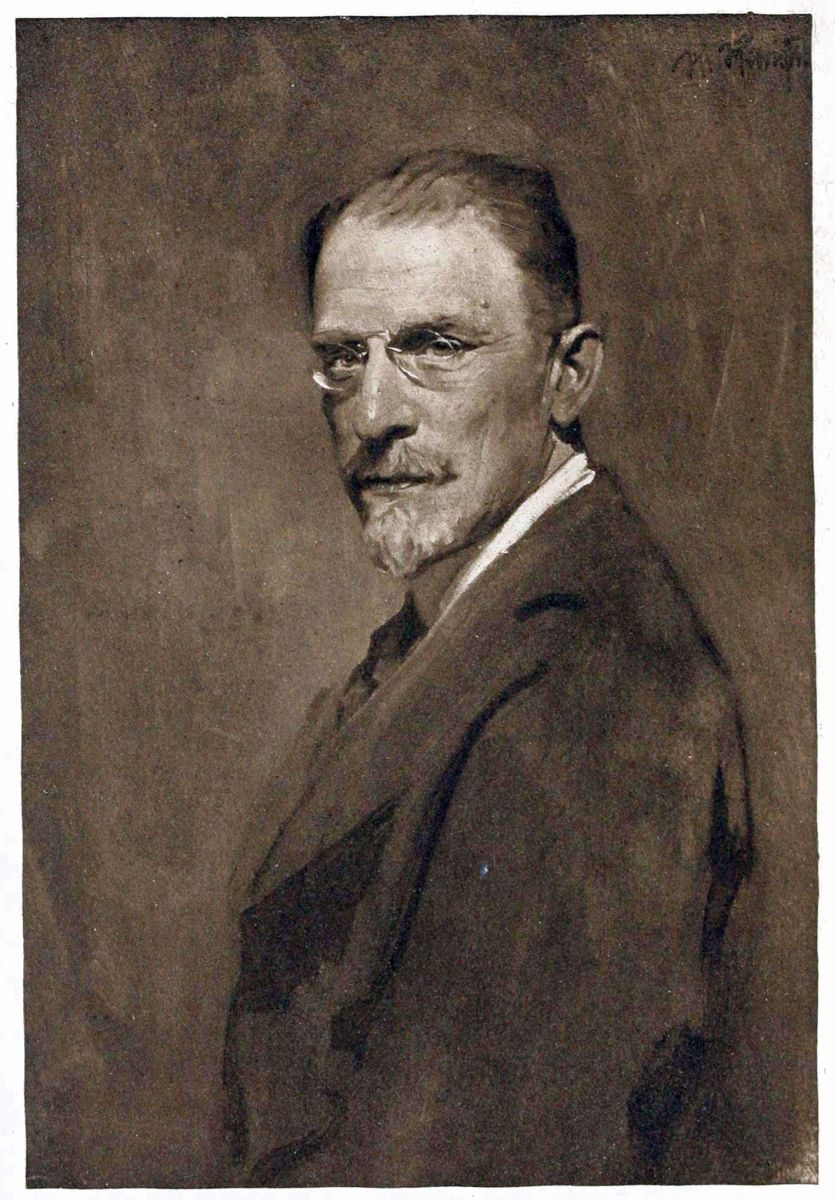

HENRY MORGENTHAU

Title: All in a Life-time

Author: Henry Morgenthau

French Strother

Release date: October 24, 2020 [eBook #63538]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif, ellinora and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

|

Contents List of Illustrations Appendix Index: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, W, Y, Z |

ALL IN A LIFE-TIME

BY

HENRY MORGENTHAU

IN COLLABORATION WITH

FRENCH STROTHER

ILLUSTRATIONS

FROM

PHOTOGRAPHS

GARDEN CITY NEW YORK

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

1922

COPYRIGHT, 1921, 1922, BY

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, INCLUDING THAT OF TRANSLATION

INTO FOREIGN LANGUAGES, INCLUDING THE SCANDINAVIAN

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES

AT

THE COUNTRY LIFE PRESS, GARDEN CITY, N. Y.

First Edition

TO

MY DEVOTED COMPANION

MY WIFE

WHO ORIGINATED SOME,

AND STIMULATED ALL,

OF MY BEST ENDEAVOURS

I WAS born in 1856, at Mannheim, in the Grand Duchy of Baden. That was the old Germany, very different from the Prussianized empire with which America was to go to war sixty years later, and very different again from the bustling life of the western world to which I was to be introduced so soon and in which I was to play a part unlike anything which my most fanciful dreams ever pictured.

Indeed, those were days of idyllic simplicity in South Germany and especially in that little city on the Rhine. The life of the people was best expressed by a word that was forever on their lips, gemütlich, that almost untranslatable word that implies contentment, ease, and satisfaction, all in one. It was a time of peace and fruitful industry and quiet enjoyment. The highest pleasure of the children was netting butterflies in the sunny fields; the great events of youth were the song festivals and public exhibitions of the “Turners” and walking excursions into the country; the recreation of the elders was at little tables in the public gardens, where, while the band played good music and the youngsters romped from chair to chair, the women plied their knitting needles over endless cups of coffee, and the men smoked their pipes and sipped their beer and talked of art and philosophy—of everything in the world, except world politics and world war.{2}

To us children who had seen no larger city, but had visited many small villages in the neighbourhood, Mannheim seemed quite an important town. It was at the point where the Neckar flows into the Rhine, and as this river flowed through the Odenwald, it constantly brought big loads of lumber and also many bushels of grain to Mannheim, which had become a distributing centre for various cereals and lumber, and was also a great tobacco centre. My father had cigar factories at Mannheim and also in Lorsch and Heppenheim and sometimes employed as many as a thousand hands. Nevertheless, the entire population of Mannheim was scarcely 21,000, and the thoughts of most of its inhabitants were bent on the sober concerns of their every-day struggles and on raising their large families, without ambition for great riches or hope of higher place. None but the nobles dreamed of such grandeur as a carriage and pair; the successful tradesman only occasionally gratified a modest love of display or travel by hiring a barouche for a drive through the hop fields and tobacco patches surrounding the city to one of the near-by villages. Those whose mental powers were of a superior order exercised them in a keen appreciation of poetry, music, and the drama; Schiller and Goethe were their demi-gods, Mozart and Beethoven their companions of the spirit. The Grand Duke’s fatherly devotion to his subjects’ welfare had won him their filial affection; with political matters they concerned themselves almost not at all.

My childhood recollections reflect the quiet colours of this atmosphere. My father was prosperous, and our home was blessed by the comforts and little elegancies that his means made possible; it shared in the artistic interests of the community by virtue both of his interest in the theatre and my mother’s passion for the best in literature and music. I was the ninth of eleven living{3} children, and I recall the visits of the music teachers who gave my sisters lessons on the piano and taught my eldest brother to play the violin. We children learned by heart the poems of Goethe and Schiller and shared the pride of all Mannheimers that the latter poet had once lived in our city and that his play, “The Robbers,” was first produced at our Stadt Theatre.

Those who like to reflect upon the smallness of the world will find it amusing to read that among the various friends of my family were quite a few with whom we are now on the most cordial relations in New York. Our physician was Dr. Gutherz, one of whose daughters married my neighbour, Nathan Straus. Their son and mine are intimate friends, and, in turn, their sons, Nathan 3d and Henry 3d, are now playmates in Central Park.

Among such associations the first ten years of my life were passed. We studied hard, but we played hard, too. Nor were our muscles forgotten: we were given regular exercises, and great was my pride when I passed the “swimming test” one summer’s day, by holding my own for the prescribed half hour against the Rhine current and so winning the right to wear the magic letters R. S.—“Rhine-Swimmer”—on my bathing suit. Life was indeed gemütlich in the Mannheim of that period.

It was not long, however, before the faraway world of America began to knock at our quiet door. A brother of my father had joined the gold rush to the Pacific and settled in San Francisco; he wrote us tales of the wild, free life of California, its adventures and its wealth. Strange gifts came back from him—a cane for the Grand Duke, its head a piece of gold-bearing quartz; for us children queer mementoes of an existence that seemed all romance. From time to time, this “Gold-Uncle,” as we called him, gave American friends touring Europe letters of introduction to my father, and these visitors enhanced{4} the charm of the United States. One such especially filled our minds with narratives of easily won riches; Captain Richardson, a bearded Forty-niner, whose accounts of the land of opportunity were so much more moving than our fairy tales as to affect even my father’s mature fancy.

