Title: Tom Newcombe; Or, the Boy of Bad Habits

Author: Harry Castlemon

Release date: December 29, 2020 [eBook #64169]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: David Edwards, Susan Carr and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

THE GO-AHEAD SERIES.

OR,

THE BOY OF BAD HABITS.

BY

HARRY CASTLEMON,

AUTHOR OF “THE GUN-BOAT SERIES,” “THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN SERIES,” ETC.

THE JOHN C. WINSTON CO.

PHILADELPHIA

CHICAGO TORONTO

FAMOUS CASTLEMON BOOKS.

| GUNBOAT SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 6 vols. 12mo. | ||

| Frank the Young Naturalist. | Frank on a Gunboat. | |

| Frank in the Woods. | Frank before Vicksburg. | |

| Frank on the Lower Mississippi. | Frank on the Prairie. | |

| ROCKY MOUNTAIN SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 3 vols. 12mo. Cloth. | ||

| Frank among the Rancheros. | Frank at Don Carlos’ Ranch. | |

| Frank in the Mountains. | ||

| SPORTSMAN’S CLUB SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 3 vols. 12mo. Cloth. | ||

| The Sportsman’s Club in the Saddle. | ||

| The Sportsman’s Club Afloat. | ||

| The Sportsman’s Club among the Trappers. | ||

| FRANK NELSON SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 3 vols. 12mo. Cloth. | ||

| Snowed Up. | Frank in the Forecastle. | The Boy Traders. |

| BOY TRAPPER SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 3 vols. 12mo. Cloth. | ||

| The Buried Treasure. | The Boy Trapper. | The Mail-Carrier. |

| ROUGHING IT SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 3 vols. 12mo. Cloth. | ||

| George in Camp. | George at the Wheel. | George at the Fort. |

| ROD AND GUN SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 3 vols. 12mo. Cloth. | ||

| Don Gordon’s Shooting Box. | Rod and Gun Club. | |

| The Young Wild Fowlers. | ||

| GO-AHEAD SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 3 vols. 12mo. Cloth. | ||

| Tom Newcombe. | Go-Ahead. | No Moss. |

| FOREST AND STREAM SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 3 vols. 12mo. Cloth. | ||

| Joe Wayring. | Snagged and Sunk. | Steel Horse. |

| WAR SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 5 vols. 12mo. Cloth. | ||

| True to his Colors. | Rodney the Partisan. | |

| Rodney the Overseer. | Marcy the Blockade-Runner. | |

| Marcy the Refugee. | ||

Other Volumes in Preparation.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1868, by

R. W. CARROLL & CO.,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

Copyright, 1896, by Charles A. Fosdick.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Tom’s Habits, | 5 |

