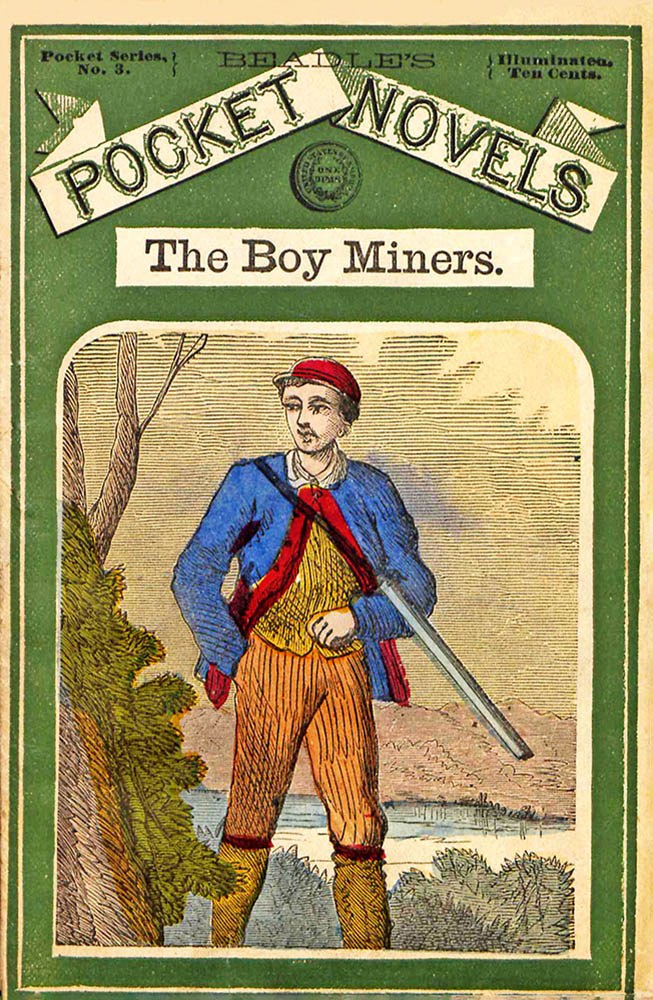

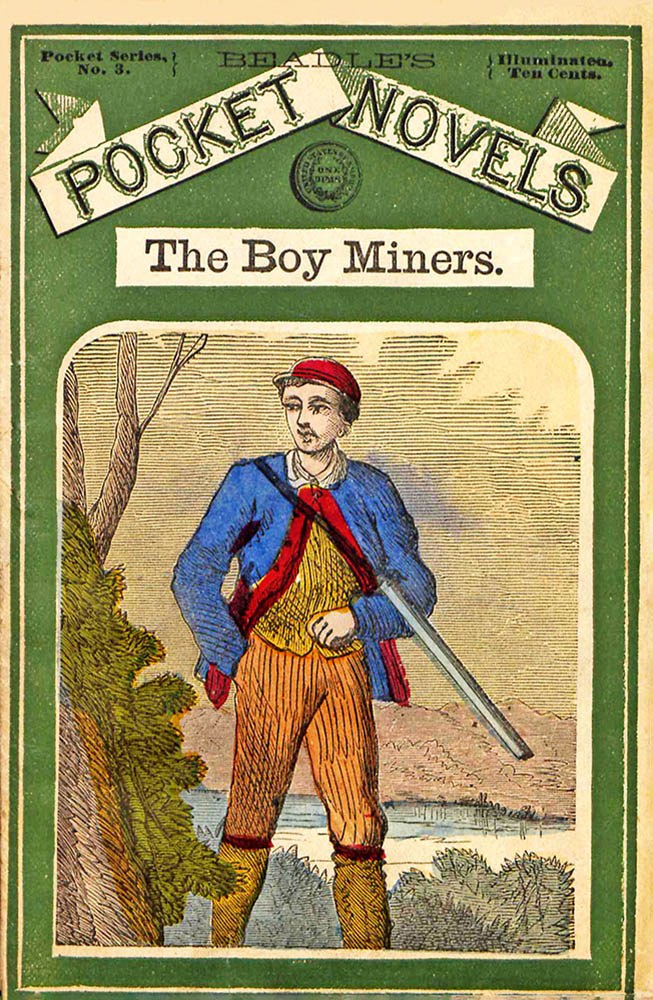

Title: The Boy Miners; Or, The Enchanted Island, A Tale of the Yellowstone Country

Author: Edward Sylvester Ellis

Release date: November 23, 2020 [eBook #63868]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: David Edwards, Jessica Hope and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (Northern Illinois

University Digital Library Nickels and Dimes Collection)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTES

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

THE BOY MINERS;

OR,

THE ENCHANTED ISLAND

A TALE OF THE YELLOWSTONE COUNTRY.

NEW YORK

BEADLE AND ADAMS, PUBLISHERS,

98 WILLIAM STREET.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1874, by

BEADLE AND ADAMS,

in the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

| CHAPTER I. | “THERE THEY COME!” |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| CHAPTER XV. |

Young Edwin Inwood leaped down from the small tree in which he had been perched for the last half hour, and ran swiftly toward the brook where his elder brother, George, and a large negro named Jim Tubbs, were waiting, ever and anon raising their heads, and looking towards the boy who was acting as sentinel, several hundred yards away, as if they were expecting some such an alarm as this.

“Quick! they’ll soon be here!” he added in his terrible excitement.

“How many are there?” inquired George, catching up his shovel at the same time with his rifle.

“I shouldn’t wonder if there were twenty. I’m sure I saw a dozen, any way.”

“More likely dar’s a tousand!” angrily exclaimed Jim, gathering his implements together, preparatory to making a move. “Dis yer’s a nonsince—jest as we gits in among de gold, dem Injins has to ’gin dar tricks.”

“Hurry, Jim,” admonished the young man, beginning to grow nervous. “It won’t do to be caught here.”

“Dey hain’t cotched dis pusson yit, an’ if dey undertooks it, somebody’ll git hurt. I can swing dat pick kind o’[10] loose when I makes up my mind to do so. I’s ready—now whar does ye pitch to?”

“Into the cane, of course.”

George Inwood, loaded down with his gun and implements, hurried up the channel of the brook, for several hundred feet, and then, making a sudden plunge to the right, disappeared as abruptly as if the earth had opened and swallowed him. The next moment, his brother Edwin, a lad some fifteen years of age—whisked after him, and then Jim came lumbering along, somewhat after the manner of an ox, when goaded off his usual plodding walk.

“Dis yer’s graceful!” he muttered, not deigning to look behind him to see whether the envious aborigines were visible, “I never did like to trot, s’pecially when an Ingin was drivin’ me, an’ only does it to please de boys.”

“Come, Jim, move faster!” called the voice of George Inwood from some subterranean point.

“Yas, yas, I’s dar!”——

Further exclamation was cut short, for at this instant the indignant African was seized by the ankle with such force, that he fell prostrate upon his back, and, despite his struggles and threats of dire punishment, was quickly drawn out of sight and hearing.

This was scarcely done, when a dozen Mohave Indians swarmed over the ridge of rocks and trees which bounded the northern part of the stream, and scattered here and there in quest of the gold hunters, whom they had been watching from a distance nearly all the afternoon. Each of them was armed with a gun, several displayed tomahawks and knives at their girdles, while the majority had large, beautifully woven and ornamented blankets thrown over their shoulders.

Running hither and thither, their sharp black eyes darting in every direction, they could not be long without discovering traces of the interlopers. A sort of halloo, something like the yelp of a large dog, when a cow flings him over the fence, told that one of the dusky scamps were on the trail. Immediately the whole pack darted up the channel, and the next moment, had halted before the mouth of a cave, the entrance being of sufficient width to admit the[11] passage of an ordinary sized man; but just now a large boulder prevented their ingress.

Certain that the gold hunters were immured here, and were within their power, the Mohaves indulged in a hop, skip, and dance around the cave, flinging their arms aloft, and shouting continually in their wild, outlandish tongue. When their clamor had somewhat subsided, a gruff voice from within the cave was heard.

“Hullo! dar I say! Hullo! I say! Can’t yese keep yer clacks still a minnit when a gemman wishes to speak?”

The singular source and sound of the human voice had the desired effect, and instant silence fell upon all.

“Am dar any ob yous dat spoke English? If dar am, please to signify it by sayin’ so, an’ if dar ain’t, also signify dat by obsarvin’ de same sign.”

Jim waited several minutes for a reply, but, receiving none, he became more indignant, and was about to burst out in a tirade against them, when George Inwood ventured to suggest that, as in all probability they could not speak the English language, as a matter of course, they were deprived of the ability of saying so.