For my father heard them at a moment when, by an odd coincidence, an act of the American Congress had caused him great damage. In 1862 a tariff had been enacted by the United States which greatly increased the duty on cigars. For many years the largest part of his production had been exported to the United States. Father had a representative in New York, and his brother in San Francisco attended to the distribution on the Pacific Coast—they both had urged him to rush over all the cigars he could and land them before the law should go into effect. Unfortunately, the slow freighter that carried the last and biggest shipment arrived one day too late. Had she docked in time, my life might have been spent differently. That day’s delay meant the difference between profit and disaster to my father; the cigars, which, when duty free, would have yielded him a good return, were a dead loss when to their cost was added the burden of the new tariff charges. These changes in any event would have compelled him to seek a new market, as they closed America forever to goods of the cheap grade of German tobacco. That might have been arranged, but when the necessity to seek new fields was coupled with the crushing loss sustained upon this shipment, his finances were so weakened that he realized he would have to start afresh and on a smaller scale.

This was a heavy blow to the pride of a man who had achieved a great business success and was a leading citizen in his community. The instinct to seek another field for the fresh start was fortified by the stories of oppor{5}tunity in the land whose laws had just dealt the blow. He resolved to emigrate to America.

I remember vividly the excitement in our household that was provoked by this momentous decision. Whatever may have been the doubts and heartburnings of our parents, to us children all was a joyous vista. We were happy at the thought of travelling to that far land of golden promise and strange people; we had visions only of adventure, and we were the envy of our playmates who were not to share with us the voyage across the Atlantic Ocean or the excitement of life in America.

The two eldest brothers and one of my sisters went ahead of us and established a home in Brooklyn. They wrote back their first impressions of New York; its great buildings and its crowded wharves; its masses of busy people hastening through the maze of streets and the novelty (to us) of horse cars pulled through the streets on railroad tracks. These letters gave us fresh thrills of emotion and new material for our active fancies. Then my father abandoned his now unprofitable business, sold his factories and home, packed our household goods and furniture, and possessed of about thirty thousand dollars in cash—all that remained of his fortune—led his wife and remaining eight children upon the expedition.

I well remember the journey down the Rhine to Cologne, where we visited the beautiful cathedral before we took the train to Bremen; the solemn interview in the latter city at the offices of the North German Lloyd, where the last formalities were disposed of; and finally settling in our cabins of the slow old steamer Hermann as she put forth on her way across the wide Atlantic.

My memories of the eleven-day voyage itself are rather vague. I recall playing around the deck with the other family of children on the ship. The daughter of one of those little playmates is now conducting a private school{6} in New York City which three of my granddaughters attend. I remember, too, that on the stormiest day of our passage, I was proud of being the only child well enough to eat his meals, and that the Captain honoured me with a seat beside him at his table.

Now, the newcomer to America, arriving at New York, stands on the deck of a swift liner and is welcomed by the Statue of Liberty and overwhelmed by the vaulting office-buildings springing high into the blue. I shall tell later how I have contributed to the creation of some of them. But on that June day of my arrival, in 1866, I simply felt that one of the momentous hours in my life had come, when I found myself stepping ashore into a vast garden of unlimited opportunities.{7}

MY family took up their residence at 92 Congress Street, Brooklyn, which my elder brothers and two sisters, our pioneers, had prepared for us, and though handicapped as we were by our small knowledge of English, we younger children began our studies at the De Graw Street Public School in the September following our arrival. Eight months later, on the first day of May, 1867, we moved to Manhattan.

It was a very simple New York to which we came. In domestic economy, portières were unknown, rugs a rarity; ingrain carpets, costing about sixty cents a yard, were the usual floor coverings; when the walls were papered, it was with the cheapest material; the only bathtubs were of zinc, and one to a house was the almost universal rule. Our home was No. 1121 Second Avenue, corner of Fifty-ninth Street—a three-storey, high-stoop brownstone house, rows of which were then being erected. It still stands there, the high stoop removed from it; stores are in the basements; the district has deteriorated to one of cheap tenements and small retail businesses. But in those days there was an effort to make Upper Second Avenue one of the chief residential streets of the city. The householders were mostly well-to-do Germans—people who had prospered on the Lower East Side and had outgrown their quarters there. The monotony of the thoroughfare was relieved only by the old-fashioned horse car that rumbled by every four or five minutes. Like the letter carriers of that period, neither the drivers nor the con{8}ductors wore uniforms. The line ended at Sixty-fourth Street where the truck-gardens began. On our way to Sunday School, at Thirty-ninth Street near Seventh Avenue, we would make a short-cut across the site where the first Grand Central Station was being erected.

I had my little difficulties in school: I well remember how one of the boys told me that he deeply sympathized with me, because I would have to overcome the double handicap of being both a Jew and a German. So I greatly rejoiced when I saw the steady disappearance of the prejudice against the Germans after they had succeeded in winning the Franco-Prussian War in 1871.

About the most picturesque and artistic parade that had ever taken place in New York was arranged by all the German societies and their sympathizers, the singing clubs and the turn vereins participating. Non-Germans lent their carriages. Among the generous people was the famous Dr. Hemholdt, of patent medicine fame. He owned a rather fantastic vehicle, which was drawn by five horses decorated with white cockades and which he lent for the occasion to an uptown club of which my brother was the secretary. I was permitted to fill in, so that I saw with my own eyes and was deeply impressed by the crowds that lined the streets and vociferously and heartily, for the first time, gave their unstinted approval of the Germans.

We children did not lose a day in our pursuit of education; for on the very day of our removal to Manhattan, I attended Grammar School No. 18, in Fifty-first Street near Lexington Avenue. At recess-time we boys used to play “tag” on the foundations of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, the construction of which had been stopped during the Civil War. I have very pleasant recollections of my early grammar school teachers, and especially of one who later was for years Clerk of the Board of Education, the effi{9}cient Lawrence D. Kiernan, who, while at School 18, was elected to the Assembly as a candidate of the “Young Democrats” and whose talks to us pupils on civic duty seemed like great orations and gave me my first impression of independence in politics.

Nevertheless, I laboured under two disadvantages—one was my English; the difference in structure between my native and my adopted language gave me considerable trouble; so did the pronunciation of the letters w and d, but my greatest difficulty was the diphthong th, and to overcome it, I compiled and learned lists of words in which it occurred and for weeks devoted some time, night and morning, to repeating: “Theophilus Thistle, the great thistle-sifter, sifted one sieve-full of unsifted thistles through the thick of his thumb.” However, as the greatest stress was laid on proficiency in arithmetic, and as I had a natural aptitude for that study, my proficiency there balanced these deficiencies and took me into the highest class at the age of eleven.

It was a general belief that all “Dutchmen” were cowards, and on the playground this idea was acted upon with considerable spirit. I was made the target of many a joke that I took in good part, until I realized that something positive was required of me. Then when a husky lad taunted me with being a “square-headed Dutchman,” and refused my demand that he “take it back,” my fighting blood was roused, and I administered a sound thrashing, the result of sheer, unscientific force. Nothing evokes the admiration of the gallant Irish so much as a good fight, and the result of that battle was the liking of my comrades, and especially one of the leaders among them, John F. Carroll, later familiar to New Yorkers as a leader in Tammany.

About this time I made up my mind to enter City College and, to prepare for that, I began looking about for a{10} school which ranked higher than No. 18. There were a number of these, foremost among which were the Thirteenth and Twenty-third Street schools. I applied at both, but they were full. The next in rank was No. 14, in Twenty-seventh Street near Third Avenue, where they admitted me to the fourth class. I gladly accepted this comparative demotion, so as to utilize advantageously the two years remaining before I reached the college-entrance age, began my studies there in March of ’68, under Miss Rosina Hartman, a fine old spinster and a good teacher, and finished both her class and the third class before I was twelve.