| II. | The Fisher-Boy, | 20 |

| III. | Tom goes to Sea, | 31 |

| IV. | Life on the Ocean Wave, | 47 |

| V. | Homeward Bound, | 63 |

| VI. | Tom goes into Business, | 81 |

| VII. | How Tom Succeeded, | 94 |

| VIII. | Tom makes new Bargains, | 103 |

| IX. | The Mystery in a Storm, | 116 |

| X. | Tom’s Game Chickens, | 126 |

| XI. | Tom Decides to be a Farmer, | 138 |

| XII. | Tom’s New Home, | 152 |

| XIII. | Life on a Farm, | 163 |

| XIV. | The “Night-Hawks,” | 177 |

| XV. | The Night-Hawks in Action, | 190 |

| XVI. | The Military School, | 208 |

| XVII. | Tom wants to be Colonel, | 226 |

| XVIII. | Tom has an Idea, | 238[iv] |

| XIX. | The Conspirators, | 251 |

| XX. | Plans and Arrangements, | 267 |

| XXI. | The Escape, | 280 |

| XXII. | The Pursuit Commenced, | 297 |

| XXIII. | The Cruise of the Swallow, | 309 |

| XXIV. | A Change of Commanders, | 321 |

| XXV. | Conclusion, | 332 |

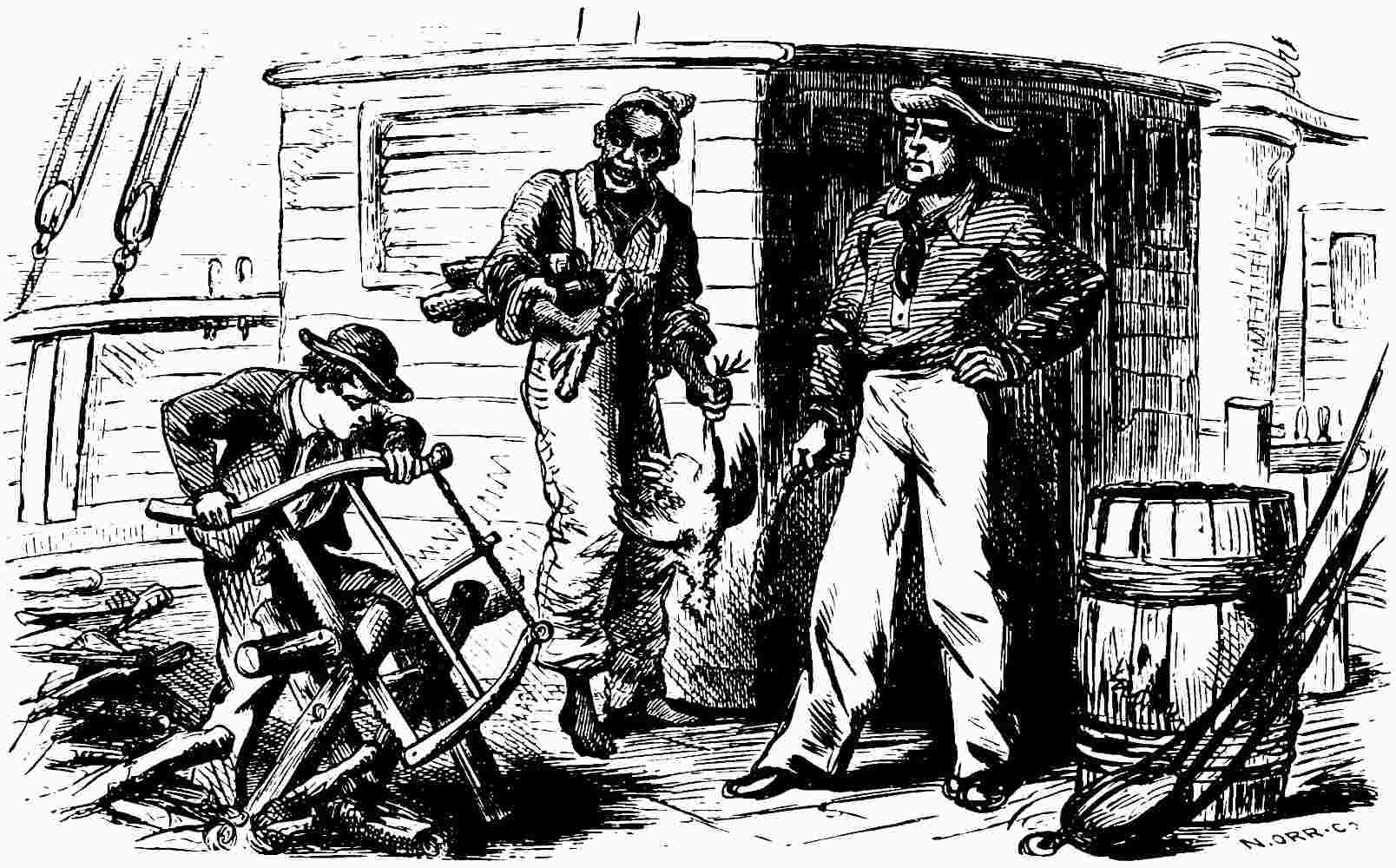

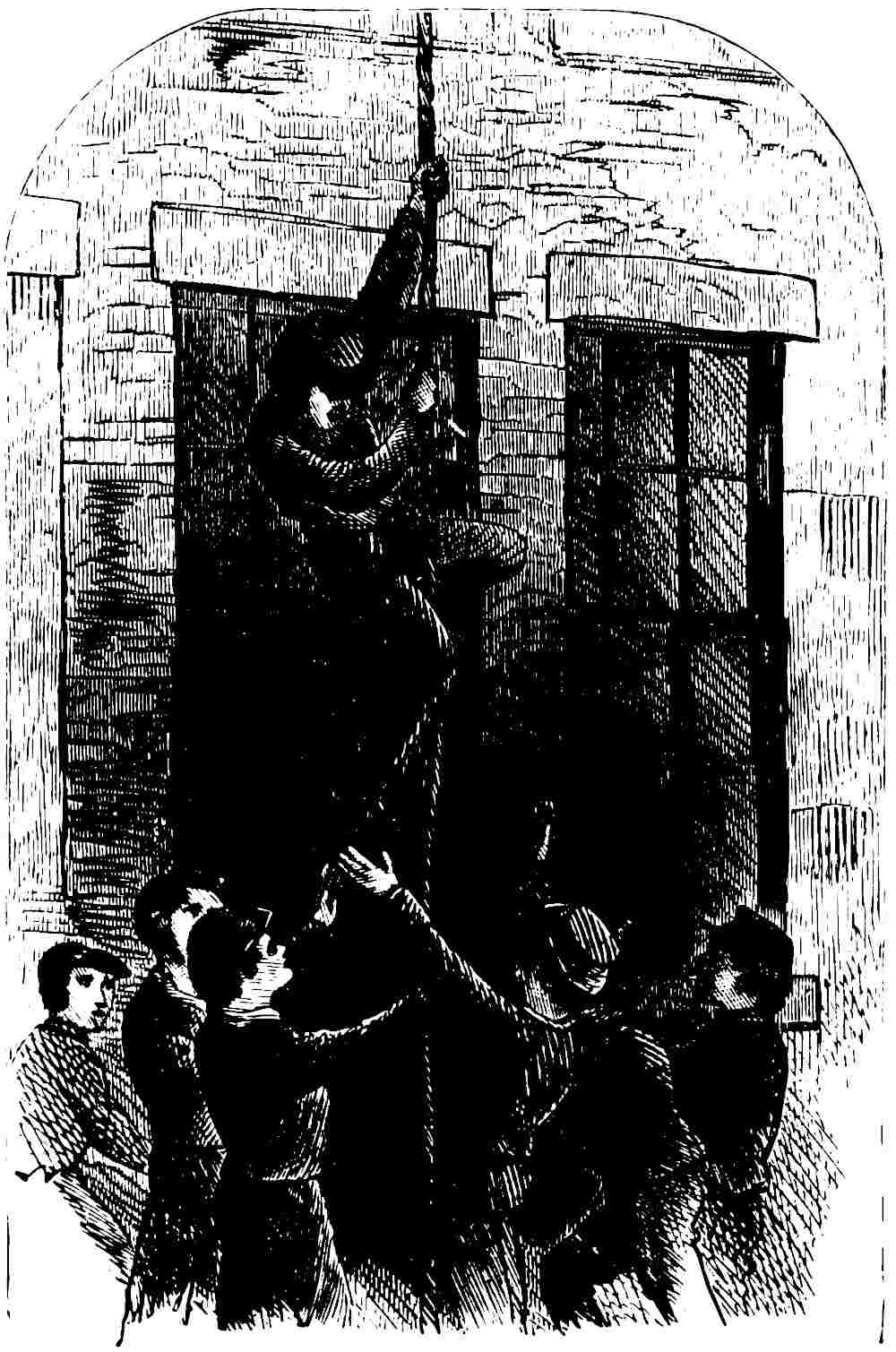

| Tom Learning to be a Sailor. | Frontispiece |

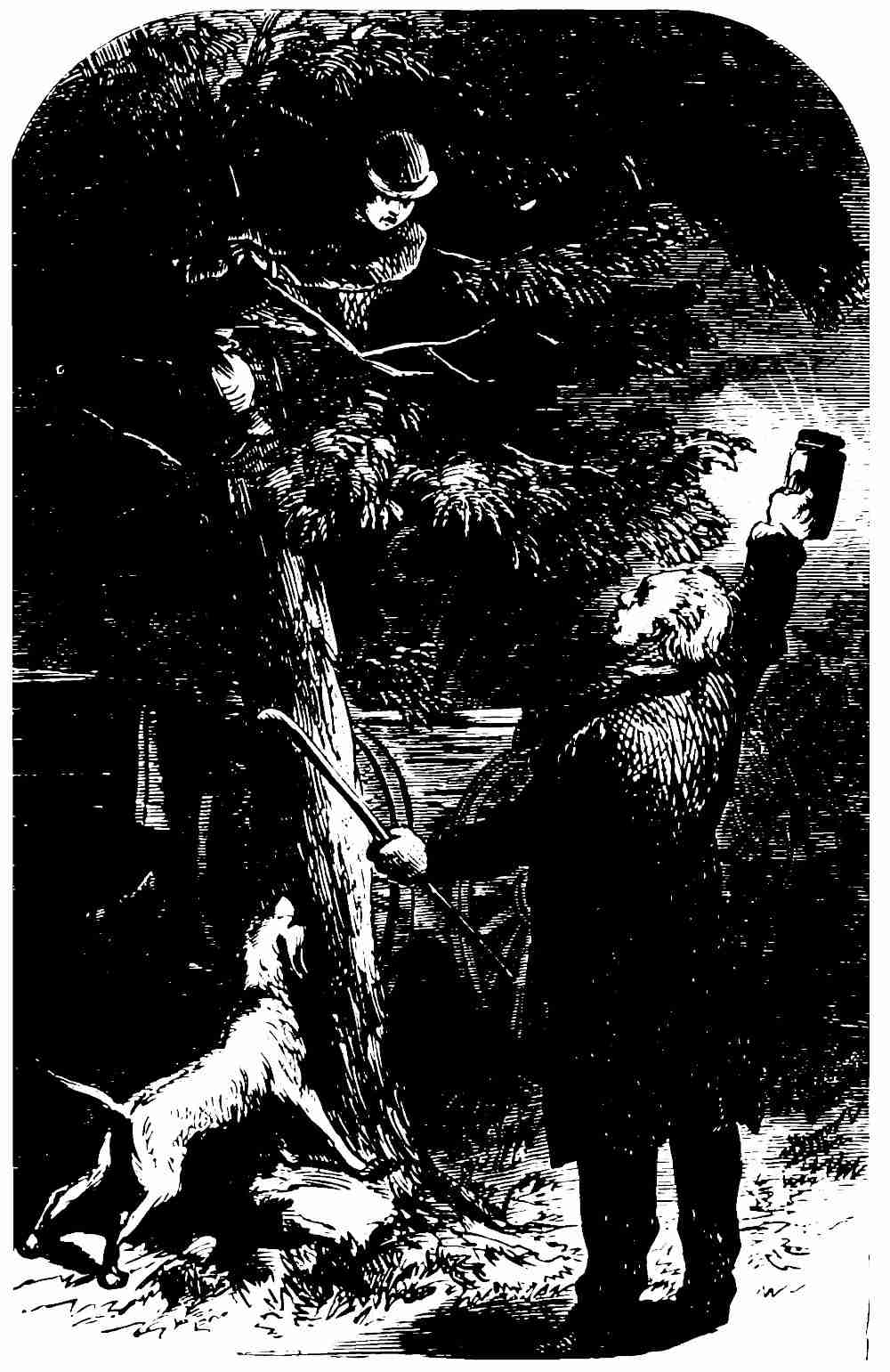

| Tom Captured by the Squire. | 205 |

| The Escape from the Academy. | 286 |

TOM NEWCOMBE;

OR,

THE BOY OF BAD HABITS.

“O NOW, I can’t learn this lesson, I know I can’t, and there’s no use in trying! I am the most unlucky boy in the whole world!”

Thus spoke Tom Newcombe, as he lay under one of the trees in his father’s yard, rolling about on the grass, and tossing his heels in the air, as if he scarcely knew what to do with himself.

Tom was not a happy boy, although all his playmates thought he ought to be. His father was the wealthiest man in the village—owned more than half the vessels that sailed from that port, and Tom lived in a large house, where he had every thing a boy of his age could ask for to make his life pass pleasantly. He owned the swiftest sail-boat about the village; had more fish-poles, foot-balls, and playthings of every description than he could possibly find use for; and, in[6] the stable, was a fine little Shetland pony, which had been bought for Tom’s express benefit. But, in spite of his pleasant surroundings, the hero of our story was very discontented; his face always wore a gloomy expression, and he invariably acted as if he were angry about something.

Tom was about fourteen years of age, as smart as any boy in the village, and might have been of some use in the world, had it not been for his numerous bad habits, which kept him in constant trouble, and were the sole cause of all his unhappiness. One of these bad habits was carelessness. He thought it was too much trouble to carry out the motto he had so often heard—“A place for every thing and every thing in its place”—and the consequence was, he was not unfrequently compelled to waste half the day in searching for some article he happened to want. His cap, especially, was the source of a great deal of annoyance and vexation to him. For example, when he came in to his meals, he would take off his cap on entering the house, and throw it somewhere, not caring where it landed; and as soon as he was ready to go out of doors again, his first question—spoken in a slow, drawling tone, as if he were almost ready to drop down with fatigue—would be:

“Now, mother, where’s my cap?”

“I am sure I don’t know, my son,” would be the answer. “What did you do with it when you came in?”

“I hung it right here!” Tom would say, pointing to the hat-rack in the hall, or to a nail behind the door, which had been placed there for his especial benefit.[7] “I know I hung it up, but it isn’t here now. I do wish folks would let my things alone! Something’s always bothering me!”

Then Tom would begin a search in all the rooms of the house, tumbling chairs about and moving tables and sofas, and the missing article would be found, sometimes in the “play-house,” sometimes under the bed, but more frequently under the trees in the yard, or on the portico.

We have spoken of Tom’s “play-house.” It was a room in the attic, nicely furnished, with carpet, tables, and chairs, and provided with a stove, so that he could be comfortable there in cold weather. In this room he kept his playthings, or rather, part of them. Those that were lost—and about half of them were missing—would have been found, some in the barn, others scattered about the yard, while the rest had been thrown under the house for safe keeping, where Tom could not get at them without soiling his clothes, and that was something he did not like to do. To have taken a single glance at the articles in his play-house, one would have thought that he ought never to have been at a loss to know how to employ himself; and that a single glance would also have been sufficient to convince any one that he never took the least care of what was given him. The only thing that ever interested Tom for any length of time, was a fine model of a ship, with sails and ropes complete, which an old sailor had given him, and which had been placed on a stand opposite the entrance to his play-house. But, having been carelessly mounted, it had fallen to the floor, and Tom, in one of his angry moods, had kicked it under the table, where it lay with its masts broken, and its sails torn, looking very much like a vessel that[8] had been wrecked at sea. His playthings were scattered about the room in all directions. Foot-balls, bows and arrows, Chinese puzzles, base-ball bats, a magic lantern, models of vessels, fish poles, hats and boots were mixed up in the most complete confusion, and every article bore evidence to the fact that it had received the roughest usage. Indeed, there was but one thing in the room that was entire, and that was a little fire-engine—a birthday present from his mother. But then this had only come into Tom’s possession two days before the commencement of our story, and it was yet new to him.

