![[Image of the book's cover unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: The castles and abbeys of England; Vol. 2 of 2

Author: William Beattie

Illustrator: W. H. Bartlett

Joseph Clayton Bentley

Samuel Bradshaw

Edward Paxman Brandard

Charles Cousen

S. T. Davis

W. Deebles

W. Whimper

Arthur Willmore

Release date: November 21, 2020 [eBook #63832]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

available at The Internet Archive)

|

List of Illustrations (etext transcriber's note) |

FROM THE NATIONAL RECORDS, EARLY CHRONICLES, AND OTHER

STANDARD AUTHORS.

BY WILLIAM BEATTIE, M.D.,

GRAD. OF EDIN.; MEMB. OF THE ROYAL COLL. OF PHYS., LONDON; OF THE HIST. INSTIT. OF FRANCE; AUTHOR OF

“SWITZERLAND,” “SCOTLAND,” “THE WALDENSES,” “RESIDENCE IN GERMANY,” ETC. ETC.

————————————

ILLUSTRATED BY UPWARDS OF TWO HUNDRED ENGRAVINGS.

———————————

SECOND SERIES.

GEORGE VIRTUE:

LONDON AND NEW YORK.

{iv}

STERIOTYPED AND PRINTED

WILLIAM MACKENZIE, 48 LONDON STREET.

GLASGOW.

{v}

| Chepstow Castle. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEEL ENGRAVINGS. | ARTISTS. | ENGRAVERS. | PAGE. | |

| Chepstow Castle, from the Iron Bridge across the Wye.—This View, looking towards the West, shows part of the Town, the Castle Gate, the Citadel, the Keep, or Marten’s Tower, the Western Gate, the House and Groves Persefield, with the precipitous banks of the River. | W. H. Bartlett. | C. Cousen. | 3 | |

| Chepstow Castle and Bridge, taken from the right bank of the Wye, near the West Gate of the Castle.—This View, looking Eastward, shows the principal features of the Castle on the right; the New Bridge, the Harbour, with the Scenery on the left bank of the Wye. | W. H. Bartlett. | E. Brandard. | 13 | |

| Chepstow Castle and Town, from the Wyndcliff, showing the windings of the Wye, its junction with the Severn, and the opposite coasts. | W. H. Bartlett. | E. Brandard. | 26, 27 | |

| WOODCUTS. | ||||

| Vignette, Castles and Abbeys. | W. Beattie. | Mason. | 1 | |

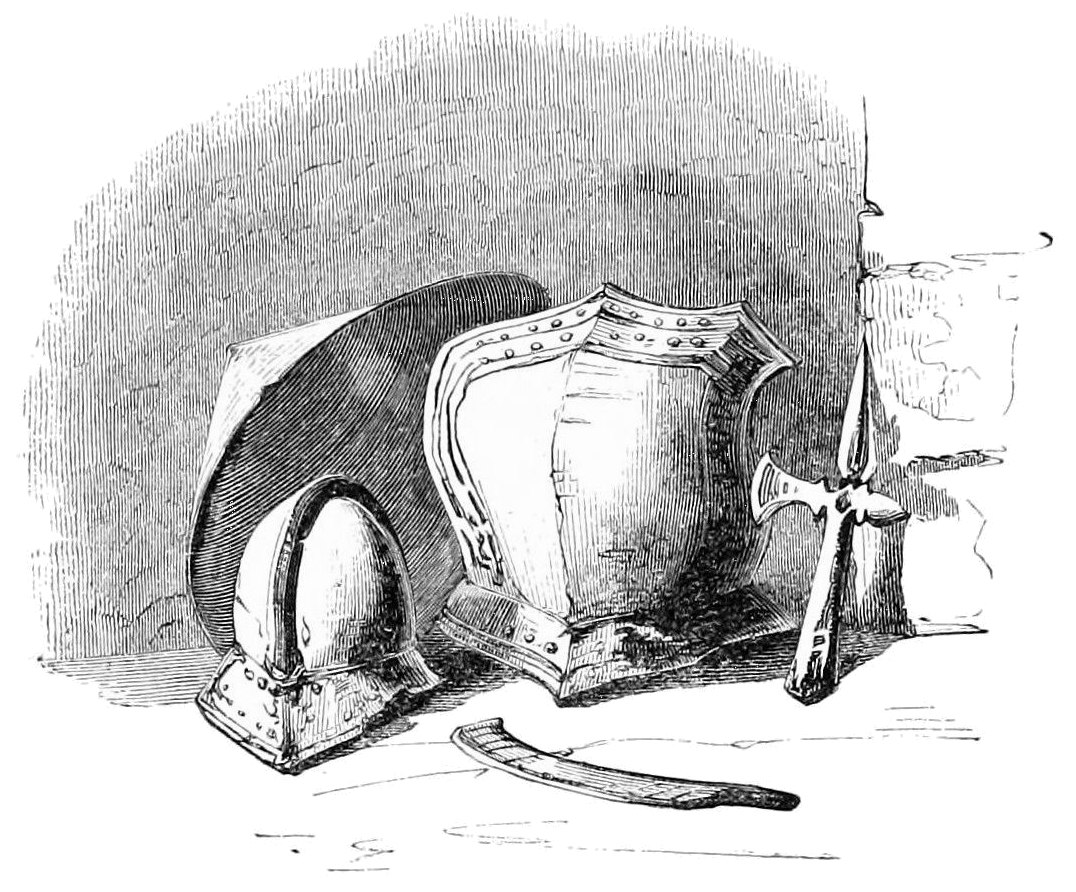

| Shield, Sword, and Helmet. | Sargent. | Evans. | 12 | |

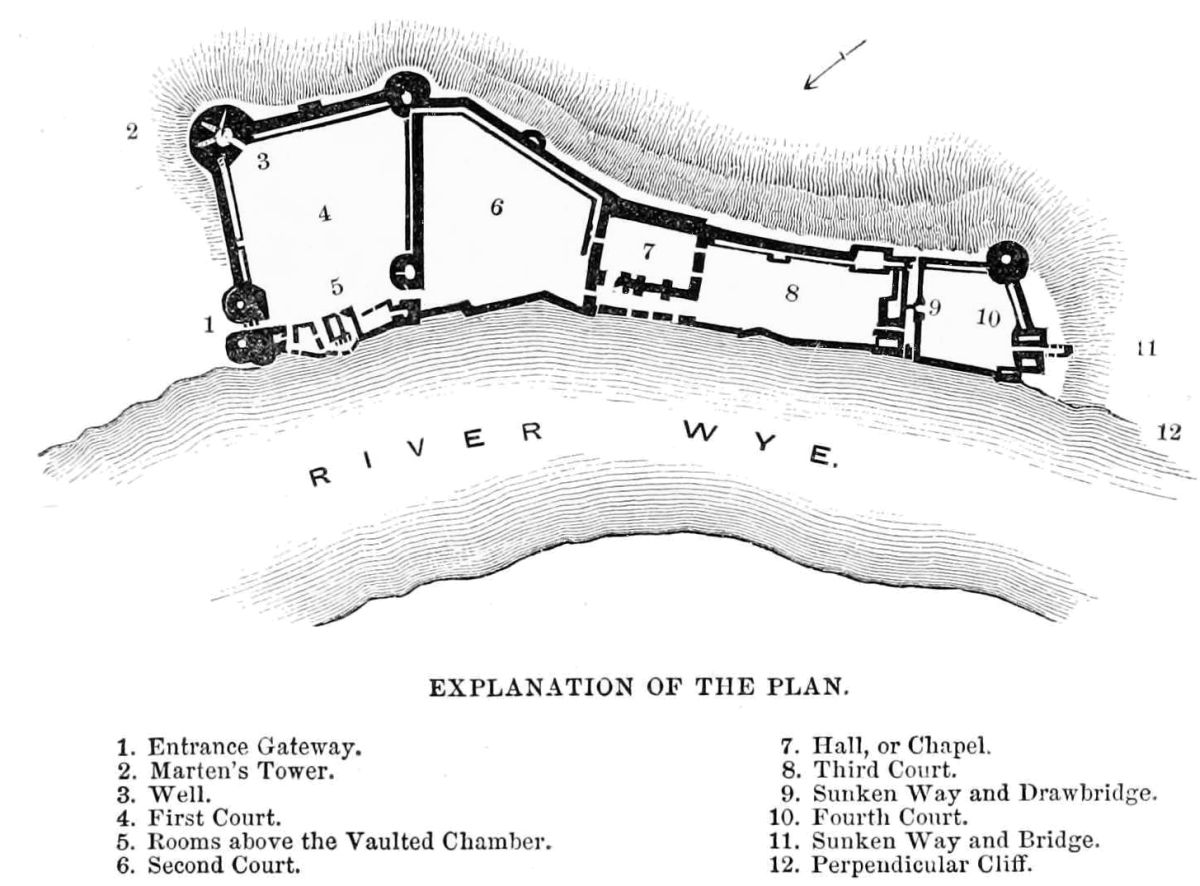

| Plan of Chepstow Castle. | W. H. Bartlett. | W. Whimper. | 13 | |

| Marten’s Tower, the ancient Keep of Chepstow Castle. | W. H. Bartlett. | W. Whimper. | 15 | |

| Ancient Oratory adjoining the Keep. | W. H. Bartlett. | W. Whimper. | 23 | |

| The Arched Chamber in the Castle Rock. | W. H. Bartlett. | W. Whimper. | 24 | |

| Passage leading to the Arched Chamber. | W. H. Bartlett. | W. Whimper. | 25 | |

| Military Trophies; Age of Chivalry. | 30 | |||

| Tinterne Abbey on the Wye. | ||||

| STEEL ENGRAVINGS. | ARTISTS. | ENGRAVERS. | PAGE. | |

| The Western Window of Tinterne Abbey.—This View is taken from a point near the Great Altar, showing in the foreground the clustered Pillars and Arches which formerly supported the Central Tower; the Door on the right leading to the Cloisters; Sepulchral Slabs, the Effigy of a Knight, with the much-admired Window to the West, and other features. | W. H. Bartlett. | A. Willmore. | 39 | |