I was hardly settled in my seat in the second class when the following incident took place:

Mr. Abner B. Holley, who taught the first class, came into the room and complained about the mathematical shortcomings of the boys just promoted into his care; he explained that in his method of teaching arithmetic, it was essential to have someone for leader, as a sort of spur for the pupils. He gave us fifteen examples: speed and accuracy were to be the tests; and the boy who solved them most quickly and correctly was to be promoted. I finished first and handed up my slate. Holley carefully compared my answers with those on his slip and, before any other pupil was ready to submit his work, rapped for attention, and said:

“As these answers are all correct, there is no need of any other boy finishing. Morgenthau wins the promotion.”

Being too young to graduate in ’69, I remained under Holley until June, 1870. He was an excellent instructor, and it required no effort on my part to keep the lead in mathematics. In fact, he took pride in displaying my efficiency, and whenever any trustee, or other visitor, came to school, they would have a general assembly of all{11} the pupils and then he would have me solve promptly some such problem in mental arithmetic as computing the interest on $350 for three years, six months, and twelve days at 6 per cent. Thus, as I required little of my time for what was, to most of the boys, our most exacting study, I devoted all my spare time to improving my pronunciation and mastering the spelling of English which is so hard for a boy not born to the language. I won 100 per cent. perfect marks throughout my second year and when, with about nine hundred other boys, I took my City College entrance-examination, I was well up among the three hundred selected for admission.

I always look back with pleasure on those years in Public School No. 14. Iron stairways, modern desks, and electric lights have been installed since my day; the Irish and German pupils have passed, the Italian tide is ebbing; on the student list Russian, Ukrainian, Greek, and Armenian names now predominate—there is sometimes even a Chinese name to be found. At exercises there, attended by three of my classmates and by Dr. John H. Finley, New York’s Commissioner of Education, I celebrated, in 1920, the fiftieth anniversary of my graduation; I took the 1,900 pupils to a moving-picture show, and commenced my now regular custom of giving four watches twice a year to members of the graduating class; but as I then reviewed the past and looked at the present, I felt that the old spirit had been well preserved and that, whatever the nationality of the children who enter the old school, they all leave it American citizens.

When I left there, I had my eyes longingly fixed upon the City College, but the law was then already my ultimate aim and wages were essential, so I spent my “vacation” as errand boy and general-utility lad in the law offices of Ferdinand Kurzman, at $4.00 a week. In those days little was known of “big business”; there were{12} no vast corporations requiring continuous legal advice, and so the lawyers clustered within three or four blocks of the court-house; Kurzman’s quarters were at 306 Broadway, at the corner of Duane Street.

My early duties were the copying and serving of papers, but the time soon came when, young though I was, I was sent to the District Court to answer the calendar and, occasionally, fight for an adjournment. Stenographers and typewriters being practically unknown, the lawyer would dictate and his clerks transcribe in longhand, make the required number of copies with pen and ink and then compare the results and correct any errors. It was only when more than twenty copies were required that printing would be resorted to.

Such was my existence from June 21st until September 16, 1870. All the while, I tried to further my education. I had joined the Mercantile Library in the previous February. Within a short time, I was attending the Cooper Institute classes in elocution and debating, and later secured instruction in grammar and composition at the Evening High School in Thirteenth Street. I tried to do as much good reading as I could, and I find that my list for 1871 ranges from Cooper’s “Spy,” “David Copperfield,” and “The Vicar of Wakefield” to Hume’s “History of England,” Mill’s “Logic,” and “The Iliad.”

Of my life at City College I wish that I could write more, because I wish I had been privileged to graduate with the Class of 1875. There were 286 of us, and I remember very vividly some of the incidents of my brief stay. The halo of military distinction that encircled the brow of the president, General Alexander S. Webb, is still bright for me, and bright that day when the great Christine Nilsson came to our classroom and sang for us. Of the faculty, Professor Doremus remains especially vivid in my memory; electricity for illuminating purposes{13} was at that time confined to powerful arc-lights; he tried to explain to us the possibility of some inventor some day subdividing the power in one of those lamps so that it could be used to illuminate private houses. Though “stumped” in anatomy and chemistry through my unfamiliarity with the long words employed, I stood well on the general roll and was No. 11. My college career was rudely ended on March 20, 1871, when my father withdrew me and put me to work. His difficulty in mastering the English language and American commercial methods were handicaps too severe for him. He lost most of his original money, and his unreinforced efforts could not support us all.

Early in our occupancy of the Second Avenue house, the back parlour had to be rented as a doctor’s office, and shortly after my mother decided that it was her duty to take in boarders. I cannot speak of my mother as she was during these trials without the deepest emotion. There is nobody to whom I owe so much; there was no debt which so profoundly affected my entire career. In Mannheim her position had always been one of comfort. I had seen her there with good friends, good books, good dramas, and good music; she was the mistress of a commodious house, with a corps of competent servants, in a city with every custom and tradition of which she was intimately familiar; respected by the community, the mother of thirteen children, she was calm, philosophic, considerate of every domestic call upon her, not only supervising our education, physical and mental, but also finding time to add continuously to her own broad culture. Now a complete change had come. She was a stranger in a strange land; most of her friends were new; the city of her husband’s adoption was a puzzle, its manners foreign, its language long almost unknown; there was small time for amusement; there was, on the contrary, the ever-constant and{14} ever-pressing strain of helping, by her own endeavours, to make both ends meet.

All of this deeply affected my young and impressionable mind. I feared lest my mother, who was my idol, and who was so superior in accomplishments and knowledge to the people that boarded with us, might, in the course of her duties, be compelled to render quasi-menial services. Luckily, two things prevented this. On the one hand, her wonderful poise and tact and her extraordinarily sweet nature won so prompt a recognition that the least gentle of our lodgers instinctively became worshippers at her shrine. On the other hand, my sisters, themselves bred to comfort, rivalled one another in a friendly struggle to shield her from every possible annoyance. High-spirited girls as they were, they did not hesitate to assume everything that might in any way hurt her sensibilities, and their devotion and self-sacrifice are among my tenderest memories.

Appreciating how things were at home, I became quickly reconciled to abandoning textbook education, and instead, to plunging into the rough school of life.

The influence of the beautiful spirit of my mother had early given me good ideals and a love of purity, and the ebb of the family fortunes developed an irrepressible ambition to accomplish four things: to restore my mother to the comforts to which she had been accustomed; to save myself from an old age of financial stress such as my father’s; to give my own children the chances in life that were all but denied to me, and to try to attain a standard of thought and conduct consonant with the fine concepts that characterized my mother’s mind and lips.

My experiences were not unique, nor were my high resolves exceptionally heroic; they are found in the life history of most men. Nevertheless, such histories are not often told at first hand, so that what may have been com{15}monplace in the happening becomes interesting in the narration. Forsaking the chronological order of my story, let me look backward and forward in an attempt to present this phase of my mental development.

I was full of energy, and had tremendous hopes as to my future success, which gave me a certain assurance that was often misconstrued into conceit, but which was really a conviction of the necessity to collect religiously a mental, moral, physical, and financial reserve guaranteeing the realization of my best desires.

Accordingly, I pursued a rather carefully ordered course. At the age of fourteen I had taken very seriously my confirmation in the Thirty-ninth Street Temple, and now I formed the habit of visiting churches of many denominations and making abstracts of the sermons that I heard delivered by Henry Ward Beecher, Henry W. Bellows, Rabbi Einhorn, Richard S. Storrs, T. De Witt Talmage, and Dr. Alger, and many others of the famous pulpit-orators who enriched the intellectual life of New York. It was the era when Emerson led American thought, and I profited by passing my impressionable years in that period whose daily press was edited by such men as Horace Greeley, William Cullen Bryant, Charles A. Dana, Henry T. Raymond, and Lawrence Godkin.

There lived with us a hunchbacked Quaker doctor, Samuel S. Whitall, a beautiful character, softened instead of embittered by his affliction, the physician at the coloured hospital, who gave half his time to charitable work among the poor. I frequently opened the door for his patients and ran his errands, and we became friends. I remember his long, religious talks, and how deeply I was impressed by Penn’s “No Cross, No Crown,” a copy of which he gave me. Largely because of it I composed twenty-four rules of action, tabulating virtues that I{16} wished to acquire and vices that I must avoid. I even made a chart of these maxims, and every night marked against myself whatever breaches of them I had been guilty of. Looking over this record for February and March of 1872, I find that I charged myself with dereliction in not heeding my self-imposed admonitions against indulgence in sweets, departures from strict veracity, too much talking, extravagance, idleness, and vanity—a heavy indictment!

