A Well-Known Tune

Title: A Village in Picardy

Author: Ruth Gaines

Author of introduction, etc.: William Allan Neilson

Illustrator: Francisque Poulbot

Release date: November 4, 2020 [eBook #63637]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: ellinora and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian

Libraries)

A VILLAGE IN PICARDY

A Well-Known Tune

A VILLAGE IN

PICARDY

BY

RUTH GAINES

AUTHOR OF “THE VILLAGE SHIELD,” ETC.

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

WILLIAM ALLAN NEILSON

President of Smith College

NEW YORK

E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY

681 FIFTH AVENUE

Copyright, 1918,

By E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

The history and the work of the Smith College Relief Unit in the Somme is known wherever reconstruction work in France is spoken of. This brief account does not purport to give anything but a small cross-section, the picture of but one of the villages in our care. It is told in the first person to make the telling easier. As I have said, of all our villages, Canizy was the most beloved. All the Unit had a share in it.

The picture is given as it was seen day by day. What was true in this section, may not be true in another. Here the German retreat was so rapid that the devastation, though appalling, was not complete; whole avenues of trees were left standing in places, and only two churches were dynamited, by contrast with the two hundred and twenty-five destroyed throughout the région dévastée. It was perhaps[viii] in more calculated ways that the Prussians here vented their spite; in the burning of family pictures, the wrecking of machinery, the cutting of the trees about the Calvaries, and the taking away of the bells from the church towers. They left behind them here, as everywhere, ruin and silence; a silence of industry, of agriculture, of all the normal ways of life; a silence which has given the plain of Picardy the name of “The Land of Death.”

Ruth Gaines.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | Un Village tout oublié | 3 |