Tom was always complaining that he never could find a thing when he wanted it; and no one about the house wondered at it in the least. To his mother’s oft-repeated inquiry why he did not put his room in order, and have a certain place for each particular thing, he would answer:

“O, now, I can’t; I haven’t got time. Let somebody else do it!”

Tom’s room, we ought to remark, was placed in perfect order every day, but it was only time and labor wasted; for, if he happened to want a fish-pole, or a ball bat, he would tumble the things about until he found the article in question, and then go out leaving the room in the greatest confusion.

Another bad trait in Tom’s character was his unconquerable pride. He was ashamed to work, and he would not do so if there was any possible way for him to avoid it. On a cold day, when it stormed too violently for him to go out of doors, he would remain in his room, with benumbed hands and chattering teeth, before he would take the trouble to build a fire. His father often[9] asked him why he stayed there in the cold, and Tom replied: “O, there’s no wood up here!”

“Well, you know where the wood-shed is. Go and get some.”

“O, I can’t,” Tom would invariably answer. “Let somebody else go. It wouldn’t look well for me to do it.”

Once or twice during the previous winter, for some offense that he had committed, he was compelled to remove the snow from the side-walk in front of the house. On these occasions, Tom, being very much afraid of soiling his gloves, handled the shovel with the ends of his fingers, and when any one passed by, he hung his head as if he did not wish to be recognized. Work of any kind was the severest punishment that could be inflicted upon him. In his estimation, it was a disgrace that never could be wiped out.

Tom also had a bad habit of saying, “O, I can’t; I know I can’t, and what’s the use in trying?” This was his favorite expression—one that he made use of at all times, and upon all occasions. If his lesson was hard, instead of going manfully at work to learn it, he would read it over carelessly a few times; and if he failed to remember it, or if he found it more difficult than he had expected, he would throw down his book, exclaiming: “O, I can’t get it. It’s too hard. Something’s always bothering me;” and that was the end of it as far as he was concerned.

“Tom,” his father would say, when he heard the boy make use of this expression, “don’t you remember the words of the old song, ‘If at first you don’t succeed, try—’”

But Tom, as soon as he found out what was coming, would interrupt him with—

“O, now, father, that’s all useless. What good does it do a fellow to try, when he knows he can’t succeed? It’s only time wasted. I’m quite sure the person who wrote that song never had any very hard things to do.”

At school, Tom never made any progress. Promised rewards or threatened punishments seldom had any lasting effect on him, and the result was, that all the boys of his age in the village soon left him far behind. He disliked very much to be beaten, and always wanted to be first in every thing; but even this failed to arouse him, and, as his school-mates termed it, he was “promoted backward,” until, at last, he found himself in a class with boys who were much younger than himself, but who, in spite of the difference in their ages, always had their lessons better than he. Finally, Mr. Newcombe, almost discouraged, took Tom out of school, and placed him under the charge of a private teacher, who lived at the mansion. When this change was made, Tom looked upon himself as a most fortunate boy; but he soon discovered a very disagreeable feature in the arrangement, and that was, his father was always in the school-room when he recited his lessons. This made Tom very uneasy. He did not wish to make a display of his ignorance before his father, and, besides, he knew that if the merchant took the matter into his own hands, something unpleasant would happen. On several occasions, he had assured Mr. Newcombe that he could recite his lessons much better if he were not present; but the latter, taking a different view of the case, was always at[11] home during the recitations, and Tom had more than once been soundly scolded for his failures.

Tom was also sadly wanting in firmness of purpose. Like many boys of his age, he looked forward with impatience to the day when he should become a man; and the question that troubled him not a little, was, what should he do when he became his “own master,” as he termed it. He was full of what he considered to be glorious ideas, but, when he had determined to enter upon any particular calling, he always found something unpleasant in it. For instance, during the previous winter he had informed his father that it was his intention to become a sailor, and that nothing could induce him to change his mind. As usual with him, he wanted to begin at once, and he scarcely allowed his father a moment’s rest, teasing him from morning until night, for permission to go to sea on one of the vessels as cabin-boy. But Mr. Newcombe, who had once been a cabin-boy himself, and who knew what Tom would be compelled to endure, would not give his consent. He was not at all opposed to his son’s going to sea, for, having been a sailor himself, he looked upon a sea-faring man as a most useful and honorable member of society; but he knew that on ship-board, Tom’s uneasy, discontented disposition would keep him in constant trouble; and before he allowed him out of his sight he wanted him to abandon his bad habits. Besides, he did not wish his son to remain a foremast hand all his life, and he knew that if Tom wished to win promotion, he must first go to school and pay more attention to his books. So Mr. Newcombe told Tom that he could not go, and this made the boy very miserable indeed. Several of[12] his playmates, who were much younger than himself, had been to sea on three or four voyages, and why couldn’t he go as well as any body? He could see no good reason for a refusal, and in order to punish his father for not allowing him to have his own way, he went into the sulks, and, for a day or two, scarcely spoke to any one. This was Tom’s favorite way of taking revenge on his father and mother, and no doubt it was the source of great satisfaction to him. But had he known how foolish he was, and how all the sensible boys of his acquaintance laughed at him, he might have taken some pains to conceal his ugly temper. He resolved that he would never abandon his idea of becoming a sailor, and every moment that he could snatch from school, was spent on the wharf, where he stood looking at the vessels, and wishing that he was his “own master,” so that he could do as he pleased. One night he took his stand on the wharf, and saw one of his father’s vessels towed into the harbor almost a wreck. Her foremast was gone, her deck and shrouds were coated with ice, her rigging all frozen, the sails useless, and those of the crew that were left, were in the most pitiable condition. This was an incident in the life of a sailor that had never entered into Tom’s calculations; and when he had seen the vessel moored at the wharf, and heard her captain tell his father that the crew, besides being badly frost-bitten, had been without food for two days, Tom started homeward, fully resolved that he would never follow the sea.

For a day or two after that, he was a most miserable boy. He did not know what to decide upon next; and he never was happy unless he had something to dream[13] about. But, one afternoon, as he stood in his father’s office, a well-to-do farmer drove up with a load of grain, and Tom suddenly saw the way out of his quandary. There were four horses hitched to the sled, and they were so slick and fat, and the farmer seemed to be so happy and contented, that Tom could not resist the thought that he would like to be a farmer. In fact, after a few moment’s consideration, he decided that he would be one, and he resolved to act upon his decision at once. After a little maneuvering, he commenced a conversation with the farmer, during which, he asked him if he “didn’t want to hire a boy!” The man replied that he did, that he was just looking for one, and, that, if Tom would go home with him, he would soon make a first-class farmer of him. Tom, delighted with the idea, at once sought an interview with his father, to whom he hurriedly explained his new scheme. Mr. Newcombe, too busy to be interrupted, answered his request that he might be permitted to go home with the farmer in the negative; but Tom, who was a great tease, was not to be put off so easily.

“You don’t understand what I want, father!” he began.

“Yes I do!” replied the merchant. “I know all about it. But there’s one thing I don’t know, and that is, what foolish notion you’ll get into your head next!”

“But, father!” said Tom impatiently, “may I go? That’s what I want to know!”

“No, sir, you may stay at home!”

“O, now, why can’t I go?” whined Tom. “Say, father, why can’t I go? I want to learn to be a farmer.”

How long Tom would have continued to tease his[14] father, it is impossible to say, had not the merchant, well-nigh out of patience, ordered his son to “go home, and stay there, until he should learn not to bother persons when they were busy.” Tom reluctantly obeyed; but the moment he reached the house again went into the sulks.

This last idea, he thought, would suit him much better than any thing he had ever before thought of. Heretofore, when he had explained his plans to his father, that gentleman had invariably said,

“Tom, you don’t know enough! Go to school and pay more attention to your books. Get your education first, and decide upon your business afterward.” But this was something the boy did not like to do. He could not bear to study, and all his calculations, as to what trade or profession he should follow when he became a man, had been made with reference to this particular object—namely, to discover some business which could be successfully conducted without a knowledge of arithmetic and geography, two things that Tom thoroughly despised. But now he had hit upon the very thing—farming; a farmer had nothing to do but drive horses, take care of cows, and spread hay; and that did not require a knowledge of arithmetic or geography. That was just the business for him; and he resolved that some day he would be a farmer.

During the remainder of the winter, Tom held firmly to this determination. He thought, and dreamed about nothing else; and a farmer’s sled or wagon was an object of great curiosity to him; at least all his playmates thought so, for every morning and evening, before and after school, and all day Saturdays, Tom was seen loitering[15] about the market-houses, looking at the horses, and talking with the farmers. This state of things, we repeat, continued until spring, and then all these ideas were driven out of his head as suddenly as they had entered it.