The fact is that I had acquired an almost monastic habit of mind and loved the conquest of my impulses much as the athlete loves the subjection of his muscles to the demands of his will. In my commonplace book for 1871 I find transcribed two quotations that governed me. The one is from Dr. Hall’s “Happy Old Age” and runs:

Stimulants ... are the greatest enemies of mankind; there is no middle ground which anyone can safely tread, only that of total and most uncompromising abstinence.

The other is from a sermon of Dr. Channing on “Self-Denial.”

Young man, remember that the only test of goodness is moral strength, self-decrying energy.... Do you subject to your moral and religious convictions the love of pleasure, the appetites, the passions, which form the great trials of youthful virtue? No man who has made any observation of life but will tell you how often he has seen the promise of youth blasted ... honorable feeling, kind affection overpowered and almost extinguished ... through a tame yielding to pleasure and the passions.

I took these warnings very seriously.

How the state of mind engendered by these forces affected me in a purely material way, we shall soon see. From the outset of my business career, when an errand boy in Kurzman’s office, I found myself surrounded by{17} employees, not perhaps more vicious than most, but certainly sharing the vices of the majority. They gave, at best, only what they were paid for, and not an ounce of energy or a minute of time beyond.

I shrank from the possibility of becoming a mere clock clerk and gave all of my best self and held back nothing. I made mistakes, I had my failures from the standard that I had set; but my purpose held fast and I cheerfully pursued the rugged uphill road to success.{18}

WHEN I left City College, my father wanted me to become a civil engineer, but a brief experience in an engineer’s office convinced me that I lacked the requisite mathematical foundation, so I gave it up and accepted a position as assistant bookkeeper and errand boy at $6 a week in the uptown branch of the Phœnix Fire Insurance Company.

In September, 1871, I improved myself by securing a $10 position with Bloomingdale & Company, who were then in the wholesale “corset and fancy-goods” business on Grand Street near Broadway. I kept the books and also helped to pack hoop-skirts, bustles, and corsets until the firm’s financial difficulties gave me an excuse for turning my ambition again to the law. I returned to Kurzman’s office, January 16, 1872.

Though Kurzman’s perspicacity could pierce directly through the intricacies of any tangled case, his accounts were shamefully neglected. His check book was his only book of entry—he trusted his memory to keep track of what his clients owed him—so I voluntarily and without informing him arranged a regular system of accounts, and shall never forget his surprise and appreciation when, at the end of the year, I showed him what he had earned and the sources and also the amounts still due him.

The most important branch of his practice was the searching of titles, and this gave me my early taste for real estate. This department was under the able manage{19}ment of Alfred McIntire, who graciously initiated me into the intricacies of his work.

We were then in the midst of a real-estate boom mostly participated in by the recently created middle class. Houses were dealt in almost as freely as merchandise, the only hindrance being the delay occasioned by the searching of titles, which was still confined to the lawyers, as there were no title insurance companies. Contracts would frequently be assigned twice and sometimes thrice, before the great event, “the closing of the title.” Then the various couples involved—the seller, the assignors of the contract, and the final purchaser—would all troop into our offices. The women invariably were the bankers and pulled out their roll of bills and sometimes Savings Bank Books, rarely checks, to consummate the transaction. The moneys invested were seldom taken out of the business, but were mostly the savings of the thrifty housewives. When everything was completed, all adjourned to a neighbouring wine cellar, to be treated to a bottle or two of Rhine wine by the vendor, and frequently I had to go along to represent Kurzman, and as the youngest listen attentively to the real estate stories told with all kinds of embellishments.

Kurzman at that time took as his partner George H. Yeaman, who had been a member of Congress from Kentucky and, more recently, American Minister to Denmark, and subsequently became a lecturer at the Columbia Law School. His native Southern chivalry had been polished by his experience at the Danish court; he was a man of splendid education and wide culture. I was fortunate in being chosen to take his dictation. I was amused in 1916 when, as Ambassador, I visited Dr. Maurice Francis Egan at our Legation in Copenhagen, and looked through the records made by Yeaman in 1865 while he was the head of that Legation.{20}

My private life I continued to order along the lines that I had laid down for myself. I would get up at 6 A. M. and go to Central Park. Then if I had not exercised at home, I would take a long walk; otherwise I would sit under the trees and read. The hour that the horse car consumed in wending its way from the Park to Duane Street I would devote to my books, and I was so thrifty that I did not even buy a newspaper. I kept myself so busy that I did not even see one, until, going home for the night, I unfolded and read such as had been left in Kurzman’s office during the day.

Thrift was, indeed, a necessary virtue. I had left commerce for the law at something of a sacrifice: in 1872, my accounts, which I kept scrupulously all this while, bear evidence of how careful I had to be of my scanty income. “Carfare, 10 cts.; Dinner, 15 cts.; Sundries, 2 cts.” That is a typical day’s expenditure.

No man that lived through the Panic of ’73 can ever forget it and on me it made an indelible impression. At the root of the trouble was railway over-expansion. The successful completion of the Union Pacific in 1869 caused the projection of many other roads. Jay Cooke launched the Northern Pacific; Fisk and Hatch, the Chesapeake & Ohio; Kenyon, Cox & Co., the Canadian Southern. The eminent New York banking concerns floated the bonds; the large rate of interest promised—N. P. paid 8½ per cent.—attracted buyers, largely clergymen, school-teachers and small professional men—and prices advanced until optimism bordered on hysteria. Issue followed issue. Then, in the May of ’73, a panic on the Vienna Bourse stopped European consumption and threw back on the New York financiers obligations that strained their credit. Early in September, after one unfortunate bank-statement followed on the heels of another, call-money was at 7⅙ and commercial paper at from nine to twelve per cent.{21}

Minor failures were numerous in the week of September 8th. Kenyon, Cox &. Co. failed on the 13th; the Eclectic Life Insurance Co. on the 17th. On the 18th, the big bolt fell; word ran round that Jay Cooke & Co., in many respects the greatest house of its time, was tottering. This news greatly startled Kurzman, who had been a persistent purchaser of Northern Pacific bonds. “On the floor of the Exchange,” said the Times, “the brokers surged out, tumbling pell-mell over each other in the general confusion, and reached their offices in race-horse time.” Those were not the days of telephones; when the panic-stricken men had got their orders, they ran back to the floor, on which absolute confusion reigned. Men shouted themselves hoarse, contradicted themselves and collapsed. A moment was enough to ruin many a dealer. Any one with money to lend was beset by a mob of lunatics. Almost immediately the effect was felt all the way down the financial line; smaller companies went the way of the big ones and many of the smallest were tottering after the smaller.

That week I took as usual all that I could spare from my scant salary and went, according to my custom, to the German Uptown Savings Bank to deposit it along with the little fund that I was laboriously setting aside. There was a big line of confident depositors bent on similar errands; many were ahead of me, and waiting my turn, as I looked into the teller’s cage, I saw the president of the bank in a very earnest conversation with three other men. Of course, I could not hear what they were saying, but I thought the president seemed worried, and that those with him also showed uneasiness.

I turned my head to find that the shuffling line had brought me before the window that was my goal. The clerk behind it was both a receiving and a paying teller. On a sudden impulse I thrust my dollar bill that I in{22}tended to deposit back into my pocket, presented my pass-book, and told the clerk that I wanted to withdraw the entire $80 that was to my credit.

Three days later that bank closed. The other depositors ultimately got about fifty cents on the dollar.

The real estate market had been as badly inflated as the stock market, and foreclosures were the order of the day. Properties like the block bounded by Park and Madison Avenue and Seventy-first and Seventy-second streets went under the hammer. John D. Crimmins and his father had paid $475,000 to James Lenox, who repurchased it for $374,150 at the foreclosure sale under the mortgage. Equities disappeared like the snow in spring-time. Where we had once been almost rushed to death with the drawing of mortgages to consummate the many sales, we were now hard pressed to keep pace with foreclosure proceedings.