| II | Le Château de Bon-Séjour | 16 |

| III | M. Le Maire | 35 |

| IV | O Crux, ave! | 48 |

| V | Mme. Gabrielle | 61 |

| VI | Voilà la Misère | 74 |

| VII | Nous sommes dix | 88 |

| VIII | Une Distribution de Dons | 100 |

| IX | En Permission | 113 |

| X | A la Ferme du Calvaire | 129 |

| XI | Les Petits Soldats | 139 |

| XII | M. L’Aumônier | 151 |

| XIII | Heureux Noël | 162 |

| XIV | Fidelissima, Picardie | 176 |

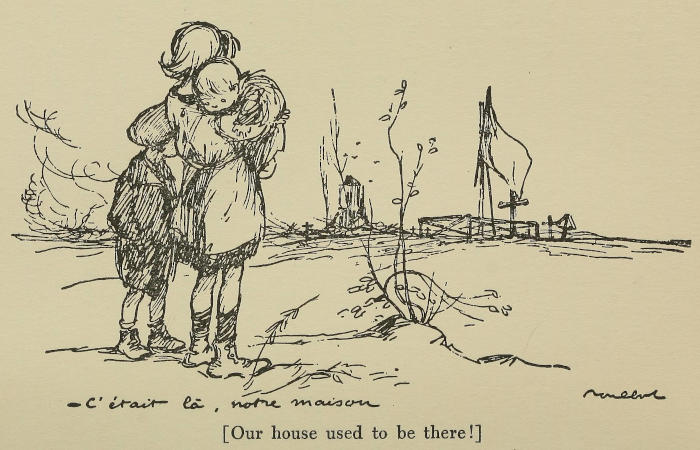

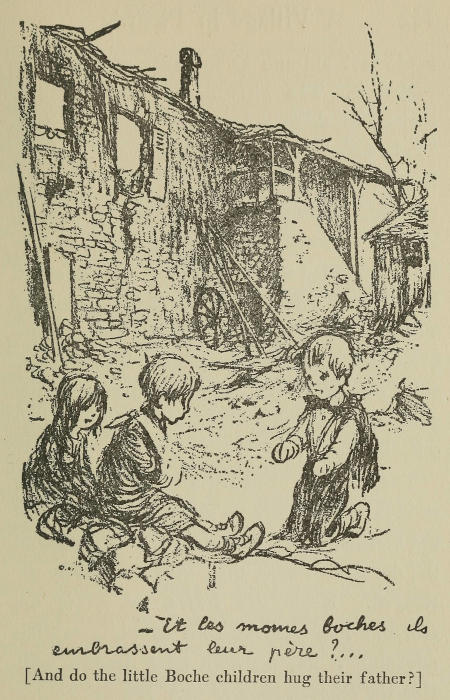

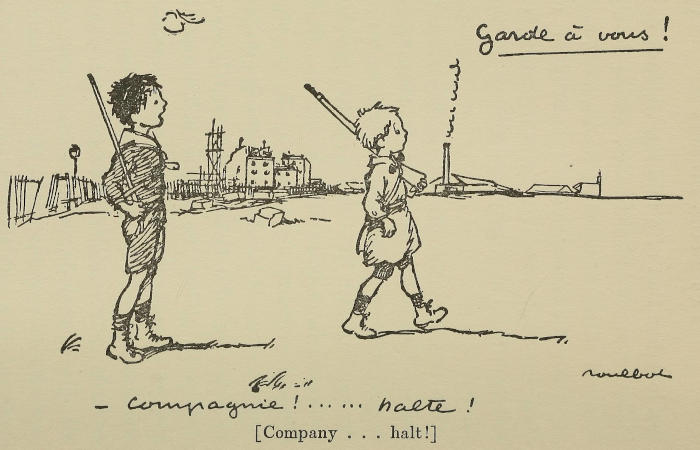

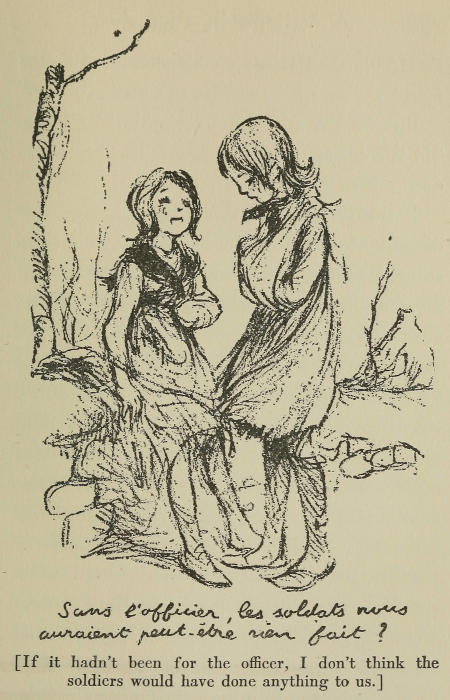

| A Well-Known Tune | Frontispiece |

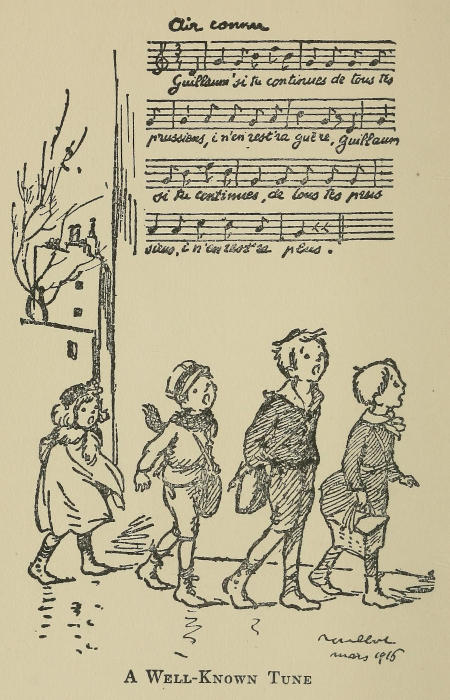

| Map of the German Retreat[2] | 2 |

| “They are over there” | 12 |

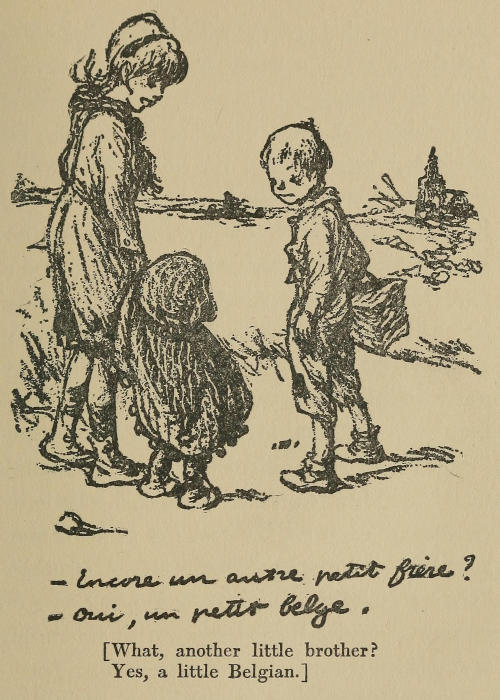

| “What, another little Brother!” | 17 |

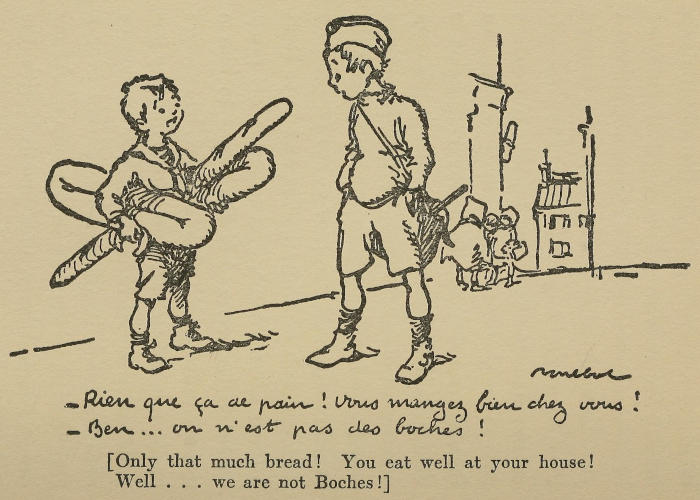

| “Only that much Bread!” | 44 |

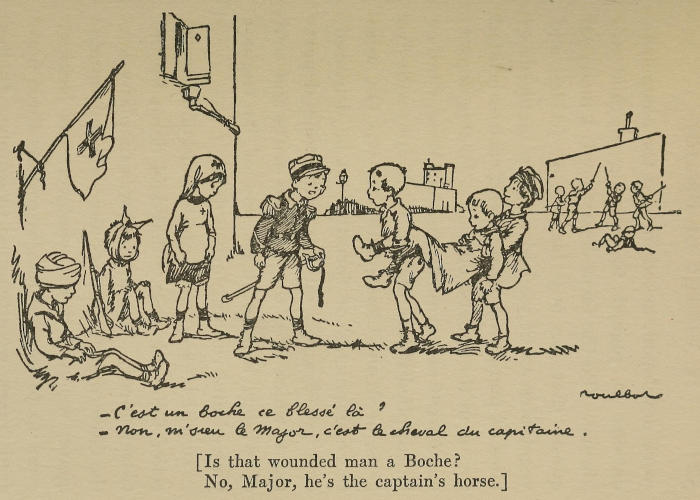

| “Is that wounded Man a Boche?” | 51 |

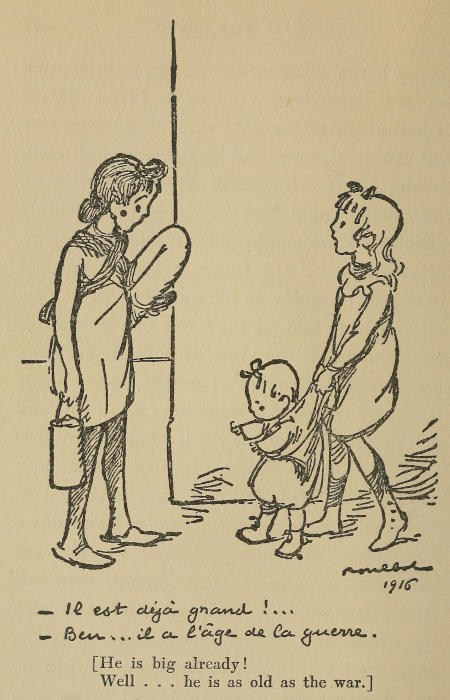

| “He is big already” | 58 |

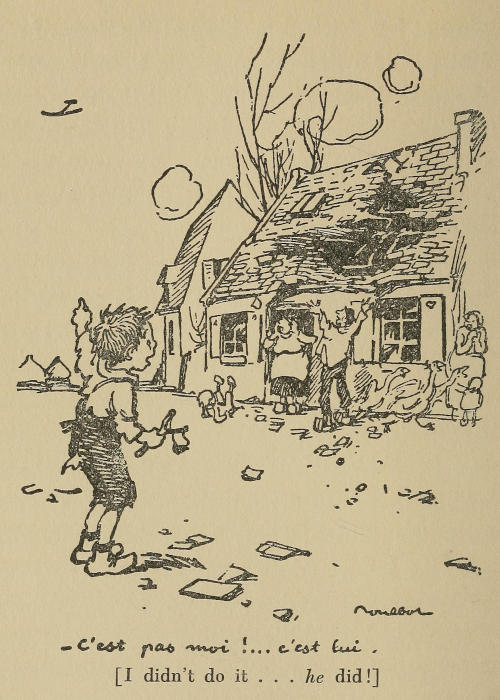

| “I didn’t do that!” | 63 |

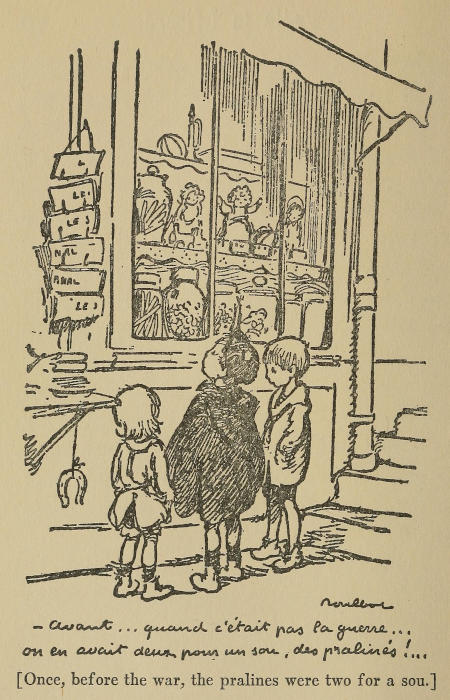

| “Once, before the War, the Pralines were two for a Sou” | 80 |

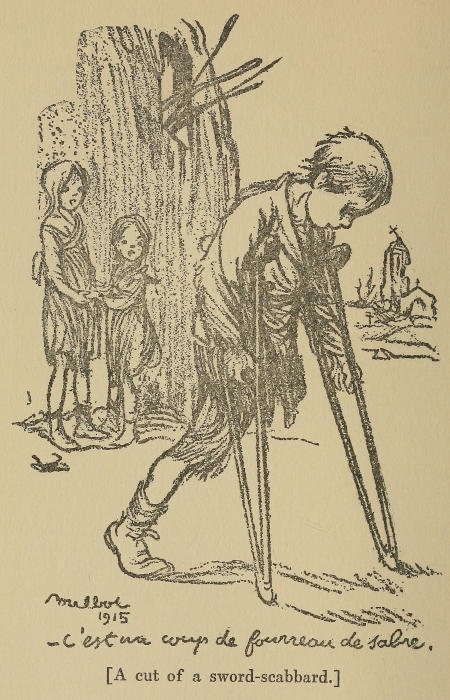

| “A Cut of a Sword-scabbard!” | 114 |

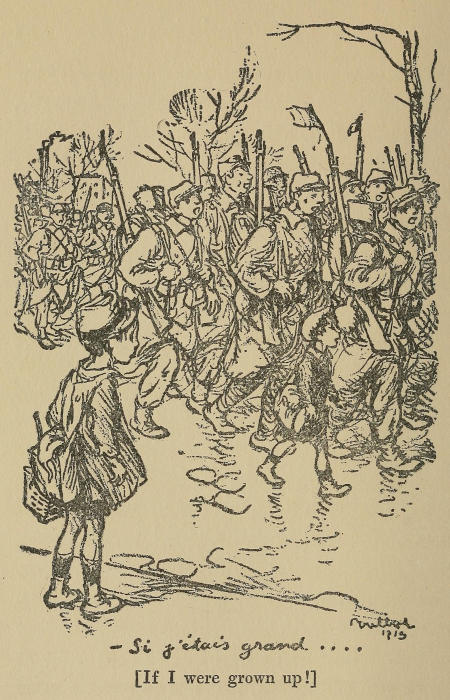

| “If I were grown up!” | 124 |

| “Our House used to be there!” | 132 |

| “And do the little Boche children hug their Father?” | 143 |

| “Company, halt!” | 148 |

| “If it hadn’t been for the Officer....” | 157 |

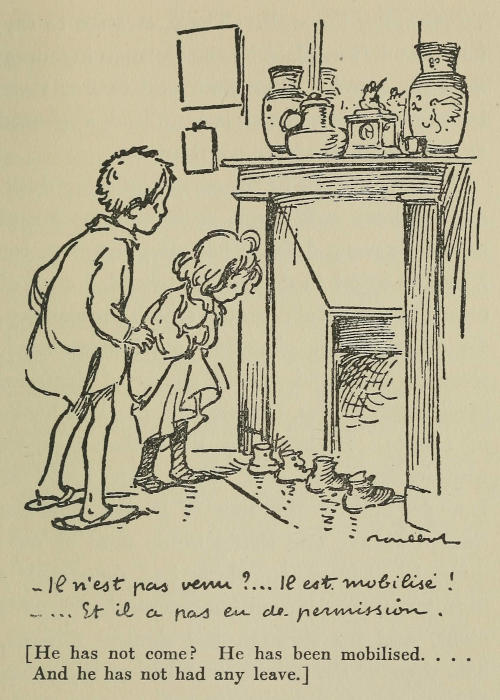

| “He has not come. He has been mobilized....” | 165 |

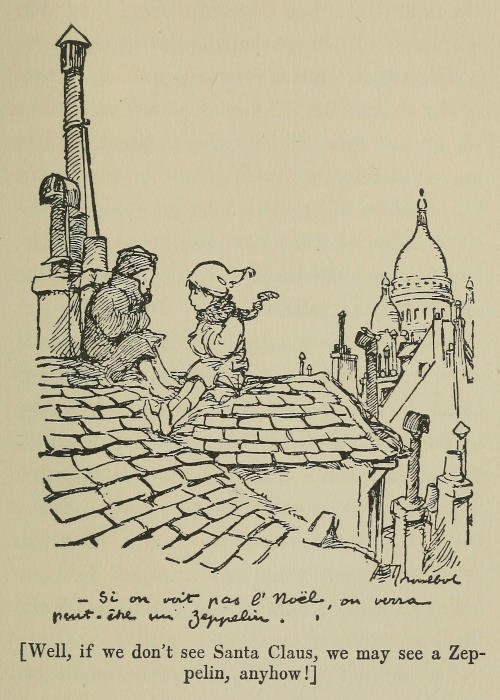

| “Well, if we don’t see Santa Claus, we may see a Zeppelin” | 171 |

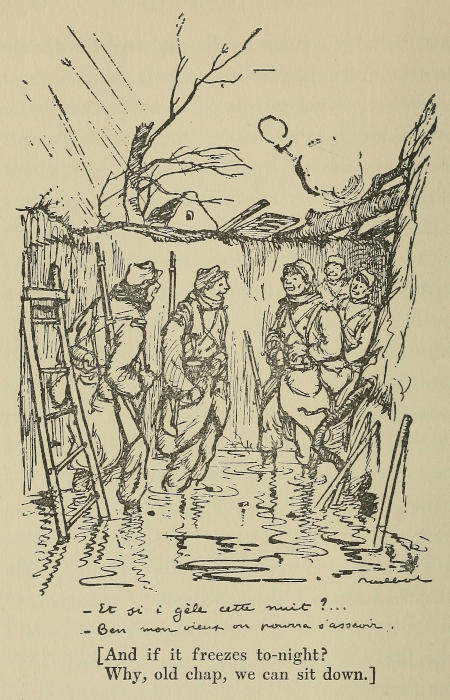

| “And if it freezes to-night?” | 174 |

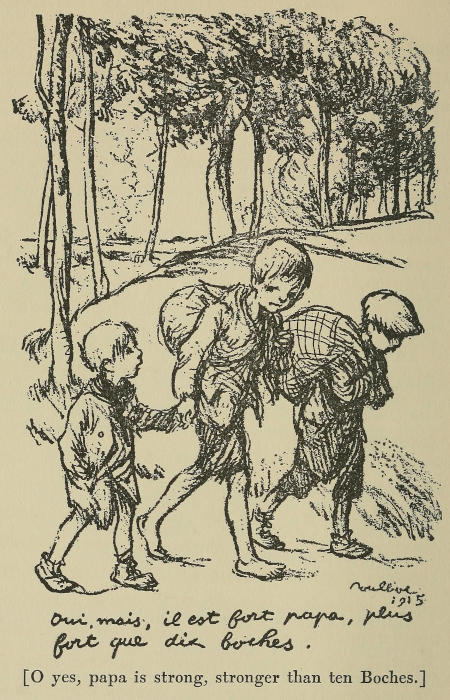

| “Oh yes, Papa is strong!” | 182 |

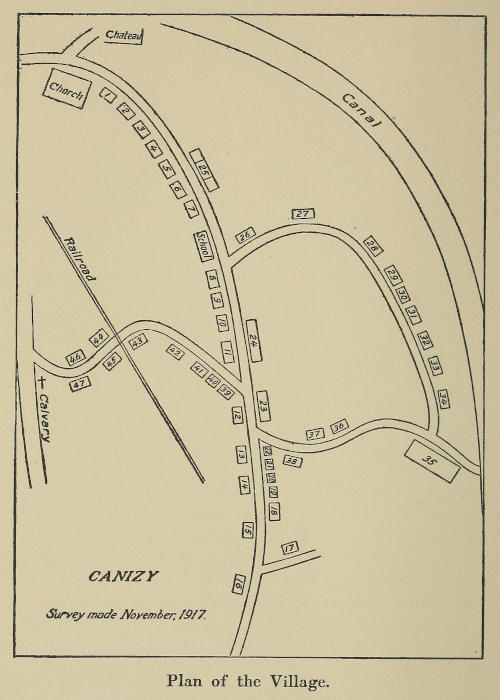

| Plan of the Village | 188 |

No one, it may safely be said, can see this war as a whole. The nations taking part in it girdle the world, and no people is unaffected by it. Real knowledge can be gained of only comparatively small sections of the conflict, and we are grateful to those who, knowing a small section, give us a faithful account of their own observation and experience, and refrain from speculation and generalisation.

Among the infinitude of tragedies few have appealed more poignantly to our imaginations than those involved in the devastation of Picardy; and among the attempts at salvage few details have attracted the sympathetic attention of America more powerfully than the efforts of the Smith College Relief Unit. Their heroic persistence in the work of evacuation under the very guns of the great offensive of March, 1918, made the members of the Unit[xiv] suddenly conspicuous; but the more picturesque feats of that terrible emergency had been preceded by a long winter of quiet work. The material results were largely wiped out; the spiritual results will remain. It is the method of that work as carried on in a single village that is described in this little book. When we have read it we know what kind of people these were who clung to the remnants of their homes in the midst of desolation. Their character and temper are depicted with kindly candour; they were very human and very much worth saving. When the time comes for reconstruction on a large scale, such an account as this will be of value in enabling us to realise the nature of the task and in teaching us how to set about it.

Smith College is proud of what these graduates have done and are doing; and this note is written to assure the Unit rather than the outside world that those who have to stay at home see and understand.

William Allan Neilson.

Smith College, Northampton, Mass.

The German Retreat

As a relief visitor, in a Unit authorized by the French Government au secours dans la région dévastée, I have lived recently in the Department of the Somme. There I had in my care a village with a personality which I venture to think is typical of Picardy. As such, I would present it to you.

It was on a winter’s morning, by snow and lantern light, that I traversed for the last time a road grown familiar to me through months of use, the road which led from our encampment, known as that of the “Dames Américaines” at Grécourt, past the railroad station of Hombleux to the hamlet of Canizy.[4] It leads elsewhere, of course, this road; to the military highway for instance, which has already seen in the last three years three momentous troop movements: the advance and retreat of the French, the advance and retreat of the Germans, and, again, the victorious sweep of the French and British armies which reclaimed, just a year ago, the valleys of the Somme. It leads to the front, that fluctuating line, some twelve miles distant, in the shelter of which we have lived and worked for the ruined countryside. It is an important route, on some occasions choked with artillery, on others with blue columned infantry swinging down its vista arched with elms. Officers’ cars flash by there, and deafening camions. But for me, until this the morning of my departure, it has led to Canizy.

There is no longer a station at Hombleux, because the Germans destroyed it. One therefore paces the platform and stamps one’s feet with the cold. Down the track, from the direction of Canizy, the headlight of the engine[5] will presently emerge. All about, the plain lies white and level; the break in the hedge where a footpath crosses the tracks to the village is almost visible. In fancy, I take it, past a fire-gutted farm house and eastward on a long curve across fields where the snow hides an untilled growth of weeds. The highway which parallels the railroad, recedes in a perspective of marching trees, till, topping a little rise, a wooden scaffold stands clear against the sky. It was formerly a German observation post. To the left, equally gaunt, rises the Calvary which marks the entrance to the village. And beyond, cupped in a gentle declivity, lie the ruins of Canizy, framed in snow. So I saw it last; so all the way to Amiens, and from Amiens to Paris, as the train bore me away, I saw it; so in its misery and its beauty, I would picture it to you.