Among other things of which the village of Newport could boast, was its military school. This institution was attended by boys of all ages, from almost all parts of the state, and, in addition to being prepared either for business or college, they were instructed in military science. The students wore a uniform of gray trimmed with blue, the “commissioned” officers being designated by shoulder-straps, and the “non-commissioned,” by two or three stripes worn on the right arm, above the elbow. Every thing in and about the academy was conducted in military order. The officers were always addressed according to their rank, captain, lieutenant, or sergeant, as the case might be, and punishment for serious offenses against the rules of the school was adjudged by courts-martial, composed of some of the teachers and students. Every spring and fall the members of the academy, with their professors at their head, went into camp, where they generally remained about two weeks; and it was during one of these camping frolics that Tom, after having witnessed a series of parades, during which, the students behaved like veteran soldiers, lost all desire to become a farmer, and decided to turn his attention to the military school. Tom had often wished that his father would permit him to sign the muster-rolls of the academy, and, in fact, he had, for a long time, been unable to determine whether he was “cut out” for a soldier or a sailor. On this point he had often debated[16] long and earnestly. It must not be supposed that Tom was endeavoring to decide in which of these two callings he could do the most good, and be of the most use to his fellow-men! Quite the contrary. He cared for no one but himself. It made no difference to him how much others were troubled or inconvenienced, as long as he could get along smoothly; and the question he was trying to answer was, Which calling held out the better promise of a life of ease? There was another question that Tom had never been able to answer to his satisfaction, and that was, of what use would his military education be to him after he left the academy? But one day, just before the camp broke up, this problem was solved by one of the students, who informed Tom that he had passed a successful examination, and had received the appointment of cadet at West Point. This showed Tom the way out of his difficulty, and, at the same time, opened before his lively imagination a scene of glory of which he had never before dreamed.

“That’s the thing for me!” he soliloquised, as he bent his steps homeward. “That’s the very place I always wanted to go to. If father would let me join this school, I’d certainly be appointed captain of one of the academy companies in two or three weeks; then, after I get through there, I’d go to West Point. I’d stay there until I completed my military education, and then go into the army. Then I would be sent off somewhere to fight the Indians, and, if I was a brave man, I might be promoted to colonel or brigadier-general. Wouldn’t that be glorious, and wouldn’t I feel gay riding around on my fine horse, with my body-guard galloping after me? It’s an easy life, too; I know it would just suit[17] me. and I am resolved that some day I will be a soldier.”

By the time Tom reached home he had worked himself up to the highest pitch of excitement, by imagining all sorts of pleasant things that would happen when he should become a general in the regular army; but what was his disappointment when his father—after he had explained to him his glowing schemes—refused to permit him to join the military academy.

“I might have expected it,” said Tom to himself, as he walked sullenly out of the house. “I always was the most unlucky boy in the whole world. I never can do any thing like other fellows, for father don’t want me to enjoy myself if he can help it. But I’ll be my own master one of these fine days, and then I’ll do as I please.”

Tom was decidedly wrong when he said that his father did not want him to enjoy himself, for Mr. Newcombe used his best endeavors to make his son happy and contented; and this was the reason he had never allowed Tom to carry out any of his numerous schemes. He knew that the boy’s bad habits would render him unhappy wherever he went, and in whatever he engaged; but he hoped that, as he grew in years, he would also grow in wisdom; that he would learn that his only chance for success in any undertaking was to “turn over a new leaf,” abandon all his bad habits, and begin work in earnest. But Tom, attributing his father’s refusal to entirely different motives, went into the sulks, and for a week scarcely spoke to any one about the house. For two months he fretted and scolded almost constantly, and all this time he was endeavoring to[18] conjure up some plan by which he might induce his father to grant his request. He declared, more than once, that he was “bound to be a general,” and that he “never would give up his idea of joining the military academy.” But one day an event transpired that caused him to forget all these resolutions, and turned his thoughts and desires into another channel.

A full-rigged ship, which had been launched at the yards early in the spring, was completed, and Tom saw her start on her first voyage. He had never before seen so beautiful an object as that ship, and, as she sailed majestically out of the harbor, the thought occurred to Tom how grand he would feel if he was the master of a vessel like that. From that hour the military school was at a discount, and Tom had again resolved to be a sailor—not a common foremast hand, but the captain of a full-rigged ship.

These are but few of the instances that might be cited to illustrate the fact that Tom was utterly lacking in firmness of purpose, for there was scarcely a trade or profession that he had not, at some time or another, wanted to follow. For a time he imagined that a man who could build and run a steam-engine ought to be very proud, and able to make his living easily, and then he wanted to be a machinist. Then he thought that the village doctor, a fat, jolly man, who rode about in his gig, and appeared to take the world very easily, ought to be a happy man, and then Tom wanted to study medicine. Next, after listening for a few moments to a Fourth of July speech, delivered by a prominent member of the bar, he decided to be a lawyer; and, after that, a civil engineer; but, upon[19] inquiry, he found that all these involved a long course of study and preparation; so they were speedily dismissed as unworthy of his attention.

Tom, we repeat, had often thought of these and many other trades and professions; but, at the period when our story commences, he was, perhaps, for the hundredth time, firmly settled in his determination to become a sailor. Mr. Newcombe had often talked to his son about his bad habits, especially his want of stability, his propensity to build air-castles, and his aversion to study; but, it is needless to say, the boy paid very little attention to what was said to him. The truth was, he did not believe that his father knew any thing at all about the matter. Besides being very stubborn—holding to his own ideas, no matter what was said against them—he had a most exalted opinion of himself, and had often made himself ridiculous by saying, “They can’t teach me—I know just what I am about.”

Tom lived to be an old man; and perhaps we shall see what he thought of these things in after life; whether or not he never regretted that he had not followed the advice of those who, being older and more experienced than himself, knew what was best for him.

THE house in which Tom lived stood on a hill that commanded a fine view of the village of Newport and the adjacent bay, and before it was a wide lawn, that sloped gently down to the water’s edge, shaded by grand old trees. On the day we introduce Tom to our readers, he had been sent out of the school-room in disgrace, not having mastered his arithmetic lesson. He lay at full length under one of the trees, stretching his arms and yawning, throwing his book about, and looking out over the bay at the vessels that were sailing in and out of the harbor. Now and then he would think of his lesson, but the thought was always dismissed with an impatient “O, I can’t learn it; I know I can’t, and what’s the use in trying?” But it was evident that he did not intend to abandon it altogether, for he would occasionally open his book and study for a few moments, with his mouth twisted on one side, as if he were on the point of crying. The fact was, Mr. Newcombe was present at the recitation that morning, when his son had made a worse failure than usual; and as he was about to leave the school-room, he turned to Tom and told him, in language too plain to be misunderstood, that if he “didn’t have that lesson by five[21] o’clock that afternoon, he would get his jacket dusted in a way that would make him open his eyes.” Tom remembered the threat, and he would now and then turn to his task with a listless, discouraged air, as if he regarded it as far beyond his comprehension. His mind, as usual, was wandering off over the bay, and to save his life he could not learn the rule for addition.

His lesson, however, was not the only thing that troubled him just then; a more important matter was on his mind, and perplexed him exceedingly. He had that morning found an insurmountable obstacle in his path—one that shut him out from all hopes of ever becoming a sailor.

When the sight of that fine ship had again turned Tom’s attention to the sea, he laid a regular siege to his father, and tried every plan he could think of to obtain his consent to ship as boy on one of his vessels; and that morning he had asked permission to go out on the “Savannah,” a schooner that was to sail in a week or two.

Mr. Newcombe had, for a long time, patiently borne his fretting and teasing; and, finally, to set the matter at rest at once and forever, he said to Tom:

“My son, when you can add up a column of figures without counting your fingers, and can tell me the capital of every State in the Union, and where it is situated, you may go to sea. Now, wake up, and see if you can’t display a little energy. The Savannah will not sail under two weeks, so you will have plenty of time to do all this.”

“O no, father,” drawled Tom, (he always spoke in a very low tone, and so slowly that it made one nervous[22] to listen to him,) “I can’t learn all that in two weeks. It’s too hard.”

Mr. Newcombe did not wait to hear what Tom had to say, but picked up his cane and started for his office, leaving his son pondering upon this new and wholly unexpected turn of events.

This was a death-blow to Tom’s hopes. It was, in his estimation, a task that would have made a Hercules hesitate. Learn all that in two weeks! Did his father take him for a walking arithmetic and geography, that he expected him to accomplish so much in so short a space of time? It was simply impossible, and he was astonished at his father for proposing such a thing. Under almost any other circumstances, Tom would have said, “Then I can’t be a sailor,” and would have immediately turned his attention to something else. But he remembered how grand that ship looked as she sailed out of the harbor, and he could not bear the thought of forever giving up all hopes of becoming the captain of a vessel like that.

Tom regarded this as one of his unlucky days. His lesson was very hard. He had been promised a whipping if he did not get it. There was that tremendous obstacle that had so suddenly risen up before him, and altogether he felt most discontented and miserable. It was no wonder he could not learn the rule.

“O, I do wish I could be a sailor,” said he, at length; “then I wouldn’t have any teachers to bother me, and ask why I place units under units, and tens under tens, when I want to add figures, and why I carry the left-hand figure to the next column when the amount exceeds nine. What good will it do me to learn all this?[23] I can manage a vessel without it. And then, if I was on board ship, there wouldn’t be any one to tell me that he’d dust my jacket for me if I didn’t get my lesson. Ah, that would be glorious! But I can’t be a sailor now; I can’t add figures, and tell the capitals of all the States—there’s too many of them. O, dear, what shall I do? I always was an unlucky boy, and something is always happening to bother me. Now, there’s Bob Jennings! He ought to be a happy fellow, having nothing to do but row about the harbor all day, ferrying and catching fish. He’s a lucky chap, and I wish I was in his place. Hullo, Bob, come up here!”

