Title: The Girl's Own Paper, Vol. XX, No. 1030, September 23, 1899

Author: Various

Release date: December 13, 2020 [eBook #64040]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Susan Skinner, Chris Curnow, Pamela Patten and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

Vol. XX.—No. 1030.]

[Price One Penny.

SEPTEMBER 23, 1899.

[Transcriber’s Note: This Table of Contents was not present in the original.]

SOLITUDE.

THE HOUSE WITH THE VERANDAH.

“UPS AND DOWNS.”

CHRONICLES OF AN ANGLO-CALIFORNIAN RANCH.

IN THE TWILIGHT SIDE BY SIDE.

HOUSEHOLD HINTS.

AYONT THAE HILLS.

SHEILA’S COUSIN EFFIE.

THE PLEASURES OF BEE-KEEPING.

GIRLS AS I HAVE KNOWN THEM.

DIET IN REASON AND IN MODERATION.

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS.

ANSWERS TO CORRESPONDENTS.

[From photo: By Photographic Union, Munich.

SOLITUDE.

All rights reserved.]

By W. T. SAWARD.

By ISABELLA FYVIE MAYO, Author of “Other People’s Stairs,” “Her Object in Life,” etc.

DESIRE FULFILLED.

The great joy grew more credible when all its story was told.

The glad tidings had been brought in by an Atlantic liner. It appeared that when the Slains Castle had got well over half of her Pacific voyage, she had encountered a great storm, and had foundered upon the reefs among a small group of islands, all her boats being lost or destroyed. The captain, disabled, with his crew and the solitary passenger, had however managed to land on one of the larger islands, whose simple natives received them kindly, and put them into the way of subsisting after their own fashion. There they had lived, roughly and hardly indeed, and cut off from all communication with home, or with civilisation, upheld only by the hope that some ship, in some way diverted from its course, might eventually discover them and take them off. Instead of such a ship, however, their party was reinforced by a solitary white man, who made his way to them from his own refuge on one of the smaller islands. How had he got there? they asked eagerly. He told them the truth: he was “a bad character”—a man who had done desperate deeds of many sorts, and he was there because he was “a castaway” from an American ship—he could scarcely tell whether by accident or design. He seemed to think the latter the most likely and the most natural alternative in his case. Hunger and solitude on a bare rock in the wide ocean, had somewhat tamed him, and the consciousness of a common fate soon absorbed him into the little brotherhood of the Slains Castle.

He had been with them some months when some of the party secured a half-broken empty open boat, which seemed to have been washed off from a passing schooner. This they patched up, and then they began to think whether some of them might not make one last dash for the release of themselves and the rest. The “castaway” was quite ready to take to the sea again; he did not seem to know fear, or he believed he held a charmed life. He was an expert seaman, and of really powerful physique. Another must go with him, and another only. The captain’s arm being still disabled, the man selected as fittest for the expedition was the first mate. Despite all dangers their wild voyage was safely accomplished; a civilised port was reached, and a little steamer was at once despatched to the island to bring off the rest of the shipwrecked party. The ship owners had determined not to be premature in giving this good news. They had waited till every report was verified. Now, any hour might bring telegrams from Captain Grant and Charlie that they were safe on American soil, and hastening across the continent to take their Atlantic passage home.[1]

Of course there was wild and glad excitement in the little house with the verandah. But Lucy’s own joy was still and solemn. The others thought her very strong and calm. But she knew that she often asked herself whether she were waking or dreaming? She knew that she realised anew the distance and the dangers between herself and her beloved. After the glad telegram duly arrived and she knew the very name of the Atlantic liner on which Charlie was speeding towards her, a clouded sky or a rising wind would suffice to make her tremble! Ah, she had learned

and the next lesson of her life was to be the bringing-down of that mountain-top vision of serenity and security, and the possessing of it still among the mists and twists of the level lands. She had learned that love is eternal, that love is safe when out of sight—now she had to learn that time is only a part of Eternity, and that what is safe out of our reach, cannot be in danger while it is within it.

She thought often in those days of Mary and Martha, the sisters of Lazarus. They, too, like her, had been through the bitterness of death. Was it henceforth abolished for them, so that they could say, “O grave, where is thy victory? O death, where is thy sting?” Or did the impression wear off their souls, so that they had to live through all their grief again?

She went on, wondering. When we are told that in the mysterious future there “is to be no more sea,” we feel that the language is only used as a powerful image, to show us that there shall be no more danger, no more parting. But after all, what are danger and parting, but for their fear and pain? Is it not really those that “shall be no more”? It seemed to Lucy that haply in the highest ministries of life’s immortal service the paths of those who would be “about their Father’s business” must still sometimes swerve from one another. If “no more sea” was a symbol of no more danger, and no more parting, did not that in turn mean an abiding sense that all is secure, a present consciousness that all parting involves joyful reunion? Then if our souls, still clad in mortal weakness, can but attain to this “perfect love which casts out fear,” should we not be in Heaven’s peace already?

Lucy resolved to go to Liverpool to meet the steamer which had Charlie on board. She resolved to go alone. For the first time since his father went away she would leave Hugh, assured now that he was surrounded by wise kindness. She longed for absolute silence and{819} solitude on her journey to this reunion, well nigh as sacred and solemn as those generally guarded by the secrecy of death.

She preferred to go without any “seeing off.” Those in her home, those who loved her best, probed her feeling on this head, and yielded to it. They parted from her on her own threshold.

“We will come to meet you both when you return,” they said.

Husband and wife met. It was in a crowd of strangers, and nobody there took particular notice of the brown, lean, sinewy man, who clasped a silvery-haired young woman in his arms. Then they held each other apart for one moment, and gazed at each other, noting all that was gone—all that was changed, and all—ay, all!—that remained for ever!

As for the conversation—the questions, the answers, the narrations—that interrupted the rapt silences of this single day reserved for themselves only, what was it but simply the story which has been already told?

“They will be all at home to receive us,” Lucy said, as, her hand clasped in her husband’s, she told of the loyal friendships which had closed around her terrible waiting-time. “They are all still there, just as they have been. The house may be small for us all, yet I felt sure this would be your wish.”

“You knew your husband,” said Charlie, “and if our friends will stay, they shall stay as we are—for another year. By that time we shall have got our lives into their regular grooves again—and then, maybe, we shall all move together into a larger house. As it is God’s will that the solitary shall be set in families, Lucy, surely it is never more so than when the solitary have upheld the family.”

(To be concluded.)

A TRUE STORY OF NEW YORK LIFE.

By N. O. LORIMER.

hen the hard frost had broken, and the streets were full of slush and melting snow, Ada had to spend her five cents going in the Fifth Avenue stage-coach to and from her business, for, even with rubbers on, she had got her feet so wet and her skirts so destroyed that she found that it was in the end cheaper to drive than to walk. The children, too, had found it necessary to drive to school. Marjory had been very troublesome of late; she had been grumbling and repining at her restricted life, saying that she would rather make friends with the girls whom Ada considered vulgar and beneath her, than have such a dull, cheerless time. Ada had noticed that her eccentric old man had not been in the stage-coach for some time past, and she wondered what had become of him. She was sitting waiting for the boarding-house dinner-bell to ring (in the public sitting-room), when the fat lady, who took such an inquisitive interest in her and her little sisters, came in.

“Well, Ada Nicoli,” she said in her rough friendly way, “don’t you wish you were the young lady.”

“What young lady?” said Ada.

The fat lady put the New York Herald down on Ada’s lap.

“Read it,” she said. “It’s the maddest thing you ever heard. The crazy old man whom you’ve often seen in the Fifth Avenue stage-coach, and who ate his bit of bread and cheese every day on the public seat in Madison Square, and looked as poor as any tramp, died a week ago.”

“Oh,” said Ada regretfully; “is he dead?”

She had grown to look upon him as one of her friends in the big cruel city, and now he had gone too.