I took charge of this work for Kurzman, who gave me 10 per cent. of the net fees; the commission was most acceptable, the experience invaluable, but a more depressing task it has never been my lot to perform. The proud and prosperous men that had been our best clients from 1871 to 1873 now returned to shed their wealth and, with it, their self-reliance. One who had owned eight or ten houses was reduced to borrowing $100 from Kurzman for temporary relief. I made up my mind never to “plunge”; if I had not lived through the Panic of ’73, I should to-day be either many times richer than I am or, what is far more likely, penniless.

The bad light in the Kurzman offices had injured my eyes, and, just after the panic had subsided, my doctor ordered a sea trip. I sailed on the barque Dora for Hamburg—thirty days for $35, and no extra charge for the excitement that was thrown in.

We were undermanned and underprovisioned. The{23} first mate was ill when we set out from Jersey Flats; because of that, two of the crew had deserted, leaving only eight men aboard. There was no doctor among these, and the Captain and I read a thumbed work on medicine that adorned his cabin, studied the remedies that it suggested, and nearly emptied the medicine chest in trying to cure the poor fellow, who lost sixty pounds under our ministrations and, at the voyage’s end, went home with his disease still undiagnosed.

Meanwhile, the crew were dissatisfied on account of the extra work forced on them by the inactivity of the mate and the absence of the deserters, and also with their rations. They won the second mate to their side, and, on a day of storm when they declared themselves too few to handle the sails, he led something like an old-fashioned mutiny. They crowded toward the Captain.

“Run and get a pistol!” he whispered to me.

I obeyed. As I returned and slipped him the weapon, the mutineers were just coming to a pause before him.

The Captain levelled his pistol. He made short work of the difficulty. He offered them cold lead or hot grog. The crew, like sensible men, chose the latter, but they continued to grumble at the food—which was mostly hard-tack and cornmeal—until, on a day when we were becalmed in the North Sea, we caught several dolphins weighing over 150 pounds. I have rarely eaten anything better than that dolphin steak.

This is not to be a record of travel, but one phase of that early journey of mine is well worthy of notice: I saw Germany just as she was entering on the imperialistic career that ended so abruptly when her crestfallen representatives signed the Treaty of Versailles. The Franco-Prussian War had just ended in triumph; the German Empire had been reborn. Its people were not the easygoing people that I remembered from my earlier{24} boyhood in Mannheim. Everywhere there were the beginnings of commercial and military activity; everywhere there was preached the doctrine of world power.

I passed several weeks at Kiel; I lived well on less than a dollar a day. I had some difficulty in becoming friendly with a pensioned wounded army captain because he held me personally responsible that American ammunition had been sold to the French. The same complaint was made to me by the German Ambassador, Baron Wangenheim, in Constantinople, in 1915. I saw the launching of the new Empire’s first battleship, the very beginning of that colossal preparation for war which, at the cost of so many millions in lives and money, was finally to bear its bloody fruit in 1914. A wrinkled old man wearing a small military cap made the speech on that occasion. It was the famous General von Moltke. I listened intently to what he said. His words reached everyone in that crowd, which was attentively listening to the great hero of the Franco-Prussian War; and when I looked into his piercing eyes, I found that they seemed to penetrate right through me, and I could understand the frequently made statement that officers used to quiver in his presence, and that his questions, accompanied by one of his fixed looks, always elicited the exact truth.

On my return to America, I entered the law office of Chauncey Shaffer, who was a leader of the New York Bar and had a nation-wide reputation. He had been retained in many important cases, and some romantic. His offices were first on the third floor in an old-fashioned private house at No. 7 Murray Street, and later, he moved into the Bennett Building, one of the city’s first modern office buildings.

In our new, well-lighted quarters, we had some interesting neighbours, and these, along with many another, were constantly dropping in on Shaffer. I still recall with{25} pleasure my acquaintance in those surroundings with Gildersleeve and Purroy, with Butzel and Bourke Cochran.

Henry A. Gildersleeve had been born on a farm in Dutchess County, and in early life was the handiest man with his fists in all that district. In the Civil War he organized a company and was elected a captain. He returned from that to complete his education and become a lawyer, but he became a crack shot, too, at the international rifle matches; and when he first visited Shaffer’s office, it was as an Apollo of a man with romance in every feature of his face and every particle of attire.

He was offered by both parties the nomination as Judge of General Sessions and came to consult Shaffer about it. I was in the room at the time.

The scene is still vivid. Shaffer never forgot his Napoleonic pose when there was anybody present to observe it, and now he moved about with one hand under his coat tails and the other thrust into his breast. The harder he thought, the harder he chewed his tobacco and the more frequent were his expectorations. Finally he stopped short in front of Gildersleeve, who had been waiting patiently for this queer oracle to speak.

“If you have to go down in this fight,” Shaffer said, “go down in good company: take the Fusion nomination.”

Gildersleeve accepted that advice. He remained on the bench until he was seventy years of age. He is in his eighties now and as keen of intellect as in those far-off days when he used to visit Shaffer. He is still one of my favourite golf companions.

On many Saturdays we did little work; the coterie met in Shaffer’s office, and we talked; it would be nearer to the mark to say that one of us talked and entertained the others by his endless flow of good stories and sparkling reminiscences. He was a student under Shaffer, and his name was Bourke Cochran. I never saw him poring{26} over Blackstone or Kent, but on Saturday when freed from his duties as principal of the Public School at Tuckahoe, this exuberant young instructor would either practise his future orations on us or pour out his flood of Cochranisms and anecdotes. Not getting my name at the first meeting, he dubbed me “Mortgagee” and still calls me so. He thrilled us with the account of his early struggles at Dublin University, roused our enthusiasm by his plans to restore oratory to the New York Bar, and evoked our applause by his determination to Patrick Henryize the Assembly at Albany. The Democrats promised him a nomination to the Assembly, but withdrew the promise when they discovered that he was not yet twenty-one.

It was while at Shaffer’s that I began to find out how human great men really are. The names of Benjamin F. Butler—the redoubtable Butler of Massachusetts—and Preston Plumb of Kansas used to move me to awe. One of my employer’s important cases involved some grants of land to the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad and was brought by John Leisenring, of Pennsylvania, whose attorney-of-record, Congressman-at-large Charles P. Albright, of the same state, had, in addition to Shaffer, associated with him in the affair, Butler and Plumb. The latter used to dash into our office without a necktie and then chafe at the former’s unpunctuality and indifference in the matter of keeping appointments.

“It’s all very well for Butler to behave like this just now,” he would say. “Wait a few more years. Then he will still be a mere Congressman, while I’ll be a United States Senator! We’ll see who’ll kowtow to the other then!”

Although Plumb was elected to the Senate not long after and served there many years, I did not hear of Ben Butler doing any kowtowing.

In the summer of 1875 I felt that obtaining a knowl{27}edge of the law in this scrappy, unsystematic fashion was unsatisfactory, and that, therefore, I would leave Shaffer’s employ, attend Columbia Law School to get a thorough grounding of the law, and arrange for future easy access the odd bits of legal knowledge that I had absorbed in the offices. As I needed an income to enable me to do this, I secured a position as night-school teacher at $15 a week in the school on Forty-second Street near Third Avenue.

At that time Forty-third Street had not yet been cut through, and on top of the rocks was a shanty-town occupied by squatters. As I had the adult class, my pupils were from eighteen to forty-five years old, some of them denizens of the rocks, while others were hardworking carpenters, brakemen, butchers, factory workers, a plumber’s assistant, a coachman, and a blacksmith.

I particularly remember the latter three, because the plumber’s assistant came to the school to inveigle some of the other boys to play cards with him in one of the rear seats, and to amuse himself by throwing tobacco quids and beans while I, with my back turned to the class, would be engaged in explaining things on the blackboard. I was nineteen years of age, husky, weighing 180 pounds, and unafraid even of a plumber’s boy. As my weekly stipend of $15 was my sole support and its retention depended upon my being able to maintain discipline and keep up the attendance, I was not going to permit this loafer’s antics to defeat me—and one evening when I caught him playing cards, I forcibly ejected him from the classroom. Thenceforth my tenure of office was assured and continued to the closing day exercises, at which I had the pleasure of rewarding the coachman, Morgan O’Toole, with a prize for the greatest advancement made by any pupil. This man was very anxious to learn fractions. During the first three weeks of the session, every Friday{28} evening I had succeeded in teaching them to him. Every following Monday evening his mind was an absolute blank as to fractions, and the fourth week I asked him to come to my house both Saturday and Sunday, and gave him private lessons. His joy on the next Monday when he found he had retained his knowledge is still a vivid memory in my mind.