“But dey orter to know ’nough to say no—any fool know dat,” persisted the African.

“But how can they understand what you say?”

“Clar—didn’t tink ob dat. What am we to do?”

“Defend ourselves—that is all that is left us.”

“I’ll go take a look at dem,” said Jim, beginning to creep along the passage toward the mouth of the cave.

“I insist that you be more careful in your dealings with them. You ought to know what a treacherous and untrustworthy set of people they are.”

Jim promised caution, as he always did in such matters, and Inwood kept close to him to see that he fulfilled his pledge. Reaching the mouth of the cave, the African gave a sneeze to proclaim his presence, emitted with such explosive vigor, that the Mohaves gathered around, startled as though the ground beneath them had suddenly reddened with heat. They recoiled a few steps, and then waited with some anxiety for the next demonstration.

Jim Tubbs had a voice, composed half-in-half of those[12] tones which are heard when a huge saw is being filed, and that which is made by the rumbling of the distant thunder. The judicious mixture made from these, it may safely be said, was terrific and rather trying to a sensitive man’s nerves; and, as he was in rather an indignant mood on the present occasion, when he called to the Mohaves, it was more forcibly than politely.

“What does yer want?”

When a person has reason to believe that the one whom he is addressing has difficulty in understanding his words, he seems to think the trouble can be overcome by increasing the loudness of his tone. Jim repeated his question each time with greater force, until the last demand partook more of the nature of a screech than anything else.

By this time, the aborigines had obtained a good view of the black face, cautiously presenting itself at the opening made by the partial withdrawing of the stone, and one of them, laying down his gun and knife, as an earnest of his pacific intention, deliberately advanced to the entrance of the cave, and reached out his hand.

“Take it, Jim,” whispered Inwood, “he means that as an offering of good will.”

“I hope yer am well,” remarked Jim, as he thrust his immense digits through the opening. “I is purty well, an’ so am all ob us—gorry nation! what am yer at?”

The Mohave had suddenly seized the hand of the negro in both his own with tremendous force, and was now pulling with such astonishing power as slowly to drag the unsuspicious African forward.

“I tell ye let go!” shouted the latter, “it won’t do! Wal, if ye wants to pull wid dis chile, why pull, an’ see who am de best feller!”

Inwood, in his apprehension for the safety of the negro, seized his leg, and endeavored with his utmost strength to stay his forcible departure, observing which, the gentleman in dispute turned his head:

“Nebber mind, George, nebber mind if dem darkeys

[Transcriber’s Note: Several lines of text are missing from the original here due to a printer’s error]

Jim was six feet three inches in height, and along his limbs was deposited an enormous quantity of muscle almost as hard as the bone itself; he was not quick, but he was a man of prodigious strength, and when he chose to exert it, there were few living men who could withstand it. If there could ever be a suitable occasion to exert it, that occasion was the present.

And Jim did call it into play. Closing his great fingers around the hand of the Mohave, he held it as firmly as if it were thrust into the jaws of a Numidian lion, and then bracing his feet against the sides of the cavern, he said:

“Now, my ’spectable friend, you pull an’ I’ll pull.”

At the first contraction of that muscular arm, the Mohave was drawn a foot forward; and, in dreadful alarm, he uttered a cry which brought several of his companions to his relief, and they, seizing him by his lower limbs, pulled as determinedly in the opposite direction.

“If yer gets dis feller back agin, I tinks he’ll be about a foot taller,” muttered Jim, as he gave another hitch with the hapless aborigine, which jerked not only him forward, but those who were clinging fast to his extremities. They, in turn, united in a “long pull, a strong pull, and a pull altogether,” with no effect, except to give the subject under debate a terrific strain.

“Yeave ho! here ye go!”

And with amazing power, Jim Tubbs drew the Mohave clear into the cave, beyond all reach from his companions.

“Now you keep still, or I’ll come de gold tuch ober you!” admonished Jim, as he hurried the captured Mohave to the rear portion of the cave, and delivered him in charge of George Inwood and his brother.

“What do you mean by the gold trick?” inquired the latter, as he caught up his gun, and placed himself in an[14] attitude to command the movements of the captured Indian.

“Why I mean dat—hullo!”

Jim turned and darted up the passage, in which he had detected a suspicious noise. He was not a moment too soon. The red men, furious at the abduction of one of their number before their eyes, had united to force away the stone, and, at the instant the negro returned, one of them had shoved his body half through the opening.

“Out ob dar!” shouted Jim, as, with uplifted pick, he made straight at the intruder. The latter, fully panic-stricken, turned about and whisked out of the cave much more rapidly than he entered, his moccasins twinkling in the air, as if the same means had been employed to extract him, that had been used to draw his venturesome companion in.

The ludicrous appearance of the Mohave, as he scrambled out among his friends, exceedingly pleased the ponderous African, who laughed loudly and heartily.

“Didn’t fancy de way I swung dat pick round! I was kinder loose wid it, an’ if I’d let it drap on him, it would’ve made him dance.”

It looked very much as if our friends, in capturing the Mohave, had, to use a common expression, secured an “elephant.” What to do with him, was the all-important question, now that he was in their power. Being without any warlike implements, he was comparatively harmless, and, as there was no escape for him, except through the passage by which he had entered, it was hardly to be supposed that, so long as he was unmolested, he would indulge in any performances likely to bring down the wrath of his captors upon him.

Withdrawing to the opposite side of the cave, (which was not more than a dozen feet in diameter) he stood silent and sullen, while Edwin Inwood, with his loaded and cocked rifle, watched him with the vigilance of a cat. George Inwood, feeling that nothing was to be apprehended from the present shape of affairs within their subterranean[15] home, passed up the narrow entrance to where Jim was, in order to learn how matters stood there.

At the moment of reaching his sable friend, the discharge of a gun was heard, and Jim hastily retreated on his hands and knees a few feet.

“Are you hit?” inquired Inwood in some alarm.

“Yes, but dey didn’t hurt me; dey hit me on de head!”

“Can they not force back the stone?”

“Not if we can git close up behind it.”

The negro spoke the truth; for, when immediately in the rear of the immense boulder, they could hold it against the combined efforts of any number of men on the outside, and, at the same time, keep themselves invisible, while, by remaining in their present position, they ran every risk of being struck. Consequently, no time was lost in creeping into the proper place, where, for the time being, they felt themselves masters of the situation.

Having successfully staved off all danger for the present, the question naturally arose, how was this matter to end? The gold hunters were walled up in a cave, with plenty of arms and ammunition, little food and no water. The Mohaves, if they chose so to do, could keep them there until they perished from thirst or starvation.

Edwin Inwood soon grew tired of standing in his constrained position, and he cautiously set down his gun, within immediate reach, and then sinking down upon one knee, resumed the work which had been so peremptorily checked by the entrance of the captured Mohave. A large stone, weighing over a dozen pounds, was held firmly in position, while he employed both hands in drilling a hole into the center. This, as all know, is quite a tedious operation, and, although he had the usual tools of the blaster of rocks, he made slow progress. Still, he was animated by that great spur to exertion, necessity, and he applied himself to his task without intermission.

While his brother and the gigantic African were parleying and debating upon their situation, he succeeded in reaching the depth desired, and then carefully removing the debris, he thoroughly cleaned the cavity, as does the skillful [16] dentist when preparing our molar for the golden filling. Into this hollow, the lower portion of which he had managed to give a globular shape, he poured several handfuls of Dupont’s best, a piece of fuse all the while standing upright, while the jetty particles arranged themselves around it. Dust and sand were then carefully dropped in, until they reached the surface of the stone, when it assumed the appearance of a solid, honest fragment of rock, with the odd-looking fuse sprouting from its side.

“There!” exclaimed the boy, with a sigh, “it is done, and I think it will answer very well.”

As he looked up, he saw the Mohave still standing silent and sullen, but with his dark eyes fixed upon the young artisan with a curious expression, as though a dim idea of the meaning of all this was gradually filtrating through his brain.

“What do you think of it?” asked the youngster, holding up the block of stone, with a smile at his own success, and at the whim which prompted the query. If the questioned had any idea of the meaning of the question, he did not choose to manifest it, but maintained the same stolid silence as before.

“I don’t suppose it will suit you very well; at any rate your friends will be more astonished than pleased with it.”

The boy called his brother, who immediately made his appearance. It took but a few moments to explain his scheme, which pleased the young man.

“It can do no harm to us to try it,” he said, as he picked it up and carried it to Jim. The latter listened to the explanation a moment, and his great eyes rolled with delight at the scheme.

