire to anything but a music hall.”

“No, and I never mean to,” was the reply of the practical Jean. “I wish you had good sense, Diane. But I love you just the same as if you had.”

Diane made no reply, and Jean was confirmed in his belief that women were the most obstinate and senseless creatures on earth when once they took a notion into their heads.

“Besides,” continued Jean, “you are too old, twenty-six, to begin training for grand opera, and you haven’t the money either. At this moment, your capital consists of two hundred and forty-six francs; you told me so yourself.”

“Two hundred and sixty-six francs,” cried Diane with flashing eyes. “You ought to be[11] more careful how you talk about such important things, Jean.”

“Anyhow,” answered Jean gruffly, “for you to try grand opera would be exactly like a cow trying to play the piano.”

Diane argued with him angrily for half an hour. She had not the slightest intention or even wish to be a grand opera singer, and knew the absurdity of the situation quite as well as Jean. But having, like all women, great powers of deception, she was carefully concealing the true object of her wishes and ambitions—to go to Paris and become a great music hall artist, a profession which she consistently derided and contemned. The simple creature, man, is no match for the complex creature, woman.

“After all,” murmured Diane, “I am in Bienville. I have dreamed three times lately of putting on my petticoat wrong side out, and that means that I shall make a great deal of money. And then I have twice dreamed of cooking onions, and that means a splendid lover.”

This was more than Jean could stand.

“Very well, Diane,” he said, “you had better[12] go to bed now, and dream of petticoats and love and onions. I am off.”

Jean got up and took Diane’s hand as she ran nimbly down the short ladder to the deck of the boat. The touch of that hand thrilled poor Jean. His heart yearned over Diane; she was such a fool, and always wanted to do things and to get in places for which she was eternally unfitted, so Jean thought. As a matter of fact, Diane was as practical as Jean, but chose to talk a little wildly.

Meanwhile, Diane in her little coop was sitting on the edge of her bed and looking through the small, square window toward the town. Afar off she heard the echo of a military band playing.

“There is a garrison here,” she thought to herself, and then suddenly remembered that the silk petticoat of which she had dreamed was red like the color of the soldiers’ trousers, and also that the onions which she had cooked in her dreams were red. Then her mind wandered to Jean. If she should have a splendid lover, how should she get on without Jean? It was he who taught her most that she knew about singing and had a peculiar scowl that he gave her[13] on the stage when she was getting off the key. Jean evidently did not fit into the plan of the splendid marriage which she was certain to make in Bienville, nor did anything seem to fit without Jean. While Diane was puzzling over this, she slipped into her narrow cot and fell asleep, the laughing stars and grinning moon gazing at her through the little window.

The next morning began the serious business of going into winter quarters at Bienville. It was a busy day for Jean. First, the horses had to be sold. Anybody who flattered Grandin could get horses or anything else out of him, so Jean felt it his duty to go with the manager to the horse mart where the horses fetched a good price.

François, who was very little use in any way, except doing his stage tricks, was with Madame Grandin and Diane, looking for lodgings. Jean had some confidence in Diane’s management of money, but this confidence was rudely shattered when he and Grandin met the two ladies at the corner of a street, and were taken to inspect the lodgings which were under consideration for the whole party. First, Jean was dubious about the street, which was much too nice. The sight of[14] the lodgings confirmed his worst suspicions. There was actually a sitting room in addition to a bedroom for the Grandins, a little kitchen, and beyond it a small white room, with a fireplace, for Diane. Under the roof was a big attic where Jean and François could be accommodated royally. The price, of course, was staggering, one hundred francs the month. For once, however, Jean found himself unable to move Diane or to bully the Grandins.

While they were all in the sitting room arguing at the top of their lungs, Diane’s high-pitched, musical voice cutting in every ten seconds, the door opened and in walked François.

“Look here, François,” said Jean, “help me to reason with these people. A hundred francs for lodgings, and we haven’t even got a hall yet, and don’t know whether anybody will come to the performances or not.”

“A hundred francs! A bagatelle!” cried François, slapping his hat down on the table. “Do you suppose when I come to a place where the Bishop and the general commanding are my friends, that I intend to stand back for a little money? No, indeed. If we are thrown out of[15] these luxurious quarters, we can all go to the workhouse anyhow.”

“Just look at this!” cried Jean, pointing to the carpet on the floor, and the mirrors on the walls.

“But come and look at my bedroom. I am sure that’s plain enough,” shrieked Diane.

“It is the best bedroom you ever had in your life,” growled Jean.

Then they all trooped back beyond the kitchen to the little white room for Diane. There was one window in it, and it looked across the street directly in the garden of a small, but very nice hotel, much frequented by officers. There was a pavilion enclosed in glass, and at that moment there were officers breakfasting there, with their swords about their legs. As Diane and the rest watched, an orderly rode up leading an officer’s horse. Then the officer came out, a handsome young man in a splendid dragoon uniform, and putting on his helmet with its gorgeous red plume waving in the sunny air. He mounted and clattered off, followed by the orderly and also by the eyes of Diane. Jean, looking at her, felt a knife enter his heart. Her eyes had been fixed upon the young officer with[16] a look of enchantment; her red lips were partly open. She was like a person hypnotized.

“Diane will be a big success with the officers of the garrison,” said François, laughing.

“You mean with the corporals,” said Jean. “François, you remind me of those soldiers called gentlemen-rankers, gentlemen, that is, who get into the ranks. They always give trouble. You don’t belong with us. You ought to go with people of your own kind, who understand your jokes.”

“But I can’t,” responded François, with unabashed good humor. “They have kicked me out long ago.”

Then, the discussion about the lodgings began all over again, everybody talking at once, except Diane who remained perfectly silent. When they were talked out, Diane spoke a word.

“I will take the whole apartment myself, if the rest of you don’t,” she said. “I have two hundred and sixty-six francs of my own.”

Jean said no more, and Grandin sent for the landlady, and made the terms, Jean looking after him that he did nothing more wildly foolish than to take the apartment at a hundred francs.

[17]When that business was over, the whole party started out to find a hall suitable for their performances. In this they had extraordinary good luck, finding a large place in the same street, the whole front of glass, and which had been lately vacated as a furniture shop. It would not take much to build a little stage, and the dressing-rooms could be divided off with canvas. Jean then piloted the whole party to the office of the agent, where Diane was put forward to make the plea for the company. The agent was a susceptible person, and Diane’s soft eyes and arguments that the place would become better known by having many persons attend it, caused him to make a ridiculously low offer, and it was promptly accepted. On the strength of this, Diane assumed to be a fine business woman, and gave herself great airs in consequence.

When all was complete, the entire arrangements were not so bad. The money received for the horses paid a month’s rent in advance and for the erection of the stage. In the latter, both Grandin and Jean helped the workmen and nailed and hammered industriously. François was willing to help too, but rather hindered by[18] his jokes and stories, which distracted the workmen and kept them laughing when they should have been working.