“Yes, he’s dead,” the fat woman said emphatically; “and he’s left a mighty pile of dollars behind him. He used to stint himself of house-fuel, and go to bed whenever he got home from business on a winter’s day to save light, and wore clothes a coloured man wouldn’t give to his father. What’s the use of saving like that if you’re going to leave all your fortune to a total stranger.”

“Poor old man,” the girl said; “he was really rather mad, but somehow I liked him; he seemed to belong more to the last century than to this.”

“Well, it appears he’s left every dollar he’s got to some girl that he thought deserved some money, a milliner’s girl, the papers say, who once saved his life in a snowstorm or something like that.”

Ada read the long and highly-dramatic account of the old man’s curious will.

“Yes, I wish I were the girl,” she said; “but I fear there’s no fairy prince in disguise watching my poor trivial round and common task. But just fancy, a girl earning her own living suddenly to find herself an heiress!”

The boarding-house bell sounded, and the hungry children came bounding down to dinner.

“Ada,” whispered Marjory at table, “a man came to see you this morning, and I said you were out. He asked me a lot of questions, and I answered before I remembered that perhaps you would rather I didn’t.”

“What sort of questions?” Ada said smiling, and hoping that at last they were going to receive news of their father.

“Where you worked, and how you went to work, and if we were your only sisters. He was quite a nice sort of man.”

“A gentleman, I think,” Sadie said with a great air of worldly wisdom. “He said he would call again after dinner to-night.”

“Did he not tell you what he wanted,” Ada asked.

“No,” Marjory said, “and it was only after he had gone that we found out how much we had told him, all about mother, and everything. Do you mind, Ada?”

“No,” Ada replied; “but try in future, Marjory, to remember that you are getting too big a girl to talk to strange gentlemen in that confidential way.”

After dinner that night the Irish servant toiled up to the top of the high house to tell Ada Nicoli that there was a strange gentleman waiting to see her down below.

“And sure and I can’t think why you want to come up to this attic in the evenin’, instead of joining with the company in the parlour. It would save my poor legs toiling up to tell you when your friends arrive.”

“It’s the first time anyone has come to see me, Bridget,” Ada answered, “and I like having the children with me in the evening.”

Ada might more truthfully have remarked that she did not wish her little sisters to enjoy the company of the young business men who frequented the boarding-house parlour in the evening.

When she entered the parlour, a keen-looking elderly man rose from his seat and bowed to her. “Have I the pleasure of addressing Miss Ada Nicoli?”

Ada bowed.

“I am Mr. Riggs.” He looked round the room. “Have you any place where I could talk to you in private, ma’am?”

Ada grew nervous from fear of some bad news, but she had learnt to control her feelings before the curious eyes of the boarders.

“I have no private sitting-room,” she said, “but perhaps I might take you into the bureau.”

“Thank you, ma’am, I will not detain you long.” When they were seated in the bureau, which the lady of the house had willingly vacated on hearing Ada’s reason, he said, “I have come to tell you a piece of news which I think will greatly astonish you. I came here this morning and learnt the information from your little sisters which identifies you in my mind with the young lady I was seeking.”

Ada was turning from hot to cold and her hands were tightly clasped together.

“My dear young lady,” he continued, “I am Mr. Riggs of the firm of Jefferson Riggs & Co., lawyers, No. 10054, Broadway. Perhaps you have read in the papers of the death of an eccentric old gentleman who was a well-known figure in the Fifth stage-coach, and in Madison Square Gardens?”

Ada nodded her head. Her heart was beating too quickly to allow her brain to seize the points of the lawyer’s story.

“I was his lawyer,” he said, “and for many years transacted all his business matters, but I had no idea of his personal wealth. He had altered his will many times during the last few years, leaving his money first to one charitable institution and then to another; but in his last will, which he made as far back as eight months ago, he has left you his entire fortune.”

“Me?” Ada gasped. “Me? What do you mean? He didn’t even know my name.”

“Yes, he did. He found it out quite easily. Yes, my dear young lady. You will now be{820} almost as wealthy as if your father had never failed.”

“Oh, stop a minute,” Ada cried, “till I can really understand it. Am I the milliner’s girl that was mentioned in the papers? Oh, I’m quite, quite certain you have made some mistake. Do have pity on me, sir; I have suffered so much,” and she put up her hand to her head and swayed a little backwards and forwards.

“Oh, please don’t faint, my dear young lady. I am no ladies’ man, and I don’t know what to do.”

“No, I will not faint,” replied Ada. “It is really wonderful what a girl can bear. But I hope you are not deceiving me.”

“I am quite sure I am not, if you are not deceiving me, and personating Ada Nicoli. I wish I could have broken it to you more gently; but I am no ladies’ man.”

“You have done it very kindly,” the girl said, with a great sob of joy in her throat, “only I wish the old man was alive, that I could thank him, and love him a little. He was very lonely, I think.”

“Yes, he was very lonely,” the lawyer said, “and it is strange what an impression you made upon him.”

“I don’t see how I could,” Ada replied simply. “I never did anything.”

“I think I can understand,” the lawyer said with a touch of gallantry which showed that he was not such a poor ladies’ man as he had asserted, bringing a pretty flush to her cheek.

After they had talked a few minutes, Ada said—

“May I call the children down to tell them?”

“Certainly,” the lawyer replied. “The affair is no secret.”

When Ada told the children that they were no longer poor, and that they need not live in the top attic-room in a boarding-house, they took the news more complacently than their sister had done.

“I’m glad we can go to a decent school,” Marjory said, little knowing how her words hurt Ada, who had worked her fingers to the bone to pay for her middle-class schooling.

“I wish we had been left a new poppa, instead of some money,” Sadie said regretfully. “If we’re rich again, you’ll drive about with mumma, I suppose, and we won’t have any fun. I like being poor.”

“And living in a hen-roost?” Ada asked laughingly.

Sadie had always called their low-roofed attic a hen-roost.

“Yes, ’cause I like sleeping with you better than with a cross nurse.”

The old lawyer got up. He had to take his spectacles off and rub them before he could see his way across the room.

“My dear young lady,” he said, “you have made their poverty so attractive that the old gentleman’s fortune is scarcely appreciated.”

“I must spend it very wisely,” the girl said, “as it was so carefully hoarded together. It is all so wonderful that I cannot believe it is true.”

“I should like the old man to have had the pleasure that has been mine in bringing you the good news,” the lawyer said, bowing himself out. “We shall have many business matters to discuss later on, but I will leave you now to enjoy the new good fortune with your sisters.” He came back and said rather nervously, “Remember, my dear, that you can draw on me for any ready money you may require. I will leave you a hundred dollars now just to pay for immediate expenses, and to-morrow you can have ten hundred more if you like.”

When Ada Nicoli was going upstairs, as if floating on wings rather than walking, she met the fat lady boarder coming down.

“Well, I declare, Ada Nicoli, you look as if the world wasn’t good enough for you to-night. There’s enough happiness in your eyes to light a whole street. Has your strange visitor brought you good news?”

“Yes,” Ada replied, “wonderful news. He has just told me that I am the little milliner’s girl whom the eccentric old gentleman thought deserved some money.”

“Sakes alive!” the fat boarder exclaimed. “Let me look at you,”—and she took the girl by her shoulders and scanned her face.

“Are you the girl he left all the money to?”

“Yes,” answered Ada; “isn’t it extraordinary? I can’t quite believe it is true! It’s just like a fairy story.”

In another moment the girl was clasped in the arms of the good-natured woman, and was so cried over and petted that all the boarders came out to hear the news, which Ada could not tell them for the fulness of her heart, and the fat boarder did it but badly, for she was laughing and crying at one and the same time.

[THE END.]

By MARGARET INNES.

THE RESERVOIR—CHINESE MEDICINES—DUST—ADVANTAGES OF THE LIFE—THE RAINS—FLOODS.

hat summer, our first on the ranch, we made a large reservoir to hold 200,000 gallons. There was a convenient gulch or dip, which drained a fair stretch of hill slope, and which lent itself well for the purpose. We meant also to run our share of the flume water into this reservoir whenever it was not being used on the ranch.

