Title: The Haven Children; or, Frolics at the Funny Old House on Funny Street

Author: Emilie Foster

Release date: September 9, 2020 [eBook #63162]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Charlene Taylor, Paul Clark and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

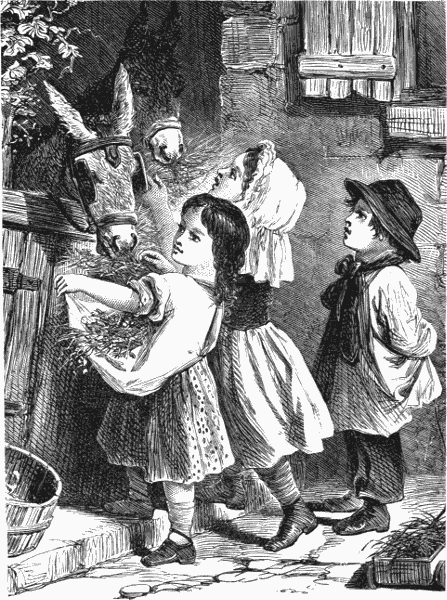

Frontispiece.

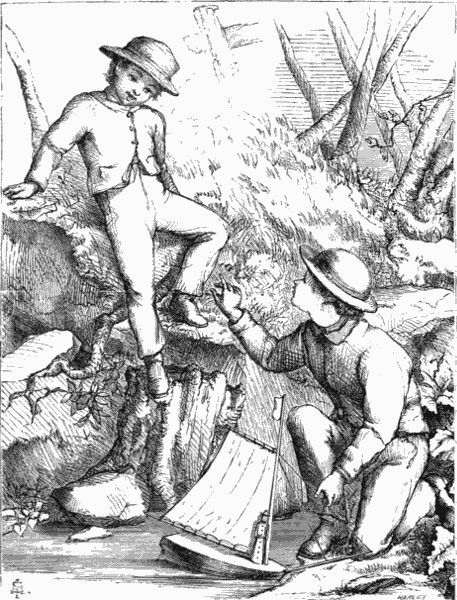

Kit and Larry Launching their Boats. Page 243.

THE HAVEN CHILDREN

OR

FROLICS AT THE FUNNY OLD HOUSE ON

FUNNY STREET

BY

EMILIE FOSTER

NEW YORK

E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY

713 Broadway

1876

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1875, by

E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

To CHRISTIAN BAYARD BÖRS,

Who, for Four Years, gave to The Funny House

on Funny Street,

so much of its Life and Brightness,

and

A Merry Band

of Nieces and Nephews,

This Little Book is Inscribed, by their loving Aunt,

Providence, 1875.

| Chap. | Page. | |

| I. | The Great Surprise, | 7 |

| II. | The Haven Family, | 19 |

| III. | Journey to Providence, | 30 |

| IV. | Sunday in the Nursery, | 47 |

| V. | Rainy-day Frolics in the Old Garret, | 69 |

| VI. | Frolics in the Garden, | 86 |

| VII. | The Fairy Feast, | 98 |

| VIII. | On the Road, | 114 |

| IX. | The Old Brown Farm, | 129 |

| X. | Tea Under the Great Elm, | 148 |

| XI. | A Sail down Narragansett Bay, | 160 |

| XII. | Jem, Kit, Ned, Grace, May, and Alice, | 179 |

| XIII. | Fourth of July at Harmony Hall, | 193 |

| XIV. | Shore Dinner and Clam Bake, | 214 |

| XV. | Tiger and Ranger, | 234 |

| XVI. | On the Yacht, bound for Rocky Point, | 250 |

| XVII. | Farewell to the Funny House on Funny Street, | 260 |

OR,

FROLICS AT THE FUNNY OLD HOUSE ON

FUNNY STREET.

Daisy Havens was awakened from a sound sleep, one bright June morning, by a fearful banging on her bedroom door, and as she rubbed her sleepy eyes, and curled herself up for another nap, there came a shrill volley of boy’s talk through the key-hole.

“I say, Daisy Havens, I’d be ashamed to[Pg 8] be such a sleepy-head. There’s no end of fun going on in the nursery. The Menagerie are all up and dressed, and Mamma has invited them to feed in the dining-room. I say, sleeping beauty, open your ears, if your eyes are shut. Mamma has a letter from Papa, with a surprise for us. So there—sleep on now, as much as you can. I’m off, for one.”

The last shot through the key-hole has taken effect, and Daisy’s bare feet patter quickly across the hall, where, leaning over the bannisters, she catches a glimpse of Artie’s blue sailor-suit, disappearing through the nursery door, from whence proceeds a merry clangor of high-pitched young sopranos and the deeper tones of desperate nurses.

Daisy hastens back, almost forgetting the surprise in store, for very vexation that “Artie couldn’t just wait a minute.”

What trials await her now! Those little elves from the “city of mischief,” so prone to visit children all agog with excitement about some expected pleasure, are all about and around her; now tangling her crimped locks, and cruelly waylaying her comb in its way through them, now whisking off a button or the tin of a boot-lace, now shaking her arm and tumbling her tooth-brush into the slop-jar. Poor Daisy! tears are in her eyes, as she bends over to fish for the troublesome little brush. Alas! her trials are not over, for turning hastily around, she forgets the full pitcher, which, in her bewilderment, she placed on the floor, and now a cool douche reminds her of its presence.

The pretty rose-buds and fern-leaves on[Pg 10] the new carpet are completely drowned. Daisy’s neat boots are weighed down with their additional weight of water, and Daisy herself stands upon a chair, “sending coals to Newcastle,” as the torrent pours from her blue eyes. Just then the door bursts open, and Jacko, the little monkey, escaped from the family menagerie keeper, shouts out, “Oh, Daisy, ain’t you coming to the exprise?” then lowering his tones as he catches sight of the catastrophe and tearful Daisy on her high perch, cries—

“Was you shipwrecked, Daisy dear, and was you throwed on the rocks? Oh, isn’t it fun to paddle? I think water is the best fun of anything.”

“Dais-y! where is the child?” sounds out a loud, ringing voice, as Rosie, the companion monkey of the family collection, appears on the[Pg 11] threshold. “Doesn’t she know what’s going on? Oh, dear, dear, what a awful splash! What ever’ll happen to you, Miss Daisy?”

With this crumb of doubtful comfort dropped, Rosie runs off panting to the nursery, to tell how “Miss Daisy, that’s always preaching to us children, is behaving a purpose.”

Now Daisy, be it known, is the family owl, and has the habit of looking very grave and wise, and using those aggravating words, “I told you so,” to the younger members of the family, so Daisy’s misfortune, this morning, is rather “nuts” for the companion monkeys to crack.

The news of the “shipwreck” reaches the nursery, and Charlotte, who has a very soft spot in her heart for little folks in distress, and whose office it is to mend the family jars and straighten out the family tangles, hastens to the floating island, rescues the family owl,[Pg 12] dries the dripping feathers, and then marshals the chattering group to the dining-room for the rare pleasure of a “high breakfast” with Mamma and Aunt Lellie.

A smiling greeting there awaits them, and then Mamma bids Artie take Papa’s place at the head of the table, and after a simple grace, enters into the general fun.

“Mamma,” pleads one, “need nobody count our cakes this morning, and may we make our own spread of marmalade?”

“Mamma, dear, can’t we have two helps of strawberries. They are so very delicious, and Charlotte will give us peppermint and sugar if they hurt.”

Aunt Lellie’s suggestion that, by way of preventive, the strawberries should be seasoned with peppermint and sugar, was received with merry laughter, and then the clamor went on.

“Oh, Mamma, just look at Rosie!”

quoted Artie.

“Oh, I ain’t either, I was just peering to see if the honey would last for another ‘go-round,’” indignantly replied Rosie, whilst the delicate touches of sweets on the end of her “tip-tilted” little nose, and on her round forehead, produced a merry laugh from all, and proved nearly fatal to Jacko, with his mouth full of buttered cakes.

The din of mingled voices, with their interrogations and exclamations, re-echoed by Baby Mocking-Bird’s accompaniment of Pap-spoon Tatto on her plate, began to grow terrific, so Mamma, by a single word, summoned the little ones to perfect quiet, whilst she unfolded “the surprise” in Papa’s letter.

Let us pass over the pleas used to convince Mamma, to the single sentence—

“I want you to send on the whole Menagerie (little Birdie excepted) with one of the nurses, by the Shore-line train, to Providence, Saturday, to accept Aunt Emma’s kind invitation to visit her. Hugh and I will meet them at the station.”

The reading of the letter was followed by an almost painful calm. Its meaning was too great to be taken in all at once, but gradually it dawned upon their bewildered little intellects that this was Saturday, and in less than four hours they would be on their journey to the far-away city and “Aunt Emma,” who was, to them, a sort of good fairy, who always remembered the six birthdays, and seemed a kind of familiar friend of Santa[Pg 15] Claus, or, as Rosie said—“She guessed they had growed up together, and been to the same school.”