“Fus’ rate, fus’ rate, almost as good as de gold trick.”

“It is as good a time as any to try it, isn’t it?”

“I s’pose so—you kin see dey’re purty thick out dere.”

Inwood produced a match and set fire to the fuse. It burned quite rapidly, like the string of a Chinese cracker.

“Throw it out as quick as it reaches the sand!” called Edwin from the cave.

“Golly, it’s dar now!” exclaimed Jim, springing up, and[17] preparing to toss it out among the Mohaves gathered outside. Unfortunately, his elbow struck the side of the entrance, and the bombshell dropped at his feet. Believing it about to explode, the negro ran back in dismay, when Inwood, with remarkable coolness, drew the huge boulder a little to one side, and, catching up the stone, swung it through the opening. Before the Mohaves could understand the intent of this, the terrible object burst into a thousand fragments, and with wild whoops of terror, the red men scattered in every direction, as though they themselves were a portion of an immense bombshell which had exploded.

The success of Edwin’s scheme, and delight of our friends were complete.

“Anybody killed?” asked Jim, and his companion peered cautiously around the edge of the boulder.

“I suppose not; but they have been hit and frightened almost out of their senses, and that will do as much good as though it had slain half a dozen of them. I don’t believe they will come back again.”

“Dunno ’bout dat; dey’re a queer set ob darkeys, am de Injins.”

“I don’t think, from what I have heard, that these Mohaves are the bravest tribe of Indians in California, and they are too much afraid of us to make much trouble so long as we remain in the cave. And that reminds me of our prisoner—what are we to do with him?”

“Kill him,” was the decided response.

“No; that will never do; we cannot murder him.”

“Let me come de gold trick ober him.”

“I haven’t learned what that is.”

“Jes’ come back where he am, an’ I’ll soon larn you.”

Inwood was apprehensive that the “gold trick,” so often referred to by his sable friend, meant something cruel, and he concluded it safer to restrain him.

“Never mind about it now, Jim; I have a plan of my own.”

“What’s dat?”

“Let him go.”

“You don’t mean dat?”

“Yes, I do; although he is our enemy, and although his own people are barbarians, who are none too good to put us to the worst kind of torture, if they had us in their power; yet, we are Christians, and cannot do such a thing.”

“Dunno but what you are right; fetch out de feller.”

“Besides,” added Inwood, as he moved away, “it may change their feelings toward us. They know we have one of their number in our power, and, if we let him go unharmed, they will have less reason to look upon us as their enemies—this one at least will regard us as a friend.”

The decision made, it was carried out without delay. The Mohave was led from the cave, carefully along the passage toward the opening. He evidently believed he was being conducted to his doom; he was as sullen and stoical as his race generally are at such times. Jim had rolled the boulder back, so as to afford him free egress, and Inwood, first taking him by the arm, motioned for him to retire. The aborigine did not comprehend his meaning, when his captor turned his face toward the opening, and gave him a gentle shove. This was a hint which could not be misunderstood, and he darted out in a twinkling, and disappeared.

“Now, I will take a look and see whether there are any of them left,” said Inwood, as he stealthily followed the liberated Mohave.

By this time it was growing dark, but objects for a considerable distance were quite distinct, and George Inwood made a thorough reconnoisance of the bed of the brook for several hundred yards up and down. At the end of a half hour, he returned with the pleasing word that the Mohaves had taken their departure.

Having given this episode in the history of the gold hunters, it is necessary to take a look at events which came to pass a few months previous.

One bleak day in the winter of 1857-8, a young man was walking slowly down Broadway, humming a lively tune in a mournful voice, and doing his utmost to keep up his spirits, which, just then, were at their lowest ebb. In the nature of things, the poor fellow could not be otherwise. While in the senior class in college, preparing for the ministry, and succeeding most brilliantly, he was summoned home to New York, just in time to receive his father’s dying blessing; his mother having fallen asleep several years before, he was thus left an orphan, with a younger brother to provide for. As his father had been a leading merchant in the great metropolis, there seemed to be little difficulty in this, and he assumed the control of affairs at once.

But the mutterings of that financial storm were already heard in the sky, and it soon burst over the land, toppling old, established houses, like so many ninepins, and carrying woe and desolation to many a hearthstone. George Inwood placed his shoulder to the wheel, and toiled manfully; but, where so many thousands of experienced merchants were swept away by the current, it would have been almost a miracle, had he been able to resist the whelming tide. Finding it useless, he threw up his arms, and went down with the multitude. When everything was gone, he found that he still owed his creditors many thousand dollars.

And so he hummed the lively air in his mournful voice, as he dreamily walked down Broadway, and asked himself[20] what was to be done. He was poverty-stricken, with his younger brother depending upon him, and the big African, Jim Tubbs, who had always lived in the family from his childhood, with no means of support.

Naturally, a hundred schemes presented themselves, as they always will to a young man, when thrown upon his own resources. He might serve as a clerk—that is if anybody wanted him, which was by no means likely; he might teach, if any school was in want of such a teacher as himself, which was equally improbable. He might do any thing, if the opportunity were given him; but, during these “hard times,” he soon learned that the worst possible place for a man out of employment, is in a large city. When he was turned away again and again, his heart failed him, and as he hummed his lively air in his mournful voice, he came to a conclusion which he ought to have made a considerable time before.

“I must leave New York; I shall soon starve here.”

When he reached his lodgings, where his brother Edwin was staying, and where Jim managed to earn his own board, by doing odd jobs around the house, he called the two together, and proposed the oft-repeated question:

“Where shall we go?”

“Let’s go to Quito,” said Edwin, who had just been studying his geography, “they always have spring weather there, and plenty to eat, and so they have in several other places in South America.”

“It is hardly the place for us, however.”

“I tells you whar to go,” said Jim.

“Where is that?”

“I’s been tinking about it for free weeks, an’ made all de ’quiries possible, an’ found out it’s jest de place for us, an’ dat’s Californy. Dere’s a man stayin’ at this house now—his name is Swill—no, Mills, an’ he’s jest got back from Californy, an’, golly! you orter hear him tell ’bout de country! It’s awful splendid,” added Jim, in his enthusiasm.

“It will be quite an undertaking to go to California, and we’ll take a day or two to think about it,” said Inwood, feeling at the same time that the Golden Gate was the door[21] through which he should pass to comfort and wealth. In the evening, he walked out alone to think over the matter.

It being nearly ten years since that flood-tide of navigation had set in toward California from every part of the world, the charm, in a great measure, was now broken, and those who went there, did so, very frequently, for other purposes than to dig gold. Yet, Inwood concluded that if he went, it should be for the purpose of extracting the yellow metal from the rocks and earth. He was twenty-five years of age, his heart was set upon being a Christian minister, and he felt that if he ever intended to become one, even with the help which his church extended to indigent men, he had no time to plod up the hill of fortune.

But right here arose the troublesome question, how was California to be reached? He had but little over a hundred dollars, barely sufficient to pay his own passage, without taking into account the necessity of carrying at least Jim with him, and the outfit which was indispensable.

But again, kind Providence smiled upon his project. After announcing his willingness to go to California, if he possessed the means, Jim Tubbs suddenly disappeared, and was gone for a couple of days. When he came back again, he was very important, and seemed as well becomes a man who carries a mighty secret in his breast.

“Doesn’t make no difference where I’ve been,” he said rather savagely, in response to the inquiries of the slip-shod, bulky landlady. “I’s been on bis’ness—dat’s whar I’ve been—on very ’portant bis’ness. Yas, ma’am.”

The tubby landlady lowered her head, as does a cow when about to charge, that her spectacles might slip down far enough on her pug nose to allow her to look over them. Then she stared at Jim a moment in mute amazement.

“A black man off on bis’ness—never heard of such a thing,” and she, lifting her skirts rather gingerly, retreated from the apartment, leaving Jim alone with the two Inwoods at the tea-table. The two latter knew that the African had some news to tell and they forebore to question him, choosing to wait until he was ready to unbosom, which was just what he didn’t want them to do. He waited and[22] waited for them to inquire of him, until he could wait no longer.

“Gorry’ation! why don’t you ax me?” he finally demanded in high dudgeon.

“Ask you what?” mildly inquired George, who saw that the secret was coming.

“Why, what I’ve got to say.”

“How did I know you had anything to say?”

“’Caus you did know it—dat’s de reason. I’s been an’ seen Captain Romaine—mighty glad to see me. ‘How are you, Jim?—how’s all de folks?—how’s George an’ Ned getting ’long? Why don’t dey come down an’ see me?’ Couldn’t do much, stuffed one so full, I liked to cracked open from my chin down to my heels.”