| The Refectory of the Abbey. | W. H. Bartlett. | C. Cousen. | 52 | |

| The Devil’s Pulpit.—This View is taken from a romantic rock so called, on the left bank of the Wye, commanding a view of the Abbey westward; the Abbot’s Meadows stretching along the right bank of the Wye; the Church of Chapel-hill; the Village of Tinterne Parva lining the rim of the River Crescent. | W. H. Bartlett. | J. C. Bentley. | 62 | |

| The Ferry at Tinterne.—This Plate, taken from the left bank of the Wye, presents a North View of the Abbey, with the Western Front, the Nave, North Transept, part of the great Eastern Window, Remains of the Cloisters, the Abbey Gate communicating with the Ferry, with other Conventual Buildings now in ruins, or transformed into Cottages. The River at this point is of sufficient depth to float a moderately-sized trading craft. | W. H. Bartlett. | J. C. Bentley. | 66 | |

| Tinterne Abbey, West Front, taken from the Road leading to the “Beaufort Arms” and the Ferry, shows the much-admired West Window, in correct and beautiful detail; the Door opening into the Nave, the Southern Aisle, Buttress, Pinnacle, Clerestory Windows, &c., with their masses of luxuriant and interlacing Ivy. | W. H. Bartlett. | A. Willmore. | 103 | |

| Doorway leading into the Cloisters. | W. H. Bartlett. | E. J. Roberts. | 105 | |

| Doorway leading into the Sacristy. | W. H. Bartlett. | E. J. Roberts. | 113 | |

| WOODCUTS. | ||||

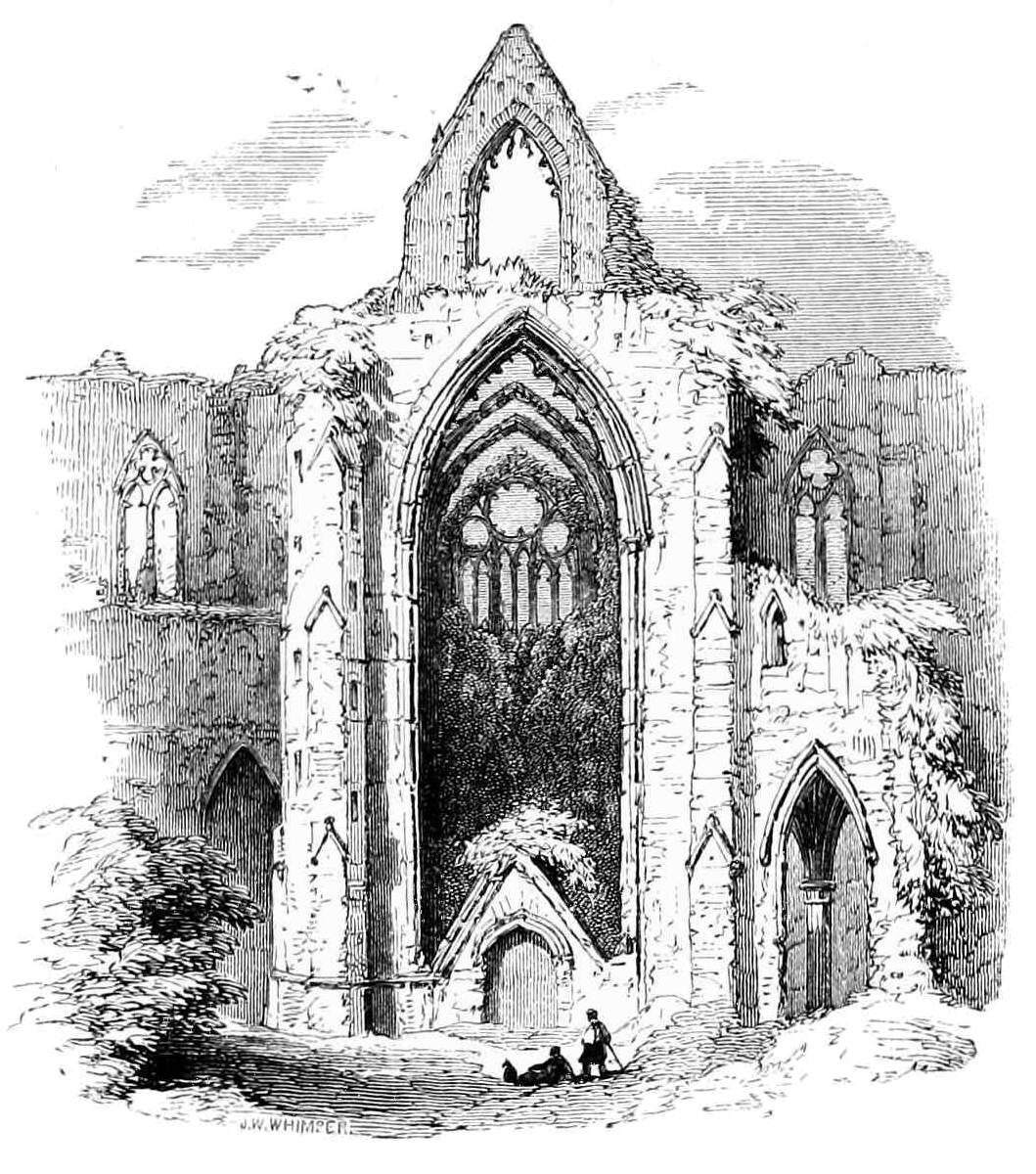

| South Transept, Tinterne Abbey. | W. H. Bartlett. | W. Whimper. | 31 | |

| Cistercian Monk. | Dugdale. | W. Whimper. | 34 | |

| View from Entrance, Tinterne Abbey, taken from the Nave, showing the great Eastern Window. | W. H. Bartlett. | W. Whimper. | 40 | |

| Initial Letters, illustrative of Baronial, Monastic, and Chivalrous Subjects. | 1, 1, 3, 13, 31 | |||

| Mutilated Effigy of Earl Strongbow, or Roger Bigod. | 41 | |||

| Shields of the Clare and Bigod Families, from the Encaustic-Tile Pavement in the Abbey. | 42 | |||

| Walter de Clare; Armorial Ensigns of the Family. | 44 | |||

| Richard de Clare; Ancient Family Shield. | 48 | |||

| Hospitium, or Guest Hall, with portions of the Refectory, and other Conventual Buildings. | 50 | |||

| Conventual Alphabet, Letter H; Abbey Gate, Procession. | 51 | |||

| Inner View; Sketch of an Altar, Tomb, &c. | 54 | |||

| Conventual Alphabet, Letter P. | 56 | |||

| Conventual Letter O. | 60 | |||

| Abbatial Crosier, Cap, and Cushion. | 62 | |||

| Letter A. | 65 | |||

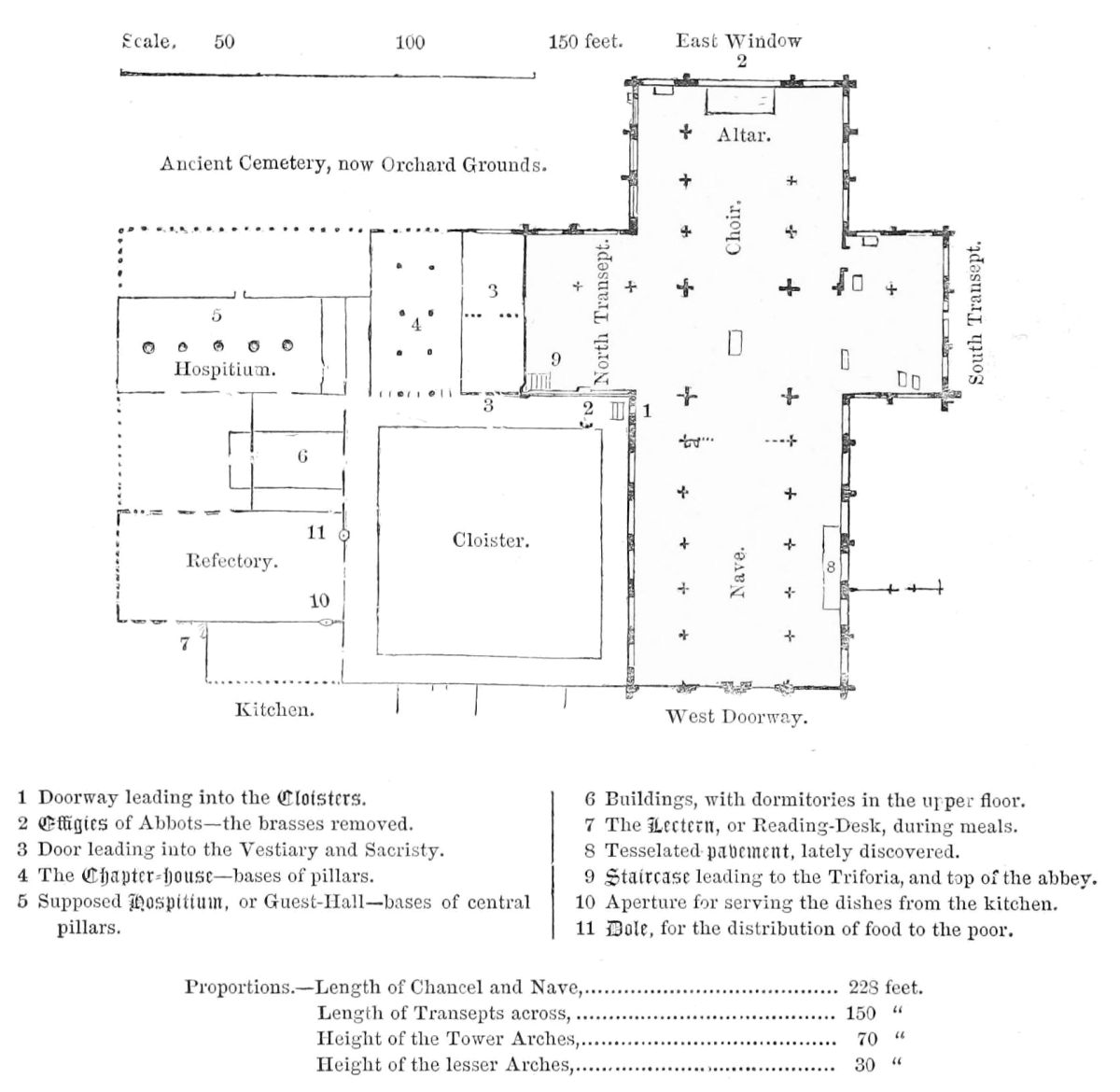

| Ground Plan of Tinterne Abbey. | 108 | |||

| Five smaller Woodcuts, illustrative of the subject. | ||||

| Goodrich Castle. | 122 | |||

| Raglan Castle. | ||||

| STEEL ENGRAVINGS. | ARTISTS. | ENGRAVERS. | PAGE. | |

| The Avenue, west of the Castle, from which the remains of the State Apartments are seen through the trees W. H. Bartlett. | J. C. Bentley. | 128 | ||