Many waggon loads of sand from the Silvero Valley had to be hauled up by the little grey team, and endless barrels of cement from the station at El Barco five miles away. It was a long tiresome job. There was plenty of rock, with which to build the dam, lying about on the hills, but to lift these pieces on to the sledge, improvised for this purpose, and bring them over hill and dale to the reservoir site and there unload them, was both very hard work and at times a little dangerous, for the rocks were often so large that they were not easily controlled, and were always threatening to roll over on to the feet or hands of the “master builder” and his men.

There were some bad bruises before all the names of the workers were written on the cement top of the wall as an artistic finish to the dam.

That was a very dry year, the summer extending till December 5th, and after a dry winter too. For this reason the breaking up of the ground was all the harder, especially that part which had been trodden hard by cattle grazing for many years.

Again the ranchers went to work to manufacture some implement that would help in this difficulty, and a “clod masher” was made out of some of the furniture cases, and it did very good work.

We planted cypress trees too, all along the windswept side of the ranch, as these grow very fast, and we wanted to break the face of the wind.

The rabbits, squirrels, and gophers gave us some anxiety that first year by nibbling at the bark of the young lemon trees. This had to be stopped at once, for if the bark is badly peeled off right round the stem of a young tree, the tree will probably die. The approved remedy is to paint the bark with blood, a most disagreeable job, especially in glaring hot weather. However, the trees were not touched after that, for the rabbits are dainty people.

A good store of firewood had to be hauled from the Silvero Valley before the rains should come, and some months earlier we had stored away our winter supply of hay in the barn. In the winter we also planted an orchard of all varieties of fruit for our own use—pears, apples, prunes, figs, apricots, peaches, vines, strawberries, and raspberries. Altogether we were very busy and worked very hard, though we took our pleasures too, sandwiched in between. We did a great deal of driving and riding about among the different mountain paths, and we still enjoy this distraction as much as ever.

To take our lunch with us and stay away all day, the boys riding ahead, with the dogs following them, darting in among the brush, wildly happy over every pretence of a scent, leaping high over every obstacle, and adding so much to our enjoyment by their evident delight, is a pleasure without flaw. I must not forget also a gun or two, stowed away in the bottom of the carriage, for something worth killing may cross our path. Jack-rabbits are not good eating but are good sport, and as they injure the trees, every rancher shoots them when he gets the chance. The dainty elegant road-runner must never be hurt, and woe be to the “tenderfoot” who is tempted to shoot that pretty, impudent-looking little fellow, the skunk, who flourishes his handsome black and white tail in your very face. If you were a Chinaman, you would secure him on any terms, even his own. All Celestial medicines and cordials seem to be compounded of the most offensive abominations that can be discovered; it follows, of course, that the skunk is a highly-prized treasure in their pharmacopœia. What deceits we have practised and what lies we have told during Wing’s reign in the kitchen! He was for ever wanting to doctor us, and had always just the right remedy by him for whatever complaint was to the fore. We soon became{821} very wary indeed of showing any sign of physical trouble before him, for we were at once pounced upon with hot drinks of villainous compounds and rank smell, and we had to be very diplomatic so as to escape drinking them there and then, and thus get the chance of pouring them down the bath sink when his back was turned.

We always felt this to be a very dangerous business, for the smell threatened to betray us.

For rheumatic pains he eagerly recommended a sort of rattlesnake jam, which is made with chunks of that attractive reptile cooked in whisky, and potted for seven years, when it is ready for use, and, according to Wing, is an infallible cure.

But though these various animals are spared for different reasons on our little excursions, the Californian quail are very delicate food, and a most welcome addition to the ranch larder, where variety is a little difficult to get. They also are very good sport. Wild pigeons, too, are not to be despised.

These driving expeditions are best, however, in the winter, spring, and early summer, when the sun is not so hot, and when the roads have been rained upon, and the terrible dust is laid. Is there any dust like the Californian dust after a dry season, I wonder? My husband insists that in Australia and the Cape, and other places where he and I have never been, the dust is infinitely worse than in California; he also reminds me of the dust in railway travelling at home, and insists that this was quite as disagreeable and much more dirty. We do not agree on this point. But as I said before, one accustoms oneself to almost anything, and though we certainly take fewer pleasure drives at the end of the summer, waiting rather always for the first rains, yet when I remember my first horror at San Sebastian, on driving through waves, and clouds, and curtains of dust, then I know by comparison that I have reached a very philosophical state of mind about this, one of the necessary and undeniable evils.

What one enjoys most in this life is, I think, the absolute freedom; that and the great stretches of space around one are a constantly increasing delight. To look across these great sweeps of mountains, range after range, and see in the distance the silver line of the Pacific, and to feel the clean, pure wind in one’s face, is like a baptism of new life.

At first the strange bareness of these mountains almost wounds one’s eyes, and their true beauty is not recognised. But as one learns to know them better, their charm grows more and more striking, and I almost doubt if after a few years one would wish for any change in their bold bare lines. In the full midday sun they are not lovely, and in some moods one would call them almost ugly, so uncompromising are they in their grimness and bareness: but their time of triumph is when the changing lights of sunset begin, when they are flooded with such matchless colouring, so delicate and rich, that they seem positively unreal.

During the winter rains all the odd jobs of repairing are done: soldering, harness-cleaning and mending, painting of waggons or carts, and carpentering.

Most Americans are clever-handed, and can turn from one job to another with unusual facility. To see a man, who earns his living by driving a delivery waggon, turn to in his spare time and build a neat and comfortable addition to his house, an extra bedroom, and perhaps an enlargement of the sitting-room, with a nice bit of verandah out of this, and all well planned and well finished, is apt to knock the conceit out of the young fellow from home, who prides himself on being so “clever with his tools.”

Our first winter was a very dry one, to our great regret. The rainfall was much below the average and much below what was needed for the land. Less than seven inches fell during the whole season, and an average good fall is about fourteen inches. So the land was never thoroughly soaked, and what was a more anxious matter still, the storage of water “way back” in the mountains was too scant, and pretty certain to run short before the long dry season should be over. So, indeed, it proved, and we were greatly harassed, when the water company began to cut down our rations, leaving us barely enough to keep our young trees going; and certainly not enough to give them a chance of doing their best, however diligently the “cultivator” might be kept at work.

All that summer we were busy, tending the trees and adding further improvements to the ranch. When the second winter came, we were hopeful then all our anxieties about water would be set at rest by a good generous rainfall.

The dry season had extended unusually far into the winter months, no rain having fallen till December 5th, when we had a few small showers. Within three weeks of this, it seemed as though we were to get our desires to the full, for the rain came down in torrents.

The Silvero river, which was supposed to flow in the pretty valley below us, of which we got such a charming glimpse from our verandahs, had hitherto appeared to be a dry sandy stretch more like a rough country road than a river, and we had laughed at the very notion of a bridge being ever needed to cross its dangerous waters.

Wonderful tales of the miraculous possibilities of the land are of course told here to the credulous tenderfoot, and we did not feel inclined to believe our friends’ accounts of that very river’s deep and dangerous waters during some rainy winters.

We had to make an apology that second winter. For nine days the waters poured down in an almost solid sheet; and with hardly any cessation night or day. We were all anxious and excited over this storm; and constantly on the watch to see what would happen. At the end of the first twenty-four hours, we had rather a scare over our reservoir. The sudden inrush of water from the hill slopes around had filled it so quickly that when my husband went up in the driving rain to see what state it was in, he found, to his dismay, that the water had reached the very tops of the dam, and was just beginning to sweep over, making at once a deep and widening cut all along the lemon trees below.