“That’s very pleasant, but had you your important business with him?”

“’Course I had—very ’portant, but you don’t seem to care much about it, so I won’t take the trouble to tell you.”

If the curiosity of Inwood had not been already aroused, he would have left the African alone, knowing that he would burst, if compelled to hold his secret a half hour longer. So he asked him:

“What was it, Jim? don’t keep us waiting.”

“Wal, the way ob it, you see, was dis way: Arter the Captain had axed about my healfh, free, four times, I tells him what had happened, an’ how we wanted to go to Californy. ‘Is dat so?’ he axed me, in a great flurry; ‘how lucky dat are. Old Mr. Inwood was allers a good friend ob mine, an’ I’m mighty glad I can do sumfin’ for his children. I’s Captain ob dis steamer, Jim,’ said he, ‘an’ we’re going to sail on Saturday. Tell George, an’ Ned, an’ yourself to git ready an’ sail wid me. I’ll land you on de Isthmus, (don’t know whar dat am) an’ give you a ticket cl’ar to San Francisco’—dat’s what he said, George—cl’ar he did.”

This was as pleasant as unexpected to George and Edwin, who expressed their delight to each other, and commended the shrewdness of Jim Tubbs.

“How came you to think of the Captain?” inquired the younger.

“Wal, you see I’ve know’d him for a dozen years. When dat steamer used to run to New Orleans, ole Mr. Inwood got him de place ob Captain on it, an’ before dat, when Captain Romaine’s wife died, an’ he was too poor to bury her, ole Mr. Inwood done it all for him. Den gitten him de place ob Captain right arter dat—why, I tell you it was almost more dan de man could stand, an’ he’s mighty glad to do anything he can for his children.”

“I’ll go down and see him to-morrow.”

“Yas, dat’s what he said he wanted you to do—you go right off, for he wants to see you mighty bad.”

“He sails on Saturday, and to-day is Thursday. We must get ready to-morrow. Well, we can do that easily enough, as we are not going to take a fortune with us to California, and a few hours are enough to get our baggage together.”

“Dar’s plenty ob room on dat steamer. I tell you, she’s a whisker, an’ she can take a big lot ob people. De Captain showed me frough ebery part ob it, an’ it war a sight to see. I told him I shouldn’t go, ’less he’d let me work my passage. He kinder laughed, an’ said if I was so anxious to make myself useful, he’d find some little jobs for me to do somewhere ’bout de boat.”

The next morning, George and Edwin Inwood went down to the wharf, and made a call upon Captain Romaine, who commanded the California steamer, “Golden Gate.” The large hearted captain was glad to see them, shook them both cordially by the hand, and, having learned how matters stood, from the loquacious Jim Tubbs, he soon put his friends at ease. They agreed to take passage with him on the following day, and then bade him good morning. As they were stepping off the plank, the captain touched the shoulder of George, and motioned him aside.

“These are dreadful times, and I know it has gone hard with you. A man who is going to California, as you are, needs quite a pile to equip him. Now, my boy, if you need anything, I hope you will do me the kindness to say so; for nothing would give me greater pleasure than to do a favor for the son of the best friend I ever had.”

Inwood thanked him, but assured him that he needed nothing. He felt that he could not receive any more favors at the hand of one who had already done so much.

On the following day, when the Golden Gate turned her head down the Atlantic, and steamed swiftly toward her distant destination, she carried with her the brothers Inwood, and the colossal African, Jim Tubbs.

There was a strong attraction which drew George Inwood toward the golden sands of California, to which we have not even hinted thus far; but it is high time it received notice.

Several years before, when the young student had just entered college, he was descending the Hudson in the ill-fated Henry Clay. On board, he formed the acquaintance of the most engaging young lady he had ever met. Intellectual, vivacious and accomplished, he felt strengthened mentally and morally when he left her presence—a condition far different from that in which one is sure to vacate the society of nine-tenths of the fashionable women of the present time.

A mutual interest sprang up between the two, and everything was progressing delightfully toward a tenderer state of feeling, when that well-remembered calamity burst upon the doomed steamer. In the confusion and tumult, Inwood, who was an excellent swimmer, became the means of saving Miss Marian Underwood and her father from death by drowning.

There can be but little doubt of the result of all this, had matters been left to take their natural course, but Inwood had just entered college, and the next tidings that reached him relating to the Underwoods was, that the father, who was quite wealthy, had removed to California, and settled quite a distance to the south of San Francisco. After deliberating a long time upon the matter, he addressed a respectful[26] but friendly letter to Marian, and then anxiously awaited the reply; but it never came, and, concluding that her hand was pre-engaged, he did not repeat the experiment, and did his best to forget her.

Absorbed in his studies and preparations for his sacred calling, he succeeded, not in forgetting her, but in preventing her occupying his thoughts so prominently, although this would have been impossible, had he known that the letter so carefully written had never reached its intended destination, and that the fair Miss Underwood often wondered and as often sighed that he did not seem to deem her worth the trouble of a letter.

But now that Inwood’s attention was drawn toward California, the image of this lady constantly rose before him, and he found himself speculating, at all times of day, regarding her. The great question was, whether there was “room” for him in her thoughts—that is, the room which he wished—that which should exclude everything else. He resolved to find out her residence, and make her a call—his subsequent course regarding her to be determined by the reception he received, and her manner toward him.

The voyage to Aspinwall was without incident worthy of mention, as was the trip across the isthmus on the new railroad, which had been finished a little over three years. The journey was an unceasing delight to Edwin, who was just of that age when everything seen and heard make such a weird impression upon the mind. The broad, surging Atlantic, the vessels which skimmed like sea-gulls along the horizon’s edge, the glimpse of the tropical islands, the majesty of the storm, the exuberant vegetation of the isthmus; these, and hundreds of other sights, made up a continual banquet for him upon which the eye could feast and never become sated.

Captain Romaine presented each of them with through tickets to San Francisco, so as to be sure of their reaching their destination without further expense.

They waited several days at Panama for the steamer which was to carry them the rest of the way, and when they went on board, found themselves greatly crowded for[27] room, and obliged to undergo much privation in the way of food; but they were as able to bear it as were the rest of the passengers, and were none the worse, when, on a bright morning in early spring, they landed in San Francisco.

The first step was to secure temporary lodgings, which was done without difficulty, and then, while Jim sat on the low porch in front of their “hotel,” and smoked his pipe, George and Edwin wandered over the new city. The curiosity of both was, perhaps, equal, and the day passed rapidly away in gazing at this wonderful giant which sprang so suddenly into full grown manhood.

By making careful inquiries, George learned that Mr. Underwood was settled to the south some fifty or sixty miles, and was one of the wealthiest land-owners and stock-raisers in that section—which was anything but pleasant information to Inwood, who would have much preferred to hear that they were in destitute circumstances—in order that he might call upon them, and feel himself upon something like equal terms. The information, indeed, seemed to make our young friend reconsider his decision of calling upon the Underwoods until he returned from the mines laden with wealth, when he could have no hesitation in doing so.

Perhaps, if he passed within the immediate vicinity of Underwood’s ranche, as some of the people termed it, he might seek occasion to get a glimpse or peep at Marian—but nothing in the world should induce him to do more.

George Inwood had about a hundred dollars—not enough to procure him the outfit he needed. He had brought three rifles, three revolvers, and some cooking utensils with him; but he still needed digging and mining implements, cloth for tents—to say nothing of a horse apiece, and one or two mules to carry their luggage.

As a matter of course, it was out of the question to think of procuring these; and, as the best that could be done under the circumstances, he bought a rickety old mule, capable of carrying all that could be piled upon his back, and going like a clock when wound up, without retarding or increasing his speed, and disposed to walk straight over[28] a precipice, if it happened to be in his way, unless he was gradually shied off by Jim Tubbs placing his shoulder against his, and forcing him to swerve from his course.

“Dat are beast’ll carry all we’ve got to carry, ’cept ourselves, an’ if thar’s only room for us to get on, he’d carry us too,” remarked the negro, when everything was ready, and they were about to start.

“Yes; he will answer for our luggage.”

“And must we walk?” inquired Edwin in dismay.

“I do not see how it is to be prevented,” replied his brother, as cheerfully as he could speak.

“Why don’t you buy free hosses?” inquired Jim.

“For the reason that I have not the funds to do it with. I haven’t enough money left to buy the poorest animal, in the shape of a horse, that walks the streets of San Francisco.”

“If you hain’t, mebbe somebody else has.”