You will not find my hamlet on any map of the région dévastée with which I am familiar; it is not listed among the destroyed villages of the Department, although it was[6] looted, dynamited and defaced, even to the cutting of the oak trees about its Calvary. You would have to search minutely in history for any mention of it among the King’s towns of Picardy which became famous in guarding his frontier of the Somme. Comparatively modern and quite insignificant, it lies beside a tree-bordered, dyked canal, one of many which tapped the rich plain and bore the produce of farm and garden to the market centres, of Péronne, Ham and St. Quentin. To this canal sloped its fields of chicory, leeks, pumpkins, potatoes, turnips, carrots and other garden truck. Crooked lanes, brick-walled or faced with trim brick cottages, led from it back through the village to higher ground. There, before the war, the grands cultivateurs, such as M. le Maire, and M. Lanne, who rents the old Château, would have ploughed and sown their winter wheat.

In those days, Canizy had a railroad also, and I have heard how for three sous one could travel by it to Nesle. It took only eight minutes[7] then,—but now! By it as well, one went more quickly than by canal to St. Quentin or Péronne with perhaps a hundred huge baskets of vegetables on market day. But the Germans tore up the bed of the railroad and destroyed the locks of the canal. They blew up, too, the bridge on the main highway which used to pass the Calvary at the foot of the village street. Cut off, reached only by a circuitous and deep-rutted road which is impassable at certain hours every day owing to mitrailleuse practice across it, Canizy lapsed into oblivion. As its mayor said on our first visit, “Look you, it has been quite forgotten,—c’est un village tout oublié.”

In 1914, Canizy had 445 inhabitants. Of these, there were perhaps half a dozen substantially well off, such as M. le Maire, possessing ten hectares of wheat land, a herd of seven cows, four horses, thirty rabbits and fifty hens. Besides, M. le Maire, or his wife, was proprietor of one of the three village épiceries. Joined with him in respectful mention by the[8] townspeople are the lessee of the Château, and various owners of property not only in Canizy but in the surrounding country. Of these gentry, not one apparently had been made prisoner by the Germans. They were to be found on their other estates, at Compiègne, at Ham, or in Paris. Even the real mayor was an absentee, so that the acting mayor, lame, red-faced and heady-eyed, was the only representative of landed interests left in the little town. He had had, however, a dozen or more neighbours scarcely less comfortably provided with worldly goods than himself: M. Picard, for instance, who owned extensive market gardens and employed six workers in the fields. He it was who did not suffer even during the German occupation, for was he not placed in charge of the ravitaillement? And though his friends the Germans took him away with them, a prisoner, did not his wife and children live well on his buried money, eh? O, Mme. Picard, elle était riche. There were the Tourets, two brothers, who held connecting[9] high-walled gardens in the centre of the village, and their next door neighbour, the comely widow, Mme. Gabrielle. Directly opposite ranged the Cordier farm, comprising an orchard of 360 trees, ten cows, two bulls, one ox, eighty-seven pigs, three horses, one hundred and fifty chickens, and one hundred and fifty rabbits. Smaller cottages there were, some rented, but most of them owned, where the families raised just enough for their own necessities, or worked for their more prosperous townsfolk. There were the village cobbler, the two store keepers who competed with the mayor, a sprinkling of factory hands who walked along the dyke a mile and a half to work in the brush factory at Offoy, and last on the street, but not least in social importance, the domestics of the Château. There were, too, the poor whom one has always; but in Canizy, so far as I could learn, they consisted of but two shiftless families.

The civic life of the village centred about its public school and its teacher, and, of course,[10] its curé and its church. The monotony of toil was relieved by market days and fête days and first communions and neighbourhood gatherings. Of these last I have seen a few pictures, groups of wrinkled grandparents and sturdy sons and grandchildren stiffly posed in Sunday best, yet happy in spite of it. Behind them pleached pear trees or grape vines make an appliqué against a patterned brick wall. But there are not many of the pictures even left, for you will understand, the Germans systematically searched them out and burned them in great piles. The one that I remember best, a poor mother had torn out of its frame the night of her flight. “I could not think well,” she said. “The Boches had wrenched my Coralie away—so lovely a child that every one on the streets of Ham turned to look at her curls as she walked—but I did save this. See, there she is,—how pretty and good, and that is my eldest, a soldier. He is dead. And that, with the accordion, is my seventeen-year-old Raoul, like his sister, a[11] prisonnier civil. What do the Boches do, think you,” she continued, “with such? One hears nothing, nothing. Never a letter, never a message. Even when Mme. Lefèvre and Mme. Ponchon returned, they brought no word. The prisoners, evidently they are separated. One is told that they work and starve,—that is all.”

A community so homogeneous in its interests, was bound to link itself intimately by marriage as well. The intricacies of the family trees of Canizy were a source of constant mental effort, as one discovered that Mme. Gense was really Mme. Butin, that is, she had at least married M. Butin, and that Germaine Tabary was so called because she was living with her maternal grandparents, whereas her father’s name again was Gense, and her mother was known by the sounding title of Mme. Gense-Tabary. “But why these distinctions?” one continually demanded upon unravelling the puzzles for purposes of record. “Because, otherwise, one would become confused,” was the reply.

—Ils sont là!!!

[They are over there!!!]

Such, peaceful, prosperous, yet stirred by family bickerings enough to spice its days, was Canizy before the war.

Canizy to-day numbers just one hundred souls, fifty being children and fifty adults. It was in March, 1917, that the village was blotted out. Two years and a half of German occupation preceded that event. In every house German soldiers had been billeted; one sees now on the door posts the number of officers and men allotted, or the last warning, perhaps, in regard to concealed fire-arms. For two years and a half the inhabitants had been prisoners, for the same length of time there had been no school and no mass. Yet the villagers do not speak unkindly of their conquerors. They fared better than many, for they fell to the lot of the Bavarians, who are reputed to be more humane than the Prussians. Besides, Picardy is inured to invasions, which for centuries have swept across her[14] plains. By them, fortitude has been inbred.