The new wooden floodgate was so swollen with the rain that it was as though riveted into its place, and refused to open. In a few moments my husband had darted down to the barn, and returning with an axe, broke the floodgate in pieces, when the danger was over, and the water rushing away in a great heavy mass found its way into a gully where it could do no mischief. We saw, from the deep cutting made in those few moments by the water when it swept over the dam, what terrible damage might be worked by these rains. But we could hardly believe our eyes or ears however, when we saw in the valley the glistening of the water in the broad river-bed, and heard the roar as though of a cataract.

During the first lull that occurred we all hurried down to the valley to examine more closely what was going on. We found such a turbulent, dangerous-looking river tearing down the valley, that we were perfectly fascinated, and would fain have stayed and watched it for hours.

The river had already cut a great deep bed for itself out of the wheat-sown meadows of the valley, and every moment a great slice of the bank would give way and silently slide down into the water, which swallowed it up relentlessly as it rushed past.

Great trees were lying in the river, in some places all across it, making rough dams where the water fought and leapt even more fiercely; and as we stood there, we were horrified to see one of the dear trees, so highly prized in this bare land, go trembling down into the flood. The sound of their roots straining and cracking as the rushing floods tried to sweep them away from their last bit of anchorage, was most painful; it seemed almost like a human struggle. All the ground was more or less like quicksand, and we had to be careful where we stepped, lest we should be “mired.” As the rain came on again heavily, we were forced to return home, though very unwillingly; it was a scene of such wonderful excitement.

We were very anxious, too, about friends whose ranches were some miles further up the valley, and whose land lay mostly rather low down and near the river-bed. We found afterwards that both had suffered considerable loss, besides great anxiety. On one ranch the river had in one night swept away eight acres of beautiful olive-trees that were in full bearing. This was a very cruel blow, over which the whole neighbourhood, I think, mourned, but which the young rancher and his wife bore with the brave cheery spirit which is, I think, a noticeable charm in most Americans. The young wife gallantly carried the heavier share of the blow, by dismissing her servant, and herself doing the housework and cooking.

(To be concluded.)

By RUTH LAMB.

THE LITTLE ONES OF THE FAMILY AND THE GLORY OF MOTHERHOOD—CONCLUSION.

“Like olive plants round about thy table.”—Psa. cxxviii. 3.

hose of you, my dear girl friends, who are members of large families, know how very soon the little ones begin to observe what is passing around them. One never-ending marvel, in connection with infant life, is the amount of knowledge gained during the first year of a child’s existence.

The little creatures come into an unknown world where everything is strange. Even the mother’s face has to be studied and learned off by heart.

How quickly the baby eyes begin to follow the movements of those around them! How soon they learn to discriminate between one face and another, one object that is pleasant to the sight and a second that inspires fear or dislike!

How marvellous is that instinct of self-preservation which moves the little hand to twine itself round an outstretched finger, or to clutch at any object within its reach!

Has it not been to you, baby’s sister, almost as much as to the mother, a source of pride and delight to observe that the new-comer was “beginning to take notice”? If the downy head is turned in your direction, there is quite a ring of triumph in your voice as you say, “I am sure he knows me.”

You see, I picture my girls as loving sisters with tender, motherly instincts, and I decline to believe that there is one amongst them who does not love these little ones.

If children begin to observe so soon, how important it is that those who are round and about the life-path, on which, as yet, they can only place a little tottering foot, should be careful that they see only what is worthy of imitation. We, who are, perforce, the patterns which the children are certain to copy, should be doubly watchful over ourselves for their dear sakes.

You and I need to be ever on the watch on our own account, and the prayer “Lord, I cry unto thee. Keep the door of my lips. Incline not my heart to any evil thing. Deliver my feet from falling,” must often go up from our hearts to God, if we are sensible of our needs and weaknesses.

Have you not a double reason for the prayer that you may be kept from sin, whether in word or deed, if you are elder sisters in homes where the children must certainly learn by your example? I would not only urge you never to utter a wrong or impure expression, but also to avoid the foolish talk which even some older people think the only kind suited to children. Use habitually the best words you know, so that the little ones may have nothing to unlearn that they have heard from your lips. Speak clearly and distinctly, avoid shrieking, boisterous laughter, and discordant tones, so that baby’s voice, imitating yours, may be clear and even musical from the first.

Be gentle and graceful in your movements. Do not throw yourselves about or be rough, careless or boisterous in manner, for if you are, you will soon see a little reflection of your doings in the toddling thing who smashes his toys and laughs at the destruction he has wrought.

Be orderly in your own habits, and teach the little ones to put away their toys when done with, in places provided for them. I may note here that children are often untidy and needlessly destructive of their toys because no provision is made for orderly ways, and no settled places given for their childish treasures. Let them thoroughly enjoy the use of these, but teach them that their toys are worth something, and that wilful destruction results in loss to themselves.

Turn a bright, happy face for a child to study, that your smile may be reflected in his. Cultivate a cheerful disposition and an even temper, that you may rejoice in seeing joyous little ones in your homes.

Apart from ill-health and the consequent bodily suffering which naturally makes the poor little people fretful and peevish, I honestly believe that many mothers are responsible for the ill-tempers of their children. If they had always cultivated habits of self-restraint, and prayerfully watched against and checked every tendency to discontent, angry passions, selfishness, etc., I am convinced they would have had less cause to mourn over peevish, passionate, ill-tempered, exacting children.

I have used the word always advisedly.

The cultivation of every pure, right, holy habit, temper and method of speech, should begin long before a young mother actually clasps her child to her breast, if he is to come into the world such as she would have him to be.

With what widely differing feelings do parents look forward to the gift of a child! In some cases it is in the hope of keeping property in the direct line, so that others may not inherit it.

Dear ones, it may be that none amongst you have need to cherish such thoughts, or to expect any great share of this world’s wealth, for those who may some day call you by the sweet name of mother. On all who bear it will devolve the solemn responsibility of training your children for something greater, higher and better than the richest earthly inheritance.

It must never be forgotten that it is the children of human mothers who are the heirs of immortality. It is the glorious privilege and duty of the mother to teach her little ones the old, old story of God’s love in Christ Jesus, and to put before them the precious truth that in Him and through Him they become children of God. “And if children, heirs of God and joint-heirs with Christ.”

Children are sometimes used as outlets for a mother’s vanity and love of display. She delights to clothe them in the richest and costliest of silks and laces, less for their comfort than to show that she is wealthy enough to do so. These things are of little real account.

The soft woollen garments knitted and fashioned by the loving hands of a poor mother, and the mere scraps of material adorned with pretty stitching by her busy fingers, and kept in snowy purity, will be just as comfortable and becoming as the more costly clothing.

In choosing a nurse to be associated with you in the care of your children, think of what you would fain be for their sakes, and try to find one who will work with you in a like spirit. Never give up your own share in the work or the supervision of the nurse’s, except from dire necessity. I would be the last to suggest that you should show a suspicious, prying spirit; but let it be understood that the nurse is your co-worker, and that, in trusting her with your children, you place your greatest treasures in her partial keeping. My own practice has always been to trust those who served in my home, unless something occurred to justify a change of opinion.

In dealing with the little ones be absolutely true. Let there be no shams or make-believes on your part, and allow none in others. Children are wonderfully quick to detect shams, or even an approach to untruth, and how keenly they study their elders! I hope it is not derogatory to the child for me to say that they and dogs are curiously alike in judging character. The child will meet the advances of one stranger with open arms, whilst no bribes or blandishments will induce her to look at another. The dog will generally make a like choice. Before reason can have much to say in the matter, the child exercises its God-given instinct in making or refusing to make friends with a new-comer.

I was in a room with a number of people one day, when a little girl of four was brought to see the visitors. All but one tried to coax her into friendliness but in vain. The exception was a sea-captain, rugged, sunburnt, and with a face seamed by small-pox. He made no attempt to entice the child, beyond smiling in response to her frequent gaze. At length she went quietly to him, laid her hand on his knee and bade him lift her up. The rugged face looked beautiful in its kindliness as he raised the child in his arms, and a moment after felt a soft kiss on his cheek, and a curly head nestling on his breast. A more lovable nature than that which dwelt beneath that man’s unpromising exterior, it would have been hard to find; and so evidently the dog of the household decided, for he followed the child and tried to push his nose beneath the captain’s one free hand.