“What do you mean?” inquired Inwood, in perplexity.

Ah! wasn’t that a moment of triumph for Jim Tubbs? How cool and deliberate he tried to be, as he shoved his great hand away down in his pantaloons pocket, until it looked as if he were fumbling at his shoe string, and finally fished up a huge leathern purse, so corpulent that it had very much the appearance of that humble kitchen edible known as the dough-nut.

“Dar!” he said, as he flung it carelessly toward the amazed George Inwood, “mebbe dar ain’t nofin’ in dat! Mebbe dat’s all counterfeit; mebbe Mr. Tubbs hain’t been sabin’ up his money dese five years! ’Spose you look at dat—p’raps dar may be sumfin’ or other in dar.”

Jim leaned back against the column of the porch, cocked his old wool hat on one side of his head, shoved both hands down into his pockets, carelessly swung one foot around the ankle of the other, so that it was supported on the toe, and then, smoking his little black pipe, looked at Inwood, as he opened the purse and counted out the yellow gold pieces one after the other, until he had finished.

“How much do you make?” asked Jim, in the same style that he would have inquired the time of day.

“Four hundred and seventy dollars. Is this all yours, Jim?” inquired Inwood, hardly comprehending the pleasant truth.

“Shouldn’t wonder now if I had sumfin’ to say ’bout it.”

The three withdrew to a more private place, where the money was again counted, and it was found to amount to the sum mentioned. Jim explained how he had been engaged in saving for the last five years, as he had an idea that there would come some “’casion” like this. He was shrewd enough to keep its existence a profound secret until the crisis in their affairs, well knowing that Inwood would have considered that moment of necessity as at hand long before.

And so the three horses were purchased, and a number of articles which they needed, and, leaving San Francisco, they took a southeast direction toward San Jose and continuing on in the same course, struck a pass in the Coast Range near the 37th parallel.

By this time, they were far beyond the limits of civilization, and traveling in a wild, savage country, where they occasionally met emigrants and miners, but more frequently encountered red men and wild beasts.

California then, as now, was rapidly filling up, but among the mountains were thousands of miles where the foot of white men had never trod, and where, beyond question, the auriferous particles lay in glittering masses, only waiting for the spade of the miner, or the rock-splitting powder of the blaster.

Before reaching the regions of the mountains, Inwood made careful inquiries, and learned that the residence of the Underwoods lay but a small distance from San Jose, and that, by a slight deviation from his course, he could take it in his path. He did so, neither his brother nor the astute African entertaining the slightest suspicions of the true object which drew him thither.

They caught sight of the large Mexican-looking building, with its low roof, broad wings and extensive outbuildings, its vast droves of cattle and sheep, which were scattered[30] here and there over an area of many miles; all these signs of the thrift and wealth of the owner, and it was with strange emotions that Inwood halted on a small eminence a short distance away, and gazed down upon the pleasant scene.

He saw no signs of life about the house. Here and there were to be seen one or two men passing hither and thither, over the hills or among the cattle, but the house itself was as still as death, and the thought once occurred to his mind that, perhaps, the proprietor lay cold and inanimate within those shaded rooms, or, perhaps, Marian herself was stretched in the robes of the tomb.

Jim proposed that they should honor the proprietor of this estate by spending the evening with him, but Inwood objected, and they encamped in an adjoining piece of wood. When everything had been made ready for the night, and the full moon had risen, Inwood left his companions, and sauntered toward the house, his heart throbbing tumultuously with its varied emotions.

As he walked slowly by, he caught the faint notes of the guitar, and heard a low, sweet voice humming a familiar song. He looked in the direction whence it came, and, through the interlacing vines, could faintly detect the form and outline of Marian Underwood. He knew it was her—he recognized the voice, and twice he paused and was about to enter the gate; but he checked himself by a painful effort of the will, and, loitering as long as he dared in the vicinity, he turned on his heel and wandered back.

“When I return, I will call!” was the comforting conclusion he gave himself.

In a few days, by patient traveling and perseverance, they reached the eastern slope of the Coast Range, and found themselves in the San Joaquin Valley, where they intended to prosecute their search for gold. Carrying out their purpose of getting into a region where there was little danger of being disturbed by any of their own race, they followed the slope to the southward, keeping among the mountains, and guarding every movement.

They “prospected” a long time, and suffered at first for[31] want of food, but they soon overcame this difficulty, and prosecuted their search for gold with greater vigor than ever. They had poor fortune for awhile, but they pushed resolutely forward, and finally came upon a small mountain stream, which contained an abundance of the shining particles among its sands.

Here they would have pitched their tent, had they not accidentally discovered a remarkable cave, which answered their purpose so well, that they carried everything within, and at once made it their quarters. Their horses were tethered in a dense grove further down the stream, where they were visited once a day to see that all was well.

They had been here but a few days, when they discovered signs of Indians, and Edwin was put on watch, while the others busied themselves in “making hay while the sun shone.” The young sentinel had been there but a short time, when he descried the troublesome visitors approaching along the slope; and what then and there took place our good readers have already learned.

The cave which afforded such an opportune retreat to Jim Tubbs and the Inwoods, was one of these natural formations which are occasionally found, and which have more the appearance of being the handiwork of some skillful architect than of nature.

A narrow passage, sufficient to admit an ordinary sized man, extended about thirty feet, when it opened into a broad chamber, which was lighted by several thin rents in the rocks overhead, they being so massive as to exclude all hope of ingress from that direction. The only disadvantage connected with this subterranean dwelling was, that during rainy weather, it required extreme care to prevent its being flooded. Occasionally, they were driven out in this manner; but there being a lower portion of the mountain close at hand, the water thus gathered, almost as speedily filtrated through the rocks into the outlet.

When George Inwood made his reconnoisance, after the departure of the Mohave Indians, he was confident of finding some of them dead, or desperately wounded; but, to his surprise, he discovered neither. He was rather pleased at this; for he had never slain a human being, and his teaching and tastes were utterly opposed to it. He more than expected that, ere he saw San Francisco again, he would be compelled to slay some of the troublesome aborigines in self-defense, but, until absolutely compelled so to do, he had resolved to abstain from it altogether.

“De next thing, I s’pose, am whedder dem hosses are wisible or inwisible. I ’clines to tink dey’re inwisible,” remarked[33] Jim, when informed that the red men had taken their final departure.

“They have been undisturbed,” replied Inwood. “I took a look at them before I came in.”

“Bless de good Lord for dat; I hopes dey will let dem animals be; for if dey tucks ’em away, we’ll hab a mighty hard road to trabbel to get back agin—carrying dem big piles ob gold.”

“Ah, Jim, we haven’t got that gold yet——”

“But ain’t we getting it, eh? I s’pose I didn’t get a pocketful dis berry arternoon, did I?” he demanded indignantly.

“We have comparatively a small quantity, and there’s no telling when that will give out.”

“I tink it’s gibbin’ out all de time, an’ if it only keeps on gibbin’ out long ’nough, we’ll soon get all we want.”

“I hope we may, but I very much doubt it; and come to think, I believe we have nothing for supper. How is that?”

“You’re right—not ’nough to feed a ’skeeter.”

“You ought to have done some fishing for us, Edwin.”

“I would, if you hadn’t put me in the tree, and set me to watching for the Indians.”

“Dat is so,” assented Jim, quite emphatically, “couldn’t watch a fish at de same time. We’ll have to go widout supper, an’ den make up when we get de chance agin; dat’s de way I ginerally fixes it. I can go a week widout eatin’ anything, but I tells you Jim Tubbs ’gins to feel holler, an’ he makes meat fly when he git de chance.”

“We can then wait until morning.”

By this time, it was completely dark in the cave. The three conversed together awhile longer, and then Jim, having finished his pipe, arose and said:

“I tinks I takes a look at de hosses.”

“You had better remain where you are. They are all right, and you may get yourself into trouble.”

“Ain’t afeerd; who can git me into trouble? Jus’ let me try de gold trick on ’em, an’ dey’ll be glad ’nough to cl’ar de track.”

“You haven’t told us what that gold trick is.”

“You’ll hab to wait now till I come back,” said Jim, as he knocked the ashes from his pipe, “takes some time to ’xplainify de science ob dat movement.”

With which information, he made his way to the mouth of the cavern, accompanied by George Inwood, who gave him a parting admonition.

“Be very careful, for some of these dogs may be loitering around, and waiting for the chance to cut you off.”

“I’ll be keerful, ob course; look out for yourselves, an’ don’t let anybody in till you knows who he am. Some ob dem darkeys may try dere tricks on you, an’ you can’t be too keerful.”