Tom’s thoughts were turned into this channel by discovering a boy, about his own age, rowing a scow up the bay. The fisher-boy had seen Tom rolling about on the grass, and, if the latter could have known the thoughts that passed through his mind, no doubt he would have been greatly astonished.

Bob Jennings was the son of a poor widow who lived in the village. His father, like the majority of men in Newport, had followed the sea for a livelihood, but, having been washed overboard from his vessel during a storm, Bob was left as the only support for his mother and two little brothers. From the time he was strong enough to handle an oar, he had been accustomed to work, and, unlike Tom, he was not ashamed of it. He was ready to undertake any thing that would enable him to turn an honest penny; and many a dime found its way into his mother’s slim purse, that Bob had earned by running errands after his day’s work was over. But, if he was obliged to work hard while his father was living, he was compelled to redouble his exertions now, for the pittance[24] his mother earned by sewing and washing could not go far toward feeding and clothing four persons. Bob well understood this, and he worked hard and incessantly. Every morning, rain or shine, he was on hand at pier Number 2, which he regarded as his own particular “claim,” ready to ferry the workmen across the harbor to the ship-yards. After this was done, he pulled down the bay to his fishing grounds, from which he returned in time to be at his pier when the six o’clock bell rang in the evening.

Bob was ambitious, and he longed to follow in the footsteps of his father. Like all the boys in Newport, who seemed to inhale a passionate love of salt water with the air they breathed, he looked forward to the day when he should become the master of a fine vessel. But his mother could not live without his assistance. His earnings, however small, were needed to procure the common necessities of life; and, thus far, Bob had been unable to take the first step toward attaining his long-cherished object. A few weeks previous to the commencement of our story, he had entered into an agreement with his mother, to the effect, that as soon as he could lay by a sum sufficient to support her and his brothers for two months, he was to be allowed so go on a short voyage. This served as an incentive to extra exertion, and Bob worked early and late to accomplish the desired end. Every cent he earned, he placed in his mother’s hands; and so impatient was he to save the amount required, that he reserved not a penny for himself, but went about his work ragged, shoeless, and almost hatless. How often, as he rowed by the elegant mansion in which Tom Newcombe lived, had he given utterance to the wish that he could find some way in[25] which he might earn as much money as the rich ship-owner allowed his son to spend foolishly every month. He was confident that it would amount to double the sum required to support his mother while he was gone on his first voyage, and would have placed it in his power to enter upon his chosen work at once. Nearly every day, as he pulled by in his leaky, flat-bottomed boat, he saw Tom rolling about under the trees; and, when he drew a contrast between their stations in life, it almost discouraged him.

Hearing Tom calling to him, Bob turned his boat toward the shore, and in a few moments reached the spot where the young student was seated. There was a great difference between the two boys. The rich man’s son was neatly clad, while Bob was barefooted, wore a brimless hat on his head, and his clothes were patched in a hundred places, and with different kinds of cloth, so that it was almost an impossibility to tell their original color. The fisher-boy thought his garments looked worse than ever by thus being brought in contrast with those of the well-dressed student, and he involuntarily seated himself on the ground, with his feet under him, as if to hide them from the gaze of his more fortunate companion. But the difference did not cease here. About the one, there were virtues that could not be hidden by ragged clothes; and in the other, there were glaring defects that made themselves apparent in spite of his well-blacked boots and broadcloth jacket; and, had a total stranger been standing by, with an errand he wished promptly executed, the successful accomplishment of which was of the utmost importance, he would, without hesitation, have selected Bob as the more reliable. There was an[26] honest, resolute look about him, which showed that he was ready for any thing, and that he felt within him the power to overcome all obstacles; while Tom had a listless, die-away manner of moving and talking, that led one to believe that he had been utterly exhausted by hard labor.

“You’re a lucky chap, Bob Jennings,” said Tom, at length, throwing down his book rather spitefully, and seating himself on the grass opposite the fisher-boy. “A most lucky chap.”

Bob looked down at his clothes, but made no reply.

“You have no arithmetic lesson to learn, as I have,” continued Tom. “All you have to do is to row about in your boat all day, and be your own master. That must be fun!”

For a moment Bob gazed at his companion in utter astonishment. Was it fun that he was compelled to work day after day, through storm and sunshine, and at such small wages that his mother could scarcely lay by half a dollar a week? Was it fun for him to pull five miles down the bay, in a leaky boat, and back, without catching a single fish, as he had done that day? If there was any fun in that, the fisher-boy thought he had never before understood the meaning of the word.

“No, I don’t see much sport in it,” answered Bob. “I call it downright hard work, and so would you if you could trade places with me for a few days. You are the one that sees all the fun. You have no work to do.”

It was now Tom’s turn to be astonished. He started up in perfect amazement, and looked at the fisher-boy for a moment without speaking.

“I see all the fun, do I?” said he, when he had recovered somewhat from his surprise. “Bob Jennings, let me tell you that you don’t know what hard work is. Did your father ever tell you that he’d dust your jacket for you if you didn’t get a difficult arithmetic lesson?”

“No,” answered, Bob, slowly.

“Well, that’s just what my father told me this morning,” continued Tom, “and he also informed me that I can’t go to sea until I can add up a column of figures, and tell him the capitals of all the States. Now, that’s a harder job than you ever had laid out for you.”

The fisher-boy did not act as though he considered that a very difficult task, for he brightened up, and said:

“I wish somebody would give me that job, and agree to support my mother while I was at sea; I’d sign shipping articles in three days. Don’t you want that book?” he added, as Tom picked up his arithmetic and threw it down the bank toward the water, as if he wished it as far as possible out of his sight. “If that book was mine I wouldn’t fling it about that way. I’d study it and try to learn something.”

“Why, I thought you wanted to be a sailor,” said Tom.

“So I do. But I don’t want to be before the mast all my life. I want to be captain; and I will, too, if I live to be a man.”

“So will I. I am going to be master of a full-rigged ship, like the one that left port about two months ago. But what’s the use of studying arithmetic?”

“Why, you can’t be captain until you understand navigation,” said Bob; “and you can’t learn that unless you know something about figures.”

As Tom heard this very disheartening piece of news, he stretched himself at full length on the grass, drew on a long face, and twisted his mouth on one side, as if he had half a mind to cry. He looked at the fisher-boy a moment, then out over the bay, and finally drawled out, “Then I can’t be a sailor! I didn’t know they had to study arithmetic. I can’t learn it, and there’s no use in trying.”

As Tom said this, he happened to glance toward the gate, and saw his father approaching. Remembering the whipping that had been promised if he again failed in his lesson, he hastily sprang to his feet and ran down the bank after his book; while Bob, thinking that the gentleman regarded him rather suspiciously, retreated to his boat and pulled toward home.

Mr. Newcombe always returned from his office at five o’clock; and Tom, knowing that it was time to recite his lesson, applied himself to his task with much more energy than he was accustomed to display. But, as usual, his mind was upon something else; for, as he read over the rule, he was pondering upon what the fisher-boy had told him—that a sailor, in order to win promotion, must know something about arithmetic. Here was another obstacle in his way. All that day Tom had cherished the hope that he might, in some manner, be able to avoid the task his father had imposed upon him, of committing to memory the capitals of the different States, and learning to add without counting his fingers; but here was something that could not be got over. In building his air-castles (for he was continually dreaming about something) he thought only of the happiness he would experience when he should[29] be able to grasp the object of his ambition. He did not believe that whatever is worth having is worth striving for! He never reflected upon the toil and privation to which he must submit before he could work his way up from “boy” to the responsible position of captain! Work! That was something he never intended to do. His idea was, that, when he arrived at the proper age, he would, in some mysterious manner, be placed in the position at which he aimed, without the necessity of labor. He was hopeful if he was unlucky; and, although he had suffered repeated disappointments in the failure of his grand schemes, he clung to the belief that, at some time during his life, something would “turn up” in his favor, and that then he would have plain sailing. There was but one way out of his present difficulty that he could discover, and that was to hope that the fisher-boy was mistaken. What did Bob Jennings—a boy who had never been to school three months in his life—know about such things? He was just as liable to make mistakes as any body; and Tom at first hoped, and ended with finally believing, that Bob knew nothing about the matter.

As these thoughts passed through Tom’s mind, he was industriously studying his lesson, but of course without comprehending one word of it, and presently the ringing of a bell summoned him to the school-room. The sound acted like a charm on Tom, for, as he arose to his feet and walked slowly toward the house, he began to study earnestly, and to such good advantage—for he learned very readily when he set himself resolutely to work—that he began to hope he might pass a creditable recitation. When he entered the[30] school-room, he found his father and the teacher waiting for him. A hasty glance at the former served to convince him that the threatened whipping would certainly be forthcoming if he failed, and just then he looked upon himself as the most abused boy in the world. The recitation commenced, and with considerable assistance from his teacher Tom managed to blunder through his lesson, but it is certain that he knew no more about it when he got through than he did when he began. Although Mr. Newcombe was far from being satisfied, Tom escaped without a whipping, and that was all he cared for.

TOM, having managed to get safely through his arithmetic lesson, put his book away in his desk, and again sauntered out on the lawn, where he threw himself under one of the trees, and thought over his hard lot in life. Study hours being over for the day, he was now at liberty to amuse himself about home in any way he chose; but, as was generally the case with him, he was at a loss to know how to pass the time until dark. He never took a book of any description in his hands if he could avoid it. Reading, he thought, was a very dull, uninteresting way of passing the time. He never looked at a newspaper, and if some one had asked him the name of the President of the United States, it would have been a question that he could not answer. As for play, he never saw any fun in that, but he was as ready to engage in any kind of mischief as any boy in the village.