I often think that our four-footed friends set us examples worthy of imitation in dealing with our little ones. Most of us would rather bear pain than see a child suffer, even if not impelled to pity and tenderness by motherly love. But we are not always sympathetic in matters which are very real trials to the children. I have heard people say, “How can one be expected to do anything but laugh at the ridiculous things children cry and grieve about?” If the trouble is a real one to the child, we may sympathise with the sorrow, though we may smile at the cause of it. Only do not let us spoil everything by allowing the child to see us smile whilst professing to pity and condole.

It is harder for some natures to sympathise with the little ones in their play than in their grievances. To do the latter is natural to every kindly heart, but very often we find it the hardest possible task to be a child with a child. The healthy little one is not often quiet in play-time, and busy mothers, weary with very real work, are glad to confine all romps within nursery walls, or to banish the players to any place out of sight and hearing. Believe me, there is no time when a mother’s supervision is more needed than during play-time. I was brought to realise this, as I had never done before, quite lately.

A young mother, herself one of a large family, said to me, “My childhood would have been one of the happiest possible, if only my mother had been oftener with us in play-hours,{823} but she had no idea how miserable I was then. One of my sisters, younger than I, had a passionate temper, a will of iron, and a selfish, exacting disposition combined with unusual beauty and—when she chose—with the most winsome ways imaginable. By these combined qualities she dominated the nursery, got all her own way, and generally succeeded in making everyone appear to be in the wrong but herself. My mother knew this too late to prevent my childish happiness from being spoiled, and both she and my father grieved over it. ‘Why did you not speak?’ they said. ‘We should have believed you, for you were always true.’

“The fact was, I felt powerless before the strong will of my sister, who succeeded in making me think myself of no account in comparison with herself. I was not beautiful like her, and she was constantly taunting me with what she called my ugliness. Well, I can thank God that whilst my parents still lived, things were put right with them, and no one was so near to them as I was. And, if I possessed a less share of good looks, I had enough to win the love of a true heart and keep it; so I must not complain. Only I cannot quite forget that I lost the happy childhood my parents meant me to have, for want of my dear mother’s more frequent presence during our play-time.”

When you attain to the glory of motherhood, beloved girl friends, let each of you learn to be a child with your children. You will not lose by this, and they will gain enormously.

I spoke of our four-footed friends. Look at puss with her kittens. Does she stand on her dignity at play-time? Or the mother doggie. Does she disdain a game at romps with her fat, roll-about puppies? Both these furnish examples for human mothers, and depend on it, such will learn far more of their children’s real dispositions during play-hours than at any other time.

Years ago I saw an outdoor picture which I have never forgotten. A little lamb had been born very late in the season, and, after all the rest of the flock had been removed, it remained with its mother the only occupants of a field. As soon as it was old enough, it showed all the ordinary tendencies of its kind, and began to skip and frolic about the field. But it had no playfellows, and would soon return, quiet and disheartened, to its mother’s side.

The ewe rose to the occasion. She still carried her winter coat which made active movements somewhat difficult, but in spite of this, she joined in a game at romps with her little one. Anything funnier, more ungainly than her efforts at skipping and prancing round, I never expect to see, but she persevered to the delight of her lamb, so long as the two remained in the field. She left in my memory one of the sweetest pictures of motherly sympathy I ever witnessed.

It is not possible to do more than touch on the duties as well as the glory of motherhood, for the subject is equally vast and important. In all our talks in the twilight our object has been rather to suggest future thought on matters of importance, than to exhaust the subject during a sitting. You, my dear ones, if spared to be mothers, will have to study many things, if you are to be worthy of such a sacred trust. You will need loving and sympathetic natures, great self-control and constant watchfulness over self, in order that your example may be good for the little ones to follow. You will need tender, enlightened consciences to keep Duty ever to the front, and Inclination subservient to its call. You will find that you must unlearn as well as learn many things in order that you may only teach what is best. You will have to study the parts that others fill in the environment of your children so that they may have pure companionship, friends and teachers whose influence shall be second only to your own in doing them good. You will have to plan in ways small and great for the growth, health and general well-being of their bodies, but above and beyond all you must never forget that something more precious than all the world has been entrusted to you—an immortal soul with each child.

I need not say that if you realise the vastness of this trust, you will be a prayerful mother. Very conscious of your own weakness and inability rightly to fulfil your God-given work, you will constantly seek the grace which is sufficient for you and for all: the strength which is made perfect in the weakness of His believing servants. “For the weakness of God is stronger than men.”

You will be ever prayerfully striving after greater nearness to the Source of strength, and so, taking your little ones in your arms or by the hand, you will lead them into the Presence, and as you lift up heart and voice in supplication and prayer, teach them to realise from their earliest days the Divine Fatherhood, and the saving love of God in Christ Jesus.

It seems coming down from the greater to the less when, leaving for a moment the teaching of the Bible about the glory and responsibility of motherhood, I open another book and quote a few words from the writings of a high-souled poetess, one who without knowing the glory, the bliss, the responsibility of hearing a child call her mother, has yet grasped, in a higher degree than any other writer I know, the reality of all these things.

It was fitting to place first of all the testimony of Bible history and teaching on the value of a child and the glories and responsibilities of motherhood. But in these days it will do us good to read some words from one of Mrs. Browning’s poems and to find that along with her great mental and poetic powers, there dwelt in her fragile frame the warmest of motherly hearts, the strongest motherly instincts. As Aurora Leigh, she writes—

I will not multiply quotations. These are more than enough to justify what I have said of the writer. I hope many of you are already familiar with the whole poem.

And now, my dear girl friends, I must close our talk to-night with the announcement that in one sense it is to be our last, but not in another.

Three years have come and gone since our Twilight Circle was first formed. Some of us met then as old acquaintances, but we have become far more than mere acquaintances to each other. I believe we shall remain true and lifelong friends. One of you, looking regretfully forward to the probable cessation of our meetings, asks quite pathetically—

“Have you nothing more to say to us, your girls?”

I feel that I still have many things to speak about, and yet that it would not be advisable to arrange for meeting at stated periods for the present. Yet I look forward to our keeping in regular touch with each other; for our dear friend the Editor has suggested a “Twilight Circle Correspondence Column” for us. In it I hope to answer some of the letters already received, and others which you may address to me in the future about our Twilight Talks. It has always been to me a source of great regret that many of your letters have perforce remained unanswered so long. I also hope to bring some of you, dear ones, into touch with each other during the coming year by means of these letters.

I pray that God will add His blessing to what has been said, and that you may all be better daughters, sisters, friends, wives, and, in due time, mothers through our many happy meetings “In the Twilight Side by Side.”

[THE END.]

It is not safe to use common cheap enamelled saucepans after they have been chipped inside. The glaze that is used is often poisonous, and the material comes off in such small pieces, that if absorbed with the food they may act as a serious irritant to the intestines and set up inflammation.

A book should be kept for cuttings of interest from newspapers and journals. These form very interesting reading.

An accomplishment which everyone should cultivate is that of writing clearly, especially one’s signature. It causes a great deal of trouble and even serious mistakes to write illegibly. While staying with a friend on a visit, a letter was handed round the table for us each to try and decipher, and all that could be read of it was the concluding sentence, “Please reply by return of post.” The signature and address were totally illegible.

Soufflé au Chocolat.—Take three eggs and beat the yolks and whites separately. Add to the yolk a tablespoonful of pounded sugar and about two ounces of chocolate. Stir all these ingredients well together, adding a teaspoonful of flour. Whisk the whites of the eggs until they form a stiff paste, and then mix lightly with the other substances. Butter a tin and bake in a moderate oven for a quarter of an hour. Serve up immediately in the tin.

A STORY FOR GIRLS.