| The Paved Stone Court | W. H. Bartlett. | S. Bradshaw. | 151 | |

| The Baronial Hall, showing the great Bay Window on the right of the Dais, with the Worcester Arms overhead; the ancient Fire-place, with W worked in brick over the Arch; the Corbel-heads that supported the Roof, &c. &c. | W. H. Bartlett. | E. J. Roberts. | 154 | |

| Gateway in the Fountain Court, with the Baronial Chapel | W. H. Bartlett. | E. Brandard. | 156 | |

| The Moat.—This View of the Keep and adjacent Towers is universally admired, both for the splendour of architectural detail and the picturesque grouping of the features which it displays | W. H. Bartlett. | C. Cousen. | 158 | |

| The Gateway Towers, as described in the text, with the Moat and part of the Donjon Tower on the left | W. H. Bartlett. | E. Brandard. | 177 | |

| The Keep or Donjon Tower, from the Moat; on the right are seen the Gateway Towers, and in the centre is the Keep. In front, opening upon the water, is the old sally-port; and on the right bank, partially concealed by trees, is the private walk, formerly ornamented with statues and shell-work, as described in the text. The Keep is represented in the same state as when it was left by General Fairfax after the siege | W. H. Bartlett. | J. C. Bentley. | 200 | |

| View from the Battlements.—This View is taken from the top of the Keep, with the Moat, the Gatehouse, the Paved Court, &c., and Landscape to the westward | W. H. Bartlett. | A. Willmore. | 220 | |

| WOODCUTS. | ||||

| Goodrich Castle | 122 | |||

| Ancient Armour | 131 | |||

| Feudal and Military Trophies | 136 | |||

| Morning of the Tournament | 138 | |||

| The Boar’s Head | 146 | |||

| Old Apartments in the Gateway Tower | 153 | |||

| Plan of the Castle | 160 | |||

| Baronial Trophies | 175 | |||

| The Armourer | 178 | |||

| The Arquebusier | 185 | |||

| The Tower of Gwent, or Keep | 194 | |||

| Window in the State Apartments | 198 | |||

| The Garter | 213 | |||

| State Gallery, with ancient Statues of the Earl and Countess of Worcester | 217 | |||

| View from the Battlements of the Keep, looking to Raglan Church | 222 | |||

| View taken from the old Bowling Green, with the Keep in the centre, and the Gate to Fountain Court on the left | 226 | |||

| Apartments called King Charles’s, carved Chimney-piece on the left, and Windows looking S. and S.W. | 227 | |||

| The old Baronial Kitchen, as described in the text | 234 | |||

| Bridge over the Monnow, described in the text | 239 | |||

| Llanthony Abbey. | ||||

| STEEL ENGRAVINGS. | ARTISTS. | ENGRAVERS. | PAGE. | |

| The Nave of Llanthony Abbey, with the Central Tower, part of the South Transept, fragments of the Chancel, and great East Window | W. H. Bartlett. | W. Deebles. | 244 | |

| Llanthony Abbey from the North-west, showing the great West Door—the two Square Towers—the Nave—North Aisle—the great Tower connecting the Transepts, with fragments of the great Eastern Window | W. H. Bartlett. | E. Brandard. | 258 | |

| Llanthony Abbey from the rising Ground north of the Ruins, showing the whole Abbey, as it now appears, in the distance, with its surrounding Scenery, as presented from that point of view | W. H. Bartlett. | S. T. Davis. | 272 | |

| WOODCUT. | ||||

| The Abbey Church from the East. | ||||

| Uske—Pembroke—Cardiff—Tenby. | ||||

| STEEL ENGRAVINGS. | ||||

| Uske Castle and Town, showing the river Uske and the Bridge in the foreground—the ancient Castle on the right, with the Town under the acclivity—in the back ground, the picturesque Scenery for which the banks of the Uske are so remarkable | W. H. Bartlett. | A. Willmore. | 283 | |

| Pembroke Castle from the Water, comprising the Principal Gateway—the Postern—the great Round Tower, or Donjon—the Outworks. On the left, part of the Tower; and westward, in the horizon, the remains of the ancient Nunnery | W. H. Bartlett. | J. Cousen. | 293 | |

| Pembroke Castle.—Interior of the Great Court—Gateway, Towers, and Fortifications | W. H. Bartlett. | J. Cousen. | 308 | |

| WOODCUTS. | ||||

| Round Tower of Uske Castle—Chamber in the same—Curthose Tower in Cardiff Castle. | 284, 286, 311 | |||

| Manorbeer Castle—Neath Abbey—Kidwelly Castle—Llanstephan Castle—Carew Castle—Margam Abbey—Appendix. | ||||

| STEEL ENGRAVINGS. | ||||

| Manorbeer Castle, near the Church | W. H. Bartlett. | 321 | ||

| Kidwelly Castle, from the Gwendraeth | W. H. Bartlett. | 332 | ||

| Kidwelly Castle, from the Inner Court—Chapel on the right | W. H. Bartlett. | 334 | ||

| WOODCUTS. | ||||

| Neath Abbey, the Crypt | 331 | |||

| Ancient Dwellings near Manorbeer Castle | 335 | |||

| Margam Abbey, the Crypt | 348 | |||

T has been justly remarked by statistical writers,

that, in point of fertility, picturesque scenery, and classic remains,

the county of Monmouth is one of the most interesting districts in the

kingdom. Highly favoured by nature, it is literally studded over with

the labours and embellishments of art. Watered by noble rivers,

sheltered by magnificent woods and forests, interspersed with

industrious towns and hamlets, and enriched by the labour and enterprise

of its inhabitants, it presents all those features of soil and scenery

which contribute to the beauty and stability of a country. From whatever

point the traveller may enter this county, historical landmarks meet him

at every step: feudal and{2} monastic ruins, rich in the history of

departed dynasties, divide his attention, and fill his mind with their

heroic deeds and pious traditions. In fields where the husbandman now

reaps his peaceful harvest, he traces the shock of contending armies;

whose deadly weapons still rust in furrows which their valour had won,

and which the blood of the Roman, the Saxon, and Briton had fertilized.

From these he turns aside to contemplate the fragments of baronial

grandeur, which attest the glory of chivalry, but now, like sepulchral

mounds, proclaim the deeds of their founders:—such is the Castle of

Raglan.

T has been justly remarked by statistical writers,

that, in point of fertility, picturesque scenery, and classic remains,

the county of Monmouth is one of the most interesting districts in the

kingdom. Highly favoured by nature, it is literally studded over with

the labours and embellishments of art. Watered by noble rivers,

sheltered by magnificent woods and forests, interspersed with

industrious towns and hamlets, and enriched by the labour and enterprise

of its inhabitants, it presents all those features of soil and scenery

which contribute to the beauty and stability of a country. From whatever

point the traveller may enter this county, historical landmarks meet him

at every step: feudal and{2} monastic ruins, rich in the history of

departed dynasties, divide his attention, and fill his mind with their

heroic deeds and pious traditions. In fields where the husbandman now

reaps his peaceful harvest, he traces the shock of contending armies;

whose deadly weapons still rust in furrows which their valour had won,

and which the blood of the Roman, the Saxon, and Briton had fertilized.

From these he turns aside to contemplate the fragments of baronial

grandeur, which attest the glory of chivalry, but now, like sepulchral

mounds, proclaim the deeds of their founders:—such is the Castle of

Raglan.

In another district, sculptures, pavements, altars, statues, coins, and inscriptions, bear testimony to Roman sway:—such is the Silurian settlement of Caerleon, with its classic vicinity.

On another hand, where the ivy has clasped its hallowed walls, as if to prop their decay, the traveller halts at some monastic rain; and, amid the crumbling fragments of its lofty arches, its richly-carved windows, shafts, and capitals, dwells with a deep and melancholy interest on the page of its eventful history. In such places the voice of Tradition is never mute: the vacant niche, the dismantled tower, the desecrated altar, the deserted choir—all discourse eloquent and impressive music; and in places where the sacred harp was once strung, its chords seem still touched by invisible hands:—such are the Abbeys of Tinterne and Llanthony.

It is among these remains and monuments of the past—the early homes of saints and heroes of the olden day—that we propose to conduct the reader. In the tour projected, we avail ourselves of such materials as personal investigation, with that of distinguished predecessors, poets, and historians, has furnished from times of remote antiquity, down to the present day.

The scenery of the Wye is of classic and proverbial beauty: it is the theme alike of poet and historian, the annual resort of pilgrims—whether admirers of the picturesque, or valetudinarians; and nowhere in the kingdom is nature more lavish of those charms which attract all classes of tourists, than in the course and confines of this beautiful and romantic river.[1] There—

hepstow is of Roman foundation—the Strigulia of

ancient authors—and was for centuries one of the favourite strongholds

of the kingdom. By the antiquarian researches, which are now conducted

with unprecedented success and spirit, numerous vestiges of ancient

times have been brought to light, and many more, it is believed, are

reserved for the labours of archæology. The vicinity abounds in military

encampments, all more or less remarkable for the strength of their

position, and pointing to those days of border warfare when ‘might was

right,’ and the sword the acknowledged lawgiver. But in the description

of Chepstow, our observations must be restricted to the subjects

selected for illustration; and these are so correctly depicted in the

scene before us, that the reader will obtain a far more correct idea

from the delineations of the pencil, than from any description that

could be conveyed by the pen. Chepstow is supposed, and with much

probability, to have been the chief seaport of the Silurian colony, as

both Caerwent and Portscwet have for many centuries been deserted by the

sea. Where the Roman galleys once flanked the beach, landing their

freight of mailed cohorts, the modern steamer now unloads her crowded

deck of peaceful tourists, merchants, mechanics, and students of the

picturesque.

hepstow is of Roman foundation—the Strigulia of

ancient authors—and was for centuries one of the favourite strongholds

of the kingdom. By the antiquarian researches, which are now conducted

with unprecedented success and spirit, numerous vestiges of ancient

times have been brought to light, and many more, it is believed, are

reserved for the labours of archæology. The vicinity abounds in military

encampments, all more or less remarkable for the strength of their

position, and pointing to those days of border warfare when ‘might was

right,’ and the sword the acknowledged lawgiver. But in the description

of Chepstow, our observations must be restricted to the subjects

selected for illustration; and these are so correctly depicted in the

scene before us, that the reader will obtain a far more correct idea

from the delineations of the pencil, than from any description that

could be conveyed by the pen. Chepstow is supposed, and with much

probability, to have been the chief seaport of the Silurian colony, as

both Caerwent and Portscwet have for many centuries been deserted by the

sea. Where the Roman galleys once flanked the beach, landing their

freight of mailed cohorts, the modern steamer now unloads her crowded

deck of peaceful tourists, merchants, mechanics, and students of the

picturesque.