But one day last spring, the Bavarians filed away northward. Prussians succeeded them. Quickly came the order for the villagers to evacuate their homes. At the same time, the able-bodied, men and women, youths and maidens, were seized and held. Weeping mothers, tottering grandfathers, and helpless children,—the remnant,—were driven forth with what scant possessions they could snatch, to the town of Voyennes, four kilometres away. There, huddled with the like refugees of other villages, they remained ten days. From it they could see the ascending smoke, black by day and red by night, and hear the detonations which marked the destruction of their homes. They returned to the blackened ruins,—as, in the words of a historian of the Thirty Years’ War, their ancestors had done. “Les paysans,” he says, “qui avaient survécu à tant de désastres étaient accourus dans leurs villages aussitôt que les ennemis s’éloignèrent de ce champ de carnage. Mais, sans ressources[15] d’aucune sorte, sans habitations, sans chevaux, sans bestiaux, sans instruments de culture, sans grains pour la semence, que pouvaient-ils faire? Mourir——”[3]

But our villagers, though equally pillaged in the year 1917, were not doomed to death. The Germans had retreated before the advancing French and British armies, and the ruins of Canizy ere long were held by Scottish troops.

In Canizy, after the Germans were through with it, not one of its forty-seven houses stood intact. Most were roofless shells, or fallen heaps of brick. An occasional ell, a barn, a rabbit hutch, or a chicken house,—such were the shelters into which the returning villagers crept. Nor was there furniture. Pillage had preceded destruction and loaded wagons had borne away the plunder of household linen, feather mattresses, clothes presses, chairs or anything practicable, into Germany. Scattered through the ruins to this day lie iron bedsteads twisted by fire, the metal stands of the housewives’ sewing machines, broken farm tools and fire-cracked stoves. One day, beside a half-demolished wall, I came upon a group of little girls playing house. They had[17] marked off their rooms with broken bricks, set up for a stove a rusty brazier, and stocked their imaginary cupboards with fragments of gay china. A grey, drizzling day it was, and their toy ménage had no roof. But was it more cheerless than the hovels they called their homes, where their mothers, like them, had gathered in the wreckage left by the Germans,—a stove here, a kettle there, and a “Boche” bed of unplaned planks, perhaps, with an improvised mattress of grass? I paused to regard the play house. “What is this room,” I inquired. “La cuisine,” was the quick reply. “And this?” “La salle à manger.” “But this next?” “Une salle à manger,” came the chorus. “Then all the rest are salles à manger?” “Assurément,” with merry laughter. “O, I see. Are you then so hungry at your house?” And I turned away with an uncomfortable conviction that they were.

—Encore un autre petit frère?

—Oui, un petit belge.

[What, another little brother?

Yes, a little Belgian.]

One after another, if you listen, the Village mothers will tell of their return; with what hope against hope they looked for some trace[19] of vanished husbands, sons and daughters; with what despair they realised the utter ruin. “My cat,” said one, “was the only living thing I found. She was waiting for me on the doorstep.” But those were fortunate who found even the door sills remaining to their homes. Those who were shelterless took possession of some semi-habitable corner of their neighbour’s outbuildings, or even of cellars, and furnished them with what they could find. As I went about among them, in an effort to supply immediate needs, I was continually told: “That cupboard, you understand, is not mine. I am taking care of it for Mme. Huillard, who is with the Boches. When she returns, I must give it up.” “This bed,”—a very comfortable one, by the way—“belongs to M. de Curé, whom the Germans made prisoner.” “Those blankets an English soldier gave me.” “This stove”—in answer to a query as to whether a new one would not be appreciated—“well, to be sure, it has no legs, but one props it with bricks, et ça marche, tout de même!” The[20] boast of the Prussians in regard to their handiwork was true: “Tout le pays n’est qu’un immense et triste désert, sans arbre, ni buisson, ni maison. Nos pionniers ont scié ou haché les arbres qui, pendant des journées entières, se sont abattus jusqu’à ce que le sol fût rasé. Les puits sont comblés, les villages anéantis. Des cartouches de dynamite éclatent partout. L’atmosphère est obscurcie de poussière et de fumée.”[4]

By the time of the arrival of our Unit, six months after the Great Retreat, our villagers had recovered from the shock of their sorrow. They had managed to save enough bedding and clothing for actual warmth; they had planted and worked their gardens; they were used to the simplest terms of life. This courage rather than the too-evident squalor, was what impressed one on a first visit to Canizy. Dumb endurance drew one’s heart as no protestations could have done. It made me long[21] to make my home among my villagers, so that I might the more quickly meet their needs.

But this could not be, because every habitable cranny was crowded to capacity. Hence it was that I lodged with the rest of the Unit, four miles away, at the Château de Bon-Séjour. Again, you will not find my château so called upon the map. It is merely a name that represents to me six months of hardship, of comradeship and of some small achievement that made the whole worth while.

At the Château, then, but not in it, lived the Unit. For the Château, a German Headquarters, and a most comfortable one, in its day, had been wrecked in the best German style. There were seventeen of us, American college women, to whom the Government had entrusted the task of reconstructing thirty-six of the 25,000 square miles of devastated France. Two were doctors, three nurses, four chauffeurs, and the rest social workers. Among them were a cobbler, a carpenter, a farmer, a domestic science expert; and of other[22] manual labor there was nothing to which they did not turn their hands. It was in the golden days of early September that my companions reached the Château allotted them in that indefinite area known as the War Zone, and became from that moment a part of the Third Army of France. But I, for reasons best known to the passport bureau of that army, did not arrive until October. The seventy-mile run from Paris was made in our own truck, driven by two of our chauffeurs. As we cleared the dusty suburbs and took the highway northward, war seemed very far away. To be sure, we often passed grey camions rumbling to or from the front, or saw fleeting automobiles containing officer’s whiz by. But the country, the fields of stacked grain or of freshly seeded wheat; the apple orchards,—sometimes miles of trees along the roadside festooned with red fruit,—poplared vistas of smoke-blue hill and valley, with church spires and red roofs in the distance,—all these spoke of peace. Even the air lay in[23] a motionless amber haze, spiced with apples and wood smoke and ferns touched by frost. But suddenly war was upon us. As we topped a sharp rise we came upon an empty dugout, about which stood a shell-shattered grove. Lopped orchards followed, zig-zag trenches, a bombarded village set in fields bearing no crop but barbed-wire entanglements and tall weeds turned brown. The country became flatter as we hurried along, intent on reaching the Château before dark. At intervals we made detours around crumpled bridges. Occasionally a sentry halted us, to be shown our permits known as feuilles bleues. By this time the sun was setting and caught and turned to gold a squadron of aeroplanes. Like great dragon-flies they coursed and wheeled and presently alighted, to run along the fields to their canvas-domed hangars. In the after-glow, we could still see occasional peasants or soldiers working late at ploughing with oxen or tractors. But otherwise, mile on mile, the[24] brown plain, dotted here and there with scraggly thickets, lay deserted.

It was dusk when we turned off the main road between the half dozen dynamited farm-houses that once formed a tiny village, past the little church, and into the gate of the Château. To the rear of this ruined mass, set in a row as soldiers would set them, were the three baraques, or temporary shacks, which the Army had made ready for us. Very cheerful they looked that night with the lamplight streaming from open doors and windows, and the smell of savoury stew upon the air.

But morning revealed what darkness had hidden: the destruction which this estate shared with the entire countryside. Of the noble spruces and poplars, which had formed the two main avenues leading the one to the church and the other to the highway, only a ragged line remained; the rest lay as they had been felled, in tangles of crossed trunks. The Château itself, an imposing building as one viewed it through the frame of a scrolled wrought-iron[25] gate, proved to be a rectangle of roofless walls. The water-tower, draped in flaming ampelopsis, no longer held the reservoir which had supplied in former days the mansion, the greenhouses, the servants’ quarters and the stables. The greenhouses themselves, the jardin d’hiver, and the orangerie, where were grown hot-house fruits, retained scarcely one unbroken pane of glass. Dynamite had been employed freely; but—an instance of German economy—the main roof of the greenhouse had been demolished by the well-calculated fall of a heavy spruce. In this same greenhouse were the remains of a white tiled tank, and a heating plant which had involved the construction of three new buildings. “Voilà,” said Marcel, the sixteen-year-old son of the gardener, as he pointed it out, “the officers’ bath.”

Marcel and his mother (whom, we think, the Germans left behind because of her too shrewd tongue) still take unbounded pride in the place. Even before repairs were made on her own cottage, Marie routed Marcel out of a[26] morning to weed the flower beds and to fence off what, by courtesy, she calls the lawn. By this last manœuvre she renders difficult both the entrance and exit of our cars. She also refuses to open for us the wicket for foot passengers, probably because in the days of Mme. la Baronne’s hospitality there were none. Here entertaining was done on a patrician scale. A French officer who stopped in passing, told us how he was in the habit of coming each year to hunt in season. There was a gallery of famous pictures. In short, the Château of his friend, Mme. la Baronne, was the show place of the countryside. “To think,” said he, as he pointed to a sign still standing beside the gate, “to think that dogs were forbidden,—and yet the Germans came here!” Marie, having been left by her mistress in charge of the property, carries the responsibility with seriousness. A letter arrives: Mme. la Baronne desires that the vegetable garden be always locked, and that no trees be cut. It is she, doubtless, who directs[27] that the lawn be preserved. “Poor Madame,” sighs Marie, “she little knows. Pray heaven she may never return to see what the Boches have done!”

With Marie’s and Marcel’s help, one can reconstruct from the ruins the gracious comfort of the old estate, the hospitable kitchen, the chambers warm in winter and tree-shaded in summer, the wide balustrades where the guests sat in long summer gloamings, courting the breeze. It was Marcel who pointed out the view one gains from the steps of the Château, straight through gaping doors and windows, to the sundial from which radiated the alleys of the grove: bronze oaks and beeches, golden plane trees, spruces and tasselled pines.

How is the beauty of that day departed! Half of the grove lies now a waste of scrubby second growth and fallen timber, for here the Germans employed Russian prisoners as lumbermen. No longer the huntsmen and their ladies pace the alleys. Now, on almost[28] any day you may see old women dragging branches from the woods to the basse-cour, to be cut up for fuel. Twenty-six of them, no men, and only two children, the wretched villagers had found in the Baronne’s stables their only shelter after the razing of their homes.

Yet we entered the winter far less warmly housed than they. Our two-room baraques were supplemented in time by six portable houses which we had brought from America; two we used as dormitories and the other four as a dispensary, a store, a kitchen, and a dining room. Our furnishings were of the simplest; camp beds, a stove for each building, a table, camp stools, and shelves. Our wood—when we had any—was chopped by a vigorous old lady who walked a mile and a half from the nearest village to do it. Our laundry was done upon a stove a foot square in a small building known as the Morgue: such having been its use during the German occupation. Marie made our cuisine on her range in a hut which she had built into the ruins of her cottage. Zélie carried[29] food and dishes in baskets to and fro from kitchen to dining room, a quarter of a mile apart. The one luxury of our existence was hot water, prepared by Marcel in a huge cauldron, and brought in covered metal pitchers to our doors.