By EVELYN EVERETT-GREEN, Author of “Greyfriars,” “Half-a-dozen Sisters,” etc.

MAY’S INVITATION.

“I should like to go, Aunt Cossart, of course; but I will not accept unless you can really spare me. Now that Effie is away, I know it is dull for you, except in the evenings when Oscar is here.”

Mrs. Cossart held in her hands the note of invitation, which a servant from Monckton Manor had just brought.

“Do you know who these friends are that Miss Lawrence thinks you would like to meet?”

“No,” answered Sheila simply. “They have a good many summer visitors at the Manor, and they are all nice people; but May does not say whether they are any I have seen before.”

“Well, I think you had better go. It is only for three days; and I’ll ask Ray to come and spend the time with me. She had half promised me a visit before this. And Oscar need not go to the office regularly—that was quite understood. Only he is such a boy for his duty that there seems no keeping him back. However, your uncle will soon be home now; and then perhaps we shall settle something different. But write your note to Miss Lawrence, and say you will be there to-morrow. I will drive you across. I want to go and see Mrs. Frost, and so it will all be on the way.”

“Oh, thank you so much, Aunt Cossart, you are very good. I shall like it very much if you are not left alone.”

Sheila ran to write her note with a light heart. Effie was away on a visit to her friends the Murchisons. It had been a great advance that she should pay a visit by herself, with only Susan in attendance. It seemed quite a step in her recovery, and all had been pleased that she wished it and felt able for it. In her absence Sheila and Oscar had become quite like the children of the house, and the girl was often surprised at the warmth of her affection towards her aunt, despite the little fussiness and lack of tact and judgment which had so often irritated her in old days.

Still, the thought of a few days with May was quite a treat. She had not been over to the Manor very often of late. May had been visiting some friends, and the girls had not met since. It was delightful of May to think of asking her for a night or two. That kind of visit was so much more satisfactory than just going over for the day.

Truth to tell, Sheila thought little of the “friends” she was asked to meet. It was May she chiefly cared to see, although the house party at the Manor when it was full of guests, was always a very pleasant one.

“May will be thinking about her wedding,” Sheila observed to her aunt as they drove along in the bright June sunshine. “Ray says that North does not see the use of waiting; and now that he has found that nice house over the bridge, and in the country, though not too far away, there doesn’t seem anything to wait for. I think he and May will be very happy together; and it will be nice to have her so much nearer.”

“Yes, North is a steady good boy, and deserves a nice wife; but I should never have guessed that he would marry into the county, as people call it. That always seemed more in Cyril’s line.”

Sheila laughed. She had seen through Cyril’s veneer long ago, and thought much more of North’s sterling worth and perfect sincerity and simplicity. It was these qualities which had attracted May, and Sheila thought she showed her sense and good feeling in being so quick to appreciate them.

May received her with open arms; and in a short time they were ensconced in one of their favourite retreats, pouring girlish confidences into each other’s ears.

May told of her approaching marriage, which was to take place in September, so that they would get a run on the continent a little later than the August rush, and yet be settled at home comfortably for the winter.

“You must come and see the house to-morrow,” cried May. “It is such a dear old place; not big, you know, but quite old-fashioned; and such a quaint old walled garden that shuts us out from the world. It is away from other houses now, close to the village of Twick; but as North says, Isingford is creeping out that way, and it won’t be country many more years; but our walls will keep us secluded, and inside it is all quite delightful. We have two acres altogether, and it is so well planted and laid out that you would think it was much more.”

Sheila was keenly interested in her friend’s prospects; and time slipped away fast. The softened light told of a westering sun, and May suddenly sprang up crying—

“I am sure it must be tea-time and past. Come along, Sheila. You must be introduced to our other guests!”

They threaded the garden paths, crossed the blazing lawns, towards the group of stately cedars beneath which several persons were seated. Sheila could not see their faces distinctly{826} through the sweeping boughs; but suddenly somebody rose and made a few forward steps, uttering a pleased little exclamation, whilst the girl gave a joyful cry and sprang forward.

“Miss Adene! Oof—how delightful! Oh, May, why did you not say that Miss Adene was here?”

The meeting was a warm one on both sides. Sheila’s glance swept round the little group, but there was no other familiar face, except that of the hostess. She was introduced to the other guests; but was quickly seated beside Miss Adene asking questions in her eager way, and telling of herself in turn.

“Yes, we think that Guy is quite recovered now,” said Miss Adene. “He is wonderfully better, even since you saw him. We went to Oratava for a little while, and then when it grew too hot there we returned to Madeira; and before we left he seemed as strong as ever, and has not lost a bit of ground since he got home. He begins to ride and drive, and walk about just as he did before his illness. Ronald declares that he will soon be quite a superfluity at the Priory. Guy is able to take everything into his own hands again.”

“I am so glad! How happy Lady Dumaresq must be! And dear little Guy, how is he?”

“Oh, as well as possible, the rogue! And he has not forgotten you. He sent you lots of kisses, and an injunction that you were to come and see him very soon. ‘Tell her if she doesn’t come soon,’ he said, ‘I shall go mad.’”

“He didn’t,” cried Sheila, laughing, “Oh, how utterly sweet of him! He is a darling; I should so like to see him again!”

Miss Adene asked after Effie, and time flew quickly by. It was so nice to have lost all that old miserable feeling Sheila once thought she must always experience if she met again these friends, whose kindness towards her had been the immediate cause of her banishment from Madeira, and who must, she knew, have guessed in some measure at the cause of it.

But Miss Adene seemed to have put that memory right away, and there was nothing but pleasure in meeting her again. It was May’s voice which interrupted the talk at last.

“Sheila, I want to get some forget-me-nots from the stream to decorate the dinner-table with. They are so lovely just now, and look exquisite with moss on the white cloth. Do come with me!”

Sheila jumped up at once, and the two girls hastened away together. May’s face was rather flushed, and her eyes were shining brightly. The stream which ran through the park was famed for its beds of blue forget-me-not, and there was no trouble in finding flowers enough and to spare.

Presently the sound of voices, men’s voices, broke upon their ears, and May jumped up, exclaiming—

“Here is North! And he is bringing back a guest of ours, who wanted to see the works. You talk to him, Sheila, and let me have a few words with North. I have so much to say.”

There was a merry gleam in May’s eyes, but Sheila suspected nothing until a sudden bend in the path brought them face to face with the approaching pair, and she saw that North’s companion was none other than Ronald Dumaresq.

Then for a moment astonishment robbed her of her self-control, and the flowers she was holding in her arm slipped in a mass to the ground. Laughingly Ronald sprang forward, picked them up, and took possession of the load.

“I hope you and your flowers are alike in nature, Miss Cholmondeley, and that I am not quite forgotten.”

He stretched out his hand and took hers, and she, looking up into the bright manly face, forgot her tremors and her embarrassment, and felt nothing but a sense of pure happiness in being face to face with him again.

“I see you do not need an introduction,” said May’s voice, with a mischievous ring in it; and then the four began pacing back slowly towards the house, falling naturally into two and two.

“You have seen my aunt?” asked Ronald.

“Yes; but she did not say that you had come too.”

“No, I asked her not. I wanted to give you a surprise. I hope it has not been a very disagreeable one.”

Sheila’s old clear laugh rang out through the wood.

“If you are fishing for compliments, sir, you won’t get any out of me!”

“And I am so fond of them,” said Ronald pathetically. “Don’t you think you might be nice and kind, and say how much you have missed me since we parted?”

“Oof!” cried Sheila, “what next am I to say?”

“Well, if you won’t say the pretty thing, I must. Do you know, Miss Cholmondeley, that after the sudden departure of a certain nameless person from Madeira, everything got so stale and unprofitable to me that I seriously threatened to come home alone; and I should have done so if they hadn’t moved on elsewhere.”

Sheila’s face was glowing, but she answered by a gay laugh; and the laugh was not forced, for was she not very, very happy?