In its general appearance—in its street architecture—Chepstow still presents some isolated features of the primitive style. Of these, the principal is the Western Gate, of unquestionable antiquity; and, in point of date, taking precedence of the castle itself. By a charter given in the 16th Henry VIII., the bailiffs were to have their prison for the punishment of offences within the Great Gate, “which they have builded by our commandment.” This is supposed to be a renewal of the ancient liberties of the town, granted by Howel Dhu, A.D. 940.

The Church, part of a Benedictine priory of Norman work, has undergone many alterations and repairs; but repairs, in some cases, are more fatal to the style and symmetry of ecclesiastical monuments, than the wasting hand of time, or even the shocks of violence—for they only disfigure what they meant to adorn; and, by deviating widely from the original plan, lose or debase all its original beauty. The nave and aisles are nearly all that remain of the original edifice.[2] The church has disappeared; but the pillars which supported the{4} central tower are still preserved on the eastern extremity, and convey some idea of the massive strength of the original edifice. The western porch is justly admired for its zigzag tracery; and, in this respect, it presents one of the finest specimens that have descended to our day, of the true Saxo-Norman character. The church contains several monuments, not remarkable for their style or antiquity; the chief of which is that to the memory of the second Earl and Countess of Worcester, with their effigies at full length, in the attitude of prayer.

The repairs and restorations lately effected in this church, were suggested and carried out by the joint taste and liberality of the late Bishop of Llandaff and the parishioners. The result is creditable to the parties concerned; and here, it is to be hoped, their pious labours will not be suffered to terminate. The original priory was an alien branch of the Benedictine monastery of Cormeilles.

The acrostic, written upon himself by the regicide Henry Martin—first discarded from the chancel, and latterly from the sacred enclosure, by a former vicar—has somewhat recovered from its disgrace, by gaining admittance into the vestry, but only on sufferance. In the town and immediate neighbourhood are some remains of religious houses, under various denominations; for the situation of Chepstow, presenting many advantages for commerce, was not less favourable for monachism.

We were told of a pleasing custom, transmitted from early times, and still observed here, that of repairing every Palm-Sunday to the graves of departed friends, and ornamenting them with flowers—much in the same way as the populace of Paris repair every All Saints’ morning to Père-la-Chaise, to scatter flowers and evergreens over the graves of their relations.

One of the finest points of view is the centre of the new iron bridge, comprising the castle, the vessels at anchor under the stupendous wall of rock on which it is erected; with the lawns and groves of Piercefield—a favourite and familiar name in the list of picturesque tours—closing the landscape. The former bridge[3] was of prodigious height, erected on piles. The present struc{5}ture was founded in 1815; and in the March of that year, the tide rose from low-water mark to the remarkable height of fifty-one feet two inches. The new bridge consists of five arches, the centre one of which is one hundred and twelve feet in span; the two adjoining arches have a span of seventy feet, and the two outer ones a span of fifty-four feet each. It is of massive cast-metal, resting on stone piers; and its total length is five hundred and thirty-two feet.

The depth of the moorings in the river here is so great, that, at low water, ships of 700 tons burthen may ride safely at anchor. The rise of tide is from thirty to nearly sixty feet, a circumstance scarcely to be paralleled—and caused by the extraordinary swell of water at the rocks of Beechley and Aust, which, by protruding far into the Severn, near the month of the Wye, obstruct the flow of tide, and thus impel it with increased rapidity into the latter.[4] In January, 1768, according to our local guide, it attained the height of seventy feet: its greatest rise of late years has been fifty-six feet.

In 1634, we are informed, Colonel Sandys attempted to make the Wye navigable by means of locks; but after much labour and expense, the experiment failed, and the locks were removed. Every one curious in the phenomena of natural history, has heard of the intermitting well of Chepstow, which ebbs and flows inversely with the tide—that is, when the tide ebbs, the well flows; and when the tide flows, the well ebbs: when the tide is at its height, the well is nearly dry; a little before which it begins to subside, and soon after the ebb it gradually returns. It is neither affected by wet nor dry weather, but is entirely regulated by the tide. It is thirty-two feet in depth, and frequently contains fourteen feet of excellent water.

In melancholy connection with the old bridge of Chepstow, is a family calamity which drew from the late poet Campbell an epitaph[5] worthy of his pen. The victims by the sudden catastrophe were a lady and her two daughters, personal friends of the poet, and for whom he entertained sentiments of great esteem and regard. The lady and her daughters were on a visit at Chepstow; and, after hearing sermon, went on the river in a boat. The tide was running strong at the time; and in his attempt to clear the centre arch of the bridge, the boatman missed his aim—the frail bark struck against the wooden pier, and upset; and the lady and her two daughters were carried down by the stream{6} and lost. Their lifeless remains were afterwards recovered, and buried in the churchyard of Monckton, where a tomb, erected to their memory, bears the following inscription:—

It is somewhat remarkable, that the text of Scripture which they had just heard expounded in the parish church the same morning, was—“For to me to live is Christ, and to die is gain.” Of the principal victim in this calamity, Campbell thus speaks in a private letter to a friend:—“We looked to Mrs. Shute as truly elevated in the scale of beings for the perfect charity of her heart. The universal feeling of lamentation for her, accords with the benign and simple-minded beauty of her character.”

As the limits and object of this work do not permit us to enlarge our remarks on the particular history of Chepstow, we now proceed to that of the castle, whose roofless walls, and moss-clad ramparts, carry us back to the Norman Conquest, and fill an ample page in its subsequent history. The present structure, on a Roman or Saxon foundation, is ascribed to William Fitzosborne, Earl of Hereford,[6] upon whom his kinsman the Conqueror had bestowed vast{7} possessions, in this and the neighbouring counties, which could only be secured by sword and stronghold. On the forfeiture of his son Roger, it passed to the Clares, another great Norman family.

The hereditary lords of the town and castle were the old Earls of Pembroke, of the house of Clare, the last of whom was the renowned Richard[7] Strongbow, ‘Earl of Striguil, Chepstow, and Pembroke,’ who died in 1176, leaving a daughter, Isabel, by whose marriage the estates and title passed into the family of Marshall, and afterwards, by a similar union, into that of Herbert. In the reign of Edward the Fourth, the castle, manor, and lordship of Chepstow, were held by Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, who was beheaded after the battle of Banbury, in 1469. By the marriage of Elizabeth, sole daughter and heiress of William Herbert—Earl of Huntingdon, and Lord Herbert of Raglan, Chepstow, and Gower—it descended to Sir Charles Somerset, who was afterwards created Earl of Worcester. It is now one of the numerous castles belonging to his illustrious descendant, the Duke of Beaufort.

During the wars of the Commonwealth, the castle was garrisoned by the king’s troops; but, in 1645, Colonel Morgan, governor of Gloucester, at the head of a small body of horse and foot, entered the town without much difficulty; and, on the 5th October, sent the following summons to Sir Robert Fitzmaurice: “Sir,—I am commanded by his Excellency, Sir Thomas Fairfax, to demand this castle for the use of the King and Parliament, which I require of you, and to lay down your arms, and to accept of reasonable propositions, which will be granted both to you and your soldiers, if you observe this summons: and further, you are to consider of what nation and religion you are; for if you refuse the summons, you exclude yourself from mercy, and are to expect for yourself and soldiers no better than Stinchcombe quarter. I expect your sudden answer, and according thereunto shall rest your friend,—Thomas Morgan.”

To this summons the governor answered: “Sir,—I have the same reason to keep this castle for my master the King, as you to demand it for General Fairfax; and until my reason be convinced, and my provisions decreased, I shall, notwithstanding my religion and menaces of extirpation, continue in my resolution, and in my fidelity and loyalty to the king. As to Stinchcombe quarter, I know not what you mean by it; nor do depend upon your intelligence for relief, which in any indigence I assure me of; and in that assurance I rest your servant,—Robert Fitzmaurice.

“P.S.—What quarter you give me and my soldiers, I refer to the consideration of all soldiers, when I am constrained to seek for any.{8}”

Stinchcombe, near Dursley on the Severn, was a place where the Parliament accused Prince Rupert of putting their men to the sword.