At the end of three days everything was settled for the winter. The beds and stools and kettles and pans had been brought from the boat, which was tied up for the season. The hall was in readiness, the license was obtained, and the big posters were out announcing three performances a week by the celebrated Grandin troupe of jugglers, singers, and dancers.

On the night of the first performance the hall was so well filled that Grandin was in ecstasies of delight, and Madame Grandin wept with joy.

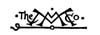

Across the street, the pavilion was full of young officers, dining. The new place evidently attracted their attention, and presently the whole crowd sallied forth through the garden of the hotel, and across the street. At that moment, François, by Grandin’s direction, went out to see if the old woman who was hired to take in the money was doing her duty. As the crowd of laughing young officers crossed the street, François, who had inspirations of genius, ran inside and pulled up the great green shade before[19] what had once been the shop windows. Within could plainly be seen Diane doing one of her best acts with Jean. She was dressed as a fishwife, her skirts tucked up high, showing a charming pair of ankles and small feet in little wooden shoes, and a delicious white cap such as the fishwomen wear flapped upon her beautiful black hair. The officers raised a shout of laughter and applause and dashed into the little hall, throwing their money at the old woman, and not waiting for change.

François pulled the curtain down, and rushed back of the stage. As the officers came clattering in, they were led by one whom François recognized as the dragoon officer who had fascinated Diane’s eyes three days before. This made François nervous, because if the same thing should happen, the act would be ruined. Diane, indeed, had seen the young officer, but the effect was exactly opposite from what François had feared. This, thought Diane, was the meaning of her dream. She sang better than ever before, and no fishwife ever had so dramatic and delightful a quarrel as she had with Jean. The end of the act was that Diane gave Jean a beating[20] with a broom, at which Jean bellowed, to the great delight of the audience.

This audience, made up wholly of soldiers and working people, except the officers, shouted with laughter, and the young officers made more noise than any one else present, led by the handsome dragoon who had struck Diane’s fancy that morning.

Diane was kept smiling and bowing, and blushing under her grease paint, before the row of candles stuck in bottles that represented the footlights. This went on for so long that the next feature on the bill, a juggling act in which Grandin and his wife did miraculous things, was delayed ten minutes. Madame Grandin, who was more nearly without jealousy than any woman François had ever known, sat quite placidly in her tights and short skirts, and wrapped in a shawl, waiting for the hullabaloo to subside. Grandin was torn by rival emotions; joy that Diane had made such a hit, and annoyance that the audience seemed to prefer singing to burning up money and making an egg come out of a pumpkin. Presently, however, Jean ruthlessly lowered the piece of canvas that did[21] duty for a curtain, and Diane came back palpitating and quivering between laughter and tears. The Grandins then went on, and François, who was not due on the stage for ten minutes, slipped on his outside clothes over his stage costume and quietly dropped into the audience and took his seat by a laughing corporal.

“Who is that young man over there?” whispered François to the corporal.

“Captain, the Marquis Egmont de St. Angel, captain of dragoons. I am in his troop.”

The corporal, as he said this, made a little motion with his mouth, of which François knew the meaning. It implied that Captain, the Marquis Egmont de St. Angel was a person to be spat upon.

François knew the name well enough; he knew the names of all the great families. He gave the corporal a wink, which was cordially returned, and then went out, and to the back of the stage. He found Diane sitting as if in a dream in the little canvas den which she shared as a dressing-room with Madame Grandin. François, who was to go on in two minutes, began jerking his arms about and bending his[22] body as if it were made of India rubber, by way of preparation, chatting meanwhile.

“Talking about love and onions and petticoats,” he said, “the young officer who led the rest into the hall happens to be a cousin of mine, about three removes, but we are blood relations, just the same, and I think he will end in a worse position than that of a juggler when he keeps sober, and a street vender when he is not quite so sober. He is the Marquis Egmont de St. Angel, called Egmont for short. I was just thinking,” continued François, making himself into a circle like a snake, “that there are no such things as trifles in this world. I went out just now and pulled up the window shade, and a certain man saw you. The pulling up of that shade was a momentous act, perhaps.”

“I knew something splendid would happen in Bienville,” murmured Diane. “The Marquis Egmont de St. Angel! What a splendid name! I never had a hand clap from a marquis before.”

Then it was time for François to go on the stage. He did his part, which was chiefly acrobatic, so badly that he came near ruining the Grandins’ act.

[23]Within the canvas den, Jean was preaching to Diane.

“Look here, Diane,” he said, “don’t let those young officers turn your head, particularly that handsome one in front. They are not good acquaintances for a girl like you.”

Diane turned on him a look as virginal as that of Jeanne d’Arc.

“No man can do me any harm,” she said, “except break my heart. I suppose some might do that. And besides, Jean, I am full of ambition. The women who misbehave and drink too much wine, lose their voices very soon and are not respectfully treated by managers. Don’t be afraid for me.”

“I am not,” answered Jean. “At least in the way you think. I am afraid of your breaking your heart and doing something foolish.”

“I shan’t do anything foolish,” promptly answered Diane.

When the Grandins and François finished their act and the curtain was down, even the placid Madame Grandin said a few mildly reproachful words to François for his carelessness which might have caused a bad accident. Grandin,[24] who was sincerely attached to his wife, was much shaken and nervous and violently angry with François.

“Never mind,” answered François coolly to Grandin’s invectives, “wives come cheap, but if you are so shaken in the next turn as you are now, your wife will be in a great deal more danger than she was with me. Behave yourself, Grandin, and get the upper hand of your nerves. A juggler who loses his nerve because another juggler hasn’t tumbled fair, isn’t any good at all and a very dangerous person.”

Grandin was much taken aback by this onslaught of François, and could only mumble:

“I don’t know why it is, François, that you always get the upper hand of me.”

“I know,” replied François. “It is because I was born a-horseback and you were born a-footback. That’s why.”

The second appearance of Diane upon the stage was greeted with greater applause and laughter than ever. Jean, who was a capital low comedian and singer, was scarcely noticed. When the act was over, it had to be repeated, and at the end money was showered upon the[25] stage. It was all silver, however, except one twenty franc gold piece which was thrown by the Marquis Egmont de St. Angel.

On the whole, the performance was a great success as far as money went, but nobody had got any applause to speak of except Diane.

It takes some time to wash off powder and lamp-black and grease paint, and to get into even the shabbiest clothes, so that the street was almost deserted when the players came out in the quiet autumn night. One person, however, was on watch. This was the Marquis Egmont de St. Angel, known as Egmont. He stepped up to Diane and said with a low bow:

“Mademoiselle, will you do me the honor of taking supper with me in the pavilion of the Hotel Metropole?”

“I thank you very much, Monsieur,” replied Diane in her flute-like voice, “but I make it a rule always to go home with my friends, Monsieur and Madame Grandin, after the performance.”

The Marquis remained silent for a moment, then he said, bowing to Madame Grandin:

“Perhaps your friends will give me the pleasure of their company too.”