However that may be, certain fact it was, that whatever wishes they had whispered up the dark chimney the week before, were sure to be realized when, Christmas morning, the Adams Express wagon left a huge box marked “Providence,” with Aunt Emma’s card fastened on to the plum pudding, so sure to form the first layer, with the good Auntie’s assurance to Mamma, “It was made, by Celia, very weak, to suit the children.”

The nurses now appeared to carry off the younger folk to the nursery, thereby making short work of Jack’s series of joy-speaking somersaults, whose chief feature, much to his elder brother’s scarcely veiled contempt, seemed to be, that the heels never[Pg 16] reached their destination, but remained dangling in the air.

Whilst the little ones, in the nursery, are riding astride the trunks which had appeared there, or tumbling over the piles of clean clothes spread out by Kitty; Artie and Daisy, as eldest son and daughter, are listening to some good advice from Mamma, who is putting the younger members of her flock under their care, urging Artie not to tease poor little Bear, who is really not well, and apt sometimes to be a little tiresome, and—cross, if we must say it. Daisy, too, is to try to be more gentle and patient with her little sister and brother. Then she bids them remember the verse which formed the subject of last Sunday evening’s talk,—“Be ye kindly affectionate one toward another, in honor preferring one another.”

She had then told them in how many ways they might bring sunshine into their own homes, the great outside world, and into their own hearts too, if they were constantly striving to be “kindly affectionate” and studying how they might

not selfishly seeking for themselves the best. She begged them to keep this little verse ever in their childish hearts, that so, with the dear Lord’s blessing, its echo might be found in their lives.

Mamma did not make her sober talk very long, for she knew the little heads and hearts had just about enough to fill them now, and she saw Artie’s big blue eyes were growing hazy, for with all his faults, he was a boy of loving heart, where Mamma reigned supreme,[Pg 18] and just then a little cloud was drifting over the bright sunny prospect before him, as he thought of leaving her without Papa or eldest son to care for her.

Little boys know how soon their sailor-coat-sleeves will dry up tearful eyes and let bright sunshine again into boy-hearts (for mammas and nurses well know that a little boy’s handkerchief is a myth), and Artie was soon chasing his sister up the stairs, “two steps at a time,” to hunt for his fishing-line, which, in New York, had only caught such fish as might present themselves, whilst angling over the bannisters, or from between the bars of nursery windows, but now the young fisherman’s eyes sparkled as he thought of squirming perch, silvery scup and tautog to be caught in old Narragansett Bay, as his Papa had done in his boy-days.

I suppose I must follow the fashion of all story-tellers, and introduce my young readers to the Haven family, one by one. I grant it is rather tiresome, but you know, the first thing in the study of grammar is to get some knowledge of all the little parts which make up the great Family of Speech; so, in your Geography, you must make the separate acquaintance of little streams and bays as well as of great rivers and oceans, tiny capes, huge promontories, and continents, before you can have much idea of the great[Pg 20] world; so, in every-day life, we get on better, and feel much more at our ease with new acquaintances, after we have learned something about them, so I will begin by telling you that Mr. and Mrs. Havens lived in a brown stone house on Madison avenue, and if you had chanced to pass Forty-second street early some Spring morning, and looked up to the third story windows of one of the houses on your left, you, most likely, would have seen six little faces looking out, six little noses and six pairs of chubby cheeks flattened against the window-panes, earnestly studying the movements of that little girl in soiled dress. Poor child! her tatters, flapping apart with the motion of the warm south wind, show two thin, stockingless, shoeless legs, telling a tale of want and neglect at home, as her little iron hook clinks against the curb-stones,[Pg 21] seeking to find hidden treasures of rags or bread-crust to fill the bag she bears. Do you guess why the thin, soiled, childish face looks up so earnestly at the window of No. 310, as she passes? It is because there she finds the one little rift of cheer which steals into the poor heart, the day long. Child as she is, knowing nothing of a true home and mother’s tenderness, she reads, with a child’s instinct, the sympathy and companionship in those bright young faces, and well remembers how, early every Sunday morning, a little basket is let down from those windows filled with nice bits which the children have saved from their Saturday’s dinner and Sunday’s breakfast, gifts costing them often a little self-denial, for which they are well repaid by the bright look in the girl’s face as she draws out the apple or the orange which, yesterday,[Pg 22] was handled over so many times, and wistfully gazed at before its owner could quite willingly consign it to the little basket. Can you not see, now, why Papa and Mamma, gazing from the windows, regard that poor child’s bag with so much interest, nay, almost reverence? They feel as if, somehow, it became the little altar on which, each Lord’s day, their dear ones offered up their gifts of that which had cost them something of self-denial, and they prayed that the Holy Dove might ever nestle in their young hearts, prompting to love and kindly deeds which, offered to those little neglected city waifs, is indeed offered to Him who has said, “Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these little ones, ye have done it unto Me.”

Those third-story windows let in, too, a deal of sunlight to the Family Menagerie, in[Pg 23] the nursery, where the Keeper, Master Artie, a bright boy of ten, when not engaged—as, very sorry I am to say it, he sometimes is—in teasing the little animals in the nursery cage, is often to be found quirled up in the wide window-seat, following Napoleon Bonaparte through his snowy Russian marches, or on the bloody, fatal field of Waterloo, or reading aloud to the never-wearied trio of the wonderful content and skilful management of that remarkable Swiss Family Robinson, who seem to have borrowed the brains as well as the daring of the great Crusoe.

Daisy, the family Owl, has a wise look beaming from her large full eyes. Seldom does eight years bring such a deal of wisdom to a young mind, such wonderful acuteness in discovering family faults, and such readiness in reproving the same; but Daisy is loving, per[Pg 24]fectly truthful, and really a great help to the nurses in the care of the little ones. She is a most devoted mother to two wax, two china, and one large rag doll. Patiently and uncomplainingly, has she watched over their sick-beds, nursing them tenderly through their various stages of whooping cough, measles, and scarlet fever, and the nurses tell “how pale Miss Daisy looked, one morning, when, on going to Felicie’s little bed, she saw the face of the young French beauty quite disfigured with what was, probably, the very disease which was then raging in New York.”

Poor Felicie was taken, for fear of infection, to the attic, and even now, bears traces of the sad disease. It was a most curious fact that Master Artie, too, was kept, that very day, in solitary confinement by Mamma for some reason, and it was whispered among[Pg 25] the servants that he could tell, better than any one else, just how and where Felicie caught the disease. Two kittens claim Daisy as their Mamma also; she is very careful of them, fearful that their lives may be brief, like those of most of her pets; and it is strange that kittens, grown in the same house with small boys, are not generally long-lived.

There is quite a miniature cemetery at the farther end of the little garden. A thrifty fish geranium shelters the grave of three little pets who once inhabited the aquarium in the nursery and delighted the little ones by their golden flashes, as they gayly tossed about.

One morning the little lake was very, very smooth and still. No more golden rays flashed forth. Three little fishes lay quite dead! Somehow, for a careful search revealed the[Pg 26] fact, their bill of fare had been changed, and Papa’s science proved very clearly that their new diet had been too rich for them.

A little farther on, tiny rose-bushes adorn the graves of kittens numberless whose life’s tales had been very short. Two tiny tablets mark the graves of a lovely bullfinch and a rare canary, whose last resting-places have been moistened by true mourners’ tears.

In the attic, a miniature house may be seen. Daisy alone keeps the key, and rarely allows visitors to enter. Peeping through the little windows, the invalid chairs and snow-white beds reveal the fact that this is the “Doll Hospital.” Incurables are admitted too, for there is a headless doll, apparently standing to look out of the window. There lies a patient with an abscess or hole in her side. I can guess what young surgeon’s knife ex[Pg 27]plored there. By this poor, thin dolly sits another, with bandaged head slightly turned on one side. In the male ward there are no end of patients, one-legged, no-legged, armless, toothless, eyeless, noseless.

A little vase of flowers on a white covered table, and various other little tokens plainly show that the little “Sister of Mercy’s” visits to the Hospital are very frequent.

I have wandered far from the nursery, and now must quickly retrace my steps, for still there is Rosie’s round, chubby face, whose archness is partly veiled by the shower of golden curls which screen the mischief their owner is sure to be hatching, and funny,[Pg 28] laughing Jack, the companion monkey. These two little folk are, generally, to be found with their heads together, conscious that the eyes of the two nurses are on the watch for their schemes.

Beg pardon Bear, or Master Harry, your six years, with their little burden of hours of pain and languor, which give your dark eyes such a wistful look, as of longing for the great health-gift which makes child-life such

entitle you to be introduced before the pair of rollicking young monkies. Dear little Bear, do you know why Mamma and nurses deal so gently with your impatience, and Sister Daisy soothes you with such loving tones? Ah me! there is a cloud-fleck somewhere in the bluest sky,—a shadow on each sun-lit path,[Pg 29] a withered leaf on every plant,—the dear Lord places a cross in every Eden, side by side with richest earthly blessings.