“You may laugh, but I assure you it was no laughing matter to me. Sheila, did you want to go off in that sudden fashion? Did you go of your own accord?”

He stopped suddenly and took her hand; she gave one swift upward glance, and then dropped her eyes.

“It was arranged for me,” she said.

“You did not want to go yourself?”

“No, not then. I was very angry about it. I had a great many wicked thoughts, which I was very much ashamed of afterwards, because it was such a good thing that I did go exactly at that time. It might just have been settled for me in the very best way possible.”

“What do you mean?” asked Ronald quickly.

“You know Oscar, my brother, fell ill of typhoid fever just as I got back. If it had not been for—for—that, I might not have been with him, and I don’t know what I should have done then.”

Ronald’s face cleared; for a moment he had looked anxious.

“I saw Oscar just now at the works,” he said. “I liked him very much indeed. You are not much alike, but there was something in his voice and expression which reminded me of you.”

“I wish I were more like Oscar,” said Sheila humbly. “He is much better than I shall ever be.”

“Don’t wish to be anything but yourself, Sheila,” said Ronald with sudden impetuosity, “for I want you just as you are.”

The blood surged up into Sheila’s face; this was taking the bull by the horns with a vengeance. Ronald seemed to know he had committed himself, and stood his ground, holding her hands fast in his, and again letting the poor forget-me-nots drop to the ground.

“Sheila, I did not mean to be so sudden, I promised not to be in such haste; they all tell me I must not expect to carry everything before me. But when I see you, I forget everything except that I love you. Oh, Sheila, won’t you try and love me too? I am so sure I could make you happy, if you would only give yourself into my keeping.”

Her eyes were on the ground, but there was that in her down-bent quivering face that gave Ronald hope and courage. He bent over her and touched her cheek with his lips.

“Sheila, won’t you say you will try to care for me a little?”

“Oh, Ronald, I do!” she suddenly exclaimed; and then they forgot everything else in that wonderful first embrace of love, in which the gates of a new world seemed flung open before them, and they walked alone in that new world, as though it were their own for evermore.

“But, Ronald,” said Sheila gravely, after those first golden moments had passed, and they began to awake to the realities of life, “you must not ask me to be impatient or selfish. I must think of other people as well, and I must not promise anything without the consent of my uncles.”

“But you are nearly of age, my darling; you will soon be your own mistress.”

“Yes, but that is not quite it, Ronald. My uncles have been very kind to me; my home is with one of them, and my aunt begins to depend upon me. I must not be selfish; you would not like me if I were. We may have to wait a little perhaps, but you won’t mind that, will you, Ronald?”

“I don’t know,” answered Ronald. “And I have an idea your aunt will set herself against this, and she rules your uncle. I won’t have you spirited away from me again, Sheila. That I can’t stand!”

She laughed and put her hand upon his lips.

“Don’t say rude things of my nice aunt and uncle. They are a great deal kinder to me than I deserve, for I did not always treat them very nicely.”

“Stuff! you were an angel; it was they who bullied you, and that Effie always wanted to come between us.”

“No, she didn’t; that is all your fancy. Effie is much nicer than you think, and is getting more sensible and stronger every week. She will be on our side, I know. And, Ronald, I only want us to be reasonable and unselfish, and not put ourselves and our affairs first. If you asked Miss Adene, she would tell you just the same.”

“I know she would,” said Ronald, laughing, and then in a graver voice he added, “Yes, Sheila, you are quite right; one must learn to take the second place, and think of other people as well as oneself. If you can be patient, so can I; and I love you all the better for your unselfishness.”

“I wish I were unselfish,” said Sheila with a sigh. “I am only trying to be, and it does not seem quite so hard when one is very, very happy.”

Then Ronald bent over her, kissed her once more, picked up the fallen flowers, and walked towards the house.

(To be concluded.)

By F. W. L. SLADEN.

Carrying out the directions given last month for preparing the hives for winter, must not be delayed later than the middle of September. All our colonies being strong and having plenty of stores, they should now be wrapped up warmly and left undisturbed until next spring. Two American flour bags placed over the quilts will be quite enough extra covering, or one of these stuffed with a little dry barley straw will answer the purpose even better, providing a warm covering over the frames from two to three inches thick. An inspection should be made of the roofs of the hives, and if they are not thoroughly weather-proof, two coats of good white-lead paint should be applied to them. The size of the entrance must not be reduced to less than three inches.

The quieter bees are kept during the winter the better they come out in the spring. Being snowed up will not hurt them as long as they get sufficient air to breathe, which they will do through two or three feet of light snow. In the middle of a warm day in February, when the bees are flying freely, it will do no harm to lift a corner of the quilts and take note of the amount of sealed stores they still possess, if care be taken not to expose and disturb them more than is necessary. If they seem to be running short of food, a box containing soft candy should be given to them over the feed-hole. Feeding liquid food would excite the bees too much so early in the year, and it should not be done until the beginning of April. If the stores are almost exhausted, feeding with candy or syrup will have to be kept up until the bees are able to find enough honey in the fields to support themselves. In some districts this may not be until June. On the other hand, it is a mistake to keep feeding our bees unless they really require it.

March and April are often trying months for the bees, the sudden changes of temperature being very unfavourable to bee-life. Colonies that are not very strong may become so reduced in numbers that they “pull through” only with difficulty, and afterwards require the whole of the following season to regain their full strength, yielding neither honey nor swarms.

On the other hand, strong colonies, under favourable conditions, during the latter part of April and May, will increase so rapidly that, unless they are given plenty of room inside the hive in good time, they will make preparations for swarming, which the bee-keeper, who wishes to work for honey and not swarm, will find it difficult to check. The usual way to give the bees more room in the spring is by inserting a frame or foundation, or of empty comb in the centre of the brood-nest. If, however, the bees are not quite strong enough to take it, and a spell of cold weather follows, some of the brood may get chilled and this will be a worse disaster than an over-crowded hive.

The spring, then, is a period which calls for constant attention and vigilance on the part of the bee-keeper, who must not be satisfied, as many are, that all is going on right because the bees show activity on a warm day, but must be acquainted with their exact condition, so that prompt assistance may be given when it is required.

Having completed my sketch of the chief events in the bee-keeper’s calendar, it only remains to add a few details which may be of use or interest.

The subject of bee diseases is one that claims our attention. There is only one serious disease that bees are subject to; but that, unfortunately, is rather common. It is known as foul brood. It is caused by a micro-organism, which attacks the brood in the combs, causing it to putrefy and die. In its earlier stages, the presence of foul brood can only be detected by a careful examination of the brood combs, in which here and there a larva or two will be found to be decomposing into a coffee-coloured ropy mass, and some of the capped cells containing pupæ will have their cappings sunken and perforated. As the disease advances, much of the brood gets affected, and a foul smell issues from the entrance of the hive, which may often be perceived several yards away. The colony becomes rapidly weak and profitless, and in the end frequently perishes altogether.

Foul brood is very contagious, and strong measures must be taken to stamp it out directly its presence is discovered. In a bad case the whole colony must be burnt. If the hive is a good one, it may be preserved, but then it must be thoroughly disinfected by being scalded and painted inside and out with carbolic acid. When the disease is discovered in an early stage the combs only need be destroyed, the bees being shaken off them and treated as a swarm. They should be put into a new hive on frames of foundation, and fed with syrup medicated with Naphthol-beta. This drug is supplied in packets by the principal dealers in bee-appliances, and full directions for use are printed on each packet. The old hive and everything connected with the diseased colony must be burnt or thoroughly disinfected. If the combs contain much honey it may be utilised for human consumption without fear; but on no account must it be given back to the bees. When fresh brood develops in the new combs, a sharp look-out must be maintained for the reappearance of the disease; if it should manifest itself, in however slight a degree, the operation of renewing hive and combs must be gone through again. The disease must be looked for in other hives, and these, if found to be affected, must at once be dealt with in a similar way. The source of infection should be ascertained, and if it be found that a neighbouring bee-keeper has any diseased colonies, he should be persuaded to take immediate steps to cure or destroy them.