The blacksmith, a man named Whitney, had been a fellow pupil of mine in Fifty-first Street School, and had been one of the best penmen. I was surprised to see him come to reacquire that ability, which he had lost through wielding the hammer and pulling the bellows.

One of the carpenters wanted to learn duodecimals. As I knew nothing about them, I told him that I wanted him to brush up on ordinary fractions for two days. In the meantime, I learned duodecimals and then taught him.

It was really a great experience to divide impartially two hours every evening so as to satisfy the twenty-five earnest seekers after knowledge.

I deeply sympathized with these men who, wearied from their day’s labour, preferred to forego needed rest or amusement and devote their evenings to extricate themselves from the ignorance in which they had been compelled, probably through poverty and the early need of self-support, to live the better part of their existence.

It spurred me to still greater efforts to increase my own knowledge and I was no longer content merely to perform my allotted tasks at the Law School, but spent several hours a day at the Astor Library and drew deep drafts from that fine well.

During that period I devoted all the daylight hours to study, principally at the Law School, sitting in the midst of these hundreds of men who had come from all parts of this country and Japan, to imbibe from the lips of this{29} great teacher, Professor Theodore W. Dwight, the basis of the law of the land.

I joined the Columbia Club and was elected one of the team to debate with the Barnard Club, all of whose members were college graduates, while we had not had that advantage. I studied the subject of the debate, “Whether Participation in Profits or Agency Is the Correct Test of Partnership,” more thoroughly than I ever did any case on which I was retained during my practice of law. Professor Dwight, who presided, praised our thorough preparation and fine team work and declared us the winners. When our class graduated, we had the great honour of having that famous leader of the Bar, Charles O’Connor, come out of his retirement to bid us “Godspeed” on our way.

I was formally admitted to the bar on June 1, 1877.

During my second year in Law School I did not teach night school, but supported myself by accepting a position from that fine Southern gentleman, General Roger A. Pryor, who had been Congressman, Minister to Spain, and finally became a Judge of the Supreme Court of the State of New York.

An interesting episode that occurred at that time was my representing General Pryor at several meetings of the owners of the Greenwich Street property, who had retained him to seek an injunction to prevent the continued use and extension of the first Elevated road, which was on their street and was propelled by a chain. They claimed that their property would be ruined for private residences, and it was. They did not visualize, however, that this was the first step forward in the solution of the transit problem of New York, which was then totally dependent upon its horse-car system; and that someone had to suffer for the general good.

A very important and valuable after-effect of my con{30}nection with Pryor’s office was my becoming acquainted with Mr. Valentine Loewi, for whom I searched the title in a mortgage transaction. Loewi doubted my experience and when Pryor confronted me with this, instead of resenting the criticism, as Loewi expected me to do, I recognized its justice, and satisfied Loewi by having my work checked up by Mr. McIntire. He became my permanent friend and one of my firm’s first clients, and through his recommendations we secured some of the most valuable clients we ever had.

A little later came the uproar consequent upon Tilton’s entering the wrong berth in a sleeping-car. He came to Pryor, and I acted as secretary while these two prepared the Tilton statement for the newspapers. Curiously, both these six-footers had the habit, when thinking intensely, of striding across the room with swinging arms, and were that day doing it in opposite directions. I was constantly on the alert for a collision. Tilton would dictate a phrase. Pryor would stop and suggest another word. Tilton would weigh and test it, and would make still further corrections. Not even my weightiest diplomatic notes from Constantinople received the care and attention that these few lines were given by these two masters of English.

In the summer of ’77, as Mr. Kurzman was going to Europe, he requested me to come back to Kurzman & Yeaman, and as they offered me a well-lighted office, I did so. Still associated with Kurzman was Alfred McIntire to whom I have already referred, and with whom I had kept up the pleasantest of relations during my clerkships with Shaffer and Pryor, both of which positions he had secured for me. McIntire was a New Englander of the very best type, considerably older than Mr. Kurzman, and recognized as one of the best conveyancers of the City of New York.{31}

One Sunday while I was visiting McIntire, we went rowing on the Harlem River, and discussed plans for a prospective partnership. He was about six foot two in height, and weighed fully 250 pounds, and I was to do the rowing. Our skiff had not proceeded fifty yards before I discovered that I could not pull such a load and get anywhere. I took this as an omen, and then and there resolved that when I did select a law partner, he should be of my own age and weight, so that he could do some of the pulling.

During this summer, one of the old clients of the office, Henry Behning, got into very serious differences with his partner Diehl. The matter became greatly complicated, and the more complicated it became, the more excited Behning grew, and the more excited he was, the more incoherent and less comprehensible was his English, so that Mr. Yeaman, who was acting as his counsel in Mr. Kurzman’s absence, despaired of understanding him. A climax was reached one day when Diehl’s attorneys had secured the appointment of a receiver. Behning was accusing the lawyers, and the judge, and everybody else of all kinds of conspiracies, and Yeaman was so bewildered that he called me in to tell Behning that he did not think he could do justice to him because he could not understand his speech, and that he had better secure a German-speaking attorney. Upon my explaining this to Behning, he said: “All right, I’ll take you.” I explained the proposition to Mr. Yeaman, and he said that if Behning would be contented to do all his consulting with me he would be very glad to steer the legal proceedings. I discovered that some of Behning’s fears of conspiracy were justified, and concluded that the only way to counteract them was to throw the firm into bankruptcy. I prepared the necessary papers, and had them signed by the judge of the United States District Court. I then{32} communicated with the pompous ex-judge who represented Diehl, and had the tremendous satisfaction of having completely checkmated him. A prompt settlement resulted. The creditors realized that if they kept on fighting, the lawyers would be dividing the assets, and therefore consented to have Behning and Diehl divide them, and each continue in business for himself, and each assume half the liabilities.

Behning greatly appreciated what I had accomplished. He wanted to give me something to prove it. As he had no spare cash, he offered, and with Yeaman’s consent I accepted, one share of the Celluloid Piano Key Company stock. At that time, Arnold, Cheney & Company had cornered the word’s ivory market, driving up the price of ivory for piano keys to $30.00 a set. The piano manufacturers tried alabaster and other substitutes with small success, when Behning thought of using celluloid and formed the Celluloid Piano Key Company, securing for it the exclusive right for the use of that substance in piano and organ keys.

The company was so successful that its president began to intrigue for its control. The president was an Englishman, the treasurer a Dane, the secretary an American, and most of the rest Germans. Themselves densely ignorant of the manipulations of corporations, they finally feared that the president was in a fair way to get the company away from them, whereupon those representing over 70 per cent. of the stock held a hurried meeting, but they could not agree on a common policy because each mistrusted the others. I proposed that they all give their proxies to one man who should obligate himself faithfully to represent the interests of all against the president; they replied that this was excellent, but they could not agree on the one man.

Then Behning spoke:{33}

“What’s the use of fencing any longer? The only one we all trust is Henry. Let’s give him all our proxies.”

They did so, slated me for secretary, and as I wanted to prevent any mischief until the next annual meeting, I called on the president, told him I had the proxies of 70 per cent. and, with the audacity of my years, warned him that, if he did anything improper for the remainder of his term, I would bring him into court.

He asked me:

“Are you going to be an officer?”

“I am to be secretary,” I said.

“Will you protect my interest, and see that I get my proportionate share of the profits?”

I went back to the others and obtained the authority to give him this assurance, which I did.

“All right,” he declared, “make out my proxy to you and I’ll sign it.”

I had bearded a lion in his den and brought a lamb out with me. My connection with this concern, in one capacity or another, continued through two decades, and I was its president when I left it.

This adventure in celluloid put me in a position where it was possible to realize my ambition to stop clerking and start for myself.