In consequence of this answer the siege was commenced, and carried on with so much vigour, that, in the course of four days, the castle surrendered, and the governor and his garrison were made prisoners of war. Later in the history of that melancholy period, it was surprised by a body of royalists, under Sir Nicholas Kemeys. Cromwell then directed his whole strength upon it, and reduced the town; but, for a time, found the castle impregnable. At last, however, exhausted with fatigue, and on the verge of famine, the garrison were forced into a parley with the besiegers; and, in the surrender of the fortress, Sir Nicholas Kemeys “was killed in cold blood.” The following is Colonel Ewer’s report[8] on the reduction of Chepstow Castle. His letter is addressed to the Honourable William Lental, Speaker of the House of Commons:—

“Sir,—Lieutenant-General Cromwell, being to march towards Pembroke Castle, left me with my regiment to take in the Castle of Chepstow, which was possessed by Sir Nicholas Kemish [or Kemeys], and with him officers and soldiers to the number of 120. We drew close about it, and kept strong guards upon them, to prevent them from stealing out, and so to make their escape. We sent for two guns from Gloucester, and two off a shipboard, and planted them against the castle. We raised [razed] the battlements of their towers with our great guns, and made their guns unusefull for them. We also plaid with our shorter pieces into the castle. One shot fell into the governor’s chamber, which caused him to remove his lodgings to the other end of the castle. We then prepared our batteries, and this morning finished them. About twelve of the clock, we made a hole through the wall, so low that a man might walk into it. The soldiers in the castle, perceiving that we were like to make a breach, cried out to our soldiers that they would yield the castle, and many of them did attempt to come away. I caused my soldiers to fire at them to keep them in. Esquire Lewis comes upon the wall, and speaks to some gentlemen of the county that he knew, and tells them that he was willing to yield to mercy. They came and acquainted me with his desire, to which I answered, that it was not my work to treat with particular men, but it was Sir Nicholas Kemish, with his officers and all his soldiers, that I aimed at; but the governor refused to deliver up the castle upon these terms that Esquire Lewis desired, but{9} desired to speak with me at the drawbridge, while I altogether refused to have any such speech with him, because he refused Lieutenant-General Cromwell’s summons; but, being overpersuaded by some gentlemen of the country that were there, presently I dismounted from my horse, and went unto the drawbridge, where he through the port-hole spake with me. That which he desired was, that he, with all his officers and soldiers, might march out of the castle without anything being taken from them; to which I answered, that I would give him no other terms but that he and all that were with him should submit unto mercy, which he swore he would not do. I presently drew off the soldiers from the castle, and caused them to stand to their arms; but he refusing to come out upon those terms, the soldiers deserted him, and came running out at the breach we had made. My soldiers, seeing them run out, ran in at the same place, and possesst themselves of the castle, and killed Sir Nicholas Kemmish, and likewise him that betrayed the castle, and wounded divers, and took prisoners as followeth:—Esquire Lewis, Major Lewis, Major Thomas, Captain Morgan, Captain Buckeswell, Captain John Harris, Captain Christopher Harris, Captain Mancell, Captain Pinner, Captain Doule, Captain Rossitre, Lieutenant Kemmish, Lieutenant Leach, Lieutenant Codd, Ensign Watkins, Ensign Morgan, with other officers and soldiers, to the number of 120. These prisoners we have put into the church, and shall keep them till I receive further orders from Lieutenant-General Cromwell.

“This is all at present, but that I am your humble servant,

“Isaac Ewer.”

“Chepstow, May 28, 1648.”

The captain who carried the news of this event to London was rewarded with fifty pounds; and Colonel Ewer, with the officers and soldiers under his command, received the thanks of parliament. This was the closing scene of its warlike history; and from that period down to the present, the Castle of Chepstow has remained a picturesque and dismantled ruin.

Of this brave but unfortunate governor of the castle, we collect the following particulars:[9]—

Sir Nicholas Kemeys, Bart.,[10] the sixteenth in descent of this honourable house, “was colonel of a regiment of horse, raised for the king’s service, and governor of Chepstow Castle, which he bravely defended against the powerful efforts of Cromwell and Colonel Ewer; nor did he surrender that fortress but with his life, fighting in the most gallant manner, till death arrested his farther exertions.”[11] There is a traditional story, that “the Parliamentary troops, as{10} soon as they entered the castle, in revenge for Sir Nicholas’ obstinate resistance, mangled his body in the most horrid manner, and that the soldiers wore his remains in their hats, as trophies of their victory; but a branch of the Kemeys family,” says the writer, “told me they considered it as one of those acts of the times, which each party adopted to stigmatize the memory of its political opponents. Not a stone, it is said, nor other tribute of recollection, in any cemetery in Monmouthshire, records the spot in which the remains of this brave officer were deposited.”[12]

A portrait of Sir Nicholas Kemeys was “in the possession of the late Mrs. Sewel[13] of Little Kemeys, near Usk, in this county, now the property of John G. Kemeys, Esq. The picture is a three-quarters length. He is drawn in armour, and seems about forty years of age. He appears to have possessed a good person, if an opinion might be formed from his portrait. He has a fine open countenance, round face, dark piercing eyes, an aquiline nose, and wore his own hair, which was black and rather curly.” According to the fashion of his day, he is represented with whiskers, and a small tuft of hair growing under the lower lip—or, in modern phraseology, an imperial. “Although it is what an artist would pronounce a dark picture, yet, on the whole, it is in good preservation. There are two more portraits of this gentleman—one in the possession of the late Sir Charles Kemeys, Bart. of Halsewell, in Somersetshire; the other at Malpas, near Usk, probably all painted at the same time and by the same artist, but whose name has not been handed down in conjunction with his works.”

The house of Kemeys,[14] “originally De Camois, Camoes, and Camys, is of Norman extraction, and the name of its patriarch is to be found on the roll of Battle Abbey. Large possessions were granted to the family in the counties of Sussex and Surrey; and, so early as the year 1258, Ralph de Camois was a baron by tenure. He was succeeded by his son, Ralph de Camois, who was summoned to parliament in the 49th year of Henry III.; and his descendants{11} sat among the peers of the realm, until the demise, issueless, of Hugh de Camois, who left his sisters (Margaret, married to Ralph Rademelde, and Aleanor, wife of Roger Lewknor) his coheirs. A branch of the family which had settled in Pembrokeshire, there enjoyed large possessions, and, as lords of Camaes and St. Dogmaels, exercised almost regal sway. In the conquest of Monmouthshire and Glamorganshire, the Camays were much distinguished, and were rewarded with grants of “Kemeys Commander” and “Kemeys Inferior.” One branch became established at Llannarr Castle, in Monmouthshire (now in the possession of Colonel Kemeys-Tynte), and another fixing itself at Began, in Glamorganshire, erected the mansion of Kevanmably, the residence of the present chief of the family.

“Edward Kemeys, son of Edward Kemeys who was at the conquest of Upper Gwent, married the daughter and heiress of Andrew de Began, lord of Began, a lineal descendant of Blethyn Maynerch, lord of Brecon, and thus acquired the lordship of Began, which, for centuries after, was the principal abode of his descendants. His great-great-great-grandson, Jenkin Kemeys of Began, married Cristley, daughter of Morgan ap Llewellyn, by whom he had one son, Jevan; and a daughter, married to Jevan ap Morgan of New Church, near Cardiff, in the county of Glamorgan, and was grandmother of Morgan Williams—living temp. Henry VIII.—who espoused the sister of Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex, and had a son, Sir Richard Williams, who assumed, at the desire of Henry VIII., the surname of his uncle Cromwell; and through the influence of that once-powerful relative, obtained wealth and station. His great-grandson was the Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell.[15] From Jenkin Kemeys was lineally descended Sir Nicholas Kemeys of Kevanmably, who represented the county of Glamorgan in parliament, and was created a baronet 13th May, 1642. This gentleman, remarkable for his gigantic stature and strength, was pre-eminently distinguished by his loyalty to Charles I., and on the breaking out of the civil war (as we have already observed), having raised a regiment of cavalry, was invested with the command of Chepstow Castle.”

Notwithstanding the alliance with the blood of Cromwell, loyalty seems to have been hereditary in the house of Kemeys. In the family biography we have the following anecdote:—“Sir Charles Kemeys—knight of the shire for Monmouth, in the last parliament of Queen Anne, and for Glamorgan in the two succeeding parliaments—when on his travels, was shown great attention by George I. at Hanover, and frequently joined the private circle of the Elector. When his majesty ascended the British throne, he was pleased to inquire why his old acquaintance Sir Charles Kemeys had not paid his respects at court;{12} and commanding him to repair to St. James’s, sent him a message, the substance of which was—that the King of England hoped Sir Charles Kemeys still recollected the number of pipes he had smoked with the Elector of Hanover in Germany. Sir Charles, who had retired from parliament, and was a stanch Jacobite, replied, that he should be proud to pay his duty at St. James’s to the Elector of Hanover, but that he had never had the honour of smoking a pipe with the King of England.”

Sir Charles Kemeys died without issue, when the baronetcy expired, and his estates devolved on his nephew, Sir Charles Kemeys-Tynte, Bart. of Halsewell, at whose demise, also issueless, his estates vested in his niece, Jane Hassell, who married Colonel Johnstone, afterwards Kemeys-Tynte,[16] and was mother of the present (1838) Colonel Kemeys-Tynte of Halsewell and Kevanmably. Through the Hassells, the family of Kemeys-Tynte claim descent from the Plantagenets.[17]

We now proceed to a brief description of the castle in its ruinous state.

Plan of Chepstow Castle.

EXPLANATION OF THE PLAN.

|

1. Entrance Gateway. 2. Marten’s Tower. 3. Well. 4. First Court. 5. Rooms above the Vaulted Chamber. 6. Second Court. |

7. Hall, or Chapel. 8. Third Court. 9. Sunken Way and Drawbridge. 10. Fourth Court. 11. Sunken Way and Bridge. 12. Perpendicular Cliff. |

UILT on a lofty perpendicular rock, that rises sheer

from the bed of the Wye, the position of the Castle is at once strong

and commanding; while, on the land side, the great height and massive

strength of its walls and outworks, present the remains of all that

ancient art could effect to render it impregnable.

UILT on a lofty perpendicular rock, that rises sheer

from the bed of the Wye, the position of the Castle is at once strong

and commanding; while, on the land side, the great height and massive

strength of its walls and outworks, present the remains of all that

ancient art could effect to render it impregnable.

The grand entrance is defended by two circular towers of unequal proportions, with double gates, portcullises, and a port-hole, through which boiling water or metallic fluids could be discharged on the heads of the besiegers. The massive door, covered with iron bolts and clasps, is a genuine relic of the feudal stronghold. The knocker now in use is an old four-pound shot. This introduces us to the great court, sixty yards long by twenty broad, and presenting the appearance of a tranquil garden. The walls are covered with a luxuriant mantle of ivy, through which the old masonry appears only at intervals; and here the owl finds himself in undisturbed possession, unless when roused by the choir of numberless birds that flit from tree to tree, or nestle among the leaves. The lover of solitude could hardly find a retreat more suited to his taste. The area, interspersed with trees, and covered with a fine grassy carpet,{14} is annually converted into a flower and fruit show, for the encouragement of horticulture, under the patronage of the noble owner.