Bees do not suffer from the attacks of many enemies in this country. Wasps are sometimes troublesome around the hive entrances in the autumn, and titmice are rather too fond of making a meal on a bee or two in the winter. The latter have an amusing way of bringing the bees out of the hive by tapping with their beaks on the alighting board, until a worker appears to see what the matter is, for which act it is immediately seized and swallowed. Field-mice like honey, and will sometimes play havoc with the combs of a weak colony; but if the entrance is not more than 3/8 inch deep, they will find it difficult to force a passage in the hive.

The most troublesome pests, when they get in the hives, are the caterpillars or the wax-moth. They riddle the combs with their numerous silk-lined tunnels, devouring all the pollen brood and honey that come in their way. It is difficult to get rid of these caterpillars without destroying the combs. All moths found in the quilts should be destroyed, for they lay the eggs which produce the caterpillars. The wax-moth is very destructive in bee-hives in America, but one seldom hears of its doing much damage in England, except in badly-kept or neglected hives. Two balls of naphthaline placed on the quilts will help to keep the wax-moth away.

A curious parasite called the bee-louse (Branla cocca) is sometimes found attached to the body of the queen, and occasionally also the workers. Though it belongs to the order of flies, it is blind and wingless, and most resembles a tiny reddish-brown spider. A few of these parasites do not seem to inconvenience the queen-bee.

Ants may be kept out of the hive by placing the legs in saucers containing water. Earwigs do no harm in the hive.

Experienced bee-keepers are often able to increase their colonies cheaply in the autumn by driving their neighbour’s bees. Unhappily there are still many owners of bees in this enlightened country to whom the hive is as a sealed book that they have never attempted to open. They do not trouble to look after their bees, and, when wanting the honey, would destroy them to obtain it, if some practical bee-keeper did not come forward and offer to do the work for them, asking to be allowed to take the bees he has saved from destruction in return for his services, a request which the owner is generally willing enough to grant. It requires a man of some little experience to drive bees successfully, so we will not go into the details of the operation here. Suffice it to say that the straw hive or skep from which the bees are to be driven is fixed in an inverted{828} position, and another skep placed over it into which the bees, by repeated rapping, are driven. Driven bees can generally be bought fairly cheaply in the autumn. Several lots of driven bees should be put together into a wooden hive provided with frames fitted with foundation, or better still, ready drawn-out combs if you have them. Rapid feeding must then be commenced at once, and sufficient food for winter stores should be taken down and sealed over before the middle of September.

We must not be surprised if our extracted honey becomes opaque and solid on the approach of cold weather. This process is called candying or granulation, and is, in fact, a proof of the purity of the honey, though some kinds granulate much sooner than others. Well-ripened honey, when granulated, will keep good for years.

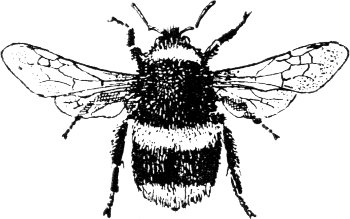

In concluding these papers a few words on the natural history of bees may be of interest. Some of my readers will be surprised when I tell them that there are about two hundred different kinds of bees to be found in England. Up to the present I have been talking only about one of these, and this one, properly speaking, is a honey-bee. Almost all the other bees are solitary in their habits, that is, they do not live in large colonies in hives, but singly or in pairs in holes in the ground, in old stumps or walls, or in the hollow stems of plants. Still they are, many of them, very interesting, and well worth studying. They all feed on honey, and may be found on various kinds of flowers throughout the spring and summer. Some of them are large and beautiful like the well-known humble-bees; others are small and inconspicuous. Some resemble our honey-bee so closely that none but an expert could tell them apart; others again have such a strong likeness to wasps that a novice would scarcely give them credit for sweeter relationships.

QUEEN HUMBLE-BEE (Bombus terrestris).

But readers of this magazine, who happen to reside abroad, might come across other kinds of honey-bees, wild perhaps, but to which, if put in hives, all the foregoing remarks would more or less apply. Several of the foreign races of the honey-bee have been tried in this country and have been found to do very well. One of these, the Italian bee, is quite naturalised, and has spread so extensively over the country that it is hard to find a colony of pure English bees now, most of our bees being a cross between the English and the Italian races. Italian bees may be readily recognised by the pale semi-transparent, orange-yellow markings on the tail, true English bees being entirely black all over. The Italian bees are more prolific than the English race and they are easier to handle because they remain quietly on their combs when the hive is opened. A good cross between the English and Italian races is generally acknowledged to be the best honey-bee for all purposes in this country, but it has acquired a name for being rather bad-tempered.

Books that will be helpful to those who are “going in” for bee-keeping are The British Beekeeper’s Guide Book (paper, 1s. 6d.), and Modern Bee-keeping (6d.), published by the British Bee-keepers’ Association.

Finally, the beginner must not be disheartened by a few difficulties and failures. They should, on the contrary, spur on to greater efforts in seeking to avoid them in the future, for it is chiefly by first failures that experience, that most important factor in every successful pursuit, is gained. Persistent effort will bring its reward, and the bees will soon become a greater source of interest than we ever thought could be possible.

By ELSA D’ESTERRE-KEELING, Author of “Old Maids and Young.”

THE TALL GIRL AND THE SMALL GIRL.

EXTREMES MEET AND KISS

“Often the cockloft is empty in those whom Nature has built many storeys high,” says quaint old Fuller.

“Long and lazy,” says the proverb.

“Divinely tall,” says Tennyson.

Now in thought go over the tall girls whom you have known. Perhaps they were not unlike the tall girls known to me.

Cicely—by herself called Thithily—is one of these. She has a little head atop of a long body, and when she laughs, which she does much, displays to view two rows of foolishly small teeth. Cicely laughs to keep herself from crying, for she has a very hard time of it.

Poor?

No. She has everything that money can buy, but lacks a thing that money cannot buy.

Muriel is the poor long girl known to me.

Muriel’s wail is, There is so much of me to dress.

When last I saw Muriel, her boots were down at heel, and to shamefacedness she added—shamefootedness.

Dearest to me of long girls is one Dorothy, big and beautiful and kind, knowing some things—not many—and wanting to know more.

Said Dorothy one day—

“Is there not such a word as ‘magnanimosity’ for ‘kindness’?”

It was hard to have to tell her that there was not, and that, if ever such a word as “magnanimosity” shall be, it will certainly not be a word for “kindness.”

Have you noticed that a big girl mostly has a small girl for her friend, and vice versâ? Shakespeare, who noticed all things, noticed that. With Helena he puts Hermia, and with Rosalind Celia.

The tall girls of prose-fiction are numerous. For A there is Blackmore’s Annie, who “never tried to look away when honest people gazed at her.” For B there is Thackeray’s Beatrix, and there is one for every other letter in the alphabet.

The “towering big” girl—to put the matter Hibernically—had a great vogue a few years ago as the heroine of Trilby, but, on the whole, the small girl has been more singled out for loving treatment by novelists than the tall girl. Dickens had a known preference for her, and his “little Nell” has eclipsed all big Nells. In the description of one Ruth, too, it may be noticed that he uses with loving iteration the word “little”—“pleasant little Ruth! cheerful, tidy, bustling, quiet little Ruth!”

In fiction subsequent to that of Dickens there is a Mary described thus—“a little dumpty body, with a yellow face and a red nose, the smile of an angel, and a heart full of many little secrets of other people’s, and of one great one of her own, which is no business of any man’s.”

A Tall Story

All readers of Kingsley’s Two Years Ago will remember that Mary.

The poets no less than the prose-writers have busied themselves with the small girl. The mere word Duchess to most people calls up a picture of stateliness, yet Browning describes a duchess as follows:—

In these days of tall girls small girls are apt to fret. There is one known to me whose case is pitifuller than that of the little fir-tree in Andersen.