Only once did Marcel fail us, and that was because the rightful owner of the cauldron left the basse-cour for her newly erected baraque. She requested our kind permission to transport thither her property. “There is another cauldron at Buverchy, which I think you could rent in place of mine,” she suggested. “It belonged to my cousin, Mme. Bouvet, and is now in Mme. Josse’s yard. No one is using it.” Marcel was dispatched to make inquiries, and later, with horse and wagon, to fetch the cauldron home. But meantime there had dawned a morning when we were not wakened by the clump-clump of Marcel’s sabots, and the setting down of the water jug with a thud upon the frozen ground.

For wood, we depended largely on the[30] chivalry of nearby encampments of troops, French, English, Canadian or American, to whom our need became apparent. For food, we were supplied by the Army with our quota of bread and a soldier, M. Jean, to fetch it. Vegetables and some fruit we obtained from our villages, of which we had sixteen in our charge. Often these were presents, thrust upon us through gratitude; nor could we pay for them. Meat was plentiful in all the towns of the Zone, where the Army was charged with supplying the civilian population with food. Anyone, going on any errand, marketed; and the dispensary jitney, which might have started in the morning with doctors, nurses, kits, and relief supplies, often returned at night overflowing with cabbages, potatoes, pounds of roast, bags of coal, and bidons of oil.

Our relief supplies came through more regular channels, largely from Paris, where one member of the Unit devoted all her time to buying. These were either shipped to the nearest railroad station, or sent by the French[31] Army, free of charge, in a thundering camion. We never knew when to expect this last, nor what it would contain. Sunday seemed a favourite day for its arrival. On one occasion, there were three pigs, loose and hungry, and no pen to put them in; seventy-five crated chickens followed, with the request that the number be verified, and the crates returned. Such were the colonel’s orders. But, seeing that the Unit carpenter had to construct a chicken yard, this command was modified by a judicious distribution of cigarettes. Mixed cargoes of Red Cross boxes, stoves, bundles of wool from the Bon Marché which had burst en route, and sundries, were even harder to deal with.

We had no store room. The cave of the Château, seeping with tons of débris which in places bent with its weight the steel ceiling, and open along one whole side to the elements,—this contained our dairy, our lumber, our fuel, our vegetables, our groceries, and our relief supplies. It abounded in rats, cats, and[32] bats. But such as it was, it was the centre of our activities. By night often weirdly lighted with candles, by day never empty, laughter rather than complaints floated from its dim interior. Here we held our first store; here the children who had trudged over from Canizy, Hombleux or Esmery-Hallon waited in line for their milk; here were assembled and tied up the thousands of packages for our fêtes de Noël. As winter advanced, we prepared for a day in the cave by encasing our feet in peasants’ socks and sabots, and our hands in worsted mittens. The soldiers in the trenches had nothing on us.

Whether at home or on the road, our days were long and arduous, and seldom what we had planned. Even Sunday became part of the working week, for then we attempted to entertain our official supervisors and co-laborers, and all chance acquaintances. M. le Commandant of the Third Army has dined with us; the ladies of the American Fund for French Wounded, under whom we held our[33] section, have come to call; the Friends walk over from Esmery-Hallon where they are building baraques for the commune; a lonesome Ambulance boy who has tramped ten miles and must retrace his steps before dark, drops in; a squad of Canadian Foresters rides through the gate; reporters, accompanied by a French officer, harry us with questions. But most frequent, and most welcome of all our visitors, are our countrymen, the—th New York Engineers. They came from home, those men, to be the first of our army under fire. But during the early days of the autumn, their talk was not of their work, but of ours. They brought us slat walks, called duck walks, to keep us out of the mud, and wood, and benches, and stoves. They came with mandolins and guitars and violins to give an entertainment to our villagers, and stayed for a buffet dinner and dance. They sent their trucks to take us in turn to a party at their encampment. But all that was before the Cambrai drive. As we, in our baraques,[34] listened night and day to that bombardment, we little knew the heroic part taken in it by our Engineers. Surprised, unarmed, with pick and shovel they stood and fought; and later, hastily equipped with rifles, helped save the day for England on the bitterly contested front. But you have doubtless read of them in the papers, for they were the first of our soldiers to die in battle and to be mentioned in the orders of the day.

By rights, Canizy belongs with three other hamlets, to the commune of Hombleux. The mayor of Hombleux is therefore in reality also the mayor of Canizy. But each of the hamlets has an acting mayor besides. And, to complicate this matter of mayors still further, the real mayor of the commune has left his post to reside in his mansion in the Boulevard Haussmann in Paris. Inquiring into the reason of his non-residence, I was told that he was broken in health, and belonged to a political party which, at the moment, was no longer in power. Hence the so-called mayors, with whom rests the welfare of our villages.

Before the war, the present mayor of Hombleux was one of the grands cultivateurs. With Mme. la Baronne, Mme. Desmarchez[36] and M. Gomart, he owned most of the rich acres encircling the town. Hombleux itself contained then about 1200 inhabitants, and was an industrial as well as an agricultural centre, having a distillery and two refineries for sugar-beets. Of the factories, practically nothing now remains, and of the inhabitants, 250 have survived the German deportations. Zélie, the kitchen maid, has told me of these last. “The first deportation,” she said, “was one of five hundred. The officers came to the doors at seven o’clock with the names, and told us to be ready to start at dawn. O Mademoiselle, the night! All the neighbours ran to and fro; all night we washed and sewed and ironed, and in the morning, each with a sack of fresh linen, my father, my sister, M. le Curé,—the flower of our village,—were marched away. And after, what weeping!” Zélie put down her broom to wring her hands, as if still dry-eyed from too much suffering. “The next time,” she continued, “the Boches gave us no warning. They came at midnight, and[37] dragged us from our beds.” “Did you then go?” I inquired. “But yes,” she replied, and her eyes flashed. “They tried to make us work; there were five of us, friends, from our village. But work for the enemies of France? We would not! They put us in prison; they fed us almost nothing, but we would not work. One day they summoned us. ‘Go,’ they said, ‘go where you like, beasts of the Somme!’ Hungry, foot-sore, travelling mostly by night from the frontier, we came home. It was midnight when we reached Hombleux. In my own house, my mother had barred the door. I tapped on the window to wake her. At first, she would not believe that it was I. Even now, she looks at me with a question in her eyes as if asking continually, ‘Zélie, is it thou?’”

Our mayors have no such heroic past! They not only saved their own skins, but reside to this day with their wives and daughters; comely daughters of an age for the German draft. Of one it is more than whispered that[38] he is a spy. Many carrier pigeons he had in his dovecote, and whether there were any connection or not, he knew of the impending German invasion, and left his comfortable house and growing crops, to spend the summer of 1914 in Normandy. Nor did he return till the summer of 1917. Meantime, his little hamlet had held a town meeting of its refugees, and elected a lady as mayor. In fact, M. Renet, on his return, found himself the only man in the village. He found also—a suspicious circumstance in the eyes of his neighbours—his house the only one undestroyed. I have talked with him there, looking out of his casement windows into a walled garden, where the fruit trees are uncut, and the walks are still bordered with close-trimmed box. He assumes an injured air, recounting his unpopularity. It is unfortunate, but since M. the Deputy has again asked him to act as mayor, que voulez-vous? He is compelled.

His superior, the mayor of the entire commune, did not fare so well. On our first visit,[39] we found him inhabiting a loft in his partially ruined barn. But despite his chubby person, this mayor is a man of action. Week after week, Hombleux receives shifting regiments of troops back from the trenches en repos. These are detailed for construction work. Carpenters set up the baraques, which the Government furnishes to homeless families; masons and bricklayers are slowly raising the walls of the village bakery. The mayor has taken his share of the materials and workmen, and is now housed in a two-room lean-to, with a new slate roof, and lace-curtained windows. Here, beside an open fire, he transacts business.

He it is to whom returning refugees come to report and register; through him claims of damage (based on pre-war valuation of property) are filed, which the Government has promised to honor after the war. To him, requests for baraques are made, and sent by him to the Sous-Préfet of the Department, to be forwarded in turn to the Minister of the[40] Interior, with whom such matters rest. The mayor calculates the amount of allocation or pension to which each family in the devastated area is entitled, varying according as they are réfugiés or rapatriés, according to the number of bread-winners imprisoned or serving with the colors, according to the number of children, or, in some cases, to the decorations won by their soldiers, for decorations carry pensions.[5] This entire matter of income is adjusted finally for our district by the Préfet at Péronne. Besides housing and pensioning, the Government[41] has undertaken to supply a certain amount of cereals, coffee, sago and the like. These the mayor distributes. Furniture as well is provided by the Government: bedsteads, mattresses (not forgetting bolsters), stoves, cupboards, chairs, tables and batteries de cuisine. Before our coming to take charge of the district, the mayor signed the furniture requisitions which were understood by the fortunate recipients to represent a part of their “indemnité de guerre.” He also had the even more delicate task of distributing relief supplies left in bulk by the Red Cross or other agencies on their hurried passage through the ruined villages. Naturally, the supply fell short of the demand; and it was with unconcealed pleasure that the Mayor at the instance of the Sous-Préfet turned over these two thankless tasks to us. Yet we found him—or rather his wife and daughter—always ready to advise and coöperate. On demand, they furnished immaculately penned lists of all inhabitants, whether grouped by sex and by age, by[42] family, or by the main division of adults and juveniles. They know the number of families in each hamlet, the number of persons in each family, the name and the age of each. Much more they know, of gossip, and of human nature, and laughed, I fear a trifle derisively, at our manifest difficulties.

All these activities, centring in the Mayor, belong to the civil administration of the Department. The Ministry of Agriculture has its share in reconstruction also, but is more independent of local officials, having an office of its own in the commune. To it belong the ploughing and seeding, the replacing of orchards, and to a certain extent of livestock. But on all these matters, as to whose fields shall be ploughed, or who shall plant two apple trees or own a goat, the verdict of the Mayor is sought. He himself, you may be sure, is dependent on no such circuitous methods. Together with two other grands cultivateurs, he has bought an American tractor, a harrow, and a mowing machine. These can even be[43] hired for the same price as the government-owned tractors, which is forty francs an hectare. Over all reconstruction, considered as a part of the civil administration, preside the Sous-Préfet and the Préfet of the Somme.