Newport, like every other place, had its two “sets” of boys, who went by the names of “Spooneys” and “Night-hawks.” The former were, in fact, the good boys of the village. They played foot-ball on the common until dark, and then went home and stayed there.[32] With these Tom rarely had intercourse. On two or three occasions he had mustered up energy enough to engage in a game of ball with them, and each time he came home crying, and complaining that “the boys played too rough,” and that “some fellow had shoved him down in the dirt.” The fact was, Tom did not like these boys, because he could not be their leader. They could all beat him running; the smallest boy on the common could kick a foot-ball further than he could; and, in choosing the sides for the game, Tom was always the last one taken. The reason for this was that Tom, besides being a very poor player, never entered into the sport as though he had any life about him. He was very much afraid of soiling his clothes, or getting dust on his boots; and this was so different from the wild, rollicking ways of his playmates, that they soon learned to despise him; and, if Tom was now and then pushed into the mud during the excitement of the game, no one pitied him or stopped to help him out.

But with the Night-hawks—those that took possession of the common at dark—Tom was a great favorite. They knew how to manage him. He was easily duped, and, if the boys wished to engage in any mischief, Tom was generally the one selected to do the work, for he made an excellent “cat’s-paw.” A few words of flattery would completely blind him, and, not unfrequently, call forth a display of recklessness that made every body wonder. If the Night-hawks wished to remove the doctor’s sign, and place it in front of a millinery store, or if they wished to fasten a string across the sidewalk, to knock off the hats of those that passed[33] by, one of them would say to Tom: “Now, Newcombe, you do it. You are the strongest and bravest fellow in the party. You are not afraid of any thing.” These words never failed to have the desired effect; for Tom would instantly volunteer his services in any scheme the Night-hawks had to propose. Any mischief that was done, anywhere within two miles of the village, was laid to these boys; but had the matter been investigated, it would have been discovered that Tom was the guilty one, for he did all the work, while his companions stood at a safe distance and looked on.

Of course Mr. Newcombe knew nothing of this. His orders to Tom were to remain in the yard after dark; but the latter regarded this as another deliberate abridgment of his privileges. The merchant often said that there was something in the night air particularly injurious to the morals of boys, but Tom did not believe it. He did not like to remain in the house while other boys were out enjoying themselves. However, he always promised obedience to his father’s commands, while, perhaps, at that very moment he was studying up some plan by which he might be able to evade them, and was revolving in his mind some scheme for mischief which he intended to propose to the Night-hawks that evening. Mr. Newcombe was a shrewd business man; he could calculate the rise and fall of the produce market to a nicety, but he was not shrewd enough to discover that Tom, in spite of the readiness with which he promised obedience to all his requirements, was deceiving him every night of his life. Perhaps he thought that Tom would not dare to disobey him; or he may have imagined that he was a boy of[34] too high principle; but, whatever may have been his thoughts, he never troubled himself about his son after giving him orders to remain in the yard, and Tom, having always escaped detection, grew bolder by degrees, until, at last, he became the acknowledged leader of the Night-hawks. He would rack his brain for days and weeks to perfect some plan for mischief, and follow it up with a patience and perseverance which, if exhibited in the line of study, would have placed him at the head of his class in a month. He was willing to work harder to obtain the approbation of a dozen young rogues like the Night-hawks, than to gain that knowledge that would enable him to be of some use in the world.

On the evening in question, Tom was sadly troubled with the “blues.” He was almost discouraged, for several things had “happened to bother him” during the day, and among them was the very disheartening piece of news which the fisher-boy had communicated to him. If it was true—and sometimes Tom almost believed that it was, for that would be “just his luck”—he knew that he must do one of two things—either abandon the idea of becoming a sailor, or pay more attention to his books. If there had been any alternative, Tom would certainly have discovered it, for he was very expert in finding a way out of a difficulty. But now, either his good fortune, in this respect, had deserted him, or else he was in a predicament from which there was no escape, for he lay thinking under the trees for nearly an hour, and finally answered the summons to supper without having been able to discover a way out of his quandary.

Tom ate his supper in silence, and so did Mr. Newcombe,[35] who was pondering upon the same subject that was at that moment occupying his son’s mind.

The result of the recitation that afternoon had convinced the merchant that something ought to be done. Tom was making no progress whatever in his studies. He had been under the charge of his private teacher for nearly six weeks, and he had not yet completed the first rule of his arithmetic. The reason for this was, that Tom had been so long in the habit of dreaming, that any thing like study or work, had become distasteful to him. The question was, how to arouse him—how to convince him that if he ever expected to be any body in the world, he must work for it. This could not be done by keeping him at his books, for that plan had been repeatedly tried, and had as often failed. He did not want to send him to the military school, or allow him to go to sea; for he knew that Tom would not be contented in either place. But something must be done; and, after thinking the matter over calmly, the merchant finally decided upon his course. He said nothing, however, during the meal, to Tom, who, when he had finished his supper, hunted up his cap, went out of the house, and walked down the lawn toward the beach, where his sail-boat, which he called the Mystery, lay at her anchorage. He had started with the intention of taking a sail; but, on second thought, he knew that he could not enjoy it, for his troubles weighed too heavily on his mind. He therefore abandoned the idea, and seating himself on the grass, pondered upon what the fisher-boy had told him, and, for the hundredth time, wondered what he should do next.

It had now begun to grow dark, and the shouts that came from the common bore evidence to the fact that the Night-hawks were ready to begin operations. Occasionally he heard a long, loud whistle, which, under almost any other circumstances, would have been promptly answered by Tom, for it told him, as plainly as words, that he was wanted. But he did not feel at all inclined to engage in any mischief that night, so the boys were obliged to get along the best they could without him. It was fortunate for Tom that he resolved to stay at home, for scarcely had he come to this determination, when he heard his father calling him. Tom obeyed the summons, and when he entered the room where Mr. Newcombe sat, the latter inquired:

“Well, Tom, have you completed your task?”

“O, no, I haven’t,” was the answer. “I can’t learn the capitals of so many States.”

“Have you tried?” asked the father.

“O, now, don’t I know what I can learn without trying?” asked Tom, throwing his cap into one corner of the room, and seating himself near his father. “If a fellow knows he can’t do a thing, what is the use of his trying? It’s only time thrown away.”

Mr. Newcombe, knowing that it would be of no use to argue the point just then, changed the subject by inquiring:

“Have you learned any thing at all during the last month?”

“O, I don’t know,” answered Tom. “I can’t study all alone. There’s no fun in it. Say, father, can’t I go to sea without learning the capitals of all the States?”

“What could you do on board a vessel, Tom? You would be a foremast hand all your life.”

“O, no, I wouldn’t! I would soon be captain. Say, father, may I go? I want to go.”

“You would have to go on a great many voyages before you could be master of a vessel. I went to sea thirteen years before any one called me captain.”

“Well, now, may I go? Say, father, may I go?”

“The discipline is very strict,” continued the merchant. “A sailor is not allowed to stop and grumble at any orders he receives. Besides, you will have to take a very low position; you will be nothing but a boy.”

“I don’t care!” said Tom, impatiently. “May I go? That’s what I want to know!”

“There are other things you must bear in mind also,” said Mr. Newcombe; but Tom, fearing that his father was about to begin a long, uninteresting lecture, interrupted him with:

“Now, why don’t you tell me whether or not I can go? Say, father may I go?”

The merchant, however, did not immediately answer his question; and Tom, giving it up in disgust, threw himself back in his chair with the air of one who expected to listen to something very unpleasant.

“You must remember,” said his father, “that there is nothing romantic about a sailor’s life. It is all drudgery and toil from one year’s end to another; and if a man wins promotion, he does it by his own abilities. How would you like to be in a vessel that was cast away?”

Tom thought of the wreck he had seen towed into the harbor, and, for a moment, he hesitated, but it was only for a moment; for when he remembered how grand that[38] ship looked as she started on her voyage, and thought how proud he would feel if he could only be the captain of a vessel like that, he decided that he would willingly risk the shipwreck, if that would enable him to gain the object of his ambition.

“And how would you like to go aloft and take in sail during a storm?” asked Mr. Newcombe.

“I wouldn’t care!” was the answer. “I wouldn’t do it long. I’d soon be captain.”

If Tom once got an idea into his head, no matter how ridiculous it was, he clung to it, and stubbornly refused to be convinced that it was impracticable. This notion of his, that he could soon learn enough about seamanship and navigation to be intrusted with the management of a vessel, was one of his pet ideas; and if all the sailors in the world had endeavored to show him that the thing was impossible, he would still have held firmly to his opinion. Mr. Newcombe had often tried to convince his son of his error, and he had discovered that there was but one way to do it, and that was to let Tom learn in the hard school of experience. A few months at sea would drive all such improbable ideas out of his head.

“Very well,” said the merchant, picking up his paper. “That’s all, Tom!”

“O, no, it isn’t, father! Why don’t you tell me whether or not I may go. Say! Say!”

But Mr. Newcombe, who appeared to be deeply interested in his paper, took no further notice of him; and Tom, vexed and disappointed, picked up his cap, went out of the house, and walked up and down the lawn. The shouts that now and then came to his ears, told[39] him that the Night-hawks still held possession of the common, and Tom had half a mind to go down and join them. But he knew, by the way his father spoke, that he had some idea of allowing him to go to sea, and he did not wish to destroy, by an act of disobedience, all the bright hopes he had so long cherished, and which he imagined could be realized if he was permitted to ship as cabin-boy on some vessel.