One more little figure attracts us, whose sunny ringlets, like a golden setting, encircle the fair face of the peerless little Lily, the Nursery Queen, at whose shrine brothers and sisters bow most loyal subjects.

Yes, little Mocking-bird, your sway is undisputed, you may pull off Aunt Kitty’s cap-strings, wring young Jacko’s saucy nose, tear the leaves of Artie’s book, or even, unrebuked, hurl your rattle at poor little Bear’s pale face. It is all right! The acts of Queen Baby are never questioned by her willing subjects.

Let us draw a curtain over the scenes of the last hour at home, for partings, though some have called them

have a deal of the bitter mingled with them, when a dear Mamma and baby-sisters have to be left behind.

The last bell has sounded, the last trunk been hurled into the baggage-car, the last “All aboard” has been shouted, and the “Shore-Line Express Train,” with its precious load of human life, is steaming out from under the[Pg 31] shelter of the Grand Central, rushing through the Forties, Fifties, Sixties, and past the beautiful Park, with hasty glimpses at its trees, Casino, lakes, and glittering equipages.

The little travelling party have a section in the Palace Car, and there they are sitting very demurely; they are not used to travelling, for Mamma’s idea has always been that “Home is the best place for little folk,” and now they are somewhat stunned by the strangeness and excitement; but suddenly Rosie, who is not apt to stay “stunned,” screams—

“O, childerns, do look out of the window. We are riding on nothing, with all the world both sides of us.”

The sight which met the young, eager eyes was indeed wonderful. Ignorant of any danger, they seemed held in the air by some magic spell. They are fairly roused now;[Pg 32] their spirits rise to the highest point, as they chatter of bridges, rocks, tiny men, women, and houses beneath, when suddenly, without any preparation, a “horror of great darkness” comes over them. What can it mean? The cold, damp dungeon, and the loud, clanging sounds? The little faces look ghastly white by the light of the flickering lamps above them, as they cling close to good Charlotte.

With the feeling of terror, to the older ones, comes back, in the twinkling of an eye, thoughts of Him to whom they have been taught “the darkness and the light are both alike.” Half unconsciously, little prayers linger on their lips, thoughts of dear Mamma, with resolves to be more “kindly affectioned,” and then they come out again into the welcome light, and as the heavy weight of fear is lifted from their childish hearts, their spirits[Pg 33] rise with every advancing mile, till their merry peals and funny speeches call forth smiles from many travellers in the car without.

Still on they go, with the ceaseless jarring and unearthly whistle’s shriek, through towns and villages, woods and meadows; now journeying side by side with the blue waters of the Sound, with its grateful breezes, its tiny craft and pebbly shore; now hiding behind some hill or grove to come springing upon the smiling water-view again.

Little eyes are growing weary of sight-seeing. To little ears the cries of conductors, pop-corn and prize-package venders have lost their freshness; the sun seems suddenly to grow very hot. The cage seems very narrow. Artie is crowding Daisy, and Bear “thinks the Monkies might stop their chatter, for his head aches.” Suddenly a cool, fresh sea-breeze[Pg 34] blows through the heated car,—a loud bell peals, a heavy jolt shakes the train, and Jack screams—

“Oh, childerns the cars is riding in a steamboat,” and Daisy reminds Charlotte—

“This is the time Mamma said we were to dine.”

What a merry pic-nic now! Hannah, the cook’s, preparation of that basket was, indeed, a labor of love.

Such rolls, with a “plenty of butter!” Such “a many chicken-wings” and “drumsticks” to be picked!

Oh, Mamma! could you have the heart to deny poor Hannah the pleasure of “smuggling” in those tiny gooseberry tartlets?

Good old Hannah! it was the thought of the pleasure those unusual dainties would give the tired travellers, which moistened your eye[Pg 35] as you stowed the basket in the carriage at the door, for you dearly love those bairnies, and have welcomed each one into the world of sorrow and gladness as you did the Mother-bird, in your younger days; and those dainty morsels are messages from your big heart, your own simple way of telling them how dear they are to those they have left behind. How you would have enjoyed the little dialogue which followed the swallowing of the last crumb!

Jack speaks: “Rosie, if I was a great King, I would have Hannah for my wife, and eat gooseberry tarts all day long, and Sundays too, and never stop.”

“Sister Daisy,” breaks in Rosie, “do you suspect if the misshenries should give the heathen-crocodiles plenty of gooseberry tarts, they would eat such a many childerns?”

Sister Daisy is, just now, occupied in peering under the napkin’s folds, if, perchance, an extra tart might be there concealed, and wondering if it would be her duty to divide it with all the little ones, so she replied, with some tartness in her tones,—

“How foolish! if you will talk sense, I will answer you,” and Jack replies meekly for his companion—

“Little folks can’t always tell sense, Sister Daisy.”

There is one more package, marked, “From Mamma; not to be opened till an hour after dinner,” and when the hour passed, there were found bright golden bananas and oranges, with their luscious juiciness, to refresh and amuse the weary little travellers.

That fruit did a double duty, for the children braided the banana rinds, made “gums”[Pg 37] of the orange-peel, and filliped the pits out of the window, till nothing was left of their feast; then, as the sun went down behind the far-away hills, the little limbs grew weary, little tempers fretful. Daisy then remembered “to be kindly affectionate one toward another,” and with a half-suppressed sigh, closed that interesting book, “Cushions and Corners,” just at that thrilling part when the two children “are making wine jelly, or rather spilling wine jelly on the kitchen floor,” and taking Rosie and Jack, one on either side, she tells them the story of the little Cushions who ever were and remained Cushions, and the little Corners that became Cushions, after much tribulation.

Daisy is well paid for her self-denial by the interest the little upturned faces show, and soothed by her gentle tones, Bear droops his[Pg 38] tired head on the shawl-pillow Artie has fixed on Charlotte’s knee.

The kind elder sister’s power of story-telling was at last quite exhausted, and her spirit ready to rebel at Jack’s continued plea.

“Do, Sister Daisy, do tell another. It’s so hot and tired here.”

Just then a pleasant face looked out of the opposite section, and a kindly voice called out—

“Come, little folk, come into my den, and I’ll tell you no end of stories.”

There was no hesitation then. Cushions and Corners, nurse, dolls, and sleeping brother were all left behind.

That section must have been made of India rubber; originally, it held but two, and its occupant, the clergyman of —— Church, Providence, who formed the centre figure of the[Pg 39] group, was no shadowy outline, but real flesh and bones, and a great deal of both, yet there was room for Artie and Daisy on either side, whilst for Rosie and Jack, there was a knee apiece, and a shoulder, too, for each tired head; for the clergyman had well conned the lesson of his Master—

“As ye have done it unto one of these little ones, ye have done it unto Me,” and so it was that the shrill whistle shrieked out their near approach to Providence, tired travellers took down their wraps and bundles from the racks above, and Bear started, with a fretful cry, before the children had thought of growing weary of the stories of Narragansett Bay, the Indians who once inhabited its shore, with hosts of boy-adventures so frightful as to make them shiver, or so funny as to make them hold their wearied sides.

The kind clergyman lifted poor little Bear, too tired to resist, and tenderly placed him in Papa’s arms, who gratefully pressed the stranger’s hand, whilst his quick eye searched for each household darling to make them over to Hugh’s care, to be piloted through the line of noisy hack and baggage-men, to the waiting carriage.

Little Jack remembered to lift his hat, as he again caught sight of the stranger clergyman disappearing in the crowd, and cried out, to his lady-like Sister Daisy’s horror—

“Good-bye, Mister Story Teller.”

Barnum’s animals, in their cages, passing through a city’s crowded streets, are remarkably quiet and well-behaved, but many an inhabitant of the good city looked up, that night, as a large, old-fashioned family carriage and two bay horses, driven by the blackest of[Pg 41] coachmen, displaying, in a very pleased and harmless way, the whitest of teeth, bearing the noisy little Madison Avenue Menagerie, rattled over the curb-stones of Exchange Place, right under the shadow of the Soldiers’ monument, through Westminster street, in its fearful narrowness, and over the Great Bridge. The carriage halted here a moment that the little animals might catch a breath of the fresh sea air coming up from the bay, through the little river which forms the lungs of Providence, and gives this beautiful city its Venetian aspect.

With mingled feelings of enjoyment and terror, the young folk see themselves ascending the steep hill-side, and are nothing loath to find the carriage halting before a quaint, old house, whose every window sends out a stream of light to welcome them.

A cheery-looking old colored woman, with a brightly-turbaned head, appears at the door, whilst a younger one peeps over her shoulder. Papa calls out in a proud, glad tone—

“Here, Celia and Nan, come get these poor, stray, hungry little creatures. I found them at the station and took pity on them. I make them over to you and wish you joy in your bargain—

Papa’s jokes were always well received and the little folk forgot the strangeness, as they were unpacked by him and Hugh, to be handed over to Celia and Nan’s tender care. Little Jack seemed to grow an inch taller at hearing Celia cry out—

“Now then, Mister John, this child be’s[Pg 43] your werry own self. Them feeters is just your own. Bless the creeter. He’s my mans.”