“You needn’t be afraid of my getting careless; you’re the one who needs the most advice.”

“O, I always keeps dark,” laughed the African, with which profound witticism, he turned the corner of the cave and disappeared. Inwood waited awhile at the opening of the passage, listening and watching, but only the murmur of the brook caught his ear, and he could see nothing but the dark wall of bank which shut out his view beyond, and above these, in the clear sky, floated the full moon. The hour and the surroundings were impressive, and he remained a long time in a kneeling position, lifting up his heart in silent communion with the only One who then saw and heard him.

When he returned, he found his younger brother somewhat apprehensive at his continued absence.

“If the Indians should come down upon us when we are separated,” said Edwin, “I don’t think we would get off as well as we did to-day.”

“No; if we hadn’t this cave to retreat to, we should have seen trouble. As it is, I am a little anxious about Jim.”

“He is careless, but he has been very fortunate. I never saw anything so strange as that which happened to him when we were coming through the mountains. Don’t you think that was strange, George?”

“Very Providential, indeed, although I did not see it myself.”

“I did; he was only a little ways ahead of us, riding along on his horse, when those two Indians sprang out from behind the trees, not more than twenty yards off, aimed both their guns straight at him, fired, and then run away.”

“And never harmed him?”

“Never touched him; he said he heard both bullets whistle past his ears.”

“It was very singular, but not unaccountable. His color and his size are such as to startle these superstitious people, and, no doubt, when these two aimed at him, their nerves were very unsteady, and to this alone their failure is to be attributed.”

“Then he has been in danger several times since we have been here, and was scratched a little this afternoon—so he told me—but he hasn’t been really hurt.”

“He is great help to us. I don’t know what we could do without him. He can do more work in a day than I can in a week, and he has got to be a good shot, too. We must arrange that, however, so that you can do the hunting for food, while we do the hunting for gold.”

“I am ready to begin at any time, and have wondered why you haven’t set me at work before,” said Edwin, with great animation, at the prospect of a day’s ramble through the woods.

“It is with some misgiving, as it is, that I consent to this step. Remember you are very young, Edwin, and there is a great deal of danger for an old hunter in this part of the country.”

“Not if he is careful, and you know I would be careful. I shall always keep a sharp look out for grizzly bears.”

“They are dangerous enough, but not so dangerous as the red men.”

“But don’t you think they are easily scared?”

“That may all be, and yet, it isn’t to be supposed that they would be much frightened at the sight of a youngster[36] tramping through the woods with a gun on his shoulder.”

“I will not wander off beyond call.”

“You must remember that; for if you get lost, I don’t know how you would ever find your way back again.”

“I should follow up the stream.”

“But do you suppose this is the only stream in the mountains? There are hundreds of such, and you would be a great deal more likely to get upon the wrong than upon the right one. I mention these facts, because I wish to impress upon you the great necessity of being careful. Boys are very seldom inclined to be thoughtful, and you are no exception to the general rule.”

Edwin repeated his resolve to take good heed of what he did, and appealed to his record since coming into California in support of his actions.

“Yes; I am glad to say that you have, but I sometimes tremble to think of what we have done.”

“You ain’t sorry, George?”

“No; but I am frightened almost. Just to think that we are entirely cut off from the civilized world, and it is known to these Indians that we are here.”

“But they can’t harm us.”

“Suppose they took it into their heads to root us out, what is to hinder them? They could soon starve us to terms, and then do as they pleased with us.”

“You seem gloomy to-night, brother.”

“No; I do not mean to be so—I wish you to understand truly our situation.”

“I am sure I do—but isn’t Jim gone a long time?”

“Hark!”

Faintly through the still night air came the far-off exclamation:

“Hold on dar! hold on dar! or I’ll come de gold trick ober you!”

When Jim Tubbs issued from his subterranean domicile, he was rather too strongly inclined to act upon the report of Inwood, that is, it had been affirmed that there was no visible danger; he believed there was none, and, accordingly, he started straight for the tethering ground of the horses and mule, to make sure that they had suffered no disturbance from the marauding Mohaves.

“Dat are place whar we put ’em, is de place dat I selected, an’ dar’s no danger ob dere being troubled while dey stay dar,” he muttered, as he walked rapidly along, occasionally pausing to make sure that no one was following him.

“I always understood hosses,” he added, as he approached the vicinity of the dense undergrowth. “Dar ain’t many——”

He paused with unutterable emotion as he drew the bushes aside, and there, where they should have been, he saw them not! For a moment he was completely stupefied, and stood like one who, from the tangled web of a dream, endeavors to form the skein of coherent thought.

But he speedily recovered himself, and was sharp enough to comprehend that the animals must have been abstracted very recently, and were within the possibility of recovery. With a muttering exclamation of impatience, he dashed headlong through the bushes into the open space beyond, and stared around. Being at the base of the mountains, he was also on the edge of a broad valley, and the bright moonlight gave him quite an extended view over the broken, rocky country.

It required but one sharp glance of the African to discover, about a quarter of a mile distant, the three horses[38] and one mule, making their way among the boulders and patches of broken land, with all the deliberation with which they would have answered the call to work. Jim paused long enough to see that no one was driving them, when, uttering the exclamation which has been given at the close of the last chapter, he started on a full run after them.

With his usual thoughtlessness, he had come out without his gun, and he was now running at his utmost speed, entirely regardless of his personal danger from the hubbub he was creating, and from withdrawing so far from his base of operations. There was something so singular in the spectacle of these four animals leisurely trotting off over the country, that he ought to have hesitated and attempted to explain the matter before venturing after them in this open, boisterous manner.

It was observable, too, that, immediately after Jim gave the terrific outcry referred to, the slow trot of the animals increased to quite a brisk gait, a thing so unusual on the part of the mule, as to cause no little wonder upon the part of the pursuer.

“Beats all natur’!” he exclaimed, as he struck his foot against a stone, and was almost thrown forward upon his hands and knees. “Fust time I ebber seed dat ole mule raise a trot; split two, free rocks ober his head, smashed all de limbs off a big tree ober his back, but no use, couldn’t get him off a walk, an’ dere he goes now swingin’ ’long like a feller on stilts. Beats all natur’!”

It was indeed so curious, that he paused to take a look at them. Just at that moment they were ascending a small swell; and, as they came in relief against the blue sky beyond, they were as plainly visible as at noon day. It was clear that none of them had a rider upon his back, nor was any one following, except him who was trying so valiantly to recapture them. What then was the explanation of this singular movement?

Jim, who had suddenly resumed his running, as suddenly paused, for he had discovered something.

“Wal, dere! if dat don’t beat eberything! dar’s an Ingin[39] right in among dem hosses, or else dat switch-tailed mare has got six legs—one or t’oder!”

It would have required a good pair of eyes to notice this curious fact, had not the mare referred to at that moment fallen somewhat in the rear, when the singular addition to her means of locomotion made the usually large eyes of the African considerably larger.

The fact was apparent that a red man was among the quadrupeds, and inciting them to their rapid gait by some outlandish means which seems to come natural to the aborigines, and which, up to this time, had escaped the attention of the pursuer.

Immediately upon this discovery, Jim broke into a fiercer gait than ever after the fugitives, shouting in his tremendous style—

“Drop dat hoss, I tell you! drop that hoss, or I’ll make you!”

Inasmuch as it was hardly possible for the marauder to hold up one of the equine specimens, if he choose to tumble, it was not exactly clear how he was to obey this command. On the contrary, the animals, including the mule, (which, having once got up a loping trot, didn’t exactly comprehend how to stop it,) increased their speed, and the indescribable whirring howl with which he accomplished it, reached the ears of the exasperated pursuer.

“O, if I only had a gun!” he muttered, as he jogged along, “wouldn’t I pepper dem legs for him!”

At this juncture, the ground assumed a rougher character, and the animals were compelled to deviate to the left to pass a canon, where the waters raged with such fury, that the shrewd Mohave did not attempt to force them into it. Observing this, Jim took the hypotenuse of the triangle, and went sailing down the course in magnificent style, gaining so rapidly, that he gave utterance to a joyous shout.

“Cl’ar de track! or I’ll run ober you! I’s comin’!”

This startling intelligence did not have the effect expected and the copper-colored gentleman evidently concluded that all was not lost, for he still maintained his position between[40] the two horses, and, just then, striking a fording place, he tumbled them turbulently in, and, scrambling up the opposite side, renewed the flight in the same admirable fashion.

“Dat ’ere beats all natur’!” he exclaimed in absolute amazement, as he witnessed the exploit. “Whoeber dreamed dare was so much go in dat mule?”