It was settled most unexpectedly. During my attendance at Law School, Abraham Goldsmith, Wilbur Larremore, son of Judge Larremore, and I used to hold weekly quizzes at my house. In that way I had renewed my friendship with Goldsmith, who had been my classmate in the City College. One evening, early in December, 1878, Goldsmith called and informed me that Samson Lachman and he contemplated starting a law firm. I had always been very fond of Goldsmith, and Samson Lachman had won my unlimited admiration when I listened to his Commencement Day oration and saw him receive eleven prizes,{34} which were about all that one man could take. Hence, Goldsmith found me very receptive, and before we separated that evening, our partnership was an accomplished fact. We both agreed that Lachman was entitled to head the firm. As Goldsmith expressed indifference as to his position, and as Lachman, Morgenthau & Goldsmith sounded more euphonious, that order was adopted. We agreed to start on January 1, 1879. Our average ages were twenty-three. We hired offices at No. 243 Broadway at an annual rental of $400. Our net receipts for the year 1879 were $1,500.

Our practice, as well as our income, grew steadily, but I shall abstain from relating many details, as most of the matters involved were not of public interest.

A rather interesting affair, because some of the participants are well known to the public, was the dissolution in February, 1893, of the firm of Wechsler & Abraham, of Brooklyn. We represented Wechsler, and William J. Gaynor, afterward Mayor of the City of New York, represented Abraham. Their partnership agreement contained a very peculiar dissolution clause. They were to meet on February 1, 1893, and bid for the business, and a bid was to be final only if the non-bidding partner had failed to increase it during a term of twenty-four hours. When we met, I drew attention to the fact that if we acted under the contract, either side could prolong the matter indefinitely, and recommended that we amend the agreement by reducing the limit to one hour. This was agreed to on condition that both parties would deposit $500,000 as an earnest of their intentions to complete their bid, the unsuccessful bidder to have his check returned to him. Isidor Straus pulled out a certified check of $500,000 and I instructed Wechsler to make out his check. When Wechsler admitted that he did not have that much in the bank, I showed them an{35} underwriting that I had secured from the Guaranty Trust Company and the Title Guarantee & Trust Company, to finance our purchase to the extent of $1,000,000. The auction then proceeded, and both factions were cautiously watching each other. Gaynor, Abraham, and the Strauses several times retired to the other end of the room for conference, Nathan Straus constantly pulling at one of his big cigars and pretending that they had about reached the limit of their bidding. I had arranged definitely with Wechsler that we would bid an amount that would produce $500,000 for the good will of the business. So, finally, when they came within reach of about $100,000 of it, I bid the exact amount that would produce the desired result. They saw what I meant, and, as it turned out, had their last conference, which lasted about ten minutes, and raised us $100. I then informed them that we would take our hour. We (Wechsler, Mr. MacNulty, who was the manager of the store, and myself) went to an adjoining restaurant to discuss the matter. Wechsler devoted fully forty minutes of the hour in trying to persuade me to reduce the fee that he had agreed to pay me. He and I had agreed that if he purchased the property, and we had to complete the financing of it, my firm’s fee was to be $25,000, while if Abraham bought him out, we were to receive $10,000. Wechsler thought we had earned it too quickly, and begged for a reduction. I was absolutely firm and finally told him the story of the dentist who, with his modern methods, had painlessly extracted two teeth for a farmer in two minutes, and when he demanded his fee of $2.50, the exorbitancy of the charge was objected to by the farmer, who stated that when he had his last tooth extracted, the dentist had pulled him around the room for half an hour, and then only charged him 50 cents for all that work. I said to Wechsler that I could have protracted this matter for thirty days, and this delay{36} would have been most injurious to him on account of his diabetic condition. He wanted me to bid another $10,000 so that Abraham would have had to pay the fee, and he would have a net $250,000 for his good will. I was firm in my advice that he was unwise to run the business alone and should not risk securing it. We returned before the hour had expired, got Wechsler’s check back, and his half interest in the business became the property of Isidor and Nathan Straus, for whom Abraham had in reality been bidding. Immediately thereafter they dropped Wechsler’s name and created the well-known firm of Abraham & Straus.

Incidentally it may be of interest to the public to know that, when Isidor and Nathan Straus divided their interests, Isidor and his sons secured the business of R. H. Macy & Co., which they owned in common, while Nathan and his sons secured the half interest in Abraham & Straus. No doubt a good share of Nathan Straus’ munificent charities are financed to-day by his share of the profits from that business.

One of the greatest surprises in our practice was when Judge Horace Russell retained me as a business lawyer to advise him what to do about the affairs of Hilton, Hughes & Company, who had succeeded to the business of A. T. Stewart & Company, and who, in turn, were later succeeded by John Wanamaker. Judge Russell’s brother-in-law, Mr. Hilton, had been increasing the volume of the business rapidly, but his expense ratio was increasing much faster in proportion, so that, at the end of the year, he showed a tremendous loss. Some of the biggest banks in New York were refusing to renew the notes, even though Judge Hilton was willing to endorse them. They said they felt safe on all the paper they had then with Judge Hilton’s endorsement and collateral, but they feared that if they permitted the losses to continue much{37} longer, it might even engulf Judge Hilton in the unavoidable catastrophe. I finally advised him that he should sell out the business and take his loss. He retained Mr. Elihu Root as counsel. The three of us went over the whole situation. I explained that, owing to the very large general expenses due primarily to the excessive salaries which Hilton had agreed to pay under five-year contracts to his buyers, heads of departments, and even the superintendent of the engine room, and the bad credit in which the firm then stood, the only wise course was to sell out the business. We concluded to do so, but in the meantime decided that it would be necessary to make a general assignment to preserve the assets and secure a reasonable settlement with the men who held long contracts. When the assignment was finally prepared, it had to be executed the following day, and Root, Russell, and I first dined together, and then remained in Russell’s office until five minutes past midnight, when young Hilton, in our presence and that of Mr. Wright, the assignee, and a notary, executed the document.

While waiting, Mr. Root told us of several cases in which he had recently been retained, where the younger generation dissipated big fortunes in a very short time. He laid particular stress on the case of Cyrus W. Field, who, in his lifetime, prided himself that he had an income of $1,000 a day, which at that time was enormous. I also recall Root telling me that night that it was unwise for any lawyer to devote himself entirely to politics, that he should, when called upon, render a public service, complete it, and then return to his profession, but be ready for any further calls that might be made upon him. Root has pursued that course most successfully.

I felt a strange sensation to be present at this midnight dénouement of the great business of A. T. Stewart & Company. I could not help but think of the causes.{38} Judge Hilton had offended the Jews in America because his hotel, the “Grand Union” in Saratoga, had refused to accommodate Joseph Seligman, whom both the New York Chamber of Commerce and Union League Club honoured by electing as one of their vice-presidents. Hilton did not then realize that this act not alone involved the loss of his Jewish customers, but it would also influence a great many of his Christian patrons who would resent such discrimination, and withdraw their custom from his firm. Most of this trade went to the rising firms of B. Altman & Co. and Stern Bros. and so strengthened them that they became great competitors of Hilton, Hughes & Company, and precipitated their downfall. John Wanamaker bought the lease and stock of goods. I remember distinctly with what satisfaction, when the transaction was closed, he told me that this was the first time that he had ever heard of so valuable a franchise being given away for nothing. Wanamaker shrewdly disregarded the short existence of Hilton, Hughes & Company, and advertised John Wanamaker as the successor of A. T. Stewart & Company.{39}

MY first purchase of real estate was No. 32 West Thirty-fifth Street, a twenty-two-foot, white marble, high-stoop building. I bought it for the modest sum of $15,000 and resold it at an advance of $500, and thought I was doing well. To-day it is worth at least $110,000. This, however, was not my first experience with real estate, for that was in 1872 when, at the request of my preceptor, Mr. Ferdinand Kurzman, I undertook for an extra compensation of $5 a month to collect for him the rents of No. 218 Chrystie Street.

The tenants of this building in 1872 were Irish and Germans, and one of the stores was occupied as a saloon by an Irishman named Ryan who catered to the worst element of the neighbourhood. Kurzman, failing to get rid of him in a peaceful way, and knowing that there was a political feud between him and Anthony Hartman, the odd though popular Justice of the District Court, waited for the first of May, when only a three-hours’ dispossess notice was required. Circumstances favoured the plan because on that day the Thomas Ryan Association were giving a picnic. So the notice was served by nailing it on the door at twelve o’clock. Judge Hartman opened court at three o’clock, called the cases of Kurzman vs. Ryan, took Ryan’s default, signed the dispossess warrant, and adjourned the court, compelling all other litigants to wait for their justice until the next day. Instead of the usual one marshal, all those attached to the court, with their assistants, were hurried{40} to No. 218 Chrystie Street, and within two hours had removed everything to the sidewalk.