“I always wanted to go to sea,” said Tom to himself, as he walked impatiently up and down the lawn; “and I’d like to know why I can’t go as well as any body? I wonder why father didn’t tell me what he is going to do about it? What good does it do to plague a fellow this way? Now, if I can go out in the Savannah, I’ll certainly learn enough to be second mate by the time we get home; then, after that, I’ll be first mate, and then captain. Then, if a war should break out, I would go into the navy, and I might be promoted to captain of a man-o’-war. Wouldn’t that be glorious!”

Tom became amazed when he saw what a bright prospect was suddenly opened up before him, and he resolved that he would not allow his father a moment’s rest until he had obtained his permission to go to sea on the Savannah.

Before he went to sleep that night, Tom had made up what he regarded as an unanswerable argument, which he intended to present for his father’s consideration in the morning. But he was saved that trouble; for, at the breakfast table, Mr. Newcombe informed him that he had decided to allow him to go to sea on the Savannah; at the same time giving him advice which, had he seen fit to follow it, would have made him a better[40] and wiser boy, and would have saved him a great deal of trouble. Tom was in ecstasies. He made the most extravagant promises in regard to good behavior and prompt obedience of orders, and repeatedly assured his father that he was “cut out” for a sailor, and that it would not be long before he would be the master of a fine vessel.

“Don’t build your hopes too high on that, Tom,” said Mr. Newcombe. “Do your duty faithfully as boy, and don’t waste your time in dreaming about being a captain; for that can only come after years of hard work.”

But Tom did not believe that. He had read about boys but little older than himself being masters of vessels, and if he wasn’t as smart as they were, he would like to know the reason why.

Tom ate but very little breakfast that morning, for the joy he experienced in receiving his father’s permission to go to sea had taken away all his appetite. He hastily swallowed a few mouthfuls, and then, catching up his cap, started toward the wharf to communicate the good news to the captain of the Savannah. Tom was well acquainted with all the officers and some of the crew of the schooner, and he looked upon them as the finest men in the world. The captain, especially, was his beau ideal of a sailor. He always wore wide pants, a tremendous neck-tie, and, when he walked, he rolled from side to side, like a vessel in a gale of wind—a style of locomotion that Tom had more than once vainly endeavored to imitate. With the older members of the crew he had always been a great favorite. Whenever they returned from a voyage, they always[41] brought something for Tom; and, besides, they invariably spoke of him as “Our young skipper,” a title which pleased the boy exceedingly.

Tom had long ago decided that his first voyage to sea should be made in the Savannah, and, for a time, it had been the height of his ambition to obtain the command of a vessel exactly like her. But now he had set his mark higher; a topsail schooner was not good enough for him—he wanted a full-rigged ship. However, the Savannah would answer his purpose just then, for he considered that it would be much pleasanter to go to sea with friends who would always treat him with the respect due the son of the owner of the vessel, than to make his first voyage in company with total strangers. He had often talked to the captain about going out with him, and that gentleman, with all a sailor’s fondness for his chosen calling, had spoken so encouragingly to him, and had appeared to take so much interest in his affairs, that Tom concluded he would be happy to know that he was to have a new cabin-boy. Toward the wharf, then, he went at the top of his speed, and reaching the Savannah, he clambered over the rail, and ran down into the cabin, where the captain was eating his breakfast.

“It’s all right, now!” shouted Tom, as the skipper shook hands with him. “It’s all right! I am going out with you!”

“I am glad to hear that,” said the captain, “for I am always happy to have good company. You are going out just for the fun of the thing, I suppose?”

“Yes, I expect to see plenty of fun, but I’m going to ship as boy. I want you to teach me all you can, for I[42] intend to be master of a ship one of these days. Now, captain,” he added, glancing at the doors of the different state-rooms in the cabin, “which is my room?”

“Why, if you ship as boy,” said the captain, “you’ll have to sleep with the sailors in the forecastle.”

“Will I?” exclaimed Tom in astonishment. “Not if I know it. Do you suppose that I am going to bunk with the hands? No, sir! I’m going to have one of these rooms, and mess with you.”

“I understood you to say that you wanted to learn all about the vessel!” said the captain.

“So I do!” replied Tom. “I want to be the best navigator and seaman that ever sailed salt water!”

“That’s an object well worth working for,” said the skipper. “But our best sailors never obtained their responsible positions by creeping in at the cabin windows. They came in at the hawse-hole for’ard, and worked their way aft.”

“That’s all well enough for those who are obliged to do it,” replied Tom. “I know I can learn just as much about a vessel by living in the cabin as I can by staying in the forecastle.”

As Tom said this he made a hurried examination of the two unoccupied rooms in the cabin, and, selecting the one he thought would suit him best, he continued:

“Now, captain, this is my room. Lock it up, and keep every body out of it! As soon as I can get my bedding ready, I will have it brought down here.”

The captain, no doubt, thought that Tom was assuming considerable authority for one who was to rate as “boy” on the shipping articles, but he made no remark, knowing that in due time he would hear the full particulars[43] of the matter from Mr. Newcombe. Tom spent some time in looking about his room, and deciding what articles of furniture he ought to bring down in order to set it off to the best advantage, and finally he left the vessel and walked toward his father’s office. A few moments later Mr. Newcombe went on board the schooner, and, after a long conversation with the captain, he returned to his office, where he found his son waiting for him.

“Now, Tom,” said the merchant, as he seated himself in a chair beside the boy, “I suppose you want to know something of the life you will lead for the next six months!”

“O, I know all about it now,” said Tom. “I’ll have a jolly time.”

Mr. Newcombe, however, thought differently, and he began to tell his son exactly what he might expect if he shipped on board the schooner. In the first place, he would be treated, in all respects as one of the crew. He would be allowed no liberties that were not granted to others; and he would begin his career as a sailor, as his father had done before him—at the “lowest round of the ladder.” All the duties expected of a boy on board ship would be required of him, and, if he disobeyed orders, he would be liable to punishment. He would receive boy’s pay—forty-eight dollars for the voyage—and when he returned home, his father would give him the money due him, and he might use it as he thought proper. If he wanted to be a speculator on a small scale, (as Tom had often thought he would be if he only had some money,) that would be capital enough for him to commence with.

“O, no, father,” said Tom, confidently, “I have given up all idea of being a trader. I’ll go to sea again at once. You seem to think that I will soon grow tired of a sailor’s life.”

Those were exactly the thoughts that were at that moment passing through the merchant’s mind; but, seeing that his son still stubbornly held to his own opinions, and knowing that he could not be talked out of them, he brought the interview to a close by turning to his desk and picking up some letters that had just been brought in. Tom was left to himself, and being too uneasy to sit still, even for a moment, he loitered about the office for a short time, and then started for home.

“Father doesn’t know what he is talking about,” he soliloquized. “I never saw a man with such funny ideas. Does he suppose that the captain of the Savannah is going to make me work? No, sir; he won’t do it. He won’t dare do it; for my father owns that schooner, and I guess I shall have a right to do as I please. I expect to go aloft and take in sail, but I don’t call that work. The captain and I understand each other, and I know that I shall get along finely.”

Tom thought the day on which the schooner was to sail never would arrive, for never before had the time hung so heavily on his hands. He was very cross and fretful, and spent the entire week in walking about the wharf, with his hands in his pockets. His private teacher had left the mansion as soon as it was decided that his pupil was to go to sea; and when Tom saw him go out of the yard, he drew a long breath of relief, as if a heavy load had been removed from his shoulders. Had he dared to do so, he would have thrown his desk[45] and all his books out after him; but as it was, he contented himself with believing that he would never again be required to open an arithmetic or geography.

How he pitied his unfortunate acquaintances who were obliged to attend school, and how they all envied Tom, when they learned that he was about to go on a voyage to Callao. Every one of them said that Callao was in Peru; but Tom stoutly maintained that it was in England, and that when he arrived there, he would persuade the skipper to take him to see the Queen.

“Look at your geography,” said one of the boys, “and you will see that you are mistaken.”

“O, no, I won’t do it,” drawled Tom. “I said I never would open that book again if I could help it, and I’m going to stick to it.”

At last, to Tom’s immense relief, the long-expected day arrived. From daylight until dark he sat on the wharf, watching the workmen who were engaged in loading the vessel, and when he went home to supper with his father, the latter informed him that the schooner would be ready to sail by ten o’clock that evening. At nine o’clock, Tom bade his mother good-by, and returned to the wharf, accompanied by his father. He was dressed in a full sailor’s “rig,” with wide pants, a blue flannel shirt, a tarpaulin, which he wore as far back on his head as he could get it; a neck-tie, that looked altogether too large for him, and, when his father was not looking at him, he tried to imitate the captain’s walk. If clothes made the sailor, Tom could certainly lay claim to that honor. Shortly after he reached the vessel, his bedding and extra clothing arrived, and Tom gave orders to have them carried[46] into the cabin. Had he taken the trouble to see how the command was obeyed, he would have found that his bundle was unceremoniously thrown down into the forecastle. At last, when every thing was ready for the start, a steamer came along-side to tow the schooner out of the harbor. Mr. Newcombe took leave of the young sailor, and sprang upon the wharf, after which, the lines were cast off, and the Savannah began her voyage.