On the other hand, food supplies in general, such as bread, are controlled by the army. In fact, every detail of life in the War Zone is their care if they choose to assume it. Troop movements delay shipments; therefore there may be no bread. Cavalry needs fodder; the sergeant at Hombleux goes out to forage with rick and trio of white horses and buys it at a fixed price. Mme. N—— is ill; the army doctor visits her, and if she seems to him a menace to the health of the soldiers, he removes her to a hospital. In view of the military importance attached to the Zone, the confidence of the French Government in giving over a section of it to the care of a group of American women, wholly unacquainted with the task before them, seems truly touching.

—Rien que ça de pain! Vous mangez bien chez vous!

—Ben ... on n’est pas des boches!

[Only that much bread! You eat well at your house!

Well ... we are not Boches!]

In fact, it seemed appalling, as I learned from day to day the problems for which I was myself responsible in Canizy. Not the least of these was its mayor. Unlike his confrère at B——, M. Thuillard had not fled his property until forced to do so with the rest of the villagers immediately prior to the Retreat of 1917. During the occupation, he kept his store as usual. And even though his horses and cattle, his fat rabbits and plump chickens, were requisitioned by the Germans, they say that he was paid for them. To see him, however, housed in a miserable hut, with a dirt floor so uneven that the very chairs looked tipsy; to hear the complaints of his querulous wife, and the references of his daughter to their former comfort, was calculated to enlist one’s sympathy. Mme. Thuillard was ill, and he was lame, and the daughter’s husband was a prisoner, and they had lost heavily, because they had the most to lose. All this they told me over the saucerless cups of black coffee which they offered me “out of a good heart.”

But when I considered the Mayor’s duty[46] to his village, my own heart hardened. Here is the entry I find in my notebook on my first survey of Canizy. “Canizy, dependence of Hombleux, Thuillard, Oscar, in charge. Curé of Voyennes has charge of the children; 4 k. away. No church, no school, no bread, no water fit to drink.” There was something, of course, in the Mayor’s own contention that the village had been forgotten; and one could understand why the Curé came only to burials when one saw him,—so ill he looked. But in M. Thuillard’s barn were two stout horses, and two carts stood before his door. On his own business, he could travel. “Why, then,” I inquired, “has he not fetched the bread supply from Hombleux to which the village is entitled?” “Because he has nothing to gain,” and the good wife I interrogated shrugged her shoulders and laughed. “Look you,” she continued, “M. Thuillard is rich; 26 kilos of money he buried, and it is not in sous.” This rumour, which gave the one-legged Mayor something of the air of a land pirate, I heard[47] on all sides. Even the school teacher of Hombleux repeated it; and her husband, an officer, nodded his head to emphasize his “Oui, c’est vrai.”

Of one of our mayors, however, I would like to record nothing but praise. Widow of a soldier, left with two little girls, and absolutely no other possession in the world, she ruled our home village at the Château with justice and dignity. She never complained. When at last the baraque on the ruins of her farm was completed, all except the fitting of the glass in the windows, she insisted on moving in so that we could make use of the space she vacated in our basse-cour. I met her one bitter evening shortly afterward, as I was returning from Canizy. “Is it not cold in the baraque, Madame?” I asked. “Oh, yes,” she replied, “but what would you? It is so good to be at home!”

As the aeroplanes fly, Canizy is perhaps three miles from the Château, or reckoned in time, half an hour by motor and an hour on foot. But by either route, one turns into the village at the stark Calvary I have already mentioned, with its half obliterated inscription: Ave, O Crux.

At our first visit, despite our novelty, Canizy regarded us with indifference. We seemed to them doubtless one more of those strange manifestations of the war which had stranded them among their ruins. Incurious, apathetic, they passed us with sidelong glances, and went their ways. But this did not last long. The “Dames Américaines” did such extraordinary things! They gathered and bought up rags; they played with the children; they walked[49] fearlessly, even at night, across the fields to tend a sick baby; they slept—so the village children who had seen their encampment reported—on lits-soldats. The village waked to a new interest, and it came about that one expected to be waited for by the gaunt old cross.

Before my arrival, the routeing of our three cars had already been decided. Three times a week the Dispensary was held at Canizy, and once a week, on Monday, our largest truck, turned into a peddler’s cart with shining tinware, sabots, soap, fascinators, stockings and other articles of clothing, made there its first stop. On the seat back of the driver and the storekeeper, or if there were not room for a seat, on top of the hampers, went also the children’s department, consisting of two members. While the mothers, grandmothers and elder sisters gathered at the honk of the horn about the truck, the children, equally eager, followed the teachers to an open field for games. Or, did it rain, I have seen them of all ages from[50] fourteen years to fourteen months, huddled in a shed, listening open-mouthed to the same tales our children love, which begin, in French as in English, with “Once upon a time.”

But when, after a three-days’ inspection of our outlying domain, I asked our Director for the village of Canizy, I was given charge of all branches of our work there. This meant not interference but close coöperation with the other members of the Unit already occupied with its problems. Of all our villages, Canizy was the most beloved, not, perhaps, because its need was greatest, but because its isolation was most complete. No one could do enough for it. Were a sewing-machine to be repaired, the head of our automobile department, a mechanical genius, spent hours making it “marcher.” The doctors, with their own hands, took time to scrub the children’s heads. They came to me with every need that they found on their rounds, with the neighbourhood gossip, and with kindly advice. The teachers gave me the names of children requiring shoes; and, as the[51] work developed, asked in turn for recommendations in regard to opening a children’s library. To the farm department, I made requests that we buy largely of fodder and vegetables, until we had literally hundreds of kilos of pumpkins, turnips and carrots bedded for us in the cellars, on call. To this department went also requisitions that Mme. Cordier be supplied with a pig, or M. Noulin with five hens, or Mme. Gense with a goat. Or, were there shipments of furniture to be delivered, one called again on the automobile department, which even through the drifts and cold of winter, kept at least one of its engines thawed and running every day.

—C’est un boche ce blessé là?

—Non, M’sieu le Major, c’est le cheval du capitaine.

[Is that wounded man a Boche?

No, Major, he’s the captain’s horse.]

It will be seen that our scheme of material relief followed closely that laid down by the Government. Our method was simple: where the Government supplies were on hand, or adequate, we used them; whatever was lacking, even up to kitchen ranges costing three hundred francs, we attempted to supply. In this we had not only our own resources to draw on,[53] but to a limited extent, those of the American Fund for French Wounded, and to a much larger extent, those of the Red Cross. In a huge truck came the goods from the Red Cross, driven by a would-be aviator who, when asked his name, replied bashfully, “Call me Dave.” “Dave” was frequently accompanied by another youth of like ambition, named Bill. And I will say that they handled their truck as if it were already a flying-machine. The first consignment of hundreds of sheets and blankets, the truck and the driver, all were overturned in our moat. It took a day to get them out. The next mishap was a head-on collision with our front gate. But the last, which I learned of just before I left, will best illustrate their imaginative turn of mind. Bill, the intrepid, having attempted to traverse a ploughed field, left his machine there mired to the body, and spent the night with us. He seemed a trifle apprehensive as to how his “boss” would take this exploit. Willing workers, however, were Dave and[54] Bill. Unannounced, they came exploding up the driveway under orders to work for us all day. And many a time have we risked our necks with them, perched on the high front seat, careering along at what seemed like sixty miles an hour.

But for my part, my usual mode of travel was on foot, and my orbit bounded by the Château, Hombleux and Canizy. In any case, even though I went over by motor, I was dropped at my village and walked back across the fields. As I grew better acquainted with the villagers, I came and went at will, spending almost all the daylight hours—few enough in winter—with them. Every one has heard of the mud in the trenches. The clayey soil of our district, admirably adapted to the making of bricks, lends itself equally well to the making of mud. Continually churned by camions and marching troops, it becomes on the highways of the consistency of a purée, through which, high-booted and short-skirted, one wades. It is therefore a relief to turn off[55] by the footpath beyond Hombleux, though it plunges for the first quarter of a mile through a bog. Of a sunny day, birds sing in the hollow, wee pinsons perched on ragged hedges answering one another with fairy flutes. Farther on, yellow-breasted finches dart over patches of mustard as yellow, and sing as they fly. Raucous crows, whose gray-barred wings make them far more decorative than ours, and the even more strikingly marked magpies, darken in great flocks the newly ploughed and seeded wheatfields which in increasing areas border the path. A sudden movement sends them whirring like a black and white cloud against the sky. Often above them courses a flier of another sort, a scout aeroplane probably, holding its way from the aviation fields in our rear, to the front. It rasps the heavens like a taut bow; by listening to the beat of its engines one can determine whether it be French or Boche. For Boche planes come over us frequently, on bombing raids; and sometimes one does not have to look or listen[56] long to know that an air battle is taking place overhead. The sharp reports; the white puffs of our guns, the black plumes of the enemy’s; the glint of the sunlight on careening sails high up in the blue,—it all passes like a panorama, of which we do not know the end. Other sounds also are familiar to us on our plain, when from the Chemin des Dames, or St. Quentin, or Cambrai, the great guns boom. Like surges they shake and reverberate; and when, as often happens, the sea-fog rolls in from the Channel, one can well fancy them the breakers of a mighty storm. So they are, out there, on our front, where the living dyke of the poilus holds back the German flood.

The highway and the railway, these are the two most coveted goals of the German bombs. For over them go up the trains of ammunition and of soldiers and supplies. Both we cross on the way to Canizy. The railroad, running between well defined hedges, would seem almost as conspicuous an object as the tree-sentinelled road. But, so far, both have escaped[57] harm. Trains whistle and puff as usual up and down from Amiens to Ham. Often I halt at the crossing, to wave to soldiers, who fill the cars; sometimes I pass through companies of red-turbaned, brown Moroccans, who are brought here by the Government to rebuild bridges and keep the roadbed in repair. Over the track the footpath carries one, on over brown stubble, to the Calvary and Canizy.

As I have said, at the Cross one is awaited. Sometimes it is only one little figure in black apron and blue soldier’s cap that stands beside it to give the signal; sometimes from the wall on the other side of the road, a half dozen girls start up, like a covey of quail. The boys usually ran away, but the girls advanced to surround one, and dance hand in hand down the street. But always before the Calvary there was a pause. Brown hands, none too clean, were raised to forehead and breast with the quick sign of the cross. One caught a whispered invocation. “But you do not do it,” five-year-old Flore protested to me one[58] day, with troubled eyes. “Why do you not salute the Calvary?” “Teach me,” I replied; and in chorus I learned the words which on the lips of the war-orphaned children are infinitely pathetic: “Glory to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Ghost.”

—Il est déjà grand!...

—Ben ... il a l’âge de la guerre.