[26]“It is as they wish,” answered Diane. “But I must return home. I cannot stay out late; it affects my voice unfavorably.”

The Marquis stared at her as if she were a lunatic; he had never known stage people of this class who refused anything to eat and drink.

Diane then, with Jean, started up the street shepherded by the Grandins. When they reached the corner, Grandin found his big, melodious voice, and thundered at Diane:

“What do you mean by declining for us to go to supper? I never went to supper with a marquis in my life; it would be worth a hundred francs’ advertising!”

François had lagged behind, and was saying to the Marquis,

“Are you Fernand or Victor Egmont de St. Angel?”

“I am Fernand,” said the Marquis. “What do you know about my family?”

“Oh, merely that we are cousins.”

The Marquis shouted out laughing, while François, rolling up his sleeve, gravely exhibited his arm tattooed with a crest and initials.

“This was done,” he said, “when I was a[27] child, in case I got lost. I have got lost since in the great, mysterious maze of the world, but I have no objection, like that young lady yonder, to go to supper with you, provided you will have a good brand of champagne. Cheap champagne is worse than bad acting.”

“Come!” cried the Marquis, “I know that crest. You have indeed got lost! But you shall have champagne at twenty francs the bottle if you will tell me all about that young lady who kicked about so beautifully in her little wooden shoes.”

François then slipped his arm within that of the Marquis and the two paraded across the quiet street singing at the top of their voices some of the songs they had heard that evening from the sweet lips of Diane.

Nothing was seen of François that night, but the next morning when Madame Grandin, who added thrift and early rising to her other virtues, was going out to the market at sunrise, she came across François lying drunk on the door-step. Madame Grandin, a good soul, instead of calling her husband or Jean, who would be likely to use François roughly, tiptoed to Diane’s door and[28] the two women very quietly managed to get François, who was a small man, up the stair, on his way to his attic. As they passed Grandin’s door, the manager appeared in a very sketchy toilette.

“What’s the matter with François?” asked Grandin.

“Drunk,” hiccoughed François, thickly, and perfectly happy. “Too much high society. Champagne at twenty francs the bottle, and my cousin, the Marquis Egmont de St. Angel, paying for it. Just let me sleep all day, and I will be as sober as a judge by six o’clock.”

And this actually happened.

It is a very serious thing for a juggler to get drunk while he is juggling, but François, who had as good artistic conscience as Jean Leroux or anybody else, never attempted his profession unless he were dead sober. That, he was, at six o’clock when he walked into the little sitting room and joined the rest of the party at supper which was cooked by the excellent Madame Grandin and Diane in collaboration.

“Don’t be afraid to do the pumpkin act with me to-night, you dear old goose,” said François[29] to Madame Grandin. “I wouldn’t risk your precious life for anything. Where would Grandin get as good a wife and as good a partner as you if I should break your neck? And besides, it would break up the show for a fortnight at least, and perhaps ruin the whole season just as Diane is in a fair way to become a marquise.”

“What do you mean, François?” asked Diane.

“I mean that the young officer who admired you so much was the Marquis Egmont de St. Angel, a cousin of mine. We got gloriously drunk together like old Socrates and the boy Alcibiades the time that Socrates came in and caught Alcibiades and a lot of Greek boys drinking, and they swore that Socrates should drink two measures of wine to one of theirs, which he did the whole night through, and in the morning left them all lying about the floor while he went and took a bath and then lectured on the true, the beautiful, and the good in the groves of Parnassus, with all the wisest men in the town at his heels.”

“And who was Parnassus?” inquired Grandin in his big voice. “His name sounds like a German university professor.”

[30]“That’s just what he was,” answered François. “One of those langsam schrecklich German professors who don’t mind having a mob of ragamuffins overrunning the place.”

All present gazed with admiration at François, amazed at his learning, as well as his great family connections.

Diane’s thoughts were with the Marquis; her face grew rose red as she wondered if the Marquis would be on hand for that night’s performance.

The Marquis, known familiarly as Egmont, was at the music hall the next night, not in his splendid dragoon uniform, nor yet in evening dress, but in ordinary clothes which suggested the notion of a disguise on Egmont’s part, to François.

Evidently, the company as a whole, and Diane in particular, had made a great hit, for the former furniture shop was packed with persons. François went through his juggling and his tricks with the Grandins without the slightest nervousness. Not so, Diane. She began to give signs of what is dangerous and even fatal to an actress—self-consciousness. No one noticed it except Jean, who saw everything with the sharp-sightedness of love.

When the performance was over, and the hall closing for the night, the old woman who took in the money at the door handed a note to Diane, who slipped it into her breast. When[32] she got home and was alone in her little white room, she took the note out and read it. Many notes of the kind had Diane received in her short theatrical career, chiefly from young shopmen and susceptible lawyers’ clerks and the like, but this was from a marquis, and written upon beautiful paper. It was very respectful in tone, and asked Diane why she had been so cruel the night before, and what evening would she honor Captain, the Marquis Egmont de St. Angel with her company at supper. The foolish Diane kissed the note and slept with it under her pillow.

The next morning about ten o’clock, Diane went out on a shopping expedition in the streets of Bienville. She was one of those women who have an instinctive knowledge of how to make the best of herself. She adopted a demure style of dress, a trim little black gown and large black hat and a thin black veil, all of which gave her a nun-like appearance. When she raised her eyes, however, there was nothing of the nun about Diane.

She walked rapidly along the bustling streets of the town, and looked like a pretty governess somewhat alarmed at being out alone. In truth,[33] Diane had been out in the world alone since her seventeenth year, and knew perfectly well how to take care of herself. She went into a paper shop to buy some writing paper elegant enough to reply to the Marquis’s note. As she walked out of the shop, she came face to face with the Marquis swinging along in his dashing uniform, and carrying his sabre in his arm. He smiled brilliantly at Diane and took off his glittering helmet with its red plumes, and bowed profoundly to her, but Diane, whose face became scarlet as the dragoon’s plumes, turned and ran as fast as she could, and was lost to sight, diving into a narrow and devious street. She heard footsteps behind her and kept her head down, thinking it was the Marquis, but the voice in her ear was that of Jean.

“That man means mischief as certainly as you live, Diane,” said Jean, who had a brusqueness and common sense sometimes most painful and uncompromising.

Diane stopped under an archway, dark even in the bright autumn morning.

“I don’t know what he means,” she said, “but neither he nor any other man can do me[34] any harm. In the first place, I am by nature a modest girl, you know that, Jean. Then, you laugh at my ambitions. Very well; when the time comes that the newspaper reporters are digging into my past, they won’t find anything disgraceful, upon that I am determined. If the Marquis wants to marry me, I shall marry him. But the only way he can reach me is through the church door.”

Jean laughed a hearty, mirthful laugh.