Papa looked at Jack’s saucy little pug nose, and felt his own Grecian feature, evidently very much struck with the great resemblance, then passed on, with Bear in his arms, to the library door, where good Aunt Emma was hugging and being hugged by the other three.

Dear old Auntie, with your plain, kindly face, and silver, corkscrew curls! The tears of joy which sprang to your eyes when you greeted your favorite nephew’s treasures, well up and course rapidly down your thin cheeks as your heart goes out in sympathy for the tired little boy with the melancholy, wistful look.

Old Celia now appears, with Jack’s fat[Pg 44] legs dangling over her arms, whilst the round face is very rosy, partly from suffocation in her tight clasp, and partly from mortification at being thus publicly “babied.”

No sooner were the greetings finished, than Celia cried out—

“Come, children to the nursery, we’ll just give a shake to them gowns and trowsers, and wipe off a bit of the dust from your little faces, and then have a bit of somethin’. Bread and water! Did ye hear tell? I guess it’s likely in this yer house, and old Celia in it! Allers Mister John must have his little joke.”

The nursery looked so cool and pleasant, and the little table with its tempting feast so inviting, that even Bear submitted without resistance to a cool face-sponging and hair-dressing.

Papa and Aunt Emma came up to see the little ones at the table enjoying the good things Celia had provided.

Papa shook his head, more than once, as tiny, light biscuits, cold chicken, and strawberries disappeared, much to Celia and Nan’s satisfaction.

Refreshed by the rest and pleasant meal, everything was “merry as a marriage bell.” Daisy thought “How easy it is going to be, here, to be ‘Cushions’ all the time, in such a nice, cool place as Providence.”

The Monkey chattered over their famous jokes, and Bear’s laugh thrilled Papa’s soul as no strain of sweet music could have done.

The older ones bade the young party “Good-night,” and left them to their nurses, Papa whispering to Aunt Emma, as they left the room—

“I am afraid we shall hear from that feast, Auntie. I shall have to spend the night reading ‘Dewees on Children’s Diseases.’ I suspect Fanny would think me very unfit to be trusted with her bairns.”

“Never fear,” merrily replied Aunt Emma, “they are breathing sea air, and are so happy, their food will do them no harm, I am quite sure, and if Celia and I can help it, they shan’t see hominy or oat-meal whilst they are here. Bless the darlings!”

Sunday morning’s sun peered long into the windows of the quaint house on Funny street; the milkmen,

completed their rounds, Grace Church chimes rang out “Jerusalem the Golden,” and the “Old Baptist” bell sent forth its loud, full tones, before the heavy eyelids of three little travellers had opened wide enough to take in any idea of their whereabouts.

Artie and Daisy, in snow-white suits, have breakfasted down stairs, and are now curled up in comfortable sofa-corners, reading the “Children’s Magazine.” Hugh’s voice is heard through the open window, as he sings—

to the accompaniment of jingling spoons and clattering dishes, whilst Celia and Nan have stolen up to the nursery for a half-hour’s chat with Charlotte, and to aid at the morning bath.

Little Bear wakes languid and fretful, entirely unwilling that good old Celia should aid, or even touch him, whilst the two Monkeys chatter and splash in their bath, good-natured and merry, as if they had only travelled to the Park and back.

Splashed and bathed, rubbed and scrubbed,[Pg 49] brushed and flushed, the little folk draw around the waiting table, and can scarcely eat for laughing at the prodigious joke that they,—

“Have real-for-fair beef-steak, like grown-up folk, and buttered toast.”

Suddenly, the door opens to admit Papa, and then the laugh has to be repeated with him, so funny it is that “little Monkeys and Bears should go to visit, and be fed on cooked beef-steak and buttered toast.”

so, carefully avoids the little buttered fingers, soon waving good-bye, for the bells are tolling Church-time, and Aunt Emma, Daisy, and Artie are waiting below.

“Do they have Sundays up here to my Aunt Emma’s house all the time, Nan, and[Pg 50] week-days too?” anxiously asks little Jack, with mouth full of buttered toast.

“That we don’t, childy,” she replies; “we don’t have Sundays here more than common, and never on a week-day as I remember; but I am just going to stop home from Church to-day and help amuse you. Let me wipe your little fingers and then I’ll just get the very same Noah’s Ark your Papa used to have when he was a child, for Miss Emma keeps it precious as gold.”

“Nan, I guess it’s best not,” timidly interrupted Bear. “Mamma lets us have picture-books and stories and pencils, but she’d a little rather we wouldn’t have out our toys Sundays. Only Lily has hers.”

“But I don’t think,” said Nan, “your Mamma would object to a Noah’s Ark, it is such a very pious toy, and I could be telling you[Pg 51] the Scripture-story, whilst the family and animals are being walked out.”

“Yes, do, Nan dear,” burst in Rosie, whilst Jack stood listening eagerly, convinced first by one party, and again by the other. “It would just do for a Bible lesson, you know, like Sunday-school.”

“But, Rosie,” remonstrated Bear, “when we are away from our Mamma, we ought to do what she likes, and you know how many times she tells us if we give up our toys on Sunday, it will be the same as a

but we might play Sunday-school, with chairs, if Charlotte would be teacher, and she can tell stories good as any book, except Mamma.”

The Sunday-school idea was eagerly seized upon, and the chairs were soon arranged in Sunday-school order. Then Nan and her class of little ones stood up in most proper order whilst they sang Charlotte’s favorite hymn—

Bear’s sweet treble blended nicely with the two women’s clear notes, whilst Rosie and Jack sang true to their own idea of time, and enjoyed the discord very much.

Then followed a mild amount of Catechism, and Bear chose, “Jerusalem the Golden,” for another “sing,” then Jack asked—

“Miss Sunday-school teacher, can’t we each another tell a true Bible story, and me begin?”

The teacher assented, and Jack began, at first, very confidently—

“Well, now, there was a little fellow, so big as me, and his name was Jofef, and his Papa made him a coat, very buful one, blue and red and buful brass buttons, like Fourth of July soldiers’ coats, only there wasn’t no pantaloons with stripes, and—and two little pockets like mine with hankshef, his Mamma put in, with his name Jack (I mean Jofef) in the corner, and he took and—and popped some corn and—er, and—er, I guess it’s your turn, Rosie.”

“Well, then, I’ll finish it. He took the popped corns out to his brethren, ten nine or twelve of them, making hay in the field, and the wicked lots of brethren just ran and tossed the poor little fellow into a pit, and took the span new coat his Papa made him, and got[Pg 54] some dreadful-for-fair blood and dipt it in, so as to make bl’eve to their father that his dear little son was dead, and killed by the wild animals that’s raging in the dark, wild wood.—Nan, I hope there’s no wild woods in Providence. No? Well, I’m glad of it.”

“Rosie, child, what are you about?” impatiently asked Bear; “don’t you know this is Sunday-school.”

“Oh, oh yes, I forgot. Well, then, where was I? Oh, I know; the father was very sad, there was nothing to eat in the pantries, nor in the barns, only there was something about a silver cup in a bag, but, and, well—a pin seems sticking in me, Charlotte, and I believe my new little bronze boot pinches a little right behind the heel. Isn’t it most Bear’s turn?”

Bear’s story was so well and truly told, that[Pg 55] the children’s interest was fairly roused, and Celia stole in upon them quite unobserved, with something hid under her apron.

The little Monkeys were the first to spy out the suspicious little heap, and the promise of something, speaking in old Celia’s eyes, so grew very restless during the last hymn, and whether by accident or otherwise, we don’t feel able to say, Jack sang out Amen at the end of the second verse, and fairly put an end to the Sunday-school by tipping over one of the chairs, in his eagerness to reach Celia’s lap, and stealing in his little chubby thumb

in the form of a fine, red-cheeked cherry, and Celia apologized for interrupting their exercises by saying—

“I thought may be you’d just like to finish[Pg 56] up with a Sunday-school pic-nic, so I brought you a few cherries.”

The little folk were quite ready for any change. The cherries were ripe and very delicious, and found a ready market amongst the little scholars. Then Nan good-naturedly assented to Jack’s request, who doubtfully watched Bear’s countenance as he uttered it,—

“Please, Nan, to make each of us a Sunday tea-kettle out of a stem-cherry?”

A few moments later Daisy enters the room and inquires, in a very eldest-sisterish tone,—

“Well, what have you young folks been doing since I left you?”

“Been singing, and telling stories, and going to pic-nics, Miss Daisy,” quickly replied Rosie.

“Oh Rosie Havens, what a naughty child to be telling a story, on Sunday too!”

“Sister Daisy, is a story worser on Sundays[Pg 57] nor on Tuesdays and Fridays?” quickly asked Jack.

Daisy pays no attention to the eager little face upturned to hers, but hurriedly passes out of the room, saying—

“I was just going to tell you about the beautiful church I went to, but I shan’t now, I will go down stairs and read instead.”