[He is big already!

Well ... he is as old as the war.]

It is not alone at Canizy that one finds the Cross, though by its aloofness above the plain this one became impressive. By every roadside stands a Calvary, sometimes embowered in trees, but more often stark and naked, with the wantonly felled trunks about its base bearing mute Witness to a desecration which respected the form, but not the spirit, of the Christ. At Hombleux, three such crucifixes marked the intersections of the village lanes, flanked by stenciled guide-posts: A Nesle, A Athies, or A Roye. They cluster in the cemeteries, above well-remembered graves; Where even the dead no longer rest inviolate, since the Germans, to their unspeakable shame, have blasted open many a tomb. Day by day, the[60] obsession grows on one that these uplifted symbols of suffering, stripped and mocked and defiled by the invader, typify the crucifixion of Picardy.

Every village, everywhere, has its stronger characters, to whom the community looks up, perhaps unconsciously. Canizy, having been deprived of its normal leaders in the Curé, a prisoner, and the teacher, transferred to the school at Hombleux, looked up in this way to Mme. Lefèvre and Mme. Gabrielle. The former was the especial friend of our medical department. In fact, she rented one of her two rooms for our use as a dispensary, and her flagged kitchen was always open to her neighbours and to us. Here I measured out milk to half the village, or distributed the loaves of bread which we ourselves purveyed from the crabbed Garde Champêtre at Hombleux. Or, had I neither the time nor the patience, Mme. Lefèvre herself[62] made the distribution, and gave me a list of the recipients, and always the correct amount of neatly stacked coppers in change. A shrewd face had Mme. Lefèvre, wrinkled by humour as well as by sorrow. She had been taken away by the Boches in their retreat, but later, for some reason unknown, was allowed to return. Her three daughters, however, and her husband, all were in the hands of the enemy. She lived alone, therefore, and busied herself in her late-planted garden, and in her neighbours’ affairs.

—C’est pas moi!... c’est lui.

[I didn’t do it ... he did!]

Most of them, it seemed, were related to her in one way or another, all the Genses being of her kin. Of these there were Mme. Gense-Tabary, already mentioned, and her swarming family of eight, bright and pretty as pictures, and dirty as little pigs. She, lodged near the bank of the canal, really had no excuse for this chronic condition, and was encouraged to scrub by object lessons, clean clothing, and gifts even of long bars of savon marseilles. I remember her yet, two or three children tagging[63] at her skirts, knocking at the door of my baraque of a Sunday morning, to tell me that she must have more soap. All the way from Canizy she had walked to get it; and she did not go back without. Mme. Gense-Tabary’s eldest daughter, known as Germaine Tabary, was the sorrow of the village, even more than its daughters who had gone into captivity; for she had become an earlier victim of the invaders, and with her unborn baby was left behind. Mme. Marie Gense, another unfortunate, was a niece by marriage of Mme. Lefèvre’s. Her husband was a soldier. She had lived in a little cottage whose blue and white tiled floor I often had occasion to admire, next the church. But being left with two growing boys, and no resources, what was she to do? What she did was to add to her family a Paul, and one bitter winter night which our doctors and nurses well remember, a Paulette. “What would you?” she expostulated. “I had no bread for the children; in this way they were fed.” That two more months were[65] added, and that her lean-to of ten feet by twelve could not accommodate them, were facts which did not seem to concern her. And of all good children, her two boys, Désiré and Robert, were certainly the best. But Aunt Lefèvre looked upon her niece’s conduct as a scandal. She was forbidden the kitchen, and it was even known that the quarrel had come to the point of knives. With the children, that was different. “Yes,” said Mme. Lefèvre on the arrival of the new baby, “Désiré may sleep in the Dispensary if you so wish. It is your room; you pay for it.” That Désiré did, though I had a bed put up for him, I misdoubt. But Robert, happy-go-lucky Robert, with his head cocked on one side and a smile rippling his brown eyes, even Aunt Lefèvre could not help loving him. There was no question of his sleeping out, however, he being nurse to the babies and to his mother as well. Another wayward connection of Mme. Lefèvre’s was a sister of Mme. Marie Gense’s, known as Mme. Payelle. She had three children[66] as cunning as you could wish to see, clean—as were Marie’s—and sunny-tempered. Their parentage also was a mystery. But this blot did not rest by rights on the village escutcheon. Mme. Payelle had been installed there by one of her admirers, a soldier en permission; she really did not belong to Canizy.

To keep her social position in the midst of these misfortunes was a tribute to Mme. Lefèvre’s worth. She was always doing kindnesses, and speaking to us on her neighbours’ behalf. Beneath her shed stood one of the four chaudières, or washing cauldrons, which survived the general destruction. These, varying in capacity from 50 to 250 litres, are an indispensable utensil of housekeeping in Picardy. In them, week by week, the soiled clothes are boiled. Not even the lack of a pump—and there was only one left in the village—was so much deplored as the loss of the cauldrons. In view of these two handicaps and the dearth of soap, the squalor of the village on our arrival seems excusable. Mme.[67] Lefèvre, at least, did her share toward remedying it. Without charge, her chaudière was in constant use, and her shed became a neighbourhood rendezvous.

It will be seen that all the Genses were by no means a bad lot, Mme. Lefèvre being one herself. Of an older generation, and I know not of what degree of kinship to her, is Mme. Hélène Gense, grandmother to Mme. Gabrielle, that energetic, substantial young Widow, not Mme. Thuillard nor yet Veuve Thuillard, but Mme. Gabrielle to all Canizy. In pre-war times, she owned, through her parents and not by marriage, the most central homestead in the village. There remain now only the arched gate into the courtyard, the brick rabbit hutches, a heap of débris, and a tottering wall. She and ten-year-old Adrien lodge, therefore, in the first house on the left as you come past the Calvary, with Grand’mère Gense. This ell, flanked though it is by the ruin of the main building, is the most cheerful spot in the village. The narrow yard before the door is[68] swept; a row of geraniums blossoms beneath the windows. Above all, there are windows, two of them, and curtains at each. Outside the door, if you are fortunate in the hour of your call, will stand two pairs of worn sabots. Or perhaps the door may be open, framing Grand’mère, bent almost at right angles, Mme. Gabrielle, and Bobbinot. Bobbinot is a dog, iron-grey, smooth-coated, with a white band on his breast and a white vest. He has no pedigree, his mistress assures me, but his brown eyes and his square, intelligent head bear out her statement that he is “très loyal.” All three welcome me; a chair is proffered near the fire. Grand’mère sinks carefully into her low seat, Mme. Gabrielle sets on a saucepan of coffee, and we sit down to chat.

It is a pleasure to look about as we talk. On the mantel, to give a note of colour, are laid a row of tiny yellow pumpkins; the floor is red, and through the window peer red geraniums. In a cupboard beyond the stove is a modest array of pans and dishes. Two panes[69] of glass, like portholes, pierce the wall to the rear. Beneath stands a sideboard, and a little to one side, a round table. Not until the coffee was heated did I notice that cups were set for four.

“But have you another guest?” I inquired, as Mme. Gabrielle poured first some syrup from a bottle, and then the steaming drink. “But no, only Adrien. Adrien, come!” She raised her voice. Then for the first time I saw the boy, head propped on elbows, poring over a book. The mother regarded him indulgently. “It is a pity for the children that we have no school. Adrien is apt; when the Germans were here, he understood everything, everything. And when the Scotch came, he learned, too. I myself try to learn English.” She brought forth from the sideboard an English-French phrase book. “This I found in a house after the English soldiers went away. It would be easy, but there is the pronunciation.” “I will teach you,” I said, and we took up the words one by one, Grand’mère laughing[70] the while, pleasant laughter, like a cracked, old bell. But the boy kept on reading and hummed a tune. “The children,” broke in the mother, “they sing; it is well.” But presently the boy shuts his book with a sigh and draws a chair to the table. “Did you like it, the story?” I inquire. “Yes, it tells of America.” On the table, clear now save for Adrien’s belated cup, is revealed an oilcloth map in lieu of a linen cover. “Where, then, is America?” His finger traces the colored squares. “Here is France, here England, here Italy, here Russia,—but America, it is so far one cannot see it.” “But yes,” rejoins his mother, “so far that never in my life did I expect to see an American. Once in my childhood I remember looking at a picture of M. Pierpont’s bank in New York—a great bank. But now I have seen Germans, Russians, English, Moroccans,—and you. The war teaches many things.”

“You have seen Russians?”

“Very many; the Germans worked our fields with Russian prisoners. A strange people![71] You and I converse; we come from different countries, but we have ideas in common. The Russians were like dumb beasts; they had no esprit de corps.”

“It is the fault of their government,” I venture.

“Yes,” she replied, “France and America are republics. It is not that our government is perfect. There are many beautiful things in France, but there is much injustice also, much.”

I knew of what Mme. Gabrielle was thinking, then; of the wheatlands of Canizy, where not one furrow had been turned for the next year’s harvest, while the grands cultivateurs and the petty politicians looked out for themselves; and of the school building, long promised and still delayed.

But Mme. Gabrielle looked beyond the confines of her small village and its grievances. Love for la belle plaine and la belle France, unreasoning, passionate, pulsed in her. Hatred of the Germans was its corollary.[72] “Mademoiselle, during the occupation, we were prisoners,” she said. “We had to have passes to go one fourth of a kilometre from our village. My mother was sick at Voyennes,—and I could not go to see her.” It came out that Bobbinot had been her constant companion. “But I should think,” I said, “that the Germans would have taken him away.” “They dared not; he would have bitten them!” was the spirited response.

At Mme. Gabrielle’s table, with the map upon it, I was destined to sit often, sometimes for luncheon and sometimes for dinner, while we took counsel over village affairs. For Mme. Gabrielle, together with Mme. Lefèvre, and the former school teacher, became an informal advisory committee to me. Through punctiliously served courses of soup, stew, salad, wine, cheese and coffee, Mme. Gabrielle offered her information, or, when asked, her opinion. It was she who reassured me on the point of selling rather than of giving the smaller articles we distributed. “I understand[73] completely; it is better for us. The American Red Cross did the same when the Germans were here. They sold the food, but very cheap. Without their help, we should have starved. We are grateful to America, which saved our lives.” It was she who advised in regard to a baby whom its half-witted mother had placed in a crèche: “For the mother,” she said, “it would doubtless be better that the child returned. But for the child—and I am a mother myself who speak—let it remain.” On the good sense and the good heart of Mme. Gabrielle one came to rely. Even as far as Hombleux she was known and respected. “O yes,” the women there told me, “Mme. Gabrielle, we know her. She is une femme très forte.”