“I believe you,” he said, “and as you always were the most persevering and most determined creature that ever lived, I think that you will stick to what you say. But neither this marquis nor any other marquis will ever want to marry you. As for this fellow, he is a scoundrel. I have heard it in the last twenty-four hours, and I see it for myself.”

“You are so prejudiced, Jean,” complained Diane. “However, I will show you the note that I shall write him, so that you can point out any mistakes in spelling I may make.”

“François is the man for spelling,” answered Jean.

Diane thought so too, so after writing her[35] little note first on a piece of wrapping paper—Diane was nothing if not economical—she showed it to François, who corrected two mistakes. It was very short, simply saying that Mademoiselle Dorian thanked the Marquis for his compliment, but that she did not accept invitations to supper.

“But I wish, Skinny,” said François, “you would go with him. He will be certain to say or do something impudent, and that will disgust you, and there will be an end of it. But you are acting, my dear, like a finished coquette.”

This Diane violently denied, as it was the truth and she did not wish it known.

The Marquis continued to haunt the little hall every night, and the effect upon Diane’s acting was not good, especially in a little love scene she had with Jean.

After a week of this, one night when the performance was over and they were all preparing to go home, Jean spoke to Diane in her little canvas den of a dressing-room.

“Something is the matter. Your acting isn’t improved, Diane,” said Jean, “by your eyes wandering over the audience, and shrinking[36] away from me when you ought to throw yourself in my arms. If you go on like this, you will never get to Paris even as a music hall artist. Your acting won’t be worth your railway fare, third class.”

“I know it,” answered Diane with pale lips. “But while I am dressing I am asking myself all the time, ‘Will the Marquis be in front?’ If he isn’t there, there doesn’t seem to me as if there were anyone in the hall; then as soon as he comes in he seems to fill the hall and to be on the stage with me. Pity me, Jean!”

“I do,” answered Jean, “from the bottom of my heart, and I have a little pity for myself, too. But, Diane, where is your courage, your resolution, of which you are always boasting?”

“It is here,” answered Diane, laying her hand upon her heart. “It is that which keeps me away from him, which drags me to my room when I want to go with the Marquis. It is that which makes me a victor every hour, for I am forever struggling to keep away from him, and I have kept away from him. But when he comes where I am—oh, Jean!”

Diane sat down on the rough box which held[37] her stage wardrobe, consisting of two costumes, and wept plentifully. Jean kneeled by her.

“But you won’t be a coward, Diane,” he cried desperately. “Keep on struggling and fighting. The fellow is a scoundrel, that I assure you. I know the kind of a fight you are making. I have had the same kind ever since I knew you. Think what it is to me to take you in my arms and then to throw you off as we do on the stage every night. Think what it is to act when one feels it.”

Jean stopped. The love of one man matters little to a woman who is desperately in love with another, but Diane, out of the depths of her own agony, looked into Jean’s eyes and realized that some one else could suffer besides herself. They both forgot that François was changing his clothes on the other side of the piece of canvas and could hear every word. Suddenly François’ head appeared above the canvas partition which was only about six feet high, and with a convenient upturned bucket François, who was a short man, could mount and see over into the next canvas den.

“That’s the way it is,” cried François, laughing.[38] “You know the Spanish proverb, ‘I am dying for you and you are dying for him who is dying for someone else.’ I haven’t even the privilege of taking you in my arms, Diane, on the stage, like Jean. This is a cursed world!”

There can be no secrets in a travelling company of five persons between whom there is seldom more than a canvas partition.

Diane did not stop crying, and Jean still knelt on the ground looking at her. Presently he glanced up at François’ grinning face, and cried:

“François, because you never loved a woman, you don’t know what it means, to see her wretched and foolish and crying her eyes out for a worthless dog, as Diane is doing now.”

“True, true, true!” laughed François, “I have done many foolish things in my life, but I never intend to love any woman, especially Diane. Ha, ha! Here, take this stage dagger and kill yourselves like a couple of lovers in grand opera. It is not much of a weapon, but it will do the job. It is the only way out of a three-cornered love affair.”

“François, you are so unfeeling,” said Diane, angrily, and drying her eyes.

[39]As the stage dagger came clattering over the canvas, François got down off his bucket on the other side.

“Never loved a woman!” muttered François to himself. He had a habit common to imaginative persons, of talking to himself when he was under a great stress. “There they go off together. I wonder if they have taken the dagger with them.”

He sat motionless, gazing into the dingy little unframed mirror hung against the canvas, apparently fascinated by the glare in his own eyes.

“Don’t stand on that bucket again, François, my man,” he said to himself between his clenched teeth. “If the dagger is on the floor— It is a clumsy thing, a blunt and horrid weapon to use on one’s self.”

In vain he tried to hold himself by his own glance into the mirror, as one man tries to cow another by his gaze. He backed away until his foot struck the overturned bucket; then he jumped up and glanced over into Diane’s dressing-room. No, there was no dagger on the floor; there was nothing but the box, which was locked,[40] and a bit of a mirror, a towel and soap, and a comb and brush. As François looked, his eyes lost their wild expression. He breathed freely like a man released from the grip of a wild beast. He even laughed, and in his excess of relief, turned a double somersault on the floor, and putting on his shabby coat and shabbier hat, went off whistling gaily. As he came out of the narrow, black alley entrance which did duty for a stage entrance, he saw the Marquis Egmont de St. Angel stepping across the street toward the Hotel Metropole. He had gone through his usual performance of watching Diane go home.

“Halloo! my dear Egmont of the Holy Angels,” cried François, “I will take supper with you to-night if you will ask me, or if you will pay for the supper, I won’t even stand on the asking.”

“Come along, then,” answered the Marquis. He was willing to pay for François’ supper in order to talk about Diane.

The Marquis got a table in an alcove of the pavilion so he could talk freely. The contrast between the two men was extreme—the Marquis, in his splendid dragoon uniform, for he had just come from a reception at the house of[41] the general commanding, and François in his shabby clothes. The waiters, who knew that François was a juggler at a cheap place, nevertheless treated him with an odd kind of respect due to a note of command which his voice had never wholly lost.

“I had to go to a dull reception at the house of the general,” said the Marquis when he and François were seated at a little table, “and got away as soon as I could. What a bore are those pink and white girls, clinging to their mothers’ skirts and as ignorant as children! They are quite colorless after Mademoiselle Diane.”

“Diane isn’t ignorant. She could not well be,” replied François, sipping his wine. “But in mind she has an eternal innocence. There is a great difference between the two things—ignorance and innocence.”

“I don’t know about that,” replied the Marquis, whose mind was low, and who was not so intelligent as François. “That capricious little music hall devil has given me more trouble to bring around to my way of thinking than half the girls I have met to-night. But she keeps me dancing after her, damn her, the little darling!”

[42]François laughed at this, and laughed still more when the Marquis inquired anxiously:

“I think it is that great, hulking fellow who sings and dances with her that frightens her. Perhaps she is in love with him; women are such crazy creatures!”