Rosie Havens is a proud little creature, and shrugs her saucy shoulders, saying,—

“Miss Daisy is so very stylish in her new Polyness dress, she can’t understand children.”

Jack, however, is unwilling to lose the chance of hearing about the beautiful church, so he runs to call over the bannisters,—

“Sister Daisy, do come and tell us all about it. Rosie was only squizzing you. It was only but a cherry pic-nic, and meant no harm, and[Pg 58] here’s a Sunday stem-cherry tea-kettle you may have for your own self.”

Sister Daisy makes no reply, then the little voice over the bannisters takes a more pleading tone,—

“Won’t you only please just to come, sister? We will be so good as ever we can.”

Surely, if Daisy would only turn and see that little chubby face flattened against the stair-railing, looking so flushed and entreating, that very little face that always has such a merry good-natured look, and is always ready to smile assent when asked to run her many older sister errands, surely she could not still pursue her down-stairs journey.

When she left church, touched and softened by what she had there heard and seen, like many an older person, she resolved to be “so good to-day, so kindly affectioned,” and as the[Pg 59] soft south wind gently brushed her ringlets, and sweet odors from summer flowers in the little door-yards she passed, greeted her, the impressions deepened, and she longed to be

Then came thoughts of home and the nursery group where she might do her “little deeds of kindness,” and Daisy said,—

“Soon as I have taken off my things, I will go and stay with the children and help amuse them.”

I think Daisy fairly meant to do this, but as she passed through the dining-room for a drink of ice-water, the cool sound of vine-leaves rustling called her attention to such a nice shaded window-ledge, where she might rest her book, enjoy her “Goldy” story, and watch the busy insects and the floating clouds,[Pg 60] by turn. The nursery path of duty didn’t look very inviting now, besides, “wasn’t she very tired, scarcely rested indeed, after yesterday’s long journey?” Then Daisy uttered aloud these not very gracious words,—

“Well, I suppose I’ve got to go and be shut up with those three troublesome children; I wish they had been left at home.”

So Daisy slowly went up stairs. She thought she was conquering self, that troublesome little enemy, but that was her mistake. She had not calculated how powerful her little enemy was, nor all the weapons he could bring to defend himself. She had, it is true, made a slight thrust at him when she said,—

“I suppose I’ve got to,” and still another and a surer, when she turned her back and started to go up stairs, but still she had not wounded him mortally, so the little fellow[Pg 61] limped up stairs after her, all unknown to the confident Daisy.

When Rosie triumphantly announced the good time “pic-nicking and story-telling,” and Daisy saw no prospect of cherries saved for her, her good resolutions grew fainter; then—then was the time for “self” to assert himself, and that time he conquered fully, and so uproarious did the little fellow grow, as Daisy turned her back upon the nursery path of duty, that Jack’s voice was nearly drowned, as little “self” hurled back his tiny cannon-balls of “good reasons” why in reply.

Somehow, the window-ledge with the story-book on it isn’t quite satisfying, after all. Goldy’s girlish face seems to turn, ever and anon, into that of a pleading little boy, and Daisy herself seems, in some strange manner, to be accountable for Goldy’s tribulations. A[Pg 62] golden butterfly lights on her book, and as her eyes follow its upward course, they rest on the pure blue of the sky, and follow the floating summer clouds in their God-directed way. Then comes to the little Christian child, a remembrance of Him who can read our every thoughts, and then self seems to shrink lower and lower, and the upward glance becomes a little prayer for

and the still, small voice of conscience repeats the verse of the lesson heard in Church that very morning—

“Not rendering evil for evil, but contrariwise, blessing,” and Daisy listens to the voice; she thrusts aside the book, and a moment later enters the nursery with bright, kindly face, saying,—

“Charlotte, wouldn’t you like to go down stairs and rest with Celia and Nan? I’ll amuse the children.”

Daisy’s kindly spirit seems to affect all the little folk. Artie takes “slippery Jack,” as he likes to call him, upon his knee, little Bear leans against his sister’s shoulder, and Rosie takes a cushion at her feet.

First, she tells them of the sound of many voices singing their favorite hymn—

which sounded far away at first, and then became louder, as a procession of men and boys came in the church, some of whom were no bigger than Artie, and yet sang the hymn very nicely.

“Then there were such lovely windows! One, where St. Stephen stood holding stones.[Pg 64] It seemed to me just as if he must love them, he was holding them so close to his heart, and when I told Aunt Emma so, she said in these very words—

“‘Perhaps you are right, Daisy. Our greatest trials, if borne meekly for the dear Lord’s sake, may become our greatest blessings. In every pain or trouble we may hear God telling us of His love for us.’”

“Say that again, Sister Daisy,” whispered little Bear; “that about pain and trouble, and sit a little closer, please.”

“There was a picture of St. Lawrence, side by side with St. Stephen. They were such great friends, and he was burned to death on hot irons because he loved the Lord so dearly. There were pictures of St. Peter and Moses, and David too. I liked so much to look at them, and Aunt Emma said Hugh[Pg 65] should take you all up there to see them after the service.”

“Oh, goody, goody,” began little Jack, but Artie clapped his hands over his mouth, and caught his flying feet, that his sister’s story might not be interrupted.

“There was one window in the church where a woman was giving clothes and bread to poor people. It was in memory of a dear, good lady, whom everybody loved, for she spent her whole life in visiting the sick and poor, and doing kind deeds and saying comforting words. The tears stood in Aunt Emma’s eyes as she looked at that window, for she had known and loved the gentle lady, and she told me that some of those very poor people would still walk miles to visit her grave, and then she said, ‘God grant, little daughter, that you may grow to be such a[Pg 66] lovely, Christian woman. You must begin by faithfully doing, with God’s help, the little every-day duties nearest you.’ Then, oh! there were lovely windows of little children, and one you must surely look at, for a dear little girl, no bigger than Rosie, is kneeling at Christ’s feet. She has lain down her cross there, which means some trouble or pain she had patiently borne, and the dear Lord was holding out for reward a lovely crown for her head. Then there was a city, and the moon was rising over it, and a white angel was going up into the moonlit sky, carrying, so tenderly, a little child.”

“Daisy, do you suppose,” interrupted little Bear, “that little child that bore the cross, ever felt fretful, and spoke cross to her sisters, and brothers, and didn’t mean to?”

“Yes, little brother; don’t you remember Mamma told us we were young Christian soldiers, and would have our little battles with our sinful nature to fight every day and hour till our life’s end? But there’s the dinner-bell, and I must go down stairs; and I forgot to tell you, Auntie wants you all to come down to dessert to-day.”

“Wait, sister darling,” pleaded Rosie, for Daisy’s kindly spirit had broken down the little wall of pride which had risen between the sisters. “I wanted to give you a sailor kiss. You are a darling dear, and beautiful as a—as a—”

“Baboon’s sister,” mischievous Artie interposed. Daisy’s gentleness took no offence at the rather impolite quotation, and Rosie, knowing only the very few animals included in the Family Menagerie, supposed[Pg 68] the phrase to be very complimentary, and added,—

“You are not looking one bit stylish in your new Pollyness dress, and I was only funnin’ to say so, darling pet.”

Alas for the best-laid plans of children, mice, and maiden aunties! Even in Providence (though only forty miles from Boston) the sun does not always shine, and so[Pg 70] it was that the first sounds that greeted the waking ears of the little folk in the Funny house on Funny street, were the patter, patter, on the window panes, drip, drip, from the house eaves,

of the stream of water, which, starting from College Hill, plunges down Funny street in its mad race to empty itself into the river basin, before its hundred fellow-streams should outstrip it.

“Why didn’t this rain put in an appearance yesterday, I should like to know? Of all the dry, poky days in a boy’s life, I do think a rainy day is just the dryest. Why couldn’t we have had a rainy Sunday and done with it?” petulantly demanded the Keeper, and[Pg 71] even the wisdom of the Owl failed to find answer.

The Keeper’s state of mind was not favorable to the peace and well-being of the little animals in his care, and he hid Bear’s stockings, flung the soapy sponge into Jacko’s eyes, and interrupted Rosie’s eighty times of

which was sure to bring sunshine, till at last Charlotte’s patience was quite exhausted, so Papa was appealed to, and the Keeper summoned to sit in the Library corner a full hour, without even a book to relieve the tiresomeness; but when Papa’s morning visit to the nursery revealed the fact that the same mischievous spirit had thickly powdered the children’s strawberries, and flavored their goblets of[Pg 72] milk with salt, Master Keeper was sentenced to solitary confinement in his own room, and in order to confuse the plans of the Evil Spirit,

Papa administered a check in the shape of a poem to be learned before the young gentleman should dine, and poor Master Artie feasted on a few of his own salt tear-drops, whilst searching ruefully for the ne’er-to-be-found handkerchief, and muttering—

“I wish I was out of this mean, old, rainy, gloomy town. Mamma would have understood how I just went in for a little fun. I’ll have it out of Charlotte yet, for this mess. She shall pay well for serving me this shabby trick. Pshaw! I do despise tell-tales. She shall hear from me. See if she don’t.”