Directly opposite Mme. Gabrielle lives Mme. Odille Delorme. One lifts the latch of a heavy wooden gate to enter her courtyard. On left and right are the remains of barn and stable, from the rafters of which depend bundles of haricots hung to dry. A half dozen chickens scurry from under foot, and at the commotion Mme. Delorme steps out. “I have come to make a little visit,” I begin. “Enter then, and see misery,” is her reply. It is a startling reply from this woman, strong, intelligent, and direct. The room of which she throws open the door is tiny; the floor is of earth; there is no window, only a hole covered with oiled linen, which lets in a ray of light but never any sun. A stove, a table, two stools, a shelf or two and a few dishes hung on[75] nails are her furnishings. In her arms she holds her sixteen-months’ baby; a little girl of three comes running in from an adjoining alcove, and is followed presently by her seven-year-old sister, Charmette. The three children look like plants blanched in a cellar. As gently as possible, I proceed with necessary questions: for in social parlance, I am making a preliminary survey of the family needs. “Your husband?” I inquire. She turns to her little girl, “Marie, tell the lady, then, where is Papa.” And Marie, smiling up into her mother’s face, repeats her lesson proudly, “Avec—les—Boches.” “Avec les Boches,” reiterates the mother, and catches the child to her in a passionate embrace. There is a pause before I can continue. “Have you beds and covers?” “See for yourself, Mademoiselle,” and she leads the way through her ménage; three passage-ways opening the one into the other, like the compartments of a train. The first contains a child’s bed of white enamel, and beneath an aperture like that in the outer room,[76] a crib. Both are canopied and ruffled in spotless white. “Yes,” Mme. Delorme says in answer to my unspoken surprise, “I bought these beds. The ruffles are made of sheets, one can but do one’s best. As you see, it is only a chicken-house after all.” Beyond, quite without light, is a space occupied by her own bed, a springless frame of planks. From nails in the walls clothes of all sizes and descriptions hang. In fact, one wonders at the amount of clothing saved by the panic-stricken peasants in their flight. They not only took away with them heavy sacks made out of sheets, but buried what they had time to. Of course, some of their hiding places were rifled; but most of the villagers have a real embarrassment of riches in their old clothes. Their first request is usually for a wardrobe, so that the mice will not nest in them.

But Mme. Delorme asked for nothing. She rested her case in the simple statement, “Voilà la misère.” At a later date, when I returned with a camera, she repeated, “What would[77] you? Take a picture of our misery?” “Yes, Madame, to carry with me to America, that they may see it there and fight the harder for knowing what the Boches have done.” “Eh, bien!” she replied, and the picture was taken. Framed in the deep gateway, from which the clusters of dried beans depend like a stage curtain, her baby in her arms, her two little girls clinging beside her, and neighbourly Adrien, broom in hand, sweeping the light snow from the path,—I see her yet amid the ruins, brave, broken-hearted Odille Delorme.

Before the war, Mme. Delorme had not the social position of her neighbour, Mme. Gabrielle. She lived on her smaller property, and attended to her truck garden and her poultry yard and her children, while her husband served the Government as bargeman on the canal. Yet the two were close friends. Mme. Gabrielle having bought a cow, shared the milk with Mme. Delorme. Mme. Gabrielle told me that Mme. Delorme needed blankets. “She would never admit it,” she explained.[78] “We are not used to accepting gifts, you see.” Or were it necessary for Mme. Delorme to go to Ham perhaps for her allocation, Mme. Gabrielle transferred the baby and Marie to her kitchen until their mother’s return.

From this extreme end of the village, by the Calvary, the street continues across the railroad track. Here, on almost any day, children may be seen digging miniature coal mines. They do it not in play, but in earnest. The ties which the Germans left have long since been used as fuel, but in the roadbed the villager still finds a scant supply of coal. Beyond the track, the first habitable building is a barn. Its interior consists of one room, earthen-floored where two makeshift beds allow it to be seen. In one corner stands a small stove. No light enters except from the open door. Here lodge the old mother, the married daughter, two children, a girl of seventeen and a boy of eleven, and their orphaned cousin, four-year-old Noël. Lydie, capable,[79] red-cheeked, crisp-haired, welcomes us and pulls forward a bench. “Be seated, please.” Her voice has a ring of youth, her mouth a ready smile. One wonders how it can be, yet it is so. The grandmother complains querulously from the untidy bed where she is lying to keep warm. Lydie tells us with perfect equanimity that she herself has no bed. Where does she sleep? On the bench. Beds would be welcome, yes, and sheets and blankets. The grandmother adds a request for warm slippers; her feet are so often cold. A pane of glass for the door I set down also in the list in my notebook, and as assets—the furniture being negligible—300 kilos of cabbages, 100 kilos of potatoes, leeks and chicory in smaller quantities.

—Avant ... quand c’était pas la guerre ... on en avait deux pour un sou, des pralinés! ...

[Once, before the war, the pralines were two for a sou.]

My next call I have been urged to make by our doctors. Here in a ramshackle ell, facing a court deep in mire, live the poorest family in the village, comprising Mme. Laure Tabary, her six children, and a black and bearded goat. The goat inhabits a rabbit hutch from[81] which her tether allows her the freedom of the narrow brick path. From the sidelong gleam in her eyes, one always expects an attack in the flank or rear. But Madame, her mistress, regards her as a pet; perhaps because she cannot regard her in any other favourable light,—since la petite gives no milk. Once past the goat, the door is quickly gained. Two rooms has Mme. Tabary, and a loft and a shed. She needs them! From forlorn Olga to forlorn Andréa, the girls of the family descend in graduated wrappings of rags. “O, Mme. Tabary,” exclaimed the school teacher, with whom I discussed the all too evident need of soap, and of clothing, “she is a very worthy woman, but she is always poor.” Always poor, always ailing, yet always humorous, were the Laure Tabarys. Did the unfortunate woman try to boil her washing, the stove must needs break, and the cauldron full of scalding water descend upon Madeleine. No sooner were her wounds dressed than Andréa developed a fever. It would be interesting to know how[82] many litres of gasoline were consumed by us in the carrying of Mme. Tabary’s children to and from hospitals located ten and twenty miles away. One would have thought the distracted mother might welcome these deportations. But, naturally enough, she distrusted them, and having faithfully promised to give up the baby to our care on a certain day, left instead for Ham. Of how she was won over,—that is a tale which belongs to the annals of the medical department rather than to me. But I have heard rumours of hair ribbons and dolls and candy and fairy stories and I know not what of similar remedies which Hippocrates and Galen never mentioned. Judge, then, whether our doctors were bugbears or no among the children of our villages!

But the ell housed another family besides the Tabarys. Across the hall lodged the Moroys; M. Edouard, an old man of eighty-four, his niece and nephew and his granddaughter, Mlle. Suzanne. All lived in the one room. It was a room with only three corners[83] as well, because in the fourth the floor rose in an arch which indicated the cellar-way. In this room were three beds, a table, a stove, three chairs and a broken sewing machine. Yet I never saw the room in disorder, nor heard any requests from the family beyond that of a little sugar for Grandpère, and, if possible, another bed, so that Charles might have a place to sleep. Meantime, Charles slept upon the floor. In this room were two windows. The one to the south interested me by chance, because the panes looked so clear. I stepped over and put out my hand. It went straight through the framework; there was no glass. “But you must be cold!” I exclaimed, knowing well the common fear of courants d’air. Besides, it was late October, and the nights were already frosty. “Yes, a little,” Mlle. Suzanne admitted in a matter of fact way. “Yes,” agreed her aunt, in a more positive tone. “And besides, Mademoiselle, our stove is too small, as you see. In fact, it is not ours, but belongs to Mme. Tabary. But she has so large[84] a family, we made an exchange. Perhaps when you distribute stoves——” I promise to remember, wondering the while if we in like circumstances would share our last crusts with like generosity. For the window, so scarce was glass, oiled linen was the best that could be done, a pity considering that it excluded the sun with the cold.

Mlle. Suzanne, with the exception of Germaine Tabary and Lydie Cerf, is the only young woman in Canizy. She had been taken captive by the Germans, but was allowed to return. Her family, however, met an unknown fate; father and brother, they were avec les Boches. A curious circumstance in this connection was that Suzanne, having been an independent worker, received no pension for her loss. She, too, seemed a Good Samaritan to her neighbours—lame Mme. Juliette depends on Suzanne to bring her her pitcher of milk; Mme. Musqua, sick and irresponsible, has only to send over her children to Mlle. Suzanne to be cared for,—what matter two[85] more or less in the crowded room? I added my quota to her labours by asking her to take charge of washing rags, and started her in with those of her next-door neighbour, Mme. Tabary. For the purpose, I have given her a cylindrical boiler, standing three feet high. This, when not in use, is placed over by the cellar-way. On washing days, it is set on an open fire in the court, where Grandpère feeds it with laboriously chopped twigs. Meantime, back of the house, patches of colour and of flapping white begin to adorn the wire fence. Suzanne also sews, by hand and, now that its frame is mended by I know not how many screws in the warped wood, by machine. We give out the sewing, and she earns by it perhaps three francs a week.

Beyond the Moroys, lives Mme. Thuillard, Charles, as the neighbours call her to distinguish her from the Thuillards, O. I have seldom found this energetic lady at home, but I often see her, and sometimes hear her, as she passes with firm step down the street to work[86] in her garden. When not playing, her ten-year-old granddaughter Orélie follows in her wake. This leaves in the unlighted recesses of the barn, her husband, M. Charles. He seems an apologetic and conciliatory soul, with whom I discuss domestic needs, such as a window, a lamp, and sheets for the beds. He will tell his wife what I say and report to-morrow when he comes for the milk. It is in his entrance-way, so to speak, that I first noticed a pile of willow-withed market baskets. “O, yes,” he said, “I had hundreds of such, but the Boches took them.” “Are they then made hereabouts?” “Before the war; but now no one is left who understands the trade.” The next day I am likely to get a report, and a sharp one, from Madame, his wife. “Sheets,” she queries, “what sort of sheets? Are they linen sheets? Blankets. Are they wool? Are they white? Look you, before the war, I had five dozen linen sheets and plenty of blankets and down quilts of the finest quality. Keep your gifts about which you make so much talk![87] I will have none of them, none of them at all!”

I have sometimes wondered if Madame were related to the contrary-minded but equally independent wife of the garde champêtre who distributes—or not—at her pleasure, the communal supply of bread. “I hear,” she began one day, as I waited for change for a hundred franc note—change which came in gold, by the way, as well as in silver—“I hear that you are to make a distribution of gifts. Do not forget me! I will receive anything, but you understand, not for payment; only as a present. Behold,” this with a playful slap on the shoulder, “any one will tell you that I have a tongue. O, là, là, là!”