“Oh, no,” cried François, beginning to attack the supper which the waiter had brought, “Diane is not in love with Jean, nor with me either, strange to say, although I was born both handsome and rich.”

The Marquis pushed his chair back a little, and the waiter being out of hearing, brought his fist down on the table.

“The infernal, proud, presumptuous little devil probably thinks she can marry me! Very well, let us see who will beat at that game. Just look at this impudent note she wrote me.”

The Marquis tore from his breast Diane’s cool little note, the only one he had ever had from her.

“She doesn’t go out to supper after the performance. She remains with Monsieur and Madame Grandin, her friends.”

The Marquis howled with laughter at this, and then kept on.

[43]“And she a singer and dancer in the cheapest music hall in this dull old town of Bienville! Oh, she has got it into her silly head that by holding off she can become a marquise, but she won’t.”

“But you are carrying around her note in your breast pocket,” suggested François.

“Oh, yes, I am fool enough for that,” calmly admitted the Marquis, putting the note back in his breast pocket and drawing his chair up to the table. “I can feel it, I can feel it there, although it is only a bit of paper. Who was her father, François?”

“The village hatter,” replied François, “like the father of Adrienne Lecouvreur. That was her prosperous period, when she enjoyed the advantages of a polite education at the village school. Then her parents died, and she was taken to the house of an uncle who owned three acres of ground, and Diane worked in the cabbage garden and tended geese.”

“And where did she learn to sing, and all those devlish, captivating little ways of hers on the stage?”

“From Nature, the mighty mother of us all.[44] She took some singing lessons from the village teacher, and used to sing at country fairs after she was sixteen. Then, a couple of years ago, we found her and took her into our company. Singing on the stage was taught her by Jean Leroux, her partner, and I taught her something of acting and little stage tricks, but I must say she was a very apt pupil. She has got it into her head to go to Paris and study for the grand opera, but she has no grand opera voice, and has two hundred and sixty-six francs to pay her expenses.” For Diane had palmed off the grand opera story on François as well as on Jean, when really her mind was set upon a big music hall.

“Everything that you tell me,” said the Marquis, “shows how admirably unfitted this wide mouthed, skinny girl is to become the Marquise Egmont de St. Angel.”

“You have hit upon her name,” cried François, laughing, “for we call her Skinny. Our little Skinny a marquise! And your title is worth at least two million francs in the open market. As for yourself, I may, with the frankness of a relative, say you would be dear at two hundred francs.”

[45]“Has anybody ever told you that you were extremely impudent, M. le Bourgeois, as you call yourself?”

“Occasionally,” replied François. “Here, waiter.” The waiter came from a distance. “Take this chicken away,” said François,—“it was hatched during the First Empire, I think,—and bring us one that isn’t old enough for military service.”

The Marquis rambled on, admiring and cursing Diane all through the supper.

When François got home an hour later and passed Diane’s door, he saw a thread of light under it, and the door opened gently, showing Diane’s pale, dispirited face. She knew well enough where François had been; nobody except the Marquis had so far asked him to supper.

“Yes,” said François in a whisper, answering the question in poor Diane’s eyes, “I have been to supper with him. It always raises me in my own esteem, for I see that I, François le Bourgeois, born in a chateau, and now juggler and acrobat when I am sober enough, am a far more respectable character than the Marquis Egmont de St. Angel; he has no more brains than my[46] shoe, and is the handsomest young officer I ever saw. I am ashamed of him as a relative.”

Diane slammed the door angrily in François’ face.

The days and the weeks crept on, and the performances in the ex-furniture shop maintained and even increased their popularity. Diane could have had supper every evening with an officer or with a young advocate or any of the gay dogs who are found in every town, but Diane, being a shrewd little person, concluded that it was worth more as an advertisement to decline these offers than to accept them. Soon it became the subject of numerous wagers among the gilded youth of Bienville as to who should first have the triumph of entertaining Diane at supper. Presently the wagers were changed; it was a question whether any of them could succeed in this commendable project.

This sudden popularity of Diane by no means weakened the devotion of the Marquis de St. Angel. She still turned an unseeing eye and a deaf ear toward him, although her heart beat wildly and her pulses were racing. One person profited by this—François. He could get supper[47] at any time out of the Marquis by merely telling about Diane, and especially of the notes and letters she received, and even the presents which she haughtily returned. The Marquis continued to pursue her and to damn her for an affected prude and subtle advertiser, and not half as handsome as a plenty of other ladies in her profession who were not so obdurate.

Grandin at first bitterly reproached Diane for not encouraging the Marquis and the other young bloods, but in the course of time he came around to her opinion.

“It’s much better advertising,” said Diane. “If I should go out to supper with one of these young gentlemen, the box office receipts would fall off fifty francs at least. And think, Grandin, how nice it is for you to have all these people following us and looking at you because you are my manager.”

“True,” replied Grandin. “I have been photographed, actually photographed when I appeared upon the street.”

One day in midwinter two great honors were paid the Grandin company of jugglers, acrobats, and singers. A card was brought up to the[48] little sitting room where Diane and Madame Grandin were making a suit of stage clothes for Grandin, who was not only without his coat, but also sans-culotte. It was a beautiful card inscribed Captain, the Marquis Egmont de St. Angel, Twenty-fifth Regiment of Chasseurs. The two Grandins and Diane were immediately beside themselves. Diane, who had on a large white apron, took it off and put it on again, frantically, and rushed to the little mirror to tidy her hair when it all came tumbling down her back in a glorious mass. Grandin tore the pinned-up jacket and short trousers off and made a dash for his clothes which Madame Grandin seized and withheld violently, mistaking them in her agitation for the stage clothes. In the midst of the commotion, while the Marquis was cooling his heels in the narrow passage below, François passed him and walked upstairs to the little sitting room.

“He is downstairs!” shrieked Diane incoherently, trying with trembling fingers to put up her rich hair. “He is downstairs, and Jean didn’t want us to take this sitting room! He said we didn’t need it, and now Madame Grandin[49] won’t give Grandin his trousers, and I don’t know what I shall do!”

François, however, with his usual coolness, knew exactly what to do. He thrust Grandin into his own room, threw the scissors and the work things and scraps into Diane’s apron, which he gathered up and flung after Grandin, and going to the top of the stairs called out, laughing:

“Come up, my Marquis Egmont of the Holy Angels.”

The Marquis walked in smiling, having heard all of the commotion. Madame Grandin greeted him with deep agitation, having never received a marquis before, as indeed, neither had Diane.

Diane’s usually pale face was scarlet, and she sat as demurely as a nun on the edge of her chair, with downcast eyes, responding “Yes, m’sieu,” and “No, m’sieu” to the Marquis’ chaste remarks. François remained so as to keep Madame Grandin and Diane from a total collapse. As he looked at the Marquis it occurred to François that any girl might fall in love with so splendid an exterior. He was certainly the most highbred-looking man François had ever[50] seen, not excepting himself. The Marquis’ undress uniform fitted him to perfection, and showed the supple beauty of his straight and sinewy figure. Then his voice was peculiarly sweet, not big and sonorous like Grandin’s, but rather low with a crispness in it like a man accustomed to giving orders.