I am afraid the rounds of Aunt Emma’s nice chairs were not improved in their appearance by the Keeper’s state of mind, so strong is the sympathy between little boys’ hearts and their feet; whilst the latter help to flee from coming danger or evil, they also seem to help them to bear present discomfort. Now, we don’t, for a moment, mean to recommend little boys in trouble to relieve themselves by disfiguring furniture—far from that—but we believe many a boy’s battle has been fought successfully, with angry, bitter feelings, many a troubled mood dispelled during a good, stirring game of foot-ball in the fresh, clear air. Try it, boys, the next time everything “bothers” and life seems “just one tangle,”—everybody saying, “Don’t do this,” or, “Why do you do that?” Sometimes it must seem to you as if there was no place for boys, so apt are[Pg 74] we, old folk, with our nerves and nice surroundings, to forget our own “long ago.” If the foot-ball plan be not possible, then make your own place for boys, by doing some helpful deed for others, stifling your love of mischief, which, if you will stop to think, you will soon find has its root in thoughtlessness and love of self. All about and around you, may be found, if you earnestly seek, plenty of material to make for yourselves places in good people’s hearts, memories, and sympathies.

Try it, boys, only test the scheme, the very effort will discover the means.

Let us go back to the Keeper caged. Is he dashing still, in fury, against the bars?

No. There he sits, quietly studying his task, with a sunlit face which bears tokens of showers lately passed.

It may be that, in fancy, he had caught a[Pg 75] glimpse of Mamma’s sad, disappointed face; very true it is that Mamma’s teaching has come to his mind, and then the morning prayer, so hurriedly said, “Deliver us from evil.” Then Artie looks upward, the promised Spirit descends as a Dove, stilling the troubled waters of the passionate boy nature, breathing in repentant feelings and helps to right doing.

The “nearest duty must first be done;” and Artie takes up the dreaded task to find his Papa has kindly chosen

and very soon troubles, vexations, and the pattering drops without, are all forgotten in the bright meaning and jolly rhythm of the

In the nursery fair weather prevailed, for Nan has made her beds and dusted her rooms in the twinkling of an eye, for her heart is in the “nussry,” and there she sits on the floor, introducing to the delighted children, Shem, Ham, and Japheth, with their wives, in their stiff red and yellow waterproof clothes, for you know, children, the wardrobe of Noah’s family must have been a very scanty one.

Nan had her own stories to tell, as the “two by twos” joined the procession, stories so well and confidently told, that the little folk feel as if they were standing on Mount Ararat itself, watching the procession go by.

Presently Jack’s bright eyes discover a pale, wistful face pressed against the window-pane of the next house, and immediately, Shem, Ham, and Japheth, and the “two by twos” are deserted for the new acquaintance.

The little boy disappears for a few moments, and then returns with a paper, on which is printed, in large inky letters,

WHO ARE YOU?

Jack makes great endeavors to communicate to his new friend his name, street, and number; and the “neighborhood boy,” as he calls him, seems content to continue the acquaintance, and brings to the window toys and picture-books for Jack’s approval.

Nan seems suddenly to be struck with a new idea, which sends her flying down the back stairs, and soon after the small boy disappears from the window, greatly to the grief of the nursery party.

Presently a heavy tread is heard, and Hugh enters the room and deposits on the floor a large bundle carefully done up in waterproof[Pg 78] cloth, which Nan, who closely follows, proceeds to unpack.

I wish you could have heard the merry shouts and clapping of hands, when slowly emerged from that huge bundle the very same smiling little fellow who had so few moments before disappeared from the other window. What a Nan!

Just listen to what she has to tell:

“Mistress has given me the day to help amuse you, and here’s the key of the big garret.”

Do you wonder that Jack’s heels were flying in the air, and Rosie dancing around and around, and Artie’s rhyming genius inspired him to cry out:

and then he rushed to call Daisy to

“Leave her girl’s flummery and make tracks for the garret stairs.”

Daisy scarcely remembered to shut Aunt Emma’s great piece-box, with its no end of remnants for dolls’ dresses, which had so captivated her.

Poor, poor little New York children, in your four-story brown stone fronts, with their flat roofs, and six feet which make a city yard! Little you know of the pleasure in a real-for-fair garret on a rainy day!

Come climb with me to the top of the funny old house on Funny street! Don’t be afraid! There are no bats to flap their dismal wings in those shadowy corners. “It is but the first step that costs.” Plunge boldly in!

What huge, strong beams for swings!

What unsuspected corners for hide-and-seek!

Those great smooth inclined planes for storing bedding are the jolliest places for sliding, second only to Winter ice-hills, and a great deal warmer and safer, too.

See those huge, broad chimneys! Your breath comes quickly as you think of what may be behind them—goblins, elves, or blackest of cats, with their green, glaring eyes, ready to spring out and chill your blood with terror.

There is all this to be said about an old garret, and yet it seems to us peopled with the ghosts of the past, the rafters still reëchoing the childish shouts of the “long, long ago,” and the very old trunks telling their musty tale of the children who had once sported here, now old men and women, with tottering step and silvery locks.

Little thought our frolicsome party of all[Pg 81] this. Drip, drip, drip, sounded the rain on the roof without, but child-life brought sunlight within, as holding tightly to Nan’s and Charlotte’s dresses, at first, they peer curiously and cautiously into all the shadowy corners, then, grown bolder, drag out from their hiding places the old trunks, dress themselves in pointed slippers, white wigs, laced bodice, ball dresses, and short clothes.

Jack rides astride an old crutch, whilst Artie, mounted on stilts, with curled wig and flying scarlet cloak, chases the screaming party into the darkest corners, or sends them climbing up the smooth shelves, where, on secure perch, they, with pillows, pelt their stilted pursuer, till his uncertain gait makes him cry out for mercy.

Charlotte and Nan may sit on high perch and gossip by the hour, for there are no disputes[Pg 82] to be settled, wounds to be bound up, or new plays to be invented. The old garret supplies merriment enough, and the dinner-hour comes too soon, and the twilight gloom, stealing in through the oval windows, finds the little party very unwillingly groping down the dark, narrow staircase on their way to nursery tea.

Aunt Emma, sitting with Papa in the Library, a little later, hears, through the key-hole, snatches of a whispered conversation, and occasionally, loud tones.

“Oh, I can’t; you are the oldest. You ought to be the one.”

“Oh, pshaw! Don’t be such a spooney; it’s girls’ business to ask favors of women, and you know if I ask they’ll be sure to think it’s a lark.”

Papa looks comically at Aunt Emma, over the top of his paper, saying—

“Some mischief is brewing. So Auntie be prepared to shake your head and look grave. But mum, I see, is the word.”

Here the door slowly opened, and Daisy appeared, looking very shy and ill at ease.

“Please, Auntie, may we have a little fun?”

“Pleasure,” was loudly whispered through the key-hole.

“Oh! I meant pleasure. Could we have a little pleasure?”

“What else have you been having all day long, I should like to know?” asked Papa.

“Yes, Papa; I know, but we want, I believe—” and Daisy, quite at loss for words, looked wistfully toward the key-hole.

“To amuse the children,” prompted Artie.

“Oh, yes, Papa! Artie and I want to amuse the children.”

“I should think Charlotte would rather be excused from having Artie’s help, but Daisy, you have our full and free permission to amuse the children to your heart’s content;” saying this, Papa very suddenly opened the door, and Artie fell in the room, headlong, whilst old Carlo, dressed in Celia’s spectacles and cap, with black shawl and white apron on, leaped over the prostrate form and sprang to his mistress’s side.

When Artie, with face very red, rose from the floor, he felt very much relieved to see Papa and Aunt Emma looking much amused at the picture Carlo presented, standing on his hind feet, as if begging to be relieved of his womanly attire.

“Papa, may we not take Carlo to the nursery, to make the children laugh?” ventured Artie.

“Yes, my boy; but the next time you have any not very pleasant duty to do, don’t put it off on your sister, and shield yourself behind the door. It doesn’t look quite manly. Indeed, to use your own, not-at-all elegant words, ‘it looks rather spooney.’ You may run along now.”

Through the open door the library party heard the creeping up stairs, the suppressed titter and the loud knock, followed by such a screaming and scampering that the Funny house on Funny street seemed to shake on its very foundations. The sound of the uproar reached Celia in the kitchen, who, armed with toasting-fork, accompanied by Hugh with the carving-knife, rushed to the rescue.

The fun lasted till Daisy, Artie, and the dog were turned out by the nurses, that the little folk might be quieted before bed-time.

Tuesday morning dawns brightly, and Tuesday’s sun soon dries up the gravelled garden walks and shady croquet ground of Aunt Emma’s pleasant, roomy garden, where the merry party of young folk are feasting, like the bees, tasting the various cups of pleasure which nature offers, in most tempting freshness, to little city children in their visits to the country.