The chase by this time had become interesting; but, if the Mohave had displayed some natural smartness in stampeding the animals, he now found himself at fault so far as regarded the mule; for this character, as he rattled down the canon with a noise like the charge of cavalry, lost his unnatural gait, and, finding himself back into his natural one, it was impossible to change it under a furlong, seeing which, the charging body dashed forward with such a burst of speed, that the Mohave and his body-guard were compelled to leave him behind. Five minutes later, Jim vaulted like an avalanche upon the saw-like back of the mule.

“Now, ole fellow,” said he, addressing the beast most affectionately, “show ’em what you can do.”

But the mule didn’t seem anxious to obey; for, although his enthusiastic rider thumped his sides with his huge heels until he nearly bounced off, the beast subsided into a moderate walk, as if he didn’t exactly comprehend the meaning of all this uproar upon his back, and all efforts to change his gait was useless. A man in a great hurry has very little patience, and it took but a little while for Jim’s to exhaust itself.

“You want de gold trick comed on you—dat’s what you do, an’ you jes’ wait till I get you home.”

Sliding off the serrated animal, he left him alone, and resumed the chase with greater vigor than ever. The few minutes’ halt which he had made, were precious moments to the Mohave, who, still keeping his body invisible, had improved them to the utmost; but the roughness of the ground was against him, and the African gained rapidly.

“Ye’d better drop dem hosses while you got de chance!” he shouted, as he came sweeping down with great velocity. A few minutes later, he observed a diminution in the speed[41] of the horses, and finally they walked, and then stood still.

“You oughter s’rendered sooner, den I might been ’sposed to show you some mercy; but I don’t know—hullo! where be you?”

He might well ask the question, for, as he came in among the horses, there was nothing to be seen of the aborigine—he had taken the occasion quietly to slip away, when he found himself compelled to relinquish his prize.

Jim stared all around, but could see nothing of him he sought, and concluded, under the circumstances, it was best to make his way back as speedily as possible.

“I tinks I’ve run ’nough to ’arn a ride,” he reflected, as he put himself astride the back of his own horse, and turned his head homeward; “an’, as dat darkey ain’t anywhere’s about, I won’t wait for him.”

When the nature of the ground would permit, he put the horses on a good swinging gallop, and, in a short time, encountered the mule walking leisurely toward him. Before this obstinate animal could be induced to take the right direction, Jim was obliged to get off his horse, and press his shoulder against that of the mule, until he had described a half circle, when he came round right, and was left to go without any other direction.

The rider exercised himself awhile in endeavoring to get him off his walk, but he speedily gave that over as useless, and rode ahead, well aware that so long as he kept a linear direction, the long-eared animal would eventually come up with him.

It was not long before he struck the canon, but at a point where it looked unsafe to cross. Believing himself above the place he had forded, he turned down its bank in quest of it; but, after going fully a mile, discovered his mistake, and was about turning back, when he caught a glimpse of a broad sheet of water, and suspected at once that here was a lake into which the stream flowed. As the roaring, compressed canon must end here, he kept steadily on, and soon halted at the view of a scene so beautiful and[42] enchanting, that his untutored mind was filled with admiration.

The canon suddenly spread out into a broad rapid stream, which flowed into a lake of about a half mile in diameter. Under the bright moonlight, it had the appearance of “liquid silver”—an expression by no means original, but so literally truthful, that we can use no other—and in the still summer night there was not a ripple upon its surface. In the center rose a small island, so abruptly, that, covered as it was with vegetation, it had the appearance of a bouquet, and would have reminded a traveler of the famous Lakes of Killarney.

Jim noticed that the opposite shore was rocky and fringed with trees, and the lake appeared to stand on the edge of a large wood.

“Dat ’ere is nice!” was his reflection, as, from the back of his horse, he looked out upon the fairy-like scene. “What a good place dat would be for George to build a house. I tink we could run a bridge ’cross to de land, or hab a ferryboat to run atween it an’ de shore.”

“Hullo! dere goes sombody,” he added, as he saw a canoe put out from the shore to his right, and head toward the island. The full moon had now sunk toward the horizon, so that the shadow of the trees and island were thrown far out upon the lake; and, as the single Indian who impelled the canoe, issued from the broad band of darkness which lay along the shore, every motion of his dusky, muscular arms was plainly seen. He managed his oar with such skill, that his body never seemed to incline a hair’s breadth to the right or left. The flash of the paddle seemed born of the paddle itself, as he held the point in the water, instead of coming from his hand, as the tail of a fish is sometimes seen to move in the water, when its body remains motionless. The canoe sped forward without the least sound, but instead of halting at the island, Jim observed that it passed behind it, and immediately disappeared.

The African now drove his horses into the water, and crossed without difficulty. As he came out, he halted a moment to take a last view of the little gem which rose[43] from the lake. The first glance nearly frightened him out of his wits; for, on the nearest point, he saw a thin, waving, arrowy point of light rise to the height of five or six feet, and then vibrate back and forth, as though held by a hand which oscillated from right to left.

While he sat amazed, a second flame, precisely similar, arose from another point of the island, and then another, and another, until fully half a dozen were visible, every one issuing from that portion of the island which touched the edge of the water. It was indeed a small representation of what Magellan, the great circumnavigator, saw in 1520, when he sailed by Terra del Fuego.

“I tinks it’s ’bout time Mr. Tubbs left dese parts,” chattered Jim, as, with a shiver of horror, he started his horses homeward.

Jim had gone but a short distance, when, still fascinated by his great terror, he reined up his horses and looked back at the moonlit lake and the little island in its center. Could he believe his eyes? Yes; it was moving. He saw it slowly float toward the wood, until, unable to control his excessive fear, he once more gave the rein to his animal, and did not pause until he was far beyond sight of the lake and its Enchanted Island.

The negro rode a considerable distance, when, as objects around him began to wear a singular look, he drew his animals down to a walk, and, on the edge of a rocky grove of small trees, came to a dead halt.

“Dis yere looks strange! I disremember dese trees; Ise afeerd Mr. Tubbs is off de track, an’ how is he gwine to git on agin, am de question.”

The country through which he was journeying, was a broad valley, interspersed with streams and canons, trees and open spaces, and huge boulders piled promiscuously here and there, and in some places so thickly strewn as to become almost impassable. There were acres where one could gallop as free as upon the beaten road, and then, for the same distance, it was the utmost that a horseman could do to pick his way along.

In the hurried manner in which Jim had made headway across the desolate tract, it was not to be supposed that he entertained a very vivid recollection of the landmarks; but he had quite a memory of places, and after he had rested his animal for a few moments, he became certain that he was lost. Under these circumstances, his only resource was to fall back on general principles, and take the course[45] which he believed would eventually lead him to the neighborhood of the cave.

By carefully studying the position of the moon, he believed he was going too much to the south, and, turning to the right, he followed this course at a slow walk, watching carefully for some landmarks which could be recognized. Discovering none, and it being well on toward midnight, he checked his horses, with the intention of waiting until morning.

Jim was pretty tired, and, tying the horses together, he lay down on the ground beside a rock, and in a few moments was asleep. He was undisturbed until daylight, when he was awakened in a manner which brought a howl of terror from him.

Some crushing weight descended upon his foot, and, starting up, he gazed about him for the cause. It proved nothing less than the baggage mule so frequently referred to, which, in journeying straight forward in the path which he had been started upon, had thus come directly upon the sleeping African.

“What!” he shouted, placing himself directly in front of the animal, and checking him in the same manner that a wall of rock would have done. “Dat ’ere is queer!” he laughed, “dat I put myself right afore you. Shouldn’t wonder now if you was on de right track; leastways we’ll try you.”

The mule was fired up, and, as it moved on again, the negro followed on the back of his own horse. To his great surprise and gratification, he had gone but a short distance when he caught sight of a small clump of trees which he recognized as a point passed by him shortly after he had started in pursuit of the Mohave and his prey.

He was highly pleased at this, and pressing on until he had reached the grove, became convinced that he was on the right track, and would rejoin his friends in the course of an hour. Beyond this spot all was familiar, and he advanced without hesitation or misgiving. Reaching the point where their animals had been tethered, he drove them in[46] among the trees, and, first securing them, started out in quest of his friends.

Jim had walked but a few yards, when it suddenly occurred to him, as he recalled the previous night’s experience, that there might be danger in advancing so openly to the cave. It was a very easy matter for a party of aborigines to conceal themselves along the banks, and rush upon and secure him before he could help himself.