They talked about nothings, as people do when the ladies of a party are not quite at ease. The Marquis was perfectly at ease, however, and had a laughing devil in his eye which responded promptly to the laughing devil in the eyes of François. Diane’s voice was ever peculiarly sweet, and it occurred to François that the talk between her and the Marquis was like a duet of birds in spring, or the rich notes of the ’cello blending with the sharp sweetness of the violin. And they were just the right height, and Diane was dark-eyed and black-haired and white-skinned, while the Marquis was chestnut-haired and blond and bronzed.

The Marquis complained gently to Diane that she would never accept his invitations to supper, and asked her if she would do him the honor to sup with him that night, when he hoped also to[51] have the company of Monsieur and Madame Grandin and Monsieur le Bourgeois.

“I thank you, no,” replied Diane sweetly. “I made a resolution before we came to Bienville not to accept any invitations to supper.”

“Oh, Diane!” burst out the excellent and too truthful Madame Grandin, “you did no such thing. You only took the notion after you got here, and besides, you were never asked to supper before by a marquis.”

“I made the resolution in my own mind,” replied Diane suavely, who had never dreamed of such a thing in her life. “It is most kind of the Marquis, but I can make no exception.”

The Marquis protested, backed up not only by Madame Grandin, but by Grandin himself, who was listening attentively at the door behind the Marquis, and put out his head, grimacing and gesticulating wildly in protest to Diane. The Marquis saw it all in the little mirror, and burst out laughing, at which Grandin’s head suddenly disappeared. But Diane was relentless, and the Marquis had to leave, asking permission, however, to call again.

“You may call every day,” replied Madame[52] Grandin. “My husband thinks it would be a very good thing for the show to have a marquis attentive to Diane. She is a perfectly good girl, I assure you. We made inquiries about her character before we engaged her.”

When the Marquis and François were out in the street and laughing together, François said:

“Beware of Diane! She is the most determined creature I ever saw in my life. If she makes up her mind to marry you, you are lost.”

François then walked off, taking his way past the Bishop’s palace, a shabby old stone house with wide iron gates before it. The Bishop was just coming out for his daily walk, and François, who was as bold with a bishop as with a rat-catcher, went up and said:

“I perceive your Grace does not recognise me. I am—or I was—François d’Artignac of the Chateau d’Artignac on the upper Loire.”

The Bishop, a gentle, unsophisticated man, overflowing with benevolence, shook hands cordially with François, saying:

“Ah, it is a great pleasure to me to meet one of your family, for I and my brother, General Bion, were both born and reared upon that estate[53] where our father and our grandfather and our great-grandfathers for many generations back were laborers. We do not seek to disguise our humble origin, my brother and I. We were always well treated by the family of d’Artignac as far back as we can remember, and I am happy and proud to meet a representative of that family.”

The Bishop was now out of the gate, and François and himself were promenading together along the street, one of the best in the little town.

“I remember you and your brother well,” answered François. “You were always reading and improving yourselves, and taking all the prizes in the village school.”

“We did our best,” replied the Bishop modestly. “But I recollect you, the little François, the beautiful boy in dainty clothes, that used to walk in the meadows with a footman behind you, while my brother and I kept the cows. Oh, they were happy days!”

François, by design, led the Bishop directly past the lodgings of the Grandin company, and looking up at the window, saw the noses of Grandin and his wife and Diane glued to the window-pane.[54] They also passed Jean, who bowed respectfully to the Bishop and then thrust his tongue in his cheek on the sly to François.

Meanwhile François had told a pretty story of his downfall in the world, and his resolute determination to earn a living when he had lost all his property and had been repudiated by his family. He did not mention various little episodes with regard to raising money through means prohibited by the law, drunkenness, and a few other shortcomings. He gave as a reason for his change of name the desire to spare the noble house of d’Artignac the mortification of such a fall.

Directly opposite the Hotel Metropole they met General Bion, a stiff, discerning person, who had a low opinion of his brother the Bishop’s insight into human nature.

“Brother,” said the Bishop, “here is an old acquaintance of ours in our boyhood. We could not call him a friend, because he was so far above us in position, being of the house of d’Artignac. He has had many misfortunes which give him only greater claim upon us.”

General Bion looked suspiciously at François,[55] with a dim recollection of having heard that François’ family had never been proud of him. His greeting, therefore, was rather cool, although being a man of sense he promptly referred to the fact that his father had been a laborer upon the estate of François’ father.

“He calls himself Le Bourgeois now, for his stage name,” said the good Bishop. “I think he shows a true spirit of Christian humility.”

The General made no response to this, which caused the Bishop to show François the greater kindness, asking him to breakfast the next morning, which François promptly accepted.

When François returned to his lodgings, the story of his grandeur had already preceded him, and all his fellow-players, except Jean, were overcome with the magnificence which was being showered upon them. Jean said good-humoredly:

“Now, François, don’t play any tricks on the good old Bishop. He is as innocent as a lamb, and it would be a sin to trick him.”

François took no offence at this, whatever.

But François was not the only one of them who walked that day with a distinguished person.[56] In the late afternoon, although the day had grown dark and a brown fog was creeping up from the river and the low-lying meadows, Diane went for the walk which she religiously consecrated to her complexion. She took her way past the Bishop’s palace through the best quarter of the town, indulging herself in dreams of the time when she would be the mistress of a mansion like the big stone houses, with gardens in front, in which the aristocracy of Bienville resided. Presently she came to the gates of the park, which she entered. It was so quiet and so deserted by the nursemaids and the children, because of the damp and the fog, that Diane could think uninterruptedly of the Marquis. The great clumps of evergreen shrubbery loomed large in the dimness of the fog, and the bare trees were lost in the mist. Diane entered a little heart-shaped maze of cedars, cut flat, and towering high over her head on each side. Here indeed was solitude; not a sound from the near-by town broke the silence, and the darkness, which was not the darkness of night, was like that of another world. She threaded the winding paths quickly and presently found herself in[57] the heart of the maze, and sat down on an iron bench. Then, to shut out the world more completely, that she might think only of the Marquis, she put up her muff to her eyes.

As she sat lost in a delicious reverie, she felt two strong hands taking her own two hands and removing them gently from her face. It was the Marquis, who was so close to her that even in the pearly mist she could distinguish his face. Never had he looked so handsome to Diane. His military cap was set jauntily over his laughing eyes, and his trim, soldierly figure, with his cavalry cloak hanging over one shoulder, was grace itself.

Poor Diane!

Having taken her hands from her face, the Marquis laid his mustache on Diane’s red lips in a long and clinging kiss, and then sat down beside her, drawing her trembling and palpitating close to him. It was like a bird in the snare of the fowler.