The Funny house on Funny street, though almost in the centre of the city’s trade and bustle, is surrounded by a large, old-fashioned[Pg 87] garden, where still may be seen those grand floral sentinels, the gay hollyhocks and the rich golden lily, whilst their lowly companions, the larkspur, sweet pea, and marigold still grace the garden borders, disdaining the urns and hanging baskets which confine their modern sisters.

The humming-bird and the golden butterfly still hover about this festive spot, and the fattest of scarlet-vested robin gentry still sing out their siren song, “Cherry ripe, cherry ripe,” from the great cherry and old pear-trees which have escaped the woodman’s axe.

Did you ever notice, children, how pert the robins are in such old city gardens?

They seem to think they are indeed privileged guests.

Aunt Emma, sitting under the shady arbor, with its drapery of clematis and honeysuckle,[Pg 88] told the children that, one June morning, she had discovered that the robins were greedily devouring her choicest strawberries, so she told Hugh to hang a bell on a stick planted in the midst of the strawberry-bed, and fasten to it a long cord which should reach to her sitting-room window.

The next morning she laughed to herself as she heard the “Cherry ripe, cherry ripe,” of the early morning pillagers, saying—

“Ha, ha! my gay visitors. For your naughtiness you shall lose your dainty breakfast. Stealing my finest berries without so much as ‘By your leave, ma’am.’”

Presently a whole flock of birdies descended upon the bed.

“‘Tinkle, tinkle,’ sounded the bell, and then such a fluttering of wings and spreading out of scarlet vests, and away flew the frightened[Pg 89] birdies, far out of sound and sight of bells and berries.

Robin’s Nest in the Old Pear-tree. Page 89.

“I was quite satisfied with my plan,” continued Aunt Emma, “and the next morning seated myself with my work at my window.

“‘Cherry ripe, cherry ripe,’ sounded out their notes, but I fancied less boldly this time. The bell tinkled, and away flew my gay visitors, but this time they perched themselves on the old pear-tree, and chirped and twittered loudly, evidently complaining of their treatment, and studying, from their high perches, their enemy’s ground.

“I told my tale triumphantly to some of my friends, and the next morning they came to visit me and see the fun themselves.

“‘Cherry ripe, cherry ripe,’ sounded out loud and clear, and oh! what a bevy of birds had come for the morning’s visit!

“‘Tinkle, tinkle, tinkle,’ sounded the bell, and would you believe it? The knowing birds turned toward the window, bobbed their saucy heads at me, and went on helping themselves with easy manners indeed.

“‘Tinkle, tinkle, tinkle, tinkle, tinkle,’ pealed the bell, and again the saucy fellows dived and dodged, winked and blinked their little bright eyes, and nodded ‘It’s all right.’

“I was completely conquered; so now I let them take their breakfast first, and then I feast on what they leave behind. Very often I find marks of their little beaks in the ruddiest berries on my plate, but they, in return, cheer me with their fullest, choicest notes, give life and brightness to my quiet garden, and guard my young plants from the ravages of devouring insects, and attract other birds, with their richer notes, to their banqueting spot.”

“Aunt Emma,” said Artie, “do you think those little thieving fellows knew you?”

“Indeed, I flatter myself, Artie, that they consider me their best friend. There is scarcely a morning, from the time when the last snow-flakes of Winter melt away, that some one or more of these gay fellows do not come to the window-sill of my sewing-room, chirp about me, and tell a long story of joy or grievance. Sometimes I fancy it’s a complaint of some fickle Jenny Wren who has left her true love for a gay English Sparrow, and again another has won for his mate a saucy Mattie Martin, and comes to me for my best wishes and the promise of my ends of thread and bits of wool to furnish the snug little home he is going to build for his little bride, up in the branches of my apple tree.”

“And does they tell you of the poor little Cock Robin that the naughty Sparrow killed with his bow-arrow?” questioned Rosie.

“I will tell you, Pet, if you are not already tired of my stories, a tale something like your Cock Robin.”

“Oh, do, do, please, Auntie, we’d never be tired of stories;” and the children stowed themselves in a little heap on the grass, at their Auntie’s feet, leaned their elbows on their knees, and rested their chubby cheeks on their hands, ready for any given quantity of tales.

“One day,” continued Aunt Emma, “having a bad headache, I sat in the part of my room farthest from the window, to be away from the light. Presently I heard a mournful sort of song, which soon became quite pitiful, and then came a quick, sharp peck[Pg 93]ing at my window-pane. I could not resist that appeal, and as I opened my window a Robin flew quickly in, fluttered in circles over my head, uttering pitiful cries. I followed him out into the garden till, near the old apple-tree, he disappeared under a bush. Carefully putting aside, with my hands, the leaves and branches, I found a poor, tiny, half-dressed Robin baby, uttering such little, sick, feeble peeps, I seem to hear them now. I think from the twinkle I afterward used to see in his eyes, that he was rather an adventurous young spirit, and very likely his Papa was a widower, for I never saw but the one parent.

“I fancy Papa Robin had gone out that morning to do the day’s marketing, after charging the younglings to stay quietly at home, and this daring little spirit had taken[Pg 94] advantage of his absence to step out on their balcony and see the world for himself; then he must have become giddy and fallen under the rose-bush, where his Papa had found him, and not knowing what to do with his wee, wounded birdie, had flown to tell me his trouble.”

“Oh! Auntie, what did you do with the poor little thing?” cried tender-hearted Daisy.

“I made a soft cotton bed for it, in a little basket, and put it on a chair near my window, in the sun, then fed it crumbs of bread wet with wine.”

“Did it live, Auntie, dear?”

“Yes, children; and now for the wonderful part of my story. Every morning the parent bird used to make a visit, bringing in his beak to his sick birdie, a bit of caterpillar, a juicy worm, or a ripe berry. I grew very[Pg 95] fond of my pet, and that I might know it, if at some distant day it should leave me, I wound a bit of silver wire about its leg. Birdie grew stronger and saucier, and its peep fuller every day. At last one bright morning—you may imagine my surprise—on entering the little sewing-room, to find my pet gone; and as I thrust my head out of the window, a loud burst of glad song, from the top of the old apple-tree, told me that birdie was—

“Did you ever see the bird again, Auntie?”

“One morning, weeks afterward, I was in my usual place, and suddenly a bird appeared, from whose tiny leg dangled my thread of silver wire; lower and lower he descended without uttering a note, then something dropped[Pg 96] upon the window-sill, and judge of my surprise, to find the very ruby ring I had lost in the garden some days before. I had mourned its loss, for it had been given me by your Papa’s own dear Mamma, on my tenth birthday. I had, for years, worn it on my watch-chain, and lost it whilst planting some seeds, as I supposed, in the mignonette bed. It might have been that the saucy robins had watched me, as I stowed away my seeds, winking their little eyes and bobbing their round heads as they marked their larder for the morrow. What a surprise to them, when, instead of a tiny seed, this bright jewel appeared. Some time after this, in my garden-walks, I found a few red and yellow feathers, a bird’s claw, and a bit of silver wire, which told the sad tale that my pet had been sacrificed by a strange cat.

“My story is ended. You have been patient little listeners for a full half hour, so, run away, dears, for a morning play.”

The merry children hasten off to welcome their little friend Charlie Leonard, who was coming to spend the day with them.

“Hallo! Charlie boy. Come along, here’s all kinds of fun. Shall we have blind-man’s-buff on the grass-plat, or will you play croquet with Daisy and me?”

“No, no, Charlie,” sounded Rosie’s beseeching tones, “come and help me gather mullein-leaves for dollies’ blankets, and these cunning pot-cheeses to play store with. See, Celia has lent her for-true scales. Only look! and Hugh has given us four cents and two ginger-snaps that weigh a pound.”

“I want Charlie to come help me chase those darling little yellow butterflies that’s ‘gathering honey from the opening flower’ to make butter of,” screamed Jack.

“Oh, Artie, just listen to that child,” said Daisy. “His mind is all askew. He’s talking about making butter of honey.”

“I guess the little chap remembers how the buckwheat cakes and honey made the butterfly last winter,” replied the Keeper, as he gave a most satisfactory send through the second wicket.

“Will you just listen to that, Charlotte?” said Nan, who, under the old pear-tree’s shade, was helping take out grass-stains from the dainty city linen.

“I tell you I never did see such sense in children in my born days. Just you wait till I run and tell Hugh and my mother ’fore it slips.”

Nan found ready listeners in the kitchen, for old Celia laid aside her soap and sand—Hugh ceased his psalm-singing, with knife-scraping accompaniment, and stood with knife and cork in either hand, and mouth and eyes opened wide to take in the “uncommon sense of Mister John’s wonderful children.”

“Well, now! only look at that, will ye?”

“Only jest to hear, if that ain’t Mister John his werry self—Oh, my! It appears to me, Nan, them childerns will be the werry death of me yet. What with peerin’ and listenin’ and laughin’, my work’s all in the drags. The werry pots and kettles seem just turnin’ into boys and girls. Oh, my! Oh, my! I say, you Nan, just go long, and if you come this yer way tellin’ any more about them childerns’ perform, I’ll harpoon you with the toasting fork,—so off with you.”