The castle, as one of its historians conjectures, is of the same antiquity as the town itself, to which it served the purposes of a citadel; but the precise epoch, neither Leland, Camden, nor any topographical writer has been able to ascertain. Stow, indeed, attributes the building of the castle to Julius Cæsar, but there is no evidence to support his supposition. Camden, on the contrary, thinks it of no great antiquity; for several affirm, says he, that “it had its rise, not many ages past, from the ancient Venta”—the Venta Silurum of Antoninus. Leland, in his Itinerary, says—“The waulles begun at the edge of the great bridge over the Wye, and so came to the castle, which yet standeth fayr and strong, not far from the ruin of the bridge. In the castle ys one tower, as I heard say, by the name of Longine.[18] The town,” he adds, “hath nowe but one paroche chirche: the cell of a blake monk or two of Bermondsey, near London, was lately there suppressed.”

During the life of Charles-Noel, fourth Duke of Beaufort, the castle was let on a lease of three successive lives to a Mr. Williams, a general merchant or trader, who adapted some of the great apartments to the following purposes, namely—the great kitchen to a sail manufactory; the store-room to a wholesale wine-cellar; the grand hall, or banqueting-room, was occupied by a glass-blower; and the circular tower by the gate, leading into the second court, was used as a nail manufactory. After the death of Mr. Williams, the roofs fell in, one after another—that of the Keep in 1799, the year in which the lease expired; and thus the stately castle was reduced to its present condition—a vast and melancholy ruin.

The only apartments now inhabitable are those of its loyal and intelligent warden and his family, whose civility and general information respecting the castle are very acceptable to its daily visitors.

One of the principal towers was converted, during the above-named lease, into a glass manufactory, the furnace of which has left its scars deeply indented in the solid masonry.

In a small chamber off the banqueting-hall, seventy-five pieces of ancient silver coin were recently discovered, and are now at Badminton Park; but of what value or of what reign we have not yet ascertained.

An ancient door—as ancient, we are told, as the castle itself—opens upon the{15} second court, of very nearly the same dimensions as the first, and now also converted into a garden. Beyond this is an apartment, supposed by some to have been the garrison chapel;[19] but its pointed arches and elaborately-carved windows, all evincing an air of stately dignity, leave no doubt of its having been the great baronial hall, where the Clares, the Marshalls, and Herberts, drew around them their chivalrous retainers.

Connected with this, by a winding path, is a third court, now cultivated as an orchard; so that, with trees, flowers, and luxuriant ivy, the whole enclosure presents a mass of vegetation, in which the stern features of warlike art have almost disappeared.

A walk along the ramparts westward from this point, commands some glimpses of beautiful scenery, with the Wye at the base of the rocks expanding in the form of a lake, where vessels are seen riding at anchor, and boats passing to and fro—here gay with pleasure parties, and there laden with foreign or inland produce.

The Keep is another object which the tourist will regard with interest, as{16} the twenty years’ prison of Henry Marten, whose vote, with those of his “fellow-regicides,” at the trial of Charles the First, consigned that unfortunate monarch to the block. To his epitaph written upon himself we have already alluded; and the reader is no stranger, probably, to Southey’s lines on the room where he was confined, which, with a sarcastic parody written by Canning, will be found in these pages.

Henry Marten, who attained such unenviable notoriety, was the son of Sir Henry Marten, a judge of the Admiralty, and M.P. for Berkshire. He was an able and active partisan of Oliver Cromwell, one of the “Executive Council;” and in the old prints representing the trial of the martyr-king, Marten occupies the chair on Cromwell’s left hand, immediately under the arms of the Commonwealth.[20] At the Restoration, he was brought to trial, and sentenced to death; but his sentence was afterwards commuted to imprisonment for life. In the keep of this castle, since called “Marten’s Tower,” he spent twenty years; but much was done to soften the rigour of his sentence. “His wife was permitted to share his imprisonment; he was attended by his own domestic servants, who were accommodated in the same tower; and he had permission to visit, and receive visits from his friends in the town and neighbourhood. He died in 1680, at the mature age of seventy-eight, neither disturbed by the qualms of conscience, nor enfeebled by the rigour of confinement; and left behind him the character of a liberal and indulgent master.” At a comparatively recent period, the principal chamber of the Keep was frequently used by the inhabitants of Chepstow as a ball-room; and there is now residing in the town a lady, who remembers having been present at more than one of these festive reunions.

For the following notice of this “stern republican,”—somewhat different from the preceding—we are indebted to Heath’s description of Chepstow:—

Henry Marten,[21] commonly called Harry Marten, was born in the city of Oxford, in the parish of St. John the Baptist, in a house opposite to Merton College Church, then lately built by Henry Sherburne, gent., and possessed, at the time of Harry’s birth, by Sir Henry, his father. After he had been in{17}structed in grammar-learning in Oxford, he became a gentleman commoner of University College in the beginning of 1617, aged fifteen years, where, and in public, giving a manifestation of his pregnant mind, had the degree of Bachelor of Arts conferred upon him in the latter end of the year 1619. Afterwards he went to one of the Inns of Court, travelled into France, and on his return married a lady of considerable worth; but with whom, it is said, “he never afterwards lived.”[22]

In the beginning of the year 1640, he was elected one of the knights for Berks, to serve in the parliament that began at Westminster the 13th of April; and again, though not legally, in October, to serve in the parliament that began at the same place on the 3d of November following. We shall not enter into his political actions on the great theatre of public life—as they are to be found in all the histories of England, from the reign of Charles I. to the Restoration—but content ourselves with noticing those parts of it which are more peculiarly interesting to the traveller in Monmouthshire, namely, the manner in which he passed his time, with occasional anecdotes, during his confinement in the castle of Chepstow.

Wood, an ultra-royalist, gives the following character of him:—“He was a man of good natural parts—was a boon familiar, witty, and quick with repartees—was exceeding happy in apt instances, pertinent and very biting; so that his company, being deemed incomparable by many, would have been acceptable to the greatest persons, only he would be drunk too soon, and so put an end to all their mirth for the present. At length, after all his rogueries, acted for near twenty years together, were passed; he was at length called to account for that grand villany, of having a considerable hand in murdering his prince, of which being easily found guilty, he was not to suffer the loss of his life, as others did, but the loss of his estate, and perpetual imprisonment, for that he came in upon the proclamation of surrender. So that, after two or three removes from prison to prison, he was at length sent to Chepstow Castle, where he continued another twenty years, not in wantonness, riotousness, and villany, but in confinement and repentance, if he had so pleased.”

“This person—who lived very poor, and in a shabbeel condition in his confinement, and would be glad to take a pot of ale from any one that would give it to him—died with meat in his mouth, that is, suddenly, in Chepstow Castle (as before mentioned), in September, 1680; and was, on the 9th day of the same month, buried in the church of Chepstow. Some time before he died he made the epitaph, by way of acrostic, on himself, which is engraved on the stone which now covers his remains.{18}”

Mrs. Williams—“wife of the person who had the care of the castle, and who died in 1798, at a very advanced age—well knew and was intimately acquainted with the women who waited and attended on Harry Marten during his confinement in the castle. They were two sisters, and their maiden name was Vick.

“From what I could learn, I am of opinion that the early part of Marten’s confinement was rather rigorous; for whatever Mrs. Williams mentioned had always a reference to the latter part of it; and in this conjecture I am supported by her remark, that though he had two daughters living, they were not indulged with sharing their father’s company in prison till near the close of his life. In the course of years, political rigour against him began to wear away, and he was permitted not only to walk about Chepstow, but to have the constant residence of his family, in order to attend upon him in the castle. This indulgence at last extended itself so far, as to permit him to visit any family in the neighbourhood, his host being responsible for his safe return to the castle at the hour appointed.

“One anecdote of Marten, as mentioned by Mrs. Williams, I shall here repeat. Among other families who showed a friendly attention to the prisoner, were the ancestors of the present worthy possessor of St. Pierre, near Chepstow. To a large company assembled round the festive dinner-board Marten had been invited. Soon after the cloth was removed, and the bottle put into gay circulation, Mr. Lewis, in a cheerful moment, jocularly said to Marten, ‘Harry, suppose the times were to come again in which you passed your life, what part would you act in them?’ ‘The part I have done,’ was his immediate reply. ‘Then, sir,’ says Mr. Lewis, ‘I never desire to see you at my table again;’ nor was he ever after invited.[23]

“Great credibility,” says our authority, “deserves to be attached to this story, as containing Marten’s political opinion at that day; and, to support a belief in it, the late Rev. J. Birt, canon of Hereford, thus speaks of him, in his letter to the Rev. J. Gardner, prefixed to his ‘Appendix to the History of Monmouthshire:’—‘Henry Marten, one of the incendiary preachers during the great rebellion, was, at the Restoration, imprisoned for life at Chepstow, and buried there. As far as I can recollect, he died as he lived, with the fierce spirit of a republican.’ The Rev. Mr. Birt, who died at the advanced age of ninety-two, held distinguished preferment in the neighbourhood of Chepstow, and had been in the habits of intimate acquaintance with all the first families in the county.{19} His testimony might therefore be said to stamp the anecdote with the sanction of truth, without seeking for farther evidence.

“Of his personal appearance, a friend of mine—on the authority of the late Mr. Harry Morgan, attorney at Usk, whose father had been in Marten’s company, and by whom he had been informed of it—says that Mr. Morgan described him, in general terms, as ‘a smart, active little man, and the merriest companion he ever was in company with in his life.’ Wood praises his social qualities, and talent for conversation; but that ‘he lived in a shabbeel condition, and would take a pot of ale from any one that would give it to him,’ may be doubted; unless he meant that the kindness shown to him by the families in and near Chepstow admitted such an interpretation.[24]

“Let us attend him to the grave. It is hardly possible to admit that such a mind as that of Marten would have penned—much less to suppose that he would have wished to have engraved on his tomb—the wretched doggerel that goes under the name of his ‘Epitaph,’ and which is said to have been written by him during his confinement in the castle. Not the smallest circumstance respecting his funeral is left on record; and whether his obsequies were marked with public procession, or whether he retired to the grave unnoticed and unregarded, tradition has not preserved the slightest memorandum.”

His biographer might, without difficulty, have concluded that—in those times, at all events—an imprisoned rebel would not be permitted to have any but the most private funeral. All that we are certain of is, that he was buried in the chancel of the church of Chepstow; and that, on a large stone from the Forest of Dean, is still to be traced the following “Epitaph, written on himself,” by way of acrostic, but now much defaced:—

(ARMS.)