“I saw you and followed you,” he said after a while. “You cannot escape me; but why are you so cruel to me?”

“Because I must be,” answered poor Diane,[58] trembling more and more. “Everybody’s past is known some time or other, and when the time comes that the newspaper reporters begin to ask about me, I don’t want to have anything ugly in my past.”

At this, the Marquis, who knew much about women, laughed.

“That is always the way,” he said. “You women think much more of your reputation than you do of your virtue. No woman kills herself because she has yielded to her lover. It is only one of three things that drives her to suicide afterward. The first is the dread of being found out; the second is to be deserted; and the third is starvation. But there is no record of any woman killing herself for the mere loss of her virtue, which shows that modesty is more highly valued than virtue by women themselves. Is that not true?”

Diane looked at him bewildered. Was it true?

“All I know is,” she said obstinately, “that I don’t intend there shall be anything in my past that anybody can twit me about. I would rather die. You may call it either modesty or virtue, but it is stronger with me than life or death.”

[59]The Marquis looked at her curiously, and saw in her eyes that peculiar, deadly obstinacy and resolution which was Diane’s strongest characteristic.

“I once read in a book,” kept on Diane, holding off a little from Egmont, “that the first time a certain royal prince saw Rachel Felix act, he wrote something on a card—I am ashamed to tell you what it was—and sent it to her back of the stage, and she laughed, and invited him to come to see her. If I had been in her place, I would have killed him!”

“Killing is rather difficult for a woman,” replied the Marquis, laughing a little uncomfortably.

Diane rose and stood before him, and seemed to grow taller as she spoke.

“God would have shown me the way,” she said. “Jael had only a nail, but she killed the enemy of her people, and Judith cut off the head of Holofernes, in his camp, surrounded by his guards.”

The light in Diane’s eyes startled the Marquis. But it melted into a dovelike softness, when Egmont drew her once more to his side.

[60]“I suppose,” he said, “you adorable little devil, that you want to bully me into marrying you?”

“No,” answered Diane, “I am so much in love with you that I don’t want to bully you into anything; only it is marriage or nothing. I don’t know why I say this, or feel this, but I tell you it is as fixed as the stars. You have a power over me so far and no farther.”

Diane, as she said this, laid her head contentedly on the Marquis’ shoulder, and his lips sought hers.

And so half an hour passed in the reproaches and confessions of the woman who loves and the man who pretends he loves. The mist was growing colder and more dense. It was as if they were alone in a white, mysterious, soundless world inhabited only by themselves.

Presently, as Diane lay on the Marquis’ breast, there sounded afar off the faint echo of a church bell from the other world which they had forgotten. At the sound, Diane suddenly and violently wrenched herself from the Marquis’ arms and stood upon her feet. Two thoughts raced through her mind, one equally as important[61] as the other. The first was the reproach of the church bell that she had allowed the Marquis to kiss her lips and put his arm about her. And the second was the iron discipline of the stage which drags men and women apart when it seems like the tearing of a heart in two; which calls them from death-beds; which makes them report at the theatre when they are more dead than alive.

“There is the cathedral bell,” cried Diane in a choking voice, “and it tells me that I have been a wicked girl, and that I may be late for the performance.”

The Marquis stood up too, laughing at the jumble of ideas in Diane’s mind, but the next moment she was gone, speeding in and out of the maze. In her agitation and the white gloom of the mist she lost her way, and the Marquis, following her, though unable to find her, could hear her sobbing on the other side of the hedge as she ran wildly about trying to find the outlet. At last, however, she escaped and was in the open path running toward the park gates.

The Marquis took his way leisurely after her, not smiling like a successful lover, but grinding[62] his teeth and cursing both her and himself. Was it possible that this presumptuous, impudent little creature meant to force him to marry her?

Diane got back to her lodging in time for supper with the Grandins, Jean, and François. François amused and delighted them all, telling them of his interview with the Bishop.

“To-morrow,” François said, “I shall be breakfasting in distinguished company, with the Bishop. He asked me, and I accepted, you may depend upon it.”

“What an advertisement!” cried Grandin, with an eye to business. “If only you could manage to get it into the newspapers!”

“Then he wouldn’t be asked to the palace any more,” responded the practical Jean. “There is a limit to advertising, Grandin, which you never know.”

“We could say,” said Grandin, meditating, “that François was passing the Bishop’s palace and fell down and hurt himself, and was taken within by the Bishop’s servants. Anything will do, just to have it known that François has been at the palace.”

[63]“Oh, Grandin!” cried Madame Grandin, “how can you invent such lies?”

They were all so interested in the story of François and his grand acquaintances, that no one except Jean noticed how silent Diane was, and that she ate no supper, although her appetite was usually remarkably good. Jean saw that something had happened, but mindful of that extraordinary loyalty to art of which the theatrical profession is the great model, forebore to ask, lest he should agitate her more.

As Diane and Jean were always partners, they invariably had a love scene in whatever they played together. To-night Diane played the love scene very badly, so badly that the audience noticed it, and she got very little applause. That waked her up, and she picked up her part, as it were, and played it with a renewed spirit that put the audience once more into a good humor with her.

When the performance was over, Diane was a long time in dressing to go home, and the Grandins and François had already gone. Jean, in his shabby, every-day clothes, was waiting for her at the stage entrance.

[64]“I am glad you took yourself by the throat,” he said to her grimly, as they picked their way through the mist which still hung over the town, in which the gas lamps made only a little yellow ring. “I thought the scene was gone at one moment, and expected you to be hissed.”

“Never!” cried Diane, for once thoroughly frightened. “But Jean, I hate love scenes on the stage.”

The next day François duly presented himself at the palace at twelve o’clock for breakfast with the Bishop. Much to his disgust, the General was present. François, who loved to fool people, assumed an air and tone of extreme virtue, and again told, with many additions, a pretty story of his reverses and his determination to earn an honest living by doing juggling and acrobating, the only things he knew how to do by which a franc could be earned. The good Bishop was lost in admiration of François, and said:

“That, my dear M. le Bourgeois, as you call yourself, is the highest form of virtue and respectability, is it not, my brother?”

General Bion maintained a stiff silence, which annoyed the good Bishop exceedingly.

The General meant to sit François out, not[66] doubting that he would contrive to borrow a small sum of money from the Bishop before leaving. But François held his ground, as his ancestors had held theirs on many a hard-fought field, and the General, called away by his military duties, had to leave the wolf in conversation with the lamb. He left a deputy, however, in the person of Mathilde, the Bishop’s housekeeper, an angular and ferocious person of sixty, who disapproved of the Bishop’s fondness for picking up stray acquaintances and lost dogs and cats and giving them the hospitality of the palace.

When François and the Bishop were left alone in the Bishop’s study, then François laid himself out to amuse his host. Soon he had the Bishop roaring with laughter over jokes and merry stories, and at two o’clock it was as much as François could do to tear himself away.

By the time he was out of the room Mathilde had stalked in and proceeded to give the Bishop a piece of her mind.