Nan hurried back to the grass-stains, only looking once over her shoulder to find her mother and Hugh “peerin’” stealthily from behind the porch, to catch, if possible, a few more crumbs from the children’s table; but, dutiful daughter as she was, she didn’t look again, but wider and wider stretched her mouth, brighter shone its ivory gems, and louder sounded out her clear, rich notes, while she sang—

as she renewed her zeal in the cause of grass-stain cleaning, which was just now bringing wrinkles to Charlotte’s anxious brow, which was ever like a page in a school-mistress’s report-book. There were wrinkles small, which meant grass-stains, bumps, rents, and childish disputes; there were wrinkles many, which told[Pg 102] of mischief wrought; but these were soon dispelled. There were deeper ones which told of graver faults,—disobedience or falsehood, and others like them, which days of anxious watching and fears of future ills had left, which could be effaced only by His hand who can truly—

Little Bear, in the meantime, was finding pleasant pastime in making larkspur wreaths and dandelion curls for his little sister’s “store,” whilst he kept an eye on Artie’s successful game, only wishing—

and pitying her, as her brother sent her balls flying to remotest parts of the garden, to be hunted out from behind currant and gooseberry bushes’ thick shade.

It was a great pleasure to this little feeble city boy, with the love of the beautiful in Nature, which so often accompanies weakness of limb, to lie back on the cushions spread by his careful nurses under the old apple-tree’s shade, and drink in all the beauties of the scene.

Like a picture-gallery seemed the quaint garden, as, looking upward, between the opening in the leafy roof above, he caught glimpses of the blue sky, and his eye followed the islets of fleecy clouds in their fleeting passage. The thick, grassy carpet at his feet brought out, in all their brightness, the colors of the golden lily and the many-tinted ladyslippers which formed borders to the broad grass-plots. Butterflies, golden and russet-brown, were flitting all around him, whilst robins and bluebirds, from their air-swung perches, sang sweetly their morning hymns, and from the earth be[Pg 104]neath, locusts and tiny crickets joined the glad chorus.

How true it is that our Father in Heaven has given a voice to every thing in Nature to praise and tell of His great Love! Can you wonder that this little feeble child, unable to join in the careless play of the merry group, taught by a Christian mother that God was all about and around him, should seem to hear His voice speaking in the beauty of the scene, and gently folding his thin, white hands, should sing, in low, sweet notes, the Morning Hymn?

Lulled by the soft music of his own notes, little Bear closes his heavy eyelids; the crickets lend their aid to sing his lullaby, while soft zephyrs whisper in his ears themes for sweetest, purest dreams.

Daisy’s watchful ear missed the murmured song, and her quick eye saw the little sleeper under his leafy canopy,—so she slips away from the merry game of blind-man’s-buff, which had taken the place of croquet, and hastes to mount guard over her precious charge, and wage war against the persistent flies, whose[Pg 106] chief delight seems to be tickling the faces of summer sleepers.

Pretty soon Jack appears with rather a rueful face, for the merry game of blind-man’s-buff has ended in his and Charlie’s tumbling headlong over one of the garden-seats, in their haste to get away from the blind man, and poor Jack’s head has made the acquaintance of a stone which has proved anything but soft.

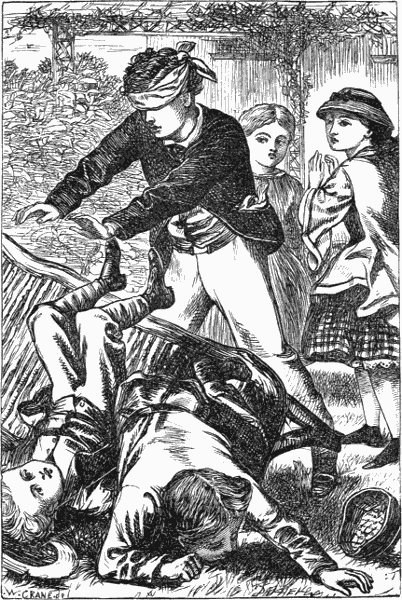

A Grave Ending to a Gay Game. Page 106.

Daisy could not find it in her heart to laugh at the funny little picture her wounded brother presented. His sailor straw hat had come to grief in the fall, and from between the parted straws, hung out tufts of fair, tangled hair, buttons had flown away, and a wide crack, in the seat of his short pants, revealed a hanging of gauze drapery; but oh, the face! It was a kind of Mosaic pattern of grass, fruit, and dust-stains, all blended together by the few tears[Pg 107] which would run down in spite of the efforts of the little dusty hand to keep them back.

Jack’s sobs ceased as he caught sight of his sleeping brother, and thoughts of aching head and scratched knees, left him, as a childish fancy sprang to his mind.

“Oh, Daisy, isn’t he just like babes in the woods? Childerns, let’s ’spose we cover him up with leaves.”

Rosie and Charlie think it would be “lovely,” and off they scamper to gather leaves and flowers, whilst Sister Daisy drops them over the sleeping child, and weaves a little wreath to rest on his pale brow, and Rosie runs to the kitchen to ask Celia and Hugh to come to see “The butifullest picture that ever was,” and wonders why Hugh turns quickly back, and Celia’s apron finds tears in the kindly eyes as she murmurs out her—

then sobs aloud as Charley Leonard whispers, “But Celia, don’t you know angels have wings?”

To the merry children, the picture of their sleeping brother, on the flower-decked couch, has only beauty and brightness, as they check their merry tones and gather around in silent admiration.

Presently Artie whispers:

“Oh, wouldn’t it be fun to spread out a little feast by his side, so when he wakes up he may think the Fairies have truly visited him? I say, Daisy Duck, let’s do it.”

“It’s just the very thing. Oh, Artie boy! however could you have thought of such a nice idea?”

A rustic table was soon made of a box nicely covered with a snow-white towel. Then[Pg 109] each child brought a contribution of currants, gooseberries, or strawberries, for which Daisy made pretty, leafy baskets, then ran to beg good Delia for a very little white sugar, for Fairies liked their berries powdered nicely.

What a surprise for Daisy!

Out of the grim oven’s mouth, that same Celia was drawing a pan of the weest cookies, dainty enough for any fairy cook-shop, with the “lovely bit of citron on top” to take away the plainness and look like a real tea-party dish.

Daisy couldn’t speak for very joy, as Celia stowed the inviting morsels on a plate hidden by grape leaves, and filled a glass with powdered sugar for “fairy snow,” while Hugh, who had disappeared a few moments before, suddenly stood before the delighted child with a package of fresh barley sticks[Pg 110] and a paper of peppermint hearts, which he said, in his judgment,—

“Wouldn’t hurt nobody nohow, and was just a set-off ’gainst that sour fruit.”

Then Hugh took pity on Daisy, as the little maid stood “embarrassed by her riches,” and offered to carry out the cakes, following soon after with a little salver bearing a pitcher of golden milk and six tiny glasses.

The excitement was now intense. Poor Jack, ignorant of the view in his rear, attempted his heels-over-head antics, but was prudently pinioned by the Keeper. Daisy holds tight hold of Charlie Leonard, whilst Rosie ran and kissed the skirt of Hugh’s linen coat to relieve herself of some of her pent-up feeling.

Then came the trying time. The fairies were all ready, but the little guest still slept.[Pg 111] The gentle zephyrs were teasing the leafy decorations to fly away and sport with them. The summer flies seemed to think the Fairy elves had placed the golden milk for their refreshment, and who could guard the feast? The waking guest must see no trace of human form, so the children have hidden behind the tall lilac’s leafy screen.

The Children Hide Behind the Lilac Bush. Page 111.

Was there ever such a five minutes?

Was there ever such a sleeper?

Jack, knowing his own weakness, is cramming his mouth with grass-tufts; Rosie has clapped both hands over hers to keep back the ringing laugh.

What a little picture! The merriment oozes out of the corners of the pent-up mouth, dances in the bright blue eyes, shimmers in the shaking golden curls, and quivers in the chubby shoulders.

Charlie Leonard is repeating

the only feather from his worn-out Mother Goose which “sticks” in his memory, and poor Artie, yielding to the temptations of the idle hour, is just about to tickle the sleeper’s nostrils with a grassy “horsetail,” when the Family Owl, who sees by day as well as by night, spies out his sly intent in time to check the roguish act.

Perhaps it was the good-natured little “scuffle” which ensued, or perhaps the sportive zephyrs were too loudly coaxing the leafy covers, or perhaps the greedy flies might have followed Artie’s bad example, and having no good elder sister-fly to call them off, might have tickled the little quivering nostrils, and made a play-ground of the fair, dewy brow; whichever or whatever the cause,[Pg 113] we cannot tell. Elf-land secrets are not written on printed page, and we have no time to seek them from tiny flower petals, murmuring brooklets, or transparent dewdrops.