HIS EPITAPH.

Having retired to that asylum which is the common lot of humanity, his ashes were for some years permitted to rest in peace. But at length a clergyman of the name of Chest, we are told, was appointed to the vicarage of Chepstow, who, glowing with admiration for those principles of the constitution which he considered had been subverted, openly declared that the bones of a regicide should never pollute the chancel of that church of which he was vicar, and immediately ordered the corpse to be disinterred, and removed to the place where it now reposes, in the middle of the north transept, and over it the stone is placed that bears the epitaph before mentioned.

About this time, as Heath informs us, “there came to reside at Chepstow a person of the name of Downton, who afterwards married a daughter of the Rev. Mr. Chest; but, whatever affection he might cherish for the lady, the father was one unceasing object of his ridicule and contempt; and when the vicar died, he publicly satyrised him in the following lines:—

Marten’s apartment, as we have said, was in “the first story of the eastern tower, or keep; for this part of the building contained only a single room on each floor, if we except those near the top. Could he have detached from his recollection the idea of Sterne’s starling—‘I can’t get out, I can’t get out’—the situation might have been chosen out of remembrance or tenderness to the rank he had formerly held in society; for though it bore the name of a prison, it was widely different from the generality of such places. The room measured fifteen paces long, by twelve paces wide, and was very lofty. On one side, in the centre, was a fire-place, two yards wide; and the windows, which were spacious, and lighted both ends of the apartment, gave an air of cheerfulness not frequent in such buildings. In addition to this, he could enjoy from its windows some of the sweetest prospects in Britain. This apartment continues to{21} bear the name of ‘Marten’s Room’ to this day, and few travellers enter the castle without making it an object of their attention.”

“Marten,” says Mr. Seward, “was a striking instance of the truth of Roger Ascham’s observation, who, in his quaint and pithy style, says—‘Commonlie, men, very quick of wit, be very light of conditions. In youth, they be readie scoffers, privie mockers, and over light and merrie. In age they are testie, very waspish, and always over miserable; and yet few of them come to any great age, by reason of their miserable life when young; and a great deal fewer of them come to show any great countenance, or beare any great authority abroade, in the world; but either they live obscurely, men wot not how, or dye obscurely, men mark not when.’[26]

“In the dining-parlour of St. Pierre, near Chepstow, there hung,” in the time of the writer, “a painting, said to be of Harry Marten. He is represented at three-quarters length, in armour. In his right hand he holds a pistol, which he seems about to discharge; while with the left he grasps the hilt of his sword. Behind him is a page, in the act of tying on a green sash; the whole conveying an idea that the person was about to undertake some military enterprise. Judging from the picture, the likeness appears to have been taken when Marten was about forty-five years of age. He there seems of thin or spare habit, with a high forehead, long visage; his hair of a dark colour, and flowing over the right shoulder. The cravat round the neck does not correspond with the age in which he lived, being tied in the fashion of modern times. There is a great deal of animation and spirit in his countenance, characteristic of the person it is said to represent.”[27]

Having adverted to Mr. Southey’s “Inscription,” and its parody by George Canning, we subjoin the following copies from the originals. The first, by Southey, is thus headed:—

Inscription

For the apartment in Chepstow Castle, where Harry Marten the regicide was imprisoned thirty years.

The next is the parody by Canning, as published in the first number of the Anti-Jacobin, 1797:—

Inscription

For the door of the cell in Newgate, where Mrs. Brownrigg the ’prentice-cide was confined

previous to her execution.

Adjoining the Keep, or Marten’s Tower, is a small chamber, or Oratory, remarkable for the elegance of its proportions, and the chaste but elaborate style of its ornaments. The lancet-pointed window, encircled by rows of delicately-carved rosettes, is in fine preservation.—See the opposite page.

The narrow path which, at a height of six feet above the ground, connects this portion of the castle with the donjon tower, commands a range of beautiful scenery, the prominent features of which are the lawns and groves of Persefield, the precipitous but picturesque banks of the river, with a noble background for the picture in the commanding summit of the Wynd Cliff, which overlooks the scene.

The West Gate, a Gothic archway, strongly defended by a double portcullis, with moat and drawbridge, opens into the fourth or principal court already{23} noticed; and as portions of Roman brick are here observed in the masonry, some doubts have arisen as to its date: but whether furnished from an earlier building on the spot, or transported hither from the ruins of Caerleon, is a question which, so far as the writer could ascertain, is still undecided. It seems very

probable, however, that the commanding site occupied by the present castle was originally that of a strong military post, built and garrisoned by the Romans, the ruins of which were converted into a Norman fortress by William Fitzosborne.

In the view from the right bank of the Wye, the western gate is seen in all its elegant and massive proportions. The square tower, with its machicolated parapet, angular turrets, and vertical balustrariæ—through which flights of arrows or other missiles met the assailants—give a striking foreground to the picture; while the contiguous towers and bastions, lessening as they recede, and assuming new and often fantastic shapes, present a vast and highly diversified mass of buildings. Here clothed with trees and shrubs, there jutting forward in bare and broken fragments, and here again rising sheer and high from the water’s edge, their huge blocks of masonry seem as if they were rather the spon{24}taneous work of nature than the laborious productions of art. In this view are comprised the whole line of embattled walls flanking the river, the new bridge, and part of the lower town; the rocky boundaries to the southward, with the modern quay, where the daily steamer discharges her cargo and passengers. The precipitous cliffs, by which the river is there confined, terminate upwards in wooded and pastoral scenes—enlivened here and there by cottages and farms, which command some remarkable and striking views of the river, the town and castle, with its western landscapes of hill, forest, and park-like scenery. A short way beyond the extreme verge of the engraving, the river Wye will shortly be spanned by a magnificent bridge, part of the South Wales Railway, now in progress.

An arched Chamber, cut in the natural rock overhanging the river at a great height, is supposed to have been used as a prison, but more probably as a store-room; for, by anchoring the boats close to the rock, their cargoes for the service of the garrison, whether provisions[28] or ammunition, could be easily hoisted into security by means of a windlass; and no doubt, under the cloud of night, and{25} with a spring-tide, many a goodly bark has been thus relieved of its freight; nor is it improbable that adventurous captives may have thus found their way to some friendly bark, and regained their freedom.[29] In the hands of a skilful romance writer, this scene might be turned to excellent account—more particularly if the descending basket contained a damsel “flying from tyrants jealous,” and her lover-knight stood in the boat to receive her—all heightened by such dramatic machinery as midnight, with the tender hopes and imminent hazards of the enterprise, would easily supply. But all this is foreign to the spirit of archæology, which turns with disdain from such puerile vanities, and beckons us forward to the breach where the iron balls of the Commonwealth were directed with such fury in the last assault. Their batteries played from the opposite height, which the guide will point out as the commanding position which rendered the cause of the defenders so useless and desperate, and added another triumph to the Parliamentary cannon.

The Passage, or gallery, leading down to the vaulted chamber, is accurately shown in the annexed woodcut. It has an air of Gothic antiquity that harmonizes well with the place, for its pointed style and proportions clearly show that it belongs to the earliest portion of the structure. The massive arch, seen through the opening, is that of the mysterious chamber already noticed. The window,[30] terminating the vista, overlooks the river, and seems to project from the precipitous rocks that{26} here form an impregnable barrier to the fortress; and even when the tide is at its full, the window seems suspended at a dizzy height above the water. The uses to which the passage and its chamber were originally applied, were probably those of a temporary refuge and retreat; and were, no doubt, well understood and appreciated by the Norman castellan, to whom the means of successful resistance or safe retreat were the grand objects in a feudal residence.

Such are the general features of this ancient stronghold.[31] But on the minuter points of its history, architecture, and internal arrangements, our restricted limits will not permit us to enlarge; but, aided by faithful engravings and woodcuts, the descriptions, however brief, may serve to convey a detailed and correct notion of the whole.

Persefield.—In the immediate environs, many objects are found to invite the traveller’s attention; but, as a combination of rich English scenery, the attractions of Persefield, or Piercefield, stand pre-eminent. The house and grounds are thus briefly described: The latter extend westward along the precipitous banks of the Wye, as shown in the engraving. On the north is the Wind-Cliff, or Wynd Cliff. The grounds are divided into the lower and upper lawn by the approach to the house, a modern edifice, consisting of a stone centre and wings, from which the ground slopes gracefully but rapidly into a valley profusely shaded with ornamental trees. To give variety to the views, and disclose the native grandeur of the position, walks have been thrown open through the woods and along the precipitous margin of the river, which command the town, castle, and bridge of Chepstow, with the Severn in the distance, backed by a vast expanse of fertile valleys and pastoral hills. But to describe the romantic features of this classic residence with the minuteness they deserve, would far exceed our limits; it is a scene calculated to inspire the poet as well as the painter; and it is gratifying to add that, by the taste and liberality of the owner, strangers are freely admitted to the grounds and walks of Persefield.

The Wynd Cliff.—This lofty eminence commands one of the finest and most varied prospects in the United Kingdom; while the scenery of the Cliff has a particular charm for every lover of the picturesque. Poet, painter, and historian, have combined their efforts to make it a place of pilgrimage; but, to be seen in all its beauty, the rich and various tints of autumn and a bright sun are indispensable accessories. It may be called the “Righi” of the Wye, commanding a vast circumference of fertile plains and wooded hills, all enlivened

with towns, villages, churches, castles, and cottages; with many a classic spot on which the stamp of history is indelibly impressed—names embodied in our poetry, and embalmed by religious associations. From the edge of the precipice, nearly a thousand feet in height, the prospect extends into eight counties—Brecon, Glamorgan, Monmouth, Hereford, Gloucester, Wilts, Somerset, and Devon.

For the enjoyment of this inspiring scene, every facility has been supplied; and even the invalid tourist, with time and caution, may reach the summit without fatigue. “The hand of art,” says the local guide, “has smoothed the path up the declivity, tastefully throwing the course into multiplied windings, which fully accord with its name, and the nature of the scenery which it commands. At every turn some pendant rock girt with ivy, some shady yew, or some novel glimpse on the vale below, caught through the thick beechy mantle of this romantic precipice, invite the beholder to the luxury of rest.” Still ascending, the tourist penetrates a dark-winding chasm, through which the path conducts him in shadowy silence to the last stage of the ascent, which gradually discloses one of the most enchanting prospects upon which the human eye can repose. From the platform to the extreme verge of the horizon, where the Downs of Wiltshire and the Mendip hills form the boundary line, the eye ranges over a vast region of cultivated fields, waving forests, and populous towns, sufficient of themselves to furnish the resources of a principality.