TOM, delighted to find himself at last on board an outward-bound vessel, remained on deck until the schooner was fairly out of the harbor. He took his stand beside the captain, thrust his hands deep into his pockets, pushed his hat on one side, and watched the movements of the sailors, who ran about the deck executing the different orders, as if he perfectly understood the meaning of every command, and had long been accustomed to every thing he saw. Occasionally he turned his eyes toward the rapidly receding lights on the wharf, but, far from experiencing a single feeling of regret at leaving home, he felt like shouting for joy. In fact, according to Tom’s way of thinking, he had nothing to be sorry for. At home he was always unhappy, something was forever happening to trouble him; but in the life before him he saw nothing but sunshine. He was entering upon the easy and romantic life of a sailor. He would soon learn enough about seamanship and navigation to be intrusted with the command of a vessel; and, when he arose in the morning, instead of looking forward to six hours’ work at his arithmetic and geography lessons, he would find before him a day of uninterrupted enjoyment.

“Ah, this is glorious!” said Tom to himself, as the schooner, having cleared the harbor, began to move more rapidly over the waves. “This is fine! This is just the life for me! I’m a land-lubber no longer! I’m a sailor; and I wouldn’t be the least bit sorry if I should never see Newport.”

Tom’s soliloquy was interrupted by an event that was as sudden as it was unexpected. He had taken no pains to keep out of the way of the sailors; and, when the crew came aft to hoist the mainsail, he was so absorbed in his reverie that he took no notice of them until he was aroused by the exclamation: “Here you are! Always in the way! Get out o’ this!” accompanied by a violent push, which sent him at full length on the deck.

“Now, look here!” drawled Tom, as he hastily arose to his feet. “I’d like to know what you are about! I’ll tell the captain.”

Surprised and indignant at such treatment, he at once started off to find the skipper, whom he at length discovered standing in the waist.

“Captain!” he exclaimed. “Did you see that fellow push me down?”

“No!” replied the captain, in a tone which implied that he was not at all interested in the matter, “I didn’t see him.”

“Well, somebody did push me down, flat on the deck,” said Tom, angrily. “I want you to haul that man up for it, for I won’t stand it.”

“Well, then,” said the captain, coolly, as he turned on his heel and walked aft, “you must keep your eyes open, and not get in any body’s way.”

Tom was astonished to find that the skipper did not sympathize[49] with him; but, believing that he did not fully understand his complaint, he started to follow him, intending to state his case more clearly, when he was roughly jostled by the second mate, who was hurrying forward to execute some order.

“Look here!” shouted Tom. “Don’t you know that this is my father’s vessel? I want you to be a little more careful about pushing me around this way. You are nothing but a mate.”

“Ay ay, my hearty!” interrupted the sailor. “I know all about that. But now, just take my advice and keep out of the way, or you’ll go overboard.”

“I will, will I?” exclaimed Tom. “I’ll tell the captain! Look here!” he continued, as he approached the skipper, who was standing beside the man at the wheel. “What do your men mean by pushing me about? I want you to remember that my father owns this vessel. I won’t stand such treatment; and I want you to put a stop to it; that’s all about it.”

Tom certainly stated his case plain enough this time, and he fully expected that the captain would at once punish the men who had treated him so disrespectfully; but what was his surprise and disappointment when that gentleman turned on his heel and walked off whistling. Tom was more than surprised at this; as the sailors would have expressed it, “he was taken all aback,” and, for a moment, he stood looking after the retreating form of the captain, as if he was utterly unable to understand what had caused this sudden change in him. Undoubtedly he had been sadly mistaken in the man. While on shore, he was good natured, and had always appeared to take great interest in every thing Tom had to say; but[50] now, he was exactly the reverse. He not only did not offer to protect him from the men, but he seemed anxious to keep as much as possible out of his way. Tom, who was not dull of comprehension, began to realize the fact that he had got himself into a most unpleasant situation. He had built his hopes high upon the captain only to be disappointed; and, with his mouth twisted on one side, as if he were on the point of crying, he went down into the cabin to arrange his bed. He went to the room he had picked out for his own use, and was astonished to discover that it had already been taken. A bed was made up in the bunk, and in one corner stood a large sea-chest, with the name J. H. Robson painted on it, showing that the room was in the possession of the second mate. His own bed-clothes where nowhere to be seen. Almost too angry to breathe, Tom was about to start in search of the captain, when he met that gentleman coming down the companion-way.

“Look here, captain!” exclaimed Tom, pointing to the bed, “your second-mate has taken possession of my room.”

“Your room!” repeated the captain. “That room doesn’t belong to you.”

“Why, captain!” said Tom, in surprise, “I picked it out for my own use, and told you to lock it up, and to allow no one in it. Don’t you remember?”

“Yes, I recollect. But I told you, at the same time, that sailors sleep in the forecastle.”

“And I also told you that I was going to sleep in the cabin, and mess with you,” said Tom, decidedly. “Tell somebody to take that bed out of there.”

“Where will Mr. Robson sleep, then?” asked the captain. “The second mate always occupies that room.”

“Well, you can put him somewhere else. I’m bound to have that room.”

“I think, Tom,” said the skipper, quietly, “that you will have to go into the forecastle. There’s where you belong. You rate as ‘boy’ on the shipping articles.”

“But I didn’t agree to go among the men,” said Tom, “and I won’t do it. What do you suppose my father would say if he knew that you wanted me to bunk in the forecastle?”

“I say, captain,” shouted the second mate down the companion-way at this moment, “is that young sea-monkey down there? Ah, here you are!” he continued, discovering Tom. “Lay for’ard into the forecastle, and take care of your donnage. Up you come with a jump.”

“Now what’s my baggage doing in the forecastle?” asked Tom, growing more and more astonished at each new turn of events. “Who put it in there? Tell one of your men to bring it into the cabin at once.”

“Sonny,” replied the mate, shaking his finger at Tom, “come up here!”

There was something in the sailor’s tone and manner that a little alarmed Tom, and led him to draw closer to the captain, as if seeking his protection. But the latter, after pulling off his coat and hanging it up in his state-room, seated himself at the table, and began to examine his chart; and Tom, finding that he was left to fight his battles alone, resolved to do so to the best of his ability. Turning to the mate he replied, angrily:

“I’ve got no business on deck. I can’t be of any use up there; besides, I am sleepy, and I want to go to bed.”

“Well, then, lay for’ard into the forecastle, where you belong,” said the mate.

“I tell you I don’t belong there!” exclaimed Tom, almost ready to cry with vexation; “and, what’s more, I am not going there. I want you to remember that this is my father’s vessel, and you had better mind what you are about. And, see here, Mr. Robson! you have put your baggage in my room, and I want you to take it out of there at once. That’s my room.”

The mate, instead of replying, came down the stairs, and, seizing Tom’s arm with a grip that brought tears to his eyes, exclaimed:

“I want no nonsense, now! If you don’t obey orders, I’ll take a bit of a rope’s-end to you. Now go for’ard on the run.”

Tom struggled desperately to free himself from the mate’s grasp, but, finding that his efforts were unavailing, he appealed to the captain for protection.

“See here, captain!” he shouted, “are you going to sit there and see me abused in this manner, when my father owns this vessel?”

“I can’t help you, Tom!” replied the captain. “That gentleman is one of the officers of this schooner, and must be obeyed. If you will take my advice, you will do just what he orders you to do.”

Tom, however, did not see fit to follow this advice, but still continued to struggle with the mate, when the latter tightened his grasp on his arm, and, pulling him up the stairs in spite of his resistance, he hurried him[53] across the deck, and pushed him down into the forecastle, exclaiming:

“Now, then, stay there! If I catch a glimpse of your ugly figure-head on deck again to-night, I’ll use a rope’s-end on you. Now, that’s gospel!”

There were several sailors in the forecastle arranging their beds, and nothing but pride restrained Tom from giving full vent to his troubled feelings in a flood of tears. But even here he was not safe; he had escaped from one source of annoyance only to be immediately assailed by another; for, as he came rapidly down the stairs, assisted by a violent push from the mate, one of the sailors exclaimed:

“Here he comes! Just look at him! Mates, that’s the chap as wants to learn to be a cap’in.”

“You don’t tell me so!” chimed in another. “Sonny does your mother know you’re here?”

“Just look at his riggin’!” said another, having reference to Tom’s suit of new clothes. “He looks like a Dutch galliot scudding under bare poles!”

“An’ them white hands,” said the one who had first spoken, “they’re just the thing for a tar-bucket.”

These were but few of the greetings Tom received upon his advent into the forecastle. Had he been wise, he would have listened to them as good-naturedly as possible; but the tone in which they were spoken irritated him, and he took no pains to conceal the fact.

“Now, you hush up,” he shouted. “This is my father’s vessel. I’ll have you taught better manners the minute we get ashore again.”

This only made matters worse. The sailors gathered about him, pulling him first one way and then another,[54] all the while ridiculing his dress or his appearance, until Tom, unable to escape from their clutches, or to endure their taunts, began to cry.

“Look at that! He’s pumping for salt water!” said one.

“Now, see here, shipmates!” exclaimed another, an old sailor with whom Tom had always been a great favorite, “it has gone far enough, now. Don’t bother the life out of the lad. Never mind ’em, sonny,” he added, patting Tom on the head, “you’ve got the right stuff in you, and you’ll make a sailor-man yet. Jack, just throw his donnage over this way. Now, Tommy, here’s a bunk that don’t seem to be in use; let me tumble up your bed for you.”