“Does your Grace remember,” she asked wrathfully, “the last adventurer your Grace took up with, who borrowed ninety francs of your Grace and then skipped off to Paris?”

[67]“Yes, my good Mathilde, I know,” responded the Bishop, using a soft answer to turn away wrath. “But this gentleman, you see—for he is a gentleman—belongs to a family which were exceedingly kind to my family, and especially my father. He was a laborer upon the estates of this gentleman’s father. Think of it!”

“That shows,” cried Mathilde, “what a good-for-nothing scamp he must have been. Who ever saw a gentleman standing on his head, like this fellow does, and playing tricks with cards? I kept my hand upon my purse in my pocket all the time I was serving the General and your Grace and this ragamuffin at breakfast.”

“Mathilde,” said the Bishop, trying to be stern, “I cannot permit you to call a guest in my house a ragamuffin.”

“Then,” cried Mathilde, “I will give him his right name, and call him a rapscallion!” And then she flounced out of the room, banging the door after her.

The Bishop sighed. He was a celibate, and yet he was henpecked worse than any man in Bienville.

François, listening outside, walked away[68] laughing and resolving to pay off Mathilde for knowing the truth about him.

Two days after that, François again met the Bishop face to face in the street in front of the palace, and was warmly greeted. François, eying the clock in the cathedral steeple, saw that it was ten minutes of twelve, and remembering the history of Scheherezade and the Arabian Nights, began telling his crack story to the Bishop. In the midst of it came the bells announcing noon, and the odor of broiled chops from the kitchen window of the old stone house known as the palace. The Bishop, like other men, was subject to temptation, and he could not do without the end of the story, and besides he had always that excellent excuse that his father had been a laborer upon the estates of François’ father.

“Come in,” said the Bishop, “and have breakfast with me. My brother will not be here.”

“Thank God,” replied François. “Now, if you could get rid of that old battleaxe of a housekeeper while we are at breakfast, it would be better still.”

“That I can’t do,” said the Bishop ruefully.[69] “But after all, she is a good creature, and my brother, the General, says it if were not for Mathilde I would never have a sous in my pocket or a coat to my back.”

“He is probably right,” answered François, taking the Bishop by the arm as they marched up the steps. “It is your cursed good nature that will always be giving you trouble.”

François’ reception at the hands of Mathilde was a trifle more hostile than before.

There are some tricks of legerdemain which can be played without the aid of a confederate. In the midst of the breakfast, while François was telling some of his best stories, the Bishop inadvertently took his purse from his pocket with his handkerchief, and left the purse lying on the table. When breakfast was over, the purse was missing.

Mathilde assumed an air of triumph, and the Bishop looked very sheepish. At once a search wits begun, Mathilde shaking the cloth, looking under the chair occupied by François, and doing everything except rifling his pockets. The purse contained eighty francs, a large sum for the poor Bishop, who lived from hand to mouth.[70] In the hunt the dining room soon looked as if a cyclone had struck it; drawers were pulled open, chairs knocked about, and Mathilde watched François with a hawk’s eye.

“That is a good bit of money to let lie around in the presence of a servant,” said François, impudently. “Come now, you woman, haven’t you got that purse in your pocket this moment?”

Mathilde, furious, thrust her hand into her own pocket where she carried a handkerchief, a notebook, a large bunch of keys, a prayer-book, a rosary, and a little figure of St. Joseph in a tin case, and her own purse. But what she brought out of her pocket was the Bishop’s purse. The Bishop laughed long and loud, and François laughed louder than the Bishop.

After this was over, the Bishop invited François into the study. François, in addition to telling some of his best stories, proceeded to go through some of his most comic antics. The good Bishop laughed until he cried, and excused himself on that ever excellent plea about his father being a laborer on the estates of François’ father. Then François went to a wheezy old piano in the room and began to play and sing[71] some simple old songs of the Bishop’s youth—the songs his mother had sung to him in the laborer’s cottage in the meadows. Presently the tears were trickling down the Bishop’s face.

“Go on, M. le Bourgeois,” he said tremulously. “I love those simple old airs that take me back to my childhood when my good mother worked for us all day, and then had the heart to sing to us in the evening. As you sing, I can hear in my heart the tinkling of the cow-bells and the sharp little cries of the birds under the thatched roof—for our roof was only thatch, you remember. Oh, my mother, my dear, dear mother! Her hands were hard with toil, her back was bent with hanging over washing-tubs and the soup pot on the fire; but in Heaven I know she is straight and soft of hand, and one day all her children will surround her and pay her homage as if she, the peasant mother, were a queen!”

François continued to play soft chords, the Bishop listening and sighing and smiling. Presently François heard from the Bishop’s big chair a gentle snore. Then François, rising noiselessly, pulled off his own shoes, which were[72] cracked, and with professional sleight-of-hand took off the Bishop’s new shoes, which he put on his own feet, and then slipped his own shoes on the Bishop’s feet. There was a desk in the room, and François scribbled on a piece of paper, “I would have taken your Grace’s stockings, but they are cotton. If I were a bishop, I would wear silk stockings. I hope your Grace will remedy this impropriety, and in the future wear silk stockings worth the taking.” This scrap of paper he pinned to the Bishop’s cassock, and went softly out through a door opening on a balcony, from which he swung himself down into the garden. As he walked along, he saw a row of beehives on a bench. Stepping gently, he took off his coat and threw it over a beehive, and then lifting it carried it out into the street. A policeman stopped him, saying:

“What have you got there, my man?”

“A beehive,” replied François, “just out of a hothouse, and the bees very active.”

The policeman suddenly backed off, and François marched away with his beehive, which he subsequently threw over the stone wall around the Bishop’s garden.

[73]Meanwhile the Bishop waked, and reading the piece of paper, looked down at his feet to find full confirmation of François’ words. In the midst of it, Mathilde tore into the room.

“Well, your Grace,” bawled Mathilde, “what does your Grace think of your rowdy friend now? He stole a beehive off the bench as he went by. Pierre, the cobbler’s boy, was passing and saw him and told the cook who told the footman who told me, and I went out, and the beehive is gone! And look at your Grace’s feet! The wretch actually stole your Grace’s shoes!”

“Why do you speak with such violence?” said the Bishop, loath to lose, for a single pair of shoes and a beehive, the joy of François’ company. “Suppose I meet a man whom I have known as a boy, when I was in very humble circumstances and he was very high up in the world, and suppose that man’s shoes are worn, and I choose to give him a good pair and take his in return? Is that anybody’s business except my own? And suppose I gave him the beehive by way of a joke, you know?”

“It would be exactly like your Grace,” snapped Mathilde. “But it was the only good[74] pair of shoes your Grace had in the world, and I shall have to go out into the town immediately to buy your Grace another pair.”

“Do,” said the Bishop, delighted to get rid of Mathilde on any terms.

When the door had slammed after the excellent Mathilde, the Bishop drew a long sigh of relief.