The pens of Reed, Warren, and Gilpin, have been successively employed in sketching the features of this magnificent panorama; but nothing can be more correct and graphic than the following description by Fosbroke:—“What a cathedral is among churches, the Wynd Cliff is among prospects. Like Snowdon, it ought to be visited at sunrise, or seen through a sunrise-glass called a Claude, which affords a sunrise view at mid-day, without the obscuration of the morning mist. This cliff is the last grand scene of the Piercefield drama. It is not only magnificent, but so novel, that it excites an involuntary start of astonishment; and so sublime, that it elevates the mind into instantaneous rapture. The parts consist of a most uncommon combination of wood, rock, water, sky, and plain—of height and abyss—of rough and smooth—of recess and projection—of fine landscapes near, and excellent prospective afar,—all melting into each other, and grouping into such capricious lines, that, although it may find a counterpart in tropic climes, it is, in regard to England, probably unique. The spectator stands upon the edge of a precipice, the depth of which is awful to contemplate, with the river winding at his feet. The right screen is Piercefield ridge, richly wooded; the left is a belt of rocks, over which, northward, appears the Severn, with the fine shores between Thornbury and Bristol, rising behind each other in admirable swells, which unite in most graceful{28} curves. The first foreground appears to the eye like a view from the clouds to the earth, and the rich contrast of green meadows to wild forest scenery,—the farm of Llancaut, clasped in the arms of the winding river, backed by hanging wood and rock. The further horn of the crescent tapers off into a craggy informal mole, over which the eye passes to a second bay; this terminates in Chepstow Castle, the town and rocks beyond all mellowed down by distance, into that fine hazy indistinctness which makes even deformities combine into harmony with the picture.”[32]

An observatory, the guide informed us, was intended some years since to have crowned this noble eminence, and a subscription was got up for the purpose; but some difference having arisen between the projectors of the scheme and the proprietor of the land, it was dropped. It was suggested by a local writer, that a few Doric columns with architraves, however rude, would have had an imposing effect on the summit of the Wynd Cliff, and reminded the classic traveller of the ruined temple of Minerva on the Sunium promontory. “It might,” he says, “be partially immersed in wood; while, in the native rock, niches might be hollowed out; and on a tablet, at the finest point of view, the following words should be inscribed:—Valentine Morris[33] introduced these sublime scenes to public view. To him be honour: to God praise.”[34] This is concise and classical; but it is reserved probably for another generation to witness the completion of the design.

The whole scene, from this point to the Abbey of Tinterne, presents an uninterrupted combination of picturesque and romantic features. Above are hanging cliffs, richly clothed in variegated woods, perfumed with flowers, irrigated by murmuring rivulets, fountains, and cascades, and rendered vocal by the songs of birds. These woody solitudes are the annual resort of nightingales, whose note is familiar to every late and early tourist, who with slow and lingering step measures his leafy way between Chepstow and Tinterne—unable to decide at what point of the road there is the richest concentration of scenery. It is, indeed, a sylvan avenue of vast and variegated beauty, reminding us of the softer features of Helvetian landscape.{29}

Far below, and seen only at intervals through its thick curtain of foliage, the classic Vaga continues its winding course. Here basking in sunshine, there sweeping along under shadowy cliffs—now expanding its waters over a broad channel, or rushing through deep ravines, it is often enlivened by boats laden with produce, or visitors in pleasure-barges, who make the “descent of the Wye,” as, in former days, pilgrims made that of the Rhine and Danube; for the boats that perform the trip from Ross to Chepstow, make, in general, but one voyage, and are otherwise employed or broken up at its conclusion—

It is but recently, says a periodical authority, that the Wye has become at all frequented on account of its scenery. About the middle of last century, the Rev. Dr. Egerton, afterwards Bishop of Durham, was collated by his father to the rectory of Ross, in which pleasant town, situated on the left bank of the river, and just at the point where its beautiful scenery begins, the worthy doctor resided nearly thirty years. He was a man of taste, and had a lively enjoyment of the pleasures of society amidst the beautiful scenery of his neighbourhood. His chief delight was to invite his friends and connections, who were persons of high rank, to pay him summer visits at Ross, and then to take them down the Wye—

which, as well as the town of Ross, had derived a new interest from the lines of Pope. For this purpose, we are told, Dr. Egerton built a pleasure-boat; and, year after year, excursions were made, until it became fashionable in a certain high class of society to visit the Wye. But when the rector of Ross was consecrated to the see of Durham, his pleasure-boat, like that of the Doges of Venice and Genoa, was suffered to rot at anchor; and with no successor of similar means and taste to follow his example, excursions on the Wye became unfrequent, because no longer fashionable. Yet the beauties of the scenery once explored, became gradually more attractive; and some pilgrim of Nature, deviating now and then from the beaten track, spoke and sang of its beauties, until, having again caught the public ear, it was admitted that we had a “Rhine” within our own borders—with no vineyards and fewer castles, but with a luxuriance of scenery peculiarly its own, and with remains of feudal and monastic grandeur which no description could exaggerate. Mr. Whately, a writer on landscape gardening, and an exquisite critic, first directed attention to the new weir at Tinterne Abbey, and one or two other scenes on its banks; and, in 1770, the Wye was visited by William Gilpin, who did good service{30} to taste and the lovers of nature by publishing his tour. The same year, a greater name connected itself with the Wye—for it was visited by the immortal author of the “Elegy in a Country Churchyard.” “My last summer’s tour,” says Gray, in one of his admirable letters to Dr. Wharton, “was through Worcestershire, Gloucestershire, Monmouthshire, Herefordshire, and Shropshire—five of the most beautiful counties in the kingdom. The very principal sight and capital feature of my journey was the river Wye, which I descended in a boat for nearly forty miles, from Ross to Chepstow. Its banks are a succession of nameless beauties.”[35] The testimony thus bequeathed to it by the illustrious Gray, has been confirmed and repeated by Wordsworth, while other kindred spirits, following each other in the same track, have sacrificed to Nature at the same altar, and recorded their admiration in immortal song:—

Authorities quoted or referred to in the preceding article:—Dugdale’s Monasticon.—Baronage.—Camden’s Britannia.—Leland’s Itinerary.—County History.—Local Guides: Heath.—Wood.—De la Beche.—Williams.—Thomas.—Roscoe.—Burke’s Peerage and Commoners.—Chronicles.—Giraldus Cambrensis.—William of Worcester.—History of the Commonwealth.—Life of Cromwell.—Notes by Correspondents.—MS. Tour on the Wye, 1848; with other sources, which will be found enumerated in the article upon Tinterne Abbey.

“There are some, I hear, who take it ill that I mention monasteries and their founders; I am sorry to hear it. But, not to give them any just offence, let them be angry if they will. Perhaps they would have it forgotten that our ancestors were, and we are, Christians; since there never were more certain indications and glorious monuments, of Christian piety than these.”—Camden’s Britannia, Pref. Ages of Faith, Book xi.

he Abbey of Tinterne, though one of the oldest in

England, makes no conspicuous figure in its history, a proof that its

abbots were neither bold nor ambitious of distinction, but devoted to

the peaceful and retiring duties of their office. We do not find that

the secluded Tinterne was ever the scene of any rebellious outbreak, or

the refuge of any notorious criminal. From age to age, the bell that

summoned to daily matins and vespers was cheerfully obeyed; and all they

knew of the great world beyond the encircling hills, was learned,

perhaps, from the daily strangers and pilgrims who took their meal and

night’s lodging in the hospitium.{32}

he Abbey of Tinterne, though one of the oldest in

England, makes no conspicuous figure in its history, a proof that its

abbots were neither bold nor ambitious of distinction, but devoted to

the peaceful and retiring duties of their office. We do not find that

the secluded Tinterne was ever the scene of any rebellious outbreak, or

the refuge of any notorious criminal. From age to age, the bell that

summoned to daily matins and vespers was cheerfully obeyed; and all they

knew of the great world beyond the encircling hills, was learned,

perhaps, from the daily strangers and pilgrims who took their meal and

night’s lodging in the hospitium.{32}

The name of Tinterne, as etymologists inform us, is derived from the Celtic words din, a fortress, and teyrn, a sovereign or chief; for it appears from history, as well as tradition, that a hermitage, belonging to Theodoric or Teudric, King of Glamorgan, originally occupied the site of the present abbey; and that the royal hermit, having resigned the throne to his son Maurice, “led an eremitical life among the rocks of Dindyrn or Tynterne.” It is also mentioned, as a remarkable coincidence in history, that two kings, who sought Tinterne as a temporary place of refuge, only left it to meet violent deaths. The first was Theodoric, who was slain in battle by the Saxons, under Ceolwilph, King of Wessex, in the year 600, having been dragged from his seclusion by his own subjects, in order that he might act once more as their leader. The next was “the unfortunate King Edward,[36] who fled from the pursuit of his queen,” Isabella. The Welsh monarch is said to have routed the Saxons at Mathern, near Chepstow, where his body was buried. Bishop Godwin says, that he there saw his remains in a stone coffin; and on the skull, after the lapse of nearly a thousand years, the wound of which he died was conspicuous—thus verifying the tradition as to the place and manner of his death.

Nothing could be more happily chosen for the seat of a religious community, than the beautiful valley of which these ruins are the unrivalled ornament. It would be difficult to picture, even with the aid of a fertile imagination, scenes more fitted to cherish devout feelings; to instruct us, from the tranquil bosom of Nature, to look up to Nature’s God; and in the exclusion of the busy world, to feel aspirations of gratitude continually ascending towards Him who enriched the valley with his bounty, and in homage to whom that temple and its altars were first erected. The latter, as the work of man, and a prey to neglect and violence, have disappeared or crumbled into ruins; but the former, as the work of God, has lost nothing of its original beauty. The woods that curtain the scene; the river that sweeps along under pendent cliffs of oak; the meadows and orchards that cover and adorn its banks,—all continue as luxuriant, as copious and abundant, as verdant and blooming, as on that day when the first pilgrim-father planted his cross in the soil, and consecrated the spot to the service of God.