By that time word had reached Ryan, and he and some of his henchmen returned. They were thoroughly aroused but quite helpless. As there was no court in session, and the marshals were in possession of the premises, Kurzman was rid of Ryan for good and all. This was the first exhibition I ever saw of how justice might be travestied.

The next day Ryan’s attorneys appeared before Hartman and attempted to have the proceedings reopened, and upon Hartman’s refusal to do so, attacked him bitterly. The Judge said that if the learned counsel would not at once stop his impudent remarks, the court would forget its dignity long enough to leave the bench and “punch him in the jaw.”

My next experience brought me in contact with even a worse element. Kurzman had foreclosed a second mortgage on some houses on West Thirty-ninth Street between Tenth and Eleventh avenues. They were part of the block that was called “Hell’s Kitchen.” Many of the tenants owned only a mattress and a few chairs, and no kitchen utensils of any kind, and frequently paid their rents in instalments of less than one dollar. Twice I saw women carried out of the buildings the worse for the “exciting arguments” they had indulged in with some of their visitors. It would not have paid us to dispossess these people, as the new ones would have been no better. We collected the rents for a few months longer until the first mortgages were foreclosed.

This condition was very general throughout the City of New York. The boom days of real estate had disappeared, and with them, the optimistic speculators. Real estate was unsalable, and those who had received mortgages in payment of some of their capital and all their profits were confronted with the choice of either abandon{41}ing their mortgages or foreclosing them and again assuming control of their property. The conferences between the delinquent owners and the mortgagees to adjust these matters reminded one as much of funerals as the joyous meetings in the wine cellars had of weddings. These middle-class investors whom I met in ’72 and ’73 were completely wiped out and never came back. Quite the contrary was the case with most of those intrepid builders and operators like John D. Crimmins and Terrence Farley, who forgot their losses and went at it again with fresh vigour and new courage as soon as the liquidation had ended. In 1879, when specie payment had been resumed, the superintendents of both the insurance and bank departments urged institutions under their supervision to market their real estate as soon as possible. Their efforts and those of other recent plaintiffs to dispose of their holdings started a new active period. Real estate again became fashionable, and the plucky operators and builders who had survived the drastic punishment they had received were soon reinforced by a new set of men, of whom I was one.

In 1880, I turned my attention to Harlem where nearly all the brownstone and brick houses that had been built in the seventies were in the hands of mortgagees, and where the owners of the old frame houses were thoroughly discouraged and could see little hope in the future. Nearly all of Harlem was for sale. I bought plots of three to five adjoining houses at a time, and quickly resold them at small profits. This activity stopped when President Garfield was shot. The suspense during his illness caused a complete cessation, so I, too, rested until October, 1885. I was then worth only $27,000, and as a large part of that was represented by my interest in the Celluloid Piano Key Company, I had but little working capital.{42}

My brother-in-law, William J. Ehrich, agreed to operate with me in real estate, he to contribute $40,000 capital and I to do the work. All profits, after paying him interest, were to be divided equally.

At that time my mother lived on One Hundred and Twenty-sixth Street in a house I had purchased, a 17-foot brown-stone house with a pleasant yard which she personally transformed into a delightful little garden. In my frequent visits there I became impressed with the prospective importance of One Hundred and Twenty-fifth Street. It was the first broad street north of Forty-second that ran from river to river, and I foresaw its future value, particularly of the block between Seventh and Eighth avenues. It seemed to me like the neck of a funnel into which the entire neighbouring population was daily poured to reach the Elevated station at One Hundred and Twenty-fifth Street and Eighth Avenue.

Ehrich and I concluded to secure some property on this block. The first that we obtained was the lease of seven lots for which, at the beginning, we paid the annual rental of $4,000. We still own this leasehold, and the gross rental now is $44,500. We subsequently purchased the adjoining plot of five lots, improved the same, and were delighted when we were enabled to sell it to the Knickerbocker Real Estate Company among whose stockholders were Solomon Loeb, of Kuhn, Loeb & Company; Henry O. Havemeyer, John D. Crimmins, and John E. Parsons, at a price which netted us a profit of $100,000. This was in 1899. Subsequently, I repurchased this plot jointly with my partners, Lachman & Goldsmith, for $250,000, and within two years thereafter sold it to Mr. Louis M. Blumstein for $425,000. This was the most profitable, but not the only transaction we had on this street. With various associates I owned, at one time or another, one half of the property on the south{43} side of that block, so that I made good use of my early judgment as to its future value.

Our operations on One Hundred and Twenty-fifth Street were not confined to that block alone. We had also purchased various plots between Fifth and Sixth avenues and, with a friend, I had collected a plot of eight lots between Lexington and Fourth avenues. This made Oscar Hammerstein one of my customers.

One day the optimistic Oscar came into my office with his serious, flat-footed walk, his French silk hat on his head, and his eternal cigar between his fingers. He had just completed the Harlem Opera House on West One Hundred and Twenty-fifth Street, and he told me that, for his success there, it was essential to have also a theatre on the East Side, and he negotiated for the eight lots that we had collected on One Hundred and Twenty-fifth Street near Park Avenue. We spent several hours arranging the details of the lease of our property, with privilege to buy, which was what he wanted. He argued me into giving it to him on a 4 per cent. basis while the building was being constructed. When he was all through, I said:

“Do not think that you have deceived me as to your real aim. You want to secure this property and pay down as little as possible until your building is completed! All of us who own property on One Hundred and Twenty-fifth Street between Seventh and Eighth avenues greatly appreciate the fine theatre you put there, and the consequent increase in the value of our property, and I am therefore willing to help you make this enterprise a success. I will at once give you a deed, and as there is no broker in the transaction, you need only pay the equivalent of six months’ rent on account of the purchase price.”

Hammerstein gratefully accepted the offer and, subsequently, told me how he financed that entire operation without any capital. He struck a sand-pit and saved all{44} costs of excavation, besides realizing over $30,000 for the sand. That furnished him nearly all the cash for the building.

A little later Hammerstein got into difficulties about an office building next to the Harlem Opera House. He wanted to borrow $25,000 on a second mortgage. He practically put a pistol to my head, and said:

“You folks must lend me this money, or I can’t finish the building—and that will force me into bankruptcy.”

I looked at him and saw not the optimistic Oscar, but the harried Hammerstein. He went on:

“You don’t know what that will mean. If I go into bankruptcy, the Bank of Harlem will also have to go. I owe them over $50,000 and they have agreed that, if I can finish the building, they will buy it from me, giving me back my notes in part payment.”

“But that bank,” I protested, “has only $100,000 capital! How could it lend you $50,000?”

“One day,” he said, “as I was seated in my little office underneath the steps of the Harlem Opera House, the president of the Bank broke in, and leaning over my shoulder, handed me a blank note, and asked me, for God’s sake, to make it out to the order of the Bank for $10,000. ‘Don’t ask any questions,’ he whispered, ‘but just do what I want, and do it quick.’ I complied with his request, I didn’t stop to put on my hat and coat, but followed him to the Bank; and just as I expected, there were the bank-examiners!”

He paused in his narrative to give me one of those knowing, piercing looks of his. This was still another Hammerstein: he was the accomplished actor awaiting applause for securing such an extensive and undeserved line of credit from so unexpected a source.

“Does that,” he asked, “explain to you how I could pull his leg?{45}”

The impresario did not then go into bankruptcy. A few of us combined and lent him the money. My activities in Harlem also included the purchase of two solid blocks of lots.

In 1887 Ehrich and I bought from Oswald Ottendorfer the entire block bounded by Lenox and Mount Morris avenues and One Hundred and Twentieth and One Hundred and Twenty-first streets. I induced the Ottendorfers to split the transaction and content themselves with our buying the Lenox Avenue front outright and their giving us an option on the Mount Morris front. This option was sold for $10,000 profit, to Walter and Frank Kilpatrick, and our total profits, which we divided in May, 1887, were $43,424.10. I always remembered the numbers because of the sequence, 43, 42, 41.