It struck him, too, as he approached the cave, that an unnatural stillness reigned around it. The sun was now up, and it was high time that his friends were bestirring themselves. A vague fear took possession of the African, as he halted some rods away, and looked furtively about him. Everything was so quiet—nothing moving except the stream, and that made scarcely a ripple as it glided over its sandy bed.

Jim was standing in this apprehensive state when a slight noise in the rear startled him. Turning his alarmed gaze, he expected to behold a whole troop of painted red men about to swoop down upon him; but, in the place of that, recognized the smiling face of young Edwin Inwood.

“Bress me, but you scart dis chile dat time!” said Jim, his teeth fairly chattering at the remembrance of his shock.

“I threw a stone to let you know I was near; I didn’t mean to frighten you.”

“It wasn’t de stone dat scart me, it was de thought dat I tink it was sumfin’ else. Whar’s George?”

“Inside the cave.”

“Had breakfast?”

“No; we were just going to prepare it. Here he comes!”

At this moment, George Inwood made his appearance above ground, and he greeted the negro with great gladness. The latter soon gave an account of his pursuit and capture of the horses, and his safe return with them.

“You have done very well, Jim, especially when we remember that you had no gun with you. There are few men who would have dared to do so, even when fully armed.”

“But, dat ain’t all,” added the colored man, as he heaved a great sigh, “I seen de most awfulest ting you ever heard tell on.”

In answer to their anxious inquiry, he gave what has already been given by us, winding up with the declaration:

“An’ when I looked back de last time, what do you ’spose I seen? Why, I seen dat island rise up, flap its wings, an’ fly away!”

“There, Jim, that’s a little too much,” laughed the elder Inwood.

“When it flapped its wings, didn’t it also crow?” asked Edwin, whose interest in the narrative was turned into equally intense amusement at this culmination.

“You folks can laugh,” retorted Jim, indignantly, “but wait till you see what I did, an’ de shivers will run all ober you.”

“It may be possible that it was a mirage,” said George, somewhat impressed by the earnest manner of his sable friend.

“A mirage by moonlight?” inquired Edwin.

“Such things have been heard of, I believe, although very rarely.”

“What’s a mirage?” demanded Jim.

By great perseverance, George succeeded in giving Jim a sort of an idea of what he meant, although, in all probability, he would have regarded the mirage itself equally mysterious and wonderful as the bodily exit of a bona fide island before his eyes.

“All I got to say is, you jes’ go an’ see it, an’ den you’ll stop laughing at dem as what undertakes to explanify it to you.”

“Perhaps we shall have the opportunity, as I have concluded to leave these quarters.”

“What fur?”

“In the first place, our safety demands it. The Indians have found out we are here, and they will hover about and watch us, until some time they will pounce down upon us before we know it.”

“What ob dat? Didn’t they do it last ebening?”

“Yes; and Providentially we were able to drive them off; but you can see that if a hundred of them should come down here, they could keep us in the cave until we died of thirst or starvation, or were compelled to surrender, and our end in each case would be the same.”

“But we hadn’t orter leave de gold jus’ as we ’gin to find it.”

“We shall leave a very small quantity of it behind. The supply has about run out. You remember that we had a small lot yesterday. The reason was that we had gathered about all there was, and so you see there is nothing to keep us here, while we have every inducement to draw us away.”

As this was undoubtedly the case, there was no gainsaying the argument of Inwood, and it was decided to move their quarters without further delay. Breakfast was prepared, during which Edwin took his station and kept a sharp watch for straggling Indians. None were discovered, and he descended and joined them in the morning meal. Their baggage was piled on the mule, the five tiny sacks which contained the yellow dust, were taken in charge by George, and while it was yet early in the day, they took up the line of march.

Very appropriately, Jim led the way, he riding his nag with all the dignity of a conqueror at the head of his army. Inwood was not so particularly anxious to see the Enchanted Island, as he was to make sure that no Mohaves were following or watching them. The most vigilant scrutiny failed to detect any of the dreaded creatures, and our friends finally ventured to believe that with due prudence they could reach a place of safety.

It was past noon, when Jim, who was riding a short distance in advance, ascended a small elevation, and then suddenly made a signal for his companions to hurry alongside of him. The next moment the three were side by side.

“Dere!” said Jim, pointing off to the east, “is de lake an’ de island.”

The beautiful, circular sheet of water lay a half mile away, and right in the center was an island about fifty feet in[49] length, and half that distance in breadth. It was covered with young trees and dense vegetation, and in the bright sunlight had a cool, fresh appearance, which made it still more pleasant than when viewed under the witching rays of the moon.

George Inwood produced a small spy-glass from his pocket, and scanned it long and narrowly. There was something about this little island, aside from the marvellous stories related of it by Jim, which awakened his curiosity. While apparently still and devoid of life, he saw signs which convinced him that more than one person was upon it.

In among the leaves he could detect a fluttering, tremulous motion, and around the edge of the island were ripples which must have been caused by human hands, as the surface of the lake in every other portion was as smooth as a mirror. He thought he heard once or twice a plashing sound, which came either from the island itself, or from directly behind it. He decided to say nothing of his suspicions until he had learned more of it, what certainly wore a singular look, to say the least.

He was on the point of lowering his glass, when a slight movement among the bushes on the eastern shore of the lake caught his eye, and he immediately directed his gaze toward that point.

The naked vision would have discovered nothing, but by the aid of the lens he discovered a man standing on the very edge of the wood, and scrutinizing the party. At first glance, he took him to be an Indian, but a continued examination satisfied Inwood that the stranger was a white man, dressed and painted as a red man. What gave this impression was the fact that his outfit was not complete, being deficient about his head. This, instead of being bare, with the long, wiry black hair stained and ornamented with eagle feathers, (as is the custom of the Mohaves and Apaches) was surmounted by a slouched hat which entirely concealed the short hair.

The painted white man gazed long and intently upon the party, from which fact Inwood judged that he was displeased[50] at their appearance and anxious to keep himself invisible. This, united with the curious facts noted regarding the appearance of the island, furnished food for speculation, and Inwood lowered his glass and placed it away with the conviction that there was some mystery connected with this lake and the tiny island resting in the center, which, perhaps, it might be well for him to attempt to fathom.

“What you tink ob him?” inquired Jim, much wondering at the continued silence of Inwood.

“It is the finest scene I have ever looked upon. Nothing could be more beautiful than the lake, and the island, and the green shores which surround, and the white mountain peaks away in the distance.”

“Wait till you see it fly away—den I guess you tink it beautifuller yet.”

“I am afraid I shall have to wait a good while,” said Inwood.

“Shall we go on?” inquired Edwin.

“I rather like the appearance of the country around here, and I think we are as likely to find gold as in any other place. We will hunt up some good spot, take up our quarters, and go to prospecting. The best plan, I think, is for us to turn square around and start back again.”

“What dat for?”

Edwin, too, looked an inquiry, but George said he had a good reason, and accordingly it was done.

The party turned about as if to retrace their steps; but the moment they had descended the hill, so as to be out of sight of the Enchanted Island, Inwood dismounted, and said to his friends:

“Now, you walk the horses as slowly as you can, and when you get beyond that grove of trees, wait for me, but don’t halt until you are there.”

Jim and Edwin looked wonderingly at him, but he waved them impatiently away, and trailing his rifle, ran rapidly around the brow of the hill from which he had taken his view of the lake, and, gaining a position where he could still see it, he screened himself from observation, and carefully awaited the confirmation of his suspicions.

He had been here about twenty minutes, when he observed an agitation in the bushes between the hill and the lake, and the next minute the head and shoulders of a man rose to view. One glance identified him as the individual whom he had surveyed through his telescope, and it is hardly necessary to say that our young friend watched his motions with intense interest.

Looking cautiously about him, as if to satisfy himself that he was unobserved, the stranger soon came fully to view, and commenced ascending the hill with a silent, cautious step. Reaching a point almost to the summit, he sank down on his hands and knees, and looked over. Watching the horsemen, who, by this time, were a third of a mile distant, for a few moments, he laid his rifle across a mound of earth, and took a long, deliberate sight.

Inwood felt very uncomfortable as he watched this operation, and he was on the point of bringing his own gun to his shoulder to prevent this murder, when the piece was discharged, and, glancing at his friends, he saw that they were not disturbed enough to cause them to look around.

“Try it again!” muttered Inwood, “that is rather too long a range for a gun like yours.”

The man, after the failure of his piece, took an upright position, and watched the horsemen with an intensity of gaze which showed that for some reason or other, he had a deep interest in their movements. Finally they rode behind the grove referred to, and the man, with a great sigh and some muttered words, turned on his heel and descended the hill.